Comparative Chromatin Accessibility in Cellular Reprogramming: From Mechanisms to Clinical Applications

This comprehensive review explores how comparative analysis of chromatin accessibility provides critical insights into cellular reprogramming mechanisms, efficiency, and outcomes.

Comparative Chromatin Accessibility in Cellular Reprogramming: From Mechanisms to Clinical Applications

Abstract

This comprehensive review explores how comparative analysis of chromatin accessibility provides critical insights into cellular reprogramming mechanisms, efficiency, and outcomes. We examine the fundamental role of chromatin dynamics in establishing new cellular identities across diverse systems, from induced pluripotency to directed differentiation. The article evaluates cutting-edge methodological approaches for mapping and comparing accessibility landscapes, addresses key technical challenges and optimization strategies, and validates computational predictions against functional reprogramming outcomes. For researchers and drug development professionals, this synthesis offers a framework for leveraging chromatin accessibility data to enhance reprogramming protocols, develop disease models, and advance regenerative therapies.

Chromatin Accessibility Dynamics: The Foundation of Cellular Reprogramming

Chromatin accessibility refers to the physical permissibility of genomic DNA to nuclear macromolecules, a fundamental property governing essential cellular processes such as transcription, replication, DNA repair, and cell fate determination [1]. This accessibility is primarily determined by nucleosome distribution and occupancy, along with other DNA-binding factors that collectively shape the genome's structural landscape [1]. The eukaryotic genome exhibits a spectrum of accessibility states, ranging from hyper-accessible "open" chromatin to inaccessible "closed" chromatin, with nucleosomes serving as the primary structural units that regulate this dynamic [2].

The nucleosome, comprising approximately 147 base pairs of DNA wrapped around an octamer of histone proteins, forms the fundamental repeating unit of chromatin [3] [1]. Its strategic positioning and structural state act as a critical determinant of DNA accessibility. Recent research has revealed that nucleosomes exist in dynamic states of wrapping and unwrapping, with DNA spending approximately 2-10% of its time in an unwrapped "breathing" state [3]. Advanced mapping techniques have further demonstrated that genomic chromatin forms distinct Nucleosome Wrapping Domains (NRDs)—classified as tightly wrapped (TiNRDs) and loosely wrapped (LoNRDs)—which precisely correspond with higher-order chromatin organization, including Hi-C A and B compartments [3].

This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of the experimental frameworks, molecular mechanisms, and biological implications of chromatin accessibility, with particular emphasis on its role in cellular reprogramming and regenerative processes.

Methodological Comparison: Profiling Accessibility Landscapes

Diverse experimental approaches have been developed to map chromatin accessibility at genome-wide scale, each with distinct principles, advantages, and limitations. The core principle underlying most methods leverages the differential susceptibility of occupied versus free DNA to enzymatic cleavage, transposition, methylation, or solubility-based separation [2] [1].

Table 1: Comparison of Major Chromatin Accessibility Profiling Methods

| Method | Principle | Resolution | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DNase-seq [2] [1] | DNase I enzyme cleaves hyper-accessible regions | ~150 bp | Well-established for mapping hypersensitive sites; rich historical data | Bias toward hyper-accessible regions; underrepresents moderately accessible regions |

| MNase-seq [2] [1] | Micrococcal nuclease digests linker DNA and accessible regions | Single nucleosome | Excellent for nucleosome positioning; can map both accessible and protected regions | Strong sequence cleavage bias; requires titration to distinguish accessibility from occupancy |

| ATAC-seq [2] [1] | Tn5 transposase inserts adapters into accessible DNA | ~100 bp | High signal-to-noise ratio; fast protocol; low cell input requirements (down to single cell) | Sensitive to mitochondrial DNA; complex data analysis |

| FAIRE-seq [2] [1] | Formaldehyde fixation followed by sonication and phenol-chloroform extraction | ~100-500 bp | No enzyme bias; simple conceptual approach | Lower resolution compared to nuclease-based methods |

| NOMe-seq [2] [1] | Methyltransferase accessibility profiling followed by bisulfite sequencing | Single molecule | Provides both accessibility and native DNA methylation information | Technically challenging; requires specialized expertise |

The emergence of single-cell and multimodal technologies represents a significant advancement, enabling researchers to simultaneously profile chromatin accessibility and gene expression within the same individual cells [4] [1]. For example, single-nuclei multiome ATAC + RNA sequencing was recently employed to investigate wound-induced reprogramming in moss, revealing that reprogramming leaf cells exhibit a partly relaxed chromatin landscape while specific transcription factors enhance accessibility at loci essential for stem cell formation [4].

Molecular Mechanisms Governing Chromatin Accessibility

Nucleosome Remodeling Complexes

ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling complexes constitute primary regulators of chromatin accessibility by controlling nucleosome positioning, composition, and stability. These multi-subunit complexes utilize ATP hydrolysis to mobilize nucleosomes, facilitating the transition between "closed" and "open" chromatin states [1]. They are categorized into four major families based on their distinct structural and functional characteristics.

Table 2: Major Chromatin Remodeling Complex Families and Their Functions

| Complex Family | Key Subunits | Primary Functions | Biological Roles in Reprogramming |

|---|---|---|---|

| SWI/SNF [1] | SMARCA2/4, ARID1A | Nucleosome sliding, eviction, histone variant exchange | Promotes accessibility at pluripotency loci; facilitates pioneer transcription factor activity |

| NuRD [1] | CHD3/4/5, HDAC1/2 | Nucleosome sliding, histone deacetylation | Suppresses somatic gene expression during reprogramming; interacts with Sall4 to reduce accessibility of anti-reprogramming genes |

| ISWI [1] | SMARCA5, BAZ1A/B | Nucleosome spacing, chromatin compaction | Maintains nucleosome periodicity; contributes to heterochromatin integrity |

| INO80 [3] [1] | INO80, YY1, actin-related proteins | Nucleosome sliding, histone variant exchange (H2A.Z) | Promotes DNA repair; facilitates transcriptional activation |

Structural studies have provided unprecedented insights into remodeling mechanisms. Recent cryo-EM structures of human CHD1 bound to nucleosomes revealed an "anchor element" that connects the ATPase motor to the nucleosome's acidic patch, alongside a "gating element" that undergoes conformational switching critical for remodeling activity [5]. These structural elements are conserved across remodeler families, suggesting a unified mechanism for nucleosome recognition and remodeling [5].

Pioneer Transcription Factors and Epigenetic Regulation

Pioneer transcription factors (PTFs) represent a specialized class of DNA-binding proteins capable of initiating chromatin opening by binding to nucleosomal DNA in closed chromatin regions [6]. Unlike conventional transcription factors that require pre-accessible DNA, PTFs can directly recognize their target sequences in compacted chromatin, subsequently recruiting additional chromatin remodelers and co-factors to establish stable accessible regions [6].

During cellular reprogramming, PTFs play instrumental roles in reshaping chromatin architecture. In wound-induced reprogramming in moss, STEMIN transcription factors selectively enhance accessibility at specific genomic loci essential for stem cell formation within a broadly relaxed chromatin environment established by wounding [4]. Similarly, in mammalian systems, the AP2/ERF transcription factor STEMIN homologs function as intrinsic mediators of reprogramming in response to injury [4].

Epigenetic modifications, including histone post-translational modifications and DNA methylation, further refine the chromatin accessibility landscape. Histone acetylation (e.g., H3K27ac) generally correlates with enhanced accessibility, while specific methylation patterns can either activate (H3K4me3) or repress (H3K27me3) chromatin states [6]. DNA methylation at promoter CpG islands typically associates with transcriptional silencing and reduced accessibility, with DNMT enzymes catalyzing methylation and TET enzymes facilitating demethylation [6].

Chromatin Accessibility in Reprogramming and Regeneration

Case Studies in Cellular Reprogramming

Chromatin accessibility dynamics play a pivotal role in cellular reprogramming across diverse biological contexts, from wound response to directed cell fate transitions. Several illuminating case studies highlight these principles:

Wound-Induced Reprogramming in Moss: Single-nuclei multiome analysis in Physcomitrium patens revealed that leaf cells undergoing reprogramming following wounding exhibit widespread chromatin relaxation, establishing a permissive environment for stem cell formation [4]. Within this broadly accessible landscape, STEMIN transcription factors selectively enhance accessibility at specific genomic loci essential for the leaf-to-stem-cell transition, demonstrating a hierarchical interplay between global chromatin changes and factor-directed local remodeling [4].

Hepatic Regeneration: Integrated RNA-seq and ATAC-seq analyses of liver regeneration identified ATF3 as an "Initiationon" transcription factor and ONECUT2 as an "Initiationoff" factor that reciprocally modulate target promoter occupancy to license hepatocytes for regeneration [7]. ATF3 binds to the Slc7a5 promoter to activate mTOR signaling, while the Hmgcs1 promoter loses ONECUT2 binding to facilitate regenerative initiation [7].

