Breaking the Translational Barrier: A Strategic Roadmap for Advancing Regenerative Pharmacology

Regenerative pharmacology stands at a pivotal crossroads, holding immense promise for curative therapies but facing a persistent translational gap between preclinical discovery and clinical application.

Breaking the Translational Barrier: A Strategic Roadmap for Advancing Regenerative Pharmacology

Abstract

Regenerative pharmacology stands at a pivotal crossroads, holding immense promise for curative therapies but facing a persistent translational gap between preclinical discovery and clinical application. This article provides a comprehensive analysis for researchers and drug development professionals, detailing the multidisciplinary strategies required to overcome these hurdles. We explore the foundational principles of integrative and regenerative pharmacology, examine cutting-edge methodological advances leveraging AI and systems biology, address critical troubleshooting in manufacturing and regulation, and evaluate frameworks for robust clinical validation. By synthesizing insights from recent literature and strategic initiatives, this work serves as a blueprint for accelerating the development of transformative regenerative therapies from bench to bedside.

Defining the Field and Diagnosing the Translational Roadblock

Integrative and Regenerative Pharmacology (IRP) represents a transformative shift in biomedical science, moving beyond the traditional goal of symptom management toward the restoration of biological structure and function of damaged tissues and organs [1]. This field operates at the nexus of pharmacology, regenerative medicine, and systems biology, creating a new therapeutic landscape focused on curative interventions [1]. For researchers and drug development professionals, this paradigm introduces unique experimental challenges and translational barriers. This technical support center provides essential troubleshooting guidance and foundational methodologies to help your research team overcome these hurdles and advance the field of restorative therapeutics.

Core Principles and Definitions

Integrative Pharmacology is defined as the systematic investigation of drug interactions with biological systems across multiple levels—from molecular and cellular to organ and system levels. It combines traditional pharmacology with signaling pathway analysis, bioinformatic tools, and multi-omics approaches (transcriptomics, genomics, proteomics, epigenomics, metabolomics, and microbiomics) to deepen our understanding of disease mechanisms and therapeutic action [1].

Regenerative Pharmacology was formally defined as "the application of pharmacological sciences to accelerate, optimize, and characterize (either in vitro or in vivo) the development, maturation, and function of bioengineered and regenerating tissues" [2]. This approach fuses pharmacological techniques with regenerative medicine principles to develop therapies that actively promote the body's innate healing capabilities [1].

Integrative and Regenerative Pharmacology (IRP) bridges these two fields, merging conventional pharmacology with targeted therapies intended to repair, renew, and regenerate rather than merely block or inhibit disease symptoms. IRP aims to restore physiological structure and function through multi-level, holistic interventions [1].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) & Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ 1: What are the most significant translational barriers facing IRP research, and how can we address them?

Answer: The transition from promising preclinical studies to successful clinical applications remains a significant challenge in IRP. The table below summarizes the primary translational barriers and potential mitigation strategies.

Table 1: Translational Barriers and Mitigation Strategies in IRP Research

| Barrier Category | Specific Challenges | Recommended Mitigation Strategies |

|---|---|---|

| Investigational Hurdles | Unrepresentative preclinical models; unclear mechanisms of action (MoA); long-term safety and efficacy concerns [1]. | Implement more human-relevant models (3D cultures, organ-on-a-chip); employ systems biology approaches to deconstruct MoA; design long-term follow-up studies [1]. |

| Manufacturing Issues | Scalability challenges; lack of automated production; need for Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) compliance [1]. | Invest in scalable bioreactor technologies; develop standardized, automated bioprocesses; establish GMP-compliant workflows early in development [1]. |

| Regulatory Complexity | Lack of unified guidelines across regions (e.g., EMA vs. FDA); complex pathways for Advanced Therapy Medicinal Products (ATMPs) [1]. | Engage with regulatory agencies early and often; participate in consensus-building initiatives for international standards [1]. |

| Economic & Accessibility | High manufacturing costs; limited reimbursement models; poor accessibility in low- and middle-income countries [1]. | Develop cost-effective biomaterials and manufacturing processes; generate robust health-economic data; explore tiered pricing models [1]. |

FAQ 2: How can we improve the clinical relevance of our preclinical IRP models?

Answer: A common failure point in IRP translation is the use of animal models or simple cell cultures that do not adequately recapitulate human clinical conditions [1]. To enhance clinical relevance:

- Incorporate Human Cells: Utilize patient-derived stem cells (e.g., mesenchymal stem cells) to create more physiologically relevant systems [3].

- Utilize Advanced Model Systems: Employ 3D tissue models, bioreactors, and organ-on-a-chip technologies that better mimic the in vivo microenvironment, including mechanical stresses and cell-cell interactions [1] [2]. Bioreactors, for instance, can apply relevant environmental cues like stretch, flow, and compression that are critical for proper tissue formation and function [2].

- Focus on Clinical Endpoints: Design preclinical studies with clinical endpoints in mind from the outset. Collaboration between basic researchers and clinicians during the study design phase is critical for this [4].

FAQ 3: What are the best practices for combining pharmacological agents with biomaterial scaffolds?

Answer: The development of 'smart' biomaterials that act as reservoirs for bioactive agents is a key strategy in IRP [1] [2]. Effective integration requires:

- Spatiotemporal Control: Design biomaterials that provide controlled release of multiple growth factors (e.g., FGF, VEGF, BMPs) in a sequence that mimics the natural healing process [2].

- Functionalization: Use immobilization techniques to tether bioactive molecules to the scaffold, enhancing local concentration and stability. For example, immobilized hyaluronidase has been shown to improve therapeutic outcomes in some regenerative models [5].

- Stimuli-Responsiveness: Develop biomaterials that alter their drug release profile or mechanical characteristics in response to specific external or internal triggers from the healing environment [1].

FAQ 4: How can we tackle the challenge of high costs and limited accessibility of IRP therapies?

Answer: The high cost of ATMPs is a major barrier to clinical adoption and accessibility [1]. Strategies to address this include:

- Drug Repurposing: Investigate existing drugs for new regenerative applications. This strategy can significantly reduce the time and cost associated with de novo drug development [6]. Computational pharmacology approaches are particularly valuable for identifying repurposing candidates [6].

- Process Optimization: Focus on streamlining and automating cell culture and tissue engineering processes to reduce labor and material costs.

- Open Science and Collaboration: Foster academic-industry-clinical partnerships to share resources, knowledge, and risks associated with IRP therapy development [1].

Essential Experimental Protocols in IRP

Protocol 1: Assessing Drug Efficacy in a 3D In Vitro Wound Healing Model

This protocol is adapted from research on microRNAs and leptin in wound healing [3].

1. Aim: To evaluate the effect of a candidate pharmacological agent (e.g., miRNA mimic/inhibitor, growth factor) on key processes in wound healing using a 3D cell culture model.

2. Materials Required:

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for 3D Wound Healing Assay

| Reagent/Material | Function | Example/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Human Dermal Fibroblasts (HDFs) | Primary cell type for tissue repair and matrix deposition. | Use early passage cells for consistency. |

| 3D Scaffold or Hydrogel | Provides a three-dimensional structure that mimics the extracellular matrix. | Collagen I hydrogel or synthetic polymer scaffolds. |

| Candidate Pharmacological Agent | The therapeutic compound being tested. | e.g., miR-21 mimic, recombinant leptin [3]. |

| Cell Culture Medium | Supports cell growth and viability. | DMEM/F12 supplemented with serum or defined growth factors. |

| Histology Reagents | For fixing, sectioning, and staining the 3D construct. | Formalin, paraffin, antibodies for immunofluorescence. |

3. Methodology: 1. 3D Construct Fabrication: Mix HDFs with a neutralized collagen I solution at a density of 1-2 million cells/mL. Pipet the solution into transwell inserts and allow it to polymerize at 37°C for 1 hour. 2. Equilibration: Add culture medium to the top and bottom of the construct and culture for 24-48 hours to allow cells to equilibrate. 3. Wound Induction: Create a uniform wound in the center of the 3D construct using a sterile biopsy punch (e.g., 3-4mm diameter). 4. Treatment Application: Add the candidate pharmacological agent to the culture medium. Include appropriate vehicle controls and positive controls (e.g., known growth factors). 5. Monitoring and Analysis: * Imaging: Capture brightfield images of the wound area at 0, 24, 48, and 72 hours to monitor closure. * Histological Analysis: At endpoint, fix constructs in formalin, embed in paraffin, section, and stain. Use H&E for general morphology, and immunofluorescence for specific markers (e.g., α-SMA for myofibroblasts, Ki-67 for proliferation, CD31 for endothelial cells if co-cultures are used). * Molecular Analysis: Isolve RNA and protein from the constructs to analyze changes in gene expression (e.g., collagen I, III, fibronectin) and key signaling pathways (e.g., PI3K/AKT, MAPK/ERK) via qPCR and western blot [3].

