Multi-Material Bioprinting for Complex Tissue Architecture: Techniques, Applications, and Future Directions in Biomedical Research

This article explores the transformative potential of multi-material bioprinting in creating complex, biomimetic tissue architectures.

Multi-Material Bioprinting for Complex Tissue Architecture: Techniques, Applications, and Future Directions in Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article explores the transformative potential of multi-material bioprinting in creating complex, biomimetic tissue architectures. It provides a comprehensive overview for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, covering the foundational principles of why tissue heterogeneity matters, the leading bioprinting technologies enabling it, and its groundbreaking applications in drug testing and disease modeling. The content further delves into critical troubleshooting for printability and cell viability, alongside validation strategies that compare the performance of bioprinted tissues against traditional models. By synthesizing the latest research, this article serves as a definitive guide on leveraging multi-material bioprinting to bridge the gap between laboratory research and clinical application.

The Imperative for Complexity: Why Single-Material Bioprinting Falls Short

The successful engineering of complex tissues relies on the precise recapitulation of the native tissue blueprint—a hierarchical and heterogeneous structure that spans multiple dimensional scales. In native tissues, biological function emerges from this carefully organized architecture, which includes specific cellular compositions, extracellular matrix (ECM) organizations, and spatial arrangements of biochemical and biophysical cues. The myocardium exemplifies this complexity, consisting of multiple cell types including cardiomyocytes (20-35% of total cells), cardiac fibroblasts, endothelial cells, smooth muscle cells, and immune cells, all arranged in a specific architectural pattern and embedded within a sophisticated ECM network [1].

This application note provides detailed protocols and analytical frameworks for researchers aiming to decode and replicate these native blueprints using advanced bioprinting methodologies. By focusing on the structural and functional elements of native tissues, we establish a foundation for creating biomimetic constructs that can bridge the gap between traditional tissue engineering and the physiological complexity required for research and clinical applications. The hierarchical organization observed in nature provides the foundational template for designing constructs that can ultimately restore, maintain, or improve tissue function [2].

Decoding the Native Cardiac Microenvironment: A Model System

The human heart represents an exemplary model system for studying hierarchical tissue organization due to its complex structural and functional properties. A comprehensive understanding of its native blueprint is essential for effective tissue engineering strategies.

Cellular Composition and Spatial Organization

The cardiac microenvironment consists of carefully organized resident cells that enable coordinated function:

- Cardiomyocytes (CMs): These primary contracting cells exist as atrial CMs, ventricular CMs, and pacemaker cells, physically connected via junctional complexes that allow cardiac impulse transfer. Their contractility is controlled by Ca²⁺ ion movement through specific channels and exchangers [1].

- Cardiac Fibroblasts (CFs): These connective tissue cells remodel ECM and produce signaling molecules (cytokines, growth factors) in response to mechanical, electrical, metabolic, and physiological cues. They communicate with CMs through gap junctions (connexins 40, 43, 45), membrane nanotubes (Ca²⁺ exchange), and paracrine signaling (angiotensin II, TGF-β, IL-6) [1].

- Endothelial Cells (ECs): Lining the extensive vascular network, ECs actively control vessel contraction, relaxation, and angiogenesis. In myocardium, ECs lie remarkably close to CMs (1-6μm in small mammals, 10-30μm in humans), enabling direct cellular communication and signaling [1].

- Additional Cell Populations: Vascular smooth muscle cells, pericytes, and immune cells further contribute to cardiac homeostasis and disease processes, creating a complex cellular ecosystem that must be replicated in engineered constructs [1].

Extracellular Matrix Architecture

The cardiac ECM provides both structural support and biochemical signaling capabilities:

- Fibrillary Components: Collagen types I (89%) and III (11%) form the primary structural framework, with additional contributions from types IV, V, and VI collagen, fibronectin, laminin, elastin, heparan sulfate proteoglycans, and fibrillin 1 [1].

- Non-fibrillary Elements: Glycosaminoglycans (GAGs), basement membrane proteins, and proteoglycans complete the matrix composition [1].

- Dynamic Reservoir Function: The ECM serves as a reservoir for signaling molecules including cytokines, proteases, growth factors, and microRNAs, creating a biologically active microenvironment [1].

- Developmental Changes: Postnatal changes include increased ventricular ECM elasticity, rising collagen/laminin/periostin/lysyl oxidase levels, and decreasing fibronectin/hyaluronic acid/agrin/proteoglycans, illustrating the dynamic nature of the matrix [1].

Table 1: Quantitative Analysis of Cardiac Extracellular Matrix Composition

| Component | Percentage/Concentration | Functional Role | Developmental Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| Collagen Type I | 89% of total collagen | Structural integrity, tensile strength | Increases postnatally |

| Collagen Type III | 11% of total collagen | Elasticity, flexibility | Increases postnatally |

| Total Collagen | 2-5% of heart weight | 3D tissue architecture | Strengthens with age |

| Laminin | Component-specific | Basement membrane structure | Increases postnatally |

| Hyaluronic Acid | Component-specific | Hydration, space filling | Decreases with age |

| Elastin | Component-specific | Recoil, energy return | Reinforces with collagen |

Microenvironmental Signaling Cues

The myocardial microenvironment provides essential cues that determine cellular fate and function through multiple signaling modalities:

- Mechanical Properties: Native heart ECM provides mechanical support ranging from 30-60 kPa, which must be replicated in engineered constructs to ensure proper cellular mechanotransduction [1].

- Electrical Conductance: The heart's conducting system spreads electrical information throughout the tissue, enabling coordination between cardiomyocytes through specialized connexin proteins [1].

- Biochemical Gradients: Spatial distributions of cytokines, growth factors, and ions create microenvironments that guide cellular behavior and tissue maturation in a region-specific manner [1].

Experimental Protocols for Native Blueprint Analysis

Protocol 1: Decellularized ECM (dECM) Hydrogel Preparation for Bioink Formulation

Principle: Native ECM harvested through decellularization preserves tissue-specific biochemical composition and structural cues, providing an ideal base material for bioink development [3].

Materials:

- Cardiac tissue samples (porcine/human)

- Triton X-100 (1%) and SDS (0.1%) solutions

- DNase/RNase solution (50 U/mL in PBS)

- Pepsin solution (0.1 M HCl, 1 mg/mL pepsin)

- Sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)

- Neutralization solution (0.1 M NaOH, 10× PBS)

Procedure:

- Tice Preparation: Mince 10g cardiac tissue into 1-2mm³ pieces using surgical scalpels in sterile conditions.

- Decellularization:

- Treat tissue with 1% Triton X-100 for 24h at 4°C with constant agitation

- Rinse with PBS (3×, 15min each)

- Incubate with 0.1% SDS for 48h at 4°C with agitation

- Treat with DNase/RNase solution for 6h at 37°C

- Lyophilization: Flash-freeze in liquid N₂ and lyophilize for 48h until complete dehydration

- Millling: Pulverize to fine powder using cryomill at -196°C

- Digestion: Digest in pepsin solution (100mg/mL) for 48h at room temperature with constant stirring

- Neutralization: Adjust pH to 7.4 using neutralization solution and dilute to final concentration of 30mg/mL

- Sterilization: Filter through 0.22μm filters and store at -80°C

Quality Control:

- DNA content <50ng/mg dry weight

- Collagen retention >90%

- GAG retention >70%

- Sterility confirmation through bacterial culture

Protocol 2: Multi-Material Bioprinting of Heterogeneous Cardiac Constructs

Principle: Extrusion-based bioprinting with multiple printheads enables spatial patterning of different cell types and matrix compositions to replicate native tissue heterogeneity [4].

Materials:

- BIO X6 bioprinter (CellInk) or equivalent multi-head system

- GelMA-based bioink (5-10% w/v)

- dECM bioink (30mg/mL)

- Primary cardiomyocytes (1×10⁶ cells/mL)

- Cardiac fibroblasts (5×10⁵ cells/mL)

- Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) (2×10⁵ cells/mL)

- Photoinitiator (LAP, 0.25% w/v)

- Crosslinking solution (UV light, 405nm)

Procedure:

- Bioink Preparation:

- Mix cell suspensions separately with respective bioinks at 4°C

- Keep bioinks on cooling plates during printing process

- Printhead Configuration:

- Printhead 1: Cardiomyocytes in dECM bioink (22°C)

- Printhead 2: Cardiac fibroblasts in GelMA (10%) (22°C)

- Printhead 3: HUVECs in GelMA (5%) (22°C)

- Printing Parameters:

- Nozzle diameter: 250μm (Printheads 1-2), 150μm (Printhead 3)

- Printing pressure: 20-25kPa (adjusted based on viscosity)

- Printing speed: 8mm/s

- Platform temperature: 15°C

- Layer-by-Layer Deposition:

- Alternate deposition patterns to create aligned fiber structure for cardiomyocytes

- Incorporate fibroblast layers at 25μm intervals

- Print endothelial channel structures using sacrificial bioinks

- Crosslinking: Apply 405nm UV light (5mW/cm²) for 60s after each complete layer

Validation:

- Cell viability >90% post-printing (Live/Dead assay)

- Spatial organization confirmation (confocal microscopy)

- Contractility assessment (video analysis of beating frequency)

Implementation Strategies for Hierarchical Tissue Engineering

Advanced Bioprinting Modalities for Hierarchical Structures

Multiple bioprinting technologies enable the replication of native tissue hierarchies:

- Microfluidic Bioprinting: Enables precise deposition of multiple materials with rapid switching capabilities, creating complex heterogeneous architectures with feature sizes as small as 10μm [4].

