Engineering Complexity: How 3D Bioprinting is Building the Future of Tissues and Therapeutics

This article explores the transformative role of 3D bioprinting in fabricating complex, biomimetic tissue architectures for advanced biomedical applications.

Engineering Complexity: How 3D Bioprinting is Building the Future of Tissues and Therapeutics

Abstract

This article explores the transformative role of 3D bioprinting in fabricating complex, biomimetic tissue architectures for advanced biomedical applications. It provides a comprehensive overview for researchers and drug development professionals, covering the foundational principles of bioprinting, from bioink design to process mechanics. The scope extends to cutting-edge methodological advances, including high-throughput systems and vascularization strategies, alongside critical troubleshooting for defect minimization and process optimization. Finally, the article examines the application and validation of these engineered tissues in drug screening and disease modeling, highlighting their superior predictive power over traditional 2D models and their growing impact on precision medicine and the drug development pipeline.

The Blueprint of Life: Core Principles of 3D Bioprinting for Tissue Architecture

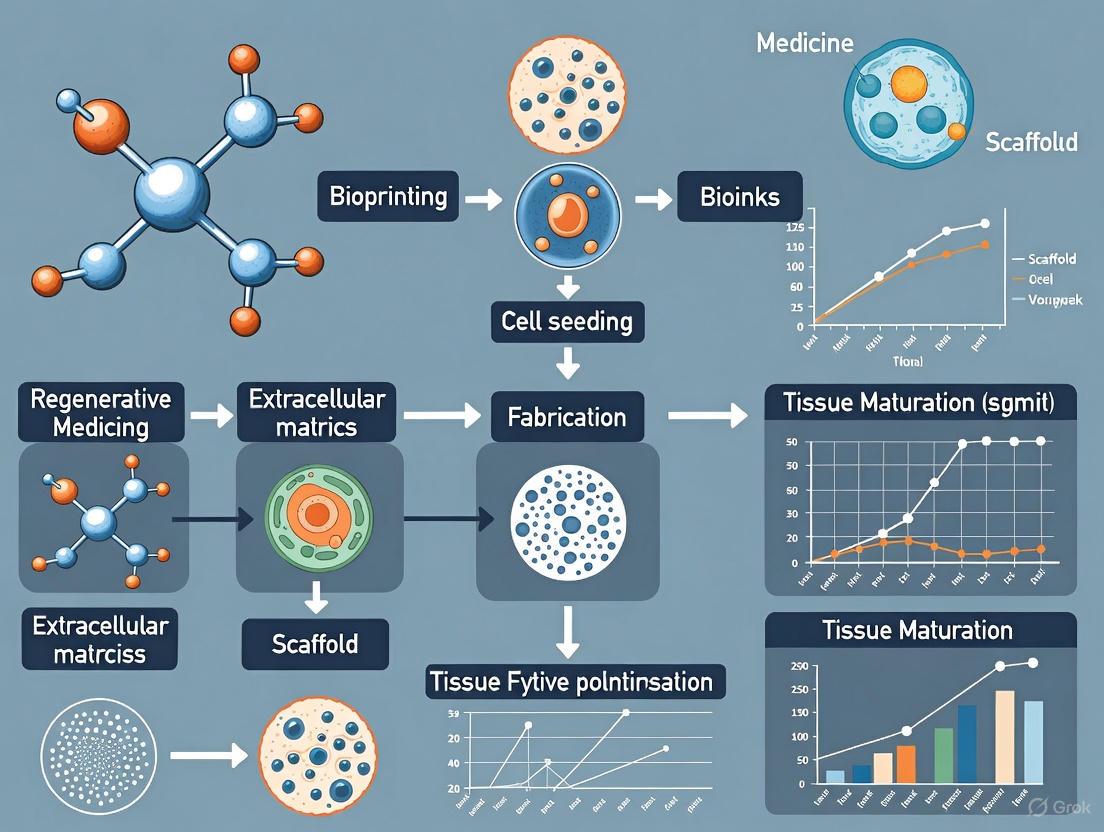

The field of tissue engineering is undergoing a revolutionary transformation through the integration of digital design tools and advanced biomanufacturing. Three-dimensional (3D) bioprinting represents an innovative technology that combines engineering, manufacturing, and medicine to create biologically relevant tissue architectures [1]. This digital workflow enables researchers to move beyond traditional two-dimensional cell culture toward constructing complex, patient-specific tissue models with precise spatial control over cellular organization and extracellular matrix composition. The process involves incorporating living cells with biocompatible materials to design required tissue or organ models in situ for various in vivo and in vitro applications, fundamentally changing approaches to disease modeling, drug discovery, and regenerative medicine [1] [2].

The significance of this digital transition extends throughout the research pipeline. For drug development professionals, 3D bioprinted tissues offer more physiologically relevant models for compound screening, potentially identifying efficacy and toxicity issues earlier in the development process [2]. For translational scientists, the technology enables creation of patient-specific tissue constructs that mirror native tissue complexity more accurately than conventional models [3]. The global market size of 3D bioprinting, valued at $1.7 billion USD in 2021 and expected to reach $1.94 billion by 2025, reflects the growing investment and confidence in these technologies [1].

The Digital Workflow: From Virtual Design to Biological Construct

The complete digital workflow for tissue design integrates multiple stages, each requiring specialized tools and protocols. The process transforms virtual designs into living biological constructs through a coordinated sequence of pre-bioprinting, bioprinting, and post-bioprinting stages.

Pre-Bioprinting Phase: Digital Design and Preparation

The foundation of successful bioprinting lies in meticulous pre-bioprinting preparation, where digital design meets biological preparation.

Imaging and 3D Model Generation: The process begins with acquiring high-resolution 3D images of the target tissue or organ architecture using diagnostic tools like MRI, CT, or micro-CT [1]. These images in DICOM format are processed through segmentation algorithms to create 3D virtual models of the defect or tissue structure. For bone regeneration applications, Cone Beam Computed Tomography (CBCT) provides the necessary resolution for creating accurate 3D bone defect models (3DBM) [4]. The segmented models are exported as Standard Tessellation Language (STL) files, which serve as the universal format for 3D printing platforms [4].

Bioink Preparation and Cell Culture: Parallel to model generation, researchers prepare bioinks—the printable materials containing living cells and biomaterials that form the tissue construct. Bioinks typically consist of a combination of natural or synthetic polymers (such as alginate, gelatin, chitosan, collagen, or hyaluronic acid) mixed with specific cell populations [1] [3]. Cells are expanded through conventional 2D culture or as 3D spheroids, which exhibit improved biological function due to their native-like tissue microenvironment that enables direct cell-cell signaling and cell-matrix interactions [3]. For applications requiring high cell density, spheroids offer a promising alternative with cell density similar to human tissue [5].

Design Principles for Bioprinting: Three main approaches guide the design process in bioprinting:

- Biomimicry: Seeking to replicate the identical biological components and configuration of native tissues, including their specific cellular organization and extracellular matrix composition [1].

- Autonomous self-assembly: Utilizing the innate mechanisms of tissue formation in embryonic development, where cells organize themselves into functional structures [1].

- Mini-tissue building blocks: Combining both approaches by creating the smallest structural and functional tissue components (spheroids, rods) and assembling them into larger constructs [1].

Table 1: Key Software Tools in the Digital Bioprinting Workflow

| Software Type | Examples | Primary Function | Compatibility/Format |

|---|---|---|---|

| Medical Imaging | CoDiagnostiX, Dental Wings | Convert DICOM images to 3D models | STL file export [4] |

| CAD Design | Meshmixer, DNA Studio | 3D modeling and mesh design | Open-source/proprietary [4] [2] |

| Printer Control | Manufacturer-specific | Printer operation and parameter control | G-code generation |

Bioprinting Phase: Fabrication Strategies and Modalities

The bioprinting phase translates digital designs into physical biological constructs through additive manufacturing approaches. The core principle involves layer-by-layer deposition of bioinks following a predetermined path generated from the digital model [2]. Different bioprinting technologies offer distinct advantages for specific tissue types and applications.

Extrusion-Based Bioprinting: This most common approach uses mechanical (piston or screw-driven) or pneumatic pressure to force bioink through a nozzle, depositing continuous filaments in a controlled pattern [1]. Researchers load cell-laden bioink into cartridges and set printing parameters including pressure, speed, and nozzle height to optimize structural integrity and cell viability [2]. A novel advancement in this category is the High-throughput Integrated Tissue Fabrication System for Bioprinting (HITS-Bio), which uses a digitally controlled nozzle array (e.g., 4×4 configuration) to manipulate multiple spheroids simultaneously, increasing printing speed by 10-fold while maintaining >90% cell viability [5].

