Designing Next-Generation Clinical Trials for Advanced Therapy Medicinal Products: Strategies, Challenges, and Regulatory Considerations

This comprehensive review examines the evolving landscape of clinical trial design for Advanced Therapy Medicinal Products (ATMPs), including cell and gene therapies.

Designing Next-Generation Clinical Trials for Advanced Therapy Medicinal Products: Strategies, Challenges, and Regulatory Considerations

Abstract

This comprehensive review examines the evolving landscape of clinical trial design for Advanced Therapy Medicinal Products (ATMPs), including cell and gene therapies. Targeting researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores foundational regulatory requirements, innovative methodological approaches, optimization strategies for common challenges, and validation frameworks. The article synthesizes recent regulatory developments from EMA and FDA, analyzes adaptive trial designs for small populations, and provides practical guidance for navigating the unique complexities of ATMP clinical development, from early-stage exploration to comparative effectiveness assessment.

Understanding the ATMP Landscape: Regulatory Frameworks and Fundamental Design Principles

The development of Advanced Therapy Medicinal Products (ATMPs), encompassing gene therapies, cell-based therapies, and tissue-engineered products, represents one of the most innovative yet regulatory-complex frontiers in modern medicine. The European Medicines Agency (EMA) has introduced a significant regulatory milestone with its "Guideline on quality, non-clinical and clinical requirements for investigational advanced therapy medicinal products in clinical trials," which comes into effect July 1, 2025 [1] [2]. This comprehensive document, adopted by EMA's Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) on January 20, 2025, consolidates guidance from over 40 separate guidelines and reflection papers into a single multidisciplinary reference [1]. Simultaneously, global regulatory bodies including the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and China's Center for Drug Evaluation (CDE) are advancing their own frameworks for these transformative therapies [3] [4]. This evolving landscape creates both challenges and opportunities for researchers and drug development professionals navigating clinical trial design for ATMPs, particularly as efforts toward global regulatory convergence accelerate while respecting regional requirements.

Comparative Analysis of EMA and FDA Regulatory Frameworks

EMA's New Clinical-Stage ATMP Guideline: Key Provisions

The EMA's new guideline provides a comprehensive framework for clinical trial applications involving investigational ATMPs in both early-phase exploratory and late-stage confirmatory trials [1]. Spanning approximately 60 pages, the document addresses quality (CMC) documentation, non-clinical studies, and clinical development requirements with special attention to first-in-human trials, confirmatory studies, and emerging technologies like genome editing [1] [2]. The guideline emphasizes that immature quality development could potentially compromise the use of clinical trial data to support marketing authorization, highlighting the critical importance of robust CMC systems from the earliest development stages [1].

The guideline intentionally mirrors the Common Technical Document (CTD) structure for Module 3, providing a roadmap for organizing CMC information in investigational or marketing applications [1]. This alignment facilitates a more standardized approach to regulatory submissions across the European Union. Notably, the guideline encourages sponsors to adopt a risk-based approach when evaluating quality, non-clinical, and clinical data generated for ATMPs and emphasizes seeking early regulatory guidance at either national member state or European level to inform development strategy [1].

FDA-EMA Convergence and Divergence in ATMP Regulation

Significant regulatory convergence has transpired between EMA and FDA regarding CMC requirements for ATMPs, though important distinctions remain that developers must navigate [1] [4]. The table below summarizes key areas of alignment and divergence between the two regulatory frameworks:

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of EMA and FDA Regulatory Approaches to ATMPs

| Regulatory Aspect | EMA Approach | FDA Approach | Convergence Status |

|---|---|---|---|

| GMP Compliance | Mandatory self-inspections with documented results providing evidence of effective quality system [1] | Phase-appropriate attestation with verification during pre-license inspection [1] | Partial Convergence |

| Donor Eligibility | Compliance with EU and member state-specific legal requirements; limited specific guidance [1] | Prescriptive requirements for screening, testing, laboratory qualifications, and pooling restrictions [1] | Divergence |

| Terminology | "Active substance" and "Investigational medicinal product" [1] | "Drug substance" and "Drug product" [1] | Terminological Divergence |

| Clinical Evidence | Acceptance of small, open-label, non-randomized studies for orphan indications [5] | Similar flexibility for orphan diseases with post-marketing requirements [5] | Substantial Convergence |

| Trial Application Review | Centralized through Clinical Trial Regulation with one EU-based opinion [6] | Traditional IND review process through CBER [1] | Procedural Divergence |

The regulatory convergence between EMA and FDA is particularly evident in the CMC domain, where the overwhelming majority of content in the EMA's quality documentation section would be familiar to FDA CMC reviewers [1]. This alignment reflects a conscious effort by regulatory authorities to address the global nature of ATMP development, though differences in implementation and specific requirements continue to present challenges for sponsors pursuing simultaneous development in multiple regions [1] [6].

Global Regulatory Expansion: China's Emerging ATMP Framework

Concurrent with developments in Western regulatory systems, China has taken significant steps toward establishing a comprehensive ATMP framework. In June 2025, China's Center for Drug Evaluation (CDE) released the "Scope, Classification, and Interpretation of Advanced Therapy Medicinal Products (Draft for Public Comments)" – the country's first systematic regulation of ATMPs [3]. This draft defines ATMPs as medicinal products developed, produced, and regulated through the pharmaceutical pathway that are "produced through ex vivo manipulation to function within the human body" [3]. The initiative aims to clarify the regulatory framework for cutting-edge biopharmaceutical fields including cell therapy and gene therapy, representing China's effort to align with global standards while optimizing review and approval processes to enhance industry competitiveness [3].

Experimental Design and Methodological Considerations

Clinical Development Strategies for ATMPs

The clinical development of ATMPs presents unique challenges that require methodologically sound approaches and sometimes departure from traditional clinical trial designs. Current regulatory approvals for ATMPs have primarily been based on small, open-label, non-randomized, single-arm studies using intermediate endpoints and historical controls [5]. This approach has been justified by the nature of target diseases (often orphan indications with high unmet medical needs) and ethical considerations regarding randomization when investigational therapies show dramatic efficacy signals [5].

Table 2: Clinical Trial Design Characteristics for Approved ATMPs

| ATMP Category | Common Trial Design Features | Typical Endpoints | Patient Population Size |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gene Therapy Products | Single-arm, historical controls, intermediate variables [5] | Biomarker response, disease-specific metrics [5] | Small (12-147 patients) [5] |

| Somatic Cell Therapies | Mixed designs (some controlled Phase III) [5] | Survival, response rates [5] | Variable (71-512 patients) [5] |

| Tissue-Engineered Products | Randomized and non-randomized designs [5] | Structural/functional improvement [5] | Moderate (138-177 patients) [5] |

