Epigenetic Remodeling in mRNA Reprogramming: Mechanisms, Therapeutics, and Clinical Translation

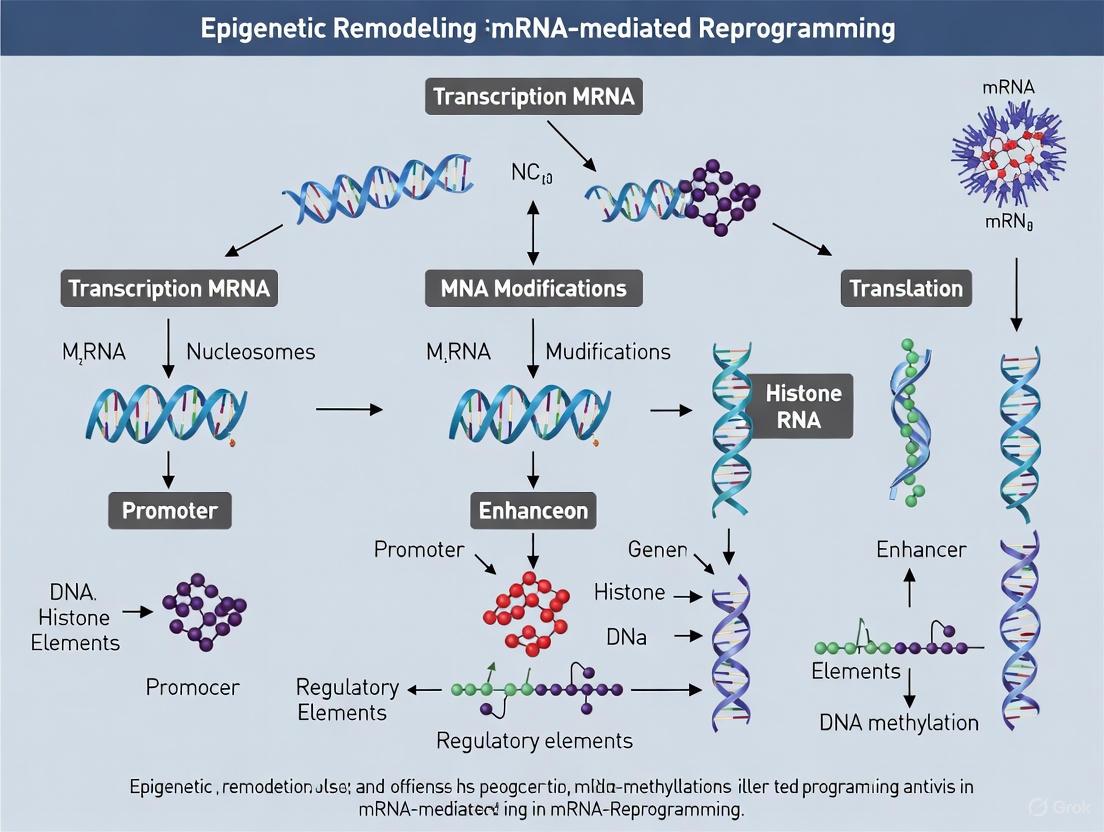

This article explores the convergence of epigenetic remodeling and mRNA technology for cellular reprogramming, a frontier in regenerative medicine and drug development.

Epigenetic Remodeling in mRNA Reprogramming: Mechanisms, Therapeutics, and Clinical Translation

Abstract

This article explores the convergence of epigenetic remodeling and mRNA technology for cellular reprogramming, a frontier in regenerative medicine and drug development. We examine the foundational epigenetic mechanisms—DNA methylation, histone modifications, and RNA epitranscriptomics—that underpin cell identity and are targeted by mRNA-delivered factors. The scope extends to methodological advances in mRNA-mediated delivery of reprogramming factors, their application in generating induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) and direct transdifferentiation, and the resultant therapeutic potential for tissue repair and aging. The content also addresses critical challenges in efficacy, safety, and specificity, while evaluating current validation strategies and comparative outcomes against other reprogramming techniques. This synthesis provides researchers and drug developers with a comprehensive overview of the current landscape and future trajectory of mRNA-based epigenetic reprogramming.

The Epigenetic Code: Foundations of Cell Identity and Plasticity

Epigenetic mechanisms represent a reversible layer of gene regulation that controls cellular identity and function without altering the underlying DNA sequence. These mechanisms—DNA methylation, histone modifications, and chromatin remodeling—collectively establish and maintain gene expression patterns that define cell states [1]. In the context of mRNA-mediated reprogramming, understanding these core epigenetic mechanisms is paramount for developing precise interventions that can redirect cell fate for therapeutic purposes. The emerging field of epigenetic editing demonstrates how targeted rewriting of epigenetic signatures can reprogram gene expression without genomic editing, offering promising avenues for therapeutic intervention across various diseases [2]. This technical guide examines the fundamental epigenetic mechanisms and their interplay within mRNA-based reprogramming strategies, providing researchers with essential knowledge and methodologies for advancing epigenetic research and therapeutic development.

Core Mechanism I: DNA Methylation

Molecular Basis and Enzymatic Machinery

DNA methylation involves the covalent addition of a methyl group to the fifth carbon of cytosine bases, primarily within CpG dinucleotides, forming 5-methylcytosine (5mC) [3]. This modification is dynamically regulated by writer, eraser, and reader proteins that establish, remove, and interpret methylation marks, respectively.

Table 1: DNA Methylation Enzymatic Machinery and Functions

| Enzyme/Protein | Classification | Primary Function | Consequence of Loss-of-Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNMT1 | Writer - Maintenance | Maintains methylation patterns during DNA replication | Apoptosis of germline stem cells; hypogonadism and meiotic arrest [3] |

| DNMT3A/B | Writer - De Novo | Establishes new methylation patterns during development | Abnormal spermatogonial function; fertility issues [3] |

| DNMT3L | Writer Cofactor | Enhances DNMT3A/B activity; targets de novo methylation | Decrease in quiescent spermatogonial stem cells [3] |

| TET Family | Eraser | Initiates DNA demethylation via 5mC oxidation | Fertile phenotype observed in TET1/2 mutants [3] |

| MBD Family | Reader | Recognizes and binds methylated DNA; recruits repressive complexes | / |

The distribution of DNA methylation is precisely controlled, with approximately 70-90% of CpG sites methylated in mammalian genomes. CpG islands—genomic regions with high G+C content (>50%) and dense CpG clustering—typically remain unmethylated, particularly when located near promoter regions or transcription start sites (TSS) [3]. DNA methylation generally correlates with transcriptional repression by altering chromatin accessibility and impeding transcription factor binding, though it can also stabilize RNA polymerase II elongation and activate transcription in specific contexts [3].

Dynamics in Cellular Programming and Reprogramming

During embryonic development and cellular reprogramming, the genome undergoes waves of global demethylation followed by de novo methylation [3]. In primordial germ cells (PGCs), the precursors to spermatogonial stem cells (SSCs), genome-wide DNA demethylation reduces 5mC levels to approximately 16.3% during migration to the gonads, significantly lower than the 75% abundance in embryonic stem cells (ESCs) [3]. This hypomethylation is driven by repression of de novo methyltransferases DNMT3A/B and elevated activity of DNA demethylation factors like TET1 [3]. Subsequently, from embryonic day 13.5 to 16.5, de novo DNA methylation is gradually reestablished [3].

In the context of aging, DNA methylation patterns undergo significant shifts. The genome is generally hypomethylated during aging, while specific genes become hypermethylated at CpG islands [1]. These predictable changes have enabled the development of epigenetic clocks that use machine learning methods based on CpG methylation states to predict chronological age and assess biological aging [1]. The first-generation epigenetic clocks, including Horvath's clock (a multi-tissue predictor based on 353 CpG sites) and Hannum's clock, have become essential tools in aging and cancer research [1].

Experimental Methodologies for DNA Methylation Analysis

Bisulfite Sequencing Protocol:

- DNA Treatment: Treat 500ng-1μg of genomic DNA with sodium bisulfite using commercial kits (e.g., EZ DNA Methylation Kit from Zymo Research), which converts unmethylated cytosines to uracils while leaving methylated cytosines unchanged.

- Library Preparation: Prepare sequencing libraries from bisulfite-converted DNA using appropriate adapters with minimal bias.

- Sequencing: Perform next-generation sequencing on Illumina platforms to achieve >10X coverage for whole-genome bisulfite sequencing (WGBS) or targeted approaches.

- Data Analysis: Map sequenced reads to a bisulfite-converted reference genome using tools like Bismark or BSMAP. Calculate methylation percentages as mC/(mC+uC) at each cytosine position.

- Differential Analysis: Identify differentially methylated regions (DMRs) using statistical packages such as methylKit or DSS, with multiple testing correction.

Alternative Method: Methylated DNA Immunoprecipitation (MeDIP)

- Principle: Immunoprecipitation of methylated DNA fragments using antibodies specific for 5-methylcytosine.

- Procedure: Shear genomic DNA to 200-500bp fragments; incubate with anti-5mC antibody; capture antibody-DNA complexes with magnetic beads; wash and elute methylated DNA; analyze via qPCR, microarray, or sequencing.

- Applications: Cost-effective for methylome profiling when combined with sequencing (MeDIP-seq); ideal for large sample cohorts.

