Comparative Efficacy of Biomaterials for Cell Delivery: From Design Principles to Clinical Translation

The efficacy of cell-based therapies is critically dependent on the biomaterial delivery platform, which influences cell viability, retention, and functional integration.

Comparative Efficacy of Biomaterials for Cell Delivery: From Design Principles to Clinical Translation

Abstract

The efficacy of cell-based therapies is critically dependent on the biomaterial delivery platform, which influences cell viability, retention, and functional integration. This review provides a comparative analysis of current biomaterial strategies for therapeutic cell delivery, targeting researchers and drug development professionals. We explore foundational material classes and their properties, evaluate methodological applications across tissue engineering and immunotherapies, address key optimization challenges, and present validation frameworks for comparative efficacy. By synthesizing design principles with preclinical and clinical outcomes, this article establishes a roadmap for selecting and engineering biomaterials to enhance the therapeutic potential of delivered cells in regenerative medicine and drug development.

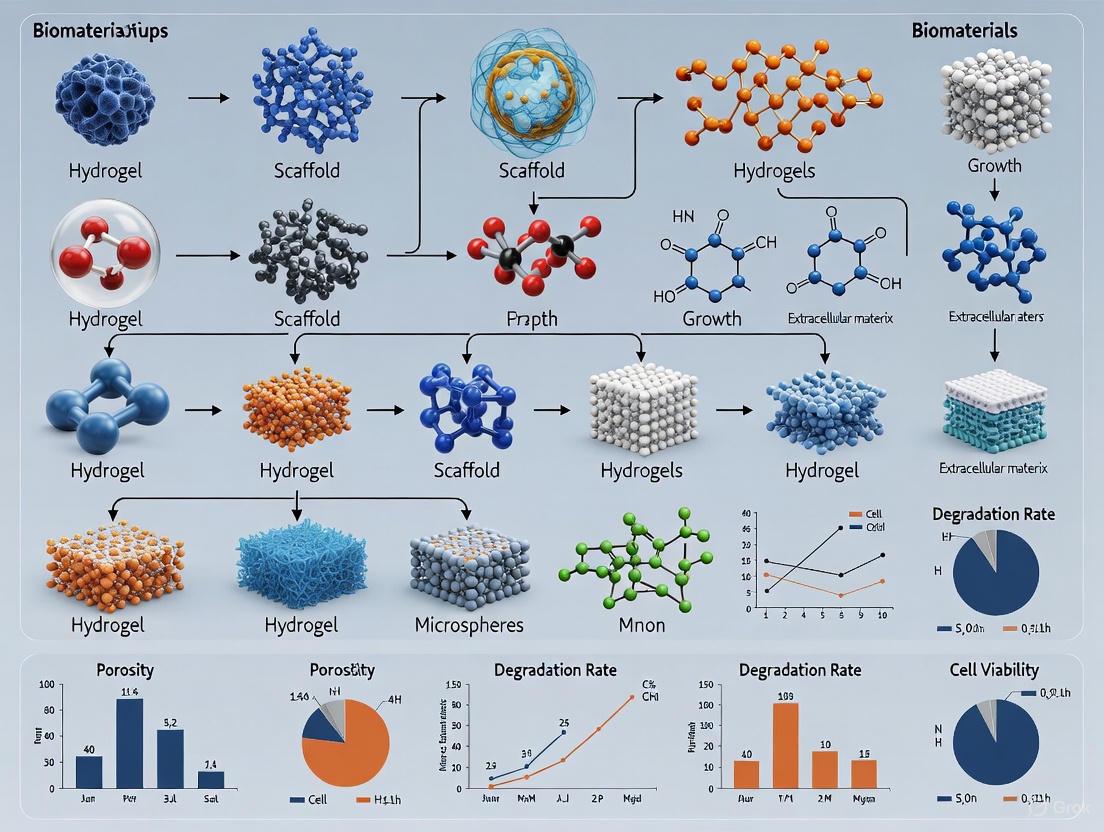

Biomaterial Platforms and Cell Types: Building Blocks for Effective Delivery

The success of advanced cell delivery strategies in regenerative medicine and tissue engineering hinges on the selection of an appropriate biomaterial scaffold. These materials provide the critical three-dimensional (3D) environment that supports cell viability, guides function, and facilitates integration with host tissues. Among the diverse classes of biomaterials available, hydrogels, nanofibers, decellularized extracellular matrix (dECM), and synthetic polymers each offer distinct advantages and limitations. Hydrogels provide highly hydrated environments that mimic native tissues, nanofibers offer topographical cues that guide cell organization, dECM delivers tissue-specific biological signals, and synthetic polymers present tunable mechanical and chemical properties. This guide objectively compares the performance of these major biomaterial classes based on experimental data, focusing on their efficacy in cell delivery applications. Understanding the comparative strengths of each material class enables researchers to make informed decisions for specific cellular delivery applications, from basic research to clinical translation.

Comparative Analysis of Major Biomaterial Classes

Table 1: Comprehensive comparison of major biomaterial classes for cell delivery applications

| Biomaterial Class | Key Composition | Mechanical Properties | Degradation Timeline | Key Advantages | Major Limitations | Primary Cell Delivery Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrogels | Natural (collagen, alginate, fibrin) or synthetic (PEG) polymers with high water content [1] | Elastic modulus typically 0.1-20 kPa, highly tunable [2] [1] | Days to months, depending on cross-linking density | High biocompatibility, excellent nutrient diffusion, can mimic tissue elasticity [1] | Often weak mechanical properties, limited structural integrity [1] [3] | Cell encapsulation, 3D bioprinting, soft tissue regeneration |

| Nanofibers | Synthetic (PCL, PLGA) or natural (collagen, chitosan) polymers | High surface area-to-volume ratio, tunable tensile strength | Weeks to years, depending on polymer composition | Mimics native ECM architecture, superior cell adhesion guidance [1] | Limited control over 3D architecture in random scaffolds, potential poor nutrient diffusion to core | Neural guidance, tendon/ligament repair, wound dressing |

| Decellularized ECM (dECM) | Tissue-derived scaffolds preserving native ECM components [4] [5] | Varies by tissue source, often requires reinforcement (e.g., 1.5-6.8 kPa for lung dECM) [2] | Weeks to months, enzyme-mediated | Tissue-specific biochemical cues, innate bioactivity, excellent cellular compatibility [6] [5] | Batch-to-batch variability, potential immunogenicity, poor mechanical integrity [3] [6] | Organoid culture, tissue-specific regeneration, bioactive coatings |

| Synthetic Polymers | PLA, PGA, PLGA, PEG, PCL [7] [8] | Highly tunable (elastic modulus from kPa to GPa) | Days to years, precisely controllable through chemistry | Highly reproducible, tunable mechanical and chemical properties, predictable degradation [8] | Lack of innate bioactivity, may provoke inflammatory response, hydrophobic varieties limit cell adhesion | Controlled release systems, bone fixation devices, structural implants |

Table 2: Experimental performance data for biomaterials in specific applications

| Biomaterial | Experimental Model | Cell Viability/Function | Tissue Regeneration Outcome | Key Measurement | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clickable dECM Hybrid-Hydrogel | Primary murine lung fibroblasts | ≈60% increase in Col1a1 and αSMA expression on stiff hydrogels (13.4 kPa) vs. soft (3.6 kPa) [2] | N/A (in vitro model) | Significant increase in myofibroblast transgenes with increased modulus | [2] |

| HA/PLGA/Bleed Scaffold | Critical bone defect in rat calvaria | Enhanced collagen I deposition throughout matrix | Superior bone regeneration at 15, 30, and 60 days vs. HA/PLGA alone | Higher Rank-L immunoexpression indicating increased remodeling | [7] |

| Photocrosslinked dECM Bioink | 3D bioprinting of various tissues | Excellent cell viability and tissue-specific differentiation | Improved structural fidelity and shape retention | Shear-thinning behavior and rapid sol-gel transitions | [6] |

| PEGαMA-dECM Hybrid | Spatial patterning of fibroblast activation | Increased Col1a1 expression on stiff regions of patterned hydrogels | N/A (in vitro model) | Spatiotemporal control over fibroblast activation | [2] |

Detailed Biomaterial Characteristics and Experimental Evidence

Hydrogels

Structural and Functional Properties: Hydrogels are 3D cross-linked insoluble, hydrophilic polymer networks capable of absorbing large amounts of water or biological fluid (up to 99%) due to their interconnected microscopic pores [1]. This high water content creates an environment that physically mimics native tissues, facilitating efficient nutrient and oxygen diffusion to encapsulated cells—a critical advantage for cell viability in 3D constructs. Hydrogels can be fabricated from both natural polymers (including collagen, hyaluronic acid, chitosan, alginate, and fibrin) and synthetic polymers (primarily poly(ethylene glycol) or PEG), with each offering distinct advantages [1] [3]. Their mechanical properties, characterized by elastic modulus typically ranging from 0.1-20 kPa, can be precisely tuned to match target tissues by adjusting polymer concentration, cross-linking density, or fabrication parameters [1].

