Evaluating Cellular Identity Preservation: From Foundational Concepts to Advanced Methods in Biomedicine

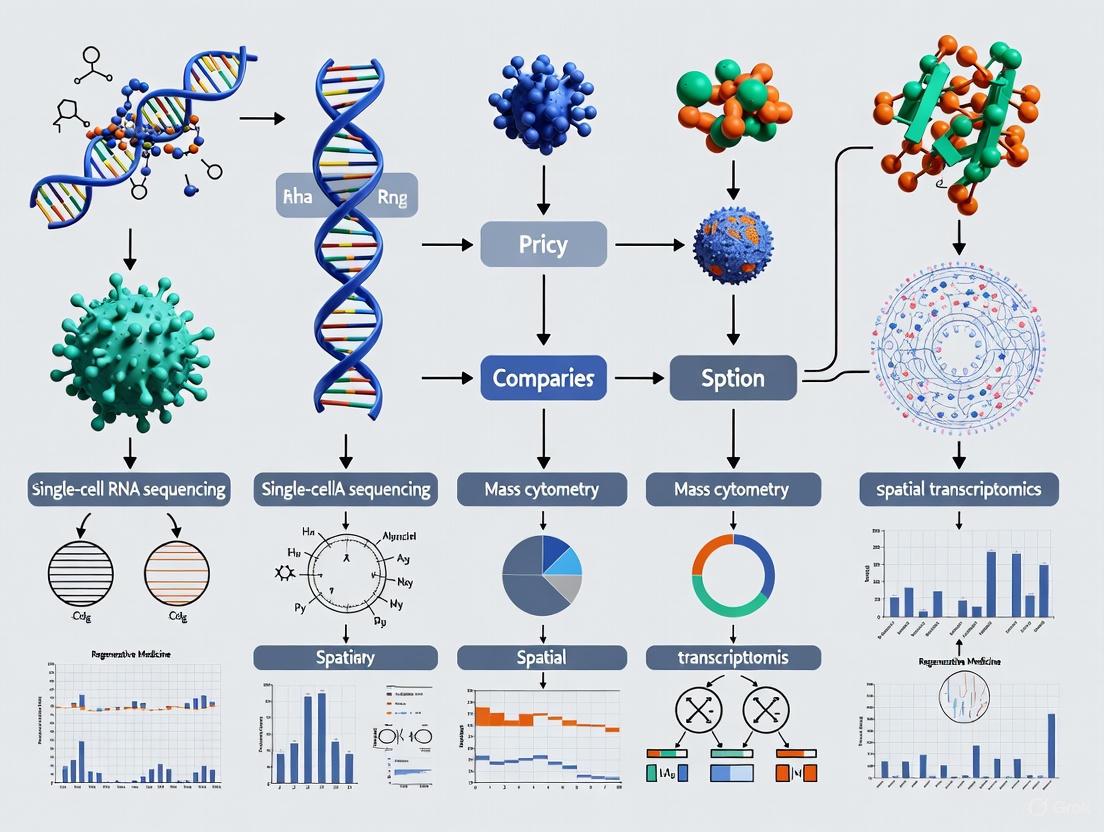

This article provides a comprehensive evaluation of methods for preserving and verifying cellular identity, a critical challenge in cell-based therapies and single-cell genomics.

Evaluating Cellular Identity Preservation: From Foundational Concepts to Advanced Methods in Biomedicine

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive evaluation of methods for preserving and verifying cellular identity, a critical challenge in cell-based therapies and single-cell genomics. It explores the fundamental principles of epigenetic memory and potency, reviews cutting-edge computational and experimental techniques for identity assessment, addresses common troubleshooting scenarios in manufacturing and analysis, and offers a comparative analysis of validation methodologies. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, this resource synthesizes the latest advances to guide the selection and optimization of identity preservation strategies, ultimately supporting the development of more reliable and effective biomedical applications.

The Cellular Identity Blueprint: Understanding Potency, Memory, and Stability

Cellular identity defines the specific type, function, and state of a cell, determined by a precise combination of gene expression patterns, epigenetic modifications, and signaling pathway activities. This identity exists on a spectrum of developmental potential, ranging from the remarkable plasticity of totipotent stem cells to the specialized, fixed state of terminally differentiated cells. Understanding this continuum is crucial for advancing regenerative medicine, developmental biology, and therapeutic drug development [1] [2].

At one extreme, totipotent cells possess the maximum developmental potential, capable of giving rise to an entire organism plus extraembryonic tissues like the placenta. As development progresses, cells transition through pluripotent, multipotent, and finally terminally differentiated states, each step involving a progressive restriction of developmental potential and the establishment of a stable cellular identity maintained through sophisticated molecular mechanisms [1]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of the key stages along this continuum and the experimental methods used to study them.

Comparative Analysis of Cellular Potency States

The following table summarizes the defining characteristics, molecular markers, and experimental applications of the major cell potency states.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Cellular Potency States

| Potency State | Developmental Potential | Key Molecular Features | Tissue Origin/Examples | Research & Therapeutic Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Totipotent | Can give rise to all embryonic and extraembryonic cell types (complete organism) [1]. | Expresses Zscan4, Eomes; open chromatin structure; distinct epigenetic landscape [1] [3]. | Zygote, early blastomeres (up to 4-cell stage in humans) [1]. | Model for early embryogenesis [3]; limited research use due to ethical constraints and rarity [1]. |

| Pluripotent | Can differentiate into all cell types from the three germ layers (ectoderm, mesoderm, endoderm) but not extraembryonic tissues [1] [2]. | High expression of Oct4, Sox2, Nanog; core pluripotency network [1] [4]. | Inner Cell Mass (ICM) of blastocyst (ESCs); Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells (iPSCs) [1]. | Disease modeling, drug screening, regenerative medicine (e.g., generating specific cell types for transplantation) [1] [2]. |

| Multipotent | Can differentiate into multiple cell types within a specific lineage [2]. | Lineage-specific transcription factors (e.g., GATA, Hox genes); more restricted chromatin access. | Adult stem cells: Hematopoietic Stem Cells (HSCs), Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs) [1] [2]. | Cell-based therapies for degenerative diseases (e.g., bone/cartilage repair, immunomodulation) [1]. |

| Terminally Differentiated | No developmental potential; maintains a fixed, specialized identity and function [5]. | Terminally differentiated genes (e.g., Hemoglobin in RBCs); repressive chromatin; often post-mitotic. | Neurons, cardiomyocytes, adipocytes, etc. | Target for tissue-specific therapies; study of age-related functional decline [6]. |

Key Experimental Methods for Assessing Cellular Identity

Researchers use a multifaceted toolkit to define and manipulate cellular identity. The following table compares the protocols, readouts, and applications of key experimental methodologies.

Table 2: Comparison of Key Experimental Methods for Assessing Cellular Identity

| Method Category | Specific Method/Protocol | Key Experimental Readout | Application in Identity Research | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| In Vivo Developmental Potential Assay | Teratoma Formation: Injection of candidate pluripotent cells into immunodeficient mice [1]. | Formation of a tumor (teratoma) containing differentiated tissues from all three germ layers. | Gold-standard functional validation of pluripotency [1]. | Time-consuming (weeks); requires animal model; tumorigenic risk. |

| In Vivo Developmental Potential Assay | Chimera Formation: Injection of donor cells into a developing host blastocyst [1]. | Contribution of donor cells to various tissues in the resulting chimeric animal. | Tests integration and developmental capacity of stem cells within a living embryo. | Technically challenging; ethically regulated; limited to certain cell types and species. |

| Epigenetic & Transcriptomic Profiling | Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) [6] [7]. | Genome-wide expression profile of individual cells; identification of cell clusters/states. | Decoding cellular heterogeneity; constructing developmental trajectories [6] [7]. | Reveals transcriptional state but not functional potential; sensitive to technical noise. |

| Epigenetic & Transcriptomic Profiling | Chromatin Accessibility Assays (ATAC-seq). | Map of open, accessible chromatin regions, indicating active regulatory elements. | Inferring transcription factor binding and regulatory landscapes that define identity. | Indirect measure of regulatory activity. |

| Cellular Reprogramming | iPSC Generation (Yamanaka Factors): Ectopic expression of Oct4, Sox2, Klf4, c-Myc in somatic cells [1] [2]. | Emergence of colonies with ESC-like morphology and gene expression. | Resetting cellular identity to pluripotency; creating patient-specific stem cells [1]. | Low efficiency; potential for incomplete reprogramming; tumorigenic risk of c-Myc. |

| Cellular Reprogramming | Transdifferentiation (Lineage-specific TF expression). | Direct conversion of one somatic cell type into another without a pluripotent intermediate. | Potential for direct tissue repair; avoids tumorigenesis risks of pluripotent cells. | Efficiency can be low; identity and stability of resulting cells must be rigorously validated. |

| Computational Analysis | Cell Decoder: Graph neural network integrating protein-protein interactions, gene-pathway maps, and pathway-hierarchy data [7]. | Multi-scale, interpretable cell-type identification and characterization. | Robust and noise-resistant cell annotation; reveals key pathways defining identity [7]. | Relies on quality of prior knowledge databases; complex model architecture. |

Signaling Pathways Governing Cell Fate and Identity

The behavior of stem cells—including self-renewal, differentiation, and the maintenance of identity—is tightly regulated by a core set of conserved signaling pathways. The diagram below illustrates the key pathways and their crosstalk in regulating pluripotency and early fate decisions.