Leukemia Reprogramming: The GATA3 noncoding variant rs3824662 drives extensive chromatin reorganization in Ph-like acute lymphoblastic leukemia, resulting in increased accessibility of GATA3 binding regions and dysregulation of oncogenes like CRLF2 [8]. Enhancer RNAs (eRNAs), including eRNAG3 and eRNAC4, show coordinated upregulation and positive correlation with CRLF2 expression, suggesting their cooperative contribution to the regulatory mechanisms governing leukemogenic reprogramming [8].

Comparative Analysis of Reprogramming Systems

Table 3: Chromatin Accessibility Dynamics Across Reprogramming Models

| Reprogramming Context | Initial Chromatin State | Key Regulatory Factors | Accessibility Changes | Functional Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wound-induced moss reprogramming [4] | Differentiated leaf cell | STEMIN transcription factors | Genome-wide relaxation with selective enhancement at stem cell loci | Direct conversion to chloronema apical stem cells |

| Hepatic regeneration [7] | Quiescent hepatocyte | ATF3 (on), ONECUT2 (off) | Transient, phase-restricted remodeling at promoters of regeneration genes | Hepatocyte proliferation and functional tissue repair |

| Oncogenic viral transformation [6] | Somatic cell | Viral oncoproteins, host pioneer factors | Viral integration into accessible regions; hijacking of host regulatory elements | Cellular transformation; persistent infection |

| Induced pluripotency [9] [1] | Differentiated somatic cell | Yamanaka factors (Oct4, Sox2, Klf4, c-Myc) | Sequential opening of pluripotency loci; closing of somatic genes | Pluripotent stem cells |

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Chromatin Accessibility Studies

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Tn5 Transposase [2] [1] | Simultaneous fragmentation and tagging of accessible genomic DNA | ATAC-seq library preparation; compatibility with low-input and single-cell protocols |

| Micrococcal Nuclease (MNase) [3] [2] | Enzymatic digestion of linker DNA and accessible regions | MNase-seq for nucleosome positioning; mapping of nucleosome wrapping states |

| DNase I [2] [1] | Cleavage of hypersensitive genomic regions | DNase-seq for mapping canonical DHSs in regulatory elements |

| M.CviPI Methyltransferase [2] | In vitro methylation of accessible GpC sites | NOMe-seq for combined accessibility and native methylation profiling |

| 10x Genomics Single Cell Multiome ATAC + RNA [4] | Simultaneous profiling of chromatin accessibility and gene expression | Identification of cell type-specific regulatory dynamics during reprogramming |

| Spike-in Controls [2] | Normalization for technical variation in nuclease digestion | Quantitative MNase-seq (q-MNase) for accurate nucleosome occupancy measurements |

Conceptual Framework and Signaling Pathways

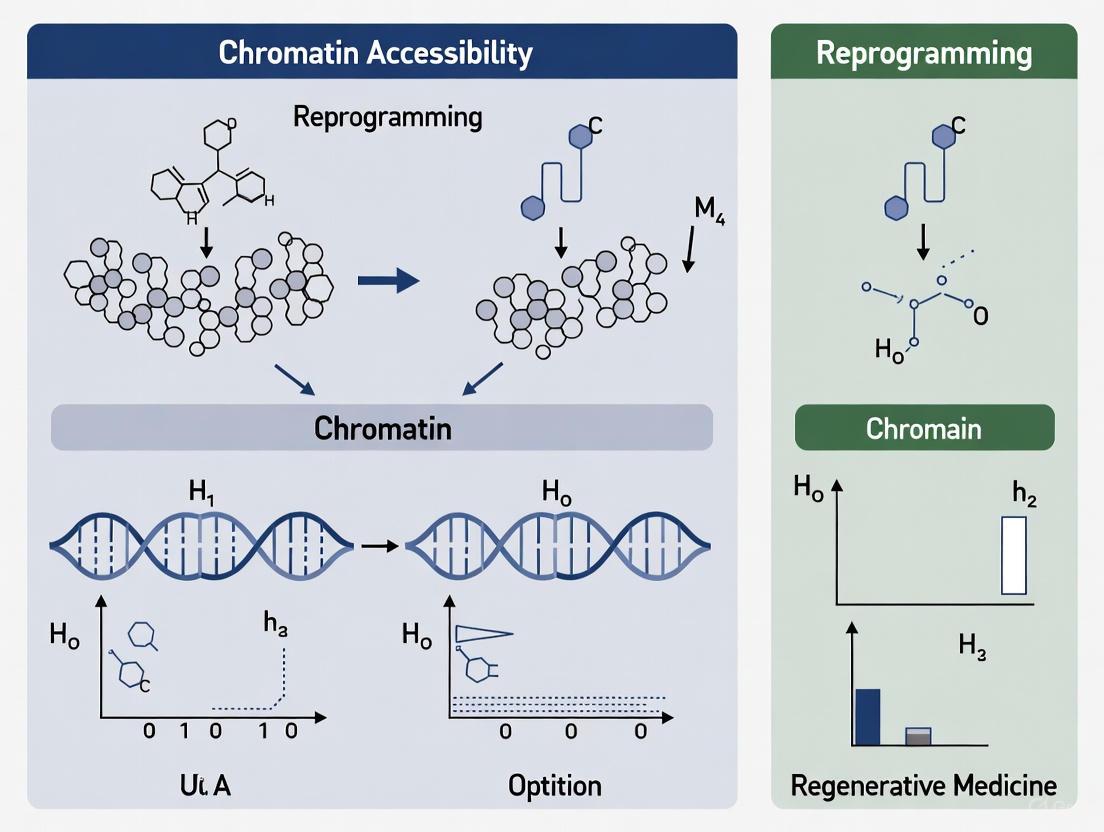

The following diagram illustrates the integrated molecular framework governing chromatin accessibility dynamics during cellular reprogramming:

Figure 1. Integrated Molecular Framework of Chromatin Accessibility in Reprogramming. This diagram illustrates the hierarchical regulatory network wherein external stimuli activate pioneer transcription factors that subsequently recruit chromatin remodeling complexes and epigenetic modifiers. These effectors collectively establish a permissive chromatin environment through relaxation and accessibility changes, enabling enhancer RNA production and gene expression alterations that ultimately drive cell fate reprogramming.

The following diagram details the experimental workflow for multimodal chromatin accessibility analysis:

Figure 2. Multimodal Experimental Workflow for Chromatin Accessibility Studies. This workflow diagram outlines the integrated experimental and computational pipeline for simultaneous profiling of chromatin accessibility and gene expression, enabling comprehensive characterization of regulatory dynamics during reprogramming processes.

The comparative analysis of chromatin accessibility across reprogramming models reveals both conserved principles and context-specific adaptations. A fundamental emerging paradigm is the hierarchical regulation wherein broad chromatin relaxation creates a permissive landscape that is subsequently refined by sequence-specific factors to establish new transcriptional programs [4]. This two-phase mechanism appears conserved from plant to mammalian systems, suggesting an evolutionarily ancient strategy for cellular plasticity.

Future research directions will likely focus on several key areas: First, the development of enhanced spatial chromatin accessibility methods will enable the mapping of regulatory landscapes within native tissue architecture, providing critical insights into microenvironmental influences on cell fate decisions [1]. Second, the integration of time-resolved multiomics with computational modeling promises to reveal the causal relationships between chromatin dynamics and functional outcomes [7] [10]. Finally, the therapeutic targeting of chromatin regulators—including ATP-dependent remodelers and pioneer factors—holds significant promise for regenerative medicine and cancer therapy, particularly for overcoming the epigenetic barriers that limit efficient reprogramming [9] [1].

The continuing refinement of chromatin accessibility mapping technologies, combined with innovative experimental models of reprogramming, will undoubtedly yield deeper insights into the fundamental principles of genome regulation and their translational applications in human health and disease.

Chromatin accessibility serves as a master regulator of cellular identity, governing gene expression by modulating DNA availability to transcriptional machinery. Within the nucleus, chromatin exists in a dynamic spectrum of states—open, permissive, and closed—each characterized by distinct structural features, histone modifications, and functional consequences. This guide systematically compares these chromatin states within the context of cellular reprogramming, examining how transcription factor binding and chromatin remodeling orchestrate cell fate transitions. We present quantitative comparisons of epigenetic features, detailed experimental methodologies for mapping accessibility, and analytical frameworks for interpreting chromatin dynamics during reprogramming events. Understanding these states provides critical insights for regenerative medicine and therapeutic development.

Chromatin, the complex of DNA and histone proteins, packages the eukaryotic genome within the nucleus while regulating access to genetic information. The term chromatin accessibility refers to the physical access that proteins have to DNA, which is profoundly influenced by local nucleosome positioning and higher-order chromatin structure [2]. Rather than existing in a binary open/closed state, chromatin occupies a continuum of accessibility that ranges from hyper-accessible ("open") to moderately accessible ("permissive") to inaccessible ("closed") states [2].