Key Experimental Evidence: Advanced hydrogel systems have been developed with dynamic capabilities that mirror the evolving nature of living tissues. One innovative approach incorporates clickable decellularized ECM crosslinker into a dynamically responsive poly(ethylene glycol)-α-methacrylate (PEGαMA) hybrid-hydrogel to recreate ECM remodeling in vitro [2]. This system utilizes dual-stage polymerization reactions, beginning with an off-stoichiometry thiol-ene Michael addition between PEGαMA and clickable dECM, resulting in hydrogels with an elastic modulus of 3.6 ± 0.24 kPa, approximating healthy lung tissue. Subsequent reaction of residual αMA groups via photo-initiated homopolymerization increases modulus values to fibrotic levels (13.4 ± 0.82 kPa) in situ [2]. This dynamic system demonstrated that increased elastic moduli, mimicking fibrotic ECM, induced a significant increase (approximately 60%) in the expression of myofibroblast transgenes (collagen 1a1 and alpha-smooth muscle actin) in primary fibroblasts from dual-reporter mouse lungs [2].

Decellularized Extracellular Matrix (dECM)

Structural and Functional Properties: Decellularized ECM represents a sophisticated biomaterial approach that preserves the complex biochemical composition of native tissues while eliminating immunogenic cellular components [5]. The dECM is composed of a complex assembly of structural proteins (primarily collagens, elastin), proteoglycans, glycoproteins, and preserved growth factors that collectively provide tissue-specific biochemical and biophysical cues [4] [5]. These materials can be processed into various forms including solid scaffolds, injectable hydrogels, and bioinks for 3D bioprinting [6] [5]. The primary advantage of dECM over other biomaterials lies in its innate bioactivity and ability to recapitulate tissue-specific microenvironments that guide cell behavior, support differentiation, and enhance functional tissue regeneration [5].

Key Experimental Evidence: Research has demonstrated that dECM hydrogels provide superior microenvironments for specialized tissue development. Studies show that mesenchymal stem cells exhibit distinct gene expression patterns when cultured in various dECM materials, with compositional variations directly influencing stem cell behavior and directing differentiation in a tissue-specific manner [6]. Furthermore, dECM serves as a superior cell culture matrix that significantly enhances the expression of genes associated with cellular maturation and specialized functions compared to traditional biological scaffolds such as Matrigel and collagen [6].

For clinical translation, dECM-based medical devices have shown promise in multiple applications. Patch-type grafts such as Alloderm and GraftJacket have been used for skin and rotator cuff repair, while injectable hydrogel forms like Ventrigel have been applied for cardiac function restoration [6]. In 3D bioprinting applications, dECM bioinks have been developed for adipose, cartilage, and cardiac tissues, providing crucial signals essential for cell implantation, viability, and sustained functionality [6]. These bioinks demonstrate suitable rheological properties including shear-thinning behavior (where viscosity decreases with increasing shear rate) and rapid sol-gel transitions, making them particularly advantageous for extrusion-based printing [6].

Synthetic Polymers

Structural and Functional Properties: Synthetic polymers including polylactic acid (PLA), polyglycolic acid (PGA), poly(lactic-co-glycolic) acid (PLGA), polycaprolactone (PCL), and polyethylene glycol (PEG) offer exceptional tunability and reproducibility as biomaterials [7] [8]. These materials provide precise control over mechanical properties, degradation kinetics, and overall scaffold architecture. Their synthesis can be engineered to achieve specific mechanical characteristics ranging from soft, flexible networks to rigid, load-bearing structures, with degradation timelines that can be programmed from days to years depending on molecular weight, crystallinity, and copolymer ratios [8]. This precise control makes synthetic polymers particularly valuable for applications requiring specific temporal profiles or mechanical support.

Key Experimental Evidence: In bone regeneration studies, composite scaffolds combining hydroxyapatite (HA) with PLGA have demonstrated significant potential as orthopedic implants [7]. In a critical bone defect model in rat calvaria, HA/PLGA scaffolds with added hemostatic polysaccharide (Bleed) showed enhanced collagen I deposition and superior bone regeneration at 15, 30, and 60 days compared to HA/PLGA alone [7]. Histological analysis revealed morphological and structural differences in the neoformed tissue between experimental groups, with the HA/PLGA/Bleed scaffold presenting the highest amount of collagen fibers in its tissue matrix across all evaluated periods [7]. Additionally, receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa-Β ligand (Rank-L) immunoexpression results were higher in the HA/PLGA/Bleed group at 30 and 60 days, indicating increased degradation of the biomaterial and enhanced remodeling activity of the bone [7].

Nanofibers

Structural and Functional Properties: Nanofibrous biomaterials create synthetic extracellular matrices with high surface area-to-volume ratios that closely mimic the topological features of native ECM [1]. These materials can be fabricated through various methods including electrospinning, self-assembly, and phase separation, producing fiber diameters typically ranging from tens to hundreds of nanometers. The high porosity and interconnected pore structure of nanofibrous scaffolds facilitate cell infiltration, nutrient diffusion, and waste removal while providing topographical cues that direct cell alignment, migration, and differentiation. Nanofibers can be composed of both synthetic (PCL, PLGA) and natural (collagen, chitosan) polymers, offering versatility in their biological and mechanical properties [1].

Functional Advantages and Evidence: The primary advantage of nanofibrous architectures lies in their ability to guide cellular organization and tissue formation through physical patterning. The high surface area promotes greater protein adsorption and enhanced cell adhesion compared to flat surfaces or conventional scaffolds [1]. Nanofibers can be aligned to create contact guidance cues that direct cell orientation, a particularly valuable property for engineering anisotropic tissues such as tendons, ligaments, nerves, and cardiac muscle. Furthermore, the mechanical properties of nanofibrous scaffolds can be tuned through material selection, fiber alignment, and processing parameters to match the requirements of target tissues.

Experimental Protocols for Key Evaluations

Protocol: Dual-Stage Polymerization for Dynamic Hydrogel Stiffening

This protocol details the methodology for creating hydrogels with dynamically tunable mechanical properties to study cellular responses to stiffness changes, as described in [2].

Materials:

- 8-arm PEGαMA (10 kg/mol)

- Clickable dECM crosslinker

- Lithium phenyl-2,4,6-trimethylbenzoulphospinate (LAP) photo-initiator

- Buffered solution (pH 7.4)

- UV light source (365 nm, 5-10 mW/cm²)

Procedure:

- Prepare precursor solution: Dissolve PEGαMA at 50-100 mg/mL in buffered solution.

- First-stage crosslinking: Mix PEGαMA solution with clickable dECM at stoichiometric ratio and initiate Michael addition by adding LAP (0.05% w/w). Incubate at 37°C for 30 minutes to form soft hydrogels (≈3-4 kPa).

- Second-stage stiffening: Expose the formed hydrogels to UV light (365 nm, 5-10 mW/cm²) for 3-5 minutes to initiate homopolymerization of residual αMA groups, increasing modulus to fibrotic levels (≈13 kPa).

- Characterization: Confirm modulus values using rheometry or atomic force microscopy.

Applications: This system enables investigation of fibroblast activation, fibrosis progression, and cellular responses to dynamic mechanical changes [2].

Protocol: In Vivo Evaluation of Bone Regeneration in Critical Defects

This protocol outlines the procedure for evaluating biomaterials in critical-sized bone defects, adapted from [7].

Materials:

- HA/PLGA and HA/PLGA/Bleed scaffolds (1.5 mm thickness, 8 mm diameter)

- Male Wistar rats (280 ± 20 g)

- Trephine drill (8-mm diameter)

- Anesthesia (ketamine/xylazine)

- Fixative (10% buffered formalin)

Procedure:

- Surgical procedure: Anesthetize rats and create critical-sized bone defects in the calvaria using an 8-mm trephine drill.

- Implantation: Implant test scaffolds (HA/PLGA or HA/PLGA/Bleed) into defects, with untreated defects as controls.

- Post-operative care: Administer analgesic and allow recovery with free access to food and water.

- Euthanasia and sample collection: Euthanize animals at 15, 30, and 60 days post-implantation and harvest calvaria for analysis.

- Histological processing: Fix samples in formalin, decalcify in EDTA, embed in paraffin, and section at 5 μm thickness.

- Analysis: Perform hematoxylin and eosin staining, collagen I immunohistochemistry, and Rank-L immunoexpression analysis.

Outcome measures: Bone regeneration extent, collagen organization, inflammation presence, and remodeling activity [7].

