Engineered vs. Natural Exosomes in Chronic Wound Models: A Comparative Analysis for Therapeutic Development

Chronic wounds, characterized by a failure to proceed through an orderly healing process, present a significant clinical challenge.

Engineered vs. Natural Exosomes in Chronic Wound Models: A Comparative Analysis for Therapeutic Development

Abstract

Chronic wounds, characterized by a failure to proceed through an orderly healing process, present a significant clinical challenge. This article provides a comprehensive analysis for researchers and drug development professionals on the therapeutic potential of natural and engineered exosomes. We explore the foundational biology of exosomes, detail advanced engineering methodologies for enhancing their function, address key challenges in translation and optimization, and present a critical comparative evaluation of their efficacy based on current preclinical and clinical evidence. The synthesis of these four intents offers a roadmap for the rational design of next-generation, exosome-based therapies for complex wound healing applications.

Understanding the Native Healer: The Biology and Innate Role of Natural Exosomes in Wound Repair

Exosomes are naturally occurring, nanoscale extracellular vesicles (EVs) with a diameter of 30-150 nm, secreted by virtually all cell types into the extracellular environment [1]. They function as crucial mediators of intercellular communication, facilitating the transfer of bioactive molecules—including proteins, lipids, nucleic acids (RNA, DNA), and metabolites—between cells, thereby influencing the physiological state and behavior of recipient cells [2] [3]. Their biogenesis through the endosomal pathway distinguishes them from other extracellular vesicles, resulting in unique composition and functional properties [4]. Within the context of chronic wound research, natural exosomes derived from sources such as mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) have demonstrated inherent therapeutic potential, promoting wound healing by modulating inflammation, enhancing angiogenesis, and encouraging tissue remodeling [1] [5]. This review delineates the biogenesis, cargo sorting, and molecular mechanisms of natural exosomes, providing a foundational comparison for evaluating engineered exosome strategies in regenerative medicine.

The Biogenesis Pathway of Natural Exosomes

The formation of exosomes is a meticulously orchestrated intracellular process that culminates in the release of these vesicles for intercellular signaling. The journey begins with endocytosis and progresses through several key stages to the release of exosomes from the cell.

Endocytosis and Early Endosome Formation

The biogenesis of exosomes initiates with the inward budding of the plasma membrane, a process that forms early endosomes [4]. This initial step is regulated by various proteins, including clathrin, which facilitates the formation of clathrin-coated pits, and caveolin-1, a marker protein associated with caveolae generation [4]. The small GTP-binding protein Rab5a serves as a specific marker for early endosomes and plays a pivotal role in regulating vesicle fusion through constant GTP binding and hydrolysis [4]. Knockdown of Rab5 has been shown to decrease exosome excretion, underscoring its importance in this pathway [4].

Formation of Multivesicular Bodies (MVBs) and Intraluminal Vesicles (ILVs)

Early endosomes subsequently mature into late endosomes, where the limiting membrane undergoes inward budding to form intraluminal vesicles (ILVs) within larger organelles known as multivesicular bodies (MVBs) [6]. The formation of ILVs, which are the precursors to exosomes, is driven by several distinct but sometimes overlapping molecular mechanisms:

- ESCRT-Dependent Pathway: The Endosomal Sorting Complex Required for Transport (ESCRT) machinery, comprising ESCRT-0, -I, -II, -III subcomplexes and the ATPase VPS4, operates in a sequential manner to mediate membrane budding and cargo sorting [6]. ESCRT-0 (containing Hrs and STAM) recognizes and recruits ubiquitinated cargo proteins. ESCRT-I and -II are then recruited and cooperate to form a saddle-shaped complex important for ESCRT-III assembly. Finally, ESCRT-III subunits polymerize and, with energy provided by VPS4, drive membrane deformation and fission to generate ILVs [6].

- ESCRT-Independent Pathways: Several alternative mechanisms exist:

- The nSMase2-Ceramide Pathway: Neutral sphingomyelinase 2 (nSMase2) converts sphingomyelin to ceramide. The cone-shaped structure of ceramide induces negative membrane curvature, promoting inward budding of the endosome membrane and ILV formation [6]. This pathway is crucial for sorting certain cargoes, such as proteolipid protein (PLP) in oligodendroglia cells [6].

- Tetraspanin-Enriched Microdomains: Tetraspanin proteins (CD63, CD9, CD81), which are canonical exosome markers, are involved in membrane budding and cargo sorting into ILVs [2] [6]. Their transmembrane domains form a cone-like structure that may promote membrane bending [2].

- The Syndecan-Syntenin-ALIX Pathway: The transmembrane proteoglycan syndecan recruits the adaptor protein syntenin, which in turn binds ALIX. ALIX then recruits ESCRT-III and VPS4 to complete ILV formation, representing a non-canonical ESCRT-dependent pathway [6].

Fate of MVBs: Degradation or Release

Once formed, MVBs face one of two destinies: they can fuse with lysosomes, leading to the degradation of their ILV contents, or they can be transported to and fuse with the plasma membrane [4]. The fusion of MVBs with the plasma membrane is a regulated process involving Rab GTPases (such as Rab27) and SNARE complexes [6]. Upon fusion, the ILVs are released into the extracellular space as exosomes [1] [7].

The following diagram illustrates the complete biogenesis pathway of natural exosomes, from their origin as early endosomes to their release as intercellular messengers.

Cargo Composition and Sorting Mechanisms

The biological activity of exosomes is largely determined by their diverse molecular cargo, which is selectively packaged during the biogenesis process. The composition of this cargo reflects the physiological state of the parent cell and dictates the functional impact on recipient cells.

Diversity of Exosomal Cargo

Natural exosomes carry a complex and heterogeneous mixture of biomolecules:

- Nucleic Acids: Exosomes contain various forms of RNA, including messenger RNA (mRNA), microRNA (miRNA), and other non-coding RNAs [3] [4]. These RNAs can be functionally transferred to recipient cells to alter gene expression and protein translation. Exosomes also carry DNA fragments [3].

- Proteins: The exosomal proteome is enriched in certain protein families, including:

- Tetraspanins (CD63, CD9, CD81): Used as canonical exosome markers and involved in cargo sorting and membrane fusion [2] [8].

- ESCRT Machinery Components (TSG101, ALIX): Often found in exosomes and serve as internal markers [6] [8].

- Heat Shock Proteins (Hsp70, Hsp90): Also used as internal markers [8].

- Membrane Transport and Fusion Proteins (GTPases, Annexins).

- Proteins reflecting the cell of origin's state and function [1] [3].

- Lipids: The exosomal membrane is enriched in cholesterol, sphingomyelin, ceramide, and phosphatidylserine, resembling lipid raft microdomains in cellular membranes. This specific lipid composition contributes to exosome stability, structure, and function [6].

Mechanisms of Cargo Sorting

The selective enrichment of molecules into ILVs is a critical step controlled by specific mechanisms:

- Ubiquitin-Dependent Sorting: The ESCRT-0 complex recognizes ubiquitinated proteins, initiating their sorting into ILVs [6].

- Lipid-Mediated Sorting: Ceramide, generated by nSMase2, facilitates the sorting of specific cargoes like proteolipid protein (PLP) in an ESCRT-independent manner [6].

- Tetraspanin-Mediated Sorting: Tetraspanins organize membrane microdomains and facilitate the sorting of associated proteins into exosomes [2] [6].

- RNA Sorting: The mechanisms for RNA sorting into exosomes are an active area of research. Certain RNA-binding proteins, such as SAFB and hnRNPK, have been implicated in this process, sometimes through interactions with the nSMase2-ceramide pathway or other yet-to-be-defined mechanisms [6].

Table 1: Key Cargo Components of Natural Exosomes and Their Proposed Functions

| Cargo Category | Specific Examples | Proposed Functions in Exosome Biology |

|---|---|---|

| Surface Proteins | Tetraspanins (CD63, CD9, CD81) | Vesicle identity, cargo sorting, cell targeting, membrane fusion [2] [8] |

| Intracellular Proteins | ESCRT components (TSG101, ALIX), Heat Shock Proteins (Hsp70, Hsp90) | MVB biogenesis, vesicle scaffolding, stress response [6] [8] |

| Nucleic Acids | miRNAs (e.g., miR-21, miR-29b), mRNAs, other non-coding RNAs | Epigenetic reprogramming of recipient cells, regulation of protein synthesis, intercellular communication [3] [4] |

| Lipids | Cholesterol, Ceramide, Phosphatidylserine | Membrane stability, structural integrity, signaling [6] |

Exosome Uptake and Intercellular Communication

Following their release, exosomes mediate intercellular communication by transferring their cargo to recipient cells. The process of uptake and functional delivery is multifaceted.

- Modes of Uptake: Recipient cells internalize exosomes through various endocytic pathways, including clathrin-dependent endocytosis, caveolin-mediated uptake, macropinocytosis, phagocytosis, and lipid raft-mediated internalization [9] [8]. Exosomes can also directly fuse with the plasma membrane of the target cell [9].

- Functional Cargo Delivery: Upon internalization, the exosomal cargo is released into the cytoplasm of the recipient cell. The delivered miRNAs, mRNAs, and proteins can then modulate cellular signaling pathways, alter gene expression, and ultimately influence the recipient cell's phenotype and function [2] [4]. This mechanism is fundamental to the role of exosomes in both physiological processes and disease progression.

