Engineering MSC Exosomes for Targeted Drug Delivery in Chronic Wounds: Mechanisms, Methods, and Clinical Translation

Chronic wounds represent a significant clinical challenge due to their complex pathophysiology and failure to progress through normal healing stages.

Engineering MSC Exosomes for Targeted Drug Delivery in Chronic Wounds: Mechanisms, Methods, and Clinical Translation

Abstract

Chronic wounds represent a significant clinical challenge due to their complex pathophysiology and failure to progress through normal healing stages. This article explores the burgeoning field of mesenchymal stem cell (MSC)-derived exosomes as engineered, cell-free therapeutic platforms for targeted drug delivery in wound management. We examine the foundational biology of exosomes and their native roles in wound healing phases, detail advanced methodologies for cargo loading and surface modification to enhance targeting and efficacy, and address key challenges in manufacturing and standardization. Furthermore, we synthesize current preclinical and clinical validation data, comparing engineered exosomes with conventional therapies and natural vesicles. By integrating recent advances from 2024-2025, this review provides a comprehensive resource for researchers and drug development professionals aiming to translate exosome-based nanomedicines from bench to bedside.

The Biology of MSC Exosomes and Their Native Role in Wound Healing

Exosomes are nanosized, lipid bilayer-delimited extracellular vesicles (EVs), typically 30–150 nm in diameter, that are naturally secreted by all cell types, including Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs) [1] [2]. They originate from the endosomal pathway and are released into the extracellular space upon fusion of Multivesicular Bodies (MVBs) with the plasma membrane [3] [4]. Once considered mere cellular waste bags, exosomes are now recognized as potent mediators of intercellular communication due to their capacity to transport a diverse array of bioactive molecules, including proteins, lipids, nucleic acids (DNA, mRNA, miRNA, circRNA), and metabolites [5] [2]. Their innate biocompatibility, low immunogenicity, stability in circulation, and ability to penetrate biological barriers make them promising natural vehicles for targeted drug delivery [5] [6] [1]. In the context of chronic wounds, engineered MSC-derived exosomes hold particular promise for delivering therapeutic cargo to precisely modulate the dysfunctional wound healing process [7].

Molecular Machinery of Exosome Biogenesis

Exosome biogenesis is a complex, multi-step process meticulously regulated by cellular machinery. It can be divided into four key stages: (1) cargo sorting, (2) MVB formation and maturation, (3) intracellular transport of MVBs, and (4) fusion of MVBs with the plasma membrane [4].

Key Biogenesis Pathways

The formation of intraluminal vesicles (ILVs) within MVBs is driven by several distinct but potentially overlapping molecular pathways.

2.1.1. The ESCRT-Dependent Pathway The Endosomal Sorting Complex Required for Transport (ESCRT) machinery is a well-studied mechanism comprising four complexes (ESCRT-0, -I, -II, -III) and associated proteins like VPS4 and ALIX [4] [8].

- ESCRT-0 (including Hrs and STAM) recognizes and sequesters ubiquitinated cargo proteins on the endosomal membrane [4] [8].

- ESCRT-I and -II are recruited to drive membrane deformation and initiate budding.

- ESCRT-III forms filaments that constrict the neck of the budding vesicle.

- The VPS4 ATPase complex provides energy for membrane scission and the recycling of ESCRT components [4]. This pathway is crucial for sorting ubiquitinated proteins and various other cargoes into nascent ILVs [5].

2.1.2. ESCRT-Independent Pathways Several mechanisms can generate ILVs without the full ESCRT apparatus.

- The nSMase2-Ceramide Pathway: Neutral sphingomyelinase 2 (nSMase2) converts sphingomyelin to ceramide on the endosomal membrane. Ceramide's conical structure promotes membrane curvature and inward budding, facilitating the sorting of cargoes like the prion protein and specific RNAs [4].

- Tetraspanin-Enriched Microdomains: Tetraspanins (e.g., CD9, CD63, CD81) are abundant on exosome membranes and can form specialized microdomains that recruit specific client proteins and promote membrane budding and fission in an ESCRT-independent manner [8]. For instance, CD63 knockdown has been shown to reduce exosome production [8].

- The Syndecan-Syntenin-ALIX Pathway: Transmembrane proteoglycans (syndecans) bind the adaptor protein syntenin, which then recruits ALIX. ALIX, in turn, engages ESCRT-III and VPS4 to facilitate ILV formation, serving as a bridge between specific cargo and the ESCRT machinery [4].

The following diagram illustrates the coordination of these primary pathways during exosome biogenesis:

Figure 1: Key Pathways of Exosome Biogenesis. This diagram illustrates the primary ESCRT-dependent and ESCRT-independent pathways (nSMase2-ceramide and tetraspanin microdomains) that drive the formation of intraluminal vesicles (ILVs) within multivesicular bodies (MVBs), culminating in exosome release.

Fate of MVBs and Exosome Release

Once formed, MVBs face one of two fates: degradation or exocytosis. MVBs destined for degradation fuse with lysosomes, leading to the breakdown of their contents. In contrast, MVBs programmed for exosome release are trafficked along microtubules to the cell periphery. This transport involves Rab GTPases (e.g., Rab27a/b, Rab11, Rab35) [8]. At the plasma membrane, SNARE complexes facilitate the docking and fusion of the MVB with the plasma membrane, releasing the ILVs into the extracellular space as exosomes [4].

Composition and Selective Cargo Sorting

The molecular composition of exosomes is not random; it is a highly regulated process that determines the exosome's functional destiny upon delivery to a recipient cell.

Major Cargo Components

Exosomes encapsulate a diverse repertoire of biomolecules that mirror their cell of origin but are often enriched through active sorting mechanisms.

Table 1: Major Cargo Components of Exosomes

| Cargo Category | Specific Examples | Functional Roles / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Proteins | Tetraspanins (CD9, CD63, CD81), ESCRT-related proteins (ALIX, TSG101), Heat shock proteins (HSP70, HSP90), Integrins, MHC molecules [5] [8] | Often used as exosome marker proteins; involved in biogenesis, targeting, and signaling. |

| Lipids | Cholesterol, Sphingomyelin, Ceramide, Phosphatidylserine, Bisphosphatidic acid (LBPA) [5] [4] | Contribute to membrane stability, curvature, and budding during biogenesis. |

| Nucleic Acids | miRNA, mRNA, lncRNA, circRNA, mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA), genomic DNA [5] [2] | Can alter gene expression and function in recipient cells. miRNA is extensively studied for therapeutic regulation. |

Mechanisms of Cargo Sorting

Cargo is selectively packaged into ILVs through specific interactions with the biogenesis machinery.

- Ubiquitin-Dependent Sorting: Ubiquitinated proteins are recognized by ESCRT-0 for incorporation into ILVs via the canonical ESCRT pathway [4] [8].

- Ubiquitin-Independent Sorting: The Syndecan-Syntenin-ALIX axis sorts cargo like fibroblast growth factor receptor (FGFR) without requiring ubiquitination [4].

- RNA Sorting: RNA-binding proteins (RBPs) such as SAFB and hnRNPK are involved in sorting specific RNAs into exosomes, sometimes through interactions with components like LC3 on the MVB membrane [4].

The following experimental workflow outlines key protocols for isolating and analyzing this exosomal cargo:

Figure 2: Experimental Workflow for Exosome Isolation and Analysis. This diagram outlines the standard protocol from cell culture to exosome characterization and cargo analysis, highlighting key techniques like nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA), transmission electron microscopy (TEM), and Western blot.

Application Notes: Engineering MSC Exosomes for Chronic Wounds

Chronic wounds are characterized by a failure to proceed through an orderly healing process, marked by persistent inflammation, impaired angiogenesis, and inadequate tissue remodeling [7]. Engineered MSC exosomes offer a novel, cell-free therapeutic strategy to overcome these challenges.

Rationale for Using MSC Exosomes

MSC-derived exosomes inherently possess pro-regenerative properties, including anti-inflammatory, pro-angiogenic, and pro-migratory effects on skin cells [7]. Their lipid bilayer protects therapeutic cargo from degradation, and their surface can be modified to enhance targeting to specific cell types in the wound bed (e.g., fibroblasts, keratinocytes, endothelial cells) [6] [1]. This makes them superior to synthetic nanoparticles for drug delivery in wound healing contexts.

Strategies for Engineering Therapeutic Exosomes

4.2.1. Cargo Loading Techniques Two primary approaches are used to load therapeutic molecules into exosomes.

Table 2: Methods for Loading Cargo into Exosomes

| Method Category | Specific Technique | Principle | Example Cargo | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cell-Based (Endogenous) | Incubation / Transfection | Donor cells (e.g., MSCs) are treated with small molecules or transfected to overexpress nucleic acids, which are then packaged into secreted exosomes [9]. | Doxorubicin, Curcumin, miRNA (e.g., miR-21, miR-146a), siRNA, mRNA [9] [7] | Simple but offers limited control over loading efficiency. |

| Non-Cell-Based (Exogenous) | Electroporation | A short electrical pulse creates temporary pores in the exosome membrane, allowing cargo diffusion into the lumen [6] [9]. | siRNA, miRNA, small molecules | Can cause cargo aggregation and exosome aggregation. |

| Sonication | Exosomes are subjected to ultrasound waves to disrupt the membrane, enabling cargo entry before membrane reassembly [6] [9]. | Proteins, small molecules | May compromise exosome membrane integrity. | |

| Incubation | Simple co-incubation of cargo with pre-isolated exosomes, relying on passive diffusion and membrane permeability [6] [9]. | Hydrophobic small molecules (e.g., Curcumin) | Simple but often has low efficiency. |

4.2.2. Targeting and Functionalization For precise delivery in chronic wounds, exosome surfaces can be engineered.

- Ligand Display: Expression of targeting peptides, antibodies, or receptor ligands on the exosome surface (e.g., via genetic fusion to abundant exosomal membrane proteins like CD63 or Lamp2b) can direct exosomes to specific cell types or the wound ECM [6] [2].

