Direct Lineage Conversion Using Modified mRNA: A Non-Integrative Strategy for Cell Reprogramming and Regenerative Medicine

This article explores the transformative potential of modified mRNA (modRNA) technology in direct lineage conversion, a process that directly reprograms one specialized cell type into another without reverting to a...

Direct Lineage Conversion Using Modified mRNA: A Non-Integrative Strategy for Cell Reprogramming and Regenerative Medicine

Abstract

This article explores the transformative potential of modified mRNA (modRNA) technology in direct lineage conversion, a process that directly reprograms one specialized cell type into another without reverting to a pluripotent state. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, we examine the foundational principles that enable modRNA to overcome the instability and immunogenicity of conventional mRNA. The scope encompasses the methodology of synthetic mRNA design and delivery, its application in generating induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) and transdifferentiated therapeutic cells (such as myoblasts and neurons), and the critical optimization of factors like nucleoside modifications and lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) for efficient transfection. Finally, we provide a comparative analysis against other reprogramming methods, validating the utility of modRNA-derived cells in disease modeling, drug screening, and the future of cell-based therapies.

The Foundations of Direct Lineage Conversion: From MyoD to Modified mRNA

Defining Direct Lineage Reprogramming and its Distinction from Pluripotency

Direct lineage reprogramming, also known as transdifferentiation, represents a groundbreaking technology in regenerative medicine that enables the direct conversion of one specialized somatic cell type into another without passing through an intermediate pluripotent state [1]. This approach fundamentally challenges traditional concepts of epigenetic stability and linear cell differentiation, offering researchers a powerful tool for generating patient-specific cells for disease modeling, drug screening, and potential cell-based therapies [2]. Unlike strategies involving induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), direct reprogramming avoids the ethical concerns associated with embryonic stem cells and eliminates the tumorigenic risks posed by residual pluripotent cells in therapeutic applications [3] [1].

The conceptual foundation of direct lineage reprogramming rests on the understanding that cellular identity is maintained primarily through epigenetic mechanisms rather than irreversible genetic alterations [3]. Although all nucleated somatic cells in an organism contain essentially the same genomic information, their diverse phenotypes emerge from specific patterns of gene expression governed by transcription factors, chromatin modifications, and non-coding RNAs [1]. The breakthrough discovery that somatic cells could be reprogrammed to pluripotency using defined factors (iPSC technology) demonstrated that differentiated cell states are reversible [4]. This pivotal finding paved the way for more direct conversion approaches that bypass the pluripotent intermediate altogether [2].

Key Mechanistic Distinctions: Direct Reprogramming vs. Pluripotency Reprogramming

Fundamental Differences in Process and Methodology

Table 1: Core Differences Between Direct Lineage Reprogramming and Pluripotency Reprogramming

| Feature | Direct Lineage Reprogramming | Pluripotency Reprogramming |

|---|---|---|

| Intermediate State | Bypasses pluripotent state [1] | Requires transition through pluripotent state [4] |

| Theoretical Basis | Transdifferentiation; direct conversion [1] | Dedifferentiation to pluripotency followed by differentiation [4] |

| Key Transcription Factors | Cell type-specific factors (e.g., Bmi1+FGFR2 for keratinocytes; SAPG for hair cells) [3] [5] | Pluripotency factors (OSKM: Oct4, Sox2, Klf4, c-Myc) [4] |

| Tumorigenic Risk | Lower risk, no teratoma formation [1] | Higher risk due to potential residual pluripotent cells [1] |

| Time Required | Typically faster (days to weeks) [5] | Generally slower (weeks to months) [4] |

| Efficiency | Variable, often low but improving with new methods [6] | Variable, can be enhanced with small molecules [6] |

| Epigenetic Remodeling | Targeted, lineage-specific changes [2] | Global reorganization to pluripotent state [4] |

| Therapeutic Applications | In vivo and in vitro direct conversion [3] [7] | Primarily in vitro differentiation followed by transplantation [4] |

Molecular Mechanisms and Signaling Pathways

The molecular events governing direct lineage reprogramming differ significantly from pluripotency reprogramming. While pluripotency reprogramming involves global epigenetic remodeling and activation of core pluripotency networks, direct reprogramming employs lineage-specific transcription factors that redirect the existing transcriptional machinery toward a new somatic cell fate [2]. During pluripotency reprogramming, the process follows a biphasic pattern: an early stochastic phase where somatic genes are silenced and early pluripotency genes activated, followed by a deterministic phase where late pluripotency genes are established [4]. This process involves profound metabolic alterations, mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition (MET), and global chromatin restructuring [4].

In contrast, direct reprogramming utilizes master regulator transcription factors specific to the target cell type to orchestrate a more focused epigenetic reorganization. For example, in fibroblast-to-keratinocyte reprogramming, the combination of Bmi1 and FGFR2 (B2 factors) activates the keratinocyte genetic program while suppressing the fibroblastic identity [3]. Similarly, reprogramming fibroblasts to induced hair cell-like cells employs SIX1, ATOH1, POU4F3, and GFI1 (SAPG factors) to directly activate the hair cell differentiation program [5]. The emerging understanding of epigenetic modifiers including RNA modifications such as m5C mediated by NSUN family methyltransferases further reveals additional layers of regulation in cell fate determination [8].

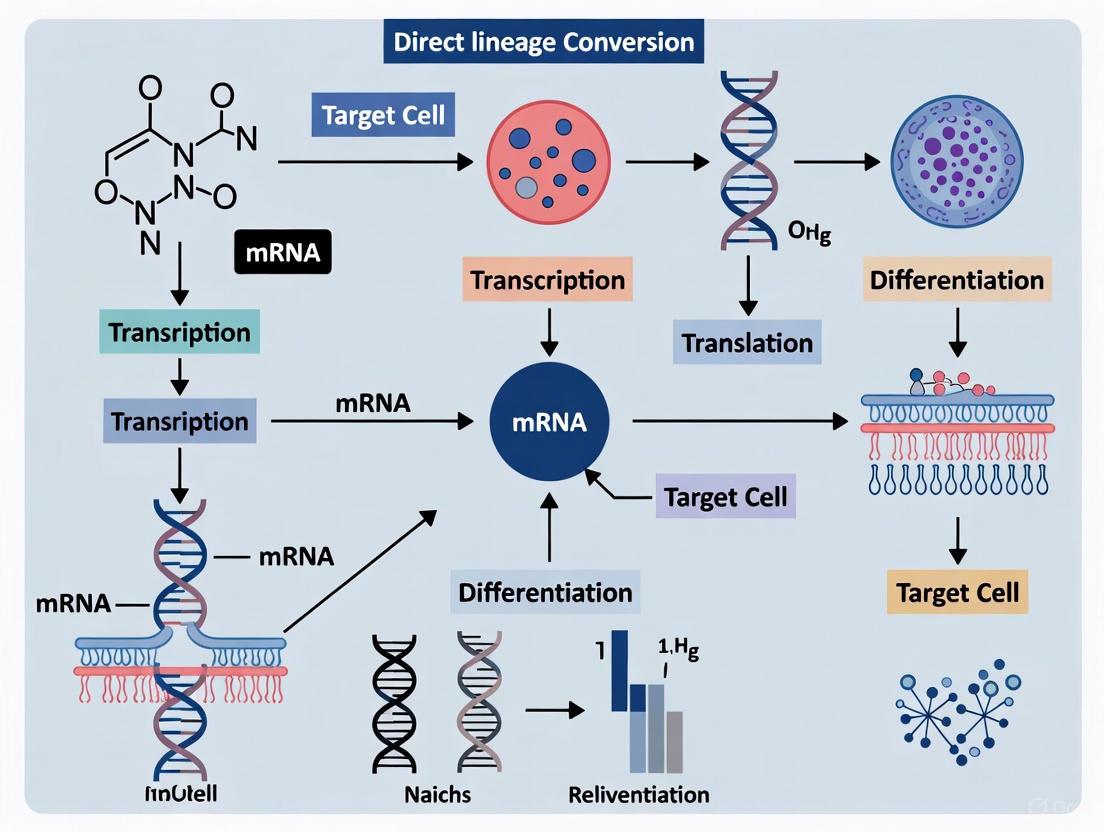

Diagram Title: Direct vs. Pluripotency Reprogramming Pathways

Experimental Protocols for Direct Lineage Reprogramming

Protocol 1: Direct Reprogramming of Fibroblasts to Keratinocyte-like Cells (iKCs) Using B2 Factors

This protocol describes the conversion of mouse fibroblasts into functional keratinocyte-like cells using BMI1 and FGFR2 (B2 combination), representing a promising approach for skin regeneration and wound healing applications [3].

Materials and Reagents:

- Source cells: Mouse fibroblasts (L929 cell line or primary mouse dermal fibroblasts)

- Reprogramming factors: BMI1 and FGFR2 genes

- Delivery vector: Adeno-associated virus serotype 9 (AAV9) vectors

- Culture media: Serum-free medium supplemented with growth factors

- Analysis tools: qRT-PCR reagents, Western blot equipment, immunofluorescence supplies

Procedure:

- Cell Preparation: Plate mouse fibroblasts at appropriate density in culture vessels and maintain in standard fibroblast growth medium until 70-80% confluent.

