Engineering Hypoimmune Cells for Allogeneic Therapy: Strategies, Applications, and Clinical Frontiers

Allogeneic cell therapies derived from healthy donors or induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) offer transformative potential for treating cancer, diabetes, and autoimmune diseases by providing 'off-the-shelf' availability.

Engineering Hypoimmune Cells for Allogeneic Therapy: Strategies, Applications, and Clinical Frontiers

Abstract

Allogeneic cell therapies derived from healthy donors or induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) offer transformative potential for treating cancer, diabetes, and autoimmune diseases by providing 'off-the-shelf' availability. However, host immune rejection remains a significant barrier. This article synthesizes current strategies for engineering hypoimmune cells, focusing on genetic modifications to evade adaptive and innate immune responses. We explore foundational immune evasion mechanisms, advanced gene-editing methodologies like CRISPR-Cas9 for targeting HLA and incorporating immunomodulatory proteins, and troubleshooting for challenges such as graft-versus-host disease (GvHD) and tumorigenicity. The content also validates these approaches through recent preclinical and clinical trial data, comparing the efficacy and safety of different hypoimmune platforms. This resource is tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals navigating the evolving landscape of universal cell therapy.

The Immunological Basis for Hypoimmune Engineering: Understanding Rejection and Evasion

The success of allogeneic cell therapies is fundamentally constrained by the host immune system's robust recognition and rejection of foreign tissues. This process, known as the allogeneic barrier, represents a complex immunological challenge for regenerative medicine and cell transplantation [1]. Adaptive immune responses to grafted tissues constitute the primary impediment to successful transplantation, driven by responses to alloantigens—proteins that vary between individuals within a species and are perceived as foreign by recipients [1]. While current approaches often rely on immunosuppressive drugs or autologous cell sources, these strategies face significant limitations in scalability, toxicity, and broad applicability [2] [3]. Consequently, understanding and engineering solutions to overcome this barrier is paramount for developing effective "off-the-shelf" allogeneic cell therapies.

The immunological basis of graft rejection was first systematically elucidated through skin transplantation studies in inbred mice, which established that while autografts (within the same individual) and syngeneic grafts (between genetically identical individuals) are universally accepted, allografts (between genetically different individuals) are consistently rejected [1]. This rejection follows a predictable timeline, with first-set rejection occurring approximately 10-13 days after initial grafting and second-set rejection occurring more rapidly (6-8 days) upon re-grafting from the same donor, demonstrating the specificity and memory of the adaptive immune response [1].

Fundamental Immunological Mechanisms of Graft Rejection

Cellular and Molecular Players in Alloimmunity

The rejection of allogeneic transplants involves a coordinated response from both innate and adaptive immune systems. The key cellular mediators include T lymphocytes, B lymphocytes, natural killer (NK) cells, antigen-presenting cells (APCs), and macrophages [4] [5].

- T Cells: Both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells play central roles. CD8+ cytotoxic T cells directly recognize and kill donor cells, while CD4+ helper T cells orchestrate the broader immune response through cytokine production and help for B cell activation [1] [5].

- B Cells: Produce donor-specific antibodies (DSA) that mediate complement-dependent cytotoxicity and opsonization of donor cells [4].

- NK Cells: Contribute to the "missing-self" response when donor cells lack sufficient MHC class I molecules, and produce pro-inflammatory cytokines including IFN-γ and TNF-α [5].

- Antigen-Presenting Cells: Including dendritic cells and macrophages, these cells initiate immune responses by presenting donor antigens to T cells through various pathways [1] [5].

The molecular recognition events are primarily focused on the major histocompatibility complex (MHC), known in humans as human leukocyte antigens (HLA). These highly polymorphic cell surface proteins present peptide antigens to T cells and are the principal targets of allorecognition [1] [3]. The extraordinary strength of alloreactive T cell responses, engaging up to 10% of the entire peripheral T-cell repertoire (compared to <0.01% for conventional antigens), underscores the potency of this barrier [5].

Pathways of Allorecognition

The immune system recognizes allogeneic grafts through three principal pathways, each with distinct mechanisms and implications for rejection.

Direct Allorecognition

Direct allorecognition occurs when recipient T cells directly recognize intact allogeneic MHC molecules on the surface of donor antigen-presenting cells [1] [5]. This pathway is particularly potent in the early post-transplantation period and is primarily mediated by passenger leukocytes—donor-derived dendritic cells that migrate from the graft to the recipient's secondary lymphoid organs [1] [5]. Following skin transplantation, donor dendritic cells, including both epidermal Langerhans cells and dermal dendritic cells, migrate from the graft via lymphatic vessels to the recipient's draining lymph nodes where they present donor antigens to naive T cells [5]. The critical role of lymphatic drainage was demonstrated in classic studies where skin grafts raised off the recipient bed while preserving blood circulation through a pedicle were not rejected until the pedicle was severed, allowing lymphatic connection [5].

Indirect Allorecognition

Indirect allorecognition involves the uptake and processing of donor alloantigens by recipient antigen-presenting cells, which then present donor-derived peptides on self-MHC molecules to recipient T cells [1]. This pathway resembles conventional T cell recognition of foreign antigens and becomes increasingly important over time as donor passenger leukocytes are replaced by recipient cells [1]. The indirect pathway can activate both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells and is particularly important for generating alloantibody responses and chronic rejection [1].

Semidirect Allorecognition

An additional pathway, the semidirect pathway, has been more recently described, wherein recipient APCs acquire intact donor MHC molecules through membrane transfer and present them to T cells [5]. This hybrid pathway allows a single APC to present both directly and indirectly recognized antigens, potentially amplifying the immune response.

Table 1: Comparison of Allorecognition Pathways

| Feature | Direct Pathway | Indirect Pathway | Semidirect Pathway |

|---|---|---|---|

| Antigen Form | Intact donor MHC molecules | Donor peptides presented by self-MHC | Intact donor MHC acquired by recipient APCs |

| Primary APCs | Donor dendritic cells | Recipient dendritic cells | Recipient dendritic cells |

| T Cell Specificity | Donor MHC | Donor peptides + self-MHC | Donor MHC on recipient APCs |

| Time Course | Dominant early post-transplant | Increases over time | Potential role in both early and late rejection |

| Main Rejection Type | Acute rejection | Chronic rejection, alloantibody response | Not fully characterized |

Classification and Timeline of Rejection Responses

Transplant rejection is classified based on the timing, mechanism, and histopathological features of the immune response. The Banff classification system, developed through international consensus, provides standardized criteria for diagnosing rejection in organ transplantation, particularly kidney grafts [4].

Table 2: Classification of Allograft Rejection Responses

| Rejection Type | Time Course | Primary Mechanisms | Key Histopathological Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hyperacute Rejection | Minutes to hours after transplantation | Pre-existing antibodies against HLA or blood group antigens | Diffuse intravascular coagulation, thrombosis, neutrophil infiltration |

| Acute T Cell-Mediated Rejection (aTCMR) | Any time post-op, peak within 3 months | T cell recognition of donor antigens | Interstitial inflammation, tubulitis, intimal arteritis |

| Active Antibody-Mediated Rejection (aABMR) | Any time post-op, peak within 30 days | Donor-specific antibodies binding vascular endothelium | Microvascular inflammation, C4d deposition in capillaries |

| Chronic Active TCMR (caTCMR) | Often >3 months post-transplant | Sustained T cell-mediated injury | Interstitial inflammation in areas of fibrosis, chronic allograft vasculopathy |

| Chronic Active ABMR (caABMR) | Months to years post-transplant | Sustained DSA-mediated microvascular injury | Features of aABMR plus chronic allograft glomerulopathy, capillary basement membrane multilayering |

Engineering Hypoimmunogenic Cells: Strategic Approaches

HLA Editing to Evade Adaptive Immunity

A primary strategy for overcoming the allogeneic barrier involves genetic engineering to eliminate or reduce the expression of polymorphic HLA molecules, thereby minimizing recognition by alloreactive T cells [3] [6] [7].

MHC Class I Disruption: HLA class I molecules, expressed on virtually all nucleated cells, present intracellular peptides to CD8+ cytotoxic T cells. Complete elimination of surface HLA class I expression can be achieved through knockout of β2-microglobulin (B2M), an essential subunit for HLA class I assembly and surface expression [3] [6]. B2M knockout cells show dramatically reduced recognition by CD8+ T cells [3].

MHC Class II Disruption: HLA class II molecules, normally expressed on professional antigen-presenting cells, can be eliminated through knockout of the Class II Major Histocompatibility Complex Transactivator (CIITA), a master regulator of HLA class II expression [6]. This approach prevents CD4+ T cell recognition via the direct pathway [6].

Selective HLA Editing: An alternative approach involves selective knockout of the most polymorphic HLA genes (HLA-A, HLA-B, and HLA-DR) while preserving less polymorphic forms [7]. This strategy aims to reduce the antigenic burden while potentially retaining some immune regulatory functions. Recent research has demonstrated that targeting HLA-DRA (the alpha chain of HLA-DR) can effectively eliminate the entire HLA-DR complex without needing to target multiple DRB genes individually [7].

Overcoming Innate Immune Recognition

Complete elimination of HLA class I expression creates a new challenge: activation of natural killer (NK) cells through "missing-self" recognition [6]. NK cells normally express inhibitory receptors that recognize self-HLA class I molecules; when these are absent, the inhibitory signal is lost, triggering NK cell activation and killing of the target cells [6].