- Hybrid Systems: Combining exosomes with functional biomaterials, such as injectable hyaluronic acid hydrogels, can create a sustained-release depot at the wound site, protecting exosomes and enhancing their local retention and efficacy [10] [7].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Tools for Exosome Research

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Specific Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Isolation Kits | Commercial kits for rapid exosome precipitation or immunoaffinity capture from cell media or biofluids. | Total Exosome Isolation kits, kits with anti-CD63/CD81 magnetic beads. |

| ESCRT Inhibitors | Chemical inhibitors to dissect the role of the ESCRT pathway in biogenesis and cargo sorting. | GW4869 (inhibits nSMase2/ceramide pathway) [4], VPS4 inhibitors. |

| Tetraspanin Antibodies | Essential for exosome characterization via Western Blot, Flow Cytometry, and Immunofluorescence. | Anti-CD9, Anti-CD63, Anti-CD81 [2] [8]. |

| Characterization Instruments | For determining the size, concentration, and morphology of isolated exosomes. | Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis (NTA) for size/concentration, Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) for morphology [2]. |

| Loading Equipment | Instruments for exogenous cargo loading into pre-isolated exosomes. | Electroporator (for electroporation), Sonicator (for sonication) [6] [9]. |

| Engineered Cell Lines | Donor cells (e.g., HEK293T, MSCs) genetically modified to stably produce exosomes with desired cargo or surface proteins. | Cells overexpressing miRNA, targeting ligands (e.g., RGD peptide), or reporter proteins (e.g., GFP) [9]. |

Exosomes represent a sophisticated natural nanocarrier system whose biogenesis and cargo loading are governed by precise molecular mechanisms. A deep understanding of the ESCRT machinery, tetraspanin networks, and lipid-mediated sorting is fundamental to leveraging these vesicles for therapeutic purposes. In chronic wound research, the ability to engineer MSC exosomes—by loading them with specific regenerative cargoes like anti-inflammatory miRNAs and functionalizing their surface for targeted delivery—offers a powerful and promising strategy. This approach holds the potential to shift the paradigm from conventional wound management to precise, effective, and cell-free nanomedicine, ultimately promoting functional tissue regeneration.

The Four Phases of Wound Healing and Exosome Participation

Chronic wounds represent a significant clinical challenge, failing to progress through the normal, orderly sequence of wound healing phases. Within the broader thesis of engineering mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) exosomes for targeted drug delivery in chronic wound research, understanding the fundamental biology of wound healing is paramount. Exosomes, nanosized extracellular vesicles secreted by cells, have emerged as promising therapeutic agents and drug delivery vehicles due to their role in intercellular communication and regenerative processes [11] [12]. These vesicles, typically 30-150 nm in diameter, carry bioactive molecules including proteins, lipids, mRNAs, and microRNAs that can modulate recipient cell behavior [13] [14]. This application note details the four phases of wound healing, examines exosome participation in each phase, and provides structured experimental data and protocols to support research into engineered MSC exosomes for chronic wound therapy.

The Four Phases of Wound Healing

Normal wound healing progresses through four highly integrated and overlapping phases: hemostasis, inflammation, proliferation, and remodeling [12] [14]. Chronic wounds are characterized by disruptions in this progression, often remaining arrested in the inflammatory phase [12]. The following sections analyze each phase and the participative role of exosomes, with supporting quantitative data.

Hemostasis Phase

Immediately following injury, the hemostasis phase initiates to stop bleeding and establish a provisional wound matrix. Platelets adhere to exposed subendothelial matrix, activate, and form a platelet plug [14]. The coagulation cascade converts fibrinogen to fibrin, stabilizing the clot [14]. Activated platelets release chemokines including platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) and transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β), initiating recruitment of inflammatory cells and fibroblasts [14].

Exosome Participation: While platelets themselves release extracellular vesicles, MSC-derived exosomes can influence this phase by modulating initial inflammatory signals and cellular recruitment. Their surface proteins facilitate binding to extracellular matrix components, potentially enhancing localization to wound sites.

Inflammatory Phase

Following hemostasis, neutrophils infiltrate to phagocytose pathogens and damaged tissue, followed by monocyte-derived macrophages which initially exhibit a pro-inflammatory (M1) phenotype before transitioning to an anti-inflammatory, pro-repair (M2) phenotype [14]. This transition is crucial for progression to subsequent healing phases. Chronic wounds often display persistent inflammation with sustained M1 polarization and elevated pro-inflammatory cytokines [12].

Exosome Participation: MSC-derived exosomes contain immunomodulatory molecules that facilitate macrophage polarization from M1 to M2 phenotype [14]. Specific exosomal miRNAs, including miR-146a and miR-223, inhibit NF-κB signaling and suppress NLRP3 inflammasome activation, resolving excessive inflammation [14]. Preconditioned MSC-derived exosomes further enhance anti-inflammatory polarization via let-7b signaling [14].

Proliferative Phase

This phase features re-epithelialization, angiogenesis, and fibroblast activation. Keratinocytes migrate across the wound bed to restore epidermis, while endothelial cells form new capillaries under guidance of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and fibroblast growth factor 2 (FGF-2) [14]. Fibroblasts infiltrate and secrete type III collagen and fibronectin, forming granulation tissue [12]. TGF-β1 activates fibroblasts to synthesize extracellular matrix (ECM) [14].

Exosome Participation: MSC and adipose-derived stem cell (ADSC) exosomes enhance fibroblast proliferation and migration via miRNAs including miR-21, miR-29a, and others [14]. They promote angiogenesis by transferring pro-angiogenic factors and miRNAs to endothelial cells [11]. Evidence indicates stem cell-derived exosomes accelerate collagen synthesis and epithelialization [11].

Remodeling Phase

The final phase can extend for months to years after wound closure, involving neovasculature regression, ECM reorganization, and collagen maturation from type III to type I [12] [14]. This process restores tissue strength and functionality. Aberrant remodeling leads to pathological scarring, characterized by excessive fibroblast proliferation and ECM deposition [12].

Exosome Participation: Exosomes modulate scar formation by regulating fibroblast differentiation and collagen deposition. Engineered exosomes (eExo) can be designed with specific "anti-scarring" properties to prevent hypertrophic scarring and keloid formation [12]. They influence TGF-β signaling pathways that control myofibroblast differentiation and activity.

Quantitative Analysis of Exosome Therapeutic Effects

Recent clinical and preclinical studies demonstrate the therapeutic potential of exosomes in wound healing. The following tables summarize key quantitative findings.

Table 1: Clinical Outcomes of Exosome Therapy in Chronic Wound Management

| Case Profile | Wound Characteristics | Exosome Treatment Protocol | Key Clinical Outcomes | Doppler Ultrasound Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 58-year-old female with diabetes and venous insufficiency [15] [16] | Chronic ulcer >6 months duration [15] [16] | Monthly applications of ADSC-derived exosomes (Exo-HL) for 3 months [15] [16] | Wound size reduction with healthy granulation tissue within 15 days [15] [16] | Arterial resistive index: 0.89→0.72; Venous reflux time: 2.8→1.2 seconds [15] [16] |

| 62-year-old female with recurrent ulcers [15] [16] | Ulcers persistent >2 years despite conventional therapy [15] [16] | Monthly applications of ADSC-derived exosomes (Exo-HL) [15] [16] | Complete granulation and re-epithelialization with no inflammation/necrosis [15] [16] | Peak systolic velocity: 28→42 cm/s; Resistive index: 0.92→0.78 [15] [16] |

| 42-year-old male with chronic venous insufficiency [15] [16] | 6-year history of recurrent ulcers refractory to treatment [15] [16] | Monthly applications of ADSC-derived exosomes (Exo-HL) over 7 months [15] [16] | Near-complete resolution with restored skin integrity by month 7 [15] [16] | Resistive index: 0.95→0.75; Venous reflux time: 3.2→1.6 seconds [15] [16] |

| 44-year-old female with post-cellulitis ulcer [16] | Chronic ulcer with recommended amputation [16] | Monthly applications of ADSC-derived exosomes (Exo-HL) [16] | Complete ulcer closure with restored skin integrity [16] | Peak systolic velocity: 15→38 cm/s; Resistive index: 0.97→0.82 [16] |

Table 2: Molecular Cargo of MSC-Derived Exosomes in Wound Healing

| Exosome Cargo Category | Specific Components | Biological Functions in Wound Healing | Target Cells/Pathways |

|---|---|---|---|

| Growth Factors [15] | VEGF, FGF, TGF-β, EGF, PDGF [15] | Stimulate angiogenesis, promote cell proliferation, enhance ECM synthesis, modulate immune response [15] | Endothelial cells, fibroblasts, keratinocytes [15] |

| MicroRNAs (miRNAs) [15] [14] | miR-21, miR-29a, miR-146a, miR-223, let-7b [14] | Regulate gene expression related to inflammation, angiogenesis, fibroblast proliferation [15] [14] | NF-κB signaling, NLRP3 inflammasome, TGF-β pathways [14] |

| Proteins [13] | Tetraspanins (CD9, CD63, CD81), ESCRT-related proteins (Tsg101, Alix), heat shock proteins (Hsp90, Hsp70) [13] [2] | Structural components, cargo sorting, cell targeting, stress response [13] [2] | Recipient cell membranes, endosomal pathways [13] |

Experimental Protocols for Evaluating Exosome Effects in Wound Healing

Protocol: Isolation and Characterization of MSC-Derived Exosomes

Principle: Exosomes are isolated from MSC conditioned media via differential ultracentrifugation and characterized for size, concentration, and marker expression [15] [2].