Biomaterial Selection Workflow

Biomaterial Selection Workflow for Cell Delivery Applications

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key research reagents and materials for biomaterial experimentation

| Reagent/Material | Function | Example Applications | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Poly(ethylene glycol)-α-methacrylate (PEGαMA) | Synthetic polymer backbone for hybrid hydrogels | Dynamic stiffness hydrogels, 3D cell culture platforms [2] | Molecular weight, degree of functionalization, water solubility |

| Lithium phenyl-2,4,6-trimethylbenzoylphosphinate (LAP) | Photo-initiator for UV-mediated crosslinking | Photopolymerizable hydrogels, bioprinting applications [2] | Cytotoxicity at high concentrations, optimal wavelength 365 nm |

| Decellularized ECM (dECM) | Tissue-specific bioactive scaffold material | Organoid culture, bioinks, regenerative scaffolds [6] [5] | Source tissue, decellularization efficiency, gelation temperature |

| Gelatin Methacryloyl (GelMA) | Photocrosslinkable natural polymer | Bioprinting, tissue engineering, drug screening [3] | Degree of methacrylation, viscosity, gelation parameters |

| Hydroxyapatite (HA) | Mineral component for bone regeneration | Bone tissue engineering, orthopedic implants [7] | Particle size, crystallinity, purity |

| Poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) | Biodegradable synthetic polymer | Controlled release systems, bone scaffolds [7] [8] | Lactide:glycolide ratio, molecular weight, degradation rate |

| Collagen Type I | Natural polymer hydrogel substrate | 3D cell culture, wound healing, soft tissue models [4] [1] | Source, concentration, fibrillogenesis conditions |

| Alginate | Ionic-crosslinked natural polymer | Cell encapsulation, bioprinting, wound dressings [3] | Molecular weight, guluronate:mannuronate ratio, purity |

The selection of biomaterials for cell delivery applications requires careful consideration of mechanical, biological, and practical parameters. Hydrogels excel in creating hydrous, diffusive environments for 3D culture; dECM provides unmatched bioactivity and tissue-specificity; synthetic polymers offer precision and reproducibility; while nanofibers deliver critical topographical guidance. The experimental data presented enables evidence-based selection, while the provided protocols facilitate standardized evaluation. As the field advances, composite approaches that combine the strengths of multiple material classes will likely yield the most effective solutions for specific cell delivery challenges in regenerative medicine and tissue engineering.

The field of regenerative medicine and immunotherapy is being transformed by advances in therapeutic cell technologies. Among the most prominent of these are Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs), Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells (iPSCs), Endothelial Colony-Forming Cells (ECFCs), and various immune cells for adoptive cell therapy (ACT). These cells offer unprecedented potential for treating a wide range of diseases, from cancer to degenerative disorders. However, their therapeutic efficacy is often limited by challenges in delivery, engraftment, and controlled functionality within the hostile in vivo environment. The integration of these cells with advanced biomaterials has emerged as a critical strategy to overcome these limitations. Biomaterials can enhance cell survival, provide three-dimensional support, enable localized delivery, and maintain therapeutic phenotypes, thereby significantly improving clinical outcomes. This guide provides a comparative analysis of these key therapeutic cell types, with a specific focus on their interactions with biomaterial-based delivery systems, to inform researchers and drug development professionals in the field.

Comparative Analysis of Therapeutic Cell Types

The table below summarizes the key characteristics, therapeutic mechanisms, and biomaterial interactions of the four major therapeutic cell types.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Key Therapeutic Cell Types

| Cell Type | Key Characteristics & Markers | Therapeutic Mechanisms | Primary Clinical Applications | Biomaterial Delivery Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MSCs [9] [10] [11] | Plastic-adherent, CD73+, CD90+, CD105+; CD34-, CD45-; Multipotent (osteogenic, chondrogenic, adipogenic) | Paracrine signaling (cytokines, growth factors), immunomodulation, mitochondrial transfer, direct differentiation [12] | Graft-versus-host disease (GVHD), osteoarthritis, spinal cord injury, COVID-19 ARDS [11] [12] | Hydrogels for viability & retention; scaffolds for osteochondral differentiation; controlled cytokine release [9] [13] |

| iPSCs [10] [14] [15] | Pluripotent (differentiate into all germ layers); Express OCT4, SOX2, NANOG; Can be genetically engineered | Source for differentiated cells (e.g., iPSC-MSCs, iPSC-NKs); Avoids embryonic destruction; Potential for autologous therapy | Age-related macular degeneration, Parkinson's disease, heart failure, cancer immunotherapy (as iPSC-NKs) [15] | Biomaterial-assisted 2D/3D differentiation into target cells; Encapsulation for teratoma risk mitigation [9] |

| Immune Cells (for ACT) [13] [16] [17] | Engineered specificity (e.g., CAR-T); Diverse types (T cells, NK cells, DCs); Activated & expanded ex vivo | Direct cytotoxicity (CAR-T, NK), antigen presentation (DCs), immunomodulation | Hematological cancers (B-cell leukemia, lymphoma), solid tumors (trials), autoimmune diseases [16] [17] | Hydrogels for localized tumor delivery; Co-delivery of cytokines (IL-15) to prevent exhaustion; scaffolds for intratumoral retention [13] [16] [17] |

| ECFCs | Highly proliferative endothelial progenitors; CD31+, CD34+, CD146+, VEGFR2+; Form vessel structures | Vasculogenesis and angiogenesis; Direct contribution to vascular lining; Paracrine pro-angiogenic signaling | Ischemic diseases (critical limb ischemia, myocardial infarction), vascularizing engineered tissues | Biofunctionalized scaffolds to guide vascular network formation; Co-delivery with perivascular cells for stability |

Quantitative Efficacy and Manufacturing Data

The following table consolidates key quantitative data from preclinical and clinical studies, highlighting the performance and manufacturing considerations of each cell type.

Table 2: Quantitative Data on Therapeutic Efficacy and Manufacturing

| Cell Type | Key Efficacy Metrics | Manufacturing & Scalability | Stability & Storage | Safety Profile & Key Risks |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MSCs | >50% reduction in aGVHD symptoms in responders [12]; Significant cartilage regeneration in osteoarthritis trials [11] | Finite expansion in 2D culture; 3D bioreactors can increase yield; Relatively scalable from allogeneic sources | Cryopreservation possible; Phenotype stable for limited passages (e.g., < P10) | Low tumorigenicity; Low immunogenicity allows allogeneic use; Some reports of pro-tumor effects [12] |

| iPSCs | iPSC-NKs: >70% tumor cell killing in vitro models [15]; iPSC-derived grafts: successful engraftment in AMD patients [15] | Virtually unlimited self-renewal; Requires complex, multi-step differentiation protocols; High scalability potential | Master cell banks can be cryopreserved long-term; Differentiated products may have limited shelf-life | Teratoma formation from undifferentiated cells; Genomic instability during reprogramming/culture [10] [15] |

| Immune Cells (for ACT) | >80% remission rates in ALL with CD19 CAR-T [16] [17]; Persistence of CAR-T cells for >10 years in some patients | Autologous: costly, variable; Allogeneic: avoids this but needs HLA editing; Manufacturing time: ~2-3 weeks | Cryopreservation of final product is standard; Limited stability after thawing for infusion | Cytokine Release Syndrome (CRS); Immune Effector Cell-Associated Neurotoxicity Syndrome (ICANS); On-target/off-tumor toxicity [16] |

| ECFCs | In vivo: Increased capillary density in murine hindlimb ischemia models; Functional perfusion recovery | Isolated from cord blood or peripheral blood; Moderate expansion capability; Less established large-scale production | Cryopreservation of isolated cells from donors; Limited replicative lifespan in culture | Theoretical risk of aberrant angiogenesis (e.g., in tumors); Generally considered safe in early trials |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Deriving MSCs from iPSCs Using a Biomaterial-Assisted Approach

This protocol details a method for generating MSCs from human iPSCs using a feeder-free, biomaterial-coated system, adapted from recent research [9] [10] [14]. The derived iPS-MSCs exhibit typical MSC characteristics and offer a solution to the heterogeneity and limited expansion potential of tissue-derived MSCs.

1. Materials and Reagents

- Human iPSCs: Maintained in a pluripotent state on a suitable substrate (e.g., Matrigel, Geltrex).

- MSC Differentiation Medium: Alpha-MEM or DMEM/F12, supplemented with 10% Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS), 1% GlutaMAX, and 1% Non-Essential Amino Acids.

- Small Molecule Inhibitor: SB431542 (a TGF-β pathway inhibitor), reconstituted in DMSO.

- Biomaterial Coatings: Matrigel, Collagen I, or specific synthetic hydrogels (e.g., PEG-based).

- Enzymes: Gentle Cell Dissociation Reagent (for iPSCs) and 0.25% Trypsin-EDTA (for MSCs).

- Characterization Reagents: Antibodies for flow cytometry (CD73, CD90, CD105, CD34, CD45, HLA-DR) and differentiation kits (osteogenic, adipogenic, chondrogenic).

2. Step-by-Step Workflow

Diagram Title: Workflow for iPSC to MSC Differentiation

3. Key Steps Elaboration

- Step 1: Seeding iPSCs: Harvest iPSCs as single cells or small clumps and seed them onto tissue culture plates coated with the chosen biomaterial (e.g., Matrigel at 1:100 dilution). The biomaterial provides critical cues that mimic the native extracellular matrix and support subsequent differentiation.

- Step 2: Differentiation Induction: Culture the cells in MSC Differentiation Medium supplemented with 5-10 µM SB431542. The medium should be changed every other day. SB431542 inhibits SMAD2/3 phosphorylation, directing the cells toward a mesodermal lineage and ultimately to an MSC fate. This step typically takes about 10 days, after which an epithelial-like monolayer should be visible.