Core Mechanism II: Histone Modifications

Major Histone Modification Types and Functional Consequences

Histone modifications represent post-translational alterations to histone proteins that regulate chromatin structure and gene accessibility. These modifications occur primarily on the N-terminal tails of histones and include methylation, acetylation, phosphorylation, ubiquitination, and others [3]. Each modification type has distinct effects on chromatin state and transcriptional activity.

Table 2: Major Histone Modifications and Their Functional Roles

| Modification Type | Histone Residues | Enzymes (Writers/Erasers) | Chromatin State Association | Functional Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H3K4me3 | H3 Lysine 4 | Writers: SET1, MLL; Erasers: LSD1, KDM5 | Euchromatin | Transcriptional activation; marks active promoters |

| H3K27me3 | H3 Lysine 27 | Writer: EZH2; Eraser: KDM6 | Facultative heterochromatin | Transcriptional repression; Polycomb-mediated silencing |

| H3K9me3 | H3 Lysine 9 | Writers: SUV39H; Erasers: KDM4 | Constitutive heterochromatin | Transcriptional repression; heterochromatin formation |

| H3K36me3 | H3 Lysine 36 | Writers: SETD2; Erasers: KDM4 | Euchromatin | Transcriptional elongation; prevents spurious initiation |

| H3K79me | H3 Lysine 79 | Writer: DOT1L | Euchromatin | Transcriptional activation; DNA damage response |

| H3/H4 Acetylation | Multiple lysines | Writers: HATs; Erasers: HDACs | Euchromatin | Chromatin relaxation; TF recruitment; transcriptional activation |

Histone methyltransferases (HMTs) and demethylases (KDMs) precisely control the methylation states of specific lysine and arginine residues, while histone acetyltransferases (HATs) and deacetylases (HDACs) regulate acetylation dynamics [1]. The recent development of CRISPR-based chromatin kinases enables programmable human histone phosphorylation and gene activation, demonstrating the potential for targeted epigenetic editing [2].

Histone Modification Dynamics in Cellular Identity and Aging

During cellular reprogramming, histone modifications undergo dramatic reorganization to establish new transcriptional programs. In the context of aging, there is a general loss of histones as well as global chromatin remodeling across multiple model systems [1]. Specific age-related changes include reduction of activating marks such as H3K4me3 and H4K16ac, and alterations in the distribution of repressive marks like H3K9me3 and H3K27me3 [1].

Histone modification patterns serve as critical barriers to reprogramming. For example, the histone methyltransferase Suv39h null mice exhibit spermatogenic failure with nonhomologous chromosome association, demonstrating the essential role of H3K9 methylation in maintaining cellular function [3]. Similarly, PRMT5 deficiency increases H3K9me2 and H3K27me2 levels and alters chromatin state of PLZF, leading to SSC developmental defects and spermatogenesis disorders [3].

Experimental Methodologies for Histone Modification Analysis

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation Sequencing (ChIP-seq) Protocol:

- Crosslinking: Treat cells with 1% formaldehyde for 10 minutes at room temperature to crosslink proteins to DNA.

- Chromatin Shearing: Lyse cells and sonicate chromatin to 200-500bp fragments using Covaris or Bioruptor systems.

- Immunoprecipitation: Incubate chromatin with 2-5μg of validated, modification-specific antibody (e.g., anti-H3K4me3, anti-H3K27ac) overnight at 4°C with rotation.

- Complex Capture: Add protein A/G magnetic beads and incubate for 2 hours; wash extensively with low- and high-salt buffers.

- Decrosslinking and Purification: Reverse crosslinks at 65°C overnight; treat with RNase A and proteinase K; purify DNA using silica membrane columns.

- Library Preparation and Sequencing: Construct sequencing libraries using NEBNext Ultra II DNA Library Prep Kit; sequence on Illumina platforms (minimum 10 million reads per sample).

- Data Analysis: Align sequences to reference genome using Bowtie2 or BWA; call peaks with MACS2; perform differential binding analysis with DiffBind.

Alternative Method: CUT&Tag for Low-Input Samples

- Principle: Uses protein A-Tn5 transposase fusion to tagmentation of antibody-bound chromatin in situ.

- Advantages: Requires significantly fewer cells (500-50,000 cells); lower background noise; can be multiplexed.

- Procedure: Permeabilize cells; incubate with primary antibody; add protein A-Tn5 adapter complex; activate tagmentation with magnesium; extract and purify DNA for library preparation.

Core Mechanism III: Chromatin Remodeling

Chromatin Remodeling Complexes and Mechanisms

Chromatin remodeling complexes (CRCs) are multi-protein machines that utilize ATP hydrolysis to slide, evict, or restructure nucleosomes, thereby regulating DNA accessibility [3]. These complexes play pivotal roles in various cellular processes including cell proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis, with their dysfunction contributing to developmental disorders and diseases [3].

Table 3: Major Chromatin Remodeling Complexes and Functions

| Complex | Core ATPase | Additional Subunits | Primary Mechanism | Biological Functions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SWI/SNF | BRG1/SMARCA4 or BRM/SMARCA2 | 10-15 subunits (BAF complex) | Nucleosome sliding, eviction | Transcriptional activation, differentiation, tumor suppression |

| ISWI | SMARCA5/SMARCA1 | 2-4 subunits | Nucleosome spacing, assembly | Chromatin compaction, transcription regulation, replication |

| CHD | CHD1-CHD9 | Variable | Nucleosome sliding, spacing | Transcriptional regulation, development, DNA repair |

| INO80 | INO80 | 15+ subunits | Nucleosome sliding, histone variant exchange | Transcriptional regulation, DNA repair, telomere maintenance |

Chromatin remodeling complexes function through several mechanistic approaches: (1) nucleosome sliding along DNA; (2) histone variant exchange (e.g., H3.3 for H3); (3) nucleosome eviction to create accessible regions; and (4) nucleosome assembly and spacing to regulate compaction [3]. The SWI/SNF (BAF) complex, in particular, has been implicated in cellular reprogramming, with specific subunit compositions determining permissiveness for pluripotency acquisition.

Chromatin Architecture in Cell Fate Decisions

During cellular differentiation and reprogramming, the chromatin landscape undergoes dramatic reorganization from a generally open configuration in pluripotent cells to a more restricted architecture in differentiated states. In spermatogenesis, chromatin remodeling complexes mediate fate determinations of spermatogonial stem cells (SSCs) to ensure normal development [3]. The precise regulation of spermatogenesis relies on synergistic interactions between genetic and epigenetic factors, with spermatogenesis failure resulting from epigenetic dysregulation [3].

In the context of aging, global chromatin reorganization represents a hallmark of cellular senescence. Aged cells typically exhibit loss of heterochromatin, particularly at repetitive elements and telomeres, leading to genomic instability and aberrant gene expression [1]. These age-related chromatin changes create barriers to reprogramming that must be overcome for efficient cell fate conversion.

Experimental Methodologies for Chromatin Architecture Analysis

Assay for Transposase-Accessible Chromatin with Sequencing (ATAC-seq) Protocol:

- Cell Preparation: Isolate 50,000-100,000 viable cells with >90% viability; avoid overfixation.

- Cell Lysis: Resuspend cells in cold lysis buffer (10mM Tris-Cl pH 7.4, 10mM NaCl, 3mM MgCl2, 0.1% IGEPAL CA-630) for 10 minutes on ice.

- Tagmentation Reaction: Incubate nuclei with Tn5 transposase (Nextera DNA Library Prep Kit) at 37°C for 30 minutes with shaking.

- DNA Purification: Clean up tagmented DNA using Zymo DNA Clean and Concentrator columns.

- Library Amplification: Amplify libraries with 10-12 cycles of PCR using barcoded primers; incorporate dual index primers for multiplexing.

- Size Selection and QC: Purify libraries using SPRIselect beads (0.5X-1.5X ratio); assess quality on Bioanalyzer or Tapestation.

- Sequencing and Analysis: Sequence on Illumina platforms (2×50bp or 2×75bp); align reads to reference genome using BWA; call peaks with MACS2; visualize in IGV.

Alternative Method: MNase-seq for Nucleosome Positioning

- Principle: Uses micrococcal nuclease to digest linker DNA between nucleosomes.

- Procedure: Isolate nuclei; digest with MNase; stop reaction with EGTA; purify mononucleosomal DNA; construct sequencing libraries.

- Applications: Maps nucleosome positions and occupancy; identifies stable versus dynamic nucleosomes.

Interplay of Epigenetic Mechanisms in mRNA-Mediated Reprogramming

Epigenetic Coordination in Cell Fate Transitions

The core epigenetic mechanisms do not function in isolation but rather form an integrated regulatory network that controls cellular identity. During mRNA-mediated reprogramming, these epigenetic layers must be coordinately remodeled to establish new gene expression programs. DNA methylation and histone modifications exhibit extensive crosstalk, with DNA methylation readers (MBD proteins) recruiting histone modifiers such as HDACs and HMTs to reinforce repressive chromatin states [3]. Similarly, specific histone modifications can influence DNA methylation patterns, creating self-reinforcing epigenetic cycles that maintain cellular states.

