Partial Reprogramming for Tissue Regeneration: Protocols, Mechanisms, and Clinical Translation

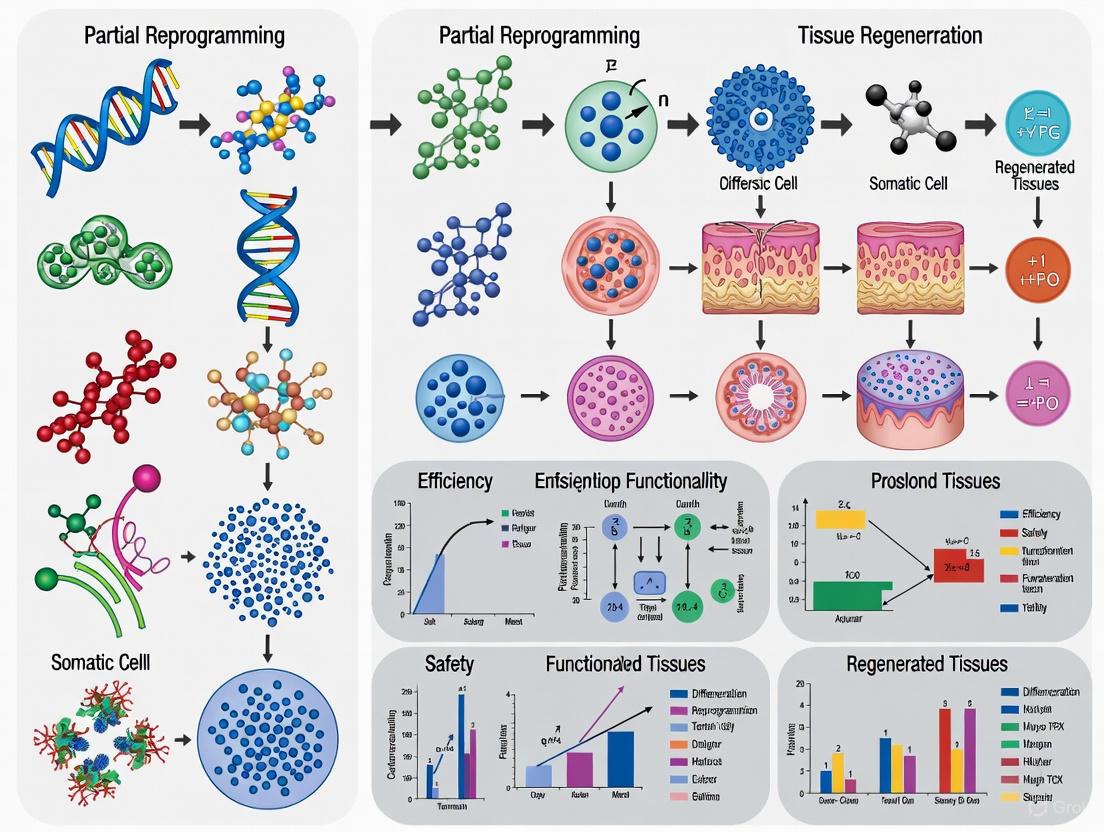

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of partial cellular reprogramming as a transformative strategy for tissue regeneration.

Partial Reprogramming for Tissue Regeneration: Protocols, Mechanisms, and Clinical Translation

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of partial cellular reprogramming as a transformative strategy for tissue regeneration. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational science of epigenetic rejuvenation, detailing the latest methodological advances in both genetic (OSK/M) and chemical reprogramming protocols. The scope extends to critical troubleshooting of safety and optimization challenges, including tumorigenicity and delivery systems. Finally, it offers a rigorous framework for validating efficacy through multi-omic aging clocks, functional assays, and comparative analysis of emerging platforms, positioning partial reprogramming at the forefront of next-generation regenerative medicine.

The Science of Epigenetic Rejuvenation: How Partial Reprogramming Resets Cellular Aging

Cellular reprogramming is a transformative technology in regenerative medicine that enables the conversion of one cell type into another by manipulating cellular identity. This field emerged from seminal discoveries by John Gurdon, who demonstrated nuclear reprogramming via somatic cell nuclear transfer (SCNT), and Shinya Yamanaka, who identified four transcription factors (OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, and c-MYC, collectively known as OSKM) capable of reprogramming somatic cells into induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) [1]. These breakthroughs revealed that cell identity and age-associated molecular features are not fixed but can be reversed, opening new avenues for treating age-related diseases and generating cells for therapeutic applications [1] [2].

Within this field, two distinct approaches have emerged: full reprogramming, which completely resets cellular identity to pluripotency, and partial reprogramming, which aims to reverse age-related deterioration while maintaining cellular identity. This distinction is crucial for therapeutic applications, as partial reprogramming offers the potential to rejuvenate aged tissues without the risks associated with complete dedifferentiation [1] [2]. The following sections provide a comprehensive examination of these approaches, their molecular mechanisms, and their applications in tissue regeneration research.

Defining Partial and Full Reprogramming

Core Concepts and Distinctions

Full reprogramming describes the complete conversion of somatic cells into induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) through sustained expression of reprogramming factors. This process erases the original cellular identity and epigenetic aging signatures, resulting in cells with unlimited self-renewal capacity and the potential to differentiate into any cell type [1] [3]. However, full reprogramming poses significant clinical risks, including teratoma formation, dysplastic cell proliferation, and unintended persistence of pluripotent cells [1] [4].

Partial reprogramming represents a refined approach that applies reprogramming factors transiently or cyclically, sufficient to reverse age-related molecular changes without erasing cellular identity. This strategy aims to restore a more youthful epigenetic landscape, transcript profile, and functional capacity while maintaining the cell's differentiated state and function [1] [2]. By carefully controlling the duration and intensity of reprogramming factor exposure, researchers can achieve "rejuvenation" without complete dedifferentiation.

Table 1: Fundamental Distinctions Between Partial and Full Reprogramming

| Feature | Partial Reprogramming | Full Reprogramming |

|---|---|---|

| Reprogramming Factor Exposure | Transient, cyclic (days) | Sustained (weeks) |

| Cellular Identity | Maintained | Erased, replaced with pluripotency |

| Epigenetic State | Youthful patterns restored, lineage-specific marks maintained | Complete epigenetic reset to embryonic ground state |

| Final Cell State | Original cell type with improved function | Induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) |

| Telomere Dynamics | May improve maintenance without full elongation | Complete elongation to embryonic lengths |

| Tumorigenic Risk | Lower (with careful control) | Significant (teratoma formation) |

| Therapeutic Applications | Rejuvenation of aged tissues, treatment of age-related diseases | Disease modeling, cell replacement therapies |

Conceptual Framework of Reprogramming Continuum

The relationship between partial and full reprogramming can be understood as a continuum, where the extent of reprogramming is determined by the duration and intensity of reprogramming factor exposure. The following diagram illustrates this conceptual framework and the critical transition points:

This conceptual framework highlights the critical importance of precise control in partial reprogramming protocols. The transition from rejuvenation to complete dedifferentiation represents a crucial threshold beyond which cellular identity is lost and tumorigenic risk increases substantially [5] [1].

Molecular Mechanisms and Hallmarks of Aging

Epigenetic Alterations

Aging is characterized by progressive epigenetic alterations, including changes in DNA methylation patterns, histone modifications, and chromatin organization [1]. Partial reprogramming specifically targets these age-related epigenetic changes by transiently activating DNA demethylases and chromatin remodeling complexes. Research has demonstrated that partial reprogramming can restore youthful DNA methylation patterns and reset epigenetic clocks without erasing cell identity, suggesting that epigenetic information can be recovered while maintaining cellular function [2] [6].

The process involves active DNA demethylation facilitated by TET enzymes, which progressively reverse age-associated hypermethylation [2]. Notably, studies have shown that the epigenetic rejuvenation during partial reprogramming occurs without the global erasure of DNA methylation characteristic of full reprogramming, preserving lineage-specific epigenetic markers that maintain cellular identity [1] [2].

Additional Hallmarks of Aging Affected by Partial Reprogramming

Beyond epigenetic alterations, partial reprogramming impacts multiple hallmarks of aging:

Mitochondrial Dysfunction: Partial reprogramming restores mitochondrial membrane potential and enhances oxidative phosphorylation capacity. Multi-omics analyses have revealed that chemical reprogramming cocktails significantly upregulate mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation complexes, leading to improved cellular respiration [6].

Cellular Senescence: Short-term reprogramming reduces markers of cellular senescence, including senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP) factors and β-galactosidase activity [7] [2].

Genomic Instability: Treatment with reprogramming cocktails decreases DNA damage markers such as γH2AX foci in aged human fibroblasts, indicating improved genomic maintenance [7].

Loss of Proteostasis: Partial reprogramming enhances protein quality control mechanisms, although the specific pathways involved require further characterization [1].

Altered Intercellular Communication: By reducing inflammatory signaling and SASP factors, partial reprogramming improves tissue microenvironment and cell-cell communication [1].

