Hydrogel-Encapsulated MSC Exosomes: A Sustained-Release Strategy for Advanced Wound Healing

Chronic wounds represent a significant clinical challenge, driving the need for innovative regenerative therapies.

Hydrogel-Encapsulated MSC Exosomes: A Sustained-Release Strategy for Advanced Wound Healing

Abstract

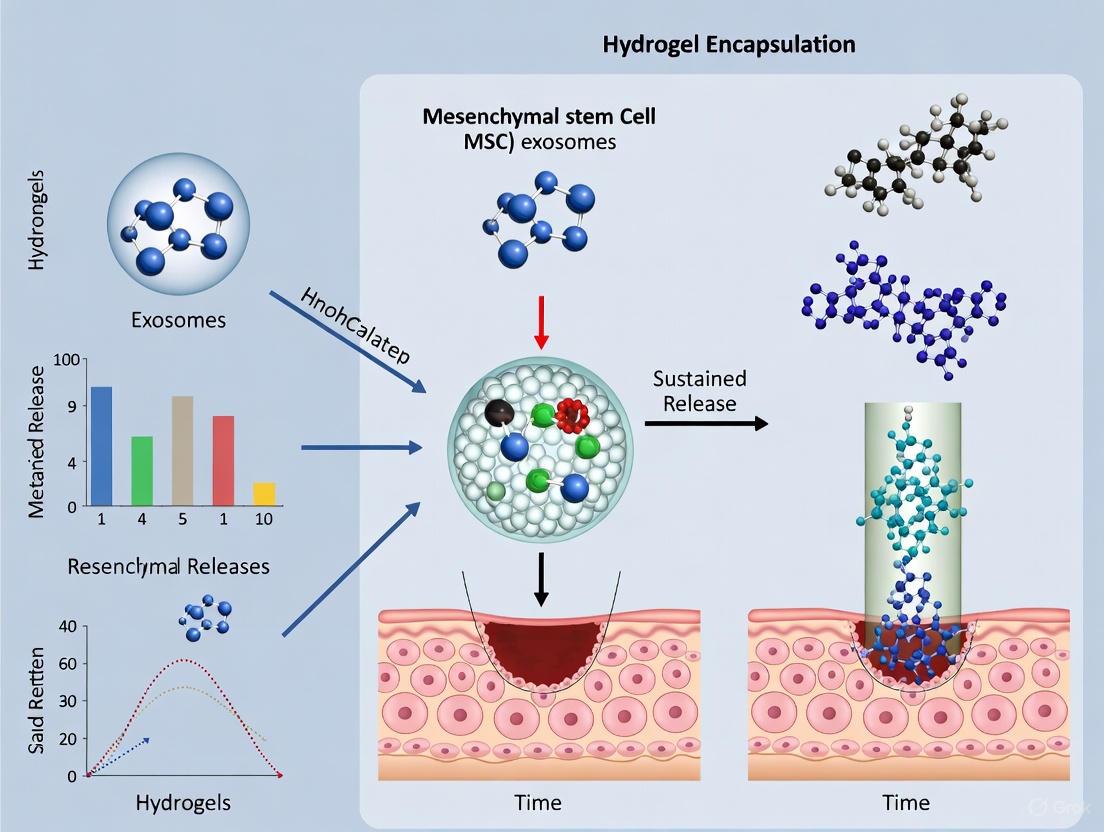

Chronic wounds represent a significant clinical challenge, driving the need for innovative regenerative therapies. This article explores the combination of mesenchymal stem cell (MSC)-derived exosomes—nanoscale vesicles with potent regenerative, anti-inflammatory, and pro-angiogenic properties—with biocompatible hydrogel delivery systems. We provide a comprehensive analysis of how hydrogel encapsulation addresses the critical limitations of rapid clearance and poor retention of freely administered exosomes, enabling their sustained and localized release at the wound site. Covering foundational biology, methodological strategies for exosome loading and release, troubleshooting of system optimization, and validation through preclinical and comparative studies, this review synthesizes current research to guide scientists and drug development professionals in advancing this promising cell-free therapy toward clinical application.

The Science of Healing: Unpacking MSC Exosomes and Hydrogel Matrices

The therapeutic application of Mesenchymal Stem Cell (MSC) exosomes represents a paradigm shift in regenerative medicine, offering a cell-free alternative with significant advantages for wound healing. These nano-sized extracellular vesicles (30-150 nm) function as essential mediators of the paracrine effects of MSCs, transferring bioactive molecules to recipient cells to orchestrate tissue repair [1] [2]. Exosomes derived from MSCs promote angiogenesis, modulate inflammatory responses, stimulate cell proliferation, and enhance extracellular matrix remodeling—all critical processes in wound healing [1] [3]. Compared to stem cell transplantation, exosome-based therapies demonstrate reduced risks of immune rejection and tumorigenicity while maintaining therapeutic efficacy [1]. However, a significant clinical challenge lies in their rapid clearance from wound sites, which limits their retention and sustained therapeutic action [1] [3]. Hydrogel encapsulation has emerged as a promising strategy to address this limitation, creating a protective reservoir that prolongs exosome retention and enables controlled release at the injury site [3]. To fully exploit the therapeutic potential of engineered exosome-hydrogel systems, a comprehensive understanding of exosome biogenesis and cargo sorting mechanisms is essential for developing standardized production protocols and optimizing their regenerative capabilities.

Molecular Machinery of Exosome Biogenesis

Exosome biogenesis is a sophisticated multistep process involving the formation, cargo sorting, and secretion of vesicles originating from the endosomal system. This process initiates with the inward budding of the plasma membrane to form early endosomes, which subsequently mature into late endosomes [4] [5]. During maturation, the limiting membrane of these endosomes undergoes inward invagination, generating intraluminal vesicles (ILVs) within large multivesicular bodies (MVBs) [4] [6]. The fate of these MVBs determines whether their contents are degraded or secreted; MVBs that fuse with lysosomes undergo degradation, while those that traffic to and fuse with the plasma membrane release their ILVs into the extracellular space as exosomes [4] [6]. The molecular machinery governing these processes ensures the specific packaging of cargo and directed secretion of exosomes, with particular significance for harnessing their therapeutic potential in wound healing applications.

ESCRT-Dependent and ESCRT-Independent Biogenesis Pathways

The formation of ILVs within MVBs occurs through two primary molecular mechanisms: the endosomal sorting complex required for transport (ESCRT)-dependent pathway and several ESCRT-independent pathways [6] [7]. The ESCRT machinery consists of four multi-protein complexes (ESCRT-0, -I, -II, and -III) that operate sequentially with associated ATPases and accessory proteins [6] [7].

- ESCRT-0 initiates the process by recognizing and clustering ubiquitinated cargo proteins through ubiquitin-binding domains, simultaneously binding to the lipid phosphatidylinositol 3-phosphate (PI3P) on the endosomal membrane via FYVE domains [6].

- ESCRT-I/II complexes are subsequently recruited, forming a saddle-shaped protein structure that plays a crucial role in initiating membrane deformation and facilitating the assembly of ESCRT-III [6] [7].

- ESCRT-III undergoes sequential polymerization, driving membrane constriction and fission to ultimately generate ILVs, a process completed with the assistance of the VPS4 ATPase which catalyzes ATP hydrolysis and ESCRT complex disassembly [6] [7].

Several alternative ESCRT-dependent mechanisms exist, primarily mediated by accessory proteins such as Alix and HD-PTP [6]. The Syndecan-Syntenin-Alix pathway represents a well-characterized alternative mechanism where the transmembrane proteoglycan syndecan interacts with the adaptor protein syntenin, which subsequently recruits Alix to nucleate ESCRT-III assembly independently of ubiquitination [6]. This pathway is particularly relevant for loading specific cargoes, including heparan sulfate proteoglycans and certain growth factor receptors [6].

ESCRT-independent mechanisms primarily center on lipid-driven processes, with the neutral sphingomyelinase 2 (nSMase2)-ceramide pathway being the most extensively studied [6] [7]. nSMase2 catalyzes the conversion of sphingomyelin to ceramide within the endosomal membrane, and the cone-shaped structure of ceramide molecules facilitates negative membrane curvature, promoting inward budding and ILV formation [6]. This pathway is especially important for the packaging of specific microRNAs and heat shock proteins into exosomes [6]. Additionally, tetraspanin-rich microdomains (enriched in CD63, CD9, and CD81) contribute to ESCRT-independent ILV formation by organizing membrane platforms for selective cargo clustering and vesicle budding [6] [7].

Table 1: Key Machinery in Exosome Biogenesis Pathways

| Pathway/Component | Key Elements | Primary Function | Therapeutic Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| ESCRT-Dependent | ESCRT-0, -I, -II, -III, VPS4 ATPase | Recognizes ubiquitinated cargo; mediates membrane deformation and scission | High cargo specificity; targetable for modulating specific protein secretion |

| Syndecan-Syntenin-Alix | Syndecan, Syntenin, Alix, ESCRT-III | Ubiquitin-independent sorting of syndecans, FGFR, KRS | Important for growth factor signaling; enhanced by heparanase activity |

| nSMase2-Ceramide | Neutral sphingomyelinase 2, ceramide | Generates ceramide to induce negative membrane curvature | Crucial for RNA and lipid cargo sorting; inhibited by GW4869 |

| Tetraspanin-Dependent | CD63, CD9, CD81 | Forms microdomains for cargo clustering and membrane budding | Defines exosome subpopulations; potential for engineered targeting |

Regulation of MVB Trafficking and Secretion

Following their formation, MVBs undergo precise intracellular trafficking, primarily along microtubules, toward the plasma membrane—a process coordinated by RAB GTPases which function as molecular switches [4]. These proteins cycle between active (GTP-bound) and inactive (GDP-bound) states, regulated by guanine nucleotide exchange factors (GEFs) and GTPase-activating proteins (GAPs) [4]. Among the numerous RAB proteins, RAB27A and RAB27B play pivotal roles in exosome secretion, though their functions can vary by cell type [4].

