MSC Exosomes vs. Stem Cell Transplantation: A Comparative Analysis of Safety and Immunogenicity for Clinical Translation

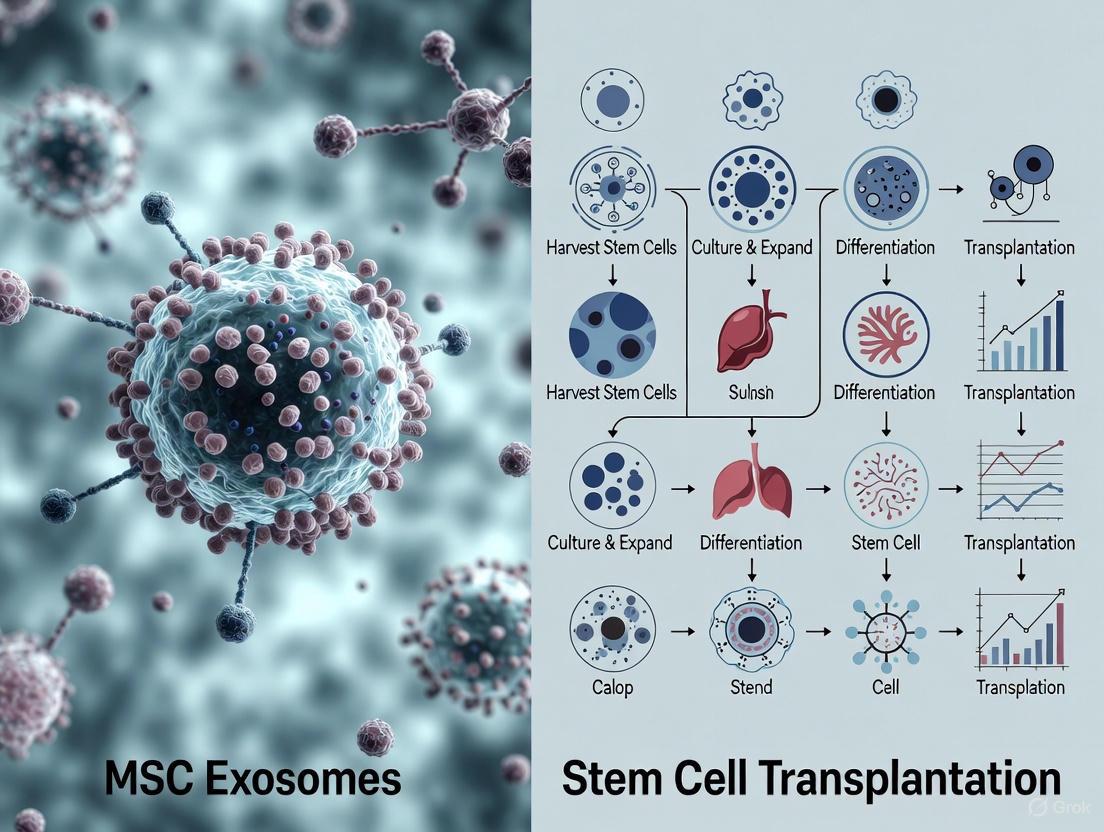

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of the safety and immunogenicity profiles of mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes (MSC-Exos) and whole MSC transplantation.

MSC Exosomes vs. Stem Cell Transplantation: A Comparative Analysis of Safety and Immunogenicity for Clinical Translation

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of the safety and immunogenicity profiles of mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes (MSC-Exos) and whole MSC transplantation. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it synthesizes current evidence on the biological foundations, therapeutic mechanisms, manufacturing challenges, and clinical validation of these two regenerative approaches. The analysis covers the inherent low immunogenicity of MSC-Exos, their paracrine-mediated therapeutic actions, standardization hurdles in production, and comparative efficacy based on recent clinical trials. The review concludes that MSC-Exos present a promising cell-free alternative with a favorable safety profile, though further standardization and rigorous clinical studies are needed to fully realize their therapeutic potential.

Understanding the Core Biology: From Whole Cells to Cell-Free Vesicles

Mesenchymal Stem (or Stromal) Cell (MSC) transplantation represents a cornerstone of regenerative medicine, offering a promising therapeutic strategy for a diverse range of diseases. The defining characteristics of MSCs—including their self-renewal capacity, multipotent differentiation potential, and immunomodulatory properties—underpin their clinical utility [1]. The International Society for Cellular Therapy (ISCT) established minimal criteria to standardize their definition, ensuring consistency across research and clinical applications [1]. These criteria mandate that MSCs must be plastic-adherent under standard culture conditions, express specific surface markers (CD73, CD90, CD105), lack expression of hematopoietic markers (CD34, CD45, CD14, CD19, HLA-DR), and possess the capacity to differentiate into osteoblasts, adipocytes, and chondrocytes in vitro [1]. MSCs can be isolated from a variety of adult and neonatal tissues, and the choice of source material significantly influences their biological properties, therapeutic potency, and suitability for specific clinical indications. This guide provides a objective comparison of MSC sources and their multipotent capabilities, framed within the critical context of safety and immunogenicity in relation to the emerging field of MSC-derived exosome therapies.

MSC Defining Criteria and Key Markers

The ISCT criteria provide a essential foundation for defining MSCs, yet it is important to recognize that MSC populations from different sources exhibit heterogeneity beyond these minimum standards. Table 1 summarizes the characteristic surface marker profile that defines MSCs, while also highlighting common markers whose expression can vary based on the tissue of origin.

Table 1: Characteristic Surface Marker Profile of Human MSCs

| Marker Category | Marker | Presence | Function / Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Positive Markers | CD73 | ≥95% | Ecto-5'-nucleotidase; catalyzes AMP to adenosine [1]. |

| CD90 | ≥95% | Thy-1 cell surface antigen; mediates cell-cell and cell-matrix interactions [1]. | |

| CD105 | ≥95% | Endoglin; type I membrane glycoprotein essential for migration and angiogenesis [1]. | |

| CD44 | Common | Hyaluronic acid receptor; involved in adhesion and migration [2]. | |

| CD29 | Common | Beta-1 integrin; involved in cell adhesion [2]. | |

| CD146 | Variable | Melanoma cell adhesion molecule; expressed on perivascular cells [2]. | |

| Negative Markers | CD34 | ≤2%+ | Hematopoietic stem and progenitor cell marker [1]. |

| CD45 | ≤2% | Pan-leukocyte marker [1]. | |

| CD14 | ≤2% | Marker for monocytes and macrophages [1]. | |

| CD11b | ≤2% | Marker for monocytes and macrophages [1]. | |

| CD19 | ≤2% | B-cell marker [1]. | |

| CD79α | ≤2% | B-cell marker [1]. | |

| HLA-DR | ≤2% | Major Histocompatibility Complex class II molecule [1]. | |

| Variable Markers | CD34 | Can be present on AT-MSCs | Often detected on adipose tissue-derived MSCs [2]. |

| SSEA-4 | Variable | Expressed on >50% of BM- and WJ-MSCs, but low on AT-MSCs [3]. | |

| MSCA-1 | Variable | Highly expressed on BM- and AT-MSCs, but not on WJ-MSCs [3]. |

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for defining and characterizing MSCs based on the established criteria.

Diagram 1: Workflow for Defining MSCs via ISCT Criteria.

MSCs are isolated from a diverse range of tissues. The source impacts their yield, proliferation capacity, and functional potency, which are critical parameters for selecting the optimal cell type for research or therapy. Table 2 provides a detailed comparison of the most common MSC sources.

Table 2: Comprehensive Comparison of MSC Sources and Properties

| Source | Isolation Yield & Proliferation | Key Advantages | Key Disadvantages/Limitations | Documented Functional Strengths |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bone Marrow (BM-MSC) | - Yield: ~0.001-0.01% of nucleated cells [4].- Proliferation: Lower; Population Doubling Time (PDT) ~99 hrs [3]. | - Considered the "gold standard" [2].- Most extensively studied [1]. | - Invasive, painful harvest [2].- Risk of infection.- Cell number and differentiation potential decrease with donor age [4]. | - Highest immunomodulatory activity (both contact & paracrine) [3].- High osteogenic potential. |

| Adipose Tissue (AT-MSC) | - Yield: ~5,000 cells/gram tissue (500x BM) [2].- Proliferation: Moderate; PDT ~40 hrs [3]. | - Minimally invasive harvest (liposuction).- Abundant tissue source.- High yield. | - - | - Comparable immunomodulatory potential to BM-MSCs, but may be lower [3].- Robust angiogenic factor secretion [3]. |

| Wharton's Jelly (WJ-MSC) | - Proliferation: High; PDT ~21 hrs [3].- Primary Culture: ~13 days to confluence [3]. | - Non-invasive harvest, no ethical concerns.- High proliferation capacity.- Low immunogenicity. | - - | - Superior neurotrophic factor secretion [3].- Pronounced neuroregenerative potential [3]. |

| Umbilical Cord (UC-MSC) | - Proliferation: High [1]. | - Non-invasive harvest.- Enhanced proliferation.- Low immunogenicity. | - - | - - |

| Peripheral Blood (PB-MSC) | - Yield: Very low colony-forming efficiency [2]. | - Minimally invasive source. | - Very rare frequency in blood. | - Immunophenotype similar to BM-MSCs [2]. |

The following diagram synthesizes the experimental workflow for comparing the functional properties of MSCs from different sources, as outlined in the literature.