Several strategies have been developed to address this challenge:

CD47 Overexpression: CD47 is a "don't eat me" signal that engages SIRPα on phagocytic cells including macrophages and some NK cells, inhibiting phagocytosis and cell killing [3] [6]. Overexpression of CD47 on engineered cells effectively protects HLA-deficient cells from innate immune attack [6]. In head-to-head comparisons of different immune evasion strategies, CD47 overexpression provided superior protection against NK cell killing compared to other approaches [6].

HLA-E or HLA-G Expression: Non-classical HLA molecules HLA-E and HLA-G can be engineered to engage inhibitory receptors on NK cells (CD94/NKG2A for HLA-E and LILRB1 for HLA-G) [6]. However, these approaches show limitations due to the restricted expression patterns of the corresponding inhibitory receptors on NK cell subsets [6].

PD-L1 Overexpression: Programmed Death-Ligand 1 (PD-L1) engages PD-1 on activated T cells and some NK cells, delivering an inhibitory signal [3]. While useful, PD-L1 overexpression alone provides incomplete protection [3].

The Hypoimmune (HIP) Cell Platform

The most promising results have emerged from combining multiple engineering approaches. The hypoimmune (HIP) platform involves simultaneous disruption of HLA class I and II expression coupled with CD47 overexpression [6]. This integrated approach addresses both adaptive and innate immune recognition:

- B2M knockout eliminates HLA class I, preventing CD8+ T cell recognition

- CIITA knockout eliminates HLA class II, preventing CD4+ T cell recognition

- CD47 overexpression protects against NK cell and macrophage-mediated killing

In rigorous preclinical testing, HIP-engineered cells demonstrated remarkable survival advantages. Rhesus macaque HIP induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) survived for 16 weeks in fully immunocompetent allogeneic recipients, while unmodified control cells were rapidly rejected [6]. Similarly, HIP-edited primary pancreatic islets survived for 40 weeks in an allogeneic rhesus macaque without immunosuppression, whereas unedited islets were quickly rejected [6].

Notably, this approach has now advanced to clinical trials. Allogeneic HIP CD19 CAR-T cells (SC291) demonstrated the ability to evade allorejection in patients with cancer and autoimmune disease, with no de novo immune response against fully edited HIP CAR T cells observed in any patient [8].

Experimental Protocols for Evaluating Alloimmune Responses

In Vitro T Cell Activation Assays

Protocol 4.1.1: Comprehensive Alloreactive T-cell Detection (cATD) Assay

Purpose: To rapidly detect and quantify alloreactive T cells in recipient samples following exposure to donor antigens [9].

Materials:

- Donor and recipient splenocytes or PBMCs

- CD19 MicroBeads (Miltenyi Biotec) for B cell isolation

- Pan T-Cell isolation kit (Miltenyi Biotec)

- Recombinant mouse CD40L multimer (100 ng/mL) and IL-4 (10 ng/mL) for B cell activation

- Anti-CD154 (MR1) and anti-CD137 (17B5) antibodies for flow cytometry

- Complete RPMI 1640 medium with supplements

Procedure:

- Stimulator Preparation: Isolate donor B cells using CD19 MicroBeads. Activate B cells by culturing with CD40L multimer and IL-4 for 24 hours. Irradiate activated B cells with 40 Gy.

- Responder Preparation: Isolate recipient T cells using Pan T-Cell isolation kit.

- Co-culture: Combine responders and stimulators at 1:1 ratio (10^6 cells each) in U-bottom plates with anti-CD154 antibody in culture medium. Incubate for 18 hours. Add monensin for the final 4 hours to inhibit cytokine secretion.

- Analysis: Stain cells with anti-CD3, CD4, CD8, CD154, and CD137 antibodies. Identify alloreactive CD4+ T cells as CD3+CD4+CD154+ and alloreactive CD8+ T cells as CD3+CD8+CD137+ populations by flow cytometry.

Applications: This assay can discriminate between rejection and tolerance states in transplantation models and is useful for monitoring immune status post-transplantation [9].

Protocol 4.1.2: Mixed Lymphocyte Reaction (MLR) Proliferation Assay

Purpose: To measure T cell proliferative responses to allogeneic stimuli [9].

Materials:

- Donor and recipient lymphocytes

- Carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester (CFSE)

- Complete RPMI 1640 medium

- Flow cytometry equipment

Procedure:

- Labeling: Label recipient splenocytes with 5 μM CFSE for 5 minutes.

- Stimulator Preparation: Prepare activated donor B cell stimulators as in Protocol 4.1.1.

- Co-culture: Combine CFSE-labeled responders and stimulators at 1:1 ratio in U-bottom plates. Culture for 4 days.

- Analysis: Analyze CFSE dilution by flow cytometry to measure T cell proliferation.

In Vivo Assessment of Hypoimmune Cells

Protocol 4.2.1: Teratoma Formation Assay for Immune Evasion

Purpose: To evaluate the immune evasion capability of engineered hypoimmune pluripotent stem cells in immunocompetent hosts [6].

Materials:

- HIP-engineered iPSCs and wild-type controls

- Firefly luciferase (FLuc)-expressing vectors for in vivo tracking

- Immunocompetent allogeneic recipients (mice or non-human primates)

- In vivo imaging system (IVIS) for bioluminescence imaging

- Matrigel for cell suspension

Procedure:

- Cell Preparation: Engineer iPSCs to express FLuc for tracking. Prepare cell suspensions in appropriate buffer with Matrigel.

- Transplantation: Inject cells intramuscularly or subcutaneously into fully immunocompetent allogeneic recipients. Include wild-type iPSC controls.

- Monitoring: Track cell survival weekly using bioluminescence imaging. Monitor for teratoma formation.

- Endpoint Analysis: Harvest tissues at predetermined endpoints for histological analysis of immune cell infiltration and differentiation potential.

Interpretation: Long-term survival of HIP cells with minimal immune infiltration indicates successful immune evasion, while rejection of wild-type controls validates the model system [6].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Hypoimmunogenicity Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Key Functions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gene Editing Tools | CRISPR-Cas9 (Alt-R Sp Cas9 Nuclease V3), gRNAs targeting B2M, CIITA, HLA-A/B/DRA | Generation of hypoimmune cell lines | Targeted disruption of HLA genes to reduce immunogenicity |

| Immune Modulator Expression Vectors | Lentiviral CD47 constructs, HLA-E/G expression plasmids | Engineering immune checkpoint expression | Protection from innate immune recognition via "don't eat me" signals |

| Cell Isolation Kits | CD19 MicroBeads, Pan T-Cell isolation kit (Miltenyi Biotec) | Preparation of cell populations for functional assays | Rapid isolation of specific immune cell subsets |

| Flow Cytometry Antibodies | Anti-CD154 (MR1), anti-CD137 (17B5), anti-CD3/CD4/CD8, HLA-specific antibodies | Immune cell phenotyping and alloreactive T cell detection | Identification and quantification of immune cell populations and activation states |

| Cytokines & Activation Reagents | Recombinant CD40L multimer, IL-2, IL-4, IFN-γ | Immune cell stimulation and differentiation | Activation of immune cells for functional assays |

| In Vivo Tracking Reagents | Firefly luciferase vectors, CFSE cell proliferation dye | Cell fate tracking in animal models | Non-invasive monitoring of cell survival and proliferation |

Signaling Pathways in Alloimmune Recognition

Direct Allorecognition Pathway

Engineering Hypoimmune Cells

The development of effective strategies to overcome the allogeneic barrier represents a frontier in regenerative medicine and cell therapy. The intricate mechanisms of immune recognition—spanning direct, indirect, and semidirect allorecognition pathways—create a formidable challenge for transplanted cells and tissues. However, recent advances in genetic engineering, particularly the HIP platform that combines HLA disruption with CD47 overexpression, demonstrate that comprehensive immune evasion is achievable [6] [8]. The successful translation of these approaches from preclinical models to clinical trials marks a significant milestone toward the realization of universally compatible "off-the-shelf" cell therapies [8]. As these technologies mature, they hold the potential to transform treatment paradigms for a wide range of conditions requiring cell replacement, from diabetes to degenerative disorders, making regenerative medicine truly scalable and accessible.

