Functional Outcomes of Reprogramming Strategies: From In Vivo Rejuvenation to Targeted Transdifferentiation

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the functional outcomes achieved by diverse cellular reprogramming strategies, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals.

Functional Outcomes of Reprogramming Strategies: From In Vivo Rejuvenation to Targeted Transdifferentiation

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the functional outcomes achieved by diverse cellular reprogramming strategies, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational principles of in vivo reprogramming and its potential for tissue regeneration and age reversal. The review details methodological advances in direct fibroblast reprogramming for specific cell types, such as cardiomyocytes and alveolar epithelial cells, and investigates the critical challenges of safety, efficiency, and controllability. Finally, it offers a comparative analysis of reprogramming outcomes across different model systems and delivery methods, synthesizing the current state of the field and its implications for future clinical translation.

Cellular Reprogramming Foundations: Mechanisms and Therapeutic Potential for Regeneration and Rejuvenation

The field of cellular reprogramming has revolutionized regenerative medicine by enabling the conversion of one cell type into another, bypassing developmental barriers. Two primary paradigms have emerged: induced pluripotency, which reverts somatic cells to a pluripotent state, and direct lineage conversion, which directly transforms somatic cells into other specific cell types without passing through pluripotency. These approaches offer complementary advantages for disease modeling, drug screening, and cell-based therapies, each with distinct functional outcomes that researchers must consider when designing experimental and therapeutic strategies.

Induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) were first established in 2006 when Takahashi and Yamanaka demonstrated that somatic cells could be reprogrammed to a pluripotent state using defined factors [1]. Since this landmark discovery, the technology has rapidly advanced, with clinical applications now emerging. As of December 2024, regulatory approvals have been granted for 115 clinical trials testing 83 human pluripotent stem cell products, primarily targeting eye, central nervous system, and cancer conditions, with over 1,200 patients already treated with no generalizable safety concerns [2]. Meanwhile, direct reprogramming has developed as a powerful alternative, enabling more rapid generation of specific cell types with potentially lower tumorigenicity risks.

Induced Pluripotency: Mechanisms and Methodologies

Fundamental Principles and Transcription Factors

Induced pluripotency involves reprogramming differentiated somatic cells back to an embryonic-like pluripotent state, enabling them to differentiate into virtually any cell type. The original reprogramming factors—Oct4, Sox2, Klf4, and c-Myc (OSKM)—function through coordinated mechanisms to erase epigenetic memory and establish pluripotency [1]. During early reprogramming, c-Myc associates with histone acetyltransferase complexes to induce global histone acetylation, facilitating binding of exogenous Oct4 and Sox2 to target loci. The specific expression levels and ratios of Sox2 and Oct4 significantly impact reprogramming efficiency and iPSC colony quality, while Klf4 suppresses somatic cell genes while activating pluripotency networks [1].

Alternative factor combinations have also been identified, including Oct4, Sox2, Nanog, and Lin28 (OSNL), where Nanog functions as an essential pluripotency maintenance factor alongside Oct4 and Sox2, and Lin28 accelerates cell proliferation during early reprogramming phases [1]. Some studies have even combined six factors (OSKMNL) to achieve a 10-fold increase in reprogramming efficiency, particularly for fibroblasts from aged donors [1].

Reprogramming Delivery Methods

The method of delivering reprogramming factors significantly impacts efficiency, safety, and clinical applicability. Early methods used integrating retroviral and lentiviral vectors, raising concerns about insertional mutagenesis and residual transgene expression. Non-integrating methods have since been developed to enhance safety profiles:

Table 1: Comparison of iPSC Reprogramming Methods

| Method | Mechanism | Efficiency | Advantages | Limitations | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sendai Virus (SeV) | Non-integrating RNA virus | High (~fold higher than episomal) [3] | Non-integrating, high efficiency, broad tropism | Viral clearance needed, potential immunogenicity | Clinical applications requiring high efficiency |

| Episomal Vectors | OriP/EBNA1 plasmids | Moderate [3] | Non-integrating, simple production | Lower efficiency, requires nucleofection | Research with stringent safety requirements |

| mRNA Transfection | Modified mRNA molecules | Moderate-High [4] | Non-integrating, controlled expression | Requires multiple transfections, potential immune response | Clinical-grade iPSC generation |

| Chemical Reprogramming | Small molecule cocktails | Improving [5] | Non-integrating, standardized production | Still optimizing efficiency across cell types | Future clinical applications |

Comparative studies evaluating these methods have found that while source material (fibroblasts, LCLs, PBMCs) does not significantly impact success rates, the Sendai virus method yields significantly higher reprogramming success rates compared to episomal methods [3]. This makes SeV particularly valuable for biobanking applications where long-term reliability and reproducibility are crucial.

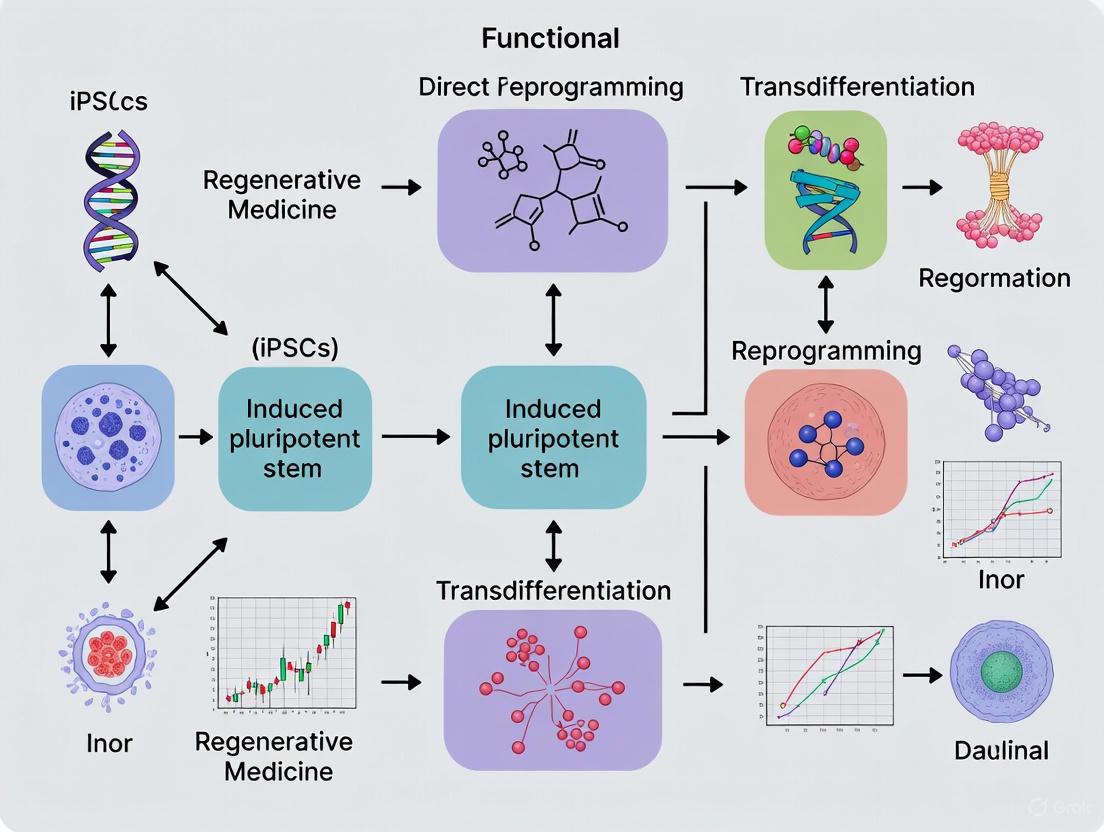

Figure 1: Induced Pluripotency Workflow: Somatic cells are reprogrammed using various methods to generate iPSCs, which can then be differentiated into target cell types.

Key Signaling Pathways in Pluripotency Induction

The molecular mechanisms governing pluripotency induction involve complex signaling networks. The canonical Wnt signaling pathway plays a particularly important role, as activation increases reprogramming efficiency by inducing chromatin remodeling and gene expression changes [6]. Endogenous Wnt activation, primarily mediated by WNT2B, is required for initiating direct reprogramming in some systems [6]. Other crucial pathways include BMP, TGF-β, and various growth factor signaling cascades that maintain pluripotency and self-renewal.

The process involves extensive epigenetic remodeling, where somatic cell identity genes are silenced through histone modification and DNA methylation, while pluripotency networks are activated. This epigenetic resetting creates cells with differentiation potential nearly equivalent to embryonic stem cells, enabling derivation of diverse cell types including neurons, cardiomyocytes, hepatocytes, and pancreatic β-cells [4].

Direct Lineage Conversion: Principles and Applications

Fundamental Concepts

Direct lineage conversion (also called transdifferentiation) enables direct reprogramming of somatic cells into other specific cell types without passing through a pluripotent intermediate. This approach offers several advantages, including faster conversion times (days rather than weeks), reduced tumorigenicity risk by avoiding pluripotent states, and preservation of epigenetic age that may be important for certain applications [7].