The Role of Natural Exosomes in Wound Healing: Mechanisms and Evidence

Natural exosomes, particularly those derived from mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), play a multifaceted role in orchestrating the complex process of wound healing. Their therapeutic effects are mediated through the coordinated regulation of different cellular players and signaling pathways across the various phases of healing.

Key Mechanistic Pathways in Wound Repair

Exosomes promote healing by modulating several critical pathways:

- Modulation of Inflammation: MSC-derived exosomes can promote the polarization of macrophages from a pro-inflammatory (M1) phenotype to an anti-inflammatory, pro-healing (M2) phenotype, thereby reducing excessive inflammation in chronic wounds [3].

- Promotion of Angiogenesis: Exosomes transfer pro-angiogenic miRNAs and proteins (e.g., from endothelial progenitor cells) that activate signaling pathways such as PI3K/Akt and ERK in endothelial cells, stimulating the formation of new blood vessels (angiogenesis) crucial for supplying nutrients and oxygen to the healing tissue [1] [5].

- Enhancement of Cell Proliferation and Migration: Exosomes derived from sources like adipose-derived MSCs have been shown to enhance the proliferation and migration of fibroblasts and keratinocytes, the key cells responsible for tissue rebuilding and re-epithelialization [1] [7]. This is achieved by regulating collagen synthesis and other components of the extracellular matrix (ECM).

Preclinical and Clinical Evidence

A growing body of evidence supports the efficacy of natural exosomes in wound healing:

- Animal Models: Studies in mouse, rat, rabbit, and canine models of diabetic and full-thickness wounds have demonstrated that exosome treatment can accelerate wound closure, improve angiogenesis, and enhance the quality of the regenerated tissue [1]. For instance, preliminary data indicate that MSC-derived exosomes can improve healing rates by 30-50% in diabetic models [10].

- Human Trials: While the clinical application is still emerging, early-phase clinical studies suggest a decrease in scarring and chronic wound inflammation following exosome therapy [10]. ClinicalTrials.gov lists ongoing trials evaluating exosome-based therapies for chronic wounds, indicating the transition from preclinical to clinical investigation [1].

Table 2: Experimental Evidence for Natural Exosome Therapeutics in Wound Healing

| Exosome Source | Model System | Key Experimental Findings | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs) | Diabetic mouse model | Improved healing rates by 30-50%, enhanced angiogenesis, modulation of collagen I:III ratio | [1] [10] |

| Adipose-Derived MSCs | Human chronic wound fibroblasts in vitro | Induced proliferation and migration of fibroblasts; enhanced in vitro angiogenesis | [7] |

| Endothelial Progenitor Cells | Cutaneous wound mouse model | Accelerated wound healing by promoting angiogenesis through Erk1/2 signaling | [10] |

| Umbilical Cord MSCs | In vitro fibroblast culture | Suppressed myofibroblast differentiation, suggesting potential for reducing scar formation | [10] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Protocols

This section details critical reagents and methodologies employed in exosome research, providing a resource for experimental design and replication.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Exosome Studies

| Reagent / Material | Primary Function in Research | Specific Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| GW4869 | Pharmacological inhibitor of nSMase2; blocks the ceramide-dependent pathway of exosome biogenesis. Used to investigate biogenesis mechanisms and reduce exosome secretion in vitro. | Validated in multiple cell lines (e.g., oligodendroglia, neuronal, cancer cells) to inhibit sorting of specific cargoes like PLP [6]. |

| Tetraspanin Antibodies | Identification, isolation, and characterization of exosomes via immunoaffinity capture. | Anti-CD63, anti-CD9, anti-CD81 antibodies are widely used for immunocapture, Western blotting, and flow cytometry [2] [8]. |

| ESCRT Component Antibodies | Detection and validation of exosomes via Western blotting; functional studies of biogenesis. | Antibodies against TSG101, ALIX, and Hrs are standard for confirming exosomal identity in isolates [6] [8]. |

| Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) | Polymer used for precipitating exosomes from biological fluids and cell culture media. | Common in commercial exosome isolation kits (e.g., ExoQuick-TC). Offers simplicity but may co-precipitate contaminants [8]. |

| Protease/RNase Inhibitors | Preservation of exosomal cargo integrity during isolation and purification procedures. | Essential for downstream -omics analyses (proteomics, transcriptomics) to prevent degradation of proteins and RNAs [3]. |

Standardized Experimental Workflow

A typical workflow for isolating and validating natural exosomes for functional studies involves several key steps, visualized in the diagram below.

Detailed Key Protocols:

- Isolation via Ultracentrifugation: The "gold standard" method [8]. Cell culture supernatant is subjected to sequential centrifugation steps: low-speed (e.g., 300 × g to remove cells), medium-speed (e.g., 10,000 × g to remove cell debris and larger vesicles), and finally high-speed ultracentrifugation (e.g., 100,000 × g for 70-120 minutes) to pellet exosomes. The pellet is washed in PBS and re-pelleted by another ultracentrifugation step to purify further [8].

- Characterization - Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis (NTA): This technique measures the size distribution and concentration of particles in an exosome preparation by tracking the Brownian motion of individual vesicles in a suspension using a laser microscope [8].

- Characterization - Western Blotting: Isolated exosomes are lysed and analyzed for the presence of positive markers (e.g., CD63, CD81, TSG101, Alix) and the absence of negative markers from the parent cells (e.g., calnexin, GRP94) to confirm purity and identity [8].

- Functional Assay - In Vitro Scratch/Wound Healing Assay: Recipient cells (e.g., fibroblasts or keratinocytes) are cultured to confluence. A scratch is made in the monolayer, and cells are treated with exosomes or PBS control. The rate of gap closure is monitored over time (e.g., 0, 24, 48 hours) via microscopy, quantifying the pro-migratory effect of exosomes [7].

Natural exosomes represent a sophisticated and intrinsic system of intercellular communication, with a well-defined biogenesis pathway originating from multivesicular bodies and a diverse cargo that dictates their functional role in tissue homeostasis and repair. In chronic wound models, their inherent ability to coordinate complex processes like immunomodulation, angiogenesis, and cell proliferation makes them potent therapeutic agents and a critical biological benchmark. A thorough understanding of their formation, cargo sorting, and mechanism of action, as detailed in this guide, is fundamental for researchers and drug development professionals. This knowledge provides the essential foundation for the rational design and objective evaluation of engineered exosome strategies, which aim to augment these natural capabilities for enhanced therapeutic outcomes in regenerative medicine.

The therapeutic application of Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs) in wound healing has progressively shifted from a cell-replacement paradigm to a paracrine-focused model, wherein secreted vesicles mediate most regenerative effects [11] [12]. Among these secretions, MSC-derived exosomes—nanoscale extracellular vesicles (30-150 nm)—have emerged as potent facilitators of tissue repair. These vesicles transport bioactive cargoes including proteins, lipids, mRNAs, and microRNAs (miRNAs), facilitating intercellular communication [11] [13]. In the context of chronic wounds, which are characterized by a failure to proceed through an orderly healing process within three months, MSC-derived exosomes target key pathological aspects: persistent inflammation, impaired angiogenesis, and dysfunctional fibroblast activity [11] [5]. This review delineates the mechanistic roles of MSC-derived exosomes in modulating these core cellular players, providing a comparative analysis of supporting experimental data within the broader research framework of engineered versus natural exosomes.

Mechanistic Insights: How MSC-Exosomes Modulate Key Cellular Processes

Modulation of the Inflammatory Response

The transition from the pro-inflammatory (M1) to the anti-inflammatory (M2) macrophage phenotype is a critical checkpoint for resolving the inflammatory phase and initiating productive healing. MSC-derived exosomes significantly expedite this transition [14] [12].

- Macrophage Polarization: In a rat full-thickness wound model, exosomes loaded onto a collagen sponge (sponge-Exo) were shown to effectively promote the shift of macrophages from an inflammatory M1 phenotype to a regenerative M2 phenotype [14]. This modulation helps suppress the prolonged inflammatory state characteristic of chronic wounds.

- Molecular Mechanisms: The anti-inflammatory effect is partly mediated by the delivery of specific microRNAs. For instance, exosomal miR-146a and miR-223 contribute to inflammation resolution by inhibiting the NF-κB signaling pathway and suppressing NLRP3 inflammasome activation, respectively [11]. Furthermore, preconditioned MSC-derived exosomes enhance anti-inflammatory polarization via let-7b signaling [11].

Promotion of Angiogenesis

Adequate blood supply is fundamental for delivering oxygen and nutrients to the wound site. MSC-derived exosomes potently stimulate the formation of new blood vessels [11] [15].

- Stimulating Endothelial Cells: Exosomes derived from human dental pulp stem cells (hDPSCs) were demonstrated to promote angiogenesis in Human Umbilical Vein Endothelial Cells (HUVECs) [14]. This pro-angiogenic effect is replicated by exosomes from various MSC sources, including those from adipose tissue and umbilical cord.

- Key Molecular Mediators: The angiogenic promotion is orchestrated through the delivery of pro-angiogenic factors and miRNAs. Exosomes transport Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF) and Fibroblast Growth Factor 2 (FGF-2), which directly stimulate endothelial cell proliferation and sprouting [11]. Notably, hypoxic preconditioning of parent MSCs can further enhance the angiogenic capacity of their exosomes by upregulating cargo such as HIF-1α and VEGF [15].