- Co-axial Bioprinting: Facilitates the creation of core-shell structures that mimic natural tissue interfaces and vascular networks with compartmentalized functionality [4].

- Multi-material Extrusion: Allows simultaneous deposition of different bioinks with varying mechanical and biochemical properties to recreate tissue-specific zoning [2] [3].

- Light-based Bioprinting: Provides high-resolution (1-50μm) patterning of complex geometrical features for replicating fine tissue details and microarchitectures [5].

Table 2: Bioprinting Modalities for Hierarchical Tissue Structures

| Bioprinting Modality | Resolution Range | Suitable Bioinks | Applications in Hierarchy | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Microfluidic Bioprinting | 10-150μm | Low-viscosity hydrogels, cell suspensions | Vascular networks, gradient interfaces | Rapid material switching, low shear stress |

| Extrusion Bioprinting | 50-500μm | High-viscosity bioinks, hydrogels, polymer melts | Bulk tissue structure, mechanical support | Structural integrity, multi-material capability |

| Co-axial Bioprinting | 100-400μm | Core-shell bioinks, sacrificial materials | Vasculature, tubulogenesis | Perfusable channels, interface engineering |

| Stereolithography | 1-50μm | Photocrosslinkable hydrogels | Microarchitecture, surface topography | High resolution, complex geometries |

| Laser-Assisted Bioprinting | 10-100μm | Cell suspensions, low-viscosity bioinks | Cellular patterning, heterotypic interfaces | No nozzle clogging, high cell viability |

Research Reagent Solutions for Cardiac Tissue Engineering

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Native-Mimetic Constructs

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Base Biomaterials | GelMA, dECM, Alginate, Collagen I | Structural scaffolding, cell encapsulation | GelMA (5-10%) optimal for cardiac constructs; dECM preserves native signals |

| Functional Additives | Nano-hydroxyapatite, SrCuSi₄O₁₀, Graphene | Mechanical reinforcement, electrical conductivity | SrCuSi₄O₁₀ enhances osteogenic signaling; graphene improves electromechanical coupling |

| Crosslinkers | LAP photoinitiator, CaCl₂, Genipin | Matrix stabilization, mechanical integrity | LAP (0.25%) enables rapid UV crosslinking with minimal cytotoxicity |

| Soluble Factors | VEGF, TGF-β, Angiotensin II | Cellular signaling, differentiation guidance | Gradients recreate developmental environments; temporal delivery crucial |

| Cell Sources | iPSC-derived CMs, Primary CFs, HUVECs | Tissue-specific functionality | Co-culture ratios critical: CMs:CFs:ECs = 70:20:10 mimics native composition |

Visualization Framework for Hierarchical Tissue Design

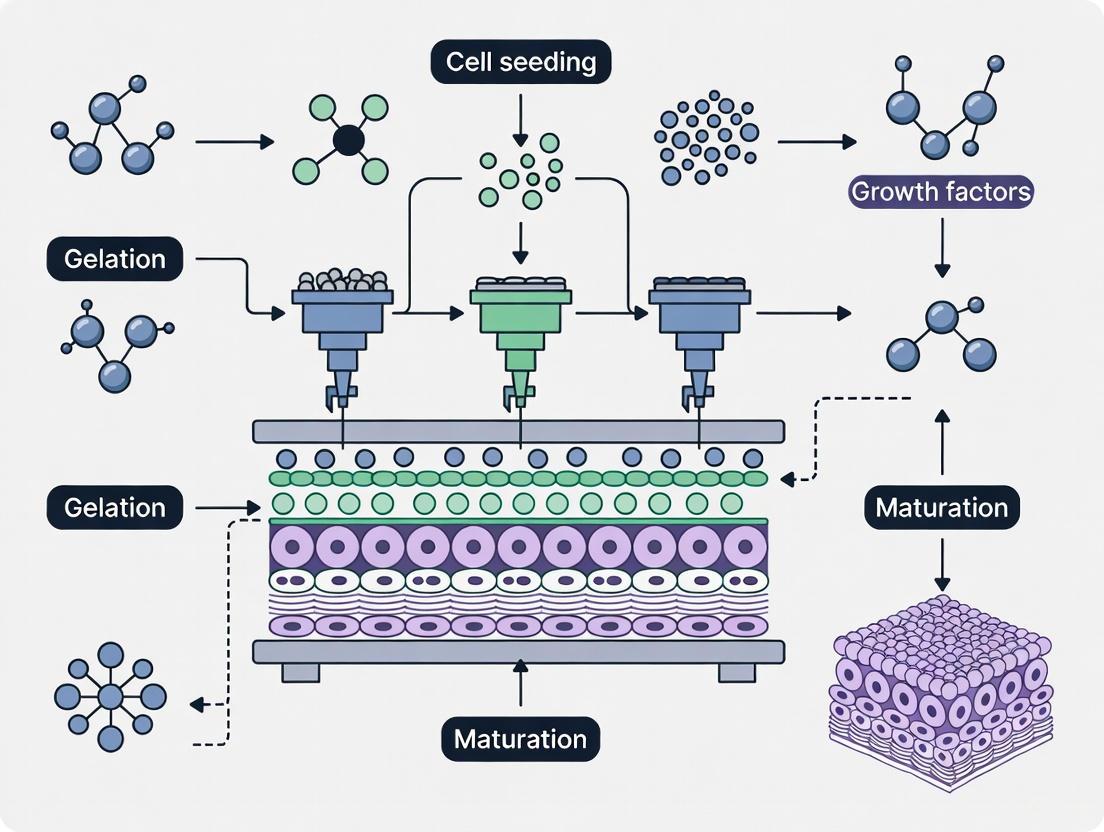

The following diagrams illustrate key relationships and workflows in hierarchical tissue engineering:

Native Cardiac Microenvironment Components

Multi-Material Bioprinting Workflow

Analytical Framework for Hierarchical Structure Validation

Protocol 3: Quantitative Assessment of Hierarchical Features

Principle: Multi-modal imaging and computational analysis enable quantitative verification of hierarchical structure replication in engineered constructs.

Methodology:

- Macro-scale Analysis (Tissue level, 100μm-1cm)

- Micro-CT scanning for 3D structural integrity

- Mechanical testing for bulk properties (30-60 kPa target)

- Porosity measurement (60-80% optimal for nutrient diffusion)

Micro-scale Analysis (Cellular level, 1-100μm)

- Confocal microscopy for 3D cell distribution

- Second harmonic generation imaging for collagen organization

- Immunofluorescence for specific marker localization

Nano-scale Analysis (Molecular level, <1μm)

- Scanning electron microscopy for surface topography

- Atomic force microscopy for local mechanical properties

- FRET-based molecular tension sensors for force transduction

Validation Metrics:

- Structural hierarchy index (SHI) >0.7 compared to native tissue

- Cell alignment index >0.8 in anisotropic regions

- Matrix composition similarity >75% to native ECM

- Functional integration score based on contractile synchronization

This application note establishes a comprehensive framework for understanding and implementing native tissue blueprints in engineered constructs. By providing detailed protocols, analytical methods, and visualization tools, we enable researchers to advance the field of hierarchical tissue engineering toward more physiologically relevant models for drug development and regenerative medicine applications.

Limitations of 2D Cultures and Animal Models in Drug Discovery

Drug discovery remains a lengthy and costly process, with a substantial failure rate during clinical trials. At least 75% of novel drugs that demonstrate efficacy during preclinical testing fail in clinical phases due to insufficient efficacy or poor safety performance [6]. This high attrition rate stems primarily from the low predictivity of current preclinical models, including traditional two-dimensional (2D) cell cultures and animal models [6]. A key challenge is that 90% of drugs successful in animal trials fail to gain FDA approval, highlighting fundamental translational gaps between model systems and human biology [7].

