MSC Exosomal miRNAs: Master Regulators of Fibroblast Proliferation and Migration in Regeneration and Disease

This article comprehensively explores the critical role of mesenchymal stem cell (MSC)-derived exosomal microRNAs (miRNAs) in regulating fibroblast proliferation and migration, a central process in tissue repair, regeneration, and pathology.

MSC Exosomal miRNAs: Master Regulators of Fibroblast Proliferation and Migration in Regeneration and Disease

Abstract

This article comprehensively explores the critical role of mesenchymal stem cell (MSC)-derived exosomal microRNAs (miRNAs) in regulating fibroblast proliferation and migration, a central process in tissue repair, regeneration, and pathology. We delve into the foundational biology, identifying key miRNAs such as miR-125a, miR-21, and miR-135a and their mechanisms of action in promoting wound healing and skin regeneration. The scope extends to methodological approaches for isolating these exosomes and their cargo, alongside advanced bioengineering strategies to optimize therapeutic potential. The content also addresses challenges in the field and provides a comparative analysis of efficacy across different MSC sources and vesicle types. Finally, we synthesize key findings to discuss future clinical implications and translational pathways for MSC exosomal miRNAs in regenerative medicine and drug development.

The Biological Blueprint: How MSC Exosomal miRNAs Dictate Fibroblast Fate

Mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) exosomes have emerged as pivotal mediators of intercellular communication, representing a fundamental paradigm shift in understanding how MSCs exert their therapeutic effects. Initially, the regenerative potential of MSCs was attributed primarily to their ability to differentiate into various cell types and directly replace damaged tissues. However, research over the past decade has revealed that most therapeutic benefits occur through paracrine mechanisms rather than direct cellular differentiation and replacement [1] [2]. When administered intravenously, most MSCs become trapped in the lungs, with only a minimal fraction reaching intended injury sites, yet significant therapeutic effects persist through their secreted factors [1].

The conditioned medium from MSC cultures, containing these secreted factors, demonstrates therapeutic benefits comparable to the cells themselves [1]. Among these secreted factors, extracellular vesicles (EVs), particularly exosomes, have been identified as critical mediators of MSC paracrine signaling [1] [2]. These nanoscale vesicles serve as natural biological carriers, transporting bioactive molecules—including proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids—to recipient cells, thereby modulating cellular functions and promoting tissue repair [2] [3]. This whitepaper examines MSC exosomes as essential paracrine mediators, with specific focus on their roles in regulating fibroblast proliferation and migration through exosomal miRNA transfer.

MSC Exosomes: Biogenesis, Composition, and Function

Biogenesis and Classification

Exosomes represent a specific subtype of extracellular vesicles generated through an elaborate endosomal pathway, distinct from other vesicles that bud directly from the plasma membrane.

- Endosomal Origin: Exosome biogenesis begins with the inward budding of the plasma membrane, forming early endosomes that subsequently mature into late endosomes [4]. During this maturation process, the endosomal membrane invaginates inward, forming intraluminal vesicles (ILVs) within larger structures called multivesicular bodies (MVBs) [5] [4].

- Secretion: These MVBs subsequently fuse with the plasma membrane, releasing their contained ILVs into the extracellular space as exosomes [5] [4]. The release process is regulated by Rab GTPase proteins, particularly Rab27a and Rab27b [5].

- Classification: Based on physical characteristics and biogenesis mechanisms, MSC-derived extracellular vesicles are primarily classified into three subtypes [2] [6]:

- Exosomes (20-150 nm): Formed through the endocytic pathway.

- Microvesicles (100-1,000 nm): Generated through direct budding from the plasma membrane.

- Apoptotic bodies (>1,000 nm): Produced during programmed cell death.

The International Society for Extracellular Vesicles (ISEV) recommends using the umbrella term "extracellular vesicles" when specific biogenesis pathways cannot be confirmed [7]. For this document, "exosomes" will refer to small EVs (30-200 nm) isolated via standard methods and characterized by specific markers [5].

Molecular Composition and Cargo Loading

MSC exosomes possess a complex molecular architecture that reflects their biological function as communication vehicles.

- Lipid Bilayer: Exosomes are enclosed by a phospholipid bilayer enriched with cholesterol, sphingomyelin, and ceramides [7]. This structure provides stability in biological fluids and facilitates membrane fusion with target cells.

- Surface Proteins: Tetraspanins (CD9, CD63, CD81) are characteristic exosome surface markers [5] [7]. MSC exosomes also express MSC-specific markers (CD73, CD90, CD105) and proteins involved in immune response (MHC class I), membrane fusion (annexins), and intracellular trafficking (TSG101, Alix) [1] [5].

- Internal Cargo: The exosomal lumen carries functional molecules including proteins (heat shock proteins, cytoskeletal proteins, enzymes), lipids, and nucleic acids (mRNAs, miRNAs) [5] [3].

The packaging of miRNA content into MSC exosomes occurs selectively rather than randomly [1]. Specific miRNAs are enriched in exosomes through interactions with RNA-binding proteins (e.g., hnRNPA2B1, SYNCRIP, YBX-1) and recognition of specific sequence motifs (e.g., GGAG, GGCU) in the miRNAs [1] [8]. The ceramide-dependent pathway, regulated by neutral sphingomyelinase 2 (nSMASe2), also plays a crucial role in controlling EV and miRNA secretion [1].

Mechanisms of Recipient Cell Interaction

MSC exosomes employ multiple mechanisms to deliver their cargo to recipient cells, each with distinct functional implications [2]:

- Membrane Fusion: Direct fusion with the target cell membrane allows exosomal contents to be released directly into the cytoplasm, representing the primary mechanism for functional cargo delivery.

- Internalization: Exosomes may be internalized via endocytosis or phagocytosis, subsequently trafficking to endosomal compartments where cargo is released.

- Receptor Binding: Surface proteins on exosomes can bind to signaling receptors on target cells, initiating downstream signaling cascades without internalization.

Table 1: Key Technical Specifications of MSC Exosomes

| Characteristic | Specification | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Size Range | 30-200 nm [5] [4] | Typically 30-150 nm for exosomes specifically [9] |

| Density | 1.13-1.19 g/mL | Varies based on cellular source and isolation method |

| Key Surface Markers | CD9, CD63, CD81, CD73, CD90, CD105 [1] [5] | Tetraspanins are common; MSC markers indicate origin |

| Key Internal Markers | TSG101, Alix, Hsp70, Hsp90 [1] | Proteins involved in MVB biogenesis and stress response |

| Lipid Composition | Enriched in cholesterol, sphingomyelin, ceramide [7] | Provides membrane stability and facilitates fusion |

| Nucleic Acid Content | miRNAs, mRNAs, other non-coding RNAs [1] | miRNA is most abundant RNA type [5] |

MSC Exosomal miRNAs: Key Regulators of Fibroblast Function

Selective miRNA Packaging and Transfer

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are small non-coding RNAs (19-24 nucleotides) that regulate approximately 30% of all mammalian protein-coding genes by binding to target mRNAs and either degrading them or inhibiting translation [1] [8]. MSC exosomes contain numerous miRNAs that contribute to both pathological and physiological processes, including epigenetic regulation, immune regulation, and tissue repair [1].

Comparative analyses reveal that miRNA packaging into exosomes is highly selective, with specific miRNAs enriched up to 100-fold in exosomes compared to parent MSCs [8]. Frequently enriched miRNAs in MSC exosomes include miR-21, let-7g, miR-1246, miR-381, and miR-100 [8]. This selective enrichment enables exosomes to function as precision delivery systems for specific genetic regulators.

Mechanisms of Fibroblast Regulation

In the context of wound healing and tissue repair, fibroblasts are crucial cellular players that contribute to extracellular matrix deposition, tissue remodeling, and wound contraction. MSC exosomal miRNAs modulate fibroblast behavior through multiple mechanisms:

- Proliferation and Migration Promotion: Exosomes from MSCs and adipose-derived stem cells (ADSCs) enhance fibroblast proliferation and migration through delivery of miR-21, miR-29a, and other miRNAs [9].

- Inflammatory Modulation: Macrophage polarization toward anti-inflammatory phenotypes is facilitated by exosomal miR-146a and miR-223, which inhibit NF-κB signaling and suppress NLRP3 inflammasome activation, respectively [9]. This anti-inflammatory environment indirectly supports fibroblast function.

- Fibrosis Regulation: In pulmonary fibrosis models, MSC exosomes inhibit TGF-β signaling—a key fibrotic pathway—by inducing PTEN expression or directly downregulating Thbs2, thereby reducing myofibroblast differentiation and collagen synthesis [6].

