Evaluating Stem Cell Potency: A Comprehensive Guide for Advanced Disease Modeling in 2025

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on evaluating the potency of stem cell-based disease models.

Evaluating Stem Cell Potency: A Comprehensive Guide for Advanced Disease Modeling in 2025

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on evaluating the potency of stem cell-based disease models. It covers the foundational principles of stem cell biology, from totipotency to unipotency, and explores advanced methodological applications including organoids, assembloids, and gene-edited models. The content addresses key challenges in standardization, maturation, and scalability, while offering frameworks for validation against traditional animal models. By synthesizing current best practices and emerging innovations, this resource aims to enhance the fidelity, reproducibility, and predictive power of stem cell models in translational research and therapeutic development.

Understanding Stem Cell Potency: From Totipotency to Lineage Restriction

Stem cells are foundational units in regenerative medicine and biological research, primarily defined by their potency—the capacity to differentiate into specialized cell types. This article provides a structured comparison of the potency hierarchy, from the broad differentiation potential of totipotent cells to the restricted fate of unipotent cells, framed within the context of their application in stem cell-based disease modeling and research.

The Spectrum of Cell Potency

Cell potency is a continuum that describes a cell's ability to differentiate into other cell types. The hierarchy is traditionally categorized based on the number and types of cells a stem cell can generate.

- Totipotent Stem Cells possess the highest differentiation potential. They can give rise to all the cell types in an organism, including both embryonic and extra-embryonic tissues (such as the placenta) [1] [2]. The only known indisputably totipotent cell is the zygote formed after fertilization, and the early blastomeres resulting from its initial divisions [3] [4].

- Pluripotent Stem Cells can differentiate into all cell types derived from any of the three embryonic germ layers—ectoderm, mesoderm, and endoderm—but they cannot generate extra-embryonic tissues [1] [5] [2]. This category includes Embryonic Stem Cells (ESCs), derived from the inner cell mass of the blastocyst, and Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells (iPSCs), which are adult somatic cells reprogrammed into a pluripotent state [3] [2].

- Multipotent Stem Cells have a more restricted potential, typically limited to differentiating into the cell types of a particular lineage or tissue [1] [4]. Examples include Hematopoietic Stem Cells (HSCs), which generate all blood cell types, and Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs), which can form bone, cartilage, and fat cells [3] [6].

- Unipotent Stem Cells have the most limited developmental potential. They can only produce a single cell type but retain the capacity for self-renewal, which distinguishes them from non-stem cells [5]. An example is a precursor cell that can only differentiate into epidermal cells [5].

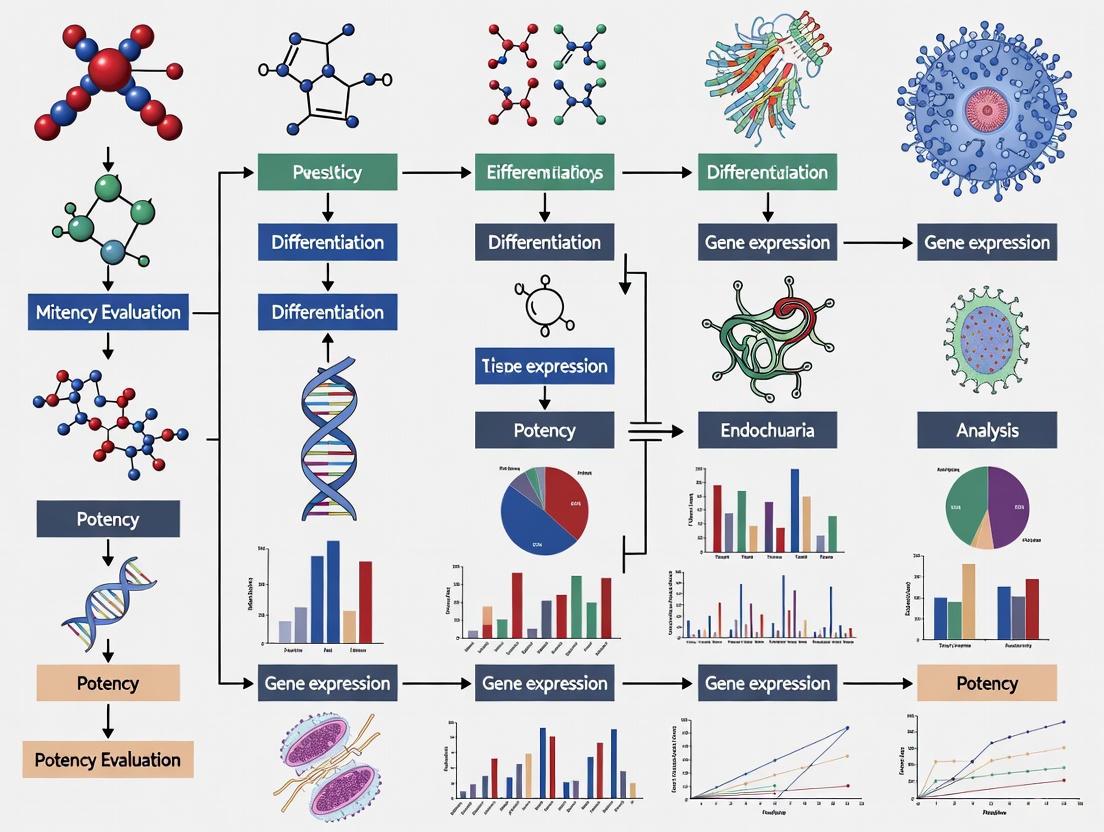

The following diagram illustrates the developmental hierarchy and the narrowing potential from totipotency to unipotency.

Comparative Analysis of Stem Cell Potency

The following table summarizes the key characteristics of the major stem cell types across the potency spectrum, highlighting their origins, differentiation potential, and research applications.

| Feature | Totipotent | Pluripotent | Multipotent |

|---|---|---|---|

| Definition | Can generate all embryonic & extra-embryonic cell types [1] [2] | Can generate all cells from the three germ layers [1] [5] | Can generate a limited range of cell types within a lineage [1] [4] |

| Origin/Source | Zygote, early blastomeres (e.g., up to morula stage) [3] [2] | Inner Cell Mass (ICM) of the blastocyst (ESCs) [3]; Reprogrammed somatic cells (iPSCs) [2] | Various adult tissues (e.g., bone marrow, adipose tissue) [1] [6] |

| Differentiation Potential | Highest; can form a complete organism [3] | High; can form any fetal or adult cell type [5] | Limited; restricted to specific tissue lineages [1] |

| Key Markers/Features | Unique molecular features (e.g., Zscan4, Eomes) [3] | Expression of core pluripotency factors (OCT4, SOX2, NANOG) [5] [3] | Expression of lineage-specific genes [1] |

| Research & Therapeutic Utility | Limited due to ethical considerations and rarity; used to study early development [3] | High; disease modeling, drug screening, developmental biology [3] [6] | High; regenerative medicine (e.g., HSC transplants, MSC therapies), fewer ethical issues [3] [6] |

Experimental Protocols for Assessing Pluripotency

For a stem cell to be classified as pluripotent in a research setting, its functional capacity must be rigorously demonstrated. The gold standard assays for this purpose are in vivo tests.

Teratoma Formation Assay

This is a widely accepted functional test for pluripotency, required for both ESCs and iPSCs [2].

- Objective: To confirm the ability of test cells to differentiate into derivatives of all three germ layers in vivo.

- Methodology:

- Cell Preparation: A suspension of the candidate pluripotent stem cells is prepared.

- Transplantation: The cells are injected into an immunodeficient mouse model. Common injection sites include the kidney capsule, intramuscular, or subcutaneous spaces [2].

- Tumor Monitoring: The injection site is monitored for the formation of a teratoma, a benign tumor.

- Histological Analysis: After several weeks, the teratoma is excised, sectioned, and stained. Proof of pluripotency is the presence of well-differentiated tissues representing:

- Considerations: The assay is costly, operationally burdensome, and requires careful standardization of factors like injection site and cell number. Histological analysis is also subject to interpretation errors [2].

Chimera Formation Assay

This assay, primarily used in mouse models, provides even stronger evidence of developmental potential [5].

- Objective: To test the ability of stem cells to integrate and contribute to all tissues of a developing embryo.

- Methodology:

- Cell Introduction: Pluripotent stem cells are injected into a host mouse blastocyst.

- Embryo Transfer: The injected blastocyst is surgically transferred into a pseudopregnant female mouse.

- Analysis of Offspring: The resulting offspring are chimeras—composed of cells from both the host embryo and the injected stem cells.