The fundamental principle involves identifying key transcription factors that function as "pioneer factors" to access closed chromatin regions and initiate transcriptional cascades that override existing cellular identity. Successful direct reprogramming typically requires combinations of factors that simultaneously suppress original cell identity while activating target cell genetic programs. This process often involves intermediate states that may represent plastic or partially reprogrammed cells before full conversion is achieved [7].

Representative Direct Reprogramming Systems

Several well-established direct reprogramming systems demonstrate the versatility and therapeutic potential of this approach:

Hair Cell-like Cells: A virus-free, inducible system using SIX1, ATOH1, POU4F3, and GFI1 (SAPG) transcription factors can reprogram human iPSCs into induced hair cell-like cells with 19-fold greater conversion efficiency compared to retroviral methods in half the time [8]. These cells express hair cell-specific markers, exhibit appropriate electrophysiological properties, and closely resemble developing fetal hair cells, offering significant potential for hearing loss treatments.

Alveolar Epithelial-like Cells: Mouse fibroblasts can be directly reprogrammed into induced pulmonary alveolar epithelial-like cells (iPULs) using Nkx2-1, Foxa1, Foxa2, and Gata6 transcription factors combined with 3D organoid culture [7]. The reprogramming efficiency significantly improved from 0.002% in 2D culture to approximately 2-3% of sorted cells in 3D culture conditions. These iPULs showed lamellar body-like structures and key properties of pulmonary alveolar epithelial cells, demonstrating potential for treating lung diseases.

Hepatic Progenitor Cells: Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) can be reprogrammed into human induced hepatic progenitor cells (hiHepPCs) using FOXA3, HNF1A, and HNF6 transcription factors [6]. Activation of canonical Wnt signaling increases reprogramming efficiency by rapidly inducing chromatin remodeling and gene expression changes, with endogenous Wnt activation mediated primarily by WNT2B.

Table 2: Direct Lineage Conversion Systems and Efficiencies

| Target Cell Type | Source Cell | Key Transcription Factors | Reprogramming Efficiency | Functional Assessment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hair Cell-like Cells | Human iPSCs | SIX1, ATOH1, POU4F3, GFI1 | 19-fold improvement vs. retroviral method [8] | Electrophysiology, marker expression, single-cell RNA-seq |

| Alveolar Epithelial-like Cells (iPULs) | Mouse fibroblasts | Nkx2-1, Foxa1, Foxa2, Gata6 | ~2-3% of sorted cells (from 0.002% in 2D) [7] | Lamellar body structures, organoid formation, in vivo integration |

| Hepatic Progenitor Cells | HUVECs | FOXA3, HNF1A, HNF6 + Wnt activation | Increased efficiency with Wnt [6] | Hepatic marker expression, functional analysis |

| Neurons | Fibroblasts | Various combinations (e.g., Ascl1, Brn2, Myt1l) | Varies by protocol | Electrophysiology, synaptic activity |

Figure 2: Direct Lineage Conversion Pathway: Somatic cells are directly converted to target cell types using specific transcription factor combinations, bypassing the pluripotent state entirely.

Comparative Functional Outcomes

Efficiency and Kinetics

The two reprogramming paradigms show marked differences in efficiency and timing. Induced pluripotency typically requires 3-4 weeks to generate established iPSC lines, followed by additional time for differentiation into specific cell types. In contrast, direct lineage conversion can produce functional target cells within 1-2 weeks [8] [7]. However, direct conversion generally yields lower percentages of fully reprogrammed cells compared to the robust efficiency of iPSC differentiation protocols once stable lines are established.

Direct reprogramming efficiency can be significantly enhanced through various strategies. Three-dimensional culture systems have shown remarkable improvements, increasing efficiency from 0.002% in 2D to 2-3% in 3D for alveolar epithelial-like cells [7]. Similarly, signaling pathway activation through Wnt stimulation boosted hepatic progenitor cell reprogramming efficiency [6]. For hair cell reprogramming, switching from retroviral methods to a virus-free inducible system increased efficiency by 19-fold while reducing the required time [8].

Safety Profiles and Genomic Integrity

Safety considerations differ substantially between the approaches. iPSC technologies carry inherent risks of teratoma formation if undifferentiated cells remain after differentiation, necessitating rigorous purification protocols. Additionally, the extensive proliferation capacity of iPSCs increases opportunities for acquiring genetic and epigenetic abnormalities during culture [1]. However, current non-integrating reprogramming methods have significantly improved the safety profile of iPSCs, with clinical trials demonstrating no generalizable safety concerns across more than 1,200 treated patients [2].

Direct lineage conversion minimizes cancer risk by avoiding pluripotent intermediates, though the potential for incomplete reprogramming or aberrant cell states remains. The use of integrating vectors in some direct reprogramming protocols raises similar insertional mutagenesis concerns as early iPSC methods, prompting development of non-integrating approaches including mRNA, protein transduction, and small molecules [8] [5].

Functional Maturation and Therapeutic Potential

Both strategies can generate cells with functional characteristics of their native counterparts, though maturation level varies. iPSC-derived cells often exhibit fetal-like properties, which may be advantageous for certain applications but limiting for others. Directly reprogrammed cells may maintain some epigenetic memory of their original identity, potentially influencing functionality [7].

Therapeutic applications are advancing for both approaches. iPSC-derived products have entered clinical trials for eye diseases, neurodegenerative disorders, and cardiovascular conditions [2] [9]. Directly reprogrammed cells show promise in disease modeling and may advance to clinical applications, particularly for tissues like lung alveoli and inner ear hair cells where access is challenging [8] [7].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Detailed iPSC Generation Protocol Using Sendai Virus

The following protocol has been optimized for high-efficiency reprogramming of fibroblasts and PBMCs using the CytoTune Sendai Reprogramming Kit [3]:

Day 0: Seeding Source Cells

- Plate 5×10^4 fibroblasts or 1×10^5 PBMCs per well in a 6-well plate with appropriate medium

- Incubate at 37°C, 5% CO₂ for 24 hours

Day 1: Viral Transduction

- Replace medium with fresh medium containing SeV vectors expressing hOCT4, hSOX2, hKLF4, hC-MYC, and EmGFP

- Incubate for 24 hours

Day 2: Medium Refresh

- Replace with fresh medium without vectors

- Culture for approximately 6 additional days with medium exchange every other day

- Monitor transduction efficiency via GFP-positive cells

Day 7-8: Replating

- Harvest transduced cells and replate onto feeder layers or Matrigel-coated plates

- Culture in essential 8 medium or similar defined medium

Day 21-28: Colony Picking

- Manually pick at least 24 colonies exhibiting typical iPSC morphology

- Expand individual clones in 12-well plates

Quality Control:

- Validate pluripotency markers (Nanog, Oct4, SSEA-4, TRA-1-60) via immunostaining

- Perform karyotyping analysis

- Test for mycoplasma contamination

- Confirm Sendai virus clearance by PCR after passage 10-12

Direct Reprogramming to Alveolar Epithelial-like Cells

This protocol details the direct conversion of mouse fibroblasts to iPULs using 4 transcription factors and 3D culture [7]:

Initial Transduction:

- Isolate mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) or tail-tip fibroblasts (TTFs)

- Transduce with retroviral vectors carrying Nkx2-1, Foxa1, Foxa2, and Gata6

- Culture in 2D for 7 days in DMEM with 10% FBS

3D Organoid Culture:

- Transfer transduced cells to low-attachment plates in serum-free medium

- Supplement with Wnt pathway activators (CHIR99021), growth factors (KGF, FGF10, FGF7), and BMP inhibitors (Noggin)

- Culture for 7-14 days, monitoring organoid formation

Cell Sorting and Purification:

- Dissociate organoids to single cells

- Sort for Sftpc-GFP⁺, Thy1.2⁻, EpCAM⁺ population using FACS

- Replate sorted cells in 3D Matrigel culture with alveolar epithelial cell medium

Functional Validation:

- Assess lamellar body formation via electron microscopy

- Measure surfactant protein expression (SP-A, SP-B, SP-C, SP-D) by qPCR and immunostaining

- Evaluate transcriptome similarity to primary AT2 cells by RNA-seq

- Test in vivo integration capability using bleomycin-induced lung injury model

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Reprogramming Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reprogramming Factors | Oct4, Sox2, Klf4, c-Myc (OSKM); SIX1, ATOH1, POU4F3, GFI1 (SAPG); Nkx2-1, Foxa1, Foxa2, Gata6 | Master regulators of cell identity and fate | Both iPSC and direct reprogramming |

| Delivery Systems | Sendai virus vectors, episomal plasmids, mRNA transfection kits | Introduce reprogramming factors into cells | Method-dependent efficiency optimization |

| Signaling Modulators | CHIR99021 (Wnt activator), Y-27632 (ROCK inhibitor), A83-01 (TGF-β inhibitor) | Enhance reprogramming efficiency and cell survival | Both paradigms; culture condition optimization |

| Culture Matrices | Matrigel, laminin-521, vitronectin | Provide structural support and signaling cues | Maintenance of pluripotency or differentiated states |

| Characterization Tools | Flow cytometry antibodies (SSEA-4, TRA-1-60), single-cell RNA-seq kits | Assess reprogramming success and purity | Quality control and mechanistic studies |

The choice between induced pluripotency and direct lineage conversion depends on specific research or therapeutic objectives. Induced pluripotency offers unparalleled versatility for generating multiple cell types from a single source and enables extensive expansion for large-scale applications. The established safety profile of iPSCs in clinical trials supports their use for therapeutic development [2]. However, the extended timeline and potential tumorigenicity risks remain important considerations.

