CRISPR-Cas9 and iPSCs: Precision Gene Correction for Therapeutic Development

This article explores the integrated application of CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing and induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) technologies for disease correction and therapeutic development.

CRISPR-Cas9 and iPSCs: Precision Gene Correction for Therapeutic Development

Abstract

This article explores the integrated application of CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing and induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) technologies for disease correction and therapeutic development. It covers foundational principles of CRISPR mechanisms and iPSC reprogramming, detailing methodological approaches for correcting mutations in monogenic disorders like Duchenne muscular dystrophy, sickle cell disease, and neurodegenerative conditions. The content addresses critical troubleshooting aspects including editing efficiency optimization, off-target effect mitigation, and delivery challenges in clinically relevant cells. Finally, it examines validation strategies through preclinical models and comparative analysis with traditional therapies, providing researchers and drug development professionals with a comprehensive resource for advancing genetically-corrected, patient-specific cell therapies toward clinical translation.

The Synergy of CRISPR-Cas9 and iPSC Platforms: Mechanisms and Therapeutic Potential

The Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR) and CRISPR-associated protein 9 (Cas9) system represents a transformative genome-editing tool derived from a natural defense mechanism in bacteria [1]. This adaptive immune system protects bacteria from viral infections by capturing and storing fragments of foreign genetic material, which allows for recognition and cleavage of subsequent invasions by the same pathogens [2]. The repurposing of this biological system into a programmable gene-editing technology has revolutionized molecular biology, enabling precise modifications to the DNA of diverse organisms, including humans [1].

The application of CRISPR-Cas9 in induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) has been particularly impactful for disease modeling and therapeutic development [2]. By reprogramming somatic cells into pluripotent stem cells, researchers can obtain an unlimited source of cell resources with a patient's specific genetic background [2]. The combination of iPSC and CRISPR technologies provides a powerful platform for personalized treatment of genetic diseases, overcoming limitations of donor shortages and immune rejection in traditional cell therapy [2] [3].

Core Mechanism: The Molecular Machinery of CRISPR-Cas9

Molecular Components

The CRISPR-Cas9 system requires two fundamental molecular components to function:

Cas9 Nuclease: The effector protein that creates double-strand breaks (DSBs) in DNA. It contains two catalytic domains, HNH and RuvC, each responsible for cleaving one DNA strand [1]. The system requires a short DNA sequence known as the Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM) adjacent to the target site for recognition, which for the commonly used Streptococcus pyogenes Cas9 is 5'-NGG-3' [1].

Guide RNA (gRNA): A synthetic chimeric RNA molecule that combines the functions of CRISPR RNA (crRNA) and trans-activating CRISPR RNA (tracrRNA) [1]. The gRNA is designed with a ~20 nucleotide spacer sequence complementary to the target DNA site, which programs Cas9 to recognize and bind specific genomic locations [2] [1].

DNA Recognition and Cleavage Mechanism

The CRISPR-Cas9 mechanism proceeds through several defined steps:

- Complex Formation: Cas9 nuclease forms a ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex with the gRNA [4].

- Target Recognition: The Cas9-gRNA complex scans DNA, identifying PAM sequences and initiating local DNA melting [1].

- Complementarity Check: If the gRNA sequence demonstrates sufficient complementarity to the target DNA adjacent to the PAM, Cas9 undergoes a conformational change that activates its nuclease domains [1].

- DNA Cleavage: The HNH domain cleaves the complementary strand, while the RuvC domain cleaves the non-complementary strand, resulting in a precise double-strand break 3-4 nucleotides upstream of the PAM site [1].

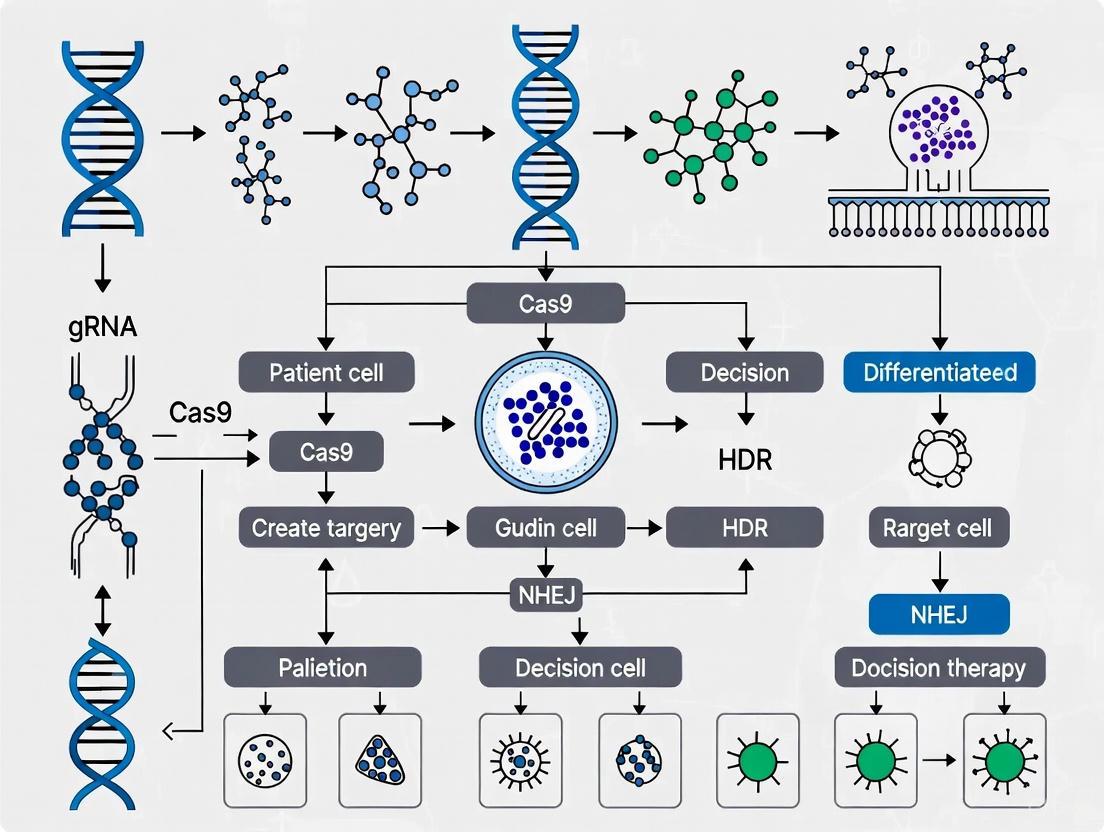

The following diagram illustrates this core mechanism:

DNA Repair Pathways and Editing Outcomes

After Cas9 creates a double-strand break, the cell engages one of two primary DNA repair pathways:

Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ): An error-prone repair pathway that directly ligates broken DNA ends, often resulting in small insertions or deletions (indels) that can disrupt gene function, making it suitable for gene knockout strategies [2] [1].

Homology-Directed Repair (HDR): A precise repair mechanism that uses a template DNA molecule (typically supplied by researchers) to incorporate specific genetic modifications at the target site, enabling precise nucleotide changes or gene insertions [2] [1].

Table 1: Comparison of DNA Repair Pathways in CRISPR-Cas9 Genome Editing

| Feature | Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ) | Homology-Directed Repair (HDR) |

|---|---|---|

| Template Requirement | No template required | Requires donor DNA template |

| Efficiency | High efficiency in most cells | Inefficient, varies by cell type and cell cycle stage |

| Primary Application | Gene knockouts, gene disruption | Precise gene correction, gene insertion |

| Cell Cycle Preference | Active throughout cell cycle | Preferentially active in S/G2 phases |

| Outcome | Error-prone, creates indels | High-fidelity, precise edits |

| Optimal for iPSCs | Relatively efficient | Challenging, requires optimization [3] |

Advanced CRISPR Systems: Enhancing Precision and Expanding Capabilities

Base Editing

Base editing represents a significant advancement that enables direct chemical conversion of one DNA base to another without creating double-strand breaks [2] [1]. These systems utilize catalytically impaired Cas9 variants (nickases) fused to nucleobase deaminase enzymes:

- Cytosine Base Editors (CBEs): Convert cytosine (C) to thymine (T through a C•G to T•A base pair change [1].

- Adenine Base Editors (ABEs): Convert adenine (A) to guanine (G through an A•T to G•C base pair change [1].

Prime Editing

Prime editing further expands CRISPR capabilities using a Cas9 nickase fused to a reverse transcriptase enzyme and a specialized prime editing guide RNA (pegRNA) [2]. This system can achieve targeted insertions, deletions, and all 12 possible base-to-base conversions without double-strand breaks, offering greater precision and reduced off-target effects [2].

CRISPR-Cas9 Nickases

Paired Cas9 nickases generate single-strand breaks instead of double-strand breaks, reducing off-target effects while maintaining editing efficiency [5]. This approach is particularly valuable for manipulating gene dosage in human iPSCs, enabling simultaneous generation of isogenic cell lines with different gene copy numbers for studying dosage-sensitive diseases like Alzheimer's disease [5].