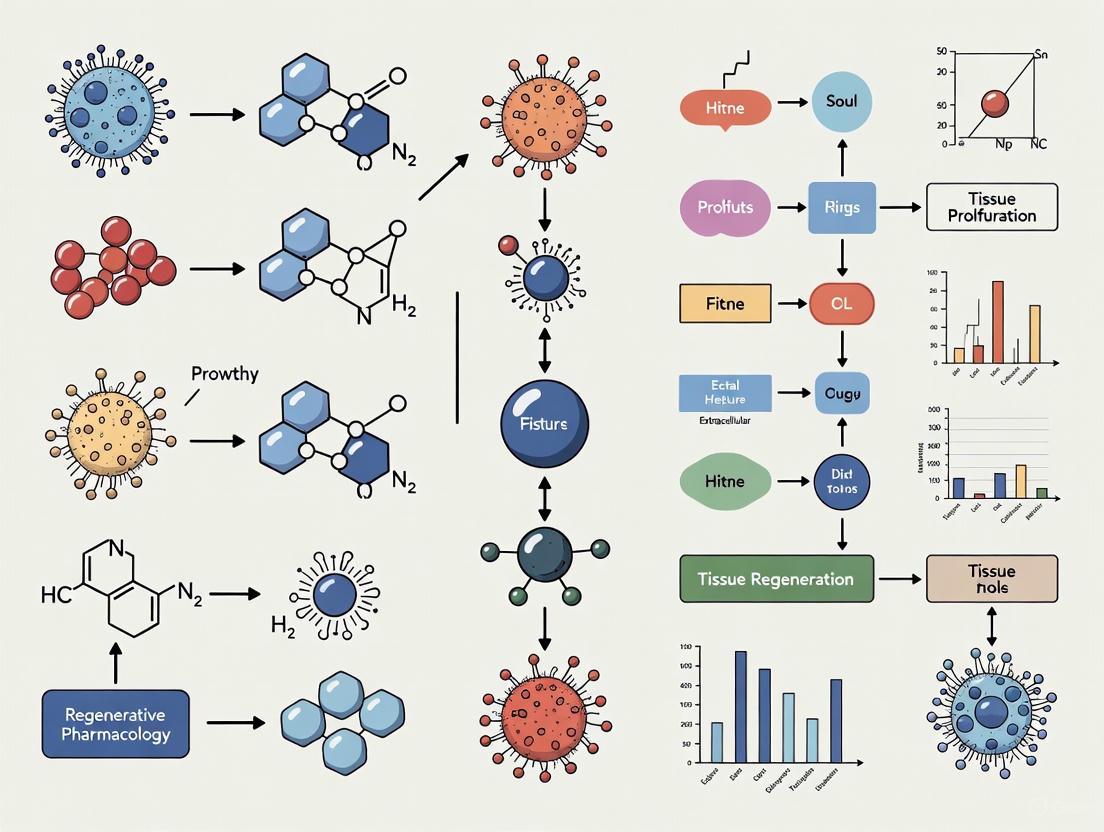

The following diagram illustrates the key signaling pathways involved in wound healing that are often targeted in IRP strategies:

Protocol 2: Evaluating a Pharmacological Agent in a Rat Model of Spinal Cord Injury

This protocol is based on a study investigating the neuroprotective effects of bumetanide [3].

1. Aim: To determine the therapeutic potential of a drug candidate for promoting repair and functional recovery after spinal cord injury (SCI).

2. Materials Required: * Adult Sprague-Dawley rats (250-300g) * Anesthetic cocktail (e.g., Ketamine/Xylazine) * Stereotaxic apparatus * Controlled impactor device for standardized SCI * Candidate drug (e.g., Bumetanide, an NKCC1 inhibitor [3]) * Osmotic minipumps for chronic delivery (optional) * Apparatus for behavioral testing (e.g., Basso, Beattie, Bresnahan (BBB) locomotor rating scale) * Tissue fixation and processing reagents for histology * Antibodies for immunohistochemistry (e.g., against GAP-43, GFAP, NeuN)

3. Methodology: 1. SCI Surgery: Anesthetize the animal and perform a laminectomy to expose the spinal cord at the desired level (e.g., T9-T10). Induce a contusion injury using a controlled impactor with a defined force (e.g., 150 kdyn). 2. Drug Administration: Administer the first dose of the candidate drug (e.g., bumetanide, 10mg/kg, i.p.) or vehicle within a critical window post-injury (e.g., 1-6 hours). Continue administration based on the drug's pharmacokinetic profile (e.g., twice daily for 7 days). 3. Functional Assessment: Evaluate locomotor function weekly for 4-8 weeks using the BBB scale, which scores hindlimb movement, trunk stability, and coordination. 4. Tissue Collection and Analysis: At the study endpoint, transcardially perfuse animals with saline followed by 4% paraformaldehyde. Extract the spinal cord and post-fix. * Histology: Section the tissue and stain with Luxol Fast Blue for myelin or H&E for general morphology. * Immunohistochemistry: Stain sections for markers of axonal regeneration (e.g., GAP-43), astrocytes (GFAP), and neurons (NeuN). Quantify staining intensity and lesion volume using image analysis software. 5. Molecular Analysis: Isolate protein from the injury epicenter to analyze changes in the expression of targets of interest (e.g., NKCC1 and KCC2 transporters) via western blot [3].

The workflow for this in vivo evaluation is summarized below:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Tools for IRP Research

| Category | Specific Reagent/Technology | Research Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Sources | Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs) | Tunable combinatorial drug manufacture and delivery systems; source for paracrine factors (secretome) [1]. | Injection into degenerated intervertebral discs for treatment of degenerative disc disease [3]. |

| Biomaterials | Stimuli-Responsive "Smart" Biomaterials | Scaffolds that alter drug release or mechanical properties in response to environmental triggers [1]. | Local, temporally controlled delivery of growth factors to orchestrate a complete regenerative response [2]. |

| Drug Delivery Systems | Nanoparticles & Nanofibers | Enhance targeted delivery and bioavailability of regenerative compounds; can be combined with imaging capabilities [1]. | Delivery of microRNAs (e.g., miR-21) to regulate key processes in wound healing [3]. |

| Model Systems | 3D Bioreactors | Devices that recapitulate in vivo physiological cues (stretch, flow, compression) for tissue maturation in vitro [2]. | Creation of advanced 3D tissue constructs (e.g., cartilage, bone) prior to implantation [2]. |

| Analytical Tools | Multi-Omics Technologies (Genomics, Proteomics) | Provide a systems-level view of drug actions and mechanisms; enable identification of novel targets and biomarkers [1]. | Profiling cellular responses to regenerative therapies to fully define the mechanism of action (MoA) [1]. |

| Computational Tools | Artificial Intelligence (AI) & Machine Learning | Predict drug-target interactions, optimize drug delivery systems, and anticipate cellular responses [1]. | Accelerating drug repurposing and predicting pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic profiles of regenerative approaches [1] [6]. |

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting Translational Barriers in Regenerative Pharmacology

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: Why do our therapeutic candidates consistently show promise in preclinical models but fail in human clinical trials?

This is a primary manifestation of the "Valley of Death," often caused by a "failure to fail" early in the qualification process [7]. The major causes of failure are typically a lack of effectiveness and poor safety profiles not predicted in preclinical studies [8]. Key culprits include:

- Over-reliance on murine models that do not faithfully reproduce human disease pathology or its temporal development [7].

- Poorly specified methods and variable, context-dependent behavior of tools and cell lines, contributing to a widely acknowledged lack of reproducibility in research findings [7].

- Use of "pure" animal models that lack the natural exposures, co-morbidities, and aged physiology of the target human population, which can critically influence therapeutic response [7].

FAQ 2: What are the most significant manufacturing and regulatory hurdles for advanced regenerative therapies?

The transition from small-scale academic production to large-scale, clinically viable manufacturing presents significant hurdles [1].

- Manufacturing Issues: Scalability, automated production methods, and adherence to Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) are major challenges [1].

- Complex Regulatory Pathways: Different regional requirements from agencies like the EMEA and FDA, with a lack of unified guidelines, complicate the approval process for Advanced Therapy Medicinal Products (ATMPs) [1].

- Characterization Hurdles: A key translational challenge is the need to optimize, characterize, and scale up the manufacturing and maturation of bioengineered and regenerating tissues [1].

FAQ 3: How can we improve the predictive value of our preclinical efficacy and safety studies?

Mitigating this risk requires a multi-faceted strategy:

- Incorporate Human-Relevant Systems: Utilize emerging technologies such as organ/disease-on-a-chip models that can be configured with patient-derived cells of the correct age and exposure history [7].