Direct lineage conversion provides faster generation of specific cell types with potentially superior safety profiles by avoiding pluripotent intermediates. The preservation of epigenetic age in directly converted cells may better model age-related diseases. However, lower efficiencies and limited expansion capacity present challenges for some applications.

Future directions will likely focus on hybrid approaches that combine strengths of both paradigms, enhanced safety through non-integrating methods, and improved maturation protocols. The continued development of chemical reprogramming using entirely small-molecule approaches promises to further transform the field by offering completely non-genetic methods for cell fate manipulation [5]. As both technologies evolve, they will increasingly enable personalized disease modeling, drug screening, and regenerative therapies across diverse medical specialties.

In vivo reprogramming represents a revolutionary approach in regenerative medicine that involves directly changing cell identity within a living organism. This strategy builds upon the foundational discovery by Shinya Yamanaka that forced expression of four transcription factors—OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, and c-MYC (collectively known as OSKM)—can reprogram specialized adult cells into induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) [10]. While initial applications focused on generating patient-specific stem cells in laboratory settings, recent advances have demonstrated that transient, controlled expression of these same factors directly in living organisms can promote tissue regeneration and reverse age-related physiological decline without requiring cell transplantation [11] [12].

The fundamental premise of in vivo reprogramming hinges on the concept of epigenetic remodeling—the ability to reset age-associated changes in gene regulation and chromatin organization [11] [13]. When applied in a partial or cyclical manner, OSKM expression appears to rejuvenate cells by restoring youthful epigenetic patterns and transcriptional profiles while avoiding complete dedifferentiation to a pluripotent state [14] [13]. This approach has demonstrated remarkable potential across diverse tissue types and disease models, though significant challenges remain in achieving precise spatiotemporal control to maximize therapeutic benefits while minimizing risks such as teratoma formation [11] [15]. The growing body of evidence supporting OSKM-mediated rejuvenation has generated substantial interest in both academic and biotechnology sectors, positioning in vivo reprogramming as a promising frontier for addressing age-related diseases and degenerative conditions [16] [14].

Mechanisms of Action: From Epigenetic Remodeling to Functional Restoration

Key Molecular Mechanisms of OSKM-Mediated Reprogramming

The OSKM factors function as powerful regulators of cellular identity by orchestrating widespread changes in gene expression patterns and chromatin architecture. At the molecular level, OCT4 and SOX2 act as pioneer factors that bind to closed chromatin regions and initiate the opening of pluripotency-associated loci, while KLF4 and c-MYC further facilitate epigenetic remodeling and cell cycle re-entry [10] [17]. During in vivo reprogramming, these factors collaboratively target thousands of genomic sites, with significant conservation of target genes between human and mouse systems despite differences in specific binding locations [17]. This initial binding triggers a cascade of epigenetic changes, including modifications to histone marks such as H3K9me3 and DNA methylation patterns, which progressively erase age-associated epigenetic signatures and restore a more youthful regulatory landscape [11] [13].

The mechanistic parallels between injury-induced dedifferentiation and OSKM-mediated reprogramming provide valuable insights into how partial reprogramming promotes regeneration. In tissues with innate regenerative capacity, such as the liver and intestine, OSKM expression appears to amplify endogenous plasticity programs rather than introducing regeneration de novo [11]. Conversely, in tissues with limited regenerative potential like the heart and retina, OSKM reprogramming functions as an exogenous driver that overcomes epigenetic barriers to induce repair [11] [18]. The process generates transient regenerative progenitors that can subsequently redifferentiate into functional tissue-specific cells, thereby restoring organ function without forming teratomas when properly controlled [11].

Signaling Pathways and Molecular Trajectories

The following diagram illustrates the core molecular pathway through which OSKM factors mediate cellular reprogramming and rejuvenation in vivo:

Figure 1: OSKM-Mediated Reprogramming Pathway. This diagram illustrates the molecular cascade initiated by OSKM factors, from epigenetic remodeling to functional tissue outcomes.

Comparative Performance Analysis Across Tissue Types

Regenerative Outcomes in Various Organs

In vivo reprogramming with OSKM factors has demonstrated remarkable potential for promoting tissue regeneration across diverse organ systems. The therapeutic effects and underlying mechanisms vary significantly depending on the intrinsic regenerative capacity of each tissue type. The following table summarizes key experimental findings from recent studies investigating OSKM-mediated regeneration in different tissues:

Table 1: Tissue-Specific Outcomes of OSKM-Mediated In Vivo Reprogramming

| Tissue/Organ | Experimental Model | Key Findings | Functional Outcomes | Proposed Mechanisms |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heart | Mouse myocardial infarction model [18] | Reprogramming of cardiac fibroblasts to cardiomyocytes | Improved ventricular contractility; Reduced fibrosis | Direct lineage conversion; Modulation of fibroblast heterogeneity |

| Skeletal Muscle | Aged mice [11] | Enhanced muscle regeneration after injury | Improved muscle function; Reduced fibrosis | Epigenetic remodeling; Enhanced satellite cell activity |

| Retina | Mouse glaucoma model [11] | Restoration of visual function | Improved visual responses; Neuronal regeneration | Dedifferentiation and redifferentiation of retinal cells |

| Liver | Mouse partial hepatectomy [11] | Accelerated tissue regeneration | Improved liver function; Enhanced regenerative capacity | Amplification of endogenous dedifferentiation programs |

| Skin | Mouse wound healing model [11] [13] | Reduced fibrotic responses; Improved repair | Accelerated wound closure; Reduced scarring | Inhibition of fibroblast-to-myofibroblast transition |

| Pancreas | Aged mice [11] | Improved β-cell function | Enhanced glucose regulation; Tissue rejuvenation | Epigenetic reset of age-related changes |

| Brain | Aged mouse model [11] | Reversal of age-related transcriptional changes | Cognitive improvements; Neuronal function restoration | Epigenetic remodeling; Reduced inflammation |

The data reveals two distinct paradigms for OSKM-mediated regeneration based on the innate regenerative capacity of the target tissue. In organs with limited regenerative potential, such as the heart, retina, and skeletal muscle, OSKM reprogramming functions as an exogenous driver that actively induces repair by overcoming epigenetic barriers [11] [18]. Conversely, in organs with inherent regenerative capacity like the liver and intestine, OSKM expression appears to amplify endogenous plasticity programs rather than introducing regeneration de novo [11]. This distinction has important implications for therapeutic development, as optimal reprogramming protocols may need to be tailored to specific tissue contexts.

Rejuvenation Effects in Aging Models

Perhaps the most striking application of in vivo reprogramming has been in the context of age reversal. Landmark studies using progeria mouse models have demonstrated that cyclic induction of OSKM factors can significantly extend lifespan and ameliorate multiple aging-related pathological features [11] [13]. In one pivotal study, progeria mice subjected to a cyclic OSKM induction regimen (2 days ON, 5 days OFF) exhibited a 33% extension in median lifespan alongside improvements in cardiovascular function, skin integrity, and spinal curvature [11] [13]. Subsequent research in naturally aged wild-type mice has confirmed that similar approaches can restore youthful DNA methylation patterns, transcriptomic profiles, and metabolic function across multiple tissues including the spleen, liver, skin, kidney, lung, and skeletal muscle [11] [14].

The rejuvenating effects of partial reprogramming appear to operate through both cell-autonomous and systemic mechanisms. At the cellular level, OSKM exposure reverses age-associated epigenetic marks, enhances mitochondrial function, reduces DNA damage accumulation, and ameliorates cellular senescence [14] [13]. These changes collectively contribute to improved tissue homeostasis and regenerative capacity in aged animals. Importantly, the rejuvenation observed following partial reprogramming is distinct from complete dedifferentiation, as treated cells maintain their tissue identity while resetting age-related molecular signatures [13]. This distinction is crucial for therapeutic applications, as it suggests that age reversal can be achieved without compromising tissue organization or function.