These chromatin states establish a fundamental regulatory layer for all DNA-templated processes, including transcription, replication, and repair. During cellular reprogramming—the process of converting differentiated cells into induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs)—the orchestrated remodeling of chromatin states enables the dramatic rewiring of gene regulatory networks necessary for identity change [11]. Transcription factors such as Oct4, Sox2, Klf4, and c-Myc (OSKM) must navigate and reshape this epigenetic landscape to activate pluripotency genes while silencing somatic programs.

Defining the Chromatin Spectrum

Molecular Definitions and Features

The chromatin accessibility spectrum comprises three principal states with distinct characteristics:

Open Chromatin: Characterized by nucleosome-depleted regions with maximal DNA accessibility, these regions are typically associated with active promoters, enhancers, and other regulatory elements. They exhibit DNase I hypersensitivity and are enriched for active histone marks such as H3K4me3 at promoters and H3K27ac at enhancers [2] [12]. During reprogramming, open chromatin sites in somatic cells represent the first class of targets bound by reprogramming factors, including genes involved in mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition (MET) [11].

Permissive Chromatin: This intermediate state features nucleosome-bound but dynamic regions that may carry both activating and repressive histone modifications. Permissive chromatin often includes bivalent domains marked by both H3K4me3 (activating) and H3K27me3 (repressive) modifications, which keep developmental genes in a transcriptionally poised state, ready for activation or silencing upon lineage commitment [11]. Enhancers in a permissive state (H3K4me1-positive but not fully open) can bind transcription factors but may require additional remodeling for full activation [11].

Closed Chromatin: Also termed heterochromatin, these regions are compacted and transcriptionally silent, presenting a significant barrier to factor binding. Closed chromatin is enriched for repressive marks such as H3K9me3 (constitutive heterochromatin) and H3K27me3 (facultative heterochromatin) [13]. During reprogramming, core pluripotency genes like Nanog often reside within this refractory chromatin in somatic cells, requiring extensive remodeling for activation [11].

The following diagram illustrates the continuum of chromatin states and their key characteristics:

Chromatin State Transitions. Chromatin exists along a dynamic continuum, with states interconverting through remodeling, activation, and repression processes.

Quantitative Comparison of Chromatin States

The table below summarizes the defining characteristics and functional associations of the three primary chromatin states:

Table 1: Comparative Features of Chromatin States

| Feature | Open Chromatin | Permissive Chromatin | Closed Chromatin |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Accessibility | High (Nucleosome-depleted) | Moderate (Nucleosome-bound) | Low (Nucleosome-occupied) |

| DNase I Sensitivity | Hypersensitive | Intermediate | Resistant |

| Representative Histone Modifications | H3K4me3, H3K27ac | H3K4me1, H3K27me3/H3K4me3 (bivalent) | H3K9me3, H3K27me3 |

| Transcriptional Activity | Active | Poised/Silent | Silent |

| Nuclear Compartment | Euchromatin (A) | Facultative Heterochromatin | Constitutive Heterochromatin (B) |

| Reprogramming Factor Binding | Immediate OKSM binding | Delayed binding requiring remodeling | Refractory to initial binding |

| Functional Associations | Active promoters, enhancers | Poised enhancers, bivalent promoters | Repetitive regions, silenced genes |

Chromatin State Dynamics in Cellular Reprogramming

Cellular reprogramming provides a powerful model for understanding how transcription factors orchestrate chromatin state transitions to enable cell fate changes. The OSKM factors target distinct chromatin environments with different kinetics and functional outcomes during iPSC generation.

Transcription Factor Engagement with Chromatin States

Reprogramming factors demonstrate hierarchical engagement with chromatin states based on accessibility:

Open Chromatin Targets: In both human and mouse fibroblasts, OSK factors initially target many closed chromatin sites, but their immediate binding occurs predominantly at already accessible regions containing active chromatin marks [14] [11]. These early targets include somatic genes that require downregulation and early MET-related genes [11].

Permissive Chromatin Engagement: A second class of targets includes distal regulatory elements with permissive features such as H3K4me1 marking [11]. These "permissive enhancers" can bind transcription factors prior to their associated promoters and before full transcriptional activation. Some factors, particularly Oct4 and Sox2, function as pioneer factors capable of binding partially accessible regions and initiating chromatin remodeling [11].

Closed Chromatin Remodeling: The most challenging targets are broad heterochromatic regions enriched for H3K9me3 that contain core pluripotency genes such as Nanog and Sox2 [11]. These regions are refractory to initial OKSM binding and require extensive, coordinated remodeling involving histone-modifying enzymes and chromatin remodelers for activation.

Comparative Analysis of Reprogramming Factors

Studies comparing OSKM binding in human and mouse reprogramming reveal both conserved and species-specific aspects of chromatin engagement:

Table 2: OSKM Binding in Early Human vs. Mouse Reprogramming

| Feature | Human System | Mouse System | Conservation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time to Reprogramming | ~3-4 weeks | ~1-2 weeks | Not conserved |

| Number of OSKM Peaks | ~2x more for Sox2, Klf4, c-Myc | Fewer peaks for these factors | Partially conserved |

| c-Myc Binding Distribution | Preferentially distal to TSS | Preferentially proximal to TSS | Not conserved |

| Primary Binding Motifs | Similar with minor variations | Similar with minor variations | Highly conserved |

| Combinatorial Binding Patterns | Shared patterns | Shared patterns | Highly conserved |

| Syntenic Binding Conservation | Limited conservation in syntenic regions | Limited conservation in syntenic regions | Poorly conserved |

Despite these differences, both systems share significant overlap in target genes and gene ontology enrichments, particularly for processes like regulation of transcription, in utero embryonic development, and Wnt signaling pathway regulation [14].

Experimental Methods for Chromatin Accessibility Profiling

Multiple biochemical methods have been developed to profile chromatin accessibility genome-wide, each with distinct advantages and limitations. The selection of an appropriate method depends on research goals, sample availability, and desired resolution.

Core Methodologies and Protocols

ATAC-Seq (Assay for Transposase-Accessible Chromatin with Sequencing)

ATAC-Seq has become the most widely used method for chromatin accessibility profiling due to its simplicity, sensitivity, and low cell input requirements [12] [15].

Experimental Principle: The method utilizes a hyperactive Tn5 transposase that simultaneously fragments DNA and inserts sequencing adapters into accessible genomic regions in a process called "tagmentation." The preferential insertion of Tn5 into nucleosome-free regions enables mapping of open chromatin [15].

Key Protocol Steps:

- Cell Lysis: Isolate nuclei from fresh cells or tissues using detergent-based buffers.

- Tagmentation: Incubate nuclei with Tn5 transposase loaded with sequencing adapters.

- DNA Purification: Recover and purify fragmented DNA.

- Library Amplification: PCR amplification with index primers to create sequencing libraries.

- Sequencing: High-throughput sequencing (typically Illumina platforms).

Advantages: Rapid protocol (~3 hours), low cell input (500-50,000 cells), no crosslinking required, and compatibility with single-cell applications [15].

Recommended Sequencing Depth: ≥50 million paired-end reads for identifying open chromatin differences; >200 million paired-end reads for transcription factor footprinting [15].

DNase-Seq (DNase I Hypersensitive Sites Sequencing)

DNase-Seq was one of the first methods developed for genome-wide chromatin accessibility mapping and remains a gold standard for identifying hypersensitive sites [2] [12].

Experimental Principle: The method exploits the preference of DNase I endonuclease to cleave nucleosome-depleted, accessible DNA over compacted chromatin. Sequencing the resulting fragments reveals regions of hypersensitivity [2].

Key Protocol Steps:

- Nuclei Isolation: Purify intact nuclei from cells.

- DNase I Digestion: Titrate DNase I enzyme to achieve limited digestion.

- DNA Extraction: Purify and size-select fragmented DNA (typically 100-500 bp).

- Library Preparation: Ligate sequencing adapters to digested fragments.

- Sequencing: High-throughput sequencing.

Advantages: Well-established protocol, excellent for mapping hypersensitive sites, comprehensive annotation of regulatory elements.

Limitations: Requires millions of cells, optimization of digestion conditions is critical, and more complex protocol than ATAC-Seq.

Methyltransferase-Based Methods

These methods use bacterial DNA methyltransferases to label accessible DNA, providing single-molecule resolution of chromatin accessibility [2] [16].

Experimental Principle: Isolated nuclei are treated with methyltransferases (e.g., EcoGII) that preferentially modify accessible adenines (A→6mA) in the presence of the methyl donor SAM. Subsequent long-read sequencing detects 6mA incorporation as a proxy for accessibility [16].

Key Protocol Steps:

- Nuclei Isolation: Preserve nuclear integrity using detergent-based buffers.

- Methyltransferase Tagging: Incubate nuclei with EcoGII enzyme and SAM.

- gDNA Extraction: Recover high molecular weight genomic DNA.

- Library Preparation: Prepare libraries for long-read sequencing (e.g., Oxford Nanopore).

- Sequencing and Analysis: Detect 6mA incorporation to identify accessible regions.

Advantages: Single-molecule resolution, captures long-range chromatin information, compatible with variant phasing.