The pharmaceutical community is increasingly adopting a "quick-win, fast-fail" paradigm to reduce this attrition rate, emphasizing the need for more predictive preclinical models that accurately simulate in-vivo features, particularly microenvironmental factors [6]. This review examines the specific limitations of 2D cultures and animal models, while framing multi-material bioprinting as an emerging solution for creating complex tissue architectures that better recapitulate human physiology.

Fundamental Limitations of 2D Cell Culture Systems

Lack of Physiological Relevance

2D cell culture, where cells proliferate on flat, rigid plastic substrates, has been the standard for drug screening due to cost-effectiveness and streamlined processes [6]. However, these models fail to replicate the intricate microenvironment found in vivo, where cells are surrounded by extracellular matrix (ECM) that mediates morphology, behavior, migration, adhesion, and gene expression [6].

The table below summarizes key comparative limitations of 2D culture systems:

Table 1: Limitations of 2D Cell Culture Models in Drug Discovery

| Parameter | 2D Culture Characteristics | Physiological Consequences |

|---|---|---|

| Cell-ECM Interaction | Limited, unnatural adhesion to rigid plastic | Altered mechanotransduction and signaling pathways |

| Cell-Cell Interaction | Primarily peripheral, monolayer configuration | Disrupted paracrine signaling and polarization |

| Spatial Organization | Flat, two-dimensional | No tissue-like architecture or structural cues |

| Nutrient/Gradient Exposure | Uniform exposure to nutrients, oxygen, drugs | Absence of physiological gradients that influence cell behavior |

| Gene Expression | Abnormal profiles adapted to 2D conditions | Does not reflect in vivo gene expression patterns |

| Drug Response | Often overestimates efficacy | Poor prediction of clinical drug efficacy and toxicity |

Functional Consequences for Drug Screening

The limitations of 2D models have direct consequences for drug discovery outcomes. When a promising cancer therapy recently failed in Phase I trials after showing efficacy in 2D cultures, investigators discovered that the flat cell culture failed to replicate the dense, three-dimensional tumor microenvironment where drugs actually operate [8]. Similarly, 2D cultures lack the oxygen, pH, and nutrient gradients found in real tissues, which dramatically influence drug penetration and activity [9].

Cancer drugs screened in 2D models particularly suffer from predictive inaccuracies. Studies comparing 2D and 3D cultured cells exposed to chemotherapy drugs have revealed significant differences in cytotoxicity responses, with 2D models often overestimating drug efficacy because they lack the physical barriers and heterogeneous cell populations of actual tumors [8].

Inherent Constraints of Animal Models

Interspecies Physiological Disconnects

While animal models have long been foundational to preclinical research, fundamental differences between animal and human biology limit their predictive accuracy. The genetic homogeneity of most laboratory test animals contrasts sharply with the vast genetic diversity in human populations, making it difficult to predict variable drug responses among different individuals [7].

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration recently acknowledged these limitations by announcing plans to phase out animal testing requirements for monoclonal antibodies and other drugs, noting that human-based testing methods can provide more relevant safety data [10]. This regulatory shift recognizes that drugs considered safe in animals have sometimes proved lethal in first-in-human trials, with immune, neurological, and first-in-class drugs presenting particularly high risks [7].

Quantitative Limitations in Predictive Value

The poor translatability of animal models is quantifiably demonstrated by current drug development success rates. The likelihood of approval for compounds entering Phase 1 clinical trials is just 6.7%, down from 10% a decade ago [11]. A significant proportion of these late-stage failures stem from safety concerns that animal models failed to detect, creating enormous economic and ethical consequences for the pharmaceutical industry.

Table 2: Limitations of Animal Models in Predicting Human Drug Responses

| Limitation Category | Specific Examples | Impact on Drug Development |

|---|---|---|

| Metabolic Differences | Species-specific variations in drug metabolism enzymes | Inaccurate prediction of drug metabolism and pharmacokinetics |

| Immune System Variance | Differing immune cell populations and signaling | Poor translation of immunotherapies and monoclonal antibodies |

| Genetic Diversity | Limited genetic variation in inbred laboratory strains | Failure to predict idiosyncratic adverse drug reactions |

| Disease Pathogenesis | Artificially induced disease states | Inaccurate modeling of spontaneous human diseases |

| Tumor Microenvironment | Fundamental differences in stroma and vasculature | Poor prediction of oncology drug efficacy |

Drug-induced liver injury (DILI) exemplifies this predictive blind spot. DILI remains one of the leading causes of clinical trial failure and drug withdrawal post-approval, yet animal models frequently fail to detect hepatotoxicity due to human-specific mechanisms or idiosyncratic responses that animals do not replicate [11].

Multi-Material Bioprinting as a Solution

Technological Foundations

Multi-material bioprinting represents a paradigm shift in preclinical modeling by enabling the creation of complex, physiologically relevant tissue architectures that address the limitations of both 2D cultures and animal models. This approach allows for the precise spatial arrangement of multiple cell types and ECM components, creating heterocellular environments that mirror human tissue organization [12].

The diagram below illustrates the conceptual framework for how bioprinting addresses current model limitations:

Advanced Bioprinting Modalities

Recent advances in bioprinting technologies have enabled unprecedented capabilities for tissue engineering. The FRESH (Freeform Reversible Embedding of Suspended Hydrogels) bioprinting technique allows for the printing of soft living cells and tissues with unprecedented structural resolution, creating fully biologic microfluidic systems with fluidic channels as small as 100-micron diameter - approaching capillary scale [13]. This advancement is critical for creating vascularized tissues that can be perfused and sustained long-term.

Hybrid bioprinting approaches that integrate multiple 3D printing modules demonstrate particular promise for complex multi-tissue engineering. These systems can achieve over a 1000-fold increase in mechanical strength compared to hydrogel-only constructs, making them suitable for load-bearing musculoskeletal and orthopedic tissue engineering [12]. The capacity to print with both soft and rigid biomaterials in a continuous process enables the creation of constructs that unite mechanical robustness with bioactivity.

Experimental Protocols for Bioprinted Tissue Models

Protocol 1: FRESH Bioprinting of Vascularized Tissues

Principle: This protocol utilizes a suspension bath to support the printing of soft biomaterials like collagen and fibrin, enabling the creation of complex vascularized tissues.

Materials:

- Collagen Type I (5-10 mg/mL)

- FRESH support bath (1.5-3% w/v gelatin microparticles)

- Primary cells or cell lines of interest

- Crosslinking agents (genipin or riboflavin)

- Perfusion bioreactor system

- Multi-material bioprinter with temperature-controlled printheads

Procedure:

- Bioink Preparation: Mix collagen with cells at 4°C to achieve final concentration of 20-30 million cells/mL. Maintain homogeneous suspension.

- Support Bath Preparation: Prepare gelatin microparticle slurry and load into printing chamber.

- Printing Parameters: Set nozzle diameter 150-300μm, pressure 15-30 kPa, print speed 5-15 mm/s.

- Layer-by-Layer Deposition: Print vascular network design with branching architecture.

- Crosslinking: Initiate with UV light (405nm, 5mW/cm² for 60-120s) or thermal crosslinking at 37°C.

- Support Removal: Gently melt support bath at 37°C and rinse with culture medium.

- Perfusion Culture: Transfer to bioreactor system with flow rates 0.1-1 mL/min, gradually increasing.

Validation: Assess viability (>85% at 24h), endothelial marker expression (CD31), and glucose-stimulated insulin release for pancreatic tissues.

Protocol 2: Multi-Material Tumor Model Bioprinting

Principle: This protocol creates heterogeneous tumor models incorporating cancer cells, stromal components, and ECM mimics to study drug penetration and efficacy.

Materials:

- Patient-derived cancer cells

- Cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs)

- Endothelial cells

- Alginate-gelatin composite bioink (5% w/v)

- Polyethylene glycol (PEG) support bioink

- Matrigel for stromal compartment

- Chemotherapeutic agents for testing

Procedure:

- Cell Preparation: Expand patient-derived organoids and dissociate to single cells.

- Compartmental Bioink Formulation:

- Compartment A: Cancer cells in alginate-gelatin (20M cells/mL)

- Compartment B: CAFs and endothelial cells in PEG-based bioink (15M cells/mL)

- Multi-Nozzle Printing: Utilize independent printheads for tumor (A) and stromal (B) compartments.

- Architectural Design: Print concentric tumor core-shell structure with surrounding stromal niche.

- Ionic Crosslinking: Use CaCl₂ solution (100mM, 10min) for alginate component.

- Long-term Culture: Maintain in air-liquid interface system with specialized cancer media.

- Drug Treatment: Apply chemotherapeutic gradients after 7 days of maturation.