Recent advances in single-cell multi-omics now enable simultaneous profiling of multiple epigenetic layers, revealing the coordinated dynamics of DNA methylation, histone modifications, and chromatin accessibility during reprogramming [3] [1]. These approaches have identified epigenetic roadblocks to reprogramming and strategies to overcome them, such as transient inhibition of DNA methylation or histone modifications to enhance plasticity.

mRNA-Based Epigenetic Editing Technologies

Emerging mRNA-based technologies enable precise epigenetic editing by delivering mRNAs encoding engineered epigenetic editors. These include:

- ZF-EDs: Zinc finger domains fused to epigenetic catalytic domains (e.g., DNMT3A for targeted methylation) [2]

- TALEs: Transcription activator-like effectors coupled to TET1 for targeted demethylation [2]

- dCas9-Epigenetic Editors: Catalytically dead Cas9 fused to writers/erasers of histone modifications [2]

These tools enable locus-specific epigenetic rewriting without altering DNA sequences, offering potential for therapeutic reprogramming in disease contexts. For instance, targeted DNA methylation of the VEGF-A promoter using engineered zinc finger-DNA methyltransferase fusions has demonstrated sustained gene silencing in cancer models [2]. Similarly, TALE-TET1 fusion proteins have enabled targeted demethylation and activation of endogenous genes [2].

Research Reagent Solutions for Epigenetic Reprogramming

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Epigenetic Reprogramming Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Methylation Modulators | 5-Azacytidine (DNMT inhibitor); DAC (Decitabine); RG108 | Global DNA demethylation; enhances reprogramming efficiency | Use at 0.5-5μM for 48-72h; monitor cytotoxicity |

| Histone Deacetylase Inhibitors | Valproic Acid (VPA); Trichostatin A (TSA); SAHA (Vorinostat) | Increases histone acetylation; chromatin relaxation | VPA at 0.5-2mM; TSA at 50-500nM; optimize for cell type |

| Histone Methyltransferase Inhibitors | DZNep (EZH2 inhibitor); GSK126 (EZH2 inhibitor); UNC0638 (G9a inhibitor) | Reduces repressive H3K27me3 and H3K9me2 marks | Critical for overcoming epigenetic barriers to reprogramming |

| mRNA Synthesis Kits | MEGAscript T7 Transcription Kit; CleanCap mRNA Kit | Produces modified mRNAs for epigenetic editor expression | Incorporate 5-methoxyuridine to reduce immunogenicity |

| Epigenetic Editor Systems | dCas9-DNMT3A; dCas9-TET1; SunTag-based systems | Locus-specific epigenetic editing | Co-express with guide RNAs targeting specific genomic loci |

| Delivery Vehicles | Lipid nanoparticles (LNPs); Electroporation systems | Efficient mRNA delivery to target cells | Optimize lipid:mRNA ratios for specific cell types |

The core epigenetic mechanisms—DNA methylation, histone modifications, and chromatin remodeling—form an integrated regulatory network that governs cellular identity and plasticity. Understanding the dynamics and interplay of these mechanisms is essential for advancing mRNA-mediated reprogramming strategies for therapeutic applications. Recent technological advances in epigenetic editing, single-cell multi-omics, and targeted delivery systems are accelerating our ability to precisely manipulate the epigenetic landscape to direct cell fate transitions.

Future directions in epigenetic reprogramming research will likely focus on achieving greater specificity in epigenetic editing, improving the persistence of epigenetic modifications, and developing strategies to overcome the epigenetic barriers of aging and disease [2] [4]. As the field progresses, the integration of epigenetic therapies with mRNA-based delivery platforms holds significant promise for developing transformative treatments for degenerative diseases, aging-related conditions, and genetic disorders.

The Role of TET Proteins and Vitamin C in Active DNA Demethylation

In mammalian genomes, DNA methylation in the form of 5-methylcytosine (5mC) represents a fundamental epigenetic mechanism regulating gene expression, genomic stability, and cellular identity [5] [6]. Historically considered a stable epigenetic mark, 5mC is now understood to undergo active reversal through enzymatic processes, providing dynamic regulation of the epigenome [5] [6]. The Ten-Eleven Translocation (TET) family of enzymes—TET1, TET2, and TET3—catalyze the sequential oxidation of 5mC, initiating the major pathway for active DNA demethylation in mammalian cells [5] [6] [7].

Vitamin C (ascorbate) serves as a critical cofactor for TET enzymes, enhancing their catalytic activity and promoting DNA demethylation [8] [9] [7]. This biochemical relationship positions vitamin C as a key environmental factor capable of modulating the epigenome, with significant implications for cellular reprogramming, differentiation, and disease treatment [8] [9] [7]. Within mRNA-mediated reprogramming research, understanding the TET-vitamin C axis provides crucial insights into epigenetic remodeling mechanisms that can enhance reprogramming efficiency and fidelity.

This technical review examines the molecular mechanisms of TET-mediated active DNA demethylation, vitamin C's role as an enzymatic cofactor, experimental evidence across biological systems, and practical methodologies for researchers investigating epigenetic reprogramming.

Molecular Mechanisms of TET-Mediated Active DNA Demethylation

The TET Enzyme Family: Structure and Catalytic Function

TET proteins constitute a family of iron (Fe²⁺) and α-ketoglutarate (α-KG)-dependent dioxygenases that share a conserved C-terminal catalytic domain [6]. This domain contains a double-stranded β-helix (DSBH) fold, a cysteine-rich region, and binding sites for both Fe²⁺ and α-KG, which are essential for catalytic activity [6]. TET1 and TET3 additionally possess a CXXC zinc finger domain at their N-terminus that enables binding to unmethylated CpG-rich DNA [6]. Structural studies reveal that the TET catalytic core preferentially binds cytosines in CpG contexts but shows minimal sequence specificity for flanking DNA regions [5] [6].

The catalytic mechanism of TET enzymes involves three sequential oxidation steps [5] [6] [7]:

- Hydroxylation: 5-methylcytosine (5mC) → 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5hmC)

- Formylation: 5hmC → 5-formylcytosine (5fC)

- Carboxylation: 5fC → 5-carboxylcytosine (5caC)

This stepwise oxidation generates intermediates with distinct properties and functions in the demethylation pathway [5].

Pathways to Unmodified Cytosine

TET oxidation products can revert to unmodified cytosine through two primary mechanisms:

* Passive Demethylation: 5hmC cannot be effectively recognized by the maintenance DNA methyltransferase DNMT1 during DNA replication. Consequently, TET-mediated oxidation leads to replication-dependent dilution of DNA methylation without enzymatic removal [6] [7]. *In vitro studies demonstrate DNMT1 activity is reduced up to 60-fold on DNA substrates containing 5hmC [6].

Active Demethylation: The TET-generated bases 5fC and 5caC are recognized and excised by thymine DNA glycosylase (TDG), which initiates the base excision repair (BER) pathway [5] [6] [7]. TDG exhibits robust activity toward 5fC and 5caC but cannot excise 5hmC [5]. Following base excision, the BER pathway completes the process by replacing the excised base with an unmodified cytosine [5] [7].

Figure 1: TET-Mediated Active DNA Demethylation Pathway. TET enzymes catalyze sequential oxidation of 5mC to 5hmC, 5fC, and 5caC. Demethylation is completed via TDG-initiated base excision repair or passive replication-dependent dilution. [5] [6] [7]

Vitamin C as a Critical Cofactor for TET Enzymes

Biochemical Mechanism of Action

Vitamin C (L-ascorbic acid) enhances TET catalytic activity by maintaining the iron cofactor in its reduced state (Fe²⁺) within the enzyme's active site [8] [7]. The TET catalytic cycle involves Fe²⁺ oxidation to Fe³⁺ during the hydroxylation reaction. Vitamin C serves as an electron donor to regenerate Fe²⁺ from Fe³⁺, enabling multiple catalytic turnovers and sustained enzymatic activity [8] [10].

This cofactor function is distinct from vitamin C's antioxidant properties. While other antioxidants like vitamin E and glutathione show minimal effects on TET activity, vitamin C specifically promotes TET-mediated DNA demethylation through its action as an enzymatic cofactor [8] [9].

Concentration-Dependent Effects on TET Activity

Vitamin C enhances TET activity at physiological concentrations (0.1-1.0 mM) comparable to those transported from bloodstream into tissues [11] [10]. These concentrations significantly increase global 5hmC levels and promote locus-specific DNA demethylation in various cellular models [11] [9] [10].

Table 1: Vitamin C Effects on TET Activity and Functional Outcomes Across Biological Systems

| Biological System | VC Concentration | Key Effects on TET/Demethylation | Functional Outcomes | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human Epidermal Equivalents | 0.1-1.0 mM | Increased global 5hmC; hypomethylation of 10,138 genomic regions; upregulation of 12 proliferation genes | Enhanced keratinocyte proliferation; increased epidermal thickness | [11] [12] [10] |

| Mouse B Cells | Physiological (unspecified) | Increased TET2/3-mediated demethylation at Prdm1 locus; enhanced STAT3 binding | Promoted plasma cell differentiation; enhanced antibody response | [9] |

| Embryonic Stem Cells/Reprogramming | 50-100 μM | Enhanced TET-mediated demethylation at pluripotency loci; prevented hypermethylation | Improved iPSC generation efficiency and quality; erased epigenetic memory | [8] |

Experimental Evidence: Vitamin C and TET in Biological Systems

Epidermal Regeneration and Proliferation

In human epidermal equivalent models, vitamin C treatment at physiologically relevant concentrations (0.1-1.0 mM) significantly increased epidermal thickness by promoting keratinocyte proliferation [11] [10]. This effect was mediated through TET-dependent DNA demethylation, as demonstrated by:

- Global 5hmC Increase: Vitamin C treatment elevated global 5-hydroxymethylcytosine levels, indicating enhanced TET activity [11] [10].