Light-Based Bioprinting: This modality uses projected light patterns to selectively polymerize photosensitive bioinks in a vat, forming complex structures with high resolution [2]. Digital Light Processing (DLP) stereolithography offers advantages for creating constructs with fine features and smooth surfaces.

Emerging Hybrid Approaches: Recent advances include 3D hybrid bioprinting platforms that integrate multiple printing modules under optimized conditions for continuous bioprinting with both soft and hard biomaterials [6]. These systems can create multi-hydrogel hybrid constructs with over 1000-fold increase in mechanical strength compared to hydrogel-only constructs, making them suitable for load-bearing musculoskeletal and orthopedic tissue engineering [6].

Table 2: Quantitative Comparison of Bioprinting Technologies

| Bioprinting Technology | Resolution Range | Speed | Cell Viability | Suitable Bioinks |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Extrusion-Based | 100-500 μm [5] | Moderate (conventional) to High (HITS-Bio: 10x faster) [5] | 80-95% [5] | High-viscosity hydrogels, cell spheroids |

| Light-Based | 10-100 μm | Fast | 75-90% | Photocrosslinkable hydrogels |

| Hybrid Systems | 50-200 μm [6] | Variable | >90% [6] | Multiple material classes |

Post-Bioprinting Phase: Maturation and Validation

The post-bioprinting phase transitions the printed construct into a functional tissue through maturation and stabilization processes.

Crosslinking and Stabilization: Most 3D bioprinted structures require crosslinking to achieve structural stability and mechanical integrity. This is typically achieved through chemical (ionic solutions) or physical (UV light) methods that create covalent bonds between polymer chains [2]. The specific crosslinking method depends on the bioink composition, with alginate-based inks often using calcium chloride solutions while gelatin methacryloyl (GelMA) requires photoinitiators and UV exposure.

Quality Control and Process Monitoring: Advanced monitoring techniques are essential for ensuring reproducible tissue fabrication. A novel approach developed at MIT integrates a modular, low-cost (<$500) monitoring system with a digital microscope that captures high-resolution images of tissues during printing [7]. An AI-based image analysis pipeline rapidly compares these images to the intended design, identifying defects such as over- or under-deposition of bioink. This system enables real-time inspection and adaptive correction, serving as a foundation for intelligent process control in embedded bioprinting [7].

Maturation and Functional Assessment: Following crosslinking, constructs are transferred to bioreactors that provide appropriate physiological stimulation (flow, compression, stretch) and nutrient delivery to promote tissue development and functionality [1]. The maturation period varies from days to weeks depending on the tissue complexity. During this phase, constructs are regularly assessed for metabolic activity, gene expression, protein secretion, and structural organization to validate their biological relevance.

Advanced Applications in Complex Tissue Architecture

The digital workflow enables fabrication of increasingly complex tissue architectures that better replicate native tissue organization and function.

Vascularized Tissue Constructs

A significant challenge in tissue engineering has been creating vascular networks that support nutrient and oxygen transport in thick constructs. Advanced bioprinting approaches now enable fabrication of hierarchical vascular structures through multi-material printing. By combining different bioinks in core-shell configurations or printing sacrificial materials that can be subsequently removed, researchers create perfusable channel networks within tissue constructs [6]. These vascularized tissues better sustain high cell densities and can be integrated with host vasculature upon implantation.

Bone and Cartilage Regeneration

Digital workflows have shown particular promise in orthopedic applications. In one approach, researchers used CAD-CAM technology to design custom titanium meshes for guided bone regeneration (GBR) [4]. The process involved creating a 3D bone defect model from CBCT scans, designing a patient-specific mesh with controlled porosity (0.3 mm pore width) and thickness (0.5 mm) using open-source software, and 3D laser printing the final titanium mesh [4]. This digital approach provided superior fit and mechanical support compared to manually shaped meshes.

For cartilage repair, the HITS-Bio platform demonstrated fabrication of one-cubic centimeter cartilage constructs containing approximately 600 spheroids in less than 40 minutes [5]. The high cell density and organization achieved through this rapid printing process facilitated formation of functional cartilage tissue with appropriate biochemical and mechanical properties.

Multi-Tissue Interfaces and Organ-on-Chip Models

Hybrid bioprinting platforms enable creation of complex multi-tissue interfaces, such as bone-cartilage or tendon-muscle junctions, by seamlessly integrating different biomaterials and cell types within a single construct [6]. These models are particularly valuable for studying tissue development, disease progression, and drug responses at tissue interfaces. Similarly, bioprinting facilitates development of sophisticated microphysiological systems (MPS) and organ-on-chip models that incorporate multiple cell types in physiologically relevant geometries [7]. These systems offer more predictive platforms for drug screening and disease modeling compared to conventional 2D cultures.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of the digital tissue design workflow requires careful selection of materials, reagents, and equipment. The following table details key components of the research toolkit for bioprinting applications.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Digital Tissue Design

| Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Natural Polymer Bioinks | Alginate, Gelatin, Chitosan, Collagen, Hyaluronic Acid, Fibrinogen [3] | Provide extracellular matrix-like environment for cell encapsulation and growth | Biocompatibility, biodegradability, cell adhesion motifs |

| Synthetic Polymer Bioinks | PEG-based hydrogels, Pluronics, Polycaprolactone (PCL) | Structural support, tunable mechanical properties | Controlled polymerization, consistent batch-to-batch properties |

| Crosslinking Agents | Calcium chloride (for alginate), Photoinitiators (Irgacure 2959), Genipin | Stabilize printed structures through chemical or physical crosslinking | Cytocompatible concentrations, rapid gelation kinetics |

| Cell Sources | Primary cells, stem cells (MSCs, iPSCs), cell lines (e.g., HEK293, HepG2) | Provide biological functionality to printed constructs | Expansion capacity, differentiation potential, functional markers |

| Software Platforms | Meshmixer, DNA Studio, CoDiagnostiX, manufacturer-specific printer software | Design, simulation, and printer control | STL compatibility, user-friendly interface, parameter adjustment capability |

| Process Monitoring Tools | Digital microscope systems, AI-based image analysis pipelines [7] | Real-time quality control during printing | High-resolution imaging, rapid comparison to design specifications |

Quality Control and Process Optimization

Implementing robust quality control measures throughout the digital workflow is essential for generating reproducible, reliable tissue constructs.

AI-Enhanced Process Monitoring

A cutting-edge approach developed by MIT researchers addresses the critical need for process control in bioprinting. This system integrates a compact digital microscope that captures high-resolution images of tissues during the printing process [7]. An AI-based image analysis pipeline then rapidly compares these images to the intended digital design, identifying defects such as over- or under-deposition of bioink. This method enables researchers to quickly identify optimal print parameters for a variety of different materials, improving inter-tissue reproducibility and enhancing resource efficiency by limiting material waste [7]. The system serves as a foundation for intelligent process control in embedded bioprinting, with potential for real-time adaptive correction and automated parameter tuning.

Characterization and Validation Methods

Comprehensive characterization of bioprinted tissues involves multiple analytical approaches:

- Structural analysis: Micro-CT, scanning electron microscopy (SEM), and histology assess architectural features and porosity.

- Mechanical testing: Compression, tension, and indentation tests evaluate mechanical properties relevant to native tissues.

- Biological validation: Cell viability assays (live/dead staining), immunostaining, gene expression analysis (qPCR, RNA-seq), and functional assays confirm tissue maturation and functionality.

Future Perspectives and Concluding Remarks

The field of digital tissue design is rapidly evolving, with several emerging trends poised to expand capabilities further. Machine learning integration is optimizing printing parameters and predicting tissue maturation outcomes, while 4D bioprinting introduces dynamic materials that change shape or functionality post-printing in response to environmental stimuli [1]. The development of novel bioinks with supramolecular functionality, reversible crosslinking polymers, and stimuli-responsive hydrogels continues to advance the complexity of printable tissues [3]. As resolution and speed improve simultaneously through technologies like HITS-Bio, the field moves closer to clinical application of bioprinted tissues for transplantation [5].

The digital workflow from CAD to cell represents a fundamental shift in how researchers approach tissue engineering and regenerative medicine. By integrating advanced imaging, computational design, and precision manufacturing with biology, this approach enables creation of tissue architectures with unprecedented control and complexity. For drug development professionals, these technologies offer more predictive models for compound screening. For translational scientists, they provide pathways to patient-specific tissue repairs. As the field continues to mature, the synergy between digital design and biological fabrication will undoubtedly yield increasingly sophisticated tissue constructs, ultimately blurring the boundaries between artificial fabrication and natural tissue formation.