Table 2: Quantitative Effects of Partial Reprogramming on Aging Hallmarks

| Aging Hallmark | Measurement Approach | Effect of Partial Reprogramming | Magnitude of Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| Epigenetic Alterations | DNA methylation clocks | Reversal of age-related methylation patterns | ~40-60% reduction in epigenetic age [6] |

| Mitochondrial Dysfunction | Oxygen consumption rate (Seahorse) | Increased oxidative phosphorylation | 1.5-2.5 fold increase in spare respiratory capacity [6] |

| Cellular Senescence | β-galactosidase staining, SASP factors | Reduced senescent cell burden | 30-50% reduction in senescence markers [7] |

| Genomic Instability | γH2AX foci quantification | Decreased DNA damage accumulation | 40-60% reduction in γH2AX foci [7] |

| Transcriptomic Alterations | RNA sequencing, aging clocks | Reversion to youthful expression patterns | 50-70% reduction in transcriptomic age [2] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Genetic Reprogramming Protocols

In Vivo Partial Reprogramming Protocol Using Doxycycline-Inducible OSKM

This protocol describes the establishment of a cyclic, transient reprogramming regimen in mice that achieves tissue rejuvenation without tumor formation [1]:

Animal Model Preparation: Utilize transgenic mice containing a doxycycline-inducible OSKM cassette (often Rosa26-M2rtTA;Col1a1-TetO-OSKM).

Reprogramming Induction:

- Administer doxycycline-containing chow (2 g/kg) or water (2 mg/mL with 5% sucrose) to induce OSKM expression.

- Implement cyclic induction patterns (e.g., 2 days on/5 days off or 3-4 consecutive days per week).

Duration and Monitoring:

- Continue cyclic treatment for 4-12 weeks depending on desired outcomes.

- Monitor for signs of distress, weight loss, or teratoma formation weekly.

- Include control groups receiving continuous doxycycline to validate partial vs. full reprogramming effects.

Tissue Analysis:

- Harvest tissues after completion of cycling for molecular and functional analyses.

- Assess epigenetic clocks using established methylation arrays (e.g., Illumina Mouse Methylation BeadChip).

- Evaluate tissue function through regeneration assays (wound healing, muscle repair) and histology.

This protocol has demonstrated successful rejuvenation in multiple tissues including skin, muscle, liver, and spleen, with improved regeneration capacity and reduced fibrosis [1].

Chemical Reprogramming Protocols

Chemical-Induced Partial Reprogramming of Human Fibroblasts

Chemical reprogramming offers a non-genetic alternative for cellular rejuvenation, potentially overcoming safety concerns associated with genetic approaches [7] [2]:

Cell Culture Preparation:

- Plate aged human dermal fibroblasts (HDFs) from donors >60 years or progeria patients at 10,000 cells/cm² in fibroblast medium.

- Allow attachment for 24 hours in standard conditions (37°C, 5% CO₂).

Chemical Cocktail Formulation:

- Prepare complete 7-compound (7c) cocktail: CHIR99021 (GSK-3β inhibitor, 3µM), DZNep (EZH2 inhibitor, 0.5µM), Forskolin (adenylyl cyclase activator, 10µM), TTNPB (RAR agonist, 0.5µM), Valproic acid (HDAC inhibitor, 1mM), Repsox (TGF-β inhibitor, 5µM), and Tranylcypromine (LSD1 inhibitor, 10µM).

- Prepare reduced 2-compound (2c) cocktail: Repsox (5µM) and Tranylcypromine (10µM) for simplified treatment.

Treatment Protocol:

- Replace culture medium with treatment medium containing chemical cocktails.

- Maintain treatment for 6 days with daily medium changes to ensure compound stability.

- Include vehicle controls (DMSO) and positive controls (OSKM mRNA transfection).

Assessment of Rejuvenation:

- Analyze DNA damage response via γH2AX immunostaining.

- Evaluate senescence through SA-β-galactosidase staining and p21 expression.

- Measure epigenetic age using established clocks (e.g., Horvath clock).

- Assess mitochondrial function via Seahorse Analyzer and membrane potential dyes.

This chemical reprogramming approach has demonstrated significant reduction in multiple aging hallmarks in human fibroblasts and extends healthspan in C. elegans models [7].

Delivery System Technologies

Tissue Nanotransfection (TNT) for In Situ Reprogramming

Tissue nanotransfection represents a cutting-edge physical delivery system for reprogramming factors that enables highly localized, efficient reprogramming in living tissues [4] [8]:

Device Setup:

- Utilize a TNT device consisting of a hollow-needle silicon chip mounted beneath a cargo reservoir.

- Connect the cargo reservoir to the negative terminal of an external pulse generator.

- Position a dermal electrode connected to the tissue as the positive terminal.

Cargo Preparation:

- Prepare plasmid DNA (highly supercoiled, circular), mRNA, or CRISPR/Cas9 components in nuclease-free buffer.

- Optimize concentration (typically 0.1-1 µg/µL for plasmids) for target cell type.

Transfection Protocol:

- Place the TNT device directly on the target tissue (skin or exposed organ).

- Apply optimized electrical pulses (typically 100-250 V/cm for 10-100 ms pulses).

- The nanochannels create transient pores (resolving in milliseconds) for cargo entry.

Post-Transfection Analysis:

- Monitor expression of reprogramming factors 24-48 hours post-transfection.

- Assess cellular identity maintenance through lineage tracing and marker expression.

- Evaluate functional improvements in tissue regeneration models.

TNT has demonstrated success in direct in vivo reprogramming of fibroblasts to neuronal and endothelial cells, promoting tissue repair without tumorigenesis [4] [8].

Research Reagent Solutions Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Partial Reprogramming Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Reprogramming | Considerations for Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genetic Factors | OSKM lentivirus, doxycycline-inducible plasmids, modified mRNA | Ectopic expression of reprogramming transcription factors | mRNA avoids genomic integration; inducible systems enable temporal control [9] |

| Chemical Cocktails | 7c cocktail (CHIR99021, VPA, Repsox, etc.), 2c cocktail (Repsox, Tranylcypromine) | Small molecule induction of rejuvenation without genetic manipulation | Reduced tumorigenic risk compared to genetic methods [7] |

| Delivery Systems | Tissue Nanotransfection (TNT) devices, electroporation systems, lipid nanoparticles | Physical delivery of reprogramming factors to target cells | TNT enables localized, in vivo reprogramming with minimal toxicity [4] [8] |

| Aging Assays | Epigenetic clock analysis (DNA methylation arrays), RNA sequencing, senescence-associated β-galactosidase | Quantification of rejuvenation effects at molecular and cellular levels | Multi-omics approaches provide comprehensive assessment of aging reversal [6] |

| Cell Culture Materials | Defined extracellular matrix substrates, low-serum media formulations, metabolic modifiers | Recreation of youthful microenvironment to support reprogrammed cells | Biomaterial scaffolds can enhance reprogramming efficiency and stability [3] |

Applications in Tissue Regeneration Research

Partial reprogramming strategies have demonstrated significant potential across multiple tissue regeneration contexts:

Musculoskeletal Regeneration: Cyclic OSKM expression in aged mice enhances muscle regeneration capacity with improved satellite cell function and reduced fibrosis following injury. Similar approaches have shown promise in intervertebral disc regeneration, restoring matrix production and cellular function [1].

Neural Tissue Repair: Partial reprogramming of retinal ganglion cells restores youthful DNA methylation patterns and reverses vision loss in aged and glaucomatous mouse models. In the brain, transient OSK expression improves cognitive function in neurodegenerative models without tumor formation [2].

Cutaneous Wound Healing: Localized partial reprogramming accelerates wound closure in aged skin through enhanced fibroblast function and improved extracellular matrix remodeling. Tissue nanotransfection delivery of reprogramming factors directly to wound sites promotes healing without scar formation [4] [8].

Cardiovascular Repair: Following myocardial injury, transient reprogramming factors improve cardiac function through enhanced cardiomyocyte proliferation, reduced fibrosis, and improved vascularization [1].

The application of partial reprogramming in these diverse tissue contexts demonstrates its broad potential for regenerative medicine while highlighting the importance of tissue-specific optimization to maximize therapeutic benefits while minimizing risks.

Partial reprogramming represents a paradigm shift in regenerative medicine, offering the potential to reverse age-related functional decline without erasing cellular identity. The distinction between partial and full reprogramming is fundamental—where full reprogramming completely resets cellular identity to pluripotency with associated tumorigenic risks, partial reprogramming aims to restore youthful function while maintaining cellular specialization. As research in this field advances, the development of increasingly precise temporal controls, tissue-specific approaches, and non-integrative delivery systems will be essential for clinical translation. The protocols and methodologies outlined herein provide a foundation for researchers exploring partial reprogramming as a strategy for tissue regeneration and age-related disease intervention.

Aging is a complex biological process characterized by a progressive decline in physiological integrity, leading to impaired function and increased vulnerability to death. This deterioration is a primary risk factor for major human pathologies, including cancer, diabetes, neurodegenerative disorders, and cardiovascular diseases. At the molecular level, aging is driven by interconnected hallmarks, among which epigenetic drift, cellular senescence, and mitochondrial dysfunction play central roles. Understanding these processes is crucial for developing interventions aimed at extending healthspan—the period of life free from age-related disease and disability.

