Transdifferentiation Mechanisms in Tissue Repair: From Cellular Reprogramming to Clinical Applications

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of transdifferentiation, the direct conversion of one differentiated cell type into another, and its transformative potential in regenerative medicine and tissue repair.

Transdifferentiation Mechanisms in Tissue Repair: From Cellular Reprogramming to Clinical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of transdifferentiation, the direct conversion of one differentiated cell type into another, and its transformative potential in regenerative medicine and tissue repair. It explores foundational biological mechanisms, including the role of master switch genes and transcription factors, while examining both natural and induced transdifferentiation phenomena. The scope encompasses cutting-edge methodological approaches—from transcription factor-mediated reprogramming to chemical induction and mRNA technology—across key therapeutic areas including neurological, cardiac, and pancreatic systems. Critical challenges such as efficiency optimization, safety evaluation, and scalability are addressed, alongside comparative analysis with alternative cell reprogramming technologies. This resource equips researchers and drug development professionals with the current state and future trajectory of transdifferentiation for developing novel therapeutic interventions.

The Biology of Cell Fate Conversion: Uncovering Natural and Pathological Transdifferentiation

Transdifferentiation, also known as direct cell reprogramming, is a process where one mature, differentiated somatic cell type is converted directly into another, without passing through an induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) state [1] [2] [3]. This approach offers a more direct, rapid, and potentially safer strategy for cell replacement therapies and regenerative medicine compared to iPSC methods, as it avoids risks of tumorigenesis and uncontrolled proliferation associated with pluripotency [1] [2]. This technical guide synthesizes current advancements in transdifferentiation, detailing its core mechanisms, key methodologies, and therapeutic applications, with a specific focus on its role in tissue repair research.

Regenerative medicine has increasingly turned toward gene-based approaches to repair or replace damaged tissues. Conventional reprogramming to iPSCs involves transforming somatic cells into a pluripotent state, which carries risks of immunogenicity, tumorigenesis, and epigenetic abnormalities [1] [2].

Transdifferentiation circumvents this pluripotent intermediate, offering a paradigm shift in cellular reprogramming. Defined as the irreversible switch of one type of differentiated cell to another, it involves a discrete change in the program of gene expression with a direct ancestor-descendant relationship between the two cell types [4]. The process typically requires dedifferentiation and cell division as essential intermediate steps, though this may not be obligatory in all cases [4]. This direct lineage conversion technology holds great practical promise for in vivo tissue repair without the risks of tumorigenesis, contamination, or cell transplantation [1].

Core Mechanisms of Cell Fate Conversion

Transdifferentiation is presumably caused by a change in the expression of a master switch gene (selector or homeotic gene), whose normal function is to distinguish the two cell types in normal development [4]. This change alters the state of developmental commitment, potentially through somatic mutation or, more commonly, induction by environmental changes [4].

Molecular Drivers and Pathways

The process is orchestrated through several interconnected molecular mechanisms:

- Transcriptional Activation: Master transcription factors (TFs) bind to regulatory regions of genes, initiating widespread changes in gene expression networks that establish a new cellular identity [2].

- Epigenetic Remodeling: Chromatin structure is modified through DNA methylation, histone modifications, and chromatin remodeling complexes, making old identity genes less accessible and new ones more accessible [1].

- Metabolic Shifts: Cells undergo metabolic reprogramming to support energy and biosynthetic requirements of the new cell type [1].

- Signaling Pathway Activation: Key developmental pathways such as Notch, PI3K/AKT, Wnt/β-catenin, and those involved in epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) are often reactivated to guide the differentiation process [5].

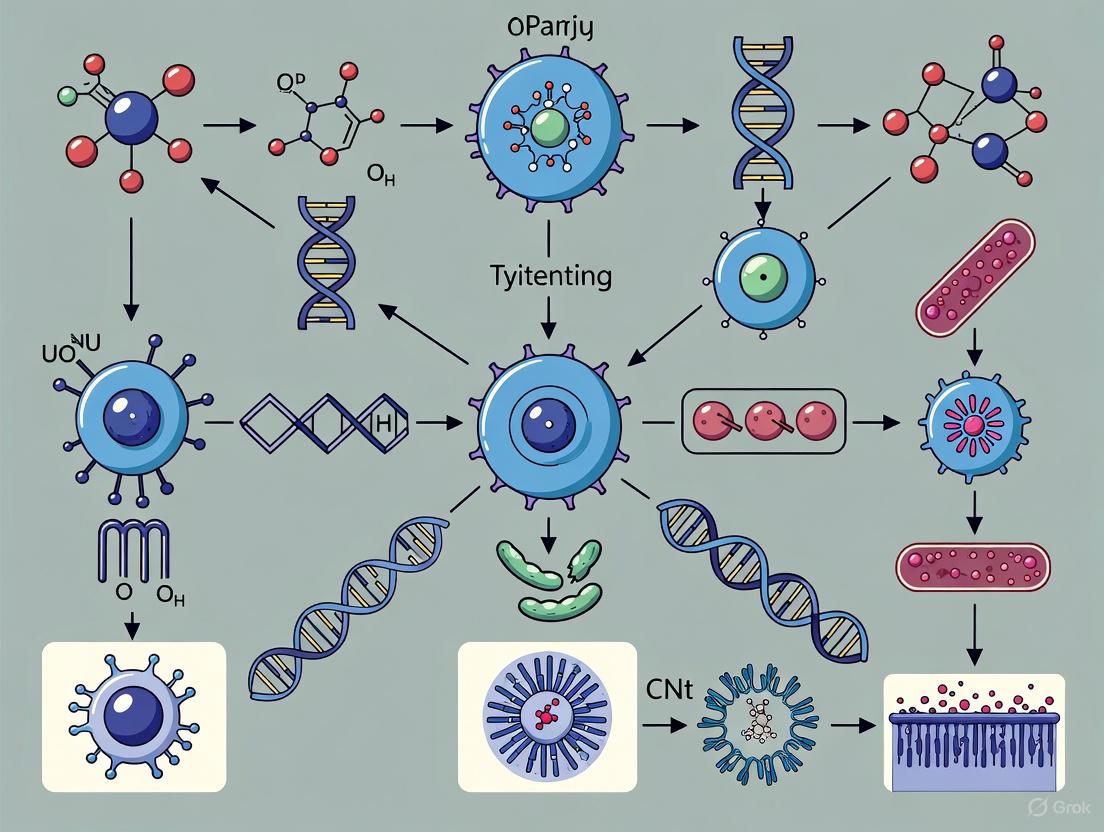

The following diagram illustrates the conceptual framework and major mechanisms driving direct lineage reprogramming.

Methodological Approaches in Direct Reprogramming

Cellular reprogramming can be achieved through multiple methods, each with distinct advantages and challenges. The primary strategies involve introducing or upregulating key reprogramming factors vital for establishing a new cellular identity.

Exogenous Transgene Overexpression

The most prevalent method uses viral vectors to introduce transgenes encoding master transcription factors.

- Lentiviruses/Retroviruses: Effectively integrate DNA into the host genome, leading to stable protein expression. Lentiviruses can infect both non-dividing and dividing cells, while retroviruses only infect dividing cells [2].

- Non-integrating Viruses (Adenoviruses, Sendai viruses): Insert transgenes for transient expression without genomic integration, resulting in lower efficiency but reduced risk of insertional mutagenesis [2].

The typical workflow involves cloning transcription factor coding DNA into viral plasmids, infecting target cells, selecting successfully transfected cells, and inducing TF overexpression to drive lineage conversion [2]. Efficiency can be improved by first overloading factors like Oct4, Sox2, KLF4, and c-Myc (OSKM) to create a "primed" state, enhancing subsequent transdifferentiation efficiency up to 34% in some studies [2].

Endogenous Gene Regulation

- CRISPR/Cas9 Systems: Catalytically inactive dCas9 fused to transcriptional or epigenetic effector domains enables programmable, modular regulation of endogenous genes without altering DNA sequence [1]. This approach offers higher specificity and efficiency compared to viral overexpression [2].

- Physical Delivery Systems: Tissue Nanotransfection (TNT) is a novel non-viral platform that uses localized nanoelectroporation to deliver genetic material (plasmid DNA, mRNA, CRISPR/Cas9 components) directly into tissues in vivo [1]. This method concentrates electric fields through hollow silicon nanochannels, creating transient nanopores in cell membranes for cargo delivery with high specificity and minimal cytotoxicity [1].

Small Molecule and Chemical Approaches

Chemical compounds and pharmacological agents can induce transdifferentiation by targeting transcriptional pathways, triggering immunological responses, or directly altering the epigenetic environment, offering a non-genetic alternative for cellular reprogramming [2].

