Breaking the Age Barrier: Strategies to Enhance Reprogramming Efficiency in Aged Somatic Cells

Reprogramming aged somatic cells into induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) faces significant efficiency challenges due to entrenched aging hallmarks.

Breaking the Age Barrier: Strategies to Enhance Reprogramming Efficiency in Aged Somatic Cells

Abstract

Reprogramming aged somatic cells into induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) faces significant efficiency challenges due to entrenched aging hallmarks. This article provides a comprehensive analysis for researchers and drug development professionals, exploring the intrinsic molecular barriers in elderly cells, such as epigenetic alterations and senescence. It details cutting-edge methodological advances, from novel transcription factors to non-integrative delivery systems like exosomes and chemical cocktails. The content further covers systematic troubleshooting and optimization protocols, including the inhibition of specific barriers and culture condition refinement. Finally, it examines rigorous validation frameworks using epigenetic clocks and functional assays, offering a holistic roadmap to overcome the recalcitrance of aged cells for regenerative medicine and disease modeling.

The Inherent Hurdles: Understanding Why Aged Cells Resist Reprogramming

Aging is characterized by a progressive loss of physiological integrity, leading to impaired cellular function and increased vulnerability to death. This deterioration represents the primary risk factor for major human pathologies, including cancer, diabetes, cardiovascular disorders, and neurodegenerative diseases [1] [2]. Contemporary aging research has identified several interconnected hallmarks that represent common denominators of aging across different organisms, with special emphasis on mammalian systems [3].

For researchers investigating reprogramming efficiency in aged cells, understanding these hallmarks is paramount. The aging microenvironment presents significant barriers to effective cellular reprogramming, from increased genomic instability to the persistent presence of senescent cells with their characteristic secretory phenotype [4] [5]. This technical support center provides targeted guidance for overcoming these challenges in experimental settings, with specific troubleshooting approaches and reagent solutions designed to enhance research outcomes in aged cell models.

The Hallmarks of Aging: A Technical Reference

The hallmarks of aging represent a framework for understanding the complex molecular and cellular processes that drive functional decline. These hallmarks fulfill three key premises: their age-associated manifestation, the acceleration of aging by experimentally accentuating them, and the opportunity to decelerate, stop, or reverse aging by therapeutic interventions [3]. The original nine hallmarks have recently been expanded to twelve, providing a more comprehensive landscape of aging biology [3].

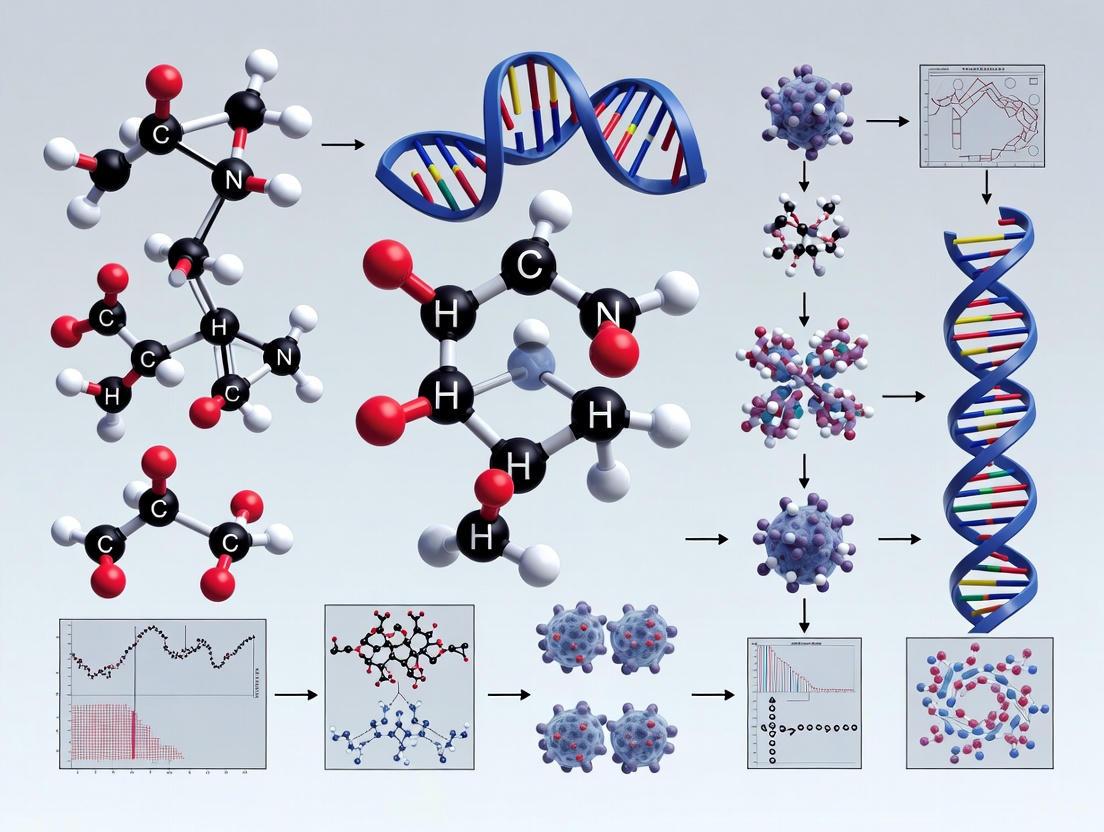

Figure 1: The Twelve Hallmarks of Aging Categorized by Type. Primary hallmarks (red) are the triggering events, antagonistic hallmarks (blue) are compensatory responses that become deleterious, and integrative hallmarks (green) directly affect tissue homeostasis [3] [5].

Quantitative Measures of Cellular Aging

Researchers can employ several quantitative methods to assess cellular aging in experimental models. The following table summarizes key biomarkers and assessment methods relevant to reprogramming studies.

Table 1: Quantitative Biomarkers and Assessment Methods for Cellular Aging

| Biomarker Category | Specific Markers/Assays | Measurement Output | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Epigenetic Clocks | DNA methylation patterns (e.g., Horvath clock) [6] | Epigenetic age (eAge) | Requires bisulfite sequencing; high correlation with chronological age |

| Transcriptomic Age | Genome-wide expression profiles [6] | Transcriptional age | RNA-seq needed; reflects functional age more than chronological age |

| Telomere Length | qPCR, TRF, STELA, Flow-FISH [1] | Telomere age | High variability between cells; average length decreases with replication |

| Cellular Senescence | SA-β-Gal, p16INK4A, p21CIP1, SASP factors [4] | Senescence burden | Heterogeneous populations; context-dependent markers |

| Mitochondrial Function | ROS production, OCR, ETC activity [4] | Metabolic age | Functional assessment; reflects oxidative stress capacity |

| DNA Damage | γ-H2AX foci, 53BP1 staining [7] [8] | Genomic instability | Direct measure of damage; sensitive but transient signal |

| Proteostasis | Protein aggregation assays, ubiquitin-proteasome activity [1] | Proteostatic competence | Functional capacity declines with age |

Troubleshooting Guides for Aged Cell Reprogramming

FAQ: Common Challenges in Aged Cell Research

Q1: Why does reprogramming efficiency decline significantly in cells from aged donors?

Aged cells accumulate multiple hallmarks that create barriers to reprogramming. These include:

- Epigenetic barriers: Aged cells exhibit accumulated epigenetic alterations that create a chromatin landscape resistant to reprogramming factors [5]. The epigenetic landscape becomes more rigid with age, requiring more potent or prolonged reprogramming stimulus.

- Energetic limitations: Mitochondrial dysfunction in aged cells reduces ATP production, limiting the energy-intensive reprogramming process [4]. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) from dysfunctional mitochondria can also damage reprogramming factors or signaling components.

- Senescence burden: Aged cell populations contain more senescent cells that resist reprogramming due to permanent cell cycle arrest and the pro-inflammatory SASP [4] [5]. The SASP creates a local microenvironment that inhibits productive reprogramming of neighboring cells.

Q2: How can I distinguish between truly rejuvenated cells and partially reprogrammed cells in aged cultures?

Several validation strategies can confirm successful rejuvenation:

- Aging clock assessment: Apply epigenetic or transcriptomic aging clocks to demonstrate reduction in biological age [6]. Truly rejuvenated cells should show age reversal across multiple clock algorithms.

- Functional assays: Assess restoration of youthful functions such as mitochondrial respiration, nutrient sensing, and protein homeostasis [5] [8]. Functional improvement should correlate with molecular age reduction.

- Identity preservation: Verify that rejuvenated cells maintain their lineage-specific identity through marker expression and functional tests [6]. Partial reprogramming may alter cellular identity without full pluripotency induction.

Q3: What strategies can overcome the heightened genomic instability in aged cells during reprogramming?

- Antioxidant supplementation: Include N-acetylcysteine or other antioxidants to reduce ROS-induced DNA damage during reprogramming [5].

- Senolytics pre-treatment: Use senolytic agents (e.g., Navitoclax/ABT263, Venetoclax) to clear senescent cells before reprogramming initiation [4]. This reduces SASP-mediated damage and inflammation.

- DDR pathway modulation: Temporarily inhibit hyperactive DNA damage response pathways that may impede reprogramming, but with careful timing to avoid increasing mutation load [1].

Q4: How does the aged extracellular matrix impact reprogramming efficiency and how can this be addressed?