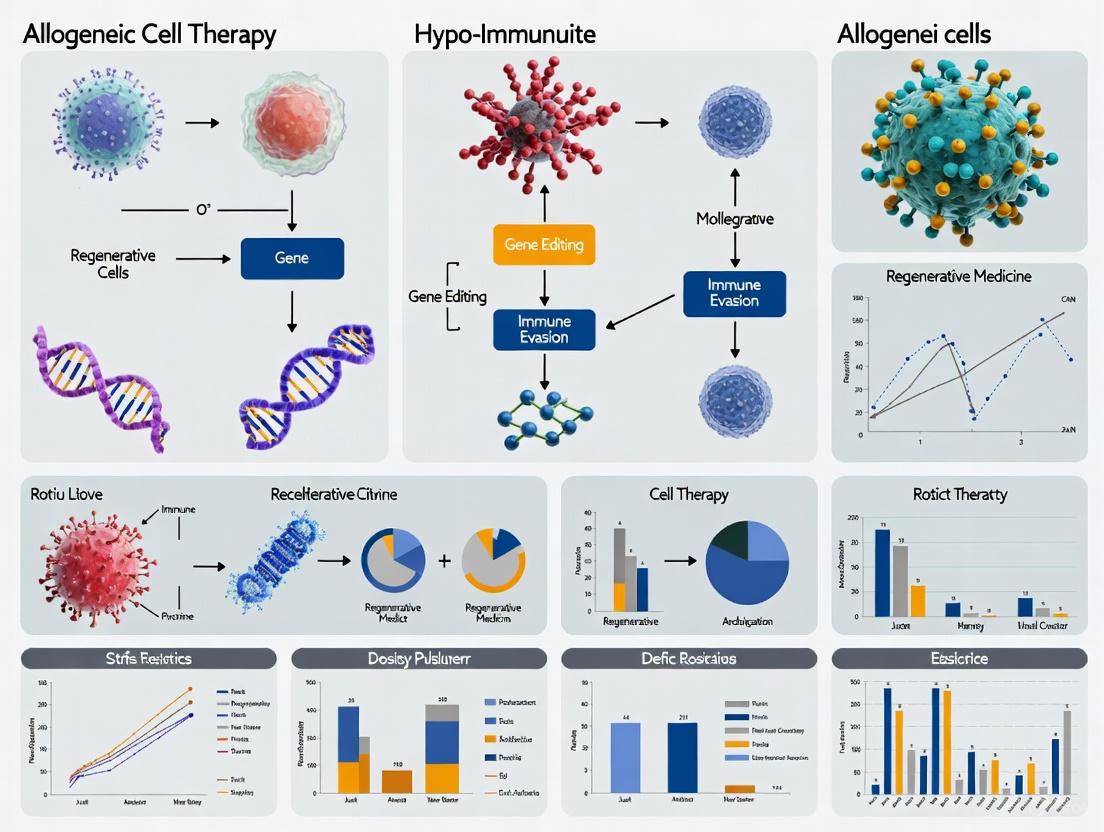

Application Note: Engineering Hypo-Immune Cells for Allogeneic Therapy

The development of "off-the-shelf" allogeneic cell therapies represents a paradigm shift in regenerative medicine and cancer treatment, aiming to overcome the limitations of patient-specific autologous products. The core engineering challenge lies in effectively evading host immune rejection while maintaining robust cell function. This is primarily addressed through strategic genetic manipulation of three key target classes: HLA molecules, co-stimulatory signals, and cellular adhesion pathways [2] [10] [11]. Successfully engineering these targets creates hypoimmune cells capable of universal application.

HLA Engineering to Mitigate Adaptive Immune Recognition: The most prominent strategy involves disrupting the Major Histocompatibility Complex (MHC) class I and II molecules, which present foreign antigens to host T cells. Knockout of Beta-2-microglobulin (B2M) ablates surface expression of MHC class I, preventing CD8+ T cell recognition. However, this can trigger missing-self recognition and elimination by natural killer (NK) cells. To counter this, a knock-in strategy is employed, expressing NK-inhibitory ligands like HLA-E or CD47 to cloak the cell from NK-mediated cytotoxicity [10] [11]. This combined edit creates a foundational hypoimmune profile.

Modulating Co-stimulatory Signals for Enhanced Potency: Beyond immune evasion, optimizing intrinsic T cell function is critical for therapeutic efficacy, particularly in CAR-T cell therapies. Second-generation CARs incorporate intracellular co-stimulatory domains, such as CD28 or 4-1BB, alongside the CD3ζ activation domain. The choice of domain dictates the functional phenotype; CD28 promotes potent effector function and rapid expansion, while 4-1BB favors enhanced persistence and memory formation [12] [13]. Fifth-generation CARs further integrate cytokine signaling (e.g., IL-2 receptor β-chain) to activate the JAK/STAT pathway, augmenting CAR-T cell activity and promoting memory formation [12].

Targeting Adhesion Pathways to Regulate Immune Synapse Formation: The innate immune response and initial T cell activation are heavily dependent on cell adhesion molecules. ICAM-1 (Intercellular Adhesion Molecule-1) and its ligand LFA-1 (composed of CD11a and CD18/ITGB2) stabilize the immune synapse between effector and target cells [14] [15]. Knockout of ICAM-1 on allogeneic cells significantly diminishes binding and adhesion of multiple immune cell types, including T cells and neutrophils, thereby reducing T cell proliferation and activation in vitro and improving graft retention in vivo [14]. Conversely, in the context of CAR-T therapy targeting B-cell malignancies, the expression of ITGB2 on tumor cells is a positive predictor of clinical response, as it facilitates the formation of a stable immunological synapse necessary for effective cytotoxicity [15].

Table 1: Core Engineering Targets for Hypo-Immune Cells

| Target Class | Key Molecular Targets | Engineering Strategy | Primary Functional Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| HLA Molecules | MHC Class I (B2M), MHC Class II | CRISPR/Cas9 knockout; HLA-E or CD47 knock-in | Prevents CD4+/CD8+ T cell allorecognition; confers NK cell evasion [10] [11] |

| Co-stimulatory Signals | CD28, 4-1BB (CD137), CD3ζ | 2nd-gen CAR design; 5th-gen CAR with cytokine receptor fusion | Enhances T-cell activation, proliferation, in vivo persistence, and antitumor efficacy [12] [13] |

| Adhesion Pathways | ICAM-1, LFA-1 (ITGB2/CD18) | CRISPR/Cas9 knockout (ICAM-1); Pharmacologic upregulation (ITGB2) | Diminishes immune cell adhesion and graft rejection; augments immune synapse and cytotoxicity [14] [15] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Generation of HLA-E-Expressing B2M Knockout Pluripotent Stem Cells

This protocol describes the creation of a first-generation hypoimmune human pluripotent stem cell (hPSC) line via simultaneous knockout of B2M and knock-in of HLA-E.

I. Materials

- Cell Line: Wild-type hPSCs (e.g., H9 line)

- Gene Editing Tool: CRISPR/Cas9 ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes

- gRNAs: Designed for B2M locus and a safe-harbor locus (e.g., AAVS1) for knock-in.

- Donor Template: AAVS1 donor vector containing HLA-E single-chain trimer fused to GFP-P2A-puromycin resistance cassette.

- Cell Culture Reagents: hPSC maintenance media (e.g., mTeSR Plus), Matrigel, CloneR supplement, Accutase.

- Validation Reagents: Flow cytometry antibodies for HLA-ABC, HLA-E, B2M; genomic DNA extraction kit, PCR reagents.

II. Procedure

- Design and Preparation: Design and validate gRNAs for B2M knockout and AAVS1-targeted knock-in. Prepare the AAVS1-HLA-E donor vector and CRISPR/Cas9 RNP complexes.

- Transfection: Harvest hPSCs as single cells using Accutase. Transfect 1x10^6 cells with RNP complexes and donor vector via nucleofection using a human stem cell-specific kit.

- Selection and Cloning: 48 hours post-transfection, begin puromycin selection (0.5-1.0 µg/mL) for 7-10 days. Subsequently, pick individual colonies manually or via single-cell sorting into 96-well plates.

- Expansion and Screening: Expand clonal lines. Screen for successful edits by:

- Flow Cytometry: Confirm loss of HLA-ABC/B2M surface expression and presence of HLA-E.

- PCR Genotyping: Validate precise integration at the AAVS1 locus and biallelic disruption of B2M.

- Characterization: Perform karyotyping (e.g., G-banding) to ensure genomic integrity. Differentiate the engineered line into target cell types (e.g., cardiomyocytes, endothelial cells) to confirm retained differentiation potential and stable transgene expression.

Protocol: In Vitro Assessment of Immune Cell Adhesion to ICAM-1 KO Grafts

This protocol quantifies the functional impact of ICAM-1 knockout on immune cell binding, a key metric for innate immune evasion.

I. Materials

- Test Cells: Isogenic pairs of WT and ICAM-1 KO hPSC-derived endothelial cells (ECs) or cardiomyocytes (CMs).

- Immune Cells: Monocytic cell line (U937) or primary human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs).

- Reagents: Cell culture media, Matrigel, recombinant human TNF-α and IFN-γ, Calcein-AM fluorescent dye, 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA).

- Equipment: 24-well culture plates, fluorescence microscope or plate reader.

II. Procedure

- Differentiation and Stimulation: Differentiate hPSCs (WT and ICAM-1 KO) into ECs or CMs using standardized protocols. Plate the cells in 24-well plates. Prior to the assay, stimulate the cells for 48 hours with TNF-α (10 ng/mL) and IFN-γ (50 ng/mL) to mimic an inflammatory microenvironment and upregulate ICAM-1 in WT cells [14].

- Immune Cell Labeling: Harvest U937 cells or PBMCs and label with 5 µM Calcein-AM in serum-free media for 30 minutes at 37°C. Wash cells twice to remove excess dye.

- Co-culture and Binding Assay: Add 2x10^5 labeled immune cells to each well containing the differentiated grafts. Co-culture for 1-2 hours at 37°C.

- Washing and Quantification: Gently wash the co-culture wells 3-5 times with PBS to remove non-adherent immune cells. Fix the remaining cells with 4% PFA for 15 minutes.

- Analysis: Quantify adherent immune cells by counting fluorescent cells in multiple microscope fields or by measuring fluorescence intensity using a plate reader. Compare adhesion to WT vs. ICAM-1 KO grafts. A significant reduction in binding to KO grafts demonstrates the efficacy of the edit.