In the rapidly advancing field of 3D bioprinting for complex tissue architecture research, the development of sophisticated bioinks represents a critical frontier. Bioinks—the cell-laden materials used in 3D bioprinting—serve as temporary, supportive scaffolds that mimic the native extracellular matrix (ECM), providing not only structural integrity but also essential biological cues for cellular adhesion, proliferation, and differentiation. Among the plethora of biomaterials investigated, three components have emerged as particularly promising: alginate, a seaweed-derived polysaccharide prized for its excellent printability and gentle crosslinking; gelatin, a collagen derivative that provides natural cell-adhesive motifs; and decellularized extracellular matrix (dECM), which offers tissue-specific biological signaling. When strategically combined, these materials create composite bioinks that overcome the limitations of individual components, enabling the fabrication of complex, functional tissue constructs for research and therapeutic applications.

The quest to replicate native tissue microenvironments in vitro demands bioinks that satisfy two often conflicting requirements: printability (the ability to form and maintain complex 3D structures during and after printing) and biofunctionality (the capacity to support cell viability and direct cellular behavior). Alginate-gelatin-dECM composites represent a sophisticated approach to balancing these demands, offering researchers a versatile platform for creating physiologically relevant tissue models for drug screening, disease modeling, and fundamental biological investigation. This technical guide decodes the formulation strategies, characterization methods, and practical applications of these advanced bioink systems, providing researchers with the foundational knowledge needed to design and optimize scaffolds for specific tissue engineering applications.

Component Fundamentals: Properties and Functions

Understanding the individual properties of each bioink component is essential for rational design of composite formulations. The table below summarizes the key characteristics, advantages, and limitations of alginate, gelatin, and dECM.

Table 1: Fundamental Properties of Core Bioink Components

| Component | Source/Origin | Key Properties | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alginate | Seaweed | Ionic crosslinking (via Ca²⁺), shear-thinning, biocompatible | Excellent printability, mild crosslinking, tunable mechanical properties | Lack of cell-adhesive motifs, limited biodegradability |

| Gelatin | Denatured collagen | Thermo-reversible gelation, RGD sequences, enzymatically degradable | Enhanced cell adhesion, biocompatibility, promotes cell proliferation | Low mechanical strength, unstable at physiological temperatures |

| dECM | Decellularized tissues | Tissue-specific biochemical composition, native ultrastructure, biomechanical cues | Recapitulates native microenvironment, contains growth factors, superior bioactivity | Poor printability, low viscosity, batch-to-batch variability |

Alginate: The Structural Backbone

Alginate, a natural polysaccharide derived from brown seaweed, serves as the structural workhorse in many composite bioinks. Its capacity for rapid ionic crosslinking in the presence of divalent cations (particularly calcium chloride) makes it exceptionally valuable for maintaining structural fidelity during and after the printing process. Alginate exhibits pseudoplastic (shear-thinning) behavior, meaning its viscosity decreases under shear stress during extrusion through printing nozzles and rapidly recovers once deposited, enabling precise deposition of filamentous structures [8]. This property is crucial for achieving high-resolution printing of complex architectures.

The mechanical properties of alginate hydrogels can be precisely tuned by adjusting parameters such as molecular weight, concentration, and crosslinking density, allowing researchers to match the stiffness of various native tissues [9]. However, a significant limitation of pure alginate is its lack of inherent cell-adhesive motifs, which can limit cell-matrix interactions crucial for tissue development. Additionally, alginate degrades primarily through slow, unpredictable dissolution rather than controlled enzymatic breakdown, which may not ideally match the timeline of new tissue formation [8].

Gelatin: The Biofunctional Enhancer

Gelatin, produced through partial hydrolysis of collagen, introduces critical biological functionality to composite bioinks. Its most valuable attribute is the presence of arginine-glycine-aspartic acid (RGD) sequences, which are recognized by integrin receptors on cell surfaces, facilitating cell adhesion, spreading, and migration [10]. Gelatin exhibits thermoresponsive behavior, transitioning from a liquid state at elevated temperatures (above ~30°C) to a gel state at lower temperatures, which can be harnessed to achieve temporary stabilization immediately after printing before permanent crosslinking of other components.

The main challenges with gelatin include its relatively low mechanical strength and thermal instability at physiological temperatures (37°C), where it tends to dissolve, compromising long-term structural integrity [10]. Consequently, gelatin is typically combined with materials that provide structural reinforcement or is chemically modified (e.g., gelatin methacryloyl or GelMA) to create stable covalent networks through photo-crosslinking. In alginate-gelatin composites, gelatin enhances cellular interactions while alginate provides the mechanical framework.

Decellularized Extracellular Matrix (dECM): The Biological Gold Standard

dECM bioinks are created by decellularizing native tissues or organs, followed by processing the remaining ECM into a printable form. The resulting material preserves tissue-specific biochemical composition and architectural cues, including collagens, glycosaminoglycans (GAGs), glycoproteins, and growth factors that regulate cellular behavior [11]. This complex biochemical microenvironment provides instructional signals that can enhance stem cell differentiation, promote tissue-specific functionality, and support the formation of sophisticated tissue structures that more closely mimic their in vivo counterparts.

The primary challenge with dECM bioinks is their poor printability and low mechanical properties when used alone. dECM solutions typically exhibit low viscosity and slow gelation, resulting in limited shape fidelity after printing [11]. Consequently, dECM is most often used as a bioactive component within composite bioinks, where it contributes biological signaling while other components (particularly alginate) provide structural integrity. The decellularization process itself is critical—overly aggressive methods can damage ECM components, while insufficient decellularization may leave immunogenic cellular material [12].

Formulation Strategies and Optimization

Creating optimal alginate-gelatin-dECM composites requires careful balancing of component ratios and crosslinking strategies to achieve the desired printability and bioactivity. The table below summarizes key formulation parameters and their effects on bioink properties.

Table 2: Bioink Formulation Optimization Parameters

| Parameter | Effects on Printability | Effects on Bioactivity | Optimal Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alginate Concentration | Higher concentration improves viscosity and shape fidelity | Very high concentrations may limit nutrient diffusion | 2-4% (w/v) |

| Gelatin Concentration | Moderate concentrations aid extrusion; too high causes nozzle clogging | Higher concentrations improve cell adhesion via RGD sequences | 5-15% (w/v) |

| dECM Content | High content reduces printability and structural stability | Higher content enhances tissue-specific bioactivity | 1-5 mg/mL |

| Crosslinker (CaCl₂) Concentration | Higher concentration increases stiffness and stability | Excessive crosslinking may reduce porosity and cell mobility | 100-200 mM |

Composite Design Principles

Successful bioink formulations leverage the complementary properties of each component. A typical approach uses alginate as the structural backbone that provides immediate shape fidelity through rapid ionic crosslinking, gelatin as a bioadhesive component that enhances cellular interactions and provides temporary thermal gelling, and dECM as a bioactive supplement that confers tissue-specific signaling [12] [13]. The specific ratios depend on the target tissue and printing methodology, but generally fall within the ranges indicated in Table 2.

Research demonstrates that the addition of gelatin to alginate significantly improves hydrophilicity and viscoelasticity, while alginate enhances mechanical properties and porosity [12]. One study reported that optimal formulations containing 15% gelatin achieved swelling ratios of 835.43 ± 130.61%, compression modulus of 9.64 ± 0.41 kPa, and porosity of 76.62 ± 4.43%—properties conducive to nutrient diffusion and cell infiltration [12]. The incorporation of dECM further enhances the biological performance without substantially altering mechanical properties when added at appropriate concentrations.

Crosslinking Strategies

Effective crosslinking is essential for maintaining structural stability in bioprinted constructs. Dual-crosslinking approaches have proven particularly effective for alginate-gelatin-dECM composites [13]. A typical strategy involves:

- Thermal gelation: Immediate stabilization after printing through gelatin gelation when the bioink cools below its gelation temperature (approximately 25°C).

- Ionic crosslinking: Subsequent immersion in calcium chloride solution to permanently crosslink the alginate network.

This combination allows for adequate time for precise printing while ensuring long-term stability under physiological conditions. In some cases, additional crosslinking methods may be employed, such as enzymatic crosslinking for gelatin or photo-crosslinking for modified polymers, providing further control over the mechanical and degradation properties of the final construct [10].

