Navigating MSC Exosome Heterogeneity: From Biological Complexity to Clinical Standardization

Mesenchymal stem cell (MSC)-derived exosomes and other extracellular vesicles (EVs) represent a promising cell-free therapeutic platform with significant advantages over whole-cell therapies.

Navigating MSC Exosome Heterogeneity: From Biological Complexity to Clinical Standardization

Abstract

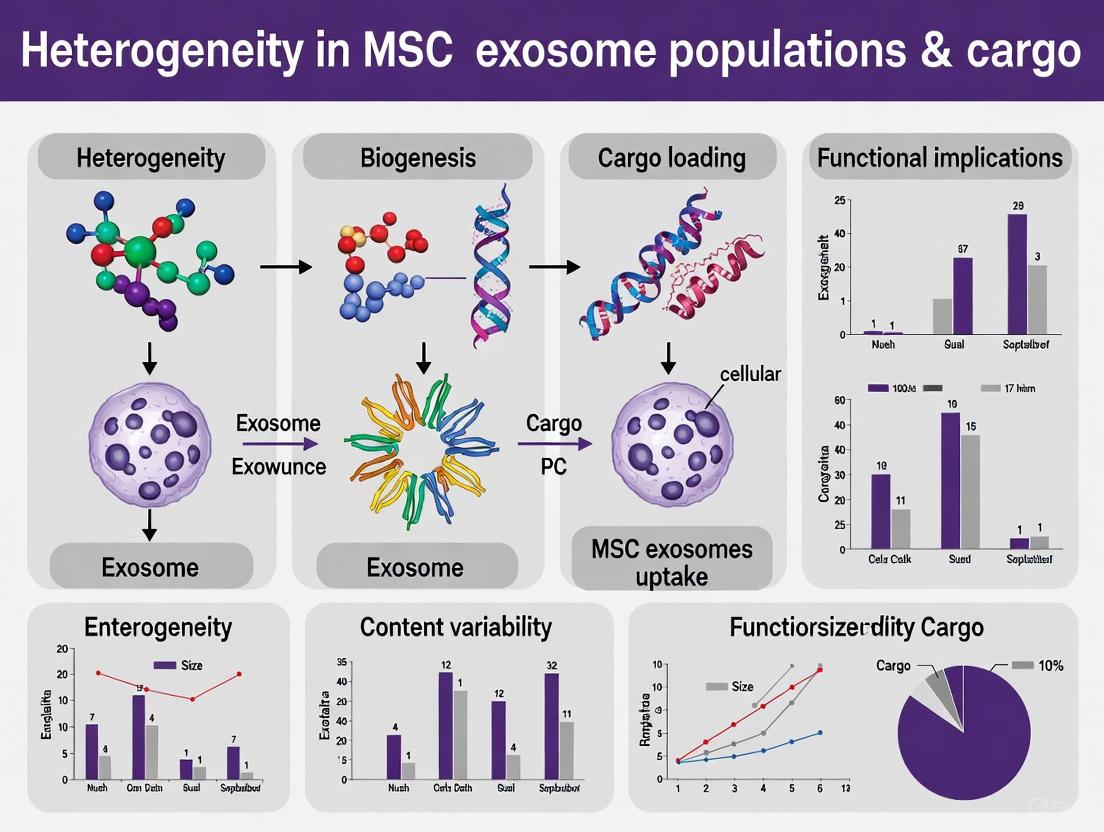

Mesenchymal stem cell (MSC)-derived exosomes and other extracellular vesicles (EVs) represent a promising cell-free therapeutic platform with significant advantages over whole-cell therapies. However, their inherent heterogeneity in population and cargo presents a major challenge for clinical translation and reproducible efficacy. This article provides a comprehensive analysis for researchers and drug development professionals, exploring the foundational sources of heterogeneity, methodological advances for its control, strategies for troubleshooting manufacturing challenges, and frameworks for validation and comparative analysis. By synthesizing the latest research and clinical data, this review aims to equip scientists with the knowledge to standardize MSC-exosome products and harness their full therapeutic potential in regenerative medicine and drug delivery.

Decoding the Sources of MSC Exosome Heterogeneity: Vesicles, Cargo, and Biological Drivers

The therapeutic potential of Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs) is now largely attributed to their secretome—the complex mixture of factors they release, which includes various types of extracellular vesicles (EVs). These EVs are nanoscale lipid bilayer-enclosed particles that act as essential messengers in intercellular communication, shuttling bioactive molecules like proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids between cells. The MSC secretome primarily contains three distinct classes of EVs: exosomes, microvesicles, and apoptotic bodies, each with unique origins, sizes, and compositional profiles. Understanding this spectrum is crucial for research and therapeutic development, as the significant heterogeneity within and between these populations directly impacts experimental reproducibility and therapeutic efficacy [1] [2].

This technical support center addresses the key challenges researchers face when working with heterogeneous MSC-EV populations. The following sections provide targeted troubleshooting guides, detailed protocols, and strategic insights to help you isolate, characterize, and functionally analyze these complex vesicle mixtures, thereby advancing your research in regenerative medicine and drug development.

FAQ: Fundamental Concepts of MSC-Derived EVs

Q1: What are the key defining characteristics that differentiate exosomes, microvesicles, and apoptotic bodies?

The three main EV types in MSC secretomes are classified based on their biogenesis, size, and molecular markers.

- Exosomes (30-150 nm) are formed intracellularly within multivesicular bodies (MVBs). When MVBs fuse with the plasma membrane, exosomes are released into the extracellular space. They are characterized by the presence of tetraspanin markers (CD63, CD81, CD9) and ESCRT-related proteins (TSG101, Alix) [1] [3] [2].

- Microvesicles (100-1000 nm) are formed directly through the outward budding and fission of the plasma membrane. Their composition reflects the parent cell's plasma membrane and they are typically enriched with proteins like selectins and integrins [1] [4] [2].

- Apoptotic Bodies (50-5000 nm) are generated during the programmed cell death (apoptosis) of MSCs. They contain cellular debris, such as fragmented organelles and condensed chromatin, and are identified by the presence of phosphatidylserine (PS) on their surface [1] [4] [5].

