mRNA Reprogramming: A Footprint-Free Path to Clinical-Grade iPSCs and Regenerative Therapies

This article provides a comprehensive overview of mRNA-based technology for cell fate reprogramming, a transformative approach in regenerative medicine and drug development.

mRNA Reprogramming: A Footprint-Free Path to Clinical-Grade iPSCs and Regenerative Therapies

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of mRNA-based technology for cell fate reprogramming, a transformative approach in regenerative medicine and drug development. It explores the foundational principles of how synthetic mRNA enables the production of induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) and direct lineage conversion without the risks of genomic integration. The scope spans from the molecular design of mRNA, including cap structures and nucleoside modifications that enhance stability and reduce immunogenicity, to advanced delivery systems like lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) and tissue nanotransfection (TNT). The content further addresses key methodological applications, critical troubleshooting steps for optimizing efficiency and safety, and a comparative analysis with other gene-editing and silencing technologies. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, this review synthesizes current advancements and future directions for deploying mRNA as a powerful, versatile, and clinically relevant tool for cellular reprogramming.

The mRNA Blueprint: Decoding the Science Behind Transient and Safe Cell Reprogramming

The unprecedented success of messenger RNA (mRNA) vaccines during the COVID-19 pandemic marked a pivotal turning point for this versatile technology. While the global deployment of SARS-CoV-2 vaccines demonstrated the feasibility, safety, and efficacy of mRNA platforms on a massive scale, these applications merely scratch the surface of its potential [1]. The core principle of mRNA therapeutics—delivering genetic instructions that direct human cells to produce specific proteins—lends itself to applications far beyond infectious disease prevention [2]. This technological paradigm is now rapidly expanding into the realm of regenerative medicine, offering innovative solutions for cellular reprogramming, tissue repair, and the treatment of chronic diseases [3]. The convergence of mRNA technology with cell fate reprogramming research represents a transformative approach in biomedical science, potentially enabling direct in vivo reprogramming of cell phenotypes without genetic integration [4]. This review explores the scientific foundations, current applications, and future directions of mRNA-based therapeutics, with particular emphasis on their role in cell engineering and regenerative medicine.

Technical Foundations of mRNA Therapeutics

Structural Components and Design Optimization

The architecture of synthetic mRNA is meticulously designed to mimic mature endogenous mRNA, comprising several critical regulatory elements that collectively influence stability, translational efficiency, and immunogenicity [1]. A standard in vitro transcribed (IVT) mRNA construct includes five essential regions: the 5' cap structure, 5' untranslated region (UTR), open reading frame (ORF) encoding the target protein, 3' UTR, and a poly(A) tail [1]. Each component serves distinct functions—the 5' cap and poly(A) tail protect against exonuclease degradation and facilitate ribosomal binding, while the UTRs contain regulatory elements that modulate translation efficiency and subcellular localization [2]. The ORF constitutes the coding sequence for the protein of interest, which can range from viral antigens for vaccines to transcription factors for cellular reprogramming [3].

Significant advances in nucleoside chemistry have been crucial for therapeutic application. The seminal work of Karikó and Weissman demonstrated that incorporating modified nucleosides such as N1-methylpseudouridine (m1Ψ) and 5-methylcytidine suppresses innate immune recognition by avoiding activation of pattern recognition receptors while simultaneously enhancing translational capacity [2] [5] [6]. This breakthrough fundamentally addressed the previously limiting issues of excessive immunogenicity and poor protein expression that hampered early mRNA therapeutic development [6].

Table 1: Key Structural Elements of Synthetic mRNA and Their Functions

| Structural Element | Composition | Primary Function | Impact on Efficacy |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5' Cap | 7-methylguanosine linked via 5'-5' triphosphate bond (Cap 0,1,2) | Ribosome recognition, initiation of translation, protection from degradation | Cap 1 structure reduces immunogenicity; Cap 2 may further evade immune detection [2] |

| 5' UTR | Nucleotide sequences upstream of ORF | Regulation of ribosome scanning and translation initiation | Optimized sequences enhance translational efficiency [1] |

| Open Reading Frame (ORF) | Protein-coding sequence with optimized codons | Encodes the therapeutic protein | Nucleoside modifications (e.g., m1Ψ) increase translation and reduce immunogenicity [5] |

| 3' UTR | Nucleotide sequences downstream of ORF | Regulation of mRNA stability and translation | Specific sequences can enhance half-life and protein yield [1] |

| Poly(A) Tail | 100-250 adenosine residues | Promotes mRNA stability and translational initiation | Optimal length crucial for protein expression; affects mRNA half-life [1] |

Advanced mRNA Synthesis and Purification Technologies

The production of therapeutic-grade mRNA relies on sophisticated in vitro transcription and purification systems. Two primary capping methodologies have emerged: post-transcriptional capping using vaccinia capping enzyme (VCE) and co-transcriptional capping using cap analogs [2]. The VCE approach, employed for Moderna's COVID-19 vaccine, enzymatically adds a Cap 0 structure to the 5' end of transcribed RNA, which can be further modified to Cap 1 by 2'-O-methyltransferase [2]. Alternatively, BioNTech/Pfizer's vaccine utilizes co-transcriptional capping with CleanCap technology, where cap analogs are incorporated during the transcription reaction [2].

A significant challenge in mRNA production has been the elimination of immunogenic byproducts, particularly double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) and 5'-uncapped mRNA. Recent innovations like the PureCap method developed by Inagaki et al. address this by employing a novel cap analog with a hydrophobic purification tag that enables chromatographic separation of fully capped mRNA from incomplete products [2]. This technology reportedly produces mRNA with translational activity more than ten times higher than conventional cap analogs and allows synthesis of the advanced Cap2 structure, which further evades immune detection [2].

Diagram 1: Synthetic mRNA structural components and their primary functions. The 5' cap facilitates ribosome binding and immune evasion, while nucleoside modifications in the ORF enhance translation and reduce immunogenicity. UTRs and the poly(A) tail collectively regulate stability and translational efficiency.

Delivery Systems: Lipid Nanoparticles and Beyond

Efficient intracellular delivery remains a critical challenge for mRNA therapeutics. Lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) have emerged as the leading delivery platform, with their composition optimized through decades of research [2] [5]. Standard LNP formulations comprise four key components: ionizable cationic lipids that complex with negatively charged mRNA, phospholipids that support lipid bilayer structure, cholesterol that enhances stability, and PEGylated lipids that improve nanoparticle pharmacokinetics [5]. These components self-assemble into approximately 100 nm particles that protect mRNA from nucleases and facilitate cellular uptake through endocytosis [5].

While current LNP systems efficiently deliver to hepatocytes and immune cells following systemic administration, their application to other tissues remains challenging. Research efforts are now focused on developing next-generation LNPs with enhanced tissue specificity through the incorporation of targeting ligands [3]. Additionally, a significant limitation of current LNP technology is the low endosomal escape efficiency—estimated at only about 2%—meaning most encapsulated mRNA never reaches the cytosol for translation [2]. Novel ionizable lipids with improved endosomolytic properties are under active investigation to address this bottleneck.

mRNA in Regenerative Medicine and Cell Fate Reprogramming

Principles of mRNA-Mediated Cellular Reprogramming

The application of mRNA technology to cell fate manipulation represents a paradigm shift in regenerative medicine. Unlike viral vector-based approaches that pose risks of genomic integration and insertional mutagenesis, mRNA offers a non-integrating alternative for transiently expressing reprogramming factors [2] [3]. This is particularly important when using oncogenic transcription factors such as Klf4 and c-Myc (Yamanaka factors), where persistent expression increases tumorigenic risk [2]. mRNA-mediated delivery provides precisely controlled, transient expression of these factors, sufficient to initiate reprogramming without permanent genetic alteration [3].

The fundamental process involves introducing synthetic mRNA encoding specific transcription factors that direct cells toward new phenotypic states. Early proof-of-concept studies demonstrated that repeated transfections of modified mRNA encoding the Yamanaka factors (Oct4, Sox2, Klf4, c-Myc) could generate induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) from human fibroblasts [3]. Subsequent research has expanded this approach to direct lineage conversion, bypassing the pluripotent intermediate stage to transdifferentiate somatic cells into various target cell types, including cardiomyocytes, neurons, and hepatocytes [3].

