Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Cellular Aging: From Molecular Mechanisms to Emerging Therapeutic Strategies

Mitochondrial dysfunction is a established hallmark of the aging process, contributing significantly to cellular senescence and the pathogenesis of age-related diseases. This article synthesizes current research for a scientific audience, exploring the foundational mechanisms—including mtDNA instability, reactive oxygen species (ROS) production, and impaired mitophagy—that drive aging. It further examines methodological approaches for assessing mitochondrial health, critically analyzes emerging therapeutic interventions targeting mitochondrial quality control, and validates strategies through recent preclinical and clinical evidence. By integrating these four intents, this review provides a comprehensive framework for understanding mitochondrial biology in aging and its implications for developing novel gerotherapeutic interventions.

Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Cellular Aging: From Molecular Mechanisms to Emerging Therapeutic Strategies

Abstract

Mitochondrial dysfunction is a established hallmark of the aging process, contributing significantly to cellular senescence and the pathogenesis of age-related diseases. This article synthesizes current research for a scientific audience, exploring the foundational mechanisms—including mtDNA instability, reactive oxygen species (ROS) production, and impaired mitophagy—that drive aging. It further examines methodological approaches for assessing mitochondrial health, critically analyzes emerging therapeutic interventions targeting mitochondrial quality control, and validates strategies through recent preclinical and clinical evidence. By integrating these four intents, this review provides a comprehensive framework for understanding mitochondrial biology in aging and its implications for developing novel gerotherapeutic interventions.

Assessing the Damage: Techniques and Models for Studying Aged Mitochondria

Cellular senescence, a state of stable cell cycle arrest, is a hallmark of aging and contributes significantly to age-related functional decline and disease [1]. Mitochondrial dysfunction is a core component of the senescent phenotype, acting as both a cause and a consequence of the aging process [2] [3]. In vitro models provide a controlled environment to unravel the intricate signaling pathways and molecular events that contribute to cellular aging, with a particular focus on how mitochondrial integrity dictates cellular fate [1]. These models are invaluable for deconstructing the complex interplay between various aging hallmarks and for testing potential therapeutic interventions, from senolytic compounds to metabolic reprogramming strategies [1] [4]. This guide details established and emerging methods for inducing, quantifying, and investigating senescence in cell culture, with special emphasis on assessing mitochondrial involvement.

Core Methods for Inducing Senescence In Vitro

A variety of established methods can be employed to induce senescence in cultured cells, each mimicking different aspects of age-related damage. The choice of model depends on the research question and cell type.

Table 1: Methods for Inducing Senescence In Vitro

| Induction Method | Key Mechanism of Action | Example Protocol & Dosage | Associated Mitochondrial Phenotypes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Replicative Senescence [1] | Progressive telomere shortening with each cell division (Hayflick limit). | Serial passaging of primary cells until proliferation cessation. Confirmed via SA-β-gal staining [1]. | Decreased respiratory capacity, reduced mitochondrial membrane potential, increased mitochondrial mass, elevated ROS [2]. |

| Therapy-Induced Senescence (TIS) [5] | DNA damage from chemotherapeutic agents. | Treat HUVECs with Etoposide (50 nM) for 48 hours [5]. Replace media with drug every 24 hours. | Mitochondrial fragmentation, increased ROS, activation of p53 signaling [5]. |

| Stress-Induced Premature Senescence (SIPS) [1] | Acute sublethal damage from genotoxic/oxidative stress. | Treatment with hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂) or other ROS-inducing agents at concentrations and durations determined empirically for each cell type. | Increased ROS production, oxidative damage to mtDNA, mitochondrial dysfunction [6] [7]. |

| Oncogene-Induced Senescence (OIS) [1] | Hyperproliferative signaling from activated oncogenes. | Introduction of an activated oncogene (e.g., RasG12V) via transduction or transfection. | Altered NAD+/NADH balance, metabolic reprogramming, potential upregulation of mitochondrial biogenesis [2]. |

Assessing the Senescent Phenotype: Key Assays and Mitochondrial Focus

Confirming senescence requires a multi-parametric approach, as no single marker is entirely specific. The following assays are standard for characterizing senescent cells.

Hallmark Senescence Assays

Senescence-Associated β-Galactosidase (SA-β-gal) Staining: A widely used histochemical marker for detecting lysosomal β-galactosidase activity at pH 6.0, which is upregulated in many senescent cells [5].

- Protocol: Cells are fixed and incubated overnight with the X-gal substrate at pH 6.0. Senescent cells are identified by blue cytoplasmic staining [5].

Cell Cycle & DNA Damage Markers:

- Immunofluorescence for p53 and p21: Key proteins in the DNA damage response and cell cycle arrest pathways [5].

- DNA Damage Foci: Staining for markers like γH2AX and 53BP1 reveals persistent DNA damage foci, a hallmark of senescence [5].

- Proliferation Marker Loss: Absence of Ki67 staining confirms cell cycle exit [5].

Senescence-Associated Secretory Phenotype (SASP): The pro-inflammatory secretome is a major functional output of senescent cells.

- Assessment: SASP is quantified via ELISA (e.g., for IL-6, IL-8) of cell culture supernatants or qRT-PCR of gene expression (e.g., IL6, IL8, CDKN1A/p21) [5].

Investigating Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Senescence

Given the central role of mitochondria in aging, their functional and structural assessment is critical.

Mitochondrial Morphology: Visualized using fluorescent probes like MitoTracker Red CMXRos.

- Protocol: Incubate live cells with 100 nM MitoTracker for 30 min, then fix and image via confocal microscopy. Senescent cells often show a fragmented mitochondrial network [5].

Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) Measurement: Senescent cells typically exhibit elevated ROS. Fluorescent dyes (e.g., MitoSOX for mitochondrial superoxide) are used for detection and quantification [2] [5].

Mitochondrial Membrane Potential (MMP): A key indicator of functional health. MMP is commonly assessed using potentiometric dyes like TMRM.

- Observation: Senescent cells frequently show a lower and more patchy TMRM staining pattern, indicating depolarization, despite potentially having higher mitochondrial mass [2].

Metabolic Phenotyping: The shift in energy production from oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) to glycolysis in senescence can be measured using a Seahorse Analyzer to assess oxygen consumption rate (OCR) and extracellular acidification rate (ECAR) [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Senescence Research

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Senescence Studies

| Reagent / Assay | Primary Function in Senescence Research | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| SA-β-gal Staining Kit [5] | Histochemical detection of senescence-associated β-galactosidase activity. | Identifying senescent cells in culture after drug treatment or serial passaging. |

| MitoTracker Probes [5] | Staining of mitochondria for assessment of network morphology and mass. | Visualizing mitochondrial fragmentation in stress-induced senescence. |

| MitoSOX Red [2] | Selective fluorescent detection of mitochondrial superoxide. | Quantifying mitochondrial ROS in senescent versus proliferating cells. |

| TMRM [2] | Fluorescent dye for measuring mitochondrial membrane potential. | Detecting mitochondrial depolarization in senescent fibroblasts. |

| Etoposide [5] | Topoisomerase II inhibitor; induces DNA damage and therapy-induced senescence. | Model: Inducing senescence in HUVECs at 50 nM for 48 hours. |

| Mito-Q [5] | Mitochondria-targeted antioxidant; modulates ROS-dependent senescence. | Testing if scavenging mitochondrial ROS can alleviate methotrexate-induced senescence. |

| Antibodies: p53, γH2AX, 53BP1, Ki67 [5] | Immunofluorescence detection of DNA damage response and proliferation arrest. | Confirming sustained DNA damage signaling and cell cycle exit. |

