MSC-Derived Exosomes in Wound Healing: Mechanisms, Clinical Translation, and the Future of Cell-Free Therapy

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the role of mesenchymal stem cell (MSC)-derived exosomes in wound healing, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

MSC-Derived Exosomes in Wound Healing: Mechanisms, Clinical Translation, and the Future of Cell-Free Therapy

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the role of mesenchymal stem cell (MSC)-derived exosomes in wound healing, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational biology of exosomes and their mechanisms of action across the four stages of wound repair. The scope extends to methodological considerations for production and isolation, advanced application strategies using biomaterial scaffolds, and troubleshooting of key challenges such as heterogeneity and manufacturing. Finally, it offers a comparative validation of exosomes against conventional therapies and parent cells, synthesizing preclinical and clinical evidence to outline a clear pathway for clinical translation and regulatory approval of this promising cell-free therapeutic.

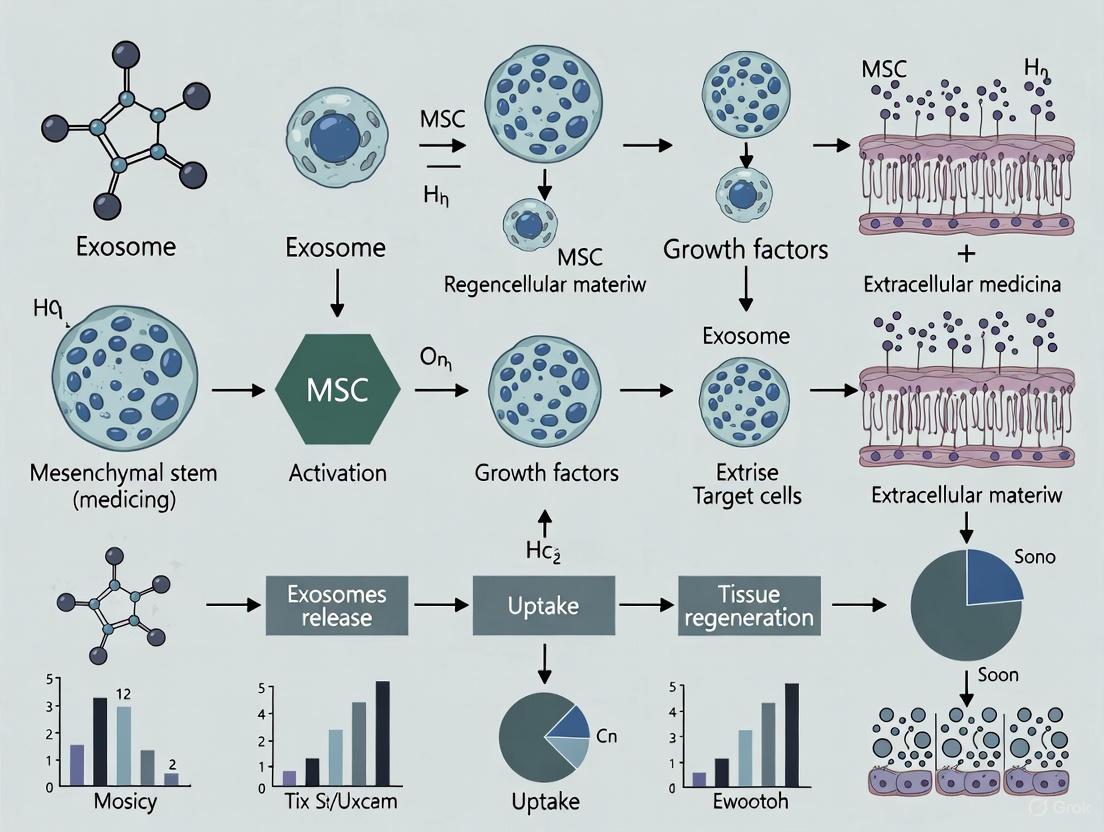

Unraveling the Biology: How MSC-Derived Exosomes Orchestrate Skin Regeneration

Biogenesis and Key Characteristics of MSC-Derived Exosomes

Mesenchymal stem cell (MSC)-derived exosomes have emerged as pivotal mediators of intercellular communication and promising cell-free therapeutic agents in regenerative medicine, particularly in the context of wound healing [1] [2]. These nanoscale extracellular vesicles transfer bioactive molecules—including proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids—from donor MSCs to recipient cells, thereby influencing various physiological and pathological processes [3] [4]. The therapeutic application of MSC-derived exosomes represents a paradigm shift from whole-cell therapies, offering enhanced stability, reduced immunogenicity, and lower risks of tumorigenicity [3] [1]. This technical guide comprehensively details the biogenesis, key characteristics, and functional mechanisms of MSC-derived exosomes, with specific emphasis on their role in promoting cutaneous wound repair through modulation of inflammation, angiogenesis, and extracellular matrix remodeling [1] [5].

Biogenesis of MSC-Derived Exosomes

The biogenesis of exosomes is a meticulously regulated, multi-step process that originates from the endosomal system [1] [6]. Understanding this biogenesis is fundamental to appreciating exosome function and harnessing their therapeutic potential.

Table 1: Key Stages in Exosome Biogenesis

| Stage | Cellular Process | Key Molecular Components |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Initiation | Invagination of the plasma membrane forms early sorting endosomes (ESEs) | Plasma membrane lipids and proteins |

| 2. MVB Formation | ESEs mature into late endosomes; inward budding creates intraluminal vesicles (ILVs) within multivesicular bodies (MVBs) | ESCRT complexes (ESCRT-0, -I, -II, -III) and associated proteins (Alix, TSG101) |

| 3. Fate Determination | MVBs are either trafficked to lysosomes for degradation or to the plasma membrane for exocytosis | Rab GTPases, SNARE proteins |

| 4. Secretion | MVBs fuse with the plasma membrane, releasing ILVs as exosomes into the extracellular space | SNARE complexes, cytoskeletal elements |

The biogenesis pathway comprises two primary mechanisms: the endosomal sorting complex required for transport (ESCRT)-dependent mechanism and ESCRT-independent mechanisms involving tetraspanins and lipids [6]. The ESCRT machinery, consisting of multiple protein complexes (ESCRT-0, -I, -II, -III), collaborates with accessory proteins to facilitate the inward budding of the endosomal membrane and vesicle scission [6]. Alternatively, ESCRT-independent biogenesis can occur through the organization of tetraspanin microdomains or the enzymatic conversion of sphingomyelin to ceramide, which promotes membrane invagination [6]. Following their formation, exosomes are released into the extracellular space upon fusion of MVBs with the plasma membrane, a process mediated by Rab GTPases and SNARE proteins [1] [6].

Diagram 1: Exosome Biogenesis Pathway

Key Characteristics and Molecular Composition

MSC-derived exosomes possess distinct physicochemical properties and carry a diverse molecular cargo that reflects their cellular origin and mediates their biological functions.

Physical and Structural Characteristics

MSC-derived exosomes are spherical, lipid bilayer-enclosed vesicles with diameters typically ranging from 30 to 150 nanometers [1] [6] [4]. Their size distinguishes them from other extracellular vesicles: microvesicles (50-1000 nm) and apoptotic bodies (800-5000 nm) [2] [6]. The lipid bilayer composition is rich in cholesterol, sphingomyelin, and ceramide, and contains lipid rafts that facilitate protein sorting and signaling [4]. This structure provides considerable stability and protects the internal cargo from degradation by extracellular RNases and other enzymes [1].

Molecular Cargo

The biological activity of MSC-derived exosomes is largely attributed to their diverse cargo, which includes proteins, nucleic acids, and lipids selectively packaged from the parent MSC.

Table 2: Characteristic Molecular Cargo of MSC-Derived Exosomes

| Cargo Type | Specific Components | Functional Roles |

|---|---|---|

| Surface Proteins | Tetraspanins (CD9, CD63, CD81), MHC class I, Integrins | Cell targeting, adhesion, immune recognition |

| Intracellular Proteins | ESCRT components (Alix, TSG101), Heat shock proteins (Hsp70, Hsp90), Rab GTPases | Vesicle biogenesis, protein folding, intracellular trafficking |

| Nucleic Acids | miRNAs (e.g., miR-21-5p, miR-26a-5p, miR-181c), mRNAs, lncRNAs, circRNAs | Post-transcriptional regulation, epigenetic reprogramming |

| Lipids | Cholesterol, sphingomyelin, ceramide, phosphatidylserine | Membrane structure, signal transduction |

The nucleic acid content, particularly microRNAs (miRNAs), represents a crucial functional component. miRNAs are short (∼22 nucleotides) non-coding RNAs that regulate gene expression at the post-transcriptional level by binding to target mRNAs [4]. MSC-derived exosomes have been shown to contain functionally significant miRNAs such as miR-26a-5p, which targets MAP2K4 in wound healing [7]; miR-181c, which attenuates burn-induced inflammation by downregulating TLR4 signaling [8]; and miR-21-5p, which promotes wound healing through the STAT3 pathway [9].

MSC-Derived Exosomes in Wound Healing: Mechanisms and Therapeutic Applications

The therapeutic potential of MSC-derived exosomes in wound healing stems from their ability to coordinately modulate multiple phases of the repair process, including inflammation, proliferation, and remodeling [1] [5].