Applications: Drug penetration studies, resistance mechanism investigation, combination therapy screening.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Advanced 3D Tissue Models

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function & Application |

|---|---|---|

| Hydrogel Systems | Collagen Type I, Fibrin, Alginate-Gelatin composites, Matrigel, Hyaluronic acid | Provide 3D extracellular matrix environment for cell growth and organization |

| Specialized Media | Organoid growth media with niche factors, Stem cell differentiation media | Support proliferation and maintenance of phenotype in 3D cultures |

| Bioink Enhancers | Laponite nanoclay, Gelatin microparticles, PEG-based crosslinkers | Improve printability, mechanical properties, and structural fidelity |

| Cell Sources | Patient-derived organoids (PDOs), Induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), Primary tissue isolates | Provide biologically relevant cellular components with patient-specific genetics |

| Characterization Tools | Live-dead staining kits, Extracellular matrix antibodies, Metabolic activity assays | Assess viability, organization, and functional capacity of printed tissues |

| Perfusion Systems | Microfluidic chips, Bioreactors with flow control, Oxygen gradient systems | Enable nutrient delivery and waste removal in vascularized constructs |

The limitations of 2D cultures and animal models in drug discovery have created an urgent need for more physiologically relevant testing platforms. Multi-material bioprinting addresses these limitations by enabling the creation of complex tissue architectures with human-specific biology that better predicts drug efficacy and toxicity. The recent FDA policy shift away from mandatory animal testing for certain drug classes further accelerates the need for these advanced models [10] [14].

While challenges remain in standardization, scalability, and regulatory acceptance, the convergence of bioprinting technologies with patient-derived cells and advanced biomaterials represents a transformative pathway toward more predictive, efficient, and personalized drug discovery. As these technologies mature, they promise to reduce the current high attrition rates in drug development while providing more clinically relevant insights at the preclinical stage.

Defining Multi-Material Bioprinting and Its Core Objectives

Multi-material bioprinting is an advanced additive manufacturing technique that constructs cell-laden structures using multiple distinct bioinks within a single fabrication process. The primary objective of this technology is to create complex, heterogeneous, and biomimetic tissues that closely resemble the spatial and functional heterogeneity of native biological tissues [4]. This approach represents a paradigm shift from conventional top-down tissue engineering methods, embracing instead a bottom-up strategy where complex tissues are assembled from engineered building blocks, potentially replicating native tissue microarchitecture and function [4].

The core challenge in tissue engineering lies in replicating the intricate architectural and cellular complexity found in natural tissues, which often demands the fabrication of multi-material and multi-cellular constructs. This complexity introduces significant challenges in material compatibility, cellular integration, and structural stability, particularly when aiming to replicate intricate tissue architectures such as vascular networks or organ-specific microenvironments [4]. Multi-material bioprinting addresses these challenges through precise spatial control over material composition and cell placement.

Key Technological Approaches and Performance Characteristics

Multiple bioprinting modalities have been developed to address the challenges of multi-material fabrication, each with distinct advantages and limitations. The integration of microfluidics has emerged as a particularly transformative development, enabling enhanced control over material flow, mixing, and deposition at the microscale [4]. The table below summarizes the key performance characteristics of major multi-material bioprinting technologies:

Table 1: Performance Characteristics of Multi-Material Bioprinting Technologies

| Technology Type | Spatial Resolution | Key Advantages | Material Compatibility | Structural Strength |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Microfluidic Bioprinting | Tens to hundreds of micrometers [4] | Precise material switching, gradient formation, low shear stress [4] | Multi-material bioinks, hydrogels [4] | Varies with crosslinking method |

| Material Jetting | 16μm layer thickness [15] | High color fidelity, smooth surfaces [15] | Photopolymer resins [15] | Medium (50-60 MPa tensile strength) [15] |

| Multi-color FDM/FFF | 100-300μm layer thickness [15] | High strength, economical [15] | Thermoplastic filaments [15] | High (50-72 MPa tensile strength) [15] |

| Binder Jetting | 100μm layer thickness [15] | Cost-effective for large models [15] | Powder materials (gypsum, nylon) [15] | Low (requires adhesive reinforcement) [15] |

Microfluidic bioprinting systems, often conceptualized as "printhead-on-a-chip" or "lab-on-a-tip" technologies, leverage several advantages including miniaturization, low reagent volumes, laminar flow regimes due to low Reynolds numbers, decreased diffusion times, and dominant surface tension and capillary forces [4]. These systems have enhanced various bioprinting modalities including extrusion-based, coaxial, droplet-based, light-based, and voxel-based bioprinting [4].

Experimental Protocol: Embedded Bioprinting of Multi-Layered Arterial Tissues

This protocol describes the fabrication of multilayered arterial tissues with controlled cellular alignment using embedded multi-material bioprinting approaches.

Materials Preparation

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Arterial Model Bioprinting

| Reagent/Material | Function | Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Bioink Formulation | Primary structural and cellular scaffold | Typically hydrogel-based (e.g., gelatin methacryloyl, alginate) with tuned viscoelastic properties |

| Support Bath Matrix | Provides temporary environment for embedded printing | Yield-stress fluid such as microparticle-filled suspensions or polymer networks |

| Crosslinking Agent | Induces bioink solidification | Ionic crosslinkers (e.g., CaCl₂ for alginate) or photoinitiators for light-cured systems |

| Cell Culture Medium | Maintains cellular viability during and post-printing | Cell-type specific medium with appropriate growth factors and supplements |

Workflow and Methodology

The following diagram illustrates the complete experimental workflow for creating multilayered arterial tissues:

Detailed Procedural Steps

Material Preparation Phase

- Bioink Formulation: Prepare primary bioink components according to targeted tissue characteristics. For arterial models, this typically involves hydrogel precursors with tuned mechanical properties to support vascular smooth muscle function [16].

- Support Bath Preparation: Fabricate yield-stress support bath materials that enable embedded printing while providing temporary structural support during the printing process.

- Cell Culture Expansion: Expand relevant cell types (e.g., vascular smooth muscle cells, endothelial cells) to appropriate confluence and viability for integration with bioink formulations.

Simulation and Planning Phase

- Flow Rate Prediction: Utilize computational models to predict optimal bioink flow rates, accounting for temperature-dependent viscosity changes and shear-thinning behavior [16].

- 3D Print Path Design: Create precise toolpaths based on targeted tissue characteristics, including layer-by-layer deposition patterns that promote cellular alignment in multilayered structures [16].

Embedded Bioprinting Execution

- Multi-layer Deposition: Sequentially deposit bioink materials within the support bath according to the predetermined toolpaths, constructing the arterial wall architecture layer by layer.

- Cellular Alignment Control: Implement printing parameters that enhance vascular smooth muscle cell alignment, modulating contractile and synthetic pathways through mechanical cues [16].

- Controlled Crosslinking: Apply appropriate crosslinking mechanisms (thermal, ionic, or photochemical) to stabilize the printed structure while maintaining cellular viability.

Biological Characterization

- Functional Assessment: Evaluate vascular smooth muscle contractile function and responsiveness to pharmacological agents.

- Structural Analysis: Characterize tissue morphology, extracellular matrix composition, and cellular organization using histological and immunohistochemical methods.

Microfluidic Printhead Design for Multi-Material Capability

The integration of microfluidics enables sophisticated multi-material capabilities through specialized printhead designs. The following diagram illustrates a conceptual microfluidic printhead system:

This microfluidic approach enables several key functionalities:

- Real-time Material Switching: Rapid alternation between different bioinks during the printing process to create discrete regional variations in material composition [4].

- On-demand Material Blending: Controlled mixing of multiple bioink precursors to create intermediate compositions with tailored properties [4].

- Spatial Gradient Generation: Establishment of continuous concentration gradients of materials, cells, or bioactive factors through controlled laminar flow and diffusion phenomena [4].

- Shear Stress Reduction: Creation of cell-friendly environments that minimize shear stress during the printing process, enhancing cellular viability and functionality [4].

Applications in Complex Tissue Architecture

Multi-material bioprinting enables several advanced applications in tissue engineering and drug development:

- Tissue Heterogeneity and Vascularization: Creation of constructs with region-specific biological properties and integrated vascular networks for nutrient transport [4].

- Tumor Microenvironment Recapitulation: Fabrication of sophisticated cancer models with heterogeneous cell populations and extracellular matrix compositions for drug screening [4].

- Cellular Microfibers: Generation of continuous fiber structures with controlled core-shell architectures and encapsulated cells for tissue assembly [4].

- Organ-on-a-Chip Systems: Integration of bioprinted tissues with microfluidic perfusion systems to create more physiologically relevant models for drug testing [4].

The protocol for arterial tissue fabrication described in Section 3 exemplifies how multi-material approaches can create structures with anatomical relevance, particularly through the control of cellular alignment patterns that enhance tissue-specific function [16].