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Major Extracellular Vesicle Types in MSC Secretomes

| Feature | Exosomes | Microvesicles | Apoptotic Bodies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biogenesis | Endosomal pathway (MVBs) | Outward budding of plasma membrane | Cell disassembly during apoptosis |

| Size Range | 30 - 150 nm | 100 - 1000 nm | 50 - 5000 nm |

| Key Markers | CD63, CD81, CD9, TSG101, Alix | Selectins, Integins, ARF6 | Phosphatidylserine, Histones |

| Key Cargo | miRNAs, mRNAs, cytoplasmic & membrane proteins | miRNAs, mRNAs, cytoplasmic proteins | Cellular debris, organelle fragments, nuclear parts |

| Primary Function | Targeted intercellular communication | Local cell signaling & communication | Clearance of apoptotic cell debris |

Q2: Why is understanding EV heterogeneity critical for my research outcomes?

EV heterogeneity is a critical variable that can significantly influence your experimental results and their interpretation. This heterogeneity arises from several factors:

- Cell Source: MSCs isolated from different tissues (e.g., bone marrow, adipose tissue, umbilical cord) produce EVs with distinct molecular cargo and functional properties [1] [5]. For instance, bone marrow MSC-EVs highly inhibit inflammatory cell accumulation, while umbilical cord-derived MSC-EVs are particularly effective at suppressing oxidative stress [1].

- Culture Conditions: The medium composition (e.g., fetal bovine serum vs. platelet lysate vs. serum/xeno-free media), 3D vs. 2D culture, use of bioreactors, and exposure to hypoxia can all alter the yield, composition, and biological activity of the EVs produced by MSCs [1] [6].

- Isolation Method: The technique used to isolate EVs (e.g., ultracentrifugation, density gradient, precipitation, size-exclusion chromatography) can selectively enrich for different EV subpopulations, directly affecting the purity and functional profile of your final sample [4] [7].

Failure to account for this heterogeneity can lead to poor reproducibility between experiments and labs, inconsistent therapeutic outcomes, and difficulty in identifying genuine EV-specific biomarkers [1] [5]. Standardizing and reporting these parameters is essential for robust science.

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Challenges

Challenge 1: Low Yield or Purity of MSC-derived EVs

Problem: The quantity of isolated EVs is insufficient for downstream analysis, or the preparation is contaminated with non-EV components like proteins or lipoprotein particles.

Solutions:

- Optimize Cell Expansion: Ensure MSCs are healthy and expanded under optimal conditions. Using human platelet lysate or defined xeno-free media instead of fetal bovine serum (FBS) can enhance EV production and reduce contaminating bovine EVs [6].

- Select the Appropriate Isolation Technique: Choose an isolation method based on your downstream application. For high purity, consider density gradient centrifugation or size-exclusion chromatography. For large volumes, tangential flow filtration is efficient [4] [8].

- Combine Methods: A common strategy is to use a combination of methods, such as ultrafiltration followed by size-exclusion chromatography (SEC), to increase both yield and purity [4] [7].

- Characterize Rigorously: Always use multiple characterization techniques to assess purity, such as Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis (NTA) for concentration and size, and Western Blot for specific markers (e.g., CD63, CD81) and the absence of negative markers like GM130 (Golgi) or calnexin (ER) [8] [5].

Challenge 2: Inconsistent Functional Results in Target Cell Assays

Problem: EV preparations from the same MSC source yield variable results in functional assays, such as proliferation, migration, or gene expression in recipient cells.

Solutions:

- Control MSC Passage Number: MSC properties can drift with repeated passaging. Use MSCs within a defined, low passage range (e.g., P3-P6) to maintain consistency in EV production [2].

- Standardize the "Cell State": The physiological state of the MSCs at the time of EV collection is critical. Implement serum-starvation during EV production if required, and control for factors like cell confluency and metabolic state [6] [5].

- Functional Titering: Do not simply dose experiments based on EV protein quantity or particle number. Perform a functional titration for your specific assay (e.g., a dose-response curve for angiogenesis or immunomodulation) to find the optimal and reproducible effective dose [1].

- Analyze Cargo: Heterogeneity in EV cargo (e.g., miRNA or protein profiles) due to slight changes in culture conditions can cause functional variation. Use techniques like RNA sequencing or proteomics to correlate cargo with function [1] [6].

Challenge 3: Inefficient Loading of Therapeutic Cargo into EVs

Problem: Low efficiency when loading drugs, nucleic acids (siRNA, miRNA), or proteins into isolated MSC-EVs for drug delivery applications.

Solutions:

- Choose the Right Loading Method: Select a method appropriate for your cargo.

- Electroporation: Common for nucleic acids like siRNA, but can cause EV aggregation and membrane damage [8].

- Sonication: Uses ultrasound to transiently disrupt the EV membrane, allowing cargo entry. Can be more efficient but requires optimization to avoid damaging EVs [8].

- Co-incubation: The simplest method; incubate the cargo with EVs. Efficiency is highly dependent on the cargo's lipophilicity and concentration gradient [8].

- Saponin-Assisted Loading: Uses saponin to create pores in the EV membrane. Can achieve high loading capacity but requires careful control and cleaning steps [8].

- Post-Loading Purification: Always include a purification step (e.g., SEC, ultrafiltration) after loading to remove unencapsulated free cargo, which can confound functional results [8].

- Verify Loading and EV Integrity: Use techniques like NTA to confirm EV size stability post-loading and a functional assay to confirm the loaded cargo is bioactive and protected [8].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Isolation of EVs from MSC Conditioned Medium via Ultracentrifugation

This protocol describes the classic "gold standard" method for isolating EVs from MSC-conditioned medium [4] [8].

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Mesenchymal Stem Cells: Source (e.g., bone marrow, adipose). Use at 70-80% confluency.

- Serum-free MSC Medium: To avoid contamination with serum-derived EVs.

- Dulbecco's Phosphate Buffered Saline (DPBS): For washing cells.

- Ultracentrifugation Tubes: Polypropylene tubes compatible with ultracentrifuge.

- Protease Inhibitor Cocktail: Added to conditioned medium to prevent protein degradation.

Method:

- Cell Culture and Conditioning: Culture MSCs to 70-80% confluency. Wash cells three times with DPBS to remove residual serum. Add serum-free medium and incubate for 24-48 hours. Using a defined and consistent conditioning time is crucial for reproducibility.

