Decoding Cell Fate: A Comprehensive Guide to Single-Cell RNA Sequencing for Stem Cell Potency Assessment

This article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a comprehensive overview of how single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) is revolutionizing the assessment of stem cell potency.

Decoding Cell Fate: A Comprehensive Guide to Single-Cell RNA Sequencing for Stem Cell Potency Assessment

Abstract

This article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a comprehensive overview of how single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) is revolutionizing the assessment of stem cell potency. We cover the foundational principles of cellular potency, from totipotency to unipotency, and detail the key scRNA-seq methodologies and computational tools, such as CytoTRACE 2 and signaling entropy, used to quantify developmental potential. The article further addresses critical troubleshooting and optimization strategies for sensitive stem cell applications and offers a comparative analysis of validation frameworks to ensure accurate and reproducible potency measurements. This guide synthesizes current best practices and emerging trends to empower robust stem cell characterization in both research and clinical settings.

Understanding Stem Cell Potency: From Totipotency to Lineage Restriction

Stem Cell Potency Hierarchy Stem cells are classified by their developmental potential, or "potency," which refers to their capacity to differentiate into various specialized cell types. This classification forms a hierarchical structure, ranging from cells that can generate a complete organism to those that can produce only a single cell type. Understanding this hierarchy is fundamental for selecting the appropriate stem cell type for specific research and therapeutic applications.

Table of Contents

- The Hierarchy of Cell Potency

- Totipotent Stem Cells

- Pluripotent Stem Cells

- Multipotent Stem Cells

- Unipotent Stem Cells

- Experimental Assessment of Potency

- The Research Toolkit

The Hierarchy of Cell Potency

The potency hierarchy categorizes stem cells based on the diversity of cell lineages they can produce. The spectrum progresses from the most versatile to the most restricted.

Comparative Overview of Stem Cell Potency

| Feature | Totipotent | Pluripotent | Multipotent | Unipotent |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Differentiation Potential | Can generate all embryonic and extra-embryonic (placental) tissues [1] [2] [3]. | Can generate all cells derived from the three germ layers (ectoderm, mesoderm, endoderm) [4] [2] [5]. | Can generate multiple, but limited, cell types within a specific lineage [6] [1] [3]. | Can generate only a single cell type [4] [3] [7]. |

| Key Examples | Zygote (fertilized egg), early blastomere cells [2] [3] [7]. | Embryonic Stem Cells (ESCs), Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells (iPSCs) [4] [2] [7]. | Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs), Hematopoietic Stem Cells (HSCs), Neural Stem Cells [6] [7] [8]. | Muscle stem cells, epidermal stem cells [4] [3] [7]. |

| Primary In Vivo Location | Early embryo (first few divisions post-fertilization) [2] [7] [8]. | Inner cell mass (ICM) of the blastocyst [6] [2] [7]. | Various adult tissues (e.g., bone marrow, adipose tissue, brain) [6] [7] [8]. | Specific niches within mature tissues [4]. |

| Expression of Pluripotency Genes | +++ (High) [1] | ++ (Medium) [1] | + (Low) [1] | - (None/Undetectable) [4] |

| Therapeutic Pros | N/A (Not used in therapy) | Unlimited self-renewal; broad differentiation potential; disease modeling [4] [8] [5]. | Fewer ethical concerns; lower risk of teratoma formation; clinically accessible (autologous use) [7] [8]. | Minimal risk of off-target differentiation; tissue-specific repair [4]. |

| Therapeutic Cons | N/A (Not used in therapy) | Ethical issues (ESCs); risk of teratoma formation; immune rejection [4] [2] [8]. | Limited differentiation scope; can be hard to isolate and expand [6] [1] [7]. | Very scarce in tissues; limited expansion capacity [4]. |

Totipotent Stem Cells

Totipotent cells sit at the pinnacle of the potency hierarchy. The term "totipotent" is derived from the Latin totus, meaning "whole" or "entire," reflecting their unique ability to form a whole organism [3]. This includes generating all the specialized cells of the embryo proper and the extra-embryonic tissues, such as the placenta, which are essential for development [1] [2]. In humans, the zygote formed at fertilization is totipotent, and this state is transiently maintained through the first few cell divisions of the early morula [2] [3]. Due to profound ethical considerations and technical challenges, totipotent cells are not used in therapeutic applications.

Pluripotent Stem Cells

Pluripotent stem cells, from the Latin plures meaning "many," represent the next level of potency [3]. These cells can give rise to all cell types derived from the three primary germ layers—ectoderm, mesoderm, and endoderm—and therefore every cell type in the adult body [4] [2] [5]. However, they cannot contribute to extra-embryonic tissues and thus cannot form a complete organism on their own [1] [2].

Key Types and Research Applications:

- Embryonic Stem Cells (ESCs): Derived from the inner cell mass of the pre-implantation blastocyst [6] [7]. They serve as a powerful tool for developmental biology studies.

- Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells (iPSCs): Artificially derived by reprogramming adult somatic cells (e.g., skin fibroblasts) through the forced expression of specific transcription factors (OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, c-MYC) [4] [2]. This groundbreaking technology, pioneered by Shinya Yamanaka, allows for the creation of patient-specific pluripotent cells, overcoming ethical concerns associated with ESCs and enabling advanced disease modeling and personalized regenerative medicine approaches [4] [2] [5].

A critical concept in pluripotency is the distinction between the "naïve" state (representing the pre-implantation epiblast) and the "primed" state (representing the post-implantation epiblast). Mouse ESCs are typically naïve, while human ESCs and EpiSCs (Epiblast Stem Cells) resemble the primed state, which has different growth requirements and molecular signatures [6] [2].

Multipotent Stem Cells

Multipotent stem cells are more restricted in their differentiation potential, typically limited to generating the cell types within a particular tissue or organ lineage [6] [1]. These cells are crucial for the body's natural maintenance, repair, and renewal throughout life.

Key Examples and Clinical Relevance:

- Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs): Found in bone marrow, adipose tissue, and umbilical cord blood, MSCs can differentiate into osteoblasts (bone cells), chondrocytes (cartilage cells), and adipocytes (fat cells) [3] [7]. They are widely investigated for their regenerative and immunomodulatory properties in treating orthopedic conditions, inflammatory diseases, and graft-versus-host disease [7] [8].

- Hematopoietic Stem Cells (HSCs): Residing in the bone marrow, HSCs are responsible for the continuous production of all blood cell lineages, including red blood cells, white blood cells, and platelets [6] [7]. Bone marrow transplants, a long-established form of stem cell therapy, rely on the potency of HSCs to reconstitute the entire blood and immune system in patients with hematological cancers or disorders [7] [5].

Unipotent Stem Cells

Unipotent stem cells have the most narrow differentiation potential, as they can only produce one single cell type [4] [3]. Despite this limitation, they are essential for the regeneration and repair of specific tissues. A key example is the muscle stem cell (satellite cell), which is responsible for generating new muscle fibers and is therefore critical for muscle growth and repair after injury [4] [7]. Their unidirectional nature minimizes the risk of generating unintended cell types, making them ideal for targeted tissue regeneration, though their scarcity can pose a challenge for clinical applications [4].

Experimental Assessment of Potency

Rigorous assays are required to definitively characterize the potency of any stem cell population. The following table summarizes key experimental methods used in the field.

Key Experimental Assays for Assessing Stem Cell Potency

| Assay Name | Key Readout | Protocol Summary | Key Data Output | Applicable Cell Types |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Teratoma Formation Assay [4] [2] | Formation of differentiated tissues from all three germ layers. | Test cells are injected into an immunodeficient mouse (e.g., kidney capsule, testis, intramuscular). The resulting tumor (teratoma) is harvested, sectioned, and histologically analyzed for the presence of tissues like cartilage (mesoderm), epithelium (ectoderm), and gut-like structures (endoderm). | Histological images and analysis confirming tissues from the three germ layers. | Pluripotent (ESCs, iPSCs) |

| In Vitro Differentiation [4] [7] | Spontaneous formation of specialized cell types. | Pluripotent cells are grown in suspension to form 3D aggregates called embryoid bodies (EBs). Without factors to maintain pluripotency, the cells spontaneously differentiate. EBs are then analyzed via PCR or immunostaining for markers of the three germ layers. | Gene expression data (qPCR) and protein markers (immunofluorescence) for ectoderm, mesoderm, and endoderm. | Pluripotent (ESCs, iPSCs) |

| Directed Differentiation [6] [9] | Efficient generation of a specific target cell type. | Pluripotent cells are exposed to a specific, timed sequence of small molecules, growth factors, and proteins (e.g., Activin A, bFGF) to mimic developmental signals and guide them toward a desired lineage, such as neurons, cardiomyocytes, or hepatocytes. | Flow cytometry or immunostaining for specific lineage markers (e.g., TUJ1 for neurons, cTnT for cardiomyocytes). High efficiency of target cell production. | Pluripotent (ESCs, iPSCs) |

| Single Cell RNA Sequencing (scRNA-seq) [10] | Unbiased, high-resolution transcriptomic profiles of individual cells. | Single cells are isolated (e.g., via FACS or microfluidics), their mRNA is reverse-transcribed and amplified to create a sequencing library, and high-throughput sequencing is performed. Computational analysis (clustering, trajectory inference) then reveals cellular heterogeneity, identifies subpopulations, and predicts developmental pathways. | t-SNE/UMAP plots showing cell clusters; lists of differentially expressed genes; pseudo-temporal trajectories showing potential differentiation paths. | All types (especially powerful for heterogeneous populations) |

The Role of Single-Cell RNA Sequencing

scRNA-seq has revolutionized stem cell research by moving beyond population-level averages to reveal the transcriptome of each individual cell [10]. This is particularly powerful for:

- Resolving Heterogeneity: Identifying distinct subpopulations within a seemingly pure culture of stem cells, which is crucial for understanding differentiation biases and functional variability [10].