- Assessment: Contribution of the test stem cells to various tissues and germlines is assessed, often using fluorescent or genetic markers. The ability to contribute to all three germ layers in a developing organism confirms pluripotency [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents for Pluripotency Research

Successful stem cell research relies on a suite of specialized reagents and tools to maintain, characterize, and manipulate pluripotent cells.

| Research Reagent/Tool | Function in Pluripotency Research |

|---|---|

| Pluripotency Transcription Factors (OCT4, SOX2, NANOG) | Core markers expressed in pluripotent cells; essential for maintaining the undifferentiated state. Often detected via immunostaining or PCR for cell characterization [5] [3]. |

| Yamanaka Factors (OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, c-MYC) | A set of transcription factors used for the forced expression that reprograms somatic cells into induced Pluripotent Stem Cells (iPSCs) [3] [2]. |

| Basic Fibroblast Growth Factor (bFGF) | A critical cytokine added to culture media to support the self-renewal and maintenance of human pluripotent stem cells [4]. |

| Leukemia Inhibitory Factor (LIF) | A cytokine used to maintain the pluripotency of mouse embryonic stem cells by activating the JAK-STAT3 signaling pathway [4]. |

| Microarray/Gene Expression Profiling | A tool used to assess the global gene expression profile of stem cells. It can distinguish different states of pluripotency and confirm the expression of pluripotency-associated genes while silencing lineage-specific genes [7] [5]. |

Potency in the Context of Cellular Therapies and Disease Modeling

In the translational and regulatory landscape, potency takes on a precise definition: "the specific ability or capacity of the product... to effect a given result" [8]. For cellular therapies, potency is a critical quality attribute that must be measured through potency assays—quantitative tests of a product's biological activity linked to its intended mechanism of action [7] [9].

- Challenges in Potency Testing: Developing these assays for cell therapies is complex due to the living nature of the product, lot-to-lot variability, limited product quantity for testing, and often an incomplete understanding of the product's precise mechanism of action [7] [9].

- Role of Pluripotent Cells: iPSCs, in particular, are powerful for disease modeling. Researchers can generate patient-specific iPSCs, differentiate them into disease-relevant cell types (e.g., dopaminergic neurons for Parkinson's disease), and use these in vitro models to study disease mechanisms and screen potential therapeutics [6]. In these models, the "potency" of the differentiation process to generate the target cell type must be carefully evaluated.

Understanding the fundamental hierarchy of stem cell potency is essential for selecting the appropriate cell type for specific research applications, from basic developmental biology to the development of next-generation regenerative medicines.

The pursuit of physiologically relevant human disease models represents a central challenge in biomedical research. Traditional animal models, while invaluable, often fail to recapitulate key aspects of human pathophysiology due to species-specific differences in genetics, morphology, and molecular pathways [10]. Stem cell-based models have emerged as a transformative platform that overcomes these limitations by providing unrestricted access to authentic human cells and tissues [11]. This comparison guide objectively analyzes the three principal stem cell types—induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), embryonic stem cells (ESCs), and mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs)—for disease modeling applications. Framed within the broader context of potency evaluation in stem cell research, this guide examines the differential capacities of these cells to self-renew and differentiate into disease-relevant cell types, providing researchers with a strategic framework for selecting the optimal cellular system for specific disease modeling objectives.

Comparative Analysis of Key Stem Cell Types

The following section provides a detailed comparison of the defining characteristics, advantages, and limitations of iPSCs, ESCs, and MSCs, with a specific focus on their utility in disease modeling.

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of Key Stem Cell Types for Disease Modeling

| Feature | Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells (iPSCs) | Embryonic Stem Cells (ESCs) | Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Origin | Reprogrammed adult somatic cells (e.g., skin fibroblasts, blood cells) [12] | Inner Cell Mass (ICM) of a blastocyst-stage embryo [12] | Various adult tissues (e.g., bone marrow, adipose tissue, umbilical cord) [13] [14] |

| Potency | Pluripotent [12] | Pluripotent [12] | Multipotent (primarily mesodermal lineage) [12] [14] |

| Self-Renewal Capacity | Unlimited in culture [13] | Unlimited in culture [13] | Limited; senesces in prolonged in vitro culture [13] [14] |

| Key Advantages | Patient-specific; avoids embryo destruction; models genetic diseases [15] [10] | Gold standard for pluripotency; genetically normal (when derived from healthy embryos) [15] | Immunomodulatory properties; clinically relevant secretome; lower tumorigenic risk [12] [14] |

| Key Limitations | Epigenetic memory; reprogramming-induced mutations; variable differentiation efficiency [15] | Ethical controversies; limited genetic diversity; immunoincompatibility with patients [15] [12] | Tissue-source and donor-age dependent heterogeneity; limited proliferative capacity [13] [14] |

Table 2: Disease Modeling Applications and Model Fidelity

| Aspect | iPSCs | ESCs | MSCs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ideal for Modeling | Monogenic diseases, complex polygenic disorders, patient-specific drug responses [15] [11] | Early human development, monogenic diseases (via genetic engineering), "proof-of-concept" models [15] | Connective tissue disorders, immune-mediated diseases, age-related pathologies [13] [14] |

| Representative Diseases Modeled | Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis, Spinal Muscular Atrophy, Long QT syndrome [15] | Lesch-Nyhan syndrome, Fragile X syndrome (via PGD-derived ESCs) [15] | Osteoarthritis, Graft-versus-Host Disease, spinocerebellar ataxia [11] [14] |

| Physiological Relevance | High for postnatal and adult-onset diseases; can capture patient's genetic background [15] [10] | High for early developmental processes; may not fully mimic postnatal disease physiology [15] | Context-dependent; influenced by donor age and tissue source, which can be a confounder [13] [14] |

Experimental Protocols for Model Generation and Validation

Protocol 1: Generating an iPSC-Based Neuronal Disease Model

This protocol outlines the key steps for modeling a neurological disorder, such as Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS), using patient-specific iPSCs [15] [11].

- Somatic Cell Reprogramming: Obtain dermal fibroblasts or peripheral blood mononuclear cells from a patient and a genetically matched healthy control. Reprogram the cells using a non-integrating Sendai virus or episomal vectors expressing the Yamanaka factors (OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, c-MYC) to generate iPSCs [12] [16].

- iPSC Characterization: Confirm pluripotency by:

- Immunocytochemistry: Detection of pluripotency markers (OCT4, NANOG, SSEA-4) [10].

- In Vitro Differentiation: Formation of embryoid bodies containing cells of all three germ layers.

- Karyotyping: Ensure genomic integrity after reprogramming.

- Neuronal Differentiation: Direct iPSCs toward motor neurons using a standardized, multi-step protocol. This typically involves:

- Dual SMAD inhibition to induce neural induction.

- Treatment with retinoic acid and a Sonic hedgehog (Shh) agonist to pattern the cells toward a spinal motor neuron fate.

- Culture for extended periods (60-100 days) to achieve mature electrophysiological properties [11].

- Phenotypic Analysis: Compare patient and control iPSC-derived motor neurons for disease-specific phenotypes, which may include:

- Protein aggregation (e.g., TDP-43).

- Neurite retraction and reduced survival.

- Electrophysiological deficits.

- Gene Editing for Isogenic Controls (Critical for Potency Evaluation): Use CRISPR-Cas9 to correct the disease-causing mutation in the patient iPSC line. This generates a genetically identical, healthy control line, ensuring that any observed phenotypic differences are solely due to the specific mutation and not background genetic variation [11].

Protocol 2: Establishing an MSC-Based Model for Osteoarthritis

This protocol details the use of primary MSCs to model a connective tissue disease like osteoarthritis [14].

- MSC Isolation and Expansion:

- Source: Isolate MSCs from bone marrow aspirate or adipose tissue (liposuction) from donors with osteoarthritis and healthy controls.

- Isolation Method: Use the explant culture method (minimizes manipulation, yields homogeneous population) or enzymatic digestion (e.g., with collagenase) [12].

- Expansion: Culture cells in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) supplemented with fetal bovine serum (FBS) and fibroblast growth factor (FGF)-2.

- MSC Characterization: Verify identity using the International Society for Cell & Gene Therapy (ISCT) criteria:

- Surface Marker Profiling: Confirm positive expression of CD105, CD73, CD90 (>95%) and negative expression of CD45, CD34, CD14/CD11b, CD79α/CD19 (<2%) via flow cytometry [12] [14].