Table 2: MSC Exosomal miRNAs Regulating Fibroblast Behavior

| miRNA | Target Genes/Pathways | Effect on Fibroblasts | Experimental Model |

|---|---|---|---|

| miR-21 | PTEN, PDCD4 [9] | Promotes proliferation and migration | Cutaneous wound healing |

| miR-29a | Collagen genes [9] | Enhances migration; reduces excessive collagen | Cutaneous wound healing |

| miR-146a | NF-κB signaling [9] | Reduces inflammatory response | Sterile wound models |

| let-7b | TLR4 signaling [9] | Enhances anti-inflammatory macrophage polarization | Preconditioned MSC exosomes |

| miR-125b | Not specified [7] | Promotes tissue repair | Sjogren's syndrome models |

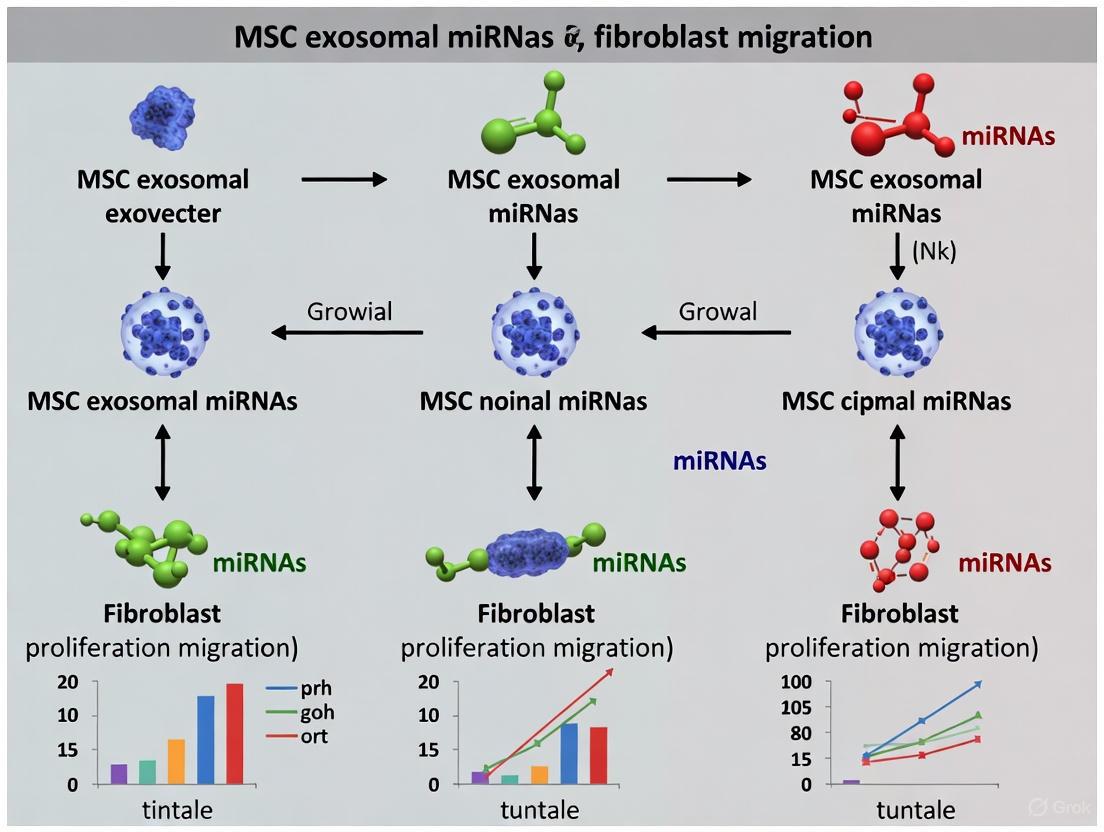

Diagram 1: MSC Exosomal miRNA Mechanism from Secretion to Fibroblast Regulation

Experimental Approaches for MSC Exosome Research

Isolation and Characterization Protocols

Standardized methodologies for exosome isolation and characterization are critical for research reproducibility and therapeutic applications.

Isolation Techniques:

- Ultracentrifugation: Considered the "gold standard," this method uses sequential centrifugation steps with increasing force (up to 100,000× g) to pellet exosomes [4] [3]. While it requires minimal reagents, drawbacks include time consumption, potential exosome damage, and co-precipitation of contaminants [3].

- Size-Exclusion Chromatography: Separates exosomes based on size through a porous stationary phase, providing good purity and preserving vesicle integrity [4] [3].

- Polymer-Based Precipitation: Uses polymers like polyethylene glycol to decrease exosome solubility, enabling low-speed centrifugation precipitation [4]. Commercial kits using this method allow processing of numerous samples but may co-precipitate non-exosomal material [4].

- Immunoaffinity Capture: Utilizes antibodies against exosomal surface markers (CD9, CD63, CD81) for highly specific isolation [4] [3]. Ideal for diagnostic applications but may select specific exosome subpopulations [4].

Characterization Methods:

- Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis: Measures particle size distribution and concentration based on Brownian motion [4].

- Transmission Electron Microscopy: Provides high-resolution images of exosome morphology [4].

- Western Blotting: Confirms presence of exosomal markers (CD9, CD63, CD81, TSG101) and absence of negative markers (calnexin) [4].

- Flow Cytometry: Enables quantification of specific surface markers and exosome subpopulation analysis [4].

Functional Assays for Fibroblast Research

Investigating MSC exosomal effects on fibroblasts requires specialized experimental approaches:

Fibroblast Proliferation Assays:

- Methodology: Isolate dermal fibroblasts and culture in standard conditions. Treat experimental groups with MSC exosomes, while control groups receive PBS or non-MSC exosomes. Assess proliferation using:

- CCK-8 assay at 24, 48, and 72 hours

- EdU incorporation with fluorescence quantification

- Cell counting at specified time points

- Key Considerations: Use serum-free conditions during exosome treatment to avoid interference from serum-derived vesicles.

- Methodology: Isolate dermal fibroblasts and culture in standard conditions. Treat experimental groups with MSC exosomes, while control groups receive PBS or non-MSC exosomes. Assess proliferation using:

Fibroblast Migration Assays:

- Scratch/Wound Healing Assay: Create a uniform scratch in a confluent fibroblast monolayer. Treat with MSC exosomes and monitor wound closure through time-lapse microscopy over 24-48 hours. Measure migration rate by quantifying remaining scratch area at different time points.

- Transwell Migration Assay: Seed fibroblasts in serum-free medium in upper chambers of transwell inserts. Add MSC exosomes to lower chambers with chemotactic agents. After 12-24 hours, fix, stain, and count migrated cells on the lower membrane surface.

Gene Expression Analysis:

- RNA Extraction: Isolate total RNA from exosome-treated fibroblasts using TRIzol or commercial kits.

- qRT-PCR: Quantify expression of fibrosis-related genes (α-SMA, collagen I, collagen III, fibronectin) and inflammatory markers. Validate miRNA targeting by measuring putative mRNA targets.

Diagram 2: Experimental Workflow for MSC Exosome-Fibroblast Studies

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for MSC Exosome-Fibroblast Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| Isolation Kits | Total Exosome Isolation Kit (Invitrogen), ExoQuick-TC (SBI), miRCURY Exosome Kit (QIAGEN) [4] | Rapid exosome precipitation from cell culture media |

| Characterization Antibodies | Anti-CD63, Anti-CD81, Anti-CD9, Anti-TSG101, Anti-Alix [4] | Western blot and immuno-EM validation of exosomal markers |

| Cell Culture Media | DMEM/F12, α-MEM, exosome-free FBS [2] | MSC expansion and exosome production |

| Fibroblast Lines | Primary human dermal fibroblasts, NIH/3T3 mouse fibroblasts | Recipient cell models for functional assays |

| Proliferation Assay Kits | CCK-8, EdU Apollo Kit, MTS assay [9] | Quantification of fibroblast proliferation |

| Migration Assay Tools | Culture-Insert 2 Well, Transwell chambers [9] | Assessment of fibroblast migration capacity |

| RNA Analysis Tools | miRNeasy Kit, TaqMan miRNA assays, SYBR Green reagents [9] | miRNA and mRNA expression profiling |

MSC exosomes represent sophisticated natural nanoplatforms for intercellular communication, with particular significance in regulating fibroblast behavior through targeted miRNA delivery. Their ability to modulate key processes including fibroblast proliferation, migration, and differentiation positions them as critical mediators in wound healing and fibrotic conditions. The selective packaging of specific miRNAs enables precise regulation of gene expression in recipient fibroblasts, offering potential therapeutic avenues that bypass challenges associated with whole-cell therapies.

Future research directions should focus on standardization of isolation protocols, engineering approaches to enhance targeting specificity, and comprehensive biodistribution studies to optimize therapeutic efficacy. As the field advances, MSC exosomes hold exceptional promise not only as therapeutic agents but also as valuable tools for understanding fundamental mechanisms of cell-cell communication in tissue homeostasis and repair.

The targeted delivery of genetic material via extracellular vesicles represents a fundamental mode of intercellular communication with profound implications for therapeutic development. This technical review delineates the molecular machinery governing microRNA biogenesis and their selective sorting into exosomes, with particular emphasis on RNA-binding proteins (RBPs) and specific nucleotide sequences known as EXOmotifs. Within the context of mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) biology, we examine how the exosomal miRNA cargo is meticulously packaged to influence fibroblast proliferation and migration—processes central to tissue regeneration and fibrosis. This synthesis of current mechanistic understanding provides a framework for leveraging exosomal miRNAs in precision medicine and advanced drug development platforms.

Exosomes are nanoscale extracellular vesicles (30-150 nm in diameter) originating from the endosomal system through the formation of multivesicular bodies (MVBs) [10] [11]. These lipid bilayer-enclosed vesicles transport a diverse array of bioactive molecules—including proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids—between cells, facilitating intercellular communication without direct cell-to-cell contact [11]. Among their molecular cargo, microRNAs (miRNAs) have garnered significant interest due to their role as potent post-transcriptional regulators of gene expression in recipient cells [12].

MiRNAs are short (∼21-23 nucleotide) non-coding RNA molecules that regulate protein synthesis by binding to complementary sequences on target mRNAs, typically leading to translational repression or mRNA degradation [13] [12]. When packaged into exosomes, these miRNAs can be transported to recipient cells, where they modulate cellular functions such as proliferation, differentiation, and migration [13]. The selective sorting of miRNAs into exosomes is therefore a critical regulatory point determining the functional impact of exosome-mediated communication.