- Factor Delivery: Transduce cells with AAV9 vectors carrying BMI1 and FGFR2 at the following concentrations:

- AAV9-BMI1: 5.28 × 10^13 vg/mL

- AAV9-FGFR2: 1.80 × 10^13 vg/mL

- Total viral concentration: 6.64 × 10^13 vg/mL

- Culture Conditions: Maintain transduced cells in serum-free medium supplemented with specific growth factors to support keratinocyte differentiation.

- Morphological Monitoring: Observe daily for morphological changes from fibroblastic to epithelial-like appearance, typically occurring within 7-14 days.

- Functional Validation: After 2-3 weeks, analyze resulting induced keratinocyte-like cells (iKCs) for:

- Gene expression: Keratinocyte markers (keratins, involucrin) by qRT-PCR

- Protein expression: Immunofluorescence for keratinocyte-specific proteins

- Functional capacity: Barrier function assays, stratification potential

Applications: This methodology shows particular promise for treating diabetic foot ulcers, with in vivo studies demonstrating significantly promoted wound closure, reconstructed stratified epithelium, and restored barrier function in diabetic mouse models [3].

Protocol 2: Virus-Free Direct Reprogramming to Hair Cell-like Cells Using Inducible SAPG Factors

This advanced protocol generates human inner ear hair cell-like cells using a virus-free, inducible system, providing a scalable platform for hearing loss research and drug screening [5].

Materials and Reagents:

- Source cells: Human induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs)

- Reprogramming construct: Doxycycline-inducible cassette expressing SIX1, ATOH1, POU4F3, and GFI1 (SAPG)

- Culture media: Appropriate iPSC maintenance and differentiation media

- Induction agent: Doxycycline

- Analysis tools: Single-cell RNA sequencing reagents, electrophysiology equipment, immunostaining supplies

Procedure:

- Cell Line Engineering: Generate a stable human iPSC line carrying doxycycline-inducible SAPG reprogramming factors targeted to the CLYBL safe harbor locus using CRISPR/Cas9-mediated knock-in.

- Factor Induction: Treat engineered iPSCs with doxycycline (typically 1-2 μg/mL) to activate simultaneous expression of all four reprogramming factors.

- Temporal Control: Maintain doxycycline induction for optimized duration (approximately 7-14 days based on target maturity).

- Efficiency Assessment: Monitor reprogramming efficiency through expression of hair cell markers such as MYO7A, ESPIN, and POU4F3.

- Functional Characterization: Perform comprehensive analysis of resulting hair cell-like cells including:

- Immunostaining for hair cell-specific proteins

- Single-cell RNA sequencing to evaluate transcriptional similarity to native hair cells

- Electrophysiological analysis to detect characteristic ion currents

Key Advantages: This virus-free system demonstrates a 19-fold increase in conversion efficiency compared to retroviral methods and achieves reprogramming in half the time. The resulting cells closely resemble developing fetal hair cells and exhibit diverse voltage-dependent ion currents, including robust, quick-activating, slowly inactivating currents characteristic of primary hair cells [5].

Protocol 3: Direct Reprogramming of Fibroblasts to Alveolar Epithelial-like Cells (iPULs)

This protocol describes the generation of induced pulmonary alveolar epithelial-like cells (iPULs) through direct reprogramming, offering potential for lung regeneration and disease modeling [9].

Materials and Reagents:

- Source cells: Mouse tail-tip fibroblasts (TTFs) or embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs)

- Reprogramming factors: Nkx2-1, Foxa1, Foxa2, and Gata6

- Delivery system: Retroviral vectors

- Culture system: 3D organoid culture conditions

- Supplements: Wnt pathway activators, growth factors, Smad inhibitors

- Sorting markers: Thy1.2 (negative selection), EpCAM (positive selection)

Procedure:

- Factor Screening: Identify optimal transcription factor combination through systematic screening. The quartet of Nkx2-1, Foxa1, Foxa2, and Gata6 demonstrates strongest induction of surfactant protein-C (Sftpc) expression.

- 3D Culture Setup: Transduce fibroblasts with retroviral vectors carrying the four factors and culture in 3D organoid system instead of traditional 2D conditions.

- Media Optimization: Supplement serum-free medium with Wnt pathway activators, specific growth factors, and Smad inhibitors to enhance reprogramming efficiency.

- Cell Sorting: After 7 days, isolate reprogrammed cells using fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) for Sftpc-GFP+ (in reporter systems), Thy1.2-, and EpCAM+ populations.

- Characterization: Validate resulting iPULs through:

- Transcriptomic analysis comparing to primary alveolar epithelial cells

- Functional assessment of lamellar body formation

- In vivo integration potential following transplantation

Efficiency and Applications: This approach achieves approximately 2-3% reprogramming efficiency of starting fibroblasts. The resulting iPULs integrate into alveolar surfaces when administered intratracheally in bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis models and form both alveolar epithelial type 1 and type 2-like cells, demonstrating therapeutic potential for lung diseases [9].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Direct Lineage Reprogramming

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Reprogramming Factors | B2 (BMI1+FGFR2), SAPG (SIX1+ATOH1+POU4F3+GFI1), NKX2-1+FOXA1+FOXA2+GATA6 | Master regulators that initiate cell fate conversion [3] [5] [9] |

| Delivery Systems | AAV9 vectors, Retroviral vectors, Doxycycline-inducible systems, Non-integrating methods | Introduce reprogramming factors into target cells [3] [5] |

| Culture Systems | 3D organoid platforms, Serum-free media, Defined growth factor cocktails | Provide appropriate microenvironment for reprogramming and maturation [9] |

| Enhancement Molecules | Wnt pathway activators, Smad inhibitors, Specific growth factors | Improve reprogramming efficiency and kinetics [6] [9] |

| Characterization Tools | scRNA-seq, Immunofluorescence, Electrophysiology, Functional assays | Validate successful reprogramming and functionality [5] |

| Cell Sorting Markers | Thy1.2 (fibroblast negative), EpCAM (epithelial positive), Lineage-specific reporters | Isate successfully reprogrammed cells from starting population [9] |

Direct lineage reprogramming represents a transformative approach in regenerative medicine that distinguishes itself from pluripotency-based strategies through its direct conversion methodology, reduced tumorigenic risk, and potential for in vivo applications. The experimental protocols outlined demonstrate the remarkable versatility of this technology across different tissue types, from skin and sensory cells to pulmonary epithelium. As the molecular mechanisms underlying cell fate determination become increasingly elucidated, particularly through advanced understanding of epigenetic regulators like RNA modifications [8], the efficiency and specificity of direct reprogramming continue to improve.

The future of direct lineage reprogramming lies in refining factor combinations, delivery methods, and microenvironmental conditions to enhance efficiency and functionality. Particularly promising are the advances in virus-free, RNA-based reprogramming techniques that align with the modified mRNA research context [10], offering improved safety profiles for potential therapeutic applications. As these technologies mature, direct lineage reprogramming stands to revolutionize personalized medicine by enabling the generation of patient-specific functional cells for disease modeling, drug screening, and regenerative therapies across a broad spectrum of degenerative conditions.

{The Pioneering Role of Transcription Factors like MyoD}

The discovery of the skeletal muscle-specific transcription factor MyoD represents a milestone in the field of transcriptional regulation during differentiation and cell-fate reprogramming [11]. MyoD was the first tissue-specific factor found capable of converting non-muscle somatic cells into skeletal muscle cells, establishing a powerful paradigm for direct lineage conversion [11]. A unique feature of MyoD, with respect to other lineage-specific factors, is its ability to dramatically change cell fate even when expressed alone, without requiring the coordinated expression of multiple transcription factors that many other reprogramming processes necessitate [11].

Within the context of modern modified mRNA research, MyoD has emerged as a particularly promising candidate for therapeutic reprogramming strategies. The transient nature of modified mRNA expression makes it ideally suited for directing cellular conversions without genomic integration, thereby enhancing safety profiles for potential clinical applications [12]. This application note details the molecular mechanisms, experimental protocols, and practical implementation strategies for leveraging MyoD in direct lineage conversion research, with particular emphasis on modified mRNA delivery systems.

Molecular Mechanisms of MyoD-Mediated Reprogramming

Transcriptional Activation and Myogenic Programming

MyoD belongs to the basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) class of transcription factors and recognizes short DNA sequences (CANNTG), termed E-box motifs, in the regulatory regions of muscle-specific target genes [11]. MyoD binding to E-boxes and subsequent transactivation require heterodimerization with ubiquitous bHLH E-proteins, such as E12 and E47 [11]. The specificity of DNA binding and target activation by MyoD is determined by several cooperating mechanisms:

- Sequence Preference: MyoD exhibits preference for internal and flanking sequences of E-boxes [11]

- Co-factor Cooperation: Transcription factors including MEF2 family members, Sp1, Pbx, and Six proteins cooperate with MyoD by directly binding to adjacent sites [11]

- Epigenetic Engagement: MyoD interacts with the epigenetic machinery to remodel chromatin and activate silent loci [11]

MyoD-induced trans-differentiation involves activation of a complex program of gene expression, beginning with direct targets such as the bHLH muscle-specific transcription factor myogenin and the co-activator MEF2 [11]. MyoD also induces its own transcription and the expression of other transcription factors, creating positive feedback loops and amplifying cascades that reinforce the myogenic commitment [11].