- Defining Novel Markers: Discovering new cell surface or genetic markers for rare stem cell subtypes, enabling their purification and further study [10].

- Predicting Lineage Trajectories: Using computational methods to reconstruct the sequence of transcriptional changes as a stem cell differentiates, mapping out the developmental "roads" it can take [10].

The Research Toolkit

Successful stem cell research requires a suite of specialized reagents and tools to maintain, differentiate, and analyze stem cells effectively.

Essential Research Reagents and Tools

| Tool / Reagent | Function in Research | Example Use Cases |

|---|---|---|

| Pluripotency Transcription Factor Kits | Detect core pluripotency factors (OCT4, SOX2, NANOG) via immunostaining or PCR. | Routine quality control of ESCs/iPSCs; confirming successful reprogramming [4]. |

| Cytokines & Growth Factors | Direct cell fate decisions during differentiation. | LIF: Maintaining mouse ESC pluripotency [6].bFGF/FGF2: Essential for human ESC/iPSC culture [6].Activin A/BMP4: For directing mesendoderm differentiation [6] [9]. |

| Small Molecule Inhibitors/Activators | Precisely modulate key signaling pathways to control self-renewal and differentiation. | Mimicking developmental cues to guide cells toward specific lineages (e.g., neurons, cardiomyocytes) [6]. |

| Defined Culture Matrices | Provide a consistent, xeno-free surface for cell attachment and growth. | Coating culture vessels to support the adherent growth of ESCs/iPSCs in defined conditions. |

| Flow Cytometry Antibody Panels | Identify and isolate specific cell types based on surface marker expression. | Isulating hematopoietic stem cells (CD34+); characterizing differentiated cell populations; assessing purity after differentiation [10] [7]. |

| scRNA-seq Kits & Platforms | Enable transcriptome-wide analysis of gene expression at single-cell resolution. | Profiling heterogeneity in stem cell cultures; discovering novel subtypes; building lineage trajectories [10]. |

| Nhs-mmaf | NHS-MMAF | NHS-MMAF reagent for antibody-drug conjugate (ADC) development. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary diagnostic or therapeutic use. |

| Rubrofusarin triglucoside | Rubrofusarin triglucoside, MF:C33H42O20, MW:758.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Understanding the defined hierarchy of stem cell potency—from totipotent to unipotent—provides a critical framework for research and drug development. This knowledge guides the selection of the most appropriate cell type for modeling diseases, screening drugs, and developing regenerative therapies. The integration of advanced technologies like single-cell RNA sequencing is adding unprecedented resolution to this framework, allowing scientists to dissect cellular heterogeneity and potency states with greater precision than ever before, thereby accelerating the translation of stem cell biology into clinical applications.

In regenerative medicine, the therapeutic potential of any stem cell-based product hinges on a fundamental biological property: potency. Potency refers to a cell's ability to differentiate into specialized cell types, a hallmark that ranges from the broad capacity of totipotent and pluripotent cells to the more restricted potential of multipotent and unipotent cells [11] [12]. Assessing this characteristic is not merely a technical checkbox for regulatory compliance; it is a biological imperative to ensure that cellular products will function as intended in patients. The loss of stemness during ex vivo expansion is a key factor behind diminished therapeutic benefits, including reduced proliferation, impaired differentiation capacity, and altered secretome profiles [13]. As the field advances, leveraging sophisticated tools like single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has become indispensable for deconvoluting cellular heterogeneity and quantifying potency, thereby providing the evidence base needed for clinical success [11] [12].

The Evolving Toolkit for Potency Assessment

The transition from traditional, reductionist assays to high-resolution, multi-omics profiling has revolutionized how scientists evaluate cell potency. Modern frameworks integrate diverse data types to build a comprehensive picture of cellular function and potential.

Computational and ScRNA-Seq Platforms Single-cell RNA sequencing sits at the core of modern potency assessment, and the choice of bioinformatics platform directly impacts the insights researchers can glean. The following table compares key tools available in 2025, highlighting their specific applicability to potency research.

| Tool Name | Best For | Key Features for Potency Research | Cost & Access |

|---|---|---|---|

| CytoTRACE 2 [11] | Predicting absolute developmental potential from scRNA-seq data. | Interpretable deep learning framework (GSBN); predicts potency categories & continuous potency score; batch effect suppression. | Academic/Non-commercial |

| Scanpy [14] [15] | Large-scale scRNA-seq analysis (Python environment). | Comprehensive preprocessing, clustering, trajectory inference (pseudotime); part of the scverse ecosystem. | Open Source |

| Seurat [14] [15] | Versatile data integration (R environment). | Robust integration across batches/modalities; native support for spatial transcriptomics and multiome data. | Open Source |

| Monocle 3 [14] | Advanced pseudotime and trajectory inference. | Graphs abstraction to model lineage branching; identifies developmental paths and cell fate decisions. | Open Source |

| scvi-tools [14] | Deep generative modeling for complex data. | Probabilistic modeling for superior batch correction; supports multiple omics modalities. | Open Source |

| Nygen [15] | Researchers needing AI insights and no-code workflows. | AI-powered automated cell annotation; intuitive dashboards; batch correction. | Freemium model |

| BBrowserX [15] [16] | Intuitive, AI-assisted analysis of large-scale datasets. | Access to a large single-cell atlas for comparison; automated cell type prediction; trajectory analysis. | Paid, on-demand pricing |

| Trailmaker [16] | User-friendly, cloud-based analysis for Parse Biosciences data. | Automated workflow from FASTQ to analysis; automatic cell annotation and trajectory analysis. | Free for academics & Parse customers |

| Grk6-IN-1 | Grk6-IN-1, MF:C22H23ClN6O2, MW:438.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Tubulin inhibitor 35 | Tubulin inhibitor 35, MF:C21H21N3O, MW:331.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Key Experimental and Molecular Profiling Methods Beyond computational analysis, a matrix of wet-lab assays is critical for a holistic potency profile, especially in advanced therapies like CAR T-cells [17] [18]. These methods move beyond single-point measures to capture dynamic functional and molecular states.

- Functional Potency Assays: These measure a cell's biological activity based on its mechanism of action. Key assays include cytotoxicity tests to measure target cell killing, cytokine release assays (e.g., IFN-γ, IL-2) to quantify immune activation, and proliferation and persistence assays to evaluate long-term therapeutic potential [17] [18].

- Multi-Omics Profiling: A layered, multi-omics approach provides a deeper molecular understanding:

- Genomics: Vector Copy Number (VCN) analysis via ddPCR is a standard safety and dosing metric, while T-cell receptor (TCR) sequencing assesses repertoire diversity, a factor linked to clinical efficacy [17] [18].

- Epigenomics: Assays like ATAC-seq and ChIP-seq characterize chromatin accessibility and transcription factor binding, revealing the epigenetic programs that underlie cell differentiation states and potency [17] [18].

- Transcriptomics: Bulk and single-cell RNA-seq identify expression patterns and transcriptional regulators of stemness, allowing for the discovery of novel potency biomarkers [11] [13].

- Metabolomics: Tools like the Seahorse XF Analyzer probe real-time cellular metabolism, as metabolic states such as cholesterol and unsaturated fatty acid synthesis are strongly linked to multipotency [11] [18].

Detailed Experimental Protocols for Key Assays

To ensure reproducibility and rigor in potency assessment, below are detailed methodologies for two cornerstone experiments: computational prediction of developmental potential and functional validation of T-cell potency.

Protocol 1: Predicting Developmental Potential with CytoTRACE 2 This protocol outlines the use of the CytoTRACE 2 algorithm to analyze scRNA-seq data and predict the developmental potency of individual cells [11].