Experimental Workflow for mRNA-Mediated Cellular Reprogramming

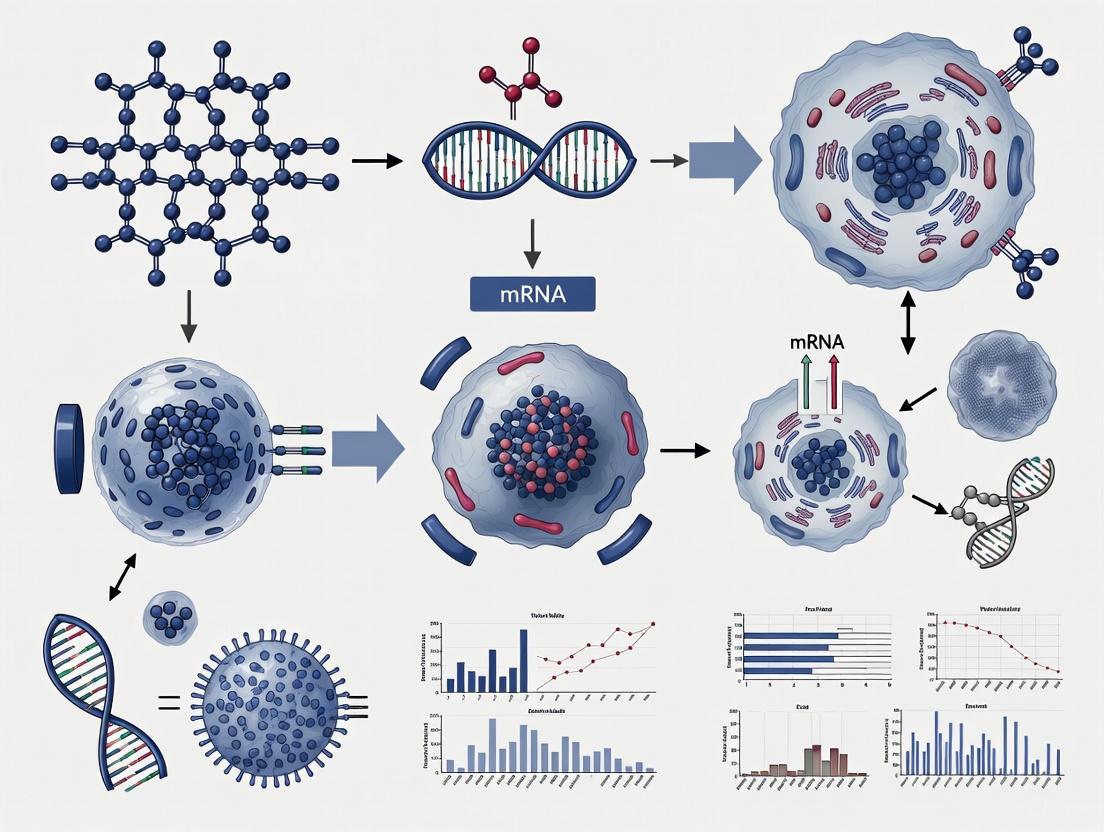

Diagram 2: Experimental workflow for mRNA-mediated cellular reprogramming. The process involves iterative mRNA transfections with critical quality control checkpoints at each stage to ensure successful phenotype conversion.

Applications in Specific Tissue Regeneration

Cardiovascular Regeneration

mRNA technology has shown significant promise in cardiovascular repair. Direct intramyocardial injection of VEGF-encoding mRNA has been investigated in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting to promote therapeutic angiogenesis [3] [6]. In preclinical models, direct reprogramming of cardiac fibroblasts into cardiomyocyte-like cells using mRNA-encoded transcription factors (Gata4, Mef2c, Tbx5) has demonstrated potential for regenerating functional myocardium without cell transplantation [3].

Neural Regeneration

The field of neurology has witnessed remarkable advances with mRNA-based reprogramming approaches. Studies have successfully demonstrated the direct conversion of human astrocytes into functional dopamine neurons using mRNA-encoded transcription factors (Ascl1, Nurr1, Lmx1a) in Parkinson's disease models [3]. Similarly, reprogramming of fibroblasts to functional neurons has been achieved using modified mRNA cocktails, offering potential for neurodegenerative disease modeling and cell-based therapies [3].

Metabolic and Hepatic Regeneration

For metabolic disorders, mRNA technology enables in vivo production of missing or deficient enzymes. Approaches include direct reprogramming of human fibroblasts to hepatocyte-like cells using synthetic mRNA encoding hepatic transcription factors (HNF1A, HNF4A, HNF6) [3]. Clinical trials are underway for mRNA-based treatments of inherited metabolic diseases like ornithine transcarbamylase deficiency and Crigler-Najjar syndrome, where mRNA-encoded enzymes correct metabolic abnormalities in preclinical models [6].

Table 2: mRNA-Based Cellular Reprogramming Approaches in Regenerative Medicine

| Target Cell Type | Reprogramming Factors | Source Cells | Key Applications | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| iPSCs | Oct4, Sox2, Klf4, c-Myc | Human fibroblasts | Pluripotency establishment, disease modeling | [3] |

| Cardiomyocytes | Gata4, Mef2c, Tbx5 | Cardiac fibroblasts | Heart regeneration after myocardial infarction | [3] |

| Dopaminergic Neurons | Ascl1, Nurr1, Lmx1a | Human astrocytes | Parkinson's disease therapy | [3] |

| Hepatocytes | HNF1A, HNF4A, HNF6 | Human fibroblasts | Liver regeneration, metabolic disease | [3] |

| Hematopoietic Progenitors | ETV2, GATA2, c-MYB | Human pluripotent stem cells | Blood cell regeneration | [3] |

Research Reagents and Methodological Toolkit

Successful implementation of mRNA-based reprogramming protocols requires specialized reagents and methodologies. The following table summarizes essential research tools and their applications in mRNA therapeutic development.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for mRNA-Based Reprogramming Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function & Application | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nucleoside Modifications | N1-methylpseudouridine, 5-methylcytidine | Reduce immunogenicity, enhance translation | Critical for in vivo applications; suppresses TLR recognition [5] |

| Capping Systems | CleanCap, VCE, PureCap | 5' cap addition for mRNA stability and translation | PureCap enables complete capping and superior purity [2] |

| In Vitro Transcription Kits | T7 polymerase-based systems | mRNA synthesis from DNA templates | Commercial systems available with optimized buffer formulations |

| Lipid Nanoparticles | Ionizable cationic lipids, PEG lipids | mRNA encapsulation and delivery | Composition affects tropism and endosomal escape efficiency [5] |

| Purification Systems | HPLC, FPLC | Removal of dsRNA contaminants and uncapped mRNA | Essential for reducing immune activation and improving yield [2] |

| Quality Control Assays | Agarose gel electrophoresis, LC-MS | mRNA purity, integrity, and modification analysis | Confirm absence of dsRNA contaminants for reduced immunogenicity |

Clinical Translation and Current Challenges

Clinical Development Landscape

The clinical application of mRNA therapeutics has expanded dramatically beyond COVID-19 vaccines. Current clinical trials encompass multiple domains, including infectious disease vaccines (influenza, RSV, HIV), cancer immunotherapies, protein replacement therapies, and regenerative medicine applications [1] [6]. Personalized cancer vaccines utilizing mRNA encoding patient-specific neoantigens have shown promising results in clinical trials, particularly when combined with immune checkpoint inhibitors [6]. In the regenerative medicine space, several mRNA-based candidates have entered clinical development, including VEGF-encoding mRNA for cardiovascular repair and mRNA-encoded enzymes for metabolic disorders [3] [6].

The manufacturing process for mRNA therapeutics has been streamlined to support clinical development, with current production timelines significantly shorter than those for traditional biologics. The entire process—from sequence design to purified mRNA—can be completed in weeks, facilitating rapid iteration and optimization [7] [1]. This agility is particularly valuable for personalized applications such as cancer neoantigen vaccines, where timely production is critical.

Technical Hurdles and Research Frontiers

Despite substantial progress, several technical challenges must be addressed to fully realize the potential of mRNA-based regenerative medicine. Precise control of protein expression dynamics remains difficult with current LNP platforms, as mRNA inherently produces transient expression requiring repeated administration for sustained effect [3]. While this transient nature is advantageous for safety, it complicates applications requiring prolonged protein expression. Emerging solutions include self-amplifying RNA (saRNA) systems derived from alphaviruses that enable longer-lasting expression from lower doses, and circular RNA (circRNA) constructs with superior stability owing to their resistance to exonuclease degradation [1].

Tissue-specific delivery represents another major hurdle. Current LNP systems predominantly target the liver following intravenous administration, limiting applications for other tissues [2] [3]. Research efforts are focused on developing selective organ targeting (SORT) LNPs through systematic modulation of lipid compositions and incorporation of targeting ligands [3]. Additionally, the inefficient endosomal escape of mRNA-LNP complexes significantly limits translational output, with typically less than 2% of internalized mRNA reaching the cytosol [2]. Novel ionizable lipids with improved endosomolytic properties are under active investigation to address this bottleneck.

