MSC-Derived Exosomes vs. Whole Cell Therapy: A Comparative Analysis of Functional Outcomes and Clinical Translation

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the functional outcomes of mesenchymal stem cell (MSC)-derived exosomes compared to whole cell MSC therapy.

MSC-Derived Exosomes vs. Whole Cell Therapy: A Comparative Analysis of Functional Outcomes and Clinical Translation

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the functional outcomes of mesenchymal stem cell (MSC)-derived exosomes compared to whole cell MSC therapy. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational biology of both therapeutic agents, detailing the paracrine mechanisms of MSCs and the biogenesis, cargo, and cell-free nature of exosomes. The review covers methodological advances in production and isolation, alongside diverse preclinical and clinical applications in neurodegenerative, autoimmune, cardiovascular, and pulmonary diseases. It critically addresses key challenges in standardization, dosing, and manufacturing scalability. Finally, the article synthesizes evidence from clinical trials and advanced imaging studies to present a balanced comparison of safety, efficacy, and therapeutic potential, offering a roadmap for the future of regenerative medicine.

Unlocking the Biology: From MSC Paracrine Action to Exosome Biogenesis

For decades, the therapeutic mechanism of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) was attributed to their ability to engraft at injury sites and differentiate into functional tissue cells. However, a paradigm shift has occurred with the emergence of the paracrine hypothesis, which posits that MSCs exert their primary therapeutic effects through the secretion of bioactive molecules rather than through direct cellular replacement [1]. This cell-free mechanism is primarily mediated through extracellular vesicles (EVs), especially exosomes, which carry a complex cargo of proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids [2] [3]. This guide objectively compares the functional outcomes of MSC-derived exosomes versus whole cell therapy, providing researchers with experimental data and methodologies relevant to drug development.

The Scientific Foundation of the Paracrine Hypothesis

From Engraftment to Secretome: An Evolving Paradigm

The traditional view held that systemically administered MSCs would migrate to damaged tissues, engraft, and differentiate into specific cell types to repair defects. However, tracking studies revealed that most infused MSCs exhibit poor long-term engraftment and survival at injury sites, despite observed therapeutic benefits [3] [1]. This discrepancy led researchers to investigate alternative mechanisms, ultimately identifying the MSC secretome – the collection of factors these cells secrete – as the primary driver of their therapeutic effects [1].

The secretome includes both soluble factors (growth factors, cytokines, chemokines) and insoluble factors contained within extracellular vesicles [3]. These vesicles, particularly exosomes (30-150 nm in diameter), have emerged as crucial mediators of intercellular communication, transferring functional biomolecules to recipient cells [4]. MSC-derived exosomes (MSC-Exos) contain diverse cargo including cytokines, growth factors, signaling lipids, mRNAs, and regulatory miRNAs that can alter target cell metabolism and function [2]. This discovery has fundamentally reshaped our understanding of MSC therapeutics and opened new avenues for cell-free regenerative approaches.

Key Paracrine Mediators and Their Functions

Table 1: Key Bioactive Components of the MSC Paracrine Secretome

| Component Category | Key Examples | Primary Functions |

|---|---|---|

| Soluble Factors | VEGF, HGF, TGF-β, PGE2, IDO | Angiogenesis, antifibrotic effects, immunomodulation, tissue repair [1] |

| Extracellular Vesicles | Exosomes, Microvesicles | Intercellular communication, cargo delivery (proteins, RNAs, lipids) [4] [3] |

| Mitochondria | Whole mitochondria | Mitochondrial transfer to damaged cells, restoration of bioenergetics [1] |

MSCs engage with parenchymal cells and facilitate the restoration and rejuvenation of damaged tissues through direct cell-cell contact and the release of these signaling molecules [4]. Damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) and alarmins generated by damaged cells trigger MSC activation, which in turn prevents apoptosis of unaffected parenchymal cells, promoting survival and multiplication [4]. The composition of the MSC secretome is not static but dynamically responsive to the local microenvironment, indicating that MSC exosome content can be altered when MSCs are cultured with tumor cells or in specific in vivo environments [2].

Comparative Analysis: MSC-Derived Exosomes vs. Whole Cell Therapeutics

Mechanism of Action Comparison

Table 2: Functional Comparison of MSC vs. MSC-Exos Therapies

| Parameter | Whole MSC Therapy | MSC-Derived Exosomes |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Mechanism | Direct differentiation (limited) & paracrine signaling [1] | Pure paracrine effect via biomolecule transfer [2] [5] |

| Immunomodulation | Inhibits T-cell proliferation, promotes M2 macrophage polarization [1] | Suppresses B-cell maturation, inhibits DC maturation, modulates T-cells [4] |

| Tissue Repair | Secretes trophic factors (VEGF, bFGF, HGF) [1] | Transfers regenerative miRNAs and proteins [3] [6] |

| Mitochondrial Transfer | Direct donation via tunneling nanotubes [1] | Not demonstrated; primarily biomolecule transfer |

| Biodistribution | Often trapped in lung microvasculature; limited target tissue homing [5] | Superior tissue penetration; crosses biological barriers including blood-brain barrier [3] |

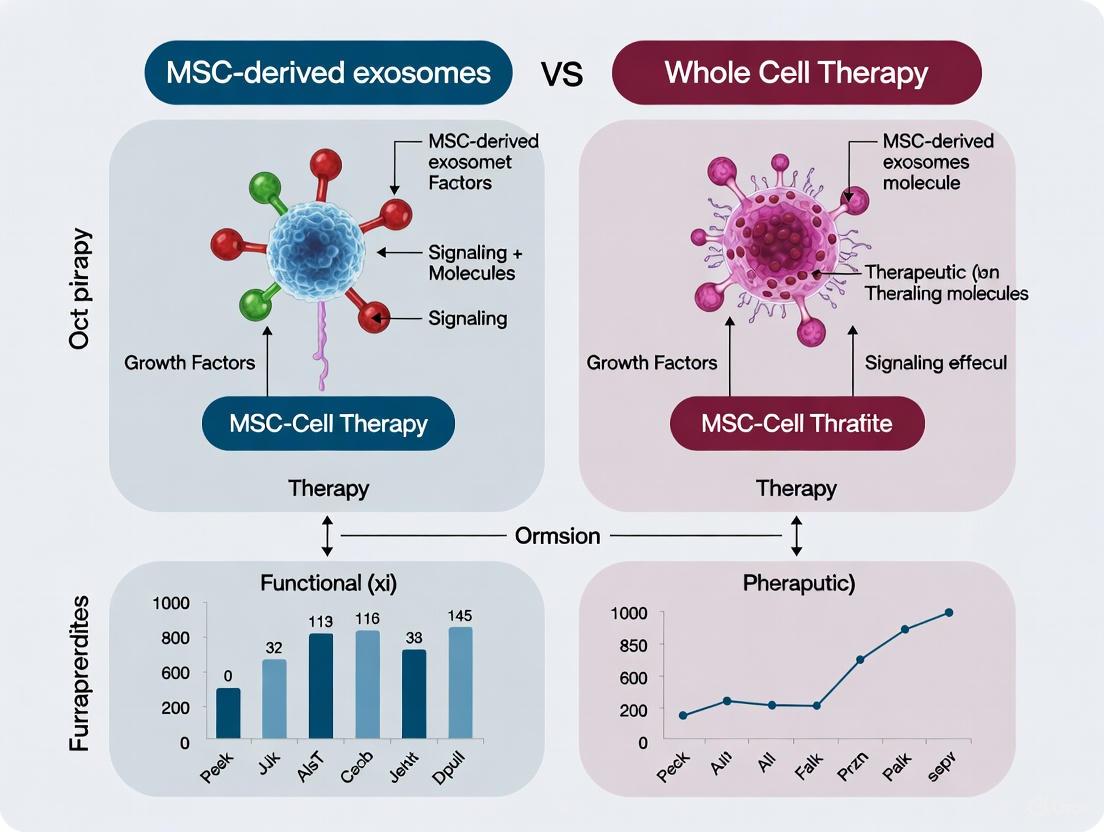

The following diagram illustrates the central hypothesis that MSCs primarily function through paracrine signaling, with exosomes as key mediators:

Therapeutic Efficacy and Clinical Translation

Table 3: Clinical Translation Status Comparison

| Aspect | Whole MSC Therapy | MSC-Derived Exosomes |

|---|---|---|

| Clinical Trial Volume | ~1,742 registered trials worldwide [7] | 64 registered clinical trials [3] |

| Approved Products | 10 approved products (Alofisel, Prochymal, etc.) [7] | None yet fully approved |

| Standardization | Established but heterogeneous [5] | Limited standardization; methods evolving [3] |

| Administration Routes | Intravenous, local implantation [5] | IV, inhalation, local; more versatile [5] |

| Safety Profile | Infusion-related toxicities, pulmonary entrapment [5] | Higher safety profile; reduced adverse effects [3] |

The therapeutic efficacy of both approaches has been demonstrated across multiple disease models. MSC-derived exosomes have shown significant benefits in animal models of neurological disorders (epilepsy, Parkinson's disease, stroke), autoimmune diseases (multiple sclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis, type 1 diabetes), and conditions requiring tissue regeneration (cardiac, hepatic, and renal) [5]. Whole MSC therapies have demonstrated clinical efficacy in graft-versus-host disease (GVHD), Crohn's disease, and myocardial infarction [1] [7].