Diagram 1: Signaling pathways in pluripotency and differentiation. Pathways like TGF-β/Nodal/Activin (yellow) promote naive pluripotency via SMAD2/3. BMP (red) has a dual role, supporting self-renewal via ID genes but also driving differentiation via SMAD1/5/8. Wnt/β-Catenin (green) and FGF (blue) pathways support self-renewal and proliferation, with Hippo signaling (red) also contributing to proliferation. The core pluripotency factors OCT4, SOX2, and NANOG form the central regulatory node [2].

Pathway Functions and Crosstalk

- TGF-β/SMAD2/3 Pathway: Activated by TGF-β, Nodal, and Activin, this pathway is crucial for sustaining the self-renewal of primed pluripotent stem cells. It promotes the expression of core pluripotency factors like NANOG [2].

- BMP/SMAD1/5/8 Pathway: This pathway demonstrates context-dependent functionality. In mouse ESCs, BMP-4 works with LIF/STAT3 to support self-renewal, partly by inducing Id genes. However, it also plays a potent role in driving differentiation into various lineages, including mesoderm and extraembryonic cell types [2].

- Wnt/β-Catenin Pathway: A key regulator of stem cell function, Wnt signaling supports self-renewal in stem cells. Its outcome is highly context-dependent, influencing cell fate decisions throughout development and in adult tissue homeostasis [2].

- Cross-regulation: The balance between these pathways determines the cell's fate. For instance, the ratio of activin/nodal signaling (promoting pluripotency) to BMP signaling (promoting differentiation) is critical for maintaining human ESCs in a undifferentiated state [2].

The Epigenetic Framework of Cellular Memory

Cellular identity is maintained across cell divisions through epigenetic mechanisms, which create a stable, heritable "memory" of gene expression patterns without altering the underlying DNA sequence. The diagram below illustrates the proposed three-dimensional loop of epigenetic memory maintenance.

Diagram 2: The 3D loop of epigenetic memory. A theoretical model proposes that epigenetic marks (yellow) influence the 3D folding of chromatin (green). This 3D structure then guides "reader-writer" enzymes (blue) to restore epigenetic marks after cell division, which partially erases them. This self-reinforcing loop ensures stable maintenance of cellular identity over hundreds of cell divisions [8].

Key Epigenetic Regulators and Recent Insights

- DNA Methylation: The addition of methyl groups to cytosine bases, typically leading to gene silencing. This process is catalyzed by DNA methyltransferases. A recent paradigm-shifting study in plants revealed that specific DNA sequences, recognized by RIM/CLASSY proteins, can actively recruit the DNA methylation machinery, demonstrating that genetic information can directly guide epigenetic patterning [9].

- Histone Modifications: Chemical modifications (e.g., acetylation, methylation) on histone tails influence chromatin accessibility. The combination of these marks forms a "histone code" that is read by various proteins to activate or repress transcription.

- Chromatin Architecture: The three-dimensional organization of the genome into active (euchromatin) and inactive (heterochromatin) compartments, along with looping structures that bring distal regulatory elements into contact with gene promoters, is a critical determinant of gene expression programs [8].

- Transcription Factors in Early Development: Factors like NF-Y play a pivotal "pioneer" role in early embryogenesis. During zygotic genome activation (ZGA) in mice, NF-Y binds to promoters at the 2-cell stage, helping to establish open chromatin regions and influencing the selection of transcriptional start sites, thereby shaping the initial gene expression programs of the embryo [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Studying Cellular Identity

| Reagent / Solution | Function / Application | Specific Examples / Targets |

|---|---|---|

| Pluripotency Transcription Factors | Reprogram somatic cells to induced Pluripotent Stem Cells (iPSCs) [1]. | Yamanaka Factors: Oct4, Sox2, Klf4, c-Myc [1] [2]. |

| Small Molecule Pathway Agonists/Antagonists | Pharmacologically modulate key signaling pathways to direct differentiation or maintain stemness [2]. | Wnt agonists (CHIR99021), TGF-β/Activin A receptor agonists, BMP inhibitors (Dorsomorphin), FGF-basic [2]. |

| Epigenetic Modifiers | Manipulate the epigenetic landscape to erase or establish cellular memory. | DNA methyltransferase inhibitors (5-Azacytidine), Histone deacetylase inhibitors (Vorinostat/SAHA). |

| Cytokines & Growth Factors | Support cell survival, proliferation, and lineage-specific differentiation in culture. | BMP-4 (for self-renewal or differentiation), FGF2 (for hESC culture), SCF, VEGF (for endothelial differentiation) [2]. |

| Cell Surface Marker Antibodies | Isolate or characterize specific cell populations via Flow Cytometry (FACS) or Magnetic-Activated Cell Sorting (MACS). | CD34 (HSCs), CD90/THY1, CD73, CD105 (MSCs), TRA-1-60, SSEA-4 (Pluripotent Stem Cells). |

| CRISPR/Cas9 Systems | Gene editing for functional knockout studies, lineage tracing, or introducing reporter genes. | Cas9 Nuclease, gRNA libraries, Base Editors for precise epigenetic manipulation [9]. |

| Single-Cell Multi-omics Kits | Simultaneously profile gene expression (RNA-seq), chromatin accessibility (ATAC-seq), or DNA methylation in individual cells. | Commercial kits from 10x Genomics, Parse Biosciences, etc., enabling the dissection of cellular heterogeneity [6] [7]. |

The established dogma of epigenetic memory has long been characterized as a binary system, where genes are permanently locked in either fully active or fully repressed states, much like an on/off switch. This paradigm is fundamentally challenged by groundbreaking research from MIT engineers, which reveals that epigenetic memory operates through a more nuanced, graded mechanism comparable to a dimmer dial [10]. This discovery suggests that cells can commit to their final identity by locking genes at specific levels of expression along a spectrum, rather than through absolute on/off decisions [10].

This shift from a digital to an analog model of epigenetic memory carries profound implications for understanding cellular identity, with potential applications in tissue engineering and the treatment of diseases such as cancer [10]. This guide objectively compares this new analog paradigm against the classical binary model, providing the experimental data and methodologies required for its evaluation.

Comparative Analysis: Binary Switch vs. Analog Dimmer Dial

The table below summarizes the core distinctions between the traditional and newly proposed models of epigenetic memory.

Table 1: Fundamental Comparison of Epigenetic Memory Models

| Feature | Classical Binary Switch Model | Novel Analog Dimmer Dial Model |

|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | Genes are epigenetically locked in a fully active ("on") or fully repressed ("off") state [10]. | Genes can be locked at any expression level along a spectrum between on and off [10]. |

| Mechanistic Analogy | A light switch | A dimmer dial [10] |

| Nature of Memory | Digital | Analog [10] [11] |

| Implied Cell Identity | Discrete, well-defined cell types | A spectrum of potential cell types with finer functional gradations [10] |

| Experimental Readout | Bimodal distribution of gene expression in cell populations. | Unimodal or broad distribution of gene expression levels across a population [10]. |

Supporting Experimental Data and Quantifiable Findings

Key Evidence for the Analog Model

The conceptual shift is supported by direct experimental evidence. Key findings from the MIT study are summarized in the table below.

Table 2: Key Experimental Findings Supporting the Analog Memory Model

| Experimental Aspect | Finding | Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Persistence of Intermediate States | Cells with gene expression set at intermediate levels maintained these states over five months and through cell divisions [10] [11]. | Intermediate states are stable and heritable, not just transient phases. |

| Role of DNA Methylation | Distinct grades of DNA methylation were found to encode corresponding, persistent levels of gene expression [12] [11]. | DNA methylation functions as a multi-level signal encoder, not just a binary repressor. |

| Theoretical Foundation | A computational model suggests that analog memory arises when the positive feedback between DNA methylation and repressive histone modifications is absent [11]. | Provides a mechanistic explanation for how graded memory can be established. |

Complementary Research in Neuroscience

Independent research in neuroscience provides a parallel line of evidence for the precise controllability of epigenetic states. A study published in Nature Genetics demonstrated that locus-specific epigenetic editing using CRISPR-dCas9 tools could precisely regulate memory expression in neurons [13].

