Engineering Synthetic mRNA for Cellular Reprogramming: Design Principles, Delivery Systems, and Therapeutic Applications

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the latest advancements in synthetic mRNA design for expressing reprogramming factors, a transformative approach in regenerative medicine and cell engineering.

Engineering Synthetic mRNA for Cellular Reprogramming: Design Principles, Delivery Systems, and Therapeutic Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the latest advancements in synthetic mRNA design for expressing reprogramming factors, a transformative approach in regenerative medicine and cell engineering. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational principles of mRNA modifications, delivery platforms like lipid nanoparticles, and methodologies for in vivo and ex vivo cellular reprogramming. The scope extends to troubleshooting immunogenicity and stability issues, optimizing translation efficiency and biodistribution, and validating efficacy through preclinical and clinical models. By synthesizing current research and future perspectives, this review serves as a strategic guide for developing next-generation mRNA-based therapies for genetic reprogramming, protein replacement, and cancer immunotherapy.

The Foundation of mRNA Reprogramming: From Basic Science to Therapeutic Concept

The Central Dogma of molecular biology describes the precise flow of genetic information from DNA to RNA to protein. Synthetic messenger RNA (mRNA) technology represents a direct and revolutionary application of this principle, harnessing the cell's own translational machinery to produce therapeutic proteins. Unlike DNA-based therapies, mRNA functions as a transient and non-integrating genetic tool; it acts as a set of temporary instructions in the cytoplasm that do not alter the host genome, thereby eliminating the risk of insertional mutagenesis [1] [2]. This profile makes it an exceptionally safe and versatile platform for a range of applications, most notably in inducing cellular reprogramming to generate induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) [3].

The clinical translation of iPSCs was initially hampered by the use of integrating viral vectors, which posed significant oncogenic risks [3]. mRNA-based reprogramming emerged as a compelling solution to this challenge. By delivering synthetic, modified mRNAs (mod-mRNAs) encoding reprogramming factors, researchers can achieve efficient, "footprint-free" reprogramming of somatic cells, producing high-quality iPSCs for regenerative medicine, disease modeling, and drug discovery [3] [4]. This whitepaper provides a technical guide to the principles, protocols, and key reagents underpinning this transformative technology.

Core Principles and Advantages of mRNA Reprogramming

Synthetic mRNA used for reprogramming is engineered to mimic mature, naturally occurring mRNA. Its key components include a 5' cap, 5' and 3' untranslated regions (UTRs), an open reading frame (ORF) encoding the reprogramming factor, and a 3' poly(A) tail [2]. These elements work in concert to ensure stability, efficient ribosome binding, and high-level protein expression.

The following table summarizes the decisive advantages of mRNA over other reprogramming methodologies.

Table 1: Comparison of Somatic Cell Reprogramming Methods

| Method | Mechanism | Genomic Integration? | Reprogramming Efficiency | Key Risks & Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Retroviral/Lentiviral Vectors [3] | Integrates transgenes into host DNA. | Yes | ~0.01% [3] | Insertional mutagenesis, tumorigenicity from reactivation. |

| Episomal Vectors [3] | Non-integrating DNA plasmid with origin of replication. | Very low frequency [3] | Low | Potential for random integration requires rigorous screening. |

| Protein Transduction [3] | Direct delivery of reprogramming factor proteins. | No | Extremely Low [3] | Inefficient cellular uptake and low potency. |

| Sendai Virus (SeV) [3] | Cytosolic, RNA-based virus vector. | No | High | Requires rigorous clearance of the persistent viral vector. |

| Synthetic mRNA (mod-mRNA) [3] [4] | Transient delivery of mRNA to cytoplasm. | No | Up to 90.7% of individually plated cells [4] | Triggers innate immune response; requires optimized delivery. |

As the table illustrates, mRNA reprogramming is uniquely positioned as the most unambiguously "footprint-free" and highly efficient method, offering supple control over factor dosing and stoichiometry [3].

Experimental Protocol for High-Efficiency mRNA Reprogramming

The following optimized protocol, adapted from a landmark study, enables ultra-high efficiency reprogramming of human primary fibroblasts [4].

Key Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for mRNA Reprogramming

| Reagent / Material | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Synthetic mod-mRNA Cocktail (e.g., 5fM3O) | A cocktail of modified mRNAs encoding reprogramming factors (e.g., M3O-OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, c-MYC, LIN28, NANOG). Nucleoside modifications enhance stability and reduce immunogenicity [4]. |

| miRNA-367/302s Mimics (m-miRNAs) | Co-delivered mature miRNA mimics that act as reprogramming enhancers, synergizing with transcription factors to dramatically boost efficiency [4]. |

| Lipofectamine RNAiMAX | A proprietary lipid-based transfection reagent optimized for the delivery of RNA molecules into a wide range of cell types. |

| Opti-MEM (pH adjusted to 8.2) | A buffered salt solution used as the transfection buffer. Adjusting the pH from the standard ~7.3 to 8.2 was critical for achieving high transfection efficiency in primary fibroblasts [4]. |

| Knock-Out Serum Replacement (KOSR) Medium | A feeder-free, defined cell culture medium that supports the growth and reprogramming of human primary fibroblasts. |

Step-by-Step Workflow

- Cell Seeding: Plate 500 human primary fibroblasts per well of a 6-well plate in KOSR-based reprogramming medium. A low seeding density is crucial to allow for sufficient cell cycles, which promotes reprogramming [4].

- Transfection Complex Preparation:

- Dilute 600 ng of the 5fM3O mod-mRNA cocktail and 20 pmol of m-miRNAs in Opti-MEM-8.2 buffer.

- Mix Lipofectamine RNAiMAX separately in the same buffer.

- Combine the diluted RNA and transfection reagent, incubate to form complexes, and add dropwise to the cells.

- Reprogramming Schedule: Transfect cells every 48 hours for a total of seven transfections [4]. Transfection intervals of 48 hours were found to be optimal, with 72-hour intervals reducing efficiency and 24-hour intervals causing cytotoxicity.

- Colony Selection and Expansion: After the transfection series, continue culture until iPSC colonies emerge. Colonies can be identified by morphological changes and stained for pluripotency markers like TRA-1-60. Positive colonies can be picked and expanded into stable cell lines [4].

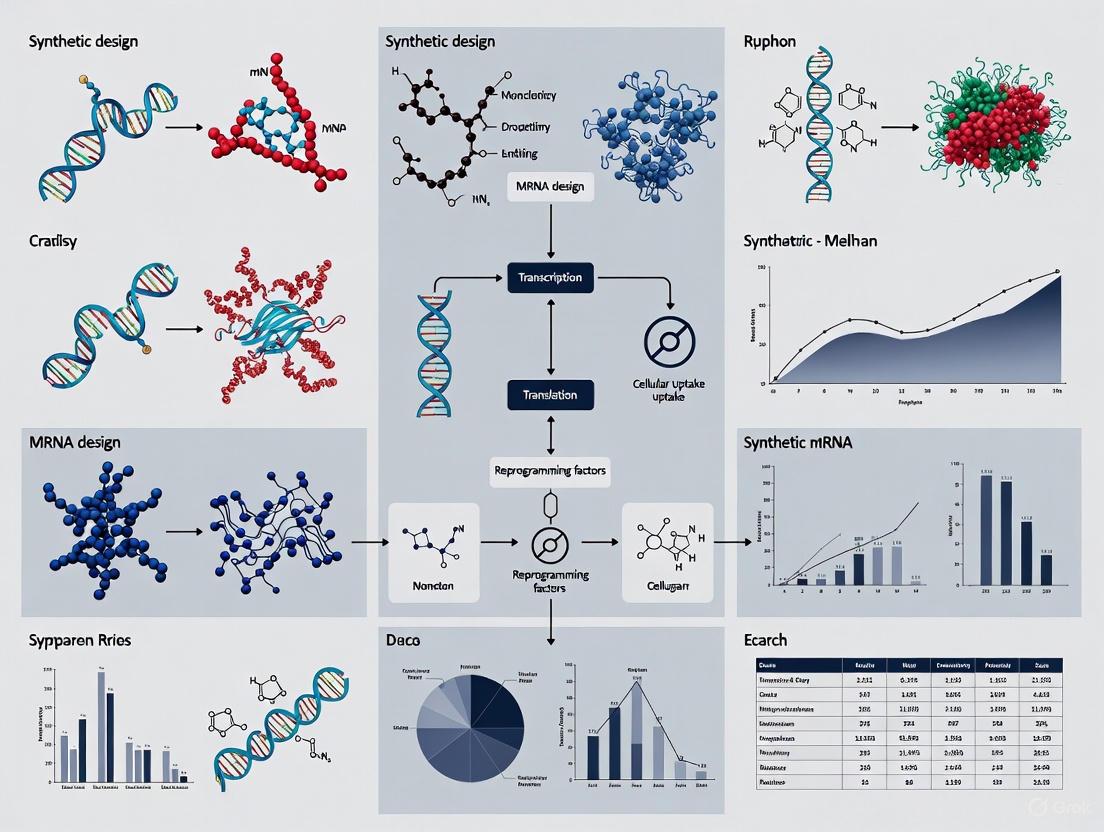

The logical flow and critical parameters of this protocol are visualized below.