- Step 3: Lineage Stabilization: After 10 days, passage the cells using trypsin and re-plate them at a defined density (e.g., 5,000 cells/cm²) in MSC Differentiation Medium without SB431542. The cells should now be maintained and expanded as a standard MSC culture. They will acquire a typical MSC-like fibroblastic morphology over 1-2 passages.

- Step 4: Expansion and Characterization: Expand the iPS-MSCs for several passages. Characterize them according to International Society for Cellular Therapy (ISCT) criteria:

- Surface Markers: Confirm >95% expression of CD73, CD90, and CD105, and <2% expression of CD34, CD45, and HLA-DR via flow cytometry.

- Trilineage Differentiation: Perform in vitro differentiation into osteocytes (mineralization with Alizarin Red staining), adipocytes (lipid droplets with Oil Red O staining), and chondrocytes (cartilage matrix with Alcian Blue staining).

- Safety: Perform karyotyping to ensure genomic stability and consider a teratoma assay in immunodeficient mice to confirm the absence of residual pluripotent cells.

Biomaterial Strategies for Enhanced Cell Delivery

Rational Design of Biomaterial Carriers

Biomaterials are engineered to address the specific limitations of each cell type, with design criteria focusing on cytocompatibility, bioactivity, and mass transfer [16] [17]. The following table outlines key material classes and their functions in cell delivery.

Table 3: The Scientist's Toolkit: Biomaterials and Reagents for Cell Delivery

| Material/Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function in Cell Therapy |

|---|---|---|

| Natural Polymer Hydrogels | Alginate, Chitosan, Collagen, Hyaluronic Acid, Fibrin | Provide a soft, hydrated 3D microenvironment that supports cell viability and can be modified with adhesion motifs (e.g., RGD). |

| Synthetic Polymer Hydrogels | Poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG), Poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) | Offer highly tunable mechanical properties, degradation rates, and minimal batch-to-batch variation. |

| Cytokines & Growth Factors | IL-15, IL-2, GM-CSF, TGF-β, VEGF | Co-delivered to maintain cell viability, promote activation (e.g., prevent T-cell exhaustion), or steer differentiation. |

| Engineered Scaffolds & Microparticles | 3D-printed polymer scaffolds, Degradable microspheres | Act as a physical reservoir for localized cell delivery and sustained release of bioactive factors. |

| Small Molecule Inhibitors/Inducers | SB431542, CHIR99021, Dorsomorphin | Used in differentiation protocols (e.g., iPSC to MSC) to precisely control signaling pathways. |

Biomaterial Applications by Cell Type

- Enhancing MSC Therapies: Biomaterials are used to overcome the limited persistence of systemically infused MSCs. Hydrogels based on alginate or PEG can encapsulate MSCs, providing mechanical protection and tethering them to the target site, thereby increasing engraftment [9]. For bone regeneration, MSCs are often loaded onto rigid, osteoconductive scaffolds (e.g., hydroxyapatite or tricalcium phosphate) that provide the structural and chemical cues necessary for osteogenic differentiation [11].

- Boosting Adoptive Immune Cell Therapy: A major challenge for CAR-T cells in solid tumors is poor infiltration and rapid exhaustion. Biomaterial solutions include injectable hydrogels that can be deposited locally in the tumor resection cavity, creating a "factory" for the sustained release of functional CAR-T cells and supportive cytokines like IL-15 [13] [16] [17]. This local delivery maintains an activated T-cell phenotype and improves tumor cell killing while reducing systemic toxicity.

- Supporting iPSC-Derived Cell Products: Biomaterials play a dual role for iPSCs. First, they are crucial for directing the efficient and scalable differentiation of iPSCs into target cells like MSCs or cardiomyocytes in 3D culture systems [9]. Second, they can be used to encapsulate and deliver the final differentiated product, potentially containing any residual undifferentiated cells and mitigating the risk of teratoma formation.

The diagram below illustrates how a biomaterial scaffold can be designed to create a supportive microenvironment for delivered therapeutic cells.

Diagram Title: Multifunctional Biomaterial Scaffold for Cell Delivery

The therapeutic landscape for MSCs, iPSCs, ECFCs, and adoptive immune cells is rapidly evolving, with biomaterials playing an increasingly critical role in translating their potential into clinical reality. As this guide illustrates, the choice of cell type is dictated by the specific clinical target, whether it is immunomodulation, tissue regeneration, or targeted cytotoxicity. However, the efficacy of these cells is no longer solely dependent on their inherent biology; it is profoundly enhanced by the smart design of biomaterial delivery systems. These systems provide a protective, instructive, and localized microenvironment that overcomes common barriers such as poor cell survival, inadequate retention, and loss of function. Future progress in the field will hinge on the development of even more sophisticated "smart" biomaterials that can actively respond to the physiological environment and the continued refinement of manufacturing protocols to ensure the consistent, safe, and scalable production of these combined cell-biomaterial therapies.

The efficacy of any biomaterial in cell delivery and regenerative medicine is fundamentally governed by its interactions with the biological environment. These interactions—dictated by biocompatibility, mechanical properties, and degradation behavior—determine host response, cell viability, and ultimate therapeutic success. A comparative analysis of biomaterial performance is therefore critical for selecting optimal platforms for specific clinical applications. This guide objectively compares the performance of major biomaterial classes used in cell delivery, supported by experimental data, to inform research and development strategies.

Comparative Performance of Biomaterial Delivery Vehicles

The choice of biomaterial vehicle significantly impacts the acute retention and survival of delivered cells, which is a critical performance metric in therapies such as cardiac regeneration after myocardial infarction. The following data summarizes key experimental findings from a controlled comparative study.

Table 1: Comparison of Biomaterial Vehicles for Acute Stem Cell Retention in the Infarcted Heart [18]

| Biomaterial Delivery Vehicle | Type | Cell Retention at 24 Hours (Fold Increase vs. Saline Control) | Approximate Percentage of Initially Transplanted Cells Retained |

|---|---|---|---|

| Saline (Clinical Standard) | Injectable | (Baseline = 1x) | ~10% |

| Alginate Hydrogel | Injectable | ~8x | ~50% |

| Chitosan/β-GP Hydrogel | Injectable | ~14x | ~50% |

| Collagen Patch | Epicardial Patch | ~47x | 50-60% |

| Alginate Patch | Epicardial Patch | ~59x | 50-60% |

Key Findings: All biomaterial carriers dramatically outperformed the saline control, with epicardial patches demonstrating superior cell retention. The alginate patch achieved the highest retention, showing a 59-fold increase over saline. Notably, all four biomaterials retained 50-60% of the cells initially present after transplantation, a five to six-fold improvement over the 10% retention with saline. [18] This highlights that the physical encapsulation and protection provided by biomaterials are crucial for overcoming the harsh in vivo environment that leads to rapid cell loss.

Experimental Protocols for Evaluating Biomaterial-Cell Interactions

Robust and standardized experimental methodologies are essential for generating reliable, comparable data on biomaterial efficacy. The following protocols detail key procedures for evaluating cell retention and host response.

Protocol: In Vivo Quantification of Cell Retention

This protocol is adapted from a comparative study of biomaterials for stem cell delivery to the heart. [18]

- Objective: To quantify and compare the acute retention of delivered cells using different biomaterial carriers in a disease model.

- Materials:

- Experimental animal model (e.g., rat myocardial infarct model).

- Cells for delivery (e.g., Human Mesenchymal Stem Cells - hMSCs).

- Test biomaterials (e.g., alginate hydrogel, chitosan/β-GP hydrogel, collagen patch, alginate patch).

- Saline control.

- Fluorescent cell tracker (e.g., CM-Dil or similar for fluorescence quantification).

- Methods:

- Induction of Myocardial Infarction: Surgically induce myocardial infarction in the animal model to create the target pathology.

- Cell Labeling: Label hMSCs with a fluorescent cell tracker according to manufacturer protocols.

- Cell-Biomaterial Preparation:

- For injectable hydrogels: Mix the fluorescently labeled cells with the pre-gel solution (e.g., alginate or chitosan/β-GP).

- For epicardial patches: Seed the labeled cells onto the pre-formed patches (e.g., collagen or alginate).

- Delivery: Implant the cell-biomaterial constructs into the target site (e.g., infarct border zone). For injectables, use direct injection; for patches, use surgical attachment.

- Quantification: After 24 hours, harvest the target tissue.

- Quantify the retained fluorescence intensity using a pre-calibrated imaging or spectrophotometric system.

- Calculate retained cell numbers based on the fluorescence signal relative to a standard curve.

- Perform immunohistochemical analysis on tissue sections to qualitatively confirm cell presence and distribution.

- Analysis: Compare the fluorescence (cell retention) across different biomaterial groups and the saline control, typically expressed as a fold-increase relative to the control.

Protocol: Assessing the Host Immune Response

- Objective: To evaluate the biocompatibility and inflammatory response elicited by a biomaterial.

- Materials:

- Biomaterial samples.

- In vitro cell culture (e.g., macrophages) or in vivo implantation model.

- ELISA kits or PCR reagents for cytokine analysis.