- Input Data Preparation: Prepare a count matrix (genes x cells) from your scRNA-seq pipeline in a standard format, such as an AnnData object for use with Scanpy in Python.

- Model Application: Run the CytoTRACE 2 algorithm on the preprocessed data. The model's Gene Set Binary Network (GSBN) architecture will assign binary weights to genes to identify highly discriminative gene sets for each potency category.

- Output Interpretation: The algorithm generates two primary outputs for each cell:

- Potency Category: The discrete potency state (e.g., pluripotent, multipotent, differentiated) with the maximum likelihood.

- Potency Score: A continuous value from 1 (highest potency, totipotent) to 0 (lowest potency, differentiated).

- Score Smoothing: To account for transcriptional noise, CytoTRACE 2 employs Markov diffusion combined with a nearest-neighbor approach to smooth individual cell potency scores, producing a more robust trajectory.

- Validation: Correlate the CytoTRACE 2 predictions with known developmental timelines or functional assay outcomes to validate the biological relevance of the predicted potency ordering.

The following diagram illustrates the core workflow and architecture of the CytoTRACE 2 analysis pipeline.

Protocol 2: A Multi-Omics Potency Assay for CAR T-Cell Products This integrated protocol assesses the potency of chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cells by combining genomic, functional, and metabolic readouts [17] [18].

Genomic Quality Control:

- Vector Copy Number (VCN): Quantify the average number of CAR vectors integrated per cell using droplet digital PCR (ddPCR). This is a critical safety and lot-release test.

- TCR Repertoire Diversity: Perform single-cell V(D)J RNA sequencing on the infusion product to assess the clonality and diversity of the T-cell population, which is associated with persistence and efficacy.

Functional Potency Assay:

- Co-culture Setup: Co-culture CAR T-cells with antigen-positive target cells at a standardized effector-to-target ratio (e.g., 1:1, 5:1) for a defined period (e.g., 24 hours).

- Cytokine Measurement: Collect the supernatant and use a multiplex immunoassay (e.g., Luminex) or ELISA to quantify the secretion of key effector cytokines like IFN-γ, TNF-α, and IL-2.

- Cytotoxicity Analysis: Measure specific lysis of target cells using a real-time cell death assay (e.g., impedance-based) or flow cytometry with a viability dye.

Metabolic Profiling:

- Utilize a Seahorse XF Analyzer to perform a Mitochondrial Stress Test and a Glycolysis Stress Test on the CAR T-cells.

- Key parameters like basal respiration, maximal respiration, and glycolytic capacity provide a readout of the cells' metabolic fitness, which is tightly linked to their long-term in vivo potency.

Visualizing the Molecular Basis of Stemness

The core signaling pathways and genetic regulators that maintain stemness are primary targets for potency assessment. Research has identified a core network of transcription factors and pathways that are essential for maintaining stemness in mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), which are widely used in clinical trials [13]. Key regulators include TWIST1, which suppresses senescence genes like p16; OCT4, which promotes proliferation and inhibits differentiation; and SOX2, which helps maintain an undifferentiated state. Furthermore, pathways like cholesterol and unsaturated fatty acid (UFA) metabolism have been empirically validated as positive correlates of multipotency [11].

The following diagram maps these key molecular relationships that underpin stem cell potency.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

A successful potency assessment strategy relies on a suite of reliable reagents and tools. The table below lists key materials and their functions in this field.

| Research Reagent / Material | Function in Potency Assessment |

|---|---|

| ddPCR Assay Kits [17] [18] | Precisely quantify Vector Copy Number (VCN) for genetically modified cell products (e.g., CAR T-cells). |

| Multiplex Cytokine Panels [17] | Simultaneously measure multiple cytokines (e.g., IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-2) from supernatant to evaluate functional immune cell activation. |

| Seahorse XF Assay Kits [17] [18] | Probe cellular metabolic phenotypes in real-time, providing data on mitochondrial respiration and glycolysis. |

| Chromatin Accessibility Kits [17] [18] | Enable epigenomic profiling via methods like ATAC-seq to reveal differentiation states and regulatory landscapes. |

| Validated Antibody Panels [17] [13] | Detect key stemness (e.g., OCT4, SOX2, NANOG) and differentiation markers via flow cytometry or CyTOF. |

| scRNA-seq Library Preps [11] [14] | Generate sequencing libraries from single cells to analyze transcriptional heterogeneity and predict potency. |

The path to reliable and effective regenerative medicines is paved with rigorous potency assessment. As this article outlines, a siloed approach is no longer sufficient. The future lies in integrated strategies that combine the predictive power of interpretable AI tools like CytoTRACE 2, the rich descriptive power of multi-omics profiling, and the definitive functional readouts of classical biological assays [11] [12] [17]. Adopting this comprehensive framework is the biological imperative that will ensure cellular therapies are not only well-characterized and consistent but also clinically potent, ultimately fulfilling their promise to patients.

In stem cell research, accurately assessing cellular potency—the ability of a cell to differentiate into various lineages—is paramount. This process is fundamentally complicated by cellular heterogeneity, the natural variation in gene expression between individual cells, even within a supposedly pure population. For decades, bulk RNA sequencing (bulk RNA-seq) has been a standard tool for transcriptome analysis. However, its limitation in resolving cellular diversity presents a significant challenge, which single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) is uniquely positioned to address. This guide objectively compares these two approaches within the context of stem cell potency research, detailing how heterogeneity impacts data interpretation and outlining robust experimental solutions.

The Fundamental Limitation of Bulk Sequencing

Bulk RNA-seq analyzes the transcriptome of a population of cells, producing an average gene expression profile for the entire sample [19]. Imagine listening to a large choir from a distance; you hear the collective sound but cannot distinguish the individual voices. Similarly, in a heterogeneous sample of stem cells at different potency stages, bulk RNA-seq measures the average expression level of each gene across all cells [19] [20].

This averaging effect has critical consequences for potency assessment:

- Masking Rare Populations: Crucial, rare cell types—such as a small subpopulation of highly potent stem cells driving regeneration or a group of drug-resistant cancer stem cells—are often invisible in bulk data. Their distinct gene expression signatures are diluted by the signals from the more abundant cell types [19] [20].

- Obscuring Dynamic Transitions: Stem cell differentiation is not a synchronized process. Bulk RNA-seq cannot capture the continuous spectrum of transitional states that cells pass through, failing to reveal the true trajectory of cellular fate decisions [21].

The following table summarizes the core differences between bulk and single-cell RNA-seq approaches in the face of heterogeneity.

| Feature | Bulk RNA-seq | Single-Cell RNA-seq |

|---|---|---|

| Resolution | Population average [19] | Individual cells [19] |

| Impact of Heterogeneity | Averages out differences, masking rare cells and states [19] | Reveals and characterizes differences, identifying rare cells and continuous states [21] [20] |

| Key Use Cases in Potency | Comparing average expression between defined sample groups (e.g., diseased vs. healthy) [19] | Identifying novel stem cell subtypes, reconstructing differentiation lineages, quantifying potency of individual cells [21] [22] [23] |

| Cost & Throughput | Lower cost per sample; simpler analysis [19] [24] | Higher cost per cell; more complex data and analysis [19] [24] |

| Ideal for Potency Assessment | No, due to lack of resolution. | Yes, enables direct in-silico potency estimation of each cell [22]. |

Single-Cell Solutions for Direct Potency Quantification

Single-cell technologies overcome the heterogeneity challenge by barcoding and sequencing the transcriptomes of thousands of individual cells in parallel [19] [20]. This allows researchers to move from a blurred average to a high-resolution census of all cell states present.

A powerful computational method derived from scRNA-seq data is signaling entropy, a robust metric for estimating the differentiation potential of a single cell [22]. This model posits that a pluripotent stem cell, capable of choosing any lineage, exhibits high signaling promiscuity or entropy. In contrast, a differentiated cell has committed to a specific fate, resulting in lower, more focused signaling activity [22].

The following diagram illustrates the core conceptual framework of signaling entropy for assessing cellular potency.

Experimental Validation of Signaling Entropy

The validity of signaling entropy as a potency measure is well-documented. In a landmark study analyzing over 1,000 single cells, pluripotent human embryonic stem cells (hESCs) showed the highest signaling entropy values. As cells differentiated into progenitors (e.g., neural, endoderm) and further into terminally differentiated cells (e.g., fibroblasts), entropy values decreased significantly and consistently [22]. The method successfully discriminated pluripotent from non-pluripotent cells with an exceptional area under the curve (AUC) of 0.96 [22].

This approach has been validated across diverse systems, including:

- Time-course differentiation: Tracking hESCs as they differentiate into definite endoderm, revealing a sharp drop in entropy around 3-4 days post-induction, aligning with known commitment timelines [22].