Table 3: Key Findings from Locus-Specific Epigenetic Editing in Memory

| Intervention | Target | Effect on Memory | Molecular Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| dCas9-KRAB-MeCP2(Epigenetic Repressor) | Arc gene promoter | Significantly reduced memory formation [13] | Decreased H3K27ac; closing of chromatin [13] |

| dCas9-VPR(Epigenetic Activator) | Arc gene promoter | Robust increase in memory formation [13] | Increased H3K27ac, H3K14ac, and Arc mRNA [13] |

| Induction of AcrIIA4(Anti-CRISPR protein) | Reversal of dCas9-VPR | Reversion of enhanced memory effect [13] | Reverted dCas9-VPR-mediated increase of Arc [13] |

This research confirms that fine-tuning the epigenetic state of a single gene locus is sufficient to regulate a complex biological function like memory, reinforcing the principle of analog control.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol for Demonstrating Analog Epigenetic Memory

The following workflow illustrates the key experiment that demonstrated analog epigenetic memory in hamster ovarian cells.

- Cell Line and Reporter: Use hamster ovarian cells (CHO-K1) engineered with a gene coupled to a fluorescent reporter (e.g., blue fluorescent protein). The brightness corresponds to the gene's expression level.

- Initialization of States: Establish a population of cells where the engineered gene is set to different expression levels—fully on, fully off, and various intermediate levels.

- Locking the State: Introduce, for a short period, an enzyme (e.g., a DNA methyltransferase) that triggers the natural DNA methylation process to lock the gene's expression state.

- Long-term Tracking: Use flow cytometry or time-lapse fluorescence microscopy to track the fluorescence intensity (and thus gene expression) of the cell population and its progeny over approximately 150 days (five months).

- Data Analysis: Analyze the fluorescence distribution over time. The stability of a wide spectrum of intensities, rather than a convergence to two peaks (on/off), confirms analog memory.

Protocol for Epigenetic Editing of Memory

The following workflow outlines the method used to demonstrate causal, locus-specific epigenetic editing of a behavioral memory.

Key Steps [13]:

- Animal Model and Viral Delivery: Use cFos-tTA mice, where the tetracycline-controlled transactivator (tTA) is expressed in neurons activated by learning. Stereotaxically inject two lentiviruses into the dentate gyrus (DG):

- One containing an epigenetic effector (e.g., dCas9-KRAB-MeCP2 for repression or dCas9-VPR for activation) under a tetracycline-responsive element (TRE) promoter.

- Another expressing single-guide RNAs (sgRNAs) targeting the promoter of a plasticity-related gene like Arc, or non-targeting (NT) sgRNAs as a control.

- Memory Formation and Effector Induction: Subject mice to a contextual fear conditioning (CFC) task. Remove doxycycline (DOX) from the diet shortly before CFC to allow the tTA to bind the TRE and express the dCas9-effector in learning-activated "engram" cells. Return mice to a DOX diet after CFC to limit further induction.

- Behavioral Phenotyping: Two days post-CFC, test memory by re-exposing mice to the context and measuring freezing behavior. Compared to NT controls, dCas9-KRAB-MeCP2 with Arc sgRNA reduces freezing, while dCas9-VPR with Arc sgRNA enhances it.

- Molecular Validation: Analyze brain tissue to confirm changes in epigenetic marks (e.g., H3K27ac via ChIP), chromatin accessibility (e.g., scATAC-seq), and target gene expression (e.g., Arc mRNA).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The following table details key reagents and tools used in the featured studies, which are essential for conducting related research on epigenetic memory.

Table 4: Key Research Reagents for Epigenetic Memory Studies

| Reagent / Tool | Function in Research | Specific Example / Target |

|---|---|---|

| Engineered Gene Reporter | To visually track and quantify gene expression levels in living cells over time. | Fluorescent protein (e.g., BFP) coupled to a gene of interest [10]. |

| Epigenetic Effectors (dCas9-based) | To precisely modify epigenetic marks at specific genomic loci. | dCas9-KRAB-MeCP2 (repressor) [13]; dCas9-VPR or dCas9-CBP (activator) [13]. |

| Synthetic Guide RNA (sgRNA) | To target dCas9-epigenetic effectors to a specific DNA sequence. | sgRNAs targeting the promoter of the Arc gene [13]. |

| Inducible Expression System | To achieve temporal control over gene or effector expression. | Tetracycline-Responsive Element (TRE) and tTA/rtTA, often combined with cFos-promoter driven systems for activity-dependent expression [13]. |

| Methylation-Sensitive Sequencing | To map DNA methylation patterns genome-wide or at specific loci. | Whole-Genome Bisulfite Sequencing (WGBS) [14]; Enzymatic Methyl-seq (EM-seq) [14]. |

| Chromatin Accessibility Assay | To infer the "openness" of chromatin and identify regulatory regions. | scATAC-seq (Assay for Transposase-Accessible Chromatin using sequencing) [13]. |

The Role of 3D Genome Architecture in Memory Stability

A theoretical model from MIT proposes that the 3D folding of the genome plays a critical role in stabilizing epigenetic memory across cell divisions [8]. The model suggests a self-reinforcing loop:

- Folding Guides Marking: The 3D structure brings specific genomic regions into proximity. "Reader-writer" enzymes, which add epigenetic marks, can then spread these marks within these spatially clustered, dense regions (e.g., heterochromatin) [8].

- Marking Guides Folding: The deposited epigenetic marks, in turn, help to maintain the 3D folded structure of the genome [8].

This reciprocal relationship creates a stable system where epigenetic memory is juggled between 3D structure and chemical marks, allowing it to be accurately restored after each cell division, even when half the marks are lost during DNA replication [8]. This model provides a plausible mechanism for how both binary and analog epigenetic states could be robustly maintained.

The concept of "identity" represents a fundamental organizing principle across biological and psychological disciplines, though its manifestation differs dramatically across scales of organization. In cellular biology, identity refers to the distinct molecular and functional characteristics that define a specific cell type and distinguish it from others, maintained through sophisticated epigenetic programming and transcriptional networks [15] [16] [17]. In psychological science, identity constitutes the coherent sense of self that integrates one's roles, traits, values, and experiences into a continuous whole across time [18] [19]. Despite these different manifestations, both domains grapple with parallel challenges: what mechanisms establish and preserve identity, what factors disrupt this integrity, and what consequences follow from its dissolution.

This comparison guide objectively evaluates the mechanisms of identity loss across these disciplinary boundaries, examining both the molecular foundations of cellular identity and the psychological architecture of selfhood. We directly compare experimental approaches, quantitative findings, and therapeutic implications, providing researchers with a structured analysis of identity preservation and disruption across systems. The emerging consensus reveals that whether examining cellular differentiation or psychological adaptation, identity maintenance requires active stabilization mechanisms, while identity loss follows characteristic pathways with profound functional consequences.

Quantitative Comparison of Identity Disruption Metrics

Table 1: Quantitative Measures of Identity Disruption Across Disciplines

| Domain | Measurement Approach | Key Metrics | Numerical Findings | Associated Consequences |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cellular Identity | scRNA-seq clustering [20] [21] | Preservation of global/local structure, Knn graph conservation | UMAP compresses local distances more than t-SNE; Knn preservation higher in continuous datasets [20] | Loss of lineage fidelity, aberrant differentiation, potential malignancy [16] |

| Cellular Identity | Orthologous Marker Group analysis [21] | Fisher's exact test (-log10FDR) for cluster similarity | 24/165 cluster pairs showed significant OMGs (FDR < 0.01) between tomato and Arabidopsis [21] | Accurate cross-species cell type identification enabled; reveals evolutionary conservation [21] |

| Cellular Identity | Epigenomic bookmarking [16] | Maintenance of protein modifications during mitosis | Removal of mitotic bookmarks disrupts identity preservation across cell divisions [16] | Daughter cells fail to maintain lineage commitment; potential transformation [16] |

| Psychological Identity | Identity disruption coding [18] | Thematic analysis of expressive writing samples | 49% (n=121) of veterans showed identity disruption in narratives [18] | Correlated with more severe PTSD, lower life satisfaction, greater reintegration difficulty [18] |

| Psychological Identity | Self-concept assessment in grief [22] | Self-fluency (number of self-descriptors), self-diversity (category breadth) | CG patients showed lower self-fluency and diversity than non-CG bereaved [22] | Identity confusion maintains prolonged grief; impedes recovery and adaptation [22] |