Limitations: Specialized equipment required, lower throughput, higher DNA input requirements.

The following diagram illustrates the core workflows for these key methodologies:

Chromatin Accessibility Method Workflows. Core experimental workflows for the three principal methods for profiling chromatin accessibility genome-wide.

Method Comparison and Selection Guidelines

Table 3: Comparative Performance of Chromatin Accessibility Methods

| Method | Sensitivity | Resolution | Cell Input | Primary Applications | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATAC-Seq | High | ~100 bp | 500 - 50,000 cells | Nucleosome mapping, TF footprinting, enhancer identification | Fast, sensitive, low input, single-cell compatible |

| DNase-Seq | High | ~100 bp | 1 - 50 million cells | DNase hypersensitive site mapping, regulatory element annotation | Gold standard for hypersensitive sites, comprehensive |

| MNase-Seq | Moderate | Nucleosome-level | 1 - 10 million cells | Nucleosome positioning, occupancy mapping | Direct nucleosome mapping, both accessible and inaccessible regions |

| FAIRE-Seq | Moderate | ~100 bp | 1 - 10 million cells | Hyper-accessible region enrichment | No enzyme bias, simple protocol |

| Methyltransferase-Based | Variable | Single-molecule | 2 million cells | Single-molecule accessibility, long-range phasing | Single-molecule resolution, long-range information |

Successful chromatin accessibility studies require specialized reagents and computational tools. The following table outlines essential solutions for experimental and analytical workflows:

Table 4: Research Reagent Solutions for Chromatin Accessibility Studies

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Example Applications | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tn5 Transposase | Simultaneous fragmentation and adapter insertion for ATAC-Seq | Bulk and single-cell ATAC-Seq | High efficiency, minimal sequence bias |

| DNase I | Enzymatic cleavage of accessible DNA | DNase-Seq, DNase I hypersensitivity mapping | Specific for nucleosome-free regions |

| EcoGII Methyltransferase | Adenine methylation (6mA) of accessible DNA | Long-read chromatin accessibility profiling | Non-native modification in mammals, single-molecule resolution |

| H3K27ac Antibody | Immunoprecipitation of active enhancers and promoters | ChIP-Seq for active regulatory elements | Marks active enhancers and promoters |

| H3K4me3 Antibody | Immunoprecipitation of active promoters | ChIP-Seq for active transcription start sites | Marks active promoters |

| H3K27me3 Antibody | Immunoprecipitation of Polycomb-repressed regions | ChIP-Seq for facultative heterochromatin | Marks Polycomb-repressed regions |

| Chromatin State Annotation Tools | Computational segmentation of chromatin states | Integrative analysis of multiple epigenetic marks | Defines regulatory elements from combined datasets |

| Hi-C Analysis Software | Mapping 3D chromatin interactions | 3D genome organization studies | Identifies chromatin loops, compartments, TADs |

The dynamic spectrum of chromatin states—open, permissive, and closed—forms an essential regulatory framework that governs cell identity and plasticity. Cellular reprogramming studies have been particularly illuminating, revealing how transcription factors hierarchically engage with these states to rewrite cellular programs. While significant progress has been made in mapping these states and understanding their transitions, several frontiers remain: achieving single-molecule resolution of chromatin dynamics, understanding the role of 3D genome organization in state maintenance, and developing therapeutic approaches to modulate chromatin states in disease contexts. The continued refinement of chromatin accessibility methods and analytical frameworks will undoubtedly yield deeper insights into the fundamental principles of epigenetic regulation across diverse biological systems.

Pioneer Transcription Factors as Architects of Chromatin Remodeling During Reprogramming

Pioneer Transcription Factors (PTFs) represent a unique class of proteins that serve as master regulators of cell fate by initiating chromatin remodeling events during cellular reprogramming. Unlike conventional transcription factors that require pre-existing chromatin accessibility, PTFs possess the remarkable ability to bind directly to closed chromatin regions, initiating a cascade of events that ultimately redefine cellular identity [17]. This capacity to engage nucleosome-wrapped DNA enables PTFs to function as initial "architects" of chromatin restructuring, making them indispensable tools in regenerative medicine and cellular reprogramming research [17] [18].

The fundamental property that distinguishes PTFs is their capacity to specifically recognize their DNA binding motifs on nucleosomal DNA, which is generally inaccessible to most transcription factors [19] [20]. Through this activity, PTFs can initiate local chromatin opening and facilitate subsequent binding of other transcription factors and co-factors in a cell-type-specific manner [20]. This review will comprehensively compare the mechanisms, experimental methodologies, and functional outcomes of major PTFs, with a specific focus on their roles in modulating chromatin accessibility during cellular reprogramming processes, including the generation of induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs).

Molecular Mechanisms of Pioneer Factor Action

Nucleosome Binding and Chromatin Opening Strategies

Pioneer Transcription Factors employ distinct structural strategies to engage with nucleosomal DNA and initiate chromatin remodeling. The molecular interactions between PTFs and nucleosomes have been elucidated through recent structural studies, revealing several key mechanisms:

Partial DNA Motif Recognition: PTFs target partial DNA motifs on nucleosomes to initiate reprogramming, often binding to suboptimal sites that would be ignored by conventional transcription factors [18]. This flexible binding mode allows initial engagement with chromatin before more stable complexes are formed.

Nucleosome Structure Modulation: Binding of PTFs like OCT4 induces significant changes to nucleosome structure, repositions nucleosomal DNA, and facilitates cooperative binding of additional factors [21]. Cryo-EM structures reveal that OCT4 binding stabilizes otherwise flexible nucleosome positioning, trapping the DNA in a specific conformation [21].

Histone Tail Interactions: The flexible activation domain of OCT4 contacts the N-terminal tail of histone H4, altering its conformation and promoting chromatin decompaction [21]. Additionally, the DNA-binding domain of OCT4 engages with the N-terminal tail of histone H3, and post-translational modifications at H3K27 modulate DNA positioning and affect transcription factor cooperativity [21].

Table 1: Chromatin Remodeling Capabilities of Key Pioneer Transcription Factors

| Pioneer Factor | Nucleosome Binding Mechanism | Chromatin Opening Effect | Cooperative Partners |

|---|---|---|---|

| OCT4 (POU5F1) | Binds linker DNA near nucleosome entry-exit site; both POUS and POUHD domains engage nucleosome | Repositions nucleosomal DNA; stabilizes DNA positioning; promotes H4 tail conformational changes | SOX2, KLF4, MYC [21] |

| SOX2 | Preferentially binds nucleosomes in presence of OCT4; recognizes internal sites | Facilitates nucleosome unwrapping; increases accessibility of adjacent sites | OCT4 (critical partnership) [21] |

| FoxA | Linker histone-like DNA binding domain; displaces linker histone H1 | Directly opens compacted chromatin; reduces dependency on nucleosome remodelers | Other hepatic transcription factors [19] |

| Klf4 | Binds partial motifs on nucleosomal DNA | Initiates local accessibility; facilitates binding of other reprogramming factors | OCT4, SOX2 [17] |

| Zelda (Zld) | Early embryonic engagement with closed chromatin | Increases DNA accessibility prior to zygotic genome activation | Bicoid, Dorsal [17] |

Epigenetic Interplay and Chromatin State Modulation

Pioneer Transcription Factors do not function in isolation but engage in dynamic interplay with the epigenetic landscape to reshape chromatin architecture:

Histone Modification Cross-Talk: PTF activity is regulated by existing histone modifications, while simultaneously inducing new epigenetic states. For example, OCT4 cooperativity with SOX2 is modulated by H3K27 modifications, with H3K27ac enhancing and H3K27me3 reducing their collaborative binding [21].

Recruitment of Chromatin Modifiers: PTFs recruit chromatin remodelers, histone modifiers, and DNA methylation machinery to establish active or poised transcriptional states [6] [18]. This includes interactions with complexes such as SWI/SNF, ISWI, INO80, Polycomb repressive complexes (PRCs), and nucleosome remodeling and deacetylase (NuRD) complexes [6] [18].

DNA Methylation Dynamics: PTFs interact with DNA methylation machinery, with OCT4 activity being both influenced by and influencing DNA methylation patterns during reprogramming [18]. The balance between DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs) and ten-eleven translocation (TET) enzymes is crucial for establishing new cell identities.

The following diagram illustrates the sequential mechanism of pioneer transcription factor action in chromatin remodeling:

Diagram 1: Sequential mechanism of pioneer transcription factor-mediated chromatin remodeling. The process begins with pioneer factor binding to closed chromatin through partial motif recognition, followed by nucleosome rearrangement, recruitment of cofactors, and ultimately establishing accessible chromatin for transcription activation.

Comparative Analysis of Pioneer Factor Activity in Reprogramming Contexts

Chromatin Accessibility Dynamics in Naïve versus Primed Pluripotency

Direct comparative studies of chromatin dynamics during reprogramming to different pluripotent states reveal distinct patterns of PTF activity. Research integrating ATAC-seq and RNA-seq data from naïve and primed reprogramming pathways demonstrates that chromatin accessibility changes precede transcriptional changes, with accessibility diverging around day 8 of reprogramming, while transcriptome differences become pronounced around day 14 [22].

