Integrating PK-PD Modeling and Natural Product Research: From Complex Challenges to Clinical Translation

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the application of Pharmacokinetic-Pharmacodynamic (PK-PD) correlation modeling in natural product research.

Integrating PK-PD Modeling and Natural Product Research: From Complex Challenges to Clinical Translation

Abstract

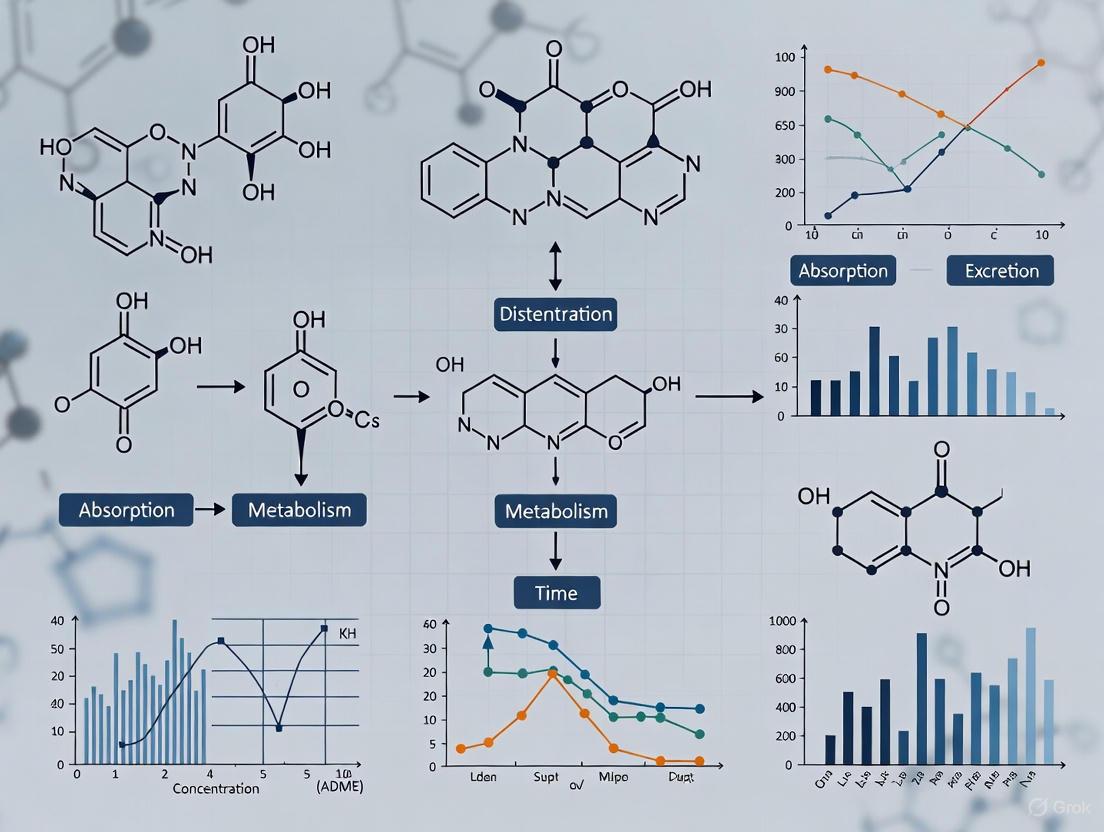

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the application of Pharmacokinetic-Pharmacodynamic (PK-PD) correlation modeling in natural product research. It addresses the unique challenges posed by the complex composition of natural products and outlines evolving strategies to establish meaningful concentration-effect relationships. The content covers foundational principles, advanced methodological approaches like physiologically-based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) modeling and coupled PK-PD frameworks, and solutions for troubleshooting common technical barriers. It also explores validation techniques and comparative analyses across different natural product classes, including botanical dietary supplements and traditional medicine formulations. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this resource highlights how mechanism-based PK-PD modeling can optimize natural product-based therapy development, improve dosing strategies, and facilitate the translation of preclinical findings into clinical practice.

Navigating Complexity: Foundational PK-PD Principles for Natural Products

Natural products present unique pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic (PK-PD) challenges that differentiate them from single-entity pharmaceutical drugs. Their complex nature arises from multi-constituent composition, variable phytochemical profiles, and multipotent biological actions that complicate traditional PK-PD modeling approaches [1]. Unlike conventional drugs designed for single-target specificity, natural products contain mixtures of bioactive compounds with individual PK profiles that can interact synergistically or antagonistically on multiple biological targets simultaneously [2]. This complexity necessitates specialized methodologies for evaluating absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (PK) parameters alongside corresponding pharmacological effects (PD).

The variable composition of herbal products introduces significant reproducibility challenges, as chemical profiles fluctuate based on plant origin, harvesting conditions, and processing methods [1]. Furthermore, natural products can interact with conventional drugs through both PK mechanisms (affecting metabolic enzymes and drug transporters) and PD mechanisms (altering pharmacological effects on targets), creating a multidimensional interaction landscape that requires sophisticated correlation modeling [1]. This Application Note outlines experimental frameworks and computational approaches to address these challenges, enabling more accurate PK-PD correlation modeling for natural product-based drug development.

Key Challenges in Natural Product PK-PD Modeling

Multi-constituent Complexity

Natural products contain numerous bioactive constituents with potentially different PK and PD properties. St. John's Wort exemplifies this challenge, containing hypericin, hyperforin, and various flavonoids that collectively exhibit multipotent actions [1]. These constituents can simultaneously inhibit and induce different metabolic enzymes, leading to complex, time-dependent PK profiles. The multi-target nature of natural products means they often interact with multiple biological pathways simultaneously, creating challenges for traditional PK-PD correlation models designed for single-target therapeutics [2].

Variable Composition and Standardization

The chemical composition of natural products varies significantly between batches due to environmental factors, genetic variations, and processing methods [1]. This variability directly impacts both PK parameters and PD responses, making reproducibility and standardization particularly challenging. Unlike single-entity drugs with consistent chemical profiles, natural products require specialized quality control measures to ensure consistent PK-PD relationships across different product batches.

Table 1: Key PK-PD Challenges of Natural Products

| Challenge Category | Specific Issue | Impact on PK-PD Modeling |

|---|---|---|

| Multi-constituent Complexity | Multiple bioactive compounds with individual PK profiles | Difficult to attribute observed effects to specific constituents |

| Compound-compound interactions (synergistic/antagonistic) | Non-linear PK-PD relationships | |

| Multi-target pharmacological actions | Complex PD profiles requiring network analysis | |

| Variable Composition | Batch-to-batch chemical variability | Inconsistent exposure-response relationships |

| Differing bioavailability of constituents | Challenging bioequivalence assessments | |

| Metabolic Interactions | Modulation of CYP450 enzymes and drug transporters | Altered metabolic clearance of co-administered drugs |

| Time-dependent inhibition/induction (e.g., St. John's Wort) | Complex, time-variant PK profiles |

Computational Approaches for PK-PD Modeling

Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning

Artificial intelligence (AI) algorithms can analyze large-scale biological data to identify molecular targets and pathways, advancing pharmacological knowledge of natural products [1]. Machine learning (ML) methods integrate diverse data sources including molecular structures, pharmacological properties, and known interaction patterns to provide mechanistic insights into natural product interactions [1]. Three primary computational approaches have shown promise for natural product PK-PD modeling:

Similarity-based methods infer interactions by evaluating similarity scores between drug profiles, including structural, gene expression, and pharmaceutical profiles [1]. These methods perform well when structurally similar natural product constituents share common targets but may generate false positives when similarity metrics are prone to noise.

Network-based methods utilize drug similarity networks or protein-protein interaction networks to predict multi-constituent interactions [1]. These approaches are more robust against noise compared to direct similarity-based methods and can capture indirect interactions, such as constituents affecting the same pathway.

Deep learning approaches handle complex, high-dimensional data effectively by integrating multi-omics datasets [3]. These methods can uncover relationships between herbal constituents and drug metabolism enzymes, predicting interactions not apparent through traditional analysis [1].

Multi-Omics Data Integration

Multi-omics technologies provide comprehensive biological information by integrating data from genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, epigenomics, and metabolomics [3]. This approach enables researchers to explore complex interactions and networks underlying natural product actions. Deep learning-based multi-omics integration methods can be categorized into non-generative methods (feedforward neural networks, graph convolutional neural networks, autoencoders) and generative methods (variational autoencoders, generative adversarial networks, pretrained transformers) [3].