- Genome-Wide Hypomethylation: Whole-genome bisulfite sequencing identified 10,138 differentially methylated regions showing hypomethylation in vitamin C-treated samples [11] [10].

- Proliferation Gene Activation: Twelve key proliferation-related genes demonstrated 1.6- to 75.2-fold upregulation associated with promoter/enhancer hypomethylation [11] [12] [10].

- TET Dependence: A TET enzyme inhibitor completely abolished vitamin C-induced epidermal thickening and gene expression changes, confirming TET-mediated mechanism [11] [10].

Plasma Cell Differentiation and Immune Function

Vitamin C potently enhances IL-21/STAT3-dependent plasma cell differentiation in both mouse and human B cells [9]. The mechanistic insights include:

- Early Activation Criticality: Vitamin C is required during early B cell activation to prime cells for subsequent differentiation [9].

- Prdm1 Locus Demethylation: Vitamin C facilitates TET2/3-mediated demethylation of multiple regulatory elements at the Prdm1 locus, which encodes BLIMP1, the master transcription factor for plasma cell differentiation [9].

- Enhanced Transcription Factor Binding: DNA demethylation enables increased STAT3 association with the Prdm1 promoter and downstream enhancer (E27), ensuring efficient gene expression [9].

This mechanism explains the historical observations of impaired antibody responses during vitamin C deficiency and highlights how micronutrients regulate epigenetic enzymes to influence cell fate decisions [9].

Cellular Reprogramming and Pluripotency

Vitamin C significantly improves the efficiency and quality of induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) generation [8]. In reprogramming somatic cells to pluripotency, vitamin C:

- Enhances TET-mediated demethylation at pluripotency gene loci (Nanog, Oct4) [8]

- Prevents aberrant hypermethylation at imprinted gene clusters (Dlk1-Dio3) [8]

- Facilitates erasure of epigenetic memory from donor cell lineages [8]

- Promotes a more naive "ground state" of pluripotency resembling blastocyst-derived ESCs [8]

These effects are specifically mediated through TET enzyme enhancement, as iron chelators or α-KG analogs that inhibit α-KGDDs impair iPSC formation [8].

Methodologies for Investigating TET and Vitamin C in Demethylation

DNA Methylation Profiling Techniques

Table 2: DNA Methylation Detection Methods for TET-Vitamin C Studies

| Method | Resolution | Key Applications | Advantages | Limitations | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Whole-Genome Bisulfite Sequencing (WGBS) | Single-base | Genome-wide methylation mapping; identifies differentially methylated regions | Comprehensive coverage; absolute methylation quantification | DNA degradation; high cost; computational intensity | [13] [14] |

| Enzymatic Methyl-Sequencing (EM-seq) | Single-base | Genome-wide methylation profiling without bisulfite | Preserves DNA integrity; reduced bias; improved CpG detection | Newer method with less established protocols | [14] |

| Illumina MethylationEPIC BeadChip | Single-CpG (850K+ sites) | Population studies; biomarker discovery | Cost-effective; standardized analysis; high throughput | Limited to predefined CpG sites; no non-CpG context | [13] [14] |

| Oxford Nanopore Sequencing | Single-base (direct detection) | Long-range methylation profiling; challenging genomic regions | No conversion needed; long reads detect haplotypes; detects 5mC/5hmC | High DNA input; lower accuracy for single CpGs | [14] |

| Reduced Representation Bisulfite Sequencing (RRBS) | Single-base (CpG-rich regions) | Cost-effective targeted methylation analysis | Focuses on informative CpG-rich regions; reduced sequencing cost | Limited genome coverage (~10-15%) | [13] |

Experimental Protocol: Assessing Vitamin C Effects on TET-Mediated Demethylation

Objective: Evaluate vitamin C-dependent DNA demethylation at specific genomic loci in cellular models.

Cell Culture and Treatment:

- Culture target cells (e.g., primary keratinocytes, B cells, or reprogramming fibroblasts) in standard medium.

- Establish experimental conditions:

- Control: Standard culture medium

- Vitamin C treatment: Medium supplemented with physiological vitamin C (0.1-1.0 mM fresh L-ascorbic acid)

- Inhibition control: Vitamin C medium + TET inhibitor (e.g, Bobcat339 or dimethyloxalylglycine)

- Maintain cultures for 7-14 days with medium changes every 48-72 hours.

Sample Collection and DNA Extraction:

- Harvest cells at appropriate time points using trypsinization or mechanical dissociation.

- Extract genomic DNA using phenol-chloroform or commercial kits with RNAse treatment.

- Quantify DNA purity and concentration (A260/280 ~1.8).

DNA Methylation Analysis:

- Perform bisulfite conversion using EZ DNA Methylation Kit (Zymo Research) or equivalent.

- Conduct whole-genome bisulfite sequencing (WGBS):

- Library preparation with bisulfite-converted DNA

- Sequencing on Illumina platform (minimum 30x coverage)

- Alignment to reference genome using Bismark or BS-Seeker

- Methylation calling and differential methylation analysis

- Validate key findings with pyrosequencing or targeted bisulfite sequencing.

Functional Validation:

- Measure global 5hmC levels with ELISA-based hydroxymethylation assay.

- Analyze gene expression of demethylated targets by RT-qPCR.

- Assess functional outcomes (proliferation, differentiation, reprogramming efficiency).

Figure 2: Experimental Workflow for Vitamin C Demethylation Studies. Key steps from cell culture to data integration for investigating TET-vitamin C mediated DNA demethylation. [11] [9] [14]

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for TET-Vitamin C Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vitamin C Formulations | L-ascorbic acid (fresh), Sodium ascorbate, Ascorbic acid 2-phosphate | TET enzyme cofactor; maintain physiological concentrations (0.1-1.0 mM) | Fresh preparation required; ascorbic acid 2-phosphate more stable in culture |

| TET Inhibitors | Bobcat339, Dimethyloxalylglycine (DMOG), 2-HG (2-hydroxyglutarate) | Inhibit TET enzymatic activity; establish TET-dependent mechanisms | DMOG inhibits broad α-KGDD family; Bobcat339 more TET-specific |

| DNA Methylation Kits | EZ DNA Methylation Kit (Zymo Research), MagMeDIP Kit | Bisulfite conversion; methylated DNA immunoprecipitation | Bisulfite conversion efficiency critical; validate with controls |

| 5hmC Detection | Hydroxymethylated DNA Immunoprecipitation (hMeDIP), 5hmC ELISA, GLIB-seq | Quantify global and locus-specific 5hmC levels | 5hmC-specific antibodies required; distinguish from 5mC |

| Cell Culture Models | Primary keratinocytes, B cells, reprogramming fibroblasts, epidermal equivalents | Relevant biological systems for vitamin C demethylation studies | Human epidermal equivalents for skin studies; primary B cells for immunity |

| Sequencing Platforms | Illumina (WGBS), Oxford Nanopore (direct detection), EPIC BeadChip | DNA methylation profiling | Choice depends on resolution, coverage, and budget requirements |

The TET-vitamin C axis represents a fundamental mechanism for dynamic regulation of the DNA methylome, with far-reaching implications for epigenetic remodeling in mRNA-mediated reprogramming research. The experimental evidence across biological systems demonstrates that vitamin C, through its enhancement of TET enzymatic activity, promotes targeted DNA demethylation that drives cellular differentiation, proliferation, and reprogramming.

For researchers in the field, key considerations include:

- Utilizing physiological vitamin C concentrations (0.1-1.0 mM) in culture systems

- Selecting appropriate DNA methylation profiling methods based on research questions

- Implementing proper TET inhibition controls to establish mechanism

- Considering tissue-specific and context-dependent effects of vitamin C

The integration of vitamin C into reprogramming protocols offers promising avenues for improving iPSC generation efficiency and quality, while the broader understanding of nutrient-epigenome interactions opens new therapeutic possibilities for regenerative medicine, cancer treatment, and immune modulation.

Histone Modifications as Bivalent Poised States in Pluripotency

Bivalent chromatin domains, characterized by the simultaneous presence of activating H3K4me3 and repressive H3K27me3 histone modifications, constitute a fundamental epigenetic mechanism for maintaining pluripotency in embryonic stem cells (ESCs). These poised promoter states enable developmental genes to remain transcriptionally silent yet primed for rapid activation upon differentiation signals. Recent advances in single-cell epigenomic profiling and epigenetic engineering have elucidated the mechanistic principles of bivalency, including nucleosomal asymmetry and dedicated reader complexes that interpret these combinatorial marks. This technical review synthesizes current understanding of bivalent chromatin architecture, its functional role in pluripotency regulation, and emerging experimental approaches for investigating and manipulating these poised states in reprogramming and disease contexts. The integration of bivalent chromatin control with mRNA-mediated reprogramming platforms represents a promising frontier for regenerative medicine and therapeutic development.