Diagram 2: Experimental Workflow for MSC Source Comparison.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Methods

The transition of MSC research from basic to clinical science requires robust, reproducible, and standardized protocols. This section details essential reagents, solutions, and methods critical for the isolation, expansion, and functional characterization of MSCs.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for MSC Studies

| Reagent / Solution | Function / Application | Protocol Notes & Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Culture Media | Basal nutrient support for cell growth. | - α-MEM often shows superior cell morphology and proliferative capacity compared to DMEM [5]. |

| Serum Supplements | Provides essential growth factors and adhesion proteins. | - Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS): Traditional supplement, but carries xenogenic risk [4].- Human Platelet Lysate (hPL): Xeno-free alternative for clinical-grade expansion; enhances proliferation [3]. |

| Growth Factors | Enhances proliferation and maintains stemness. | - Recombinant Human FGF-2 (rhFGF-2): Adding 10 ng/ml reduces population doubling time and increases success rate for reaching target cell doses [4]. |

| Isolation Reagents | Enzymatic digestion of tissues. | - Collagenase: Used for isolating MSCs from adipose tissue and other dense tissues [2]. |

| sEV/Exosome Isolation Kits | Isolating exosomes from conditioned medium. | - Ultracentrifugation (UC): Traditional "gold standard" but can cause aggregation [6].- Tangential Flow Filtration (TFF): Higher particle yield than UC, more suitable for large-scale GMP production [5]. |

| Flow Cytometry Antibodies | Confirmation of ISCT-defined surface marker profile. | - Positive Panel: CD73, CD90, CD105.- Negative Panel: CD34, CD45, CD11b/CD14, CD19/CD79α, HLA-DR. |

MSC Exosomes vs. Whole Cell Transplantation: A Safety and Immunogenicity Perspective

A critical advancement in the field is the recognition that many therapeutic benefits of MSCs are mediated through their paracrine activity, particularly via secreted extracellular vesicles like exosomes [7]. This has led to the development of cell-free therapies using MSC-derived exosomes (MSC-Exos).

Key Mechanisms of MSC-Exos: MSC-Exos exert their effects by transferring bioactive molecules (proteins, lipids, miRNAs) to recipient cells. They play central roles in modulating immune responses, inhibiting fibrotic pathways, and promoting tissue repair and angiogenesis [7]. Their immunomodulatory effects include influencing macrophage polarization towards an anti-inflammatory M2 phenotype, inhibiting dendritic cell maturation, suppressing T-cell and B-cell activity, and promoting regulatory T-cell proliferation [7].

Comparative Safety and Immunogenicity:

- Immunogenicity: Whole MSCs, while considered immunoprivileged, still express low levels of MHC-I and can elicit immune responses under inflammatory conditions. In contrast, MSC-Exos have lower immunogenicity and do not replicate, eliminating risks associated with uncontrolled cell division [7] [8].

- Safety Profile: MSC transplantation carries potential risks such as pulmonary embolism due to cell aggregation [8]. MSC-Exos, being nanoscale vesicles, offer a better safety profile with a lower risk of vascular occlusion and no risk of malignant transformation [7].

- Therapeutic Efficacy: MSC-Exos can mimic the therapeutic effects of their parent cells, making them a promising cell-free alternative. Preclinical studies have demonstrated their efficacy in attenuating fibrosis, modulating immune responses, and reversing pathology in disease models like systemic sclerosis and retinal degeneration [7] [5].

The field of MSC transplantation is defined by rigorous cellular criteria but is also characterized by significant functional heterogeneity across different tissue sources. The comparative data presented in this guide underscores that source selection is a primary determinant of experimental and therapeutic outcomes, influencing proliferation rates, secretome profiles, and specialized functions like neuroprotection or immunomodulation. Furthermore, the emergence of MSC-derived exosomes represents a pivotal shift towards cell-free therapeutics, offering a potentially superior safety and immunogenicity profile while retaining much of the therapeutic potency of whole cells. For researchers and drug developers, the choice between a specific MSC source and an exosome-based approach must be guided by the specific pathological mechanism being targeted, balanced against considerations of scalability, safety, and regulatory pathway.

What Are MSC Exosomes? Biogenesis, Cargo, and Natural Role in Intercellular Communication

Mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) exosomes have emerged as a pivotal cell-free therapeutic paradigm, shifting the regenerative medicine landscape from whole-cell transplantation to nano-scale vesicle-based interventions. These extracellular vesicles, ranging from 30-150 nanometers in diameter, serve as natural couriers of bioactive molecules, mediating intercellular communication through horizontal transfer of proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids. Within the context of safety and immunogenicity comparisons between MSC exosomes and stem cell transplantation, compelling evidence indicates exosomes retain therapeutic efficacy while demonstrating reduced immunogenicity, diminished tumorigenic risk, and enhanced biocompatibility. This comprehensive analysis delineates the biogenesis pathways, molecular cargo profiles, and fundamental communication mechanisms of MSC exosomes, providing researchers and drug development professionals with structured experimental data and methodological frameworks for informed therapeutic strategy development.

The therapeutic application of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) has been historically predicated on their multipotent differentiation capacity and paracrine activity. However, emerging research has illuminated that many therapeutic benefits previously attributed to whole MSCs are actually mediated through their secreted factors, particularly exosomes [9]. MSC exosomes represent a novel therapeutic entity that transcends the limitations of cell-based therapies while preserving multidimensional therapeutic functions including immunomodulation, angiogenesis promotion, and tissue regeneration [10] [11].

From a safety and immunogenicity perspective, MSC exosomes offer distinct advantages over their cellular counterparts. As acellular nanoparticles, they circumvent risks associated with whole-cell transplantation, including ectopic tissue formation, microvasculature occlusion, and immune rejection [12] [13]. Their lower immunogenicity profile stems from reduced expression of major histocompatibility complexes, making them promising candidates for allogeneic applications without triggering robust immune responses [14] [9]. This comprehensive guide systematically examines the biogenesis, cargo composition, and communication mechanisms of MSC exosomes while providing direct comparative analysis with MSC transplantation to inform therapeutic decision-making.

Biogenesis of MSC Exosomes

Exosome biogenesis in MSCs follows a sophisticated intracellular pathway that transforms early endosomes into secreted nano-vesicles, a process meticulously regulated by molecular switches and external stimuli [11] [12].

Endosomal Pathway and MVB Formation

The biogenesis journey initiates with the inward budding of the plasma membrane, forming early endosomes that mature into late endosomes [15]. These compartments subsequently evolve into multivesicular bodies (MVBs) through a second inward budding event that generates intraluminal vesicles (ILVs) within the MVB lumen [16] [17]. The fate of MVBs diverges at this juncture: they may fuse with lysosomes for content degradation or traffick to and fuse with the plasma membrane, releasing ILVs as exosomes into the extracellular space [11] [9].

Molecular Regulators of Biogenesis

The endosomal sorting complex required for transport (ESCRT) machinery serves as the primary regulatory system for exosome biogenesis, comprising four complexes (ESCRT-0, -I, -II, and -III) and associated proteins (ALIX, VPS4, VTA1) that collectively mediate cargo sorting and vesicle formation [11]. ESCRT-independent pathways utilizing ceramides and tetraspanin proteins (CD81, CD82, CD9) provide complementary biogenesis mechanisms [11]. The RAB family of small GTPase proteins (Rab27a, Rab27b, Rab35, Rab7) functions as intracellular traffic controllers, directing MVB movement to the plasma membrane for exosome release [11] [12].

Figure 1: MSC Exosome Biogenesis Pathway. Exosomes form through the endosomal pathway, regulated by ESCRT complexes, tetraspanins, Rab GTPases, and ceramides. MVBs either fuse with the plasma membrane to release exosomes or are degraded by lysosomes.

Enhancement Strategies for Research and Therapy

Research demonstrates that exosome biogenesis and secretion can be experimentally enhanced through specific molecular interventions. Combining N-methyldopamine and norepinephrine robustly increased exosome production by three-fold in MSCs without altering their regenerative capacity [16]. Additional upregulation strategies include inducing hypoxia (1.3-fold enrichment), overexpressing tetraspanin CD9 (2.4-fold enrichment in HEK293), or overexpressing hypoxia-inducible factor-1α (2.2-fold enrichment in MSCs) [16]. External stimuli such as hypoxia or inflammation significantly influence biomolecule packaging into exosomes, with hypoxia-conditioned MSC-derived exosomes demonstrating enhanced angiogenic activity compared to normoxic exosomes [11].

Composition and Cargo of MSC Exosomes

MSC exosomes encapsulate a diverse molecular repertoire that mirrors their parental cells, facilitating multifaceted therapeutic effects through coordinated molecular transfers.