Application Notes: CRISPR-Cas9 in iPSC Gene Correction

Disease Modeling and Therapeutic Correction

The combination of CRISPR-Cas9 and iPSC technology has enabled groundbreaking advances in modeling and treating genetic diseases:

Monogenic Diseases: CRISPR-corrected iPSCs have been successfully generated for Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD), sickle cell disease, β-thalassemia, and cystic fibrosis, with demonstrated functional recovery in differentiated cells [2].

Neurodegenerative Disorders: For Alzheimer's disease, CRISPR-Cas9 has been used in iPSCs to modify pathogenic variants in AD-related genes (APP, PSEN1, PSEN2) and study their effects on amyloid-beta secretion and Tau hyperphosphorylation [6] [5].

Isogenic Controls: A key application involves creating genetically matched control lines by correcting disease-causing mutations in patient-derived iPSCs, providing powerful experimental models for studying disease mechanisms and drug screening [2] [3].

Quantitative Data on Editing Efficiencies in iPSCs

Recent protocol optimizations have significantly improved editing efficiencies in iPSCs, as demonstrated by the following comparative data:

Table 2: Editing Efficiencies in Human iPSCs Using Optimized CRISPR-Cas9 Protocols

| Experimental Condition | Target Gene | Edit Type | Base Protocol Efficiency | Optimized Protocol Efficiency | Fold Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| p53 inhibition + HDR enhancer | EIF2AK3 (rs867529) | Point mutation | 2.8% | 59.5% | 21x [3] |

| p53 shRNA only | EIF2AK3 (rs867529) | Point mutation | 2.8% | 30.8% | 11x [3] |

| Final optimized protocol | EIF2AK3 (rs13045) | Point mutation | 4% | 25% | 6x [3] |

| Final optimized protocol | APOE Christchurch | Knock-in | N/A | 49-99% (bulk), 100% (subclones) | N/A [3] |

| Final optimized protocol | PSEN1 E280A | Reverse mutation | N/A | 97-98% (bulk), 100% (subclones) | N/A [3] |

Experimental Protocols: Genome Editing in Human iPSCs

Optimized Workflow for High-Efficiency Editing

The following comprehensive workflow integrates the most effective strategies for achieving high-efficiency genome editing in human iPSCs:

Critical Protocol Details

gRNA Design and RNP Complex Formation

gRNA Design: Use computational tools (e.g., Invitrogen GeneArt CRISPR Search and Design Tool) to identify optimal target sequences with high on-target and low off-target activity [7] [4]. Prefer targets located less than 10 nucleotides from the intended mutation to maximize HDR efficiency [3].

RNP Complex Formation: Combine 0.6 µM gRNA with 0.85 µg/µL of Alt-R S.p. HiFi Cas9 Nuclease V3 and incubate at room temperature for 20-30 minutes before transfection [3]. RNP delivery significantly reduces off-target effects compared to plasmid-based expression [4].

Enhancement of HDR Efficiency

p53 Suppression: Co-transfect with pCXLE-hOCT3/4-shp53-F plasmid (50 ng/µL) encoding shRNA against p53 to temporarily inhibit the p53-dependent DNA damage response and dramatically improve HDR rates [3].

Pro-survival Supplements: Include 1% Revitacell and 10% CloneR in the cloning media to enhance single-cell survival after editing [3]. ROCK inhibitor (Y-27632) is essential for preventing apoptosis in dissociated iPSCs [4].

HDR Enhancers: Add commercial HDR enhancer compounds (e.g., from IDT) to further boost homologous recombination efficiency [3].

Delivery Methods for iPSCs

Table 3: Comparison of CRISPR-Cas9 Delivery Methods for Human iPSCs

| Method | Components Delivered | Efficiency | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lipofectamine CRISPRMAX | RNP complex | >50% cleavage efficiency [4] | Simple protocol, minimal equipment | Lower efficiency than electroporation |

| Neon Transfection System | RNP complex | >80% cleavage efficiency [4] | Highest efficiency, direct delivery | Requires specialized equipment |

| Neon Transfection System | gRNA + Cas9 mRNA | Variable, protocol-dependent [4] | Sustained expression | Increased off-target risk |

| Lipofectamine CRISPRMAX | gRNA + Cas9 plasmid | Lower than RNP delivery [4] | Cost-effective | High off-target risk, cytotoxicity |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Essential Reagents for CRISPR-Cas9 Genome Editing in iPSCs

| Reagent Category | Specific Products | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cas9 Enzymes | Alt-R S.p. HiFi Cas9 Nuclease V3, GeneArt Platinum Cas9 Nuclease | Creates double-strand breaks at target sites | HiFi variants reduce off-target effects [3] [4] |

| gRNA Synthesis | GeneArt Precision gRNA Synthesis Kit, custom synthetic gRNAs | Targets Cas9 to specific genomic loci | In vitro transcription or synthetic formats [4] |

| Delivery Reagents | Lipofectamine CRISPRMAX, Neon Transfection System | Introduces editing components into cells | Neon system provides highest efficiency [4] |

| Cell Culture Supplements | RevitaCell Supplement, CloneR, ROCK inhibitor (Y-27632) | Enhances single-cell survival | Critical for clonal expansion after editing [3] [4] |

| HDR Enhancers | IDT HDR Enhancer, p53 shRNA plasmid | Boosts homologous recombination rates | p53 inhibition increases HDR efficiency 11-fold [3] |

| Detection Kits | GeneArt Genomic Cleavage Detection Kit | Assesses editing efficiency | Used 48-72 hours post-transfection [4] |

Quality Control and Safety Considerations

Off-Target Effect Assessment

Comprehensive off-target analysis is essential for clinical applications of CRISPR-edited iPSCs:

- Computational Prediction: Use tools like Cas-OFFinder to identify potential off-target sites based on sequence similarity to the gRNA [3].

- Empirical Methods: Employ GUIDE-seq, Digenome-seq, or CIRCLE-seq to experimentally profile genome-wide off-target activity [2].

- Whole Genome Sequencing: Perform WGS on edited clones to detect unexpected modifications, including large structural variations [3].

Genomic Integrity Monitoring

- Karyotype Analysis: Regular G-banding analysis to detect chromosomal abnormalities that may arise during editing and clonal expansion [3].

- Pluripotency Verification: Confirm that edited iPSCs maintain pluripotency markers and differentiation potential after editing [2].

- Identity Testing: STR profiling to ensure cell line identity throughout the editing process [2].

The integration of CRISPR-Cas9 technology with human iPSCs has created a powerful platform for studying genetic diseases and developing personalized therapies. The core principles of CRISPR-Cas9—from its origin as a bacterial immune mechanism to its current application as a precision genome-editing tool—provide the foundation for ongoing innovations in gene correction strategies. Through continued optimization of editing efficiency, delivery methods, and safety assessment protocols, this combined technological approach promises to accelerate the development of transformative treatments for genetic disorders.

The convergence of induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) technology and CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing has revolutionized biomedical research by enabling the creation of physiologically relevant human disease models. iPSCs, generated through the reprogramming of patient somatic cells, provide unlimited access to patient-specific tissues while retaining the complete donor genetic background [8] [9]. When combined with CRISPR-Cas9, researchers can precisely introduce or correct disease-causing mutations in an isogenic background, establishing highly controlled systems for investigating disease mechanisms and developing therapeutic interventions [8] [9]. This powerful integrated platform has become indispensable for modeling neurodegenerative diseases, cardiac disorders, and rare genetic conditions, accelerating the path toward precision medicine [8] [9] [10].

Reprogramming Methodologies: From Somatic Cells to Pluripotency

The generation of iPSCs from somatic cells has evolved significantly since its initial discovery, with modern protocols prioritizing safety, efficiency, and clinical applicability.

Key Reprogramming Protocols

Table 1: Comparison of iPSC Reprogramming Methods

| Method | Mechanism | Advantages | Disadvantages | Reprogramming Efficiency | Genomic Integration |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Retro/Lentiviral | Integrative viral vectors delivering OCT-4, SOX-2, KLF-4, c-MYC | High efficiency | Potential insertional mutagenesis; persistent transgene expression | High | Yes |

| Cre-excisable Lentivirus | Integrative vectors removable via Cre-lox recombination | Eliminates transgene post-reprogramming | Requires lengthy subcloning and validation | High | Temporary |

| Non-integrating Episomal Plasmids | Epstein-Barr virus-derived plasmid vectors | Non-integrating; simple delivery | Lower efficiency compared to viral methods | Moderate | No |

| Sendai Virus (SeV) | Negative-sense RNA virus-based vector | Non-integrating; high efficiency; broad tropism | Difficult to clear residual virus; requires multiple clonal expansions | High | No |

| Self-replicating RNA (Simplicon) | Synthetic RNA mimicking viral RNA | Non-integrating; high efficiency; single transfection; easily eliminated | Requires interferon pathway inhibition | Very High | No |

Detailed Reprogramming Protocol: Simplicon RNA Technology

The Simplicon RNA reprogramming system represents a advanced non-integrating approach that combines high efficiency with enhanced safety profiles [11].

Day 0: Target Cell Seeding

- Determine optimal seeding density for target human fibroblasts to achieve 60-80% confluency after 24 hours. For a 6-well plate, seed between 1×10^5 to 1×10^6 cells per well in fibroblast growth medium.

- Determine optimal puromycin selection concentration by performing a kill curve assay. The working concentration should achieve 50% cell death by days 4-5.

