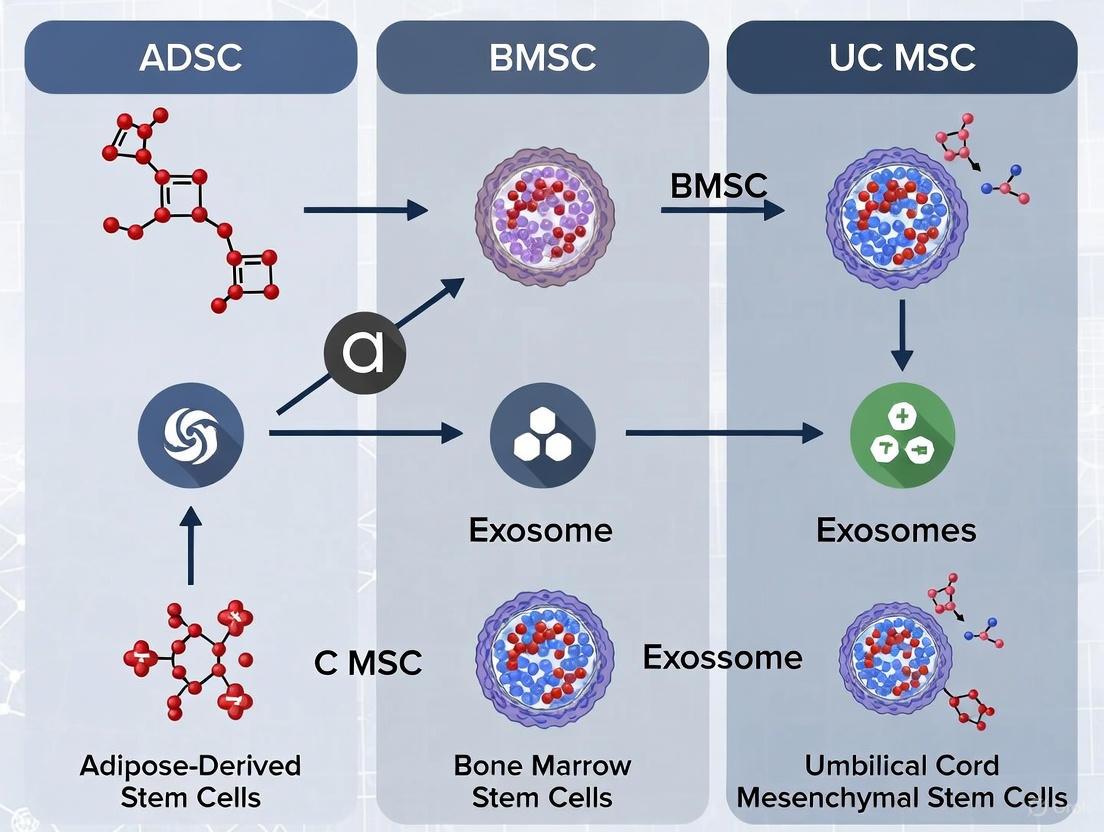

Comparative Analysis of ADSC, BMSC, and UC-MSC Exosomes for Angiogenesis: Sources, Efficacy, and Clinical Translation

Exosomes derived from mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) are emerging as potent acellular therapeutic agents for promoting angiogenesis in regenerative medicine and drug development.

Comparative Analysis of ADSC, BMSC, and UC-MSC Exosomes for Angiogenesis: Sources, Efficacy, and Clinical Translation

Abstract

Exosomes derived from mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) are emerging as potent acellular therapeutic agents for promoting angiogenesis in regenerative medicine and drug development. This review provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of exosomes from three key sources: Adipose-Derived Stem Cells (ADSCs), Bone Marrow-Mesenchymal Stem Cells (BMSCs), and Umbilical Cord-Mesenchymal Stem Cells (UC-MSCs). We systematically evaluate their inherent angiogenic potential, the impact of cell culture and isolation methodologies on exosome bioactivity, and strategies for optimizing their therapeutic efficacy. By synthesizing findings from foundational, methodological, and validation-focused studies, this article serves as a strategic guide for researchers and scientists in selecting and engineering the most appropriate exosome source for specific vascular regeneration applications, thereby accelerating the path to clinical translation.

Understanding the Native Angiogenic Potential of MSC Exosomes

Biogenesis and Core Composition of Pro-Angiogenic Exosomes

Exosomes, nanoscale extracellular vesicles (30-150 nm in diameter), have emerged as critical mediators of intercellular communication and promising therapeutic agents in regenerative medicine, particularly for their pro-angiogenic capabilities. These vesicles are secreted by various cell types, with mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) representing a particularly rich and therapeutically valuable source. This review provides a comprehensive comparison of exosomes derived from three prominent MSC sources: adipose-derived stem cells (ADSCs), bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells (BMSCs), and umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells (UCMSCs). We systematically analyze their biogenesis pathways, core molecular compositions, and relative efficacies in promoting angiogenesis, supported by experimental data and detailed methodologies. The objective comparison presented herein aims to guide researchers and drug development professionals in selecting optimal exosome sources for specific angiogenic applications.

Exosomes are formed via a highly conserved biogenetic pathway originating from the endosomal system. The process begins with the inward budding of the limiting membrane of early endosomes, leading to the creation of intraluminal vesicles (ILVs) within large multivesicular bodies (MVBs). These MVBs subsequently fuse with the plasma membrane, releasing ILVs into the extracellular space as exosomes [1] [2]. This biogenesis occurs through both endosomal sorting complex required for transport (ESCRT)-dependent and ESCRT-independent mechanisms, the latter involving tetraspanin microdomains and lipids such as ceramide [1].

The pro-angiogenic potency of exosomes is largely dictated by their molecular cargo, which includes proteins, lipids, and various nucleic acid species. This cargo is selectively packaged from the parent cell, reflecting its physiological state and environmental conditions [1]. MSC-derived exosomes contain growth factors, cytokines, and a diverse profile of microRNAs (miRNAs) that collectively target pathways critical for endothelial cell proliferation, migration, and tube formation—the fundamental processes underpinning angiogenesis [3] [2]. The composition of this cargo, and thus the exosome's functional capacity, varies significantly depending on the cellular source of the exosomes, necessitating a systematic comparison for research and therapeutic development.

The selection of parent cell type is a primary determinant of exosome function. ADSCs, BMSCs, and UCMSCs are among the most extensively studied MSC sources, each offering distinct advantages and characteristic cargo profiles that influence their angiogenic potential.

Source-Specific Advantages and Limitations

- Adipose-Derived Stem Cells (ADSCs): ADSCs are isolated from lipoaspirated subcutaneous adipose tissue. This source is characterized by its high accessibility and abundance, with colony-forming units significantly surpassing those of BMSCs [4]. ADSCs exhibit robust proliferative capacity in vitro and possess low immunogenicity, making them suitable for allogeneic applications [5] [6]. The autologous nature of adipose tissue minimizes immune rejection risks compared to allogeneic sources [4].

- Bone Marrow Mesenchymal Stem Cells (BMSCs): As the first discovered and most historically studied MSC source, BMSCs are considered a gold standard in many contexts. However, their isolation from bone marrow aspirates is more invasive and traumatic for donors compared to adipose tissue harvesting. Furthermore, the yield of stem cells from bone marrow is generally lower, often necessitating extensive in vitro expansion to obtain clinically relevant numbers [5].

- Umbilical Cord Mesenchymal Stem Cells (UCMSCs): UCMSCs are obtained from Wharton's jelly and other cord tissues, which are medical waste after birth. This makes them a source with minimal ethical concerns [5]. They are considered immunologically naive and possess a strong proliferative potential. However, their use is limited to allogeneic settings, and scalability can be challenged by donor variability [4].

Quantitative Comparison of Pro-Angiogenic Cargo

The therapeutic efficacy of MSC-derived exosomes in angiogenesis is largely mediated by their cargo of specific proteins and miRNAs. The table below summarizes key pro-angiogenic molecules identified in exosomes from different MSC sources.

Table 1: Key Pro-Angiogenic Cargo in MSC-Derived Exosomes

| Molecule Type | Specific Molecule | ADSC-Exos | BMSC-Exos | UCMSC-Exos | Function in Angiogenesis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proteins | VEGF | Present [6] | Present [2] | Information Missing | Stimulates endothelial cell proliferation and permeability |

| FGF2 | Present [6] | Information Missing | Information Missing | Promotes endothelial cell proliferation and migration | |

| Ang-1 | Present [6] | Present [7] | Information Missing | Stabilizes newly formed blood vessels | |

| HGF | Present [6] | Information Missing | Information Missing | Enhances endothelial cell migration and tubulogenesis | |

| MicroRNAs | miR-21-5p | Information Missing | Promoted angiogenesis in stroke [7] | Information Missing | Targets PTEN, activating AKT pathway; enhances HUVEC migration/proliferation |

| miR-126 | Promoted angiogenesis via PI3K/Akt [6] | Information Missing | Information Missing | Enhances VEGF signaling; promotes endothelial cell proliferation/migration | |

| miR-31a | Information Missing | Information Missing | Information Missing | Promotes endothelial cell proliferation and tube formation | |

| let-7f | Information Missing | Information Missing | Information Missing | Suppresses TGF-β signaling; enhances endothelial cell migration | |

| miR-146a | Present [6] | Information Missing | Information Missing | Inhibits NF-κB signaling, reducing inflammation in vascular repair |

Experimental Data on Angiogenic Potency

Direct comparisons and individual studies demonstrate the functional consequences of these cargo differences.