- Cancer stem cells: Identifying drug-resistant cancer stem-cell phenotypes within tumors, including those derived from circulating tumor cells [22].

Experimental Protocols for Stem Cell Potency Assessment

For researchers aiming to implement these approaches, below is a comparative overview of key experimental workflows.

Protocol 1: Bulk RNA-seq for Population-Level Analysis

Bulk RNA-seq remains a valid tool for specific, non-heterogeneity-focused applications. The protocol involves digesting the entire tissue or cell population to extract total RNA, followed by conversion to cDNA and the preparation of a sequencing library. The final data represents a composite, average gene expression profile for the entire sample [19]. This method is suitable for comparing gross transcriptional differences between well-defined sample groups but cannot deconvolve cellular heterogeneity.

Protocol 2: Single-Cell RNA-seq for Resolving Heterogeneity

The scRNA-seq workflow is designed to capture and preserve cell-to-cell differences [19] [24].

- Generation of Single-Cell Suspension: The tissue of interest is dissociated into a viable suspension of single cells through enzymatic or mechanical means. This is a critical step that requires optimization to minimize stress-induced transcriptional artifacts [19] [24].

- Single-Cell Partitioning and Barcoding: Single cells are isolated into individual reaction vessels. In droplet-based systems (e.g., 10x Genomics), cells are partitioned into oil-based droplets (GEMs) together with barcoded beads. Each bead contains millions of oligonucleotides with a unique cell barcode (to tag all RNAs from one cell) and a unique molecular identifier (UMI) to count individual mRNA molecules accurately [19] [20].

- Library Preparation and Sequencing: Within each droplet, cells are lysed, and mRNA is reverse-transcribed into barcoded cDNA. The cDNA is then pooled for sequencing library preparation and ultimately sequenced [19].

The following diagram contrasts the key stages of both experimental workflows.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms

Selecting the right tools is critical for a successful single-cell study. The table below lists key solutions and their functions in the context of stem cell research.

| Tool / Reagent | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| 10x Genomics Chromium | A widely adopted droplet-based microfluidics system for partitioning single cells, barcoding their RNA, and preparing sequencing libraries [19] [20]. |

| Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting (FACS) | Used to sort live or fixed cells based on specific surface markers (e.g., stem cell markers), enriching for target populations before scRNA-seq library preparation [21] [24]. |

| Enzymatic Dissociation Mix | A cocktail of enzymes (e.g., collagenase, trypsin) tailored to specific tissues to break down extracellular matrix and generate high-quality single-cell suspensions with high viability [19] [24]. |

| Viability Stains | Dyes used to distinguish and remove dead cells from the suspension, which is crucial for reducing background noise in scRNA-seq data [24]. |

| Single Cell Multiplexing Kit | Reagents that allow sample barcoding, enabling the pooling of multiple samples in a single scRNA-seq run to reduce batch effects and per-sample costs [19]. |

| SCENT Algorithm | A computational tool (Single-Cell Entropy) that uses scRNA-seq data and a protein interaction network to compute signaling entropy and estimate the differentiation potency of individual cells [22]. |

| Sotuletinib dihydrochloride | Sotuletinib dihydrochloride, CAS:2222138-40-9, MF:C20H24Cl2N4O3S, MW:471.4 g/mol |

| (S)-Sunvozertinib | (S)-Sunvozertinib, MF:C29H35ClFN7O3, MW:584.1 g/mol |

Cellular heterogeneity is not a minor complication but a central feature of stem cell biology that fundamentally limits the utility of bulk RNA-seq for potency assessment. By averaging the transcriptome, bulk approaches obscure the very cellular diversity that drives fate decisions, masking rare stem cell populations and critical transitional states. Single-cell RNA sequencing, coupled with advanced computational metrics like signalling entropy, directly addresses this heterogeneity challenge. It transforms the "blurred average" into a precise, high-resolution map of cellular states, enabling accurate quantification of potency at the individual cell level. For researchers focused on stem cell potency, embracing single-cell technologies is no longer optional but essential for generating biologically accurate and impactful insights.

Pluripotency, the capacity of a cell to differentiate into all derivatives of the three primary germ layers, represents a foundational concept in developmental biology and regenerative medicine. The transcription factors OCT4, SOX2, and NANOG form the core of the pluripotency gene regulatory network (PGRN), governing the delicate balance between self-renewal and differentiation in embryonic stem cells (ESCs) and induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs). With the advent of single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq), our understanding of this network has transformed from a static circuitry to a dynamic, heterogeneous system.

Recent advances in single-cell technologies have revealed unprecedented details about how these factors operate within complex cell populations. The development of sophisticated computational tools like CytoTRACE 2, an interpretable deep learning framework that predicts developmental potential from scRNA-seq data, has enabled researchers to decode the hierarchical organization of cellular potency from totipotency to fully differentiated states [11]. This technological evolution provides the context for reassessing the specific roles, interactions, and regulatory relationships between OCT4, SOX2, and NANOG—an assessment crucial for both basic developmental biology and applied stem cell research.

Molecular Profiles and Expression Dynamics of Core Pluripotency Factors

Defining Characteristics and Expression Patterns

The core pluripotency transcription factors, though often discussed as a unified network, exhibit distinct expression patterns and molecular characteristics that underlie their specialized functions.

Table 1: Core Pluripotency Transcription Factors: Characteristics and Expression Patterns

| Marker | Gene Name | Protein Type | Pre-implantation Expression | Post-implantation Expression | Key Regulatory Role |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OCT4 | POU5F1 | POU-domain transcription factor | All cells of compacted morulae; maintained in ICM | Widely expressed in epiblast | Master regulator of pluripotency; essential for ICM formation |

| SOX2 | SOX2 | HMG-box transcription factor | First expressed in inside cells of morula; marks ICM precursors | Becomes restricted to anterior epiblast; repressed by NANOG in posterior epiblast | Partners with OCT4; essential for establishing pluripotent state |

| NANOG | NANOG | Homeobox transcription factor | Co-expressed with SOX2 in ICM | Segregated from SOX2; high in posterior epiblast | Guardian of pluripotency; promotes self-renewal; represses differentiation |

OCT4 (encoded by POU5F1) exhibits one of the most consistent expression profiles across early development. It is expressed in all cells of the compacted morula and becomes restricted to the inner cell mass (ICM) as the blastocyst forms [25]. In the post-implantation embryo, OCT4 remains widely expressed throughout the epiblast, even as other core factors demonstrate regional specificity [26]. This persistent expression suggests OCT4 plays fundamental roles beyond initial pluripotency establishment.

SOX2 expression initiates slightly later than OCT4, first appearing in the inside cells of the morula, making it one of the earliest markers distinguishing inner from outer cells [25]. This spatially restricted expression pattern foreshadows its complex post-implantation dynamics, where it becomes repressed in the posterior epiblast by NANOG—a surprising regulatory relationship that contrasts with their cooperative function in pre-implantation stages [26].

NANOG demonstrates the most dynamic expression pattern of the three factors. In pre-implantation embryos, NANOG and SOX2 protein levels positively correlate, but following implantation, NANOG protein becomes undetectable at E5.5 before re-emerging with a striking anticorrelated relationship to SOX2 as gastrulation approaches [26]. This expression segregation occurs before primitive streak formation, suggesting NANOG's role extends beyond pluripotency maintenance to facilitating the onset of differentiation in specific embryonic regions.

Functional Interdependence and Regulatory Relationships

The functional relationships between these factors form a complex network of interdependence, cooperation, and context-dependent regulation. In the early ICM, OCT4 and SOX2 gradually establish a cooperative relationship, activating pluripotency-related genes through composite OCT-SOX enhancers [25]. This cooperativity is essential for the substantial reorganization of the chromatin landscape and transcriptome that occurs during the transition to the pluripotent epiblast state.

However, this cooperative relationship appears to be stage-specific. Recent research has revealed that in post-implantation development, NANOG actually represses SOX2 expression in the posterior epiblast, creating a NANOG-high/SOX2-low region that precociously loses pluripotency [26]. This repression is functionally significant—embryos with post-implantation deletion of Nanog maintain posterior SOX2 expression, suggesting that one of NANOG's key roles during this stage is to actively extinguish the pluripotent state in specific regions through SOX2 repression.

The sensitivity of this network to dosage is further highlighted by research on NANOG enhancers in human ESCs. Deletion of a single copy of specific NANOG enhancers significantly reduces NANOG expression, compromising self-renewal and increasing differentiation propensity [27]. This dosage sensitivity underscores the precision required in the regulatory relationships between these core factors.

Experimental Assessment of Pluripotency Markers

Methodologies for Marker Analysis

Accurate assessment of pluripotency markers requires sophisticated methodological approaches, each with distinct advantages and limitations in specificity, sensitivity, and throughput.