Table 2: Chromatin Accessibility Dynamics During Naïve versus Primed Reprogramming

| Reprogramming Aspect | Naïve Pluripotency Path | Primed Pluripotency Path |

|---|---|---|

| Timeline of Chromatin Opening | Significant accessibility changes at day 6-8; major transcriptome shift at day 14 | Accessibility changes at day 6-8; transcriptome shift around day 8 |

| Closed-to-Open (CO) Regions | Progressive increase throughout reprogramming; peaks at iPSC stage | Progressive increase throughout reprogramming; peaks at iPSC stage |

| Open-to-Closed (OC) Regions | Outnumber CO regions until day 20; associated gene expression decreases from day 8 | Outnumber CO regions until day 20; associated gene expression slightly up-regulated |

| Permanently Open (PO) Regions | Minimal expression changes in associated genes | Significant up-regulation of associated genes |

| Functional Enrichment in CO Regions | Pluripotency and early embryonic development processes | Pluripotency and developmental processes |

| Key Regulatory Factors | PRDM1 isoforms (PRDM1α and PRDM1β) with distinct roles | Different factor requirements than naïve state |

During both naïve and primed reprogramming, regions transitioning from closed to open (CO) are associated with genes involved in pluripotency and early embryonic development, while regions transitioning from open to closed (OC) are linked to somatic cell lineages and differentiated state functions [22]. The divergent roles of PRDM1 isoforms (PRDM1α and PRDM1β) in naïve reprogramming highlight the complexity of PTF function, with different isoforms potentially targeting distinct genomic sites and exerting different effects on target genes [22].

Yamanaka Factor Cooperation and Hierarchical Actions

The classic reprogramming factors OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, and c-Myc (OSKM) display hierarchical and cooperative relationships in initiating chromatin reprogramming:

OCT4 as a Primary Pioneer: OCT4 expression is necessary and sufficient to initiate reprogramming in some contexts, and it enhances the nucleosome binding of SOX2, KLF4, and MYC [21]. OCT4 binding induces nucleosome structural changes that facilitate cooperative binding of additional factors.

SOX2 Cooperativity: SOX2 binding is significantly enhanced by prior OCT4 engagement, with the OCT4-SOX2 partnership being critical for pluripotency establishment [21]. Structural studies show that OCT4 binding creates favorable conditions for SOX2 recruitment to adjacent sites.

Differential Chromatin Engagement: During initial reprogramming stages, OCT4, SOX2, and KLF4 act as pioneer factors that access closed chromatin, while c-Myc preferentially binds to pre-existing open chromatin sites that are already DNase-hypersensitive and contain activating histone modifications [17].

Promiscuous Initial Binding: The initial binding events of OSKM factors in somatic cell reprogramming are quite promiscuous, distinct from definitive binding patterns in established pluripotent cells, with subsequent reorganization required to establish stable pluripotency networks [17].

Experimental Approaches for Assessing Pioneer Factor Activity

Methodologies for Mapping Chromatin Accessibility and Factor Binding

Several well-established experimental protocols enable the comprehensive assessment of PTF activity and chromatin dynamics:

Integrated Multi-Omics Workflow for Pioneer Factor Characterization

Diagram 2: Experimental workflow for identifying and characterizing pioneer transcription factors, combining chromatin accessibility mapping, nucleosome positioning analysis, transcription factor binding profiling, and computational integration.

ATAC-seq (Assay for Transposase-Accessible Chromatin with sequencing):

- Purpose: Maps genome-wide chromatin accessibility by measuring regions of open chromatin.

- Protocol: Cells are lysed, and the transposase Tn5 is added to simultaneously fragment and tag accessible DNA regions with sequencing adapters. The tagged DNA is then purified and prepared for sequencing [19] [22].

- Data Interpretation: Open chromatin regions appear as peaks in sequencing data; comparison across reprogramming timepoints identifies regions changing from closed to open (CO) or open to closed (OC) states [22].

ChIP-seq (Chromatin Immunoprecipitation followed by sequencing):

- Purpose: Identifies genomic binding sites for specific transcription factors or histone modifications.

- Protocol: Cells are cross-linked to preserve protein-DNA interactions, chromatin is sheared, and an antibody specific to the protein of interest is used to immunoprecipitate the protein-DNA complexes. After cross-link reversal and DNA purification, sequencing identifies bound regions [19].

- Data Interpretation: Binding peaks indicate direct or indirect association with genomic regions; when combined with nucleosome positioning data, can distinguish nucleosome-bound versus nucleosome-free binding [20].

MNase-seq (Micrococcal Nuclease sequencing):

- Purpose: Maps nucleosome positions and occupancy across the genome.

- Protocol: MNase enzyme digests linker DNA between nucleosomes, followed by sequencing of the protected nucleosomal DNA fragments [19].

- Data Interpretation: Protected regions indicate nucleosome occupancy; comparison with ATAC-seq and ChIP-seq data identifies transcription factors binding to nucleosomal versus nucleosome-free DNA [19] [20].

Computational Prediction of Pioneer Factors

Recent computational approaches have been developed to systematically identify PTFs based on their binding preferences for nucleosomal DNA:

Motif Enrichment Analysis: Calculates enrichment of transcription factor binding motifs in nucleosomal regions compared to nucleosome-depleted regions. True PTFs show enrichment in nucleosomal regions, while conventional factors show depletion [20].

Integrated Data Analysis: Combines ChIP-seq, MNase-seq, and DNase-seq data to assess cell-type-specific ability of transcription factors to bind nucleosomes [20].

Validation Benchmarks: Uses known PTF sets (e.g., factors involved in embryonic stem cell maintenance or reprogramming) as positive controls to validate prediction accuracy [20].

This approach has successfully discriminated pioneer from canonical transcription factors and predicted new potential cell-type-specific PTFs in H1, K562, HepG2, and HeLa-S3 cell lines [20].

Research Reagent Solutions for Pioneer Factor Studies

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Pioneer Transcription Factor Investigation

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Antibodies for Chromatin Profiling | Anti-OCT4, Anti-SOX2, Anti-FoxA1 | ChIP-seq for mapping transcription factor binding sites | Quality critical for signal-to-noise ratio; validate with knockout controls |

| Chromatin Assay Kits | ATAC-seq kits, MNase digestion kits | Mapping chromatin accessibility and nucleosome positioning | ATAC-seq sensitivity requires careful titration of transposase; MNase requires optimization of digestion conditions |

| Reprogramming Systems | Doxycycline-inducible OSKM vectors, Secondary reprogramming systems | Controlled induction of pioneer factors in somatic cells | Secondary systems reduce heterogeneity and improve synchronization |

| Epigenetic Modulators | DNMT inhibitors (azacitidine, decitabine), HDAC inhibitors | Manipulating epigenetic landscape to study pioneer factor interplay | Dose optimization essential to avoid pleiotropic effects |

| Cell Line Models | H1, K562, HepG2, HeLa-S3, Mouse Embryonic Fibroblasts (MEFs) | Cell-type-specific pioneer factor activity assessment | Different cell lines exhibit distinct chromatin environments and pioneer factor responses |

| Structural Biology Tools | Cryo-EM platforms, Crosslinking reagents | Structural characterization of pioneer factor-nucleosome complexes | Technical expertise intensive; requires specialized equipment |

Pioneer Transcription Factors function as architectural specialists in chromatin remodeling, employing distinct but complementary mechanisms to initiate cell fate reprogramming. The comparative analysis of their activities reveals a spectrum of chromatin engagement strategies, from OCT4's nucleosome restructuring capabilities to FoxA's linker histone displacement. The hierarchical cooperation between factors like OCT4 and SOX2 demonstrates the sophisticated division of labor in chromatin opening processes.

The experimental frameworks for studying PTFs have evolved to integrate multi-omics approaches, with ATAC-seq, ChIP-seq, and MNase-seq providing complementary perspectives on chromatin dynamics. These methodologies consistently demonstrate that PTF binding precedes chromatin accessibility changes, with OCT4, SOX2, and Klf4 capable of initial engagement with closed chromatin during reprogramming.

Future research directions will likely focus on understanding how the epigenetic landscape regulates PTF activity, with histone modifications such as H3K27ac and H3K27me3 already shown to modulate OCT4 cooperativity [21]. Additionally, the development of more sophisticated computational prediction methods will enable systematic identification of novel PTFs across diverse cellular contexts. As our understanding of these architectural regulators deepens, so too will our ability to harness their potential for therapeutic reprogramming and regenerative medicine applications.