Activation of Fibroblast Function and ECM Remodeling

Fibroblasts are the primary architects of the new extracellular matrix (ECM). MSC-derived exosomes enhance fibroblast activity to support the proliferative phase of healing.

- Enhancing Proliferation and Migration: Studies confirm that MSC-derived exosomes enhance the migration and proliferation of human dermal fibroblasts (HDFs) [14]. This is crucial for populating the wound bed with matrix-producing cells.

- Collagen Synthesis and ECM Regulation: Exosomes promote fibroblast secretion of type III collagen and fibronectin, forming the granulation tissue scaffold [11]. This process is facilitated by the delivery of miRNAs like miR-21-5p and miR-29a-5p, which are significantly upregulated in healing exosomes and target genes involved in cell migration and ECM dynamics [14]. The activation of transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1) in fibroblasts further stimulates ECM synthesis [11].

Table 1: Key Cargos in MSC-Derived Exosomes and Their Functions in Wound Healing

| Exosomal Cargo | Type | Primary Function in Wound Healing | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| miR-146a | miRNA | Inhibits NF-κB signaling, resolves inflammation [11]. | In vitro macrophage studies [11]. |

| miR-223 | miRNA | Suppresses NLRP3 inflammasome activation [11]. | In vitro macrophage studies [11]. |

| miR-21-5p | miRNA | Enhances fibroblast migration and proliferation [14]. | NGS analysis of exosomes from rat model [14]. |

| miR-29a-5p | miRNA | Promotes cellular proliferation and modulates ECM [14]. | NGS analysis of exosomes from rat model [14]. |

| VEGF | Protein | Stimulates angiogenesis and endothelial cell growth [11] [15]. | In vitro HUVEC tube formation assays [15]. |

| FGF-2 | Protein | Promotes angiogenesis and fibroblast proliferation [11]. | In vitro studies with fibroblasts and endothelial cells [11]. |

| TGF-β1 | Protein/Cytokine | Activates fibroblasts for ECM synthesis [11]. | In vitro fibroblast activation studies [11]. |

Diagram 1: Multimodal Mechanism of MSC-Derived Exosomes in Wound Healing. This diagram illustrates how a single exosome simultaneously coordinates three key healing processes by delivering specific molecular cargo to different target cells.

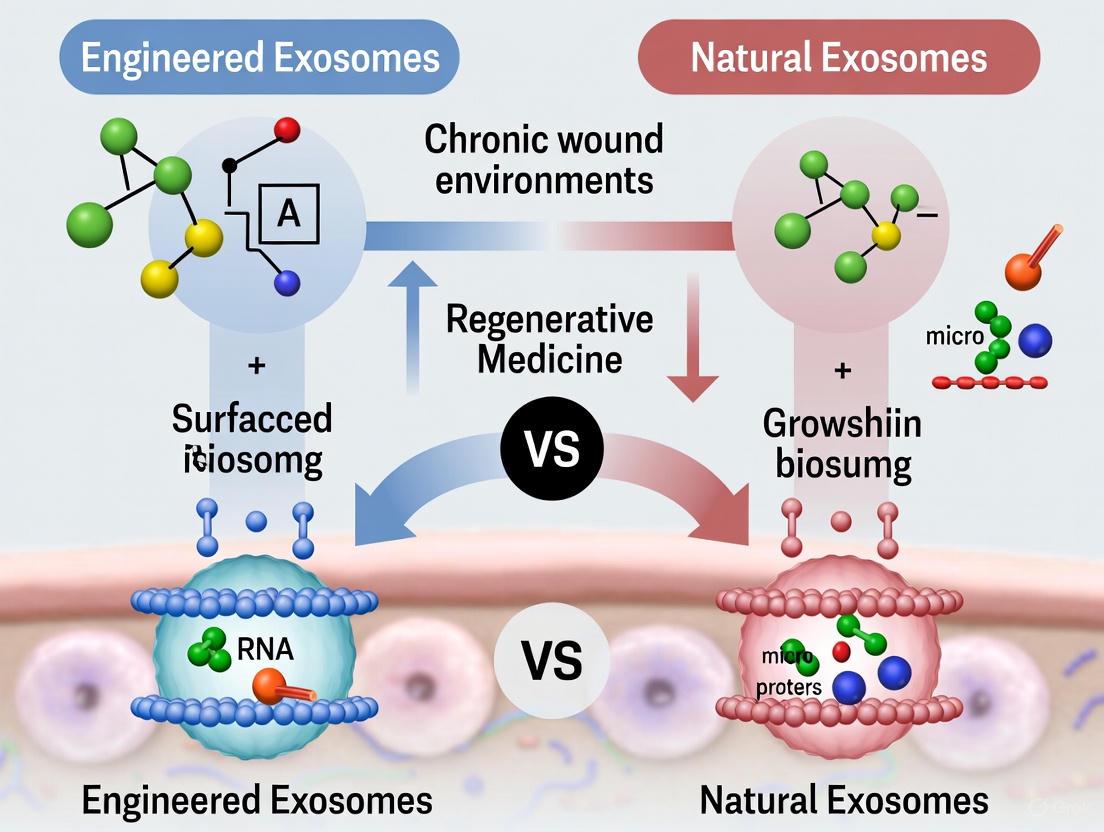

Comparative Therapeutic Platforms: Natural vs. Engineered Exosomes

While natural exosomes show inherent therapeutic potential, bioengineering strategies are being employed to enhance their efficacy, stability, and specificity, forming a critical comparison in modern research.

Natural Exosomes

Natural exosomes are isolated directly from MSC cultures without further modification. Their efficacy can be influenced by the MSC source and preconditioning strategies.

- Source-Dependent Efficacy: A meta-analysis of preclinical studies indicated that among commonly used MSC sources, Adipose-Derived Stem Cells (ADSCs) demonstrated the best effect on wound closure rate and collagen deposition, while Bone Marrow MSCs (BMMSCs) were more effective in promoting revascularization [16].

- Preconditioning: Modifying the cell microenvironment prior to exosome collection can enhance the therapeutic potency of the resulting natural exosomes. For example, preconditioning MSCs under hypoxic conditions or with specific biochemical cues like 3,3′-diindolylmethane (DIM) can upregulate pro-regenerative cargoes such as Wnt11, thereby enhancing their wound-healing capacity [15].

Engineered Exosomes (eExo)

Engineered exosomes are designed to overcome the limitations of natural exosomes, such as rapid clearance and non-specific uptake [5] [17]. Engineering strategies focus on cargo loading and surface modification.

- Cargo Loading: This involves loading specific therapeutic molecules (e.g., miRNAs, proteins) into exosomes to enhance their biological activity. For instance, engineering synovial MSCs to overexpress miR-126-3p resulted in exosomes that more effectively promoted the proliferation of epidermal fibroblasts and vascular endothelial cells [15].

- Surface Modification: Altering the surface proteins of exosomes can improve their targeting specificity and retention at the wound site. This is often achieved by transfecting parent cells with plasmids encoding targeting peptides or directly modifying purified exosomes via click chemistry [5].

Table 2: Comparison of Natural and Engineered MSC-Derived Exosomes

| Feature | Natural Exosomes | Engineered Exosomes (eExo) |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Vesicles isolated without modification from MSC cultures. | Vesicles modified to enhance cargo or targeting properties. |

| Key Advantages | Innate biocompatibility; inherent biological activity; simpler production [13]. | Enhanced targeting; increased therapeutic payload; improved stability and retention [5] [17]. |

| Primary Limitations | Heterogeneous cargo; rapid clearance; potential off-target effects [12] [5]. | More complex manufacturing; higher cost; need for stringent safety profiling [5]. |

| Example Strategy | Preconditioning MSCs with hypoxia to boost pro-angiogenic cargo [15]. | Overexpressing miR-126-3p in parent MSCs to enhance pro-healing effects [15]. |

| Ideal Use Case | Initial proof-of-concept studies; platforms for holistic therapy. | Targeting specific pathological pathways; overcoming delivery barriers. |

Experimental Data and Methodologies

Supporting Animal Model Data

Robust preclinical data from animal models underpins the therapeutic potential of MSC-derived exosomes. A comprehensive meta-analysis of 83 preclinical studies confirmed that MSC-derived extracellular vesicles significantly enhance wound closure rate, reduce scar width, and increase blood vessel density and collagen deposition in both diabetic and non-diabetic animal models [16]. The analysis further revealed that the subcutaneous injection of exosomes demonstrated a greater improvement in wound closure and revascularization compared to topical application via dressing/covering [16].

Key Experimental Protocols

Standardized methodologies are critical for the isolation and characterization of exosomes, ensuring the reproducibility and validity of experimental data.

- Exosome Isolation and Purification (Differential Ultracentrifugation):

- Cell Culture: MSC conditioned medium is collected after a period of culture in exosome-depleted serum.

- Centrifugation Steps: The medium is sequentially centrifuged at:

- 500 × g for 10 minutes to remove cells.

- 2,000 × g for 10 minutes to remove dead cells.

- 10,000 × g for 30 minutes to remove cell debris.