Experimental Protocols and Methodological Approaches

Key Experimental Systems for In Vivo Reprogramming

Research on OSKM-mediated in vivo reprogramming has employed several sophisticated genetic systems to achieve precise temporal control over factor expression. The most widely utilized approach involves transgenic mouse models with doxycycline (Dox)-inducible OSKM cassettes, enabling researchers to initiate reprogramming through simple administration of Dox in drinking water or food [11]. The most common models include:

- 4Fj and 4Fk mice: Feature OSKM or OKSM cassettes inserted at the Col1a1 locus using Tet-On systems [11]

- 4F-A (4FsA) and 4F-B (4FsB) models: Contain OSKM cassettes integrated at the Neto2 and Pparg loci, respectively [11]

- Progeria mouse models: Express mutant lamin A to mimic human Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome (HGPS), allowing assessment of rejuvenation effects [11] [10]

These systems demonstrate striking tissue specificity in OSKM activation, with robust induction typically observed in the intestine, liver, and skin, and comparatively lower activation in the brain, heart, and skeletal muscle [11]. This variability reflects inherent differences in chromatin accessibility and promoter activity across tissues, highlighting the importance of considering tissue-specific responses when designing reprogramming protocols.

Beyond transgenic models, recent studies have explored viral delivery methods for OSKM factors, particularly adeno-associated viruses (AAVs) with tissue-specific tropism [18] [13]. For example, AAV9 vectors have been used to deliver OSK factors (excluding c-MYC to reduce tumorigenic risk) to multiple tissues in wild-type mice, resulting in significant extension of remaining lifespan in aged animals [13]. This gene therapy approach offers potential translational advantages over transgenic models, as it could theoretically be applied to human patients without requiring germline genetic modifications.

Induction Protocols and Regimen Optimization

The specific parameters of OSKM induction critically determine the balance between therapeutic efficacy and safety concerns. Research has identified several key variables that influence reprogramming outcomes:

- Induction duration: Short-term induction (typically 1-7 days) favors partial reprogramming and rejuvenation, while prolonged continuous induction (weeks) frequently leads to teratoma formation [11]

- Cyclical regimens: Protocols such as "2 days ON, 5 days OFF" or "1 day ON, 6 days OFF" have demonstrated efficacy in promoting rejuvenation while minimizing tumorigenic risks [11] [13]

- Factor composition: Some studies omit c-MYC from the cocktail (using only OSK) to reduce oncogenic potential while retaining significant rejuvenation capacity [13]

- Tissue-specific optimization: Delivery methods and induction parameters may require customization based on the target tissue's accessibility, cellular composition, and intrinsic plasticity [18]

The timing of intervention also appears to influence reprogramming efficiency, with aged cells generally exhibiting reduced transdifferentiation capacity compared to their younger counterparts [18]. This age-dependent decline in reprogramming efficiency presents a particular challenge for clinical translation, as the patients most likely to benefit from rejuvenation therapies are typically older. Overcoming this limitation may require complementary approaches such as metabolic interventions or modulation of age-related signaling pathways [18].

Safety Considerations and Risk Mitigation Strategies

Primary Safety Concerns in OSKM Reprogramming

The tremendous therapeutic potential of in vivo reprogramming is balanced against significant safety considerations that must be addressed before clinical translation. The most serious risks associated with OSKM expression include:

- Teratoma formation: Continuous induction of OSKM over several weeks reliably generates teratomas in multiple organs, while even transient induction (7 days) can initiate dysplastic changes and tumor formation in susceptible tissues like the pancreas, liver, and kidney [11] [15]

- Erosion of cellular identity: Uncontrolled reprogramming can lead to loss of tissue-specific functions through dedifferentiation [11] [12]

- Organ dysfunction: Studies have reported instances of liver failure and intestinal dysfunction following OSKM induction, potentially resulting from disrupted tissue homeostasis [11] [14]

- Cancer promotion: In certain contexts, OSKM expression can accelerate cancer development by driving dedifferentiation of already transformed cells [11]

Interestingly, the relationship between reprogramming and cancer is complex and context-dependent. While OSKM can promote tumorigenesis in some settings, it has also been shown to selectively eradicate leukemia cells bearing the MLL-AF9 fusion gene while sparing normal hematopoietic cells [11]. This paradoxical effect underscores the importance of understanding the specific molecular and cellular contexts in which reprogramming factors operate.

Approaches to Enhance Safety Profiles

Research has identified several promising strategies to mitigate the risks associated with in vivo reprogramming:

Table 2: Safety Challenges and Mitigation Strategies in OSKM Reprogramming

| Safety Challenge | Risk Mitigation Approaches | Experimental Support |

|---|---|---|

| Teratoma formation | Cyclical induction; Factor dosage optimization; Exclusion of c-MYC | [11] [13] |

| Loss of cell identity | Partial reprogramming protocols; Limited induction duration | [11] [12] |

| Inadequate tissue targeting | Tissue-specific promoters; Targeted delivery systems (AAVs, nanoparticles) | [18] [13] |

| Off-target effects | Transient mRNA delivery; Small molecule alternatives | [16] [13] |

| Age-related efficiency reduction | Metabolic interventions; Autophagy enhancement; Mitochondrial optimization | [18] |

The following diagram illustrates the key safety considerations and corresponding mitigation strategies in OSKM-mediated in vivo reprogramming:

Figure 2: Safety Considerations and Mitigation Strategies in OSKM Reprogramming. This diagram outlines major risks associated with in vivo OSKM expression and corresponding approaches to enhance safety profiles.

Research Reagent Solutions and Technical Tools

The investigation of OSKM-mediated reprogramming relies on specialized reagents and technical tools that enable precise control and monitoring of the reprogramming process. The following table outlines key research solutions essential for conducting in vivo reprogramming studies:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for In Vivo Reprogramming Studies

| Reagent/Tool | Function/Application | Examples/Specifics | Experimental Utility |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dox-inducible OSKM systems | Controlled factor expression | 4Fj, 4Fk, 4F-A, 4F-B mouse models [11] | Enables temporal regulation via doxycycline administration |

| Lineage tracing models | Fate mapping of reprogrammed cells | Tcf21-iCre, Fsp1-Cre, Postn-lineage tracing [18] | Tracks cellular origins and conversion outcomes |

| AAV delivery vectors | In vivo factor delivery | AAV9-OSK constructs [13] | Facilitates translational gene therapy approaches |

| Epigenetic clocks | Assessment of biological age | DNA methylation patterns; Multi-omics profiles [14] [13] | Quantifies rejuvenation effects at molecular level |

| Pluripotency markers | Monitoring reprogramming status | SSEA-4, TRA-1-60, NANOG, alkaline phosphatase [16] | Identifies intermediate reprogramming states |

| Senescence assays | Detection of age-related changes | β-galactosidase activity; p16/p21 expression [10] | Evaluates rejuvenation efficacy |

| AI-enhanced factors | Improved reprogramming efficiency | RetroSOX, RetroKLF variants [16] | Increases reprogramming efficiency (>50-fold) |

Recent advances in reagent development have substantially enhanced the efficiency and specificity of in vivo reprogramming approaches. Notably, AI-guided protein engineering has yielded novel factor variants such as RetroSOX and RetroKLF that demonstrate dramatically improved reprogramming efficiency compared to wild-type factors [16]. In vitro testing of these engineered variants has shown over 50-fold higher expression of pluripotency markers and enhanced DNA damage repair capabilities, suggesting superior rejuvenation potential [16]. The availability of such optimized tools will accelerate both basic research and therapeutic development in the reprogramming field.

In vivo reprogramming with OSKM factors represents a paradigm-shifting approach with demonstrated potential for promoting tissue regeneration and reversing age-related physiological decline. The accumulating evidence from diverse animal models indicates that partial, cyclical reprogramming can rejuvenate cellular function across multiple tissues without inducing teratoma formation or complete loss of cellular identity [11] [13]. The mechanistic insights gleaned from these studies highlight the crucial role of epigenetic remodeling in restoring regenerative capacity and reversing age-associated molecular signatures.

Despite these promising advances, significant challenges remain in translating OSKM-based therapies to clinical applications. The dualistic nature of reprogramming—balancing therapeutic rejuvenation against risks of tumorigenesis and loss of tissue function—necessitates exquisite control over factor expression, delivery, and duration [11] [15] [14]. Future research directions will likely focus on developing more precise spatiotemporal control systems, optimizing factor combinations and delivery methods for specific tissues, and identifying small molecule alternatives that can mimic or enhance the rejuvenating effects of OSKM factors [16] [13]. As these technical hurdles are addressed, in vivo reprogramming may ultimately transform approaches to treating degenerative diseases and age-related functional decline.

Aging is characterized by a progressive decline in physiological function and an increased susceptibility to chronic diseases, driven by conserved biological processes often termed the "hallmarks of aging" [19]. Among the most promising strategies for intervening in the aging process is partial cellular reprogramming. This technique involves the transient expression of reprogramming factors, such as the Yamanaka factors (OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, c-MYC, collectively OSKM), to reverse age-related epigenetic and transcriptional changes without fully erasing cellular identity [13] [10]. Unlike full reprogramming to induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs)—which carries a high risk of teratoma formation—partial reprogramming aims to rejuvenate aged cells and tissues while maintaining their functional specialization and avoiding tumorigenesis [13] [10].

