DNA Methylation in Tissue Regeneration: Epigenetic Mechanisms and Therapeutic Applications

This article explores the pivotal role of DNA methylation, a key epigenetic mechanism, in governing tissue regeneration.

DNA Methylation in Tissue Regeneration: Epigenetic Mechanisms and Therapeutic Applications

Abstract

This article explores the pivotal role of DNA methylation, a key epigenetic mechanism, in governing tissue regeneration. It details how dynamic methylation and demethylation processes, mediated by DNMT and TET enzymes, precisely control the gene expression networks essential for stem cell differentiation and regenerative responses. The content covers foundational principles, comparative analyses of regenerative models, the consequences of dysregulation in fibrotic disease, and the translation of this knowledge into emerging diagnostic and therapeutic strategies. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, this review synthesizes current evidence to highlight DNA methylation as a central regulator and promising target for advancing regenerative medicine.

The Epigenetic Blueprint: How DNA Methylation Governs Regenerative Pathways

DNA methylation, the process of adding a methyl group to the cytosine base in DNA, represents a fundamental layer of epigenetic regulation crucial for guiding cellular identity and function during tissue regeneration [1]. In mammalian cells, this modification primarily occurs at cytosine-guanine dinucleotides (CpG sites) and is dynamically regulated by two antagonistic enzyme families: DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs) and Ten-eleven translocation (TET) dioxygenases [2] [3]. The balance between these enzymes establishes DNA methylation patterns that control gene expression without altering the underlying DNA sequence, serving as a critical mechanism for directing cellular differentiation, reprogramming, and regenerative responses [4]. Understanding the core principles of these enzymatic systems provides the foundation for developing innovative epigenetic engineering strategies aimed at promoting tissue repair and reversing aging-associated epigenetic alterations [5] [6].

Enzymatic Machinery of DNA Methylation and Demethylation

DNA Methyltransferases (DNMTs): Establishing and Maintaining Methylation Patterns

The DNMT family in mammals includes multiple enzymes with specialized functions in establishing and maintaining DNA methylation patterns. DNMT1 is predominantly responsible for maintenance methylation, demonstrating a strong preference for hemimethylated DNA substrates that occur following DNA replication [2] [1]. This enzyme ensures the faithful propagation of methylation patterns to daughter cells during cell division, a critical function for maintaining cellular identity in regenerating tissues. In contrast, DNMT3A and DNMT3B function primarily as de novo methyltransferases, establishing new methylation patterns during embryonic development and cellular differentiation [2] [3]. These enzymes are essential for the epigenetic reprogramming that occurs during tissue regeneration, where they help define new cellular identities. A regulatory cofactor, DNMT3L, although catalytically inactive, enhances the methylation activity of DNMT3A and DNMT3B [3]. Notably, DNMT2 represents an evolutionary outlier that primarily methylates transfer RNA rather than DNA, highlighting functional diversification within this enzyme family [3].

All catalytically active DNMT enzymes utilize S-adenosyl methionine (SAM) as the methyl group donor [2]. The one-carbon metabolism that produces SAM therefore significantly influences DNA methylation homeostasis, with implications for regenerative processes as SAM availability affects the global methylation capacity of cells [2].

Table 1: DNA Methyltransferases (DNMTs) and Their Functions

| Enzyme | Primary Function | Key Domains | Biological Role in Regeneration |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNMT1 | Maintenance methylation | RFTS, CXXC, BAH, MTase | Preserves cellular identity during cell division in regenerating tissues |

| DNMT3A | De novo methylation | PWWP, ADD, MTase | Establishes new methylation patterns during cellular differentiation |

| DNMT3B | De novo methylation | PWWP, ADD, MTase | Works with DNMT3A to set new methylation landscapes |

| DNMT3L | Regulatory cofactor | ADD | Enhances activity of DNMT3A/3B; important for imprinting |

| DNMT2 | RNA methylation | MTase | Methylates transfer RNA; limited DNA methylation activity |

TET Dioxygenases: Catalyzing Active DNA Demethylation

The TET enzyme family—comprising TET1, TET2, and TET3—functions as the primary catalytic machinery for active DNA demethylation through an iterative oxidation process [7] [3]. These Fe(II)/α-ketoglutarate (αKG)-dependent dioxygenases catalyze the stepwise oxidation of 5-methylcytosine (5mC) to 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5hmC), then to 5-formylcytosine (5fC), and finally to 5-carboxylcytosine (5caC) [2] [8]. This oxidation cascade initiates DNA demethylation through two primary mechanisms: (1) passive dilution during DNA replication, where 5hmC is not recognized by maintenance DNMTs and thus becomes progressively lost through cell divisions; and (2) active excision via thymine DNA glycosylase (TDG)-mediated base excision repair (BER), which specifically recognizes 5fC and 5caC intermediates and replaces them with unmodified cytosine [7] [8].

The TET-mediated demethylation pathway provides a mechanism for rapid epigenetic reprogramming in response to regenerative signals, allowing for dynamic changes in gene expression patterns necessary for tissue repair [7]. Each TET family member exhibits distinct expression patterns and functional specializations: TET1 and TET3 are critical for embryonic development and stem cell differentiation, while TET2 dysfunction is particularly linked to hematopoietic malignancies [3].

Table 2: TET Dioxygenases and the Active Demethylation Pathway

| Enzyme | Function | Catalytic Cofactors | Oxidation Products | Role in Regeneration |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TET1 | 5mC oxidation | Fe(II), α-ketoglutarate | 5hmC, 5fC, 5caC | Embryonic development, stem cell differentiation |

| TET2 | 5mC oxidation | Fe(II), α-ketoglutarate | 5hmC, 5fC, 5caC | Hematopoietic differentiation; commonly mutated in cancers |

| TET3 | 5mC oxidation | Fe(II), α-ketoglutarate | 5hmC, 5fC, 5caC | Early embryonic development, neuronal differentiation |

| TDG | Base excision | N/A (DNA glycosylase) | Excises 5fC/5caC | Completes demethylation via BER pathway |

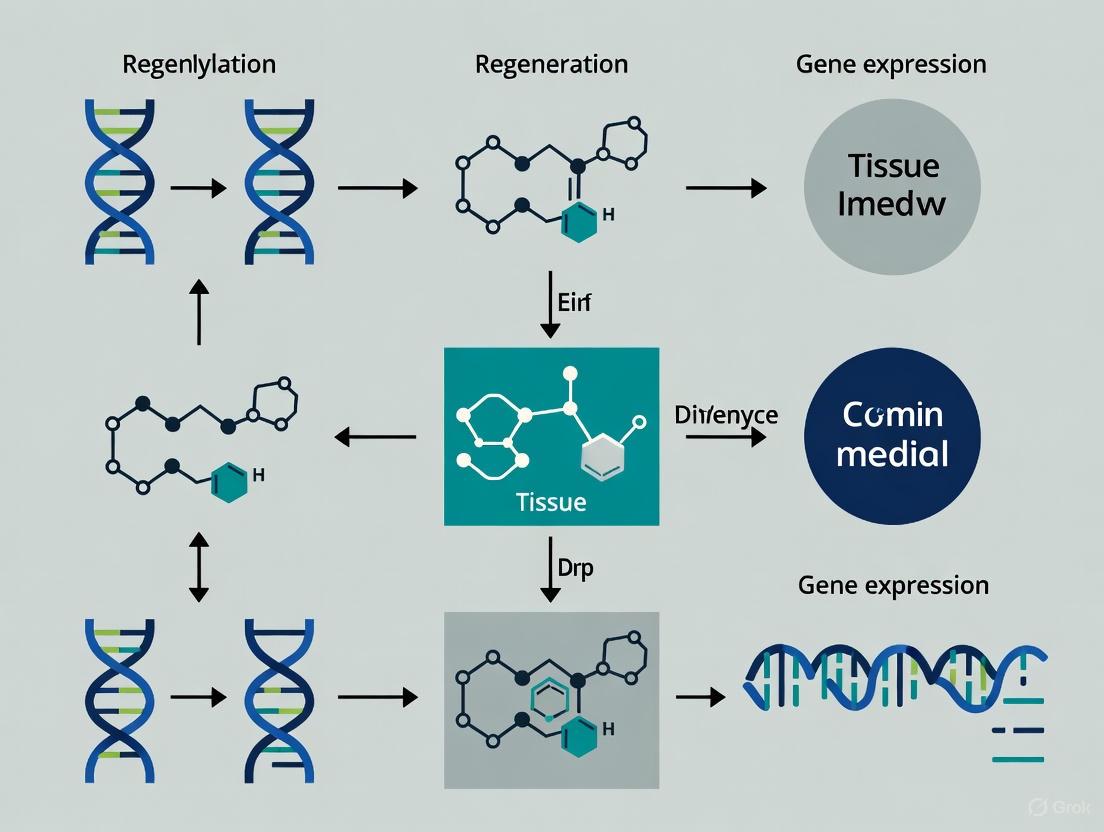

Integrated Methylation-Demethylation Cycle

The coordinated actions of DNMT and TET enzymes establish a dynamic cycle of cytosine modification that enables precise epigenetic regulation [7]. This cycle begins with unmodified cytosine being converted to 5mC by DNMT enzymes, followed by stepwise oxidation to 5hmC, 5fC, and 5caC by TET enzymes. The process culminates with TDG-mediated base excision repair that restores unmodified cytosine, completing the demethylation cycle [8]. The balance between these opposing enzymatic activities creates an epigenetic landscape that can respond to developmental cues, environmental signals, and regenerative requirements, allowing cells to maintain stability while retaining plasticity for fate transitions during tissue repair [3].