Table 2: Key Reagent Solutions for Hypo-Immune Cell Engineering

| Research Reagent | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR/Cas9 System | Precise genomic editing (knockout, knock-in) | Disruption of B2M, TRAC, or ICAM-1 loci [14] [10] |

| TALENs/mRNA | Alternative nuclease for gene editing | TCR disruption in UCART19 [10] |

| Anti-ICAM-1 Blocking Antibody | Functional validation of adhesion target | In vitro blockade to confirm reduced leukocyte binding [14] |

| Pro-inflammatory Cytokines (TNF-α, IFN-γ) | Mimic inflammatory TME in vitro | Upregulation of MHC and ICAM-1 on target cells for functional assays [14] |

| Flow Cytometry Antibodies | Phenotypic validation of surface protein expression | Confirmation of MHC-I/II loss, HLA-E, or ICAM-1 expression [14] [10] |

| Venetoclax | BCL-2 inhibitor that upregulates ITGB2 | Pharmacological enhancement of immune synapse in B-cell malignancies for improved CAR-T efficacy [15] |

Signaling Pathway and Workflow Visualizations

Diagram 1: Hypoimmune Cell Engineering Workflow

Diagram 2: CAR-T Cell Co-stimulatory Signaling Pathways

Diagram 3: ICAM-1/LFA-1 Mediated Immune Synapse

Immune privilege refers to the remarkable ability of certain tissues and organs to tolerate the introduction of foreign antigens without mounting a destructive immune response. This biological phenomenon represents nature's solution to preventing inflammatory damage to vital tissues, and it offers invaluable lessons for advancing allogeneic cell therapies. Two particularly instructive examples of naturally immune-privileged tissues are the cornea and placenta. The cornea maintains transparency for vision by avoiding inflammatory reactions to environmental antigens, while the placenta enables fetal development by preventing maternal immune rejection of paternal antigens. Both tissues employ sophisticated, multi-layered strategies to modulate immune responses—strategies that researchers are now harnessing to engineer "hypo-immune" therapeutic cells that can evade rejection without systemic immunosuppression.

Understanding these natural mechanisms of immune regulation provides a blueprint for overcoming the fundamental challenge in allogeneic cell therapy: how to protect transplanted cells from host immune rejection while maintaining their therapeutic function. This application note examines the key mechanisms of immune privilege in cornea and placenta, translates these biological principles into engineered strategies for cell therapies, and provides detailed protocols for implementing these approaches in research settings.

Mechanisms of Natural Immune Privilege

Corneal Immune Privilege

The cornea enjoys one of the most robust forms of immune privilege in the human body, with first-time corneal transplants achieving >90% success rates without HLA matching or systemic immunosuppression [16] [17]. This privileged status stems from multiple integrated mechanisms:

Table 1: Mechanisms of Corneal Immune Privilege

| Mechanism Category | Specific Components | Function in Immune Privilege |

|---|---|---|

| Anatomical Barriers | Avascularity, Lack of lymphatic drainage | Prevents immune cell infiltration and antigen presentation to immune system |

| Molecular Factors | Soluble VEGFR-2, Endostatin | Inhibits hemangiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis |

| Immunomodulatory Molecules | TGF-β, PD-L1, CD86 | Induces T-cell anergy and generates regulatory T cells |

| Cellular Mechanisms | Anterior chamber-associated immune deviation (ACAID) | Generates systemic immune tolerance to ocular antigens |

The avascular nature of the normal cornea represents a cornerstone of its immune privilege, creating a physical barrier that limits both the afferent (recognition) and efferent (effector) arms of the immune response [17]. This avascular state is actively maintained by multiple anti-angiogenic factors, including endostatin and soluble VEGFR-2, which inhibit both blood (hemangiogenesis) and lymphatic (lymphangiogenesis) vessel formation [17]. When corneal avascularity is compromised—such as in chemical burns, infection, or inflammatory conditions—the risk of corneal graft rejection increases dramatically from <10% to 50-70% [18] [16]. The critical importance of lymphatics in corneal graft rejection was demonstrated in experiments showing that selective blockade of lymphangiogenesis (while preserving hemangiogenesis) dramatically improved corneal allograft survival [17].

The cornea also employs numerous immunomodulatory factors that actively suppress immune responses. The aqueous humor contains multiple immunomodulatory factors including TGF-β, which inhibits T-cell activation and promotes the generation of regulatory T cells (Tregs) [17]. The phenomenon of anterior chamber-associated immune deviation (ACAID) represents a sophisticated systemic component of corneal immune privilege, inducing antigen-specific suppression of delayed-type hypersensitivity and promoting the production of non-complement-fixing antibodies [17].

Placental Immune Privilege

The human placenta, particularly the amniotic membrane and its derived cells, has evolved sophisticated mechanisms to prevent maternal immune rejection of the semi-allogeneic fetus. Human amniotic mesenchymal stromal cells (hAMSCs) exhibit potent immunomodulatory properties that make them particularly valuable for regenerative medicine applications [19]:

Table 2: Immune Modulatory Properties of Human Amniotic Mesenchymal Stromal Cells (hAMSCs)

| Property | Mechanism | Therapeutic Application |

|---|---|---|

| Low Immunogenicity | Low MHC-I expression, absence of MHC-II and co-stimulatory molecules (CD40, CD80, CD86) | Evades T-cell recognition and activation |

| Immunosuppressive Secretome | Releases cytokines (FGF-2, IGF-1, HGF, VEGF, EGF) with proliferative and anti-apoptotic effects | Modulates local immune environment and promotes tissue repair |

| T-cell Modulation | Suppresses T-cell proliferation and activation through both direct contact and soluble factors | Reduces adaptive immune responses against allografts |

| Angiogenic Regulation | Expresses pro-angiogenic (VEGF-A, angiopoietin-1) and anti-angiogenic factors depending on microenvironment | Supports vascularization while preventing pathological neovascularization |

hAMSCs possess a unique immune-privileged status essential for maternal-fetal tolerance. They exhibit low expression of MHC-I and lack expression of MHC-II as well as co-stimulatory molecules (CD40, CD80, CD86), thereby evading immune recognition [19]. This low immunogenicity profile makes them ideal candidates for allogeneic transplantation. Beyond their inherent low immunogenicity, hAMSCs actively modulate immune responses through their secretome, releasing cytokines (FGF-2, IGF-1, HGF, VEGF, EGF) that exert proliferative and anti-apoptotic effects while creating an immunosuppressive local environment [19]. These properties have been leveraged in various preclinical models, including intracameral injection of hAMSCs in a corneal injury model, which reduced neovascularization, opacity, and inflammatory infiltration [19].

Engineering Hypo-Immune Cells: From Biological Principles to Therapeutic Applications

The natural immune evasion strategies of cornea and placenta provide a roadmap for engineering hypo-immune therapeutic cells. Several key approaches have emerged, focusing on modifying critical immune recognition and activation pathways.

HLA Engineering Strategies

Major Histocompatibility Complex (MHC) molecules, known as Human Leukocyte Antigens (HLA) in humans, represent the primary barrier to allogeneic cell transplantation. HLA class I molecules (HLA-A, -B, and -C) are expressed on nearly all nucleated cells and present intracellular antigens to CD8+ T cells, initiating cytotoxic killing [20]. Current HLA engineering strategies aim to disrupt this recognition while avoiding natural killer (NK) cell activation:

Diagram: HLA Engineering Strategies and Challenges. Disruption of HLA class I (e.g., via B2M knockout) prevents T-cell recognition but risks NK cell activation via "missing self" signals. Co-expression of non-classical HLA molecules (HLA-E, HLA-G), retention of HLA-C, or expression of CD47 can mitigate NK cell activation.

Complete elimination of HLA class I expression, typically achieved through β2-microglobulin (B2M) knockout, prevents CD8+ T cell recognition but creates a "missing self" signal that activates NK cells [20]. To address this, researchers have developed complementary strategies including:

- Expression of non-classical HLA molecules: HLA-E and HLA-G serve as ligands for NK cell inhibitory receptors (NKG2A and KIR2DL4, respectively) [20]. One successful approach uses B2M−/− pluripotent stem cells with co-expression of the minimally polymorphic HLA-E [20].

- Retention of HLA-C: Unlike HLA-A and -B, HLA-C interacts with killer immunoglobulin-like receptors (KIRs) on NK cells to deliver inhibitory signals [20].

- Combinatorial approaches: CIITA knockout (eliminating HLA class II) with expression of PD-L1, HLA-G, and CD47 has shown promise in protecting allografts [20].

Expression of Immunomodulatory Molecules

Beyond HLA modification, engineering cells to express natural immunomodulatory molecules represents a powerful strategy to actively suppress immune responses:

Diagram: Engineered Immunomodulatory Pathways for Hypo-Immune Cells. Surface expression of PD-L1, CD47, HLA-G, and CTLA-4-Ig on engineered cells engages inhibitory receptors on immune cells (T cells, macrophages, NK cells), suppressing effector functions through multiple mechanisms.

Key immunomodulatory molecules for engineering include:

- PD-L1 (Programmed Death-Ligand 1): Engagement of PD-1 on T cells delivers inhibitory signals that suppress T-cell activation and promotes T-cell exhaustion [20]. Expression of PD-L1 on graft cells provides localized immunosuppression without systemic effects.

- CD47: This "don't eat me" signal binds to SIRPα on macrophages and dendritic cells, inhibiting phagocytosis [20]. CD47 expression protects cells from innate immune clearance and complements HLA engineering strategies.

- HLA-G: A non-classical HLA class I molecule with potent immunosuppressive properties, HLA-G inhibits NK cell cytotoxicity, T-cell proliferation, and dendritic cell maturation [20].