The integration of transcriptome, proteome, phosphoproteome, and acetylproteome datasets has proven valuable for systematic analysis of complex biological systems [4]. For natural products, this multi-layered information can elucidate how multiple constituents collectively influence biological networks, enabling more accurate PK-PD correlation modeling that accounts for multi-target effects.

Table 2: Multi-Omics Data Types for Natural Product PK-PD Modeling

| Data Type | Application in PK-PD Modeling | Technology Platforms |

|---|---|---|

| Genomics | Identifying genetic factors affecting metabolism of natural product constituents | Whole-genome sequencing, SNP arrays |

| Transcriptomics | Analyzing gene expression changes in response to natural product exposure | RNA sequencing, microarrays |

| Proteomics | Quantifying protein expression and post-translational modifications | LC-MS/MS, protein arrays |

| Metabolomics | Profiling endogenous metabolites and natural product constituents | NMR, LC-MS, GC-MS |

| Epigenomics | Assessing epigenetic modifications induced by natural products | ChIP-seq, bisulfite sequencing |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: High-Throughput Screening for Bioactivity Assessment

Purpose: To rapidly identify bioactive constituents in natural products and characterize their multi-target activities.

Materials and Reagents:

- Natural product extract library

- Target-based assay kits (kinase, GPCR, ion channel, nuclear receptor)

- Cell culture reagents and cell lines

- High-content screening instrumentation

- Fluorescence/luminescence detection reagents

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare natural product extracts using standardized extraction protocols. Create dilution series for concentration-response studies.

- Assay Selection: Implement a panel of target-based assays representing key therapeutic areas and potential off-target interactions.

- Automated Screening: Transfer samples to assay plates using liquid handling systems. Add assay reagents according to established protocols.

- Signal Detection: Measure activity using appropriate detection methods (fluorescence, luminescence, absorbance).

- Data Analysis: Calculate activity scores for each natural product extract against all targets. Apply hit identification algorithms to distinguish true actives from false positives.

- Multi-Target Profiling: Generate target interaction profiles for promising natural product extracts, identifying patterns of selectivity and promiscuity.

High-throughput screening (HTS) technology, based on molecular or cellular level experimental methods, has become a powerful tool for accelerating natural product research due to its characteristics of being trace, fast, sensitive, and efficient [2]. Currently, commonly used HTS systems are divided into biochemical screening systems (primarily based on fluorescence or absorbance to detect binding of purified target proteins to drugs or impact on enzyme activity) and cell screening systems (typically detecting drug-induced cell phenotypes without knowing the target) [2].

Protocol 2: Multi-Omics Integration for Mechanism Elucidation

Purpose: To comprehensively characterize the effects of natural products on biological systems using integrated multi-omics approaches.

Materials and Reagents:

- Tissue or cell samples treated with natural products

- RNA extraction kits

- Protein extraction and digestion reagents

- LC-MS/MS instrumentation

- Next-generation sequencing platforms

- Multi-omics data integration software

Procedure:

- Experimental Design: Treat biological systems with natural products across multiple time points and concentrations. Include appropriate controls.

- Sample Collection: Harvest cells or tissues at predetermined time points. Divide samples for different omics analyses.

- Transcriptome Analysis: Extract RNA and prepare sequencing libraries. Perform RNA sequencing on appropriate platform.

- Proteome Analysis: Extract proteins, digest with trypsin, and label if using multiplexed approaches. Analyze peptides by LC-MS/MS.

- Data Processing: Process raw data using specialized pipelines for each omics type. Identify differentially expressed genes/proteins.

- Integrative Analysis: Use network-based methods to integrate multi-omics datasets. Identify key pathways and networks affected by natural product treatment.

- Validation: Confirm key findings using orthogonal methods such as western blotting or qPCR.

Integration of multi-omics data can provide information on biomolecules from different layers to illustrate complex biology systematically [4]. Recent advances in multi-omics integration have enabled construction of comprehensive biological atlases containing transcripts, proteins, and post-translationally modified proteins across multiple biological conditions [4].

Protocol 3: Population Pharmacokinetic Modeling for Natural Products

Purpose: To characterize the population pharmacokinetics of natural product constituents and identify sources of variability.

Materials and Reagents:

- Standardized natural product formulation

- LC-MS/MS system for bioanalysis

- Population pharmacokinetic modeling software

- Clinical data management system

Procedure:

- Study Design: Conduct clinical trial with intensive or sparse sampling design based on research objectives.

- Bioanalytical Method: Develop and validate LC-MS/MS methods for simultaneous quantification of multiple natural product constituents in biological matrices.

- Data Collection: Collect drug concentration-time data alongside patient characteristics (demographics, organ function, concomitant medications).

- Base Model Development: Identify structural model that best describes concentration-time profiles of natural product constituents.

- Covariate Model Building: Identify patient factors that explain interindividual variability in PK parameters.

- Model Validation: Evaluate model performance using diagnostic plots and predictive checks.

- Model Application: Utilize final model to simulate exposure under different dosing regimens and patient characteristics.

Machine learning approaches to population pharmacokinetic modeling automation can significantly reduce development time compared to traditional manual methods [5]. Automated approaches using optimization algorithms implemented in platforms like pyDarwin can efficiently handle diverse drugs and identify model structures comparable to manually developed expert models in less than 48 hours on average [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms for Natural Product PK-PD Studies

| Tool Category | Specific Products/Platforms | Application in Natural Product Research |

|---|---|---|

| Bioanalytical Instruments | LC-MS/MS systems (Sciex, Thermo, Agilent) | Simultaneous quantification of multiple natural product constituents in biological matrices |

| High-Throughput Screening Platforms | Automated liquid handlers, multimode readers | Rapid activity profiling of natural product libraries against multiple targets |

| Multi-Omics Technologies | Next-generation sequencers, mass spectrometers | Comprehensive molecular profiling of natural product effects |

| Computational Tools | Molecular networking software, AI/ML platforms | Predicting PK-PD relationships and identifying bioactive constituents |

| Cell-Based Assay Systems | Reporter gene assays, high-content imaging systems | Evaluating functional responses to natural product treatment |

| Metabolic Enzyme Assays | CYP450 inhibition kits, recombinant enzymes | Assessing drug interaction potential of natural products |

The unique PK-PD challenges presented by natural products—particularly their multi-constituent complexity and variable composition—require integrated experimental and computational approaches. The protocols and methodologies outlined in this Application Note provide a framework for addressing these challenges, enabling more robust correlation of natural product exposure with pharmacological effects. By implementing high-throughput screening, multi-omics integration, and advanced population PK-PD modeling, researchers can advance the development of natural product-based therapies with improved efficacy and safety profiles. The continued evolution of AI and machine learning approaches will further enhance our ability to decipher the complex relationships between the multi-component nature of natural products and their multifaceted biological effects, ultimately supporting their integration into contemporary evidence-based medicine.

In natural product drug discovery, identifying the specific plant constituents responsible for observed pharmacological effects or pharmacokinetic natural product-drug interactions (NPDIs) is a fundamental challenge. The inherent chemical complexity of botanical extracts necessitates rigorous analytical and biological approaches to pinpoint precipitant phytoconstituents—those individual compounds that precipitate a biological response. Two principal methodologies have emerged as cornerstones for this identification process: bioactivity-directed fractionation, which isolates active compounds based on observed biological effects, and structural alert screening, which predicts bioactivity based on specific molecular features known to be associated with pharmacological or toxicological effects [6] [7]. Within the framework of pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic (PK-PD) correlation modeling, accurately identifying these precipitants is crucial for developing robust models that can predict the in vivo behavior and therapeutic potential of natural products [8] [9]. This protocol details integrated experimental and computational strategies to address this critical need in natural product research.

Bioactivity-Directed Fractionation: An Experimental Workflow

Bioactivity-directed fractionation is an iterative process that systematically separates crude natural product extracts based on their biological activity, ultimately leading to the identification of active constituents [10] [7].

Initial Extraction and Solvent Selection

The process begins with the preparation of a crude extract from authenticated plant material.

- Objective: To extract a wide spectrum of phytoconstituents using solvents of varying polarity.

- Protocol:

- Plant Material Preparation: Air-dry plant material and grind to a homogeneous powder to increase surface area for extraction [6].

- Solvent Selection: Select solvents based on the polarity of target compounds and safety considerations. Common solvents in order of increasing polarity include n-hexane, chloroform, ethyl acetate, acetone, ethanol, methanol, and water [6].

- Extraction Method: Employ appropriate extraction techniques such as maceration, Soxhlet extraction, or ultrasound-assisted extraction. Maceration involves soaking plant material in solvent for an extended period (e.g., 24-72 hours) with occasional agitation [6].