Bivalent chromatin domains represent a specialized epigenetic state first described in embryonic stem cells (ESCs) where key developmental gene promoters simultaneously harbor both activating histone H3 lysine 4 trimethylation (H3K4me3) and repressive histone H3 lysine 27 trimethylation (H3K27me3) marks [15] [16]. This unique configuration maintains genes in a transcriptionally poised state—neither fully active nor permanently silenced—allowing pluripotent cells to rapidly initiate lineage-specific differentiation programs in response to developmental cues. The balance between these antagonistic marks is dynamically regulated by opposing chromatin-modifying complexes: the COMPASS/Trithorax complex for H3K4 methylation and the Polycomb Repressive Complex 2 (PRC2) for H3K27 methylation [15].

The functional significance of bivalency extends beyond developmental gene regulation to cellular reprogramming and cancer biology. During induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) generation, somatic cells undergo extensive epigenetic remodeling to reestablish bivalent domains at critical developmental loci [15]. Similarly, cancer stem cells (CSCs) often exploit bivalent chromatin to maintain plasticity and therapeutic resistance [15]. Recent research has revealed that bivalent nucleosomes frequently exhibit an asymmetric conformation with each sister histone H3 carrying only one of the two modifications, creating specialized platforms for recruitment of distinct reader proteins [17]. This architectural principle enables precise control of gene expression dynamics during cell fate transitions.

Core Mechanisms of Bivalent Domain Establishment and Maintenance

Chromatin Modifying Complexes and Their Regulatory Dynamics

Table 1: Key Chromatin-Modifying Complexes Regulating Bivalent Domains

| Complex/Enzyme | Catalytic Function | Histone Modification | Role in Bivalency |

|---|---|---|---|

| PRC2 (EZH2) | H3K27 methyltransferase | H3K27me3 | Establishes repressive component of bivalency |

| COMPASS/TrxG | H3K4 methyltransferase | H3K4me3 | Establishes active component of bivalency |

| KDM6B (JMJD3) | H3K27 demethylase | Removes H3K27me3 | Resolves bivalency toward activation |

| KDM5B (JARID1B) | H3K4 demethylase | Removes H3K4me3 | Resolves bivalency toward repression |

| KAT6B | Histone acetyltransferase | H3K23ac? | Promotes activation of bivalent genes during differentiation |

The establishment and maintenance of bivalent domains require precisely coordinated activities of opposing chromatin-modifying complexes. PRC2, containing the catalytic subunit EZH2, deposits H3K27me3 marks at developmental gene promoters in ESCs [15]. Concurrently, COMPASS-family complexes catalyze H3K4me3 at these same loci. This counteracting modification system creates a metastable chromatin state that is resolved during differentiation through the recruitment of tissue-specific transcription factors and chromatin regulators that tip the balance toward either activation or stable repression [16].

Recent structural studies have revealed that bivalent nucleosomes exhibit nucleosomal asymmetry, with each sister histone H3 carrying only one of the two modifications [17]. This asymmetric configuration preferentially recruits repressive H3K27me3 readers while failing to enrich activating H3K4me3 binders, thereby promoting a transcriptionally poised state. Surprisingly, the bivalent mark combination also promotes recruitment of specific chromatin proteins not recruited by each mark individually, including the lysine acetyltransferase KAT6B, which is critical for proper activation of bivalent genes during differentiation [17].

Functional Consequences of Bivalent Chromatin Manipulation

Table 2: Experimental Manipulation of Bivalent Marks and Functional Outcomes

| Experimental Approach | Biological System | Key Findings | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| H3K4M mutation | Mouse hematopoietic system | H3K4 methylation loss blocked progenitor maturation; HSC maintenance unaffected | [16] |

| H3K4me3 inhibition | Chicken germ cell differentiation | Enhanced PGCLC induction by blocking BMP antagonists | [18] |

| EZH2 inhibition | Multiple cancer models | Reduced CSC populations, restored differentiation capacity | [15] |

| KAT6B knockout | Mouse ESCs | Impaired neuronal differentiation, defective bivalent gene activation | [17] |

Functional studies manipulating bivalent marks have demonstrated their essential role in developmental transitions. In murine hematopoiesis, global depletion of H3K4 methylation via a dominant histone H3-lysine-4-to-methionine (H3K4M) mutation caused lethal depletion of all mature blood cell types, despite normal numbers of hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) and committed progenitors [16]. This indicates that H3K4 methylation is dispensable for HSC maintenance but essential for progenitor cell maturation. Mechanistically, H3K4 methylation opposes the deposition of repressive H3K27 methylation at differentiation-associated genes enriched for bivalent chromatin in HSCs and progenitors. Concomitant suppression of H3K27 methylation in H3K4-methylation-depleted mice rescued the acute lethality and hematopoietic failure, demonstrating the functional interaction between these two crucial chromatin marks [16].

In avian germ cell development, diminished H3K4me3 facilitates the specification of the germ cell lineage by regulating transitions of bivalent states into repressive configurations. Selective erasure of H3K4me3 modifications was shown to block expression of BMP signaling antagonists, thereby enhancing the creation of primordial germ cell-like cells (PGCLCs) in chicken [18]. This research provides epigenetic strategies to enhance the production of germ cells for agricultural and conservation applications.

Advanced Methodologies for Bivalent Chromatin Analysis

Single-Cell Epigenomic Profiling Technologies

Recent advances in single-cell epigenomic technologies have revolutionized our ability to study bivalent chromatin dynamics during cellular reprogramming and differentiation. The Target Chromatin Indexing and Tagmentation (TACIT) method enables genome-coverage single-cell profiling of multiple histone modifications across individual cells [19]. This approach has been applied to mouse early embryos, generating maps of seven histone modifications (H3K4me1, H3K4me3, H3K27ac, H3K27me3, H3K36me3, H3K9me3, and H2A.Z) across 3,749 cells from zygote to blastocyst stages.

For investigating coordinated regulation, CoTACIT enables simultaneous profiling of multiple histone modifications in the same single cell through sequential rounds of antibody binding, protein A-Tn5 transposon (PAT) incubation, and tagmentation [19]. This multi-modal profiling reveals that H3K27ac profiles exhibit marked heterogeneity as early as the two-cell stage, preceding substantial heterogeneity in H3K4me3 and other marks, suggesting that cells may begin to display functional heterogeneity through establishment of H3K27ac at this early developmental timepoint.

Figure 1: CoTACIT workflow for simultaneous profiling of multiple histone modifications in single cells.

Epigenome Editing Approaches

Programmable epigenetic engineering has emerged as a powerful approach for directly manipulating bivalent domains and assessing functional outcomes. The CRISPRoff/CRISPRon system enables stable epigenetic silencing or activation without permanent DNA alterations [20]. CRISPRoff consists of dCas9 fused to DNMT3A, DNMT3L, and ZNF10 KRAB protein domains, writing heritable silencing programs that persist through numerous cell divisions. Conversely, CRISPRon uses dCas9 fused to a TET1 catalytic domain for targeted erasure of DNA methylation.

In primary human T cells, optimized mRNA-based delivery of CRISPRoff achieves durable gene silencing comparable to Cas9 knockout but without genotoxic double-strand breaks [20]. This platform has been successfully combined with genetic engineering approaches, enabling targeted chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) knock-in at the TRAC locus with simultaneous CRISPRoff silencing of therapeutically relevant genes to improve preclinical CAR-T cell function.

For mRNA-mediated reprogramming, tissue nanotransfection (TNT) provides a non-viral nanotechnology platform for in vivo gene delivery through localized nanoelectroporation [21]. This approach enables direct cellular reprogramming via transcriptional activation and epigenetic remodeling, offering advantages of high specificity, non-integrative delivery, and minimal cytotoxicity compared to viral vectors.

Experimental Protocols for Bivalent Chromatin Investigation

Protocol: CRISPRoff-Mediated Epigenetic Silencing in Primary Human T Cells

Principle: This protocol enables durable, heritable gene silencing without DNA damage by targeting epigenetic editors to specific genomic loci, maintaining silencing through multiple cell divisions and restimulation cycles [20].

Step-by-Step Methodology:

- sgRNA Design: Select 3-6 sgRNAs targeting within a 250-bp region immediately downstream of the transcription start site (TSS) of the target gene using optimized prediction algorithms.

- mRNA Preparation: Generate CRISPRoff mRNA (CRISPRoff 7 design) incorporating "design 1" codon optimization, Cap1 mRNA cap, and 1-Me-ps-UTP base modifications for enhanced potency and stability.

- Cell Preparation: Isolate primary human T cells and activate using anti-CD2/CD3/CD28 soluble antibodies for 24 hours prior to electroporation.

- Electroporation: Co-electroporated CRISPRoff mRNA (1-2 µg) and pooled sgRNAs (0.5-1 µg each) using Lonza 4D Nucleofector system with pulse code DS-137.

- Culture and Validation: Maintain cells in complete T-cell media with IL-2 (100 U/mL), restimulating every 9-10 days with soluble antibodies. Assess silencing efficiency by flow cytometry at days 7, 14, 21, and 28 post-electroporation.

- Validation: Confirm target specificity through RNA-seq and whole-genome bisulfite sequencing (WGBS) to verify DNA methylation patterns specifically at the target locus.

Key Applications: Multiplexed epigenetic programming of therapeutic cells, silencing immune checkpoints (PD-1, CTLA-4), or enhancing stemness factors without genomic alterations.