Quantitative Data and Optimization

The success of the protocol is highly dependent on specific conditions. The data below highlights the impact of key variables.

Table 3: Impact of Transfection Buffer pH on Reprogramming Efficiency [4]

| Transfection Buffer pH | MWasabi Transfection Efficiency | TRA-1-60+ Colonies per 500 Cells |

|---|---|---|

| Opti-MEM (pH 7.3) | Low | 0 |

| Opti-MEM (pH 8.2) | ~65% | 3,896 ± 131 |

| Opti-MEM (pH 8.6) | High | 0 (Cytotoxic) |

Table 4: Effect of Transfection Interval on Colony Yield [4]

| Transfection Interval | Minimum Transfections Required | Relative Reprogramming Efficiency |

|---|---|---|

| 24 hours | - | Caused significant cell death |

| 48 hours | 3 | High (Optimal) |

| 72 hours | 3 | Reduced |

Signaling Pathways in mRNA-Induced Reprogramming

The delivered mod-mRNAs hijack the cell's native machinery to initiate a complex genetic reprogramming cascade. The encoded transcription factors (e.g., OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, c-MYC) bind to specific genomic targets, activating a self-reinforcing pluripotency network while silencing somatic cell programs [3]. The co-delivered m-miRNAs further enhance this process by repressing pro-differentiation and cell cycle checkpoint genes [4]. The entire process is enabled by the transient, high-level expression of proteins without genetic integration, as depicted in the following pathway.

Discussion and Future Perspectives

The methodology outlined herein demonstrates that mRNA technology has overcome major historical barriers in somatic cell reprogramming. The achievement of near-clonal efficiency, where up to 90.7% of individually plated cells can be reprogrammed, underscores the platform's potency and reliability [4]. The defined, feeder-free conditions make the resulting iPSCs highly suitable for clinical applications.

Future directions in mRNA reprogramming research will focus on several key areas:

- Novel Formulations: Continued development of lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) and other delivery systems to improve targeting and reduce innate immune sensing [2].

- Industrialization: Scaling the production of clinical-grade iPSCs using automated systems and single-use bioreactors, leveraging the inherent scalability of mRNA manufacturing [5].

- Broader Applications: Extending mRNA-based protein expression beyond reprogramming to treat a wide spectrum of diseases, including cancer, rare genetic disorders, and cardiovascular conditions [1] [2] [5].

In conclusion, synthetic mRNA has successfully reimagined a fundamental biological principle into a powerful, transient, and non-integrating genetic tool. Its application in cellular reprogramming marks a paradigm shift in regenerative medicine, providing a safe and highly efficient path to generate patient-specific iPSCs that will form the basis of next-generation therapies.

The field of cellular reprogramming, particularly the generation of induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), holds transformative potential for regenerative medicine and disease modeling. Traditional reprogramming methodologies have frequently relied on viral vectors, such as retroviruses or lentiviruses, for the delivery of reprogramming factors. While effective, these vectors present significant safety concerns for clinical translation, primarily due to their potential for insertional mutagenesis and oncogene activation [6] [7]. The emergence of synthetic mRNA as a versatile modality for transient gene expression offers a promising alternative that effectively mitigates these risks. This whitepaper details the key technical advantages of synthetic mRNA over viral vectors, focusing on its mechanisms for avoiding genomic integration and reducing tumorigenicity, thereby providing a safer framework for reprogramming factor delivery in research and therapeutic development.

Mechanisms of Action and Associated Risks

Viral Vectors: The Challenge of Genomic Integration

Viral vector systems are engineered to achieve high-efficiency gene transfer. Retroviruses and lentiviruses, for instance, are prized for their ability to integrate a transgene into the host cell's genome, enabling stable, long-term expression of reprogramming factors like OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, and c-MYC (OSKM) [6] [7]. However, this very mechanism underlies their most significant drawbacks:

- Random Genomic Integration: The integration process is non-targeted, posing a risk of insertional mutagenesis. Integration can disrupt tumor suppressor genes or activate oncogenes, potentially initiating malignant transformation [6]. A systematic investigation revealed that over 20% of human pluripotent stem cell (hPSC) samples possessed cancer-associated mutations, with 64% of these involving the TP53 tumor suppressor gene [7].

- Persistent Transgene Expression: The sustained, unregulated expression of reprogramming factors, particularly the oncogene c-MYC, following integration can directly contribute to tumorigenesis [7].

Table 1: Key Risks Associated with Viral Vector Systems

| Risk Factor | Underlying Mechanism | Potential Consequence |

|---|---|---|

| Insertional Mutagenesis | Random integration of viral DNA into the host genome [6]. | Disruption of tumor suppressor genes or activation of oncogenes [7]. |

| Oncogene Activation | Persistent expression of transgenes, including potent oncogenes like c-Myc [7]. | Uncontrolled cell proliferation and tumor formation [7]. |

| Immunogenicity | Immune recognition of viral capsid or envelope proteins [8]. | Immune-mediated clearance of transfected cells and reduced efficacy. |

Synthetic mRNA: A Non-Integrative and Transient Alternative

Synthetic mRNA technology fundamentally bypasses the risk of genomic integration by operating entirely within the cytoplasm. The mRNA molecule is translated by ribosomes without the need to enter the nucleus, thus eliminating the possibility of insertional mutagenesis [6]. Its activity is inherently transient, as the mRNA is subject to natural degradation processes, which prevents prolonged expression of reprogramming factors and mitigates the risk of tumorigenesis driven by factors like c-MYC [6] [7].

The following diagram illustrates the central dogma of molecular biology and highlights the key mechanistic differences between viral DNA vectors and synthetic mRNA, underscoring mRNA's cytoplasmic localization and non-integrative nature.

Experimental Validation and Methodologies

In Vitro and In Vivo Safety Profiling

Robust experimental protocols are essential for quantifying the safety advantages of mRNA-based reprogramming. Key methodologies include:

Protocol: Southern Blot Analysis for Genomic Integration

- Objective: To detect the physical integration of viral DNA into the host genome.

- Procedure: Genomic DNA is extracted from reprogrammed cells, digested with restriction enzymes, separated by gel electrophoresis, and transferred to a membrane. A labeled probe complementary to the viral vector sequence is used for hybridization.

- Expected Outcome: Cells treated with viral vectors will show distinct bands, indicating integration sites. mRNA-reprogrammed cells will show no bands, confirming the absence of integrated vector sequences [6].

Protocol: Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) for Off-Target Analysis

- Objective: To comprehensively assess the genomic integrity of iPSC lines.

- Procedure: Whole-genome sequencing (WGS) or targeted sequencing of known cancer-associated loci (e.g., TP53) is performed on mRNA- and virus-derived iPSC clones.

- Expected Outcome: mRNA-derived clones demonstrate a significantly lower burden of structural variants and indels at sensitive genomic loci compared to viral vector-derived clones [7].

Protocol: Tumorigenicity Assay In Vivo

- Objective: To evaluate the potential of reprogrammed cells to form tumors.

- Procedure: iPSCs are injected into immunodeficient mice (e.g., NSG mice). The animals are monitored for teratoma or tumor formation over several weeks.

- Expected Outcome: While all pluripotent cells can form teratomas, iPSCs generated with integrating viral vectors, especially those with persistent c-MYC expression, may form more aggressive, malignant tumors. mRNA-iPSCs show a more controlled and safer profile [7].

Quantitative Data on Efficacy and Safety

Research directly comparing reprogramming methods consistently highlights the superior safety profile of mRNA-based approaches.

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of Reprogramming Vector Safety and Efficacy

| Parameter | Viral Vectors (Retro/Lenti) | Synthetic mRNA | Experimental Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genomic Integration | Yes, random integration [6]. | No, cytoplasmic expression only [6]. | Southern Blot / NGS |

| Oncogene Transgene Persistence | Sustained, uncontrolled expression [7]. | Transient, lasting hours to days [6]. | qRT-PCR / Immunoblot |

| Tumorigenic Potential | Elevated risk due to integration and persistent transgene expression [7]. | Mitigated risk [7]. | In vivo teratoma assay |

| Reprogramming Efficiency | High, but variable [7]. | Can exceed viral methods with repeated transfections [6]. | Alkaline Phosphatase+ colony count |

| Immunogenicity | High (viral capsid/proteins) [8]. | Modifiable (can be reduced with nucleotide modifications) [9] [6]. | IFN-β ELISA / ISG expression analysis |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for mRNA Reprogramming