Day 1: Pre-treatment and Transfection

- Pre-treat target cells with 200 ng/mL B18R protein in 1 mL DMEM for 2 hours to inhibit innate interferon response.

- Prepare RNA-transfection complexes by mixing 0.5 μL VEE-OKS-iG RNA (encoding OCT4, KLF4, SOX2) and 0.5 μL B18R RNA in 250 μL Opti-MEM with 4.0 μL RiboJuice transfection reagent.

- Add RNA-transfection complexes dropwise to cells, incubate for 4 hours at 37°C, 5% CO2.

- After incubation, supplement with DMEM containing 10% FBS, 1X glutamine, and 200 ng/mL B18R protein.

Days 2-11: Selection and Colony Expansion

- Replace medium daily with fresh medium containing 200 ng/mL B18R protein and the predetermined optimal puromycin concentration.

- Monitor cell death daily, adjusting puromycin concentration to maintain 30-60% cell death until day 11.

- When puromycin-resistant cells reach 70-90% confluency (typically between days 9-18), passage onto Matrigel-coated plates or inactivated MEF feeder layers.

Days 18-30: Colony Picking and Expansion

- Monitor for emergence of compact iPSC colonies with defined borders.

- Pick colonies reaching approximately 200 cells using manual selection or automated picking systems.

- Expand selected colonies in PluriSTEM Human ES/iPSC medium or similar defined culture system for further characterization and banking [11].

Alternative Protocol: PBMC Reprogramming Using STEMCCA Lentivirus

Day 0: PBMC Isolation and Expansion

- Isolate peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) using density gradient centrifugation with CPT tubes.

- Centrifuge at 1,800 × g for 30 minutes at room temperature, collect buffy coat layer.

- Wash cells with PBS, centrifuge at 300 × g for 15 minutes.

- Resuspend 1-2×10^6 cells in 2 mL expansion medium containing QBSF-60 stem cell medium supplemented with 50 μg/mL ascorbic acid, 50 ng/mL SCF, 10 ng/mL IL-3, 2 U/mL EPO, 40 ng/mL IGF-1, 1 μM dexamethasone, and 1% Pen/Strep.

- Culture at 37°C, 5% CO2.

Days 3 and 6: Medium Refresh

- Transfer cells to conical tubes, wash to collect adherent cells, centrifuge at 300 × g for 10 minutes.

- Resuspend in fresh expansion medium, return to culture.

Day 9: STEMCCA Lentiviral Transduction

- Harvest cells, wash, and centrifuge as above.

- Resuspend in 1 mL fresh expansion medium containing 5 μg/mL polybrene and STEMCCA lentivirus at MOI 1-10.

- Transfer to 12-well plate, spinoculate at 2,250 rpm for 90 minutes at 25°C.

- After spinoculation, add additional 1 mL expansion medium with polybrene, culture at 37°C, 5% CO2.

Day 10: Post-transduction Processing

- Harvest transduced cells, wash with QBSF-60 medium, centrifuge at 300 × g for 10 minutes.

Day 11: Plating on Feeder Layers

- Seed transduced cells on 0.1% gelatin-coated plates containing inactivated mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) in appropriate iPSC culture medium [11].

Quality Control and Characterization of iPSCs

Rigorous quality control is essential for ensuring the integrity, safety, and functionality of iPSC lines, particularly for clinical applications and disease modeling research.

Comprehensive QC Assay Panel

Table 2: iPSC Quality Control and Characterization Methods

| Test Category | Specific Assay | Purpose | Key Outcome Measures |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genetic Integrity | Karyotyping (G-banding) | Detect chromosomal abnormalities | Chromosome number, structural variations |

| High-throughput sequencing | Identify point mutations, off-target effects | Mutation load, specific variants | |

| Pluripotency Status | Alkaline Phosphatase staining | Detect undifferentiated cells | Enzyme activity, colony staining intensity |

| PluriTest (microarray/RNA-seq) | Transcriptomic pluripotency assessment | Pluripotency score, novelty score | |

| Teratoma formation | In vivo differentiation potential | Three germ layer formation | |

| Differentiation Potential | ScoreCard (qPCR-based) | Quantitative differentiation capacity | Expression of germ layer markers |

| Flow cytometry | Surface marker quantification | TRA-1-60, SSEA-4, OCT4 positivity | |

| In vitro trilineage differentiation | Directed differentiation capability | Morphology, lineage-specific markers | |

| Functional Characterization | Telomere length analysis (Q-FISH) | Replicative capacity assessment | Telomere length, telomerase activity |

| Microfluidic chip detection | Rare undifferentiated cell detection | Sensitivity to 0.001% residual iPSCs |

Advanced Pluripotency Assessment

The PluriTest platform provides a bioinformatics-based assessment of pluripotency through comparison of transcriptomic data against established reference databases [12]. This assay requires only small cell numbers and can be performed early during iPSC establishment, providing a quantitative pluripotency score and novelty score that indicate similarity to reference pluripotent stem cells [12].

For teratoma formation assays, the TeratoScore algorithm enables quantitative evaluation of differentiation potential by analyzing gene expression patterns in teratomas, moving beyond subjective morphological assessment [12]. This approach establishes differentiation efficiency scores across germ layers, providing standardized metrics for comparison between cell lines.

Telomere analysis has emerged as a critical quality attribute, with telomere length maintenance and telomerase activation serving as indicators of successful reprogramming and differentiation potential [12]. Techniques such as quantitative fluorescence in situ hybridization (Q-FISH) and telomeric repeat amplification protocol (TRAP) assess telomere length and telomerase activity respectively, providing functional readouts of iPSC quality [12].

CRISPR-Cas9 Mediated Genome Editing in iPSCs

The integration of CRISPR-Cas9 technology with iPSCs enables precise genetic manipulation for disease modeling, creating isogenic cell lines that differ only at specific pathogenic loci.

CRISPR-Cas9 Systems for iPSC Engineering

The most widely used CRISPR system derives from Streptococcus pyogenes (SpCas9) and requires an NGG protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) for target recognition [8]. Recent advancements have expanded the CRISPR toolbox to include:

- CRISPR-Cpf1: Recognizes broader PAM sequences, generates 5' overhangs instead of blunt ends, and requires only a single RNA guide [8]

- Base editors: Enable precise single-nucleotide changes without creating double-strand breaks [9]

- CRISPR interference/activation (CRISPRi/CRISPRa): Utilize catalytically dead Cas9 (dCas9) fused to repressor (KRAB) or activator (VP64) domains to modulate gene expression without altering DNA sequence [8]

Isogenic iPSC Line Generation Protocol

Step 1: gRNA Design and Vector Construction

- Design 2-3 single guide RNAs (sgRNAs) targeting the genomic region of interest using validated design tools

- Clone sgRNAs into appropriate Cas9 expression vectors (e.g., all-in-one or separate expression systems)

- For knock-in approaches, design donor templates with 500-800 bp homology arms flanking the desired modification

Step 2: iPSC Transfection and Editing

- Culture iPSCs in defined media such as Essential 8 or B8 on Matrigel-coated plates [10]

- At 60-70% confluency, dissociate to single cells using EDTA or TrypLE

- Transfect using electroporation (Amaxa Nucleofector) or lipofection methods

- For homology-directed repair, include ssODN or plasmid donor templates

- Include ROCK inhibitor (Y27632, 10 μM) for 24 hours post-transfection to enhance viability [10]

Step 3: Single-Cell Cloning and Expansion

- 48-72 hours post-transfection, dissociate and seed at clonal density (500-1000 cells/10 cm plate)

- Isolate individual colonies using manual picking or automated systems

- Expand clones in 96-well plates for screening

Step 4: Genotypic Validation

- Screen clones using PCR amplification of targeted locus

- Confirm edits by Sanger sequencing or next-generation sequencing

- Perform off-target analysis by examining top predicted off-target sites

- Validate pluripotency maintenance post-editing through flow cytometry and differentiation potential assays

Step 5: Banking and Characterization

- Expand validated clones, cryopreserve multiple vials

- Perform full quality control including karyotyping, mycoplasma testing, and identity confirmation [9] [13]

Disease Modeling Applications and Protocols

The CRISPR-iPSC platform has enabled unprecedented precision in modeling human diseases, particularly for neurological disorders and cardiac conditions.