- Histological staining supplies.

- Methods:

- Implantation: Implant the biomaterial subcutaneously or in the target organ.

- Tissue Collection: Harvest the surrounding tissue and the implant site at predetermined time points (e.g., 3, 7, 14 days).

- Analysis:

- Histology: Process tissue for sectioning and stain with Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) to visualize general tissue architecture and immune cell infiltration. Use specific stains (e.g., for macrophages) to identify immune cell types.

- Cytokine Profiling: Homogenize tissue and analyze the supernatant for pro-inflammatory (e.g., TNF-α, IL-6) and anti-inflammatory (e.g., IL-10) cytokines using ELISA.

- Analysis: A more biocompatible material will typically show a resolved, mild inflammatory response over time, while a poor material will trigger a sustained, severe inflammatory reaction.

Signaling Pathways in Material-Cell Interactions

The interaction between a biomaterial and a cell is not passive; it initiates a cascade of intracellular signals that dictate cell fate. The extracellular matrix (ECM) is a natural scaffold that provides critical biochemical and mechanical cues. [19] Synthetic biomaterials are engineered to mimic these functions. The following diagram illustrates the core signaling pathway activated when a cell engages with a biomaterial via integrin receptors.

Biomaterial Induced Cell Signaling [19] [20]

This pathway highlights how biomaterials directly influence cell behavior by activating specific genetic programs.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Successful research into material-cell interactions relies on a suite of specialized reagents and materials. The following table details essential tools and their functions in this field.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Biomaterial-Cell Interaction Studies

| Research Reagent / Material | Function and Role in Biomaterial Studies |

|---|---|

| Alginate | A natural polymer used to form gentle, injectable hydrogels or patches; ideal for cell encapsulation and delivery due to its biocompatibility and tunable properties. [18] |

| Chitosan/β-Glycerophosphate (β-GP) | A temperature-sensitive hydrogel that is liquid at room temperature and gels at body temperature; enables minimally invasive injection of cells. [18] |

| Collagen | A major component of the natural ECM; used as patches or hydrogels to provide a bioactive and highly biocompatible scaffold that promotes cell adhesion and integration. [18] |

| Poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) | A biodegradable synthetic polymer and a cornerstone of controlled-release drug delivery systems; its degradation rate and drug release profile can be finely tuned. [21] |

| Human Mesenchymal Stem Cells (hMSCs) | A primary cell type frequently used in regenerative medicine research due to their multipotent differentiation potential, immunomodulatory properties, and relevance for cell therapy. [18] |

| Fluorescent Cell Trackers (e.g., CM-Dil) | Vital dyes used to label living cells prior to transplantation, allowing for their quantification and tracking within the host tissue over time using fluorescence imaging or spectrometry. [18] |

| ECM Proteins (Fibronectin, Laminin) | Proteins used to coat biomaterial surfaces to enhance cell adhesion and activity by mimicking the natural cellular environment and presenting specific integrin-binding motifs. [19] |

The efficacy of stem cell therapies is governed not solely by the intrinsic potential of the cells themselves but by the highly specialized microenvironments, or niches, in which they reside. A stem cell niche is an anatomical unit that integrates structural, biochemical, and mechanical cues to regulate stem cell self-renewal, quiescence, and differentiation [22] [23]. The core premise of modern regenerative medicine is that successful therapeutic outcomes depend on treating stem cells and their microenvironment as an inseparable unit [24] [23]. This represents a significant paradigm shift from a cell-centric to a niche-centric model, rationalizing the design of biomaterial delivery systems that recapitulate key aspects of the native stem cell niche to enhance cell survival, retention, and functional integration post-transplantation [25] [26].

The following sections provide a comparative analysis of biomaterial strategies for stem cell delivery, presenting quantitative data on their performance, detailing key experimental methodologies, and dissecting the molecular mechanisms through which they exert their effects.

Quantitative Comparison of Biomaterial Delivery Vehicles

A critical challenge in cell therapy is the acute loss of transplanted cells. Comparative studies have systematically evaluated various biomaterial carriers against the saline injection control, which represents the current clinical standard. The table below summarizes the acute cell retention performance of different biomaterial vehicles in a rat myocardial infarct model, a common testbed for regenerative therapies [27].

Table 1: Acute Cell Retention of Biomaterial Delivery Vehicles in a Rat Myocardial Infarct Model

| Delivery Vehicle | Vehicle Type | Fold Increase in Retention (vs. Saline Control) | Approximate Retained Cells at 24 Hours |

|---|---|---|---|

| Saline (Control) | Injectable | (Baseline) | ~10% of immediately transplanted cells |

| Alginate Hydrogel | Injectable | 8-fold | ~50-60% of immediately transplanted cells |

| Chitosan/β-GP Hydrogel | Injectable | 14-fold | ~50-60% of immediately transplanted cells |

| Collagen Patch | Epicardial Patch | 47-fold | ~50-60% of immediately transplanted cells |

| Alginate Patch | Epicardial Patch | 59-fold | ~50-60% of immediately transplanted cells |

The data reveals two key findings: first, all biomaterials significantly outperformed the saline control, with epicardial patches demonstrating superior retention; and second, all four biomaterials retained over half of the cells present immediately after transplantation, a five to six-fold improvement over the saline control [27]. This highlights the profound impact of a supportive microenvironment on cell survival.

Beyond simple retention, mimicking niche properties can enhance the functional potency of the cells themselves. Research on cardiac-derived cells demonstrates that culturing them as three-dimensional cardiospheres recapitulates a niche-like microenvironment, leading to enhanced therapeutic efficacy [25].

Table 2: Functional Benefits of Niches in Stem Cell Culture and Delivery

| Culture/Delivery Method | Key Niche-Mimicking Features | Impact on Cell Properties & Therapeutic Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Traditional Monolayer Culture | Two-dimensional, lacks complex cell-cell/cell-ECM interactions | Standard for expansion but does not fully emulate native niche conditions. |

| Cardiosphere Culture | 3D suspension culture; rich in stemness and cell-matrix interactions; upregulated ECM and adhesion molecules (e.g., integrin-α2, laminin-β1) [25] | Higher proportion of c-kit+ cells; upregulated stemness factors (SOX2, Nanog); enhanced resistance to oxidative stress; improved engraftment and myocardial function in infarcted hearts [25]. |

| Dissociated Cardiospheres | Loss of 3D structure and cell-matrix interactions | Decreased expression of ECM and adhesion molecules; undermined stress resistance; negated functional benefit in vivo [25]. |

Experimental Protocols for Evaluating Biomaterial Efficacy

To ensure the reliability and reproducibility of comparative data, researchers employ standardized experimental protocols. The following outlines key methodologies used to generate the performance data presented in this guide.

Protocol for Quantifying Acute Cell Retention

This protocol is designed to objectively compare the efficiency of different biomaterials in delivering and retaining cells at the target site [27].

- Step 1: Cell Preparation and Labeling. Human Mesenchymal Stem Cells (hMSCs) are expanded in culture. Before implantation, cells are labeled with a fluorescent marker, such as a lipophilic membrane dye (e.g., DiI, CM-Dil) or a fluorescent reporter gene (e.g., GFP, Luciferase), to enable tracking.

- Step 2: Biomaterial Cell Encapsulation. For injectable hydrogels (e.g., alginate, chitosan/β-GP), the labeled cells are gently mixed with the polymer solution under sterile conditions. The mixture is kept on ice to prevent premature gelling. For epicardial patches, cells are seeded onto pre-formed collagen or alginate scaffolds and allowed to adhere.

- Step 3: In Vivo Delivery to Infarcted Heart. A rodent model (typically rat or mouse) of myocardial infarction is used. The infarction is induced surgically, often by permanent ligation of the left anterior descending coronary artery. After a set period, the animal is re-anesthetized, and the cell-biomaterial construct is delivered to the infarct border zone. Saline-injected animals serve as the control group.

- Step 4: Quantification at Endpoint. At a predetermined time point (e.g., 24 hours post-implantation), the heart is explanted and processed. Quantification is performed using fluorescence imaging. The total fluorescence signal from the heart is measured and compared to a standard curve created from a known number of labeled cells to calculate the absolute number of retained cells. This data is confirmed qualitatively by immunohistochemistry, where tissue sections are stained with fluorescent antibodies against the human cells [27].

Protocol for Assessing Functional Potency via Cardiosphere Formation

This method evaluates how a 3D niche-like culture system enhances stem cell function [25].

- Step 1: Isolation of Cardiac-Derived Cells. Human cardiac stem and supporting cells are obtained from endomyocardial biopsies.

- Step 2: Cardiosphere Culture. The cardiac-derived cells are plated on a low-attachment surface in a serum-free, growth factor-supplemented medium. This non-adherent condition promotes the self-assembly of cells into three-dimensional spherical structures, the cardiospheres, over several days.

- Step 3: In Vitro Functional Assays.

- Gene Expression Analysis: RNA is extracted from cardiospheres and compared to monolayer-cultured cells via quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) and PCR arrays to assess the upregulation of stemness factors (e.g., SOX2, Nanog), ECM molecules, and pro-survival genes (e.g., IGF-1) [25].