Modulation of Inflammatory Responses

MSC-derived exosomes play a crucial role in tempering excessive inflammation, a common feature of chronic wounds. They promote the polarization of macrophages from the pro-inflammatory M1 phenotype to the anti-inflammatory M2 phenotype [9], and directly modulate immune cell activity. For instance, exosomal miR-146a downregulates the NF-κB pathway, a key regulator of inflammatory responses [4]. Similarly, miR-181c in human umbilical cord MSC-derived exosomes has been shown to suppress the TLR4 signaling pathway, significantly reducing levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines TNF-α and IL-1β while increasing anti-inflammatory IL-10 in burn models [8].

Promotion of Angiogenesis

A critical aspect of wound healing is the re-establishment of vascular networks to supply oxygen and nutrients to the repairing tissue. MSC-derived exosomes robustly promote angiogenesis by transferring pro-angiogenic miRNAs to endothelial cells [1] [2]. For example, exosomes from antler MSCs containing miR-21-5p were found to stimulate the migration and tube formation of human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) through the STAT3 signaling pathway [9]. These exosomal miRNAs enhance endothelial cell proliferation, migration, and the formation of new blood vessels, thereby improving perfusion in the wound bed.

Enhancement of Extracellular Matrix Remodeling

Proper synthesis, deposition, and organization of extracellular matrix (ECM) components are essential for effective wound healing with minimal scarring. MSC-derived exosomes modulate fibroblast behavior to optimize ECM remodeling [7] [9]. They promote fibroblast proliferation and migration while regulating collagen synthesis and maturation. Studies have demonstrated that exosomes from antler MSCs facilitate the conversion of collagen type III to collagen type I, resulting in restored epidermal thickness without aberrant hyperplasia and reduced scar formation [9]. Similarly, exosomes from miR-26a-5p-modified adipose MSCs upregulate collagen types I and III (Col1a1 and Col3a1) while downregulating inflammatory mediators [7].

Diagram 2: Exosome-Mediated Intercellular Communication in Wound Healing

Experimental Methodologies for MSC-Derived Exosome Research

Isolation and Purification Protocols

The isolation of high-purity exosomes is crucial for both research and therapeutic applications. Differential ultracentrifugation remains the most widely used method, involving sequential centrifugation steps to remove cells, debris, and larger vesicles, followed by high-speed ultracentrifugation (typically 100,000-120,000 × g) to pellet exosomes [9]. This method was successfully employed to isolate exosomes from antler MSCs, with the pellet resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for further analysis [9]. Alternative isolation techniques include size-exclusion chromatography, polymer-based precipitation, immunoaffinity capture using exosome-surface markers (e.g., CD63, CD81), and microfluidic technologies [2].

Characterization Techniques

Comprehensive characterization of isolated exosomes is essential to confirm their identity and quality. Standard characterization includes:

- Nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA) to determine particle size distribution and concentration

- Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) for morphological assessment

- Western blot analysis for detection of exosomal markers (e.g., CD9, CD63, CD81, TSG101, Alix) and absence of negative markers (e.g., calnexin, GM130)

- Flow cytometry with bead-coupled antibodies for immunophenotyping [9]

Additionally, miRNA sequencing and proteomic analyses are employed to comprehensively profile exosomal cargo and identify potential functional components [7] [9].

Functional Validation Experiments

In vitro and in vivo models are utilized to validate the functional efficacy of MSC-derived exosomes in wound healing:

- Cellular assays: Proliferation (CCK-8 assay), migration (scratch assay), and tube formation assays using keratinocytes (HaCaT), fibroblasts, and endothelial cells (HUVECs) [9]

- Animal models: Full-thickness skin defect models in mice or rats to assess wound closure rates, histopathological analysis (H&E staining, Masson's trichrome for collagen), and immunohistochemistry for specific markers (e.g., CD31 for angiogenesis) [7] [9]

- Mechanistic studies: Gain- and loss-of-function experiments using miRNA mimics or inhibitors to establish causal relationships between specific exosomal components and observed functional effects [7] [8]

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Experimental Tools

| Reagent/Tool Category | Specific Examples | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Culture Media | DMEM/F12 supplemented with exosome-depleted FBS | MSC expansion and exosome production without contaminating vesicles |

| Isolation Kits | Polymer-based precipitation kits, size-exclusion chromatography columns | Alternative exosome isolation methods beyond ultracentrifugation |

| Characterization Antibodies | Anti-CD9, CD63, CD81, TSG101, Alix | Western blot and flow cytometry validation of exosomal markers |

| Functional Assay Kits | CCK-8 proliferation assay, Transwell migration chambers, Matrigel tube formation assay | Assessment of exosome effects on cellular behaviors |

| Animal Models | Full-thickness excisional wound model in mice/rats | In vivo evaluation of exosome therapeutic efficacy |

| Analysis Reagents | H&E staining, Masson's trichrome, anti-CD31 antibodies | Histological assessment of wound healing and angiogenesis |

MSC-derived exosomes represent sophisticated natural nanoplatforms that coordinate multiple aspects of wound healing through their complex molecular cargo. Their biogenesis through the endosomal pathway results in stable vesicles capable of transferring functional proteins and regulatory RNAs to recipient cells. The documented roles of specific exosomal miRNAs, such as miR-26a-5p targeting MAP2K4, miR-181c suppressing TLR4 signaling, and miR-21-5p activating STAT3, provide mechanistic insights into how these vesicles modulate inflammation, promote angiogenesis, and enhance extracellular matrix remodeling. While challenges remain in standardization of isolation protocols and scalable production, the continued elucidation of MSC-derived exosome biogenesis and function solidifies their position as promising therapeutic agents in regenerative medicine and wound care. Future research directions include bioengineering approaches to enhance exosome targeting and payload capacity, ultimately improving their therapeutic efficacy for complex wound healing scenarios.

Exosomes, defined as nanoscale extracellular vesicles (EVs) with a diameter of 30-150 nm, are secreted by nearly all cell types and play a crucial role in intercellular communication [10]. These vesicles are formed via the endosomal pathway and carry a diverse cargo of proteins, lipids, nucleic acids (including DNA, mRNA, miRNA, and long non-coding RNA), and other bioactive molecules [11] [12] [13]. For researchers and drug development professionals, exosomes derived from mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) represent a promising acellular therapeutic strategy that overcomes the limitations associated with whole-cell therapies, such as tumorigenic risk, immunogenicity, and ethical concerns [12] [14].

The therapeutic potential of MSC-derived exosomes is particularly relevant for wound healing, a complex process that, when impaired, results in chronic wounds or pathological scarring [14]. Chronic wounds—including diabetic foot ulcers, venous leg ulcers, and pressure ulcers—are characterized by a failure to proceed through an orderly and timely healing process, leading to prolonged inflammation, inability to re-epithelialize, and impaired angiogenesis [11] [14]. Current treatment options often fall short, necessitating innovative approaches that target the underlying pathophysiological mechanisms [11]. This whitepaper examines the role of exosomes within the precise sequence of wound healing phases, focusing on mechanistic insights and experimental methodologies relevant to therapeutic development.

The Four Phases of Wound Healing and Exosomal Mechanisms

The normal wound healing cascade comprises four precisely programmed and overlapping phases: hemostasis, inflammation, proliferation, and remodeling [14]. The following sections detail the cellular events of each phase and the specific contributions of MSC-derived exosomes, with summarized findings presented in Table 1.

Table 1: Key Effects of MSC-Derived Exosomes on the Four Phases of Wound Healing

| Healing Phase | Key Cellular Events | Exosomal Cargo & Mechanisms | Demonstrated Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hemostasis | Platelet activation, fibrin clot formation | Delivery of pro-coagulant microRNAs; Surface tissue factor [14] [10] | Accelerated clot formation; Initial scaffold for cell migration |

| Inflammation | Neutrophil/monocyte recruitment; Macrophage differentiation (M1/M2) | lncRNAs (e.g., MEG3) regulating TGF-β; miRNAs inhibiting NF-κB; Promotion of M2 phenotype [12] [14] | Reduced pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-1, TNF-α); Resolution of inflammation |

| Proliferation | Angiogenesis; Fibroblast proliferation; Re-epithelialization; ECM deposition | lncRNA KLF3-AS1 increasing VEGFA; miR-126-3p stimulating proliferation; Transfer of growth factors (VEGF, HGF) [11] [12] | Enhanced endothelial cell tube formation; Increased fibroblast migration/proliferation |

| Remodeling | ECM reorganization; Collagen cross-linking; Scar maturation | lncRNA-ASLNCS5088 suppressing miR-200c-3p; Regulation of MMPs/TIMPs; MEG3 reducing collagen [12] [14] | Balanced ECM deposition/degradation; Reduced fibrosis and pathological scarring |

Hemostasis Phase

The hemostasis phase begins immediately after injury and involves vasoconstriction, platelet activation, and fibrin clot formation to prevent further blood loss [14]. This phase establishes a provisional extracellular matrix (ECM) that serves as a scaffold for invading cells.