Recent research has focused on partial cellular reprogramming as a promising strategy to counteract these hallmarks of aging. Unlike full reprogramming to pluripotency, partial reprogramming applies reprogramming factors transiently to reverse age-related molecular changes without erasing cellular identity, offering potential for therapeutic application in age-related diseases and tissue regeneration.

Epigenetic Drift in Aging

Mechanisms and Consequences

Epigenetic drift refers to the progressive alteration of epigenetic marks throughout the genome during aging. These changes include predictable shifts in DNA methylation patterns, histone modifications, and chromatin remodeling. The most extensively studied alteration is DNA methylation drift, characterized by:

- Global hypomethylation: A progressive loss of DNA methylation across the genome, particularly in heterochromatic regions and repetitive elements [10].

- CpG island hypermethylation: Focal gains of DNA methylation at specific regulatory regions, particularly at promoter-associated CpG islands [10] [11].

- Increased methylation variability: Age-associated variably methylated positions (aVMPs) show increased stochastic methylation changes between individuals with age [11].

These changes result from the imperfect maintenance of epigenetic marks by DNA methyltransferases (DNMT1, DNMT3A, DNMT3B) and ten-eleven translocation (TET) enzymes, creating epigenetic mosaicism in aging stem cells that can restrict their plasticity and contribute to age-related functional decline [10].

Table 1: DNA Methylation Changes in Aging Mammalian Tissues

| Methylation Type | Genomic Location | Aging Change | Functional Consequences |

|---|---|---|---|

| Global methylation | Repetitive elements, heterochromatin | Decreased | Genomic instability, reactivation of transposable elements |

| CpG island methylation | Gene promoters | Increased | Silencing of tumor suppressors, developmental genes |

| Gene body methylation | Gene bodies | Variable | Alternative splicing alterations |

| aVMPs | Various | Increased variability | Tissue-specific functional decline |

Assessment and Measurement

The epigenetic clock represents a highly accurate biomarker of biological age based on DNA methylation patterns at specific CpG sites. Several epigenetic clocks have been developed with increasing precision:

- Horvath's clock: Multi-tissue predictor using 353 CpG sites [11].

- Hannum's clock: Blood-based predictor using 71 CpG sites [11].

- DNAm PhenoAge: Incorporates clinical parameters to predict mortality risk [11].

These clocks demonstrate that epigenetic age can be decoupled from chronological age and accelerated in association with various diseases and environmental exposures.

Experimental Protocol: Assessing Epigenetic Age

Protocol 1: DNA Methylation Analysis Using Illumina EPIC Array

Materials:

- Bisulfite conversion kit (e.g., EZ DNA Methylation Kit)

- Illumina Infinium HD Assay Methylation Kit

- Illumina iScan System

- Genomic DNA (500 ng) from target tissue

Procedure:

- Bisulfite Conversion: Treat genomic DNA with bisulfite using manufacturer's protocol, converting unmethylated cytosines to uracils while leaving methylated cytosines unchanged.

- Whole-Genome Amplification: Amplify bisulfite-converted DNA followed by enzymatic fragmentation.

- Array Hybridization: Hybridize samples to Illumina EPIC array containing >850,000 methylation sites.

- Single-Base Extension: Add fluorescently labeled nucleotides to probe-DNA hybrids.

- Array Scanning: Detect fluorescence signals using iScan system.

- Data Analysis: Process intensity data to calculate β-values (methylation levels) using minfi or similar packages in R.

- Age Calculation: Apply published epigenetic clock algorithms to estimate biological age.

Quality Control:

- Include technical replicates to assess reproducibility

- Monitor bisulfite conversion efficiency

- Exclude probes with detection p-value > 0.01

- Normalize data using standard preprocessing pipelines

Cellular Senescence in Aging

Pathways and Biomarkers

Cellular senescence is defined as irreversible cell cycle arrest in response to various stressors, including telomere shortening (replicative senescence), DNA damage, oxidative stress, and oncogene activation. Senescent cells accumulate in tissues with age and contribute to aging through multiple mechanisms [12].

The two major senescence-associated pathways are:

- p53/p21 pathway: Triggered primarily by DNA damage response (DDR), leading to initial cell cycle arrest.

- p16INK4A/pRB pathway: Maintains senescence in established senescent cells [12].

Senescent cells exhibit characteristic features, including:

- Morphological changes: Enlarged, flattened cell shape.

- Senescence-associated β-galactosidase (SA-β-gal) activity: Detectable at pH 6.0 due to increased lysosomal mass.

- Senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP): Secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines, chemokines, growth factors, and proteases.

- Resistance to apoptosis: Upregulation of anti-apoptotic pathways (SCAP) [12].

Table 2: Key Biomarkers for Detecting Cellular Senescence

| Senescent Feature | Biomarker | Detection Method | Specificity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell cycle arrest | p16INK4A, p21 | IHC, WB, IF | High for established senescence |

| Lysosomal activity | SA-β-gal | Enzymatic staining (pH 6.0) | General but sensitive |

| DNA damage | γH2AX, 53BP1 | IF, IHC | Damage-induced senescence |

| Secretory phenotype | IL-6, IL-8, MMPs | ELISA, WB | SASP-positive senescence |

| Chromatin changes | SAHFs, H3K9me3 | DAPI/Hoechst, IF | Heterochromatin formation |

| Nuclear membrane | Lamin B1 loss | WB, IF, qPCR | General senescence |

Experimental Protocol: Senescence Detection and Validation

Protocol 2: Comprehensive Senescence Assessment

Materials:

- SA-β-gal staining kit (e.g., Cell Signaling Technology #9860)

- Primary antibodies: anti-p16INK4A, anti-p21, anti-γH2AX, anti-Lamin B1

- Secondary antibodies with fluorescent conjugates

- Cell culture reagents

- Propidium iodide or DAPI for nuclear staining

Procedure: Part A: SA-β-gal Staining

- Wash cells with PBS and fix with 2% formaldehyde/0.2% glutaraldehyde for 5 minutes.

- Wash cells and incubate with SA-β-gal staining solution (1 mg/mL X-gal, 5 mM potassium ferrocyanide, 5 mM potassium ferricyanide, 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM MgCl2 in 40 mM citric acid/sodium phosphate, pH 6.0) at 37°C without CO2 for 12-16 hours.

- Examine under brightfield microscopy for blue staining.

Part B: Immunofluorescence for Senescence Markers

- Culture cells on chamber slides, fix with 4% PFA for 15 minutes, permeabilize with 0.2% Triton X-100 for 10 minutes.

- Block with 5% BSA for 1 hour, incubate with primary antibodies (1:200-1:500) overnight at 4°C.

- Incubate with fluorescent secondary antibodies (1:1000) for 1 hour at room temperature, counterstain with DAPI.

- Image using fluorescence or confocal microscopy.

Part C: SASP Analysis

- Collect conditioned media from cells, concentrate using 3kDa centrifugal filters.

- Analyze SASP factors using multiplex ELISA or proteomic approaches.

- Quantify IL-6, IL-8, MMP-3 using commercial ELISA kits according to manufacturer's instructions.

Interpretation:

- Senescent cells show SA-β-gal positivity, increased p16/p21 expression, γH2AX foci, reduced Lamin B1, and SASP secretion.

- Use at least three complementary markers to confirm senescence, as no single marker is definitive.

Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Aging

Mechanisms and Consequences

Mitochondrial dysfunction is a central hallmark of aging characterized by:

- Declining ATP production: Reduced oxidative phosphorylation efficiency.

- Increased ROS production: Elevated reactive oxygen species leading to oxidative damage.

- Mitochondrial DNA mutations: Accumulation of mtDNA deletions and point mutations.

- Altered mitochondrial dynamics: Imbalanced fission and fusion.

- Diminished mitophagy: Impaired clearance of damaged mitochondria [13] [14].

Aging mitochondria exhibit structural changes, including swollen morphology, disrupted cristae, and decreased membrane potential. The mitochondrial theory of aging posits that accumulated mitochondrial damage and resultant energy deficit drive functional decline in aged tissues [14].

The interaction between mitochondrial dysfunction and other aging hallmarks creates vicious cycles that accelerate aging. For example:

- Mitochondrial ROS causes nuclear DNA damage and epigenetic changes.

- mtDNA mutations impair OXPHOS, increasing ROS production.

- Metabolic alterations from mitochondrial dysfunction influence nutrient-sensing pathways and epigenetic regulation [13].

Assessment and Measurement

Table 3: Key Parameters for Assessing Mitochondrial Function in Aging

| Parameter | Assessment Method | Age-Related Change | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Membrane potential | JC-1, TMRM staining | Decreased | Reduced ATP production capacity |

| ROS production | DCFDA, MitoSOX | Increased | Oxidative damage to macromolecules |

| Oxygen consumption | Seahorse Analyzer | Decreased | Impaired OXPHOS efficiency |

| mtDNA copy number | qPCR | Variable tissue-specific changes | Mitochondrial biogenesis |

| mtDNA mutations | Sequencing, long-range PCR | Increased | Impaired ETC function |

| ATP levels | Luciferase assay | Decreased | Bioenergetic deficit |

| Mitophagy | Mt-Keima, LC3-II/p62 | Impaired | Accumulation of damaged mitochondria |

Experimental Protocol: Comprehensive Mitochondrial Assessment

Protocol 3: Mitochondrial Functional Analysis

Materials:

- Seahorse XF Analyzer and XF Cell Mito Stress Test Kit

- MitoSOX Red mitochondrial superoxide indicator

- TMRE mitochondrial membrane potential dye

- ATP determination kit

- Mitochondrial isolation kit

- DNA extraction and qPCR reagents

Procedure: Part A: Mitochondrial Respiration (Seahorse Analyzer)

- Seed cells in XF microplates at optimal density (typically 20,000-40,000 cells/well).