- Trilineage Differentiation Assay: Differentiate MSCs into osteocytes, adipocytes, and chondrocytes in vitro to confirm multipotency [12].

- Disease Phenotype Induction and Analysis:

- Chondrogenic Differentiation: Pellet the MSCs and culture in a chondrogenic medium containing TGF-β3 to form cartilage-like tissue.

- Phenotypic Analysis: Compare the chondrogenic capacity and cartilage matrix composition (e.g., collagen type II, proteoglycans) between MSCs from osteoarthritic and healthy donors. Assess the production of inflammatory mediators in the culture supernatant.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful disease modeling requires a suite of well-defined reagents and materials. The following table details essential solutions for working with iPSCs, ESCs, and MSCs.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Stem Cell Disease Modeling

| Reagent / Material | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Yamanaka Factor Cocktail | Set of transcription factors (OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, c-MYC) for somatic cell reprogramming to pluripotency [12]. | Use non-integrating delivery methods (e.g., Sendai virus, episomal vectors) for clinical-grade iPSCs. |

| CRISPR-Cas9 System | RNA-guided gene editing tool for generating isogenic control lines or introducing disease-associated mutations [11] [16]. | Critical for establishing causality between genotype and phenotype; requires careful off-target effect analysis. |

| Small Molecule Inhibitors (e.g., SB431542) | Inhibits TGF-β/Activin A signaling; used for efficient neural induction and differentiation of iPSCs/ESCs into MSCs [12]. | Enables directed, monolayer differentiation without embryoid body formation, improving protocol reproducibility. |

| Cytokine & Growth Factor Cocktails | Direct lineage-specific differentiation (e.g., TGF-β3 for chondrogenesis; Retinoic Acid/Shh for motor neuron fate) [12] [14]. | Concentrations and timing are protocol-critical; use GMP-grade factors for preclinical and clinical work. |

| Defined Culture Matrices (e.g., Matrigel, Laminin-521) | Provides a surrogate extracellular matrix for pluripotent stem cell attachment and growth in xeno-free conditions. | Reduces batch-to-batch variability and improves experimental reproducibility compared to mouse feeder layers. |

| Flow Cytometry Antibody Panels | Characterization of surface markers (CD105, CD73, CD90 for MSCs; SSEA-4, TRA-1-60 for PSCs) to assess cell population purity [12] [14]. | Essential for quality control and confirming the identity of both starting populations and differentiated cells. |

The choice between iPSCs, ESCs, and MSCs for disease modeling is not a matter of superiority but of strategic alignment with the specific research question. The following diagram illustrates the decision-making workflow for selecting the optimal stem cell type.

- iPSCs are unparalleled for modeling patient-specific, polygenic diseases and for personalized drug screening, despite challenges related to epigenetic memory and phenotypic variability [15] [10]. Their ability to be gene-edited to create isogenic controls remains a gold standard for establishing genotype-phenotype relationships [11].

- ESCs serve as a critical benchmark for pluripotency and are powerful tools for studying early human development and generating "proof-of-concept" disease models via genetic engineering, though their use is constrained by ethical considerations and limited genetic diversity [15].

- MSCs offer a more direct path for modeling connective tissue and immune-mediated diseases and are already widely used in clinical trials [14]. However, their utility in modeling can be confounded by donor-to-donor heterogeneity and limited expansion potential [13]. The emergence of induced MSCs (iMSCs) generated from iPSCs presents a promising solution, offering a more uniform and scalable source of MSCs with consistent potency [13].

The future of stem cell-based disease modeling lies in leveraging the unique strengths of each cell type, often in combination, and in the continued refinement of differentiation protocols and analytical methods to enhance the physiological relevance and reproducibility of these powerful models.

The Critical Link Between Pluripotency and Disease Model Fidelity

Pluripotency—the capacity of a stem cell to differentiate into any cell type of the body—is the foundational property that enables the creation of sophisticated human disease models in a laboratory setting. The fidelity of these models, meaning how accurately they recapitulate the molecular and phenotypic hallmarks of a human disease, is directly dependent on the quality and stability of the pluripotent stem cell (PSC) starting material. National and international initiatives are now establishing large repositories of human PSCs specifically for modeling disorders, underscoring their critical role in biomedical research [17]. These models, derived from either embryonic stem cells (ESCs) or induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), have been successfully developed for a wide spectrum of conditions, including monogenic, chromosomal, and complex disorders [17]. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding and controlling the factors that link pluripotency to model fidelity is paramount for producing reliable, reproducible data for mechanistic studies and drug screening campaigns.

Pluripotent Stem Cells as a Platform for Disease Modeling

The utility of PSCs in disease modeling stems from their dual capabilities of self-renewal and multilineage differentiation. This allows for the generation of a virtually unlimited supply of patient-specific cell types that are otherwise inaccessible, such as functional neurons or cardiomyocytes.

- Overcoming Animal Model Limitations: Experimental modeling of human disorders is essential for defining disease mechanisms and developing therapies. PSCs help overcome the significant limitations of animal models for certain human disorders, providing a more direct and often more relevant system for study [17].

- iPSC Technology: The groundbreaking development of iPSC technology, which involves reprogramming adult somatic cells (like fibroblasts or peripheral blood cells) back to a pluripotent state using defined factors, revolutionized the field [17] [18]. This enabled the creation of personalized disease models from virtually any patient.

- Disease-in-a-Dish: The core approach involves deriving patient-specific iPSCs, differentiating them into the cell type(s) affected by the disease (e.g., motor neurons for ALS), and then comparing their characteristics to control cells from healthy individuals. This "disease-in-a-dish" paradigm facilitates the study of cellular and molecular phenotypes and provides a platform for drug screening [17] [18].

Table 1: Applications of PSCs in Disease Modeling and Drug Discovery

| Application Area | Description | Example Disorders Modeled |

|---|---|---|

| Monogenic Disorders | Modeling diseases caused by a mutation in a single gene. | Fragile X syndrome, Lesch-Nyhan disease, sickle cell anemia [17] [18]. |

| Chromosomal Disorders | Studying conditions caused by large-scale chromosomal abnormalities. | Down syndrome, Turner's syndrome [17]. |

| Complex & Psychiatric Disorders | Investigating diseases with multifactorial genetic and environmental causes. | Schizophrenia, Alzheimer's disease, autism spectrum disorder [17]. |

| Drug Discovery & Screening | Using differentiated cells to identify and validate new therapeutic compounds. | Screens for 25+ neurological disorders; drugs identified are progressing to the clinic [17]. |

| Personalized Therapy | Using patient-specific iPSCs for disease modeling and autologous cell transplantation after genome editing. | Fanconi anemia, dyskeratosis congenita, Diamond-Blackfan anemia [18]. |

Methodological Framework: From Pluripotency to Disease Phenotypes

Establishing a high-fidelity disease model requires a rigorous and standardized workflow, from validating the initial pluripotent stem cells to thoroughly characterizing the resulting differentiated cell populations. The following diagram outlines the key stages and critical quality control checkpoints in this process.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

1. Generation and Validation of Patient-Specific iPSCs

- Reprogramming: Patient somatic cells (e.g., dermal fibroblasts or peripheral blood mononuclear cells) are transfected with a set of defined transcription factors (e.g., OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, c-MYC) to induce pluripotency. This can be achieved using integrating methods (lentiviruses) or non-integrating methods (Sendai virus, episomal plasmids) [17] [18].

- Pluripotency Validation: Established iPSC lines must be rigorously tested. The gold standard for human stem cell pluripotency is teratoma formation in immunodeficient mice, where the cells form complex tumors containing tissues from all three germ layers (ectoderm, mesoderm, and endoderm). Additional validation includes demonstrating robust in vitro multilineage differentiation potential and confirming the expression of key pluripotency markers (e.g., NANOG, SSEA-4) via immunostaining or flow cytometry [18].

2. Directed Differentiation and Perturbation

- Protocol Optimization: Differentiating PSCs into a target cell type requires carefully optimized protocols that mimic developmental signaling cues. For example, a mesendoderm-directed differentiation protocol might initiate differentiation using a GSK3β inhibitor (CHIR99021) to activate WNT signaling, followed by specific growth factors to steer cells toward cardiovascular or other mesodermal lineages [19].

- Signaling Perturbation Studies: To understand the role of specific pathways in development and disease, researchers systematically perturb signaling during differentiation. As demonstrated in a recent 2025 atlas, small molecules or recombinant proteins targeting pathways like WNT, BMP4, and VEGF are added at the germ layer stage, and the resulting changes in lineage specification are analyzed using single-cell RNA sequencing [19].