Experimental Protocols and Characterization

Bioink Preparation and Sterilization

Protocol: dECM-Enriched Alginate-Gelatin Bioink Formulation

- Materials: Porcine liver dECM powder, gelatin (Type A, 300 bloom), sodium alginate, Dulbecco's Phosphate Buffered Saline (DPBS), calcium chloride, pepsin.

- Procedure:

- dECM Solution Preparation: Digest dECM powder at 10 mg/mL in 0.1 M acetic acid containing 1 mg/mL pepsin. Stir for 48-72 hours at 4°C until fully dissolved. Neutralize to pH 7.4 using NaOH and dilute with DPBS to desired concentration [11].

- Gelatin Solution Preparation: Dissolve gelatin in DPBS at 37°C for 1 hour on a rotational shaker to achieve final concentration of 5-15% (w/v).

- Composite Bioink Preparation: Add sodium alginate (2-4% w/v final concentration) to the gelatin solution and mix at 37°C for 3 hours. Slowly incorporate the dECM solution into the alginate-gelatin mixture while stirring. Maintain at 37°C until printing to prevent gelation [12].

- Sterilization: Filter sterilize through 0.22 μm filters under aseptic conditions. Validate sterility by inoculating aliquots into bacterial culture media and monitoring turbidity [10].

Rheological and Printability Assessment

Characterizing the flow behavior and printing performance is essential for bioink optimization. Key assessments include:

- Rheological Testing: Using a rotational rheometer, measure viscosity versus shear rate to confirm shear-thinning behavior. Perform time sweeps to monitor storage (G') and loss (G") moduli during gelation. Bioinks should exhibit G' > G" after crosslinking, indicating solid-like behavior [9].

- Printability Tests:

- Filament Collapse Test: Print filaments across gaps of 1-16 mm and measure deflection angles. Smaller angles indicate better structural integrity [10].

- Fusion Test: Print grid structures with varying spacing between filaments to determine minimum printable feature size without pore closure [9].

- Shape Fidelity Assessment: Print multi-layered structures and compare actual dimensions to digital models using quantitative metrics like printability (Pr) value [9].

The following workflow diagram illustrates the key stages in bioink development and characterization:

Diagram 1: Bioink Development and Characterization Workflow. This diagram outlines the key stages in formulating, characterizing, and validating alginate-gelatin-dECM bioinks, from initial component selection through functional assessment of bioprinted constructs.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Bioink Development and Evaluation

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Base Biomaterials | Sodium alginate, Gelatin (Type A), dECM powders | Structural and bioactive components of bioink formulation |

| Crosslinking Agents | Calcium chloride (CaCl₂), Glutaraldehyde | Induce hydrogel formation and stabilize printed structures |

| Cell Culture Reagents | DMEM/F12, Fetal Bovine Serum, Penicillin-Streptomycin | Maintain cell viability during and after bioprinting process |

| Cell Viability Assays | Calcein-AM, Propidium Iodide, CCK-8 kit | Assess live/dead cell distribution and metabolic activity |

| Decellularization Agents | Triton X-100, Sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), DNase/RNase | Remove cellular material from native tissues to produce dECM |

| Characterization Tools | Rotational rheometer, Compression tester, Micro-CT | Evaluate mechanical properties, printability, and scaffold architecture |

Advanced Applications and Future Perspectives

Current Research Applications

Alginate-gelatin-dECM bioinks have demonstrated success across multiple tissue engineering applications. In vascular tissue engineering, researchers have developed self-supporting, multi-layered constructs using aorta-derived dECM combined with alginate-gelatin, achieving structural stability comparable to native blood vessels [13]. For skin tissue engineering, optimized formulations containing 15% gelatin crosslinked with 150 mM CaCl₂ supported the formation of bilayer skin models with homogeneous cell distribution and sustained viability over 14 days [10]. In cancer research, 3D breast tumor models fabricated with liver-derived dECM, gelatin, and alginate more accurately replicated the tumor microenvironment, enabling improved drug screening and study of metastasis mechanisms [12].

Emerging Trends and Future Directions

The field of bioink development is rapidly evolving, with several emerging trends poised to advance capabilities:

- Intelligent Process Control: Integration of AI-driven monitoring systems that use real-time imaging to detect print defects and automatically adjust parameters, improving reproducibility and reducing material waste [7].

- 4D Bioprinting: Development of bioinks that change shape or functionality over time in response to environmental stimuli, enabling creation of dynamic tissue models that better mimic physiological processes [8].

- Advanced Vascularization Strategies: Incorporation of sacrificial bioinks and angiogenic factors to create perfusable vascular networks within thick tissue constructs, addressing the critical challenge of nutrient and oxygen diffusion [8] [14].

- Multi-Material Bioprinting: Development of printing systems capable of depositing multiple bioinks with spatially controlled composition, enabling recreation of tissue interfaces and gradients found in native organs [14].

The following diagram illustrates the advanced crosslinking mechanisms that enhance bioink performance:

Diagram 2: Advanced Crosslinking Mechanisms for Bioinks. This diagram categorizes the primary crosslinking strategies used to stabilize alginate-gelatin-dECM bioinks, from physical methods to sophisticated dual-crosslinking approaches that combine multiple mechanisms.

As these technologies mature, alginate-gelatin-dECM bioinks are poised to become increasingly sophisticated, ultimately enabling the fabrication of complex tissue architectures that more faithfully replicate native tissue structure and function. This progress will accelerate drug development through more physiologically relevant in vitro models and advance the field toward clinically applicable tissue replacements.

The advancement of complex tissue architecture research is intrinsically linked to the development and refinement of 3D bioprinting technologies. Among the plethora of available methods, extrusion, inkjet, and laser-assisted bioprinting have emerged as the three cornerstone technologies, each offering a unique balance of strengths and limitations. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical comparison of these core bioprinting modalities, detailing their working principles, operational parameters, and suitability for specific biomedical applications. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding this "bioprinting trinity" is crucial for selecting the appropriate technology to fabricate physiologically relevant tissue models, thereby accelerating progress in regenerative medicine, drug screening, and disease modeling.

Three-dimensional (3D) bioprinting is an innovative additive manufacturing technology that revolutionizes the field of biomedical applications by combining engineering, manufacturing, and medicine [1]. This process involves the layer-by-layer deposition of bioinks—a combination of living cells, biomaterials, and bioactive molecules—to design and fabricate 3D tissue and organ models in situ for various in vivo and in vitro applications [1]. The transition from conventional 3D printing to bioprinting incorporates additional biological complexities, including material choice, cell types, and their growth and differentiation factors [1].

The global 3D bioprinting market, valued at approximately USD 1.3 billion in 2024 and projected to reach USD 2.8 billion by 2030, reflects the growing importance and adoption of this technology across research and clinical domains [15]. The field is driven by critical medical needs, including the severe global shortage of donor organs—with over 103,000 individuals on the national transplant waiting list in the U.S. alone—and the increasing demand for more predictive models in pharmaceutical development [16] [15]. For complex tissue architecture research, the fundamental challenge lies in replicating the intricate microenvironments, cell densities, and vascular networks of native tissues, a challenge that demands precise understanding and selection of available bioprinting technologies.

Core Bioprinting Technologies: A Technical Deep Dive

Extrusion-Based Bioprinting

Working Principle: Extrusion-based bioprinting (EBB) utilizes mechanical (piston or screw) or pneumatic pressure to force continuous filaments of bioink through a nozzle, depositing them layer-by-layer according to a digital design [17]. It is characterized by its ability to handle a wide range of material viscosities.

Key Characteristics:

- Bioink Viscosity: Handles high-viscosity materials (30-6×10⁷ mPa·s) [17].

- Cell Density: Supports higher cell densities, crucial for achieving physiologically relevant tissue constructs [17].

- Resolution: Typically ranges from 5 μm to hundreds of microns, influenced by nozzle diameter, pressure, and print speed [17].

- Speed: Generally has a lower printing speed compared to other methods, which can be a limitation for large-scale tissue fabrication [17].

Impact on Cells: The process subjects cells to substantial shear stress, which can compromise cell viability and affect cell adhesion, proliferation, morphology, and metabolic activity [18] [19]. In cancer research, shear stress has been shown to induce epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition, a hallmark of cancer metastasis, and alter gene expression [19].

Inkjet-Based Bioprinting

Working Principle: Inkjet bioprinting operates on a drop-on-demand principle, using thermal or acoustic forces to generate precisely controlled picoliter-sized droplets of bioink [20] [21]. The technology is known for its non-contact nature, which reduces risks of cross-contamination [21].