- Stress Resistance Assay: Cardiospheres and dissociated single cells from cardiospheres are exposed to oxidative stress (e.g., hydrogen peroxide). Cell viability is measured after a set period to compare resistance.

- Step 4: In Vivo Functional Assessment. Cardiospheres or dissociated cardiosphere-derived cells are implanted into the infarcted hearts of immunodeficient (e.g., SCID) mice. Control groups receive monolayer-cultured cells.

- Engraftment: After several weeks, heart sections are analyzed to quantify the number of persisting human cells.

- Functional Improvement: Global heart function is assessed using echocardiography to measure parameters like Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction (LVEF) and fractional shortening, comparing pre- and post-implantation values [25].

Molecular Mechanisms: Signaling Pathways Animating the Niche

The enhanced functional potency observed in niche-mimicking environments is mediated by conserved signaling pathways that are activated by specific microenvironmental cues. The following diagram illustrates the core signaling axes that are critical for maintaining stem cell behavior and how biomaterials can be designed to modulate these pathways.

The diagram shows how engineered biomaterials are designed to replicate the signaling functions of the native niche. Key pathways include [24] [23]:

- Wnt/β-catenin: Promotes stem cell self-renewal and proliferation. Its activation in cardiospheres and through biomaterial-bound ligands enhances "stemness" [25].

- Notch: Maintains stem cell quiescence and regulates cell-fate decisions. This is crucial for preventing premature differentiation and preserving the stem cell pool.

- Bone Morphogenetic Protein (BMP): Often functions in a balance with Wnt signaling to regulate the switch between proliferation and differentiation.

- Integrin-mediated signaling: Activated by interactions between cell surface integrins and the extracellular matrix (ECM) of the niche or biomaterial. This signaling enhances cell survival, resistance to stress, and is a key reason for the superior performance of 3D cultures like cardiospheres and ECM-mimicking hydrogels [25] [27].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Translating niche biology into therapeutic applications requires a specific set of research tools. The table below details key reagents and materials essential for developing and testing niche-mimicking biomaterials for stem cell delivery.

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Niche-Mimicking Biomaterial Research

| Research Reagent / Material | Function and Application in Niche Research |

|---|---|

| Alginate | A natural polysaccharide used to form injectable hydrogels or patches; its stiffness and degradation can be tuned to mimic mechanical properties of the native ECM [27]. |

| Chitosan/β-Glycerophosphate (β-GP) | A thermo-responsive polymer system that is liquid at low temperatures and forms a gel at body temperature, enabling minimally invasive injection and cell encapsulation [27]. |

| Collagen Type I | A major component of the native ECM; used as a base for epicardial patches and 3D scaffolds to provide natural cell-adhesion motifs and biological cues [27]. |

| Laminin & Fibronectin | Core ECM proteins often incorporated into biomaterials to promote specific integrin-mediated cell adhesion and activation of pro-survival signaling pathways [25] [23]. |

| Recombinant Growth Factors (e.g., IGF-1, VEGF, FGF) | Soluble signaling molecules used to supplement culture media or to be bound within biomaterials to replicate the biochemical signaling of the niche (e.g., IGF-1 upregulation in cardiospheres) [25] [24]. |

| Fluorescent Cell Labeling Dyes (e.g., CM-Dil, DiI) | Lipophilic membrane dyes for labeling cells before transplantation, allowing for quantitative tracking and retention studies using fluorescence imaging [27]. |

| Antibodies for Flow Cytometry (e.g., CD44, CD133, c-Kit) | Used for the identification and isolation of specific stem cell populations based on surface markers, a critical step in purifying cells for therapy [28]. |

| qRT-PCR Assays for Stemness Markers | Primer-probe sets for genes like SOX2 and Nanog to quantitatively assess the "stemness" state of cells cultured under different niche-mimicking conditions [25]. |

The comparative data and methodologies presented in this guide underscore a fundamental principle: the therapeutic efficacy of stem cells is inextricably linked to their microenvironment. Biomaterial strategies that move beyond passive cell delivery to actively mimic the structural, mechanical, and biochemical properties of the native stem cell niche—from injectable hydrogels and patches to 3D cardiospheres—consistently demonstrate superior outcomes in terms of cell retention, survival, and functional potency. The future of regenerative medicine lies in a nuanced, niche-centric approach, where engineered microenvironments are tailored to specific tissues and clinical indications to unlock the full potential of stem cell therapy.

Application-Specific Delivery Strategies Across Therapeutic Areas

3D Bioprinting and Scaffold-Based Approaches for Tissue Engineering

The field of regenerative medicine is fundamentally centered on the challenge of effectively delivering functional cells to repair or replace damaged tissues and organs. Within this context, two dominant yet philosophically distinct paradigms have emerged: scaffold-based tissue engineering and scaffold-free cell-based therapies [29]. The core thesis of this comparison is that while scaffold-based strategies, particularly those employing 3D bioprinting, offer superior structural control and the ability to create complex, anatomically-shaped constructs, scaffold-free strategies excel in biomimicry by leveraging native cell-to-cell interactions and often face fewer regulatory hurdles due to the absence of exogenous materials [29]. The choice between these approaches is not a matter of superiority but of strategic alignment with the target clinical application, balancing the need for mechanical support, biological complexity, and translational feasibility.

The critical need for advanced cell delivery systems is underscored by the profound limitations of direct cell suspension injections. Conventional delivery methods, such as intravenous infusion or direct intra-tissue injection, result in exceptionally low cell retention and survival, with studies showing that less than 5% of injected cells persist at the site of injury within the first days post-transplantation [29]. This failure to engraft significantly undermines therapeutic efficacy and has driven the development of engineered strategies that protect cells, enhance localization, and support their long-term survival and function.

Comparative Analysis of Scaffold-Based and Scaffold-Free Approaches

The following table provides a high-level comparison of the core characteristics, advantages, and challenges associated with scaffold-based and scaffold-free tissue engineering strategies.

Table 1: Core Characteristics of Scaffold-Based and Scaffold-Free Approaches

| Aspect | Scaffold-Based Approaches | Scaffold-Free Approaches |

|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | Cells are seeded onto or encapsulated within a biodegradable, porous 3D matrix [30] [31] | Cells autonomously self-assemble and secrete their own extracellular matrix to form tissue-like surrogates [29] [32] |

| Key Advantages | High mechanical integrity; design control over architecture (porosity, interconnectivity); wide range of tunable materials [30] [33] | Superior biocompatibility; dense cell packing; strong cell-cell interactions; minimal risk of foreign body response [29] |

| Primary Challenges | Potential for inflammatory response to degradation products; difficulty in replicating native ECM complexity [30] [34] | Limited initial structural strength; lengthy culture times to develop ECM; scalability issues for large tissues [29] [32] |

| Ideal Applications | Large bone defects, load-bearing cartilage, and tissues requiring immediate mechanical function [33] [31] | Tubular structures (vessels, nerves), cell sheets for surface repair, and miniature tissue models for drug screening [29] |

Quantitative Performance Data

To move beyond theoretical comparison, the table below summarizes key quantitative findings from experimental studies, highlighting the performance metrics of specific implementations within both paradigms.

Table 2: Experimental Data from Representative Studies

| Construct / Strategy | Key Quantitative Findings | Experimental Context | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tissue Strands (Scaffold-Free) | Ultimate tensile strength increased from 283.1 kPa (Week 1) to 3,371 kPa (Week 3); Young's Modulus reached 5,316 kPa by Week 3 [32] | In vitro culture of chondrocyte-based tissue strands for articular cartilage engineering [32] | Scientific Reports (2016) |

| Cell Sheet (Scaffold-Free) | A single cell sheet from human endometrial gland-derived MSCs had a thickness of ~50 µm [29] | In vitro formation of cell sheets using temperature-responsive culture surfaces [29] | npj Regenerative Medicine (2021) |

| Direct Cell Injection | <5% cell retention at the site of injury post-transplantation; survival rates as low as 1% [29] | Preclinical and clinical trials of cell therapy via intravenous/intra-arterial infusion or direct injection [29] | npj Regenerative Medicine (2021) |

| 3D Bioprinted Scaffold | Enables creation of complex structures with pore size, porosity, and mechanical properties controlled via computer-aided design [33] | Fabrication of tissue engineering scaffolds for nerve, skin, bone, and vascular repair [33] | Frontiers in Materials (2022) |

Experimental Protocols for Key Methodologies

Protocol 1: Fabrication and Bioprinting of Scaffold-Free Tissue Strands

The development of scalable, scaffold-free "tissue strands" represents an advanced biofabrication method that combines high cell density with printability [32].

- Coaxial Extrusion of Tubular Capsules: A coaxial nozzle system is used to directly print long, semi-permeable, tubular alginate capsules. The average luminal and outer diameters are precisely controlled, typically around 709 µm and 1,248 µm, respectively [32].

- Cell Microinjection: A high-density cell pellet (e.g., chondrocytes) is microinjected into the lumen of the tubular alginate capsule using a gas-tight microsyringe. This process can accommodate large cell numbers (e.g., ~200 million cells) [32].