Signaling Pathway Integration and Regulation

MyoD-dependent transcription integrates extracellular cues through several signaling cascades. The table below summarizes key pathways that regulate or enhance MyoD-mediated reprogramming:

Table 1: Signaling Pathways Regulating MyoD Activity in Cellular Reprogramming

| Pathway | Effect on MyoD | Key Modulators | Experimental Utility |

|---|---|---|---|

| p38 MAPK | Promotes MyoD activity | Targets co-factors (MEF2, E proteins) and chromatin complexes [11] | Enhances terminal differentiation |

| JNK | Inhibition enhances reprogramming | SP600125 (JNK inhibitor) [12] | Increases Pax7+ iMPC formation (~55-60% vs ~30% with F/R/C alone) [12] |

| JAK/STAT | Inhibition enhances reprogramming | CP690550 (JAK inhibitor) [12] | Increases Pax7+ iMPC formation [12] |

| Notch | Inhibits MyoD function | Hes1/Hey1 (bHLH repressors competing for E-box binding) [11] | Modulates proliferation vs differentiation balance |

| Mitogenic Signals | Inhibit MyoD function | Id proteins, cyclin/cdk complexes [11] | Serum withdrawal promotes terminal differentiation |

The following diagram illustrates the core molecular interactions and signaling pathways involved in MyoD-mediated reprogramming:

Figure 1: Core Molecular Mechanisms of MyoD-Mediated Reprogramming. MyoD heterodimerizes with E-proteins, binds E-box motifs, and activates a myogenic transcriptional program while engaging chromatin remodeling machinery. Key signaling pathways modulate this process.

Experimental Protocols for MyoD-Mediated Reprogramming

Transgene-Free Direct Conversion Using Modified mRNA

Recent advances have enabled highly efficient transgene-free approaches to directly convert mouse fibroblasts into induced myogenic progenitor cells (iMPCs) by overexpression of synthetic MyoD-mRNA in concert with enhanced small molecule cocktails [12]. The optimized protocol achieves robust and rapid reprogramming in as little as 10 days, with resulting iMPCs expressing characteristic myogenic stem cell markers, extensive proliferative capacity in vitro, and the ability to differentiate into multinucleated, contractile myotubes [12].

Table 2: Modified mRNA Reprogramming Protocol for Fibroblast to iMPC Conversion

| Step | Procedure | Duration | Key Components | Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Cell Preparation | Plate Rep-MEFs or primary fibroblasts | 24 hours | DMEM + 10% FCS [13] | Establish subconfluent culture |

| 2. Mesendoderm Priming | Treat with mesendoderm-inducing factors | 3 days | CHIR99021, BMP4 [14] | Enhance chromatin accessibility for myogenic programming |

| 3. MyoD-mRNA Transfection | Daily transfection with synthetic MyoD-mRNA | 7 days | Modified MyoD-mRNA (pseudouridine, 5-methylcytidine) [12] | Activate myogenic transcriptional program |

| 4. Small Molecule Cocktail | Continuous treatment with pathway modulators | Entire reprogramming period | F/R/C + SP600125 + CP690550 [12] | Enhance conversion efficiency and Pax7+ stem cell population |

| 5. Colony Selection | Manual picking or FACS of Pax7+ cells | Day 10-14 | Pax7-nGFP reporter or immunostaining [12] | Isolate pure iMPC population |

The following workflow diagram visualizes the complete reprogramming protocol:

Figure 2: Workflow for Transgene-Free iMPC Generation. This optimized protocol converts fibroblasts into functional induced myogenic progenitor cells using modified MyoD-mRNA and small molecule cocktails.

Critical Parameters for Successful Reprogramming

Several parameters critically influence the success and efficiency of MyoD-mediated reprogramming:

- MRNA Modifications: Incorporation of pseudouridine and 5-methylcytidine is essential to mitigate cellular immune reactions against exogenous mRNA molecules [12]

- Transfection Frequency: Daily transfections for 7 days are required to sustain MyoD protein expression due to the transient nature of mRNA [14]

- Cell Density: Initial plating at appropriate density (30-50% confluence) is crucial for successful reprogramming [13]

- Small Molecule Timing: Continuous presence of pathway modulators throughout the reprogramming process enhances conversion efficiency [12]

Research Reagent Solutions for MyoD Reprogramming

The table below summarizes essential research reagents and their applications in MyoD-mediated direct lineage conversion studies:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for MyoD Reprogramming Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| MyoD Delivery Systems | Modified MyoD-mRNA (pseudouridine) [12], Lentiviral vectors (Tet-On) [13] | Ectopic MyoD expression | Modified mRNA avoids genomic integration; viral methods offer higher efficiency [12] |

| Small Molecule Enhancers | Forskolin (F), RepSox (R), CHIR99210 (C) [12], SP600125 (JNK inhibitor), CP690550 (JAK inhibitor) [12] | Enhance reprogramming efficiency | JNK and JAK/STAT inhibition increases Pax7+ population (~2-fold) [12] |

| Cell Culture Media | DMEM + 10% FCS (proliferation) [13], Serum-free media (differentiation) [11] | Support cell growth and differentiation | Serum withdrawal promotes terminal differentiation [11] |

| Reporter Systems | Pax7-CreERT2; R26-LSL-ntdTomato [12], Pax7-nuclear GFP [12] | Track reprogramming efficiency | Enable FACS-based isolation of iMPCs |

| Analysis Tools | Anti-MyoD, anti-Desmin, anti-α-actin antibodies [13] | Validate reprogramming success | Immunofluorescence and Western blot analysis |

Applications and Therapeutic Translation

In Vivo Engraftment and Regeneration

Transgene-free iMPCs generated via MyoD-mRNA reprogramming demonstrate significant therapeutic potential. Upon transplantation into skeletal muscles of Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) mouse models, these cells robustly engraft and restore dystrophin expression in hundreds of myofibers [12]. This demonstrates the functional capacity of the reprogrammed cells and their potential for regenerative medicine applications.

Technology Integration and Advanced Delivery Systems

Emerging technologies are further enhancing the potential of MyoD-based reprogramming strategies:

- Tissue Nanotransfection (TNT): A novel non-viral nanotechnology platform that enables in vivo gene delivery and direct cellular reprogramming through localized nanoelectroporation [15]

- Optimized mRNA Design: Algorithms like LinearDesign can optimize mRNA sequences for improved stability and immunogenicity, potentially enhancing MyoD expression and reprogramming efficiency [16]

- Organ-on-Chip Models: Microfluidic platforms enable direct on-chip programming of human pluripotent stem cells into skeletal myocytes using MYOD modified mRNA [14]

MyoD continues to serve as a paradigm for transcription factor-mediated direct lineage conversion, with modern modified mRNA technologies addressing critical safety concerns associated with viral delivery methods. The optimized protocols and reagent systems detailed in this application note provide researchers with robust methodologies for generating functional myogenic cells through transgene-free reprogramming. As mRNA design algorithms and delivery technologies continue to advance, MyoD-based cellular reprogramming holds increasing promise for regenerative medicine, disease modeling, and therapeutic development for muscular disorders.

The therapeutic application of messenger RNA (mRNA) represents a revolutionary platform for a wide range of biomedical applications, from infectious disease vaccines to protein replacement therapies and direct lineage conversion. The core principle involves introducing in vitro transcribed (IVT) mRNA into target cells to direct the synthesis of specific proteins that can elicit immune responses, replace deficient proteins, or even reprogram cell identity. However, the clinical translation of mRNA-based therapeutics faces two interconnected fundamental challenges: mRNA instability and innate immunogenicity [17] [18]. These properties are intrinsically linked to mRNA's biological function as a transient information carrier in cells.

Naked, unmodified mRNA is inherently unstable and rapidly degraded by extracellular and intracellular nucleases, leading to insufficient protein expression for therapeutic efficacy [18] [19]. Compounding this instability, foreign mRNA is recognized by the host's innate immune system through pattern recognition receptors (PRRs), triggering potent antiviral responses and inflammatory cytokine production that can severely limit protein expression and potentially cause adverse effects [17] [20]. For researchers pursuing direct lineage conversion—the process of transforming one somatic cell type directly into another without reverting to a pluripotent state—these challenges are particularly pronounced. Successful reprogramming requires sustained expression of key transcription factors at appropriate levels, which is difficult to achieve when the mRNA instructions are rapidly degraded or when immune responses alter the cellular environment in ways that might inhibit reprogramming efficiency.

This Application Note provides a structured framework for overcoming these challenges through optimized mRNA design, chemical modifications, and delivery strategies, with particular emphasis on protocols suitable for lineage conversion research.

Molecular Mechanisms Underlying mRNA Instability and Immunogenicity

Pathways of mRNA Recognition and Degradation

Understanding the molecular mechanisms that govern mRNA stability and immunogenicity is essential for developing effective therapeutic mRNA constructs. The cellular machinery that normally regulates endogenous mRNA half-life and quality control represents the same barriers that exogenous therapeutic mRNA must overcome.