Reagents and Equipment:

- MSC culture medium (e.g., DMEM with 10% exosome-depleted FBS)

- Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)

- Ultracentrifuge with fixed-angle and swinging-bucket rotors

- Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis (NTA) instrument

- Transmission Electron Microscope (TEM)

- Western blot equipment

- Antibodies against exosomal markers (CD9, CD63, CD81, Tsg101)

Procedure:

- Cell Culture: Culture MSCs to 70-80% confluence in complete medium. Replace with serum-free medium or medium containing exosome-depleted FBS for 48 hours [2].

- Conditioned Media Collection: Collect conditioned media and perform sequential centrifugation: 300 × g for 10 min (remove cells), 2,000 × g for 20 min (remove dead cells), 10,000 × g for 30 min (remove cell debris) [2].

- Ultracentrifugation: Transfer supernatant to ultracentrifuge tubes. Centrifuge at 100,000 × g for 70 minutes at 4°C. Discard supernatant, resuspend pellet in PBS, and repeat ultracentrifugation [15] [2].

- Resuspension: Resuspend final exosome pellet in PBS and store at -80°C [15].

- Characterization:

- NTA: Dilute exosomes in PBS and analyze using NTA to determine size distribution and concentration [15] [2].

- TEM: Apply exosomes to formvar/carbon-coated grids, negative stain with uranyl acetate, and image via TEM to assess morphology [2].

- Western Blot: Confirm presence of exosomal markers (CD9, CD63, CD81, Tsg101) and absence of negative markers (e.g., calnexin) [2].

Protocol: In Vitro Wound Healing Assay (Scratch Assay) with Exosome Treatment

Principle: This assay evaluates the effect of exosomes on fibroblast and keratinocyte migration, critical processes in the proliferative phase of wound healing.

Reagents and Equipment:

- Human dermal fibroblasts or keratinocytes

- Cell culture plates (6-well or 24-well)

- Exosome preparations (20-100 μg/mL)

- Mitomycin C (optional, to inhibit proliferation)

- Time-lapse microscope or standard inverted microscope

- ImageJ software with wound healing plugin

Procedure:

- Cell Seeding: Seed fibroblasts or keratinocytes in 6-well plates at high density (2-5×10^5 cells/well) and culture until 90-100% confluent.

- Scratch Creation: Create a straight scratch in the cell monolayer using a sterile 200 μL pipette tip. Wash gently with PBS to remove detached cells.

- Exosome Treatment: Add exosomes suspended in serum-free medium at desired concentration (typically 20-100 μg/mL). Include controls (vehicle alone).

- Image Acquisition: Capture images at the beginning (0 hour) and at regular intervals (e.g., 6, 12, 24 hours) at the same location using a microscope.

- Quantitative Analysis: Measure scratch area using ImageJ software. Calculate percentage wound closure: [(Initial area - Area at time t)/Initial area] × 100.

- Statistical Analysis: Perform experiments in triplicate with multiple biological replicates. Analyze using Student's t-test or ANOVA with post-hoc tests.

Protocol: In Vivo Evaluation of Engineered Exosomes in Diabetic Wound Healing

Principle: This protocol assesses the efficacy of engineered MSC exosomes in a diabetic mouse wound healing model, monitoring wound closure, histology, and vascularization.

Reagents and Equipment:

- Diabetic mice (e.g., db/db mice or STZ-induced diabetic C57BL/6 mice)

- Engineered MSC exosomes

- Hydrogel delivery system (e.g., hyaluronic acid hydrogel) [10]

- Digital calipers or photographic wound measurement system

- Histology equipment

- CD31 antibodies for immunohistochemistry

Procedure:

- Wound Creation: Anesthetize mice and create full-thickness excisional wounds on dorsal skin (typically 6-8 mm diameter).

- Exosome Administration:

- Wound Monitoring: Photograph wounds daily with scale reference. Calculate wound area using image analysis software.

- Tissue Collection: Euthanize mice at predetermined time points (e.g., days 7, 14, 21). Harvest wound tissue with surrounding normal skin.

- Histological Analysis:

- Process tissue for paraffin embedding and sectioning.

- Perform H&E staining to assess re-epithelialization and granulation tissue formation.

- Use Masson's trichrome staining to evaluate collagen deposition and organization.

- Conduct immunohistochemistry for CD31 to quantify angiogenesis (microvessel density).

- Data Analysis: Compare wound closure rates, complete healing time, and histological parameters between treatment groups.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Exosome Wound Healing Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Key Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Exosome Isolation Kits | Total Exosome Isolation Kit, miRCURY Exosome Kit | Isolation of exosomes from cell culture media or biological fluids | Rapid extraction of exosomes using polymer-based precipitation or immunoaffinity methods |

| Characterization Instruments | Nanoparticle Tracking Analyzer (NTA), qNano | Size distribution and concentration analysis of exosome preparations | Quantitative analysis of exosome size and concentration through light scattering and Brownian motion tracking |

| Surface Marker Antibodies | Anti-CD9, Anti-CD63, Anti-CD81, Anti-Tsg101 | Identification and validation of exosomes via Western blot, flow cytometry | Confirmation of exosomal identity through detection of characteristic surface and internal proteins |

| Engineered Exosome Systems | HEK293T-derived engineered exosomes, MSC-derived exosomes with modified surface proteins | Targeted drug delivery to specific wound cell types | Enhanced specificity and therapeutic efficacy through surface engineering with targeting ligands (peptides, antibodies) |

| Hydrogel Delivery Systems | Hyaluronic acid hydrogel, Chitosan hydrogel | Sustained release of exosomes at wound site | Provision of moist wound environment with controlled release kinetics for prolonged exosome activity [10] |

| Cell Culture Models | Human dermal fibroblasts, Keratinocytes (HaCaT), Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) | In vitro assessment of exosome effects on cellular processes | Modeling cellular responses including migration, proliferation, and tube formation relevant to wound healing phases |

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

Diagram 1: The Four Phases of Wound Healing and Exosome Participation. This workflow illustrates the sequential progression through hemostasis, inflammation, proliferation, and remodeling phases, with specific exosome-mediated mechanisms participating in each phase [12] [14].

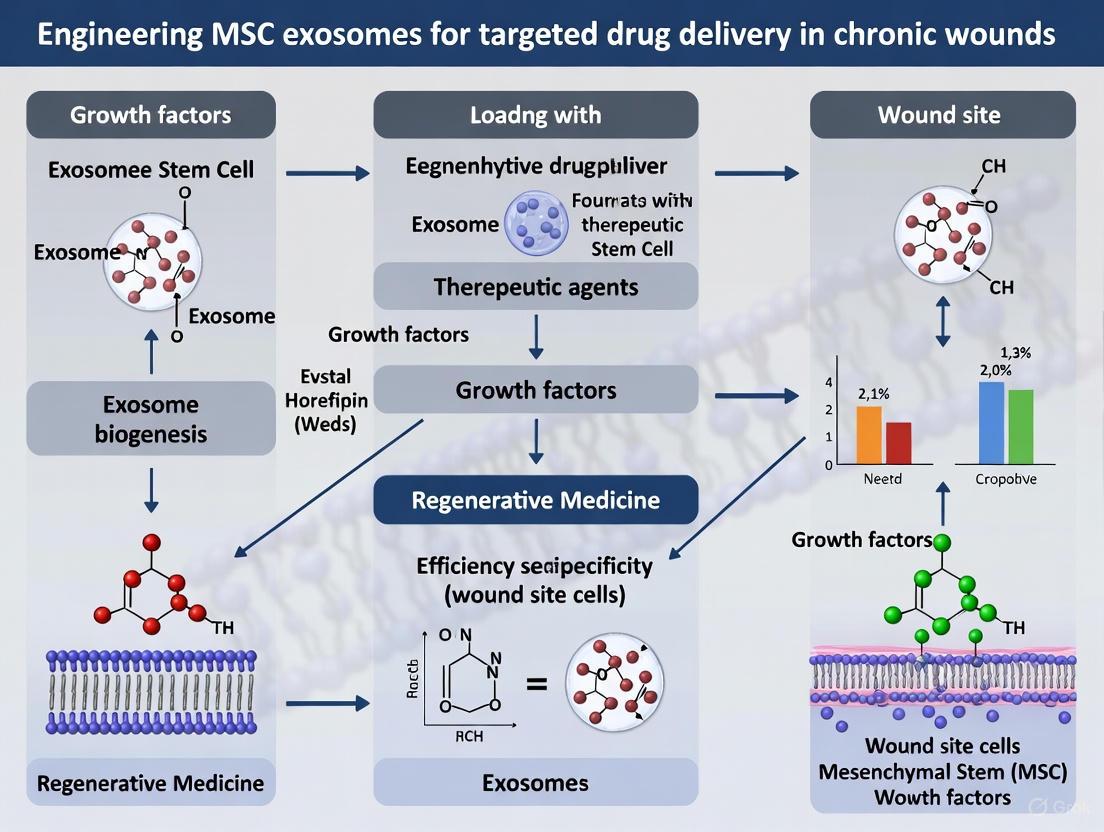

Diagram 2: Engineered Exosome Workflow for Chronic Wound Therapy. This diagram outlines the process from MSC source selection through exosome isolation, engineering, delivery, and therapeutic mechanisms leading to improved healing outcomes [11] [10] [12].