The aged ECM exhibits increased stiffness and altered composition that can impede reprogramming through mechanotransduction pathways. Strategies include:

- ECM remodeling: Use MMPs or other ECM-modifying enzymes to rejuvenate the matrix [5].

- Soft substrate culture: Culture aged cells on hydrogels with youthful stiffness (0.5-2 kPa) to provide appropriate mechanical cues [5].

- Integrin signaling modulation: Adjust integrin engagement through RGD peptide presentation or other matrix cues to overcome age-related mechanosignaling dysfunction.

Technical Troubleshooting Guide

Table 2: Troubleshooting Common Problems in Aged Cell Reprogramming

| Problem | Potential Causes | Solutions | Preventive Measures |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low reprogramming efficiency in aged cells | High senescence burden, epigenetic barriers, mitochondrial dysfunction [4] [5] | Pre-treat with senolytics (e.g., Navitoclax), use epigenetic modifiers, extend reprogramming timeframe [4] | Use early-passage aged cells, optimize donor selection criteria, pre-condition with metabolic stimuli |

| Increased differentiation in reprogrammed cultures | Incomplete epigenetic resetting, persistent age-related transcriptional noise [9] [5] | Optimize reprogramming factor stoichiometry, include small molecules to stabilize pluripotency, improve colony picking precision [9] | Use defined matrices, optimize culture conditions, implement sequential reprogramming protocol |

| Genomic instability in reprogrammed clones | Age-associated DNA damage carryover, replication stress during reprogramming [1] [2] | Include antioxidants, optimize cell cycle synchronization, implement rigorous genomic quality control [2] | Use non-integrating reprogramming methods, limit passage number, perform regular karyotyping |

| Heterogeneous reprogramming outcomes | Stochastic nature of aged cell reprogramming, donor-to-donor variability [6] [8] | Single-cell cloning, optimized bulk culture conditions, donor-specific protocol adjustments | Standardize donor screening, use pooled cells from multiple donors when possible |

| Poor cell survival during reprogramming | Age-related apoptosis sensitivity, metabolic insufficiency, proteostatic failure [1] [5] | Optimize nutrient composition, use caspase inhibitors temporarily, employ gradual reprogramming protocols | Pre-condition with pro-survival factors, use gentle dissociation methods, optimize seeding density |

Experimental Protocols for Aging and Rejuvenation Research

Assessing Cellular Age: The NCC Assay Protocol

The Nucleocytoplasmic Compartmentalization (NCC) assay provides a quantitative measure of cellular aging based on the well-conserved deterioration of nuclear integrity in aged cells [8].

Principle: Aging and cellular senescence are accompanied by substantial reorganization of the nuclear envelope and breakdown in nucleocytoplasmic trafficking, including altered expression and degradation of Lamin B1 and formation of cytoplasmic chromatin fragments [8].

Protocol Steps:

- Reporter Construction: Generate lentiviral vectors containing mCherry-NLS (nuclear localization signal) and eGFP-NES (nuclear export signal) constructs.

- Cell Transduction: Transduce target cells (e.g., human fibroblasts from young and old donors) with the NCC reporter system using standard lentiviral transduction protocols.

- Image Acquisition: Culture cells in low serum conditions to suppress cell division and image using confocal microscopy with standardized exposure settings.

- Quantitative Analysis: Calculate Pearson correlation coefficient between mCherry and eGFP signals. Young, healthy cells show distinct separation (low correlation), while aged/senescent cells exhibit significant colocalization (high correlation) [8].

Validation: Compare fibroblasts from young (22-year-old) and old (94-year-old) donors, as well as Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome (HGPS) patients as accelerated aging models [8].

Partial Reprogramming Protocol for Age Reversal

Partial reprogramming using transient expression of Yamanaka factors can reverse cellular aging without erasing cellular identity [6] [8].

Figure 2: Partial Reprogramming Workflow for Cellular Age Reversal. The critical window of 3-13 days represents the optimal period for age reprogramming without permanent loss of cellular identity [6].

Key Parameters:

- Factor Selection: OCT4, SOX2, KLF4 (OSK) without c-MYC for reduced oncogenic risk, or novel AI-engineered variants with enhanced efficiency [7] [8].

- Expression Duration: 3-13 days represents the "critical window" for age reprogramming with minimal identity loss [6]. Beyond 13 days, rejuvenation effects may diminish due to accumulating senescence markers.

- Delivery Method: Non-integrating methods preferred (episomal vectors, mRNA, proteins, or small molecules) especially for aged cells with compromised DNA repair [7] [8].

Validation Metrics:

- Molecular Age: Epigenetic clocks (DNA methylation patterns) and transcriptomic age [6].

- Functional Rejuvenation: Restoration of mitochondrial function, reduced DNA damage markers (γ-H2AX foci), improved nutrient sensing [7] [8].

- Identity Retention: Lineage-specific marker expression and functional capacity maintenance [6].

Chemical Reprogramming Protocol for Age Reversal

Recent advances have identified chemical cocktails that can reverse cellular aging without genetic manipulation [8].

Six Chemical Cocktails Identified: Through high-throughput screening using transcription-based aging clocks and the NCC assay, researchers have identified six chemical cocktails that restore youthful transcript profiles in less than one week without compromising cellular identity [8].

Implementation Strategy:

- Baseline Assessment: Establish transcriptomic age and NCC status before treatment.

- Cocktail Application: Apply chemical cocktails for 4-7 days in optimized concentrations.

- Validation: Assess rejuvenation through transcriptomic analysis, functional assays, and NCC improvement.

Advantages: Lower safety concerns compared to genetic approaches, potentially lower costs, and easier translational application [8].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Aged Cell Reprogramming Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Aging Research | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reprogramming Factors | Wild-type OSKM, RetroSOX/RetroKLF (AI-engineered) [7] | Induce pluripotency or partial reprogramming | AI-engineered variants show >50x higher expression of reprogramming markers [7] |

| Senescence Modulators | Navitoclax (ABT263), Venetoclax, Fisetin, Quercetin [4] | Clear senescent cells prior to reprogramming | Navitoclax reverses immunosuppression in tumor microenvironment [4] |

| Epigenetic Modifiers | TET activators, HDAC inhibitors, DNMT inhibitors [10] [8] | Facilitate epigenetic remodeling during reprogramming | Essential for resetting age-related epigenetic marks |

| Age Assessment Tools | Methylation clock assays, Transcriptomic arrays, NCC reporter systems [6] [8] | Quantify biological age pre/post intervention | NCC systems distinguish young from old cells based on nuclear integrity [8] |

| Cell Culture Matrices | Vitronectin XF, Laminin-521, Synthetic hydrogels [9] | Provide age-appropriate mechanical and biochemical cues | Matrix stiffness significantly influences aged cell behavior |

| Metabolic Optimizers | Antioxidants (NAC), Mitochondrial nutrients, AMPK activators [5] | Address age-related metabolic dysfunction | Critical for supporting energy-intensive reprogramming |

| DNA Repair Enhancers | NAD+ precursors, Sirtuin activators [1] [2] | Mitigate age-related genomic instability | Particularly important for maintaining genome integrity in reprogrammed aged cells |

Advanced Applications: AI-Engineered Reprogramming Factors

Recent breakthroughs in AI-assisted protein engineering have created enhanced variants of Yamanaka factors with dramatically improved efficiency [7].

RetroSOX and RetroKLF Development:

- Design Process: GPT-4b micro, a specialized AI model, was trained on protein sequences with evolutionary and functional context to design novel variants [7].

- Efficiency Gains: Over 30% of AI-proposed SOX2 variants outperformed wild-type, with some differing by more than 100 amino acids [7].

- Performance: Combined RetroSOX/RetroKLF cocktails produced >50x higher expression of pluripotency markers with accelerated onset [7].

Functional Advantages:

- Enhanced Rejuvenation: Reduced DNA damage (γ-H2AX intensity) more effectively than wild-type factors [7].

- Broader Compatibility: Effective across multiple delivery methods (viral, mRNA) and cell types, including mesenchymal stromal cells from middle-aged donors [7].

- Faster Kinetics: Late pluripotency markers appeared several days sooner than with wild-type OSKM [7].

Understanding the interconnected hallmarks of aging provides a strategic framework for optimizing reprogramming protocols for aged cells. The progressive accumulation of cellular damage across multiple domains - genomic, epigenetic, proteostatic, and metabolic - creates a compounded barrier to reprogramming that requires multi-faceted approaches [1] [3] [5].

Successful reversal of aging phenotypes in experimental models demonstrates that the aged epigenome retains a "back-up copy" of youthful information that can be reset through partial reprogramming [6] [8]. Both genetic (OSK expression) and purely chemical approaches can achieve this resetting without erasing cellular identity, offering complementary paths forward for therapeutic development [8].

The emerging toolkit for aged cell reprogramming - from senolytics to clear resistant populations, to AI-engineered factors with enhanced efficiency, to chemical cocktails that avoid genetic manipulation - provides researchers with increasingly sophisticated methods to overcome the specialized challenges of working with aged cellular material [4] [7] [8]. As these technologies mature, they promise to accelerate progress in regenerative medicine for age-related diseases.

