Small Molecules in Epigenetic Reprogramming: Mechanisms, Applications, and Clinical Translation

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the rapidly advancing field of epigenetic reprogramming using small molecules.

Small Molecules in Epigenetic Reprogramming: Mechanisms, Applications, and Clinical Translation

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the rapidly advancing field of epigenetic reprogramming using small molecules. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational mechanisms by which small molecules target epigenetic enzymes to reverse cell fate and restore pluripotency. It delves into methodological advances, including the generation of induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) and the induction of rejuvenation without complete dedifferentiation. The content addresses key challenges in reprogramming efficiency and safety, and offers a critical comparative analysis with genetic reprogramming methods. Finally, it examines the validation of these approaches for disease modeling, drug discovery, and the development of next-generation regenerative therapies, synthesizing the current landscape and future directions for clinical application.

The Epigenetic Landscape: How Small Molecules Rewrite Cellular Identity

Epigenetics involves heritable, reversible changes in gene activity that do not alter the underlying DNA sequence, serving as a critical regulatory layer in development, cellular identity, and disease [1]. The three core mechanisms—DNA methylation, histone modifications, and chromatin remodeling—collectively regulate chromatin architecture and DNA accessibility, thereby controlling gene expression patterns [2] [3]. In the context of epigenetic reprogramming, these mechanisms provide the molecular targets for small molecules to reverse differentiated cellular states, combat age-related deterioration, or reverse disease-associated gene expression profiles without genetic alteration [4] [5].

The dynamic and reversible nature of epigenetic modifications makes them particularly attractive therapeutic targets. Research has demonstrated that small molecules can effectively modulate these mechanisms to induce pluripotency in somatic cells, reverse cancerous phenotypes, or restore youthful function in aged tissues [6] [7] [5]. This application note details the experimental frameworks for investigating and manipulating these core epigenetic mechanisms using small molecule approaches, providing standardized protocols for researchers pursuing epigenetic reprogramming strategies.

DNA Methylation

Mechanism and Biological Function

DNA methylation involves the covalent addition of a methyl group to the carbon-5 position of cytosine residues within cytosine-guanine (CpG) dinucleotides, forming 5-methylcytosine (5mC) [2] [1]. This modification is catalyzed by DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs), with DNMT3A and DNMT3B establishing de novo methylation patterns, and DNMT1 maintaining these patterns during DNA replication [3] [1]. CpG islands—genomic regions with high G+C content and dense CpG clustering—are typically unmethylated in promoter regions, allowing gene expression, while methylation of these regions leads to transcriptional repression through chromatin condensation and impeded transcription factor binding [3].

In mammalian genomes, 70-90% of CpG sites are normally methylated, while CpG islands at promoter regions remain largely unmethylated to maintain a transcriptionally permissive state [3]. The Ten-eleven translocation (TET) enzyme family catalyzes DNA demethylation through a stepwise oxidation process, converting 5mC to 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5hmC), then to 5-formylcytosine (5fC), and finally to 5-carboxylcytosine (5caC), leading to eventual base excision repair and restoration of unmethylated cytosine [1].

Experimental Assessment Protocols

Bisulfite Sequencing for DNA Methylation Analysis

Principle: Bisulfite conversion deaminates unmethylated cytosines to uracils (which amplify as thymines in PCR), while methylated cytosines remain unchanged, allowing single-base resolution methylation mapping.

Protocol:

- DNA Isolation: Extract high-quality genomic DNA using phenol-chloroform or column-based methods.

- Bisulfite Conversion: Treat 500ng-1μg DNA with sodium bisulfite using commercial kits (e.g., EZ DNA Methylation Kit). Incubate at 95°C for 10 minutes, then 50-60°C for 4-16 hours.

- Purification: Desalt and purify converted DNA according to kit specifications.

- PCR Amplification: Design primers specific for bisulfite-converted DNA. Amplify target regions with hot-start DNA polymerase.

- Sequencing: Clone PCR products and sequence 10-20 clones per sample, or utilize next-generation sequencing platforms for genome-wide analysis.

- Data Analysis: Calculate methylation percentage as (number of methylated cytosines / total cytosines) × 100 at each CpG site.

Applications: Targeted analysis of specific gene promoters or genome-wide methylation profiling [8].

Methylated DNA Immunoprecipitation (MeDIP)

Principle: Antibodies specific for 5-methylcytosine immunoprecipitate methylated DNA fragments for enrichment and quantification.

Protocol:

- DNA Shearing: Fragment 1-5μg genomic DNA to 200-1000bp by sonication or enzymatic digestion.

- Immunoprecipitation: Incubate with anti-5mC antibody overnight at 4°C with rotation.

- Recovery: Add protein A/G beads, incubate 2 hours, then wash with low-salt and high-salt buffers.

- Elution and Purification: Elute DNA with elution buffer containing proteinase K.

- Analysis: Quantify enriched DNA by qPCR for specific loci or subject to microarray/high-throughput sequencing.

Applications: Genome-wide methylation screening and comparative methylation analysis [3].

Small Molecule Targeting Strategies

Small molecule DNMT inhibitors can reverse aberrant hypermethylation patterns in cancer or during reprogramming. These include nucleoside analogs like 5-aza-2'-deoxycytidine (decitabine) that incorporate into DNA and trap DNMTs, leading to their degradation and passive demethylation [2] [7].

Table: Small Molecule Modulators of DNA Methylation

| Small Molecule | Target | Concentration Range | Application in Reprogramming |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5-aza-dC | DNMT1 | 0.5-5 μM | DNA demethylation, enhances reprogramming efficiency |

| RG108 | DNMT1 | 10-50 μM | Non-nucleoside DNMT inhibition |

| Decitabine | DNMT1 | 0.1-1 μM | Cancer therapy, hypomethylation |

| Vitamin C | TET enzymes | 50-200 μg/mL | Enhances TET activity, promotes demethylation |

Histone Modifications

Mechanism and Biological Function

Histone modifications represent post-translational alterations to histone proteins that regulate chromatin structure and DNA accessibility. These include methylation, acetylation, phosphorylation, ubiquitination, and sumoylation of specific amino acid residues, primarily on histone N-terminal tails [2] [3]. The combinatorial nature of these modifications forms a "histone code" that can be read by specialized protein complexes to influence transcriptional states [1].

Histone acetylation, mediated by histone acetyltransferases (HATs) and removed by histone deacetylases (HDACs), generally correlates with transcriptional activation by neutralizing histone positive charges and relaxing chromatin structure. Histone methylation can either activate or repress transcription depending on the modified residue and methylation state (mono-, di-, or tri-methylation); for example, H3K4me3 marks active promoters, while H3K27me3 characterizes facultative heterochromatin [2] [9].

Experimental Assessment Protocols

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP)

Principle: Antibodies specific to histone modifications or chromatin-associated proteins immunoprecipitate crosslinked DNA-protein complexes, enabling mapping of epigenetic marks genome-wide.

Protocol:

- Crosslinking: Treat cells with 1% formaldehyde for 10 minutes at room temperature to fix protein-DNA interactions.

- Cell Lysis and Sonication: Lyse cells and shear chromatin to 200-500bp fragments using sonication.

- Immunoprecipitation: Incubate chromatin with specific antibody (1-5μg) overnight at 4°C.

- Recovery and Washing: Collect complexes with protein A/G beads, wash with low-salt, high-salt, and LiCl buffers.

- Reverse Crosslinking and Purification: Incubate at 65°C overnight with proteinase K, then purify DNA.

- Analysis: Quantify by qPCR for specific loci or prepare libraries for sequencing (ChIP-seq).

Applications: Mapping histone modification patterns, transcription factor binding sites, and chromatin regulator localization [3].

Histone Modification Quantification by Western Blot

Principle: Specific antibodies detect global levels of histone modifications, providing quantitative assessment of epigenetic states.

Protocol:

- Histone Extraction: Acid extract histones from cell nuclei using 0.2M H₂SO₄ overnight at 4°C.

- Precipitation and Washing: Precipitate with trichloroacetic acid, wash with acetone, and resuspend in water.

- Electrophoresis: Separate 2-5μg histone extract on 15% SDS-PAGE gels.

- Transfer and Blocking: Transfer to PVDF membranes, block with 5% non-fat milk.

- Antibody Incubation: Incubate with primary antibodies specific to modifications (1:1000 dilution) overnight at 4°C, then with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies.

- Detection: Develop with enhanced chemiluminescence substrate and quantify band intensity.

Applications: Screening epigenetic drug effects and monitoring global histone modification changes [2].

Small Molecule Targeting Strategies

Small molecule inhibitors targeting histone-modifying enzymes have shown significant promise in reprogramming and cancer therapy. HDAC inhibitors (e.g., valproic acid, trichostatin A) promote open chromatin states and enhance reprogramming efficiency, while histone methyltransferase inhibitors (e.g., DZNep targeting EZH2) can reverse repressive chromatin marks [7].

Table: Small Molecule Modulators of Histone Modifications

| Small Molecule | Target | Concentration Range | Application in Reprogramming |

|---|---|---|---|

| Valproic Acid (VPA) | HDAC Class I/II | 0.5-2 mM | Chromatin relaxation, reprogramming enhancement |

| Trichostatin A | HDAC Class I/II | 0.5-1 μM | Potent HDAC inhibition, increases histone acetylation |

| DZNep | EZH2 (H3K27 methyltransferase) | 0.5-5 μM | Reduces H3K27me3, enhances reprogramming |

| Parnate | LSD1 (H3K4 demethylase) | 5-20 μM | Increases H3K4 methylation |

| BIX-01294 | G9a (H3K9 methyltransferase) | 1-5 μM | Reduces H3K9me2, facilitates reprogramming |

Diagram: Histone Modification Regulatory Pathway. Histone modifications are dynamically regulated by writer (HATs, HMTs), eraser (HDACs, HDMs), and reader proteins, ultimately influencing transcriptional states. Acetylation generally promotes activation, while methylation effects depend on specific residues modified.