3. Phenotypic Characterization and Potency Assessment

- Molecular & Functional Phenotyping: Disease-relevant phenotypes in differentiated cells are identified through a combination of techniques, including transcriptomics (e.g., scRNA-seq to reveal heterogeneity), electrophysiology (for neurons or cardiomyocytes), and metabolic assays.

- Defining Potency: For cell therapies and models, potency is defined as "the attribute of a product that enables it to achieve its intended mechanism of action" [9]. A potency test is a quantitative bioassay that measures this attribute. For a neuronal disease model, this could be the measured output of a specific electrophysiological function or the secretion of a specific neurotransmitter in response to a stimulus.

Evaluating Model Fidelity: The Role of Potency and Mechanism of Action

A critical challenge in the field is establishing a clear link between the cellular model and the clinical disease it represents. This involves deep understanding of the model's mechanism of action (MOA) and how to measure its functional capacity, or potency.

The following framework illustrates the logical relationship between these key concepts, distinguishing between laboratory-based measurements and clinical outcomes—a common point of confusion during product development [9].

Key Considerations for Potency Assays

- Separating MOA from Potency: It is crucial to distinguish the biological mechanism (MOA) from the measurable attribute (potency). This separation allows for the possibility that a chosen potency assay might not perfectly capture the true MOA, which is often uncertain for complex cell products [9]. For example, a CAR-T cell's MOA is target cell killing, but a common potency test measures IFN-γ secretion upon target engagement—a correlate that may not always predict clinical efficacy [9].

- Correlation with Clinical Outcome: While it is desirable for a laboratory potency test to predict clinical benefit, this correlation is not always required for regulatory approval. The primary roles of the potency test are to ensure manufacturing consistency and product stability [9].

Table 2: Benchmarking Disease Model Fidelity with Computational Tools

| Tool / Approach | Primary Function | Role in Ensuring Fidelity |

|---|---|---|

| Single-Cell RNA Sequencing (scRNA-seq) | High-throughput analysis of gene expression in individual cells. | Identifies heterogeneity in differentiated cultures and benchmarks the resulting cell states against in vivo reference atlases of human development [19]. |

| CellNet | A network biology-based computational platform. | Assesses the fidelity of cellular engineering more accurately than prior methods by comparing the gene regulatory networks of derived cells to their in vivo counterparts [18]. |

| Kinetic Modeling & Design Space | Model-based determination of optimal cultivation parameters. | Uses prediction intervals to define robust regions (seeding density, harvest time) for consistent cell output, improving process reliability for MSC cultivation [20]. |

Building a robust pluripotent stem cell-based disease model requires a suite of specialized reagents and tools. The following table details key solutions used in the field.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for PSC Disease Modeling

| Reagent / Resource | Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Vitronectin XF | A defined, recombinant substrate for coating cell culture plates. | Provides an xeno-free attachment matrix for the maintenance of human PSCs in a undifferentiated state [19]. |

| mTeSR1 Media | A defined, serum-free maintenance medium. | Supports the growth and pluripotency of human ESCs and iPSCs in feeder-free culture conditions [19]. |

| CHIR99021 | A small molecule inhibitor of GSK-3. | Used in differentiation protocols to activate WNT signaling; e.g., to initiate mesendoderm specification [19]. |

| ROCK Inhibitor (Y-27632) | A small molecule inhibitor of Rho-associated coiled-coil kinase. | Significantly improves the survival of PSCs after dissociation into single cells (passaging or thawing) [19]. |

| TotalSeq-A Cell Hashing Antibodies | Antibodies conjugated to oligonucleotide barcodes. | Enables multiplexing of scRNA-seq samples by tagging cells from different conditions with unique barcodes, allowing them to be pooled and sequenced together [19]. |

| BMP4 / VEGF (rh) | Recombinant human growth factors. | Used as signaling perturbations during differentiation to direct lineage specification toward specific mesodermal fates [19]. |

The fidelity of stem cell-based disease models is inextricably linked to the quality of the underlying pluripotent cells and the rigor of the methods used to differentiate and validate them. As the field progresses, the standardization of protocols, coupled with advanced computational tools for benchmarking and a deeper understanding of product potency and MOA, will be critical. By systematically addressing the critical link between pluripotency and model fidelity, researchers can enhance the predictive power of their in vitro systems, thereby accelerating the discovery of novel therapeutic targets and the development of effective new drugs.

Molecular Markers and Functional Assays for Assessing Pluripotent States

Pluripotency, defined as the capacity of a cell to self-renew and differentiate into all derivatives of the three primary germ layers (ectoderm, mesoderm, and endoderm), represents a fundamental property underpinning stem cell-based disease modeling and regenerative medicine [5] [21]. Rigorous assessment of this potential is critical for ensuring the validity of scientific research and the safety of therapeutic applications. The evaluation of pluripotent states relies on two complementary approaches: the analysis of molecular markers that indicate the pluripotent state and functional assays that demonstrate pluripotent function [22]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of the key methodologies, markers, and experimental protocols used to assess pluripotency, offering researchers a framework for selecting appropriate characterization strategies based on their specific project requirements.

Molecular Markers of Pluripotency

Molecular markers serve as essential tools for the initial characterization and routine monitoring of pluripotent stem cells (PSCs). These include transcription factors, surface antigens, and enzymatic activities associated with the pluripotent state.

Traditional and Novel Marker Genes

Conventional pluripotency markers have been widely used for years, but recent research reveals significant limitations and recommends novel, more specific alternatives.

Table 1: Traditional vs. Validated Marker Genes for Pluripotency and Differentiation

| Cell State | Traditional Markers | Validated Novel Markers [23] | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pluripotency | OCT4, SOX2, NANOG | CNMD, NANOG, SPP1 | SOX2 shows considerable overlap with ectoderm; GDF3 overlaps with endoderm [23]. |

| Endoderm | SOX17, CXCR4 | CER1, EOMES, GATA6 | - |

| Mesoderm | T/BRACHYURY, CD140b | APLNR, HAND1, HOXB7 | NCAM1 shows overlap with ectoderm [23]. |

| Ectoderm | PAX6, SOX1 | HES5, PAMR1, PAX6 | OTX2 shows considerable overlap with endoderm [23]. |

A landmark 2024 study using long-read nanopore transcriptome sequencing identified 172 genes linked to cell states not covered by current guidelines and rigorously validated 12 genes as unique markers for specific cell fates [23]. This work highlighted that many markers recommended for embryoid body (EB) analysis are not directly applicable for evaluating trilineage-differentiated induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), revealing overlapping expression patterns that compromise their specificity [23].

Protein-Level Markers and Quality Control

At the protein level, immunocytochemistry and flow cytometry are routinely employed to detect key pluripotency-associated transcription factors (OCT4, SOX2, NANOG) and extracellular membrane proteins (SSEA-4, TRA-1-60) [22] [21]. However, the expression of these markers in isolation does not confirm functional pluripotency, and some are not fully exclusive to PSCs [22]. Quality control procedures for iPSC lines include short tandem repeat analysis for identity confirmation, residual vector testing to ensure reprogramming vectors are not integrated, karyotyping to detect culture-driven mutations, and viral testing [21]. Single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) arrays provide approximately 50 times higher resolution than karyotyping for detecting genomic abnormalities [21].

Functional Assays for Assessing Pluripotency

Functional assays remain the gold standard for demonstrating developmental potency, as they provide direct evidence of a cell's capacity to differentiate. These assays range from simple in vitro methods to complex in vivo tests.

Table 2: Comparison of Functional Assays for Assessing Pluripotency

| Technique | Key Principle | Advantages | Disadvantages | Evidence Level |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spontaneous Differentiation | Removal of pluripotency maintenance conditions [22] | Inexpensive, accessible, rapid; can reveal lineage biases [22] | Produces immature tissues; stochastic differentiation; culture conditions affect reproducibility [22] | Moderate |

| Directed Differentiation | Addition of exogenous morphogens to induce specific cell fates [22] | Controllable; can generate specific cell types; relatively inexpensive [22] | May not represent full differentiation capacity; mature phenotypes not always achieved [22] | High for specific lineages |

| Embryoid Body (EB) Formation | Cells self-organize into 3D spheres and differentiate [22] | Accessible techniques; presence of three germ layers indicates differentiation capacity [22] | Immature structures with haphazard organization; hypoxia in core may limit studies [22] | Moderate to High |

| Teratoma Assay | PSCs implanted into immunocompromised mice form differentiated tumors [22] | Provides conclusive proof of ability to form complex tissues; gold standard; assesses malignancy [22] | Labour-intensive, expensive, ethical concerns; primarily qualitative; protocol variability [22] | High (Gold Standard) |

| Modern 3D Organoids | Combination of chemical cues and 3D culture to form tissue rudiments [22] [24] | Can generate morphologically identifiable tissues; greater control; avoids animal use [22] | Technically challenging to optimize; requires specialized equipment/reagents [22] | Emerging |

The Teratoma Assay: Protocol and Considerations

The teratoma assay is widely regarded as the most rigorous method for confirming the pluripotency of human PSCs [22]. The standard protocol involves:

- Cell Preparation: Harvest undifferentiated PSCs and prepare a single-cell suspension.