Immunogenicity concerns persist even with nucleoside-modified mRNA, particularly for regenerative applications where immune activation is undesirable. While modifications reduce recognition by innate immune sensors, they do not eliminate it completely [1]. Further refinement of purification methods to remove immunogenic contaminants like dsRNA, combined with advanced cap structures and sequence engineering, may address this limitation.

mRNA technology has undergone a remarkable transformation from a pandemic response tool to a versatile platform with far-reaching implications for regenerative medicine and cellular reprogramming. The foundational breakthroughs in nucleoside chemistry, delivery systems, and manufacturing processes have positioned mRNA therapeutics as a disruptive force in biomedical science. As research advances, the convergence of mRNA technology with gene editing tools like CRISPR-Cas9 presents particularly exciting opportunities, with mRNA-encoded editors offering transient, efficient genome modification without the risks associated with viral delivery [3].

The future trajectory of mRNA-based regenerative medicine will likely focus on several key areas: development of novel delivery systems with enhanced tissue specificity and endosomal escape efficiency; creation of more sophisticated mRNA constructs with tunable expression kinetics; and integration of mRNA technology with tissue engineering approaches for complex organ regeneration. As these innovations mature, mRNA-based cell fate reprogramming stands to revolutionize therapeutic approaches for degenerative diseases, traumatic injuries, and genetic disorders, ultimately fulfilling the promise of regenerative medicine to restore form and function to damaged tissues and organs.

The discovery that somatic cells could be reprogrammed into induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) using defined transcription factors marked a transformative milestone in regenerative medicine [8]. Traditional reprogramming methodologies, particularly those employing viral vectors such as retroviruses and lentiviruses, have been instrumental in advancing the field but present significant clinical translation challenges due to their inherent risk of genomic integration [8] [9]. These integrating vectors can disrupt host genomes, increase tumorigenic potential through insertional mutagenesis, and lead to persistent transgene expression that may interfere with iPSC differentiation and function [10] [9]. In response to these limitations, messenger RNA (mRNA)-based reprogramming has emerged as a powerful "footprint-free" alternative that avoids genomic integration while offering unprecedented control over reprogramming factor expression [11] [9]. This technical guide examines the scientific basis, methodological protocols, and emerging applications of mRNA technology in iPSC generation, framing this discussion within the broader context of mRNA-based cell fate reprogramming research.

The Viral Vector Challenge: Safety and Limitations

Initial iPSC generation relied heavily on viral delivery systems for introducing the Yamanaka factors (OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, and c-MYC). While effective, these systems present considerable hurdles for clinical translation:

- Genomic Integration Risks: Retroviral and lentiviral vectors integrate into the host genome, creating potential for insertional mutagenesis and oncogene activation [9]. This poses significant safety concerns for therapeutic applications.

- Persistent Transgene Expression: Integrated transgenes can remain active in iPSCs and their derivatives, potentially interfering with differentiation capacity and functional maturation of target cells [11].

- Immune Recognition: Viral components may trigger immune responses against both the delivery vector and the reprogrammed cells [12].

- Ethical and Regulatory Hurdles: The use of viral vectors involves more complex regulatory approval pathways compared to non-integrating methods [8].

Although non-integrating viral approaches such as Sendai virus have been developed, complete clearance of viral remnants from reprogrammed cells requires lengthy culture periods and rigorous validation [9].

mRNA Technology: A "Footprint-Free" Alternative

Fundamental Advantages

mRNA-based reprogramming represents a fundamentally different approach that addresses the core limitations of viral vectors:

- No Genomic Integration: As mRNA functions entirely in the cytoplasm without entering the nucleus, it presents zero risk of insertional mutagenesis [11] [9]. The reprogramming factors never interact with the host genome.

- Transient Expression Profile: mRNA has a relatively short intracellular half-life (typically 24-48 hours), allowing for precise, temporal control over reprogramming factor expression through repeated transfections [11].

- Rapid Clearance: Unlike DNA vectors or viruses, mRNA does not require a "cleanup phase" to purge residual reprogramming elements once pluripotency is established [11].

- High Reprogramming Efficiency: Modern mRNA protocols can achieve reprogramming efficiencies equaling or surpassing viral methods [11].

Key Technological Innovations

The practical implementation of mRNA reprogramming has been enabled by several critical innovations:

- Nucleotide Modification: Incorporation of modified nucleosides such as pseudouridine (ψU) and 5-methylcytidine (5mC) reduces innate immune recognition by pattern recognition receptors (TLR7, TLR8), minimizing interferon responses that otherwise inhibit reprogramming [9] [1].

- Optimized UTR Designs: Engineering 5' and 3' untranslated regions (UTRs) derived from highly stable endogenous mRNAs (e.g., α-globin, β-globin) significantly enhances mRNA stability and translational efficiency [9].

- Advanced Capping Systems: Anti-reverse cap analogs (ARCAs) ensure proper 5' cap orientation, improving ribosomal binding and translation initiation while protecting against exonuclease degradation [9].

Table 1: Comparison of iPSC Reprogramming Methods

| Method | Genomic Integration | Reprogramming Efficiency | Safety Profile | Technical Complexity | Clinical Translation Potential |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Retroviral/Lentiviral | Yes | 0.01%-0.1% [9] | Low (insertional mutagenesis risk) | Moderate | Limited |

| Sendai Virus | No | 0.01%-1% [9] | Moderate (viral persistence concerns) | Moderate | Moderate |

| Episomal Plasmids | No (low frequency) | 0.04%-0.3% [9] | Moderate (potential plasmid persistence) | Moderate | Moderate |

| mRNA-Based | No | ~1-4% [11] | High (truly footprint-free) | High | High |

Experimental Protocols: Implementing mRNA Reprogramming

Core Workflow and Methodology

The following workflow outlines the optimized procedure for mRNA-based iPSC generation:

Detailed Protocol Components

mRNA Reprogramming Cocktail Formulation

Advanced mRNA cocktails have evolved beyond the canonical Yamanaka factors to enhance reprogramming kinetics and efficiency:

- Engineered Transcription Factors: The M3O variant of Oct4, incorporating an N-terminal MyoD transactivation domain, demonstrates significantly improved reprogramming efficiency compared to wild-type Oct4 [11].

- Supplemental Factors: Addition of Nanog to the core cocktail (OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, c-Myc, LIN28) dramatically improves colony formation efficiency [11].

- Stability-Optimized Constructs: The c-Myc-T58A mutation enhances protein stability by eliminating phosphorylation-dependent degradation signals [11].

Feeder-Free Culture Conditions

Modern protocols have eliminated the requirement for feeder layers through strategic culture optimization:

- Matrix Substitution: Use of synthetic substrates (e.g., Matrigel, vitronectin) replaces mouse embryonic fibroblasts, removing a source of variability and potential xeno-contamination [11].

- Density Optimization: Precise initial plating densities (e.g., 10,000 BJ fibroblasts per well in 12-well plates) maintain cell viability while preventing premature confluence that impedes transfection efficiency [11].

- Dynamic Suspension Culture: Implementation of suspension culture systems significantly enhances reprogramming efficiency for GO-PEI-RNA complex delivery [10].

mRNA Delivery and Transfection

Successful mRNA reprogramming requires optimized delivery strategies:

- Daily Transfection Protocol: Repeated transfection over 12-18 days is typically required to establish and stabilize pluripotency [11].

- Advanced Delivery Vehicles: Graphene oxide-polyethylenimine (GO-PEI) complexes demonstrate efficient mRNA delivery while protecting transcripts from RNase degradation [10].

- Dose Optimization: mRNA concentrations must balance expression efficiency against cytotoxicity, typically ranging from 0.5-1.0 µg per well in 12-well plates [11].

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for mRNA Reprogramming

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function | Optimization Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reprogramming mRNAs | M3O-Oct4, Sox2, Klf4, c-Myc-T58A, Lin28, Nanog [11] | Induce pluripotency in somatic cells | M3O-Oct4 variant provides 3x efficiency improvement vs. wild-type |

| Delivery Vehicles | GO-PEI complexes [10], lipid nanoparticles | Protect mRNA and facilitate cellular uptake | GO-PEI protects from RNase degradation; enables single-transfection |

| Culture Matrices | Matrigel, vitronectin, synthetic peptides | Replace feeder cells in xeno-free systems | Enables feeder-free reprogramming and clinical compliance |

| mRNA Modifications | Pseudouridine (ψU), 5-methylcytidine (5mC) [9] | Reduce immunogenicity, enhance stability | Critical for minimizing interferon response |

| Small Molecule Enhancers | Valproic acid, 8-Br-cAMP [13] | Improve reprogramming efficiency | 8-Br-cAMP with VPA increases efficiency 6.5-fold |

Molecular Mechanisms: How mRNA Reprogramming Reshapes Cell Identity

The process of mRNA-mediated reprogramming involves sophisticated molecular restructuring:

Key Mechanistic Insights

- Transient Factor Expression: Daily mRNA transfections create pulsatile expression of reprogramming factors that progressively reshape the epigenetic landscape without genomic integration [11].

- Metabolic Reprogramming: The reprogramming process induces a shift from oxidative phosphorylation to glycolysis, essential for establishing pluripotency [8].

- Epigenetic Restructuring: mRNA-derived factors activate TET enzymes that promote DNA demethylation at pluripotency loci like the OCT4 promoter [8].

