Mapping the Epigenetic Landscape: Mechanisms and Models in Regenerative Biology

This article explores the dynamic role of the epigenetic landscape in guiding cellular reprogramming and tissue regeneration in model organisms.

Mapping the Epigenetic Landscape: Mechanisms and Models in Regenerative Biology

Abstract

This article explores the dynamic role of the epigenetic landscape in guiding cellular reprogramming and tissue regeneration in model organisms. It synthesizes foundational concepts, from Waddington's original metaphor to modern epigenomic profiles, with cutting-edge methodological approaches for analyzing chromatin states. The content provides a critical evaluation of troubleshooting strategies in epigenetic manipulation and offers a comparative analysis of regenerative capabilities across species. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, this review highlights how deciphering epigenetic controls in regenerative models can unlock novel therapeutic paradigms for human disease and tissue repair.

The Blueprint of Regeneration: Core Epigenetic Concepts and Landscape Dynamics

Conrad Waddington's epigenetic landscape, conceived in the 1940s and iconically depicted in 1957, provides a powerful metaphor for cellular development, picturing a cell's differentiation path as a ball rolling through a terrain of branching valleys [1] [2]. Each branch point represents a cell fate decision where a cell chooses between alternative developmental paths. While this visual metaphor has profoundly influenced developmental biology, recent efforts have focused on converting this concept into quantitative, testable models that can predict cellular behavior [1]. This transition from metaphor to mathematical framework is particularly relevant in regenerative medicine, where understanding and controlling cell fate is paramount. Modern revisitation of the landscape integrates insights from gene regulatory networks (GRNs), dynamical systems theory, and catastrophe theory, providing a foundation for analyzing cell fate decisions in developing and regenerating tissues [1]. This review explores how this quantitative reframing of Waddington's landscape offers new principles for understanding cellular potency and fate decisions in regenerative model organisms.

Theoretical Foundations: The Mathematics of Cell Fate Decisions

The modern interpretation of Waddington's landscape is grounded in dynamical systems theory, where cell fates correspond to attractors—stable steady states of the underlying GRN [1]. The landscape itself is described by a potential function, where valleys represent basins of attraction toward these fates, and ridges represent barriers between them.

Formalizing the Landscape: Gradient Systems and Dynamics

In quantitative terms, the landscape is not merely a height function but a gradient system defined by both a potential function (F) and a Riemannian metric (G). The system's dynamics are given by the differential equation: ẋ = -Gâ»Â¹âˆ‡F [1]. Crucially, the metric G influences the paths cells take through the landscape (their differentiation trajectories) without altering the stable states themselves. This explains why cells with identical genetic potential can follow different developmental paths under different environmental conditions—a concept fundamental to regenerative processes where microenvironmental cues direct differentiation.

Decision Archetypes: Binary Fate Choices

Theoretical analysis reveals that binary cell fate decisions conform to a small number of archetypes. In a progenitor cell (state P) choosing between two successor fates (A and B), two primary decision mechanisms exist:

- All-or-Nothing Decision: Three attractors (P, A, B) are linearly arranged, with the precursor P situated between A and B. An inductive signal triggers a local bifurcation, eliminating the P basin and forcing cells to commit to either A or B [1]. The choice is determined by which saddle point collides with P during this landscape reshaping.

- Distributed Allocation: The P attractor is connected to both A and B via specific trajectories. Cells are distributed between fates A and B based on their initial positions within the P basin and noise-induced variability, without the progenitor state being eliminated [1].

These decision structures provide a classification scheme for cell fate decisions that is independent of the specific molecular details of the underlying GRNs, suggesting universal design principles in developmental systems.

Table 1: Fundamental Cell Fate Decision Archetypes

| Decision Archetype | Topological Structure | Key Dynamics | Developmental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| All-or-Nothing | Linearly arranged attractors (A-P-B) | Local bifurcation eliminates progenitor state | Signal-induced commitment; unidirectional differentiation |

| Distributed Allocation | Progenitor (P) basin connected to multiple fates | Initial conditions and noise determine fate proportion | Heterogeneous progenitor populations; stochastic fate choice |

Figure 1: Waddington Landscape Topology. Cell fates (A, B) as attractors connected via saddle points (S1, S2).

Quantitative Modeling of Epigenetic Landscapes

Computational Tools and Approaches

Translating the Waddington metaphor into predictive models requires specialized computational tools. NetLand is an open-source software designed for this purpose, enabling quantitative modeling and 3D visualization of Waddington's epigenetic landscape for GRNs of any complexity [3]. This tool facilitates the simulation of kinetic dynamics and allows researchers to explore stem cell differentiation and reprogramming scenarios in silico.

A Practical Workflow for Landscape Construction

A practicable analytical strategy has emerged for constructing quantitative landscape models from experimental data:

- Data Acquisition: Utilize single-cell expression data (e.g., from scRNA-seq) to capture transcriptional states of differentiating cells.

- State Space Reconstruction: Employ dimensionality reduction techniques to map single-cell data onto a low-dimensional state space.

- Potential Function Inference: Calculate a probabilistic potential from the data, which defines the topography of the Waddington landscape. This potential (U) relates to the probability density (P) of cells in state space by U(x) = -log P(x) [3].

- Trajectory and Decision Point Mapping: Identify attractors (cell states), saddles (decision points), and their connecting manifolds (differentiation trajectories) [1].

This approach is "dimension-agnostic," meaning it can infer landscape structure regardless of the original data's dimensionality, directly addressing the challenge posed by genome-wide profiling technologies [1].

Table 2: Key Signaling Molecules and Their Roles in Lung Development

| Molecule/Regulator | Functional Category | Role in Lung Development | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNMT1 | DNA Methyltransferase | Maintenance methylation; essential for early branching morphogenesis and proximal cell fate [4]. | Dnmt1 null mice: embryonic lethality by E11.0; branching defects in lung [4]. |

| TET2 | DNA Demethylase | Active demethylation; highly expressed in late murine lung development [4]. | Expression profiling during murine lung development [4]. |

| VEGF-A | Growth Factor | Vascular growth of cardiopulmonary system; regulated by promoter methylation [4]. | CpG island methylation in promoter in fetal distal lung epithelial cells [4]. |

| Apaf-1 | Apoptotic Factor | Embryonic morphogenesis; methylation regulates its expression [4]. | Methylation observed in human embryonic lung cells; inhibition upregulates expression [4]. |

The Experimentalist's Guide to Mapping Cell Fate Landscapes

Core Methodologies for Landscape Analysis

Mapping the epigenetic landscape in a developing or regenerating system requires the integration of specific experimental and computational methodologies.

- Single-Cell RNA Sequencing (scRNA-seq): This is the foundational technology for modern landscape reconstruction. It provides the high-resolution data on cellular heterogeneity needed to identify distinct cell states and transitional populations. The protocol involves: (1) tissue dissociation into a single-cell suspension; (2) capturing individual cells and barcoding their transcripts; (3) library preparation and sequencing; and (4) bioinformatic analysis to cluster cells by transcriptional similarity and order them along pseudotemporal trajectories.

- Live-Cell Imaging and Lineage Tracing: To validate predicted fate choices and dynamics, live imaging of fluorescent reporter cell lines is essential. This allows direct observation of a cell's journey through the landscape. Combined with inducible genetic lineage tracing, this methodology definitively maps the fate potential and outcomes of progenitor populations in their native tissue context.

- Perturbation Experiments: Testing landscape models requires perturbation of hypothesized key regulators (e.g., transcription factors, signaling molecules). This can be achieved via CRISPR-Cas9 knockout, RNAi knockdown, or small molecule inhibitors. A robust model should accurately predict how the landscape and cell fate probabilities shift in response to these perturbations.

Figure 2: Experimental Workflow for Landscape Mapping.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Landscape Studies

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Cell Fate Studies

| Research Reagent | Function in Experiment | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| SOX2 Antibodies [2] | Immunofluorescent detection and quantification of SOX2 protein, a core pluripotency factor. | Identifying and localizing pluripotent stem cells in culture or tissue sections during reprogramming. |

| OCT4/OCT3/4 Antibodies [2] | Marker for pluripotent state; essential for reprogramming to iPSCs. | Confirming the successful generation of induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs). |

| KLF4 Antibodies [2] | Detection of KLF4, one of the Yamanaka reprogramming factors. | Assessing expression levels of key transcription factors during cell fate conversion. |

| LIN28 Antibodies [2] | Marker for pluripotency; used in alternative reprogramming factor combinations. | Validating pluripotent stem cell identity via Western Blot (WB) analysis. |

| DNMT1 Inhibitors | Chemical perturbation of DNA methylation patterns. | Experimentally altering the epigenetic landscape to test its role in fate restriction. |

| 6-Methylnona-4,8-dien-2-one | 6-Methylnona-4,8-dien-2-one|Research Chemical | |

| 2,9-Dimethyldecanedinitrile | 2,9-Dimethyldecanedinitrile|C14H24N2|For Research | High-purity 2,9-Dimethyldecanedinitrile for research applications. This product is for laboratory research use only (RUO) and not for human use. |

Case Study: Epigenetic Landscapes in Lung Development

The developing lung serves as an exemplary model for applying the Waddington landscape framework to a complex, branching organ. Lung development involves the progressive differentiation of a foregut endodermal rudiment into numerous specialized epithelial, mesenchymal, and endothelial cell types [4].