- CTLA-4-Ig: A fusion protein that blocks CD28-B7 co-stimulation, preventing T-cell activation. Expression of CTLA-4-Ig on graft cells provides localized co-stimulation blockade [20].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Generation of HLA-Engineered Hypo-Immune Pluripotent Stem Cells

This protocol describes the creation of hypo-immune pluripotent stem cells (PSCs) through CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene editing and transgene expression.

Materials:

- Human PSCs (hESCs or hiPSCs)

- CRISPR/Cas9 reagents (ribonucleoprotein complexes for B2M and CIITA)

- Donor template for HLA-E/GFP knock-in to B2M locus

- Electroporation system (e.g., Neon Transfection System)

- mTeSR1 or equivalent PSC maintenance medium

- Rock inhibitor (Y-27632)

- Flow cytometry antibodies: HLA-ABC, HLA-DR, HLA-E, B2M

- PCR reagents for genotyping

Procedure:

Design and Preparation of Editing Reagents:

- Design guide RNAs targeting B2M exon 1 and CIITA exon 2

- Design donor template containing HLA-E with B2M signal sequence followed by T2A-GFP

- Form ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes by incubating sgRNAs with Cas9 protein

Cell Preparation and Electroporation:

- Culture PSCs to 70-80% confluence in 6-well plates

- Harvest cells with Accutase and resuspend in electroporation buffer

- Mix 1×10^5 cells with RNP complexes (10 μg each) and donor template (2 μg)

- Electroporate using appropriate settings (e.g., 1400V, 10ms, 3 pulses for Neon system)

- Plate transfected cells in mTeSR1 with Rock inhibitor on Matrigel-coated plates

Selection and Screening:

- After 48 hours, analyze GFP expression by flow cytometry to assess knock-in efficiency

- Single-cell sort GFP+ cells into 96-well plates

- Expand clones for 2-3 weeks, then harvest for genotyping

- Confirm B2M and CIITA knockout by sequencing and flow cytometry

- Verify HLA-E expression by flow cytometry using HLA-E specific antibodies

Functional Validation:

- Differentiate edited PSCs into target cell type (e.g., β-cells, cardiomyocytes)

- Perform mixed lymphocyte reaction assays to assess T-cell activation

- Conduct NK cell cytotoxicity assays using primary NK cells

- Validate in vivo survival in humanized mouse models

Protocol: Assessment of Immune Evasion Properties

This protocol describes comprehensive in vitro assessment of the immune evasion capacity of engineered hypo-immune cells.

Materials:

- Engineered hypo-immune cells and unmodified controls

- Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from multiple donors

- NK cell isolation kit

- Anti-CD3/CD28 activation beads

- CFSE cell proliferation dye

- Flow cytometry antibodies: CD3, CD4, CD8, CD56, CD107a, IFN-γ, Granzyme B

- ELISA kits for IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-2

- Incucyte Live-Cell Analysis System (optional)

Procedure:

T-cell Activation Assay:

- Label PBMCs with CFSE and activate with anti-CD3/CD28 beads

- Co-culture activated PBMCs with engineered cells at 10:1 and 5:1 ratios

- After 5 days, analyze T-cell proliferation by CFSE dilution

- Collect supernatants for cytokine analysis by ELISA

- Perform intracellular staining for IFN-γ and Granzyme B

NK Cell Cytotoxicity Assay:

- Isolate NK cells from PBMCs using negative selection

- Culture NK cells with IL-15 (10 ng/mL) for 24 hours to enhance cytotoxicity

- Label target cells with Calcein-AM and co-culture with NK cells at various E:T ratios

- After 4 hours, measure Calcein release in supernatants

- Analyze CD107a expression on NK cells as a degranulation marker

Macrophage Phagocytosis Assay:

- Differentiate monocytes to macrophages with M-CSF (50 ng/mL) for 7 days

- Label target cells with pHrodo Red (fluorescence increases in acidic phagosomes)

- Co-culture macrophages with labeled target cells at 5:1 ratio

- Monitor phagocytosis by flow cytometry or live-cell imaging over 24 hours

- Quantify phagocytic index: (percentage of pHrodo+ macrophages) × (mean fluorescence intensity)

Statistical Analysis:

- Perform experiments with at least 3 different PBMC donors

- Use one-way ANOVA with post-hoc Tukey test for multiple comparisons

- Express data as mean ± SEM, with p < 0.05 considered significant

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Hypo-Immune Cell Engineering

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Application/Function |

|---|---|---|

| Gene Editing Tools | CRISPR/Cas9 (B2M, CIITA gRNAs), TALENs | Targeted disruption of HLA and related genes |

| Vector Systems | Lentiviral vectors (PD-L1, CD47, HLA-G), AAVS1 safe harbor targeting | Stable expression of immunomodulatory transgenes |

| Cell Culture Reagents | mTeSR1, StemFlex, Recombinant Laminin-521 | Maintenance of pluripotent stem cells during engineering |

| Differentiation Kits | STEMdiff Pancreatic Progenitor Kit, Cardiomyocyte Differentiation Kit | Generation of target cell types from engineered PSCs |

| Flow Cytometry Antibodies | Anti-HLA-ABC, HLA-DR, CD47, PD-L1, B2M, CD3, CD56 | Characterization of engineered cells and immune responses |

| Functional Assay Kits | CFSE Cell Division Tracker, LDH Cytotoxicity Assay, Cytokine ELISA Kits | Assessment of immune evasion properties in vitro |

The natural immune privilege mechanisms of cornea and placenta provide powerful paradigms for engineering hypo-immune cells for allogeneic therapy. The cornea teaches us the importance of physical barriers (avascularity), local immunomodulation, and systemic tolerance induction, while the placenta demonstrates the efficacy of low immunogenicity combined with active immunosuppression. By translating these principles through genetic engineering—particularly through HLA modification and expression of immunomodulatory molecules like PD-L1 and CD47—researchers are making significant progress toward creating universally compatible allogeneic cell products.

The emerging clinical success of hypo-immune engineered cells, particularly in the diabetes field where genetically modified allogeneic islets have shown positive six-month clinical results [20], validates this bioinspired approach. As the field advances, key challenges remain, including ensuring long-term safety of engineered cells, preventing potential off-target effects of gene editing, and addressing regulatory considerations. Nevertheless, learning from nature's solutions to immune tolerance continues to provide the most promising roadmap for overcoming the immune barriers to allogeneic cell therapy, potentially enabling off-the-shelf cellular therapeutics that can benefit broad patient populations without the need for lifelong immunosuppression.

The advancement of allogeneic cell therapies is fundamentally constrained by the host immune response to transplanted cells. Successfully engineering hypo-immune cells requires a deep understanding of the inherent immunogenic profiles of different cellular source materials. The two principal sources for these therapies are primary donor cells, obtained directly from healthy donors, and induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), which are master cell lines capable of unlimited expansion and differentiation. Each source presents a distinct set of immunological challenges and advantages that dictate the engineering strategy required to achieve a "stealth" therapeutic product. This application note provides a comparative analysis of the immunogenic profiles of iPSCs and primary donor cells, summarizes key quantitative data for informed decision-making, and outlines essential experimental protocols for profiling and mitigating immune responses in the context of developing hypo-immune cell therapies for research.

The choice between primary donor cells and iPSCs has profound implications for the immunogenicity of the final therapeutic product. Key factors include the expression of Human Leukocyte Antigen (HLA) molecules, which are the primary triggers of adaptive immune rejection, and the susceptibility to innate immune effector cells like Natural Killer (NK) cells.

Table 1: Immunogenic Profile of Primary Donor Cells vs. iPSCs

| Feature | Primary Donor Cells (T/NK Cells) | Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells (iPSCs) |

|---|---|---|

| HLA Class I Expression | High and constitutive [21] [22] | Low in undifferentiated state; can increase upon differentiation or IFN-γ exposure [22] |

| HLA Class II Expression | Can be present and upregulated by IFN-γ (e.g., on antigen-presenting cells) [22] | Typically negative, and not robustly upregulated by IFN-γ [22] |

| Susceptibility to T-Cell Alloreactivity | High, due to full HLA expression and presence of endogenous TCR (for T cells) [10] [23] [11] | Variable; can be low in undifferentiated state but increases with differentiation [21] [24] |

| Risk of Graft-versus-Host Disease (GvHD) | High for αβ T cells without TCR disruption [23] [11] | Negligible for differentiated non-immune cells; relevant for iPSC-derived T/iT cells unless TCR is disrupted [25] |

| Susceptibility to NK Cell "Missing-Self" Killing | Lower, due to high HLA class I expression engaging NK inhibitory receptors [21] | Higher, particularly for HLA-engineered (e.g., β2M KO) or HLA-homozygous cells, which may lack ligands for all NK inhibitory receptors [21] [24] |

| Batch-to-Batch Variability | High, due to donor-to-donor genetic and physiological differences [10] | Low, as a single, well-characterized master iPSC clone can be used for all products [10] [26] |

A critical consideration for allogeneic therapies is the "missing-self" response mediated by recipient NK cells. NK cells are equipped with inhibitory receptors that recognize "self" HLA class I molecules. When they encounter a cell with absent or insufficient expression of these self-ligands, as is the case with HLA-downregulated or HLA-homozygous cells, they become activated and kill the target cell [21] [24]. Therefore, while knocking out HLA class I protects from T cell rejection, it can simultaneously render the cell vulnerable to NK cell-mediated killing.

Experimental Protocols for Immunogenicity Assessment

Robust preclinical assessment of immune responses is essential for developing successful hypo-immune cell therapies. The following protocols outline key in vitro and in vivo experiments to evaluate and benchmark the immunogenic profile of your candidate cell products.