- Endogenous Network Activation: Ultimately, exogenous factor expression is replaced by activation of endogenous pluripotency networks, establishing a self-sustaining pluripotent state [8].

Technical Challenges and Optimization Strategies

Despite its advantages, mRNA reprogramming presents specific technical challenges that require strategic optimization:

- Interferon Response: Unmodified mRNA can activate pattern recognition receptors (TLR7, TLR8), triggering type I interferon secretion that inhibits reprogramming. This is mitigated through nucleoside modifications (ψU, 5mC) [9].

- Cytotoxicity: Repeated transfections and robust transgene expression can induce cellular stress and apoptosis. Optimization of mRNA dosage and transfection intervals is critical [11].

- Labor Intensity: The requirement for daily transfections over 12+ days makes the process more hands-on than viral methods. Partial automation and suspension culture formats can alleviate this constraint [10].

- Cell Type Variability: Certain somatic cell types (especially blood cells) exhibit lower transfection efficiency. Pre-conditioning strategies and alternative delivery systems may be required [11].

Emerging Applications and Future Directions

mRNA-mediated iPSC generation serves as a foundational technology enabling numerous advanced applications:

Disease Modeling and Drug Discovery

iPSCs generated via mRNA reprogramming provide unique opportunities for human disease modeling:

- Neurological Disorders: Patient-specific iPSCs have been differentiated into motor neurons to study amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) mechanisms and screen potential therapeutics [13].

- Cardiac Conditions: iPSC-derived cardiomyocytes enable modeling of inherited arrhythmias and functional drug testing in human-relevant systems [8].

- Personalized Medicine: mRNA-reprogrammed iPSCs from individual patients facilitate development of patient-specific disease models and therapeutic screening platforms [14].

Clinical Translation and Therapeutic Applications

The footprint-free nature of mRNA-reprogrammed iPSCs positions them ideally for clinical applications:

- Regenerative Medicine: Multiple clinical trials are underway using iPSC-derived dopaminergic progenitors for Parkinson's disease treatment, demonstrating safety and functional integration [8].

- Retinal Therapies: iPSC-derived retinal pigment epithelial (RPE) products like Eyecyte-RPE have received regulatory approval for geographic atrophy associated with age-related macular degeneration [8].

- Personalized Cell Therapies: Autologous iPSC-derived dopamine neuron trials pioneer the use of patient-specific cells without immune suppression [8].

Technological Convergence

The future of mRNA reprogramming lies in its integration with other cutting-edge technologies:

- CRISPR-Cas9 Integration: Combined mRNA and CRISPR systems enable correction of genetic defects in patient-derived iPSCs before differentiation and transplantation [8] [15].

- AI-Guided Optimization: Machine learning approaches are being applied to predict differentiation outcomes, classify colony morphology, and enhance standardization in iPSC manufacturing [8] [15].

- Organoid Generation: mRNA-reprogrammed iPSCs facilitate development of complex 3D organoid models that better recapitulate tissue architecture and disease pathology [15].

mRNA-based reprogramming represents a paradigm shift in iPSC generation, effectively overcoming the fundamental safety limitations of viral vector systems. Through its footprint-free mechanism, precise temporal control, and high reprogramming efficiency, this technology has established itself as the gold standard for clinical-grade iPSC generation. The continued refinement of mRNA design, delivery systems, and culture protocols will further enhance the accessibility and applicability of this powerful technology. As mRNA reprogramming converges with advances in gene editing, bioengineering, and computational biology, it promises to accelerate the development of personalized regenerative therapies and human disease models, ultimately fulfilling the transformative potential of iPSC technology in both research and clinical domains.

The development of mRNA-based technologies for cell fate reprogramming represents a paradigm shift in regenerative medicine. The core of this technology lies in the sophisticated engineering of mRNA structural elements: the 5' cap, 5' and 3' untranslated regions (UTRs), open reading frame (ORF), and poly(A) tail. Together, these components determine the stability, translational efficiency, and immunogenicity of mRNA transcripts, enabling safe and efficient reprogramming of somatic cells without genomic integration. This technical guide examines the precise function and optimization strategies for each mRNA component within the context of induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) generation, providing researchers with a foundation for developing advanced mRNA therapeutics for cell fate conversion.

mRNA-based technology has emerged as a powerful platform for cell fate reprogramming since the landmark discovery that synthetic mRNA can encode transcription factors to convert somatic cells into induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) [16]. Unlike viral vectors that pose risks of genomic integration and insertional mutagenesis, mRNA offers a transient, non-integrating approach for expressing reprogramming factors such as OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, and c-Myc (OSKM) [9] [16]. The successful application of mRNA for somatic reprogramming depends on the careful engineering of its structural components to maximize protein expression while minimizing innate immune responses [17] [18]. This guide provides an in-depth examination of these structural elements and their optimization for therapeutic applications, particularly in cell fate reprogramming research.

Structural Components of Therapeutic mRNA

The 5' Cap

Function and Importance: The 5' cap is a modified guanine nucleotide (m7G) added to the 5' end of mRNA via a 5'-5'-triphosphate linkage [9] [19]. This structure is critical for nuclear export, protection from RNase degradation, and recruitment of translation initiation factors [18] [19]. Perhaps most importantly, the cap structure allows differentiation between self and non-self mRNA molecules, with specific cap configurations evading innate immune recognition [19].

Optimization Strategies: Cap 0 (m7GpppN) undergoes methylation to form Cap 1, which evades recognition by cytosolic innate immune receptors like RIG-I [19]. Anti-reverse cap analogs (ARCAs) are designed to incorporate exclusively in the correct orientation, preventing degradation by Dcp2 and significantly enhancing translation efficiency and mRNA stability [9] [19]. Recent advances include trimeric cap analogs that yield Cap 1 structures with improved capping efficiency and gene expression profiles ideal for therapeutic applications [19].

Table 1: 5' Cap Structures and Their Characteristics

| Cap Type | Structure | Immune Recognition | Translation Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cap 0 | m7GpppN | High (RIG-I recognized) | Moderate |

| Cap 1 | m7GpppNmN | Low (evades RIG-I) | High |

| ARCA Cap | Modified m7GpppN | Low | Very High |

| Trimetric Cap | Complex m7GpppNmN | Very Low | Very High |

5' and 3' Untranslated Regions (UTRs)

Function and Importance: UTRs flank the coding region and contain regulatory elements that influence mRNA stability, subcellular localization, and translational efficiency [9] [18]. The 5' UTR facilitates ribosome binding and scanning, while the 3' UTR contains binding sites for regulatory proteins and miRNAs that influence mRNA half-life [9].

Optimization Strategies: Effective UTR optimization involves several key principles: (1) eliminating upstream start codons that might disrupt ORF translation, (2) avoiding highly stable secondary structures that impede ribosome scanning, and (3) implementing shorter UTRs that generally enhance translation efficiency [18]. For therapeutic mRNA, UTRs from highly expressed genes like α-globin and β-globin are frequently employed because they contain sequence features that significantly enhance both translation and stability [20] [18]. Some advanced designs incorporate two consecutive 3' UTRs in a head-to-tail orientation to further enhance stability and expression levels [18].

Coding Region (Open Reading Frame)

Function and Importance: The open reading frame (ORF) contains the protein-coding sequence, beginning with a start codon (AUG) and ending with a stop codon [9]. For reprogramming applications, the ORF typically encodes transcription factors such as the Yamanaka factors (OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, c-Myc) or their optimized variants [21].

Optimization Strategies:

- Codon Optimization: Replacing rare codons with frequently used synonymous codons enhances translation efficiency by matching tRNA abundance in target cells [18] [19]. This optimization must also consider that some proteins require delayed translation facilitated by rare codons for proper folding [18].

- Nucleotide Modification: Incorporating modified nucleosides such as pseudouridine (ψ), 5-methylcytidine (m5C), and N1-methylpseudouridine (m1ψ) reduces immunogenicity by evading Toll-like receptor recognition while increasing translation efficiency [9] [18] [19]. These modifications were crucial in the development of successful mRNA reprogramming protocols [16].

- GC Content: Increasing GC-content can enhance translation efficiency, though excessive GC-richness may create problematic secondary structures [18].

Poly(A) Tail

Function and Importance: The poly(A) tail is a stretch of adenosine residues (typically 70-200 nucleotides in length) at the 3' end of mRNA that plays critical roles in stability, nuclear export, and translation efficiency [22] [23]. In the cytoplasm, poly(A) binding protein (PABPC) binds the tail and interacts with translation initiation factors at the 5' end, forming a closed-loop complex that enhances ribosomal recycling and protects mRNA from degradation [22] [23].

Optimization Strategies: Poly(A) tail length significantly influences translational efficiency, with optimal lengths typically ranging from 100-150 nucleotides for therapeutic applications [23]. While longer tails generally enhance stability and translation, excessively long tails may interfere with closed-loop formation [23]. Two primary methods exist for adding poly(A) tails to in vitro transcribed (IVT) mRNA: template-encoded polyadenylation (which produces consistent tail lengths) and enzymatic polyadenylation (which offers flexibility but yields variable lengths) [23].