This review objectively compares the functional outcomes of different reprogramming strategies, with a focus on partial reprogramming. We summarize quantitative data from key preclinical studies, provide detailed experimental protocols, and illustrate core signaling pathways. By comparing partial reprogramming against alternative strategies like full reprogramming and transdifferentiation, we aim to provide researchers and drug development professionals with a clear framework for evaluating the therapeutic potential and safety profile of each approach.

Comparative Analysis of Reprogramming Strategies

The field of cellular rejuvenation has developed several distinct strategies to reverse aging hallmarks. Table 1 provides a systematic comparison of three core approaches: partial reprogramming, full reprogramming, and transdifferentiation, highlighting their differential impacts on aging hallmarks and tumorigenic risk.

Table 1: Functional Outcome Comparison of Reprogramming Strategies for Aging Amelioration

| Reprogramming Strategy | Impact on Aging Hallmarks | Effect on Cellular Identity | Tumorigenesis Risk | Key Functional Outcomes in Model Systems |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Partial Reprogramming | Reverses epigenetic aging clocks, reduces cellular senescence, restores mitochondrial function [13] [14] [20]. | Maintains original cell identity with restored function [13] [10]. | Lower risk; no teratomas in mice with cyclic induction, but requires careful dosing [13] [10]. | Lifespan extension (up to 109% in old wild-type mice), improved wound healing, muscle regeneration, restored visual function in mice [13] [20]. |

| Full Reprogramming (iPSC) | Resets epigenetic age and telomere length to an embryonic state [10] [14]. | Erases somatic identity, creates pluripotent stem cells [10]. | High risk of teratoma formation post-transplantation [10]. | Used for disease modeling; not suitable for direct in vivo rejuvenation due to tumor risk [10]. |

| Transdifferentiation | Impact on hallmarks is variable and less studied; may retain some age-related signatures [14]. | Converts one somatic cell type directly into another [14]. | Context-dependent; risk if pathway involves proliferative intermediates. | Retains senescent phenotype in aged fibroblasts directly converted to neural stem cells [14]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols for Key Studies

To facilitate replication and further development, this section details the methodologies from seminal studies demonstrating the efficacy and safety of partial reprogramming.

In Vivo Partial Reprogramming in Progeria and Wild-Type Mice

Objective: To assess the potential of cyclic, short-term OSKM expression to reverse aging phenotypes in vivo and extend healthspan and lifespan without inducing tumors [13].

Key Reagents & Models:

- Genetic Model: LAP-MerCreMer transgenic mice (for whole-body, Dox-inducible OSKM expression) or wild-type mice injected with AAV9-OSK vectors.

- Induction Agent: Doxycycline (Dox) in drinking water or chow.

- Key Reagents: AAV9 vectors packaging OSK (OCT4, SOX2, KLF4) and rtTA.

Experimental Workflow:

- Animal Grouping: Progeroid (e.g., LAKI) and wild-type mice are divided into treatment (Dox-induced) and control groups.

- Cyclic Induction: Administration of Dox in cycles (e.g., 2 days on, 5 days off) for multiple cycles (e.g., 35 cycles in progeria models) or long-term (7-10 months) in wild-type mice.

- In Vivo Monitoring: Regular assessment of healthspan parameters (frailty index, skin regeneration, wound healing) and observation for teratoma formation.

- Endpoint Analysis:

- Lifespan: Survival analysis compared to controls.

- Molecular Phenotyping: Multi-omics analysis (transcriptomics, epigenomics, lipidomics) of tissues like liver, skin, and spleen to assess rejuvenation.

- Histopathology: Comprehensive analysis of major organs for teratomas or other abnormalities.

Outcome Summary: This protocol achieved a 33% median lifespan extension in progeroid mice and a 109% remaining lifespan extension in old wild-type mice, with no reported teratoma formation [13].

Partial Chemical Reprogramming of Fibroblasts

Objective: To rejuvenate aged somatic cells using non-integrating, small-molecule cocktails, thereby avoiding genetic manipulation [13].

Key Reagents:

- Cell Source: Mouse or human primary fibroblasts from young and old donors.

- Chemical Cocktail: The "7c" cocktail, consisting of small molecules that modulate key signaling pathways (e.g., TGF-β, GSK3).

- Assay Kits: For measuring mitochondrial function (e.g., ROS, OXPHOS), RNA/DNA sequencing for epigenetic clocks, and senescence-associated beta-galactosidase (SA-β-Gal).

Experimental Workflow:

- Cell Culture: Primary fibroblasts are maintained in standard culture conditions.

- Chemical Treatment: Cells are treated with the 7c cocktail for a defined period (e.g., 10-14 days), with medium changes every few days.

- Assessment of Rejuvenation:

- Cellular Markers: SA-β-Gal staining to quantify senescent cell burden.

- Functional Assays: Measurement of mitochondrial ROS and oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) capacity.

- Molecular Profiling: RNA-seq and DNA methylation analysis (e.g., using epigenetic clocks) to demonstrate a shift to a younger transcriptional and epigenetic profile.

Outcome Summary: Treatment with the 7c cocktail reversed epigenetic and transcriptomic aging clocks and ameliorated age-associated metabolic profiles in human fibroblasts, notably without inducing rapid cell proliferation [13].

Visualization of Core Concepts and Pathways

The following diagrams, generated using DOT language, illustrate the logical relationships and signaling pathways central to partial reprogramming and its contrast with tumorigenic processes.

Partial vs. Full Reprogramming Workflow

Senescence and Reprogramming Signaling Network

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful investigation into partial reprogramming relies on a suite of specialized reagents and tools. Table 2 lists key solutions and their applications for researchers in this field.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Partial Reprogramming Studies

| Research Reagent / Tool | Function in Partial Reprogramming Research | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Doxycycline (Dox)-Inducible OSKM Systems | Enables precise, transient expression of Yamanaka factors in vitro and in vivo [13]. | Cyclic induction of OSKM in transgenic mouse models (e.g., 2 days on/5 days off) to achieve rejuvenation without teratomas [13]. |

| AAV9 Vectors | Efficient in vivo gene delivery system with broad tissue tropism for OSK(M) factors [13]. | Delivery of OSK factors to aged wild-type mice to extend lifespan and improve healthspan, excluding c-Myc to reduce oncogenic risk [13]. |

| Chemical Reprogramming Cocktails (e.g., 7c) | Non-integrating, small-molecule approach to induce rejuvenation, avoiding genetic manipulation [13]. | Reversal of epigenetic age and restoration of mitochondrial function in aged human fibroblasts in culture [13]. |

| DNA Methylation Clocks | Biomarker tool to quantify biological age pre- and post-reprogramming intervention [13] [21]. | Validation of epigenetic rejuvenation in treated cells (e.g., fibroblasts) and tissues (e.g., liver, spleen) from animal models [13]. |

| Senescence Assays (SA-β-Gal, SASP) | Measures a key aging hallmark—cellular senescence—to assess intervention efficacy [21] [20]. | Quantifying reduction in senescent cell burden following partial reprogramming treatment in tissue sections or cell culture [20]. |

Partial reprogramming represents a frontier in therapeutic rejuvenation, demonstrating a remarkable capacity to ameliorate core aging hallmarks—particularly epigenetic alterations and cellular senescence—while presenting a manageably lower tumorigenic risk compared to full reprogramming [13] [21]. The functional outcomes, including extended healthspan and lifespan in mouse models, underscore its transformative potential [13].

However, the path to clinical translation requires overcoming significant hurdles. Key challenges include optimizing delivery systems for precise spatiotemporal control in humans, fine-tuning dosing to maximize efficacy while eliminating any residual risk of teratoma formation or loss of cellular identity, and developing robust, human-validated biomarkers to track biological age in clinical trials [13] [19] [10]. Future research must prioritize the development of safer, non-genetic delivery methods (e.g., refined chemical cocktails or protein-based approaches) and rigorously assess the long-term functional benefits and safety of these interventions in more complex mammalian models. For researchers and drug developers, the strategic selection of reprogramming factors, delivery vectors, and dosing protocols will be paramount in harnessing the promise of partial reprogramming to transform the treatment of aging and age-related diseases.

Direct reprogramming, or transdifferentiation, represents a paradigm shift in regenerative medicine by enabling the direct conversion of one differentiated somatic cell type into another, bypassing an intermediary pluripotent stem cell state [22] [23]. This groundbreaking approach offers a promising therapeutic strategy for tissue repair and regeneration. A particularly compelling application is the reprogramming of fibroblasts—the primary drivers of pathological fibrosis—into functional tissue-specific cells [22].