- Hydrate sensor cartridge in XF calibrant at 37°C in non-CO2 incubator overnight.

- Replace medium with Seahorse XF Base Medium supplemented with 1 mM pyruvate, 2 mM glutamine, and 10 mM glucose.

- Load compounds for Mito Stress Test: oligomycin (1.5 μM), FCCP (1-2 μM), rotenone/antimycin A (0.5 μM).

- Run Mito Stress Test protocol on Seahorse XF Analyzer.

- Calculate key parameters: basal respiration, ATP production, proton leak, maximal respiration, spare respiratory capacity.

Part B: Mitochondrial ROS Production

- Incubate cells with 5 μM MitoSOX Red in PBS for 30 minutes at 37°C.

- Wash with PBS, analyze by flow cytometry or fluorescence microscopy.

- Quantify fluorescence intensity normalized to cell number.

Part C: Mitochondrial Membrane Potential

- Incubate cells with 50-100 nM TMRE for 30 minutes at 37°C.

- Wash with PBS, analyze by flow cytometry or plate reader.

- Include control with FCCP (uncoupler) to confirm specificity.

Part D: mtDNA Analysis

- Isolate total DNA using standard protocols.

- Perform qPCR with primers for mitochondrial genes (e.g., ND1, CYTB) and nuclear gene (e.g., B2M, 18S rRNA) as reference.

- Calculate mtDNA copy number as ratio of mitochondrial to nuclear DNA.

- For mutation analysis, perform long-range PCR of mtDNA followed by sequencing.

Data Interpretation:

- Aged tissues typically show reduced basal and maximal respiration, decreased spare capacity, increased proton leak, and elevated ROS production.

- Combine multiple assays for comprehensive assessment of mitochondrial health.

Partial Reprogramming for Reversal of Aging Hallmarks

Principles and Mechanisms

Partial cellular reprogramming represents a novel approach to reverse age-related changes without inducing pluripotency. This technique utilizes transient expression of Yamanaka factors (Oct4, Sox2, Klf4, c-Myc; OSKM) to reset epigenetic age and restore youthful function while maintaining cellular identity [1] [15].

The mechanisms underlying partial reprogramming include:

- Epigenetic resetting: Reversal of age-related DNA methylation patterns and histone modifications.

- Mitochondrial rejuvenation: Restoration of mitochondrial function and reduction of ROS.

- Senescence clearance: Reduction of senescent cell burden through various mechanisms.

- Proteostasis restoration: Improvement in protein homeostasis and aggregation clearance [1].

Key studies demonstrate that:

- Transient OSKM expression for 5-15 days reduces epigenetic age in human fibroblasts by up to 30 years [15].

- In vivo partial reprogramming (IVPR) improves tissue function and extends healthspan in mouse models [1] [15].

- A "critical window" of reprogramming exists (approximately days 3-13) where age reprogramming occurs with minimal loss of cellular identity [15].

Experimental Protocol: In Vitro Partial Reprogramming

Protocol 4: Transient Reprogramming for Cellular Rejuvenation

Materials:

- Doxycycline-inducible OSKM lentiviral vectors (Addgene)

- Polybrene (8 μg/mL)

- Doxycycline (2 μg/mL)

- Fibroblast culture medium with appropriate growth factors

- Senescence and mitochondrial assessment reagents (as in Protocols 2 & 3)

Procedure:

- Cell Preparation: Plate early passage or aged fibroblasts at 30-50% confluence.

- Viral Transduction:

- Add polybrene to lentiviral OSKM particles (MOI 5-10) in culture medium.

- Incubate cells with virus-containing medium for 24 hours.

- Replace with fresh medium for 24 hours recovery.

- Reprogramming Induction:

- Add doxycycline (2 μg/mL) to culture medium to induce OSKM expression.

- Culture cells for optimal duration (typically 7-13 days, titrate for specific cell type).

- Change medium with doxycycline every 2 days.

- Reprogramming Withdrawal:

- Remove doxycycline and culture in standard medium for 7-14 days to allow stabilization.

- Monitor for retention of cell identity using lineage-specific markers.

- Rejuvenation Assessment:

- Evaluate epigenetic age using DNA methylation clocks (Protocol 1).

- Assess senescence markers (Protocol 2).

- Analyze mitochondrial function (Protocol 3).

- Perform transcriptomic analysis to confirm youthful gene expression patterns.

Critical Considerations:

- Optimization of reprogramming duration is essential—too short may be ineffective, too long may induce pluripotency or transformation.

- Include controls: non-transduced cells, doxycycline-treated non-transduced cells, and fully reprogrammed iPSCs.

- Rigorously validate retention of cellular identity using functional assays and marker expression.

Integrated Intervention Strategies

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Reagents for Aging Hallmark Research

| Research Area | Key Reagents | Function/Specificity | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Epigenetic Analysis | Illumina EPIC Array | Genome-wide methylation profiling | Epigenetic clock analysis |

| Bisulfite Conversion Kits | DNA treatment for methylation analysis | Targeted methylation studies | |

| Anti-5-methylcytosine | Detection of methylated DNA | Immunofluorescence, Dot blot | |

| Senescence Detection | SA-β-gal Staining Kit | Detection of lysosomal β-gal at pH 6 | Primary senescence screening |

| Anti-p16INK4A antibody | Specific senescence marker | IHC, WB confirmation | |

| SASP Array | Multiplex cytokine detection | SASP characterization | |

| Mitochondrial Assessment | Seahorse XF Kits | Metabolic phenotype analysis | OXPHOS function |

| MitoTracker dyes | Mitochondrial mass and membrane potential | Imaging and flow cytometry | |

| MitoSOX Red | Mitochondrial superoxide detection | Oxidative stress measurement | |

| Partial Reprogramming | Doxycycline-inducible OSKM | Inducible reprogramming factor expression | In vitro rejuvenation |

| Sendai viral vectors | Non-integrating reprogramming | Clinical applications | |

| Pluripotency antibodies | Confirmation of incomplete reprogramming | Quality control |

Integrated Diagram of Aging Hallmarks and Intervention

Diagram 1: Interconnections between aging hallmarks and intervention strategies. Arrows indicate direction of influence, with colored lines showing specific targeting of interventions.

Experimental Workflow for Comprehensive Assessment

Diagram 2: Comprehensive experimental workflow for assessing aging interventions. This integrated approach enables rigorous evaluation of interventions across multiple aging hallmarks.

The molecular hallmarks of aging—epigenetic drift, cellular senescence, and mitochondrial dysfunction—represent interconnected processes that collectively drive functional decline and age-related disease. Targeting these hallmarks through interventions such as partial reprogramming offers promising avenues for extending healthspan and improving tissue regeneration capacity.

The protocols and methodologies outlined here provide researchers with comprehensive tools to quantitatively assess these aging hallmarks and evaluate potential interventions. As the field advances, key challenges remain, including optimizing partial reprogramming protocols for specific tissues, minimizing potential risks such as tumorigenicity, and developing delivery systems for clinical translation.

Future research should focus on:

- Identifying minimal factor combinations for effective rejuvenation.

- Developing tissue-specific reprogramming approaches.

- Understanding the molecular mechanisms that separate rejuvenation from dedifferentiation.

- Exploring synergistic combinations of reprogramming with other anti-aging interventions.

By systematically targeting the fundamental mechanisms of aging, we move closer to the goal of not just extending lifespan, but significantly expanding healthspan—the period of life spent in good health—with profound implications for medicine and society.

The discovery that somatic cell fate could be reversed through the ectopic expression of specific transcription factors represents a paradigm shift in regenerative medicine and aging research. In 2006, Takahashi and Yamanaka demonstrated that overexpression of just four transcription factors—Octamer-binding transcription factor 3/4 (Oct3/4), Sex-determining region Y-box 2 (Sox2), Krüppel-like factor 4 (Klf4), and cellular Myc (c-Myc), collectively known as the Yamanaka factors or OSKM—could reprogram terminally differentiated fibroblasts into induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) [16] [17]. This groundbreaking discovery, awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 2012, demonstrated that cellular identity is not fixed and can be reprogrammed, challenging the long-standing "Weismann barrier" theory that cellular differentiation was a one-way path [16] [17]. Subsequent research has revealed that transient, non-integrating application of these factors can achieve partial reprogramming, reversing age-associated cellular hallmarks without completely erasing cellular identity, thus opening revolutionary avenues for tissue regeneration and rejuvenation research [18] [19] [20].

Molecular Mechanisms of Action

The reprogramming of somatic cells to a pluripotent state via OSKM is a complex, multi-stage process involving profound epigenetic remodeling, transcriptional changes, and metabolic shifts. The mechanism can be understood through several models and the distinct roles of each factor.