Neurodegenerative Disease Modeling: Epilepsy Case Study

A compelling application of this technology involves investigating SCN1A loss-of-function mutations associated with Dravet syndrome and other epileptic disorders [13]. The experimental approach included:

Step 1: Isogenic Line Generation

- Derived iPSCs from a patient with SCN1A mutation (Q1923R)

- Corrected the mutation using TALEN-mediated gene editing to create an isogenic control

- Introduced tdTomato fluorescent reporter into the GAD1 locus to label GABAergic neurons

Step 2: Neural Differentiation

- Differentiated iPSCs into mixed neuronal cultures containing both GABAergic and glutamatergic neurons

- Used specific patterning factors to enhance GABAergic neuronal production

Step 3: Electrophysiological Analysis

- Performed whole-cell patch clamp recordings on tdTomato-positive GABAergic neurons

- Measured sodium current properties, action potential parameters, and synaptic activity

- Recorded spontaneous inhibitory and excitatory postsynaptic currents (sIPSCs/sEPSCs)

Key Findings:

- Patient-derived GABAergic neurons showed reduced sodium current density and altered activation properties

- Action potential amplitudes were reduced and thresholds increased in mutant neurons

- sIPSC frequencies were significantly decreased in patient-derived neuronal networks

- The balance of synaptic activity shifted from inhibition-dominated to excitation-dominated, explaining the epileptogenesis mechanism [13]

High-Content Analysis for Neurodegenerative Disease Phenotyping

High-content imaging (HCI) approaches enable quantitative analysis of complex neurodegenerative disease phenotypes in iPSC-derived neurons [14]. Standardized protocols include:

Neurite Outgrowth and Morphology Analysis

- Plate iPSC-derived neurons in 96-well imaging plates

- Fix at specific timepoints and immunostain for neuronal markers (βIII-tubulin, MAP2)

- Acquire images using automated microscopes (Operetta CLS, Opera Phenix)

- Analyze using CellProfiler or ImageJ with NeuriteTracer plugin

- Quantify: total neurite length, branching points, soma size, process complexity

Mitochondrial Function Assessment

- Label mitochondria with MitoTracker or immunostaining for TOM20

- Measure mitochondrial membrane potential using TMRE or JC-1 dyes

- Quantify mitochondrial morphology (network connectivity, area, aspect ratio)

- Assess mitochondrial distribution along neurites

Synaptic Density and Protein Aggregation Analysis

- Co-stain for pre- and post-synaptic markers (synapsin, PSD95)

- Quantify synaptic puncta density and colocalization

- Measure intracellular protein aggregation (tau, α-synuclein) using conformation-specific antibodies

- Employ super-resolution microscopy (STED, SIM) for nanoscale analysis of synaptic structures [14]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for iPSC Generation, Culture, and Differentiation

| Category | Specific Reagent | Function | Example Products |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reprogramming | VEE-OKS-iG RNA | Synthetic self-replicating RNA encoding OCT4, KLF4, SOX2 | Simplicon RNA Reprogramming Kit |

| B18R Protein | Interferon inhibitor, enhances RNA reprogramming efficiency | Recombinant B18R | |

| Culture Media | Essential 8 / B8 | Chemically defined, xeno-free maintenance media | Thermo Fisher, Stemcell Technologies |

| mTeSR1 | Defined maintenance medium for pluripotent stem cells | Stemcell Technologies | |

| Culture Matrices | Matrigel | Basement membrane extract for attachment and signaling | Corning Matrigel |

| Vitronectin | Recombinant attachment substrate for defined culture | Synthemax, VTN-N | |

| Differentiation | RPMI/B27 | Standard medium for cardiac differentiation | Thermo Fisher |

| Y-27632 | ROCK inhibitor, enhances single-cell survival | STEMCELL Technologies | |

| Genome Editing | SpCas9 | CRISPR endonuclease for DNA cleavage | Various suppliers |

| Alt-R CRISPR-Cas9 | Synthetic CRISPR system with high efficiency | Integrated DNA Technologies | |

| Characterization | PluriTest | Bioinformatics assay for pluripotency assessment | PluriTest |

| ScoreCard | qPCR-based differentiation potential assay | TaqMan Scorecard Panel |

The integration of iPSC technology with CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing has created a powerful paradigm for human disease modeling and therapeutic development. The protocols and applications detailed in this technical review provide researchers with comprehensive frameworks for generating patient-specific disease models, conducting precise genetic manipulations, and performing quantitative phenotypic analyses. As these technologies continue to evolve through improvements in reprogramming efficiency, editing precision, and analytical capabilities, they will increasingly enable the deconstruction of complex disease mechanisms and accelerate the development of targeted interventions for personalized medicine applications.

The efficacy of CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing is fundamentally governed by the cellular DNA repair machinery that responds to Cas9-induced double-strand breaks (DSBs). Three primary pathways—Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ), Homology-Directed Repair (HDR), and Microhomology-Mediated End Joining (MMEJ)—compete to determine editing outcomes, presenting a critical challenge for researchers seeking precise genetic modifications in induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) for disease modeling and correction [15] [16]. Understanding the distinct mechanisms, kinetics, and factors influencing these pathways is essential for developing strategies that favor desired editing outcomes over error-prone repair.

NHEJ operates throughout the cell cycle and functions without a repair template, directly ligating broken DNA ends in an error-prone manner that often introduces small insertions or deletions (indels) [16]. This makes NHEJ the dominant and most efficient pathway for generating gene knockouts. In contrast, HDR requires a donor DNA template with homology arms and is restricted primarily to the S and G2 phases of the cell cycle, enabling precise edits including nucleotide substitutions or gene insertions [15] [16]. MMEJ represents a third pathway that utilizes 5-25 base pair microhomology regions flanking the DSB for repair, resulting in predictable deletions and serving as an intermediate option between the randomness of NHEJ and the precision of HDR [15].

The competitive balance between these pathways varies significantly across cell types, with iPSCs and primary cells presenting particular challenges due to their preference for NHEJ over HDR and frequently residing in quiescent states [17] [16]. Recent advances have revealed that editing kinetics further differentiate these pathways, with short indels from NHEJ occurring faster than longer deletions, while HDR kinetics fall between NHEJ and MMEJ [17]. This complex interplay necessitates sophisticated experimental approaches to steer editing outcomes toward precise genome modifications required for therapeutic applications.

Comparative Analysis of DNA Repair Pathways

Mechanism and Kinetics

Table 1: Characteristics of Major DNA Repair Pathways in CRISPR Editing

| Feature | NHEJ | HDR | MMEJ |

|---|---|---|---|

| Repair Template | Not required | Homologous donor DNA required | Uses microhomology (5-25 bp) |

| Cell Cycle Phase | All phases | S and G2 phases | M and early S phases |

| Repair Fidelity | Error-prone (indels common) | High-fidelity, precise | Predictable deletions |

| Kinetics (T50) | Fastest (especially +A/T indels) | Intermediate | Slower than NHEJ |

| Key Enzymes | Ku70/80, DNA-PKcs, XLF, XRCC4 | Rad51, BRCA2, Rad52 | POLQ (DNA polymerase theta), PARP1 |

| Primary Outcome | Gene knockouts | Precise edits, knock-ins | Defined deletions, alternative knock-in |

| Advantages | Highly efficient, works in non-dividing cells | Precise, versatile for various edits | Easier donor design than HDR, more predictable than NHEJ |

| Disadvantages | Unpredictable indels, low precision | Low efficiency, cell cycle dependent | Still introduces deletions, less characterized |

The kinetic competition between repair pathways significantly influences editing outcomes. Research quantifying T50 (time to reach half of the maximum editing frequency) has demonstrated that short indels, particularly +A/T events, occur more rapidly than longer (>2 bp) deletions, with HDR kinetics positioned between NHEJ and MMEJ [17]. This temporal hierarchy means that AAV6-mediated HDR effectively competes with longer MMEJ-mediated deletions but cannot outcompete faster NHEJ-mediated indels [17]. These kinetic properties underscore the importance of timing when introducing donor templates and implementing interventions to modulate pathway activity.

Pathway Competition and Editing Outcomes

Table 2: Quantitative Comparison of Editing Outcomes Across Repair Pathways

| Parameter | NHEJ | HDR | MMEJ |

|---|---|---|---|

| Relative Frequency | Dominant pathway in most cells [18] | Typically <10-30% of edits [16] | Variable by cell type (5-20%) [15] |

| Efficiency with Inhibition | Reduced by NHEJ inhibitors (e.g., Alt-R HDR Enhancer V2) [19] | Enhanced 3-fold with NHEJ inhibition [19] | Reduced by POLQ inhibition (ART558) [19] |

| Indel Pattern | Short insertions/deletions (<50 bp) [19] | Precise integration | Large deletions (≥50 bp) with microhomology [19] |

| HDR/NHEJ Ratio | Highly variable by locus, nuclease, and cell type [18] | Can exceed NHEJ under optimized conditions [18] | Not applicable |

| Perfect HDR Efficiency with NHEJi | Not applicable | 16.8% (Cpf1) to 22.1% (Cas9) [19] | Not applicable |

The distribution of editing outcomes across these pathways exhibits substantial variability depending on experimental conditions. Systematic quantification has revealed that HDR/NHEJ ratios are highly dependent on the target gene locus, nuclease platform, and cell type, with some conditions surprisingly yielding more HDR than NHEJ events [18]. This challenges the conventional wisdom that NHEJ generally dominates editing outcomes and highlights the importance of empirical optimization for specific experimental systems. Even with NHEJ inhibition, perfect HDR events may constitute less than half of all integration events, with the remainder comprising various imprecise repair patterns including asymmetric HDR, blunt integration, and MMEJ-derived outcomes [19].

Experimental Modulation of Repair Pathways

Strategies for Enhancing HDR in iPSCs

Achieving high-efficiency HDR in iPSCs requires multipronged approaches that address both technical and biological barriers. A primary consideration is HDR template design, where optimal homology arm lengths are critical—30-60 nucleotides for single-stranded oligodeoxynucleotide (ssODN) donors and 200-300 base pairs for plasmid-based templates [16]. The positioning of edits relative to the cleavage site further influences strand preference, with PAM-proximal edits favoring the targeting strand while PAM-distal edits benefit from non-targeting strand orientation [16]. For larger insertions such as fluorescent proteins, plasmid donors with 500 base pair homology arms delivered via electroporation typically yield superior results compared to single-stranded templates [16].