Successful implementation of mRNA reprogramming requires a suite of specialized reagents to ensure high efficiency, stability, and minimal immune activation.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for mRNA Reprogramming

| Reagent / Material | Function | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Pseudouridine-modified mRNA | Replaces uridine to reduce innate immune recognition by pattern recognition receptors (e.g., TLRs, RIG-I) and enhance translational efficiency [9] [6]. | Critical for enabling repeated transfections without triggering a potent IFN response. |

| Anti-Reverse Cap Analog (ARCA) | Co-transcriptional capping ensures proper orientation of the 5' cap structure (m7GpppG), enhancing mRNA stability and translation initiation [6]. | Superior to enzymatic capping post-transcription. |

| Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) | Synthetic delivery vehicles that protect mRNA from degradation and facilitate cellular uptake via endocytosis [9] [10]. | Formulation optimization is key for efficiency and minimizing cytotoxicity. |

| Immunosuppressive Adjuvants (e.g., B18R) | A decoy receptor for type I interferons that can be added to the culture medium to suppress the innate immune response to transfected mRNA, further boosting protein expression [6]. | Particularly useful in the initial stages of reprogramming. |

| Pattern Recognition Receptor Inhibitors | siRNAs or small molecules targeting PKR, TLRs, or other immune sensors can be co-delivered to create a more permissive environment for mRNA translation [6]. | An alternative or complement to nucleotide modification. |

| Apostatin-1 | Apostatin-1, MF:C19H27N3OS, MW:345.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| H-D-Phe-Pip-Arg-pNA dihydrochloride | H-D-Phe-Pip-Arg-pNA dihydrochloride, MF:C27H38Cl2N8O5, MW:625.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Synthetic mRNA technology represents a paradigm shift in the delivery of reprogramming factors, directly addressing the critical safety limitations of viral vectors. Its non-integrative nature and transient expression profile systematically dismantle the risks of insertional mutagenesis and oncogene-driven tumorigenicity. For researchers and drug developers aiming to translate iPSC technologies into clinically viable therapies, the adoption of mRNA-based reprogramming is no longer just an alternative but a necessary step toward ensuring patient safety and regulatory success. Future advancements in mRNA design, delivery, and immune modulation will continue to solidify its position as the cornerstone of safe cellular engineering.

In the realm of regenerative medicine and reprogramming factors research, synthetic messenger RNA (mRNA) has emerged as a powerful, transient vehicle for directing cellular fate and function. The technology enables researchers to instruct cells to produce specific therapeutic proteins without risking genomic integration, a significant advantage over viral vector systems [8]. The structural integrity of a synthetic mRNA construct is paramount to its success, dictating its stability, translational efficiency, and ultimately, its biological activity. A mature, in vitro-transcribed (IVT) mRNA is a sophisticated molecular entity composed of five core components: the 5' cap, the 5' untranslated region (UTR), an open reading frame (ORF) encoding the target protein, the 3' untranslated region (UTR), and the poly(A) tail [9]. Each element plays a critical and interdependent role in the mRNA's lifecycle, from nucleation to translation and eventual degradation. This guide provides an in-depth technical examination of these components, with a specific focus on their optimization for applications in cellular reprogramming and regenerative medicine.

Detailed Analysis of Structural Components

The 5' Cap

Function and Mechanism: The 5' cap is a modified nucleotide structure added to the extreme 5' end of the mRNA molecule. Its primary function is to protect the mRNA from degradation by 5' exonucleases and to serve as a recognition signal for the eukaryotic translation initiation machinery [9]. The cap structure interacts directly with the eukaryotic initiation factor 4E (eIF4E), a key component of the cap-binding complex that recruits the 43S pre-initiation complex to the mRNA, a critical first step in protein synthesis [11].

Technical Considerations for Reprogramming: For reprogramming applications involving prolonged protein expression, such as the induction of pluripotency or transdifferentiation, a cap analog that ensures high-fidelity capping is essential. The use of anti-reverse cap analogs (ARCAs) is standard practice, as they are incorporated exclusively in the correct orientation during IVT, leading to superior translation efficiency compared to non-ARCA caps.

The 5' and 3' Untranslated Regions (UTRs)

Function and Mechanism: The UTRs are non-coding sequences that flank the ORF. They are critical regulators of mRNA stability, subcellular localization, and translation efficiency [12]. The 5' UTR, located between the cap and the start codon, is instrumental in ribosome recruitment, scanning, and start codon selection [12]. Its length, nucleotide composition, and secondary structure are crucial; lengthy or GC-rich 5' UTRs can form complex secondary structures that impede ribosome scanning, thereby reducing translation efficiency [12]. The 3' UTR contains binding sites for various regulatory elements, including microRNAs (miRNAs) and RNA-binding proteins (RBPs), which influence the mRNA's half-life and translational output [13].

Optimization Strategies: Empirical screening and computational tools are employed to identify optimal UTR pairs for a given application.

- 5' UTR Selection: Research has demonstrated that the human β-globin 5' UTR consistently supports high levels of protein expression in mRNA vaccines and therapeutics [12]. Other effective 5' UTRs include those derived from cytochrome B-245 alpha chain (CYBA) and albumin genes [12]. The key design principles involve avoiding upstream AUG codons and minimizing GC content to prevent the formation of stable secondary structures.

- 3' UTR Selection: Studies have highlighted the potential of 3' UTRs from genes such as VP6 and superoxide dismutase (SOD) to enhance mRNA stability and expression [13]. These UTRs are enriched with stability elements that protect the mRNA from rapid deadenylation and decay.

Table 1: Evaluation of Common 5' UTRs in mRNA Design

| 5' UTR Source | Reported Expression Level | Key Characteristics | Suitability for Reprogramming |

|---|---|---|---|

| β-globin | Very High [12] | Minimal secondary structure, well-characterized | Excellent for sustained, high-level factor expression |

| α-globin | Moderate [12] | Similar to β-globin, commonly used | Reliable for general use |

| CYBA | High (plasmid); Low (mRNA) [12] | Performance varies with delivery method | Requires experimental validation |

| Albumin | Moderate to High [12] | Contains regulatory elements | Good potential, but context-dependent |

| Minimal/Synthetic | Moderate [12] | Short, designed to lack complex structure | Useful for reducing immunogenicity |

The Open Reading Frame (ORF) and Coding Sequence

Function and Mechanism: The ORF is the protein-coding core of the mRNA, comprising a start codon, the sequence encoding the amino acid chain, and a stop codon. For reprogramming research, the ORF typically encodes transcription factors (e.g., OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, c-MYC) or other morphogenic signals.

Optimization Strategies:

- Codon Optimization: The genetic code is degenerate, meaning multiple codons can encode the same amino acid. However, cells exhibit a bias for certain codons over others. Codon optimization involves replacing rare codons with synonymous, frequently used codons to enhance translational efficiency and accuracy, thereby maximizing protein yield.

- Nucleotide Modification: A pivotal breakthrough in mRNA technology was the discovery that incorporating modified nucleosides, such as N1-methylpseudouridine (m1Ψ), markedly reduces the immunogenicity of synthetic mRNA by evading recognition by innate immune sensors like Toll-like receptors [9] [14]. This suppression of interferon responses is critical for high-level protein expression, particularly for reprogramming factors that require prolonged expression without inducing a cellular antiviral state.

The Poly(A) Tail

Function and Mechanism: The poly(A) tail is a stretch of adenosine nucleotides at the 3' end of the mRNA. It plays a dual role in protecting the mRNA from exonucleolytic degradation and in enhancing translation by recruiting poly(A)-binding proteins (PABPs) [11] [9]. The PABPs bound to the tail interact with the eIF4F complex at the 5' end, effectively circularizing the mRNA and promoting ribosome recycling.

Recent Advances and Structural Innovations: While tail length (typically 100-150 nucleotides) is a known factor in stability, recent research explores the impact of tail structure.

- Linear Tails: The traditional design, a homopolymeric A-tail, is effective but can be susceptible to rapid deadenylation.

- Structured Tails: Introducing heterologous sequences or loop structures within the poly(A) tail can significantly enhance mRNA stability and expression. A 2025 study demonstrated that a design with a complementary linker sequence (A50L50LO) forming a small loop structure exhibited superior and more sustained protein expression both in vitro and in vivo compared to standard linear tails [11]. This is attributed to the secondary structure impeding the deadenylation process mediated by the CCR4–NOT complex [11]. Another study confirmed the high potency of a novel heterologous A/G tail (containing guanosine residues) as an alternative to traditional designs [13].

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of Poly(A) Tail Designs

| Poly(A) Tail Design | Description | Reported Performance | Mechanistic Insight |

|---|---|---|---|

| A120 (Linear) | Homopolymeric adenosine tail | Baseline stability and expression [11] | Standard design, susceptible to deadenylation |

| A30L70 (Linear) | Split tail with a linker (e.g., BioNTech design) | Good expression, positive control [11] | Prevents homopolymeric sequence recombination during IVT |

| A50L50LO (Loop) | Split tail with complementary linker forming a loop | Highest and most sustained expression [11] | Secondary structure impedes deadenylation, enhancing stability |

| Heterologous A/G Tail | Tail incorporating non-adenosine (G) residues | As potent as established platform tails [13] | Altered sequence chemistry may inhibit nuclease activity |

The following diagram illustrates the coordinated interactions between the core components of an optimized synthetic mRNA construct during the initiation of translation.

Experimental Protocols for mRNA Component Evaluation

In Vitro Screening of UTR and Poly(A) Tail Variants

Objective: To quantitatively compare the translation efficiency and stability of mRNA constructs with different UTRs or poly(A) tail designs.

Methodology:

- Construct Design: Clone the UTR or tail variants upstream or downstream of a reporter gene, such as firefly luciferase (F/L) or enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP), within a plasmid vector containing a bacteriophage promoter (e.g., T7).