Models of Reprogramming

The process of OSKM-induced reprogramming is not uniform across all cells and can be explained by different mechanistic models:

- The Stochastic Model: This theory posits that OSKM expression initiates a probabilistic process in a broad population of somatic cells. The transition through successive, distinct states occurs with varying latencies, and only a small fraction of cells successfully navigate the entire sequence to reach pluripotency. The process involves stages such as the downregulation of somatic genes, a mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition (MET), metabolic reprogramming from oxidative phosphorylation to glycolysis, and finally, the activation of the pluripotency network. Failure at any point causes the reprogramming process to abort [17].

- The Seesaw Model (Stoichiometry Model): This model emphasizes the critical balance in the expression levels of the different factors. Specifically, an

OCT3/4highSOX2lowstoichiometry appears favorable for efficient reprogramming. In the early phases, OCT3/4 and SOX2 can have opposing effects on lineage-specific genes, creating a "seesaw" that must be balanced to guide cells toward a pluripotent state rather than an alternative lineage. Imbalanced expression can lead to aberrant reprogramming or differentiation [17].

Individual Factor Functions

Each Yamanaka factor plays a unique and synergistic role in orchestrating the reprogramming process.

Table 1: Core Functions of the Yamanaka Factors in Reprogramming

| Factor | Primary Function in Reprogramming | Key Molecular Interactions |

|---|---|---|

| Oct3/4 | Master regulator of pluripotency; essential for establishing and maintaining the pluripotent network. Directs epigenetic remodeling. | Recruits the BAF chromatin remodeling complex; binds enhancers of Polycomb-repressed genes; forms autoregulatory loops with other pluripotency factors; upregulates histone demethylases KDM3A/KDM4C [19]. |

| Sox2 | Partners with Oct3/4 as a pioneering factor to open chromatin and activate pluripotency genes. Critical for neural development. | Heterodimerizes with Oct3/4; engages chromatin first to prime binding sites for Oct3/4; co-occupies enhancers and promoters to drive pluripotency [19]. |

| Klf4 | Initiates the first wave of transcriptional activation; possesses dual activator/repressor functions. | Binding is enhanced by Oct3/4-Sox2 complexes; activates Nanog; involved in the MET and cell cycle progression [19]. |

| c-Myc | Potent amplifier of reprogramming; drives widespread transcriptional activation and promotes proliferation. Does not act as a pioneer factor. | Binds to a methylated region of chromatin; increases global OSK binding; heterodimerizes with Max; upregulates metabolic and biosynthetic genes [19]. |

The following diagram illustrates the synergistic interaction of these factors in initiating the reprogramming process, from somatic cell state towards pluripotency.

Quantitative Data in Reprogramming and Rejuvenation

The efficiency and outcomes of OSKM-mediated reprogramming vary significantly based on the cell type, factor combination, and delivery method. The tables below summarize key quantitative data from the literature.

Table 2: Reprogramming Efficiency Across Different Cell Types and Factor Cocktails

| Original Cell Type | Reprogramming Factors | Reported Efficiency | Key Contextual Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fibroblasts [16] | OSKM | < 1% | Original Yamanaka protocol; efficiency is often below 1% [16]. |

| Keratinocytes [16] | OSKM | Up to 1% | Slightly higher efficiency than fibroblasts. |

| CD133+ Stem Cells (Cord Blood) [16] | Oct3/4, Sox2 | Successful reprogramming | Endogenous expression of some factors allows for a reduced cocktail. |

| Fetal Neural Stem Cells [16] | Oct3/4 | Successful reprogramming | High endogenous Sox2 levels enable reprogramming with a single factor. |

| Postmitotic Neurons [16] | OKSM + p53 shRNA | Successful reprogramming | p53 knockdown is indispensable for reprogramming this cell type. |

| Human Dermal Fibroblasts [18] | OSK (c-Myc excluded) | Successful in vivo rejuvenation | AAV9 delivery; extended lifespan by 109% in old mice without teratomas [18]. |

Table 3: In Vivo Rejuvenation Outcomes from Partial OSKM Reprogramming

| Model System | Intervention | Key Rejuvenation Outcomes | Safety Observations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Progeria Mouse Model (HGPS) [20] | Cyclic OSKM (2-days ON, 5-days OFF) | 33% lifespan extension; improved skin integrity, cardiovascular function, and spine curvature; restored H3K9me3 levels. | No teratoma formation. |

| Wild-Type Mice [18] | Cyclic OSKM (Long-term: 7-10 months) | Transcriptome, lipidome, metabolome reverted to younger state; increased skin regeneration. | No teratoma formation reported. |

| Wild-Type Mice (124-week-old) [18] | Cyclic OSK via AAV9 gene therapy (1-day ON, 6-days OFF) | 109% extension of remaining lifespan; improved frailty index score. | Exclusion of c-Myc to reduce tumorigenic risk. |

| Human Dermal Fibroblasts In Vitro [18] | Partial Reprogramming | Reversal of epigenetic age (DNA methylation clocks); reduction of transcriptional aging signatures. | Cell identity maintained. |

Application Notes & Experimental Protocols

This section provides detailed methodologies for implementing OSKM-based reprogramming and rejuvenation protocols in a research setting, framed within the context of partial reprogramming for tissue regeneration.

Protocol: In Vitro Partial Reprogramming of Human Dermal Fibroblasts for Rejuvenation

Objective: To transiently reset age-associated epigenetic and transcriptional marks in human dermal fibroblasts without inducing pluripotency, for the purpose of generating rejuvenated cell populations for tissue engineering and in vitro disease modeling.

Materials & Reagents:

- Primary Cells: Human dermal fibroblasts (HDFs) from young and aged donors.

- Reprogramming Factors: Non-integrating mRNA cocktails for OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, and c-MYC (e.g., commercial mRNA kits).

- Delivery Reagent: mRNA transfection reagent compatible with primary cells.

- Culture Vessels: 6-well plates coated with appropriate ECM (e.g., Fibronectin).

- Media: Fibroblast growth medium, serum-free mRNA transfection medium.

- Supplements: Immune suppressants (e.g., B18R interferon inhibitor) to counter mRNA-induced innate immune response.

Procedure:

- Cell Seeding: Seed early-passage HDFs at a density of 1.5 x 10^5 cells per well in a 6-well plate in complete fibroblast growth medium. Incubate at 37°C, 5% CO2 for 24 hours to achieve ~80% confluency at time of transfection.

- mRNA Transfection:

- Prepare mRNA-lipid complexes according to the manufacturer's instructions. For a partial reprogramming cocktail, use equal masses of OSKM mRNAs. A typical starting concentration is 50-100 ng of each mRNA per well.

- Replace cell culture medium with fresh, pre-warmed serum-free transfection medium.

- Add the mRNA-lipid complex dropwise to the cells. Gently swirl the plate to ensure even distribution.

- Incubate cells for 4-6 hours, then replace the transfection medium with standard fibroblast growth medium supplemented with B18R (e.g., 100 ng/mL).

- Cyclic Induction (Critical for Partial Reprogramming):

- Repeat the transfection procedure (Step 2) every 24 hours for a defined short course. A common protocol for partial rejuvenation is 4-6 cycles over 4-6 days [18] [18]. Optimization is required: The number of cycles is the critical variable determining whether the outcome is rejuvenation, full reprogramming, or no effect.

- Recovery and Analysis:

- After the final cycle, allow cells to recover in standard growth medium for 48-72 hours.

- Passage cells and assess outcomes using the following analytical methods:

- Senescence-Associated β-Galactosidase (SA-β-Gal) Staining: Quantify the reduction in senescent cells.

- DNA Methylation Clocks: Perform targeted bisulfite sequencing (e.g., using the Horvath or Skin&Blood clock panels) to quantify epigenetic age reversal [18] [19].

- Transcriptomic Analysis: RNA-seq to confirm upregulation of youthful gene expression patterns and downregulation of senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP) factors, while verifying maintenance of key fibroblast identity markers (e.g., VIM, COL1A1).

- Functional Assays: Conduct collagen contraction or migration assays to confirm enhanced fibroblast functionality.

Protocol: In Vivo Tissue Rejuvenation via Cyclic OSKM Induction

Objective: To ameliorate age-related functional decline and promote tissue regeneration in a mouse model using a doxycycline-inducible OSKM system, while minimizing the risk of teratoma formation.

Materials & Reagents:

- Animal Model: Transgenic mice harboring a doxycycline-inducible polycistronic OSKM cassette (e.g., Col1a1-targeted "4Fj" or "4Fk" mice) [20].

- Inducing Agent: Doxycycline hyclate (Dox) in drinking water or administered via diet.

- Control: Age-matched transgenic mice not exposed to Dox.

- Analytical Tools: Epigenetic clock analysis for mouse tissues, histology reagents, RNA/DNA extraction kits.

Procedure:

- Experimental Groups: Establish cohorts of aged mice (e.g., 18-24 months) and, if relevant, progeria models. Include both Dox-treated transgenic mice and untreated transgenic controls.

- Cyclic Induction Regimen:

- Administer Dox (e.g., 2 mg/mL in drinking water supplemented with 1% sucrose) for a defined "ON" period. A widely cited safe and effective regimen is a 2-day ON, 5-day OFF cycle, repeated weekly for several months [20].