- Implantation: Inject cells (typically 1-5 million) into an immunocompromised murine host, either subcutaneously, intramuscularly, or under the testis capsule.

- Tumor Growth: Allow tumors to develop for 8-16 weeks, monitoring growth periodically.

- Histological Analysis: Harvest tumors, fix, section, and stain with hematoxylin and eosin. Examine for the presence of differentiated tissues representing all three germ layers (e.g., neural rosettes for ectoderm; cartilage, muscle for mesoderm; gut-like epithelium for endoderm).

Despite its status as a gold standard, the teratoma assay has significant limitations, including cost, time requirements, ethical concerns regarding animal use, inter-tumor heterogeneity, and minimal standardization between laboratories [22].

In Vitro Trilineage Differentiation and Analysis

Directed trilineage differentiation provides a standardized alternative to spontaneous differentiation assays. Commercial kits are available for efficient differentiation into the three germ layers. The subsequent analysis of differentiation outcomes typically employs:

- Immunofluorescence/Flow Cytometry: To detect germ layer-specific proteins at single-cell resolution.

- qPCR Analysis: To quantify expression of germ layer-specific marker genes.

A critical advancement in this area is the "hiPSCore" machine learning-based scoring system, trained on 15 iPSC lines and validated on 10 more, which accurately classifies pluripotent and differentiated cells and predicts their potential to become specialized cells [23]. This system reduces the time, subjectivity, and resource use associated with traditional pluripotency assessment.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Pluripotency Assessment

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Reprogramming Factors | OSKM (OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, c-MYC); OSNL (OCT4, SOX2, NANOG, LIN28) [24] [25] | Induction of pluripotency in somatic cells; different combinations vary in efficiency and safety profiles. |

| Pluripotency Markers (Antibodies) | Anti-OCT4, Anti-SOX2, Anti-NANOG, Anti-SSEA-4, Anti-TRA-1-60 [22] [21] | Immunodetection of pluripotency-associated proteins via flow cytometry or immunocytochemistry. |

| Germ Layer Markers (Antibodies) | Anti-SOX17 (endoderm), Anti-PAX6 (ectoderm), Anti-T/Brachyury (mesoderm) [23] [22] | Validation of differentiation potential in functional assays. |

| Validated Novel Marker Panels | CNMD, SPP1 (pluripotency); CER1, EOMES, GATA6 (endoderm); APLNR, HAND1, HOXB7 (mesoderm); HES5, PAMR1 (ectoderm) [23] | Specific, non-overlapping markers for unequivocal identification of differentiation states. |

| Critical Culture Supplements | Leukemia Inhibitory Factor (LIF); FGF2; GDNF; Small molecule inhibitors (2i) [26] | Maintenance of pluripotent state in culture; enhancement of reprogramming efficiency. |

| Directed Differentiation Kits | Commercial trilineage differentiation kits | Standardized protocols for efficient differentiation into the three germ layers. |

Signaling Pathways in Pluripotency and Reprogramming

The molecular mechanisms governing pluripotency maintenance and somatic cell reprogramming involve complex signaling networks. Key pathways include those mediated by Toll-like receptors (TLR), GDNF/RET, interleukins (ILs), FGF/FGFR, and SMAD, alongside activation of NIMA kinases [26]. The process of reprogramming somatic cells to iPSCs involves profound remodeling of chromatin structure and the epigenome, changes in metabolism, cell signaling, intracellular transport, and proteostasis [24] [25]. During the initial phase of reprogramming, c-Myc associates with histone acetyltransferase complexes to induce global histone acetylation, enabling exogenous Oct4 and Sox2 to bind their target loci [25]. The ratio of Sox2 to Oct4 is critical for reprogramming efficiency and iPSC colony quality [25].

Diagram Title: Key Molecular Events in Cellular Reprogramming

The comprehensive assessment of pluripotency requires an integrated approach combining multiple molecular and functional techniques. While traditional markers and the teratoma assay have historically formed the foundation of pluripotency evaluation, recent advances offer more standardized and precise alternatives. The identification of novel, specific marker genes through long-read sequencing and the development of computational tools like hiPSCore represent significant progress toward more objective, efficient quality control [23]. Researchers should select assessment strategies based on their specific application, considering that in vitro models of increasing complexity, such as 3D organoids, may eventually reduce reliance on animal-based assays [22]. As the field advances, continued refinement of pluripotency assessment protocols will enhance the reliability of stem cell-based disease models and accelerate the development of safe, effective regenerative therapies.

Ethical and Regulatory Considerations in Stem Cell Sourcing

The foundation of robust and reproducible stem cell-based disease modeling rests upon the consistent and ethical procurement of starting cellular materials. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, the choice of stem cell source is not merely a technical decision but one fraught with significant ethical and regulatory implications that directly impact experimental validity and clinical translation. Stem cell sourcing refers to the processes of obtaining, characterizing, and banking stem cells for research and therapeutic applications. These processes are governed by an intricate framework of ethical principles and regulatory requirements that vary based on the cellular origin and intended application [27] [28].

The moral weight assigned to different stem cell sources directly influences regulatory scrutiny, funding eligibility, and public perception of research outcomes. Within the context of potency evaluation for disease modeling, understanding these considerations is paramount, as the developmental potential and functional capacity of stem cells are inextricably linked to their origin and the ethical integrity of their procurement [29]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of major stem cell sources, focusing on the ethical and regulatory landscapes that researchers must navigate to ensure their work is both scientifically sound and socially responsible.

The choice of stem cell source carries distinct implications for research applications, particularly in disease modeling and drug development. The table below provides a detailed comparison of the key characteristics of different stem cell sources.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Stem Cell Sources for Research and Disease Modeling

| Stem Cell Source | Key Ethical Considerations | Regulatory Classification (U.S. FDA Example) | Key Markers for Potency Evaluation | Primary Research Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human Embryonic Stem Cells (hESCs) | Destruction of human embryos; moral status of the embryo [27] [30]. | Typically regulated as biologic drugs; require extensive preclinical data [27]. | OCT4, SOX2, NANOG (Pluripotency TFs) [29]. | Studying early development; disease mechanisms; generating diverse cell types [11]. |

| Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells (iPSCs) | Avoids embryo destruction; donor consent for somatic cell source; potential for germline modification [27] [11] [30]. | Subject to FDA oversight as cell-based products; regulatory pathway depends on manipulation and use [27] [24]. | OCT4, NANOG; Teratoma formation in vivo; Embryoid body formation [29] [24]. | Patient-specific disease modeling; personalized drug screening; autologous cell therapy development [11] [24]. |

| Adult Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs) | Minimal ethical controversy; informed consent for tissue donation (e.g., bone marrow, adipose) [27] [31]. | "Minimally manipulated" products may have different regulatory pathways; more than minimal manipulation triggers stricter oversight [27]. | CD73, CD90, CD105 (surface markers); differentiation into osteocytes, chondrocytes, adipocytes [32] [29]. | Immunomodulation studies; hematopoietic support; regenerative medicine for bone/cartilage [11] [31]. |

| Fetal Stem Cells | Ethical concerns regarding elective abortion; informed consent from donor [27]. | Strictly regulated; sourcing often restricted by law in many jurisdictions. | Varies by tissue source; often tissue-specific progenitors. | Studies of specific developmental stages; certain neurodegenerative diseases. |

Ethical Frameworks and Principles

Stem cell research and sourcing are guided by established ethical frameworks to ensure responsible scientific practice. The following diagram illustrates the application of core bioethical principles to stem cell sourcing.

Figure 1: Ethical principles and their practical applications in stem cell sourcing. The principles of biomedical ethics directly inform specific operational requirements for ethically sound research.