- BMSC-Exos in Cerebral Ischemia: In a mouse model of ischemic stroke, administration of BMSC-Exos significantly improved neurological function, reduced infarct volume, and upregulated microvessel density. This pro-angiogenic effect was mechanistically linked to the transfer of miR-21-5p, which enhanced the proliferation, migration, and tube formation of human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) in vitro by increasing the expression of VEGF, VEGFR2, Ang-1, and Tie-2 [7].

- ADSC-Exos in Wound Healing: ADSC-Exos have shown remarkable efficacy in promoting wound healing, a process dependent on robust angiogenesis. They enhanced wound closure rates, collagen deposition, and neovascularization in preclinical models. Their potency can be further amplified through preconditioning strategies; for example, hypoxia-exposed ADSCs produce exosomes with higher concentrations of angiogenic proteins like VEGF, FGF2, and PDGF [8] [4] [6].

- Comparative Performance: A review of studies suggests that ADSC-Exos may hold an advantage in terms of accessibility and yield. ADSCs are more abundant and easier to obtain than BMSCs, and they exhibit greater genetic stability and proliferative capacity in prolonged culture [6]. This makes ADSC-Exos a highly practical and efficient source for large-scale production required for clinical applications.

Table 2: Functional Comparison of MSC-Exos in Angiogenesis Models

| Exosome Source | Experimental Model | Key Findings | Proposed Mechanism | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMSC-Exos | Mouse MCAO (Stroke) | Improved neurological function, reduced infarct volume, increased microvessel density | miR-21-5p transfer; upregulation of VEGF/VEGFR2/Ang-1/Tie-2 | [7] |

| ADSC-Exos | Wound Healing (in vivo) | Accelerated wound closure, enhanced collagen remodeling, increased capillary density | Activation of PI3K/Akt pathway via miR-126; delivery of VEGF and FGF2 | [4] [6] |

| ADSC-Exos | HUVEC Tube Formation (in vitro) | Enhanced endothelial cell proliferation, migration, and tube formation capacity | Contained pro-angiogenic miRNAs (e.g., miR-126, miR-146a) and proteins | [6] |

Experimental Protocols for Pro-Angiogenic Exosome Research

Standardized Isolation and Characterization of Exosomes

To ensure reproducibility and reliability in angiogenesis research, adhering to standardized protocols for exosome isolation and characterization is paramount, in line with MISEV (Minimal Information for Studies of Extracellular Vesicles) guidelines [8].

- Isolation via Ultracentrifugation: The most widely used method involves a series of differential centrifugations. Cell culture supernatant is sequentially centrifuged at:

- 300 × g for 10 min to remove live cells.

- 2,000 × g for 10 min to remove dead cells.

- 10,000 × g for 30 min to remove cell debris.

- 100,000 × g for 70 min to pellet exosomes, followed by a wash in PBS and a final ultracentrifugation at 100,000 × g for 70 min [7].

- Characterization: Isolated exosomes must be characterized by:

- Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis (NTA): To determine particle size distribution and concentration [7].

- Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM): To confirm classic cup-shaped morphology [7].

- Western Blot: To detect positive markers (e.g., CD9, CD63, CD81, TSG101, Alix) and absence of negative markers (e.g., calnexin) [7] [1].

Key Methodologies for Assessing Angiogenic Potential

The following in vitro and in vivo assays are fundamental for evaluating the pro-angiogenic capacity of MSC-derived exosomes.

- In Vitro HUVEC Functional Assays:

- Proliferation Assay: HUVECs are treated with exosomes, and proliferation is measured via CCK-8 or EdA assay after 24-48 hours [7].

- Migration Assay: A scratch ("wound") is created in a confluent HUVEC monolayer. The rate of gap closure over 12-24 hours, with and without exosome treatment, is quantified to assess migration [7].

- Tube Formation Assay: HUVECs are seeded on a Matrigel matrix and treated with exosomes. The formation of capillary-like structures is imaged after 4-8 hours, and parameters like mesh number, tube length, and junction number are quantified [7].

- In Vivo Models:

- Ischemic Stroke Model (MCAO): Mice/rats undergo middle cerebral artery occlusion to induce cerebral ischemia. Exosomes are administered intravenously post-injury. Outcomes include neurological scoring, infarct volume measurement, and immunohistochemical analysis of microvessel density (e.g., using BrdU/vWF staining) [7].

- Wound Healing Model: Full-thickness skin wounds are created on rodents. Exosomes are applied topically, often via a biomaterial scaffold (e.g., hydrogel). Wound closure rate and histological analysis of granulation tissue thickness and CD31+ blood vessels are performed [4].

Visualization of Key Signaling Pathways

The pro-angiogenic effects of MSC-exosomes are mediated through the activation of several key signaling pathways in recipient endothelial cells. The following diagram illustrates the primary molecular mechanisms facilitated by the transfer of exosomal cargo.

Pro-Angiogenic Signaling Pathways Activated by MSC-Exosomes

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents for Exosome Angiogenesis Research

| Reagent / Kit | Specific Example | Function in Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Culture Medium | DMEM/F12 or RPMI-1640 with Exosome-Free FBS | To culture parent cells (MSCs) and ensure that isolated exosomes originate from the cells of interest and not serum. |

| Isolation Kits | Size-Exclusion Chromatography (SEC) columns; Polymer-based precipitation kits | Alternative methods to ultracentrifugation for isolating exosomes from conditioned medium or biofluids. |

| Characterization Instruments | Nanoparticle Tracking Analyzer (e.g., Malvern NanoSight); Transmission Electron Microscope | For determining exosome size, concentration, and morphological confirmation. |

| Endothelial Cell Line | Human Umbilical Vein Endothelial Cells (HUVECs) | The standard in vitro model for conducting proliferation, migration, and tube formation assays. |

| Extracellular Matrix | Growth Factor-Reduced Matrigel | A basement membrane matrix used for the in vitro tube formation assay to support the development of capillary-like structures. |

| Antibodies for Western Blot | Anti-CD63, Anti-CD81, Anti-CD9, Anti-TSG101, Anti-Alix | For confirming the presence of exosome-specific marker proteins after isolation. |

| Antibodies for Immunofluorescence | Anti-CD31 (PECAM-1), Anti-vWF | For staining and identifying endothelial cells and newly formed blood vessels in in vivo tissue sections. |

Pro-angiogenic exosomes from ADSCs, BMSCs, and UCMSCs all demonstrate significant potential for advancing therapeutic angiogenesis in conditions like ischemic diseases and wound healing. While they share a common biogenesis pathway, their core composition and functional efficacy are distinctly shaped by their cellular origin. ADSC-Exos present a compelling profile due to their source abundance, practical isolability, and potent cargo rich in angiogenic factors and miRNAs. BMSC-Exos remain a well-characterized option with proven efficacy, notably through mechanisms like miR-21-5p transfer. UCMSC-Exos offer an ethically favorable alternative. The choice of exosome source should be guided by the specific requirements of the research or therapeutic application, considering factors such as cargo profile, required yield, and functional potency as validated through standardized in vitro and in vivo assays. Future research will benefit from enhanced isolation standardization and engineering strategies to further optimize the angiogenic potential of these remarkable natural nanotherapeutics.

Mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes (MSC-Exos) have emerged as pivotal acellular therapeutic agents in regenerative medicine, primarily functioning through sophisticated paracrine communication [9] [10]. These nano-sized vesicles (30-150 nm) transfer bioactive cargo—including proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids—to recipient cells, orchestrating crucial biological processes such as angiogenesis, immunomodulation, and tissue repair [6] [11]. Among the various MSC sources, adipose-derived stem cells (ADSCs), bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells (BMSCs), and umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells (UC-MSCs) represent the most extensively investigated and therapeutically relevant populations [9]. The angiogenic potential of their exosomal cargo varies significantly based on parental cell origin, creating a compelling landscape for comparative analysis. This guide systematically evaluates the inherent angiogenic profiles of ADSC, BMSC, and UC-MSC exosomes, providing researchers and drug development professionals with objective, data-driven insights for selecting optimal exosome sources for specific vascular regeneration applications.

Comparative Angiogenic Potential of MSC Exosomes

Quantitative Comparison of Angiogenic Cargo and Efficacy

The therapeutic efficacy of MSC exosomes in promoting angiogenesis is intrinsically linked to their biomolecular composition, which varies significantly across source tissues. The table below summarizes key comparative data on angiogenic cargo and functional outcomes.