DNA Methylation Directs Branching Morphogenesis

DNA methylation, mediated by DNMT1, plays a critical role in the branching morphogenesis of the lung. Dnmt1 deficiency in mouse models leads to severe developmental defects, including disrupted epithelial polarity, failed proximal endodermal specification, and premature differentiation of distal alveolar type 2 cells [4]. This demonstrates that the proper topographic structure of the landscape—specifically, the maintenance of progenitor valleys and the suppression of premature differentiation paths—requires DNMT1-mediated methylation. Furthermore, stage-specific methylation of promoters like VEGF-A and Apaf-1 ensures the correct temporal execution of vascular growth and morphogenetic programs [4].

Non-Coding RNAs as Landscape Modulators

Non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs), including microRNAs (miRNAs) and long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs), function as critical modulators of the epigenetic landscape during lung development [4]. They fine-tune the expression of key transcription factors and signaling components within the GRN, thereby shaping the slopes and valleys of the landscape and guiding cells through canalicular, saccular, and alveolar stages.

Implications and Future Directions in Regenerative Medicine

The quantitative reframing of Waddington's landscape has profound implications for regenerative medicine. First, it provides a conceptual and practical framework for reprogramming cell fates. The generation of induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) can be visualized as pushing a ball (a somatic cell) back up the landscape and over a high barrier to return it to the pluripotent plateau [2]. Similarly, trans-differentiation (direct conversion between somatic cell types) corresponds to moving a cell from one valley to another across a ridge, without first returning to the pluripotent state [2].

Future research must focus on several key challenges:

- Spatiotemporal Control: Can we manipulate epigenetic marks precisely in a spatiotemporal and locus-specific manner to sculpt desired landscape topographies? [4]

- Global Bifurcations: Most research has focused on local bifurcations. Understanding global bifurcations—which alter large-scale connection topology between states—will be crucial for comprehending complex reprogramming phenomena [1].

- Integration of Microenvironment: How do microenvironmental cues link to epigenetic alterations to reshape the local landscape within tissues? [4]

In conclusion, Waddington's landscape has evolved from a static metaphor into a dynamic, quantitative framework for understanding cellular decision-making. By integrating dynamical systems theory with high-resolution molecular data, this revisited landscape provides a powerful paradigm for guiding regenerative strategies, offering the promise of rationally directing cell fate for therapeutic purposes.

Epigenetics encompasses the study of heritable changes in gene function that occur without alteration to the underlying DNA sequence [5]. These dynamic and reversible modifications provide a crucial regulatory layer that controls gene expression patterns during development, in response to environmental cues, and in disease states [5] [6]. The three fundamental pillars of epigenetic regulation—DNA methylation, histone modifications, and non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs)—collectively establish the chromatin landscape that determines cellular identity and function [5] [7]. In the context of regenerative biology, epigenetic mechanisms assume particular significance as they orchestrate the complex processes of cellular reprogramming, differentiation, and tissue morphogenesis that enable remarkable regenerative capabilities in certain model organisms [8] [9].

Research in various regenerative model systems, including botryllid ascidians, zebrafish, and axolotl, has revealed that epigenetic regulation underpins the cellular plasticity necessary for whole-body regeneration [8] [9]. The dynamic interplay between DNA methylation, histone modifications, and ncRNAs establishes gene expression programs that guide the regeneration of complex structures from minimal cellular material [8]. Understanding these epigenetic mechanisms in highly regenerative organisms provides invaluable insights that may inform therapeutic strategies for enhancing regenerative capacity in humans and address the challenges of therapeutic resistance in diseases like cancer [7].

DNA Methylation: Establishment and Maintenance of Methylation Patterns

DNA methylation involves the covalent addition of a methyl group to the fifth carbon of cytosine bases, primarily within CpG dinucleotides in mammals, forming 5-methylcytosine (5mC) [5] [6]. This epigenetic mark is established and maintained by a family of DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs) with specialized functions [6]. DNMT3A and DNMT3B serve as de novo methyltransferases that initiate methylation patterns during embryonic development and gametogenesis, while DNMT1 functions as the maintenance methyltransferase that preserves methylation patterns during DNA replication [6]. DNMT3L, though catalytically inactive, acts as a crucial cofactor that stimulates de novo methylation by DNMT3A [6].

The interpretation of DNA methylation marks is mediated by methyl-CpG-binding domain proteins (MBD family), which recognize methylated DNA and recruit additional chromatin-modifying complexes such as histone deacetylases (HDACs) to reinforce transcriptional repression [6]. DNA methylation dynamics play pivotal roles in various biological processes, including transcriptional silencing, genomic imprinting, X-chromosome inactivation, and suppression of transposable elements [5] [6]. During spermatogenesis, for instance, male germ cells undergo waves of global DNA demethylation and remethylation, with precise regulation being essential for fertility [6].

Table 1: DNA Methyltransferases and Their Functions in Mammalian Systems

| Enzyme | Type | Primary Function | Consequence of Loss-of-Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNMT1 | Maintenance methyltransferase | Maintains methylation patterns during DNA replication | Apoptosis of germline stem cells; hypogonadism and meiotic arrest [6] |

| DNMT3A | De novo methyltransferase | Establishes new methylation patterns during development | Abnormal spermatogonial function [6] |

| DNMT3B | De novo methyltransferase | Establishes new methylation patterns during development | Fertility with no distinctive phenotype [6] |

| DNMT3C | De novo methyltransferase | Specialized for transposable element silencing | Severe defect in DNA repair and homologous chromosome synapsis during meiosis [6] |

| DNMT3L | Cofactor (catalytically inactive) | Stimulates de novo methylation by DNMT3A | Decrease in quiescent spermatogonial stem cells [6] |

The dynamic nature of DNA methylation is further regulated by TET (ten-eleven translocation) family enzymes, which catalyze the oxidation of 5mC to 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5hmC) and further derivatives, initiating DNA demethylation pathways [6]. This active demethylation process creates additional complexity in the epigenetic landscape and provides a mechanism for rapid changes in gene expression patterns in response to developmental and environmental signals.

Histone Modifications: The Histone Code and Chromatin States

Histone modifications represent a second fundamental pillar of epigenetic regulation, comprising post-translational chemical modifications to histone proteins that alter chromatin structure and function [7] [10]. These modifications include acetylation, methylation, phosphorylation, ubiquitination, and an expanding repertoire of newly discovered chemical groups such as crotonylation, succinylation, and 2-hydroxyisobutyrylation [7]. The combinatorial nature of these modifications has led to the "histone code" hypothesis, which proposes that specific combinations of histone modifications determine functional outcomes for associated genomic regions [10].

The establishment and interpretation of histone modifications are mediated by specialized classes of enzymes often categorized as "writers," "erasers," and "readers" [7]. Writers, such as histone acetyltransferases (HATs) and histone methyltransferases (HMTs), add modifying groups; erasers, including histone deacetylases (HDACs) and histone demethylases (KDMs), remove these modifications; and reader proteins containing specialized domains (e.g., bromodomains, chromodomains) recognize specific modifications and recruit effector complexes to execute downstream functions [7]. Different histone modifications are associated with distinct chromatin states and transcriptional outcomes as summarized in Table 2.

Table 2: Major Histone Modifications and Their Functional Associations

| Histone Modification | Chromatin Association | Transcriptional Correlation | Primary Genomic Locations |

|---|---|---|---|

| H3K4me3 | Active chromatin | Positive | Promoters of transcribed genes [10] |

| H3K4me1 | Primed/enhancer chromatin | Variable (enhancer activity) | Enhancer regions [10] |

| H3K27ac | Active chromatin | Positive | Active enhancers and promoters [10] |

| H3K27me3 | Facultative heterochromatin | Negative | Developmentally regulated gene promoters [10] |

| H3K9me3 | Constitutive heterochromatin | Negative | Repetitive elements, silent regions [7] |

| H3K36me3 | Active transcription | Positive | Gene bodies of actively transcribed genes [7] |

During embryonic development of the Pacific white shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei), specific histone modifications demonstrate dynamic changes that correlate with transcriptional states [10]. H3K4me3 marks promoters of actively transcribed genes, H3K4me1 identifies enhancer regions, H3K27ac distinguishes active enhancers and promoters, while H3K27me3 is associated with transcriptional repression of key developmental genes [10]. The balance between activating and repressing histone modifications changes progressively through developmental stages, reflecting the dynamic chromatin landscape that guides embryogenesis [10].