- Concentration: Filter the extract and concentrate using rotary evaporation under reduced pressure.

- Initial Bioactivity Screening: Screen the crude extract for the desired biological activity (e.g., enzyme inhibition, antimicrobial activity, etc.) to establish a baseline for subsequent fractionation steps.

Table 1: Common Extraction Solvents and Their Properties [6]

| Solvent | Polarity Index | Typical Target Compounds | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n-Hexane | 0.009 | Waxes, fats, essential oils | Excellent for non-polar compounds; highly selective | Highly flammable; requires careful handling |

| Chloroform | 0.259 | Alkaloids, terpenoids | Good for medium-polarity compounds; colorless | Carcinogenic; requires fume hood |

| Ethyl Acetate | 0.228 | Flavonoids, terpenoids | Medium polarity; evaporates easily | Flammable |

| Ethanol | 0.654 | Polar compounds like flavonoids, saponins | Safe for human consumption at low concentrations; versatile | Does not dissolve gums and waxes; flammable |

| Water | 1.000 | Polysaccharides, tannins, glycosides | Non-flammable; non-toxic; cheap | Can promote microbial growth; high energy for concentration |

Liquid-Liquid Fractionation

The active crude extract is partitioned into fractions of different polarity to begin separation.

- Objective: To separate the crude extract into distinct polarity-based fractions for initial activity mapping.

- Protocol:

- Dissolution: Dissolve the concentrated crude extract in a polar solvent (e.g., methanol or water).

- Sequential Partitioning: Sequentially partition the solution against immiscible organic solvents of increasing polarity (e.g., n-hexane, chloroform, ethyl acetate, n-butanol) [10].

- Separation: After each addition, thoroughly mix the solvents in a separatory funnel, allow the layers to separate completely, and then collect each solvent layer.

- Concentration and Screening: Concentrate each fraction and screen for biological activity. The active fraction(s) are selected for further separation.

Chromatographic Separation and Isolation

The active fraction undergoes further separation using chromatographic techniques to isolate pure compounds.

- Objective: To isolate pure, active compounds from the bioactive fraction.

- Protocol:

- Selection of Stationary Phase: Choose an appropriate chromatographic medium:

- Sample Preparation: Adsorb the sample onto a small amount of stationary phase (e.g., silica gel) for dry loading.

- Column Packing: Pack a glass column with the selected stationary phase as a slurry in the starting mobile phase.

- Gradient Elution: Elute compounds using a gradient of solvents of increasing polarity (e.g., from pure n-hexane to ethyl acetate to methanol). Collect multiple fractions (e.g., 50-100 mL each) [6].

- Thin-Layer Chromatography (TLC) Analysis: Analyze collected fractions by TLC to group similar fractions.

- Bioactivity Screening: Screen combined groups for biological activity. The active group is then subjected to further chromatographic steps (e.g., preparative TLC, HPLC) until pure active compounds are isolated [10].

Structural Elucidation of Active Compounds

The final step involves determining the chemical structure of the isolated active compound.

- Objective: To unequivocally identify the chemical structure of the isolated bioactive compound.

- Protocol:

- Spectroscopic Analysis:

- Mass Spectrometry (MS): Determines molecular weight and formula [6].

- Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Spectroscopy: (¹H-NMR, ¹³C-NMR, 2D-NMR) provides detailed information about carbon and hydrogen connectivity, yielding the complete planar structure [6].

- Infrared (IR) Spectroscopy: Identifies functional groups present in the molecule.

- Comparison with Literature: Compare spectral data with existing databases and published literature for known compounds.

- Spectroscopic Analysis:

The following workflow diagram illustrates the complete bioactivity-directed fractionation process:

Structural Alerts: A Predictive Tool for Bioactivity

Structural alerts are molecular substructures or functional groups associated with specific biological activities, including desired pharmacological effects or potential toxicity [12] [13]. They serve as a critical in silico tool for prioritizing compounds for further investigation.

Common Structural Alerts in Natural Products

Natural products contain various functional groups that can serve as structural alerts for different types of bioactivities, particularly concerning pharmacokinetic interactions.

Table 2: Common Structural Alerts in Phytoconstituents and Their Associated Bioactivities [8]

| Structural Alert | Alert Substructure | Example Natural Product/Class | Potential Bioactivity / Interaction |

|---|---|---|---|

| Catechol | Flavonoids, Phenylpropanoids (e.g., in Echinacea) | Time-dependent inhibition of cytochrome P450 enzymes via reactive intermediates [8] | |

| Masked Catechol | Isoquinoline alkaloids (e.g., in Goldenseal) | Can be metabolically unmasked to form a catechol, leading to mechanism-based enzyme inhibition [8] | |

| Methylenedioxyphenyl | Isoquinoline alkaloids (e.g., in Goldenseal), Terpenoids (e.g., in Cinnamon) | Time-dependent inhibition of cytochrome P450 enzymes via stable heme coordination [8] | |

| α,β-Unsaturated Aldehyde | Cinnamaldehyde (e.g., in Cinnamon) | Michael acceptor; can form covalent adducts with proteins, leading to enzyme inhibition or sensitization [8] [13] | |

| α,β-Unsaturated Ketone | Curcuminoids (e.g., in Turmeric) | Michael acceptor; can form covalent adducts with biological nucleophiles [8] [13] | |

| Terminal/Subterminal Acetylene | Polyacetylenes (e.g., in Echinacea) | Can be metabolized to reactive ketene intermediates, causing irreversible enzyme inhibition [8] |

Limitations and Strategic Application of Structural Alerts

While valuable, structural alerts have significant limitations that researchers must consider.

- Risk of False Positives: A primary limitation is the high rate of false positives. The mere presence of an alert does not guarantee activity, as the overall molecular structure and physicochemical properties can modulate or negate the reactivity of the alert [12].

- Lack of Quantification: Structural alerts are qualitative tools; they indicate potential activity but do not predict the potency or concentration at which the effect might occur [12].

- Integration with Experimental Data: Structural alerts should be used as hypotheses-generating tools to prioritize compounds for experimental testing, not as standalone predictors. They are most powerful when integrated with bioactivity-guided fractionation and quantitative models [12] [8].

The following decision diagram outlines the strategic process for incorporating structural alert analysis into natural product research:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful identification of precipitant phytoconstituents relies on a suite of specific reagents, materials, and instruments.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

| Item | Function / Application | Examples / Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Extraction Solvents | To extract phytoconstituents from plant material based on polarity. | n-Hexane, Chloroform, Ethyl Acetate, Methanol, Water (HPLC grade) [6] |

| Chromatography Media | Stationary phases for separating compounds based on different properties. | Silica Gel (60-120 mesh for column), Sephadex LH-20 (size exclusion), C18-bonded silica (reverse-phase HPLC) [6] [11] |

| In Vitro Bioassay Kits | For rapid bioactivity screening of fractions and compounds. | Enzyme inhibition assays (e.g., CYP450 isoforms), antioxidant assays (e.g., DPPH, ORAC), antimicrobial susceptibility tests [8] [10] |

| Analytical Standards | For calibration and compound identification via chromatographic comparison. | Commercially available pure compounds (e.g., Squalene, Berberine, Curcumin) [10] |

| Deuterated Solvents | For NMR spectroscopy structural elucidation. | Deuterated Chloroform (CDCl₃), Deuterated Dimethyl Sulfoxide (DMSO-d₆), Deuterated Methanol (CD₃OD) [6] |

| UF Membranes | For fractionation of peptide hydrolysates or large extracts by molecular weight. | Polyethersulfone (PES) membranes with specific MWCO (e.g., 1 kDa, 3 kDa, 10 kDa) [11] |

Integration with PK-PD Correlation Modeling

Identifying precipitant phytoconstituents is not an endpoint but a critical step for building meaningful PK-PD models for natural products.

- Informing Model Structure: The identity and physicochemical properties of the active compound(s) determine key PK parameters in a model, such as absorption, distribution, and clearance [9].

- Defining the Pharmacophore: Understanding the active molecular structure allows researchers to hypothesize the pharmacophore, which is essential for understanding the PD relationship [9] [14].

- Addressing Synergy and Matrix Effects: When pure compounds do not fully explain the activity of a crude extract (as seen in the Syzygium polyanthum study), PK-PD models must account for synergistic interactions or matrix effects that enhance bioavailability or activity [10].

- Quantifying Target Engagement: For covalent drugs or irreversible inhibitors found in natural products, advanced PK-PD models (e.g., intact protein PK/PD models) that use target engagement metrics, rather than just free drug concentration, are required for accurate predictions [14].