Chromatin Remodeling

Mechanism and Biological Function

Chromatin remodeling complexes (CRCs) utilize ATP hydrolysis to slide, evict, or restructure nucleosomes, thereby regulating DNA accessibility [3]. These complexes fall into four major families: SWI/SNF, ISWI, CHD, and INO80, each with distinct functions in chromatin organization [3]. Through their nucleosome repositioning activities, CRCs control fundamental processes including gene transcription, DNA replication, and DNA repair by making specific genomic regions more or less accessible to the cellular machinery [2].

In cellular reprogramming, chromatin remodeling represents a critical barrier that must be overcome to enable fate conversion. The BAF complex, in particular, has been identified as essential for reprogramming, as it facilitates the opening of chromatin at pluripotency gene loci in cooperation with pioneer transcription factors like OCT4 [5].

Experimental Assessment Protocols

Assay for Transposase-Accessible Chromatin with Sequencing (ATAC-seq)

Principle: Hyperactive Tn5 transposase simultaneously fragments and tags accessible genomic regions with sequencing adapters, providing a genome-wide accessibility map.

Protocol:

- Cell Preparation: Harvest 50,000 viable cells, wash with cold PBS, and lyse with hypotonic buffer.

- Tagmentation Reaction: Incubate nuclei with Tn5 transposase for 30 minutes at 37°C.

- DNA Purification: Purify tagmented DNA using column-based purification.

- PCR Amplification: Amplify libraries with barcoded primers for 10-12 cycles.

- Library Purification and Sequencing: Size-select libraries (150-500bp) and sequence on appropriate platforms.

- Data Analysis: Map sequencing reads, call accessible peaks, and compare between conditions.

Applications: Genome-wide chromatin accessibility profiling in reprogramming time courses and epigenetic drug screening [5].

MNase Sensitivity Assay

Principle: Micrococcal nuclease preferentially digests linker DNA between nucleosomes, revealing nucleosome positioning and chromatin organization.

Protocol:

- Nuclei Isolation: Lyse cells with NP-40 buffer and isolate nuclei by centrifugation.

- MNase Digestion: Treat nuclei with 0.5-5 units MNase for 5-15 minutes at 37°C.

- DNA Extraction: Stop reaction with EDTA/SDS, purify DNA with phenol-chloroform.

- Analysis: Separate DNA on 1.5% agarose gels or subject to sequencing.

Applications: Nucleosome positioning analysis and higher-order chromatin structure assessment [3].

Integrated Experimental Approaches for Reprogramming

Small Molecule Cocktails for Epigenetic Reprogramming

Combining small molecules targeting multiple epigenetic mechanisms has proven highly effective for cellular reprogramming. These cocktails typically include epigenetic modifiers, signaling pathway inhibitors, and metabolic switches to cooperatively reset cellular identity [7].

Table: Representative Small Molecule Cocktails for Cell Reprogramming

| Cocktail Component | Category | Target | Typical Concentration | Function in Reprogramming |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CHIR99021 | Metabolic modifier | GSK3 inhibitor | 3-6 μM | Promotes glycolytic switch |

| RepSox | Signaling modifier | TGFβ inhibitor | 2-10 μM | Replaces Sox2, inhibits differentiation |

| Valproic Acid | Epigenetic modifier | HDAC inhibitor | 0.5-2 mM | Chromatin relaxation |

| Parnate | Epigenetic modifier | LSD1 inhibitor | 5-20 μM | Increases H3K4 methylation |

| Forskolin | Signaling modifier | cAMP activator | 5-20 μM | Can replace Oct4 |

| DZNep | Epigenetic modifier | EZH2 inhibitor | 0.5-5 μM | Reduces H3K27me3 |

Experimental Workflow for Small Molecule Reprogramming

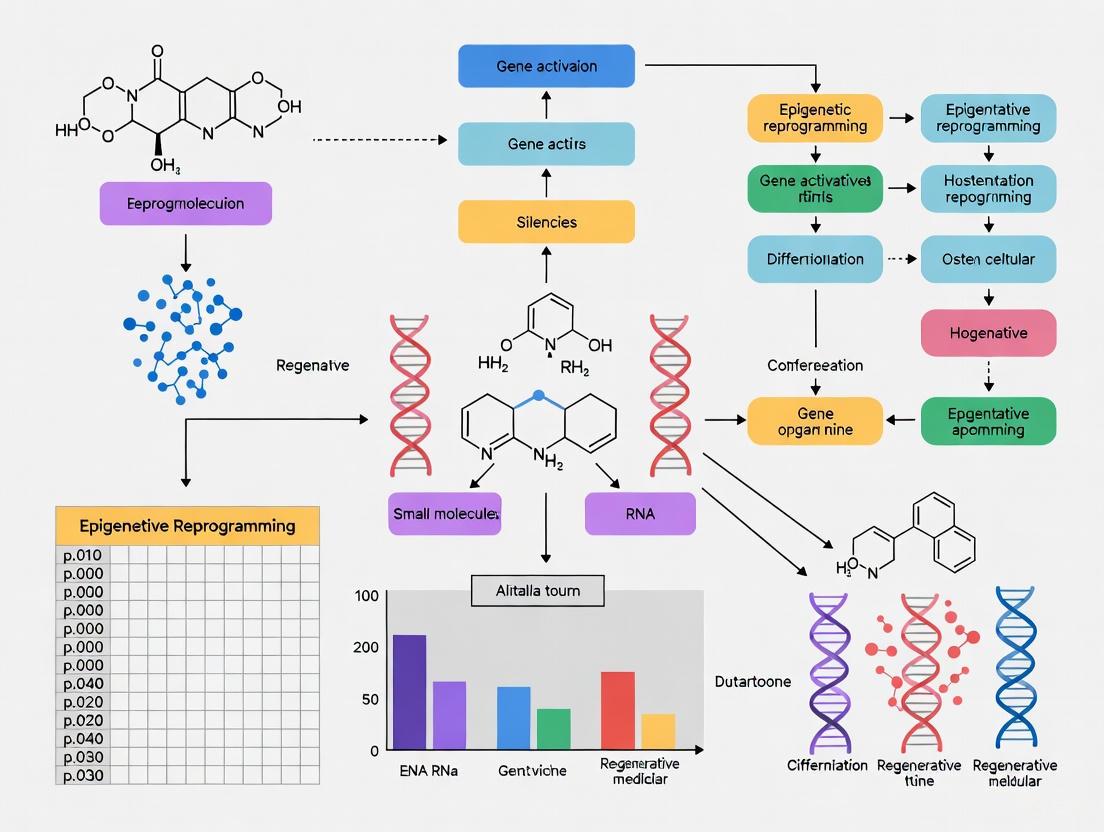

Diagram: Small Molecule Reprogramming Workflow. The schematic outlines key steps in epigenetic reprogramming using small molecules, from initial cell preparation through molecular validation and functional characterization of reprogrammed cells.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table: Key Research Reagents for Epigenetic Reprogramming Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Application | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNMT Inhibitors | 5-aza-dC, RG108, Decitabine | DNA demethylation | 5-aza-dC is cytotoxic at high concentrations; use optimal concentration ranges |

| HDAC Inhibitors | Valproic Acid, Trichostatin A, Sodium Butyrate | Histone acetylation enhancement | VPA is less potent but well-tolerated for long-term treatment |

| HMT Inhibitors | DZNep, BIX-01294, EPZ004777 | Reduction of repressive histone marks | Target specific methyltransferases (EZH2, G9a, DOT1L respectively) |

| Signaling Inhibitors | RepSox, A-83-01, SB431542 | TGFβ pathway inhibition | Can replace Sox2 in reprogramming cocktails |

| Metabolic Modulators | CHIR99021, Forskolin | Glycolytic switch, cAMP activation | CHIR99021 is a GSK3 inhibitor; Forskolin can replace Oct4 |

| Detection Antibodies | Anti-5mC, Anti-H3K27ac, Anti-H3K4me3, Anti-H3K27me3 | Epigenetic mark detection | Validate antibodies for specific applications (ChIP, Western, IF) |

| Sequencing Kits | Bisulfite conversion kits, ChIP-seq kits, ATAC-seq kits | Genome-wide epigenetic profiling | Consider coverage requirements and single-cell vs bulk applications |

| Mtams | MTAMs (Microtube Array Membranes) for Biomedical Research | Explore MTAMs for advanced Encapsulated Cell Therapy and 3D cell culture applications. This product is For Research Use Only. Not for human, veterinary, or household use. | Bench Chemicals |

| Maoto | Maoto (Ma-Huang-Tang) | Maoto is a traditional Japanese Kampo medicine used in research for influenza, antiviral mechanisms, and immunomodulation. For Research Use Only. Not for human use. | Bench Chemicals |

The core epigenetic mechanisms—DNA methylation, histone modifications, and chromatin remodeling—represent interconnected regulatory layers that maintain cellular identity and can be targeted for therapeutic reprogramming. The protocols and small molecule strategies outlined here provide researchers with standardized approaches to investigate and manipulate these mechanisms in various contexts, from regenerative medicine to cancer therapy. As the field advances, increasingly sophisticated small molecule cocktails that precisely modulate these epigenetic pathways will enable more efficient and safe cellular reprogramming for research and clinical applications.