Protocol: In Vitro Mixed Lymphocyte Reaction (MLR) to Assess T Cell Alloreactivity

Purpose: To quantitatively measure the ability of candidate therapeutic cells (stimulators) to provoke proliferation of allogeneic T cells (responders), thereby assessing their potential to cause T cell-mediated immune rejection [22].

Materials:

- Responder Cells: Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) isolated from healthy donors.

- Stimulator Cells: Candidate therapeutic cells (e.g., differentiated iPSC-derived cells or primary donor cells).

- Culture Medium: RPMI-1640 supplemented with 10% human AB serum, L-glutamine, and penicillin/streptomycin.

- Mitomycin C or irradiation source for stimulator cell arrest.

- Flow Cytometer with antibodies for T cell markers (CD3, CD4, CD8) and proliferation dyes (e.g., CFSE).

Method:

- Stimulator Cell Preparation: Treat candidate therapeutic cells with Mitomycin C (e.g., 25 µg/mL for 30 minutes at 37°C) or irradiate (e.g., 30-100 Gy) to arrest proliferation. Wash cells thoroughly.

- Responder Cell Preparation: Islect PBMCs from fresh blood or a cryopreserved vial of a healthy donor using Ficoll density gradient centrifugation.

- Co-culture Setup: Plate stimulator cells (e.g., 1x10^5 per well) with responder PBMCs (e.g., 1x10^5 to 1x10^6 per well) in a 96-well U-bottom plate in culture medium. Include controls: responders alone (negative control) and responders with a potent stimulator like anti-CD3/CD28 beads (positive control).

- Culture and Analysis: Culture cells for 5-7 days. To track proliferation, label responder PBMCs with CFSE prior to co-culture. Analyze T cell proliferation by flow cytometry, gating on CD3+ T cells and measuring CFSE dilution.

Data Interpretation: High proliferation in test wells compared to the negative control indicates strong alloreactivity. Hypo-immune engineered cells should show significantly reduced T cell proliferation.

Protocol: In Vitro NK Cell Cytotoxicity Assay to Assess "Missing-Self" Response

Purpose: To evaluate the susceptibility of HLA-engineered candidate cells to lysis by allogeneic NK cells, a key risk for hypo-immune cells with low HLA class I expression [21] [24].

Materials:

- Target Cells: Candidate therapeutic cells (e.g., HLA-engineered iPSC-derived cells).

- Effector Cells: NK cells isolated from healthy donor PBMCs (e.g., using negative selection kit).

- Culture Medium: As above, supplemented with 100-200 U/mL of recombinant human IL-2 for NK cell pre-activation (optional, for enhanced activity).

- Lactate Dehydrogenase (LDH) Release Detection Kit or flow cytometry-based cytotoxicity assay (e.g., using Annexin V/Propidium Iodide).

Method:

- Effector Cell Preparation: Isolate and if desired, pre-activate NK cells by culturing with IL-2 for 16-24 hours.

- Target Cell Preparation: Harvest candidate cells and label with a fluorescent marker if using flow cytometry-based readout.

- Co-culture Setup: Plate target cells in a 96-well plate. Add effector NK cells at varying Effector:Target (E:T) ratios (e.g., 5:1, 10:1, 20:1). Include controls for spontaneous release (targets alone) and maximum release (targets with lysis solution).

- Incubation and Measurement: Incubate for 4-6 hours at 37°C. Measure specific lysis using the LDH kit according to the manufacturer's instructions. Alternatively, for flow cytometry, analyze the percentage of dead/dying target cells using viability dyes.

Data Interpretation: High specific lysis at low E:T ratios indicates high susceptibility to NK cell killing. Successful hypo-immune strategies may require additional engineering (e.g., HLA-E or CD47 overexpression) to inhibit NK cell activity.

Protocol: Utilizing Humanized Immune System (HIS) Mouse Models for In Vivo Rejection Studies

Purpose: To assess the survival, engraftment, and immune rejection of candidate hypo-immune cells in a more physiologically relevant in vivo context that includes both human T and NK cell compartments [21].

Materials:

- HIS Mice: Immunodeficient mice (e.g., NSG) reconstituted with a human immune system via engraftment of human CD34+ hematopoietic stem cells.

- Candidate Cells: Luciferase-expressing therapeutic cells for in vivo tracking.

- In Vivo Imaging System (IVIS) to monitor cell persistence.

- Recombinant Human IL-15 cytokine or engineered vectors for enhancing human NK cell reconstitution in HIS mice [21].

Method:

- Model Validation: Confirm robust reconstitution of human T and NK cells in HIS mice by flow cytometry prior to study initiation. Administer IL-15 or other cytokines if needed to boost NK cell numbers [21].

- Cell Administration: Inject luciferase-expressing candidate cells (test group) and appropriate control cells (e.g., non-engineered, immunogenic cells) into HIS mice.

- Longitudinal Monitoring: Track the bioluminescent signal from the injected cells weekly using IVIS imaging.

- Endpoint Analysis: At the end of the study, harvest tissues (e.g., blood, spleen, liver) to analyze human cell persistence and immune cell infiltration by flow cytometry and histology.

Data Interpretation: A stable or increasing bioluminescent signal over time indicates successful evasion of immune rejection. A rapidly declining signal suggests rejection by human T or NK cells in the HIS model.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents for Hypo-Immune Cell Research

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Hypo-Immune Cell Engineering and Profiling

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR-Cas9 Gene Editing System | Disruption of immunogenicity genes (e.g., B2M for HLA-I, CIITA for HLA-II, TRAC for TCR) [10] [11]. | High efficiency but requires careful off-target analysis. Newer systems (e.g., base editing) may offer improved safety. |

| AAV or Lentiviral Vectors | Delivery of transgenes for "stealth" molecules (e.g., HLA-G, HLA-E, CD47) [23] [11]. | AAV has a larger payload capacity; lentivirus integrates into the genome for stable expression. |

| Recombinant Human Cytokines (IL-2, IL-15) | Expansion and activation of NK cells for in vitro cytotoxicity assays [21]. | IL-15 is critical for NK cell development and survival. |

| HIS Mouse Models (e.g., NSG with human CD34+ cells) | In vivo assessment of immune rejection in a model with a functional human immune system [21]. | Reconstitution levels of different immune lineages (T, NK, myeloid) can be variable and must be quantified. |

| Flow Cytometry Antibodies | Characterization of HLA expression, immune cell markers, and detection of cell death in co-culture assays. | Panels should include antibodies against HLA-A,B,C, HLA-II, CD3, CD56, and viability dyes. |

Visualizing the Hypo-Immune Cell Engineering Workflow

The development of a hypo-immune cell therapy from iPSCs involves a multi-step process of differentiation, genetic engineering, and rigorous immunogenicity testing. The following diagram outlines a generalized workflow for creating and validating an iPSC-derived, hypo-immune cell product.

Diagram 1: A generalized workflow for developing an iPSC-derived hypo-immune cell therapy, involving key steps of genetic engineering, differentiation, and multi-layered immunogenicity validation.

The core challenge in hypo-immune engineering is balancing the evasion of the adaptive immune system (T cells) with the risk of triggering the innate immune system (NK cells). The following diagram illustrates this "Immunogenicity Balancing Act" and common engineering strategies to address it.

Diagram 2: The core challenge in hypo-immune cell engineering. Ablating HLA to avoid T cell recognition can paradoxically activate NK cell killing via the 'missing-self' response, necessitating complementary engineering strategies to inhibit NK cells.

Genetic Engineering Toolkit: Designing and Building Hypoimmune Cell Products

The development of "off-the-shelf" or allogeneic cell therapies represents a transformative advancement in biomedical science, aiming to overcome the limitations of patient-specific (autologous) treatments. A central challenge in this field is preventing immune-mediated rejection of donor cells by the recipient's immune system. The engineering of hypo-immune cells—donor cells with reduced immunogenicity—is therefore a critical research focus. This process strategically involves the knockout of key immune genes to minimize graft-versus-host disease (GvHD) and host-versus-graft rejection [27] [11]. Three powerful gene-editing technologies—CRISPR-Cas9, TALENs, and ZFNs—serve as the primary workhorses for creating these engineered cells. This application note provides a detailed comparison of these platforms and standard protocols for their use in knocking out immunogenic genes, specifically targeting the T-cell receptor (TCR) and Major Histocompatibility Complex (MHC) molecules, to generate universal allogeneic cell therapies.

The following table summarizes the core characteristics of the three major gene-editing platforms.

Table 1: Comparison of Major Gene-Editing Technologies

| Feature | ZFNs | TALENs | CRISPR-Cas9 |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Recognition Mechanism | Protein-DNA (Zinc Finger domains) | Protein-DNA (TALE repeats) | RNA-DNA (guide RNA) |

| Target Sequence Length | 9-18 bp [28] | 14-20 bp [28] | 20 bp + PAM sequence [29] |

| Nuclease | FokI dimer [28] | FokI dimer [28] | Cas9 [30] |

| Efficiency | Moderate [29] | Moderate [29] | High [29] |

| Specificity | Lower [29] | Moderate [29] | High, though off-target effects remain a concern [29] |

| Multiplexing Capability | Single | Single | Multiple (via co-delivery of multiple gRNAs) [31] |

| Design & Cloning | Complicated; requires protein engineering [28] | Complicated; repetitive TALE array cloning [28] | Simple; requires only sgRNA synthesis [29] |

| Clinical Trial Prevalence | Moderate [29] | Low [29] | High [29] |

Mechanism of Action for Gene Knockout

All three technologies function by inducing a double-strand break (DSB) at a specific genomic locus. The cell's primary repair pathway, Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ), is error-prone and often results in small insertions or deletions (indels) at the break site. When these indels occur within a protein-coding exon, they can cause a frameshift mutation, leading to a premature stop codon and effectively knocking out the gene [32] [28]. This principle is harnessed to disrupt genes responsible for immune recognition.