Table 2: Experimental Protocols for Assessing Identity Status

| Methodology | Sample Preparation | Data Collection | Analysis Approach | Domain |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single-cell RNA sequencing [20] [21] | Tissue dissociation, single-cell suspension, library preparation | High-throughput sequencing (10x Genomics, inDrop, Drop-seq) | Dimensionality reduction (PCA, t-SNE, UMAP), clustering, trajectory inference | Cellular |

| Orthologous Marker Groups (OMG) [21] | Identification of top N marker genes (N=200) per cell cluster | OrthoFinder for orthologous gene groups across species | Pairwise Fisher's exact tests comparing clusters across species | Cellular |

| Methylome Analysis [15] [17] | Bisulfite conversion, single-cell bisulfite sequencing | Sequencing of methylation patterns at CpG islands | NMF followed by t-SNE; correlation to reference databases | Cellular |

| Expressive Writing Coding [18] | Participant writing about disruptive life experiences | Thematic analysis of writing samples | Qualitative coding for identity disruption themes; correlation with psychosocial measures | Psychological |

| Self-Concept Mapping [22] | Verbal Self-Fluency Task: "Tell me about yourself" | Recording and transcription of self-descriptions | Categorization of self-statements; fluency, diversity, and content analysis | Psychological |

Experimental Approaches for Investigating Identity

Cellular Identity Assessment Protocols

Single-Cell RNA Sequencing Workflow: The fundamental protocol for assessing cellular identity begins with tissue dissociation into single-cell suspensions, followed by cell lysis and reverse transcription with barcoded primers. After library preparation and high-throughput sequencing, bioinformatic analysis involves quality control to remove low-quality cells, normalization to account for technical variation, and dimensionality reduction using principal component analysis (PCA). Researchers then apply clustering algorithms (Louvain, k-means) to group cells with similar expression profiles, followed by differential expression analysis to identify marker genes defining each cluster's identity [20] [21]. Validation typically involves immunofluorescence or flow cytometry for protein-level confirmation of identified cell types.

Orthologous Marker Groups Protocol: For cross-species cell type identification, the OMG method begins with identifying the top 200 marker genes for each cell cluster using standard tools like Seurat. Researchers then employ OrthoFinder to generate orthologous gene groups across multiple species. The core analysis involves pairwise comparisons using Fisher's exact test to identify statistically significant overlaps in orthologous marker groups between clusters across species. This approach successfully identified 14 dominant groups with substantial conservation in shared cell-type markers across monocots and dicots, demonstrating its robustness for evolutionary comparisons of cellular identity [21].

Psychological Identity Assessment Protocols

Identity Disruption Coding Method: In psychological studies, identity disruption is often assessed through expressive writing samples where participants write about disruptive life experiences. Using thematic analysis, researchers develop a coding scheme to identify identity disruption themes, such as disconnectedness between past and present self or difficulty integrating new experiences into one's self-concept. Two independent coders typically analyze the content, with inter-rater reliability measures ensuring consistency. Quantitative scores for identity disruption are then correlated with standardized measures of psychological functioning, such as PTSD symptoms, life satisfaction, and social support [18].

Self-Concept Mapping Procedure: The Verbal Self-Fluency Task directly assesses self-concept by asking participants to "tell me about yourself" for five minutes. Responses are recorded, transcribed, and divided into distinct self-statements. Each statement is coded into one of nine categories: preferences, activities, traits, identities, relationships, past, future, body, and context. Researchers then calculate self-fluency (total number of valid self-statements) and self-diversity (number of unique categories represented). This approach revealed that individuals with complicated grief have less diverse self-concepts with fewer preferences and activities compared to those without complicated grief [22].

Visualization of Identity Pathways

Diagram 1: Comparative Pathways of Identity Preservation and Disruption. This visualization illustrates parallel mechanisms maintaining identity integrity across biological and psychological domains, highlighting how disruptive events challenge stability and the protective factors that promote preservation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Tools for Identity Research

| Reagent/Tool | Application | Function in Identity Research | Example Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| 10x Genomics Chromium [20] | Single-cell RNA sequencing | Enables high-throughput transcriptomic profiling of individual cells | Characterizing cellular identity heterogeneity in complex tissues |

| OrthoFinder [21] | Phylogenetic orthology inference | Identifies orthologous gene groups across species | Cross-species cell type identification using Orthologous Marker Groups |

| Seurat [21] | Single-cell data analysis | Standard toolkit for scRNA-seq analysis including clustering and visualization | Identifying marker genes defining cellular identity |

| Anti-methylcytosine antibodies [15] | DNA methylation detection | Enables mapping of epigenetic patterns that maintain cellular identity | Assessing epigenetic stability during cell differentiation |

| Identity Style Inventory (ISI) [23] | Psychological assessment | Measures identity processing styles (informational, normative, diffuse-avoidant) | Predicting adaptation to disruptive life events |

| Prolonged Grief Disorder Scale [22] | Clinical assessment | Quantifies severity of complicated grief symptoms | Linking identity confusion to grief pathology |

Comparative Analysis of Findings

Commonalities Across Disciplinary Boundaries

Despite the different scales of analysis, striking parallels emerge in the mechanisms of identity maintenance and disruption across cellular and psychological domains. Both systems demonstrate that identity is actively maintained rather than passively sustained—through epigenetic programming in cells and through identity processing styles in psychology. Cellular research reveals that specialized bookmarking mechanisms preserve transcriptional identity during cell division [16], while psychological studies show that adaptive identity processing (informational style) helps maintain self-continuity through life transitions [23].

Additionally, both domains identify disruption as a consequence of stability mechanisms failing. In cellular systems, degradation of mitotic bookmarks leads to identity loss and potential malignancy [16]. In psychological systems, avoidance-based identity processing predicts identity disruption and psychopathology following loss [23] [22]. Quantitative measures in both fields reveal that identity dissolution has measurable structural consequences—simplified gene expression profiles in cells [21] and constricted self-concepts in psychology [22].

Implications for Therapeutic Development

The parallel findings across disciplines suggest novel therapeutic approaches. Cellular reprogramming strategies might benefit from incorporating psychological insights about gradual identity transition supported by multiple group memberships [24]. Conversely, psychological interventions for identity disruption might incorporate principles from cellular biology regarding the need for stability factors during transitional periods.

For drug development professionals, these cross-disciplinary insights highlight that successful cellular reprogramming requires not only initiating new transcriptional programs but also actively maintaining them through stability factors—mirroring how psychological identity change requires both initiating new self-narratives and maintaining them through social validation. The quantitative frameworks developed in cellular identity research [17] may also inform more rigorous assessment of identity outcomes in mental health trials.

This comparative analysis reveals that despite different manifestations, identity systems across biological and psychological domains face similar challenges and employ analogous preservation strategies. Both require active maintenance mechanisms, both undergo disruption when these mechanisms fail, and both exhibit structural degradation as a consequence of identity loss. For researchers and therapy developers, these parallels suggest novel approaches that might transfer insights across disciplinary boundaries—potentially leading to more effective interventions for identity-related pathologies at both cellular and psychological levels. The consistent finding that identity preservation requires both internal coherence mechanisms and supportive external contexts offers a unifying principle that transcends disciplinary silos.

Cell identity is determined by precise spatiotemporal control of gene expression. While transcriptional and epigenetic mechanisms are well-established regulators, recent research highlights post-transcriptional control through membraneless ribonucleoprotein (RNP) granules as a critical, previously underappreciated layer of regulation. Among these granules, P-bodies have emerged as central players in directing cell fate transitions by selectively sequestering translationally repressed mRNAs. This guide compares the roles of P-bodies and related RNP granules across different biological contexts, examining their composition, regulatory mechanisms, and functional outcomes, with particular relevance for developmental biology and disease modeling.

P-bodies are dynamic cytoplasmic condensates composed of RNA-protein complexes that regulate mRNA fate by sequestering them from the translational machinery. Unlike stress granules, which form primarily during cellular stress, P-bodies are constitutive structures that enlarge during stress and undergo compositional shifts. Their ability to store specific mRNAs and release them in response to developmental cues represents a powerful mechanism for controlling protein expression without altering the underlying DNA sequence or transcription patterns [25] [26].

Comparative Analysis of RNP Granules: P-Bodies vs. Stress Granules

Understanding the distinct properties of cytoplasmic RNP granules is essential for evaluating their roles in cell fate determination. The table below provides a systematic comparison between P-bodies and stress granules based on current research findings.