The reversible nature of epigenetic modifications continues to make them attractive targets for intervention. Future directions will likely focus on improving the specificity of epigenetic modulators, developing more precise temporal control over reprogramming processes, and combining epigenetic approaches with other regenerative strategies to enhance therapeutic outcomes while minimizing potential risks such as tumorigenicity [4] [5].

Small Molecules as Tools to Target Writers, Erasers, and Readers of the Epigenetic Code

The eukaryotic genome is regulated by a complex layer of information known as the epigenetic code, which controls gene expression without altering the underlying DNA sequence [10]. This code comprises covalent modifications to DNA and histone proteins, which dictate chromatin states ranging from transcriptionally permissive euchromatin to repressed heterochromatin [10]. The enzymes and proteins that interpret, add, and remove these modifications are categorized into three functional classes: Writers that deposit epigenetic marks, Erasers that remove them, and Readers that recognize the marks and recruit effector proteins to implement transcriptional outcomes [10] [11]. In cancer and other diseases, this regulatory system is frequently dysregulated, leading to aberrant silencing of tumor suppressor genes or activation of oncogenes [2] [10]. Small molecules designed to target these epigenetic tools have therefore emerged as a promising therapeutic strategy. Their primary advantage lies in the reversible nature of epigenetic modifications, allowing for the potential resetting of diseased cellular states [2]. This application note details the key protein targets within each class and provides standardized protocols for evaluating small-molecule inhibitors in a research setting, framing this methodology within the broader thesis of achieving controlled epigenetic reprogramming for therapeutic benefit.

The Epigenetic Toolkit: Targets for Small-Molecule Intervention

Writers

Epigenetic writers are enzymes that catalyze the addition of chemical groups to DNA or histone proteins. Key writer families include DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs) and histone methyltransferases (HMTs) and acetyltransferases (HATs).

- DNA Methyltransferases (DNMTs): DNMTs, including DNMT1, DNMT3A, and DNMT3B, add a methyl group to the 5-position of cytosine in CpG dinucleotides, leading to transcriptional repression [2] [10]. DNMT1 is primarily responsible for maintaining methylation patterns during DNA replication, while DNMT3A and DNMT3B mediate de novo methylation [2]. Global hypomethylation and promoter-specific hypermethylation of tumor suppressor genes are hallmarks of cancer, making DNMTs attractive drug targets [2].

- Histone Acetyltransferases (HATs): HATs, such as p300/CBP and MYST family members, catalyze the transfer of an acetyl group to lysine residues on histone tails. This neutralizes the positive charge of histones, relaxing chromatin structure and promoting an open, transcriptionally active state [10].

- Histone Methyltransferases (HMTs): HMTs, like EZH2 (which catalyzes H3K27me3) and DOT1L (which catalyzes H3K79me), add methyl groups to lysine or arginine residues on histones [10] [12]. The functional outcome of methylation depends on the specific residue and the degree of methylation (mono-, di-, or tri-methylation), and can be associated with either transcriptional activation or repression.

Erasers

Erasers are enzymes that remove epigenetic marks, providing dynamic control over the epigenetic landscape.

- Histone Deacetylases (HDACs): HDACs remove acetyl groups from histone lysine residues, promoting chromatin condensation and transcriptional repression [11]. They are divided into classes based on structure and function. HDAC inhibitors can reactivate silenced genes and have been successfully approved for treating certain hematologic cancers [11].

- Ten-Eleven Translocation (TET) Enzymes and others: TET enzymes initiate the demethylation of DNA by oxidizing 5-methylcytosine [13]. Lysine-specific demethylase 1 (LSD1) is another key eraser that removes methyl groups from histone H3 lysine 4 (H3K4), a mark associated with active transcription [10] [12].

Readers

Reader proteins contain specialized domains that recognize and bind to specific epigenetic marks, translating the histone code into biological functions.

- Bromodomains: These modules are readers of acetylated lysine residues [10]. Proteins of the BET (bromodomain and extra-terminal) family, such as BRD4, contain bromodomains and are critical regulators of gene expression, making them prominent targets in oncology [13] [11].

- Methyl-Lysine Readers: This diverse group includes proteins with chromodomains (e.g., HP1, which binds H3K9me3), Tudor domains, and plant homeodomain (PHD) fingers, which recognize specific methylated lysine states [10].

- Methyl-CpG Binding Domain Proteins (MBDs): Proteins like MeCP2 bind to methylated CpG dinucleotides and recruit additional complexes to enforce transcriptional silencing [10].

Table 1: Key Epigenetic Regulator Families and Example Targets

| Epigenetic Tool | Protein Family | Example Targets | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Writers | DNA Methyltransferases | DNMT1, DNMT3A/B | Catalyzes DNA methylation, leading to gene silencing [2] |

| Histone Acetyltransferases | p300/CBP, MYST family | Catalyzes histone acetylation, promoting open chromatin [10] | |

| Histone Methyltransferases | EZH2, DOT1L | Catalyzes histone methylation; effect is residue-specific [10] [12] | |

| Erasers | Histone Deacetylases | HDAC1, HDAC6 | Removes histone acetyl groups, leading to condensed chromatin [11] |

| Histone Demethylases | LSD1, JMJD family | Removes methyl groups from histones [10] [12] | |

| Readers | Bromodomains | BRD4, BRD2 | Binds acetylated lysine residues on histones [10] |

| Chromodomains | HP1 | Binds methylated lysine (e.g., H3K9me3) [10] | |

| Methyl-CpG Binding | MeCP2, MBD1 | Binds methylated DNA and recruits repressor complexes [10] | |

| Mttch | Mttch, CAS:99096-13-6, MF:C11H16O4, MW:212.24 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Gmlsp | Gmlsp, CAS:77160-86-2, MF:C37H51N7O7S, MW:737.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Experimental Protocols for Screening Small-Molecule Epigenetic Modulators

Protocol: In Vitro Screening of DNMT Inhibitor Activity

This protocol assesses the potency of small-molecule inhibitors against recombinant DNMT enzymes.

- Reagent Preparation: Prepare a reaction buffer (e.g., 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.8, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, 100 µg/mL BSA). Dilute recombinant human DNMT1 or DNMT3A enzyme to a working concentration. Prepare a double-stranded CpG-rich DNA substrate (e.g., from the promoter region of a known tumor suppressor gene like p16INK4a). Prepare S-adenosylmethionine (SAM) as the methyl donor group. Prepare serial dilutions of the test compound (e.g., 5-Azacytidine, RG108) and a positive control inhibitor [12].

- Enzymatic Reaction: In a 96-well plate, mix the following for each reaction:

- DNA substrate (50-100 ng)

- DNMT enzyme (10-100 nM)

- SAM (0.5-5 µM)

- Test compound or vehicle control (DMSO)

- Reaction buffer to a final volume of 50 µL.

- Incubate the reaction at 37°C for 1-4 hours.

- Methylation Quantification:

- Option A (ELISA-based): Use a commercial methylated DNA quantification kit. Stop the reaction and transfer the DNA to a streptavidin-coated plate if using a biotinylated substrate. Follow kit instructions to detect methylated cytosine using an anti-5-methylcytosine antibody and a colorimetric or fluorometric readout.

- Option B (Liquid Scintillation Counting): Use tritium-labeled SAM (³H-SAM) as the methyl donor. Stop the reaction and transfer the mixture to a filter plate that binds DNA. Wash away unincorporated ³H-SAM and measure the radioactivity on the filter, which is proportional to DNMT activity.

- Data Analysis: Calculate the percentage of inhibition for each compound concentration compared to the vehicle control. Plot dose-response curves to determine the half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50).

Protocol: Cellular Assessment of HDAC Inhibitor Activity via Histone Hyperacetylation

This protocol evaluates the on-target effect of HDAC inhibitors in cultured cells by measuring the accumulation of acetylated histones.

- Cell Treatment: Seed cancer cell lines (e.g., HeLa or hematologic cancer cells) in 6-well plates and allow to adhere overnight. Treat cells with a range of concentrations of the HDAC inhibitor (e.g., Vorinostat/SAHA, Trichostatin A/TSA, Valproic Acid) or a DMSO vehicle control for 6-24 hours [12] [11].

- Histone Extraction: Harvest cells by trypsinization and wash with PBS. Lyse cells using a hypotonic lysis buffer (e.g., 10 mM HEPES pH 7.9, 1.5 mM MgClâ‚‚, 10 mM KCl, protease inhibitors) on ice. Isolate nuclei by centrifugation. Extract histones from the nuclear pellet using 0.4 N sulfuric acid. Precipitate histones with trichloroacetic acid (TCA) and wash with acetone.

- Western Blot Analysis: Resolve the extracted histones (2-5 µg) on a 4-20% SDS-PAGE gel. Transfer proteins to a PVDF membrane. Block the membrane and probe with a primary antibody against acetylated histone H3 (e.g., Ac-H3K9/K14) or acetylated histone H4, followed by an HRP-conjugated secondary antibody. Re-probe the blot with an antibody against total histone H3 as a loading control.

- Data Analysis: Visualize bands using chemiluminescence. Densitometric analysis of the acetyl-histone bands, normalized to total histone H3, will reveal a dose-dependent increase in histone acetylation, confirming successful target engagement by the HDAC inhibitor.

The following workflow diagram illustrates the key steps in this cellular protocol.