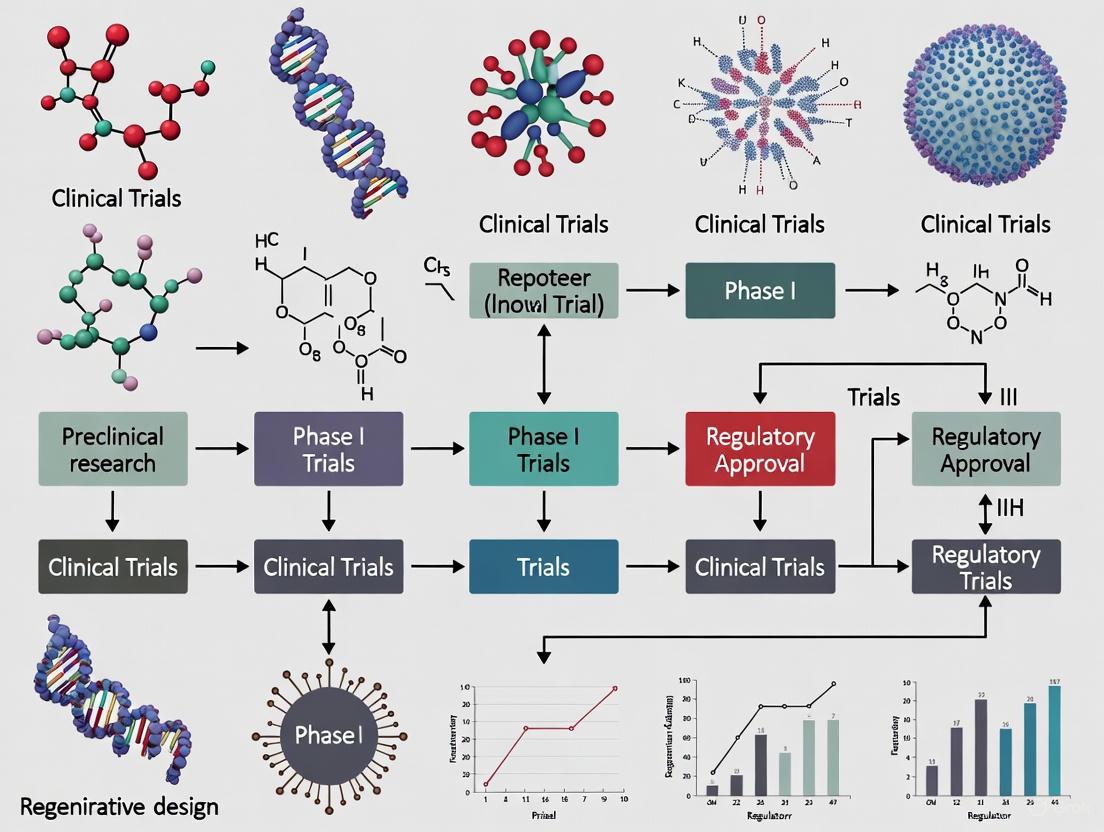

The following workflow diagram illustrates the key decision points in designing ATMP clinical development programs that meet regulatory requirements across multiple jurisdictions:

Quality and Manufacturing Considerations

The EMA guideline dedicates approximately 70% of its content to quality documentation requirements, underscoring the critical importance of CMC considerations in ATMP development [1]. The guideline emphasizes that a weak quality system could prevent authorization of a clinical trial if deficiencies pose risks to participant safety or data robustness [1]. Concurrently, the EMA has proposed revisions to Part IV of the EU Guidelines on Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) specific to ATMPs, which focus on alignment with the revised Annex 1, integration of ICH Q9 and Q10 principles, and adaptation to technological advancements in manufacturing [7].

Key areas of focus in ATMP manufacturing and quality control include:

- Starting Materials: Proper characterization and testing of human cell-based starting materials, with compliance to regional requirements for donor screening and testing for infectious diseases [1]

- Manufacturing Process Controls: Implementation of closed single-use systems, automated technologies, and appropriate cleanroom classifications with barrier systems [7]

- Quality Control Testing: Development of validated assays for potency, identity, purity, and safety, considering the often limited shelf-life of cellular products [6]

- Comparability Protocols: Establishment of strategies for managing manufacturing changes while maintaining product consistency [1]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The development and quality control of ATMPs requires specialized reagents and materials to ensure product safety, identity, purity, and potency. The following table outlines key research reagent solutions essential for ATMP development:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for ATMP Development

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in ATMP Development |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Separation Media | Ficoll-Paque, Magnetic bead-based separation kits | Isolation of specific cell populations from starting materials [5] |

| Cell Culture Supplements | Serum-free media, Cytokines (IL-2, IL-7, IL-15), Growth factors | Ex vivo expansion and maintenance of cellular products [5] |

| Gene Delivery Vectors | Lentiviral vectors, Retroviral vectors, AAV vectors, Transposon systems | Genetic modification of cells for gene and engineered cell therapies [1] [5] |

| Characterization Antibodies | Flow cytometry antibodies, Immunofluorescence reagents | Phenotypic characterization of cell products and assessment of identity [5] |

| Potency Assay Reagents | Cytokine detection kits, Target cells, Cytotoxicity reagents | Measurement of biological activity and potency [1] |

| Safety Testing Materials | Mycoplasma detection kits, Endotoxin testing reagents, Sterility testing media | Assessment of product safety and freedom from contaminants [1] [7] |

Regulatory Convergence Initiatives and Future Directions

The global development of ATMPs has stimulated increased attention to regulatory convergence initiatives aimed at aligning requirements across jurisdictions while respecting regional legal frameworks and public health needs [1] [4]. The FDA's Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research (CBER) defines regulatory convergence as the alignment of requirements across countries or regions that results in incremental adoption of "internationally recognized technical guidance documents, standards and scientific principles, common or similar practices and procedures" [1]. This concept has become a recurring topic at international conferences focused on cell and gene therapy, with sessions dedicated to opportunities for harmonization in CMC requirements, building global standards, and balancing convergence efficiencies against unique regional requirements [1].

Current initiatives promoting regulatory convergence include:

- Public-Private Consortia: Organizations like the Bespoke Gene Therapy Consortium (BGTC), which includes FDA participation, aim to build platforms and standards to accelerate gene therapy development [6]

- International Collaboration: Efforts between regulatory authorities, industry, non-profit, and academic organizations to develop harmonized approaches to ATMP evaluation [6]

- Mutual Recognition: While current mutual recognition agreements for GMP do not extend to ATMPs, there have been exceptions based on product limitations (e.g., Luxturna, Zolgensma), suggesting potential evolution in this area [6]

The following diagram illustrates the key components and stakeholders in the global regulatory convergence ecosystem for ATMPs:

The introduction of EMA's new clinical-stage ATMP guideline effective July 2025, coupled with ongoing global regulatory developments, presents both challenges and opportunities for researchers and drug development professionals. Successful navigation of this evolving landscape requires a strategic approach to clinical trial design and regulatory planning that incorporates several key considerations:

First, sponsors should engage early with regulatory authorities through scientific advice procedures at both national and European levels to align development plans with evolving expectations [1]. Second, implementing a risk-based approach to quality, non-clinical, and clinical development can help prioritize resources while maintaining regulatory compliance [1]. Third, developers should consider global regulatory strategies from the outset, acknowledging both convergent and divergent requirements across regions to enable efficient multi-jurisdictional development [4] [6].

As the ATMP field continues to evolve, regulatory frameworks will undoubtedly undergo further refinement. The EMA has indicated that the current guideline will be updated to include additional information on gene-editing products as experience accumulates [1]. Similarly, ongoing initiatives to modernize ICH guidelines to better accommodate ATMP-specific challenges may further facilitate global harmonization [6]. By maintaining awareness of these developments and adopting proactive, strategic approaches to ATMP development, researchers and drug development professionals can navigate this complex regulatory environment while advancing transformative therapies for patients with serious unmet medical needs.

Advanced Therapy Medicinal Products (ATMPs) represent a innovative class of biopharmaceuticals that encompass gene therapy medicines, somatic cell therapy medicines, and tissue-engineered medicines [8]. These therapies are highly research-driven and characterized by complex, innovative manufacturing processes [9]. According to European regulations, ATMPs are biological medicinal products that contain or consist of engineered cells or tissues and are used with a view to treating, preventing, or diagnosing diseases through pharmacological, immunological, or metabolic actions, or to regenerating, repairing, or replacing human tissue [10]. The European Medicines Agency (EMA) plays a central role in the scientific assessment of these therapies through its Committee for Advanced Therapies (CAT), which provides expertise needed to evaluate their quality, safety, and efficacy [8] [11].

The development of ATMPs has grown significantly in recent years, with clinical trials investigating these innovative therapies spanning various disease areas including cancer, cardiovascular diseases, musculoskeletal disorders, and immune system diseases [12]. These products differ fundamentally from traditional chemical medicines—they often comprise viable cells or genetically modified materials, work through complex mechanisms of action, and may integrate into or be rejected by the recipient's body [9]. This complexity demands specialized regulatory frameworks and development approaches, which have been established in the European Union through Regulation (EC) No 1394/2007 and supporting guidelines [11] [9].

Classification and Definitions of ATMP Categories

Gene Therapy Medicinal Products (GTMPs)

Gene therapy medicinal products contain genes that lead to a therapeutic, prophylactic, or diagnostic effect [8]. These products work by inserting 'recombinant' genes into the body, typically to treat a variety of diseases including genetic disorders, cancer, or long-term diseases [8]. A recombinant gene is a stretch of DNA created in the laboratory that brings together DNA from different sources [8]. The classification of a product as a GTMP depends on the addition of a recombinant nucleic acid sequence [9]. In the European regulatory framework, GTMPs are defined according to Part IV of Annex I to Directive 2001/83/EC [11].