Table 1: Comparative Angiogenic Profiles of MSC Exosomes from Different Sources

| Exosome Source | Key Angiogenic Cargo | Target Pathways/Mechanisms | Documented Functional Outcomes | Relative Efficacy Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ADSC-Exos | miR-205, miR-126, VEGF, FGF2, IL-10, HGF, Ang-1 [6] | miR-205 suppresses cardiomyocyte apoptosis; miR-126 activates PI3K/Akt in endothelium; FGF2 & VEGF promote angiogenesis [6]. | Enhanced capillary density in myocardial infarction models; reduced pulmonary edema; improved cardiac function post-MI [6]. | Potent immunomodulatory properties; effective across multiple organ systems; high proliferation rate of parent cells [6] [5]. |

| BMSC-Exos | VEGF, miR-21, miR-196a, BMPs, various growth factors [12] [11] | Promotes angiogenesis and osteogenesis via Wnt/β-catenin pathway; key in bone regeneration [12] [13]. | Improved functional scores in neurological and musculoskeletal disorders; promotes bone regeneration and vascularization [9] [12]. | Considered one of the most effective sources per umbrella review; high efficacy in neurological and renal models [9]. |

| UC-MSC-Exos | Specific cargo less documented; generally rich in growth factors and cytokines [11] | Regulates AMPK/NR4A1, TGF-β1/Smad3, Wnt/β-catenin, and Hippo signaling pathways [11]. | Significant improvement in functional recovery; effective in treating premature ovarian failure via angiogenesis [11]. | Highly effective alongside BMSC and ADSC exosomes; modified UC-MSC exosomes show enhanced outcomes [9]. |

A 2025 umbrella review analyzing 47 meta-analyses across 27 diseases established that exosomes derived from bone marrow, adipose tissue, and umbilical cord are the most effective sources, with modified EVs consistently showing enhanced therapeutic outcomes [9]. The choice of source often involves a trade-off between angiogenic potency, tissue-specificity, and practical considerations like cell harvest yield and expansion potential.

ADSCs offer the significant advantage of being easily obtained from autologous adipose tissue in large quantities with minimal ethical concerns, and they exhibit a high proliferation rate [5]. BMSCs, while more invasive to harvest, are often considered a "gold standard" and demonstrate high efficacy, particularly in neurological and renal applications [9] [14]. UC-MSCs represent a potent allogeneic source with robust paracrine activity [11].

Experimental Protocols for Angiogenic Assessment

Standard Workflow for Exosome Isolation and Characterization

To ensure the reliability and reproducibility of comparative data, standardized protocols for exosome production and validation are critical. The following workflow is commonly employed, with variations depending on the required scale and purity.

Figure 1: Standard workflow for MSC exosome isolation and characterization. Key steps include cell culture, conditioned media collection, isolation (choosing between Ultracentrifugation for lab scale or Tangential Flow Filtration for GMP scale), and multi-method characterization [14] [15].

Key Methodological Details:

- Cell Culture: BMSCs cultured in α-MEM show a higher expansion ratio and particle yield compared to those cultured in DMEM, though not always statistically significant [14].

- Isolation Methods: Tangential Flow Filtration (TFF) provides a statistically higher particle yield compared to traditional Ultracentrifugation (UC) and is more suitable for large-scale, GMP-compliant production [14] [15].

- Characterization: Isolated particles must be confirmed as exosomes through multiple techniques:

- Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis (NTA): Determines particle size (~100-150 nm) and concentration [14].

- Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM): Confirms classic cup-shaped morphology [14].

- Western Blotting: Verifies the presence of exosomal surface markers (CD9, CD63, CD81, TSG101) and the absence of negative markers like calnexin [14] [15].

Functional Assays for Angiogenic Potential

The pro-angiogenic capacity of isolated MSC exosomes is typically validated using a combination of in vitro and in vivo models.

Table 2: Standard Functional Assays for Angiogenic Validation

| Assay Type | Specific Model/Test | Measured Parameters | Interpretation of Angiogenic Potential |

|---|---|---|---|

| In Vitro | Human Umbilical Vein Endothelial Cell (HUVEC) Assay [6] | Tube formation (number, length, junctions); Cell proliferation & migration; Gene expression (VEGFR2, Ang-1) [6]. | Enhanced tube formation and cell migration indicate strong pro-angiogenic activity. |

| In Vivo | Myocardial Infarction (MI) Rodent Model [6] | Capillary density in border zone; Infarct size reduction; Cardiac function (ejection fraction) [6]. | Increased capillary density and improved cardiac function demonstrate therapeutic angiogenesis. |

| In Vivo | Hindlimb Ischemia Model | Blood perfusion (Laser Doppler); New vessel formation (histology) | Improved perfusion and visible new vessels confirm functional vessel growth. |

| Molecular Analysis | RNA Sequencing / PCR [13] | miRNA and mRNA expression profiles (e.g., miR-206, miR-126) [6] [13]. | Identifies specific pro-angiogenic cargo and upstream molecular mechanisms. |

Key Angiogenic Signaling Pathways

The therapeutic effects of MSC exosomes are mediated through the activation or inhibition of specific signaling pathways in recipient cells. The following diagram illustrates the central mechanisms by which ADSC exosomes, in particular, promote angiogenesis, drawing from detailed cargo analyses [6].

Figure 2: Key angiogenic signaling pathways activated by ADSC-exosome cargo. Exosomal miRNAs and proteins coordinate to promote endothelial cell survival, proliferation, and new vessel formation through parallel pathways [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful research into MSC exosomes requires a suite of specialized reagents and equipment. The following table details key solutions essential for isolation, characterization, and functional analysis.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for MSC Exosome Studies

| Reagent / Solution | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Alpha Minimum Essential Medium (α-MEM) | Cell culture medium for MSC expansion. | Found to yield higher BMSC proliferation and exosome yield compared to DMEM [14]. |

| Human Platelet Lysate (hPL) | Xeno-free supplement for cell culture media. | Used as a serum alternative in GMP-compliant MSC culture systems [14]. |

| Trypsin-EDTA | Enzymatic detachment of adherent cells. | Standard procedure for passaging and harvesting MSCs. |

| Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) | Washing buffer and exosome resuspension. | Used for washing cells and as a vehicle for exosome storage and injection. |

| CD9, CD63, CD81 Antibodies | Exosome surface marker detection. | Critical for Western Blot characterization of isolated vesicles [14] [15]. |

| TSG101, ALIX Antibodies | Luminal exosome marker detection. | Further confirmation of exosomal identity via Western Blot [15]. |

| Calnexin Antibody | Negative marker for exosome purity. | Detection of this endoplasmic reticulum protein indicates contamination with cell debris [14]. |

| Paraformaldehyde (PFA) | Fixation agent for cell and tissue samples. | Used in preparing samples for imaging techniques like TEM and immunofluorescence. |

| Triton X-100 | Permeabilization detergent. | Permeabilizes cell membranes for intracellular staining in immunoassays. |

| DAPI Staining Solution | Nuclear counterstain. | Labels cell nuclei in fluorescence microscopy. |

| Alexa Fluor-conjugated Antibodies | Fluorescent labeling for detection. | Used in flow cytometry and immunofluorescence to detect specific antigens. |

| Matrigel | Basement membrane matrix. | Used for in vitro tube formation assays with HUVECs to assess angiogenic potential. |

This comparative analysis elucidates that ADSC, BMSC, and UC-MSC exosomes possess distinct inherent angiogenic profiles, driven by their unique biomolecular cargo. ADSC exosomes are particularly notable for their rich miRNA content targeting endothelial survival and vascular stability. BMSC exosomes demonstrate robust efficacy in integrating angiogenesis with osteogenesis. UC-MSC exosomes present a potent, less invasive option with strong regenerative signaling. The ongoing standardization of isolation protocols and a deeper mechanistic understanding of their cargo will further empower researchers to select and potentially engineer the most optimal exosome source for targeted angiogenic therapies.

Key Signaling Pathways (VEGF, PI3K/Akt, Wnt) and Cargo (miRNAs, Proteins)

The selection of an optimal exosome source is a critical determinant of success in angiogenesis research and therapeutic development. Exosomes derived from Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs) have emerged as potent mediators of intercellular communication, capable of transferring bioactive cargo such as microRNAs (miRNAs) and proteins to recipient cells, thereby influencing key signaling pathways central to blood vessel formation [8] [4]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of exosomes from three prominent sources—Adipose-Derived Stem Cells (ADSCs), Bone Marrow-Mesenchymal Stem Cells (BMSCs), and Umbilical Cord-Mesenchymal Stem Cells (UCMSCs)—focusing on their distinct impacts on VEGF, PI3K/Akt, and Wnt signaling pathways. We synthesize experimental data and methodologies to equip researchers with evidence-based insights for selecting the most appropriate exosome source for specific angiogenic applications.

Exosome Biogenesis and Cargo Selection

Exosomes are nano-sized extracellular vesicles (30-150 nm in diameter) that originate from the endosomal system [16]. Their biogenesis begins with the inward budding of the endosomal membrane, leading to the formation of intraluminal vesicles (ILVs) within multivesicular bodies (MVBs) [17] [16]. These MVBs subsequently fuse with the plasma membrane, releasing ILVs as exosomes into the extracellular space [17].