Table 1: Comparison of Major Transdifferentiation Delivery Methods

| Method | Mechanism | Efficiency | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lentiviral Vectors [2] | Genomic integration of transgenes | Variable (e.g., ~7.7% for neurons) [2] | Stable expression; infects dividing & non-dividing cells | Insertional mutagenesis risk; immunogenicity |

| Adenoviral Vectors [2] | Transient episomal expression | Lower (e.g., ~2.7% for neurons) [2] | Reduced integration risk; high transduction efficiency | Transient expression; immunogenicity |

| CRISPR/dCas9 Systems [1] [2] | Epigenetic/transcriptional regulation of endogenous genes | High (improves efficiency) [2] | Programmable, specific; no foreign gene integration | Off-target effects potential; complex delivery |

| Tissue Nanotransfection (TNT) [1] | Nanoelectroporation for physical delivery | High for in vivo applications | Non-viral, minimal cytotoxicity; high specificity | Localized delivery; optimization of parameters needed |

| Small Molecules [2] [3] | Chemical induction of reprogramming | Variable | Non-genetic; controllable timing/dosing | Lower efficiency in some cases; off-target effects |

The following workflow diagram outlines a generalized protocol for conducting a viral vector-mediated transdifferentiation experiment.

Key Experimental Applications in Tissue Repair

Transdifferentiation has demonstrated significant potential across various tissue regeneration contexts, with particular progress in neural and cardiac applications.

Neural System Repair

Neurodegenerative diseases and central nervous system injuries have been a major focus of transdifferentiation research. Proof-of-principle was established in 2013 when resident astrocytes and transplanted fibroblasts in adult mouse brain were successfully converted into functional neurons using Ascl1, Myt1l, and Brn2a transcription factors delivered via viral vector [3]. This approach has since been extended to treat disease models:

- Spinal Cord Injury: Lentiviral delivery of Sox2 to astrocytes in mouse spinal cord induced conversion to neuroblasts (3-6% efficiency), which matured into neurons that synapsed with resident neurons [3].

- Alzheimer's Disease Models: Retroviral delivery of NeuroD1 to astrocytes in mouse brain with stab injury resulted in conversion to neurons with 90% efficiency [3].

Cardiac Tissue Regeneration

Myocardial infarction represents another promising application, where converting cardiac fibroblasts into cardiomyocytes could directly repair damaged heart tissue.

- Initial Studies: Early work demonstrated that adenoviral delivery of MyoD could convert cardiac fibroblasts into skeletal myofibers (2-14% efficiency) in freeze-thaw injured rat hearts [3].

- Cardiomyocyte Generation: The GMT combination (Gata4, Mef2c, Tbx5) delivered via retrovirus converted cardiac fibroblasts into cardiomyocyte-like cells in mouse myocardial infarction models (10-15% efficiency), reducing infarct size and significantly decreasing cardiac dysfunction [3].

- Enhanced Protocols: Adding Hand2 to create GHMT improved conversion efficiency to approximately 7%, while microRNA combinations (miR-1, 133, 208, 499) achieved 12-25% efficiency, both resulting in functional improvement [3].

Table 2: Representative Transdifferentiation Applications in Disease Modeling and Tissue Repair

| Disease/Injury Model | Source Cell | Target Cell | Key Reprogramming Factors | Delivery Method | Efficiency | Functional Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CNS/Brain Repair [3] | Astrocyte, Fibroblast | Induced Neuron (iN) | Myt1l, Ascl1, Brn2a | Lentiviral (in vivo) | 0.4% to 5.9% | iNs integrated in tissue |

| Spinal Cord Injury [3] | Astrocyte | Induced Adult Neuroblast | Sox2 | Lentiviral (stereotactic) | 3-6% | Mature neurons formed synapses |

| Alzheimer's Model [3] | Astrocyte | Induced Neuron (iN) | NeuroD1 | Retroviral (stereotactic) | 90% | Transdifferentiated iNs in tissue |

| Myocardial Infarction [3] | Cardiac Fibroblast | Cardiomyocytes | GMT (Gata4, Mef2c, Tbx5) | Retroviral (intramyocardial) | 10-15% | Reduced infarct size; improved function |

| Myocardial Infarction [3] | Cardiac Fibroblast | Cardiomyocytes | microRNAs 1, 133, 208, 499 | Lentiviral (intramyocardial) | 12-25% | Fibroblast conversion; moderate functional improvement |

| Complete Heart Blockage [3] | Ventricular Cardiomyocyte | Pacemaker Cells | Tbx18 | Adenovirus (percutaneous) | 24.5% | Biological pacemaker; improved bradycardia |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful transdifferentiation experiments require carefully selected reagents and tools. The following table summarizes key materials used in the field.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Transdifferentiation Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Experimental Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transcription Factors [2] [3] | Ascl1, Brn2, Myt1l (neurons); GMT combo (cardiomyocytes); MyoD (myoblasts) | Master regulators that initiate lineage conversion; often used in combinations | TF choice is critical; developmental regulators are common starting points |

| Viral Vectors [2] | Lentivirus, Retrovirus, Adenovirus | Delivery of genetic cargo into target cells | Lentiviruses preferred for non-dividing cells; integration vs. non-integration strategies |

| Gene Editing Systems [1] [2] | CRISPR/dCas9 with effector domains | Targeted epigenetic and transcriptional regulation | Enables endogenous gene regulation without transgene integration |

| Physical Delivery Systems [1] | Tissue Nanotransfection (TNT) chips | Nanoelectroporation for in vivo gene delivery | Non-viral approach; uses localized electrical pulses for membrane poration |

| Small Molecules [2] [3] | Chemical cocktails for epigenetic modulation | Induce reprogramming without genetic modification | Offers temporal control; lower immunogenicity concern |

| Cell Type Markers [5] | CD133, Nestin, SOX2 (stemness); CD31, CD34 (endothelial); α-SMA (myofibroblasts) | Identification and validation of starting and target cell populations | Multiple markers often needed due to heterogeneity and plasticity |

| Selection Agents [2] | Antibiotics (e.g., puromycin) | Enrichment of successfully transfected/transduced cells | Requires vector incorporation of resistance genes |

| 2-Iodo-1,1'-binaphthalene | 2-Iodo-1,1'-binaphthalene | 2-Iodo-1,1'-binaphthalene is a key synthetic intermediate for chiral ligands. This product is For Research Use Only. Not for diagnostic or personal use. | Bench Chemicals |

| 1-Decyl-4-isocyanobenzene | 1-Decyl-4-isocyanobenzene, CAS:183667-68-7, MF:C17H25N, MW:243.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Transdifferentiation represents a transformative approach in regenerative medicine, enabling direct lineage conversion for tissue repair without pluripotent intermediates. While significant challenges remain in efficiency, phenotypic stability, and scalable clinical translation, emerging technologies like CRISPR-based regulation and tissue nanotransfection offer promising avenues for advancement. As mechanistic understanding deepens and delivery methods refine, direct reprogramming holds exceptional potential for generating functional cell types to address complex degenerative diseases and tissue injuries, ultimately enabling novel therapeutic strategies in precision regenerative medicine.

This whitepaper explores the phenomenon of transdifferentiation—the direct conversion of one mature, differentiated cell type into another—as a fundamental mechanism in tissue repair and regeneration. By examining two classic paradigms, lens regeneration in newts and pancreatic α-to-β-cell conversion, we dissect the cellular and molecular blueprints that enable such remarkable cellular plasticity. Understanding these evolutionarily conserved mechanisms provides critical insights for developing novel regenerative therapies for human diseases, including diabetes and ocular disorders. The content is framed within a broader thesis on harnessing endogenous repair mechanisms for therapeutic intervention, providing drug development professionals with a technical overview of the field's current state and future directions.

Transdifferentiation represents a powerful mode of tissue regeneration observed across phylogeny, wherein terminally differentiated cells reprogram their transcriptional identity without reverting to a pluripotent state [6]. Unlike stem cell-driven regeneration, this process leverages existing specialized cells within tissues, offering potentially safer and more efficient pathways for therapeutic intervention. The study of natural transdifferentiation models provides invaluable insights into the molecular logic of cell fate control. Among vertebrates, salamanders—particularly newts and axolotls—demonstrate exceptional regenerative capacities, functionally regenerating a wide spectrum of tissues from limbs to cardiac muscle and neural tissues [7]. This review focuses on two exemplary models: the Wolffian lens regeneration in newts, and pancreatic islet cell conversion in mammals, with emphasis on their underlying mechanisms and potential translational applications.

Lens Regeneration in Newts: A Classic Model of Transdifferentiation

Historical Context and Phenomenology

Lens regeneration in adult newts was first documented by Collucci (1891) and independently by Wolff (1895), after whom the process is often termed "Wolfian regeneration" [6]. This remarkable process involves the complete regeneration of a functional lens following surgical removal (lentectomy). The newt remains the only urodele amphibian known to regenerate its lens throughout its adult life, with no diminishment in capacity even after repeated regeneration or with advanced age [6]. Astoundingly, individual Japanese newts (Cynops pyrrhogaster) have been documented to regenerate perfect lenses 18 times over a 16-year period, with the regenerated lenses from the final cycles exhibiting cellular and biochemical properties identical to those of younger animals [6].

