MSC Exosomes vs Whole Cell Therapy: A New Paradigm for Diabetic Ulcer Treatment

Diabetic foot ulcers (DFUs) represent a severe complication with high rates of amputation and mortality, driven by a complex microenvironment that often resists conventional care.

MSC Exosomes vs Whole Cell Therapy: A New Paradigm for Diabetic Ulcer Treatment

Abstract

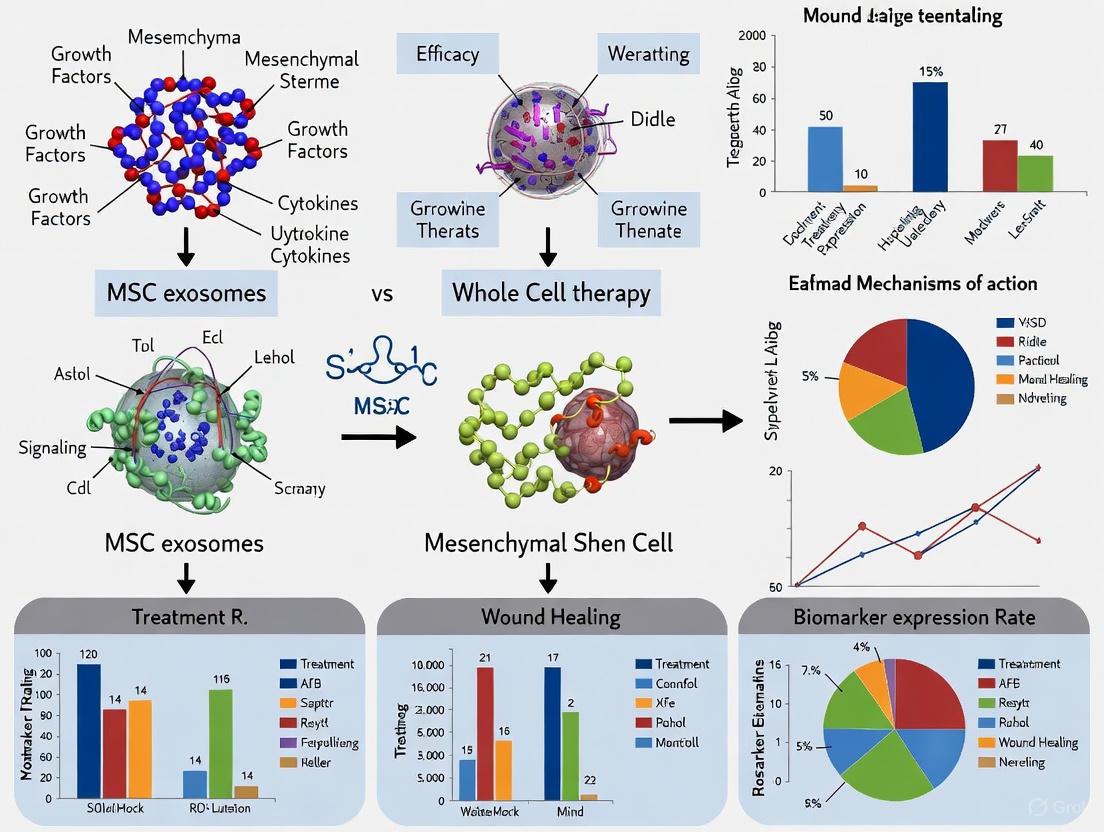

Diabetic foot ulcers (DFUs) represent a severe complication with high rates of amputation and mortality, driven by a complex microenvironment that often resists conventional care. This article provides a comprehensive analysis for researchers and drug development professionals on the evolving landscape of mesenchymal stem cell (MSC)-based therapies. It explores the foundational biology, methodological applications, and current clinical validation of both whole MSC therapies and the emerging frontier of MSC-derived exosomes. By comparing their mechanisms of action, from angiogenesis and immunomodulation to practical challenges in standardization and delivery, this review synthesizes evidence to guide future therapeutic development and clinical translation for refractory diabetic wounds.

The Biological Battlefield: Understanding the DFU Microenvironment and Core Healing Mechanisms

Diabetic foot ulcers (DFUs) represent a severe and debilitating complication of diabetes mellitus, affecting approximately 15-25% of patients during their lifetime and contributing to over 85% of non-traumatic lower limb amputations [1] [2]. The global health burden of DFUs is substantial, with annual healthcare costs exceeding $40 billion worldwide [1]. The pathophysiology of DFUs is multifactorial, arising from a complex interplay of metabolic dysfunction, diabetic neuropathy, peripheral arterial disease, and immune dysregulation [1] [3] [4]. Understanding these underlying mechanisms is crucial for developing effective therapeutic strategies.

DFUs are characterized by epidermal and partial dermal disruptions that progress through distinct stages, beginning with callus formation due to neuropathy and culminating in subcutaneous hemorrhage and ulceration from repeated trauma [2]. The three primary components of DFUs are neuropathy, peripheral arterial disease, and infection, which collectively create a challenging microenvironment resistant to conventional healing processes [2]. Persistent hyperglycemia drives multiple pathological pathways, including increased oxidative stress, advanced glycation end-product (AGE) accumulation, endothelial dysfunction, and chronic inflammation, all of which contribute to impaired wound healing [1] [3].

In recent years, regenerative medicine approaches have emerged as promising strategies for DFU treatment. Among these, mesenchymal stem cell (MSC)-based therapies and their derivatives, particularly exosomes, have garnered significant attention for their potential to address the multifaceted pathophysiology of DFUs [5] [6] [7]. This review will examine the core pathophysiological mechanisms of DFUs while framing the discussion within the context of comparing MSC exosomes versus whole cell therapy as innovative treatment approaches.

Pathophysiological Triad: Inflammation, Ischemia, and Neuropathy

Chronic Inflammation and Immune Dysregulation

Chronic inflammation is a hallmark of the diabetic wound environment and a significant contributor to DFU pathogenesis. Hyperglycemia-induced oxidative stress triggers the activation of nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB), leading to the overproduction of pro-inflammatory cytokines including tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β), and interleukin-6 (IL-6) [1]. These cytokines perpetuate a pro-inflammatory state that impairs wound healing and promotes tissue destruction.

A critical aspect of immune dysregulation in DFUs involves macrophage polarization imbalance. Under normal healing conditions, macrophages transition from a pro-inflammatory M1 phenotype to an anti-inflammatory M2 phenotype that promotes tissue repair. However, in diabetic wounds, this transition is impaired, resulting in a prolonged presence of M1 macrophages that produce high levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines and matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), leading to excessive degradation of extracellular matrix components essential for wound repair [1]. The persistent inflammatory environment also features neutrophil dysfunction and regulatory T cell depletion, further exacerbating the chronic inflammatory state [1].

Advanced glycation end products (AGEs), formed under hyperglycemic conditions through non-enzymatic glycation of proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids, contribute significantly to inflammation by binding to their receptor (RAGE) on immune cells, activating pro-inflammatory pathways that exacerbate tissue injury [1]. This sustained inflammatory response creates a microenvironment that is hostile to the cellular processes necessary for effective wound healing.

Microvascular Dysfunction and Ischemia

Peripheral arterial disease and microvascular dysfunction play pivotal roles in DFU development and impaired healing. Diabetes is associated with significant endothelial dysfunction, which reduces nitric oxide (NO) availability, impairs vasodilation, and decreases capillary perfusion, all of which delay ulcer healing [1]. NO plays a critical role in regulating vascular tone, and its suppression results in increased vascular resistance and reduced oxygen and nutrient delivery to wounded tissues.

Persistent hyperglycemia leads to thickening of the capillary basement membrane due to excessive deposition of AGE-modified extracellular matrix proteins, impairing the exchange of oxygen and nutrients between blood and tissues and contributing to hypoxia in ulcerated areas [1]. Additionally, diabetes promotes a pro-thrombotic state by increasing platelet aggregation and reducing fibrinolytic activity, leading to microvascular occlusions that further impair perfusion in ischemic tissues [1].

The hexosamine biosynthetic pathway, activated under hyperglycemic conditions, results in excessive glycosylation of proteins involved in wound healing, such as growth factors and signaling molecules, impairing their function and further delaying wound repair [1]. Hyperglycemia-induced dyslipidemia also promotes endothelial damage by increasing levels of oxidized low-density lipoprotein (oxLDL), which triggers inflammation and atherosclerotic changes within the microvasculature [1].

Diabetic Neuropathy

Diabetic neuropathy, affecting up to 70% of individuals with diabetes, is one of the primary factors in DFU development [1] [4]. This condition is characterized by sensory, motor, and autonomic dysfunction, all of which contribute to ulcer formation and chronicity.

Sensory neuropathy causes loss of protective sensations, including pain, temperature, and pressure perception. This leads to unnoticed trauma, microabrasions, and repetitive pressure injuries that contribute to ulcer formation [1] [3]. Motor neuropathy results in damage to motor neurons, leading to muscle atrophy and imbalance that cause foot deformities such as claw toes, hammertoes, and Charcot foot. These deformities alter pressure distribution on the plantar surface, creating areas of excessive pressure that predispose to ulceration [1].