- RAB27A typically localizes to MVBs and regulates their docking at the plasma membrane through interactions with effector proteins like Slp4 [4].

- RAB27B often associates with MVBs in the perinuclear region and mediates their transport along microtubules to the cell periphery via effector proteins such as Slac2b [4].

The final steps of exosome secretion involve the docking and fusion of MVBs with the plasma membrane, processes facilitated by SNARE complexes and tethering factors [4]. The cytoskeleton, particularly actin networks and microtubules, provides the structural framework and tracks for MVB transport, with molecular motors like kinesins and dyneins enabling directional movement [4].

Mechanisms of Cargo Sorting into Exosomes

The selective packaging of biomolecules into exosomes is a highly regulated process that determines the functional properties and therapeutic potential of the secreted vesicles. Exosomes carry a diverse repertoire of cargo, including proteins, lipids, nucleic acids (RNA and DNA), and metabolites [7]. The composition of exosomal cargo is dynamic and can change in response to cellular conditions and environmental stimuli, reflecting the physiological state of the parent cell [7]. This cargo-sorting mechanism is particularly relevant for MSC exosomes, as their therapeutic efficacy in wound healing depends on the specific miRNAs, growth factors, and immunomodulatory proteins they contain [1] [3].

Protein and RNA Cargo Sorting

Protein sorting into exosomes occurs through multiple mechanisms, often involving specific sorting signals or interactions with sorting machinery. Ubiquitination serves as a primary signal for ESCRT-dependent sorting of many transmembrane proteins, including growth factor receptors like EGFR [6] [7]. As described previously, the Syndecan-Syntenin-Alix pathway mediates ubiquitin-independent sorting of specific transmembrane proteins [6]. Additionally, tetraspanin networks facilitate the clustering of specific proteins (e.g., integrins, MHC molecules) into exosome-bound microdomains [6] [7]. Certain cytosolic proteins, including heat shock proteins (HSP70, HSP90) and annexins, are enriched in exosomes through interactions with lipid membranes or other sorted proteins [7].

RNA sorting into exosomes is equally selective, with specific miRNAs and other non-coding RNAs being enriched in exosomes compared to their parent cells [7]. This process involves RNA-binding proteins (RBPs) that recognize specific motifs or modifications in RNA molecules. For instance, the RBP FAN (also known as NSFL1C) binds to the 3' end of specific miRNAs and interacts with the exosomal membrane protein LC3, facilitating miRNA loading via the nSMase2-ceramide pathway [6]. Other RBPs, such as hnRNPs and MVP, have also been implicated in the selective packaging of miRNAs and other RNAs into exosomes [7]. Some RNA sequences contain EXOmotifs or zipcodes—short nucleotide sequences recognized by RBPs that direct them to exosomes [7].

Table 2: Select Cargo Molecules in MSC Exosomes and Their Roles in Wound Healing

| Cargo Type | Example Molecules | Function in Wound Healing | Sorting Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|

| miRNA | miR-125a, miR-31, miR-192-5p | Promote angiogenesis; regulate scar formation | RBP-mediated (e.g., FAN); nSMase2-dependent |

| Growth Factors | VEGF, TGF-β, HGF | Stimulate angiogenesis; fibroblast proliferation | Syndecan-Syntenin-Alix pathway; Tetraspanin networks |

| Immunomodulatory Proteins | TSG-6, IL-10 | Polarize macrophages to M2 anti-inflammatory phenotype | ESCRT-dependent; Ubiquitin-independent mechanisms |

| Extracellular Matrix Proteins | Fibronectin, Collagen | Support cell migration; tissue structure | Lipid raft-mediated; Tetraspanin-associated |

Impact of Cellular Environment on Cargo Loading

The cellular microenvironment significantly influences exosome cargo sorting, a consideration of paramount importance for producing therapeutic MSC exosomes. Pathological conditions such as hypoxia, inflammation, and nutrient starvation can alter the expression and activity of sorting machinery components, thereby modifying the composition and function of secreted exosomes [4] [6]. For example, in cancer cells, oncogenic signaling can upregulate the Syndecan-Syntenin-Alix pathway, increasing the secretion of exosomes that promote metastasis [6]. Similarly, inflammatory cytokines can modulate the sorting of immunomodulatory miRNAs into MSC exosomes, enhancing their anti-inflammatory potential—a highly desirable characteristic for wound healing applications [1] [3]. Understanding these regulatory mechanisms provides opportunities for preconditioning MSCs during culture to tailor the therapeutic properties of their exosomes for specific wound healing indications.

Experimental Protocols for Studying Exosome Biogenesis and Cargo

Protocol: Isolation and Characterization of MSC Exosomes

This protocol describes standard methods for obtaining high-purity exosomes from MSC culture supernatants, a critical first step for both basic research and therapeutic development [5] [8].

Materials:

- Cell Culture: Mesenchymal Stem Cells (from bone marrow, adipose tissue, or umbilical cord), appropriate growth medium (e.g., DMEM/F12 with 10% FBS), exosome-depleted FBS.

- Isolation Reagents: Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), sterile ultracentrifugation tubes.

- Characterization Reagents: Primary antibodies (anti-CD63, anti-CD81, anti-CD9, anti-TSG101, anti-Calnexin), glutaraldehyde (for TEM).

Procedure:

- Cell Culture and Conditioned Media Collection:

- Culture MSCs to 70-80% confluence in standard growth medium.

- Replace with fresh medium containing exosome-depleted FBS and culture for 24-48 hours.

- Collect conditioned media and perform sequential centrifugation: 300 × g for 10 min (remove cells), 2,000 × g for 20 min (remove dead cells), and 10,000 × g for 30 min (remove cell debris and large vesicles).

Exosome Isolation via Ultracentrifugation:

- Transfer the supernatant to ultracentrifugation tubes.

- Centrifuge at 100,000 × g for 70 minutes at 4°C.

- Carefully discard the supernatant and resuspend the exosome pellet in a suitable volume of PBS.

- Filter the suspension through a 0.22 μm filter.

- Perform a second ultracentrifugation wash under the same conditions (100,000 × g, 70 min).

- Resuspend the final purified exosome pellet in PBS and aliquot for storage at -80°C.

Exosome Characterization:

- Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis (NTA): Dilute exosomes in PBS and inject into the NTA system to determine particle size distribution and concentration.

- Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM): Fix exosomes with glutaraldehyde, adsorb onto Formvar-carbon coated grids, negative stain with uranyl acetate, and image to confirm cup-shaped morphology.

- Western Blotting: Lyse exosomes and analyze for the presence of positive markers (CD63, CD81, TSG101) and absence of negative markers (Calnexin, GM130).

Protocol: Inhibiting Exosome Biogenesis to Confirm Functional Roles

This protocol utilizes pharmacological inhibitors to disrupt specific biogenesis pathways, allowing researchers to link exosome secretion to specific functional outcomes in wound healing assays [6].

Materials:

- Inhibitors: GW4869 (nSMase2 inhibitor), Manumycin A (RAS and exosome secretion inhibitor), DMVAA (VPS4 inhibitor).

- Cell Culture: MSC cultures, wound healing assay reagents (e.g., migration plates, angiogenesis kits).

Procedure:

- Treatment of MSCs:

- Culture MSCs to 60-70% confluence.

- Treat cells with optimized concentrations of inhibitors (e.g., 10-20 μM GW4869, 5-10 μM Manumycin A) or vehicle control (DMSO) in exosome-depleted medium for 24-48 hours.

Validation of Inhibition:

- Collect conditioned media from treated and control cells.

- Iserve exosomes using the protocol in 4.1.

- Quantify exosome yield using NTA. A significant reduction in particle count confirms effective inhibition.

Functional Wound Healing Assays:

- Collect conditioned media from inhibitor-treated and control MSCs. This media contains secreted factors but a depleted level of exosomes in the inhibitor group.

- Apply this conditioned media to in vitro wound healing models:

- Cell Migration Scratch Assay: Treat fibroblasts or keratinocytes with the conditioned media and measure the rate of gap closure in a scratch wound.

- Tube Formation Assay: Seed endothelial cells on Matrigel and treat with conditioned media. Quantify the number of tubular structures formed.

- Compare the pro-migratory and pro-angiogenic effects of media from inhibitor-treated versus control MSCs. A significant reduction in functionality with inhibitor-treated media confirms the critical role of MSC exosomes in these processes.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Studying Exosome Biogenesis and Function

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Biogenesis Inhibitors | GW4869, Manumectin A, DMVAA | Chemically disrupts specific biogenesis pathways (nSMase2, RAB27, VPS4) to study exosome function. |

| Isolation Kits | Total Exosome Isolation Kits, Size-Exclusion Chromatography Columns, PEG-based Precipitation Kits | Rapid isolation of exosomes from cell culture media or biological fluids; alternatives to UC. |

| Characterization Antibodies | Anti-CD63, Anti-CD81, Anti-CD9, Anti-TSG101, Anti-Alix, Anti-Calnexin | Confirm exosome identity via Western Blot, flow cytometry, or immuno-EM. |

| Fluorescent Tracking Dyes | PKH67, PKH26, DiI, CFSE | Label exosome membranes for uptake, tracking, and biodistribution studies in recipient cells. |

| Engineering Tools | Electroporators, Sonication Devices, Transfection Reagents (for parental cells) | Load therapeutic cargo (drugs, nucleic acids) into exosomes via exogenous or endogenous methods. |

Integration with Hydrogel Encapsulation for Wound Healing

The controlled biogenesis and cargo loading of MSC exosomes find their ultimate therapeutic application in their integration with hydrogel-based delivery systems. Hydrogels address the critical pharmacokinetic challenge of rapid exosome clearance from wound sites, providing a three-dimensional scaffold that protects exosomes and enables their sustained, localized release [9] [1] [3]. The porous structure of hydrogels can be fine-tuned to modulate diffusion rates, while their biocompatibility ensures a moist wound environment conducive to healing [3]. Integrating exosomes with hydrogels often involves simple mixing during hydrogel formation (e.g., with chitosan, hyaluronic acid) or more sophisticated methods like microfluidic encapsulation [1] [3].

The future of exosome-based wound therapies lies in engineered exosomes [10] [8]. Knowledge of biogenesis and cargo sorting enables the production of exosomes loaded with specific therapeutic molecules (e.g., growth factors, RNA interference agents) or surface-modified with targeting ligands (e.g., using peptide tags) to enhance their homing to specific wound cell types like fibroblasts or endothelial cells [10] [8]. When such precisely engineered exosomes are encapsulated within a hydrogel, the result is a sophisticated "smart" therapeutic system capable of providing localized, sustained, and targeted treatment for chronic wounds, ultimately bridging the gap between fundamental cell biology and clinical regenerative medicine.

Mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes (MSC-Exos) have emerged as powerful acellular nanotherapeutics in regenerative medicine, particularly in the context of wound healing and tissue repair. These nanoscale vesicles (30-150 nm in diameter) mediate the paracrine effects of their parent cells by transferring functional proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids to recipient cells [11] [12]. When encapsulated in hydrogels for sustained wound release, MSC-Exos offer significant advantages over traditional cell-based therapies, including low immunogenicity, enhanced stability, and the ability to penetrate biological barriers [11] [13]. Their therapeutic potential stems from their sophisticated mechanisms for modulating inflammation, promoting angiogenesis, and facilitating tissue remodeling—the three critical phases of wound healing.

Molecular Mechanisms of Action

Immunomodulation and Inflammation Control

MSC-Exos precisely regulate the immune response throughout the wound healing process, primarily through their microRNA cargo and surface proteins:

Macrophage Polarization: MSC-Exos modulate the balance between pro-inflammatory M1 and anti-inflammatory M2 macrophages. Depending on the wound microenvironment, they can promote polarization toward the M2 phenotype via regulation of the JAK1/STAT1/STAT6 signaling pathway and miR-146a release, reducing excessive inflammation [12]. Conversely, in fibrotic environments, they may stimulate M1 differentiation to counteract fibrosis [12].

Lymphocyte Regulation: MSC-Exos suppress aberrant adaptive immune responses by inhibiting T-cell proliferation and activity through miR-125a-3p, maintaining Th1/Th2 balance, and suppressing Th17 expansion [12]. They also inhibit B-cell proliferation and antibody production via miR-155-5p [12].

Dendritic Cell Modulation: Through release of miR-21-5p, MSC-Exos inhibit dendritic cell maturation and reduce expression of MHC-II and costimulatory molecules, thereby decreasing antigen presentation [12].

Table 1: Key Immunomodulatory Components in MSC Exosomes

| Molecular Cargo | Target Cell/Pathway | Biological Effect | Therapeutic Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| miR-146a | Macrophages JAK1/STAT1/STAT6 | Promotes M2 polarization | Reduces inflammation |

| miR-21-5p | Dendritic cells | Inhibits maturation | Decreases antigen presentation |

| miR-155-5p | B cells | Inhibits proliferation & antibody production | Suppresses adaptive immunity |

| miR-125a-3p | T cells | Suppresses T cell activity | Maintains Th1/Th2 balance |

| TGF-β | NK cells, SMAD2 pathway | Inhibits NK cell cytotoxicity | Reduces immune activation |

Angiogenic Programming

MSC-Exos directly address microvascular dysfunction in chronic wounds by activating multiple pro-angiogenic pathways:

Growth Factor Activation: Exosomes promote angiogenesis primarily through Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF), FGF2, and PDGF signaling, stimulating endothelial cell proliferation, migration, and tube formation [14].

miRNA-Mediated Angiogenesis: Specific microRNAs such as miR-126 play crucial roles in enhancing angiogenic responses. MSC-Exos deliver these bioactive molecules directly to endothelial cells, activating Wnt/β-catenin, Notch, and PI3K/Akt pathways that are essential for new blood vessel formation [14].

Hypoxic Preconditioning: Under hypoxic conditions, MSC-Exos are enriched with additional angiogenic factors that prevent tissue ischemia, making them particularly effective for treating wounds with compromised blood supply [12].

Tissue Remodeling and Repair

MSC-Exos facilitate the proliferative and remodeling phases of wound healing through multiple mechanisms:

Extracellular Matrix Regulation: Exosomes modulate fibroblast activity and collagen deposition by regulating MMPs and their inhibitors, ensuring proper balance between matrix synthesis and degradation [15]. This prevents abnormal scar formation while supporting functional tissue reconstruction.

Cellular Proliferation and Migration: Through transfer of growth factors and regulatory RNAs, MSC-Exos enhance the migration and proliferation of keratinocytes, fibroblasts, and endothelial cells essential for re-epithelialization and granulation tissue formation [15].

Anti-fibrotic Effects: In conditions characterized by excessive fibrosis, MSC-Exos deliver anti-fibrotic miRNAs that suppress collagen overproduction and myofibroblast differentiation, particularly important for treating hypertrophic scars and fibrotic diseases [12].

Quantitative Analysis of MSC Exosome Effects

Table 2: Therapeutic Effects of MSC Exosomes in Wound Healing Applications

| Therapeutic Effect | Key Molecular Mediators | Experimental Evidence | Efficiency/Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Angiogenesis | VEGF, FGF2, miR-126, PI3K/Akt | Increased capillary density in diabetic wounds [14] | 3.7-fold reduction in amputation risk in microvascular disease [14] |

| Immunomodulation | miR-146a, miR-21-5p, TGF-β | Shift from M1 to M2 macrophages in chronic wounds [12] | Significant reduction in pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-6) [12] |

| Re-epithelialization | FGFs, KGFs, IGF-1 | Accelerated keratinocyte migration and wound closure [15] | 5-fold acceleration in wound closure in preclinical models [14] |

| Anti-fibrosis | Regulatory miRNAs, TIMP1 | Reduced collagen deposition in fibrotic models [12] [15] | Improved tissue flexibility and function |

| Clinical Translation | Multiple combined mechanisms | 64 registered clinical trials for MSC-EVs [11] | Completed trials show significant wound healing progress [11] |

Experimental Protocols for MSC Exosome Research

Protocol: Isolation and Characterization of MSC Exosomes

Purpose: To isolate and characterize exosomes from mesenchymal stem cell culture supernatants for wound healing applications.

Materials:

- MSC culture (bone marrow, adipose tissue, or umbilical cord derived)

- Serum-free MSC culture medium

- Ultracentrifugation equipment

- Transmission Electron Microscope (TEM)

- Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis (NTA) system

- Western blot equipment

- Antibodies for CD63, CD81, CD9, CD73, CD90, CD105

Procedure:

- Cell Culture: Culture MSCs in serum-free medium for 48 hours to accumulate exosomes in conditioned medium.

- Differential Centrifugation:

- 300 × g for 10 min to remove cells

- 2,000 × g for 20 min to remove dead cells

- 10,000 × g for 30 min to remove cell debris

- 100,000 × g for 70 min to pellet exosomes

- Purification: Wash exosome pellet in PBS and repeat ultracentrifugation at 100,000 × g for 70 min.

- Characterization:

- Size and Concentration: Use NTA to determine particle size distribution (should be 30-150 nm) and concentration.

- Morphology: Confirm spherical morphology using TEM.

- Surface Markers: Verify presence of exosomal markers (CD63, CD81, CD9) and MSC markers (CD73, CD90, CD105) via western blot.

- Storage: Resuspend in PBS and store at -80°C until use.

Quality Control: Ensure negative staining for calnexin (non-exosomal marker) and appropriate particle-to-protein ratio.

Protocol: Hydrogel Encapsulation of MSC Exosomes

Purpose: To encapsulate MSC exosomes in hyaluronic acid hydrogel for sustained release in wound healing applications.

Materials:

- Purified MSC exosomes

- Hyaluronic acid (HA, 1-2% w/v)

- Crosslinking agent (e.g., divinyl sulfone or adipic acid dihydrazide)

- Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS), pH 7.4

- BCA protein assay kit

- ELISA kits for exosome markers

Procedure:

- Hydrogel Preparation: Dissolve hyaluronic acid in PBS to achieve 1.5% (w/v) solution.

- Exosome Incorporation: Mix purified exosomes (50-200 μg protein equivalent) with HA solution at 4°C.

- Crosslinking: Add crosslinking agent at optimized concentration and incubate at 37°C for 2 hours to form stable hydrogel.

- Characterization:

- Rheology: Measure storage (G') and loss (G") moduli to confirm hydrogel formation.

- Release Kinetics: Immerse exosome-loaded hydrogel in PBS at 37°C with gentle shaking. Collect supernatant at predetermined time points and quantify exosome release using BCA protein assay and CD63 ELISA.

- Bioactivity Assessment: Test released exosomes in endothelial tube formation assay to confirm retained angiogenic activity.

Optimization Notes: Adjust crosslinking density to achieve desired release profile (typically sustained over 7-14 days). Sterilize final product via gamma irradiation for in vivo applications.

Protocol: Functional Validation of MSC Exosome Bioactivity

Purpose: To validate the functional capabilities of MSC exosomes in modulating inflammation, angiogenesis, and tissue remodeling.

Materials:

- Isolated MSC exosomes

- Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs)

- Macrophage cell line (e.g., THP-1)

- Fibroblast cell line (e.g., HDF)

- Matrigel for tube formation assay

- Transwell migration chambers

- ELISA kits for TNF-α, IL-10, VEGF

- RNA extraction kit and qPCR equipment

Angiogenesis Assay:

- Endothelial Tube Formation: Seed HUVECs on Matrigel-coated plates. Treat with MSC exosomes (10-50 μg/mL). After 4-8 hours, quantify tube formation by measuring total tube length and branch points.

- Endothelial Migration: Use scratch wound assay or Transwell chambers to assess HUVEC migration toward exosome-treated conditioned medium.

Immunomodulation Assay:

- Macrophage Polarization: Differentiate THP-1 cells into M0 macrophages, then treat with LPS/IFN-γ for M1 or IL-4/IL-13 for M2 polarization in presence of MSC exosomes.

- Cytokine Profiling: After 24-48 hours, measure TNF-α, IL-6 (M1 markers) and IL-10, TGF-β (M2 markers) using ELISA.

- Surface Marker Analysis: Assess CD86 (M1) and CD206 (M2) expression by flow cytometry.

Tissue Remodeling Assay:

- Fibroblast Function: Treat fibroblasts with exosomes and assess:

- Collagen production (Sirius Red staining)

- MMP expression (zymography)

- Migration capacity (scratch assay)

- Gene Expression: Analyze fibrotic markers (α-SMA, collagen I, collagen III) via qPCR.

Data Interpretation: Compare results with appropriate controls (PBS-treated) and calculate statistical significance. Effective MSC exosomes should enhance tube formation, promote M2 macrophage polarization, and modulate fibroblast collagen production.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for MSC Exosome Studies in Wound Healing

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Isolation Kits | Total Exosome Isolation Kit, miRCURY Exosome Kit | Rapid exosome isolation from conditioned medium | Compare yield/purity with ultracentrifugation; may vary by MSC source |

| Characterization Antibodies | Anti-CD63, CD81, CD9, CD73, CD90, CD105 | Confirm exosome identity and MSC origin | Include negative markers (calnexin) for purity assessment |

| Hydrogel Components | Hyaluronic acid, chitosan, PEG-based polymers | Create sustained release delivery systems | Adjust crosslinking density to control release kinetics |

| Angiogenesis Assays | Matrigel, HUVECs, VEGF ELISA | Quantify pro-angiogenic potential | Include positive (VEGF) and negative controls |

| Immunomodulation Assays | THP-1 cells, LPS/IFN-γ, IL-4/IL-13, cytokine ELISA | Assess macrophage polarization | Characterize both M1 and M2 markers for balanced assessment |

| Cell Migration Assays | Transwell chambers, scratch assay reagents | Evaluate cellular migration enhancement | Standardize initial wound size and serum conditions |

| qPCR Components | Primers for miR-126, miR-146a, inflammatory genes | Analyze miRNA delivery and gene expression changes | Normalize using appropriate housekeeping genes |

MSC exosomes represent a sophisticated acellular nanotherapeutic platform that coordinately modulates inflammation, angiogenesis, and tissue remodeling through delivery of complex molecular cargo. Their encapsulation in hydrogels for sustained wound release addresses critical challenges in regenerative medicine, particularly for chronic wounds characterized by microvascular dysfunction and persistent inflammation [14] [11]. The mechanistic insights and standardized protocols provided in this application note establish a foundation for reproducible research and development in this rapidly advancing field.

Future directions include engineering exosomes for enhanced target specificity, developing combination therapies with growth factors or pharmaceuticals, and establishing scalable production methods for clinical translation [11] [13]. As research progresses, MSC exosome-hydrogel composites hold significant promise for revolutionizing the treatment of complex wounds and other ischemic conditions.

Hydrogels are highly hydrophilic, three-dimensional network structures composed of cross-linked polymers that can swell in water while retaining a large volume of water without dissolving [16]. These biopolymer networks serve as foundational scaffolds in tissue engineering and regenerative medicine, providing a protective microenvironment that mimics the natural extracellular matrix (ECM). Their unique physical and chemical properties make them particularly valuable for the controlled delivery of therapeutic agents, including mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes (MSC-Exos), which require sustained release and protection from rapid clearance to effectively promote tissue repair [17] [16]. The biocompatibility, tunable mechanical properties, and capacity for controlled bioactive molecule release position hydrogels as essential components in advanced wound healing strategies, particularly for complex diabetic wounds characterized by prolonged inflammation, oxidative stress, and impaired angiogenesis [18] [17].

The structural integrity of hydrogels arises from physical or chemical cross-linking of polymer chains, creating a mesh-like architecture with defined porosity that can be engineered to control the diffusion and release kinetics of encapsulated therapeutics [19]. Natural polymer-based hydrogels, such as those derived from recombinant human collagen (RHC) or hyaluronic acid, offer enhanced biocompatibility and biological recognition sites that support cellular activities and tissue integration [9] [19]. When integrated with MSC-Exos, hydrogels form a composite therapeutic system that synergistically combines the structural support and controlled release capabilities of the hydrogel with the multifaceted regenerative signals of the exosomes, establishing a paradigm-shifting approach for managing diabetic complications and other chronic wounds [17].

Key Characteristics of Hydrogel Networks

Table 1: Fundamental Properties of Hydrogel Networks for Therapeutic Applications

| Property | Structural Basis | Functional Significance | Influence on Exosome Delivery |

|---|---|---|---|

| Porous Structure | Interconnected 3D network of polymer chains with tunable pore size (micro to nano scale) [16] [19] | Enables nutrient/waste diffusion and cell infiltration while controlling therapeutic agent release [16] | Determines exosome encapsulation efficiency and release kinetics; smaller pores prolong release [19] |

| Hydration Capacity | Highly hydrophilic polymer chains with water absorption capacity up to 90% of total mass [16] | Maintains moist wound environment; facilitates metabolite transport; mimics native tissue conditions [17] | Preserves exosome bioactivity in aqueous environment; prevents premature degradation [17] |

| Mechanical Properties | Cross-linking density and polymer composition (compressive stress: 47.9-136.8 kPa adjustable) [19] | Provides structural support to wound bed; mechanical cues influence cell behavior and tissue regeneration [19] | Higher cross-linking density creates more stable exosome reservoir with slower release profile [18] [19] |

| Biocompatibility | Natural polymer composition (e.g., recombinant human collagen) with minimal immune reaction [19] | Enables safe clinical application; supports cell adhesion and proliferation without cytotoxicity [19] | Maintains exosome membrane integrity and biological function; ensures therapeutic efficacy [17] [19] |

| Tunable Degradation | Engineered cross-linkers (enzymatically cleavable, photodegradable) with controllable kinetics [17] | Matches degradation rate to tissue regeneration timeline; prevents foreign-body reactions [17] | Synchronizes exosome release with healing phases; provides sustained bioactive cargo delivery [18] [17] |

Quantitative Performance Data of Hydrogel-Exosome Systems

Table 2: Experimental Performance Metrics of Advanced Hydrogel-Exosome Formulations

| Hydrogel System | Exosome Source | Release Kinetics | Therapeutic Outcomes | Key Mechanisms |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Methacrylated ADM (Exo@AMCN) [18] [20] | Human umbilical cord MSC (hUCMSC-Exo) | Controlled release over 2-7 days via adjustable cross-linking density [18] | Residual wound area reduced to 1.07 ± 1.27% in 14 days; >85% antibacterial efficacy [18] [20] | Macrophage polarization to anti-inflammatory M2 phenotype; enhanced angiogenesis and collagen deposition [18] |

| Recombinant Human Collagen (RHCMA) [19] | ucMSC-exos, BMSC-exos, ADSC-exos | 56.27 ± 4.48% release in first 12 h; 92.27 ± 3.19% after 48 h (10% RHCMA) [19] | ucMSC-exos@RHCMA showed best healing with accelerated inflammatory resolution and angiogenesis [19] | ucMSC-exos enhanced macrophage regulation, oxidative stress reduction, and collagen formation [19] |

| Protein-based Q5 Hydrogel [21] | Adipose-derived MSC exosomes | Sustained release via topical application without injections [21] | Significant reduction in healing time vs. exosome injection in diabetic mouse models [21] | Upper critical solution temperature (UCST) gelation provides mechanical strength for localized exosome delivery [21] |

| GelMA-ZIF-8 Composite [22] | MSC-Exos (miR-23a-3p enriched) | Sustained release of exosomes and zinc ions [22] | Enhanced new bone formation and angiogenesis with maintained low inflammation [22] | miR-23a-3p targets PTEN to activate AKT pathway for osteogenesis; ZIF-8 induces M2 polarization [22] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Fabrication of Sprayable Photocrosslinkable Hydrogel for Exosome Delivery

This protocol describes the synthesis of a methacrylated acellular dermal matrix (ADM) hydrogel for controlled co-delivery of hUCMSC-derived exosomes and therapeutic compounds, adapted from studies demonstrating significant wound healing efficacy in diabetic models [18] [20].

Materials:

- Methacrylation-modified acellular dermal matrix (ADM)

- Lithium phenyl-2,4,6-trimethylbenzoylphosphinate (LAP) photoinitiator

- hUCMSC-derived exosomes (100-150 nm diameter, characterized by TEM and DLS)

- β-cyclodextrin-borneol inclusion complexes (CN)

- 405 nm blue light source

- Phosphate buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4)

- Sterile spray applicator

Procedure:

- Hydrogel Precursor Preparation:

- Dissolve methacrylated ADM in PBS at 10-15% (w/v) concentration

- Add LAP photoinitiator at 0.05-0.1% (w/v) and mix until fully dissolved

- Incorporate hUCMSC-Exos (50-100 μg/mL) and β-cyclodextrin-borneol complexes (1-2% w/v) into the precursor solution under gentle agitation

Application and Cross-linking:

- Transfer the precursor solution to a sterile spray applicator

- Apply evenly to the wound surface using a sweeping motion to cover the entire area

- Immediately expose to 405 nm blue light at 5-15 mW/cm² intensity for 10-300 seconds

- Adjust exposure duration based on desired cross-linking density: shorter times (10-30 s) for softer gels with faster release; longer times (120-300 s) for denser gels with prolonged release

Characterization and Validation:

- Verify gel formation through visual inspection and mechanical testing

- Assess exosome release kinetics by measuring fluorescently labeled exosomes in PBS supernatant over 7 days

- Confirm antibacterial activity against common pathogens (S. aureus, P. aeruginosa) using zone of inhibition assays

Protocol: Recombinant Human Collagen Hydrogel for Comparative Exosome Studies

This methodology enables direct comparison of therapeutic efficacy between different MSC-derived exosomes encapsulated within a tunable recombinant human collagen hydrogel platform, supporting identification of optimal exosome sources for specific wound healing applications [19].

Materials:

- Recombinant human collagen (RHC)

- Methacrylate anhydride (MA)

- Photoinitiator (Irgacure 2959 or similar)

- MSC-derived exosomes (ucMSC-exos, BMSC-exos, ADSC-exos)

- NMR spectrometer for chemical validation

- Scanning electron microscope

- UV light source (365 nm, 5-10 mW/cm²)

- CCK-8 assay kit for cytotoxicity testing

Procedure:

- RHCMA Synthesis:

- Modify RHC macromolecular chains with methacrylate anhydride via condensation reaction

- Confirm successful modification using ¹H NMR spectroscopy: verify signals at 5.4 and 5.6 ppm (acrylic protons) and 1.8 ppm (methyl groups in methacrylate)

- Prepare pre-gel solutions at varying concentrations (10%, 12.5%, 15%, 17.5% w/v) in PBS

Hydrogel Characterization:

- Expose pre-gel solutions to UV light (365 nm) for 5-10 minutes to initiate cross-linking

- Analyze microstructure using SEM: confirm decreasing pore size with increasing RHCMA concentration

- Perform compression testing: expected maximum compressive stress of 47.9 ± 6.6 kPa for 10% concentration to 136.8 ± 9.6 kPa for 17.5% concentration

- Determine swelling ratio: 14.5 ± 0.6 for 10% concentration to 7.3 ± 1.0 for 17.5% concentration after 60 minutes immersion

Exosome Encapsulation and Release Profiling:

- Isolate exosomes from ucMSCs, BMSCs, and ADSCs using ultracentrifugation method

- Characterize exosomes by TEM (bilayer vesicle structure, 100-110 nm diameter) and dynamic light scattering

- Incorporate exosomes into 10% RHCMA pre-gel solution at 50-100 μg/mL concentration

- Conduct in vitro release studies using DID-fluorescently labeled exosomes in PBS at 37°C over 72 hours

- Sample release medium at predetermined intervals (1, 3, 6, 12, 24, 48, 72 h) and measure fluorescence intensity

Signaling Pathways in Hydrogel-Exosome Mediated Healing

The diagram above illustrates the coordinated molecular and cellular pathways through which hydrogel-loaded MSC exosomes promote tissue regeneration. The sustained release of exosomes from the hydrogel matrix enables multi-phase regulation of the healing process, particularly critical in diabetic wounds characterized by chronic inflammation [17]. Key exosomal miRNAs including miR-23a-3p and miR-219-5p drive the polarization of macrophages from pro-inflammatory M1 to anti-inflammatory M2 phenotypes, creating a conducive microenvironment for regeneration [16] [22]. Simultaneously, exosome-mediated activation of VEGF/VEGFR signaling pathways stimulates angiogenesis, while PTEN targeting and AKT pathway activation promotes osteogenic differentiation for bone repair [17] [22]. These parallel processes collectively enhance extracellular matrix remodeling and collagen deposition, addressing the fundamental pathophysiological barriers to healing in chronic wounds.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Hydrogel-Exosome Formulation and Analysis

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function & Application | Experimental Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrogel Polymers | Recombinant Human Collagen (RHC), Methacrylated ADM, GelMA, Hyaluronic Acid [9] [18] [19] | Provides 3D scaffold structure; enables tunable mechanical properties and degradation kinetics | Recombinant human collagen offers superior biocompatibility; methacrylation allows photopolymerization [19] |

| Cross-linking Agents | Lithium phenyl-2,4,6-trimethylbenzoylphosphinate (LAP), Irgacure 2959, Methacrylate Anhydride [18] [20] [19] | Initiates photopolymerization; controls cross-linking density and subsequent release kinetics | LAP enables visible light cross-linking (405 nm); cross-linking time (10-300 s) controls degradation [18] |

| Exosome Sources | ucMSC-Exos, BMSC-Exos, ADSC-Exos [16] [19] | Provides therapeutic cargo (miRNAs, proteins, lipids) for immunomodulation, angiogenesis, and tissue repair | ucMSC-Exos show superior anti-inflammatory effects; ADSC-Exos enhance angiogenesis [19] |

| Characterization Tools | Transmission Electron Microscopy, Dynamic Light Scattering, NMR Spectroscopy [16] [19] | Validates exosome morphology/size and hydrogel chemical modification | Exosomes should show bilayer structure, 100-110 nm size; NMR confirms methacrylation [19] |

| Therapeutic Adjuvants | β-cyclodextrin-borneol complexes, ZIF-8 [18] [22] | Enhances antibacterial activity, ROS scavenging, and immunomodulation in composite formulations | Borneol complexes provide >85% antibacterial efficacy; ZIF-8 induces M2 macrophage polarization [18] [22] |

| Release Tracking | DID fluorescent dye, Fluorescence spectroscopy [19] | Quantifies exosome release kinetics from hydrogel systems | 10% RHCMA releases 56.27±4.48% exosomes in first 12h; reaches 92.27±3.19% by 48h [19] |

Advanced Formulation Design Workflow

The workflow illustrates the systematic approach to developing advanced hydrogel-exosome formulations, beginning with careful selection of both polymer base and exosome source based on target application [19]. Chemical modification through methacrylation introduces photopolymerizable groups that enable subsequent light-controlled cross-linking, while parallel exosome isolation and characterization ensures therapeutic cargo quality and consistency [18] [19]. The encapsulation process employs physical mixing to maintain exosome integrity, followed by precision cross-linking that determines subsequent release kinetics and mechanical properties [19]. Comprehensive release profiling validates the sustained delivery capabilities of the system, while in vitro and in vivo efficacy testing confirms therapeutic performance through assessment of macrophage polarization, angiogenesis, collagen deposition, and wound closure metrics [18] [19]. This integrated approach enables researchers to tailor hydrogel-exosome systems for specific clinical requirements, particularly for complex wound healing scenarios where controlled spatiotemporal delivery of regenerative signals is essential for optimal outcomes.

Chronic wounds, characterized by a failure to proceed through the normal, orderly, and timely healing process within three months, represent a severe and growing global health challenge [23]. These wounds, including diabetic foot ulcers, venous leg ulcers, and pressure injuries, are defined by a pathological microenvironment featuring prolonged inflammation, excessive reactive oxygen species (ROS), impaired angiogenesis, slowed cell proliferation, and delayed extracellular matrix (ECM) remodeling [23]. Current clinical strategies, such as negative pressure wound therapy, antibiotic-based infection control, and wound debridement, primarily target local wound conditions and offer only short-term relief, failing to achieve sustained functional regeneration [24].

Cell-based therapies, particularly those utilizing mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), have emerged as promising alternatives due to their ability to suppress inflammation, stimulate angiogenesis, and promote cellular proliferation [24]. However, the therapeutic potential of MSCs is significantly limited by low post-transplantation survival rates, risks of immune rejection, and potential tumorigenicity [16] [24]. Consequently, research attention has shifted toward the paracrine mechanisms of MSCs, particularly their secreted exosomes, as a cell-free therapeutic alternative [24]. Exosomes are nano-sized extracellular vesicles (30-150 nm in diameter) secreted by all cell types, consisting of a phospholipid bilayer that carries bioactive molecules including proteins, lipids, mRNAs, and miRNAs [24]. These vesicles facilitate intercellular communication and contribute to tissue regeneration by exerting anti-inflammatory effects, promoting angiogenesis, and supporting extracellular matrix remodeling [24].

Despite their therapeutic potential, standalone exosome therapies face significant delivery challenges, including rapid clearance from the target site, enzymatic degradation, and poor retention in irregular wound geometries [16] [17]. This application note examines the synergistic rationale for combining exosomes with hydrogel-based delivery systems to overcome these limitations and enhance therapeutic outcomes in wound care.

Hydrogel-Exosome Synergy: Comparative Advantages and Mechanisms

The integration of exosomes within hydrogel systems creates a synergistic therapeutic platform that addresses the critical limitations of standalone exosome therapies while amplifying their regenerative potential. The comparative advantages of this combination are substantial and multifaceted.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Standalone Exosomes versus Hydrogel-Encapsulated Exosomes for Wound Therapy

| Characteristic | Standalone Exosomes | Hydrogel-Exosome Composite |

|---|---|---|

| Retention Time | Rapid clearance from administration site [16] | Sustained release over extended periods (e.g., 72-hour VEGF delivery) [17] |

| Bioactivity Protection | Susceptible to enzymatic degradation [17] | Enhanced stability and maintained biological activity [25] |

| Spatial Control | Limited localization at wound site | Prolonged retention at targeted tissues [16] |

| Therapeutic Efficacy | Suboptimal due to rapid clearance | Enhanced therapeutic efficacy; ~30% increased wound healing rate in rodent models [17] |

| Mechanical Properties | No structural support | Provides conducive 3D environment for cell regeneration [16] |

| Adaptation to Wound Bed | Limited | Conformal encapsulation adapting to wound cavity geometry [17] |

The fundamental mechanisms underlying the hydrogel-exosome synergy operate through three primary delivery strategies:

- In situ hybrid cross-linking for stimuli-triggered gelation and cavity-conformal encapsulation [17]

- Post-preloading cross-linking for covalent exosome-polymer integration [17]

- Physical adsorption exploiting hydrogel swelling dynamics to control exosome release [17]

These mechanisms collectively orchestrate spatiotemporal exosome release, bioactive cargo protection, and bidirectional molecular crosstalk, thereby establishing a paradigm-shifting approach to overcoming the enzymatic degradation, rapid clearance, and irregular tissue geometries inherent to diabetic complications and other chronic wounds [17].

Experimental Protocols: Hydrogel-Exosome Formulation and Evaluation

Protocol: Development of Injectable Hyaluronic Acid Hydrogel Loaded with MSC-Derived Exosomes

This protocol outlines the methodology for creating an injectable hyaluronic acid hydrogel incorporating mesenchymal stem cell (MSC)-derived exosomes, adapted from recent research on enhanced chronic wound healing [9].

Materials:

- Hyaluronic acid (HA, molecular weight: 100-500 kDa)

- MSC-derived exosomes (concentration: 1-5 mg/mL in PBS)

- Crosslinking agent (e.g., divinyl sulfone or adipic acid dihydrazide)

- Phosphate buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4)

- Sterile filtration units (0.22 μm)

Procedure:

- Hyaluronic Acid Modification:

- Dissolve hyaluronic acid in PBS to achieve a 2% (w/v) solution.

- Modify HA with crosslinkable functional groups (e.g., methacrylate groups for photopolymerization) by reacting with glycidyl methacrylate (0.1:1 molar ratio) under gentle stirring for 12 hours at 4°C.

- Purify via dialysis against distilled water for 48 hours and lyophilize.

Exosome Isolation and Characterization:

- Culture MSCs in serum-free media for 48 hours.

- Collect conditioned media and isolate exosomes using differential ultracentrifugation: 300 × g for 10 min, 2,000 × g for 20 min, 10,000 × g for 30 min, followed by 100,000 × g for 70 min.

- Characterize exosomes using nanoparticle tracking analysis, transmission electron microscopy, and Western blotting for CD63, CD81, and TSG101 markers [16].

Hydrogel-Exosome Composite Formation:

- Reconstitute modified HA in PBS to form a 3% (w/v) solution.

- Mix MSC-derived exosomes (final concentration: 100-500 μg/mL) with the HA solution.

- Initiate crosslinking by adding the crosslinking agent (0.05:1 molar ratio to HA repeating units) and maintain at 37°C for 60 minutes.

- The resulting hydrogel should exhibit injectability through an 18-22 gauge needle.

Quality Control:

- Assess gelation time via vial tilting method.

- Evaluate rheological properties using oscillatory shear rheometry.

- Determine exosome encapsulation efficiency via BCA protein assay on supernatant.

Protocol: In Vitro Assessment of Bioactivity and Release Kinetics

This protocol details methods for evaluating the therapeutic functionality of hydrogel-released exosomes, critical for establishing dosage and release parameters.

Materials:

- Human dermal fibroblasts (HDFs)

- Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs)

- Macrophage cell line (RAW 264.7)

- Cell culture media (DMEM, EGM-2)

- Transwell migration chambers

- Tube formation assay kit (e.g., Cultrex Basement Membrane Extract)

- ELISA kits for VEGF, IL-10, TNF-α

Procedure:

- Release Kinetics Study:

- Place 1 mL of exosome-loaded hydrogel in 5 mL of PBS at 37°C with gentle shaking.

- Collect release medium (200 μL) at predetermined time points (1, 3, 6, 12, 24, 48, 72 hours) and replace with fresh PBS.

- Quantify exosome release using micro-BCA protein assay or exosome-specific ELISA.

Fibroblast Migration Assay:

- Culture HDFs to 90% confluence and create a scratch wound using a 200 μL pipette tip.

- Treat with: (1) hydrogel-released exosomes, (2) fresh exosomes, (3) control media.

- Image at 0, 12, and 24 hours and calculate migration area using ImageJ software.

Angiogenic Potential Assessment:

- Seed HUVECs (1 × 10^4 cells/well) on Basement Membrane Extract.

- Treat with conditioned media from release study.

- After 6 hours, quantify tube formation by measuring total tube length and branch points.

Macrophage Polarization Study:

- Differentiate RAW 264.7 cells to M1 phenotype using LPS (100 ng/mL) and IFN-γ (20 ng/mL).

- Treat with hydrogel-released exosomes for 48 hours.

- Analyze M2 markers (CD206, Arg-1) via flow cytometry and ELISA for IL-10.

Therapeutic Mechanisms and Signaling Pathways

The therapeutic efficacy of exosome-loaded hydrogels in wound healing is mediated through multiple interconnected mechanisms that target key pathological processes in chronic wounds. The following diagram illustrates the primary signaling pathways through which MSC-derived exosomes encapsulated in hydrogels promote wound healing:

The molecular mechanisms illustrated above translate to measurable improvements in wound healing parameters. Preclinical studies have demonstrated that hypoxia-pretreated adipose-derived stem cell (ADSC)-derived exosome-embedded hydrogels increased the wound healing rate by approximately 30% and enhanced angiogenesis in rodent models [17]. The hydrogel platform provides programmable release kinetics, enabling 72-hour sustained VEGF delivery in vitro, and facilitates multifunctional regulation of the inflammatory microenvironment through coordinated antioxidant, immunomodulatory, and pro-angiogenic activities [17].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of hydrogel-exosome wound therapy research requires specific materials and characterization tools. The following table details essential research reagent solutions for developing and evaluating these therapeutic systems.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Hydrogel-Exosome Wound Therapy Development

| Category | Specific Examples | Research Function | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrogel Polymers | Hyaluronic acid [9], Gelatin methacryloyl (GelMA) [26], Chitosan [16], Dopamine-modified polymers [26] | 3D scaffold providing structural support and controlled release | Biocompatibility, tunable mechanical properties, biodegradability |

| Exosome Sources | MSC-derived exosomes [9], ADSC-derived exosomes [16], Plant exosomes (e.g., Momordica charantia) [26] | Primary therapeutic cargo delivering bioactive molecules | Cell-specific miRNA profiles, regenerative capacity, anti-inflammatory activity |

| Characterization Tools | Nanoparticle tracking analysis [16], Transmission electron microscopy [16], Western blot (CD63, CD81, TSG101) [16] | Verification of exosome identity, size, and concentration | Accurate quantification, morphological assessment, marker confirmation |

| Functional Assays | Tube formation assay (HUVECs) [24], Scratch wound assay [24], Macrophage polarization flow cytometry (CD206, Arg-1) [27] | Assessment of angiogenic, migratory, and immunomodulatory potential | Quantification of biological activity, mechanism validation |

| Animal Models | Diabetic mouse models (db/db or STZ-induced) [17], Full-thickness excisional wounds [26] | Preclinical evaluation of therapeutic efficacy | Pathologically relevant microenvironment, translational predictive value |

The selection of appropriate materials should be guided by the specific research objectives. For instance, GelMA and dopamine-based hydrogels offer superior antioxidant properties beneficial for diabetic wounds [26], while hyaluronic acid systems provide excellent biocompatibility and tunable physical characteristics [9]. Similarly, exosomes from different cellular sources exhibit distinct miRNA profiles and functional properties, enabling researchers to select exosomes with specific therapeutic activities aligned with their targeted wound healing applications.

The integration of exosomes within hydrogel delivery systems represents a paradigm shift in wound care therapeutics, effectively addressing the critical limitations of standalone exosome therapies while amplifying their regenerative potential through sustained, localized delivery. The synergistic combination leverages the high bioactivity and biocompatibility of exosomes with the protective and retention capabilities of hydrogels, creating a therapeutic platform capable of modulating the complex wound microenvironment through multiple coordinated mechanisms.

Future research directions should focus on personalizing exosome-hydrogel formulations using disease-stage-adjusted protocols that integrate diabetes subtypes, complication severity, and immune-genetic profiles for precision medicine [17]. Additional promising avenues include diversifying exosome sources using tissue-specific progenitors to enhance angiogenic and anti-inflammatory bioactivity [17], and engineering 3D-printed patient-specific hydrogels with lesion-matching porosity via digital light processing for anatomical precision [17]. The development of biodegradable hydrogels with tunable degradation kinetics via enzymatically cleavable crosslinkers will help prevent foreign-body reactions while ensuring complete exosome release [17].

As research in this field advances, hydrogel-exosome therapies hold tremendous promise for transforming the clinical management of chronic wounds, potentially offering solutions for millions of patients worldwide who currently lack effective treatment options. The continued refinement of these systems through rigorous preclinical evaluation and innovative bioengineering approaches will be essential for translating this promising technology into clinical practice.

Building the Delivery System: Methods for Loading and Characterizing Exosome-Laden Hydrogels

The isolation and characterization of exosomes, small extracellular vesicles (sEVs) with a size range of 30 to 150 nm, is a critical foundation for research in therapeutic delivery systems [28] [16]. Within the context of hydrogel encapsulation of mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) exosomes for sustained wound release, obtaining a pure and functionally intact exosome population is paramount [16]. These vesicles mirror the molecular composition of their parent cells, making them invaluable couriers of bioactive molecules that can promote cell proliferation, differentiation, and tissue regeneration [28] [16]. This application note provides detailed protocols for major exosome isolation techniques, with a focus on ultracentrifugation, and outlines the principal characterization methods—Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM), Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis (NTA), and Western Blot—to ensure researchers can reliably isolate and validate exosomes for downstream applications in regenerative medicine.

Major Exosome Isolation Protocols

Selecting an appropriate isolation method is crucial and depends on experimental goals, sample type, and the required balance between yield, purity, and scalability [28]. The following section details the most common techniques.

Differential Ultracentrifugation

Differential ultracentrifugation (UC) is the most established exosome isolation protocol [28]. It involves sequential centrifugation steps to remove cells, apoptotic debris, and larger vesicles, ultimately pelleting exosomes at high forces (typically greater than 100,000 × g) [28] [29]. While considered a gold standard for its high purity, the protocol is time-consuming and requires specialized equipment [29]. Recent comparative studies show that UC yields a medium particle count but achieves high purity, as indicated by a high particle-to-protein ratio [29].

Size-Exclusion Chromatography (SEC)

SEC separates exosomes based on their size and hydrodynamic properties using a porous column [28] [29]. Larger particles, such as exosomes, are eluted first, while smaller proteins and contaminants are retained in the pores. This method is highly reproducible, maintains exosome structural integrity, and is suitable for sensitive downstream analyses [28]. However, it may be less effective for complex biological fluids and can exhibit variability in fraction-wise concentration distribution across different sample types [29].

Precipitation-Based Methods

Precipitation protocols use reagents, such as polyethylene glycol (PEG), to force exosomes out of solution [28]. These methods are fast, require only a standard centrifuge, and yield high particle counts [28] [29]. The main drawback is lower purity due to co-precipitation of non-vesicular contaminants like lipoproteins and protein aggregates [28] [29]. A novel, efficient cocktail strategy integrating chemical precipitation with a two-step ultrafiltration process (CPF) has been developed to enhance purity while maintaining ease of use [29].

Immunoaffinity Capture

This technique employs antibodies targeting specific exosomal surface markers (e.g., CD9, CD63, CD81) for subtype-specific isolation [28] [30]. It provides very high selectivity and is ideal for studying exosome subpopulations. Its limitations include limited throughput, high cost, and the requirement for specific antibodies [28]. Advanced applications of this principle use genetic engineering to label exosomes from specific cell types in vivo for precise isolation from complex tissues [30].

Comparative Performance of Isolation Methods

The table below summarizes the key performance metrics of the primary isolation techniques, aiding in method selection.

Table 1: Comparative performance metrics for exosome isolation protocols

| Method | Purity | Yield | Scalability | Instrumentation | Time Requirement |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ultracentrifugation | High | Medium | Medium | Ultracentrifuge | High (Time-consuming) |

| SEC | Medium-High | Medium | High | Chromatography system | Medium |

| Precipitation | Low | High | High | Centrifuge | Low (Rapid) |

| Immunoaffinity Capture | Very High | Low | Low | Antibody-conjugated surfaces | Medium |

Table 2: Quantitative comparison of sEVs isolated from cell culture media using different methods (adapted from [29])

| Method | Particle Concentration (Particles/mL) | Mean Particle Size (nm) | Particle-to-Protein Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|

| CP (Precipitation) | 1.46E+10 | 76.13 ± 4.4 | Low |

| CPF (Precipitation + Filtration) | Successively higher than UC | 84.97 ± 8.2 (SEC example) | Higher than CP |

| UC | 1.3E+09 | 88.13 ± 5.1 | High |

| SEC | Successively lower than CP | 95.5 ± 8.9 | High |

Essential Characterization Techniques

Validating isolated exosomes is critical to confirm their identity, purity, and integrity. According to MISEV guidelines, characterization should combine complementary techniques [30] [31].

Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis (NTA)

NTA determines particle size distribution and concentration by tracking the Brownian motion of individual particles in a suspension [28] [29]. It is a vital tool for quantifying exosome yield and confirming the isolated population falls within the expected 30-200 nm size range [29]. Studies consistently show differences in particle concentration and size distribution based on the isolation method used [29].

Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM)

TEM provides high-resolution imaging of exosome morphology and ultrastructure [29] [31]. Properly isolated exosomes appear as round, cup-shaped vesicular structures with a visible lipid bilayer when visualized via negative stain TEM [29]. It is particularly useful for confirming the presence of a lipid bilayer and the absence of significant non-vesicular contaminants [29]. Recent studies have introduced (semi-)automated ImageJ-based algorithms to streamline the quantification of EV diameter from TEM images, enhancing objectivity and efficiency [31].

Western Blot

Western Blot analysis is used to detect the presence of specific exosomal protein markers, confirming the vesicular origin of the preparation [29]. Key positive markers include tetraspanins (CD9, CD63, CD81) and endosomal-related proteins (TSG101, Alix) [30] [29]. The absence of negative markers, such as Grp94 (endoplasmic reticulum protein) or calnexin, should also be confirmed to rule out contamination from other cellular compartments [29]. Robust bands for CD63 (between 30-60 kDa), CD9 (around 50 kDa), and TSG101 (around 44 kDa) are indicative of successful isolation [29].

Experimental Workflow and Signaling Pathways

The following diagrams, generated with Graphviz, illustrate the core experimental workflow for exosome isolation and application, as well as the functional role of MSC exosomes in wound healing.

Figure 1: Integrated workflow for MSC exosome isolation and hydrogel application for wound healing.

Figure 2: MSC exosome-mediated activation of key signaling pathways in recipient cells at the wound site.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential materials and reagents for exosome isolation and characterization

| Item | Function/Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) | Precipitates exosomes from solution in precipitation-based kits [29]. | Enables high yield but may co-precipitate contaminants; requires purity validation [29]. |

| Anti-Tetraspanin Antibodies (CD63, CD81, CD9) | Immunoaffinity capture and Western Blot validation of exosomes [30] [29]. | Critical for subtype-specific isolation and confirming exosomal identity per MISEV guidelines [30]. |

| Protein A/G Agarose Beads | Used in conjunction with antibodies for immunoprecipitation of specific EV subpopulations [31]. | Essential for pulldown assays; requires blocking with BSA to reduce non-specific binding [31]. |

| Total Exosome Isolation Reagent | Commercial precipitation-based solution for isolating exosomes from serum or plasma [31]. | Streamlined, rapid alternative to UC; suitable for clinical samples [31]. |

| Size-Exclusion Chromatography (SEC) Columns | Isolation of exosomes based on size and hydrodynamic radius [28] [29]. | Maintains vesicle integrity and biological activity; effective for removing soluble proteins [29]. |

Chronic wounds, characterized by a failure to proceed through an orderly and timely healing process, represent a significant and growing clinical burden globally. It is predicted that 20–60 million people worldwide will be affected by chronic wounds by 2026 [32]. These wounds, including diabetic foot ulcers, venous leg ulcers, and pressure ulcers, persist due to factors such as chronic inflammation, infection, vascular insufficiency, and impaired cellular responses [32]. The mortality rate over 5 years for chronic wounds appears to be higher than for certain prevalent types of cancer, underscoring the urgent need for more effective therapeutic interventions [32].

