Mechano-Epigenetic Reprogramming: Engineering Biomaterial Scaffolds for Cell Fate Control and Regenerative Therapy

This article synthesizes the latest advances in scaffold-based strategies for epigenetic reprogramming, a cutting-edge approach at the intersection of biomaterials science, epigenetics, and regenerative medicine.

Mechano-Epigenetic Reprogramming: Engineering Biomaterial Scaffolds for Cell Fate Control and Regenerative Therapy

Abstract

This article synthesizes the latest advances in scaffold-based strategies for epigenetic reprogramming, a cutting-edge approach at the intersection of biomaterials science, epigenetics, and regenerative medicine. We explore how engineered biomaterial scaffolds provide not only structural support but also essential biophysical and biochemical cues that work in concert with epigenetic modulators to direct cell fate. The content covers foundational principles of epigenetic regulation and mechanotransduction, details the design parameters of tunable biomaterial platforms, addresses key challenges in spatiotemporal control and safety, and evaluates current validation models and clinical translation potential. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this resource provides a comprehensive framework for developing next-generation therapies that co-target the mechanical and epigenetic drivers of disease and aging.

The Mechano-Epigenetic Nexus: How Scaffolds Instruct Cell Fate

Epigenetics refers to heritable changes in gene expression that occur without altering the underlying DNA sequence, enabling specialization of function between cells that share the same genetic code [1] [2]. These mechanisms control how the genome is accessed in different cell types and during development and differentiation [1]. The template for these modifications is chromatin, the complex of DNA, RNA, and histone proteins that efficiently packages the genome within the nucleus [1] [2]. The basic unit of chromatin is the nucleosome, an octamer of core histone proteins (H2A, H2B, H3, and H4) around which 147 base pairs of DNA are wound [1]. The state of chromatin—whether transcriptionally permissive (euchromatin) or repressive (heterochromatin)—is dynamically regulated by specific modifications to histone proteins and DNA, and the recognition of these marks by other protein complexes [1] [2] [3].

The orchestration of the epigenetic state involves four key classes of proteins: "writers" that deposit epigenetic marks, "erasers" that remove them, "readers" that recognize and interpret the marks, and "remodelers" that restructure chromatin [1]. Beyond the biochemical modifications lies the critical concept of the nucleoscaffold, a physical nuclear framework that safeguards cellular fate [4]. This scaffold, composed of proteins like Lamin A/C, maintains the three-dimensional architecture of the genome, constraining silent heterochromatin domains and ensuring stable gene expression programs [4]. Manipulating this nucleoscaffold has been shown to potentiate cellular reprogramming kinetics, highlighting its fundamental role as a guardian of cell identity [4]. This article details the core mechanisms and provides practical protocols for their investigation, framed within the context of scaffold manipulation for epigenetic reprogramming research.

Core Epigenetic Components

Writers: The Architects of the Epigenetic Code

Writers are enzymes that catalyze the addition of chemical groups to DNA and histone proteins. They lay down the patterns that constitute the epigenetic code.

- DNA Methyltransferases (DNMTs): DNMTs catalyze the transfer of a methyl group from S-adenosylmethionine (SAM) to the 5' position of cytosine bases, primarily in CpG dinucleotides [5] [2]. This modification is generally associated with transcriptional repression. DNMT1 maintains methylation patterns during DNA replication, while DNMT3A and DNMT3B establish de novo methylation [3].

- Histone Methyltransferases (HMTs): These enzymes transfer methyl groups to lysine or arginine residues on histone tails [1]. Protein lysine methyltransferases (PKMTs) and protein arginine methyltransferases (PRMTs) can produce varying degrees of methylation (mono-, di-, or tri-methylation for lysine), with distinct functional consequences [1].

- Histone Acetyltransferases (HATs): HATs catalyze the addition of acetyl groups to lysine residues on histones. This neutralizes the positive charge of the lysine, weakening the interaction between histones and the negatively charged DNA backbone, which typically leads to a more open chromatin state and facilitates transcription [2].

Erasers: The Editors of the Epigenome

Erasers are enzymes that remove epigenetic marks, providing dynamic reversibility to the epigenetic landscape.

- Ten-Eleven Translocation (TET) Enzymes: TET enzymes catalyze the iterative oxidation of 5-methylcytosine (5mC) to 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5hmC) and further derivatives, initiating the DNA demethylation pathway [3].

- Histone Demethylases (HDMs): HDMs remove methyl groups from histone lysine and arginine residues. The two main families are the flavin-dependent amine oxidases (e.g., LSD1) and the Jumonji C (JmjC) domain-containing families, which utilize iron and α-ketoglutarate as cofactors [1].

- Histone Deacetylases (HDACs): HDACs remove acetyl groups from histone lysine residues, restoring the positive charge and promoting a tighter, more transcriptionally repressive chromatin structure [1] [2].

Readers: The Interpreters of Epigenetic Marks

Reader proteins contain specialized domains that recognize and bind to specific epigenetic modifications, translating the marks into downstream biological effects.

- Methyl-CpG-Binding Domain (MBD) Proteins: Proteins such as MeCP2 bind to methylated CpG dinucleotides and recruit additional complexes, like histone deacetylases, to reinforce a repressive chromatin state [3].

- Royal Family Domains: This superfamily includes proteins with Tudor, Chromo, Malignant Brain Tumor (MBT), PWWP, and plant homeodomain (PHD) fingers. These domains recognize methylated lysine residues via an aromatic cage structure [1]. For example, the chromodomain of HP1 binds to H3K9me3, a hallmark of heterochromatin.

- Bromodomains: Bromodomains are modules that specifically recognize and bind to acetylated lysine residues, recruiting transcriptional co-activators and other machinery to sites of active transcription [1].

Remodelers: The Masters of Chromatin Architecture

Remodelers are multi-protein complexes that use the energy of ATP hydrolysis to slide, evict, or restructure nucleosomes, physically altering access to the DNA.

- SWI/SNF Complex: This is a canonical example of an ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling complex. It disrupts histone-DNA contacts to slide nucleosomes along the DNA or evict them entirely, making regulatory regions accessible to the transcriptional machinery [3] [6].

- Nuclear Scaffold Proteins: While not enzymes, structural components of the nucleus, such as Lamin A/C, function as ultimate remodelers and organizers of chromatin architecture. They tether large genomic regions known as Lamina-Associated Domains (LADs) to the nuclear periphery, maintaining them in a transcriptionally silent heterochromatic state [4]. Manipulation of Lamin A/C disrupts this architecture, opening silenced heterochromatin and potentiating cellular reprogramming [4].

Table 1: Core Epigenetic Machinery: Writers, Erasers, Readers, and Remodelers

| Category | Function | Key Examples | Target/Modification |

|---|---|---|---|

| Writers | Deposit covalent modifications | DNMTs (DNMT1, DNMT3A/B) | DNA methylation (CpG) |

| Histone Methyltransferases (e.g., G9a, MLL) | Histone lysine/arginine methylation | ||

| Histone Acetyltransferases (HATs) | Histone lysine acetylation | ||

| Erasers | Remove covalent modifications | TET Enzymes | DNA demethylation |

| Histone Demethylases (e.g., LSD1, JMJD3) | Histone demethylation | ||

| Histone Deacetylases (HDACs) | Histone deacetylation | ||

| Readers | Bind specific modifications | MBD Proteins (e.g., MeCP2) | Methylated DNA |

| Royal Family Proteins (e.g., HP1) | Methylated histones | ||

| Bromodomain Proteins (e.g., BRD4) | Acetylated histones | ||

| Remodelers | Restructure nucleosomes | SWI/SNF Complex | ATP-dependent nucleosome sliding/eviction |

| Nuclear Scaffold (e.g., Lamin A/C) | Anchors heterochromatin, maintains 3D genome organization |

Quantitative Profiling of Epigenetic Modifications

Accurate measurement of epigenetic mark abundance is fundamental. The table below summarizes key quantitative techniques.

Table 2: Assay Technologies for Epigenetic Modification Analysis

| Assay Type | Detection Principle | Target | Throughput | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ELISA/DELFIA/AlphaScreen | Antibody-based detection with secondary reporter (HRPO, Europium, beads) [1] | Specific histone modifications (e.g., H3K4me3) | High | Amenable to HTS; high sensitivity |

| Microfluidic Capillary Electrophoresis (e.g., Caliper LabChip) | Methylation-sensitive proteolysis; separates methylated/unmethylated peptides [1] | Peptide methylation status | Medium-High | Label-free; quantitative; useful for kinetics |

| Radioactive Assay | Incorporation of ³H-labeled methyl group from ³H-SAM [1] | Histone or DNA methylation | Low | Highly sensitive; works with nucleosomes |

| Enzyme-Coupled Cofactor Detection | Measures SAH (via ThiGlo) or formaldehyde (via FDH) production [1] | PKMT or PKDM activity | Medium | Homogeneous; avoids antibody use |

Application Note: Scaffold Manipulation for Enhanced Reprogramming

Rationale

Somatic cell fate is maintained by gene silencing of alternate fates through physical interactions with the nuclear scaffold [4]. The core protein components of this scaffold, such as Lamin A/C, tether transcriptionally silent heterochromatin domains to the nuclear periphery, creating a mechanical and biochemical barrier to reprogramming. We hypothesized that transient disruption of the nucleoscaffold would open these silenced domains, increase chromatin accessibility, and potentiate the kinetics of cellular reprogramming to pluripotency.