Protocol: Functional Phenotypic Screen for Reprogramming Enhancement

This protocol tests the ability of small molecules to enhance the reprogramming of somatic cells into induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), a process heavily dependent on epigenetic remodeling.

- Reprogramming Initiation: Use mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) engineered to express a pluripotency reporter (e.g., Oct4-GFP). Transduce cells with a doxycycline-inducible lentivirus expressing OSKM (Oct4, Sox2, Klf4, c-Myc) factors at a low multiplicity of infection (MOI) to achieve low reprogramming efficiency [12].

- Small Molecule Treatment: From day 2 post-transduction, treat cells with the test compound (e.g., Valproic Acid, Vitamin C, CHIR99021, EPZ004777) [12]. Refresh the medium containing the compound every day. Include control groups with DMSO and a positive control (e.g., high MOI OSKM).

- Colony Formation and Analysis: Culture cells for 14-21 days. Fix and stain colonies for alkaline phosphatase (AP) activity or score based on Oct4-GFP expression.

- Data Analysis: Count the number of AP-positive or GFP-positive colonies. A significant increase in colony number in the test compound group compared to the low-MOI DMSO control indicates an enhancement of reprogramming efficiency.

Table 2: Example Small Molecules for Epigenetic Research and Their Applications

| Small Molecule | Primary Target | Function/Effect | Example Use in Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5-Azacytidine (Vidaza) | DNMTs | Nucleoside analog; incorporates into DNA, leading to irreversible DNMT binding and global hypomethylation [11]. | Reactivation of hypermethylated, silenced tumor suppressor genes in cell lines [2]. |

| Vorinostat (SAHA) | HDACs (Class I, II) | Pan-HDAC inhibitor; increases global histone acetylation, relaxing chromatin [11]. | Induces cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in cancer cell lines; used in studies of CTCL [11]. |

| Valproic Acid (VPA) | HDACs (Class I) | HDAC inhibitor; promotes histone acetylation [12]. | Enhances efficiency of iPSC generation when combined with transcription factors [12]. |

| EPZ004777 | DOT1L | Selective inhibitor of H3K79 methyltransferase DOT1L [12]. | Used to study MLL-rearranged leukemia; reduces H3K79me2 at target genes [12]. |

| JQ1 | BET Bromodomains | Competitively binds to bromodomains of BRD4, displacing it from chromatin [11]. | Suppresses oncogene expression (e.g., MYC) in hematologic cancer models [11]. |

| BIX-01294 | G9a/GLP | Inhibitor of H3K9 methyltransferases G9a and GLP [12]. | Used in reprogramming studies to reduce repressive H3K9me2 marks and facilitate cell fate change [12]. |

Visualization of the Epigenetic Regulatory Axis and Therapeutic Intervention

The following diagram illustrates the coordinated action of Writers, Erasers, and Readers in maintaining the epigenetic code, and the points of intervention for small-molecule inhibitors.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Epigenetic Modulator Research

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Recombinant Epigenetic Enzymes (e.g., DNMT3A/3L, HDAC1) | In vitro biochemical assays for high-throughput screening and mechanistic studies of inhibitor potency and kinetics. | Available from various suppliers; purity and activity should be validated. |

| Cell Lines with Epigenetic Dysregulation (e.g., MLL-rearranged leukemia lines, DNMT3A-mutant lines) | Models for cellular and functional assays to test compound efficacy in a disease-relevant context. | Choice depends on the target and disease of interest. |

| Antibodies for Specific Epigenetic Marks (e.g., anti-5-methylcytosine, anti-H3K27me3, anti-acetyl-H3) | Detection and quantification of epigenetic mark changes via Western Blot, ELISA, or ChIP. | Specificity and lot-to-lot consistency are critical. |

| Nucleoside Analog DNMT Inhibitors (5-Azacytidine, Decitabine) | Positive controls for global DNA demethylation and gene reactivation experiments. | Cytotoxic at high doses; handle with care. |

| Pan-HDAC Inhibitors (Trichostatin A - TSA, Vorinostat - SAHA) | Positive controls for inducing global histone hyperacetylation and studying its functional consequences. | |

| Reprogramming-Reporter Cell Lines (e.g., MEFs with Oct4-GFP) | Functional phenotypic screening for compounds that modulate cellular plasticity and epigenetic barriers. | Enables quantification of iPSC colony formation. |

| Bapps | Bapps, CAS:83592-07-8, MF:C29H38N4O8S, MW:602.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Ddctp | Ddctp, CAS:66004-77-1, MF:C9H16N3O12P3, MW:451.16 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The field of cellular reprogramming has undergone a revolutionary transformation, shifting from the transfer of entire nuclei to the precise manipulation of a cell's own transcriptional machinery. This journey began with somatic cell nuclear transfer (SCNT), which demonstrated that the oocyte contains potent factors capable of resetting a somatic cell's epigenetic landscape to a totipotent state [14]. The seminal discovery of induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) by Takahashi and Yamanaka in 2006 marked a pivotal turning point, revealing that a defined set of transcription factors could achieve similar reprogramming without the need for oocytes [15] [16]. This paradigm shift not only circumvented ethical controversies associated with embryonic stem cells but also opened unprecedented opportunities for disease modeling, drug screening, and regenerative medicine [16] [17]. The broader thesis of epigenetic reprogramming with small molecules research builds upon this historical foundation, seeking to replace genetic factors with chemical interventions to achieve safer, more controllable reprogramming outcomes. This article traces the key experimental milestones in this field and provides detailed protocols that have enabled these breakthroughs.

Historical Milestones and Key Experiments

The conceptual foundation for reprogramming was laid in the mid-20th century with nuclear transfer experiments. The first breakthrough came in 1952 when Briggs and King demonstrated that embryonic nuclei could support development when transferred into enucleated amphibian eggs [16] [14]. A decade later, Gurdon provided direct evidence of cellular plasticity by successfully reprogramming differentiated intestinal epithelial cells to an embryonic state using SCNT [16] [14]. These early discoveries established the fundamental principle that the developmental state of adult cells could be reversed, despite the process being inefficient and poorly understood.

The field advanced significantly with the birth of Dolly the sheep in 1996, the first animal cloned from an adult somatic cell, which definitively proved that the genome of a fully differentiated cell retains the capacity to direct embryonic development [16]. This milestone confirmed that developmental restrictions are governed by reversible epigenetic modifications rather than permanent genetic changes, sparking intensive efforts to identify the specific oocyte factors responsible for this reprogramming capability [14].

The most transformative breakthrough came in 2006 when Takahashi and Yamanaka demonstrated that retroviral introduction of four transcription factors—OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, and c-MYC (the "OSKM" factors)—could reprogram mouse fibroblasts into pluripotent stem cells [15] [16]. This discovery of iPSCs provided both a molecular mechanism for reprogramming and a technically accessible platform for further research. The following year, this achievement was extended to human cells, simultaneously by Yamanaka's group and James Thomson's laboratory, the latter using an alternative factor combination (OCT4, SOX2, NANOG, LIN28) [15] [17].

Table 1: Key Historical Milestones in Nuclear Reprogramming

| Year | Discovery | Key Researchers | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1952 | First nuclear transfer experiments in frogs | Briggs and King | Demonstrated embryonic nuclei could support development [14] |

| 1962 | Cloned tadpoles from intestinal cells | Gurdon | Provided direct evidence of cellular plasticity [16] [14] |

| 1996 | Birth of Dolly the sheep | Wilmut et al. | First mammal cloned from adult somatic cell [16] |

| 2006 | Induced pluripotent stem cells (mouse) | Takahashi and Yamanaka | Reprogramming with defined factors (OSKM) [15] [16] |

| 2007 | Human iPSCs | Takahashi et al.; Thomson et al. | Extended reprogramming technology to human cells [15] [17] |

| 2013 | First iPSC-derived cell transplant in humans | Masayo Takahashi | iPSC-derived retinal sheets for macular degeneration [17] |

Since the discovery of iPSCs, the field has focused on improving safety and efficiency by developing non-integrating delivery methods, identifying alternative reprogramming factors, and increasingly, replacing transcription factors with small molecules that modulate epigenetic barriers and signaling pathways [15] [16]. The most recent advances include the development of "chemical reprogramming" methods that can generate iPSCs without any genetic manipulation, representing the ultimate application of the small molecule approach to reprogramming [15].

Technical Approaches and Methodologies

Somatic Cell Nuclear Transfer (SCNT) Protocol

The SCNT technique involves transferring the nucleus of a somatic cell into an enucleated oocyte, leveraging the oocyte's cytoplasmic factors to reprogram the somatic genome. Recent optimizations have significantly improved the efficiency of this process.

Protocol: Efficient SCNT with Epigenetic Barrier Overcoming

Step 1: Oocyte Collection and Enucleation

- Collect in vivo matured metaphase II (MII) oocytes from donors shortly after retrieval.

- Remove the spindle-chromosomal complexes using a piezoelectric drill or laser-assisted system under visualization with a polarized microscope (e.g., Oosight system) [18].

- Confirm complete enucleation by verifying the absence of birefringent spindle structures.

Step 2: Somatic Cell Preparation

- Use primary human fibroblasts or other somatic cell types.

- Synchronize cells in G0/G1 phase of the cell cycle through serum starvation or contact inhibition to ensure non-replicated (2n2c) genomes [18].

Step 3: Nuclear Transfer

- Fuse the G0/G1-arrested somatic cells with enucleated oocytes using viral fusogenic proteins or electrical fusion methods.

- Monitor premature metaphase onset by observing de novo spindle formation using polarized microscopy. Visible spindles typically appear within 1-2 hours post-fusion [18].