Comparative Analysis of Naïve versus Primed Pluripotency Chromatin Landscapes

Pluripotent stem cells possess the remarkable capacity to differentiate into any cell type of the adult body. Within this broad potential exist distinct pluripotent states, primarily categorized as naïve and primed, which correspond to pre- and post-implantation embryonic stages, respectively [23] [24]. These states are not merely defined by their transcriptomes but are fundamentally underpinned by distinct epigenetic landscapes. The chromatin architecture—its accessibility, histone modifications, and DNA methylation—varies significantly between these states, creating a unique regulatory environment that governs their developmental potential, signaling dependencies, and stability [23]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of the chromatin landscapes in naïve and primed pluripotency, synthesizing recent high-throughput sequencing data to objectively outline their defining features. Framed within the context of reprogramming and comparative chromatin accessibility research, this resource is designed to inform experimental design and interpretation for researchers and drug development professionals.

Fundamental Chromatin Landscape Differences

The chromatin of naïve and primed pluripotent states differs in its global organization, accessibility, and epigenetic modifications. These differences create a permissive environment for naïve-specific gene networks while progressively restricting developmental potential as cells transition to the primed state.

Global Chromatin Organization: Naïve pluripotent cells, such as mouse embryonic stem cells (mESCs) cultured in 2i/LIF conditions, exhibit a generally more open chromatin configuration with reduced levels of repressive histone marks like H3K27me3 at developmental genes [24]. In contrast, primed cells, such as mouse Epiblast Stem Cells (mEpiSCs) or conventional human pluripotent stem cells (hPSCs), display a chromatin state that is more condensed and lineage-restricted [23]. This is reflected in global DNA methylation levels, which are markedly hypomethylated in naïve cells cultured in 2i/LIF, whereas primed cells are hypermethylated, a distinction particularly evident in in vitro cultures [23].

Enhancer Reconfiguration: A hallmark of the state transition is the dynamic rewiring of enhancer elements. Naïve and primed cells utilize distinct enhancers for the same key pluripotency genes. A quintessential example is the OCT4 (POU5F1) locus, where the distal enhancer (DE) is active in the naïve state, and the proximal enhancer (PE) is favored in the primed state [23]. This switch in enhancer usage reflects a broader reorganization of the transcriptional regulatory network and is mediated by changes in the binding of core transcription factors like OCT4 and SOX2, whose genomic targets are re-directed during the exit from naïve pluripotency [25].

X-Chromosome Inactivation: In female cells, the status of the X chromosomes serves as a key epigenetic marker. Naïve pluripotent cells typically possess two active X chromosomes, while primed cells have undergone X-chromosome inactivation (Xi), a clear indicator of a more developmentally advanced and restricted state [23].

Table 1: Core Characteristics of Naïve and Primed Pluripotent States

| Feature | Naïve Pluripotency | Primed Pluripotency |

|---|---|---|

| Developmental Analogue | Pre-implantation epiblast | Post-implantation epiblast |

| Colony Morphology | Dome-shaped, three-dimensional | Flat, two-dimensional monolayer |

| Signaling Dependence | LIF/STAT3; BMP (mESCs in Serum/LIF); MEK/GSK3 inhibition (2i) | FGF/Activin A/TGF-β |

| X-Chromosome Status | Two active X chromosomes (XaXa) | Inactive X chromosome (Xi) |

| Global DNA Methylation | Hypomethylated | Hypermethylated |

| Prominent Chromatin State | More open, less repressive marks | More condensed, restricted accessibility |

Comparative Chromatin Accessibility Dynamics

Assay for Transposase-Accessible Chromatin using sequencing (ATAC-seq) has been instrumental in mapping the dynamic changes in chromatin architecture during the establishment of and transition between pluripotent states. These analyses reveal that chromatin remodeling is a pivotal early event in cell fate change.

Chromatin Dynamics During Reprogramming to Naïve and Primed States

Reprogramming of somatic cells towards pluripotency involves extensive chromatin remodeling. Studies using secondary human reprogramming systems have shown that while the overall number of chromatin accessibility changes is similar during naïve and primed reprogramming, the specific genomic loci affected are distinct [22]. During the early phases of reprogramming, there is a widespread closure of chromatin regions associated with somatic identity (Open-to-Closed regions), which outnumbers the opening of new regions until later stages [22]. The opening of chromatin at pluripotency-associated loci is a progressive process, with the number of Closed-to-Open (CO) regions increasing over time and peaking in established iPSCs.

Gene Ontology analysis of these dynamic regions reveals a clear functional separation: CO regions are enriched near genes involved in "cell fate commitment," "regulation of stem cell proliferation," and "regulation of embryonic development," while Open-to-Closed (OC) regions are associated with "neuron differentiation," "T cell activation," and "fibroblast migration" [22]. This indicates that the chromatin landscape is systematically cleared of somatic memory and reconfigured to support a pluripotent identity.

Discordance Between Accessibility and Transcription

A critical insight from recent studies is that an open chromatin state does not always equate to active transcription, highlighting the complexity of gene regulation. Research tracking the primed-to-naïve transition in human cells using a dual fluorescent reporter system found that chromatin remodeling precedes transcriptional activation [26]. Specifically, ATAC-seq signals indicative of naïve-specific chromatin—enriched with motifs for OCT, SOX, and KLF transcription factors—were detected in cells that did not yet express the corresponding naïve pluripotency genes [26]. This demonstrates that the opening of chromatin is a necessary but insufficient step for gene activation, which can be further modulated by additional layers of regulation, such as the specific activity of transcription factors and other epigenetic modifications like histone marks.

Distinct Trajectories Revealed by Integrated Analysis

When transcriptomic and chromatin accessibility data are integrated, the divergent trajectories of naïve and primed reprogramming become apparent. Principal Component Analysis (PCA) of such multi-omics data shows that chromatin accessibility differences between the two pathways emerge earlier than transcriptomic differences [22]. A significant shift in chromatin accessibility is observed around day 8 of reprogramming, preceding the major transcriptome divergence that occurs around day 14 [22]. This positions chromatin remodeling as a upstream driver of the transcriptional programs that define naïve and primed pluripotency.

Table 2: Key Chromatin Accessibility and Transcriptional Dynamics

| Dynamic Event | Naïve Reprogramming | Primed Reprogramming | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Onset of Chromatin Divergence | Day 8 [22] | Day 8 [22] | Based on ATAC-seq PCA |

| Major Transcriptome Shift | Day 14 [22] | Day 8 [22] | Based on RNA-seq PCA |

| Relationship at Naïve Loci | Chromatin opening can precede transcriptional activation [26] | Not Applicable | Observed during primed-to-naïve transition |

| Enhancer Usage (e.g., OCT4) | Distal Enhancer (DE) [23] | Proximal Enhancer (PE) [23] | Validated by ChIP-seq |

Key Regulatory Mechanisms and Molecular Players

The distinct chromatin landscapes of naïve and primed states are established and maintained by a network of transcription factors, chromatin remodelers, and signaling pathways.

Transcription Factor Networks

The core pluripotency factors OCT4, SOX2, and NANOG form the foundation of the regulatory network in both states, but their binding profiles and interaction partners differ.

- Naïve State Factors: In the naïve state, OCT4 and SOX2 co-occupy and activate most naïve-specific enhancers [25]. Factors like KLF4, KLF2, TFCP2L1, and ESRRB are highly expressed and help maintain the naïve gene regulatory network. ESRRB, for instance, has been suggested to guide core factors to new binding sites during the initial phase of differentiation [25].

- Primed State and Transition Factors: During the exit from naïve pluripotency, a cascade of new transcription factors is expressed. OTX2 acts as a critical interaction partner that redirects OCT4 binding from naïve-specific enhancers to those primed for differentiation [25]. Other factors like FOXD3, OCT6, and ZIC3 contribute to the active dismantling of the naïve state by repressing naïve-specific enhancers [25].

The following diagram summarizes the key regulators involved in the transition from naïve to primed pluripotency:

Chromatin Remodelers and Modifiers

ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling complexes are essential for manipulating nucleosome positions to open or close chromatin.

- SWI/SNF Complex: This complex, particularly through its subunit SMARCA4 (BRG1), promotes chromatin opening at key loci. For example, it is recruited to super-enhancers to facilitate the expression of genes critical for cell identity [1].

- NuRD Complex: In contrast to SWI/SNF, the NuRD complex often acts as a repressor. During somatic cell reprogramming, NuRD interacts with SALL4 to reduce the chromatin accessibility of anti-reprogramming genes, thereby facilitating the transition to pluripotency [1]. Another study showed that FOXAs and PRDM1 recruit NuRD to maintain an accessible nucleosome state during human endoderm differentiation [1].

- Non-Canonical Regulators: Recent research has identified IκBα, the inhibitor of NF-κB, as a chromatin-associated factor with a non-canonical role in naïve pluripotency. IκBα accumulates in the chromatin fraction of naïve mouse pluripotent stem cells, and its depletion causes profound epigenetic rewiring, including alterations in H3K27me3, and arrests cells in the naïve state, preventing their exit to primed pluripotency. This function is independent of its classical role in NF-κB signaling [27].