Exosomal Roles: Exosomes contribute to hemostasis by providing a pro-coagulant surface. Chargaff and West initially discovered that a "particulate fraction" of vesicles sedimented at high g-forces possessed high clotting potential [14]. MSC-derived exosomes can express surface tissue factor and phosphatidylserine, which promote thrombin generation and accelerate clot formation [10]. The clot also serves as a reservoir for exosomes, which are subsequently released to influence subsequent healing phases.

Inflammation Phase

The inflammation phase involves the recruitment of neutrophils and monocytes to the wound site, with subsequent differentiation of monocytes into macrophages [14]. A critical transition from a pro-inflammatory (M1) to an anti-inflammatory, pro-resolving (M2) macrophage phenotype is essential for normal healing [12] [14]. Chronic wounds are characterized by a failure to resolve this inflammatory phase.

Exosomal Roles: MSC-derived exosomes play a pivotal role in modulating the immune response. They can promote the polarization of macrophages toward the M2 phenotype, which reduces inflammation and supports tissue repair [12]. This occurs through exosomal transfer of long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) such as MEG3, which reduces fibrosis-related protein and collagen expression [12]. Additionally, exosomes can carry miRNAs that inhibit the NF-κB signaling pathway, a key driver of pro-inflammatory cytokine production [14]. By regulating the balance between M1 and M2 macrophages, exosomes help resolve inflammation and create a microenvironment conducive to proliferation.

Proliferation Phase

The proliferation phase is characterized by the formation of granulation tissue, which involves the in-growth of fibroblasts and blood vessels, as well as re-epithelialization [11] [14]. Key processes include angiogenesis, fibroblast proliferation, and ECM deposition.

Exosomal Roles in Angiogenesis: MSC-derived exosomes significantly promote the formation of new blood vessels—a process critical for delivering oxygen and nutrients to the healing tissue. They achieve this by transferring pro-angiogenic factors and genetic materials. For instance, exosomal lncRNA KLF3-AS1 from bone marrow MSCs (BMSCs) has been shown to increase the expression of VEGFA—a potent angiogenic factor—by sponging a regulatory miRNA [12]. Hypoxic preconditioning of parent MSCs further enhances the angiogenic capacity of their exosomes by upregulating cargo such as HIF-1α and VEGF [11] [14].

Exosomal Roles in Cell Proliferation and Migration: Exosomes directly stimulate the proliferation and migration of fibroblasts and keratinocytes, the key cellular players in tissue rebuilding. Engineered exosomes overexpressing specific miRNAs, such as miR-126-3p, have demonstrated enhanced stimulating effects on the proliferation of epidermal fibroblasts and vascular endothelial cells [11]. Exosomes also carry growth factors like VEGF and HGF, which activate recipient cells via paracrine signaling [12].

Remodeling Phase

The final remodeling phase can last for months to years and involves the reorganization and maturation of the ECM, with a shift from collagen type III to type I, and cross-linking of collagen fibers [14]. An imbalance in this phase can lead to either weak wounds or pathological scarring (hypertrophic scars and keloids).

Exosomal Roles: MSC-derived exosomes contribute to balanced ECM remodeling by regulating the activity of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and their inhibitors (TIMPs). They can mitigate excessive scarring; for example, exosomes from human BMSCs containing lncRNA MEG3 have been shown to prevent keloid formation by reducing collagen expression [12]. Conversely, in a TGF-β1-rich environment, exosomes from M2 macrophages containing lncRNA-ASLNCS5088 can promote fibroblast activation and ECM production, which is necessary for tissue repair but must be carefully controlled to prevent fibrosis [12]. This dual potential highlights the importance of precise exosomal engineering for therapeutic applications.

Experimental Protocols for Exosome Research

The isolation and characterization of exosomes are critical for research and therapeutic development. Below are detailed methodologies for key experimental procedures.

Isolation of Exosomes from Human Plasma via Ultracentrifugation

Ultracentrifugation remains a widely used benchmark method for exosome isolation [15] [13].

- Sample Collection: Collect whole blood (e.g., 9 mL) into citrate tubes via venipuncture.

- Plasma Separation: Centrifuge the sample at 1,500 × g for 20 minutes at 4°C to separate cells from plasma. Transfer the supernatant to a new tube.

- Cell-Free Plasma: Centrifuge the supernatant at 2,800 × g for 20 minutes at 4°C to remove all remaining cells. Transfer the resulting cell-free plasma (CFP) to ultracentrifugation tubes (1 mL per tube).

- Exosome Pellet: Centrifuge the CFP at 100,000 × g for 90 minutes at 4°C to pellet the exosomes. Carefully remove 900 µL of supernatant.

- Wash Step: Re-suspend the pellet in the remaining 100 µL. Add 900 µL of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) to wash. Centrifuge again at 100,000 × g for 30 minutes at 4°C.

- Final Resuspension: Remove 900 µL of supernatant and re-suspend the final exosome pellet in the remaining 100 µL of PBS.

- Filtration (Optional): For particle measurement, a fraction (5-20 µL) of the suspension can be diluted in 40 mL of distilled water and filtered through a 450 nm filter to separate exosomes from larger particles [15].

Characterization via Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis (NTA)

Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis (NTA) is used to determine the size distribution and concentration of isolated exosomes [15] [13].

- Instrument Startup: Initialize the NTA instrument (e.g., ZetaView) and perform an automated startup procedure, including a cell quality check and auto-alignment.

- System Flushing: Flush the instrument's cell channel with 10 mL of distilled water using a syringe to ensure it is free of air bubbles and contaminants.

- Sample Injection: Inject the prepared exosome suspension into the channel.

- Parameter Adjustment: Adjust key software parameters:

- Sensitivity: Determine the optimal sensitivity level by generating a "Number of Particles vs. Sensitivity" curve. Select a sensitivity level just before the curve's maximum slope.

- Focus and Camera Shutter/Frame Rate: Manually adjust the focus for sharp particle images. Set the camera shutter to 100 and the frame rate to 30 frames per second as potential starting points [15].

- Measurement and Analysis: Initiate the measurement. The software will track the Brownian motion of particles, calculating their size and concentration based on the Stokes-Einstein equation. Results are displayed as a size distribution profile and concentration measurement.

Functional Analysis: In Vitro Tube Formation Assay

This assay evaluates the pro-angiogenic capacity of exosomes by measuring their ability to promote endothelial cell network formation.

- Matrigel Coating: Thaw Matrigel on ice and coat the wells of a pre-chilled 96-well plate (50-100 µL per well). Incubate the plate at 37°C for 30-60 minutes to allow polymerization.

- Cell Preparation: Harvest human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) and re-suspend them in serum-free medium. Seed the cells onto the surface of the polymerized Matrigel at a density of 1-2 x 10^4 cells per well.

- Exosome Treatment: Immediately add the test sample (e.g., MSC-derived exosomes, hypoxic preconditioned exosomes, or PBS as a negative control) to the seeded cells.

- Incubation: Incubate the plate at 37°C with 5% CO2 for 4-18 hours.

- Imaging and Quantification: Capture images of the tubular networks using an inverted light microscope. Quantify the pro-angiogenic effect by measuring parameters such as the total tube length, number of branching points, and number of meshes per field of view using image analysis software.

Research Reagent Solutions Toolkit

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Tools for Exosome Research

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Notes / Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Ultracentrifuge | Isolation of exosomes from biofluids/cell media via high g-forces [15] | Essential for classic ultracentrifugation protocol; requires significant bench time. |

| NTA Instrument (e.g., ZetaView) | Measures exosome size distribution and concentration [15] [13] | Provides real-time analysis ideal for particles in the 70-160 nm range. |

| Transmission Electron Microscope (TEM) | Visualizes exosome morphology and confirms cup-shaped structure [13] | Requires extensive sample preparation (fixation, negative staining). |

| CD63, CD9, CD81 Antibodies | Western Blot (WB) and Immunoaffinity Capture for exosome identification/isolation [10] [13] | Tetraspanins are common exosome surface markers for characterization. |

| TSG101 Antibody | Western Blot for identification of exosomal markers [13] | An endosomal-related protein commonly used to confirm exosomal identity. |

| Size-Exclusion Chromatography (SEC) Kit | Isolation of exosomes based on size [13] | Offers excellent purity and is scalable; an alternative to ultracentrifugation. |

| Human Umbilical Vein Endothelial Cells (HUVECs) | In vitro model for angiogenesis (tube formation) assays [11] | Standard cell model for testing the pro-angiogenic capacity of exosomes. |

| Matrigel | Basement membrane matrix for tube formation assays [11] | Provides a substrate for endothelial cells to form tubular networks. |

| 6-Bromo-5-fluoroquinoxaline | 6-Bromo-5-fluoroquinoxaline | |

| Copper chlorophyllin B | Copper Chlorophyllin B Reagent|RUO | High-purity Copper Chlorophyllin B for research. Explore its applications in antiviral, antioxidant, and cancer research. For Research Use Only. Not for human use. |

Visualization of Signaling Pathways

The following diagrams, generated using Graphviz DOT language, illustrate key signaling pathways and experimental workflows discussed in this whitepaper. The color palette is restricted to the specified brand colors for visual consistency.