Cellular Mechanisms and Source Tissue

The regenerated lens originates not from residual lens tissue but via transdifferentiation of pigment epithelial cells (PECs) from the dorsal iris [6]. This process occurs in two distinct phases:

Dedifferentiation and Proliferation Phase (Days 1-8): The double-layered iris tissue at its dorsal edge disorganizes, PECs lose their pigmentation, re-enter the cell cycle, and upregulate early lens genes including Pax6, Sox2, and MafB [6]. This phase is characterized by increased synthesis of ribosomal RNA through amplification of rRNA genes and elevated transcriptional activity.

Transdifferentiation Phase (Days 8-16): Dedifferentiated cells form a lens vesicle and subsequently differentiate into lens fibers, ultimately restoring a fully functional lens [6].

Molecular Triggers and Signaling Pathways

Fibroblast growth factor 2 (FGF-2) has been identified as a critical initiator of lens regeneration. Key evidence includes:

- Upregulation of FGF-2 in PECs alongside early lens genes post-lentectomy [6].

- High expression of FGFR3 receptor in dorsal iris PECs [6].

- Inhibition of regeneration upon injection of a soluble form of FGFR3 to titrate FGF-2, which blocks all molecular and morphological changes in PECs [6].

- Ectopic lens formation from dorsal iris PECs upon FGF-2 injection into the intact eye, which subsequently replaces the degenerating primary lens [6].

Emerging research is beginning to elucidate the epigenetic and post-transcriptional regulators involved. Studies have revealed the upregulation of cancer-associated genes, apoptosis genes, and chromatin-modifying enzymes during dedifferentiation [6]. Furthermore, microRNAs, particularly miR-124a, appear to play significant roles, with differential regulation of miR-148 and let-7b implicated in controlling proliferation genes [6].

Table 1: Key Molecular Players in Newt Lens Regeneration

| Molecule | Role in Lens Regeneration | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| FGF-2 | Master initiator; triggers dedifferentiation and lens gene expression | Injection inhibits regeneration; ectopic expression induces lens formation [6] |

| Pax6 | Master regulatory gene for eye development and regeneration | Upregulated in dedifferentiating PECs [6] |

| Sox2 | Early lens gene; pluripotency factor | Upregulated in dedifferentiating PECs [6] |

| MafB | Transcription factor | Upregulated during dedifferentiation phase [6] |

| miR-124a | Potential regulator of dedifferentiation | Highly expressed in dedifferentiating PECs [6] |

Experimental Protocol: Lentectomy and Lens Regeneration Analysis

Objective: To surgically remove the lens and monitor the process of regeneration from the dorsal iris pigment epithelium.

Procedure:

- Animal Preparation: Adult newts (e.g., Notophthalmus viridescens or Cynops pyrrhogaster) are anesthetized using a 0.1% ethyl 3-aminobenzoate methanesulfonate (MS-222) solution.

- Lentectomy: A corneal incision is made, and the native lens is carefully removed using fine forceps without damaging the dorsal iris.

- Post-operative Care: Animals are maintained in a controlled aquatic environment and allowed to recover. Regeneration is monitored over 2-4 weeks.

- Tissue Collection and Analysis: At designated time points (e.g., 5, 10, 15, 20, 30 days post-lentectomy), eyes are enucleated and processed for:

- Histology: Tissue fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, embedded in paraffin, sectioned, and stained with Hematoxylin and Eosin to visualize tissue morphology and regenerative stages [6].

- Immunohistochemistry: Staining for markers such as Pax6 to identify early lens cell commitment, and crystallins for terminal lens fiber differentiation [6].

- In situ hybridization: To localize specific mRNA transcripts (e.g., FGF-2, Sox2) in regenerating tissue.

Diagram Title: Newt Lens Regeneration Process

Pancreatic α- to β-Cell Conversion: A Mammalian Paradigm for Diabetes Therapy

Biological Rationale and Therapeutic Potential

The global prevalence of diabetes mellitus underscores the urgent need for therapies that address the fundamental pathophysiological deficit: a reduction in functional pancreatic β-cell mass [8] [9]. Traditional treatments with exogenous insulin or oral hypoglycemic agents often fail to achieve optimal glycemic control, leading to severe complications [8]. Research has consequently focused on replenishing the β-cell population, with transdifferentiation of pancreatic α-cells emerging as a promising therapeutic avenue [8]. α-cells are ideal candidates for conversion due to several factors:

- Developmental Similarity: α-cells and β-cells share a common developmental origin from endocrine progenitors in the pancreatic endoderm, controlled by a network of transcription factors including Pdx1 and Ngn3 [8].

- Close Physical Association: In both mouse and human islets, over 90% of α-cells are in direct contact with β-cells, facilitating potential paracrine interactions and conversion [8].

- Compensatory Proliferation: α-cell proliferation is commonly observed in diabetic animal models and patients, providing a substantial cellular resource for reprogramming [8].

- Functional Redundancy: Significant reduction in α-cell numbers does not adversely affect glucose metabolism, and converting α-cells may mitigate the deleterious effects of glucagon on glycemic control [8].

Molecular Mechanism of Fate Switching

The transdifferentiation of α-cells to β-cells is a tightly regulated process demonstrating the plasticity of pancreatic endocrine cells. It can be divided into three main stages:

- Proliferation of α-cells in response to extensive β-cell loss in diabetic environments [8].

- Reprogramming of α-cell identity, which requires the coordinated suppression of α-cell-maintaining factors and activation of the β-cell transcriptional program.

- Stabilization of the new β-cell identity to prevent reversion or transformation into other cell types.

Table 2: Key Transcription Factors in α- to β-Cell Transdifferentiation

| Transcription Factor | Role in Cell Identity | Effect on Transdifferentiation |

|---|---|---|

| Arx | Maintains α-cell phenotype; suppresses β-cell genes | Deletion induces α-to-β cell conversion, normalizes blood glucose [8] |

| MafB, Brn4, Pax6 | Regulate glucagon production and α-cell stability | Downregulation facilitates transdifferentiation initiation [8] |

| Pdx1 | β-cell identity and function; crucial for insulin production | Upregulation is essential for establishing and maintaining β-cell phenotype [8] |

| MafA | β-cell maturation and function | Upregulation helps stabilize the transdifferentiated state [8] |

| Nkx6.1 | β-cell identity | Upregulation supports the β-cell transcriptional program [8] |

Recent Advances and Human Islet Heterogeneity

Recent single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) studies have revealed unprecedented complexity in human pancreatic α-cells, identifying five distinct α-cell subclusters (α1, α2, α3, α4, and AB) with unique transcriptomic profiles [10]. Of particular interest is the AB subcluster, a multihormonal population expressing both GCG (glucagon) and INS (insulin), which may represent a transitional state. Trajectory inference analyses suggest that in non-diabetic islets, cell fate trajectories are bifurcated, while in type 2 diabetic (T2D) islets, trajectories become unidirectional, moving from β-cells to α-cells, indicating β-cell dedifferentiation towards an α-cell-like phenotype [10]. This analysis identified SMOC1 as a key gene in this pathological trajectory. SMOC1, typically an α-cell gene, is expressed in β-cells in T2D. Functional studies demonstrate that enhanced SMOC1 expression in β-cells reduces insulin expression and secretion while increasing dedifferentiation markers, establishing it as an inducer of β-cell dysfunction in diabetes [10].

Experimental Protocol: Assessing β-Cell Mass and Transdifferentiation

Objective: To quantify β-cell mass and identify transdifferentiating cells in pancreatic tissue sections.

Procedure (Automated Quantification using Virtual Slide Technology) [9]:

- Tissue Preparation: Pancreata are weighed, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, dehydrated, and embedded in paraffin. Longitudinal sections are cut at 5-μm thickness and collected systematically at 250-μm intervals.

- Immunohistochemistry: Sections are immunolabeled with primary guinea pig anti-insulin antibody, followed by HRP-conjugated secondary antibody. Insulin signal is visualized with DAB chromogen, and sections are counterstained with Eosin-Y.

- High-Resolution Slide Scanning: Entire pancreatic sections are scanned using a high-resolution slide scanner (e.g., ScanScope CS) at 20x magnification.

- Automated Image Analysis (Genie Algorithm Training):

- Class Definition: Three object classes are defined in the image analysis software:

Glass(background),Eosin(exocrine and other tissue), andDAB(insulin-positive β-cells). - Algorithm Training: The algorithm is trained by manually assigning representative regions of the image to each class, encompassing variations in staining intensity and tissue morphology. The training aims for >97% sensitivity and specificity.

- Batch Analysis: The trained macro is run on all pancreatic sections from the study to automatically quantify the total β-cell area (DAB-positive) and pancreatic area.

- Class Definition: Three object classes are defined in the image analysis software:

- Calculation of β-Cell Mass:

β-cell mass = (Total β-cell area / Total pancreatic area) * Pancreas weight - Analysis of Transdifferentiation: Consecutive or double-labeling immunofluorescence for insulin and glucagon is used to identify bihormonal (INS+GCG+) cells, which are quantified manually or via automated analysis to assess the frequency of putative transdifferentiating events [10].