Application: Engineering Allogeneic CAR-T Cells

Chimeric Antigen Receptor (CAR)-T cell therapy has revolutionized cancer treatment, but its autologous nature presents challenges of high cost, manufacturing delays, and variable cell quality [27] [11]. Creating universal allogeneic CAR-T cells from healthy donors requires specific gene knockouts to ensure safety and efficacy, as illustrated in the workflow below.

Key Knockout Targets for Hypo-immune CAR-T Cells

Table 2: Essential Immune Gene Knockouts for Allogeneic CAR-T Cells

| Target Gene | Function | Purpose of Knockout | Result of Knockout |

|---|---|---|---|

| TRAC (T-cell receptor α constant) | Encodes a constant region of the T-cell receptor α chain [27] | Prevent Graft-versus-Host Disease (GvHD) [33] | Eliminates TCR surface expression, preventing donor T cells from attacking host tissues [27] [11] |

| B2M (β-2-microglobulin) | Essential component of the MHC Class I complex [33] | Prevent Host-versus-Graft Rejection [33] | Abolishes surface MHC I expression, evading recognition and elimination by host CD8+ T cells [33] |

| Regnase-1 | RNA-binding protein that degrades inflammatory mRNAs [33] | Enhance CAR-T cell persistence and potency [33] | Increases cytokine secretion and effector function, improving anti-tumor efficacy [33] |

| TGFBR2 (Transforming growth factor beta receptor 2) | Mediates immunosuppressive TGF-β signaling [33] | Confer resistance to tumor microenvironment [33] | Maintains CAR-T cell activity even in high TGF-β environments [33] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Multiplexed Knockout of TRAC and B2M in Human T Cells Using CRISPR-Cas9

This protocol is designed for the simultaneous knockout of two key immunogenic genes to generate a universal CAR-T cell base.

4.1.1 Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for CRISPR-Cas9 Knockout in T Cells

| Reagent | Function | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR-Cas9 System | Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex for DNA cleavage. | Recombinant SpCas9 protein and synthetic sgRNAs targeting TRAC and B2M. |

| sgRNAs | Guides the Cas9 nuclease to the specific DNA target. | Design sgRNAs with high on-target and low off-target scores. Target sequences: TRAC exon 1; B2M exon 1. |

| T Cell Activation Kit | Stimulates T cell proliferation and enhances editing efficiency. | Anti-CD3/CD28 magnetic beads. |

| Electroporation System | Enables efficient delivery of RNP complexes into T cells. | Lonza 4D-Nucleofector. |

| Cell Culture Media | Supports the growth and expansion of edited T cells. | OpTmizer T Cell Expansion SFM, supplemented with IL-2 and IL-7. |

4.1.2 Step-by-Step Workflow

sgRNA Design and Preparation:

- Design sgRNAs targeting the first exons of the TRAC (e.g., within the leader or variable domain) and B2M genes.

- Ensure the target sequence is followed by a 5'-NGG-3' Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM).

- Synthesize sgRNAs commercially or in vitro.

T Cell Isolation and Activation:

- Isolate peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from a leukapheresis product of a healthy donor.

- Isolate T cells using a negative selection kit.

- Activate T cells using anti-CD3/CD28 beads at a 1:1 bead-to-cell ratio in culture media supplemented with IL-2 (100 U/mL) for 24-48 hours.

Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) Complex Formation:

- For each knockout, combine 10 µg of SpCas9 protein with a 1.5x molar ratio of each sgRNA (e.g., TRAC sgRNA and B2M sgRNA for multiplexing).

- Incubate at room temperature for 10-20 minutes to form the RNP complex.

Electroporation:

- Harvest activated T cells and wash with PBS.

- Resuspend 1-2 million T cells in 100 µL of proprietary electroporation buffer.

- Add the pre-formed RNP complex to the cell suspension.

- Electroporate using a pre-optimized program for human T cells (e.g., DS-130 on the 4D-Nucleofector).

Post-Electroporation Culture and Expansion:

- Immediately transfer electroporated cells to pre-warmed culture media with cytokines (IL-2 and IL-7).

- Remove activation beads 3-5 days post-electroporation.

- Expand cells for 7-14 days, maintaining a cell concentration between 0.5-2 x 10^6 cells/mL.

Validation and Analysis:

- Flow Cytometry: At day 7-10, stain cells with antibodies against TCRα/β and MHC I to confirm knockout efficiency at the protein level.

- T7 Endonuclease I Assay or Sanger Sequencing: Genomically DNA extract and assess the frequency of indels at the target loci.

Protocol 2: Knockout of TRAC using TALENs or ZFNs

While CRISPR-Cas9 is more common, TALENs and ZFNs are still effectively used, especially in clinical settings.

4.2.1 Key Considerations:

- Design Complexity: Both TALENs and ZFNs require the design of two proteins that bind flanking sequences on opposite DNA strands, with the FokI nuclease domain dimerizing to create the DSB [28].

- Delivery: Unlike CRISPR's RNA-based targeting, TALENs and ZFNs are typically delivered as mRNA encoding the engineered proteins.

4.2.2 Workflow for TALEN-mediated TRAC Knockout:

- TALEN Design: Design a TALEN pair targeting the TRAC gene's constant region. The binding sites should be 14-20 bp in length and separated by a 12-20 bp spacer [28].

- mRNA Synthesis: Clone the TALEN sequences into an appropriate plasmid vector and perform in vitro transcription to produce capped and polyadenylated mRNA.

- T Cell Activation: (Same as Protocol 1, Step 2).

- Electroporation: Electroporate activated T cells with 2-5 µg of each TALEN mRNA.

- Culture and Expansion: (Same as Protocol 1, Step 5).

- Validation: (Same as Protocol 1, Step 6).

CRISPR-Cas9, TALENs, and ZFNs are powerful technologies enabling the precise knockout of immune genes to create hypo-immune cells for allogeneic therapy. CRISPR-Cas9 currently leads in popularity due to its simplicity, high efficiency, and ease of multiplexing. The choice of platform depends on the specific application, regulatory considerations, and required precision. The protocols outlined here provide a foundational methodology for researchers to engineer the next generation of universal, off-the-shelf cell therapies, paving the way for more accessible and cost-effective treatments for cancer and other diseases.

The development of allogeneic cell therapies represents a paradigm shift in regenerative medicine and cancer treatment, offering the potential for "off-the-shelf" cellular products that can be manufactured at scale and made readily available to patients. However, a significant biological barrier impedes this vision: host versus graft immune rejection. When cells from a donor are introduced into a recipient, the recipient's immune system recognizes foreign human leukocyte antigen (HLA) molecules on the donor cells, triggering their elimination through adaptive immune responses [34]. This immunogenic recognition is primarily mediated by T cells responding to HLA class I and II complexes, necessitating strategies to engineer cells that can evade this detection [35] [20].

The molecular basis of this immune recognition lies in the HLA complex, where HLA class I molecules (HLA-A, -B, and -C) are expressed on nearly all nucleated cells and present intracellular peptides to CD8+ cytotoxic T cells. These molecules require β2-microglobulin (B2M) for stable cell surface expression. Conversely, HLA class II molecules (HLA-DP, -DQ, and -DR) are typically expressed on antigen-presenting cells and present exogenous antigens to CD4+ helper T cells, with their expression critically dependent on the class II transactivator (CIITA) [34] [36]. The strategic knockout of B2M and CIITA thus disrupts the assembly and surface expression of both HLA classes, forming the cornerstone of hypoimmune cell engineering [35] [37].

This application note provides a comprehensive framework for implementing B2M and CIITA targeting strategies to create hypoimmune cells, detailing experimental protocols, validation methodologies, and reagent solutions to support researchers in advancing allogeneic cell therapies.

Molecular Strategies for HLA Ablation

Core Gene Editing Approaches

Multiple gene editing platforms can be employed to disrupt B2M and CIITA genes, each with distinct advantages for hypoimmune cell engineering.

CRISPR-Cas9 Systems: The most widely utilized approach employs the Cas9 nuclease complexed with sequence-specific guide RNAs (gRNAs) to create double-strand breaks in target genes. The cell's subsequent repair via error-prone non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) introduces insertion/deletion (indel) mutations that disrupt the reading frame, effectively knocking out the gene. This method has been successfully demonstrated in induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) to generate clones with biallelic B2M and CIITA knockouts [37]. For enhanced specificity, nickase variants (Cas9n) can be used, which require two adjacent gRNAs to generate a double-strand break, significantly reducing off-target effects [37].

RNA Interference (shRNA): For applications where transient or partial knockdown is preferred over complete knockout, or to circumvent potential challenges with CRISPR editing efficiency, short hairpin RNA (shRNA) constructs provide an alternative. Lentiviral vectors can deliver shRNAs that specifically target transcripts of the HLA-ABC heavy chain or B2M. A key advantage is the ability to design shRNAs that selectively knock down classical HLA-A, -B, and -C without affecting the non-classical HLA-E, which is crucial for evading Natural Killer (NK) cell responses [38].