Table 2: Methodologies for Assessing Pluripotency Markers

| Methodology | Key Applications | Advantages | Limitations | Example Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single-cell RNA-seq | Transcriptome-wide profiling of pluripotency networks; heterogeneity assessment | Reveals cellular heterogeneity; identifies novel subpopulations | High dropout rates; technical noise | CytoTRACE 2 identifies potency gradients from scRNA-seq data [11] |

| Low-input ATAC-seq | Chromatin accessibility mapping in limited cell numbers (e.g., early embryos) | Identifies regulatory elements; reveals transcription factor binding | Requires specialized protocols; limited by cell number | Revealed OCT4/SOX2 co-binding at enhancers in early ICM [25] |

| Long-read transcriptome sequencing | Comprehensive isoform characterization; novel gene discovery | Detects full-length transcripts; identifies novel isoforms | Higher error rate than short-read; computationally intensive | Identified 172 genes linked to cell states not covered by current guidelines [28] |

| Immunofluorescence/Flow Cytometry | Protein-level validation; spatial localization in embryos and colonies | Single-cell resolution; quantitative protein data | Limited by antibody specificity and availability | Revealed anticorrelated NANOG/SOX2 protein expression in epiblast [26] |

Single-cell RNA sequencing has emerged as particularly transformative for pluripotency research. Optimized workflows for stem cells, such as those developed for hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells (HSPCs), emphasize careful cell sorting, library preparation, and quality control to ensure biologically meaningful results [29]. These technical refinements are crucial given the unique transcriptional profiles of stem cells and the critical importance of capturing rare subpopulations.

The computational interpretation of scRNA-seq data has similarly advanced. CytoTRACE 2 represents a significant evolution in potency prediction, employing a gene set binary network (GSBN) architecture that assigns binary weights (0 or 1) to genes, identifying highly discriminative gene sets that define each potency category [11]. This interpretable deep learning approach outperforms previous methods in predicting developmental hierarchies and has confirmed the premier importance of established pluripotency factors, with Pou5f1 and Nanog ranking within the top 0.2% of pluripotency genes identified by the algorithm [11].

Standardized Differentiation Assays and Marker Validation

Pluripotency testing faces significant challenges in standardization, with researchers choosing between various methods and markers without established thresholds or reporting guidelines [28]. Common assessment methods include:

- Embryoid Body (EB) Formation: Spontaneous differentiation in 3D aggregates; cost-effective but stochastic

- Teratoma Assay: In vivo differentiation in immunocompromised mice; considered gold standard but ethically concerning and variable

- Directed Trilineage Differentiation: Defined media driving specific germ layer fate; potentially more standardized but protocol-dependent

Recent reassessment of marker genes using long-read nanopore transcriptome sequencing has identified significant limitations in current marker recommendations. Many traditionally recommended markers show overlapping expression patterns between germ layers, complicating unambiguous cell state identification [28]. For instance, GDF3 shows considerable overlap between undifferentiated iPSCs and endoderm, while SOX2 overlaps between undifferentiated iPSCs and ectoderm [28].

This work has validated 12 genes as unique markers for specific cell fates, including NANOG for pluripotency, with the development of a machine learning-based scoring system ("hiPSCore") that accurately classifies pluripotent and differentiated cells and predicts their differentiation potential [28]. Such approaches address the critical need for standardized, quantitative assessment tools in pluripotency research.

Regulatory Networks and Signaling Pathways

The core pluripotency transcription factors do not operate in isolation but within complex regulatory circuits that maintain the balance between self-renewal and differentiation. The following diagram illustrates the dynamic regulatory relationships between OCT4, SOX2, and NANOG across developmental stages:

Diagram 1: Dynamic Regulatory Relationships Between Core Pluripotency Factors. The network transitions from cooperative activation pre-implantation to antagonistic relationships post-implantation, with NANOG repressing SOX2 in the posterior epiblast.

The regulatory dynamics extend beyond the core transcription factors to include signaling pathways that modulate their expression and activity. Key pathways include:

- TGF-β/Activin A Signaling: Promotes NANOG expression and maintains pluripotency in human ESCs; inhibited by SB 431542 [30]

- Wnt/β-catenin Signaling: Supports self-renewal through regulation of target genes; enhanced by CHIR 99021 (GSK-3 inhibitor) [30]

- ERK Signaling: Promotes differentiation; inhibited by PD0325901 (MEK inhibitor) to maintain ground-state pluripotency [25]

The experimental workflow for analyzing these relationships in stem cell biology typically involves integrated genomic and functional approaches:

Diagram 2: Integrated Experimental Workflow for Pluripotency Research. Combined genomic and functional approaches enable comprehensive characterization of pluripotency networks.

Research Reagents and Experimental Tools

Contemporary research on pluripotency markers relies on specialized reagents and tools that enable precise manipulation and measurement of the core regulatory network.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Pluripotency Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Small Molecule Inhibitors | Y-27632 (ROCK inhibitor), SB 431542 (TGF-βRI inhibitor), CHIR 99021 (GSK-3 inhibitor) | Modulate signaling pathways to control self-renewal vs. differentiation | Improves stem cell survival after freezing; enables reprogramming; directs differentiation [30] |

| Cell Surface Markers | SSEA-3, SSEA-4, TRA-1-60, TRA-1-81, CD34, CD133 | Identification and isolation of specific stem cell populations by FACS | Enrichment of hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells; purification of pluripotent populations [31] [29] |

| CRISPR Tools | CRISPRi screens, enhancer deletion constructs | Functional validation of regulatory elements | Identified essential NANOG enhancers in hESCs; validated OCT4/SOX2 co-binding sites [27] [25] |

| scRNA-seq Reagents | Chromium Next GEM Chip G Single Cell Kit, Gel Bead kits | High-throughput single-cell transcriptome profiling | Analysis of hematopoietic stem cell heterogeneity; potency prediction [11] [29] |

The selection of appropriate cell surface markers requires special consideration between species. While human pluripotent stem cells express SSEA-3 and SSEA-4, mouse embryonic stem cells express SSEA-1 but not SSEA-3/4 [31]. These carbohydrate antigens, while useful for identification and isolation, are not exclusive to pluripotent cells and should be interpreted with caution—none serve as definitive proof of pluripotency alone [31].

Small molecule inhibitors have become indispensable for controlling stem cell states. Y-27632, a selective ROCK inhibitor, significantly improves the survival of human embryonic stem cells after cryopreservation [30]. CHIR 99021 enables reprogramming of fibroblasts into iPSCs by inhibiting GSK-3 and activating Wnt signaling, while SB 431542 induces proliferation and differentiation of ESC-derived endothelial cells through TGF-β pathway inhibition [30]. These tools provide precise temporal control over signaling pathways that modulate the core pluripotency network.

The integration of single-cell technologies with computational approaches has revealed unprecedented complexity in the pluripotency network. Rather than a static circuit, we now understand the OCT4/SOX2/NANOG axis as a dynamic system whose regulatory relationships evolve across developmental stages. The surprising finding that NANOG represses SOX2 in the posterior epiblast to facilitate loss of pluripotency underscores this dynamic nature [26].

Future research directions will likely focus on several key areas: First, understanding how the dosage sensitivity of these factors and their enhancers [27] contributes to developmental precision and how perturbations lead to disease states. Second, leveraging long-read sequencing technologies [28] to discover previously overlooked markers and regulatory relationships. Third, integrating multi-omics data across temporal and spatial dimensions to build predictive models of cell fate decisions.

For researchers and drug development professionals, these advances translate to more refined tools for quality control—such as the hiPSCore scoring system [28]—and more precise manipulation of stem cell states for therapeutic applications. As single-cell technologies continue to evolve, so too will our understanding of the fundamental regulators that orchestrate the remarkable phenomenon of pluripotency.

scRNA-seq in Action: Techniques and Computational Tools for Potency Analysis

Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has fundamentally transformed biological research by enabling the resolution of cellular heterogeneity at an unprecedented resolution, moving beyond the limitations of bulk RNA sequencing which obscures critical differences between individual cells [32]. This technological evolution is particularly crucial for stem cell potency assessment research, where understanding the transcriptomic landscape of individual cells is paramount for quantifying differentiation potential and functional plasticity [22] [33]. The ability to quantify differentiation potency at a single-cell level represents a task of critical importance for developmental biology, regenerative medicine, and therapeutic discovery [22].

Over the past decade, scRNA-seq methodologies have diversified into two primary categories: full-length transcript methods like Smart-seq2 that provide superior gene coverage, and high-throughput droplet-based systems that enable massive parallelization for analyzing thousands of cells simultaneously [34] [32]. This guide provides an objective comparison of core scRNA-seq platforms, focusing on their performance characteristics, technical requirements, and applicability for stem cell potency research, supported by experimental data from systematic benchmarking studies.