- In Vitro Transcription (IVT): Linearize the plasmid templates and perform IVT reactions using a kit that incorporates clean cap analogs (e.g., Cap 1) and N1-methylpseudouridine.

- Cell Transfection: Transfect equimolar amounts of the purified mRNA constructs into a relevant cell line (e.g., HEK293T, A549, or target primary cells) using a lipid-based transfection reagent.

- Expression Analysis:

- Luminescence/Fluorescence: Measure reporter signal at multiple time points (e.g., 6, 24, 48, 72 hours post-transfection). Luminescence provides a quantitative measure, while fluorescence allows for visualization and counting of positive cells via immunofluorescence or flow cytometry [11] [12].

- Western Blot: For antigen-specific constructs (e.g., HIV gp145), confirm protein expression and size via Western blot analysis [12].

- Data Interpretation: Constructs that yield higher and more persistent reporter signal indicate superior UTR or tail configurations. The A50L50LO poly(A) tail, for instance, demonstrated sustained high luminescence in vivo where other tails showed rapid decline [11].

In Vivo Expression and Immunogenicity Profiling

Objective: To validate the performance of lead mRNA candidates in a live animal model, assessing both expression kinetics and immune responses.

Methodology:

- Formulation: Encapsulate the mRNA in lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) using microfluidic mixing. Characterize the resulting LNPs for size, polydispersity index (PDI), and encapsulation efficiency using dynamic light scattering (DLS) [11].

- Administration: Administer the mRNA-LNP formulation to mice via an appropriate route (e.g., intramuscular for vaccines, intravenous for systemic delivery).

- Expression Kinetics:

- Immune Response Analysis: For vaccine applications, immunize mice and analyze humoral and cellular immunity.

- Humoral Immunity: Measure antigen-specific antibody titers via ELISA.

- Cellular Immunity: Isolate splenocytes and analyze antigen-specific T-cell activation (e.g., CD8+ T-cells) by flow cytometry, measuring cytokine production (IFN-γ, TNF-α) and activation markers (CD69, CD25) [11].

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for mRNA Synthesis and Analysis

| Reagent / Tool | Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| T7 RNA Polymerase | Drives high-yield in vitro transcription from a T7 promoter. | Synthesizing milligram quantities of mRNA from a linearized DNA template. |

| N1-methylpseudouridine (m1Ψ) | Modified nucleotide that suppresses mRNA immunogenicity and enhances translation. | Replacing UTP in the IVT reaction to produce therapeutic-grade mRNA for reprogramming. |

| CleanCap Analog | Co-transcriptional capping reagent for adding Cap 1 structure with high efficiency. | Ensuring a high percentage of properly capped mRNA molecules for optimal translation initiation. |

| Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) | The leading delivery system for in vivo mRNA delivery, protecting mRNA and facilitating cellular uptake. | Formulating mRNA for intravenous or intramuscular injection in animal studies. |

| RNAfold / mfold | Bioinformatics tools for predicting mRNA secondary structure. | Evaluating 5' UTR sequences for stable, minimal structures that facilitate ribosome scanning [15]. |

| NetMHCpan | Algorithm for predicting peptide binding to Major Histocompatibility Complex (MHC). | In vaccine design, for in silico screening of encoded neoantigens for immunogenic potential [15]. |

The rational design of synthetic mRNA constructs, through the meticulous optimization of the 5' cap, UTRs, coding sequence, and poly(A) tail, is fundamental to unlocking the full potential of mRNA technology in reprogramming and regenerative medicine. The field is moving beyond simple linear designs towards sophisticated architectures, such as loop-stabilized poly(A) tails, that confer enhanced stability and prolonged protein expression. The integration of bioinformatics and artificial intelligence is further accelerating this progress, enabling the prediction of optimal UTRs, coding sequences, and secondary structures in silico [15]. As these tools mature, the design of patient- or application-specific mRNA constructs for precise cellular reprogramming will become increasingly efficient and robust, solidifying mRNA's role as a cornerstone of next-generation biotherapeutics.

The Role of Natural mRNA Modifications in Cellular Regulation and Their Synthetic Application

The epitranscriptome, comprising post-transcriptional chemical modifications to mRNA, represents a critical regulatory layer in gene expression. For researchers focused on synthetic mRNA design for reprogramming factors, understanding these natural modifications is paramount. These chemical marks dynamically influence mRNA stability, translation efficiency, immunogenicity, and subcellular localization. The strategic incorporation of key naturally occurring modifications into synthetic mRNA systems has already revolutionized therapeutic applications, most notably in vaccine development, and offers immense potential for refining the delivery and expression of reprogramming factors. This technical guide synthesizes current epitranscriptomic research with practical methodologies, providing a framework for leveraging natural RNA biology to advance synthetic mRNA design for cell fate manipulation.

The Landscape of Natural mRNA Modifications

Over 300 RNA modifications have been cataloged in the MODOMICS database, with a specific subset occurring in messenger RNA (mRNA) [16]. These modifications form a sophisticated regulatory network, often termed the "epitranscriptome," that fine-tunes gene expression without altering the underlying nucleotide sequence. While historically understudied compared to transfer and ribosomal RNA modifications, mRNA modifications are now recognized as dynamic, reversible marks that control critical aspects of RNA metabolism.

The research emphasis on different modifications varies significantly, often reflecting the availability of detection tools and established biological roles. Table 1 ranks the most studied mRNA modifications based on prevalence in scientific literature, providing insight into their current research prominence and perceived biological importance [16].

Table 1: Prevalence of Key mRNA Modifications in Scientific Literature

| Modification | Common Abbreviation | Relative Research Emphasis | Primary Functional Roles |

|---|---|---|---|

| N6-methyladenosine | m6A | Highest (e.g., >7000 PubMed citations) | mRNA stability, translation, splicing, nuclear export |

| Pseudouridine | Ψ | High | mRNA stability, translation, reduced immunogenicity |

| 5-methylcytidine | m5C | High | RNA export, translation, stability |

| Adenosine-to-Inosine Editing | A-to-I | High | Recoding potential, miRNA target site modulation |

| N1-methyladenosine | m1A | Medium | Translation regulation, structural modulation |

| N7-methylguanosine | m7G | Medium | 5' cap stability, translation initiation |

| 2'-O-methylation | Nm | Medium | Cap structure, stability, immune evasion |

| 5-hydroxymethylcytidine | hm5C | Emerging | Transcript-specific regulation, function under investigation |

The functional impact of these modifications is mediated by a system of "writers" (enzymes that add the modification), "erasers" (enzymes that remove it), and "readers" (proteins that recognize the mark and execute downstream functions) [16]. For instance, the m6A modification is installed by the METTL3-METTL14 methyltransferase complex, can be removed by the demethylases FTO and ALKBH5, and is interpreted by reader proteins such as the YTHDF family [16]. This regulatory apparatus allows the cell to respond rapidly to developmental and environmental cues by adjusting the transcriptome's output.

Core Functional Mechanisms of Key Modifications

m6A: The Master Regulator

N6-methyladenosine (m6A) is the most extensively studied mRNA modification. It is typically enriched in the 3' untranslated region (UTR) and near stop codons, where it plays a pivotal role in regulating mRNA decay, translational control, alternative splicing, and nuclear export [16]. Its influence on transcript dosage is crucial in processes such as embryonic stem cell differentiation, where it destabilizes pluripotency factor mRNAs, and in stress responses, where it enhances the translation of heat-shock proteins [16]. Dysregulation of m6A is implicated in several diseases, including cancer, where METTL3 overexpression can stabilize oncogenic transcripts [16].

Ψ and m5C: Stability and Fidelity

Pseudouridine (Ψ) is an isomer of uridine with a carbon-carbon glycosidic bond, which enhances base stacking and RNA rigidity. This leads to increased mRNA stability and improved translation fidelity [16]. In synthetic mRNA, Ψ is a key modification for reducing innate immune recognition, thereby decreasing stimulation of sensors like RIG-I and Toll-like receptors [17].

5-methylcytidine (m5C) influences mRNA export from the nucleus to the cytoplasm, translation efficiency, and mRNA stability [16] [18]. The contradictory results sometimes reported for m5C functions highlight its context-dependent roles, which can vary by cell type and physiological condition.

Cap-Associated Modifications: Controlling Translation and Immunity

The 5' cap structure of mRNA is critical for its stability and translation. The native m7G cap is recognized by the translation initiation factor eIF4E [17]. Further modifications, such as 2'-O-methylation (Nm) of the first transcribed nucleotide(s) to form Cap1 (m7GpppNm) or Cap2 structures, are instrumental in protecting mRNA from degradation and, crucially, in evading the innate immune system by preventing recognition by RIG-I [16] [17]. Synthetic cap analogs with improved properties, such as phosphorothioate substitutions or tetraphosphate bridges, have been developed to enhance translation and stability further [17].

m1A: An Emerging Player in Regulation

N1-methyladenosine (m1A) is gaining attention for its role in gene regulation. Recent quantitative studies using advanced LC-MS/MS techniques like mRQuant have revealed that m1A levels are significantly altered in cancer cells and in response to drug treatments like cisplatin and paclitaxel [19]. Knocking down m1A writer or eraser proteins in HeLa cells resulted in altered cell viability, cell cycle progression, and apoptosis, suggesting a significant role for this modification in cancer biology [19].