The molecular cargo of exosomes—including proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids—is not packaged randomly but through highly regulated mechanisms [16]. The Endosomal Sorting Complex Required for Transport (ESCRT) machinery plays a pivotal role in sorting ubiquitinated proteins into ILVs [17] [16]. Additionally, ESCRT-independent pathways exist, involving tetraspanins (e.g., CD63, CD81, CD9) and lipids such as ceramide [4] [16]. The selective sorting of miRNAs is governed by RNA-binding proteins (RBPs) like hnRNPA2B1, which recognize specific nucleotide sequences in miRNAs known as EXOmotifs, ensuring their enrichment in exosomes [17].

Table: Key Machinery in Exosome Biogenesis and Cargo Sorting

| Component | Function | Key Examples |

|---|---|---|

| ESCRT Complex | Recognizes ubiquitinated cargo and mediates inward budding of endosomal membrane [16] | ESCRT-0, -I, -II, -III, VPS4, ALIX, TSG101 [17] |

| Tetraspanins | Organize membrane microdomains for cargo clustering; serve as common exosome markers [4] | CD63, CD81, CD9 [4] |

| RNA-Binding Proteins (RBPs) | Recognize specific motifs (e.g., EXOmotifs) to selectively load miRNAs into exosomes [17] | hnRNPA2B1, AUF1 [17] |

| Lipids | Promote membrane curvature and ILV formation in ESCRT-independent pathways [4] | Ceramide [4] |

Diagram 1: Exosome Biogenesis, Cargo Sorting, and Angiogenic Function. This diagram illustrates the pathway from exosome formation through endocytosis to the activation of key signaling pathways in a recipient cell, highlighting major cargo sorting mechanisms.

The therapeutic potential of MSC-derived exosomes in angiogenesis is significantly influenced by the tissue of origin, which dictates their molecular cargo and functional properties [8] [18].

ADSC-Exosomes (Adipose-Derived Stem Cell Exosomes)

ADSC-Exos are noted for their accessibility and high yield, as adipose tissue is abundant and easily obtainable via liposuction [4]. They demonstrate potent pro-angiogenic capabilities, largely through the delivery of specific miRNAs that enhance endothelial cell function and vessel stability [4]. Studies highlight their efficacy in wound healing models, where they promote cellular proliferation, migration, and new blood vessel formation [4].

UCMSC-Exosomes (Umbilical Cord Mesenchymal Stem Cell Exosomes)

UCMSC-Exos are often characterized by their strong pro-angiogenic potential. Direct comparative studies have shown that UCMSCs exhibit greater pro-angiogenesis activity than ADMSCs in vitro and in vivo, as evidenced by enhanced tube formation in assays [18]. This makes them a highly promising candidate for applications requiring robust blood vessel growth, such as in myocardial infarction repair [18].

BMSC-Exosomes (Bone Marrow Mesenchymal Stem Cell Exosomes)

While BMSCs were one of the first MSC types to be studied, their exosomes can be influenced by donor age. For instance, exosomes derived from older BMSCs exhibit diminished effects in osteogenic and lipogenic abilities compared to those from younger BMSCs [8]. This suggests that donor-related factors are a critical consideration when using BMSC-Exos.

Table: Comparative Profile of MSC-Exosome Sources for Angiogenesis

| Feature | ADSC-Exosomes | UCMSC-Exosomes | BMSC-Exosomes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Key Advantages | Easily accessible source, high yield, low immunogenicity [4] | Strong pro-angiogenic potential, young donor source [18] | Extensive historical data and characterization [19] |

| Documented Pro-Angiogenic Cargo | miR-125a, miR-31, miR-21-5p, miR-424 [4] | Not specified in results | Not specified in results |

| Reported Functional Efficacy | Promotes wound healing, endothelial cell proliferation & migration [4] | Superior tube formation in vitro compared to ADMSCs [18] | Efficacy can be donor-age dependent [8] |

| Considerations | Varies with donor site and collection method [8] | Direct comparative data vs. ADMSCs shows superior angiogenesis [18] | Functional heterogeneity and potential for age-related decline [8] |

Key Signaling Pathways in Angiogenesis

Exosomes mediate their angiogenic effects primarily by modulating three core signaling pathways.

VEGF Signaling Pathway

The Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF) pathway is a master regulator of angiogenesis. When VEGF ligands bind to their receptors (e.g., VEGFR2) on endothelial cells, it triggers receptor dimerization and autophosphorylation, initiating a downstream signaling cascade [18]. This cascade promotes endothelial cell survival, proliferation, migration, and ultimately the formation of new blood vessels. MSC-exosomes can carry VEGF protein itself or miRNAs that modulate the expression of VEGF and its receptors [18] [4].

PI3K/Akt Signaling Pathway

The PI3K/Akt pathway is a crucial downstream effector of VEGF signaling and a key promoter of endothelial cell survival. Activation of receptor tyrosine kinases (like VEGFR) recruits and activates PI3K, which converts PIP2 to PIP3. This leads to the phosphorylation and activation of Akt [20]. Activated Akt then phosphorylates several substrates, including endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS), which promotes vasodilation and angiogenesis, and Bad, which inhibits apoptosis [20]. The pathway is negatively regulated by the phosphatase PTEN [20].

Wnt Signaling Pathway

The Wnt/β-catenin (canonical) pathway is highly conserved and involved in development and tissue homeostasis [21] [22]. In the "off" state (without Wnt ligand), a destruction complex (containing APC, Axin, CK1α, GSK3β) phosphorylates β-catenin, targeting it for ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation [21] [22]. When a Wnt ligand binds to its Frizzled receptor and LRP5/6 co-receptor, it disrupts the destruction complex. This allows β-catenin to accumulate in the cytoplasm and translocate to the nucleus, where it partners with TCF/LEF transcription factors to activate target genes like c-MYC and VEGF, which can promote angiogenesis and cell proliferation [21] [22] [20].

Diagram 2: Core Angiogenic Signaling Pathways. This diagram outlines the key components and sequence of events in the VEGF, PI3K/Akt, and Wnt/β-catenin pathways, highlighting their role in promoting angiogenesis.

Experimental Data and Protocols for Angiogenesis Assessment

Key Experimental Models and Data

Robust in vitro and in vivo models are essential for evaluating the pro-angiogenic capacity of different MSC-exosomes.

Table: Summary of Key Experimental Findings

| Exosome Source | Experimental Model | Key Quantitative Findings | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| UCMSC | Mouse Myocardial Infarction (MI) | Improved cardiac function, decreased infarction area, promoted angiogenesis post-MI [18] | [18] |

| UCMSC vs ADMSC | In Vitro Tube Formation Assay | UCMSCs presented greater pro-angiogenesis activity than ADMSCs [18] | [18] |

| ADSC | In Vivo Wound Healing | 200 μg/mL exosome concentration showed efficacy in promoting wound healing [8] | [8] |

| BMSC | Sciatic Nerve Crush Injury | Effective at a concentration of 0.9 × 10^10 particles/mL in vitro [8] | [8] |

Detailed Methodologies for Key Assays

Endothelial Cell Tube Formation Assay

This in vitro assay is a fundamental test for assessing the ability of exosomes to stimulate blood vessel-like structure formation.

- Procedure [18]:

- Matrigel Coating: Coat a 96-well plate with 50 μL of growth factor-reduced Matrigel per well. Allow the Matrigel to polymerize for 1 hour at 37°C.

- Cell Seeding: Harvest Human Umbilical Vein Endothelial Cells (HUVECs) and seed them onto the solidified Matrigel at a density of 20,000 cells per well. The cells should be suspended in the conditioned medium collected from the MSC cultures (containing the exosomes to be tested) or in a control medium.

- Incubation: Incubate the plate at 37°C with 5% CO2 for 6-8 hours.

- Imaging and Analysis: After incubation, randomly photograph the formed capillary-like networks using a microscope. Analyze the images with software such as ImageJ to quantify key parameters, including:

- Total Tube Length: The combined length of all tubular structures.

- Number of Nodes: The branching points within the network.

- Number of Junctions: The connection points between tubes.

Matrigel Plug Assay

This in vivo assay evaluates the ability of exosomes to stimulate new blood vessel growth in a living organism.

- Procedure [18]:

- Plug Preparation: Mix the test MSCs (e.g., 5 x 10^5 cells) or their exosomes with liquid Matrigel (stored on ice). Matrigel alone serves as a negative control.

- Implantation: Anesthetize mice (e.g., female BALB/C nude mice) with isoflurane. Subcutaneously inject the Matrigel mixture (e.g., 200 μL per site) into the left and right groin of each mouse.

- Harvesting: After a set period (e.g., 14 days), euthanize the mice and surgically retrieve the Matrigel plugs.

- Analysis: The plugs can be analyzed by:

- Visual Inspection: Assessing the degree of vascularization (visible blood vessels) on the plug surface.