Protein Cargo

Exosomal membranes are enriched with tetraspanins (CD9, CD63, CD81), fusion proteins (annexins, Rab GTPases), antigen presentation molecules (MHC I/II), and biogenesis-related proteins (Alix, TSG101) [11] [9]. Proteomic analyses of bone marrow MSC-derived exosomes have identified approximately 730 functional proteins governing cell growth, proliferation, adhesion, migration, and morphogenesis [11]. Characteristic MSC surface markers including CD73, CD90, and CD105 are consistently present on exosomes, affirming their cellular origin while maintaining lower immunogenicity than intact cells [11].

Nucleic Acid Cargo

The nucleic acid composition of MSC exosomes includes microRNAs (miRNAs), mRNAs, mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA), and other non-coding RNAs that are selectively packaged rather than randomly incorporated [11]. System-level miRNA analyses have identified 23 predominant miRNAs within MSC exosomes that collectively promote angiogenesis, tissue remodeling, and cardiomyocyte proliferation [11]. Comparative assessments reveal that while bone marrow and adipose-derived MSC exosomes share similar RNA compositions, they exhibit striking differences in tRNA species that reflect their differentiation status and tissue origin [11].

Table 1: Quantitative Cargo Analysis of MSC Exosomes

| Cargo Category | Specific Components | Quantitative Presence | Functional Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Surface Proteins | CD9, CD63, CD81 | >95% expression [9] | Vesicle identity, cellular uptake |

| CD73, CD90, CD105 | >95% expression [9] | MSC lineage identification | |

| Internal Proteins | Alix, TSG101 | ~70-80% of exosomes [11] | Biogenesis regulation |

| Heat shock proteins | Variable by cell state [11] | Stress response, protein folding | |

| Nucleic Acids | miRNAs | 23 predominant angiogenic miRNAs [11] | Post-transcriptional regulation |

| mRNAs | Specific "zipcode" sequences [11] | Horizontal gene transfer | |

| DNA fragments | Large dsDNA (>10 kb) [11] | Genetic information transfer | |

| Lipids | Cholesterol, ceramide | Conserved, cell-type specific [17] | Membrane stability, signaling |

Intercellular Communication Mechanisms

MSC exosomes function as sophisticated intercellular messengers through multiple mechanistic pathways that collectively mediate their therapeutic effects.

Uptake Mechanisms by Recipient Cells

Exosomes employ diverse entry mechanisms depending on recipient cell type and physiological context. These include membrane fusion, which directly releases exosomal contents into the cytoplasm; clathrin-mediated endocytosis; caveolin-dependent uptake; macropinocytosis; and receptor-ligand interactions that initiate downstream signaling cascades without internalization [12] [13]. The specific uptake route significantly influences subsequent cargo activity and biological outcomes.

Functional Effects on Recipient Cells

Once internalized, MSC exosomes exert multifaceted effects on recipient cells. They promote anti-inflammatory responses by transferring regulatory miRNAs like miR-21, miR-146a, and miR-181 that polarize macrophages toward the anti-inflammatory M2 phenotype [10]. They enhance tissue repair by stimulating collagen synthesis, angiogenesis, and re-epithelialization through Wnt/β-catenin signaling activation [10]. They modulate cell survival by inhibiting apoptosis through AKT signaling activation and suppressing nuclear translocation of pro-apoptotic factors [10].

Figure 2: MSC Exosome Intercellular Communication. Exosomes employ multiple uptake mechanisms (membrane fusion, endocytosis pathways, receptor binding) to deliver cargo that mediates diverse therapeutic effects in recipient cells.

Direct Comparison: MSC Exosomes vs. Stem Cell Transplantation

The therapeutic transition from whole MSC transplantation to MSC exosome application represents a paradigm shift grounded in substantial comparative evidence regarding safety, immunogenicity, and practical implementation.

Safety and Immunogenicity Profile

MSC exosomes demonstrate superior safety profiles compared to whole cell transplants. Xenogeneic studies reveal that while MSCs significantly increase circulating anti-human antibodies, exosomes trigger diminished humoral responses despite altering splenic B-cell populations [14]. This reduced immunogenicity stems from lower expression of major histocompatibility complexes and higher phosphatidylserine expression in exosomes [14]. Additionally, exosomes eliminate risks of ectopic tissue formation and microvasculature occlusion associated with larger cellular entities [10] [12].

Table 2: Safety and Immunogenicity Comparison: MSC Exosomes vs. Cell Transplantation

| Parameter | MSC Transplantation | MSC Exosomes | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Immunogenicity | Can induce allogenic immune rejection [11] | Considered non-immunogenic [11] | Xenogeneic models show MSCs trigger greater antibody production [14] |

| Tumorigenic Risk | Potential for dysregulated proliferation [10] | Non-replicative, reduced risk [9] | No evidence of tumor formation in exosome studies [9] |

| In Vivo Tracking | Limited engraftment, host clearance [9] | Enhanced tissue penetration [12] | Few MSCs reach target site; exosomes cross biological barriers [9] |

| Therapeutic Stability | Senescence after passages [16] | Consistent potency across batches [16] | MSC proliferation weakens with passages; exosomes stable [16] |

| Storage & Handling | Complex cryopreservation, viability concerns [9] | Easy preservation, extended shelf-life [13] | Exosomes withstand freezing without function loss [13] |

| Dosing Precision | Variable cell potency | Quantifiable nanoparticle dosing | Protein/nanoparticle tracking allows precise quantification [16] |

Experimental Evidence from Comparative Studies

In a pivotal study investigating immune rejection mechanisms, human MSCs and their daughter exosomes were administered to mice with renal artery stenosis. Results demonstrated that MSCs more potently triggered systemic antibody production, while exosomes altered splenic B-cell levels without significant kidney rejection [14]. This suggests exosomes may evade robust immune responses that challenge cellular therapies. Additional research confirms that exosomes from MSCs mimic therapeutic benefits of their parent cells—including reduction of renal inflammation, improvement of medullary oxygenation, and decreased fibrosis—but through divergent, potentially safer mechanisms [14].

Experimental Protocols for MSC Exosome Research

Standardized methodologies are critical for rigorous MSC exosome research and therapeutic development.

Isolation and Purification Techniques

Differential ultracentrifugation remains the gold standard for exosome isolation, involving sequential centrifugation steps: 500×g to remove cells; 10,000×g to eliminate apoptotic bodies; and 100,000–120,000×g for 60–120 minutes to pellet exosomes [16] [17]. Density gradient ultracentrifugation provides higher purity separation using iodoxinol, CsCl, or sucrose gradients [17]. Alternative approaches include size-exclusion chromatography, immunoaffinity capture, and precipitation-based techniques, each with distinct advantages in purity, yield, and scalability [13].

Characterization and Validation Methods

Nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA) characterizes exosome size distribution and concentration through light scattering and Brownian motion [16]. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) visualizes morphological features, typically revealing cup-shaped vesicles of 30–150 nm diameter [16]. Western blotting detects exosomal markers (CD9, CD63, CD81, TSG101, Alix) to verify isolation purity [16]. Flow cytometry with imaging capabilities enables surface marker quantification and heterogeneity assessment [14].

Functional Assays

The MTT assay evaluates cellular viability and proliferation responses to exosome treatment [16]. Gene expression analysis via RT-qPCR assesses functional effects on recipient cells, such as collagen expression in cardiac fibroblasts following exosome treatment [16]. Macrophage polarization assays measure immunomodulatory capacity through M1/M2 marker expression [10]. Angiogenesis assays examine tubule formation in endothelial cells to quantify pro-angiogenic effects [16].

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for MSC Exosome Studies

| Research Tool | Specific Examples | Experimental Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Isolation Reagents | Ultracentrifugation reagents | Physical separation by density/size | High-volume exosome isolation [16] |

| Size-exclusion chromatography columns | Size-based separation | High-purity preparation [13] | |

| Characterization Antibodies | Anti-CD63, CD9, CD81 | Tetraspanin detection | Exosome identification [16] |

| Anti-CD73, CD90, CD105 | MSC marker confirmation | Cellular origin verification [9] | |

| Enhancement Molecules | N-methyldopamine hydrochloride | Biogenesis upregulation | 3-fold production increase [16] |

| Norepinephrine bitartrate | Secretion enhancement | Combinatorial stimulation [16] | |

| Analytical Instruments | Nanoparticle Tracking Analyzer | Size/concentration measurement | NTA characterization [16] |

| Transmission Electron Microscope | Morphological visualization | Structural validation [16] |

MSC exosomes represent a transformative advancement in regenerative medicine, offering a sophisticated intercellular communication system that coordinates tissue repair, immunomodulation, and cellular homeostasis. Their defined biogenesis pathways, diverse molecular cargo, and multifaceted mechanisms of action position them as compelling therapeutic agents that effectively bridge the efficacy of MSC-based therapies with enhanced safety profiles. Direct comparative analyses substantiate that MSC exosomes maintain therapeutic potency while mitigating critical risks associated with whole-cell transplantation, including immunogenicity, tumorigenic potential, and practical delivery challenges. As research methodologies standardize and production technologies advance, MSC exosomes are poised to transition from investigative tools to mainstream clinical applications, potentially redefining regenerative medicine paradigms through cell-free therapeutic strategies that maximize efficacy while minimizing patient risk.