Step 4: Epigenetic Modifier Treatment

- To overcome pre-implantation epigenetic barriers, treat reconstructed SCNT embryos with a combination of epigenetic modulators:

Step 5: Tetraploid Complementation

- To address post-implantation barriers related to defective extraembryonic lineages, use tetraploid complementation.

- Fuse two-cell embryos to create tetraploid embryos, then inject them with SCNT-derived inner cell mass cells.

- The tetraploid cells form primarily the extraembryonic tissues, while the SCNT-derived cells form the embryo proper, overcoming imprinting defects [19].

Step 6: Embryo Culture and Transfer

- Culture developed blastocysts in sequential media systems.

- Transfer qualified embryos to synchronized surrogate mothers for full-term development.

This optimized protocol has achieved approximately 30% full-term development efficiency in mouse models, representing the highest SCNT efficiency reported in mammals [19].

iPSC Generation Protocol

The original iPSC generation method has been refined to enhance safety and efficiency, with particular focus on reducing tumorigenic risks and improving reproducibility.

Protocol: Integration-Free iPSC Generation with Small Molecule Enhancement

Step 1: Somatic Cell Source Selection and Preparation

- Select appropriate somatic cells (e.g., dermal fibroblasts, peripheral blood mononuclear cells, or keratinocytes).

- Culture cells in optimized media specific to the cell type to ensure robust growth and viability before reprogramming.

Step 2: Factor Delivery Using Non-Integrating Methods

- Choose a non-integrating delivery system to minimize genomic alteration risk:

- Sendai Virus: RNA-based viral vector that remains in the cytoplasm [16].

- Episomal Plasmids: DNA plasmids with Epstein-Barr virus replication origin that replicate extrachromosomally [16].

- Synthetic mRNA: In vitro transcribed modified mRNA that reduces innate immune response [16].

- Recombinant Protein: Direct delivery of reprogramming factor proteins [16].

- Choose a non-integrating delivery system to minimize genomic alteration risk:

Step 3: Enhanced Reprogramming with Small Molecules

- Supplement the culture medium with small molecules that enhance reprogramming efficiency:

- Valproic Acid (VPA): Histone deacetylase inhibitor that opens chromatin structure [15] [16].

- CHIR99021: GSK3β inhibitor that activates Wnt signaling [16].

- Sodium Butyrate: Histone deacetylase inhibitor [15].

- 8-Br-cAMP: Cyclic AMP analog that enhances reprogramming efficiency, particularly when combined with VPA [15].

- RepSox: TGF-β receptor inhibitor that replaces SOX2 in some reprogramming cocktails [15].

- Supplement the culture medium with small molecules that enhance reprogramming efficiency:

Step 4: Culture in Defined Conditions

- Use defined culture systems to minimize variability:

- Maintain intracellular Ca2+ signaling, which has been identified as crucial for pluripotency maintenance in defined conditions [20].

Step 5: iPSC Colony Selection and Characterization

- Manually pick emerging iPSC colonies based on embryonic stem cell-like morphology between days 21-28.

- Characterize fully expanded clones through:

- Pluripotency marker analysis (OCT4, SOX2, NANOG) by immunostaining or flow cytometry.

- PluriTest assay to verify pluripotency gene expression signature [20].

- Karyotype analysis to confirm genomic integrity.

- In vitro differentiation into three germ layers.

Table 2: Small Molecules for Enhancing iPSC Generation

| Small Molecule | Target/Mechanism | Effect on Reprogramming | Concentration Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Valproic Acid (VPA) | HDAC inhibitor | Increases histone acetylation, chromatin accessibility | 0.5-2 mM [15] [16] |

| CHIR99021 | GSK3β inhibitor | Activates Wnt/β-catenin signaling | 3-6 μM [16] |

| Sodium Butyrate | HDAC inhibitor | Enhances epigenetic remodeling | 0.25-1 mM [15] |

| 8-Br-cAMP | cAMP analog | Activates PKA signaling, synergizes with VPA | 100-250 μM [15] |

| RepSox | TGF-β receptor inhibitor | Replaces SOX2, induces MET | 2-5 μM [15] |

| PD0325901 | MEK inhibitor | Reduces differentiation, enhances clonality | 0.5-1 μM |

| Tranylcypromine | LSD1 inhibitor | Demethylates H3K4, enhances efficiency | 5-10 μM |

Visualization of Key Workflows and Signaling Pathways

Diagram 1: Comparative overview of SCNT, iPSC, and small molecule reprogramming pathways. SCNT relies on oocyte factors, while iPSC uses defined transcription factors, with small molecules enhancing both efficiency and safety.

Diagram 2: Epigenetic barriers to reprogramming and interventional strategies. Different barriers require specific interventions, with some addressing pre-implantation development and others necessary for post-implantation success.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Reprogramming Research

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reprogramming Factors | OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, c-MYC (OSKM); OCT4, SOX2, NANOG, LIN28 (OSNL) | Core transcription factors for inducing pluripotency | c-MYC alternatives (L-MYC, SALL4) reduce tumorigenicity [15] |

| Delivery Systems | Sendai virus, episomal plasmids, synthetic mRNA, recombinant protein | Non-integrating methods for factor delivery | Sendai virus offers high efficiency; mRNA minimal genomic integration [15] [16] |

| Epigenetic Modulators | Trichostatin A, Valproic Acid, Sodium Butyrate, 5-aza-cytidine | Remove epigenetic barriers to reprogramming | HDAC inhibitors enhance chromatin accessibility [19] [15] |

| Signaling Modulators | CHIR99021 (GSK3β inhibitor), RepSox (TGF-β inhibitor), PD0325901 (MEK inhibitor) | Enhance reprogramming efficiency through pathway modulation | Small molecules can replace some transcription factors [15] [16] |

| Defined Culture Components | Laminin-521, Vitronectin, Essential 8 (E8) medium | Xeno-free, defined culture systems for clinical applications | Reduce batch variability and enhance reproducibility [20] |

| Characterization Tools | PluriTest, flow cytometry antibodies (OCT4, SOX2, NANOG), karyotyping | Quality control and pluripotency verification | PluriTest assesses pluripotency without animal testing [20] |

| L-NIL | L-NIL, MF:C8H17N3O2, MW:187.24 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Dhpde | Dhpde|1,2-Dihexanoylphosphatidylethanolamine Supplier | High-purity 1,2-Dihexanoylphosphatidylethanolamine (Dhpde) for lipid membrane research. CAS 6060-30-6. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. | Bench Chemicals |

Current Applications and Future Directions

The transition from SCNT to iPSC technology has created diverse applications across biomedical research and therapeutic development. iPSCs now serve as invaluable tools for disease modeling, particularly for neurological conditions like amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), where patient-specific iPSC-derived motor neurons enable the study of disease mechanisms and drug screening [15]. The technology has advanced to clinical trials, with ongoing studies for Parkinson's disease using iPSC-derived dopaminergic progenitors, retinal conditions using iPSC-derived retinal pigment epithelial cells, and graft-versus-host disease using iPSC-derived mesenchymal stem cells [16] [17].

Recent innovations continue to build upon this historical foundation. "Mitomeiosis" approaches combine SCNT with experimental reductive cell division to generate cells with reduced chromosome ploidy, potentially enabling in vitro gametogenesis for infertility treatment [18]. Artificial intelligence and machine learning are now being integrated into reprogramming research, with companies like NewLimit reporting a 12% improvement in discovery rates from reprogramming AI that designs more effective transcription factor combinations [21] [22]. Meanwhile, fully defined culture conditions have significantly reduced inter-line variability in iPSC cultures, highlighting the importance of standardization for both research and clinical applications [20].

The convergence of reprogramming technologies with small molecule research continues to advance the field toward the ultimate goal of safe, efficient epigenetic reprogramming for regenerative medicine and therapeutic intervention. As the molecular mechanisms of reprogramming become increasingly elucidated, the precision and applicability of these techniques will continue to expand, building upon the historical foundation established by both SCNT and iPSC technologies.

Chemical reprogramming represents a paradigm shift in regenerative medicine, offering a novel method for generating pluripotent stem cells without genetic modification. This process utilizes specific combinations of small molecules to manipulate cell fate by targeting key signaling and epigenetic pathways, effectively reversing the developmental clock of somatic cells [23]. Unlike traditional methods that rely on viral vectors to introduce exogenous transcription factors, chemical reprogramming provides a more precise, flexible, and clinically promising approach for resetting cellular identity [24] [23].

The establishment of human chemically induced pluripotent stem (hCiPS) cells marks a significant milestone in the field [25]. This technology leverages the ability of small molecules to target epigenetic regulators, thereby overcoming the safety concerns associated with viral integration and oncogene activation that have plagued transcription-factor-based approaches [15] [26]. Recent clinical advancements, including the transplantation of insulin-producing cells derived from hCiPS cells for type 1 diabetes treatment, underscore the considerable therapeutic potential of this technology [24].

This protocol outlines the principles and methodologies for efficient chemical reprogramming of human somatic cells, with particular emphasis on accessible cell sources such as blood cells, to support applications in disease modeling, drug discovery, and cell-based therapies.

Chemical reprogramming employs a defined sequence of small molecule treatments to orchestrate a fundamental transformation of cellular identity. This process unfolds through three distinct yet interconnected molecular stages, each characterized by specific epigenetic and transcriptional alterations.