Diagram 1: DNA methylation-demethylation cycle. DNMTs add methyl groups using SAM, while TET enzymes oxidize 5mC in stepwise reactions. TDG with BER completes active demethylation.

Experimental Methodologies for Analyzing DNA Methylation Dynamics

Bisulfite Sequencing and Its Variations

Bisulfite conversion represents the gold standard technique for detecting DNA methylation at single-base resolution [8]. This method relies on the differential sensitivity of cytosine and 5-methylcytosine to bisulfite treatment: unconverted cytosines are read as thymine in subsequent sequencing, while methylated cytosines remain protected and are still detected as cytosines [8]. Several bisulfite-based approaches have been developed for different research applications:

- Whole-Genome Bisulfite Sequencing (WGBS) provides comprehensive methylation maps across the entire genome, offering single-base resolution but requiring substantial sequencing depth [8].

- Reduced Representation Bisulfite Sequencing (RRBS) uses methylation-sensitive restriction enzymes to enrich for CpG-dense regions, providing a cost-effective alternative for analyzing methylation patterns in genomic regions of high interest [8].

- Targeted Bisulfite Sequencing approaches focus on specific genomic regions of interest, allowing for higher throughput analysis of predetermined loci [8].

A significant limitation of conventional bisulfite sequencing is its inability to distinguish between 5mC and 5hmC, as both modifications protect cytosines from conversion [8]. This challenge has led to the development of additional techniques specifically designed to resolve oxidized methylation intermediates.

Immunoprecipitation-Based Methods

DNA immunoprecipitation (DIP) offers an alternative approach for mapping DNA modifications using antibodies specific to modified cytosine variants [8]. This methodology involves shearing genomic DNA, immunoprecipitating fragments containing the modification of interest, and then analyzing the pulled-down DNA by quantitative PCR (DIP-qPCR), microarray (DIP-chip), or sequencing (DIP-seq) [8]. The key advantages of DIP include its relatively low cost compared to WGBS and the ability to specifically interrogate 5mC, 5hmC, 5fC, and 5caC when appropriate antibodies are available [8]. However, this technique provides lower resolution than bisulfite-based methods and is dependent on antibody specificity.

Diagram 2: Experimental workflows for DNA methylation analysis. Two main approaches are bisulfite conversion and immunoprecipitation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for DNA Methylation Studies

| Reagent/Technique | Function | Application in Regeneration Research |

|---|---|---|

| Bisulfite Conversion Reagents | Chemical deamination of unmethylated cytosine | Distinguishes methylated vs. unmethylated cytosines in tissue samples |

| 5mC/5hmC/5fC/5caC Specific Antibodies | Immunoprecipitation of modified DNA | Enrichment of specific methylation states for genomic mapping |

| DNMT Inhibitors (e.g., Zebularine, RG108) | Chemical inhibition of DNMT activity | Probing the functional role of methylation in regenerative processes |

| TET Activity Assays | Measurement of oxidation activity | Determining TET enzyme function in stem cell differentiation |

| SAM/SAH Analysis Kits | Quantification of methyl donor availability | Assessing metabolic regulation of methylation in regenerating tissues |

| CRISPR/dCas9 Epigenetic Editors | Targeted methylation or demethylation | Precise epigenetic manipulation of regenerative gene pathways |

| Nanoelectroporation Systems | Efficient delivery of epigenetic editors | In vivo reprogramming for tissue regeneration [4] |

| Acetylene--thiirane (1/1) | Acetylene--thiirane (1/1)|High-Purity Research Chemical | Acetylene--thiirane (1/1) is a high-purity chemical complex for research applications. This product is For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

| Cobalt--ruthenium (2/3) | Cobalt--ruthenium (2/3), CAS:823185-74-6, MF:Co2Ru3, MW:421.1 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

DNMT and TET Dynamics in Tissue Regeneration and Cellular Reprogramming

Epigenetic Reprogramming in Regenerative Processes

The dynamic interplay between DNMT and TET enzymes facilitates the epigenetic reprogramming necessary for successful tissue regeneration [4]. During cellular reprogramming for regenerative applications, somatic cells can be converted to alternative fates through several approaches: induced pluripotency (iPSCs), direct lineage conversion (transdifferentiation), or partial cellular rejuvenation [4]. Each of these strategies involves significant reconfiguration of DNA methylation patterns orchestrated by coordinated DNMT and TET activity. Direct reprogramming approaches are particularly promising for regenerative medicine as they enable in vivo cell fate conversion without traversing a pluripotent state, thereby reducing tumorigenesis risks [4].

Emerging technologies such as tissue nanotransfection (TNT) leverage nanoelectroporation to deliver epigenetic effectors directly into tissues, enabling in vivo reprogramming for regenerative applications [4]. This approach demonstrates the translational potential of targeting DNA methylation dynamics for therapeutic tissue repair, including applications in wound healing, ischemia repair, and age-related tissue dysfunction [4].

Aging and DNA Methylation Dynamics

Aging is associated with progressive changes in DNA methylation patterns, including both generalized hypomethylation and locus-specific hypermethylation, which contribute to reduced tissue function and regenerative capacity [5]. Recent comprehensive mapping of DNA methylation changes across human organs has revealed that the precision of DNA methylation maintenance declines with age, leading to alterations in gene expression that are linked to age-related tissue dysfunction [5]. These age-associated epigenetic changes represent potential therapeutic targets for regenerative interventions aimed at restoring youthful epigenetic patterns and improving tissue repair capacity in aging individuals.

Partial reprogramming approaches using transient expression of reprogramming factors (Oct4, Sox2, Klf-4, c-Myc) have demonstrated the ability to reverse aging-associated epigenetic alterations, including resetting DNA methylation clocks, without fully altering cellular identity [4]. This strategy represents a promising avenue for combating age-related decline in regenerative capacity through epigenetic rejuvenation.

Emerging Technologies and Future Directions

Epigenetic Engineering for Regenerative Medicine

Recent discoveries revealing that specific DNA sequences can instruct de novo DNA methylation patterns represent a paradigm shift in epigenetic engineering [6]. This finding enables the development of precision epigenetic editing approaches where engineered transcription factors can be designed to target DNA methylation machinery to specific genomic loci, creating predetermined methylation patterns that could enhance cellular function [6]. The ability to use DNA sequences to target methylation has broad implications for regenerative medicine, as it would allow epigenetic defects to be corrected with high specificity, potentially restoring proper gene expression patterns in diseased or damaged tissues [6].

CRISPR/dCas9-based epigenetic editing systems provide a versatile platform for implementing targeted methylation changes [4]. When coupled with advanced delivery systems such as tissue nanotransfection, these technologies enable precise in vivo epigenetic manipulation for regenerative applications [4]. The ongoing optimization of these systems focuses on improving specificity, efficiency, and persistence of the desired epigenetic changes while minimizing off-target effects.

Clinical Implications and Therapeutic Applications

The dynamic regulation of DNA methylation by DNMT and TET enzymes offers promising therapeutic targets for enhancing tissue regeneration. Dysregulation of these enzymes is implicated in various disease states, including cancers, neurodegenerative diseases, and developmental disorders [2]. In cancer development, for instance, global hypomethylation accompanied by localized hypermethylation of tumor suppressor genes is a common feature, with demethylation affecting approximately 5-20% of methylated CpG sites [9]. Understanding these disease-associated epigenetic alterations provides insights for developing targeted epigenetic therapies that could potentially reverse pathological methylation patterns and restore normal cellular function.

In regenerative contexts, modulating DNMT and TET activity represents a strategy for promoting cellular plasticity, enhancing stem cell function, and reversing age-related epigenetic changes that impair tissue repair [5] [4]. As our understanding of the intricate balance between DNA methylation and demethylation continues to evolve, so too will opportunities for developing innovative epigenetic interventions for tissue regeneration and repair.

The journey from a pluripotent stem cell to a fully differentiated somatic cell is governed by a complex interplay of genetic and epigenetic factors. Among these, DNA methylation—the addition of a methyl group to a cytosine base—serves as a critical mechanism for regulating gene expression without altering the underlying DNA sequence. Within the context of tissue regeneration research, understanding and potentially directing these methylation dynamics offers promising therapeutic avenues. DNA methylation works in concert with other epigenetic marks, including histone modifications, to establish and maintain cellular identity by precisely controlling which genes are accessible for transcription [10]. This in-depth technical guide explores the mechanisms by which DNA methylation directs stem cell differentiation and proliferation, providing researchers and drug development professionals with current experimental insights and methodologies.