- Tissue Strand Maturation: The injected capsules are cultured in vitro. Cells within the non-adhesive capsule aggregate and self-assemble, forming a cohesive, cylindrical tissue strand. Over 10-14 days, the strand undergoes radial contraction, stabilizing at a diameter of approximately 500 µm while maintaining high cell viability (>85%) [32].

- Bioink Preparation & Bioprinting: The alginate capsule is dissolved to release the mature tissue strand. This strand, now a "bioink," is loaded into a bioprinter and robotically deposited in a predefined 3D architecture without the need for a support mold or liquid delivery medium [32].

- Post-Printing Fusion & Maturation: The bioprinted strands are cultured further, where they rapidly fuse with neighboring strands (fusion initiation within 12 hours, near completion by 7 days) and continue to mature, depositing tissue-specific ECM [32].

Protocol 2: 3D Bioprinting of a Cell-Laden Hydrogel Scaffold

Bioprinting of scaffold-based constructs is a multi-step process that integrates living cells with scaffold materials to create structured tissue analogues [33] [35].

- Pre-Bioprinting:

- Digital Design: A 3D model of the target tissue or organ is created using computer-aided design (CAD) software, often derived from medical imaging data (e.g., CT or MRI scans) [33] [35].

- Bioink Formulation: A bioink is prepared by combining a biocompatible hydrogel (e.g., alginate, collagen, hyaluronic acid, or a composite) with cultured patient cells. The bioink must have tailored rheological properties for printability and cell viability [33] [35] [34].

- Bioprinting Process: The bioink is loaded into a printing cartridge and deposited layer-by-layer onto a build platform according to the digital model. The most common method is extrusion-based bioprinting, which uses pneumatic or mechanical pressure to dispense the bioink through a nozzle [33] [35].

- Crosslinking: Immediately after deposition, each layer is stabilized (crosslinked) to solidify the structure. Crosslinking is achieved via methods specific to the bioink chemistry, such as exposure to ultraviolet light, specific ions (e.g., calcium for alginate), or temperature changes [35] [34].

- Post-Bioprinting Maturation: The printed construct is transferred to a bioreactor for incubation. The bioreactor provides dynamic nutrient exchange and mechanical stimulation (e.g., perfusion, compression) to promote cell proliferation, differentiation, and ECM production, leading to a functional tissue-engineered graft [35].

Visualizing Workflows and Biological Principles

The following diagrams illustrate the logical workflows and core biological principles underpinning the two main approaches to tissue engineering.

Scaffold-Based versus Scaffold-Free Bioprinting Workflow

The Cell-Scaffold Biointerface in Tissue Regeneration

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful execution of the protocols described above requires a suite of specialized reagents and materials. The following table details key solutions essential for research in both scaffold-based and scaffold-free tissue engineering.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Tissue Engineering

| Reagent / Material | Core Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Natural Polymer Hydrogels(e.g., Alginate, Chitosan, Collagen, Hyaluronic Acid) [34] | Serve as the primary component of bioinks and scaffolds; provide a hydrous, biocompatible 3D environment that mimics the native extracellular matrix (ECM). | Chosen for biocompatibility, biodegradability, and tunable physical properties (e.g., stiffness, gelation kinetics). Alginate is easily ionically crosslinked, while collagen offers innate cell-adhesion motifs [34]. |

| Temperature-Responsive Polymers(e.g., poly(N-isopropylacrylamide - pNIPAM) [29] | Enable scaffold-free cell sheet engineering. Surfaces are hydrophobic at 37°C for cell culture and become hydrophilic below 32°C, allowing detachment of intact cell sheets with preserved ECM. | Critical for harvesting contiguous cell sheets without enzymatic digestion, preserving cell-cell junctions and deposited ECM proteins for enhanced transplantation efficacy [29]. |

| Crosslinking Agents(e.g., Ca²⁺ for alginate, UV initiators for synthetic hydrogels) [35] [34] | Stabilize and solidify deposited bioinks post-printing, providing the necessary mechanical integrity for 3D constructs. | Must be cytocompatible. Crosslinking density directly influences scaffold stiffness and degradation rate, which in turn affects cell behavior and nutrient diffusion [34]. |

| Growth Factors & Bioactive Molecules(e.g., bFGF, TGF-β) [31] [34] | Direct cell fate (proliferation, differentiation) and promote tissue-specific maturation (e.g., chondrogenesis, osteogenesis). Often incorporated into hydrogel matrices. | Short half-lives in vivo require delivery systems for controlled release. Can be encapsulated within microspheres or covalently bound to the scaffold to prolong activity [31]. |

| Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs) | A primary adult stem cell source for many tissue engineering applications due to their multipotency (ability to differentiate into bone, cartilage, fat) and relative ease of isolation [31]. | Sourced from bone marrow, adipose tissue, or other origins. Their use in clinical strategies requires careful expansion and characterization to ensure safety and potency [29] [31]. |

The comparative analysis reveals that the strategic selection between scaffold-based and scaffold-free approaches hinges on the specific clinical requirement. Scaffold-based bioprinting is indispensable for engineering large, structurally complex tissues where mechanical support from the outset is critical, such as in bone or load-bearing osteochondral defects [33]. The ability to precisely control the scaffold's microarchitecture and composition provides a powerful tool for guiding tissue formation. Conversely, scaffold-free methods, including cell sheets and tissue strands, offer a path to creating biologically dense and authentic tissues that are ideal for repairing thinner or more homogenous tissues, such as in corneal or endothelial repair, and may face a more straightforward regulatory path due to the absence of synthetic materials [29].

The future of the field lies in the convergence of these paradigms. Emerging trends focus on creating hybrid strategies, such as 3D bioprinting scaffold-free tissue strands within a temporary, biodegradable support structure, or fabricating "smart" biomaterial scaffolds that incorporate stimulus-responsive hydrogels and sophisticated growth factor delivery systems to actively guide cellular processes [30] [34]. The ultimate goal remains the consistent and scalable fabrication of clinical-grade, functional human tissues, a mission that will continue to be driven by interdisciplinary collaboration across cell biology, materials science, and biofabrication engineering.

Injectable Hydrogels for Minimally Invasive MSC Delivery in Wound Healing

The field of regenerative medicine increasingly recognizes mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs) for their significant potential in treating chronic wounds, owing to their multipotent differentiation capacity, secretion of trophic factors, and immunomodulatory properties [36]. However, a critical challenge hindering their clinical translation is the low retention and transient survival of directly injected cells at the wound site [36]. Rapid cell death and washout due to mechanical forces severely compromise therapeutic efficacy [36]. To address these limitations, injectable hydrogels have emerged as a promising strategy for minimally invasive delivery. These biomimetic platforms provide a three-dimensional (3D) microenvironment that recapitulates key features of the native extracellular matrix (ECM), supporting MSC viability, retention, and function upon transplantation [36]. This review provides a comparative analysis of injectable hydrogel systems for MSC delivery in wound healing, evaluating their performance based on recent experimental data to guide researchers and therapy developers.

Comparative Analysis of Hydrogel Systems for MSC Delivery

Injectable hydrogels for MSC delivery can be broadly categorized based on their material origin and design strategy. The table below summarizes the key characteristics and performance metrics of major hydrogel types as demonstrated in preclinical wound healing studies.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Injectable Hydrogel Systems for MSC Therapy in Wound Healing

| Hydrogel Type | Key Components | Mechanism of Action | Reported Efficacy (Wound Closure) | Key Advantages | Identified Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Natural Polymer-Based | Hyaluronic Acid, Collagen, Fibrin [36] [37] | Provides ECM-like 3D structure; supports cell adhesion and infiltration [37] | Accelerated closure in diabetic wounds; enhanced re-epithelialization & angiogenesis [38] | High biocompatibility; inherent bioactivity [37] | Rapid degradation; limited mechanical strength [36] |

| Synthetic Polymer-Based | Polyethylene Glycol (PEG), Polyvinyl Alcohol (PVA) [36] | Highly tunable mesh size & mechanical properties; controlled release [36] | Sustained therapeutic activity; prolonged growth factor release [36] | Excellent mechanical tunability & reproducibility [36] | Lack of cell-adhesion motifs (often requires functionalization) [36] |

| Composite/Hybrid | ECM components + Synthetic polymers (e.g., HA-PEG) [36] | Combines bioactivity of natural materials with stability of synthetics [36] | Superior cell retention and regenerative capacity vs. single-component hydrogels [36] | Balanced bioactivity and structural stability [36] | More complex fabrication process; potential batch variability [36] |

| Cell-Free/Secretome-Loaded | HA hydrogel loaded with MSC-derived exosomes [38] | Sustained release of exosomes carrying bioactive molecules (mRNAs, lipids, cytokines) [38] [39] | Significant acceleration of wound closure in diabetic models; enhanced angiogenesis [38] [39] | Off-the-shelf potential; avoids cell viability issues; controls macrophage polarization [39] | Limited duration of action compared to living, secreting MSCs [39] |

Beyond the material origin, the design of "smart" hydrogels that respond to physiological stimuli (e.g., pH, temperature, enzymatic activity) enables controlled release of cells or bioactive molecules in response to local wound cues [36]. Furthermore, the functionalization of these hydrogels with bioactive molecules such as arginine–glycine–aspartic acid (RGD) peptides enhances cell adhesion and activates integrin-mediated signaling pathways [36].

Experimental Data and Methodologies in Preclinical wound Healing

Standardized Protocols for Hydrogel-MSC Construct Evaluation

Robust experimental models are critical for evaluating the efficacy of hydrogel-MSC therapies. The following workflow outlines a standard protocol for fabricating and testing these constructs in a preclinical setting, synthesizing methodologies from key studies.

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for evaluating hydrogel-MSC constructs.

1. Hydrogel Preparation and MSC Encapsulation: Hydrogels like hyaluronic acid (HA) are often modified to form injectable systems that crosslink in situ [38]. MSCs are typically harvested from bone marrow (BM-MSCs) or adipose tissue (AD-MSCs) and expanded in vitro. For encapsulation, a cell-polymer mixture is prepared, and gelation is triggered by physical (e.g., temperature) or chemical (e.g., crosslinker addition) cues to form a 3D cell-laden network [36].

2. In Vitro Characterization: Critical assays include:

- Cell Viability and Proliferation: Using live/dead staining and metabolic assays (e.g., MTT) to confirm the hydrogel supports MSC survival and growth [36] [38].

- Mechanical and Rheological Testing: Assessing elastic modulus, stress relaxation, and shear-thinning behavior to ensure injectability and appropriate mechanical support [36] [40].

- Bioactivity Assessment: ELISA or multiplex assays to quantify the secretion of pro-regenerative factors (e.g., VEGF, FGF) from encapsulated MSCs [39].

3. In Vivo Wound Healing Models: The most common model is the full-thickness excisional wound in diabetic (e.g., db/db) mice or rats [38] [39]. The hydrogel-MSC construct is injected intradermally around the wound or applied directly into the wound bed. The control groups are crucial and typically include untreated wounds, blank hydrogel-treated wounds, and free MSC-injected wounds.

4. Outcome Assessment: Efficacy is evaluated through:

- Wound Closure Kinetics: Tracking wound area reduction over time (e.g., days 7, 14, 21) [39].

- Histological and Immunohistochemical Analysis: Using stains like H&E and Masson's trichrome to assess tissue architecture, collagen deposition, and re-epithelialization. Key metrics include granulation tissue thickness and scar quality [38].

- Molecular Analysis: Immunostaining for CD31 to quantify neovascularization and for specific cytokines to understand the immunomodulatory effects [38] [39].

Quantitative Efficacy Data from Animal Studies

The table below consolidates quantitative findings from recent preclinical studies, providing a basis for comparing the therapeutic efficacy of different hydrogel-based strategies.

Table 2: Comparative Preclinical Efficacy Data in Animal Wound Models

| Therapeutic Formulation | Animal Model | Wound Closure Rate | Key Histological Outcomes | Source/Study Focus |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MSC-laden HA Hydrogel | Diabetic rat model | ~95% closure by day 14 | Significant enhancement in re-epithelialization and mature angiogenesis [38] | MSC-derived exosomes injectable hyaluronic acid hydrogel [38] |

| Hydrogel + Cell Conditioned Medium (H-CM) | Full-thickness skin defect | Significant improvement vs. hydrogel alone | Enhanced collagen deposition, tissue remodeling, and macrophage polarization towards M2 phenotype [39] | Advancing wound healing by hydrogel-based dressings loaded with cell-conditioned medium [39] |

| Dynamic Crosslinking Hydrogel | In vivo release model | Reduced initial burst release by ~40% | Sustained long-term delivery of protein cargo over several weeks [40] | Evolving transport properties of dynamic hydrogels [40] |

Mechanisms of Action: How Hydrogel-Enhanced MSCs Accelerate Healing

The therapeutic action of hydrogel-delivered MSCs in wound healing is a multifactorial process, primarily mediated by paracrine signaling rather than direct cell differentiation. The diagram below illustrates the key cellular and molecular pathways involved.

Diagram 2: Signaling pathways in hydrogel-MSC mediated wound repair.

Sustained Paracrine Signaling: The hydrogel acts as a depot, protecting MSCs and facilitating a sustained release of their secretome. This includes growth factors like Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF) and Fibroblast Growth Factor (FGF), which are crucial for promoting angiogenesis—the formation of new blood vessels that supply oxygen and nutrients to the healing tissue [36] [39]. Furthermore, MSC-derived exosomes delivered via hydrogel carry miRNAs and other bioactive molecules that facilitate intercellular communication, reducing excessive inflammation and supporting the proliferation of endothelial cells and fibroblasts [38].

Immunomodulation: A key mechanism by which MSCs aid healing is by modulating the hostile inflammatory environment of chronic wounds. The hydrogel-localized MSCs secrete anti-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-10 and IL-1Ra, which help shift the macrophage population from the pro-inflammatory M1 phenotype to the pro-healing M2 phenotype [39]. This transition is critical for resolving inflammation and initiating the proliferation phase of healing.

Direct Cellular Interactions: The 3D hydrogel scaffold not only delivers MSCs but also facilitates the infiltration and activity of host cells like fibroblasts and keratinocytes. By providing an ECM-mimetic structure and presenting adhesion motifs, the hydrogel promotes the migration and proliferation of these cells, leading to improved collagen deposition, re-epithelialization, and tissue remodeling [36] [37].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The development and testing of injectable hydrogel-MSC systems rely on a specific set of materials and reagents. The following table details key components and their functions for researchers building their experimental toolkit.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Hydrogel-MSC Wound Healing Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function in Research | Common Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Hyaluronic Acid (HA) | Base polymer for hydrogel formation; high biocompatibility and native bioactivity [38] [37] | Methacrylated HA (MeHA) for photo-crosslinking; oxidized HA for Schiff base formation |

| Synthetic Polymers (PEG) | Provides a tunable, reproducible, and mechanically stable network; "blank slate" for functionalization [36] | PEG-diacrylate (PEGDA); multi-armed PEG-NHS or PEG-Maleimide |

| Cell-Adhesion Peptides | Functional motif incorporated into synthetic hydrogels to enable MSC adhesion and survival [36] | RGD (Arginine-Glycine-Aspartic acid) peptide sequences |

| Protease-Degradable Linkers | Allows hydrogel degradation by cell-secreted enzymes, facilitating cell migration and matrix remodeling [36] | Peptide crosslinkers (e.g., VPMS↓MRGG, cleavable by MMP-2) |

| MSC-Specific Media | For the in vitro expansion and maintenance of MSCs prior to encapsulation [41] | Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) supplemented with Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS) and growth factors (e.g., FGF-2) |

| Viability/Cytotoxicity Assays | To quantify the survival and metabolic activity of MSCs after encapsulation and delivery [36] | Live/Dead staining (Calcein AM/EthD-1); AlamarBlue; MTT assay |

| Angiogenesis Assay Kits | To evaluate the pro-angiogenic potential of the MSC secretome released from hydrogels in vitro [38] [39] | Tube formation assay using HUVECs; ELISA for quantifying VEGF |

Injectable hydrogels represent a transformative platform for overcoming the delivery challenges of MSC-based wound therapies. Comparative analysis confirms that no single hydrogel type is universally superior; rather, the choice involves a trade-off between the robust bioactivity of natural polymers and the controllable mechanics of synthetic systems. The emerging trend towards composite, "smart," and cell-free secretome-loaded hydrogels holds particular promise for enhancing therapeutic efficacy and simplifying regulatory pathways [36] [38] [39]. For clinical translation, future work must focus on standardizing fabrication using xeno-free, GMP-compliant components and designing larger, controlled clinical studies to firmly establish safety and efficacy in humans [36]. The integration of these advanced biomaterial strategies with the potent biological functions of MSCs is poised to significantly advance the treatment of debilitating chronic wounds.

Biomaterial-Assisted Immune Cell Delivery for Cancer and Inflammatory Diseases

The development of biomaterials for immune cell delivery represents a paradigm shift in managing cancer and inflammatory diseases. These advanced platforms are engineered to overcome fundamental therapeutic challenges: in cancer immunotherapy, they enhance the precision and persistence of antitumor responses while minimizing systemic toxicities [42] [43]; in inflammatory diseases, they provide spatiotemporal control over anti-inflammatory agents, disrupting pathological cycles while preserving protective immunity [44]. The comparative efficacy of these systems hinges on their material properties, targeting mechanisms, and biological interactions, which collectively determine their clinical performance across different disease contexts.

This guide provides a structured comparison of biomaterial platforms based on their intended application, target cells, and experimental outcomes. By examining quantitative data across standardized parameters, researchers can identify optimal material configurations for specific therapeutic objectives, accelerating the rational design of next-generation delivery systems.

Comparative Efficacy of Biomaterial Platforms

Biomaterial Platforms for Cancer Immunotherapy

Table 1: Comparative performance of biomaterial platforms in cancer immunotherapy

| Biomaterial Platform | Target Cell/Process | Key Experimental Findings | Efficacy Metrics | Reference Model | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|