Non-Coding RNAs: Diverse Regulators of Epigenetic States

Non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs) constitute a heterogeneous class of RNA molecules that do not encode proteins but function as crucial regulators of gene expression at transcriptional and post-transcriptional levels [11] [7]. These molecules include microRNAs (miRNAs), long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs), piwi-interacting RNAs (piRNAs), circular RNAs (circRNAs), and various other subtypes that differ in length, structure, biogenesis, and mechanisms of action [11] [12]. The diverse functions of ncRNAs position them as integral components of the epigenetic regulatory network, with particular significance in fine-tuning gene expression patterns during development and disease [12].

ncRNAs participate in epigenetic regulation through multiple mechanisms. miRNAs, typically 20-22 nucleotides in length, primarily function by binding to complementary sequences in target mRNAs, leading to translational repression or mRNA degradation [12]. In T lymphocytes, specific miRNAs such as miR-21, miR-148a, and miR-155 show increased expression in autoimmune conditions, where they promote proinflammatory responses by regulating the abundance of DNA methyltransferases and signaling molecules [12]. Conversely, decreased expression of miR-146a, GAS5, and IL21AS1 is associated with aberrant epigenetic patterns in autoimmunity [12].

lncRNAs, generally defined as transcripts longer than 200 nucleotides, employ more diverse mechanisms including: serving as scaffolds for chromatin-modifying complexes; functioning as decoys that sequester transcription factors or miRNAs; guiding ribonucleoprotein complexes to specific genomic loci; and facilitating the formation of nuclear compartments [13] [12]. A notable example is Fos ecRNA (extra-coding RNA), which directly inhibits DNMT3A activity in neurons, leading to hypomethylation of the FOS gene and contributing to long-term fear memory formation [13]. This inhibition occurs through binding of Fos ecRNA to the tetramer interface of DNMT3A, modulating its activity in a manner that can be restored by interaction with DNMT3L [13].

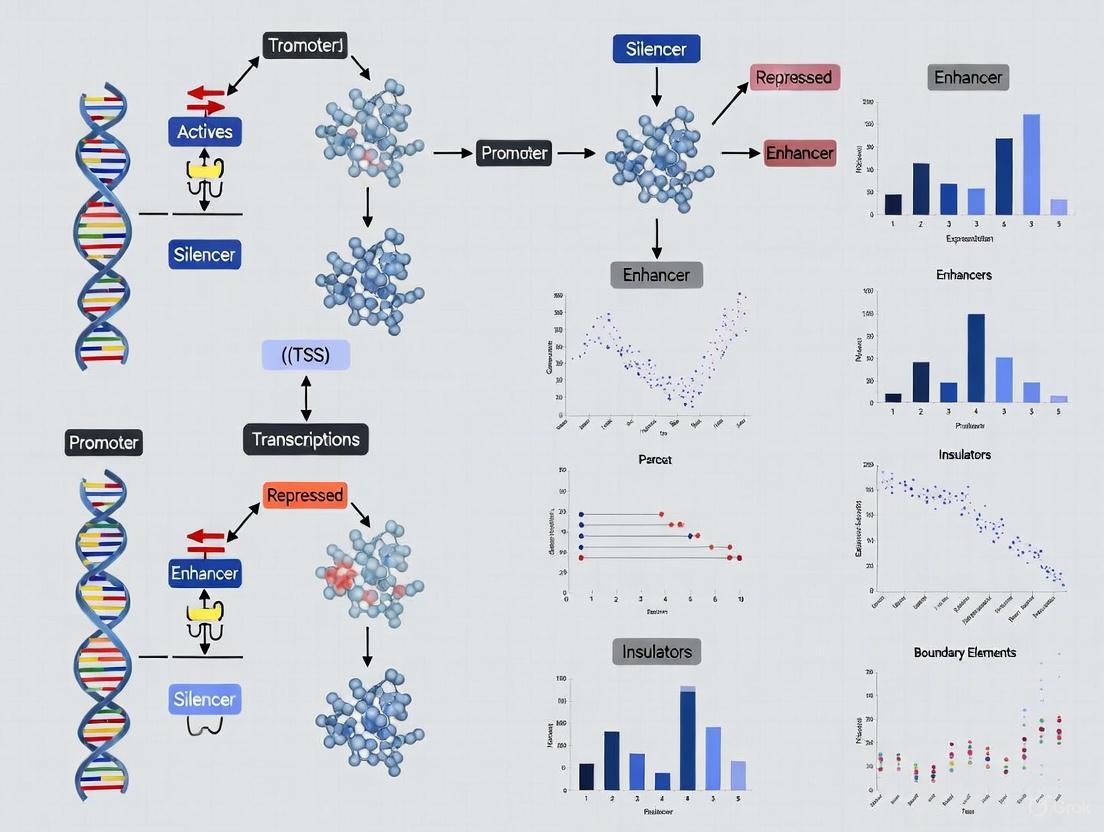

Figure 1: Non-Coding RNA Mechanisms in Epigenetic Regulation. ncRNAs regulate gene expression through diverse mechanisms including mRNA targeting, chromatin complex recruitment, and direct modulation of epigenetic enzymes.

Experimental Methods for Epigenetic Analysis

DNA Methylation Detection Methods

Bisulfite sequencing remains the gold standard technique for mapping DNA methylation patterns at single-nucleotide resolution [5]. This method relies on the selective deamination of unmethylated cytosines to uracils by sodium bisulfite treatment, while methylated cytosines remain protected from conversion [5]. Subsequent PCR amplification and sequencing reveal methylation status based on C-to-T transitions in the resulting sequences [5]. Various bisulfite-based approaches have been developed to address different research needs:

Whole-Genome Bisulfite Sequencing (WGBS) provides the most comprehensive analysis, covering nearly all CpG sites in the genome but requiring high sequencing depth and being resource-intensive [5]. Reduced Representation Bisulfite Sequencing (RRBS) offers a cost-effective alternative by using restriction enzymes to enrich for CpG-rich regions, making it suitable for large-cohort studies though with more limited genome coverage [5]. Ultrafast Bisulfite Sequencing (UBS-Seq) was developed to overcome limitations of conventional BS-seq, particularly DNA fragmentation and incomplete conversion issues [5].

Alternative methods include enzymatic methyl sequencing approaches that avoid bisulfite-induced DNA damage, and third-generation sequencing technologies (nanopore and SMRT sequencing) that enable direct detection of modified bases without chemical pretreatment [5]. The selection of an appropriate method depends on the specific research question, required resolution, genome coverage needs, and available resources.

Histone Modification Profiling Techniques

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation followed by sequencing (ChIP-seq) has been the traditional method for genome-wide mapping of histone modifications and transcription factor binding sites [10]. However, CUT&Tag (Cleavage Under Targets and Tagmentation) has emerged as a superior alternative with several advantages, including higher signal-to-noise ratio, greater sensitivity, reduced experimental time, and lower cell requirements [10]. The CUT&Tag method utilizes a protein A-Tn5 transposase fusion protein targeted to specific chromatin features by antibodies, enabling simultaneous cleavage and adapter incorporation specifically at sites of interest [10].

In practice, CUT&Tag has been successfully applied to profile histone modifications during embryonic development in the Pacific white shrimp, revealing dynamic changes in H3K4me1, H3K4me3, H3K27ac, and H3K27me3 patterns across developmental stages from blastula to nauplius [10]. This approach has provided insights into the epigenetic regulation of key developmental processes such as zygotic genome activation, molting, body segmentation, and neurogenesis [10].

Figure 2: CUT&Tag Workflow for Histone Modification Profiling. This method uses antibody-directed tagmentation for high-resolution mapping of histone marks.

Non-Coding RNA Analysis Methods

Comprehensive analysis of ncRNAs typically involves RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) approaches tailored to specific RNA classes. Small RNA sequencing specializes in capturing miRNAs and other small RNAs, while total RNA-seq or ribosomal RNA-depleted RNA-seq enables detection of lncRNAs and circRNAs [12]. Single-cell RNA sequencing provides resolution at the individual cell level, revealing cell-to-cell heterogeneity in ncRNA expression [12]. For functional studies, techniques such as single-molecule fluorescent in situ hybridization (smFISH) allow visualization of individual ncRNA transcripts within cells, providing spatial information about their expression and localization [13].