- Histology: Fixing, sectioning, and staining the plugs with antibodies against endothelial cell markers like CD31 to identify and quantify the newly formed blood vessels within the plug.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Reagents and Kits for Exosome and Angiogenesis Research

| Reagent/Kits | Function/Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Growth Factor-Reduced Matrigel | Provides a basement membrane matrix for in vitro tube formation assays and in vivo Matrigel plug assays [18] | Mimics the complex extracellular environment; essential for HUVEC tube formation [18] |

| Human Umbilical Vein Endothelial Cells (HUVECs) | Standard primary cell model for studying endothelial cell biology and angiogenesis in vitro [18] | Responsive to pro-angiogenic factors; form capillary-like tubes on Matrigel [18] |

| CD31 (PECAM-1) Antibody | Histological marker for identifying and quantifying endothelial cells in tissue sections (e.g., from Matrigel plugs) [18] | Well-established immunohistochemical marker for vascularization [18] |

| CD63, CD81, CD9 Antibodies | Detection of exosome-specific tetraspanins by western blot, flow cytometry, or immuno-EM for exosome characterization [4] [16] | Common surface markers used to identify and validate exosome isolates [4] |

| Ultracentrifugation & SEC Kits | Standardized methods for isolating and purifying exosomes from cell culture conditioned medium or biological fluids [8] | Ultracentrifugation is widely used but time-consuming; SEC can preserve exosome integrity and bioactivity [8] |

Production, Isolation, and Functional Characterization for Angiogenesis

The isolation of high-purity exosomes is a critical prerequisite for advancing angiogenesis research and therapeutic development. Exosomes derived from Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs)—including those from adipose tissue (ADSC), bone marrow (BMSC), and umbilical cord (UC-MSC)—carry distinct pro-angiogenic cargo that holds great potential for treating ischemic diseases and supporting tissue regeneration [8] [23]. The recovery of these bioactive molecules is highly dependent on the isolation technique employed. Ultracentrifugation (UC) remains the most commonly used method, but emerging techniques like Size-Exclusion Chromatography (SEC) and combined approaches claim improvements in yield, purity, and functionality [24] [25]. This guide provides an objective, data-driven comparison of these core isolation methodologies to inform protocol selection for angiogenesis research.

Comparative Analysis of Isolation Techniques

Principles and Trade-offs of Major Methods

The choice of isolation method directly impacts exosome yield, purity, and biological activity, which are critical parameters for downstream angiogenesis applications.

- Ultracentrifugation (UC): This method relies on applying high centrifugal forces over extended periods to pellet exosomes based on their size and density. While it is considered the "gold standard" and is cost-effective for consumables, it is often criticized for being time-consuming, requiring specialized equipment, and potentially compromising exosome integrity through high shear forces. A significant drawback is its moderate purity, as it frequently co-precipitates non-exosomal proteins and lipoproteins [24] [26] [25].

- Size-Exclusion Chromatography (SEC): SEC separates exosomes from smaller soluble proteins by passing the sample through a porous gel matrix. Smaller molecules enter the pores and are delayed, while larger exosomes pass through more quickly. This method is praised for its speed, excellent preservation of exosome integrity and biological activity, and superior purity in removing contaminating proteins. However, its primary limitations are a lower yield and a relatively small sample processing volume [24] [8] [27].

- Combined Methods (UC-SEC): Hybrid protocols, such as an initial UC step to concentrate exosomes followed by SEC for final polishing, aim to balance the benefits of both parent methods. This approach typically results in higher purity than UC or SEC alone and maintains good exosome integrity. The trade-off is increased protocol complexity and total processing time [24].

Quantitative Performance Comparison

The following table summarizes key performance metrics for these methods, drawing from direct comparative studies.

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of Exosome Isolation Method Performance

| Method | Purity (Protein Contamination) | Yield (Particle Recovery) | Exosome Integrity | Processing Time | Scalability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ultracentrifugation (UC) | Moderate (High contaminant protein) [24] | Moderate (Potential particle loss/aggregation) [25] | Variable (Potential damage from shear forces) [26] [25] | Long (>4 hours) [26] | Low to Moderate [25] |

| Size-Exclusion Chromatography (SEC) | High (Effectively removes >95% of soluble proteins) [24] | Lower (Diluted samples, limited load volume) [24] [8] | High (Preserves structure and function) [8] [25] | Short (~1-2 hours) [27] | Low [25] |

| Combined UC-SEC | Very High (Significantly higher than SEC alone) [24] | High (Concentration via UC step) [24] | High (Final gentle SEC step) [24] | Long (Combined time of both methods) [24] | Moderate [25] |

| Tangential Flow Filtration-SEC (TFF-SEC)* | High [25] | Very High (Superior to UC) [25] | High (Gentle filtration) [25] | Moderate [25] | High (Suitable for large volumes) [25] |

Note: TFF-SEC is an advanced, scalable method included for context. It uses cross-flow filtration to concentrate exosomes from large volumes before a polishing SEC step [25].

Impact on Angiogenesis Research

The isolation method can directly influence the outcomes of angiogenesis studies by determining the quality and composition of the exosome preparation.

- Preservation of Pro-Angiogenic Cargo: Gentle methods like SEC and TFF-SEC are superior at maintaining the integrity of key pro-angiogenic molecules, such as miRNAs and proteins, which are crucial for stimulating endothelial cell migration and tube formation [8] [25].

- Purity and Specificity: High-purity isolates from SEC or combined methods minimize the co-isolation of contaminating proteins that could confound experimental results or trigger unintended immune responses in therapeutic applications [24] [19]. For instance, one study noted that UC-isolated exosomes from serum had several times higher serum protein contamination than those purified with an optimized UC-SEC method [24].

- Functional Yield: While UC may provide a high particle count, the presence of aggregates or damaged vesicles can overestimate the functional yield. Methods that ensure integrity, like SEC, provide a more accurate count of bioactive exosomes capable of inducing angiogenesis [28] [25].

Experimental Protocols for Isolation

Optimized Ultracentrifugation Protocol for Serum/Plasma

This protocol is adapted from a study comparing isolation methods for human serum exosomes [24].

- Sample Pre-processing: Dilute serum or plasma with an equal volume of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) to reduce viscosity. Centrifuge at 2,000 × g for 10 minutes at 4°C to remove cells and debris. Transfer the supernatant to a new tube.

- High-Speed Centrifugation: Centrifuge the supernatant at 10,000 × g for 30 minutes at 4°C to pellet larger extracellular vesicles and organelles. Carefully collect the resulting supernatant.

- Ultracentrifugation (First Cycle): Transfer the supernatant to ultracentrifuge tubes. Centrifuge at 100,000 × g for 120 minutes at 4°C using a fixed-angle rotor.

- Wash Cycles: Carefully discard the supernatant, leaving a small volume to avoid disturbing the pellet. Resuspend the pellet in a large volume of PBS (e.g., 4 mL). Repeat ultracentrifugation at 100,000 × g for 70 minutes at 4°C. This wash cycle is typically repeated 3-4 more times to adequately reduce protein contamination [24].

- Final Resuspension: After the final wash, resuspend the purified exosome pellet in a small volume of PBS (50-200 µL) and store at 4°C for short-term use or -80°C for long-term storage.

Size-Exclusion Chromatography Protocol

This protocol outlines the use of commercial SEC columns (e.g., qEV columns from Izon Science) for plasma exosome isolation [24] [27].

- Sample Preparation and Column Equilibration: Pre-process the plasma or serum sample as described in Steps 1 and 2 of the UC protocol. Meanwhile, equilibrate the SEC column by rinsing with 15 mL of PBS.

- Sample Loading and Elution: Load the pre-processed sample onto the column (typically 0.5 mL per column). Continuously add PBS to the column to prevent it from running dry. Discard the first 3.5 mL of eluent (void volume), which contains larger proteins and vesicles.

- Fraction Collection: Collect the next 0.5-1.0 mL of eluent. This fraction is enriched with exosomes.

- Column Regeneration: After collection, flush the column with 30 mL of PBS, followed by 10 mL of 0.5 M NaOH for cleaning. Re-equilibrate with 50 mL of PBS before the next use.

- Exosome Concentration (Optional): If a more concentrated sample is required, the collected fraction can be concentrated using a final ultracentrifugation step (100,000 × g for 70 minutes) [24].

Combined UC-SEC Workflow Protocol

The combined method leverages the concentration power of UC and the high purity of SEC [24].

- Initial Concentration via UC: Follow Steps 1 through 3 of the Ultracentrifugation protocol to obtain a crude exosome pellet.

- Pellet Resuspension: Resuspend the pellet in a small, defined volume of PBS (e.g., 0.5 mL).

- Final Purification via SEC: Load the entire resuspended sample onto a pre-equilibrated SEC column and follow Steps 2 through 4 of the SEC protocol to obtain the purified exosome fraction.