Multi-material bioprinting represents a significant advancement in tissue engineering, enabling the fabrication of complex, heterogeneous constructs that better mimic native tissues. The technology's core objectives focus on replicating spatial and functional heterogeneity through precise control over material composition and cellular organization. As microfluidic integrations and other technical innovations continue to evolve, multi-material bioprinting is poised to transform regenerative medicine, disease modeling, and drug development by providing more physiologically relevant tissue models. Future directions will likely focus on enhancing scalability, standardizing protocols, and simplifying workflows to broaden accessibility and adoption across the research community [4].

The ultimate goal of three-dimensional (3D) in vitro models is to reproduce physiologically and biologically realistic human model systems outside the body. In the human body, the vascular network represents a hierarchical organization that serves for the efficient exchange of nutrients and oxygen and for the removal of wastes within and between tissues and organs. The presence of vascularization in engineered tissues not only maintains cell viability and function but also supports cross-talk between diverse cell and tissue types, effectively mimicking human biological responses. Thus, engineering functional vasculature is a prerequisite for the successful engineering of physiologically relevant in vitro models [17].

Overcoming the challenge of vascularization represents a significant bottleneck in advancing tissue engineering. Without vasculature, the size and complexity of an engineered tissue is limited, as the lack of nutrition and accumulation of waste will inevitably lead to cell death in bioprinted tissue structures. This limitation has driven the development of sophisticated 3D bioprinting strategies that can create perfusable, hierarchical vascular networks within engineered tissues, enabling applications from disease modeling to regenerative medicine [17] [18].

Multi-Material Bioprinting Strategies for Vascularization

Advanced Bioprinting Techniques for Vascular Networks

Multiple bioprinting strategies have been developed to vascularize in vitro tissues by spatially controlled patterning of vascular precursors or generating readily perfusable vascular structures. The table below summarizes the major 3D bioprinting strategies for developing vascular structures [17].

Table 1: Major 3D Bioprinting Strategies for Vascular Structure Development

| Bioprinting Strategy | Description | Key Benefits for Vascularization |

|---|---|---|

| Coordinated Patterning | Spatial arrangement of cell-laden inks to produce 3D constructs with interconnected pre-vascular networks | Precise spatial localization of cell types and bioactive molecules; high design flexibility [17] |

| Sacrificial Printing | Deposition of fugitive ink followed by casting and removal to create endothelialized channels | Creates perfusable microchannels; high freedom in designing channel geometries and size ranges [17] |

| Embedding Printing | Extrusion of ink into a liquid suspension bath to support printed filaments during fabrication | Improves printability of soft bioinks; enhances structural integrity with high resolution [17] |

| Coaxial Printing | Simultaneous extrusion of different materials through core/shell configuration to create hollow tubes | Direct printing of freestanding tubular structures with controllable diameter and wall thickness [17] |

| Scaffold-Free Mandrel | Using a rotating mandrel to create tubular structures without artificial scaffolds | Enables high cell density with low foreign body response; omits long culturing times [18] |

The Scaffold-Free Approach for Vascular Conduits

A scaffold-free approach using a rotating mandrel method has been successfully employed to create functional vascular conduits. This method circumvents limitations associated with artificial scaffolds, including potential immune responses and the challenge of matching scaffold degradation rates with tissue formation. By using a high cell concentration and scaffold-free techniques, the lengthy culturing times typically required after bioprinting can be significantly reduced [18].

In practice, this approach has been used to bioprint a rat aorta using rat fibroblasts and smooth muscle cells. The bioink contained smooth muscle cells (SMC) and fibroblasts (FC)—the elastic smooth muscle cell and fibroblast mixture layer mimics the tunica media, and the layer of fibroblasts mimics the tunica adventitia. The resulting 3D-bioprinted aortas were well-tolerated when implanted into rats, showed successful integration into native vasculature, and demonstrated physiological behavior of a native vessel [18].

Protocol: Bioprinting a Functional Vascular Conduit

Bioink Preparation and Formulation

This protocol details the methodology for creating an implantable vascular conduit using a scaffold-free rotating mandrel approach, based on successful implantation studies in animal models [18].

Table 2: Bioink Formulation for Vascular Conduit Bioprinting

| Component | Specification | Function |

|---|---|---|

| Hyaluronic Acid | From HyStem-C Kit | Provides compression strength, allows cell motility and adhesion [18] |

| Gelatin | From HyStem-C Kit | Contains RGD motifs for cell attachment; promotes cell growth [19] [18] |

| PEGDA | Polyethylene glycol diacrylate from HyStem-C Kit | Forms covalent bonds during cross-linking; provides long-term stability [19] [18] |

| Smooth Muscle Cells | Rat venous SMCs; passage ≤10 | Forms tunica media layer; 70% of cellular composition (42×10⁶ cells) [18] |

| Fibroblasts | Rat aortic FCs; passage ≤10 | Forms tunica adventitia layer; 30% of cellular composition [18] |

| Cell Density | 100×10⁶ cells/mL | High cell density to support scaffold-free approach [18] |

Preparation Steps:

- Culture rat venous SMCs and rat aortic FCs in individual flasks, harvesting at passage 10 or less upon reaching 80-90% confluence.

- Prepare hydrogel precursor using the HyStem-C Kit according to manufacturer specifications.

- Encapsulate cells at a density of 100×10⁶ cells/mL in the crosslinked hydrogel mixture, maintaining the 70:30 SMC:FC ratio.

- Prepare two separate bioinks with identical composition except for cell type: one with SMCs and one with FCs for layered deposition.

Bioprinting Process and Parameters

The following workflow outlines the complete process for bioprinting vascular conduits using a rotating mandrel system:

Critical Bioprinting Parameters:

- Printing Temperature: Maintain at 20-24°C throughout the printing process to ensure optimal hydrogel viscosity and cell viability.

- Cross-linking Protocol: Employ dual-crosslinking approach:

- Layer Height: 50-300 μm, depending on vascular wall thickness requirements

- Printing Speed: 1-5 mm/s, optimized to balance structural fidelity and cell viability

- Post-printing Maturation: Culture in bioreactor with dynamic flow conditions for 7-14 days to promote tissue maturation

Quality Assessment and Functional Validation

Rigorous assessment of bioprinted vascular constructs is essential before application in disease modeling or implantation:

Structural Integrity Tests:

- Uniaxial tensile testing to determine mechanical properties and compare to native vessel

- Burst pressure measurement to assess resistance to physiological pressures

- Suture retention strength testing to evaluate surgical handling capabilities

Biological Function Validation:

- Cell viability assessment via live/dead staining at 24, 48, and 72 hours post-printing

- Immunohistochemistry for tissue-specific markers (α-SMA for SMCs, vimentin for fibroblasts)

- Permeability assays using fluorescent dextrans of varying molecular weights

- In vivo implantation in animal models with periodic patency checks via Doppler ultrasound

Application in Disease Modeling and Drug Screening

Engineering Physiological and Pathological Models

Vascularized tissue models created through multi-material bioprinting enable more accurate study of human physiology and pathology. These models hold promise as alternatives to conventional cell cultures or animal models for translational application to model human physiology/pathology and drug screening [17].

Cancer Metastasis Models: Multi-material stereolithography has been used to construct simplified models of intratumoral heterogeneity with two separate sub-populations of cancer cells, which together grow over 14 days to form a dense regional interface. These models appropriately develop invasive protrusions in response to hTGF-β1, demonstrating phenotypically appropriate behaviors that enable study of tumor invasion [20].

Cardiovascular Disease Models: Bioprinted vascular structures can replicate the pathophysiology of conditions like atherosclerosis, which is characterized by buildup of plaque in the vessel lumen, resulting in stiffening of the arterial wall. These models allow for studying the progression of stenosis and ischemic injury in a controlled environment [18].