- Collection and Pre-Clearing: Collect the conditioned medium and centrifuge at 376 × g for 10 minutes at 4°C to remove floating cells.

- Sequential Centrifugation:

- Transfer supernatant to new tubes and centrifuge at 2,000 × g for 20 minutes at 4°C to remove dead cells and large debris.

- Transfer supernatant and centrifuge at 10,000 × g for 30 minutes at 4°C to pellet larger microvesicles and organelles.

- Filter the resulting supernatant through a 0.22 µm pore filter to remove remaining large particles.

- Ultracentrifugation: Transfer the filtered supernatant to ultracentrifuge tubes. Pellet EVs by ultracentrifugation at 100,000 - 120,000 × g for 70-90 minutes at 4°C.

- Washing and Resuspension: Carefully discard the supernatant. Gently wash the pellet (often not visible) with a large volume of DPBS. Perform a second ultracentrifugation under the same conditions (100,000 - 120,000 × g, 70-90 min). Finally, resuspend the final EV pellet in a small volume of DPBS or your chosen storage buffer (e.g., with trehalose). Aliquot and store at -80°C.

Diagram 1: Ultracentrifugation Workflow for EV Isolation

Protocol 2: Characterization of Isolated EVs using Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis (NTA) and Western Blot

This protocol confirms the size, concentration, and presence of EV-specific markers in your isolation [8] [5].

Research Reagent Solutions:

- DPBS, filtered (0.1 µm): For diluting EV samples for NTA.

- RIPA Lysis Buffer: For lysing EVs for protein analysis.

- BCA Assay Kit: For quantifying protein concentration.

- Primary Antibodies: Anti-CD63, anti-CD81, anti-TSG101, anti-Calnexin.

- Secondary Antibodies: HRP-conjugated antibodies.

- SDS-PAGE Gel, PVDF Membrane, ECL Reagent: For Western Blot.

Method: Part A: Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis (NTA)

- Dilution: Thaw an EV aliquot on ice. Dilute the sample 100- to 1000-fold in filtered (0.1 µm) DPBS to achieve an ideal concentration for the NTA instrument (e.g., 10^8 - 10^9 particles/mL).

- Instrument Calibration: Calibrate the NTA instrument according to the manufacturer's instructions using standard beads of known size.

- Measurement: Inject the diluted sample. Capture several 30-60 second videos. Ensure the particle count is within the linear range of the camera.

- Analysis: Use the instrument's software to analyze the videos, which tracks the Brownian motion of individual particles to calculate the hydrodynamic diameter and concentration of the EV population.

Part B: Western Blot Analysis

- EV Lysis: Mix a volume of EV suspension with an equal volume of 2X RIPA buffer containing protease inhibitors. Incubate on ice for 30 minutes.

- Protein Quantification: Use the BCA assay to determine the protein concentration of the lysate.

- Gel Electrophoresis: Load 10-20 µg of EV protein per well on an SDS-PAGE gel. Include a molecular weight marker. Run the gel at constant voltage.

- Membrane Transfer: Transfer the separated proteins from the gel to a PVDF membrane.

- Immunoblotting: Block the membrane with 5% non-fat milk. Incubate with primary antibodies (e.g., CD63, TSG101) overnight at 4°C. Wash and incubate with an HRP-conjugated secondary antibody. Develop the membrane using ECL reagent and image.

- Control for Purity: Probe for negative markers like Calnexin (an endoplasmic reticulum protein), which should be absent or significantly reduced in a pure EV preparation compared to a whole cell lysate.

Table 2: Comparison of Major EV Isolation Techniques

| Method | Principle | Advantages | Disadvantages | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ultracentrifugation (UC) | Sequential centrifugation based on size/density | Considered gold standard; no chemical additives; good for large volumes | Time-consuming; requires expensive equipment; can cause co-precipitation & EV damage | Large-scale prep; initial EV research |

| Size-Exclusion Chromatography (SEC) | Separation by size using porous polymer beads | High purity; preserves EV integrity & function; simple protocol | Sample dilution; limited volume per run; may not separate similar-sized particles | High-purity isolates for functional studies |

| Precipitation (e.g., PEG) | Reduce solubility using polymers | Simple; high yield; no special equipment | Co-precipitation of contaminants (proteins, lipoproteins); difficult downstream analysis | Quick, crude isolation for diagnostics |

| Tangential Flow Filtration (TFF) | Size-based separation with parallel flow | Scalable; high yield; good for processing large volumes | Membrane fouling; requires optimization; initial equipment cost | Industrial-scale manufacturing |

| Immunoaffinity Capture | Antibody-binding to surface markers | High specificity & purity; isolates specific EV subtypes | High cost; low yield; dependent on antibody specificity | Isolating specific EV subpopulations |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for MSC-EV Work

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Xeno-Free/SFDA-Compliant Cell Media | Expands MSCs for clinical translation | Eliminates bovine EV contaminants; ensures reproducible, GMP-compliant EV production [6]. |

| Human Platelet Lysate (hPL) | Serum-substitute for MSC culture | Enhances MSC proliferation and EV yield; human-derived reduces immunogenicity risks [6]. |

| Size-Exclusion Chromatography (SEC) Columns | High-purity EV isolation | Preserves EV biological activity and morphology; ideal for functional studies [4] [7]. |

| Nanoparticle Tracking Analyzer (NTA) | Measures EV size distribution & concentration | Essential for quantitative quality control of EV preparations [8] [5]. |

| Tetraspanin Antibody Panel (CD63, CD81, CD9) | EV characterization via Western Blot/Flow Cytometry | Confirms the vesicular nature of isolates; standard markers for exosomes [3] [8]. |

| MicroRNA/RNA Extraction Kits (EV-specific) | Isolates RNA cargo from EVs | Designed for low-abundance RNA from small volumes; enables cargo profiling [5]. |

| Trehalose or Sucrose-based Cryoprotectant | Long-term storage of EV samples | Helps maintain EV integrity and function during freeze-thaw cycles [4]. |

Signaling Pathways in MSC-EV Mediated Effects

MSC-derived EVs exert their therapeutic effects by modulating key signaling pathways in recipient cells through the transfer of proteins, miRNAs, and other bioactive molecules. The diagrams below illustrate two critical pathways involved in immune regulation and tissue repair.