Key Characteristics:

- Bioink Viscosity: Limited to low-viscosity bioinks (3-12 mPa·s) to facilitate droplet formation [17].

- Cell Density: Constrained by the requirement for low-viscosity bioinks, limiting achievable cell concentrations [17].

- Resolution: Offers high printing accuracy, generating identical small droplets with high positional precision [21].

- Speed: Provides high printing speeds, making it suitable for applications requiring rapid patterning [20].

- Cost: Recognized as a low-cost bioprinting approach [21].

Impact on Cells: While shear stress is less pronounced than in extrusion-based methods, it can still occur during droplet formation and impact cell viability and function.

Laser-Assisted Bioprinting

Working Principle: Laser-assisted bioprinting (LAB) uses laser-induced forward transfer (LIFT) or related techniques, where a laser pulse is focused on a donor layer (often called a "ribbon") coated with bioink, generating a high-pressure bubble that propels a droplet of the bioink onto a substrate [16]. This is a nozzle-free approach.

Key Characteristics:

- Bioink Viscosity: Can handle a broad range of viscosities (1-300 mPa·s) [16].

- Cell Density: Enables high cell densities without compromising printability, as it is not limited by nozzle clogging.

- Resolution: Provides exceptional, sub-micron precision and high resolution, allowing for the fabrication of complex microarchitectures [16].

- Speed: Generally has a slower printing speed compared to other methods, particularly for larger constructs [16].

- Viability: Maintains high cell viability and function due to its gentle, nozzle-free process [16].

Impact on Cells: The primary cellular stressor in LAB is phototoxicity from the UV or near-UV laser, which can cause DNA damage and potentially lead to carcinogenesis [18] [19]. However, modern systems are optimized to minimize this risk.

Quantitative Technology Comparison

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Core Bioprinting Technologies

| Parameter | Extrusion-Based | Inkjet-Based | Laser-Assisted |

|---|---|---|---|

| Working Principle | Pneumatic or mechanical extrusion | Thermal or acoustic droplet generation | Laser-induced forward transfer |

| Max Resolution | 5 - 500 μm [17] | < 1 picoliter droplet volume [20] | Sub-micron precision [16] |

| Bioink Viscosity | Very High (30 - 60,000,000 mPa·s) [17] | Low (3 - 12 mPa·s) [17] | Medium (1 - 300 mPa·s) [16] |

| Cell Density | High [17] | Low [17] | High [16] |

| Cell Viability | Lower (subject to high shear stress) [17] | >90% (with optimized parameters) [20] | High (>95%) [16] |

| Relative Speed | Medium | High (ten times faster than some techniques) [17] | Low [16] |

| Relative Cost | Medium | Low [21] | Very High [16] |

| Key Advantage | High structural integrity, multi-material printing | High speed, low cost, contactless printing [21] | Excellent resolution, high cell viability, no nozzle clogging [16] |

| Primary Limitation | Shear stress on cells, limited resolution | Low bioink viscosity constraints, potential nozzle clogging [17] | Phototoxicity risk, low throughput, high equipment cost [16] |

Table 2: Application Suitability for Tissue Engineering

| Application | Recommended Technology | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Vascular Grafts | Laser-Assisted or Inkjet | High resolution is critical for mimicking fine capillary networks [16]. |

| Dense Connective Tissues (Bone, Cartilage) | Extrusion-Based | Ability to handle high-viscosity, mechanically robust bioinks [17]. |

| High-Throughput Drug Screening | Inkjet-Based | Speed and low cost are advantageous for printing large numbers of uniform tissue models [20] [21]. |

| Volumetric Tissue Constructs | Advanced Extrusion (e.g., HITS-Bio) | High-throughput integrated systems can achieve physiologically relevant cell densities at scale [17]. |

| Multi-Cellular Co-cultures | Laser-Assisted | High precision allows for precise spatial arrangement of different cell types [16]. |

| Skin & Epithelial Tissues | Inkjet or Extrusion | Balances speed, resolution, and the ability to create stratified layers [15]. |

Advanced Experimental Protocol: High-Throughput Spheroid Bioprinting for Bone Regeneration

The following protocol details a cutting-edge application of extrusion bioprinting, HITS-Bio (High-throughput Integrated Tissue Fabrication System for Bioprinting), which addresses the critical challenge of achieving physiologically relevant cell densities in engineered tissues [17].

The diagram below illustrates the HITS-Bio workflow for calvarial bone regeneration, from spheroid preparation to in vivo implantation.

Detailed Methodology

Step 1: Spheroid Formation and Differentiation

- Cell Source: Isolate and expand human adipose-derived stem cells (hASCs) under standard culture conditions.

- Spheroid Generation: Use a low-adhesion U-bottom plate to promote self-assembly of hASCs into spheroids (approximately 500 μm diameter) via the hanging drop method or forced aggregation.

- Osteogenic Commitment: Transfer spheroids to osteogenic differentiation media. Implement combinatorial microRNA (miR) technology—specifically, transfection with osteo-inductive miRNAs (e.g., miR-26a)—to enhance and accelerate osteogenic differentiation prior to printing [17].

Step 2: HITS-Bio Bioprinting Process

- Equipment Setup: The HITS-Bio platform consists of a digitally-controlled nozzle array (DCNA), a high-precision XYZ linear stage, and an extrusion head for depositing a gel substrate. The system is assembled inside a biosafety hood [17].

- Bioink Preparation: Prepare a supportive, printable hydrogel bioink (e.g., a blend of Gelatin Methacryloyl (GelMA) and Hyaluronic Acid) to act as a scaffold for the spheroids. The bioink should be photo-crosslinkable.

- Spheroid Aspiration: Move the DCNA to the spheroid chamber suspended in culture medium. Apply controlled aspiration pressure to selectively open nozzles and pick up multiple spheroids simultaneously. The process is monitored via integrated bottom-view cameras [17].

- Substrate Deposition and Spheroid Placement: Using the extrusion head, deposit a thin layer of the bioink substrate onto the printing bed. Transfer the DCNA loaded with spheroids over the substrate. Gently bring the spheroids into contact with the bioink and cut off the aspiration pressure to deposit them with high positional precision. This multi-spheroid placement process is repeated to form the desired structure [17].

- Encapsulation and Crosslinking: After spheroid placement, deposit a final layer of bioink to envelop the structure. Photo-crosslink the entire construct using a 405 nm light-emitting diode (LED) light source for 60 seconds to stabilize the 3D architecture [17].

Step 3: In Vivo Implantation and Analysis

- Animal Model: Utilize a rat model with a critical-sized calvarial bone defect (e.g., ~5 mm diameter).

- Intraoperative Bioprinting (IOB): For direct in situ repair, the HITS-Bio system can be used intraoperatively to print the miR-transfected spheroids directly into the defect site, significantly reducing surgery time [17].

- Assessment: Monitor bone regeneration over 3-6 weeks using micro-CT imaging for volumetric analysis and histology (e.g., H&E, Masson's Trichrome staining) to evaluate new bone formation, tissue integration, and vascularization. This protocol has demonstrated near-complete defect closure (bone coverage area of ~91% at 3 weeks and ~96% at 6 weeks) [17].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents for Advanced 3D Bioprinting Research

| Reagent/Material | Function | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Gelatin Methacryloyl (GelMA) | Photocrosslinkable hydrogel bioink; provides a cell-adhesive, tunable 3D matrix. | Serves as the primary scaffold material in extrusion and light-based bioprinting [17] [19]. |

| Live/Dead Viability Kit (e.g., Calcein AM/EthD-1) | Fluorescent staining to quantify live (green) and dead (red) cells within a bioprinted construct. | Standard post-printing quality control to assess cell viability after the printing process [18] [19]. |

| Annexin-V / Propidium Iodide (PI) | Flow cytometry or imaging assays to differentiate between live, apoptotic (Annexin-V+/PI-), and necrotic (Annexin-V+/PI+) cells. | Detailed analysis of cell death pathways triggered by printing-induced stress [19]. |

| Cell Painting Kits (Phenotypic Dyes) | A multiplexed fluorescent staining kit targeting multiple organelles (nuclei, nucleoli, mitochondria, actin, Golgi, ER). | High-content screening to assess subtle printing-induced changes in cell morphology and phenotype in 3D cultures [19]. |

| Fluorescently Tagged Antibodies | Immunofluorescence staining for specific markers (e.g., Ki67 for proliferation, CD31 for endothelial cells). | Validation of cell identity, proliferation status, and functional maturation within bioprinted tissues [18] [19]. |

| hASCs (Human Adipose-Derived Stem Cells) | A multipotent cell source capable of differentiating into osteogenic, chondrogenic, and other lineages. | Ideal cell type for regenerative applications, as used in the HITS-Bio bone regeneration protocol [17]. |

| microRNA Transfection Reagents | Facilitate the introduction of osteo-inductive miRNAs (e.g., miR-26a) into cells to direct differentiation. | Used to pre-condition cells within spheroids before bioprinting to enhance tissue-specific outcomes [17]. |

Technology Selection Workflow for Research Applications

The following decision diagram provides a systematic approach for selecting the optimal bioprinting technology based on key research requirements.