The Three-Stage Molecular Trajectory

The reprogramming journey begins with the erasure of somatic cell identity, where the stable molecular profile of the starting cell is disrupted. This initial phase involves targeting signaling and epigenetic pathways to dismantle the existing cellular state [23]. Subsequently, cells enter a transient intermediate plastic state characterized by enhanced chromatin accessibility, activation of early embryonic developmental genes, and a gene expression signature analogous to regenerative progenitor cells observed in limb regeneration models [15] [23]. This plastic state exhibits heightened proliferative capacity and metabolic reprogramming, providing a crucial foundation for pluripotency acquisition [23]. The final stage involves the establishment of a stable pluripotency network, where cells transition through a primitive endoderm-like (XEN-like) state before maturing into fully defined hCiPS cells capable of differentiating into all three germ layers [25] [23].

Table 1: Key Molecular Events During Chemical Reprogramming

| Reprogramming Stage | Key Epigenetic Events | Transcriptional Signature | Cellular Phenotype |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stage 1: Erasure | DNA demethylation; Loss of H3K27me3 repressive marks | Downregulation of lineage-specific genes | Cell cycle arrest; Metabolic shift |

| Stage 2: Plastic State | Global chromatin opening; H3K4me3 activation marks | Emergence of regeneration-associated genes | Enhanced proliferation; Morphological changes |

| Stage 3: Pluripotency Establishment | De novo methylation; X chromosome reactivation | Activation of OCT4, SOX2, NANOG | Colony formation; Self-renewal capacity |

Signaling Pathways and Molecular Targets

The chemical cocktails used in reprogramming strategically target specific epigenetic modifiers and signaling pathways. Critical targets include histone deacetylases (HDACs), DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs), and key developmental pathways such as TGF-β, Wnt, and BMP signaling [26] [23]. The sequential application of these small molecules creates a permissive environment for epigenetic remodeling, enabling the rewiring of gene regulatory networks toward pluripotency without permanent genetic alteration.

The following diagram illustrates the core signaling pathways and their logical relationships during the chemical reprogramming process:

Comparative Analysis of Reprogramming Methodologies

Chemical vs. Transcription Factor-Based Reprogramming

When compared to traditional OSKM (OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, c-MYC) approaches, chemical reprogramming demonstrates distinct advantages in safety profile and mechanistic operation. While OSKM methods directly introduce master transcription factors to force pluripotency, chemical reprogramming employs small molecules that target the endogenous epigenetic machinery, allowing for a more gradual and naturalistic transition through developmental intermediate states [15] [23]. This fundamental difference translates to reduced risks of tumorigenesis and insertional mutagenesis, addressing critical safety concerns for clinical translation.

Recent studies directly comparing both methodologies in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (hPBMCs) have demonstrated the superior efficiency of chemical reprogramming, with significantly higher colony formation rates and more consistent results across different donor samples [25]. The chemical approach also facilitates more precise temporal control over the reprogramming process, enabling researchers to fine-tune the progression through each molecular stage by adjusting small molecule concentrations and treatment durations.

Table 2: Efficiency Comparison Across Cell Types and Methods

| Cell Source | Reprogramming Method | Reprogramming Efficiency | Time to Pluripotency | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human Cord Blood Mononuclear Cells | Chemical reprogramming | High efficiency in optimized conditions | 35-45 days | Donor versatility; Scalable |

| Human Peripheral Blood Cells | Chemical reprogramming | Higher than OSKM-based approach [25] | 30-40 days | Minimal invasiveness; Banking potential |

| Finger-prick Blood Samples | Chemical reprogramming | Robust colony formation [25] | 35-45 days | Extreme accessibility; Patient-friendly |

| Dermal Fibroblasts | OSKM factors | Variable (0.01%-0.1%) | 25-30 days | Well-established protocol |

| Dermal Fibroblasts | Chemical reprogramming | Improved with 8-Br-cAMP + VPA (6.5-fold increase) [15] | 40-50 days | Non-integrating; Better standardization |

Chemical Reprogramming Across Cell Types

The application of chemical reprogramming has expanded to include various somatic cell sources, with blood cells emerging as particularly promising due to their accessibility and availability from biobanks [25]. Research has demonstrated that mononuclear cells from both human cord blood and peripheral blood can be effectively reprogrammed using optimized small-molecule combinations, with successful results even from minimal input materials such as finger-prick blood samples [25].

The reprogramming efficiency varies across cell types, reflecting differences in epigenetic landscapes and metabolic states. Blood-derived cells often require specific preconditioning strategies, such as expansion in erythroid progenitor cell culture conditions with cytokines (SCF, IL-3, IL-6, EPO) and small molecules (CHIR99021, SB431542) to enhance their responsiveness to reprogramming cues [25]. This preconditioning phase helps establish a receptive epigenetic foundation that facilitates subsequent molecular interventions.

Chemical Reprogramming Protocol for Human Blood Cells

Cell Isolation and Preconditioning

Materials Required:

- Ficoll-Paque Premium for density gradient centrifugation

- Erythroid Progenitor Cell (EPC) expansion medium: IMDM supplemented with 2% FBS, 1% penicillin-streptomycin, 50 ng/mL SCF, 10 ng/mL IL-3, 10 ng/mL IL-6, and 2 U/mL EPO

- Preconditioning small molecules: 3-5 μM CHIR99021 (GSK-3β inhibitor) and 5-10 μM SB431542 (TGF-β inhibitor)

- Tissue culture plates coated with 0.1% gelatin

Procedure:

- Isolate mononuclear cells from human cord blood or peripheral blood using standard density gradient centrifugation with Ficoll-Paque.

- Seed cells at 1-2×10^6 cells/mL in EPC expansion medium and culture for 7-10 days.

- Supplement the medium with preconditioning small molecules (CHIR99021 and SB431542) throughout the expansion phase.

- Monitor cell morphology and expansion rates daily, maintaining cell density between 0.5-2×10^6 cells/mL.

- After 7-10 days, harvest the expanded cells for the reprogramming phase.

Sequential Chemical Reprogramming

Stage 1: Identity Erasure (Days 1-15)

- Culture Vessel: 12-well tissue culture plate coated with 0.1% gelatin

- Base Medium: DMEM/F12 supplemented with N2, B27, and 1% penicillin-streptomycin

- Small Molecule Cocktail A:

- 0.5-1 mM VPA (Valproic acid) - HDAC inhibitor

- 5-10 μM CHIR99021 - GSK-3β inhibitor

- 10 μM SB431542 - TGF-β inhibitor

- 50 μg/mL L-Ascorbic acid - Antioxidant

- Procedure: Seed preconditioned cells at 5-10×10^4 cells/cm² in Cocktail A. Change medium every 2-3 days. Monitor the emergence of adherent cells with morphological changes.

Stage 2: Intermediate Plastic State (Days 16-30)

- Base Medium: DMEM/F12 supplemented with N2, B27, and 1% penicillin-streptomycin

- Small Molecule Cocktail B:

- 0.5-1 mM VPA

- 5-10 μM CHIR99021

- 10 μM SB431542

- 50 μg/mL L-Ascorbic acid

- 10 μM DZNep - Histone methylation inhibitor

- 5-10 μM TTNPB - Retinoic acid receptor agonist

- Procedure: Continue culture with Cocktail B, changing medium every 2-3 days. Observe formation of compact cell clusters with translucent boundaries indicating transition to plastic state.

Stage 3: Pluripotency Establishment (Days 31-45)

- Base Medium: DMEM/F12 supplemented with N2, B27, and 1% penicillin-streptomycin

- Small Molecule Cocktail C:

- 5-10 μM CHIR99021

- 2-5 μM 8-Br-cAMP - cAMP analog

- 10 μM VPA

- 50 μg/mL L-Ascorbic acid

- 20 ng/mL bFGF - Basic fibroblast growth factor

- Procedure: Transition cells to Cocktail C with medium changes every 2-3 days. hCiPS cell colonies should emerge with defined borders and high nucleus-to-cytoplasm ratio.

The experimental workflow for the complete chemical reprogramming process is visualized below:

hCiPS Cell Colony Selection and Characterization

Colony Picking and Expansion:

- Between days 35-45, identify and mechanically pick well-defined hCiPS cell colonies using a pulled glass pipette.

- Transfer individual colonies to 96-well plates pre-coated with Matrigel and containing mTeSR Plus medium supplemented with 10 μM Y-27632 (ROCK inhibitor).

- Passage colonies every 5-7 days using gentle cell dissociation reagent.

Quality Control and Characterization:

- Immunofluorescence: Confirm expression of pluripotency markers (OCT4, SOX2, NANOG, TRA-1-60, TRA-1-81) using standard immunostaining protocols.

- Trilineage Differentiation: Assess differentiation potential using commercial kits or defined media for ectoderm, mesoderm, and endoderm formation.

- Karyotyping: Perform G-band karyotyping at passage 10-15 to confirm genomic stability.