The following diagram illustrates the functional roles and spatial distribution of these key modifications on a canonical mRNA molecule.

Quantitative Profiling of the mRNA Epitranscriptome

Comprehensive quantification of mRNA modifications is essential for understanding their stoichiometry, dynamics, and functional impact. Liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) remains the gold standard for sensitive, specific, and simultaneous analysis of multiple modified ribonucleosides [19].

The mRQuant Methodology

The mRQuant technique represents a significant advancement, enabling the highly sensitive, high-throughput, and robust quantification of 84 different modified ribonucleosides in cellular mRNA [19]. The detailed protocol is as follows:

- mRNA Purification: Isolate high-purity mRNA from total RNA using methods such as oligo(dT) pull-down to minimize contamination from abundant non-coding RNAs (e.g., rRNA, tRNA).

- Enzymatic Digestion: Digest the purified mRNA (e.g., 500 ng) to individual ribonucleosides using a cocktail of nucleases, including Benzonase, phosphodiesterase I, and alkaline phosphatase.

- LC-MS/MS Analysis: Inject the digested sample into the LC-MS/MS system.

- Chromatography: Use a reversed-phase C18 column (e.g., Hypersil GOLD aQ, 150 × 2.1 mm, 3 μm) with a gradient of mobile phases A (1% Formic Acid in H₂O) and B (1% Formic Acid in ACN). The elution is performed at 36°C and a flow rate of 400 µL/min.

- Mass Spectrometry: Utilize a triple quadrupole mass spectrometer (e.g., Thermo Fisher TSQ Altis) with an electrospray ionization source in positive mode. Operate in Dynamic Multiple Reaction Monitoring (DMRM) mode for optimal sensitivity and specificity. Parameters include: Ion Transfer Tube Temp = 350°C, Sheath Gas = 45 Arb, and Spray Voltage = 3500 V.

- Quantification: Use standard curves generated from pure modified nucleoside standards for absolute quantification. The use of stable isotope-labeled internal standards (e.g., 15N5-dA) is recommended for highest accuracy.

Advanced Sequencing-Based Detection

While LC-MS/MS provides quantitative data on modification abundance, sequencing methods are required to map their precise locations. Nanopore direct RNA sequencing allows for the detection of RNA modifications in native RNA molecules without prior conversion or amplification, showing great promise for discovering novel modifications [16]. For specific modifications, chemical conversion methods are highly effective:

BACS for Pseudouridine (Ψ) Detection: The 2-bromoacrylamide-assisted cyclization sequencing (BACS) method enables quantitative profiling of Ψ at single-base resolution [20].

- Chemical Labeling: React RNA with 2-bromoacrylamide, which selectively labels Ψ, leading to a cyclized product (nce1,2Ψ).

- Library Preparation & Sequencing: Perform reverse transcription and next-generation sequencing. The cyclized nce1,2Ψ induces a specific Ψ-to-C mutation during RT.

- Data Analysis: The U-to-C mutation rate at each position quantitatively reflects the Ψ modification level. BACS offers high conversion rates (~87.6%) and low false-positive rates (<1% for most sequence contexts), allowing for precise mapping even in consecutive uridine tracts [20].

Table 2: Key Reagents for mRNA Modification Research

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Target | Application in Research |

|---|---|---|

| mRQuant LC-MS/MS Platform | Quantitative analysis of 84 modified ribonucleosides | Epitranscriptome-wide quantification; discovery of modification signatures in cancer and drug resistance [19] |

| BACS (2-bromoacrylamide) | Detection and quantification of Pseudouridine (Ψ) | Base-resolution mapping of Ψ in mRNA and ncRNA; validation of PUS enzyme targets [20] |

| Nanopore Direct RNA Seq | Direct sequencing of native RNA molecules | Discovery of novel modifications; detection of modification patterns in environmental RNA (eRNA) [16] |

| METTL3-METTL14 Complex | Writer complex for m6A deposition | Functional studies of m6A; manipulation of m6A levels in cellular models [16] [21] |

| METTL16 (Writer) | m6A modification of U6 snRNA and specific mRNAs (e.g., MAT2A) | Studying m6A in splicing regulation and SAM homeostasis; structural studies of methylation mechanisms [21] |

| FTO, ALKBH5 (Erasers) | Removal of m6A and m6Am modifications | Functional studies of reversible mRNA methylation; investigating links to obesity and cancer [16] |

| YTHDF1-3, YTHDC1 (Readers) | Recognition and interpretation of m6A marks | Elucidating mechanistic pathways downstream of m6A (e.g., decay, translation) [16] |

| Anti-m6A Antibodies | Immunoprecipitation of m6A-modified RNA (MeRIP) | Enrichment and sequencing of m6A-modified transcripts (MeRIP-seq, miCLIP) [16] |

Application in Synthetic mRNA Design for Reprogramming Factors

The primary challenges for synthetic mRNA, especially for delivering reprogramming factors, are its inherent instability, high immunogenicity, and suboptimal translation efficiency. Natural mRNA modifications provide a blueprint to overcome these hurdles.

Enhancing Stability and Reducing Immunogenicity

Unmodified synthetic mRNA is vulnerable to degradation by ribonucleases and is readily recognized by cytoplasmic (PKR, RIG-I) and endosomal (TLR3, TLR7/8) innate immune sensors, triggering type I interferon and pro-inflammatory cytokine responses [17]. The incorporation of naturally occurring modifications is a proven strategy to mitigate these issues.

- Nucleoside Modifications: Replacing uridine with pseudouridine (Ψ) and cytidine with 5-methylcytidine (m5C) in the coding sequence significantly reduces immune activation and enhances the stability and translational capacity of synthetic mRNA [17]. This approach was critical to the success of COVID-19 mRNA vaccines.

- Cap Modifications: Using a synthetic Cap1 analog (m7GpppNm) is essential for efficient translation and for evading RIG-I-mediated immune recognition [16] [17]. Further advanced cap analogs, such as those with phosphorothioate linkages (e.g., m2 7,2′ O-GppspG) or the "2S" cap (combining tetraphosphate and disulphur substitution), confer resistance to decapping enzymes and increase protein yield [17].

Algorithm-Driven mRNA Design

Beyond single modifications, holistic computational design of the mRNA molecule is crucial. The LinearDesign algorithm addresses the problem of designing maximally stable mRNA sequences for a given protein [22]. The challenge is the astronomically large sequence space due to codon degeneracy. LinearDesign formulates this as a lattice parsing problem, efficiently finding the mRNA sequence with the optimal balance of thermodynamic stability (lowest minimum-free-energy) and codon optimality (highest Codon Adaptation Index) [22]. This approach has been shown to dramatically improve mRNA half-life, protein expression, and in vivo immunogenicity (e.g., up to a 128-fold increase in antibody titer in mice for a COVID-19 vaccine antigen) compared to traditional codon optimization [22].

The workflow below integrates these elements into a coherent strategy for designing high-performance synthetic mRNA for reprogramming factors.

The interplay between natural mRNA modifications and synthetic mRNA design represents a powerful synergy. The epitranscriptome provides a rich repository of functional elements that can be co-opted to engineer superior synthetic mRNAs. For the demanding application of delivering reprogramming factors—which requires sustained, high-level expression of multiple proteins with minimal cytotoxicity—a multi-pronged approach is essential. This includes algorithm-driven sequence optimization, strategic incorporation of immune-evasive modifications like Ψ and m5C, and the use of advanced cap analogs.

Future directions will likely involve the deliberate, context-specific incorporation of regulatory modifications like m6A to fine-tune the half-life and translation of synthetic transcripts. Furthermore, the application of synthetic biology principles to create responsive RNA circuits could allow for self-regulating mRNA systems [23]. As detection technologies like nanopore sequencing and mRQuant continue to unveil the complexity of the epitranscriptome, they will provide an ever-expanding toolkit for the rational design of next-generation mRNA therapeutics for cell reprogramming and beyond.

The ability to deliberately reprogram a somatic cell's identity represents one of the most transformative breakthroughs in modern biology. This paradigm shift began with the generation of induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) and is rapidly advancing toward direct in vivo cell fate conversion using synthetic mRNA technologies. The core principle underpinning these technologies is that cellular identity is maintained not by irreversible changes to the DNA sequence, but by stable yet reversible epigenetic mechanisms and sustained expression of lineage-defining transcription factors [24]. The emergence of sophisticated synthetic mRNA design has been pivotal in advancing these approaches, offering a precise, non-integrating method for delivering reprogramming factors with transient, dose-controllable expression [25]. This technical guide examines the key historical breakthroughs, molecular mechanisms, and methodologies that have defined the evolution of cellular reprogramming, with particular emphasis on the role of synthetic mRNA in enabling both in vitro iPSC generation and direct in vivo transdifferentiation for research and therapeutic applications.

Historical Foundations of Cellular Reprogramming

The conceptual journey toward cellular reprogramming began with foundational experiments challenging the dogma of irreversible cell differentiation. Table 1 summarizes the pivotal milestones that established the core principles of cellular plasticity.

