Matrix Rigidity as an Epigenetic Switch: Engineering Cell Fate for Regeneration and Disease Modeling

The extracellular matrix (ECM) is no longer viewed as merely a structural scaffold; its mechanical properties, particularly rigidity, are now recognized as potent regulators of the cellular epigenome.

Matrix Rigidity as an Epigenetic Switch: Engineering Cell Fate for Regeneration and Disease Modeling

Abstract

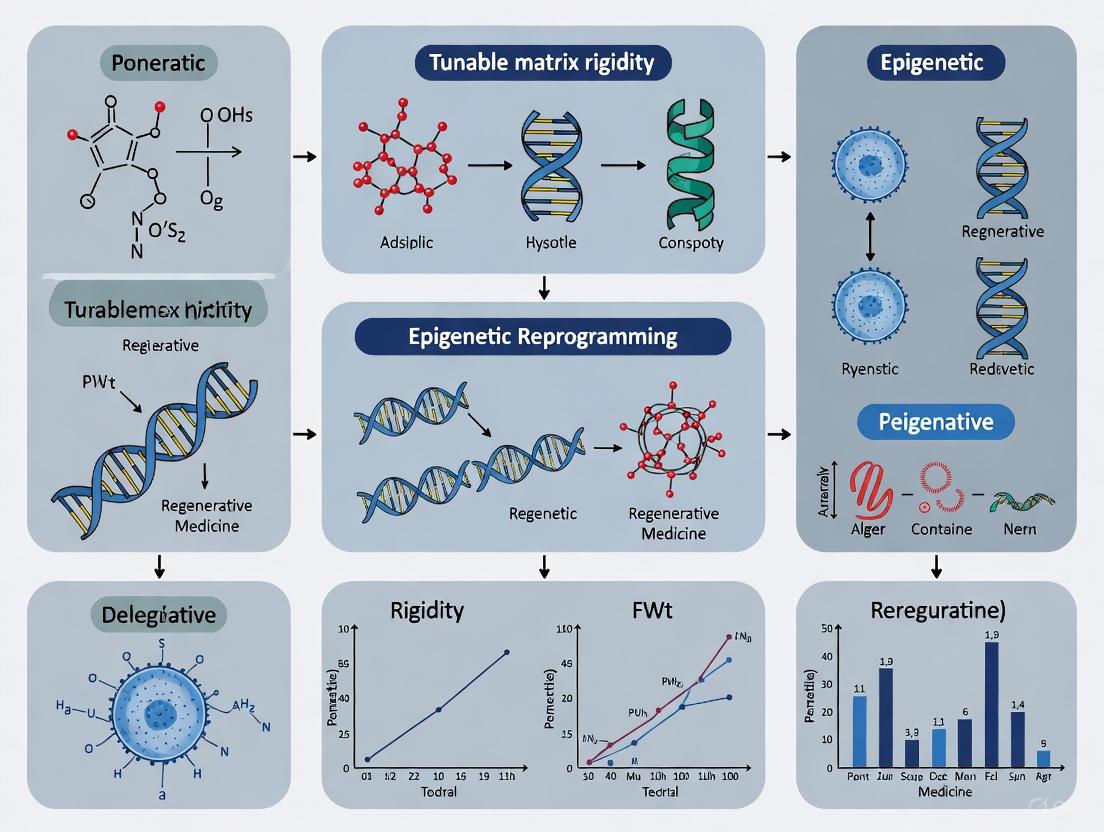

The extracellular matrix (ECM) is no longer viewed as merely a structural scaffold; its mechanical properties, particularly rigidity, are now recognized as potent regulators of the cellular epigenome. This article synthesizes cutting-edge research demonstrating how tunable matrix stiffness acts as a biphasic regulator of epigenetic states, directing chromatin reorganization, histone modifications, and DNA methylation to control cellular reprogramming and differentiation. We explore foundational mechano-epigenetic principles, methodological advances in biomaterial engineering for controlling matrix rigidity, and strategies for optimizing reprogramming efficiency. By integrating validation frameworks and comparative analyses across cell lineages, this review provides researchers and drug development professionals with a comprehensive guide for leveraging matrix mechanics to enhance regenerative medicine, disease modeling, and therapeutic discovery.

The Mechano-Epigenetic Link: How Matrix Rigidity Directs Nuclear Reorganization and Chromatin State

The extracellular matrix (ECM) provides more than just structural support to cells; it is a dynamic biomechanical environment that actively instructs cellular fate and function. Emerging research has established that the physical properties of the ECM, particularly its stiffness, can profoundly influence fundamental cellular processes, including gene expression, differentiation, and reprogramming. This application note explores the groundbreaking concept of the "Goldilocks Principle" of matrix stiffness—a biphasic regulatory mechanism where an intermediate stiffness creates the ideal condition for epigenetic remodeling. We will detail the experimental evidence, methodologies, and practical reagents that underpin this principle, providing researchers with a framework for leveraging tunable matrix rigidity in epigenetic reprogramming research.

Key Quantitative Findings

The foundational study revealed that matrix stiffness acts as a potent biphasic regulator of fibroblast-to-neuron conversion. The efficiency of this reprogramming was not monotonic but peaked at a specific, intermediate stiffness [1] [2].

Table 1: Biphasic Effect of Matrix Stiffness on Cell Reprogramming and Epigenetic State

| Matrix Stiffness | Reprogramming Efficiency | Chromatin Accessibility | Nuclear HAT Activity | Key Observations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ~1 kPa (Soft) | Modest | Increased vs. stiff surfaces | Lower than 20 kPa | Reduced nuclear transport limits HAT activity despite high G-actin/cofilin [1] [2]. |

| ~20 kPa (Intermediate) | Maximized | Highest at neuronal gene promoters | Peak Level | Optimal balance of G-actin/cofilin and importin-9 enables peak HAT nuclear transport [1] [2]. |

| ~40 kPa / Glass (Stiff) | Modest | Lower than softer surfaces | Lower than 20 kPa | Lower levels of G-actin/cofilin co-transporters reduce HAT shuttling into the nucleus [1] [2]. |

This "just right" stiffness of approximately 20 kPa coincided with peak levels of histone acetylation and chromatin accessibility at neuronal gene loci, establishing a direct link between a physical cue and the epigenetic landscape [1] [2]. Inhibiting histone acetyltransferase (HAT) activity abolished the stiffness-mediated enhancement of reprogramming, confirming the functional role of this epigenetic mechanism [1].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Fabrication of Tunable Stiffness Polyacrylamide Hydrogels

This protocol describes the creation of cell-culture substrates with finely controlled stiffness using polyacrylamide (PAAm) hydrogels, a standard in mechanobiology studies [2].

Principle: The elastic modulus of PAAm hydrogels is tuned by adjusting the ratio of acrylamide monomer to bis-acrylamide crosslinker during fabrication. Higher crosslinker densities yield stiffer gels [2].

Materials:

- Acrylamide (40%) solution

- Bis-acrylamide (2%) solution

- 1 M HEPES buffer

- Ammonium persulfate (APS)

- Tetramethylethylenediamine (TEMED)

- 18 mm glass coverslips

- 3-Aminopropyltrimethoxysilane

- Glutaraldehyde

- Sulfosuccinimidyl 6-(4'-azido-2'-nitrophenylamino)hexanoate (Sulfo-SANPAH) or recombinant fibronectin

Procedure:

- Preparation of Coverslips: Clean glass coverslips and treat with 3-aminopropyltrimethoxysilane for 5 minutes, followed by washing. Apply 0.5% glutaraldehyde for 30 minutes to functionalize the surface, then rinse and dry.

- Polymerization Solution: For a specific stiffness (e.g., ~20 kPa), prepare the polymerization solution on ice:

- 1 mL of acrylamide/bis-acrylamide mixture (specific ratios must be optimized; e.g., 10% acrylamide, 0.1% bis for softer gels, and 10% acrylamide, 0.3% bis for stiffer gels).

- 50 µL of 1 M HEPES.

- Initiation of Polymerization: Add 2.5 µL of 10% APS and 0.2 µL TEMED to the solution. Mix quickly.

- Gel Casting: Immediately pipette 25 µL of the solution onto a functionalized coverslip. Carefully place a second clean coverslip on top to create a uniform gel layer. Allow polymerization to proceed for 30-45 minutes at room temperature.

- Hydration and Functionalization: Gently separate the coverslips and immerse the gel-attached coverslip in PBS. To conjugate the ECM protein (e.g., fibronectin):

- For Sulfo-SANPAH: Expose the gel to UV light for 10 minutes. Apply a Sulfo-SANPAH solution (0.2 mg/mL in HEPES) and UV again for 10 minutes. Wash and incubate with fibronectin (10 µg/mL in PBS) overnight at 4°C.

- Alternatively, use light-activated recombinant fibronectin.

- Validation: Confirm gel stiffness using atomic force microscopy (AFM)-based indentation [3] or rheology.

Protocol: Assessing Reprogramming Efficiency on Stiffness Gradients

This protocol outlines the process of transducing fibroblasts and quantifying their conversion into induced neuronal (iN) cells on the fabricated hydrogels.

Principle: Fibroblasts are genetically reprogrammed using defined factors. The substrate stiffness modulates the epigenetic state, thereby influencing the efficiency of this conversion, which is quantified by immunostaining for neuronal markers [2].