- Adopt a Holistic Pharmacology Approach: Implement Integrative and Regenerative Pharmacology (IRP) strategies, which include studies ranging from in vitro and ex vivo systems to animal models that better recapitulate human clinical conditions [1].

- Focus on Mechanopharmacology: Consider the effects of drugs on cellular mechanics and, critically, the effects of the mechanical environment on drug actions, as this is often non-physiological in standard assays [7].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Troubleshooting Preclinical Translation Failures

| Observed Problem | Potential Causes | Recommended Solutions & Methodologies |

|---|---|---|

| Lack of efficacy in Phase II trials | Poor target validation; unrepresentative animal models; irreproducible data [7] [8]. | - Target Identification: Employ systems biology approaches. Use omics (genomics, proteomics) and bioinformatic tools to identify targets within disease networks [1].- Model System: Develop more physiologically relevant models. Use 3D cell cultures, organoids, and organ-on-a-chip technology to better mimic human pathophysiology [1] [7]. |

| Unexpected toxicity or immune reactions | Poor predictive value of standard toxicological methods; species-specific differences [8] [9]. | - Improved Safety Screening: Utilize human stem cell-derived tissues in organ-on-a-chip systems for more relevant toxicology screening [7].- Biomaterial Testing: For regenerative applications, rigorously test biomaterials (e.g., natural/synthetic polymers) for immune response and degradation profiles in advanced model systems [10]. |

| Inconsistent product quality and function | Lack of standardized, scalable manufacturing processes; insufficient product characterization [1] [11]. | - Process Development: Implement Quality by Design (QbD) principles early in process development.- Characterization Protocols: Develop robust assays to characterize critical quality attributes (CQAs) of the product, such as cell phenotype, secretome, and biomaterial properties [1]. |

Guide 2: Navigating the Translational Pathway - Quantitative Hurdles

The following table summarizes the stark quantitative challenges of crossing the "Valley of Death," based on industry-wide analyses [8].

| Translational Stage | Attrition Rate / Quantitative Challenge | Primary Reasons for Failure |

|---|---|---|

| Basic Research to Human Trials | 80-90% of research projects fail before human testing [8]. | Irrelevance to human disease; lack of funding and technical expertise to advance [8]. |

| Phase III Clinical Trials | ~50% of experimental drugs fail in Phase III [8]. | Lack of effectiveness; poor safety profiles [8]. |

| Overall Process (Discovery to Approval) | Only 0.1% of candidates become approved drugs [8]. | High cumulative attrition across all stages [8]. |

| Development Cost & Time | ~$2.6 billion and >13 years per approved drug [8]. | High failure rates, lengthy timelines, and regulatory costs [8]. |

Experimental Protocols for Overcoming Translational Challenges

Protocol 1: Establishing a Predictive Organ-on-a-Chip Model for Efficacy Screening

This methodology aims to address the limitation of traditional animal models by using a human cell-based system that better mimics the in vivo mechanical and cellular environment [7].

- Chip Design and Fabrication: Select or fabricate a microfluidic device with relevant chamber geometry. The device should incorporate flexible membranes if mechanical strain is a pathophysiological factor.

- Cell Sourcing and Differentiation: Source primary human cells or patient-specific induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC)-derived cells relevant to the target tissue (e.g., endothelial cells, parenchymal cells).

- Seeding and Culture: Seed cells into the respective chambers of the device under sterile conditions. Allow cells to adhere and form a confluent monolayer or 3D structure.

- Disease Modeling: Induce a disease state in vitro using chemical, mechanical, or genetic stimuli. Validate the model by confirming known disease biomarkers or functional changes.

- Therapeutic Testing: Introduce the therapeutic candidate (small molecule, biologic, or cell therapy) at clinically relevant doses. Include appropriate controls.

- Endpoint Analysis: Assess efficacy using functional readouts (e.g., barrier integrity, contraction force, albumin production), molecular analyses (e.g., qPCR, RNA-seq), and immunohistochemistry.

The workflow for developing and validating such a model is outlined below.

Protocol 2: Implementing a Biomaterial-Based Localized Drug Delivery System

This protocol is for developing localized drug delivery systems (DDSs) to promote healing without systemic side-effects, a key goal in regenerative pharmacology [1] [10].

- Biomaterial Selection: Choose a biomaterial based on application needs. Common options include:

- Natural Polymers: Alginate, collagen, hyaluronic acid (good biocompatibility).

- Synthetic Polymers: PLGA, PCL (tunable degradation and mechanical properties).

- Drug/Bioactive Molecule Incorporation: Incorporate the therapeutic agent (e.g., growth factor, small molecule, siRNA) into the biomaterial matrix. Methods include physical adsorption, covalent bonding, or encapsulation within nanoparticles.

- System Fabrication: Fabricate the final DDS. This could involve electrospinning to create nanofibrous scaffolds, 3D bioprinting to create structured constructs, or crosslinking to form hydrogels.

- In Vitro Release Kinetics and Bioactivity Testing: Immerse the DDS in a buffer solution (PBS) at 37°C. Sample the release medium at predetermined time points and quantify the released drug via HPLC or ELISA. Test the bioactivity of the released compound on target cells.

- In Vivo Efficacy and Safety Testing: Implant the drug-loaded DDS in a relevant animal model of disease/injury. Assess functional recovery over time and upon endpoint, analyze the tissue for regeneration, integration, and immune response (histology).

The following diagram illustrates the decision-making process for developing such a system.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

This table details essential materials and platforms used in advanced translational research for regenerative pharmacology.

| Research Reagent / Platform | Function in Translational Research |

|---|---|

| Organ-on-a-Chip Microfluidic Devices | Micro-engineered systems that recapitulate organ-level physiology and disease pathology for more predictive drug efficacy and toxicity testing than conventional models [7]. |

| Natural & Synthetic Biomaterials | Polymers (e.g., alginate, collagen, PLGA) used as scaffolds or drug delivery vehicles to provide mechanical support and sustained, local release of bioactive molecules in tissue engineering [1] [10]. |

| Stimuli-Responsive "Smart" Biomaterials | Biomaterials engineered to alter their properties (e.g., shape, drug release profile) in response to internal or external triggers (e.g., pH, enzyme activity), enabling targeted and controlled therapy [1]. |

| Patient-Derived Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells (iPSCs) | A source of patient-specific cells for creating disease models, screening drugs, and developing personalized cell therapies, directly supporting precision medicine goals [1] [11]. |

| Advanced Omics Profiling Tools | Platforms for genomics, proteomics, and metabolomics that help deconstruct mechanisms of action, identify biomarkers, and map disease networks for better target identification [1]. |

Troubleshooting Guide: Navigating Common Translational Roadblocks

This guide provides targeted solutions for frequent challenges encountered in translational regenerative pharmacology, helping you advance your research from the bench to the bedside.

FAQ: My cell-based therapy shows inconsistent efficacy in animal models. How can I troubleshoot this?

Problem: Variable therapeutic outcomes in preclinical testing of regenerative therapies.

Solution: Implement a systematic troubleshooting protocol to identify the root cause [12] [13].

Step 1: Verify Cellular Material Quality Check for genetic and epigenetic variants that emerge during in vitro culture, as these can create aberrant subpopulations with reduced regenerative potency [14]. Use fluorescence-activated cell sorting to isolate subpopulations with validated markers of therapeutic efficacy [14].

Step 2: Assess Biomaterial-Tissue Interaction Confirm your delivery system (e.g., hydrogel) interacts appropriately with the host environment. Inconsistent cell-material interactions due to improper protein adsorption or interfacial geometry can drastically alter therapeutic outcomes [14].

Step 3: Analyze the Host Immune Response The host immune system significantly impacts therapy integration and performance [14]. Evaluate innate and adaptive immune responses to your therapeutic construct, as uncontrolled inflammation can destroy regenerative potential.

Preventive Measures:

- Implement rigorous pre-screening of cell subpopulations before transplantation [14].

- Use biomaterials with tissue-matched mechanical properties that provide appropriate spatial and temporal cues [14].

Table: Troubleshooting Inconsistent Preclinical Efficacy

| Problem Area | Diagnostic Tests | Potential Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Cellular Variability | Genetic screening, potency assays, FACS analysis | Isolate therapeutic subpopulations; optimize culture conditions [14] |

| Biomaterial Integration | Histology, mechanical testing, protein adsorption assays | Modify material hydrophilicity; incorporate cell-binding domains [14] |

| Host Immune Rejection | Cytokine profiling, immune cell infiltration analysis | Use immunosuppressants; employ immune-modulating biomaterials [14] |

FAQ: How can I navigate the complex regulatory pathways for Advanced Therapy Medicinal Products (ATMPs)?