Diagram Title: Experimental Workflow for Exosome Isolation

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Materials for Exosome Isolation

| Item | Function/Application | Example Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Ultracentrifuge | High-speed centrifugation for pelleting exosomes. | Beckman Coulter Optima series with fixed-angle rotors (e.g., 50.2 Ti) [24]. |

| SEC Columns | Gel filtration for separating exosomes from soluble proteins. | qEV columns (Izon Science) or lab-packed Sepharose CL-2B columns [24] [27]. |

| Ultracentrifuge Tubes | Tubes capable of withstanding high G-forces. | Beckman Ultra-Clear tubes or equivalent [24]. |

| PBS Buffer | Universal suspension and dilution buffer. | 0.22 µm filtered, pH 7.4 [24] [27]. |

| Exosome-Depleted FBS | For cell culture to prevent bovine exosome contamination. | FBS ultracentrifuged at 100,000g overnight or commercially available [25]. |

| Filtration Units | Sterile filtration of buffers and sample pre-clearing. | 0.22 µm pore size PVDF or PES membranes [27] [25]. |

| Protein Assay Kits | Quantifying total protein to assess purity. | BCA or Bradford Assay kits [24]. |

| Antibodies for Characterization | Confirming exosome identity via Western Blot. | Anti-CD9, CD63, CD81, TSG101, Alix [8] [27] [23]. |

The selection of an exosome isolation technique is a fundamental decision that directly shapes research outcomes in angiogenesis. Ultracentrifugation offers a established, low-cost method but suffers from variable purity and potential vesicle damage. SEC provides superior purity and preserves bioactivity at the cost of lower yield. For the most demanding applications where both high purity and functional integrity are paramount, such as profiling the subtle angiogenic differences between ADSC-, BMSC-, and UC-MSC-derived exosomes, combined UC-SEC methods or advanced alternatives like TFF-SEC present the most robust and reliable choice. Researchers should align their selection with the specific priorities of their experimental or therapeutic goals.

In the field of angiogenesis research, exosomes derived from Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs) have emerged as powerful cell-free therapeutic agents. These nanoscale vesicles transfer bioactive molecules that can promote new blood vessel formation, a critical process in tissue regeneration and repair. The three most common MSC sources are Adipose-Derived Stem Cells (ADSCs), Bone Marrow-derived MSCs (BMSCs), and Umbilical Cord-derived MSCs (UCSCs). However, the angiogenic potency of their exosomes is not solely defined by the cellular source; it is profoundly influenced by the culture environment in which the parent cells are grown. The choice between serum-contained media, traditionally supplemented with Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS), and chemically defined serum-free media (SFM) is a critical decision that impacts exosome yield, purity, bioactivity, and ultimately, their therapeutic potential. This guide provides an objective comparison of these two culture systems, underpinned by experimental data, to inform research and development strategies.

Direct Comparison: Key Parameters at a Glance

The following tables summarize the comparative impact of serum-free and serum-contained media on MSC exosomes, based on aggregated experimental findings.

Table 1: Impact on Exosome Characteristics and Production

| Parameter | Serum-Contained Media (FBS) | Serum-Free Media (SFM) | Supporting Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Exosome Purity | Lower; high risk of contamination with bovine serum-derived EVs and proteins [29] [30]. | Higher; eliminates contaminating animal-derived vesicles and undefined serum components [29] [31]. | |

| Production Yield | Variable; can be high but requires a starvation period that stresses cells and reduces yield [29]. | Higher; specialized SFM can support continuous production without starvation, enhancing total output [29] [32]. | |

| Immunogenicity Risk | Higher; MSCs can internalize and present bovine antigens (e.g., Neu5Gc), risking immune reactions [31]. | Lower; absence of xeno-antigens reduces the potential for immune responses, favoring allogeneic therapy [31]. | |

| Batch-to-Batch Consistency | Lower; undefined serum composition leads to variability between production runs [31]. | Higher; chemically defined composition ensures superior reproducibility [31]. | |

| Therapeutic Angiogenesis | Potent pro-angiogenic effects demonstrated in various models. | Enhanced or Comparable; studies show SFM-cultured exosomes can have superior or equal wound healing and angiogenic capacity [29] [33]. |

Table 2: Impact on Parent MSC Characteristics

| Parameter | Serum-Contained Media (FBS) | Serum-Free Media (SFM) | Supporting Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Proliferation Rate | Generally robust but can lead to increased senescence at later passages [31]. | More Stable; can provide a more consistent population doubling time into later passages [31]. | |

| Cellular Senescence | Higher levels observed in ADSCs cultivated long-term in FBS-media [31]. | Reduced; ADSCs in SFM showed lower levels of cellular senescence [31]. | |

| Genetic Stability | Lower compared to SFM-cultured cells [31]. | Higher; ADSCs cultivated in SFM demonstrated superior genetic stability [31]. | |

| Chondrogenic Differentiation | Maintains chondrogenic potential, supporting cartilage repair in vivo [34]. | Variable; SFM-expanded MSCs may show poor in vivo cartilage repair despite high proliferation, indicating differentiation potential is media-dependent [34]. |

Experimental Data and Detailed Methodologies

Enhancing Exosome Bioactivity for Angiogenesis

Objective: To compare the angiogenic and wound-healing efficacy of exosomes derived from human Umbilical Cord MSCs (UCMSCs) cultured under serum-free versus serum-contained conditions [29].

Experimental Protocol:

- Cell Culture: UCMSCs were cultured in two different media:

- Normal Media (NM): 10% FBS-supplemented DMEM.

- Chemically Defined Media (CDM): CellCor CD MSC SFM.

- Exosome Isolation:

- For the NM group, the medium was replaced with serum-free DMEM for 48 hours (starvation) to isolate UCMSC-derived exosomes without FBS contamination.

- For the CDM group, the same serum-free medium was used continuously for culture and exosome isolation.

- Exosomes were isolated from the conditioned media using Tangential Flow Filtration (TFF) with a 500 kDa molecular weight cut-off filter.

- Analysis:

- Characterization: Particle size and concentration were determined via Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis (NTA). Morphology was confirmed by Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM). Purity was verified by Western blotting for exosome markers (CD63, CD81).

- Cytokine Analysis: The expression levels of angiogenic and pro-inflammatory cytokines in the exosomes were compared.

- Functional Assays:

- In Vitro Wound Healing: A scratch assay was performed to measure cell migration.

- In Vitro Angiogenesis: A tube formation assay on Matrigel using Human Umbital Vein Endothelial Cells (HUVECs) was conducted.

Key Findings:

- Exosomes from the SFM (CDM) group showed higher expression of regeneration-related cytokines and lower levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines.

- These exosomes demonstrated enhanced wound healing and significantly improved angiogenic activity in the tube formation assay compared to exosomes derived from starved cells in the NM group [29].

Ensuring Safety and Genetic Stability

Objective: To comprehensively compare the safety and characteristics of Adipose-Derived Stem Cells (ADSCs) cultivated in SFM versus FBS-containing media [31].

Experimental Protocol:

- Cell Culture: Human ADSCs from multiple donors were expanded in parallel using commercial SFM (CellCor, StemPro, MesenCult) and traditional FBS-containing media.

- Long-Term Analysis: Cells were passaged repeatedly to assess:

- Population Doubling Time (PDT) and Accumulated Cell Number (ACN).

- Surface Markers: Flow cytometry for standard MSC markers (CD73, CD90, CD105) and immunogenicity markers (HLA-DR, Neu5Gc).

- Cellular Senescence: Senescence-associated β-galactosidase staining.

- Genetic Stability: Karyotype analysis.

- Multi-Omics Profiling: Differential expression analysis of mRNAs and proteins.

Key Findings:

- ADSCs in SFM showed a more stable PDT to later passages and could produce more cells in a shorter time.

- SFM-cultured ADSCs exhibited lower cellular senescence, lower immunogenicity (minimal Neu5Gc expression), and higher genetic stability than FBS-cultured cells.

- mRNA and protein analysis revealed that genes related to apoptosis, immune response, and inflammation were significantly up-regulated in FBS-cultured ADSCs [31].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents for MSC Exosome Production and Angiogenesis Research

| Reagent / Solution | Function / Application | Considerations for Use |

|---|---|---|

| Chemically Defined SFM (e.g., CellCor CD MSC, StemPro MSC SFM) | Supports the expansion of MSCs and production of exosomes in a serum-free, xeno-free environment. | Requires validation for specific MSC sources and therapeutic applications (e.g., chondrogenesis may be impaired [34]). |

| Tangential Flow Filtration (TFF) System | Scalable and efficient method for isolating and concentrating exosomes from large volumes of conditioned media. | Superior for reducing albumin contamination compared to ultracentrifugation; allows for high recovery rates [29] [30]. |

| Human Platelet Lysate (hPL) | Human-derived supplement alternative to FBS for clinical-grade MSC manufacturing. | Must be processed to deplete endogenous EVs and fibrinogen to ensure exosome purity [30]. |

| Annexin V / Propidium Iodide | Staining kits to assess cell viability and apoptosis during culture, crucial for monitoring cell health in SFM. | |

| Angiogenesis Antibody Array | Multiplexed protein detection tool to profile a panel of pro- and anti-angiogenic factors in exosomes or conditioned media [33]. | Provides a more comprehensive functional profile than single-analyte ELISAs. |

Visualizing the Workflow and Signaling Impact

The following diagrams illustrate the core experimental workflow for comparing culture media and how the resulting exosomes functionally influence angiogenesis.

Diagram 1: Experimental comparison workflow for MSC exosomes from different culture systems.

Diagram 2: Functional impact of exosome cargo on angiogenesis pathways.

The collective evidence indicates that serum-free media offer significant advantages for manufacturing MSC-derived exosomes intended for angiogenesis research and therapeutic development. The benefits of SFM—including superior exosome purity, reduced immunogenicity, enhanced genetic stability of parent cells, and potentially greater bioactivity—are compelling reasons to transition away from traditional FBS-contained systems. While the choice of SFM must be validated for specific MSC sources and targeted applications, the move towards defined, xeno-free culture conditions is essential for achieving reproducible, safe, and potent exosome-based regenerative therapies.