Cellular Senescence and Reprogramming: A Complex Interplay Cellular senescence and cellular reprogramming represent two fundamentally intertwined processes that profoundly influence aging and cancer [11]. Senescence is characterized by permanent cell-cycle arrest and the development of a senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP), which encompasses a diverse collection of secreted cytokines, chemokines, growth factors, and proteases [11] [12]. While initially serving as a tumor-suppressive mechanism, the chronic accumulation of senescent cells contributes significantly to tissue dysfunction, aging, and age-related diseases by creating a pro-inflammatory, pro-tumorigenic environment [11]. Conversely, induced reprogramming of somatic cells—exemplified by the introduction of Yamanaka factors (OSKM: Oct4, Sox2, Klf4, c-Myc)—resets cellular age and epigenetic marks, offering potential to rejuvenate aged cells [11].

This technical support article addresses the formidable challenges that cellular senescence and the SASP pose to reprogramming efficiency, particularly in the context of aged cells. We provide researchers with targeted troubleshooting guidance, experimental protocols, and strategic approaches to overcome these barriers, framed within the broader thesis of improving reprogramming outcomes for regenerative medicine and drug development.

FAQs: Critical Questions on Senescence and Reprogramming

Q1: How exactly does cellular senescence act as a barrier to reprogramming?

Senescence creates multiple barriers to successful reprogramming through both cell-autonomous and non-autonomous mechanisms. The irreversible proliferation arrest prevents the cell division required for epigenetic remodeling during reprogramming [12]. Additionally, senescent cells exhibit profound epigenetic resetting characterized by formation of senescence-associated heterochromatin foci (SAHF), redistribution of histone modifications (H3K9me3, H3K27me3), and deposition of histone variants (H3.3, H2A.J) that create a chromatin landscape resistant to reprogramming factors [13]. The SASP further creates a hostile microenvironment through secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines that can inhibit reprogramming in both autocrine and paracrine fashions [11].

Table: Key Senescence Barriers to Reprogramming

| Barrier Type | Specific Mechanisms | Impact on Reprogramming |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Cycle Arrest | p53/p21 and p16/Rb pathway activation | Prevents cell division needed for epigenetic resetting |

| Epigenetic Landscape | SAHF formation, histone variant deposition (H3.3, H2A.J) | Creates chromatin resistance to reprogramming factors |

| Secretory Phenotype | SASP (IL-6, IL-8, MMPs, growth factors) | Creates inflammatory microenvironment inhibitory to reprogramming |

| Metabolic Changes | Altered nutrient sensing, mitochondrial dysfunction | Disrupts energy metabolism required for reprogramming |

Q2: Can senescent cells be reprogrammed, and if so, what strategies can overcome this barrier?

Yes, evidence confirms that bona fide iPSC lines can be derived from cells of old donors, including centenarians [14]. However, reprogramming efficiency declines with donor age—studies in mice show a 2-5 fold reduction in fibroblasts from old versus young mice [14]. Successful strategies to overcome this barrier include:

- Senolytic pre-treatment: Removing senescent cells prior to reprogramming attempts using senolytics like ABT263 (Navitoclax) [15]

- SASP modulation: Using JAK2/STAT3 inhibitors (e.g., ruxolitinib) to suppress immunosuppressive SASP components while preserving immunostimulatory factors [16] [17]

- Partial reprogramming approaches: Transient expression of reprogramming factors that rejuvenates cells without complete dedifferentiation [18]

- p53 pathway modulation: Transient inhibition of p53 can enhance reprogramming efficiency but requires careful control due to safety concerns [18]

Q3: What are the most reliable methods for detecting and quantifying senescence in reprogramming experiments?

Accurate detection of senescence is crucial for troubleshooting reprogramming experiments. The table below summarizes key methodologies organized by analytical level:

Table: SASP and Senescence Detection Methods

| Analysis Level | Method | Sample Types | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| RNA | qRT-PCR | Cell culture, tissue | IL-6/IL-8 in senescent fibroblasts [12] |

| RNA-seq | Cell culture, tissue | SASP Atlas; diversity across cell types [12] | |

| Protein | ELISA | Cell culture, plasma | IL-6, IL-8 in OIS fibroblasts [12] |

| Western Blotting | Cell culture, tissue lysate | IL-1α; mTOR phosphorylation [12] | |

| Multiplex Assays (Luminex, MSD) | Cell culture, tissue, plasma | Multiple cytokines in MSCs, senescent ECs [12] | |

| Functional & Spatial | SA-β-Galactosidase staining | Cells, tissue sections | Gold standard senescence detection [16] |

| Immunofluorescence | Cells, tissues | IL-6 in stromal fibroblasts; spatial localization [12] |

A multiparametric approach is essential, combining at least one method from each category. For instance, SA-β-Galactosidase staining with SASP protein quantification (ELISA/MSD) and transcriptomic analysis provides comprehensive senescence characterization [12].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: SASP Modulation to Enhance Reprogramming Efficiency

This protocol adapts the SASP reprogramming strategy from [16] for improving reprogramming efficiency in aged cells.

Principle: The JAK2/STAT3 inhibitor ruxolitinib reduces immunosuppressive SASP components (GM-CSF, M-CSF, IL-10, IL-13) while preserving immunostimulatory SASPs (ICAM-1, CCL5, MCP-1) that may support reprogramming.

Materials:

- Senescence inducer: Alisertib (Aurora kinase inhibitor) [16]

- SASP modulator: Ruxolitinib (JAK2/STAT3 inhibitor) [16]

- Reprogramming factors: OSKM (Oct4, Sox2, Klf4, c-Myc)

- Aged primary fibroblasts (e.g., from human donors >60 years)

- Appropriate cell culture media and reagents

Procedure:

- Cell Preparation: Plate aged primary fibroblasts at 5,000 cells/cm²

- Senescence Induction (Optional): Treat with 100 nM alisertib for 72 hours to establish senescence baseline [16]

- SASP Modulation: Add 1 μM ruxolitinib to culture media 24 hours pre-reprogramming

- Reprogramming Initiation: Introduce OSKM factors via preferred method (lentiviral transduction, mRNA)

- Continuous SASP Modulation: Maintain ruxolitinib throughout early reprogramming phase (7-10 days)

- Efficiency Assessment: Quantify iPSC colonies at day 21-28 using pluripotency markers (e.g., alkaline phosphatase, Nanog)

Troubleshooting:

- If reprogramming efficiency remains low, consider:

- Testing alternative SASP modulators (BAY 11-7082 for NF-κB inhibition, SB203580 for p38MAPK inhibition) [16]

- Pre-treatment with senolytics (e.g., 100 nM navitoclax for 48 hours) to clear senescent cells pre-reprogramming [15]

- Optimizing ruxolitinib concentration (test 0.5-5 μM range) for specific cell type

Protocol: Quantitative SASP Profiling for Reprogramming Experiments

Comprehensive SASP characterization is essential for understanding reprogramming barriers.

Materials:

- Conditioned media from reprogramming experiments

- Multiplex cytokine assay (Luminex or MSD) panels including IL-6, IL-8, IL-1α, GM-CSF, MCP-1

- RNA extraction kit

- qRT-PCR reagents

Procedure:

- Conditioned Media Collection:

- Culture cells in serum-free media for 24 hours

- Collect conditioned media and centrifuge (500 × g, 5 min) to remove cells/debris

- Aliquot and store at -80°C

Protein-Level SASP Quantification:

- Use multiplex immunoassay per manufacturer's protocol

- Include standards and quality controls

- Measure at least: IL-6, IL-8, IL-1α, GM-CSF, MCP-1 [12]

RNA-Level SASP Analysis:

- Extract RNA from cell pellets

- Perform qRT-PCR for SASP factor transcripts

- Use GAPDH or 18S rRNA as reference genes

Data Interpretation:

- Compare SASP profiles between young vs. aged donor cells

- Correlate specific SASP factors with reprogramming efficiency

- Identify which SASP components are most predictive of reprogramming success

Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Reagents for Overcoming Senescence Barriers in Reprogramming

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Senescence Inducers | Alisertib (Aurora kinase inhibitor) [16] | Establish senescence models for screening |

| SASP Modulators | Ruxolitinib (JAK2/STAT3 inhibitor) [16] | Suppress immunosuppressive SASP components |

| BAY 11-7082 (NF-κB inhibitor) [16] | Alternative SASP modulation pathway | |

| Senolytics | ABT263 (Navitoclax) [15] | Eliminate senescent cells pre-reprogramming |

| Venetoclax [15] | BCL-2 inhibitor for senescent cell clearance | |

| Reprogramming Factors | OSKM (Oct4, Sox2, Klf4, c-Myc) [11] | Standard reprogramming factor combination |

| OSK (excluding c-Myc) [18] | Reduced risk of teratoma formation | |

| Partial Reprogramming | 7c chemical cocktail [18] | Non-genetic alternative for rejuvenation |

| Detection Reagents | SA-β-Galactosidase kit [16] | Gold standard senescence detection |

| Multiplex cytokine panels [12] | Comprehensive SASP profiling |

Signaling Pathways and Workflows

Diagram: Senescence Barriers and Intervention Points. This pathway illustrates how senescence inducers trigger multiple barriers to reprogramming and strategic interventions to overcome them.

Diagram: Strategic SASP Reprogramming with JAK2 Inhibition. Selective suppression of immunosuppressive SASP components while preserving immunostimulatory factors creates a favorable microenvironment for reprogramming.