Experimental Evidence and Methodologies

Key Experimental Models Demonstrating Paracrine Effects

Transwell Coculture Systems

Protocol Overview: This methodology examines paracrine communication without direct cell-cell contact. MSCs are cultured in the upper chamber while target cells (e.g., myogenic cells, immune cells) are placed in the lower chamber, separated by a semi-permeable membrane [8].

Key Findings: In studies examining muscle regeneration, both iPSC-derived MSCs (iMSCs) and bone marrow-derived MSCs (BM-MSCs) promoted the proliferation and differentiation of human myogenic cells in this system [8]. The fusion index of human myogenic cells increased significantly when cocultured with MSCs, demonstrating enhanced maturation through paracrine factors alone.

Data Interpretation: This experimental setup provides direct evidence for the paracrine hypothesis by eliminating the possibility of direct differentiation or cell-cell contact. The results confirm that soluble factors and vesicles secreted by MSCs can independently mediate therapeutic effects.

Substrate Mechanical Properties Studies

Protocol Overview: MSCs are cultured on polyacrylamide hydrogels of varying stiffness (0.2 kPa vs. 100 kPa) to investigate how mechanical cues influence paracrine activity [9].

Key Findings: Conditioned medium from MSCs cultured on soft substrates (0.2 kPa) promoted MSC osteogenesis and adipogenesis, enhanced angiogenesis, and increased macrophage phagocytosis. In contrast, conditioned medium from stiff substrates (100 kPa) boosted MSC proliferation [9]. Proteomic analysis identified differential secretion of IL-6, OPG, TIMP-2, MCP-1, and sTNFR1 based on substrate stiffness.

Data Interpretation: These findings demonstrate that the MSC secretome is not static but dynamically responsive to physical microenvironmental cues. This has significant implications for manufacturing potent MSCs for specific clinical applications and designing biomaterials that optimize MSC activity after delivery.

The following diagram illustrates the experimental workflow for evaluating paracrine effects:

Immunomodulatory Mechanisms of MSC-Exosomes

MSC-derived exosomes exert comprehensive effects on both innate and adaptive immune systems. The following diagram details their key immunomodulatory pathways:

Specific immunomodulatory effects include:

- B-cell Regulation: MSC-exosomes are internalized by activated B cells, resulting in inhibition of B cell proliferation, differentiation, antibody production, and maturation of memory B cells [4]. They prompt B cells to downregulate the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway via miR-155-5p, inhibiting B cell proliferation and diminishing activation potential [4].

- Macrophage Polarization: MSC-exosomes guide macrophage polarization by converting pro-inflammatory M1 macrophages into anti-inflammatory M2 phenotypes through signaling molecules like interleukin-10 (IL-10) and transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β) [1].

- T-cell Modulation: MSC-exosomes inhibit T-cell proliferation through the secretion of immunosuppressive agents such as prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO), and programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1), thereby tempering overactive immune responses [1].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Methodologies

Table 4: Key Research Reagents and Experimental Solutions

| Reagent/Solution | Function in Paracrine Research | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Transwell Systems | Permeable supports for coculture without direct contact | Studying paracrine effects on target cells [8] |

| Polyacrylamide Hydrogels | Tunable stiffness substrates | Investigating mechanotransduction on secretome [9] |

| Ultracentrifugation | Gold standard for exosome isolation | MSC-Exos purification for functional studies [5] |

| Tangential Flow Filtration | Scalable EV purification | Clinical-grade exosome production [5] |

| CD73/CD90/CD105 Antibodies | MSC characterization markers | Confirming MSC phenotype per ISCT criteria [1] |

| Cytokine Array Kits | Multiplex secretome analysis | Identifying key paracrine factors [8] |

| Alizarin Red/Oil Red O | Differentiation capacity assessment | Verifying MSC multipotency [8] |

The selection of appropriate reagents and methodologies is critical for rigorous investigation of MSC paracrine activities. Researchers should implement quality control measures including:

- Characterization Standards: Follow MISEV2018 guidelines for extracellular vesicle characterization, including positive markers (CD63, CD81, CD9) and negative markers [5].

- Potency Assays: Establish disease-relevant functional assays rather than relying solely on particle count or protein content [5].

- GMP Compliance: Implement good manufacturing practice standards for clinical-grade production, including monitoring of cell culture environment, cultivation system, and culture medium [5].

The evidence supporting the paracrine hypothesis has transformed our approach to MSC therapeutics, shifting focus from cell replacement to biomolecule delivery. MSC-derived exosomes represent a promising cell-free therapeutic tool with significant advantages in safety, standardization, and manufacturing. However, whole cell therapies maintain unique capabilities such as mitochondrial transfer and dynamic response to local microenvironments.

Future research directions should address key challenges in MSC-exosome therapeutics, including standardization of production processes, enhancement of targeting capabilities for in vivo delivery, and generation of comprehensive long-term biodistribution data [3]. Interdisciplinary technologies such as 3D dynamic culture, genetic engineering, and intelligent slow-release systems are expected to facilitate the transition of MSC-exosomes from laboratory tools to clinically approved "programmable nanomedicines" [3].

For drug development professionals, the evolving landscape suggests a complementary rather than exclusive approach to whole cell versus exosome therapies. The choice between these modalities should be guided by specific clinical indications, mechanism of action requirements, and manufacturing considerations. As the field advances, the paracrine hypothesis continues to open new avenues for precision medicine in regenerative applications.

Exosomes, nanosized extracellular vesicles formed within multivesicular bodies (MVBs) and released via fusion with the plasma membrane, have emerged as pivotal mediators of intercellular communication. This review delineates the fundamental biological principles of exosomes, focusing on their complex biogenesis, diverse molecular cargo, and functional roles. Particular emphasis is placed on exosomes derived from mesenchymal stromal/stem cells (MSCs) and their emerging potential as cell-free therapeutic agents. Within the context of a broader thesis on functional outcomes, this article provides a direct comparison between MSC-derived exosomes and whole cell therapy, evaluating their respective mechanisms, therapeutic efficacy, and practical applications in regenerative medicine and immunomodulation. By synthesizing current scientific evidence, we aim to provide researchers and drug development professionals with a comprehensive framework for understanding exosomes as key MSC messengers and their translational potential.

Exosomes are small, membrane-bound extracellular vesicles with a diameter typically ranging from 30 to 150 nanometers, though some sources extend this range to 200 nm [10] [11]. First discovered in the 1980s during studies of reticulocyte maturation, exosomes were initially regarded as cellular waste disposal mechanisms [12] [13]. The term "exosome" was coined by Rose Johnstone in 1987, reflecting the process that seemed akin to reverse endocytosis, with internal vesicular contents released rather than external molecules internalized [13] [14]. However, over the past two decades, extensive research has revealed that exosomes play crucial roles in intercellular communication by transferring functional proteins, lipids, nucleic acids, and other bioactive molecules between cells [10] [15].

These vesicles are now recognized as key mediators in various physiological and pathological processes, including immune responses, tissue repair, central nervous system communication, and cancer progression [10]. The composition of exosomes reflects their cell of origin and their biological status, making them valuable as potential diagnostic biomarkers and therapeutic vehicles [15] [16]. Among different exosome sources, those derived from mesenchymal stromal/stem cells (MSCs) have garnered significant research interest due to their robust immunomodulatory and regenerative properties, positioning them as promising cell-free therapeutic alternatives to whole cell therapy [11] [2] [5].

Exosome Biogenesis: From Endocytosis to Secretion

Exosome biogenesis is a complex, multi-step process that occurs within the endosomal system, culminating in the release of intraluminal vesicles (ILVs) into the extracellular space as exosomes. This sophisticated cellular machinery involves several coordinated stages:

Endocytosis and Early Endosome Formation

The biogenesis pathway initiates with the inward budding of the plasma membrane, forming early endosomes that encapsulate extracellular components and membrane proteins [12] [10]. These early endosomes serve as the sorting stations for cargo destined for various intracellular destinations, including degradation, recycling, or secretion.

MVB Formation and ILV Generation

Early endosomes mature into late endosomes or multivesicular bodies (MVBs) through a process characterized by the inward budding of the endosomal membrane, generating numerous intraluminal vesicles (ILVs) within the lumen of the organelles [12] [13] [15]. These ILVs eventually become exosomes upon secretion. The formation of ILVs is mediated through several distinct but sometimes overlapping molecular mechanisms:

ESCRT-Dependent Pathway

The Endosomal Sorting Complex Required for Transport (ESCRT) machinery is a well-characterized pathway for ILV formation [12] [10] [16]. Comprising four complexes (ESCRT-0, -I, -II, -III) and associated proteins (particularly VPS4 ATPase), this system works sequentially to mediate membrane budding and scission. ESCRT-0, consisting of Hrs and STAM, recognizes and clusters ubiquitinated cargo proteins. ESCRT-I and -II are then recruited to drive membrane deformation, while ESCRT-III forms filaments that constrict the membrane neck before VPS4-mediated ATP hydrolysis enables membrane fission and ILV release [12] [16].