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Solutions for Epigenetic Studies

| Reagent Type | Specific Examples | Primary Applications | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Methylation-sensitive restriction enzymes | MspI (for RRBS) | Reduced Representation Bisulfite Sequencing | Enzyme specificity determines genomic coverage [5] |

| Anti-histone modification antibodies | Anti-H3K4me3, Anti-H3K27ac, Anti-H3K27me3 | ChIP-seq, CUT&Tag, immunostaining | Specificity validation is critical [10] |

| Bisulfite conversion kits | EZ DNA Methylation kits | Bisulfite sequencing | Conversion efficiency impacts data quality [5] |

| DNMT inhibitors | 5-azacytidine, decitabine | Functional studies of DNA methylation | Cytotoxicity and off-target effects [7] |

| HDAC inhibitors | Vorinostat, trichostatin A | Functional studies of histone acetylation | Pan-inhibitors vs. class-specific [7] |

| CUT&Tag kits | Hyperactive Universal CUT&Tag Assay Kit | Histone modification profiling | Cell number requirements (~50,000 nuclei) [10] |

Epigenetic Regulation in Regenerative Model Organisms

Regenerative model organisms exhibit extraordinary capabilities to regenerate complex tissues, organs, or entire bodies, processes governed by sophisticated epigenetic reprogramming [8] [9]. The colonial tunicate Botrylloides leachi, for example, demonstrates whole-body regeneration (WBR) from minute fragments of blood vessels, a process classified as Type 1 regeneration that relies on pluripotent adult stem cells and follows a somatic-embryogenesis mode of development [8]. This regenerative strategy contrasts with Type 2 regeneration seen in organisms like salamanders, which utilize fate-restricted stem cells and blastema-mediated regeneration [8].

Epigenetic mechanisms facilitate the cellular plasticity required for regeneration by enabling dramatic changes in gene expression programs. In botryllid ascidians, regeneration involves dynamic DNA methylation changes, histone modification shifts, and ncRNA activity that collectively reprogram somatic cells to regenerate entirely new organisms from vascular fragments [8]. Similarly, in zebrafish, epigenetic reprogramming enables the regeneration of complex structures like fins and heart tissue through the activation of developmental gene regulatory networks [9].

The comparison of regenerative capabilities across closely related species provides powerful insights into the epigenetic basis of regeneration. Studies comparing zebrafish and medaka, for instance, have revealed significant differences in regenerative potential despite their phylogenetic proximity, with variations in epigenetic regulation contributing to distinct regenerative outcomes [9]. Similarly, within tunicates, different species exhibit remarkably varied regenerative capacities despite shared ancestry, suggesting frequent evolutionary gains and losses of regenerative ability linked to changes in epigenetic regulation [9].

The integrated activities of DNA methylation, histone modifications, and non-coding RNAs establish the complex epigenetic landscape that governs gene expression patterns during development, tissue homeostasis, and regeneration. Continued advances in epigenetic technologies—including improved bisulfite sequencing methods, CUT&Tag for histone modification profiling, and single-cell multi-omics approaches—are providing unprecedented resolution for studying these dynamic processes [5] [10].

In regenerative biology, future research should prioritize comparative studies across regenerative models to identify conserved epigenetic modules that enable exceptional regenerative capabilities [9]. The integration of multi-omics datasets through computational approaches and artificial intelligence will be essential for deciphering the complex interactions between different epigenetic layers [5] [7]. Furthermore, translating insights from highly regenerative organisms to mammalian systems holds promise for developing novel therapeutic strategies that enhance regenerative capacity in humans, potentially addressing conditions such as tissue damage, degenerative diseases, and aging [8] [9].

As epigenetic editing technologies such as CRISPR-based systems continue to advance, researchers will gain increasingly precise tools for manipulating the epigenetic landscape to probe functional relationships and potentially direct regenerative outcomes [5]. These approaches, combined with a deeper understanding of natural epigenetic variation across regenerative models, will accelerate progress toward harnessing epigenetic mechanisms for therapeutic applications in regenerative medicine.

The enduring regenerative capacity of model organisms is governed by robust epigenetic mechanisms that establish and maintain defined cellular states. This whitepaper explores the concept of epigenetic attractors—stable, self-reinforcing states within the epigenetic landscape that lock cells into specific fates during regeneration. We provide a comprehensive analysis of the core epigenetic modifications that constitute these attractors, summarize quantitative data on their dynamics, detail experimental protocols for their interrogation, and visualize the complex regulatory networks. Understanding these principles is paramount for developing novel regenerative and anti-cancer therapies aimed at reprogramming cellular identities.

The term "epigenetic landscape" was introduced by Conrad Hal Waddington in the 1940s as a visual metaphor for cellular differentiation during embryonic development [14]. In this metaphor, a cell is represented by a marble rolling down a rugged hillside towards its final fate, with the valleys symbolizing distinct, stable cellular states [15]. The modern interpretation of this landscape is shaped by molecular processes that confer cellular memory, enabling the inheritance of gene expression patterns without changes to the DNA sequence itself [16]. These processes include DNA methylation, histone modifications, and non-coding RNA activity [7] [15].

In the context of regenerative model organisms, this landscape is exceptionally plastic, allowing for the dedifferentiation and reprogramming of cells to replace lost or damaged tissues. Epigenetic attractors are the deep, stable valleys in this landscape that represent terminal cell fates, such as being a hepatocyte or a neuron. Regeneration requires a controlled destabilization of these attractors and a guided transition to new ones. Dysregulation of these same mechanisms, particularly the stability of these attractor states, is a hallmark of cancer, where cells become trapped in a pathological, proliferative state [7]. The following sections dissect the molecular components that define these attractors and provide a toolkit for their experimental manipulation.

Core Molecular Mechanisms of Epigenetic Attractors

Epigenetic attractors are established and maintained by a complex, self-reinforcing network of molecular regulators. These modifications are dynamically added and removed by specialized enzymes, often termed "writers," "erasers," and "readers" [7].

DNA Methylation and Hydroxymethylation

DNA methylation involves the addition of a methyl group to the 5-carbon of cytosine, primarily in CpG dinucleotides, forming 5-methylcytosine (5mC). This modification typically leads to transcriptional repression by recruiting proteins that promote chromatin compaction [7]. In regenerative contexts and the brain, 5mC can be oxidized to 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5hmC) by the TET family of enzymes. 5hmC is often associated with active gene expression and is a key intermediate in DNA demethylation pathways [15]. This active demethylation process is crucial for the dramatic epigenetic reprogramming required for regeneration.

Histone Post-Translational Modifications

Histones are subject to a wide array of reversible chemical modifications, including acetylation, methylation, phosphorylation, and ubiquitination. These modifications alter chromatin structure and serve as docking sites for other regulatory proteins [7].

- Histone Acetylation: Generally associated with open, transcriptionally active chromatin.

- Histone Methylation: Can be associated with either activation or repression, depending on the specific lysine residue methylated and the degree of methylation (e.g., H3K4me3 for activation, H3K27me3 for repression). More novel modifications, such as citrullination, crotonylation, and succinylation, are continually being discovered and linked to specific biological processes and disease states [7].

Non-Coding RNAs and RNA Modifications

Non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs), including microRNAs (miRNAs) and long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs), are pivotal regulators of epigenetic states. They can guide chromatin-modifying complexes to specific genomic loci to silence or activate genes [7] [16]. Furthermore, chemical modifications to RNA itself, such as N6-methyladenosine (m6A), influence RNA stability, translation, and are critically involved in cell fate decisions and cancer progression [7].

Quantitative Profiling of Epigenetic Modifications

A comprehensive understanding of epigenetic attractors requires quantitative data on the prevalence and dynamics of these modifications. The following tables summarize key quantitative aspects relevant to regenerative studies.

Table 1: Common DNA Methylation and Hydroxymethylation Levels in Mammalian Tissues

| Tissue/Cell Type | Average % 5mC (CpG context) | Average % 5hmC (CpG context) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Embryonic Stem Cells | 70-80% | 0.1-0.2% | Dynamic, low 5hmC |

| Adult Liver | ~80% | 0.3-0.5% | Stable, differentiated state |

| Adult Brain | ~70% | 0.5-1.5% | Highest 5hmC levels in body |

| Hepatocellular Carcinoma | Highly Variable (Global hypomethylation) | Often Reduced | Loss of attractor stability |

Table 2: Key Histone Modifications and Their Functional Correlates

| Histone Mark | Common Function/Association | Enzymes (Writers/Erasers) |

|---|---|---|

| H3K4me3 | Active gene promoters | COMPASS complex / LSD1, KDM5B |

| H3K27ac | Active enhancers | p300/CBP / HDAC1-3 |

| H3K36me3 | Actively transcribed gene bodies | SETD2 / - |

| H3K27me3 | Facultative heterochromatin, gene repression | PRC2 / KDM6A (UTX), KDM6B |

| H3K9me3 | Constitutive heterochromatin | SUV39H1/2 / - |

Experimental Protocols for Mapping Epigenetic States

To define epigenetic attractors, researchers must profile the genomic distribution of various modifications. Below are detailed protocols for key methodologies.

Whole-Genome Bisulfite Sequencing (WGBS) for 5mC Detection

Principle: Bisulfite treatment converts unmethylated cytosines to uracils (read as thymines in sequencing), while methylated cytosines remain unchanged. This allows for single-base resolution mapping of 5mC [15].

Protocol:

- DNA Extraction: Isolate high-molecular-weight genomic DNA from target tissues (e.g., regenerating limb, liver).

- DNA Fragmentation: Shear DNA to ~200-300 bp fragments via sonication.