Table 2: Impact of Poly(A) Tail Length on mRNA Function

| Tail Length (nt) | Stability | Translation Efficiency | Production Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| <50 | Low | Low | Easy to produce |

| 70-100 | Moderate | Moderate | Standard production |

| 100-150 | High | High (optimal) | Ideal balance |

| >150 | Very High | Potential decrease | Difficult to clone and maintain |

Experimental Protocols for mRNA Reprogramming

mRNA Synthesis and Modification

Template Design: Clone the gene of interest (e.g., OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, c-Myc) into an IVT vector containing optimized 5' and 3' UTRs (e.g., α-globin or β-globin UTRs) and a template-encoded poly(A) tail of defined length (100-120 nucleotides) [23]. For large-scale production, segmented poly(A) approaches with spacer sequences between poly(A) segments reduce plasmid recombination in E. coli [19].

In Vitro Transcription: Perform IVT reactions using T7 RNA polymerase with modified nucleotides (e.g., N1-methylpseudouridine instead of uridine) to reduce immunogenicity [9] [19]. Include ARCA cap analogs or use enzymatic capping methods post-transcription to ensure proper Cap 1 formation [19]. Purify the resulting mRNA using HPLC or cellulose-based methods to remove double-stranded RNA contaminants that trigger innate immune responses [20].

Cell Transfection and Reprogramming

Cell Preparation: Culture human fibroblasts or other target somatic cells in appropriate growth media. For reprogramming, cells should be at early passages and 50-80% confluent at the time of first transfection [16] [21].

mRNA Transfection: Transfect cells daily with 0.5-1 µg/mL of each modified mRNA encoding reprogramming factors using appropriate transfection reagents [16]. Daily transfections are necessary to maintain sufficient levels of reprogramming factors due to mRNA's relatively short half-life [16].

Immunogenicity Management: Include interferon inhibitors such as B18R in the culture medium to suppress antiviral responses triggered by exogenous mRNA [16]. The combination of nucleotide modifications and interferon suppression enables sustained protein expression without excessive cytotoxicity [16].

Reprogramming Timeline: Continue daily transfections for approximately 2-3 weeks, monitoring for emergence of embryonic stem cell-like colonies expressing pluripotency markers (SSEA-4, TRA-1-60, NANOG) [16] [21]. The entire process using optimized mRNA factors is significantly faster (about two times) and more efficient (35-fold higher) than viral methods [16].

Visualization of mRNA Structure and Function

mRNA Closed-Loop Model and Translation

Diagram 1: mRNA Closed-Loop Model for Efficient Translation. This illustrates how the 5' cap and 3' poly(A) tail interact via protein complexes to form a circular structure that enhances translational efficiency by promoting ribosomal recycling.

mRNA Reprogramming Workflow

Diagram 2: mRNA-Based Cellular Reprogramming Workflow. This chart outlines the key steps in converting somatic cells to induced pluripotent stem cells using modified mRNA, highlighting the cyclical nature of daily transfections required for successful reprogramming.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents for mRNA Reprogramming Research

| Reagent / Material | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| IVT Vector with UTRs | Template for mRNA synthesis | Contains optimized 5' and 3' UTRs (e.g., β-globin) |

| Modified Nucleotides | Reduce immunogenicity, enhance stability | N1-methylpseudouridine, 5-methylcytidine |

| ARCA Cap Analogs | Ensure proper 5' capping | Prevent reverse incorporation, enhance translation |

| T7 RNA Polymerase | In vitro transcription | High-yield mRNA synthesis |

| Poly(A) Polymerase | Enzymatic polyadenylation | Alternative to template-encoded tails |

| B18R Interferon Inhibitor | Suppress innate immune response | Critical for repeated transfections |

| Lipid Nanoparticles | mRNA delivery vehicles | Protect mRNA, enhance cellular uptake |

| Pluripotency Markers | Assess reprogramming success | Antibodies for SSEA-4, TRA-1-60, NANOG |

Applications in Cell Fate Reprogramming

The structural optimization of mRNA components has been crucial for advancing cell fate reprogramming technologies. Modified mRNA encoding Yamanaka factors has demonstrated remarkable efficiency in generating iPSCs from various somatic cell types, including fibroblasts, mesenchymal stem cells, and amniotic fluid stem cells [9]. Recent advances include AI-assisted engineering of enhanced reprogramming factors, such as RetroSOX and RetroKLF variants, which have shown a 50-fold increase in expression of stem cell reprogramming markers compared to wild-type factors [21]. These optimized factors also demonstrate enhanced DNA damage repair capabilities, suggesting improved rejuvenation potential [21].

The versatility of mRNA technology extends beyond iPSC generation to direct lineage conversion, where specialized cell types are produced without transitioning through a pluripotent state [16]. Furthermore, mRNA-synthesized chimeric antigen receptors (CARs) enable the production of safer CAR-T cells without genomic integration risks [17]. The transient nature of mRNA expression is particularly advantageous for precise control over reprogramming dynamics, allowing researchers to fine-tune the duration and levels of transcription factor expression [16].

The precise engineering of mRNA structural elements—5' cap, UTRs, coding region, and poly(A) tail—has transformed mRNA from a simple genetic messenger to a powerful therapeutic tool for cell fate reprogramming. Through strategic modifications that enhance stability, translation, and immune evasion, researchers have developed mRNA platforms that safely and efficiently reprogram somatic cells to pluripotency. As optimization strategies continue to evolve, including AI-assisted protein design and novel nucleotide modifications, mRNA technology holds unprecedented potential for regenerative medicine, disease modeling, and personalized cell therapies. The continued refinement of each mRNA component promises to further enhance the efficacy and applicability of this transformative technology.

The groundbreaking work of Katalin Karikó and Drew Weissman, awarded the 2023 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, addressed a fundamental barrier that had hindered mRNA therapeutic development for decades: the innate immune system's violent reaction to externally delivered mRNA [24] [25]. Their discovery that nucleoside base modifications could render synthetic mRNA non-immunogenic has not only enabled the development of effective COVID-19 vaccines but has also created a powerful new platform for cell fate reprogramming research. This whitepaper details the technical underpinnings of this breakthrough, its application in somatic cell reprogramming, and the essential toolkit for researchers leveraging this technology.

The conceptual appeal of using messenger RNA (mRNA) as a therapeutic or research tool is profound. It enables the cell's own machinery to produce almost any protein of interest, without the risk of genomic integration posed by viral vectors [26]. However, early attempts to harness this potential were thwarted by a critical obstacle. In vitro transcribed (IVT) mRNA was recognized as foreign by the host's immune system, triggering robust inflammatory responses and leading to the suppression of protein translation [24] [2].

This innate immune detection occurs through various pattern recognition receptors (PRRs), including Toll-like receptors (TLR7, TLR8) in endosomes and cytosolic sensors like RIG-I and PKR [27] [26]. Upon binding exogenous RNA, these receptors activate signaling cascades that result in the production of type I interferons and pro-inflammatory cytokines, effectively halting the practical application of mRNA technologies [27]. Karikó and Weissman's seminal insight was to investigate how mammalian cells distinguish their own native mRNA, which is not inflammatory, from synthetic IVT mRNA.

The Breakthrough Discovery: Mimicking Self

Core Hypothesis and Experimental Rationale

Karikó and Weissman hypothesized that the key distinction lay in the chemical composition of the nucleosides. They observed that bases in RNA from mammalian cells are frequently chemically modified, whereas standard IVT mRNA incorporates only natural, unmodified nucleosides [24]. This led them to investigate whether the absence of these altered bases in IVT mRNA explained its unwanted immunogenicity.

Key Experimental Methodology

To test their hypothesis, they produced multiple variants of mRNA, each with unique chemical alterations in their bases. They focused on modifications naturally found in mammalian RNA, particularly the replacement of uridine with pseudouridine (Ψ) [24]. The experimental workflow involved:

- In Vitro Transcription: Synthesis of mRNA using modified nucleoside triphosphates (e.g., pseudouridine-5'-triphosphate).

- Cell Transfection: Delivery of these base-modified mRNA variants to dendritic cells, which are key sentinels of the immune system.

- Immune Response Assessment: Measurement of inflammatory cytokine release and interferon signaling to quantify the immune activation.

- Protein Expression Analysis: Evaluation of the translational capacity of the modified mRNA by detecting the encoded protein.

Seminal Results and Impact

Their results, published in the landmark 2005 paper, were striking. The inflammatory response was almost abolished when base modifications like pseudouridine were incorporated into the mRNA [24]. This represented a paradigm shift in understanding how cells recognize and respond to different forms of RNA. Subsequent work in 2008 and 2010 demonstrated that base-modified mRNA not only evaded immune detection but also exhibited markedly increased protein production due to reduced activation of enzymes like PKR that suppress translation [24].