Diagram Title: Molecular Path of α- to β-Cell Conversion

Comparative Analysis and Research Toolkit

Cross-Species Mechanistic Commonalities

Despite the vast phylogenetic distance and differences in the specific tissues involved, newt lens regeneration and pancreatic α-to-β-cell conversion share fundamental mechanistic principles central to the thesis of transdifferentiation in tissue repair:

- Master Regulator Switching: Both processes are governed by the downregulation of fate-defining transcription factors for the starting cell type (e.g., Arx in α-cells, pigment-specific factors in PECs) and concomitant upregulation of master regulators for the target cell type (e.g., Pdx1 in β-cells, Pax6/Sox2 in lens cells) [8] [6].

- Developmental Pathway Reactivation: Key signaling pathways essential during embryonic development, particularly the FGF pathway, are reactivated to drive the reprogramming process [6].

- Cellular Plasticity Precedes Conversion: In both systems, the starting cell must first undergo a degree of dedifferentiation or become more plastic, entering a less stable, progenitor-like state before committing to a new fate [6] [10].

- Role of the Niche: The local microenvironment, or niche, provides critical signals. In newts, the dorsal iris position is crucial, while in the pancreas, close physical contact between α- and β-cells and signals from the diabetic milieu influence the transdifferentiation potential [8] [6].

Table 3: The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Transdifferentiation Research

| Research Reagent / Tool | Function/Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Anti-Insulin Antibody | Immunohistochemical identification of β-cells and insulin-producing cells | Quantifying β-cell area/mass in pancreatic sections; identifying transdifferentiated cells [9] |

| Anti-Glucagon Antibody | Immunohistochemical identification of α-cells | Co-staining with insulin to identify bihormonal (transitional) cells [10] |

| Anti-Pax6 Antibody | Marker for early lens cell commitment and eye development | Staining newt iris sections during early lens regeneration [6] |

| FGF-2 (Recombinant Protein) | Soluble signaling factor to trigger dedifferentiation and proliferation | Testing sufficiency to induce lens transdifferentiation in newt iris culture [6] |

| Soluble FGFR3 | Decoy receptor to sequester and inhibit FGF signaling | Testing necessity of FGF signaling in lens regeneration [6] |

| scRNA-seq/snRNA-seq | Unbiased profiling of cell populations and trajectory inference | Identifying α-cell subclusters and β-to-α cell trajectories in human diabetic islets [10] |

| Aperio ScanScope & Genie Algorithm | High-resolution slide scanning and automated image analysis | High-throughput, accurate quantification of β-cell mass in whole pancreatic sections [9] |

| 2-Oxetanone, 4-cyclohexyl- | 2-Oxetanone, 4-cyclohexyl-, CAS:132835-55-3, MF:C9H14O2, MW:154.21 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Propyl perfluoroheptanoate | Propyl Perfluoroheptanoate|C10H7F13O2 | High-purity Propyl perfluoroheptanoate for research on PFAS. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary diagnostic or therapeutic use. |

The natural paradigms of lens regeneration in newts and pancreatic α-to-β-cell conversion provide a powerful conceptual framework for understanding transdifferentiation. They reveal that the potential for significant cellular reprogramming is retained in specific contexts even in adult vertebrates. For drug development professionals, these models highlight key molecular targets (e.g., Arx, SMOC1, FGF-signaling) and strategic considerations, such as the need to manage the stability of the newly acquired cell fate. Future research must focus on refining the efficiency and safety of targeted transdifferentiation in human tissues, potentially by combining transcriptional manipulation with modulation of the local microenvironment. Leveraging these endogenous blueprints for repair holds the promise of developing next-generation regenerative therapies that restore tissue function by harnessing the body's own cellular plasticity.

Within the field of regenerative medicine, a paradigm shift is underway, moving beyond the use of pluripotent stem cells toward the direct conversion of one mature cell type into another. This process, known as transdifferentiation, is fundamentally governed by a class of proteins called "master switch" transcription factors (TFs). These TFs, such as MyoD and Pax6, commandeer cellular identity by reprogramming gene expression networks. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical examination of how these factors operate, detailing their mechanisms, key experimental methodologies, and their profound implications for directing cell fate in therapeutic contexts, particularly tissue repair. By elucidating the control logic of cell identity, we unlock novel strategies for regenerative medicine and drug development.

Transdifferentiation is defined as the irreversible conversion of one differentiated cell type into another, without proceeding through a pluripotent intermediate state [4] [11]. This phenomenon represents a powerful tool for regenerative medicine, as it offers the potential to directly replace lost or damaged cells from a patient's own resident tissues, thereby circumventing the risks of tumorigenesis and ethical concerns associated with pluripotent stem cells [11].

At the heart of transdifferentiation are master switch genes. These genes encode transcription factors that, when expressed, can initiate and enforce an entire genetic program sufficient to define a specific cell lineage. The seminal discovery of MyoD demonstrated that a single TF could convert fibroblasts into striated muscle cells, establishing the conceptual foundation for this field [11]. Similarly, the TF Pax6 is essential for the development of the eye, pancreas, and central nervous system, and its dysfunction is linked to human diseases [12] [13]. These factors function as nodal points in gene regulatory networks (GRNs), activating batteries of genes characteristic of the target cell type while simultaneously repressing genes associated with alternative fates [12] [13]. The growing understanding of these mechanisms provides a rational basis for designing transdifferentiation protocols for tissue repair, positioning master switch genes as high-value targets for therapeutic intervention.

Core Mechanisms of Action

Master switch TFs exert control over cell identity through coordinated and multi-layered regulatory mechanisms.

2.1 Transcriptional Activation and Repression: These TFs bind to specific DNA sequences in the regulatory regions (promoters and enhancers) of their target genes. For instance, Pax6 directly binds to and activates genes required for neuronal development, such as Ift74, which is critical for neuronal migration [13]. Concurrently, Pax6 represses genes of alternative lineages; in pancreatic β-cells, it directly represses genes encoding hormones like glucagon and somatostatin, which are hallmarks of α- and δ-cells, respectively [12]. This dual function ensures the stability of the desired cellular phenotype.

2.2 Cooperation with Other Factors: The activity of a master TF is not executed in isolation. It often depends on synergistic interactions with the cellular environment and other TFs. A prime example is the cooperation between Pax6 and Sox2 in neural progenitor cells. These factors co-occupy a large number of promoters, where they functionally cooperate to regulate genes underlying neuronal specification [13]. This cooperativity allows for a more robust and specific control of the transcriptional program.

2.3 Epigenetic Remodeling: Large-scale changes in chromatin architecture are a prerequisite for cell fate conversion. The process of transdifferentiation involves genome-wide chromatin reorganization, which is closely linked to cellular plasticity [14]. Master TFs can pioneer these changes by binding to closed chromatin and initiating the opening of new regulatory regions, thereby making genes accessible for transcription.

The following diagram illustrates the core mechanisms by which a master switch transcription factor, such as Pax6, governs cell identity.

Key Master Switch Genes: MyoD and Pax6

3.1 MyoD: The Master Regulator of Myogenesis MyoD is the prototypical master regulator. Its forced expression is sufficient to induce a skeletal muscle program in a variety of cell types, including fibroblasts. It operates by activating the expression of muscle-specific genes, such as those for myosin and creatine kinase, while concurrently halting the cell cycle.

3.2 Pax6: A Multifunctional Regulator in Development and Disease Pax6 is a paired box and homeodomain-containing TF with pleiotropic roles. Its function is highly context-dependent, and it acts as a master regulator in several tissues.

Table 1: Key Functions of the Pax6 Master Regulator

| Tissue/Cell Type | Primary Function of Pax6 | Consequence of Loss-of-Function | Key Target Genes/Pathways |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pancreatic β-cells | Maintains β-cell identity and function by repressing alternative islet cell genes (ghrelin, glucagon, somatostatin) [12]. | Lethal hyperglycemia and ketosis; loss of β-cell function and expansion of α-cells [12]. | Direct activator of β-cell genes; repressor of ARX, GCG, SST [12]. |

| Neural Progenitors | Activates neuronal (ectodermal) genes while repressing mesodermal and endodermal genes, ensuring unidirectional neurogenesis [13]. | Reduced neurons in cerebral cortex; misspecified neurons that undergo cell death [13]. | Sox2 (cooperation), Ift74 (neuronal migration), Neurog2, components of Notch signaling [13]. |

| Corneal Epithelium | Transcriptional activator of CXCL14 post-injury, enhancing stemness, proliferation, and migration of central corneal epithelial cells [15]. | Impaired repair of corneal injury and disrupted homeostasis [15]. | CXCL14 (activator), which engages SDC1 receptor and NF-κB pathway [15]. |

| Lens Development | Regulates expression of crystallin genes and other factors essential for lens development and homeostasis [16]. | Abnormal lens fiber cells and persistent corneal-lenticular stalk (in heterozygotes) [16]. | c-Maf, Foxe3, Mab21l2, Tgfb2, crystallin genes [16]. |

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies

Studying master switch genes requires a suite of advanced molecular and cellular techniques to validate their function and mechanisms.

4.1 In Vitro Transdifferentiation Protocols A common approach involves the forced expression of TFs in a somatic cell to induce transdifferentiation.

- Starting Cells: Fibroblasts remain the most commonly used starting population [11].