The participation of exosomes across all four phases of wound healing underscores their therapeutic potential for chronic wound management. Engineered MSC exosomes represent a promising platform for targeted drug delivery, addressing multiple pathological aspects of chronic wounds simultaneously. The structured data, experimental protocols, and reagent solutions provided in this application note offer researchers a foundation for advancing this innovative therapeutic approach. As the field progresses, standardization of isolation methods, optimization of engineering strategies, and comprehensive safety profiling will be essential for clinical translation. Future research should focus on personalized exosome therapeutics tailored to specific wound etiologies and patient profiles.

The therapeutic potential of mesenchymal stem cell (MSC)-derived exosomes in chronic wound healing stems from their diverse cargo of biologically active molecules. These nano-sized extracellular vesicles (30-150 nm) function as sophisticated intercellular communication systems, delivering specific miRNAs, proteins, and lipids that collectively modulate the wound microenvironment [14] [17]. By transferring these bioactive components to recipient cells, MSC exosomes promote anti-inflammatory responses, enhance angiogenesis, stimulate cellular proliferation and migration, and facilitate extracellular matrix remodeling—addressing multiple pathological aspects of chronic wounds simultaneously [18] [19] [12]. The inherent biocompatibility, low immunogenicity, and targetability of exosomes present significant advantages over whole-cell therapies, positioning them as promising next-generation therapeutics for recalcitrant wounds [14] [19] [20].

Recent advances in exosome engineering have further enhanced their therapeutic potential by enabling precise cargo loading and surface modifications for improved targeting and efficacy [12]. This Application Note provides a comprehensive overview of key therapeutic cargos in MSC exosomes, detailed experimental protocols for their analysis and engineering, and advanced delivery strategies optimized for chronic wound applications. The integration of engineered exosomes into biomaterial scaffolds represents a particularly promising approach for creating pro-regenerative wound dressings that provide sustained release of therapeutic factors at the wound site [12] [21].

Quantitative Analysis of Key Exosomal Cargos

Therapeutic miRNAs in MSC Exosomes for Skin Regeneration

Table 1: Key Exosomal miRNAs and Their Functions in Wound Healing

| miRNA | Biological Target/Pathway | Primary Functions | Therapeutic Effects | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| miR-21 | PTEN/PDCD4 | Anti-apoptotic, promotes fibroblast migration | Regulates apoptosis, enhances cell survival | [18] [22] |

| miR-126 | PI3K/Akt, SPRED1 | Angiogenesis promotion | Increases tube formation, accelerates wound closure | [18] [23] |

| miR-124 | p250GAP, anti-inflammatory pathways | Neuroprotection, anti-inflammatory | Reduces neural tissue inflammation, promotes neuronal growth | [22] |

| miR-133b | RhoA, PI3K/Akt pathways | Neural regeneration | Improves nerve cell survival, promotes nerve regeneration | [22] |

| miR-146a | NF-κB signaling | Anti-inflammatory | Inhibits NF-κB, reduces inflammatory response | [14] |

| miR-29a | ECM proteins | Fibrosis regulation | Promotes fibroblast migration, reduces scarring | [14] |

| miR-135a | LATS2 (Hippo pathway) | Promotes epithelialization | Enhances keratinocyte and fibroblast migration | [23] |

| miR-210 | HIF-1 signaling, DNA repair | Angiogenesis, cellular survival | Enhances DNA repair in hypoxic conditions | [23] |

| miR-17-92 | PTEN/Akt/FOXO1 | Angiogenesis, cell survival | Promotes neural regeneration | [22] |

| let-7b | Inflammatory signaling | Macrophage polarization | Enhances anti-inflammatory polarization | [14] |

The miRNA cargo within MSC-derived exosomes represents a master regulatory network that coordinates multiple aspects of wound repair. These small non-coding RNAs (typically 19-24 nucleotides in length) function through partial complementarity to target mRNAs, leading to mRNA degradation or translational repression [18]. The selective sorting of specific miRNAs into exosomes ensures their protected delivery to recipient cells in the wound microenvironment, where they simultaneously modulate clusters of genes involved in inflammation, angiogenesis, and tissue remodeling [18] [24].

Mechanistically, miR-126 exemplifies the pro-angiogenic capacity of exosomal miRNAs by targeting SPRED1 and enhancing VEGF signaling through the PI3K/Akt and MAPK pathways, directly addressing the impaired angiogenesis characteristic of chronic wounds [18] [23]. Similarly, miR-21 modulates apoptosis through FasL/PTEN/PDCD4 pathways, promoting fibroblast survival in the hostile wound environment [18] [22]. The anti-inflammatory miRNA-146a suppresses NF-κB signaling, thereby reducing persistent inflammation that impedes chronic wound healing [14]. These miRNAs operate in concert, creating a coordinated regenerative program that makes exosomes uniquely suited for addressing the multifactorial pathology of chronic wounds.

Protein and Lipid Cargos in MSC Exosomes

Table 2: Functional Protein and Lipid Cargos in MSC Exosomes

| Cargo Type | Specific Components | Biological Functions | Therapeutic Effects | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tetraspanins | CD63, CD9, CD81 | Exosome biogenesis, cellular uptake | Facilitates target cell recognition and fusion | [18] [19] |

| Heat Shock Proteins | HSP70, HSP90 | Protein folding, membrane fusion | Enhances cellular stress response, promotes vesicle fusion | [19] |

| Annexins | Annexin I, II, V | Membrane fusion, anti-inflammatory | Mediates exosome-cell membrane fusion | [19] |

| Growth Factors | VEGF, FGF, TGF-β1 | Angiogenesis, cell proliferation | Stimulates new blood vessel formation, tissue regeneration | [14] [17] |

| ECM Proteins | Fibronectin, Collagens | Matrix organization, cell adhesion | Supports granulation tissue formation | [17] |

| Lipids | Cholesterol, Sphingolipids, Phosphatidylserine | Membrane stability, signaling | Maintains structural integrity, enables cell recognition | [18] [17] |

| Rab GTPases | Rab27a/b | Exosome secretion, trafficking | Regulates exosome release and intracellular trafficking | [19] |

The protein and lipid components of MSC exosomes contribute significantly to their therapeutic efficacy through both structural and functional roles. Tetraspanins (CD63, CD9, CD81) not only serve as characteristic exosome markers but also facilitate cellular uptake and target cell recognition [18] [19]. Heat shock proteins, particularly HSP70 and HSP90, contribute to protein folding and enhance cellular stress response in recipient cells, while also participating in membrane fusion processes [19]. Growth factors including VEGF, FGF, and TGF-β1 are frequently identified in MSC exosomes and work synergistically with miRNA cargo to promote angiogenesis and tissue repair [14] [17].

The lipid bilayer of exosomes contains cholesterol, sphingolipids, and phosphatidylserine, which not only provide structural integrity but also participate in signaling and cellular recognition [18] [17]. The lipid composition contributes to the stability of exosomes in biological fluids and influences their fusion capabilities with target cell membranes. This complex integration of proteins and lipids with nucleic acid cargo creates a multifaceted therapeutic system that surpasses single-factor approaches for chronic wound management.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Isolation and Characterization of MSC-Derived Exosomes

Principle: Isolate and characterize exosomes from MSC-conditioned media using ultracentrifugation and validate through size, concentration, and marker expression analysis.

Materials:

- Human MSCs (bone marrow or adipose-derived)

- Serum-free MSC culture medium

- Differential ultracentrifugation equipment

- PBS (phosphate-buffered saline)

- Transmission Electron Microscope (TEM)

- Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis (NTA) system

- BCA protein assay kit

- Antibodies for CD63, CD81, CD9, TSG101, Calnexin

Procedure:

- Cell Culture and Conditioning: Culture MSCs to 70-80% confluence in complete medium. Replace with serum-free medium and culture for 48 hours. Collect conditioned medium and remove cells and debris by centrifugation at 2,000 × g for 30 minutes [17] [20].

Exosome Isolation: Ultracentrifuge the supernatant at 10,000 × g for 30 minutes to remove larger vesicles. Filter through a 0.22 μm membrane. Ultracentrifuge at 100,000 × g for 70 minutes. Wash pellet in PBS and repeat ultracentrifugation. Resuspend final exosome pellet in PBS [17] [12].

Characterization:

- NTA: Dilute exosomes 1:1000 in PBS and analyze using Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis to determine size distribution and concentration [17].

- TEM: Fix exosomes in 2% paraformaldehyde, deposit on Formvar-carbon coated grids, negative stain with 2% uranyl acetate, and image by transmission electron microscopy to confirm cup-shaped morphology [18] [17].

- Western Blotting: Confirm presence of exosomal markers (CD63, CD81, CD9, TSG101) and absence of negative marker (Calnexin) [17] [12].

- Protein Quantification: Determine protein concentration using BCA assay [17].

Quality Control: Ensure particle size distribution of 30-150 nm with peak around 100 nm. Confirm presence of at least three positive markers and absence of negative markers. Maintain sterility throughout the process for therapeutic applications.