The integration of bioactivity-directed fractionation and structural alert analysis provides a powerful, synergistic framework for identifying precipitant phytoconstituents. While the experimental fractionation workflow offers definitive proof of activity and structure, the computational screening for structural alerts enables intelligent prioritization, saving time and resources. Together, these methods provide the foundational data required to develop predictive PK-PD models that can bridge the gap between traditional use and modern therapeutic application of natural products, ultimately guiding dose selection and predicting clinical outcomes.

Natural products (NPs) and their derivatives represent a cornerstone of modern therapeutics, accounting for a significant proportion of approved drugs, particularly in areas like oncology and infectious diseases [15]. The efficacy and safety of these compounds are governed by their pharmacokinetic (PK) properties—what the body does to the drug—and their pharmacodynamic (PD) effects—what the drug does to the body [16]. Robust PK-PD correlation modeling is therefore essential for natural product research but hinges on access to high-quality, well-characterized chemical and biological data. This application note provides detailed protocols for sourcing structural and physicochemical data from open-access repositories, which serves as the critical foundation for building predictive physiologically-based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) and population PK/PD (PopPK/PD) models [8] [17]. The recommended approaches are framed within the research priorities of the Center of Excellence for Natural Product Drug Interaction Research (NaPDI Center), which emphasizes the need for rigorous data to predict complex natural product-drug interactions (NPDIs) [8].

Data Source Compendium

A critical first step in model development is the identification and curation of data from reliable sources. The tables below catalog key repositories for natural product structures, physicochemical properties, and bioactivity data, which are indispensable for parameterizing in silico models.

Table 1: Open-Access Data Repositories for Natural Product Research

| Repository/Resource Name | Primary Data Type | Key Features & Applicability to PK-PD Modeling |

|---|---|---|

| CHEMFATE [8] | Physicochemical Data | Curates physicochemical parameters for numerous chemical entities; essential for predicting absorption and distribution. |

| Public NP Screening Libraries (e.g., COCONUT) [15] | Natural Product Structures | Provides diverse chemical structures for virtual screening and initial hit identification. |

| NaPDI Center Recommended Approaches [8] | Research Guidelines | Provides frameworks for sourcing, characterizing, and modeling NP data, promoting reproducibility. |

| Knowledge Graphs (e.g., NP-KG) [18] | Integrated Mechanistic Data | Integrates ontologies and literature to uncover plausible mechanisms for pharmacokinetic NPDIs. |

Table 2: Commercially Available Natural Product Libraries for Experimental Screening

| Library/Provider | Library Composition | Key Data and Features |

|---|---|---|

| National Cancer Institute (NCI) Natural Products Repository [19] | >230,000 crude extracts; >400 purified compounds; Traditional Chinese medicine extracts. | One of the world's most comprehensive collections; available in HTS formats at no cost for materials. |

| Life Chemicals Natural Product-like Library [15] | >15,000 synthetic compounds designed to mimic natural products. | Includes calculated molecular descriptors (MW, cLogP, H-bond donors/acceptors, TPSA) crucial for PK prediction. |

| MEDINA [19] | >200,000 microbial-derived extracts. | One of the world's largest microbial libraries; available for testing at partner sites. |

| ChromaDex Natural Compound Libraries [19] | Pure reference standards and a proprietary botanical extract library. | Focus on well-characterized phytochemicals; includes extensively characterized fractions. |

| Greenpharma Natural Compound Library [19] | Diverse pure compounds from plants and bacteria. | Provides electronic files with structures, sources, and calculated physicochemical descriptors. |

| InterBioScreen [19] | Natural compounds, derivatives, and synthetic analogs. | Includes compounds isolated from plants, fungi, and marine organisms. |

Protocols for Data Acquisition and Pre-Processing

Protocol 1: Sourcing and Curating Data for Static NPDI Risk Prediction

This protocol outlines the steps for identifying a natural product's key phytoconstituents and gathering the necessary data to perform an initial, static assessment of its drug interaction potential.

I. Materials and Reagents

- Computer with Internet Access: For database queries.

- Literature Search Engine: (e.g., PubMed, Google Scholar).

- Chemical Database Access: As listed in Table 1 and Table 2.

- Chemical Drawing Software: (e.g., ChemDraw) for visualizing and analyzing structures.

- Spreadsheet Software: (e.g., Microsoft Excel) for data curation.

II. Procedure

- Compound Identification:

- Identify the major phytoconstituents of the target natural product through literature review [8].

- For commercially sourced products, request the vendor's certificate of analysis for compositional data.

Structural Alert Screening:

- Draw or obtain the chemical structures of the identified major constituents.

- Systematically screen each structure for known structural alerts associated with enzyme inhibition or induction (see Table 3) [8].

- Example: Identify methylenedioxyphenyl groups (a known alert for time-dependent CYP inhibition) or catechol groups.

Data Harvesting:

- For constituents deemed high-priority based on structural alerts, query open-source databases (Table 1) to collate available physicochemical data.

- Key parameters to collect include: molecular weight (MW), acid dissociation constant (pKa), and octanol-water partition coefficient (Log P).

Data Curation:

- Consolidate all harvested data into a structured table.

- Flag any missing critical data points (e.g., pKa for an ionizable compound) that may require in vitro assays or in silico estimation.

Table 3: Common Structural Alerts for Pharmacokinetic Interactions [8]

| Structural Alert | Example Constituents/NPs | Potential PK Interaction Mechanism |

|---|---|---|

| Methylenedioxyphenyl | Isoquinoline alkaloids (Goldenseal), Schisandrins | Time-dependent inhibition of Cytochrome P450 enzymes |

| Catechol | Flavonoids (Echinacea) | Time-dependent inhibition of Cytochrome P450 enzymes |

| Masked Catechol | Isoquinoline alkaloids (Goldenseal), Terpenoids (Cinnamon) | Metabolic unmasking to a catechol |

| α,β-Unsaturated Aldehyde | Cinnamaldehyde (Cinnamon) | Michael addition; covalent binding to proteins |

| α,β-Unsaturated Ketone | Curcuminoids (Turmeric) | Michael addition; covalent binding to proteins |

| Terminal/Subterminal Acetylene | Polyacetylenes (Echinacea) | Mechanism-based inactivation of Cytochrome P450 enzymes |

III. Data Analysis

- The compiled data table forms the basis for a qualitative or static risk assessment of NPDI potential.

- Constituents with structural alerts and favorable physicochemical properties for absorption (e.g., medium Log P, low molecular weight) should be prioritized for further experimental investigation.

Protocol 2: Constructing a Dataset for PBPK Model Development

This protocol describes a chemoinformatic workflow to build a curated dataset of natural product constituents suitable for parameterizing and verifying a mechanistic PBPK model.

I. Materials and Reagents

- Computational Environment: A scripting environment (e.g., Python with pandas, RDKit) or statistical software (e.g., R).

- Database Access: As per Protocol 1.

- PBPK Software Platform: (e.g., GastroPlus, Simcyp, PK-Sim).

II. Procedure

- Define Dataset Scope:

- Select a specific natural product (e.g., Green Tea or Kratom [18]) and define its major bioactive constituents (e.g., EGCG for green tea).

Computational Data Aggregation:

- Programmatically access open-source NP databases (Table 1) via available APIs to download structural and property data for the target constituents.

- If data is scarce, use reliable in silico tools to predict missing physicochemical parameters (e.g., pKa, Log P).

Apply Natural-Product-Likeness Filters:

- Calculate key molecular descriptors for all collected compounds: Molecular Weight (MW), cLogP, Hydrogen Bond Donors/Acceptors, Topological Polar Surface Area (TPSA), and Rotatable Bond Count [15].

- Filter the dataset based on typical natural product chemical space, which often has higher molecular weight and oxygen content compared to synthetic drugs [15].

Curate Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, and Excretion (ADME) Parameters:

- Mine scientific literature and dedicated ADME databases for in vitro parameters for the target compounds.

- Critical parameters include:

- Permeability: (e.g., Caco-2 or P-gp substrate status).

- Metabolism: Relevant CYP enzyme inhibition/induction kinetics (Ki, IC50, kinact) and UGT substrate status.

- Protein Binding: Fraction unbound in plasma (fu).

- Transport: Interactions with key transporters (e.g., OATP, BCRP).

Dataset Verification and Validation:

- Incorporate available human pharmacokinetic data (e.g., Cmax, Tmax, AUC, half-life) from clinical literature to serve as a benchmark for model verification [8].

- Ensure the dataset is internally consistent and formatted for ingestion into the chosen PBPK platform.