Somatic Cell Therapy Medicinal Products (sCTMPs)

Somatic cell therapy medicinal products contain cells or tissues that have been manipulated to change their biological characteristics or cells or tissues not intended to be used for the same essential functions in the body [10] [8]. These products are intended for the prevention, diagnosis, and/or treatment of diseases through pharmacological, immunological, or metabolic actions [10]. The European definition specifies that sCTMPs must contain or consist of cells or tissues that have been subject to substantial manipulation so that biological characteristics, physiological functions, or structural properties relevant for the intended clinical use have been altered, or consist of cells or tissues that are not intended to be used for the same essential function in the recipient and the donor [10]. The full legal definition is provided in Directive 2009/120/EC, Directive 2003/63/EC part IV, and Directive 2001/83/EC Annex I part IV [10].

Tissue-Engineered Products (TEPs)

Tissue-engineered products contain cells or tissues that have been modified so they can be used to repair, regenerate, or replace human tissue [10] [8]. According to the European guidelines, TEPs contain or consist of engineered cells or tissues, and cells or tissues are considered 'engineered' if they fulfill at least one of two conditions: (1) the cells or tissues have been subject to substantial manipulation, so that biological characteristics, physiological functions, or structural properties relevant for the intended regeneration, repair, or replacement are achieved, or (2) the cells or tissues are not intended to be used for the same essential function in the recipient as in the donor [10]. These products are presented as having properties for, or are used in or administered to human beings with a view to regenerating, repairing, or replacing a human tissue [10]. The regulatory definition is provided in article 2(1)(b) of the Clinical Trial Regulation (1394/2007/EG) [10].

Combined ATMPs

Some ATMPs may contain one or more medical devices as an integral part of the medicine, which are referred to as combined ATMPs [8]. An example includes cells embedded in a biodegradable matrix or scaffold [8]. These combination products are not only regulated under the guidelines for medicinal products but also for medical devices [13]. The regulatory framework for these combined products involves interaction between the CAT and notified bodies to prepare draft opinions [13].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of ATMP Categories

| Category | Key Components | Substantial Manipulation Required | Primary Intended Use | Regulatory Definition Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene Therapy Medicinal Products (GTMPs) | Recombinant nucleic acids | Not necessarily (based on nucleic acid content) | Treatment, prevention, or diagnosis of disease through gene expression | Directive 2001/83/EC Annex I part IV [11] |

| Somatic Cell Therapy Medicinal Products (sCTMPs) | Cells or tissues | Yes (unless non-homologous use) | Treatment, prevention, or diagnosis of disease through pharmacological, immunological, or metabolic actions | Directive 2009/120/EC [10] |

| Tissue-Engineered Products (TEPs) | Engineered cells or tissues | Yes (unless non-homologous use) | Regeneration, repair, or replacement of human tissue | Regulation (EC) No 1394/2007 [10] [11] |

| Combined ATMPs | ATMP combined with medical device | Dependent on cellular component | Dependent on primary mode of action | Regulation (EC) No 1394/2007 [8] |

Regulatory Framework and Classification Procedures

The European Regulatory Landscape

The regulatory framework for ATMPs in the European Union is established by Regulation (EC) No 1394/2007, which came into force on December 30, 2008 [11] [9]. This regulation provides the overall framework for ATMPs and amended previous legislation including Directive 2001/83/EC and Regulation (EC) No 726/2004 [11]. The framework is further supported by Commission Directive 2009/120/EC, which updated the definitions and detailed scientific and technical requirements for gene therapy medicinal products and somatic cell therapy medicinal products [11]. This directive also established detailed requirements for tissue-engineered products and for ATMPs containing devices and combined ATMPs [11].

A key feature of the European regulatory system is the mandatory centralized procedure for marketing authorization applications (MAAs) for ATMPs [13] [9]. This ensures that these innovative products benefit from a single evaluation and authorization procedure applicable across the EU member states [8]. The centralized procedure may grant marketing authorization through three pathways: standard marketing authorization, conditional marketing authorization (for innovative medicines addressing unmet medical needs), and marketing authorization under exceptional circumstances (for rare diseases or difficult-to-measure clinical endpoints) [13].

The Committee for Advanced Therapies (CAT)

The Regulation (EC) No 1394/2007 established the Committee for Advanced Therapies (CAT) as a multidisciplinary committee within the European Medicines Agency [11]. The CAT is composed of members with specific expertise in ATMPs, including gene therapy, cell therapy, tissue engineering, medical devices, pharmacovigilance, and ethics, with representatives of patient associations and clinicians also included [9]. The primary responsibility of the CAT is to assess the quality, safety, and efficacy of ATMPs [11]. During the assessment procedure, the CAT prepares a draft opinion on the advanced therapy medicine, which it sends to the Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) [8]. The CHMP then adopts an opinion recommending or not recommending the authorization of the medicine by the European Commission [8].

Beyond product evaluation, the CAT has several other important responsibilities: providing recommendations on the classification of advanced therapy medicines, evaluating applications for certification of quality and non-clinical data for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), contributing to scientific advice on advanced therapy medicines, and assisting in the elaboration of documents related to the objectives of the ATMP Regulation [8]. The CAT also works to encourage the development of advanced therapy medicines and provides scientific expertise for initiatives related to innovative medicines and therapies [8].

ATMP Classification Procedure

The CAT provides scientific recommendations on ATMP classification in accordance with Article 17 of the ATMP Regulation [11]. This classification procedure helps developers determine whether their product falls within the definition of an ATMP based on scientific grounds [9]. The recommendations are based on definitions laid down in EU legislative texts, particularly Regulation (EC) No 1394/2007 for tissue-engineered products and combined ATMPs, and Part IV of Annex I to Directive 2001/83/EC for gene therapy and somatic cell therapy medicinal products [11].

The classification as a tissue-engineered product or somatic cell therapy product depends on whether the cells are 'engineered,' which requires fulfillment of one of two conditions: (1) the cells have been subject to substantial manipulation, or (2) the cells are not intended to be used for the same essential function in the recipient and the donor (non-homologous use) [9]. Substantial manipulation is defined as processing that alters biological characteristics, physiological functions, or structural properties relevant for the intended regeneration, repair, or replacement [9]. The CAT has published a Reflection Paper on Classification of Advanced Therapy Medicinal Products to provide further guidance on classification, including discussion of borderline cases [9].

Table 2: ATMP Clinical Trial Landscape (Based on 939 Registered Trials)

| Trial Characteristic | Category | Number/Percentage of Trials | Phase Distribution |

|---|---|---|---|

| ATMP Category | Somatic Cell Therapies | 53.6% | Phase I, I/II: 64.3% [12] |

| Tissue-Engineered Products | 22.8% | Phase II, II/III: 27.9% [12] | |

| Gene Therapies | 22.4% | Phase III: 6.9% [12] | |

| Combined ATMPs | 1.2% | ||

| Therapeutic Area | Cancer | 24.8% | |

| Cardiovascular Diseases | 19.4% | ||

| Musculoskeletal | 10.5% | ||

| Immune System and Inflammation | 11.5% | ||

| Neurology | 9.1% | ||

| Trial Size | Small trials (<25 patients) | 47.2% |

The ATMP classification procedure is a non-mandatory, free-of-charge service that provides legally non-binding recommendations [9]. Despite being non-binding, it serves as an important tool for developers to clarify the applicable regulatory framework and development path [9]. It also offers an opportunity to initiate dialogue with regulatory bodies early in the development process [9]. Between 2011 and 2013, the CAT classified 71 medicinal products, with the majority (87%) classified as ATMPs distributed nearly equally between the three product categories [9].

Experimental Protocols for ATMP Development

Quality Control and Characterization Protocols

Quality control of ATMPs requires sophisticated testing strategies that differ significantly from those used for conventional chemical compounds [14]. The complexity of these products, particularly those containing genetically modified cells, necessitates comprehensive characterization to address potential risks such as malignant transformation and off-target effects [14]. The following protocols outline key quality assessment methodologies for ATMPs.