Table 1: Key Historical Milestones in Cellular Reprogramming

| Year | Breakthrough | Key Researchers | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1962 | Somatic Cell Nuclear Transfer (SCNT) in frogs | John Gurdon [24] | Demonstrated somatic cell nucleus contains complete genetic information for development; proved cellular differentiation is reversible |

| 1981 | Isolation of mouse Embryonic Stem Cells (ESCs) | Evans, Kaufman, Martin [24] | Established in vitro pluripotent cell reference point |

| 1997 | Mammalian cloning (Dolly the sheep) | Wilmut et al. [26] | Confirmed mammalian somatic cell nuclear totipotency |

| 1998 | Isolation of human ESCs | James Thomson [24] | Provided human pluripotent cell platform |

| 2006 | First mouse iPSCs | Takahashi and Yamanaka [27] [24] | Identified OSKM factors sufficient for reprogramming fibroblasts to pluripotency |

| 2007 | First human iPSCs | Yamanaka/Takahashi and Thomson groups [27] [24] | Extended iPSC technology to human cells using OSKM and OSNL factors |

| 2009-2010 | Non-integrating reprogramming methods | Multiple groups [3] [28] | Developed Sendai virus, episomal plasmids, and mRNA methods to address clinical safety concerns |

| 2013 | Chemical reprogramming (mouse) | Deng group [27] | Achieved pluripotency induction using small molecules alone |

| 2018-Present | mRNA-based direct in vivo reprogramming | Multiple groups [25] | Advanced synthetic modified mRNA for direct cell fate conversion in living tissues |

The critical theoretical foundation was established by John Gurdon's seminal SCNT experiments in Xenopus laevis frogs, which demonstrated that a nucleus isolated from a terminally differentiated intestinal epithelial cell could support the development of a complete, germline-competent organism when transferred into an enucleated egg [24]. This fundamentally disproved the Weismann barrier theory of irreversible somatic cell fate restriction and suggested that epigenetic factors in the egg cytoplasm could reset the developmental clock of a somatic nucleus.

Nearly half a century later, Shinya Yamanaka and Kazutoshi Takahashi systematically identified the minimal transcription factor combination required to induce pluripotency. Their innovative screening approach using 24 candidate factors in mouse embryonic fibroblasts expressing the Fbxo15 pluripotency reporter led to the landmark discovery that just four transcription factors—Oct4, Sox2, Klf4, and c-Myc (OSKM)—could reprogram somatic cells into iPSCs [27] [24]. This breakthrough was rapidly extended to human cells by both Yamanaka's group (using OSKM) and James Thomson's group (using OCT4, SOX2, NANOG, and LIN28) in 2007 [27] [26] [24].

Molecular Mechanisms of Cell Fate Conversion

The Molecular Dynamics of iPSC Reprogramming

The process of reprogramming somatic cells to iPSCs involves profound remodeling of the epigenome and global changes in gene expression. Reprogramming occurs in two broad phases: an early, largely stochastic phase where somatic genes are silenced and early pluripotency-associated genes are activated, followed by a late, more deterministic phase where late pluripotency genes are activated and a stable self-renewing state is established [24]. During the early phase, exogenous reprogramming factors must overcome epigenetic barriers, including closed chromatin configurations at pluripotency loci, to initiate the rewiring of the transcriptional network [26]. This process involves widespread changes to histone modifications, DNA methylation patterns, and chromatin architecture [24].

A critical event in fibroblast reprogramming is the mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition (MET), which is driven by the suppression of somatic-specific transcription factors and activation of pluripotency networks [24]. The exogenous factors gradually activate a self-reinforcing "pluripotency network" of endogenous transcription factors that maintains the embryonic gene expression pattern, eventually making sustained expression of the exogenous factors unnecessary [3] [26]. Recent research has identified key epigenetic regulators that control the pace of this process, including Menin and SUZ12, which modulate developmental timing by regulating the balance of H3K4me3 (activating) and H3K27me3 (repressing) marks at bivalent promoters of key developmental genes [29].

Direct Lineage Conversion

Building on the principles of iPSC reprogramming, direct lineage conversion (transdifferentiation) bypasses the pluripotent state altogether by expressing specific combinations of transcription factors that directly convert one somatic cell type into another. This approach typically involves introducing "master regulator" transcription factors that define the target cell identity while often suppressing the original cell identity [25]. The emergence of synthetic mRNA technology has been particularly transformative for direct reprogramming applications, as it enables transient, dose-controlled expression of reprogramming factors without genomic integration [25]. Direct conversion strategies are being actively explored for generating various therapeutic cell types, including neurons, cardiomyocytes, and hepatocytes, both in vitro and directly in vivo [25].

Evolution of Reprogramming Delivery Methods

The initial iPSC generation methods relied on integrating retroviral and lentiviral vectors, which posed significant clinical safety concerns due to insertional mutagenesis and residual transgene expression [30] [3]. This limitation spurred the development of non-integrating delivery systems, each with distinct advantages and limitations for research and clinical applications. Table 2 provides a comparative analysis of the primary reprogramming delivery methods in use today.

Table 2: Comparison of Reprogramming Factor Delivery Methods

| Delivery Method | Genetic Integration | Key Advantages | Key Limitations | Reprogramming Efficiency | Best Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Retroviral/Lentiviral | Yes (persistent) | High efficiency; stable expression during critical early phase | Tumorigenesis risk; insertional mutagenesis; residual expression | High (≈0.1-1%) [3] | Basic research; proof-of-concept studies |

| Sendai Virus (SeV) | No (cytoplasmic RNA virus) | High efficiency; does not enter nucleus; eventually diluted | Persistent viral replication requires careful clearance screening; immunogenic | High (significantly higher than episomal) [30] | Research applications requiring high efficiency |

| Episomal Vectors | No (but rare integration possible) | DNA-based; simple production; low immunogenicity | Lower efficiency; requires repeated transfections | Moderate (lower than SeV) [30] | Clinical applications where viral methods are problematic |

| Synthetic mRNA | No (entirely cytoplasmic) | Footprint-free; precise dosing control; transient expression; high efficiency | Requires repeated transfections; innate immune activation must be managed | High (comparable to viral methods) [3] [25] | Clinical applications; direct in vivo reprogramming |

| Protein Transduction | No | Completely non-genetic; minimal safety concerns | Extremely low efficiency; technically challenging | Very Low [3] | Specialized applications with strictest safety requirements |

Among non-integrating methods, Sendai virus (SeV) and synthetic mRNA have emerged as particularly prominent due to their high efficiency and favorable safety profiles. A 2025 comparative analysis from a biobanking perspective found that Sendai virus reprogramming yielded significantly higher success rates than episomal methods across various starting cell types (fibroblasts, LCLs, PBMCs), while source material itself did not significantly impact success rates [30].

The mRNA Reprogramming Revolution

Synthetic mRNA reprogramming represents a particularly advanced approach for clinical translation. This method involves repeated transfections of in vitro transcribed mRNA encoding the reprogramming factors, typically including modified nucleosides to reduce innate immune recognition and enhance stability [3] [25]. The first demonstration of mRNA-based reprogramming in 2010 provided a truly "footprint-free" method that avoided both genomic integration and the persistence concerns associated with DNA-based methods [28]. Modern mRNA reprogramming protocols have achieved efficiencies comparable to viral methods while offering unparalleled control over factor stoichiometry and temporal expression patterns [3].

The following diagram illustrates the complete workflow for synthetic mRNA-based cellular reprogramming, from mRNA design to the establishment of fully reprogrammed iPSCs:

Diagram Title: Synthetic mRNA Reprogramming Workflow

Synthetic mRNA Design for Reprogramming Factors

The effectiveness of mRNA-based reprogramming hinges on sophisticated mRNA engineering to optimize stability, translational efficiency, and immunogenicity. Key design elements include:

Nucleoside Modifications

Incorporation of modified nucleosides is critical for reducing the innate immune response against exogenous mRNA. Naturally occurring modifications such as pseudouridine (Ψ), N1-methylpseudouridine (m1Ψ), and 5-methylcytidine (m5C) have been shown to significantly decrease recognition by Toll-like receptors and cytoplasmic RNA sensors while enhancing translational efficiency [17] [25]. These modifications mimic naturally occurring RNA modifications in cellular mRNA, thereby evading pathogen-associated molecular pattern recognition.

Cap and Tail Optimization

The 5' cap structure and 3' poly(A) tail are essential for mRNA stability and efficient translation. Anti-reverse cap analogs (ARCA) with 3'-O-Me modification prevent backward incorporation and ensure proper capping orientation, while novel cap designs with sulfur modifications or tetraphosphate bridges enhance binding to eIF4E and resistance to decapping enzymes [17]. The poly(A) tail length is optimized typically to 100-150 nucleotides and can be encoded directly in the DNA template or added enzymatically post-transcription [17].

UTR and Codon Optimization

The 5' and 3' untranslated regions significantly influence mRNA stability, subcellular localization, and translational efficiency. Engineering UTRs from highly expressed genes such as α-globin or β-globin can dramatically enhance protein production [25]. Additionally, codon optimization of the coding sequence enhances translation fidelity and efficiency while reducing secondary structure formation that might impede ribosomal progression.

Experimental Protocols for mRNA Reprogramming

mRNA Reprogramming of Human Fibroblasts

This protocol describes a robust method for generating integration-free human iPSCs using synthetic modified mRNA, adapted from contemporary best practices [3] [25].

- Starting Material: Human dermal fibroblasts (neonatal or adult), cultured in fibroblast medium (DMEM + 10% FBS + 1% GlutaMAX).

- Key Reagents:

- Synthetic modified mRNA encoding hOCT4, hSOX2, hKLF4, hc-MYC (with Ψ and m5C modifications)

- mRNA Reprogramming Medium (commercial system or formulated with mTeSR1/E8 base plus supplements)

- Transfection reagent (e.g., lipid-based nanoparticles or polymer formulations)

- Innate immune suppressor (e.g., B18R protein or small molecule inhibitors)

- Procedure:

- Day -2: Plate fibroblasts at 15,000-20,000 cells/cm² in appropriate culture vessels.

- Day -1: Pre-treat cells with immune suppressor (e.g., 100 ng/mL B18R) 12-24 hours before first transfection.

- Day 0: Prepare mRNA-lipid nanoparticle complexes according to manufacturer's instructions. Replace medium with fresh medium containing immune suppressor. Transfert cells with the mRNA cocktail.

- Days 1-18: Repeat transfections daily. Change medium 4-6 hours post-transfection to remove transfection complexes.

- Days 7-21: Monitor for emergence of compact, ESC-like colonies with defined borders.

- Days 18-28: Manually pick established iPSC colonies and transfer to fresh culture plates pre-coated with Matrigel or similar substrate.

- Expansion and Validation: Expand clonal lines and characterize using standard assays (pluripotency marker staining, karyotyping, trilineage differentiation potential).

Direct In Vivo Transdifferentiation via mRNA

This protocol outlines the key considerations for direct cell fate conversion in living tissue using synthetic mRNA [25].

- Target Cell/Tissue Selection: Identify accessible somatic cell population with potential for conversion to desired cell type.

- mRNA Cocktail Design: Identify key transcription factor combination for direct lineage conversion. Common combinations include:

- Neurons: Ascl1, Brn2, Myt1l

- Cardiomyocytes: Gata4, Mef2c, Tbx5

- Hepatocytes: Hnf1a, Hnf4a, Hnf6, ATBF1

- In Vivo Delivery System: Optimize lipid nanoparticles or other delivery vehicles for target tissue accessibility.

- Dosing Regimen: Determine optimal dosing schedule and duration based on target cell turnover and mRNA persistence.

- Validation: Assess conversion efficiency via immunohistochemistry, functional analysis, and electrophysiological profiling.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for mRNA-Based Reprogramming

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function & Application |

|---|---|---|

| Reprogramming Factors | OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, c-MYC (OSKM); NANOG, LIN28 | Core transcription factor cocktails for pluripotency induction; available as modified mRNA |

| mRNA Modification Enzymes | T7 RNA Polymerase, Vaccinia Capping System, Poly(A) Polymerase | In vitro transcription for mRNA production; 5' capping and polyadenylation |

| Nucleoside Modifications | N1-methylpseudouridine (m1Ψ), 5-methylcytidine (m5C), Pseudouridine (Ψ) | Reduce immunogenicity and enhance stability/translation of synthetic mRNA |

| Delivery Vehicles | Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs), Cationic Polymers, Electroporation Systems | Protect mRNA and facilitate cellular uptake through endosomal escape |

| Immune Suppressors | B18R protein, Type I IFN receptor blockers, TLR inhibitors | Counteract innate immune activation against exogenous RNA |

| Cell Culture Media | mTeSR1, StemFlex, E8 medium | Support pluripotent stem cell growth and maintenance |

| Characterization Tools | Anti-TRA-1-60, Anti-OCT4, Anti-SSEA4 antibodies; Pluritest, Scorecard Assay | Validate pluripotency status and differentiation potential |

| cyclo(RLsKDK) | cyclo(RLsKDK), MF:C31H57N11O9, MW:727.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Chroman 1 dihydrochloride | Chroman 1 dihydrochloride, MF:C24H30Cl2N4O4, MW:509.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Technical Considerations and Challenges

Despite significant advances, several technical challenges remain in optimizing mRNA-based reprogramming:

Innate Immune Activation: Although nucleoside modifications substantially reduce immunogenicity, residual immune recognition can still impede reprogramming efficiency. Combination approaches using immune suppressors like B18R or small-molecule inhibitors of RNA sensors are often necessary [25].

Delivery Efficiency: Consistent delivery of mRNA to target cells, particularly in vivo, remains challenging. Optimization of lipid nanoparticle formulations with tissue-specific targeting ligands is an active area of research [25].

Factor Stoichiometry: Precise control over the relative expression levels of different reprogramming factors is crucial for efficiency. This can be addressed by adjusting the ratio of individual mRNAs in the transfection cocktail [3] [25].

Tumorigenicity Risk: While mRNA methods eliminate integration risks, the potential for teratoma formation remains if partially reprogrammed cells are used therapeutically. Thorough characterization and purification of converted cells is essential [28].

The field of cellular reprogramming has evolved dramatically from the initial discovery of iPSCs to the current era of precise mRNA-mediated cell fate conversion. Synthetic mRNA technology represents a particularly powerful platform for both basic research and clinical applications, offering unprecedented control over reprogramming factor expression without genetic modification. As mRNA design continues to advance with improved modifications, delivery systems, and manufacturing processes, the potential for developing transformative therapies for degenerative diseases, injury, and aging continues to expand. The convergence of mRNA technology with other emerging fields such as CRISPR-based epigenome editing and artificial intelligence-guided factor discovery promises to further accelerate this rapidly evolving field, potentially enabling previously unimaginable precision in cellular engineering and regenerative medicine.

Methodological Toolkit: Designing, Delivering, and Applying mRNA Reprogramming Factors

The advent of synthetic messenger RNA (mRNA) as a modality for therapeutic protein expression has revolutionized the fields of vaccinology, regenerative medicine, and cell reprogramming. A principal challenge in its application, however, is the inherent immunogenicity of in vitro transcribed (IVT) mRNA. The innate immune system recognizes exogenous RNA through pattern recognition receptors (PRRs), such as Toll-like receptors (TLRs) and retinoic acid-inducible gene I (RIG-I)-like receptors (RLRs), triggering inflammatory responses that can inhibit translation and compromise therapeutic efficacy [31] [32]. Strategic nucleoside modification has emerged as a foundational strategy to circumvent this barrier. By incorporating naturally occurring modified nucleosides, researchers can significantly dampen immune activation and enhance the translational capacity and stability of mRNA [31] [32]. This technical guide details the core mechanisms, comparative performance, and experimental protocols for the three most prominent nucleoside modifications—pseudouridine (Ψ), 5-methylcytidine (m5C), and N1-methylpseudouridine (m1Ψ)—within the context of engineering mRNA for delivering reprogramming factors.

Core Mechanisms: How Nucleoside Modifications Reduce Immunogenicity

The immunogenicity of unmodified IVT mRNA primarily stems from its recognition by specific PRRs. Incorporating modified nucleosides alters the molecular structure of the mRNA, disrupting these recognition events and downstream signaling cascades.

Ψ and m1Ψ are uridine analogues that effectively suppress activation of endosomal TLRs (particularly TLR7 and TLR8) and cytosolic sensors like RIG-I [31] [32]. The presence of m1Ψ in mRNA has been shown to drastically reduce the mRNA levels of innate immune markers such as RIG-I, RANTES, IL-6, and IFN-β1 in transfected cells [33]. A key mechanism involves diminished activation of protein kinase R (PKR) and its subsequent phosphorylation of the eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2α (eIF2α), a pathway that normally shuts down protein synthesis in response to viral infection [32]. Furthermore, these modifications increase resistance to degradation by RNase L, enhancing mRNA stability [32].

m5C, a methylation of cytosine at the carbon-5 position, is another widespread epitranscriptomic mark. While its direct role in immunomodulation is an active area of research, it is frequently used in combination with uridine modifications to further optimize mRNA performance [32] [34]. The immunogenic recognition of mRNA is not mediated by a single receptor but through a network of pathways. The diagram below illustrates how modified nucleosides interfere with these pathways to promote successful translation.

Figure 1: Nucleoside Modifications Disrupt Immune Sensing Pathways. Modified nucleosides (Ψ, m1Ψ, m5C) in IVT mRNA prevent recognition by TLRs, RIG-I, and PKR, thereby avoiding the inflammatory cascade and translation shutdown that otherwise limits therapeutic protein production.

Comparative Analysis of Key Nucleoside Modifications

The choice of nucleoside modification significantly impacts the pharmacological profile of the mRNA therapeutic. The following table provides a structured comparison of the immunogenicity, translational capacity, and stability conferred by Ψ, m5C, and m1Ψ, based on empirical data.