The dynamic nature of the epigenome is particularly evident in stem cells, which utilize precise methylation patterns to maintain pluripotency while retaining the capacity to differentiate into all three germ layers. As stated in one review, "The molecular mechanisms that regulate stem cell pluripotency and differentiation has shown the crucial role that methylation plays in this process" [10]. This methylation machinery involves "writer" enzymes (DNA methyltransferases, or DNMTs) that establish methylation patterns, "eraser" enzymes (Ten-Eleven Translocation, or TET, proteins) that remove these marks, and "reader" proteins that interpret them, creating a dynamic, responsive system for gene regulation [10]. In regenerative medicine, the ability to reset or redirect these epigenetic patterns through technologies like tissue nanotransfection (TNT) or cellular reprogramming represents a frontier for developing novel therapies aimed at repairing damaged tissues and reversing age-related degeneration.

Methylation Dynamics in Development and Aging

Prenatal Programming and Postnatal Decline

Methylation dynamics exhibit distinct patterns across the human lifespan, with particularly pronounced activity during prenatal development. A comprehensive study profiling genome-wide DNA methylation across the human cortex from 6 post-conception weeks to 108 years of age identified widespread, developmentally regulated changes, with pronounced shifts occurring during early- and mid-gestation [11]. These prenatal methylation changes were notably distinct from age-associated modifications occurring in the postnatal cortex. Through fluorescence-activated nuclei sorting of SATB2-positive neuronal nuclei, researchers demonstrated that these dynamics follow cell-type-specific trajectories, underscoring the precision of epigenetic programming during development [11].

Critically, these developmentally dynamic DNA methylation sites were significantly enriched near genes implicated in autism and schizophrenia, providing a mechanistic link between epigenetic dysregulation during critical developmental windows and the pathogenesis of neurodevelopmental disorders [11]. This finding highlights the importance of precise temporal and cell-type-specific methylation control for normal brain development and function.

In contrast to the targeted methylation changes during development, aging is characterized by more generalized epigenetic alterations. As noted in a recent news article discussing a large epigenetic atlas, "The epigenetic process of DNA methylation — the addition or removal of tags called methyl groups — becomes less precise as we age. The result is changes to gene expression that are linked to reduced organ function and increased susceptibility to disease" [5]. This age-related erosion of epigenetic precision contributes to the functional decline of tissues and organs.

Replicative Stress and Hematopoietic Stem Cell Aging

The relationship between proliferative history and epigenetic aging has been particularly well-documented in hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs). A 2024 study induced forced replication of HSCs in vivo through cyclical treatment with low-dose fluorouracil (5FU) and demonstrated that proliferative stress induces several aging phenotypes, including altered leukocyte counts, decreased lymphoid progenitors, and reduced reconstitution potential [12]. Importantly, the divisional history of HSCs was imprinted in the DNA methylome, consistent with functional decline.

The DNA methylation changes observed in aged HSCs included global hypermethylation in non-coding regions and similar frequencies of hypo- and hyper-methylation at promoter regions, particularly affecting genes targeted by the Polycomb Repressive Complex 2 (PRC2) [12]. These findings suggest that HSC proliferation can drive aging phenotypes primarily through epigenetic mechanisms, independent of initial functional decline.

Table 1: DNA Methylation Changes in Hematopoietic Stem Cell Aging

| Parameter | Prenatal/Young HSCs | Aged/Stressed HSCs | Functional Consequence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Global Methylation Pattern | Developmentally programmed | Erosion of precision | Increased disease susceptibility |

| Non-coding Regions | Balanced methylation | Global hypermethylation | Genomic instability |

| Promoter Regions | Tissue-specific patterns | PRC2 target disruption | Altered differentiation capacity |

| Lymphoid Output | High | Decreased | Immune dysfunction |

| Reconstitution Potential | Robust | Reduced | Impaired tissue maintenance |

Novel Mechanisms and Methodologies

Synergistic Histone Modifications in Cell Fate Determination

Beyond DNA methylation, other epigenetic marks work in concert to direct cell fate. Recent research has revealed a remarkable synergy between two histone modifications—H3K79 methylation and H3K36 trimethylation—that critically orchestrates gene expression during cell differentiation [13] [14]. Using CRISPR-based genetic engineering to generate stem cell models deficient in enzymes responsible for these modifications, researchers discovered that while loss of either mark alone caused minor changes, concomitant absence triggered unexpected gene hyperactivation and blocked the cells' ability to differentiate into neurons [13].

This finding overturned the previous assumption that these histone marks solely facilitate gene activation, revealing instead a nuanced regulatory system where they also function as critical modulators preventing excessive transcriptional activity. The investigation further identified a hyperactive YAP-TEAD transcriptional pathway that becomes unleashed when both methylation marks are lost, pointing to a potential therapeutic target for cancers, including leukemia, characterized by such epigenetic dysregulation [13] [14].

Diagram 1: Synergistic histone regulation of cell fate.

Genetic Regulation of Epigenetic Patterning

A paradigm-shifting discovery in the field of epigenetics has revealed that DNA methylation can be regulated by genetic mechanisms, not just by pre-existing epigenetic marks. Research in Arabidopsis thaliana identified that specific DNA sequences, recognized by proteins called RIMs (a subset of REPRODUCTIVE MERISTEM transcription factors), act with CLASSY3 proteins to establish DNA methylation at specific genomic targets [6]. When researchers disrupted these DNA sequences, the entire methylation pathway failed.

This discovery of sequence-driven DNA methylation represents a fundamental shift in understanding how novel methylation patterns arise during development, moving beyond the model where pre-existing epigenetic modifications solely guide new methylation [6]. As the senior author noted, "This finding represents a paradigm shift in the field's view of how methylation is regulated in plants. All previous work pointed to pre-existing epigenetic modifications as the starting place for targeting methylation, which didn't explain how novel methylation patterns could arise. Now we know the DNA itself can instruct new methylation patterns, too" [6]. This mechanism has significant implications for epigenetic engineering strategies aimed at generating specific methylation patterns to repair or enhance cell function.

Cell Cycle as an Epigenetic Regulator

The intersection of cell cycle dynamics and epigenetic remodeling represents another emerging frontier in understanding cell fate regulation. A recent study demonstrated that enhancing the activities of transcription factors OCT4 and SOX2 by fusing them with the herpesvirus VP16 activation domain (creating OvSvK complex) significantly accelerated somatic cell reprogramming into induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) [15]. Single-cell analyses revealed that OvSvK restructures the cell cycle, shortening the G1 phase while extending S phase, thereby establishing an embryonic stem cell-like pattern.

This cell cycle restructuring directly influences epigenetic inheritance, particularly the restoration of H3K27me3 marks during the G1 phase [15]. The shortened G1 phase impedes the complete restoration of repressive H3K27me3 marks, consequently elevating expression of genes that facilitate pluripotency. This research establishes cell cycle dynamics as key epigenetic modulators for cell fate transitions, providing fundamental insights into reprogramming mechanisms with significant implications for regenerative medicine.

Advanced Technologies for Epigenetic Manipulation

EPI-Clone: Transgene-Free Lineage Tracing

Recent methodological advances have expanded our ability to track cell fate decisions at unprecedented resolution. EPI-Clone is a novel method that exploits targeted single-cell profiling of DNA methylation at single-CpG resolution to track clones while providing detailed cell-state information [16]. This approach distinguishes between two types of CpG sites: those whose methylation status reflects cellular differentiation, and those that undergo stochastic epimutations and can serve as digital barcodes of clonal identity.

Applied to mouse and human haematopoiesis, EPI-Clone has revealed that in mouse ageing, myeloid bias and low output of old haematopoietic stem cells are restricted to a small number of expanded clones, whereas many functionally young-like clones persist in old age [16]. In human ageing, clones with and without known driver mutations of clonal haematopoiesis display similar lineage biases, suggesting convergent mechanisms of age-related clonal expansion. This transgene-free lineage tracing method enables accurate single-cell lineage tracing on hematopoietic cell state landscapes at scale, providing powerful insights into the clonal dynamics of aging and differentiation.

Tissue Nanotransfection for In Vivo Reprogramming

Tissue nanotransfection (TNT) has emerged as a novel non-viral platform capable of delivering genetic material directly into tissues via localized nanoelectroporation, enabling cellular reprogramming in situ [4]. The TNT device consists of a hollow-needle silicon chip mounted beneath a cargo reservoir containing genetic material. When electrical pulses are applied, the hollow needles concentrate the electric field at their tips, temporarily porating nearby cell membranes and enabling targeted delivery of charged genetic material into tissue.