Protocol 1: Potency Assay Development for Cell-Based ATMPs Potency assays must be developed prior to first-in-human studies and should quantitatively measure the biological activity linked to the product's mechanism of action [15]. For cell-based ATMPs, this typically involves:

- Identify Critical Quality Attributes (CQAs): Determine specific phenotypic markers, secretory profiles, or functional activities that correlate with biological activity

- Select Appropriate Assay Format: Implement flow cytometry for surface marker quantification, ELISA for secretory factor measurement, or co-culture systems for functional assessment

- Establish Reference Standards: Create well-characterized reference materials for assay calibration and normalization

- Validate Assay Performance: Determine accuracy, precision, specificity, and linearity across the anticipated potency range

- Implement Quality Control Procedures: Include appropriate controls for each assay run to ensure reliability

Protocol 2: Genetic Modification Characterization for GTMPs For gene therapy products and genetically modified cell therapies, comprehensive characterization of the genetic modification is essential [14]:

- Vector Copy Number Determination: Use digital droplet PCR to quantify vector copies per cell

- Integration Site Analysis: Employ next-generation sequencing methods to identify genomic integration sites

- Off-Target Editing Assessment: For gene-edited products, conduct whole-genome sequencing or in silico prediction tools to identify potential off-target effects

- Expression Analysis: Quantify transgene expression using RT-qPCR, RNA-seq, or Western blot

- Vector Integrity Verification: Perform restriction mapping or full vector sequencing to confirm construct integrity

Manufacturing and Process Development Protocols

ATMP manufacturing must comply with Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) guidelines, though these products present unique challenges due to their biological complexity and frequently small-scale, personalized production [14]. The EMA's guideline on clinical-stage ATMPs emphasizes that immature quality development may compromise the use of clinical trial data to support marketing authorization [16].

Protocol 3: Process Comparability Studies When manufacturing process changes occur during development, comparability must be demonstrated through rigorous assessment [15]:

- Define Analytical Similarity Margins: Establish pre-defined acceptance criteria for critical quality attributes

- Conduct Side-by-Side Testing: Manufacture multiple lots using both old and new processes for direct comparison

- Perform Extended Characterization: Go beyond routine quality control testing to include comprehensive molecular and functional analyses

- Assess Impact on Biological Function: Evaluate potency, differentiation potential, and other functional endpoints

- Document Justification for Changes: Provide scientific rationale supporting the manufacturing modification

Protocol 4: Allogeneic Donor Screening and Testing For allogeneic cell-based ATMPs, comprehensive donor screening is essential to prevent transmission of communicable diseases [16]:

- Donor Medical History Review: Assess donor health history and risk factors for communicable diseases

- Infectious Disease Marker Testing: Screen for relevant communicable disease agents using serological and molecular methods

- Quality Assurance of Testing Laboratories: Ensure testing is performed in qualified laboratories with appropriate certifications

- Donor Eligibility Determination Documentation: Maintain complete records of donor eligibility determination

- Quarantine Procedures: Implement appropriate quarantine of cellular materials pending completion of testing

Diagram 1: ATMP Classification Decision Pathway. This workflow outlines the key decision points for classifying products as Advanced Therapy Medicinal Products according to European regulatory criteria.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for ATMP Development

| Reagent/Material | Category | Function in ATMP Development | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| GMP-grade Cytokines and Growth Factors | Cell Culture Supplements | Direct cell differentiation, expansion, and maintenance | TEP manufacturing, sCTMP process development |

| Vector Packaging Systems | Gene Delivery | Facilitate genetic modification of target cells | Lentiviral/retroviral packaging for GTMPs |

| Cell Separation Media and Reagents | Cell Processing | Isulate specific cell populations from heterogeneous mixtures | Density gradient media, magnetic bead separation |

| Flow Cytometry Antibody Panels | Characterization | Identify and quantify cell surface and intracellular markers | Phenotypic characterization, potency assessment |

| PCR and qPCR Reagents | Molecular Biology | Detect and quantify genetic elements, vector copies | Vector copy number analysis, mycoplasma testing |

| Extracellular Matrix Components | Tissue Engineering | Provide structural support for tissue development | Scaffolds for TEPs, 3D culture systems |

| Cell Counting and Viability Assays | Quality Control | Determine cell number, viability, and metabolic activity | Trypan blue exclusion, MTT assays |

| Mycoplasma Detection Kits | Safety Testing | Screen for mycoplasma contamination in cell cultures | Required safety testing for all cell-based ATMPs |

| Endotoxin Testing Reagents | Safety Testing | Detect and quantify bacterial endotoxins | Product release testing for parenteral administration |

| Cryopreservation Media | Cell Banking | Maintain cell viability during frozen storage | Master/working cell bank creation, product storage |

Recent Regulatory Developments and Future Perspectives

The regulatory landscape for ATMPs continues to evolve rapidly, with significant new guidelines recently adopted. Effective July 1, 2025, the EMA's new Guideline on quality, non-clinical, and clinical requirements for investigational advanced therapy medicinal products in clinical trials comes into effect [16]. This comprehensive document consolidates information from over 40 separate guidelines and reflection papers, providing a unified framework for gene therapy, somatic cell therapy, and tissue-engineered products [16]. The guideline emphasizes a risk-based approach to ATMP development and addresses several critical areas including potency assay requirements, genome editing products, continuous manufacturing, and ATMP-device combinations [15].

Another significant development is the implementation of the new SoHO (Substances of Human Origin) regulation (2024/1938), which affects traceability requirements for ATMPs containing human cells or tissues [15]. This regulation aims to harmonize standards for donation, procurement, testing, processing, preservation, storage, and distribution of human tissues and cells across the European Union [15]. Additionally, the guideline explicitly addresses continuous manufacturing for the first time and provides clarified expectations for comparability studies aligned with ICH Q5E [15].

The field of ATMPs continues to face challenges related to manufacturing complexity, characterization difficulties, and the need for specialized regulatory expertise [14]. However, ongoing regulatory science initiatives aim to address these challenges through the development of new tools, standards, and approaches to assess the safety, efficacy, quality, and performance of these innovative products [14]. As the field advances, regulatory convergence between major regions like the European Union and United States is becoming increasingly important to facilitate global development of these promising therapies [13] [16].

Diagram 2: ATMP Regulatory Pathway in the European Union. This diagram illustrates the key regulatory procedures and interactions between sponsors and regulatory bodies throughout the ATMP development lifecycle.

First-in-human (FIH) trials represent a milestone step in translational science, transforming basic scientific discoveries into therapeutic applications by advancing drug candidates from preclinical studies to initial human testing [17]. These trials serve as the crucial link to advance new promising drug candidates and are conducted primarily to determine the safe dose range for further clinical development [17]. For Advanced Therapy Medicinal Products (ATMPs), including gene therapies, somatic cell therapies, and tissue-engineered products, FIH trials present unique challenges due to their groundbreaking nature in treating previously untreatable diseases [18]. The European Medicines Agency (EMA) emphasizes that establishing appropriate strategies to minimise risk in early phase clinical trials is necessary and should be a priority for the safety and wellness of clinical trial participants, whether patients or healthy volunteers [19].

Key Design Considerations for FIH Trials

Core Objectives and Regulatory Alignment

FIH trials for both traditional therapeutics and ATMPs share common objectives but require different emphases based on product characteristics. The primary goals include determining human pharmacology, tolerability, and safety profiles, while gaining early evidence of effectiveness [19] [20]. For ATMPs specifically, additional objectives include feasibility assessment of complex manufacturing and administration processes [20].

Table 1: Key Objective Comparisons Across Therapeutic Modalities

| Objective Component | Small Molecules & Biologicals [20] | Cellular & Gene Therapies [20] |

|---|---|---|

| Safety Evaluation | Determine side effects associated with increasing doses | Evaluate specific risks (e.g., delayed infusion reactions, autoimmunity, graft failure, GVHD) |

| Pharmacology | Determine metabolism and pharmacologic actions | Assess biodistribution, persistence, and functional activity |

| Effectiveness | Gain early evidence of effectiveness | Gather preliminary evidence of effectiveness and activity |

| Dosing | Estimate relationship of effects to dose | Explore dose regimen and define therapeutic window |

| Feasibility | Assess feasibility of administration | Evaluate complex manufacturing and administration processes |

Population Selection and Dose Strategy

The choice between healthy volunteers and patients requires careful consideration of toxicities, PK variability, lifestyle conditions, benefits to patients, and special populations [19]. Studies with healthy volunteers must have inclusion/exclusion criteria that require vital signs, ECGs, and clinical laboratory assessments to be normal [19].