Signaling Pathways in Senescence and Mitochondrial Crosstalk

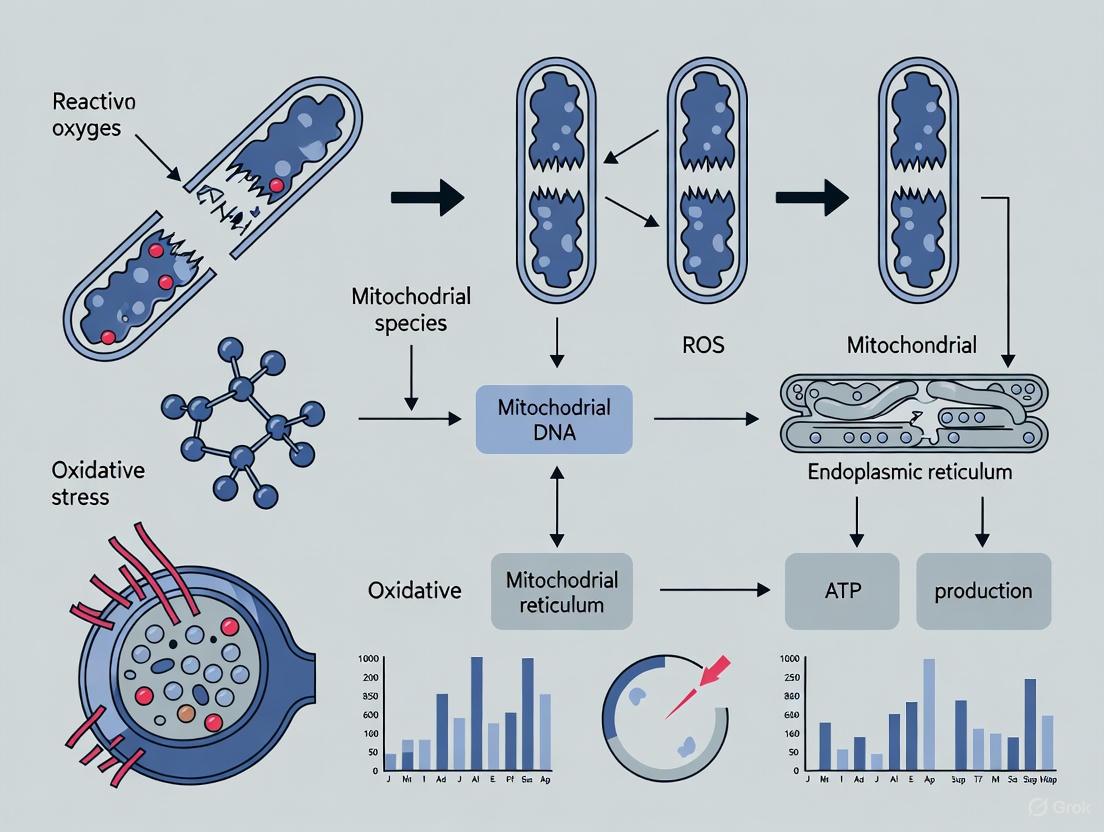

The establishment and maintenance of senescence involve complex signaling networks where mitochondrial dysfunction is a key node. The diagram below integrates the core pathways.

Experimental Workflow for a Senescence Study

A robust experimental design for studying senescence, particularly with a mitochondrial focus, follows a logical sequence from induction to validation. The workflow below outlines key steps.

In vitro models of cellular senescence are powerful tools for dissecting the mechanisms of aging and age-related diseases. The integration of mitochondrial parameters—from functional assays like MMP and ROS measurement to morphological analysis—is no longer optional but essential for a complete understanding of the senescent state. The methods and tools detailed in this guide provide a framework for researchers to rigorously induce, validate, and probe senescence in cell culture, with a particular focus on the central role of mitochondrial dysfunction. As the field advances, these models will be crucial for testing novel interventions, such as senolytics or mitochondrial-targeted therapies, aimed at improving healthspan and treating age-related pathologies [1] [4].

Intervention Strategies: Correcting and Bypassing Mitochondrial Failures

Mitochondrial dysfunction is a cornerstone of the aging process, characterized by a progressive decline in the ability of cells to maintain energy homeostasis and manage reactive oxygen species (ROS). As the primary source of cellular ATP, mitochondria consume approximately 98% of cellular oxygen, converting an estimated 1-2% of it into ROS as a byproduct of oxidative phosphorylation [8] [9]. While ROS serve as important signaling molecules at physiological levels, their excessive accumulation induces oxidative damage to lipids, proteins, and DNA, creating a vicious cycle of mitochondrial impairment and cellular senescence [9]. This oxidative stress landscape has positioned mitochondrial-targeted antioxidant strategies as promising therapeutic interventions to disrupt age-related cellular decline.

Two particularly significant antioxidant compounds have emerged in this context: the endogenous electron carrier Coenzyme Q10 (CoQ10) and its engineered derivative, MitoQ (mitoquinone mesylate). CoQ10, residing primarily in the mitochondrial inner membrane, plays dual roles in electron transport and antioxidant defense [10] [11]. Its reduced form, ubiquinol, is one of the most potent lipophilic antioxidants in cell membranes [10]. MitoQ represents a strategic advancement in antioxidant design—through covalent attachment of the ubiquinol antioxidant moiety to a lipophilic triphenylphosphonium (TPP+) cation, this compound accumulates within the mitochondrial matrix at concentrations up to 1000-fold higher than conventional antioxidants [12]. This targeted delivery system enables more efficient neutralization of ROS at their primary source, offering a potentially superior approach to mitigating age-related mitochondrial oxidative damage.

Molecular Mechanisms and Comparative Actions

Coenzyme Q10: Dual-Function Mitochondrial Component

CoQ10 functions centrally in the mitochondrial electron transport chain, shuttling electrons from Complexes I and II to Complex III while simultaneously undergoing reduction to ubiquinol [10] [11]. This reduced form provides potent antioxidant protection against lipid peroxidation in mitochondrial and cellular membranes. Beyond its redox functions, CoQ10 participates in pyrimidine biosynthesis through its role as a cofactor for dihydroorotate dehydrogenase and may modulate apoptosis and mitochondrial uncoupling proteins [10]. With aging, endogenous CoQ10 levels frequently decline, potentially exacerbating mitochondrial dysfunction and increasing cellular vulnerability to oxidative damage.

MitoQ: Targeted Antioxidant Delivery

MitoQ's molecular design addresses a fundamental limitation of conventional antioxidants—the inability to efficiently penetrate mitochondrial membranes and achieve therapeutic concentrations at the site of maximal ROS production [12]. The TPP+ cation leverages the negative mitochondrial membrane potential (approximately 150-180 mV, negative inside) to drive accumulation, while the lipophilic carbon chain enables traversal across phospholipid bilayers [12]. Once inside mitochondria, MitoQ is reduced to its active ubiquinol form by complex II, where it effectively scavenges superoxide and other reactive oxygen species before they can damage mitochondrial components [13]. Notably, MitoQ exhibits a regenerative capacity—after neutralizing free radicals, it can be repeatedly reduced back to its active form by the respiratory chain, creating a sustainable antioxidant cycle within mitochondria [12].

Table 1: Comparative Molecular Properties of CoQ10 and MitoQ

| Property | Coenzyme Q10 | MitoQ |

|---|---|---|

| Chemical Structure | Endogenous benzoquinone with isoprenoid side chain | Ubiquinone derivative linked to dodecyl-triphenylphosphonium cation |

| Mitochondrial Targeting | Natural localization to inner membrane | Active accumulation driven by membrane potential |

| Mitochondrial Concentration | Physiological levels | Up to 1000-fold higher than conventional antioxidants [12] |

| Primary Antioxidant Mechanism | Electron shuttling and direct free radical neutralization | Targeted free radical scavenging at production source |

| Recyclability | Reduced by complex II and electron-transferring flavoproteins | Regenerated by mitochondrial respiratory chain [12] |

| Bioavailability | Limited due to hydrophobicity and large molecular size | Enhanced cellular uptake via lipophilic cation |

Molecular Pathways in Aging and Age-Related Dysfunction

The interplay between mitochondrial ROS production and aging manifests through several interconnected pathways. Excessive ROS damages mitochondrial DNA, which accumulates mutations more rapidly than nuclear DNA due to proximity to generation sites and limited repair mechanisms [9]. ROS also promotes mitochondrial dynamics dysregulation, favoring excessive fission over fusion events and disrupting quality control mechanisms like mitophagy [13] [9]. Additionally, mitochondrial ROS activate inflammatory pathways through damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs), particularly mitochondrial DNA fragments, which trigger inflammasome activation and perpetuate chronic low-grade inflammation associated with aging [9]. These pathways collectively contribute to cellular senescence and tissue degeneration.