TNT can deliver various genetic cargoes, including plasmid DNA, mRNA, and CRISPR/Cas9 components, for different reprogramming strategies:

- Induced pluripotency: Transforming somatic cells into a pluripotent state

- Direct reprogramming (transdifferentiation): Converting one somatic cell type into another without a pluripotent intermediate

- Partial reprogramming (cellular rejuvenation): Transient factor expression to reverse aging-related changes without altering cell identity [4]

The optimization of electrical pulse parameters—voltage amplitude, pulse duration, and inter-pulse intervals—is critical for maximizing delivery efficiency while preserving cellular viability during the nanotransfection process [4].

Diagram 2: Tissue nanotransfection workflow for epigenetic reprogramming.

Experimental Protocols and Research Tools

Key Methodologies for Studying Methylation Dynamics

Isolation of Cell-Type-Specific Nuclei for Methylation Analysis The protocol for isolating neuron-specific nuclei from human cortex tissue exemplifies approaches for cell-type-specific epigenetic analysis [11]:

- Tissue Preparation: Fresh or frozen human cortex tissue is homogenized in a sucrose-based buffer with detergent to create a nuclear suspension.

- Fluorescence-Activated Nuclei Sorting (FANS): Nuclei are incubated with a SATB2 antibody (a neuronal marker) conjugated to a fluorescent tag.

- Flow Cytometry: SATB2-positive neuronal nuclei are sorted from SATB2-negative non-neuronal nuclei using a fluorescence-activated cell sorter.

- DNA Extraction and Bisulfite Treatment: Genomic DNA is extracted from sorted nuclei and treated with bisulfite, which converts unmethylated cytosines to uracils while leaving methylated cytosines unchanged.

- Genome-Wide Methylation Profiling: Bisulfite-treated DNA is subjected to whole-genome bisulfite sequencing or reduced representation bisulfite sequencing to determine methylation status at single-base resolution.

In Vivo Hematopoietic Stem Cell Aging Model To study the effects of proliferative stress on HSC aging [12]:

- Animal Model: 3-month-old C57BL/6 J female mice are used at study start.

- 5-FU Treatment: 5-Fluorouracil is administered at 150 mg/kg by intraperitoneal injection, once every 3 weeks.

- Monitoring: Animals are continuously monitored for general health and body weight.

- HSC Isolation: At experimental endpoints, bone marrow is harvested from hind legs, pelvis, femur, and tibia. HSCs are isolated using c-Kit enrichment followed by fluorescence-activated cell sorting for PI-Lin−cKit+Sca1+CD34−Flk2−CD150+ cells.

- Downstream Analysis: Isolated HSCs can be used for transplantation assays, DNA methylation analysis by RRBS, DNA damage assays (alkaline comet assay, gH2AX assay), or mRNA expression profiling.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for Methylation Dynamics Studies

| Reagent/Technology | Function/Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| SATB2 Antibody | Marker for sorting neuronal nuclei | Isolation of neuron-specific nuclei for methylation analysis in human cortex [11] |

| 5-Fluorouracil (5-FU) | Chemotherapeutic agent inducing proliferative stress | In vivo model of HSC aging through forced replication [12] |

| LARRY Barcoding System | Lentiviral genetic barcoding for lineage tracing | Ground-truth dataset for clonal identity in haematopoiesis [16] |

| scTAM-seq | Single-cell targeted analysis of methylome | High-resolution DNA methylation profiling at single-CpG level [16] |

| CRISPR-based Genetic Engineering | Targeted gene knockout or editing | Generating stem cell models deficient in specific histone-modifying enzymes [13] [14] |

| OCT4-VP16/SOX2-VP16 | Enhanced transcription factors with VP16 activation domain | Accelerated somatic cell reprogramming to iPSCs [15] |

| TNT Device | Nanoelectroporation for in vivo gene delivery | Direct cellular reprogramming in tissue regeneration [4] |

| Mission Bio Tapestri Platform | Microfluidic platform for single-cell multi-omics | Implementation of scTAM-seq for DNA methylation analysis [16] |

| 4-(Diethylamino)but-2-enal | 4-(Diethylamino)but-2-enal|RUO | 4-(Diethylamino)but-2-enal for research use only. A high-purity building block for organic synthesis. Get quotes and spec sheets. Not for human use. |

| Furan;tetramethylazanium | Furan;tetramethylazanium CAS 396101-14-7 Supplier |

The precise control of DNA methylation dynamics represents a central mechanism directing stem cell fate decisions throughout development, aging, and disease. The emerging picture reveals an increasingly complex regulatory network where DNA methylation interacts with histone modifications, genetic sequences, cell cycle dynamics, and environmental cues to maintain cellular identity or enable fate transitions. The recent discoveries of sequence-driven DNA methylation and cell cycle-mediated epigenetic remodeling represent significant paradigm shifts in our understanding of how epigenetic patterns are established and maintained.

For tissue regeneration research, the ability to manipulate these methylation dynamics through technologies like tissue nanotransfection, epigenetic editing, and directed reprogramming offers promising pathways for therapeutic intervention. The finding that partial reprogramming can reset epigenetic age without altering cellular identity suggests potential strategies for rejuvenating aged or damaged tissues. Meanwhile, the identification of specific epigenetic synergies, such as that between H3K79 and H3K36 methylation, reveals new therapeutic targets for diseases characterized by epigenetic dysregulation.

As methodologies for tracking and manipulating methylation dynamics continue to advance—with technologies like EPI-Clone enabling high-resolution lineage tracing and TNT facilitating in vivo reprogramming—researchers and drug development professionals are equipped with an increasingly sophisticated toolkit for probing and directing cell fate. These advances hold significant promise for developing novel regenerative therapies that harness the epigenetic control of cellular identity and function.

The differentiation of mesenchymal stem/stromal cells (MSCs) into osteogenic, chondrogenic, and adipogenic lineages is a tightly regulated process crucial for tissue homeostasis and regeneration. These lineage commitments are controlled by complex interactions between transcription factors, signaling pathways, and epigenetic modifications [17] [18]. Recent advances in transcriptome analysis and epigenetics have revealed the intricate regulatory networks that determine stem cell fate. Understanding these mechanisms is paramount for developing effective regenerative medicine strategies for conditions ranging from osteoporosis to cartilage repair [17] [18] [19]. This review synthesizes current knowledge on the key regulators, signaling pathways, and emerging role of DNA methylation in controlling lineage-specific differentiation of MSCs, with implications for targeted therapeutic interventions.

Transcriptional Regulation of Lineage Commitment

The fate of MSCs is primarily directed by core transcription factors that activate lineage-specific gene programs while suppressing alternative pathways. The balance between these transcriptional regulators determines differentiation outcomes.

Core Transcription Factors

- Chondrogenesis: SOX9 is the master regulator that works in concert with SOX5 and SOX6 to induce chondrocyte differentiation and maintain chondrocytic phenotypes. SOX9 directly regulates type II collagen (COL2A1) and aggrecan (ACAN) expression [17]. RUNX2 also promotes chondrogenic differentiation in certain contexts [17].

- Adipogenesis: PPARγ serves as the central regulator that is both necessary and sufficient for adipogenesis. The C/EBP family members (C/EBPα, C/EBPβ, and C/EBPδ) work in coordination with PPARγ to drive adipocyte differentiation, with C/EBPα being particularly required for white adipocyte differentiation [17].

- Osteogenesis: RUNX2 is the critical transcription factor directing osteogenic differentiation, activating expression of bone-specific genes including osteocalcin and bone sialoprotein [18].

Transcriptional Crosstalk and Antagonism

Complex antagonistic relationships exist between transcription factors of different lineages, creating mutually exclusive differentiation paths:

- SOX9 downregulation appears necessary for adipocyte differentiation, as it can bind to and suppress C/EBPβ and C/EBPδ promoter activity [17].

- Conversely, C/EBPα, C/EBPβ, and C/EBPδ suppress chondrogenic marker genes COL2A1, ACAN, and SOX9 in ATDC5 cells [17].

- The balance between adipogenic and osteogenic transcription factors is crucial for bone homeostasis, with PPARγ activation promoting adipogenesis at the expense of osteogenesis [18].

Table 1: Key Transcription Factors in MSC Lineage Differentiation

| Lineage | Master Regulator | Co-factors | Target Genes | Antagonists |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chondrogenesis | SOX9 | SOX5, SOX6 | COL2A1, ACAN | C/EBP family |

| Adipogenesis | PPARγ | C/EBPα, C/EBPβ, C/EBPδ | FABP4, LPL | SOX9, RUNX2 |

| Osteogenesis | RUNX2 | OSX, ATF4 | Osteocalcin, Bone sialoprotein | PPARγ |

Signaling Pathways Governing Lineage Determination

Multiple signaling pathways interact to guide MSC fate decisions, often exhibiting contrasting effects on different lineages. The precise outcome depends on specific ligands, concentrations, temporal activation, and cellular context.