Experimental Workflow

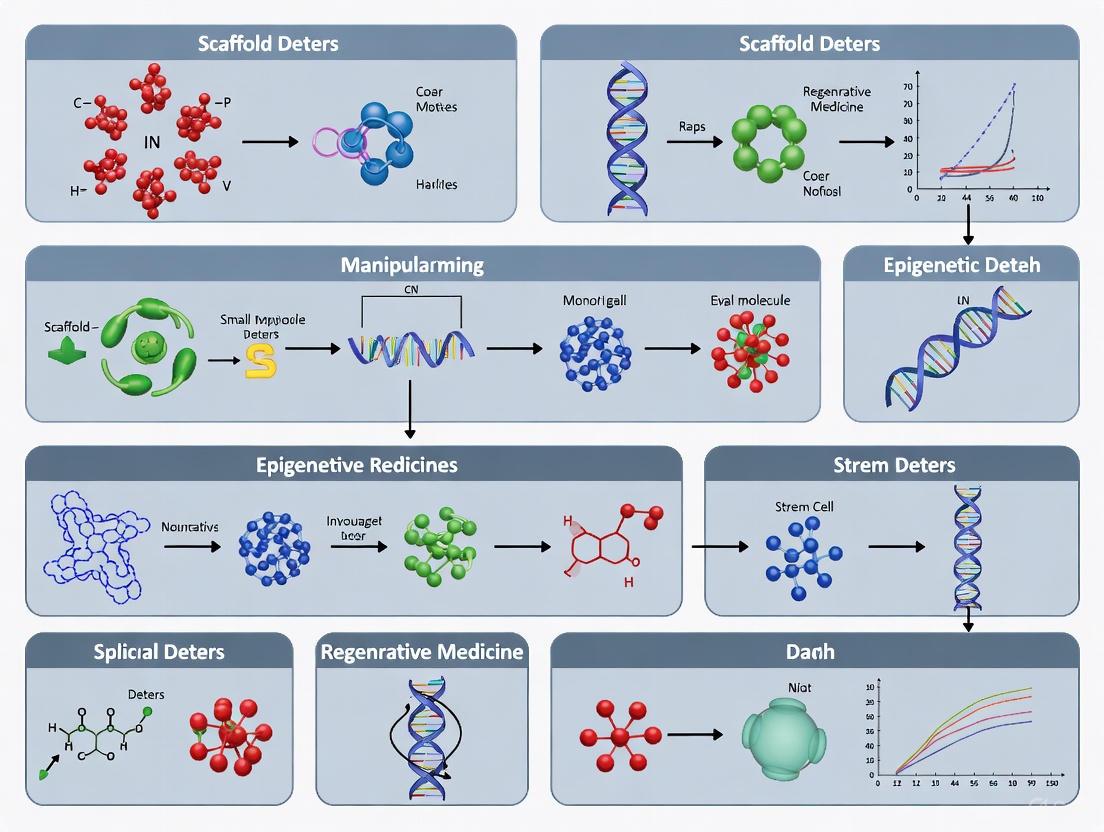

The following diagram illustrates the integrated protocol for assessing the role of the nuclear scaffold in epigenetic reprogramming:

Detailed Protocol

Protocol 4.3.1: Transient Knockdown of Lamin A/C and Nuclear Phenotyping

Objective: To disrupt the nuclear scaffold and characterize subsequent nuclear and chromatin changes.

Materials:

- Cells: Human Dermal Fibroblasts (HDFs)

- Reagents: Lamin A/C-specific siRNA or shRNA constructs; Non-targeting siRNA (scramble control); Lipofectamine RNAiMAX; Growth Medium (DMEM + 10% FBS); Paraformaldehyde (4%); Triton X-100; DAPI; Antibodies for Lamin A/C and H3K9me3.

- Equipment: Confocal microscope; Microfluidic cellular squeezing device (e.g., from CellScale or custom-built); Sonication system for ChIP.

Procedure:

- Cell Seeding: Plate HDFs at 60-70% confluence in 6-well plates 24 hours prior to transfection.

- Transfection: Transfect cells with Lamin A/C siRNA or non-targeting control using Lipofectamine RNAiMAX according to the manufacturer's protocol. Incubate for 48-72 hours.

- Efficiency Validation: Harvest a subset of cells and validate Lamin A/C knockdown at the protein level via western blotting.

- Nuclear Morphology Analysis:

- Fix cells with 4% PFA for 15 min, permeabilize with 0.1% Triton X-100, and stain for Lamin A/C and DNA (DAPI).

- Image using a 63x oil objective on a confocal microscope. Quantify nuclear circularity and surface irregularities using ImageJ software.

- Nuclear Mechanics Assay:

- Harvest transfected cells and resuspend in serum-free medium at 1x10⁶ cells/mL.

- Load cell suspension into the microfluidic squeezing device. Measure nuclear deformation (strain) in response to applied compressive stress. Calculate the apparent nuclear stiffness.

- Chromatin Accessibility Assessment (ChIP-qPCR):

- Perform chromatin immunoprecipitation using an antibody against H3K9me3 or a marker of active chromatin like H3K27ac on transfected and control cells.

- Crosslink proteins to DNA with 1% formaldehyde for 10 min. Quench with glycine.

- Lyse cells and sonicate chromatin to an average size of 200-500 bp.

- Immunoprecipitate with target antibody. Reverse crosslinks and purify DNA.

- Analyze precipitated DNA by qPCR with primers designed for Lamina-Associated Domains (LADs) and active, non-LAD regions.

Protocol 4.3.2: Cellular Reprogramming and Kinetic Analysis

Objective: To assess the impact of scaffold manipulation on induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) generation kinetics.

Materials:

- Cells: HDFs from Protocol 4.3.1 (Lamin A/C KD and control).

- Reagents: Sendai virus vectors expressing OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, and c-MYC (CytoTune-iPS Kit); Essential 8 Medium; TRA-1-60 Live Stain Antibody.

- Equipment: Flow cytometer; Tissue culture microscope.

Procedure:

- Reprogramming Induction: 72 hours post-Lamin A/C knockdown, transduce cells with Sendai virus containing the Yamanaka factors (OSKM). Include a mock-transduced control.

- Culture Maintenance: 24 hours post-transduction, replace the medium with Essential 8 pluripotency medium. Change the medium every other day.

- Kinetic Monitoring:

- Time-point 1 (Day 7): Analyze early pluripotency marker expression (e.g., NANOG, SSEA4) by qRT-PCR and flow cytometry.

- Time-point 2 (Day 14-21): Perform live staining for the surface marker TRA-1-60. Quantify the percentage of TRA-1-60 positive colonies using flow cytometry and image-based colony counting.

- Endpoint Analysis: Pick and expand individual colonies. Confirm full pluripotency via immunocytochemistry for a panel of markers (OCT4, SOX2, NANOG, SSEA4) and, if required, teratoma formation assays.

Expected Results and Interpretation

- Lamin A/C KD cells should show misshapen nuclei, reduced nuclear stiffness, decreased H3K9me3 signal at LADs, and accelerated emergence of TRA-1-60 positive colonies compared to controls [4].

- Progerin-mutant cells, in contrast, are expected to exhibit severe nuclear abnormalities but induce a senescent phenotype that inhibits reprogramming, highlighting the delicate balance between scaffold disruption and cellular viability [4].

- Conclusion: Transient, but not pathological, disruption of the nucleoscaffold lowers the epigenetic barrier to cell fate change, validating it as a potent target for enhancing reprogramming protocols.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Epigenetic and Scaffold Research

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Target | Key Application |

|---|---|---|

| 5-Azacytidine (DNMT Inhibitor) | Nucleoside analog that incorporates into DNA and inhibits DNMTs, causing DNA hypomethylation [2]. | Epigenetic reprogramming; cancer therapy (FDA-approved for MDS) [2]. |

| Trichostatin A (TSA; HDAC Inhibitor) | Potent inhibitor of Class I and II HDACs, leading to hyperacetylated histones and open chromatin [2]. | Studying the role of histone acetylation in memory, cancer, and reprogramming [3]. |

| JQ1 (Bromodomain Inhibitor) | Competitive antagonist that displaces BET family readers (e.g., BRD4) from acetylated chromatin [1]. | Cancer research (e.g., targeting oncogenic drivers); anti-inflammatory studies. |

| Lamin A/C siRNA/shRNA | Silences the LMNA gene, reducing levels of the Lamin A/C protein and disrupting the nuclear scaffold [4]. | Probing the role of nuclear architecture in cell fate, mechanobiology, and reprogramming. |

| dCas9-Epigenetic Effectors (CRISPR) | Catalytically dead Cas9 fused to writer/eraser domains (e.g., dCas9-DNMT3A, dCas9-p300) for targeted epigenome editing [6]. | Locus-specific epigenetic modification without altering DNA sequence; functional genomics. |

The coordinated action of epigenetic writers, erasers, readers, and remodelers defines cellular identity and function. As detailed in these application notes, the manipulation of the physical nucleoscaffold presents a powerful, novel frontier for epigenetic reprogramming research. By integrating quantitative biochemical assays with mechanical and structural analyses, researchers can dissect the complex interplay between the genome's biochemical code and its physical architecture. The protocols provided offer a roadmap for leveraging scaffold manipulation to enhance cellular reprogramming, with significant potential implications for regenerative medicine, disease modeling, and the development of next-generation epigenetic therapies.

The extracellular matrix (ECM) provides far more than mere structural support; it is a dynamic source of mechanical cues that profoundly influence cellular behavior through nuclear mechanotransduction [7] [8]. The biophysical properties of the ECM—including its stiffness, topology, and spatial confinement—orchestrate cellular responses by regulating nuclear mechanics and chromatin organization, ultimately determining cell fate across diverse pathophysiological contexts [7]. In the field of regenerative medicine, scaffold-based approaches have emerged as powerful tools to direct cell fate by recapitulating this physiological microenvironment. These scaffolds function not only as structural templates but as active instructors that co-target mechanotransduction and epigenetic reprogramming, thereby disrupting self-reinforcing pathological barriers and promoting tissue regeneration [9]. This application note details the experimental frameworks and protocols for investigating how mechanical signals propagate from the plasma membrane to the nucleus, modulating nuclear envelope tension, chromatin accessibility, and epigenetic landscapes to drive cellular reprogramming.