Problem: Regulatory approval processes for regenerative therapies are complex, vary by region, and contribute significantly to development timelines [15] [1].

Solution: Develop a proactive regulatory strategy that begins early in development.

Engage Regulatory Agencies Early: Seek input from the FDA, EMA, and other relevant bodies during early development stages to clarify expectations and study design requirements [15]. Pre-IND meetings can prevent costly delays later.

Understand Regional Differences: Regulatory frameworks differ significantly across regions [15] [1]. While the FDA emphasizes randomized controlled trials, the EMA often requires additional real-world evidence for certain drug classes [15].

Utilize Accelerated Pathways: For therapies addressing unmet medical needs, explore designated pathways like the FDA's Breakthrough Therapy Designation or the EMA's PRIME initiative, which can expedite reviews [15].

Implement Robust Quality Systems: Adhere to Good Manufacturing Practices (GMP) and establish a comprehensive Quality Management System (QMS). Non-compliance can result in approval delays or post-market recalls, even for effective therapies [15] [16].

Critical Documentation:

- Maintain meticulous records of preclinical and clinical trial data, pharmacokinetics, toxicology reports, and manufacturing protocols [15].

- Ensure all regulatory submissions are complete and properly formatted to avoid rejection or requests for additional data [15].

FAQ: My regenerative therapy faces manufacturing scalability challenges. What should I consider?

Problem: Transitioning from laboratory-scale production to commercially viable manufacturing while maintaining quality and consistency.

Solution: Address key manufacturing hurdles through strategic planning and technology adoption.

Automate Production Processes: Invest in automated production methods and technologies to ensure consistency and reduce contamination risks [1] [17].

Implement Digital Quality Systems: Leverage AI-driven analytics to monitor environmental conditions and predict equipment failures, mitigating risks that can halt production [17].

Adopt Modular Manufacturing Platforms: Consider portable, scalable bioreactors that reduce cross-contamination risks and offer production flexibility [17].

Plan for Economic Sustainability: High manufacturing costs limit accessibility, particularly in low and middle-income countries [1]. Develop cost-effective manufacturing strategies early in development.

Table: Comparative Analysis of Regulatory Pathways for ATMPs

| Regulatory Aspect | U.S. (FDA) | European Union (EMA) | Accelerated Pathways |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Authority | Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research (CBER) | Committee for Advanced Therapies (CAT) | Breakthrough Therapy, Fast Track (FDA); PRIME (EMA) [15] |

| Clinical Evidence | Emphasizes randomized controlled trials [15] | May require additional real-world evidence [15] | Substantial improvement over existing therapies [15] |

| Manufacturing Standards | Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) [15] | Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) [1] | Same rigorous standards but with more agency collaboration [15] |

| Post-Market Surveillance | Required long-term safety monitoring [15] | Required long-term safety monitoring [1] | Often enhanced monitoring requirements [15] |

Experimental Protocols for Translational Research

Protocol: Standardized Procedure for Evaluating MSC-Hydrogel System Efficacy

Purpose: To systematically assess the therapeutic potential of mesenchymal stem cell (MSC)-hydrogel systems for burn wound regeneration [18].

Materials:

- Research Reagent Solutions:

- Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs): Primary therapeutic agents; promote angiogenesis, modulate inflammation [18] [14].

- Hydrogel Scaffold: 3D biomaterial network; provides structural support, controls cell delivery [18] [14].

- Chondrogenic Lineage Markers: Antibodies for CD44, CD73, CD90; verify MSC phenotype and differentiation potential [14].

- Angiogenesis Assay Kit: Quantifies vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) secretion; measures pro-angiogenic activity [18].

- TNF-α & IL-6 ELISA Kits: Measures inflammatory cytokine levels; assesses immunomodulatory capacity [18].

Methodology:

- Cell Preparation: Isolate and expand MSCs using fluorescence-activated cell sorting to isolate highly chondrogenic subpopulations [14].

- Hydrogel Encapsulation: Seed MSCs into hydrogel system at optimized density. For advanced systems, use 3D-bioprinted scaffolds or exosome-enriched hydrogels [18].

- In Vivo Implantation: Apply MSC-hydrogel construct to burn wound model. Include appropriate controls (hydrogel only, untreated wound) [18].

- Efficacy Assessment:

- Monitor wound closure rates weekly

- Collect tissue biopsies for histology at predetermined endpoints

- Assess angiogenesis (CD31 staining), inflammation (CD45 staining), and ECM deposition (Masson's trichrome)

- Quantify regenerative biomarkers via ELISA or qPCR [18]

- Statistical Analysis: Perform appropriate statistical tests with significance set at P<0.05 [19].

Troubleshooting Notes:

- If wound healing is impaired, check MSC viability post-encapsulation and inflammatory status of wound bed [14].

- For excessive inflammation, consider modifying hydrogel properties or adding anti-inflammatory factors [18].

Protocol: Systematic Troubleshooting of Experimental Failures

Purpose: To provide a structured approach for identifying and resolving research problems [12] [13].

Methodology:

- Identify the Problem: Clearly define what went wrong without speculating on causes [13]. Example: "No PCR product detected" rather than "Taq polymerase was bad" [13].

- List All Possible Explanations: Brainstorm both obvious and non-obvious potential causes [13]. For molecular biology experiments, consider reagents, equipment, and procedural variations [12].

- Collect Data: Systematically investigate each potential cause, starting with the easiest to check [13].

- Verify equipment function

- Review control results

- Check reagent storage conditions and expiration dates

- Compare your procedure with established protocols [12]

- Eliminate Explanations: Based on collected data, rule out factors that are not contributing to the problem [13].

- Check with Experimentation: Design targeted experiments to test remaining hypotheses. Change only one variable at a time to isolate the true cause [12] [19].

- Identify the Cause: Once determined, implement corrective actions and document the solution thoroughly [13].

Key Principles:

- Always repeat experiments unless cost or time prohibitive [12].

- Maintain meticulous documentation in a lab notebook [12] [13].

- Consult with experienced colleagues who may have encountered similar issues [12].

Visualizing Translational Workflows

Regenerative Therapy Translation Path

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Key Reagents for Regenerative Pharmacology Research

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs) | Primary therapeutic agents; promote angiogenesis, modulate inflammation, differentiate into multiple lineages [18] [14] | Source carefully (autologous vs. allogeneic); screen for genetic variants; isolate subpopulations with enhanced potency [14] |

| 3D-Bioprinted Scaffolds | Provide structural support for tissue formation; enable spatial control of cell delivery [18] | Use stimuli-responsive systems that alter properties in response to environmental triggers [18] [1] |

| Exosome-Enriched Hydrogels | Enhanced regenerative capacity; cell-free alternative to whole-cell therapies [18] | Isolate from conditioned media of therapeutic cells; characterize cargo before use [18] |

| Stimuli-Responsive Biomaterials | "Smart" materials that release bioactive compounds in response to specific triggers [1] | Design to respond to physiological cues (pH, enzymes) for localized, controlled drug delivery [1] |

| Quality Control Assays | Ensure safety, potency, and consistency of regenerative products [15] [14] | Include genetic stability tests, potency assays, sterility testing, and characterization of critical quality attributes [14] |

Integrative and Regenerative Pharmacology (IRP) represents a paradigm shift in biomedical science, merging pharmacology, systems biology, and regenerative medicine to develop therapies that restore physiological structure and function rather than merely managing symptoms [1]. This approach faces significant translational barriers that delay the movement of promising therapies from bench to bedside. Interestingly, researchers in neurodegenerative diseases and rare diseases confront strikingly similar challenges, particularly regarding biological barriers, manufacturing complexity, and regulatory hurdles. This technical support center synthesizes troubleshooting guidance and methodological approaches from these analogous fields, providing regenerative pharmacology researchers with practical strategies to overcome critical translational roadblocks.

Technical Troubleshooting Guides

Challenge 1: Overcoming Biological Barriers for Targeted Delivery

Core Issue: The blood-brain barrier (BBB) prevents more than 98% of small molecules and all biologics from entering the central nervous system, while similar biological barriers impede delivery to target tissues in regenerative therapies [20] [21].

| Solution Approach | Underlying Principle | Key Limitations | Translational Readiness |

|---|---|---|---|

| Receptor-mediated transcytosis | Utilizes endogenous transport systems (TfR, IR, LRP1) for brain delivery [20] | Limited receptor capacity, immunogenicity concerns | Clinical stage (bispecific antibodies) |

| Ligand-decorated nanoparticles | Surface-functionalized carriers for active targeting [20] | Scalability, batch-to-batch variability | Preclinical/early clinical |

| Focused ultrasound + microbubbles | Temporarily disrupts BBB under image guidance [20] [21] | Precision required, safety concerns for repeated use | Mid-stage clinical trials |

| Cell-based "Trojan horse" | Uses cells (e.g., stem cells, macrophages) as carriers [20] | Cell viability, limited payload capacity | Preclinical development |

| Intranasal delivery | Bypasses BBB via olfactory and trigeminal pathways [20] | Limited dosage, mucosal clearance | Early clinical evaluation |

Recommended Experimental Protocol: Screening for BBB Permeability

- In silico prediction: Utilize machine learning models (e.g., SwissSimilarity, Pharmit) to screen compound libraries based on physicochemical properties and structural similarity to known CNS-active drugs [22].