Table 1: Key Nucleoside Modifications and Their Effects

| Nucleoside Modification | Replaces | Key Immunogenic Effects | Impact on Translation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pseudouridine (Ψ) | Uridine | Reduces activation of TLR7, TLR8, PKR, and RIG-I [27] [28] | Increases protein production [24] |

| N1-methylpseudouridine (m1Ψ) | Uridine | Superior reduction of immunogenicity; used in COVID-19 vaccines [27] [28] | Further enhances translational capacity [28] |

| 5-methylcytidine (m5C) | Cytidine | Attenuates innate immune sensing [29] | Improves mRNA stability and expression |

| 5-methyluridine (m5U) | Uridine | Reduces recognition by immune receptors [28] | Can improve stability and translation |

This breakthrough provided the foundational technology to finally realize the potential of mRNA therapeutics, paving the way for vaccines and new approaches to cell reprogramming.

Application in Cell Fate Reprogramming

The ability to safely and efficiently express specific proteins in cells is the cornerstone of directed cell fate change. The nucleoside modification technology enabled a new, superior method for generating induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells.

Overcoming Limitations of Traditional Reprogramming

The original method for creating iPS cells, pioneered by Shinya Yamanaka, involved introducing four transcription factors (OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, c-MYC) using integrating retroviral vectors [2] [30]. This approach carries the risk of insertional mutagenesis and potential tumorigenesis, as the oncogenes c-Myc and Klf4 are integrated into the genome [2] [29]. While subsequent non-integrating methods were developed, they often suffered from very low reprogramming efficiencies [29].

mRNA-Based Reprogramming Protocol

The modified mRNA platform offers a safe and highly efficient alternative. A seminal study demonstrated that repeated transfections of modified mRNA encoding the reprogramming factors could reprogram human somatic cells to pluripotency [29]. The key procedural steps are outlined below.

The critical technical considerations for this protocol include:

- Modified Nucleosides: The mRNA is synthesized to incorporate pseudouridine (Ψ) and 5-methylcytidine (5mC), which dramatically reduce cytotoxicity and interferon responses, allowing for sustained daily transfections [29].

- Interferon Suppression: The culture medium is supplemented with the B18R protein, a decoy receptor for type I interferons, to further dampen any residual innate immune signaling [29].

- Transfection Regimen: A daily, repeated transfection schedule is required to maintain high levels of protein expression because the mRNA and its protein products are transiently expressed [29].

Outcomes and Advantages

This mRNA-based strategy results in reprogramming efficiencies and kinetics substantially superior to established viral protocols [29]. The resulting RNA-induced pluripotent stem (RiPS) cells are genomically pristine, free of vector integration, and can be further differentiated into desired cell lineages using the same modified mRNA technology to express differentiation factors [29]. This creates a completely non-integrating, highly controllable pipeline for regenerative medicine research.

Implementing nucleoside-modified mRNA technology requires a suite of key reagents, each with a specific function crucial for success.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for mRNA-Based Reprogramming

| Reagent / Material | Function | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Modified Nucleoside Triphosphates (e.g., N1-methylpseudouridine-5'-TP) | Incorporation into IVT mRNA to evade innate immune recognition and enhance translation [24] [28]. | Total replacement of uridine is standard. Co-modification with 5-methylcytidine can offer further benefits [29]. |

| In Vitro Transcription Kit | Enzymatic synthesis of mRNA from a linear DNA template using T7, T3, or SP6 RNA polymerase [28]. | Must be compatible with modified NTPs. Critical to minimize double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) contaminants [26]. |

| 5' Capping Reagent | Adds a 5' cap structure (e.g., Cap 1) to mRNA, essential for translation initiation and reducing immune sensing by RIG-I [2] [26]. | Co-transcriptional capping (e.g., CleanCap) or enzymatic post-transcription capping (e.g., VCE) can be used. |

| Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) | Formulate mRNA for efficient cellular delivery; protect mRNA from degradation; facilitate endosomal escape [27] [2]. | Ionizable lipids are key for adjuvant activity and endosomal disruption. Tissue-specific LNP formulations are an area of active research. |

| B18R Recombinant Protein | Inhibits type I interferons by acting as a decoy receptor, mitigating residual interferon-driven cytotoxicity during repeated transfections [29]. | Particularly important in sensitive primary cell types. |

| Cationic Transfection Reagent | Complexes with negatively charged mRNA to facilitate cellular uptake via endocytosis for in vitro applications. | Suitable for repeated transfections with low baseline cytotoxicity. |

Karikó and Weissman's discovery of nucleoside base modifications was a transformative event in biomedical science. By solving the problem of mRNA immunogenicity, they unlocked a versatile and powerful platform that extends far beyond vaccines. In the field of cell fate reprogramming, this technology provides researchers with an unprecedentedly safe, efficient, and precise tool to manipulate cellular identity for basic research, disease modeling, and the development of future regenerative therapies. As innovations in mRNA design, delivery, and application continue to emerge, this platform is poised to remain at the forefront of biological research and therapeutic development.

The advent of mRNA-based technology has revolutionized the field of cell fate reprogramming, offering two primary pathways for engineering cellular identity: induced pluripotency, which reverts somatic cells to a pluripotent state, and direct lineage conversion, which transdifferentiates one somatic cell type directly into another. This whitepaper provides a technical guide to these endpoints, detailing the underlying mechanisms, experimental protocols, and key advantages of mRNA reprogramming. Framed within the broader context of mRNA technology for cell fate engineering, we highlight how synthetic mRNA, through its precision, safety, and transience, enables efficient reprogramming without genomic integration. For researchers and drug development professionals, this document synthesizes current methodologies, quantitative data, and essential reagent toolkits to advance therapeutic applications in regenerative medicine and disease modeling.

Messenger RNA (mRNA) technology has emerged as a transformative platform for programming and reprogramming human cell fate. Its application in reprogramming leverages the cell's own translational machinery to transiently express proteins that dictate cellular identity, a process that is both non-integrating and highly controllable [29] [31]. In the context of a broader thesis on mRNA-based cell fate research, this technology represents a pivotal tool for manipulating cellular function for basic research, disease modeling, and regenerative medicine [32].

Cellular reprogramming approaches can be broadly categorized. Reprogramming to induced pluripotency reverses mature, specialized cells to a pluripotent state, regaining the potential to differentiate into any cell type. In contrast, direct reprogramming or transdifferentiation converts one somatic cell type directly into another without passing through an intermediate pluripotent stage [33]. mRNA technology has proven applicable to both strategies, enabling efficient derivation of RNA-induced pluripotent stem (RiPS) cells and direct differentiation into terminally differentiated cells, such as myogenic cells [29].

The fundamental advantage of mRNA technology lies in its safety profile and efficiency. Unlike DNA-integrative methods (e.g., retroviruses, lentiviruses), mRNA does not pose a risk of insertional mutagenesis [31]. Furthermore, the use of modified ribonucleosides (e.g., pseudouridine, 5-methylcytidine) dramatically reduces the immunogenicity of synthetic mRNA by evading innate antiviral defenses, allowing for sustained protein expression through repeated transfections and resulting in reprogramming efficiencies that surpass established viral protocols [29] [34].

Comparative Analysis: Induced Pluripotency vs. Direct Lineage Conversion

The choice between reprogramming to pluripotency or directly to another lineage depends on the application's specific requirements for developmental potential, safety, and time. The table below summarizes the core characteristics of these two endpoints.

Table 1: Defining the Endpoints of mRNA Reprogramming

| Feature | Induced Pluripotency | Direct Lineage Conversion |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Reprogramming of differentiated cells to a pluripotent state, capable of generating all embryonic lineages [33] [31]. | Direct conversion of one somatic cell type into another without an intermediate pluripotent state [33]. |

| Also Known As | Reprogramming | Transdifferentiation, Direct Reprogramming [33] [31] |

| Key mRNA Cargo | Pluripotency transcription factors (e.g., OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, c-MYC, NANOG, LIN28) [29] [31]. | Lineage-specific transcription factors and/or miRNAs (e.g., MyoD for myogenesis) [29] [31]. |

| Developmental Path | Multistep process erasing somatic memory and establishing pluripotency [33]. | Often a shortcut, though may involve a plastic intermediate progenitor state [31]. |

| Key Advantage | Unlimited self-renewal and differentiation potential; ideal for generating diverse cell types from a single source. | Avoids the theoretical risk of teratoma formation from residual pluripotent cells; can be faster. |

| Primary Challenge | Requires a subsequent, often complex, differentiation step to obtain target somatic cells; risk of incomplete differentiation. | May yield immature cells that lack full functional maturity of the target tissue; efficiency can be variable [33]. |

| Therapeutic Application | Disease modeling, drug screening, generation of autologous cells for regenerative therapies. | In situ regeneration, direct cell replacement therapies, rapid generation of specific cell types. |

Core mRNA Technology and Experimental Design

The efficacy of mRNA reprogramming hinges on sophisticated molecular design and delivery strategies to ensure high protein expression while minimizing cellular toxicity.

mRNA Construct Design and Synthesis

The synthetic mRNA used for reprogramming is engineered to mimic mature eukaryotic mRNA, incorporating specific structural elements to enhance stability, translation, and safety [34].