High-Content Screening Applications

The reproducibility and physiological relevance of bioprinted vascularized tissues make them valuable platforms for drug discovery. Key applications include:

- Drug Permeability Studies: Assessing compound transport across endothelial barriers

- Toxicity Screening: Evaluating drug candidate effects on vascular integrity and function

- Angiogenesis Inhibition/Activation: Testing pro- or anti-angiogenic compounds in physiologically relevant contexts

- Metastasis Inhibition: Screening compounds that block tumor cell extravasation through vascular walls

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Vascular Tissue Bioprinting

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Bioprinting |

|---|---|---|

| Structural Hydrogels | Alginate (Alg), Carboxymethyl Cellulose (CMC), Gelatin Methacrylate (GelMA) | Provides 3D scaffold for cell encapsulation; optimal formulations include 4% Alg–10% CMC–GelMA (8-16%) [19] |

| Photoinitiators | LAP (Lithium phenyl-2,4,6-trimethylbenzoylphosphinate) | Initiates polymerization when exposed to light; enables UV crosslinking of methacrylated bioinks [21] [20] |

| Crosslinkers | CaCl₂ for ionic crosslinking; UV light for covalent bonds | Enables hydrogel solidification; dual-crosslinking provides variable stiffness [19] |

| Vascular Cell Sources | Endothelial cells, Smooth Muscle Cells (SMCs), Fibroblasts (FCs) | Recapitulates native vessel composition; forms intact endothelium, media, and adventitia layers [18] |

| Support Materials | Agarose, CELLINK Start | Acts as fugitive ink for sacrificial printing or support material for complex structures [21] |

| Basement Membrane Matrix | Matrigel | Provides complex extracellular matrix environment; supports capillary formation and cell differentiation [21] |

Future Perspectives and Challenges

The field of vascularized tissue bioprinting continues to evolve with several emerging trends. The integration of artificial intelligence and real-time monitoring systems represents a significant advancement, enabling rapid identification of print defects and adaptive correction during the printing process. This approach improves inter-tissue reproducibility and enhances resource efficiency by limiting material waste [22].

However, challenges remain in replicating the full complexity of native vasculature, including its hierarchical organization, mechanical properties, and physiological functionality. Future work must focus on improving vascular maturity, ensuring long-term stability, and enabling seamless integration with host tissues upon implantation. As these challenges are addressed, bioprinted vascularized tissues will become increasingly valuable for both basic research and clinical applications, potentially revolutionizing how we model diseases, screen drugs, and ultimately perform regenerative medicine.

Bioprinting Technologies and Bioinks for Architecturally Complex Tissues

Within the broader context of advancing multi-material bioprinting for complex tissue architecture research, selecting the appropriate fabrication modality is paramount. The fundamental challenge in this field lies in replicating the intricate spatial heterogeneity and biomechanical properties of native human tissues. Extrusion-based, stereolithography (SLA), and projection-based bioprinting have emerged as leading technologies, each offering distinct capabilities and facing specific limitations in the pursuit of manufacturing biologically relevant constructs. This application note provides a comparative analysis of these three core bioprinting modalities, framing them as essential tools for researchers and scientists focused on drug development and complex tissue modeling. The content is structured to deliver actionable, quantitative data and detailed protocols to inform experimental design and technology selection for multi-material biofabrication projects.

Technology Comparison and Quantitative Analysis

The core bioprinting technologies operate on different physical principles, which directly influences their performance in key metrics critical to tissue engineering: printing efficiency, precision, and cell viability. A fundamental trade-off exists among these parameters; optimizing for one often compromises another [23]. The following table summarizes the quantitative performance characteristics of each modality.

Table 1: Quantitative Performance Comparison of Bioprinting Modalities

| Performance Metric | Extrusion-Based | Stereolithography (SLA) | Projection-Based (PBP) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Basic Patterning Unit | Line (1D Filament) [23] | Point/Vector (Laser) or Surface (DLP) | Surface (2D Plane) [24] |

| Printing Efficiency | 0.00785–62.83 mm³/s [23] | Varies (Lower for laser scanning) | 0.648–840 mm³/s [23] |

| Theoretical Resolution | ~100 μm [24] | ~10-50 μm | ~10-25 μm [24] [25] |

| Minimum Feature Size | 100 μm [23] | <10 μm (Laser), ~25 μm (DLP) [25] | ~2 μm [23] |

| Cell Viability | 40–90% [23] | High (Limited shear stress) | High (Limited shear stress) |

| Key Advantage | High Cell Density, Multi-material Feasibility [26] | High Resolution, Structural Fidelity [20] | Highest Resolution/Manufacturing Time Ratio [24] |

| Key Limitation | High Shear Stress, Nozzle Clogging [23] [27] | Material Optical Properties, Potential Cytotoxicity [23] | Material Interface Control, Cross-contamination [24] |

Analysis of Comparative Data

- Extrusion-Based Bioprinting excels in depositing high-viscosity bioinks and achieving high cell densities, but its resolution is limited by nozzle diameter, and the associated shear stress can significantly impact cell viability [23] [27]. Its efficiency can span a wide range depending on nozzle size and printing speed.

- Stereolithography (SLA), particularly digital light processing (DLP), offers high resolution and excellent structural fidelity by curing layers simultaneously, minimizing the structural seams and voids common in extrusion methods [20]. However, it imposes strict requirements on the optical properties of bioinks (e.g., light transmittance, photosensitivity) and the potential chemical toxicity of photoinitiators must be carefully managed [23].

- Projection-Based Bioprinting (PBP), a form of vat polymerization, boasts the highest resolution-to-manufacturing time (RTM) ratio among the technologies, a key metric for combining precision with efficiency [24]. Its primary challenge lies in managing material interfaces and preventing cross-contamination during multi-material printing, which requires sophisticated rinsing and cleaning protocols [24] [28].

Experimental Protocols for Multi-Material Bioprinting

The following protocols outline standardized procedures for multi-material fabrication using each modality, designed to ensure high fidelity and minimize cross-contamination.

Protocol: Multi-Material Extrusion Bioprinting

Objective: To fabricate a heterogeneous tissue construct using a multi-nozzle extrusion bioprinter. Applications: Creating anisotropic constructs such as osteochondral tissue or vascularized tissue models [26].

Bioink Preparation:

- Formulate bioinks according to architectural requirements. Natural polymers (e.g., Gelatin, Hyaluronic Acid) are preferred for bioactivity, while synthetic polymers (e.g., PCL, PLA) provide mechanical robustness [26].

- Adjust bioink viscosity to ensure printability, balancing high viscosity for structural stability against lower viscosity for higher cell viability [23].

Printer Setup:

- Load individual bioinks into separate syringes fitted onto independent printheads.

- Calibrate the nozzle alignment and height for all printheads to ensure precise spatial deposition.

- Set the printing stage temperature to 4-10°C to aid in the initial gelation of thermosensitive bioinks.

Printing Process:

- Use a CAD model derived from medical imaging (e.g., MRI, CT) to guide deposition [26].

- Optimize printing parameters: Nozzle pressure (10-150 kPa for pneumatic systems) and print speed (5-20 mm/s) are critical and must be tuned for each bioink to minimize shear-induced cell damage [23] [26].

- For core-shell structures, employ a coaxial nozzle to simultaneously extrude different materials.

Post-Processing:

- Crosslink the printed construct immediately after deposition using appropriate methods (e.g., UV light for photocrosslinkable bioinks, ionic crosslinking for alginate).

- Transfer the crosslinked construct to a bioreactor for maturation, providing necessary biochemical and mechanical stimulation.

Protocol: Multi-Material Stereolithography Bioprinting

Objective: To create a high-resolution, heterogeneous 3D hydrogel construct with discrete cellular and acellular domains. Applications: Cancer microenvironment models, interface tissue engineering (e.g., skin-to-muscle) [20].

Bioink Preparation:

- Prepare photopolymerizable bioinks (e.g., GelMA, PEGDA) with a photoinitiator (e.g., LAP at 0.1-0.5% w/v).

- Ensure bioinks are optically clear for efficient UV penetration. Filter-sterilize if incorporating cells.

System Setup:

Printing and Material Switching:

- Lower the build platform into the first bioink vat, creating a thin layer for exposure.

- Project the UV light pattern to crosslink the first material. Adhesion should be to the build platform, not the vat.

- Lift the platform and active structure out of the vat.

- Rinsing Step: Move the platform to a washing station and manually or automatically rinse with 2-5 mL of PBS (optionally containing dilute subsequent photopolymer at 2.5-10 wt% to improve lamination) to remove residual bioink [20]. Wick away excess saline.

- Move the platform into the next bioink vat and repeat the exposure and rinsing process for each material and layer.

Post-Processing:

- After the final layer, perform a final rinse with sterile PBS.

- Culture the construct in appropriate media, changing regularly to remove any leached photoinitiator.

Protocol: Multi-Material Projection-Based Bioprinting (PBBP)

Objective: To achieve standardized, high-fidelity, and high-resolution printing of composite structures using bioinks with diverse mechanical properties [24] [28]. Applications: Reconstruction of intricate biological structures with soft-hard tissue junctions, such as bone-cartilage interfaces.

Bioink Preparation and Characterization:

- Select bioinks based on a "bonding rulebook" derived from fracture energy analysis to ensure compatibility and strong interfacial bonding between materials with different stiffnesses [28].

- Characterize the photo-cross-linking behavior (e.g., curing time, energy dose) for each bioink to standardize parameters.

System Setup:

- Utilize a multi-material PBBP system equipped with a vat-switching device (supporting up to 6 materials), a fluid rinsing system, and a negative-pressure drying device [24].

- Calibrate the optical system (e.g., DMD) to ensure precise resolution (e.g., 25 μm).

