In Vivo Yamanaka Factor Delivery: Methods, Applications, and Safety for Therapeutic Reprogramming

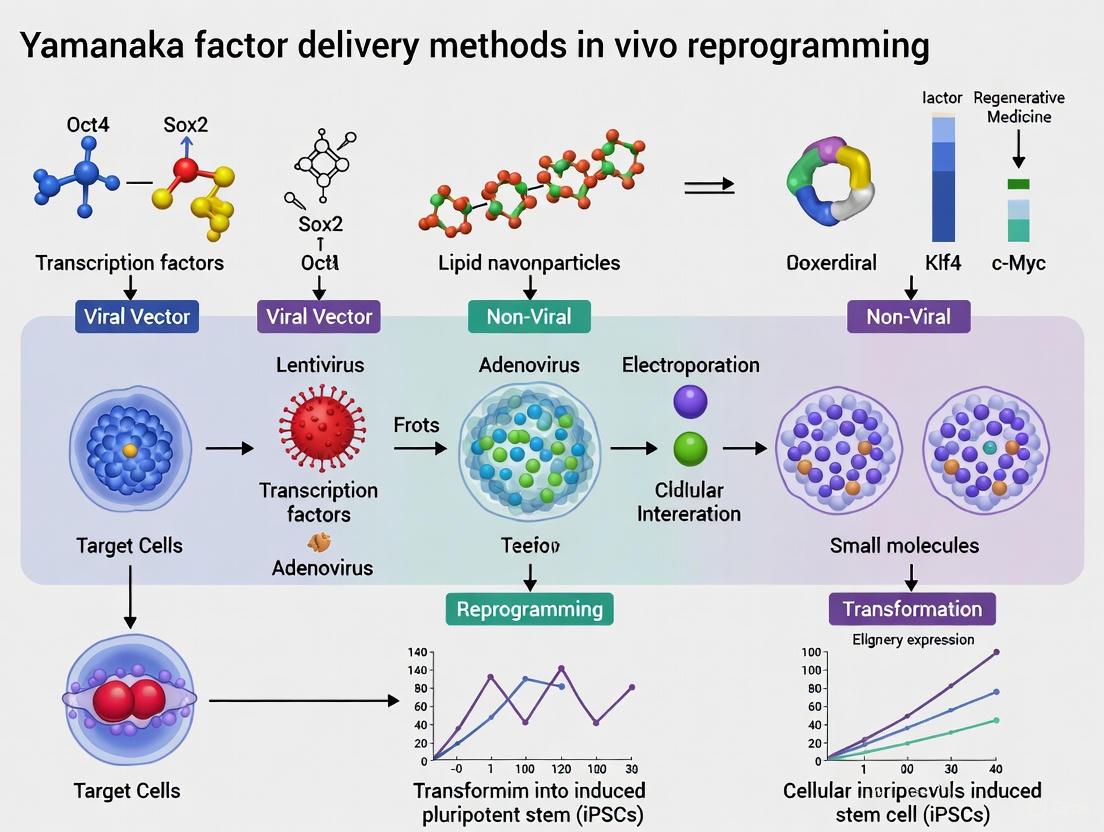

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of current methods for delivering Yamanaka factors (OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, c-MYC) for in vivo reprogramming, a transformative approach in regenerative medicine.

In Vivo Yamanaka Factor Delivery: Methods, Applications, and Safety for Therapeutic Reprogramming

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of current methods for delivering Yamanaka factors (OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, c-MYC) for in vivo reprogramming, a transformative approach in regenerative medicine. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational principles of cellular reprogramming and its potential to reverse age-related phenotypes and enhance tissue regeneration. The scope covers the full spectrum of viral and non-viral delivery systems, their mechanisms, and application-specific selection. It further details strategies for optimizing efficiency and safety, including cyclic induction and AI-engineered factors, and concludes with rigorous validation frameworks and comparative analyses of different methodologies to guide preclinical and clinical translation.

The Science of Cellular Reprogramming: From Yamanaka Factors to In Vivo Rejuvenation

The discovery that somatic cells can be reprogrammed to a pluripotent state represents a paradigm shift in developmental biology and regenerative medicine. Cellular reprogramming is the process that allows the conversion of differentiated cells back into a pluripotent state, fundamentally challenging the long-held belief that cell differentiation is an irreversible process [1] [2]. This groundbreaking achievement, pioneered by Shinya Yamanaka in 2006, demonstrated that the forced expression of four specific transcription factors—OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, and c-MYC (collectively known as the OSKM or Yamanaka factors)—could revert specialized adult cells to induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) [2] [3]. The implications of this discovery extend far beyond basic science, opening new avenues for regenerative medicine, disease modeling, and the emerging field of epigenetic rejuvenation [1] [4].

Over the past decade, research has revealed that transient expression of these nuclear reprogramming factors can combat age-related deterioration at cellular, tissue, and organismal levels without completing the full reprogramming cycle to pluripotency [1]. This partial reprogramming approach has demonstrated remarkable potential for rejuvenation—restoring cellular or organismal functions to a more youthful state while retaining differentiated cell identity [1] [3]. The progressive nature of aging and its influence by external factors suggests the process likely stems from failures in maintenance mechanisms that ultimately impact epigenetic regulation and gene expression [1]. Among the hallmarks of aging, the loss of epigenetic information has been proposed as a critical cause that precedes many other aspects of age-related deterioration [1].

The Molecular Basis of Epigenetic Reset

Epigenetic Landscape of Aging and Reprogramming

Aging is characterized by progressive epigenetic alterations, including changes in DNA methylation patterns, histone modifications, and chromatin organization [1] [3]. These changes disrupt normal gene expression patterns and cellular function, contributing to the phenotypic manifestations of aging. The epigenetic clock, a biomarker of aging based on DNA methylation patterns, accurately predicts biological age across tissues and cell types [3]. During natural embryonic development and in cellular reprogramming, this epigenetic information is reset to a more youthful state [4] [3].

The fundamental principle underlying epigenetic reset is that somatic cell identity is dictated primarily by epigenetic changes rather than alterations in genomic DNA sequence [3]. When cells are reprogrammed to pluripotency, either via somatic cell nuclear transfer (SCNT) or induced pluripotency, aged epigenetic signatures are erased and reset to a ground state [3]. iPSCs generated through OSGM-mediated reprogramming show complete epigenetic rejuvenation, with epigenetic clocks reset to zero and telomeres elongated to lengths comparable to embryonic stem cells [3]. This resetting occurs even when reprogramming cells from patients with accelerated aging conditions like Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome (HGPS) and from supercentenarians [3].

Key Epigenetic Modifications in Reprogramming

DNA demethylation is a crucial step in epigenetic reset during reprogramming. Genome-wide DNA demethylation erases somatic cell memory and allows for the establishment of a new pluripotent or rejuvenated epigenetic state [5]. This process involves both passive replication-dependent demethylation and active enzymatic demethylation mechanisms. The ten-eleven translocation (TET) family of proteins, particularly TET1, plays a vital role in active DNA demethylation during germline epigenetic reprogramming and somatic cell reprogramming [5].

Histone modifications also undergo comprehensive remodeling during reprogramming. Changes in histone methylation (e.g., H3K9me2/3, H3K27me3), acetylation, and other post-translational modifications contribute to the chromatin state transition from a somatic to a more plastic or pluripotent configuration [1] [4]. OCT4 directly recruits chromatin remodeling complexes like the BAF complex to promote a euchromatic state and binds enhancers of Polycomb-repressed genes to induce conversion of their associated promoters from monovalent to bivalent domains [1]. These coordinated epigenetic changes enable the dramatic transcriptional reorganization required for identity reset.

The OSKM Factors: Molecular Mechanisms and Functions

OCT4: The Master Regulator of Pluripotency

OCT4 (encoded by the POU5F1 gene) is a POU-family transcription factor widely regarded as the master regulator of epigenetic reprogramming [1]. It is expressed in every cell during early stages of murine and human development, where it upregulates genes related to pluripotency, self-renewal, and stem cell maintenance [6]. During reprogramming, OCT4 operates through multiple distinct mechanisms. First, it directly recruits the BAF chromatin remodeling complex to promote a euchromatic state that enhances binding access for other reprogramming factors [1]. Second, OCT4 binds enhancers of Polycomb group-repressed genes to induce conversion of their associated promoters [1]. Third, it binds regulatory regions of pluripotency network genes to establish an autoregulatory pluripotency network [1]. Finally, OCT4 directly upregulates histone demethylases KDM3A and KDM4C, which remove repressive H3K9 methylation marks at pluripotency gene promoters [1]. Optimal reprogramming requires a threefold excess of OCT4 relative to other factors, underscoring its pivotal role [1]. Remarkably, OCT4 overexpression alone can induce pluripotency when other canonical reprogramming factors are endogenously expressed or in the presence of chromatin-remodeling chemical factors [1] [7].

SOX2: The Chromatin Priming Partner

SOX2 is a high-mobility group (HMG) box transcription factor essential for early development and the maintenance of pluripotency [1] [6]. During reprogramming, most studies focus on its heterodimerization and cooperative function with OCT4 [1]. Single-molecule imaging reveals that SOX2 engages chromatin first and primes target sites for subsequent OCT4 binding [1]. This pioneering function is supported by in vivo studies showing SOX2 alone can open chromatin and bind target DNA sites before OCT4 arrival [1]. OCT4/SOX2 shared binding sites show the most profound increase in accessibility during early reprogramming, and this partnership is critical for inducing pluripotency [1]. SOX2 promotes ectodermal gene expression while reducing mesodermal gene expression during the reprogramming process [2].

KLF4: The Dual-Function Transcriptional Regulator

KLF4 is a zinc-finger transcription factor containing both activator and repressor domains, conferring dual functionality during cell differentiation and reprogramming [1]. While OCT4 and SOX2 primarily increase chromatin accessibility during reprogramming, KLF4 drives the first wave of transcriptional activation [1]. Co-immunoprecipitation and ChIP-seq studies reveal that OCT4-SOX2 binding increases KLF4 binding by several folds, predominantly in chromatin regions that are closed in human fibroblasts [1]. KLF4 upregulates expression of NANOG, a critical pluripotency factor [6]. The stoichiometry of KLF4 expression significantly impacts reprogramming efficiency, with precise levels required for optimal results [2].

c-MYC: The Reprogramming Amplifier

In contrast to the other three factors, c-MYC does not function as a pioneer factor during reprogramming but serves as a potent amplifier of the process [1]. Although not strictly required for reprogramming initiation, c-MYC substantially increases efficiency and kinetics [1] [7]. The presence of c-MYC increases OSK binding by two-fold, and this modulatory relationship is bidirectional—MYC binding increases by 40-fold in the presence of OSK [1]. c-MYC can upregulate up to 15% of genes in the human genome through chromatin structure modification and is involved in numerous molecular pathways [6]. Its strong pro-proliferative effects contribute to its oncogenic potential, necessitating caution for in vivo applications [1] [7]. Alternative factors like L-MYC or N-MYC can substitute for c-MYC with reduced tumorigenic risk [7].

Table 1: Core OSKM Reprogramming Factors and Their Molecular Functions

| Factor | Gene Family | Key Functions in Reprogramming | Molecular Mechanisms | Essentiality |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OCT4 | POU transcription factor | Master regulator of pluripotency | Recruits BAF chromatin remodeler; establishes autoregulatory pluripotency network; induces permissive chromatin state | Essential |

| SOX2 | HMG-box transcription factor | Chromatin priming partner for OCT4 | Opens chromatin for OCT4 binding; forms heterodimers with OCT4; regulates ectodermal genes | Essential |

| KLF4 | Zinc-finger transcription factor | Dual activator/repressor; early transcriptional wave | Activated by OCT4-SOX2; upregulates NANOG; binds closed chromatin regions | Non-essential but enhances efficiency |

| c-MYC | Basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor | Reprogramming amplifier; proliferation driver | Modifies chromatin structure; enhances OSK binding; promotes metabolic switching | Non-essential |

Partial Reprogramming for Epigenetic Rejuvenation

Conceptual Framework and Definition

Partial reprogramming represents a modified approach to cellular reprogramming where cells are exposed to Yamanaka factors for sufficient duration to produce epigenetic rejuvenation but not long enough to complete dedifferentiation to pluripotency [8] [3]. This strategy aims to separate the rejuvenative properties of reprogramming from the loss of cellular identity, creating a potential therapeutic window for anti-aging interventions [3]. During partial reprogramming, cells undergo epigenetic remodeling that restores youthful patterns of gene expression while maintaining their differentiated state and function [1] [8].

The theoretical basis for partial reprogramming stems from observations that aging and reprogramming represent opposing epigenetic trajectories [4] [3]. If aging involves progressive accumulation of epigenetic errors and loss of epigenetic information, then reprogramming factors might reverse this process by restoring more youthful epigenetic patterns [1]. Partial reprogramming approaches typically involve transient expression of OSKM factors using doxycycline-inducible systems or non-integrating delivery methods in short cycles that prevent full dedifferentiation [4].

Evidence from Experimental Models

Multiple studies have demonstrated the feasibility of partial reprogramming for epigenetic rejuvenation. In progeric mouse models, cyclic induction of OSKM factors extended median lifespan by 33% and ameliorated age-related physiological changes without causing teratomas [4]. Similarly, in wild-type aged mice, long-term cyclic OSKM induction restored youthful transcriptomic, lipidomic, and metabolomic profiles across multiple tissues including spleen, liver, skin, kidney, lung, and skeletal muscle [4]. This regimen also promoted functional regeneration, improving wound healing and reducing fibrosis [4].

At the cellular level, partial reprogramming has been shown to reverse epigenetic age as measured by DNA methylation clocks in human cells [3]. Transcriptomic analyses reveal that partially reprogrammed cells adopt gene expression profiles characteristic of younger cells while retaining lineage-specific markers [1] [4]. These changes are associated with functional improvements including enhanced mitochondrial function, reduced oxidative stress, and restoration of nuclear architecture [4] [3].

Chemical Reprogramming Alternatives

Recent advances in chemical reprogramming offer a non-genetic alternative for epigenetic rejuvenation [4]. Small molecule cocktails can induce partial reprogramming without exogenous transcription factor expression, potentially enhancing safety profiles for therapeutic applications [4] [7]. For example, a two-chemical reprogramming procedure extended C. elegans lifespan by 42.1% while reducing DNA damage and ameliorating epigenetic age-related marks [4]. Another study demonstrated that a 7c chemical cocktail could rejuvenate mouse fibroblasts at a multi-omics scale, reversing both transcriptomic and epigenomic aging clocks [4].

Notably, chemical reprogramming appears to operate through distinct mechanisms from OSKM-mediated approaches. While OSKM reprogramming typically downregulates the p53 pathway, chemical reprogramming with the 7c cocktail upregulates p53 activity [4]. Furthermore, chemical reprogramming achieves epigenetic rejuvenation without increasing cell proliferation rates, suggesting that active epigenetic remodeling rather than passive dilution through cell division underlies the rejuvenation effects [4].

Experimental Protocols for In Vivo Reprogramming

Transgenic Mouse Models for Inducible Reprogramming

The most established method for studying in vivo reprogramming utilizes transgenic mice with doxycycline-inducible OSKM expression cassettes [4]. These models enable precise temporal control over reprogramming factor expression through administration of doxycycline in drinking water or food. The following protocol represents a standardized approach for in vivo partial reprogramming studies:

Materials:

- TRE-OSKM transgenic mice (often with reverse tetracycline-controlled transactivator, rtTA)

- Doxycycline hyclate

- Standard mouse chow or drinking water delivery system

Cyclic Induction Protocol:

- Administration Phase: Administer doxycycline (typically 0.1-2 mg/mL in drinking water with 1-5% sucrose) for 1-3 days to induce OSKM expression.

- Withdrawal Phase: Remove doxycycline for 4-7 days to allow transgene silencing and cellular recovery.

- Cycle Repetition: Repeat this cycle for predetermined durations (e.g., 10-35 cycles) depending on experimental goals.

- Monitoring: Regularly assess health parameters, including weight, activity, and blood markers, to detect potential adverse effects.

This cyclic approach has been successfully employed in multiple studies demonstrating partial reprogramming benefits while minimizing the risk of teratoma formation [4]. The specific cycle duration and total treatment period must be optimized for each experimental context and desired outcome.

Viral Vector-Mediated Delivery Systems

For translation to potential therapeutic applications, viral vector systems offer an alternative to transgenic models. Adeno-associated viruses (AAVs), particularly AAV9 with its broad tissue tropism, have been successfully used for in vivo delivery of reprogramming factors [4]. The following protocol outlines this approach:

Materials:

- AAV vectors encoding OSKM factors (often with TRE promoter)

- AAV encoding rtTA (if using inducible system)

- Appropriate viral vector controls

- Injection equipment (syringes, needles, etc.)

Delivery Protocol:

- Vector Preparation: Package OSKM factors into AAV9 capsids for optimal tissue distribution. Exclusion of c-Myc reduces tumorigenic risk [4].

- Systemic Administration: Administer AAV vectors via intravenous injection (typical dose: 10^11-10^12 vector genomes per mouse).

- Induction Cycles: If using inducible system, administer doxycycline cycles as described above.

- Efficiency Assessment: Monitor transduction efficiency and transgene expression using appropriate reporters or molecular assays.

This approach has demonstrated efficacy in aged wild-type mice, with one study reporting 109% extension of remaining lifespan in 124-week-old mice treated with OSK (excluding c-Myc) delivered via AAV9 [4].

Table 2: In Vivo Reprogramming Delivery Systems and Parameters

| Delivery Method | Key Features | Advantages | Limitations | Typical Induction Protocol |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transgenic (dox-inducible) | Genetically integrated OSKM with rtTA | Precise temporal control; reproducible expression | Not translatable to humans; potential background effects | 2-day dox ON, 5-day dox OFF (cyclic) |

| AAV Vectors | Viral delivery of OSKM genes | Applicable to any genetic background; potential clinical translation | Immune response concerns; variable transduction efficiency | Single injection with or without cyclic dox induction |

| Sendai Virus | RNA-based viral vector | Non-integrating; high efficiency | Transient expression; potential immunogenicity | Single injection (transient expression) |

| Chemical Reprogramming | Small molecule cocktails | Non-genetic; tunable; potentially safer | Lower efficiency; complex optimization | Continuous or cyclic treatment |

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for OSKM Reprogramming Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reprogramming Factors | OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, c-MYC (OSKM) | Induction of pluripotency and epigenetic reset | Can be delivered as genes, mRNAs, or proteins; optimal stoichiometry critical |

| Delivery Vectors | Retrovirus, Lentivirus, Sendai virus, AAV, Episomal plasmids | Vehicle for factor delivery | Non-integrating methods (Sendai, episomal) preferred for clinical translation |

| Induction Systems | Doxycycline, rtTA, TRE promoter | Temporal control of expression | Allows cyclic induction for partial reprogramming |

| Small Molecule Enhancers | Valproic acid, 5'-azacytidine, RepSox, CHIR99021 | Epigenetic modulators and signaling pathway inhibitors | Improve efficiency; some can replace transcription factors |

| Cell Culture Media | Advanced RPMI, DMEM/F12, StemFlex | Support cell growth during reprogramming | Often supplemented with specific growth factors |

| Assessment Tools | DNA methylation clocks, RNA sequencing, Immunofluorescence markers | Evaluation of reprogramming efficiency and rejuvenation | Multi-omics approaches provide comprehensive assessment |

Signaling Pathways in Epigenetic Reset

The following diagram illustrates the key signaling pathways and molecular interactions involved in OSKM-mediated epigenetic reset:

OSKM-Mediated Epigenetic Reset Signaling Pathway

This diagram illustrates the core signaling cascade initiated by OSKM expression, leading to coordinated epigenetic remodeling, transcriptional reprogramming, and ultimately cellular rejuvenation. The process begins with OSKM factors binding to target sequences and initiating widespread epigenetic changes through chromatin remodeling, DNA demethylation, and histone modifications [1]. These epigenetic changes enable transcriptional reprogramming characterized by silencing of somatic genes, activation of pluripotency networks, and metabolic shifting toward glycolysis [2]. The cumulative effect of these molecular changes is the improvement of key cellular phenotypes associated with aging, including mitochondrial function, telomere maintenance, and reduced senescence [3].

The OSKM factors represent powerful tools for epigenetic reset with significant potential for both basic research and therapeutic applications. Their ability to remodel the epigenetic landscape and reverse age-associated changes positions them uniquely in the arsenal of regenerative medicine strategies. However, significant challenges remain in translating these findings into safe and effective therapies.

Future research directions should focus on several key areas. First, achieving precise spatiotemporal control over reprogramming factor expression will be essential to minimize risks such as teratoma formation and loss of cellular identity [4]. Second, development of non-integrating delivery methods and chemical alternatives to genetic reprogramming will enhance safety profiles for potential clinical translation [4] [7]. Third, a deeper understanding of the molecular mechanisms underlying partial reprogramming and epigenetic rejuvenation will enable more targeted and efficient approaches [1] [3].

As the field advances, the core principles of OSKM-mediated epigenetic reset continue to provide a foundation for innovative strategies to combat age-related decline and disease. The careful balance between harnessing the rejuvenative potential of these factors while maintaining cellular identity represents the next frontier in reprogramming research, with profound implications for the future of regenerative medicine and healthy aging.

The discovery that somatic cells could be reprogrammed to pluripotency using the Yamanaka factors (OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, and c-MYC, collectively OSKM) represented a fundamental breakthrough in regenerative medicine [7]. This process, which produces induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), initially offered unprecedented potential for disease modeling and cell therapy. However, the clinical application of full reprogramming faced significant barriers, particularly the risk of teratoma formation and the complete loss of cellular identity [6] [8].

The paradigm has since evolved from achieving pluripotency to utilizing partial reprogramming—a controlled, transient exposure to reprogramming factors that rejuvenates cells without altering their identity [4]. This approach leverages the remarkable discovery that OSKM expression can reset epigenetic aging signatures while maintaining cellular differentiation, offering a potential strategy to combat age-related degeneration and enhance tissue repair [9] [4]. This Application Note frames these advances within the context of Yamanaka factor delivery methods for in vivo reprogramming research, providing researchers with quantitative comparisons, detailed protocols, and essential resource guidance.

Quantitative Analysis of In Vivo Reprogramming Approaches

The efficacy and safety of in vivo reprogramming are highly dependent on the methodology, including the specific factors used, delivery system, and induction regimen. The tables below summarize key quantitative data from foundational studies.

Table 1: Comparison of In Vivo Reprogramming Factor Configurations

| Factor Combination | Key Features & Rationale | Efficiency & Safety Notes | Reported Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|

| OSKM (Oct4, Sox2, Klf4, c-Myc) | Original Yamanaka factors; potent reprogramming [7] | High efficiency but significant tumorigenic risk due to c-Myc [7] [4] | Extends lifespan in progeria mice by ~33%; teratoma formation with continuous induction [9] |

| OSK (Oct4, Sox2, Klf4) | Exclusion of oncogenic c-Myc for improved safety [4] | Reduced tumorigenic risk; lower efficiency than OSKM [7] [4] | Extends remaining lifespan in aged wild-type mice by 109%; improves frailty index [4] |

| OSKMLN (OSKM, LIN28, NANOG) | Expanded factor set to enhance reprogramming [9] | Used in selective regeneration studies; safety profile under investigation [9] | Promotes rejuvenation capacity in mouse models [9] |

| Chemical Cocktails | Non-genetic integration; small molecule delivery [4] | Favorable safety profile; multi-step process with lower potency [4] | Rejuvenates fibroblasts on multi-omics scale; increases C. elegans lifespan by 42.1% [4] |

Table 2: Analysis of Delivery Systems and Induction Regimens for In Vivo Reprogramming

| Delivery Method | Induction Regimen | Animal Model | Key Results & Safety Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dox-Inducible Transgene (Tet-O system) | Cyclic (2 days ON, 5 days OFF) [9] | Progeria mice (HGPS model) [9] | Lifespan Extension: 33%Safety: No teratomas with cyclic induction [9] |

| Dox-Inducible Transgene (Tet-O system) | Long-term (7-10 months) & Short-term (1 month) cyclic [4] | Wild-type mice [4] | Rejuvenation: Younger transcriptome, lipidome, metabolome in multiple tissues; improved skin regeneration; no teratomas [4] |

| AAV9 Gene Therapy | Cyclic (1 day ON, 6 days OFF) [4] | Aged wild-type mice (124 weeks old) [4] | Lifespan Extension: 109% increase in remaining lifespanHealthspan: Improved frailty index score (6.0 vs. 7.5 in controls) [4] |

| Continuous Induction | Constitutive OSKM expression for several weeks [9] | 4Fj, 4Fk, 4F-A, 4F-B mouse models [9] | Safety Risk: Teratoma formation in multiple organs; dysplasia in pancreas, liver, kidney [9] |

Experimental Protocols for Key In Vivo Applications

Protocol: Cyclic Partial Reprogramming in a Progeria Mouse Model

This protocol is adapted from the landmark study that demonstrated partial reprogramming can ameliorate age-related phenotypes in vivo [9].

Objective: To extend healthspan and lifespan in a HGPS mouse model via cyclic, transient expression of OSKM factors without inducing teratomas.

Materials:

- Animal Model: Progeroid LAKI mice harboring a Dox-inducible polycistronic OSKM cassette (e.g., 4Fj or 4Fk models) [9].

- Inducing Agent: Doxycycline hyclate (Dox) administered in drinking water (e.g., 2 mg/mL with 1% sucrose) or via diet.

- Control Groups: Progeria mice without the transgene, and progeria mice with the transgene but without Dox administration.

Methodology:

- Induction Schedule: Begin cyclic induction at weaning or upon onset of phenotypic signs. A representative effective schedule is a 2-day ON / 5-day OFF cycle, repeated weekly for the duration of the study [9].

- Dox Administration: Provide Dox-medicated water ad libitum during the "ON" phases. Replace with normal water during "OFF" phases. Shield water and cages from light to maintain Dox stability.

- Health Monitoring: Weigh animals weekly and monitor for established progeria phenotypes (e.g., spine curvature, skin integrity, overall activity).

- Endpoint Analysis:

- Lifespan: Record survival to determine median lifespan extension.

- Tissue Collection: Harvest tissues (e.g., skin, cardiovascular, liver) for histopathological analysis. Key assessments include:

Protocol: AAV9-Mediated OSK Delivery for Rejuvenation in Aged Wild-Type Mice

This protocol details a gene therapy approach for organism-wide rejuvenation, excluding the oncogene c-Myc [4].

Objective: To deliver OSK factors via AAV9 to aged wild-type mice and evaluate the impact on healthspan and lifespan using a cyclic induction system.

Materials:

- Animal Model: Aged wild-type mice (e.g., 124 weeks old) [4].

- Viral Vectors:

- AAV9-TRE-OSK: AAV9 vector containing a Tet-On responsive element (TRE) driving expression of OSK.

- AAV9-rtTA: AAV9 vector expressing the reverse tetracycline-controlled transactivator (rtTA).

- Inducing Agent: Doxycycline.

Methodology:

- Vector Delivery: Co-administer AAV9-TRE-OSK and AAV9-rtTA via systemic injection (e.g., intravenous or intraperitoneal) to the aged mice. Allow 2-4 weeks for widespread vector distribution and transgene expression stabilization.

- Cyclic Induction: Initiate a chronic cyclic induction regimen, such as 1 day ON / 6 days OFF, via oral Dox administration (e.g., in food or water) [4].

- Phenotypic Assessment:

- Frailty Index: Calculate a non-invasive frailty index based on standard criteria (e.g., coat condition, gait, hearing loss) at regular intervals.

- Functional Tests: Conduct behavioral assays relevant to aging (e.g., grip strength, rotarod, cognitive tests).

- Molecular Analysis: Upon study completion, perform multi-omics analysis (e.g., transcriptomics, epigenomics) on tissues like liver, spleen, and skin to confirm a shift toward younger molecular signatures [4].

Visualization of Key Concepts and Workflows

Diagram 1: Full vs. Partial Reprogramming Cell Fate. Partial reprogramming avoids pluripotency to rejuvenate somatic cells.

Diagram 2: In Vivo Delivery Method Trade-offs. Each delivery platform offers distinct advantages and limitations for research and translation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for In Vivo Reprogramming Research

| Reagent / Tool | Function & Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Dox-Inducible Mouse Models (4Fj, 4Fk, 4F-A, 4F-B) [9] | Provides a genetically defined system for spatiotemporal control of OSKM expression via Dox administration. | Ideal for proof-of-concept and mechanistic studies. Choice of model (integration locus) can affect expression levels and patterns [9]. |

| AAV Vectors (e.g., AAV9, AAV-DJ) | Enables gene delivery in wild-type animals; AAV9 offers broad tissue tropism [4]. | Crucial for translational research. Requires careful titer optimization. Immune response and potential integration are key safety considerations. |

| Tet-On System Components (rtTA, TRE Promoter) | Allows controlled, dose-dependent transgene expression in combination with Dox [9] [4]. | The core of controllable systems. Leaky expression without Dox can be an issue; newer generations (rtTA2, rtTA3) offer improved specificity. |

| Small Molecule Cocktails (e.g., 7c) [4] | Provides a non-genetic method for inducing partial reprogramming, enhancing clinical safety. | Efficiency can be lower than OSKM. Mechanisms may differ (e.g., p53 pathway activation vs. OSKM-mediated downregulation) [4]. |

| Alternative Reprogramming Factors (L-Myc, N-Myc, LIN28, NANOG) [7] | Used to replace oncogenic c-Myc or enhance reprogramming efficiency and safety. | L-Myc is a common, less tumorigenic substitute for c-Myc [7]. OSKMLN combination is used for enhanced rejuvenation effects [9]. |

| Epigenetic Age Clocks (e.g., DNA methylation clocks) [4] | Quantitative biomarkers to assess the degree of cellular rejuvenation following partial reprogramming. | Critical for validating efficacy. Multi-omic clocks (transcriptomic, epigenomic, metabolomic) provide a more comprehensive picture [4]. |

Partial reprogramming has firmly established itself as a potent strategy for reversing age-related cellular decline and enhancing regenerative capacity in vivo. The successful application of cyclic OSKM or OSK induction, via either transgenic models or AAV delivery, to extend lifespan in progeroid and aged wild-type mice provides compelling evidence for its therapeutic potential [9] [4].

Future research must prioritize the refinement of delivery systems to achieve precise spatiotemporal control, minimizing the risks of tumorigenesis and loss of cellular identity [10] [9]. The development of efficient, non-integrating delivery methods and the exploration of chemical reprogramming cocktails represent the most promising paths toward clinical translation [7] [4]. As these technologies mature, partial reprogramming is poised to revolutionize the treatment of age-related diseases and regenerative medicine.

Aging is characterized by a progressive decline in physiological function, driven by a set of interconnected cellular and molecular processes known as the hallmarks of aging [11] [12]. These include genomic instability, telomere attrition, epigenetic alterations, loss of proteostasis, mitochondrial dysfunction, and cellular senescence, among others. In recent years, cellular reprogramming has emerged as a transformative strategy to combat these hallmarks. This approach, particularly using the Yamanaka factors (OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, c-MYC, collectively OSKM), can reverse age-related deterioration at the molecular and cellular level [4] [13].

This Application Note delineates the molecular mechanisms by which reprogramming, especially in vivo partial reprogramming, counteracts key hallmarks of aging. We provide a detailed framework for researchers and drug development professionals, focusing on practical protocols, key signaling pathways, and essential reagents for investigating reprogramming-based rejuvenation in the context of in vivo delivery systems.

Molecular Interplay: Reprogramming and the Hallmarks of Aging

Partial reprogramming does not erase cellular identity but applies a transient, controlled pressure that resets aged cells to a more youthful state, effectively targeting multiple hallmarks of aging simultaneously [8] [13]. The table below summarizes the mechanistic counteractions.

Table 1: How Partial Reprogramming Counters Hallmarks of Aging

| Hallmark of Aging | Effect of Partial Reprogramming | Key Molecular Changes & Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| Epigenetic Alterations | Reversal of age-related epigenetic changes and restoration of youthful gene expression patterns. | Restoration of youthful DNA methylation patterns and histone marks (e.g., H3K9me3); resetting of epigenetic clocks [4] [9] [13]. |

| Cellular Senescence | Reduction in senescent cell burden and suppression of the Senescence-Associated Secretory Phenotype (SASP). | Downregulation of p53/p21 pathways; reduction in SASP factor release; reversal of nucleocytoplasmic compartmentalization (NCC) defects [13]. |

| Mitochondrial Dysfunction | Improvement in mitochondrial function and restoration of energy metabolism. | Enhancement of oxidative phosphorylation; reduction in mitochondrial ROS [4] [13]. |

| Stem Cell Exhaustion | Rejuvenation of tissue-specific stem and progenitor cells, enhancing regenerative capacity. | Improved function of muscle stem cells; enhanced tissue regeneration in skin, pancreas, and muscle after injury [4] [9]. |

| Altered Intercellular Communication | Amelioration of chronic, age-related inflammation. | Reduction in pro-inflammatory signaling; reshaping of the extracellular matrix (ECM) and secretome [4] [14]. |

| Genomic Instability | Potential indirect effects via improved DNA repair and redox homeostasis. | Reduction of DNA damage markers; though noted, this is not a primary mechanism and reprogramming cannot repair DNA damage [8]. |

Figure 1: Logical flow depicting how partial reprogramming interventions target and counteract specific hallmarks of aging through distinct molecular mechanisms, leading to a rejuvenated state.

Quantitative Evidence from Key In Vivo Studies

In vivo studies have demonstrated the efficacy of partial reprogramming in extending healthspan and lifespan, with outcomes highly dependent on the delivery and expression protocol.

Table 2: Summary of Key In Vivo Reprogramming Studies in Aging Models

| Animal Model / Delivery Method | Reprogramming Factors & Regimen | Key Quantitative Outcomes | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Progeric LAKI Mice(Dox-inducible transgenic) | OSKMCyclic: 2-day ON, 5-day OFF | 33% increase in median lifespanReduction of mitochondrial ROSRestoration of H3K9me levelsNo teratomas after 35 cycles | [4] |

| Wild-Type Mice(AAV9 gene therapy delivery) | OSKCyclic: 1-day ON, 6-day OFF | 109% extension of remaining lifespan (from 124 weeks)Frailty index score: 6.0 (Treated) vs. 7.5 (Untreated) | [4] |

| Wild-Type Mice(Dox-inducible transgenic) | OSKMLong-term (7-10 months) & short-term (1 month) induction | Rejuvenation of transcriptome, lipidome, metabolome in multiple tissuesIncreased skin regeneration capacityNo teratoma formation | [4] |

| C. elegans(Chemical reprogramming) | Two-chemical cocktailNot specified | 42.1% lifespan extensionReduced DNA damage, oxidative stressAmelioration of H3K9me3/H3K27me3 | [4] |

Core Signaling Pathways in Reprogramming-Induced Rejuvenation

The rejuvenating effects of partial reprogramming are mediated through specific molecular pathways. Understanding these is critical for optimizing protocols and developing targeted therapies.

The HGF/MET/STAT3 Signaling Axis

Single-cell transcriptomics and secretome analysis of high-efficiency reprogramming in microfluidic devices have identified the HGF/MET/STAT3 axis as a critical pathway. This pathway functions as a cell-non-autonomous mechanism where specific sub-populations of reprogramming cells secrete HGF (Hepatocyte Growth Factor), which accumulates in the confined extracellular environment and signals through the MET receptor tyrosine kinase on other cells, activating STAT3. This extrinsic signaling enhances the overall efficiency of the reprogramming process and contributes to the rejuvenation of the cellular population [14].

TET-DNA Demethylase Pathway

The restoration of youthful DNA methylation patterns is a hallmark of epigenetic rejuvenation. Research has shown that the vision-improving effects of OSK expression in aged and glaucomatous mice require the activity of TET DNA demethylases [13]. This indicates that the active, enzymatic process of DNA demethylation is a crucial mechanism downstream of Yamanaka factor expression for resetting the epigenetic clock and restoring tissue function.

Figure 2: Key signaling pathways in reprogramming, including the extrinsic HGF/MET/STAT3 axis and the intrinsic TET-mediated DNA demethylation pathway.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

This section provides a foundational methodology for conducting in vivo reprogramming studies, adaptable for various research objectives.

Protocol: Cyclic Induction of Yamanaka Factors in Dox-Inducible Mouse Models

Application: For long-term rejuvenation studies in progeria and wild-type aged mice. Background: This protocol is based on the seminal study by Ocampo et al. (2016) and follow-up work, which demonstrated lifespan extension and multi-tissue rejuvenation without teratoma formation [4] [9].

Materials:

- Animal Model: Reprogrammable mouse model with Dox-inducible OSKM or OSK cassette (e.g., 4F-B, i4F-B, or similar [9]).

- Inducing Agent: Doxycycline hyclate (Dox) dissolved in drinking water (e.g., 2 mg/mL with 1-5% sucrose) or administered via diet.

- Control: Age-matched littermates receiving normal water/diet.

Procedure:

- Animal Weaning & Genotyping: Wean mice at 3-4 weeks and genotype to confirm the presence of the transgene.

- Baseline Characterization: Prior to induction, collect baseline data (e.g., body weight, frailty index, blood samples for omics analysis).

- Cyclic Dox Administration:

- Induction Cycle: Administer Dox-water/diet for a defined "ON" phase (e.g., 2 days).

- Washout Cycle: Replace with regular water/diet for a defined "OFF" phase (e.g., 5 days).

- Repetition: Repeat this cycle for the study duration (e.g., weekly cycles for up to 10 months in wild-type mice [4]).

- In-Life Monitoring: Monitor mice weekly for weight, signs of distress, and tumor formation. Conduct functional tests (e.g., grip strength, rotarod) periodically.

- Tissue Collection & Analysis: At endpoint, collect tissues for:

- Histology: Assess tissue architecture, fibrosis (e.g., Masson's Trichrome), and senescence (e.g., SA-β-Gal staining).

- Molecular Analysis: Perform RNA-seq, whole-genome bisulfite sequencing (WGBS), and metabolomics/lipidomics to evaluate transcriptomic and epigenetic age reversal [4].

Safety Note: Continuous induction of OSKM for more than a week can lead to teratoma formation and organ failure [9]. Cyclic induction with adequate OFF periods is critical for safety.

Protocol: Assessing Rejuvenation Markers in Human Cells Using a Nucleocytoplasmic Compartmentalization (NCC) Assay

Application: High-throughput screening for chemical rejuvenation cocktails or genetic interventions. Background: The breakdown of nucleocytoplasmic compartmentalization (NCC) is a conserved hallmark of aging and senescence. This assay quantifies NCC integrity as a proxy for cellular youth [13].

Materials:

- Cell Lines: Human fibroblasts from young and old donors, or replicatively senescent fibroblasts.

- Reporter Construct: Lentivirus encoding an NCC reporter (e.g., mCherry-NLS and eGFP-NES).

- Induction System: Lentivirus with Tet-On inducible OSK/OSKM polycistronic construct or chemical cocktails.

- Imaging: Automated fluorescence microscope and image analysis software (e.g., ImageJ).

Procedure:

- Cell Culture & Senescence Induction: Culture young and old fibroblasts in low-serum conditions to suppress cell division. Generate replicatively senescent cells by serial passaging until growth arrest.

- Stable Cell Line Generation: Transduce fibroblasts with the NCC reporter and the inducible reprogramming construct. Select with appropriate antibiotics.

- Intervention:

- Genetic: Add Dox to the medium to induce OSK expression for a partial reprogramming duration (e.g., 3-7 days).

- Chemical: Treat cells with candidate small molecule cocktails.

- Image Acquisition & Quantification:

- Image live cells using an automated microscope.

- Quantify the Pearson correlation coefficient between mCherry (nuclear) and eGFP (cytoplasmic) signals. A lower correlation indicates better NCC integrity and a more youthful state [13].

- Validation: Correlate NCC findings with other aging biomarkers, such as transcriptomic aging clocks and SASP factor secretion (e.g., IL-6, IL-8).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for In Vivo Reprogramming Studies

| Reagent / Tool | Function & Utility in Reprogramming Research | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Dox-Inducible Mouse Models(e.g., 4F-B, i4F-B) | Enables precise temporal control of OSKM expression in vivo via oral Dox administration. | Long-term cyclic rejuvenation studies; tissue-specific regeneration assays [4] [9]. |

| AAV9 Vectors | Efficient in vivo gene delivery vehicle for widespread transduction across tissues, including the CNS. | Delivery of OSK factors in a gene therapy approach for lifespan studies [4] [15]. |

| Sendai Virus (SeV) Vectors | Non-integrating, cytoplasmic RNA virus for high-efficiency reprogramming of human cells in vitro. | Generating high-quality, patient-specific iPSCs with low risk of genomic integration [16]. |

| Chemical Cocktails (e.g., 7c) | Non-genetic method to induce partial reprogramming and rejuvenation. | Reversing transcriptomic age in human fibroblasts; exploring alternative rejuvenation pathways [4] [13]. |

| Tet-On System | Inducible gene expression system allowing controlled timing and dosage of transgene expression. | Controlled OSK expression in stable cell lines for in vitro rejuvenation assays [13]. |

| scRNA-seq & Secretome Analysis | Tools for resolving cellular heterogeneity and characterizing the extracellular protein environment. | Identifying key signaling pathways (e.g., HGF/MET) and intermediate cell states during reprogramming [14]. |

The discovery that somatic cells can be reprogrammed using the Yamanaka factors (OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, and c-MYC, collectively OSKM) has opened transformative avenues for regenerative medicine. While initially developed for in vitro applications, this technology has evolved to include in vivo reprogramming, a strategy with profound implications for treating age-related diseases, including progeroid syndromes. This application note synthesizes key proof-of-concept studies conducted in both progeria and wild-type mouse models, providing a detailed examination of the protocols, quantitative outcomes, and essential reagents that underpin this promising field. The content is framed within a broader thesis investigating Yamanaka factor delivery methods, highlighting the critical transition from in vitro validation to in vivo therapeutic application.

Core Concepts and Signaling Pathways

Figure 1 illustrates the primary molecular mechanism of Hutchinson-Gilford Progeria Syndrome (HGPS) and the conceptual framework of the in vivo reprogramming strategy discussed in this note.

Figure 1: Molecular Pathogenesis of HGPS and In Vivo Reprogramming Strategy. The diagram illustrates the dominant-negative effect of the LMNA G608G mutation, which leads to progerin production and nuclear dysfunction [6]. Conversely, transient induction of Yamanaka factors (OSKM) promotes partial reprogramming, enabling epigenetic rejuvenation without complete dedifferentiation [9].

Hutchinson-Gilford Progeria Syndrome (HGPS) is a rare genetic disorder characterized by accelerated aging. It is predominantly caused by a de novo point mutation (c.1824 C>T; p.G608G) in the LMNA gene, which encodes nuclear lamins A and C [6]. This mutation activates a cryptic splice site, leading to the production of a truncated, permanently farnesylated protein called progerin. Progerin accumulation causes nuclear envelope abnormalities, genomic instability, and premature cellular senescence [6] [17]. Cardiovascular complications stemming from these defects are the primary cause of mortality.

In vivo reprogramming using Yamanaka factors offers a compelling strategy to counteract these effects. Unlike full reprogramming, which aims to create induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), partial reprogramming involves the transient expression of OSKM. This brief exposure is sufficient to reverse age-associated epigenetic marks, such as DNA methylation patterns and heterochromatin loss, without erasing cellular identity or forming teratomas [8] [9]. The conceptual pathway from the HGPS mutation to its potential rescue via OSKM is outlined in Figure 1.

Key In Vivo Studies and Quantitative Outcomes

Research in animal models has provided crucial proof-of-concept evidence for the efficacy and therapeutic potential of in vivo reprogramming. The following table summarizes the designs and key quantitative findings from landmark studies in both progeria and wild-type mouse models.

Table 1: Summary of Key In Vivo Reprogramming Studies in Mouse Models

| Animal Model | Intervention | Key Quantitative Outcomes | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| HGPS Mouse Model(LmnaG609G/G609G) | Cyclic OSKM expression(2 days ON / 5 days OFF) | • Lifespan extension: Significant• Epigenetic reset: Restoration of H3K9me3 markers• Functional improvement: Better skin integrity, reduced spine curvature, enhanced cardiovascular function [9]. | |

| HGPS Mouse Model(Homozygous for human LMNA c.1824 C>T) | AAV9-delivered ABE(Single injection at P14) | • Mutation correction: 20-60% across organs at 6 months• Lifespan extension: Median lifespan increased from 215 to 510 days (2.4-fold)• Vascular rescue: Normalized VSMC counts, prevented fibrosis [17]. | |

| Wild-Type C57BL/6 Mice(Aged) | Cyclic OSKM expression(Long-term cycling) | • Molecular rejuvenation: Restored youthful DNA methylation, transcriptomic, and lipidomic profiles in spleen, liver, skin, kidney, lung, muscle.• Tissue regeneration: Enhanced muscle repair and wound healing, reduced fibrosis [8] [9]. | |

| Wild-Type C57BL/6 Mice(Aged, 55 weeks old) | Single-cycle OSKM expression(1 week duration) | • Systemic epigenetic impact: DNA methylation reprogramming in pancreas, liver, spleen, and blood [8]. | |

| Reprogrammable i4F-B Mice(Cerebral Ischemia) | Doxycycline-inducible OSKM(7-day infusion) | • Neural regeneration: Generation of new neurons (NeuN+)• Behavioral recovery: Improved performance in rotarod and ladder walking tests [15]. |

The data from these studies robustly demonstrate that in vivo reprogramming can mitigate complex aging phenotypes. In progeria models, the strategy not only extends lifespan but also rescues specific pathological hallmarks, particularly at the vascular level [17]. In wild-type aged mice, the approach reverses molecular signatures of aging and enhances innate regenerative capacity across multiple tissues [8] [9].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

This section provides detailed methodologies for two pivotal types of experiments referenced in Table 1: the induction of partial reprogramming in progeria mice and the assessment of its effects in wild-type aged mice.

Protocol 1: Cyclic In Vivo Reprogramming in a Progeria Mouse Model

This protocol is adapted from the landmark study by Ocampo et al. (2016) that demonstrated lifespan extension in a progeroid model [9].

A. Animal Model and Genetic Tools

- Animals: Use progeroid LmnaG609G/G609G mice or transgenic mice harboring a doxycycline-inducible OKSM cassette (e.g., 4F-A, 4F-B models with OSKM integrated at the Col1a1, Neto2, or Pparg loci) [9].

- Genotyping: Confirm genotype via PCR from tail-tip DNA using primers specific for the LmnaG609G allele or the transgenic OSKM cassette [18].

B. Induction of Partial Reprogramming

- Compound: Administer doxycycline (Dox) in the drinking water (e.g., 2 mg/mL with 1-5% sucrose) or via diet.

- Cyclic Regimen: Implement a cyclic schedule of 2 consecutive days of Dox administration, followed by 5 days without Dox. Repeat this cycle weekly, starting from weaning until endpoint [9].

- Control Groups: Include both progeroid and wild-type littermates receiving standard water/diet without Dox.

C. Tissue Harvesting and Analysis (Endpoints)

- Lifespan Monitoring: Monitor survival daily. Record age at death or humane endpoint.

- Tissue Collection: At specified timepoints or endpoint, harvest tissues (e.g., skin, aorta, liver, spleen) for analysis.

- For histology: Immersion-fix in 4% PFA or 3% NBF for 2-24 hours depending on tissue, then cryoprotect in 30% sucrose before embedding and cryo-sectioning [18].

- For molecular analysis: Snap-freeze tissue in liquid nitrogen and store at -80°C.

- Phenotypic Scoring: Quantify age-related phenotypes such as spine curvature (via X-ray), body weight, and dorsal skin integrity.

- Molecular Analysis:

- Immunofluorescence: Stain tissue sections for H3K9me3, progerin, and lamin A/C to assess nuclear lamina integrity and epigenetic marker restoration [9].

- DNA Methylation Analysis: Isolate genomic DNA and perform whole-genome bisulfite sequencing (WGBS) or targeted analysis to assess epigenetic age reversal [8].

Protocol 2: Assessing Rejuvenation in Wild-Type Aged Mice

This protocol outlines the procedure for inducing and analyzing the effects of partial reprogramming in physiologically aged, wild-type mice [8] [9].

A. Animal Model and Induction

- Animals: Use aged (e.g., 18-24 month old) wild-type C57BL/6 mice. For targeted reprogramming, use transgenic models (e.g., i4F-B) with inducible OSKM.

- Reprogramming Induction:

B. Functional Regeneration Assays

- Muscle Injury and Repair:

- One week after a Dox cycle, induce muscle injury in the tibialis anterior muscle via intramuscular injection of cardiotoxin (e.g., 50 µL of 10 µM solution).

- Harvest muscles at 5-, 10-, and 15-days post-injury.

- Analyze regeneration by quantifying centrally nucleated myofibers on H&E-stained sections and performing IF for embryonic myosin heavy chain (eMyHC) [9].

- Skin Wound Healing:

- Create full-thickness skin wounds (e.g., 4 mm biopsy punch) on the dorsum.

- Monitor wound closure daily via digital photography and planimetric analysis.

- Harvest wound tissue at various stages for analysis of re-epithelialization, collagen deposition (Masson's Trichrome stain), and reduction in fibrosis [9].

C. Molecular Phenotyping

- Multi-Omics Analysis:

- DNA Methylation: Use liver/spleen DNA to profile methylation clocks via WGBS or array-based platforms (e.g., Illumina MethylationEPIC) [8].

- Transcriptomics: Perform RNA-seq on tissues like liver, skin, and skeletal muscle to assess reversion to youthful gene expression profiles [8] [9].

- Lipidomics: Conduct mass spectrometry-based lipidomic profiling on plasma and liver tissue to evaluate restoration of youthful lipid composition [8].

Figure 2 visualizes the core workflow of these protocols, from animal preparation to data analysis.

Figure 2: General Workflow for In Vivo Reprogramming Studies. The diagram outlines the key stages of a typical in vivo reprogramming experiment, from the initial animal model preparation to the final data analysis, as described in the protocols above.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Successful execution of in vivo reprogramming studies relies on a specific set of research reagents and tools. The following table catalogs essential items for building this experimental pipeline.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for In Vivo Reprogramming Studies

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Inducible OSKM Mouse Models | Enables spatiotemporally controlled expression of Yamanaka factors in vivo. | • 4Fj, 4Fk (Col1a1 locus)• 4F-A/4FsA (Neto2 locus)• 4F-B/4FsB (Pparg locus) [9]. |

| Adeno-Associated Virus (AAV) | Efficient in vivo delivery vector for reprogramming factors or editors. | • AAV9: Broad tropism, crosses blood-brain barrier. Used for ABE delivery [17]. |

| Doxycycline (Dox) | Inducer for Tet-On systems; activates OSKM transgene expression. | Administered in drinking water (2 mg/mL with sucrose) or diet [9]. |

| Adenine Base Editor (ABE) | Corrects the point mutation causing HGPS (A•T to G•C) without double-strand breaks. | ABE7.10max-VRQR: Used to correct LMNA c.1824 C>T in HGPS mice [17]. |

| Histology & Staining Reagents | For tissue fixation, processing, and phenotypic analysis. | • Fixatives: 4% PFA, 3% NBF, Mirsky's fixative [18].• Cryoprotectant: 30% sucrose [18].• Staining: X-Gal solution for reporter mice (e.g., Hmox1, p21) [18]. |

| Antibodies for Phenotyping | Detection of key proteins to assess reprogramming efficacy and safety. | • Progerin/Lamin A/C: Nuclear integrity.• H3K9me3: Heterochromatin marker for epigenetic age.• NeuN: Neuronal differentiation [15] [9] [17]. |

| Reporter Mouse Models | Early detection of cellular stress and DNA damage in vivo. | • Hmox1 reporter: Oxidative stress/inflammation.• p21 reporter: DNA damage/senescence [18]. |

Critical Safety Considerations and Risk Mitigation

The translational potential of in vivo reprogramming is currently balanced against significant safety considerations. The powerful nature of the Yamanaka factors necessitates rigorous control to avoid adverse outcomes. Key risks identified in the literature include:

- Teratoma Formation: Continuous, unregulated expression of OSKM can lead to the formation of teratomas in multiple organs [8] [9]. This is the most significant risk associated with full reprogramming.

- Tissue Dysfunction and Cancer: In some studies, OSKM induction has been linked to dysplastic changes and cancer in organs like the pancreas, liver, and kidney. For instance, in the context of existing mutations (e.g., Kras), OSKM can drive cancer development through dedifferentiation-associated epigenetic changes [9].

- Loss of Cellular Identity: Prolonged exposure to reprogramming factors can cause cells to lose their specialized identity, leading to tissue dysfunction [8].

Risk Mitigation Strategies:

- Cyclic Induction: The use of intermittent, short-cycle induction (e.g., 2 days ON/5 days OFF) has proven effective in achieving rejuvenation benefits, such as lifespan extension in progeria mice, without triggering teratoma formation [9].

- Alternative Factors: Exploring the use of fewer factors (e.g., OSK without c-MYC) or non-integrating delivery systems (e.g., AAV, mRNA) can reduce oncogenic potential [6].

- Tissue-Specific Targeting: Utilizing tissue-specific promoters to restrict reprogramming activity to targeted cell types can minimize off-target effects in sensitive organs [19] [17].

- Novel Editing Approaches: The use of base editing (ABE) to correct the root cause of HGPS, as demonstrated by Koblan et al., represents a highly specific alternative that avoids the pleiotropic effects of OSKM overexpression [17].

The proof-of-concept studies detailed in this application note firmly establish in vivo reprogramming as a potent strategy with demonstrable efficacy in mitigating complex aging phenotypes. Key experiments in progeria models show that both cyclic OSKM expression and targeted genetic correction can significantly extend lifespan and rescue tissue pathology. Parallel studies in wild-type aged mice confirm the ability of partial reprogramming to restore youthful epigenetic and transcriptomic profiles and enhance tissue regeneration. The provided protocols and reagent toolkit offer a foundational roadmap for researchers aiming to replicate and build upon these findings. As the field progresses, the central challenge remains the refinement of delivery and control systems to maximize the therapeutic benefits of reprogramming while unequivocally minimizing its risks, thereby paving the way for clinical translation.

Delivery Systems for In Vivo Reprogramming: Viral Vectors, mRNA, and Chemical Approaches

The delivery of reprogramming factors, such as the Yamanaka cocktail (Oct4, Sox2, Klf4, c-Myc, or OSKM), is a foundational step in in vivo reprogramming and rejuvenation research [4] [20]. The choice of viral vector is critical, as it determines the efficiency, durability, and safety of cellular reprogramming. Adeno-associated viruses (AAVs), lentiviruses (LVs), and adenoviruses (Ad) are the most prominently used vectors, each with distinct advantages and limitations concerning packaging capacity, tropism, duration of expression, and immunogenicity [21] [22] [23]. This application note provides a structured comparison of these viral vectors and detailed protocols for their use in delivering reprogramming factors for in vivo applications.

Vector Comparison and Selection Criteria

Selecting the appropriate viral vector requires a careful assessment of the experimental goals, including the desired expression kinetics, size of the genetic payload, and target tissue. The following tables summarize the key characteristics and selection criteria for the three major viral vector systems.

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of Viral Vectors for Factor Expression

| Feature | Adeno-Associated Virus (AAV) | Lentivirus (LV) | Adenovirus (Ad) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genome Material | Single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) | Single-stranded RNA (ssRNA) | Double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) |

| Packaging Capacity | ~4.5 - 5.0 kb [24] [23] | ~8 kb [21] [23] | Up to ~36 kb [23] |

| Integration Profile | Predominantly non-integrating (episomal) [24] [22] | Integrates into host genome [21] [22] | Non-integrating [21] |

| Expression Duration | Long-term (months to years) [24] [23] | Long-term (stable integration) [21] [23] | Short-term/Transient (days to weeks) [21] [23] |

| Typical In Vivo Use | In vivo gene delivery [22] | Ex vivo cell modification [22] | In vivo vaccination, transient expression [21] [23] |

| Primary Safety Concerns | Pre-existing immunity, dose-dependent liver toxicity [24] | Risk of insertional mutagenesis [21] [22] | Strong innate immune response [21] [23] |

Table 2: Application-Based Selection Guide for Reprogramming Research

| Criterion | Adeno-Associated Virus (AAV) | Lentivirus (LV) | Adenovirus (Ad) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ideal for Long-Term Expression | Excellent - Sustained episomal expression in non-dividing cells [24] [21] | Excellent - Stable genomic integration [21] [23] | Poor - Transient expression due to immune clearance [21] |

| Ideal for Large Genetic Payloads | Poor - Limited to ~5 kb [24] [23] | Good - Capacity up to ~8 kb [21] [23] | Best - Can accommodate very large inserts [23] |

| Immunogenicity | Low immunogenicity [21] [22] | Low immunogenicity [25] | High immunogenicity [21] [23] |

| Key Advantage for Reprogramming | High safety profile and specificity via serotype tropism (e.g., AAV9 for systemic CNS delivery) [24] [4] | Ability to deliver large or multiple factor cassettes and create stable engineered cell lines ex vivo [21] [22] | High transduction efficiency and rapid onset of expression for proof-of-concept studies [21] [23] |

Experimental Protocols for In Vivo Reprogramming

AAV-Mediated In Vivo Delivery of Yamanaka Factors

This protocol details the methodology for systemic in vivo reprogramming using AAV vectors, based on studies that have demonstrated efficacy in murine models [26] [4].

Key Reagents:

- Plasmids: AAV transfer plasmid(s) containing the gene(s) of interest (e.g., OSK or OSKM) under a constitutive or inducible promoter (e.g., CMV, CAG), flanked by AAV Inverted Terminal Repeats (ITRs) [24] [26].

- Packaging System: AAV rep/cap plasmid (serotype-specific, e.g., AAV8 or AAV9 for broad tropism) and adenoviral helper plasmid [24] [26].

- Cells: HEK293T cells for vector production.

- Transfection Reagent: Polyethylenimine (PEI) or commercial equivalent.

- Purification Materials: Iodixanol gradient solutions, Amicon ultra-concentrator columns.

- Animals: Adult wild-type or disease model mice.

- Optional: Doxycycline (dox) for inducible systems (e.g., Tet-On) [4].

Procedure:

- Vector Production: Co-transfect HEK293T cells with the AAV transfer plasmid, rep/cap plasmid, and helper plasmid using PEI transfection [26].

- Harvest and Lysis: Collect cells 48-72 hours post-transfection. Lyse cells via freeze-thaw cycles and release viral particles using benzonase nuclease to degrade unpackaged nucleic acids.

- Purification: Purify AAV vectors using iodixanol density gradient ultracentrifugation. Recover the virus-containing fraction from the 40% iodixanol layer.

- Concentration and Buffer Exchange: Concentrate and desalt the viral preparation using Amicon ultra-concentrator columns with PBS-MK buffer (PBS with 1 mM MgCl₂ and 2.5 mM KCl).

- Titration: Determine the genomic titer (vector genomes/mL, vg/mL) of the purified AAV via quantitative PCR (qPCR) against a standard curve.

- In Vivo Administration: Administer AAV vectors systemically via intravenous (IV) injection (e.g., tail vein) into adult mice. A common dose for systemic expression ranges from (1 \times 10^{11}) to (1 \times 10^{12}) vg per mouse [26]. For an inducible system, also deliver an AAV vector expressing rtTA.

- Induction of Expression (for Inducible Systems): Initiate transgene expression by administering doxycycline (dox) in the drinking water (e.g., 2 mg/mL with sucrose) or via chow. Cyclic induction protocols (e.g., 2-days on/5-days off) have been used to promote rejuvenation while minimizing teratoma risk [4].

- Validation: Analyze reprogramming efficiency and functional outcomes through immunohistochemistry, RNA sequencing, and behavioral assays several weeks post-induction.

Lentiviral Vector Production for Ex Vivo Cell Engineering

While less common for direct in vivo reprogramming, lentiviral vectors are powerful tools for ex vivo engineering of cells, such as fibroblasts or stem cells, which can subsequently be used in vivo.

Key Reagents:

- Plasmids: Second or third-generation lentiviral packaging system (e.g., psPAX2, pMD2.G for VSV-G pseudotyping), and transfer plasmid containing the gene of interest [22] [23].

- Cells: HEK293T cells for production; target cells (e.g., fibroblasts, stem cells) for transduction.

- Transfection Reagent: PEI or commercial equivalent.

- Concentration Reagents: Lenti-X concentrator or ultracentrifugation equipment.

- Safety: All work must be conducted in appropriate biosafety level (BSL-2) containment.

Procedure:

- Vector Production: Co-transfect HEK293T cells with the lentiviral transfer plasmid and packaging plasmids (psPAX2, pMD2.G) [23].

- Harvest Supernatant: Collect the virus-containing supernatant at 48 and 72 hours post-transfection. Pool and filter the supernatant through a 0.45 µm filter to remove cellular debris.

- Concentration: Concentrate the lentiviral particles using Lenti-X Concentrator solution according to the manufacturer's instructions, or via ultracentrifugation.

- Titration: Determine the functional titer (Transducing Units/mL, TU/mL) on target cells (e.g., HEK293T) by serial dilution and measurement of reporter expression (e.g., fluorescence) after 48-72 hours.

- Ex Vivo Transduction: Isolate and culture primary target cells. Transduce cells with the lentiviral vector in the presence of a transduction enhancer like Polybrene (e.g., 8 µg/mL).

- Selection and Expansion: If the vector contains a selectable marker (e.g., puromycin resistance), apply selection pressure 48 hours post-transduction to eliminate untransduced cells and expand the polyclonal population.

- Validation and Implantation: Validate reprogramming factor expression in vitro and then transplant the engineered cells back into the animal model for further study.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Viral Reprogramming Experiments

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| HEK293T Cells | Production workhorse for AAV, LV, and Ad vectors due to high transfection efficiency and provision of adenoviral E1 genes. | Critical for high-titer virus production; requires rigorous quality control to prevent contamination [26] [23]. |

| Polyethylenimine (PEI) | Cationic polymer used for transient transfection of packaging cells with viral plasmids. | Cost-effective and scalable alternative to commercial transfection reagents [23]. |

| Iodixanol Gradient | Medium for density-based purification of AAV vectors via ultracentrifugation. | Effective method for separating full AAV capsids from empty capsids and cellular impurities [26]. |

| Lenti-X Concentrator | A commercial solution that precipitates lentiviral particles from large volumes of supernatant. | Simplifies LV concentration without the need for ultracentrifugation [23]. |

| Doxycycline (Dox) | Small molecule inducer for Tet-On/Tet-Off inducible gene expression systems. | Enables temporal control over Yamanaka factor expression, crucial for partial reprogramming and safety [4] [20]. |

| qPCR Reagents | For absolute quantification of viral vector genomic titer (vg/mL). | Essential for standardizing the dose administered in experiments [26]. |

Pathway and Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the critical steps in the AAV vector transduction pathway, from cellular binding to transgene expression, which underlies its application in reprogramming.

The delivery of reprogramming factors, such as the Yamanaka factors (Oct4, Sox2, Klf4, c-Myc, collectively OSKM), represents a cornerstone of modern in vivo reprogramming research for regenerative medicine. While viral vectors have been widely used, their clinical application faces significant challenges including robust immunogenicity, insertional mutagenesis risks, and complex manufacturing processes [27]. Non-viral delivery systems have emerged as promising alternatives with superior safety profiles and scalable manufacturing characteristics [27] [28]. This application note provides detailed protocols and frameworks for utilizing mRNA and episomal plasmid-based delivery systems specifically for Yamanaka factor delivery in in vivo reprogramming research, enabling safer therapeutic development for neurodegenerative disorders, age-related conditions, and tissue regeneration.

Technology Platforms: Comparative Analysis

The selection of an appropriate delivery vehicle depends on research goals, target cell type, and required expression duration. The table below summarizes the key characteristics of mRNA and episomal plasmid systems for Yamanaka factor delivery.