Angiogenesis, the process of new blood vessel formation from pre-existing vasculature, is a critical phenomenon in physiological processes like embryonic development and tissue repair, as well as in pathological conditions such as cancer and cardiovascular diseases [35]. In vitro angiogenesis assays serve as essential tools for evaluating the pro- or anti-angiogenic effects of various stimuli, including potential therapeutic compounds [35]. These assays primarily focus on key stages of the angiogenic process: endothelial cell proliferation, migration, and the formation of tubular structures that mimic capillary networks [35].

The choice between in vitro and ex vivo models represents a critical methodological consideration. While in vitro models involve cultivating isolated tissue components in controlled environments, ex vivo models utilize tissues or organs extracted from living organisms, thereby retaining more natural architecture and metabolic processes [35]. Recent advances have introduced more physiologically relevant human-centric models, including organ-on-a-chip technologies and 3D bioprinting, which better represent human physiology than conventional animal models [35].

This guide focuses on the foundational in vitro methods—tube formation, migration, and proliferation assays—within the specific context of evaluating the angiogenic potential of exosomes derived from different mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) sources: adipose-derived (ADSC), bone marrow-derived (BMSC), and umbilical cord-derived (UC MSC).

MSCs are multipotent stromal cells capable of self-renewal and differentiation into various mesodermal lineages [36]. They have emerged as a promising source of therapeutic exosomes for angiogenesis research due to their paracrine signaling capabilities. The tissue origin of MSCs significantly influences their biological properties, secretory profile, and consequently, their therapeutic potential [18] [37] [36].

Table 1: Comparison of MSC Sources for Angiogenesis Research

| MSC Source | Key Angiogenic Properties | Advantages for Research | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adipose-Derived (ADSC) | Strong anti-apoptotic effects; promotes cardiomyocyte survival post-MI [18] | Easily harvested with high yield; minimal invasiveness [36] | Weaker chondrogenic differentiation potential [38] |

| Bone Marrow-Derived (BMSC) | High differentiation potential; strong immunomodulatory effects [36] | Most extensively studied; well-characterized [36] | Invasive extraction procedure; donor-age-related functional decline [37] [38] |

| Umbilical Cord-Derived (UC MSC) | Superior pro-angiogenic activity; high levels of pro-angiogenic factors [18] | Non-invasive harvest; high proliferative capacity; low immunogenicity [37] [36] | Immunomodulatory effects may diminish with in vivo aging [38] |

The paradigm in MSC research has shifted from cell replacement therapy to recognizing their secreted factors as primary therapeutic effectors [37]. The MSC secretome—comprising soluble proteins, cytokines, growth factors, and extracellular vesicles (including exosomes)—mediates beneficial effects through paracrine signaling [37]. Key functional components include proangiogenic factors like vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1), and hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), which collectively promote new blood vessel formation [37].

Comparative studies reveal that UCMSCs present greater pro-angiogenesis activity than ADMSCs in both in vitro and in vivo settings, while ADMSCs exert stronger anti-apoptotic effects on residual cardiomyocytes [18]. This functional specialization suggests that optimal MSC source selection depends on the specific therapeutic goal—whether promoting new vessel growth or protecting existing tissues is paramount.

Core Angiogenesis Assay Methodologies

Tube Formation Assay

The tube formation assay represents the most commonly used in vitro method for evaluating angiogenic properties by measuring the formation of tubular structures from vascular endothelial cells (ECs) [39] [40]. This assay models the final stage of angiogenesis where ECs differentiate and form capillary-like structures.

Standard Protocol:

- Matrix Preparation: Coat 24-well plates with ice-cold, phenol red-free Matrigel (approximately 50-300 μL/well depending on desired thickness) and incubate at 37°C for 30-60 minutes to allow polymerization [39] [40].

- Cell Seeding: Harvest endothelial cells (HUVECs or ECFCs) and seed them onto the polymerized Matrigel at a density of 15×10⁴ cells/well in 1 mL of reduced serum medium (2% FBS) [40].

- Treatment Application: Add experimental treatments (MSC-derived exosomes, growth factors, or inhibitors) to appropriate wells. Include positive controls (VEGF 30-50 ng/mL or FGF-2) and negative controls (untreated or vehicle-treated) [40].

- Incubation and Imaging: Incubate cells at 37°C with 5% CO₂ for 6-12 hours. Image tubular structures using phase contrast microscopy at regular intervals (e.g., every 1-4 hours) [40].

- Image Analysis: Quantify parameters including total tube length, number of nodes, number of junctions, and number of meshes using image analysis software such as ImageJ with the Angiogenesis Analyzer plugin [39].

Advanced Modifications:

- Real-time Monitoring: Use a real-time cell recorder to track tube formation every hour for up to 48 hours, capturing the dynamic progression of tube formation, elongation, and regression [40].

- Image Stitching: Employ image-stitching software to create larger observation areas (e.g., 2×2 stitched images from 4× objective lens), minimizing analysis error due to limited observation fields [40].

- Alternative Cell Sources: Utilize endothelial colony-forming cells (ECFCs) instead of HUVECs. ECFCs, as endothelial precursors, demonstrate robust proliferative capacity and more defined angiogenic characteristics compared to mature ECs [40].

The tube formation assay is particularly valuable for its simplicity, rapidity, and cost-efficiency, providing initial evidence of angiogenic properties before moving to more complex in vivo studies [40].

Migration Assay

Endothelial cell migration is a critical early step in angiogenesis, enabling cells to move toward angiogenic stimuli. The scratch wound (wound healing) assay is a common method to evaluate this process.

Standard Protocol:

- Cell Culture: Seed endothelial cells in well plates and incubate until 90% confluency is reached [35].

- Wound Creation: Scrape the cell monolayer using a 200 μL pipette tip or cell scraper to create a linear "wound" [35].

- Washing and Treatment: Wash the plate with PBS to remove floating cells and debris. Add fresh medium containing experimental treatments (MSC-derived exosomes, controls) [35].

- Imaging and Analysis: Observe the wound area immediately after scratching (0 hour) and at regular intervals (e.g., 6, 12, 24 hours) using an inverted microscope. Measure the remaining wound area and calculate migration rate [35].

This approach enables assessment of fundamental cell migration properties including speed, persistence, and polarity [35]. For example, in studies evaluating the α7-nAChR agonist ISO-1, the scratch assay demonstrated significant pro-migratory effects at concentrations of 10⁻⁶ and 10⁻⁴ M, similar to responses observed with nicotine and choline [41].

Proliferation Assay

Endothelial cell proliferation provides the necessary cellular expansion to support new vessel growth. The MTS assay offers a colorimetric method for quantifying this process.

Standard Protocol:

- Cell Seeding: Seed endothelial cells in 96-well plates at optimal density (e.g., 3×10⁴ cells/well) and incubate for 24 hours [35] [41].

- Treatment Application: Replace medium with treatment-containing medium (MSC-derived exosomes, controls) and incubate for desired duration (typically 24-72 hours) [41].

- MTS Reagent Addition: Add 10 μL of MTS reagent to each well and incubate plates for 3-5 hours at 37°C [35].

- Absorbance Measurement: Remove media and add 100 μL of DMSO to solubilize the formazan product. Measure absorbance at 570 nm using a spectrophotometer [35].

The MTS assay measures mitochondrial activity as a surrogate for cell viability and proliferation. The yellow tetrazole compound is converted to purple formazan in metabolically active cells, with color intensity correlating with cell number [35]. Alternative methods include the sulforhodamine B (SRB) assay, which measures cellular protein content, and DNA synthesis assays using BrdU incorporation [35] [41].

Table 2: Key Parameters for Core Angiogenesis Assays

| Assay Type | Primary Readout | Incubation Duration | Key Endpoints |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tube Formation | Capillary-like structure formation | 6-12 hours (up to 48h for real-time) | Total tube length, number of nodes, number of junctions, number of meshes [39] [40] |

| Migration (Scratch) | Wound closure | 6-24 hours | Migration rate, wound closure percentage [35] |

| Proliferation (MTS) | Metabolic activity | 24-72 hours | Absorbance at 570nm, cell viability percentage [35] |

Comparative Experimental Data

Direct comparisons of MSC sources reveal distinct angiogenic profiles that inform exosome research. A 2025 study comparing UCMSCs and ADMSCs in a mouse myocardial infarction model demonstrated that while both MSC types improved cardiac function and decreased infarction area, they exhibited different mechanistic strengths [18].

Transcriptomic profiling through RNA sequencing revealed differences in gene expression related to angiogenesis and apoptosis pathways between UCMSCs and ADMSCs [18]. Functional assessments demonstrated that UCMSCs presented greater pro-angiogenesis activity in both in vitro and in vivo settings, while ADMSCs exerted stronger cardioprotective functions and more potent anti-apoptotic effects on residual cardiomyocytes [18].

The Fibrin Bead Assay (FBA), an alternative 3D model, provides complementary information to the traditional tube formation assay. In this assay, Cytodex beads are coated with HUVECs and embedded in a fibrin gel matrix with fibroblasts seeded on top, promoting the growth of 3D capillary-like patterns [39] [42]. When analyzed using the Angiogenesis Analyzer for ImageJ, this method allows quantification of sprouting initiation capacities and pseudo-vascular tree length, parameters that correlate with different biological stages of angiogenesis compared to traditional tube formation metrics [39].