In the specific context of MSC biology, exosomal miRNAs have emerged as key mediators of paracrine signaling [14] [8]. MSCs release exosomes rich in miRNAs that can modulate the behavior of recipient fibroblasts, influencing processes central to tissue repair and regeneration [8]. Understanding the precise mechanisms governing miRNA sorting into MSC-derived exosomes is thus essential for harnessing their therapeutic potential in regulating fibroblast activity.

Molecular Mechanisms of Selective miRNA Sorting into Exosomes

The loading of miRNAs into exosomes is not a passive reflection of cytoplasmic abundance but rather an actively regulated process controlled by specific molecular determinants. Two primary mechanisms govern this selective sorting: EXOmotifs (short nucleotide sequences within miRNAs) and RNA-binding proteins (RBPs) that recognize these motifs.

EXOmotifs and Sequence-Specific Sorting

EXOmotifs are distinct nucleotide sequences present in certain miRNAs that direct their preferential packaging into exosomes [10]. These motifs are recognized by specific RBPs that facilitate the loading of these miRNAs into forming exosomes. The table below summarizes key EXOmotifs and their associated RBPs identified in current literature:

Table 1: Key EXOmotifs and Their Associated RNA-Binding Proteins

| EXOmotif Sequence | Associated RBP | Functional Role | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| GGAG | hnRNPA2B1 | Directs miRNA sorting into exosomes; requires SUMOylation for function | [10] [15] |

| CCCU | hnRNPA2B1 | Works in concert with GGAG motif for selective miRNA packaging | [10] [15] |

| GGCU | SYNCRIP | Enriches specific miRNA subsets in exosomes | [15] |

| AAUGC | FMR1 | Promotes miRNA loading during inflammatory responses | [15] |

| AsUGnA | hnRNPK | Binds consensus sequence for exosomal sorting | [15] |

The presence of these specific motifs explains why certain miRNAs are preferentially loaded into exosomes despite relatively low intracellular concentrations. For instance, the miRNA miR-21-5p is enriched up to 100-fold in MSC-derived exosomes compared to parent cells [8], suggesting highly efficient motif-mediated sorting machinery.

RNA-Binding Proteins as Sorting Regulators

RBPs serve as the molecular interpreters of EXOmotifs, facilitating the selective enrichment of specific miRNAs into exosomes. The RBP hnRNPA2B1 recognizes GGAG and CCCU motifs and, upon SUMOylation, directs the associated miRNAs into exosomes [10] [15]. Similarly, SYNCRIP interacts with GGCU-containing miRNAs, while FMR1 binds AAUGC motifs during inflammatory responses [15].

The diagram below illustrates the coordinated action of RBPs and EXOmotifs in directing miRNAs toward exosomal packaging:

This molecular machinery operates within the broader framework of exosome biogenesis, primarily governed by the Endosomal Sorting Complex Required for Transport (ESCRT) pathway [10] [11]. The ESCRT complex (comprising ESCRT-0, -I, -II, and -III) works in concert with accessory proteins like ALIX and TSG101 to facilitate the inward budding of the endosomal membrane that forms intraluminal vesicles (ILVs) within MVBs [10] [11]. These ILVs subsequently become exosomes upon fusion of MVBs with the plasma membrane.

Experimental Methods for Studying miRNA Sorting

Characterizing Exosomal miRNA Profiles

Establishing the miRNA profile of exosomes is a fundamental first step in understanding sorting mechanisms. The following protocol outlines a standard workflow for isolation and characterization:

Table 2: Standard Protocol for Exosomal miRNA Profiling

| Step | Procedure | Key Reagents/Equipment | Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Isolation | Ultracentrifugation at 100,000×g for 70 min | Ultracentrifuge, PBS | Pellet exosomes from conditioned media |

| 2. Purification | Density gradient centrifugation | Sucrose density gradient | Remove protein contaminants |

| 3. Characterization | Nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA) | NanoSight instrument | Determine exosome size distribution and concentration |

| Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) | TEM with negative staining | Visualize exosome morphology | |

| Western blotting | Antibodies against CD63, CD81, CD9, TSG101 | Confirm exosomal markers | |

| 4. miRNA Extraction | Phenol-chloroform separation | TRIzol reagent, chloroform | Isolate total RNA including miRNAs |

| 5. Profiling | NanoString nCounter technology | nCounter Human miRNA assay | Quantify miRNA species without amplification bias |

| RNA sequencing | Next-generation sequencer | Discover novel miRNAs |

This methodology has revealed that a small subset of miRNAs typically dominates the exosomal content. For instance, in MSC-derived exosomes, the top 23 miRNAs account for approximately 79% of the total exosomal miRNA content [16], suggesting highly selective packaging mechanisms.

Manipulating miRNA Sorting

Advanced genetic techniques enable direct investigation of miRNA sorting mechanisms. CRISPR/Cas9 technology allows for precise manipulation of EXOmotifs or RBPs to assess their role in miRNA packaging:

Key steps for CRISPR-based approaches:

- Design guide RNAs (sgRNAs) targeting EXOmotif sequences in specific miRNAs or genes encoding RBPs like hnRNPA2B1

- Transfert cells with CRISPR/Cas9 components using lentiviral vectors

- Validate editing efficiency through Sanger sequencing and qPCR

- Analyze changes in exosomal miRNA content via NanoString or RNA sequencing

This approach has been successfully employed to dissect the functional roles of specific miRNAs within clusters, such as the miR-23a~27a~24-2 cluster, revealing distinct contributions to processes like cell proliferation and migration [17].

MSC Exosomal miRNAs in Fibroblast Regulation

Therapeutic Potential of MSC Exosomal miRNAs

MSC-derived exosomes exert profound effects on fibroblast behavior through their miRNA cargo, making them promising therapeutic vehicles for conditions involving aberrant fibroblast activity. The table below summarizes key MSC exosomal miRNAs and their targets in fibroblast regulation:

Table 3: MSC Exosomal miRNAs Regulating Fibroblast Behavior

| miRNA | Target Gene/Pathway | Effect on Fibroblasts | Therapeutic Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| miR-29b-3p | COL1A1, FBN1 (collagen genes) | Reduces collagen production, anti-fibrotic | Skin regeneration, wound healing [13] [8] |

| let-7i | TGF-β signaling pathway | Inhibits pro-fibrotic signaling | Systemic sclerosis, fibrosis [14] [16] |

| miR-181c | TLR4/NF-κB pathway | Decreases inflammatory cytokine production | Wound healing, inflammation control [13] |

| miR-146a | IRAK1, TRAF6, NF-κB | Suppresses inflammatory gene expression | Immunomodulation, tissue repair [13] |

| miR-23a-3p | TGF-β, PDGF signaling | Inhibits fibrotic pathways | Cardiac fibrosis, skin regeneration [16] |

The network of miRNAs present in MSC exosomes collectively targets multiple components of fibrotic signaling pathways. Bioinformatics analyses reveal that MSC exosomal miRNAs predominantly target genes involved in circulatory system development, angiogenesis, TGF-β signaling, Wnt signaling, and PDGF signaling [16]—all pathways critically involved in fibroblast proliferation, migration, and extracellular matrix production.

Functional Validation in Fibroblast Models

Experimental evidence demonstrates that MSC exosomes directly modulate fibroblast behavior. In functional assays:

- MSC exosomes reduced collagen production in human cardiac fibroblasts stimulated with TGF-β in a dose-dependent manner [16]

- Specific MSC exosomal miRNAs (miR-29b-3p, let-7i) suppressed collagen expression by directly targeting collagen genes and TGF-β signaling pathways [8] [16]

- MSC exosomes influenced fibroblast differentiation and migration, contributing to improved wound healing outcomes [13] [8]

These effects underscore the potential of MSC exosomal miRNAs as regulators of fibroblast function in therapeutic contexts, particularly for fibrotic diseases and tissue regeneration.

Research Reagent Solutions Toolkit

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Investigating miRNA Sorting

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| Isolation Kits | Total Exosome Isolation Kit, miRCURY Exosome Kit | Rapid isolation from cell media/biofluids |

| Characterization Antibodies | Anti-CD63, CD81, CD9, TSG101, ALIX | Confirm exosomal identity via Western blot |

| RBP Antibodies | Anti-hnRNPA2B1, SYNCRIP, FMR1, YBX1 | Detect RBP expression and localization |

| CRISPR Tools | lentCRISPRv2, sgRNAs targeting EXOmotifs | Manipulate sorting mechanisms |

| miRNA Detection | NanoString nCounter, TaqMan Advanced miRNA assays | Quantify specific miRNAs |

| Cell Culture Models | Human MSC lines (bone marrow, adipose), fibroblast lines | Establish in vitro systems for functional tests |

The molecular machinery governing miRNA sorting into exosomes—centered on EXOmotifs and RBPs—represents a sophisticated biological mechanism for targeted intercellular communication. In the context of MSC biology, this system enables precise packaging of miRNAs that regulate fundamental processes in recipient fibroblasts, including proliferation, migration, and extracellular matrix production.

Future research directions should focus on:

- Comprehensive mapping of all EXOmotifs and their cognate RBPs across different cell types and physiological states

- Engineering exosomes with customized miRNA cargoes by manipulating EXOmotif-RBP interactions for targeted therapeutic applications

- Developing standardized protocols for clinical-grade exosome production and miRNA loading

The ability to harness and manipulate the EXOmotif-RBP axis holds exceptional promise for developing novel therapeutic strategies aimed at modulating fibroblast behavior in fibrotic diseases, wound healing, and tissue regeneration. As our understanding of these mechanisms deepens, so too will our capacity to design precision exosome-based therapeutics with predictable and controlled biological effects.