Table 1: Characteristic Comparison Between P-Bodies and Stress Granules

| Feature | P-Bodies | Stress Granules |

|---|---|---|

| Formation Conditions | Constitutive under normal conditions; enlarge during stress [25] | Induced primarily during cellular stress (e.g., arsenite exposure) [25] |

| Primary Functions | mRNA decay, translational repression, RNA storage [27] [25] | Temporary storage of translationally stalled mRNAs during stress [25] |

| RNA Composition | Enriched in poorly translated mRNAs under non-stress conditions [25] | Composed of non-translating mRNAs during stress conditions [25] |

| Key Protein Components | LSM14A, EDC4, DDX6 (decay machinery) [28] | G3BP1, TIA1 (core scaffolding proteins) [25] |

| Response to Arsenite Stress | Transcriptome shifts to resemble stress granule composition [25] | Become prominent with distinct transcriptome enriched in long mRNAs [25] |

| Methodological Challenges | Purification requires immunopurification after differential centrifugation [25] | Differential centrifugation alone insufficient; requires immunopurification [25] |

This comparison reveals both specialized functions and overlapping properties. During arsenite stress, when translation is globally repressed, the P-body transcriptome becomes remarkably similar to the stress granule transcriptome, suggesting that translation status is a dominant factor in mRNA targeting to both granule types [25]. However, their distinct protein compositions indicate different regulatory mechanisms and potential functional specializations in directing cell fate decisions.

Experimental Approaches for P-Body Transcriptome Profiling

Multiple methodologies have been developed to characterize the RNA content of P-bodies, each with distinct advantages and limitations. The table below summarizes key technical approaches and their applications in P-body research.

Table 2: Methodologies for P-Body Transcriptome Analysis

| Method | Principle | Applications | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Differential Centrifugation + Immunopurification | Isolation of RNP granules based on size/density followed by antibody-based purification [25] | High-specificity analysis of P-body and stress granule transcriptomes [25] | Revealed that P-bodies are enriched in poorly translated mRNAs; composition shifts during stress [25] |

| RNA Granule (RG) Pellet | Differential centrifugation alone without immunopurification [25] | Initial approximation of RNP granule transcriptomes | Simpler but contains nonspecific transcripts (e.g., mitochondrial); less accurate for granule-specific composition [25] |

| P-body-seq | Fluorescence-activated particle sorting of GFP-tagged P-bodies (e.g., GFP-LSM14A) [28] | Comprehensive profiling of P-body contents from specific cell types | Identified selective enrichment of untranslated RNAs encoding cell fate regulators in stem cells [27] [28] |

| Single-Cell RNA Sequencing | Analysis of gene expression at individual cell level [29] | Identification of cell-type specific markers and states across species | Developed Orthologous Marker Gene Groups for cell type identification; conserved markers across plants [29] |

Each methodology offers distinct insights, with immunopurification approaches providing higher specificity by reducing contamination from non-granule RNAs. The development of P-body-seq represents a significant advancement, enabling direct correlation between P-body localization and translational status through integration with ribosome profiling data [28].

Experimental Workflow: P-body-seq

The P-body-seq method provides a comprehensive approach for profiling P-body contents with high specificity:

- Cell Engineering: Express GFP-tagged P-body markers (e.g., GFP-LSM14A) in HEK293T or other cell types [28]

- Validation: Confirm GFP-LSM14A puncta colocalization with endogenous P-body markers (e.g., EDC4) via immunofluorescence [28]

- Flow Cytometry: Sort GFP-LSM14A+ P-bodies using fluorescence-activated particle sorting [28]

- RNA Extraction and Sequencing: Ispute RNA from sorted P-bodies and prepare RNA-seq libraries [28]

- Bioinformatic Analysis: Identify P-body-enriched transcripts compared to cytoplasmic controls and integrate with translational efficiency data [28]

This workflow enables direct quantification of RNA enrichment in P-bodies, revealing that P-body-enriched mRNAs have significantly shorter polyA tails and lower translation efficiency compared to cytoplasm-enriched mRNAs [28].

Diagram 1: P-body-seq experimental workflow for transcriptome profiling.

P-Body Functions in Cell Fate Transitions: Comparative Evidence

P-bodies regulate cell identity across diverse biological contexts, from embryonic development to cancer. The table below synthesizes evidence from multiple systems, highlighting conserved mechanisms and context-specific functions.

Table 3: P-body Functions in Different Biological Contexts

| Biological Context | P-body Role | Key Sequestered RNAs | Functional Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stem Cell Differentiation | Sequester RNAs from preceding developmental stage [27] | Pluripotency factors, Germ cell determinants [27] [30] | Prevents reversion to earlier state; directs differentiation [27] |

| Primordial Germ Cell Formation | Storage of repressed RNAs encoding germline specifiers [27] | Key germ cell fate determinants [27] | Enables proper germline development when released [27] |

| Acute Myeloid Leukemia | Hyper-assembly sequesters tumor suppressor mRNAs [31] | Potent tumor suppressors [31] | Sustains leukemic state; disruption induces differentiation [31] |

| Cellular Stress Response | Dynamic reshuffling of transcriptome during stress [25] | Poorly translated mRNAs; shifts to stress-responsive transcripts [25] | Promotes cell survival under stress conditions [25] |

| Totipotency Acquisition | Release of specific RNAs drives transition to totipotent state [27] | RNAs characteristic of earlier developmental potential [27] | Enables formation of totipotent-like cells [27] |

The evidence across these systems demonstrates that P-bodies function as decision-making hubs in cell fate determination. In stem cells, they prevent translation of RNAs characteristic of earlier developmental stages, thereby "locking in" cell identity during differentiation [27]. In cancer, this mechanism is co-opted to suppress differentiation and maintain progenitor states, highlighting the therapeutic potential of modulating P-body assembly [31].

Regulatory Mechanisms Controlling RNA Sequestration in P-Bodies

Multiple molecular pathways regulate the sorting and retention of specific mRNAs in P-bodies, forming an integrated control system for post-transcriptional gene regulation.

microRNA-Directed Targeting

microRNAs play a crucial role in directing specific transcripts to P-bodies. Research indicates that noncoding RNAs called microRNAs help drive RNA sequestration into P-bodies [27]. This process involves AGO2 and other components of the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC), which recognize specific mRNA sequences and facilitate their localization to P-bodies. Experimentally, perturbing AGO2 function profoundly reshapes P-body contents, demonstrating its essential role in determining which RNAs are sequestered [30].

Translational Status as a Determinant

The translation efficiency of mRNAs strongly correlates with their P-body localization. Genome-wide studies show that poorly translated mRNAs are significantly enriched in P-bodies under non-stress conditions [25] [28]. This relationship is maintained during stress, though the specific transcriptome composition shifts dramatically. During arsenite stress, when translation is globally repressed, the P-body transcriptome becomes similar to the stress granule transcriptome, suggesting that translation status is a primary targeting mechanism [25].

Sequence Features and polyA Tail Length

Specific sequence characteristics influence mRNA partitioning to P-bodies. Research reveals that P-body-enriched mRNAs have significantly shorter polyA tails compared to cytoplasmic mRNAs [28]. Additionally, perturbing polyadenylation site usage reshapes P-body composition, indicating an active role for polyA tail length in determining RNA sequestration [30]. This provides a mechanistic link between alternative polyadenylation and cell fate control through P-body localization.

Diagram 2: Regulatory mechanisms controlling RNA sequestration in P-bodies.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Methods

This section catalogues key experimental tools and methodologies essential for investigating P-body functions in cell fate decisions.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Methods for P-body Studies

| Reagent/Method | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| GFP-LSM14A | Marker for P-body visualization and purification [28] | P-body-seq; live-cell imaging of P-body dynamics [28] |

| DDX6 Knockout | Disrupts P-body assembly [28] | Testing functional consequences of P-body loss [28] |

| AGO2 Perturbation | Alters microRNA-directed RNA targeting [30] | Reshaping P-body RNA content; testing microRNA dependence [30] |

| Arsenite Treatment | Induces stress granule formation and global translation repression [25] | Studying stress-induced granule remodeling [25] |

| P-body-seq | Comprehensive profiling of P-body transcriptomes [28] | Identifying cell type-specific sequestered RNAs [27] [28] |

| Orthologous Marker Gene Groups | Computational cell type identification [29] | Comparing cell identities across species [29] |

| Immunopurification | Specific isolation of RNP granules [25] | High-specificity transcriptome analysis [25] |

These tools enable researchers to manipulate P-body assembly, analyze their contents, and determine their functional roles. The combination of genetic perturbations (e.g., DDX6 knockout) with advanced sequencing methods (e.g., P-body-seq) has been particularly powerful in establishing causal relationships between P-body composition and cell fate outcomes [28].