Immunogenicity Mechanisms: The innate immune system detects foreign RNA primarily through Toll-like receptors (TLRs) located in endosomal membranes and retinoic acid-inducible gene I (RIG-I)-like receptors (RLRs) in the cytoplasm [17]. Specifically, TLR3, TLR7, and TLR8 recognize single-stranded and double-stranded RNA motifs, while RIG-I and MDA-5 detect cytoplasmic RNA. These recognition events trigger signaling cascades that result in type I interferon (IFN) production and subsequent upregulation of interferon-stimulated genes (ISGs), creating an antiviral state that strongly inhibits translation of the exogenous mRNA [17] [18]. This immune activation not only reduces protein expression but may also alter the cellular phenotype in ways that could interfere with directed differentiation or lineage conversion protocols.

Instability Mechanisms: Endogenous mRNA degradation occurs through multiple pathways, including deadenylation (removal of the 3' poly(A) tail), decapping (removal of the 5' cap structure), and nuclease-mediated cleavage [19]. Exogenous IVT mRNA is particularly susceptible to these degradation pathways. The half-life of IVT mRNA in cells is typically limited to hours, while many therapeutic applications—especially those involving cell reprogramming—require sustained protein expression over several days to effectively alter cell identity and function [19] [20].

The following diagram illustrates the key cellular pathways that detect and degrade conventional mRNA, highlighting potential intervention points for engineered solutions:

Quantitative Impact on Protein Expression

The combined effects of immunogenicity and instability significantly limit both the magnitude and duration of protein expression from conventional mRNA. The following table summarizes key quantitative findings from preclinical studies:

Table 1: Quantitative Impact of mRNA Instability and Immunogenicity on Protein Expression

| Parameter | Conventional mRNA | Modified/Optimized mRNA | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protein expression duration | <24-48 hours | Extended to several days | VEGF mRNA expression declined within 24 hours after intradermal administration in clinical trials [19] |

| Antibody response | Baseline (reference) | Up to 128-fold increase | LinearDesign-optimized COVID-19 vaccines in mice [16] |

| mRNA half-life | Minutes to hours | Significantly prolonged | circRNA half-life "significantly exceeds" linear mRNA [20] |

| Immunogenicity | High IFN and cytokine production | Greatly reduced | Ψ and m1Ψ modifications reduce PRR activation [17] |

Research Reagent Solutions for mRNA Engineering

Overcoming the challenges of immunogenicity and instability requires a multifaceted approach combining specialized reagents, optimized sequences, and delivery systems. The following table catalogs key reagents and their functions for developing enhanced mRNA constructs:

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for mRNA Engineering

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function & Mechanism | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nucleotide Analogs | Pseudouridine (Ψ), N1-methylpseudouridine (m1Ψ), 5-methylcytidine (m5C) | Reduce immunogenicity by evading pattern recognition receptors | m1Ψ used in COVID-19 vaccines; note potential for ribosomal frameshifting [17] |

| Capping Reagents | CleanCap analogs, anti-reverse cap analogs (ARCA) | Enhance translation initiation and protect from 5' decay | Critical for protein expression yield; affects capping efficiency [21] [20] |

| Stabilizing Sequences | Optimized 5' and 3' UTRs, structured elements | Increase half-life by impeding nuclease access | Algorithmic design (e.g., LinearDesign) improves stability [16] |

| Poly(A) Tail Enzymes | Poly(A) polymerases, defined-length tails | Control tail length for stability and translation | Optimal length typically 100-150 nucleotides [21] [20] |

| Purification Kits | HPLC, FPLC systems, dsRNA removal | Remove immunogenic impurities (e.g., dsRNA) | Essential for reducing innate immune activation [21] |

Experimental Protocols for mRNA Evaluation

Protocol 1: Assessment of mRNA Immunogenicity in Vitro

Purpose: To quantitatively evaluate the innate immune response activation by novel mRNA constructs in mammalian cells.

Materials:

- HEK293T or THP-1 cell lines

- Test mRNA constructs (including unmodified control)

- Transfection reagent (e.g., Lipofectamine MessengerMAX)

- RNA extraction kit

- qRT-PCR reagents for IFN-β, IL-6, and other cytokines

- ELISA kits for IFN-α, IFN-β, TNF-α

- Cell culture media and standard lab equipment

Procedure:

- Cell Seeding: Seed 2×10^5 cells per well in 24-well plates 24 hours before transfection to achieve 70-80% confluency.

- mRNA Transfection: Prepare complexes of test mRNA (100 ng/well) with transfection reagent according to manufacturer's instructions. Include an unmodified mRNA control and a mock transfection control.

- Incubation: Incubate cells with mRNA complexes for 6-24 hours at 37°C, 5% CO₂.

- RNA Extraction and qRT-PCR:

- Extract total RNA using appropriate kits

- Synthesize cDNA using reverse transcriptase

- Perform qPCR with primers for IFN-β, IL-6, and RIG-I

- Normalize to housekeeping genes (GAPDH, β-actin)

- Protein Analysis:

- Collect cell culture supernatants at 24 hours

- Measure secreted cytokine levels using ELISA

- Data Analysis: Calculate fold changes relative to mock-transfected controls. Statistical analysis should include at least three independent experiments.

Troubleshooting: High baseline immunity in control cells may indicate endotoxin contamination. Use nuclease-free techniques and endotoxin-free reagents throughout.

Protocol 2: Determination of mRNA Stability and Half-Life

Purpose: To quantitatively measure the intracellular stability and decay kinetics of mRNA constructs.

Materials:

- Appropriate cell line for application (e.g., fibroblasts for lineage conversion)

- Test mRNA constructs

- Actinomycin D (5 μg/mL) or other transcription inhibitors

- RNA extraction kit

- qRT-PCR reagents

- Capillary electrophoresis system (e.g., Fragment Analyzer)

Procedure:

- Cell Seeding and Transfection: Seed cells as described in Protocol 1 and transfert with test mRNA constructs.

- Transcription Inhibition: At 4 hours post-transfection, add actinomycin D to inhibit new RNA synthesis.

- Time-Course Sampling: Collect cell samples at 0, 2, 4, 8, 12, and 24 hours after actinomycin D addition.

- RNA Quantification:

- Extract total RNA from each time point

- Analyze mRNA integrity using capillary electrophoresis

- Perform qRT-PCR with assays targeting the encoded transgene

- Half-Life Calculation:

- Normalize mRNA levels to internal controls

- Plot remaining mRNA (%) versus time

- Calculate decay constant (k) from logarithmic plot

- Determine half-life using t½ = ln(2)/k

Alternative Approach: For applications requiring longer observation, use tet-inducible systems or photoactivatable nucleotides to monitor decay without global transcription inhibition.

The following workflow diagram illustrates the key steps in designing, producing, and evaluating enhanced mRNA constructs for research applications:

Analytical Methods for mRNA Characterization

Rigorous characterization of mRNA constructs is essential for understanding structure-function relationships and ensuring reproducible results. The following analytical approaches are recommended:

Integrity and Purity Assessment:

- Capillary Gel Electrophoresis (CGE): Provides high-resolution analysis of mRNA size distribution and identifies truncated species [21]. Critical for quantifying full-length product percentage.

- Agarose Gel Electrophoresis: Useful for initial quality assessment but less quantitative than CGE.

- Ion-Pair Reversed-Phase Liquid Chromatography (IP-RP LC): Separates mRNA based on hydrophobic interactions, resolving impurities and degradation products [21].

Structural Characterization:

- Mass Spectrometry: LC-MS/MS enables precise identification of chemical modifications and sequence verification [21].

- Direct RNA Sequencing: Confirms sequence identity and can detect nucleotide modifications [21].

Functional Characterization:

- In Vitro Translation Assays: Cell-free systems to assess translation efficiency without delivery complications.

- Western Blotting: Quantifies protein production levels and confirms protein identity.

- Cell-Based Assays: Measures biological activity in relevant cellular models.

For lineage conversion applications specifically, additional functional assays should include immunocytochemistry for cell-type-specific markers and RNA sequencing to evaluate transcriptional programs indicative of successful reprogramming.

Emerging Platforms and Future Perspectives

Beyond conventional linear mRNA, several innovative platforms show promise for applications requiring sustained protein expression such as lineage conversion:

Self-Amplifying RNA (saRNA): Derived from alphavirus genomes, saRNA contains replicase genes that enable intracellular amplification of the original RNA dose, dramatically extending duration of expression and reducing the required dose [17] [20]. However, the larger size (approximately 9-12 kb) presents delivery challenges, and the prolonged expression may increase safety concerns for some applications.

Circular RNA (circRNA): These covalently closed RNAs lack free ends, conferring exceptional resistance to exonuclease-mediated degradation [17] [22] [20]. The extended half-life makes circRNA particularly attractive for lineage conversion protocols that require sustained transcription factor expression. Recent studies have also revealed that circRNAs can directly interact with linear mRNAs to regulate their stability and translation [22], adding another layer of regulatory complexity to consider in experimental design.