The interplay between cellular senescence and reprogramming represents both a formidable challenge and a therapeutic opportunity. While senescence creates multiple barriers to reprogramming—including cell cycle arrest, epigenetic resistance, and SASP-mediated inflammatory signaling—strategic approaches can overcome these obstacles. The development of senotherapeutics (senolytics and senomorphics) combined with partial reprogramming protocols offers promising avenues to enhance reprogramming efficiency in aged cells.

Future directions should focus on tissue-specific reprogramming strategies, given that senescence manifests differently across tissues [18]. Additionally, chemical reprogramming approaches that avoid genetic integration present exciting opportunities for clinical translation [18]. As the field advances, integrating aging clock technologies with senescence modulation will enable more precise monitoring of reprogramming efficacy and safety [15].

By systematically addressing the barriers outlined in this technical support guide, researchers can develop more effective strategies for cellular rejuvenation, with significant implications for regenerative medicine, age-related disease modeling, and therapeutic development.

Technical Support & Troubleshooting Hub

This section addresses common experimental challenges in aging and epigenetic reprogramming research, providing targeted solutions to enhance reproducibility and efficacy.

Frequently Asked Questions & Troubleshooting Guides

Q1: Our in vivo partial reprogramming experiment in aged mice shows no rejuvenation effects and instead has led to significant toxicity. What could be the cause?

- Potential Cause 1: Inappropriate Reprogramming Dosage and Timing. Excessive or prolonged expression of reprogramming factors can lead to teratoma formation or tissue dysfunction [19] [18].

- Troubleshooting:

- Titrate Factor Expression: Utilize a doxycycline-inducible system and empirically determine the shortest effective exposure time (e.g., a 1-2 day "pulse" followed by a 5-7 day "chase" has been effective in studies) [18].

- Monitor Early Senescence Markers: Check for upregulation of p53, p21, and p16INK4A before and during treatment. Sustained activation indicates excessive stress.

- Exclude c-Myc: Consider using only OSK (Oct4, Sox2, Klf4) factors, as omitting c-Myc has been shown to reduce tumorigenic risk while still extending lifespan in wild-type mice [18].

- Potential Cause 2: Inefficient or Off-Target Vector Delivery. The delivery method may not be efficiently targeting the desired tissues or may be affecting non-target organs.

- Troubleshooting:

- Validate Delivery System: Use AAV9 capsids for broad tissue tropism or tissue-specific promoters for targeted delivery. Quantify vector biodistribution post-mortem.

- Employ Chemical Reprogramming: As a non-genetic alternative, explore small molecule cocktails (e.g., the "7c" cocktail) which can offer easier delivery and potentially a better safety profile [18].

Q2: We observe inconsistent epigenetic clock reversal in our partially reprogrammed human fibroblast lines. How can we improve the consistency and validation of rejuvenation?

- Potential Cause 1: Heterogeneous Cell Population and "Mesenchymal Drift". Aged cell populations are often heterogeneous and undergo a transcriptomic shift towards a mesenchymal state, which may respond variably to reprogramming [20].

- Troubleshooting:

- Characterize Pre-Treatment Heterogeneity: Perform single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) on your starting fibroblast population to identify distinct subpopulations.

- Monitor Mesenchymal Markers: Use flow cytometry or RT-qPCR to track the expression of mesenchymal genes (e.g., CDH2, VIM, SNAI2) before and after reprogramming. Successful reprogramming should reverse this drift [20].

- Potential Cause 2: Incomplete Multi-Omic Validation. Relying on a single epigenetic clock metric may not capture the full scope of rejuvenation.

- Troubleshooting:

- Implement Multi-Omic Aging Clocks: Correlate DNA methylation age with transcriptomic and proteomic aging clocks.

- Assess Functional Rejuvenation: Move beyond molecular clocks to functional assays, such as mitochondrial ROS production, metabolomic profiling (e.g., restoration of NAD+ levels), and SASP factor secretion (e.g., reduction of IL-6, TNF-α) [21] [18].

Q3: When attempting to reprogram aged somatic cells, we face extremely low efficiency. What are the key molecular barriers, and how can we overcome them?

- Potential Cause: Age-Related Chromatin Locking via AP-1 and Loss of Pro-Youthfulness TFs. The chromatin in aged cells becomes progressively inaccessible at youth-associated gene loci while becoming hyper-accessible at senescence-promoting loci, largely driven by the pioneer factor AP-1 [22].

- Troubleshooting:

- Target the AP-1 Complex: Co-express reprogramming factors with inhibitors of AP-1 components (e.g., JUN, FOS). Research shows that FOXM1 can repress AP-1 and reset chromatin to a more youthful state [22].

- Modulate Upstream Pathways: Enhance the expression or activity of TEAD and FOXM1, which are pro-youthfulness transcription factors whose binding site accessibility is lost with aging.

- Experiment with Small Molecule Adjuvants: Utilize molecules that modulate the p53 pathway (e.g., transient inhibition) or chromatin-modifying enzymes (e.g., HDAC inhibitors) to create a more permissive chromatin environment [18] [23].

Core Signaling Pathways & Workflows

The diagrams below illustrate the key molecular pathways and a standard experimental workflow for partial reprogramming.

Figure 1. Molecular Pathway of Aging and Reprogramming. This diagram illustrates the antagonistic relationship between pro-aging (AP-1) and pro-youthfulness (FOXM1/TEAD) transcription factors, and the point of intervention for reprogramming therapies [20] [22].

Figure 2. Partial Reprogramming Experimental Workflow. A standard protocol for inducing and validating cellular rejuvenation, highlighting the critical cyclic induction and multi-level assessment [18] [20].

Key Experimental Data & Protocols

Quantitative Data on Reprogramming and Rejuvenation

Table 1. Key Findings from In Vivo Partial Reprogramming Studies in Mice

| Reprogramming Factor | Delivery Method | Animal Model | Key Outcome | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OSKM (cyclic) | Dox-inducible transgene | Progeria (LAKI) mice | 33% median lifespan increase; Reduced mitochondrial ROS | [18] |

| OSK (cyclic) | AAV9 gene therapy | Wild-type mice (124 weeks old) | 109% remaining lifespan extension; Improved frailty index | [18] |

| OSKM (cyclic) | Dox-inducible transgene | Wild-type mice | Rejuvenated transcriptome & metabolome; Enhanced skin regeneration | [18] |

| Two-chemical cocktail | N/A | C. elegans | 42.1% lifespan increase; Reduced DNA damage & oxidative stress | [18] |

Table 2. Age-Associated Chromatin Accessibility Changes in Human Dermal Fibroblasts (HDFs) [22]

| Chromatin Feature | Neonatal-Specific (Open) | Elderly-Specific (Open) | Functional Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Enriched Transcription Factor Motifs | TEAD1-4, FOXM1, FOXO3 | AP-1 complex (JUN, FOS, JUNB, ATF3) | Youthful state vs. Senescence activation |

| Number of Accessible Regions | 18,377 sequences | 39,611 sequences | Global loss of youthful identity |

| Genomic Location | Primarily distal enhancer-like elements | Primarily distal enhancer-like elements | Altered long-range gene regulation |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Partial Reprogramming of Aged Human Fibroblasts

This protocol is adapted from multiple studies demonstrating successful epigenetic rejuvenation in vitro [18] [22] [24].

Objective: To reverse age-associated epigenetic marks and restore functional parameters in aged human dermal fibroblasts (HDFs) without inducing pluripotency.

Materials:

- Cells: Early-passage HDFs from aged (e.g., >60 years) and neonatal donors.

- Reprogramming Factor Delivery:

- Option A (Genetic): Doxycycline-inducible lentivirus expressing polycistronic OKSM (Addgene #20328).

- Option B (Chemical): Commercially available small molecule cocktails.

- Culture Media: Standard fibroblast growth medium (e.g., DMEM + 10% FBS) and induction medium.

- Key Reagents: Doxycycline hyclate, Polybrene, Puromycin.

Procedure:

- Cell Preparation: Seed aged HDFs at a density of 2.5 x 10^4 cells per well in a 6-well plate. Allow cells to adhere for 24 hours.

- Viral Transduction (For Genetic Approach):

- Pre-treat cells with a suitable volume of virus-containing supernatant and 8 µg/mL Polybrene.

- Centrifuge the plate at 800 x g for 45 minutes at 32°C (spinfection).

- Replace the transduction medium with fresh growth medium and culture for another 24 hours.

- Select transduced cells with appropriate antibiotics (e.g., 1-2 µg/mL Puromycin) for 3-5 days.

- Partial Reprogramming Induction:

- Cyclic Induction Protocol: Treat cells with 2 µg/mL doxycycline for 48 hours to "pulse" the expression of reprogramming factors.

- Remove doxycycline and maintain cells in standard medium for the next 5 days (the "chase" period).

- Repeat this cycle 3-4 times. Crucially, monitor daily for any morphological changes indicative of dedifferentiation.

- Validation and Analysis:

- Epigenetic Clock Analysis: Harvest genomic DNA and perform bisulfite sequencing (e.g., using the Illumina EPIC array) to calculate DNA methylation age.

- Chromatin Accessibility: Perform ATAC-seq on treated and control cells to assess the reversal of age-related chromatin closure, specifically checking for reduced accessibility at AP-1 binding sites.

- Functional Assays:

- SASP: Quantify secretion of IL-6 and IL-8 via ELISA.