The emerging understanding of P-bodies as regulators of cell fate decisions has significant implications across biological disciplines. In regenerative medicine, the ability to direct stem cell differentiation by manipulating P-body assembly or microRNA activity offers new approaches for generating clinically relevant cell types [27]. In cancer biology, the discovery that P-bodies maintain myeloid leukemia by sequestering tumor suppressor mRNAs reveals new therapeutic vulnerabilities [31].

Future research directions should focus on developing more precise tools for manipulating specific RNA sequestration events, understanding the dynamics of RNA release from P-bodies, and exploring the therapeutic potential of modulating P-body assembly in disease contexts. As our knowledge of these structures grows, they may represent promising targets for controlling cell identity in both developmental and pathological contexts.

Cellular identity encompasses the unique structural, functional, and molecular characteristics that define a specific cell type and its biological competence. In the context of biopreservation, maintaining this identity is paramount—the ultimate goal is not merely to ensure post-thaw survival but to preserve the intricate architecture, signaling pathways, and developmental potential that distinguish functional cells and tissues. The cryopreservation method selected profoundly influences how successfully this identity is conserved through the rigorous thermodynamic stresses of cooling, storage, and rewarming [32].

Slow freezing and vitrification represent two fundamentally different approaches to stabilizing biological specimens at cryogenic temperatures. Slow freezing involves controlled, gradual cooling that promotes extracellular ice formation and consequent cellular dehydration, while vitrification uses ultra-rapid cooling and high cryoprotectant concentrations to solidify water into a non-crystalline, glass-like state [32] [33]. Both techniques aim to mitigate the lethal damage associated with ice crystal formation, but they impose distinct stresses on cellular systems—from osmotic shock and solute effects in slow freezing to cryoprotectant toxicity and devitrification risks in vitrification [32]. This comprehensive analysis examines how these competing methods impact the preservation of cellular identity across diverse mammalian biospecimens, drawing upon comparative experimental data to inform method selection for research and clinical applications.

Fundamental Principles and Technological Approaches

Slow Freezing: Equilibrium Cryopreservation

The slow freezing process follows a carefully controlled thermodynamic path where biospecimens are cooled at precisely determined rates, typically ranging from -0.3°C/min to -2°C/min [34] [35]. This gradual cooling promotes extracellular ice formation, which increases the solute concentration in the unfrozen fraction and establishes an osmotic gradient that draws water out of cells. The resulting cellular dehydration minimizes intracellular ice formation, which is almost universally lethal to cells [32]. The process requires a programmable biological freezer to control cooling rates and incorporates a "seeding" step where ice nucleation is manually induced at approximately -6°C to -7°C to control the freezing process [34] [36].

The success of slow freezing hinges on optimizing cooling rates for specific cell types—too slow causes excessive dehydration and solute damage, while too rapid permits deadly intracellular ice crystallization [32]. Cryoprotective agents (CPAs) like dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), ethylene glycol (EG), and 1,2-propanediol (PrOH) are employed at relatively low concentrations (typically 1.0-1.5 M) to protect cells during this process [36] [32]. These permeating CPAs penetrate cells and replace water, while non-permeating solutes like sucrose (0.1-0.3 M) create extracellular osmotic gradients that facilitate controlled dehydration [34] [37].

Vitrification: Non-Equilibrium Cryopreservation

Vitrification represents a radical departure from equilibrium-based slow freezing. This technique employs ultra-rapid cooling rates (up to -20,000°C/min) combined with high CPA concentrations (up to 6-8 M) to achieve a direct transition from liquid to a glass-like amorphous solid without ice crystal formation [32] [33]. The extremely high cooling viscosity prevents water molecules from reorganizing into crystalline structures, effectively "suspending" the cellular contents in their native state [32].

The method's success depends on several critical factors: high cooling/warming rates, high CPA concentrations, and minimal sample volumes [32] [33]. To mitigate CPA toxicity, practitioners often use compound mixtures (e.g., DMSO with EG or PrOH) at reduced individual concentrations and employ a multi-step loading procedure where cells are exposed to increasing CPA concentrations [32] [35]. Technologically, vitrification utilizes specialized devices like Cryotops, Cryoloops, or microvolumetric straws to achieve the high surface-to-volume ratios necessary for rapid heat transfer [36] [32].

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of Cryopreservation Methods

| Parameter | Slow Freezing | Vitrification |

|---|---|---|

| Cooling Rate | Slow (0.3-2°C/min) | Ultra-rapid (up to 20,000°C/min) |

| CPA Concentration | Low (1.0-1.5 M) | High (up to 6-8 M) |

| Physical Principle | Equilibrium freezing | Non-equilibrium vitrification |

| Ice Formation | Extracellular only | None (in ideal conditions) |

| Primary Equipment | Programmable freezer | Vitrification devices, liquid nitrogen |

| Sample Volume | Larger volumes possible | Minimal volumes required |

| Critical Risks | Intracellular ice, solute effects | CPA toxicity, devitrification |

Comparative Experimental Data Across Biospecimens

Oocyte Cryopreservation Outcomes

Oocyte cryopreservation presents particular challenges due to the cell's large size, high water content, and sensitivity to spindle apparatus alterations. Comparative data reveals significant differences in outcomes between preservation methods. A 2025 retrospective evaluation of oocyte thawing/warming cycles demonstrated that a modified rehydration method for slow-frozen oocytes achieved survival rates of 89.8%, comparable to the 89.7% survival rate for vitrified oocytes, both significantly higher than the 65.1% survival with traditional slow-freezing rehydration [34]. Clinical pregnancy rates followed similar patterns, with the modified slow-freezing approach achieving 33.8% compared to 30.1% for vitrification [34].

The meiotic spindle apparatus—critical for chromosomal segregation and developmental competence—shows distinctive recovery patterns post-thaw. Research indicates that while spindle recovery is faster after vitrification, after 3 hours of incubation, spindle recuperation becomes similar between vitrification and slow freezing [33]. This recovery timeline influences fertilization scheduling, with intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) typically performed at 3 hours post-thaw for slow-frozen oocytes and 2 hours for vitrified oocytes to align with spindle restoration while minimizing oocyte aging [33].

Embryo and Ovarian Tissue Preservation

Comparative effectiveness extends to embryonic development and tissue-level preservation. A study of human cleavage-stage embryos demonstrated markedly different outcomes: vitrification achieved 96.9% survival with 91.8% displaying excellent morphology (all blastomeres intact), while slow freezing yielded 82.8% survival with only 56.2% showing excellent morphology [36]. These cellular-level differences translated to clinical outcomes, with vitrification producing higher clinical pregnancy (40.5% vs. 21.4%) and implantation rates (16.6% vs. 6.8%) [36].

In ovarian tissue cryopreservation, a 2024 transplantation study revealed nuanced differences. While vitrification generally outperformed slow freezing, particularly in preserving follicular morphology and minimizing stromal cell apoptosis, slow freezing demonstrated advantages in revascularization potential post-transplantation as indicated by CD31 expression [35]. Hormone production restoration—a critical indicator of functional tissue identity—showed significantly higher estradiol levels in vitrification groups at 6 weeks post-transplantation [35].

Table 2: Comparative Performance Across Biospecimen Types

| Biospecimen | Outcome Measure | Slow Freezing | Vitrification |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oocytes | Survival Rate | 75% (65.1-89.8% with modification) [34] [33] | 84-99% [33] |

| Oocytes | Clinical Pregnancy Rate | 23.5-33.8% [34] | 30.1% [34] |

| Cleavage-Stage Embryos | Survival Rate | 82.8% [36] | 96.9% [36] |

| Cleavage-Stage Embryos | Excellent Morphology | 56.2% [36] | 91.8% [36] |

| Ovarian Tissue | Normal Follicles (6 weeks) | Lower proportion [35] | Higher proportion [35] |

| Ovarian Tissue | Stromal Cell Apoptosis | Higher at 4 weeks [35] | Lower at 4 weeks [35] |

Impact on Cellular Identity and Functional Integrity

Structural and Molecular Identity Preservation

Cellular identity depends fundamentally on structural integrity, particularly for specialized organelles and molecular complexes. The meiotic spindle apparatus in oocytes exemplifies this vulnerability—its microtubule arrays are exceptionally sensitive to thermal changes and readily depolymerize during cooling [33]. While both methods cause spindle disassembly, the recovery trajectory differs. Vitrification's rapid transition through dangerous temperature zones appears to cause less sustained damage, facilitating faster spindle repolymerization [33]. However, the high CPA concentrations required for vitrification may potentially affect membrane composition and protein function differently than the dehydration stresses of slow freezing.