Materials:

- Primary mouse or human fibroblasts

- Doxycycline-inducible lentivirus containing Ascl1, Brn2, and Myt1l (BAM factors)

- Polybrene

- Doxycycline

- Growth medium (DMEM + 10% FBS)

- Neuronal induction medium

- Paraformaldehyde (4%)

- Triton X-100

- Blocking buffer (e.g., 5% normal goat serum)

- Primary antibody: Anti-Tuj1 (neuron-specific class III β-tubulin)

- Secondary antibody with fluorescent tag

- DAPI stain

Procedure:

- Cell Seeding and Transduction: Seed BAM-transduced fibroblasts onto the fibronectin-coated PAAm gels and glass controls at a defined density (e.g., 50,000 cells/cm²). Allow cells to attach for 24-48 hours.

- Induction of Reprogramming: Switch the culture medium to neuronal induction medium supplemented with doxycycline (e.g., 2 µg/mL) to activate the BAM factors. Refresh the medium every 2-3 days.

- Fixation and Immunostaining: After 7-10 days, fix cells with 4% PFA for 15 minutes. Permeabilize with 0.1% Triton X-100 for 10 minutes, and block with blocking buffer for 1 hour.

- Cell Labeling: Incubate with anti-Tuj1 primary antibody (1:500) overnight at 4°C. Wash and incubate with the appropriate secondary antibody (1:1000) for 1 hour at room temperature. Counterstain nuclei with DAPI.

- Quantification and Imaging: Image multiple random fields using a fluorescence microscope. The reprogramming efficiency is calculated as the percentage of Tuj1-positive cells with a neuronal morphology relative to the total number of DAPI-positive cells. A minimum of 1000 total cells per condition should be counted for statistical robustness.

Mechanism and Signaling Pathways

The biphasic regulation is governed by the efficiency of nuclear transport of the epigenetic enzyme Histone Acetyltransferase (HAT), which is mechanically regulated by two counteracting factors [1] [2].

Diagram: The biphasic regulation of HAT nuclear transport by matrix stiffness. On soft matrices, high levels of G-actin/cofilin co-transporters are counteracted by low importin-9, limiting transport. On stiff matrices, importin-9 is high but co-transporters are low. The intermediate stiffness achieves an optimal balance, leading to peak HAT nuclear entry, histone acetylation, chromatin accessibility, and reprogramming efficiency [1] [2].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Reagents for Mechano-Epigenetic Reprogramming Research

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Description | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Polyacrylamide Hydrogels | Synthetic, biologically inert hydrogels with tunable stiffness via crosslinker density [2]. | Standard substrate for 2D stiffness sensing studies. |

| Alginate-based Hydrogels | Ionically crosslinked hydrogels enabling independent tuning of stiffness and viscoelasticity [4]. | Studying combined effects of stiffness and stress relaxation. |

| Recombinant Fibronectin | ECM protein for functionalizing synthetic hydrogels to support cell adhesion. | Coating PAAm gels to provide integrin-binding sites [2]. |

| HAT Inhibitors (e.g., C646) | Small molecule inhibitors of histone acetyltransferase activity. | Validating the functional role of HAT activity in mechano-epigenetic signaling [1]. |

| ATAC-seq Kit | Assay for Transposase-Accessible Chromatin with sequencing. | Genome-wide profiling of chromatin accessibility changes in response to stiffness [2]. |

| Anti-Acetylated Histone H3 Antibody | Antibody for detecting levels of histone acetylation by immunofluorescence or Western blot. | Quantifying global or locus-specific histone acetylation changes. |

The discovery that matrix stiffness biphasically regulates the epigenetic state via control of HAT nuclear transport provides a powerful mechano-epigenetic framework for understanding cell fate control. This "Goldilocks Principle" underscores that physical cues are not merely permissive but are instructive and have an optimal range for eliciting desired biological outcomes, such as enhanced cellular reprogramming. Moving forward, the field is expanding to consider more complex mechanical properties, such as viscoelasticity, which more closely mimics native tissues and has been shown to further promote chromatin decondensation and cellular plasticity [4]. Integrating these principles into the design of advanced biomaterials and mechanomedicine strategies holds immense promise for improving the efficiency of regenerative medicine protocols, disease modeling, and drug discovery platforms.

Nuclear mechanotransduction describes the process by which mechanical forces from the extracellular environment are transmitted into the nucleus, resulting in changes in chromatin organization and gene expression. This process represents a crucial signaling mechanism that allows cells to sense and respond to their mechanical microenvironment, with significant implications for development, disease progression, and regenerative medicine [5]. The transmission pathway involves an interconnected network of cellular components, beginning with mechanosensitive receptors at the cell surface and culminating with epigenetic modifications and transcriptional reprogramming within the nucleus [6]. Understanding these mechanisms provides researchers with powerful tools to manipulate cell fate decisions through engineered microenvironments, particularly in the context of tunable matrix rigidity for epigenetic reprogramming research.

The fundamental pathway of nuclear mechanotransduction follows a specific sequence: (1) mechanical forces are sensed at the cell membrane through receptors such as integrins and mechanosensitive ion channels; (2) these signals are transmitted intracellularly via the cytoskeleton; (3) forces are transferred across the nuclear envelope through the LINC complex; and (4) nuclear deformation leads to chromatin remodeling and altered gene expression [5] [6]. This pathway enables conversion of physical signals into biochemical responses, ultimately influencing cellular phenotypes in health and disease. Recent advances have demonstrated that extracellular matrix properties, including stiffness and viscoelasticity, can be harnessed to direct stem cell differentiation and cellular reprogramming through these mechanotransductive pathways [4] [7].

Mechanical Force Sensing and Transduction

Integrin-Mediated Force Sensing

Integrins serve as primary mechanoreceptors that connect the extracellular matrix to the intracellular cytoskeleton. These transmembrane receptors exist as heterodimers composed of α and β subunits, with mammalian systems expressing 18 α and 8 β subunits that combine to form 24 distinct integrins with varying ligand specificities [8]. Upon binding to ECM components such as fibronectin, collagen, or laminin, integrins undergo conformational changes from inactive bent states to active extended states, initiating the formation of focal adhesion complexes [6].

The mechanosensitive function of integrins enables cells to detect and respond to specific mechanical properties of their microenvironment. Research indicates that different mechanical stimulation patterns selectively activate specific integrin subtypes. For instance, applying 1Hz/20pN mechanical stimulation to ovarian cancer cell spheroids preferentially activated αvβ3 integrin (expression increased 2.8 times), while 0.5Hz/10pN stimulation preferentially induced membrane localization of αvβ6 integrin (increased 3.2 times) [6]. This frequency- and amplitude-dependent response originates from unique force-induced conformational changes in integrin subunits, highlighting the specificity of mechanical signal detection.

Table 1: Major Integrin Families and Their Mechanical Sensing Functions

| Integrin Family | Representative Members | Primary Ligands | Mechanical Sensing Role |

|---|---|---|---|

| RGD-binding integrins | αvβ3, αvβ5, αvβ6, α5β1 | Fibronectin, Vitronectin, Osteopontin | Sense matrix stiffness and composition through RGD motifs |

| Collagen-binding integrins | α1β1, α2β1, α10β1, α11β1 | Collagen types I-IV | Detect collagen organization and density |

| Laminin-binding integrins | α3β1, α6β1, α7β1, α6β4 | Laminin | Sense basement membrane mechanical properties |

| Leukocyte adhesion integrins | α4β1, αLβ2, αMβ2 | VCAM-1, ICAM-1, MadCAM-1 | Mediate mechanical forces during immune cell migration |

Mechanosensitive Ion Channels

Mechanosensitive ion channels, particularly Piezo and TRPV family channels, provide an additional mechanism for cellular mechanical sensing. These channels respond to membrane tension changes by opening to allow cation flux, primarily Ca2+, which initiates downstream signaling cascades [6]. The Piezo family channels (Piezo1 and Piezo2) employ a unique "nano-bowl" structure that flattens under membrane tension, driving pore opening through a lever-like beam mechanism that amplifies mechanical force [6].

Piezo channels form mechanical coupling systems with the actin cytoskeleton through E-cadherin/β-catenin complexes, allowing precise transmission of cytoskeletal tension to force-sensitive channel regions [6]. This positioning enables them to function as critical regulators of mechanosensitive pathways, including YAP/TAZ signaling and calcium-dependent gene expression. In vascular endothelial cells and erythrocytes, Piezo1 dominates the perception of blood flow shear stress, demonstrating its importance in physiological mechanical sensing [6].

Force Transmission to the Nucleus

Cytoskeletal Mediation

The cytoskeleton serves as the primary intracellular force transmission network, composed of actin filaments, microtubules, intermediate filaments, and associated cross-linking proteins [5]. This interconnected system distributes mechanical forces throughout the cell, ultimately directing them toward the nucleus. Actin filaments play a particularly crucial role, as they connect directly to both focal adhesions at the cell membrane and the LINC complex at the nuclear envelope, forming a continuous physical linkage from ECM to nucleus [6].

Mechanical forces transmitted through the cytoskeleton induce actin polymerization and remodeling, which in turn influences nuclear deformation and mechanotransductive signaling. The Rho/ROCK pathway serves as a key regulator of actin dynamics in response to mechanical stimuli, controlling actomyosin contractility that generates intracellular tension [5]. Inhibition of ROCK kinases with compounds such as Y-27632 or fasudil reduces cytoskeletal tension and downstream mechanotransductive signaling, demonstrating the critical role of actin organization in force transmission to the nucleus [5].