Timed intervention with small molecule inhibitors provides powerful control over pathway competition. Combined treatment with M3814 (an NHEJ inhibitor) and Trichostatin A (a histone deacetylase inhibitor) increases HDR efficiency approximately 3-fold by suppressing dominant error-prone repair while potentially opening chromatin structure to enhance donor accessibility [17]. Similarly, Alt-R HDR Enhancer V2 potently inhibits NHEJ, increasing knock-in efficiency from approximately 5.2% to 16.8% for Cpf1-mediated editing and from 6.9% to 22.1% for Cas9-mediated editing in human cells [19]. Additional pathway-specific inhibitors including ART558 for MMEJ (via POLQ inhibition) and D-I03 for single-strand annealing (via Rad52 inhibition) offer further precision for steering repair outcomes, with MMEJ suppression particularly effective at reducing large deletions and complex indels [19].

Diagram 1: DNA Repair Pathway Competition and Outcomes. CRISPR-Cas9 induced double-strand breaks are resolved through competing repair pathways whose balance can be modulated by specific inhibitors to steer outcomes toward precise editing.

The PITCh System: MMEJ for Efficient Knock-in

The Precise Integration into Target Chromosome (PITCh) system represents an innovative approach that leverages MMEJ rather than HDR for gene knock-in, offering particular advantages in cell types with low HDR activity [15]. This method requires only very short microhomology regions (5-25 bp) compared to extensive homology arms needed for HDR, significantly simplifying vector construction while maintaining precision. The system has demonstrated remarkable efficiency, with proper insertion achieved in 80% of clones at the 5' junction and 50% at the 3' junction when integrating a GFP-Puro cassette into the FBL locus of HEK293 cells [15].

The PITCh protocol involves a series of carefully orchestrated steps beginning with the generation of microhomology arms in the donor vector through PCR, followed by co-transfection with vectors expressing Cas9 and both generic PITCh-gRNA and locus-specific gRNA [15]. Selection of puromycin-resistant cells enables enrichment of successfully modified cells, with subsequent PCR amplification and sequencing confirming precise integration. This MMEJ-based strategy has proven particularly valuable in challenging systems such as the pathogenic fungus Aspergillus fumigatus, where traditional HDR approaches are inefficient due to NHEJ dominance [15]. The versatility of the PITCh system makes it a powerful alternative to HDR for knock-in experiments in iPSCs and other therapeutically relevant primary cells.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Modulating DNA Repair Pathways

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| NHEJ Inhibitors | Alt-R HDR Enhancer V2, M3814 | Suppresses dominant NHEJ pathway to enhance HDR efficiency | Increases HDR efficiency 3-fold; treatment for 24h post-electroporation [17] [19] |

| MMEJ Inhibitors | ART558 | Inhibits POLQ to reduce MMEJ-mediated deletions | Reduces large deletions (≥50 bp) and complex indels [19] |

| SSA Inhibitors | D-I03 | Suppresses Rad52 to reduce asymmetric HDR | Decreases imprecise donor integration patterns [19] |

| HDAC Inhibitors | Trichostatin A (TSA) | Chromatin modification to potentially improve donor accessibility | Used in combination with NHEJ inhibitors [17] |

| HDR Donor Templates | AAV6 serotype, ssODNs, dsDNA donors | Provides repair template for precise editing | AAV6 effective for HDR in iPSCs; ssODNs for point mutations [17] [16] |

| Cas Nuclease Systems | Cas9, Cpf1 (Cas12a) | Induces targeted double-strand breaks with different cleavage patterns | Cas9 (blunt ends) vs Cpf1 (staggered ends) affect repair outcomes [19] |

Diagram 2: Optimized Workflow for CRISPR Knock-in Experiments. This streamlined protocol incorporates critical decision points for selecting between HDR and MMEJ systems and includes key steps for enhancing precise editing through pathway modulation.

Advanced Methodologies and Protocol

Comprehensive Protocol for HDR Enhancement

A robust protocol for enhancing HDR efficiency in iPSCs begins with careful experimental design. For the nuclease component, the use of Cas9 ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes rather than plasmid-based expression significantly reduces off-target effects and enables more rapid editing [17]. Guide RNA design should position the cut site within 10 base pairs of the intended edit and consider PAM orientation, with the targeting strand preferred for PAM-proximal edits and the non-targeting strand for PAM-distal modifications [16]. For the HDR donor, select appropriate template architecture: ssODNs with 30-60 nucleotide homology arms for small edits (<50 bp) or plasmid donors with 200-500 base pair homology arms for larger insertions [16].

Critical cell culture handling precedes editing. For iPSCs, transient cell cycle synchronization through serum starvation or chemical treatments can increase the proportion of cells in S/G2 phases where HDR is active [16]. Prepare RNP complexes by combining purified Cas9 protein with synthetic guide RNA and incubating for 10-20 minutes at room temperature. For electroporation, combine RNP complexes with donor template at a 1:2 molar ratio and deliver using optimized settings for stem cells [16]. Immediately following delivery, treat cells with pathway modulators—typically NHEJ inhibitors like Alt-R HDR Enhancer V2 or M3814 combined with Trichostatin A for 24 hours, the critical window when most repair occurs [17] [19].

Post-editing processing and validation complete the protocol. Allow 72-96 hours for expression of resistance genes or fluorescent markers before initiating selection. For precise quantification of editing outcomes, employ digital PCR (ddPCR) assays that can simultaneously detect HDR and NHEJ events at endogenous loci [18]. Alternatively, long-read amplicon sequencing with PacBio platforms coupled with computational frameworks like knock-knock enables comprehensive characterization of repair patterns, including perfect HDR, imprecise integration, and various indel outcomes [19]. Screen multiple clones to account for heterogeneity, and validate through Southern blotting or functional assays to ensure intended edits without off-target effects.

Troubleshooting and Optimization

Common challenges in achieving precise editing include low HDR efficiency and high indel background. When facing insufficient HDR rates, consider these evidence-based solutions: First, optimize donor design by testing both single-stranded and double-stranded templates and adjusting homology arm length [16]. Second, titrate nuclease dosage to balance between efficient cutting and minimizing cytotoxicity that can reduce HDR [18]. Third, employ small molecule combinations such as M3814 with Trichostatin A, which synergistically enhance HDR efficiency [17].

When imprecise integration persists despite NHEJ inhibition, investigate contributions from alternative repair pathways. MMEJ inhibition via ART558 specifically reduces large deletions and complex indels [19]. For asymmetric HDR patterns where only one junction is precise, SSA suppression through D-I03 treatment may improve perfect HDR rates [19]. Systematic quantification of all repair outcomes using the ddPCR assay or long-read sequencing provides essential feedback for iterative optimization, revealing how specific pathway manipulations alter the balance between precise and imprecise editing [18] [19].

For challenging cell types like iPSCs where HDR efficiency remains stubbornly low despite optimization, consider alternative approaches such as the PITCh system that leverages MMEJ rather than HDR [15]. This method's requirement for only short microhomology regions simplifies donor design while achieving comparable knock-in efficiency to HDR-based approaches, particularly valuable in translationally relevant primary cells where HDR activity is inherently limited.

The treatment of monogenic disorders, which are caused by mutations in a single gene and affect over 300 million people worldwide, represents a significant challenge for modern medicine due to their low prevalence and consequent limited research investment [20]. CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing has emerged as a transformative therapeutic platform that directly addresses the genetic root cause of these conditions, offering the potential for durable, "one-and-done" treatments that circumvent the limitations of conventional symptom-management approaches [20]. This technology enables precise genetic correction in patient-derived induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), creating a renewable source of autologous, gene-corrected cells for transplantation [21] [22]. The versatility of CRISPR-Cas9 allows researchers to target diverse mutation types—including exonic point mutations, deep intronic variants, and dominant gain-of-function mutations—through tailored editing strategies [21]. When combined with iPSC technology, CRISPR correction facilitates the generation of multilineage therapeutic cell types, providing a comprehensive framework for addressing both systemic and tissue-specific manifestations of monogenic diseases [22].