Diagram 2: MSC-EV Modulation of T Cell Immune Response

Diagram 3: MSC-EV Mediated Tissue Repair Signaling

Mesenchymal stem cell (MSC)-derived exosomes are increasingly recognized as potent mediators of intercellular communication, capable of transferring diverse bioactive cargoes—including miRNAs, proteins, and lipids—to recipient cells to modulate their function [1] [9]. This cargo dictates the exosomes' targeting specificity and functional roles upon delivery [9]. A central challenge in harnessing these vesicles for therapeutic applications is their inherent heterogeneity; the composition and biological effects of MSC-derived exosomes are profoundly influenced by the MSC source, culture conditions, and isolation methods [1] [10]. This technical support center is designed to help researchers troubleshoot the complexities of analyzing variable exosomal cargo, providing targeted FAQs and detailed guides to ensure reproducible and reliable results within the broader thesis of addressing heterogeneity in MSC exosome research.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: Our MSC-exosome preparations show high variability in miRNA cargo yield between batches. What are the primary factors we should investigate?

Batch-to-batch variability in miRNA cargo is often linked to upstream process parameters. You should systematically investigate:

- Cell Source: MSCs from different tissues (e.g., bone marrow, adipose tissue, umbilical cord) inherently produce exosomes with distinct molecular compositions and functional properties [1].

- Culture Conditions: Factors like the use of 3D culture systems, bioreactors, and exposure to hypoxia can significantly alter the cargo profile of the resulting exosomes [1].

- Cell Physiological State: The age of the donor and the passage number of the MSCs in culture can impact their exosomal output. Aging MSCs, for instance, show functional decline and altered cargo secretion [10].

FAQ 2: When analyzing exosomal proteins, we encounter significant contamination from non-vesicular components. How can we improve purity for more accurate cargo analysis?

The isolation method is critical for purity. While differential ultracentrifugation is common, it can co-pellet non-vesicular contaminants. Consider these alternatives:

- Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC): This method effectively separates exosomes from soluble proteins based on size, resulting in higher purity preparations [11].

- Density Gradient Centrifugation: This technique separates components based on buoyant density, offering a high-purity exosome fraction, though it can be more time-consuming [11]. Always pair your isolation with robust characterization (e.g., NTA, Western Blot for CD63, CD81, TSG101) to confirm the presence of exosomes and assess purity.

FAQ 3: What are the primary biological mechanisms that explain why specific miRNAs and proteins are selectively loaded into MSC-exosomes?

Cargo sorting is a regulated process. The key mechanisms include:

- ESCRT-Dependent Pathway: The Endosomal Sorting Complexes Required for Transport (ESCRT) machinery, comprising complexes ESCRT-0, -I, -II, and -III, works with accessory proteins like ALIX and TSG101 to ubiquitinate and sort cargo into intraluminal vesicles (ILVs) that become exosomes [9].

- ESCRT-Independent Pathways: These rely on lipids like ceramide, which promotes membrane invagination, and tetraspanins (e.g., CD63), which help form protein microdomains for cargo selection [9].

- RNA-Binding Proteins: Proteins such as hnRNPs can bind specific RNA sequences and facilitate their packaging into exosomes [12].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Low and Inconsistent Yield of Exosomal RNA

Issue: Inadequate quantity or quality of RNA isolated from MSC-exosomes for downstream sequencing or qPCR analysis.

Investigation and Resolution:

| Investigation Step | Recommended Action | Expected Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Confirm Exosome Yield | Quantify exosome particles before lysis using Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis (NTA). | Verifies sufficient starting material; if low, revisit cell culture and exosome isolation steps. |

| Check Cell Viability | Ensure >90% viability of MSC cultures before exosome collection. Apoptotic cells release different vesicles (apoptotic bodies) [1]. | Improves consistency of exosome population and its cargo. |

| Optimize Lysis Protocol | Use a commercial exosomal RNA isolation kit with a vigorous lysis step. Include a DNase digest step. | Maximizes RNA recovery and removes genomic DNA contamination. |

| Quality Control | Assess RNA quality with a Bioanalyzer (e.g., RIN >7). | Confirms RNA is intact and suitable for sequencing. |

Detailed Protocol: Isolation of Exosomal RNA for miRNA Sequencing

- Exosome Isolation: Isolate exosomes from 20 mL of MSC-conditioned media using differential ultracentrifugation (2000 × g for 30 min, 10,000 × g for 45 min, followed by 100,000 × g for 70 min) [12].

- Validation: Resuspend the pellet and validate exosome presence via Western Blot for CD63 and CD81 and characterize size by NTA.

- RNA Extraction: Lysate the exosome pellet with a denaturing lysis buffer. Perform RNA extraction using acid-phenol:chloroform, followed by precipitation with isopropanol and glycogen.

- rRNA Depletion: Treat the RNA with a ribosomal RNA depletion kit to enrich for miRNA and other small RNAs.

- Library Prep and Sequencing: Construct sequencing libraries using a small RNA library preparation kit and sequence on an appropriate platform (e.g., Illumina) [12].

Problem 2: Unclear Functional Transfer of Exosomal Cargo to Recipient Cells

Issue: Difficulty in verifying that a specific exosomal cargo (e.g., mRNA, lncRNA) is delivered to a recipient cell and is functionally active.

Investigation and Resolution:

| Investigation Step | Recommended Action | Expected Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Track Exosomes | Label isolated exosomes with a fluorescent lipid dye (e.g., PKH67) and image uptake in recipient cells over 24h. | Confirms physical transfer of exosomes into target cells. |

| Monitor Functional mRNA Transfer | Isolate exosomes from donor MSCs and co-culture with recipient cells. Use qPCR and Western Blot in recipient cells to detect exosome-derived mRNA and its protein product. | Demonstrates functional delivery, as shown with Rab13 mRNA transfer [12]. |

| Employ CRISPR-based Tracking | For non-coding RNAs, use a CRISPR/Cas9-based RNA-tracking system in donor cells with export signals from secreted RNAs [12]. | Allows direct visualization and confirmation of functional RNA transfer to recipient cells. |

Detailed Protocol: Validating Functional mRNA Transfer

- Exosome Collection: Collect exosomes from donor MSCs (e.g., mutant KRAS cells known to enrich specific mRNAs like Rab13) [12].