The field of 3D bioprinting is rapidly evolving beyond the core technologies discussed here. Key emerging trends include 4D bioprinting, which incorporates smart materials that change shape or properties over time in response to stimuli, and the integration of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning to optimize print parameters, predict cell behavior, and enable real-time process control for enhanced reproducibility [20] [7] [16]. Furthermore, the convergence of bioprinting with organ-on-a-chip technology and the ongoing challenge of vascularizing bioprinted tissues represent critical frontiers for achieving truly functional, clinically relevant tissue constructs [20] [7].

In conclusion, the "bioprinting trinity" of extrusion, inkjet, and laser-assisted technologies provides a versatile toolkit for researchers aiming to engineer complex tissue architectures. The choice of technology is not a matter of identifying a universal best, but rather of strategically matching the unique characteristics of each method—be it the structural robustness of extrusion, the speed and affordability of inkjet, or the superb resolution of laser-assisted systems—to the specific requirements of the intended biological model and research goal. As these technologies continue to mature and converge with advances in materials science, AI, and stem cell biology, their collective impact on disease modeling, drug discovery, and regenerative medicine is poised to be transformative.

In tissue engineering and regenerative medicine, the concept of the native stem cell niche has emerged as a fundamental principle guiding the development of functional biological constructs. The niche represents a dynamic, complex microenvironment where stem cells reside, communicating with their surroundings to maintain homeostasis, respond to injury, and dictate tissue function [22]. Rather than being passive inhabitants, stem cells actively serve as architects of their own niches, generating and modifying their microenvironment to control their own destiny [22]. This intricate bidirectional communication between cells and their environment is essential for proper tissue development, maintenance, and repair.

The pursuit of 3D bioprinting for complex tissue architecture research hinges on recapitulating this sophisticated niche environment. Traditional two-dimensional (2D) cell culture systems fail to replicate the three-dimensional (3D) spatial organization, mechanical cues, and biochemical gradients that define native tissues [23]. As the field advances, the critical challenge lies not merely in arranging cells in three dimensions, but in reconstructing the full complexity of the native tissue niche—a goal that requires integration of multiple cell types, biochemical signaling factors, and precise physical and architectural cues [23] [24].

Deconstructing the Native Tissue Niche

The native tissue niche is a multimolecular engine that drives cellular turnover and tissue regeneration throughout an organism's lifetime. Understanding its components is essential for efforts to mimic it in engineered tissues.

Core Components of the Stem Cell Niche

Native tissues comprise multiple cell types residing within a complex, continuously changing 3D microenvironment consisting of numerous inputs that combine to drive collective tissue function [23]. The stem cell niche encompasses several key elements:

Extracellular Matrix (ECM): The basement membrane rich in ECM and stem cell growth factors provides structural support and biochemical signaling [22]. Cells themselves produce major ECM components, creating a feedback loop that controls their polarity, proliferation, and maintenance [22].

Cellular Constituents: Heterologous niche components include blood vessels, lymphatic capillaries, nerves, stromal, adipose, and various tissue-resident immune cells that function with stem cells to guard against tissue damage and pathogens [22].

Soluble Factors: Cytokines, neurotrophic factors, growth factors, and differentiation cues are constantly synthesized, secreted, transported, and depleted within the niche [24].

Dynamic Niche Communication Networks

Stem cells within their niches follow sophisticated paradigms for transitioning between quiescent and regenerative states [22]. These communication networks break down during aging, often involving deterioration of extrinsic niche components rather than the intrinsic self-renewal capacity of the stem cells themselves [22]. The spatial distribution of individual cells controls structure and function within a tissue, creating microenvironments where factors like oxygen tension vary and influence stem cell maintenance and differentiation [24].

Table 1: Key Components of the Native Tissue Niche and Their Functions

| Niche Component | Key Elements | Primary Functions |

|---|---|---|

| Extracellular Matrix | Collagen, laminin, fibronectin, proteoglycans | Structural support, mechanical signaling, biochemical cue presentation |

| Soluble Factors | Growth factors, cytokines, differentiation cues | Cell fate determination, proliferation control, migration signals |

| Cellular Elements | Immune cells, endothelial cells, stromal cells | Paracrine signaling, immune surveillance, vascular support |

| Physical Cues | Matrix stiffness, topography, interstitial flow | Mechanotransduction, differentiation guidance, migration control |

Technological Approaches to Niche Mimicry

3D Bioprinting Strategies

Three-dimensional bioprinting has emerged as a powerful tool for replicating the structure and function of real biological tissues, with applications in disease modeling, drug discovery, and implantable grafts [7]. The process typically involves:

Digital Model Creation: Tissues are digitized using medical imaging technologies (MRI, ultrasound) to generate a 3D model converted to Standard Triangle Language (STL) format [25].

Bioink Formulation: Living cells are combined with biocompatible materials and growth factors to create bioinks that emulate the target tissue [7] [25].

Layer-by-Layer Deposition: 2D layers of bioinks are deposited into a support bath to build a 3D structure using additive manufacturing techniques [7].

Tissue Maturation: Printed constructs are maintained in specialized bioreactors for maturation before use or study [25].

Recent advances have addressed significant limitations in conventional bioprinting approaches. A major drawback has been the lack of process control methods that limit defects in printed tissues [7]. New techniques incorporate intelligent monitoring systems that capture high-resolution images of tissues during printing and rapidly compare them to intended designs using AI-based image analysis pipelines [7].

Advanced Bioprinting Modalities

High-Throughput Spheroid Bioprinting

A novel technique developed at Penn State uses spheroids (clusters of cells) to create complex tissue with high cell density essential for developing functional tissue for clinical use [5]. The High-throughput Integrated Tissue Fabrication System for Bioprinting (HITS-Bio) employs a digitally controlled nozzle array that manipulates multiple spheroids simultaneously, organizing them in customized patterns to create complex tissue architecture [5]. This approach produces tissue 10-times faster than existing methods while maintaining more than 90% cell viability, enabling the creation of a one-cubic centimeter structure containing approximately 600 spheroids in less than 40 minutes [5].

Hybrid Bioprinting for Multi-Tissue Engineering

Hybrid bioprinting approaches address limitations in integrating soft and rigid multifunctional components for complex multi-tissue applications [6]. These platforms integrate multiple 3D printing modules under optimized conditions for continuous bioprinting with multiple soft and hard biomaterials [6]. Compared with commonly fabricated hydrogel-only constructs, hybrid constructs achieve over a 1000-fold increase in mechanical strength and demonstrate enhanced osteogenic differentiation, underscoring their suitability for load-bearing musculoskeletal and orthopedic tissue engineering [6].

Engineered Biomaterials for Niche Recapitulation

Decellularized ECM (dECM) Biomaterials

dECM biomaterials support specialized cell types and trigger innate regenerative processes by providing a microenvironment close to the native target tissue [23]. During decellularization, cells and immunogenic molecules are removed while structural proteins (collagen, elastin, fibronectin) and macromolecules (proteoglycans, GAGs) are preserved [23]. These biomaterials can be processed into various forms:

- Injectable Hydrogels (53% of dECM-particle biomaterials): Less invasive, adapt to irregular shapes, retain growth factors and bioactive signaling cues [23].

- Bioprinted Scaffolds (20%): Can be designed with layers of differential mechanical properties and tissue-specific cells to replicate varying characteristics of layered ECM structures [23].

- Electrospun Scaffolds (15%): Layered microfibers approximate ECM architecture, with controlled fiber diameter and distribution to induce cell-specific functions [23].

Engineered Peptide and Protein Materials

Engineered peptide and protein materials provide the advantages of a biological matrix with the control of a synthetic polymer [24]. These materials are designed at the molecular level to mimic critical aspects of the stem cell niche, combining predictable amino acid interactions with bioactive sequences. Common amino acid sequences employed to replicate the in vivo niche include cell-adhesive domains derived from:

- Collagen: DGEA, RGD

- Laminin: IKVAV, RGD, YIGSR

- Fibronectin: REDV, RGDS [24]

These designer materials allow researchers to isolate individual variables, such as stiffness, without varying others, such as the density of ligands for integrin binding [24]. This control enables systematic studies of how specific niche parameters influence cell behavior.