- 5' Cap: A modified guanine nucleotide (7-methylguanosine) added to the 5' end is essential for ribosome recognition and protects the mRNA from exonuclease degradation [29] [34] [35].

- 5' and 3' Untranslated Regions (UTRs): These flanking regions impact translation efficiency, localization, and stability. They can be adapted (e.g., using alpha-globin 3' UTR) to improve protein expression [29] [34].

- Coding Sequence (CDS): This open reading frame contains the gene of interest. Codon optimization and nucleotide modification are critical. The incorporation of modified nucleosides like pseudouridine (ψ) and 5-methylcytidine (5mC) is a key innovation that reduces immunogenicity by preventing activation of pattern recognition receptors such as TLRs, RIG-I, and PKR [29] [34].

- Poly(A) Tail: A 3' tail of adenosine residues is crucial for mRNA stability and translational efficiency. Its length can be optimized for performance [29] [34].

The manufacturing process involves in vitro transcription (IVT) from a linearized DNA template, followed by capping, tailing, and purification to remove contaminants like double-stranded RNA (dsRNA), a potent inducer of interferon responses [29] [34].

Workflow for mRNA Reprogramming

The following diagram illustrates the generalized workflow for conducting mRNA reprogramming experiments, from mRNA preparation to the final fate endpoints.

Overcoming Innate Immune Recognition

A central challenge in mRNA reprogramming is the innate immune system's robust response to exogenous RNA. The successful strategy involves:

- Nucleoside Modification: Using pseudouridine and 5-methylcytidine to make the mRNA "invisible" to immune sensors [29].

- Phosphatase Treatment: Removing 5' triphosphates from IVT RNA to avoid RIG-I activation [29].

- Interferon Inhibition: Supplementing culture media with a recombinant interferon inhibitor (e.g., B18R protein) to block the positive-feedback loop of interferon signaling [29].

These modifications are critical for enabling the repeated transfections needed over days or weeks to sustain factor expression and achieve successful reprogramming without significant cytotoxicity [29].

Quantitative Data and Protocol Efficiency

The performance of mRNA reprogramming is quantified by its efficiency, kinetics, and the functional quality of the resulting cells.

Table 2: Quantitative Metrics of mRNA Reprogramming Protocols

| Reprogramming Endpoint | Reprogramming Factors | Reported Efficiency | Time to Emergence | Key Functional Validation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Induced Pluripotency (RiPS) | KLF4, c-MYC, OCT4, SOX2 (KMOS) [29] | Efficiencies that "greatly surpass" established viral protocols (0.01-0.02%) [29] [31] | Can be completed in as little as one week [36] | Pluripotency marker expression (NANOG), teratoma formation, in vitro differentiation into all three germ layers [29] |

| Direct Myogenic Conversion | Not specified, but demonstrated as feasible using mRNA technology [29] | Described as "efficient" terminal differentiation [29] | Not explicitly quantified | Expression of terminal differentiation markers, formation of contractile myotubes, functional response to stimuli [29] [33] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for mRNA Reprogramming

Successful implementation of mRNA reprogramming protocols requires a suite of specialized reagents and tools.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for mRNA Reprogramming

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Explanation | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| Modified Nucleosides | Reduces immunogenicity of synthetic mRNA by evading innate immune sensors. | Pseudouridine (ψ), 1-methylpseudouridine, 5-methylcytidine (5mC) [29] [34] |

| In Vitro Transcription (IVT) Kit | Synthesizes mRNA from a linearized DNA template. | Must support co-transcriptional capping and incorporation of modified NTPs. Scalability from research to GMP is key [34]. |

| Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) | Delivery system that protects mRNA and facilitates cellular uptake via endocytosis. | Biodegradable, lower toxicity than viral vectors; essential for efficient in vivo delivery [37] [34]. |

| Interferon Inhibitor | Suppresses the innate immune response to repeated mRNA transfections, improving cell viability. | Recombinant B18R protein (a vaccinia virus decoy receptor for Type I interferons) [29] |

| cGMP-Grade Reprogramming mRNA | Clinically relevant, quality-controlled mRNA for therapeutic development. | Commercially available services offer end-to-end cGMP reprogramming and iPSC banking with a validated quality management system [36]. |

Signaling Pathways in Cell Fate Conversion

Cell fate decisions, whether toward pluripotency or a specific lineage, are governed by complex intracellular signaling networks. The following diagram maps the core signaling pathways and regulatory logic involved in these processes.

mRNA technology provides a powerful, versatile, and clinically relevant platform for programming human cell fate. The choice between induced pluripotency and direct lineage conversion as an endpoint depends on the specific research or therapeutic goal, balancing factors such as developmental potential, time, and safety. The high efficiency and non-integrating nature of mRNA reprogramming, achieved through modified nucleosides and sophisticated delivery systems, position it as a cornerstone technology for the future of regenerative medicine, disease modeling, and drug development. As single-cell technologies and computational models advance, they will further refine our ability to guide these reprogramming processes with unprecedented precision, enabling the generation of functionally mature cell types for a new era of cellular therapies.

From Synthesis to Delivery: Methodologies and Clinical Applications of mRNA Reprogramming

The choice of mRNA capping strategy is a critical determinant of success in cell fate reprogramming research, directly influencing translational yield, transcript stability, and immunogenic profile. This technical guide provides an in-depth comparison between two predominant capping methodologies: co-transcriptional capping using CleanCap technology and post-transcriptional capping employing the Vaccinia Capping Enzyme (VCE). For researchers developing mRNA-based reprogramming factors, the selection between these methods balances trade-offs in capping efficiency, structural fidelity, process simplicity, and scalability. Quantitative data and protocol details herein are synthesized to inform experimental design, ensuring the production of high-quality mRNA that maintains precise control over protein expression—a foundational requirement for deterministic cell fate manipulation.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Co-transcriptional and Post-Transcriptional Capping Methods

| Feature | Co-transcriptional Capping (CleanCap) | Post-Transcriptional Capping (VCE) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Mechanism | Cap analog incorporated during IVT by RNA polymerase [39] [40] | Enzymatic addition of cap to purified, uncapped mRNA post-IVT [39] [41] |

| Typical Cap Structure | Cap 1 (m7GpppNm) [42] [40] | Cap 0 (m7GpppN), requires a separate methyltransferase (e.g., 2'-O-MTase) for Cap 1 [39] [43] |

| Reported Capping Efficiency | >95% [42] [40] | High, but dependent on enzyme purity and reaction optimization [41] [43] |

| Workflow Complexity | Simplified, "one-pot" reaction; fewer steps [39] [42] | Multi-step process requiring additional enzymatic reaction and purification [39] [41] |

| Key Advantage | High efficiency and simplicity; streamlined workflow [42] [40] | Control over cap structure; all caps are incorporated in the correct orientation [39] [43] |

| Key Disadvantage | Cost of cap analog; patent/licensing considerations [40] | Longer process time; requires additional reagents and purification steps [39] [41] |

| Ideal Application Context | High-throughput production of mRNAs where Cap 1 structure and high yield are priorities [42] | Applications requiring specific, non-standard cap structures or stringent control over capping [39] |

In the realm of mRNA-based cell fate reprogramming, the 5' cap is not merely a protective modification but a master regulator of transcript function and cellular perception. The cap structure, a 7-methylguanosine (m7G) linked to the first nucleotide via a 5'-5' triphosphate bridge (m7GpppN), is essential for mRNA stability, efficient translation initiation, and nuclear export [39] [41]. For cell reprogramming applications, where the precise and robust expression of transcription factors like Oct4, Sox2, Klf4, and c-Myc is paramount, an inadequate cap leads to poor protein yield and failed experiments.

The cap structure evolves from Cap 0 (m7GpppN) to Cap 1 (m7GpppNm) through 2'-O-methylation of the first transcribed nucleotide. This Cap 1 structure is particularly crucial for immune evasion. It enables the synthetic mRNA to be recognized as "self" by the cell, thereby avoiding potent innate immune sensors such as RIG-I and MDA5 [39] [41]. Unwanted immune activation can derail reprogramming by altering the cellular transcriptome, inducing apoptosis, or provoking an inflammatory state that is incompatible with precise lineage conversion. Consequently, achieving a near-homogeneous Cap 1 structure is a non-negotiable objective for reliable reprogramming protocols.