TGF-β/BMP Superfamily

The TGF-β/BMP pathway plays particularly important roles in lineage specification with different members showing distinct effects:

- TGF-β (especially TGF-β2 and TGF-β3) strongly promotes chondrogenic differentiation of human BMSCs at concentrations around 10 ng/mL, while simultaneously inhibiting adipogenesis [17]. TGF-β1 induces dominant chondrogenesis while suppressing adipogenic differentiation in CL-1 cells and human BMSCs [17]. Mechanistically, TGF-β signals through Smad3 to inhibit adipogenesis by associating with C/EBPβ and C/EBPδ, resulting in decreased PPARγ expression [17].

- BMP family members show diverse effects: BMP2 is the most effective in promoting chondrogenic differentiation compared to BMP4 and BMP6 in human BMSCs [17]. Interestingly, BMP2 also stimulates adipogenesis in 3T3-L1 cells and rat BMSCs when associated with a PPARγ activator [17]. BMP7 serves as a unique brown fat inducer, while BMP2 and BMP4 act as white adipogenic factors [17].

Additional Signaling Pathways

- Wnt Signaling: Wnt proteins prevent MSCs from proceeding toward adipogenic lineage while promoting osteogenesis [17].

- Hedgehog Signaling: Similar to Wnt, Hedgehog proteins are important for MSC myogenic lineage commitment but inhibit adipogenic differentiation [17].

The following diagram illustrates the key signaling pathways and their interactions in regulating MSC lineage commitment:

Diagram 1: Signaling Pathways in MSC Lineage Commitment. Arrows indicate activation, while T-bars indicate inhibition.

Epigenetic Regulation: The Role of DNA Methylation

Beyond transcription factors and signaling pathways, epigenetic mechanisms including DNA methylation provide an additional layer of regulation in lineage-specific differentiation. DNA methylation patterns are dynamically regulated during cellular differentiation and play crucial roles in defining cell identity.

Mechanisms of DNA Methylation Patterning

Recent research has revealed that transcription factors can actively instruct DNA methylation patterns in specific tissues:

- In plant reproductive tissues, REPRODUCTIVE MERISTEM (REM) transcription factors target the RNA-directed DNA methylation (RdDM) machinery to distinct loci, generating tissue-specific epigenomes [19]. These REM INSTRUCTS METHYLATION (RIM) factors are required for methylation at specific targets in anther or ovule tissues [19].

- Disruption of DNA-binding domains in these transcription factors or the motifs they recognize blocks RNA-directed DNA methylation, demonstrating the direct link between genetic information and epigenetic patterning [19].

- This mechanism represents a departure from the traditional view that DNA methylation patterns are regulated primarily by chromatin features rather than DNA sequence motifs [19].

DNA Methylation in Mammalian Lineage Differentiation

While the precise mechanisms of DNA methylation in mammalian MSC differentiation are still being elucidated, several key principles emerge:

- DNA methylation patterns are established through coordinated action of DNA methyltransferases and demethylases that respond to differentiation signals.

- Lineage-specific transcription factors may recruit epigenetic modifiers to establish methylation patterns that stabilize the differentiated state.

- The interplay between genetic information (transcription factor binding) and epigenetic mechanisms (DNA methylation) creates stable cellular identities necessary for tissue function and regeneration.

Table 2: Experimental Approaches for Studying DNA Methylation in Lineage Differentiation

| Method | Application | Key Readouts | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bisulfite Sequencing | Genome-wide methylation mapping | Methylation levels at single-base resolution | Distinguishes between CG, CHG, CHH contexts |

| smRNA-seq | siRNA profiling at methylated loci | siRNA cluster abundance | Identifies active RdDM targets |

| Methyl-Cutting PCR Assays | Rapid screening of methylation status | Methylation at specific loci | Medium-throughput candidate validation |

| Genetic Screens (EMS mutants) | Identification of novel methylation factors | DNA methylation defects | Follow-up mapping required |

Experimental Methodologies for Lineage Differentiation

Standardized protocols have been established for directing MSCs toward specific lineages in vitro. These methodologies enable the study of differentiation mechanisms and screening of potential therapeutic compounds.

Chondrogenic Differentiation Protocol

- Cell Culture Format: Pellet culture or micromass systems to enhance cell-cell interactions [17].

- Basal Medium: High-glucose DMEM supplemented with ITS+1 premix (insulin, transferrin, selenium), ascorbate-2-phosphate, sodium pyruvate, proline, and dexamethasone [17].

- Key Inducers: TGF-β1, TGF-β2, or TGF-β3 at 10 ng/mL concentration [17]. TGF-β2 and TGF-β3 are more effective than TGF-β1 in human BMSCs [17].

- Duration: 14-28 days with medium changes every 2-3 days.

- Validation: Histological staining for sulfated proteoglycans (Alcian blue, Safranin O), immunohistochemistry for type II collagen, and gene expression analysis of SOX9, COL2A1, and ACAN.

Adipogenic Differentiation Protocol

- Cell Culture Format: Monolayer culture at high density (confluent).

- Basal Medium: DMEM with high glucose, supplemented with fetal bovine serum.

- Induction Cocktail: IBMX (0.5 mM), dexamethasone (1 μM), indomethacin (200 μM), and insulin (10 μg/mL) [18].

- Maintenance Medium: DMEM with high glucose and insulin (10 μg/mL) only.

- Cycling Protocol: 2-3 cycles of induction/maintenance (2-3 days each) followed by culture in maintenance medium for an additional 7-14 days.

- Validation: Oil Red O staining of lipid droplets, gene expression analysis of PPARγ, C/EBPα, and FABP4.

Osteogenic Differentiation Protocol

- Cell Culture Format: Monolayer culture at 50-70% confluence.

- Basal Medium: DMEM with low glucose, supplemented with fetal bovine serum.

- Key Inducers: Dexamethasone (100 nM), ascorbate-2-phosphate (50-100 μM), and β-glycerophosphate (10 mM) [18].

- Duration: 14-21 days with medium changes every 3-4 days.

- Validation: Alizarin Red S or Von Kossa staining of mineralized matrix, alkaline phosphatase activity assay, gene expression analysis of RUNX2, osteocalcin, and osteopontin.

The following workflow diagram outlines a comprehensive experimental approach for studying lineage differentiation and DNA methylation:

Diagram 2: Experimental Workflow for Studying Lineage Differentiation and DNA Methylation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Studying Lineage Differentiation

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lineage Inducers | TGF-β1/2/3 (10 ng/mL), BMP2 (500 ng/mL) | Chondrogenic differentiation | Concentration-dependent effects [17] |

| Dexamethasone (0.1-1 μM), IBMX (0.5 mM), Insulin (10 μg/mL) | Adipogenic differentiation | Cocktail required for efficient differentiation [18] | |

| Dexamethasone (100 nM), Ascorbate-2-phosphate (50-100 μM), β-glycerophosphate (10 mM) | Osteogenic differentiation | Required for matrix mineralization [18] | |

| Cell Markers | CD105, CD73, CD90 (>95% positive) | MSC identification | Minimum criteria per ISCT guidelines [18] |

| CD45, CD34, CD14/CD11b, CD79α/CD19, HLA-DR (<2% positive) | Hematopoietic contamination exclusion | Essential for MSC purity assessment [18] | |

| Epigenetic Tools | Bisulfite conversion reagents | DNA methylation analysis | Distinguishes methylated/unmethylated cytosines [19] |

| siRNA/miRNA inhibitors | Functional studies of non-coding RNAs | Identifies regulatory networks [18] | |

| Analysis Kits | Alcian Blue, Oil Red O, Alizarin Red S | Histological validation of differentiation | Quantitative extraction possible |

| RNA-seq library preparation kits | Transcriptome analysis | Full-length transcript information [18] | |

| 1,2-Bis(sulfanyl)ethan-1-ol | 1,2-Bis(sulfanyl)ethan-1-ol | Get 1,2-Bis(sulfanyl)ethan-1-ol (C2H6OS2), also known as 1,2-dimercaptoethanol. This product is designated For Research Use Only and is not intended for diagnostic or personal use. | Bench Chemicals |

| Octa-1,7-diene-1,8-dione | Octa-1,7-diene-1,8-dione, CAS:197152-47-9, MF:C8H10O2, MW:138.16 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

The lineage-specific differentiation of MSCs into osteogenic, chondrogenic, and adipogenic cells is governed by sophisticated transcriptional networks, signaling pathways, and epigenetic mechanisms. The emerging understanding of how transcription factors instruct DNA methylation patterns provides new insights into how stable cellular identities are established during tissue regeneration. Future research focusing on the interplay between genetic and epigenetic information will undoubtedly yield novel therapeutic approaches for regenerative medicine, potentially enabling more precise control over stem cell fate decisions in clinical applications.

The precise orchestration of tissue repair following injury represents a critical biological process where the balance between regenerative healing and pathological fibrosis determines clinical outcomes. DNA methylation, the covalent addition of a methyl group to the carbon-5 position of cytosine in CpG dinucleotides, has emerged as a fundamental epigenetic mechanism governing this balance [20] [21]. This whitepaper examines how dynamic DNA methylation patterns direct cellular responses during wound healing, where proper regulation leads to tissue regeneration, while dysregulation drives aberrant repair processes including fibrosis and chronic wounds [22] [20] [23]. The context of a broader thesis on DNA methylation in tissue regeneration research frames this exploration, highlighting the therapeutic potential of targeting epigenetic mechanisms to redirect pathological healing toward regenerative outcomes. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding these mechanisms provides a foundation for developing novel epigenetic-based interventions that could revolutionize treatment for fibrotic diseases and chronic wounds.