Exosomal Regulation of Macrophage Polarization

Pro-Angiogenic Signaling by Exosomal lncRNA KLF3-AS1

Experimental Workflow for Exosome Isolation & Characterization

Mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes (MSC-Exos) have emerged as pivotal mediators of tissue regeneration, primarily through their sophisticated molecular cargo delivery system. These nanoscale vesicles transport proteins, microRNAs (miRNAs), and lipids that collectively orchestrate the complex process of wound healing. The therapeutic efficacy of MSC-Exos in cutaneous wound repair stems from their ability to modulate inflammation, promote angiogenesis, stimulate cellular proliferation, and facilitate extracellular matrix (ECM) remodeling. This whitepaper provides a comprehensive analysis of the specific molecular constituents within MSC-Exos, their mechanistic roles in wound healing pathways, and the experimental methodologies essential for advancing this promising field toward clinical applications. Understanding these key molecular cargos is fundamental to harnessing the full regenerative potential of exosome-based therapies for acute and chronic wounds.

Exosomes are nanosized extracellular vesicles (30-150 nm in diameter) bounded by a lipid bilayer and formed via the endosomal pathway, specifically through the inward budding of multivesicular bodies (MVBs) that subsequently fuse with the plasma membrane for release [16]. As critical mediators of intercellular communication, MSC-Exos mirror the therapeutic potential of their parent cells while offering advantages such as lower immunogenicity, minimal tumorigenic risk, and enhanced stability [17]. Their cargo—comprising proteins, nucleic acids (including miRNAs and long non-coding RNAs), and lipids—is selectively packaged and transferred to recipient cells, thereby modulating key physiological processes in wound healing [18] [12].

The functional significance of these molecular cargos is particularly evident in chronic wound environments, where MSC-Exos have demonstrated capacity to rescue impaired healing processes. For diabetic wounds characterized by delayed closure and disrupted immune responses, MSC-Exos delivered via hydrogels can overcome the limitations of rapid diffusion and poor retention, enabling sustained therapeutic effects through their diverse biomolecular constituents [19]. The following sections provide a detailed examination of these cargo components, their quantitative profiles, functional mechanisms, and the experimental approaches used to characterize their roles in wound healing.

Comprehensive Analysis of Molecular Cargos

Protein Cargo: Composition and Functional Significance

Table 1: Key Protein Cargos in MSC-Derived Exosomes and Their Roles in Wound Healing

| Protein Category | Specific Examples | Functional Roles in Wound Healing | Mechanistic Insights |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tetraspanins | CD9, CD63, CD81 | Facilitate cellular uptake and target cell interaction [20] | Mediate exosome adhesion and fusion with recipient cell membranes; serve as canonical exosome markers |

| Endosomal Biogenesis Proteins | ALIX, TSG101 | Regulate exosome formation and cargo sorting [20] | Part of ESCRT-dependent and independent biogenesis pathways; ensure proper vesicle formation |

| Heat Shock Proteins | HSP70, HSP90 | Promote cell survival under stress conditions [20] | Enhance cellular stress resistance in the wound microenvironment; facilitate protein folding |

| Growth Factors & Cytokines | VEGF, FGF, TGF-β, IL-10 | Stimulate angiogenesis and modulate immune responses [18] | VEGF and FGF promote blood vessel formation; TGF-β and IL-10 suppress excessive inflammation |

| Anti-inflammatory Factors | IL-10, TGF-β | Control inflammatory phase resolution [18] | Shift macrophages from pro-inflammatory M1 to anti-inflammatory M2 phenotype; reduce pro-inflammatory cytokine production |

The protein cargo of MSC-Exos comprises both universal exosome markers and specialized functional proteins that directly contribute to wound repair. Tetraspanins (CD9, CD63, CD81) not only serve as identification markers but also facilitate membrane fusion and cellular uptake, ensuring efficient cargo delivery to target cells in the wound bed [20]. The growth factors and cytokines carried by MSC-Exos, particularly those derived from adipose tissue MSC-Exos (ADSC-Exos), play crucial roles in coordinating the healing process. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and fibroblast growth factor (FGF) directly stimulate angiogenesis, while transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) and interleukin-10 (IL-10) modulate the immune response by suppressing excessive inflammation and promoting transition to the proliferative phase of healing [18].

The biogenesis proteins ALIX and TSG101, in addition to their role in exosome formation, may indirectly influence wound healing by ensuring the proper packaging of therapeutic cargo. Heat shock proteins (HSP70, HSP90) contribute to cellular protection in the often hostile wound microenvironment, particularly in chronic wounds characterized by elevated oxidative stress [20]. This diverse protein portfolio enables MSC-Exos to simultaneously address multiple pathological aspects of impaired wound healing.

miRNA Cargo: Regulatory Networks and Mechanisms

Table 2: Key miRNA Cargos in MSC-Derived Exosomes and Their Functions in Wound Healing

| miRNA | Target Genes/Pathways | Primary Functions in Wound Healing | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| miR-26a-5p | MAP2K4 (MAPK signaling) [7] | Inhibits inflammation, enhances angiogenesis, promotes ECM synthesis [7] | Downregulates Il6, Il1β, Tnf-α; upregulates Col1a1, Cd31, Col3a1 in mouse models |

| miR-23a-3p | Angiogenesis pathways [21] | Promotes vascular development and tube formation | Targets >90 genes in circulatory system development; confirmed in HUVEC assays |

| miR-29b-3p | COL1A1, TGF-β pathway [21] | Anti-fibrotic; reduces excessive collagen deposition | Directly targets collagen isoforms; inhibits TGF-β signaling in cardiac fibroblasts |

| Let-7i | TGF-β pathway, fibrotic genes [21] | Anti-fibrotic; modulates ECM remodeling | Targets multiple collagen genes; reduces scar formation |

| miR-130a-3p | Angiogenesis pathways [21] | Stimulates blood vessel formation | Targets vascular development genes; promotes endothelial cell function |

| miR-144-3p | Angiogenesis pathways [21] | Promotes vascular development | Targets >90 genes in circulatory system development |

MicroRNAs represent one of the most biologically active components of MSC-Exos, functioning as master regulators of gene expression in recipient cells. Systems-level analyses have revealed that the top 23 miRNAs in MSC-Exos account for approximately 79.1% of the total miRNA content and collectively target 5,481 genes involved in critical wound healing processes [21]. These miRNA networks predominantly regulate pathways related to cardiovascular development, angiogenesis, inflammation control, and extracellular matrix organization.

A notable example is miR-26a-5p, identified as a hub miRNA in ADSC-derived exosomes, which accelerates wound healing by targeting MAP2K4, a key regulator of the MAPK signaling cascade [7]. This targeting results in downstream suppression of pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-6, IL-1β, TNF-α) while simultaneously enhancing expression of collagen genes (Col1a1, Col3a1) and the endothelial marker CD31, thereby coordinating inflammation resolution with tissue regeneration [7].

The miR-29 family and Let-7 miRNAs exhibit potent anti-fibrotic activity by directly targeting multiple collagen isoforms and TGF-β signaling components, preventing excessive scar formation during the remodeling phase [21]. Additionally, angiogenic miRNAs like miR-23a-3p, miR-130a-3p, and miR-144-3p collectively target over 90 genes involved in vascular development, stimulating the robust angiogenesis necessary for nutrient delivery and waste removal in healing tissue [21].

Diagram 1: miRNA-Mediated Regulatory Networks in Wound Healing. This diagram illustrates how specific exosomal miRNAs target key genes and pathways to coordinate multiple aspects of wound repair.

Lipid Cargo: Structural and Functional Roles

While less extensively characterized than proteins and miRNAs, the lipid composition of MSC-Exos contributes significantly to their stability and function. The lipid bilayer not only provides structural integrity but also facilitates membrane fusion with target cells and participates in signal transduction. MSC-Exos contain a diverse lipid profile including cholesterol, sphingomyelin, phosphatidylserine, and ceramides that contribute to their biological activities [20].

The lipid composition enables MSC-Exos to withstand enzymatic degradation in the proteolytic wound environment, ensuring the protected delivery of their cargo to recipient cells. Specific lipid components also participate directly in signaling processes; for instance, phosphatidylserine externalization can mediate immunomodulatory effects, while ceramides play a role in organizing membrane microdomains that cluster specific proteins and facilitate their sorting into exosomes [20]. This lipid-mediated cargo sorting represents a crucial mechanism for ensuring the therapeutic composition of MSC-Exos.

Experimental Methodologies for Cargo Analysis

Exosome Isolation and Characterization Techniques

Table 3: Standard Methodologies for MSC-Exosome Isolation and Characterization

| Method Category | Specific Technique | Key Parameters | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Isolation | Ultracentrifugation | Sequential spins: 300×g, 2000×g, 100,000×g [16] | Gold standard; no reagent requirement | Time-consuming; potential protein contamination |

| Isolation | Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC) | Porous bead matrix [16] | Preserves exosome integrity; good purity | May not completely remove co-eluting proteins |

| Isolation | Immunoaffinity Capture | Antibodies against CD63, CD81, CD9 [16] | High specificity for exosome subpopulations | Lower yield; selective for surface markers |

| Characterization | Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis (NTA) | Hydrodynamic diameter measurement [21] | Size distribution and concentration | Size differences between hydrated vs. dry states |

| Characterization | Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) | Morphological visualization [21] | Direct imaging; size confirmation (~55.5±11.1 nm) | Sample dehydration may alter apparent size |

| Characterization | Western Blotting | Protein markers: CD63, CD81, CD9, TSG101 [20] | Confirms exosomal identity | Semi-quantitative; dependent on antibody quality |

Standardized isolation and characterization are prerequisites for reliable exosome research. Ultracentrifugation remains the most widely used isolation technique, employing sequential centrifugation steps to remove cells, debris, and larger vesicles before pelleting exosomes at high speeds (100,000×g or higher) [16]. Alternative methods include size exclusion chromatography (SEC), which separates vesicles based on size while preserving structural integrity, and immunoaffinity capture using antibodies against surface tetraspanins (CD63, CD81, CD9) for highly specific isolation of exosome subpopulations [16].

Comprehensive characterization requires multiple orthogonal techniques. Nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA) measures the hydrodynamic diameter and concentration of exosomes in suspension (typically ~98 nm), while transmission electron microscopy (TEM) provides detailed morphological information and precise size measurements (approximately 55.5±11.1 nm) [21]. Western blotting confirms the presence of characteristic exosomal markers (tetraspanins, ALIX, TSG101) and absence of negative markers to ensure isolation purity [20].

Diagram 2: Experimental Workflow for MSC-Exosome Isolation and Characterization. This diagram outlines the standard methodologies for obtaining and validating exosomes prior to cargo analysis.

Cargo Profiling and Functional Validation

miRNA Profiling: High-throughput techniques such as NanoString nCounter analysis and RNA sequencing enable comprehensive miRNA profiling. The standard protocol involves RNA extraction from purified exosomes using TRIzol or commercial kits, followed by quality assessment and library preparation. Bioinformatics analysis then identifies highly abundant miRNAs and predicts their target genes and pathways using databases such as miRDIP and functional enrichment tools like PANTHER [21].

Protein Analysis: Western blotting confirms the presence of specific exosomal proteins using antibodies against tetraspanins (CD63, CD81, CD9) and biogenesis markers (ALIX, TSG101) [20]. For comprehensive profiling, mass spectrometry provides an unbiased analysis of the entire protein cargo, revealing both constitutive and cell source-specific proteins that contribute to wound healing functions.

Functional Assays: In vitro validation includes:

- Angiogenesis assays: Tube formation using HUVECs on Matrigel to assess pro-angiogenic effects [21]

- Fibroblast proliferation/migration: Scratch assays and cell counting kits to measure effects on dermal fibroblasts [22]

- Collagen production: ELISA or qRT-PCR to quantify collagen I and III expression in TGF-β-stimulated fibroblasts [21]

- Anti-inflammatory effects: Macrophage polarization assays measuring cytokine levels (IL-6, IL-1β, TNF-α) via ELISA [7]

In vivo validation typically employs rodent wound models (e.g., full-thickness excisional wounds, diabetic db/db mice) with measurements of wound closure rate, histopathological analysis of re-epithelialization, collagen maturity, and capillary density [19] [7].

Advanced Engineering and Delivery Strategies

Biomaterial-Assisted Delivery Systems

To overcome the challenges of rapid clearance and limited retention in dynamic wound environments, advanced delivery systems have been developed. Injectable hydrogels, particularly those based on hyaluronic acid (HA), have demonstrated excellent efficacy for sustained exosome delivery. These systems exhibit desirable cytocompatibility, biodegradability, and skin-like rheology while their porous structure enables in situ retention of exosomes, significantly enhancing therapeutic efficacy in chronic wound models [19].

The HA-based hydrogel system allows for in situ cross-linking, creating a scaffold that progressively releases functional exosomes while maintaining a moist wound environment conducive to healing. This approach addresses the critical limitation of direct exosome application, which often results in rapid diffusion away from the wound site before exerting their full therapeutic effects [19].

Engineered Exosomes for Enhanced Therapeutics

Genetic modification of parent MSCs represents a powerful strategy to enhance the therapeutic potential of their exosomes. Overexpression of specific miRNAs, such as miR-26a-5p in ADSCs, creates exosomes with enriched cargo that more potently modulates healing processes [7]. Preconditioning strategies, including hypoxic treatment and pharmacological priming, can further optimize exosome cargo composition by activating specific cellular pathways that enhance their regenerative properties [18].

These engineering approaches enable the production of "designer exosomes" with tailored cargo profiles optimized for specific aspects of wound repair, such as enhanced anti-inflammatory activity, superior angiogenic potential, or improved collagen remodeling capabilities.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for MSC-Exosome Wound Healing Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Primary Applications | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Isolation Kits | Ultracentrifugation kits, SEC columns, Polymer-based precipitation kits | Exosome isolation from conditioned media | Selection depends on required purity, yield, and downstream applications |

| Characterization Antibodies | Anti-CD63, CD81, CD9, TSG101, ALIX | Western blot, immunoaffinity capture, flow cytometry | Essential for confirming exosomal identity and purity |

| Cell Culture Media | MesenGro hMSC medium, DMEM with 10% FBS | MSC expansion and exosome production | Use exosome-depleted FBS for production phases |

| miRNA Analysis Tools | NanoString nCounter, miRNA sequencing kits, qRT-PCR assays | miRNA profiling and validation | NanoString provides digital counting without amplification bias |

| Functional Assay Kits | Tube formation assay (Matrigel), cell proliferation kits, ELISA collagen kits | In vitro validation of exosome effects | HUVEC tube formation assesses angiogenic potential |

| Animal Models | Diabetic db/db mice, full-thickness excisional wounds | In vivo therapeutic efficacy | Diabetic models critical for chronic wound healing studies |

| Hydrogel Systems | Hyaluronic acid-based injectable hydrogels | Delivery vehicle for sustained release | Provides scaffold structure and prolongs exosome retention |

| Donepezil Benzyl Chloride | Donepezil Benzyl Chloride, MF:C31H36ClNO3, MW:506.1 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Diisooctyl glutarate | Diisooctyl glutarate, CAS:28880-25-3, MF:C21H40O4, MW:356.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

This toolkit comprises essential reagents and models that form the foundation of rigorous MSC-Exos research in wound healing. Isolation methods must be selected based on specific research needs, with ultracentrifugation remaining the benchmark for many applications, while newer techniques like size exclusion chromatography offer advantages in preserving exosome integrity [16]. Characterization antibodies against tetraspanins (CD63, CD81, CD9) and biogenesis markers (TSG101, ALIX) are indispensable for confirming exosomal identity and ensuring preparation purity [20].

For functional analysis, HUVEC tube formation assays on Matrigel provide robust assessment of angiogenic potential, while fibroblast proliferation and collagen production assays evaluate effects on ECM synthesis [22] [21]. Animal models, particularly diabetic mouse models, are essential for validating therapeutic efficacy in physiologically relevant systems that mimic human chronic wounds [19] [7]. Finally, hydrogel delivery systems, especially hyaluronic acid-based formulations, have emerged as critical tools for enhancing exosome retention and sustained release in wound environments [19].

The molecular cargos of MSC-derived exosomes—proteins, miRNAs, and lipids—represent a sophisticated biological delivery system that coordinately regulates the complex process of wound healing. Through their diverse biomolecular constituents, MSC-Exos modulate inflammation, stimulate angiogenesis, promote cellular proliferation, and guide extracellular matrix remodeling, making them promising therapeutic agents for both acute and chronic wounds.

Future research directions should focus on standardizing isolation protocols to ensure reproducible cargo profiles, optimizing engineering strategies to enhance specific therapeutic functions, and addressing scalability challenges for clinical translation. As our understanding of these molecular cargos deepens, the potential for developing precision exosome-based therapies that target specific pathological aspects of non-healing wounds becomes increasingly feasible. The integration of biomaterial science with exosome biology, particularly through advanced delivery systems like injectable hydrogels, represents a promising avenue for maximizing the clinical impact of MSC-Exos in regenerative medicine.

The systematic characterization of MSC-Exos cargo composition and function, as outlined in this technical guide, provides a foundation for advancing these novel therapeutics from bench to bedside, potentially offering new solutions for the significant clinical challenge of impaired wound healing.

Exosome-Mediated Intercellular Communication with Fibroblasts, Keratinocytes, and Immune Cells

Exosomes, nano-sized extracellular vesicles secreted by nearly all cell types, have emerged as pivotal mediators of intercellular communication within the skin microenvironment. These vesicles facilitate the transfer of bioactive molecules—including proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids—between mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), structural skin cells, and immune cells, thereby orchestrating complex processes essential for wound healing and tissue regeneration. This whitepaper delineates the specific mechanisms through which MSC-derived exosomes modulate the functions of fibroblasts, keratinocytes, and immune cells, highlighting the key signaling pathways involved. Furthermore, it provides a detailed compendium of experimental methodologies for investigating these interactions and discusses the translational potential of engineered exosomes as next-generation therapeutic agents in regenerative dermatology.

Exosomes are lipid bilayer vesicles, typically 30-150 nm in diameter, that originate from the endosomal system and are secreted by virtually all cell types into the extracellular environment [23] [14]. They are enriched in a conserved set of biomarker proteins, including tetraspanins (CD63, CD81, CD9), heat shock proteins (HSP70, HSP90), and biogenesis-related proteins (ALIX, TSG101) [23]. Their cargo, comprising proteins, lipids, mRNAs, microRNAs (miRNAs), long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs), and circular RNAs (circRNAs), reflects their parental cell's physiological state and endows them with the capacity to regulate fundamental cellular processes in recipient cells [23].

The skin, being the body's largest organ, relies on intricate communication between its constituent cells—keratinocytes, fibroblasts, melanocytes, and resident immune cells—to maintain barrier function and execute coordinated wound healing responses [23]. Exosomes have been identified as crucial signaling intermediaries in this network. The dysregulation of exosome-mediated communication is implicated in the pathogenesis of various inflammatory and autoimmune skin diseases, while the therapeutic application of MSC-derived exosomes presents a promising cell-free strategy for promoting skin regeneration and resolving chronic wounds [23] [24].

This review is framed within the context of a broader thesis on the role of MSC-derived exosomes in wound healing research, focusing specifically on their multifaceted interactions with fibroblasts, keratinocytes, and immune cells.

Mechanisms of MSC-Exosome Communication with Skin Cells

Communication with Fibroblasts

Fibroblasts are the primary architects of the extracellular matrix (ECM), and their regulation is critical for effective wound healing and prevention of pathological scarring. MSC-derived exosomes (MSC-exos) modulate fibroblast behavior through the targeted delivery of molecular cargo, primarily miRNAs.

A pivotal study demonstrated that exosomes derived from miR-26a-5p-modified adipose-derived MSCs (AMSCs) significantly accelerated wound healing in a mouse skin defect model [7]. These engineered exosomes functioned by delivering miR-26a-5p to dermal fibroblasts, where it directly targeted and downregulated MAP2K4, a key upstream kinase in the MAPK signaling cascade. This downregulation led to a suppression of pro-inflammatory cytokines (Il6, Il1β, Tnf-α) and a concurrent upregulation of crucial ECM components, including Col1a1, Col3a1, and α-SMA, thereby enhancing collagen synthesis and tissue remodeling [7]. The table below summarizes the key quantitative findings from this study.

Table 1: Effect of miR-26a-5p-Overexpressing AMSC Exosomes on Wound Healing Markers in Vivo

| Parameter Measured | Effect vs. Control | Proposed Mechanism |

|---|---|---|

| Wound Closure Rate | Significantly increased | Enhanced proliferation and matrix synthesis |

| MAP2K4 Expression | Down-regulated | Direct targeting by miR-26a-5p |

| Inflammatory Markers (Il6, Il1β, Tnf-α) | Down-regulated | Inhibition of MAPK pathway |

| ECM Components (Col1a1, Col3a1, Col2a1) | Up-regulated | Enhanced fibroblast synthetic activity |

| Angiogenesis Marker (Cd31) | Up-regulated | Improved neovascularization |

Beyond modulating individual genes, MSC-exos possess broader anti-fibrotic properties. They have been shown to mitigate the progression of pathological scarring, such as keloids and hypertrophic scars, by counteracting the triggers of fibrosis: immune dysregulation, mechanical stress, and hypoxia [14]. They achieve this by regulating key pro-fibrotic pathways, including NF-κB and TGF-β1, and by modulating the activity of mechanosensors like YAP/TAZ [14].

Communication with Keratinocytes

Keratinocytes, the predominant cells of the epidermis, are responsible for re-epithelialization, a critical step in wound closure. MSC-exos directly promote the proliferation and migration of keratinocytes, facilitating the restoration of the epidermal barrier.

The cargo within MSC-exos is instrumental in this process. Specific miRNAs, such as miR-21-3p and miR-31-5p, have been identified as upregulated during wound healing and are associated with enhanced keratinocyte function [7]. Furthermore, exosomes from human umbilical cord MSCs (hUCMSCs) and epidermal stem cells (ESCs) have demonstrated efficacy in improving the skin environment and promoting epithelial regeneration [23] [25]. The ability of topically applied exosomes to localize within the stratum corneum of human skin underscores their potential for direct therapeutic application in cutaneous wounds [23].

Communication with Immune Cells

The immunomodulatory capacity of MSC-exos is a cornerstone of their therapeutic effect, primarily achieved through the regulation of macrophage polarization. In the wound microenvironment, a shift from a pro-inflammatory M1 phenotype to an anti-inflammatory, pro-healing M2 phenotype is essential for the resolution of inflammation and the transition to the proliferation phase.

MSC-exos are potent inducers of this M1-to-M2 transition. They carry specific miRNAs that modulate key signaling pathways in macrophages. For instance, miR-146a delivered by exosomes has been shown to reduce cartilage degradation in osteoarthritis by shifting synovial macrophages towards the M2 phenotype via the TLR4/TRAF6/NF-κB pathway [26]. Similarly, in the context of skin, this polarization leads to increased secretion of anti-inflammatory cytokines like IL-10 and IL-4, which collectively alleviate inflammation and promote a regenerative microenvironment [27]. This immunomodulatory effect not only accelerates healing but also reduces the risk of fibrosis and scarring.

Table 2: MSC-Exosome Cargo and Their Immunomodulatory Targets

| Exosomal Cargo | Source Cell | Target Immune Cell/Pathway | Biological Outcome | Reference Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| miR-146a | Fibroblast-like synoviocytes | Macrophage; TLR4/TRAF6/NF-κB pathway | M2 polarization; Reduced inflammation | [26] |

| miR-26a-5p | Engineered AMSCs | MAP2K4 pathway | Downregulation of Il6, Il1β, Tnf-α | [7] |

| TSG-6, PGE2, IDO | MSC Spheroids | T-cells; Macrophages | Suppression of immune cell proliferation; M2 polarization | [27] |

| let-7a miRNA | Hypoxic Tumor Cells | Macrophage Metabolism | Induction of OXPHOS, M2-like polarization | [28] |

The following diagram illustrates the central signaling pathways through which MSC-derived exosomes influence fibroblasts, keratinocytes, and macrophages to promote wound healing.

Experimental Protocols for Studying Exosome-Cell Interactions

To investigate the mechanisms outlined above, robust and standardized experimental protocols are essential. Below is a detailed methodology for a key experiment that validates the functional role of exosomal miRNA in modulating fibroblast behavior, based on the study by Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology [7].

Detailed Protocol: Validating Exosomal miRNA Function in Fibroblasts

Objective: To investigate the mechanism by which miR-26a-5p-enriched AMSC-exos promote wound healing by targeting MAP2K4 in fibroblasts.

Materials:

- Primary human dermal fibroblasts

- Adipose-derived MSCs (AMSCs)

- miR-26a-5p agomir (mimic) and antagomir (inhibitor)

- Transfection reagent (e.g., Lipofectamine)

- Exosome isolation kit (e.g., ultracentrifugation or commercial precipitation kit)

- Antibodies for characterization (CD63, CD81, TSG101)

- Dual-luciferase reporter assay system

Methodology:

Exosome Isolation and Engineering:

- Culture AMSCs and transfect them with miR-26a-5p agomir or a scrambled control using an appropriate transfection reagent.

- 48 hours post-transfection, collect the conditioned media.

- Isolate exosomes via sequential ultracentrifugation: centrifuge media at 300 × g for 10 min (remove cells), then 2,000 × g for 20 min (remove dead cells), followed by 10,000 × g for 30 min (remove cell debris). Finally, ultracentrifuge at 100,000 × g for 70 min to pellet exosomes.

- Wash the pellet in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and repeat the ultracentrifugation.

- Resuspend the final exosome pellet in PBS and store at -80°C.

Exosome Characterization:

- Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis (NTA): Determine the size distribution and concentration of isolated exosomes.

- Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM): Visualize the morphology and confirm the cup-shaped structure of exosomes.

- Western Blotting: Confirm the presence of positive exosomal markers (CD63, CD81, TSG101) and the absence of a negative marker (e.g., Calnexin).

Functional In Vitro Assay:

- Treat primary human dermal fibroblasts with the following:

- Group 1: PBS (Control)

- Group 2: Exosomes from control AMSCs (Ctrl-Exos)

- Group 3: Exosomes from miR-26a-5p-overexpressing AMSCs (miR-26a-5p-Exos)

- Group 4: miR-26a-5p agomir directly

- Incubate for 24-48 hours.

- Treat primary human dermal fibroblasts with the following:

Downstream Analysis:

- Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay: Clone the wild-type and mutant 3'UTR of the MAP2K4 gene into a luciferase reporter vector. Co-transfect these constructs with miR-26a-5p agomir or control into HEK293T cells. Measure luciferase activity after 48 hours to confirm direct binding.

- qRT-PCR: Isolve total RNA from treated fibroblasts. Quantify the mRNA expression levels of MAP2K4, inflammatory cytokines (Il6, Il1β, Tnf-α), and ECM genes (Col1a1, Col3a1).

- Western Blotting: Analyze protein expression levels of MAP2K4 and other relevant pathway components.

In Vivo Validation:

- Utilize a mouse skin defect model.

- Create full-thickness excisional wounds on the dorsum of mice.

- Topically apply the following to the wounds daily:

- Group A: PBS

- Group B: Ctrl-Exos

- Group C: miR-26a-5p-Exos

- Monitor and photograph wounds daily to calculate the wound closure rate.

- Harvest wound tissues on specific days post-injury for histological analysis (H&E staining, Masson's trichrome for collagen) and immunohistochemistry (for CD31, α-SMA, etc.).

The following diagram outlines the core workflow of this experimental protocol.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Advancing research in exosome-mediated communication requires a suite of reliable and well-characterized reagents. The table below details essential tools for isolating, characterizing, and functionally analyzing exosomes and their interactions with target cells.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Exosome Studies

| Reagent/Material | Primary Function | Specific Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs) | Source of therapeutic exosomes | Adipose-derived MSCs (AMSCs), human umbilical cord MSCs (hUCMSCs). hUCMSCs offer superior immunomodulatory properties and minimal donor variation [27]. |

| Transfection Reagents | Engineering exosome cargo | For modifying parent MSCs with miRNA agomirs/antagomirs or plasmid DNA (e.g., Lipofectamine, electroporation systems). |

| Ultracentrifuge | Gold-standard exosome isolation | Enriches exosomes from conditioned media via high-speed centrifugation [7]. |

| Commercial Kits | Alternative exosome isolation | Polymer-based precipitation kits (e.g., ExoQuick-TC). Useful for smaller sample sizes but may co-precipitate contaminants. |

| Nanoparticle Tracker | Physicochemical characterization | Instruments like Malvern Nanosight for determining exosome size distribution and concentration (NTA) [7]. |

| Antibodies for Markers | Confirm exosome identity | Anti-tetraspanins (CD63, CD81, CD9), anti-biogenesis markers (TSG101, ALIX). Negative control: Calnexin or GM130. |

| Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay | Validate direct miRNA-mRNA binding | System to clone the 3'UTR of a putative target gene (e.g., MAP2K4) and confirm direct interaction with an exosomal miRNA [7]. |

| Animal Wound Models | In vivo functional validation | Mouse or rat models of full-thickness excisional wounds or diabetic ulcers to test the therapeutic efficacy of exosomes [7]. |

| Hydrogel Delivery Systems | Application in vivo | Pluronic F-127 or gelatin sponge/polydopamine scaffolds (GS-PDA) for sustained release and improved retention of exosomes at the wound site [7] [14]. |

| 3-Ethyl-4-methylhexane | 3-Ethyl-4-methylhexane, CAS:3074-77-9, MF:C9H20, MW:128.25 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Psoralen-c 2 cep | Psoralen-c 2 cep | Psoralen-c 2 cep (CAS 126221-83-8) is a high-purity biochemical for research into nucleic acid interactions. This product is For Research Use Only and is not for human or veterinary use. |

The evidence is compelling that MSC-derived exosomes serve as master regulators of cutaneous wound healing by orchestrating the activities of fibroblasts, keratinocytes, and immune cells through sophisticated paracrine communication. By shuttling specific miRNAs and other bioactive molecules, they precisely modulate key signaling pathways such as MAPK and NF-κB, leading to reduced inflammation, enhanced ECM synthesis, accelerated re-epithelialization, and a pro-regenerative immune environment.

The future of this field lies in moving beyond natural exosomes toward precision engineering. Strategies such as loading exosomes with specific therapeutic miRNAs (e.g., miR-26a-5p) or modifying their surface to enhance tissue targeting are already under investigation [7] [14]. Furthermore, overcoming the challenge of effective delivery through the use of biomaterial-based scaffolds (e.g., hydrogels) that ensure controlled and sustained release at the wound site will be crucial for clinical translation [24]. As we deepen our understanding of exosome biology and refine engineering and delivery techniques, MSC-derived exosomes are poised to revolutionize regenerative medicine, offering a potent, cell-free, and scalable therapeutic paradigm for treating acute and chronic skin wounds.

Chronic wounds, including diabetic foot ulcers (DFUs), venous leg ulcers (VLUs), and pressure ulcers (PUs), represent a significant and growing global health challenge, affecting an estimated 2% of the world's population and approximately 6.5 million patients in the United States alone [29]. These wounds are characterized by a failure to progress through the normal stages of wound healing—hemostasis, inflammation, proliferation, and remodeling—often remaining in a state of persistent inflammation and impaired tissue repair [30] [31]. The economic burden is substantial, with annual treatment costs in the U.S. estimated at $20–25 billion [29].

Within the broader thesis on the role of mesenchymal stem cell (MSC)-derived exosomes in wound healing research, this review focuses on the core pathophysiological drivers of chronic wounds, specifically the mechanisms underlying persistent inflammation and impaired angiogenesis. Recent advances in "omics" technologies have deepened our understanding of chronic wound pathology at cellular and molecular levels, revealing specific dysregulations in keratinocytes, fibroblasts, immune cells, and endothelial cells [29]. Concurrently, MSC-derived exosomes have emerged as a promising cell-free therapeutic alternative, demonstrating the ability to modulate these pathological processes and promote healing [31] [1].

This technical guide provides an in-depth analysis of the molecular mechanisms perpetuating chronic wounds, with particular emphasis on how MSC-exosomes target these pathways. We summarize quantitative data in structured tables, detail experimental methodologies, visualize key signaling pathways, and catalog essential research reagents to support ongoing drug development and basic research efforts in this field.

Pathophysiological Hallmarks of Chronic Wounds

Persistent Inflammation and Immune Dysregulation

In normal wound healing, the inflammatory phase is transient, characterized by sequential recruitment of neutrophils and monocytes/macrophages that clear debris and pathogens before transitioning to a pro-reparative state [30] [31]. In chronic wounds, this process becomes dysregulated, leading to a state of persistent inflammation that prevents progression to proliferation and remodeling phases.

Cellular Dysregulation:

- Neutrophils: Show reduced infiltration and migration across endothelial cells but remain in the wound for extended periods, releasing proteases such as matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and reactive oxygen species (ROS) that damage newly formed tissue [30].

- Macrophages: Exhibit impaired transition from pro-inflammatory M1 to anti-inflammatory M2 phenotypes. The M1 macrophage profile persists, characterized by uncontrolled production of inflammatory mediators including TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 [30] [31]. Reduced induction of the M2 macrophage profile limits the production of reparative factors such as IL-10, VEGF, PDGF, and FGFs [30].

- Lymphocytes: Abnormal T-cell function contributes to the dysregulated immune response, though the exact mechanisms in chronic wounds are still being elucidated [31].

Molecular Mediators: Chronic wounds exhibit dysregulated cytokine/growth factor levels with increased pro-inflammatory signaling. Key mediators include sustained elevated levels of TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6, which perpetuate the inflammatory state [31]. Protease activity is significantly increased, with MMP levels exceeding their tissue inhibitors (TIMPs), causing degradation of the extracellular matrix (ECM), growth factors, and receptors [29] [30].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Inflammatory Phase in Acute vs. Chronic Wounds

| Aspect | Acute Wounds | Chronic Wounds | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inflammation Duration | Transient (days) | Persistent (weeks to months) | [30] [31] |

| Neutrophil Activity | Timely infiltration and clearance | Prolonged persistence, impaired migration | [30] |

| Macrophage Polarization | Balanced M1 to M2 transition | Sustained M1 phenotype, impaired M2 transition | [30] [31] |

| Cytokine Profile | Coordinated pro- and anti-inflammatory signals | Dominance of pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6) | [31] |

| Protease Activity | Balanced MMP/TIMP ratio | Elevated MMPs, degraded growth factors & ECM | [29] [30] |

Impaired Angiogenesis

Angiogenesis, the formation of new blood vessels from existing vasculature, is crucial for delivering oxygen and nutrients to the healing wound. In chronic wounds, this process is severely compromised, contributing to tissue hypoxia and impaired repair.

Dysfunctional Endothelial Cells: Endothelial cells in chronic wounds exhibit reduced proliferative and migratory capacity, impairing new blood vessel formation [29]. The diabetic microenvironment, characterized by hyperglycemia, further damages endothelial cells through increased oxidative stress and the formation of advanced glycation end products (AGEs) [32].

Molecular Mechanisms of Impaired Angiogenesis:

- Growth Factor Dysregulation: Despite the pro-inflammatory environment, the bioavailability and activity of key angiogenic growth factors, particularly VEGF, are often reduced due to increased degradation and impaired signaling [29] [32].

- Oxidative Stress: Chronic hyperglycemia in diabetic wounds promotes excessive production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), causing mitochondrial dysfunction in endothelial cells and reducing their capacity to form vessels [32].

- Altered Nitric Oxide (NO) Bioavailability: Changes in amino acid metabolism, particularly arginine deficiency, compromise NO synthesis, a critical mediator of vasodilation and angiogenesis [32].

Table 2: Mechanisms of Impaired Angiogenesis in Chronic Wounds

| Mechanism | Pathophysiological Consequences | Impact on Healing | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Endothelial Cell Dysfunction | Reduced proliferation and migration | Failed neovascularization, tissue hypoxia | [29] |

| VEGF Signaling Impairment | Decreased growth factor bioavailability | Insufficient angiogenic stimulus | [29] [32] |

| Oxidative Stress | Mitochondrial damage, cellular senescence | Compromised endothelial cell function | [32] |

| Reduced NO Bioavailability | Impaired vasodilation & endothelial signaling | Dysfunctional microcirculation | [32] |

MSC-Derived Exosomes as a Therapeutic Modality

Biogenesis and Composition of MSC-Exosomes

Exosomes are nano-sized extracellular vesicles (30-150 nm in diameter) of endocytic origin, secreted by virtually all cell types, including MSCs [30] [1]. Their biogenesis begins with the inward budding of the endosomal membrane, forming intraluminal vesicles within multivesicular bodies. These multivesicular bodies subsequently fuse with the plasma membrane, releasing the vesicles as exosomes into the extracellular space [1].

MSC-exosomes inherit specific biological components from their parent cells, including proteins, lipids, mRNA, and miRNA, which enable them to mediate intercellular communication [1]. They function as natural transporters of these bioactive molecules, which can be internalized by recipient cells through endocytosis, membrane fusion, or ligand-receptor interactions, thereby altering the recipient cell's phenotype and function [30] [1].

Mechanisms of Action in Targeting Chronic Wound Pathophysiology

Extensive research demonstrates that MSC-exosomes can mitigate the core pathophysiological features of chronic wounds through multiple mechanisms.

Modulation of Inflammation: MSC-exosomes facilitate the transition of macrophages from the pro-inflammatory M1 phenotype to the anti-inflammatory M2 phenotype [31]. This immunomodulatory effect is partly mediated by exosomal miRNAs, such as miR-146a and miR-223, which inhibit key pro-inflammatory signaling pathways like NF-κB and suppress NLRP3 inflammasome activation [31]. Furthermore, exosomes from preconditioned MSCs can enhance anti-inflammatory polarization via let-7b signaling [31].

Promotion of Angiogenesis: MSC-exosomes are enriched with pro-angiogenic factors and miRNAs that stimulate new blood vessel formation. They promote the proliferation, migration, and tube formation of endothelial cells [31] [33]. Specific exosomal miRNAs, including miR-126-3p, directly target genes that inhibit angiogenesis, such as PIK3R2, thereby activating the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway, a key regulator of endothelial cell survival and vascular maturation [33].

Enhancement of Cell Proliferation and Migration: MSC-exosomes enhance the activity of keratinocytes and fibroblasts, which are critical for re-epithelialization and ECM reconstruction. They activate pathways such as AKT and ERK/MAPK in these cells, boosting their proliferative and migratory capacity [33]. This helps overcome the hyperproliferative but non-migratory phenotype of keratinocytes observed at the non-healing edge of chronic ulcers [29].

The following diagram illustrates the multifaceted therapeutic mechanisms of MSC-derived exosomes in the chronic wound microenvironment:

Therapeutic Mechanisms of MSC-Exosomes in Chronic Wounds.

Engineering and Delivery Strategies for Enhanced Efficacy

Natural exosomes face challenges such as rapid clearance and limited targeting. Bioengineering approaches are being developed to overcome these limitations and enhance therapeutic potential.

Content Engineering: Genetic modification of parent MSCs can enrich exosomes with specific therapeutic miRNAs or proteins. For instance, ADSC-exosomes overexpressing miR-21-5p have been shown to significantly promote diabetic wound healing through enhanced re-epithelialization, collagen remodeling, and angiogenesis [33]. Similarly, miR-146a-modified ADSC-exosomes promoted fibroblast proliferation and migration and stimulated neovascularization [33].

Delivery Systems: To address the rapid clearance of exosomes, hydrogel-based scaffolds and other biocompatible materials are being investigated for sustained release [34]. These systems prolong the presence of therapeutic exosomes at the wound site, maintaining optimal concentrations and improving functional outcomes.

Experimental Models and Methodologies

Standardized Experimental Workflow

A typical research workflow for evaluating the efficacy of MSC-exosomes in wound healing involves a sequence of critical steps, from exosome isolation to functional validation in vivo. The following diagram outlines this standardized protocol:

Workflow for MSC-Exosome Wound Healing Research.

Detailed Methodological Protocols

1. Isolation and Characterization of MSC-Exosomes:

- Cell Culture: Culture MSCs from selected sources (e.g., bone marrow, adipose tissue, umbilical cord) in serum-free media to avoid contamination with bovine exosomes. Expand cells to 70-80% confluence [1] [33].

- Exosome Isolation: Collect conditioned media and perform sequential centrifugation: 300 × g for 10 min to remove cells; 2,000 × g for 20 min to remove dead cells; 10,000 × g for 30 min to remove cell debris; and finally, ultracentrifugation at 100,000 × g for 70 min to pellet exosomes [1] [33].

- Characterization:

- Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis (NTA): Determine the size distribution and concentration of exosomes.

- Western Blotting: Confirm the presence of exosomal markers (CD63, CD81, TSG101) and absence of negative markers (e.g., GM130) [1] [33].

- Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM): Visualize the morphology and ultrastructure of exosomes.

2. In Vitro Functional Assays:

- Cell Migration Assay (Scratch Assay): Culture fibroblasts or keratinocytes to confluence. Create a uniform scratch and treat with MSC-exosomes. Monitor and quantify cell migration into the scratch area over 24-48 hours [33].

- Tube Formation Assay:

- Materials: Matrigel matrix, endothelial cells (e.g., HUVECs), MSC-exosomes, tissue culture plates.

- Protocol: Coat plates with Matrigel and allow polymerization. Seed HUVECs on the Matrigel and treat with MSC-exosomes. After 4-18 hours, image the tubes and quantify parameters like total tube length, number of nodes, and branching points [33].

- Gene Expression Analysis: Isulate RNA from exosome-treated cells and perform qRT-PCR to analyze the expression of genes related to angiogenesis (VEGF, Ang-1), inflammation (IL-1β, IL-6, IL-10), and ECM remodeling (Collagen I, III, MMPs, TIMPs) [33].

3. In Vivo Efficacy Testing:

- Diabetic Wound Model:

- Animals: Use genetically diabetic mice (e.g., db/db mice) or induce diabetes in C57BL/6 mice with streptozotocin.

- Wound Creation: Anesthetize mice and create one or two full-thickness excisional wounds on the dorsum using a biopsy punch.

- Treatment: Randomize animals into groups. Apply MSC-exosomes (e.g., 100 µg in 50 µL PBS) topically to the wound bed every other day. Control groups receive vehicle alone.

- Outcome Measures:

- Wound Closure: Digitally photograph wounds daily and calculate wound area as a percentage of original size.

- Histology: Harvest wound tissue at specified endpoints for H&E staining (re-epithelialization, granulation tissue), Masson's Trichrome (collagen deposition), and immunohistochemistry (CD31 for angiogenesis, F4/80 for macrophages) [33] [34].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for MSC-Exosome Wound Healing Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Function | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|

| MSC Sources | Bone Marrow-MSCs (BM-MSCs), Adipose-Derived Stem Cells (ADSCs), Human Umbilical Cord-MSCs (hUC-MSCs) | Provide biologically relevant exosomes for therapeutic testing; different sources may have varying potency. | [31] [33] |

| Characterization Antibodies | Anti-CD63, Anti-CD81, Anti-TSG101, Anti-Calnexin (negative control) | Confirm exosome identity and purity via Western Blot or flow cytometry. | [1] [33] |

| Cell Lines for In Vitro Assays | Human Umbilical Vein Endothelial Cells (HUVECs), Human Dermal Fibroblasts (HDFs), HaCaT Keratinocytes | Model the responses of key skin cell types (angiogenesis, ECM production, re-epithelialization). | [31] [33] |

| In Vivo Model Systems | db/db Mice, Streptozotocin-induced Diabetic Mice | Provide a pathophysiologically relevant model of impaired healing for testing therapeutic efficacy. | [33] [34] |

| Hydrogel Delivery Systems | Hyaluronic acid-based hydrogels, Chitosan scaffolds, Collagen matrices | Provide sustained release of exosomes at the wound site, enhancing retention and therapeutic effect. | [34] |

The pathophysiology of chronic wounds, dominated by persistent inflammation and failed angiogenesis, presents a complex therapeutic challenge. MSC-derived exosomes represent a promising cell-free therapeutic strategy that directly targets these core pathological mechanisms. Through their diverse cargo, they can reprogram the hostile wound microenvironment, shifting it from a state of chronic inflammation to one conducive to active repair, while simultaneously stimulating robust new blood vessel formation.

Future research should focus on standardizing isolation protocols, optimizing bioengineering strategies for enhanced targeting and potency, and conducting rigorous, large-animal preclinical studies to facilitate clinical translation. As a key component of the broader thesis on MSC-exosomes, the evidence presented in this review solidifies their position as a next-generation therapeutic modality with the potential to fundamentally change the management of chronic wounds.

From Lab to Bedside: Production, Isolation, and Advanced Delivery Systems for Exosome Therapies

Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) are nonhematopoietic, multipotent stem cells characterized by their capacity for self-renewal, multilineage differentiation, and immunomodulatory functions [35]. First identified in bone marrow, MSCs can now be isolated from numerous tissues, with bone marrow (BM), adipose tissue (AT), and umbilical cord (UC) being among the most clinically relevant sources [36]. The therapeutic potential of MSCs has been widely explored for conditions ranging from autoimmune and inflammatory disorders to orthopedic injuries and wound healing [35].