- Pharmacophore modeling: Develop ligand-based pharmacophore models using approved CNS drugs as templates for virtual screening [22].

- BBB permeability classification: Apply BBB prediction models to classify compounds as permeable (CNS+) or non-permeable (CNS-) based on brain-to-blood ratio calculations [22].

- ADME and toxicity profiling: Evaluate pharmacokinetics, toxicophores, and drug-likeness properties to prioritize lead compounds [22].

- In vitro validation: Use human brain microvascular endothelial cell models to confirm BBB permeation predicted in silico.

Challenge 2: Manufacturing and Scalability Constraints

Core Issue: The complex, personalized nature of regenerative therapies and cell/gene therapies presents significant challenges for scaled production, particularly with the limited number of production facilities and high costs associated with small-batch production [23].

Troubleshooting Strategies:

- Implement advanced automation: Streamline manufacturing processes to improve efficiency and scalability while reducing contamination risks [23].

- Establish decentralized production hubs: Create regional manufacturing centers to facilitate quicker, localized access to therapies [23].

- Develop "off-the-shelf" approaches: Where possible, engineer universal donor cell lines or standardized biomaterial platforms to reduce personalization requirements [1].

- Optimize cryopreservation protocols: Enhance cell viability and functionality post-thaw to improve logistics and extend shelf-life.

- Adopt quality-by-design (QbD) principles: Implement systematic approaches to process development that ensure product quality through design rather than through end-product testing alone.

Challenge 3: Clinical Translation and Regulatory Navigation

Core Issue: Complex regulatory pathways, challenges in patient recruitment for rare diseases, and lack of historical precedent for novel therapeutic modalities create significant delays in approval and clinical adoption [23] [1].

Troubleshooting Strategies:

- Engage regulatory agencies early: Pursue pre-IND meetings with FDA/EMA to align on development plans, endpoints, and CMC requirements [23].

- Incorporate real-world evidence (RWE): Collect and standardize RWE alongside traditional clinical trial data to provide additional insights into effectiveness and safety [23].

- Leverage expedited regulatory programs: Pursue appropriate designations (RMAT, Breakthrough Therapy, Priority Review) that can shorten development timelines [23] [24].

- Implement decentralized trial designs: Utilize remote monitoring and telemedicine to enhance patient accessibility and recruitment [23].

- Collaborate with patient advocacy groups (PAGs): Partner with PAGs for patient education, support, and enrollment, while gaining actionable insights into real-world needs [23].

Experimental Workflow: From Target Identification to Translation

The following diagram illustrates an integrative workflow that incorporates lessons from neurodegenerative and rare disease research to overcome translational barriers in regenerative pharmacology.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Research Reagent / Tool | Primary Function | Application Context | Translational Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Machine learning prediction models | In silico BBB permeability and CNS activity screening [22] | Early compound prioritization | Reduces late-stage attrition; requires experimental validation |

| Ligand-decorated nanoparticles | Targeted drug delivery across biological barriers [20] | Preclinical proof-of-concept studies | Surface chemistry critical for targeting efficacy; scalability challenges |

| Stimuli-responsive biomaterials | Spatiotemporally controlled drug release [1] | Tissue engineering and regenerative applications | Responsiveness to physiological triggers must match disease environment |

| Human brain microvascular endothelial cells | In vitro BBB model development [22] | Permeability and transport mechanism studies | Limited complexity compared to in vivo neurovascular unit |

| Real-world evidence (RWE) frameworks | Post-marketing safety and effectiveness monitoring [23] | Clinical development and regulatory submissions | Requires standardized data collection and validation methodologies |

| Patient-derived cellular models | Disease modeling and personalized therapy screening [1] | Preclinical efficacy assessment | Better predicts human response than animal models; genetic stability concerns |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What computational approaches are most effective for early prediction of blood-brain barrier permeability in regenerative therapy candidates?

A: Machine learning models that incorporate physicochemical properties and structure-activity relationships have demonstrated high predictability for BBB permeability [22]. Implement a tiered approach beginning with ligand-based virtual screening using tools like Pharmit and SwissSimilarity, followed by BBB-specific classification models, and finally ADME/toxicity profiling. This sequential filtering can identify CNS-active molecules with appropriate barrier penetration properties while reducing late-stage attrition [22].

Q2: How can we address the manufacturing scalability challenges for personalized regenerative therapies?

A: Advanced automation and data analytics can streamline complex manufacturing processes [23]. Consider establishing decentralized production hubs to facilitate localized access [23]. For cell-based approaches, invest in "off-the-shelf" technologies such as universal donor cell lines that reduce personalization requirements. Early collaboration with regulatory agencies on Chemistry, Manufacturing, and Controls (CMC) strategies is essential to avoid scalability-related delays.

Q3: What regulatory strategies can accelerate the development of regenerative pharmacology products?

A: Pursue expedited regulatory programs such as the Regenerative Medicine Advanced Therapy (RMAT) designation, which provides intensive FDA guidance throughout development [24]. Incorporate real-world evidence (RWE) collection into development plans to support effectiveness claims [23]. Engage patient advocacy groups early for insights on meaningful endpoints and to support recruitment, as their involvement is increasingly valued by regulators.

Q4: How can we improve patient recruitment for clinical trials of rare disease treatments?

A: Implement artificial intelligence-driven patient matching to efficiently identify eligible participants [23]. Adopt decentralized trial designs with remote monitoring to reduce geographic and mobility barriers [23]. Collaborate closely with patient advocacy groups (PAGs) for patient education and outreach, as they are instrumental in building trust and awareness within rare disease communities.

Q5: What targeted delivery approaches show most promise for overcoming the blood-brain barrier?

A: Ligand-decorated nanoparticles functionalized with transferrin receptor or insulin receptor antibodies show significant promise by leveraging receptor-mediated transcytosis [20]. Bispecific antibody shuttles that engage endogenous transport systems while targeting disease-specific pathways are advancing clinically [20]. Focused ultrasound-mediated BBB disruption offers temporary, image-guided barrier opening for localized delivery, though it requires specialized equipment and expertise [20] [21].

Key Signaling Pathways in Neuroregeneration

The following diagram illustrates major signaling pathways involved in neuroregeneration and their modulation by pharmacological interventions, integrating knowledge from neurodegenerative disease research.

Bridging the Gap: Technological Innovations and Disruptive Tools

FAQs: Foundational AI Concepts for Drug Discovery

Q1: What are the core AI technologies used in modern drug discovery troubleshooting? Modern AI-driven drug discovery primarily leverages Machine Learning (ML), Deep Learning (DL), and Natural Language Processing (NLP) to identify, diagnose, and resolve technical issues. ML models analyze vast datasets to predict equipment failures and diagnose root causes. DL, including architectures like Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) and Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs), is used for complex tasks such as predicting drug-target interactions and drug sensitivity. NLP systems power intelligent chatbots and analyze scientific literature to provide context-aware support and extract hidden biological connections [25] [26].

Q2: Why is data quality often cited as the most critical factor for AI success? The principle of "garbage in, garbage out" is paramount. AI models are only as reliable as their input data. Poor quality data—such as inconsistent formats, unreproducible results, or outdated information—can lead to incorrectly chosen drug targets, biased models, and ultimately, failed experiments. High-quality, structured data is the non-negotiable foundation for generating accurate, trustworthy AI insights [27] [28].

Q3: What are the FAIR data principles and why are they important for AI? FAIR stands for Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable. Adhering to these principles ensures that data is:

- Findable: Richly described with metadata for easy discovery.

- Accessible: Available through standard protocols.

- Interoperable: Structured and integrated for use across different projects and platforms.

- Reusable: Well-described and governed to support replication and further research. Implementing FAIR principles prevents data silos, facilitates seamless data integration for AI models, and creates a scalable foundation for innovation [27].

Q4: How does AI-powered technical support enhance the research workflow? AI-powered support systems transform research efficiency by providing:

- 24/7 Availability: Continuous assistance without human intervention.

- Predictive Analytics: Identifying potential issues before they cause downtime.

- Automated Ticketing: Categorizing and prioritizing support requests based on urgency.