Molecular Mechanisms of DNA Methylation in Healing

The DNA Methylation Machinery

DNA methylation is catalyzed by DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs), which transfer methyl groups from S-adenosylmethionine (SAM) to cytosine bases [21] [24]. DNMT3A and DNMT3B establish de novo methylation patterns, while DNMT1 maintains these patterns during cell division, ensuring faithful inheritance of methylation marks [21] [24]. This methylation process is counterbalanced by demethylation enzymes, particularly the ten-eleven translocation (TET) family, including TET1, TET2, and TET3, which oxidize 5-methylcytosine (5mC) to 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5hmC) and further to 5-formylcytosine (5fC) and 5-carboxylcytosine (5caC) [20] [24]. The dynamic interplay between these "writers" and "erasers" enables precise temporal and spatial control of gene expression during the complex process of tissue repair [21].

The functional consequences of DNA methylation depend critically on genomic context. Methylation within gene promoter regions, particularly at CpG islands, typically leads to transcriptional repression by physically impeding transcription factor binding or recruiting methyl-CpG-binding proteins (MBPs) like MeCP2, MBD1, and MBD2, which subsequently associate with histone deacetylases (HDACs) to promote chromatin condensation [20] [21]. In contrast, gene body methylation often correlates with transcriptional activity, potentially suppressing spurious transcription initiation or regulating alternative splicing [21]. This contextual understanding is essential for deciphering how methylation changes direct healing outcomes.

Interplay with Other Epigenetic Mechanisms

DNA methylation does not function in isolation but participates in extensive crosstalk with other epigenetic regulatory systems. A bidirectional relationship exists between DNA methylation and histone modifications, where DNA methylation can template specific histone modifications after DNA replication, and histone methylation can help direct DNA methylation patterns [20]. Similarly, complex feedback loops connect DNA methylation with non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs); DNA methylation regulates the expression of some microRNAs (miRNAs), while another subset of miRNAs controls the expression of DNMTs and other epigenetic regulators [20]. For instance, Dakhlallah et al. identified a miRNA-DNMT regulatory circuit in pulmonary fibrosis where reduced expression of the miR-17~92 cluster was associated with increased DNMT1 expression and a pro-fibrotic phenotype [20]. This sophisticated epigenetics-miRNA regulatory circuit organizes global gene expression profiles, and its disruption can interfere with normal wound healing processes.

DNA Methylation in Normal Wound Healing

Spatiotemporal Regulation of Healing Phases

Normal wound healing progresses through highly coordinated phases—hemostasis, inflammation, proliferation, and remodeling—each characterized by distinct gene expression patterns guided by epigenetic modifications [22]. DNA methylation dynamically regulates these phase transitions by controlling key genes and pathways. During the hemostasis and inflammatory phases, methylation changes influence platelet function and immune cell activity; for example, DNA methylation of genes like platelet endothelial aggregation receptor 1 can impact platelet function [22]. As healing progresses to the proliferation phase, methylation patterns direct fibroblast proliferation, angiogenesis, and temporary matrix deposition [22] [25].

The final remodeling phase, where the balance between matrix synthesis and degradation determines regenerative versus fibrotic outcomes, is particularly influenced by epigenetic controls. During this phase, myofibroblasts—the primary ECM-producing cells—typically undergo apoptosis or revert to a quiescent phenotype [20]. DNA methylation helps regulate this critical transition; proper methylation patterns ensure the timely elimination of myofibroblasts, preventing excessive ECM accumulation [20]. The spatiotemporal precision of these methylation changes ensures that healing progresses efficiently from inflammation to resolution, restoring tissue integrity without pathological scarring.

Key Regulated Genes and Pathways

Table 1: DNA Methylation Changes in Key Genes During Normal Healing

| Gene/Pathway | Methylation Change | Biological Effect | Phase of Healing |

|---|---|---|---|

| Platelet endothelial aggregation receptor 1 | Hypermethylation | Modulates platelet function | Hemostasis |

| Cell cycle-related genes | Dynamic methylation | Controls fibroblast proliferation | Proliferation |

| ECM component genes | Temporal methylation | Regulates collagen deposition | Proliferation/Remodeling |

| Pro-inflammatory cytokines | Progressive methylation | Resolves inflammation | Inflammation/Remodeling |

| Myofibroblast apoptosis genes | Demethylation | Promotes myofibroblast elimination | Remodeling |

Multiple specific genes and pathways critical to healing outcomes are regulated by DNA methylation. For instance, methylation of cell cycle-related genes influences the proliferation and differentiation of skin cells, ensuring adequate cellular expansion during the proliferative phase while preventing excessive growth [22]. Genes encoding extracellular matrix (ECM) components like collagens and fibronectin undergo temporal methylation changes that control their expression patterns, facilitating initial matrix deposition followed by controlled remodeling [22] [25]. Additionally, methylation of genes involved in growth factor signaling pathways, such as TGF-β and its receptors, helps modulate their activity at different healing stages [25] [26]. The coordinated regulation of these diverse genetic elements through DNA methylation enables the precise cellular behaviors necessary for regenerative healing.

Aberrant DNA Methylation in Pathological Healing

Fibrotic Healing and Scarring

Fibrosis represents an exaggerated wound healing response characterized by excessive ECM deposition and scarring, which can disrupt normal organ architecture and function [20] [25]. DNA methylation changes play a fundamental role in driving this pathological process, particularly through the establishment of persistent myofibroblast activation. During normal healing, myofibroblasts undergo apoptosis or revert to quiescence as repair resolves; in fibrosis, however, these cells persist due to stable phenotypic changes maintained by epigenetic alterations [20]. Supporting this concept, fibroblasts isolated from fibrotic tissue maintain their hyperactive phenotype ex vivo even without continued pro-fibrotic stimulation, suggesting heritable epigenetic changes underpin their persistent activation [20].

Multiple specific methylation changes have been identified in fibrotic conditions. Profibrotic genes often display hypomethylation leading to their sustained expression, while genes promoting matrix degradation or myofibroblast apoptosis may become hypermethylated and silenced [20]. This aberrant methylation landscape creates a self-sustaining profibrotic environment. The origins of these persistent myofibroblasts vary, with contributions from resident fibroblast proliferation, epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT), endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EndMT), and other sources [20] [25]. Regardless of origin, the maintained hyperactive state appears fundamentally enabled by stable alterations in DNA methylation patterns that are faithfully propagated through cell division.

Chronic Wounds

In contrast to fibrosis, chronic wounds represent a state of deficient healing characterized by failure to re-epithelialize and reconstitute functional tissue [23]. Diabetic foot ulcers, venous leg ulcers, and pressure injuries exemplify this condition, exhibiting delayed granulation tissue formation, persistent inflammation, and impaired angiogenesis [23]. Emerging evidence indicates that aberrant DNA methylation contributes significantly to this pathological state, potentially through the establishment of a "chronic wound memory"—a maladaptive epigenetic program that perpetuates abnormal cellular behaviors even in ideal wound environments [23].

This pathological epigenetic code appears particularly impactful on dermal fibroblasts and keratinocytes, dictating abnormal traits that persist through successive cell passages in vitro [23]. In diabetic wounds, hyperglycemia-induced epigenetic imprinting forms the foundation for metabolic memory that perpetuates cellular senescence and dysfunction through an inflammotoxic secretome [23]. Key processes impaired in chronic wounds, including growth factor responsiveness, antioxidant defense, and stem cell functionality, are all influenced by DNA methylation changes [23]. The identification of specific methylation signatures associated with chronicity could provide both prognostic biomarkers and therapeutic targets for these challenging clinical conditions.

Analytical Approaches and Research Methodologies

DNA Methylation Detection Techniques

Table 2: Technical Approaches for DNA Methylation Analysis in Wound Healing Research

| Method | Resolution | Throughput | Key Applications | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Whole-Genome Bisulfite Sequencing (WGBS) | Single-base | High | Comprehensive methylation mapping, DMR discovery | High cost, computational demands [27] [24] |

| Reduced Representation Bisulfite Sequencing (RRBS) | Single-base | Medium | Cost-effective methylation profiling | Limited genomic coverage [24] |

| Illumina Methylation BeadChip arrays | Single-CpG site | High | Population studies, clinical biomarker development | Targeted to predefined CpG sites [27] [24] |

| Methylated DNA Immunoprecipitation (MeDIP) | 100-500 bp | Medium | Methylome studies without bisulfite conversion | Lower resolution, antibody-dependent [24] |

| Pyrosequencing | Single-base | Low | Validation of targeted CpG sites | Limited multiplexing capability [24] |

Advanced methodologies for detecting DNA methylation patterns have dramatically accelerated research into wound healing epigenetics. Whole-genome bisulfite sequencing (WGBS) provides comprehensive, single-base resolution methylation mapping across the entire genome, enabling unbiased discovery of differentially methylated regions (DMRs) [27] [24]. For large-scale studies, Illumina Infinium Methylation BeadChip arrays offer a cost-effective solution for profiling methylation at predefined CpG sites, making them suitable for clinical biomarker development [27] [24]. Emerging techniques like single-cell bisulfite sequencing (scBS-Seq) are particularly promising as they resolve methylation heterogeneity at cellular resolution, revealing the epigenetic diversity within the complex cellular milieu of healing tissues [24].