The LINC Complex and Nuclear Envelope

The LINC (Linker of Nucleoskeleton and Cytoskeleton) complex forms the physical bridge across the nuclear envelope, directly connecting the cytoskeleton to the nuclear interior. This complex consists of SUN domain proteins (SUN1, SUN2) located in the inner nuclear membrane that bind to KASH domain proteins (nesprins) in the outer nuclear membrane [5] [6]. SUN proteins interact with nuclear lamins and chromatin, while KASH proteins connect to various cytoskeletal components, thereby completing the mechanical linkage from ECM to chromatin.

The LINC complex cooperates with nuclear lamins to establish a mechanical conduction pathway that mediates precise transmission of mechanical signals into the nucleus [6]. Under external tensile force, the LINC complex promotes the dissociation of emerin protein from the nuclear envelope, releasing its constraint on heterochromatin regions marked by H3K9me3 and thereby enhancing chromatin accessibility [6]. This direct mechanical effect on chromatin organization represents a fundamental mechanism of nuclear mechanotransduction.

Table 2: Core Components of the Nuclear Mechanotransduction Machinery

| Component | Subcellular Location | Mechanical Function | Experimental Targeting Approaches |

|---|---|---|---|

| SUN1/SUN2 | Inner nuclear membrane | Connect nuclear lamina to KASH proteins | siRNA knockdown [5] [9] |

| KASH proteins (Nesprins) | Outer nuclear membrane | Connect SUN proteins to cytoskeleton | Dominant-negative constructs |

| Lamin A/C | Nuclear lamina and nucleoplasm | Determines nuclear stiffness, tethers chromatin | siRNA knockdown, LMNA mutations [9] |

| Emerin | Inner nuclear membrane | Tethers heterochromatin to nuclear envelope | Mechanical force-induced dissociation [6] |

Chromatin Response to Mechanical Forces

Chromatin Accessibility and Architecture

Mechanical forces transmitted to the nucleus directly influence chromatin organization and accessibility. Research using ATAC-seq (Assay for Transposase-Accessible Chromatin with sequencing) has demonstrated that mechanical stimulation can induce widespread changes in chromatin accessibility, predominantly affecting promoter regions [9]. In lamin A/C-deficient human myotubes subjected to mechanical stretching, researchers observed a global increase in chromatin accessibility, accompanied by increased H3K4me3 euchromatin marks and decreased heterochromatin-associated H3K27me3 [9]. These findings establish a direct link between nuclear deformation and epigenetic remodeling.

The role of lamin A/C in maintaining chromatin stability during mechanical stress appears crucial. In normal skeletal muscle myotubes, lamin A/C provides mechanical reinforcement to the nucleus, dampening the chromatin response to stretch [9]. However, in lamin A/C-deficient cells, mechanical stress leads to pronounced nuclear deformation and chromatin reorganization, with downregulation of transcriptional pathways involved in histone deacetylation, DNA methylation, and muscle differentiation, while pathways related to cytokine activity, extracellular matrix organization, and cell adhesion become upregulated [9]. This demonstrates how mechanical signals can directly reprogram cellular identity through chromatin remodeling.

Viscoelastic Matrix Effects on Chromatin

Recent research has revealed that the viscoelastic properties of extracellular matrices, not just their stiffness, significantly influence nuclear architecture and epigenome. Fibroblasts cultured on viscoelastic substrates display larger nuclei, lower chromatin compaction, and differential expression of genes related to cytoskeleton and nuclear function compared to those on elastic surfaces [4]. Slow-relaxing viscoelastic substrates particularly reduce lamin A/C expression and enhance nuclear remodeling, accompanied by a global increase in euchromatin marks and local increases in chromatin accessibility at cis-regulatory elements associated with neuronal and pluripotent genes [4].

These mechanical-epigenetic effects have functional consequences for cellular plasticity. Viscoelastic substrates significantly improve reprogramming efficiency from fibroblasts into neurons and induced pluripotent stem cells, suggesting that matrix viscoelasticity enhances epigenetic remodeling to facilitate cell fate transitions [4]. The most pronounced effects occur on softer surfaces (2 kPa), where slow-relaxing viscoelastic substrates induce greater changes in nuclear volume and chromatin compaction compared to elastic substrates, indicating stiffness-dependent viscoelastic effects [4].

Table 3: Quantitative Effects of Matrix Properties on Nuclear Parameters

| Matrix Property | Nuclear Volume Change | Chromatin Compaction | Reprogramming Efficiency | Key Experimental Models |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Elastic (2 kPa) | Baseline | Baseline | Baseline | Fibroblasts on alginate hydrogels [4] |

| Slow-relaxing viscoelastic (2 kPa) | Increased | Decreased | Enhanced | Fibroblasts on ionically crosslinked alginate [4] |

| Fast-relaxing viscoelastic (20 kPa) | Increased on stiff surfaces | Decreased on stiff surfaces | Moderate enhancement | Fibroblasts on fast-relaxing alginate [4] |

| Lamin A/C deficiency | Increased deformation under stretch | Significant decrease under stretch | Not tested | Human myotubes with siRNA knockdown [9] |

Application Notes and Protocols

Protocol: Measuring Chromatin Accessibility Response to Mechanical Stretch in Skeletal Muscle Cells

This protocol describes how to assess stretch-induced chromatin accessibility changes in human skeletal muscle cells, adapted from research published in Cell Communication and Signaling [9].

Materials and Reagents:

- Immortalized human muscle precursor cells (MyoLine platform)

- BioFlex 6-well plates (Flexcell International)

- Matrigel Growth Factor Reduced Basement Membrane Matrix

- Differentiation medium: DMEM with 50 μg/mL gentamycin

- Lipofectamine RNAiMAX transfection reagent

- Lamin A/C siRNA and non-targeting control siRNA

- ATAC-seq kit

- RNA-seq library preparation kit

- Paraformaldehyde (4% in PBS)

- Antibodies for immunostaining: lamin A/C, myosin heavy chain, YAP/TAZ

Procedure:

- Cell Culture and Differentiation:

- Culture human muscle precursor cells in growth medium until 90% confluence

- Switch to differentiation medium to induce myotube formation

- Culture myotubes for 72 hours total differentiation time

Lamin A/C Knockdown (Optional):

- At 24 and 48 hours after differentiation induction, transfect cells with 50 nM lamin A/C siRNA or control siRNA using Lipofectamine RNAiMAX

- Analyze target gene or protein expression 72 hours after first transfection

Mechanical Stimulation:

- Seed cells onto Matrigel-coated BioFlex plates

- At 68 hours of differentiation, subject myotubes to 4 hours of equibiaxial cyclic stretch (10% strain, 0.5 Hz)

- Include control samples maintained under static conditions

Nuclear Deformation Analysis:

- Fix cells with 4% PFA for 20 minutes at room temperature

- Permeabilize with 0.5% Triton X-100 and block with 5% BSA

- Stain F-actin with Phalloidin-Alexa 568 and nuclei with Hoechst

- Image using confocal microscopy and quantify nuclear shape parameters

- Calculate chromatin heterogeneity using coefficient of variation of Hoechst intensity

Chromatin Accessibility Assessment:

- Collect cells after mechanical stimulation

- Perform ATAC-seq library preparation according to manufacturer protocol

- Sequence libraries and analyze data for accessible chromatin regions

- Perform RNA-seq in parallel to correlate accessibility with gene expression

Epigenetic Marker Analysis:

- Perform histone extraction using commercial kits

- Analyze H3K4me3 and H3K27me3 levels by Western blot

- Use specific antibodies for euchromatin and heterochromatin marks

Troubleshooting Tips:

- Optimize stretch parameters for different cell types

- Include multiple time points to capture dynamic changes

- Verify lamin A/C knockdown efficiency by Western blot

- Use appropriate controls for ATAC-seq background signal

Protocol: Assessing Viscoelastic Matrix Effects on Chromatin and Reprogramming

This protocol evaluates how matrix viscoelasticity influences chromatin organization and cellular reprogramming efficiency, based on methodology from Nature Communications [4].

Materials and Reagents:

- Alginate-based hydrogels with tunable stiffness (2, 10, 20 kPa) and stress relaxation

- RGD-coupled alginate polymers for cell adhesion

- Primary fibroblasts from adult mice

- Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM)

- 5-ethynyl-2'-deoxyuridine (EdU) for proliferation assay

- DAPI for chromatin compaction analysis

- Reprogramming factors for iPS generation or neuronal differentiation

- Rheometer for mechanical characterization

Procedure:

- Substrate Preparation:

- Fabricate alginate hydrogels with controlled stiffness (2, 10, 20 kPa) and stress relaxation properties (τ1/2 ~200 s and ~1000 s)

- Use covalent crosslinking for elastic controls and ionic crosslinking for viscoelastic substrates

- Characterize mechanical properties using rheology and compression tests

- Confirm stable mechanical properties during culture period

Cell Culture on Engineered Substrates:

- Seed primary fibroblasts on RGD-functionalized alginate gels

- Culture cells for 48 hours for initial responses or longer for reprogramming studies

- Assess cell viability using live/dead staining

- Measure cell proliferation using EdU incorporation

Nuclear and Chromatin Analysis:

- Fix cells and stain nuclei with DAPI

- Measure nuclear volume using 3D reconstruction from z-stack images

- Calculate chromatin compaction index as integrated DAPI intensity divided by nuclear volume

- Perform RNA-seq to analyze transcriptome changes

Epigenetic Remodeling Assessment:

- Analyze global changes in euchromatin and heterochromatin marks

- Assess local chromatin accessibility at pluripotency or neuronal gene promoters