In the evolving landscape of regenerative medicine, mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) and their secreted extracellular vesicles, particularly exosomes (MSC-Exos), represent two distinct therapeutic paradigms. While MSCs have been investigated for decades for their regenerative capabilities, recent research has increasingly highlighted the role of MSC-Exos as crucial mediators of therapeutic effects [18] [7]. This shift recognizes that many benefits of MSC transplantation stem not from the cells themselves differentiating and replacing damaged tissue, but from their potent paracrine signaling activity [19] [7]. MSC-Exos, as natural bioactive carriers, offer a cell-free alternative with significant advantages in safety and handling [19]. This comparison guide provides a detailed, evidence-based analysis of the structural and functional characteristics of both therapeutic agents, focusing on their implications for research and drug development within the critical context of safety and immunogenicity.

Fundamental Definitions and Characteristics

Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs)

MSCs are non-hematopoietic, multipotent stromal cells first identified in bone marrow by Alexander Friedenstein in the 1970s [19] [1]. According to the International Society for Cellular Therapy (ISCT), MSCs are defined by three minimum criteria: adherence to plastic under standard culture conditions; positive expression of surface markers CD73, CD90, and CD105 (≥95%) and lack of expression of CD34, CD45, CD14 or CD11b, CD79α or CD19, and HLA-DR (≤2%); and capacity to differentiate into osteoblasts, adipocytes, and chondrocytes in vitro [8] [1]. These cells can be isolated from various tissues including bone marrow (BM-MSCs), adipose tissue (AD-MSCs), umbilical cord (UC-MSCs), and dental pulp [1].

MSC-Derived Exosomes (MSC-Exos)

MSC-Exos are a specific subtype of extracellular vesicles (EVs) with diameters of 30-150 nanometers [18] [20]. They are formed within cells through the endosomal pathway, originating from multivesicular bodies (MVBs) that fuse with the plasma membrane to release their contents into the extracellular space [18]. Unlike whole cells, exosomes are not capable of self-replication but function as sophisticated communication vehicles, transferring functional proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids (including miRNAs, mRNAs, and transcription factors) from their parent MSCs to recipient cells [18] [7]. Their membrane is a phospholipid bilayer enriched with cholesterol, sphingomyelin, ceramides, and characteristic tetraspanins (CD63, CD81, and CD9) [7].

Table 1: Core Structural and Compositional Differences

| Characteristic | MSCs | MSC-Exos |

|---|---|---|

| Nature | Live, nucleated cells | Non-living, acellular nanovesicles |

| Size | 15-30 micrometers (cell diameter) | 30-150 nanometers |

| Membrane Structure | Phospholipid bilayer with surface receptors | Phospholipid bilayer enriched with tetraspanins |

| Key Surface Markers | CD73, CD90, CD105, CD44 [8] | CD63, CD81, CD9, plus parental MSC markers [7] |

| Internal Cargo | Full cellular machinery: nucleus, mitochondria, organelles | Proteins, lipids, miRNAs, mRNAs, no organelles |

| Self-Renewal | Capable | Not capable |

Mechanism of Action: A Comparative Analysis

Therapeutic Mechanisms of MSCs

The therapeutic potential of MSCs is realized through two primary mechanisms: direct differentiation and potent paracrine activity.

- Direct Differentiation: MSCs retain the capacity to differentiate into multiple cell lineages, including osteoblasts (bone), chondrocytes (cartilage), and adipocytes (fat) [8] [1]. This allows them to potentially replace damaged or lost cells in diseased tissues.

- Paracrine Signaling: It is now widely accepted that a significant portion of the therapeutic effect is mediated by the bioactive molecules they secrete [19] [1]. This secretome includes growth factors, cytokines, chemokines, and extracellular vesicles like exosomes. These factors collectively promote tissue repair by modulating the immune response, reducing inflammation, inhibiting fibrosis, and stimulating angiogenesis [8] [1].

- Cell-Cell Interactions: MSCs can directly interact with various immune cells (T cells, B cells, dendritic cells, macrophages) via cell-surface receptors to modulate their function and polarize macrophages toward an anti-inflammatory M2 phenotype [7] [1].

Therapeutic Mechanisms of MSC-Exos

MSC-Exos primarily execute the paracrine functions of their parent cells, acting as natural, targeted delivery systems for bioactive molecules.

- Intercellular Communication: MSC-Exos facilitate the transfer of functional biomolecules from MSCs to recipient cells [18] [7]. Upon release into the extracellular environment, they fuse with the membrane of a target cell and release specific mediators that alter signal transduction pathways and gene expression profiles [7].

- Cargo-Driven Effects: The specific effects of MSC-Exos are dictated by their molecular cargo. For instance, they are rich in microRNAs that can modulate gene expression in target cells. The exosomal transfer of miR-146a has been shown to reduce inflammation, while miR-125a-3p can suppress T cell activity and maintain Th1/Th2 balance [7].

- Microenvironment Responsiveness: The content of MSC-Exos is not random; it depends on the cell of origin, its metabolic status, and external stimuli. For example, under hypoxic conditions, MSC-Exos are loaded with angiogenic factors that help prevent tissue ischemia [7].

Diagram 1: Comparative therapeutic mechanisms of MSCs and MSC-Exos. MSCs act via differentiation, paracrine signaling, and direct interaction, while MSC-Exos act primarily via cargo transfer after membrane fusion with target cells.

Safety and Immunogenicity Profile

The safety and immunogenicity profile is a critical differentiator between these two therapeutic entities and forms a core part of the thesis context.

MSC Safety and Immunogenicity

- Low Immunogenicity: MSCs are considered to have low immunogenicity due to their low expression of Major Histocompatibility Complex (MHC) class I molecules and absence of MHC class II molecules under normal conditions [8]. This allows for allogeneic transplantation without perfect matching.

- Substantial Risks: Despite their low immunogenicity, MSCs are living entities that carry non-trivial risks. These include:

- Infusion Toxicity: Potential for pulmonary embolism after intravascular administration [19] [8].

- Tumorigenicity: A theoretical risk of uncontrolled differentiation or formation of benign tumors, though the actual risk is considered low [19].

- Immune Reactions: Despite their immunomodulatory properties, they can still elicit immune responses under certain conditions.

- Complications in Transplants: For hematopoietic stem cell transplants (HSCT), which is a distinct therapy, risks include Graft-versus-Host Disease (GVHD) and graft failure [21] [22]. A meta-analysis of allo-HSCT for sickle cell disease showed rates of 20% for acute GVHD and 14% for chronic GVHD [22].

MSC-Exos Safety and Immunogenicity

MSC-Exos offer a potentially superior safety profile as an acellular therapeutic strategy.

- Inherently Low Immunogenicity: As nanoparticles, exosomes are biocompatible and have low immunogenicity, significantly reducing the risk of immune rejection [19].

- Elimination of Key Risks:

- No Tumorigenic Risk: Exosomes cannot replicate once administered, which "significantly mitigates the risk of carcinogenesis" associated with cell-based therapies [19].

- No Embolism Risk: Their nano-size prevents the risk of vascular occlusion or pulmonary embolism, a concern with MSC infusion [19] [8].

- No Risk of Graft-versus-Host Disease (GVHD): As cell-free agents, they circumvent this major complication of whole-cell transplants [19].

Table 2: Comprehensive Safety and Immunogenicity Profile

| Safety Parameter | MSCs | MSC-Exos |

|---|---|---|

| Immunogenicity | Low immunogenicity, but can elicit responses [8] | Very low immunogenicity [19] |

| Tumorigenic Risk | Low, but theoretical risk [19] | No risk of tumor formation [19] |

| Infusion Toxicity | Risk of pulmonary embolism [19] [8] | No embolism risk [19] |

| GVHD Risk | Present in HSCT (14-20% incidence) [22] | No GVHD risk [19] |

| Storage & Handling | Requires careful cryopreservation of live cells | Stable at -80°C for extended periods, maintains activity after freeze-thaw [19] |

Therapeutic Applications and Clinical Translation

Therapeutic Applications

Both MSCs and MSC-Exos have demonstrated broad therapeutic potential across numerous disease areas, often with comparable efficacy despite their structural differences.

- MSC Applications: Clinical trials have explored MSCs for conditions including osteoarthritis, traumatic brain injury, septic shock, diabetic nephropathy, respiratory infections, and autoimmune diseases like systemic sclerosis [19] [7] [1]. Their mechanisms include modulating immune responses, promoting tissue repair, and secreting angiogenic factors.

- MSC-Exos Applications: As cell-free agents, MSC-Exos are being investigated for many of the same indications. They have shown promise in treating respiratory diseases (including COVID-19 pneumonia), neurodegenerative diseases, myocardial infarction, skin wounds, and osteoarthritis [20] [19]. They exert therapeutic effects by delivering their cargo to modulate inflammation, inhibit fibrotic pathways, and promote repair [7].

Analysis of Clinical Trial Data

A 2025 review of 66 global clinical trials provided critical insights into the clinical translation of MSC-EVs and Exos [20]. Key findings include:

- Administration Routes: Intravenous infusion and aerosolized inhalation were the predominant methods. Notably, nebulization therapy for lung diseases achieved therapeutic effects at doses around 10^8 particles, significantly lower than those required for intravenous routes [20].

- Dosing Challenges: The review highlighted "large variations in EVs characterization, dose units, and outcome measures" across trials, underscoring a critical lack of harmonized reporting standards [20]. This variability complicates comparisons and dose optimization.

- Efficacy Evidence: In some studies, exosomes derived from stem cells have demonstrated significant therapeutic potential. For example, exosomes from induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes improved myocardial function in a porcine model of ischemia-reperfusion injury [18].

Experimental Protocols and Research Tools

For researchers designing studies to compare MSCs and MSC-Exos, standardized protocols are essential for generating reproducible and comparable data.

Key Experimental Workflows

MSC Isolation and Culture:

- Source Selection: Choose tissue source (e.g., bone marrow, adipose tissue, umbilical cord).

- Isolation: Isolate mononuclear cells via density gradient centrifugation.

- Culture: Plate cells in adherent culture flasks with standard MSC media.

- Expansion: Passage cells upon reaching 70-80% confluence.

- Characterization: Confirm phenotype via flow cytometry for CD73, CD90, CD105 (positive) and CD34, CD45, HLA-DR (negative). Validate trilineage differentiation potential (osteogenic, adipogenic, chondrogenic) [8] [1].

MSC-Exos Isolation and Characterization:

- Conditioned Media Collection: Culture MSCs until 70-80% confluent, replace with exosome-depleted media, and collect conditioned media after 24-48 hours.

- Isolation: Isolate exosomes using differential ultracentrifugation, density gradient centrifugation, or size-exclusion chromatography [18] [20].

- Characterization: Confirm identity and purity using:

Diagram 2: Core experimental workflows for MSC culture and MSC-Exo isolation. The process begins with MSC selection and culture, which serves as the foundation for subsequent exosome production and characterization.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for MSC and MSC-Exos Research

| Reagent / Material | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Flow Cytometry Antibodies (CD73, CD90, CD105, CD34, CD45, HLA-DR) | Phenotypic characterization and purity verification of MSCs [8] [1] | Essential for confirming MSC identity per ISCT criteria before exosome harvest or therapy |

| Trilineage Differentiation Kits (Osteo, Adipo, Chondro) | Functional validation of MSC multipotency [1] | Quality control for MSC cultures; confirms stemness of parent cells |

| CD63 / CD81 / CD9 Antibodies | Detection of exosome-specific surface tetraspanins [7] | Critical for confirming successful exosome isolation and purity |

| Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis (NTA) | Determine exosome size distribution and concentration [20] | Standardized quantification of exosome preparations for dosing |

| Differential Ultracentrifuge | Isolation of exosomes from conditioned media based on size/density [18] [20] | Primary method for obtaining purified exosome samples for research |

MSCs and MSC-Exos represent two interconnected yet distinct pillars of regenerative medicine. MSCs are living, multifunctional units capable of differentiation and complex paracrine signaling, while MSC-Exos are specialized, cell-derived nanocarriers that mediate many of the therapeutic effects of MSCs through sophisticated intercellular communication. The choice between them for research or therapeutic development is not a simple matter of superiority but depends on the specific application, desired mechanism of action, and risk tolerance. MSC-Exos present a compelling safety profile with their low immunogenicity, absence of tumorigenic risk, and elimination of embolism and GVHD concerns, aligning with the broader thesis on safety. However, challenges in standardized production, characterization, and dosing of exosomes remain significant hurdles to clinical translation [20]. Future research should focus on optimizing isolation protocols, establishing potency assays, and conducting rigorous comparative efficacy studies in specific disease models to fully delineate the appropriate applications for each of these powerful therapeutic agents.

The paracrine hypothesis has reshaped our understanding of stem cell-based therapies, proposing that the therapeutic benefits of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) are mediated primarily through their secreted factors rather than direct cell replacement [23] [24]. Among these secreted factors, small extracellular vesicles, particularly exosomes, have emerged as crucial mediators of intercellular communication [25] [26]. These nanoscale vesicles transport bioactive molecules—including proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids—from donor to recipient cells, modulating immune responses, reducing inflammation, and promoting tissue repair [27] [26].

This comparison guide objectively evaluates the therapeutic profiles of MSC-derived exosomes against traditional stem cell transplantation within the critical framework of safety and immunogenicity. As the field advances toward clinical applications, understanding these distinctions is paramount for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals selecting appropriate therapeutic strategies for regenerative medicine.

Head-to-Head Comparison: MSC Exosomes vs. Stem Cell Transplantation

The following tables summarize key comparative data from preclinical studies evaluating the therapeutic efficacy and safety profiles of MSC exosomes versus stem cell transplantation.

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of Therapeutic Efficacy in a POI Mouse Model

| Parameter | MSC Transplantation | MSC-Derived Exosomes |

|---|---|---|

| Pregnancy Rate (First Breeding) | 60% to 100% | 30% to 50% |

| Pregnancy Rate (Second Breeding) | 60% to 80% | 0% (Infertile again) |

| Estrous Cycle Restoration | Restored | Restored |

| Serum Hormone Level Restoration | Restored | Restored |

Source: Data adapted from a direct comparison study in a chemotherapy-induced primary ovarian insufficiency (POI) mouse model [28].

Table 2: Summary of Key Safety and Immunogenicity Profiles

| Characteristic | MSC Transplantation | MSC-Derived Exosomes |

|---|---|---|

| Risk of Tumorigenicity | Potential risk due to uncontrolled cell division and genomic integration [28] [25] | Lower risk; no nucleus, not self-replicating [28] [25] |

| Immunogenicity | Low but present; risk of immune rejection [25] | Very low immunogenicity [25] [29] |

| Biodistribution & Targeting | Limited homing to target site; trapped in capillaries [25] [29] | Can cross biological barriers like the blood-brain barrier [25] [27] |

| Storage & Handling | Complex, requires viable cells [28] | More stable, easier to store and standardize [28] |

| Acute Toxicity (in mice) | Not directly comparable | No significant changes in body weight, feed intake, or blood composition observed at 6x10^10 particles [29] |

Experimental Protocols for Key Comparative Studies

To critically assess the data presented in the comparisons, an understanding of the underlying experimental methodologies is essential. Below are the detailed protocols from two pivotal studies that directly inform the safety and efficacy profiles outlined above.

Protocol 1: Efficacy Comparison in a POI Mouse Model

This protocol outlines the methods used to generate the efficacy data in Table 1 [28].

- Disease Model Induction: A chemotherapy-induced primary ovarian insufficiency (POI) model was established in C57/BL6 mice using intraperitoneal injection of cyclophosphamide and busulfan.

- Therapeutic Administration:

- MSC Group: Mice received intravenous retro-orbital injections of human bone marrow-derived MSCs (hBM-MSCs) at three different doses: 1x10^4, 1x10^5, and 1x10^6 cells.

- Exosome Group: Mice received intravenous injections of MSC-derived exosomes at particle counts calculated to be equivalent to the cell doses (based on a yield of ~1500 particles/cell/24h): 1.5x10^7, 1.5x10^8, and 1.5x10^9 particles.

- Outcome Assessment:

- Molecular Analysis: Serum and ovarian tissue samples were analyzed for hormone levels (e.g., FSH, AMH) and molecular changes.

- Functional Fertility Assessment: A separate cohort of mice underwent breeding experiments to measure the restoration of fertility, quantified by pregnancy rates over two consecutive breeding rounds.

Protocol 2: Immunological Safety Evaluation of Exosomes

This protocol details the methodology for the safety data summarized in Table 2, specifically for exosomes [29].

- Exosome Production and Characterization:

- Source: Exosomes were isolated from the culture supernatant of human umbilical cord MSCs (hucMSCs) expanded in a 3D bioreactor system under hypoxic conditions.

- Isolation Method: A sequential combination of tangential flow filtration (TFF) and ultracentrifugation (UC) was employed. The supernatant was processed through a 300 kD membrane followed by two rounds of UC at 100,000× g.

- Characterization: Isolated particles were confirmed as exosomes via:

- Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis (NTA): For determining particle size distribution and concentration.

- Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM): For visualizing characteristic cup-shaped morphology.

- Western Blotting: For detecting positive markers (CD9, TSG101, HSP70) and the absence of the negative marker Calnexin.

- In Vivo Safety Testing:

- Animal Model: 8-week-old C57BL/6 mice.

- Dosing: Mice received a single tail vein injection of 6×10^10 particles of hucMSC-exosomes in 100 µL of PBS. The control group received PBS only.

- Toxicity Endpoints: Over 14 days, the following were monitored:

- General Toxicity: Body weight, feed intake.

- Hematology: Complete blood count using an automatic analyzer.

- Immunotoxicity: Blood levels of immunoglobulins (IgA, IgM, IgG), cytokines (IFN-γ, IL-10), and lymphocyte subpopulations (CD4+, CD8+, CD19+) using flow cytometry and ELISA.

- Histopathology: Gross and microscopic examination of major organs (e.g., thymus, spleen).

Visualizing Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

The following diagrams illustrate the core concepts of the paracrine hypothesis and the key experimental workflows used in the cited comparative studies.

Paracrine Mechanism of MSC-Derived EVs

Exosome Isolation and Characterization Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful research in this field relies on a specific set of reagents and methodologies. The table below catalogs key solutions and materials used in the featured experiments.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for MSC Exosome Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example from Search Results |

|---|---|---|

| Human Platelet Lysate (hPL) | Serum-free supplement for xeno-free MSC culture media. | Used in BM-MSC culture media (DMEM/α-MEM) for sEV production [5]. |

| Tangential Flow Filtration (TFF) | Scalable method for isolating and concentrating exosomes from large volumes of conditioned media. | Used for large-scale isolation of BM-MSC-sEVs and hucMSC-exosomes; yielded higher particles than UC [5] [29]. |

| Ultracentrifugation (UC) | Traditional, gold-standard method for exosome isolation via high-speed centrifugation. | Used as a classical method for EV isolation; often combined with TFF for final purification [26] [29]. |

| Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis (NTA) | Instrumentation to determine the size distribution and concentration of particles in an exosome preparation. | Used to analyze the size and yield of isolated BM-MSC-sEVs and hucMSC-exosomes [5] [29]. |

| Antibodies for Characterization | Essential reagents for confirming exosome identity via Western Blot. Key targets include CD9, CD63, CD81, TSG101, and Alix. | hucMSC-exosomes characterized using antibodies against CD9, TSG101, and HSP70, with Calnexin as a negative control [29]. |

| Flow Cytometry Antibodies | Used for immunophenotyping of MSCs and for analyzing immune cell populations in safety studies. | In safety studies, antibodies against CD4, CD8, and CD19 were used to profile lymphocyte subsets in mice [29]. |

From Bench to Bedside: Production, Dosing, and Clinical Application Strategies

Standardized Protocols for MSC Expansion and Characterization According to ISCT Guidelines

The field of regenerative medicine has increasingly recognized the therapeutic potential of Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs) for treating degenerative diseases, autoimmune conditions, and tissue injuries. The International Society for Cellular Therapy (ISCT) established fundamental criteria to define human MSCs, creating a essential foundation for standardizing research and clinical applications across the global scientific community [9]. These standards ensure that MSCs used in different laboratories and clinical trials possess consistent biological properties, enabling valid comparisons between studies and reliable assessment of therapeutic outcomes.

As research has evolved, a significant paradigm shift has occurred toward understanding that many therapeutic benefits of MSCs are mediated through paracrine mechanisms rather than direct cell replacement [9]. This discovery has sparked considerable interest in MSC-derived exosomes (MSC-Exos)—nanoscale extracellular vesicles that carry bioactive molecules from their parent cells—as a promising cell-free therapeutic alternative [7] [9]. This guide examines the standardized protocols for MSC expansion and characterization according to ISCT guidelines while contextualizing their application within the rapidly advancing field of MSC exosome research, providing researchers with essential methodologies for both cellular and exosome-based investigations.

ISCT Standards for MSC Characterization

Minimum Defining Criteria

According to ISCT standards, human MSCs must satisfy three fundamental criteria [9]:

- Plastic Adherence: MSCs must adhere to plastic surfaces when maintained in standard culture conditions.

- Specific Surface Marker Expression: ≥95% of the MSC population must express CD105, CD73, and CD90, while ≤2% must lack expression of CD45, CD34, CD14 or CD11b, CD79α or CD19, and HLA-DR.

- Multipotent Differentiation Potential: MSCs must demonstrate capacity for in vitro differentiation into osteoblasts, adipocytes, and chondrocytes when induced under standard differentiation protocols.

Comprehensive Characterization Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the complete experimental workflow for MSC characterization and subsequent exosome isolation based on ISCT guidelines:

Comparative Analysis: MSC Exosomes vs. Stem Cell Transplantation

Therapeutic Mechanisms and Applications

MSC Transplantation represents the traditional cellular approach, where living cells are administered with the potential to engraft and differentiate or secrete therapeutic factors. In contrast, MSC-derived exosomes constitute a cell-free paradigm, utilizing nanovesicles to deliver therapeutic cargo without cellular risks [18].

The therapeutic benefits of MSCs were initially attributed to their differentiation capacity and direct engraftment. However, compelling evidence now indicates that paracrine secretion represents the predominant mechanism, with exosomes serving as crucial mediators [9]. These natural nanoparticles range from 30-150 nm in diameter and contain proteins, lipids, mRNAs, and microRNAs that modulate recipient cell behavior [7] [26]. For autoimmune conditions like systemic sclerosis, MSC-Exos demonstrate remarkable immunomodulatory properties by regulating macrophage polarization, suppressing autoreactive lymphocytes, and reversing fibrosis [7].

Advantages and Disadvantages Comparison

Table 1: Comprehensive comparison between MSC exosomes and stem cell transplantation

| Parameter | MSC Exosomes | Stem Cell Transplantation |

|---|---|---|

| Therapeutic Mechanism | Paracrine signaling via biomolecule transfer | Direct differentiation and paracrine effects |

| Immunogenicity | Lower immunogenicity [30] | Potential immune reactions [30] |

| Tumorigenic Risk | No risk of tumor formation [30] [9] | Potential oncological complications [30] |

| Manufacturing Challenges | Complex isolation/purification; batch variation [30] [20] | Easier expansion at large scale [30] |

| Storage & Stability | Long-term frozen storage; lyophilization possible [30] | Challenging storage/transportation [30] |

| Administration Routes | Multiple (IV, inhalation, localized) [30] [20] | Primarily intravenous or localized injection |

| Regulatory Status | Limited standards and regulations [30] | Established FDA guidelines [30] |

| Clinical Trials | 158 studies (as of Feb 2023) [30] | 7,018 studies (as of Feb 2023) [30] |

| Ethical Considerations | No ethical issues [30] | Ethical concerns for certain sources [30] |

Safety and Immunogenicity Profile

The safety profiles of these two therapeutic approaches differ substantially. MSC transplantation carries risks of infusion toxicity due to cell embolization in lungs, potential immune reactions particularly with allogeneic sources, and tumorigenic concerns including teratoma formation [30] [9]. In contrast, MSC-derived exosomes exhibit lower immunogenicity and cannot self-replicate, eliminating tumor formation risks [30] [9]. Their nanoscale size enables sterilization by filtration and avoids lung entrapment [30].

Recent clinical evidence reinforces the favorable safety profile of MSC-Exos. A review of 66 clinical trials registered between 2014-2024 identified predominant administration routes as intravenous infusion and aerosolized inhalation, with no serious adverse events reported across these studies [20]. Nebulization therapy achieved therapeutic effects at approximately 10^8 particles—significantly lower than intravenous requirements—suggesting a favorable dose-response relationship for respiratory applications [20].

Experimental Protocols for MSC Expansion

Cell Culture and Expansion

Materials Required:

- MSC sources (bone marrow, adipose tissue, umbilical cord)

- Culture flasks (T-flasks, multilayer bioreactors, or hollow-fiber systems)

- Complete culture medium (α-MEM/DMEM with fetal bovine serum)

- Supplementation (growth factors, antibiotics)

- Trypsin/EDTA for cell detachment

- Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS)

Procedure:

- Isolation: Extract MSCs from chosen tissue source using collagenase digestion or explant method

- Primary Culture: Seed cells at 5,000-10,000 cells/cm² in culture flasks with complete medium

- Medium Changes: Replace medium every 2-3 days to remove non-adherent cells

- Subculturing: Harvest cells at 80-90% confluence using trypsin/EDTA

- Expansion: Replate at 1,000-2,000 cells/cm² for continued propagation

- Cryopreservation: Freeze cells in liquid nitrogen using DMSO-containing freezing medium

For large-scale production suitable for exosome manufacturing, hollow-fiber bioreactors are increasingly employed due to their superior surface-to-volume ratio and capacity for high-density cell culture [31]. These systems facilitate GMP-compliant exosome production by supporting cell attachment and efficient nutrient transport [31].