The Divergent Roles of PRDM1 Isoforms

The PRDM1 gene encodes two isoforms, PRDM1α and PRDM1β, which exhibit divergent functions during human naïve reprogramming. While both are involved in the process, they target distinct genomic loci and have different impacts on the transcriptome. Utilizing techniques like CUT&Tag, researchers discovered that these isoforms bind to different sites, suggesting a "yin-yang" regulatory model where they exert opposing effects on target genes, potentially mediated through interactions with SPRED2 and DDAH1, respectively [22]. This highlights the intricate specificity within the regulatory networks governing chromatin landscape dynamics.

Experimental Protocols for Chromatin Landscape Analysis

To generate the comparative data discussed in this guide, several key high-throughput methodologies are employed. Below is a detailed protocol for the central technique, ATAC-seq.

Detailed ATAC-Seq Protocol

The Assay for Transposase-Accessible Chromatin using sequencing (ATAC-seq) is a powerful and sensitive method for mapping genome-wide chromatin accessibility [1].

Principle: The hyperactive Tn5 transposase simultaneously fragments and tags accessible genomic DNA with sequencing adapters. Regions tightly bound by nucleosomes or other proteins are protected from cleavage, providing a footprint of in vivo chromatin accessibility [1].

Workflow Steps:

- Cell Preparation and Lysis: Harvest approximately 50,000–100,000 viable cells. Critical: Avoid over-crosslinking or using frozen nuclei for initial experiments, as this can reduce data quality. Wash cells in cold PBS and resuspend in cold lysis buffer (e.g., 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 10 mM NaCl, 3 mM MgCl₂, 0.1% Igepal CA-630) to isolate nuclei.

- Tagmentation Reaction: Immediately following lysis, pellet the nuclei and resuspend in the transposition reaction mix containing the Tn5 transposase. Incubate at 37°C for 30 minutes. The reaction volume and Tn5 concentration must be optimized for cell type and input amount.

- DNA Purification: Clean up the tagmented DNA using a standard DNA clean-up kit (e.g., MinElute PCR Purification Kit). Elute in a small volume of elution buffer or nuclease-free water.

- Library Amplification and Barcoding: Amplify the purified DNA by PCR (typically 10–14 cycles) using primers that add full Illumina sequencing adapters and sample-specific barcodes. Determine the optimal cycle number using a qPCR side reaction to avoid over-amplification.

- Library Purification and Quality Control: Purify the final library using SPRI beads. Assess library quality and fragment size distribution using an Agilent Bioanalyzer or TapeStation. A successful ATAC-seq library shows a characteristic periodicity of ~200 base pairs, corresponding to nucleosome-free regions, mononucleosomes, dinucleosomes, etc.

- Sequencing: Sequence the library on an Illumina platform. Paired-end sequencing (e.g., 2 x 50 bp or 2 x 75 bp) is recommended to better map nucleosome positions.

The experimental workflow for chromatin analysis, from cell state transition to data generation, can be visualized as follows:

Integrating ATAC-seq with Other Modalities

For a comprehensive understanding, ATAC-seq is often paired with other assays:

- RNA-seq: Provides correlative and discriminatory data between chromatin accessibility and transcriptional output [22] [26].

- CUT&Tag: For mapping histone modifications (e.g., H3K27me3, H3K27ac) and transcription factor binding (e.g., PRDM1 isoforms) in low-input samples [22] [27].

- Multiome-seq: Newer technologies allow for the simultaneous sequencing of chromatin accessibility and transcriptome from the same single cell, directly linking regulatory landscape to gene expression [1].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagent Solutions for Naïve/Primed Chromatin Research

| Reagent / Solution | Function in Research | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| 5iLAF / t2iLGo Naïve Media | Chemically defined culture medium to induce and maintain human naïve pluripotency. | Establishing naïve PSCs from primed hPSCs; maintaining ground state pluripotency for chromatin studies [26]. |

| Dual Fluorescent Reporter Cells | Cell lines with reporters (e.g., OCT4-ΔPE-GFP, ALPG-RFP) to track pluripotency state transitions via flow cytometry. | Isulating pure populations of intermediates during primed-to-naïve reprogramming for ATAC-seq and RNA-seq [26]. |

| Hyperactive Tn5 Transposase | Enzyme for ATAC-seq that fragments and tags accessible DNA. | Mapping genome-wide chromatin accessibility landscapes in naïve, primed, and transitioning cells [1]. |

| Mek Inhibitor (PD0325901) | Small molecule inhibitor used in 2i/LIF medium to maintain naïve pluripotency and induce global DNA hypomethylation. | Culturing mouse ESCs in a ground state; studying the effects of ERK signaling inhibition on chromatin architecture [24]. |

| GSK3 Inhibitor (CHIR99021) | Small molecule inhibitor used in 2i/LIF medium to support naïve self-renewal. | Working with PD0325901 to maintain a homogeneous, naïve pluripotent population [24]. |

| Leukemia Inhibitory Factor (LIF) | Cytokine that activates STAT3 signaling to support naïve pluripotency in mouse cells. | A key component of naïve (serum/LIF and 2i/LIF) culture conditions [24]. |

Cellular reprogramming, the process by which differentiated cells revert to a stem cell state, is a cornerstone of regenerative biology and a focal point for therapeutic development. A critical step in this process is the remodeling of chromatin architecture, which transitions from a tightly packed, transcriptionally repressive state (heterochromatin) to a more open, accessible one (euchromatin) [1]. This review will objectively compare the phenomenon of wounding-induced chromatin relaxation across different biological systems, with a specific emphasis on the moss Physcomitrium patens as a pioneering model. We will summarize key quantitative findings, detail experimental protocols, and visualize the core regulatory pathways, providing a structured resource for researchers and drug development professionals working in the field of comparative chromatin accessibility.

Model System Comparison: Wounding-Induced Reprogramming

The following table provides a comparative overview of wounding-induced chromatin relaxation and reprogramming across three distinct model organisms.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Wounding-Induced Chromatin Remodeling Across Model Systems

| Feature | Moss (Physcomitrium patens) | Mammalian Liver Regeneration | Planarian (Schmidtea mediterranea) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inducing Stimulus | Leaf wounding [4] | Partial hepatectomy (PHx) or CCl4 treatment [7] | Tissue amputation [28] |

| Key Outcome | Reprogramming of leaf cells into chloronema apical stem cells [4] | Initiation of hepatocyte proliferation and liver regeneration [7] | Activation of neoblasts (stem cells) for tissue regeneration [28] |

| Chromatin Changes | Genome-wide chromatin relaxation; selective opening at STEMIN-target loci [4] [29] | Remodeling of transcriptional landscapes and chromatin accessibility [7] | BPTF-dependent maintenance of chromatin accessibility at gene promoters [28] |

| Key Transcription Factor(s) | AP2/ERF factors (STEMIN1/2/3) [4] | ATF3 ("Initiationon") and ONECUT2 ("Initiationoff") [7] | BPTF (subunit of the NuRF chromatin remodeling complex) [28] |

| Core Regulatory Mechanism | STEMIN factors selectively enhance accessibility within a permissive, relaxed chromatin environment [29] | ATF3 binds Slc7a5 promoter to activate mTOR signaling; ONECUT2 loses binding to Hmgcs1 promoter [7] | BPTF binds H3K4me3 marks to maintain promoter accessibility for stem cell genes [28] |

| Experimental Evidence | Multimodal single-nuclei RNA-seq and ATAC-seq on 20,883 nuclei [4] | Integrated analysis of RNA-seq and ATAC-seq [7] | ATAC-seq, ChIP-seq, and RNA-seq on isolated stem cells [28] |

Experimental Data and Protocols in Moss

The study of wounding-induced chromatin relaxation in Physcomitrium patens provides a robust quantitative dataset and a clear methodological workflow.

Key Quantitative Findings

The following table summarizes core experimental data from the seminal study on STEMIN-mediated reprogramming.

Table 2: Key Experimental Data from Moss Reprogramming Study [4]

| Experimental Parameter | Measurement / Finding |

|---|---|

| Total Nuclei Profiled | 20,883 high-quality nuclei |

| Identified Cell Clusters | 11 distinct cell types |

| Key Cell Population | Reprogramming leaf cells |

| Chromatin State in Reprogramming Cells | Partly relaxed, more permissive landscape |

| Genetic Requirement | Triple mutant ∆stemin (delayed stem cell formation) |

| Proposed Mechanism | Wounding causes broad relaxation; STEMIN factors drive selective, locus-specific opening |

Detailed Experimental Workflow

The protocol for investigating chromatin dynamics during wounding-induced reprogramming in moss involved a multi-omics approach [4].

- Sample Preparation and Nuclei Isolation: Gametophores, protonemata, and cut leaves from both wild-type and ∆stemin mutant plants were collected over specific time intervals (3–6 h, 10–14 h, and 24–36 h post-wounding). Nuclei were released from the tissues and isolated.

- Fluorescence-Activated Nuclei Sorting (FANS): Isolated nuclei were sorted based on fluorescence to ensure quality and to pool equal numbers of nuclei from different time windows, creating heterogeneous samples for analysis.