- Recipient Cell Treatment: Treat recipient cells (e.g., 50% confluency) with 50 μg/mL of isolated exosomes for 48 hours.

- RNA/Protein Isolation: Harvest recipient cells. Split the sample for parallel RNA and protein extraction.

- Downstream Analysis:

- Perform RT-qPCR on the recipient cell RNA using sequence-specific primers for the gene of interest (e.g., Rab13).

- Perform Western Blot on the recipient cell lysates using an antibody against the corresponding protein (e.g., Rab13).

- A significant increase in both the mRNA and protein levels in recipient cells confirms functional transfer.

Experimental Pathways and Workflows

Diagram: Mechanisms of Cargo Sorting in Exosome Biogenesis

Diagram: Troubleshooting Workflow for Exosomal Cargo Heterogeneity

Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Materials for MSC-Exosome Cargo Analysis

| Item | Function/Application in Research |

|---|---|

| CD63 / CD81 / TSG101 Antibodies | Standard markers for identifying and validating exosomes via Western Blot or flow cytometry [9]. |

| ALIX Antibody | Protein marker associated with the ESCRT pathway and exosome biogenesis; used for validation [9]. |

| rRNA Depletion Kits | Critical for library preparation in RNA-seq to enrich for informative coding and non-coding RNAs over abundant ribosomal RNA [12]. |

| Nanoparticle Tracking Analyzer (NTA) | Instrument for determining the size distribution and concentration of exosome particles in a preparation [11]. |

| Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC) Columns | Used for high-purity isolation of exosomes away from soluble protein contaminants [11]. |

| PKH67 / PKH26 Fluorescent Cell Linkers | Lipophilic dyes used to fluorescently label the exosome membrane for tracking and uptake studies in recipient cells. |

The therapeutic potential of Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs) is significantly influenced by their tissue of origin. Bone marrow (BM), umbilical cord (UC), and adipose tissue (AT) are the most common sources, each imparting distinct functional and compositional characteristics to the cells and their secreted exosomes. Understanding these differences is critical for experimental design and clinical application. The table below summarizes the key comparative characteristics.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of MSC Tissue Sources

| Feature | Bone Marrow (BM) | Umbilical Cord (UC), notably Wharton's Jelly | Adipose Tissue (AT) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Isolation Invasiveness | Highly invasive (bone marrow aspiration) [13] | Non-invasive; uses medical waste (birth tissue) [14] [13] | Minimally invasive (mini-liposuction) [13] |

| Cell Yield & Proliferative Capacity | Lower yield; proliferation potential decreases significantly with donor age [13] [10] | High volume in Wharton's Jelly; cells from younger donors have higher proliferation rates [14] [13] | Very high yield (~5,000 MSCs/gram of tissue); robust proliferative capacity in vitro [13] |

| Donor Age Impact | High impact; cellular function declines with age [14] [13] | Low impact; sourced from birth, representing a "young" cell population [14] | Moderate impact; more resilient to age-related decline than BM-MSCs [13] |

| Differentiation Potential | High osteogenic (bone) affinity; multipotent [13] | Multipotent; limited heterogeneity and some unique properties [14] | Multipotent; high proliferative and differentiation capacity [13] |

| Immunomodulatory Properties | Potent immunomodulation; first MSC product (Prochymal) for GvHD [14] | Strong immunomodulatory properties; lower immunogenicity of UC-MSC exosomes [14] [1] | Strong immunomodulatory and immunosuppressive effects [10] |

| Key Advantages | Extensive historical data and clinical research track record [13] | No ethical concerns; no risk to donor; ease of isolation [14] | High tissue abundance; simple extraction; suitable for autologous therapy [13] |

| Key Challenges | Painful donor procedure; lower cell numbers [13] | For adults, typically requires allogeneic donation with associated matching needs [13] | Not suitable for individuals with very low body fat [13] |

This heterogeneity directly influences the resulting exosome populations. MSC-derived exosomes from different sources have been shown to possess different molecular cargoes (proteins, miRNAs) and, consequently, varying therapeutic efficacies for specific disease models [1]. For instance, BM-MSC exosomes highly inhibit inflammatory cells, while UC-MSC exosomes are particularly effective at suppressing oxidative stress [1].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) & Troubleshooting

Q1: Our team is getting inconsistent results in our exosome-based angiogenesis assays. Could the MSC tissue source be a factor?

Yes, absolutely. The angiogenic potential of MSC-exosomes varies by source. For example, UC-MSC exosomes have been highlighted for their strong pro-angiogenic effects, promoting blood vessel formation in fracture healing and cardiovascular disease models [1] [15]. BM-MSC exosomes also supply pro-angiogenic factors to damaged tissues [15]. If your assays are inconsistent, first confirm and standardize your MSC source. Furthermore, consider pre-conditioning strategies (e.g., 3D culture or hypoxia) to enhance and standardize the angiogenic cargo of your exosomes [16].

Q2: We are scaling up exosome production but are concerned about donor-related variability. Which source is most suitable?

For large-scale production, source consistency is paramount.

- Umbilical Cord (Wharton's Jelly): Often the preferred choice for allogeneic biobanking because the cells are derived from a young, healthy donor population, reducing age and health-related variability [14] [17].

- Adipose Tissue: Provides a high initial yield of MSCs, which is advantageous for scaling [13]. However, for autologous therapies, variability between individual donors (age, health status) will persist.

- Bone Marrow: Generally less suitable due to lower cell yield and higher sensitivity to donor age [13].

To mitigate variability, implement strict donor screening criteria and use early-passage cells, as cellular aging in long-term culture alters exosome production and functionality [18].

Q3: Why are our intravenously injected MSC-exosomes not homing effectively to the target tissue?

The homing efficiency of MSCs and their exosomes is influenced by multiple factors. The tissue source can affect the expression of homing receptors (e.g., CXCR4), which can be lost during in vitro culture [14]. Furthermore, a significant proportion of intravenously infused MSCs/exosomes can become trapped in capillary networks, particularly in the lungs [14]. Troubleshooting Steps:

- Characterize Homing Markers: Check the expression of key homing-related receptors (like CXCR4) on your parent MSCs.