Figure 1: Molecular Pathways of Mitochondrial ROS in Aging and Antioxidant Intervention Points

Quantitative Research Findings: Efficacy and Comparative Analysis

Cardiovascular Protection and Vascular Function

Substantial evidence demonstrates the protective effects of both compounds against age-related vascular dysfunction. In a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled crossover study with healthy older adults (60-79 years), six weeks of MitoQ supplementation (20 mg/day) significantly improved vascular endothelial function, increasing brachial artery flow-mediated dilation by 42% compared to placebo [14]. This improvement was associated with reduced markers of oxidative stress, including significantly lower plasma oxidized low-density lipoprotein [14]. Additionally, MitoQ reduced aortic stiffness (carotid-femoral pulse wave velocity) in participants with elevated baseline levels, suggesting a reversal of age-related vascular aging [14]. At the cellular level, MitoQ (1 μM) protected human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes from hydrogen peroxide-induced mitochondrial dysregulation, significantly blunting mitochondrial ROS production, preventing mitochondrial hyperpolarization, and reducing cell death [13].

Skeletal Muscle and Systemic Effects

Research in healthy middle-aged men (50±1 year) revealed that both MitoQ (20 mg/day) and CoQ10 (200 mg/day) supplementation for six weeks mildly suppressed skeletal muscle mitochondrial hydrogen peroxide levels during leak respiration [15]. MitoQ additionally elevated muscle catalase expression, enhancing endogenous antioxidant capacity [15]. Notably, neither supplement significantly altered mitochondrial respiration capacity or density markers, suggesting their primary action lies in redox modulation rather than fundamental changes to mitochondrial biogenesis [15].

Comparative Efficacy and Tissue-Specific Actions

The search results indicate a potential efficacy advantage for MitoQ in certain contexts due to its enhanced mitochondrial targeting. In cardiomyocyte studies, MitoQ but not its dTPP targeting moiety alone (lacking the ubiquinone antioxidant component) effectively reduced hydrogen peroxide-induced mitochondrial ROS and cell death, confirming the importance of combined targeting and antioxidant activity [13]. Both MitoQ and dTPP exhibited pro-mitochondrial fusion effects by preserving mitochondrial network integrity and reducing fragmentation under oxidative stress conditions, suggesting the targeting moiety itself may influence mitochondrial dynamics independent of antioxidant effects [13].

Table 2: Quantitative Research Findings from Preclinical and Clinical Studies

| Study Model | Intervention | Key Findings | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Human older adults (60-79 years) | MitoQ (20 mg/day, 6 weeks) | 42% improvement in flow-mediated dilation; Reduced aortic stiffness; Lower plasma oxidized LDL | [14] |

| Human middle-aged men (50±1 year) | MitoQ (20 mg/day) vs. CoQ10 (200 mg/day, 6 weeks) | Both suppressed mitochondrial H₂O₂; Only MitoQ increased muscle catalase; No effect on mitochondrial respiration | [15] |

| Human cardiomyocytes (hiPSC-CM) | MitoQ (1 μM) vs. dTPP (1 μM) | MitoQ blunted H₂O₂-induced mtROS and cell death; Both preserved mitochondrial network integrity | [13] |

| CoQ10 deficient fibroblasts (various mutations) | Endogenous CoQ10 levels correlated with pathology | 30-50% residual CoQ10 associated with increased ROS and cell death; Severe deficiency (<15%) showed different pathology | [10] |

Experimental Design and Research Methodologies

In Vitro Models for Cardiomyocyte Protection Studies

The investigation of MitoQ's cardioprotective effects employed sophisticated cellular models, including H9C2 rat cardiomyoblasts and human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes (hiPSC-CM) [13]. Researchers exposed these cells to oxidative stress using hydrogen peroxide (100 μM) with concurrent treatment of either MitoQ (1 μM) or its targeting moiety control dTPP (1 μM) for periods ranging from acute (5-60 minutes) to chronic (48 hours) exposure [13]. This experimental design enabled precise dissection of the contributions of mitochondrial targeting versus antioxidant activity.

Key measurements included quantification of total cellular ROS, mitochondrial-specific superoxide production using fluorescent probes, assessment of mitochondrial membrane potential with potentiometric dyes, and evaluation of cell death markers [13]. Mitochondrial network morphology was visualized using fluorescent staining and microscopy, with fragmentation and fusion characteristics quantitatively analyzed. The inclusion of dTPP as a control allowed researchers to confirm that the observed benefits specifically required the combination of mitochondrial targeting and antioxidant capacity, rather than either component alone [13].

Human Clinical Trial Design for Vascular Function Assessment

The translational investigation of MitoQ in human vascular aging employed a rigorous randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled crossover design [14]. Healthy older adults (60-79 years) with confirmed endothelial dysfunction (flow-mediated dilation <6%) received either MitoQ (20 mg/day) or placebo for six weeks before crossing over to the alternate treatment [14]. This design controlled for interindividual variability and enhanced statistical power.

Vascular function assessments included flow-mediated dilation of the brachial artery using high-resolution ultrasonography, measurement of aortic stiffness via carotid-femoral pulse wave velocity, and assessment of endothelium-independent dilation using sublingual nitroglycerin [14]. Mechanistic insight was gained through a novel functional bioassay where endothelial function was measured before and after an acute supra-therapeutic MitoQ dose (160 mg) following both treatment phases, allowing researchers to quantify the residual mtROS suppression of endothelial function [14]. Additional biomarkers included plasma MitoQ levels, oxidized LDL, and inflammatory markers.

Figure 2: Clinical Trial Workflow for Assessing Mitochondrial Antioxidant Efficacy

Skeletal Muscle Bioenergetics Assessment Protocol

Research examining the effects of MitoQ and CoQ10 on skeletal muscle mitochondrial function in middle-aged men implemented comprehensive assessment techniques [15]. Muscle biopsies were obtained before and after the six-week supplementation period for high-resolution respirometry measurements. Researchers quantified mitochondrial hydrogen peroxide production rates during various respiratory states, including leak respiration (induced by providing substrates without ADP), and oxidative phosphorylation capacity (with saturating ADP) [15].

Mitrial respiration was assessed using multiple substrate-uncoupler-inhibitor titration protocols to probe specific electron transport chain components. Mitochondrial density was evaluated through citrate synthase activity measurements, mitochondrial DNA to nuclear DNA ratio quantification, and assessment of OXPHOS protein expression [15]. Systemic oxidative stress markers included urine F2-isoprostanes and plasma thiobarbituric acid-reactive substances, while muscle antioxidant defenses were analyzed via catalase and superoxide dismutase expression levels [15].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Models

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Mitochondrial Antioxidant Studies

| Reagent/Model | Specifications | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| Human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes (hiPSC-CM) | Commercially available or differentiated in-house | Human-relevant cardiotoxicity and protection models [13] |

| H9C2 rat cardiomyoblasts | ATCC CRL-1446 | Rodent-based screening model for cardiac effects [13] |

| MitoQ (Mitoquinone mesylate) | 1-20 mg/day for in vivo; 0.1-1 μM for in vitro | Primary mitochondrial-targeted antioxidant intervention [13] [14] |

| dTPP control compound (dodecyl-triphenylphosphonium) | 1 μM for in vitro studies | Control for mitochondrial targeting moiety without antioxidant [13] |

| Hydrogen peroxide | 100 μM for oxidative stress induction | Standardized oxidative challenge in cellular models [13] |

| Tetramethylrhodamine ethyl ester (TMRE) | 50-500 nM concentration range | Mitochondrial membrane potential assessment [10] |

| MitoSOX Red mitochondrial superoxide indicator | 5 μM working concentration | Specific detection of mitochondrial superoxide production [13] |

| High-resolution respirometry systems (Oroboros O2k) | Multiple substrate-uncoupler-inhibitor titration protocols | Comprehensive mitochondrial functional assessment [15] |

The accumulating evidence positions mitochondrial-targeted antioxidant strategies as promising interventions for addressing age-related mitochondrial dysfunction. MitoQ's demonstrated efficacy in improving vascular endothelial function and reducing oxidative stress in human studies [14], coupled with its protective effects in cardiomyocyte models [13], underscores its potential therapeutic value. While both MitoQ and conventional CoQ10 can moderate mitochondrial ROS production, MitoQ's enhanced targeting efficiency and tissue-specific benefits in certain contexts suggest it may offer advantages for specific age-related conditions.

Future research directions should include longer-term clinical trials to establish sustained efficacy and optimal dosing regimens across different age-related conditions. Investigation into potential synergistic combinations of mitochondrial-targeted antioxidants with other interventions targeting mitochondrial quality control, such as mitophagy inducers or mitochondrial biogenesis activators, represents a promising avenue. Additionally, further mechanistic studies are needed to elucidate the specific signaling pathways through which these compounds influence mitochondrial dynamics, inflammatory responses, and cellular senescence pathways. As our understanding of mitochondrial biology in aging continues to evolve, so too will opportunities for refining these antioxidant approaches to maximize their potential for promoting healthy cellular aging.

Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) mutations are a cornerstone of the broader thesis on mitochondrial dysfunction in cellular aging research. Aging is a multidimensional phenomenon characterized by progressive cellular decline, where mitochondrial dysfunction emerges as a central driver [4]. The accumulation of somatic mtDNA mutations throughout a lifespan contributes significantly to this decline, acting as a key pathological mechanism in aging and age-related diseases [4] [16]. Unlike nuclear DNA, mtDNA is more vulnerable to mutation due to its proximity to reactive oxygen species (ROS) generated by the electron transport chain and its limited repair mechanisms [4]. In the context of aging, these mutations can lead to impaired oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS), increased ROS production, and bioenergetic failure, creating a vicious cycle of cellular damage [4]. Furthermore, recent research indicates that mitochondrial dysfunction, fueled by mtDNA mutations, is intricately linked to other hallmarks of aging, including epigenetic alterations, telomere attrition, and loss of proteostasis [4]. Understanding and addressing mtDNA mutations is therefore not merely about treating rare genetic disorders but is fundamental to deciphering the mechanisms of cellular aging itself.

The Challenge of mtDNA Biology and Heteroplasmy

The unique biology of mtDNA presents distinct challenges for gene therapy and editing. Each cell contains hundreds to thousands of copies of the 16.5 kb circular mtDNA molecule, which encodes 13 essential subunits of the OXPHOS system, 22 tRNAs, and 2 rRNAs [17]. The concept of heteroplasmy is critical—this describes the coexistence of mutant and wild-type mtDNA within a single cell [17]. The severity of mitochondrial disease is largely dependent on this heteroplasmy level; a biochemical defect typically manifests only when the percentage of mutated mtDNA exceeds a critical threshold, often around 60-90%, which disrupts overall cellular function [17]. This threshold varies based on the specific mutation and the energy demands of the tissue [16]. Consequently, the goal of many therapeutic strategies is to shift heteroplasmy, selectively reducing the mutant load below this pathological threshold. Adding to this complexity is the random nature of mitochondrial segregation during cell division, which can lead to unpredictable shifts in heteroplasmy in daughter cells [16]. This biological landscape makes mtDNA an elusive target, requiring highly specific tools capable of discriminating and editing a single mutant species among thousands of wild-type genomes.

Established mtDNA Editing Platforms: Protein-Based Nucleases

Before the advent of CRISPR, researchers developed programmable protein-based nucleases to manipulate mtDNA heteroplasmy. These tools were engineered to selectively degrade mutant mtDNA molecules, leveraging the fact that linearized mtDNA is rapidly degraded due to the lack of efficient double-strand break repair mechanisms in mitochondria [17].

- MitoTALENs (Transcription Activator-Like Effector Nucleases): These are fusion proteins consisting of a mitochondrial targeting sequence (MTS), a DNA-binding domain derived from TAL effectors that can be engineered to recognize specific mtDNA sequences (typically ~17 bp), and a FokI nuclease domain. Upon dimerization, FokI creates a double-strand break in the mutant mtDNA [17]. An alternative version, mitoTev-TALE, uses the I-TevI nuclease instead of FokI [17].

- MitoZFNs (Zinc-Finger Nucleases): Similar in principle to mitoTALENs, mitoZFNs use zinc-finger proteins as the DNA-binding domain (recognizing ~12 bp) fused to the FokI nuclease [17].

- mtREs (Mitochondrial-Targeted Restriction Endonucleases): This early approach utilized naturally occurring restriction enzymes that could cleave specific sites within mutant mtDNA. However, its application is limited because a unique restriction site arises in only a small fraction of known pathogenic mtDNA mutations [17].

Table 1: Comparison of Protein-Based Nuclease Platforms for mtDNA Editing

| Platform | DNA Recognition Mechanism | Recognition Sequence Length | Key Features | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MitoTALEN | TAL effector protein domain | ~17 nucleotides | High specificity; successfully used in cell and animal models [17] | Laborious protein design and validation for each new target [17] |

| MitoZFN | Zinc-finger protein domain | ~12 nucleotides | Proven efficacy in shifting heteroplasmy [17] | Limited sequence specificity; challenging and costly protein engineering [17] |

| mtRE | Native restriction enzyme | Fixed site (e.g., XmaI) | Simple design if a site exists | Extremely limited application; only useful for a small subset of mutations [17] |

Experimental Protocol: Assessing mtDNA Editing Efficiency with Protein-Based Nucleases

The following workflow outlines a standard methodology for evaluating the efficacy of mitoTALENs or mitoZFNs in cell culture models, incorporating modern techniques for heteroplasmy assessment.

- Vector Construction: Clone the sequence encoding the mitoTALEN or mitoZFN into an appropriate expression plasmid. The construct must include an N-terminal mitochondrial targeting sequence (MTS) to direct the protein to the organelle. A common choice is the MTS from cytochrome c oxidase subunit 8 (COX8) [18].

- Cell Transfection/Transduction: Deliver the constructed vector into a heteroplasmic cell model (e.g., cybrid cells harboring a known pathogenic mtDNA mutation like m.3243A>G for MELAS). This can be achieved via lipid-based transfection, electroporation, or viral delivery (noting that the large size of TALEN constructs can exceed adeno-associated virus (AAV) capacity [17]).

- Isolation of Transfected Cells: After 48-72 hours, isolate successfully transfected cells. If the vector contains a fluorescent marker (e.g., GFP), use Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting (FACS) to collect the positive population for downstream analysis [18].

- DNA Extraction and Heteroplasmy Analysis: Extract total DNA from sorted cells. Quantify the shift in mtDNA heteroplasmy using one of the following methods:

- Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS): Perform ultra-deep amplicon sequencing (≥10,000x coverage) of the mtDNA region spanning the target mutation. This is the gold standard for quantifying heteroplasmy levels with high accuracy and sensitivity [18].

- Restriction Fragment Length Polymorphism (RFLP): If the mutation creates or destroys a restriction enzyme site, PCR-amplify the target region, digest the product with the appropriate enzyme, and analyze the fragment patterns by gel electrophoresis. The ratio of cleaved to uncleaved products reflects the heteroplasmy level.

- Functional Validation:

- Respirometry: Use a high-resolution respirometer (e.g., Oroboros O2k) to measure oxygen consumption rates in permeabilized treated and control cells, assessing the recovery of mitochondrial OXPHOS function [19].

- Biochemical Assays: Measure the activity of respiratory chain complexes (e.g., Complex I or IV) spectrophoto-metrically.

Diagram Title: Protein-Based Nuclease Workflow

The CRISPR-Cas9 Conundrum and Base Editing Breakthroughs

The CRISPR-Cas9 system has revolutionized nuclear genome editing, but its application to mtDNA has been fraught with difficulty. The primary obstacle is the delivery of guide RNA (gRNA) into the mitochondrial matrix [17] [18]. While the Cas9 protein can be efficiently imported by attaching an MTS, the double-membrane structure of mitochondria poses a formidable barrier to RNA import, and the mechanism for importing endogenous nucleus-encoded RNAs is not fully understood [17]. Early reports of successful mtDNA editing with CRISPR-Cas9 were met with skepticism and have not been robustly replicated, with subsequent studies suggesting that observed effects were likely due to off-target activity in the absence of successful gRNA import [18].

This challenge has spurred the development of CRISPR-free base editing technologies, representing a paradigm shift in the field.

- DdCBEs (DddA-derived Cytosine Base Editors): This breakthrough technology bypasses the need for CRISPR. DdCBEs are composed of a split bacterial cytidine deaminase (DddA) attached to mitoTALE proteins that target specific mtDNA sequences. The system also includes a uracil glycosylase inhibitor to prevent repair of the edited base [17] [20]. It catalyzes precise C•G to T•A conversions without creating double-strand breaks, enabling the correction of specific T-to-C pathogenic mutations [17].

- TAMs (Transcription Activator-like effector-linked deaminases) and mitoABEs (Mitochondrial Adenine Base Editors): Expanding on the DdCBE concept, these newer tools use a similar architecture but are designed for A•T to G•C base editing, broadening the range of correctable mutations [20].

Table 2: Emerging Base Editing Platforms for mtDNA

| Platform | Editing Type | Key Component | Mechanism | Current Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DdCBE | C•G → T•A | Split-DddA deaminase + TALE array | Catalyzes deamination of cytidine to uridine, leading to a permanent base change [17] | Successfully demonstrated in human cells and animal models; high target specificity [17] [20] |

| TAM/mitoABE | A•T → G•C | Engineered deaminase + TALE array | Catalyzes deamination of adenine to inosine [20] | Proof-of-concept established; expands the scope of editable mutations [20] |

Advanced Research Methodologies for Mitochondrial Function

Evaluating the success of mtDNA editing requires a multifaceted assessment of mitochondrial function beyond simply measuring heteroplasmy. Relying on a single metric can be misleading, and a combination of techniques is recommended [16] [19].

- High-Resolution Respirometry: This is considered a gold standard for assessing mitochondrial function. Using instruments like the Oroboros O2k, researchers can measure oxygen consumption rates in isolated mitochondria or permeabilized cells under various substrate-inhibitor titration protocols, providing a detailed profile of OXPHOS capacity and integrity [16] [19].

- Mitochondrial Membrane Potential (MMP) Assessment: MMP (ΔΨm) is a key indicator of mitochondrial health and a primary driver for ATP synthesis. Fluorescent dyes like TMRE or JC-1 are used to measure MMP via flow cytometry or fluorescence microscopy. A loss of MMP indicates functional impairment [16].

- Metabolic Flux Analysis: Utilizing Seahorse XF Analyzers, this technique measures the extracellular acidification rate (ECAR) and oxygen consumption rate (OCR) in live cells in real-time, providing an integrated view of both glycolytic and mitochondrial function [16].

- Quantitative Proteomics for Mitochondrial Enrichment: A critical and often overlooked methodological step is normalizing functional data to mitochondrial content. As shown in [19], common markers like Citrate Synthase (CS) activity do not reliably reflect mitochondrial content across different tissues. Mass spectrometry-based quantification of mitochondrial proteins (using databases like MitoCarta) allows for the calculation of a Mitochondrial Enrichment Factor (MEF), enabling unbiased comparison of intrinsic bioenergetic efficiency [19].

Diagram Title: mtDNA Editing Validation Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagent Solutions for mtDNA Editing Research

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Heteroplasmic Cybrid Cells | A standard in vitro model for mtDNA disease. Created by fusing mtDNA-less (ρ0) cells with enucleated patient-derived cytoblasts. | Provides a homogenous nuclear background with a defined, stable mtDNA mutation for testing editors [17]. |

| Mitochondrial Targeting Sequence (MTS) | A peptide sequence that directs fused proteins to the mitochondrial matrix. | Commonly derived from genes like COX8 or SOD2. Essential for mitoTALEN, mitoZFN, and mitoBase-editor delivery [18]. |

| TALE Array & Zinc-Finger Modules | Programmable DNA-binding domains that confer specificity to protein-based nucleases and editors. | TALEs recognize single nucleotides; Zinc Fingers recognize nucleotide triplets. Design and assembly can be labor-intensive [17]. |

| DddA-derived Deaminase (DddA) | The core catalytic domain in DdCBEs that catalyzes cytidine deamination in double-stranded DNA. | Used in a split-protein configuration to prevent uncontrolled deamination and toxicity, improving safety [17]. |

| Mito-TEMPO & MitoQ | Mitochondria-targeted antioxidants. | Used as experimental controls to dissect the contribution of ROS to observed phenotypes following editing. |

| Oroboros O2k & Seahorse XF Analyzer | Instruments for high-resolution respirometry and metabolic flux analysis, respectively. | Critical for validating the functional recovery of mitochondrial OXPHOS after successful mtDNA editing [16] [19]. |

Clinical Translation and Future Perspectives in Aging Research

The transition of mtDNA editing from bench to bedside is underway, though still in early stages. Clinical trials have primarily focused on small molecule approaches, such as elamipretide for primary mitochondrial myopathy, with mixed results [21]. However, the first-in-human application of a gene therapy-adjacent approach, Mitochondrial Replacement Therapy (MRT), has reported promising outcomes. A recent UK study demonstrated that MRT, alongside preimplantation genetic testing (PGT), could significantly reduce or eliminate pathogenic mtDNA mutations, resulting in the birth of healthy infants [22]. This represents a powerful preventive strategy for mothers carrying pathogenic mtDNA mutations.

Looking forward, the integration of mtDNA editing tools into aging research holds immense promise. The ability to precisely install or correct age-associated mtDNA mutations (e.g., the "common deletion") in animal models will allow for direct testing of the causal role of specific mtDNA mutations in the aging process [4]. As base editors continue to evolve, their combination with delivery modalities capable of targeting specific tissues affected in aging (e.g., neurons, muscle) will be critical. The ultimate goal is to move beyond treating monogenic mitochondrial diseases toward intervening in the gradual accumulation of mtDNA damage that underpins cellular aging, potentially opening new avenues for extending healthspan.

From Bench to Bedside: Evaluating Preclinical and Clinical Evidence

Safety and Tolerability Profiles of Leading Mitochondrial-Targeted Compounds

Mitochondrial dysfunction is a cornerstone of cellular aging, characterized by a progressive decline in metabolic efficiency, increased reactive oxygen species (ROS) production, and impaired energy homeostasis [23]. These dysfunctions contribute significantly to the aging process and the pathogenesis of numerous age-related diseases [4]. In response, the field has developed targeted therapeutic strategies designed to restore mitochondrial integrity and function. The advancement of these mitochondrial-targeted compounds from preclinical models to clinical application hinges on a comprehensive understanding of their safety and tolerability profiles. This review provides a systematic evaluation of these critical parameters for leading mitochondrial-targeted compounds, contextualized within the framework of aging research and therapeutic development. We synthesize available data from clinical trials, preclinical studies, and regulatory submissions to offer drug development professionals and researchers a detailed assessment of the current landscape.

Comprehensive Compound Profiles

Table 1: Safety and Tolerability Profiles of Leading Mitochondrial-Targeted Compounds

| Compound Name | Mechanism of Action | Development Stage | Reported Adverse Events | Tolerability Findings | Key Clinical Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Elamipretide | Binds to cardiolipin, stabilizes mitochondrial cristae, improves ETC efficiency [24] | NDA Resubmission (2025) for Barth Syndrome [24] | Not specified in detail; general safety profile supported for accelerated approval [24] | Favorable enough for regulatory consideration in an ultra-rare pediatric disease [24] | Priority Review, Fast Track, Orphan Drug Designation. Potential first approved therapy for Barth syndrome [24]. |

| Urolithin A | Induces mitophagy [25] | Phase II (Completed) [25] | Well-tolerated; adverse event profile similar to placebo (e.g., upper respiratory tract infections) [25] | No significant changes in kidney or liver function parameters vs. placebo [25] | 4-week, 1000 mg/day dose in healthy middle-aged adults; safe and well-tolerated [25]. |

| C458 | Mild inhibition of mitochondrial complex I (mtCI), activating neuroprotective pathways [26] | Preclinical [26] | No toxicity at physiologically relevant concentrations; minimal off-target effects [26] | Excellent brain penetrance and favorable pharmacokinetics in mouse models [26] | Represents a new class of safe, brain-penetrant mtCI inhibitors for neurodegenerative diseases [26]. |

| MitoQ | Mitochondria-targeted antioxidant (Coenzyme Q10 analog) [27] | Clinical trials for various conditions [27] | Detailed safety profile not provided in search results | Generally reported as tolerable in clinical studies [27] | Used in research to neutralize mitochondria-derived ROS [27]. |

| Nicotinamide Riboside (NR) | Augments NAD+ biosynthesis [27] | Clinical trials [27] | Detailed safety profile not provided in search results | Detailed tolerability findings not provided in search results | Dietary supplement aimed at counteracting age-related NAD+ decline [27]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols for Safety and Efficacy Assessment

The safety profiles summarized in Table 1 are derived from rigorous experimental methodologies. Understanding these protocols is essential for interpreting the generated data.

In Vitro Safety and Selectivity Screening

For novel small molecules like C458, the initial safety assessment employs a high-throughput drug discovery funnel. This typically involves:

- Cytoprotection Assays: Compounds are tested in models of Aβ toxicity, such as human neuroblastoma MC65 cells. Cell death is measured after 72 hours under Tet-Off (Aβ-expressing) conditions to confirm efficacy without acute toxicity [26].

- Selectivity Profiling: Off-target effects are minimized through extensive structure-activity relationship (SAR) studies. Specificity for mtCI is confirmed using cellular models like AMPKα1/α2 knockout mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs), which verify that the compound's protective effects are mediated through the intended energetic stress pathway (AMPK activation) [26].

- Pharmacokinetic Screening: Early assessment of blood-brain barrier (BBB) penetrance is conducted using in vitro models, a key step for prioritizing compounds for neurological indications [26].

In Vivo Tolerability and Toxicology Studies

- Rodent Models: Chronic oral administration studies in transgenic mouse models (e.g., APP/PS1 mice) are standard. These studies last from several months to over a year and include detailed assessment of long-term potentiation (LTP), metabolic parameters via in vivo ³¹P-NMR spectroscopy, blood cytokine panels, and oxidative stress markers. The lack of observed toxicity in these models at physiologically relevant doses is a critical indicator of tolerability [26].

- Large Animal Studies: Prior to human trials, compounds typically undergo toxicological assessment in higher-order species to establish safe starting doses for clinical trials.

Clinical Trial Safety Monitoring

Controlled human trials provide the most definitive safety data.

- Adverse Event Recording: As demonstrated in the Urolithin A trial, all adverse events (AEs) are systematically recorded and classified. A similar number of AEs (mostly minor infections) in both treatment and placebo groups strengthens the conclusion of good tolerability [25].

- Biochemical Safety Analysis: Standard panels of metabolic markers, kidney function parameters, and liver enzymes are measured at baseline and post-intervention. The absence of significant changes in these parameters, as seen with Urolithin A, supports the compound's safety [25].

- Vital Signs and Physical Examination: Regular monitoring of participants' vital signs and overall health status is conducted throughout the study period [25].

Key Mitochondrial Signaling Pathways in Aging and Therapeutics

The therapeutic strategies discussed target specific pathways implicated in mitochondrial dysfunction during aging. The following diagrams illustrate the core mechanisms.

Mitophagy Induction Pathway

Urolithin A operates through this pathway, which is crucial for clearing damaged mitochondria that accumulate with age.

Mitochondrial Stress Response Pathway

Compounds like C458 and elamipretide modulate this pathway, which is central to the aging-related decline in cellular energy metabolism.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Investigating Mitochondrial-Targeted Compounds

| Reagent / Assay | Specific Example | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Lines for Neuroprotection | MC65 human neuroblastoma (Aβ toxicity model); SH-SY5Y APPSWE [26] | Screening compound efficacy against amyloid-beta toxicity and related pathways. |

| Genetically Modified Cells | AMPKα1/α2 knockout MEFs [26] | Verifying on-target mechanism of action and pathway specificity. |

| Primary Neuronal Cultures | Cortical neurons from neonatal mice (e.g., P1) [26] | Assessing compound effects in a physiologically relevant, non-transformed system. |

| Transgenic Animal Models | APP/PS1, 3xTgAD mice [26] | In vivo evaluation of efficacy and safety in models of age-related proteinopathies. |

| Antibodies for Key Pathways | p-AMPK (Thr172), AMPK, Sirt1, Sirt3, SOD1 [26] | Detecting activation of mitochondrial biogenesis and stress response pathways via Western blot. |

| Functional Metabolic Assays | In vivo ³¹P-NMR spectroscopy [26] | Non-invasive monitoring of cellular energetics and mitochondrial function in live animals. |

| Spectral Cytometry Panels | Cell surface markers and transcription factors for immune subsets [25] | Deep immunophenotyping to assess compound effects on immune aging and inflammation. |

The safety and tolerability data emerging for leading mitochondrial-targeted compounds are largely promising, supporting their continued development as interventions for aging-related dysfunction. Urolithin A has demonstrated an excellent safety profile in human trials, while elamipretide's regulatory progress underscores a positive risk-benefit assessment for a severe rare disease. The preclinical profile of C458 suggests that next-generation compounds with improved selectivity and brain penetrance can be developed with minimal off-target effects. Future work must focus on long-term safety data, interactions in polypharmacy scenarios common in aged populations, and the differential effects of timing interventions, as early developmental mitochondrial dysfunction has been shown to have distinct consequences compared to adult-onset dysfunction [28]. As the field progresses, the integration of multi-omics techniques in clinical trials will be crucial for identifying robust biomarkers of target engagement and safety, ultimately accelerating the development of safe and effective mitochondrial therapies for aging and age-related diseases.

Mitochondrial dysfunction emerges as a central mechanism driving the pathological aging process across multiple disease states, serving as a critical link between neurodegenerative and metabolic disorders. This shared pathophysiology is characterized by bioenergetic failure, redox imbalance, and metabolic reprogramming that accelerates cellular senescence and tissue degeneration [4] [23] [9]. The intricate interplay between mitochondrial quality control, inflammatory signaling, and energy metabolism creates a self-perpetuating cycle that exacerbates both neurological decline and metabolic insufficiency in aging organisms [23] [9].

Understanding the convergent and divergent mitochondrial pathways in these disease classes provides a unique opportunity for therapeutic cross-pollination. Recent evidence from genetic causal inference analyses, including Mendelian randomization studies, has identified specific mitochondrial genes with cross-disease implications, such as PDK1, which demonstrates causal associations with both Alzheimer's disease and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis when genetically predicted expression is increased [29]. This mechanistic overlap underscores the potential for shared intervention strategies targeting mitochondrial resilience.

Comparative Pathophysiology: Shared Mitochondrial Mechanisms

Metabolic Reprogramming in Neurodegeneration and Metabolic Disorders

Aging-related metabolic reprogramming represents a fundamental cellular adaptation to mitochondrial dysfunction, characterized by a shift from oxidative phosphorylation toward glycolytic metabolism regardless of tissue origin [4]. In both neurodegenerative and metabolic contexts, this reprogramming is driven by mitochondrial respiratory chain impairment and hyperactivation of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway, creating a Warburg-like effect that perpetuates energy crisis and oxidative damage [4].

Table 1: Comparative Metabolic Reprogramming Features in Neurodegenerative and Metabolic Disorders

| Metabolic Feature | Neurodegenerative Disorders | Metabolic Disorders | Shared Mechanisms |

|---|---|---|---|

| Glucose Metabolism | Reduced neuronal OXPHOS capacity, glycolytic shift in supporting cells [4] | Hepatic and muscular OXPHOS impairment, systemic glycolytic dominance [30] | PI3K/AKT/mTOR hyperactivation, reduced PDHC activity [4] |

| Lipid Metabolism | Lipid droplet accumulation in glial cells, mitochondrial β-oxidation defects [4] | Hepatic lipid accumulation, defective fatty acid oxidation [4] [30] | CPT1/CPT2 downregulation, membrane lipid peroxidation [4] |

| Oxidative Stress | Neuronal ROS susceptibility, antioxidant depletion [31] [32] | Tissue-specific ROS production, coenzyme Q deficiency [30] | Complex I/III ROS generation, GSH system impairment [9] |

| Inflammatory Signaling | Microglial activation, SASP propagation [4] [23] | Macrophage infiltration, adipokine dysregulation [23] | NF-κB activation, cGAS-STING pathway engagement [4] [9] |

The metabolic transitions observed across disease states share remarkable similarities in their molecular drivers. The sirtuin family (SIRT1, SIRT3) serves as a critical regulatory node, maintaining mitochondrial homeostasis through modulation of PGC-1α and FOXO3 targets in both neurological and metabolic tissues [4]. Age-related decreases in sirtuin activity lock cells into a glycolysis-dominant state, creating a metabolic environment conducive to cellular senescence and functional decline [4].

Mitochondrial Quality Control Disruption

The maintenance of mitochondrial integrity through balanced dynamics and selective autophagy is compromised in both neurodegenerative and metabolic conditions, though with tissue-specific manifestations.

Mitochondrial dynamics are regulated by a delicate equilibrium between fusion and fission proteins. In neurodegenerative contexts, neuronal survival depends on proper mitochondrial trafficking and distribution, requiring tightly regulated dynamics mediated by MFN1/2, OPA1, and DRP1 [32]. Similarly, in metabolic tissues such as liver and muscle, mitochondrial dynamics regulate substrate utilization and energy production, with disruption leading to metabolic inflexibility [9].

Mitophagic clearance of damaged mitochondria represents another shared vulnerability. The PINK1-Parkin pathway, first identified in Parkinson's disease, plays crucial roles in metabolic tissues, with deficiency contributing to insulin resistance and hepatic steatosis [31] [32]. The accumulation of dysfunctional mitochondria due to impaired mitophagy creates a source of persistent oxidative stress that propagates cellular damage in both disease classes [9] [32].

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies

Genetic Causal Inference and Cross-Disease Validation

The establishment of causal rather than correlative relationships between mitochondrial dysfunction and disease pathogenesis requires sophisticated genetic approaches. Mendelian randomization (MR) and colocalization analyses have emerged as powerful tools for disentangling complex mitochondrial disease mechanisms [29].

Table 2: Key Methodologies for Mitochondrial Cross-Disease Research

| Methodology | Application | Key Findings | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mendelian Randomization | Testing causal relationships between mitochondrial gene expression and disease risk [29] | PDK1 upregulation causal for AD (OR=1.041) and ALS (OR=1.037) [29] | Requires large GWAS sample sizes, sensitive to horizontal pleiotropy |

| Machine Learning Classification | Disease stratification using mitochondrial gene expression signatures [29] | SVM and MLP effectively classify AD, ALS, MS, PD (MS most predictable, accuracy=0.758) [29] | Cross-tissue validation essential, batch effect correction critical |

| Multi-omics Integration | Combining genomic, transcriptomic, and metabolomic data [29] | Identification of shared (PDK1) and specific (SLC25A38 for PD) mitochondrial vulnerabilities [29] | Computational intensive, requires specialized normalization approaches |

| Reverse Electron Transport (RET) Assessment | Measuring site-specific mitochondrial ROS production [30] | Coenzyme Q deficiency drives RET at Complex I in obesity [30] | Tissue-specific protocols needed, complex I isolation critical |

The precise identification of mitochondrial ROS production sites requires systematic evaluation across disease contexts. The following protocol adapts methodology from obesity research [30] for application in neurodegenerative models:

Tissue Homogenization and Mitochondrial Isolation

- Prepare mitochondrial fractions from target tissues (liver, muscle, brain regions) using differential centrifugation

- Preserve mitochondrial integrity by maintaining 4°C throughout isolation

- Use mitochondrial respiration buffer (130mM KCl, 5mM K2HPO4, 20mM MOPS, 2.5mM MgCl2, 0.1mM EGTA, pH 7.4)

Comprehensive ROS Source Interrogation

- Assess all potential ROS-generating sites sequentially:

- Complex I (RET): NADH (2.5mM) + succinate (5mM) + rotenone (500nM)

- Complex I (Forward): NADH-linked substrates + ADP

- Complex II: Succinate (10mM) + rotenone

- Complex III: Succinate/rotenone + antimycin A (1µM)

- Detect ROS using Amplex Red (5µM) + horseradish peroxidase (1U/mL)

- Assess all potential ROS-generating sites sequentially:

Coenzyme Q Metabolite Profiling

- Extract coenzyme Q isoforms using hexane:ethanol (5:2)

- Quantify using HPLC with electrochemical detection

- Calculate reduced/to oxidized coenzyme Q ratios as functional indicators

Data Normalization and Cross-Tissue Comparison

- Normalize ROS production to citrate synthase activity

- Express results as fold-change relative to control conditions

- Perform comparative analysis across tissue types and disease models

This systematic approach enables researchers to identify not just the magnitude but the precise subcellular sources of mitochondrial oxidative stress, facilitating targeted therapeutic development [30].

Signaling Pathways and Molecular Mechanisms

The p53-PGC-1α Axis in Telomere-Mitochondria Communication

Telomere shortening represents a canonical aging hallmark that directly influences mitochondrial function through the p53-PGC-1α signaling axis. This pathway creates a direct link between nuclear aging events and mitochondrial deterioration relevant to both neurodegenerative and metabolic conditions [4].

Figure 1: The p53-PGC-1α signaling axis creates a vicious cycle connecting telomere attrition to mitochondrial dysfunction. Telomere damage activates p53, which transcriptionally represses PGC-1α, a master regulator of mitochondrial biogenesis. The resulting OXPHOS decline increases ROS production, which further damages telomeres, accelerating cellular senescence [4].

This pathway demonstrates particular significance in age-related conditions, as telomere shortening directly inhibits mitochondrial biosynthesis through the p53-PGC-1α axis, leading to oxidative stress accumulation and progressive organ dysfunction [4]. Therapeutic strategies aimed at disrupting this cycle may yield benefits across multiple age-related conditions.

Reverse Electron Transport in Metabolic and Neurological Diseases

Recent research has identified reverse electron transport (RET) at mitochondrial Complex I as a shared mechanism in metabolic and neurodegenerative pathology. RET occurs when electrons from reduced coenzyme Q are forced backward through Complex I, generating substantial ROS production [30].

Figure 2: Reverse electron transport pathway initiated by coenzyme Q deficiency. In obesity and age-related conditions, coenzyme Q deficiency increases mitochondrial membrane potential, driving electrons backward through Complex I (RET). This process generates excessive mitochondrial ROS that promotes metabolic dysregulation, inflammatory signaling, and neuronal damage [30].

This mechanism is particularly significant because it represents a highly specific source of pathological ROS generation, explaining the failure of broad-spectrum antioxidant therapies and highlighting the need for targeted interventions such as coenzyme Q restoration or RET inhibition [30].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Mitochondrial Cross-Disease Investigations

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Functional Role |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mitochondrial Dyes | MitoTracker Red CMXRos, TMRM, JC-1 | Live-cell imaging of membrane potential | Quantitative assessment of mitochondrial health and function |

| ROS Detection | MitoSOX Red, Amplex Red, H2DCFDA | Site-specific ROS measurement | Selective detection of mitochondrial vs. cytosolic ROS sources |

| Metabolic Probes | Seahorse XFp Analyzer reagents | Real-time metabolic profiling | Simultaneous assessment of glycolytic and OXPHOS capacity |

| Pathway Modulators | SR-18292 (PGC-1α activator), Metformin (AMPK activator) | Mechanistic dissection | Target validation in metabolic and neuronal models |

| Genomic Tools | mitoTALENs, DdCBE, TALEDs [33] | Mitochondrial gene editing | Precise manipulation of mtDNA heteroplasmy |

These research tools enable the dissection of complex mitochondrial pathways across disease contexts, facilitating the identification of shared therapeutic targets. The emergence of mitochondrial gene editing technologies, including mitochondrial-targeted base editors (DdCBE) and transcription activator-like effector-linked deaminases (TALEDs), represents a particularly promising advancement for mechanistic studies [33].

Therapeutic Implications and Future Directions

The convergent mitochondrial pathways identified across neurodegenerative and metabolic disorders reveal promising targets for therapeutic intervention. Several strategically important approaches emerge from current evidence:

Metabolic Pathway Modulation represents a cornerstone strategy with cross-disease potential. Targeting the PDK1-pyruvate metabolism axis, identified through causal inference analyses as shared across AD and ALS, may yield broad benefits [29]. Computational drug enrichment analyses highlight Celecoxib as a potential PDK1 modulator, with molecular docking predicting strong binding affinity (docking score S = -6.522 kcal/mol) [29]. Similarly, sirtuin-activating compounds show promise for restoring mitochondrial homeostasis in both metabolic and neurological contexts [4].

Site-Specific Antioxidant Approaches must evolve beyond broad-spectrum strategies that have demonstrated limited efficacy. The precise targeting of reverse electron transport at Complex I, through coenzyme Q restoration or Complex I-directed compounds, represents a more promising approach based on mechanistic studies in metabolic disease [30]. Similarly, enhancing mitochondrial glutathione import via SLC25A39 modulation may bolster endogenous antioxidant capacity across tissues [9].

Emerging Mitochondrial Engineering technologies offer transformative potential. Artificial mitochondrial transfer and mitochondrial gene editing have advanced from conceptual stages to demonstrated applications in model systems [33]. The timeline of these developments reveals accelerating progress: mitochondrial zinc-finger nucleases (2008) enabled heteroplasmy shifting, mitochondrial TALENs (2013) achieved this in vitro, and mitochondrial-targeted meganucleases (2021) realized heteroplasmy shifting in vivo [33]. Most recently, double-stranded DNA cytosine base editors (2022) enable novel mtDNA point mutations, expanding the toolkit for precision mitochondrial medicine [33].

The continued development of these approaches, coupled with improved biomarkers for detecting mitochondrial pathology prior to overt symptom manifestation, holds promise for meaningful interventions in the aging process shared across neurodegenerative and metabolic conditions. Future research directions should prioritize the identification of critical developmental windows for mitochondrial intervention, as emerging evidence suggests that the timing of mitochondrial dysfunction dramatically shapes long-term health trajectories and stress resilience [28].

Conclusion

Mitochondrial dysfunction is unequivocally positioned as a central regulator of cellular aging, intricately linked to other hallmarks through mechanisms like metabolic reprogramming, chronic inflammation, and genomic instability. The convergence of research across foundational mechanisms, assessment methodologies, therapeutic interventions, and clinical validation paints a promising yet complex picture. Future directions must focus on translating these findings into clinically viable strategies, with key priorities including the development of combinatorial therapies that simultaneously target multiple facets of mitochondrial biology, the refinement of mitochondrial transplantation techniques, and the identification of robust biomarkers to stratify patients for targeted interventions. For researchers and drug developers, the challenge and opportunity lie in leveraging this integrated understanding to not merely extend lifespan but to significantly improve healthspan, mitigating the burden of age-related diseases.

References

- 1. Cellular Models of Aging and Senescence - PMC [https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC12384970/]

- 2. Mitochondrial dysfunction in cell senescence and aging [https://www.jci.org/articles/view/158447]

- 3. Mitochondrial proteins as biomarkers of cellular ... [https://www.aging-us.com/article/206305/text]

- 4. Mitochondrial dysfunction and aging: multidimensional ... [https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC12241157/]

- 5. Diversity of oxidative stress and senescence phenotypes ... [https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-025-20652-z]

- 6. Mitochondrial dysfunction and its association with age-related ... [https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11250148/]

- 7. The Mitochondrial Basis of Aging and Age-Related Disorders [https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5748716/]

- 8. Advancements in Mitochondrial-Targeted Antioxidants [https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2667137925000232]

- 9. Mitochondria in oxidative stress, inflammation and aging [https://www.nature.com/articles/s41392-025-02253-4]

- 10. Reactive oxygen species, oxidative stress, and cell death ... [https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC2996902/]

- 11. Coenzyme Q10 and Xenobiotic Metabolism: An Overview [https://www.mdpi.com/1422-0067/26/12/5788]

- 12. 深度解读中新两国备忘录:MitoQ分子解锁抗衰密码 [https://www.medsci.cn/article/show_article.do?id=020c83269ecb]

- 13. Protects Against Oxidative Stress-Induced MitoQ ... Mitochondrial [https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/40686505/]

- 14. Chronic supplementation with a mitochondrial antioxidant ... [https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5945293/]

- 15. and CoQ MitoQ supplementation mildly suppresses skeletal muscle... 10 [https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00421-020-04396-4]

- 16. Overview of methods that determine mitochondrial function in ... [https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC12250752/]

- 17. Current Progress of Mitochondrial Genome Editing by ... [https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9108280/]

- 18. Site-specific CRISPR-based mitochondrial DNA ... [https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-022-21794-0]

- 19. Novel approach to quantify mitochondrial content and ... [https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-020-74718-1]

- 20. Faulty mitochondria cause deadly diseases: fixing them is ... [https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-025-03307-x]

- 21. Clinical trials in mitochondrial disorders, an update - PMC - NIH [https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7537630/]

- 22. Encouraging results from mitochondrial replacement ... [https://sites.wustl.edu/prosper/encouraging-results-from-mitochondrial-replacement-therapy-study-in-the-uk/]

- 23. Mitochondrial dysfunction in the regulation of aging and aging ... [https://biosignaling.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12964-025-02308-7]

- 24. STEALTH BIOTHERAPEUTICS RESUBMITS NEW DRUG ... [https://stealthbt.com/stealth-biotherapeutics-resubmits-new-drug-application-for-elamipretide-for-the-treatment-of-barth-syndrome/]

- 25. Effect of the mitophagy inducer urolithin A on age-related ... [https://www.nature.com/articles/s43587-025-00996-x]

- 26. Therapeutic assessment of a novel mitochondrial complex I ... [https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC12466149/]

- 27. Mitochondrial dysfunction: mechanisms and advances in ... [https://www.nature.com/articles/s41392-024-01839-8]

- 28. Timing of Mitochondrial Dysfunction Found to Shape ... [https://wms-site.com/press-media/1350-timing-of-mitochondrial-dysfunction-found-to-shape-lifespan]

- 29. Convergent and Divergent Mitochondrial Pathways as Causal ... [https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC12384102/]

- 30. Newly discovered mechanism of mitochondrial dysfunction ... [https://hsph.harvard.edu/news/newly-discovered-mechanism-of-mitochondrial-dysfunction-in-obesity-may-drive-insulin-resistance-and-type-2-diabetes/]

- 31. Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Neurodegenerative Diseases [https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39996748/]

- 32. Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Neurodegenerative Diseases [https://www.mdpi.com/2227-9059/13/2/327]

- 33. Engineered mitochondria in diseases: mechanisms ... [https://www.nature.com/articles/s41392-024-02081-y]