- Continuous Learning: Improving diagnostic accuracy over time by learning from new data and user interactions [25]. This allows research teams to focus on complex, high-value problems while routine troubleshooting is automated.

Troubleshooting Guides: Common Experimental Scenarios

Guide 1: Troubleshooting Poor AI Model Performance

Problem: Your AI model for predicting drug-target interactions is producing inaccurate or unreliable results.

Solution:

- Step 1: Audit Your Data Quality and Quantity

- Verify data provenance and ensure rigorous quality control procedures are in place. Every data point should be overseen by a human expert where possible [28].

- Assess if you have enough high-quality data. AI-first methods can be limited by the extremely small fraction of the drug-like chemical universe for which experimental data exists [29].

- Check for a lack of "negative data" (e.g., failed experiments), which is as crucial as positive findings for training a robust model [29].

- Step 2: Validate Against a Benchmark Dataset

- Test your model on established, public benchmark datasets to determine if the problem is with your model or your proprietary data. Commonly used datasets include those for Drug-Target Interactions (DTIs) and Drug-Drug Interactions (DDIs) [26].

- Step 3: Increase Model Transparency

- For instilling confidence, document and communicate the model's constraints, inherent assumptions, and validation processes. Use tools that provide visibility into which features (e.g., mechanism of action, clinical trial history) are positively or negatively affecting a prediction [28].

- Step 4: Foster Cross-Disciplinary Collaboration

- Ensure close collaboration between data scientists and therapeutic area experts. Generalist platforms relying solely on data scientists often lack the granular life science insights needed for meaningful outputs [28].

Guide 2: Troubleshooting Assay Integration with AI Predictions

Problem: There is a significant discrepancy between AI-predicted compound activity and experimental assay results.

Solution:

- Step 1: Verify Instrumentation and Reagents

- A complete lack of an assay window often points to an instrument setup problem. Consult instrument setup guides for specific assay types (e.g., TR-FRET) [30].

- For TR-FRET assays, the single most common failure point is the use of incorrect emission filters. Ensure you are using the exact filters recommended for your instrument [30].

- Test your microplate reader’s setup using control reagents before running your main experiment [30].

- Step 2: Analyze Compound and Stock Solutions

- Differences in EC50/IC50 values between labs are frequently traced back to differences in stock solution preparation [30].

- In cell-based assays, consider if the compound is unable to cross the cell membrane, is being pumped out, or is targeting an inactive form of the kinase, which would not be active in a biochemical assay [30].

- Step 3: Implement Robust Data Analysis

- For TR-FRET, always use ratiometric data analysis (acceptor signal / donor signal). This accounts for pipetting variances and lot-to-lot reagent variability [30].

- Use the Z'-factor to assess assay robustness. An assay with a large window but high noise (low Z'-factor) is less reliable than one with a smaller window and low noise. A Z'-factor > 0.5 is generally considered suitable for screening [30].

Guide 3: Troubleshooting ADMET Prediction Errors

Problem: AI models accurately predict a compound's potency, but it fails due to poor Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, or Toxicity (ADMET) properties.

Solution:

- Step 1: Integrate Specialized ADMET Tools

- Use AI platforms specifically tailored for ADMET optimization, which use custom deep-learning architectures to predict complex assay outcomes in real-time during the compound design phase [31].

- Step 2: Leverage Consortium Data

- Participate in or utilize models trained on pre-competitive, shared ADMET data from multiple pharma partners. This "flywheel effect" expands the training dataset with high-quality, experimental ADMET data, improving model accuracy for challenges like metabolic stability and permeability [31].

- Step 3: Prioritize Explainable Predictions

- Choose platforms that provide probability estimates and highlight which specific parts of a molecule are likely causing the ADMET issue, allowing chemists to make informed design adjustments before synthesis [31].

Data Presentation: AI Platforms & Data Management

Comparison of Leading AI Drug Discovery Platforms

Table 1: Top AI Platforms for Drug Discovery in 2025: Features, Pros, and Cons

| Platform Name | Best For | Standout Feature | Key Pros | Key Cons/Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exscientia [32] | Large pharma, Oncology | Centaur AI for rapid drug design | Reduces early-stage development time by up to 70%; High Phase I success rate. | Complex setup for teams without AI expertise; Focus primarily on small molecules. |

| BenevolentAI [32] | Rare diseases, Drug repurposing | Massive knowledge graph for uncovering hidden biological connections | Cuts development costs by up to 70%; Strong focus on rare diseases. | High dependency on input data quality; Requires robust computational infrastructure. |

| Insilico Medicine [32] | End-to-end drug discovery | Pharma.AI suite (target discovery to clinical prediction) | Comprehensive, validated suite; High success rate in identifying actionable targets. | Steep learning curve; Pricing can be prohibitive for small startups. |

| Atomwise [32] | Biotech startups, Rare diseases | AtomNet for structure-based drug design & binding affinity prediction | Fast screening reduces early-stage timelines; Accessible for academic teams. | Requires high-quality structural data; Limited focus on clinical trial prediction. |

| Inductive Bio [31] | ADMET optimization | Custom deep learning for real-time, molecular-level ADMET insights | Solves a key bottleneck; Real-time, explainable predictions for chemists. | Focused exclusively on ADMET, not a full pipeline solution. |

Essential Data Management Practices for AI-Ready Research

Table 2: Key Practices to Overcome Data Pitfalls in AI-Driven Discovery

| Practice Category | Specific Action | Function & Benefit |

|---|---|---|

| Data Structuring [27] | Organize data into standardized, machine-readable formats with consistent naming conventions. | Lays the groundwork for AI; enables models to extract meaningful insights efficiently. |

| Centralized Management [27] | Implement a specialized Laboratory Information Management System (LIMS). | Prevents data fragmentation; ensures all teams access the same structured, consistent data. |

| FAIR Principles [27] | Make data Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable. | Creates a robust, scalable foundation for AI; prevents data silos and enables data reuse. |

| Governance & Curation [28] | Establish data provenance and implement continuous quality checks for new data. | Ensures output reliability; helps avoid decisions based on outdated or biased information. |

| Cross-Disciplinary Collaboration [28] | Foster collaboration between data scientists and domain experts. | Combines technical know-how with therapeutic insight to develop effective, reliable models. |

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Protocol: AI-Human Partnership for Drug Repurposing

This protocol outlines a hybrid workflow for identifying new drug targets for existing compounds, leveraging the strengths of both AI and human expertise [28].

- AI-Powered Knowledge Extraction: Use algorithms to extract and analyze knowledge from integrated drug discovery databases (e.g., Cortellis Drug Discovery Intelligence) and public sources.

- Machine Learning Prioritization: Apply ML models to the extracted data to generate an initial list of prioritized drug targets for a given disease indication.

- Expert Review and Refinement: Subject matter experts review the AI-generated list. This involves manual mechanism reconstruction and applying deep domain knowledge to refine the target list.

- Report Generation: Produce a final report for each prioritized target, detailing supporting evidence, mechanism of action, relevant pathways, and clinical status of modulating drugs.

The following workflow diagram illustrates this collaborative, multi-stage process:

Protocol: Troubleshooting a Failed TR-FRET Assay

This guide provides a step-by-step methodology for diagnosing a TR-FRET assay that shows no signal or a poor assay window [30].

Reader Setup Verification:

- Consult the instrument compatibility portal for your specific microplate reader model.

- Confirm that the exact recommended emission and excitation filters for TR-FRET are correctly installed. This is the most common point of failure.

- Use control reagents from your assay kit to test the reader's TR-FRET functionality before using precious experimental samples.

Reagent and Compound Check:

- Verify the preparation of all stock solutions and dilutions. Inconsistent compound stocks are a primary reason for EC50/IC50 discrepancies between labs.

- Confirm the activity and specificity of enzymes (e.g., kinases) and other biological reagents.

Ratiometric Data Analysis:

- Calculate the emission ratio (Acceptor Signal / Donor Signal, e.g., 520nm/495nm for Tb). Do not rely on raw RFU values from a single channel.

- The donor signal acts as an internal reference, normalizing for pipetting variance and lot-to-lot reagent variability.

Assay Robustness Calculation:

- Calculate the Z'-factor using the formula:

Z' = 1 - [3*(σ_positive_control + σ_negative_control) / |μ_positive_control - μ_negative_control|]. - A Z'-factor > 0.5 indicates a robust assay suitable for screening. A large assay window with high noise (low Z'-factor) is not reliable.