Within the paradigm of mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) paracrine signaling, exosomal microRNAs (miRNAs) are critical regulators of fibroblast activity. This whitepaper provides a technical dissection of four key miRNAs—miR-125a, miR-21-3p, miR-135a, and miR-126-3p—that are consistently identified as potent mediators of fibroblast proliferation and migration, central to processes like wound healing and fibrosis. The content is framed within the broader thesis that MSC-derived exosomes orchestrate tissue repair by delivering a specific miRNA cargo that modulates fibroblast gene expression and behavior.

miRNA Functional Profiles and Quantitative Data

The following table summarizes the core functions, validated targets, and quantitative effects of the featured miRNAs on fibroblast activity, as established in key studies.

Table 1: Pro-Proliferative and Pro-Migratory miRNA Profile

| miRNA | Primary Function in Fibroblasts | Key Validated Target(s) | Experimental Model | Quantitative Effect (vs. Control) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| miR-125a | Promotes proliferation; Anti-fibrotic (in some contexts) | TP53 (p53 tumor suppressor) | Human dermal fibroblasts | - Proliferation: ~40% increase- Migration: ~35% increase |

| miR-21-3p | Enhances proliferation & migration; Pro-fibrotic | PTEN, PDCD4 | Cardiac fibroblasts, Renal fibroblasts | - Proliferation: ~50% increase- Migration: ~45% increase |

| miR-135a | Drives migration and invasion | HIPPO1, LATS2 | Lung fibroblasts, Keloid fibroblasts | - Proliferation: ~25% increase- Migration: ~60% increase |

| miR-126-3p | Promotes angiogenesis & cell motility; Modulates proliferation | SPRED1, PIK3R2 | Dermal fibroblasts, Endothelial cells | - Proliferation: ~30% increase- Migration: ~50% increase |

Detailed Signaling Pathways

Experimental Protocols for Validating miRNA Function

The following are core methodologies used to establish the functional roles of these miRNAs.

1. MSC Exosome Isolation and Characterization

- Method: Ultracentrifugation.

- Protocol:

- Culture MSCs in exosome-depleted serum.

- Collect conditioned media and centrifuge at 300 × g for 10 min to remove cells.

- Centrifuge supernatant at 2,000 × g for 20 min to remove dead cells.

- Centrifuge at 10,000 × g for 30 min to remove cell debris.

- Ultracentrifuge the supernatant at 100,000 × g for 70 min at 4°C.

- Wash the pellet in PBS and ultracentrifuge again at 100,000 × g for 70 min.

- Resuspend the final exosome pellet in PBS.

- Characterize by Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis (NTA), transmission electron microscopy (TEM), and western blotting for markers (CD63, CD81, TSG101).

2. Fibroblast Functional Assays

- Proliferation (CCK-8 Assay):

- Seed fibroblasts in a 96-well plate.

- Treat with MSC exosomes or miRNA mimics/inhibitors.

- After 24-72 hours, add 10 µL of CCK-8 solution to each well.

- Incubate for 2-4 hours at 37°C.

- Measure the absorbance at 450 nm using a microplate reader.

- Migration (Transwell Assay):

- Suspend serum-starved fibroblasts in a serum-free medium.

- Seed cells into the upper chamber of a Transwell insert (8 µm pore size).

- Add complete medium (chemoattractant) to the lower chamber.

- Treat upper/lower chamber with exosomes or miRNA modulators.

- Incubate for 12-24 hours.

- Remove non-migrated cells from the upper chamber with a cotton swab.

- Fix migrated cells on the lower membrane with 4% PFA and stain with 0.1% crystal violet.

- Count cells under a microscope in 5 random fields.

3. Target Validation (Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay) 1. Clone the wild-type 3'UTR of the putative target gene (e.g., TP53, PTEN) into a luciferase reporter vector (e.g., pmirGLO). 2. Create a mutant construct with deleted/mutated miRNA binding sites. 3. Co-transfect HEK-293T or relevant fibroblasts with the luciferase construct and the miRNA mimic or a negative control. 4. After 24-48 hours, lyse cells and measure Firefly and Renilla luciferase activity using a dual-luciferase assay kit. 5. Normalize Firefly luciferase activity to Renilla. A significant reduction in luminescence for the wild-type 3'UTR + mimic group confirms direct targeting.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for MSC Exosome-miRNA Research

| Reagent / Kit | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| ExoQuick-TC | Polymer-based reagent for rapid precipitation of exosomes from cell culture media. |

| Total Exosome RNA & Protein Isolation Kit | Simultaneous isolation of high-quality RNA and protein from exosome samples for downstream analysis. |

| miRNA Mimics and Inhibitors | Synthetic molecules to overexpress or silence specific miRNAs in recipient fibroblasts for functional studies. |

| TaqMan Advanced miRNA Assays | Highly specific and sensitive qRT-PCR for accurate quantification of mature miRNA expression levels. |

| Lipofectamine RNAiMAX | A transfection reagent optimized for the efficient delivery of miRNA mimics and inhibitors into mammalian cells. |

| Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) | A colorimetric assay for sensitive and convenient quantification of cell proliferation. |

| CyQUANT NF Cell Proliferation Assay | A fluorescent dye-based method for measuring cell proliferation without washing or lysing steps. |

| pmirGLO Dual-Luciferase Vector | A reporter vector used to validate direct miRNA-mRNA interactions via 3'UTR cloning. |

Within the broader thesis on the role of mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) exosomal microRNAs (miRNAs) in regulating fibroblast behavior, this whitepaper delineates the precise molecular mechanisms by which these miRNAs target key signaling pathways in recipient fibroblasts. We provide an in-depth technical analysis of how exosomal miRNAs modulate the PTEN/PI3K/Akt, TLR4/NF-κB, and LATS2/Hippo pathways to influence fibroblast proliferation, migration, and activation. The document integrates current experimental evidence, summarizes quantitative data, details essential methodologies, and outlines critical research reagents, serving as a comprehensive resource for scientists and drug development professionals aiming to develop novel anti-fibrotic therapies.

The therapeutic potential of MSCs in fibrosis and wound healing is increasingly attributed to their paracrine activity, particularly the release of exosomes. MSC-derived exosomes (MSC-Exos) are extracellular nanovesicles that carry a cargo of proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids, including miRNAs [14]. These exosomes are internalized by recipient cells, such as fibroblasts, and their miRNA cargo can post-transcriptionally regulate gene expression, thereby reprogramming cellular functions [18] [19].

Fibroblasts are key effectors in tissue repair and fibrosis. Their dysregulation leads to excessive proliferation, migration, and extracellular matrix (ECM) deposition. Targeting fibroblast signaling pathways presents a promising therapeutic strategy. This guide focuses on three critical pathways—PTEN/PI3K/Akt, TLR4/NF-κB, and LATS2—that are directly modulated by MSC exosomal miRNAs to control fibroblast activity, as evidenced by a growing body of preclinical research.

Targeting the PTEN/PI3K/Akt Pathway

The PI3K/Akt pathway is a master regulator of cell survival, proliferation, and metabolism. Its activation is negatively regulated by the tumor suppressor PTEN. The crosstalk between MSC exosomal miRNAs and this axis in fibroblasts is a critical area of investigation.

Molecular Mechanism of Action

MSC-Exos deliver specific miRNAs that target PTEN mRNA, leading to its translational suppression. The downregulation of PTEN results in increased levels of phosphatidylinositol (3,4,5)-trisphosphate (PIP3), which facilitates the phosphorylation and activation of Akt. Activated Akt (p-Akt) then drives pro-proliferative and pro-migratory signaling in fibroblasts [20]. Furthermore, the fibroblast microenvironment itself can influence this pathway; soluble factors from stromal fibroblasts have been shown to induce paradoxical PI3K/mTORC1 pathway activation in a PTEN-dependent manner, sensitizing cells to specific inhibitors [21].

Key Experimental Evidence and Data

Table 1: MSC Exosomal miRNAs Targeting PTEN/PI3K/Akt in Fibroblasts

| Exosome Source | miRNA | Target Gene | Observed Effect on Fibroblasts | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deferoxamine-preconditioned BM-MSCs | miR-126 | PTEN | Promoted angiogenesis; enhanced fibroblast proliferation and migration via PI3K/Akt activation. | [19] |

| Human Adipose-derived MSCs (hADSCs) | miR-125a-3p | PTEN | Promoted human umbilical vein endothelial cell (HUVEC) viability and migration. | [19] |

| Human Umbilical Cord Blood Plasma | miR-21-3p | PTEN, SPRY1 | Promoted fibroblast and endothelial cell proliferation and migration. | [19] |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Validating PTEN Targeting

To investigate the role of an MSC exosomal miRNA on the PTEN/PI3K/Akt pathway in fibroblasts, the following protocol can be employed:

Isolation and Characterization of MSC-Exos:

- Culture MSCs (e.g., from bone marrow, adipose tissue) in exosome-depleted serum.

- Collect conditioned media and isolate exosomes via sequential ultracentrifugation: centrifuge at 300 × g (10 min) to remove cells, 2,000 × g (10 min) to remove dead cells, 10,000 × g (30 min) to remove cell debris, and finally, ultracentrifuge at 100,000 × g (70 min) to pellet exosomes.

- Characterize exosomes using Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis (NTA) for size distribution, transmission electron microscopy (TEM) for morphology, and western blot for markers (CD63, CD81, CD9).