Table 2: Quantitative Comparison of Advanced Bioprinting Techniques

| Bioprinting Technique | Throughput/Speed | Cell Viability | Key Advantages | Representative Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High-Throughput Spheroid Bioprinting (HITS-Bio) | 10x faster than conventional methods | >90% | High cell density, scalable, precise spheroid placement | Cartilage tissue, bone repair |

| Hybrid Bioprinting | Varies by platform | High with optimized conditions | 1000x mechanical strength increase, multi-material integration | Load-bearing tissues, orthopedic engineering |

| Intelligent Bioprinting with AI Monitoring | Enhanced by reduced defects | Improved by defect correction | Real-time defect detection, adaptive parameter tuning | Complex tissue architectures, vascularized constructs |

Experimental Protocols for Niche Mimicry

Protocol: Modular Monitoring for Bioprinting Process Control

This protocol enables real-time quality control during bioprinting processes, addressing the critical need for process optimization in tissue engineering [7].

Materials:

- Standard 3D bioprinter

- Digital microscope (compact, high-resolution)

- AI-based image analysis pipeline

- Bio-inks (cells in soft gel)

- Support bath

Methodology:

- System Integration: Integrate the digital microscope into the bioprinting setup to capture high-resolution images during the printing process.

- Layer-by-Layer Imaging: Capture images of each deposited layer immediately after printing.

- AI-Pattern Analysis: Utilize the AI-based image analysis pipeline to rapidly compare captured images with the intended digital design.

- Defect Identification: Flag discrepancies such as over-deposition or under-deposition of bio-ink.

- Parameter Optimization: Use identified defects to refine printing parameters for different materials.

This modular, low-cost (less than $500) monitoring technique is printer-agnostic and can be readily implemented on any standard 3D bioprinter [7]. It serves as a foundation for intelligent process control in embedded bioprinting by enabling real-time inspection, adaptive correction, and automated parameter tuning [7].

Protocol: Decellularized ECM (dECM) Hydrogel Preparation

dECM hydrogels provide tissue-specific physical and chemical cues that promote the body's intrinsic capacity for self-repair and regeneration [23].

Materials:

- dECM particles (from target tissue)

- Pepsin solution

- Hydrochloric acid (HCl)

- Sodium hydroxide (NaOH)

- Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)

- Collagen buffer (for collagen-containing tissues)

Methodology:

- Particle Suspension: Suspend dECM particles in a solution of pepsin and hydrochloric acid.

- Solubilization: Gently mix the suspension at 4°C without generating air bubbles until fully solubilized.

- pH Neutralization: Adjust the pH to physiological level (7.2-7.4) using NaOH and appropriate buffers.

- Gelation: Incubate at physiological temperature (37°C) to induce hydrogel formation.

- Cross-linking (Optional): Apply chemical or physical crosslinking to improve gelation kinetics and mechanical properties.

This methodology retains growth factors and bioactive signaling cues of native ECM while possessing high water content similar to natural tissue [23].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Tissue Niche Engineering

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Niche Engineering |

|---|---|---|

| Structural Hydrogels | GelMA, ColMA, HAMA, Matrigel | Provide 3D scaffold mimicking native ECM, support cell growth and organization |

| Photoinitiators | LAP (lithium phenyl-2,4,6-trimethylbenzoylphosphinate) | Initiate polymerization reactions when exposed to light for structural integrity |

| Thermoplastics | PCL (polycaprolactone) | Provide biodegradable reinforcing structure for tissue-loading constructs |

| Bioink Modifiers | Reconstitution Agents A & P, Collagen Buffer | Adjust pH and isotonicity for cell culture compatibility |

| Engineered Peptides | IKVAV, RGD, YIGSR, DGEA | Reproduce specific cell-adhesive domains from native ECM proteins |

| Support Materials | CELLINK Start | Provide temporary support for complex structures and porous constructions |

Visualizing Experimental Workflows

Intelligent Bioprinting Workflow

Diagram 1: Intelligent bioprinting with AI feedback

Native Niche Component Integration

Diagram 2: Native niche component integration

The field of tissue engineering is progressively bridging the complexity gap between reductionist 2D in vitro cell culture and complex native in vivo tissues [23]. This intermediate complexity allows for producing realistic models and devices while maintaining control and interrogation capabilities not possible in native tissues [23]. Future advances will likely focus on developing materials with multiple layers of bi-directional feedback between cells and matrices, creating more advanced mimics of highly dynamic stem cell niches [24].

The path toward developing improved microsystems and material platforms will involve applying tools from systems biology to the analysis of tissue dynamics and structure—an intersection termed systems tissue engineering [23]. As these technologies mature, they hold the promise of producing truly functional engineered tissues that faithfully recapitulate the architectural and functional complexities of native human tissues, ultimately revolutionizing regenerative medicine, disease modeling, and drug development.

From Print to Function: Advanced Techniques and Real-World Applications

Three-dimensional (3D) bioprinting has made progressive impacts on medical sciences, demonstrating great potential to facilitate the fabrication of functional tissues for transplantation, disease modeling, and drug screening [17]. A significant limitation in the field has been the difficulty in achieving physiologically-relevant cell densities (100-500 million cells/mL) that are essential for effective tissue repair and regeneration [17]. While tissue spheroids—cellular aggregates that exhibit native-like cell density and extracellular matrix secretion—have emerged as promising building blocks for tissue fabrication, most existing bioprinting techniques have been constrained by low throughput, processing only one spheroid at a time and significantly prolonging the bioprinting process (approximately 20 seconds per spheroid) [17]. This review examines a transformative technological advancement known as HITS-Bio (High-throughput Integrated Tissue Fabrication System for Bioprinting), which addresses this long-standing problem through a multi-nozzle array approach that increases fabrication speed by an order of magnitude while maintaining high cell viability (>90%) [17].

Core Technology: The HITS-Bio Platform

System Architecture and Working Mechanism

The HITS-Bio platform represents a significant departure from conventional bioprinting systems through its implementation of a digitally-controlled nozzle array (DCNA) for simultaneous spheroid positioning [17]. The platform features three main components:

- Multi-nozzle DCNA: A digitally-controlled nozzle array that enables selective application of aspiration pressure to multiple nozzles simultaneously [17]

- High-precision XYZ linear stage: Provides 3-axis movement control for the DCNA assembly [17]

- Extrusion head: Deposits gel substrate to support the bioprinted spheroids [17]

The system is operated by custom-made software with a control algorithm and integrates three microscopic cameras for real-time visualization (isometric, bottom, and side views) to verify the precise position of the DCNA in 3D space [17]. This comprehensive visualization system enables quality control throughout the bioprinting process.

The HITS-Bio Bioprinting Process

The HITS-Bio process follows a meticulously optimized workflow:

Spheroid Aspiration: The DCNA moves to a Petri dish containing spheroids suspended in culture medium. Using controlled aspiration pressure through selectively opened nozzles, multiple spheroids are simultaneously lifted from the chamber [17].

Substrate Deposition: A bioink substrate is extruded onto the printing surface to receive the spheroids [17].

Spheroid Placement: The DCNA, loaded with spheroids, transfers over the substrate. When spheroids contact the substrate, aspiration pressure is terminated to deposit them precisely [17].

Encapsulation: After spheroid placement, an additional layer of bioink is deposited to envelop the spheroids, followed by photo-crosslinking using a 405 nm LED light source for 1 minute [17].

This streamlined process eliminates the need for viscous fluid support baths, instead operating within culture medium to simplify handling and avoid challenges associated with increased shear and compression forces [17].