The field of mRNA therapeutics continues to evolve rapidly, with ongoing research addressing remaining challenges in targeted delivery, precise temporal control of expression, and reducing unwanted immunogenicity while maintaining effective immune responses for vaccine applications. For lineage conversion research, these advances will enable more efficient and reproducible reprogramming protocols with potential applications in disease modeling, drug discovery, and regenerative medicine.

The application of synthetic messenger RNA (mRNA) as a therapeutic agent represents a paradigm shift in modern medicine, particularly for precise interventions like direct lineage conversion. Historically, its path was hindered by two major biological hurdles: innate instability leading to rapid degradation, and inherent immunogenicity triggering undesirable inflammatory responses [23] [24]. Overcoming these challenges was a prerequisite for the clinical success of mRNA technologies. Through strategic chemical modifications and sophisticated design, researchers have engineered modified mRNA (modRNA) that is both highly stable and minimally immunogenic [25] [26]. These advancements are foundational to its use in direct lineage conversion, where controlled, transient, and efficient protein expression is required to safely reprogram cell fate. This Application Note details the core mechanisms, key quantitative data, and essential protocols that underpin the development of effective modRNA for research in regenerative medicine and drug development.

Core Mechanisms: How Modifications Confer Stability and Reduce Immunogenicity

The historical limitations of unmodified mRNA have been systematically addressed through targeted engineering of its structure. The following diagrams and sections outline the key mechanisms and logical workflow for developing optimized modRNA.

Enhanced mRNA Stability

The stability of mRNA is critical for achieving sufficient therapeutic protein expression. Three primary structural elements are engineered to resist degradation:

- 5' Cap Analogues: The 5' cap protects mRNA from exonuclease degradation and recruits translation initiation factors. Anti-Reverse Cap Analogue (ARCA) ensures proper cap orientation, significantly enhancing translation [25]. Advanced Cap 1 structures (e.g., via CleanCap technology), which include a 2'-O-methylation on the first transcribed nucleotide, further increase stability and protein yield by reducing immune recognition compared to Cap 0 [24].

- Nucleotide Modifications: The strategic substitution of natural nucleotides with modified analogues is a cornerstone of stability enhancement. Recent research indicates that position-specific introduction of ribose modifications, such as 2'-fluoro (2'-F) at the first nucleoside of a codon, can significantly bolster mRNA stability without compromising translational efficiency [27].

- Optimized UTRs and Poly(A) Tail: The 5' and 3' Untranslated Regions (UTRs) are engineered using sequences from highly expressed genes (e.g., α-globin or β-globin) to enhance mRNA stability and regulate translational efficiency [23] [24]. A poly(A) tail of optimal length (typically 120-150 nucleotides) is also crucial for protecting the mRNA from rapid decay [23].

Reduced Immunogenicity

Unmodified mRNA is recognized by pattern recognition receptors (e.g., TLR7, TLR8), triggering the production of type I interferons and other inflammatory cytokines, which can inhibit translation and cause cell death [23].

- Nucleotide Substitution: Incorporating modified nucleotides such as N1-methylpseudouridine (N1mΨ) or pseudouridine (Ψ) and 5-methylcytidine (5mC) is the primary strategy to evade immune detection. These modifications cloak the mRNA, preventing its recognition by innate immune sensors and thereby drastically reducing interferon responses [25] [23] [27].

- Purification and Delivery: Following in vitro transcription (IVT), rigorous purification is necessary to remove double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) contaminants, which are potent inducers of innate immunity [25]. Furthermore, delivery systems like Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) protect the mRNA from extracellular RNases and facilitate efficient cellular uptake, further minimizing immune activation [28] [24].

Key Experimental Data and Comparative Analysis

The impact of specific modifications can be quantified through protein expression and immunogenicity assays. The table below summarizes key findings from optimization studies.

Table 1: Quantitative Impact of modRNA Optimization Strategies

| Optimization Strategy | Experimental System | Key Outcome Metric | Result vs. Control | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ARCA 10 Protocol (High ARCA, lower N1mΨ) | In vitro transfection (HeLa, HUVEC, primary cardiac cells) | Luciferase & GFP protein expression | Significantly increased expression vs. standard ARCA 5 protocol | [25] |

| Nucleotide Modification (N1mΨ substitution) | In vitro transfection; in vivo delivery | Interferon-α/β levels; Protein expression | Reduced immunogenicity; Increased protein expression vs. unmodified mRNA | [25] [23] |

| Position-specific 2'-F modification (1st nucleoside in codon) | Cell-free translation system (HeLa lysate) | Peptide expression (ELISA) | Enhanced stability & high translational activity vs. unmodified and other modification patterns | [27] |

| Terminal Modifications (2'-O-MOE with phosphorothioate) | Cell-free translation system | Peptide expression (ELISA) | Increased peptide production vs. non-terminally modified mRNA | [27] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol: modRNA Synthesis via In Vitro Transcription (IVT) and Purification

This protocol is adapted from optimized procedures for cost-effective production of high-yield, low-immunogenicity modRNA [25].

I. Reagent Setup (Nucleotide Composition for ARCA 10 Protocol):

- Template DNA: Linearized plasmid DNA template with T7 promoter and poly(A) region (85% reduction from traditional amounts).

- Nucleotide Master Mix:

- ARCA (Cap Analog): 10 mM

- GTP: 2.7 mM

- ATP: 8.1 mM

- CTP: 8.1 mM

- N1-methylpseudouridine-5'-triphosphate (N1mΨTP): 2.7 mM

- 10X T7 Reaction Buffer

- T7 RNA Polymerase

II. Step-by-Step Procedure:

- IVT Reaction: Combine the nucleotide master mix, template DNA, and T7 RNA Polymerase. Incubate at 37°C for 2-4 hours.

- DNase I Treatment: Add DNase I to the reaction and incubate for 15 minutes at 37°C to digest the DNA template.

- Primary Purification (Desalting): Use Amicon centrifugal filters (e.g., 100K MWCO) to remove unincorporated nucleotides and salts. This step is as effective as more expensive kit-based purification for this purpose [25].

- Poly(A) Tailing (If not encoded in template): If the poly(A) tail is not encoded, use Poly(A) Polymerase to add a tail of ~150 nucleotides to the 3' end.

- Final Purification: Purify the modRNA using a commercial RNA cleanup kit (e.g., MEGAclear) to remove enzymes, salts, and any residual dsRNA contaminants. This step is critical for reducing immunogenicity.

- Quality Control: Quantify modRNA by spectrophotometry (A260/A280). Assess integrity and purity using a bioanalyzer (e.g., Agilent Bioanalyzer).

Protocol: Assessing modRNA Immunogenicity and Expression In Vitro

I. Reagent Setup:

- Test modRNA: Prepared using the protocol above.

- Control RNA: Unmodified mRNA.

- Cell Line: HEK293 cells or primary human fibroblasts.

- Delivery Vehicle: Cationic lipid transfection reagent.

- Assay Kits: ELISA kits for Human IFN-α and IFN-β.

II. Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Cell Seeding: Seed cells in a 24-well plate to reach 70-80% confluence at transfection.

- Transfection Complex Formation: For each well, dilute 0.5 µg of modRNA (test or control) in opti-MEM. In a separate tube, dilute lipid transfection reagent in opti-MEM. Combine the diluted RNA and lipid reagent, incubate for 15-20 minutes.

- Transfection: Add the complexes to the cells.

- Incubation: Incubate cells for 24 hours.

- Harvest and Analysis:

- Immunogenicity: Collect cell culture supernatant at 24 hours post-transfection. Measure IFN-α and IFN-β levels using ELISA kits. modRNA with successful modification should show significantly reduced cytokine levels compared to unmodified mRNA controls [25].

- Expression Analysis: For encoded reporter genes (e.g., GFP, Luciferase), assay directly at 24-48 hours. For other proteins, lysate cells and perform Western blot or other functional assays to confirm high-level protein production.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Reagents for modRNA Research and Their Functions

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Key Notes |

|---|---|---|

| N1-methylpseudouridine (N1mΨ) | Modified nucleotide | Reduces immunogenicity, enhances translational efficiency. A key replacement for uridine. |

| Anti-Reverse Cap Analogue (ARCA) | 5' capping | Ensures proper cap orientation for high translation initiation efficiency. |

| CleanCap AG | Co-transcriptional capping | Enables one-step synthesis of the superior Cap 1 structure with high efficiency (>94%) [24]. |

| Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) | Delivery system | Protects modRNA, facilitates cellular uptake and endosomal escape; the gold standard for in vivo delivery. |

| T7 RNA Polymerase | In vitro transcription | High-yield enzyme for synthesizing mRNA from a DNA template. |

| β-globin UTRs | mRNA structural elements | Engineered into the construct to enhance mRNA stability and translational efficiency. |

Application in Direct Lineage Conversion: A Pathway View

In direct lineage conversion, modRNA encodes transcription factors that reprogram cell identity. The stability and low immunogenicity of modRNA are crucial for the repeated transfections required without triggering an antiviral state that would block reprogramming. The following diagram illustrates this application pathway.