III. Data Analysis

- The final, curated dataset enables the development of a compound file for the natural product within a PBPK simulator.

- The model's predictive performance should be evaluated by comparing simulated plasma concentration-time profiles against the curated clinical PK data.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Materials

Table 4: Essential Reagents and Resources for NP PK-PD Research

| Item | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| High-Quality, Characterized NP Extracts [8] | Provides a physiologically relevant mixture for in vitro testing; ensures research reproducibility. |

| Validated Chemical Standards (e.g., from ChromaDex [19]) | Serves as authentic references for quantitative analysis and bioactivity testing. |

| In Vitro ADME Assay Systems (e.g., CYP inhibition, hepatocyte stability) | Generates critical input parameters (e.g., Ki, CLint) for PBPK and PopPK models [8]. |

| Electronic Lab Notebook (ELN) (e.g., SciNote [20]) | Manages experimental protocols, tracks data provenance, and ensures data integrity and traceability. |

| Bioactivity-Directed Fractionation Materials [8] | Enables isolation and identification of precipitant phytoconstituents responsible for NPDIs. |

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the integrated computational and experimental workflow for sourcing data and developing PK-PD models for natural products, as detailed in the protocols.

Integrated Workflow for NP PK-PD Modeling

The path to establishing robust PK-PD correlations for natural products is critically dependent on the quality and breadth of the underlying chemical and biological data. By systematically leveraging the open-source and commercial resources outlined in this document, researchers can construct reliable datasets that power predictive computational models. Adherence to the detailed protocols for data curation—from initial structural screening to the assembly of complex ADME parameter sets—ensures model robustness and reproducibility. This structured approach to data sourcing and model parameterization, visualized in the provided workflow, is fundamental to de-risking the development of natural product-based therapies and accurately predicting their complex interactions with conventional drugs.

Pharmacokinetic-Pharmacodynamic (PK-PD) modeling is a mathematical approach that integrates the time course of drug concentrations (pharmacokinetics, PK) with the intensity of pharmacological effects (pharmacodynamics, PD) [9]. Mechanism-based PK-PD models are particularly powerful because they separate parameters related to the drug from those related to the biological system, enabling better prediction and translation of findings [21] [22]. This separation is fundamental for rational drug development, especially for complex natural products, as it allows researchers to understand whether variability in drug response stems from the drug's properties or the patient's physiological state [9] [22].

For natural products research, this distinction is critically important. Natural products often contain multiple active constituents with complex interactions, making it essential to identify whether observed effects are due to the drug's inherent properties or system-specific factors that may vary between individuals [8]. The following sections detail the core parameters, their experimental determination, and application within translational research.

Core Parameter Definitions and Theoretical Foundations

Mechanism-based PK-PD models are founded on the integration of several key principles: the factors controlling plasma and tissue drug concentrations (PK), the law of mass action governing drug-receptor interactions (often described by the Hill equation), and the physiological turnover of the response system (homeostasis) [21]. The table below provides a definitive classification of drug-specific and system-specific parameters.

Table 1: Classification of Drug-Specific and System-Specific Parameters in PK-PD Modeling.

| Parameter Category | Specific Parameters | Definition and Role | Typical Units |

|---|---|---|---|

| Drug-Specific Parameters | EC₅₀ | Drug concentration producing 50% of the maximum effect; a measure of potency [21]. | Mass/volume (e.g., ng/mL) |

| Eₘₐₓ | Maximum achievable effect; a measure of efficacy [21]. | Effect units | |

| Hill Coefficient (γ) | Steepness of the concentration-effect curve [21]. | Dimensionless | |

| Clearance (CL) | Volume of plasma cleared of drug per unit time [21] [9]. | Volume/time | |

| Volume of Distribution (V) | Apparent volume into which a drug distributes [21] [9]. | Volume | |

| System-Specific Parameters | Turnover Rate (kᵢₙ, kₒᵤₜ) | Zero-order production rate (kᵢₙ) and first-order loss rate constant (kₒᵤₜ) of a physiological substance [21]. | Mass/time, 1/time |

| Baseline Response (R₀) | Steady-state value of the response before drug administration (R₀ = kᵢₙ/kₒᵤₜ) [21]. | Effect units | |

| Receptor Density | Abundance of pharmacological targets in a tissue [21]. | Various | |

| Blood Flow Rates | Physiological flow rates influencing drug distribution [21] [9]. | Volume/time | |

| Expression of Enzymes/Transporters | Levels of proteins governing drug metabolism and transport [8] [9]. | Various |

The relationship between these parameters is often visualized using a schematic diagram that outlines the complete chain of events from administration to effect.

Experimental Protocols for Parameter Identification

Protocol for Characterizing Drug-Specific Parameters

Objective: To determine the fundamental PK and PD properties of a drug candidate, specifically clearance (CL), volume of distribution (V), EC₅₀, and Eₘₐₓ.

Background: Drug-specific parameters describe the intrinsic behavior of the drug within a biological system. Accurate determination of these parameters is essential for predicting dosing regimens and efficacy [21] [9].

Materials: Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for PK-PD Experiments.

| Reagent/Material | Function in Protocol | Critical Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Animal Model (e.g., rat, mouse) | In vivo system for studying drug absorption, distribution, and effect. | Defined strain, sex, weight range. Health status monitoring. |

| Formulated Drug Product | The test article administered to the biological system. | Known purity, stability in vehicle, concentration. |

| Vehicle Solution | Solvent for dissolving and delivering the drug. | Biocompatibility (e.g., saline, DMSO/PBS mix). |

| Blood Collection Tubes (with anticoagulant) | Collection and preservation of plasma samples for PK analysis. | EDTA or heparin-treated; validated for analyte stability. |

| Analytical Standard (drug reference) | Quantification of drug concentrations in biological matrices via LC-MS/MS. | Certified purity (>98%), structurally confirmed. |

| Enzyme/Transporter Assay Kits | In vitro assessment of metabolic stability and transporter interactions. | Human or species-specific recombinant enzymes (e.g., CYP450s). |

| PD Biomarker Assay Kit | Quantification of pharmacological response (e.g., ELISA for neopterin). | Validated sensitivity, specificity, and dynamic range. |

Procedure:

- Study Design: Conduct a single-dose and/or multiple-dose study in the animal model. Administer the drug via the intended route (e.g., intravenous for absolute bioavailability) across a wide range of doses to fully characterize the concentration-effect relationship [21] [22].

- Sample Collection: Collect serial blood/plasma samples at predetermined time points post-dose for PK analysis. Simultaneously, record the time course of the pharmacological effect (PD measurement).

- Bioanalysis: Quantify drug concentrations in plasma using a validated analytical method (e.g., LC-MS/MS). Measure the PD biomarker levels using a specific assay (e.g., ELISA).

- PK Modeling: Fit the concentration-time data to an appropriate compartmental model (e.g., one-, two-, or three-compartment) using nonlinear regression software to estimate CL, V, and other PK parameters [9]. The model equations for a one-compartment intravenous bolus are:

dA/dt = - (CL/V) * Awhere A is the amount of drug in the body [9].Cp = A / Vwhere Cp is the plasma concentration.

- PD Modeling: Fit the effect-concentration data to the Hill equation (Eq. 1) to estimate EC₅₀, Eₘₐₓ, and the Hill coefficient (γ) [21].

E = (Eₘₐₓ * Cγ) / (EC₅₀γ + Cγ)[21]

Protocol for Characterifying System-Specific Parameters

Objective: To estimate system-specific parameters, such as the turnover rate (kₒᵤₜ) of an endogenous biomarker or the baseline response (R₀).

Background: System-specific parameters reflect the physiological state of the organism and are often conserved across species, which is critical for translational modeling [21]. For natural products, identifying precipitant constituents that alter these system parameters is a key step [8].

Materials:

- Materials from Table 2.

- Indirect Response Model (mathematical framework).

Procedure:

- Baseline Characterization: Measure the PD biomarker levels in the absence of drug treatment to establish the baseline (R₀). Ensure the system is at steady state.

- Perturbation Experiment: Administer the drug at a dose known to produce a measurable effect. The drug may either inhibit/stimulate the production (kᵢₙ) or the loss (kₒᵤₜ) of the biomarker [21].

- Time-Course Monitoring: Collect frequent PD measurements to capture the full dynamics of the biomarker response, including its return to baseline.