Protocol 2: miRNA Cargo Analysis by qRT-PCR

Principle: Isolate and quantify specific miRNAs from exosomes to characterize their cargo profile and potential therapeutic activity.

Materials:

- Isolated exosomes (from Protocol 1)

- miRNeasy Mini Kit or equivalent

- miScript II RT Kit

- miScript SYBR Green PCR Kit

- miRNA-specific primers

- Real-time PCR system

Procedure:

- RNA Extraction: Add Qiazol to exosome sample (max 200 μL). Add chloroform and centrifuge at 12,000 × g for 15 minutes. Transfer aqueous phase to new tube and add 1.5 volumes ethanol. Pass through RNeasy column, wash, and elute in RNase-free water [18] [22].

cDNA Synthesis: Use miScript HiFlex Buffer to reverse transcribe all RNAs including miRNAs. Use 1 μg total RNA in 20 μL reaction. Incubate at 37°C for 60 minutes, then 95°C for 5 minutes [18].

qPCR Amplification: Prepare reactions with 2× QuantiTect SYBR Green PCR Master Mix, 10× miScript Primer Assay (specific for target miRNAs), template cDNA, and RNase-free water. Run with activation at 95°C for 15 minutes, followed by 40 cycles of 94°C for 15 seconds, 55°C for 30 seconds, and 70°C for 30 seconds [18] [22].

Data Analysis: Use the 2^(-ΔΔCt) method to calculate relative expression levels. Normalize to spiked-in cel-miR-39 or endogenous controls (e.g., RNU6B, SNORDs) [22].

Troubleshooting: Low RNA yield may indicate inefficient exosome isolation. Include positive controls for RNA extraction and RT steps. Ensure primer specificity for mature miRNAs, not precursors.

Protocol 3: Engineering MSC Exosomes for Enhanced miRNA Loading

Principle: Modify MSC exosomes to enrich specific therapeutic miRNAs using electroporation-based loading methods.

Materials:

- Isolated exosomes (from Protocol 1)

- Synthetic miRNA mimics or inhibitors

- Electroporation system with cuvettes (2-4 mm gap)

- Opti-MEM reduced serum medium

- Heparin (to prevent aggregation)

- RNase inhibitor

Procedure:

- Preparation: Isolate exosomes as in Protocol 1. Resuspend in sterile PBS. Synthesize or purchase synthetic miRNA mimics with modified sequences for enhanced stability [12].

Electroporation: Mix exosomes (100-500 μg protein) with miRNA (10-100 pmol) in electroporation buffer. Transfer to pre-chilled electroporation cuvette. Apply optimized electroporation parameters (typically 400-700 V, 125-150 μF, ∞ resistance) [12].

Post-treatment: Immediately after electroporation, incubate on ice for 30 minutes. Add RNase inhibitor to final concentration of 0.5 U/μL to degrade unencapsulated miRNA. Add heparin (10 U/mL) to prevent aggregation [12].

Purification: Remove unencapsulated miRNAs using size-exclusion chromatography (e.g., qEV columns) or ultracentrifugation. Validate loading efficiency using qRT-PCR (Protocol 2) [12].

Validation: Compare miRNA levels before and after loading. Assess exosome integrity by TEM and NTA. Confirm functional delivery to recipient cells using reporter assays.

Signaling Pathway Diagrams

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Exosome Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Considerations | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Isolation Kits | Total Exosome Isolation Kit, qEV size exclusion columns | Rapid exosome purification from conditioned media | Balance between purity, yield, and cost for specific applications | [17] |

| Characterization Instruments | Nanoparticle Tracking Analyzer, TEM, Western Blot apparatus | Size distribution analysis, morphological confirmation, marker validation | NTA provides size/concentration; TEM confirms morphology; WB validates markers | [17] [12] |

| miRNA Analysis Kits | miRNeasy kits, miScript PCR kits, TaqMan MicroRNA assays | RNA extraction, cDNA synthesis, miRNA quantification | Select appropriate normalization controls (spiked-in synthetic miRNAs recommended) | [18] [22] |

| Engineering Tools | Electroporation systems, Lipofectamine, Click Chemistry reagents | Loading therapeutic cargo into exosomes, surface modifications | Electroporation optimizes miRNA loading; surface modifications enhance targeting | [12] |

| Cell Culture reagents | Serum-free MSC media, characterization antibodies (CD73, CD90, CD105) | MSC expansion, phenotype confirmation | Use serum-free conditions for therapeutic exosome production | [17] [20] |

| Functional Assay Kits | Tube formation assay kits, migration assay kits, apoptosis detection kits | In vitro validation of exosome bioactivity | Test relevant functions: angiogenesis, migration, anti-apoptotic effects | [14] [23] |

Advanced Delivery Systems for Chronic Wounds

The translation of exosome therapeutics into clinical applications for chronic wounds requires advanced delivery systems that protect exosomes and provide controlled release at the wound site. Biomaterial-based scaffolds have emerged as particularly promising delivery platforms that can maintain exosome viability and extend their retention in the dynamic wound environment [12] [21].

Hydrogel systems, including hyaluronic acid, chitosan, and alginate-based formulations, offer tunable physical properties that can be customized to match specific wound characteristics. These hydrophilic networks protect exosomes from degradation while allowing controlled diffusion to the wound bed. Recent advances include the development of thermosensitive hydrogels that transition from liquid to gel at body temperature, facilitating conformal application to irregular wound surfaces [12]. Additionally, scaffold systems incorporating exosomes within nanofibrous matrices mimic the native extracellular architecture, providing both structural support and sustained release of therapeutic factors.

Innovative delivery formats such as lyophilized exosome powders, dissolvable microneedle arrays, and sprayable formulations address the practical challenges of clinical wound care. Lyophilization preserves exosome stability during storage while allowing reconstitution at the point of care, with trehalose-based cryoprotectants demonstrating particular efficacy in maintaining vesicle integrity [19]. These advanced delivery strategies significantly enhance the translational potential of MSC exosome therapies by improving handling, stability, and application efficiency.

MSC-derived exosomes represent a sophisticated natural delivery system for multiple therapeutic cargos that collectively address the complex pathophysiology of chronic wounds. The coordinated action of miRNAs, proteins, and lipids within these nanovesicles enables simultaneous modulation of inflammation, angiogenesis, cellular migration, and extracellular matrix remodeling—key processes that are dysregulated in non-healing wounds. The experimental protocols outlined in this Application Note provide a foundation for the isolation, characterization, and engineering of MSC exosomes to enhance their therapeutic potential.

Future developments in exosome therapeutics will likely focus on precision engineering approaches to create customized vesicles with optimized cargo loading and cell-specific targeting capabilities. The integration of multi-omics technologies will enable more comprehensive characterization of exosome cargo profiles and their functional correlates. Additionally, standardized manufacturing protocols and rigorous quality control measures will be essential for clinical translation. As the field advances, combination therapies integrating engineered exosomes with advanced biomaterials and conventional wound care approaches offer promising strategies for addressing the significant clinical challenge of chronic wounds.

Mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes (MSC-Exos) represent a transformative advancement in regenerative medicine, particularly for chronic wound treatment, by addressing critical safety concerns associated with whole-cell therapies. While mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) themselves have demonstrated therapeutic potential, their clinical application is hampered by significant risks, including immunogenicity, tumorigenicity, and embolism formation from cell entrapment in pulmonary capillaries [25] [26]. MSC-derived exosomes, as natural, nanoscale extracellular vesicles (30-150 nm in diameter), encapsulate the therapeutic components of MSCs—such as proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids—while exhibiting markedly reduced risks [25] [27]. Their inherent biological properties make them particularly suitable for the complex, dysregulated microenvironment of chronic wounds, offering a sophisticated, cell-free system for targeted drug delivery and tissue regeneration.

Key Advantages of MSC Exosomes Over Cell-Based Approaches

Reduced Immunogenicity

The low immunogenic potential of MSC-Exos is a cornerstone of their therapeutic safety profile, stemming from several intrinsic characteristics:

- Absence of Major Histocompatibility Complex (MHC) Molecules: Unlike their parent MSCs, MSC-Exos lack major histocompatibility complex class I (MHC-I) molecules and do not express MHC-II molecules under normal conditions [25] [26]. This fundamental difference significantly lowers the risk of immune recognition and rejection upon administration [25].

- Surface Marker Profile: MSC-Exos carry surface markers common to all exosomes (CD63, CD81, CD9) as well as markers from the original stem cell (CD44, CD73, CD90) [27]. This profile contributes to their biocompatibility and minimizes nonspecific immune activation.

The practical consequence of these properties is that MSC-Exos can be administered allogeneically (from a donor to a non-identical recipient) without triggering a significant immune response, thereby eliminating the need for patient-specific, autologous cell harvesting and expansion [25]. This advantage is particularly valuable in chronic wound management, where repeated applications may be necessary over extended periods.

Minimal Tumorigenicity Risk

The tumorigenicity risk of MSC-Exos is substantially lower compared to whole-cell therapies due to their non-replicative nature:

- Lack of Replicative Capacity: As acellular vesicles, exosomes cannot replicate or divide, eliminating the risk of uncontrolled growth or formation of ectopic tissue [25] [28]. This intrinsic safety feature addresses one of the most significant concerns surrounding stem cell-based interventions.