Synchronized Printing and Cleaning:

- For each layer, the system positions the build platform over the designated bioink vat.

- After exposure, the platform lifts, and the vat switches.

- Synergistic Cleaning: Implement a "fluid-controlled rinsing with negative pressure-assisted capillary adsorption" strategy. This involves a precise fluid flush followed by negative pressure to eliminate residual liquid from porous structures, effectively preventing cross-contamination [28].

Quality Control:

- Use the system's integrated visual observation module for real-time monitoring.

- Employ a standardized multi-material print resolution evaluation model to assess printing accuracy and identify error sources [24].

Visualizing Workflows and System Architectures

The following diagrams illustrate the logical workflows and key system components for the featured bioprinting modalities, highlighting their approach to multi-material integration.

Figure 1: Multi-Material Bioprinting Workflow Comparison. This diagram outlines the generalized workflows for the three main bioprinting modalities, highlighting the distinct approaches to multi-material fabrication: multi-nozzle deposition for extrusion and vat-switching for SLA/PBP.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful multi-material bioprinting requires careful selection of materials and reagents. The following table details key components for constructing heterogeneous tissue models.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Multi-Material Bioprinting

| Category | Item | Function & Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Base Biomaterials | Gelatin Methacryloyl (GelMA) | A photocrosslinkable hydrogel derived from ECM; highly tunable mechanical properties and excellent cell responsiveness [23] [25]. |

| Poly(ethylene glycol) diacrylate (PEGDA) | A synthetic, bioinert hydrogel; often used as a mechanically stable frame or to create controlled microenvironments [20] [25]. | |

| Alginate | A natural polymer used extensively in extrusion bioprinting; rapidly crosslinks with divalent cations (e.g., Ca²⁺) [26]. | |

| Crosslinking Agents | Photoinitiators (e.g., LAP) | Absorbs light energy to generate free radicals, initiating the crosslinking of photopolymerizable bioinks (e.g., GelMA, PEGDA) [20]. |

| Calcium Chloride (CaCl₂) | Ionic crosslinker for alginate-based bioinks; can be applied as a post-print mist or bath or co-extruded in coaxial setups [26]. | |

| Cell Culture & Analysis | Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF) | A key biochemical cue to promote vascularization within bioprinted constructs; can be encapsulated in hydrogels for sustained release [25]. |

| Cell Viability/Cytotoxicity Assay Kits | Essential for quantifying the percentage of live cells post-printing (e.g., Calcein AM/EthD-1 live/dead staining) to optimize printing parameters [23]. | |

| Hardware Components | Microfluidic Printhead | A "printhead-on-a-chip" device enabling real-time switching, mixing, and gradient formation of multiple bioinks during printing [4]. |

| Digital Micro-mirror Device (DMD) | A spatial light modulator used in SLA/PBP to dynamically project high-resolution patterns for layer-by-layer crosslinking [24] [25]. |

Multi-Material Stereolithography (MMSLA) represents a significant advancement in additive manufacturing for tissue engineering, enabling the fabrication of complex, heterogenous tissue constructs with high-resolution interfaces. As a subset of vat polymerization, MMSLA builds upon the principles of stereolithography (SLA) by incorporating multiple photoresponsive bioinks into a single printing process [29] [30]. This capability is crucial for replicating the intricate architectural and compositional nuances of native tissues, where sharp transitions between different cell types and extracellular matrices are essential for proper biological function [3]. The technology's exceptional resolution, typically ranging from 5-50 micrometers, allows for precise spatial control over material placement, facilitating the creation of sophisticated tissue models that more accurately mimic in vivo conditions for research and drug development applications [29].

The evolution of MMSLA technology coincides with a paradigm shift in tissue engineering toward creating biomimetic environments that recapitulate the complex microenvironments found in living organisms [3]. Traditional single-material bioprinting approaches face limitations in reproducing the natural interfaces between different tissue types, such as those between vascular networks and parenchymal tissues, or the graduated transition from bone to cartilage in osteochondral constructs [31]. MMSLA addresses these challenges by enabling the fabrication of constructs with spatially controlled biochemical and mechanical properties, making it particularly valuable for creating advanced in vitro models for drug screening, disease modeling, and the development of implantable tissue constructs [29] [32].

Comparative Analysis of Bioprinting Technologies

The landscape of 3D bioprinting technologies encompasses several distinct approaches, each with unique advantages and limitations for specific applications in tissue engineering. Understanding the relative capabilities of these technologies provides essential context for appreciating the specific value proposition of MMSLA in creating high-resolution interfaces.

Table 1: Comparison of Major 3D Bioprinting Technologies

| Technology | Resolution | Speed | Cell Viability | Material Versatility | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inkjet-based | 20-100 μm [30] | Moderate [29] | >85% [29] | Low viscosity bioinks only [29] | High-throughput screening, patterned cell deposition [29] |

| Extrusion-based | ≥100 μm [29] | Slow (10-50 μm/s) [29] | 40-95% (shear-dependent) [30] | High viscosity materials, high cell densities [29] [30] | Organoids, vascularized tissues, bone/cartilage scaffolds [29] [3] |

| Laser-assisted | Single cell (∼10 μm) [30] | Very slow [30] | >95% [30] | Limited by ribbon preparation [30] | High-precision cell patterning, stem cell niches [30] |

| SLA/DLP-based | <20-50 μm [29] [30] | Fast (volumetric) [29] | >90% (UV exposure-dependent) [30] | Photocrosslinkable hydrogels [29] | High-resolution scaffolds, microfluidic devices, complex tissue interfaces [29] |

As evidenced in Table 1, MMSLA and related light-based bioprinting technologies offer a favorable combination of high resolution and printing speed compared to other modalities. The digital nature of SLA-based processes enables exceptional precision in material placement, which is paramount for creating defined interfaces between different biomaterials and cell types [29]. Furthermore, the layerless continuous printing capability of advanced DLP systems significantly reduces printing time and eliminates artificial interfaces between layers, resulting in constructs with improved mechanical integrity [29]. These characteristics make MMSLA particularly suitable for applications requiring precise spatial control, such as recreating the complex tissue interfaces found in organ-on-a-chip systems, vascular networks, and multi-tissue constructs [31].

MMSLA Experimental Protocol for Complex Tissue Interfaces

Equipment and Reagent Setup

The successful implementation of MMSLA requires careful preparation of both hardware and bioink components to ensure reproducible fabrication of high-resolution interfaces.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for MMSLA

| Reagent/Material | Composition | Function | Example Formulation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Photocrosslinkable Hydrogels | GelMA, PEGDA, Hyaluronic acid methacrylate [29] [3] | Structural scaffold providing biomechanical support and cell adhesion sites | 5-15% (w/v) GelMA with 0.1-0.5% (w/v) LAP photoinitiator [3] |

| Cell Suspensions | Primary cells, stem cells, or cell lines in culture medium [29] [3] | Biological component for tissue formation and function | 1-10 million cells/mL in bioink [3] |

| Photoinitiators | Lithium phenyl-2,4,6-trimethylbenzoylphosphinate (LAP), Irgacure 2959 [3] | Initiate polymerization upon light exposure | 0.1-0.5% (w/v) in hydrogel precursor solution [3] |

| Support Baths | Carbopol, gelatin microparticles, Pluronic F127 [31] | Temporary support for overhanging structures during multi-material printing | 1-3% (w/v) Carbopol in PBS [31] |

| Functional Additives | RGD peptides, growth factors, ECM proteins [3] | Enhance bioactivity and direct cell behavior | 0.1-1 mg/mL RGD peptides in bioink [3] |

Prior to printing, the MMSLA system requires calibration and preparation. The digital light processing (DLP) engine, typically comprising a digital micromirror device (DMD) chip with approximately two million micromirrors, must be calibrated to ensure precise pattern projection [29]. The bioink reservoirs should be filled with respective photopolymerizable bioinks, taking care to minimize bubble formation. For multi-material printing, a cleaning mechanism between material swaps is essential to prevent cross-contamination [29]. The building platform should be leveled and the z-axis precision verified to ensure dimensional accuracy throughout the printing process.

Multi-Material Printing Procedure

The following protocol details the step-by-step process for fabricating a complex tissue construct with high-resolution interfaces using MMSLA:

Digital Design and Slicing: Create a 3D model of the desired tissue construct using computer-aided design (CAD) software or medical imaging data (e.g., CT, MRI) converted to STL format [3]. For multi-material constructs, assign specific regions to different materials using appropriate software features. Slice the model into sequential layers corresponding to the printing resolution, typically 10-50 μm thick [29].