Autonomic neuropathy reduces the function of sweat and sebaceous glands, resulting in dry, cracked skin that serves as an entry point for bacterial infections. Additionally, arteriovenous shunting impairs blood flow regulation, further compromising tissue perfusion and wound healing [1] [3]. The interaction between sensory, motor, and autonomic neuropathy forms a callus in the foot that, after repeated trauma, leads to subcutaneous hemorrhage and skin ulceration [3].

Table 1: Pathophysiological Mechanisms in Diabetic Foot Ulcers

| Pathophysiological Component | Key Mechanisms | Cellular/Molecular Effects |

|---|---|---|

| Chronic Inflammation | Macrophage polarization imbalance (M1/M2); Neutrophil dysfunction; Regulatory T cell depletion; AGE-RAGE activation | Elevated TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6; Increased matrix metalloproteinases; Oxidative stress; NF-κB pathway activation |

| Ischemia and Microvascular Dysfunction | Endothelial dysfunction; Basement membrane thickening; Pro-thrombotic state; Reduced nitric oxide availability | Impaired vasodilation; Capillary perfusion reduction; Tissue hypoxia; Microvascular occlusions |

| Neuropathy | Sensory nerve damage; Motor neuron impairment; Autonomic dysfunction | Loss of protective sensation; Muscle atrophy and foot deformities; Dry, cracked skin; Altered pressure distribution |

MSC-Based Therapeutic Approaches for DFUs

Whole MSC Therapy

Mesenchymal stem cell therapy represents a promising approach for DFU treatment by targeting multiple pathophysiological pathways simultaneously. MSCs can be derived from various sources, including bone marrow (BM-MSCs), adipose tissue (ADSCs), and umbilical cord (UC-MSCs), each with distinct advantages [5].

Whole MSCs promote wound healing through several mechanisms: promoting angiogenesis via secretion of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and other growth factors; modulating immune responses by shifting macrophage polarization from pro-inflammatory M1 to anti-inflammatory M2 phenotypes; reducing oxidative damage through antioxidant enzyme systems; and enhancing extracellular matrix remodeling [5]. These multifactorial actions make MSC therapy particularly suited to address the complex pathophysiology of DFUs.

Clinical studies have demonstrated the potential of whole MSC therapy. In a study by Andersen et al., a single application of BM-MSCs improved clinical outcomes in DFU patients over a six-month observation period [5]. Similarly, Anterogen's Allo-ASC-DFU, an ADSC-based therapy, demonstrated safety and efficacy in improving wound healing in DFU patients during Phase II clinical trials [5].

Genetic engineering approaches have been explored to enhance MSC therapeutic potential. In a preclinical study, genetically modified human umbilical cord-derived MSCs (hUMSCs) engineered to overexpress three anti-inflammatory factors (IL-4, IL-10, IL-13) significantly promoted diabetic wound healing with a wound closure rate exceeding 96% after 14 days of treatment [6]. These modified cells effectively induced phenotypic polarization of pro-inflammatory M1 macrophages toward anti-inflammatory M2 macrophages, addressing a key aspect of DFU pathophysiology [6].

MSC-Derived Exosome Therapy

MSC-derived exosomes have emerged as a promising cell-free alternative to whole cell therapy. Exosomes are natural nanovesicles that mediate intercellular communication by transferring functional molecules including proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids [8] [9]. They offer several potential advantages over whole cell therapy, including lower immunogenicity, easier storage and handling, and potentially better safety profile [9].

Exosomes derived from Wharton's jelly MSCs (WJ-MSCs) have demonstrated particular promise for DFU treatment. These exosomes promote wound healing through multiple mechanisms: stimulating keratinocyte migration and proliferation; enhancing M2 macrophage polarization over M1 by regulating inflammatory cytokine levels; promoting neovascularization through exosome-mediated delivery of hepatocyte growth factor (HGF); and reducing scar formation by transferring specific miRNAs that inhibit myofibroblast activation [9].

A randomized controlled clinical trial involving 110 patients with persistent DFUs evaluated the safety and efficacy of WJ-MSC exosomes [9]. Participants receiving topical WJ-MSC exosome application weekly for four weeks showed significantly improved outcomes compared to controls. The mean time to full recovery was 6 weeks in the treatment group versus 20 weeks in the control group, demonstrating the potent healing capabilities of exosome therapy [9].

Another phase I/II clinical trial investigated allogeneic human umbilical cord mesenchymal stromal cell derivatives (hUC-MSCD), including conditioned media, extracellular vesicles, and exosomes, administered via perilesional injection in patients with chronic DFUs [7]. All ten enrolled patients achieved complete ulcer closure within a mean of 4.2 weeks, with no ulcer recurrence during a 24-month follow-up period, providing strong preliminary evidence for the safety and efficacy of this approach [7].

Table 2: Comparison of Whole MSC Therapy vs. MSC-Derived Exosomes for DFU Treatment

| Therapeutic Characteristic | Whole MSC Therapy | MSC-Derived Exosomes |

|---|---|---|

| Mechanism of Action | Direct differentiation; Paracrine signaling; Cell-cell contact | Cargo delivery (proteins, lipids, nucleic acids); No direct differentiation |

| Key Mediators | Cells themselves; Secreted growth factors; Extracellular vesicles | miRNAs (miR-21, miR-23a, miR-125b, miR-145); Proteins (HGF, FGB) |

| Angiogenic Potential | VEGF, HGF secretion; Differentiation into endothelial cells | miR-21, miR-23a mediated angiogenesis; HGF delivery |

| Immunomodulatory Effects | Macrophage polarization (M1 to M2); T cell regulation via IDO | Enhanced M2 polarization; Treg differentiation via Foxp3/IDO |

| Clinical Efficacy | ~96% wound closure in 14 days (preclinical) [6] | 100% ulcer closure in 4.2 weeks (clinical) [7] |

| Administration Route | Local injection; Topical application | Perilesional injection; Topical gel |

| Safety Considerations | Potential immunogenicity; Cell survival concerns | Lower immunogenicity; No risk of tumor formation |

Experimental Models and Methodologies

Preclinical Study Designs

Preclinical studies investigating MSC-based therapies for DFUs typically employ standardized animal models and experimental protocols. A representative preclinical study design is outlined below, based on investigations of genetically modified MSCs promoting diabetic wound healing [6].

Animal Models and Ethics: Studies typically use C57BL/6J mice (6-8 weeks old), NOD-SCID immunodeficient mice, and SD rats maintained under controlled conditions. All procedures should be performed in accordance with institutional guidelines for animal care and use [6].

Isolation and Culture of MSCs: Human umbilical cord-derived MSCs (hUMSCs) are isolated from Wharton's jelly of healthy full-term cesarean-delivered fetuses. The amniotic membrane is removed, and Wharton's jelly is dissected into tissue blocks and cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium/F12 (DMEM/F12) supplemented with fetal bovine serum and penicillin/streptomycin [6].

Characterization of MSCs: MSC identity is confirmed via flow cytometry analysis of positive markers (CD105, CD73, CD90) and negative markers (CD14, CD19, HLA-DR, CD34, CD45). Multilineage differentiation potential is assessed by culture in osteogenic, adipogenic, and chondrogenic differentiation media followed by specialized staining [6].

Genetic Modification: Lentiviral vectors are used for genetic modification. hUMSCs are seeded in culture plates and infected with virus diluted in culture medium supplemented with polybrene. Groups typically include unaltered MSCs, vector-control MSCs, and genetically modified MSCs [6].

In Vitro Functional Assays: Macrophage polarization assays are performed using Raw264.7 cells. Flow cytometry and quantitative real-time PCR assess polarization markers. Scratch assays evaluate cell migration capabilities [6].

In Vivo Wound Healing Assessment: A diabetic wound model is created in mice. Wound healing is evaluated through healing rate calculation, H&E staining, Masson staining, and immunohistochemical analysis of relevant markers including PCNA, F4/80, CD31, CD86, CD206, IL-4, IL-10, and IL-13 [6].

Clinical Trial Protocols

Clinical trials investigating MSC derivatives for DFU treatment follow standardized protocols with specific inclusion criteria and outcome measures, as demonstrated in recent studies [7] [9].

Patient Selection: Eligible patients are typically adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus and chronic DFUs classified as Texas Grade II-III that are refractory to standard care. Exclusion criteria often include severe renal or hepatic impairment, malignancy, and pregnancy [7].

Preparation of Therapeutic Agents: For exosome-based therapies, Wharton's jelly MSC-derived exosomes are isolated and characterized. The isolation process involves collecting conditioned media from MSC cultures, centrifugation to remove cells and large vesicles, and ultracentrifugation at 110,000×g to pellet exosomes [9]. Characterization includes flow cytometry for surface markers (CD9, CD63, CD81, HSP70) and transmission electron microscopy for morphology assessment [9].

Treatment Administration: In exosome clinical trials, participants typically receive weekly topical applications or perilesional injections of the therapeutic agent. Control groups receive standard of care alone or with a placebo vehicle [7] [9].

Outcome Measures: Primary safety outcomes include frequency and severity of adverse events. Primary efficacy outcomes include rate and duration of ulcer closure, with treatment success defined as complete healing within a specified timeframe [7]. Secondary outcomes may include recurrence rates during follow-up periods that can extend to 24 months [7].