Core scRNA-seq Platform Comparisons

Comprehensive Performance Metrics

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Major scRNA-seq Methods

| Method | Throughput | Genes/Cell | UMIs | Key Strengths | Key Limitations | Cost Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Smart-seq2 | Low (96-384 cells) | Highest (~8,000) [35] | No [34] | Full-length transcript coverage; superior sensitivity [36] [35] | Not strand-specific; transcript length bias [37] | Less efficient for large cell numbers [34] |

| CEL-seq2 | Medium | Medium | Yes [34] | Reduced amplification noise [34] | Lower sensitivity than Smart-seq2 [34] | Cost-effective for intermediate throughput [34] |

| Drop-seq | High (thousands of cells) | Medium | Yes [34] | High cell throughput; cost-effective [34] | Lower genes/cell than Smart-seq2 [34] | Most cost-effective for large numbers [34] |

| 10X Genomics | High (thousands of cells) | Medium (1,000-5,000) [32] | Yes [32] | Optimized workflow; high cell capture efficiency (65-75%) [32] | mRNA capture efficiency 10-50% [32] | Higher per-cell cost than alternatives [32] |

| MARS-seq | High | Medium | Yes [34] | Quantified mRNA with less amplification noise [34] | - | Efficient for fewer cells [34] |

| FLASH-seq | Medium | High (more than Smart-seq3) [35] | Optional [35] | Fast protocol (~4.5 hours); high sensitivity [35] | Newer method with less established track record [35] | - |

| smRandom-seq | High (single microbes) | ~1,000 (E. coli) [38] | Yes [38] | Applicable to bacteria; high species specificity (99%) [38] | Specialized for microbial applications [38] | - |

Recent Methodological Advancements

Table 2: Emerging scRNA-seq Methods and Features

| Method | Year | Key Innovation | Detected Features | Transcriptome Diversity | Strand Invasion Reduction |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FLASH-seq | 2022 | Combined RT-PCR; SSRTIV enzyme [35] | Highest in HEK293T cells [35] | Captures more diverse isoforms [35] | Yes (riboguanosine replaces LNA) [35] |

| Smart-seq3 | 2020 | UMI incorporation [35] | High | Good isoform detection [35] | Limited (strand invasion issues) [35] |

| VASA-seq | 2023 | Whole transcriptome coverage [39] | High metrics [39] | - | - |

| HIVE | 2023 | - | Good results with no automation [39] | - | - |

Systematic comparisons of scRNA-seq methods reveal that bulk transcriptome sequencing still detects more unique transcripts than any single-cell method, highlighting an inherent limitation of current scRNA-seq technologies [39]. However, newer methods like FLASH-seq and VASA-seq demonstrate superior performance metrics, including increased feature detection, suggesting that methodological development continues to advance the field substantially [39] [35]. Notably, a 2023 benchmarking study comparing eight methods concluded that older methods should be phased out in favor of these more recent developments that offer improved performance characteristics [39].

Technical Protocols and Workflows

Full-Length Transcript Protocols

The Smart-seq2 protocol represents a foundational method for full-length scRNA-seq and involves a detailed workflow that takes approximately 2 days from cell picking to final library preparation [36]. The methodology begins with cell lysis in a buffer containing dNTPs and oligo(dT)-tailed oligonucleotides with a universal 5'-anchor sequence [37]. Reverse transcription is performed using template-switching oligos (TSO) carrying riboguanosines and a modified guanosine to produce a locked nucleic acid (LNA) [37]. After first-strand synthesis, cDNA is amplified using a limited number of cycles, followed by tagmentation to construct sequencing libraries efficiently [37]. While this method provides excellent sensitivity and full-length coverage across transcripts, it lacks strand specificity and cannot detect non-polyadenylated RNA [36].

FLASH-seq (FS) represents a significant evolution of the SMART-seq protocol, reducing hands-on time to approximately 4.5 hours while maintaining high sensitivity [35]. Key modifications include combining reverse transcription and cDNA preamplification into a single step, replacing Superscript II with the more processive Superscript IV reverse transcriptase, and shortening the RT reaction time [35]. Additionally, FLASH-seq increases the amount of dCTP to favor C-tailing activity of the reverse transcriptase and replaces the 3'-terminal locked nucleic acid guanidine in the TSO with riboguanosine to reduce strand-invasion artifacts [35]. The method can be miniaturized to 5-μl reaction volumes, reducing reagent costs while maintaining efficiency, and can proceed directly to tagmentation without intermediate purification steps in the FS-LA (low amplification) variant [35].

Droplet-Based High-Throughput Workflows

Droplet-based scRNA-seq methods, such as the 10X Genomics Chromium system, utilize sophisticated microfluidic technology to partition individual cells into nanoliter-scale droplets [32]. The process begins with preparation of a high-quality single-cell suspension optimized for concentration (700-1,200 cells/μL) and viability (>85%) [32]. As this suspension passes through precisely engineered microfluidic channels, it merges with barcoded gel beads and partitioning oil to generate monodisperse droplets [32]. Within each droplet, cell lysis releases mRNA that binds to the bead's oligo(dT) primers, followed by reverse transcription to produce cDNA molecules tagged with unique cellular identifiers and unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) [32]. This elegant barcoding strategy enables subsequent computational deconvolution of pooled sequencing data while accounting for amplification biases through molecular counting [32].

The smRandom-seq protocol adapts droplet-based technology for bacterial single-cell RNA sequencing, which presents unique challenges since bacterial mRNAs lack poly(A) tails [38]. This method fixes bacteria with paraformaldehyde, permeabilizes them, then uses random primers with a PCR handle to capture total RNAs through multiple temperature cycling [38]. After in situ cDNA conversion, poly(dA) tails are added to the 3' hydroxyl terminus of the cDNAs by terminal transferase, creating a binding site for the poly(T) barcoded beads used in droplet encapsulation [38]. The method incorporates CRISPR-based rRNA depletion to dramatically reduce rRNA percentage from 83% to 32%, significantly enriching mRNA reads for sequencing [38].

Experimental Visualization of Methodologies

scRNA-seq Workflow Diagram

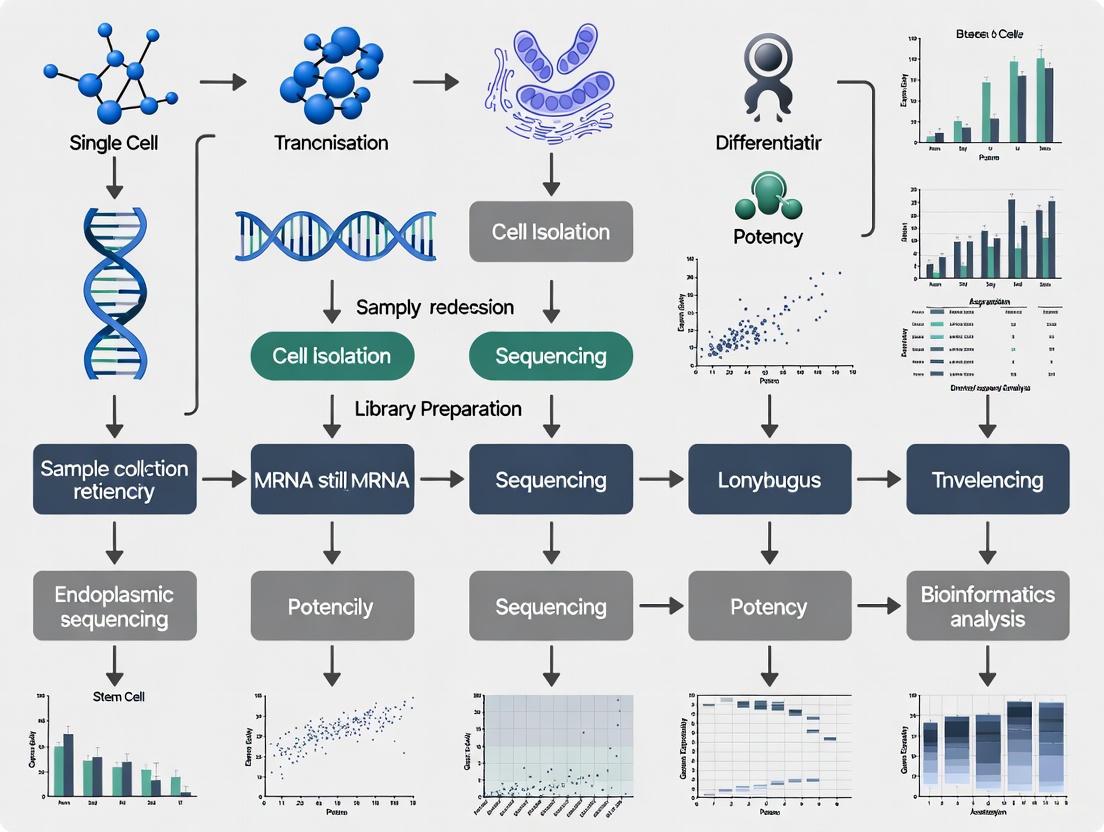

Figure 1: Core scRNA-seq Experimental Workflow. This diagram illustrates the generalized workflow for single-cell RNA sequencing, highlighting key methodological variations between platforms. Common steps include single-cell suspension preparation, microfluidic partitioning, cell lysis with mRNA capture, cDNA synthesis with barcoding, amplification, library preparation, sequencing, and bioinformatic analysis. Method-specific variations occur primarily during the mRNA capture and barcoding steps, with different platforms utilizing poly(dT) primers (10X Genomics, Drop-seq), random primers (smRandom-seq), or template switching (Smart-seq2, FLASH-seq). Additional variations include the incorporation of UMIs for reducing amplification noise and CRISPR-based rRNA depletion for enhancing microbial transcriptome analysis [36] [38] [35].