- TF Delivery: Transient forced expression is achieved via viral vectors (e.g., lentiviruses, adenoviruses) or non-viral methods like transfection. For example, a combination of Brn2, Ascl1, and Myt1l (BAM) can convert fibroblasts into induced neurons (iNs) [11].

- Enhancing Efficiency: Culture conditions are critical. Hypoxia (which activates HIFs) can enhance conversion efficiency, as shown in the transdifferentiation of human fibroblasts to dopaminergic neurons [11]. Suppression of p53 or inducing cell cycle arrest also increases efficiency [11].

4.2 Key Analytical Techniques

- Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP): This is the definitive method to identify direct genomic targets of a TF. ChIP, followed by sequencing (ChIP-seq), revealed that Pax6 binds thousands of promoters in neural progenitors, many of which are co-occupied by Sox2 and marked by active histone marks like H3K4me2 [13].

- Lineage Tracing: This in vivo technique uses genetic labeling to trace the fate of specific cell populations and their progeny, confirming that one cell type has converted into another.

- Functional Assays: The ultimate validation of transdifferentiated cells involves functional tests. For neurons, this includes patch-clamp electrophysiology to demonstrate action potentials and synaptic activity. For other cell types, it may involve measuring secreted hormones or demonstrating regenerative capacity in injury models.

The workflow for a typical experiment investigating a master switch gene is outlined below.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Investigating Master Switch Genes and Transdifferentiation

| Reagent / Tool | Function and Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Specific TF Antibodies | Used for Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP), immunofluorescence, and Western blot to localize and quantify TF expression. | Affinity-purified Pax6 antibody for ChIP to map its genomic targets in neural progenitors [13]. |

| Lentiviral/Adenoviral Vectors | For efficient and stable (lentivirus) or transient (adenovirus) delivery of TF genes into target somatic cells. | Overexpressing CXCL14 via lentivirus in corneal epithelial cells to study its role in wound healing [15]. |

| Lineage Tracing Systems | Genetically labels a specific cell population and all its descendants in vivo to track cell fate changes. | Confirming the conversion of supporting cells into hair cells in the cochlea after manipulating Notch signaling [17]. |

| Organoid Cultures | 3D in vitro models that recapitulate tissue architecture, used to study TF function in a near-physiological context. | Using intrahepatic cholangiocyte organoids to study transdifferentiation into hepatocytes [14]. |

| scRNA-seq / snATAC-seq | Single-cell/nucleus assays to profile gene expression (RNA-seq) and chromatin accessibility (ATAC-seq) simultaneously. | Uncovering transcriptomic and epigenetic mechanisms in cholangiocyte transdifferentiation [14]. |

| Dodeca-4,11-dien-1-ol | High-purity Dodeca-4,11-dien-1-ol for research (RUO). A key intermediate in synthetic chemistry and aroma composition. Not for human or household use. | |

| 3-Cyclopropyl-1H-indene | 3-Cyclopropyl-1H-indene |

Implications for Tissue Repair and Therapeutic Outlook

The manipulation of master switch genes holds immense promise for regenerative medicine, offering novel strategies for treating a wide array of degenerative diseases and injuries.

- Neurodegenerative Diseases: Direct transdifferentiation of a patient's glial cells into functional neurons in situ represents a potential therapeutic avenue for conditions like Parkinson's and Alzheimer's disease. Protocols have been established to generate dopaminergic iNs and motor iNs from fibroblasts, which can be used for disease modeling and cell therapy [11].

- Metabolic Disorders: In diabetes, the transdifferentiation of pancreatic α-cells or other cell types into functional, glucose-responsive β-cells could restore insulin production. The role of Pax6 in maintaining β-cell identity makes it a critical target for such approaches [12].

- Organ Repair and Regeneration: The liver exhibits remarkable plasticity. Recent human studies show that cholangiocytes (bile duct cells) can transdifferentiate into hepatocytes in chronic liver disease, a process driven by TFs like HNF4G and involving extensive epigenetic remodeling [14]. Similarly, the PAX6/CXCL14 axis has been identified as a critical driver of corneal epithelial repair, with recombinant CXCL14 protein showing therapeutic potential for corneal injuries [15].

The future of the field lies in refining the specificity and safety of these interventions. This includes developing non-integrating delivery methods for TF genes, using small molecules to induce or enhance transdifferentiation [11], and achieving precise spatial and temporal control over the process to ensure the generation of fully functional, region-specific cell types for effective tissue repair.

Metaplasia is defined as the conversion of one differentiated cell type into another and represents a critical adaptive response in pathology, often serving as a precursor state to both cancer and fibrosis. This phenomenon belongs to a wider class of cell type transformations that includes transdifferentiation, which is more specifically defined as the irreversible switch of one type of differentiated cell to another, typically involving dedifferentiation and cell division as intermediate processes [4]. In pathological contexts, metaplasia occurs as a tissue healing response to chronic injury, inflammation, or environmental stressors. However, when these insults persist, the metaplastic state can be co-opted toward pathological outcomes, serving as a critical crossroads in disease progression toward carcinogenesis or fibrotic remodeling [18] [4].

The clinical significance of metaplastic transitions is twofold. First, metaplasia predisposes to certain forms of neoplasia, with one of the best-studied examples being Barrett's esophagus, where stratified squamous epithelium undergoes metaplastic transformation to intestinal-type epithelium, creating a precursor to esophageal adenocarcinoma [4]. Second, metaplastic changes are increasingly recognized as fundamental drivers of fibrotic processes across multiple organ systems, including pulmonary, hepatic, and cardiac tissues [19] [20]. Understanding the molecular mechanisms governing these cellular plasticity events provides crucial insights for developing early detection strategies and targeted interventions for these debilitating conditions [4] [21].

Metaplasia as a Precursor to Gastric Cancer

The Correa Cascade and Gastric Intestinal Metaplasia

Gastric cancer represents the fifth most commonly diagnosed cancer and the fourth leading cause of cancer-related mortality worldwide, with approximately 26,780 new U.S. cases annually and a poor 5-year survival of 36% [22] [23]. The majority of gastric cancers follow the established Correa cascade, a stepwise progression from chronic gastritis through a series of precursor lesions—atrophic gastritis, intestinal metaplasia, and dysplasia—before developing into invasive cancer [23]. Within this sequence, gastric intestinal metaplasia (GIM) represents a potentially irreversible state with increased cancer risk, particularly when extending into the corpus [22].

Global prevalence estimates highlight the significance of GIM, with a worldwide prevalence of 17.5%, though with considerable geographic variation ranging from 8.3% in Africa to 18.6% in the Americas [23]. The progression rates of these precursor lesions to gastric cancer provide critical data for surveillance strategies, with global pooled estimates indicating that the annual progression rate per 1,000 person-years is 2.09 for atrophic gastritis, 2.89 for intestinal metaplasia, and 10.09 for dysplasia [23]. These findings underscore the importance of metaplastic transitions as key intervention points for gastric cancer prevention.

Table 1: Progression Rates of Gastric Precancerous Lesions to Gastric Cancer

| Precursor Lesion | Annual Progression Rate (per 1,000 person-years) | 95% Confidence Interval |

|---|---|---|

| Atrophic Gastritis | 2.09 | 1.46–2.99 |

| Intestinal Metaplasia | 2.89 | 2.03–4.11 |

| Dysplasia | 10.09 | 5.23–19.49 |

Molecular Mechanisms and Microenvironment

Recent single-cell transcriptomic analyses have revealed that diverse injury stimuli, including Helicobacter pylori infection and autoimmune gastritis, induce cancer-associated metaplasia through both convergent and divergent pathways [18]. These studies have identified a transcriptionally diverse array of metaplastic lineages, with spasmolytic polypeptide-expressing metaplasia (SPEM) representing a particularly consequential program. Although SPEM was initially considered a reparative lineage, persistent injury leads to the emergence of mature chief cells as cryptic progenitors for metaplasia, creating a cellular context susceptible to malignant transformation [18] [23].

The tissue microenvironment plays a crucial role in metaplastic progression. Apposition of fibroblasts with metaplastic gastric cells promotes dysplastic transition, indicating that stromal-epithelial crosstalk establishes a permissive niche for malignant transformation [18]. Specific biomarkers have emerged as promising indicators of progression risk, including ANPEP/CD13, which shows elevated expression in gastric metaplasia with higher potential for malignant progression [18]. Additionally, gastrokine 3 and cadherin-17 (CDH17) have been identified as molecular markers associated with metaplastic development and early-stage gastric cancer prognosis [18].

Figure 1: Molecular Pathways of Gastric Metaplasia and Cancer Progression. The diagram illustrates the key steps in the Correa cascade, highlighting the role of transdifferentiation and microenvironmental signaling in driving progression from metaplasia to gastric cancer.

Metaplasia in Fibrotic Diseases

The Global Burden of Fibrosis and Metaplastic Involvement

Fibrotic diseases contribute to nearly half of all deaths in industrialized countries, with a steadily increasing global burden. Recent analyses of Global Burden of Disease (GBD) 2021 data across 204 countries and territories revealed that from 1990 to 2021, fibrosis-related disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) and mortality increased by 16.71% and 4.83%, respectively [19]. This growing burden is disproportionately concentrated in regions with low socio-demographic index (SDI), where limited diagnostic capabilities prevent early detection and intervention [19].