Protocol: Single-Cell Histone Modification Profiling with TACIT

Principle: TACIT enables genome-wide mapping of histone modifications at single-cell resolution with high coverage, allowing characterization of epigenetic heterogeneity during cellular reprogramming [19].

Step-by-Step Methodology:

- Cell Preparation: Fix single-cell suspensions from ESCs or reprogramming cultures with 1% formaldehyde for 10 minutes at room temperature, then quench with 125 mM glycine.

- Chromatin Extraction: Lyse cells in RIPA buffer and digest chromatin with 0.5 µL MNase for 5 minutes at 37°C to generate mononucleosomes.

- Immunoprecipitation: Incubate with histone modification-specific antibodies (e.g., anti-H3K4me3, anti-H3K27me3) overnight at 4°C with rotation.

- PAT Complex Assembly: Prepare protein A-Tn5 transposome (PAT) by mixing equal volumes of protein A (0.2 µg/µL) and Tn5 transposase (0.2 µg/µL), incubate 30 minutes at room temperature.

- Tagmentation: Add PAT complex to immunoprecipitated chromatin, incubate 1 hour at 37°C with shaking to simultaneously capture histone-marked nucleosomes and fragment DNA.

- Library Preparation: Reverse crosslinks, purify DNA, and amplify libraries with 8-12 cycles of PCR using indexed primers.

- Sequencing and Analysis: Sequence on Illumina platforms (minimum 50,000 non-duplicated reads per cell) and process data using dedicated pipelines for single-cell histone modification analysis.

Key Applications: Mapping epigenetic heterogeneity during iPSC reprogramming, identifying subpopulations with distinct differentiation potentials, characterizing aberrant bivalent domains in disease models.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Investigating Bivalent Chromatin

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Epigenetic Editors | CRISPRoff-V2.3, CRISPRon | Targeted gene silencing/activation without DNA damage | Optimized mRNA design with 1-Me-ps-UTP enhances stability [20] |

| Histone Mutants | H3K4M, H3K27M | Dominant inhibition of specific histone methylation | Acts as hypomorph without disrupting methyltransferases [16] |

| Small Molecule Inhibitors | EZH2 inhibitors (GSK126), HDAC inhibitors (VPA) | Modulate histone modification levels | VPA enhances reprogramming efficiency [15] [22] |

| Reprogramming Factors | OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, c-Myc (OSKM) | Induce pluripotency in somatic cells | L-Myc reduces tumorigenic risk vs c-Myc [22] |

| Delivery Systems | Tissue Nanotransfection (TNT), mRNA electroporation | Non-viral delivery of reprogramming factors | Enables in vivo reprogramming with minimal cytotoxicity [21] |

| Detection Antibodies | H3K4me3, H3K27me3, H3K27ac | Chromatin immunoprecipitation, immunostaining | Validate specificity with knockout controls |

Integration with mRNA-Mediated Reprogramming Research

The intersection of bivalent chromatin biology with mRNA-mediated reprogramming represents a frontier in regenerative medicine. mRNA-based delivery of reprogramming factors (OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, c-Myc) offers transient, tunable expression without genomic integration, overcoming key safety concerns associated with viral vectors [22]. However, efficient reprogramming requires the establishment of appropriate bivalent domains at developmental genes, which can be enhanced through epigenetic modulation.

Strategies to improve mRNA reprogramming efficiency include:

- Combination with epigenetic modifiers: Co-delivery of mRNA encoding chromatin regulators (KDM5B, KDM6A) or small molecule inhibitors (VPA, 5-aza-cytidine) to facilitate epigenetic remodeling [22].

- Sequential delivery protocols: Staged introduction of reprogramming factors and epigenetic modifiers to mimic natural developmental transitions.

- Enhanced mRNA design: Incorporation of modified nucleotides (1-Me-ps-UTP) and optimized codon usage to increase stability and translational efficiency while reducing immunogenicity [20].

Figure 2: Integration of epigenetic modulation with mRNA-mediated reprogramming.

Recent advances demonstrate that targeted manipulation of bivalent domains can enhance reprogramming outcomes. In chicken germ cell differentiation, selective inhibition of H3K4me3 deposition enhanced primordial germ cell-like cell induction by modulating BMP signaling [18]. Similarly, in murine systems, balanced modulation of H3K4 and H3K27 methylation states improved the quality and functionality of iPSC-derived cells [16]. These approaches highlight the potential of epigenetic engineering to overcome current limitations in cellular reprogramming for therapeutic applications.

Bivalent chromatin represents a fundamental epigenetic mechanism for maintaining cellular plasticity during development and reprogramming. The dynamic balance between H3K4me3 and H3K27me3 at key developmental genes creates a poised state that enables rapid transcriptional responses to differentiation signals. Recent technical advances in single-cell epigenomic profiling, epigenetic editing, and mRNA-mediated reprogramming have provided powerful tools to investigate and manipulate these domains with unprecedented precision.

Future research directions include developing more precise epigenetic editors capable of writing specific combinatorial histone modifications, advancing single-cell multi-omics to simultaneously capture histone modifications, chromatin accessibility, and gene expression in the same cell, and optimizing delivery systems for clinical translation of epigenetic therapies. The integration of bivalent chromatin control with mRNA reprogramming platforms holds particular promise for generating clinically relevant cell types for regenerative medicine, disease modeling, and cancer immunotherapy. As our understanding of bivalent chromatin mechanisms deepens, so too will our ability to harness this knowledge for therapeutic innovation.

The pursuit of cellular rejuvenation and tissue regeneration increasingly converges on the principles of embryonic development. This technical guide explores the paradigm that transient expression of embryonic transcription factors can orchestrate extensive epigenetic remodeling, effectively reversing aged or damaged cellular states to a more plastic, progenitor-like condition. We detail how key developmental cues, particularly the Yamanaka factors (OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, c-MYC), are harnessed in mRNA-mediated reprogramming to reset the epigenetic landscape. Within the broader context of regenerative medicine, this review synthesizes cutting-edge protocols, quantitative data on reprogramming efficacy, and the underlying mechanisms that recapitulate developmental plasticity for therapeutic applications, providing a foundational resource for researchers and drug development professionals.

Embryonic development is characterized by precise, temporally regulated gene expression patterns that guide cellular differentiation and tissue formation. Central to this process is epigenetic remodeling—the dynamic alteration of chromatin architecture and DNA methylation patterns that stabilize cell fate decisions without changing the underlying genetic code [23]. The groundbreaking discovery that forced expression of the embryonic transcription factors OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, and c-MYC (OSKM) could induce pluripotency in somatic cells revealed that developmental pathways can be reactivated to reverse cellular aging and injury [24].

The emerging frontier of mRNA-mediated reprogramming leverages these embryonic cues while addressing critical safety concerns associated with traditional gene therapy. Unlike integrating viral vectors, mRNA-based delivery offers a transient, non-integrative strategy for expressing reprogramming factors, significantly reducing the risk of insertional mutagenesis and genomic instability [25] [26]. This approach provides precise temporal control over factor expression, enabling the partial reprogramming strategies necessary to reverse aging phenotypes or enhance regeneration without inducing teratoma formation [24] [27].

The core thesis of this review posits that embryonic cues guide reprogramming primarily through epigenetic resetting, reversing age-associated heterochromatin loss and DNA methylation patterns to restore cellular plasticity. As demonstrated in progeria mouse models, cyclic induction of OSKM factors restores youthful epigenetic markers like H3K9me3 and promotes tissue regeneration, effectively extending healthspan and lifespan [24]. The following sections detail the molecular mechanisms, experimental protocols, and therapeutic applications of this transformative technology.

Molecular Mechanisms: Embryonic Factors as Epigenetic Regulators

The Yamanaka Factors and Their Developmental Roles

The core embryonic factors used in reprogramming each play distinct yet interconnected roles in establishing pluripotency:

- OCT4 (POU5F1): A pioneer transcription factor critical for maintaining pluripotency in the inner cell mass. It binds to compacted chromatin and initiates opening of pluripotency-associated loci, working in concert with SOX2 to activate key target genes [24].

- SOX2: Partners with OCT4 in a precise stoichiometric ratio to regulate hundreds of pluripotency-associated genes. It promotes dedifferentiation by binding to enhancer elements and facilitating chromatin accessibility [24] [26].

- KLF4: Contributes to epigenetic reprogramming through multiple mechanisms, including regulation of p53 signaling and modulation of histone acetylation patterns. It promotes a permissive chromatin state for reprogramming [27].

- c-MYC: Enhances global transcriptional activity and promotes chromatin accessibility at pluripotency loci, though its use requires careful regulation due to oncogenic potential [24].

Epigenetic Remodeling During Reprogramming

The OSKM factors collaboratively orchestrate extensive epigenetic restructuring that mirrors embryonic epigenetic resetting:

- DNA Methylation Reprogramming: OSKM induction reverses age-associated hypermethylation and hypomethylation patterns. This includes erasure of differential methylation at promoter regions of developmental genes, restoring a more embryonic methylation landscape [24] [23].

- Histone Modification Reset: Partial reprogramming restores youthful patterns of histone modifications, including reduction of age-associated H4K20me3 and restoration of H3K9me3 heterochromatin marks [27]. These changes correlate with suppressed expression of senescence markers p16INK4a and p21CIP1.