Stem Cell Potency Assessment Framework

Figure 2: Signaling Entropy Framework for Potency Assessment. This diagram illustrates the computational framework for estimating stem cell differentiation potency using scRNA-seq data through signaling entropy analysis. The method integrates single-cell transcriptomic profiles with protein-protein interaction networks to construct a cell-specific stochastic matrix representing signaling probabilities [22]. The entropy rate of this network-based signaling process quantifies the differentiation potential of individual cells, with pluripotent cells exhibiting high entropy (signaling promiscuity) and differentiated cells showing low entropy (focused signaling) [22]. This approach provides a robust, quantitative potency metric that correlates strongly with established pluripotency signatures and can accurately discriminate between pluripotent and differentiated cell states without requiring feature selection [22].

Research Reagent Solutions Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for scRNA-seq Experiments

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function | Method Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reverse Transcriptases | Superscript II, Superscript IV [35] | cDNA synthesis from RNA templates | Smart-seq2, FLASH-seq |

| Template-Switching Oligos | TSO with riboguanosines [35] [37] | Enable full-length cDNA amplification | Smart-seq2, Smart-seq3, FLASH-seq |

| Barcoded Beads | 10X Gel Beads [32] | Cellular barcoding and mRNA capture | 10X Genomics, Drop-seq |

| Unique Molecular Identifiers | UMI-containing primers [34] [38] | Quantitative mRNA counting | CEL-seq2, Drop-seq, MARS-seq, 10X |

| Cell Lysis Reagents | Specific buffers with dNTPs [37] | Cell membrane disruption and RNA stabilization | Smart-seq2, Droplet methods |

| cDNA Amplification Kits | PCR master mixes with optimized cycles [36] | cDNA library amplification | All full-length methods |

| Library Preparation Kits | Tagmentation enzymes [35] | Sequencing library construction | Smart-seq2, FLASH-seq |

| rRNA Depletion Reagents | CRISPR-based depletion systems [38] | Microbial mRNA enrichment | smRandom-seq |

| Microfluidic Chips | 10X Chromium Chip [32] | Single-cell partitioning | 10X Genomics, Drop-seq |

| NAMPT inhibitor-linker 2 | NAMPT inhibitor-linker 2, MF:C34H33FN6O5, MW:624.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| BLI-489 hydrate | BLI-489 hydrate, MF:C13H12N3NaO5S, MW:345.31 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Application to Stem Cell Potency Research

The application of scRNA-seq platforms to stem cell potency assessment represents a particularly powerful use case, with specific methodological considerations. Research demonstrates that signaling entropy - computed by integrating scRNA-seq data with protein-protein interaction networks - provides an excellent proxy for differentiation potential at the single-cell level [22]. This approach quantifies the degree of signaling promiscuity in a cell's transcriptome, with pluripotent cells exhibiting high entropy (reflecting equal probability of all lineage choices) and differentiated cells showing low entropy (reflecting commitment to specific lineages) [22].

Experimental validation across diverse cell types confirms the utility of this approach. In a study of 1,018 single-cell transcriptomes spanning pluripotent human embryonic stem cells (hESCs) and various progenitor cells, signaling entropy accurately discriminated pluripotent from non-pluripotent states with remarkable accuracy (AUC=0.96) [22]. Pluripotent hESCs consistently exhibited the highest signaling entropy values, followed by multipotent neural progenitors and definitive endoderm progenitors, with terminally differentiated fibroblasts showing the lowest values [22]. This method outperformed conventional pluripotency gene expression signatures, demonstrating particular strength in identifying varying degrees of potency beyond simple pluripotency classification [22].

For stem cell researchers selecting scRNA-seq platforms, full-length methods like Smart-seq2 and FLASH-seq offer advantages for potency assessment due to their superior sensitivity and ability to detect more genes per cell [34] [35]. This enhanced detection capability is particularly valuable for capturing the complex transcriptional landscape of pluripotent cells. However, for large-scale studies tracking differentiation trajectories across thousands of cells, droplet-based methods provide the necessary throughput to capture rare transitional states and heterogeneous subpopulations that emerge during stem cell differentiation [32].

The integration of scRNA-seq with functional genomics approaches further enhances its utility in stem cell research. CRISPR screening technologies coupled with scRNA-seq, such as Perturb-seq, enable systematic functional assessment of gene networks regulating pluripotency and differentiation [33]. These methods can identify key regulators of cell fate decisions by measuring transcriptomic responses to targeted perturbations across thousands of individual stem cells, providing unprecedented insight into the molecular mechanisms controlling potency and lineage specification [33].

The ability to assess a cell's developmental potential—its capacity to differentiate into other cell types—is fundamental to advancing stem cell research, developmental biology, and regenerative medicine. Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has transformed our ability to study cell fate decisions, but interpreting these complex data to determine cellular potency remains challenging [11]. Computational methods have emerged as essential tools for quantifying this potential, allowing researchers to move beyond descriptive analyses to predictive modeling of cellular hierarchies.

Two prominent computational frameworks for potency assessment are signaling entropy, a network-theoretical approach, and CytoTRACE 2, an interpretable deep learning framework. While both aim to quantify features of cellular potency, they differ fundamentally in their underlying principles, methodologies, and applications. Signaling entropy quantifies the uncertainty or randomness in cellular signaling networks by integrating gene expression data with protein interaction networks [40] [41]. In contrast, CytoTRACE 2 employs deep learning to predict absolute developmental potential directly from scRNA-seq data by learning multivariate gene expression programs associated with different potency states [11] [42]. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of these frameworks, enabling researchers to select appropriate tools for their specific experimental needs.

Theoretical Foundations and Methodologies

The CytoTRACE 2 Framework

CytoTRACE 2 is an interpretable deep learning framework designed to predict both potency categories and a continuous "potency score" from scRNA-seq data. Its development addressed key limitations of previous methods, including the inability to perform cross-dataset comparisons of cellular potency [11] [42]. The framework was trained on an extensive atlas of human and mouse scRNA-seq datasets with experimentally validated potency levels, spanning 33 datasets, nine platforms, 406,058 cells, and 125 standardized cell phenotypes [11].

The core innovation of CytoTRACE 2 is its Gene Set Binary Network (GSBN) architecture, which assigns binary weights (0 or 1) to genes, identifying highly discriminative gene sets that define each potency category [11]. This design provides two key advantages: (1) identification of interpretable gene programs driving potency predictions, and (2) generation of absolute potency scores calibrated from 1 (totipotent) to 0 (differentiated), enabling direct comparison across datasets and experimental conditions [11] [43].

The method further refines its predictions through Markov diffusion combined with a nearest neighbor approach to smooth individual potency scores based on the assumption that transcriptionally similar cells occupy related differentiation states [11]. This integrated approach allows CytoTRACE 2 to learn conserved biological principles of development while suppressing batch and platform-specific variations.

Signaling Entropy Framework

Signaling entropy adopts a network-theoretical framework based on statistical mechanical principles to quantify the uncertainty in cellular signaling pathways [40] [44]. This approach integrates scRNA-seq data with protein-protein interaction (PPI) networks to model signaling flows and compute entropy measures that reflect the complexity and variability of intracellular communication [41].

The fundamental premise of signaling entropy is that cellular potency correlates with signaling diversity. In Waddington's epigenetic landscape metaphor, cells with higher developmental potential occupy higher elevations with more possible differentiation paths, which corresponds to higher signaling entropy [41] [44]. As cells differentiate and their fate options become restricted, their signaling entropy decreases accordingly.