Application of Core Principles in Sourcing

Respect for Autonomy and Informed Consent: The informed consent process is fundamental for all stem cell research involving human donors. This is particularly critical for vulnerable populations and when using biospecimens that might be used to generate iPSC lines, which have the potential for indefinite self-renewal. Consent forms must clearly state the scope of research, including the possibility of future uses, commercial applications, and whether cells will be shared with other researchers [27] [28]. The complexity of stem cell science necessitates that information is delivered in an accessible manner, ensuring true understanding from donors.

Justice and Equitable Access: The benefits of stem cell research must be distributed justly to avoid exacerbating existing health disparities. The high cost of developing stem cell therapies can limit access for disadvantaged populations, creating an ethical imperative for researchers, funders, and policymakers to develop mechanisms that promote broad accessibility [27] [28]. Furthermore, the burdens of research, such as participating in early-phase clinical trials, should not fall disproportionately on populations unlikely to benefit from the resulting therapies.

Regulatory Landscapes and Oversight

A complex global regulatory landscape governs stem cell sourcing and application, ensuring safety and efficacy while fostering innovation. The following diagram outlines a generalized regulatory pathway for stem cell-based products.

Figure 2: A simplified U.S. FDA regulatory pathway for stem cell-based products. The level of regulatory oversight depends heavily on the degree of manipulation and intended use of the cells.

International Standards and Guidelines

The International Society for Stem Cell Research (ISSCR) Guidelines: The ISSCR provides comprehensive, internationally recognized guidelines for stem cell research and clinical translation, which are updated regularly to reflect scientific advances. The 2025 guidelines emphasize rigor, oversight, and transparency. They provide specific recommendations for sensitive areas, including research on human embryos, stem cell-based embryo models (SCBEMs), chimeras, and organoids. A key update in 2025 retired the classification of embryo models as "integrated" or "non-integrated" in favor of the inclusive term SCBEMs, and it prohibits the culture of SCBEMs to the point of potential viability (ectogenesis) [28].

Global Regulatory Variations: Regulatory approaches to stem cell therapies vary significantly worldwide. For example, in Mexico, the regulatory agency COFEPRIS oversees cell therapies, treating them as health inputs requiring sanitary authorization. However, the country has faced challenges with a proliferation of clinics offering unproven stem cell treatments, exploiting regulatory gaps. Mexico is actively working on specific regulations, such as the proposed NOM-260, to provide clearer oversight and curb the marketing of unvalidated "miracle cures" [33]. This highlights the importance for researchers to be aware of not only their local regulations but also international standards, especially when collaborating across borders.

Experimental Protocols for Potency Evaluation

Evaluating the functional potency of sourced stem cells is a critical step in validating their utility for disease modeling. The following section outlines standard experimental workflows.

In Vitro Pluripotency Assessment

Aim: To confirm the differentiation capacity of pluripotent stem cells (PSCs), such as hESCs and iPSCs, into derivatives of the three primary germ layers in a controlled laboratory setting.

Protocol:

- Embryoid Body (EB) Formation: Harvest PSCs and culture them in low-attachment plates in a medium that does not support pluripotency (e.g., without bFGF for hPSCs). This encourages the formation of 3D aggregates known as embryoid bodies [29].

- Spontaneous Differentiation: Maintain EBs in suspension culture for 7-10 days, allowing for spontaneous differentiation.

- Directed Differentiation (Optional): To enhance the yield of a specific germ layer, supplement the culture medium with specific growth factors (e.g., Activin A for endoderm, BMP4 for mesoderm, FGF2 for ectoderm).

- Analysis: After 14-21 days, harvest the EBs. Assess differentiation potential via:

- Immunocytochemistry: Fix EBs, section them, and stain for germ layer-specific markers. Common markers include:

- Ectoderm: β-III-Tubulin (TUJ1) for neurons, Nestin for neural progenitors.

- Mesoderm: Smooth Muscle Actin (SMA) for smooth muscle, Brachyury for early mesoderm.

- Endoderm: Sox17, FoxA2 for definitive endoderm, Alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) for hepatic lineage [29].

- RT-qPCR: Analyze the gene expression of the aforementioned markers relative to undifferentiated PSCs.

- Immunocytochemistry: Fix EBs, section them, and stain for germ layer-specific markers. Common markers include:

In Vivo Teratoma Formation Assay

Aim: To provide definitive evidence of pluripotency by demonstrating the ability of PSCs to form complex, differentiated tissues from all three germ layers in an in vivo environment.

Protocol:

- Cell Preparation: Harvest a concentrated suspension of PSCs (e.g., 1-5 million cells) in a suitable buffer like PBS or Matrigel.

- Transplantation: Immunocompromised mice (e.g., NOD-SCID or NSG strains) are used as hosts to prevent graft rejection. Inject the cell suspension intramuscularly, subcutaneously, or under the testis capsule.

- Monitoring and Tumor Harvest: Monitor the injection site for tumor formation over 8-16 weeks. The growth of a palpable, solid tumor (teratoma) is indicative of successful engraftment and proliferation.

- Histopathological Analysis:

- Surgically remove the teratoma and fix it in formalin.

- Process the tissue for paraffin embedding and sectioning.

- Stain tissue sections with Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E).

- A qualified pathologist must examine the sections for the presence of well-differentiated tissues derived from all three germ layers, such as:

- Ectoderm: Neural rosettes, pigmented cells (retinal epithelium), keratinocytes.

- Mesoderm: Cartilage, bone, muscle, adipose tissue.

- Endoderm: Gut-like epithelial structures, respiratory tubules [29].

Table 2: Key Assays for Functional Potency Evaluation of Pluripotent Stem Cells

| Assay Type | Key Readouts | Advantages | Disadvantages | Regulatory Relevance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| In Vitro (Embryoid Body) | Immunostaining for germ layer markers (e.g., TUJ1, SMA, AFP); RT-qPCR analysis. | Relatively quick and inexpensive; avoids animal use. | May not fully replicate in vivo complexity; spontaneous differentiation can be heterogeneous. | Supports initial characterization; required for lot-release in some therapeutic applications. |

| In Vivo (Teratoma) | Histological identification of differentiated tissues from all three germ layers. | Considered the "gold standard" for demonstrating pluripotent capacity. | Time-consuming (8-16 weeks); expensive; requires animal facility; ethical considerations for animal use. | Often required by regulatory bodies as part of the safety package for PSC-based therapies. |

| Flow Cytometry | Quantification of pluripotency surface markers (e.g., SSEA-4, Tra-1-60, Tra-1-81). | High-throughput, quantitative, can be applied to a single-cell suspension. | Does not demonstrate functional differentiation potential; marker expression can be culture-dependent. | Used for routine quality control and stability assessment of cell banks. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Stem Cell Research

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Stem Cell Sourcing and Characterization

| Reagent / Material | Function in Research | Example Application in Sourcing/Potency Evaluation |

|---|---|---|

| Pluripotency Transcription Factor Antibodies | Molecular markers for confirming pluripotent state via immunocytochemistry or Western blot. | Detecting OCT4, SOX2, NANOG in newly derived iPSC or hESC lines to confirm successful reprogramming or culture [29]. |

| Germ Layer-Specific Antibodies | Identifying differentiated cell types derived from PSCs. | Staining for β-III-Tubulin (ectoderm), Smooth Muscle Actin (mesoderm), and Sox17 (endoderm) in embryoid bodies to validate multilineage differentiation potential [29]. |

| Reprogramming Factors (OSKM) | Key tools for generating induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) from somatic cells. | Lentiviral or sendai viral vectors expressing OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, and c-MYC used to reprogram patient fibroblasts for disease modeling [30] [24]. |

| Defined Culture Media & Matrices | Providing a consistent, xeno-free environment for the maintenance and differentiation of stem cells. | TeSR-E8 or mTeSR1 media combined with recombinant laminin-521 to support the feeder-free culture of PSCs, reducing variability and enhancing reproducibility [11]. |

| Flow Cytometry Panels | Quantitative analysis of cell surface markers for characterization and purity assessment. | Using antibodies against CD73, CD90, CD105 (positive markers) and CD34, CD45, HLA-DR (negative markers) to characterize mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) populations [32] [29]. |

The ethical and regulatory dimensions of stem cell sourcing are not peripheral concerns but are central to the scientific integrity and translational potential of stem cell-based disease models. As the field progresses with the development of complex organoids and assembloids, these considerations will only increase in complexity. A deep understanding of the ethical principles of autonomy, justice, beneficence, and non-maleficence, combined with a rigorous adherence to evolving international guidelines and regulatory pathways, is indispensable for researchers. By integrating these considerations from the earliest stages of experimental design—including careful source selection, robust informed consent procedures, and comprehensive potency evaluation—scientists can ensure their work on potency evaluation in disease modeling is built upon a responsible, reproducible, and ethically sound foundation.