- Controlled Biological Activity: While MSC-Exos actively modulate recipient cell behavior through cargo delivery (e.g., microRNAs, proteins), they do not integrate into the host genome or possess transformative potential, further minimizing theoretical oncogenic risks [17].

This safety profile is especially relevant for chronic wound patients, who may have underlying conditions that predispose them to neoplastic transformations, and for whom long-term therapeutic safety is paramount.

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of Key Safety Parameters Between MSCs and MSC-Exos

| Safety Parameter | MSC-Based Therapy | MSC-Exosome Therapy | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Immunogenicity Profile | Expresses MHC-I; potential for immune recognition | Lacks MHC complexes; minimal immune activation | [25] [26] |

| Tumorigenic Potential | Theoretical risk of uncontrolled differentiation/growth | Non-replicative; no risk of uncontrolled growth | [25] [28] |

| Administration Risks | Risk of pulmonary embolism from cell entrapment | Nanoscale size prevents vascular occlusion | [25] [26] |

| Therapeutic Precision | Broad paracrine signaling with variable effects | Targeted delivery of specific bioactive cargo | [12] [28] |

Experimental Protocols for Evaluating Immunogenicity and Tumorigenicity

Robust assessment of immunogenicity and tumorigenicity is essential for validating the safety profile of MSC-Exos in chronic wound applications. The following protocols provide standardized methodologies for these critical evaluations.

Protocol 1: In Vitro Immunogenicity Assessment

This protocol evaluates the potential of MSC-Exos to stimulate immune cell proliferation and activation, key indicators of immunogenicity.

Materials and Reagents:

- Isolation: Ficoll-Paque PLUS density gradient medium

- Culture: RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 10% exosome-depleted FBS, 1% penicillin-streptomycin, 2 mM L-glutamine

- Stimulation: Phytohemagglutinin (PHA)

- Detection: CFSE cell proliferation dye, anti-human CD3/CD28 activation antibodies, flow cytometry antibodies for CD4, CD8, CD25, CD69

Procedure:

- Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cell (PBMC) Isolation: Isolate PBMCs from healthy human donors using density gradient centrifugation with Ficoll-Paque PLUS.

- CFSE Labeling: Resuspend PBMCs at 1×10^7 cells/mL in PBS containing 1 μM CFSE and incubate for 10 minutes at 37°C. Quench staining with 5 volumes of ice-cold complete media.

- Co-culture Setup: Seed CFSE-labeled PBMCs (1×10^5 cells/well) in 96-well U-bottom plates with:

- Negative control: Media alone

- Positive control: PHA (5 μg/mL)

- Experimental groups: MSC-Exos (1×10^10 particles/mL) or whole MSCs (1:10 MSC:PBMC ratio)

- Incubation and Analysis: Culture for 5 days at 37°C with 5% CO2. Harvest cells and stain with anti-CD3, CD4, CD8, CD25, and CD69 antibodies. Analyze T cell proliferation (CFSE dilution) and activation (CD25/CD69 expression) using flow cytometry.

Expected Outcomes: MSC-Exos should demonstrate significantly reduced T cell proliferation and activation marker expression compared to PHA-positive controls and whole MSCs, confirming their low immunogenicity.

Protocol 2: In Vivo Tumorigenicity Assay

This protocol assesses the potential for in vivo tumor formation following MSC-Exo administration, using an immunodeficient mouse model that permits the growth of human cells.

Materials and Reagents:

- Animals: NOD.Cg-Prkdcscid Il2rgtm1Wjl/SzJ (NSG) mice, 6-8 weeks old

- Test Articles: MSC-Exos (1×10^11 particles), whole MSCs (1×10^6 cells)

- Injection: Sterile PBS, 27-gauge needles

- Monitoring: Calipers, in vivo imaging system (if using luciferase-labeled MSCs)

Procedure:

- Preparation: Resuspend MSC-Exos in 100 μL sterile PBS for injection. Prepare whole MSCs similarly as a positive control group.

- Administration: Divide NSG mice into three groups (n=10/group):

- Group 1: Subcutaneous injection of MSC-Exos into the right flank

- Group 2: Subcutaneous injection of whole MSCs into the right flank

- Group 3: Subcutaneous injection of PBS (vehicle control)

- Observation Period: Monitor mice twice weekly for 16 weeks for:

- Palpable mass formation at injection site

- Body weight and general health status

- Any signs of distress or morbidity

- Terminal Analysis: At 16 weeks, euthanize all remaining animals and conduct complete necropsy. Weigh and preserve any masses for histological analysis (H&E staining).

Expected Outcomes: The MSC group may develop palpable masses confirming the model's sensitivity, while the MSC-Exos group should show no evidence of tumor formation, comparable to the PBS control group.

Research Reagent Solutions for MSC Exosome Studies

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for MSC Exosome Characterization and Functional Analysis

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Key Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Isolation Kits | ExoQuick-TC, Total Exosome Isolation Kit | Exosome purification from cell culture media | Polymer-based precipitation for high-yield recovery |

| Characterization Antibodies | Anti-CD63, CD81, CD9, Alix, TSG101 | Western blot, flow cytometry, immunoelectron microscopy | Confirmation of exosomal identity and purity |

| MSC Marker Antibodies | Anti-CD73, CD90, CD105, CD44 | Flow cytometry of parent cells and exosomes | Verification of MSC origin |

| Nanoparticle Tracking | NanoSight NS300, ZetaView | Size distribution and concentration analysis | Quantitative measurement of exosome preparation |

| miRNA Analysis | miRNeasy Mini Kit, TaqMan MicroRNA Assays | Cargo analysis and functional studies | Identification of therapeutic miRNAs in exosomes |

Signaling Pathways in MSC Exosome-mediated Wound Healing

The therapeutic effects of MSC-Exos in chronic wounds are mediated through precise modulation of key signaling pathways. The following diagram illustrates the primary molecular mechanisms through which MSC-Exos promote healing while avoiding excessive immune activation or fibrotic responses.

The demonstrated safety advantages of MSC-derived exosomes—specifically their low immunogenicity and minimal tumorigenicity risk—position them as superior therapeutic agents compared to whole-cell therapies for chronic wound management. These intrinsic safety characteristics, combined with their robust regenerative capabilities, facilitate their transition from research tools to clinical therapeutics. The standardized protocols and analytical frameworks presented herein provide researchers with validated methodologies for rigorously assessing these critical safety parameters, ensuring that future MSC-Exo applications in wound healing continue to meet the highest standards of efficacy and safety. As the field advances, engineered exosomes with enhanced targeting specificity and controlled cargo release will further amplify these inherent advantages, ultimately offering personalized, precise therapeutic interventions for patients suffering from chronic wounds.

Engineering Strategies for Enhanced Targeting and Cargo Delivery

The therapeutic potential of mesenchymal stem cell (MSC)-derived exosomes in chronic wound healing is increasingly recognized, with their ability to modulate inflammation, promote angiogenesis, and enhance tissue regeneration [14] [12]. A critical step in engineering these exosomes for targeted drug delivery involves the efficient loading of therapeutic cargoes, such as nucleic acids, proteins, or small molecule drugs. This application note provides a detailed comparison and standardized protocols for three fundamental loading techniques: transfection, electroporation, and sonication, specifically framed within the context of chronic wound research.

Comparative Analysis of Loading Techniques

The choice of loading method significantly impacts the loading efficiency, exosome integrity, and subsequent biological activity. The table below summarizes the key characteristics of each technique for loading MSC exosomes.

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of Exosome Cargo Loading Techniques

| Parameter | Transfection | Electroporation | Sonication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Mechanism | Chemical-based complex formation and endocytosis [29] | Electrical field-induced membrane pores [29] | Ultrasonic cavitation and mechanical disruption [30] |

| Typical Loading Efficiency | Variable; highly cargo-dependent | ~10-20% for miRNAs/siRNAs; can be lower for plasmids [29] | High for small molecules and proteins |

| Cargo Type | Nucleic acids (DNA, RNA), proteins [29] | Primarily nucleic acids (siRNA, miRNA, plasmid DNA) [29] | Proteins, small molecule drugs, nucleic acids |

| Exosome Integrity Risk | Low to Moderate | High (can cause cargo aggregation & membrane damage) | Moderate to High (over-sonication causes irreversible damage) |

| Throughput | High (easily scalable) | Medium | Medium |

| Key Advantage | Compatibility with diverse cargo types; ease of use | Direct, physical method for nucleic acid loading | Efficient for a broad range of cargo sizes and types |

| Key Limitation | Potential cytotoxicity; need for optimization of reagent:cargo ratio | Risk of exosome aggregation and cargo precipitation [29] | Requires precise parameter control to avoid destruction |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Transfection of Parent MSCs

This protocol involves loading the desired cargo into parent MSCs, leading to the secretion of naturally packaged exosomes.

Workflow: Transfection of Parent MSCs

Materials:

- MSCs: Human adipose-derived or bone marrow MSCs (Passage 3-5) [14] [15].

- Therapeutic Cargo: e.g., plasmid DNA encoding an anti-inflammatory cytokine (e.g., IL-10) or miRNA mimic/inhibitor.

- Transfection Reagent: A commercial cationic polymer or lipid-based reagent (e.g., polyethyleneimine (PEI) [29]).

- Opti-MEM Reduced Serum Medium.

Procedure:

- Cell Seeding: Seed 5 x 10^5 MSCs into a T-75 culture flask and incubate overnight until 60-80% confluent.

- Complex Formation:

- Dilute 5 µg of plasmid DNA in 250 µL of Opti-MEM. Mix gently.