- Model Fitting: Fit the PD data to an appropriate indirect response model [21]. The fundamental equation for a simple indirect response model where the drug inhibits the production of the response is:

dR/dt = kᵢₙ * (1 - (C / (IC₅₀ + C))) - kₒᵤₜ * R[21]- Here, R is the response, kᵢₙ is the zero-order production rate, kₒᵤₜ is the first-order loss rate constant, C is the drug concentration, and IC₅₀ is the drug concentration producing 50% inhibition. From this fitting, kₒᵤₜ can be estimated, and kᵢₙ can be derived as kᵢₙ = R₀ * kₒᵤₜ.

The workflow for integrating these experimental approaches is outlined below.

Application in Translational Pharmacology and Natural Products Research

The ultimate goal of distinguishing these parameters is to build predictive, translational PK-PD models that can extrapolate findings from pre-clinical models to humans, and from one drug class to another [21]. This is particularly valuable for natural product-drug interaction (NPDI) research, where the complex composition of natural products presents unique challenges [8].

Key Applications:

- First-in-Human Dose Prediction: Preclinical drug-specific parameters (EC₅₀) can be combined with allometrically scaled system-specific parameters (e.g., kₒᵤₜ) to predict human doses. Physiological times and turnover rates often follow allometric principles (θ = a·Wᵇ), where W is body weight and the exponent b is often ~0.25 for physiological times [21].

- De-risking Natural Product Development: For botanical natural products, mechanism-based modeling helps identify which constituent(s) are the precipitant phytoconstituents responsible for an observed interaction. Bioactivity-directed fractionation can be used to isolate the bioactive constituents, and their drug-specific parameters (e.g., Ki for enzyme inhibition) can be incorporated into static or dynamic (PBPK) models to predict interaction risk [8].

- Optimizing Drug Delivery Systems: In the development of complex formulations like liposomes or antibody-drug conjugates, PK-PD modeling allows for the separation of carrier-specific parameters (e.g., release rate) from drug-specific (e.g., receptor binding) and system-specific (e.g., target expression) parameters. This helps in rational design and dosing regimen selection [9].

The paradigm of drug development is undergoing a significant shift, moving away from single-target models towards a more integrated, holistic approach. This is particularly critical in the realm of natural products and complex multi-component therapies, where the therapeutic effect emerges from the synergistic interactions of multiple active constituents rather than a single molecule [23]. The prevailing biomedical model, which often prioritizes isolated chemical interventions, is increasingly seen as insufficient for capturing the complexity of such therapies [23]. Natural products, such as those derived from Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM), operate on principles of multi-target and multi-pathway modulation, presenting a unique challenge for modern pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic (PK-PD) correlation modeling [24]. Establishing robust exposure-response relationships for these mixtures requires a departure from conventional methods. This document provides detailed application notes and protocols for applying advanced, holistic PK-PD modeling strategies to quantitatively evaluate the efficacy and synergistic potential of multi-component therapies, thereby bridging the gap between traditional holistic medicine and contemporary drug development science.

Application Notes: A Framework for Multi-Component PK-PD

The Rationale for a Holistic PK-PD Approach

The biological activity of a complex natural product cannot be fully understood by merely summing the contributions of its individual parts. Synergistic interactions, where the combined effect of components is greater than the sum of their individual effects, are a hallmark of such therapies [24]. A holistic PK-PD framework is designed to capture these interactions. It moves beyond analyzing components in isolation to model their behavior as an integrated system, accounting for how co-administration can alter the pharmacokinetics (e.g., metabolic rate, volume of distribution) of individual compounds and how these PK changes collectively drive a combined pharmacodynamic response [24]. This approach aligns with the holistic perspectives found in systems like TCM and Ayurvedic medicine, which focus on strengthening the whole person by balancing energy rather than reacting to reductionist aspects of illness [23].

Key Modeling Strategies and a Representative Case Study

A pivotal study on the combination of Hydroxysafflor Yellow A (HSYA) and Calycosin (CA) for treating ischemic stroke provides a concrete example of a holistic PK-PD modeling approach [24]. The researchers developed a novel coupled PK-PD model to quantitatively evaluate their synergistic effects.

- Coupled Pharmacokinetics: The model incorporated interaction terms to describe how the drugs influenced each other's in vivo metabolism. For instance, it revealed that HSYA and CA significantly increased each other's metabolic rates, a PK-level interaction that would be missed in isolated studies [24].

- Coupled Pharmacodynamics: The PD model used effect compartment concentrations to link the PK data with multiple biomarkers of efficacy (Caspase-9, IL-1β, and SOD). The model successfully quantified a synergistic effect between HSYA and CA on all three pharmacodynamic markers, with HSYA contributing more significantly to the overall effect [24].

This "coupled" methodology, which introduces parameter heterogeneity, effect compartments, and independent effectiveness, represents a powerful tool for the natural products field. It overcomes the limitations of traditional compartmental models, which struggle to capture interactions between components and often overlook drug onset lag, leading to insufficient coupling of PK and PD [24].

Table 1: Key PK Parameters from a Coupled PK-PD Study of HSYA and CA

| Parameter | Hydroxysafflor Yellow A (HSYA) | Calycosin (CA) |

|---|---|---|

| Mean Retention Time | Shorter | Not Specified |

| Elimination Half-life | Shorter | Not Specified |

| Apparent Volume of Distribution | Smaller | Larger |

| Clearance | Lower | Higher |

| Metabolic Interaction | Increased by CA | Increased by HSYA |

Table 2: Summary of PD Effects from a Coupled PK-PD Study of HSYA and CA

| Pharmacodynamic Marker | Biological Role | Synergistic Effect Observed? | Notable Contributor |

|---|---|---|---|

| Caspase-9 | Apoptosis (cell death) | Yes | HSYA |

| IL-1β | Inflammation | Yes | HSYA |

| SOD (Superoxide Dismutase) | Antioxidant | Yes | HSYA |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Establishing a PK Profile for Multi-Component Therapies in a Rat Model

This protocol outlines the procedure for generating pharmacokinetic data for multi-component therapies, adapted from a study on ischemic stroke [24].

I. Materials and Reagents

- Test Compounds: High-purity standards of the active components (e.g., HSYA, CA).

- Vehicles: Appropriate solvents for each compound (e.g., saline, propylene glycol:anhydrous ethanol mixture).

- Animals: Sprague-Dawley (SD) male rats (260-300 g), housed under standard conditions with a 12/12 h light/dark cycle.

- Equipment: LC-MS/MS system (e.g., SHIMADZU LC-MS 8050), centrifuge, vortex mixer, -80°C freezer, heparinized centrifuge tubes.

II. Dosing and Plasma Sample Collection

- Formulation: Precisely weigh and dissolve each compound in its respective vehicle to formulate a mixture of specific concentrations.

- Administration: Administer the mixture via tail-vein injection at time 0 min. Example doses: HSYA at 2 mg/kg and CA at 1 mg/kg [24].

- Serial Blood Sampling: Collect plasma samples from the submandibular venous plexus at predetermined time points post-administration (e.g., 0.083, 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, 12, 24 hours).

- Plasma Processing: Centrifuge blood samples at 4500 rpm for 12 minutes at 4°C. Collect the supernatant (plasma) and store at -80°C until analysis.

III. LC-MS Analysis

- Chromatographic Conditions:

- Column: ZORBAX Eclipse XDB-C18 (4.6 × 150 mm, 5 μm).

- Mobile Phase: Gradient elution with 0.1% formic acid aqueous solution (A) and methanol (B).

- Flow Rate: 0.4 mL/min.

- Injection Volume: 10 µL.

- Mass Spectrometry Conditions:

- Ion Source: Electrospray ionization (ESI).

- Mode: Negative ion mode.

- Detection: Multi-reaction ion monitoring (MRM).

- Sample Pretreatment: Accurately transfer 100 µL of plasma. Add 10 µL of internal standard (IS) solution and 300 µL of methanol. Vortex for 2 minutes, then centrifuge at 12,000 rpm for 15 minutes at 4°C. Evaporate the supernatant to dryness and reconstitute the residue in 100 µL of methanol-water solution (1:1, v:v) for analysis [24].

Protocol: Pharmacodynamic Biomarker Assessment

This protocol runs in parallel to PK sampling to establish the exposure-response relationship.

I. Materials and Reagents

- ELISA Kits: Specific kits for target biomarkers (e.g., Caspase-9, IL-1β, SOD).

- Equipment: Microplate reader.

II. Procedure

- Sample Source: Use the plasma samples collected during the PK study.

- Biomarker Quantification: Perform the assay in strict accordance with the product instructions of the ELISA kits.

- Data Correlation: The expression levels of biomarkers at each time point are used to plot efficacy-drug concentration curves, forming the basis of the PD model [24].