- The supernatant is filtered through a 0.22 μm filter.

- Ultracentrifugation at 100,000 × g for 70 minutes to pellet exosomes.

- The pellet is washed in PBS and ultracentrifuged again at 100,000 × g for 70 minutes [14] [17].

- Exosome Characterization:

- Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis (NTA): Used to determine the size distribution and concentration of particles [14].

- Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM): Employed to confirm the spherical, cup-shaped morphology and size of exosomes [14].

- Western Blotting: Used to detect the presence of exosomal marker proteins (e.g., CD63, CD9, CD81, TSG101) and the absence of negative markers (e.g., calnexin) [14] [16].

Table 3: The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials for Exosome Research

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example Usage in Experiments |

|---|---|---|

| Collagen Sponge/Hydrogel | A biomaterial scaffold for exosome delivery; provides sustained release and protects exosome bioactivity [14] [18]. | Used as "sponge-Exo" in rat models to gradually release exosomes, promoting healing [14]. |

| Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) | Base cell culture medium for culturing MSCs and producing conditioned medium for exosome isolation [14]. | Standard medium for hDPSC culture prior to exosome collection [14]. |

| Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS) | Nutrient supplement for cell culture. Must be centrifuged to remove bovine vesicles for exosome-production cultures. | Used in MSC proliferation medium [14]. |

| Antibodies (CD63, CD9, CD81) | Key reagents for characterizing exosomes via Western Blot or flow cytometry, confirming vesicle identity. | Detection of positive exosomal markers during characterization [14] [17]. |

| Phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride (PMSF) | Protease inhibitor added to lysis buffers to prevent protein degradation during exosome protein extraction. | Used in protein extraction for Western Blot analysis of exosomal cargo [14]. |

| Streptozotocin (STZ) | Chemical used to induce type 1 diabetes in rodent models for creating diabetic wound models. | Used in 30 of the reviewed preclinical studies to model diabetic wounds [16]. |

Diagram 2: Standard Workflow for MSC-Exosome Isolation and Characterization. This diagram outlines the key experimental steps from cell culture to the final application of exosomes, highlighting critical quality control checkpoints.

MSC-derived exosomes represent a sophisticated cell-free therapeutic platform that coordinately addresses the multifaceted pathology of chronic wounds. By simultaneously modulating inflammation, promoting angiogenesis, and activating fibroblasts, they effectively shift the wound environment from a state of chronic stagnation to one of active regeneration. The compelling preclinical data, consolidated through systematic reviews, provides a strong foundation for clinical translation. The ongoing evolution from natural to precision-engineered exosomes (eExo) promises to further enhance therapeutic efficacy by optimizing drug delivery and targeting specific pathological pathways. Future research must focus on standardizing isolation protocols, scaling up production under Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) guidelines, and conducting rigorous safety and efficacy clinical trials to fully realize the potential of this promising therapy for patients with chronic wounds.

Chronic wounds, including diabetic foot ulcers, venous leg ulcers, and pressure injuries, represent a significant clinical and economic burden worldwide [19] [20]. These "hard-to-heal" wounds are conceptually defined as wounds that have not reduced in size by more than 40-50% or healed within one month, exhibiting a slow rate of size reduction of ≤1 mm/week [19]. The underlying pathology of chronic wounds deviates fundamentally from the normal, highly coordinated healing process, which progresses through hemostasis, inflammation, proliferation, and remodeling phases [21].

At the cellular and molecular level, chronic wounds are propelled and distinguished by a triad of interplaying loops involving persistent inflammation, oxidative stress, and cellular senescence [19]. This pathological microenvironment creates self-sustaining cycles that prevent healing progression. Decades of research have focused on identifying key endogenous, predisposing factors that drive both chronicity and recurrence, with emerging evidence pointing toward the existence of an epigenetic pathologic code that originates and perpetuates a "chronic wound memory" sheltered in dermal fibroblasts and keratinocytes [19].

Within this complex pathological landscape, exosome-based therapies have emerged as promising regenerative strategies. This review systematically compares the therapeutic performance of engineered versus natural exosomes across the core hallmarks of chronic wounds, providing experimental data and methodological guidance for researchers and drug development professionals.

Core Pathological Mechanisms: Beyond the Surface

Persistent Inflammation: A Self-Sustaining Pathological Loop

In normal wound healing, the inflammatory phase is transient, characterized by initial neutrophil infiltration followed by a transition from pro-inflammatory M1 to anti-inflammatory M2 macrophages [21]. In chronic wounds, this resolution fails, creating a self-perpetuating inflammatory environment. CD4+ and CD8+ lymphocytes accumulate in significant numbers within skin wounds, peaking on days 5-10 and 7-10 post-injury, respectively [11]. The sustained presence of pro-inflammatory M1 macrophages leads to continuous production of tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), interleukin-1β (IL-1β), and matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) that degrade the extracellular matrix and damage newly formed tissue [11] [21].

Experimental models demonstrate that this inflammatory dysregulation creates a vicious cycle where persistent inflammation generates oxidative stress, which in turn promotes further inflammatory signaling [19]. In diabetic wound models, elevated pro-inflammatory markers (IL-1β, TNF-α, MMP9) and reduced anti-inflammatory/angiogenic factors (IL-10, VEGF-A) reflect the chronic inflammatory and angiogenic imbalance characteristic of non-healing diabetic ulcers [22].

Impaired Angiogenesis: The Vascular Deficit

Angiogenesis, the formation of new blood vessels from existing ones, is crucial for delivering oxygen and nutrients to the wound bed. In chronic wounds, this process is fundamentally impaired due to multiple factors. Hyperglycemia in diabetic wounds creates a systemic cytotoxic environment where advanced glycation end-products (AGEs) accumulate in dermal collagen and impair fibroblast physiology, provoking precocious cutaneous aging while perpetuating chronic inflammation [19].

The diabetic wound microenvironment exhibits disrupted dermal-vascular cell crosstalk and defective angiogenesis, with recent models highlighting endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EndMT) as a critical pathological feature under diabetic stress [22]. This results in reduced levels of key angiogenic growth factors, particularly vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and fibroblast growth factor 2 (FGF-2), which are essential for endothelial cell migration and capillary formation [11] [21].

Failed Re-epithelialization: The Barrier Restoration Failure

Re-epithelialization requires the coordinated migration, proliferation, and differentiation of keratinocytes across the wound bed. In chronic wounds, this process is disrupted through multiple mechanisms. The persistent inflammatory environment generates high levels of proteases that degrade growth factors and extracellular matrix components necessary for epithelial migration [19]. Cellular senescence establishes a senescent cell society, particularly of "diseased fibroblasts," and dysfunction of stem cell populations, creating a microenvironment hostile to keratinocyte function [19].

The establishment of a senescence cell society, especially of "diseased fibroblasts," and the dysfunctionality of stem cell populations are significant pathophysiological ingredients for diabetic wound chronicity [19]. This is further compounded by the hyperglycemia-derived imprinting that acts as the foundation of metabolic memory, perpetuating the senescent phenotype in fibroblasts and keratinocytes through an inflammotoxic secretome [19].

Experimental Models: Methodologies for Studying Chronic Wounds

In Vitro Models: From Simple to Complex Systems

Traditional two-dimensional (2D) cell culture systems have provided fundamental insights into cellular behavior but lack the physiological complexity of the wound microenvironment. Standard protocols involve:

Fibroblast-Keratinocyte Co-culture: Human dermal fibroblasts and keratinocytes are cultured in Transwell systems to study paracrine interactions. Fibroblasts are typically seeded in the lower chamber, with keratinocytes in the upper insert, allowing shared medium without direct contact [11].

Macrophage Polarization Assays: Human monocyte cell lines (THP-1) or primary monocytes are differentiated into macrophages using phorbol myristate acetate (PMA), then polarized toward M1 (using LPS and IFN-γ) or M2 (using IL-4) phenotypes to study their effects on other wound cells [11].

Senescence-Associated β-galactosidase Staining: Cells from chronic wound environments are fixed and incubated with X-gal solution at pH 6.0 to detect senescent cells, which show blue staining [19].

Advanced three-dimensional (3D) models better recapitulate the wound environment:

Diabetic Wound-on-a-Chip (DWOC): This microfluidic platform integrates human dermal fibroblasts and macrophages within a collagen I matrix to mimic the dermis, alongside endothelial cells embedded in Matrigel to represent the vascular compartment [22]. The system is subjected to hyperglycemic conditions with added advanced glycation end-products (AGEs) and lipopolysaccharide (LPS), alongside normoglycemic controls [22].

3D Bioprinted Skin Constructs: Fibroblasts and keratinocytes are encapsulated in bioinks (typically collagen-based or synthetic polymers) and printed in layered structures to simulate native skin architecture [1].

In Vivo Models: Preclinical Assessment

Animal models remain essential for evaluating therapeutic interventions in a physiological context:

Diabetic Mouse Models: Type 1 diabetes is induced in C57BL/6 mice using streptozotocin (STZ) injections (50-60 mg/kg for 5 consecutive days). After confirmation of hyperglycemia (>300 mg/dL), full-thickness excisional wounds are created on the dorsal skin using biopsy punches (6-8 mm diameter) [11].