Quantitative Performance Metrics

Comparative Bioprinting Performance

Table 1: Performance comparison of spheroid bioprinting technologies

| Technology | Throughput | Cell Viability | Positioning Precision | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HITS-Bio | Ten times faster than existing techniques | >90% | High (visualized by 3 cameras) | Limited by number of nozzles in array |

| Aspiration-Assisted Bioprinting (AAB) | ~20 seconds per spheroid | >90% | ~11% of spheroid size | Processes one spheroid at a time |

| Extrusion Bioprinting | Moderate (random mixing) | Lower due to shear stress | Limited control over placement | Substantial shear stress, limited placement control |

| Kenzan Method | Low | Damage from needle arrays | Fixed by needle arrangement | Low throughput, spheroid damage, restricted versatility |

| Droplet-Based Bioprinting | Moderate | Varies with viscosity | Limited precision | Constrained by bioink viscosity and droplet formation |

Fabrication Scale and Speed Metrics

Table 2: Quantitative output metrics demonstrated in validation studies

| Application | Construct Size | Spheroid Count | Fabrication Time | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cartilage Construct | 1 cm³ | ~600 spheroids | <40 minutes | High-throughput efficiency for volumetric defects |

| Calvarial Bone Regeneration | ~30 mm³ | Not specified | Not specified | Near-complete defect closure (91% bone coverage in 3 weeks, 96% in 6 weeks) |

The data demonstrates HITS-Bio's capacity for scalable tissue fabrication, achieving construction of clinically relevant tissue volumes in timeframes compatible with research and potential clinical applications [17].

Enabling Technologies: Spheroid Production and Quality Control

Advanced Spheroid Sorting Platforms

The success of high-throughput bioprinting depends on the availability of homogeneous, high-quality spheroids. Recent advancements in sorting platforms address this critical need:

- Fully Automated Sorting: Integrated systems now provide image acquisition, analysis, and individual spheroid transfer directly from culture plates in a single streamlined process [26]

- Deep Learning Classification: Machine learning algorithms enable label-free characterization of spheroids based on brightfield images, assessing viability and bioprinting compatibility without invasive fluorescent labels [26]

- Transfer Learning Efficacy: Effective model training even with limited spheroid image datasets enhances practicality for diverse research settings [26]

- High-Throughput Capacity: Systems demonstrated sorting of over 12,500 tri-cellular liver spheroids for a single 0.5 cm³ liver construct [26]

Spheroid Sorting Platform Specifications

Table 3: Technical specifications of automated spheroid sorting platforms

| Parameter | Specification | Application Benefit |

|---|---|---|

| Sorting Method | Individual spheroid picking and harvesting | Maintains spheroid integrity and enables selective quality control |

| Imaging Modality | Brightfield microscopy with deep learning analysis | Label-free viability assessment preserves spheroid physiology |

| Handling Precision | Capillary tube (250 μm ID) with automated linear stage | Gentle manipulation of 150 μm-diameter spheroids |

| Throughput | Optimized for thousands of spheroids per session | Supports fabrication of implant-scale tissue constructs |

| Compatibility | Standard biosafety cabinets and culture plates | Integrates with existing laboratory workflows |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

HITS-Bio Bioprinting Protocol

Objective: Precise spatial arrangement of multiple spheroids into defined tissue architectures using high-throughput bioprinting.

Materials:

- HITS-Bio platform with DCNA module

- Mature tissue spheroids (150-500 μm diameter)

- Compatible bioink (e.g., gelatin-based hydrogel)

- Cell culture medium

- Photoinitiator (if using light-crosslinkable bioinks)

- 405 nm LED light source

Procedure:

- Spheroid Preparation: Culture spheroids using preferred method (hanging drop, ultra-low attachment plates, or microfluidic devices) until desired maturity and size are achieved.

- System Calibration: Calibrate DCNA height and aspiration pressure settings using test spheroids to optimize pickup and release.

- Bioink Preparation: Prepare bioink according to manufacturer protocols, maintaining sterility throughout.

- Substrate Printing: Deposit a thin base layer of bioink onto the printing surface using the extrusion head.

- Spheroid Bioprinting:

- Program the desired spheroid arrangement pattern into the control software

- Execute simultaneous aspiration of multiple spheroids via DCNA

- Transfer spheroids to target positions and release via pressure cutoff

- Repeat until complete design is deposited

- Encapsulation: Overlay with additional bioink to fully embed spheroids.

- Crosslinking: Initiate hydrogel crosslinking via appropriate method (photo-crosslinking for 1 minute with 405 nm LED for light-sensitive bioinks).

- Culture: Transfer constructs to appropriate culture conditions for maturation.

Technical Notes:

- Optimal spheroid size depends on nozzle diameter; adjust accordingly

- Aspiration pressure must balance reliable pickup with avoidance of spheroid damage

- Bioink rheology should support spheroid suspension without imposing excessive shear stress

Automated Spheroid Sorting Protocol

Objective: Selection of uniform, high-quality spheroids for bioprinting applications using label-free morphological analysis.

Materials:

- SpheroidSorter platform or equivalent

- Spheroid populations in standard culture plates

- Sterile capillary tubes (250 μm ID)

- Collection reservoirs for sorted spheroids

Procedure:

- System Setup: Initialize sorting platform according to manufacturer specifications.

- Dataset Preparation: Acquire representative brightfield images of spheroids for training classification model.

- Model Training: Implement deep learning algorithm to classify spheroids based on size, circularity, and morphological features predictive of viability.

- Sorting Parameters: Define acceptance criteria based on classification output.

- Automated Sorting: Execute sorting process:

- Platform images each spheroid in culture plate

- Classification algorithm assesses each spheroid against criteria

- Acceptable spheroids remain in plate for harvesting

- Unacceptable spheroids are removed via picking system

- Quality Control: Validate sorted population homogeneity through random sampling.

Technical Notes:

- Transfer learning approaches reduce required training dataset size

- Platform compatibility with standard culture plates facilitates workflow integration

- Sorting criteria should be validated against biological outcomes for specific applications

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential materials for high-throughput spheroid bioprinting

| Reagent/Equipment | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Digitally-Controlled Nozzle Array (DCNA) | Simultaneous aspiration and deposition of multiple spheroids | Core component of HITS-Bio; nozzle count determines throughput multiplier |

| Tri-cellular Liver Spheroids | Physiological liver tissue modeling | Demonstrates platform capability with complex multi-cellular systems |

| Photo-crosslinkable Bioinks | Structural support for bioprinted spheroids | Must balance printability with cell compatibility; 405 nm crosslinking typical |

| Deep Learning Classification Software | Label-free spheroid quality assessment | Enables sorting based on viability and morphology without fluorescent markers |

| MicroRNA-Transfected Spheroids | Enhanced osteogenic differentiation capability | Enables intraoperative bioprinting for bone regeneration applications |

| Automated Spheroid Sorting Platform | High-throughput selection of uniform spheroids | Critical for ensuring population homogeneity before bioprinting |

Application Case Studies

Intraoperative Bioprinting for Bone Regeneration

A compelling application of HITS-Bio technology is in intraoperative bioprinting (IOB) for calvarial bone regeneration [17]. The approach combines several advanced technologies:

- Osteogenically-Committed Spheroids: Human adipose-derived stem cell spheroids transfected with combinatorial microRNA technology to enhance osteogenic differentiation [17]

- On-Demand Fabrication: HITS-Bio enables simultaneous or sequential aspiration and bioprinting of miR-transfected spheroins directly at the surgical site [17]

- Rapid Regeneration: In a rat model, this approach achieved near-complete defect closure with approximately 91% bone coverage area in 3 weeks and 96% in 6 weeks, representing approximately 30 mm³ of regenerated bone [17]

This application highlights the clinical potential of high-throughput spheroid bioprinting to reduce surgical time while improving outcomes through precise, biologically-active tissue fabrication.

Scalable Cartilage Construction

The utility of HITS-Bio for fabricating larger tissue volumes was demonstrated through creation of cm³-scale cartilage constructs [17]:

- High-Throughput Efficiency: Each construct containing approximately 600 chondrogenically committed spheroids was assembled in under 40 minutes [17]

- Volumetric Defect Repair: The scale and composition of these constructs indicates potential for addressing clinically relevant cartilage defects [17]

- Architectural Precision: The multi-nozzle array enables precise spatial organization of spheroids, critical for functional tissue outcomes [17]

The development of high-throughput bioprinting systems represents a paradigm shift in tissue engineering, directly addressing the critical bottleneck of fabrication speed that has limited clinical translation. The HITS-Bio platform, with its multi-nozzle DCNA technology, demonstrates that order-of-magnitude improvements in throughput are achievable while maintaining cell viability and positional precision. When integrated with complementary advances in automated spheroid sorting and deep learning quality control, these systems enable fabrication of tissue constructs at scales relevant for clinical application.

Future developments will likely focus on increasing nozzle density in DCNA systems, enhancing bioink formulations to better support spheroid fusion and maturation, and integrating real-time monitoring systems for closed-loop process control. As these technologies mature, high-throughput spheroid bioprinting holds potential not only to accelerate research in drug screening and disease modeling but also to enable clinical applications in intraoperative tissue fabrication and ultimately organ-scale engineering.