- Correlate epigenetic changes with reprogramming efficiency

Reprogramming Efficiency Quantification:

- Induce fibroblast to neuron or iPS cell reprogramming

- Quantify reprogramming efficiency by cell counting and marker expression

- Compare outcomes between elastic and viscoelastic substrates

Applications:

- Enhanced cellular reprogramming for regenerative medicine

- Investigation of mechanical-epigenetic coupling in disease models

- Development of advanced biomaterials for cell fate engineering

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Reagents for Nuclear Mechanotransduction Research

| Research Tool | Supplier Examples | Specific Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| BioFlex Culture Plates | Flexcell International | Application of controlled mechanical stretch | Compatible with various imaging methods; multiple well formats available |

| Tunable Alginate Hydrogels | Custom fabrication | Studying stiffness and viscoelasticity effects | RGD coupling required for cell adhesion; mechanical properties must be verified |

| Lamin A/C siRNA | Various commercial sources | Assessing nuclear envelope function | Knockdown efficiency must be verified; off-target effects should be controlled |

| YAP/TAZ Inhibitors (Verteporfin) | Sigma-Aldrich, Tocris | Inhibiting mechanosensitive pathway | Concentration optimization required; cell viability should be monitored |

| ROCK Inhibitors (Y-27632, Fasudil) | Multiple suppliers | Reducing cytoskeletal tension | Effects are reversible; concentration and timing must be optimized |

| ATAC-seq Kits | Illumina, Active Motif | Assessing chromatin accessibility | Sample quality critical; appropriate controls essential |

| Mechanosensitive Ion Channel Modulators | Alomone Labs, Tocris | Activating/inhibiting Piezo and TRPV channels | Specificity varies; concentration response should be established |

Signaling Pathway and Experimental Workflow Diagrams

Nuclear Mechanotransduction Signaling Pathway

Nuclear Mechanotransduction Experimental Workflow

Matrix Stiffness as a Regulator of Histone Modifications and HAT Nuclear Transport

The extracellular matrix (ECM) provides not only biochemical but also essential biophysical cues that profoundly influence cell behavior. Among these cues, matrix stiffness has emerged as a critical regulator of cellular functions, including differentiation, proliferation, and reprogramming. Recent research has unveiled that mechanical signals from the ECM are transduced to the nucleus, where they directly influence epigenetic states by regulating histone modifications and chromatin organization. This mechano-epigenetic regulation represents a pivotal mechanism through which physical microenvironmental properties can modulate gene expression patterns and cell fate decisions.

Central to this process is the regulation of histone acetyltransferase (HAT) nuclear transport. HATs catalyze the acetylation of histones, leading to chromatin relaxation and increased gene accessibility. The nuclear translocation of HATs is precisely controlled by matrix stiffness through an intricate mechanotransduction pathway, creating a direct link between physical microenvironmental cues and epigenetic regulation. Understanding these mechanisms provides valuable insights for tissue engineering, regenerative medicine, and disease modeling, particularly in the context of tunable matrix systems designed for epigenetic reprogramming research.

Key Quantitative Findings on Stiffness-Dependent Epigenetic Regulation

Recent studies have quantitatively demonstrated the significant impact of matrix stiffness on epigenetic states and cellular reprogramming efficiency. The relationship between stiffness and epigenetic response follows a biphasic pattern, with optimal effects observed at intermediate stiffness levels.

Table 1: Matrix Stiffness Effects on Epigenetic States and Cellular Reprogramming

| Matrix Stiffness | HAT Nuclear Localization | Histone Acetylation | Chromatin Accessibility | Reprogramming Efficiency | Cellular Model |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 kPa (Soft) | Low | Reduced | Moderately increased | Modest | Fibroblast-to-Neuron [2] [1] |

| 20 kPa (Intermediate) | Peak Level | Maximum | Highest | Significantly Enhanced | Fibroblast-to-Neuron [2] [1] |

| 40 kPa (Stiff) | Intermediate | Intermediate | Reduced compared to 20 kPa | Modest | Fibroblast-to-Neuron [2] |

| Glass (~50 GPa) | Low | Reduced | Lowest | Low | Fibroblast-to-Neuron [2] |

| 2 kPa (Soft) | N/A | N/A | Less accessible | Quiescent HSC phenotype | Hepatic Stellate Cells [10] |

| 40 kPa (Stiff) | N/A | N/A | More accessible | Activated myofibroblast phenotype | Hepatic Stellate Cells [10] |

Table 2: Molecular Regulators of HAT Nuclear Transport Identified in Stiffness Studies

| Molecular Factor | Function in HAT Transport | Stiffness Regulation | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| G-actin | Cotransporter for HAT nuclear shuttle | Increases with decreasing stiffness | Higher on soft matrices [2] |

| Cofilin | Cotransporter for HAT nuclear shuttle | Increases with decreasing stiffness | Higher on soft matrices [2] |

| Importin-9 | Nuclear import receptor | Reduced on soft matrices | Limits nuclear transport on soft surfaces [2] [1] |

| HAT Activity | Histone acetyltransferase function | Peak at intermediate stiffness (20 kPa) | Abolishes stiffness effects when inhibited [2] |

| AP-1 (p-JUN) | Transcription factor activation | Increased on stiff matrices (40 kPa) | Chromatin priming in hepatic stellate cells [10] |

The data reveal a consistent pattern across different cell types where specific stiffness ranges optimize epigenetic responsiveness. For fibroblast-to-neuron reprogramming, the biphasic regulation peaks at 20 kPa, coinciding with maximal HAT activity, histone acetylation, and chromatin accessibility at neuronal gene loci [2]. In contrast, for hepatic stellate cell fibrogenesis, a stiffer 40 kPa matrix promotes chromatin accessibility at fibrosis-associated genes through AP-1 activation [10]. This cell-type-specific optimal stiffness highlights the importance of tailoring biomaterial properties to particular reprogramming applications.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Assessing Epigenetic Responses to Matrix Stiffness

This protocol enables researchers to evaluate how matrix stiffness influences histone modifications, HAT nuclear transport, and chromatin accessibility using tunable hydrogel systems.

Materials and Reagents:

- Polyacrylamide (PAAm) hydrogel components: acrylamide, bis-acrylamide

- Stiffness calibration standards: 1 kPa, 20 kPa, 40 kPa formulations

- Fibronectin or other ECM proteins for coating

- Cells of interest (e.g., fibroblasts, hepatic stellate cells)

- Immunofluorescence reagents: paraformaldehyde, Triton X-100, blocking buffer

- Antibodies: anti-acetylated histone H3, anti-HAT1, anti-importin-9

- Nuclear staining: DAPI or Hoechst 33342

- HAT activity assay kit

- ATAC-seq or RNA-seq reagents as needed

Procedure:

- Hydrogel Fabrication:

Cell Seeding and Culture:

- Seed cells at appropriate density (e.g., 50,000 cells/cm² for fibroblasts).

- Culture cells for predetermined timepoints (typically 2-4 days) to allow mechanical adaptation.

Histone Modification Analysis:

- Fix cells with 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 minutes at room temperature.

- Permeabilize with 0.1% Triton X-100 for 30 minutes.

- Block with 1% BSA for 15 minutes.

- Incubate with primary antibodies against acetylated histones (1:200 dilution) overnight at 4°C.

- Apply fluorescent secondary antibodies (1:200 dilution) for 1 hour at room temperature.

- Counterstain nuclei with DAPI (1:3000 dilution) for 5 minutes.

- Image using confocal microscopy and quantify fluorescence intensity.

HAT Nuclear Localization Assessment:

- Perform immunostaining as above using HAT-specific antibodies.

- Calculate nuclear-to-cytoplasmic fluorescence ratio for quantitative analysis.

- Alternatively, isolate nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions for Western blot analysis.

Chromatin Accessibility Profiling (ATAC-seq):

- Harvest cells after stiffness conditioning.

- Perform transposase reaction on intact nuclei using Nextera DNA Library Prep Kit.

- Purify and amplify library for sequencing.

- Analyze sequencing data for differential accessibility regions.

Troubleshooting Tips:

- Ensure consistent hydrogel polymerization by controlling temperature and catalyst concentrations.

- Validate stiffness values across multiple hydrogel batches.

- Include HAT inhibitor controls (e.g., anacardic acid) to confirm mechanism specificity.

Protocol 2: Monitoring Real-Time Cellular Responses to Dynamic Stiffness Changes

This protocol utilizes quantitative phase imaging to assess how dynamic stiffness alterations influence cell growth, migration, and dry mass distribution without requiring labels.

Materials and Reagents:

- Tunable hydrogel systems (e.g., light-responsive PAAm)

- Spatial Light Interference Microscopy (SLIM) system

- Cell culture reagents and media

- Patterned PDMS stamps for substrate patterning (optional)

Procedure:

- Dynamic Stiffness Substrate Preparation:

- Utilize hydrogels with dynamically tunable stiffness (e.g., photosensitive crosslinkers).

- Characterize stiffness transition ranges and kinetics.

Cell Seeding and Adaptation:

- Seed cells as in Protocol 1 and allow attachment for 24 hours.

- Establish baseline measurements before stiffness modulation.

Stiffness Modulation and SLIM Imaging:

- Apply stiffness-altering stimulus (e.g., light exposure for photosensitive gels).

- Acquire time-lapse SLIM images at regular intervals (e.g., every 30 minutes for 24 hours).

- Maintain environmental control (temperature, CO₂, humidity) throughout imaging.