Pressure Ulcer Models: Rats are subjected to controlled pressure application using magnetic plates or indentation systems to create ischemic wounds that simulate pressure injuries [19].

Venous Insufficiency Models: Rodents undergo ligation of femoral veins to create venous hypertension, mimicking human venous leg ulcers [20].

Standard outcome measures include wound closure rate (measured by planimetry), histological analysis (H&E for general morphology, Masson's trichrome for collagen, CD31 immunohistochemistry for vessels), and molecular analysis (ELISA for cytokines, RT-qPCR for gene expression) [11].

Natural vs. Engineered Exosomes: Comparative Therapeutic Profiles

Characterization and Production Metrics

Table 1: Comparative Characterization of Natural and Engineered Exosomes

| Parameter | Natural Exosomes | Engineered Exosomes |

|---|---|---|

| Size Range | 30-150 nm [1] [11] | 40-160 nm [7] |

| Production Yield | Variable depending on cell source and culture conditions [23] | More consistent yields through engineering approaches [7] |

| Isolation Method | Ultracentrifugation, size-exclusion chromatography, polymer precipitation [13] [23] | Similar isolation methods with potential for affinity-based purification [7] |

| Cargo Composition | Proteins, lipids, mRNAs, miRNAs reflecting parental cell state [1] [11] | Enhanced or modified cargo through loading strategies [7] [13] |

| Surface Markers | Tetraspanins (CD9, CD63, CD81), antigen-presenting complexes [13] | Modified surface with targeting peptides or antibodies [7] |

| Storage Stability | Limited; affected by repeated freezing/thawing [23] | Potentially enhanced stability through engineering [7] |

Natural exosomes are isolated from various cellular sources, primarily mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), adipose-derived stem cells (ADSCs), and immune cells [11] [13]. The production yield varies significantly based on cell source, with MSCs producing substantial exosomes while dendritic cells produce more limited quantities [23]. Preconditioning strategies, including hypoxia, cytokine stimulation, or 3D culture, can enhance yield and modify therapeutic properties [13] [23].

Engineered exosomes are designed to overcome limitations of natural exosomes through three primary strategies:

Surface Engineering: Modifying the exosomal membrane to improve targeting capabilities, circulation time, and uptake by specific cell types [7] [23]. This includes conjugation of targeting peptides (e.g., RGD for integrin targeting) or antibodies via chemical or genetic approaches [7].

Cargo Loading: Incorporating therapeutic effector molecules, such as drugs, RNA, or proteins, into exosomes using electroporation, sonication, extrusion, or incubation methods [7] [23].

Genetic Modification: Manipulating donor cells to express particular proteins or RNAs that are subsequently incorporated into exosomes [23]. This includes transfection of donor cells with genes encoding therapeutic agents [13].

Efficacy Comparison in Chronic Wound Models

Table 2: Comparative Efficacy of Natural vs. Engineered Exosomes in Chronic Wound Models

| Therapeutic Function | Natural Exosomes | Engineered Exosomes | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anti-inflammatory Effects | Moderate reduction of TNF-α, IL-6; promotion of M2 macrophage polarization [11] | Enhanced anti-inflammatory activity; up to 70% greater reduction in pro-inflammatory cytokines [7] | Diabetic mouse model showing 50% vs. 85% reduction in TNF-α [7] |

| Angiogenic Potential | Increased VEGF expression; improved capillary density [11] | Significantly enhanced angiogenic response; 2.1-fold increase in capillary formation [7] | CD31 immunohistochemistry showing 30% vs. 65% increase in vessel density [7] |

| Re-epithelialization | Accelerated keratinocyte migration and wound closure [11] | Superior epithelial regeneration; near-complete closure 7 days faster [7] | Diabetic wound model showing 60% vs. 95% closure at day 14 [7] |

| Targeting Efficiency | Limited tissue specificity; widespread distribution [7] | Significantly improved targeting to wound site with reduced off-target effects [7] | Fluorescence imaging showing 3.5-fold higher retention in target tissue [7] |

| Collagen Organization | Improved collagen deposition but suboptimal organization [11] | Enhanced collagen alignment and maturation similar to native skin [7] | Histology showing more organized collagen bundles with engineered exosomes [7] |

The therapeutic efficacy of exosomes is influenced by multiple factors, including donor cell condition, dosage, and administration route [23]. Aging in donor cells generally leads to a decline in exosome quality, with exosomes from older BMSCs exhibiting diminished effects in regenerative capabilities [23]. Dosage optimization is critical, with studies in traumatic brain injury models showing that 100 μg exosomes per rat demonstrated more significant efficacy compared to 50 μg or 200 μg groups [23]. The therapeutic dose of exosomes commonly ranges from 10 to 100 μg of protein in mouse models [23].

Experimental Protocols: Key Methodologies for Exosome Research

Exosome Isolation and Characterization Protocol

Standard Ultracentrifugation Protocol:

- Cell Culture: Expand MSC cultures in serum-free medium conditioned for 48-72 hours [13] [23].

- Collection: Collect conditioned medium and perform sequential centrifugation: 300 × g for 10 min (remove cells), 2,000 × g for 20 min (remove dead cells), 10,000 × g for 30 min (remove cell debris) [13].

- Ultracentrifugation: Centrifuge at 100,000 × g for 70 min at 4°C to pellet exosomes [13] [23].

- Washing: Resuspend pellets in PBS and repeat ultracentrifugation at 100,000 × g for 70 min [13].

- Resuspension: Resuspend final pellet in PBS and store at -80°C [23].

Characterization:

- Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis: Dilute exosomes 1:1000 in PBS and analyze using Nanosight NS300 to determine particle size and concentration [13].

- Transmission Electron Microscopy: adsorb exosomes to Formvar-carbon coated grids, stain with 2% uranyl acetate, and image under TEM [13].

- Western Blotting: Confirm presence of exosomal markers (CD9, CD63, CD81) and absence of negative markers (calnexin) [13] [23].

Surface Engineering Protocol: Targeting Peptide Conjugation

Metabolic Labeling and Click Chemistry Approach:

- Parent Cell Incubation: Incubate parent cells (MSCs) with 50 μM azidopropionate mannosamine (Ac4ManNAz) for 3 days to incorporate azide groups onto exosome surfaces [7].

- Exosome Isolation: Isolate exosomes using standard ultracentrifugation protocol [13].

- Conjugation Reaction: React azide-labeled exosomes with DBCO-modified targeting peptides (e.g., RGD, 100 μM) in PBS for 2 hours at room temperature with gentle rotation [7].

- Purification: Remove unreacted peptides using size exclusion chromatography (PBS-equilibrated PD-10 columns) [7].

- Validation: Confirm conjugation efficiency using flow cytometry with fluorescently-labeled secondary antibodies [7].

In Vivo Efficacy Testing Protocol

Diabetic Mouse Wound Healing Model:

- Diabetes Induction: Inject C57BL/6 mice (8-10 weeks old) with streptozotocin (50 mg/kg i.p. for 5 consecutive days) [11].

- Wound Creation: After confirming hyperglycemia (>300 mg/dL), create two full-thickness excisional wounds (6 mm diameter) on the dorsal skin using biopsy punch under anesthesia [11].

- Treatment Administration: Apply exosomes (100 μg in 50 μL PBS) topically to wound bed every 3 days for 15 days [7]. Control groups receive PBS or no treatment.

- Wound Monitoring: Capture digital images daily and calculate wound area using ImageJ software [11].

- Tissue Collection: Harvest wound tissue at days 7, 14, and 21 for histological and molecular analysis [11].

Signaling Pathways: Mechanisms of Action

Exosome-Mediated Signaling in Wound Healing Pathways

The diagram illustrates the key molecular mechanisms through which exosomes target the core pathological hallmarks of chronic wounds. Through delivery of specific microRNAs and proteins, exosomes simultaneously address persistent inflammation, impaired angiogenesis, and failed re-epithelialization [11] [7].

For inflammation resolution, exosomal miR-146a inhibits NF-κB signaling, reducing production of pro-inflammatory cytokines like TNF-α and promoting the transition from M1 to M2 macrophages [11]. In parallel, miR-223 suppresses NLRP3 inflammasome activation, further resolving inflammation [11]. Preconditioned MSC-derived exosomes enhance anti-inflammatory polarization through let-7b signaling [11].

For angiogenesis promotion, exosomal miR-21 plays a pivotal role by inhibiting PTEN, leading to AKT activation and subsequent VEGF upregulation [11]. This stimulates endothelial cell proliferation and capillary formation. Additional angiogenic factors including FGF-2 delivered by exosomes further enhance this process [11] [7].

For re-epithelialization, exosomes from MSCs and ADSCs enhance fibroblast proliferation and migration by delivering miR-29a, which enhances collagen production, and other factors that directly stimulate keratinocyte migration and differentiation [11].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Exosome and Wound Healing Research

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Key Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Culture | Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs), Human Dermal Fibroblasts, Keratinocytes | In vitro mechanistic studies | Source of exosomes; wound healing assays [11] [13] |

| Characterization | CD63, CD81, CD9 antibodies, TSG101, Calnexin | Exosome validation | Confirm exosome identity and purity [13] [23] |

| Molecular Biology | miR-146a, miR-21, miR-29a mimics/inhibitors | Mechanism investigation | Modulate exosomal miRNA function [11] [7] |

| Animal Models | Streptozotocin, Biopsy Punches, Wound Imaging Systems | In vivo efficacy testing | Create diabetic wounds; monitor healing [11] [22] |

| Biomaterials | Chitosan hydrogels, Alginate films, Collagen scaffolds | Delivery system development | Enhance exosome stability and retention [1] [24] |

| Cytokine Analysis | TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-10, VEGF ELISA kits | Therapeutic response assessment | Quantify inflammatory and angiogenic factors [11] [22] |

Additional critical reagents include 3D culture systems such as the diabetic wound-on-a-chip platform, which integrates multiple cell types within engineered matrices to better mimic the chronic wound microenvironment [22]. Hypoxia chambers are essential for preconditioning cells to enhance exosome therapeutic potential, as hypoxia upregulates pro-angiogenic factors in MSCs [23]. Microfluidic devices enable precise isolation and analysis of exosomes, particularly important for engineered exosome characterization [13] [23].

The comparative analysis of natural versus engineered exosomes reveals a rapidly evolving landscape in chronic wound therapeutics. While natural exosomes demonstrate significant therapeutic potential across the core hallmarks of chronic wounds, engineered exosomes show enhanced efficacy through targeted delivery and optimized cargo. The future of exosome-based therapies lies in the development of precision medicine approaches that account for wound-specific microenvironments, patient-specific factors, and stage-specific healing requirements.

Critical research priorities include standardizing potency assays that correlate exosome characteristics with therapeutic outcomes, optimizing scalable production methodologies for clinical translation, and establishing rigorous biodistribution and safety profiles for engineered variants. As the field progresses, the integration of exosome therapies with advanced biomaterials and personalized medicine approaches holds promise for finally addressing the clinical challenge of chronic wounds.

Exosomes are nanoscale, lipid-bilayer-enclosed extracellular vesicles (EVs) secreted by almost all cell types and are present in virtually all biological fluids [25]. They are fundamental mediators of intercellular communication, facilitating the transfer of bioactive molecules—including proteins, lipids, and various forms of RNA—between cells to influence the behavior and function of recipient cells [1] [7]. In the context of wound healing, this natural cargo is intricately involved in orchestrating the complex sequence of events required for tissue repair [15]. The therapeutic potential of stem cell-derived exosomes, particularly from mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), has emerged as a promising cell-free strategy, leveraging these innate healing pathways while circumventing challenges associated with whole-cell transplantation, such as tumorigenicity and immune rejection [1].

This guide provides a detailed, evidence-based comparison of the performance of natural exosomes against emerging engineered alternatives in chronic wound models. It is structured within a broader thesis that while natural exosomes provide a multifaceted, innate therapeutic signal, engineered exosomes are being developed to enhance specificity, potency, and stability for recalcitrant healing scenarios.

Mechanisms of Action: Decoding the Natural Cargo

Natural exosomes exert their healing effects by delivering a complex cargo that regulates critical wound healing phases: inflammation, proliferation, and remodeling. The table below summarizes the key cargo components and their primary functions in healing pathways.

Table 1: Key Cargo in Natural Exosomes and Their Roles in Wound Healing

| Cargo Type | Specific Examples | Primary Functions in Wound Healing | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| microRNAs (miRNAs) | miR-126-3p, miR-21, miR-124a, miR-199a, miR-210, miR-20, miR-429, miR-34a [26] [15] | Promotes angiogenesis, enhances keratinocyte/fibroblast proliferation & migration, regulates inflammation, supports epidermal & hair follicle development [26] [15]. | SMSC-Exos loaded with miR-126-3p shown to stimulate fibroblast & endothelial cell proliferation in vitro; miR-21 & hypoxia-induced miR-210 regulate granulation tissue formation & wound closure [26] [15]. |

| Proteins | Tetraspanins (CD63, CD9, CD81), Syntenin, ALIX, Growth Factors, Cytokines [1] [26] [25] | Regulates exosome biogenesis & targeting; modulates immune signaling, cell adhesion; directly promotes cell growth & angiogenesis [1] [25]. | Exosomes from HIF-1α-overexpressing MSCs showed altered protein/miRNA levels & enhanced angiogenic capacity; surface proteins facilitate recipient cell binding via tetraspanins, integrins, proteoglycans [25] [15]. |

| Lipids | Sphingolipids, Cholesterol, Phospholipids, Phosphatidylserine [1] [3] | Forms membrane structure, protects internal cargo; involved in membrane curvature, budding, & signaling; influences exosome stability & cellular uptake [1] [25]. | Lipid composition (cholesterol, sphingomyelin) contributes to rigidity/stability; external phosphatidylserine in apoptotic bodies attracts macrophages for clearance [1] [26]. |

The coordinated action of this cargo regulates healing through several key pathways, as illustrated in the following experimental workflow for studying these mechanisms.

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for studying natural exosome mechanisms in wound healing. Key steps include exosome isolation from various mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) sources, functional testing in established wound models, and analysis of their impact on critical healing pathways such as inflammation, proliferation, and angiogenesis.

Performance Comparison: Natural vs. Engineered Exosomes in Chronic Wound Models

The transition from basic mechanistic understanding to therapeutic application requires rigorous comparison in biologically relevant models. The following table synthesizes experimental data from chronic wound studies, directly comparing the performance of natural and engineered exosomes.

Table 2: Experimental Data Comparison in Chronic Wound Models

| Performance Metric | Natural Exosomes | Engineered Exosomes | Experimental Context & Protocol Details |

|---|---|---|---|

| Angiogenic Potential | ↑ Tube formation ~1.5-2x control; improved vascularization in diabetic mouse models [15]. | ↑↑ Tube formation ~2.5-3x control; significantly enhanced vs. natural exosomes via cargo overexpression (e.g., miR-126, VEGF) [7] [15]. | Protocol: HUVEC tube formation assay on Matrigel. Exosomes (50 µg/mL) co-cultured with cells for 4-18h. Vessel branches/nodes quantified. In-vivo, topical application in db/db mouse wound model, histology at day 7-10 for CD31+ vessels [15]. |

| Anti-inflammatory Effect | Promote M1 to M2 macrophage switch; reduce TNF-α, IL-1β in wound fluid by ~40-60% [1] [3]. | Enhanced M2 polarization via targeted delivery of anti-inflammatory miRNAs (e.g., miR-124a); cytokine reduction >70% [7] [15]. | Protocol: Bone marrow-derived macrophages stimulated with LPS ± exosomes (20 µg/mL). M1/M2 markers (iNOS, CD206) via FACS/qPCR after 24h. Wound fluid collected via absorbent foam, cytokines measured by ELISA [1] [15]. |

| Cell Proliferation & Migration | ↑ Fibroblast/keratinocyte migration by ~50-80% in scratch assay; ↑ proliferation by ~30-50% [1] [26]. | ↑↑ Migration >100% vs. control; proliferation ↑ ~70-90% via overexpression of mitogenic miRNAs/proteins [7] [15]. | Protocol: Scratch assay: confluent fibroblasts/keratinocytes scratched, treated with exosomes (50 µg/mL). Wound closure imaged at 0, 12, 24h. Proliferation measured by CCK-8/MTS assay after 48-72h [26] [7]. |

| Wound Closure Rate (In-Vivo) | ~40-60% closure by day 7 in diabetic rodent models [1] [15]. | ~70-90% closure by day 7; faster re-epithelialization and granulation tissue formation [7] [15]. | Protocol: Full-thickness excisional wound (8mm diameter) on db/db mouse back. Exosomes (100 µg in 100 µL PBS) applied topically with hydrogel every 3 days. Wound area quantified via planimetry daily. Tissue harvested for histology at days 7, 14 [15]. |

| Targeting Efficiency | Limited inherent targeting; relies on general tropism [7]. | Significantly enhanced via surface modification (e.g., RGD peptides for endothelial cells, CP05 peptide for keratinocytes) [7]. | Protocol: Fluorescently labeled exosomes applied to wound. After 24h, tissue sections analyzed via fluorescence microscopy/IVIS. Uptake in specific cell types (e.g., endothelial cells, fibroblasts) quantified [7]. |

The molecular pathways through which natural exosome cargo achieves these outcomes are complex and highly coordinated. The following diagram maps the primary signaling mechanisms influenced by key cargo components.

Diagram 2: Signaling pathways influenced by natural exosome cargo. Key cargo components, including specific miRNAs, proteins, and lipids, interact with and regulate multiple cellular pathways central to wound healing. These interactions converge to promote accelerated wound closure and tissue regeneration.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Translating the mechanistic insights of exosome biology into experimental data requires a specific toolkit. The following table catalogues essential reagents and their functions based on the methodologies cited in the literature.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Exosome Wound Healing Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function in Research | Example Application in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs) | Primary cellular source for therapeutic exosome production. | Isolated from human bone marrow, adipose tissue, or umbilical cord. Cultured in serum-free media to avoid bovine EV contamination [1] [3]. |

| Ultracentrifugation System | Gold-standard method for isolating exosomes from cell culture supernatant. | Sequential centrifugation steps: 300g (cells), 2000g (debris), 10,000g (microvesicles), 100,000g+ (exosomes) [7] [25]. |

| Size-Exclusion Chromatography (SEC) | High-purity isolation of exosomes based on size, separates from protein aggregates. | Using columns (e.g., qEV) to fractionate sample; exosomes elute in early fractions separate from contaminating proteins [3]. |

| Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis (NTA) | Characterizes exosome size distribution and concentration. | Instrument (e.g., Malvern Nanosight) tracks Brownian motion of particles in suspension to calculate hydrodynamics diameter [1] [7]. |

| CD63/CD81/CD9 Antibodies | Detect tetraspanin markers for exosome identification via Western Blot (WB) or flow cytometry. | WB confirmation of exosome markers; absence of negative markers (e.g., GM130, Calnexin) ensures purity [26] [25]. |

| Matrigel Basement Membrane Matrix | In-vitro assay for evaluating exosome pro-angiogenic potential. | HUVECs are seeded with exosomes on polymerized Matrigel; tube formation (length, branches, nodes) is quantified [15]. |

| Hydrogel Delivery System (e.g., Chitosan) | Biomaterial scaffold for sustained exosome release at wound site. | Mixing exosomes with hydrogel (e.g., chitosan, hyaluronic acid) protects from degradation and allows controlled local delivery in animal models [1] [15]. |

| db/db or STZ-induced Diabetic Mice | Standard preclinical model for studying chronic wounds (diabetic foot ulcers). | Creating full-thickness excisional wounds to test the efficacy of exosome therapies in an impaired healing environment [15]. |

Natural exosomes function as sophisticated, multi-component signaling packages that coordinately regulate inflammation, proliferation, and remodeling to promote wound healing. The experimental data demonstrate their efficacy in modulating key cellular players and pathways in chronic wound models. However, limitations such as variable potency and limited targeting present opportunities for bioengineering.

The future of exosome therapeutics lies in the intelligent design of engineered vesicles. Strategies such as pre-conditioning parent cells (e.g., with hypoxia or inflammatory cytokines) to alter cargo [15], direct loading of specific therapeutic miRNAs (e.g., miR-126-3p) [7] [15], and surface modification with targeting ligands (e.g., RGD peptides) are actively being pursued [7]. These approaches aim to create next-generation exosome products that retain the beneficial safety profile of natural exosomes while exhibiting enhanced, targeted, and more predictable therapeutic activity for treating complex chronic wounds.

Precision Engineering: Methodologies for Enhancing Exosome Potency and Specificity

The therapeutic efficacy of exosomes in chronic wound healing is profoundly influenced by the strategies employed to load them with therapeutic cargo. The choice of loading technique directly impacts key performance metrics, including cargo encapsulation efficiency, stability of the resulting loaded exosomes, and crucially, the preservation of their biological integrity and function. As research pivots from using natural exosomes to engineered counterparts for enhanced chronic wound therapy, selecting an optimal loading method has become a central focus in biotherapeutic development [5] [7]. This guide provides a objective comparison of the three primary loading strategies—transfection, incubation, and electroporation—based on current experimental data, to inform selection for preclinical chronic wound research.

Comparative Analysis of Cargo Loading Strategies

The following tables summarize the core characteristics and performance data of the three main loading strategies, synthesizing findings from recent studies.

Table 1: Key Parameters and Experimental Outcomes of Cargo Loading Strategies

| Loading Strategy | Mechanism of Action | Optimal Cargo Types | Typical Incubation Parameters | Reported Loading Efficiency | Key Experimental Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transfection | Genetic modification of parent cells to secrete pre-loaded exosomes [8]. | miRNA, siRNA, plasmid DNA [7] [8]. | Co-culture: 24-48 hours [8]. | Variable; depends on transfection efficiency of parent cells [8]. | Enables spontaneous cargo integration but requires extensive tuning; low to medium yield [8]. |

| Incubation | Passive diffusion via concentration gradient; hydrophobic drugs interact with lipid bilayer [8]. | Small hydrophobic molecules, proteins. | 1-12 hours at Room Temperature (RT) - 37°C [8]. | Lower compared to active loading methods [8] [1]. | Simple and straightforward; increased solubility for hydrophobic drugs [8]. |

| Electroporation | Electric pulses create transient pores in exosome membrane [8]. | siRNA, miRNA, hydrophobic drugs [8]. | Field strength: 125-278 kV/m; Buffer: Low conductivity (e.g., 9×10⁻³ S/m) [27] [8]. | Effective for nucleic acids and hydrophobic drugs [8]. | Can incorporate hydrophobic drugs and nucleic acids; may have lower drug encapsulation capacity than sonication [8] [5]. |

| Sonication | Ultrasonic waves temporarily disrupt exosome membrane [8] [28]. | Small molecules, nucleic acids, proteins. | Not specified in results. | Higher drug encapsulation capacity than electroporation and incubation [8] [1] [5]. | Superior encapsulation property and drug loading efficacy compared to incubation and electroporation [8] [1]. |

Table 2: Functional Advantages and Limitations in Chronic Wound Research

| Loading Strategy | Preservation of Exosome Integrity | Therapeutic Payload in Chronic Wound Models | Major Advantages | Major Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transfection | High; maintains natural exosome biogenesis [8]. | miRNA for immunomodulation (e.g., miR-21) and angiogenesis [7] [24]. | Ideal for stable expression of RNA cargo; uses native cellular machinery [8]. | Low yield and efficiency; complex, time-consuming process [8]. |

| Incubation | High; no physical disruption to membrane [8]. | Angiogenic factors (e.g., VEGF) [24]. | Maximally preserves exosome structure and function; technically simple [8]. | low loading efficiency, particularly for large or hydrophilic molecules [8]. |

| Electroporation | Variable; risk of cargo aggregation and membrane damage [8]. | siRNA against pro-inflammatory targets [8]. | Rapid process; applicable to a wide range of cargo types [8]. | Risk of cargo aggregation and damage to exosome membrane [8]. |

| Sonication | Lower; potential for permanent membrane damage and protein denaturation [8]. | Not specified in results. | Highest reported loading efficiency and encapsulation capacity [8] [1]. | Potential for permanent membrane damage and protein denaturation [8]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Passive Incubation

Principle: This method relies on the passive diffusion of cargo across the exosome membrane, driven by a concentration gradient. It is particularly suitable for small hydrophobic molecules that can partition into the lipid bilayer [8].

Protocol:

- Isolate and purify exosomes from a chosen source (e.g., Mesenchymal Stem Cell culture supernatant) using standard methods like ultracentrifugation or size-exclusion chromatography [29] [3].

- Resuspend the purified exosomes in a suitable buffer, such as Phosphate-Buffered Saline (PBS) or a low-conductivity electroporation buffer.

- Mix the exosome suspension with the therapeutic cargo (e.g., a small molecule drug). Literature often uses a cargo concentration in the range of 10-100 µM, but this requires optimization for specific cargo [8].

- Incubate the mixture for 1 to 12 hours at room temperature or 37°C to allow for diffusion and membrane interaction [8].

- Remove unencapsulated cargo by ultracentrifugation (e.g., 100,000× g for 70 minutes) or using purification columns. The resulting pellet is the cargo-loaded exosomes, which should be resuspended in an appropriate buffer for storage or downstream application [8].

Electroporation

Principle: Application of a controlled electrical field creates transient, nanoscale pores in the exosome's lipid bilayer, allowing hydrophilic cargo such as nucleic acids to enter. The membrane reseals after the pulse [8].

Protocol:

- Prepare exosome and cargo mixture: Combine purified exosomes with the cargo (e.g., siRNA or miRNA) in a low-conductivity electroporation buffer. A typical ratio is 100-200 µg of exosomes with 10-100 pmol of siRNA, though this must be optimized [8].

- Transfer to cuvette: Place the mixture into an electroporation cuvette with a specific gap width (e.g., 4 mm).

- Apply electrical pulse: Use an electroporator system (e.g., Bio-Rad Gene Pulser). Parameters must be optimized; a representative protocol for cells uses a single square wave pulse of 20 msec, 300 V, 2000 µF, and 1000 Ohms [28]. For a microfluidic system with an 80 µm channel height, a voltage amplitude of ~10 V can achieve a field strength of 125 kV/m [27].

- Incubate and purify: Following electroporation, incubate the mixture at room temperature for 10-30 minutes to allow membrane recovery. Remove unincorporated cargo via ultracentrifugation or size-exclusion chromatography [8].

Sonication

Principle: Ultrasonic energy applied to the exosome-cargo mixture generates shear forces that temporarily disrupt the lipid membrane, facilitating cargo influx. This method is noted for its high loading efficiency [8] [1].

Protocol:

- Mix exosomes and cargo: Combine purified exosomes with the therapeutic cargo in a microcentrifuge tube.

- Sonicate: Place the tube in a water bath or on a probe sonicator. A common parameter is to sonicate at a power of 20-40% amplitude for 3-6 cycles of 30 seconds "on" and 30 seconds "off" on ice to prevent overheating [8].

- Recover and purify: After sonication, incubate the mixture at 37°C for 1 hour to allow membrane resealing. Separate loaded exosomes from free cargo using ultracentrifugation or chromatography [8].