Metaplastic changes are increasingly recognized as fundamental components of fibrotic processes across multiple organ systems. In pulmonary fibrosis, a fatal disease characterized by progressive scarring of lung tissue with a median post-diagnosis survival of only 2-6 years, "proximalized epithelial metaplasia" represents a hallmark finding [24] [25]. This process involves the appearance of conducting airway cell types in the distal lung epithelium, disrupting normal alveolar structure and function [25]. Similarly, in cardiogenic liver disease, biliary metaplasia defines the cellular landscape, with hepatocytes undergoing phenotypic conversion to biliary-like epithelium in response to congestive hepatopathy [20].

Molecular Drivers of Fibrosis-Associated Metaplasia

The molecular pathways driving metaplasia in fibrotic contexts share common features across organs, centered on aberrant activation of developmental programs and response to mechanical stress. In pulmonary fibrosis, spatial transcriptomic analyses of 1.6 million cells from 35 unique lungs have identified a VGLL3-mediated pathway as central to fibrotic remodeling [19] [25]. VGLL3 is a transcriptional co-regulator rich in intrinsically disordered regions that is consistently upregulated in multi-organ fibrosis and mediates early activation of fibroblasts in response to matrix stiffness [19].

Single-cell RNA sequencing has revealed that in the remodeling lung, a spectrum of activated "fibrotic" fibroblasts expressing varying levels of CTHRC1, FAP, and POSTN concentrate in subepithelial regions underlying areas of extensive epithelial metaplasia [25]. These fibroblasts create a pro-fibrotic niche that perpetuates metaplastic changes and extracellular matrix deposition. Similarly, metabolic reprogramming, particularly disorders of lipid metabolism, has been identified as a significant characteristic of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF), with specific metabolites like palmitoyl ethanolamide (PEA) and 2-amino-1,3,4-octadecanetriol serving as potential biomarkers for diagnosis and prognosis evaluation [26].

Table 2: Key Biomarkers in Fibrosis-Associated Metaplasia

| Biomarker | Role in Metaplasia and Fibrosis | Pathological Context |

|---|---|---|

| VGLL3 | Transcriptional co-regulator mediating early fibroblast activation in response to matrix stiffness | Multi-organ fibrosis [19] |

| CTHRC1 | Expressed by activated fibrotic fibroblasts in subepithelial regions underlying metaplastic epithelium | Pulmonary fibrosis [25] |

| KRT5-/KRT17+ | Aberrant basaloid cells located in proximity to activated fibroblasts in remodeling lung | Pulmonary fibrosis [25] |

| PEA | Lipid metabolite significantly increased in IPF patients; potential diagnostic and prognostic biomarker | Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis [26] |

| LCN2 | Lipocalin 2 associated with macrophage activation in biliary metaplasia | Cardiogenic liver disease [20] |

Experimental Models and Methodologies

Animal Models of Metaplasia

Animal models have been instrumental in elucidating the pathogenesis of metaplasia and its progression to cancer and fibrosis. For gastric cancer, the mouse model represents the most commonly utilized system, with several established approaches [23]:

Helicobacter infection models: C57BL/6 mice infected with Helicobacter felis closely mirror the progression from chronic gastritis through metaplasia to dysplasia, though these models primarily produce SPEM rather than true intestinal metaplasia.

Chemical carcinogen models: Utilizing compounds like N-methyl-N′-nitro-N-nitrosoguanidine (MNNG) or N-methyl-N-nitrosourea (MNU) reliably produces tumors but often bypasses intermediate precancerous stages.

Genetically engineered mouse models: Stomach-specific inducible Cre recombinase systems targeting gastric progenitor cells have yielded models that faithfully reproduce the spectrum of human gastric cancer subtypes with metastatic features.

Standardized evaluation of these models is crucial, with the internationally recognized "Histologic Scoring of Gastritis and Gastric Cancer in Mouse Models" system providing a comprehensive framework for assessing active inflammation, chronic inflammation, atrophy, SPEM, intestinal metaplasia, and dysplasia through semi-quantitative scoring [23].

Spatial Transcriptomics in Fibrosis Research

Cutting-edge spatial transcriptomic approaches have revolutionized our understanding of metaplasia in fibrotic diseases. Recent investigations utilizing image-based spatial transcriptomics have analyzed the gene expression of 1.6 million cells from 35 unique lungs, enabling unprecedented resolution of the spatial contexts driving disease pathogenesis [25]. The experimental workflow typically involves:

Tissue Preparation and Imaging:

- Fresh frozen tissue sections (typically 10μm thickness) mounted on specialized slides

- Permeabilization to release RNA for capture

- Hybridization with gene-specific probes with barcodes corresponding to spatial location

Data Acquisition and Analysis:

- Automated cell segmentation using nuclear boundaries

- Quality filtering to retain high-confidence cellular transcriptomes

- Complementary cell-based and cell-agnostic computational approaches to identify spatial niches

- Graph neural network models to aggregate local neighborhood information and define embedding spaces

This approach has enabled researchers to characterize the localization of disease-emergent cell types, establish the cellular and molecular basis of classical histopathologic features, and identify distinct molecularly defined spatial niches in control and fibrotic lungs [25].

Biomarker Detection Methodologies

Advanced detection methodologies are crucial for identifying and validating biomarkers associated with metaplastic progression:

VGLL3-Targeted Immunoassay Protocol [19]:

- Antigen Design: Five truncated VGLL3 variants (residues 1–168, 1–194, 1–237, 1–251, and 1–297) designed based on domain prediction

- Protein Expression: Recombinant plasmids transformed into E. coli HST08 cells, grown in LB medium with kanamycin

- Antibody Generation: Laying hens immunized with purified VGLL3 (1–237) antigen, initial dose of 250μg emulsified in Freund's complete adjuvant

- Assay Performance: Detection range of 27.01–2512.36 nM with limit of detection of 12.55 nM

Serum Metabolomics for IPF Biomarkers [26]:

- Metabolite Extraction: 100μL liquid sample mixed with 400μL prechilled methanol, incubated on ice, centrifuged

- LC-MS/MS Analysis: Vanquish UHPLC system coupled with Orbitrap Q Exactive HF mass spectrometer

- Chromatographic Conditions: Hyperil Gold column (C18), 40°C column temperature, 0.2 mL/min flow rate

- Multivariate regression analysis and correlation network modeling to analyze relationships between metabolites and clinical parameters

Figure 2: Spatial Transcriptomics Workflow for Metaplasia Research. The diagram outlines key methodological steps from tissue preparation through computational analysis to identify spatially-resolved biomarkers in metaplastic and fibrotic tissues.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Metaplasia and Transdifferentiation Studies

| Reagent/Material | Application | Function |

|---|---|---|

| Recombinant VGLL3 antigens (residues 1-237) | Fibrosis biomarker studies | Immunogen for generating specific antibodies; detects early fibrotic remodeling [19] |

| Anti-VGLL3 avian antibodies | VGLL3 detection assays | Cost-effective alternative to mammalian IgG with superior stability and specificity for immunoassays [19] |

| CK7 antibody | Hepatic metaplasia studies | Marker for biliary differentiation in cardiogenic liver disease [20] |

| ANPEP/CD13 antibody | Gastric cancer progression studies | Identifies metaplastic cells with higher potential for malignant progression [18] |

| pET-28a(+) vector with N-terminal SUMO tag | Recombinant protein expression | Enhances solubility of difficult-to-express proteins like VGLL3 for antibody production [19] |

| Liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) | Metabolomic profiling | Identifies lipid metabolites (PEA, 2-amino-1,3,4-octadecanetriol) as potential IPF biomarkers [26] |

| Xenium spatial transcriptomics platform | Spatial gene expression analysis | Enables subcellular resolution mapping of 343 genes across tissue sections to identify metaplastic niches [25] |

| Stomach-specific inducible Cre recombinase systems | Genetic mouse models | Targets gastric progenitor cells to recapitulate human gastric cancer progression from metaplasia [23] |

| 2,2'-Diethyl-3,3'-bioxolane | 2,2'-Diethyl-3,3'-bioxolane | 2,2'-Diethyl-3,3'-bioxolane is for research use only (RUO). It is a high-purity chemical for applications in organic synthesis and as a specialty solvent. Not for human consumption. |

| 1-Iodonona-1,3-diene | 1-Iodonona-1,3-diene, CAS:169339-71-3, MF:C9H15I, MW:250.12 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Therapeutic Implications and Future Directions

The investigation of metaplasia as a precursor to cancer and fibrosis holds significant implications for therapeutic development. In gastric cancer prevention, surveillance strategies for patients with gastric intestinal metaplasia are being refined through standardized coding practices, with the 2021 introduction of specific ICD-10-CM codes (K31.A) for GIM allowing precise classification of anatomical specificity and dysplasia status, providing a novel opportunity to improve risk stratification and endoscopic surveillance [22]. Studies have demonstrated a 3-4 fold increase in documented GIM cases following implementation of these standardized codes, suggesting previous systematic underdiagnosis that potentially affected surveillance strategies and risk assessment for gastric cancer prevention [22].