- Protect the Dox-water from light and change it twice weekly.

- Closely monitor mice for signs of distress, weight loss, or tumor formation throughout the study.

- Tissue Analysis:

- At predetermined endpoints (e.g., after 8-10 weeks of cycling), euthanize mice and harvest target tissues (e.g., skin, liver, kidney, muscle).

- Histopathological Analysis: Process tissues for H&E staining to assess tissue architecture, fibrosis, and screen for dysplasia or teratomas.

- Molecular Analysis:

- Functional Tests: Perform tissue-specific functional tests relevant to the tissue of interest (e.g., wound healing assays in skin, grip strength tests for muscle, or metabolic tests for liver).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Successful and safe research into OSKM-mediated reprogramming and rejuvenation relies on a suite of critical reagents and tools. The following table details essential solutions for designing experiments.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for OSKM-Based Reprogramming and Rejuvenation Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function & Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| Factor Delivery Systems | ||

| Non-Integrating Viral | Sendai Virus (SeV), Adenoviruses, IDLV | High-efficiency delivery; transient expression; SeV is cytoplasmic and does not enter the nucleus, making it a popular choice for footprint-free reprogramming [16]. |

| Non-Viral / mRNA | OSKM mRNA Kit | Commercially available; high efficiency for in vitro work; enables precise temporal control over protein expression; requires careful handling to minimize innate immune response [16]. |

| Non-Viral / Physical | Tissue Nanotransfection (TNT) | A novel nanoelectroporation platform for highly localized, non-viral in vivo gene delivery of plasmids or mRNA; minimizes off-target effects [4]. |

| Inducible Systems | Doxycycline-inducible OKSM Cassette (e.g., in Col1a1 locus) | The gold standard for in vivo partial reprogramming studies in mice; allows precise temporal control via oral Dox administration, enabling the critical cyclic induction protocols [20]. |

| Small Molecule Enhancers | ||

| Senolytics | Dasatinib + Quercetin | Can be used prior to or in conjunction with reprogramming to clear senescent cells, which can act as a barrier to efficient reprogramming and tissue rejuvenation. |

| Metabolic Modulators | Sodium Butyrate (HDAC inhibitor) | Improves reprogramming efficiency by modulating the epigenetic landscape. |

| Validation Tools | ||

| Pluripotency Markers | Antibodies for NANOG, SSEA-4, TRA-1-60 | Used to confirm full reprogramming to iPSCs. Their absence is a key indicator of successful partial reprogramming where pluripotency is avoided. |

| Aging Biomarkers | DNA Methylation Clock Panels (e.g., HorvathClock) | Quintessential tools for quantifying biological age and demonstrating epigenetic rejuvenation in both in vitro and in vivo samples [18] [19]. |

| Cell Identity Markers | Antibodies for cell-type specific proteins (e.g., Vimentin for fibroblasts) | Critical for confirming that partial reprogramming has not abolished the target cell identity, a key safety check. |

Signaling Pathways and Workflow Visualization

The transition from a fully differentiated somatic cell to a rejuvenated state or a pluripotent stem cell involves a defined sequence of molecular events. The following diagram maps this core reprogramming workflow and the key pathway interactions.

Concluding Remarks and Future Directions

The application of the Yamanaka factors has evolved far beyond the generation of iPSCs, emerging as a powerful, though delicate, tool for cellular rejuvenation and tissue regeneration. The critical challenge and primary focus of current research lie in achieving a perfectly calibrated "partial reset"—reversing the deleterious epigenetic and functional marks of aging without triggering dedifferentiation to a pluripotent state, which carries the risk of teratoma formation [18] [20]. Future directions will focus on several key areas: 1) the development of safer, non-genetic delivery methods such as tissue nanotransfection (TNT) and chemical reprogramming cocktails [4]; 2) the identification of novel, single-gene targets that can decouple rejuvenation from pluripotency induction, as exemplified by the discovery of SB000 [21]; and 3) the refinement of cyclic, tissue-specific induction protocols for in vivo human therapies. As the molecular mechanisms underlying OSKM-mediated rejuvenation become clearer, the prospect of developing effective therapies for age-related diseases and injuries moves closer to reality, heralding a new era in regenerative medicine.

Mesenchymal drift (MD) has been identified as a pervasive transcriptomic signature of aging, characterized by the progressive acquisition of mesenchymal traits by epithelial and endothelial cells, leading to eroded lineage identity and compromised tissue function [22]. Analysis of gene expression data from over 40 human tissues revealed that mesenchymal programs consistently intensify with age, with correlation coefficients exceeding 0.3 across nearly all tissues after controlling for confounders [22]. This drift represents a maladaptive transition that disrupts organ integrity across multiple systems including lung, liver, kidney, heart, and brain [22]. Importantly, recent research demonstrates that partial cellular reprogramming using Yamanaka factors can effectively reverse mesenchymal drift, offering a promising therapeutic strategy for age-related tissue dysfunction [23] [24].

Quantitative Evidence of Mesenchymal Drift in Aging and Disease

Association with Mortality and Morbidity

Table 1: Mesenchymal Drift as a Predictor of Clinical Outcomes

| Condition | Measurement | Effect Size | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis | Median Survival (High vs Low MD) | 59 vs 2,498 days | Direct correlation with mortality [22] |

| Multiple Age-Related Diseases | MD Signature Enrichment | Consistent upregulation in affected tissues | Association with disease severity [24] |

| UK Biobank Cohort | Mortality-Associated Plasma Proteins | Strong EMT pathway enrichment | Association with systemic aging [22] |

Tissue-Specific Manifestations

Table 2: Mesenchymal Drift Across Physiological Systems

| Tissue/Organ System | Key Molecular Markers | Functional Consequences |

|---|---|---|

| Lung (IPF) | VIM, FN1, COL1A1/3A1, SNAI/ZEB families | Progressive fibrosis, respiratory failure [22] |

| Liver (MASLD spectrum) | Hepatocyte and stellate cell activation | Steatosis to cirrhosis progression [22] |

| Kidney (CKD) | Tubular and podocyte mesenchymal features | Impaired filtration, fibrosis [22] |

| Heart (Failure) | Distinct MD signatures | Myocardial dysfunction [22] |

| Skin (Aged) | Loss of epithelial markers, gain of mesenchymal markers | Impaired barrier function, reduced regeneration [24] |

Experimental Protocols for Mesenchymal Drift Reversal

Genetic Partial Reprogramming Protocol

Objective: To reverse mesenchymal drift using inducible Yamanaka factors while maintaining cellular identity.

Materials:

- Doxycycline-inducible OSKM or OSK cassette (AAV9 or lentiviral delivery systems)

- Wild-type or progeroid mouse models (aged 12-24 months)

- Doxycycline chow or drinking water (1-2 mg/mL)

Methodology:

- Factor Delivery: Administer OSKM/OSK via AAV9 systemic injection or use transgenic models with tetracycline-responsive elements [18].

- Cyclic Induction: Implement pulsed regimen (2-day ON/5-day OFF for OSKM; 1-day ON/6-day OFF for OSK) to prevent full dedifferentiation [18].

- Duration: Continue treatment for 2-4 weeks for short-term studies or 7-10 months for long-term rejuvenation assessment [18] [24].

- Monitoring: Track teratoma formation via histological analysis and measure MD markers every 2 weeks [18].

Key Considerations:

- Exclusion of c-MYC reduces tumorigenic risk while maintaining efficacy [18]

- Intermediate timepoints (3-7 days) capture maximal MD suppression before pluripotency activation [23]

- Cell-type specific responses necessitate optimization for different tissues [24]

Chemical Reprogramming Protocol

Objective: To achieve MD reversal using non-genetic chemical approaches.

Materials:

- Six chemical cocktails identified through NCC screening [25] [2]

- Replicatively senescent human fibroblasts (40+ passages)

- Low serum conditions (0.5% FBS) to suppress cell division

Methodology:

- Senescence Induction: Culture fibroblasts through serial passaging (1:3-1:5 dilution) until complete growth arrest for 2 weeks [25].

- NCC Assay Validation: Confirm senescence using nucleocytoplasmic compartmentalization reporter (mCherry-NLS, eGFP-NES) with Pearson correlation >0.7 indicating senescence [25] [2].

- Chemical Treatment: Apply rejuvenation cocktails for ≤7 days in low serum conditions [25].

- Assessment: Measure transcriptomic age reversal via aging clocks and MD gene expression (VIM, FN1, COL1A1 reduction; EPCAM, CDH1 increase) [25] [2].

Key Considerations:

- Chemical approach avoids genomic integration risks [25]

- 7c cocktail operates through p53-upregulation pathway, distinct from OSKM mechanism [18]

- Treatment duration critical to avoid dedifferentiation [25]

Signaling Pathways and Molecular Mechanisms

Figure 1: Molecular Pathways of Mesenchymal Drift and Intervention Points. MD is driven by TGF-β/SMAD signaling, YAP/TAZ activation, and chronic inflammation, culminating in ZEB1/SNAI upregulation. Partial reprogramming and chemical interventions target multiple points in this pathway to restore epithelial identity.