Fibrosis, characterized by excessive extracellular matrix (ECM) deposition and tissue scarring, contributes significantly to organ dysfunction across numerous chronic diseases [22]. Activated fibroblasts and myofibroblasts are central players in this process, secreting massive amounts of collagen and other ECM components that disrupt normal tissue architecture and function [22] [23]. Direct reprogramming strategically targets these pathogenic cells, simultaneously reducing the fibrotic cell population while regenerating lost or damaged functional cells [22]. This dual-action mechanism addresses both tissue degeneration and the pathological microenvironment that perpetuates disease progression.

This review comprehensively compares the performance of diverse direct reprogramming strategies across multiple organ systems, evaluating their efficacy in cell fate conversion and anti-fibrotic outcomes within the context of functional recovery. We synthesize experimental data from recent studies to provide researchers and drug development professionals with a rigorous assessment of this rapidly advancing field.

Comparative Analysis of Direct Reprogramming Strategies

Table 1: Cardiac Fibroblast to Induced Cardiomyocyte (iCM) Reprogramming Strategies

| Reprogramming Factor Combination | Delivery Method | Model System | Reprogramming Efficiency | Functional Outcomes | Anti-Fibrotic Effects |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GMT (GATA4, MEF2C, TBX5) [22] | Retroviral | In vivo (Mouse MI) | Not specified | Improved cardiac function; iCMs exhibited action potentials and spontaneous contraction | Reduced scar area |

| GMTH (GMT + HAND2) [22] | Retroviral | In vivo (Mouse MI) | Higher than GMT | Generation of more iCMs; improved cardiac function | Accelerated reduction in fibrotic area |

| MYΔ3A + ASCL1 [22] | Not specified | In vivo (Mouse acute & chronic MI) | Not specified | Improved cardiac function | Alleviated cardiac fibrosis |

| miRNA combo (miR-1, miR-133, miR-208, miR-499) [22] | Lentiviral; Nanoparticle (FNLM) | In vivo (Mouse MI) | Not specified | iCMs with calcium transients and beating capacity; Enhanced conversion with targeted delivery | Significant reduction in cardiac fibrosis |

| Small Molecule Cocktail (CRFVPTM) [22] | Not specified | In vivo | Not specified | Generated iCMs with action potentials | Significantly reduced scar area |

| Small Molecules (SB431542 + Baricitinib) + MT [22] | Not specified | In vitro | Not specified | Selective reprogramming of CFs over other fibroblasts | Not specified |

Table 2: Reprogramming Strategies Across Other Tissues

| Target Cell | Reprogramming Factors | Starting Cell Type | Model System | Key Functional Markers | Therapeutic Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Induced Keratinocyte-Like Cells (iKCs) [24] | BMI1 + FGFR2b (B2) | Mouse fibroblasts (L929) | In vitro; In vivo (diabetic mouse wound model) | Expression of keratinocyte markers (KRT10, KRT14) | Promoted wound closure, reconstructed stratified epithelium, restored barrier function, reduced mortality |

| Induced Pulmonary Alveolar Epithelial-like Cells (iPULs) [7] | Nkx2-1, Foxa1, Foxa2, Gata6 | Mouse tail-tip fibroblasts; Mouse embryonic fibroblasts | In vitro (3D organoid culture); In vivo (bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis mouse model) | Surfactant protein-C (Sftpc); Lamellar body-like structures | Integrated into alveolar surface, formed AT1 and AT2-like cells |

| Induced Cardiomyocytes (iCMs) [23] | Gata4, Mef2c, Tbx5 (GMT) | Cardiac fibroblasts | In vitro; In vivo | Cardiomyocyte-like gene expression; Action potentials; Spontaneous beating | Improved heart function; Reduced fibrosis after cardiac injury |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Cardiac Reprogramming Protocol

The foundational protocol for cardiac reprogramming was established by Ieda et al. (2010), demonstrating that a combination of three cardiac transcription factors—Gata4, Mef2c, and Tbx5 (GMT)—could reprogram cardiac fibroblasts into induced cardiomyocytes (iCMs) in vitro [22] [23]. This methodology involves:

Factor Delivery: Transcription factors are typically delivered via retroviral vectors to ensure stable integration and expression in target fibroblasts [22]. For in vivo applications, retroviral GMT is delivered directly to injured hearts in myocardial infarction mouse models [22].

Culture Conditions: Reprogrammed cells are maintained in standard cardiac cell culture media, with spontaneous beating typically observed in a subset of cells within 1-2 weeks post-transduction [22].

Functional Validation: Successful reprogramming is confirmed through multiple assays including patch-clamp electrophysiology to record action potentials, calcium imaging to detect transients, and observation of spontaneous contraction [22].

In Vivo Assessment: In animal models, functional recovery is evaluated through echocardiography to measure cardiac function, while fibrotic area is quantified using histological staining methods (e.g., Masson's trichrome for collagen) [22].

Protocol enhancements have included polycistronic constructs with "self-cleaving" 2A sequences to ensure coordinated expression of multiple factors, with the M-G-T transcriptional order demonstrating highest conversion efficiency [22]. Additional factors like HAND2 have been incorporated to improve reprogramming efficiency and anti-fibrotic effects [22].

Pulmonary Alveolar Epithelial Cell Reprogramming

The generation of induced pulmonary alveolar epithelial-like cells (iPULs) from fibroblasts involves a sophisticated screening and culture approach:

Factor Screening: An initial screen of 14 candidate genes associated with pulmonary alveolar epithelial cell differentiation identified NKX2-1 as essential for inducing surfactant protein-C (Sftpc) expression [7]. Systematic elimination revealed the optimal combination as NKX2-1, FOXA1, FOXA2, and GATA6.

3D Organoid Culture: Transduced mouse embryonic fibroblasts are cultured in three-dimensional organoid systems instead of traditional 2D cultures, significantly improving reprogramming efficacy [7].

Serum-Free Media Supplementation: Culture media is supplemented with Wnt pathway activators, various growth factors, and Smad inhibitors to support alveolar epithelial cell differentiation and maturation [7].

Cell Sorting and Purification: Fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) is employed to isolate successfully reprogrammed cells using the marker combination Sftpc-GFP+ Thy1.2- EpCAM+ [7]. This purification step typically yields 2-3% iPULs from the initial fibroblast population by day 7 post-transduction.

In Vivo Validation: iPULs are administered via intratracheal instillation in bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis mouse models, with subsequent assessment of alveolar integration and differentiation into both AT1 and AT2-like cells [7].

Keratinocyte-Like Cell Reprogramming for Cutaneous Wound Healing

The direct conversion of fibroblasts into induced keratinocyte-like cells (iKCs) for diabetic wound repair utilizes a streamlined two-factor approach:

Factor Combination: The B2 combination (BMI1 + FGFR2b) is delivered via adeno-associated virus 9 (AAV9), which exhibits high epithelial transduction efficiency [24].

In Vivo Delivery: AAV9 vectors encoding BMI1 and FGFR2b are administered directly to wound sites in diabetic (db/db) mouse models through subcutaneous injection or topical application [24].

Molecular Validation: Successful reprogramming is confirmed through qRT-PCR analysis of keratinocyte markers (KRT10, KRT14), Western blot, immunofluorescence, and transcriptomic analysis [24].

Functional Assessment: Wound closure rates are quantified, and histological examination evaluates re-epithelialization, stratification, and restoration of barrier function [24].

Signaling Pathways and Molecular Mechanisms

Direct reprogramming efficiency is critically influenced by the fibrotic microenvironment, with several key signaling pathways acting as barriers to complete cell fate conversion.

The TGF-β signaling pathway represents a major barrier to reprogramming, sustaining fibroblast identity through SMAD-dependent transcription of pro-fibrotic genes [22]. Successful reprogramming strategies often incorporate TGF-β pathway inhibitors (e.g., SB431542, A83-01) to facilitate epigenetic remodeling.

Mechanical signaling from the stiffened extracellular matrix in fibrotic tissues activates YAP/TAZ signaling, reinforcing myofibroblast identity and presenting both physical and biochemical resistance to lineage conversion [22].

Epigenetic modifiers play dual roles in maintaining fibrotic programs and enabling reprogramming. Small molecule inhibitors targeting DNA methyltransferases and histone modifiers can disrupt fibrotic epigenetic memory while opening chromatin at target cell-specific loci [22].