- Chromatin Accessibility: OSKM factors function as pioneer factors that bind condensed chromatin and initiate localized decompaction, enabling activation of previously silenced developmental gene networks [24] [28].

Table 1: Key Epigenetic Modifications in Cellular Reprogramming

| Epigenetic Mark | Aging/Senescent State | Post-Reprogramming State | Functional Consequence |

|---|---|---|---|

| H3K9me3 | Decreased | Restored | Regains heterochromatin integrity, reduced genomic instability |

| H4K20me3 | Increased | Decreased | Attenuated senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP) |

| Promoter DNA Methylation | Hypermethylation of developmental genes | Demethylation | Reactivation of pluripotency and progenitor gene networks |

| Chromatin Accessibility | Reduced at pluripotency loci | Increased | Activation of embryonic gene expression programs |

Experimental Platforms and Methodologies

mRNA-Based Reprogramming Systems

mRNA technology has emerged as a leading platform for reprogramming due to its transient nature and high efficiency [25]. Key methodological considerations include:

- mRNA Design and Modification: Incorporation of modified nucleotides (e.g., pseudouridine) reduces innate immune recognition and enhances translational efficiency [25]. Optimized 5' and 3' UTRs further increase protein expression levels and duration.

- Delivery Systems: Lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) and exosome-based vehicles protect mRNA from degradation and facilitate cellular uptake. For instance, Cavin2-modified exosomes (M-Exo) demonstrate enhanced delivery efficiency to senescent nucleus pulposus cells [27].

- Dosing Regimens: Cyclic induction protocols (e.g., 2 days ON/5 days OFF) prevent complete reprogramming to pluripotency while achieving epigenetic resetting, thereby minimizing teratoma risk [24].

In Vivo Reprogramming Models

Transgenic mouse models enable controlled investigation of OSKM-mediated reprogramming in living organisms:

- Inducible Systems: The well-established 4F models (4Fj, 4Fk, 4F-A, 4F-B) feature OSKM cassettes inserted at specific genomic loci (Col1a1, Neto2, Pparg) under control of a Tet-O promoter system [24]. Administration of doxycycline (Dox) enables precise temporal control of factor expression.

- Tissue-Specific Variations: OSKM expression patterns show striking tissue dependence, with robust induction in intestine, liver, and skin, and comparatively lower activation in brain, heart, and skeletal muscle [24].

- Safety Considerations: Continuous OSKM induction over weeks produces teratomas in multiple organs, while transient induction (7 days) can initiate dysplastic changes. However, cyclic induction protocols have demonstrated safety in multiple tissue contexts [24].

Table 2: In Vivo Reprogramming Models and Their Applications

| Model System | Genetic Features | Induction Method | Key Applications | Safety Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4Fj/4Fk Mice | OSKM at Col1a1 locus | Doxycycline | Lifespan extension in progeria models [24] | Teratomas with continuous induction |

| OKS@M-Exo | Plasmid in modified exosomes | Direct injection | IVDD treatment [27] | No teratoma formation reported |

| SeV Reprogramming | Non-integrating RNA virus | Transduction | hiPSC generation from fibroblasts/PBMCs [26] | Lower genomic alteration risk vs. episomal |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for mRNA-Mediated Reprogramming

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function in Reprogramming | Experimental Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reprogramming Factors | OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, c-MYC (OSKM) | Induce pluripotency and epigenetic resetting | c-MYC optional for partial reprogramming [27] |

| Delivery Vectors | LNPs, Cavin2-modified exosomes, Sendai virus | Protect mRNA and enhance cellular uptake | Exosomes show superior tissue penetration [27] |

| Small Molecule Enhancers | Y-27632 (ROCK inhibitor) | Improves cell viability post-transfection | Critical for clonal expansion [26] |

| Quality Control Assays | Alkaline phosphatase staining, karyotyping, STR analysis | Validate reprogramming success and genomic integrity | Essential for biobanking applications [26] |

| Senescence Assays | SA-β-Gal staining, p16/p21 quantification | Assess age-reversal effects | Key for evaluating rejuvenation [27] |

Analytical Approaches and Validation Methods

Assessing Reprogramming Efficacy

Rigorous quality control measures are essential for validating reprogramming outcomes:

- Pluripotency Marker Analysis: Immunostaining for canonical markers (NANOG, SSEA-1, TRA-1-60) confirms acquisition of pluripotent state in fully reprogrammed cells [26].

- Epigenetic Landscape Mapping: Genome-wide profiling of DNA methylation (Whole Genome Bisulfite Sequencing) and histone modifications (ChIP-seq) provides comprehensive assessment of epigenetic remodeling [24] [27].

- Transcriptomic Analysis: RNA sequencing reveals expression changes in age-related pathways and pluripotency networks, demonstrating reversal of aging signatures [27].

- Functional Assays: In vivo teratoma formation assays test pluripotency, while transplantation models assess functional integration and tissue repair capacity [24].

Safety and Tumorigenicity Assessment

The potential for neoplastic transformation represents the primary safety concern in reprogramming approaches:

- Dysmplasia Monitoring: Histopathological examination of liver, pancreas, and kidney tissues following OSKM induction identifies pre-neoplastic changes [24].

- Long-Term Fate Tracing: Lineage tracing models track the fate of reprogrammed cells over extended durations to assess stability and transformation risk.

- Alternative Factor Combinations: The OKS combination (omitting c-MYC) demonstrates reduced tumorigenic potential while maintaining rejuvenation capacity in multiple tissue contexts [27].

The following diagram illustrates the core experimental workflow for mRNA-mediated reprogramming and epigenetic validation:

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for mRNA-mediated reprogramming, showing key steps from cell preparation through validation, with critical decision points influencing therapeutic outcomes.

Therapeutic Applications and Tissue-Specific Outcomes

Regeneration in Tissues with Limited Native Capacity

The therapeutic potential of reprogramming is particularly promising for tissues with restricted innate regenerative capacity:

- Intervertebral Disc Regeneration: In rat IVDD models, OKS@M-Exo treatment ameliorated senescence markers (p16INK4a, p21CIP1), reduced DNA damage, restored proliferation, and maintained disc height and hydration through epigenetic remodeling [27].

- Cardiac Repair: Partial reprogramming enhances regenerative competence in cardiomyocytes, promoting functional recovery following injury through dedifferentiation and epigenetic resetting [24].

- Retinal and Neural Regeneration: OSKM induction restores plasticity in retinal cells and certain neuronal populations, enabling repair of age-related degeneration and injury [24].

Enhancement of Endogenous Regenerative Programs

In tissues with inherent regenerative capacity, reprogramming augments natural repair mechanisms:

- Liver Regeneration: OSKM-mediated reprogramming parallels injury-induced dedifferentiation of hepatocytes, amplifying their natural plasticity to enhance regeneration without complete loss of cellular identity [24].

- Intestinal Epithelial Renewal: The intestine exhibits robust OSKM activation in inducible models, suggesting particular susceptibility to reprogramming-based enhancement of its naturally high turnover rate [24].

- Skeletal Muscle Repair: Partial reprogramming improves muscle regeneration following injury in aged mice, indicating reversal of age-related epigenetic barriers to satellite cell function [24].

The following diagram illustrates the key molecular pathways activated during reprogramming-mediated tissue regeneration:

Diagram 2: Molecular pathways in reprogramming, showing how OSKM expression triggers epigenetic and senescence changes that ultimately restore cellular plasticity and tissue function.

The strategic application of embryonic cues through mRNA-mediated reprogramming represents a paradigm shift in regenerative medicine. By harnessing developmental pathways to remodel the epigenetic landscape, this approach offers unprecedented potential for reversing age-associated cellular decline and enhancing tissue repair. The critical advance lies in achieving partial rather than complete reprogramming—a transient reset that rejuvenates cellular function without inducing tumorigenicity.

Future research directions should focus on optimizing factor combinations and delivery systems for specific tissue contexts, developing more precise temporal control over reprogramming duration, and establishing comprehensive safety profiles for clinical translation. As the field progresses, integration of embryonic guidance principles with mRNA technology promises to unlock novel therapeutic strategies for degenerative diseases, age-related decline, and injury repair, ultimately fulfilling the regenerative potential hinted at in our earliest developmental stages.

Cellular reprogramming represents a paradigm shift in regenerative medicine, enabling the conversion of a specific somatic cell identity into another. This process is fundamentally governed by epigenetic remodeling, which involves the erasure of the existing somatic epigenetic memory and the active establishment of a new epigenetic identity [29]. Within the context of modern therapeutic development, mRNA-based technology has emerged as a transformative tool for directing this process, offering a non-integrative, controllable, and transient expression of reprogramming factors [25] [30]. The precision and safety profile of mRNA-mediated delivery make it particularly suited for applications in engineered regenerative medicine, from cardiac repair to in vivo transdifferentiation [25]. This technical guide delves into the core hallmarks of reprogramming, framing the discussion within the mechanisms of epigenetic resetting and the innovative methodologies that are pushing the field toward clinical translation.

Molecular Mechanisms of Epigenetic Erasure

The initial phase of reprogramming involves dismantling the somatic cell's epigenetic landscape, a process critical for erasing cellular memory and enabling identity conversion.