Experimental Workflow for MD Reversal Studies

Figure 2: Experimental Workflow for MD Reversal Studies. The stepwise protocol emphasizes baseline characterization, intervention optimization, efficacy assessment, and safety validation to ensure meaningful results.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Mesenchymal Drift and Reprogramming Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Reprogramming Factors | OSKM (OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, c-MYC); OSK (excluding c-MYC) | Induction of partial reprogramming; MD reversal [1] [18] |

| Delivery Systems | AAV9 vectors; Doxycycline-inducible systems; Tissue Nanotransfection (TNT) | Efficient, controlled factor delivery with minimal integration risk [18] [4] |

| MD Assessment Tools | Mesenchymal gene panels (VIM, FN1, COL1A1); Epithelial markers (EPCAM, CDH1) | Quantification of drift magnitude and reversal efficacy [22] [24] |

| Senescence Assays | NCC reporter system; β-galactosidase staining; p21 expression analysis | Validation of aging phenotype pre-intervention [25] [2] |

| Chemical Cocktails | Six identified mixtures; 7c cocktail; TGF-β inhibitors (RepSox) | Non-genetic rejuvenation; MD pathway inhibition [25] [22] [2] |

| Epigenetic Clocks | Horvath clock; PhenoAge; Transcriptomic aging signatures | Biological age assessment pre- and post-intervention [18] [24] |

Mesenchymal drift represents a mechanistically grounded, pervasive signature of aging that is functionally reversible through partial reprogramming approaches. The experimental protocols outlined provide a framework for researchers to quantitatively assess and therapeutically target MD across tissue types. The convergence of genetic and chemical rejuvenation strategies on MD suppression underscores its fundamental role in aging biology and highlights promising translational avenues for addressing multiple age-related pathologies through a unified mechanistic framework.

Resetting Epigenetic Clocks and Restoring Youthful Gene Expression Profiles

Epigenetic reprogramming represents a frontier in regenerative medicine, aiming to reverse age-associated functional decline and restore tissue homeostasis. Central to this process is the resetting of epigenetic clocks, biomarkers of biological age based on DNA methylation patterns, and the restoration of youthful gene expression profiles without altering cellular identity [26]. This application note details the core principles, key quantitative outcomes, and practical protocols for achieving epigenetic rejuvenation through partial reprogramming, providing a structured resource for researchers and drug development professionals in the field of tissue regeneration.

Key Concepts and Mechanisms

The foundational principle of epigenetic rejuvenation is the Information Theory of Aging, which posits that aging is driven by a loss of epigenetic information leading to disordered gene expression [27] [2]. During aging, mammalian cells experience epigenetic drift, characterized by cumulative changes in DNA methylation patterns and histone modifications, which disrupts gene expression and cellular function [26]. Evidence suggests that despite this drift, mammalian cells retain a faithful, accessible copy of youthful epigenetic information, which can be reactivated to restore function [27].

Partial reprogramming describes the transient application of reprogramming factors, such as the Yamanaka factors (OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, c-MYC, or OSKM), or chemical alternatives. Unlike full reprogramming to pluripotency, this brief exposure aims to remodel the epigenome towards a more youthful state while maintaining the cell's differentiated identity, thereby avoiding the risks of teratoma formation [2] [5]. The process is thought to work by promoting a controlled, rejuvenation-associated epigenetic restructuring, which can involve active DNA demethylation mediated by enzymes like TET1 and TET2 [27] [2].

Quantitative Outcomes of Epigenetic Rejuvenation

The efficacy of rejuvenation strategies is quantified using epigenetic clocks and functional metrics. The table below summarizes key results from recent, influential studies.

Table 1: Key Quantitative Outcomes from Epigenetic Rejuvenation Studies

| Intervention / Study Model | Key Metric of Age Reversal | Reported Outcome | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| OSK (OCT4, SOX2, KLF4) In Vivo Expression (Mouse retinal ganglion cells) | Vision loss reversal in aged mice & glaucoma model | Restored vision; promoted axon regeneration after injury | [27] |

| TRIIM Trial (Thymus Regeneration, Immunorestoration, and Insulin Mitigation) in humans (9 volunteers) | Epigenetic age (GrimAge clock) | Mean epigenetic age decreased by ~1.5 years after one year of treatment (2.5-year change vs. controls) | [28] |

| Chemical-Induced Partial Reprogramming (7-compound cocktail in aged human fibroblasts) | DNA damage (γH2AX levels) | Significant decrease in DNA damage marker | [7] |

| Chemical-Induced Partial Reprogramming (2-compound cocktail in C. elegans) | Median Lifespan | Extension of median lifespan by over 42% | [7] |

| Vigorous Physical Activity (Professional soccer players) | Epigenetic age (DNAmGrimAge2, DNAmFitAge) | Significant decreases observed immediately after games | [28] |

| Semaglutide (Phase IIb trial in adults with HIV-associated lipohypertrophy) | 11 organ-system epigenetic clocks | Concordant decreases, most prominent in inflammation, brain, and heart clocks | [28] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

In Vivo Partial Reprogramming using OSK for Optic Nerve Regeneration

This protocol, derived from a seminal study, details the use of AAV-delivered OSK to reverse vision loss in aged mice and mouse models of glaucoma [27].

Key Research Reagent Solutions: Table 2: Essential Reagents for OSK In Vivo Reprogramming

| Reagent / Material | Function / Rationale |

|---|---|

| AAV2 with Tetracycline Response Element (TRE) promoter | Safe, efficient gene delivery vehicle with tight, inducible control over transgene expression in retinal cells. |

| Polycistronic OSK Construct | Ensures coordinated, stoichiometric expression of Oct4, Sox2, and Klf4 within the same cell, which is critical for efficacy. |

| Tet-Off System (tTA) | Allows transgene induction in the absence of doxycycline (Dox), providing precise temporal control. |

| Doxycycline (Dox) | Used to suppress the system and verify that observed effects are dependent on OSK expression. |

Workflow:

- Virus Preparation: Generate high-titer AAV2 vectors containing a polycistronic OSK sequence under the control of a TRE promoter, and a separate AAV2 vector expressing the tTA transactivator.

- In Vivo Delivery: Anesthetize mice and perform intravitreal injection of the AAV2-TRE-OSK and AAV2-tTA viruses into the eye.

- Incubation: Allow a minimum of two weeks for robust viral transduction and transgene expression in retinal ganglion cells (RGCs) before inducing injury or assessing outcomes.

- Optic Nerve Crush (Injury Model): Perform optic nerve crush surgery to induce axon damage. OSK expression is already active due to the Tet-Off system.

- Assessment: After 2-5 weeks, assess axon regeneration by injecting an anterograde axonal tracer (e.g., Alexa Fluor 555-conjugated CTB) into the vitreous and quantifying axon regrowth. Assess RGC survival via immunohistochemistry.

- Validation of Mechanism: To confirm the necessity of DNA demethylation, repeat experiments in conjunction with knockdown or inhibition of TET1/TET2 demethylases.

The following diagram illustrates the core logical relationship and workflow of the AAV-OSK system used in this protocol.

Chemical-Induced Partial Reprogramming in Aged Human Cells

This protocol outlines a chemical approach to reverse cellular aging, offering a potential alternative to genetic manipulation [7] [2].

Key Research Reagent Solutions: Table 3: Essential Reagents for Chemical Reprogramming

| Reagent / Material | Function / Rationale |

|---|---|

| Seven-Compound (7c) Cocktail (CHIR99021, DZNep, Forskolin, TTNPB, VPA, Repsox, TCP) | A combination of epigenetic, signaling, and metabolic modulators identified for their ability to induce pluripotency and reverse aging hallmarks. |

| Reduced Two-Compound (2c) Cocktail | An optimized combination (specific compounds not fully detailed in results) sufficient to ameliorate senescence, heterochromatin loss, and genomic instability. |

| Aged Primary Human Dermal Fibroblasts | A clinically relevant, human cell model for studying aging. |

| Assays for Aging Hallmarks | γH2AX immunofluorescence (DNA damage), SA-β-Gal staining (senescence), and ROS detection assays. |

Workflow:

- Cell Culture: Establish cultures of primary human dermal fibroblasts from aged donors.

- Chemical Treatment: Treat cells with either the full 7c cocktail or the optimized 2c cocktail for a period of 6 days. Include a DMSO vehicle control.

- Media Refreshment: Refresh the culture medium containing the compounds daily to ensure consistent exposure.

- Post-Treatment Analysis: After the 6-day treatment, harvest cells and perform multi-parametric analysis to assess rejuvenation:

- Genomic Instability: Quantify DNA damage foci via immunofluorescence staining for γH2AX.

- Cellular Senescence: Assess the percentage of senescent cells using Senescence-associated β-galactosidase (SA-β-Gal) staining.

- Epigenetic Alterations: Analyze changes in heterochromatin marks (e.g., H3K9me3) via immunostaining or western blot.

- Transcriptomic Age: Extract RNA and perform RNA-seq to analyze genome-wide transcript profiles and calculate transcriptomic aging clocks.

- In Vivo Validation: For promising cocktails (e.g., the 2c cocktail), proceed to in vivo testing in model organisms like C. elegans to assess lifespan and healthspan extension.

The diagram below summarizes the experimental workflow and the key aging hallmarks targeted for assessment.