ESCRT-Independent Pathways

Several ESCRT-independent mechanisms also contribute to exosome biogenesis. The most studied involves neutral sphingomyelinase 2 (nSMase2), which catalyzes the conversion of sphingomyelin to ceramide [12]. Ceramide molecules possess cone-shaped structures that spontaneously induce membrane curvature, facilitating ILV formation. This pathway has been shown to mediate the sorting of specific cargoes, such as proteolipid protein in oligodendroglia cells and certain RNAs in cancer cells [12]. Other ESCRT-independent mechanisms involve tetraspanin proteins (CD63, CD9, CD81) and lipids like lysobisphosphatidic acid (LBPA), which can promote ILV formation through specific molecular interactions [12] [10].

MVB Fate and Exosome Release

Once formed, MVBs face one of two potential fates: degradation through fusion with lysosomes or autophagosomes, or secretion through fusion with the plasma membrane [12] [13]. The fate decision appears to depend on specific MVB subpopulations, with only certain MVBs destined for exosome release [13]. For instance, in B-lymphocytes, cholesterol-rich MVBs are more likely to fuse with the plasma membrane and release exosomes [13]. The transport of MVBs to the plasma membrane involves the cytoskeletal network and Rab GTPase proteins, while SNARE complexes facilitate the fusion process itself [10]. Upon fusion, ILVs are released into the extracellular space as exosomes, ready to participate in intercellular communication.

Table 1: Key Molecular Machinery in Exosome Biogenesis

| Biological Process | Key Molecular Components | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| Cargo Recognition | ESCRT-0 (Hrs, STAM), Ubiquitin | Identifies and clusters cargo proteins for sorting |

| Membrane Budding | ESCRT-I/-II, Ceramide, Tetraspanins | Mediates inward budding of endosomal membrane |

| Vesicle Scission | ESCRT-III, VPS4 ATPase | Executes membrane abscission to form ILVs |

| MBV Transport | Rab GTPases, Cytoskeletal Elements | Moves MVBs to plasma membrane |

| Membrane Fusion | SNARE Proteins, Annexins | Mediates fusion of MVBs with plasma membrane |

Figure 1: Exosome Biogenesis Pathways. This diagram illustrates the key steps in exosome formation, including both ESCRT-dependent and ESCRT-independent mechanisms, culminating in MVB fusion with the plasma membrane and exosome release.

Molecular Composition of Exosomes

Exosomes possess a sophisticated molecular architecture that reflects their biogenesis pathway and cellular origin. Their composition is not random; rather, it represents a selective enrichment of specific biomolecules that define exosome identity and function.

Protein Cargo

Exosomes carry a diverse array of proteins that can be broadly categorized into three groups:

Conserved Universal Proteins: These include proteins involved in exosome biogenesis such as ESCRT components (TSG101, Alix), tetraspanins (CD9, CD63, CD81), heat shock proteins (HSP70, HSP90), fusion proteins (Annexins, Rab GTPases), and cytoskeletal components [10] [15] [16]. These molecules are commonly used as exosome markers for identification and characterization.

Cell-Type-Specific Proteins: Exosomes carry proteins characteristic of their cell of origin. For instance, MSC-derived exosomes contain factors related to immunomodulation and tissue repair, while exosomes from antigen-presenting cells may carry MHC class I and II molecules [10] [11].

Context-Dependent Proteins: The protein profile of exosomes can change based on the physiological or pathological state of the parent cell. Cancer-derived exosomes, for example, often contain oncoproteins, growth factors, and matrix metalloproteinases that facilitate tumor progression [12] [16].

Nucleic Acid Cargo

Exosomes are rich in various nucleic acid species that can be transferred to recipient cells to alter gene expression and cellular function:

RNAs: Exosomes contain diverse RNA populations, including messenger RNAs (mRNAs), microRNAs (miRNAs), long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs), transfer RNAs (tRNAs), ribosomal RNAs (rRNAs), and other non-coding RNAs [10] [15] [16]. miRNAs are among the most studied exosomal RNAs, with demonstrated roles in post-transcriptional regulation in recipient cells.

DNA Content: Exosomes can carry various forms of DNA, including single-stranded DNA, double-stranded DNA, mitochondrial DNA, and even genomic DNA fragments, particularly from cancer cells [15] [16]. This DNA content has implications for both disease diagnosis and progression.

Lipid Composition

The lipid bilayer of exosomes is enriched in specific lipid species that contribute to their structure and function:

Table 2: Major Lipid Components of Exosomes

| Lipid Category | Specific Molecules | Functional Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Structural Lipids | Cholesterol, Phosphatidylserine, Phosphatidylcholine | Membrane integrity, rigidity, and stability |

| Sphingolipids | Ceramide, Sphingomyelin | Membrane curvature, microdomain formation, signaling |

| Glycolipids | Gangliosides, Glycosphingolipids | Cell recognition, adhesion, and receptor function |

| Phospholipids | Lysobisphosphatidic acid (LBPA) | Endosomal membrane organization, Alix interaction |

This unique lipid composition not only provides structural stability but also facilitates exosome uptake by recipient cells and participates in cellular signaling pathways [10] [15].

MSC-Derived Exosomes as Therapeutic Agents

Mesenchymal stromal/stem cells (MSCs) have demonstrated significant potential in regenerative medicine and immunomodulation. However, growing evidence indicates that many of their therapeutic effects are mediated primarily through paracrine factors, with exosomes emerging as key mediators [11] [2] [14]. MSC-derived exosomes (MSC-Exos) retain the biological activity of their parent cells while offering several advantages as cell-free therapeutics.

Functional Mechanisms of MSC-Exos

MSC-Exos exert their therapeutic effects through multiple interconnected mechanisms:

Immunomodulation: MSC-Exos can modulate immune responses by transferring regulatory molecules to immune cells. They have been shown to promote anti-inflammatory M2 macrophage polarization, suppress T-cell proliferation, and increase regulatory T-cell populations through the transfer of miRNAs like miR-21, miR-146a, and miR-181, as well as immunomodulatory proteins [11] [17].

Tissue Regeneration: MSC-Exos enhance tissue repair by stimulating angiogenesis, cell proliferation, and differentiation while inhibiting apoptosis. For instance, in wound healing models, MSC-Exos accelerate re-epithelialization, collagen deposition, and neovascularization by activating Wnt/β-catenin and AKT signaling pathways [17].

Anti-fibrotic Effects: In models of organ fibrosis (liver, kidney, lung), MSC-Exos have demonstrated the ability to reduce fibrotic tissue formation by decreasing the activation of profibrotic pathways and reducing extracellular matrix deposition [11].

Neuroprotection: MSC-Exos support neuronal survival and regeneration in neurological disorders by transferring neuroprotective factors, promoting neurite outgrowth, and modulating inflammatory responses in the central nervous system [5].

Comparative Analysis: MSC-Exos vs. Whole Cell Therapy

The transition from MSC-based cell therapy to exosome-based cell-free therapy represents a paradigm shift in regenerative medicine. The table below provides a direct comparison of these two approaches:

Table 3: Functional Comparison: MSC-Derived Exosomes versus Whole Cell Therapy

| Parameter | MSC-Derived Exosomes | Whole MSC Therapy |

|---|---|---|

| Therapeutic Cargo | Proteins, lipids, nucleic acids (pre-packaged) | Live cells producing various factors |

| Immunogenicity | Low (reduced MHC expression) | Moderate to high (risk of immune recognition) |

| Tumor Risk | Minimal (non-replicative) | Potential concern with uncontrolled differentiation |

| Delivery Safety | Reduced risk of vascular occlusion (nanoscale) | Risk of pulmonary embolism (microscale cells) |

| Production & Storage | More stable, suitable for off-the-shelf use | Cryopreservation challenges, viability concerns |

| Dosing Precision | Quantifiable by particle count or protein content | Challenging (cell number ≠ functional potency) |

| Manufacturing | Scalable under GMP conditions | Complex expansion, higher contamination risk |

| Regulatory Pathway | Evolving as biological products/bioengineered drugs | Complex cellular therapy regulations |

| Targeting Potential | Modifiable surface for enhanced specificity | Limited homing efficiency, poor target retention |

| Mechanistic Clarity | Defined molecular cargoes | Multiple overlapping mechanisms |

Clinical Translation of MSC-Exos

The therapeutic potential of MSC-Exos is being actively explored in clinical settings. As of 2023, seven clinical studies have been published, and at least 14 clinical trials are registered, investigating MSC-Exos for conditions including acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), kidney diseases, graft-versus-host disease (GvHD), osteoarthritis, stroke, Alzheimer's disease, and type 1 diabetes [5]. These studies utilize MSC-Exos from various sources, with adipose tissue being the most common (7 studies), followed by bone marrow (5 studies) and umbilical cord (4 studies) [5].