Dose selection protocols need to outline and explain the estimated initial drug dose, maximum dose exposure, and subsequent dose escalation steps [19]. All available non-clinical information, such as toxicology profiles, should be considered for starting doses, dose escalation, and maximum exposure in early phase clinical trials [17].

Table 2: Quantitative Dose Escalation Considerations

| Design Element | Traditional FIH Trials [19] | ATMP-Specific Adaptations [18] |

|---|---|---|

| Starting Dose | Based on non-clinical toxicology profiles | May consider minimal anticipated biological effect level (MABEL) |

| Dose Escalation | Defined steps with clear criteria | May require longer intervals between cohorts for immunogenicity monitoring |

| Sentinel Dosing | Required for first SAD and MAD cohorts (one active, one placebo) | Particularly critical for novel mechanisms with unknown safety profiles |

| Maximum Dose | Based on exposure margins from toxicology studies | May be limited by manufacturing capabilities or vector-related toxicities |

| Stopping Rules | Defined for individuals, cohorts, and entire study | Must account for delayed effects common with cellular and gene therapies |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

FIH Trial Protocol Development Workflow

ATMP-Specific Safety Assessment Protocol

For Advanced Therapy Medicinal Products, safety evaluation requires specialized methodologies that account for their unique mechanisms of action and potential delayed effects. The protocol must include comprehensive plans for long-term follow-up, immunogenicity assessment, and product-specific safety concerns [18] [20].

Methodology:

- Baseline Assessment: Comprehensive clinical laboratory tests, imaging studies, and functional assessments specific to the product mechanism

- Acute Monitoring: Continuous monitoring for immediate adverse events (e.g., cytokine release syndrome, infusion reactions) with predefined management algorithms

- Long-Term Follow-Up: Minimum 15-year follow-up for gene therapies to monitor for delayed adverse effects, including secondary malignancies [18]

- Immunogenicity Testing: Regular assessment of immune responses against the therapeutic product (e.g., neutralizing antibodies against AAV vectors)

- Product-Specific Endpoints: Monitoring for ectopic tissue formation, graft failure, viral reactivation, or autoimmunity [20]

Research Reagent Solutions for ATMP Development

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for ATMP Characterization

| Reagent/Category | Function/Application | Specific Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Viral Vector Quantification | Measures genome titer of viral vectors | GelGreen dye, GelRed dye, picoGreen, qPCR, ddPCR assays [21] |

| Cell Characterization | Identifies and quantifies cell populations | Flow cytometry antibodies, cell viability assays, functional potency assays |

| Process-Related Impurities | Detects residuals from manufacturing | ELISA kits for host cell proteins, DNA quantification assays, endotoxin tests |

| Product Potency | Measures biological activity | Cell-based bioassays, enzymatic activity tests, functional response assays |

| Vector Genome Integrity | Assesses vector quality and stability | Alkaline agarose gel electrophoresis, southern blotting, sequencing assays [21] |

Integrated Protocol Design for Efficient Development

Modern FIH trials increasingly utilize integrated protocols that combine different study parts to optimize knowledge gain while ensuring participant safety [19]. These complex protocols require meticulous planning and clear criteria for transitioning between study components.

Integration Principles and Decision Criteria

Integrated protocols combine single ascending dose (SAD), multiple ascending dose (MAD), and sometimes food effect or drug-drug interaction (DDI) components within a single trial [19]. The criteria to move from one part of a study, such as SAD to MAD, must be explicitly defined in the protocol [19]. While it is acceptable to overlap SAD and MAD portions of a trial, it is necessary for the expected exposure to already have been evaluated in a SAD cohort prior to being evaluated in a MAD cohort [19]. Food effect studies can be conducted in parallel with the SAD, provided the dose level in the food effect trial has been evaluated in a prior SAD cohort [19]. However, drug-drug interaction studies should not be integrated into FIH and dose escalation protocols unless there is a need that requires a specific concomitant medication in the initial patient studies [19].

Risk Mitigation and Safety Monitoring Framework

Effective risk mitigation strategies are essential for protecting participant safety while advancing innovative therapies. The EMA guideline emphasizes improved strategies to identify and mitigate risks for trial participants [19].

Safety Monitoring Protocol

Methodology:

- Sentinel Dosing: At minimum, sentinel dosing of two subjects (one active, one placebo) is required for the first SAD and MAD cohorts [19]

- Stopping Rules Definition: Protocols must define stopping rules for individuals, cohorts, dose escalation, and the entire study, specifying whether the rule is temporary or final [19]

- Safety Review Process: Independent data monitoring committees with predefined review timelines and decision-making criteria

- Dose-Limiting Toxicity Criteria: Explicit definition of DLTs, including grading scales, relationship assessment, and duration criteria

- Emergency Management: Site preparedness for medical emergencies with access to emergency supplies and specialized equipment [19]

Site Selection and Monitoring Considerations

FIH clinical trials should be conducted at facilities with investigators and staff possessing necessary training and experience in early phase clinical trials [19]. These studies must occur under controlled conditions with close supervision of trial participants during and after dosing [19]. While FIH studies should ideally be conducted at a single site, if multiple sites are required for enrolment, protocols should include a description of measures to reduce risks that might occur from the use of multiple sites [19].

Well-designed FIH trials balance the need for efficient drug development with comprehensive safety assessment, particularly crucial for novel therapeutic modalities like ATMPs. By implementing robust protocols, clear decision criteria, and appropriate risk mitigation strategies, researchers can advance promising therapies while safeguarding participant welfare. The integration of adaptive designs and strategic early-phase planning ultimately accelerates the delivery of innovative treatments to patients in need.

For developers of Advanced Therapy Medicinal Products (ATMPs), the chemistry, manufacturing, and controls (CMC) section is a critical strategic element that directly shapes clinical trial design and execution. The inherent complexity and sensitivity of cell and gene therapies (CGT) mean that manufacturing variability can directly impact patient safety and the assessment of treatment efficacy in clinical studies [22]. Consequently, CMC considerations are not merely regulatory checkpoints but fundamental components that influence trial feasibility, endpoint selection, and data interpretation. This article details the specific CMC requirements that clinical researchers must integrate into trial designs for ATMPs, providing actionable protocols and analytical frameworks to navigate this complex landscape.

CMC-Driven Design Considerations for Clinical Trials

Regional Regulatory Nuances in CMC Requirements

Global development of ATMPs requires careful navigation of regional CMC differences. The requirements of major regulatory agencies, while aligned on many ICH principles, contain critical distinctions in key areas that impact clinical trial planning and product characterization [22]. The following table summarizes these pivotal differences.

Table 1: Key Regional CMC Regulatory Nuances Impacting Clinical Trial Design for ATMPs

| CMC Consideration | FDA (US) Position | EMA (EU) Position |

|---|---|---|

| Starting/Raw Materials | Uses 'critical raw materials'; expects enhanced material control based on risk and development stage [22]. | Has a regulatory definition for 'starting materials' (materials that become part of the drug substance); requires GMP principles for their preparation [22]. |

| Viral Vector Classification | Classifies in vitro viral vectors used to modify cell therapy products as a drug substance [22]. | Considers in vitro viral vectors to be starting materials [22]. |

| Potency Testing for Viral Vectors | A validated functional potency assay is essential for assessing the efficacy of the drug product used in pivotal studies [22]. | Infectivity and transgene expression are often sufficient in early phases, with less functional assays sometimes acceptable later [22]. |

| Replication Competent Virus (RCV) Testing | Requires testing on the final cell-based drug product [22]. | If absence of RCV is demonstrated on the in vitro vector, further testing on the resulting genetically modified cells is typically not required [22]. |

| Demonstrating Comparability | Detailed in FDA CGT-specific draft guidance (July 2023). Extent of testing increases with development stage [22]. | Guided by EMA Q&A documents and multidisciplinary guidelines. Extent of testing increases with development stage [22]. |

| Use of Historical Data for Comparability | Inclusion of historical data is recommended [22]. | Comparison to historical data is not required or recommended [22]. |

The Impact of Manufacturing Controls on Trial Integrity

Manufacturing process controls and their verification are paramount for ATMPs. The complexity of manufacturing and the living nature of these products mean that process changes during a clinical program are likely. A well-defined comparability protocol is therefore not just a regulatory requirement but a crucial tool for maintaining the integrity of an ongoing clinical trial [23]. If a manufacturing change occurs mid-trial without a pre-defined and agreed-upon strategy, the entire clinical dataset may be compromised, as it becomes difficult to attribute clinical outcomes to a single, well-defined product.

Furthermore, the analytical control strategy must be robust enough to detect subtle changes in product quality that could impact efficacy or safety. This is particularly important for trial designs that rely on long-term follow-up or are targeted at chronic conditions. The inability to demonstrate product consistency throughout the clinical program introduces significant variability and risk.

Diagram: The logical workflow integrating CMC strategy directly into clinical trial design to ensure robust outcomes.

Application Note: A Proactive CMC Strategy for Phase I-III ATMP Trials

Objective

To outline a phase-appropriate, integrated CMC and clinical development strategy that ensures the continuous supply of a consistent, high-quality ATMP for clinical trials while meeting evolving regulatory requirements from first-in-human to pivotal studies.

Detailed Protocol and Experimental Workflow

A successful clinical program for an ATMP depends on a CMC strategy that is both rigorous and adaptable. The following workflow and detailed steps ensure that manufacturing and quality considerations are embedded in the clinical development plan from the outset.

Diagram: The parallel and iterative development of CMC and clinical strategies across trial phases.

Phase I - Proof-of-Concept and Initial Safety

- CMC Objectives: The primary goal is to ensure patient safety. Generate materials under GMP-like conditions with a focus on sterility, identity, and safety-potency.

- Clinical Trial Design Impact:

- Dosing Strategy: Trial design must account for limited initial product stability. Dosing schedules and patient recruitment are contingent on real-time release data.

- Site Selection: Trials are typically limited to a small number of sites in close proximity to the manufacturing facility to simplify logistics and minimize product hold times.

- Endpoint Selection: Primary endpoints focus on safety and feasibility, which are directly dependent on the CMC-controlled product attributes.

Phase II - Dose Optimization and Process Refinement

- CMC Objectives: Demonstrate process consistency across multiple manufacturing runs. Refine and validate analytical methods. Formalize the control strategy for raw materials, especially critical ones like viral vectors or cell sources [22].

- Clinical Trial Design Impact:

- Multi-Center Trials: With improved process consistency and longer preliminary stability data, trials can expand to multiple centers.

- Dosing and Efficacy: This phase often explores different dosing regimens. The CMC team must be prepared to manufacture and characterize different product presentations (e.g., different doses) and establish comparability between them if needed.

- Blinding: The product's physical characteristics (e.g., appearance, packaging) must be considered to enable effective blinding, which is often managed under CMC's container closure system design.

Phase III - Pivotal Trial and Commercial Readiness

- CMC Objectives: The process must be locked, validated, and commercially viable. All analytical methods must be fully validated. Generate comprehensive long-term stability data to support the proposed shelf life for marketing approval.

- Clinical Trial Design Impact:

- Global Trial Supply: The CMC strategy must support a complex global supply chain, which may involve technology transfer to additional GMP facilities, shipping validation across different climatic zones, and managing a multi-national comparability protocol [24].

- Definitive Endpoints: The product used must be representative of the to-be-marketed product. Any critical quality attributes (e.g., potency, purity) must be tightly controlled and monitored, as they will be linked to the clinical outcomes in the marketing application.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The characterization of ATMPs relies on a suite of sophisticated analytical tools. The following table details key reagents and their functions in ensuring product quality and supporting the link between CMC data and clinical outcomes.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for ATMP Characterization and Testing

| Research Reagent / Material | Function & Rationale |

|---|---|

| Reference Standards | Qualified materials used as benchmarks in analytical assays (e.g., potency, identity). Essential for ensuring data consistency and demonstrating comparability throughout clinical development [23]. |

| Cell-Based Potency Assays | Functional assays that measure the biological activity of the product relative to its mechanism of action. Critical for linking a specific CQA (potency) to the clinical effect and is a major focus for both FDA and EMA [22]. |

| Vector Copy Number (VCN) Assays | qPCR or ddPCR-based assays to quantify the number of viral vector integrations per cell in genetically modified therapies. A key safety and consistency attribute [22]. |

| Replication Competent Virus (RCV) Assays | Biosafety assays to detect the presence of replication-competent virus in viral vector-based products. Required for patient safety, with regional differences in testing requirements [22]. |

| Characterized Cell Banks | Master and Working Cell Banks used in production. Their thorough characterization (identity, sterility, freedom from adventitious agents) forms the foundation of product quality and safety [23]. |

The integration of a robust, forward-looking CMC strategy is not ancillary but central to the successful design and execution of clinical trials for ATMPs. From the classification of starting materials and the implementation of comparability protocols to the development of phase-appropriate analytical methods, CMC considerations directly dictate critical trial parameters including site selection, patient dosing, endpoint reliability, and global supply chain logistics. Sponsors who embed CMC planning into the earliest stages of clinical development, and who proactively engage with regulators to align on region-specific requirements, will be best positioned to generate interpretable clinical data, maintain trial integrity, and ultimately advance these complex therapies to patients efficiently and safely.

Advanced Therapy Medicinal Products (ATMPs), including cell and gene therapies, represent a groundbreaking class of biologics that treat diseases by altering, augmenting, or replacing pathological organs, tissues, cells, and genes [25]. The conventional centralized manufacturing model poses significant challenges for autologous ATMPs, where patient-specific starting materials undergo complex logistics and face time constraints due to short product shelf lives [26]. This has catalyzed the development of decentralized manufacturing and point-of-care (POC) production frameworks, which relocate manufacturing to facilities near the patient's bedside [27] [26].

Regulatory agencies worldwide are establishing novel frameworks to govern these innovative approaches. The United Kingdom's Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) has pioneered this effort by implementing the first comprehensive regulatory framework for point-of-care manufacture of ATMPs, effective July 23, 2025 [28] [27]. This article examines these emerging regulatory frameworks, provides implementation protocols, and discusses their implications for clinical trial design in ATMP research.

Regulatory Frameworks for Decentralized Manufacturing

The MHRA Regulatory Framework

The MHRA has established a tailored regulatory framework under The Human Medicines (Amendment) (Modular Manufacture and Point of Care) Regulations 2025 (U.K. Statutory Instruments 2025 No. 87), which amends the Human Medicines Regulations 2012 [28] [27]. This framework introduces two distinct manufacturing pathways:

- Point of Care (POC) Manufacturing: Medicinal products that, for reasons relating to method of manufacture, shelf life, constituents, or administration, can only be manufactured at or near the place of use [28].

- Modular Manufacture (MM) Manufacturing: Medicinal products that, for deployment reasons, must be manufactured or assembled in a relocatable modular unit [28].

The framework creates corresponding license types: "manufacturer's licence (POC)" and "manufacturer's licence (MM)", each requiring a designated Control Site that maintains supervision over manufacturing activities [27]. The Control Site holds responsibility for creating and maintaining Master Files (POC master file or MM master file) that detail arrangements for manufacturing or assembly [28].

Table 1: Key Definitions in the MHRA Regulatory Framework

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| POC Medicinal Product | A product that can only be manufactured at or near its place of use due to shelf life, constituents, or administration method [28] |

| Manufacturer's Licence (POC) | A license for manufacturing or assembling specified POC medicinal products [28] |

| POC Control Site | Premises where the license holder supervises and controls POC manufacturing [28] |

| POC Master File | Detailed description of arrangements for manufacturing or assembling a POC product [28] |

| Modular Unit | A relocatable manufacturing unit [28] |

Control Site Model and Responsibilities

The Control Site serves as the regulatory nexus in decentralized manufacturing models, maintaining ultimate responsibility for product quality and regulatory compliance [26]. Its key functions include:

- Serving as the primary point of interaction with regulatory agencies

- Maintaining and controlling the POC Master File

- Providing quality assurance oversight and Qualified Person (QP) services

- Ensuring consistency across all decentralized manufacturing sites

- Implementing and maintaining the overarching Quality Management System (QMS) [26]

This model enables product release at the centralized manufacturing facility rather than at the bedside, significantly simplifying the release process while maintaining quality assurance [27].

International Regulatory Landscape

Other regulatory agencies are also advancing frameworks for decentralized manufacturing:

- FDA: Through the Emerging Technology Program and Framework for Regulatory Advanced Manufacturing Evaluation (FRAME), the FDA is exploring distributed manufacturing platforms that can be deployed to multiple locations [26]. The agency emphasizes demonstrating product comparability across different manufacturing locations [26].

- EMA: Has acknowledged decentralized manufacturing potential in its Network Strategy 2025 and provides guidelines for batch release processes in decentralized manufacturing settings [26].

Table 2: Global Regulatory Approaches to Decentralized Manufacturing

| Regulatory Agency | Approach to Decentralized Manufacturing | Key Features |

|---|---|---|

| MHRA (UK) | Comprehensive regulatory framework effective July 2025 | Specific POC and MM licenses, Control Site model, Master Files [28] [27] |

| FDA (US) | Emerging framework through FRAME initiative | Emphasis on product comparability across sites, distributed manufacturing platforms [26] |

| EMA (EU) | Acknowledgment in strategic documents | Guidelines for batch release in decentralized settings, GMP specific to ATMPs [26] |

Implementation Framework for POC Manufacturing

Quality Management System for Decentralized Manufacturing

Implementing a robust Quality Management System (QMS) is paramount for successful decentralized manufacturing. The proposed QMS framework integrates current Good Manufacturing Practice (cGMP) principles with regulatory oversight through the Control Site model [26]. Key components include:

- Centralized QMS Administration: The Control Site establishes and maintains standardized procedures, quality control measures, and documentation systems across all manufacturing sites [26].

- Automated Closed-System Technologies: Implementing closed-system automated manufacturing platforms minimizes process variability and hardware deviations, enhancing product quality consistency [26].

- Standardized Training Platforms: Comprehensive training programs ensure consistent operations across all manufacturing sites, covering technical procedures, quality standards, and emergency protocols [26].

- Documentation Control: The POC Master File, maintained by the Control Site, provides detailed manufacturing instructions and must be followed by all satellite sites [27].

Technology Platform Selection

Decentralized manufacturing requires specialized technology platforms that support consistency and compliance across multiple sites:

- Closed-System Automated Bioreactors: Enable standardized cell expansion with minimal operator intervention, reducing contamination risk and variability [26] [29].

- Deployable Prefabricated Units: Modular GMP-compliant units allow rapid expansion of manufacturing capacity and can be installed at treatment centers [26].

- Digital Monitoring Systems: Real-time data capture and monitoring platforms enable the Control Site to oversee operations across all manufacturing locations [30] [26].

Diagram 1: POC Control Site Regulatory Model

Clinical Trial Design Considerations

Pre-Trial Planning (6-12 Months Before Trial Start)

Early phase advanced therapy trials require meticulous planning across regulatory, operational, and scientific domains [30]. Critical steps include:

- Engage Key Opinion Leaders (KOLs): Consult experienced KOLs early to shape trial design, endpoints, and patient selection criteria, ensuring alignment with scientific and regulatory nuances of ATMPs [30].

- Involve Patient Advocacy Groups (PAGs): Especially for rare diseases, work with advocacy groups to improve protocol feasibility and patient engagement [30].

- Request Scientific Advice: Seek early regulatory feedback from EMA or MHRA to align expectations on nonclinical and clinical data requirements [30].

- Classify Your Product: Submit a formal ATMP classification request to appropriate regulatory agencies, which can unlock access to specific incentives [30].

- Assess Competitive Landscape: Study comparable ATMP pipelines, focusing on their safety, efficacy, target population, and trial designs to anticipate regulatory hurdles [30].

Manufacturing and Logistics Strategy

Developing a robust manufacturing and logistics strategy is essential for decentralized trials:

- Confirm Intellectual Property & Manufacturing Strategy: Protect critical elements such as vectors, cell lines, or gene editing tools. Select GMP-certified manufacturers with ATMP experience [30].

- Scale-Out Planning: While early trial batch sizes may be small, consider how manufacturing will be scaled across multiple sites for late-stage trials and commercialization [30] [26].

- Cold-Chain Logistics: Implement specialized logistics for cell-based therapies, including EU-specific customs processes and UK-specific regulations where applicable [30].

Table 3: Clinical Trial Timeline for ATMPs with POC Manufacturing

| Time Before Trial Start | Critical Activities | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| 6-12 Months | Pre-Trial Planning | KOL engagement, regulatory advice, product classification, competitive assessment [30] |

| 6-12 Months | Manufacturing Strategy | IP protection, GMP manufacturer selection, scale-out planning [30] |

| 6-9 Months | Vendor Selection | Choose CROs with ATMP expertise, specialized assay development, cold-chain logistics [30] |

| 4-6 Months | Protocol Development | Prepare CTA and IMPD, incorporate risk-based approach, long-term follow-up plans [30] |

| 1-3 Months | Pre-Trial Execution | GMO clearance (if applicable), site training, system validation [30] |

Regulatory Submissions and Documentation

For clinical trials involving POC manufacturing, specific regulatory submissions are required:

- Clinical Trial Application (CTA): Unlike the IND process in the US, the EU and UK require a CTA, including the Investigational Medicinal Product Dossier (IMPD) [30].

- Investigational Medicinal Product Dossier (IMPD): Must outline product composition, manufacturing process, preclinical data, and proposed trial design with safety monitoring [30].

- Risk-Based Approach: For ATMPs, include detailed risk assessment addressing product-specific risks such as immunogenicity and off-target effects [30].

- Long-Term Follow-Up (LTFU): Build LTFU requirements upfront into trial design due to durable therapeutic effects of ATMPs [30].

Experimental Protocols for POC Manufacturing

Protocol: Technology Transfer to POC Sites

Objective: Establish comparable manufacturing processes across multiple POC sites to ensure consistent product quality.

Materials:

- Master cell bank

- GMP-grade culture media and supplements

- Closed-system automated bioreactors

- Quality control testing reagents

- Standard operating procedures (SOPs)

Methodology:

- Process Definition: Document and validate the entire manufacturing process at the Control Site, establishing critical process parameters (CPPs) and critical quality attributes (CQAs) [26] [29].

- Equipment Qualification: Ensure identical equipment configurations across all POC sites, performing installation qualification (IQ), operational qualification (OQ), and performance qualification (PQ) [26].

- Personnel Training: Implement standardized training programs for operators at all POC sites, including theoretical and hands-on components [26].

- Process Performance Qualification: Execute three consecutive successful manufacturing runs at each POC site, demonstrating process consistency and product comparability [26] [29].

- Comparative Analysis: Conduct extensive analytical comparability assessment between products manufactured at Control Site and POC sites, including potency assays, identity tests, and purity assessments [26].

Acceptance Criteria: All POC sites must demonstrate manufacturing success rates ≥95% and product characteristics falling within predefined specifications established at the Control Site.

Protocol: Environmental Monitoring for POC Sites

Objective: Ensure aseptic manufacturing conditions at POC sites with equivalent quality standards to centralized facilities.

Materials:

- Active air samplers

- Settle plates

- Surface contact plates

- Particulate counters

- Microbial identification systems

Methodology:

- Baseline Assessment: Perform comprehensive environmental monitoring before initiating manufacturing, including viable and non-viable particle counts in critical areas [29].

- Continuous Monitoring: Implement real-time particulate monitoring in Grade A and B areas during manufacturing operations [29].

- Microbial Monitoring: Place settle plates for airborne viable contamination and use contact plates for surface monitoring at predetermined locations [29].

- Personnel Monitoring: Perform gowning qualification and regular monitoring of operators through finger plates and garment contact plates [29].

- Data Integration: Incorporate environmental monitoring data into batch records and establish alert and action limits based on historical data [26] [29].

Acceptance Criteria: Meet ISO Class 5 (Grade A) conditions in critical processing areas with no recoverable microbial contamination during manufacturing operations.

Diagram 2: POC Manufacturing Quality Assurance Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Materials for POC ATMP Manufacturing

| Research Reagent | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| GMP-grade Cell Culture Media | Supports cell growth and maintenance | Formulated without animal components; quality testing includes sterility, endotoxin, and mycoplasma assessments [29] |

| Cell Separation Reagents | Isolates specific cell populations | Magnetic-activated cell sorting (MACS) or fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) reagents with defined purity specifications [29] |

| Viral Vector Systems | Delivers genetic material to cells | GMP-produced lentiviral or retroviral vectors with certificates of analysis including titer, sterility, and identity [25] [29] |

| Cryopreservation Media | Preserves cellular products for storage | Formulated with defined DMSO concentrations; undergoes container compatibility and stability testing [29] |

| Quality Control Assay Kits | Characterizes final product attributes | Includes flow cytometry panels, potency assays, sterility tests, and mycoplasma detection kits [26] [29] |

| Closed-System Bioreactors | Scalable cell expansion platforms | Automated, functionally closed systems with predefined protocols and parameter controls [26] [29] |

The emergence of regulatory frameworks for point-of-care manufacturing and decentralized trials represents a transformative development for ATMPs. The MHRA's pioneering regulations provide a structured pathway for implementing these innovative manufacturing approaches while maintaining rigorous quality standards. The Control Site model with Master File documentation offers a practical solution for overseeing decentralized manufacturing networks.

Successful implementation requires robust Quality Management Systems, standardized technology platforms, and meticulous clinical trial planning. As regulatory agencies worldwide continue to refine their approaches to decentralized manufacturing, researchers and developers must maintain flexibility and engage early with regulators. These evolving frameworks promise to enhance the accessibility, scalability, and cost-effectiveness of ATMPs, ultimately benefiting patients through accelerated access to groundbreaking therapies.

Innovative Trial Methodologies for ATMPs: Adaptive Designs, Endpoints, and Statistical Approaches

Single-arm trials (SATs) represent a specialized clinical study design in which all enrolled subjects receive the same investigational treatment, conducted without a parallel control group. These trials serve as a vital alternative to randomized controlled trials (RCTs) in specific scenarios where traditional trial designs are impractical or unethical [31]. In the context of advanced therapy medicinal products (ATMPs) research—which often targets rare diseases, complex malignancies, and conditions with high unmet medical need—SATs enable expedited evaluation of therapeutic interventions and can form the foundation for regulatory approvals [31] [32].

The fundamental characteristic of SATs is their single-treatment-group structure, which eliminates randomization processes and control or placebo groups that are hallmark features of RCTs [33]. Instead, researchers utilize treatment effects observed in comparable patient populations as a reference standard, either through predetermined efficacy thresholds or external controls for comparative analysis [33]. This design obviates the need for concurrent controls, resulting in simpler implementation, shorter timelines, and smaller sample size requirements compared to traditional RCTs [31] [33].

For ATMP developers facing challenges with patient recruitment, ethical constraints, or urgent medical needs, SATs offer a potentially accelerated pathway for drug development and approval [33]. However, this design presents significantly greater interpretation complexity compared to RCTs, requiring sophisticated analytical approaches and careful consideration of multiple assumptions that are inherently controlled for in randomized designs [33]. The growing accessibility of historical data and real-world evidence has further motivated interest in leveraging external controls to enhance the scientific validity of SATs in ATMP research [34].

Applications and Appropriate Use Cases

Single-arm trials are strategically employed in specialized clinical contexts where randomized controlled trials face significant practical or ethical challenges. Understanding the appropriate applications of SATs is crucial for their effective implementation in ATMP research.

Established Applications

SATs find their strongest justification in several well-defined scenarios frequently encountered in advanced therapy development. Rare diseases and orphan drug development represent a primary application, where constrained patient recruitment pools make large-scale randomized trials impractical [31] [33]. In these contexts, SATs become a viable alternative for generating pivotal efficacy evidence. Similarly, advanced malignancies with no effective treatment options often warrant SAT designs, particularly for oncology drugs targeting life-threatening conditions where SATs may provide early evidence of efficacy in urgent situations [33].

The evaluation of novel treatment modalities, including many ATMPs such as gene therapies and cellular products, represents another key application area [31]. When these therapies demonstrate dramatic effects in early studies, SATs can serve as confirmatory evidence. Furthermore, SATs are applicable in contexts involving life-threatening conditions where ethical concerns prevent the use of placebo or standard-of-care control groups [31] [32]. In such scenarios, the ethical feasibility of SATs includes preventing the assignment of unsuitable patients to a control group receiving potentially ineffective treatment [33].

Regulatory Context and Acceptance

Regulatory agencies including the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and European Medicines Agency (EMA) have established specific contexts where SATs may be acceptable for supporting efficacy claims. Historically, both agencies have accepted SATs in exceptional cases, typically when a condition has a highly predictable and dire natural history, treatment effects are dramatic and unprecedented, or randomization is deemed unethical or impractical [35]. However, recent regulatory guidance reflects increasingly stringent expectations.

The 2024 EMA Reflection Paper marks a pivotal shift, stating unequivocally that "Single-arm trials lack the internal validity to support stand-alone conclusions on efficacy and safety unless exceptional justifications apply" [35]. Similarly, the FDA has warned sponsors not to expect approval based solely on single-arm data, with recent market withdrawals exposing the fragility of SAT-based strategies [35]. Both regulators now emphasize that SATs may only be justified if all feasible alternatives have been ruled out, and even then, often must be followed by well-powered confirmatory trials [35].

Advantages in ATMP Research

For ATMP developers, SATs offer several compelling advantages that align with the unique challenges of advanced therapy development. Smaller sample size requirements address the practical constraints of studying therapies for rare diseases [31] [32]. Faster implementation timelines enable more rapid evaluation of promising therapies for conditions with urgent unmet needs [31]. Reduced operational complexity simplifies trial execution in specialized medical centers with limited research infrastructure [32]. Ethical acceptability in contexts where randomization to control may be problematic [32]. These advantages make SATs particularly relevant for ATMPs targeting rare genetic disorders, ultra-orphan indications, and conditions with predictable natural history and high mortality.

Table: Applications of Single-Arm Trials in ATMP Research

| Application Area | Key Characteristics | Regulatory Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Rare Diseases | Small patient populations; Limited recruitment pools | Acceptance higher for ultra-rare diseases (<1:50,000) |

| Advanced Malignancies | No effective treatment options; Life-threatening conditions | Often under Accelerated Approval pathways |

| Novel ATMP Modalities | Dramatic treatment effects; Unprecedented mechanisms | Require strong biological plausibility |

| Conditions with Predictable Natural History | Well-characterized disease progression; Consistent endpoints | Historical control data must be high-quality |

| Ethically Constrained Contexts | Randomization to control problematic; Equipoise concerns | Requires strong ethical justification |

Limitations and Methodological Challenges

Despite their operational advantages, single-arm trials face significant methodological limitations that can compromise the validity and reliability of their findings. Understanding these challenges is essential for appropriate design, interpretation, and regulatory acceptance of SATs in ATMP research.

Threats to Validity and Reliability

The fundamental absence of randomization in SAT designs creates an intrinsic limitation in establishing definitive causal attribution of therapeutic effects [33]. In randomized controlled trials, the methodological cornerstone of random allocation ensures approximate equipoise in both measured and latent prognostic factors across treatment arms, establishing a statistically robust framework for causal inference. SATs inherently lack methodological safeguards against confounding from unmeasured prognostic determinants [33]. This inability to account for latent variables systematically compromises internal validity in therapeutic effect estimation.

The same methodological limitation engenders dual threats to external validity, which precludes the direct quantification of treatment effects [33]. The quantification must rely on two critical assumptions: (1) precise characterization of counterfactual outcomes (the hypothetical disease trajectory without intervention), and (2) prognostic equipoise between study participants and external controls across both measured and latent biological determinants [33]. Consequently, SATs-derived efficacy estimates exhibit an inherent context-dependence nature, constrained to narrowly defined patient subgroups under protocol-specified conditions, with limited generalizability beyond the trial's operational parameters [33].

In single-arm trials, the reliability of therapeutic effect estimates may be inherently compromised [33]. Efficacy estimates become particularly susceptible to sampling variability, especially in studies characterized by limited sample sizes and/or high outcome variability. While RCTs rely on statistical properties inherent to randomization that mitigate uncertainty, SATs only directly observe variability within the experimental group, while the variability of a hypothetical control group remains unknown [33].

Specific Biases in SATs