Signaling Pathways in Epigenetic Reprogramming

Understanding the signaling pathways is critical for optimizing reprogramming protocols. The BMP signaling pathway has been identified as a key driver of epigenetic reprogramming and differentiation in human primordial germ cell-like cells (hPGCLCs) [29]. Furthermore, the efficacy of OSK-induced reprogramming is dependent on downstream DNA demethylation pathways [27].

The following diagram illustrates the core signaling pathway involved in this form of epigenetic reprogramming.

The protocols and data outlined herein demonstrate that resetting epigenetic clocks and restoring youthful gene expression profiles is an achievable, though complex, objective. The convergence of genetic (OSK) and chemical reprogramming strategies provides a versatile toolkit for researchers. The field is progressing towards greater precision, with ongoing efforts focused on achieving spatiotemporal control to maximize therapeutic benefits—such as enhanced tissue regeneration and extended healthspan—while minimizing risks like tumorigenesis and loss of cellular identity [28] [5]. The translation of these promising preclinical results into safe and effective clinical interventions represents the next major challenge in the field of regenerative medicine.

Protocols and Delivery Systems: Implementing Genetic and Chemical Reprogramming In Vivo

The foundational paradigm of cellular reprogramming was established with the discovery that somatic cells can be reprogrammed to pluripotency using defined transcription factors. The core combination of Oct4, Sox2, Klf4, and c-Myc (OSKM) has become the benchmark for induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) generation [30]. These factors initiate a complex rewiring of the cellular transcriptional and epigenetic landscape, driving cells toward a pluripotent state. A critical variation involves using only Oct4, Sox2, and Klf4 (OSK), omitting the proto-oncogene c-Myc, which represents a key comparative point in reprogramming protocol optimization, particularly for its implications in therapeutic safety and efficiency [30].

Comparative studies between human and mouse systems reveal that while both OSK and OSKM can achieve reprogramming, their dynamics and efficiency differ significantly. Mouse cells can be reprogrammed with OSK alone, whereas ectopic c-Myc expression appears more critical for efficient reprogramming in human cells [30]. The binding patterns of these factors also show species-specific variations; while the primary binding motifs and combinatorial patterns are largely conserved, a limited number of binding events occur in syntenic regions between human and mouse, suggesting detailed regulatory networks have diverged [30].

Table 1: Core Reprogramming Factor Combinations and Properties

| Factor Combination | Key Functions | Efficiency | Species-Specific Considerations | Primary Binding Pattern |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OSKM (Oct4, Sox2, Klf4, c-Myc) | Initiates pluripotency network; promotes proliferation | Higher efficiency; faster reprogramming | c-Myc more critical in human systems | Targets both proximal and distal regions; M binds distally in human, proximally in mouse |

| OSK (Oct4, Sox2, Klf4) | Core pluripotency circuitry; epigenetic remodeling | Lower efficiency; slower reprogramming | Sufficient for mouse reprogramming | Predominantly binds regions distal to transcriptional start sites (TSS) |

Inducible Genetic Reprogramming Systems

Inducible systems represent a significant advancement in reprogramming technology, enabling precise temporal control over factor expression. These systems circumvent the limitations of viral delivery, particularly the risk of insertional mutagenesis and variable factor expression. A prominent example is the doxycycline-inducible system used to express hair cell reprogramming factors (SIX1, ATOH1, POU4F3, and GFI1, collectively termed SAPG) in a stable human induced pluripotent stem cell line [31].

This virus-free approach utilizes a single polycistronic construct targeted to the CLYBL safe harbor locus via CRISPR/Cas9-mediated knock-in, ensuring consistent expression of all factors from a single transcript through 2A self-cleaving peptide sequences [31]. The inducible system demonstrates substantial improvements over traditional methods, achieving a 19-fold greater conversion efficiency to the target cell fate in half the time required by retroviral methods [31]. This enhanced efficiency stems from consistent expression of all reprogramming factors in every cell, avoiding the heterogeneity of infection efficiency and viral silencing that plagues multi-viral approaches.

Table 2: Comparison of Reprogramming Delivery Systems

| Delivery Method | Key Features | Reprogramming Efficiency | Time to Conversion | Safety Considerations | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Retroviral/Lentiviral | Multiple viruses; random integration | Variable; only subset infected by all viruses | ~4 weeks (human fibroblasts) | Insertional mutagenesis risk | Basic research; mouse models |

| Inducible System | Single polycistronic cassette; targeted integration | ~19x higher than viral methods | ~2 weeks (half the time) | Avoids permanent integration; precise temporal control | Therapeutic screening; human iPSC reprogramming |

| Chemical Reprogramming | Small molecule cocktails; non-genetic | Varies by cocktail (2c vs 7c) | Several days to weeks | Minimal safety concerns; reversible | Rejuvenation studies; age reversal |

Cyclic and Partial Reprogramming Regimens

Partial reprogramming through cyclic, short-term expression of reprogramming factors offers a promising strategy for reversing age-related cellular attributes without completely erasing cellular identity. This approach aims to achieve cellular rejuvenation – shifting cells to younger states – while avoiding the risk of teratoma formation associated with full reprogramming [6].

Chemical reprogramming represents a particularly advanced cyclic regimen. Studies utilizing cocktails of small-molecule compounds (such as the 7c cocktail containing repsox, trans-2-phenylcyclopropylamine, DZNep, TTNPB, CHIR99021, forskolin, and valproic acid) have demonstrated the ability to ameliorate hallmarks of aging in human fibroblasts while preserving cellular identity [6]. Multi-omics characterization of partial chemical reprogramming in fibroblasts from young and aged mice revealed evidence of reduced biological age according to both epigenetic and transcriptomic clocks, with the most notable signature being upregulation of mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation [6].

Functional assessments demonstrate that partial chemical reprogramming with the 7c cocktail significantly increases spare respiratory capacity and basal mitochondrial membrane potential, indicating improved mitochondrial function – a key aspect of cellular rejuvenation [6]. These changes occur without the dramatic morphological changes associated with full pluripotency reprogramming, positioning cyclic partial reprogramming as a viable strategy for combating age-related degeneration in therapeutic contexts.

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Protocol: Establishing an Inducible Reprogramming Cell Line

This protocol outlines the creation of a stable, inducible reprogramming cell line for direct lineage conversion, adapted from successful generation of hair cell-like cells [31].

Materials:

- Reprogramming Factors cDNA: SIX1, ATOH1, POU4F3, GFI1 (or OSKM/OSK for pluripotency)

- Tet-On Inducible Vector: Containing TRE3G or similar inducible promoter

- CRISPR/Cas9 Components: Cas9 nuclease, gRNA targeting CLYBL safe harbor locus

- Host Cell Line: Human induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs)

- Selection Antibiotics: Appropriate for the selection marker in the vector (e.g., puromycin)

Method:

- Vector Construction: Clone the reprogramming factors into the Tet-On inducible vector, separating them with 2A self-cleaving peptide sequences (e.g., P2A, T2A) to ensure equivalent expression from a single transcript.

- gRNA Design: Design and validate guide RNAs targeting the CLYBL safe harbor locus to ensure minimal disruption of endogenous genes post-integration.

- Cell Transfection: Co-transfect the inducible vector and CRISPR/Cas9 components into human iPSCs using an appropriate method (e.g., electroporation).

- Selection and Expansion: Select successfully transfected cells with antibiotics for 7-14 days, then expand individual clones.

- Validation: Validate integration site and inducible expression by treating clones with doxycycline (1-2 μg/mL) and assessing factor expression via RT-qPCR and immunostaining after 24-48 hours.

Protocol: Partial Chemical Reprogramming with 7c Cocktail

This protocol describes the application of chemical reprogramming cocktails for partial cellular rejuvenation, based on multi-omics characterization studies [6].

Materials:

- 7c Chemical Cocktail: repsox (TGF-β inhibitor), trans-2-phenylcyclopropylamine (LSD1 inhibitor), DZNep (EZH2 inhibitor), TTNPB (retinoic acid receptor agonist), CHIR99021 (GSK-3 inhibitor), forskolin (adenylyl cyclase activator), valproic acid (HDAC inhibitor)

- Control Cocktail: 2c cocktail (repsox and trans-2-phenylcyclopropylamine) for comparison

- Fibroblast Culture: Young (4-month) and aged (20-month) mouse dermal fibroblasts

- Assessment Reagents: TMRM for mitochondrial membrane potential, Seahorse XFp Analyzer reagents for mitochondrial stress test

Method:

- Cell Preparation: Plate fibroblasts at appropriate density (e.g., 10,000 cells/cm²) and culture until 70-80% confluent.

- Treatment: Treat cells with 7c or 2c cocktail for 6 days, refreshing media and compounds every 48 hours.

- Functional Assessment:

- Mitochondrial Membrane Potential: Measure TMRM fluorescence via flow cytometry after treatment.

- Metabolic Analysis: Perform Seahorse Mito Stress Test to assess oxygen consumption rates (OCR), specifically basal respiration, proton leak, and spare respiratory capacity.

- Molecular Analysis: Harvest cells for multi-omics analysis – transcriptomics (RNA-seq), epigenomics (ATAC-seq, ChIP-seq), proteomics, and metabolomics – to evaluate rejuvenation signatures.

Signaling Pathways and Molecular Mechanisms