Strategic Workflow and Method Selection

The following diagram illustrates the decision-making workflow for selecting an appropriate cargo loading strategy, based on the target cargo and experimental goals.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of loading strategies requires specific reagents and instrumentation. This table lists key solutions used in the protocols cited in this guide.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Exosome Cargo Loading

| Item Name | Function/Application | Specific Examples from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Lipofectamine 2000 | A cationic lipid reagent for chemical transfection of parent cells. | Used for lipofection in Vero cell line transfections [30]. |

| TurboFect | A cationic polymer transfection reagent for chemical transfection of parent cells. | Demonstrated superior transfection efficiency in Vero cells compared to electroporation and lentivirus [30]. |

| Low Conductivity Electroporation Buffer | Provides optimal ionic environment for efficient electroporation by minimizing current and heat generation. | Used in continuous-flow electroporation platform (conductivity: 9 × 10⁻³ S/m) [27]. |

| Electroporation Cuvettes / Flow Chips | Vessels that hold the sample during electroporation, with defined electrode gaps to ensure uniform electric field. | 4-mm gapped cuvette for standard electroporation [30]; planar microfluidic flow chip (80 µm channel height) for continuous-flow systems [27]. |

| Size-Exclusion Chromatography (SEC) Columns | For purifying and isolating exosomes from biological fluids or culture supernatants after loading to remove unencapsulated cargo and contaminants. | A method for isolating and purifying exosomes [3] [8]. |

| Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) | Used in precipitation-based methods for isolating exosomes. | A polymer used to precipitate exosomes, facilitating their isolation [8]. |

| Saponin | A surfactant that permeabilizes the exosome membrane by complexing with cholesterol, used as an alternative loading method. | Used in saponin treatment-mediated drug loading into exosomes [8]. |

| Ultracentrifuge | Essential for high-speed pelleting of exosomes during isolation and post-loading purification steps. | The "gold standard" method for isolating exosomes via high-speed centrifugation [29] [8]. |

The move toward engineered exosomes for chronic wound therapy demands robust and efficient cargo loading. No single strategy is universally superior; the choice is a trade-off between loading efficiency, cargo type, and the preservation of exosome function. Incubation offers simplicity and integrity for hydrophobic molecules, electroporation provides versatility for nucleic acids, and transfection enables endogenous loading of genetic material. Sonication stands out where high loading efficiency is the paramount concern. Researchers must align their choice with their therapeutic cargo and the specific pathophysiological targets within the complex chronic wound microenvironment. As the field advances, the refinement of these protocols and the development of novel hybrid methods will be crucial for translating engineered exosome therapies from the bench to the bedside.

The treatment of chronic wounds, a significant global health burden, is being revolutionized by advanced therapeutic strategies involving exosomes and biomaterial scaffolds. A critical factor influencing the efficacy of these strategies is the precise delivery and retention of therapeutics at the dynamic and complex wound site. Surface modification with targeting ligands, such as the Arg-Gly-Asp (RGD) peptide family, has emerged as a powerful technique to enhance the wound homing capabilities of both natural and engineered exosomes, as well as the performance of wound-healing matrices. The RGD motif is a quintessential example, serving as a primary recognition sequence for extracellular integrin receptors that are profoundly involved in cell adhesion, migration, and proliferation during the healing process [31] [32]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of how RGD and similar ligands are engineered to improve targeting, focusing on their application within the burgeoning field of exosome-based therapies for chronic wounds. It objectively compares the performance of different ligand-functionalization approaches, supported by experimental data and detailed methodologies, to inform researchers and drug development professionals.

Ligand Function and Integrin Signaling in Wound Repair

RGD Peptides and Integrin Binding

The RGD sequence is a ubiquitous cell-adhesion motif found in numerous extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins, including fibronectin, vitronectin, and fibrinogen [32] [33]. Its primary function is to act as a ligand for a subset of integrin receptors, including αvβ3, αvβ5, αvβ6, α5β1, and αIIbβ3 [32]. In the context of wound healing, which progresses through hemostasis, inflammation, proliferation, and remodeling phases, integrin-mediated signaling is crucial [33]. The binding of RGD to its cognate integrins on the surface of cells such as fibroblasts, keratinocytes, and endothelial cells promotes their attachment, spreading, and survival, thereby facilitating re-epithelialization, angiogenesis, and the formation of granulation tissue [31] [33]. This makes RGD-functionalized surfaces highly conducive to tissue regeneration.

Key Signaling Pathways

The engagement of RGD with integrins initiates outside-in signaling that activates key intracellular pathways, driving cellular processes essential for repair. A pivotal pathway is the PI3K/AKT axis, which promotes cell survival, growth, and proliferation. For instance, in a study using a self-assembling peptide hydrogel (RGDmix) to deliver human amniotic mesenchymal stem cells (hAMSCs) for wound healing, the incorporation of the RGDSP ligand enhanced the secretion of therapeutic growth factors. This effect was demonstrated to be mediated specifically through the RGDSP/Integrin αv/PI3K/AKT signaling pathway, as silencing either integrin αv or key components of the PI3K/AKT pathway abolished the beneficial paracrine effects [34]. This pathway, along with others, orchestrates the cellular response to RGD-presenting biomaterials, underscoring the ligand's role beyond simple adhesion.

Diagram 1: RGD-activated integrin αv/PI3K/AKT signaling pathway in wound healing.

Comparative Performance of Ligand-Engineered Systems

The functionalization of therapeutic platforms with RGD peptides significantly enhances their performance in chronic wound models. The table below summarizes key comparative data from preclinical studies.

Table 1: Performance comparison of RGD-functionalized systems in wound models.

| Therapeutic Platform | Ligand Used | Key Experimental Findings | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| RGDmix SAPH (RADA16-RGDSP) | RGDSP | Significantly improved hAMSCs viability, proliferation, and growth factor secretion; Accelerated wound re-epithelialization and angiogenesis in a murine model via integrin αv/PI3K/AKT. | [34] |

| Nano-P(3HB-co-4HB) Scaffold | Biomimetic RGD | Enhanced H9c2 myoblast cell attachment and proliferation; Increased surface wettability (15 ± 2° contact angle). | [35] |

| RGD–Alginate Scaffold | cyclic RGD (cRGD) | Promoted organized cardiac tissue formation; Prevented cardiomyocyte apoptosis; Increased levels of N-Cadherin and connexin-43. | [31] |

| Lysine-cyclic RGD (LcRGD) | c[RGDfK]-20K | Combined specific integrin binding with rapid, nonspecific adhesion via positive charge, improving osteogenic progenitor cell retention. | [31] |

Beyond standalone RGD, other ECM-derived peptides also contribute to wound healing. The PHSRN sequence from fibronectin acts synergistically with RGD to enhance integrin binding, promoting superior keratinocyte and fibroblast adhesion, spreading, and proliferation compared to RGD alone [33]. Similarly, laminin-derived sequences such as IKVAV and YIGSR support the adhesion and proliferation of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) and endothelial cells, further promoting angiogenesis [33].

Experimental Protocols for Ligand Evaluation

Protocol: Evaluating RGD-Peptide Hydrogels for Stem Cell Delivery

This protocol is adapted from a 2024 study investigating RGDSP-functionalized self-assembling peptide hydrogels (SAPH) for delivering hAMSCs to wounds [34].

Objective: To determine if a composite RGDmix hydrogel can support hAMSCs survival, regulate their paracrine function, and enhance their therapeutic efficacy in a murine wound model, and to elucidate the involved signaling pathway.

Materials:

- Peptides: RADA16 and RADA16-RGDSP (Ac-RADARADARADARADAGGRGDSP-CONH2).

- Cells: Human amniotic mesenchymal stem cells (hAMSCs), isolated and characterized via flow cytometry for surface markers (CD73, CD90, CD105) and trilineage differentiation.

- Animals: C57BL/6 mice (6-8 weeks old).

- Key Reagents: CellTiter 96 AQueous One Solution Reagent (MTS assay), Live/Dead assay kit, siRNA for gene silencing (e.g., against integrin αv).

Methodology:

- Hydrogel Preparation: The RGDmix SAPH is prepared by mixing RADA16-RGDSP solution with RADA16 solution at a 7:3 ratio. The mixture is sonicated and stored at 4°C to form a stable hydrogel.

- Cell Encapsulation: hAMSCs are trypsinized, resuspended, and carefully mixed with an equal volume of 1% RGDmix or control (RADA16-only) solution. The cell-hydrogel mixture is added to a well, and culture medium is gently overlaid to trigger gelation.

- In Vitro Analysis:

- Viability/Proliferation: Assessed using Live/Dead staining and CCK-8 assay at designated time points (e.g., 1, 3, 5 days).

- Cell Adhesion: hAMSCs are seeded on pre-formed hydrogel membranes, and adherent cells are quantified after 1 and 3 hours using a CCK-8 assay.

- Paracrine Function: The concentration of secreted growth factors (e.g., VEGF, FGF) in the conditioned medium is measured via ELISA.

- Pathway Inhibition: hAMSCs are transfected with siRNA targeting integrin αv or treated with a PI3K/AKT pathway inhibitor prior to encapsulation. Subsequent changes in growth factor secretion and cell behavior are analyzed.

- In Vivo Wound Healing Model:

- A full-thickness excisional wound (e.g., 8 mm diameter) is created on the dorsum of each mouse.

- The mice are randomly assigned to treatment groups: Control, hAMSCs in RADA16 hydrogel, and hAMSCs in RGDmix hydrogel.