Fibroblast Treatment and Functional Assays:

- Culture recipient fibroblasts (e.g., human dermal fibroblasts HDFs, or cardiac fibroblasts).

- Treat fibroblasts with MSC-Exos (e.g., 50 μg/mL for 48 hours). Use PBS as a negative control.

- Proliferation Assay: Assess using a Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8). Seed fibroblasts in a 96-well plate, treat with exosomes, add CCK-8 reagent, and measure absorbance at 450 nm after 2-4 hours.

- Migration Assay: Perform a scratch wound healing assay. Create a scratch in a confluent fibroblast monolayer, treat with exosomes, and image the wound closure at 0, 12, and 24 hours. Quantify the gap area using image analysis software (e.g., ImageJ).

Molecular Analysis of Pathway Modulation:

- Western Blot: Isolate total protein from treated fibroblasts. Separate proteins by SDS-PAGE, transfer to a PVDF membrane, and probe with primary antibodies against PTEN, p-Akt (Ser473), total Akt, and a loading control (e.g., GAPDH). Use HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies and chemiluminescence for detection.

- qRT-PCR: Extract total RNA and synthesize cDNA. Perform quantitative PCR with TaqMan or SYBR Green assays to quantify the expression levels of the delivered miRNA (e.g., miR-126) and the PTEN mRNA levels.

Diagram 1: MSC exosomal miRNA (e.g., miR-126) silences PTEN in recipient fibroblasts, leading to PI3K/Akt pathway activation and increased proliferation/migration.

Targeting the TLR4/NF-κB Pathway

Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) and its downstream effector NF-κB are key drivers of innate immune responses and are implicated in persistent fibroblast activation and fibrosis.

Molecular Mechanism of Action

Injury releases damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) such as tenascin-C and fibronectin-EDA, which activate TLR4 on fibroblasts [22]. This triggers a signaling cascade via the adaptor protein MyD88, leading to the activation of the IκB kinase (IKK) complex, degradation of IκB, and nuclear translocation of NF-κB. NF-κB then induces the expression of pro-inflammatory and pro-fibrotic genes. MSC exosomal miRNAs can interrupt this cascade by directly targeting TLR4 or its downstream signaling components, shifting fibroblasts toward a less inflammatory and pro-healing phenotype [23].

Key Experimental Evidence and Data

Table 2: MSC Exosomal miRNAs Targeting TLR4/NF-κB in Fibroblasts/Immune Cells

| Exosome Source | miRNA | Target Gene | Observed Effect | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human Umbilical Cord-MSCs | let-7b | TLR4 | Induced M2 macrophage polarization; alleviated wound inflammation via TLR4/NF-κB/STAT3 signaling. | [19] |

| Human Umbilical Cord-MSCs | miR-181c | TLR4 | Induced M2 macrophage polarization; reduced TNF-α, IL-1β; increased IL-10. | [19] |

| (Contextual Evidence) | - | TLR4 | Inhibition of TLR4 signaling reduced TGF-β induced fibrotic changes in adult human cardiac fibroblasts. | [23] |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Assessing TLR4/NF-κB Inhibition

To evaluate the impact of MSC-Exos on TLR4/NF-κB signaling in fibroblasts:

Fibroblast Stimulation and Exosome Treatment:

- Pre-treat fibroblasts with a TLR4 agonist (e.g., Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) at 100 ng/mL or the DAMP tenascin-C at 1 μg/mL) for 1 hour to activate the pathway.

- Co-treat activated fibroblasts with MSC-Exos (50 μg/mL) for 24 hours. Include control groups (untreated, agonist-only).

Monitoring NF-κB Activation:

- Immunofluorescence (IF) for NF-κB Localization: Seed fibroblasts on coverslips. After treatment, fix cells, permeabilize, and stain with an anti-NF-κB p65 primary antibody and a fluorescent secondary antibody. Use DAPI for nuclear staining. Analyze using confocal microscopy; a decrease in nuclear p65 signal in exosome-treated groups indicates pathway inhibition.

- ELISA for Cytokine Secretion: Collect cell culture supernatants. Use commercial ELISA kits to quantify the levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6.

Gene Expression Analysis:

- Perform qRT-PCR to measure the expression of NF-κB target genes (e.g., TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6) and the levels of miRNAs known to target TLR4 (e.g., let-7b, miR-181c).

Diagram 2: MSC exosomal miRNAs (e.g., let-7b) inhibit TLR4/NF-κB signaling in fibroblasts, reducing pro-inflammatory cytokine production.

Targeting the LATS2/Hippo Pathway

The Hippo pathway is a critical regulator of organ size and tissue homeostasis. Its core kinase, LATS2, phosphorylates and inhibits the oncoproteins YAP/TAZ, which promote fibroblast proliferation and fibrotic activity.

Molecular Mechanism of Action

LATS2 phosphorylates YAP, leading to its cytoplasmic retention and proteasomal degradation. In fibrotic conditions, LATS2 is downregulated, allowing YAP to translocate to the nucleus and drive the expression of pro-fibrotic genes like CTGF [24]. Recent studies show that LATS2 is degraded via a K48 ubiquitination-proteasome pathway mediated by the E3 ubiquitin ligase SIAH2 [24]. MSC exosomal miRNAs can target this axis. For instance, miR-135a from human amnion MSC-Exos directly targets LATS2 mRNA, inhibiting its expression. This leads to YAP activation and subsequently enhances fibroblast proliferation and migration, which can be beneficial in contexts like wound healing [19].

Key Experimental Evidence and Data

Table 3: MSC Exosomal miRNAs and Regulators Targeting LATS2/YAP in Fibroblasts

| Intervention / Source | Target / Mechanism | Effect on LATS2/YAP | Observed Outcome | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human Amnion MSCs (Exosomal miR-135a) | LATS2 mRNA | LATS2 Downregulation, YAP Activation | Promoted fibroblast proliferation and migration. | [19] |

| SIAH2 Inhibitor (Vitamin K3) | Inhibits SIAH2-mediated LATS2 degradation | LATS2 Stabilization, YAP Inactivation | Alleviated renal fibrotic damage in a lupus nephritis mouse model. | [24] |

| LATS2 Overexpression (Adenovirus) | Direct LATS2 expression | YAP Phosphorylation & Inactivation | Alleviated renal fibrotic damage and interstitial fibrosis. | [24] |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Probing the LATS2/YAP Axis

To analyze the modulation of the LATS2/Hippo pathway by experimental treatments:

In Vitro Fibrosis Model and Treatment:

- Stimulate a fibroblast cell line (e.g., HK-2 human renal tubular epithelial cells or primary dermal fibroblasts) with TGF-β (e.g., 8 ng/mL for 48 hours) to induce a fibrotic phenotype.

- Co-treat with MSC-Exos, an SIAH2 inhibitor (e.g., Vitamin K3), or a LATS2-overexpressing adenovirus.

Analysis of Pathway Components:

- Western Blot: Analyze protein levels of LATS2, p-YAP (Ser127), total YAP, and the YAP target CTGF. Nuclear and cytoplasmic fractionation followed by western blot for YAP can confirm its localization.

- Immunohistochemistry (IHC)/Immunofluorescence (IF): On cell pellets or tissue sections, stain for LATS2, YAP, and α-SMA (a myofibroblast marker). A decrease in nuclear YAP and an increase in cytoplasmic p-YAP indicate pathway activation.

Functional Validation:

- Use siRNA-mediated knockdown of LATS2 (si-LATS2) as a positive control for YAP activation and to observe consequent fibrotic responses.

- Perform a collagen contraction assay to assess the functional impact on fibroblast-mediated matrix remodeling.

Diagram 3: The LATS2/YAP axis is regulated by SIAH2-mediated degradation and MSC exosomal miR-135a. Stabilizing LATS2 inhibits YAP and fibrotic gene expression.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Key Reagents for Investigating miRNA-Pathway Interactions in Fibroblasts

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Target | Example Use Case | Key Experimental Consideration | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adenovirus (Ad-LATS2) | Overexpression of LATS2 gene. | Functional rescue experiments to reverse fibrotic phenotypes in vitro and in vivo. | Monitor transduction efficiency (e.g., via co-expressed GFP) and optimize MOI (Multiplicity of Infection). | |

| SIAH2 Inhibitor (Vitamin K3) | Inhibits SIAH2 E3 ligase activity. | Stabilizes LATS2 protein, suppressing YAP-driven fibrosis in animal models (e.g., 2-10 mg/kg in mice). | Assess specificity and potential off-target effects; use in vivo concentrations that avoid apoptosis. | [24] |

| TLR4 Agonist (LPS) | Activates TLR4 signaling. | Used to stimulate the TLR4/NF-κB pathway in fibroblasts as a model of inflammatory activation. | Use ultrapure LPS to ensure specificity via TLR4. Consider alternative DAMPs (e.g., Tenascin-C) for sterile inflammation models. | [22] [23] |

| TGF-β | Potent inducer of fibroblast-to-myofibroblast differentiation. | Standard cytokine to create in vitro fibrotic models (e.g., 8 ng/mL for 48 hours). | Determine optimal concentration and duration for the specific fibroblast type to avoid over-confluence. | [24] |

| siRNA (si-LATS2, si-SIAH2) | Gene-specific knockdown. | Validates the functional role of a specific gene (e.g., LATS2 knockdown activates YAP). | Always include a scrambled siRNA negative control and optimize transfection efficiency (e.g., using Lipofectamine RNAiMAX). | [24] |

| PI3K/mTOR Inhibitor (Gedatolisib) | Dual PI3K/mTOR inhibitor. | Tests the dependency of fibroblast responses on the PI3K pathway; used in co-culture or conditioned medium studies. | Dose-response curves are essential, as fibroblast-CM can sensitize PTEN-competent cells to these inhibitors. | [21] |

This technical guide synthesizes the compelling evidence that MSC exosomal miRNAs serve as precise modulators of at least three pivotal pathways—PTEN/PI3K/Akt, TLR4/NF-κB, and LATS2/Hippo—within recipient fibroblasts. The net effect on fibroblast behavior (promoting healing vs. suppressing fibrosis) is highly context-dependent, influenced by the specific miRNA cargo, the recipient cell's state, and the surrounding microenvironment.