- Consider Alternative Administration Routes: For localized injuries, direct injection (e.g., intra-arterial, intramyocardial) can dramatically increase the number of exosomes reaching the target site [14].

- Explore Engineering Strategies: Surface modification of exosomes with targeting ligands (e.g., RGD peptides) can improve their specific binding to injured tissues [15] [16].

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Preconditioning MSCs to Modulate Exosome Cargo

A key strategy to address heterogeneity and enhance exosome potency is to precondition MSCs before exosome collection. The following protocol details a method using hypoxic conditioning, which mimics the physiological niche and can enhance the therapeutic properties of secreted exosomes [16].

Protocol: Hypoxic Preconditioning of MSCs to Enhance Angiogenic Exosome Yield

Objective: To increase the production and angiogenic potential of exosomes derived from MSCs.

Materials:

- Cell Source: Mesenchymal Stem Cells (e.g., from BM, UC, or AT) at passage 3-5.

- Basal Medium: DMEM/F-12.

- Supplements: Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS), exosome-depleted. Penicillin-Streptomycin.

- Culture Vessels: T-175 flasks.

- Hypoxia Chamber/Workstation: Capable of maintaining 1-3% O₂, 5% CO₂, and balance N₂.

- Standard Cell Culture Incubator: (Normoxic conditions: 21% O₂, 5% CO₂).

- Other Reagents: PBS, Trypsin-EDTA.

Method:

- Cell Seeding: Seed MSCs at a consistent density (e.g., 5,000 cells/cm²) in T-175 flasks using complete medium supplemented with 10% exosome-depleted FBS.

- Pre-attachment: Incubate the cells under standard normoxic conditions (21% O₂, 5% CO₂) for 24 hours to allow for cell attachment.

- Hypoxic Induction: After 24 hours, carefully move the experimental group of flasks to the hypoxia chamber, pre-set to 1% O₂, 5% CO₂, at 37°C. The control group remains in the normoxic incubator.

- Conditioning Period: Culture the cells under these respective conditions for 48-72 hours.

- Collection of Conditioned Medium: After the conditioning period, carefully collect the culture medium from all flasks.

- Exosome Isolation: Isolate exosomes from the conditioned medium using your standard method (e.g., ultracentrifugation, size-exclusion chromatography). It is critical to process normoxic and hypoxic samples in parallel.

- Characterization: Characterize the isolated exosomes for particle size and concentration (NTA), specific markers (CD63, CD81, TSG101 via western blot), and morphology (TEM). To confirm enhanced efficacy, perform functional assays, such as a tube formation assay using Human Umbilical Vein Endothelial Cells (HUVECs).

Workflow Diagram:

Signaling Pathways: MSC Exosome-Mediated Angiogenesis

The pro-angiogenic effect of MSC-exosomes is a key therapeutic mechanism, particularly in cardiovascular and bone regeneration. The following diagram illustrates the primary signaling pathway by which MSC-exosomes can promote the formation of new blood vessels.

Diagram: MSC Exosome-mediated Angiogenic Signaling Pathway

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Reagents for MSC Exosome Research

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Exosome-Depleted FBS | Essential for cell culture to prevent contamination of isolated exosomes with bovine vesicles [18]. | Validate the depletion efficiency. Alternatives include using serum-free media or human platelet lysate. |

| Isolation Kits (e.g., Precipitation) | Rapid isolation of exosomes from conditioned medium or biofluids [15] [18]. | Can co-precipitate contaminants like proteins and lipoproteins. Not suitable for all downstream applications. |

| Antibodies for Characterization | Identification of exosomal markers (CD63, CD81, CD9, TSG101, Alix) via western blot or flow cytometry [15] [16]. | Always include negative markers (e.g., calnexin, GM130) to confirm exosomal purity. |

| Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis (NTA) | Measures the size distribution and concentration of particles in an exosome preparation [15]. | The gold standard for physical characterization. Tunable Resistive Pulse Sensing (TRPS) is another common alternative. |

| PKH67 / Other Lipophilic Dyes | Fluorescent labeling of exosomes for tracking their uptake by recipient cells in vitro [15]. | Can form dye aggregates that are mistaken for exosomes. Proper controls are critical. |

| 3D Culture Systems (e.g., Bioreactors) | Scalable production of MSCs and exosomes in an environment that more closely mimics the in vivo niche [16]. | Can significantly increase exosome yield and enhance biological activity compared to 2D culture. |

Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ 1: How Does Donor Age Affect the Cargo and Function of MSC-Derived Exosomes?

Problem Statement: Researchers observe inconsistent therapeutic outcomes in experiments using MSC-derived exosomes from different donors and suspect donor age as a contributing factor.

Explanation: Donor age is a critical factor introducing heterogeneity in MSC-derived exosomes. Aging impacts the molecular cargo of exosomes, shifting their functional profile from regenerative to senescent or pro-inflammatory. This occurs because MSCs themselves undergo functional decline with age, which is reflected in their secretome, including exosomes [10] [19].

Solution:

- Action 1: Source MSCs from Younger Donors: When targeting regenerative applications, prioritize MSCs from younger donors, such as umbilical cord tissue (UC-MSCs) or Wharton’s Jelly (WJ-MSC). Studies indicate these sources often exhibit superior regenerative and anti-aging potential compared to those from older adults [10] [19].

- Action 2: Pre-screen Exosome Cargo: For critical experiments, pre-characterize exosome cargo from donors of different ages. Key markers to analyze include:

- Action 3: Consider Pooling Strategies: To mitigate individual age-related variability, create a pool of exosomes isolated from MSCs derived from multiple, age-matched donors. This can help average out extreme phenotypes and produce a more consistent product [19].

Preventive Measures: Establish a standardized donor screening and age-tracking protocol for your cell bank. Clearly document the donor age for every MSC line and its corresponding exosome batch.

FAQ 2: How Do Underlying Health Conditions of the Donor Influence Exosome Function in Disease Models?