- DNA Methylation Analysis: Verify epigenetic reprogramming through bisulfite sequencing of pluripotency gene promoters.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Chemical Reprogramming

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Reprogramming | Working Concentration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Epigenetic Modulators | VPA (Valproic Acid); DZNep | Histone deacetylase inhibition; H3K27me3 demethylation | 0.5-1 mM; 10 μM |

| Signaling Pathway Modulators | CHIR99021; SB431542; TTNPB | GSK-3β inhibition; TGF-β inhibition; Retinoic acid signaling activation | 3-10 μM; 5-10 μM; 5-10 μM |

| Metabolic Regulators | 8-Br-cAMP; L-Ascorbic acid | cAMP pathway activation; Antioxidant support | 2-5 μM; 50 μg/mL |

| Cytokines and Growth Factors | bFGF; SCF; IL-3; IL-6; EPO | Pluripotency maintenance; Erythroid progenitor expansion | 10-20 ng/mL; 50 ng/mL; 10 ng/mL; 10 ng/mL; 2 U/mL |

| Cell Culture Supplements | N2 Supplement; B27 Supplement | Defined culture conditions; Neuronal and general support | 1X; 1X |

| Cell Surface Markers | Anti-TRA-1-60; Anti-TRA-1-81 | Pluripotency verification by flow cytometry or immunofluorescence | Manufacturer's recommendation |

Chemical reprogramming technology has fundamentally expanded the methodological arsenal for generating human pluripotent stem cells. The complete avoidance of genetic integration, coupled with the precise temporal control afforded by small molecule treatments, positions this approach as particularly valuable for clinical translation. The successful application to readily accessible cell sources like blood samples further enhances its potential for personalized medicine applications [25].

Future directions for chemical reprogramming research include optimizing universal protocols applicable across diverse somatic cell types and donor backgrounds, enhancing reprogramming efficiency through novel small-molecule combinations, and developing more defined, xeno-free culture systems for clinical-grade hCiPS cell production [24] [23]. As understanding of the underlying epigenetic mechanisms deepens, chemical reprogramming is poised to become an indispensable technology for regenerative medicine, disease modeling, and drug discovery.

Chemical Reprogramming in Action: Protocols, Pathways, and Therapeutic Applications

Epigenetic reprogramming with small molecules represents a transformative approach in modern biology, offering reversible control over gene expression without altering the DNA sequence. This paradigm is particularly relevant for therapeutic intervention in cancer and regenerative medicine, where dynamic epigenetic states dictate cellular fate and function. Key epigenetic regulators include DOT1L, a histone methyltransferase; histone deacetylases (HDACs); and DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs). These enzymes, often dysregulated in disease, can be precisely targeted by small molecule inhibitors and degraders. When used in rational combinations, these compounds form potent cocktails that can reverse aberrant epigenetic marks, reshape the chromatin landscape, and ultimately redirect cell behavior. This Application Note provides a detailed guide to the mechanisms, protocols, and reagent solutions for employing these key small molecule cocktails in a research setting.

DOT1L-Targeting Approaches

Disruptor of Telomeric Silencing-like (DOT1L) is the sole histone methyltransferase responsible for mono-, di-, and tri-methylation of histone H3 lysine 79 (H3K79) [27]. This enzyme plays a critical role in gene transcription, cell cycle progression, and DNA damage response [27] [28]. Its aberrant activity, particularly through recruitment by oncogenic MLL fusion proteins, is a key driver in certain leukemias, making it a high-value therapeutic target [27] [29].

Key Small Molecule Inhibitors and Degraders

Table 1: DOT1L-Targeting Small Molecules

| Compound Name | Mechanism of Action | Reported Potency (ICâ‚…â‚€/ECâ‚…â‚€) | Key Applications & Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pinometostat (EPZ-5676) | SAM-competitive inhibitor [28] [29] | ICâ‚…â‚€ = 0.4 nM (biochemical) [29] | Advanced to clinical trials for MLL-r leukemia; administered via continuous IV infusion [28]. |

| EPZ004777 | SAM-competitive inhibitor [29] | ICâ‚…â‚€ = 0.4 nM; KD = 0.25 nM [29] | Prototype inhibitor; showed in vivo efficacy in MLL-r models [29]. |

| SGC0946 | SAM-competitive inhibitor [29] | ICâ‚…â‚€ = 0.3 nM; KD = 0.06 nM [29] | Brominated analogue of EPZ004777; improved cellular potency [29]. |

| Compound 2 | Binds an induced pocket adjacent to the SAM site [28] | Not specified | Improved PK properties in rodents; used as a ligand for PROTAC development [28]. |

| MS2133 | First-in-class DOT1L PROTAC degrader [28] | DCâ‚…â‚€ ~100-200 nM; Degrades >95% of DOT1L [28] | Induces degradation via VHL E3 ligase; targets both enzymatic and scaffolding functions [28]. |

Experimental Protocol: Assessing DOT1L Inhibition and Degradation

A. Cell Treatment and Viability Assay (e.g., for MLL-r Leukemia Cells)

- Cell Seeding: Seed MLL-rearranged leukemia cells (e.g., MV4;11) in a 96-well plate at a density of 5,000-10,000 cells per well in complete growth medium.

- Compound Treatment: After 24 hours, treat cells with a concentration gradient of the DOT1L inhibitor (e.g., Pinometostat, 1 nM - 10 µM) or degrader (e.g., MS2133, 10 nM - 10 µM). Include a DMSO vehicle control.

- Incubation: Incubate cells for 72-96 hours, maintaining standard culture conditions (37°C, 5% CO₂).

- Viability Measurement: Assess cell viability using an ATP-based assay (e.g., CellTiter-Glo). Record luminescence and calculate the percentage viability relative to the DMSO control to determine GIâ‚…â‚€ values.

B. Analysis of Epigenetic and Molecular Efficacy

- Western Blotting:

- Lysate Preparation: Harvest treated cells and lyse using RIPA buffer supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitors.

- Electrophoresis and Transfer: Separate proteins via SDS-PAGE and transfer to a PVDF membrane.

- Immunoblotting: Probe the membrane with antibodies against:

- Total H3K79me2 (to confirm on-target inhibition of DOT1L methylation activity)

- DOT1L (to confirm protein degradation by PROTACs)

- Cleaved Caspase-3 (to assess apoptosis induction)

- β-Actin (as a loading control)

- qRT-PCR for Gene Expression:

- Extract total RNA from treated cells and synthesize cDNA.

- Perform quantitative PCR to monitor transcript levels of key DOT1L target genes (e.g., HOXA9 and MEIS1). Use GAPDH or ACTB for normalization. A significant downregulation of these genes is expected upon successful DOT1L inhibition.

The following diagram illustrates the mechanistic logic of DOT1L targeting:

HDAC Inhibitor Applications

Histone deacetylases (HDACs) remove acetyl groups from lysine residues on histones and other proteins, leading to chromatin condensation and gene silencing [30] [31]. Inhibition of HDACs results in hyperacetylated chromatin, which promotes a more open structure and facilitates gene transcription. HDAC inhibitors have shown efficacy in cancer treatment and are being explored for neurodegenerative and psychiatric disorders [30].

Key HDAC Inhibitor Classes

Table 2: Classes of HDAC Inhibitors with Examples

| Chemical Class | Compound Examples | Mechanism & Key Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Hydroxamic Acids | Trichostatin A (TSA), Suberoylanilide Hydroxamic Acid (SAHA/Vorinostat) | Pan-HDAC inhibitors; widely used in research and clinic for cancer [30]. |

| Short-Chain Fatty Acids | Valproic Acid (VPA), Sodium Butyrate, Phenylbutyrate | Class I/II HDAC inhibitors; VPA is an anti-epileptic drug; used in reprogramming cocktails [30] [32]. |

| Benzamides | Entinostat (MS-275) | More selective for specific HDAC classes (e.g., Class I) [30]. |

| Epoxyketones | Trapoxin | Irreversible inhibitors of HDACs [30]. |

Experimental Protocol: Evaluating HDAC Inhibition in Cellular Models

A. Treatment for Altered Gene Expression

- Cell Preparation: Plate cells appropriate for your study (e.g., cancer cell lines, primary neurons) in multi-well plates or dishes.

- Inhibitor Treatment: Treat cells with a selected HDAC inhibitor (e.g., 1 mM Valproic Acid or 0.5 µM Trichostatin A) for 12-48 hours. The optimal concentration and duration should be determined empirically for each cell type.

- Downstream Analysis:

- Western Blotting: Detect global histone acetylation levels using antibodies against acetylated histone H3 (e.g., Ac-H3K9, Ac-H3K14) or histone H4.

- qRT-PCR or RNA-Seq: Analyze the transcriptome to identify genes reactivated or modulated by HDAC inhibition.

B. Viability/Cytotoxicity Assay

- Cell Seeding and Treatment: Seed cancer cells in a 96-well plate and allow them to adhere. Treat with a dose range of an HDAC inhibitor (e.g., SAHA, 0.1 - 10 µM) for 72 hours.

- Viability Assessment: Use a standard MTT or CellTiter-Glo assay to measure cell viability/proliferation. HDAC inhibitors can induce cell cycle arrest, differentiation, and apoptosis in transformed cells.

DNMT Inhibitor Strategies

DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs), including DNMT1, DNMT3A, and DNMT3B, catalyze the addition of methyl groups to cytosine residues in DNA, leading to stable gene silencing [33] [34] [2]. In cancer, tumor suppressor genes are often silenced by promoter hypermethylation. DNMT inhibitors can reverse this silencing and are approved for the treatment of certain hematological malignancies [33] [34].