- Metabolic Health: Measure mitochondrial membrane potential and ROS production using JC-1 and MitoSOX dyes, respectively.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3. Essential Research Reagents for Epigenetic Rejuvenation Studies

| Reagent / Tool | Category | Primary Function in Research | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inducible OSKM Cassette | Genetic Tool | Allows controlled, transient expression of Yamanaka factors for partial reprogramming. | In vivo rejuvenation studies in transgenic mice [18]. |

| AAV9 Vectors | Delivery System | Efficient in vivo gene delivery vehicle with broad tissue tropism. | Delivering OSK factors to wild-type mice for systemic rejuvenation [18]. |

| 7c Chemical Cocktail | Small Molecules | Non-genetic method to induce partial reprogramming and epigenetic reset. | Rejuvenating human fibroblasts in vitro; potential for therapeutic development [18]. |

| DNA Methylation Clock | Analytical Tool | A multi-CpG site algorithm to accurately predict biological age pre- and post-intervention. | Quantifying the degree of epigenetic rejuvenation in treated cells/tissues [21] [18]. |

| AP-1 Inhibitors | Small Molecules | Chemically inhibits the senescence-associated pioneer factor AP-1. | Testing synergy with reprogramming factors to enhance rejuvenation efficiency [22]. |

| FOXM1 Expression Vector | Genetic Tool | Enables overexpression of a pro-youthfulness transcription factor that antagonizes AP-1. | Resetting aged chromatin profiles to a more youthful state in human fibroblasts [22]. |

Molecular Mechanisms: How do p53, p21, and INK4a/ARF function as roadblocks in cellular reprogramming?

The proteins p53, p21, and those encoded by the INK4a/ARF locus (p16INK4a and p14ARF/p19ARF) constitute a major defense network that somatic cells activate in response to the stress of reprogramming. Their activation leads to outcomes that are antagonistic to the acquisition of pluripotency, such as apoptosis, senescence, and cell-cycle arrest [25].

The p53-p21 Axis: The tumor suppressor p53 is a central node in the DNA damage response. Upon activation, it transcriptionally upregulates p21 (a cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor encoded by the CDKN1A gene) [26] [27]. p21 enforces a stable cell cycle arrest by inhibiting cyclin E-CDK2 complexes, preventing the phosphorylation of the retinoblastoma protein (pRB) and halting the G1 to S phase transition [28] [29]. This arrest limits the proliferation necessary for successful reprogramming [25].

The INK4a/ARF Locus: This unique genetic locus encodes two distinct tumor suppressors through alternative reading frames: p16INK4a and p14ARF (p19ARF in mice) [30] [29].

- p16INK4a directly inhibits CDK4 and CDK6, which also leads to hypophosphorylated, active pRB and G1 cell cycle arrest [29] [27].

- p14/p19ARF stabilizes p53 by binding to and inhibiting MDM2, the primary ubiquitin ligase responsible for p53 degradation. This leads to the activation of the p53-p21 pathway described above [30] [29].

These pathways are integrated through regulatory feedback loops and are potently activated by the stresses inherent to reprogramming, including DNA damage and oncogenic signaling from factors like c-Myc [25].

Diagram 1: The core signaling pathways of key molecular roadblocks.

Quantitative Evidence: What is the experimental data showing the impact of these roadblocks?

Inhibition of the p53 pathway and the INK4a/ARF locus significantly enhances reprogramming efficiency and kinetics across various experimental models. The quantitative data below summarizes key findings from foundational studies.

Table 1: Impact of p53 and INK4a/ARF Pathway Inhibition on Reprogramming Efficiency

| Experimental Manipulation | Cell Type | Reprogramming Factors Used | Key Effect on Reprogramming | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| p53 Knockout | Mouse embryonic fibroblasts | Oct4, Sox2, Klf4 (without c-Myc) | Enhanced efficiency | [25] |

| p53 Knockout | Terminally differentiated mouse T cells | Oct4, Sox2, Klf4 | Enabled iPS cell generation from terminally differentiated cells | [25] |

| p19ARF Knockdown (low expression) | Primary mouse fibroblasts | Oct4, Sox2, Klf4, c-Myc | Up to 3-fold faster kinetics and higher efficiency | [25] |

| p53/ARF Pathway Knockout | Immortal mouse fibroblasts (lack intact pathway) | Oct4, Sox2, Klf4, c-Myc | Reprogrammed with near-unit efficiency | [25] |

| p21 Overexpression | Mouse/Human fibroblasts | Oct4, Sox2, Klf4, c-Myc | Suppressed iPS cell generation, mimicking p53 effect | [25] |

| MDM2 Overexpression | Mouse/Human fibroblasts | Oct4, Sox2, Klf4, c-Myc | Enhanced iPS cell generation, mimicking p53 suppression | [25] |

Protocols & Troubleshooting: What are the specific methodologies for targeting these roadblocks?

A. Genetic Silencing via RNA Interference

This protocol details the transient knockdown of p53 to enhance reprogramming efficiency, a method particularly useful when permanent genetic modification is undesirable.

- Step 1: Design and Selection of siRNA. Select validated siRNA sequences targeting the p53 mRNA transcript. A non-targeting scrambled siRNA with the same nucleotide composition should be used as a negative control.

- Step 2: Cell Seeding and Transfection. Plate somatic cells (e.g., human dermal fibroblasts) at an optimal density (e.g., 5 x 10^4 cells per well in a 6-well plate) 24 hours before transfection to achieve 30-50% confluency at the time of transfection. Transfect cells with the p53-specific or control siRNA using a lipid-based transfection reagent suitable for the cell type, following the manufacturer's protocol.

- Step 3: Validation of Knockdown. 48-72 hours post-transfection, harvest a subset of cells to validate p53 knockdown efficiency. This can be done via:

- Western Blotting: To assess reduction in p53 protein levels.

- qPCR: To quantify reduction in p53 mRNA levels.

- Step 4: Initiation of Reprogramming. Initiate reprogramming on the transfected cells, typically 48 hours post-transfection, using your method of choice (e.g., lentiviral transduction with OSKM factors). The reprogramming process should be conducted in parallel on control siRNA-treated cells.

- Step 5: Monitoring and Analysis. Monitor for the emergence of iPSC colonies. Quantify reprogramming efficiency by counting alkaline phosphatase (AP)-positive colonies or Tra-1-60-positive colonies 3-4 weeks post-reprogramming induction. Compare the number and appearance kinetics of colonies between p53-knockdown and control groups [25].

Troubleshooting Note: A common issue is low transfection efficiency, which leads to inconsistent knockdown and variable reprogramming outcomes. To mitigate this, optimize transfection conditions for your specific cell type and consider using high-efficiency transfection reagents or viral delivery (e.g., shRNA) for more stable knockdown, bearing in mind that this is less transient.

B. Pharmacological Inhibition of p53

This protocol uses a small molecule inhibitor of MDM2 to transiently activate p53, which can suppress the senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP) in senescent cells, providing a "senomorphic" effect.

- Step 1: Senescence Induction. Induce senescence in primary human fibroblasts (e.g., IMR90 cells) using a defined stressor such as 10 Gy of ionizing radiation or 10 µM etoposide.

- Step 2: Inhibitor Treatment. Four days after senescence induction, treat cells with a low dose of the MDM2 inhibitor RG7388 (e.g., 12.5 nM) or a vehicle control (e.g., DMSO). The treatment medium should be refreshed every 2-3 days.

- Step 3: Confirmation of Senomorphic Effect. After 5-7 days of treatment, assess key senescence and SASP markers to confirm the effect.

- CCF Formation: Analyze by immunofluorescence staining for γH2A.X in the cytoplasm. MDM2i treatment should suppress CCF formation.

- SASP Analysis: Quantify expression of key SASP factors (e.g., IL-8) via qPCR or ELISA. MDM2i treatment should suppress the inflammatory SASP.

- Cell Cycle Arrest: Confirm that the senescence-associated cell cycle arrest is not reversed by performing an EdU incorporation assay. MDM2i at this dose is senomorphic, not senolytic [31].

- Step 4: Application in Reprogramming. For reprogramming experiments, this pharmacological suppression of the SASP and related inflammatory signals can be applied during the early stages of reprogramming, particularly when using aged or pre-senescent donor cells, to create a more permissive microenvironment for reprogramming.

Troubleshooting Note: The concentration and timing of inhibitor treatment are critical. High doses may induce apoptosis or other off-target effects. It is essential to perform a dose-response curve to identify the minimal effective dose that achieves the desired senomorphic effect without causing cell death.

Diagram 2: Experimental workflow for enhancing reprogramming by targeting p53.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Investigating Reprogramming Roadblocks

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Mechanism | Example Application in Research |

|---|---|---|

| p53-Targeting siRNA/shRNA | Induces transient or stable knockdown of p53 mRNA, reducing protein levels and its pathway activity. | Used to demonstrate the direct role of p53 in limiting reprogramming efficiency in wild-type somatic cells [25]. |

| p53/MDM2 Interaction Inhibitors (e.g., RG7388) | Small molecule that blocks MDM2 from binding p53, leading to p53 stabilization and activation. Used at low doses for senomorphic effect. | Suppresses CCF formation and the inflammatory SASP in senescent cells without reversing cell cycle arrest [31]. |

| p21 (CDKN1A) Antibodies | Detect and quantify p21 protein levels via Western Blot or immunofluorescence. A key downstream effector of p53. | Used to validate activation of the p53-p21 pathway during failed reprogramming attempts and to confirm its suppression after experimental intervention. |

| p16INK4a Antibodies | A specific marker for detecting senescent cells in culture or tissue sections. | Identifying and quantifying the fraction of pre-senescent or senescent cells in a starting somatic cell population, which are notoriously difficult to reprogram [29]. |

| Ink4a/ARF Locus Knockout Cells | Primary cells derived from genetically engineered mice where the entire Cdkn2a locus (encoding p16Ink4a and p19Arf) is deleted. | Used to dissect the individual and combined contributions of p16 and p19 to the reprogramming barrier, independent of p53 [25]. |

FAQs on Molecular Roadblocks and Reprogramming

Q1: Why does inhibiting p53, a tumor suppressor, improve reprogramming efficiency? Reprogramming somatic cells into iPSCs is a highly stressful process that activates DNA damage and stress signals. The p53 pathway is primed to respond to such stress by initiating cell cycle arrest, apoptosis, or senescence to prevent the propagation of damaged cells. While this is a beneficial tumor-suppressive mechanism in vivo, it becomes a major roadblock in vitro by eliminating cells undergoing reprogramming. Inhibiting p53 allows stressed cells to survive and continue the reprogramming process, thereby increasing efficiency [25].

Q2: What is the difference between a "senolytic" and a "senomorphic" strategy in this context? A senolytic strategy aims to selectively kill and eliminate senescent cells from the population (e.g., using dasatinib and quercetin). A senomorphic strategy, in contrast, does not kill senescent cells but instead modifies their phenotype, typically by suppressing the pro-inflammatory SASP. For example, low-dose MDM2 inhibitors can act as senomorphics by activating p53 to enhance DNA repair and suppress CCF-driven inflammation, making the cellular environment more conducive to reprogramming without clearing the cells [31].

Q3: Can we completely remove p53 to achieve perfect reprogramming efficiency? While complete genetic ablation of p53 (e.g., using p53-null cells) dramatically improves reprogramming efficiency and even allows reprogramming of terminally differentiated cells, it is not a clinically viable strategy. Permanent p53 loss poses a significant cancer risk due to genomic instability. Furthermore, studies show that p53 plays a role in maintaining genomic integrity during reprogramming; its absence can lead to iPSCs with elevated mutation loads. Therefore, the field is moving towards transient inhibition (e.g., using RNAi or small molecules) rather than permanent deletion [25].

Q4: How does donor age influence the impact of these molecular roadblocks? Aging is associated with an increased burden of senescent cells and higher basal expression of roadblock proteins like p16INK4a and activators of p53. Studies in mice consistently show that fibroblasts from old mice reprogram less efficiently than those from young mice. This is linked to the upregulation of the INK4a/ARF locus during aging. Therefore, targeting these age-associated pathways becomes increasingly critical for the successful reprogramming of cells from older donors [14] [25].

Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ: How does age-related metabolic dysregulation specifically impact cellular reprogramming efficiency?

Aging introduces significant metabolic and functional declines in somatic cells that create barriers to reprogramming. The table below summarizes the key metabolic and functional changes in aged cells and their direct impact on the reprogramming process.

Table: Impact of Aged Cell Characteristics on Reprogramming

| Aged Cell Characteristic | Impact on Reprogramming Process | Supporting Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| General Metabolic Decline [14] | Contributes to a less supportive cellular environment for the energetically demanding reprogramming process. | Observed as a general functional decline in cells and tissues [14]. |

| Impaired Glucose Metabolism [32] | Disrupts the quiescent state and impedes the ability of old Neural Stem Cells (NSCs) to activate and proliferate, a key step in reprogramming. | Knockout of glucose transporter gene Slc2a4 (GLUT4) identified as a top intervention to boost old NSC activation [32]. |

| Mitochondrial Dysfunction [14] [33] | Fails to meet the high bioenergetic demands of reprogramming, potentially through reduced oxidative phosphorylation and increased ROS. | Listed as a core hallmark of aging targeted by rejuvenation therapies; includes accumulation of mitochondrial ROS [14] [18] [33]. |

| Reduced Proliferative Capacity [34] | Slows down or stalls the cell divisions that are essential for the epigenetic remodeling during reprogramming. | Aged cells experience replicative senescence and a slowed cell cycle [34]. |

FAQ: What experimental strategies can counteract metabolic barriers in aged cells?

Several targeted strategies can be employed to overcome the metabolic deficiencies of aged cells and improve reprogramming outcomes.

Table: Strategies to Counteract Metabolic Barriers in Aged Cells

| Strategy | Methodology | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Partial Reprogramming [18] | Cyclic Induction: Transient expression of Yamanaka factors (OSKM or OSK) using a doxycycline-inducible system in vivo (e.g., 2-day on/5-day off cycles).Chemical Reprogramming: Use of small molecule cocktails (e.g., 7c cocktail) to reset epigenetic age without full pluripotency. | Avoids the full, stressful process of complete reprogramming. Resets epigenetic age and restores mitochondrial function, potentially by allowing metabolic reset without immediate high energy demand [18]. |

| Modulating Metabolic Pathways [32] | Genetic Knockout: Use CRISPR-Cas9 to knockout genes that impair old cell function (e.g., glucose transporter Slc2a4).Nutrient Manipulation: Transient glucose starvation of aged NSCs in culture. | Directly targets and removes identified metabolic bottlenecks specific to aged cells, such as dysregulated glucose uptake, which can restore a more youthful functional state [32]. |

| Optimizing Culture Conditions [34] | Using Young ECM: Seeding aged induced cardiomyocytes (iCMs) onto a young extracellular matrix (ECM). | The young ECM provides a more supportive microenvironment and metabolic cues, which can rejuvenate quiescent aged cells and enhance functional parameters [34]. |

FAQ: How can I verify if metabolic issues are affecting my reprogramming experiment?

A systematic approach, from design to validation, is crucial for diagnosing and resolving metabolic-related inefficiencies in reprogramming aged cells.

Design & Controls:

- Test Multiple Guides: When using CRISPR-based interventions, test 2-3 different guide RNAs per target to find the most efficient one [35].

- Include Young Controls: Always perform parallel reprogramming experiments with cells from a young donor. This provides a baseline for optimal efficiency and allows you to quantify the age-related deficit [14].

- Use Ribonucleoproteins (RNPs): Deliver the Cas9 protein pre-complexed with guide RNA as an RNP. This method leads to high editing efficiency, reduces off-target effects, and is a "DNA-free" method that can be beneficial for sensitive primary cells [35].

Monitor Metabolic and Aging Phenotypes:

- Measure Metabolic Output: Use indirect calorimetry to track oxygen consumption (VO₂) and carbon dioxide production (VCO₂) in culture, which can indicate shifts in metabolic capacity [36].

- Assess Mitochondrial Health: Quantify mitochondrial ROS and oxidative phosphorylation capacity [18] [34].

- Check Senescence Markers: Monitor expression of markers like p16, p21, and β-galactosidase activity (SA-β-gal) before and after intervention [34].

Validate Editing and Efficiency:

- Confirm Genomic Edits: After CRISPR manipulation, extract genomic DNA and sequence the target locus to confirm the introduction of indels or precise edits [36] [37].

- Check Protein Expression: Validate knockout or overexpression at the protein level via western blot or immunofluorescence. Be aware that alternative splicing can create protein isoforms; ensure your CRISPR target is in a constitutive exon [37].

- Quantify Reprogramming Efficiency: Use standardized metrics beyond colony counts, such as flow cytometry for pluripotency markers (e.g., alkaline phosphatase, Nanog) and functional assays like teratoma formation or directed differentiation [14].

Experimental Protocols

Detailed Protocol: In Vivo Partial Reprogramming to Ameliorate Age-Related Metabolic Decline

This protocol is based on studies that have successfully reversed age-related metabolic and functional declines in wild-type mice using cyclic, inducible expression of Yamanaka factors [18].

Objective: To reverse age-related metabolic dysregulation in an aged animal model to create a more favorable cellular environment for subsequent reprogramming experiments.

Materials:

- Subjects: Aged wild-type mice (e.g., 124-week-old).

- Key Reagents:

- AAV9 vectors carrying reverse tetracycline-controlled transactivator (rtTA) and TRE-OSK (doxycycline-responsive element driving Oct4, Sox2, Klf4). c-Myc is excluded to minimize tumorigenic risk [18].

- Doxycycline (dox) chow or injectable solution.

- Equipment for metabolic phenotyping (indirect calorimetry system, DXA scanner).

Workflow:

Procedure:

- Vector Delivery: Systemically administer AAV9-TRE-OSK and AAV9-rtTA to the aged mice via a suitable route (e.g., tail vein injection) to ensure broad tissue distribution [18].

- Cyclic Induction: Initiate the cyclic induction protocol after allowing time for viral expression.

- Pulse: Provide doxycycline for 1 day to induce OSK expression.

- Chase: Remove doxycycline for 6 days, allowing the cells to recover and avoid full dedifferentiation.

- Repeat: Continue this cycle for multiple weeks (e.g., 10+ cycles) to achieve a sustained rejuvenation effect [18].

- Metabolic Assessment: During and after the cycling protocol, monitor key metabolic parameters.

- Use indirect calorimetry to measure Oxygen Consumption (VO₂), Carbon Dioxide Production (VCO₂), and calculate the Respiratory Exchange Ratio (RER) and Energy Expenditure. An improvement indicates a shift towards a more youthful metabolic state [36].

- Use Dual-Energy X-ray Absorptiometry (DXA) to track changes in body composition (lean mass, fat mass) [36].

- Conduct glucose and insulin tolerance tests to assess insulin sensitivity [36].

- Tissue Collection & Analysis: After the final cycle, sacrifice the animals and isolate tissues/cells of interest.

- Analyze epigenetic aging clocks (e.g., DNA methylation) and transcriptomic profiles to confirm a reversal of aging signatures [18].

- Isulate primary fibroblasts or other somatic cells for subsequent reprogramming experiments.

Detailed Protocol: CRISPR-Cas9 Screen to Identify Metabolic Regulators of Aged Cell Function

This protocol outlines a high-throughput screening approach to systematically identify genes whose knockout can enhance the function of aged cells, such as neural stem cells (NSCs) [32].

Objective: To perform a genome-wide CRISPR-Cas9 knockout screen in primary aged NSCs to discover metabolic regulators that act as barriers to NSC activation.

Materials:

- Cells: Primary quiescent Neural Stem Cells (qNSCs) isolated from the subventricular zone (SVZ) of aged (e.g., 18-21 month) Cas9-expressing transgenic mice.

- Key Reagents:

- Lentiviral sgRNA library (genome-wide, ~10 sgRNAs/gene).

- Growth factors for NSC culture (EGF, FGF-2).

- Antibodies for FACS (e.g., anti-Ki67).

- Reagents for next-generation sequencing (NGS).

Workflow:

Procedure:

- Cell Preparation and Transduction: Expand and then induce quiescence in primary aged qNSCs from Cas9-expressing mice. Transduce a large population of these qNSCs (e.g., >400 million cells) with the lentiviral sgRNA library at a low MOI to ensure most cells receive only one sgRNA. Maintain high coverage of the library (e.g., 500x) [32].

- Phenotypic Selection: After transduction, activate the qNSC culture by adding growth factors (EGF and FGF-2). Allow the cells to proliferate for a set period (e.g., 4-14 days).

- Cell Sorting and Analysis:

- At 4 days post-activation: Harvest cells and use Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting (FACS) to isolate the population of successfully activated NSCs, gating for a proliferation marker like Ki67 [32].

- At 14 days post-activation: Harvest the entire population, which will be enriched for cells with knockouts that confer a long-term growth or survival advantage.

- Sequencing and Hit Identification: Extract genomic DNA from the selected populations and the original library pool. Amplify the integrated sgRNA sequences and subject them to high-throughput sequencing. Use bioinformatic tools (e.g., CasTLE analysis) to compare sgRNA abundance between selected populations and the starting pool. Significantly enriched sgRNAs indicate gene knockouts that promote aged NSC activation [32].

- Hit Validation: Select top candidate genes (e.g., those involved in glucose transport or cilium organization) and individually validate them by creating specific knockouts in a new batch of aged NSCs, then reassessing the activation phenotype [32].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Reagents for Investigating Metabolism in Aged Cell Reprogramming

| Research Reagent / Tool | Function in Experiment | Specific Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Inducible Reprogramming Systems | Allows for transient, controlled expression of reprogramming factors to avoid full dedifferentiation and teratoma formation. | Dox-inducible OSKM or OSK cassettes (AAV or transgenic). Exclusion of c-Myc reduces cancer risk [18]. |

| CRISPR-Cas9 Screening Libraries | Enables systematic, genome-wide identification of genes that enhance or impede the function of aged cells. | Genome-wide lentiviral sgRNA libraries (e.g., ~10 sgRNAs/gene for ~23,000 genes) [32]. |

| Chemically Modified Guide RNAs | Increases stability and editing efficiency of CRISPR components while reducing cellular immune responses and toxicity. | Alt-R CRISPR-Cas9 guide RNAs with proprietary modifications (e.g., 2'-O-methyl at terminal residues) [35]. |

| Metabolic Phenotyping Platforms | Quantifies the physiological metabolic status of cells or organisms, providing key data on energy metabolism. | Indirect Calorimetry (measures VO₂/VCO₂), DXA (body composition), Glucose/Insulin Tolerance Tests [36]. |

| Senescence and Aging Biomarkers | Measures cellular aging and the effectiveness of rejuvenation interventions at the molecular level. | SA-β-gal staining, p16/p21 expression (IF/WB), DNA methylation clocks (epigenetic aging), Telomere length analysis [14] [34]. |

Advanced Reprogramming Toolkits: From Yamanaka Factors to Chemical Cocktails

The generation of induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) represents a pivotal technology for regenerative medicine, disease modeling, and drug screening. The foundational method, involving the forced expression of OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, and c-MYC (OSKM), faces significant challenges including low efficiency and protracted timelines. These hurdles are particularly pronounced when working with aged somatic cells, where the accumulated burdens of aging create substantial reprogramming barriers. To overcome these limitations, researchers have identified a class of "enhancer factors," such as GLIS1, FOXH1, and SALL4, which can dramatically improve the reprogramming process. This technical support center provides troubleshooting guidance and detailed protocols for incorporating these potent enhancers into your reprogramming workflow, specifically within the context of aging research.

FAQs: Enhancer Factors and Aging Cell Reprogramming

Q1: Why is reprogramming efficiency lower in aged somatic cells, and how can enhancer factors help?

A1: Aging is associated with the accumulation of various cellular deficits, including genomic instability, telomere erosion, mitochondrial dysfunction, and profound epigenetic alterations. These changes establish formidable barriers to reprogramming. In mice, studies have consistently shown an age-dependent decline in reprogramming efficiency, with cells from old mice generating significantly fewer iPSC colonies than those from young counterparts [14]. Enhancer factors like GLIS1 and FOXH1 help overcome these age-related barriers by activating pro-reprogramming pathways, facilitating key processes like mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition (MET), and directly modulating the expression of pluripotency genes, thereby effectively boosting the likelihood of successful reprogramming even in aged cell populations [38] [39].

Q2: What are the key differences in how GLIS1 and FOXH1 enhance reprogramming?

A2: While both are potent enhancers, GLIS1 and FOXH1 act at distinct stages and through different mechanisms:

- GLIS1: Primarily functions during the early phases of reprogramming. It physically interacts with the OSK complex to activate pro-reprogramming target genes. Its mechanism is independent of the p53 pathway and involves stimulating Wnt signaling and genes related to MET [38] [39].

- FOXH1: Acts predominantly at the late stages of reprogramming. It facilitates the completion of MET in TRA-1-60+ intermediate cells, a critical step for achieving full pluripotency. Inhibition of FOXH1 has been shown to block iPSC generation, underscoring its importance [38].

Q3: Can enhancer factors replace core Yamanaka factors in reprogramming aged cells?

A3: Certain enhancer factors have demonstrated the capacity to replace specific core factors, which is a significant advantage for reducing the oncogenic potential of the reprogramming cocktail (e.g., omitting c-MYC). For instance, members of the Fox transcription factor family, including FOXH1, FOXD3, FOXD4, and FOXG1, have been shown to effectively replace OCT4 in combination with SOX2 and KLF4 to generate fully pluripotent iPSCs [40]. This suggests that a strategic combination of enhancer factors could potentially be used to create non-canonical, safer reprogramming cocktails for aged cells.

Q4: Beyond genetic factors, are there alternative strategies to enhance reprogramming in aged cells?

A4: Yes, partial reprogramming and chemical reprogramming are highly promising alternatives. Partial reprogramming using short, cyclic expression of Yamanaka factors (OSK or OSKM) has been shown to reverse epigenetic age, restore youthful gene expression patterns, and improve cellular function in vivo without fully erasing cellular identity [18] [8]. Furthermore, recent advances have identified specific chemical cocktails that can reverse transcriptomic aging signatures without any genetic manipulation, offering a potentially safer and more controllable path toward rejuvenating aged cells [8].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Consistently Low Reprogramming Efficiency in Fibroblasts from Aged Donors

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause 1: Heightened Senescence and Apoptotic Responses. Aged cells have elevated levels of tumor suppressors like p53, which act as a potent reprogramming barrier.

- Solution: Consider transiently inhibiting the p53 pathway using RNA interference (siRNA) or small molecules. However, exercise caution due to the associated cancer risks and use this as a last resort [38].

- Cause 2: Failure to Initiate MET. The initial phase of reprogramming requires a mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition, which can be impaired in aged fibroblasts.

- Cause 3: Stubborn Epigenetic Barriers. The epigenome of aged cells is more locked into a somatic state, resisting the activation of pluripotency networks.

Problem: Incomplete Reprogramming and Poor Quality of Resulting iPSC Colonies

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause 1: Inadequate Activation of Endogenous Pluripotency Network.

- Solution: Ensure your enhancer factor combination effectively targets the core pluripotency circuitry. SALL4 is a known core regulator that interacts with OCT4, SOX2, and NANOG. Its inclusion can help reinforce the pluripotency network [41]. Other factors like GBX2 and NANOGP8 have also been identified to play roles in maintaining pluripotency and can be tested [42] [41].

- Cause 2: Persistent Expression of Somatic or Senescence Genes.

- Solution: Perform rigorous quality control. Use RNA-sequencing to compare your iPSC lines' transcriptome to established ESC standards. Verify the silencing of the reprogramming transgenes and the endogenous activation of core pluripotency genes like OCT4 and NANOG [42].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Enhancing Reprogramming with GLIS1

Objective: To significantly increase the efficiency of iPSC generation from human dermal fibroblasts (including aged donors) by incorporating GLIS1 into the OSK reprogramming cocktail.

Materials:

- Table: Key Research Reagents for GLIS1 Protocol

| Item | Function in Protocol |

|---|---|

| Human dermal fibroblasts (HDFs) | Somatic cell source for reprogramming |

| Lentiviral vectors for OSK | Core reprogramming factors |

| Lentiviral vector for GLIS1 | Pro-reprogramming enhancer factor |

| p53 siRNA (optional) | Temporary inhibition of a major reprogramming barrier |

| Fibroblast culture medium | Expansion and maintenance of HDFs |

| iPSC/ESC culture medium | Supports the growth and maintenance of pluripotent stem cells |

Methodology:

- Cell Preparation: Culture and expand your target HDFs. It is critical to perform experiments at low passage numbers to avoid replicative senescence.

- Viral Transduction: Co-transduce HDFs with lentiviral vectors carrying OCT4, SOX2, KLF4 (OSK), and GLIS1 (OSKG). Include control groups transduced with OSK only.

- Optional p53 Knockdown: If efficiency remains low, especially with aged cells, consider transiently transfecting cells with p53 siRNA 24-48 hours post-transduction.

- Plating and Culture: After 48-72 hours, re-plate the transduced cells onto Matrigel-coated plates and switch to iPSC culture medium.

- Colony Monitoring and Analysis: Monitor for the emergence of embryonic stem cell-like colonies from day 10 onwards. The number of alkaline phosphatase-positive colonies in the OSKG group should be compared to the OSK control. GLIS1 has been reported to increase colony formation up to 30-fold relative to OSK alone [38] [39].

Protocol 2: Identifying Novel Enhancer Factors via RNA-Seq

Objective: To identify novel transcription factors that enhance reprogramming efficiency by analyzing differentially expressed genes in iPSCs generated from donor cells with high innate reprogramming capacity.

Materials:

- High-quality RNA from parent somatic cells and derived iPSC lines.

- RNA-sequencing library prep kit and access to a sequencing platform (e.g., Illumina HiSeq).

- Bioinformatics software for differential gene expression analysis (e.g., CLC Genomics Workbench).

Methodology:

- Generate and Characterize iPSCs: Reprogram somatic cells from multiple donors (e.g., healthy, diseased, aged) using a standard method (e.g., OSKM). Note any donors that show exceptionally high reprogramming efficiency.

- RNA Extraction and Sequencing: Isolate high-quality RNA (RIN > 8) from the parent somatic cells and the resulting iPSC lines. Prepare and sequence RNA-seq libraries.

- Bioinformatic Analysis: Map reads to the reference genome and perform differential gene expression analysis. Identify transcription factors that are significantly upregulated in iPSCs, particularly those derived from the high-efficiency donor.

- Validation: Select candidate TFs (e.g., GBX2, SP8, ZIC1) for functional validation by testing their ability to enhance reprogramming efficiency when added to the OSKM cocktail in a new round of reprogramming experiments [42] [41].

Signaling Pathways and Workflows

The following diagram illustrates the coordinated action of enhancer factors in overcoming age-related barriers during reprogramming, highlighting the distinct stages at which key factors like GLIS1 and FOXH1 operate.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Key Research Reagents for Exploring Reprogramming Enhancers

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function in Reprogramming |

|---|---|---|

| Core Factors | OCT4, SOX2, KLF4 | Foundational induction of pluripotency. |

| Enhancer Factors | GLIS1, FOXH1, SALL4 | Boost efficiency; act at early/late stages; replace core factors. |

| Novel Enhancer TFs | GBX2, NANOGP8, SP8, PEG3, ZIC1 | Potential new tools to enhance efficiency, identified via transcriptomics [42] [41]. |

| Fox Family TFs | FOXD3, FOXD4, FOXG1 | Can replace OCT4 in mouse reprogramming with SOX2 and KLF4 [40]. |

| Small Molecules | Vitamin C, Pitstops 1 & 2 | Modulate epigenetics and signaling pathways to enhance reprogramming [38]. |

| Barrier Inhibitors | p53 siRNA, p21 siRNA | Transiently silence key senescence pathways to improve efficiency [38]. |

Troubleshooting Common Delivery Issues

FAQ: Overcoming Key Experimental Hurdles

Q1: My non-viral delivery system shows high cytotoxicity. What could be the cause and how can I mitigate it?

- Cause: High cytotoxicity is often linked to the positive surface charge of cationic carriers, which can disrupt cell membranes [43]. The length of the polycationic chain (e.g., PLL) is directly correlated with cell viability; longer chains typically show higher toxicity [43].

- Solution:

- Optimize polymer structure: Use carriers with shorter polycationic blocks. For instance, a PLL block with a degree of polymerization (DP) of 20 (PNL-20) demonstrated higher transfection efficiency with minimal cytotoxicity compared to longer chains [43].

- Incorporate shielding groups: Modify the surface with hydrophilic polymers like Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) to provide "stealth" properties, reducing unwanted interactions with cell membranes and blood proteins [43] [44].

- Consider self-immolative carriers: New systems like Discrete Immolative Guanidinium Transporters (DIGITs) are designed to irreversibly neutralize their charge at physiological pH, enhancing cargo release and reducing toxic interactions [45].

Q2: The transfection efficiency of my plasmid DNA (pDNA) is low. How can I improve it?

- Cause: Low pDNA efficiency can stem from poor cellular uptake, inefficient endosomal escape, and degradation before nuclear entry [46] [43] [47].

- Solution:

- Enhance complexation and release: Use copolymers that balance tight pDNA condensation with efficient intracellular release. For example, the copolymer PNL-20 effectively condensed pDNA into stable polyplexes (60-90 nm) and showed the highest transfection efficiency in its series [43].

- Promote endosomal escape: Formulate delivery systems with components that facilitate endosomal escape via the "proton sponge effect" (e.g., ionizable lipids, PEI) or membrane fusion (e.g., helper lipid DOPE) [44].

- Optimize physical parameters: For electroporation-based methods like Tissue Nanotransfection (TNT), carefully optimize electrical pulse parameters (voltage, duration, interval) to maximize delivery without compromising cell viability [46].

Q3: I am not achieving the desired organ/cell specificity. What strategies can enhance targeting?

- Cause: Standard non-viral vectors, like many LNPs, naturally accumulate in the liver and spleen due to clearance by the mononuclear phagocyte system (MPS) [44] [48].

- Solution:

- Exploit novel chemical transporters: Systems like DIGITs can be tuned through structural variations to selectively target organs like the lung (94% selectivity) or spleen (98% selectivity) upon intravenous administration [45].

- Utilize targeted ligands: Functionalize vectors with targeting ligands (e.g., aptamers, peptides, antibodies) that recognize specific cell surface receptors [47] [44].

- Employ "don't-eat-me" signals: Modify nanoparticle surfaces with CD47-derived peptides to evade phagocytic clearance, increasing circulation time and opportunity to reach target tissues [44].

Q4: The protein expression from my mRNA is lower than expected. What steps should I take?

- Cause: Rapid degradation by ubiquitous RNases and failure to escape endosomes are primary obstacles [49] [44].

- Solution:

- Optimize mRNA chemistry: Incorporate nucleotide modifications (e.g., pseudouridine-Ψ, 5-methylcytidine-m5C) to enhance stability and reduce immunogenicity, which can otherwise suppress translation [50] [49].

- Ensure efficient delivery: Use proven LNP systems that protect mRNA and facilitate endosomal escape. Ionizable lipids in LNPs are protonated in acidic endosomes, promoting disruptive endosomal escape via the proton sponge effect [44].

- Verify mRNA integrity: Use high-quality, purified IVT mRNA with optimized 5' cap and 3' poly(A) tail structures to maximize stability and translational efficiency [49].

Quantitative Data Comparison

Table 1: Comparison of Non-Viral Delivery Systems for Nucleic Acids

| Delivery System | Nucleic Acid Type | Key Characteristics | Typical Efficiency/Performance | Primary Target Organs/Cells | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) [49] [44] [48] | mRNA, siRNA, pDNA | - Ionizable lipids, PEG-lipids, cholesterol, phospholipids.- Size: ~80-100 nm. | - High efficiency for mRNA vaccines.- siRNA therapy (Patisiran) approved. | Liver, spleen, lung (standard formulations). | - Proven clinical success.- Scalable production.- Protects RNA from nucleases. |

| Discrete Immolative Guanidinium Transporters (DIGITs) [45] | mRNA, circRNA, pDNA | - Discrete guanidinium-containing esters.- Synthesized in 4 steps.- Charge neutralization at pH 7.4. | - Selective organ targeting: Lung (94%), Spleen (98%).- Reticulocyte transfection: 12%. | Lung, spleen, immature red blood cells. | - Organ selectivity.- Minimal toxicity and inflammatory response.- Simple formulation. |

| Polymer-Based Polyplexes (e.g., PLL-PEG Copolymers) [43] | Plasmid DNA | - Cationic polymer (PLL) blocks of varying length.- PEG grafts for stealth.- Size: 60-90 nm. | - Transfection efficiency is PLL length-dependent.- PNL-20 showed highest efficiency with low cytotoxicity. | Cancer cell lines (in vitro studies). | - Biocompatible.- Tunable architecture.- Stable polyplex formation. |