Problem Statement: MSC-derived exosomes intended for a disease model (e.g., cancer) show unexpected effects, potentially because the MSCs were isolated from a donor with an unrelated health condition.

Explanation: The health status of the donor directly shapes MSC phenotype and the composition of their exosomes. Cells derived from diseased individuals can produce exosomes with altered molecular profiles that may carry pathological cargo or have impaired therapeutic functionality [22] [19]. For instance, MSCs from diabetic or obese donors may have a different secretome profile compared to those from healthy individuals [19].

Solution:

- Action 1: Implement Rigorous Donor Health Screening: Define strict health exclusion criteria for donors. These should encompass chronic conditions (diabetes, cardiovascular disease, autoimmune disorders), infectious diseases, and recent surgical history [20] [21].

- Action 2: Functional Validation in a Relevant Assay: Do not rely solely on marker expression. Before committing a batch to a large study, functionally test the exosomes in a small-scale, disease-specific assay to confirm the intended biological effect.

- Action 3: Use Disease-Specific Donor Cells with Caution: If studying a specific disease, using MSCs from a diseased donor might be intentional. However, be aware that this introduces a specific and highly variable phenotype. Always compare against a healthy donor control to understand the disease-specific contribution [22].

Preventive Measures: Maintain detailed and annotated donor health records. For the most consistent results in fundamental research, source MSCs from healthy, screened donors whenever possible.

FAQ 3: How Can We Control for Genetic Background and Inter-Individual Variation in Preclinical Studies?

Problem Statement: Significant experiment-to-experiment variability is observed, even when using MSCs from donors of the same age and health status, likely due to inherent genetic and individual differences.

Explanation: Even among demographically similar healthy donors, inherent genetic and epigenetic differences lead to inter-individual variation in MSCs. This results in differences in their proliferation, differentiation potential, and exosome cargo, creating a "batch effect" that is a major challenge in clinical translation [10] [19]. Single-cell RNA sequencing has confirmed that MSCs are a heterogeneous population with distinct functional subpopulations, the balance of which can vary between individuals [19].

Solution:

- Action 1: Standardize the MSC Source: For a given study or project, use MSCs isolated from a single, well-characterized tissue source (e.g., only umbilical cord or only adipose tissue) to minimize source-induced heterogeneity [1] [10].

- Action 2: Characterize Multiple Donor Lines: If possible, establish and characterize several MSC lines from different donors. Test their exosomes for key properties (cargo, uptake, function in a target assay) and select the one with the most desirable and consistent profile for your research [19].

- Action 3: Employ a Pooling Strategy: As with age, pooling exosomes from multiple, genetically diverse but phenotypically screened donors can create a more standardized and reproducible research material, reducing the impact of any single donor's outlier characteristics [19].

Preventive Measures: Build a characterized biobank of MSC lines. Report the specific donor tissue source, passage number, and all characterization data (e.g., surface markers, differentiation potential) for the MSCs used to produce exosomes in any publication, as per ISCT guidelines [10] [19].

Table 1: Summary of Age-Related Changes in MSC-Derived and Plasma Exosomes

| Parameter | Change with Aging | Experimental Evidence | Functional Consequence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Exosome Concentration | Decreases in plasma [23]. MSC source impact is area of active research. | Longitudinal study showed EV concentration in plasma decreased over ~5 years and correlated with age [23]. | May indicate altered intercellular communication and reduced availability of signaling vesicles. |

| Pro-apoptotic Cargo | Increases (e.g., BAX/BCL-2 ratio) [21]. | HSCs treated with exosomes from older donors showed significant upregulation of BAX and downregulation of BCL-2 [21]. | Can promote apoptotic pathways in recipient cells, potentially counteracting regenerative processes. |

| Aging-Related Markers | Increase (e.g., P21 protein) [20]. | HSCs treated with exosomes from older donors showed significantly increased P21 protein expression [20]. | Induces cell cycle arrest and contributes to a senescent phenotype in target cells. |

| Regenerative Signaling | Decreases (e.g., HIF-1α expression) [20]. | HSCs treated with exosomes from younger donors showed increased HIF-1α gene expression, which was decreased with exosomes from older donors [20]. | Impairs cellular responses to hypoxia, a key mechanism in tissue repair and stem cell maintenance. |

Table 2: Impact of Donor Tissue Source on MSC-Exosome Properties

| Tissue Source | Reported Functional Specialization | Key References / Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Bone Marrow (BM-MSC) | Immunomodulation; B-cell maturation/activation [1]. | Considered the "gold standard" source, widely used for immune-related studies. |

| Umbilical Cord (UC-MSC) | Suppression of oxidative stress; angiogenesis; wound healing [1] [10]. | Younger cell source with high proliferative potential and strong paracrine activity. |

| Adipose Tissue (AD-MSC) | Wound healing; treatment of inflammation and transplantation [1]. | Easily accessible, used prominently in plastic/aesthetic surgery and wound healing research. |

| Pluripotent Stem Cell-Derived (Pluri-MSC) | Treatment of liver, musculoskeletal diseases; low immunogenicity [1]. | Offers a scalable and potentially more uniform source, but requires careful differentiation. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Assessing the Functional Impact of Donor Age on Exosomes in a Hematopoietic Stem Cell (HSC) Aging Model

Objective: To evaluate the effect of young vs. old donor-derived plasma exosomes on markers of aging (HIF-1α, P21) in HSCs [20].

Materials:

- Plasma from young (e.g., 25-44 years) and old (e.g., 60-75 years) male donors, health-screened [20] [21].

- Umbilical cord blood for HSC isolation.

- Ficoll-Paque for density gradient centrifugation.

- MACS CD34+ isolation kit and magnetic separator.

- RPMI-1640 culture medium with antibiotics.

- Ultracentrifuge.

- Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS).

- BCA Protein Assay Kit.

- TEM, DLS/Zeta sizer, and CD63 antibody for exosome characterization.

- qRT-PCR setup for HIF-1α.

- Western Blot setup for P21 protein.

Methodology:

- Exosome Isolation (Ultracentrifugation):

- Thaw plasma and dilute 1:3 in PBS.

- Centrifuge at 17,000 × g for 30 min at 4°C to remove debris and apoptotic bodies.

- Transfer supernatant to ultracentrifuge tubes and centrifuge at 100,000 × g for 75 min at 4°C.