Technical Deep Dive: Capping Methodologies

Co-transcriptional Capping with CleanCap Technology

Mechanism and Workflow

Co-transcriptional capping introduces a cap analog directly into the in vitro transcription (IVT) reaction mixture. The RNA polymerase incorporates this analog at the initiation of transcription, capping the mRNA as it is synthesized [39] [40]. CleanCap technology represents a third-generation advance in cap analogs. It is a trinucleotide analog (e.g., m7GpppA2'pG) that is recognized by the polymerase and results in the direct synthesis of a natural Cap 1 structure in a single step [42] [40]. This process is highly efficient because the analog is designed to be the preferred initiator of transcription.

Performance and Protocol Considerations

- Efficiency: The primary advantage of CleanCap is its exceptional capping efficiency, consistently reported at >95% Cap 1 structure formation [42] [40]. This high efficiency minimizes the population of uncapped, immunostimulatory transcripts.

- Yield and Simplicity: The protocol is streamlined, eliminating post-transcription enzymatic steps and subsequent purifications. This "one-pot" reaction saves time and reduces the risk of mRNA degradation or loss during handling [39]. Yields can be very high, with protocols reporting up to 5 mg/mL of IVT mRNA [42].

- Template Design: A critical requirement for using CleanCap AG reagent is a DNA template with a transcription start site sequence of AGG [40]. This sequence complements the trinucleotide analog to ensure efficient incorporation.

Post-Transcriptional Capping with Vaccinia Capping Enzyme (VCE)

Mechanism and Workflow

Post-transcriptional capping is a two-step process. First, standard IVT is performed to produce uncapped mRNA. Second, the purified mRNA is used as a substrate for a multi-enzyme reaction. The Vaccinia Capping Enzyme (VCE), a viral enzyme widely adopted for in vitro use, possesses both RNA triphosphatase and guanylyltransferase activities. It catalyzes the cleavage of the 5' γ-phosphate and the addition of a GMP moiety to form the Cap 0 structure. To achieve the critical Cap 1 structure, a second enzyme, mRNA Cap 2'-O-Methyltransferase (2'-O-MTase), must be added to the reaction to methylate the 2'-O position of the first nucleotide [39] [43].

Performance and Protocol Considerations

- Control and Fidelity: A key strength of the enzymatic method is that it guarantees the cap is added in the biologically correct orientation, as the enzyme is specific for its RNA substrate [39] [43]. This provides robust control over the final cap structure.

- Workflow and Time: The requirement for a separate enzymatic reaction and at least one additional purification step post-IVT makes this a more time-consuming and labor-intensive process compared to co-transcriptional capping [39] [41].

- Enzyme Considerations: The reaction requires multiple enzymes and co-factors (GTP, S-adenosylmethionine (SAM)). While VCE is common, the Faustovirus Capping Enzyme (FCE) is a noted alternative with broader temperature tolerance and higher reported activity on some substrates [39] [43].

Quantitative Comparison and Method Selection

Table 2: Direct Comparison of Capping Methods for Reprogramming Applications

| Performance Metric | CleanCap | VCE + 2'-O-MTase |

|---|---|---|

| Capping Efficiency (Cap 1) | >95% [42] [40] | High, but variable; requires optimization [41] |

| Typical IVT mRNA Yield | Very High (e.g., 5 mg/ml) [42] | High, but can be reduced by purification losses [39] |

| Immune Evasion Profile | Excellent (Low immunogenicity due to high Cap 1 purity) [42] | Excellent, if 2'-O-methylation is complete [39] |

| Process Scalability | Highly scalable; simplified workflow is amenable to automation [42] | Scalable, but complex multi-step process can be a bottleneck [39] |

| Development Time | Shorter (Single-step reaction) | Longer (Multiple steps and purifications) |

| Relative Cost | Higher reagent cost per reaction | Lower reagent cost, but higher labor/process cost |

Selection Guide for Reprogramming Workflows

The decision between CleanCap and VCE capping should be guided by the specific goals and constraints of the research program.

For most reprogramming applications, CleanCap is the recommended choice. The primary rationale is its superior efficiency and simplicity. The guarantee of >95% Cap 1 formation directly translates to a more potent and consistent reprogramming mRNA, minimizing batch-to-batch variability and the confounding effects of the innate immune response. The streamlined workflow allows researchers to focus on the biological assessment of their mRNA constructs rather than complex production processes [42] [40].

Select VCE-based enzymatic capping in the following scenarios:

- Template Incompatibility: When the DNA template or experimental design necessitates a transcription start site that is incompatible with CleanCap trinucleotide analogs.

- Requirement for Exotic Cap Analogs: When research demands the use of specialized, non-standard cap structures (e.g., for pull-down assays or specific mechanistic studies) that cannot be incorporated co-transcriptionally [39].

- Established GMP Processes: For translational work where existing, validated manufacturing processes are built around enzymatic capping methods [43].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Protocols

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Reagents for mRNA Capping Workflows

| Reagent / Kit | Function | Example Provider(s) |

|---|---|---|

| CleanCap Reagent AG | Trinucleotide cap analog for co-transcriptional synthesis of Cap 1 mRNA. | TriLink BioTechnologies [42], Takara Bio [40], NEB [43] |

| Vaccinia Capping Enzyme (VCE) | Adds Cap 0 structure to the 5' end of uncapped RNA via its triphosphatase and guanylyltransferase activities. | Takara Bio [40], New England Biolabs (NEB) [43] |

| mRNA Cap 2'-O-Methyltransferase | Converts Cap 0 to Cap 1 by methylating the 2'-O position of the first transcribed nucleotide. | Takara Bio [40], NEB [43] |

| HiScribe T7 mRNA Kit with CleanCap | All-in-one kit for IVT including T7 RNA polymerase, NTPs, buffer, and CleanCap reagent for simplified Cap 1 mRNA production. | NEB [43] |

| Takara IVTpro mRNA Synthesis System | A system for high-yield mRNA synthesis, compatible with both CleanCap and ARCA capping methods. | Takara Bio [40] |

| Faustovirus Capping Enzyme (FCE) | An alternative capping enzyme with high activity and a broader temperature range than VCE. | NEB [43] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol for Co-transcriptional Capping with CleanCap

This protocol is adapted from commercial kit instructions and published methodologies [42] [40] [43].

- Template Design: Ensure your DNA template (linearized plasmid or PCR product) has a T7 promoter and a transcription start site of AGG.

- IVT Reaction Assembly: Combine the following components in a nuclease-free tube:

- 1 µg of DNA template

- 10 µL 2X IVT buffer (supplied with kit, typically contains rNTPs, DTT)

- 2 µL T7 RNA Polymerase mix

- 2 µL CleanCap Reagent AG (e.g., TriLink)

- Nuclease-free water to 20 µL total volume

- Incubation: Mix gently and incubate at 37°C for 2 hours.

- DNase I Treatment: Add 2 µL of DNase I (RNase-free) and incubate for 15 minutes at 37°C to digest the DNA template.

- mRNA Purification: Purify the mRNA using a LiCl precipitation method or a silica membrane-based purification kit. Validate yield and purity by spectrophotometry (NanoDrop) and integrity by agarose gel electrophoresis.

Protocol for Post-Transcriptional Capping with VCE

This protocol utilizes enzymes from suppliers like NEB and Takara Bio [40] [43].

- Produce Uncapped mRNA: Perform a standard IVT reaction without any cap analog. Purify the resulting uncapped mRNA.

- Capping Reaction Assembly: Combine the following:

- 10 µg of purified, uncapped mRNA

- 5 µL 10X Capping Buffer (supplied with enzyme)

- 5 µL 2 mM GTP (for VCE)

- 5 µL 2 mM S-adenosylmethionine (SAM) - (for methyltransferase activity)

- 5 µL Vaccinia Capping Enzyme (VCE)

- 2.5 µL mRNA Cap 2'-O-Methyltransferase (for Cap 1 formation)

- Nuclease-free water to 50 µL total volume

- Incubation: Mix gently and incubate at 37°C for 1 hour.

- Purification: Purify the capped mRNA using a standard method (e.g., LiCl precipitation or column purification) to remove enzymes and excess reagents.

Quality Control and Capping Efficiency Analysis

Rigorous QC is essential. Beyond standard yield and purity checks, analyzing capping efficiency is critical.

- LC-MS/MS: The gold-standard method for direct identification and quantification of Cap 0, Cap 1, and Cap 2 structures [39].

- Cap-Specific Assays: Techniques like reverse transcription-qPCR (RT-qPCR) can be used, as capped 5' ends are necessary for efficient reverse transcription priming [39]. Cap-specific antibodies in an ELISA format can also quantify cap structures [39].

In the rapidly advancing field of mRNA-based cell fate reprogramming, the reliability of the underlying technology is a prerequisite for biological discovery. The capping method forms a cornerstone of this reliability. While both CleanCap and VCE-based methods are capable of producing high-quality, functional mRNA for reprogramming factors, the co-transcriptional CleanCap method offers a compelling combination of superior efficiency, a simplified workflow, and exceptional performance that aligns with the needs of most research programs.