- Calculate the Z'-factor using the formula:

The logical troubleshooting path for this scenario is as follows:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Their Functions in AI-Integrated Discovery

| Reagent / Tool Category | Specific Example(s) | Primary Function in Experimentation |

|---|---|---|

| TR-FRET Assay Kits [30] | LanthaScreen Eu/Tb Kinase Binding Assays | Enable homogeneous, high-throughput screening and profiling of compound-target interactions by measuring resonance energy transfer. |

| Validation Controls [30] | 100% Phosphopeptide Control, 0% Phosphorylation Control (Substrate) | Provide reference points for assay window (Z'-factor) calculation and verify proper functioning of the assay development reaction. |

| Specialized LIMS [27] | Biologics LIMS | Centralizes and structures complex biologics data (samples, assays, entities); ensures data is AI-ready and FAIR-compliant. |

| AI for ADMET Optimization [31] | Inductive Bio's Compass Platform | Provides real-time, explainable predictions on absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity during compound design. |

| Multi-Omics Data Sources [28] [26] | Genomic, Proteomic, Patient-Centric Data | Provides the high-quality, diverse biological data required to train AI models for target identification and patient stratification. |

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

This section addresses common experimental challenges in the development of advanced biomaterials and smart scaffolds for regenerative pharmacology, providing targeted solutions to help overcome key translational barriers.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: Our 3D-bioprinted construct lacks sufficient vascularization for larger tissue models. What strategies can improve this?

- Challenge: A primary translational barrier for engineered tissues is the inability to create perfusable, complex vascular networks that supply nutrients and oxygen to core regions, leading to necrotic centers [33] [34].

- Solutions:

- Co-printing with Bio-inks: Utilize bio-inks laden with endothelial cells and supporting cells (like pericytes) in a defined architecture alongside your primary tissue bio-ink [33].

- Incorporation of Angiogenic Factors: Design your scaffold material to controllably release angiogenic growth factors, such as VEGF (Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor) or SDF-1 (Stromal Cell-Derived Factor-1), to promote host-derived vasculature infiltration and network formation [35].

- Sacrificial Printing: Employ a fugitive bio-ink (e.g., Pluronic F127 or gelatin) that is printed into a network pattern and then liquefied and removed, leaving behind patent, perfusable channels that can be seeded with endothelial cells [33].

FAQ 2: The immune response to our scaffold is causing excessive fibrosis and encapsulation, hindering integration. How can this be modulated?

- Challenge: The foreign body response can lead to fibrotic encapsulation, isolating the scaffold from the host tissue and impairing its function [36] [34].

- Solutions:

- Use Immune-Modulatory Biomaterials: Select or functionalize materials with known anti-inflammatory or pro-regenerative macrophage polarization properties. Examples include certain types of chitosan, decellularized extracellular matrix (ECM), or polymers incorporating IL-10 or TGF-β [37] [35].

- Modify Surface Physicochemical Properties: Tune surface topography (e.g., using micro- and nano-patterning), stiffness, and wettability to create a surface that minimizes the pro-fibrotic immune response and promotes a healing environment [34].

- Controlled Release of Immunomodulators: Load the scaffold with controlled-release systems (e.g., PLGA nanoparticles) containing immune-modulating cytokines or small molecules to actively direct the local immune response toward a regenerative, anti-fibrotic phenotype [38] [37].

FAQ 3: How can I achieve a sustained, multi-stage release of multiple growth factors (e.g., for proliferation followed by differentiation) from a single scaffold?

- Challenge: Native tissue repair occurs in distinct phases, each requiring different biochemical cues. A major translational challenge is replicating this dynamic signaling in vivo [35].

- Solutions:

- Multi-Material Scaffolds: Fabricate a composite scaffold with distinct compartments (e.g., core-shell fibers or multi-layered hydrogels). Each compartment can be tailored with different material properties (e.g., degradation rate) to release its specific payload sequentially [33] [38].

- Layered Incorporation: Incorporate growth factors into the scaffold using different methods for each factor. For instance, one factor can be physically adsorbed for a quick release, while another is encapsulated within slower-degrading microspheres embedded in the scaffold matrix for delayed release [35].

- Stimuli-Responsive Systems: Develop "smart" scaffolds using biomaterials that release their cargo in response to specific physiological stimuli (e.g., matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) present during remodeling, or a shift in pH) that coincide with different stages of healing [33] [38].

FAQ 4: Our nanoparticle-based delivery system for genes/ drugs shows low encapsulation efficiency and rapid burst release. What are the key parameters to optimize?

- Challenge: Low encapsulation efficiency wastes expensive therapeutic cargo (e.g., DNA, RNA, growth factors), and an initial burst release prevents sustained, long-term delivery, potentially causing off-target effects [38] [37].

- Solutions:

- Optimize Formulation Parameters: Systematically vary the polymer-to-drug ratio, surfactant concentration (e.g., PEGylation for PLGA NPs), and solvent selection during the emulsion process to improve drug loading and control release kinetics [37].

- Explore Alternative Materials: Consider cationic polymers like Polyethyleneimine (PEI), which strongly complex nucleic acids through electrostatic interactions, offering high encapsulation and protection from degradation, though its cytotoxicity must be managed [37].

- Post-Formulation Modifications: After nanoparticle formation, surface modification with targeting ligands (e.g., peptides, antibodies) can enhance specificity, while cross-linking the surface can slow down the initial diffusion-based release and provide a more sustained profile [38].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Workflows

Issue: Poor Cell Viability and Infiltration in 3D-Bioprinted Constructs

| Observation | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low cell viability immediately after printing. | Shear stress during extrusion. Nozzle clogging. | Optimize printing pressure and nozzle diameter. Use bio-inks with higher cell viability, such as peptide-based hydrogels or thermo-responsive polymers. Increase bio-ink concentration to reduce shear. |

| Cells fail to proliferate and migrate into the scaffold core. | Scaffold porosity is too low. Pore size is too small. Material is too stiff. | Adjust fabrication parameters (e.g., print temperature, crosslinking density) to create larger, interconnected pores. Select a softer hydrogel material that mimics the native tissue modulus to facilitate cell migration. |

| Viability decreases over time in culture. | Lack of vascularization leading to nutrient/waste diffusion limits. Inadequate degradation creating a physical barrier. | Incorporate angiogenic factors as in FAQ 1. Design the scaffold with a degradation rate that matches tissue ingrowth, using hydrogels sensitive to cell-secreted enzymes (e.g., MMP-sensitive peptides) [33]. |

Issue: Inconsistent or Uncontrolled Drug Release from Smart Scaffolds

| Observation | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| High initial "burst release" of therapeutic agent. | Drug is adsorbed on or near the surface of the scaffold/microparticles. | Increase the density of the polymer matrix or cross-linking. Use a core-shell structure where the shell acts as a diffusion barrier. Switch from physical adsorption to encapsulation methods. |

| Release kinetics do not respond to the intended stimulus (e.g., enzyme, pH). | The stimuli-responsive linker is inaccessible or inefficiently cleaved. The material's responsiveness is not tuned to the physiological range. | Ensure the responsive elements are located in the main degradation pathway of the scaffold. Validate the sensitivity of the material in vitro using relevant concentrations of the stimulus (e.g., specific MMPs at physiological levels). |

| Incomplete release of the encapsulated payload. | The therapeutic agent becomes denatured or trapped within the non-degraded polymer matrix. | Screen for compatibility between the drug and polymer. Consider using a more readily degradable polymer or a polymer blend. Incorporate porogens to create additional release pathways. |

Experimental Protocols & Data Presentation

Detailed Protocol: Fabrication and Characterization of a Dual-Growth Factor Releasing, Core-Shell Fibrous Scaffold

This protocol provides a methodology for creating a scaffold that sequentially releases multiple growth factors, addressing the challenge of replicating the dynamic signaling of natural healing processes [35].

1. Materials Synthesis

- Core Solution: Prepare a 10% w/v solution of slow-degrading polymer (e.g., PLGA 75:25) in an organic solvent (e.g., Dichloromethane, DCM). Encapsulate the differentiation factor (e.g., BMP-2) into this solution.

- Shell Solution: Prepare a 5% w/v solution of fast-degrading polymer (e.g., PLGA 50:50) or a natural polymer like gelatin in a compatible solvent/water. Encapsulate the proliferation factor (e.g., FGF-2) into this solution.

2. Scaffold Fabrication via Coaxial Electrospinning

- Set up a coaxial electrospinning apparatus with two separate syringes pumping the core and shell solutions through a coaxial spinneret.

- Key Parameters:

- Flow Rates: Optimize core and shell flow rates (e.g., 0.5 mL/h and 1.0 mL/h, respectively).

- Voltage: Apply a high voltage (e.g., 15-20 kV) to the spinneret.

- Collector Distance: Maintain a fixed distance (e.g., 15 cm) between the spinneret and the grounded collector drum.

- Collect the core-shell fibers on the drum to form a non-woven mat.

3. Scaffold Sterilization and Hydration

- Sterilize the fibrous mats by exposure to UV light on each side for 30 minutes.