- Bisulfite Conversion: Treat fragmented DNA with sodium bisulfite using a commercial kit (e.g., EZ DNA Methylation-Lightning Kit). Optimize incubation time and temperature to ensure complete conversion while minimizing DNA degradation.

- Library Preparation & Sequencing: Prepare a sequencing library from the converted DNA using adapters compatible with your sequencing platform (e.g., Illumina). Amplify and sequence to a minimum coverage of 30x.

- Bioinformatic Analysis: Align sequences to a bisulfite-converted reference genome using tools like Bismark or BSMAP. Calculate methylation percentage for each cytosine.

Oxidative Bisulfite Sequencing (oxBS-seq) for 5hmC Detection

Principle: This method combines bisulfite treatment with selective chemical oxidation of 5hmC to 5-formylcytosine (5fC), which is then converted to uracil by bisulfite. Comparing standard BS-seq (detects 5mC+5hmC) to oxBS-seq (detects only 5mC) allows precise quantification of 5hmC [15].

Protocol:

- Split Sample: Divide the same fragmented genomic DNA sample into two aliquots.

- Oxidation Reaction: Treat one aliquot with potassium perruthenate (KRuO~4~) to oxidize 5hmC to 5fC. The second aliquot is an untreated control.

- Bisulfite Conversion: Subject both aliquots to standard bisulfite treatment.

- Library Prep & Sequencing: Process both libraries independently and sequence.

- Bioinformatic Analysis: Align reads from both libraries. The subtraction of methylation levels in the oxBS-seq dataset from the BS-seq dataset yields the 5hmC level at each base.

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation Sequencing (ChIP-seq)

Principle: Antibodies specific to a histone modification (e.g., H3K27ac) or chromatin-associated protein are used to immunoprecipitate cross-linked DNA-protein complexes. The associated DNA is then sequenced to map the binding sites or modification patterns genome-wide.

Protocol:

- Cross-linking: Treat cells or tissue with 1% formaldehyde for 10 minutes at room temperature to cross-link proteins to DNA.

- Chromatin Shearing: Lyse cells and sonicate chromatin to fragments of 200-600 bp.

- Immunoprecipitation: Incubate chromatin with a validated, specific antibody. Use Protein A/G beads to capture the antibody-chromatin complex.

- Washing & Elution: Wash beads stringently to remove non-specific binding. Elute the immunoprecipitated chromatin.

- Reverse Cross-linking & Purification: Heat eluate to reverse cross-links and digest proteins with Proteinase K. Purify the DNA.

- Library Prep & Sequencing: Prepare a sequencing library from the purified DNA.

Visualizing Regulatory Networks and Workflows

The following diagrams, generated using DOT language, illustrate the core concepts and experimental workflows described in this whitepaper.

Diagram 1: A simplified view of the Waddington landscape, depicting stable attractor states (cell fates) and the key molecular mechanisms that reinforce them.

Diagram 2: A proposed experimental workflow for profiling and validating dynamic changes to the epigenetic landscape during regeneration in model organisms.

The following table details key reagents and tools essential for experimental research in epigenetic regulation of regeneration and cell fate.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Epigenetic Studies

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Example Specifics |

|---|---|---|

| TET Enzyme Inhibitors (e.g., Bobcat339) | Selectively inhibits TET1, reducing 5hmC production. Used to probe the functional role of active DNA demethylation in reprogramming. | Cell-permeable small molecule. |

| DNMT Inhibitors (e.g., 5-Azacytidine, Decitabine) | Incorporate into DNA and inhibit DNMT1, causing global DNA hypomethylation. Used to test stability of epigenetic attractors. | Used in clinical oncology and research. |

| BET Bromodomain Inhibitors (e.g., JQ1) | Displaces "reader" proteins from acetylated histones, disrupting enhancer-driven gene expression programs. | Useful for studying super-enhancers in cell identity. |

| Validated ChIP-grade Antibodies | Essential for specific and efficient pull-down in ChIP-seq experiments for histone marks (e.g., H3K27ac, H3K4me3, H3K27me3). | Critical to use validated antibodies (e.g., from CIP, Diagenode). |

| Bisulfite Conversion Kits | High-efficiency conversion of unmethylated cytosine for downstream sequencing (WGBS). | EZ DNA Methylation series (Zymo Research). |

| Single-Cell Multi-omics Platforms | Allows simultaneous profiling of chromatin accessibility (scATAC-seq), DNA methylation (scBS-seq), and transcriptome (scRNA-seq) from the same cell. | 10x Genomics Multiome, other emerging technologies. |

The remarkable regenerative capabilities of model organisms such as axolotls, zebrafish, and planarians provide a fundamental window into the cellular processes that could revolutionize regenerative medicine. Underpinning these complex morphological transformations is the epigenetic landscape, a dynamic regulatory layer that controls gene expression without altering the underlying DNA sequence. Characterization of this epigenome provides the essential baseline for discerning the regulatory mechanisms that enable regeneration, a process that declines with age in mammals. This whitepaper details the core techniques and methodologies for profiling the foundational epigenetic state, with a specific focus on DNA methylation, the most common epigenetic modification in both prokaryotic and eukaryotic genomes. A precise understanding of these baseline states is the critical first step in developing potential therapeutic applications for human tissue repair and age-related regenerative decline [17] [18].

Quantitative Profiling of Global DNA Methylation

While sequencing techniques can map methylation sites to specific genomic locations, global methylome analysis provides a rapid, cost-effective, and quantitative overview of the total methylation burden in a sample. This approach is invaluable for initial screenings and comparing multiple samples or conditions before undertaking more resource-intensive sequencing projects [19] [20].

Mass Spectrometry-Based Quantification

Liquid chromatography coupled with high-resolution mass spectrometry (LC-MS) enables the direct, sensitive, and absolute quantification of methylated nucleobases independent of their sequence context. A recently established method using acid hydrolysis with hydrochloric acid (HCl) offers a robust alternative to enzymatic digestion, which can be inefficient for highly methylated DNA [19].

Table 1: Key Steps in Acid Hydrolysis and UHPLC-HRMS for Global DNA Methylation Analysis [19]

| Step | Description | Key Parameters |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Hydrolysis | Chemical breakdown of DNA into individual nucleobases using HCl. | Avoids formic acid to prevent formylated side-products; superior for highly methylated DNA. |

| Chromatography | Separation of hydrolyzed products via Ultra-High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (UHPLC). | Enables resolution of 5-methylcytosine (5mC), 6-methyl adenine (6mA), and their unmodified counterparts. |

| Detection & Quantification | Analysis using High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry (HRMS) with an Orbitrap mass analyzer. | Provides high sensitivity and accuracy; allows for absolute quantification using internal standards. |

| Data Analysis | Calculation of the global degree of methylation. | Uncomplicated analysis facilitates quick comparison across biological contexts. |

This method has been successfully applied in a proof-of-principle study to identify changes in methylation signatures in the marine macroalga Ulva mutabilis, demonstrating its utility in ecological and developmental epigenetics [19].

Comparison with Sequencing-Based Techniques

The choice between global quantification and sequencing depends on the research question. The table below summarizes the core differences.

Table 2: Comparison of DNA Methylation Analysis Techniques [19]

| Feature | Global Analysis (UHPLC-HRMS) | Bisulfite Sequencing | Long-Read Sequencing (SMRT, Nanopore) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Information | Quantitative data on the overall degree of methylation. | Location of 5mC in a genomic context. | Indirect detection of multiple DNA modifications in a genomic context. |

| Throughput | Rapid, high-throughput. | Time-consuming. | Time-consuming. |

| Cost | Cost-efficient. | Expensive. | Expensive. |

| DNA Amount | Requires only small amounts of DNA. | Requires more DNA. | Requires high amounts of high-quality DNA. |

| Bioinformatics | Not dependent on lengthy bioinformatic analyses. | Relies on complex bioinformatic data analysis. | Requires complex bioinformatic data analysis. |

| Key Limitation | No locus-specific information. | Harsh conditions; misidentification of 4mC. | Relies on databases for known modifications; challenging for novel modifications. |

Experimental Protocol: Acid Hydrolysis and UHPLC-HRMS

The following section provides a detailed methodology for the quantitative analysis of global DNA methylation, based on the protocol established for profiling the methylome of Ulva mutabilis [19].

Reagents and Equipment

- Analytical Standards: Cytosine, 5-methylcytosine, 2ˈ-deoxycytidine, 2ˈ-deoxy-5-methylcytidine. Internal standards: 2ˈ-deoxycytidine-13C1,15N2 and 2ˈ-deoxy-5-methylcytidine-13C1,15N2.

- DNA Standards: Commercially available DNA with 100% unmodified or methylated cytosines for calibration and validation.

- Hydrolysis Agent: Hydrochloric acid (HCl).

- Instrumentation: Ultra-High-Performance Liquid Chromatography system coupled to a High-Resolution Mass Spectrometer equipped with an Orbitrap mass analyzer.