Building Better Models: Techniques for Potent Stem Cell Differentiation and Application

Advanced Differentiation Protocols for Specific Lineages

The successful derivation of specific, functional cell lineages from pluripotent stem cells is a cornerstone of modern regenerative medicine, disease modeling, and drug development. However, achieving consistent, high-efficiency differentiation remains a significant challenge across multiple tissue types. This comparison guide objectively evaluates advanced differentiation protocols for hematopoietic, myogenic, and renal lineages, framing the analysis within the broader context of potency evaluation for stem cell-based disease models. By examining direct experimental comparisons of efficiency, reproducibility, and functional outcomes, this guide provides researchers with evidence-based recommendations for protocol selection and implementation.

The following analysis reveals substantial variability in the performance of differentiation protocols across key metrics. For hematopoietic differentiation, a modified 2D-multistep approach demonstrates superior efficiency and cost-effectiveness. For myogenic differentiation, monolayer-based protocols with defined signaling pathway modulation outperform embryoid body-based methods. Meanwhile, kidney organoid generation continues to evolve toward more complex assembloid models despite persistent maturation challenges.

Table 1: Overall Differentiation Protocol Performance Ratings

| Lineage | Top-Performing Protocol | Efficiency | Reproducibility | Functional Maturation | Technical Complexity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hematopoietic | 2D-Multistep with AhR activation | High | High | Medium | Medium |

| Myogenic | Protocol III (Monolayer) | High | Medium-High | Medium-High | High |

| Renal | Assembled Organoid Models | Medium | Medium | Low-Medium | Very High |

Direct Comparative Analysis of Hematopoietic Differentiation Methods

A rigorous direct comparison of four serum-free, feeder-free hematopoietic differentiation methods revealed striking differences in performance metrics [34]. Researchers improved upon an existing 2D-multistep method incorporating aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) hyperactivation, then compared it against three other established approaches: two utilizing embryoid body (EB) formation (one simple, one multistep) and one additional 2D monolayer method with simpler stages.

Table 2: Quantitative Comparison of Hematopoietic Differentiation Protocols

| Method Type | CD34+ Cell Yield | Functional Progenitors (CFU) | Cost per Well | Hands-on Time | Disease Modeling Sensitivity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2D-Multistep (Improved) | 7× original protocol | Highest (Robust multilineage) | 50% of original | 40% reduction | Accurately recapitulated DS and β-thalassemia phenotypes |

| 2D-Simple | Medium | Medium | Low | Low | Not assessed |

| EB-Multistep | Medium | Medium | High | High | Moderate |

| EB-Simple | Low | Low | Medium | Medium | Low |

The optimized 2D-multistep method generated significantly higher numbers of CD34+ progenitor cells (7-fold increase over the original protocol) and functional hematopoietic progenitors capable of forming multilineage colonies, while simultaneously reducing costs by 50% and hands-on time by 40% [34]. This protocol demonstrated superior sensitivity in disease modeling, accurately recapitulating expected hematopoietic defects in Down syndrome and β-thalassemia patient-derived iPSCs.

The methodology involved a staged approach: initial mesoderm induction followed by hematopoietic specification enhanced by AhR activation using 6-formylindolo[3,2-b]carbazole (FICZ). Key modifications included extending Wnt activation, eliminating unnecessary media changes, and adding reagents directly to existing cultures to minimize disturbance [34].

Myogenic Differentiation Protocol Comparison

A side-by-side evaluation of three transgene-free myogenic differentiation protocols revealed clear differences in efficiency based on hierarchical myogenic regulatory factor expression and myotube formation [35].

Table 3: Myogenic Differentiation Protocol Efficiency

| Protocol | Approach | Key Signaling Modulators | MYF5/MYOD Expression | Myotube Formation | CD56 Specificity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protocol I | EB-based with selection | ITS, collagen adhesion | Moderate | Low | Not specific |

| Protocol II | EB-based with strong induction | BIO, forskolin, bFGF | Moderate | Medium | Not specific |

| Protocol III | Monolayer with defined media | CHIR99021, DAPT, FGF2 | High | High | Not specific |

Protocol III, employing a monolayer system with defined temporal application of small molecules to precisely manipulate key developmental signaling pathways, demonstrated superior efficiency in generating myogenic cells [35]. The protocol achieved this through sequential media formulations: initial WNT activation using CHIR99021 to induce mesodermal commitment, followed by simultaneous TGF-β and BMP inhibition to promote myotome formation, and finally maturation factors to support terminal differentiation.

The critical methodological insight was that CD56, often used as a myogenic marker, demonstrated poor specificity across all protocols, suggesting researchers should rely instead on the hierarchical expression of myogenic regulatory factors (MYF5, MYOD, MYOG) and structural proteins like embryonic and adult myosin heavy chains (MYH3, MYH2) [35].

Advanced Technology Integration in Differentiation Optimization

Machine Learning for Early Efficiency Prediction

The extended timeframes required for many differentiation protocols (often 80+ days) present significant bottlenecks in optimization and quality control. Researchers have developed a non-destructive prediction system using phase-contrast imaging and machine learning to forecast muscle stem cell differentiation efficiency approximately 50 days before protocol completion [36].

This approach employs Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) feature extraction from cellular images taken between days 14-38, followed by random forest classification to predict final MYF5+ cell percentage on day 82. The system achieved accurate classification of high and low-efficiency samples, enabling early quality assessment without destructive sampling [36]. This methodology is particularly valuable for optimizing protocols and selecting high-quality cultures early in lengthy differentiation processes.

Design of Experiments for Systematic Optimization

Traditional "one-factor-at-a-time" optimization approaches are inefficient for complex differentiation protocols with multiple interacting variables. Design of Experiments (DOE) methodologies enable researchers to strategically screen numerous culture conditions through reduced experimental runs while capturing interaction effects between factors [37].

Fractional factorial designs, orthogonal arrays, and response surface methodology have been successfully applied to optimize pluripotent stem cell differentiation processes, offering more efficient condition screening and quantitative modeling of differentiation outcomes. These approaches are increasingly recommended by regulatory authorities for cell production process development [37].

Systems Biology and Artificial Intelligence

The integration of systems biology and artificial intelligence (SysBioAI) is transforming stem cell differentiation protocol development by enabling holistic analysis of large-scale multi-omics datasets [38]. This approach helps address persistent challenges in stem cell therapy development, including product heterogeneity, incomplete mechanistic understanding, and limited predictive power of traditional trial designs.

SysBioAI tools can analyze molecular-level data (transcriptomics, proteomics), cellular and tissue-level characteristics (3D spatial features), and complex system behaviors to identify critical quality attributes and optimize differentiation protocols through iterative refinement cycles [38].

Signaling Pathways Governing Lineage Specification

The differentiation protocols examined share common principles of developmental biology, manipulating conserved signaling pathways to direct cell fate decisions. The diagram below illustrates the key pathways targeted in the most effective protocols.

Kidney Organoid Differentiation: Advances and Challenges

Recent advances in kidney differentiation have progressed from simple nephron-containing organoids to more complex models incorporating ureteric epithelium and stromal components [39]. The latest protocols generate ureteric organoids that can be combined with nephron-forming organoids to create integrated assembloid models, better recapitulating native kidney architecture.

However, significant challenges remain in evaluating the transcriptional complexity of these models, eliminating off-target cell types, achieving postnatal maturation levels, and ensuring quality control for potential therapeutic applications [39]. Current kidney differentiation protocols primarily model embryonic development, limiting their utility for studying adult-onset kidney diseases.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Key Reagents for Advanced Differentiation Protocols

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Differentiation | Protocol Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wnt Pathway Modulators | CHIR99021 (agonist) | Mesoderm induction, hematopoietic specification | Myogenic (Protocol III), Hematopoietic |

| TGF-β/BMP Inhibitors | SB431542, LDN193189 | Promote myogenesis, inhibit alternative fates | Myogenic (Protocol III) |

| AhR Activators | FICZ (6-formylindolo[3,2-b]carbazole) | Expand hematopoietic progenitors | Hematopoietic (2D-Multistep) |

| Growth Factors | bFGF, VEGF, SCF, TPO, IGF-1, HGF | Support proliferation and lineage specification | Hematopoietic, Myogenic |

| Extracellular Matrices | Matrigel, Collagen I | Provide structural support and biochemical cues | Myogenic, General iPSC culture |

| Metabolic Regulators | ITS (Insulin-Transferrin-Selenium) | Support cell growth and differentiation | Myogenic (Protocol I) |

The direct comparison of differentiation protocols reveals that methods incorporating precise temporal control of developmental signaling pathways, whether through small molecules or growth factors, consistently outperform less targeted approaches. The optimal 2D-multistep hematopoietic protocol and monolayer myogenic method both demonstrate the importance of staged, chemically-defined conditions that mirror embryonic development.