Traditional wound care methods often fail to address the complex microenvironment of chronic wounds. In response, advanced wound dressings, particularly hydrogels, have gained considerable attention for their proficiency in establishing ideal conditions for wound healing [32]. Hydrogels are three-dimensional, hydrophilic polymeric networks capable of absorbing and retaining large quantities of water or biological fluids while maintaining structural integrity [33]. Their unique properties—high porosity, biocompatibility, tunable degradation, ability to maintain a moist wound environment, and structural resemblance to the native extracellular matrix (ECM)—create favorable conditions for cellular migration and proliferation [32] [33].

The emergence of "active dressings" represents a significant advancement in wound care. These innovative systems are created by infusing hydrogels with bioactive molecules such as antibiotics, stem cells, anti-inflammatory agents, antioxidants, and growth factors to actively accelerate the healing process [32]. Particularly promising is the encapsulation of mesenchymal stem cell (MSC)-derived exosomes within hydrogels, which combines the regenerative capabilities of exosomes with the sustained delivery and protective environment provided by the hydrogel matrix [3] [34]. This approach addresses critical limitations of conventional therapies and opens new avenues for targeted, effective wound management.

Material Foundations: Natural vs. Synthetic Hydrogels

Hydrogels can be systematically classified based on their origin into natural, synthetic, and hybrid categories. Each class offers distinct advantages and limitations for wound healing applications, as summarized in Table 1.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Natural and Synthetic Hydrogels for Wound Healing

| Property | Natural Hydrogels | Synthetic Hydrogels |

|---|---|---|

| Biocompatibility | Inherently high due to biological origin [35] | Must be engineered; can achieve excellent biocompatibility [33] |

| Biodegradability | Enzymatically degraded; products are naturally metabolized [35] | Degradation must be designed into polymer structure [33] |

| Mechanical Strength | Generally poor and variable between batches [33] | Highly tunable and reproducible [33] |

| Bioactive Signals | Intrinsic cell-adhesive motifs and bioactivity [35] | Typically bio-inert unless functionalized [33] |

| Batch-to-Batch Variability | High due to natural sourcing [33] | Very low due to controlled synthesis [33] |

| Degradation Control | Difficult to control precisely [33] | Highly controllable via crosslinking density and chemistry [33] |

| Cost | Generally lower cost [32] | Can be more expensive [32] |

| Representative Polymers | Alginate, Chitosan, Gelatin, Hyaluronic Acid, Collagen [32] [35] | Poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG), Poly(vinyl alcohol) (PVA), Poly(acrylic acid) (PAA) [32] [36] |

Natural Hydrogels

Natural hydrogels are derived from biological sources such as polysaccharides and proteins. Their foremost advantage is their inherent biocompatibility, biodegradability, and presence of native bioactive motifs that support cellular adhesion and proliferation [35].

- Alginate: Derived from brown seaweed, alginate forms gentle gels in the presence of divalent cations like calcium. It is highly absorbent, creating a moist wound environment, but has limited mechanical strength and cell adhesion sites unless modified [32] [35].

- Chitosan: A polysaccharide obtained from chitin in crustacean shells, chitosan is notably biocompatible, biodegradable, and possesses inherent antimicrobial properties, making it particularly valuable for infected wounds [32] [35].

- Gelatin: Derived from denatured collagen, gelatin contains arginine-glycine-aspartic acid (RGD) sequences that promote cell adhesion and migration. It is a key component of many hybrid systems and is widely used in biofabrication [36] [37].

- Hyaluronic Acid (HA): A major component of the native ECM, HA plays crucial roles in inflammation and tissue regeneration. HA-based hydrogels can be modified to create scaffolds that guide the wound healing process [37].

Synthetic Hydrogels

Synthetic hydrogels are produced from man-made polymers, offering precise control over their physical and chemical properties, including mechanical strength, degradation rate, and water content [33].

- Poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG): PEG is a neutral, hydrophilic polymer known for its "stealth" properties and resistance to protein adsorption. It is highly tunable through various crosslinking mechanisms, including photopolymerization, but requires functionalization with adhesive ligands to support cell attachment [33] [37].

- Poly(vinyl alcohol) (PVA): PVA can form hydrogels through physical crosslinking (e.g., freeze-thaw cycles) or chemical crosslinking. It is known for its high water content, elasticity, and ability to form stable matrices, as demonstrated in its use with gelatin and borax to create self-healing dressings [36].

Hybrid and "Smart" Hydrogels

Hybrid hydrogels combine natural and synthetic polymers to harness the advantages of both material classes [32] [33]. A prominent example is gelatin-methacrylate (GelMA), which integrates the bioactivity of gelatin with the controllable photopolymerization of synthetic chemistry [33].

Furthermore, "smart" or stimuli-responsive hydrogels that react to environmental cues such as pH, temperature, enzymes, or light are at the forefront of wound care innovation [33]. These systems can provide on-demand drug release or adapt their properties in response to the dynamic wound microenvironment.

Advanced Application: Hydrogel Encapsulation of MSC Exosomes

Rationale for Exosome Encapsulation

Mesenchymal stem cell (MSC)-derived exosomes have emerged as a powerful cell-free therapeutic paradigm for regenerative medicine. These nano-sized extracellular vesicles (30-150 nm) act as intercellular communicators, transferring a cargo of proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids (e.g., microRNAs) that can modulate inflammation, promote angiogenesis, inhibit apoptosis, and enhance cell migration and proliferation [3] [34]. Compared to whole MSC therapy, exosomes offer significant advantages: they lack tumorigenic potential, do not self-replicate, present a lower risk of immune rejection, and are easier to store and handle [3] [34].

However, the therapeutic efficacy of free exosomes is limited by their rapid clearance from the body and short half-life at the injury site [3] [34]. Hydrogel encapsulation provides a strategic solution to these challenges by serving as a protective reservoir that localizes the exosomes and enables their sustained, controlled release at the wound site [3] [37]. This synergistic combination enhances retention and bioavailability, thereby potentiating the therapeutic effect.

Exosome-Laden Hydrogel System Design

The design of an effective exosome-laden hydrogel dressing requires careful consideration of multiple components and their interactions. The following diagram illustrates the key functional layers and their roles in promoting wound healing.

Protocol: Fabrication and Characterization of an Exosome-Laden Injectable Hydrogel

This protocol details the development of an injectable hyaluronic acid-based hydrogel loaded with MSC-derived exosomes for chronic wound healing, based on established methodologies [3] [9] [34].

Part A: Isolation and Characterization of MSC-Derived Exosomes

Cell Culture and Conditioning:

- Culture human MSCs (e.g., from adipose tissue or bone marrow) in standard growth medium to 70-80% confluence.

- Replace growth medium with a serum-free, exosome-depleted conditioning medium.

- Incubate for 24-48 hours. Collect the conditioned medium.

Exosome Isolation (Differential Ultracentrifugation):

- Centrifuge the conditioned medium at 300 × g for 10 minutes to remove cells.

- Transfer supernatant and centrifuge at 2,000 × g for 20 minutes to remove dead cells.

- Transfer supernatant and centrifuge at 10,000 × g for 30 minutes to remove cell debris.

- Filter the supernatant through a 0.22 µm filter.

- Ultracentrifuge the filtrate at 100,000 × g for 70 minutes at 4°C.

- Discard supernatant and resuscent the exosome pellet in sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS).

- Repeat the ultracentrifugation wash step.

- Resuspend the final, purified exosome pellet in a small volume of PBS (e.g., 100-200 µL).

Exosome Characterization:

- Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis (NTA): Dilute exosome sample in PBS and inject into the NTA system to determine particle size distribution and concentration.

- Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM): Adhere exosomes to a Formvar-carbon coated grid, stain with 1-2% uranyl acetate, and image to confirm cup-shaped morphology.

- Western Blotting: Lyse exosomes and probe for positive markers (e.g., CD63, CD81, TSG101) and negative markers (e.g., Calnexin).

Part B: Fabrication of the Injectable Hydrogel

Hydrogel Precursor Solution:

- Dissolve thiolated hyaluronic acid (HA-SH) and maleimide-functionalized PEG (PEG-MAL) in a chilled, degassed PBS solution (pH 7.4) at a predetermined stoichiometric ratio (e.g., 1:1 thiol:maleimide) to a final polymer concentration of 2-4% w/v.

- Gently mix the two precursor solutions on ice to slow the gelation kinetics.

Exosome Loading:

- Immediately after mixing the polymer precursors, add the concentrated exosome suspension (from Part A) to the solution and mix gently by pipetting to ensure homogeneous distribution. A typical loading concentration is 1-5 × 10^10 exosome particles per mL of hydrogel precursor.