Data Analysis:

- Calculate dry mass surface density using the relationship: ρ(x,y) = λ/2πη · φ(x,y), where λ is wavelength, η = 0.2 mL/g, and φ is phase values [11].

- Determine total dry mass by integrating ρ over cellular areas.

- Analyze cell migration velocity using tracking software.

- Apply Dispersion Phase Spectroscopy (DPS) to quantify intracellular mass transport dynamics.

Applications:

- Real-time assessment of mechanoadaptation kinetics

- Correlation of biophysical parameters with epigenetic states

- Single-cell analysis of heterogeneous responses to stiffness

Signaling Pathways and Molecular Mechanisms

The mechanotransduction pathway linking matrix stiffness to histone modifications involves several key molecular players and regulatory steps, as illustrated below:

Diagram 1: Biphasic Regulation of HAT Nuclear Transport by Matrix Stiffness. The pathway illustrates how intermediate stiffness (20 kPa) optimally balances G-actin/cofilin availability and importin-9-mediated nuclear import to maximize HAT translocation, histone acetylation, and subsequent epigenetic reprogramming [2] [1].

In hepatic stellate cells, a different mechanosensitive pathway operates, particularly in response to stiffer matrices:

Diagram 2: Stiffness-Induced Chromatin Priming in Fibrogenesis. The pathway demonstrates how stiff matrices (40 kPa) activate AP-1 transcription factors that promote chromatin accessibility at fibrosis-associated genes, leading to hepatic stellate cell activation and establishing a vicious cycle of ECM deposition and increasing stiffness [10] [12].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Mechano-Epigenetics Studies

| Category | Specific Reagents | Function/Application | Key Findings Enabled |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tunable Hydrogels | Polyacrylamide hydrogels (1-40 kPa) | Mimic physiological stiffness ranges; cell culture substrate | Identification of biphasic epigenetic response [2] [10] |

| Stiffness Measurement Tools | Atomic force microscopy, rheometry | Quantify substrate mechanical properties | Correlation of specific stiffness values with epigenetic effects [2] |

| HAT Activity Assays | HAT activity fluorometric/colorimetric kits | Quantify histone acetyltransferase activity | Peak HAT activity at 20 kPa stiffness [2] |

| Chromatin Accessibility Tools | ATAC-seq reagents | Genome-wide chromatin accessibility profiling | Increased accessibility at neuronal genes on 20 kPa matrices [2] [10] |

| Mechanosensing Inhibitors | HAT inhibitors (anacardic acid), ROCK inhibitors (Y-27632) | Pathway perturbation studies | Established necessity of HAT activity for stiffness effects [2] |

| Imaging Tools | Confocal microscopy, SLIM systems | Subcellular localization and label-free mass quantification | Nuclear HAT translocation; dry mass dynamics [2] [11] |

| Nuclear Transport Assays | Importin-9 antibodies, nuclear fractionation kits | Nuclear import mechanism analysis | Identified importin-9 as limiting factor on soft matrices [2] |

Application Notes for Epigenetic Reprogramming Research

The findings on stiffness-dependent epigenetic regulation have significant implications for designing biomaterials for targeted epigenetic reprogramming:

Optimizing Reprogramming Platforms: For fibroblast-to-neuron conversion, intermediate stiffness (~20 kPa) maximizes epigenetic responsiveness and reprogramming efficiency. Biomaterial systems should incorporate this optimal stiffness range to enhance direct reprogramming protocols [2].

Dynamic Stiffness Systems: Implementing matrices with temporally regulated stiffness allows sequential control over different reprogramming phases. Initial softer stages may promote epigenetic priming, followed by intermediate stiffness for full transcriptional activation.

Cell-Type-Specific Optimization: Different target cell types require stiffness tuning based on their native mechanical microenvironment. Hepatic stellate cell activation, for instance, is preferentially enhanced on stiffer matrices (~40 kPa) resembling fibrotic liver tissue [10].

Clinical Translation Considerations: Incorporating stiffness cues into therapeutic scaffolds could enhance cellular reprogramming in situ for regenerative applications. Understanding the molecular mechanisms enables rational design of such systems.

Screening Applications: Standardized stiffness platforms enable high-throughput screening for epigenetic modifiers that synergize with mechanical cues to enhance reprogramming efficiency.

These application principles provide a framework for utilizing matrix stiffness as a precise engineering parameter in epigenetic reprogramming research, offering complementary approaches to biochemical and genetic reprogramming strategies.

{/* Main Content Begins */}

Global Chromatin Decompaction: Viscoelasticity-Induced Epigenetic Priming

Application Notes

This document provides key experimental data and detailed protocols for researchers investigating how the viscoelastic properties of synthetic extracellular matrices (ECMs) induce global chromatin decompaction and epigenetic priming. This priming enhances cellular plasticity, a critical factor in epigenetic reprogramming and cell fate engineering for regenerative medicine and drug development.

Recent groundbreaking research demonstrates that biomimetic viscoelastic hydrogels can directly regulate nuclear architecture and epigenome, resulting in enhanced chromatin accessibility and improved efficiency in cellular reprogramming [4]. The tables below summarize the core quantitative findings and substrate parameters from these studies.

Table 1: Summary of Substrate Properties and Key Nuclear Phenotypes

| Substrate Property | Measured Parameters | Observed Nuclear/Cellular Phenotype |

|---|---|---|

| Stiffness (Elastic Modulus) | 2 kPa, 10 kPa, 20 kPa [4] | Softer surfaces (2 kPa) show more pronounced viscoelastic effects [4]. |

| Stress Relaxation Half-Time (τ₁/₂) | ~200 s (Fast-relaxing), ~1000 s (Slow-relaxing) [4] | Slow-relaxing substrates most effective for nuclear remodeling and reducing chromatin compaction [4]. |

| Chromatin Compaction Index | Ratio of DAPI intensity to nuclear volume [4] | Significant decrease on viscoelastic substrates, especially 2 kPa slow-relaxing and 20 kPa fast-relaxing gels [4]. |

| Nuclear Volume | Quantified via 3D confocal imaging [4] | Significant increase on soft slow-relaxing (2 kPa) and stiff fast-relaxing (20 kPa) substrates [4]. |

Table 2: Functional Outcomes of Viscoelasticity-Induced Epigenetic Priming

| Functional Assay | Experimental Readout | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|

| Chromatin Accessibility | ATAC-seq; H3K9ac marks [4] | Global increase in euchromatin marks; local increase at cis-regulatory elements of neuronal/pluripotent genes [4]. |

| Cellular Reprogramming | Efficiency of fibroblast-to-neuron and iPSC generation [4] | Viscoelastic substrates significantly improve reprogramming efficiency [4]. |

| Cellular Sensitivity | Cell viability and ROS levels after low-dose chemical exposure [13] | 3D nanofiber scaffolds that decompact chromatin heighten cell response to low-dose toxins [13]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Fabrication of Tunable Viscoelastic Alginate Hydrogels

This protocol describes the synthesis of alginate-based hydrogels with independently tunable stiffness and viscoelasticity, as utilized in foundational studies [4].

Materials

- Sodium Alginate (High molecular weight)

- RGD Peptide: For coupling to alginate to provide cell-adhesion ligands [4].

- Crosslinkers:

- Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's Medium (DMEM)

Method

- Polymer Modification: Couple the RGD peptide to the sodium alginate polymer to create a cell-adhesive substrate.

- Crosslinking for Viscoelastic Gels:

- Prepare a solution of RGD-alginate in DMEM.

- Slowly add a slurry of CaSO₄ while mixing vigorously to ensure homogeneity. The concentration and molecular weight of alginate control the stress relaxation half-time (τ₁/₂ ~200 s or ~1000 s) [4].

- Quickly pipette the solution into mold and allow it to crosslink for 30 minutes at room temperature.

- Crosslinking for Elastic Control Gels:

- Crosslink the RGD-alginate solution using a covalent crosslinker as per manufacturer's instructions. This creates hydrogels with minimal stress relaxation [4].

- Characterization:

- Confirm elastic modulus (e.g., 2, 10, 20 kPa) via rheology or atomic force microscopy (AFM).

- Validate stress relaxation properties via compression testing.

Protocol 2: Assessing Chromatin Decompaction and Epigenetic State

This protocol outlines methods to quantify the nuclear and chromatin changes induced by culture on viscoelastic substrates.

Materials

- Primary Fibroblasts (e.g., from mouse dermis) [4]

- Fixation and Permeabilization Buffer

- DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole)

- Antibodies for epigenetic marks (e.g., anti-H3K9ac)

- ATAC-seq Kit

Method

- Cell Culture: Seed fibroblasts at a defined density (e.g., 10,000 cells/cm²) on the fabricated hydrogels and culture for 48-72 hours [4].

- Nuclear Volume and Chromatin Compaction Analysis:

- Fix and stain cell nuclei with DAPI.

- Acquire high-resolution 3D confocal image stacks.

- Use image analysis software (e.g., ImageJ) to:

- Calculate nuclear volume in 3D.

- Determine the chromatin compaction index by dividing the integrated DAPI fluorescence intensity of a nucleus by its volume [4].

- Assessment of Chromatin Accessibility:

Protocol 3: Functional Validation via Cellular Reprogramming

This protocol tests the functional consequence of viscoelasticity-induced priming by assessing reprogramming efficiency.

Materials

- Reprogramming Factors: Specific transcription factors for target cell type (e.g., Ascl1, Brn2, Myt1l for neurons) or Yamanaka factors (for iPSCs).

- Cell Culture Media for target cell type.