In fibrosis treatment, the identification of VGLL3 as a key transcriptional regulator opens promising avenues for therapeutic intervention. VGLL3 responds to changes in matrix stiffness, binds to TEAD, and directly mediates fibroblast collagen production, playing a key role in liver, cardiac, and skin fibrosis [19]. In VGLL3 knockout studies, mice showed significantly reduced fibrosis after myocardial infarction and improved cardiac function, highlighting its potential as a therapeutic target [19]. Similarly, in keloids, VGLL3 promotes fibroblast proliferation by activating the Wnt pathway, suggesting that pathway inhibition could mitigate fibrotic progression [19].

Future research directions will likely focus on integrating advanced technologies such as single-cell RNA sequencing with existing animal models, developing more sophisticated organoid models of metaplasia, and investigating the complex interactions among genetic predisposition, microbial infection, and environmental factors in driving metaplastic progression [23]. The convergence of multi-omics technologies is fostering the development of multidimensional biomarker frameworks encompassing molecular, histological, imaging, and functional parameters that hold promise for enhancing precision in early screening, target identification, dynamic monitoring, and prognostic evaluation of both cancerous and fibrotic conditions [24] [26].

As these fields advance, the concept of targeting metaplastic transitions themselves—rather than waiting for established cancer or fibrosis—represents a paradigm shift in therapeutic strategy. By intercepting the molecular drivers of pathological metaplasia, particularly through modulation of master switch genes and microenvironmental signaling, future therapies may potentially reverse or stabilize these precursor states before they progress to irreversible endpoint diseases.

Within the context of regenerative medicine, the concept of transdifferentiation—the direct conversion of one differentiated cell type into another—presents a promising therapeutic avenue. A significant hurdle in this field is the developmental boundary imposed by embryonic germ layers. This whitepaper assesses the current understanding of the limits of cross-conversion between the ectoderm, mesoderm, and endoderm. We synthesize contemporary evidence from developmental biology, single-cell transcriptomics, and mechanical reprogramming, framing the discussion within the broader thesis of harnessing transdifferentiation mechanisms for tissue repair. The document provides a technical guide for researchers and drug development professionals, incorporating structured quantitative data, detailed experimental protocols, and essential visualization tools to advance the field.

The three primary germ layers—ectoderm, mesoderm, and endoderm—are fundamental to embryonic development, giving rise to all tissues and organs in a multicellular organism. The ectoderm forms the epidermis and the entire nervous system; the mesoderm generates connective tissues, the circulatory system, and muscles; and the endoderm differentiates into the linings of the gastrointestinal and respiratory tracts and associated organs [27]. The classical view posits that once cells are committed to a specific germ layer lineage, their developmental potential is severely restricted.

However, the field of regenerative medicine has challenged this dogma through the study of transdifferentiation, a direct cell fate conversion that bypasses a pluripotent intermediate state. The core thesis of this whitepaper is that a detailed understanding of the molecular and biophysical determinants of germ layer boundaries will unlock novel strategies for tissue repair. Successful cross-conversion across these boundaries could enable the regeneration of tissues lost to disease or injury, such as creating pancreatic beta cells (endodermal) from a patient's skin fibroblasts (ectodermal). This guide will explore the limits of such conversions, evaluating both the barriers and the emerging methodologies to overcome them.

Molecular Specification of Germ Layers

The establishment of the three germ layers during gastrulation is governed by a highly conserved Gene Regulatory Network (GRN) involving key signaling pathways. Seminal work in amphibian embryos established the "three-signal model" for mesoderm and endoderm formation [28].

- Initial Induction: The process begins with the induction of mesendoderm, a bipotent precursor, from naive ectoderm. This is primarily driven by signals from the vegetal endoderm, with key secreted factors including members of the Nodal/Activin and Wnt families [28].

- Patterning and Segregation: The mesendoderm is subsequently patterned into definitive mesoderm and endoderm. This involves a combination of signaling gradients; for instance, high levels of Nodal/Activin signaling promote endodermal fate, while intermediate levels direct mesodermal fates. Fibroblast Growth Factors (FGFs) play a critical role in this stage, often acting as competence factors that enable cells to respond to TGF-β signals like Activin [28].

- Ectoderm Specification: The default state of the embryo is often considered to be ectodermal. The formation of neuroectoderm versus epidermal ectoderm is then determined by signals from the underlying mesoderm, particularly from the Spemann-Mangold organizer, which secretes inhibitors of BMP signaling to induce neural tissue [28].

The stability of these germ layer fates in post-embryonic life is maintained by the epigenetic landscape that reinforces the GRN, presenting a significant barrier to transdifferentiation.

Current Research and Quantitative Data on Cross-Conversion

Recent advances in high-resolution spatial transcriptomics and mechanical biology provide new insights into the plasticity of germ layer identity and the potential for cross-conversion. The following table summarizes key quantitative findings from contemporary research.

Table 1: Quantitative Evidence for Germ Layer Cross-Conversion and Associated Mechanisms

| Research Area | Key Finding | Quantitative Data / Outcome | Relevance to Cross-Conversion |

|---|---|---|---|

| Digital Embryo Reconstruction [29] | Identification of a Primordium Determination Zone (PDZ) at the embryonic-extraembryonic interface. | PDZ characterized at E7.75; coordinates signaling for cardiac primordium (mesoderm) formation. | Reveals native signaling hubs where germ layer interactions and potential fate decisions occur. |

| Mechanical Reprogramming [30] | Fibroblasts (mesoderm) on tissue-mimicking hydrogels form aggregates with enhanced multipotency. | Aggregates showed elevated stemness genes and bidirectional (adippo- & osteo-) differentiation potential. | Demonstrates that biophysical cues alone can reverse lineage commitment and enhance plasticity. |

| Germ Layer Origin & Cancer Therapy [31] | Correlation between germ layer origin and cancer therapy response. | Mesoderm-derived hematologic malignancies showed 85.3% ORR to CAR-T; endoderm-derived cancers showed 43.7% ORR to targeted protein inhibition. | Suggests inherent, lineage-based biological properties persist in disease and influence cellular responses. |

| Organoids for Tissue Repair [32] | Use of organoid derivatives in regenerative medicine. | Organoids generated from stem cells of various germ layer origins used for tissue repair. | Provides a platform for in vitro testing of transdifferentiation protocols across germ layers. |

Furthermore, systematic reviews have begun to quantify the relationship between developmental origin and cellular behavior. A meta-analysis of 127 studies (n=487,293 patients) confirmed that germ layer origin is a significant factor in therapeutic response, though it is often superseded by molecular biomarkers like MSI and TMB [31]. This underscores that while germ layer boundaries are influential, they are not absolute and can be modulated.

Experimental Protocols for Assessing Germ Layer Conversion

To empirically assess the limits of germ layer cross-conversion, researchers employ a suite of well-established and novel protocols. Below are detailed methodologies for key experiments in this field.

This protocol generates a high-resolution spatiotemporal transcriptome map to identify transitional cell states during fate conversion.

- Sample Collection: Serial sections are collected from multiple embryos at precise developmental time points (e.g., E7.5-E8.5 for mouse).

- Library Preparation and Sequencing: Single-cell RNA-seq libraries are prepared from dissociated sections using a platform like 10x Genomics. Sequencing is performed to a depth sufficient for robust gene detection.

- Data Integration and 3D Reconstruction: Computational tools (e.g., SEU-3D) are used to integrate the single-cell transcriptomic data with spatial coordinates from the serial sections, reconstructing a full "digital embryo."

- Analysis:

- Cluster Identification: Unsupervised clustering reveals distinct and transitional cell populations.

- Gene-Cell Co-embedding: A space-informed co-embedding approach maps gene expression back into the native spatial context of the embryo.

- Trajectory Inference: Algorithms (e.g., PAGA, Monocle) are used to construct potential differentiation trajectories and infer cells that are transitioning between states.

- Signaling Network Analysis: Ligand-receptor pairing analysis is performed to elucidate signaling networks across germ layers.

This protocol uses a biomimetic mechanical microenvironment to induce reprogramming of mesenchymal cells, testing the role of biophysics in overcoming lineage barriers.

- Hydrogel Fabrication:

- Prepare an interpenetrating network (IPN) hydrogel by combining:

- Viscoelastic component: 10 mg/ml Alginate (shear-thinning).

- Nonlinear elastic component: 1.5 mg/ml Collagen (provides structural nonlinearity).

- Cross-link the alginate by adding Calcium Chloride at varying concentrations (e.g., 5-15 mM) to tune the initial storage modulus.

- Incubate at 37°C for 30 minutes for complete gelation.

- Prepare an interpenetrating network (IPN) hydrogel by combining:

- Cell Seeding and Culture:

- Seed fibroblasts (e.g., 3T3-L1) or other target cells on the surface of the polymerized hydrogel.

- Culture in standard media (e.g., DMEM + 10% FBS) and observe over 24-72 hours.