- Multimodal Single-Nuclei Sequencing: The sorted nuclei were processed using the 10x Genomics Chromium system to generate both single-nuclei RNA sequencing (snRNA-seq) and single-nuclei Assay for Transposase-Accessible Chromatin sequencing (snATAC-seq) libraries simultaneously.

- Bioinformatic Data Integration: The sequenced data from both modalities were processed using the Cellranger-ARC pipeline. Downstream analysis, including batch correction with Harmony and the construction of a multiomic atlas, was performed using Seurat v4 for RNA data and Signac for ATAC data, which were then merged using weighted nearest neighbors (WNN) analysis.

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for multiomic analysis of chromatin relaxation in moss.

Core Signaling Pathways and Molecular Mechanisms

The molecular pathway from wounding to stem cell reprogramming involves a hierarchical series of events integrating broad chromatin changes with precise transcription factor activity.

The Hierarchical Pathway of Chromatin Reprogramming

Diagram 2: Hierarchical pathway from wounding to cellular reprogramming.

The Role of Pioneer and Tissue-Specific Transcription Factors

In many systems, including mammalian cells, the opening of chromatin is facilitated by pioneer transcription factors (PTFs). These are a unique class of transcription factors that can bind to closed, heterochromatic regions and initiate chromatin remodeling, "opening" it up to make these regions transcriptionally active [6]. They recruit chromatin remodelers and histone modifiers to establish active transcriptional states. Within this open landscape, tissue-specific or lineage-determining factors, such as the AP2/ERF family factors in plants (e.g., STEMIN) or FOXA1/FOXA2 in mammals, act to refine the regulatory output [30]. These factors work synergistically, with pioneer factors creating a permissive environment and specific factors activating the precise gene networks required for the new cell fate [30]. This two-step mechanism ensures both the plasticity and fidelity of cellular reprogramming.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The following table catalogs key reagents and methodologies essential for researching chromatin accessibility and reprogramming.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Chromatin Accessibility Studies

| Reagent / Method | Primary Function | Key Application in Field |

|---|---|---|

| ATAC-seq [1] | Profiles genome-wide chromatin accessibility by using a hyperactive Tn5 transposase to integrate adapters into open chromatin regions. | The gold-standard method for mapping accessible chromatin regions in bulk or single-cell samples. |

| Single-Cell/Nuclei Multiome [4] [31] | Allows for simultaneous measurement of chromatin accessibility (ATAC) and gene expression (RNA) from the same single cell/nucleus. | Enables direct correlation of epigenetic state with transcriptional output, defining cell-type-specific regulatory events. |

| P. patens ∆stemin mutant [4] | A triple knockout mutant lacking the STEMIN1, STEMIN2, and STEMIN3 genes. | Critical for establishing the necessity of STEMIN transcription factors in selective chromatin remodeling during reprogramming. |

| BPTF/NURF Complex [28] | An ISWI-containing ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling complex that slides nucleosomes. | Essential for maintaining promoter accessibility at H3K4me3-marked genes in stem cells, as shown in planarians. |

| Pioneer Transcription Factors (e.g., FOXA1, OCT4) [6] [30] | Bind to closed chromatin and initiate its opening, creating a permissive state for other factors. | Key drivers of chromatin remodeling and cell fate changes in development, reprogramming, and cancer. |

Comparative analysis across moss, mammalian liver, and planarian models reveals a conserved paradigm in wounding-induced cellular reprogramming: an initial broad relaxation of chromatin creates a permissive environment, which is subsequently refined by specific transcription factors that selectively open key genomic loci to drive new cell fates. The moss Physcomitrium patens, with its well-defined STEMIN pathway and the ability to profile reprogramming at single-cell resolution, provides a powerful, simplified model to dissect this hierarchy. Understanding these conserved mechanisms of chromatin relaxation offers profound insights for regenerative medicine and drug development, potentially informing strategies to manipulate cellular plasticity in human disease.

The central dogma of transcriptional regulation posits that changes in chromatin accessibility precede and enable gene expression changes. This comparative guide examines the predictive relationship between chromatin accessibility and transcription across biological models, including cancer metastasis, cellular reprogramming, and signal response. We objectively evaluate experimental data that both supports and challenges this paradigm, providing researchers with a critical analysis of methodological approaches and their appropriate applications. The evidence reveals that while chromatin accessibility often serves as a leading indicator in differentiation processes, its predictive value varies considerably across biological contexts and perturbation types.

Chromatin accessibility refers to the physical permissibility of genomic DNA to nuclear macromolecules, primarily determined by nucleosome distribution and occupancy of DNA-binding factors [1]. The prevailing model suggests that opening of chromatin creates a permissive environment for transcription factor binding and subsequent gene activation, positioning accessibility changes as upstream regulators of transcriptional programs. This guide systematically compares how this temporal relationship holds across different experimental systems, examining the strength of evidence and contextual limitations.

Advanced sequencing technologies, particularly ATAC-seq, have enabled genome-wide profiling of chromatin accessibility dynamics [1]. When combined with transcriptomic measurements, these tools allow researchers to establish causal and predictive relationships between chromatin state and gene expression. Understanding these dynamics is crucial for drug development professionals seeking to manipulate transcriptional programs in diseases like cancer, where epigenetic dysregulation is a therapeutic target.

Comparative Evidence: Support and Challenges Across Biological Systems

Supporting Evidence: Accessibility as a Predictor

Table 1: Systems Where Chromatin Accessibility Predicts Transcriptional Changes

| Biological System | Temporal Relationship | Key Findings | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Osteosarcoma Metastasis [32] | Accessibility changes define subsequent transcriptional states | Distinct chromatin states at 1 vs. 22 days post-injection correlated with metastatic programs | ATAC-seq/RNA-seq time course in mouse models |

| Naïve Pluripotency Reprogramming [22] | Chromatin changes precede transcriptome divergence | Accessibility differences emerged by day 8, preceding day 14 transcriptional divergence | Paired ATAC-seq/RNA-seq during reprogramming |

| Plant Symbiosis Establishment [33] | Predictive regulatory models from accessibility | Chromatin accessibility predicted transcriptome dynamics with identified regulators | Dynamic Regulatory Module Networks (DRMN) |

| Neural Progenitor Differentiation [34] | Early 5-hmC changes precede accessibility | Hydroxymethylation initiates before accessibility and TF occupancy | Time-course methylome and accessibility profiling |

Metastatic Progression Modeling

In osteosarcoma metastasis, temporal chromatin accessibility profiling revealed dynamic changes defining essential transcriptional states for lung colonization [32]. Researchers performed ATAC-seq and RNA-seq on metastatic human osteosarcoma cells harvested from mouse lungs at 1 and 22 days post-inoculation. Through k-means clustering of accessibility patterns, they identified distinct regulatory clusters (early, pan-in vivo, and late) whose accessibility patterns correlated with transcriptional outputs of associated genes. For example, IL32 showed early-specific accessibility increases correlated with expression changes, while MMP2 displayed late-specific accessibility and expression patterns [32].

Cellular Reprogramming Trajectories

In human induced pluripotent stem cell reprogramming, integrated ATAC-seq and RNA-seq analysis revealed that chromatin accessibility changes preceded major transcriptome divergence between naïve and primed reprogramming paths [22]. Accessibility differences emerged by day 8 post-reprogramming initiation, while significant transcriptional divergence wasn't apparent until day 14. This temporal advance of accessibility changes was observed despite both processes sharing similar overall chromatin dynamics, with regions transitioning from closed-to-open (CO) and open-to-closed (OC) states [22].

Figure 1: Reprogramming Timeline Showing Chromatin Accessibility Changes Preceding Transcriptional Divergence

Challenging Evidence: Contextual Limitations

Table 2: Systems Demonstrating Discordant Accessibility-Expression Relationships

| Biological System | Nature of Discordance | Key Findings | Experimental Approach |

|---|---|---|---|

| MCF-7 Signal Response [35] | Expression changes without accessibility alterations | Two gene classes: those with/without accessibility changes despite expression changes | Tandem bulk ATAC-seq/RNA-seq after RA/TGF-β |

| Glucocorticoid Signaling [35] | TF binding to pre-accessible sites | Glucocorticoid receptor binds pre-existing accessible chromatin without new accessibility | Combined ChIP-seq/accessibility profiling |

| Enhancer Regulation [34] | Temporal discordance with DNA methylation | DNA methylation changes unidirectional and temporally discordant with chromatin | Time-course multi-omic profiling |

Single-Factor Perturbation Models

In MCF-7 breast carcinoma cells exposed to retinoic acid or TGF-β, researchers observed significant discordance between chromatin accessibility and transcriptional changes [35]. Through tandem bulk ATAC-seq and RNA-seq measurements at 72 hours post-stimulation, they identified two distinct classes of differentially expressed genes: those with corresponding accessibility changes in nearby chromatin, and those with strong expression changes but virtually no accessibility alterations. This dissociation was particularly pronounced in response to these single-factor perturbations compared to the stronger concordance observed in multifactorial processes like hematopoietic differentiation [35].

Pre-established Accessibility Paradigms