Step-by-Step Procedure

- DNA Preparation: Extract and purify genomic DNA from the target model organism (e.g., regenerating tissue from axolotl or zebrafish) using a standard phenol-chloroform protocol or commercial kit. Determine DNA concentration and purity via spectrophotometry.

- Acid Hydrolysis:

- Aliquot a defined amount of DNA (e.g., 100-500 ng) into a hydrolysis-resistant vial.

- Add a specific volume of HCl to achieve optimal hydrolysis conditions (e.g., 2M HCl at 100°C for 30 minutes). Note: Conditions must be optimized for different sample types.

- After hydrolysis, neutralize the reaction and centrifuge to remove any precipitate.

- UHPLC-HRMS Analysis:

- Inject the hydrolyzed sample into the UHPLC system.

- Chromatography: Use a reverse-phase C18 column. Employ a water-methanol or water-acetonitrile gradient with a volatile buffer (e.g., formic acid or ammonium acetate) to separate the nucleobases.

- Mass Spectrometry: Operate the HRMS in positive electrospray ionization (ESI+) mode. Set the Orbitrap mass analyzer to a high resolution (e.g., >60,000 FWHM) for accurate mass detection. Use Selected Ion Monitoring (SIM) or parallel reaction monitoring (PRM) for high sensitivity quantification of the target masses: cytosine (111.0553 m/z) and 5-methylcytosine (125.0709 m/z).

- Quantification and Data Analysis:

- Use calibration curves generated from the analytical standards for absolute quantification.

- Employ stable isotope-labeled internal standards (e.g., 2ˈ-deoxycytidine-13C1,15N2) to correct for sample loss and matrix effects during analysis.

- Calculate the global DNA methylation percentage as:

[5mC / (5mC + C)] × 100.

The following workflow diagram illustrates the complete experimental and analytical process.

Emerging Paradigms: Sequence-Driven DNA Methylation

A groundbreaking study using the plant model Arabidopsis thaliana has revealed a paradigm shift in understanding the origins of epigenetic patterns. While it was previously understood that DNA methylation is regulated by pre-existing epigenetic features, this research discovered a new mode of targeting driven by genetic sequences themselves [18].

Specific transcription factors, named RIMs (a subset of REPRODUCTIVE MERISTEM proteins), were found to dock at specific DNA sequences and recruit the CLASSY3 protein to establish new DNA methylation patterns in reproductive tissues. This finding that the DNA itself can instruct de novo methylation provides a crucial mechanistic insight into how novel epigenetic patterns can arise during development and regeneration, opening new paths for precise epigenetic engineering [18].

The following diagram illustrates this novel mechanism for establishing new DNA methylation patterns.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

This table details key reagents and materials essential for conducting the epigenetic profiling experiments described in this guide.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Epigenomic Profiling

| Item | Function / Application | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Methylation Standards | Absolute quantification via calibration curves. | Cytosine, 5-methylcytosine, 2ˈ-deoxy-5-methylcytidine (Zymo Research) [19]. |

| Isotope-Labeled Internal Standards | Correct for sample loss and matrix effects in MS. | 2ˈ-deoxycytidine-13C1,15N2; 2ˈ-deoxy-5-methylcytidine-13C1,15N2 (Toronto Research Chemicals) [19]. |

| Control DNA | Method validation and quality control. | DNA with 100% unmodified or methylated cytosines [19]. |

| UHPLC-HRMS System | Separation and highly sensitive detection of nucleobases. | System equipped with Orbitrap mass analyzer for high mass accuracy [19]. |

| CLASSY & RIM Protein Antibodies | Investigating novel DNA methylation targeting mechanisms. | For immunoprecipitation or imaging in plant and cross-species studies [18]. |

| Model Organism Resources | Source for biologically relevant study systems. | Axolotl, zebrafish, planarians, Ulva mutabilis, Arabidopsis thaliana [19] [17] [18]. |

| 1-tert-Butoxyoctan-2-ol | 1-tert-Butoxyoctan-2-ol, CAS:86108-32-9, MF:C12H26O2, MW:202.33 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 3-Methylfluoranthen-8-OL | 3-Methylfluoranthen-8-OL | 3-Methylfluoranthen-8-OL is a high-purity fluoranthene derivative for research applications. This product is for Research Use Only (RUO). Not for human or veterinary use. |

The comprehensive characterization of the epigenome in regenerative model organisms demands a multifaceted analytical approach. While sequencing technologies provide invaluable locus-specific information, mass spectrometry-based global methylome analysis offers an indispensable tool for rapid, quantitative, and cost-effective profiling. The recent discovery of sequence-driven DNA methylation further enriches our understanding of how these patterns originate. Together, these methodologies and insights form a robust foundation for profiling the baseline epigenetic state, a critical prerequisite for unlocking the mechanisms that govern regeneration and for informing future epigenetic engineering strategies with profound implications for medicine and agriculture.

Decoding the Regenerative Code: Advanced Profiling and Intervention Techniques

Regenerative biology seeks to understand the remarkable capacity of certain organisms to restructure damaged or worn-out organs and tissues. Central to processes like blastema formation in axolotls and transdifferentiation in zebrafish is a substantial reprogramming of the epigenome, which modifies local genome activity without changing the underlying DNA sequence [21] [22]. This epigenetic reprogramming enables dedifferentiated cells to regain developmental plasticity, a fundamental requirement for restoring complex structures [21]. To unravel these dynamics, researchers rely on powerful epigenomic tools that map the regulatory landscape of cells. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical guide to three cornerstone technologies—ATAC-seq, ChIP-seq, and Whole-Genome Bisulfite Sequencing—framed within the context of discovering the epigenetic basis of regeneration.

Assay for Transposase-Accessible Chromatin with Sequencing (ATAC-seq)

2.1.1 Principle and Applications ATAC-seq identifies regions of open, accessible chromatin genome-wide, which typically correspond to active regulatory elements such as enhancers and promoters [23]. During regenerative processes, such as limb or heart regeneration, chromatin accessibility must be dynamically altered to activate embryonic gene programs; ATAC-seq is the premier tool for profiling these changes [24].

2.1.2 Detailed Experimental Protocol The ATAC-seq protocol is renowned for its simplicity and low cell number requirements [23].

- Nuclei Isolation: Cells or tissues are homogenized, and nuclei are isolated and collected. Critical note: For tissues involved in regeneration (e.g., blastemas), careful dissociation is required to obtain a clean nuclear preparation.

- Tagmentation: The purified nuclei are incubated with the Tn5 transposase, which has been pre-loaded with sequencing adapters. The Tn5 enzyme simultaneously fragments accessible DNA and ligates the adapters in a single "tagmentation" step. The tightly packed nucleosomal DNA is inaccessible to Tn5, whereas DNA in open chromatin regions is preferentially fragmented and tagged [23].

- Purification and Amplification: The tagmented DNA is purified, and PCR is performed with barcoded primers to create the final sequencing library.

- Sequencing and Analysis: The libraries are sequenced on a high-throughput platform. Subsequent bioinformatic analysis identifies peaks of signal, which correspond to regions of open chromatin.

The key innovation of ATAC-seq lies in the use of the hyperactive Tn5 transposase, which streamlines library preparation into an efficient two-step process [23]. It is crucial to acknowledge that Tn5 transposase exhibits sequence-dependent binding bias, though computational tools have been developed for correction [23].

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation with Sequencing (ChIP-seq)

2.2.1 Principle and Applications ChIP-seq directly identifies the genomic binding sites of specific DNA-associated proteins, such as transcription factors (TFs) or histone modifications with specific chemical marks (e.g., H3K27ac) [23] [25]. In regeneration research, it is used to pinpoint how key transcription factors bind to regeneration enhancer elements or how histone modifications are reprogrammed to facilitate gene expression changes during dedifferentiation [26].

2.2.2 Detailed Experimental Protocol The traditional ChIP-seq technique is a multi-step process designed to capture DNA bound to specific proteins [23].

- Cross-linking: DNA and proteins are cross-linked in situ using formaldehyde to fix their interactions.

- Chromatin Fragmentation: The cross-linked chromatin is fragmented, typically via sonication, into small fragments of 200–600 base pairs.

- Immunoprecipitation: An antibody specific to the protein or histone mark of interest is used to pull down the DNA-protein complexes. This step is critical and requires a high-quality, validated antibody to ensure specificity.

- Reversal of Cross-linking and Purification: The immunoprecipitated complexes are de-crosslinked, and the bound DNA is purified.

- Library Preparation and Sequencing: The released DNA undergoes standard library preparation steps (end repair, adapter ligation) and is sequenced [23] [25].

A key experimental control is the use of 'input DNA'—non-immunoprecipitated, fragmented genomic DNA—which helps identify and adjust for sequencing biases [25]. A limitation of traditional ChIP-seq is its requirement for a considerable number of cells (10^5 to 10^7), which can be a hurdle when working with limited blastema material. However, low-cell-number and single-cell methods (e.g., scChIP-seq, ULI-NChIP) have been developed to overcome this [23].