- Phenotypic Monitoring:

- Use time-lapse microscopy to track cell migration and aggregation behavior.

- Fix cells at specific time points and perform immunofluorescence for cytoskeletal markers (e.g., F-actin with phalloidin) and contractility markers (e.g., phospho-myosin light chain).

- Assessment of Reprogramming:

- Gene Expression: Use qRT-PCR to assess the expression of pluripotency genes (e.g., Oct4, Sox2, Nanog) and lineage-specific markers.

- Differentiation Potential: Challenge the formed aggregates with adipogenic and osteogenic induction media to assess their multipotency.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The following table catalogues key reagents and their applications in research on germ layer boundaries and transdifferentiation.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Germ Layer and Transdifferentiation Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function in Research | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Tissue-Mimicking IPN Hydrogel (Alginate-Collagen) [30] | Provides a physiologically relevant mechanical microenvironment (viscoelastic & nonlinear) to study mechanotransduction in cell fate. | Used to demonstrate mechanical reprogramming of fibroblasts into multipotent aggregates. |

| Recombinant Growth Factors (Nodal/Activin, FGF, Wnt) [28] | Key soluble inducers for directed differentiation and transdifferentiation; activate GRNs for specific germ layers. | Used in vitro to direct pluripotent stem cells towards definitive endoderm or mesoderm. |

| Single-Cell RNA Sequencing Kits (e.g., 10x Genomics) [29] | Enables high-resolution profiling of transcriptomes in individual cells to identify novel or transitional states. | Used to construct spatiotemporal atlases of developing embryos and identify signaling interactions. |

| ACT Rule for Contrast Testing [33] | A standardized digital accessibility guideline that ensures sufficient color contrast in visualizations. | Applied to the design of scientific diagrams and software interfaces to guarantee readability for all researchers. |

| N-bromobenzenesulfonamide | N-Bromobenzenesulfonamide|High-Purity|RUO | |

| Methanol;nickel | Methanol;nickel Research Catalyst | Methanol;nickel catalyst for alcohol electro-oxidation and fuel cell research. This product is for Research Use Only (RUO). Not for personal use. |

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

The following diagrams, generated with Graphviz DOT language, illustrate core concepts and experimental workflows discussed in this whitepaper. The color palette and contrast have been designed for optimal readability according to WCAG guidelines [33] [34].

Germ Layer Specification Network

Title: Key signals in germ layer specification.

Mechanical Reprogramming Workflow

Title: Path from tissue-mimicking hydrogel to multipotency.

Reprogramming Toolkits: Engineering Cell Fate for Neurological, Cardiac, and Metabolic Repair

Transdifferentiation, or direct reprogramming, represents a paradigm shift in regenerative medicine. It refers to the conversion of one somatic cell type directly into another, bypassing the pluripotent state, and is a key mechanism under investigation for in situ tissue repair [35] [36]. In the context of tissue damage—such as myocardial infarction, neuronal loss, or pancreatic dysfunction—the goal is to directly reprogram abundant local cells, like fibroblasts, into the functional cells that have been lost [37] [36]. This approach minimizes risks associated with cell transplantation, such as immune rejection and tumorigenicity, by leveraging the body's own cellular resources [38]. Transcription factor (TF) cocktails are the primary tools for orchestrating this cell fate conversion, as they can reactivate silenced genetic programs and initiate new transcriptional networks, effectively rewriting a cell's identity [39]. This technical guide details the key TF combinations and emerging methodologies for generating neurons, cardiomyocytes, and beta cells, framing them within the practical framework of developing therapies for tissue repair and regeneration.

Transcription Factor Cocktails for Target Cell Types

The core of direct reprogramming lies in identifying the minimal set of key transcription factors that can act as master regulators to define a target cell's identity. The tables below summarize the established and optimized TF combinations for generating neurons, cardiomyocytes, and the investigational cocktails for beta cells, incorporating critical data on efficiency and maturation.

Table 1: Transcription Factor Cocktails for Neuronal and Cardiomyocyte Generation

| Target Cell Type | Key Transcription Factor Cocktail | Reprogramming Factors (Abbreviations) | Reprogramming Efficiency | Notable Characteristics | Primary Source Cell |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Induced Motor Neurons (iMNs) | Neurogenin 2, Islet-1, LIM Homeobox 3 | Ngn2, Isl1, Lhx3 | ~21% (with DDRR* cocktail) [39] | Optimized minimal 3-factor cocktail; high purity and functional maturity [39]. | Mouse Embryonic Fibroblasts (MEFs) [39] |

| Induced Cardiomyocytes (iCMs) | GATA Binding Protein 4, Myocyte Enhancer Factor 2C, T-Box Transcription Factor 5 | Gata4, Mef2c, Tbx5 (GMT) | Low efficiency in early studies [37] [40] | Foundational cocktail; functional but relatively immature state [37]. | Cardiac Fibroblasts [37] [36] |

| Induced Cardiomyocytes (iCMs) | Gata4, Mef2c, Tbx5, Hand2 | GHMT | Improved efficiency over GMT [37] | Enhanced reprogramming for a more robust cardiac phenotype. | Cardiac Fibroblasts [37] |

| Ethyl benzoylphosphonate | Diethyl Benzoylphosphonate | Research-grade Diethyl Benzoylphosphonate for synthesis and C-C bond formation. This product is for laboratory research use only; not for human consumption. | Bench Chemicals | ||

| 14-Sulfanyltetradecan-1-OL | 14-Sulfanyltetradecan-1-OL, CAS:131215-94-6, MF:C14H30OS, MW:246.45 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Table 2: Investigational and Alternative Reprogramming Approaches

| Target Cell Type | Key Transcription Factor Cocktail | Reprogramming Factors (Abbreviations) | Reprogramming Efficiency | Notable Characteristics | Primary Source Cell |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beta Cells | Information Not Specified in Search Results | N/A | N/A | Direct TF combinations for beta cells not detailed in available sources. | N/A |

| Chemically Induced Cardiomyocytes (hCiCMs) | Small Molecule Cocktail (15 compounds) | N/A (Non-genetic) | 15.08% (Day 30), ~96.67% purity (Day 60) [40] | Xeno-free, chemically defined method; avoids genetic integration [40]. | Human Urine-Derived Cells (hUCs) [40] |

| Partial Reprogramming | Oct4, Sox2, Klf4, c-Myc (OSKM) | OSKM | N/A | Transient activation reverses aging markers without changing cell identity for rejuvenation [35]. | Senescent cells [35] |

Note: DDRR cocktail consists of p53DD, HRASG12V, and the TGF-β inhibitor RepSox [39].

Experimental Protocols for Direct Reprogramming

High-Efficiency Direct Conversion to Motor Neurons

This protocol is adapted from a 2025 study that achieved a high yield of induced motor neurons (iMNs) by minimizing extrinsic variation and leveraging a hyperproliferative cell state [39].

- 1. Cell Source and Culture: Use Mouse Embryonic Fibroblasts (MEFs) from transgenic reporter mice (e.g., Hb9::GFP) for easy visualization of motor neurons. Culture cells in standard fibroblast medium.

- 2. Viral Transduction:

- Vector: Use a single polycistronic lentiviral vector encoding the minimal TF cocktail (Ngn2, Isl1, Lhx3).

- Infection: Transduce MEFs with the viral supernatant. The use of a single vector ensures consistent stoichiometric delivery of all TFs into each cell.

- 3. Hyperproliferation Induction (DDRR Cocktail): Following transduction, treat cells with the DDRR chemo-genetic cocktail to induce a transient state of hyperproliferation:

- p53DD: A dominant-negative p53 mutant.

- HRASG12V: An oncogenic form of HRAS.

- RepSox: A small molecule inhibitor of the TGF-β pathway.

- Cells with this hyperproliferative (hyperP) history convert to iMNs at a 4-fold higher rate.

- 4. Media Switch and Maturation: 48-72 hours post-transduction, replace the fibroblast medium with motor neuron maturation medium, typically containing neurotrophic factors like BDNF, CNTF, and GDNF.

- 5. Functional Validation: After 2-3 weeks, validate iMNs using:

- Immunostaining: for TUBB3 (neuronal marker) and ISL1/2 (motor neuron markers).

- Patch-Clamp Electrophysiology: to confirm the ability to generate action potentials.

- Calcium Imaging: to demonstrate electrical activity.

Chemical Reprogramming of Human Urine-derived Cells to Cardiomyocytes

This 2025 protocol outlines a non-integrating, xeno-free method for generating human cardiac-induced cardiomyocytes (hCiCMs) [40].

- 1. Cell Source and Isolation: Collect fresh human urine samples (approx. 50 ml). Centrifuge at 500 × g for 5 minutes to pellet cells. Resuspend the pellet in a specific medium (1:1 DMEM/F12 and Keratinocyte SFM, supplemented with 5% FBS and antibiotics) and seed onto culture plates.

- 2. Expansion of Human Urine-derived Cells (hUCs): Culture the isolated cells in hUC medium, changing the medium every two days until colonies form. Passage cells at 70-80% confluency.

- 3. Chemical Induction: