Epigenetic Regulation of Stem Cell Plasticity: Mechanisms, Disease Roles, and Therapeutic Targeting

This article comprehensively explores the epigenetic mechanisms governing stem cell plasticity, a pivotal process in development, tissue homeostasis, and disease.

Epigenetic Regulation of Stem Cell Plasticity: Mechanisms, Disease Roles, and Therapeutic Targeting

Abstract

This article comprehensively explores the epigenetic mechanisms governing stem cell plasticity, a pivotal process in development, tissue homeostasis, and disease. We detail how dynamic changes in DNA methylation, histone modifications, and non-coding RNAs enable stem cells to switch between self-renewal and differentiation states. For researchers and drug development professionals, the content covers foundational principles, advanced methodological approaches for investigation, challenges in therapeutic targeting, and validation strategies through comparative epigenomic analyses. A particular focus is placed on the role of epigenetic dysregulation in cancer stem cells, aging, and therapy resistance, synthesizing recent findings to highlight emerging therapeutic opportunities aimed at modulating the epigenome to control cell fate.

Core Epigenetic Mechanisms Governing Stem Cell Fate and Plasticity

Stem cell plasticity, the fundamental capacity of stem cells to alter their fate in response to intrinsic and extrinsic cues, represents a cornerstone of regenerative medicine and developmental biology. This whitepaper delineates the conceptual evolution of stem cell plasticity from Waddington's classical epigenetic landscape to contemporary molecular understandings, with particular emphasis on the central role of epigenetic regulation. We examine the dynamic interplay between DNA methylation, histone modifications, and chromatin remodeling in mediating cell fate decisions, and provide a technical overview of experimental methodologies for investigating plasticity mechanisms. Within the broader context of epigenetic regulation in stem cell research, this resource offers scientists and drug development professionals a comprehensive framework for navigating this rapidly advancing field, supported by quantitative data and standardized experimental workflows.

The metaphor of the "epigenetic landscape," conceived by Conrad Waddington in 1942, elegantly depicted cellular differentiation as a ball rolling down a hillside through branching valleys toward irreversible fate commitments [1]. In this original conception, stem cell plasticity was inherently unidirectional. The contemporary post-Yamanaka era has radically transformed this paradigm, recognizing that cellular differentiation is not a one-way trajectory. Modern research demonstrates that somatic cells can be reprogrammed upward toward pluripotency, transdifferentiated sideways across lineages, and that tissue-specific stem cells exhibit remarkable dynamic flexibility in response to physiological demands and environmental signals [2].

This paradigm shift necessitates a refined definition: stem cell plasticity is the capacity of stem cells to alter their differentiation potential, fate decisions, and functional states in response to developmental cues, environmental signals, and experimental manipulations, mediated by reversible epigenetic and transcriptional mechanisms. This operational definition underscores the regulated malleability of stem cell states, which sits at the very heart of their therapeutic potential and physiological function. The molecular basis of this plasticity is governed predominantly by epigenetic mechanisms—heritable changes in gene expression that occur without alterations to the underlying DNA sequence [3] [1]. These mechanisms, including DNA methylation, histone modifications, and chromatin remodeling, form the molecular interface between environmental signals and gene expression programs, thereby enabling dynamic cellular responses while maintaining genomic integrity.

Molecular Mechanisms of Epigenetic Regulation

The epigenetic machinery governing stem cell plasticity operates through several interconnected systems that establish and maintain cell identity. The coordinated action of these systems enables both the stability of cell fate decisions and the dynamic reversibility essential for plasticity.

DNA Methylation and Demethylation Dynamics

DNA methylation, involving the covalent addition of a methyl group to cytosine bases primarily at CpG dinucleotides, provides a stable mechanism for gene silencing that can be maintained through cell divisions [1]. In stem cells, this process is dynamically regulated:

- DNA Methyltransferases (DNMTs): DNMT1 maintains methylation patterns during DNA replication, while DNMT3A and DNMT3B establish de novo methylation [1]. The balance of these enzymes is critical for stem cell function. In hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs), loss of DNMT1 impairs both self-renewal and differentiation, causing skewed lineage output toward myelopoiesis [3]. Conversely, conditional knockout of Dnmt3a in HSCs leads to increased self-renewal at the expense of differentiation [3].

- Ten-Eleven Translocation (TET) Enzymes: TET proteins catalyze the oxidation of 5-methylcytosine (5mC) to 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5hmC) and further oxidized derivatives, initiating active DNA demethylation pathways [3] [1]. The functional consequences of TET-mediated demethylation are context-dependent; loss of TET2 in HSCs profoundly increases self-renewal and leads to myeloid skewing, while TET1 deficiency in neural progenitor cells decreases their self-renewal potential without affecting differentiation capacity [3].

Table 1: Key Enzymes Regulating DNA Methylation in Stem Cell Plasticity

| Enzyme | Function | Impact on Stem Cell Plasticity | Associated Phenotypes from Loss-of-Function Studies |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNMT1 | Maintenance methylation | Balanced self-renewal and differentiation | HSCs: Impaired self-renewal, skewed lineage output [3] |

| DNMT3A/B | De novo methylation | Restriction of self-renewal, promotion of differentiation | HSCs: Increased self-renewal, impaired differentiation [3] |

| TET1 | Active demethylation | Regulation of lineage-specific genes | Neural Progenitors: Decreased self-renewal [3]; HSCs: Enhanced self-renewal, B-cell bias [3] |

| TET2 | Active demethylation | Control of differentiation potential | HSCs: Enhanced self-renewal, myeloid skewing, CMML-like disease [3] |

Histone Modifications and Chromatin Architecture

Post-translational modifications of histone tails create a "histone code" that influences chromatin accessibility and gene expression [1]. The combinatorial nature of these modifications generates enormous regulatory complexity:

- Histone Acetylation: Generally associated with open chromatin and active transcription, histone acetylation is dynamically regulated by histone acetyltransferases (HATs) and histone deacetylases (HDACs) [1]. This modification neutralizes the positive charge of histones, reducing chromatin compaction.

- Histone Methylation: The functional consequences depend on the specific residue modified and the degree of methylation. For example, H3K4me3 is associated with active promoters, while H3K27me3 marks facultative heterochromatin and repressed genes [1]. The bivalent presence of both activating (H3K4me3) and repressing (H3K27me3) marks at promoters of developmental genes in pluripotent stem cells maintains them in a "poised" state, ready for rapid activation or silencing upon differentiation [1].

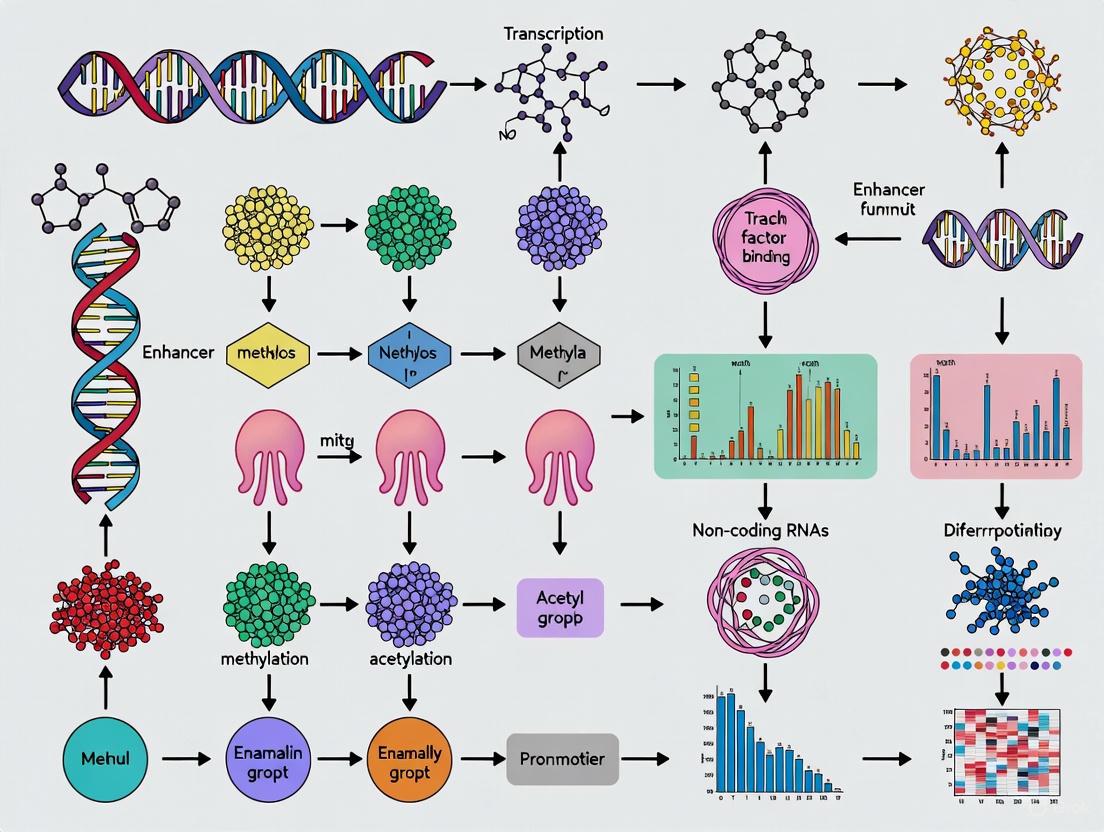

Diagram 1: Epigenetic Regulation of Cell Fate. External signals activate epigenetic "writers" and "erasers" that modify chromatin state, which is interpreted by "reader" proteins to influence gene expression and ultimate cell fate decisions.

Non-Coding RNAs

Non-coding RNAs, including microRNAs, long non-coding RNAs, and piwi-interacting RNAs, contribute to epigenetic regulation by guiding chromatin-modifying complexes to specific genomic loci, influencing DNA methylation patterns, and promoting histone modifications [1]. These mechanisms work in concert to establish the precise patterns of gene expression that define stem cell states and enable plasticity.

Experimental Approaches for Investigating Stem Cell Plasticity

Rigorous experimental design is essential for dissecting the mechanisms of stem cell plasticity. The following methodologies represent cornerstone approaches in the field.

Lineage Tracing and Fate Mapping

Lineage tracing enables the reconstruction of developmental histories and fate choices of individual stem cells and their progeny within living tissues.

Detailed Protocol:

- Genetic Labeling System: Utilize inducible Cre-lox systems (e.g., CreER[T2]) under tissue-specific promoters to achieve temporal control of recombination.

- Reporter Activation: Administer tamoxifen (0.1-1 mg/g body weight, intraperitoneally) to activate CreER[T2], inducing recombination and permanent labeling of target stem cell populations.

- Time-Course Analysis: Harvest tissues at multiple time points (e.g., 1, 7, 30 days post-induction) to track lineage progression.

- Tissue Processing: Prepare cryosections or whole mounts for fluorescence microscopy and immunohistochemistry.

- Quantitative Analysis: Calculate lineage bias, clone sizes, and differentiation kinetics using automated image analysis software.

Key Controls:

- Tamoxifen-only controls to assess leakiness of CreER[T2] system

- Vehicle-only controls to confirm inducibility

- Heterozygous controls to account for gene dosage effects

Epigenomic Profiling

Comprehensive mapping of epigenetic landscapes provides insights into the regulatory mechanisms governing cell fate decisions.

Detailed Protocol for Low-Input CUT&Tag:

- Cell Preparation: Isolate 50,000-100,000 target stem cells by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) using validated surface markers.

- Chromatin Immobilization: Bind cells to Concanavalin A-coated magnetic beads.

- Antibody Incubation: Incubate with primary antibody (e.g., anti-H3K27ac, 1:50 dilution) in antibody buffer overnight at 4°C.

- Tagmentation: Add protein A-Tn5 transposase complex (1:250 dilution) and incubate for 1 hour at 37°C.

- Library Preparation and Sequencing: Extract DNA and amplify libraries with barcoded primers for 12-14 cycles. Sequence on Illumina platform (recommended depth: 10-20 million reads per sample).

- Bioinformatic Analysis: Process reads using standard pipelines (e.g., Bowtie2 for alignment, MACS2 for peak calling). Identify differentially accessible regions and integrate with RNA-seq data.

Table 2: Quantitative Market Data for Stem Cell Research Tools (2024-2033 Projections)

| Market Segment | 2021 Market Size (USD Million) | 2025 Projected Market Size (USD Million) | 2033 Projected Market Size (USD Million) | CAGR (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Global Stem Cell Therapy Market | 185.444 [4] | 456.1 [4] | 2759.02 [4] | 25.231 [4] |

| North America Market | 93.835 [4] | 227.822 [4] | 1343.64 [4] | 24.835 [4] |

| Asia Pacific Market | 32.453 [4] | 83.694 [4] | 557.322 [4] | 26.744 [4] |

| Stem Cell Concentration Systems | 345.7 (2024) [5] | N/A | 1032.4 [5] | 10.46 [5] |

Functional Assays for Plasticity Assessment

In vitro and in vivo functional assays directly test the differentiation potential and lineage flexibility of stem cell populations.

Detailed Protocol for Clonal Differentiation Assay:

- Single-Cell Sorting: Isolate individual stem cells into 96-well plates pre-coated with extracellular matrix using FACS with index sorting to record surface marker expression.

- Multilineage Differentiation Conditions: Culture clones in parallel under distinct differentiation conditions:

- Myeloid Conditions: SCF (100 ng/mL), GM-CSF (50 ng/mL), IL-3 (20 ng/mL)

- Lymphoid Conditions: Flt3L (100 ng/mL), IL-7 (10 ng/mL)

- Erythroid Conditions: EPO (5 U/mL), SCF (100 ng/mL)

- Culture Duration: Maintain cultures for 14-21 days with medium changes every 3-4 days.

- Endpoint Analysis: Harvest cells and analyze lineage commitment by flow cytometry using validated antibody panels (CD11b/Gr-1 for myeloid, B220/CD19 for B cells, CD4/CD8 for T cells).

- Data Interpretation: Calculate lineage bias and plasticity indices based on clone composition across conditions.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful investigation of stem cell plasticity requires carefully selected reagents and systems. The following table details essential tools for experimental design.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Investigating Stem Cell Plasticity

| Reagent/Solution | Function | Example Applications | Key Providers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stem Cell Concentration Systems | Isolate, concentrate, and process stem cells | Cell therapy development, regenerative medicine research | Terumo Corporation, Lonza Group AG, Miltenyi Biotec [5] |

| Magnetic-Activated Cell Sorting (MACS) | High-quality cell separation | Isolation of pure stem cell populations for functional assays | Miltenyi Biotec [5] |

| Automated Bioprocessing Platforms | Cell culture, expansion, and concentration | Scale-up of stem cell cultures for therapeutic applications | Lonza Group AG, Thermo Fisher Scientific [5] |

| DNMT Inhibitors (5-azacytidine, decitabine) | DNA methyltransferase inhibition | Experimental manipulation of DNA methylation patterns to assess impact on plasticity | Multiple pharmaceutical and biotech suppliers |

| HDAC Inhibitors (TSA, SAHA) | Histone deacetylase inhibition | Increase histone acetylation to study chromatin accessibility in fate decisions | Multiple pharmaceutical and biotech suppliers |

| TET Activators (Vitamin C) | Enhancement of TET-mediated demethylation | Promote DNA demethylation to study reprogramming and plasticity | Multiple pharmaceutical and biotech suppliers |

| Cytokine Cocktails | Directed differentiation | Assess lineage potential under defined conditions | PeproTech, R&D Systems, STEMCELL Technologies |

Signaling Pathways Governing Plasticity Decisions

Multiple signaling pathways integrate extracellular information to modulate the epigenetic machinery and influence stem cell fate decisions. The following diagram illustrates key pathway interactions.

Diagram 2: Signaling-Epigenetic Axis in Fate Decisions. Extracellular signals activate core pathways that modulate epigenetic effectors to establish specific gene expression programs and cell fate outcomes.

The contemporary understanding of stem cell plasticity has transcended Waddington's original unidirectional landscape, revealing a dynamic system where epigenetic mechanisms serve as the molecular interpreters of environmental cues, enabling remarkable cellular adaptability. The experimental frameworks and technical resources outlined in this whitepaper provide a foundation for advancing this knowledge toward therapeutic applications. As the field progresses, key challenges remain, including the precise control of plasticity for regenerative purposes without risking tumorigenesis, the understanding of context-dependent epigenetic memory, and the development of strategies to manipulate these mechanisms safely in clinical settings. The integration of single-cell multi-omics, advanced genome engineering, and computational modeling will continue to refine our understanding of stem cell plasticity, ultimately enabling the rational design of cell-based therapies that harness this fundamental biological property for regenerative medicine and disease treatment.

The regulation of stem cell fate, encompassing the fundamental processes of self-renewal and differentiation, is orchestrated by a complex interplay of genetic and epigenetic mechanisms. Among these, DNA methylation represents a crucial epigenetic modification that dynamically controls gene expression patterns without altering the underlying DNA sequence. This reversible modification is centrally regulated by two antagonistic enzyme families: DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs), which catalyze the addition of methyl groups to cytosine bases, and ten-eleven translocation (TET) proteins, which mediate active DNA demethylation through iterative oxidation of 5-methylcytosine (5mC) [6] [7]. The precise balance between these opposing activities establishes methylation patterns that guide stem cell fate decisions, maintain pluripotency, and direct lineage specification [8] [9]. Disruption of this equilibrium contributes to various pathologies, including cancer, where aberrant DNA methylation patterns support the maintenance of cancer stem cells (CSCs) and promote tumorigenesis [8] [10]. This review comprehensively examines the molecular mechanisms, functional roles, and experimental approaches for studying DNMTs and TET proteins in the context of stem cell biology, providing researchers with both theoretical foundations and practical methodological guidance.

Molecular Mechanisms of DNA Methylation and Demethylation

DNA Methyltransferases (DNMTs): Establishment and Maintenance of Methylation Patterns

The DNMT family in mammals comprises several enzymes with specialized functions in establishing and maintaining DNA methylation patterns. DNMT1, DNMT3A, and DNMT3B represent the primary catalytically active enzymes, while DNMT3L serves as a catalytically inactive regulatory cofactor, and DNMT2 primarily methylates RNA rather than DNA [11] [12].

Table 1: DNA Methyltransferase Family Members and Functions

| Protein | Primary Function | Key Structural Domains | Role in Stem Cell Biology |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNMT1 | Maintenance methylation during DNA replication | CXXC, RFTS, BAH domains | Sustains self-renewal; represses differentiation genes [8] |

| DNMT3A | De novo methylation | PWWP, ADD domains | Establishes methylation patterns during differentiation [11] |

| DNMT3B | De novo methylation | PWWP, ADD domains | Works with DNMT3A in developmental methylation [12] |

| DNMT3L | Catalytic enhancer for DNMT3A/B | - | Stimulates de novo methylation in early development [11] |

| DNMT2 | tRNA methylation | - | Limited role in DNA methylation; methylates specific tRNAs [11] |

DNMT1 functions as the primary maintenance methyltransferase, exhibiting a strong preference for hemimethylated CpG sites that arise during DNA replication. This specificity enables DNMT1 to faithfully copy methylation patterns from the parent strand to the daughter strand, thereby preserving epigenetic information across cell divisions [6] [10]. Structurally, DNMT1 contains several specialized domains including the replication focus targeting sequence (RFTS) domain, which mediates its localization to replication forks, and CXXC and bromo-adjacent homology (BAH) domains that facilitate chromatin interactions [11].

In contrast, DNMT3A and DNMT3B function primarily as de novo methyltransferases, establishing new methylation patterns during early development and cellular differentiation. These enzymes contain PWWP domains that target them to specific genomic regions, particularly heterochromatic regions and gene bodies [11] [12]. DNMT3L, though catalytically inactive, enhances the methylation activity of DNMT3A and DNMT3B by stabilizing their conformation and promoting their recruitment to specific genomic loci [11].

TET Proteins: Mediators of Active DNA Demethylation

The TET protein family, comprising TET1, TET2, and TET3, catalyzes the stepwise oxidation of 5mC to 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5hmC), 5-formylcytosine (5fC), and finally 5-carboxycytosine (5caC) in an Fe(II) and α-ketoglutarate-dependent manner [6] [7]. This oxidation cascade initiates active DNA demethylation through two primary mechanisms: (1) the canonical TET-TDG-BER pathway, where thymine DNA glycosylase (TDG) recognizes and excises 5fC and 5caC, initiating base excision repair that restores unmethylated cytosine; and (2) replication-dependent dilution, where oxidation products passively dilute during cell division due to impaired recognition by maintenance DNMTs [6] [7].

Table 2: TET Family Proteins and Their Characteristics

| Protein | Key Domains | Expression Patterns | Catalytic Dependencies |

|---|---|---|---|

| TET1 | CXXC, CRD, DSBH | Embryonic tissues, ESCs | Fe(II), α-ketoglutarate, O₂ [7] |

| TET2 | CRD, DSBH | Hematopoietic tissues, widespread | Fe(II), α-ketoglutarate, O₂ [7] |

| TET3 | CXXC, CRD, DSBH | Neural tissues, oocytes | Fe(II), α-ketoglutarate, O₂ [7] |

Structurally, all TET proteins share a conserved C-terminal catalytic domain consisting of a cysteine-rich domain (CRD) and a double-stranded β-helix (DSBH) region that houses the catalytic center [7]. TET1 and TET3 additionally contain N-terminal CXXC domains that facilitate binding to CpG-rich sequences, while TET2 lost this domain through chromosomal inversion during evolution [7]. This structural difference likely contributes to their distinct genomic localization patterns, with TET1 and TET3 enriched at CpG-rich promoters and TET2 preferentially targeting gene bodies and enhancers [7].

The enzymatic activity of TET proteins is regulated by various cellular metabolites and cofactors. α-ketoglutarate serves as an essential cosubstrate, while succinate and fumarate act as competitive inhibitors [8]. Notably, mutated isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH) enzymes produce the oncometabolite 2-hydroxyglutarate, which inhibits TET function and contributes to DNA hypermethylation in cancer [8]. Vitamin C has also been shown to enhance TET activity by promoting enzyme folding and Fe(II) recycling [7].

Figure 1: DNA Methylation and Demethylation Pathway. This diagram illustrates the dynamic cycle of cytosine modification, highlighting the antagonistic relationship between DNMTs and TET proteins. SAM: S-adenosylmethionine; TDG: thymine DNA glycosylase; BER: base excision repair.

DNMT and TET Functions in Stem Cell Fate Decisions

Regulation of Pluripotency and Self-Renewal

In embryonic stem cells (ESCs), DNMTs and TET proteins collaborate to establish a precise epigenetic landscape that maintains the balance between self-renewal and differentiation capacity. TET1 plays a particularly important role in this context by binding to and demethylating promoters of pluripotency factors such as NANOG, facilitating their expression [7] [9]. Similarly, TET1 interacts with the pluripotency factor NANOG at specific genomic loci to activate genes essential for maintaining the undifferentiated state [7].

DNMTs contribute to pluripotency maintenance by repressing differentiation-associated genes. DNMT3A and DNMT3B establish de novo methylation at lineage-specific promoters, silencing them while preserving a transcriptionally permissive state at pluripotency loci [8]. This balanced methylation landscape creates "bivalent domains" at developmentally important genes—regions marked by both activating (H3K4me3) and repressing (H3K27me3) histone modifications—that keep genes in a poised state ready for rapid activation upon differentiation signals [9].

The critical balance between DNMT and TET activities is exemplified by studies showing that simultaneous depletion of all three DNMTs in ESCs leads to global hypomethylation and loss of differentiation capacity, while TET deficiency results in hypermethylation and impaired lineage specification [8] [7].

Control of Differentiation and Lineage Commitment

During stem cell differentiation, both DNMTs and TET proteins undergo dramatic changes in expression and localization to direct lineage-specific gene expression programs. TET-mediated demethylation activates differentiation programs by removing methylation marks from lineage-specific genes. For instance, during neural differentiation, TET proteins demethylate and activate neurogenesis-related genes, with different oxidation products potentially directing distinct fate decisions—hydroxymethylation driving neurogenesis while formylation and carboxylation promote gliogenesis [13].

DNMTs simultaneously establish repressive methylation at pluripotency gene promoters to prevent reversion to an undifferentiated state. The coordinated action of these enzymes ensures proper lineage commitment while restricting alternative fate choices. In hematopoietic stem cells, TET2-mediated demethylation activates key differentiation genes such as GATA2 and members of the HOX gene family, and TET2 deficiency leads to hypermethylation of these loci, blocking differentiation and promoting self-renewal [8].

Table 3: Stem Cell Fate Regulation by DNMT and TET Proteins

| Biological Process | Key DNMT Functions | Key TET Functions | Representative Target Genes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pluripotency Maintenance | Repress differentiation genes | Demethylate pluripotency promoters | NANOG, OCT4, SOX2 [8] [9] |

| Neural Differentiation | Methylate pluripotency genes | Oxidize cytosine in neurogenic genes | NEUROG1, NEUROD1 [13] |

| Hematopoietic Differentiation | Establish lineage-specific methylation | Demethylate erythroid/myeloid genes | GATA2, HOX clusters [8] |

| Mesenchymal Differentiation | Silence alternative lineages | Activate adipogenic/osteogenic programs | PPARγ, RUNX2 [6] |

Experimental Approaches for Studying DNA Methylation Dynamics

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for DNA Methylation Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Experimental Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNMT Inhibitors | 5-azacytidine, decitabine | Cytosine analogs that trap DNMTs; cause hypomethylation | Used clinically (e.g., for MDS); can induce stem cell differentiation [8] |

| TET Activators | Vitamin C (ascorbate) | Enhances TET activity by promoting Fe(II) recycling | Improves iPSC generation efficiency; modulates 5hmC levels [7] |

| Metabolic Modulators | DMOG (α-KG analog), IDH1/2 inhibitors | Alter cofactor availability for TET enzymes | DMOG inhibits TETs; IDH mutations produce 2-HG, a TET inhibitor [8] |

| HDAC Inhibitors | Valproic acid, trichostatin A | Increase histone acetylation, synergize with DNMT inhibitors | Enhance reprogramming efficiency; open chromatin structure [9] |

| Antibodies | Anti-5mC, anti-5hmC, anti-5fC, anti-5caC | Detect specific cytosine modifications | Key for immunostaining, dot blot, and enrichment-based methods [7] |

| Reporter Systems | 5hmC/5mC reporters | Visualize methylation status in live cells | Enable tracking of methylation dynamics in real-time [14] |

Methodologies for Assessing DNA Methylation Status

Advanced methodologies have been developed to precisely map and quantify various cytosine modifications at base resolution across the genome. Bisulfite sequencing remains the gold standard for detecting 5mC, while oxidative bisulfite sequencing (oxBS-seq) and TET-assisted bisulfite sequencing (TAB-seq) provide specific quantification of 5hmC by distinguishing it from 5mC [7]. For higher-resolution analysis of TET activity, chemical-labeling enrichment methods can map 5fC and 5caC distributions, though these modifications occur at much lower frequencies than 5hmC.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation followed by sequencing (ChIP-seq) enables researchers to profile the genomic binding sites of DNMT and TET proteins, revealing their target loci and potential regulatory functions. When combined with methylation data, this approach can establish direct relationships between enzyme binding and methylation changes at specific genomic regions.

For functional studies, CRISPR-based epigenetic editing tools allow targeted recruitment of catalytic domains of DNMTs or TETs to specific genomic loci, enabling precise manipulation of methylation status at individual genes to investigate causal relationships between methylation and gene expression [7].

Figure 2: Experimental Approaches for DNA Methylation Analysis. This workflow outlines key methodologies for investigating DNA methylation dynamics, from sample preparation to data analysis, highlighting techniques specific to different cytosine modifications.

Dysregulation in Cancer and Therapeutic Implications

DNMT and TET Alterations in Cancer Stem Cells

Cancer stem cells (CSCs) utilize DNMT and TET dysregulation to maintain stem-like properties while resisting differentiation and conventional therapies. DNMT1 is frequently overexpressed in CSCs, where it silences tumor suppressor genes and differentiation pathways through promoter hypermethylation [8]. In acute myeloid leukemia (AML), DNMT1 collaborates with EZH2 to establish repressive chromatin marks that block differentiation, while in breast cancer, DNMT1 hypermethylates and silences transcription factors like ISL1 and FOXO3 that normally balance stemness and differentiation [8].

TET2 function is commonly impaired in hematological malignancies through inactivating mutations or inhibition by oncometabolites. TET2 loss leads to hypermethylation and repression of differentiation genes such as GATA2 and HOX family members, reinforcing self-renewal and stemness potential [8]. In glioblastoma, SOX2 indirectly inhibits TET2 to preserve self-renewal capacity of glioma stem cells, and TET2 reconstitution suppresses tumor growth in preclinical models [8].

IDH1/2 mutations produce the oncometabolite D-2-hydroxyglutarate, which inhibits TET enzymes and causes widespread DNA hypermethylation, supporting CSC maintenance while limiting differentiation [8]. Similarly, BCAT1 activity supports leukemia stem cell engraftment by disrupting α-ketoglutarate homeostasis, thereby inhibiting TET function and promoting hypermethylation [8].

Epigenetic Therapy Strategies

The reversible nature of epigenetic modifications makes DNMTs and TET proteins attractive therapeutic targets. DNMT inhibitors azacitidine and decitabine are already approved for hematological malignancies like myelodysplastic syndromes and are being investigated in solid tumors [8] [10]. These hypomethylating agents demonstrate efficacy in eradicating CSCs by reactivating silenced tumor suppressor genes and differentiation programs.

Emerging strategies focus on combining epigenetic therapies with other treatment modalities. HDAC inhibitors synergize with DNMT inhibitors to enhance gene reactivation, while combinations with immunotherapy may help overcome immune evasion by CSCs [9] [10]. Metabolic interventions that modulate α-ketoglutarate levels or vitamin C supplementation represent alternative approaches to enhance TET activity and promote differentiation of CSCs [7].

Novel therapeutic approaches include developing specific inhibitors against mutant IDH enzymes, targeted degradation of DNMTs, and epigenetic editing using CRISPR-based systems to precisely correct aberrant methylation patterns at specific genomic loci [7] [10]. These advanced strategies offer the potential for more specific interventions with reduced off-target effects compared to current epigenetic drugs.

DNMTs and TET proteins constitute a fundamental regulatory system that dynamically controls DNA methylation status to guide stem cell fate decisions. Their balanced activities establish epigenetic landscapes that maintain pluripotency while allowing responsive lineage commitment during differentiation. Dysregulation of this system contributes significantly to cancer pathogenesis, particularly through effects on cancer stem cells that drive tumor initiation, progression, and therapy resistance.

Future research directions should focus on elucidating the precise mechanisms that recruit DNMTs and TET proteins to specific genomic loci, understanding how different oxidation products (5hmC, 5fC, 5caC) exert distinct biological effects, and deciphering the complex crosstalk between DNA methylation and other epigenetic modifications. From a therapeutic perspective, developing more specific epigenetic modulators and delivery systems represents a promising avenue for targeting CSCs while minimizing toxicity to normal stem cells.

The rapid advancement of epigenetic editing technologies offers unprecedented opportunities for both basic research and therapeutic applications. By enabling precise manipulation of methylation status at individual genes, these tools will help establish causal relationships between specific methylation events and stem cell behaviors while potentially paving the way for novel epigenetic therapies for cancer and other diseases characterized by stem cell dysfunction.

The histone code represents a fundamental epigenetic mechanism whereby post-translational modifications (PTMs) to histone proteins regulate chromatin structure and DNA accessibility without altering the underlying genetic sequence. This complex language of chemical modifications serves as a critical interface between the genome and cellular identity, particularly in stem cell plasticity and lineage commitment. Through effector-mediated recognition by specialized protein domains, histone modifications establish heritable transcriptional states that maintain pluripotency or drive differentiation. Disruption of these epigenetic pathways contributes significantly to cancer stemness and therapy resistance. This technical review examines the molecular machinery of histone code interpretation, its quantitative analysis, and therapeutic targeting in regenerative medicine and oncology.

The histone code hypothesis posits that post-translational modifications to histone proteins constitute an information-rich system that extends the genetic message by regulating chromatin-templated processes [15]. Histones comprise the major protein component of chromatin, the scaffold in which the eukaryotic genome is packaged, and are subject to more than 20 types of PTMs, especially on their flexible N-terminal tails [16] [17]. These modifications include acetylation, methylation, phosphorylation, ubiquitination, and sumoylation, among others, creating a complex combinatorial landscape that helps manage epigenetic information [15] [16].

The mechanisms by which histone modifications influence chromatin function operate through two primary models: the "direct" model, where PTMs directly affect chromatin compaction by altering charge states or internucleosomal interactions; and the emerging "effector-mediated" paradigm, where histone PTMs are specifically recognized and "read" by protein modules termed effectors, facilitating downstream events via recruitment or stabilization of chromatin-templated machinery [15]. This effector-mediated recognition represents a crucial mechanism for translating the histone code into biological outcomes, particularly in developmental processes and cellular identity.

Molecular Mechanisms of Histone Code Interpretation

Reader Domains and Effector-Mediated Recognition

Chromatin effector modules target their cognate covalent histone modifications through specialized structural domains that exhibit specific readout mechanisms for individual marks [15]. A diverse family of "reader pockets" has evolved to interpret the histone code through distinct molecular recognition principles:

Bromodomains: These approximately 110-amino acid modules form left-handed antiparallel four-helix bundles with hydrophobic binding pockets that recognize acetylated lysine residues [15]. The acetylated lysine inserts into a deep, narrow binding pocket where the acetyl carbonyl forms a hydrogen bond with a conserved asparagine residue, while the pocket's hydrophobic character provides complementary interactions [15]. Different arrangements of bromodomains enable diverse recognition capabilities, as exemplified by TAF1's double bromodomains that bind dually acetylated H4 tails with the two acetyllysine-binding pockets separated by approximately 25Å, and Rsc4p's tandem bromodomains that fold as a single structural unit with binding pockets oriented on the same face and separated by ~20Å [15].

Methyl-Lysine Readers: Multiple protein families recognize methylated lysine residues through distinct structural mechanisms. Chromo, Tudor, PHD, MBT, PWWP, WD, ADD, zf-CW, BAH, and CHD domains all function as methyllysine readers [16]. These domains typically engage methylated lysine through aromatic cage structures that coordinate the methylammonium group via cation-π interactions, with surrounding residues providing additional specificity for the modification state and flanking histone sequence [15].

The combinatorial nature of histone modification recognition enables precise control of chromatin states, where modified histone tails act as integrating platforms permitting chromatin-associated complexes to receive information from upstream signaling cascades [15]. This multifaceted recognition system allows for sophisticated regulation of nuclear processes including transcription, DNA repair, replication, and epigenetic inheritance.

Writer and Eraser Enzymes

The dynamic nature of the histone code is maintained by opposing enzyme families that establish ("write") or remove ("erase") histone modifications:

Table 1: Major Histone-Modifying Enzyme Families

| Enzyme Class | Function | Representative Enzymes | Histone Targets |

|---|---|---|---|

| Histone Acetyltransferases (HATs) | Add acetyl groups to lysine residues | Gcn5p, PCAF, p300/CBP, TIP60 | H3K9, H3K14, H3K18, H3K27, H4K5, H4K8, H4K12, H4K16 |

| Histone Deacetylases (HDACs) | Remove acetyl groups from lysine residues | Rpd3p, HDAC1-11 | Multiple acetylated lysines |

| Histone Methyltransferases (HMTs) | Add methyl groups to lysine or arginine residues | EZH2 (H3K27), Set1/Set7/9 (H3K4), Suv39h (H3K9) | H3K4, H3K9, H3K27, H3K36, H3K79, H4K20 |

| Histone Demethylases (HDMs) | Remove methyl groups from lysine or arginine residues | LSD1, JMJD family | Multiple methylated lysines/arginines |

| Kinases | Add phosphate groups to serine, threonine, or tyrosine residues | Aurora B, MSK1/2, IKK-α | H3S10, H3S28, H3T3, H3T11, H4S1 |

These enzyme families work in coordination to maintain the dynamic equilibrium of histone modifications, with their activities fine-tuned by cellular signaling pathways, metabolic states, and developmental cues. Dysregulation of these enzymes features prominently in disease states, particularly cancer, where mutations in histone-modifying enzymes can disrupt normal epigenetic control [19] [8].

Histone Modifications in Stem Cell Plasticity and Lineage Commitment

Chromatin Dynamics in Pluripotency and Differentiation

Embryonic stem (ES) cells exhibit a unique chromatin architecture characterized by a loosely packed mesh of fibers with less condensed chromatin than somatic cells [20]. Super-resolution microscopy reveals that nucleosomes in ES cells form smaller, less dense clusters than in differentiating cells, reflecting a more open chromatin configuration permissive for pluripotency [20]. This plastic state is maintained by a specific histone modification landscape:

Activation-Associated Marks: ES cells display abundant H3K4me3 at promoters of active genes and bivalent domains containing both H3K4me3 (activation-associated) and H3K27me3 (repression-associated) marks at developmental regulator genes [20]. These bivalent domains are thought to maintain genes in a "poised" state, ready for rapid activation or stable repression upon differentiation cues.

Repression-Associated Marks: H3K27me3, deposited by Polycomb Repressive Complex 2 (PRC2) with EZH2 catalytic subunit, maintains repression of developmental genes in ES cells while preserving their potential for future activation [19] [20]. The dynamic balance between H3K27me3 and H3K27me1 (associated with active transcribed regions) illustrates the complexity of modification-specific functional outcomes [20].

During lineage commitment, the histone modification landscape undergoes extensive reorganization, with resolution of bivalent domains toward monovalent active or repressive states, reinforcing cell fate decisions through stable epigenetic patterns [20].

ATP-Dependent Chromatin Remodeling Complexes in Neural Development

Chromatin remodeling complexes work in concert with histone modifications to regulate lineage commitment, particularly in neural development where their dysfunction is linked to neurodevelopmental disorders [21]. These complexes are categorized into four major families based on their catalytic subunits:

SWI/SNF Complexes: The Brg1/Brm-associated factor (BAF) complex is essential for neural progenitor cell self-renewal and proliferation. BAF complex disruption leads to cortical thinning, midbrain and cerebellar hypoplasia, and neuronal migration defects [21]. During later neurogenesis, the BAF complex limits progenitor proliferation and promotes neuronal differentiation by preventing H3K27me3-mediated silencing of neuronal differentiation genes [21].

CHD Complexes: CHD family members display diverse, sometimes opposing functions in neural development. CHD4 deletion reduces cortical thickness and causes premature cell cycle exit, while CHD8 haploinsufficiency increases progenitor proliferation leading to megalencephaly [21]. CHD proteins also regulate neuronal migration, with CHD5 establishing neuronal polarity and early radial migration, while CHD3 regulates late migration and cortical layering [21].

ISWI Complexes: Smarca1 controls neural progenitor proliferation by binding the Foxg1 promoter, while Smarca5 regulates cerebellar granule neuron progenitor proliferation [21].

INO80 Complexes: Ino80 maintains neural progenitor populations by supporting DNA repair mechanisms; its deletion triggers p53-dependent microcephaly and apoptosis [21].

The coordination between ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling and histone modifications represents a crucial regulatory layer in lineage commitment, with mutations in these systems contributing significantly to developmental disorders and disease.

Figure 1: Histone Modification Dynamics During Lineage Commitment. Embryonic stem cells maintain bivalent chromatin domains at developmental genes, which resolve toward active or repressed states during differentiation through coordinated action of histone-modifying enzymes. [8] [20]

Analytical Methods for Histone Modification Analysis

Mass Spectrometry-Based Proteomics

Mass spectrometry has emerged as a powerful tool for comprehensive histone modification analysis, enabling identification and quantification of PTMs in an unbiased manner [16]. Key methodological approaches include:

Bottom-Up MS Proteomics: This widely adopted approach involves protease digestion (typically with ArgC-like specificity) of acid-extracted histones followed by LC-MS/MS analysis on high-resolution instruments like Orbitrap systems [19]. The method provides >90% sequence coverage for histones H3 and H4, enabling quantification of dozens of unique modification patterns across cell lines [19]. Normalization strategies typically compare all detected modified forms of a common peptide backbone against each other, allowing relative quantification of PTM stoichiometry.

Quantitative Proteomic Atlas Construction: Large-scale profiling of cancer cell lines has quantified 37 unique histone H3 modification patterns and 19 H4 modification patterns, revealing cancer-type specific epigenetic signatures [19]. For example, H3K27 methylation is especially enriched in breast cancer cell lines, and EZH2 depletion in mammary xenograft models significantly reduces tumor burden, demonstrating the predictive utility of proteomic approaches [19].

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation Sequencing (ChIP-seq)

ChIP-seq remains the gold standard for genome-wide mapping of histone modifications, though traditional methods suffer from quantitative limitations. Recent advances have addressed these challenges:

- siQ-ChIP (sans spike-in Quantitative ChIP): This method establishes an absolute quantitative scale for ChIP-seq without spike-in reagents by leveraging the equilibrium binding reaction in chromatin immunoprecipitation [22]. The quantitative scaling factor (α) is derived as:

where vin is input sample volume, V-vin is IP reaction volume, mIP and min are IP and input masses, and m_loaded represents masses loaded for sequencing [22]. This approach enables direct comparison of histone modification abundance across samples and experimental conditions.

- Track Interpretation Constraints: siQ-ChIP reveals that sequencing tracks must be interpreted as probability density distributions rather than qualitative enrichment profiles [22]. This constraint has implications for how cellular perturbations are assessed, as traditional normalization methods can lead to misinterpretation of histone modification dynamics.

Integrated Multi-Omics Approaches

Combining proteomic and genomic analyses provides complementary insights into histone modification states. While transcript levels of histone-modifying enzymes often correlate with resulting PTM patterns, several PTMs are regulated independently of enzyme expression, highlighting the importance of post-translational regulation of modifying enzymes themselves [19]. Integrated approaches thus provide a more comprehensive understanding of the regulatory networks controlling the histone code.

Table 2: Quantitative Histone Modification Patterns in Cancer Cell Lines [19]

| Histone Modification | Function | Breast Cancer Lines | Leukemia Lines | Cervical Cancer Lines |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H3K4me3 | Transcriptional activation | Variable | Variable | Variable |

| H3K9me3 | Heterochromatin formation | Moderate | Low | Moderate |

| H3K27me3 | Polycomb repression | High | Low | Moderate |

| H3K36me3 | Transcriptional elongation | Moderate | Low | Moderate |

| H3K79me2 | Euchromatin maintenance | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate |

| H4K16ac | Transcriptional activation | Moderate | Low | High |

| H4K20me3 | Heterochromatin | Low | Low | Moderate |

Histone Modifications in Cancer Stemness and Therapeutic Targeting

Epigenetic Regulation of Cancer Stem Cells

Cancer stem cells (CSCs) utilize histone modification patterns to maintain stem-like properties including self-renewal capacity, differentiation blockade, and therapy resistance [8]. Key mechanisms include:

Polycomb-Mediated Repression: EZH2, the catalytic subunit of PRC2, is frequently overexpressed in cancers and contributes to CSC maintenance by depositing H3K27me3 marks at tumor suppressor and differentiation genes [19] [8]. In acute myeloid leukemia (AML), EZH2 collaborates with DNMT1 to establish repressive chromatin states, while in breast cancer, it silences transcription factors that balance stemness and differentiation [8].

Metabolic-Epigenetic Crosstalk: Metabolic alterations in CSCs influence histone modifications through metabolic co-factors. Lactate has been shown to increase histone acetylation, epigenetically activating MYC expression in intestinal tumor organoids [14]. This regulation depends on bromodomain-containing protein 4 (BRD4), connecting metabolism with chromatin reading. Similarly, mutations in isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH1/2) produce the oncometabolite D-2-hydroxyglutarate, which inhibits histone demethylases and TET DNA demethylases, promoting CSC maintenance [8].

Pluripotency Factor Regulation: CSCs exhibit distinct DNA methylation and histone modification patterns at promoters of pluripotency factors like OCT4, SOX2, and NANOG [8]. Hypomethylation of these loci in circulating tumor cells correlates with increased tumor-repopulating potential, highlighting how epigenetic mechanisms preserve stemness programs in cancer [8].

Therapeutic Targeting of Histone Modifications

The dynamic nature of epigenetic modifications makes them attractive therapeutic targets. Several classes of epidrugs have been developed:

Bromodomain Inhibitors: Compounds targeting BRD4 show promise in disrupting the recognition of acetylated histones by CSCs, particularly in combination with metabolic interventions [14]. These inhibitors displace BRD4 from chromatin, suppressing MYC expression and other stemness regulators.

EZH2 Inhibitors: Selective inhibition of EZH2 catalytic activity can reverse H3K27me3-mediated silencing of tumor suppressors, promoting differentiation and reducing tumor burden in preclinical models [19] [8]. Several EZH2 inhibitors are in clinical development for hematological malignancies and solid tumors.

HDAC Inhibitors: Broad-spectrum and isoform-selective HDAC inhibitors can alter the histone acetylation landscape, potentially reactivating silenced differentiation genes in CSCs [8]. Drugs like suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid (SAHA) are approved for certain cancer indications and are being explored in combination therapies.

Figure 2: Targeting Histone Modifications in Cancer Stem Cells. Metabolic-epigenetic crosstalk and histone-modifying enzymes maintain cancer stemness, providing targets for epigenetic therapies including BRD4, EZH2, and HDAC inhibitors. [14] [8]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Methodologies

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Histone Code Investigation

| Reagent/Methodology | Function | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|

| siQ-ChIP | Quantitative ChIP-seq without spike-ins | Absolute quantification of histone modification genome-wide distribution [22] |

| Bottom-Up Mass Spectrometry | Comprehensive PTM identification and quantification | Global histone modification profiling across cell states [16] [19] |

| Histone Modification-Specific Antibodies | Immunodetection of specific PTMs | Western blot, immunofluorescence, ChIP-seq validation [18] [22] |

| Bromodomain Inhibitors (e.g., JQ1) | Competitive binding to acetyl-lysine pockets | Disruption of histone acetylation reading in stemness regulation [14] |

| EZH2 Inhibitors (e.g., GSK126) | Selective inhibition of H3K27 methyltransferase | Reversal of Polycomb-mediated silencing in CSCs [19] [8] |

| HDAC Inhibitors (e.g., SAHA) | Blockade of histone deacetylase activity | Increasing histone acetylation, promoting differentiation [8] |

| Organoid Culture Systems | 3D models maintaining cellular hierarchy | Studying histone modifications in tissue context and cancer stemness [14] |

| CellPhenTracker | Machine learning-based cell tracking | Lineage tracing with metabolic and epigenetic monitoring [14] |

The histone code represents a sophisticated epigenetic regulatory system that integrates environmental cues, metabolic states, and developmental signals to control chromatin structure and cellular identity. In stem cell biology and cancer, specific histone modification patterns maintain plastic states capable of self-renewal while retaining differentiation potential. The dynamic nature of these epigenetic marks, mediated by opposing writer and eraser enzymes and interpreted by reader domains, provides a mechanism for rapid response to changing conditions without altering DNA sequence.

Future research directions will likely focus on understanding the spatial organization of histone modifications in the 3D nuclear context, particularly how chromatin looping and topologically associated domains interface with the histone code to regulate gene expression programs. Additionally, the development of more precise epigenetic editing tools, such as engineered reader domains coupled to functional effectors, will enable targeted manipulation of specific histone modification states for both basic research and therapeutic applications. As single-cell epigenomic technologies advance, we will gain unprecedented resolution into the heterogeneity of histone modification landscapes within stem cell and cancer populations, potentially revealing new regulatory principles and therapeutic vulnerabilities.

The integration of histone modification analysis into clinical practice represents another promising frontier, with potential applications in cancer diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment selection. As epigenetic therapies continue to develop, combination approaches targeting multiple components of the histone code machinery may prove most effective in overcoming the plasticity and adaptability of cancer stem cells. Ultimately, deciphering the complex language of histone modifications will continue to provide fundamental insights into the epigenetic regulation of development, disease, and cellular identity.

Stemness—the capacity for self-renewal and multilineage differentiation—and cellular plasticity are fundamentally regulated by epigenetic mechanisms. Within this regulatory framework, non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs) have emerged as master conductors, establishing complex networks that control the gene expression programs defining stem cell identity and fate. These RNA molecules, which do not code for proteins, constitute the majority of the human transcriptome and have evolved as critical layers of epigenetic regulation in stem cell biology [23] [24]. The interplay between ncRNAs and other epigenetic mechanisms—including DNA methylation and histone modifications—creates a dynamic regulatory system that maintains stem cell populations while allowing responsive differentiation to diverse cellular lineages [25] [26]. In pathological contexts, particularly cancer, this regulatory system becomes subverted, where cancer stem cells (CSCs) exploit ncRNA-mediated circuits to sustain their self-renewing capabilities, promote tumor heterogeneity, and drive therapeutic resistance [27]. This review examines the molecular mechanisms through which diverse ncRNA classes govern stemness and plasticity, providing a technical guide for researchers investigating stem cell biology and developing novel therapeutic strategies.

Classification and Molecular Functions of Key ncRNA Families

Non-coding RNAs are broadly categorized by length and molecular function. The major classes involved in regulating stemness include microRNAs (miRNAs), long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs), circular RNAs (circRNAs), and PIWI-interacting RNAs (piRNAs). Table 1 summarizes the defining characteristics and primary functions of these ncRNA classes in stem cell regulation.

Table 1: Major Non-Coding RNA Classes in Stemness Regulation

| ncRNA Class | Size Range | Key Biogenesis Factors | Primary Mechanisms of Action | Documented Roles in Stemness |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| miRNA | ~22 nt | Drosha, Dicer, AGO2 | mRNA degradation; translational repression | Maintains pluripotency; controls differentiation timing; regulates stem cell quiescence/proliferation balance [28] [29] |

| lncRNA | >200 nt | RNA Pol II/III | Chromatin modification; transcriptional regulation; molecular scaffolding | X-chromosome inactivation; nuclear organization; stem cell lineage specification [30] [24] |

| circRNA | Variable | Back-splicing | miRNA sponging; protein scaffolding | Stem cell maintenance; pluripotency factors regulation [27] [28] |

| piRNA | 24-31 nt | PIWI proteins | Transposon silencing; DNA methylation | Genome stability in germline and somatic stem cells [24] |

The biogenesis pathways for these ncRNA classes are highly specialized. MicroRNAs (miRNAs) undergo either canonical or non-canonical processing. The canonical pathway involves transcription of primary miRNAs (pri-miRNAs) by RNA polymerase II, nuclear cleavage by the Drosha-DGCR8 complex to form precursor miRNAs (pre-miRNAs), export to the cytoplasm via Exportin-5, and final processing by Dicer to generate mature ~22 nucleotide miRNAs that load into the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC) [28] [29]. Non-canonical pathways include mirtrons that bypass Drosha processing through splicing mechanisms [28]. In contrast, long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) are primarily transcribed by RNA polymerase II and undergo processing similar to mRNAs, including 5' capping, splicing, and polyadenylation, though they exhibit more tissue-specific expression patterns [30] [29]. Circular RNAs are generated through back-splicing events where downstream 5' splice sites join with upstream 3' splice sites, forming covalently closed loop structures that confer exceptional stability [28].

Molecular Mechanisms of ncRNA-Mediated Stemness Regulation

ncRNA Control of Pluripotency and Self-Renewal Networks

Non-coding RNAs regulate stemness through sophisticated interactions with core transcriptional networks and signaling pathways. In embryonic stem cells (ESCs), miRNAs such as the miRNA-302/367 cluster and miRNA-290 cluster directly target core transcription factors including NR2F2, CDKN1A, and RBL2, thereby reinforcing the pluripotent state by suppressing differentiation programs [29]. Similarly, lncRNAs like Xist mediate X-chromosome inactivation through recruitment of chromatin-modifying complexes, establishing epigenetic silencing that is essential for proper development and maintaining female pluripotent stem cell populations [24]. Single-cell transcriptomic analyses have revealed that lncRNA expression patterns are highly cell-type-specific throughout hematopoietic differentiation, with distinct lncRNA signatures characterizing hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs) compared to differentiated lineages [30]. This precise developmental regulation underscores the importance of lncRNAs in maintaining cellular identity during stem cell differentiation.

Exosomal ncRNAs in Intercellular Communication

A particularly significant mechanism in stem cell regulation involves exosomal ncRNAs that mediate intercellular communication within specialized microenvironments. In cancer, exosomes serve as critical vehicles for transferring ncRNAs between cell populations, creating a bidirectional communication network that reinforces stemness properties. As illustrated in Figure 1, this exosome-mediated crosstalk establishes a feed-forward loop that amplifies stem cell characteristics and promotes tumor progression.

Figure 1: Bidirectional Exosomal ncRNA Communication Between CSCs and Non-CSCs. Cancer stem cells (CSCs) and non-CSC tumor cells exchange exosomes containing distinct ncRNA cargoes, creating a self-reinforcing loop that promotes tumor progression through enhanced stemness, metastasis, and therapy resistance [27].

The molecular consequences of this exosome-mediated communication are profound. Non-CSC-derived exosomal ncRNAs enhance CSC stemness by upregulating stemness marker expression (including OCT4, EpCAM, and ALDH) and activating stemness-reinforcing signaling pathways such as Wnt/β-catenin, Notch, and PI3K/AKT/mTOR [27]. Reciprocally, CSC-derived exosomal ncRNAs promote tumor progression by enhancing stemness, metastasis, angiogenesis, chemoresistance, and immune suppression in non-CSCs. For example, lung CSC-derived exosomal lncRNA Mir100hg activates H3K14 lactylation to potentiate metastatic activity in non-CSCs, while circRNAs such as circZFR function as molecular sponges for miRNAs, sequestering them and indirectly upregulating expression of downstream targets that promote proliferation and migration [27].

Epigenetic Circuitry in Cellular Plasticity

Non-coding RNAs participate in sophisticated feedback loops within the broader epigenetic landscape. They recruit and guide chromatin-modifying complexes to specific genomic loci, establishing heritable gene expression states that define cellular identity. For instance, certain lncRNAs interact with polycomb repressive complex 2 (PRC2) to catalyze H3K27 trimethylation, leading to stable gene silencing of differentiation promoters in stem cells [24]. Similarly, miRNAs can target components of the DNA methylation machinery, such as DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs), creating interconnected regulatory layers that modulate cellular plasticity [25] [24]. This epigenetic plasticity enables both normal differentiation processes and pathological states, as seen in cancer where transient non-CSC populations can regain stem-like properties through ncRNA-mediated reprogramming [27].

Experimental Approaches for ncRNA-Stemness Research

Core Methodologies and Workflows

Investigating ncRNAs in stemness requires specialized methodological approaches. Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has emerged as a powerful tool for delineating ncRNA expression heterogeneity across stem cell populations. The experimental workflow, as illustrated in Figure 2, enables researchers to capture the dynamic regulation of ncRNAs during stem cell differentiation and in heterogeneous populations like CSCs.

Figure 2: Single-Cell RNA Sequencing Workflow for ncRNA Analysis in Stem Cells. This pipeline enables comprehensive profiling of ncRNA expression across heterogeneous stem cell populations, facilitating identification of stemness-associated ncRNA signatures [30].

Key technical considerations for scRNA-seq studies include the use of custom lncRNA references that incorporate annotations from databases like NONCODE to ensure comprehensive ncRNA capture [30]. Bioinformatics processing typically involves alignment to combined references (GENCODE for protein-coding genes and NONCODE for lncRNAs), followed by dimensionality reduction, unsupervised clustering using algorithms like Leiden, and differential expression analysis to identify stemness-associated ncRNAs [30]. For functional validation, reverse transcription quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) provides precise quantification of candidate ncRNAs, while flow cytometry enables sorting of distinct stem cell subpopulations based on surface markers (e.g., CD44, CD133, ALDH) for subsequent molecular analyses [27] [30].

Essential Research Reagents and Tools

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for ncRNA-Stemness Investigations

| Reagent/Tool Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stem Cell Markers | CD44, CD133, OCT4, EpCAM, ALDH | Identification and isolation of stem cell populations | Marker expression varies by stem cell type and species [27] |

| ncRNA Inhibition/Overexpression | Anti-miRNAs, miRNA mimics, siRNA, CRISPR-based editors | Functional perturbation of ncRNA activity | Consider compensation effects; use multiple approaches for validation [28] |

| Exosome Isolation Methods | Ultracentrifugation, immunoaffinity capture, size-exclusion chromatography | Purification of exosomes for ncRNA cargo analysis | Method choice affects exosome yield and purity [27] |

| scRNA-seq Platforms | 10X Genomics, Fluidigm C1 | High-resolution transcriptomic profiling | 10X offers higher throughput; custom ncRNA references enhance detection [30] |

| Bioinformatics Tools | Seurat, Scanpy, BBKNN | Analysis of scRNA-seq data | Enable batch effect correction and differential ncRNA expression analysis [30] |

Therapeutic Implications and Translational Applications

The pivotal role of ncRNAs in regulating stemness and plasticity presents compelling therapeutic opportunities. From a diagnostic perspective, the remarkable stability of ncRNAs in bodily fluids and their tissue-specific expression patterns make them promising biomarkers for liquid biopsy applications [28] [29]. In oncology, exosomal ncRNAs derived from CSCs hold potential for early detection of metastasis and monitoring therapeutic responses [27]. Therapeutically, multiple strategies are being explored to target ncRNA networks in stem cell populations, particularly for overcoming therapy resistance in cancer. These approaches include anti-miRNA oligonucleotides that inhibit oncogenic miRNAs, miRNA mimics to restore tumor-suppressive miRNA functions, and engineered exosomes designed to deliver therapeutic ncRNAs specifically to CSCs [27] [28].

The clinical translation of ncRNA-based therapies faces several challenges, including delivery efficiency, tissue specificity, and potential off-target effects. Innovative solutions such as modified oligonucleotides (e.g., locked nucleic acids) that enhance stability and specificity, and targeted delivery systems using nanoparticle formulations are advancing toward clinical application [28]. Furthermore, combination therapies that integrate epigenetic drugs with conventional chemotherapy, targeted therapy, or immunotherapy show synergistic potential for eliminating therapy-resistant CSCs by disrupting the ncRNA-mediated circuits that sustain stemness [25]. As precision medicine advances, ncRNA profiling promises to enable more individualized treatment strategies that account for the dynamic plasticity of stem cell populations in both normal tissue homeostasis and disease.

Non-coding RNAs constitute a critical regulatory layer in the epigenetic control of stemness and cellular plasticity. Through diverse mechanisms—including exosome-mediated intercellular communication, guidance of chromatin-modifying complexes, and integration with core signaling pathways—ncRNAs establish dynamic networks that maintain stem cell populations while permitting responsive differentiation. In pathological conditions, particularly cancer, these regulatory circuits are co-opted to sustain Cancer Stem Cells that drive tumor progression and therapy resistance. Advanced technologies such as single-cell transcriptomics, coupled with innovative therapeutic approaches targeting ncRNA networks, are rapidly advancing our ability to investigate and manipulate these fundamental biological processes. As research continues to unravel the complexities of ncRNA functions in stem cell biology, these insights promise to catalyze the development of novel diagnostic and therapeutic strategies for regenerative medicine and oncology.

The interplay between cellular metabolism and epigenetic regulation constitutes a fundamental biological axis governing cell fate decisions, particularly within the context of stem cell plasticity. This whitepaper delineates the mechanistic roles of three key metabolites—acetyl-CoA, S-adenosylmethionine (SAM), and α-ketoglutarate (α-KG)—as essential substrates and cofactors for chromatin-modifying enzymes. We synthesize current evidence demonstrating how fluctuations in the availability of these metabolites, driven by metabolic reprogramming, directly shape the epigenetic landscape to influence stemness, differentiation, and cellular reprogramming. Furthermore, we explore the pathological implications of this metabolic-epigenetic interplay in cancer stem cells (CSCs), highlighting emerging therapeutic strategies. Supported by structured data summaries, experimental workflows, and pathway visualizations, this review serves as a technical guide for researchers and drug development professionals aiming to target these pathways for regenerative medicine and oncology applications.

The physiological identity and functional capacity of every cell are maintained by highly specific transcriptional networks, which are themselves governed by the epigenetic landscape—a dynamic layer of chemical modifications to DNA and histone proteins that regulates gene expression without altering the underlying DNA sequence [31]. A paradigm shift in our understanding of epigenetic control has revealed that the enzymes responsible for adding or removing these modifications are acutely sensitive to the cellular concentrations of specific intermediary metabolites [32] [33]. This creates a direct molecular link between the metabolic state of a cell and its transcriptional output.

Among these metabolites, three stand out for their widespread and critical roles: acetyl-CoA, the substrate for protein acetylation; S-adenosylmethionine (SAM), the universal methyl donor for methylation reactions; and α-ketoglutarate (α-KG), an essential co-substrate for a large family of dioxygenases, including histone and DNA demethylases [32] [31]. The nuclear availability of these metabolites allows the cell to synchronize its gene expression program with its metabolic status, a mechanism that is crucial for cell fate transitions such as those occurring during stem cell differentiation, somatic cell reprogramming, and the acquisition of stem-like properties in cancer [33] [8] [9].

This review provides an in-depth examination of how acetyl-CoA, SAM, and α-KG mechanistically control the epigenome to influence stem cell plasticity. We frame this discussion within the broader context of stem cell research, emphasizing how metabolic cues are integrated into the regulatory circuits that determine self-renewal and differentiation, and how their dysregulation contributes to the pathogenesis of cancer stem cells.

Molecular Mechanisms of Metabolite-Dependent Epigenetic Control

Acetyl-CoA: Fueling Open Chromatin and Transcriptional Activation

Acetyl-CoA is a central metabolic hub, produced from the catabolism of glucose, fatty acids, and amino acids. Its role as the sole donor of acetyl groups for histone acetylation directly couples energy status to chromatin state [31].

- Enzymatic Actors: Histone acetyltransferases (HATs) such as Gcn5, MYST, and p300/CBP utilize acetyl-CoA to modify lysine residues on histones [32]. The removal of these marks is catalyzed by histone deacetylases (HDACs), including the NAD+-dependent sirtuins [32] [31].

- Mechanism of Action: The transfer of an acetyl group to a lysine residue neutralizes its positive charge, weakening the electrostatic interaction between histones and the negatively charged DNA backbone. This results in a more relaxed chromatin structure (euchromatin) that is permissive to transcription [31]. Furthermore, acetylated lysines serve as docking sites for bromodomain-containing reader proteins, which recruit additional transcriptional co-activators [33].

- Metabolic Sensors and Nuclear Availability: Nuclear acetyl-CoA levels are dynamically regulated. Key mechanisms include:

- The ATP-citrate lyase (ACLY) pathway: Glucose-derived citrate is exported from the mitochondria and cleaved by ACLY in the nucleus and cytosol to generate acetyl-CoA [33] [31].

- The Acetyl-CoA Synthetase 2 (ACSS2) pathway: Under metabolic stress such as hypoxia, acetate is utilized by ACSS2 to generate acetyl-CoA in the nucleus [32] [33].

- Nuclear translocation of the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex (PDC): This enables direct conversion of pyruvate to acetyl-CoA within the nucleus [32].

The following diagram illustrates the major pathways governing nuclear acetyl-CoA production and its subsequent impact on histone acetylation and gene regulation:

Figure 1: Nuclear acetyl-CoA generation and its epigenetic role. Acetyl-CoA is produced in the nucleus via multiple pathways involving ACLY, ACSS2, and PDC, fueling HAT activity to promote histone acetylation, open chromatin, and gene activation.

S-Adenosylmethionine (SAM): The Master Methyl Donor

SAM is the primary donor of methyl groups for DNA methylation and histone methylation, thereby serving as a critical nexus between one-carbon metabolism and the epigenetic control of gene expression [32] [33].

- Enzymatic Actors: SAM is utilized by DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs) and histone methyltransferases (HMTs), such as EZH2, which catalyzes the repressive H3K27me3 mark [32] [33] [8]. The reaction product, S-adenosylhomocysteine (SAH), is a potent competitive inhibitor of these methyltransferases. Thus, the SAM/SAH ratio is a crucial indicator of cellular methylation capacity [32] [33].

- Metabolic Regulation: SAM is synthesized from ATP and methionine by methionine adenosyltransferase (MAT). Its levels are influenced by nutrient availability, including dietary intake of methionine, folate, and vitamin B12, which feed into the one-carbon metabolism cycle [33].

- Influence on Cell Fate: Fluctuations in SAM availability can have site-specific effects on histone methylation. For instance, in yeast, H3K4 methylation by Set1 is particularly sensitive to disruptions in SAM biosynthesis, while Dot1-mediated methylation is less so, due to differences in enzyme affinity (Km) for SAM [32]. In intestinal stem cells and cancer models, SAM availability influences the balance between self-renewal and differentiation by modulating the methylation of key promoters [33] [8].

Table 1: Key Methylation Reactions Dependent on S-Adenosylmethionine (SAM)

| Epigenetic Mark | Enzyme(s) | Functional Outcome | Sensitivity to SAM |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA (5mC) | DNMT1, DNMT3A/B | Transcriptional repression | High (low SAM → global hypomethylation) |

| H3K4me3 | SET1/COMPASS, MLL | Transcriptional activation | High (e.g., yeast Set1) |

| H3K27me3 | EZH2 (PRC2) | Transcriptional repression | Moderate |

| H3K36me3 | SETD2 | Transcriptional elongation | Varies by context |

| H3K79me | DOT1L | Transcriptional activation | Low (due to low Km of DOT1) |

α-Ketoglutarate (α-KG): A Key Regulator of Demethylation

α-KG (also known as 2-oxoglutarate) is a tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle intermediate that serves as an essential co-substrate for the Jumonji C (JmjC) domain-containing histone demethylases (KDMs) and the Ten-eleven translocation (TET) family of DNA demethylases [32] [8].

- Enzymatic Mechanism: These enzymes are Fe²⁺/α-KG-dependent dioxygenases. They catalyze reactions that couple the oxidative decarboxylation of α-KG to succinate and CO₂, with the hydroxylation of their substrate (methylated DNA or histone), leading to demethylation [32].

- Metabolic Sensors and Inhibitors: The activity of these dioxygenases is therefore dependent on oxygen availability, Fe²⁺, and the cellular α-KG/succinate ratio. Importantly, structurally similar metabolites like 2-hydroxyglutarate (2-HG), an oncometabolite produced by mutant isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH) in some cancers, act as competitive inhibitors [33] [8]. This inhibition leads to a hypermethylated epigenetic landscape that blocks differentiation and promotes a stem-like state in malignancies like AML and GBM [8].

- Role in Pluripotency and Differentiation: By facilitating the removal of repressive methylation marks, α-KG-dependent demethylases help to activate genes necessary for lineage specification. In pluripotent stem cells, TET enzymes promote a hypomethylated state of pluripotency gene enhancers, while their inhibition locks cells in a less differentiated, stem-like state [8] [9].

Table 2: α-Ketoglutarate-Dependent Demethylation Enzymes and Their Roles

| Enzyme Family | Targets | Biological Function | Inhibitors |

|---|---|---|---|

| TET Dioxygenases | 5-Methylcytosine (DNA) | DNA demethylation, activation of gene expression | 2-HG, Succinate, Fumarate |

| JmjC KDMs | H3K9me2/3, H3K27me3, H3K36me2/3, etc. | Histone demethylation, chromatin relaxation | 2-HG, Succinate, Fumarate |

| ALKB Homologs | Methylated DNA/RNA (repair) | DNA alkylation damage repair | - |

The interconnected roles of these three metabolites in shaping the chromatin landscape are summarized in the pathway diagram below:

Figure 2: Metabolic control of the epigenome. The diagram illustrates how acetyl-CoA, SAM, and α-KG, derived from central metabolic pathways, regulate the activities of epigenetic enzymes to influence the balance between stem cell self-renewal and differentiation. Inhibitory interactions are shown in orange.

Experimental Approaches for Investigating Metabolic-Epigenetic Axis

Studying the metabolic control of the epigenome requires a multidisciplinary approach, combining metabolic manipulation, epigenomic profiling, and functional validation.

Key Methodologies and Workflows

A standard experimental workflow for establishing a causal link between a metabolite, its associated epigenetic mark, and a functional cell fate outcome is outlined below. This typically begins with the modulation of metabolite availability, followed by comprehensive molecular profiling and functional assays.

Figure 3: A generalized experimental workflow for investigating the metabolic-epigenetic axis. The process involves perturbing metabolism, analyzing molecular changes, validating functional outcomes, and elucidating deeper mechanisms.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The following table catalogs critical reagents and tools used in this field to manipulate and measure the metabolic-epigenetic interplay.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Studying Metabolic Control of the Epigenome

| Reagent/Tool | Category | Function/Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| DMKG (Dimethyl-alpha-ketoglutarate) | Metabolite Agonist | Cell-permeable α-KG precursor; boosts α-KG levels | Rescue experiments in α-KG-deficient conditions; promote differentiation [8] |

| Methionine-Free Media | Metabolic Modulator | Depletes intracellular SAM pools; reduces methylation capacity | Study effects of hypomethylation on stemness and differentiation [33] |

| Sodium Acetate | Metabolic Modulator | Source for acetyl-CoA production via ACSS2 | Investigate acetate-dependent histone acetylation in hypoxia [32] [33] |

| BET Inhibitors (e.g., JQ1) | Epigenetic Inhibitor | Blocks binding of bromodomain readers to acetylated histones | Dissect functional outcomes of histone hyperacetylation [14] |

| EZH2 Inhibitors (e.g., GSK126) | Epigenetic Inhibitor | Inhibits H3K27me3 deposition; de-represses targets | Target SAM-dependent methylation in cancers with EZH2 dependency [8] |

| Etonostat | Epigenetic Inhibitor | Pan-HDAC inhibitor; increases histone acetylation | Enhance reprogramming efficiency or induce differentiation [9] |

| LC-MS/MS | Analytical Platform | Quantifies absolute levels of metabolites (SAM, SAH, acetyl-CoA, α-KG) | Correlate metabolite abundance with epigenetic mark levels [33] |

| CUT&Tag / ChIP-seq | Epigenomic Profiling | Maps genome-wide localization of histone modifications | Identify loci where metabolic changes alter histone marks [8] [9] |

Implications in Stem Cell Plasticity and Cancer

The metabolic control of the epigenome is a cornerstone of stem cell plasticity—the ability of stem cells to self-renew or differentiate—and its dysregulation is a hallmark of cancer, particularly in cancer stem cells (CSCs).

- Pluripotency and Reprogramming: The balance of activating (H3K4me3, H3K27ac) and repressive (H3K27me3) histone marks maintains pluripotent stem cells in a "poised" state, ready to rapidly respond to differentiation signals [9]. During reprogramming of somatic cells to induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), a metabolic shift toward glycolysis increases acetyl-CoA production, facilitating a hyperacetylated chromatin state that enhances the expression of pluripotency factors like OCT4 and NANOG [31] [9]. HDAC inhibitors like valproic acid can significantly improve reprogramming efficiency [9].