Table 1: Platform Comparison for Yamanaka Factor Delivery

| Characteristic | mRNA-LNP Platform | Episomal Plasmid Platform |

|---|---|---|

| Mechanism of Action | Cytoplasmic translation; no nuclear entry required | Nuclear entry required; episomal replication |

| Onset of Expression | Hours | Days |

| Expression Duration | Transient (days to weeks) | Prolonged (weeks to months) |

| Risk of Genomic Integration | Nonexistent | Very low (non-integrating by design) |

| Immunogenicity | Moderate to high (can be modulated via nucleoside modifications) | Low to moderate (depends on CpG content) |

| Cargo Capacity | Limited by LNP size constraints | High (can accommodate multiple gene cassettes) |

| Key Safety Advantages | No risk of insertional mutagenesis; precise temporal control | No viral elements; reduced genotoxicity risk compared to integrating vectors |

| Primary Challenges | Controlled LNP biodistribution; managing innate immune response | Low delivery efficiency in vivo; ensuring mitotic stability in dividing cells |

| Ideal Application in Reprogramming | Partial reprogramming; cyclic induction for rejuvenation | Stable reprogramming; long-term factor expression requirements |

mRNA-LNP Platform: Application Notes and Protocols

The mRNA-LNP platform encapsulates in vitro transcribed (IVT) mRNA encoding reprogramming factors within lipid nanoparticles that protect the nucleic acid and facilitate cellular delivery [29] [30]. After cellular uptake via endocytosis, the ionizable lipids within LNPs become protonated in the acidic endosomal environment, promoting endosomal membrane disruption and release of mRNA into the cytoplasm for translation [29]. This system is ideal for transient expression of Yamanaka factors, enabling controlled partial reprogramming strategies that have shown promise in reversing age-related cellular changes without complete dedifferentiation [4].

Critical Reagent Specifications

- Ionizable Lipids: Critical for encapsulation and endosomal escape. Modern designs (e.g., DLin-MC3-DMA, SM-102, ALC-0315) are biodegradable with improved safety profiles [29] [30].

- mRNA Construct: Must include 5' cap structure (ARCA or trimeric cap), 5' and 3' untranslated regions (UTRs), coding sequence for a single Yamanaka factor, and poly(A) tail [30]. Nucleoside modifications (e.g., N1-methylpseudouridine) significantly enhance translation and reduce immunogenicity [30].

- Helper Lipids: Typically include phospholipids (e.g., DSPC), cholesterol, and PEGylated lipids to form stable, serum-stable nanoparticles [29].

Detailed Protocol: mRNA-LNP Formulation and In Vivo Delivery

Protocol 1: LNP Formulation via Microfluidic Mixing

This protocol describes the preparation of LNPs encapsulating mRNA encoding a single Yamanaka factor (e.g., Oct4). For complete reprogramming, formulate separate LNPs for each factor and mix prior to administration or administer sequentially.

Materials:

- mRNA Solution: 0.1 mg/mL mRNA in 10 mM citrate buffer (pH 3.0)

- Lipid Mixture: Ionizable lipid, DSPC, cholesterol, DMG-PEG 2000 (50:10:38.5:1.5 molar ratio) dissolved in ethanol

- Microfluidic Device (e.g., NanoAssemblr, Precision NanoSystems)

- Dialysis Membrane (MWCO 100 kDa)

- PBS (pH 7.4)

Procedure:

- Prepare Solutions: Filter both mRNA solution and lipid mixture through 0.22 µm filters.

- Microfluidic Mixing: Load the aqueous (mRNA) and organic (lipid) phases into separate syringes. Pump through a microfluidic device at a flow rate ratio of 3:1 (aqueous:organic) with a total flow rate of 12 mL/min.

- Dialyze: Immediately collect the LNP formulation and dialyze against a 100-fold volume of PBS (pH 7.4) for 18 hours at 4°C to remove ethanol.

- Concentrate and Characterize: Concentrate using centrifugal filters if necessary. Characterize particles for size (70-100 nm expected), polydispersity index (<0.2 expected), encapsulation efficiency (>90% expected), and endotoxin levels.

Protocol 2: In Vivo Administration for Partial Reprogramming

This protocol utilizes a cyclic induction strategy to achieve transient Yamanaka factor expression for cellular rejuvenation without teratoma formation, as demonstrated in progeria and wild-type mouse models [4].

Materials:

- Formulated LNPs: A mixture of Oct4-, Sox2-, Klf4-, and c-Myc mRNA-LNPs in PBS. (Note: c-Myc may be excluded to reduce oncogenic risk [4]).

- Animal Model: Reprogrammable inducible mice (e.g., i4F-B) or wild-type mice receiving AAV9 delivery vectors for rtTA expression [4].

- Doxycycline: 2 mg/mL in drinking water with 2% sucrose.

Procedure:

- Prime the System: For transgenic models, administer doxycycline water to activate the inducible system.

- Systemic LNP Administration: Inject mRNA-LNP mixture intravenously via tail vein at a dose of 0.5 mg mRNA per kg body weight.

- Cyclic Induction Regimen: Follow a precise cycle of induction. A typical protocol for rejuvenation is a 2-day pulse of LNP administration with doxycycline, followed by a 5-day chase period without treatment [4]. Repeat this cycle for the desired duration (e.g., 35 cycles over 10 months in wild-type mice [4]).

- Monitor Outcomes: Assess reprogramming efficacy via epigenetic clock analysis, transcriptomic profiling, and functional tissue improvement. Monitor closely for teratoma formation.

The diagram below illustrates the key molecular pathway and workflow for mRNA-mediated in vivo reprogramming.

Episomal Plasmid Platform: Application Notes and Protocols

Episomal plasmid vectors are non-integrating DNA molecules that persist in the nucleus through replication mechanisms independent of the host chromosome [31]. These systems typically employ elements from viruses (e.g., Epstein-Barr Virus' oriP/EBNA1) or cellular components (e.g., Scaffold/Matrix Attachment Regions - S/MAR) to enable long-term persistence in dividing cells without integration [31] [32]. This makes them particularly valuable for reprogramming applications requiring sustained expression of Yamanaka factors over multiple cell divisions while minimizing genotoxic risks associated with integrating vectors.

Critical Reagent Specifications

- Replication Origin: oriP from EBV for latent replication or S/MAR sequences for chromatin attachment and replication initiation [31] [32].

- Nuclear Retention Elements: Family of Repeats (FR) from EBV or S/MAR sequences for mitotic stability [31].

- Transgene Cassette: Multiple Yamanaka factors can be delivered on a single plasmid, separated by self-cleaving 2A peptides or internal ribosome entry sites (IRES) [31].

- Selection System: Optional antibiotic resistance genes for in vitro work, though these should be excluded from clinical preparations.

Detailed Protocol: Episomal Plasmid Delivery for Stable Reprogramming

Protocol 1: Plasmid Design and Preparation for Yamanaka Factor Expression

This protocol covers the design and preparation of S/MAR-based episomal plasmids, which are preferred over viral-element plasmids due to their completely non-viral nature and reduced safety concerns [31] [32].

Materials:

- Backbone Vector: S/MAR-containing plasmid backbone (e.g., pEPI)

- Yamanaka Factor Genes: cDNA sequences for Oct4, Sox2, Klf4, c-Myc

- Promoter: Ubiquitous promoter (e.g., CAGGS) or tissue-specific promoter

- Restriction Enzymes and T4 DNA Ligase

- Competent E. coli (e.g., Stbl3 for unstable inserts)

Procedure:

- Vector Design: Clone Yamanaka factor genes into the episomal backbone. For single-plasmid delivery, connect factors using P2A self-cleaving peptide sequences.

- Bacterial Transformation: Transform competent E. coli with the constructed plasmid using heat shock or electroporation.

- Plasmid Amplification: Culture transformed bacteria in selective medium (e.g., containing appropriate antibiotic) for 16-18 hours at 32°C for S/MAR vectors to minimize recombination.

- Plasmid Purification: Use an endotoxin-free maxiprep kit to purify plasmid DNA. Determine concentration and purity (A260/A280 ratio >1.8).

Protocol 2: In Vivo Delivery and Analysis of Reprogramming

This protocol describes the delivery of episomal plasmids to the central nervous system for in vivo reprogramming of glial cells to neurons, a promising approach for neurodegenerative diseases [15].

Materials:

- Purified Episomal Plasmid: S/MAR-based plasmid encoding all four Yamanaka factors

- Complexation Agent: Linear polyethylenimine (PEI, 25 kDa) or commercial transfection reagent suitable for in vivo use

- Animal Model: Mouse model of neurodegenerative disease (e.g., Parkinson's disease, brain injury model)

- Stereotactic Injection Apparatus

Procedure:

- Plasmid Complex Formation: Complex 5 µg of episomal plasmid with PEI at an N/P ratio of 8 in 5% glucose solution. Vortex and incubate for 15 minutes at room temperature.

- Stereotactic Intracranial Injection: Anesthetize and secure animal in stereotactic frame. Inject plasmid complexes into target brain regions (e.g., cerebral cortex, lateral ventricle) at a rate of 0.2 µL/min. Multiple injection sites may be used for larger areas.

- Post-Procedure Monitoring: Monitor animals for behavior changes and sacrifice at predetermined time points (e.g., 2, 4, 8 weeks post-injection).

- Tissue Analysis: Analyze reprogramming efficiency via immunohistochemistry for neuronal markers (NeuN, Map2), synaptic markers, and absence of glial markers (GFAP) [15]. Assess functional integration via electrophysiology.

The diagram below illustrates the key mechanism and workflow for episomal plasmid-based reprogramming.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for Non-Viral Yamanaka Factor Delivery

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Reprogramming |

|---|---|---|