Bioink Preparation and Loading: Prepare each photopolymerizable bioink according to Table 2 formulations. Gently mix cell suspensions into hydrogel precursor solutions at the recommended cell densities. Centrifuge at low speed (200-500 g) to remove air bubbles. Load each bioink into separate reservoirs of the MMSLA system, ensuring temperature control if necessary (e.g., maintaining 4-10°C for thermosensitive materials).

Initial Layer Fabrication: Lower the build platform into the first bioink reservoir until a layer thickness of 25-100 μm is achieved. Project the first slice pattern using UV light (typically 365-405 nm) at an intensity of 5-20 mW/cm² for 5-30 seconds exposure time, depending on bioink photosensitivity [29]. Retract the build platform to separate from the resin tank.

Multi-Material Switching and Interface Formation: For layers requiring material transitions, implement the following sequence:

- Move the build platform to the cleaning station and perform a gentle wash using appropriate buffer solution.

- Translate the platform to the subsequent bioink reservoir.

- Lower the platform into the new bioink, ensuring precise alignment with the previously printed layers.

- Project the next slice pattern, paying particular attention to interface regions where materials meet.

- Repeat this process for each layer, with material switches occurring as dictated by the digital design.

Post-Printing Processing: Upon completion of the final layer, carefully retrieve the construct from the build platform. Rinse with sterile PBS to remove uncrosslinked material and processing solutions. Perform additional post-crosslinking if necessary using a broad UV exposure (2-5 minutes at 5-10 mW/cm²) to ensure complete polymerization.

Cell Culture and Maturation: Transfer the construct to cell culture medium and maintain under standard culture conditions (37°C, 5% CO₂). Change medium every 24-48 hours, monitoring cell viability and tissue maturation over time. For vascularized constructs, consider implementing flow conditions using bioreactors to enhance tissue development and functionality [31].

Diagram 1: MMSLA fabrication workflow for complex tissue constructs with high-resolution interfaces. The process highlights the critical material switching steps that enable multi-material capability.

Quality Assessment and Characterization

Rigorous characterization of the printed constructs is essential to validate the formation of high-resolution interfaces and ensure biological functionality:

Structural Analysis: Employ scanning electron microscopy (SEM) to examine the microstructure and interface integrity between different materials [33]. Utilize micro-computed tomography (μCT) for non-destructive 3D analysis of internal architecture and interface continuity.

Mechanical Testing: Perform nanoindentation at interface regions to measure spatial variations in mechanical properties. Conduct tensile tests to evaluate interfacial strength and durability.

Biological Assessment: Monitor cell viability at interface regions using live/dead staining protocols. Evaluate cell morphology and organization through immunohistochemistry and confocal microscopy. For functional assessments, measure tissue-specific markers and metabolic activity.

Applications in Complex Tissue Engineering

MMSLA technology enables the fabrication of sophisticated tissue models with anatomically relevant interfaces that are crucial for advancing drug development and tissue engineering research.

Vascularized Tissue Constructs

Creating functional vasculature within engineered tissues represents one of the most significant challenges in tissue engineering. MMSLA facilitates the fabrication of complex, hierarchical vascular networks through precise spatial patterning of endothelial cells and supportive pericytes within a tissue-specific ECM [31]. The technology enables the creation of vessel structures with decreasing diameters from arterioles to capillaries, mimicking the natural vascular architecture essential for nutrient and oxygen delivery throughout thick tissue constructs [31]. These vascularized tissues can maintain cell viability in regions nearly ten times thicker than avascular constructs, addressing a critical limitation in engineering clinically relevant tissue volumes [31].

Organ-on-a-Chip and Disease Models

The high resolution of MMSLA makes it ideal for creating sophisticated organ-on-a-chip systems with integrated microfluidic networks and tissue-tissue interfaces [29]. For instance, the technology has been used to create the first entirely 3D-printed heart-on-a-chip with integrated soft strain sensors that monitor tissue contractility [31]. These systems can incorporate multiple tissue types separated by permeable membrane-like interfaces that mimic physiological barriers in the human body, such as the blood-brain barrier or alveolar-capillary interface [29]. The capacity to precisely control these interfaces enables more accurate modeling of drug transport and disease processes, providing valuable platforms for pharmaceutical screening and disease mechanism studies.

Osteochondral and Interface Tissue Engineering

MMSLA excels at fabricating constructs with graduated transitions between different tissue types, such as the interface between bone and cartilage in osteochondral tissues [3]. By strategically depositing materials with distinct mechanical and biochemical properties, MMSLA can recreate the natural zonal organization of these interface tissues, which is crucial for their functional performance [3]. The technology enables precise control over mineral concentration, collagen alignment, and growth factor distribution across the interface region, promoting the formation of continuous tissue integration rather than sharp, mechanically weak junctions.

Diagram 2: Tissue engineering applications leveraging MMSLA's capability to create high-resolution interfaces. Each application utilizes specific architectural features enabled by multi-material printing.

Technical Considerations and Optimization Strategies

Achieving high-resolution interfaces with MMSLA requires careful attention to several technical aspects throughout the printing process. The following optimization strategies can enhance interface quality and biological performance:

Interface Bonding Optimization: To ensure strong adhesion between different materials, design interdigitated or graded interfaces rather than sharp boundaries. Incorporate chemical functional groups that promote covalent bonding between layers, such as acrylate groups in both materials [3]. Adjust exposure parameters at interface regions to ensure adequate crosslinking between materials.

Resolution Enhancement: For features approaching the theoretical resolution limits of MMSLA, optimize the photoinitiator concentration and light absorption properties to minimize light scattering [30]. Utilize computed tomography-inspired optimization algorithms to account for light penetration and scattering effects during pattern projection [29].

Cell Viability Maintenance: To preserve cell viability during the printing process, carefully optimize UV exposure time and intensity, implementing multiple short exposures rather than continuous illumination for thick layers [30]. Incorporate radical scavengers in the bioink formulation to mitigate oxidative stress, and maintain physiological temperature throughout the printing process [3].

Multi-Material Stereolithography represents a transformative technology for engineering complex tissue architectures with high-resolution interfaces. By enabling precise spatial control over multiple biomaterials and cell types, MMSLA facilitates the creation of biologically relevant tissue models that more accurately mimic native tissue organization and function. The protocols and applications outlined in this document provide researchers with a framework for leveraging MMSLA capabilities in tissue engineering and drug development research. As the technology continues to evolve, advancements in bioink development, printing resolution, and vascularization strategies will further enhance our ability to recreate sophisticated tissue interfaces for both basic research and clinical applications.

The pursuit of engineering complex, biomimetic tissues demands technologies capable of replicating the intricate spatial and functional heterogeneity found in native organs. Multi-material bioprinting stands at the forefront of this challenge, aiming to fabricate constructs with precise arrangements of cells and extracellular matrix components. A significant advancement in this field is the integration of microfluidic technology with bioprinting, leading to the development of sophisticated “printhead-on-a-chip” systems [4]. These systems enable real-time material switching, gradient formation, and enhanced printing resolution by leveraging the principles of microscale fluid dynamics [4]. This capability is critical for creating complex tissue architectures, such as vascular networks and organ-specific microenvironments, which are essential for advanced research in tissue engineering, disease modeling, and drug development [4]. This protocol details the application of microfluidic bioprinting for precision deposition and dynamic switching between bioinks, providing a foundational methodology for multi-material tissue construct fabrication.

Quantitative Benchmarking of Bioink Performance

Selecting and evaluating bioinks based on quantitative performance metrics is crucial for successful bioprinting. The following criteria should be assessed to ensure cell compatibility during the printing process [34].

Table 1: Quantitative Benchmarks for Bioink Performance

| Performance Criterion | Testing Protocol Summary | Key Quantitative Metrics | Exemplary Bioink Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Sedimentation | Incubate cell-laden bioink in printing cartridge for 1 hour; measure homogeneity [34]. | Homogeneity of cell distribution; percentage of settled cells [34]. | GelMA & RAPID inks: Prevent appreciable sedimentation.PEGDA alone: Significant cell settling [34]. |

| Cell Viability During Extrusion | Print cells at constant flow rate (e.g., 75 µL/min); immediately test membrane integrity [34]. | Percentage of cells with membrane damage post-extrusion [34]. | RAPID inks: < 4% damage.PEGDA/GelMA: < 10% damage [34]. |

| Cell Viability After Curing | Expose cells to curing conditions (e.g., light, CaCl₂) for 5 minutes; test membrane integrity [34]. | Percentage of cells damaged after curing, particularly at droplet edges [34]. | RAPID inks (CaCl₂): < 20% damage.PEGDA/GelMA (Light): > 50% damage [34]. |

Table 2: Comparison of Bioprinting Techniques for Multi-Material Fabrication

| Bioprinting Technique | Typical Resolution | Cell Viability | Suitability for Multi-Material | Key Advantages |