- Hydrate the scaffolds by immersing in 70% ethanol followed by serial washes in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS).

4. In Vitro Release Kinetics Assay

- Cut scaffold samples to a standardized size and mass (e.g., 1 cm² discs, 10 mg).

- Immerse each sample in 1 mL of release medium (PBS with 0.1% BSA) in a microcentrifuge tube.

- Incubate at 37°C under gentle agitation.

- At predetermined time points (e.g., 1, 3, 6, 12, 24 hours, then daily), completely remove the release medium and replace it with fresh pre-warmed medium.

- Analyze the collected medium using an ELISA to quantify the concentration of each growth factor released over time.

Table 1: Characteristic Properties of Common Biomaterials Used in Drug Delivery and Scaffolding

| Material | Type | Key Properties | Common Applications | Key Translational Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PLGA [37] | Synthetic Polymer | Biocompatible, biodegradable, tunable degradation rate, FDA-approved for some uses. | Sustained release microparticles/nanoparticles, 3D scaffolds. | Acidic degradation products can cause local inflammation; burst release can be an issue. |

| Chitosan (CS) [37] | Natural Polymer | Bioadhesive, mucoadhesive, inherent hemostatic and antimicrobial properties. | Nasal/vaccine delivery, wound healing dressings, hydrogel matrices. | Poor solubility at neutral/basic pH; batch-to-batch variability. |

| Polyethyleneimine (PEI) [37] | Synthetic Polymer | High cationic charge density, "proton-sponge" effect for high transfection efficiency. | Gene/drug delivery, nucleic acid complexation. | Dose-dependent cytotoxicity; limited biodegradability. |

| Fibrin | Natural Polymer (Biologically Derived) | Naturally derived from clotting cascade, excellent cell adhesion and biocompatibility. | Hydrogel for cell encapsulation, nerve guide conduits, cardiac patch. | Rapid, uncontrolled degradation; low mechanical strength. |

Table 2: Example In Vitro Release Kinetics Data from a Hypothetical Core-Shell Scaffold

This table summarizes expected data from the protocol in Section 2.1, demonstrating sequential release.

| Time Point (Days) | Cumulative FGF-2 Release from Shell (%) | Cumulative BMP-2 Release from Core (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 45.2 ± 5.1 | 8.5 ± 2.1 |

| 3 | 78.6 ± 4.3 | 15.3 ± 3.0 |

| 7 | 92.1 ± 2.8 | 25.7 ± 4.2 |

| 14 | 95.5 ± 1.5 | 48.9 ± 5.6 |

| 21 | 96.8 ± 1.2 | 72.4 ± 6.1 |

| 28 | 97.5 ± 1.0 | 89.7 ± 4.8 |

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

Key Signaling Pathways in Osteogenic Differentiation

This diagram illustrates the primary signaling pathways targeted for bone regeneration, a common goal in regenerative pharmacology. The release of growth factors like BMP-2 and FGF-2 from scaffolds activates these pathways to direct stem cell fate.

Workflow for Developing a Smart Scaffold

This flowchart outlines a generalized experimental workflow for the design, fabrication, and validation of a smart, responsive scaffold, from initial concept to pre-clinical testing.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Smart Scaffold Development

| Item | Function / Rationale | Example & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| PLGA (Poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid)) [37] | A versatile, FDA-approved biodegradable polymer for creating sustained-release microparticles and 3D scaffolds. | Available in various LA:GA ratios (e.g., 50:50, 75:25) to control degradation rate from weeks to months. |

| MMP-Sensitive Peptide Crosslinker | Enables creation of "smart" hydrogels that degrade specifically in response to cell-secreted enzymes during tissue remodeling. | Sequence: GGPQGIWGQGK (cleavable by MMP-2 and MMP-9). Used in PEG-based or other hydrogels. |

| Chitosan [37] | A natural, bioadhesive polymer with intrinsic antimicrobial properties, ideal for wound healing and mucosal delivery applications. | Often chemically modified (e.g., trimethyl chitosan) to improve solubility and enhance penetration. |

| Recombinant Growth Factors (BMP-2, FGF-2, VEGF) [35] | Key signaling molecules to direct cell proliferation, differentiation, and angiogenesis within the engineered construct. | Highly sensitive to denaturation. Requires careful incorporation and release kinetics testing to ensure bioactivity. |

| Polyethyleneimine (PEI) [37] | A cationic polymer for efficient complexation and delivery of nucleic acids (DNA, siRNA) to cells within the scaffold. | Branched PEI (25 kDa) is common but cytotoxic. Linear PEI or lower molecular weight versions are often better tolerated. |

| RGD Peptide | A common cell-adhesive ligand (Arg-Gly-Asp) grafted onto biomaterial surfaces to promote integrin-mediated cell attachment and spreading. | Crucial for synthetic materials like PEG that lack inherent cell-binding domains. |

| Dual-Syringe Coaxial Electrospinning Setup | Apparatus for fabricating core-shell fibrous scaffolds that allow for sequential or dual delivery of therapeutics. | Allows for spatial control over the location of different drugs/growth factors within a single fiber. |

Harnessing Multi-Omics and Systems Biology for Patient Stratification and Mechanism Deconvolution

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the primary advantage of a multi-omics approach over single-omics studies in translational research? A multi-omics approach provides a more comprehensive molecular profile by integrating data from various biological layers (e.g., genome, transcriptome, proteome, metabolome). This integration is crucial for understanding complex diseases, as a single omics layer cannot fully capture the causal relationships and regulatory mechanisms underlying disease pathogenesis. Multi-omics enables the identification of robust biomarkers, patient subtypes, and dysregulated pathways that would be missed in single-omics studies, thereby enhancing the potential for successful clinical translation [39] [40].

FAQ 2: How can multi-omics data integration help in identifying novel drug targets? Multi-omics integration can uncover key molecular players and signaling pathways involved in disease pathology. By combining genomics, transcriptomics, and proteomics, researchers can move beyond mere associations to understand causal mechanisms. This allows for the identification of "actionable" targets, particularly at the proteome level which is closer to the phenotype. Furthermore, this approach can facilitate drug repurposing by revealing new disease contexts for existing drugs [40] [41].

FAQ 3: What are the key computational challenges in multi-omics data integration, and how can they be addressed? Key challenges include data heterogeneity (different technologies/platforms), data wrangling (ID mapping, normalization, imputation), and dimensionality. To address these:

- Data Wrangling: Implement careful sample registration and robust metadata recording. Use transformation (scaling, normalization) and mapping (harmonizing IDs across omics) processes [41].

- Data Heterogeneity & Dimensionality: Employ tools designed for integration, such as those using matrix factorization, network fusion, or factor analysis (e.g., MOFA, mixOmics, SNF) for dimension reduction and feature extraction [41].

FAQ 4: What is cellular deconvolution, and why is it important for analyzing bulk tissue samples? Cellular deconvolution is a computational technique used to estimate the proportion of different cell types within a bulk tissue sample based on omics data (e.g., gene expression). This is critical because bulk samples are a mixture of cell types, and variations in cell type composition can confound analyses like differential gene expression. Deconvolution helps dissect this cellular heterogeneity, leading to more accurate interpretation of results and reducing confounding effects in functional analyses [42] [43].

FAQ 5: How can multi-omics profiling be applied to patients who are currently healthy? Multi-omics can stratify healthy individuals into subgroups with distinct molecular profiles, uncovering subclinical risk factors. For example, one study identified a subgroup of healthy individuals with molecular patterns associated with dyslipoproteinemia, suggesting a predisposition to future cardiovascular issues. This enables a framework for precision medicine aimed at early prevention and targeted monitoring strategies [44].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Troubleshooting Patient Stratification and Subtype Identification

Problem: Unstable or biologically irrelevant patient clusters derived from multi-omics data.

| Problem Cause | Diagnostic Checks | Corrective Actions |

|---|---|---|

| High Technical Variation | Check for batch effects using PCA colored by batch. | Apply batch effect correction methods (e.g., ComBat). Include batch as a covariate in models. |

| Inappropriate Data Preprocessing | Verify each omic layer is properly normalized and scaled. | Normalize data per platform-specific best practices. Use variance-stabilizing transformations. |

| Noisy or Irrelevant Features | Assess if clustering is driven by a small number of features. | Perform feature selection (e.g., select most variable features) prior to integration and clustering. |

| Poor Choice of Integration Method | Evaluate if the method can handle your data types and sample size. | Select a method suited for your goal (see Table 2). Consider benchmark studies (e.g., from [40]). |

Recommended Workflow:

- Preprocessing: Normalize and scale each omics dataset individually.

- Batch Correction: Identify and correct for technical batch effects.

- Integration: Use a dedicated multi-omics clustering tool (see Table 2).