Protocol: Physiologically-Based Pharmacokinetic (PBPK) Modeling for Natural Products

PBPK modeling is a powerful "bottom-up" or "middle-out" mechanistic approach that is exceptionally well-suited for predicting the behavior of complex natural products in humans based on preclinical data [25].

I. Model Construction Workflow

- Define Model Architecture: Select the anatomical compartments (e.g., liver, gut, kidney, brain, adipose) relevant to the drug's ADME processes.

- Gather System Data: Incorporate species-specific physiological parameters (e.g., organ volumes, blood flow rates) from standardized databases.

- Integrate Compound Data: Input drug-specific parameters: molecular weight, LogP, pKa, solubility, permeability, plasma protein binding, and in vitro metabolic clearance data.

- Calibrate and Validate: Calibrate the preliminary model using in vivo PK data from animal studies (e.g., the rat model above). Validate the model with an independent dataset.

- Simulate and Predict: Apply the validated model to simulate human PK, predict drug-drug interactions (DDIs), and assess effects in special populations [25].

II. Common PBPK Software Table 3: Common PBPK Software Platforms for Drug Development

| Software | Developer | Key Features | Typical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Simcyp Simulator | Certara | Extensive physiological libraries, virtual population modeling | Human PK prediction, DDI assessment, pediatric modeling |

| GastroPlus | Simulation Plus | Focus on modeling oral absorption and dissolution | Formulation optimization, biopharmaceutics modeling |

| PK-Sim | Open Systems Pharmacology | Open-source, whole-body PBPK modeling | Cross-species extrapolation, research and development |

Visualizing Workflows and Relationships

Graphical Abstract: Holistic PK-PD Modeling Workflow for Multi-Component Therapies. This diagram illustrates the integrated pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic processes, highlighting key interaction points (in red) where components can synergistically influence metabolism and network effects.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Multi-Component PK-PD Studies

| Item | Function/Description | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| High-Purity Phytochemical Standards | Provide the defined active components for controlled dosing and analytical quantification. | Hydroxysafflor Yellow A (HSYA) and Calycosin (CA) standards with purity ≥98% [24]. |

| LC-MS/MS System | The core analytical instrument for sensitive and specific quantification of multiple drug components and metabolites in biological samples. | SHIMADZU LC-MS 8050 system with electrospray ionization (ESI) and MRM capability [24]. |

| Specific ELISA Kits | Enable the quantitative measurement of pharmacodynamic biomarkers (e.g., cytokines, enzymes) in plasma or tissue homogenates to link exposure to effect. | Rat IL-1β, SOD, and Caspase-9 ELISA Kits [24]. |

| PBPK Modeling Software | Mechanistic simulation platforms that integrate physiological, genetic, and drug-specific data to predict PK in virtual populations. | Simcyp, GastroPlus, PK-Sim [25]. |

| Animal Disease Model | Provides a physiologically relevant in vivo system to study the integrated PK and PD of the therapy. | Middle Cerebral Artery Occlusion (MCAO) rat model for ischemic stroke [24]. |

Advanced PK-PD Modeling Techniques: From Static Models to Synergistic Couplings

The pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic (PK-PD) correlation modeling for natural products represents a critical frontier in modern phytomedicine research, addressing the unique challenges posed by complex botanical formulations. Unlike single-chemical entities, natural products contain multiple active constituents with potential synergistic or antagonistic interactions, variable composition, and often sparse human pharmacokinetic data [26] [27]. This complexity necessitates a spectrum of modeling approaches—from static models for initial risk assessment to dynamic physiologically based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) and mechanism-based PK-PD models for predictive simulations. The application of these modeling techniques enables researchers to transcend the limitations of conventional pharmacokinetic studies, which often fail to predict drug exposure in target organs, account for multi-component interactions, or address special population variability [27].

The inherent phytochemical complexity of natural products presents distinctive challenges for modeling, including identification of precipitant phytoconstituents, variable composition among marketed products, and potential synergistic or inhibitory interactions between constituents [26]. Furthermore, the limited plasma exposure data for most commercially available natural products and the general absence of physicochemical data for their major phytoconstituents represent significant impediments to developing robust models [26]. Despite these challenges, mathematical modeling of natural product drug interactions (NPDIs) has emerged as a vital tool for predicting clinically significant interactions and optimizing therapeutic outcomes, particularly as the popularity of botanical supplements continues to grow among patients with chronic illnesses managed on complex drug regimens [26].

Model Typology and Comparative Framework

Classification of Modeling Approaches

The modeling spectrum for natural products encompasses three primary approaches, each with distinct capabilities and applications. Static models serve as initial screening tools that provide a conservative estimate of interaction potential using fixed concentration inputs and predefined safety thresholds. These models are particularly valuable for triaging natural products with high interaction risk before investing in more resource-intensive approaches [26]. Dynamic PBPK models represent a more sophisticated approach that simulates the time-dependent absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME) of substances by incorporating physiological and anatomical characteristics, physicochemical drug properties, and system-specific parameters [25] [28] [27]. Finally, mechanism-based PK-PD models integrate drug-target binding kinetics with physiological system parameters to predict both exposure and response, making them particularly valuable for understanding the multi-target actions often exhibited by natural products [9] [24].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Modeling Approaches for Natural Products

| Model Characteristic | Static Models | Dynamic PBPK Models | Mechanism-Based PK-PD Models |

|---|---|---|---|

| Complexity Level | Low | High | High |

| Computational Demand | Low | High | High |

| Temporal Resolution | Fixed timepoints | Continuous | Continuous |

| Key Input Parameters | • Inhibitory potency (Ki, IC50)• Precipitant concentration• Enzyme/transporter affinity | • Physiological parameters (organ volumes, blood flows)• Drug-specific parameters (logP, pKa, solubility)• In vitro metabolism data | • Drug-receptor binding kinetics (kon, koff)• System-specific parameters (receptor density, signal transduction rates)• Biomarker response data |

| Handling of Multi-Component Systems | Limited to individual perpetrator constituents | Can incorporate multiple constituents with defined parameters | Can model synergistic/antagonistic effects through interaction terms |

| Regulatory Acceptance | Screening purposes only | Accepted for specific applications (e.g., DDI, special populations) | Emerging acceptance for dose justification |

| Best Use Applications | • Initial interaction risk assessment• Priority setting for further evaluation | • Prediction of tissue concentrations• DDI prediction in special populations• Formulation optimization | • Target occupancy predictions• Dose-effect relationship quantification• Combination therapy optimization |

Structural Alerts for Natural Product-Drug Interactions

The identification of precipitant phytoconstituents represents a critical first step in modeling NPDIs. Structural alerts can guide researchers in anticipating interaction potential based on specific functional groups present in natural product constituents [26].

Table 2: Structural Alerts for Natural Product-Drug Interactions

| Constituent/Natural Product | Structural Alert | Alert Substructure | Potential Interaction Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|

| Flavonoids, phenylpropanoids/Echinacea | Catechols | Catechol group | Time-dependent inhibition of CYP enzymes via reactive intermediates |

| Isoquinoline alkaloids/Goldenseal | Masked catechol | Mechanism-based inhibition | |

| Shizandrins/Schisandra spp. | Methylenedioxyphenyl | Methylenedioxyphenyl group | Stable heme coordination and CYP inhibition |

| Cycloartenol/Black cohosh | Subterminal olefin | Subterminal double bond | Potential metabolic activation |

| Polyacetylenes/Echinacea | Terminal and subterminal acetylenes | Mechanism-based inhibition | |

| Terpenoids/Cinnamon | Terminal olefin | Terminal double bond | Metabolic liability |

| Cinnamaldehyde/Cinnamon | α,β-Unsaturated aldehyde | Aldehyde conjugated to double bond | Protein adduction and enzyme inhibition |

| Curcuminoids/Turmeric | α,β-Unsaturated ketone | Ketone conjugated to double bond | Michael acceptor capability |

Application Notes and Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Static Model Implementation for Initial NPDI Risk Assessment

Purpose: To provide a standardized methodology for conducting initial static model assessments of natural product-drug interaction risk.

Materials and Equipment:

- Inhibitory potency data (IC50 or Ki values) for natural product constituents against relevant enzymes/transporters

- Maximum plasma concentration (Cmax) data for precipitant constituents

- Computational software (e.g., R, Python, Excel) for implementing static model equations

Procedure:

- Identify Precipitant Constituents: Conduct bioactivity-directed fractionation or literature mining to identify natural product constituents with inhibition/induction potential against clinically relevant drug metabolizing enzymes (e.g., CYPs, UGTs) and transporters (e.g., P-gp, OATPs) [26].