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of Nucleoside Modification Effects on mRNA Properties

| Modification | Reduction in Immunogenicity | Effect on Translation Efficiency | Effect on mRNA Stability | Key Findings & Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pseudouridine (Ψ) | Significant reduction in TLR activation [32]. | Enhanced compared to unmodified mRNA [32]. | Increased [32]. | The pioneering modification that demonstrated the feasibility of engineering highly translatable mRNA. |

| N1-methylpseudouridine (m1Ψ) | Superior to Ψ; high modification ratios (e.g., 100%) show the greatest reduction in RIG-I and cytokine signaling [33] [32]. | Variable based on modification ratio; low ratios (5-20%) can outperform unmodified mRNA, while high ratios (≥50%) may reduce efficiency in cells [33]. | Positively correlated with modification ratio; higher ratios confer greater stability against serum nucleases [33]. | The current state-of-the-art; used in approved COVID-19 vaccines. Can cause ribosomal +1 frameshifting at slippery sequences, potentially generating off-target antigens [35]. |

| 5-methylcytidine (m5C) | Often used in combination to further reduce immunogenicity [32]. | When used alone, similar to unmodified mRNA; combined with m1Ψ or Ψ can enhance expression [32] [35]. | Contributes to mRNA stability [36] [34]. | A natural mRNA modification; plays roles in nuclear export and stability via reader proteins like ALYREF and YBX1 [37] [34]. |

| Cdk12-IN-4 | Cdk12-IN-4|CDK12 Inhibitor|For Research Use | Cdk12-IN-4 is a potent, selective CDK12 inhibitor for cancer research. It is for research use only and not for human or veterinary diagnostic or therapeutic use. | Bench Chemicals | |

| Sniper(abl)-044 | Sniper(abl)-044, MF:C51H64F3N9O8S, MW:1020.2 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

A critical and recent finding is that the benefit of m1Ψ is not solely a function of its presence but also its proportion within the mRNA molecule. Research indicates a non-linear relationship between the m1Ψ modification ratio and protein output.

Table 2: Impact of m1Ψ Modification Ratio on mRNA Performance in Cell Culture

| m1Ψ Modification Ratio | Protein Expression Level | Immunogenicity | Cellular Viability (Cell-type Dependent) | Recommended Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low (5%-20%) | Higher than unmodified mRNA and high-ratio m1Ψ-mRNA in multiple cell lines [33]. | Reduced compared to unmodified mRNA, but low ratios (e.g., 5%) can still elevate some immune markers [33]. | Can be lower than higher ratios in some cells (e.g., HEK-293T) [33]. | Ideal for applications requiring high, transient protein expression where minimal immune activation is acceptable. |

| High (50%-100%) | Lower than low-ratio mRNA and sometimes unmodified mRNA in cellular systems [33]. | Significantly reduced; the most potent suppression of immune markers [33]. | Improved compared to unmodified mRNA [33]. | Suited for therapies where minimizing inflammatory responses is paramount, and moderate protein yield is sufficient. |

| Note | In a cell-free translation system, high ratios (75%-100%) tended to enhance protein yield, highlighting the role of cellular factors in the observed effects [33]. | The cytotoxicity of unmodified mRNA was effectively rescued by m1Ψ modification [33]. | Optimization is required for each specific mRNA sequence and target cell type. |

Experimental Protocols for Evaluating Modified mRNA

This section provides a detailed methodology for synthesizing and testing nucleoside-modified mRNA, enabling researchers to empirically validate its properties.

Protocol: In Vitro Transcription with Modified Nucleotides

This protocol describes the synthesis of mRNA incorporating modified nucleoside triphosphates (NTPs).

- Template Design: Prepare a plasmid DNA template linearized downstream of the poly(A) tract. The template must contain a bacteriophage promoter (e.g., T7, SP6) upstream of the sequence of interest, which includes the 5' UTR, open reading frame (ORF), and 3' UTR [31].

- IVT Reaction Setup: Assemble the following reaction in a nuclease-free microcentrifuge tube:

- Linearized DNA template: 1 µg

- 10x Transcription Buffer: (as supplied with the polymerase)

- NTP Mix (including modified NTPs): 7.5 mM each of ATP, GTP, CTP, UTP (or substitute with Ψ-TP, m1Ψ-TP, and/or m5C-TP)

- RNase Inhibitor: 1 U/µL

- Bacteriophage RNA Polymerase (T7/SP6): 2 U/µL

- Nuclease-free water: to final volume

- Incubation: Incubate at 37°C for 2-4 hours.

- 5' Capping: Post-synthesis, add a synthetic Cap analog (e.g., CleanCap) co-transcriptionally or use a capping enzyme (e.g., Vaccinia Capping System) post-transcriptionally to add a 5' cap structure [31].

- Poly(A) Tailing: If not encoded in the template, use Poly(A) Polymerase to add a ~100-150 nucleotide poly(A) tail.

- DNase Treatment: Add DNase I (RNase-free) and incubate for 15 minutes at 37°C to digest the DNA template.

- mRNA Purification: Purify the mRNA using spin-column-based kits or HPLC to remove proteins, free NTPs, and short abortive transcripts. Verify integrity by agarose gel electrophoresis and quantify by spectrophotometry.

Protocol: Assessing Immunogenicity of Modified mRNA in Cell Culture

This protocol measures the activation of innate immune pathways in response to transfected mRNA.

- Cell Seeding: Seed appropriate reporter cells (e.g., HEK-293T, A549, or primary cells relevant to your research) in a 24-well plate to reach 70-90% confluency at the time of transfection.

- mRNA Transfection: Transfect cells with a standardized amount (e.g., 100-500 ng) of purified, modified or unmodified mRNA using a lipid nanoparticle (LNP) or a commercial lipofection reagent. Include a negative control (e.g., mock transfection) and a positive control (e.g., unmodified mRNA).

- Incubation: Incubate cells for 6-24 hours post-transfection.

- RNA Extraction and qPCR Analysis: Harvest cells and extract total RNA. Perform reverse transcription followed by quantitative PCR (qPCR) to measure the expression levels of innate immune markers.

- Key Target Genes: IFN-β1, IL-6, RIG-I, RANTES.

- Normalization: Normalize expression to a housekeeping gene (e.g., GAPDH, β-actin).

- Data Interpretation: Compare the fold-change in gene expression for cells transfected with modified mRNA relative to those transfected with unmodified mRNA. Effective modifications will show significant downregulation of these immune genes.

The workflow for the synthesis and testing of modified mRNA is summarized in the following diagram.

Figure 2: Workflow for Synthesis and Testing of Modified mRNA. The process begins with template preparation and in vitro transcription (IVT) using modified nucleotides, followed by purification and cell transfection, culminating in multiple analytical readouts to assess mRNA performance.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The following table lists key reagents and their applications for researching nucleoside-modified mRNA.

Table 3: Essential Reagents for mRNA Engineering Research

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Modified NTPs | Substrates for IVT to produce modified mRNA. | Ψ-TP, m1Ψ-TP, m5C-TP (e.g., from Trilink BioTechnologies). Purity is critical for high-yield transcription. |

| T7/SP6 RNA Polymerase | Enzyme for synthesizing RNA from a DNA template in IVT. | High-yield, RNase-free versions are essential for producing full-length mRNA. |

| CleanCap Analog | Co-transcriptional 5' capping reagent. | Enables the synthesis of Cap 1 structures, which are superior for translation and reducing immunogenicity. |

| Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) | The leading delivery system for in vitro and in vivo mRNA delivery. | Composed of ionizable lipids, phospholipids, cholesterol, and PEG-lipids. Protect mRNA and enhance cellular uptake. |

| Reporter Constructs | Quantifying translation efficiency and fidelity. | Plasmids encoding EGFP, luciferase, or secretable alkaline phosphatase. Frameshift reporter constructs can detect aberrant translation [35]. |

| Immune Reporter Cell Lines | Sensitively measuring immunogenicity. | HEK-293 cells stably overexpressing specific TLRs (e.g., TLR3, TLR7/8) or containing IFN-stimulated response element (ISRE) luciferase reporters. |

| I-Bet282E | I-Bet282E, MF:C26H34N4O7S, MW:546.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Microtubule inhibitor 8 | Microtubule inhibitor 8, MF:C21H15N3O2S, MW:373.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Implications for Synthetic mRNA Design in Reprogramming Factors Research

The strategic selection of nucleoside modifications is paramount for the success of mRNA-based delivery of reprogramming factors (e.g., Oct4, Sox2, Klf4, c-Myc). These applications often require sustained, high-level expression of multiple transcription factors without triggering an immune response that could compromise reprogramming efficiency or lead to apoptosis [38].

The finding that m1Ψ can induce ribosomal frameshifting necessitates careful sequence inspection and optimization [35]. For reprogramming factors like c-Myc, which is oncogenic, the production of unintended frameshifted protein products poses a significant safety risk. Therefore, it is critical to:

- Identify "Slippery Sequences": Analyze the coding sequences of your reprogramming factors for motifs known to be prone to frameshifting (e.g., homopolymeric runs).

- Implement Synonymous Codon Substitution: Replace codons in these slippery sequences with synonymous alternatives that do not facilitate frameshifting, thereby eliminating off-target translation without altering the amino acid sequence [35].