Quality Control During Expansion

Maintaining MSC quality during expansion requires rigorous monitoring:

- Population Doubling Time: Calculate at each passage to detect senescence

- Morphology Assessment: Document spindle-shaped, fibroblast-like appearance

- Viability Testing: Perform trypan blue exclusion assay post-harvest

- Mycoplasma Testing: Conduct regular screening for contamination

- Karyotype Analysis: Perform at regular intervals to ensure genetic stability

Experimental Protocols for MSC Characterization

Surface Marker Analysis by Flow Cytometry

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Flow Cytometer: Instrument for analyzing surface marker expression

- Fluorescent-Antibody Panels: CD105-FITC, CD73-PE, CD90-APC, CD45-PerCP, CD34-PE, HLA-DR-FITC

- Isotype Controls: Matching immunoglobulin controls for background subtraction

- Staining Buffer: PBS with 1-2% FBS for antibody dilution

- Fixation Solution: 1-4% paraformaldehyde for cell preservation

Procedure:

- Cell Preparation: Harvest MSCs at 80% confluence, wash with PBS

- Antibody Staining: Incubate 1×10^6 cells with antibody cocktails (20-25 μL/test) for 30 minutes at 4°C in darkness

- Washing: Centrifuge at 300×g for 5 minutes, discard supernatant, resuspend in staining buffer

- Fixation: Add 200-500 μL of fixation solution if analysis isn't immediate

- Acquisition: Analyze 10,000 events per sample on flow cytometer using appropriate laser configurations

- Analysis: Use software to determine percentage positive populations, applying isotype control corrections

Trilineage Differentiation Assays

Table 2: Standardized protocols for trilineage differentiation potential assessment

| Differentiation Pathway | Induction Medium Components | Differentiation Period | Staining Methods | Key Morphological Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Osteogenic | 0.1 μM dexamethasone, 50 μM ascorbate-2-phosphate, 10 mM β-glycerophosphate | 21-28 days | Alizarin Red S (calcium deposits) | Mineralized matrix nodules |

| Adipogenic | 1 μM dexamethasone, 0.5 mM IBMX, 10 μg/mL insulin, 100 μM indomethacin | 14-21 days | Oil Red O (lipid vacuoles) | Intracellular lipid droplets |

| Chondrogenic | 0.1 μM dexamethasone, 50 μg/mL ascorbate-2-phosphate, 40 μg/mL proline, 10 ng/mL TGF-β3 | 21-28 days | Alcian Blue (proteoglycans) | Pellet formation with cartilaginous matrix |

Procedure for Osteogenic Differentiation:

- Seed MSCs at 20,000 cells/cm² in growth medium

- At 100% confluence, replace with osteogenic induction medium

- Change medium twice weekly for 21-28 days

- Fix cells with 4% formaldehyde for 15 minutes

- Stain with 2% Alizarin Red S (pH 4.2) for 20-30 minutes

- Document calcium deposition microscopically

Procedure for Adipogenic Differentiation:

- Seed MSCs at 50,000 cells/cm² in growth medium

- At 100% confluence, initiate three cycles of induction/maintenance

- Induction: 3 days in adipogenic induction medium

- Maintenance: 1-3 days in adipogenic maintenance medium

- Repeat cycles 3-5 times total

- Fix with 4% formaldehyde, stain with Oil Red O working solution

- Document lipid vacuole formation microscopically

Procedure for Chondrogenic Differentiation:

- Harvest 2.5×10^5 MSCs by centrifugation at 300×g for 5 minutes

- Form micromass pellet in 15 mL conical polypropylene tube

- Add chondrogenic medium without disturbing pellet

- Loosen caps for gas exchange, change medium every 2-3 days

- After 21-28 days, fix pellets, embed in paraffin, section, stain with Alcian Blue

MSC Exosome Isolation and Characterization

Exosome Isolation Techniques

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Ultracentrifuge: Equipment for high-speed exosome pelleting

- Size Exclusion Columns: Chromatography matrices for size-based separation

- Polymer-Based Precipitation: Commercial kits for exosome precipitation

- Density Gradients: Sucrose or iodixanol solutions for purification

- Filtration Units: 0.22 μm filters for sterilization and size exclusion

Isolation Methods:

- Ultracentrifugation: Gold standard method involving sequential centrifugation steps (300×g for 10 min, 2,000×g for 20 min, 10,000×g for 30 min, 100,000×g for 70 min) [26]

- Size Exclusion Chromatography: Gentle separation preserving vesicle integrity and function [31]

- Precipitation Methods: Commercial polymer-based kits offering convenience but potential impurity co-precipitation

- Immunoaffinity Capture: Antibody-based isolation using surface markers (CD63, CD81, CD9) for high purity but lower yield [26]

Exosome Characterization

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Nanoparticle Tracking Analyzer: Instrument for size and concentration analysis

- Transmission Electron Microscope: Equipment for morphological assessment

- Western Blot Equipment: For protein marker detection

- Antibody Panels: Anti-CD63, CD81, CD9, TSG101, Alix for exosome identification

- RNA Extraction Kits: For cargo analysis (microRNAs)

Characterization Methods:

- Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis: Determines size distribution (30-150 nm) and concentration [31]

- Transmission Electron Microscopy: Visualizes characteristic cup-shaped morphology [9]

- Western Blot: Detects positive markers (CD63, CD81, CD9, TSG101) and negative markers (calnexin) [9]

- Flow Cytometry: With fluorescent antibodies confirms surface marker expression [31]

- MicroRNA Profiling: RNA sequencing to characterize therapeutic cargo [7]

The following diagram illustrates the relationship between MSC characterization and exosome profiling within the context of therapeutic development:

Applications in Regenerative Medicine

Therapeutic Mechanisms of MSC-Exosomes

MSC-derived exosomes demonstrate multifaceted therapeutic effects through several key mechanisms:

Immunomodulation: MSC-Exos regulate both innate and adaptive immunity through macrophage polarization (M1/M2 balance), dendritic cell maturation suppression, T-cell and B-cell activity modulation, and Treg cell promotion [7] [9]. Specific microRNAs like miR-146a and miR-125b play crucial roles in these processes [7].

Anti-fibrotic Effects: In systemic sclerosis models, MSC-Exos attenuate fibrosis by modulating collagen deposition and fibroblast activity through specific miRNA transfer [7].

Angiogenesis Promotion: Under hypoxic conditions, MSC-Exos acquire enhanced angiogenic properties, stimulating blood vessel formation to prevent tissue ischemia [7] [32].

Tissue Regeneration: MSC-Exos promote wound healing through increased collagen synthesis, epithelialization, and neovascularization [32].

Clinical Translation Considerations

The clinical application of MSC exosomes presents both opportunities and challenges. Current clinical trials investigate MSC-Exos for diverse conditions including respiratory diseases, COVID-19-associated lung injury, orthopedic disorders, and autoimmune conditions [20] [31]. Different administration routes significantly impact dosing requirements, with aerosolized inhalation achieving therapeutic effects at substantially lower doses (approximately 10^8 particles) compared to intravenous administration [20].

Critical considerations for clinical translation include:

- Scalable Manufacturing: Transition from flask-based culture to bioreactor systems (hollow-fiber, stirred-tank) [31]

- Potency Assays: Development of reliable potency measurements correlating with clinical effects

- Standardization: Implementation of harmonized protocols for isolation, characterization, and dosing [20]

- Quality Control: Comprehensive characterization of physicochemical properties and biological cargo [31]

- Regulatory Frameworks: Adaptation of existing regulatory pathways for cell-free therapeutic products

Standardized protocols for MSC expansion and characterization following ISCT guidelines provide the essential foundation for rigorous research and successful clinical translation in regenerative medicine. These standards ensure consistent cellular populations that yield reproducible exosome products with predictable therapeutic effects. The evolving paradigm toward MSC-derived exosomes as cell-free therapeutics offers significant advantages in safety, immunogenicity, and storage stability while maintaining therapeutic efficacy through targeted molecular delivery.

As the field advances, integrating robust MSC characterization with comprehensive exosome profiling will enable researchers to establish clearer correlations between cellular properties and vesicle function. This approach will ultimately enhance both basic understanding and clinical applications, potentially revolutionizing treatment strategies for degenerative diseases, autoimmune conditions, and tissue injuries. The continued refinement of standardized protocols across both cellular and exosome research remains crucial for realizing the full potential of MSC-based therapies in regenerative medicine.

{Abstract} The transition towards mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosome (MSC-Exo) therapies represents a significant advancement in regenerative medicine, offering a cell-free paradigm with a superior safety profile. This shift necessitates the development of robust, scalable isolation methods. This guide provides a comparative analysis of the two predominant techniques—ultracentrifugation (UC) and tangential flow filtration (TFF)—evaluating their performance, impact on exosome integrity, and suitability for clinical translation.

{Introduction: The Centrality of Isolation in MSC-Exo Therapeutics} The therapeutic application of mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes (MSC-Exos) is predicated on their ability to mediate tissue repair, modulate immune responses, and facilitate intercellular communication without the risks associated with whole-cell transplantation, such as immunogenicity, infusion toxicity, and microvasculature occlusion [13] [12]. The efficacy and safety of these exosomal therapeutics are profoundly influenced by the methods used for their isolation and purification. Ultracentrifugation (UC) has long been the historical benchmark for exosome isolation [33] [17]. However, the demand for large-scale, reproducible, and high-quality exosome production for clinical applications has highlighted the limitations of UC and brought Tangential Flow Filtration (TFF) to the forefront as a powerful alternative [34] [26]. This guide objectively compares these two core technologies, providing experimental data and methodological context to inform their use in preclinical and clinical drug development.

{Direct Technical Comparison: UC vs. TFF} The fundamental difference between UC and TFF lies in their separation mechanism, which directly dictates their performance characteristics. UC separates particles based on size, shape, and density through the application of extreme centrifugal force (typically ~100,000–120,000 × g) [33] [17]. In contrast, TFF is a filtration-based technique where the sample flows tangentially across a membrane, preventing clogging and enabling efficient concentration and purification of exosomes based primarily on size [34] [35].

Table 1: Head-to-Head Performance Comparison of UC and TFF

| Performance Metric | Ultracentrifugation (UC) | Tangential Flow Filtration (TFF) |

|---|---|---|

| Mechanism of Separation | Density and particle size under centrifugal force [33] [17] | Size-based separation via cross-flow filtration [34] |

| Typical Exosome Yield | Lower; pellets can be inconsistent [34] | Significantly higher and more consistent [34] [35] |

| Purity | Moderate to Low; co-pellets protein aggregates and lipoproteins [34] [33] | High, especially when coupled with SEC [34] [26] |

| Processing Time | Lengthy (often > 4 hours) [34] [17] | Rapid (typically < 2 hours) [34] |

| Scalability | Limited by rotor capacity [17] | Highly scalable for industrial production [34] [26] |

| Impact on Exosome Integrity | Can cause aggregation and mechanical damage [34] | Preserves structural integrity and biological activity [34] [35] |

| Cost & Infrastructure | High initial equipment cost [13] | Requires specialized TFF equipment; cost-effective for large scale [34] |

{Experimental Data and Workflow Analysis} A direct comparative study investigating the isolation of small extracellular vesicles (sEVs) from cancer cell lines provides critical, data-driven insights. The study demonstrated that while both UC and TFF (with subsequent Size Exclusion Chromatography purification) could isolate sEV populations with consistent size distributions (up to 200 nm), TFF consistently achieved significantly higher yields [34]. Furthermore, the study concluded that TFF surpassed UC in reproducibility, time-efficiency, and cost-effectiveness, making it more suitable for large-scale research and therapeutic applications [34].

The workflows for these two methods, from cell culture conditioned media to purified exosomes, are distinct and are best understood visually. The following diagram illustrates the key steps involved in each protocol.

Diagram 1: A comparative workflow of Ultracentrifugation (UC) and Tangential Flow Filtration (TFF) for MSC-Exo isolation. The TFF process is notably more streamlined.

{The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials} Successful isolation using either method relies on a foundation of specific laboratory reagents and equipment.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for MSC-Exo Isolation

| Reagent / Material | Function | Application in UC & TFF |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Culture Media with EV-depleted FBS | Provides nutrients for MSC growth while preventing contamination by bovine EVs [34]. | Essential preconditioning step for both methods to ensure pure exosome harvest. |

| Dulbecco's Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) | Isotonic buffer for washing cells and resuspending crude exosome pellets [34]. | Used in cell washing and post-UC pellet resuspension. |

| Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC) Columns | Separates exosomes from contaminating proteins and other soluble factors based on hydrodynamic volume [34] [26]. | Often used as a critical polishing step after TFF and sometimes after UC for enhanced purity. |

| 0.22 µm Pore Filters | Removes large particle contaminants, cells, and debris from conditioned media before isolation [34]. | Standard clarification step in both protocols. |

| Protease Inhibitors | Prevents degradation of exosomal proteins during the isolation process [33]. | Added to conditioned media and buffers in both methods to preserve cargo integrity. |

{Implications for Safety and Immunogenicity Research} The choice of isolation method is not merely technical; it has direct consequences for the safety and immunogenicity profile of the final MSC-Exo product, a core consideration for clinical translation.

Preserving Integrity for Lower Immunogenicity: MSC-Exos are inherently low in immunogenicity as they lack major histocompatibility complex (MHC) molecules, reducing the risk of immune rejection [12]. However, harsh processing can compromise this. UC-induced aggregation or damage may expose novel epitopes or increase the likelihood of unwanted immune recognition. TFF, being a gentler method, better preserves exosome membrane integrity, thereby supporting the natural low immunogenicity profile of MSC-Exos [34] [35].

Ensuring Purity for Safety: The therapeutic safety of exosome preparations is contingent on their purity. Co-isolation of contaminating proteins, aggregates, or lipoproteins with UC can not only confound experimental results but also introduce unpredictable biological effects or immune responses in a clinical setting [34] [33]. The high purity achieved by TFF, especially when combined with SEC, minimizes these risks, ensuring that the observed therapeutic or immunological effects are attributable to the exosomes themselves.

{Conclusion and Future Perspectives} For decades, ultracentrifugation has served as the default technique for MSC-Exo isolation in basic research. However, the evolving landscape of regenerative medicine, with its emphasis on clinical-grade, reproducible, and safe therapeutics, demands a reevaluation of this standard. Tangential Flow Filtration emerges as a superior technology for applications where high yield, preserved biological activity, scalability, and high purity are paramount. These attributes are indispensable for robust safety and immunogenicity testing and for the eventual mass production of MSC-Exo therapies. While UC remains a viable option for small-scale proof-of-concept studies, TFF represents the forward-looking methodology that aligns with the stringent requirements of modern drug development for cell-free regenerative products.

Within the rapidly advancing field of regenerative medicine, the therapeutic comparison between stem cell transplantation and stem cell-derived exosomes has become a central focus of research. A critical, yet sometimes underexplored, factor influencing the safety and efficacy of these therapies is the method of administration. The route of delivery directly impacts biodistribution, local concentration at the target site, and the magnitude of immune response, thereby shaping the overall therapeutic outcome. This guide provides a detailed, objective analysis of three primary administration routes—intravenous infusion, aerosolized inhalation, and local injection—within the broader context of safety and immunogenicity comparisons between mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) exosomes and whole-cell transplantations. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, this review synthesizes current experimental data and protocols to inform preclinical and clinical study design.

The choice of administration route is dictated by the target pathology, the physical properties of the therapeutic agent (whole cells vs. nanoscale exosomes), and the desired balance between systemic and localized effects. The table below summarizes the core characteristics, advantages, and challenges of each route.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Administration Routes for Stem Cell and Exosome Therapies

| Administration Route | Therapeutic Agent | Key Advantages | Major Limitations & Risks | Primary Target Indications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intravenous (IV) Infusion | Stem Cells | Simplicity, systemic distribution, suitability for disseminated diseases [30] | Infusion toxicity: First-pass pulmonary entrapment due to large cell size; risk of systemic hypotension [30] [36]. Immunogenicity: Potential for systemic immune recognition and rejection [37] [14]. | Haematological reconstitution, systemic inflammatory/autoimmune diseases [30] |

| MSC Exosomes | Systemic distribution without pulmonary entrapment; reduced immunogenicity; can be engineered for targeted drug delivery [30] [13] | Rapid clearance by the mononuclear phagocyte system; potential batch-to-batch variability; undefined pharmacokinetics [30] [13] | Systemic inflammatory conditions, cardiovascular diseases, as targeted drug delivery vehicles [30] [13] | |

| Aerosolized Inhalation | Stem Cells | Potential for direct lung tissue engraftment | Physical shear stress during nebulization can compromise cell viability and function; risk of post-procedural bronchospasm [18] | Pulmonary diseases (e.g., idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, ARDS) |

| MSC Exosomes | Non-invasive pulmonary delivery; bypasses the blood-brain barrier; achieves high local concentration with minimal systemic exposure; stability for lyophilization and storage [30] [18] | Complex dosage standardization due to aerosol dynamics; limited data on long-term retention [30] | Respiratory diseases (e.g., COVID-19, pulmonary fibrosis, asthma), potential for direct-to-brain delivery [30] | |

| Local Injection | Stem Cells | High local concentration at injury site; minimizes systemic exposure and off-target effects | Invasive procedure; potential for tissue injury at injection site; limited diffusion from injection site [8] | Orthopedic injuries (cartilage, tendon), localized autoimmune lesions, cosmetic and wound healing applications [7] [8] |

| MSC Exosomes | High local concentration; minimal invasiveness and superior tissue penetration compared to cells; reduced risk of immune rejection at site [7] [13] | Technically challenging for deep-seated organs; potential for leakage from injection site [13] | Myocardial infarction, neurological disorders, muscular injuries, ovarian function restoration [7] [13] [8] |

Experimental Protocols and Data Analysis

Intravenous Administration: Quantifying Immunogenicity

Objective: To compare the humoral immune response elicited by intravenously administered xenogeneic MSCs versus their daughter exosomes in a murine model [14].

Experimental Workflow:

- Animal Model: 129-S1 mice assigned to Sham, RAS (Renal Artery Stenosis), RAS+MSC, and RAS+EV groups [14].

- Therapeutic Administration:

- Outcome Measures:

- Systemic Humoral Response: Measured by levels of circulating anti-human antibodies in murine serum using an MSC-reactive assay [14].

- Splenic B-Cell Profile: Analyzed via immunofluorescence staining for CD19+ and IgM+ B-cells in splenic tissue [14].

- Local Immune Rejection: Assessed by quantifying intrarenal T-cell (CD3+) and macrophage (F4/80+) accumulation [14].

Key Findings:

- MSCs triggered a significantly greater systemic antibody (IgM) production compared to exosomes [14].