Other Nuclease Platforms: Transcription activator-like effector nucleases (TALENs) and zinc-finger nucleases (ZFNs) represent earlier generation editing tools that can also be applied for B2M and CIITA disruption. While these are less commonly used today due to the ease of CRISPR, they may still be valuable in specific contexts where CRISPR off-target concerns are paramount.

Addressing the "Missing Self" Response

A critical consequence of ablating HLA class I expression (e.g., via B2M knockout) is the creation of a "missing self" signal, which can trigger lysis by NK cells [35] [20] [36]. NK cells possess inhibitory receptors (e.g., NKG2A) that normally engage with HLA class I molecules, transmitting a "self" signal that prevents activation. The absence of this interaction, coupled with activating signals, leads to NK cell-mediated killing of the HLA-deficient cells [36]. Therefore, a complete hypoimmune strategy must incorporate mechanisms to mitigate this innate immune response. The most prominent solutions include:

Overexpression of "Don't Eat Me" Signals: Engineering cells to overexpress CD47, a ligand for the inhibitory receptor SIRPα on macrophages and some NK cells, can provide a potent "don't eat me" signal that inhibits phagocytosis [35] [34]. CD24 has also been identified as a key ligand that engages Siglec-10 on macrophages to suppress phagocytosis, and its overexpression has been successfully combined with B2M/CIITA knockout in iPSCs [35].

Expression of Non-Classical HLA Molecules: Retaining or introducing ligands for NK cell inhibitory receptors is another validated strategy. This includes the expression of non-polymorphic HLA-E, which can be engineered as a single-chain trimer (fusion of HLA-E heavy chain, B2M, and a peptide) to ensure surface expression even in a B2M-knockout background. HLA-E effectively engages NKG2A on NK cells and a subset of T cells, delivering a strong inhibitory signal [38] [36].

Overexpression of Immune Checkpoints: Engineering cells to express PD-L1, the ligand for the PD-1 receptor on activated T cells, can directly suppress T cell activity. This not only helps counter residual T cell recognition but has also been shown to enhance the persistence and function of allogeneic cell products like CAR-NK cells [38].

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for designing a comprehensive hypoimmune engineering strategy, integrating both HLA ablation and innate immune evasion components.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol 1: CRISPR-Cas9-Mediated B2M/CIITA Knockout in iPSCs

This protocol outlines the key steps for generating clonal B2M/CIITA knockout iPSC lines using CRISPR-Cas9.

- gRNA Design and Cloning: Design gRNAs targeting critical early exons of the B2M and CIITA genes to ensure frameshift mutations result in non-functional proteins. The B2M gRNA sequence

CACCGAAGTTGACTTACTGAAGAAand CIITA gRNA sequenceCACCGCCTGGCTCCACGCCCTGCThave been successfully used [37]. Clone annealed oligonucleotides into a Cas9-plasmid (e.g., pX462, which allows for puromycin selection). - Cell Culture and Transfection: Culture human iPSCs in feeder-free conditions (e.g., on Matrigel-coated plates with mTeSR1 medium). For electroporation, harvest 1×10^5 cells and resuspend in an appropriate buffer. Mix with 6 µg of the guide plasmid DNA and electroporate using a system like the Neon Transfection System (1100 V, one 10 ms pulse) [37].

- Selection and Clonal Isolation: After transfection, apply puromycin selection for 48-72 hours to eliminate non-transfected cells. Subsequently, dissociate cells into single cells and seed at a very low density for clonal expansion. Isolate individual colonies using cloning discs or by serial dilution in 100-mm dishes.

- Genotype Validation: Extract genomic DNA from expanded clones. Perform PCR amplification of the targeted regions and subject the products to Sanger sequencing. Analyze chromatograms for the presence of indels. Confirm the absence of B2M and HLA class I protein expression by flow cytometry and Western blotting [37].

Protocol 2: In Vitro Immune Cell Activation Assay

This assay quantitatively measures the ability of engineered hypoimmune cells to mitigate the activation of allogeneic immune cells.

- Co-culture Setup: Isolate peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from healthy human donors by density gradient centrifugation. Seed engineered hypoimmune cells (e.g., B2M−/−CIITA−/− iPSCs or their differentiated derivatives) as adherent monolayers. Add allogeneic PBMCs at a standardized effector-to-target ratio (e.g., 10:1) in complete RPMI medium. Include control wells with wild-type cells and PBMCs alone.

- Activation Readout: After 3-5 days of co-culture, harvest the PBMCs and stain with fluorescent antibodies for activation markers. Key markers include CD69 (early activation) and CD25 (IL-2 receptor alpha chain) on T cells (CD3+). Analyze by flow cytometry.

- Data Analysis: Quantify the percentage of CD3+ T cells that are CD69+ or CD25+ in each condition. Successful engineering is indicated by a significantly lower percentage of activated T cells in co-cultures with B2M/CIITA knockout cells compared to wild-type controls. This reduced T cell activation has been demonstrated in multiple studies [35] [37].

Protocol 3: In Vivo Assessment in Humanized Mouse Models

This protocol describes the use of humanized mouse models for pre-clinical validation of hypoimmune cell survival and function.

- Model Generation: Utilize immunodeficient mice such as NOD-scid IL2Rγnull (NSG). Humanize the mice by intravenously injecting CD34+ hematopoietic stem cells isolated from human umbilical cord blood. Allow 12-16 weeks for full reconstitution of a human immune system [35].

- Cell Transplantation and Disease Modeling: For disease modeling, such as peripheral arterial disease (PAD), induce hindlimb ischemia in the humanized mice by ligating and excising the femoral artery. Subsequently, transplant the therapeutic hypoimmune cells (e.g., universal iPSC-derived endothelial cells, U-ECs) into the ischemic muscle [35].

- Outcome Assessment:

- Cell Survival: After a set period (e.g., 4 weeks), harvest the tissue and quantify the persistence of human cells (e.g., by human-specific antigen staining or luciferase imaging) [35].

- Immune Infiltration: Analyze tissue sections by immunohistochemistry for infiltration of human T cells (CD3+), B cells (CD20+), and NK cells (CD56+) [37].

- Functional Efficacy: Assess the functional recovery, such as restoration of blood flow in the PAD model measured by laser Doppler perfusion imaging [35].

Table 1: Key In Vivo Findings from Pre-clinical Studies of Hypoimmune Cells

| Cell Type | Model | Genetic Modifications | Key Outcome | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human iPSCs | Monkey wound model | B2M−/− CIITA−/− | Reduced T & B cell infiltration; enhanced survival & wound healing vs. single KO or WT. | [37] |

| iPSC-derived Endothelial Cells (U-ECs) | Humanized PAD mouse (hindlimb ischemia) | B2M−/− CIITA−/− CD24OE | Significant blood flow restoration; greater cell survival & weaker immune response vs. WT-ECs. | [35] |

| CAR-NK Cells | Xenograft mouse model | shRNA-HLA-ABC + PD-L1 or SCE OE | Evaded host CD8+ T & NK cell rejection; enhanced tumor control & improved safety profile. | [38] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

A successful hypoimmune cell engineering project relies on a suite of specialized reagents and tools. The table below catalogs essential solutions for key experimental stages.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Hypoimmune Cell Engineering

| Product Category | Specific Example | Application/Function | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gene Editing Platform | CRISPR-Cas9 plasmids (e.g., pX462); Cas9 protein + synthetic gRNA | Creates targeted double-strand breaks in B2M and CIITA genes. | Optimize delivery method (electroporation, lipofection); validate gRNA efficiency and specificity. |

| Cell Culture Systems | Feeder-free iPSC culture (mTeSR1 medium; GFR Matrigel) | Maintains pluripotency of iPSCs during and after gene editing. | Essential for preserving differentiation potential post-knockout. |

| Validation Antibodies | Anti-B2M (flow cytometry/WB); Anti-HLA-ABC (flow); Anti-CIITA (WB) | Confirms loss of target protein expression in engineered clones. | Use isotype controls; confirm antibody specificity for the target. |

| Immune Assay Reagents | Anti-human CD3, CD4, CD8, CD69, CD25; Mixed Lymphocyte Reaction (MLR) kits | Measures T cell activation and proliferation in response to engineered cells. | Use fresh or properly thawed PBMCs from multiple donors for robust allogeneic response. |

| Innate Evasion Modalities | Lentiviral vectors for CD47, CD24, PD-L1, or single-chain HLA-E (SCE) | Provides "don't eat me" signals and inhibits NK cell and T cell activity. | Monitor transduction efficiency; consider multi-cistronic vectors for co-expression. |

| Animal Models | Immunodeficient mice (e.g., NSG); CD34+ HSCs from human cord blood | Creates in vivo humanized model for testing cell survival and immune evasion. | Long lead time (12+ weeks) for immune system reconstitution; confirm engraftment level. |

Data Presentation and Analysis

Quantitative data from immune activation assays and in vivo studies are crucial for validating the success of hypoimmune engineering. The following table summarizes typical experimental outcomes that demonstrate reduced immunogenicity.

Table 3: Representative Quantitative Data from Hypoimmune Cell Studies

| Experimental Readout | Wild-Type (WT) Control Cells | B2M/CIITA Knockout Cells | Notes / Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| T Cell Activation (% CD3+CD69+) | 45.2% ± 5.1% | 12.8% ± 2.9% | Measured after 5-day co-culture with allogeneic PBMCs [35]. |

| Proliferation of Allogeneic T cells | High (Reference = 1.0) | Reduced by ~70% | Compared to stimulation index of WT-iPSCs [37]. |