Metabolic reprogramming accompanies successful cell fate conversion, with a shift from glycolysis toward fatty acid oxidation observed during fibroblast-to-cardiomyocyte conversion, mirroring metabolic maturation in native cardiomyocytes [23].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Direct Reprogramming Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function in Reprogramming |

|---|---|---|

| Transcription Factors | Gata4, Mef2c, Tbx5, HAND2, Nkx2-1, Foxa1, Foxa2, Gata6, BMI1, FGFR2b | Master regulators that initiate gene expression programs of target cell type |

| Viral Delivery Systems | Retrovirus, Lentivirus, Adeno-associated virus (AAV9) | Stable or transient delivery of reprogramming factors to target cells |

| Small Molecule Inhibitors/Activators | CHIR99021 (GSK-3 inhibitor), A83-01 (TGF-β inhibitor), SB431542 (TGF-β inhibitor), Valproic acid (HDAC inhibitor), Forskolin (cAMP activator) | Modulate signaling pathways and epigenetic barriers to enhance reprogramming |

| miRNA/siRNA Tools | miR-1, miR-133, miR-208, miR-499 | Non-coding RNA regulators that can alone or in combination induce reprogramming |

| Culture Systems | 3D organoid culture, Serum-free media with specialized supplements | Provide microenvironmental cues that support maturation and maintenance of reprogrammed cells |

| Cell Sorting Markers | Thy1.2 (fibroblast exclusion), EpCAM (epithelial inclusion), Sftpc-GFP (AT2 cell reporter) | Isolation and purification of successfully reprogrammed cells from heterogeneous populations |

| Animal Disease Models | Myocardial infarction (MI) models, Bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis, Diabetic (db/db) wound models | In vivo validation of therapeutic efficacy and anti-fibrotic effects |

Direct reprogramming represents a transformative strategy with dual therapeutic benefits—regenerating functional tissue while simultaneously reducing pathogenic fibrosis. The comparative analysis presented herein demonstrates that while factor combinations and delivery methods must be optimized for specific tissue contexts, the core principle of directly converting fibroblasts into functional parenchymal cells remains consistently viable across organ systems.

The functional outcomes observed in preclinical models, including improved cardiac function, enhanced wound healing, and alveolar regeneration, underscore the therapeutic potential of this approach. The concurrent reduction in fibrotic area across these models highlights how direct reprogramming strategically addresses both tissue loss and the pathological microenvironment.

For researchers and drug development professionals, the ongoing challenges include optimizing reprogramming efficiency, ensuring the functional maturity of converted cells, and developing safe, targeted delivery systems for clinical translation. As understanding of the molecular mechanisms deepens and technologies for precise cellular engineering advance, direct reprogramming continues to emerge as a promising pathway for addressing fibrotic diseases through dual-action regenerative therapy.

In the field of regenerative medicine and cellular engineering, the targeted reprogramming of cellular identity represents a transformative approach for disease modeling, drug discovery, and therapeutic development. Central to this paradigm is the identification of precise transcription factor (TF) cocktails—specific combinations of DNA-binding proteins that can orchestrate the conversion of one cell type to another by activating or repressing critical genetic programs. Within the broader context of functional outcomes in reprogramming strategies research, understanding these key molecular drivers, their target genes, and the experimental evidence supporting their efficacy is fundamental for advancing the field beyond serendipitous discovery toward rational design principles.

This guide systematically compares the performance of established and emerging TF cocktails across different cellular contexts, providing researchers with structured experimental data and methodological frameworks. The convergence of single-cell technologies, computational prediction models, and high-throughput screening methods has dramatically accelerated the identification of effective TF combinations, moving the field from laborious iterative testing to more directed approaches. By examining the quantitative outcomes, target gene networks, and implementation protocols of these reprogramming strategies, scientists can make informed decisions when selecting or developing TF cocktails for specific applications in drug development and cellular therapeutics.

Comparative Analysis of Transcription Factor Cocktails

The following tables provide a structured comparison of transcription factor cocktails, their target cell types, efficiency metrics, and key functional outcomes based on recent experimental studies.

Table 1: Transcription Factor Cocktails for Direct Cell Fate Conversion

| Target Cell Type | Transcription Factor Cocktail | Starting Cell Type | Reprogramming Efficiency | Key Validated Target Genes | Functional Validation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Microglia-like cells (TFiMGLs) [25] | SPI1, CEBPA, FLI1, MEF2C, CEBPB, IRF8 | Human iPSCs | 4 days; efficient yield across multiple iPSC lines | ITGAM, P2RY12, CX3CR1, TMEM119, TREM2 | Transcriptional similarity to primary microglia; key functional features of human primary microglia |

| Epicardial-like cells [26] | Gata6, Hand2, Tbx5 | Mouse Embryonic Fibroblasts (MEFs) | 36.9% of cells in cluster expressing epicardial markers | Wt1, Bnc1 (endogenous activation) | Morphological and functional similarity to genuine epicardial cells |

| Skeletal muscle cells [26] | MyoD1 | Mouse Embryonic Fibroblasts (MEFs) | Distinct cluster formation; outcompetes 47 other factors | Muscle development genes | Significant enrichment for muscle development gene ontology annotations |

Table 2: Performance Metrics and Experimental Outcomes of Reprogramming Strategies

| TF Cocktail | Screening/Identification Method | Time to Phenotype | Stability Assessment | Key Advantages | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SPI1, CEBPA, FLI1 [25] | Iterative, high-throughput single-cell TF screening | 4 days | Reproducible across distinct iPSC lines | Rapid, efficient; works in standard culture media without additional factors | scRNA-seq confirmation of transcriptional similarity; functional assays |

| Gata6, Hand2 [26] | Reprogram-Seq: scRNA-seq of perturbed cell library | N/A | Derived from reprogramming, not progenitor proliferation | Identified from large combinatorial space without prior bias | Co-expression with endogenous epicardial markers; distinct cluster formation |

| MyoD1 [26] | Reprogram-Seq from 48-factor cardiac library | N/A | Forms distinct, stable cell cluster | Single-factor efficacy; outcompetes numerous other factors | Exclusive cluster formation; enrichment of muscle gene ontology terms |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Iterative Single-Cell Transcription Factor Screening for Microglia

The differentiation of human induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) into microglia-like cells exemplifies a robust, high-throughput methodology for identifying optimal TF combinations. The protocol involves a sequential screening approach to pinpoint factors that drive efficient cell fate conversion [25].

Primary Screening Phase: Researchers first selected 40 candidate TFs based on literature surveys of microglial development, epigenetic patterns, and gene regulatory networks. Each TF was cloned into a PiggyBac transposon vector featuring a doxycycline-inducible expression system and a unique 20-nucleotide barcode inserted between the stop codon and poly-A sequence to distinguish exogenous from endogenous TF transcripts. The plasmid library was transfected into iPSCs at a DNA dose of 5μg, determined to optimally integrate approximately 5-9 TF copies per cell. After puromycin selection for successfully integrated cells, differentiation was induced with doxycycline for four days [25].

Analysis and Validation: Transfected cells were analyzed using fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) for consensus microglial surface proteins (CX3CR1, P2RY12, CD11b). Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) was performed on approximately 10,000 TRA-1-60 negative (differentiated) cells. The barcoding strategy allowed for simultaneous detection of single-cell gene expression and TF integration through amplicon sequencing of co-amplified TF and cell barcodes from cDNAs. Computational analysis comparing TF expression in cells with versus without microglial gene expression identified the most potent inducers—SPI1, FLI1, and CEBPA. These top candidates were then tested in various polycistronic configurations (linked with 2A peptides) to ensure co-expression and optimize relative expression levels, ultimately yielding the final six-factor combination (SPI1, CEBPA, FLI1, MEF2C, CEBPB, IRF8) for efficient microglia production [25].

Reprogram-Seq for Epicardial Cell Reprogramming

The Reprogram-Seq platform provides a generalizable framework for identifying TF cocktails that reprogram fibroblasts to specific cell types by combining single-cell perturbation with computational analysis [26].

Library Construction and Screening: A retroviral library of 48 cardiac-related TFs and genes was packaged and used to infect mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) at high infectivity, ensuring individual cells expressed multiple exogenous TFs. This created a diverse library of perturbed cells expressing various TF combinations. scRNA-seq was then performed to capture the full transcriptome of each cell, enabling identification of cell clusters where exogenous TFs drove transcriptional reprogramming toward target fates without relying on distal barcoding [26].

Data Analysis and Hit Identification: The single-cell transcriptomes were integrated with a reference atlas of 15,684 primary P0 mouse heart cells. Clusters containing mixtures of in vivo target cells (e.g., epicardial cells) and MEF-derived cells suggested successful reprogramming. The expression of exogenous TFs was examined in these mixed clusters—MEF-derived cells in the epicardial-containing cluster showed significant enrichment for Gata6 (78.6% vs. 22.1% in other MEF-derived cells) and Hand2 (48.8% vs. 9.6%), indicating their reprogramming activity. Functional validation confirmed that the resulting cells not only expressed epicardial markers (Wt1, Bnc1) but also resembled genuine epicardial cells morphologically and functionally [26].

Visualization of Experimental Workflows

The following diagrams illustrate the core methodologies discussed in this review, providing visual representations of the experimental workflows for transcription factor screening and reprogramming.

Figure 1: Iterative TF screening workflow for generating microglia from iPSCs.

Figure 2: Reprogram-Seq workflow for unbiased TF cocktail discovery.