The selection of appropriate methylation detection methods depends on research goals, balancing resolution, coverage, throughput, and cost. For discovery-phase research, genome-wide approaches like WGBS or BeadChip arrays are ideal, while targeted methods like pyrosequencing provide higher accuracy for validating specific CpG sites [24]. Additionally, specialized techniques like enhanced linear splint adapter sequencing (ELSA-seq) have emerged for liquid biopsy applications, enabling sensitive detection of circulating tumor DNA methylation for cancer monitoring [24]. This methodological diversity provides researchers with a versatile toolkit for investigating DNA methylation in various wound healing contexts.

Data Analysis and Computational Approaches

The analysis of DNA methylation data presents unique computational challenges, particularly for genome-wide datasets comprising millions of CpG sites. Machine learning (ML) approaches have revolutionized this field, enabling pattern recognition and predictive modeling from complex methylation data [24]. Conventional supervised methods, including support vector machines, random forests, and gradient boosting, have been widely employed for classification, prognosis, and feature selection across tens to hundreds of thousands of CpG sites [24]. These approaches can identify methylation signatures predictive of healing outcomes or fibrotic progression.

More recently, deep learning architectures have demonstrated superior capability for capturing nonlinear interactions between CpGs and genomic context directly from data [24]. Multilayer perceptrons and convolutional neural networks have been successfully applied to tumor subtyping, tissue-of-origin classification, and survival risk evaluation. Transformer-based foundation models like MethylGPT and CpGPT, pretrained on extensive methylome datasets (over 150,000 human methylomes), show exceptional promise for cross-cohort generalization and contextually aware CpG embeddings that transfer efficiently to age and disease-related outcomes [24]. These advanced computational approaches are essential for extracting biologically and clinically meaningful insights from the vast datasets generated by modern epigenetic studies.

Experimental Models and Research Tools

In Vivo and In Vitro Models

Appropriate experimental models are crucial for investigating the role of DNA methylation in wound healing and fibrosis. Murine models of cutaneous wound healing, particularly those utilizing diabetic (db/db) or genetically modified mice, have been instrumental in establishing causal relationships between specific methylation changes and healing outcomes [22] [20]. For fracture healing and bone regeneration, murine tibia fracture models have revealed essential functions for DNMTs; for example, DNMT3b loss in chondrocytes delayed endochondral ossification and impaired cartilage-to-bone transition, reducing the mechanical strength of healed bone [28]. Similarly, ablation of DNMT3b in Gli1-positive periosteal stem cells significantly impaired fracture repair, demonstrating the importance of cell-type-specific methylation patterns [28].

In vitro systems provide complementary approaches for mechanistic studies. Primary human fibroblasts from normal and fibrotic tissues or chronic wounds enable investigation of cell-intrinsic epigenetic differences [20] [23]. These cells maintain their differential methylation patterns and phenotypic characteristics in culture, supporting the concept of stable epigenetic memory [20] [23]. Three-dimensional culture systems, including engineered skin equivalents and organoid models, more closely recapitulate the tissue context of healing and allow manipulation of methylation machinery in a controlled environment [25]. For instance, oxidative stress-induced DNA methylation changes mediated by DNMT3a were shown to regulate osteogenic differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells within 3D scaffold environments mimicking post-implantation conditions [28].

The Researcher's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for DNA Methylation Studies in Wound Healing

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Functional Role |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNMT Inhibitors | 5-azacytidine, 5-aza-2'-deoxycytidine | Experimental demethylation | Reduce global DNA methylation, reactivate silenced genes [20] |

| TET Activators | Vitamin C, 2-oxoglutarate analogs | Promote active demethylation | Enhance TET enzyme activity, facilitate DNA demethylation [24] |

| SAM Analogs | Sinefungin, periodate-oxidized adenosine | Methylation inhibition | Compete with SAM, reduce methyl group availability [21] |

| CRISPR-dCas9 Systems | dCas9-DNMT3A, dCas9-TET1 | Locus-specific methylation editing | Precisely target methylation or demethylation to specific genomic loci [21] |

| Methylation-Specific Antibodies | Anti-5mC, anti-5hmC | Methylation detection and enrichment | Immunoprecipitation, imaging, and quantification of methylation marks [24] |

| 2-Iodylbut-2-enedioic acid | 2-Iodylbut-2-enedioic acid, CAS:185116-76-1, MF:C4H3IO6, MW:273.97 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Piperidin-4-YL pentanoate | Piperidin-4-YL Pentanoate| | Piperidin-4-YL Pentanoate for research. Explore its potential as a biochemical building block. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. | Bench Chemicals |

A diverse array of research reagents enables precise investigation and manipulation of DNA methylation in wound healing contexts. Pharmacological inhibitors of DNMTs, such as 5-azacytidine and 5-aza-2'-deoxycytidine, have been widely used to reduce global DNA methylation and assess the functional consequences on healing processes [20]. These compounds incorporate into DNA during replication and form covalent complexes with DNMTs, leading to their degradation and subsequent DNA hypomethylation [20]. Conversely, compounds that enhance methylation, such as SAM analogs or DNMT expression vectors, allow testing of the opposite manipulation.

Advanced epigenome editing tools based on CRISPR-Cas9 technology represent particularly powerful approaches for establishing causal relationships. Catalytically dead Cas9 (dCas9) fused to DNMT3A or TET1 catalytic domains enables locus-specific methylation or demethylation, respectively [21]. These tools allow researchers to precisely modify methylation at specific genes or regulatory elements suspected to influence healing outcomes, then directly assess the functional consequences. For example, targeting dCas9-DNMT3A to the promoter of an anti-fibrotic gene could test whether its silencing is sufficient to drive fibrotic responses in healing-relevant cell types. Additional essential reagents include methylation-specific antibodies for techniques like methylated DNA immunoprecipitation (MeDIP) and bisulfite conversion kits that form the basis of most sequencing-based methylation detection methods [24].

Visualization of Molecular Pathways

DNA Methylation Dynamics in Normal vs. Aberrant Healing

DNA Methylation in Healing Outcomes

The diagram illustrates how dynamic DNA methylation patterns direct healing toward regenerative versus pathological outcomes. In normal healing (green pathway), coordinated methylation changes ensure proper phase progression: transient demethylation of inflammatory genes followed by re-methylation prevents persistent inflammation; temporal methylation of cell cycle genes controls proliferation; and demethylation of myofibroblast apoptosis genes enables resolution [22] [20]. This precise regulation by DNMTs and TET enzymes restores tissue architecture with minimal scarring.

In contrast, aberrant healing (red pathway) features methylation dysregulation at multiple phases: sustained hypomethylation of inflammatory genes perpetuates inflammation; aberrant methylation of growth control genes leads to sustained myofibroblast activation; and hypermethylation of apoptosis genes prevents myofibroblast elimination [20] [23]. The resulting imbalance favors excessive ECM deposition in fibrosis or prevents proper healing in chronic wounds. This visualization highlights the therapeutic potential of correcting specific methylation defects to redirect pathological healing toward regenerative outcomes.

DNA Methylation Analysis Workflow

Methylation Analysis Experimental Pipeline

The experimental workflow for DNA methylation analysis in wound healing research encompasses multiple stages from sample collection to data interpretation. Sample types include tissue biopsies from normal, fibrotic, or chronic wounds; primary cells such as fibroblasts and keratinocytes; and blood samples for liquid biopsy approaches [27] [24] [23]. Following DNA extraction, bisulfite conversion represents a critical step that deaminates unmethylated cytosines to uracils while leaving methylated cytosines unchanged, enabling discrimination based on methylation status [24].

Detection platforms offer different tradeoffs: array-based methods (Infinium BeadChip) provide cost-effective profiling of predefined CpG sites; sequencing-based approaches (WGBS, RRBS) offer comprehensive or targeted genome-wide coverage; and targeted methods (pyrosequencing) deliver high accuracy for specific loci [27] [24]. Downstream bioinformatic analysis includes quality control, normalization to address technical variation, identification of differentially methylated regions (DMRs), integration with transcriptomic data to link methylation changes to gene expression, and pathway enrichment analysis to extract biological meaning [27] [24]. This pipeline supports diverse applications including biomarker discovery, therapeutic target identification, and mechanistic investigation of healing processes.