- Dilulate the transfection reagent (volume according to manufacturer's instructions, e.g., a 2:1 reagent:DNA ratio for PEI) in 250 µL of Opti-MEM. Incubate for 5 minutes at room temperature.

- Combine the diluted DNA and diluted transfection reagent. Mix gently and incubate for 20 minutes at room temperature to allow complex formation.

- Transfection:

- Aspirate the growth medium from the MSCs and wash once with PBS.

- Add 5 mL of fresh, pre-warmed complete growth medium to the flask.

- Add the DNA-transfection reagent complex dropwise onto the cells. Gently swirl the flask to distribute evenly.

- Incubation and Exosome Harvest:

- Incubate cells at 37°C for 6 hours.

- Carefully aspirate the medium containing the complexes, wash cells with PBS, and add 15 mL of exosome-depleted complete medium.

- Incubate for 48 hours to allow exosome secretion.

- Exosome Isolation:

Electroporation of Isolated Exosomes

This protocol describes the direct loading of cargo into pre-isolated MSC exosomes.

Workflow: Direct Exosome Electroporation

Materials:

- Purified MSC Exosomes: 1 x 10^10 particles in PBS.

- Cargo: e.g., 2 nmol of siRNA targeting a pro-fibrotic gene (e.g., TGF-β1) for scar revision [12].

- Electroporation Buffer: Low-conductivity buffer, such as 250 mM sucrose or specialized commercial buffers.

- Electroporator and corresponding 2- or 4-mm gap cuvettes.

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Mix the purified exosomes with the siRNA cargo in a final volume of 100-200 µL of electroporation buffer. Gently pipette to mix.

- Electroporation:

- Transfer the mixture to a pre-chilled electroporation cuvette.

- Apply a single electrical pulse. Optimization Note: For siRNA loading, parameters in the range of 150-500 V and a 5-10 ms pulse length are a common starting point. Excessive voltage can cause exosome aggregation [29].

- Post-Pulse Recovery: Immediately after electroporation, incubate the cuvette on ice for 30-60 minutes to allow pore resealing.

- Purification: To remove unencapsulated siRNA, use a centrifugal ultrafiltration device (e.g., 100 kDa MWCO) or size-exclusion chromatography. Resuspend the final loaded exosomes in PBS for downstream applications.

Sonication of Isolated Exosomes

This protocol uses ultrasound to transiently disrupt the exosome membrane for cargo loading.

Workflow: Sonication for Exosome Loading

Materials:

- Purified MSC Exosomes: 1 x 10^10 particles in PBS.

- Cargo: e.g., 50 µM of an anti-inflammatory small molecule drug (e.g., Curcumin) or a fluorescent dye for tracking.

- Probe Sonicator with a micro-tip.

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Mix the purified exosomes with the cargo in a total volume of 100-200 µL in a microcentrifuge tube. Keep the tube on ice throughout the procedure.

- Sonication:

- Insert the sterilized micro-tip of the sonicator into the sample. Ensure the tip is fully immersed but not touching the tube walls.

- Sonicate the mixture on ice. A typical protocol uses a pulse sequence of 5 seconds ON and 10 seconds OFF, for a total ON time of 60-120 seconds, at a power output of 20-40 W [30]. Critical Note: Power and time must be optimized to balance loading efficiency with exosome integrity. Over-sonication leads to irreversible damage.

- Recovery and Purification: After sonication, incubate the sample on ice for 30-60 minutes to allow membrane recovery. Remove unincorporated cargo using a centrifugal ultrafiltration device (e.g., 100 kDa MWCO).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Materials for Exosome Engineering

| Item | Function/Description | Example & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Cationic Polymers | Complex with nucleic acids for transfection; facilitate cellular uptake and endosomal escape [29]. | Polyethyleneimine (PEI): High efficiency but can be cytotoxic; requires ratio optimization. |

| Electroporation Buffer | Low-conductivity medium for electroporation; minimizes heat generation and preserves exosome viability. | 250 mM Sucrose solution: A common, non-ionic buffer that provides a suitable environment for pulse delivery. |

| Ultrafiltration Devices | Concentrate and purify exosomes; remove unincorporated cargo and small contaminants post-loading. | 100 kDa MWCO centrifugal filters: Effectively retain exosomes while allowing free small molecules and salts to pass through. |

| Exosome-Depleted FBS | Used in cell culture during exosome production; ensures that isolated exosomes are host cell-derived, not serum-derived. | Commercial FBS, ultracentrifuged or filtered: Critical for controlled experiments and therapeutic applications. |

| Probe Sonicator | Applies high-frequency sound waves to disrupt exosome membranes for sonication-based loading. | Micro-tip sonicator: Essential for small sample volumes (100-500 µL); must be used on ice to prevent overheating. |

Concluding Remarks

The selection of an optimal cargo loading technique is a critical determinant for the success of engineered MSC exosome therapies in chronic wound healing. Transfection is ideal for pre-loading nucleic acids via parent cells, while direct electroporation offers a rapid method for nucleic acid encapsulation into pre-formed exosomes, albeit with aggregation risks. Sonication provides versatility for various cargo types but requires careful parameter control. The protocols outlined herein provide a foundation for researchers to standardize and optimize the engineering of MSC exosomes, paving the way for advanced, cell-free therapeutics for complex wound management.

Within the broader thesis focus on engineering mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) exosomes for targeted drug delivery in chronic wound therapy, precise surface functionalization is paramount. Chronic wounds are characterized by a complex microenvironment featuring persistent inflammation, impaired angiogenesis, and excessive proteolytic activity [31] [12]. Surface engineering enables the decoration of exosomes with specific targeting ligands, such as peptides, to direct these natural nanocarriers to particular cell types within the wound bed—such as endothelial cells, keratinocytes, or macrophages—thereby enhancing therapeutic efficacy and reducing off-target effects [32] [33]. This Application Note details the core ligand conjugation strategies and provides standardized protocols for achieving robust and reproducible exosome targeting.

Ligand Conjugation Strategies: A Comparative Analysis

Multiple post-production strategies exist for conjugating targeting ligands to extracellular vesicles (EVs), including MSC-derived exosomes. The choice of strategy significantly impacts the conjugation efficiency, ligand orientation, and ultimately, the targeting specificity. The following table summarizes the primary technical approaches.

Table 1: Comparison of Post-Production Ligand Conjugation Strategies for MSC Exosomes

| Strategy | Mechanism | Key Advantages | Key Limitations | Typical Ligand Density (Per 100 nm²) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrophobic Insertion | Ligand-lipid conjugates (e.g., DSPE-PEG-MAL) insert into the exosome membrane via hydrophobic interactions [34] [32]. | Simple procedure; high conjugation efficiency (>90%); high ligand density [32]. | Potential ligand leakage; possible formation of micelle contaminants [32]. | Several to tens of ligands [32]. |

| Enzyme-Mediated Conjugation | Phospholipase D (e.g., sPLD) catalyzes the transfer of functional groups (e.g., maleimide) onto surface phospholipids for subsequent ligand coupling [32]. | Uniform ligand distribution; minimal disruption to endogenous surface proteins; superior targeting performance in some systems [32]. | Requires optimized enzyme activity and concentration [32]. | High, can be tuned by enzyme dose [32]. |

| Chemical Coupling (Protein) | Disulfide bonds on exosome surface proteins are reduced to thiols, allowing covalent conjugation to maleimide-functionalized ligands [32]. | Covalent bond ensures stability; high conjugation efficiency (>90%) [32]. | Can alter native structure/function of surface proteins; may affect inherent exosome tropism [32]. | Varies, can decrease at high reductant concentrations [32]. |

The following workflow diagram illustrates the decision-making process for selecting and implementing a conjugation strategy.

Conjugation Strategy Workflow

Experimental Protocols

This section provides detailed, step-by-step methodologies for two prominent surface engineering techniques: enzyme-mediated conjugation and hydrophobic insertion.

Protocol: Enzyme-Mediated Conjugation via sPLD

This protocol describes the use of Streptomyces phospholipase D (sPLD) to introduce maleimide groups onto exosome surfaces for precise, covalent ligand attachment [32].

Principle: The sPLD enzyme catalyzes the transphosphatidylation of phosphatidylcholine (PC) on the exosome membrane, replacing the choline headgroup with a maleimide-functionalized alcohol (e.g., HEMI). This introduces a bio-orthogonal handle for site-specific conjugation of thiol-containing ligands [32].

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for sPLD Conjugation

| Item | Function/Description | Exemplary Supplier/Type |

|---|---|---|

| MSC-Exosomes | The therapeutic nanocarrier to be functionalized. | Isolated from MSC conditioned media via ultracentrifugation or SEC [31]. |

| sPLD Enzyme | Catalyzes the headgroup exchange on surface phospholipids. | Recombinant Streptomyces phospholipase D [32]. |

| N-(2-Hydroxyethyl)maleimide (HEMI) | Substrate providing maleimide handle for conjugation. | Chemical synthesis supplier [32]. |

| Thiolated Targeting Ligand | The peptide or other molecule conferring target specificity. | Synthesized peptide with C-terminal cysteine [33]. |

Procedure:

- Exosome Preparation: Isolate and purify MSC-derived exosomes using size-exclusion chromatography (SEC) or ultracentrifugation. Resuspend the exosome pellet in reaction buffer (e.g., 25 mM HEPES, 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.4) to a concentration of 1-5 × 10¹¹ particles/mL.