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details essential reagents and materials used in the transcription factor screening and reprogramming experiments described in this guide.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Transcription Factor Reprogramming Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Specific Examples from Studies |

|---|---|---|

| PiggyBac Transposon System | Genomic integration of transcription factor genes; enables stable expression | Used for integrating 40 TF library into iPSCs with doxycycline-inducible promoter [25] |

| Barcoded TF Vectors | Distinguishes exogenous from endogenous TF transcripts; enables tracking in pooled screens | 20-nucleotide barcode between stop codon and poly-A sequence [25] |

| Doxycycline-Inducible System | Controls timing of TF expression; allows synchronized differentiation | Used to induce TF expression after puromycin selection [25] |

| Retroviral/Lentiviral Vectors | Efficient delivery and integration of TF genes; suitable for hard-to-transfect cells | Retroviral library for delivering 48 cardiac factors to MEFs [26] |

| Single-Cell RNA Sequencing | Comprehensive transcriptome profiling; identifies cell states and reprogramming efficacy | 10x Genomics platform for analyzing differentiated cells; identifies microglial gene expression [25] |

| Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting | Isolation of specific cell populations based on surface markers | Sorting for CX3CR1, P2RY12, CD11B microglial markers or TRA-1-60 negative cells [25] |

| Polycistronic Vectors | Ensures co-expression of multiple TFs from single construct; controls relative expression levels | 2A peptide-linked TF cassettes with different gene orders to optimize expression [25] |

The systematic comparison of transcription factor cocktails presented in this guide highlights significant progress in the rational design of cell fate reprogramming protocols. The emergence of high-throughput screening technologies like iterative single-cell TF screening and Reprogram-Seq has transformed the identification of effective TF combinations from a largely empirical process to a more directed, data-driven endeavor. Quantitative assessments reveal that optimized cocktails can achieve rapid cellular conversion—within just four days for microglia differentiation—with efficiencies sufficient for research and potential therapeutic applications.

Critical examination of the experimental data demonstrates that successful reprogramming strategies share common features: they activate endogenous master regulator genes, establish stable transcriptional networks, and produce functionally competent cells. The methodologies and reagents detailed provide researchers with a toolkit for implementing these approaches across different cellular systems. As the field advances, integrating computational prediction models like GET with experimental screening will likely further accelerate the discovery of TF cocktails for increasingly specific cell subtypes, ultimately enhancing both fundamental understanding of cell fate control and the development of targeted cellular therapies for human diseases.

Reprogramming in Action: Methodologies and Organ-Specific Applications for Functional Recovery

Cardiovascular disease remains a leading cause of mortality worldwide, with myocardial infarction (MI) resulting in the loss of approximately one billion cardiomyocytes [27]. The adult human heart possesses minimal regenerative capacity, and the damaged myocardium is typically replaced by non-contractile fibrotic tissue, ultimately leading to heart failure [18] [28]. Traditional pharmacological interventions and device-based therapies primarily manage symptoms rather than addressing the fundamental loss of contractile cells [18]. While heart transplantation offers a definitive solution, it is constrained by donor scarcity and the necessity for lifelong immunosuppression [18].

Regenerative medicine has emerged as a promising frontier for fundamentally addressing heart failure by restoring lost cardiac tissue [18]. Among various strategies, direct cardiac reprogramming has gained significant traction for its potential to directly convert endogenous cardiac fibroblasts (CFs) into induced cardiomyocytes (iCMs) in situ [18] [28]. This approach leverages the abundant fibroblast population that contributes to pathological scarring post-MI, aiming to simultaneously reduce fibrosis and regenerate functional myocardium [18] [28]. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of the transcription factor cocktails that drive this cellular transformation, detailing their experimental protocols, efficiencies, and functional outcomes.

Comparative Analysis of Major Reprogramming Cocktails

Direct cardiac reprogramming involves the forced expression of specific transcription factors or microRNAs to directly convert one somatic cell type into another without reverting to a pluripotent state [28]. The following table summarizes the key reprogramming cocktails developed for generating iCMs.

Table 1: Key Transcription Factor Cocktails for Direct Cardiac Reprogramming

| Reprogramming Cocktail | Key Components | Reported Reprogramming Efficiency | Starting Cell Type | Notable Functional Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MGT [28] | Gata4, Mef2c, Tbx5 | Not precisely quantified (initial study) | Neonatal and adult mouse cardiac fibroblasts, tail-tip fibroblasts | Generation of cardiomyocyte-like cells; spontaneous contraction; action potentials; electrical coupling [28] |

| GHMT [28] | Gata4, Hand2, Mef2c, Tbx5 | ~9.2% (αMHC-GFP+ and cTnT+ cells) [28] | Adult tail-tip fibroblasts and cardiac fibroblasts | ~4-fold increase in iCM yield vs. MGT; ventricular-like action potentials [28] |

| microRNA Combo [28] | miR-1, miR-133, miR-208, miR-499 | Not specified | Neonatal mouse cardiac fibroblasts | Generation of cardiomyocyte-like cells; spontaneous contraction; action potentials [28] |

| MGT + miR-133 [28] | Gata4, Mef2c, Tbx5 + miR-133 | ~4-fold increase in cTnT+ cells; ~6-fold more beating cells vs. MGT alone [28] | Mouse embryonic fibroblasts | Sharp increase in functional iCM generation [28] |

| Small Molecule Cocktail [28] | CRFVPTZ (various inhibitors) | Generation of beating cardiomyocyte-like cells | Mouse embryonic fibroblasts | Spontaneous contraction; action potentials; avoids exogenous genetic material [28] |

The field has evolved from the initial MGT cocktail to more complex combinations including additional transcription factors like Hand2 (GHMT) or non-coding RNAs like miR-133 to enhance efficiency and functional maturation [28]. A critical advancement has been the demonstration that these cocktails can successfully reprogram resident cardiac fibroblasts into iCMs within injured mouse hearts, leading to improved vascular perfusion, reduced scar size, and enhanced cardiac function [28] [29].

Experimental Protocols for In Vitro and In Vivo Reprogramming

Standard In Vitro Reprogramming Protocol

The foundational protocol for converting fibroblasts into iCMs in a dish involves several key steps, as standardized across multiple laboratories [28].

- Fibroblast Isolation and Culture: Fibroblasts are typically isolated from neonatal or adult mouse hearts via enzymatic digestion (e.g., collagenase). For lineage tracing, fibroblasts are often harvested from transgenic mice expressing Cre recombinase under fibroblast-specific promoters like Tcf21 or Fsp1 [18].

- Viral Transduction: Isolated fibroblasts are transduced with lentiviral or retroviral vectors carrying the reprogramming factors (e.g., MGT or GHMT). Viruses are added to the culture medium, often in the presence of polybrene to enhance infection efficiency [28].

- Culture and Phenotypic Monitoring: Post-transduction, cells are maintained in standard culture media. The first signs of successful reprogramming, such as spontaneous contraction and sarcomeric organization, can be observed as early as 1-3 weeks [28].

- Validation of Reprogramming:

- Molecular Analysis: Quantitative PCR (qPCR) and immunofluorescence staining are used to detect the upregulation of cardiomyocyte-specific genes and proteins (e.g., cardiac Troponin T, α-actinin) and the downregulation of fibroblast markers (e.g., fibroblast-specific protein-1) [28].

- Functional Analysis: Techniques such as calcium flux imaging, measurement of action potentials, and assessment of response to pharmacological agents are employed to confirm the functional maturity of the newly formed iCMs [28].

In Vivo Reprogramming for Cardiac Repair

Translating this technology to live animals, particularly in models of myocardial infarction, follows a targeted delivery approach.

- Animal Model Creation: Myocardial infarction is induced in mice, commonly through permanent ligation of the left anterior descending (LAD) coronary artery [28].

- Delivery of Reprogramming Factors: Shortly after injury, the reprogramming factors are delivered directly to the infarcted heart and border zone. This is achieved using:

- Viral Vectors: Direct intramyocardial injection of adeno-associated viruses (AAVs) or lentiviruses engineered for cardiac tropism and containing the reprogramming cocktail [18] [28].

- Non-Viral Methods: Alternative strategies include the injection of modified mRNA or extracellular vesicles loaded with reprogramming microRNAs to avoid genomic integration [18] [27].

- Functional and Histological Assessment: Weeks post-injection, hearts are analyzed for functional improvement (e.g., via echocardiography to measure ejection fraction) and histological evidence of reprogramming (e.g., lineage tracing to confirm the fibroblast origin of new iCMs, reduction in scar size, and improved vascularization) [18] [28] [29].

Figure 1: Experimental Workflow for In Vivo Cardiac Reprogramming. This diagram outlines the key steps from myocardial injury to functional repair through fibroblast conversion.

Signaling Pathways and Molecular Mechanisms

The process of direct reprogramming is governed by profound shifts in gene regulatory networks and epigenetic landscapes. Key signaling pathways are modulated to suppress the fibroblast gene program and activate the cardiomyocyte gene program.