Whole-Genome Bisulfite Sequencing (WGBS)

2.3.1 Principle and Applications WGBS is the gold-standard method for profiling DNA methylation at single-base-pair resolution across the entire genome [22]. It is based on the differential sensitivity of cytosines to bisulfite conversion. DNA methylation is a key epigenetic mark involved in cell fate commitment, and its large-scale reprogramming is a hallmark of regenerative processes [21] [24]. WGBS can reveal these genome-wide methylation dynamics.

2.3.2 Detailed Experimental Protocol The WGBS protocol hinges on the chemical conversion of DNA by sodium bisulfite [22] [25].

- DNA Extraction and Fragmentation: Genomic DNA is isolated and fragmented.

- Bisulfite Conversion: The DNA is treated with sodium bisulfite. This chemical reaction converts unmethylated cytosines to uracil by deamination, while methylated cytosines (5-methylcytosine) remain unconverted.

- Purification and Amplification: The bisulfite-treated DNA is purified. During subsequent PCR amplification, uracil residues are converted to thymine.

- Sequencing and Analysis: The resulting library is sequenced. By comparing the resulting sequence to the original genomic reference, researchers can identify cytosines that were protected from conversion (methylated) versus those that were converted to thymine (unmethylated) [22].

A significant challenge is the reduced sequence complexity after bisulfite conversion, which complicates read alignment. Furthermore, standard bisulfite treatment cannot distinguish between 5mC and its oxidation derivative 5hmC; specialized protocols like OxBS-seq or TAB-seq are required for this discrimination [22].

Comparative Analysis of Epigenomic Technologies

The selection of an appropriate epigenomic toolkit depends on the research question, experimental constraints, and desired outcomes. The table below provides a direct comparison of the three core technologies.

Table 1: Comparative overview of ATAC-seq, ChIP-seq, and Whole-Genome Bisulfite Sequencing

| Parameter | ATAC-seq | ChIP-seq | Whole-Genome Bisulfite Sequencing (WGBS) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Application | Mapping open chromatin regions, nucleosome positioning, and inference of transcription factor binding [23] | Direct identification of specific DNA-protein interactions (Transcription Factors, Histone Modifications) [23] | Genome-wide profiling of DNA methylation at single-base resolution [22] |

| Key Output | Genome-wide accessibility landscape (peaks) | Genome-wide binding sites for protein of interest (peaks) | Methylation status of each cytosine in context (e.g., CpG) |

| Resolution | ~ single-base (for footprinting) to nucleosome-scale | Defined by antibody and peak-calling, typically 100-1000 bp | Single-base pair [22] |

| Sample Input | Low (500–5,000 cells) [23] | High (10âµâ€“10â· cells for standard protocol) [23] | Varies; can be performed on low-input samples with optimization [22] |

| Protocol Duration | Fast (~1 day) | Lengthy (3-5 days) | Moderate, bisulfite conversion step is time-sensitive |

| Key Strengths | Simple protocol, low input, identifies multiple chromatin features simultaneously | Direct measurement of specific protein-DNA interactions, well-established | Gold standard for methylation, provides comprehensive, unbiased coverage |

| Key Limitations | Sequence bias of Tn5 transposase, indirect inference of TF binding | Antibody-dependent quality and specificity, high cell input required | High cost, complex data analysis, DNA degradation during conversion [22] |

The Power of Multi-Omic Integration

While each technology is powerful alone, combining them provides a more comprehensive and profound understanding of the chromatin regulatory landscape during regeneration [23]. For instance:

- ATAC-seq + ChIP-seq: ATAC-seq can identify differentially accessible enhancers in a regenerating tissue. Subsequent ChIP-seq for specific histone marks (e.g., H3K27ac) or transcription factors can validate and functionally annotate these regions, confirming their active status and revealing which TFs drive the regenerative gene program [23].

- ATAC-seq/WGBS + RNA-seq: Integrating chromatin accessibility or DNA methylation data with transcriptomic profiles (RNA-seq) allows researchers to directly link regulatory changes to the expression of key regeneration genes.

Public data-mining suites like ChIP-Atlas 3.0 are invaluable resources for such integrative analyses. This platform provides pre-analyzed data from over 376,000 public ChIP-seq, ATAC-seq, and other epigenomic experiments, allowing researchers to explore and overlay these datasets with regulatory elements and genetic variants [27]. Furthermore, specialized databases like the Regeneration Roadmap systematically collect high-throughput sequencing data from regeneration experiments across multiple species and tissues, providing a dedicated resource for the field [26].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful execution of epigenomic assays requires careful selection of critical reagents. The following table details essential materials and their functions.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Epigenomic Workflows

| Reagent / Material | Function | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Tn5 Transposase | Enzyme that fragments accessible DNA and ligates sequencing adapters in ATAC-seq [23]. | Hyperactive form is standard; commercial kits ensure high activity. Exhibits sequence bias that may require computational correction [23]. |

| Specific Antibodies | Binds and immunoprecipitates the target protein or histone modification in ChIP-seq [23] [25]. | The most critical factor for ChIP-seq quality. Must be validated for ChIP-seq application, with high specificity and immunoprecipitation efficiency. |

| Sodium Bisulfite | Chemical agent that deaminates unmethylated cytosine to uracil in WGBS, enabling methylation detection [22] [25]. | Reaction conditions must be optimized to ensure complete conversion while minimizing DNA degradation. Commercial kits are widely used. |

| Cellular Barcodes | Short DNA sequences used to label individual cells or nuclei in single-cell protocols. | Enables pooling of samples, reducing batch effects and costs. Essential for single-cell epigenomic applications (scATAC-seq, scChIP-seq). |

| Methylation Controls | DNA with known methylation status. | Used as a positive control to monitor the efficiency and completeness of the bisulfite conversion reaction. |

| 1-Octen-4-ol, 2-bromo- | 1-Octen-4-ol, 2-bromo-, CAS:83650-02-6, MF:C8H15BrO, MW:207.11 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 2-Cyano-2-phenylpropanamide | 2-Cyano-2-phenylpropanamide | High-purity 2-Cyano-2-phenylpropanamide for life sciences research. This product is For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

ATAC-seq, ChIP-seq, and Whole-Genome Bisulfite Sequencing form an indispensable toolkit for deconstructing the epigenetic logic of regeneration. By mapping chromatin accessibility, protein-DNA interactions, and DNA methylation, these technologies allow researchers to move beyond correlation toward mechanistic insights into how epigenetic reprogramming controls cellular plasticity and tissue restoration. As the field advances, the integration of these datasets, supported by public resources and the development of low-input methods, will be pivotal for translating discoveries from highly regenerative models into novel therapeutic paradigms for regenerative medicine.

Regenerative biology seeks to understand the remarkable capacity of certain organisms to repair and replace damaged tissues, a process governed not by changes in the DNA sequence itself, but by dynamic epigenetic reprogramming. Single-cell epigenomics has emerged as a transformative approach for deconstructing the heterogeneity of regenerating tissues, enabling researchers to map the regulatory landscapes of individual cells as they transition through states of quiescence, activation, proliferation, and differentiation. This technical guide explores how modern single-cell technologies are illuminating the epigenomic principles underlying regeneration, with profound implications for therapeutic development in regenerative medicine. Unlike bulk sequencing methods that average signals across cell populations, single-cell epigenomic methods capture the nuanced variation between cells, revealing rare progenitor populations, transient intermediate states, and divergent lineage trajectories that would otherwise be obscured [28]. The integration of these tools with spatial transcriptomics and computational modeling is creating an unprecedented view of how cellular identity is reprogrammed during tissue repair, offering new paradigms for understanding the epigenetic circuitry that controls regenerative capacity.

Technological Foundations of Single-Cell Epigenomics

Core Methodological Approaches

The study of epigenomics at single-cell resolution requires specialized methodologies capable of capturing different layers of epigenetic regulation from limited input material. Several powerful approaches have been developed, each focusing on distinct epigenetic features and offering unique insights into the regulatory architecture of individual cells.