Advanced transcriptomic approaches like TRAP sequencing (Translating Ribosome Affinity Purification) have been applied to 3D angiogenesis models, revealing distinct gene expression changes during morphogenesis [42]. This technology enables enrichment of endothelial RNA in co-culture systems, overcoming limitations of bulk RNA sequencing when studying minority cell types [42]. These studies have identified dynamic changes in the endothelial translatome, particularly in genes involved in mitogenesis, blood vessel development, and NOTCH signaling pathway during 3D morphogenesis [42].

Signaling Pathways in Angiogenesis

Angiogenesis is regulated by complex signaling pathways that can be modulated by MSC-derived exosomes. The diagram below illustrates key pathways involved in endothelial cell activation during angiogenesis.

Key Signaling Mechanisms:

PI3K/Akt Pathway: Central to angiogenesis regulation, this pathway is activated by various stimuli including VEGF, FGF-2, and calcium influx through α7-nAChR receptors [41]. PI3K signaling orchestrates cytoskeletal remodeling, adherens junction dynamics, and directed cell migration essential for angiogenesis [41].

NOTCH Signaling: Critical for regulating tip cell and stalk cell specification during sprouting angiogenesis [42]. TRAP sequencing studies in 3D cultures show dynamic regulation of NOTCH pathway genes throughout morphogenesis, highlighting its importance in vascular patterning [42].

Calcium-Mediated Signaling: Activation of α7-nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (α7-nAChRs) on endothelial cells increases intracellular Ca²⁺ concentration, promoting kinase activation and subsequent pro-angiogenic responses [41].

MSC-derived exosomes can modulate these pathways through their cargo of miRNAs, cytokines, and growth factors, with variations in exosome composition across different MSC sources contributing to their distinct angiogenic profiles.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Angiogenesis Assays

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Endothelial Cells | HUVECs, HDMECs, ECFCs | Primary cells for angiogenesis assays; ECFCs offer robust proliferation [35] [40] |

| Extracellular Matrices | Matrigel, Collagen, Fibrin Gel | Provide 3D substrate for tube formation and sprouting assays [39] [40] |

| Pro-angiogenic Factors | VEGF (30-50 ng/mL), FGF-2 | Positive controls for assay validation [40] |

| Angiogenesis Inhibitors | Vatalanib, α-bungarotoxin | Negative controls; receptor-specific inhibitors [40] [41] |

| Cell Tracking Reagents | MTS, Neutral Red, SRB | Measure cell viability, proliferation, and cytotoxicity [35] [41] |

| Image Analysis Tools | ImageJ Angiogenesis Analyzer | Quantify network parameters in tube formation assays [39] |

| Specialized Assay Systems | Real-time cell recorder, Microfluidic chips | Dynamic monitoring and advanced modeling of angiogenesis [40] |

In vitro angiogenesis assays—tube formation, migration, and proliferation—provide complementary data for evaluating the angiogenic potential of MSC-derived exosomes. The selection of appropriate assay combinations should align with specific research questions, recognizing that 3D models and real-time monitoring approaches offer enhanced physiological relevance compared to traditional 2D endpoint analyses [40] [43].

The comparative analysis of MSC sources indicates that UCMSCs demonstrate superior pro-angiogenic activity, while ADMSCs exhibit enhanced anti-apoptotic properties, and BMSCs offer well-characterized immunomodulatory effects [18] [36]. This functional specialization suggests that target application should guide MSC source selection for exosome production in angiogenesis research.

Future directions in the field include increased standardization of exosome isolation and characterization methods, integration of more complex 3D and organ-on-a-chip models, and application of advanced transcriptomic technologies like TRAP sequencing to elucidate temporal changes in endothelial cell gene expression during exosome-mediated angiogenesis [42] [43].

In the field of regenerative medicine, the comparative analysis of exosome sources derived from Adipose-Derived Stem Cells (ADSCs), Bone Marrow Mesenchymal Stem Cells (BMSCs), and Umbilical Cord Mesenchymal Stem Cells (UCMSCs) requires robust and standardized in vivo validation models. These models serve as critical platforms for evaluating the pro-angiogenic capacity of therapeutic candidates, providing essential data on their functional performance in complex biological systems. Among the most established and widely utilized systems are wound healing models, myocardial infarction (MI) models, and Matrigel plug assays, each offering unique insights into different aspects of the angiogenic process. Wound healing models replicate the complex cascade of events in tissue repair, including neovascularization; MI models simulate the ischemic conditions that drive therapeutic angiogenesis in cardiac tissue; and Matrigel plug assays provide a quantifiable system for directly assessing new blood vessel formation. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding the specific applications, experimental protocols, and data interpretation for each model is paramount when comparing the efficacy of different exosome sources. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of these three fundamental in vivo validation models, with a specific focus on their application in evaluating ADSC, BMSC, and UC-MSC derived exosomes for angiogenesis research.

The therapeutic potential of mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes varies significantly based on their tissue of origin. ADSCs, BMSCs, and UCMSCs each possess distinct secretory profiles that influence their angiogenic capabilities [37]. These differences arise from variations in their inherent biological properties, including gene expression patterns, proliferative capacity, and paracrine activity [18] [36]. Understanding these source-dependent characteristics is essential for selecting the most appropriate exosome type for specific angiogenic applications.

Table 1: Comparative Characteristics of MSC Sources for Angiogenesis Research

| Parameter | ADSCs | BMSCs | UCMSCs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Key Angiogenic Factors | VEGF-A, HGF, bFGF, IGF-1 [44] | VEGF, bFGF, Angiopoietin-1 [36] | High levels of VEGF, FGF2, miR-126 [45] |

| Relative Angiogenic Potency | Moderate to high (enhanceable via electrical stimulation) [44] | Moderate (documented decline with donor age) [37] | High intrinsic pro-angiogenic activity [18] [37] |

| Primary Mechanisms | VEGFA-VEGFR2 signaling pathway activation [44] | Paracrine secretion of growth factors and cytokines [36] | Wnt/β-catenin, Notch, and PI3K/Akt pathways [45] |

| Documented Effects in Models | Strong cardioprotective and anti-apoptotic effects in MI; improved blood flow recovery in hindlimb ischemia [18] [44] | Tissue repair and angiogenesis promotion through bioactive molecule release [36] | Superior tube formation and pro-angiogenesis activity in vitro and in vivo [18] |

| Research Advantages | Easier to harvest and higher yields; responsive to potentiation strategies [44] [36] | Most extensively studied; strong immunomodulatory effects [36] | Non-invasive harvest; low immunogenicity; high proliferative capacity [37] [36] |

The selection of MSC source material significantly impacts the angiogenic potential of derived exosomes. UCMSCs consistently demonstrate superior pro-angiogenic activity in direct comparisons, with one study revealing they present "greater pro-angiogenesis activity than ADMSCs in vitro and in vivo" [18]. This enhanced activity is attributed to their rich content of angiogenic factors and activation of key signaling pathways including Wnt/β-catenin, Notch, and PI3K/Akt [45]. ADSCs offer a valuable alternative with the distinct advantage of being relatively easy to harvest in high yields and responsive to potentiation strategies such as electrical stimulation, which can significantly upregulate their secretion of VEGF-A and other angiogenic factors [44]. BMSCs, while historically the most extensively studied, may show functional decline with donor age but remain valuable for their well-characterized immunomodulatory properties [37] [36].

In Vivo Validation Models: Experimental Data and Applications

Matrigel Plug Assay

The Matrigel plug assay serves as a fundamental direct assessment tool for quantifying angiogenesis in vivo. This model involves the subcutaneous injection of Matrigel basement membrane matrix mixed with the test substance into laboratory animals, typically mice. The Matrigel forms a solid plug at body temperature, creating a defined environment where blood vessel infiltration can be measured after a predetermined period, usually 7-14 days [18] [44].

Table 2: Matrigel Plug Assay Protocol and Data Interpretation

| Aspect | Standardized Protocol | Key Measurements | Applications for Exosome Comparison |

|---|---|---|---|

| Plug Preparation | Mix exosomes (50-100 µg) with growth factor-reduced Matrigel (400-500 µL) on ice; optional addition of heparin (10-50 U/mL) and basic FGF (100-500 ng/mL) as positive controls [44] | Hemoglobin content (Drabkin's method), CD31+ endothelial cell infiltration (immunohistochemistry), vessel counting (histology) [44] | Direct comparison of angiogenic potency between ADSC, BMSC, and UC-MSC exosomes |

| Implantation | Subcutaneous injection into ventral region of mice (200-500 µL/site); multiple plugs per animal possible | Visual inspection for color (pale vs. reddish), plug weight, vascular density | Quantification of functional blood vessel formation induced by different exosome sources |

| Harvest & Analysis | Harvest at day 7-14; formalin fixation and paraffin embedding for sectioning; H&E staining and immunostaining | Microscopic analysis of vessel structures, quantification of functional vessels per field | Assessment of specific cell recruitment (endothelial cells, pericytes) mediated by exosome cargo |