At the tissue level, ovarian tissue transplantation models reveal method-specific patterns of damage. Slow freezing appears to cause more significant stromal cell apoptosis at early post-transplantation time points (4 weeks), while vitrification better preserves stromal integrity [35]. Conversely, slow-frozen tissues demonstrate enhanced revascularization potential, suggesting better preservation of endothelial cell function or extracellular matrix components critical for angiogenesis [35]. These findings highlight the complex tradeoffs in preserving different cellular components within heterogeneous tissues.

Functional Competence and Developmental Potential

Beyond structural preservation, functional competence represents the ultimate validation of identity maintenance. For oocytes and embryos, developmental competence—the ability to complete fertilization, undergo cleavage, reach blastocyst stage, and establish viable pregnancies—provides the most clinically relevant functional assessment. The comparable clinical pregnancy rates between optimized slow-freezing protocols and vitrification (33.8% vs. 30.1%) suggest that when properly executed, both methods can effectively preserve oocyte developmental potential [34].

Parthenogenetic activation studies provide additional insights into functional preservation. Slow-frozen oocytes subjected to modified rehydration protocols showed similar activation (76.0% vs. 64.6%) and blastocyst development rates (15.2% vs. 9.4%) compared to vitrified oocytes, indicating comparable retention of cytoplasmic factors necessary for embryonic development [34]. For ovarian tissue, the restoration of endocrine function—demonstrated by resumption of estrous cycles and estradiol production in transplantation models—confirms the preservation of functional identity critical for fertility preservation [35].

Experimental Protocols and Methodological Details

Representative Slow Freezing Protocol for Oocytes

The slow freezing protocol with modified rehydration that achieved outcomes comparable to vitrification involves specific technical steps [34]:

Pre-freezing Preparation: Oocytes are incubated in base solution for 5-10 minutes at room temperature, then transferred to freezing solution containing 1.5 M PrOH and 0.3 M sucrose for 15 minutes total incubation.

Loading and Cooling: 1-5 oocytes are loaded into straws and placed in a programmable freezer. Cooling begins at -2°C/min from 20°C to -6.5°C, followed by a 5-minute soak before manual seeding.

Controlled Freezing: After 10 minutes holding at -6.5°C, straws are cooled at -0.3°C/min to -30°C, then rapidly cooled at -50°C/min to -150°C before transfer to liquid nitrogen.

Modified Thawing/Rehydration: Straws are warmed in air for 30 seconds followed by a 30°C water bath. Cryoprotectant removal employs a three-step sucrose system (1.0 M, 0.5 M, 0.125 M) to reduce cell swelling, mimicking approaches used for vitrified specimens [34].

Representative Vitrification Protocol for Oocytes

The vitrification protocol for oocytes that yielded high survival and pregnancy rates typically involves [33]:

CPA Loading: Oocytes are equilibrated in lower concentration CPA solutions (e.g., 7.5% ethylene glycol + 7.5% DMSO) for 10-15 minutes, then transferred to vitrification solution (e.g., 15% ethylene glycol + 15% DMSO + sucrose) for less than 60 seconds.

Loading and Cooling: Minimal volumes (<1μL) containing oocytes are loaded onto vitrification devices and immediately plunged into liquid nitrogen.

Warming and CPA Dilution: Rapid warming in pre-warmed sucrose solutions (e.g., 37°C) is followed by stepwise dilution of CPAs in decreasing sucrose concentrations (1.0 M, 0.5 M, 0.25 M, 0.125 M) to prevent osmotic shock.

Diagram 1: Comparative Workflow of Cryopreservation Methods highlighting critical stress factors that impact cellular identity.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Cryopreservation Research

| Reagent/Material | Function | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Permeating CPAs (DMSO, ethylene glycol, 1,2-propanediol) | Penetrate cells, lower freezing point, reduce ice formation | Standard component of both slow freezing and vitrification solutions [34] [35] |

| Non-permeating CPAs (Sucrose, trehalose) | Create osmotic gradient, promote controlled dehydration | Critical for slow freezing (0.2-0.3M) and vitrification warming solutions [34] [37] |

| Programmable Freezer | Controlled rate cooling | Essential for slow freezing protocols [34] [36] |

| Vitrification Devices (Cryotop, Cryoloop, straws) | Minimal volume containment, rapid heat transfer | Required for achieving ultra-rapid cooling rates [32] |

| Liquid Nitrogen | Cryogenic storage medium | Long-term storage at -196°C for both methods [34] [32] |

| Stereo Microscope with Warm Stage | Oocyte/embryo handling | Maintaining physiological temperature during processing [34] |

| Culture Media (M199, MEM, L-15 with supplements) | Maintain viability during processing | Base solutions for CPA dilutions, post-thaw culture [34] [35] |

The choice between slow freezing and vitrification for preserving cellular identity involves careful consideration of biospecimen characteristics, available resources, and intended applications. Vitrification generally demonstrates superior performance for sensitive individual structures like oocytes and cleavage-stage embryos, particularly in preserving structural elements like the meiotic spindle and delivering higher survival rates [36] [33]. However, optimized slow-freezing protocols with modified rehydration approaches can achieve comparable outcomes for oocytes while potentially offering advantages for tissue-level revascularization [34] [35].

The evolving landscape of biopreservation research continues to address the limitations of both methods. Advances in CPA toxicity reduction through cocktail formulations, improved vitrification device design for enhanced heat transfer, and universal warming protocols that simplify post-preservation processing represent promising directions [32] [38]. Particularly noteworthy is the development of modified rehydration approaches for slow-frozen specimens that narrow the performance gap with vitrification, potentially offering new value for the many slow-frozen specimens currently in storage [34]. As these technologies mature, the strategic selection of cryopreservation methods will increasingly depend on specific application requirements rather than presumed universal superiority of either approach, with cellular identity preservation serving as the fundamental metric for success.

A Methodologist's Toolkit: Computational and Experimental Approaches for Identity Assessment

The hierarchical organization of cells in multicellular life, from the totipotent fertilized egg to fully differentiated somatic cells, represents a fundamental principle of developmental biology. A cell's developmental potential, or potency—defined as its ability to differentiate into specialized cell types—has remained challenging to quantify molecularly despite advances in single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) technologies. Computational methods for reconstructing developmental hierarchies from scRNA-seq data have emerged as essential tools for developmental biology, regenerative medicine, and cancer research. Within this context, a new generation of deep learning frameworks has recently transformed our approach to potency prediction, with CytoTRACE 2 representing a significant advancement over previous methodologies.

The evaluation of cellular identity preservation across computational methods represents a critical thesis in single-cell genomics research. As methods attempt to reconstruct developmental trajectories, their ability to faithfully preserve and interpret genuine biological signals versus technical artifacts remains paramount. This comparison guide objectively benchmarks CytoTRACE 2 against established alternatives, providing supporting experimental data to inform researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals in selecting appropriate tools for their specific research applications.

Evolution of Computational Approaches

The original CytoTRACE 1 method, introduced in 2020, operated on a relatively simple biological principle: the number of genes expressed per cell correlates with its developmental maturity [39]. While effective in many contexts, this approach provided predictions that were dataset-specific, making cross-dataset comparisons challenging [40]. Other methods for developmental hierarchy inference have included RNA velocity, Monocle, CellRank, and various trajectory inference algorithms, each with distinct theoretical foundations and limitations [40].

The recently introduced CytoTRACE 2 represents a paradigm shift from its predecessor through its implementation of an interpretable deep learning framework [40] [39]. This approach moves beyond simple gene counting to learn complex multivariate gene expression programs that define potency states. The model was trained on an extensive atlas of human and mouse scRNA-seq datasets with experimentally validated potency levels, spanning 33 datasets, nine platforms, 406,058 cells, and 125 standardized cell phenotypes [40]. These phenotypes were grouped into six broad potency categories (totipotent, pluripotent, multipotent, oligopotent, unipotent, and differentiated) and further subdivided into 24 granular levels based on known developmental hierarchies [40].

Core Architectural Innovation: Gene Set Binary Networks

The fundamental innovation in CytoTRACE 2 is its gene set binary network (GSBN) architecture, which assigns binary weights (0 or 1) to genes, thereby identifying highly discriminative gene sets that define each potency category [40]. Inspired by binarized neural networks, this design offers superior interpretability compared to conventional deep learning architectures, as the informative genes driving model predictions can be easily extracted [40]. The framework provides two key outputs for each single-cell transcriptome: (1) the potency category with maximum likelihood and (2) a continuous 'potency score' ranging from 1 (totipotent) to 0 (differentiated) [40].