The direct conversion of one somatic cell type into another, known as direct lineage conversion, represents a transformative approach in regenerative medicine for generating therapeutic cell types without passing through a pluripotent intermediate state. Within this field, modified mRNA (modRNA) technology has emerged as a superior non-integrative and controllable strategy for driving cell fate decisions. Unlike DNA-based methods that pose a risk of genomic integration and insertional mutagenesis, modRNA-based reprogramming delivers genetic instructions transiently through synthetic, chemically modified mRNA molecules. This approach provides a safe, efficient, and precise means of expressing transcription factors and other reprogramming molecules to orchestrate lineage conversion, offering significant potential for future clinical applications [29] [10].

Core Technological Advantages of Modified mRNA

The superiority of modRNA for cell fate manipulation is rooted in its distinct biological mechanism and safety profile compared to traditional vector-based systems. The table below summarizes its key advantages.

Table 1: Key Advantages of Modified mRNA for Cell Fate Manipulation

| Feature | Mechanistic Basis | Functional Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Non-Integrative | Remains in the cytoplasm and does not enter the nucleus; degraded by normal cellular processes [28] [10]. | Eliminates risk of insertional mutagenesis and permanent genomic alteration; favorable safety profile for clinical use. |

| Controllable/Transient | Protein expression is transient, typically lasting from hours to a few days, dependent on mRNA half-life [29]. | Allows for precise, pulsed expression of reprogramming factors; avoids sustained transgene expression that can cause tumorigenesis. |

| High Reprogramming Efficiency | Efficient transfection and direct translation in the cytoplasm bypasses the nuclear barrier; modified nucleotides enhance protein yield [10]. | Achieves high-efficiency lineage conversion; suitable for hard-to-transfect primary cells. |

| Rapid and Scalable Production | Manufactured via in vitro transcription (IVT), a cell-free process [28]. | Enables rapid production of research and therapeutic batches; platform can be quickly adapted to encode different proteins. |

The following diagram illustrates the workflow for direct lineage conversion using modified mRNA, from design to functional cell analysis.

Diagram 1: modRNA Lineage Conversion Workflow.

Quantitative Comparison of Reprogramming Technologies

Selecting an appropriate delivery method is a critical determinant of success and safety in lineage conversion experiments. The table below provides a comparative analysis of the most common technologies.

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of Cell Reprogramming and Lineage Conversion Technologies

| Technology | Reprogramming Efficiency | Genomic Integration? | Key Advantages | Key Limitations & Risks |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Modified mRNA (modRNA) | High (superior to non-integrative DNA methods) [10] | No [28] [10] | Non-integrative, controllable, high protein yield, rapid production. | Requires repeated transfections; can trigger innate immune response without modification. |

| Sendai Virus (SeV) | High [10] | No (RNA virus, replicates in cytoplasm) [10] | Highly efficient transduction, works in hard-to-transfect cells. | Requires diligent clearance; potential for cytopathogenicity. |

| Episomal Plasmads | Low [10] | No (but foreign DNA is present) [10] | Simple to use, no viral components. | Very low efficiency; potential risk of random integration. |

| Integrating Lenthviruses | High [10] | Yes [10] | Highly efficient, stable long-term expression. | High risk of insertional mutagenesis and oncogenesis; unsuitable for clinical use. |

| Protein Transduction | Very Low [10] | No [10] | Completely DNA-free; minimal safety concerns. | Extremely low efficiency; costly and technically challenging. |

Application Notes & Protocol: Direct Lineage Conversion Using modRNA

This protocol outlines a standardized procedure for converting human fibroblasts into induced neurons (iNs) using modified mRNA, based on established reprogramming methodologies.

Background and Principle

Direct lineage conversion allows for the trans-differentiation of a somatic cell into another somatic cell type by forced expression of specific transcription factors, bypassing the pluripotent state [10]. Using modRNA to deliver these factors combines the high efficiency of viral methods with the enhanced safety profile of a non-integrative, transient system. This is particularly critical for generating neuronal cells for disease modeling and regenerative therapies.

Experimental Protocol

Part I: Preparation of Modified mRNA

- Template Design: Clone the open reading frames (ORFs) of key pro-neural transcription factors (e.g., Brn2/Pou3f2, Ascl1, Myt1l) into an in vitro transcription (IVT) plasmid vector containing 5' and 3' untranslated regions (UTRs) known to enhance stability and translation (e.g., alpha-globin UTRs) [28].

- Template Linearization: Linearize the plasmid template downstream of the poly-A tail sequence using a restriction enzyme. Purify the linearized DNA.

- In Vitro Transcription (IVT): Synthesize mRNA using an IVT kit. To reduce immunogenicity and enhance stability, replace standard nucleotides with a modified nucleotide cocktail (e.g., pseudouridine-5'-triphosphate and 5-methylcytidine-5'-triphosphate) [10].

- Capping and Polyadenylation: Co-transcriptionally add a Cap 1 structure to the 5' end. Enzymatically add a poly-A tail to the 3' end if not encoded in the template, aiming for a tail of ~150 adenosine residues to maximize translational efficiency [28].

- Purification and Quality Control: Purify the modRNA product using LiCl precipitation or column-based methods. Analyze integrity via agarose gel electrophoresis and quantify concentration via spectrophotometry. Aliquot and store at -80°C.

Part II: Cell Culture and Transfection

- Cell Culture: Maintain human dermal fibroblasts in standard culture medium. One day before transfection, plate cells at a density of 5 x 10^4 cells per well in a 24-well plate coated with poly-L-ornithine/laminin.

- Transfection Complex Formation: For each well, prepare two solutions.

- Solution A (modRNA): Dilute a total of 1-2 µg of modRNA (a cocktail of the pro-neural factors) in 100 µL of serum-free medium.

- Solution B (Transfection Reagent): Dilute a commercial lipid-based transfection reagent in 100 µL of serum-free medium.

- Combine Solutions A and B, mix gently, and incubate for 10-20 minutes at room temperature to allow complex formation.

- Transfection: Add the entire 200 µL of complexes dropwise to the cells in fresh culture medium. Incubate cells at 37°C, 5% CO2.

- Transfection Regimen: Repeat the transfection process every 24 hours for a period of 10-14 days. The repetitive delivery is crucial for maintaining sufficient levels of the transient reprogramming factors to drive the conversion process [10].

Part III: Post-Transfection and Analysis

- Culture Maintenance: 4-6 hours after each transfection, perform a complete medium change. This is critical to minimize cellular toxicity and innate immune responses triggered by RNA and transfection reagents.

- Immunostaining: After 10-14 days, fix cells and perform immunocytochemistry for neuronal markers such as Tuj1 (neuron-specific class III β-tubulin) and Map2 (microtubule-associated protein 2) to confirm neuronal identity.

- Functional Analysis: Assess the electrophysiological properties of the induced neurons using patch-clamp recording to validate the presence of active sodium and potassium channels and the ability to fire action potentials.

The following diagram visualizes the molecular mechanism of how the delivered modRNA leads to protein expression and subsequent cell fate change.

Diagram 2: modRNA Mechanism of Action.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful implementation of modRNA-based lineage conversion requires a suite of specialized reagents and tools.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for modRNA Lineage Conversion

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function & Importance |

|---|---|---|

| IVT Plasmid Vectors | pIVT2, pGEM series | Backbone for template DNA; contains bacteriophage promoter (T7, SP6) for high-yield mRNA synthesis. |

| Modified Nucleotides | Pseudouridine-5'-Triphosphate, 5-Methylcytidine-5'-Triphosphate | Replaces UTP and CTP; critical for reducing innate immune recognition and enhancing translational efficiency [10]. |

| Capping Reagents | Trivalent Cap 1 Analog (CleanCap) | Enables co-transcriptional capping for superior translation initiation and mRNA stability. |

| Transfection Reagents | Lipid-based (e.g., Lipofectamine RNAiMAX, Messenger Max) | Forms protective complexes with modRNA for efficient cellular uptake and endosomal escape. |

| Immune Suppressors | B18R protein, IFN-γ receptor blocking antibodies | Optional supplements to further suppress PKR pathway activation and interferon response, boosting protein yield. |

| Cell Culture Matrix | Poly-L-ornithine/Laminin, Geltrex | Provides a supportive surface for sensitive cell types like neurons during and after conversion. |

Engineering Cell Fate: Methodology and Therapeutic Applications of modRNA

Modified messenger RNA (modRNA) has emerged as a powerful tool for direct lineage conversion, enabling the reprogramming of somatic cells into specific target cell types without genomic integration. The structural components of synthetic mRNA—the 5' cap, 5' and 3' untranslated regions (UTRs), nucleoside modifications, and codon-optimized open reading frame (ORF)—collectively determine its translational efficiency, stability, and immunogenicity [17] [23]. For lineage conversion protocols, where precise temporal control and high levels of protein expression are critical for efficient reprogramming, optimizing each of these elements is paramount. This application note provides detailed methodologies and current optimization strategies for constructing high-performance modRNAs, with particular emphasis on their application in direct lineage conversion research.

5' Cap Analogs: Enhancing Translation Initiation and Stability

The 5' cap is a critical modification that promotes translation initiation, protects the mRNA from exonuclease degradation, and influences immunogenicity. Recent innovations have moved beyond the canonical m7G cap to analogs that confer enhanced properties.

Advanced Cap Analogs and Their Properties

Table 1: Performance Characteristics of Select 5' Cap Analogs

| Core Modification | Notable Structure(s) | eIF4E Affinity (Kd-fold vs. m7GpppG) | Half-life in Cytosolic Extract (t½-fold) | In Vitro Translation Boost (RLU-fold) | Reported Immunogenicity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phosphorothioate [30] | m7G-PS-ppG | ~1.1 | 6-8× | ~2.0 | Low (IFIT1 evasion) |

| Tetraphosphate Extension [30] | m7Gppppm7G | ~3.2 | ~2× | ~2.5 | Moderate |

| 7-Benzylguanine [30] | BN7mGpppG | ~2.1 | ~3× | ~3.0 | Very Low |

| Dithiodiphosphate [30] | m7G-S-S-ppG | ~1.3 | ~10× | ~1.8 | Low |

| Trinucleotide (CleanCap AG) [30] | m7GpppAm2′-O-Ψ | ~1.4 | ~4× | ~2.1 | Ultra-Low |

Protocol: In Vitro Transcription with Co-transcriptional Capping

This protocol is optimized for producing high-yield, 5'-capped modRNA using the CleanCap AG analog, which achieves >94% Cap-1 structure incorporation [30].

- Template Preparation: Linearize a plasmid DNA template containing the gene of interest downstream of a bacteriophage promoter (e.g., T7, SP6) or use a PCR-amplified template with an appended promoter. Purify the template via phenol-chloroform extraction and isopropanol precipitation.

- IVT Reaction Setup: Assemble the following reaction on ice:

- Nuclease-free water to 100 μL final volume

- 1x Transcription Buffer (e.g., 200 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.9, 30 mM MgCl₂, 10 mM spermidine)

- DNA template (5–10 μg)

- Nucleoside triphosphates (NTPs, 7.5 mM each of ATP, CTP, UTG, GTP). For modified mRNA, replace UTP with N1-methylpseudouridine-5'-triphosphate (m1Ψ TP).

- 10 mM CleanCap AG trinucleotide cap analog [30].

- Recombinant T7 RNA Polymerase (2000 U).

- Incubation: Incubate the reaction at 37°C for 2–4 hours.

- DNase Treatment: Add 2 U of DNase I (RNase-free) and incubate at 37°C for 15 minutes to digest the DNA template.

- mRNA Purification: Purify the mRNA using magnetic bead-based clean-up kits or lithium chloride precipitation. Assess cap incorporation efficiency by LC-MS or differential enzymatic digestion followed by gel electrophoresis.

Specialized Application: Photocaged "FlashCaps" for Spatiotemporal Control

For lineage conversion studies requiring precise temporal activation, photocaged cap analogs offer a unique solution. These analogs, such as the DMNB- or NPM-caged "FlashCaps," incorporate a photo-cleavable group at the N2 position of the cap guanosine, which prohibits binding to eIF4E and thus inhibits translation [31].

- Workflow: modRNA is synthesized using the FlashCap analog via standard IVT. Upon transfection into cells, the mRNA remains translationally inactive. Irradiation with 365–420 nm light for 60–120 seconds removes the caging group, restoring the native cap structure and triggering robust protein expression [31].

- Application: This system is ideal for dosing transcription factors in a pulsed manner, a critical parameter for enhancing the efficiency and fidelity of direct lineage conversion.

UTR Engineering: Balancing Stability and Translational Efficiency

UTRs are pivotal for mRNA stability and the regulation of translation. While endogenous UTRs from globin genes are commonly used, engineered UTRs can offer superior performance.

Deep Learning-Driven UTR Design

Deep learning models, such as Optimus 5-Prime, can be used to design de novo 5'UTR sequences that maximize the Mean Ribosome Load (MRL), a proxy for translation efficiency [32].

- Protocol: Designing UTRs with Optimus 5-Prime:

- Input: Provide the model with the sequence of your coding region (CDS) and specify the desired UTR length.

- Prediction: The model, trained on MPRAs from multiple cell types (HEK293T, HepG2, T cells), will score a vast number of sequence variants [32].

- Optimization: Use gradient descent (Fast SeqProp) or generative neural networks (DENs) to generate candidate 5'UTR sequences with predicted high MRL [32].

- Validation: Cloning the top candidate UTRs into reporter vectors and testing them in the target cell type for lineage conversion is essential, as the best-performing UTR can be cargo- and cell-type specific [32].

Nucleoside Modifications: Reducing Immunogenicity and Enhancing Expression

Nucleoside modifications are a cornerstone of modern modRNA design, primarily serving to dampen the innate immune response and improve translational efficiency.

Common Modifications and Considerations

The replacement of uridine with pseudouridine (Ψ) or N1-methylpseudouridine (m1Ψ) is a widely adopted strategy to avoid detection by Toll-like receptors (TLRs) and other pattern recognition receptors [17] [23]. This significantly reduces immunogenicity and can increase protein output. However, a recent finding indicates that m1Ψ can cause ribosomal frameshifting during translation, potentially leading to the production of off-target protein variants [17]. Researchers should weigh this potential risk against the benefit of reduced immunogenicity for their specific application.

Protocol: Screening Modified Nucleotides for Lineage Conversion

Different cell types may exhibit varying responses to nucleoside modifications. This protocol outlines a screen for optimal modification profiles.

- mRNA Synthesis: Synthesize a reporter mRNA (e.g., encoding GFP) or a lineage-specifying transcription factor using a panel of different modified NTPs (e.g., Ψ, m1Ψ, 5-methylcytidine (5mC), or combinations thereof).

- Cell Transfection: Transfert the modified mRNAs into your target primary somatic cells (e.g., fibroblasts) using a non-viral method such as cationic lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) or electroporation.

- Assessment:

- Immunogenicity: 24 hours post-transfection, measure the secretion of interferon-beta (IFN-β) and other pro-inflammatory cytokines via ELISA.

- Protein Expression: Quantify the expression level and duration of the encoded protein via flow cytometry (for reporters like GFP) or western blot (for transcription factors).

- Cell Viability: Assess cell health to ensure the modification and delivery method are not overly cytotoxic.

Codon Optimization: Maximizing Protein Yield

Codon optimization is the process of enhancing mRNA translation and stability by selecting synonymous codons without altering the amino acid sequence. Next-generation tools now use deep learning to move beyond simple rule-based approaches.

Advanced Optimization Frameworks

RiboDecode is a deep learning framework that optimizes mRNA sequences by directly learning from large-scale ribosome profiling (Ribo-seq) data. It can optimize for translation efficiency, mRNA stability (via Minimum Free Energy, MFE), or a weighted combination of both [33]. RNop is another deep learning tool that simultaneously optimizes for multiple factors, including species-specific codon adaptation index (CAI), tRNA adaptation index (tAI), and MFE, while employing a specialized loss function (GPLoss) to guarantee 100% amino acid sequence fidelity [34].

Table 2: Comparison of Codon Optimization Tools

| Feature | Traditional Methods (e.g., CAI) | LinearDesign | RiboDecode | RNop |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Core Approach | Rule-based, codon frequency | Dynamic programming | Deep learning / Ribo-seq | Deep learning / multi-factor |

| Key Optimization Factors | Codon usage bias | CAI, MFE | Translation level, MFE | CAI, tAI, MFE, Fidelity |

| Context Awareness | No | No | Yes (cellular environment) | Yes (target species) |

| Validation | - | In vitro & in vivo | In vitro, in vivo (mouse model) | In vitro, in vivo (functional proteins) |

Protocol: Optimizing a Gene Sequence with RNop

- Input: Provide the wild-type amino acid sequence or cDNA of the transcription factor to be expressed.

- Parameter Selection: Specify the target organism (e.g., H. sapiens) and the relative weights for the different loss functions (e.g., balance between CAILoss for codon usage and MFELoss for secondary structure).

- Sequence Generation: Run the RNop model, which uses a transformer-based architecture to generate high-fidelity optimized codon sequences.

- In Silico Validation: Check the resulting sequences for improved metrics (e.g., higher CAI, lower MFE) compared to the wild-type and sequences optimized by other methods.

- Synthesis and Testing: Proceed with gene synthesis and IVT to produce the modRNA for experimental validation of protein expression.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for modRNA Workflows

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| CleanCap AG Analog [30] | Co-transcriptional capping for high-efficiency Cap 1 formation. | Standard production of highly translatable, low-immunogenicity modRNA. |

| N1-methylpseudouridine (m1Ψ) [17] | Modified nucleoside to reduce immunogenicity and enhance translation. | Replaces uridine in IVT to create therapeutic-grade modRNA. |

| FlashCap Analogs (e.g., NPM) [31] | Photocaged cap for light-activated translation. | Spatiotemporal control of transcription factor expression in lineage conversion. |

| Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) | Non-viral delivery vector for efficient mRNA transfection. | Delivery of modRNA encoding reprogramming factors to primary somatic cells. |

| T7 RNA Polymerase | Bacteriophage RNA polymerase for in vitro transcription. | Enzymatic synthesis of modRNA from a DNA template. |

Integrated Workflow and Pathway Diagram

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship and workflow for integrating the optimization strategies discussed to create an effective modRNA for direct lineage conversion.

The efficacy of direct lineage conversion using modified mRNA critically depends on the delivery platform that protects the genetic cargo, facilitates its cellular uptake, and ensures its intracellular release. Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) represent the most clinically advanced non-viral delivery system, notably enabling the rapid deployment of mRNA COVID-19 vaccines [35]. Their success is attributed to high encapsulation efficiency, robust protection of mRNA, and facilitated endosomal escape [36]. Alternatively, polymer-based systems offer a modular platform with tremendous versatility in structure, composition, and architectural complexity, allowing for tailored parameters including mRNA protection, loading efficacy, and targeted release [37]. This document provides detailed application notes and experimental protocols for these critical delivery platforms, contextualized within the framework of modified mRNA research for direct lineage conversion.

Platform Composition and Rational Design

The functional performance of delivery platforms is dictated by their constituent materials and formulation parameters.

Lipid Nanoparticle (LNP) Components

LNPs are complex, multi-component systems where each lipid plays a distinct functional role. The ionizable lipid is perhaps the most critical, as it is positively charged at acidic pH during formulation, enabling efficient mRNA encapsulation, and neutral at physiological pH, reducing toxicity. It is primarily responsible for facilitating endosomal escape [35]. The table below summarizes the core components of a standard LNP formulation for mRNA delivery.

Table 1: Core Components of mRNA-LNPs and Their Functions

| Component Class | Key Examples | Primary Function | Rationale for Direct Lineage Conversion |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ionizable Lipid | DLin-MC3-DMA, ALC-0315, SM-102 [38] [35] | mRNA encapsulation, endosomal escape | Enables cytosolic delivery of reprogramming mRNA; efficiency is a key determinant of protein expression levels. |

| Phospholipid (Helper Lipid) | DSPC, DOPE [38] [35] | LNP structure, bilayer stability, fusion | DOPE may enhance endosomal escape through its fusogenic properties, critical for mRNA release. |

| Cholesterol | Cholesterol, β-Sitosterol [35] | Membrane integrity, fluidity, stability | Modulates LNP permeability and stability, influencing pharmacokinetics and biodistribution. |

| PEGylated Lipid | DMG-PEG, ALC-0159 [38] [35] | Stability, circulation time, particle size | Shields LNPs, reduces aggregation, and controls particle size; its kinetics can impact cellular uptake. |

Advanced LNP systems are emerging to overcome the natural liver tropism of first-generation LNPs. For instance, the PILOT (Peptide-Ionizable Lipid Nanoparticle) platform uses peptides conjugated to ionizable lipids to achieve organ-specific mRNA delivery to the lungs, spleen, and thymus in mice [39]. Furthermore, the internal structure of LNPs, with mRNA residing at the interface of water clusters and lipids, is crucial for RNA entrapment and release [40].

Polymer-Based System Components

Polymeric architectures for mRNA delivery are categorized based on their charge and responsiveness. Their key advantage is synthetic tunability, which allows for precise manipulation of properties like molecular weight, branching, and the incorporation of functional groups [37].

Table 2: Classes of Polymers for mRNA Delivery

| Polymer Class | Key Examples | Mechanism of Complexation | Advantages and Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cationic Polymers | Polyethylenimine (PEI), Poly-L-lysine (PLL) [37] [41] | Electrostatic interaction with anionic mRNA | High transfection efficiency but often associated with significant cytotoxicity. |

| Non-Cationic Polymers | Chitosan, PLGA [37] [41] | Entrapment within a biodegradable matrix | Improved biocompatibility but may require optimization for efficient mRNA loading and endosomal escape. |

| Stimuli-Responsive Polymers | pH- or redox-sensitive polymers [37] | Conditional release in specific intracellular environments | Enhances specificity and reduces off-target effects; design complexity can be high. |

Experimental Protocols for Formulation and Characterization

Protocol 1: Microfluidic Formulation of mRNA-LNPs

This protocol describes the preparation of mRNA-LNPs using a microfluidic device, which ensures high reproducibility, controlled mixing, and consistent nanoformulations with high encapsulation efficiency [37].

Materials:

- Lipid Stock Solution: Ionizable lipid, phospholipid (e.g., DSPC), cholesterol, and PEG-lipid dissolved in ethanol (e.g., 90% ethanol with 10% pH 4 citrate buffer) [37]. Typical molar ratios are ~50% ionizable lipid, 10% phospholipid, 38.5% cholesterol, and 1.5% PEG-lipid [35].

- mRNA Solution: Purified, modified mRNA (e.g., N1-methylpseudouridine-modified) in aqueous buffer (e.g., 10 mM citrate, pH 4).

- Dialysis Buffer: PBS or another physiologically relevant buffer (pH 7.4).

- Equipment: Microfluidic mixer (e.g., NanoAssemblr, Staggered Herringbone Micromixer), syringe pumps, dialysis membranes (MWCO 100 kDa).

Procedure:

- Prepare Solutions: Dissolve the lipid mixture in ethanol to a final concentration. Dissolve mRNA in the aqueous buffer to a target concentration. Filter both solutions through a 0.22 µm filter.

- Set Up Microfluidics: Load the lipid and mRNA solutions into separate syringes. Connect them to the microfluidic device with tubing. Set the flow rate ratio (aqueous:organic) typically between 3:1 and 1:1 [37]. The total flow rate is a critical parameter influencing particle size.

- Mixing and Formation: Initiate simultaneous pumping. The rapid mixing in the microfluidic channel leads to a controlled change in polarity, inducing lipid self-assembly and mRNA encapsulation.

- Dialyze: Collect the effluent and immediately transfer it to a dialysis membrane. Dialyze against a large volume of dialysis buffer for 18-24 hours at 4°C to remove ethanol and adjust the external pH to 7.4, trapping the mRNA within the LNP [40].

- Characterize: Measure particle size (e.g., 80-120 nm), polydispersity index (PDI), zeta potential, and mRNA encapsulation efficiency (using a dye exclusion assay like RiboGreen).

The following workflow diagram illustrates the key stages of this LNP formulation process:

Diagram 1: LNP formulation workflow.

Protocol 2: Direct Mixing for Polymer-based Polyplexes

This protocol covers the formation of mRNA-polymer complexes (polyplexes) via direct mixing, a common and relatively simple method.

Materials:

- Polymer Solution: Cationic or ionizable polymer (e.g., PEI, custom biodegradable polymer) dissolved in a water-miscible organic solvent like DMSO or a mild acidic aqueous buffer.

- mRNA Solution: Modified mRNA in nuclease-free water or buffer.

- Equipment: Vortex mixer, pipettes.

Procedure:

- Prepare Stock Solutions: Dilute the polymer and mRNA to working concentrations in the same buffer to ensure compatibility.

- Mixing: Rapidly add the polymer solution to the mRNA solution while vortexing. The order of addition can impact particle size and homogeneity.

- Incubation: Allow the mixture to incubate for 15-30 minutes at room temperature to facilitate complexation.

- Characterize: Determine the N:P ratio (Nitrogen in polymer to Phosphate in RNA), which critically determines complexation, size, stability, and transfection efficiency. Measure particle size, PDI, and zeta potential.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of delivery platforms requires a suite of critical reagents and analytical tools.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Delivery Platform Development

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example Specifications / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Ionizable Lipids | Core functional lipid for mRNA encapsulation and endosomal escape. | DLin-MC3-DMA (established), novel lipids (e.g., from AI-designed libraries [42]). |

| Cationic Polymers | Electrostatic complexation with mRNA for polyplex formation. | Branched PEI (25 kDa, high transfection, high toxicity), linear PEI, PLL. |

| PEG-Lipids | Stabilize nanoparticles, control size, reduce opsonization. | DMG-PEG2000, DSG-PEG2000, ALC-0159; consider diffusible vs. non-diffusible PEG. |

| Modified mRNA | The therapeutic cargo; modifications enhance stability and reduce immunogenicity. | N1-methylpseudouridine base modification, optimized 5' cap (Cap 1), and poly-A tail length [37]. |

| Microfluidic Device | Reproducible, scalable formulation of LNPs and some polymer systems. | NanoAssemblr, lab-made staggered herringbone mixer (SHM). |

| Analytical Instrumentation | Characterizing Critical Quality Attributes (CQAs) of nanoparticles. | DLS for size/PDI, zeta potential analyzer, Ribogreen assay for encapsulation efficiency, SAXS for internal structure [40]. |

Advanced Applications and Future Perspectives in Lineage Conversion

The application of LNPs and polymer-based systems extends far beyond vaccines into the realm of gene editing and cellular reprogramming.

- Gene Editing In Vivo: The PILOT platform has been used to deliver mRNA encoding prime editors to specific organs in mice, achieving editing rates of 13.1% in the liver and 7.4% in the lungs [39]. This demonstrates the potential for correcting genetic defects underlying lineage-specific diseases.

- Computational Design: The use of transformer-based neural networks like COMET, trained on large LNP datasets (LANCE), can predict LNP efficacy based on lipid components and their ratios. This AI-driven approach can rapidly identify novel LNP formulations optimized for specific tasks, such as delivering reprogramming factors to particular cell types [42].