Quantitative Landscape of CRISPR-Cas9 Applications

Therapeutic Editing Strategies by Mutation Class

Table 1: CRISPR-Cas9 strategies for different genetic mutation types

| Mutation Type | Disease Example | Target Gene | Editing Approach | Efficiency Reported | Key Outcome Measures |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exonic (homozygous) | Retinitis Pigmentosa | MAK | HDR with ssODN donor | 31.2% cutting efficiency [21] | Restoration of retinal transcript and protein [21] |

| Deep Intronic | Leber Congenital Amaurosis | CEP290 | NHEJ-mediated excision | Not quantified | Correction of transcript splicing and protein expression [21] |

| Dominant Gain-of-Function | Autosomal Dominant RP | RHO | Allele-specific NHEJ | Not quantified | Selective disruption of mutant allele [21] |

| Splice Site | Tuberous Sclerosis Complex | TSC2 | HDR-mediated correction | Successful clone generation [23] | Creation of isogenic lines for disease modeling [23] |

| Small Deletion | Recessive Dystrophic Epidermolysis Bullosa | COL7A1 | HDR with dsDNA donor | 12/17 clones showed HDR [22] | Gene-corrected iPSCs with restored collagen VII [22] |

Advanced CRISPR Tool Selection Guide

Table 2: CRISPR-based editing systems and their applications

| Editing System | Molecular Components | Mechanism of Action | Therapeutic Application | Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CRISPR-Cas9 Nuclease | Cas9 nuclease + sgRNA | Creates DSBs, repaired by NHEJ or HDR [24] | Gene disruption, knock-in via HDR [24] | High efficiency for gene knockout [25] |

| Base Editors (CBE, ABE) | Cas9 nickase + deaminase + UGI | Direct chemical conversion of C•G to T•A or A•T to G•C base pairs [20] | Correcting point mutations without DSBs [20] | Avoids DSB-associated risks; theoretically corrects ~95% of pathogenic transition mutations [20] |

| Prime Editors | Cas9 nickase + reverse transcriptase + pegRNA | Uses RT template to copy edited sequence [24] | All 12 possible base-to-base conversions, small insertions/deletions [24] | No DSBs or donor templates needed; highly versatile [24] |

| CRISPRa/i | dCas9 + transcriptional regulators | Activates or represses gene expression without editing DNA sequence [24] | Gene dosage compensation, metabolic pathway regulation [24] | Reversible modulation; no permanent genomic changes [24] |

Experimental Protocol: High-Efficiency Gene Correction in iPSCs

iPSC Culture and Nucleofection

Maintain iPSCs in feeder-free conditions using StemFlex or mTeSR Plus medium on Matrigel-coated plates [26]. For nucleofection, ensure cells are at 80-90% confluency in a 6-well plate and change to cloning media (StemFlex with 1% Revitacell and 10% CloneR) one hour pre-treatment [26]. Dissociate cells with Accutase for 4-5 minutes to create a single-cell suspension. Prepare the ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex by combining 0.6 µM guide RNA (IDT) and 0.85 µg/µL of Alt-R S.p. HiFi Cas9 Nuclease V3 (IDT #108105559) with incubation at room temperature for 20-30 minutes [26]. For homology-directed repair, add 5 µM single-stranded oligonucleotide (ssODN) repair template to the RNP complex. To significantly enhance HDR efficiency, co-deliver 50 ng/µL pCXLE-hOCT3/4-shp53-F plasmid (Addgene #27077) for transient p53 inhibition [26].

Enhanced HDR Protocol with Pro-Survival Factors

Building upon the base protocol, incorporate the following modifications to dramatically improve cell survival and editing efficiency: Include an HDR enhancer (IDT), electrophoresis enhancers (IDT), and CloneR (STEMCELL Technologies) in the nucleofection mixture [26]. These components address the significant cell death associated with CRISPR-induced double-stranded breaks and single-cell cloning. Following nucleofection, plate cells in cloning media and maintain with daily media changes. This optimized approach has demonstrated remarkable improvements in HDR efficiency, achieving rates up to 59.5% in bulk sequencing—a 21-fold increase over the base protocol—and exceeding 90% homologous recombination in some iPSC lines [26]. The combination of p53 inhibition and pro-survival small molecules creates a synergistic effect that allows edited cells to recover and proliferate, reducing the timeline for generating isogenic lines to as little as 8 weeks [26].

Clone Screening and Validation

After puromycin selection (if using a selection cassette), plate cells at low density for clonal isolation and expansion [22]. Screen clones using a combination of PCR-based genotyping and Sanger sequencing to identify precisely edited clones. For comprehensive off-target assessment, employ whole genome sequencing on edited clones using tools like Cas-OFFinder to analyze potential off-target sites [26]. Perform karyotype analysis via G-banding to confirm genomic integrity, as the use of pro-survival factors, while beneficial for efficiency, raises theoretical concerns about promoting chromosomal abnormalities [26]. Validated studies have demonstrated that short-term exposure to these anti-apoptotic compounds does not increase the selection of abnormal karyotypes [26].

Figure 1: High-efficiency CRISPR-Cas9 gene correction workflow in iPSCs, featuring p53 inhibition and pro-survival factors to enhance HDR rates.

Disease-Specific Application Notes

Neurological Disorders: Alzheimer's Disease Modeling

For neurodegenerative conditions like Alzheimer's disease, CRISPR-corrected iPSCs enable precise disease modeling and drug screening platforms. Target early-onset AD genes (APP, PSEN1, PSEN2) in patient-derived iPSCs to create isogenic controls that recapitulate disease pathology in vitro, including Aβ plaque formation and tau tangles [6]. Differentiate corrected iPSCs into neurons, microglia, and astrocytes to study cell-type-specific contributions to disease pathogenesis. Gene-edited iPSCs have demonstrated reduced abnormal Aβ and tau protein accumulation in AD models, with subsequent improvement in cognitive function in animal studies [6]. The integration of stem cell technology with CRISPR editing provides a platform for both disease modeling and developing autologous cell replacement strategies, addressing the limitations of current pharmacological treatments that only manage symptoms without altering disease progression [6].

Metabolic and Hepatic Disorders

The liver has emerged as a particularly amenable target for CRISPR therapies due to the preferential accumulation of lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) in hepatic tissue following systemic administration [27]. Ongoing clinical trials have demonstrated the feasibility of in vivo CRISPR-Cas9 approaches for liver-directed therapies, with Intellia Therapeutics' phase I trial for hereditary transthyretin amyloidosis (hATTR) showing durable ~90% reduction in disease-related protein levels sustained over two years [27]. This systemic LNP delivery approach represents a significant advancement over ex vivo editing strategies, as it eliminates the need for cell transplantation and enables direct in vivo genetic correction. Similar success has been observed with hereditary angioedema (HAE), where LNP-delivered CRISPR therapies reduced kallikrein levels by 86% and dramatically decreased inflammation attacks [27].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key reagents for CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing in iPSCs

| Reagent Category | Specific Product/System | Manufacturer | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cas9 Nuclease | Alt-R S.p. HiFi Cas9 Nuclease V3 | IDT | High-fidelity genome editing | Reduces off-target effects [26] |

| iPSC Culture | StemFlex Medium | Gibco | Maintains pluripotency | Feeder-free culture system [26] |

| iPSC Culture | mTeSR Plus | STEMCELL Technologies | Maintains pluripotency | Alternative feeder-free system [26] |

| Transfection | Nucleofection System | Lonza | Efficient RNP delivery | Higher efficiency than lipofection [26] |

| HDR Enhancement | HDR Enhancer | IDT | Improves homology-directed repair | Increases precise editing efficiency [26] |

| Cell Survival | CloneR | STEMCELL Technologies | Enhances single-cell survival | Critical for clonal expansion [26] |

| p53 Inhibition | pCXLE-hOCT3/4-shp53-F | Addgene | Temporary p53 suppression | Boosts HDR efficiency 11-fold [26] |

| Matrix | Matrigel | Corning | iPSC attachment surface | Essential for feeder-free culture [26] |

Mechanism of CRISPR-Cas9 Action and DNA Repair Pathways

Figure 2: CRISPR-Cas9 mechanisms and DNA repair pathways for different genetic outcomes.

The integration of CRISPR-Cas9 technology with iPSC-based disease modeling has created a powerful platform for addressing monogenic disorders through genetic correction. The development of refined editing approaches—including high-efficiency HDR protocols, base editing systems that avoid double-strand breaks, and improved delivery methods like lipid nanoparticles—has accelerated the translation of these technologies toward clinical applications [26] [20] [27]. The recent success of in vivo CRISPR therapies in clinical trials, coupled with the creation of personalized treatments for rare genetic conditions, demonstrates the remarkable potential of this approach to address previously untreatable diseases [27]. As the field advances, key challenges remain in optimizing delivery efficiency, minimizing off-target effects, and establishing international regulatory frameworks [28]. However, the continuous refinement of CRISPR-based therapeutics promises to expand the treatment landscape for monogenic disorders, ultimately enabling personalized, curative approaches that target the fundamental genetic causes of disease rather than merely managing symptoms.

The combination of CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing and human induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) has revolutionized disease modeling by enabling the creation of isogenic cell pairs—genetically identical lines differing only at a specific locus of interest [29]. These meticulously controlled cellular models provide an unprecedented ability to establish causative relationships between genetic variations and disease phenotypes, free from the confounding effects of divergent genetic backgrounds [30] [29]. This application note details the methodologies, applications, and technical considerations for leveraging CRISPR-Cas9 in iPSCs to generate isogenic pairs for functional studies, with particular emphasis on their critical role in advancing disease correction research.

The fundamental power of isogenic pairs lies in their capacity to isolate the functional impact of a single genetic variable. While patient-derived iPSCs retain the complete genetic background of the donor, including all natural genetic variations that can obscure phenotypic analysis, isogenic controls provide a solution to this limitation [9]. Through precise genome editing, researchers can either introduce a specific pathogenic mutation into a healthy iPSC line or correct the disease-causing mutation in a patient-derived line, resulting in genetically matched pairs that differ only at the target locus [29] [9]. This approach has become indispensable for validating disease mechanisms and conducting high-content drug screens with enhanced sensitivity and specificity [30] [9].