DNA Demethylation and the Role of TET Enzymes

Genome-wide DNA demethylation is a cornerstone of epigenetic erasure. This process can occur passively, through the inhibition of maintenance DNA methyltransferases during cell division, or actively, mediated by enzymes such as TET (Ten-eleven translocation) dioxygenases [31] [32]. The functional importance of active demethylation is highlighted by studies showing that TET1-deficient human primordial germ cell-like cells (hPGCLCs) fail to fully activate genes critical for gametogenesis and instead aberrantly differentiate into extraembryonic lineages like amnion [31]. This demonstrates that TET1 is essential for directing proper epigenetic reprogramming and lineage fate. Furthermore, in vivo studies on mouse retinal ganglion cells have shown that the beneficial effects of OSK (Oct4, Sox2, Klf4) reprogramming—including axon regeneration and vision restoration—are dependent on the presence of TET1 and TET2 [32].

Histone Modification Remodeling

Concurrent with DNA demethylation, the reprogramming process involves a comprehensive resetting of histone post-translational modifications [29]. This includes changes to marks such as histone H3 lysine 4 dimethylation/trimethylation (H3K4me2/me3) and histone H3 lysine 27 acetylation (H3K27ac), which are associated with active promoters and enhancers. The removal of repressive marks and the installation of activating ones facilitate the opening of chromatin and the activation of pluripotency or new lineage-specific gene networks. The role of reprogramming factors is to recruit or co-opt these epigenetic modifiers to initiate this genome-wide remodeling [29].

Attenuation of Somatic Signatures

A key step in erasing somatic memory is the downregulation of somatic cell-type-specific genes and the silencing of their associated regulatory elements. This involves the decommissioning of somatic enhancers, which are often enriched for transcription factor motifs like AP-1 (Jun, Fos) [33]. During the early phases of reprogramming, the ectopic expression of factors such as OKSM (Oct4, Klf4, Sox2, c-Myc) can sequester these somatic transcription factors, leading to the loss of activating marks and the eventual silencing of these regulatory domains [33].

Table 1: Key Molecules in Epigenetic Erasure and Their Functions

| Molecule/Process | Primary Function | Experimental Outcome of Disruption |

|---|---|---|

| TET1/TET2 Enzymes | Active DNA demethylation | Failure to activate germline genes; aberrant differentiation into amnion [31]; impaired axon regeneration in OSK-treated RGCs [32] |

| Passive Demethylation | Replication-dependent loss of 5mC | Promoted by BMP signaling and inhibition of maintenance DNMTs in hPGCLC differentiation [31] |

| H3K9me3 Demethylation | Removal of repressive chromatin mark | Concentrated in regions of epigenetic memory; reconfiguration is essential for full reprogramming [33] |

| Somatic Enhancer Decommissioning | Silencing of cell-of-origin gene networks | Associated with AP-1 factor sequestration and loss of H3K27ac [33] |

Establishing a New Cellular Identity

Following the erasure of somatic memory, the cell must activate a new transcriptional program to establish a stable identity, whether pluripotent or another somatic cell type.

Activation of Pluripotency and Lineage-Specific Networks

The establishment of a new identity is driven by the activation of key transcription factors that define the target cell state. In reprogramming to pluripotency, the core factors OCT4, SOX2, and KLF4 (OSK) are sufficient to initiate this process without inducing tumorigenesis when delivered transiently [32]. These factors bind to and activate promoters and enhancers of pluripotency-associated genes, establishing a self-reinforcing regulatory network. Similarly, in direct lineage conversion (transdifferentiation), the expression of a specific set of transcription factors can directly activate the gene regulatory network of the target cell type, bypassing a pluripotent intermediate [30].

The Role of Signaling Pathways

Extracellular signaling cues are critical for stabilizing the new cellular identity. In the differentiation of hPGCLCs into pro-spermatogonia or oogonia, Bone Morphogenetic Protein (BMP) signaling is a master regulator [31]. BMP signaling stabilizes the germ cell fate and promotes epigenetic reprogramming by attenuating the MAPK (ERK) pathway and modulating DNA methyltransferase activities. Furthermore, other pathways like WNT and NODAL require precise modulation, as their inhibition can help minimize de-differentiation and maintain the trajectory toward the target cell fate [31].

Phases of Reprogramming

Reprogramming is not an instantaneous event but a multi-stage process:

- Initiation: A rapid, stochastic phase characterized by widespread transcriptional changes, proliferation upregulation, and a mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition (MET) [29].

- Maturation: A slower, more deterministic phase where the core regulatory network of the new cell identity is consolidated and begins to stabilize [29].

- Stabilization: The final phase, where the expression of exogenous reprogramming factors can be silenced, and the cell autonomously maintains its new identity through its endogenous gene regulatory network [29].

Figure 1: The Multi-Phase Progression of Cellular Reprogramming.

mRNA-Mediated Reprogramming: A Modern Therapeutic Platform

The delivery method of reprogramming factors is crucial for safety and efficacy. mRNA-based technology offers a compelling approach for transient, non-integrative reprogramming.

Advantages of mRNA Technology

Unlike viral vectors that can lead to permanent genomic integration, mRNA transfection allows for transient expression of reprogramming factors, significantly reducing the risk of insertional mutagenesis and tumorigenesis [25] [30]. mRNA is translated in the cytoplasm, bypassing the need for nuclear entry, which results in faster onset of protein expression compared to plasmid DNA [30]. Advances in mRNA chemistry, such as nucleoside modifications and optimized codons, have greatly enhanced stability and reduced immunogenicity, making it a viable platform for in vivo applications [25].

In Vivo Delivery and Tissue Nanotransfection (TNT)

A groundbreaking application of mRNA technology is Tissue Nanotransfection (TNT). This non-viral, nanoelectroporation-based platform enables localized in vivo delivery of genetic cargo, including mRNA, directly into tissue cells [30]. The TNT device uses a nanochannel chip to create transient pores in cell membranes, allowing for the efficient uptake of mRNA. This method is highly specific, has minimal cytotoxicity, and avoids the off-target effects associated with viral vectors [30]. TNT has demonstrated success in various therapeutic contexts, including direct in vivo reprogramming for wound healing, ischemia repair, and antimicrobial therapy [30].

Figure 2: mRNA-Based Reprogramming via Tissue Nanotransfection (TNT).

Advanced Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

This section details key experimental approaches for studying and applying cellular reprogramming, with a focus on quantitative outcomes.

In Vitro Reconstitution of Epigenetic Reprogramming

A recent protocol for modeling human germ cell epigenetic reprogramming involves the differentiation of pluripotent stem cells into human PGCLCs (hPGCLCs) [31].

- hPGCLC Induction: Incipient mesoderm-like cells (iMeLCs) are first induced from human iPSCs and subsequently differentiated into hPGCLCs using cytokine cocktails.

- BMP-Driven Differentiation and Amplification: hPGCLCs are cultured in advanced RPMI medium supplemented with a BMP2 signal (e.g., 25-100 ng/mL) and a WNT signaling inhibitor (e.g., IWR1). This culture can be passaged approximately every 10 days, leading to extensive amplification (>10^10-fold) and differentiation into DAZL/DDX4-positive pro-spermatogonia or oogonia-like cells.

- Monitoring: The process is tracked using reporters for germ cell markers (e.g., TFAP2C-eGFP, DAZL-tdTomato) and analysis of DNA demethylation at key loci.

Transient Naive Reprogramming (TNT) for Epigenetic Correction

To address epigenetic aberrations and memory in human iPS cells, a novel protocol termed Transient Naive-Treatment (TNT) reprogramming has been developed [33].

- Naive Conversion: Conventional primed hiPS cells or reprogramming intermediates are transitioned into a naive pluripotent state culture condition for a short, defined period.

- Emulating Embryonic Reset: This transient exposure to a naive environment promotes a more complete epigenome reset, effectively reducing epigenetic memory and correcting aberrant DNA methylation patterns, particularly at H3K9me3-marked and lamin-B1-associated domains.

- Outcome: TNT-reprogrammed hiPS cells are molecularly and functionally more similar to hES cells, showing corrected gene expression and improved differentiation efficiency.

In Vivo Partial Reprogramming for Tissue Regeneration

For therapeutic in vivo applications, a safe and controllable method for expressing reprogramming factors is essential [32].

- Viral Delivery: A dual adeno-associated virus (AAV) system is used. One AAV encodes a transactivator (e.g., rtTA for Tet-On), and the other carries the polycistronic OSK transgene under a TRE promoter.

- Induction: Reprogramming is induced by administering doxycycline (Dox) in the drinking water. This allows for transient, cyclical expression of OSK.

- Validation: In a mouse model of optic nerve crush, this method demonstrated robust axon regeneration and reversal of vision loss in aged mice and a glaucoma model, without inducing teratomas.

Table 2: Quantitative Outcomes of Key Reprogramming Protocols

| Protocol / Study | Reprogramming Factors | Key Quantitative Result | Epigenetic Change Measured |

|---|---|---|---|

| BMP-driven hPGCLC Differentiation [31] | BMP2 Signaling | >10^10-fold cell expansion; differentiation to DAZL+ cells | DNA demethylation at ER-activated gene promoters (e.g., GTSF1, PRAME) |

| In Vivo OSK Reprogramming [32] | OSK (Oct4, Sox2, Klf4) | Axon regeneration >5mm; reversal of vision loss in glaucoma model | Restoration of youthful DNA methylation patterns and transcriptomes |