Future protocol development will increasingly leverage computational approaches, including DOE for systematic optimization, machine learning for non-destructive quality prediction, and systems biology for mechanistic understanding. As the field progresses toward clinical applications, standardization, scalability, and rigorous potency assessment will become increasingly critical for translating stem cell technologies into reliable research tools and ultimately transformative therapies.

Organoid and Assembloid Technology for Complex Tissue Modeling

The pursuit of physiologically relevant models that accurately recapitulate human biology has long been a challenge in biomedical research. Traditional two-dimensional (2D) cell cultures, while valuable for many applications, lack the three-dimensional architecture, cellular diversity, and cell-cell interactions characteristic of native tissues [40]. Similarly, animal models, despite their contributions to scientific discovery, present significant species differences that limit their translational potential for human disease [41]. The advent of three-dimensional (3D) organoid technology has revolutionized our approach to modeling human tissues in vitro. Organoids are self-organizing 3D structures derived from pluripotent stem cells (PSCs) or adult stem cells (AdSCs) that mimic the cellular composition, structure, and function of organs [42] [40]. These miniature organ-like structures can be generated from either human pluripotent stem cells (hPSCs), including embryonic stem cells (ESCs) and induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), or tissue-specific resident stem cells [42] [43].

Building upon organoid technology, assembloids represent a more recent advancement that enables the modeling of complex interactions between different tissue types or brain regions. Assembloids are 3D preparations formed by the integration of multiple organoids or their combination with other specialized cell types, creating systems that recapitulate inter-regional communication and cellular migration [44]. This modular approach allows researchers to reconstruct specific biological pathways and investigate emergent properties that arise from cellular crosstalk, providing unprecedented opportunities for studying human development, disease mechanisms, and therapeutic interventions [45] [44]. The progression from organoids to assembloids marks a significant evolution in stem cell technology, offering increasingly sophisticated tools for modeling the intricate complexity of human tissues and their interactions in health and disease.

Technological Foundations: From Organoids to Assembloids

The foundation of both organoid and assembloid technologies lies in the stem cells from which they are derived. The most commonly used stem cells for generating brain organoids and assembloids are embryonic stem cells (ESCs) and induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) [43]. Human ESCs (hESCs) are pluripotent cells isolated from the inner cell mass of blastocysts and were first established in 1998 [40]. These cells can self-renew indefinitely while maintaining the potential to differentiate into derivatives of all three germ layers. However, the use of hESCs raises ethical concerns regarding embryo destruction, prompting the search for alternative approaches [43].

The development of induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) addressed these ethical limitations and opened new avenues for personalized disease modeling. iPSCs are generated by reprogramming adult somatic cells through the introduction of specific pluripotency factors, initially demonstrated using the OSKM factors (Oct3/4, Sox2, Klf4, and c-Myc) [43] [40]. These "embryonic stem cell-like" cells share the pluripotency and self-renewal capabilities of ESCs while maintaining the genetic background of the donor, making them particularly valuable for modeling genetic disorders and developing patient-specific therapies [43]. Significant advancements have been made to improve reprogramming efficiency and safety, including the use of non-integrating delivery methods and small molecules that enhance the reprogramming process [43].

Table 1: Comparison of Stem Cell Sources for Organoid and Assembloid Generation

| Stem Cell Type | Origin | Pluripotency | Advantages | Limitations | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Embryonic Stem Cells (ESCs) | Inner cell mass of blastocysts | Pluripotent | Well-established differentiation protocols; Genetically stable | Ethical concerns; Immunological rejection upon transplantation | Early human development studies; Disease modeling (non-patient specific) |

| Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells (iPSCs) | Reprogrammed somatic cells | Pluripotent | Patient-specific modeling; No ethical concerns; Broadly applicable | Potential genetic instability during reprogramming; Variable reprogramming efficiency | Personalized disease modeling; Drug screening; Regenerative medicine |

| Adult Stem Cells (AdSCs) | Specific adult tissues | Multipotent or unipotent | Tissue-specific maturity; Faster protocol; Maintain age-related characteristics | Limited expansion potential; Restricted to certain tissues | Modeling adult tissues; Infectious diseases; Cancer research |

Beyond PSCs, neural progenitor cells (NPCs) represent another important cell source for neural-specific models. NPCs are multipotent neural stem cells capable of self-renewal and differentiation into neurons and glial cells, though they do not give rise to non-neuronal cells of the central nervous system [43]. These cells can be found throughout the CNS during development and in adult brains, and can also be generated in vitro through the differentiation of ESCs or iPSCs using specific neural induction growth factors [43].

The choice between PSC-derived and AdSC-derived organoids depends on the research objectives. PSC-derived organoids typically undergo a stepwise differentiation process that mimics embryonic development, resulting in complex cellular compositions that may include multiple lineage descendants [40]. These models are particularly valuable for studying early organogenesis and developmental disorders. In contrast, AdSC-derived organoids are directly generated from tissue-specific stem cells and generally exhibit greater maturity and similarity to adult tissues, making them suitable for studying tissue homeostasis, adult-onset diseases, and infectious processes [40].

Organoid Generation and Regional Specification

Organoid generation typically involves a series of carefully orchestrated steps that guide stem cells through processes resembling in vivo development. The methodology generally revolves around three main steps: (1) induction or inhibition of key signaling pathways to establish appropriate regional identity during stem cell differentiation; (2) implementation of media formulations that support terminal differentiation of required cell types; and (3) propagation of cells in three-dimensional environments using extracellular matrix scaffolds to support complex tissue architecture [42].

Regional specification of organoids is achieved through the timed administration of specific patterning factors that mimic embryonic signaling centers. For brain organoids, these patterning cues establish positional identities along the dorsal-ventral (D-V) and anterior-posterior (A-P) axes, leading to the formation of distinct brain regions [40]. For example, the generation of dorsal spinal cord organoids involves modifying protocols for ventral spinal cord organoids by excluding ventralizing cues [45], while cerebral cortical organoids are generated through inhibition of both WNT and transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) signaling [40]. The continuous refinement of differentiation protocols has resulted in organoids with increasingly complex architectures and cellular diversity, better recapitulating the complexity of native tissues [42].

Assembloid Integration Strategies

Assembloids represent a significant advancement beyond single organoids by enabling the study of interactions between different tissue types or brain regions. These integrated systems are typically created by combining pre-differentiated organoids in a way that promotes their functional integration [44]. The assembly process must be carefully timed to match the developmental maturity of the components and provide appropriate environmental cues to support the formation of functional connections.

Current assembloid strategies can be categorized into four main types: multi-region assembloids that combine different brain areas; multi-lineage assembloids that incorporate cells from different germ layers; multi-gradient assembloids that establish positional signaling cues; and multi-layer assembloids that stack different tissue types [46]. For example, in the nervous system, forebrain assembloids have been created by combining pallial (dorsal forebrain) organoids containing primarily glutamatergic neurons with subpallial organoids rich in GABAergic neurons, enabling the study of interneuron migration and integration [44]. More complex four-part assembloids have recently been developed to model the entire ascending somatosensory pathway, incorporating somatosensory, spinal, thalamic, and cortical organoids [45].

The successful integration of assembloids requires not only physical proximity but also the establishment of functional connections. This process is supported by the inherent migratory and axon guidance mechanisms of the component cells, which, when provided with the appropriate environmental cues, can recapitulate aspects of natural circuit formation [44]. The resulting models enable researchers to study processes that were previously inaccessible in vitro, such as neural circuit assembly, long-distance cell migration, and complex inter-tissue signaling.

Comparative Analysis: Organoids vs. Assembloids

Structural and Functional Complexity

The fundamental distinction between organoids and assembloids lies in their architectural complexity and functional capabilities. Organoids typically model single tissue units or specific organ regions, exhibiting remarkable internal organization but limited capacity to represent interactions between different tissues. For instance, cerebral organoids can recapitulate aspects of human cortical development, including the formation of progenitor zones and layered neuronal organization [40], while intestinal organoids contain functional enterocytes, goblet cells, Paneth cells, and neuroendocrine cells [42]. However, these models often lack the supporting stroma and tissue-tissue interfaces characteristic of intact organs.