Key DNMT Inhibitors

Table 3: DNA Methyltransferase Inhibitors

| Compound Name | Type | Mechanism of Action | Key Applications & Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Azacitidine (Vidaza) | Nucleoside Analog | Incorporated into RNA and DNA; covalently traps and depletes DNMTs, leading to DNA hypomethylation [34]. | FDA-approved for MDS; used in AML; explored in combination therapies [33] [34]. |

| Decitabine (Dacogen) | Nucleoside Analog | Incorporated primarily into DNA; mechanism similar to Azacitidine, leading to potent DNA hypomethylation [33] [34]. | FDA-approved for MDS and CML; targets both DNMT1 and DNMT3A [34]. |

| Zebularine | Nucleoside Analog | Orally bioavailable; covalently traps DNMT1 and disrupts its interaction with other epigenetic regulators like G9a [34]. | More stable and less toxic than Azacitidine/Decitabine in preclinical models [34]. |

| Guadecitabine (SGI-110) | Next-Generation Nucleoside Analog | Dinucleotide of Decitabine and deoxyguanosine; resistant to degradation by cytidine deaminase, allowing for longer exposure [33]. | Clinical investigation for AML, particularly in DNMT3A-mutant cohorts [33]. |

Experimental Protocol: Demethylation and Gene Reactivation

A. Low-Dose Demethylation Protocol

- Cell Culture: Grow target cells (e.g., a cancer cell line with a known hypermethylated tumor suppressor gene) in standard medium.

- Low-Dose Treatment: Treat cells with a low, non-cytotoxic concentration of a DNMT inhibitor (e.g., 0.1 - 1 µM Decitabine or Azacitidine). The medium containing the drug should be replaced every 24 hours for 3-5 days due to the instability of nucleoside analogs.

- Analysis of DNA Methylation:

- Post-Treatment: Post-treatment, extract genomic DNA.

- Bisulfite Conversion: Treat DNA with bisulfite, which converts unmethylated cytosines to uracils but leaves methylated cytosines unchanged.

- Analysis: Perform bisulfite sequencing (BS-Seq) or pyrosequencing of the promoter region of interest to quantify changes in methylation levels.

- Analysis of Gene Reactivation:

- Isolate total RNA after the treatment period.

- Perform qRT-PCR to measure the mRNA levels of the previously silenced tumor suppressor gene (e.g., CDKN2A or MLH1). Reactivation indicates successful epigenetic reversal.

The workflow for targeting DNMTs and HDACs, often used in combination, is summarized below:

Rational Combination Cocktails

Combining epigenetic agents with each other or with other therapeutic modalities can overcome the limitations of monotherapies, such as transient responses and drug resistance [33]. The following combinations are supported by recent research.

DNMTi + HDACi Combination

- Rationale: DNMT inhibitors can demethylate DNA and initiate gene expression, while HDAC inhibitors can open up the chromatin structure further, potentially leading to more robust and sustained re-expression of silenced genes [33] [34].

- Example Protocol: Treat cells with a low dose of Decitabine (0.5 µM) for 72-96 hours, followed by exposure to an HDAC inhibitor like Valproic Acid (1 mM) or Trichostatin A (0.5 µM) for an additional 24-48 hours. Analyze gene re-expression and global epigenetic changes as described in previous sections.

DOT1Li + Signaling/Other Pathways

- Rationale: In MLL-r leukemia, the efficacy of DOT1L inhibition can be enhanced by simultaneously targeting other survival pathways or parallel epigenetic mechanisms.

- Example in Reprogramming: In cellular reprogramming studies, the DOT1L inhibitor EPO004777 has been used in cocktails containing a Retinoic Acid Receptor (RAR) agonist (Ch55 or AM580), a GSK-3 inhibitor (CHIR99021), a TGF-β inhibitor (616452), and an S-adenosylhomocysteine hydrolase inhibitor (DZNep) to enhance the generation of induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) from neural and intestinal epithelial cells [32].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Reagents for Epigenetic Targeting Studies

| Reagent / Assay | Function / Target | Example Products & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| DOT1L Inhibitors | Pharmacological inhibition of H3K79 methylation | Pinometostat (EPZ-5676), EPZ004777 (commercially available for research) |

| HDAC Inhibitors | Pan or selective inhibition of histone deacetylases | Trichostatin A (TSA), Valproic Acid (VPA), Suberoylanilide Hydroxamic Acid (SAHA) |

| DNMT Inhibitors | DNA demethylating agents | Azacitidine, Decitabine (commercially available for research) |

| PROTAC Molecules | Targeted protein degradation | MS2133 (DOT1L degrader) [28] |

| H3K79me2 Antibody | Readout for DOT1L activity | For Western Blot, ChIP; validate for specificity |

| Acetyl-Histone H3 Antibody | Readout for HDAC inhibition | For Western Blot, ChIP; detects marks like H3K9ac, H3K14ac |

| Cell Viability Assay | Measure of compound cytotoxicity | CellTiter-Glo (ATP-based), MTT assay |

| Bisulfite Conversion Kit | Preparation for DNA methylation analysis | From various suppliers (e.g., Qiagen, Zymo Research) |

| ML042 | ML042|Bfl-1 Inhibitor|Research Compound | ML042 is a potent, selective Bfl-1 inhibitor for cancer research. This product is For Research Use Only. Not for diagnostic or personal use. |

| UpApU | UpApU (UAU) - 752-71-6 - Research Trinucleotide | UpApU, a tyrosine RNA codon for protein synthesis research. CAS 752-71-6. For Research Use Only. Not for human use. |

Within the field of regenerative medicine, epigenetic reprogramming with small molecules represents a transformative approach for reversing cellular aging and altering cell fate. This protocol details a fully defined, stepwise model for chemically reprogramming human somatic cells into pluripotent stem cells, a significant advance toward potentially safer, transgene-free generation of human induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) for therapeutic applications [35]. By utilizing precise combinations of chemical compounds, researchers can overcome the innate stability of the human somatic epigenome, which traditionally posed a significant barrier to reprogramming [35]. The process methodically guides cells through three critical phases: the erasure of the original somatic cell identity, transit through an intermediate plastic state, and the ultimate establishment of naive pluripotency. This document provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with detailed application notes and protocols to implement this methodology, including comprehensive quantitative data, experimental workflows, and essential reagent solutions.

The following tables summarize the key quantitative aspects of the chemical reprogramming protocol, including the specific small molecules used and the associated cellular outcomes.

Table 1: Core Small Molecule Cocktail for Human Chemical Reprogramming

| Reprogramming Stage | Function / Pathway Targeted | Key Small Molecules | Concentration / Duration (Typical) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stage I: Erasure of Somatic Identity | Suppresses somatic gene network; Activates regeneration-like program [35] | TTNPB, 616452, CHIR99021, Forskolin, Y-27632, A-83-01 | 6 molecules; ~16 days [35] |

| Stage II: Epigenetic Modulation | Promotes DNA demethylation; Increases chromatin accessibility [35] | DZNep, AMI-5, Vitamin C | 3 additional molecules; ~16 days [35] |

| Stage III: Plastic Intermediate State | Formation and stabilization of XEN-like state [35] | (Continuation from previous stages) | ~8 days [35] |

| Stage IV: Establishment of Pluripotency | Activates core pluripotency network [35] | (Further small molecule additions) | ~20 days [35] |

Table 2: Experimental Outcomes and Efficiency Metrics

| Parameter | Result / Measurement | Notes / Context |

|---|---|---|

| Overall Reprogramming Efficiency | Up to 2.56% [35] | For both fetal and adult human somatic cells. |

| Key Pathway Barriers Identified | JNK pathway; Pro-inflammatory pathways (TNF/IL-1β) [35] | Their inhibition was indispensable for successful reprogramming. |

| Characterization of hiPSCs | Embryonic stem cell-like transcriptome, epigenome, and functionality [35] | Confirmed via in vitro and in vivo assays. |

| Genomic Integrity | Maintained in "primed" culture conditions [35] | Stable for over 20 passages; unstable in "naïve" conditions. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol

Stage I: Erasure of Somatic Identity (Approximately 16 Days)

Objective: To suppress the expression of the somatic cell gene network and initiate a regeneration-like gene program, breaking the initial epigenetic barrier.

Methodology:

- Cell Preparation: Begin with human fetal or adult somatic cells (e.g., dermal fibroblasts). Culture cells in standard maintenance media until 70-80% confluent.

- Stage I Medium Formulation: Prepare the base reprogramming medium. Supplement with the six small molecules of Stage I: TTNPB (a retinoic acid receptor agonist), 616452 (a TGF-β receptor inhibitor), CHIR99021 (a GSK-3β inhibitor and Wnt activator), Forskolin (an adenylate cyclase activator), Y-27632 (a ROCK inhibitor), and A-83-01 (an additional TGF-β inhibitor) [35].

- Culture and Monitoring: Replace the culture medium with the Stage I reprogramming medium. Refresh the medium every other day. Monitor cells for morphological changes, including a shift towards a more compact, epithelial-like appearance. This stage typically lasts for 16 days.

Stage II: Epigenetic Modulation and Induction of Plasticity (Approximately 16 Days)

Objective: To induce widespread epigenetic changes, specifically DNA demethylation, leading to increased chromatin accessibility and the formation of a plastic intermediate state.

Methodology:

- Medium Transition: After 16 days in Stage I medium, switch to the Stage II reprogramming medium.

- Stage II Medium Formulation: To the base medium, add the three Stage II small molecules: DZNep (an histone methyltransferase inhibitor), AMI-5 (a protein arginine methyltransferase inhibitor), and Vitamin C (an antioxidant that promotes DNA demethylation) [35]. The existing Stage I molecules may be continued.

- Formation of Plastic State: Culture the cells in Stage II medium for an additional 16 days. During this phase, cells will undergo significant epigenetic remodeling and begin to enter a highly plastic, proliferative intermediate state. Single-cell RNA-sequencing has shown this state to be similar to extraembryonic endoderm (XEN) cells in mice and shares features with developing human limb bud cells, characterized by the upregulation of genes like LIN28A and SALL4 [35].

Stage III: Stabilization of the Intermediate State (Approximately 8 Days)