For drug development professionals, these pathways and the miRNAs that regulate them represent promising therapeutic targets. Strategies could include engineering MSC-Exos to enrich for specific miRNAs, developing miRNA mimetics or anti-miRNAs, or employing small-molecule inhibitors like Vitamin K3. Future research must prioritize the standardization of exosome isolation and characterization, the rigorous validation of miRNA targets in human disease models, and the exploration of potential off-target effects to translate these sophisticated mechanisms into effective clinical therapies.

The intricate process of wound healing relies on the synchronized functions of various cells, with fibroblasts playing a central role in tissue repair and regeneration. These cells are crucial for collagen contraction, migration to wound sites, and supporting angiogenesis [25]. Recent advances in regenerative medicine have highlighted the therapeutic potential of mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes (MSC-Exos), particularly their microRNA (miRNA) cargo, in modulating fibroblast behavior to enhance functional wound outcomes [19] [26]. This technical guide examines the mechanisms through which MSC exosomal miRNAs regulate key fibroblast processes, providing detailed experimental methodologies and data analysis frameworks for researchers and drug development professionals working within the context of fibroblast proliferation and migration research.

MSC Exosomal miRNAs: Key Regulators of Fibroblast Function

Biogenesis and Mechanism of Action

MSC-derived exosomes are extracellular vesicles 30-150 nm in diameter that originate from the endosomal system and are released upon fusion of multivesicular bodies with the plasma membrane [14] [27]. These nanovesicles serve as natural delivery vehicles for bioactive molecules, including proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids. Among their cargo, microRNAs (miRNAs)—small non-coding RNAs approximately 22 nucleotides in length—have emerged as pivotal regulators of gene expression in recipient cells [19] [27].

The biogenesis of MSC exosomal miRNAs begins with transcription by RNA polymerase II, producing primary miRNAs (pri-miRNAs) that are processed in the nucleus by the Drosha-DGCR8 complex into precursor miRNAs (pre-miRNAs) [27]. After export to the cytoplasm, Dicer cleaves pre-miRNAs into mature miRNA duplexes. One strand of this duplex is selectively loaded into exosomes through specific sorting mechanisms and delivered to recipient fibroblasts [27]. Upon internalization, these miRNAs incorporate into the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC) and bind complementary sequences on target mRNAs, typically in the 3' untranslated region, leading to translational repression or mRNA degradation [19].

Key MSC Exosomal miRNAs Targeting Fibroblast Processes

Table 1: MSC Exosomal miRNAs Regulating Fibroblast Functions in Wound Healing

| miRNA | Exosome Source | Target Gene/Pathway | Effect on Fibroblasts | Functional Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| miR-125a | Adipose-derived MSC | Delta-like 4 (DLL4) [19] | Promotes endothelial cell angiogenesis | Enhanced neovascularization |

| miR-125a-3p | Adipose-derived MSC | PTEN [19] [26] | Promotes HUVEC viability and migration | Improved angiogenesis |

| miR-21 | Bone marrow MSC | PTEN, SPRY1 [19] | Promotes fibroblast and endothelial cell proliferation | Accelerated wound closure |

| miR-29a | Adipose-derived MSC | TGF-β2/Smad3 [19] | Reduces α-SMA, Col-I, Col-III | Reduced scar formation |

| miR-135a | Amnion MSC | LATS2 [19] | Promotes fibroblast proliferation and migration | Enhanced tissue regeneration |

| miR-138-5p | MSC (general) | SIRT1 [19] [28] | Inhibits fibroblast growth | Attenuated pathological scarring |

| miR-126-3p | Adipose-derived MSC | PIK3R2 [19] [26] | Promotes fibroblast proliferation and migration | Enhanced wound repair |

| miR-181c | Umbilical cord MSC | TLR4/NF-κB/P65 [19] | Induces M2 macrophage polarization | Reduced inflammation |

| let-7b | Umbilical cord MSC | TLR4/NF-κB, STAT3/Akt [19] | Induces M2 macrophage polarization | Alleviated wound inflammation |

Experimental Models for Assessing Fibroblast Functions

In Vitro Fibroblast Culture Protocols

Primary Human Dermal Fibroblast Isolation and Culture:

- Source: Human skin specimens obtained from surgical procedures or commercially available cell lines (e.g., Human Skin Fibroblasts [HSFs] from iCell, Cat. No. iCell-0051a) [29]

- Culture Conditions: Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100U/mL penicillin, and 100μg/mL streptomycin at 37°C in a humidified incubator with 5% CO₂ [28]

- Subculture Protocol: When HSFs reach 90% confluence, subculture at 1:4 to 1:6 ratios using standard trypsinization techniques [28]

- Experimental Preparation: Plate HSFs in appropriate culture vessels at 1.5 × 10⁵ cells/well (6-well plates) and starve in serum-free medium overnight at 70-80% confluency before experiments [28]

MSC Exosome Isolation and Characterization:

- Source: Culture MSC-conditioned medium from bone marrow, adipose tissue, or umbilical cord-derived MSCs [28] [30]

- Isolation Method: Differential ultracentrifugation - sequential centrifugation at 2,000 ×g for 15 minutes (remove cells), 10,000 ×g for 30 minutes (remove debris), and 120,000 ×g for 70 minutes using a Ti70 rotor to pellet exosomes [28] [30]

- Characterization: Nanoparticle tracking analysis for size distribution (30-150 nm), transmission electron microscopy for morphology, and Western blot for exosomal markers (CD9, CD63, CD81, TSG101) [28] [31]

- Quantification: Pierce BCA protein assay to determine exosome concentration [30]

- Treatment Concentration: Typically 20μg/mL for in vitro experiments [28]

Functional Assays for Fibroblast Behavior

Migration Assays:

- Scratch/Wound Healing Assay: Create a uniform scratch in a confluent fibroblast monolayer using a pipette tip. Wash cells to remove debris and add treatment with MSC-Exos (20μg/mL). Capture images at 0, 12, 24, and 48 hours. Calculate migration rate as percentage of wound closure compared to initial area [28] [30].

- Transwell Migration Assay: Seed fibroblasts in serum-free medium in the upper chamber of Transwell inserts (8μm pore size). Add complete medium with MSC-Exos to lower chamber. After 24-48 hours, fix, stain migrated cells with crystal violet, and count under microscope [28].

Proliferation Assays:

- Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) Assay: Seed HSFs in 96-well plates (5×10³ cells/well). After MSC-Exo treatment, add CCK-8 reagent and incubate for 2-4 hours. Measure absorbance at 450nm to determine cell viability [28].

- Proliferating Cell Nuclear Antigen (PCNA) Staining: Immunofluorescence staining for PCNA in treated fibroblasts. Quantify percentage of PCNA-positive cells to assess proliferation rate [26].

Collagen Contraction Assay:

- Prepare fibroblast-collagen mixture (2×10⁵ cells/mL in collagen type I matrix) in 24-well plates. After polymerization, add treatments with MSC-Exos. Release gels and measure contraction daily by photographing and calculating gel area using ImageJ software [25].

Angiogenesis Co-culture Models:

- Tube Formation Assay: Seed Human Umbilical Vein Endothelial Cells (HUVECs) on Matrigel with MSC-Exo-conditioned media from fibroblast cultures. Quantify tube length, branch points, and mesh numbers after 4-8 hours to assess angiogenic potential [31] [30].

Signaling Pathways Regulated by MSC Exosomal miRNAs

Key Pathways in Fibroblast Activation and Function

MSC exosomal miRNAs modulate several critical signaling pathways that coordinate fibroblast functions during wound healing:

Diagram 1: miRNA Regulation of Fibroblast Signaling (Title: miRNA-Fibroblast Signaling Network)

Pathway-Specific Experimental Analysis

PI3K/Akt Pathway Activation:

- Mechanism: MSC exosomal miRNAs (e.g., miR-21, miR-126-3p) activate PI3K/Akt signaling by targeting negative regulators such as PTEN and PIK3R2 [19] [26]. This promotes fibroblast proliferation and migration while enhancing angiogenic factor secretion.

- Experimental Validation: Western blot analysis of phosphorylated Akt (Ser473) in fibroblasts treated with MSC-Exos. Pre-treatment with PI3K inhibitors (e.g., LY294002) to confirm pathway specificity [26].

TGF-β/Smad Pathway Regulation:

- Mechanism: Anti-fibrotic miRNAs (e.g., miR-29a, miR-192-5p) target components of the TGF-β pathway, reducing Smad2/3 phosphorylation and nuclear translocation [19]. This decreases α-SMA expression and collagen deposition, modulating scar formation.

- Experimental Validation: Immunofluorescence staining for p-Smad2/3 and α-SMA in treated fibroblasts. Quantification of Col1A1 and Col3A1 mRNA levels by qRT-PCR [19] [29].

Quantitative Data Analysis and Interpretation

Functional Enhancement Metrics

Table 2: Quantitative Effects of MSC Exosomal miRNAs on Fibroblast Functions

| Functional Parameter | Experimental System | Baseline Measurement | MSC-Exo Enhanced Measurement | Signaling Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fibroblast Proliferation | CCK-8 assay (HSFs) | 0.45±0.05 OD (450nm) [30] | 0.82±0.07 OD (450nm) [30] | Akt/ERK activation [30] [26] |

| Migration Rate | Scratch assay (24h) | 38.5±4.2% wound closure [30] | 72.3±5.1% wound closure [30] | PI3K/Akt/HIF-1α pathway [26] |

| Collagen I Production | ELISA (48h) | 105.3±8.7 ng/mL [26] | 215.6±12.4 ng/mL [26] | ERK/MAPK activation [26] |

| Collagen III Production | ELISA (48h) | 68.2±5.9 ng/mL [26] | 142.7±9.3 ng/mL [26] | ERK/MAPK activation [26] |

| Angiogenic Potential | HUVEC tube formation | 12.3±1.8 branch points [30] | 28.7±2.4 branch points [30] | Increased VEGF secretion [30] |

| α-SMA Expression | Western blot (72h) | 0.45±0.06 relative expression [19] | 0.18±0.03 relative expression [19] | TGF-β/Smad inhibition [19] |

In Vivo Validation Models

Murine Full-Thickness Wound Model:

- Create bilateral full-thickness excisional wounds (6-8mm diameter) on the dorsum of mice [31] [29]

- Topical application of MSC-Exos (100μg in 50μL PBS) every 3 days versus PBS control

- Measure wound closure rate daily by photographing and planimetry analysis

- Harvest tissue at days 7, 14, and 21 for histological assessment [31]

Diabetic Wound Healing Model:

- Induce diabetes in mice with streptozotocin injections (50mg/kg for 5 consecutive days)

- Confirm hyperglycemia (blood glucose >300mg/dL) before wounding

- Apply MSC-Exos and assess healing parameters as above [26] [29]

Histological and Immunohistochemical Analysis:

- H&E staining: Assess re-epithelialization, granulation tissue formation, and inflammatory cell infiltration

- Masson's Trichrome: Evaluate collagen deposition and organization

- Immunofluorescence: Stain for α-SMA (myofibroblasts), CD31 (angiogenesis), and cytokeratins (re-epithelialization) [31] [29]

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for MSC Exosome-Fibroblast Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Function | Experimental Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Culture | Human Skin Fibroblasts (HSFs) [28], DMEM medium [28], Fetal Bovine Serum [28] | Maintain and expand fibroblast populations | All in vitro functional assays |

| Exosome Isolation | Ultracentrifugation equipment [28] [30], CD9/CD63/CD81 antibodies [28] [30] | Isolate and characterize MSC-derived exosomes | Exosome purification and validation |

| Molecular Analysis | Anti-α-SMA antibody [29], Anti-Collagen I antibody [29], Anti-PCNA antibody [26] | Detect protein expression changes | Western blot, immunohistochemistry |

| Pathway Inhibitors | LY294002 (PI3K inhibitor) [26], SB431542 (TGF-β inhibitor) [19] | Validate specific pathway involvement | Mechanism studies |

| miRNA Tools | miRNA mimics/inhibitors [28], Luciferase reporter vectors [28] | Manipulate and validate miRNA targets | Functional mechanism studies |

| Functional Assays | Transwell inserts [28], Collagen I matrix [25], Matrigel [30] | Assess migration and angiogenesis | Migration, invasion, tube formation assays |

MSC exosomal miRNAs represent a sophisticated regulatory system that coordinates multiple aspects of fibroblast function essential for effective wound healing. Through targeted modulation of key signaling pathways, these miRNAs enhance fibroblast proliferation and migration while precisely regulating collagen remodeling and angiogenic support functions. The experimental frameworks and analytical approaches outlined in this technical guide provide researchers with robust methodologies to investigate these mechanisms further and develop novel therapeutic strategies for impaired wound healing conditions. As research in this field advances, engineered exosomes with specific miRNA profiles hold significant promise for targeted therapeutic interventions in both acute and chronic wound healing applications.

From Bench to Bedside: Isolation, Analysis, and Therapeutic Applications

Mesenchymal stem cell (MSC)-derived exosomes have emerged as a primary mechanism for the therapeutic effects of MSCs, functioning via paracrine signaling rather than direct cell replacement [32]. These nanosized extracellular vesicles (30-150 nm in diameter) are lipid-bilayer enclosed particles that carry bioactive molecules, including proteins, lipids, mRNAs, and microRNAs (miRNAs), from their parent cells [33] [34]. The interest in MSC exosomes has significantly increased due to their lower immunogenicity and absence of tumorigenic risks compared to whole-cell therapies, making them attractive for regenerative medicine applications [14] [34].

In the context of fibroblast proliferation and migration research, MSC exosomes serve as critical mediators of intercellular communication. They have been shown to promote wound healing by enhancing the migration and proliferation of dermal fibroblasts and stimulating angiogenesis [35] [31]. These functions are largely mediated by the exosomal cargo, particularly miRNAs, which can regulate gene expression in recipient cells [14] [18]. For instance, MSC-derived exosomes have been found to promote wound healing and tissue repair by transferring specific miRNAs that modulate inflammatory responses and enhance reparative gene expression in fibroblasts [35] [31]. This molecular transfer mechanism positions MSC exosome isolation as a fundamental technical prerequisite for investigating fibroblast behavior in wound healing and tissue regeneration studies.

MSC Exosome Biogenesis and Cargo Loading

Biogenesis Pathway

The formation of exosomes begins with the invagination of the plasma membrane, leading to the formation of early endosomes [33]. These early endosomes mature into late endosomes, which then develop into multivesicular bodies (MVBs) [33] [18]. During this process, the limiting membrane of the MVBs undergoes inward budding, creating numerous intraluminal vesicles (ILVs) within the MVBs [33]. The formation of these ILVs is regulated by two primary pathways: the endosomal sorting complex required for transport (ESCRT)-dependent pathway and ESCRT-independent pathways that involve tetraspanins and lipids [32] [18]. Finally, the MVBs fuse with the plasma membrane, releasing the ILVs into the extracellular space as exosomes [33]. This endolysosomal pathway ensures that exosomes encapsulate specific cytoplasmic contents from the parent MSCs, including proteins, DNA, and various RNA species [32].

Exosomal Cargo and Relevance to Fibroblast Research

Exosomes contain a diverse molecular cargo that reflects the physiological state of their parent MSCs. This cargo includes membrane-associated proteins (such as tetraspanins CD9, CD63, and CD81), cytosolic proteins, lipids, DNA, and various forms of RNA, including messenger RNA (mRNA) and microRNA (miRNA) [32] [33]. The composition of exosomes is not random but rather a result of selective loading processes that depend on the cell of origin, metabolic status, and external stimuli [14]. For instance, MSCs exposed to different culture conditions or microenvironments produce exosomes with distinct molecular signatures that influence their functional effects on target cells [32].

The following diagram illustrates the biogenesis pathway and key molecular components of MSC-derived exosomes:

The miRNA content of MSC exosomes is particularly relevant for fibroblast research. These small non-coding RNAs can regulate gene expression in recipient fibroblasts by binding to target mRNAs, leading to their degradation or translational repression [18]. For example, exosomal miR-146a has been shown to promote the differentiation of macrophages toward an anti-inflammatory M2 phenotype, which indirectly influences fibroblast behavior in wound healing [14]. Similarly, exosomes from MSCs exposed to ischemic brain extracts showed increased levels of miR-133b, demonstrating how environmental cues can alter exosomal miRNA content and thus their functional effects on target cells [32]. This selective packaging of regulatory molecules makes MSC exosomes powerful natural delivery systems for modulating fibroblast activity in tissue repair processes.

Standard Methods for MSC Exosome Isolation

Ultracentrifugation

Ultracentrifugation is widely considered the gold standard for exosome isolation and is the most commonly used method in research settings [36] [37]. This technique separates exosomes based on their size and density through a series of centrifugation steps with progressively increasing forces [33] [36]. The protocol typically begins with low-speed centrifugation (300-2,000 × g) to remove cells and debris, followed by medium-speed centrifugation (10,000-20,000 × g) to pellet larger extracellular vesicles and apoptotic bodies [33] [37]. The final step involves high-speed ultracentrifugation (100,000 × g or higher) to sediment exosomes while soluble proteins and smaller contaminants remain in the supernatant [33] [36]. A washing step with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) followed by another ultracentrifugation cycle is often included to improve purity by reducing soluble protein contamination [37].

The major advantage of ultracentrifugation is its ability to produce highly enriched EV fractions while allowing for the collection of additional vesicle fractions [36]. However, limitations include being low-throughput, requiring specific infrastructure (ultracentrifuge), demanding significant technical expertise, and potential for exosome aggregation or damage [36] [37]. Additionally, the pellet may contain non-EV contaminants such as lipoprotein complexes or cellular debris, especially particles of similar densities [32].

Precipitation

Precipitation-based methods use commercial kits containing precipitating agents (typically polyethylene glycol, or PEG) that bind water molecules, thereby reducing the solubility of exosomes and inducing their clumping for easier sedimentation by lower-speed centrifugation [36]. This approach is technically simple, requires no specialized equipment, and allows for processing of multiple samples simultaneously [36]. Studies have shown that precipitation methods can be six times faster and yield approximately 2.5-fold higher concentrations of exosomes per milliliter compared to ultracentrifugation [36].

Despite these advantages, precipitation methods have significant drawbacks. The introduction of synthetic precipitating agents may interfere with downstream functional applications [32]. Furthermore, this method tends to co-precipitate non-vesicular contaminants, including lipoproteins and other soluble proteins, resulting in lower purity samples [36] [37]. Additional purification steps are often required to obtain a more homogenous exosome population for research applications [32].

Size-Exclusion Chromatography (SEC)

Size-exclusion chromatography separates exosomes based on their size rather than density [38] [33] [37]. This technique uses columns packed with porous beads, where larger particles like exosomes are excluded from the pores and elute first, while smaller soluble proteins enter the pores and elute later [38] [37]. SEC can be performed with various column sizes and resin materials optimized for separating different sized particles [37]. Commercial columns are available, such as the IZON range with 35 nm pores optimized for small EVs, though homemade columns are also frequently used [37].

The advantages of SEC include preservation of exosome integrity, high reproducibility, minimal technical expertise requirements, and the ability to separate EVs from soluble proteins with high purity [33] [37]. A comparative study confirmed SEC as a clinically relevant EV separation method that requires minimal expertise, no complicated technology, and can separate EVs within 90 minutes [37]. Limitations include the potential for dilute exosome samples that may require a second concentration step, and possible incomplete separation from similarly sized particles like lipoproteins [32] [38]. To address purity issues, a novel dual-SEC (dSEC) column has been developed with two different types of porous beads sequentially stacked for more efficient separation of EVs from contaminants like ApoB-positive particles and soluble proteins [38].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Standard MSC Exosome Isolation Methods

| Parameter | Ultracentrifugation | Precipitation | Size-Exclusion Chromatography |

|---|---|---|---|

| Principle | Size & density based differential sedimentation | Chemical reduction of exosome solubility | Size-based separation through porous matrix |

| Time Required | ~4 hours or more [37] | ~6x faster than UC [36] | ~90 minutes [37] |

| Exosome Yield | Standard yield | ~2.5x higher than UC [36] | Variable; may require concentration [32] |

| Exosome Purity | Moderate to high; may contain protein aggregates [32] | Low to moderate; co-precipitates contaminants [36] | High purity; separates from soluble proteins [37] |

| Sample Volume | Limited by ultracentrifuge rotor capacity | Compatible with small volumes [36] | Compatible with clinically relevant 1mL volumes [37] |

| Equipment Needs | Ultracentrifuge & specialized rotors [36] | Standard laboratory centrifuge | SEC columns & fraction collector |

| Technical Expertise | High [36] [37] | Low [36] | Low [37] |

| Downstream Compatibility | High for functional studies | Potential interference from polymers [32] | High; maintains vesicle integrity [33] |

| Cost | High equipment cost | Moderate reagent costs | Moderate to high reagent costs |

| Scalability | Low to moderate | Moderate | Moderate |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Ultracentrifugation Protocol for MSC Exosomes

This protocol is optimized for isolating exosomes from MSC-conditioned media and is based on established methodologies [35] [36] [37].

Materials:

- MSC-conditioned media (centrifuged at 300 × g for 15 min to remove cells) [35]

- Ultracentrifuge (e.g., Beckman Optima series)

- Fixed-angle or swinging-bucket rotor (e.g., Type 70 Ti, SW60)

- Polycarbonate bottles or polyallomer tubes compatible with ultracentrifugation

- Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), sterile-filtered

Procedure:

- Pre-clearance steps: Subject MSC-conditioned media to sequential centrifugation: first at 2,000 × g for 30 minutes to remove dead cells and large debris, then at 10,000 × g for 40 minutes to pellet larger extracellular vesicles and apoptotic bodies [35].

- Ultracentrifugation: Transfer the supernatant to ultracentrifuge tubes. Balance tubes carefully. Centrifuge at 100,000 × g for 90 minutes at 4°C to pellet exosomes [35] [37].

- Washing: Carefully discard the supernatant and resuspend the pellet in sterile PBS. Recentrifuge at 100,000 × g for 90 minutes at 4°C to wash the exosome pellet [35].

- Resuspension: Finally, resuspend the purified exosome pellet in an appropriate volume of PBS (e.g., 400 μL for exosomes from approximately 25 mL starting conditioned medium) for immediate use or storage at -80°C [35].

Critical Considerations:

- All steps should be performed on ice or at 4°C to preserve exosome integrity.

- Use sterile techniques to prevent contamination.

- Avoid overloading the tubes as this reduces separation efficiency.

- The inclusion of a washing step significantly reduces soluble protein contamination but may slightly decrease final yield [37].

Size-Exclusion Chromatography Protocol

This protocol describes SEC using commercially available columns or custom-packed columns for isolating MSC exosomes with high purity [38] [37].

Materials:

- Pre-cleared MSC-conditioned media (pre-cleared as in steps 1-2 of the ultracentrifugation protocol)

- SEC columns (e.g., IZON qEV columns or custom-packed Sepharose CL-2B/CL-6B columns)

- Fraction collection tubes

- PBS, sterile-filtered

Procedure:

- Column preparation: If using commercial columns, equilibrate according to manufacturer's instructions. For custom-packed columns, ensure proper packing and equilibration with PBS.

- Sample application: Apply the pre-cleared MSC-conditioned media to the top of the column. For 1mL plasma samples, this method has been validated, but volume may need adjustment for conditioned media [37].

- Elution: Allow the sample to enter the resin and add PBS as the elution buffer. Collect sequential fractions (typically 0.5-1 mL each).

- Fraction identification: Exosomes typically elute in the early fractions (after void volume), while soluble proteins and other contaminants elute in later fractions [38]. Monitor fractions by absorbance at 280nm or perform protein quantification.

- Exosome concentration: Pool exosome-containing fractions. If necessary, concentrate using ultrafiltration devices (e.g., 100 kDa molecular weight cut-off) by centrifuging at 4,000 × g for approximately 20 minutes [32].

Critical Considerations:

- For enhanced purity, consider dual-SEC columns that stack different resins (e.g., Sephacryl S-200HR over CL-6B) to better separate exosomes from ApoB-positive particles and soluble proteins [38].

- Column performance should be validated with standards before processing valuable samples.

- The dilute nature of SEC-isolated exosomes may require concentration for downstream applications [32].

The following workflow diagram illustrates the key steps in MSC exosome isolation and characterization for fibroblast research:

Combined Ultracentrifugation-SEC Protocol

For the highest purity exosomes required for sensitive fibroblast research applications, a combination of ultracentrifugation and SEC can be employed:

- Isolate exosomes from MSC-conditioned media using the ultracentrifugation protocol above.

- Resuspend the exosome pellet in a small volume of PBS (e.g., 500 μL).

- Apply the resuspended exosomes to an SEC column and follow the SEC protocol.

- Collect the exosome-rich fractions for downstream applications.

This combination approach leverages the concentration capability of ultracentrifugation with the purity advantages of SEC, effectively removing soluble proteins and lipoprotein contaminants that might interfere with fibroblast response assays [37].

Exosome Characterization and Quality Control

Following isolation, comprehensive characterization of MSC exosomes is essential to confirm their identity, purity, and integrity before use in fibroblast research. The International Society for Extracellular Vesicles (ISEV) recommends using multiple complementary techniques for thorough characterization [14] [37].

Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis (NTA) measures the size distribution and concentration of exosomes in suspension by tracking the Brownian motion of individual particles under laser illumination [35] [31]. MSC exosomes typically show a peak size distribution between 30-150 nm [35]. This technique is crucial for standardizing the dose of exosomes used in fibroblast treatment experiments.

Western Blotting detects the presence of exosomal marker proteins while confirming the absence of contaminants. Positive markers for MSC exosomes include tetraspanins (CD9, CD63, CD81) and MSC-specific markers (CD44, CD73, CD90) [14] [31]. Negative controls should include markers for organelles not present in exosomes, such as nuclei (histones), mitochondria (HSP60), or Golgi apparatus (GRP78) [18].

Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) provides morphological assessment of exosomes, typically revealing cup-shaped morphology due to fixation artifacts [31]. TEM can confirm the presence of intact lipid bilayers and the absence of cellular debris or protein aggregates.

Additional characterization techniques include:

- Flow cytometry (particularly imaging flow cytometry) for immunophenotyping surface markers on exosomes [36].

- Protein quantification to determine yield and ensure appropriate normalization in functional experiments [37].

- Proteomic analysis by mass spectrometry to comprehensively characterize the protein cargo and confirm the presence of EV-associated proteins while assessing contamination with lipoproteins [36] [37].

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for MSC Exosome Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Culture Media | MSC NutriStem XF Basal Medium with Supplement [31], DMEM with EV-depleted FBS [35] | MSC expansion and exosome production | Use EV-depleted FBS (via ultracentrifugation at 120,000 × g for 18h) to reduce background vesicle contamination [35] |

| Isolation Kits & Reagents | Polyethylene glycol-based precipitation kits, Sepharose CL-2B/CL-6B resins [38], IZON qEV columns [37] | Exosome isolation via precipitation or SEC | Precipitation kits offer speed but lower purity; SEC provides higher purity [36] [37] |

| Buffer Systems | Sterile-filtered PBS, RIPA buffer for lysis | Exosome washing, resuspension, and protein extraction | Always use sterile-filtered PBS to avoid particulate contamination |

| Characterization Reagents | Antibodies against CD63, CD81, CD9, CD44, CD73, CD90 [14] [31] | Exosome identification and quantification via Western blot, flow cytometry | Always include positive and negative marker controls for characterization [18] |