Table 1: Core Single-Cell Epigenomic Technologies

| Technology | Target Epigenetic Feature | Key Principle | Resolution | Applications in Regeneration |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| scATAC-seq | Chromatin accessibility | Tn5 transposase integration into open chromatin regions | ~500-50,000 loci per cell | Identification of regenerative enhancers, trajectory inference |

| scDNA-methyl-seq | DNA methylation | Bisulfite conversion of unmethylated cytosines | ~10-50% of CpG sites | Stability of cell identity, silencing of alternative fates |

| scChIP-seq | Histone modifications | Antibody-based enrichment of modified histones | Limited by antibody specificity | Mapping active/repressive regulatory elements |

| scNOME-seq | Nucleosome positioning + DNA methylation | GpC methyltransferase treatment + bisulfite sequencing | Combined chromatin accessibility and methylation | Multi-modal profiling of chromatin states |

| scHi-C | 3D chromatin architecture | Proximity ligation of interacting chromatin regions | 0.1-1Mb resolution | Changes in nuclear organization during regeneration |

The application of scATAC-seq (single-cell Assay for Transposase-Accessible Chromatin using sequencing) has been particularly transformative, as it maps genome-wide chromatin accessibility at single-cell resolution, revealing active regulatory elements including promoters, enhancers, and insulators. This method utilizes a hyperactive Tn5 transposase that simultaneously fragments and tags accessible genomic regions with sequencing adapters in an approach called "tagmentation" [28]. When applied to regenerating tissues, scATAC-seq can identify cell-type-specific regulatory elements that become dynamically accessible during different phases of the repair process, pointing to key transcriptional regulators that drive cellular reprogramming.

Single-cell bisulfite sequencing (scBS-seq) provides a complementary view of the epigenome by mapping DNA methylation patterns across the genome. This method employs post-bisulfite adapter tagging (PBAT) to overcome the substantial DNA degradation caused by bisulfite conversion, enabling measurement of methylation at up to 50% of CpG sites in a single cell [28]. In regeneration research, this approach can reveal how methylation patterns are erased and re-established during cellular reprogramming, potentially identifying epigenetic barriers that limit regenerative capacity in non-regenerative species.

Multimodal Single-Cell Approaches

A critical advancement has been the development of multimodal assays that simultaneously capture multiple molecular layers from the same single cell. Techniques like scM&T-seq enable parallel profiling of the methylome and transcriptome from individual cells, allowing direct correlation of epigenetic states with gene expression patterns [28]. Similarly, methods like SNARE-seq combine scATAC-seq with RNA-seq to link chromatin accessibility to transcriptional outputs. These integrated approaches are particularly powerful for studying regeneration, as they can reveal how epigenetic changes directly influence gene expression programs that control cell fate decisions during tissue repair.

Analytical Frameworks for Single-Cell Epigenomic Data

Computational and Topological Approaches

The high-dimensionality and sparsity of single-cell epigenomic data present substantial analytical challenges that require specialized computational frameworks. Topological data analysis (TDA) has emerged as a powerful mathematical approach for capturing the intrinsic shape of complex single-cell datasets, complementing traditional statistical methods. TDA tools like persistent homology and the Mapper algorithm can detect subtle, multiscale patterns including rare cell populations, transitional states, and branching trajectories that are often obscured by conventional approaches [29]. These methods are particularly suited for identifying continuous biological processes like cellular differentiation during regeneration, as they can model the gradual epigenomic changes that occur as cells transition between states without imposing discrete clustering boundaries.

Single-Cell Epigenomics Analysis Workflow

Spatial Mapping of Epigenomic States

A significant frontier in single-cell epigenomics is the integration of spatial context, which is particularly critical for understanding tissue regeneration where cellular position often determines fate potential. Methods like CMAP (Cellular Mapping of Attributes with Position) enable precise mapping of single cells to their spatial locations by integrating single-cell epigenomic data with spatial transcriptomics [30]. This approach uses a divide-and-conquer strategy with three levels: spatial domain division to assign cells to broad tissue regions, optimal spot alignment to map cells to specific locations, and precise location assignment to determine exact coordinates within the tissue context. Such spatial mapping reveals how the tissue microenvironment influences epigenomic states during regeneration and how cellular heterogeneity is organized within the regenerating tissue architecture.

Experimental Design and Protocols

A Framework for scATAC-seq in Regenerating Tissues

The successful application of single-cell epigenomics to regenerating tissues requires careful experimental design from tissue dissociation to library preparation and bioinformatic analysis. Below is a detailed protocol for scATAC-seq tailored to the unique challenges of regenerative models:

Sample Preparation and Nuclei Isolation

- Tissue Dissociation: Gently dissociate regenerating tissue using mechanical disruption followed by enzymatic digestion optimized to preserve nuclear integrity. Avoid over-digestion that can damage chromatin accessibility patterns.

- Nuclei Extraction: Lyse cells in ice-cold lysis buffer (10mM Tris-HCl, 10mM NaCl, 3mM MgCl2, 0.1% IGEPAL CA-630) for 3-5 minutes on ice. Centrifuge at 500-800g for 5 minutes at 4°C to pellet nuclei.

- Nuclei Quality Control: Assess nuclei integrity and concentration using automated cell counters or fluorescence microscopy with DAPI staining. Aim for >80% intact nuclei with minimal cytoplasmic contamination.

Tagmentation and Library Preparation

- Tagmentation Reaction: Combine 10,000-50,000 nuclei with Tagment DNA Buffer and Tn5 transposase (Illumina Tagment DNA TDE1 Enzyme and Buffer Kits). Incubate at 37°C for 30 minutes with gentle mixing.

- DNA Cleanup: Purify tagmented DNA using MinElute PCR Purification Kit (Qiagen) or SPRI beads. Elute in 10-20μL Elution Buffer.

- Library Amplification: Amplify libraries with 10-12 cycles of PCR using barcoded primers to index samples. Use SYBR Green to monitor amplification and stop reactions before saturation.

Quality Control and Sequencing

- Library QC: Assess library quality using Bioanalyzer High Sensitivity DNA chips (Agilent) or Fragment Analyzer. Expect a nucleosomal pattern with fragments multiples of ~200bp.

- Sequencing: Sequence on Illumina platforms (NovaSeq 6000, NextSeq 2000) with paired-end sequencing (2×50bp recommended). Target 25,000-100,000 read pairs per cell depending on genome size and complexity.

Integrating scATAC-seq with Spatial Transcriptomics

To contextualize epigenomic states within the tissue architecture during regeneration, scATAC-seq can be integrated with spatial transcriptomic methods:

Parallel Sample Processing

- Split regenerating tissue samples into adjacent sections for scATAC-seq and spatial transcriptomics (10x Genomics Visium, Xenium, or Slide-seq).

- Process matched samples in parallel to enable cross-modality integration.

Computational Integration

- Utilize tools like CMAP to map single-cell epigenomic profiles to spatial locations [30].

- Apply harmony, Seurat, or Signac for integration of scATAC-seq with spatial transcriptomics datasets.

- Validate spatial mapping using known marker genes and histological landmarks.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for Single-Cell Epigenomics

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function in Experimental Pipeline |

|---|---|---|

| Nuclei Isolation | IGEPAL CA-630, Triton X-100, DAPI | Cell membrane lysis while preserving nuclear integrity; nuclei quantification |

| Tagmentation | Tn5 Transposase (Illumina Tagment DNA TDE1) | Simultaneous fragmentation and adapter tagging of accessible chromatin |

| Library Prep | NEBNext High-Fidelity 2X PCR Master Mix, SPRIselect beads | Amplification and size selection of tagmented fragments |

| Single-Cell Platform | 10x Genomics Chromium Controller, Fluidigm C1 | Partitioning of individual cells/nuclei into nanoliter reactions |

| Sequencing | Illumina sequencing reagents (NovaSeq, NextSeq 2000) | High-throughput sequencing of barcoded libraries |

| Spatial Mapping | Visium Spatial Gene Expression Slide, Xenium reagents | Tissue context preservation and spatial coordinate assignment |

Applications in Regenerative Model Organisms

Case Study: Limb Regeneration in Axolotl

The application of single-cell epigenomics to highly regenerative organisms like the axolotl has revealed fundamental principles of epigenetic reprogramming during complex tissue regeneration. scATAC-seq analyses of regenerating limbs have identified:

- Blastema-specific enhancers: Accessible chromatin regions that emerge specifically in the regenerating blastema, often linked to genes involved in pattern formation and proliferation.

- Epigenetic memory: Preservation of chromatin accessibility patterns from the original tissue identity that may guide appropriate regeneration of specific structures.

- Dynamic accessibility changes: Rapid reconfiguration of chromatin landscape during the transition from wound healing to regenerative outgrowth.

These findings suggest that successful regeneration requires both the erasure of differentiation-associated epigenetic marks to enable cellular plasticity and the preservation of positional information to guide appropriate pattern formation.

Case Study: Heart Regeneration in Zebrafish

Zebrafish possess a remarkable capacity for cardiac regeneration, and single-cell epigenomic approaches have illuminated how cardiomyocytes reprogram their epigenome to re-enter the cell cycle and regenerate damaged tissue. Key insights include:

- Partial dedifferentiation signatures: Chromatin accessibility changes in regenerating cardiomyocytes that resemble developmental states but maintain certain mature characteristics.

- Enhancer reactivation: Re-emergence of embryonic cardiac enhancers that drive expression of proliferation-associated genes in adult cardiomyocytes after injury.

- Metabolic-epigenetic coupling: Changes in chromatin accessibility at metabolic gene regulators that may facilitate the shift from oxidative to glycolytic metabolism necessary for proliferation.