Key Methodological Approaches

Strategic Workflow for Isogenic Pair Generation

The generation of isogenic iPSC pairs follows a systematic workflow that can be adapted based on the nature of the genetic modification and the starting cell line. Table 1 outlines the primary strategic approaches for creating these critical research tools.

Table 1: Strategic Approaches for Generating Isogenic iPSC Pairs

| Strategy | Starting Cell Line | Genetic Modification | Research Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Disease Introduction | Healthy control iPSC line | Introduce pathogenic mutation via HDR [9] | Model disease mechanisms from wild-type baseline |

| Therapeutic Correction | Patient-derived iPSC line | Correct disease-causing mutation via HDR [30] [29] | Study reversal of pathology; autologous therapy development |

| SNP Installation | iPSC line heterozygous at target SNP | Edit to homozygous states using ssODN templates [31] | Functional validation of disease-associated non-coding variants |

The following diagram illustrates the core decision-making workflow for selecting and implementing the appropriate strategy based on research objectives and starting materials:

High-Efficiency CRISPR-Cas9 Editing Protocol

Recent methodological advances have dramatically improved the efficiency of precise genome editing in iPSCs. The protocol below incorporates key enhancements that achieve homologous recombination rates exceeding 90% by addressing the primary challenges of cell death and low HDR efficiency in pluripotent stem cells [3].

Pre-editing Preparation

- gRNA Design: Identify a target site within 10 nucleotides of the intended edit using specialized software (e.g., Benchling) [3] [31]. When possible, design silent mutations in the Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM) site in the repair template to prevent re-cutting [3].

- Repair Template Design: For single nucleotide changes, design single-strand oligonucleotides (ssODNs) with approximately 65 bp homology arms flanking the target site [31]. For larger edits, consider using double-stranded DNA templates with longer homology arms.

- Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) Complex Assembly: Combine 0.6 µM guide RNA with 0.85 µg/µL of high-fidelity Cas9 nuclease and incubate at room temperature for 20-30 minutes to form RNP complexes [3]. This approach minimizes off-target effects compared to plasmid-based expression systems.

Cell Preparation and Transfection

- Culture Conditions: Maintain iPSCs in feeder-free conditions using Matrigel-coated plates and defined media (e.g., mTeSR Plus or StemFlex) [3] [31].

- Transfection Enhancements: Change to cloning media supplemented with pro-survival additives 1 hour prior to transfection. The optimized formulation includes:

- Nucleofection: Harvest cells at 80-90% confluency using Accutase. Combine the pre-formed RNP complex with 5 µM ssODN repair template and 50 ng/µL pCXLE-hOCT3/4-shp53-F plasmid (for transient p53 suppression) [3]. Use appropriate nucleofection program for your iPSC line.

Post-transfection Recovery and Clonal Isolation

- Recovery Culture: Plate transfected cells at appropriate density in cloning media with pro-survival additives. Maintain cultures for 48-72 hours without disturbance to support recovery.

- Antibiotic Selection: If using a selection strategy, apply appropriate antibiotics 72 hours post-transfection to enrich for successfully edited cells [31].

- Single-Cell Cloning: Using limiting dilution or FACS, isolate single cells into 96-well plates pre-coated with Matrigel and containing conditioned cloning media [3] [31]. Culture for 2-3 weeks with regular media changes until colonies form.

- Screening and Validation: Expand clones and screen using a combination of:

Technical Optimization and Troubleshooting

Enhancing Editing Efficiency

The inherently low efficiency of homology-directed repair in iPSCs represents a significant technical challenge. Table 2 summarizes key optimization strategies that dramatically improve HDR rates while maintaining cell viability.

Table 2: Optimization Strategies for Improving HDR Efficiency in iPSCs

| Challenge | Solution | Mechanism of Action | Reported Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low HDR efficiency | HDR enhancers (e.g., from IDT) | Modulates DNA repair pathway choice | Up to 21-fold increase [3] |

| Cell death post-transfection | p53 suppression (shRNA) | Reduces apoptosis from DNA damage response | 11-fold increase in HDR [3] |

| Single-cell survival | CloneR supplement | Enhances viability of dissociated cells | Critical for clonal expansion [3] |

| Electroporation stress | ROCK inhibitor (Y-27632) | Prevents anoikis in single cells | Standard in iPSC culture [3] |

Advanced Editing Systems

While CRISPR-Cas9 remains the most widely used platform, emerging CRISPR systems offer additional capabilities:

- CRISPR-Cas12a: This system enables multiplexed genome editing and has demonstrated utility in studying complex genetic interactions in disease models [32] [33]. Cas12a recognizes different PAM sequences than Cas9, expanding the targetable genomic space.

- Base Editing: For precise single-nucleotide changes without double-strand breaks, base editing systems offer an alternative with potentially reduced indel formation [9].

- Prime Editing: This newer technology allows for precise small insertions, deletions, and all possible base-to-base conversions without requiring double-strand breaks or donor templates.

Applications in Disease Modeling and Drug Development

Neurodegenerative Disease Modeling

The CRISPR-iPSC platform has generated significant insights into neurodegenerative disease mechanisms:

- Huntington's Disease: Isogenic iPSC lines with corrected CAG repeats in the Huntingtin gene have demonstrated recovery from phenotypic abnormalities and gene expression changes in derived neural cells [30]. These models have elucidated pathways involving mitochondrial dysfunction, excitotoxicity, and transcriptional dysregulation [30].

- Alzheimer's Disease: Introduction of APP and PSEN1 mutations into isogenic backgrounds has successfully reproduced early pathological features including Aβ deposition and tau phosphorylation in iPSC-derived neurons [9].

- Parkinson's Disease: Isogenic lines with LRRK2 G2019S mutations exhibit mitochondrial dysfunction and enhanced vulnerability in dopaminergic neurons, providing platforms for mechanistic studies and compound screening [9].

High-Throughput Screening Applications

Isogenic iPSC pairs provide exceptional model systems for drug discovery through:

- Target Validation: By comparing compound effects between isogenic pairs, researchers can confidently establish whether therapeutic efficacy is mutation-specific [9].

- Toxicity Assessment: iPSC-derived cardiomyocytes with mutations in KCNQ1 or SCN5A generated via CRISPR editing are widely used for cardiac safety pharmacology [9].

- Personalized Medicine: Creating multiple isogenic lines from different genetic backgrounds allows assessment of how individual genomes influence drug response, advancing precision medicine approaches [9].

The following diagram illustrates the integrated pipeline from isogenic line generation to drug screening applications:

Research Reagent Solutions

Successful generation of isogenic iPSC pairs requires carefully selected reagents and systems. Table 3 catalogizes essential research reagents with their specific functions in the editing workflow.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for CRISPR-iPSC Workflows

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| CRISPR Components | Alt-R S.p. HiFi Cas9 Nuclease V3 [3], sgRNAs | Precision DNA cleavage | High-fidelity Cas9 reduces off-target effects |

| Repair Templates | ssODNs [31], dsDNA donors | Homology-directed repair | 65 bp homology arms optimal for ssODNs [31] |

| Cell Culture | mTeSR Plus [3], StemFlex [31], Matrigel | Maintain pluripotency | Feeder-free culture systems preferred |

| Transfection | FuGENE HD [31], Nucleofection systems | Deliver editing components | Liposome-based for simple edits; electroporation for challenging edits |

| Survival Enhancers | CloneR [3], RevitaCell [3], Y-27632 | Enhance single-cell viability | Critical step for clonal expansion post-editing |

| p53 Inhibition | pCXLE-hOCT3/4-shp53-F plasmid [3] | Temporary p53 suppression | Increases HDR efficiency 11-fold [3] |

| Validation Tools | Sanger sequencing, Karyotyping, ICE analysis [3] | Confirm edits and genomic integrity | Essential quality control steps |

The creation of isogenic iPSC pairs through CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing represents a transformative methodology for functional genetic studies. By eliminating confounding genetic variables, these models enable researchers to establish definitive causal relationships between genetic mutations and disease phenotypes. The optimized protocols detailed in this application note—incorporating p53 suppression, pro-survival additives, and refined delivery methods—have dramatically improved editing efficiencies to practically feasible levels.

As the field advances, emerging technologies including CRISPR-Cas12a for multiplexed editing [32] [33], base editing for precision single-nucleotide changes, and organoid differentiation for complex tissue modeling are further expanding the applications of isogenic pairs. When combined with automated screening platforms and computational approaches, these tools are accelerating the pace from disease gene discovery to therapeutic development. The continued refinement of these protocols will undoubtedly enhance our understanding of disease mechanisms and contribute to the development of targeted interventions for genetic disorders.

Implementing CRISPR-iPSC Workflows: From Target Selection to Corrected Cell Lines

Guide RNA Design and Validation Strategies for High-Efficiency Editing

The success of CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing in induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) for disease modeling and correction hinges on the design and validation of highly efficient guide RNAs (gRNAs). The gRNA serves as the molecular GPS, directing the Cas9 nuclease to a specific genomic locus with precision. In the context of therapeutic applications, where the goal is to correct disease-causing mutations in patient-derived iPSCs, achieving high editing efficiency with minimal off-target effects is paramount. This protocol details comprehensive strategies for designing and validating gRNAs to achieve homologous recombination rates exceeding 90% in human iPSCs, a critical benchmark for generating isogenic controls in disease research [26] [34].