- Obtain Input Parameters: For each precipitant constituent, collect or experimentally determine:

- Inhibitory potency (IC50 or Ki) from human-derived in vitro systems

- Maximum intestinal concentration (Igut) after oral administration

- Maximum systemic concentration (Cmax) at steady-state

- Fraction unbound in plasma (fu)

- Calculate Interaction Potential: Apply basic static model equations:

- For reversible inhibition: R = 1 + (Igut/Ki) × (1/fugut) [26]

- For time-dependent inhibition: Incorporate enzyme degradation rate (kdeg) and inactivation parameters (kinact/KI)

- Interpret Results: Apply conservative thresholds (typically R ≥ 1.02 warrants further evaluation) to identify natural products requiring dynamic modeling or clinical assessment.

Troubleshooting Tips:

- If constituent concentration data is unavailable, consider using published Cmax values from clinical studies of standardized extracts

- For natural products with multiple inhibitory constituents, apply the most conservative approach by considering the constituent with highest [I]/Ki ratio

- When in vitro inhibitory potency data is conflicting, prioritize studies using human recombinant enzymes or human hepatocytes

Protocol 2: Development and Verification of PBPK Models for Natural Products

Purpose: To establish a systematic framework for developing, validating, and applying PBPK models for natural products and their major constituents.

Materials and Equipment:

- Physiological parameters for population of interest (e.g., organ volumes, blood flow rates)

- Drug-specific parameters for natural product constituents (e.g., logP, pKa, molecular weight, protein binding)

- In vitro metabolism and transport data

- PBPK software platform (e.g., GastroPlus, Simcyp, PK-Sim)

- Clinical PK data for model verification

Procedure:

- Model Construction:

- Define anatomical compartments corresponding to organs/tissues (e.g., liver, gut, kidney, brain)

- Incorporate species-specific physiological parameters from established databases

- Integrate drug-specific parameters obtained from in vitro assays or computational predictions [25]

- For multi-constituent natural products, develop individual PBPK models for each major bioactive constituent

Parameter Optimization:

- Calibrate model using available in vivo PK data from preclinical or clinical studies

- Adjust poorly defined parameters (e.g., tissue partition coefficients) to improve fit to observed data

- Apply sensitivity analysis to identify critical parameters driving model output

Model Verification:

- Validate model using independent datasets not employed during model development

- Compare simulated concentration-time profiles with observed clinical data

- Establish acceptance criteria (e.g., within 2-fold of observed values for AUC and Cmax)

Model Application:

- Simulate DDI risk with conventional medications using verified model

- Predict exposure in special populations (e.g., hepatic impairment, elderly) by modifying physiological parameters

- Estimate target tissue concentrations for pharmacodynamic assessment

Case Example: A PBPK model for the natural product glycyrrhizin (from licorice) was successfully developed and applied to predict interactions with rifampin, demonstrating the utility of this approach for natural product DDI prediction [27].

Protocol 3: Mechanism-Based PK-PD Modeling for Natural Product Combinations

Purpose: To implement mechanism-based PK-PD modeling approaches for quantifying synergistic effects in natural product combinations, using coupled PK-PD models with interaction terms.

Materials and Equipment:

- Animal model of disease (e.g., MCAO model for ischemic stroke)

- LC-MS/MS system for bioanalysis

- ELISA kits for biomarker quantification

- Mathematical modeling software (e.g., MATLAB, R, NONMEM)

Procedure:

- Experimental Design:

- Administer natural product constituents individually and in combination to disease model (e.g., rats with MCAO)

- Collect serial blood samples for PK analysis of all major constituents

- Measure relevant PD biomarkers at multiple timepoints (e.g., caspase-9, IL-1β, SOD for ischemic stroke) [24]

- Include sufficient subjects to characterize population variability (typically n ≥ 6 per group)

Coupled PK Modeling:

- Develop PK models for individual constituents that incorporate interaction terms

- Implement coupled differential equations to account for metabolic interactions: where C1 and C2 represent constituent concentrations, k1 and k2 are elimination rate constants, and k̃1 and k̃2 are interaction terms [24]

Effect Compartment Modeling:

- Incorporate effect compartments to account for hysteresis between plasma concentrations and pharmacological effects

- Link effect site concentrations to biomarker responses using appropriate functional relationships (e.g., Emax models, indirect response models)

Synergy Quantification:

- Compare observed combination effects to predictions based on additive models

- Quantify contribution of each constituent to overall therapeutic effect through parameter estimates and model simulations

Case Example: A coupled PK-PD model successfully revealed synergistic effects between Hydroxysafflor Yellow A and Calycosin in the treatment of ischemic stroke, demonstrating that these compounds significantly increased each other's metabolic rates while producing enhanced anti-inflammatory and anti-apoptotic effects [24].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Natural Product Modeling Studies

| Reagent/Material | Specifications | Function/Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Human Hepatocytes | Cryopreserved, metabolically competent | Assessment of metabolic stability and metabolite identification | Determination of intrinsic clearance for PBPK modeling |

| Recombinant CYP Enzymes | Human isoforms (CYP3A4, 2D6, 2C9, etc.) | Enzyme inhibition and kinetic studies | Measurement of inhibitory potency (Ki, IC50) for static models |

| Caco-2 Cell Monolayers | Passage number 25-40, TEER > 300 Ω·cm² | Intestinal permeability assessment | Prediction of oral absorption in PBPK models |

| LC-MS/MS System | Triple quadrupole, ESI source, MRM capability | Bioanalysis of natural product constituents and metabolites | Quantification of plasma and tissue concentrations for PK model development |

| ELISA Kits | Validated for target species, appropriate sensitivity | Biomarker quantification for PD modeling | Measurement of pharmacological response endpoints |

| PBPK Software Platforms | GastroPlus, Simcyp, PK-Sim | PBPK model development and simulation | Prediction of natural product disposition and DDI risk |

| Natural Product Standards | High purity (>98%), structurally characterized | Bioanalytical method development and validation | Preparation of calibration standards and quality control samples |

Visualizing Modeling Approaches and Workflows

Integrated Modeling Workflow for Natural Products

Coupled PK-PD Model Structure for Natural Product Combinations

The application of static, dynamic PBPK, and mechanism-based PK-PD models represents a powerful spectrum of approaches for addressing the unique challenges posed by natural products research. As demonstrated through the protocols and case examples presented, each modeling approach offers distinct advantages that can be leveraged at different stages of the research continuum—from initial risk assessment to comprehensive prediction of therapeutic outcomes. The ongoing development of coupled PK-PD models with interaction terms represents a particularly promising direction for quantifying the synergistic effects that often underlie the therapeutic benefits of complex natural products [24].

Future advancements in natural product modeling will likely focus on several key areas, including the development of more sophisticated multi-scale models that integrate molecular interactions with whole-body physiology, the creation of specialized databases for natural product physicochemical and pharmacokinetic parameters, and the implementation of population-based approaches to address inter-individual variability in natural product exposure and response. Furthermore, as regulatory agencies increasingly recognize the value of mechanistic modeling in drug development [25] [27], the application of these approaches to natural products research will play an increasingly vital role in bridging the gap between traditional knowledge and evidence-based phytotherapy.

This document details the application of build-up libraries and in-situ screening for optimizing the pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic (PK-PD) properties of Natural Product (NP)-based therapeutics. Within model-informed drug development (MIDD), these innovative library strategies enable the systematic exploration of NP chemical space and the rapid identification of candidates with favorable PK-PD correlations. By integrating quantitative PK-PD modeling early in the screening process, these methods provide a powerful framework for prioritizing NP-derived leads with a higher probability of clinical success, thereby accelerating the transition from discovery to development.

Table 1: Key PK-PD Parameters for NP Optimization

| Parameter | Description | Relevance to NP Optimization |

|---|---|---|

| AUC(_{24})/MIC | Ratio of 24-hour Area Under the Curve to Minimum Inhibitory Concentration; a key predictor for concentration-dependent antibiotics [29]. | Guides dose selection for NPs with concentration-dependent antimicrobial activity. |

| T>MIC% | Percentage of dosing interval that drug concentration remains above the MIC; critical for time-dependent antibiotics [29]. | Informs dosing regimen optimization (e.g., infusion duration, frequency) for NPs. |

| IC(_{50}) | Half-maximal inhibitory concentration; measures potency [30]. | Serves as a key PD endpoint during in-situ screening to rank compound efficacy. |

| Imax | Maximum fractional inhibition of a pharmacological response [30]. | Used in indirect response models to quantify the maximal effect of an NP. |

| CL/F | Apparent Clearance; determines maintenance dose [30]. | A critical PK parameter to estimate from early screening data for lead prioritization. |