Statistical Analysis: Continuous variables are expressed as mean ± standard deviation, with 95% confidence intervals. Changes in ulcer surface area are assessed using paired t-tests, while differences in healing time between ulcer grades are evaluated using non-parametric tests such as the Mann-Whitney U test [7].

Signaling Pathways and Molecular Mechanisms

The therapeutic effects of MSC-based therapies for DFUs are mediated through multiple signaling pathways that address the core pathophysiological mechanisms. The diagram below illustrates the key signaling pathways involved in MSC-mediated wound healing.

MSC Signaling Pathways in DFU Healing

The diagram above illustrates how MSC-based therapies target multiple pathophysiological aspects of DFUs through coordinated signaling pathways. The angiogenic effects are primarily mediated through VEGF and HGF secretion, activating PI3K/Akt and MAPK pathways, while MALAT1 expression further enhances vascularization [5] [10]. Immunomodulation occurs through macrophage polarization from M1 to M2 phenotypes mediated by TSG-6, IL-10, and exosomal miRNAs, along with Treg cell differentiation [5] [9]. Tissue repair is facilitated through fibroblast activation, collagen deposition, keratinocyte migration, and miRNA transfer that collectively promote extracellular matrix remodeling and accelerated wound closure [5] [9].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Investigating MSC Therapies in DFUs

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Function in Experimental Design |

|---|---|---|---|

| MSC Markers | CD105, CD73, CD90 (positive); CD14, CD19, CD34, CD45, HLA-DR (negative) | MSC identification and characterization | Confirm MSC phenotype and purity via flow cytometry [6] [7] |

| Macrophage Polarization Markers | CD86 (M1); CD206 (M2) | Immunomodulation assessment | Evaluate MSC effects on macrophage phenotype switching [6] |

| Angiogenesis Assays | CD31 (PECAM-1); VEGF ELISA; HGF ELISA | Neovascularization measurement | Quantify blood vessel formation and angiogenic factor secretion [7] [10] |

| Exosome Characterization | CD9, CD63, CD81, HSP70 | Vesicle identification and quantification | Confirm exosome identity and purity [9] |

| Cytokine/Chemokine Analysis | IL-4, IL-10, IL-13, TNF-α, TGF-β1 ELISA | Inflammatory microenvironment assessment | Measure pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokine profiles [6] [7] |

| Genetic Modification Tools | Lentiviral vectors (IL-4, IL-10, IL-13) | MSC functional enhancement | Enhance MSC therapeutic potential through gene overexpression [6] |

| Histological Stains | H&E, Masson's Trichrome, Alizarin Red, Oil Red O, Alcian Blue | Tissue morphology and differentiation analysis | Evaluate tissue architecture, collagen deposition, and differentiation potential [6] [7] |

The pathophysiology of diabetic foot ulcers involves a complex interplay of chronic inflammation, ischemia, and neuropathy that creates a microenvironment resistant to conventional healing approaches. Mesenchymal stem cell-based therapies and their derivatives, particularly exosomes, offer promising strategies that target multiple pathophysiological mechanisms simultaneously.

While whole MSC therapy demonstrates significant potential through direct cellular engagement and paracrine signaling, MSC-derived exosomes present distinct advantages as a cell-free alternative with lower immunogenicity and potentially better safety profiles. Current evidence from both preclinical and clinical studies supports the efficacy of both approaches in promoting wound healing, modulating immune responses, and enhancing tissue regeneration in DFUs.

Future research directions should focus on optimizing delivery methods, standardizing preparation protocols, and conducting larger, randomized controlled trials to directly compare the therapeutic efficacy of whole MSC therapy versus MSC-derived exosomes. Additionally, further investigation into the specific molecular cargo of exosomes and the development of engineered exosomes with enhanced therapeutic properties may unlock new possibilities for treating this debilitating complication of diabetes.

Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) represent a cornerstone of regenerative medicine, offering a multifaceted therapeutic approach for complex conditions like diabetic foot ulcers (DFUs). Unlike targeted therapies that address single pathological pathways, whole MSC therapy exerts simultaneous effects across multiple healing mechanisms, including angiogenesis, immunomodulation, and direct cellular differentiation. This multimodal action is particularly valuable in the DFU microenvironment, which is characterized by chronic inflammation, ischemia, neuropathy, and impaired cellular repair capacity [5]. The therapeutic efficacy of whole MSCs arises from both their direct engagement with damaged tissues and their sophisticated paracrine activity, which involves the secretion of growth factors, cytokines, and extracellular vesicles that collectively orchestrate the healing process [11]. This review delineates the mechanistic actions of whole MSC therapy and provides a direct comparison with the emerging cell-free approach utilizing MSC-derived exosomes.

Core Mechanisms of Action

Whole MSCs facilitate wound healing through several interconnected biological processes. The diagram below synthesizes these primary mechanisms and their functional outcomes in the diabetic wound microenvironment.

Pro-Angiogenic Action

The ischemic nature of DFUs necessitates robust angiogenic responses, which whole MSCs effectively initiate through multiple pathways. These cells secrete a potent combination of pro-angiogenic factors including vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), basic fibroblast growth factor (FGF-2), and platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) [5]. These factors collectively activate critical signaling pathways, particularly the PI3K/AKT pathway, which promotes endothelial cell survival, proliferation, and new blood vessel formation [5]. Additional secreted factors like epidermal growth factor (EGF) and CXCL12/SDF-1α further enhance this process by stimulating endothelial migration and proliferation [7]. This comprehensive pro-angiogenic activity directly counteracts the microvascular dysfunction that characterizes diabetic wounds, thereby improving tissue perfusion and oxygen delivery to the ischemic limb.

Immunomodulatory Capacity

DFUs are characterized by a persistent pro-inflammatory environment with excessive M1 macrophage presence and impaired transition to the healing M2 phenotype. Whole MSCs fundamentally reshape this dysfunctional immune landscape through sophisticated regulatory mechanisms. They secrete factors like tumor necrosis factor-inducible gene 6 (TSG-6) and interleukin-10 (IL-10) that actively promote macrophage polarization from the pro-inflammatory M1 state to the anti-inflammatory and pro-regenerative M2 phenotype [5]. Furthermore, MSCs suppress excessive T-cell activation and proliferation through indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO)-mediated degradation of tryptophan, creating an immunosuppressive local environment [5]. This immunomodulatory capability is crucial for breaking the cycle of chronic inflammation that prevents DFU healing.

Direct Differentiation Potential

Beyond paracrine signaling, whole MSCs possess the capacity for direct differentiation into multiple cell lineages essential for wound repair. They can differentiate into keratinocytes, fibroblasts, and endothelial cells, thereby directly contributing to re-epithelialization, granulation tissue formation, and vascularization [12] [11]. This direct cellular incorporation provides structural elements for tissue regeneration that extends beyond the transient signaling effects of their paracrine factors. The differentiation potential is particularly valuable in chronic wounds where resident progenitor cells may be depleted or functionally impaired due to the diabetic microenvironment.

Experimental Models and Methodologies

Standardized Experimental Workflow

Research into whole MSC therapy for DFUs follows a structured experimental workflow that progresses from cell isolation and characterization through to efficacy assessment. The diagram below outlines this standardized methodology.

Key Research Reagents and Materials

The following table details essential reagents and materials used in whole MSC therapy research, providing researchers with practical experimental considerations.

Table 1: Essential Research Reagents for Whole MSC Therapy Studies

| Reagent/Material | Specific Function | Experimental Application |

|---|---|---|

| Flow Cytometry Antibodies (CD73, CD90, CD105, CD34, CD45, HLA-DR) | MSC phenotype verification according to ISCT criteria [11] | Quality control to confirm MSC identity prior to experimentation |

| Trilineage Differentiation Kits (Osteogenic, Chondrogenic, Adipogenic) | Differentiation potential assessment | In vitro validation of MSC multipotency [7] [11] |

| ELISA Kits (VEGF, FGF-2, PDGF, IL-10, TSG-6) | Quantification of secretory profile | Measurement of paracrine factor production [7] |

| Cell Culture Media (Alpha-MEM with platelet lysate) | MSC expansion and maintenance | Cell culture under standardized conditions [7] |

| Animal Models (db/db mice, streptozotocin-induced diabetic rodents) | Diabetic wound healing assessment | Preclinical efficacy testing in pathophysiologically relevant models [5] |

Comparative Clinical Outcomes: Whole MSC Therapy vs. Emerging Alternatives

Clinical Efficacy Metrics

Recent clinical investigations have generated comparative data on the performance of whole MSC therapy versus MSC-derived exosomes. The table below summarizes key efficacy outcomes from clinical trials.

Table 2: Comparative Clinical Outcomes for DFU Therapies

| Therapy Type | Patient Population | Healing Rate | Time to Complete Closure | Recurrence Rate | Key Study Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Whole MSC Therapy (hUC-MSCD) [7] | 10 patients with chronic DFUs refractory to standard care | 100% achieved complete closure | Mean: 4.2 weeks | 0% recurrence at 24-month follow-up | Significant ulcer surface area reduction (p<0.00001); Texas Grade II-III ulcers |

| MSC-Exosomes (WJ-MSC derived) [13] | 110 patients with persistent DFUs | 62% fully recovered by study end | Mean: 6 weeks (range: 4-8) | Not specified | Significantly higher complete recovery vs. controls (20 weeks to healing) |

| Standard of Care (SOC) [13] [7] | DFU patients across studies | Variable, often incomplete | 20 weeks (range: 12-28) [13] | High lifetime recurrence (19-34%) [5] | Limited efficacy in refractory wounds; addresses symptoms not underlying pathology |

Technical and Manufacturing Comparison

The translational potential of therapeutic approaches depends significantly on their technical and manufacturing characteristics. The following table compares these practical aspects.

Table 3: Technical and Manufacturing Comparison

| Characteristic | Whole MSC Therapy | MSC-Derived Exosomes |

|---|---|---|

| Mechanistic Scope | Multimodal: Direct differentiation + paracrine signaling [11] | Primarily paracrine signaling [14] |

| Manufacturing Complexity | High (live cell culture, viability maintenance) [15] | Moderate (cell culture + vesicle isolation) [15] |

| Storage & Stability | Cryopreservation required; limited shelf life [15] | Enhanced stability; simpler storage [15] |

| Immunogenicity Risk | Low but present (allogeneic applications) [5] | Very low (acellular) [14] [15] |

| Dosing Regimen | Typically single application [5] | Often multiple applications required [13] |

| Theoretical Safety Concerns | Minimal risk of microvascular occlusion [15] | No tumorigenicity risk observed [15] |

| Scalability Potential | Moderate (limited by cell expansion capacity) | High (industrial bioprocessing possible) |

Whole MSC therapy represents a robust therapeutic modality with demonstrated efficacy in promoting healing of refractory diabetic foot ulcers. Its multimodal mechanism of action, encompassing direct differentiation capacity coupled with potent paracrine signaling, provides a comprehensive biological response to the complex pathophysiology of diabetic wounds. Clinical evidence confirms impressive healing rates (100% in a recent phase I/II trial) with rapid wound closure (mean 4.2 weeks) and remarkably durable outcomes (0% recurrence at 24-month follow-up) [7].

While MSC-derived exosomes offer distinct advantages in storage stability and reduced immunogenicity, the comprehensive mechanistic profile of whole MSCs presents a compelling case for their continued investigation and therapeutic application. Future research should focus on optimizing delivery techniques, standardizing cell preparation protocols, and identifying patient-specific factors that predict treatment response. The integration of whole MSC therapies with advanced biomaterials to enhance local retention and controlled release represents a promising direction for maximizing therapeutic potential while potentially reducing cell requirements. For researchers and drug development professionals, these findings underscore the value of maintaining whole MSC approaches within the therapeutic portfolio for diabetic wound complications, particularly in cases where the complexity of the wound microenvironment demands the multifaceted intervention that whole MSCs uniquely provide.

Within the field of regenerative medicine for diabetic wound repair, a significant paradigm shift is underway: the transition from mesenchymal stem cell (MSC)-based therapies to the use of their secreted exosomes. These nano-sized extracellular vesicles are now recognized as primary mediators of the therapeutic effects historically attributed to their parent cells, primarily through powerful paracrine actions. This guide provides a comprehensive, data-driven comparison of MSC-derived exosomes versus whole cell therapies, detailing their biogenesis, cargo, functional mechanisms, and therapeutic efficacy, with a specific focus on diabetic wound healing. It is designed to equip researchers and drug development professionals with the current experimental data and methodologies propelling this cell-free approach to the forefront of clinical translation.

The pursuit of effective treatments for diabetic ulcers, a devastating complication of diabetes, has long been a challenge in regenerative medicine. MSC-based therapies emerged as a promising strategy due to their multipotent differentiation potential and regenerative capabilities [16]. However, significant drawbacks, including potential tumorigenicity, immune rejection after transplantation, risks of microvascular occlusion, and considerable challenges in storage and standardization, have hampered their clinical application [15] [17].

This landscape is being reshaped by the understanding that the therapeutic benefits of MSCs are largely mediated through paracrine secretion rather than direct cell engraftment and differentiation [18] [16]. Among these secreted factors, MSC-derived exosomes (MSC-Exos) have surfaced as the leading effector. These natural nanoparticles, typically 30–150 nm in diameter, carry a complex cargo of proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids that mirror the biological function of their parent cells [15] [19]. They facilitate intercellular communication by transferring bioactive molecules to recipient cells, modulating the local microenvironment, and regulating key cellular processes involved in tissue repair [15]. For diabetic wound healing, this translates to the potential to comprehensively address abnormalities in all phases of the healing process—excessive inflammation, impaired angiogenesis, and faulty tissue remodeling—without the risks associated with whole-cell therapies [16].

Defining the Powerhouse: Biogenesis and Cargo of MSC-Exos

Biogenesis and Key Characteristics

MSC-Exos are formed through a sophisticated endosomal pathway. The process begins with the inward budding of the plasma membrane to form an early endosome. This endosome matures into a late endosome, or multivesicular body (MVB), which accumulates intraluminal vesicles (ILVs) via further inward budding of its own membrane. The MVBs subsequently fuse with the plasma membrane, releasing these ILVs into the extracellular space as exosomes [20] [19].

This biogenesis relies on two primary mechanistic pathways:

- The ESCRT machinery: The Endosomal Sorting Complex Required for Transport (ESCRT), comprising four complexes (ESCRT-0, -I, -II, and -III) and associated proteins like ALIX and TSG101, is crucial for sorting ubiquitinated proteins and facilitating membrane invagination [20].

- ESCRT-independent mechanisms: These involve lipids like ceramide, which promotes domain-induced membrane budding, and tetraspanin proteins (e.g., CD9, CD63, CD81) that help in sorting specific cargo and forming microdomains [20].

The release of exosomes is regulated by Rab GTPase proteins (e.g., Rab27a, Rab27b) and is influenced by the MSC's microenvironment, such as conditions of hypoxia or inflammation [20].

The Therapeutic Cargo

The potency of MSC-Exos lies in their diverse molecular cargo, which enables them to orchestrate complex therapeutic responses. The table below categorizes the key bioactive components found in MSC-Exos.

Table 1: Key Cargo Components of MSC-Derived Exosomes and Their Functions

| Cargo Type | Key Examples | Documented Functions in Therapy |

|---|---|---|

| Proteins | Tetraspanins (CD9, CD63, CD81), Heat shock proteins (HSP70, HSP90), MHC class II, ESCRT components (ALIX, TSG101), Growth factors, Cytokines | Structural integrity, cell targeting, immunomodulation, intracellular trafficking, angiogenesis, tissue repair [15] [20] [17] |

| Nucleic Acids | miRNAs (e.g., miR-146a, miR-150), mRNAs, long non-coding RNAs, Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) | Regulation of gene expression in recipient cells, modulation of inflammation (e.g., inhibition of IFN-γ from T cells), promotion of cell survival and proliferation, epigenetic remodeling [15] [20] [18] |

| Lipids | Cholesterol, Ceramide, Phosphatidylserine, Sphingomyelin, Saturated fatty acids | Membrane stability, protection of internal cargo, signal transduction, promoting membrane fusion and uptake [20] [19] |

This cargo is not static; it is dynamically influenced by the MSC's tissue source and physiological condition. For instance, exosomes from adipose-derived MSCs (ADMSCs) exhibit greater angiogenic capability, while those from bone marrow MSCs (BMSCs) are particularly potent in immunomodulation [15] [18]. Furthermore, MSCs subjected to hypoxia or inflammatory priming secrete exosomes with enhanced angiogenic or anti-inflammatory activity, respectively [20].

Head-to-Head Comparison: MSC-Exos vs. Whole MSC Therapy

For the development of diabetic ulcer treatments, the choice between MSC-Exos and whole MSCs involves a multi-faceted evaluation. The following table provides a direct, data-driven comparison based on current scientific evidence.

Table 2: Comparative Analysis: MSC-Derived Exosomes vs. Whole MSCs for Diabetic Wound Therapy

| Parameter | MSC-Derived Exosomes | Whole MSC Therapy | Supporting Experimental & Clinical Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Therapeutic Mechanism | Primarily paracrine; mediated via cargo delivery (miRNAs, proteins) to recipient cells [18]. | Direct differentiation and paracrine action; but low engraftment rates observed [16]. | Preclinical studies show exosomes mimic MSC benefits in immunomodulation and regeneration [18] [17]. |

| Immunogenicity | Considered non-immunogenic or low immunogenicity; lack MHC complexes, enabling allogeneic use [20] [19]. | Low immunogenicity but can trigger allogeneic immune rejection in some cases [15]. | In vivo studies note no acute immune rejection with exosomes [20]. |

| Safety Profile | Nanoscale size prevents lung entrapment/microthrombosis; no self-replication avoids tumorigenicity risk [18] [17]. | Risks of pulmonary embolism from cell aggregation, potential tumorigenicity, and unknown long-term effects [15] [17]. | A phase I trial for retinitis pigmentosa found MSC injection safe but with manageable severe events; exosomes proposed to mitigate risks [21]. |

| Production & Storage | No senescence; scalable production from immortalized cells; stable, easier storage [20] [19]. | Senescence after few passages; expensive large-scale production; complex storage and transport [20]. | Studies highlight exosome production scalability via TFF and UC methods [18] [21]. |

| Targeting & Delivery | Native tissue tropism; can be engineered for enhanced specific targeting [18] [19]. | Limited by poor migration and retention at target sites; host scavenging [17]. | Engineered exosomes show promise in targeted drug delivery [19]. |

| Clinical Translation | Early-stage clinical trials (e.g., for wound healing, ARDS, GVHD); emerging regulatory framework [18]. | Over 60 FDA-approved trials; more established but with known risks [17]. | Seven published clinical studies and 14 ongoing trials using MSC-Exos as of 2023 [18]. |

| Documented Efficacy in Diabetic Wounds | Promotes all wound healing stages: regulates inflammation, boosts angiogenesis, enhances proliferation, and improves collagen remodeling [16]. | Promotes wound healing but efficacy can be inconsistent due to variable cell quality and poor survival in hostile wound environment [16]. | Preclinical models demonstrate exosomes improve healing in diabetic chronic wounds (DCWs) and foot ulcers (DFUs) [16]. |

Insights from Clinical Trials and Preclinical Models

Current Status of Clinical Trials

The translation of MSC-Exos into clinical applications is advancing rapidly. As of a 2023 review, there are seven published clinical studies and 14 ongoing clinical trials investigating MSC-Exos for a range of conditions [18]. These include trials for graft-versus-host disease (GvHD), acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), osteoarthritis, stroke, Alzheimer's disease, and type 1 diabetes [18].

In the context of wound healing, while specific trials for diabetic ulcers are still emerging, the foundational principles are being established in related areas. For instance, a trial is assessing MSC-Exos for the healing of macular holes (NCT03437759), demonstrating the confidence in their regenerative potential for delicate tissues [18]. The most common sources for exosomes in these clinical trials are adipose tissue, bone marrow, and umbilical cord [18].

Efficacy Data from Preclinical Wound Models

Preclinical studies provide compelling evidence for the efficacy of MSC-Exos in diabetic wound healing. Their mechanism is multi-modal, targeting the core pathophysiological defects in chronic wounds:

- Immunomodulation: MSC-Exos can shift macrophages from the pro-inflammatory M1 phenotype to the pro-healing M2 phenotype, reducing levels of TNF-α and IL-6 while increasing IL-10 [16] [17]. This directly counteracts the persistent inflammation seen in diabetic wounds.

- Angiogenesis: They promote the formation of new blood vessels by transferring pro-angiogenic miRNAs and proteins (e.g., VEGF) to endothelial cells, enhancing their proliferation and tube-forming capability [16].

- Cell Proliferation and Migration: MSC-Exos stimulate the proliferation and migration of keratinocytes and fibroblasts, crucial for re-epithelialization and granulation tissue formation [16].

- Oxidative Stress Reduction: The cargo within exosomes can enhance the antioxidant capacity of recipient cells, protecting them from the high oxidative stress environment of a diabetic wound [16].

A meta-analysis of experimental studies, including one on a psoriasis model, found that exosome treatment significantly reduced clinical severity scores and epidermal thickness, underscoring their potent anti-inflammatory and regenerative effects [22].

Experimental Protocols: From Production to Functional Validation

For researchers entering this field, understanding the standard workflows for exosome isolation and efficacy testing is critical. The following diagram and details outline the core experimental protocols.

Detailed Methodologies

MSC Culture & Exosome Production:

- Cell Source: Human MSCs are isolated from bone marrow, adipose tissue, or umbilical cord. The choice of source should be documented as it influences exosome cargo [15] [18].

- Culture Conditions: Cells are typically expanded in standard media like α-MEM or DMEM, supplemented with 10% human platelet lysate (hPL) to avoid bovine exosome contamination [21]. Studies show α-MEM may support higher exosome yields compared to DMEM, though not always statistically significant [21].

- Pre-conditioning: To enhance therapeutic potency, MSCs can be pre-conditioned before exosome collection. This involves exposing them to hypoxia or inflammatory cytokines (e.g., TNF-α), which alters the exosomal cargo to be more anti-inflammatory or pro-angiogenic [20] [16].

Exosome Isolation and Purification:

- Ultracentrifugation (UC): This is the traditional "gold standard" method. It involves a series of centrifugation steps at increasing speeds (up to 100,000–150,000 × g) to pellet exosomes. While it yields highly enriched EV fractions, it is time-consuming and can cause exosome aggregation [18] [23] [21].

- Tangential Flow Filtration (TFF): This method is gaining traction for clinical-scale production. It uses a filtration system to separate exosomes based on size and can process large volumes more quickly. A 2025 study directly comparing methods found that TFF provided a statistically higher particle yield than UC [21].

- Other Methods: Size-exclusion chromatography (SEC) and immunoaffinity capture are also used, offering advantages in maintaining exosome integrity and purity, respectively [23].

Exosome Characterization:

- Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis (NTA): Used to determine the size distribution (typically 30–150 nm) and concentration of particles in a solution [22] [21].

- Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM): Visualizes the classic cup-shaped morphology of exosomes, confirming their structure [22] [21].

- Immunoblotting (Western Blot): Confirms the presence of exosomal marker proteins (e.g., CD9, CD63, CD81, TSG101, ALIX) and the absence of negative markers like calnexin (an endoplasmic reticulum protein) [22] [18].

In Vitro Functional Assays (e.g., for Diabetic Wounds):

- A common model involves inducing damage in human retinal pigment epithelium (ARPE-19) cells or dermal fibroblasts with hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂) to simulate oxidative stress [21].

- Cells are treated with MSC-Exos (e.g., at 50 μg/mL) either before (pre-treatment) or after (post-treatment) H₂O₂ exposure.

- Viability is measured using assays like MTT or CCK-8. One study showed H₂O₂ reduced viability to ~38%, but exosome treatment restored it to over 52% [21].

- Apoptosis is quantified using flow cytometry with Annexin V/PI staining, typically showing a significant reduction in total apoptotic cells after exosome treatment [21].

- Cytokine/Chemokine Secretion is profiled using ELISA or multiplex assays to demonstrate immunomodulatory effects (e.g., reduction of IL-17A, TNF-α) [22].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents and Kits for MSC-Exos Research

| Item | Function/Application | Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Human Platelet Lysate (hPL) | Xeno-free supplement for MSC culture medium to avoid contaminating bovine exosomes. | Essential for GMP-compliant, clinical-grade exosome production [21]. |

| Ultracentrifuge | Equipment for isolating exosomes via the UC method. | Beckman Coulter Optima series with Type 50.2 Ti rotor is commonly used [22]. |

| Tangential Flow Filtration (TFF) System | System for large-scale, high-yield exosome isolation and concentration. | Increasingly preferred for clinical-scale production due to higher efficiency [18] [21]. |

| Nanoparticle Tracking Analyzer | Instrument for characterizing exosome size and concentration. | ZetaView PMX 110 (Particle Metrix) is an example used in recent studies [22]. |

| Antibody Panel for WB | For confirming exosome identity and purity. | Anti-CD9, anti-CD63, anti-ALIX/TSG101 (positive markers); anti-Calnexin (negative marker) [22] [21]. |

| Imiquimod (IMQ) | Topical agent to induce a psoriatic inflammation model in mice for testing anti-inflammatory effects. | Used in murine studies at 5% concentration [22]. |

| H₂O₂ (Hydrogen Peroxide) | Chemical to induce oxidative stress and cell damage in in vitro models. | Used to create a model of cellular injury to test exosome therapeutic efficacy [21]. |

MSC-derived exosomes represent a definitive and powerful evolution in the field of regenerative medicine, truly embodying the concept of "paracrine powerhouses." For researchers focused on the formidable challenge of diabetic ulcer treatment, the evidence is compelling: MSC-Exos offer a cell-free therapeutic strategy that can effectively modulate inflammation, promote angiogenesis, and stimulate regeneration, while concurrently overcoming the significant safety and practical hurdles of whole MSC therapy.

The path forward is rich with research opportunities. Key areas include the optimization of exosome sources and pre-conditioning protocols to tailor cargo for specific therapeutic outcomes, the refinement of scalable production and isolation methods like TFF, and the development of engineered exosomes for targeted drug delivery. As standardization and regulatory frameworks mature, MSC-Exos are poised to transition from a promising research tool to a mainstream clinical therapeutic, potentially heralding a new dawn for the treatment of diabetic wounds and other degenerative diseases.

Diabetic foot ulcers (DFUs) represent a severe and costly complication of diabetes, with a global prevalence of approximately 6.3% and a lifetime incidence estimated at 19-34% [5]. These chronic wounds are characterized by a complex microenvironment involving ischemia, chronic inflammation, neuropathy, and oxidative stress, which conventional therapies often fail to address effectively [5]. In recent years, regenerative medicine approaches utilizing mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) have emerged as promising strategies, with mounting evidence suggesting that their therapeutic benefits are largely mediated through paracrine secretion rather than direct cell differentiation and engraftment [24] [16] [15].

This paradigm shift has brought MSC-derived exosomes (MSC-Exos) to the forefront as a novel "cell-free" therapeutic alternative to whole MSC therapy. Exosomes are natural nanovesicles (30-150 nm in diameter) that facilitate intercellular communication by transporting functional molecular cargoes, including proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids [9]. Both therapeutic approaches converge on a set of shared regenerative pathways critical for diabetic wound healing: angiogenesis through secretion of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and fibroblast growth factor-2 (FGF-2); immunomodulation via macrophage polarization from pro-inflammatory M1 to anti-inflammatory M2 phenotypes; and extracellular matrix (ECM) remodeling through regulation of collagen deposition and organization [5].

This review provides a comprehensive comparison of MSC exosomes versus whole cell therapies, focusing on their relative effectiveness in activating these shared regenerative pathways, supported by experimental data and detailed methodologies from current research.

Comparative Analysis of Therapeutic Performance

Quantitative Comparison of Efficacy Outcomes

Table 1: Comparative performance of MSC exosomes versus whole cell therapies in DFU treatment

| Performance Parameter | MSC Exosomes | Whole MSC Therapy | Supporting Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Angiogenic Capacity | High (via VEGF, FGF-2, HGF delivery) [24] [9] | High (via VEGF, FGF-2 secretion) [5] | Increased capillary density in preclinical models [24] [9] |

| Macrophage Polarization | Promotes M1 to M2 shift via miRNA, TSG-6 [5] [15] | Promotes M1 to M2 shift via TSG-6, IL-10 [5] | Reduced TNF-α, IL-6; increased IL-10 in wound tissue [5] [9] |

| ECM Remodeling | Enhanced collagen deposition & organization [9] | Improved collagen synthesis & maturation [5] | Better collagen alignment, reduced scarring [5] [9] |

| Wound Closure Rate | ~62% complete healing in clinical trial [9] | Improved vs. controls in clinical studies [5] | Randomized controlled trial data [9] |

| Time to Complete Healing | 6 weeks (range: 4-8) with exosomes [9] | Varies by MSC source & delivery [5] | Clinical comparison to 20 weeks with standard care [9] |

| Anti-inflammatory Effects | Strong (↓TNF-α, IL-1β; ↑IL-10) [9] | Significant (↓TNF-α, IL-6; ↑IL-10, TGF-β) [5] | Cytokine modulation in wound microenvironment [5] [9] |

| Targeted Delivery | Superior (nanoparticle characteristics) [24] | Limited (cell homing challenges) [15] | Enhanced biodistribution & tissue penetration [24] |

Table 2: Comparison of practical and safety parameters

| Characteristic | MSC Exosomes | Whole MSC Therapy | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Immunogenicity | Low (low membrane-bound proteins) [15] | Low but present (risk of immune rejection) [15] | Evidenced by reduced host immune response [15] |

| Tumorigenic Risk | Minimal (no replicative capacity) [15] | Potential concern with direct transplantation [16] | Theoretical safety advantage for exosomes [16] [15] |

| Storage & Stability | Superior (long-term preservation possible) [15] | Limited (requires viable cell maintenance) [15] | Practical advantage for clinical translation [15] |

| Dosing Precision | High (quantifiable nanoparticles) [24] | Moderate (variable cell viability/potency) [5] | More standardized manufacturing potential [24] |

| Production Scalability | Challenging but improving [15] | Complex, expensive [5] [15] | Current limitation for both approaches [5] [15] |

| Regulatory Pathway | Evolving (as biological product) | Established but complex (as cell therapy) | Different regulatory frameworks |

MSC Source-Based Performance Variation

The therapeutic potential of both whole MSCs and their exosomes varies depending on the tissue source, with each offering distinct advantages:

- Bone Marrow-MSCs (BM-MSCs): Most extensive clinical track record; require invasive harvesting but demonstrate strong angiogenic potential [5] [25].

- Adipose-Derived Stem Cells (ADSCs): Abundant tissue source, easy harvesting via liposuction; favorable for autologous applications with strong paracrine activity [5].

- Umbilical Cord-MSCs (UC-MSCs): High proliferation capacity, biologically young cells, low immunogenicity; particularly advantageous for allogeneic applications [5] [9] [25].

- Wharton's Jelly-MSCs (WJ-MSCs): Enhanced angiogenic and immunomodulatory properties; used in recent clinical trials demonstrating significant wound healing efficacy [9].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standardized Protocol for MSC-Exosome Isolation and Characterization

Exosome Isolation via Ultracentrifugation:

- Cell Culture: Culture MSCs (from bone marrow, adipose, or umbilical cord) in complete media until 70-80% confluent [9].

- Serum Starvation: Replace media with exosome-depleted FBS media for 48 hours to eliminate bovine exosome contamination [9].

- Conditioned Media Collection: Collect supernatant and perform sequential centrifugation: 10 minutes at 13,000×g to remove cells and debris, followed by 10 minutes at 45,000×g to remove larger vesicles [9].

- Ultracentrifugation: Centrifuge at 110,000×g for 5 hours using a Beckman Coulter ultracentrifuge to pellet exosomes [9].

- Washing and Resuspension: Resuspend exosome pellet in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for immediate use or storage at -80°C [9].

Exosome Characterization:

- Flow Cytometry: Confirm exosome surface markers (CD9, CD63, CD81, HSP70) using antibody-coated beads [9].

- Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM): Verify exosome morphology and size distribution (typically 30-150 nm) [9].

- Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis: Quantify exosome concentration and size distribution [15].

Preclinical Diabetic Wound Healing Model Protocol

Animal Model Establishment:

- Diabetic Induction: Administer streptozotocin (STZ, 50-60 mg/kg for 5 consecutive days) to induce type 1 diabetes in mice/rats [5].

- Wound Creation: After confirming hyperglycemia (>300 mg/dL), create full-thickness excisional wounds (6-8 mm diameter) on the dorsal skin [5] [9].

- Treatment Groups: Randomize animals into: (1) MSC-Exo group (topical application), (2) Whole MSC group (local injection), (3) Control group (vehicle only), (4) Standard care group [9].

Treatment Application:

- MSC-Exo Group: Apply exosomes (100-200 μg in total) topically to wound bed using a hydrogel vehicle (e.g., hyaluronic acid hydrogel) every 3-4 days [26] [9].

- Whole MSC Group: Intradermally inject 1-2×10^6 MSCs around the wound periphery in a single administration [5].

- Assessment: Monitor wound closure daily through digital photography and planimetry; harvest tissue at days 7, 14, and 21 for histological and molecular analysis [9].

Clinical Trial Protocol for DFU Treatment

Study Design (Randomized Controlled Trial):

- Participant Recruitment: Enroll 110 patients with persistent DFUs (University Hospital setting) [9].

- Randomization: Allocate participants to three groups: (1) WJ-MSC exosome + standard of care (SOC), (2) SOC alone, (3) Placebo (carboxymethyl cellulose vehicle) + SOC [9].

- Treatment Protocol: Apply WJ-MSC exosome gel topically to wounds weekly for 4 weeks alongside standard debridement, infection control, and off-loading [9].

- Endpoint Assessment: Primary endpoints include complete wound closure rate and time to full epithelialization; secondary endpoints include incidence of adverse events, recurrence rate, and biomarker analysis [9].

Signaling Pathways in Regenerative Mechanisms

Shared Molecular Pathways in Diabetic Wound Healing

Diagram 1: Shared regenerative pathways activated by MSC exosomes and whole cell therapies

Pathway Activation Mechanisms

Angiogenesis Pathways

Both MSC exosomes and whole MSCs promote angiogenesis through coordinated activation of multiple signaling pathways. They secrete and deliver VEGF and FGF-2, which activate the PI3K/Akt and MAPK pathways in endothelial cells, promoting their migration, proliferation, and tube formation [5]. MSC exosomes additionally deliver Hepatocyte Growth Factor (HGF) which further activates the PTEN/PI3K/Akt pathway, enhancing vascular stability and maturation [9]. This coordinated signaling addresses the impaired angiogenesis characteristic of DFUs, which results from chronic hypoxia and endothelial dysfunction [27].

Macrophage Polarization Pathways

The chronic inflammation in DFUs features persistent M1 macrophage dominance. Both therapeutic approaches promote polarization to anti-inflammatory M2 macrophages through multiple mechanisms. Tumor necrosis factor-stimulated gene 6 (TSG-6) secretion and IL-10 upregulation play central roles in this transition [5]. MSC exosomes additionally deliver specific microRNAs that inhibit the NF-κB signaling pathway, reducing production of pro-inflammatory cytokines like TNF-α and IL-6 [5] [15]. This immunomodulation creates a regenerative microenvironment conducive to healing.

ECM Remodeling Pathways

Effective wound healing requires balanced extracellular matrix synthesis and remodeling. Both therapies activate the TGF-β/Smad signaling pathway, enhancing fibroblast function and collagen production [5] [24]. MSC exosomes exhibit additional regulation through delivery of specific miRNA clusters (miR-21, miR-23a, miR-125b, miR-145) that modulate myofibroblast differentiation, reducing excessive actin production and collagen deposition, thereby minimizing scar formation [9]. This precise regulation helps reestablish the normal ECM architecture disrupted in chronic wounds.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential research reagents and materials for MSC and exosome research

| Category | Specific Reagents/Materials | Research Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| MSC Culture | DMEM/F12 + 15% FBS [9] | MSC expansion and maintenance | Basic cell culture for all MSC types |

| Collagenase Type I (1 mg/mL) [9] | Tissue dissociation for MSC isolation | Primary MSC isolation from tissue | |

| Penicillin/Streptomycin/Amphotericin B [9] | Prevention of microbial contamination | Cell culture antibiotic/antimycotic | |

| Exosome Isolation | Ultracentrifuge (Beckman Coulter) [9] | Exosome purification from conditioned media | Essential for exosome isolation |

| CD9, CD63, CD81 antibodies [9] | Exosome characterization via flow cytometry | Exosome marker identification | |

| TEM with uranyl acetate staining [9] | Exosome morphology and size analysis | Quality assessment of exosomes | |

| In Vivo Modeling | Streptozotocin (STZ) [5] | Induction of diabetic animal models | Preclinical diabetes modeling |

| Hyaluronic acid hydrogel [26] | Exosome delivery vehicle | Topical application in wound models | |

| Planimetry software [9] | Quantitative wound closure measurement | Objective efficacy assessment | |

| Molecular Analysis | TNF-α, IL-6, IL-10 ELISA kits [5] | Cytokine profiling in wound tissue | Inflammation monitoring |

| CD31, α-SMA antibodies [5] | Immunohistochemistry for vascular markers | Angiogenesis assessment | |

| Masson's Trichrome stain [5] | Collagen deposition and organization visualization | ECM remodeling evaluation |

The comparative analysis of MSC exosomes versus whole cell therapies reveals a complex landscape where both approaches activate shared regenerative pathways through often overlapping but distinct mechanisms. While whole MSC therapy benefits from established protocols and extensive clinical experience, MSC exosomes offer significant advantages in safety profile, precision of action, and manufacturing standardization potential.

Current evidence indicates that exosomes recapitulate most therapeutic benefits of their parent cells while mitigating risks associated with whole cell transplantation. The convergence on critical pathways—angiogenesis (VEGF, FGF-2), macrophage polarization (M1 to M2), and ECM remodeling—underscores the fundamental biological processes essential for diabetic wound healing. However, important challenges remain in standardized production, optimal dosing, and delivery strategies for both approaches.

Future research directions should focus on head-to-head comparative studies, optimization of exosome manufacturing processes, development of targeted delivery systems, and identification of biomarkers predictive of treatment response. As the field advances, both therapeutic modalities are likely to find complementary roles in the clinical management of diabetic ulcers, potentially representing a new paradigm in regenerative medicine for chronic wound treatment.

From Bench to Bedside: Translational Strategies and Delivery Platforms

The therapeutic landscape for diabetic foot ulcers (DFU) is undergoing a significant paradigm shift, moving from whole mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) transplantation toward precision cell-free approaches utilizing MSC-derived exosomes. This transition addresses critical challenges in cell-based therapies, including poor cell viability post-transplantation, potential immunogenic reactions, and complex regulatory pathways. Exosomes, nano-sized extracellular vesicles carrying functional cargos of proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids from their parent cells, offer targeted therapeutic effects while minimizing risks associated with whole cell transplantation [9] [28]. Within this evolving framework, selecting the optimal cellular source for these therapies becomes paramount. This guide provides a systematic comparison of the three primary MSC sources—bone marrow (BM-MSC), adipose tissue (ADSC), and umbilical cord (UC-MSC)—equipping researchers with the experimental data and methodological insights necessary to advance next-generation DFU treatments.

The selection of an MSC source involves balancing multiple factors, including therapeutic potency, scalability, and practical clinical considerations. The table below provides a quantitative and qualitative comparison of these key cell sources.

Table 1: Comprehensive Comparison of MSC Sources for DFU Therapy

| Parameter | Bone Marrow (BM-MSC) | Adipose Tissue (ADSC) | Umbilical Cord (UC-MSC) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Key Advantages | Most extensive clinical history; Strong, well-characterized paracrine activity [29] [30] | High cell yield from minimally invasive harvest; Favorable autologous profile [5] [25] | Superior proliferation rate; Immunologically naive; Non-controversial sourcing [9] [11] [25] |

| Major Limitations | Invasive, painful harvest; Declining cell quality/quantity with age [29] [30] | Donor age and metabolic status may affect cell function [25] | Primarily allogeneic; Requires access to umbilical cords [5] |

| Therapeutic Efficacy (Wound Healing) | Promotes angiogenesis, re-epithelialization, and granulation tissue formation [29] | Effective in promoting angiogenesis and immunomodulation [5] | High efficacy demonstrated in clinical trials for chronic DFUs [9] |

| Quantitative Healing Data | Improved ABI, TcO₂, and pain-free walking distance in clinical trials [29] | OR = 5.23 for wound healing (95% CI: 2.76–9.90) [31] | Significantly higher complete recovery rate (62%) vs. controls; Faster mean time to heal (6 weeks vs. 20 weeks) [9] |

| Angiogenic Potential | High VEGF, FGF secretion; Promotes robust neovascularization [29] [30] | Strong secretome for promoting blood vessel growth [5] | Enriched pro-angiogenic factors (e.g., HGF) and miRNAs [9] [28] |

| Immunomodulatory Strength | Suppresses T-cell proliferation and IFN-γ production [29] | Promotes macrophage polarization to M2 phenotype [5] | Potent anti-inflammatory effects; induces Treg differentiation via IDO [9] |

| Ideal Application Context | Autologous therapy in younger patients; Established protocol settings | High-cell-number autologous therapies; Cosmetic and soft tissue repair | Off-the-shelf allogeneic products; Standardized exosome manufacturing |

Table 2: Meta-Analysis Findings on Wound Healing Rates by Cell Source

| Cell Source | Odds Ratio (OR) for Healing | 95% Confidence Interval | Heterogeneity (I²) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Peripheral Blood | 7.31 | 2.90 – 18.47 | 0.00% |

| Adipose Tissue (ADSC) | 5.23 | 2.76 – 9.90 | 0.00% |

| Umbilical Cord (UC-MSC) | 4.94 | 0.61 – 40.03 | 88.37% |

| Bone Marrow (BM-MSC) | 4.36 | 2.43 – 7.85 | 26.31% |

| Other Sources | 3.16 | 1.83 – 5.45 | 30.62% |

Data adapted from a systematic review and meta-analysis of 24 studies involving 1,321 patients [31].

Experimental Data and Therapeutic Mechanisms

Key Signaling Pathways in MSC-Mediated Wound Healing

MSCs from all sources facilitate healing through shared core mechanisms, primarily via paracrine signaling. The following diagram illustrates the key pathways involved in angiogenesis, immunomodulation, and extracellular matrix (ECM) remodeling.

Diagram 1: Core signaling pathways in MSC-mediated wound healing.

UC-MSC Exosome Clinical Workflow

A recent randomized controlled trial demonstrated the efficacy of Wharton's Jelly-derived MSC exosomes for DFU treatment. The following diagram outlines the experimental workflow and key findings.

Diagram 2: UC-MSC exosome clinical trial workflow and outcomes.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Isolation and Characterization of UC-MSC-Derived Exosomes

This protocol is adapted from a 2025 randomized controlled trial demonstrating the efficacy of Wharton's Jelly-derived MSC exosomes for DFU treatment [9].

Step 1: UC-MSC Isolation and Culture

- Obtain human umbilical cord tissue from healthy donors with informed consent.

- Dissect Wharton's jelly (WJ) under sterile conditions and wash in PBS containing antibiotics (100 U/ml penicillin, 100 µg/ml streptomycin, 2 µg/ml amphotericin B).

- Digest the tissue with 1 mg/ml collagenase type I and 0.7 mg/ml hyaluronidase for 1 hour at 37°C.

- Centrifuge the digest at 340×g to pellet cells and resuspend in DMEM/F12 medium supplemented with 15% fetal bovine serum (FBS).

- Culture cells at 37°C with 5% CO₂, replacing media every 3-4 days until 70-80% confluence.

- Confirm MSC phenotype via flow cytometry for positive markers (CD73, CD105) and negative markers (CD14, CD34) [9].

Step 2: Exosome Isolation and Purification

- Culture UC-MSCs in serum-free medium for 48 hours to condition the media.

- Collect conditioned media and perform sequential centrifugation: 10 minutes at 13,000×g followed by 10 minutes at 45,000×g to remove cells and large debris.

- Ultracentrifuge the supernatant at 110,000×g for 5 hours to pellet exosomes.

- Resuspend the exosome pellet in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for immediate use or storage at -80°C.

Step 3: Exosome Characterization

- Confirm exosome identity by flow cytometry analysis of surface markers (CD9, CD63, CD81, HSP70) using antibody-coated beads.

- Validate exosome morphology and size (typically 30-150 nm) by transmission electron microscopy (TEM).

- Quantify exosome protein content using the bicinchoninic acid (BCA) assay.

- The isolation and characterization process should be repeated three times to confirm reproducibility and consistency in results [9].

Protocol 2: In Vivo Assessment of MSC Therapies for DFU

This protocol summarizes key methodological considerations for evaluating MSC therapies in diabetic wound models, derived from multiple preclinical studies [29] [30].

Animal Model Establishment

- Utilize diabetic mouse models (e.g., db/db mice) or induce diabetes in rats or rabbits with streptozotocin.

- Create full-thickness cutaneous wounds on the dorsal skin or ear to simulate DFU.

- Randomize animals into treatment groups: MSC therapy (whole cells or exosomes) vs. control (vehicle or standard care).

Treatment Administration

- For whole cell therapy: administer 1-5×10⁶ MSCs via local injection around the wound or systemic intravenous injection.

- For exosome therapy: apply 100-500 µg of exosomes topically in a hydrogel formulation or via local injection.

- For biomaterial-assisted delivery: incorporate MSCs or exosomes into collagen scaffolds, hydrogels, or decellularized extracellular matrix (dECM) scaffolds to enhance retention [28].

Outcome Assessment

- Monitor wound closure rates weekly through photographic documentation and planimetric analysis.

- Assess histological changes at endpoint (typically 2-4 weeks) via H&E staining (for re-epithelialization and granulation tissue thickness) and Masson's trichrome staining (for collagen deposition).

- Evaluate angiogenesis through immunohistochemical staining for CD31+ microvessels and VEGF expression.

- Analyze inflammatory response via immunostaining for macrophage markers (CD68 for total macrophages, iNOS for M1 phenotype, CD206 for M2 phenotype).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents for MSC and Exosome Research

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Culture Media | DMEM/F12, α-MEM | MSC expansion and maintenance | Provides essential nutrients for cell growth |

| Growth Supplements | Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS), Platelet Lysate | Supporting MSC proliferation | Supplies growth factors and adhesion proteins |

| Characterization Antibodies | CD73, CD90, CD105 (positive); CD14, CD34, CD45 (negative) | MSC phenotype verification | Confirms identity via flow cytometry |

| Exosome Markers | CD9, CD63, CD81, HSP70, TSG101 | Exosome characterization and quantification | Validates exosome isolation and purity |

| Differentiation Kits | Osteogenic: Dexamethasone, β-glycerophosphate; Adipogenic: IBMX, Indomethacin | Multilineage differentiation potential testing | Confirms MSC trilineage differentiation capacity |

| Cytokine Assays | VEGF, FGF, PDGF, IL-10, TGF-β ELISA kits | Paracrine factor secretion profiling | Quantifies therapeutic factor secretion |

| Angiogenesis Assays | Matrigel tube formation assay; HUVEC migration assay | Functional assessment of pro-angiogenic potential | Measures ability to stimulate blood vessel formation |

| Animal Models | db/db mice; streptozotocin-induced diabetic rodents | In vivo efficacy testing for DFU therapies | Provides pathophysiologically relevant wound healing models |

The comprehensive analysis of MSC sources reveals a nuanced landscape for DFU therapy development. BM-MSCs offer the most extensive clinical validation history, ADSCs provide practical advantages for autologous applications, while UC-MSCs demonstrate superior potential for standardized, off-the-shelf exosome production. The meta-analysis data confirms that all sources significantly improve healing outcomes compared to standard care, with source-specific effect sizes informing strategic decisions [31].

Future research directions should prioritize the optimization of exosome manufacturing protocols, functional enhancement through preconditioning strategies, and the development of advanced biomaterial scaffolds for sustained local delivery. The integration of dECM scaffolds with exosome therapies represents a particularly promising approach, creating biomimetic microenvironments that enhance wound healing through synergistic effects [28]. As the field progresses toward clinical translation, standardization of isolation methods, potency assays, and comprehensive safety profiling will be essential for regulatory approval and successful commercialization of MSC-based DFU therapies.

Within regenerative medicine for diabetic foot ulcers (DFUs), the therapeutic potential of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) is well-established. The central debate, however, revolves around the optimal delivery strategy: using the whole cells themselves or their secreted products, particularly exosomes. This guide objectively compares the three primary administration routes for whole-cell therapy—intramuscular, topical, and systemic delivery—by synthesizing current preclinical and clinical data. The efficacy of any cell-based therapy is inextricably linked to its delivery pathway, which influences cellular retention, homing, paracrine signaling, and ultimately, therapeutic success [32]. Framed within the broader thesis of MSC exosomes versus whole-cell therapy, this analysis provides drug development professionals with a data-driven comparison of whole-cell administration protocols to inform preclinical and clinical strategy.

Comparative Efficacy of Administration Routes

The choice of administration route is a critical determinant in the safety, efficacy, and practical application of whole-cell therapy for DFUs. The three primary routes—intramuscular (IM), topical, and systemic (intra-arterial or intravenous)—leverage different biological mechanisms and offer distinct advantages and limitations, as summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Comparison of Whole Cell Therapy Administration Routes for Diabetic Foot Ulcers

| Administration Route | Key Advantages | Key Limitations & Risks | Common Cell Types Used | Evidence Level (Clinical) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intramuscular (IM) | - High local cell density at the ischemic site [33]- Simplicity and minimal technical requirements [32]- Avoids first-pass pulmonary clearance | - Limited diffusion from injection site [32]- Potential for compartment syndrome [32] | Bone Marrow-MNC (BM-MNC), Peripheral Blood-MNC (PB-MNC) [32] [33] | Widespread use in clinical trials for critical limb ischemia [33] |

| Topical | - Direct delivery to the wound bed [32]- Maximizes local paracrine effects [5]- Minimizes systemic exposure and risks | - Requires a scaffold or hydrogel for cell retention [5] [32]- Challenging for uneven wound surfaces | Adipose-Derived Stem Cells (ADSCs), Bone Marrow-MSCs (BM-MSCs) [5] [32] | Investigated in multiple case series and RCTs [32] |

| Systemic (Intra-arterial/IV) | - Potential to target multiple ischemic areas [32]- Utilizes natural homing signals to injured tissue | - Significant cell trapping in pulmonary capillaries [32]- Low efficiency of delivery to target tissue [32]- Potential for systemic immunogenic reactions | Bone Marrow-MNC (BM-MNC), Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs) [32] | Limited clinical data; more common in preclinical studies [32] |

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Robust experimental design is essential for evaluating the efficacy of different administration routes. The following section details standard protocols for both preclinical animal models and human clinical trials, providing a methodological foundation for the data presented in this guide.

Preclinical Murine DFU Model Protocol

The murine model is a cornerstone for initial efficacy and mechanistic studies.

- Animal Model Induction: Diabetes is typically induced in mice (e.g., C57BL/6) or rats via intraperitoneal injection of streptozotocin (STZ) to chemically ablate pancreatic β-cells. Animals with sustained hyperglycemia are selected for experimentation [32].

- Ulcer Creation: Following diabetes confirmation, a full-thickness wound is created on the dorsal skin or footpad. A 5-6 mm biopsy punch is most frequently used to ensure wound uniformity [32].

- Cell Preparation & Administration:

- Cells: Human Bone Marrow-MSCs (BM-MSCs) or Adipose-Derived Stem Cells (ADSCs) are expanded in vitro [32].

- Topical Application: Cells are resuspended in a saline vehicle or, more effectively, in a scaffold like a collagen hydrogel or fibrin spray, and applied directly onto the wound [5] [32].

- Intramuscular Injection: Cells are injected at multiple sites (e.g., 2-4 sites) around the wound or in the ischemic hindlimb musculature. A common volume is 20-50 μL per injection site [32].

- Outcome Assessment: Wounds are monitored regularly. Primary outcomes include:

- Wound Closure Rate: Measured by the reduction in wound area over time, with full epithelialization as the endpoint [9] [13].

- Histological Analysis: Post-sacrifice, tissue sections are stained (e.g., H&E, Masson's trichrome) to assess epithelial thickness, collagen deposition, and capillary density (via CD31+ immunostaining) [5].

Clinical Trial Protocol for Intramuscular Delivery

This protocol is common for patients with chronic limb-threatening ischemia (CLTI) who are not candidates for revascularization ("no-option" patients) [33].

- Patient Population: Adults with DFU and confirmed CLTI (rest pain, gangrene, or ulcer for >2 weeks) where angioplasty or bypass is not feasible [33].

- Cell Harvesting & Preparation:

- Bone Marrow Aspiration: Approximately 100-200 mL of bone marrow is aspirated from the patient's iliac crest under local or general anesthesia [32] [33].

- Cell Processing: Mononuclear cells (MNCs), containing the stem and progenitor cell population, are isolated from the marrow using density-gradient centrifugation (e.g., Ficoll-Paque). The final product is formulated in saline with human serum albumin [33].

- Administration: The cell suspension is administered via multiple (30-50) intramuscular injections into the ischemic calf muscle and around the ulcer bed using a standard syringe and needle [32] [33].

- Outcome Measures:

- Efficacy: Major amputation rate, ulcer healing rate (complete epithelialization), pain reduction (analog scale), and improvement in perfusion (Ankle-Brachial Index or transcutaneous oxygen pressure) [33].

- Safety: Monitoring for adverse events like infection, compartment syndrome, and systemic inflammatory responses over a follow-up period of 6-12 months [32].

Mechanisms of Action and Signaling Pathways

Whole MSC therapies promote wound healing through complex, multi-faceted mechanisms rather than a single pathway. The following diagram synthesizes these core interactions into a unified signaling network.

Figure 1: Unified Signaling Network of Whole MSC Therapy in DFU Healing.

The mechanisms illustrated above are enabled by specific administration routes:

- Topical Delivery maximizes the Paracrine Signaling and ECM Remodeling effects, as cells directly secrete factors into the wound bed [5].