Optimized gRNA design must account for multiple factors, including the sequence context of the target site, the choice of Cas9 variant, and the unique biological characteristics of iPSCs. The advent of high-fidelity Cas9 variants and sophisticated deep learning models for gRNA activity prediction has dramatically improved the predictability of editing outcomes. This document integrates these advanced tools with wet-lab validation protocols to provide a complete framework for researchers aiming to develop precise disease models through genome editing [35].

Key Principles of gRNA Design

Sequence Determinants of gRNA Activity

The guide RNA sequence is the primary determinant of both on-target efficiency and off-target specificity. The ideal gRNA spacer sequence is 20 nucleotides long, although some Cas9 orthologs like FrCas9 show optimal activity with 21-22 bp guides [36]. The sequence must be complementary to the target DNA and must be immediately adjacent to a Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM). For the most commonly used Cas9 from Streptococcus pyogenes (SpCas9), the PAM sequence is 5'-NGG-3' [37].

Several sequence features influence gRNA activity. A guanine (G) at the first position of the spacer sequence is often beneficial when using the human U6 promoter, though the mouse U6 promoter can initiate transcription with either adenine (A) or G, expanding targetable sites [35]. The melting temperature and local DNA geometry of the target site also contribute to editing efficiency. Furthermore, research has revealed that DNA repair from double-strand breaks is asymmetric, favoring repair in one direction. This property can be exploited by designing gRNAs and repair templates to favor the desired repair outcome [37].

Advanced gRNA Design Tools and Models

Traditional gRNA design rules based on sequence features have been superseded by deep learning models trained on large-scale activity datasets. These models offer superior predictive power for gRNA on-target efficiency.

For instance, the DeepHF tool uses a combination of a recurrent neural network (RNN) and important biological features to predict gRNA activity for wild-type SpCas9 and two high-fidelity variants, eSpCas9(1.1) and SpCas9-HF1 [35]. This tool was developed from a genome-scale screen measuring the indel rates of over 50,000 gRNAs covering approximately 20,000 genes, providing an extensive data foundation for its predictions.

When designing gRNAs for complex genomes, additional considerations apply. For example, in hexaploid wheat, a crop with a large, repetitive genome, researchers must perform exhaustive BLAST analyses to ensure gRNA specificity and avoid off-target editing across highly similar gene homologs [38]. While this example is from plant biology, the principle is equally relevant when targeting gene families with high sequence homology in human iPSCs.

Table 1: Key Design Parameters for High-Efficiency gRNAs

| Design Parameter | Optimal Characteristic | Impact on Editing |

|---|---|---|

| Spacer Length | 20 nt (SpCas9), 21-22 nt (FrCas9) [36] | Ensures proper Cas9 binding and cleavage |

| PAM Sequence | 5'-NGG-3' (SpCas9); 5'-NNTA-3' (FrCas9) [36] | Defines targetable genomic sites |

| 5' Nucleotide | G (hU6 promoter); A or G (mU6 promoter) [35] | Affects gRNA transcription initiation |

| Target Location | <10 bp from desired mutation [26] | Maximizes HDR efficiency for point mutations |

| GC Content | Moderate (40-60%) | Precludes overly stable or unstable binding |

Computational Design and In Silico Validation

gRNA Design Workflow

The initial design phase involves identifying potential gRNA targets within your gene of interest and rigorously filtering them for predicted efficiency and specificity.

Step 1: Target Site Identification. Using a design tool like the one provided by IDT, input the genomic sequence flanking your target site, such as a disease-associated SNP. The tool will output all possible gRNA spacer sequences with their corresponding PAMs [34].

Step 2: Efficiency Scoring. Score the resulting gRNAs using a predictive algorithm like DeepHF, which integrates sequence features and deep learning to rank gRNAs by their predicted on-target activity [35].

Step 3: Specificity Analysis. Perform a BLAST search or use dedicated off-target prediction tools to identify genomic loci with high sequence similarity to your candidate gRNA. A high-quality gRNA should have minimal (≤3) off-target sites with 1-3 mismatches, especially in seed regions near the PAM [38].

Step 4: Secondary Structure Check. Analyze the candidate gRNA sequence for potential secondary structures or self-complementarity that could impede its binding to the Cas9 protein or the target DNA. Tools like RNAfold can predict secondary structures and calculate Gibbs free energy, where a less negative ΔG indicates a more stable and functional gRNA [38].

The following diagram illustrates the core decision-making workflow for selecting a candidate gRNA:

Designing the Repair Template

For precise gene correction via Homology-Directed Repair (HDR), a single-stranded oligodeoxynucleotide (ssODN) repair template must be co-designed with the gRNA. The repair template should contain the desired corrective mutation flanked by homology arms.

To prevent re-cleavage of the edited locus by Cas9, introduce silent mutations in the PAM sequence or in the seed region of the protospacer within the repair template. This is a critical step for enriching HDR-edited cells [26]. The repair template should be designed so the mutation is located close to the Cas9 cut site (ideally within 10 bp) to maximize HDR efficiency [26].

Experimental Validation of gRNA Efficiency

A High-Efficiency Workflow for iPSCs

Achieving high editing efficiency in iPSCs requires not only a well-designed gRNA but also optimized delivery and cell culture conditions to enhance cell survival post-editing. The following protocol, which can be completed in approximately 8 weeks, has been shown to achieve homologous recombination rates over 90% in human iPSCs [34].

Key Reagents and Materials:

- Biological Material: Human iPSC line (e.g., NDC1)

- Culture Medium: mTeSR Plus or Stemflex medium, supplemented with CloneR and RevitaCell to support single-cell survival.

- Nucleofection System: Lonza 4D Nucleofector with P3 Primary Cell Solution.

- CRISPR Components:

- Alt-R S.p. HiFi Cas9 Nuclease V3 (IDT)

- Synthetic sgRNA (IDT, custom)

- ssODN repair template (IDT, 4 nmol Ultramer scale)

- Pro-Survival Supplements:

- Alt-R Cas9 HDR enhancer (IDT)

- p53 shRNA plasmid (e.g., pCXLE-hOCT3/4-shp53-F from Addgene)

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for iPSC Editing

| Reagent / Solution | Function / Purpose | Example Source / Catalog |

|---|---|---|

| Alt-R S.p. HiFi Cas9 V3 | High-fidelity nuclease for targeted DNA cleavage | IDT #10810559 |

| Synthetic sgRNA | Guides Cas9 to the specific genomic target; increases efficiency and reproducibility | IDT (custom) |

| ssODN Repair Template | Single-stranded DNA donor for introducing precise edits via HDR | IDT Ultramer |

| P3 Primary Cell Solution | Buffer optimized for nucleofection of sensitive cells like iPSCs | Lonza |

| CloneR & RevitaCell | Supplements that inhibit ROCK and improve single-cell survival post-editing | STEMCELL Technologies |

| Alt-R HDR Enhancer | Small molecule that improves the frequency of homology-directed repair | IDT #1081062 |

| p53 shRNA Plasmid | Knocking down p53 reduces CRISPR-induced apoptosis, improving cell survival | Addgene #27077 |

Step-by-Step Protocol:

- In Silico Design: Design sgRNA and ssODN using the IDT online tool. The ssODN should contain your desired edit and silent mutations to disrupt the PAM [34].

- RNP Complex Formation: For each nucleofection reaction, combine 0.85 µg/µL HiFi Cas9 V3 and 100 µM sgRNA in Duplex Buffer. Incubate at room temperature for 20-30 minutes to form the Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex [34].

- Cell Preparation: Culture iPSCs to 80-90% confluency in a 6-well plate. Pre-treat cells by changing to cloning media (Stemflex with 1% RevitaCell and 10% CloneR) 1 hour before nucleofection. Dissociate cells into a single-cell suspension using Accutase and count them [34].

- Nucleofection Reaction: For each test reaction, combine:

- 1 µL shp53-f2 plasmid (50 ng/µL)

- 1 µL Alt-R Electroporation Enhancer

- 1 µL ssODN (100 µM)

- 5 µL prepared RNP complex

- ~1 million cells in 11 µL

- Complete to 20 µL with P3 nucleofector solution mix. Include controls: a GFP-only control for transfection efficiency and a no-pulse control for viability [34].

- Nucleofection and Recovery: Transfer the reaction to a 16-well Nucleocuvette Strip and nucleofect using the appropriate program (e.g., CA-137 for iPSCs). Immediately after nucleofection, add pre-warmed Nucleofection Media (CloneR media with HDR enhancer) and transfer the cells to a Matrigel-coated plate [34].

- Culture and Analysis: Change the media to cloning media the next day. After 48-72 hours, extract genomic DNA using a kit like Zymo quick DNA MicroPrep. Analyze editing efficiency using TIDE decomposition or ICE analysis (Synthego) on PCR-amplified target sites [26] [34].

The entire experimental journey, from design to validation, is summarized below:

Validation and Analysis

Following editing, precise validation is crucial.

- Initial Efficiency Check: Use TIDE (Tracking of Indels by Decomposition) or ICE (Inference of CRISPR Edits) analysis on bulk PCR products from the edited cell population. This provides a quantitative estimate of the indel frequency or HDR efficiency without the need for single-cell cloning [26].