Quantitative Data: Matrix Properties and Cellular Responses

The following tables summarize key quantitative relationships between scaffold properties, induced cellular responses, and subsequent nuclear changes, essential for designing reprogramming experiments.

Table 1: Scaffold Stiffness and Corresponding Cellular Outcomes

| Scaffold Stiffness | Biological Context | Observed Cellular & Nuclear Response |

|---|---|---|

| 1 - 5 kPa [9] | Physiological alveolar ECM; Compliant scaffold regions | Promotes epithelial cell adhesion and proliferation; Inhibits YAP/TAZ activity [9]. |

| 15 ± 5 kPa [10] | Optimal myogenic matrix | Significantly enhanced trans-differentiation of ADSCs into myoblast-like cells when combined with 5-Aza-CR treatment [10]. |

| > 20 kPa [9] | Pathological fibrotic ECM; Rigid scaffold domains | Drives fibroblast-to-myofibroblast transdifferentiation; Upregulates profibrotic genes (e.g., Col1a1, ACTA2); Promotes RhoA/ROCK signaling [9]. |

Table 2: Epigenetic Modulator Dosage and Effects in 3D Culture

| 5-Azacytidine (5-Aza-CR) Dose | Observed Effect on ADSCs in 3D Col-Tgel |

|---|---|

| < 0.125 ng (Low) | No significant enhancement of trans-differentiation [10]. |

| 1.25 - 12.5 ng (Intermediate) | Maximum effect on trans-differentiation into myoblast-like cells; Reduced β-Gal staining in aged cells; Upregulation of pluripotency marker Oct4 [10]. |

| > 67.5 ng (High) | No significant enhancement of trans-differentiation; Induction of apoptosis via caspase 3/7 activation [10]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Fabrication of Tunable Stiffness Scaffolds for Reprogramming Studies

This protocol describes the preparation of transglutaminase cross-linked gelatin (Col-Tgel) hydrogels with tunable mechanical properties, ideal for studying the interaction between matrix stiffness and epigenetic modulators [10].

Materials:

- Gelatin (from bovine or porcine skin)

- Microbial transglutaminase (mTGase)

- Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS), 1X

- Adipose-derived stromal cells (ADSCs) or other target primary cells

- Cell culture plates (e.g., 24-well plates)

Procedure:

- Gelatin Solution Preparation: Prepare sterile gelatin solutions at varying concentrations (e.g., 5%, 8%, 10% w/v) in 1X PBS. The concentration of gelatin directly determines the final stiffness of the hydrogel.

- Cross-linking Initiation: Add microbial transglutaminase to the gelatin solution at a standardized activity unit ratio (e.g., 10 U/g of gelatin). Mix thoroughly but gently to avoid bubble formation.

- Casting and Gelation: Immediately transfer the mixture to the desired cell culture plate. Allow gelation to proceed for 30-60 minutes in a humidified incubator at 37°C.

- Stiffness Validation: Characterize the elastic modulus (Young's modulus) of each gel formulation using Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM). Expected values are Soft:

0.9 ± 0.1 kPa, Medium:15 ± 5 kPa, and Stiff:40 ± 10 kPa[10]. - Cell Encapsulation: Prior to gelation, trypsinize and resuspend the target cells (e.g., ADSCs) in the gelatin-mTGase mixture. Plate the cell-polymer suspension and proceed with gelation as in step 3. A final cell density of 1-2 million cells/mL is recommended.

Protocol: Combined Epigenetic Modulator and Scaffold-Based Reprogramming

This protocol outlines the process of treating scaffold-encapsulated cells with the DNA methylation inhibitor 5-Azacytidine (5-Aza-CR) to synergistically enhance reprogramming efficiency [10].

Materials:

- Col-Tgel scaffolds with encapsulated cells (from Protocol 3.1)

- 5-Azacytidine (5-Aza-CR) stock solution

- Complete cell culture medium

- Paraformaldehyde (4% in PBS) for fixation

- Triton X-100 for permeabilization

- Antibodies for immunocytochemistry (e.g., against Oct4, MyoD)

- RNA extraction kit and RT-PCR reagents

Procedure:

- Post-Encapsulation Culture: After gelation, carefully overlay the scaffolds with complete culture medium. Culture the constructs for 24 hours to allow cells to acclimate.

- Epigenetic Modulator Treatment: Prepare working concentrations of 5-Aza-CR in fresh culture medium. The recommended effective dose range is 1.25 to 12.5 ng/mL [10].

- Medium Exchange: Aspirate the existing medium and add the medium containing 5-Aza-CR. Incubate the constructs for 48-72 hours. Include control scaffolds with untreated medium.

- Post-Treatment Culture: After treatment, replace the medium with standard culture medium without 5-Aza-CR. Refresh the medium every 2-3 days. The total culture period can range from 7 to 21 days depending on the target differentiation lineage.

- Endpoint Analysis:

- Immunostaining: Fix constructs in 4% PFA, permeabilize with 0.1% Triton X-100, and stain for pluripotency (e.g., Oct4) or lineage-specific (e.g., myogenic) markers [10].

- Gene Expression: Extract total RNA from the entire scaffold and perform RT-PCR to quantify the upregulation of genes like OCT4, ABCG2, and HIF1A [10].

- Phenotypic Assessment: Use stains like Oil Red O for adipocyte loss or β-galactosidase for senescence to confirm the loss of original cell phenotypes [10].

Protocol: Assessing Nuclear Remodeling via Lamin A/C Manipulation

This protocol describes methods to perturb the nuclear scaffold and evaluate its impact on nuclear mechanics and reprogramming kinetics, which can be applied to cells within 3D scaffolds [4].

Materials:

- siRNA targeting Lamin A/C or a non-targeting control siRNA

- Transfection reagent suitable for the target cells

- Microfluidic cellular squeezing device (e.g., from CellScale or other vendors)

- Antibodies for Lamin A/C and heterochromatin markers (e.g., H3K9me3)

- DNA dyes (e.g., DAPI)

Procedure:

- Nuclear Scaffold Disruption: Culture cells in 2D or retrieve them from 3D scaffolds at an early time point. Transfect with Lamin A/C-targeting siRNA using a standard protocol. Validate knockdown efficiency via immunoblotting or immunofluorescence after 48-72 hours.

- Nuclear Mechanical Testing: Harvest transfected cells and resuspend in a suitable buffer. Load the cell suspension into a microfluidic squeezing device. Measure nuclear deformation under a defined applied strain and the subsequent relaxation kinetics. Lamin A/C deficiency is expected to result in greater deformation and altered relaxation profiles, indicating reduced nuclear stiffness [4].

- Chromatin Accessibility Analysis: Fix control and Lamin A/C-deficient cells. Co-stain for Lamin A/C and a heterochromatin mark such as H3K9me3. Image using confocal microscopy. Successful disruption of the nuclear scaffold should show disrupted nuclear morphology and a loss of peripheral heterochromatin, indicating increased chromatin accessibility [4].

- Reprogramming Kinetics Assay: Following Lamin A/C knockdown, initiate a standard cellular reprogramming protocol (e.g., to induced pluripotent stem cells). Compare the rate and efficiency of the emergence of pluripotency markers (e.g., Nanog, SSEA-1) between control and knockdown groups. Transient Lamin A/C loss is known to accelerate reprogramming kinetics [4].

Pathway Visualization and Workflows

The following diagrams, generated with Graphviz DOT language, illustrate the core mechanotransduction pathway and a key experimental workflow.

Diagram Title: Core Mechanotransduction Pathway from ECM to Nucleus

Diagram Title: Combined Scaffold and Epigenetic Drug Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Mechano-Epigenetic Studies

| Research Tool | Function/Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Tunable Hydrogels (e.g., Col-Tgel) [10] | Provides a 3D microenvironment with controllable stiffness to study effects of mechanical cues on cell fate. | Gelatin concentration directly correlates with final scaffold stiffness. Cross-linking density must be optimized for reproducibility. |

| DNA Methyltransferase Inhibitor (e.g., 5-Azacytidine) [10] | Epigenetic modulator that induces DNA demethylation, reactivating silenced genes and enhancing cellular plasticity. | Dose-response is critical. High doses induce apoptosis. Effective window for reprogramming in 3D is typically 1.25-12.5 ng/mL [10]. |

| Lamin A/C siRNA [4] | Knocks down a core nuclear scaffold protein to study its role in nuclear mechanics and as a barrier to reprogramming. | Transient knockdown is often sufficient to potentiate reprogramming kinetics. Efficiency must be confirmed via Western Blot or immunofluorescence. |

| Microfluidic Squeezing Device [4] | Quantifies nuclear deformability and mechanical properties as a functional readout of nuclear scaffold integrity. | Provides a high-throughput method to assess nuclear stiffness changes following genetic or chemical perturbation. |

| YAP/TAZ Inhibitors (e.g., Verteporfin) [9] | Inhibits key mechanotransduction effectors to dissect their role in translating matrix stiffness into transcriptional programs. | Useful for confirming the mechanosensitive pathway involvement in observed phenotypic changes. |

| CRISPR/dCas9 Epigenetic Editors [9] [11] | Enables precise, targeted manipulation of epigenetic marks (e.g., methylation, acetylation) at specific genomic loci. | Emerging tool to directly rewrite the epigenetic code in conjunction with mechanical cues, offering unparalleled precision. |

1. Introduction Within the framework of scaffold manipulation for epigenetic reprogramming, understanding the pathological mechanical environment is paramount. This document details the key mechanisms and provides standardized protocols for quantifying how altered biomechanics—particularly increased extracellular matrix (ECM) stiffness—create a self-reinforcing, disease-locked state. This process, central to organ fibrosis, disrupts native cellular functions and presents a major barrier to epigenetic resetting and functional tissue recovery [12].

2. Quantitative Data Summary The following tables summarize core quantitative relationships and experimental parameters in the study of pathological mechanotransduction.

Table 1: Key Mechanosensors and Their Roles in Fibrosis

| Mechanosensor | Primary Stimulus | Major Downstream Pathways | Profibrotic Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Integrins | Increased ECM Stiffness | FAK/Src, RhoA/ROCK | Myofibroblast activation, ECM production [12] |

| Piezo1 | Matrix roughness, Shear stress | Calcium influx, Calcineurin-NFAT | Fibroblast differentiation, ECM remodeling [12] |

| TRPV4 | Matrix roughness, Shear stress | Calcium influx, Pro-inflammatory signaling | Amplification of inflammatory and fibrotic responses [12] |

| YAP/TAZ | Cytoskeletal tension (from stiffness) | TEAD-mediated transcription | Upregulation of ACTA2 (α-SMA), COL1A1 [12] |

Table 2: Experimental Parameters for Modulating Scaffold Mechanics In Vitro

| Parameter | Physiological Range | Pathological Range | Common In Vitro Model Systems |

|---|---|---|---|

| Substrate Stiffness (Elastic Modulus) | ~0.1 - 5 kPa (tissue-dependent) [12] | >10 kPa, often 20-50 kPa [12] | Polyacrylamide (PAA) gels, Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) |

| Matrix Topography | Organized, porous fiber networks | Aligned, dense collagen bundles; increased roughness [12] | Electrospun fibers, micropatterned surfaces |

| Key Readout: YAP/TAZ Localization | Predominantly cytoplasmic | Predominantly nuclear [12] | Immunofluorescence, cell fractionation with Western Blot |

3. Experimental Protocols

Protocol 3.1: Assessing YAP/TAZ Nuclear Translocation in Response to Substrate Stiffness

3.1.1 Principle The YAP/TAZ pathway is a core mechanotransduction cascade. On soft, physiological substrates, YAP/TAZ are phosphorylated and sequestered in the cytoplasm. On pathologically stiff substrates, they translocate to the nucleus to drive pro-fibrotic gene expression, serving as a direct readout of mechanical activation [12].

3.1.2 Materials

- Cells: Primary human hepatic stellate cells (HSCs) or fibroblasts.

- Substrata: Polyacrylamide (PAA) hydrogels with tunable stiffness (e.g., 1 kPa for "soft" and 25 kPa for "stiff").

- Reagents: Cell culture media, PBS, 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA), 0.1% Triton X-100, blocking buffer (5% BSA in PBS), primary antibodies (anti-YAP/TAZ), fluorescently-labeled secondary antibodies, DAPI, mounting medium.

3.1.3 Procedure

- Cell Plating: Seed HSCs at a density of 10,000 cells/cm² onto the soft (1 kPa) and stiff (25 kPa) PAA gels in a 24-well plate.

- Incubation: Culture cells for 48 hours in standard growth conditions.

- Fixation: Aspirate media, wash with PBS, and fix cells with 4% PFA for 15 minutes at room temperature.

- Permeabilization: Wash with PBS, then permeabilize with 0.1% Triton X-100 for 10 minutes.

- Blocking: Incubate with 5% BSA blocking buffer for 1 hour.

- Primary Antibody Incubation: Incubate with anti-YAP/TAZ antibody (diluted in blocking buffer) overnight at 4°C.

- Secondary Antibody Incubation: Wash with PBS, then incubate with fluorescent secondary antibody and DAPI (for nuclei) for 1 hour at room temperature, protected from light.

- Imaging and Analysis: Image using a fluorescence microscope. Quantify the ratio of nuclear to cytoplasmic YAP/TAZ fluorescence intensity for at least 100 cells per condition using image analysis software (e.g., ImageJ).

Protocol 3.2: Quantifying Barrier Integrity in a Blood-Brain Barrier (BBB) Model Under Stiffness Stress

3.2.1 Principle The Blood-Brain Barrier is a critical functional barrier, the integrity of which is maintained by tight junction proteins. Pathological mechanical stress disrupts tight junctions, leading to barrier dysfunction, a hallmark of many neurological disorders [13]. This protocol uses Transendothelial Electrical Resistance (TEER) to quantify this integrity.

3.2.2 Materials

- Cells: Human Brain Microvascular Endothelial Cells (HBMECs).

- Substrata: Collagen-coated Transwell inserts with tunable membrane stiffness or placed on underlying PAA gels.

- Reagents: Endothelial cell media, PBS, EVOM volt/ohm meter with STX electrodes.

- Equipment: Transwell plates, cell culture incubator.

3.2.3 Procedure

- Model Setup: Plate HBMECs at confluent density on collagen-coated Transwell inserts that are placed atop soft (0.5 kPa) or stiff (50 kPa) PAA gels.

- TEER Measurement:

- Sterilize the STX electrodes with 70% ethanol and rinse with PBS.

- Measure the blank resistance (Rblank) of a cell-free insert with media.

- Measure the resistance of the insert with the cell monolayer (Rsample).

- Calculate TEER using the formula: TEER (Ω·cm²) = (Rsample - Rblank) × Membrane Area (cm²).

- Monitoring: Perform TEER measurements every 24 hours to monitor the development and stability of the barrier under different mechanical conditions. A lower TEER value on stiff substrates indicates impaired barrier integrity [13].

4. Signaling Pathway & Workflow Visualizations

Diagram 1: The Core Stiffness Reinforcement Loop (62 characters)

Diagram 2: Mechanobiology Assay Workflow (47 characters)

5. The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Mechanotransduction and Barrier Integrity Research

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Key Experimental Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Tunable Stiffness Hydrogels | Provides a biologically relevant, adjustable substrate to mimic physiological and pathological mechanical environments. | Polyacrylamide gels are inert and widely used. Functionalize with collagen I or fibronectin for cell adhesion [12]. |

| FAK (Focal Adhesion Kinase) Inhibitors | Small molecule (e.g., PF-562271) used to pharmacologically disrupt mechanosensing via the integrin-FAK pathway. | Validates the role of specific mechanosensors. Use dose-response curves to establish efficacy and minimize off-target effects [12]. |

| YAP/TAZ siRNA / shRNA | Gene silencing tools to knock down YAP/TAZ expression, confirming their necessity in the mechanical response. | A critical control to link nuclear YAP/TAZ to downstream transcriptional changes and phenotypic outcomes [12]. |

| Antibody: Anti-Claudin-5 | Tight junction marker for assessing Blood-Brain Barrier integrity via immunofluorescence or Western Blot. | Loss of CLN-5 signal correlates with increased barrier permeability and is a hallmark of BBB dysfunction [13]. |

| EVOM Voltmeter with STX Electrodes | Gold-standard equipment for non-invasively measuring Transendothelial Electrical Resistance (TEER) in real-time. | High, stable TEER values indicate a functional, intact barrier monolayer. A drop in TEER signifies disruption [13]. |

Epigenetic reprogramming involves the forced alteration of a cell's epigenetic landscape to change its identity or function, a process central to both induced pluripotency and cancer therapy. The nuclear scaffold, a network of proteins including lamins that provides structural integrity to the nucleus, acts as a critical guardian of cellular fate. It stabilizes the epigenetic state by tethering heterochromatin and repressing alternative gene expression programs. Recent research demonstrates that the manipulation of this nucleoscaffold, particularly through the depletion or mutation of Lamin A/C, disrupts nuclear morphology and mechanical properties, promoting the opening of silenced heterochromatin domains and accelerating cellular reprogramming kinetics [4]. Established epigenetic modulators, specifically DNA methyltransferase (DNMT) and histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors, function not only by modifying specific biochemical marks but also by inducing profound physical and architectural changes within the nucleus. These changes work in concert to overcome the epigenetic barriers maintained by the nuclear scaffold, facilitating the rewiring of gene expression networks for research and therapeutic applications [14] [15] [4].

Core Mechanisms of Action

DNMT Inhibitors: Releasing DNA Methylation-Mediated Repression

DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs) catalyze the addition of methyl groups to cytosine bases in DNA, leading to the formation of compact, transcriptionally repressive heterochromatin. In pathologies such as glioma and multiple myeloma, this often results in the hypermethylation and silencing of tumor suppressor and pro-apoptotic genes [16] [17]. DNMT inhibitors (DNMTis), such as the nucleoside analog 5-azacytidine, function by incorporating into DNA and trapping DNMT enzymes, leading to their proteasomal degradation. This results in global DNA demethylation and, crucially, the reactivation of genes that control apoptosis, differentiation, and DNA repair [16] [17]. A key functional outcome is the reversal of a malignant, stem-like state; in glioma, for instance, DNMT1 inhibition has been shown to revert aggressive cells to a less aggressive state through epigenetic reprogramming [16].

HDAC Inhibitors: Modulating Chromatin Accessibility and Nuclear Architecture

Histone deacetylases (HDACs) remove acetyl groups from lysine residues on histone tails, promoting a condensed chromatin state that is inaccessible to transcription factors. HDAC inhibitors (HDACis), such as MS-275 and sodium butyrate, block this activity, leading to histone hyperacetylation, a more open chromatin configuration, and activation of gene expression [14] [15]. Beyond modifying histones, HDACis induce significant physical alterations to the nucleus. Treatment with HDACis causes an increase in nuclear area and volume, correlating with increased expression of active histone marks and lamins, and a decrease in repressive marks [14] [15]. Furthermore, HDACis dysregulate nucleoporins, the components of nuclear pore complexes, thereby affecting nucleo-cytoplasmic transport and contributing to the observed nuclear expansion. This intricate mechanism links epigenetic regulation directly to the physical and mechanical properties of the nucleus [14] [15].

Interplay with the Nucleoscaffold and Epigenetic Crosstalk

The efficacy of DNMTis and HDACis is deeply connected to their interaction with the nucleoscaffold. The nuclear scaffold, with Lamin A/C as a core component, maintains heterochromatin at the nuclear periphery, stabilizing the differentiated cell state. Inhibition of DNMTs and HDACs disrupts this stabilization. For example, HDACi-induced hyperacetylation of lamins can alter their function and the mechanical properties of the nucleus [4]. Moreover, a strong mechanistic interplay exists between DNMTs and other epigenetic complexes, such as the Polycomb Repressive Complex 2 (PRC2). In multiple myeloma, a physical interaction between DNMT1 and EZH2 (the catalytic subunit of PRC2) has been observed, indicating coordinated gene silencing through concurrent DNA methylation and H3K27me3 histone methylation [17]. This crosstalk explains the enhanced efficacy of combinatorial epigenetic targeting, as disrupting one repressive mechanism can sensitize the epigenome to the effects of another.

Table 1: Functional Outcomes of Epigenetic Modulation in Different Cellular Contexts

| Cell/Tumor Type | Epigenetic Modulator | Key Molecular Effect | Phenotypic/Functional Outcome | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Multiple Myeloma | 5-azacytidine (DNMTi) | DNA demethylation; Reactivation of PRF1, CASP6, ANXA1 | Induction of apoptosis; Reduced cell viability | [17] |

| Cervical Cancer (HeLa) | MS-275, Sodium Butyrate (HDACi) | Increased H3/H4 acetylation; Altered nucleoporin expression | Increased nuclear area/volume; Disrupted nucleocytoplasmic transport | [14] [15] |

| Human Fibroblasts | Lamin A/C knockdown (Scaffold manipulation) | Loss of heterochromatin at lamina-associated domains | Accelerated reprogramming to pluripotency | [4] |

| Glioma | DNMT1 inhibition | Promoter demethylation; Altered histone modifications | Reversion to less aggressive state; Enhanced therapy response | [16] |

| Multiple Myeloma | UNC1999 (EZH2i) + 5-azacytidine (DNMTi) | Loss of H3K27me3 & DNAme | Synergistic suppression of proliferation; G2/M arrest | [17] |

Application Notes and Quantitative Data

The application of DNMT and HDAC inhibitors requires careful consideration of dosage and treatment schedule, as these parameters dictate whether the outcome is cytotoxic or reprogramming.

DNMT Inhibitor Application: The Low-Dose Prolonged Schedule

In multiple myeloma research, a prolonged low-dose regimen of 5-azacytidine (e.g., 12.5 - 50 nM over 12 days) effectively reduces DNMT1 and DNMT3A protein levels and induces DNA demethylation at hypermethylated loci without causing significant cell death. This schedule is optimal for epigenetic reprogramming studies, as it primes the cells for differentiation or combination therapies. Higher doses (100-200 nM) are associated with cytotoxicity and apoptosis, which may be desirable in therapeutic contexts but not in reprogramming experiments [17].

HDAC Inhibitor Application: Dosing for Nuclear Reprogramming

Treatment of HeLa cells with 1-2 mM Sodium Butyrate (NaB) or 2-4 µM MS-275 for 24-48 hours has been shown to effectively induce histone hyperacetylation and the characteristic increase in nuclear area, key indicators of successful chromatin decompaction. These changes are reversible upon withdrawal, allowing for dynamic studies of epigenetic memory [14] [15].

Table 2: Quantitative Effects of Combinatorial Epigenetic Inhibition in Multiple Myeloma Data derived from [17]

| Treatment Condition | Global DNA Methylation | H3K27me3 Level | Gene Reactivation (e.g., CASP6) | Cell Viability | Apoptotic Rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Baseline (High at specific loci) | Baseline | Baseline | 100% | Low (Baseline) |

| 5-azacytidine (50 nM) | ↓↓ | ↑↑ | ~80% | Slight Increase | |

| UNC1999 (EZH2i) | ↓↓ | ↑ | ~75% | Slight Increase | |

| 5-azacytidine + UNC1999 | ↓↓↓ | ↓↓↓ | ↑↑↑ | <50% | Significant Increase |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Combinatorial DNMT and EZH2 Inhibition for Epigenetic Reprogramming

This protocol is adapted from studies in multiple myeloma and demonstrates how to synergistically dismantle co-repressive epigenetic complexes to activate silenced gene programs [17].

Objective: To induce epigenetic reprogramming in cancer cells by concurrently inhibiting DNA methylation and H3K27 methylation, leading to suppressed proliferation and activation of apoptosis and cell cycle genes.

Materials:

- Cell Line: INA-6 multiple myeloma cell line (or other relevant model).

- Reagents:

- 5-azacytidine (DNMTi), stock solution in DMSO or PBS.

- UNC1999 (EZH2i), stock solution in DMSO.

- Appropriate cell culture medium and supplements.

- DMSO vehicle control.

- Apoptosis detection kit (e.g., Annexin V/PI).

- RNA/DNA extraction kits.

- Reagents for qRT-PCR, Western blot.

Procedure:

- Cell Seeding: Seed cells at an optimal density (e.g., 2 x 10^5 cells/mL) in complete medium.

- Drug Treatment:

- Experimental Groups: Control (vehicle), 5-azacytidine (50 nM), UNC1999 (1 µM), and Combination (50 nM 5-azacytidine + 1 µM UNC1999).

- Treatment Duration: Treat cells for 6-12 days, with fresh drug and medium replenished every 2-3 days.

- Monitoring and Harvesting:

- Monitor cell viability daily using a trypan blue exclusion assay or an automated cell counter.

- Harvest cells at designated time points for downstream analysis.

- Downstream Analysis:

- Apoptosis Assay: At day 12, quantify apoptotic cells using an Annexin V/PI staining kit followed by flow cytometry.

- Gene Expression Analysis: Extract total RNA after 6 days of treatment. Perform qRT-PCR for pro-apoptotic genes (e.g., PRF1, CASP6, ANXA1) and cell cycle regulators.

- DNA Methylation Analysis: Perform Infinium MethylationEPIC BeadChip array or bisulfite sequencing on genomic DNA to assess demethylation at promoter regions.

- Protein Analysis: Perform Western blotting to confirm reduction of DNMT1, EZH2, and H3K27me3 levels.

Protocol: Assessing HDAC Inhibitor-Induced Nuclear Architectural Changes

This protocol details how to quantify the physical changes in nuclear morphology and component expression following HDAC inhibition, linking epigenetic modulation to nuclear scaffold alterations [14] [15].

Objective: To treat cervical cancer cells with HDAC inhibitors and measure the resulting changes in nuclear area, volume, and the expression of nuclear envelope proteins.

Materials:

- Cell Line: HeLa (cervical carcinoma) cells.

- Reagents:

- HDAC inhibitors: Sodium Butyrate (NaB, 1-2 mM) and MS-275 (2-4 µM).

- Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS).

- Fixative: 4% Paraformaldehyde (PFA).

- Permeabilization buffer: 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS.

- Blocking buffer: 1-5% BSA in PBS.

- Primary antibodies: Anti-Lamin A/C, Anti-NUP58.

- Fluorescently-labeled secondary antibodies.

- DAPI stain.

- Mounting medium.

- Equipment: Confocal or high-content fluorescence microscope, Image analysis software (e.g., ImageJ, Fiji).

Procedure:

- Cell Culture and Treatment:

- Seed HeLa cells on glass coverslips in a 12-well plate.

- Allow cells to adhere for 24 hours.

- Treat cells with NaB (1-2 mM) or MS-275 (2-4 µM) for 24-48 hours. Include a DMSO vehicle control.

- Cell Fixation and Staining:

- Aspirate medium and wash cells gently with PBS.

- Fix cells with 4% PFA for 15 minutes at room temperature.

- Permeabilize with 0.1% Triton X-100 for 10 minutes.

- Block with 1-5% BSA for 1 hour.

- Incubate with primary antibodies (e.g., Lamin A/C, NUP58) diluted in blocking buffer overnight at 4°C.

- Wash with PBS and incubate with fluorescent secondary antibodies and DAPI for 1 hour at room temperature in the dark.

- Wash and mount coverslips onto glass slides.

- Image Acquisition and Analysis:

- Acquire high-resolution z-stack images using a confocal microscope.

- Use image analysis software to measure the nuclear cross-sectional area and volume from DAPI-stained images (minimum n=100 cells per condition).

- Quantify fluorescence intensity of nuclear envelope markers (Lamins, NUP58) to assess expression changes.

Signaling Pathways and Workflows

The following diagrams illustrate the core mechanistic pathway of combined epigenetic inhibition and the experimental workflow for analyzing nuclear architecture changes.

Diagram Title: Pathway of Combinatorial Epigenetic Inhibition

Diagram Title: Workflow for Nuclear Architecture Analysis

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Epigenetic Reprogramming Research

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Target | Example Product/Catalog Number | Key Application in Reprogramming |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5-Azacytidine | DNMT Inhibitor | Sigma A2385 | Induces DNA demethylation and reactivates silenced genes at low doses (12.5-50 nM). |

| Decitabine | DNMT Inhibitor | Sigma A3656 | Potent DNMTi used in hematopoietic malignancy models. |

| MS-275 (Entinostat) | Class I HDAC Inhibitor | Selleckchem S1053 | Promotes histone hyperacetylation, chromatin opening, and nuclear expansion (2-4 µM). |

| Sodium Butyrate (NaB) | Pan-HDAC Inhibitor | Sigma B5887 | Induces global H3/H4 acetylation and increases nuclear area (1-2 mM). |

| UNC1999 | EZH2 Inhibitor | Cayman Chemical 16972 | Orally bioavailable inhibitor of H3K27me3 deposition; used in combination therapy. |

| Anti-Lamin A/C Antibody | Nuclear Scaffold Marker | Abcam ab108595 | Labels the nuclear lamina for quantifying structural changes post-treatment. |

| Anti-NUP58 Antibody | Nucleoporin Marker | Santa Cruz Biotechnology sc-271786 | Assesses changes in nuclear pore complex composition upon HDAC inhibition. |

| Anti-H3K27me3 Antibody | Repressive Histone Mark | Cell Signaling Technology 9733 | ChIP-seq or IF to monitor loss of PRC2-mediated silencing. |

| Annexin V Apoptosis Kit | Apoptosis Detection | Thermo Fisher Scientific V13242 | Quantifies apoptotic cells following epigenetic therapy-induced stress. |

The field of regenerative medicine is progressively redefining the role of biomaterial scaffolds, transitioning from passive structural "pathways" to active, multifunctional "platforms" capable of orchestrating complex biological processes [18]. This paradigm shift is particularly evident in epigenetic reprogramming research, where scaffolds function as synthetic niches that integrate biophysical and biochemical signals to direct cellular fate. The core premise is that cell fate is maintained through tight epigenetic regulation, including spatial organization of chromatin through physical interactions with nuclear structures such as the lamina [19]. Emerging evidence demonstrates that disrupting these physical associations, whether through biochemical modulation or by providing extrinsic physical cues via engineered scaffolds, can potentiate reprogramming by opening previously silenced heterochromatin domains [19] [10]. This application note details protocols and experimental approaches for leveraging scaffold-based systems to investigate and direct epigenetic reprogramming, providing a practical resource for researchers and drug development professionals working at the intersection of biomaterials engineering and epigenetics.

Foundational Concepts and Mechanisms

The Nuclear Scaffold as a Guardian of Cellular Fate

The nucleus itself possesses an intrinsic "scaffold" – the nuclear lamina – that plays a fundamental role in safeguarding cellular identity. The lamina, a meshwork of A-type and B-type lamin proteins at the nuclear periphery, organizes chromatin by tethering transcriptionally inactive heterochromatin in Lamina-Associated Domains (LADs) [19]. These domains cover over one-third of the genome and are characterized by repressed gene expression. During natural differentiation processes or induced reprogramming, repressed genes detach from lamins and relocate to the nuclear interior, facilitating their activation [19]. Consequently, manipulation of the nucleoscaffold presents a powerful strategy for modulating cellular plasticity.

Key Findings:

- Transient Knockdown of Lamin A/C: Disrupts nuclear morphology, increases heterochromatin marker H3K9me3, and enhances chromatin accessibility in LADs, creating a permissive environment for reprogramming transcription factors [19].

- HGPS Mutation (Progerin): Causes permanent dysfunction of Lamin A/C, leading to aberrant nuclear morphology and reduced heterochromatin, but induces senescence that inhibits reprogramming [19].

- Mechanical Coupling: The nucleus's ability to resist mechanical deformation is regulated by separate contributions from lamins and heterochromatin, positioning lamins at the nexus of chromatin organization, nuclear mechanics, and fate specification [19].

Epigenetic Priming for Cellular Reprogramming

Epigenetic reprogramming to induced pluripotency proceeds in a stepwise manner where chromatin and its regulators are critical controllers [20]. DNA methylation, a major "silencing" epigenetic mark, can be pharmacologically inhibited to reactivate silenced pluripotency genes. Prototype inhibitors like 5-azacytidine (5-Aza-CR) powerfully suppress DNA methylation and induce gene expression and differentiation in cultured cells [10]. However, the efficiency of this process is profoundly influenced by the three-dimensional microenvironment, which provides cues beyond the capability of conventional 2-D culture systems [10].

Application Notes & Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: 3D Epigenetic Reprogramming in Tunable Gelatin Hydrogels

This protocol details a methodology for investigating the combined effects of matrix rigidity and epigenetic modulators on reprogramming adipose-derived stromal cells (ADSCs) into myoblast-like cells, adapting approaches from published research [10].

Materials and Reagent Setup

- Tunable Transglutaminase Cross-linked Gelatin (Col-Tgel):

- Function: Mimics the physiological microenvironment, provides spatially and temporally defined template for tissue formation, and serves as a delivery carrier for cells and chemical stimuli [10].

- Preparation: Prepare gelatin solutions at varying concentrations (e.g., 5%, 10%, 15% w/v) in PBS to achieve target rigidities. Cross-link with microbial transglutaminase (e.g., 10 U/g gelatin) for 2 hours at 37°C. Verify stiffness via rheometry or atomic force microscopy.

- Epigenetic Modulator: 5-Azacytidine (5-Aza-CR):

- Function: DNA methyltransferase inhibitor that induces DNA demethylation, reactivates epigenetically silenced genes (including pluripotency genes), and enhances cellular plasticity [10].

- Stock Solution: Prepare 1 mg/mL stock in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). Aliquot and store at -20°C. Avoid freeze-thaw cycles.

- Adipose-Derived Stromal Cells (ADSCs):

- Isolation: Isolate from subcutaneous adipose tissue of rats or humans via enzymatic digestion (e.g., collagenase type I, 1 mg/mL in PBS with 1% BSA) for 30-60 minutes at 37°C with agitation. Filter through 100-70 μm strainers and culture in growth medium (α-MEM with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin) [10].

- Staining and Analysis Reagents:

- Viability/Apoptosis: Caspase 3/7 staining solution for apoptosis detection [10].

- Lineage Markers: Oil Red O solution for adipocyte staining; β-galactosidase (β-Gal) staining solution for senescence; antibodies for immunostaining (Oct4, MyoD, Myogenin).

- Cytoskeleton: Phalloidin conjugates for F-actin staining.

Step-by-Step Procedure

Pre-culture and Pre-treatment:

- Culture isolated ADSCs in growth medium until 70-80% confluence (Passage 3-5).

- Optional: Pre-treat ADSCs in 2D culture with 5-Aza-CR at determined optimal doses (e.g., 1.25 - 12.5 ng/mL) for 24-48 hours prior to encapsulation to prime the cells.

3D Encapsulation:

- Trypsinize ADSCs and resuspend in the prepared Col-Tgel solution prior to cross-linking to achieve a final density of 5-10 × 10^6 cells/mL.

- Pipet the cell-gel mixture into appropriate molds (e.g., 48-well plate, 100 μL/well) and incubate at 37°C for 30 minutes to complete gelation.

- Carefully overlay gels with growth medium.

In-Gel Epigenetic Modulation:

- After 24 hours of encapsulation, refresh culture medium containing the predetermined effective dose of 5-Aza-CR (e.g., 1.25 - 12.5 ng/mL). Use medium with equivalent DMSO concentration (e.g., <0.1%) for vehicle controls.

- Treat constructs for 72 hours, then replace with standard growth medium. Refresh medium every 2-3 days.

Assessment of Phenotypic Changes:

- Loss of Original Phenotype (Day 7):

- Fix constructs in 4% PFA for 1 hour and process for frozen sectioning (10-20 μm thickness).

- Perform Oil Red O staining to quantify lipid droplet content (loss of adipogenic phenotype).

- Perform β-Gal staining to assess senescence reduction.

- Activation of Pluripotency and Myogenic Genes (Day 7-14):

- Extract total RNA from digested gels (collagenase, 1 mg/mL, 37°C, 30 min) and analyze by RT-PCR/qPCR for Oct4, Abcg2, Hif1a, MyoD, and Myogenin.

- Perform immunostaining on sections for Oct4 and myogenic transcription factors.

- Morphological Analysis:

- Stain F-actin with phalloidin to visualize cytoskeletal organization and cell morphology (e.g., transition to larger, spherical, multinucleated cells).

- Loss of Original Phenotype (Day 7):

In Vivo Implantation (Optional):

- Implant cell-laden gels subcutaneously or into muscle injury models in immunodeficient mice.

- Explant constructs after 4-8 weeks for histological analysis of myoblast-like cell formation and integration.

Protocol 2: Modifying the Nuclear Scaffold to Enhance Reprogramming

This protocol outlines methods for transiently knocking down Lamin A/C in human fibroblasts to disrupt the nuclear scaffold and assess its impact on reprogramming kinetics, based on mechanistic studies [19].

Materials and Reagent Setup

- DsiRNAs Targeting LMNA:

- Function: Dicer-substrate small interfering RNAs for highly efficient and transient knockdown of Lamin A/C mRNA, disrupting LADs and increasing chromatin accessibility [19].

- Preparation: Resuspend lyophilized DsiRNAs in nuclease-free buffer to 100 µM stock concentration.

- Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs):

- Function: Delivery vehicle for efficient intracellular transfer of DsiRNAs.

- Preparation: Formulate DsiRNAs into LNPs per manufacturer's or established protocols.

- Human Dermal Fibroblasts:

- Culture in DMEM with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin.

- Assay Kits and Reagents:

- Omni-ATAC-Seq Kit: For assessing chromatin accessibility in LADs [19].

- Antibodies: For Lamin A/C, H3K9me3, HP1a, and reprogramming factors (OCT4, KLF4, SOX2, c-MYC).

Step-by-Step Procedure

Transient LMNA Knockdown:

- Seed fibroblasts at 50-60% confluence in 6-well plates 24 hours before transfection.

- Transfert cells with LNP-formulated LMNA DsiRNAs (e.g., 50-100 nM final concentration) using standard transfection protocols. Include non-targeting DsiRNA as a negative control.

- Incubate for 48-72 hours before analysis or subsequent reprogramming experiments.

Validation of Knockdown and Nuclear Phenotype:

- Efficiency Check: Harvest cells for Western blot analysis to confirm Lamin A/C protein reduction and qRT-PCR to assess mRNA knockdown (>75% reduction target).

- Nuclear Morphology: Fix cells and immunostain for Lamin A/C and heterochromatin markers (H3K9me3, HP1a). Image using confocal microscopy and quantify nuclear circularity, presence of protrusions/cavities, and rupture incidence.

Chromatin Accessibility Assessment (Omni-ATAC-Seq):

- Harvest transfected cells and isolate nuclei.

- Perform Omni-ATAC-Seq according to established protocols [19] to map genome-wide changes in open chromatin regions, with particular focus on LADs.

- Analyze sequencing data for increased accessibility around pro-reprogramming factors and transposable elements. Integrate datasets with constitutive LAD (cLAD) maps.

Reprogramming Kinetics Assay:

- Initiate standard iPSC reprogramming protocol (e.g., using OKSM factors) in control and LMNA KD fibroblasts 72 hours post-transfection.

- Monitor reprogramming efficiency by tracking emergence of pluripotency marker-positive colonies (e.g., TRA-1-60, SSEA4) over 2-3 weeks.

- Compare kinetics and final reprogramming efficiency between LMNA KD and control groups.

Data Presentation and Analysis

Table 1: Combined Effects of Matrix Rigidity and 5-Aza-CR on ADSC Reprogramming Markers [10]

| Parameter | Soft Gel (0.9 kPa) | Medium Gel (15 kPa) | Stiff Gel (40 kPa) | Significance (p<) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oct4 Expression (Fold Change vs. Soft, Untreated) | 1.0 ± 0.2 | 1.8 ± 0.3 | 1.7 ± 0.3 | 0.001 |

| Abcg2 Expression (Fold Change vs. Soft, Untreated) | 1.0 ± 0.3 | 1.7 ± 0.4 | 1.7 ± 0.3 | 0.001 |

| Reduction in Oil Red O Staining (% vs. Untreated Control) | ~40% | ~75% | ~70% | 0.001 |

| Reduction in β-Gal+ Cells (% vs. Untreated Control) | ~25% | ~50% | ~45% | 0.05 |

| Optimal 5-Aza-CR Dose Range | 1.25 - 12.5 ng | 1.25 - 12.5 ng | 1.25 - 12.5 ng | N/A |

Table 2: Impact of Lamin A/C Manipulation on Nuclear Properties and Reprogramming [19]

| Parameter | Control Fibroblasts | LMNA KD Fibroblasts | HGPS (Progerin) Fibroblasts |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nuclear Morphology | Normal, smooth contour | Protrusions/Cavities, Membrane Ruptures | Aberrant, misshapen |

| H3K9me3 Level | Baseline | Increased | Decreased |

| Chromatin Accessibility in LADs | Baseline | Increased | Increased |

| Enriched Transcription Factor Motifs | AP-1, TEAD4 (Guardians) | SNAI1/2/3, HES1, YY2 (Pro-Reprogramming) | N/D |

| Reprogramming Kinetics | Baseline | Accelerated | Inhibited (Senescence) |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagent Solutions for Scaffold-Based Epigenetic Reprogramming Research

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application in Research | Example Context |

|---|---|---|

| Tunable Col-Tgel Hydrogels | Provides a 3D microenvironment with controllable stiffness to study the interaction of mechanical cues with epigenetic drugs. | Optimizing myogenic trans-differentiation of ADSCs [10]. |

| 5-Azacytidine (5-Aza-CR) | DNA methyltransferase inhibitor; used for epigenetic priming to erase methylation marks and enhance cellular plasticity. | Reactivating silenced pluripotency and myogenic genes in 3D culture [10]. |

| LMNA-Targeting DsiRNAs | Enables transient knockdown of Lamin A/C to disrupt the nuclear scaffold and increase chromatin accessibility for reprogramming factors. | Potentiating fibroblast reprogramming to pluripotency [19]. |

| Omni-ATAC-Seq Reagents | For mapping genome-wide chromatin accessibility changes following physical or chemical perturbation of the (nucleo)scaffold. | Identifying opened chromatin regions and TF binding in LADs after LMNA KD [19]. |

Integrated Workflow and Pathway Diagrams

Designing the Epigenetic Toolkit: Biomaterials, Delivery Systems, and Engineering Strategies

The emergence of advanced biomaterial platforms has fundamentally expanded the toolkit for biological research and therapeutic development. Hydrogels, tunable gelatin (Col-Tgel), and 3D matrices have transitioned from passive cell culture substrates to active, directive components that can mimic the complex biophysical and biochemical cues of the native extracellular matrix (ECM). These platforms are particularly transformative for epigenetic reprogramming research, as they provide the necessary three-dimensional context to study how mechanical and structural signals influence nuclear architecture and gene expression. Scaffold manipulation enables precise control over microenvironmental parameters—such as stiffness, topography, and ligand presentation—that directly impact cell fate through mechanotransduction pathways. This application note details the practical use of these biomaterial platforms, providing standardized protocols, quantitative data, and visualization tools to facilitate their adoption in research aimed at directing cellular function for regenerative medicine and drug development.

The selection of an appropriate biomaterial platform is critical for experimental success. The table below summarizes the key properties and applications of hydrogel, Col-Tgel, and advanced 3D matrix systems.

Table 1: Characteristics of Biomaterial Platforms for Epigenetic Research

| Platform | Key Composition | Tunable Stiffness Range | Key Applications in Reprogramming | Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrogels | Gelatin-MA (GelMA), Hyaluronic Acid, PEG-based polymers | 0.5 - 20+ kPa [9] [21] | 3D stem cell culture, controlled release of epigenetic modifiers (e.g., DNMTi, HDACi) [9] [22] | High water content, excellent nutrient diffusion, biocompatible, injectable formulations. |

| Tunable Gelatin (Col-Tgel) | Microbial Transglutaminase (mTG) cross-linked gelatin [10] [21] | 0.9 kPa (Soft) to 40 kPa (Stiff) [10] [21] | Epigenetic drug screening (e.g., 5-Azacytidine), myogenic and osteogenic trans-differentiation [10] | Natural RGD motifs for cell adhesion, enzyme-mediated tunability, cost-effective. |

| 3D Matrices | Collagen, Fibrin, Electrospun Nanofibers, 3D-Printed Scaffolds | 1 - 5 kPa (physiological) to >20 kPa (fibrotic) [9] [23] | Investigating cell migration (haptotaxis, durotaxis), and spatial epigenetic patterning [23] [24] | Recapitulates native ECM architecture, provides contact guidance, enables complex spatial patterning. |

The mechanical properties of these platforms are paramount. Physiological tissue stiffness typically falls between 1-5 kPa, while fibrotic tissues can exceed 20 kPa [9]. Gelatin-mTG (Col-Tgel) systems offer a particularly wide tunable range, from 0.9 ± 0.1 kPa (Soft) to 40 ± 10 kPa (Stiff), covering both healthy and diseased tissue mechanics [10] [21]. Furthermore, the stability of these scaffolds in culture is a key practical consideration. Studies show that hydrogels incubated in different media (e.g., PBS vs. M199) can exhibit varying stiffness profiles over a 72-hour period, which must be accounted for in experimental design [21].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Fabrication and Stiffness Tuning of Col-Tgel Hydrogels

This protocol describes the fabrication of mechanically tunable gelatin hydrogels cross-linked with microbial transglutaminase (mTG), suitable for studying stiffness-dependent epigenetic remodeling.

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Gelatin Solution: 300 bloom Type A gelatin dissolved in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) at 55°C to final concentrations of 4%, 8%, 10%, or 20% (w/v).

- Cross-linker Solution: Microbial transglutaminase (mTG, e.g., Moo Gloo) dissolved in PBS at room temperature to create 1.6% or 2% (w/v) solutions. Filter sterilize using a 0.22 µm filter.

- Incubation Media: PBS or serum-free culture medium (e.g., Medium 199) for pre-incubation stability testing.

Methodology:

- Direct Mixing: Combine equal volumes of pre-warmed gelatin solution and filtered mTG solution. For example, mix 1 mL of 8% gelatin with 1 mL of 2% mTG to yield a final gel with 4% gelatin and 1% mTG [21].

- Casting: Immediately pipette the gelatin-mTG mixture into sterile silicone molds or onto prepared glass substrates (e.g., APTES-silanized coverslips).

- Gelation: Allow the cast solution to set at room temperature for 2 hours to form stable hydrogel cubes or thin films [21].

- Post-processing: For thin films, a PDMS stamp may be used to create a flat surface. Sterilize via UV-ozone (UVO) exposure for 3 minutes, noting that UVO may cause a slight decrease in hydrogel modulus [21].

- Equilibration: Prior to cell seeding, incubate the hydrogels in the chosen culture medium (e.g., M199) at 37°C for 24-48 hours to allow for mechanical stabilization, as the modulus can change upon hydration [21].

Protocol: Epigenetic Reprogramming of ADSCs on Col-Tgel

This protocol outlines the combined use of Col-Tgel stiffness and the epigenetic modulator 5-Azacytidine (5-Aza-CR) to direct adipose-derived stromal cell (ADSC) trans-differentiation.

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Cell Source: Adipose-derived stromal cells (ADSCs).

- Col-Tgel Platforms: Soft (0.9 kPa), Med (15 kPa), and Stiff (40 kPa) Col-Tgels prepared as in Protocol 3.1 [10].

- Epigenetic Modulator: 5-Azacytidine (5-Aza-CR) at an intermediate working dose of 1.25 - 12.5 ng. Note: Low (<0.125 ng) and high (>67.5 ng) doses are ineffective or induce apoptosis, respectively [10].

Methodology:

- 3D Cell Encapsulation: Suspend ADSCs in the liquid gelatin-mTG solution prior to casting and gelation, thereby encapsulating them within the 3D matrix.

- Epigenetic Treatment: After gelation, culture the cell-laden hydrogels in medium containing the optimal dose of 5-Aza-CR (1.25-12.5 ng).

- Culture and Analysis: Maintain cultures for up to 14 days, refreshing the medium and 5-Aza-CR as needed.

- Outcome Assessment:

- Immunostaining: Assess loss of original ADSC markers (e.g., lipid droplets via Oil Red O) and gain of pluripotency (Oct4) or myogenic markers.

- qRT-PCR: Quantify the upregulation of genes such as Oct4, Abcg2, and Hif1a.

- Morphology: Use phalloidin staining to visualize actin cytoskeleton reorganization. Treated ADSCs typically become larger and more spherical, with multinucleated clusters on stiffer matrices [10].

Signaling Pathways in Mechano-Epigenetic Coupling

Biomaterial scaffolds function by influencing intracellular signaling cascades that bridge the extracellular mechanical environment to nuclear epigenetic changes. The following diagram illustrates the core mechanotransduction pathway and its link to epigenetic regulation.

Mechano-Epigenetic Coupling Pathway

The pathway initiates when ECM Stiffness is sensed by cells through integrin-mediated Focal Adhesion Activation [9]. This triggers actomyosin-dependent Cytoskeletal Tension, which is a primary regulator of the YAP/TAZ co-transcriptional activators [9] [25]. Upon activation, YAP/TAZ translocate to the nucleus (Nuclear Shuttling), where they interact with and influence the activity of Epigenetic Regulators such as DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs) and histone deacetylases (HDACs) [9]. This mechanical signaling ultimately leads to alterations in the Chromatin State & Gene Expression, for instance, by promoting the hypermethylation and silencing of anti-fibrotic genes in stiff, fibrotic environments [9]. This pathway establishes a self-reinforcing "mechanical memory" that can be disrupted by scaffold-based interventions.

Integrated Experimental Workflow

A typical experiment integrating these platforms follows a logical sequence from scaffold preparation to mechanistic analysis. The workflow below outlines the key steps for conducting a mechano-epigenetic reprogramming study.

Mechano-Epigenetic Experiment Workflow

The workflow begins with Scaffold Fabrication (Step 1), selecting the appropriate material and stiffness based on the biological question. This is followed by rigorous Characterization (Step 2) of the scaffold's mechanical properties (e.g., using nanoindentation) and architecture [21]. Cells are then introduced via Seeding/Encapsulation (Step 3) into the 3D environment [10] [23]. The core Experimental Intervention (Step 4) involves applying biochemical cues like 5-Azacytidine or imposing dynamic mechanical strain [9] [10]. Subsequently, Phenotypic Analysis (Step 5) quantifies changes in cell morphology, differentiation markers, and gene expression. Finally, Mechanistic Analysis (Step 6) probes deeper into the activation of mechanotransduction pathways (e.g., YAP/TAZ localization) and specific epigenetic modifications (e.g., histone acetylation, DNA methylation) at target genes [9] [10] [25].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Scaffold-Based Reprogramming

| Item | Function/Description | Example Usage & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Microbial Transglutaminase (mTG) | Natural enzyme for crosslinking gelatin; enhances thermal stability and controls mechanical properties [10] [21]. | Used at 0.8-1% (w/v) final concentration to create Col-Tgel with stiffness from 0.9 to 40 kPa. FDA-approved. |

| 5-Azacytidine (5-Aza-CR) | DNA methyltransferase inhibitor (DNMTi); promotes DNA demethylation and reactivation of silenced genes [10]. | Use intermediate doses (1.25-12.5 ng) for reprogramming. High doses (>67.5 ng) are cytotoxic. |

| Gelatin Methacryloyl (GelMA) | Photo-crosslinkable gelatin derivative; allows for high-precision 3D patterning (e.g., via bioprinting) [26]. | Ideal for creating complex 3D architectures with defined mechanical properties for dental pulp and bone regeneration. |

| Triton X-100 / Tween-20 | Detergents for cell lysis and immunofluorescence washing buffers. | Standard concentrations (0.1-0.5%) are compatible with hydrogel scaffolds for permeabilization and staining. |

| Rhodamine Phalloidin | High-affinity F-actin stain for visualizing cytoskeletal organization and cell morphology. | Critical for assessing cytoskeletal remodeling in response to substrate stiffness. |

| DAPI | Fluorescent nuclear counterstain. | Used in immunofluorescence to visualize cell nuclei within 3D hydrogel matrices. |

| Anti-YAP/TAZ Antibody | For immunofluorescence detection and localization of key mechanotransduction effectors. | Nuclear vs. cytoplasmic localization indicates pathway activation status. |

| HDAC & DNMT Inhibitors | Pharmacological agents (e.g., HDACi, DNMTi) to target epigenetic machinery. | Can be encapsulated in hydrogels for controlled local release to disrupt pathological epigenetic states [9]. |

In the field of scaffold-based epigenetic reprogramming, the physical and chemical properties of biomaterials are not merely passive structural elements but active participants in directing cell fate. The engineering parameters of a scaffold—specifically its stiffness, elastic modulus, and degradation kinetics—profoundly influence cellular behavior by modulating mechanotransduction pathways and epigenetic states. These material properties function as potent environmental cues that can be designed to reverse pathological epigenetic marks, promote tissue regeneration, and enhance the efficacy of cellular reprogramming. This document provides detailed application notes and experimental protocols for the quantification, analysis, and utilization of these key parameters within research focused on scaffold manipulation for epigenetic reprogramming.

Defining and Quantifying Core Engineering Parameters

Stiffness and Elastic Modulus

In biomaterials science, the terms "stiffness" and "elastic modulus" are often used interchangeably, yet they refer to distinct mechanical properties. The elastic modulus (Young's modulus) is an intrinsic material property that quantifies a material's resistance to elastic deformation under stress. In contrast, stiffness is an extrinsic property that depends on both the material's elastic modulus and the geometric structure of the construct.

For hydrogel-based scaffolds, such as those made from poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) or transglutaminase-cross-linked gelatin (Col-Tgel), the elastic modulus is typically controlled by varying the cross-linking density, polymer concentration, or reaction conditions. These materials are particularly valuable for epigenetic studies as their mechanical properties can be tuned to mimic specific tissue microenvironments, from soft brain tissue (0.1-1 kPa) to stiff, pre-calcified bone (25-40 kPa) [10] [27].

Table 1: Target Elastic Moduli for Tissue-Specific Microenvironments in Reprogramming Research

| Tissue Type | Target Elastic Modulus | Primary Epigenetic/Reprogramming Application |

|---|---|---|

| Neural Tissue | 0.1 - 1 kPa | Neuronal differentiation of hMSCs; chromatin decondensation [27] |

| Adipose Tissue | 2 - 5 kPa | Maintenance of stem cell pluripotency; regulation of OCT4 expression [10] |

| Skeletal Muscle | 8 - 17 kPa | Myogenic differentiation of hMSCs and ADSCs [10] [27] |

| Fibrotic Niche | > 20 kPa | Modeling pathological stiffness; studying mechano-epigenetic barriers in pulmonary fibrosis [9] |

| Bone Tissue | 25 - 40 kPa | Osteogenic differentiation of hMSCs [27] |

Degradation Kinetics

Scaffold degradation kinetics refer to the rate and mechanism by which a biomaterial breaks down in a biological environment. Controlled degradation is critical for matching the rate of new tissue formation and for the timely release of encapsulated epigenetic modulators. The primary mechanisms include:

- Hydrolytic Degradation: Breakdown of ester bonds in polymers like PLGA through reaction with water, often following first-order kinetics [28] [29].

- Enzymatic Degradation: Cell-mediated degradation, where cell-secreted enzymes (e.g., Matrix Metalloproteinases - MMPs) cleave specific sequences in the scaffold. This often follows Michaelis-Menten kinetics and dominates in cell-laden hydrogels [28].

- Autocatalytic Degradation: A phenomenon observed in larger PLGA samples where acidic degradation products accumulate internally, accelerating the hydrolysis process [29].

Table 2: Degradation Mechanisms and Kinetics of Common Scaffold Materials

| Material | Primary Degradation Mechanism | Kinetic Model | Key Factors Influencing Rate |

|---|---|---|---|

| PLGA | Hydrolytic (with autocatalysis) | First-order kinetics; Reaction-diffusion models | Molecular weight, crystallinity, sample size/geometry, pH [29] |

| PEG-Norbornene with MMP-sensitive cross-linker | Enzymatic (cell-mediated) | Michaelis-Menten kinetics | Cell type and density (MMP concentration), cross-linker density, peptide sequence [28] |

| Col-Tgel (Gelatin-based) | Enzymatic (e.g., by collagenases) | Tunable via cross-linking density | Gelatin concentration, cross-linking degree, enzyme concentration [10] |

Experimental Protocols for Parameter Quantification

Protocol: Bulk Rheology for Measuring Elastic Modulus of Hydrogels

This protocol details the characterization of the elastic modulus (G′) for soft hydrogel scaffolds using small amplitude oscillatory shear, as employed in studies of hMSC-laden PEG hydrogels [28].

Research Reagent Solutions:

- PEG-Norbornene (PEG-N): A four-arm star PEG functionalized with norbornene; forms the hydrogel backbone.

- MMP-degradable cross-linker (KCGPQG↓IWGQCK): A peptide sequence cleaved by cell-secreted MMPs; enables cell-mediated degradation.

- Photoinitiator (e.g., LAP): Enables photopolymerization of the hydrogel.

- Cell Culture Medium: For hydration and incubation of formed hydrogels.

Methodology:

- Hydrogel Fabrication: a. Prepare the pre-gel solution by dissolving PEG-N, the MMP-degradable cross-linker, and photoinitiator in an appropriate buffer (e.g., PBS). b. For cell-laden hydrogels, resuspend cells (e.g., hMSCs) homogenously in the pre-gel solution. c. Transfer the solution to a rheometer plate and initiate cross-linking via UV light exposure (e.g., 365 nm, 5-10 mW/cm² for 5-10 minutes).

Rheological Measurement: a. Use a rheometer with a parallel plate geometry (e.g., 8-20 mm diameter). b. Set the experimental temperature to 37°C to mimic physiological conditions. c. Perform a strain sweep (e.g., 0.1-10% strain at 1 Hz) to determine the linear viscoelastic region (LVR). d. Conduct a frequency sweep (e.g., 0.1-100 rad/s) within the LVR to measure the storage modulus (G′) and loss modulus (G″). The plateau value of G′ in the low-frequency region is reported as the elastic modulus.