A key challenge in signaling entropy calculation is its dependence on the quality and completeness of PPI networks. Both experimental and computational methods for detecting molecular interactions are prone to false positives and false negatives, which can affect entropy measurements [41]. The framework requires careful selection of PPI databases—such as Pathway Commons, STRING, or BioGRID—and may involve correction strategies to mitigate the impact of spurious interactions.

Key Conceptual Differences

The table below summarizes the fundamental differences between these two computational frameworks:

| Feature | CytoTRACE 2 | Signaling Entropy |

|---|---|---|

| Theoretical Basis | Interpretable deep learning | Statistical mechanics & information theory |

| Core Principle | Learns gene expression programs from training data | Quantifies uncertainty in signaling networks |

| Primary Input | scRNA-seq expression matrix | scRNA-seq data + Protein-protein interaction network |

| Key Output | Absolute potency score (0-1) and discrete categories | Entropy rate (continuous measure) |

| Interpretability | High (identifies specific gene programs) | Moderate (depends on network topology) |

| Training Requirement | Requires pre-training on annotated datasets | does not require pre-training |

| Cross-Dataset Comparison | Directly supported through absolute scaling | Possible but dependent on network consistency |

Performance Comparison and Benchmarking

Experimental Design for Method Evaluation

Comprehensive benchmarking of CytoTRACE 2 against multiple computational strategies provides critical insights into their relative performance. The developers of CytoTRACE 2 established a rigorous evaluation framework using two complementary metrics: (1) "absolute order" comparing predictions to known potency levels across datasets, and (2) "relative order" ranking cells within each dataset from least to most differentiated [11]. Performance was quantified using weighted Kendall correlation to ensure balanced evaluation and minimize bias.

The benchmarking encompassed diverse biological systems, including 33 scRNA-seq datasets with experimentally validated potency levels, 62 developmental time points from mouse embryogenesis, and cancer datasets including acute myeloid leukemia and oligodendroglioma [11]. This diverse validation set ensured robust assessment of each method's generalizability across tissues, species, and experimental platforms.

Quantitative Performance Metrics

The table below summarizes the key performance metrics from comprehensive benchmarking studies:

| Performance Metric | CytoTRACE 2 | Signaling Entropy | Other Methods (Average) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Multiclass F1 Score (potency categorization) | 0.89 (median) | Not reported | 0.41-0.72 (range) |

| Mean Absolute Error (potency prediction) | 0.15 | Not reported | 0.31-0.58 (range) |

| Relative Ordering Correlation | 0.81 (mean) | Not reported | 0.50 (mean) |

| Absolute Ordering Correlation | 0.79 (mean) | Not reported | Not applicable |

| Cross-Dataset Generalizability | High (train-test AUC: 0.87-0.92) | Moderate (network-dependent) | Variable |

| Run-time Efficiency | ~2 minutes for 2,850 cells | Varies with network size | Method-dependent |

In direct comparisons, CytoTRACE 2 outperformed eight state-of-the-art machine learning methods for cell potency classification across 33 datasets, achieving a higher median multiclass F1 score and lower mean absolute error [11]. Additionally, it surpassed eight developmental hierarchy inference methods for both cross-dataset (absolute) and intra-dataset (relative) performance, demonstrating over 60% higher correlation on average for reconstructing relative orderings in 57 developmental systems [11].

Biological Validation

Beyond computational metrics, both methods have been validated against experimental gold standards. CytoTRACE 2 predictions were confirmed through multiple approaches:

CRISPR screen validation: The top 100 positive multipotency markers identified by CytoTRACE 2 were enriched for genes whose knockout promotes differentiation, while the top 100 negative markers were enriched for genes whose knockout inhibits differentiation (Q = 0.04) [11].

Pathway discovery: CytoTRACE 2 identified cholesterol metabolism and unsaturated fatty acid synthesis genes (Fads1, Fads2, Scd2) as key multipotency-associated pathways, which were experimentally validated via quantitative PCR on sorted mouse hematopoietic cells [11].

Cancer stem cell identification: In oligodendroglioma, CytoTRACE 2 correctly identified cells with known multilineage potential, highlighting its applicability to cancer biology [11].

Signaling entropy has similarly been validated through its ability to:

- Discriminate cells according to differentiation potential and cancer status [40]

- Correlate with drug resistance in cancer cell lines, where high signaling entropy correlates with robustness to therapeutic intervention [40] [44]

- Identify critical regulatory networks in disease models through differential entropy analysis [41]

Experimental Protocols and Implementation

CytoTRACE 2 Workflow Protocol

Implementing CytoTRACE 2 involves the following key steps:

Data Preparation: Format input data as a raw count matrix (cells × genes) with gene symbols as column names and cell identifiers as row names. The package supports both R and Python implementations [45].

Package Installation: Install the CytoTRACE 2 package using devtools in R:

Running Analysis: Execute the main function with default parameters:

Result Visualization: Generate plots integrating predictions with annotations:

For human data, users should specify species = "human" parameter. The method automatically handles normalization and preprocessing [45].

Signaling Entropy Calculation Protocol

The standard protocol for signaling entropy calculation involves:

Network Selection: Choose an appropriate protein-protein interaction network. Commonly used databases include Pathway Commons, STRING, and BioGRID, each with different coverage and confidence levels [41].

Data Integration: Map gene expression values onto the network nodes, creating a weighted network where edge weights reflect expression levels of interacting proteins.

Entropy Calculation: Compute local and global signaling entropy measures using random walk-based algorithms that quantify the uncertainty in information flow through the network [40] [44].

Validation and Correction: Apply correction strategies for false-positive interactions in the PPI networks to improve reliability. This may involve confidence filtering or integration of multiple database sources [41].

The signaling entropy framework is implemented in R and available from sourceforge.net/projects/signalentropy/files/ [44].

Research Reagent Solutions

The table below outlines essential computational tools and resources for implementing these potency assessment frameworks:

| Resource | Type | Function | Availability |

|---|---|---|---|

| CytoTRACE 2 Package | Software Tool | Predicts absolute developmental potential from scRNA-seq data | GitHub: digitalcytometry/cytotrace2 |

| Signaling Entropy Package | Software Tool | Calculates signalling entropy from expression and PPI data | sourceforge.net/projects/signalentropy/ |

| Pathway Commons | PPI Database | Curated protein-protein interactions for entropy calculations | pathwaycommons.org |

| STRING Database | PPI Database | Predictive and known protein interactions with confidence scores | string-db.org |

| BioGRID | PPI Database | Literature-curated molecular interactions | thebiogrid.org |

| Tabula Sapiens | Reference Data | Cross-tissue scRNA-seq atlas for validation | tabulasapiens.org |

| Pancreas Epithelium Data | Example Dataset | Mouse developmental dataset for testing methods | Provided in CytoTRACE 2 vignette |

Applications in Stem Cell and Cancer Research

Developmental Biology Applications

Both frameworks have proven valuable for reconstructing developmental hierarchies from scRNA-seq data. CytoTRACE 2 has successfully captured the progressive decline in potency across 258 phenotypes during mouse development without requiring data integration or batch correction [11]. It accurately reconstructed the temporal hierarchy of mouse embryogenesis across 62 timepoints, demonstrating superior performance compared to other methods [11] [46].

In studying pancreatic epithelial development, CytoTRACE 2 correctly ordered cells from multipotent progenitors to differentiated endocrine cells, with predictions meticulously aligning with known biology [45]. The method also corroborated a pluripotency program in cranial neural crest cell precursors and correctly distinguished datasets with and without immature cells [11].

Cancer Research Applications

In oncology, both methods provide insights into cancer stem cells and tumor heterogeneity. CytoTRACE 2 predictions aligned with known leukemic stem cell signatures in acute myeloid leukemia and identified multilineage potential in oligodendroglioma [11]. The method has enabled identification of cancer cell stages and marker genes at the single-cell level, associating them with therapy response and survival [42].

Signaling entropy has demonstrated particular value in understanding drug resistance mechanisms, where high entropy correlates with robustness to therapeutic intervention [40] [44]. The method has identified critical signaling pathways that serve as "Achilles' heels" in cancer cells, potentially informing combination therapy strategies [40].

Biomarker Discovery

A key advantage of both frameworks is their utility for biomarker discovery. CytoTRACE 2's interpretable architecture enables direct identification of gene programs driving potency predictions, leading to discoveries like the association between cholesterol metabolism and multipotency [11] [42]. This capability narrows the search space for potential drug targets, boosting the efficiency of therapeutic development.

Signaling entropy analysis enables identification of critical nodes in regulatory networks whose perturbation disproportionately affects system behavior, highlighting potential therapeutic targets in cancer and other diseases [40] [41].

Integrated Analysis Framework

The complementary strengths of these frameworks suggest value in their integrated application. The following diagram illustrates a potential workflow for combining both approaches in a comprehensive potency assessment strategy: