MSC Exosome Efficacy in Wound Healing: A Comparative Analysis of Performance Across Preclinical Animal Models

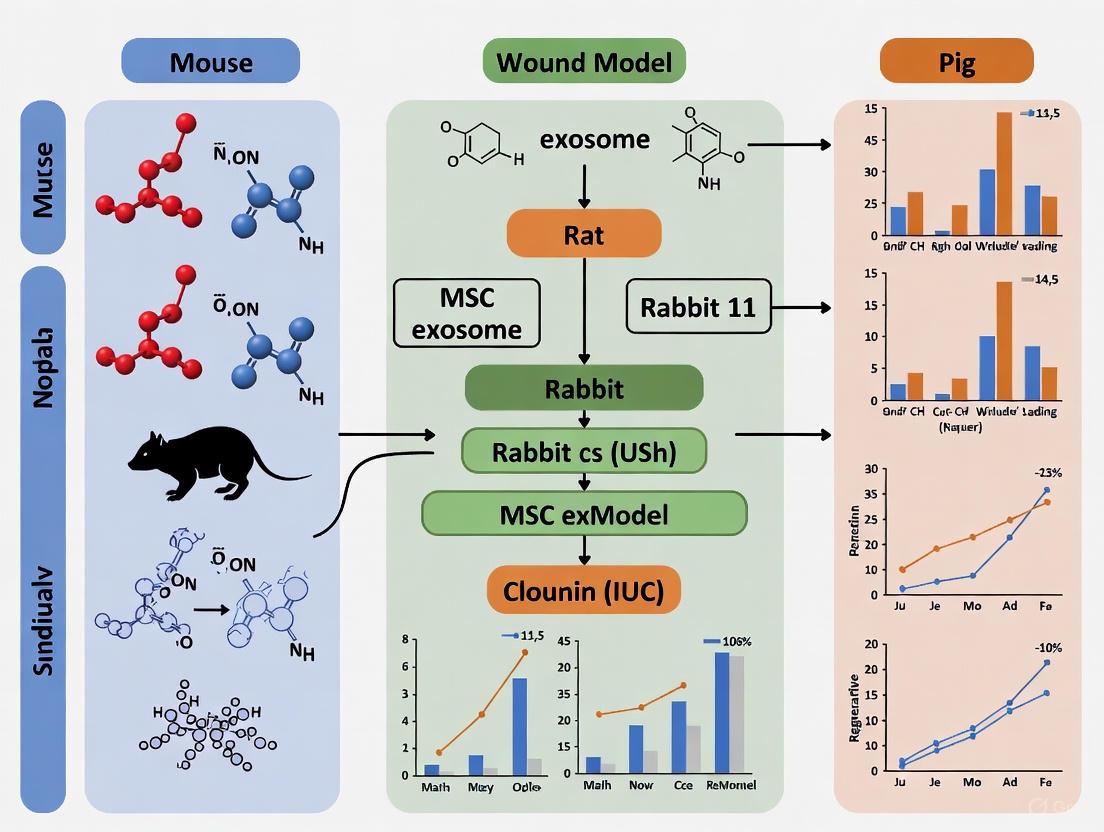

This article synthesizes current evidence on the therapeutic performance of mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes (MSC-exosomes) in various animal wound models.

MSC Exosome Efficacy in Wound Healing: A Comparative Analysis of Performance Across Preclinical Animal Models

Abstract

This article synthesizes current evidence on the therapeutic performance of mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes (MSC-exosomes) in various animal wound models. It provides a foundational understanding of MSC-exosome biology and mechanisms in wound repair, explores methodological considerations for their application in different preclinical models, addresses key challenges and optimization strategies in exosome manufacturing and testing, and offers a critical validation of comparative efficacy across animal species and wound types. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this review serves as a comprehensive resource for designing robust preclinical studies and advancing the clinical translation of MSC-exosome-based therapies for wound healing.

Unlocking the Mechanism: How MSC Exosomes Drive Healing at the Cellular Level

Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) have long been recognized for their remarkable therapeutic potential in regenerative medicine. Originally valued for their ability to differentiate into multiple cell types, research over the past decade has revealed that their healing capacity is primarily mediated through paracrine signaling rather than direct cellular replacement [1] [2]. Among these paracrine factors, MSC-derived exosomes (MSC-Exos) have emerged as powerful mediators of tissue repair, offering a cell-free alternative that maintains therapeutic benefits while circumventing the risks associated with whole-cell transplantation [3] [4].

MSC-exosomes are nanoscale extracellular vesicles (30-150 nm) that facilitate intercellular communication by transferring bioactive molecules—including proteins, lipids, mRNAs, and microRNAs—from parent MSCs to recipient cells [5] [6]. These vesicles demonstrate multifaceted biological functions including immunomodulation, angiogenesis promotion, and tissue repair, making them promising therapeutic agents for wound healing applications [3]. This guide provides a systematic comparison of MSC-exosome performance across different experimental parameters and wound models, offering researchers evidence-based insights for therapeutic development.

Performance Comparison Across Wound Models and Parameters

Therapeutic Efficacy in Preclinical Wound Models

Table 1: MSC-Exosome Performance Across Different Wound Models

| Wound Model | Exosome Source | Key Outcomes | Mechanistic Insights | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cutaneous wound (mouse) | Umbilical cord MSC | Accelerated wound closure; Enhanced re-epithelialization and angiogenesis | Suppressed AIF nuclear translocation; Upregulated PARP-1/PAR | [2] |

| Burn injury (preclinical models) | Various MSC sources | Enhanced wound closure (SMD=3.97 short-term); Improved angiogenesis (SMD=6.24) | Increased collagen deposition; Modulated inflammatory cytokines | [7] |

| Full-thickness skin wound (mouse) | Umbilical cord blood MSC; Plasma | Accelerated wound healing; Reduced scar width | Reduced TGF-β signaling; Enhanced Wnt pathway activation | [8] |

| Diabetic wounds | MSC-derived EVs | Improved healing in compromised models | Modulated macrophage polarization; Reduced inflammation | [3] [5] |

| Radiation-induced skin injury | Engineered MSC-Exos | Promoted healing of radiation-induced damage | Suppressed inflammatory responses; Modulated macrophage polarization | [3] |

Impact of Production Variables on Exosome Yield and Characteristics

Table 2: Methodological Comparisons in MSC-Exosome Production and Efficacy

| Parameter | Comparison | Key Findings | Implications for Research | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Isolation Method | Ultracentrifugation (UC) vs. Tangential Flow Filtration (TFF) | TFF demonstrated statistically higher particle yields than UC | Enhanced production efficiency for clinical translation | [6] |

| Culture Medium | DMEM vs. α-MEM | α-MEM showed higher cell proliferation and particle yields (4,318.72 ± 2,110.22 particles/cell) | Medium selection impacts both cell growth and exosome production | [6] |

| Therapeutic Timing | Pre-treatment vs. Post-treatment (H₂O₂-induced damage) | Both pre- and post-treatment increased cell viability (54.60 ± 3.59% and 52.68 ± 0.49% vs. 37.86% control) | MSC-exosomes effective both prophylactically and therapeutically | [6] |

| Source Efficacy | Bone marrow vs. Adipose vs. Umbilical cord | BM-, AD-, and UC-derived EVs all effective; UC-MSCs with lower immunogenicity | Source selection depends on application requirements | [4] [1] |

| Combination Therapy | MSC-Exos alone vs. with biomaterials | Synergistic application with advanced biomaterials significantly enhanced therapeutic efficacy | Scaffolds provide protective niche for enhanced effect | [3] [7] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodological Insights

Standardized Wound Healing Assessment Protocol

The following methodology, synthesized from multiple studies, represents a comprehensive approach for evaluating MSC-exosome efficacy in cutaneous wound models:

Animal Model Establishment: Utilize 6-8 week old male BALB/c mice (26-30g). Create full-thickness cutaneous wounds under sterile conditions [8].

Exosome Administration: Locally inject MSC-exosomes (concentration: 80-100 μg/mL in PBS) around the wound periphery. Multiple administration timepoints may be used throughout the healing process [8] [2].

Wound Closure Assessment: Document wound healing progression through:

- Daily photographic documentation

- Wound area measurement using ImageJ software

- Calculation of wound closure rate: (Initial area - Remaining area)/Initial area × 100 [8]

Histological and Molecular Analysis: Upon sacrifice, collect tissue samples for:

- Histological examination of re-epithelialization and angiogenesis

- Scar width measurement

- Spatial transcriptomics analysis to investigate heterogeneity of major cell types [8]

Mechanistic Evaluation: Perform immunohistochemistry and Western blotting for key pathway components including TGF-β, Wnt signaling, apoptosis markers (AIF, PARP-1), and macrophage polarization markers [8] [2].

Exosome Isolation and Characterization Workflow

In Vitro Functional Assays

Cell Scratch/Migration Assay:

- Seed human dermal fibroblast-adult cells (HDF-a) in multi-well plates

- Create uniform scratch with pipette tip

- Wash with D-PBS and add serum-free medium with MSC-exosomes (100 μg/mL)

- Capture images at 0, 12, and 24 hours

- Calculate migration area: (A₀ - Aₙ)/A₀ × 100, where A₀ is initial scratch area and Aₙ is remaining area [8]

Cell Proliferation Assay:

- Treat HDF-a cells with MSC-exosomes

- Assess proliferation using standardized assays (e.g., MTT, CCK-8)

- Optimal results observed at 50-100 μg/mL concentration [6]

Apoptosis Suppression Assay:

- Induce apoptosis in HaCaT keratinocytes with H₂O₂

- Treat with MSC-exosomes

- Evaluate apoptosis rates via flow cytometry

- Assess nuclear translocation of apoptosis-inducing factor (AIF) and PARP-1 expression [2]

Signaling Pathways in MSC-Exosome Mediated Repair

The molecular mechanisms through which MSC-exosomes mediate tissue repair involve multiple interconnected signaling pathways. In cutaneous wound healing, MSC-exosomes have been shown to reduce TGF-β signaling while increasing Wnt pathway activation, resulting in improved healing with reduced scar formation [8]. Additionally, they attenuate cell death by suppressing apoptosis-inducing factor (AIF) nuclear translocation and enhancing poly ADP ribose polymerase 1 (PARP-1) and poly (ADP-ribose) (PAR) expression [2].

A critical mechanism involves immunomodulation through regulation of macrophage polarization. MSC-exosomes suppress pro-inflammatory M1 polarization while enhancing anti-inflammatory M2 polarization, creating a microenvironment conducive to tissue repair [3] [5]. They also modulate several key signaling pathways in recipient cells, including PI3K/AKT, JAK/STAT, TGF-β/Smad, and Wnt/β-catenin, collectively coordinating the regeneration process in target tissues [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for MSC-Exosome Wound Healing Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Function | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Culture Media | α-MEM, DMEM, RPMI-1640 | MSC expansion and exosome production | α-MEM shows superior cell proliferation and particle yields | [6] |

| Characterization Antibodies | Anti-CD63, Anti-TSG101, Anti-CD9 | Exosome identification and validation | Confirm presence of exosome surface markers | [8] [6] |

| Isolation Systems | Ultracentrifuge, Tangential Flow Filtration | Exosome purification from conditioned media | TFF provides higher yields for large-scale production | [6] |

| Animal Models | BALB/c mice, C57BL/6J mice | In vivo wound healing assessment | BALB/c mice (6-8 weeks) standard for cutaneous wound models | [8] [7] |

| Cell Lines | HDF-a, HaCaT | In vitro mechanistic studies | Assess fibroblast and keratinocyte responses | [8] [2] |

| Imaging & Analysis | TEM, NTA, Western Blot, Spatial Transcriptomics | Exosome characterization and mechanism elucidation | Comprehensive analysis of size, concentration, and molecular effects | [8] [6] |

The accumulated evidence demonstrates that MSC-exosomes represent a promising therapeutic tool for wound repair, with efficacy documented across multiple wound models including cutaneous injuries, burns, and diabetic wounds. The consistency of therapeutic outcomes—accelerated wound closure, enhanced angiogenesis, reduced inflammation, and improved scar quality—across diverse experimental conditions underscores their robust reparative potential.

Current research indicates that several factors significantly influence therapeutic outcomes:

- Source selection (umbilical cord, bone marrow, adipose tissue)

- Isolation methodology (with TFF outperforming ultracentrifugation for yield)

- Dosage and administration timing (effective both pre- and post-injury)

- Combination strategies (enhanced efficacy with biomaterial scaffolds)

For drug development professionals, these findings support continued investment in MSC-exosome therapeutics while highlighting the importance of standardization in production protocols and mechanistic understanding. Future research directions should prioritize clinical translation through optimized delivery systems, enhanced targeting strategies, and comprehensive safety profiling—paving the way for a new generation of cell-free regenerative therapies.

The therapeutic potential of Mesenchymal Stem Cell (MSC) transplantation, once attributed primarily to cell differentiation and replacement, is now understood to be largely mediated by paracrine factors released by these cells [9] [10] [11]. Among these factors, exosomes—nanoscale extracellular vesicles ranging from 30-150 nm in diameter—have emerged as pivotal mediators of intercellular communication and the principal effectors of tissue repair and immunomodulation [9] [10] [11]. These vesicles serve as protective carriers for a diverse array of bioactive molecular cargo, including proteins, lipids, mRNAs, and microRNAs (miRNAs), which they deliver to recipient cells to alter gene expression and cellular function [10] [12] [13]. The composition of this cargo is not random; it is a selectively packaged reflection of the parent MSC's source and physiological state, endowing exosomes with the ability to coordinate complex processes such as angiogenesis, immunoregulation, and extracellular matrix remodeling [9] [12] [5]. This article delves into the key molecular components of MSC-derived exosomes, comparing their performance and mechanisms across different experimental wound models, thereby providing a crucial resource for researchers and drug development professionals in the field of regenerative medicine.

Decoding the Cargo: Core Molecular Components of MSC Exosomes

The therapeutic efficacy of MSC exosomes is governed by their molecular payload. The tables below catalog the critical growth factors, miRNAs, and proteins identified in MSC exosomes, along with their primary documented functions.

Table 1: Key Growth Factors and Proteins in MSC Exosomes and Their Functions

| Molecular Cargo | Type | Primary Documented Functions | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|

| TGF-β1 (Transforming Growth Factor Beta 1) | Growth Factor | Immunoregulation, inhibition of epithelial-mesenchymal transition, fibrosis modulation | [9] [12] |

| HGF (Hepatocyte Growth Factor) | Growth Factor | Immunoregulation, tissue repair, stimulation of hepatocyte proliferation | [10] [12] |

| IL-10 (Interleukin 10) | Cytokine | Anti-inflammatory signaling, immunomodulation | [10] [12] |

| VEGF (Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor) | Growth Factor | Stimulation of angiogenesis, fundamental for tissue repair | [10] |

| EMMPRIN (Extracellular Matrix Metalloproteinase Inducer) | Protein | Stimulation of angiogenesis | [10] |

| MMP-9 (Matrix Metalloproteinase 9) | Enzyme | Stimulation of angiogenesis, extracellular matrix remodeling | [10] |

| Tetraspanins (CD63, CD81, CD9) | Membrane Proteins | Common exosome surface markers used for isolation and characterization | [9] [10] |

| HSPs (Heat Shock Proteins: HSP60, HSP70, HSP90) | Chaperone Proteins | Stress response, common exosomal proteins | [10] |

| ALIX & TSG101 | Cytosolic Proteins | Involved in MVB biogenesis and exosome formation | [10] |

Table 2: Key MicroRNAs (miRNAs) in MSC Exosomes and Their Target Pathways/Functions

| microRNA (miRNA) | Primary Documented Functions / Target Pathways | Key References |

|---|---|---|

| miR-125a-3p | Suppresses T cell activity, maintains Th1/Th2 balance, inhibits Th17 expansion | [9] [13] |

| miR-146a | Down-regulates the NF-κB pathway, attenuating inflammatory response | [9] [13] |

| miR-21-5p | Inhibits dendritic cell maturation, promotes CCR7 degradation | [9] [13] |

| miR-155-5p | Inhibits B cell proliferation, antibody production, and memory B cell development | [9] |

| miR-223-3p | Prevents dendritic cell maturation by acting on CD83 gene | [13] |

| miR-27a-5p | Promotes odontogenic differentiation via TGFβ1/Smad pathway | [13] |

| miR-451a, miR-205-5p, miR-150-5p, miR-320a | Experimental evidence for inhibition of inflammatory responses (e.g., in rheumatoid arthritis) | [9] |

Cargo in Action: Comparative Performance in Preclinical Wound Models

Systematic reviews and meta-analyses of preclinical studies provide compelling evidence for the therapeutic efficacy of MSC-derived extracellular vesicles (MSC-EVs) in wound healing. A 2025 meta-analysis of 83 preclinical studies demonstrated that MSC-EVs significantly enhance wound closure rate, reduce scar width, and improve blood vessel density and collagen deposition in both diabetic and non-diabetic animal models [14]. The performance, however, varies significantly based on the type of vesicle, the source of MSCs, and the route of administration.

Table 3: Comparative Efficacy of MSC-EVs in Preclinical Wound Models Based on a 2025 Meta-Analysis

| Experimental Variable | Findings from Preclinical Meta-Analysis | Key References |

|---|---|---|

| Overall Efficacy | Significant improvement in wound closure rate, scar width, blood vessel density, and collagen deposition in diabetic and non-diabetic models. | [14] |

| Vesicle Type Comparison | ApoSEVs (Apoptotic Small EVs) showed better efficacy in wound closure and collagen deposition than ApoBDs (Apoptotic Bodies) and sEVs (small EVs). sEVs were more effective than ApoEVs in promoting revascularization. | [14] |

| MSC Source Comparison | ADSCs (Adipose-Derived Stem Cells) demonstrated the best effect on wound closure rate and collagen deposition. BMMSCs (Bone Marrow MSCs) were more effective in promoting revascularization. | [14] |

| Administration Route | Subcutaneous injection outperformed topical dressing/covering in wound closure, collagen deposition, and revascularization. | [14] |

The mechanisms by which this cargo executes its functions are complex and involve the modulation of key signaling pathways in recipient cells. For instance, exosomal miRNAs and proteins can coordinately regulate the PI3K/Akt pathway to promote cell survival and proliferation, the TGF-β/Smad pathway to modulate fibrosis and differentiation, and the Wnt/β-catenin pathway to influence tissue regeneration [15] [5]. The following diagram illustrates a simplified workflow of how MSC exosomes are isolated, characterized, and applied in wound healing research, leading to specific cellular outcomes through these key pathways.

Experimental Workflow in MSC Exosome Wound Healing Research

The molecular cargo delivered by MSC exosomes activates critical signaling pathways within target cells—such as keratinocytes, fibroblasts, and endothelial cells—to promote healing. The diagram below details how specific exosomal components, particularly miRNAs, interact with these pathways to coordinate the repair process.

Exosomal Cargo Activates Key Healing Pathways

Essential Protocols for Exosome Isolation and Characterization

The reproducibility of MSC exosome research hinges on standardized and well-documented experimental protocols. The following sections detail key methodologies for isolating and characterizing exosomes from MSC-conditioned media.

Detailed Protocol: Differential Ultracentrifugation for Exosome Isolation

Differential Ultracentrifugation (DUC) remains the most commonly employed method for exosome isolation, accounting for approximately 56% of all methods used in research [11]. The following steps outline a typical DUC protocol:

- MSC Culture and Conditioned Media Collection: Culture MSCs (e.g., from bone marrow, adipose tissue, or umbilical cord) to 70-80% confluence. Replace the growth medium with a serum-free exosome-depleted medium. After 24-48 hours, collect the conditioned media and perform initial processing.

- Low-Speed Centrifugation: Centrifuge the conditioned media at 300 × g for 10 minutes at 4°C to pellet floating cells.

- Moderate-Speed Centrifugation: Transfer the supernatant to a new tube and centrifuge at 2,000 × g for 20 minutes at 4°C to remove dead cells and large debris.

- High-Speed Centrifugation: Transfer the resulting supernatant to ultracentrifuge tubes and centrifuge at 10,000 × g for 30-45 minutes at 4°C to pellet larger vesicles and organelles.

- Ultracentrifugation for Exosome Pellet: Carefully transfer the supernatant to fresh ultracentrifuge tubes. Pellet the exosomes by ultracentrifugation at 100,000 - 120,000 × g for 70-120 minutes at 4°C.

- Washing and Final Pellet: Discard the supernatant and resuspend the exosome pellet in a large volume of sterile, cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Perform a final ultracentrifugation at 100,000 - 120,000 × g for 70 minutes at 4°C to wash the exosomes. Resuspend the final, purified exosome pellet in a small volume of PBS and aliquot for storage at -80°C [11].

Detailed Protocol: Characterizing Exosomes and Confirming Cargo

Post-isolation, a combination of techniques is required to confirm the identity, purity, and cargo of the isolated exosomes.

- Size and Concentration Analysis (Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis - NTA): Dilute the exosome preparation in PBS and inject it into the NTA system. This analysis provides the particle size distribution profile (confirming the expected 30-150 nm range) and the particle concentration [14].

- Morphology Examination (Transmission Electron Microscopy - TEM): Place a drop of the exosome suspension on a carbon-coated grid, stain with 1-2% uranyl acetate, and image under TEM. This confirms the classic cup-shaped spherical morphology and membrane integrity of the vesicles [14].

- Surface Marker Profiling (Western Blot): Lyse an aliquot of the exosomes and subject it to SDS-PAGE and Western blotting. Probe for the presence of positive markers common to most exosomes (e.g., CD63, CD81, CD9, ALIX, TSG101) and the absence of negative markers (e.g., Grp94, calnexin) to ensure minimal contamination from cellular components [9] [14].

- Cargo Analysis (qRT-PCR and Proteomics): To confirm the presence of functional cargo:

- For miRNA analysis, extract total RNA from the exosomes and perform quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) using primers specific for miRNAs of interest (e.g., miR-146a, miR-21-5p) [12] [13].

- For protein cargo, subject the exosomal lysate to mass spectrometry-based proteomic analysis to identify and quantify the presence of key growth factors and cytokines (e.g., VEGF, HGF, TGF-β1) [10].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for MSC Exosome Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example Usage & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| MSC Culture Media | Expansion and maintenance of mesenchymal stem cells. | Often supplemented with FBS that has been ultracentrifuged to remove bovine exosomes. |

| Exosome-Depleted FBS | Provides essential growth factors for cell culture without contaminating the conditioned media with bovine exosomes. | Crucial for producing clean exosome preps for downstream analysis and functional assays. |

| Protease Inhibitors | Prevent degradation of the protein cargo within exosomes during isolation and storage. | Added to conditioned media immediately after collection. |

| PBS (Phosphate Buffered Saline) | Washing and resuspension of the final exosome pellet; also used as a buffer for in vivo injections. | Must be sterile and cold for washing steps. |

| Antibodies for Characterization | Identification and validation of exosomes via Western Blot, Flow Cytometry, or ELISA. | Key targets: CD63, CD81, CD9 (positive markers); Grp94, Calnexin (negative markers). |

| qRT-PCR Assays | Quantification of specific exosomal microRNAs (e.g., miR-146a, miR-21-5p). | Requires specialized RNA extraction kits optimized for low-concentration, small RNAs. |

| Near-Infrared (NIR) Dyes (e.g., DiR, DiD) | Labeling exosomes for in vivo tracking and biodistribution studies. | High signal-to-noise ratio makes them ideal for imaging [10]. |

| Advanced Biomaterials (e.g., Hydrogels) | Serve as scaffolds to enhance exosome retention and provide sustained release at the wound site. | Improves therapeutic efficacy by preventing rapid clearance [15] [3]. |

The systematic comparison of molecular cargo and its context-dependent functionality underscores that MSC exosomes are sophisticated, information-rich nanoparticles. Their performance in wound healing is not a singular phenomenon but a variable outcome influenced by the MSC source, vesicle type, and mode of delivery. The convergence of exosome biology with advanced biomaterials engineering promises to enhance therapeutic outcomes by ensuring targeted and sustained delivery. However, the field must address significant challenges, primarily the high heterogeneity in collection conditions, separation methods, and characterization standards observed across studies [14]. Future research must prioritize standardization in line with MISEV (Minimal Information for Studies of Extracellular Vesicles) guidelines [14] and explore engineered exosomes to achieve precise control over their cargo and function. By deepening our understanding of the key molecular cargo—the growth factors, miRNAs, and proteins—researchers can unlock the full potential of MSC exosomes as a powerful, cell-free therapeutic paradigm in regenerative medicine.

Exosomes are nano-sized extracellular vesicles, typically ranging from 30 to 150 nm in diameter, that are secreted by virtually all cell types and play a crucial role in intercellular communication [16] [17]. These lipid bilayer-enclosed vesicles transport a diverse cargo of proteins, lipids, mRNAs, miRNAs, and DNA from parent cells to recipient cells, influencing their biological functions [17] [18]. In the context of skin biology and wound healing, exosomes derived from mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) and resident skin cells have emerged as key regulators of tissue repair and regeneration [19] [20]. Their ability to modulate the behavior of fibroblasts, keratinocytes, and immune cells makes them particularly promising as therapeutic agents for enhancing wound healing, especially in challenging clinical contexts such as diabetic wounds [19] [4].

The therapeutic potential of MSC-derived exosomes (MSC-EVs) has been demonstrated across numerous preclinical models, showing robust benefits in functional recovery, inflammation reduction, and tissue regeneration [4]. Unlike whole-cell therapies, exosomes offer advantages including lower immunogenicity, enhanced stability, and the ability to cross biological barriers [4] [20]. This review systematically examines how exosomes precisely target and modulate the key cellular players in skin repair—fibroblasts, keratinocytes, and immune cells—and provides a comparative analysis of MSC exosome performance across different animal wound models, supported by experimental data and methodologies.

Exosome Modulation of Key Skin Cells

Fibroblasts: Activation and Extracellular Matrix Remodeling

Exosomes profoundly influence fibroblast behavior, directing critical processes of extracellular matrix (ECM) synthesis and remodeling essential for wound healing. MSC-derived exosomes promote fibroblast proliferation, migration, and collagen synthesis, thereby enhancing tissue regeneration [20].

Key Mechanisms:

- Collagen Production: Exosomes from human umbilical cord MSCs (hucMSCs) have been shown to increase collagen type I and type III synthesis in fibroblasts, with a shift toward a more favorable collagen I/III ratio that improves tissue tensile strength [20].

- Matrix Metalloproteinase Regulation: Keratinocyte-derived exosomes carry matrix metalloproteinases (MMP-1, MMP-3, MMP-8, MMP-9) that degrade extracellular matrix components during the early phases of wound repair, facilitating cell migration [21].

- Phenotypic Differentiation: Exosomes can modulate fibroblast differentiation into myofibroblasts, the key effector cells responsible for wound contraction, through transfer of TGF-β and other signaling molecules [21].

Experimental evidence indicates that exosomal miRNAs play a particularly important role in regulating fibroblast function. For instance, miR-21, miR-23a, and miR-125b transferred via exosomes can suppress fibroblast apoptosis and promote proliferation, while miR-29a modulates collagen expression [17].

Keratinocytes: Migration, Proliferation, and Re-epithelialization

Keratinocytes, the predominant cells of the epidermis, are crucial for re-epithelialization during wound healing. Exosomes significantly accelerate this process by enhancing keratinocyte migration and proliferation [21].

Key Mechanisms:

- Accelerated Migration: MSC-derived exosomes have been shown to activate the ERK/MAPK and AKT signaling pathways in keratinocytes, enhancing their migratory capacity [17].

- Proliferation Stimulation: Exosomes from adipose-derived stem cells (ADSCs) promote keratinocyte proliferation through transfer of cyclins and cyclin-dependent kinases [22].

- Differentiation Regulation: Keratinocyte-derived exosomes themselves contain proteins involved in differentiation regulation, including involucrin and kallikrein 7 (KLK7) [21].

The bidirectional communication between keratinocytes and other skin cells via exosomes creates a sophisticated network that coordinates the healing process. For example, exosomes from activated keratinocytes can modulate fibroblast behavior, while fibroblast-derived exosomes can influence keratinocyte migration and differentiation [21].

Immune Cells: Inflammation Control and Macrophage Polarization

Perhaps the most sophisticated function of exosomes in wound healing is their modulation of the immune response. Exosomes can either activate or suppress immune functions depending on their cellular origin and cargo, making them powerful regulators of inflammation [16] [17].

Key Mechanisms:

- Macrophage Polarization: MSC-derived exosomes promote the switch from pro-inflammatory M1 macrophages to anti-inflammatory M2 phenotypes, which is crucial for transitioning from the inflammatory to proliferative phase of healing [17]. This polarization is mediated through exosomal transfer of miRNAs such as let-7b and miR-223 that target inflammatory pathways [23].

- Lymphocyte Regulation: Exosomes can carry immunomodulatory molecules like TGF-β and PD-L1 that suppress excessive T-cell activation, preventing uncontrolled inflammation [23].

- Neutrophil Recruitment: Keratinocyte-derived exosomes regulate neutrophil infiltration and neutrophil extracellular trap (NET) formation through activation of NF-κB and p38 MAPK pathways [17].

In diabetic wound models, MSC-exosomes have demonstrated remarkable ability to correct the prolonged inflammation characteristic of these chronic wounds, resulting in accelerated healing [19] [4].

Table 1: Key Exosomal Cargos and Their Cellular Effects in Wound Healing

| Exosomal Cargo | Source | Target Cell | Biological Effect | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| miR-21 | MSC, Keratinocyte | Fibroblast | Promotes proliferation and migration | [17] [21] |

| miR-29a | MSC | Fibroblast | Regulates collagen synthesis | [17] |

| miR-125b | MSC | Keratinocyte | Enhances migration capacity | [17] |

| TGF-β | Keratinocyte, Immune cell | Fibroblast, Immune cell | Drives myofibroblast differentiation; immune suppression | [21] [23] |

| MMPs (1,3,8,9) | Keratinocyte | Extracellular matrix | ECM remodeling during migration | [21] |

| PD-L1 | Immune cell, Tumor cell | T-cell | Suppresses T-cell activation | [23] |

| let-7 miRNA family | Keratinocyte | Multiple targets | Regulates proliferation, differentiation, apoptosis | [21] |

Comparative Performance of MSC Exosomes in Animal Wound Models

An umbrella review of meta-analyses evaluating MSC-EVs in preclinical models has demonstrated their high efficacy across diverse disease models, including wound healing [4]. The therapeutic outcomes vary significantly based on MSC source, exosome dosage, and administration route.

Table 2: MSC Exosome Performance Across Animal Wound Models

| Animal Model | MSC Source | Most Effective Dosage | Administration Route | Key Outcomes | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diabetic mouse | Umbilical cord | 100 μg per wound | Local injection | Accelerated closure, enhanced angiogenesis, macrophage polarization to M2 | [4] [17] |

| Rat burn model | Adipose tissue | 200 μg/mL | Topical application | Improved re-epithelialization, collagen deposition, neovascularization | [22] [20] |

| Diabetic rat | Bone marrow | 10-100 μg protein | Local injection | Enhanced angiogenesis, fibroblast proliferation, miR-126 mediated repair | [4] [22] |

| Mouse full-thickness wound | Umbilical cord | 1010 particles/mL | In vitro administration | Promoted fibroblast and keratinocyte migration, TGF-β signaling activation | [22] |

| Rabbit ear wound | Bone marrow | 200 μg/0.5 mL | Intravenous | Improved healing quality, reduced scarring, enhanced collagen organization | [20] |

Key Findings from Comparative Analysis:

- Source-Dependent Efficacy: Bone marrow-, adipose-, and umbilical cord-derived EVs consistently demonstrate the highest efficacy in wound models, with modified EVs showing enhanced outcomes [4].

- Dosage Optimization: The therapeutic dose of exosomes commonly ranges from 10 to 100 μg of protein in mouse models, with a threshold beyond which additional exosomes may not provide further benefits [22].

- Route-Specific Effects: Local administration (intradermal, topical) generally provides superior results compared to systemic delivery for cutaneous wounds, as it minimizes clearance and off-target effects [22] [20].

The umbrella review noted that despite high efficacy, methodological quality of preclinical studies was moderate, with frequent risk of bias due to poor randomization and blinding [4]. This highlights the need for standardized protocols in future research.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standardized Exosome Isolation and Characterization

Isolation Protocols:

- Ultracentrifugation: The most widely used method involving sequential centrifugation steps to isolate exosomes from conditioned media [22]. Despite its popularity, this technique can co-isolate other vesicles and requires significant time [22].

- Size-Exclusion Chromatography (SEC): Separates exosomes based on size, preserving integrity and bioactivity but potentially lacking purity [22].

- Combined Approaches: Techniques combining multiple complementary methods (e.g., ultracentrifugation followed by SEC) demonstrate improved purity and reduced contamination [22].

Characterization Requirements: According to MISEV (Minimal Information for Studies of Extracellular Vesicles) guidelines, characterization should include:

- Nanoparticle tracking analysis for size distribution (30-150 nm expected)

- Transmission electron microscopy for morphological assessment

- Western blot for marker proteins (CD63, CD81, CD9, TSG101, ALIX) [22]

- Exclusion of non-vesicular contaminants (lipoproteins, protein aggregates)

Functional Assays for Cellular Modulation

Fibroblast Experiments:

- Migration Assay: Scratch/wound healing assay measuring fibroblast closure over 24-48 hours with exosome treatment

- Proliferation Assay: CCK-8 or EdU incorporation assays comparing fibroblast growth with/without exosomes

- Gene Expression: qRT-PCR analysis of collagen I, collagen III, α-SMA, and elastin expression

- Protein Analysis: Western blot or immunofluorescence for ECM proteins and signaling pathway components

Keratinocyte Experiments:

- Re-epithelialization Model: In vitro scratch assay measuring keratinocyte migration

- Differentiation Assessment: Expression analysis of differentiation markers (keratin 10, involucrin, loricrin)

- Proliferation Tracking: Ki-67 staining or flow cytometry for cell cycle analysis

Immune Modulation Experiments:

- Macrophage Polarization: Flow cytometry for M1 (CD86) and M2 (CD206) surface markers following exosome treatment

- Cytokine Profiling: ELISA or multiplex assays for inflammatory (TNF-α, IL-6) and anti-inflammatory (IL-10, TGF-β) cytokines

- T-cell Suppression Assays: Mixed lymphocyte reactions or T-cell proliferation assays with exosome treatment

Diagram 1: Experimental Workflow for Exosome Research. This diagram outlines the standard methodology for exosome isolation, characterization, and functional cellular assays commonly used in wound healing research.

Signaling Pathways in Exosome-Mediated Wound Healing

Exosomes modulate wound repair through several key signaling pathways that coordinate cellular responses across fibroblasts, keratinocytes, and immune cells.

Wnt/β-catenin Pathway: MSC-exosomes activate Wnt/β-catenin signaling in fibroblasts and keratinocytes, promoting proliferation and migration. This pathway is particularly important for hair follicle neogenesis during wound healing [17].

TGF-β/Smad Pathway: Essential for fibroblast-to-myofibroblast differentiation and collagen production, this pathway is activated by exosomal TGF-β and SMAD proteins transferred from various cell sources [21].

PI3K/Akt Pathway: Activation of this survival pathway by exosomal cargo protects cells from apoptosis and enhances proliferation, particularly important in the high-stress environment of diabetic wounds [17].

NF-κB Pathway: Exosomes from MSCs can suppress excessive activation of the NF-κB pathway in immune cells, reducing pro-inflammatory cytokine production and shifting the balance toward tissue repair [19] [17].

Diagram 2: Key Signaling Pathways in Exosome-Mediated Repair. This diagram illustrates the primary signaling pathways through which exosomes modulate cellular activities during wound healing, highlighting the interconnected nature of these regulatory mechanisms.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Exosome Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Experimental Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Isolation Kits | Total Exosome Isolation Kit, miRCURY Exosome Kit | Rapid isolation from biofluids and conditioned media | Enables high-throughput processing but may compromise purity [22] |

| Characterization Tools | Nanoparticle Tracking Analyzer, CD63/CD81/CD9 antibodies, TSG101 antibody | Size quantification, concentration measurement, protein marker confirmation | MISEV guidelines recommend multiple complementary techniques [22] |

| Cell Tracking Dyes | PKH67, PKH26, DiI, CFSE | Labeling exosomes for uptake and trafficking studies | Potential dye aggregation may cause artifacts; controls essential [22] |

| MSC Culture Media | MesenCult, StemMACS, Custom formulations | Expansion of parent MSC populations | Serum-free, xeno-free media preferred to avoid contaminating vesicles [22] |

| Engineering Tools | Lentiviral vectors, Electroporators, Sonication equipment | Genetic modification of parent cells, cargo loading | Enables production of enhanced functionality exosomes [24] |

| Animal Model Reagents | Streptozotocin (diabetes induction), Imiquimod (inflammatory models) | Creating disease-specific wound models | Critical for evaluating exosome efficacy in pathological conditions [17] |

Exosomes represent a sophisticated biological communication system that coordinates wound healing through precise modulation of fibroblasts, keratinocytes, and immune cells. The cumulative evidence from preclinical models strongly supports the therapeutic potential of MSC-derived exosomes, particularly for challenging wound environments like diabetic ulcers. The comparative analysis presented here reveals that efficacy depends critically on multiple factors including MSC source, exosome dosage, and administration route.

Future research directions should focus on standardizing isolation and characterization protocols, optimizing engineering strategies for enhanced targeting and functionality, and addressing the methodological limitations identified in current preclinical studies. As our understanding of exosome biology deepens, these natural nanocarriers hold exceptional promise for developing effective, cell-free therapies that address the complex challenges of impaired wound healing. The integration of exosome-based approaches with advanced biomaterials and delivery systems represents a particularly promising frontier for clinical translation.

Mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes (MSC-Exos) have emerged as a revolutionary acellular therapeutic platform in regenerative medicine. These nanoscale extracellular vesicles recapitulate the therapeutic effects of their parent cells by orchestrating key wound healing processes: immunomodulation, angiogenesis, and extracellular matrix (ECM) remodeling. This comprehensive analysis synthesizes current preclinical evidence and mechanistic insights into MSC-Exo functions across various animal wound models. We systematically compare therapeutic efficacy based on exosome sources, isolation methods, and administration protocols, providing researchers with standardized experimental frameworks and technical considerations for translating MSC-Exo biology into clinical applications for tissue repair and regeneration.

The therapeutic paradigm in regenerative medicine has shifted from direct cell transplantation to utilizing the paracrine factors secreted by mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs). Among these factors, extracellular vesicles, particularly exosomes (30-150 nm in diameter), have been identified as primary mediators of MSC functionality [25] [26]. MSC-derived exosomes (MSC-Exos) are lipid-bilayer enclosed vesicles loaded with bioactive molecules including proteins, lipids, mRNAs, and microRNAs that mediate intercellular communication [27]. These nanovesicles offer significant advantages over whole-cell therapies, including lower immunogenicity, absence of tumorigenic risk, ability to cross biological barriers, and easier storage and standardization [25] [28]. As natural bioactive carriers, MSC-Exos precisely regulate the inflammatory response, angiogenesis, and tissue repair processes in target tissues, making them ideal candidates for therapeutic intervention in wound healing [25].

The following diagram illustrates the multifaceted role of MSC-Exos in coordinating wound healing through different cellular pathways:

Diagram Title: MSC-Exo Mediated Coordination of Wound Healing

Comparative Efficacy Across Animal Wound Models

MSC-Exos have demonstrated robust therapeutic potential across diverse preclinical wound models. The table below summarizes quantitative efficacy data from systematic analyses of animal studies, highlighting the consistency of therapeutic effects across different wound types.

Table 1: MSC-Exo Efficacy Across Preclinical Wound Models

| Wound Model Type | Key Therapeutic Effects | Exosome Sources | Efficacy Metrics | Reference Support |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diabetic Wounds | Enhanced wound closure, angiogenesis, collagen deposition, macrophage polarization to M2 phenotype | BM-MSC, AD-MSC, UC-MSC | 1.5-2.2-fold faster wound closure; ~80% reduction in pro-inflammatory cytokines | [4] [27] |

| Radiation-Induced Skin Injury | Modulation of macrophage polarization, suppression of inflammatory responses, epithelial regeneration | AD-MSC, UC-MSC | Significant improvement in healing rate; enhanced keratinization and collagen deposition | [3] [27] |

| Burns and Excisional Wounds | Accelerated re-epithelialization, neovascularization, fibroblast proliferation | AD-MSC, BM-MSC | ~50% increase in angiogenesis; 2.1-fold higher collagen synthesis | [4] [29] |

| Ischemic Wounds | Promotion of angiogenesis via VEGF, FGF2, miR-126; improved perfusion | BM-MSC, UC-MSC | 40-60% improvement in blood flow recovery; capillary density increased by 3.1-fold | [30] [27] |

| Complex Perianal Fistulas | Tissue regeneration, modulation of inflammatory microenvironment | AD-MSC, UC-MSC | Fistula closure in preclinical models; reduced inflammation | [25] [4] |

An umbrella review of 47 meta-analyses covering 27 diseases confirmed that MSC-EVs consistently improve functional scores, reduce inflammation, and promote regeneration across neurological, renal, wound healing, liver, musculoskeletal, respiratory, and reproductive disorders [4]. The analysis revealed that bone marrow-, adipose-, and umbilical cord-derived EVs were most effective, with modified EVs showing enhanced outcomes compared to native exosomes [4].

Experimental Protocols for MSC Exosome Research

Standardized Workflow for MSC-Exo Wound Healing Studies

The following diagram outlines a standardized experimental workflow for evaluating MSC-Exo therapeutic efficacy in animal wound models:

Diagram Title: Experimental Workflow for MSC-Exo Wound Studies

Detailed Methodological Considerations

Exosome Production and Characterization

- Cell Culture: MSC-Exos are typically produced using immortalized cell lines grown in serum-free media under controlled conditions [22]. Bioreactor systems, particularly hollow-fiber cartridges, enable large-scale production while maintaining MSC characteristics and preventing senescence [29].

- Isolation Methods: Ultracentrifugation remains the gold standard, though combination approaches (e.g., size-exclusion chromatography with ultrafiltration) improve purity and yield [22]. The Minimal Information for Studies of Extracellular Vesicles (MISEV) guidelines provide critical standardization for isolation and characterization protocols [22].

- Characterization: Essential parameters include nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA) for size distribution (30-150 nm expected), transmission electron microscopy for structural integrity, and western blot or flow cytometry for surface markers (CD9, CD63, CD81) [29].

Animal Model Considerations

- Diabetic Models: Streptozotocin-induced diabetic mice or rats with dorsal excisional wounds represent standard models for diabetic wound healing studies [27].

- Ischemic Models: Hindlimb ischemia or ischemic flap models evaluate pro-angiogenic effects [30].

- Control Groups: Essential controls include vehicle-treated wounds and possibly MSC-transplanted groups for comparative efficacy.

Administration Protocols

- Dosing: Effective doses in rodent models typically range from 10-100 μg of exosomal protein, with optimization required for specific models [22]. For instance, in traumatic brain injury models, 100 μg exosomes per rat showed more significant efficacy than 50 μg or 200 μg doses [22].

- Routes: Local application (topical or peri-wound) enhances target tissue retention compared to systemic administration [22]. Biomaterial-assisted delivery (hydrogels, scaffolds) improves retention and sustained release [3] [30].

Core Healing Pathways: Molecular Mechanisms

Inflammatory Modulation

MSC-Exos precisely regulate the inflammatory phase of wound healing through multiple mechanisms:

- Macrophage Polarization: Exosomal miRNAs (miR-146a, miR-223, let-7b) promote transition of pro-inflammatory M1 macrophages to anti-inflammatory M2 phenotype [27]. This transition is mediated through inhibition of NF-κB signaling and NLRP3 inflammasome activation [27].

- Cytokine Regulation: Engineered AD-MSC exosomes (eXo3) demonstrate potent reduction of inflammatory cytokines (IL-6, IL-8, MCP-1) in primary human fibroblast models [29].

- Lymphocyte Modulation: MSC-Exos influence CD4+ and CD8+ lymphocyte accumulation and activation kinetics in wound beds, though wound closure proceeds normally even in lymphocyte-deficient models [27].

Angiogenic Activation

MSC-Exos promote robust neovascularization through multiple pathways:

- Growth Factor Delivery: Exosomes carry and transfer pro-angiogenic factors including VEGF, FGF2, PDGF, and TGF-β to endothelial cells [30] [27].

- miRNA-Mediated Signaling: miR-126 activates Wnt/β-catenin and PI3K/Akt pathways, while other exosomal miRNAs (miR-21, miR-29a) regulate endothelial cell proliferation and migration [30] [27].

- Notch Pathway Activation: MSC-Exos modulate Notch signaling to stabilize newly formed vessels and promote functional maturation [30].

ECM Remodeling and Tissue Regeneration

MSC-Exos directly influence structural cells to orchestrate tissue repair:

- Fibroblast Activation: Exosomes stimulate fibroblast proliferation, migration, and collagen synthesis (types I and III) through miRNA and protein cargo delivery [29] [27].

- Re-epithelialization: Keratinocyte migration and proliferation are enhanced by MSC-Exos, accelerating wound epithelial coverage [27].

- Collagen Organization: Tuned AD-MSC exosomes promote improved collagen deposition and alignment, enhancing tensile strength in healed tissue [29].

The following diagram summarizes the key molecular pathways through which MSC-Exos coordinate these healing processes:

Diagram Title: Molecular Pathways of MSC-Exo in Wound Healing

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for MSC Exosome Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| MSC Sources | Bone marrow-MSC (BM-MSC), Adipose-derived MSC (AD-MSC), Umbilical cord-MSC (UC-MSC) | Comparative efficacy studies; source selection optimization | AD-MSCs show higher proliferation rates and resistance to senescence; UC-MSCs demonstrate strong immunomodulation [4] [26] |

| Isolation Kits | Ultracentrifugation systems, Size-exclusion chromatography, Precipitation kits, Immunoaffinity capture | Exosome purification from conditioned media | Combination methods improve purity; MISEV guidelines critical for standardization [22] [28] |

| Characterization Tools | Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis, Transmission Electron Microscopy, MACSPlex Exosome Kit | Size distribution, morphology, surface marker validation | CD9, CD63, CD81 as canonical markers; BCA protein quantification for standardization [29] |

| Animal Models | Diabetic (db/db mice), Excisional wound, Burn injury, Ischemic flap | Preclinical efficacy assessment | Streptozotocin-induced diabetes common for diabetic wound models [27] |

| Biomaterial Carriers | Hydrogels, Scaffolds, Wound matrices | Enhanced exosome retention and sustained release | OASIS Wound Matrix shows efficacy in clinical comparisons [30] |

| Analysis Antibodies | CD31, α-SMA, Collagen I/III, TNF-α, IL-10 | Histological and molecular analysis of healing outcomes | M1/M2 macrophage polarization markers critical for inflammation assessment [27] |

| Cell Culture Reagents | Serum-free media, Hollow-fiber bioreactors, 3D culture systems | Large-scale exosome production under controlled conditions | Bioreactor systems maintain genetic stability during expansion [29] |

MSC-derived exosomes represent a promising acellular therapeutic platform that effectively orchestrates the core healing pathways of inflammation modulation, angiogenesis, and ECM remodeling. The comprehensive analysis of preclinical studies demonstrates consistent therapeutic efficacy across diverse wound models, with variations in performance based on MSC source, isolation methods, and administration protocols.

Future research directions should focus on standardization of production protocols, enhancement of targeting capabilities through engineering approaches, and thorough investigation of long-term biodistribution and safety profiles. The integration of biomaterials and combination therapies presents particularly promising avenues for clinical translation. As the field progresses, interdisciplinary collaboration between stem cell biologists, material scientists, and clinicians will be essential to fully realize the potential of MSC exosomes in regenerative medicine.

From Bench to Bedside: Applying MSC Exosomes in Diverse Wound Models

The evaluation of mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes (MSC-exosomes) for wound healing therapies relies heavily on appropriate preclinical animal models. The transition from basic research to clinical application depends on selecting models that most accurately recapitulate human disease pathophysiology and treatment responses. This guide provides an objective comparison of the most commonly used animal models in MSC-exosome research, presenting key experimental data and methodologies to inform researchers' experimental design decisions. Understanding the strengths and limitations of each model system is crucial for generating translatable data in regenerative medicine and drug development.

Model Comparison: Physiological and Practical Considerations

Selecting an appropriate animal model requires balancing physiological relevance with practical experimental constraints. The table below compares key characteristics across common preclinical models used in wound healing and exosome therapy research.

Table 1: Physiological and Practical Comparison of Preclinical Models

| Characteristic | Mouse | Rat | Rabbit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adult Body Weight | 20-40g | 300-500g (LEW/W strain) | 2-5kg |

| Gestation Period | 19-21 days | 21-23 days | 28-35 days |

| Time to Sexual Maturity | 5-6 weeks | 8-10 weeks | 16-24 weeks |

| Genetic Tools Availability | Extensive | Moderate | Limited |

| Surgical Procedure Ease | Challenging due to small size | Good for most procedures | Excellent for complex surgeries |

| Relative Cost | Low | Moderate | High |

| Social Behavior | Territorial, stress-prone in social situations | Social, less stressed with handling | Variable by species |

| Cognitive Testing | Maze learning requires substantial training | Superior maze-learning with strategy | Limited data |

Quantitative Performance Metrics in Stem Cell Research

The yield and quality of biological materials vary significantly across species, impacting experimental design and feasibility. The following data compiled from comparative studies highlights these practical considerations.

Table 2: Adipose-Derived Stem Cell (ASC) Yields Across Species

| Species/Strain | Tissue Source | Average ASC Yield (cells/g tissue) | Proliferation Potential |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mouse | Gonadal fat | Very low (specific numbers not provided) | Moderate |

| Rat (LEW/W) | Gonadal fat | High (∼1.2×10^6 cells/g) | High |

| Rat (WAG) | Gonadal fat | Moderate (∼0.8×10^6 cells/g) | High |

| Rabbit | Subcutaneous fat | Moderate to High | High |

Experimental Protocols for Wound Healing Studies

Exosome Isolation and Characterization

Protocol Source: Adapted from standardized methodologies for MSC-exosome preparation [31] [32]

Materials Required:

- Mesenchymal Stem Cells (bone marrow, adipose, or umbilical cord-derived)

- Serum-free culture medium

- Ultracentrifugation equipment

- Transmission Electron Microscope

- Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis system

- Western blot apparatus

Methodology:

- Cell Culture: Expand MSCs in serum-free medium to avoid contamination with bovine exosomes.

- Conditioned Media Collection: Collect media after 48-72 hours of cell culture.

- Differential Centrifugation:

- 300 × g for 10 min to remove cells

- 2,000 × g for 20 min to remove dead cells

- 10,000 × g for 30 min to remove cell debris

- 100,000 × g for 70 min to pellet exosomes

- Washing: Resuspend exosome pellet in PBS and repeat ultracentrifugation.

- Characterization:

- Size distribution: Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis (30-150 nm expected)

- Morphology: Transmission Electron Microscopy

- Marker expression: Western blot for CD63, CD81, CD9, TSG101

Full-Thickness Excisional Wound Model

Protocol Source: Standardized wound healing assessment across species [20] [33]

Materials Required:

- Animal model (mouse, rat, or rabbit)

- Depilatory cream

- Biopsy punch (size varies by species)

- Test articles (MSC-exosomes in buffer)

- Transparent dressings

- Digital imaging system

- Histology equipment

Methodology:

- Preoperative Preparation:

- Anesthetize animals according to approved protocols

- Remove hair from dorsal area using electric clippers followed by depilatory cream

- Disinfect skin with alternating betadine and 70% alcohol scrubs

Wound Creation:

- Use biopsy punch to create full-thickness excisional wounds

- Recommended sizes:

- Mouse: 6-8 mm diameter

- Rat: 15-20 mm diameter

- Rabbit: 20-25 mm diameter

- Include panniculus carnosus in excision

Treatment Administration:

- Apply exosomes topically in hydrogel vehicle or via intradermal injection

- Include appropriate controls (vehicle alone, untreated)

- Cover with transparent semi-occlusive dressing

Monitoring and Assessment:

- Measure wound area every 2-3 days using digital planimetry

- Calculate percentage closure: [(Initial area - Current area)/Initial area] × 100

- Collect tissue for histology at predetermined endpoints (days 7, 14, 21)

MSC-Exosome Mechanisms in Wound Healing

MSC-exosomes accelerate wound healing through multiple coordinated mechanisms targeting distinct phases of the healing process. The following diagram illustrates key pathways and cellular processes modulated by exosomal cargo.

Mechanisms of MSC-Exosomes in Wound Healing

Model-Specific Applications and Validation

Murine Models: Genetic Manipulation and Immunological Studies

Mice represent the most extensively used model in preliminary MSC-exosome research, primarily due to the availability of sophisticated genetic tools and well-characterized immunological reagents.

Strengths:

- Genetic tractability: Transgenic strains enable study of specific pathways; the first recombinant mouse model was created in 1987, long preceding rat models (2010) [34]

- Humanized models: Can be engineered to express human genes or immune systems

- Cost-effectiveness: Lower maintenance costs and drug requirements due to small size

- Optogenetics: Smaller brain size facilitates light penetration for neurological wound healing studies

Limitations:

- Size constraints: Challenging surgical procedures and limited blood/tissue sampling

- Behavioral differences: Less complex social behaviors compared to rats, limiting psychological aspect of healing studies

- Stress susceptibility: More prone to handling stress, potentially confounding results

Rat Models: Surgical Feasibility and Behavioral Relevance

Rats provide an optimal balance between physiological similarity to humans and practical experimental handling, particularly for complex wound healing scenarios.

Strengths:

- Surgical practicality: Larger size facilitates precise surgical interventions and repeated sampling

- Cardiovascular research: Preferred for cardiovascular studies relevant to wound healing angiogenesis [35]

- Behavioral complexity: Exhibit richer social behaviors that better mimic human responses; critical for studying psychological impacts on healing

- Social behavior validation: In FMR1 gene knockout studies, rats showed social impairments paralleling human autism spectrum symptoms, while mice showed elevated social interactions [35]

Limitations:

- Genetic tools: Fewer available transgenic strains compared to mice

- Space requirements: Higher housing costs than murine models

- Reagent availability: Fewer species-specific antibodies and molecular tools

Rabbit Models: Surgical Precision and Clinical Translation

Rabbits serve as valuable intermediate models bridging small rodents and large animals, particularly for surgical technique development.

Strengths:

- Surgical versatility: Size permits complex surgical procedures mimicking clinical interventions

- Orthopedic research: Well-established for musculoskeletal and cartilage healing studies

- Skin physiology: Larger wound areas enable multiple sampling timepoints

Limitations:

- Cost factors: Higher acquisition and maintenance expenses

- Genetic resources: Limited availability of genetically modified strains

- Molecular tools: Fewer species-specific research reagents

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Tools for MSC-Exosome Wound Healing Research

| Category | Specific Tool/Reagent | Function/Application | Example Products |

|---|---|---|---|

| Exosome Isolation | Ultracentrifugation | Standard method for exosome purification | Beckman Optima XPN series |

| Size-exclusion Chromatography | High-purity exosome isolation | qEV columns | |

| Polymer-based Precipitation | Rapid exosome concentration | ExoQuick-TC | |

| Characterization | Nanoparticle Tracking | Size distribution and concentration | Malvern NanoSight |

| Western Blot | Protein marker validation | CD63, CD81, CD9 antibodies | |

| Electron Microscopy | Morphological confirmation | TEM with negative staining | |

| Animal Management | Anesthesia Equipment | Surgical procedures and imaging | Isoflurane systems |

| Wound Measurement | Quantitative healing assessment | Digital planimetry software | |

| Animal Monitoring | Health and behavior tracking | Automated monitoring systems | |

| Data Analysis | Statistical Software | Experimental data analysis | GraphPad Prism, SPSS |

| Imaging Software | Histological and wound analysis | ImageJ, Zen software | |

| Sample Size Calculation | Experimental power analysis | G*Power software [36] |

Experimental Design Considerations

Sample Size Calculation and Statistical Power

Appropriate sample size determination is critical for generating statistically valid results in preclinical studies.

Power Analysis Method:

- Effect size: Determine minimum clinically significant difference from prior studies

- Standard deviation: Estimate variability from pilot studies or literature

- Statistical power: Typically set at 80% (β=0.2)

- Significance level: Usually α=0.05

- Software tools: G*Power, nQuery Advisor [36]

Resource Equation Method:

- Applied when effect size estimation is unavailable

- Calculate E = Total animals - Total groups

- Maintain E between 10-20 for adequate power [36]

- Example: For 5 groups (control + 4 treatments), 5 animals/group gives E=20

Regulatory and Compliance Aspects

The transition of MSC-exosomes toward clinical application requires adherence to evolving regulatory standards.

Manufacturing Standards:

- Follow Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) protocols for clinical-grade exosomes

- Implement serum-free media to avoid xenogeneic contaminations

- Establish quality control metrics for potency and homogeneity [31]

Characterization Requirements:

- Define critical quality attributes (size, marker expression, cargo)

- Establish release criteria for batch consistency

- Develop potency assays relevant to wound healing mechanisms [32]

The field of MSC-exosome research continues to evolve with emerging technologies enhancing both model systems and therapeutic applications. Engineered exosomes (eExo) represent the next frontier, with modified surfaces for improved targeting and cargo loading for enhanced therapeutic efficacy [37]. As of January 2025, 64 registered clinical trials investigate MSC-EVs for various diseases, indicating growing translation potential [32].

The selection of an appropriate preclinical model should be guided by specific research questions, with murine models offering genetic flexibility, rat models providing surgical practicality and behavioral relevance, and rabbit models enabling technical refinement. Future research directions include developing standardized protocols for exosome characterization, establishing disease-specific model validation criteria, and creating integrated databases correlating model responses with clinical outcomes. As engineering strategies advance, preclinical models will continue to serve as essential platforms for validating the safety and efficacy of next-generation exosome-based wound healing therapies.

The pursuit of effective therapies for chronic and acute wounds relies heavily on robust preclinical animal models that accurately recapitulate human disease pathophysiology. Among emerging regenerative approaches, mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes (MSC-exosomes) have demonstrated remarkable therapeutic potential as a cell-free alternative to whole-cell therapies, offering advantages including low immunogenicity, targeted delivery capabilities, and biochemical stability [38] [31]. However, the translational success of these nanotherapeutics depends on selecting appropriate animal models that faithfully mirror the distinct healing impairments present in different wound types. This review systematically compares three primary wound models—diabetic, burn, and full-thickness excisional wounds—by synthesizing current data on MSC-exosome performance, therapeutic mechanisms, and experimental outcomes. Through objective analysis of quantitative preclinical data and detailed methodological protocols, we provide a framework for researchers to select optimal models for specific research questions and accelerate the development of exosome-based wound therapies.

Comparative Analysis of Wound Models and MSC-Exosome Performance

Model Characteristics and Pathophysiological Features

The selection of an appropriate wound model fundamentally shapes experimental outcomes and therapeutic efficacy assessments. Each major model type recapitulates distinct aspects of human pathophysiology, presenting unique advantages and limitations for evaluating MSC-exosome therapies as detailed in Table 1.

Table 1: Comparative Characteristics of Major Wound Healing Models

| Model Characteristic | Diabetic Wounds | Burn Wounds | Full-Thickness Excisional Wounds |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Pathological Features | Impaired angiogenesis, chronic inflammation, hyperglycemia-induced cellular dysfunction [39] | Coagulative necrosis, intense inflammatory response, multi-organ involvement in severe cases [40] | Complete epidermal and dermal removal, well-characterized healing phases [14] |

| Common Induction Methods | Streptozotocin (STZ) injection (T1D); genetically modified db/db mice (T2D) [14] | Thermal, electrical, chemical, or radiation exposure with controlled temperature/duration [40] | Surgical excision of defined diameter using biopsy punch or scalpel [14] |

| Healing Timeline | Delayed (21-28 days or non-healing) [39] | Variable by depth: superficial (7-14 days), deep (weeks to months) [40] | Predictable closure (10-14 days in mice) [14] |

| Key Clinical Relevance | Diabetic foot ulcers, chronic non-healing wounds [39] | Thermal injuries, scar formation, multi-organ dysfunction [40] | Surgical wounds, acute trauma, healing mechanism studies [14] |

| Advantages for Exosome Studies | Tests efficacy in complex metabolic dysfunction; ideal for angiogenesis studies [41] | Evaluates anti-inflammatory and anti-scarring effects; tests tissue regeneration capacity [38] | Standardized, highly reproducible; ideal for mechanism elucidation and screening [14] |

Quantitative Outcomes of MSC-Exosome Therapies Across Models

Recent meta-analyses of preclinical studies provide compelling evidence for the therapeutic efficacy of MSC-exosomes across wound types. Systematic evaluation of 83 preclinical studies revealed that MSC-exosome treatment significantly enhanced multiple healing parameters, with model-specific variations in responsiveness [14]. The following table synthesizes quantitative outcomes from controlled studies comparing MSC-exosome performance across the three wound models.

Table 2: Quantitative Outcomes of MSC-Exosome Treatment Across Wound Models

| Healing Parameter | Diabetic Wounds | Burn Wounds | Full-Thickness Excisional Wounds |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wound Closure Rate | 25-45% acceleration vs. controls [39] [14] | 20-35% improvement in re-epithelialization [38] [40] | 30-50% faster closure in acute models [14] |

| Angiogenesis (Vessel Density) | 1.8-2.5-fold increase in CD31+ vessels [41] [14] | Moderate improvement (1.5-1.8-fold) in neovascularization [38] | Significant enhancement (2.0-2.8-fold) in vascular density [14] |

| Collagen Deposition | Improved organization with 1.5-2.0-fold increase in mature collagen [39] | Enhanced remodeling with reduced hypertrophic scarring [40] | 1.8-2.2-fold increase in collagen density and maturation [14] |

| Re-epithelialization | Significant acceleration despite hyperglycemia (1.6-2.0-fold) [39] | Marked improvement in epidermal regeneration (1.7-2.1-fold) [38] | Rapid and complete epithelialization (1.9-2.4-fold) [14] |

Notably, subgroup analyses from the meta-analysis revealed that specific MSC sources demonstrated enhanced efficacy for particular wound types. Adipose-derived MSC-exosomes showed superior performance in diabetic wound closure rates, while bone marrow-derived MSC-exosomes exhibited the strongest pro-angiogenic effects across models [14]. Additionally, small extracellular vesicles (sEVs) demonstrated better revascularization outcomes compared to apoptotic extracellular vesicles (ApoEVs), though ApoEVs showed advantages in collagen deposition [14].

Experimental Protocols for MSC-Exosome Wound Healing Studies

Standardized Methodology for Wound Model Induction

Diabetic Wound Model Creation: For type 1 diabetes modeling, induce diabetes in 8-10 week old C57BL/6 mice via intraperitoneal streptozotocin (STZ) injections (50-60 mg/kg/day for 5 consecutive days) [14]. Confirm hyperglycemia (blood glucose >300 mg/dL) after one week. Anesthetize mice and create dorsal full-thickness excisional wounds using 6-8 mm biopsy punches. For type 2 diabetes modeling, utilize genetically modified db/db mice with identical wounding procedures [39].

Burn Wound Model Establishment: Anesthetize animals and shave dorsal hair. Create standardized contact burns using custom brass blocks (1-2 cm²) heated to 95-100°C in water bath, applied to dorsal skin for 10-15 seconds with uniform pressure [40]. This protocol typically yields deep partial-thickness burns with reproducible injury depth. Adminiate postoperative analgesia following institutional guidelines.

Full-Thickness Excisional Wound Creation: Anesthetize animals and prepare surgical site. Create bilateral dorsal wounds using sterile disposable biopsy punches (6-8 mm diameter for mice, 10-15 mm for rats) [14]. Extend wounds through panniculus carnosus muscle to ensure full-thickness injury. Apply wound dressing according to experimental requirements.

MSC-Exosome Isolation and Characterization Protocol

Exosome Isolation via Ultracentrifugation: Culture MSCs in serum-free media for 48 hours prior to collection. Centrifuge conditioned media at 300 × g for 10 minutes to remove cells, followed by 2,000 × g for 20 minutes to eliminate dead cells and debris [11]. Filter supernatant through 0.22 μm membrane and ultracentrifuge at 100,000 × g for 70 minutes at 4°C. Wash pellet in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and repeat ultracentrifugation. Resuspend final exosome pellet in PBS and quantify protein content via BCA assay [11].

Exosome Characterization: Validate exosome identity through multiple complementary approaches: (1) Nanoparticle tracking analysis to confirm size distribution (30-150 nm); (2) Transmission electron microscopy for morphological assessment; (3) Western blotting for positive markers (CD63, CD81, TSG101, Alix) and negative marker (calnexin); (4) Flow cytometry with tetraspanin antibodies for immunophenotyping [11] [41].

Exosome Administration and Wound Assessment Methods

Therapeutic Administration Protocols: For topical application, incorporate exosomes (typically 50-200 μg protein equivalent) into hydrogel delivery systems (e.g., hyaluronic acid, chitosan, Pluronic F-127) to enhance retention and controlled release [39] [42]. Apply directly to wound beds and cover with appropriate dressings. For systemic delivery, administer via subcutaneous or intravenous injection (50-200 μg exosome protein in 100-200 μL PBS) adjacent to or circulating toward wound sites [14].

Wound Healing Assessment: Monitor wound closure daily through standardized digital photography with reference scale. Calculate wound area using ImageJ software with the formula: Percentage closure = [(Initial area - Current area)/Initial area] × 100 [14]. For histological analysis, harvest wound tissue at predetermined endpoints for H&E staining (re-epithelialization, granulation tissue), Masson's trichrome (collagen deposition), and immunohistochemistry for CD31 (angiogenesis) and specific cell markers [39].

Molecular Mechanisms of MSC-Exosome Action in Wound Healing

Key Signaling Pathways Modulated by MSC-Exosomes

MSC-exosomes accelerate healing through sophisticated molecular mechanisms that vary based on wound pathophysiology and exosome cargo. The diagram below illustrates the primary signaling pathways through which MSC-exosomes promote healing across different wound environments.

The multifaceted mechanisms depicted above work synergistically to overcome model-specific healing impairments. In diabetic wounds, MSC-exosomes correct the characteristic angiogenic deficit through sophisticated RNA-mediated pathways. Research demonstrates that exosomal circMYO9B promotes angiogenesis by facilitating the translocation of hnRNPU from nucleus to cytoplasm, subsequently destabilizing CBL and reducing ubiquitination of KDM1A, ultimately increasing VEGFA expression in endothelial cells [41]. This mechanism is particularly relevant for addressing the impaired neovascularization observed in diabetic wounds.

Simultaneously, MSC-exosomes modulate the chronic inflammatory environment common to non-healing wounds. They promote transition from pro-inflammatory M1 to anti-inflammatory M2 macrophage phenotypes through transfer of regulatory miRNAs like miR-21, miR-146a, and miR-181c [38]. This immunomodulatory activity is especially beneficial in burn wounds where excessive inflammation delays healing. Additionally, MSC-exosomes activate Wnt/β-catenin signaling to enhance keratinocyte proliferation and migration while inhibiting apoptosis through AKT pathway activation, directly addressing re-epithelialization deficits across wound types [38].

Exosome Cargo Engineering for Enhanced Therapeutic Efficacy

Emerging bioengineering approaches enable customization of MSC-exosome cargo to enhance specific therapeutic functions. Preconditioning strategies include treating MSCs with melatonin to enhance anti-inflammatory exosome properties [38] or culturing under hypoxic conditions to augment pro-angiogenic cargo. Direct engineering approaches involve transfecting MSCs to overexpress specific miRNAs (e.g., miR-125a, miR-135a) or circRNAs (e.g., circMYO9B) that subsequently package into exosomes [41]. These engineered exosomes demonstrate significantly improved efficacy, with studies reporting 30-50% greater wound closure rates compared to naive exosomes [41].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for MSC-Exosome Wound Healing Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Products/Solutions | Primary Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| MSC Culture | Serum-free MSC media (e.g., MesenCult), fetal bovine serum (exosome-depleted), trypsin/EDTA | MSC expansion and maintenance | Use serum-free or exosome-depleted FBS to avoid contaminating vesicles [11] |

| Exosome Isolation | Ultracentrifuge, polycarbonate bottles, 0.22 μm filters, PBS buffer | Exosome purification from conditioned media | Density gradient ultracentrifugation provides higher purity [11] |

| Exosome Characterization | CD63/CD81/CD9 antibodies, TSG101 antibody, calnexin antibody, nanoparticle tracker | Vesicle validation and quantification | Combine multiple characterization methods per MISEV guidelines [14] |

| Wound Model Creation | Biopsy punches (6-8 mm), STZ solution, heating apparatus for burns, analgesics | Standardized wound induction | Adjust anesthetic/analgesic protocols per IACUC guidelines |

| Exosome Delivery | Hyaluronic acid hydrogel, chitosan scaffolds, Pluronic F-127, fibrin matrices | Therapeutic application vehicles | Hydrogels extend exosome retention and controlled release [42] |

| Histological Assessment | Formalin, paraffin, H&E stain, Masson's trichrome kit, CD31 antibody | Tissue analysis and quantification | Plan harvest timepoints to capture all healing phases |

This systematic comparison of wound models reveals that while MSC-exosomes demonstrate therapeutic benefits across all wound types, their efficacy is highly context-dependent. Diabetic wounds respond best to exosomes with enhanced pro-angiogenic cargo, particularly those from adipose-derived MSCs. Burn wounds benefit most from exosomes with potent immunomodulatory properties, while full-thickness excisional wounds show robust healing acceleration with standard MSC-exosome preparations. These model-specific response patterns underscore the importance of aligning research questions with appropriate preclinical models.

Future research directions should prioritize standardization of MSC-exosome isolation and characterization protocols to improve inter-study comparability [14]. Additionally, the development of increasingly sophisticated wound-specific bioengineering approaches to customize exosome cargo will enhance therapeutic potency. Advanced delivery systems that provide sustained exosome release represent another critical innovation frontier. As these technologies mature, MSC-exosome therapies promise to revolutionize treatment for diverse wound pathologies, potentially offering solutions for currently intractable healing impairments.

The therapeutic potential of Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs) has been increasingly attributed to their potent paracrine activity, rather than their differentiation capacity alone [1] [43]. A key component of this paracrine effect is mediated through extracellular vesicles, particularly exosomes [43]. These nanoscale vesicles (30-150 nm in diameter) are laden with a diverse array of bioactive molecules—including proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids—that can be transferred to recipient cells to modulate their function [44] [45]. Compared to whole-cell therapies, MSC-derived exosomes (MSC-Exos) present significant advantages, including a higher safety profile, lower risk of immunogenicity, reduced concerns regarding tumorigenicity, and the inability to form emboli in lung microvasculature due to their nano-size [46] [43]. However, the therapeutic efficacy of these exosomes is not uniform; it is profoundly influenced by the tissue source of the parent MSCs. This guide provides a systematic, data-driven comparison of exosomes derived from three predominant MSC sources: bone marrow (BM), adipose tissue (AT), and umbilical cord (UC), to inform preclinical research and therapeutic development.

Comparative Efficacy Across Disease Models