Table 1: Key Features of CytoTRACE 2 Architecture

| Feature | Description | Advantage |

|---|---|---|

| GSBN Design | Uses binary weights (0 or 1) for genes | Enhanced interpretability of driving features |

| Multiple Gene Sets | Learns multiple discriminative gene sets per potency category | Captures heterogeneity within potency states |

| Absolute Scaling | Provides continuous potency scores from 1 (totipotent) to 0 (differentiated) | Enables cross-dataset comparisons |

| Markov Diffusion | Smoothes individual potency scores using nearest neighbor approach | Improves robustness to technical noise |

| Batch Suppression | Incorporates multiple mechanisms to suppress technical variation | Enhances biological signal detection |

To visualize the core workflow and architecture of CytoTRACE 2:

Quantitative Benchmarking: Performance Comparison Across Multiple Metrics

Experimental Design for Method Evaluation

The benchmarking of CytoTRACE 2 against alternative methods employed rigorous experimental protocols based on a compendium of ground truth datasets [40]. Performance evaluation assessed both the accuracy of potency predictions and the ordering of known developmental trajectories using two distinct definitions:

- Absolute Order: Compares predictions to known potency levels across diverse datasets

- Relative Order: Ranks cells within each dataset from least to most differentiated [40]

The agreement between known and predicted developmental orderings was quantified using weighted Kendall correlation to ensure balanced evaluation and minimize bias [40]. The testing framework extended to unseen data comprising 14 held-out datasets spanning nine tissue systems, seven platforms, and 93,535 evaluable cells to validate generalizability [40].

Comparative Performance Against Classification Methods

In comprehensive benchmarking across 33 datasets, CytoTRACE 2 outperformed eight state-of-the-art machine learning methods for cell potency classification, achieving a higher median multiclass F1 score and lower mean absolute error [40]. The method demonstrated robustness to differences in species, tissues, platforms, or phenotypes that were absent during training, indicating conserved potency-related biology across biological systems [40].

Table 2: Performance Comparison Across Developmental Hierarchy Inference Methods

| Method | Absolute Order Performance | Relative Order Performance | Cross-Dataset Comparability | Interpretability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CytoTRACE 2 | Highest weighted Kendall correlation | >60% higher correlation on average | Yes (absolute scale) | High (gene sets extractable) |

| CytoTRACE 1 | Limited | Moderate | No (dataset-specific) | Moderate |

| RNA Velocity | Not applicable | Variable | No | Low |

| Monocle | Not applicable | Moderate | No | Moderate |

| CellRank | Not applicable | Moderate | No | Low |

| SCENT | Limited | Low | Limited | Low |

Performance in Developmental Trajectory Reconstruction

For reconstructing relative orderings across 57 developmental systems, including data from Tabula Sapiens, CytoTRACE 2 demonstrated over 60% higher correlation with ground truth compared to eight developmental hierarchy inference methods [40]. The method also outperformed nearly 19,000 annotated gene sets and scVelo, a generalized RNA velocity model for predicting future cell states [40]. Notably, CytoTRACE 2 accurately captured the progressive decline in potency across 258 evaluable phenotypes during mouse development without requiring data integration or batch correction [40].

Experimental Protocols and Validation Frameworks

Training Dataset Curation and Model Development

The development of CytoTRACE 2 followed a structured experimental protocol beginning with extensive data curation. Researchers compiled a potency atlas from human and mouse scRNA-seq datasets with experimentally validated potency levels, ensuring robust ground truth for model training [40]. The training set included 93 cell phenotypes from 16 tissues and 13 studies, with remaining data reserved for performance evaluation [40]. Model hyperparameters were evaluated through cross-validation, with minimal performance variation observed across a wide range of values, leading to selection of stable hyperparameters for the final model [40].

To visualize the experimental workflow for model development and validation:

Biological Validation Using Functional Genomic Data

Beyond computational benchmarking, CytoTRACE 2 underwent rigorous biological validation using data from a large-scale CRISPR screen in which approximately 7,000 genes in multipotent mouse hematopoietic stem cells were individually knocked out and assessed for developmental consequences in vivo [40]. Among the 5,757 genes overlapping CytoTRACE 2 features, the top 100 positive multipotency markers were enriched for genes whose knockout promotes differentiation, while the top 100 negative markers were enriched for genes whose knockout inhibits differentiation [40]. This functional validation confirmed that the learned molecular representations correspond to biologically meaningful potency regulators.

Signaling Pathways and Molecular Determinants of Potency

Interpretable Feature Selection for Biological Insights

A key advantage of CytoTRACE 2's GSBN design is its inherent interpretability, allowing researchers to explore the molecular programs driving potency predictions [40]. Analysis of top-ranking genes revealed conserved signatures across species, platforms, and developmental clades, identifying both positive and negative correlates of cell potency [40]. Core transcription factors known to regulate pluripotency, including Pou5f1 and Nanog, ranked within the top 0.2% of pluripotency genes, validating the method's ability to identify biologically relevant markers [40].

Pathway enrichment analysis of genes ranked by feature importance revealed cholesterol metabolism as a leading multipotency-associated pathway [40]. Within this pathway, three genes related to unsaturated fatty acid (UFA) synthesis (Fads1, Fads2, and Scd2) emerged as top-ranking markers that were consistently enriched in multipotent cells across 125 phenotypes in the potency atlas [40]. Experimental validation using quantitative PCR on mouse hematopoietic cells sorted into multipotent, oligopotent, and differentiated subsets confirmed these computational predictions [40].

To visualize the key molecular pathways identified through CytoTRACE 2 analysis:

Practical Implementation and Research Applications

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Computational Potency Prediction

| Resource | Function | Availability |

|---|---|---|

| CytoTRACE 2 Software | Predicts absolute developmental potential from scRNA-seq data | R/Python packages at https://github.com/digitalcytometry/cytotrace2 |

| Potency Atlas | Reference dataset with experimentally validated potency levels | Supplementary materials of original publication |

| Seurat Toolkit | Single-cell data preprocessing and analysis | Comprehensive R package |

| Scanpy | Single-cell data analysis in Python | Python package |

| CellChat | Cell-cell communication analysis from scRNA-seq data | R package |

| Monocle | Trajectory inference and differential expression analysis | R package |

Application Across Biological Contexts

CytoTRACE 2 has demonstrated utility across diverse biological contexts beyond normal development. In cancer research, the tool identified known leukemic stem cell signatures in acute myeloid leukemia and revealed multilineage potential in oligodendroglioma [40]. The method has also been applied to identify previously unknown stem cell populations, as when researchers used the original CytoTRACE to discover a novel intestinal stem cell population in mice [39]. These applications highlight the tool's potential for biomarker discovery and therapeutic target identification in disease contexts.

For drug development professionals, CytoTRACE 2 offers a more efficient approach to identifying gene targets for human cancers. Traditional approaches involve considerable guesswork, where scientists identify a few potentially interesting genes and test them in model systems. With CytoTRACE 2, researchers can directly analyze human data, identify cells with higher potency states, and pinpoint molecules important for maintaining these states, thereby narrowing the search space and enhancing the discovery of valuable drug targets [39].

The benchmarking data presented in this comparison guide demonstrates that CytoTRACE 2 represents a significant advancement in computational potency prediction. Its interpretable deep learning framework, absolute scaling from totipotent to differentiated states, and robust performance across diverse biological contexts position it as a valuable tool for researchers studying developmental hierarchies. The method's ability to preserve cellular identity across datasets and experimental conditions addresses a critical challenge in single-cell genomics.

For the research community, CytoTRACE 2 offers not just improved predictive accuracy but also biological interpretability through its gene set binary networks. The identification of molecular pathways like cholesterol metabolism in multipotency underscores how this tool can generate novel biological insights beyond trajectory reconstruction. As single-cell technologies continue to evolve, tools like CytoTRACE 2 will play an increasingly important role in transforming raw genomic data into meaningful biological understanding with applications across developmental biology, cancer research, and therapeutic development.

Single-Cell Resolution Communication Analysis with Scriabin

Inference of cell-cell communication (CCC) from single-cell RNA sequencing data is a powerful technique for uncovering intercellular communication pathways. Traditional methods perform this analysis at the level of the cell type or cluster, discarding single-cell-level information. Scriabin represents a breakthrough as a flexible and scalable framework for comparative analysis of cell-cell communication at true single-cell resolution without cell aggregation or downsampling [41] [42]. This approach is particularly significant within the broader context of evaluating cellular identity preservation across methods research, as it maintains the unique transcriptional identity of individual cells throughout the communication analysis process, thereby revealing communication networks that can be obscured by agglomerative methods [43].