Method

- Induction: Transduce fibroblasts cultured on viscoelastic or control elastic hydrogels with lentiviral vectors expressing the reprogramming factors.

- Culture and Differentiation: Switch to culture conditions that promote the survival and maturation of the target cell type (e.g., neurons or pluripotent stem cells).

- Efficiency Quantification:

- After 2-4 weeks, fix the cells and immunostain for specific markers of the target cell type (e.g., Tuj1 for neurons, Oct4 for pluripotent stem cells).

- Count the number of positive colonies/cells and divide by the initial number of seeded fibroblasts to calculate the reprogramming efficiency. A significant enhancement is expected on slow-relaxing viscoelastic substrates [4].

Signaling Pathway and Experimental Workflow Visualization

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Mechano-Epigenetic Reprogramming Research

| Reagent / Material | Function / Role | Specific Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Alginate Hydrogel System | Tunable biomaterial substrate to dissect stiffness and viscoelasticity. | Use ionically crosslinked (CaSO₄) for viscoelasticity; covalently crosslinked for elastic controls [4]. |

| RGD Peptide | Provides integrin-binding sites for cell adhesion and mechanosensing. | Must be coupled to alginate polymer to enable cell spreading and force transmission [4]. |

| Trichostatin A (TSA) | Histone Deacetylase Inhibitor (HDACi). Chemical control for inducing chromatin decompaction. | Used to validate that chromatin decompaction enhances cellular plasticity and sensitivity [15]. |

| DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole) | Fluorescent DNA dye. | Enables quantification of chromatin compaction index (Intensity/Nuclear Volume) [4]. |

| ATAC-seq Kit | Genome-wide mapping of chromatin accessibility. | Key for confirming epigenetic priming at cis-regulatory elements [4] [14]. |

| Polycaprolactone (PCL) | Polymer for electrospinning 3D nanofiber scaffolds. | Used to create 3D microenvironments that prime chromatin and enhance cell sensitivity [13]. |

{/* Main Content Ends */}

This application note details the significant influence of extracellular matrix (ECM) stiffness—a key mechanical property of the cellular microenvironment—on the dynamics of two pivotal DNA methylation marks: N6-methyladenine (6mA) and 5-methylcytosine (5mC). Mounting evidence indicates that aberrant matrix stiffness, a hallmark of pathological states such as cancer and fibrosis, can actively reprogram the cellular epigenome. This document provides a consolidated quantitative summary of these effects, detailed protocols for investigating mechano-epigenetic responses, and essential resource lists to empower research in tunable matrix rigidity for epigenetic reprogramming.

The following tables synthesize key quantitative findings on how substrate stiffness regulates global DNA methylation levels.

Table 1: Documented Cellular Responses to Substrate Stiffness

| Cell Type | Substrate Stiffness | Methylation Type | Observed Effect on Global Methylation | Key Regulatory Molecules | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Colorectal Cancer (CRC) Cells | Increased Stiffness | DNA 6mA | Significantly reduced 6mA level | ALKBH1 (demethylase) | [16] |

| Human Lung Fibroblasts | Increasing Stiffness (G' 0.5 to 8 kPa) | DNA 5mC | Initial increase, then decrease over time | MRTF-A | [17] |

| Human Umbilical Vein Endothelial Cells (HUVECs) | Stiffer vs. Compliant substrates | DNA 5mC | Lower levels on stiffer substrates | DNMT1 | [18] |

Table 2: Characteristics and Enzymatic Regulation of DNA Methylation Marks

| Epigenetic Mark | Primary Genomic Context & Association | Key Writers (Methyltransferases) | Key Erasers (Demethylases) | General Response to Increased Stiffness |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6mA (N6-methyladenine) | Enriched around transcriptional start sites (TSS); positively correlated with gene expression in plants and mammals. | N6MT1 (Mammals), METTL4 (Plants) | ALKBH1 | Decrease (as observed in CRC) [16] |

| 5mC (5-methylcytosine) | CpG islands in promoters; generally associated with transcriptional repression. | DNMT1, DNMT3 (Mammals) | TET proteins, TDG (Mammals) | Variable; dependent on cell type and exposure time [17] [18] |

Experimental Protocols for Mechano-Epigenetic Analysis

Below are detailed methodologies for key experiments cited in this field.

Protocol: Fabricating Polyacrylamide Gels with Tunable Stiffness

This protocol is adapted from methods used to study CRC and endothelial cells [16] [18].

Objective: To create hydrogel substrates with defined elastic moduli for cell culture. Principle: Varying the ratio of acrylamide (monomer) to bis-acrylamide (crosslinker) controls the polymer mesh density and final stiffness.

Materials:

- 40% Acrylamide stock solution

- 2% Bis-acrylamide stock solution

- Ammonium persulfate (APS), 10% solution in water

- N, N, N', N'-Tetramethylethylenediamine (TEMED)

- Sulfo-SANPAH (0.5 mg/mL in PBS)

- Collagen Type I (0.1 mg/mL)

- UV light source (254-264 nm)

Procedure:

- Gel Solution Preparation: In a tube, mix the 40% acrylamide and 2% bis-acrylamide stock solutions with deionized water to achieve the desired final stiffness. For example:

- Soft Gels (~0.5 kPa): Use a higher water-to-monomer ratio.

- Stiff Gels (~8-40 kPa): Use a higher total monomer and crosslinker concentration.

- Polymerization: Add 10% APS and TEMED to the solution to initiate free-radical polymerization. Mix thoroughly and immediately pipet the solution onto activated glass coverslips. Place a second coverslip on top to create a uniform gel film.

- Surface Activation: After polymerization, remove the top coverslip and incubate the gel with Sulfo-SANPAH solution. Expose to UV light for crosslinking ECM proteins onto the gel surface.

- ECM Coating: Incubate the activated gels with Collagen Type I solution (0.1 mg/mL) for 1 hour at room temperature to promote cell adhesion.

- Sterilization and Seeding: Rinse gels with sterile PBS before seeding cells. Use cells at low passage number for experiments.

Protocol: Modulating and Assessing 6mA Methylation in Response to Stiffness

This protocol is based on research into colorectal cancer mechanisms [16].

Objective: To manipulate the 6mA demethylase ALKBH1 and evaluate its functional role in mechanotransduction.

Materials:

- Lentiviral vectors for ALKBH1 knockdown (shRNA) and overexpression (ALKBH1-flag)

- Mutant ALKBH1 plasmid (catalytically inactive, e.g., R24A/K25A/R28A/R31A)

- Puromycin (2 mg/mL) for selection

- X-tremeGENE HP DNA Transfection Reagent

- Antibodies for ALKBH1, 6mA, P53, CDKN1A (p21)

Procedure: Part A: Genetic Manipulation

- Knockdown: Infect target cells (e.g., HCT116, RKO) with lentivirus carrying shRNA targeting ALKBH1 or a non-targeting control (shNC). Select stable pools with puromycin for 2 days.

- Overexpression: Transfect cells with plasmids expressing wild-type ALKBH1 or the catalytically inactive mutant using a transfection reagent. Perform subsequent experiments 48 hours post-transfection.

- P53 Interaction Studies: Use P53-knockout cells to validate the specificity of the ALKBH1 mechanism.

Part B: Functional Readouts

- 6mA Level Quantification: Measure global DNA 6mA levels using immunofluorescent staining or commercial ELISA-like assays.

- Gene Expression Analysis: Evaluate mRNA levels of ALKBH1 and its target CDKN1A via qPCR.

- Mechanistic Chromatin Studies: Perform Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays to assess P53 binding to the CDKN1A promoter under different stiffness conditions.

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

The ALKBH1/6mA Mechanotransduction Pathway in CRC

This diagram illustrates the established mechanism by which matrix stiffness regulates gene expression in colorectal cancer cells via 6mA demethylation [16].

Workflow for a Comprehensive Mechano-Epigenetic Study

This workflow outlines the key steps for a complete investigation into DNA methylation responses to substrate mechanics, integrating protocols from above.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Mechano-Epigenetics Research

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Polyacrylamide (PA) Gels | Tunable, elastic substrates for 2D cell culture to study stiffness effects. | Standard for independent control of stiffness; coated with collagen or fibronectin [16] [18]. |

| Hyaluronic Acid (HA) Hydrogels | Biomimetic, viscoelastic platforms to model complex tissue mechanics. | Allows independent tuning of stiffness and viscoelasticity; more physiologically relevant for some tissues [17]. |

| Magnetic Elastomers | Dynamic substrates for real-time stiffening/softening studies. | Enables investigation of short-term cellular responses to changing mechanics [19]. |

| ALKBH1 Modulators | Target 6mA demethylation (shRNA, overexpression, mutant constructs). | Critical for establishing causal links between stiffness, 6mA, and phenotype [16]. |

| 5mC/6mA Detection Kits | Quantify global DNA methylation levels (ELISA, immunofluorescence). | Essential for measuring the core epigenetic output. |

| NCM460 & HCT116 Cells | In vitro models for colorectal cancer mechano-epigenetics. | NCM460: normal colon epithelial; HCT116: colorectal carcinoma [16]. |

Engineering the Mechano-Epigenetic Niche: Biomaterials, Tools, and Reprogramming Protocols

Hydrogels, three-dimensional hydrophilic polymer networks, serve as foundational tools in biomedical research for mimicking the cellular microenvironment. Their significance is particularly pronounced in the emerging field of mechano-epigenetics, which explores how biophysical cues from the extracellular matrix are transduced into biochemical signals that regulate chromatin organization and gene expression. This application note provides a detailed comparison of two central hydrogel systems—polyacrylamide (PAAm) and alginate-based hydrogels—for designing platforms with tunable matrix rigidity. We include standardized protocols for their fabrication and characterization, enabling researchers to systematically investigate how matrix mechanics govern epigenetic states and cellular reprogramming.

System Comparison: Polyacrylamide vs. Alginate-Based Hydrogels

The choice between PAAm and alginate-based systems is dictated by their distinct mechanical properties, tuning capabilities, and suitability for specific biological questions. The table below provides a quantitative comparison of their core characteristics.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Polyacrylamide and Alginate-Based Hydrogel Systems

| Property | Polyacrylamide (PAAm) Hydrogels | Alginate-Based Hydrogels |

|---|---|---|

| Stiffness Tuning Range | 1 kPa to over 100 kPa [2] | Wide range, highly dependent on cross-linking method and density [20] [21] |

| Key Tuning Parameter(s) | Concentration of bis-acrylamide cross-linker (MBAA) and total monomers [20] [2] | Cross-linker type (e.g., Ca²⁺, Zn²⁺) and concentration; polymer concentration [20] [21] |

| Viscoelasticity | Primarily elastic; stress relaxation can be tuned via cross-link density [20] | Can be engineered to exhibit significant viscoelasticity and stress relaxation [22] |

| Functionalization | Covalent conjugation of ECM proteins (e.g., fibronectin, collagen) to the polymer network via reactive groups (e.g., NHS-acrylate) [2] | Natural cell adhesion ligands can be introduced via coupling chemistry (e.g., RGD peptides); or by forming IPNs with collagen [22] [23] |

| Epigenetic Research Relevance | Ideal for 2D studies on stiffness-mediated histone acetylation and chromatin accessibility; demonstrates biphasic epigenetic regulation [2] | Suitable for 3D culture and mimicking tissue-level viscoelasticity; IPNs can promote cell aggregation, a reprogramming phenotype [22] |

| Key Advantages |

|

|

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Reagents for Fabricating Tunable Hydrogel Platforms

| Item | Function/Description | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Acrylamide (40%) / Bis-Acrylamide (2%) Solution | Pre-mixed stock solutions of monomer (acrylamide) and cross-linker (bis-acrylamide) for PAAm hydrogels. | Foundation for creating the PAAm polymer network. Varying the ratio tunes stiffness [2]. |

| Ammonium Persulfate (APS) & Tetramethylethylenediamine (TEMED) | Initiator (APS) and catalyst (TEMED) for the free-radical polymerization of PAAm hydrogels. | Triggers the cross-linking reaction of PAAm solutions [2]. |

| Sulfo-SANPAH | A heterobifunctional cross-linker that is light-activatable for conjugating ECM proteins to the PAAm hydrogel surface. | Covalently links fibronectin or collagen to the otherwise inert PAAm gel for cell adhesion [2]. |

| Sodium Alginate | A natural polysaccharide polymer derived from seaweed; forms hydrogels via ionic cross-linking. | Base polymer for alginate-based hydrogel systems [20] [22] [21]. |

| Cross-Linking Ions (Ca²⁺, Zn²⁺) | Divalent cations that ionically cross-link guluronic acid residues in alginate chains ("egg-box" model). | Zn²⁺ can provide denser cross-linking and added antifungal properties compared to Ca²⁺ [21]. |

| ε-Poly-L-lysine (PLL) | A cationic polymer used to form polyelectrolyte complexes with anionic alginate for dual-cross-linking. | Enhances mechanical and bioadhesive properties of alginate hydrogels and can add antimicrobial activity [21]. |

| Collagen Type I | A major ECM protein that can be interpenetrated with alginate to create a composite hydrogel. | Provides natural cell adhesion sites and non-linear elasticity to better mimic native tissue [22]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Fabricating Stiffness-Tunable Polyacrylamide Hydrogels

This protocol details the creation of PAAm hydrogels on glass coverslips for 2D cell culture, allowing for precise independent control over substrate stiffness.

Workflow Overview

Materials:

- Glass coverslips (12-25 mm diameter)

- 3-Aminopropyltriethoxysilane (APTES)

- Glutaraldehyde (0.5%)

- Acrylamide and Bis-acrylamide stock solutions

- Ammonium Persulfate (APS): 10% (w/v) solution in water, prepared fresh.

- Tetramethylethylenediamine (TEMED)

- Sulfo-SANPAH

- Fibronectin or Collagen I solution

- Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS)

Procedure:

- Coverslip Silanization: Clean glass coverslips with ethanol and air dry. Treat with APTES vapor for 30 minutes, followed by exposure to 0.5% glutaraldehyde for 30 minutes. Wash thoroughly with distilled water and dry.

- Monomer Solution Preparation: For a specific stiffness (e.g., ~20 kPa, which enhances fibroblast-to-neuron reprogramming [2]), prepare the monomer solution. A representative formulation for a 1 mL final volume is:

- Degassing (Optional): Degas the monomer solution for 10-15 minutes to remove dissolved oxygen, which can inhibit polymerization.

- Polymerization Initiation: Add 10 µL of 10% APS and 1 µL TEMED per 1 mL of monomer solution. Mix thoroughly by pipetting.

- Gel Casting: Immediately pipette 20-30 µL of the activated solution onto a parafilm sheet. Invert a silanized coverslip onto the droplet, ensuring no bubbles are trapped.

- Polymerization: Allow the gel to polymerize for 30-45 minutes at room temperature.

- Gel Hydration: Carefully separate the coverslip-gel construct and immerse in PBS to hydrate and swell for at least 1 hour.

- Surface Functionalization:

- Replace PBS with a solution of Sulfo-SANPAH (0.2-0.5 mg/mL in water).

- Expose to UV light (e.g., 365 nm) for 5-10 minutes to activate the cross-linker.

- Rinse gels with PBS to remove excess Sulfo-SANPAH.

- Incubate with a solution of fibronectin or collagen (e.g., 25 µg/mL in PBS) for at least 2 hours at 37°C or overnight at 4°C.

- Rinse with PBS before plating cells.

Protocol: Creating a Tissue-Mimicking Alginate-Collagen IPN Hydrogel

This protocol creates an interpenetrating network (IPN) hydrogel that combines the viscoelasticity of alginate with the biological activity and non-linear elasticity of collagen, suitable for 3D cell culture and studies requiring tissue-like mechanics [22].

Materials:

- Sodium Alginate (e.g., from Macrocystis pyrifera)

- Collagen Type I, rat tail

- Calcium Sulfate (CaSO₄) or other cross-linking salt (e.g., Zn(OAc)₂ [21])

- HEPES Buffered Saline Solution

- Sodium Hydroxide (NaOH)

Procedure:

- Alginate Solution Preparation: Dissolve sodium alginate in HEPES buffered saline to a final concentration of 10 mg/mL [22]. Sterilize by filtering (0.22 µm syringe filter) and keep on ice.

- Collagen Solution Preparation: Neutralize sterile Collagen Type I on ice according to the manufacturer's instructions to a final concentration of 1.5 mg/mL [22].

- IPN Precursor Mixing: Gently mix the alginate and collagen solutions in a 1:1 volume ratio. Maintain the solution on ice to prevent premature collagen polymerization.

- Cross-linking Initiation: To the alginate-collagen mixture, add a calculated volume of a sterile CaSO₄ slurry (to achieve a final concentration of, for example, 15 mM for a stiffer gel or 5 mM for a softer gel [22]). Mix quickly and thoroughly by pipetting.

- Gel Casting: Immediately pipette the solution into the desired culture mold (e.g., 24-well plate).

- Gelation: Transfer the plate to a 37°C incubator for 30-60 minutes. This step allows for simultaneous ionic cross-linking of alginate by Ca²⁺ and thermal gelation of collagen, forming the IPN.

- Equilibration: After gelation, add warm cell culture medium to equilibrate the hydrogels before cell seeding.

Application in Epigenetic Reprogramming: A Case Study

Background: Matrix stiffness is a biphasic regulator of epigenetic state. Research shows that an intermediate stiffness of ~20 kPa in PAAm hydrogels maximizes histone acetyltransferase (HAT) activity, histone acetylation, chromatin accessibility, and the efficiency of fibroblast-to-neuron conversion [2].

Mechanistic Insight and Workflow The following diagram illustrates the mechano-epigenetic signaling pathway elucidated using tunable PAAm hydrogel platforms and a generalized experimental workflow for validation.

Key Experimental Steps:

- Hydrogel Preparation: Fabricate PAAm hydrogels of varying stiffness (e.g., 1 kPa, 20 kPa, 40 kPa, glass) as per Protocol 4.1.

- Cell Seeding and Reprogramming: Seed fibroblasts transduced with inducible reprogramming factors (e.g., BAM factors: Ascl1, Brn2, Myt1l) onto the hydrogels [2].

- Efficiency Assessment: After 7-14 days, fix cells and immunostain for neuronal markers (e.g., Tubb3) to quantify reprogramming efficiency.

- Epigenetic Analysis:

- ATAC-seq: Perform on cells cultured on different stiffnesses to map genome-wide chromatin accessibility [2].

- Histone Modification Analysis: Use immunostaining or Western Blot to assess levels of histone acetylation (e.g., H3K9ac, H3K27ac).

- HAT Activity: Measure HAT activity in nuclear extracts from cells on different substrates.

Concluding Remarks

Both polyacrylamide and alginate-based hydrogel systems offer powerful and complementary approaches for designing tunable mechanical microenvironments. The selection of a system should be driven by the specific biological question: PAAm hydrogels are the gold standard for reductionist 2D studies requiring precise, independent control over stiffness, while alginate-based IPNs excel in modeling the complex, viscoelastic, and 3D nature of native tissues. By leveraging the protocols and insights provided, researchers can systematically dissect the fundamental mechanisms of mechano-epigenetic regulation, advancing the fields of regenerative medicine, disease modeling, and cell reprogramming.

The extracellular environment exerts profound influence on cellular fate through mechano-epigenetic signaling—a process where physical cues are transduced into biochemical signals that ultimately reshape the epigenome. This application note provides a structured framework for selecting and implementing 2D versus 3D culture systems to investigate how spatial context and matrix properties influence epigenetic reprogramming. We detail specific protocols, experimental workflows, and analytical tools to advance research in tunable matrix rigidity for epigenetic reprogramming.

The fundamental difference between these systems lies in their physiological relevance. While 2D cultures grow cells in a single layer on flat surfaces, 3D cultures permit growth in all directions, mimicking tissue-like architecture and enabling complex cell-cell and cell-extracellular matrix (ECM) interactions [24]. This distinction is critical for mechano-epigenetic studies, as the spatial presentation of mechanical signals directly impacts force transmission to the nucleus and subsequent chromatin remodeling [4].

Model Selection Guide: 2D vs. 3D Culture Systems

Decision Framework for Model Selection

Table 1: Experimental Model Selection Guide Based on Research Objectives

| Research Objective | Recommended Model | Rationale | Key Mechano-Epigenetic Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| High-throughput compound screening | 2D Culture | Cost-effective, scalable, compatible with well-established protocols and automation [24] [25] | Limited physiological force context; uniform mechanical environment |

| Studies requiring tissue architecture (e.g., solid tumors, liver, skin) | 3D Culture | Recapitulates tissue-specific mechanical gradients and cell-ECM interactions [24] | Enables study of spatial mechanical heterogeneity (e.g., hypoxia, nutrient gradients) |

| Mechanistic pathway studies with uniform conditions | 2D Culture | Simplified system with uniform nutrient access, oxygenation, and drug exposure [25] | Ideal for isolating specific mechanotransduction pathways (e.g., integrin-focal adhesion axis) |

| Drug penetration & resistance studies | 3D Culture | Models physiological barriers to diffusion and mechanisms of drug resistance [24] | Captures mechano-mediated drug resistance through pressure and tension gradients |

| Genetic manipulations (e.g., CRISPR knockouts) | 2D Culture | Technical simplicity and high efficiency of genetic modification [24] | Facilitates functional validation of specific mechanosensors (e.g., Piezo channels, integrins) |

| Personalized therapy testing | Patient-derived Organoids (3D) | Maintains patient-specific genetic background and drug response profiles [24] [25] | Preserves native mechanical memory and individual epigenetic patterning |

Quantitative Comparison of Culture Systems

Table 2: Performance Characteristics of 2D vs. 3D Culture Models

| Parameter | 2D Culture | 3D Culture | Implications for Mechano-Epigenetics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell-Cell Interactions | Limited to flat, peripheral contacts | Extensive, spatially complex networks | Enhanced mechanical coupling between cells via cadherins and gap junctions |

| Spatial Organization | None—monolayer | Self-assembly into structures (spheroids, organoids) | Emergence of tissue-scale tension patterns and mechanical boundaries |

| Gene Expression Fidelity | Altered due to unnatural adhesion | More in vivo-like expression profiles [24] | Better preservation of mechanoresponsive gene networks (e.g., YAP/TAZ targets) |

| Drug Sensitivity Prediction | Often overestimates efficacy [24] | More accurate prediction of clinical response | Mechanical confinement regulates drug access and efficacy |

| Cellular Lifespan & Function | Rapid loss of specialized functions (e.g., CYP activity in hepatocytes) [25] | Long-term functional maintenance (4-6+ weeks) [25] | Extended maintenance of mechano-epigenetic memory and tissue-specific identity |

| Technical Complexity | Low—standardized protocols | High—requires specialized materials and expertise | Requires advanced imaging and force inference methodologies [26] |

Experimental Protocols for Mechano-Epigenetic Research

Protocol 1: Establishing Tunable Viscoelastic Hydrogel Platforms for 2D Culture

Purpose: To create substrate systems with independently tunable stiffness and stress relaxation properties for investigating how matrix viscoelasticity regulates nuclear architecture and epigenome.

Materials:

- Alginate-based hydrogel system: RGD-coupled alginate polymers (2-20 kPa range)

- Crosslinkers: Covalent (for elastic substrates) and ionic (for viscoelastic substrates) [4]

- Cell source: Primary fibroblasts or other relevant cell types

Methodology:

- Substrate Fabrication: Prepare alginate hydrogels with target initial elastic moduli (2, 10, 20 kPa) using controlled crosslinking protocols.

- Viscoelastic Tuning: For slow-relaxing substrates (τ₁/₂ ~1000 s): Use specific ionic crosslinkers. For fast-relaxing substrates (τ₁/₂ ~200 s): Adjust ionic crosslinker concentration and molecular weight [4].

- Mechanical Validation: Characterize stress relaxation profiles using rheometry and confirm stable mechanical properties under culture conditions for at least 7 days.

- Cell Seeding: Seed cells at appropriate density (e.g., 50,000 cells/cm² for fibroblasts) on RGD-functionalized substrates.

- Epigenetic Endpoint Analysis: After 48-72 hours, assess nuclear volume, chromatin compaction (DAPI intensity/volume), and epigenetic marks (e.g., H3K27ac, H3K9me3) [4].

Key Applications:

- Investigate how viscoelasticity-induced nuclear deformation influences chromatin accessibility and epigenetic remodeling

- Test cellular reprogramming efficiency on defined mechanical substrates

Protocol 2: Imaging and Analysis of 3D Mechano-Epigenetic Responses

Purpose: To quantify spatial patterns of mechanical force and correlate with epigenetic states in 3D culture models.

Materials:

- 3D culture platform: Spheroids in U-bottom ultra-low attachment plates or matrix-embedded organoids [26]

- Imaging system: Automated confocal microscope with water immersion objectives (e.g., ImageXpress Micro Confocal) [26]

- Staining reagents: High concentration dyes (2X-3X standard) with extended incubation (2-3 hours for Hoechst) [26]

Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Generate uniform spheroids using U-bottom plates to maintain central positioning during imaging [26].

- 3D Immunostaining: Optimize antibody and dye penetration using increased concentrations and extended incubation periods (2-3 hours for nuclear stains vs. 15-20 minutes in 2D) [26].

- Z-stack Acquisition: Implement optimized imaging parameters:

- 10X objective: 8-10 µm between Z-slices

- 20X objective: 3-5 µm between Z-slices

- Use Maximum Projection algorithm to combine in-focus areas [26]

- Mechanical Force Inference: Apply computational pipeline to segment cell boundaries and infer intracellular pressures and junctional tensions from 3D image data [27].

- Spatial Correlation Analysis: Map epigenetic markers (e.g., H3K9me3, H3K27ac) against mechanical force maps to identify mechano-epigenetic relationships [27].

Key Applications:

- Correlate spatial patterns of interfacial tension with heterochromatin organization at tissue compartment boundaries

- Map how pressure gradients in tumor spheroids influence epigenetic states of drug resistance

Molecular Mechanisms of Mechano-Epigenetic Signaling

Core Mechanotransduction Pathways to the Epigenome

The transmission of mechanical signals from the extracellular environment to epigenetic effectors occurs through several well-defined pathways:

Diagram: Core mechanotransduction pathway from ECM to epigenetic regulation. Mechanical signals are sensed at the membrane, transmitted via the cytoskeleton and LINC complex, ultimately causing epigenetic changes.

Advanced Computational Framework for Spatial Mechano-Transcriptomics

Workflow Implementation:

Diagram: Computational pipeline for spatial mechano-transcriptomics analysis, enabling correlation of mechanical forces with transcriptional and epigenetic states.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Mechano-Epigenetic Studies

| Category | Specific Product/Platform | Function in Mechano-Epigenetics |

|---|---|---|

| Tunable Hydrogel Systems | Alginate-based viscoelastic hydrogels (2-20 kPa) [4] | Independent control of stiffness and stress relaxation to dissect their individual roles in epigenetic regulation |

| 3D Culture Platforms | Corning U-bottom spheroid plates [26] | Maintain spheroids in centered position for consistent imaging and mechanical analysis |

| Mechanical Force Inference | Variational Method of Stress Inference (VMSI) Python package [27] | Quantify junctional tensions and intracellular pressures from segmented images |

| Advanced Imaging Systems | ImageXpress Micro Confocal with water immersion objectives [26] | High-resolution 3D imaging of large spheroids and organoids with reduced background |

| Spatial Transcriptomics | seqFISH/MERFISH with membrane staining [27] | Correlate gene expression patterns with mechanical forces at cellular resolution |

| Epigenetic Editing Tools | CRISPR-based targeted epigenetic modifiers | Functional validation of mechano-sensitive epigenetic regulators identified in screening approaches |

The investigation of mechano-epigenetic signaling requires thoughtful model selection guided by specific research questions. For reductionist studies of molecular mechanisms, 2D cultures on tunable substrates provide unmatched simplicity and control. For physiological relevance and translational prediction, 3D models capture emergent mechanical properties that drive epigenetic reprogramming in tissue context.