Therapeutic Implications and Future Directions

The growing understanding of DNA methylation's role in healing balance opens promising therapeutic avenues. Epigenetic therapies targeting DNMTs, particularly 5-azacytidine and related compounds, have demonstrated potential in experimental models of fibrosis [20]. These agents can reverse pathological methylation patterns and attenuate fibrotic processes, though their genome-wide effects present challenges for specific therapeutic application. More targeted approaches using CRISPR-based epigenetic editors (e.g., dCas9-DNMT3A, dCas9-TET1) offer the potential for locus-specific methylation manipulation to correct specific dysregulated genes without global epigenetic disruption [21]. Additionally, small molecule inhibitors targeting methylation regulatory proteins or readers represent another strategic approach.

Future research directions should focus on elucidating the cell-specific and spatiotemporal dynamics of methylation changes throughout healing, leveraging single-cell methylation technologies [22] [24]. The development of tissue-specific epigenetic editors would enhance therapeutic precision, while combinatorial approaches targeting multiple epigenetic mechanisms simultaneously may yield enhanced efficacy [21]. For clinical translation, DNA methylation signatures show exceptional promise as prognostic biomarkers to predict healing outcomes or stratify patients for targeted therapies [24] [23]. The ongoing development of comprehensive methylation databases like MethAgingDB, which includes tissue-specific differentially methylated sites (DMSs) and regions (DMRs), will significantly accelerate these efforts [27]. As these research fronts advance, epigenetic interventions that selectively promote regenerative healing while preventing fibrosis represent a promising frontier in regenerative medicine.

From Bench to Bedside: Analyzing Methylation and Developing Epigenetic Therapies

The role of DNA methylation in tissue regeneration represents a dynamic frontier in epigenetic research, where precise profiling of methylation patterns is crucial for understanding cellular reprogramming and differentiation. As reviewed in Nature, DNA methylation is a canonical epigenetic mark extensively implicated in transcriptional regulation, playing a critical role in lineage specification during regenerative processes [29]. Detecting organ and tissue damage is essential for early diagnosis, treatment decisions, and monitoring disease progression, with methylation-based assays offering a promising approach for identifying regenerative biomarkers [30]. Within this context, advanced profiling techniques like Genome-Wide Bisulfite Sequencing (WGBS) and Methylation-Sensitive Amplified Polymorphism (MSAP) provide powerful tools for mapping epigenetic landscapes during tissue repair and regeneration. These methods enable researchers to uncover the epigenetic mechanisms that facilitate tissue restoration, offering potential therapeutic avenues for enhancing regenerative capacity in clinical applications.

Whole-Genome Bisulfite Sequencing (WGBS)

Principles: WGBS is considered the gold standard for DNA methylation analysis, providing single-base resolution across the entire genome. The core principle relies on bisulfite conversion of genomic DNA, where unmethylated cytosines are chemically deaminated to uracils, while methylated cytosines remain unchanged [31] [32]. After PCR amplification and sequencing, the original unmethylated cytosines appear as thymines in the sequencing data, allowing for precise mapping of methylation status by comparing the sequencing data with the reference genome.

Applications in Tissue Regeneration: WGBS enables comprehensive analysis of methylation dynamics during cellular differentiation and tissue repair processes. Its applications in regeneration research include:

- Mapping complete methylomes of stem cells during differentiation

- Identifying differentially methylated regions (DMRs) in regenerative pathways

- Analyzing cell-free DNA methylation patterns as biomarkers of tissue damage and repair [30] [32]

Methylation-Sensitive Amplified Polymorphism (MSAP)

Principles: MSAP is a modified AFLP (Amplified Fragment Length Polymorphism) technique that utilizes the differential sensitivity of isoschizomer enzymes HpaII and MspI to methylation status at 5'-CCGG-3' recognition sites [33]. HpaII only cleaves sites with hemimethylated external cytosines (mCCGG), whereas MspI cleaves at hemi- or fully methylated internal cytosines (CmCGG) [33]. The resulting fragment patterns from parallel digestions provide a methylation profile without requiring prior genome sequence knowledge.

Applications in Tissue Regeneration: MSAP offers a practical approach for methylation screening in regeneration studies, particularly when analyzing multiple samples or non-model organisms:

- Rapid assessment of global methylation changes during tissue repair

- Identification of methylation polymorphisms in regeneration-associated genes

- Epigenetic stability assessment in engineered tissues and regenerative therapies [33]

Comparative Technical Analysis

Performance Characteristics and Method Selection

Table 1: Technical comparison of WGBS and MSAP methodologies

| Parameter | Whole-Genome Bisulfite Sequencing | Methylation-Sensitive Amplified Polymorphism |

|---|---|---|

| Resolution | Single-base resolution [31] [32] | Site-specific (5'-CCGG-3' contexts) [33] |

| Genomic Coverage | ~80% of all CpG sites [34] | Limited to CCGG sites; no requirement for prior sequence knowledge [33] |

| DNA Input | μg-level requirements; degraded after bisulfite treatment [31] | Lower input requirements; minimal DNA degradation [33] |

| Throughput | Lower throughput due to computational demands [35] | Higher throughput suitable for population-level studies [33] |

| Cost Considerations | Higher sequencing and computational costs [31] | Lower cost per sample; minimal equipment requirements [33] |

| Ideal Use Cases | Comprehensive methylome mapping, biomarker discovery [32] | Population epigenetics, methylation screening [33] |

Practical Implementation Considerations

For tissue regeneration research, method selection depends on specific experimental goals and resource constraints. WGBS provides unparalleled comprehensive data but requires significant bioinformatics infrastructure and higher-quality DNA inputs [31]. Recent advancements have addressed some limitations through techniques like tagmentation-based WGBS (T-WGBS) and post-bisulfite adaptor tagging (PBAT) for low-input samples [35]. EM-seq (Enzymatic Methyl-seq) has emerged as an alternative that reduces DNA damage through enzymatic conversion rather than bisulfite treatment, showing high concordance with WGBS while better preserving DNA integrity [34] [31].

MSAP remains valuable for studies requiring rapid methylation assessment across multiple samples, particularly in non-model organisms or when working with degraded DNA from clinical specimens [33]. Its limitation to CCGG sites provides less comprehensive coverage but offers practical advantages for focused hypothesis testing in regeneration research.

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Whole-Genome Bisulfite Sequencing Protocol

Sample Preparation and Quality Control:

- Extract high-molecular-weight DNA using phenol-chloroform or column-based methods

- Quantify DNA using fluorometric methods (e.g., Qubit) to ensure accurate concentration measurement

- Assess DNA integrity via agarose gel electrophoresis or Fragment Analyzer; 260/280 ratio should be 1.8-2.0 [31] [32]

Library Preparation and Bisulfite Conversion:

- Fragment DNA to desired size (200-300bp) via sonication or enzymatic fragmentation

- Perform end-repair, A-tailing, and adapter ligation using methylated adapters for Illumina platforms

- Treat with bisulfite reagent (e.g., EZ DNA Methylation Kit) under optimized conditions: incubation at 95°C for 30-45 seconds followed by 50°C for 15-60 minutes [35] [32]

- Purify bisulfite-converted DNA using column-based cleanups

- Amplify library with 8-12 PCR cycles using uracil-tolerant polymerases [35]

Sequencing and Data Analysis:

- Sequence on Illumina platforms (150bp paired-end recommended)

- Process data through bioinformatics pipeline: quality control (FastQC), adapter trimming (Trim Galore!), alignment (Bismark, BWA-meth), methylation extraction, and DMR calling (methylKit, DSS) [35]

Methylation-Sensitive Amplified Polymorphism (MSAP) Protocol

Restriction-Ligation Reaction:

- Set up parallel digestion reactions with EcoRI/HpaII and EcoRI/MspI

- Use 100-500ng genomic DNA per reaction

- Incubate at 37°C for 4-16 hours for complete digestion [33]

- Perform ligation of appropriate adapters to restriction fragments

Pre-Amplification and Selective Amplification:

- Perform pre-amplification with primers complementary to adapter sequences

- Conduct selective amplification using fluorescently labeled primers with 1-3 selective nucleotides

- Optimize primer combinations through empirical testing [33]

Fragment Analysis and Data Processing:

- Separate amplification products via capillary electrophoresis

- Analyze fragment patterns using genotyping software (e.g., GeneMapper)

- Score methylation polymorphisms as present/absent fragments between HpaII and MspI profiles

- Calculate methylation percentages using formula: (number of polymorphic fragments / total fragments) × 100 [33]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key reagents and materials for DNA methylation profiling

| Reagent/Material | Function | Specific Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Bisulfite Conversion Kits | Chemical deamination of unmethylated cytosines | EZ DNA Methylation Kit (Zymo Research) [34] |

| Methylation-Sensitive Restriction Enzymes | Differential cleavage based on methylation status | HpaII, MspI isoschizomers [33] |

| Methylated Adapters | Library preparation for bisulfite sequencing | Illumina TruSeq DNA Methylated Adapters [35] |