- Maleimide Functionalization: To the exosome solution, add HEMI to a final concentration of 1 mM and sPLD at an optimized concentration (e.g., 1-10 U/mL). Incubate the reaction mixture for 2 hours at 37°C with gentle agitation [32].

- Purification: Remove excess HEMI and enzyme by passing the mixture through a SEC column (e.g., qEVoriginal) equilibrated with conjugation buffer (e.g., PBS, pH 7.0).

- Ligand Conjugation: Immediately incubate the maleimide-functionalized exosomes with the thiolated targeting peptide (e.g., at a 50:1 molar ratio of peptide to exosomes) for 4-16 hours at 4°C, protected from light.

- Purification of Final Product: Separate conjugated exosomes from unreacted peptide using a SEC column. Collect the exosome-rich fractions and characterize the ligand density and size (e.g., via nFCM, NTA) [32].

Protocol: Hydrophobic Insertion of Peptide-Lipid Conjugates

This protocol outlines a method to modify exosomes by incorporating synthesized peptide-PEG-lipid conjugates directly into the lipid bilayer [32] [35].

Principle: Amphiphathic molecules, such as DSPE-PEG-MAL (1,2-distearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine-N-[maleimide(polyethylene glycol)]), spontaneously insert their hydrophobic lipid tails into the exosome membrane via hydrophobic interactions. The PEG spacer improves solubility and ligand presentation, while the terminal maleimide group allows for covalent conjugation to thiolated peptides [32] [35].

Procedure:

- Peptide-Lipid Conjugate Preparation: Synthesize or obtain the DSPE-PEG-MAL conjugate. Alternatively, first incorporate DSPE-PEG-MAL into exosomes, then conjugate the peptide. For the latter, incubate purified exosomes with DSPE-PEG-MAL (e.g., at a 1:5000 molar ratio of lipid to exosomes) for 1-2 hours at room temperature [35].

- Purification of Intermediate: Remove unincorporated DSPE-PEG-MAL by SEC.

- Peptide Coupling: Incubate the DSPE-PEG-MAL-bearing exosomes with a thiolated homing peptide (e.g., CRPPR, which targets SDF-1 expressing sites in wounds) [34] at a predetermined optimal ratio. React for 4-16 hours at 4°C with gentle mixing, protected from light.

- Purification of Final Product: Separate peptide-conjugated exosomes from free peptide using SEC.

- Quality Control: Analyze the final product for particle concentration, size distribution, and conjugation efficiency. Techniques like nano-flow cytometry (nFCM) are highly suitable for quantifying ligand density on individual particles [32].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The following table catalogs key materials required for the surface engineering of exosomes as discussed in this note.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Exosome Surface Engineering

| Category | Reagent | Specific Function |

|---|---|---|

| Isolation & Purification | Size-Exclusion Chromatography (SEC) Columns | Isolate exosomes from contaminants and free labels based on size [32]. |

| Targeting Ligands | CRPPR Peptide | A homing peptide that targets sites expressing the chemokine SDF-1, relevant in wound healing [34]. |

| RGD Motif Peptides | Target integrins overexpressed on endothelial cells during angiogenesis [33] [35]. | |

| Chemical Linkers | DSPE-PEG-MAL | Amphiphilic polymer for membrane insertion and providing a maleimide group for peptide coupling [32] [35]. |

| Enzymatic Tools | Streptomyces Phospholipase D (sPLD) | Engineered phospholipase D for precise functionalization of surface phosphatidylcholine [32]. |

| Characterization | Nano-Flow Cytometry (nFCM) | Single-particle analysis for quantifying ligand density, size, and heterogeneity [32]. |

| Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) | Validates structural integrity of exosomes post-modification [32]. |

Concluding Remarks

The strategic application of surface engineering is a critical component in advancing MSC exosome-based therapies for chronic wounds. The protocols outlined herein for enzyme-mediated conjugation and hydrophobic insertion provide robust, quantifiable methods to equip exosomes with targeting ligands. The choice of method depends on the specific requirements for stability, ligand density, and preservation of native exosome function. As the field progresses, the standardization of these protocols and rigorous characterization using techniques like nFCM will be essential for translating engineered exosomes from a research tool to a clinically viable therapeutic for targeted drug delivery in chronic wound repair.

The therapeutic potential of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) in regenerative medicine, particularly for complex conditions such as chronic wounds, is primarily mediated through their potent paracrine activity. A significant component of this activity is attributed to MSC-derived exosomes (MSC-Exos), which are nano-sized extracellular vesicles that facilitate intercellular communication by transferring proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids to recipient cells [36] [37]. However, the inherent variability and often subdued potency of naïve MSCs and their exosomes following in vivo administration present significant clinical challenges. To overcome these limitations, preconditioning has emerged as a critical strategy. This process involves the deliberate exposure of MSCs to sub-lethal physiological or pathological stimuli ex vivo, thereby enhancing their subsequent therapeutic efficacy [38] [39].

Preconditioning operates on the principle of hormesis, where a moderate stressor triggers an adaptive cellular response, leading to improved function and resilience. In the context of a thesis focused on engineering MSC exosomes for targeted drug delivery in chronic wounds, preconditioning is a pivotal first step. It is a form of primary engineering that optimizes the "raw material"—the exosomes themselves—by enriching their cargo with beneficial miRNAs, proteins, and growth factors, thereby boosting their innate regenerative, anti-inflammatory, and angiogenic capabilities [39] [12]. This document provides detailed application notes and standardized protocols for three cornerstone preconditioning strategies: hypoxia, inflammatory cytokines, and lipopolysaccharide (LPS).

Preconditioning Strategies: Mechanisms and Quantitative Effects

Preconditioning enhances the immunomodulatory and regenerative functions of MSCs and their exosomes by mimicking the hostile environments of injury sites, such as chronic wounds. The table below summarizes the key effects and optimal conditions for each strategy.

Table 1: Summary of Preconditioning Strategies for MSCs

| Preconditioning Stimulus | Key Mediators/Pathways Upregulated | Primary Functional Outcomes | Optimal Protocol Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hypoxia | HIF-1α, AKT, VEGF, ANG, FGF, BDNF [38] | Enhanced cell survival, angiogenesis, & migration [38] | 1-5% O₂ for 24-72 hours [38] |

| Cytokines (IFN-γ & TNF-α) | IDO, PGE2, COX-2, Factor H [40] [38] | Potent immunomodulation; shifts macrophages to M2 anti-inflammatory phenotype [38] | IFN-γ: 10-50 ng/mL; TNF-α: 10-20 ng/mL; Duration: 24-48 hours [38] [39] |

| Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) | let-7 microRNA, TLR/NF-κB/STAT3/AKT pathway, miR-146a, miR-181a-5p [38] [39] | Enhanced anti-microbial & anti-inflammatory priming; promotes M2 macrophage polarization [38] [39] | Low-dose: 0.1 - 1 µg/mL; Duration: 24-48 hours [39] |

The quantitative enhancement of MSC secretome through preconditioning is particularly evident in the increased secretion of critical growth factors. The following table compiles experimental data demonstrating this effect.

Table 2: Quantitative Enhancement of Growth Factor Secretion in Preconditioned MSCs (Sample Data)

| Growth Factor | Naïve MSCs-S (pg/mL) | AA + IFN-γ Preconditioned MSCs-S (pg/mL) | Fold Change | Function |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HGF | ~1250 | ~3500 | ~2.8x | Mitogenesis, Angiogenesis [40] |

| NGF | ~7.5 | ~25 | ~3.3x | Neurite outgrowth, Cell survival [40] |

| VEGF | ~40 | ~125 | ~3.1x | Angiogenesis, Vascular permeability [40] |

| FGF2 | ~7 | ~20 | ~2.9x | Angiogenesis, Wound repair [40] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Hypoxic Preconditioning

Principle: Culturing MSCs in a low-oxygen environment (1-5% O₂) to mimic the ischemic nature of chronic wounds and stabilize Hypoxia-Inducible Factor-1α (HIF-1α), activating a pro-survival and angiogenic genetic program [38].

Materials:

- Confluent (70-80%) flask of human MSCs (e.g., BM-MSCs or UC-MSCs).

- Standard MSC growth medium.

- Hypoxia chamber or multi-gas CO₂ incubator.

- Pre-mixed gas mixture (1% O₂, 5% CO₂, balanced N₂).

- Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) and trypsin/EDTA.

Procedure:

- Cell Preparation: Harvest MSCs using standard trypsin/EDTA protocol. Count and seed cells at a density of 5,000-8,000 cells/cm² in standard growth medium. Allow cells to adhere for 24 hours under normal culture conditions (37°C, 5% CO₂, 21% O₂).

- Preconditioning: After 24 hours, replace the medium with fresh, pre-warmed growth medium.

- Hypoxia Induction: Quickly transfer the culture flasks/plates to the pre-equilibrated hypoxia chamber or incubator set to 1% O₂ and 5% CO₂ at 37°C.

- Incubation: Incubate the cells under hypoxic conditions for 48 hours. Ensure the chamber maintains a tight seal to prevent oxygen leakage.

- Collection of Conditioned Media (for Exosome Isolation): After 48 hours, carefully collect the conditioned media from the hypoxic cultures.

- Cell/Exosome Processing: Proceed to isolate exosomes immediately from the conditioned media using your method of choice (e.g., ultracentrifugation, tangential flow filtration). Alternatively, pre-conditioned MSCs can be harvested for direct therapy or analyzed for efficacy.