Dosing in these clinical studies varies considerably, with some calculating exosome amount by weight (micrograms), others by particle number, and some simply stating the number of MSCs used to generate the exosomes [5]. This highlights the need for standardization in exosome quantification and dosing protocols for clinical applications.

Experimental Methodologies in Exosome Research

Robust experimental protocols are essential for advancing exosome research and therapeutic applications. This section outlines key methodologies for exosome isolation, characterization, and functional analysis.

Exosome Isolation Techniques

Several methods are employed for exosome isolation, each with distinct advantages and limitations:

Ultracentrifugation-Based Methods

Differential Ultracentrifugation (DUC): This remains the gold standard and most widely used method (approximately 56% of studies) [14]. The protocol involves sequential centrifugation steps: (1) 300 × g for 10 min to remove cells; (2) 2,000 × g for 10 min to remove cell debris; (3) 10,000 × g for 30 min to remove larger vesicles and organelles; and (4) 100,000-120,000 × g for 70 min to pellet exosomes. The final pellet is resuspended in PBS or appropriate buffer [14]. While suitable for large volumes, DUC may co-isolate non-exosomal components like protein aggregates and lipoproteins.

Density Gradient Ultracentrifugation (DGUC): This method provides higher purity by separating vesicles based on buoyant density in iodixanol, CsCl, or sucrose gradients [14]. Exosomes typically band at densities of 1.13-1.19 g/ml in sucrose gradients. Though more time-consuming, DGUC effectively separates exosomes from soluble proteins and other contaminants.

Alternative Isolation Methods

Tangential Flow Filtration (TFF): This size-based filtration method uses hollow fiber membranes to concentrate and purify exosomes from large volume samples [5]. TFF offers advantages for scalable GMP-compliant production and has been used in some clinical trials [5].

Precipitation Methods: Commercial polymer-based kits precipitate exosomes by reducing their solubility. While user-friendly and rapid, these methods may co-precipitate non-vesicular contaminants.

Immunoaffinity Capture: Antibodies against exosome surface markers (CD9, CD63, CD81) enable highly specific isolation but may select subpopulations and are less suitable for large-scale preparation.

Exosome Characterization

Comprehensive exosome characterization should include multiple complementary approaches, following MISEV2018 guidelines [5]:

Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis (NTA): Determines particle size distribution and concentration based on Brownian motion.

Electron Microscopy: Visualizes exosome morphology, typically showing cup-shaped structures after chemical fixation and dehydration.

Western Blotting: Confirms presence of exosome markers (CD9, CD63, CD81, TSG101, Alix) and absence of negative markers (calnexin, GM130).

Flow Cytometry: Enumerates exosomes and detects surface markers using antibody-conjugated beads or high-sensitivity flow cytometers.

Functional Assays for MSC-Exos

To evaluate the therapeutic potential of MSC-Exos, researchers employ various functional assays:

In Vitro Uptake Studies: Fluorescent labeling (PKH67, DID) followed by confocal microscopy or flow cytometry to track exosome internalization by recipient cells.

Migration/Proliferation Assays: Scratch/wound healing assays, Transwell migration chambers, and MTT/XTT assays to assess effects on cell motility and growth.

Angiogenesis Assays: Tube formation assays using endothelial cells on Matrigel to evaluate pro-angiogenic properties.

Immunomodulation Assays: Mixed lymphocyte reactions, T-cell proliferation assays, and macrophage polarization studies to assess immune regulatory functions.

Animal Disease Models: In vivo administration in clinically relevant models (e.g., myocardial infarction, skin wounds, neurological disorders) to evaluate therapeutic efficacy.

Figure 2: Experimental Workflow for Exosome Research. This diagram outlines the key steps in exosome isolation, characterization, and functional analysis, highlighting major methodological approaches at each stage.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful exosome research requires specialized reagents and materials for isolation, characterization, and functional analysis. The following table details essential tools for working with MSC-derived exosomes:

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Exosome Studies

| Category | Specific Reagents/Materials | Primary Application | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Isolation Materials | Polycarbonate ultracentrifuge bottles/tubes, 0.22μm filters, Sucrose/iodixanol gradients, Tangential Flow Filtration systems | Exosome purification | Choose appropriate tube materials compatible with high g-forces; pre-clear samples to reduce contaminants |

| Characterization Antibodies | Anti-CD63, Anti-CD9, Anti-CD81, Anti-TSG101, Anti-Alix, Negative markers (Calnexin, GM130) | Exosome identification and validation | Combine multiple positive markers for definitive identification; include negative controls |

| Visualization Reagents | PKH67/PKH26 lipophilic dyes, DID membrane labels, Colloidal gold (EM), Uranyl acetate (negative staining) | Exosome tracking and morphology | Optimize dye concentration to avoid aggregation artifacts; use appropriate fixation for EM |

| Functional Assay Kits | MTT/XTT cell proliferation kits, Transwell migration chambers, Matrigel for tube formation, ELISA cytokine panels | Assessment of exosome bioactivity | Include appropriate controls (e.g., donor cell-conditioned media, heat-inactivated exosomes) |

| Molecular Analysis Tools | RNA isolation kits (with small RNA protection), Protease inhibitors, BCA/ Bradford protein assays, RNA sequencing libraries | Cargo analysis | Implement rigorous quality control for RNA/protein extraction from limited exosome samples |

| Animal Study Materials | In vivo imaging systems, Fluorescent dyes (DIR/DID), IVIS imaging chambers, Tissue fixation/permeabilization buffers | In vivo tracking and efficacy | Consider route of administration (IV, local, inhalation) based on target tissue |

Exosomes represent sophisticated natural nanovehicles that play essential roles in intercellular communication, particularly as key messengers for MSC-mediated therapeutic effects. Their defined biogenesis pathways, selective cargo loading mechanisms, and ability to horizontally transfer bioactive molecules position them as crucial components of the MSC paracrine system. The comparative analysis presented in this review demonstrates that MSC-derived exosomes offer significant advantages over whole cell therapies, including reduced risks, improved safety profiles, and more precise therapeutic targeting.

As the field advances, standardizing isolation protocols, enhancing exosome engineering for specific targeting, and establishing regulatory frameworks will be critical for clinical translation. The ongoing clinical trials with MSC-derived exosomes highlight the growing interest in this cell-free therapeutic approach. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding the fundamental biology of exosomes and their functional comparison with whole cell therapies provides a foundation for developing next-generation regenerative medicines that leverage the natural communicative properties of these remarkable extracellular vesicles.

The field of regenerative medicine is witnessing a paradigm shift from whole-cell therapies toward cell-free approaches utilizing extracellular vesicles (EVs). Mesenchymal stromal/stem cells (MSCs) have been central to this evolution, with their therapeutic effects increasingly attributed to paracrine signaling rather than direct cell replacement [18]. This guide provides a detailed comparison of the physical and functional properties of MSC-derived exosomes (MSC-Exos) versus whole MSC therapies, offering researchers a scientific framework for therapeutic development. MSC-Exos represent a distinct class of nanoscale biologics with unique biophysical characteristics that fundamentally differentiate them from cellular therapeutics [19] [18]. Understanding these differences is critical for selecting appropriate therapeutic platforms for specific applications in drug development.

Physical and Biological Properties Comparison

Table 1: Comparative physical and biological properties of MSC-derived exosomes versus whole MSCs

| Property | MSC-Derived Exosomes | Whole MSC Therapeutics |

|---|---|---|

| Size Range | 30-150 nm [18] [20] | 15-30 μm (cellular scale) [19] |

| Structure | Lipid bilayer vesicles, no organelles [20] | Complete cellular structure with organelles [19] |

| Biogenesis | Endosomal pathway via multivesicular bodies [18] [20] | Cell division and differentiation [19] |

| Cargo Content | Proteins, lipids, nucleic acids (miRNA, mRNA) [18] | Complete cellular machinery, organelles, genetic material [19] |

| Primary Mechanism | Paracrine signaling via biomolecule transfer [18] | Direct differentiation and paracrine signaling [19] |

| Blood-Brain Barrier Penetration | Demonstrated capability [21] [22] | Limited without disruption [18] |

| Storage Requirements | -80°C with stabilizers; avoid freeze-thaw cycles [23] | Cryopreservation with DMSO; requires viability testing [18] |

| Circulation Half-life | Approximately 10-30 minutes post-IV injection [21] | Short persistence; rapid clearance after administration [18] [24] |

| Immunogenicity | Low; lack MHC complexes [18] | Low but present; risk of immune rejection [18] |

| Tumorigenic Risk | Minimal; non-replicative [18] | Theoretical concerns despite low probability [18] |

| Scalable Production | Challenging; requires advanced bioreactor systems [18] | Established expansion protocols [18] |

Experimental Methodologies for Characterization

Isolation and Purification Protocols

MSC-Exos Isolation Techniques

- Ultracentrifugation: Considered the gold standard; involves sequential centrifugation steps to remove cells, debris, and larger vesicles, followed by high-speed centrifugation (100,000-120,000 × g) to pellet exosomes [23]. Limitations include time consumption, requirement for large sample volumes, and potential for protein co-precipitation [23].

- Size-Exclusion Chromatography: Separates vesicles based on hydrodynamic radius; preserves vesicle integrity and functionality while providing high purity by effectively removing contaminating proteins [23].

- Polymer-Based Precipitation: Utilizes hydrophilic polymers to decrease exosome solubility; enables rapid processing with good recovery but may yield lower purity with co-precipitation of contaminants [23].

- Tangential Flow Filtration: Suitable for large-scale production; uses membrane filters with specific molecular weight cutoffs to concentrate and purify exosomes from large volume samples [23].

MSC Culture and Expansion

- Source Materials: Isolate MSCs from bone marrow, adipose tissue, umbilical cord, or placental compartments [18] [25].

- Culture Conditions: Maintain in serum-free or xeno-free media with essential growth factors (FGF-2, PDGF) at 37°C with 5% CO₂ [18].

- Characterization: Verify MSC identity through flow cytometry for CD73, CD90, CD105 positivity and CD34, CD45 negativity; demonstrate trilineage differentiation potential (osteogenic, adipogenic, chondrogenic) [23].

Characterization Techniques

Physical Characterization

- Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis: Quantifies particle concentration and size distribution by tracking Brownian motion [23].

- Dynamic Light Scattering: Determines hydrodynamic diameter and size distribution [23].

- Transmission Electron Microscopy: Visualizes ultrastructure and morphology; confirms cup-shaped morphology characteristic of exosomes [23].

- Resistive Pulse Sensing: Measures particle size distribution and concentration based on electrical impedance [23].

Molecular Characterization

- Western Blot: Detects exosomal markers (CD9, CD63, CD81, TSG101, ALIX) and absence of negative markers (GM130, calnexin) [23].

- RNA Sequencing: Profiles miRNA, mRNA, and other RNA species in exosomal cargo [24].

- Proteomic Analysis: Identifies protein composition through mass spectrometry [18].

- Lipidomic Analysis: Characterizes lipid composition of exosomal membranes [18].

Therapeutic Mechanisms and Signaling Pathways

MSC-Exos Mechanisms of Action

Diagram 1: MSC-Exos therapeutic mechanisms via biomolecule transfer

MSC-Exos exert therapeutic effects through multiple interconnected mechanisms. They facilitate intercellular communication by transferring functional miRNAs, proteins, and lipids to recipient cells, modulating key biological processes including immunoregulation, tissue repair, and cellular metabolism [18] [24]. Specific miRNAs such as miR-146a, miR-21, and miR-181a play crucial roles in mediating these effects, particularly in modulating inflammatory responses and promoting tissue regeneration [24].

Whole MSC Therapeutic Mechanisms

Diagram 2: Whole MSC therapeutic mechanisms and limitations

Whole MSCs function through more complex mechanisms including direct differentiation into tissue-specific cells, extensive paracrine signaling, cell-cell contact mediated effects, and even mitochondrial transfer to damaged cells [19] [18]. However, these mechanisms are constrained by practical limitations including low engraftment rates, short in vivo lifespan, and potential safety concerns that have motivated the shift toward MSC-Exos [18] [24].

Research Reagent Solutions Toolkit

Table 2: Essential research reagents and materials for MSC and MSC-Exos research

| Category | Specific Reagents/Materials | Research Application | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Isolation Kits | Total Exosome Isolation Kits, ExoQuick-TC | MSC-Exos precipitation from conditioned media | Polymer-based; suitable for small volumes [23] |

| Chromatography | qEV Original Columns, SEPAX Nanobio Analyzer | Size-based MSC-Exos separation | Preserves vesicle integrity; ideal for functional studies [23] |

| Characterization | CD9/CD63/CD81 antibodies, TSG101, ALIX | MSC-Exos identification via Western blot | Confirm exosomal markers; check for contaminants [23] |

| Cell Culture | Serum-free MSC media, FGF-2, PDGF-AB | MSC expansion and conditioning | Maintain stemness; prevent differentiation [18] |

| Preconditioning | LPS, TNF-α, IL-1β, hypoxia chambers | Enhance therapeutic potential of MSC-Exos | Modifies miRNA content (e.g., increases miR-146a) [24] |

| Storage | Trehalose, BSA, DMSO, cryovials | Preservation of MSC-Exos and MSCs | Avoid freeze-thaw cycles; use stabilizers for MSC-Exos [23] |

| Imaging | NIR-II fluorescent probes, lipophilic dyes | In vivo tracking of MSC-Exos biodistribution | Real-time visualization of pharmacokinetics [23] |

| Engineering | CRISPR/Cas9 systems, transfection reagents | Genetic modification of MSCs for enhanced MSC-Exos production | Modify parent MSCs to alter MSC-Exos cargo [21] |

Discussion and Future Perspectives

The comparative analysis reveals distinct advantages and limitations for both therapeutic platforms. MSC-Exos offer significant safety benefits with lower immunogenicity and tumorigenic potential, coupled with enhanced biodistribution capabilities including blood-brain barrier penetration [21] [18]. However, challenges remain in scalable production, standardization, and rapid clearance post-administration [21] [18].

Whole MSCs provide the complete cellular machinery for complex tissue integration but face challenges with inconsistent engraftment, potential embolic risks, and storage complications [18]. Current research focuses on engineering approaches to enhance MSC-Exos targeting and therapeutic efficacy through surface modifications and cargo loading [21]. Genetic engineering of parent MSCs enables production of MSC-Exos with enhanced therapeutic cargo, while chemical modification and membrane fusion techniques allow for improved tissue-specific targeting [21]. These advancements position MSC-Exos as increasingly viable alternatives to whole-cell therapies across multiple therapeutic domains, particularly for neurological disorders, cardiovascular diseases, and immune modulation [21] [18] [22].

The field of regenerative medicine has been significantly shaped by the therapeutic potential of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), which have demonstrated robust capabilities in modulating immune responses and promoting tissue repair. However, the clinical application of whole MSC therapies faces significant challenges, including low cell survival rates after transplantation, potential immune rejection, and ethical concerns [26]. In recent years, a paradigm shift has occurred towards understanding that many of the therapeutic benefits of MSCs are mediated through their paracrine activity, particularly via the release of extracellular vesicles [5]. Among these vesicles, exosomes—nanosized extracellular vesicles (30-150 nm in diameter) released by MSCs—have emerged as a promising cell-free therapeutic alternative [26] [3].

MSC-derived exosomes (MSC-Exos) are lipid-bilayer enclosed vesicles that carry a diverse array of bioactive molecules, including proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids (such as mRNA and microRNA), which they transfer to recipient cells to affect cellular processes [26] [27]. These "tiny giants of regeneration" share many therapeutic benefits with their parent MSCs but offer significant advantages, including lower immunogenicity, enhanced biological barrier penetration, avoidance of infusion-related toxicities, and easier storage stability [3]. This review comprehensively compares the mechanisms of action of MSC-derived exosomes against whole cell therapy across three critical domains: immunomodulation, tissue repair, and cross-barrier delivery, providing researchers and drug development professionals with an evidence-based assessment of these complementary therapeutic approaches.

Comparative Mechanisms of Action

Immunomodulatory Mechanisms

Whole MSC Immunomodulation: Whole MSCs exert their immunomodulatory effects through direct cell-cell contact and secretion of soluble factors. They interact with parenchymal cells and facilitate restoration of damaged tissues through the release of signaling molecules [4]. When activated by damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) and alarmins generated by damaged cells, MSCs inhibit apoptosis of unaffected parenchymal cells while suppressing inflammatory activity of monocytes, neutrophils, T lymphocytes, and natural killer (NK) cells [4]. Crucially, MSCs stimulate the production and development of immunosuppressive T regulatory cells (Tregs), resulting in the overall reduction of inflammation [4]. The immunomodulatory function of whole MSCs is dynamic and depends on the inflammatory microenvironment, requiring viable, functional cells that can respond to environmental cues.

MSC-Exos Immunomodulation: MSC-derived exosomes mediate immunomodulation through the transfer of bioactive molecules that regulate both innate and adaptive immune responses [4]. These nano-sized vesicles facilitate signal transmission via receptor-ligand interactions or endocytosis in recipient cells, delivering physiologically active chemicals, cytokines, chemokines, and immuno-regulatory factors to modulate cellular activity [4]. The mechanisms are more targeted and specific compared to whole MSCs:

B-Cell Regulation: MSC-Exos are internalized by activated CD19+/CD86+ B cells, resulting in the inhibition of B cell proliferation, differentiation, antibody production, and maturation of memory B cells [4]. They demonstrate dose-dependent anti-inflammatory effects by suppressing B cell maturation and promoting regulatory B cells (Bregs) in lymph nodes within disease models [4]. MSC-Exos prompt B cells to downregulate the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway via miR-155-5p, inhibiting B cell proliferation and diminishing the activation potential of B lymphocytes [4].

T-Cell Regulation: MSC-Exos carry anti-inflammatory molecules, including IL-10 and TGF-β, which help suppress excessive immune responses and modulate T-cell activity [27]. They inhibit T-cell proliferation and inflammatory responses through the transfer of specific miRNAs and proteins that alter signaling pathways in recipient immune cells [4].

Macrophage Polarization: MSC-Exos promote the transition of pro-inflammatory M1 macrophages to anti-inflammatory M2 phenotypes, supporting the resolution of inflammation and transition to tissue repair phases [28]. This polarization is crucial for orchestrating the transition from inflammatory to regenerative environments in damaged tissues.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Immunomodulatory Actions

| Immune Component | Whole MSC Therapy | MSC-Derived Exosomes |

|---|---|---|

| B-cells | Moderate suppression via direct contact and soluble factors | Strong suppression of proliferation, differentiation, and antibody production via miR-155-5p/PI3K/Akt pathway |

| T-cells | Direct interaction and stimulation of Treg production; context-dependent effects | Inhibition of proliferation via miRNA transfer; promotion of anti-inflammatory cytokine profiles |

| Macrophages | Paracrine signaling inducing M1 to M2 transition | Efficient macrophage polarization via exosomal cargo transfer |

| NK Cells | Suppression of inflammatory activity | Modulation of IFN-γ production and cytotoxic activity |

| Therapeutic Consistency | Variable based on cell viability and microenvironment | More consistent due to stable cargo composition |

| Onset of Action | Slower (requires cell engraftment and activation) | Faster (immediate delivery of bioactive molecules) |

Tissue Repair and Regenerative Mechanisms

Whole MSC Tissue Repair: Whole MSCs promote tissue repair through multiple parallel mechanisms. The primary approaches include direct differentiation into target cell types to replace damaged cells, secretion of growth factors and cytokines that promote endogenous repair processes, and extensive paracrine signaling that modulates the tissue microenvironment [29]. MSCs have the capability to differentiate into multiple cell types, including osteoblasts, chondrocytes, and adipocytes, making them ideal for repairing damaged tissues [29]. In the complex process of tissue repair, which involves hemostasis, inflammation, repair, and remodeling phases, MSCs participate by interacting with various immune cells to modulate the tissue microenvironment [28]. However, the effectiveness of whole MSCs depends on their successful migration to injury sites, adhesion, survival, retention, and functional integration into host tissues—factors that have proven challenging to control in clinical applications [3].

MSC-Exos Tissue Repair: MSC-derived exosomes promote tissue repair through the coordinated delivery of regenerative cargo to injured cells. As natural bioactive molecular carriers, MSC-Exos precisely regulate the inflammatory response, angiogenesis, and tissue repair processes in target tissues by delivering functional RNA, proteins, and other signaling elements [3]. The mechanisms include:

Anti-apoptotic Effects: MSC-Exos deliver miRNAs and proteins that inhibit programmed cell death in injured tissues, promoting cell survival and maintaining tissue architecture [27].

Angiogenic Induction: Through transfer of pro-angiogenic factors (such as miRNAs, proteins, and lipids), MSC-Exos stimulate the formation of new blood vessels, enhancing oxygen and nutrient supply to regenerating tissues [27] [3].

Stem Cell Recruitment and Activation: MSC-Exos promote the maintenance and recruitment of endogenous stem cells, amplifying the body's innate regenerative capacity without requiring exogenous cell engraftment [5].

Extracellular Matrix Remodeling: By delivering matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and their inhibitors, MSC-Exos facilitate the balanced remodeling of extracellular matrix components essential for functional tissue restoration [28].

Oxidative Stress Reduction: MSC-Exos contain and transfer antioxidant molecules that mitigate oxidative damage in inflamed or injured tissues, creating a more favorable microenvironment for regeneration [28].

Table 2: Tissue Repair Mechanisms Comparison

| Repair Mechanism | Whole MSC Therapy | MSC-Derived Exosomes |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Replacement | Direct differentiation and integration | Indirect stimulation of endogenous stem cells |

| Paracrine Signaling | Broad secretion of soluble factors | Targeted delivery via vesicular cargo |

| Angiogenesis | Factor secretion and sometimes pericyte-like function | Efficient induction via miRNA/protein transfer |

| Anti-apoptotic Effect | Moderate through secreted factors | Potent via direct delivery of anti-apoptotic miRNAs |

| Extracellular Matrix Modulation | Cell-mediated and paracrine actions | Delivery of MMPs and TIMPs for balanced remodeling |

| Therapeutic Window | Limited by cell survival | Extended due to sustained bioactivity of cargo |

Cross-Barrier Delivery Capabilities

Whole MSC Barrier Penetration: Whole MSCs, with diameters typically ranging from 30-60 μm, face significant challenges in traversing biological barriers [5]. After systemic administration, MSCs often become physically trapped in the lung microvasculature, with only a small percentage reaching the intended target tissues [5]. This limited barrier penetration necessitates higher cell doses to achieve therapeutic effects, increasing the risk of infusion-related toxicities, including pulmonary embolism [5]. While some MSCs can migrate to sites of injury following inflammatory cues, their relatively large size fundamentally limits their ability to cross tight physiological barriers like the blood-brain barrier (BBB) or penetrate deep into avascular or densely structured tissues.

MSC-Exos Barrier Penetration: MSC-derived exosomes demonstrate superior capabilities in crossing biological barriers, primarily due to their nanoscale size (30-150 nm) and natural biocompatibility [3] [30]. Their small dimensions and biological properties allow them to traverse protective barriers, including the blood-brain barrier, without causing embolism or transmission of infections [3]. The blood-brain barrier, which restricts the development of drug delivery systems for the brain, hinders the potential applications of numerous pharmaceutical agents for treating central nervous system diseases [31]. MSC-Exos overcome this limitation through multiple mechanisms:

Transcellular Penetration: Their lipid bilayer membrane enables fusion with cellular membranes, facilitating direct delivery of contents into the cytoplasm of target cells [3].

BBB Transcytosis: MSC-Exos can utilize various transcytosis mechanisms, including receptor-mediated transcytosis, to cross the tightly joined endothelial cells of the BBB [31] [30].

Enhanced Tissue Distribution: The small size of exosomes allows for more homogeneous distribution within tissues and access to compartments inaccessible to whole cells [3].

Multiple Administration Routes: MSC-Exos can be administered via various routes, including intravenous infusion, inhalation, or local administration, with studies showing different accumulation patterns based on the delivery method [5].

Table 3: Cross-Barrier Delivery Capabilities

| Delivery Parameter | Whole MSC Therapy | MSC-Derived Exosomes |

|---|---|---|

| Size Profile | 30-60 μm (cells) | 30-150 nm (vesicles) |

| BBB Penetration | Minimal to none | Efficient via transcytosis mechanisms |

| Lung Entrapment | Significant (~80% after IV administration) | Minimal due to nanoscale size |

| Tissue Distribution | Limited to perfused areas with appropriate cues | Wide distribution including avascular areas |

| Administration Routes | Primarily intravenous or local implantation | IV, inhalation, local, and even oral delivery possible |

| Targeting Efficiency | Limited homing relying on inflammatory signals | Enhancable via surface engineering |

Experimental Models and Methodologies

Standardized Isolation and Characterization Protocols

The isolation and characterization of MSC-derived exosomes require standardized methodologies to ensure reproducibility and reliability of experimental results. The most commonly used techniques include:

Isolation Methods:

- Ultracentrifugation: This remains the most frequently used method for isolating MSC-Exos in clinical trials. Suspension components are separated using centrifugation based on their sizes, shapes, densities, centrifugal vigor, and solvent stickiness. Significant centrifugal forces of up to 1,000,000×g are utilized in ultracentrifugation to separate MSC-Exos from various sample components [5].

- Tangential Flow Filtration (TFF): This method concentrates conditioned medium and purifies MSC-Exos based on vesicle sizes. A cell culture medium is filtered with a sterile hollow fiber polyether-sulfone membrane with a specific pore size (in µm) to remove cell debris and retain biomolecules. After washing with sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), the MSC-Exos are concentrated and diafiltrated using a sucrose buffer [5].

- Size-Exclusion Chromatography: This technique separates vesicles based on size through a porous stationary phase, providing high purity exosome preparations suitable for therapeutic applications [30].

Characterization Protocols: MSC-Exos intended for research or clinical applications should meet the minimal characterization criteria for extracellular vesicles as stated in the MISEV2018 guidelines, which include both marker and physical characterizations [5]. Marker characterization should be evaluated by:

- Positive presence of transmembrane proteins (e.g., CD9, CD63, CD81)

- Presence of cytosolic proteins (e.g., TSG101, Alix)

- Negative markers (e.g., absence of endoplasmic reticulum proteins such as calnexin) Physical characterization includes:

- Nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA) for size distribution and concentration

- Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) for morphological assessment

- Dynamic light scattering (DLS) for hydrodynamic diameter measurement [5]

In Vitro and In Vivo Experimental Models

Immunomodulation Assays:

- T-cell and B-cell Proliferation Assays: MSC-Exos are co-cultured with activated immune cells using mitogens like phytohemagglutinin (PHA) or anti-CD3/CD28 antibodies. Proliferation is measured via 3H-thymidine incorporation or CFSE dilution using flow cytometry [4].

- Macrophage Polarization Models: Human monocyte cell lines (THP-1) or primary monocytes are differentiated into macrophages and treated with MSC-Exos alongside polarizing cytokines (IFN-γ/LPS for M1; IL-4/IL-13 for M2). Polarization is assessed via surface marker expression (CD80/CD86 for M1; CD206/CD163 for M2) and cytokine secretion profiles [28] [4].

- Mixed Lymphocyte Reaction (MLR): This assay evaluates the effect of MSC-Exos on T-cell activation in response to allogeneic antigens, measuring the suppression of proliferation and inflammatory cytokine production [4].

Tissue Repair Models:

- Wound Healing Assays: In vitro scratch assays using fibroblast or epithelial cell lines evaluate the effect of MSC-Exos on cell migration and gap closure rates [3].

- Angiogenesis Assays: Tube formation assays using human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) on Matrigel quantify the pro-angiogenic potential of MSC-Exos by measuring tube length, branching points, and network complexity [3].

- Organoid and 3D Culture Models: Complex 3D tissue models incorporating multiple cell types provide more physiologically relevant systems for evaluating the regenerative effects of MSC-Exos on tissue morphogenesis and function [3].

Blood-Brain Barrier Penetration Studies:

- In Vitro BBB Models: Transwell systems with brain microvascular endothelial cells cultured on porous membranes recreate the BBB. The permeability of fluorescently labeled MSC-Exos is measured and compared to whole MSCs [31] [30].

- In Vivo Tracking Studies: MSC-Exos are labeled with near-infrared dyes or radioactive tags and administered to animal models. Biodistribution is tracked using imaging systems (IVIS, PET) and ex vivo tissue analysis [30].

- Disease-Specific Animal Models: Neurological disorder models (stroke, Alzheimer's, Parkinson's) are used to evaluate the therapeutic efficacy of MSC-Exos compared to whole MSCs, assessing functional recovery, biomarker modulation, and target engagement [31] [30].

Signaling Pathways and Molecular Mechanisms

Key Signaling Pathways in Immunomodulation

The immunomodulatory effects of MSC-derived exosomes are mediated through several key signaling pathways that regulate immune cell function and inflammatory responses:

Diagram 1: Immunomodulatory Signaling Pathways Activated by MSC-Derived Exosomes

Tissue Repair and Regenerative Pathways

MSC-derived exosomes activate multiple interconnected signaling pathways that coordinate tissue repair processes:

Diagram 2: Tissue Repair Pathways Activated by MSC-Derived Exosomes

Research Reagent Solutions Toolkit

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for MSC-Exosome Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Isolation Kits | Total Exosome Isolation Kit, exoEasy Maxi Kit | Exosome purification from conditioned media | Rapid isolation with minimal equipment requirements |

| Characterization Antibodies | Anti-CD63, CD81, CD9, TSG101, Alix, Calnexin | Western blot, flow cytometry, immuno-EM | Confirmation of exosomal identity and purity |

| Tracking Dyes | PKH67, PKH26, DiD, DiR, CFSE | In vitro and in vivo tracking | Visualization of exosome uptake and biodistribution |

| Cell Culture Media | Serum-free MSC media, exosome-depleted FBS | MSC expansion and exosome production | Ensuring consistent exosome yield without serum contaminants |

| Analysis Instruments | Nanoparticle Tracking Analyzer, DLS, TEM | Physical characterization | Size distribution and morphological assessment |

| ELISA/Kits | TNF-α, IL-10, TGF-β, IFN-γ ELISA kits | Immunomodulation assessment | Quantification of inflammatory mediators |

| Animal Models | CIA mice, EAE mice, stroke models | In vivo efficacy testing | Disease-specific therapeutic evaluation |

The comparative analysis of MSC-derived exosomes versus whole cell therapy reveals a complex landscape of complementary mechanisms with distinct advantages for each approach. Whole MSC therapies offer the potential for direct cellular integration and dynamic response to microenvironments but face significant challenges related to cell viability, consistency, and biological barrier penetration. In contrast, MSC-derived exosomes provide a cell-free alternative with enhanced targetability, superior safety profile, and remarkable stability, though they may lack the adaptive responsiveness of living cells.

From a functional outcomes perspective, MSC-exosomes demonstrate particular strength in applications requiring precise immunomodulation, efficient biological barrier crossing (especially CNS targets), and reduced risk of infusion-related adverse events. Whole MSC therapies may still hold advantages in scenarios requiring continuous, adaptive paracrine signaling or direct cellular integration, though the evidence for meaningful long-term engraftment remains limited.

For researchers and drug development professionals, the choice between these therapeutic modalities should be guided by specific disease pathophysiology, target tissue accessibility, and desired mechanism of action. Future research directions should focus on standardizing isolation protocols, engineering exosomes for enhanced targeting, and conducting direct comparative studies in disease-relevant models. As the field advances, MSC-derived exosomes represent a promising next-generation therapeutic tool that may overcome many of the limitations associated with whole cell therapies while harnessing the fundamental regenerative capabilities of mesenchymal stem cells.

From Bench to Bedside: Production, Isolation, and Therapeutic Applications

The field of regenerative medicine is undergoing a significant transformation, moving from whole cell-based therapies toward acellular strategies that offer enhanced safety and scalability. Within this context, Mesenchymal Stem Cell (MSC)-derived exosomes have emerged as a potent therapeutic alternative, mirroring the regenerative and immunomodulatory functions of their parent cells without the associated risks of immunogenicity, infusion toxicity, or tumorigenicity [32] [3]. The efficacy of these exosomes, however, is critically dependent on the methods used for their production and isolation. This guide provides a objective comparison of two core isolation techniques—ultracentrifugation (UC) and tangential flow filtration (TFF)—framed within the broader thesis that MSC-derived exosomes represent a superior functional outcome to whole cell therapy for research and clinical applications.

The Superiority of MSC-Derived Exosomes Over Whole Cell Therapy

The therapeutic application of MSCs, while promising, is fraught with challenges that hinder clinical translation. MSC-derived exosomes present a viable solution to these limitations, offering a more controlled and safer therapeutic profile.

Table 1: Functional Advantages of MSC-Derived Exosomes vs. Whole Cell Therapy

| Aspect | Whole MSC Therapy | MSC-Derived Exosome Therapy | Key Advantage of Exosomes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Immunogenicity | Higher risk of immune rejection [3] | Low immunogenicity; non-immunogenic [32] [3] | Reduced risk of adverse reactions |

| Tumorigenic Risk | Potential for ectopic tissue formation or uncontrolled differentiation [32] | No risk of tumorigenicity [32] [33] | Enhanced safety profile |

| Delivery & Engraftment | Poor engraftment; cells can lodge in lung microvasculature [33] | Can cross biological barriers; no risk of vascular occlusion [3] | Superior biodistribution and targeting |

| Storage & Stability | Requires cryopreservation; sensitive to freeze-thaw cycles [3] | Stable at -80°C for long periods; retains activity [3] | Simplified logistics and storage |

| Production Scalability | Difficult to scale; senesce during in vitro expansion [33] | Scalable production using bioreactors and advanced isolation [34] [3] | More feasible for industrial production |

| Therapeutic Mechanism | Complex, paracrine and cell-contact dependent [3] | Defined, primarily via delivery of cargo (proteins, RNA) [3] [33] | More predictable and reproducible effects |

The consensus from recent literature is that the therapeutic benefits of MSCs are largely mediated by their paracrine secretions, with exosomes being a key effector [3] [33]. These nanosized vesicles act as natural delivery systems, transferring functional proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids to recipient cells to promote processes like tissue regeneration, immunomodulation, and angiogenesis [32] [33]. This positions exosomes as the active pharmaceutical ingredient, making their high-quality, scalable isolation a paramount research and clinical objective.

Optimizing the Starting Material: Culture Media and Systems

The yield and potency of exosomes are profoundly influenced by the culture conditions of the parent MSCs.

- 3D Culture Systems: Transitioning from traditional 2D flasks to 3D cultures, such as microcarrier-based bioreactors, has been shown to dramatically increase exosome yield. One study demonstrated that 3D culture yielded 20-fold more exosomes than 2D culture when combined with differential ultracentrifugation. When further paired with TFF, the yield was 7-fold higher than the 3D-UC output [34].

- Media Composition and Stimulation: The biochemical environment, including oxygen tension and the presence of specific cytokines (e.g., IFN-γ, TNF-α), can influence the cargo and subsequent biological activity of the harvested exosomes [3]. For consistent results, the use of EV-depleted fetal bovine serum (FBS) in culture media is essential to avoid contamination with bovine vesicles [35].

Head-to-Head Comparison: Ultracentrifugation vs. Tangential Flow Filtration

The isolation method is a critical determinant of exosome yield, purity, and, most importantly, biological functionality. The following experimental data and workflows compare the two primary techniques.

Experimental Protocols for Direct Comparison

To ensure a fair comparison, studies have directly contrasted UC and TFF, often with a subsequent polishing step like Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC) to enhance purity.

Protocol for Ultracentrifugation (UC-SEC):

- Clarification: Conditioned media is centrifuged at 500 × g for 10 minutes to remove detached cells [35].

- Filtration: The supernatant is filtered through a 0.22 µm filter to remove large debris and particles [35].

- Ultracentrifugation: The clarified media is centrifuged at high force (e.g., 100,000 × g) for 70-120 minutes at 4°C to pellet crude exosomes [36] [35].

- Washing (Optional): The pellet is resuspended in PBS and subjected to a second round of ultracentrifugation [35].

- Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC): The final pellet is resuspended and loaded onto a SEC column (e.g., qEV columns) to separate exosomes from contaminating proteins [36].

Protocol for Tangential Flow Filtration (TFF-SEC):

- Clarification & Filtration: Identical to the UC protocol (steps 1-2) [35].

- Concentration & Diafiltration: The clarified media is processed through a TFF system. The flow is directed tangentially across a membrane (typically with a pore size of 100-500 kDa), concentrating the exosomes and simultaneously exchanging the buffer (e.g., from culture media to PBS) [36] [37].

- Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC): The concentrated retentate is then purified using SEC to remove soluble protein contaminants, yielding a pure exosome preparation [36] [35].

Quantitative Performance Data

Direct comparisons in rigorous studies reveal clear performance differences between the two isolation methodologies.

Table 2: Experimental Outcome Comparison: UC-SEC vs. TFF-SEC

| Performance Metric | Ultracentrifugation-SEC (UC-SEC) | Tangential Flow Filtration-SEC (TFF-SEC) | Experimental Details |

|---|---|---|---|

| Particle Yield | Baseline (Reference) | Up to 23-fold higher than UC-SEC [36] | Tunable Resistive Pulse Sensing (qNano) analysis [36] |

| Process Time | > 4 hours [36] [37] | < 4 hours; >40% time saving [36] [37] | For processing large volume samples [36] |

| Cost & Scalability | Limited scale; high cost for large volumes [36] | Highly scalable; cost < one tenth of UC [36] | Suitable for industrial-scale production [36] [37] |

| Exosome Integrity | Risk of damage/aggregation from high g-forces [36] [35] | Gentle process; preserves integrity & function [36] [37] | TEM shows cup-shaped morphology for both [36] |

| Purity | Moderate; co-isolation of contaminants [35] [37] | Similar particle-to-protein ratio; high purity with SEC [36] | Nano-flow cytometry confirmed specific markers [36] |

| Functional Potency | N/A | 7x more potent in siRNA delivery to neurons [34] | Comparison of 3D-TFF-exosomes vs 2D-UC-exosomes [34] |

The data consistently demonstrates that TFF surpasses UC in critical areas for research and development: it provides a substantially higher yield of functional exosomes in a shorter time and at a lower cost, making it inherently more scalable [36] [34] [35].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Successful isolation of MSC-derived exosomes requires specific reagents and equipment to ensure quality and reproducibility.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Exosome Isolation

| Item | Function in Protocol | Example / Specification |

|---|---|---|

| EV-Depleted FBS | Provides growth nutrients for MSC culture without contaminating the sample with bovine vesicles [35]. | Ultracentrifuged or commercially available EV-depleted FBS. |

| TFF System & Membranes | Concentrates and purifies exosomes from large volumes of conditioned media via cross-flow filtration [37]. | Systems from Pall (Minimate), Spectrum Labs; 100-500 kDa MWCO membranes. |

| Size Exclusion Columns | Polishing step to remove contaminating proteins and other soluble factors from exosome preparations [36]. | qEV columns (Izon Science) or Sepharose-based CL-2B columns. |

| Ultracentrifuge & Rotors | High-speed centrifugation to pellet exosomes based on density and size (for UC protocol) [35]. | Beckman Coulter Optima XPN with Type 50.2 Ti fixed-angle rotor. |

| Characterization Reagents | Validate exosome identity, size, and concentration after isolation. | Antibodies for tetraspanins (CD63, CD81, CD9); NTA for size distribution. |

Within the evolving paradigm that prioritizes MSC-derived exosomes over whole cell therapy, the choice of isolation technique is a cornerstone of successful research and translation. The experimental data leads to a clear conclusion: Tangential Flow Filtration (TFF), coupled with a polishing step like SEC, presents a superior isolation strategy for most applications, particularly those requiring scalability, high yield, and preserved biological function.

While ultracentrifugation remains a widely used benchmark, its drawbacks in yield, scalability, and potential for vesicle damage are significant [36] [35]. TFF effectively addresses these limitations, enabling the robust production of functional exosomes necessary for both advanced in vitro studies and the growing pipeline of clinical trials [3] [33]. For researchers aiming to optimize the production of therapeutic MSC-derived exosomes, investing in TFF methodology is a rational and data-supported decision.

In the evolving landscape of regenerative medicine, mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes (MSC-Exos) have emerged as a promising cell-free therapeutic tool, offering significant advantages over whole MSC therapy. These nano-sized extracellular vesicles (30-150 nm in diameter) encapsulate the therapeutic paracrine potential of their parent cells—carrying proteins, lipids, mRNAs, and microRNAs—while mitigating risks associated with whole-cell transplantation, such as infusion-related toxicities, pulmonary embolism, and tumorigenicity [2] [3] [5]. The efficacy of these "tiny giants of regeneration," however, is profoundly influenced by the administration route, which determines their biodistribution, targeting efficiency, and therapeutic potency [38] [5]. This guide provides a detailed comparative analysis of the three primary administration routes—intravenous infusion, local injection, and nebulized inhalation—to inform preclinical and clinical protocol development.

Comparative Analysis of Administration Routes

Table 1: Direct Comparison of MSC-Derived Exosome Administration Routes

| Parameter | Intravenous Infusion | Local Injection | Nebulized Inhalation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Key Characteristics | Systemic delivery; broad distribution [5] | Direct targeting to a specific site [5] | Local delivery to the respiratory tract [39] |

| Primary Advantages | Suitable for systemic conditions (e.g., GvHD, systemic lupus) [5] | High local concentration; avoids first-pass metabolism [5] | Non-invasive; direct targeting to lungs; superior safety profile [38] [39] [40] |

| Key Limitations | Rapid clearance; potential accumulation in liver/spleen; lower disease-site bioavailability [5] | Invasive; not suitable for disseminated diseases [5] | Limited application to respiratory diseases [39] |

| Typical Doses in Clinical Trials | Varied units (μg, particle number); often higher doses required [38] [5] | Dependent on target tissue/organ [5] | ~10^8 particles (notably lower than IV doses for similar efficacy in lung diseases) [38] |

| Common Clinical Applications | GvHD, ARDS, stroke, type 1 diabetes [5] | Osteoarthritis, wound healing, Alzheimer's disease (intranasal) [5] | ARDS, COVID-19, lung fibrosis, bronchopulmonary dysplasia [38] [39] |

| Therapeutic Efficacy | Well-documented for immunomodulation [5] | High efficacy in localized tissue repair [3] [5] | High clinical efficacy rates in lung diseases; can achieve effects at lower doses than IV [38] [41] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

The following section outlines standard experimental protocols for evaluating administration routes, reflecting current practices in clinical trials and preclinical studies.

Protocol for Intravenous Infusion of MSC-Exos

This protocol is commonly employed for systemic conditions like graft-versus-host disease (GvHD) and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) [5].

Exosome Production and Isolation:

- Cell Source: Human bone marrow, adipose tissue, or umbilical cord-derived MSCs are cultured under GMP-grade conditions [5] [42].

- Isolation Method: Ultracentrifugation is the most frequently used method. Conditioned medium is sequentially centrifuged at low speeds (e.g., 2,000 × g) to remove cells and debris, followed by high-speed ultracentrifugation (e.g., 100,000 × g) to pellet exosomes [5] [42]. Tangential Flow Filtration (TFF) is also used for its scalability [5].

- Characterization: Isolated exosomes must be characterized per MISEV2018 guidelines. This includes nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA) for size and concentration, transmission electron microscopy (TEM) for morphology, and flow cytometry or Western blot for surface markers (e.g., CD9, CD63, CD81) [5] [42].

Formulation and Dosing:

Administration Technique:

- The exosome suspension is administered via slow bolus injection into the tail vein of mice or a peripheral vein in humans [5].

- Monitoring for potential adverse effects, such as cytokine release syndrome, is recommended.

Protocol for Nebulized Inhalation of MSC-Exos

This route is optimized for treating respiratory diseases, offering targeted delivery with potentially lower effective doses [38] [39].

Exosome Preparation for Aerosolization:

- Exosomes are isolated and characterized as described in the IV protocol.

- A critical quality control step is assessing exosome integrity and biological activity post-nebulization. Techniques like NTA and functional assays are used to confirm stability after passing through the nebulizer [39].

Nebulization and Delivery:

- The exosome suspension is loaded into a vibrating-mesh or jet nebulizer. These devices generate an aerosol with a particle size distribution (typically 1-5 μm) suitable for deep lung deposition [39].