- Resuspend pellet in 2 mL PBS and filter through a 0.22 µm filter.

- Dilute filtered suspension to 13 mL with PBS and repeat ultracentrifugation (100,000 × g, 75 min, 4°C).

- Resuspend final pellet in 0.5-1 mL PBS.

- Quantify exosome protein concentration using BCA assay [20] [21].

- Exosome Characterization:

- HSC Isolation:

- Isolate mononuclear cells from cord blood using Ficoll density gradient centrifugation.

- Isolate CD34+ HSCs using the MACS CD34+ MicroBead kit according to the manufacturer's protocol [20].

- Cell Treatment & Analysis:

- Culture isolated HSCs and treat with exosomes (e.g., 5 µg/mL and 10 µg/mL concentrations) from young and old donors for 24 hours. Include an untreated control.

- Viability Check: Perform MTT assay to confirm non-toxicity of exosome doses.

- Gene Expression: Extract RNA and perform qRT-PCR to analyze HIF-1α mRNA expression.

- Protein Expression: Perform Western Blot on cell lysates to detect P21 protein levels [20].

Expected Outcome: HSCs treated with exosomes from older donors are expected to show decreased HIF-1α mRNA and increased P21 protein, indicating a pro-aging effect, compared to those treated with exosomes from younger donors.

This experimental workflow is outlined in the diagram below:

Protocol 2: Evaluating Pro-Apoptotic Effects of Donor-Derived Exosomes

Objective: To determine if exosomes from older donors can induce a pro-apoptotic shift in the BAX/BCL-2 ratio in recipient HSCs [21].

Materials: (As in Protocol 1, with a focus on apoptosis markers.) Methodology:

- Exosome Isolation & Characterization: Follow steps 1 and 2 from Protocol 1.

- HSC Isolation & Treatment: Follow steps 3 and 4 from Protocol 1.

- Apoptosis Marker Analysis:

- After 24-hour treatment with exosomes, extract RNA from HSCs.

- Perform qRT-PCR using primers for BAX (pro-apoptotic) and BCL-2 (anti-apoptotic) genes.

- Calculate the BAX/BCL-2 mRNA expression ratio, a key indicator of apoptotic tendency [21].

Expected Outcome: HSCs treated with exosomes from older donors are expected to show a significantly higher BAX/BCL-2 ratio compared to the control and young exosome-treated groups.

Signaling Pathways

The molecular mechanisms underlying the aging effects mediated by exosomes involve key signaling pathways. The following diagram integrates findings from the provided research, showing how exosomal cargo from aged donors can influence recipient HSCs, promoting a senescent and pro-apoptotic phenotype.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Studying Donor-Derived Exosome Variability

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Ficoll-Paque | Density gradient medium for isolation of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) or HSCs from cord blood [20] [21]. | Ensure proper density and osmolarity for the specific cell type being isolated. |

| MACS CD34+ MicroBead Kit | Immunomagnetic positive selection for highly pure CD34+ Hematopoietic Stem Cells [20] [21]. | Purity should be confirmed by flow cytometry (e.g., >90% CD34+CD45-). |

| Ultracentrifuge | Gold-standard equipment for high-speed isolation of exosomes from plasma or cell culture media [20] [21] [24]. | Protocol parameters (g-force, time, temperature) must be strictly standardized for reproducibility. |

| CD63 Antibody | Primary antibody for Western Blot confirmation of exosomal markers, validating successful isolation [20] [21] [24]. | Part of the MISEV guidelines for minimal characterization of extracellular vesicles. |

| Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) / NTA | Instruments for determining exosome size distribution and particle concentration [20] [23] [24]. | NTA is often preferred for its direct visualization and sizing capabilities. |

| TEM (Transmission Electron Microscopy) | Imaging technique for confirming the classic "cup-shaped" morphology and size of isolated exosomes [20] [24]. | Requires specialized equipment and sample preparation. |

| BCA Protein Assay Kit | Colorimetric quantification of total protein in exosome samples, used for normalizing doses in functional experiments [20] [21]. | A common and sensitive method for protein quantification in dilute samples. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) on Exosome Heterogeneity

Q1: What is exosome heterogeneity, and why is it a critical consideration in research?

Exosome heterogeneity refers to the existence of distinct subpopulations of exosomes that differ in their biophysical properties, molecular composition, and biological functions. Cells do not release a single, uniform population of exosomes but rather a diverse mixture of vesicles [25] [26]. This heterogeneity arises from variations in biogenesis pathways, the cell's physiological state, and the cell source [1] [27]. Recognizing this is critical because different exosome subpopulations can have unique and sometimes opposing effects on recipient cells. Ignoring this complexity can lead to inconsistent experimental results and misinterpretation of data.

Q2: Are there specific markers that can identify all exosomes or their subpopulations?

Currently, there is no single, universal marker that identifies all exosomes or exclusively defines specific subpopulations [28] [29]. The research community recommends a combination of markers for verification. The most commonly used tetraspanins (CD9, CD63, CD81) are found in many exosome preparations but are not universally present; for example, Jurkat cells release exosomes that are CD9 negative [28]. Other common markers include ESCRT-related proteins like ALIX and TSG101 [26]. It is equally important to test for the absence of contaminants from other cellular compartments using markers for the endoplasmic reticulum (e.g., calnexin), Golgi (e.g., GM130), mitochondria (e.g., cytochrome C), and nucleus (e.g., histones) [28].

Q3: How does the source of Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs) impact exosome heterogeneity?

The tissue source of MSCs is a major determinant of exosome heterogeneity, leading to variations in their molecular cargo and therapeutic functions [1]. For instance:

- Bone marrow MSC-EVs highly inhibit inflammatory and apoptotic cells and affect B-cell maturation [1].

- Umbilical cord MSC-EVs suppress oxidative stress in kidney injury and promote angiogenesis for wound healing [1].

- Pluripotent stem cell-derived MSC-EVs show low immunogenicity and are used for liver and musculoskeletal diseases [1]. This indicates that the choice of MSC source should be tailored to the specific therapeutic application.

Q4: What are the primary challenges in loading therapeutic cargo into exosomes?

Loading cargo into exosomes remains a significant technical challenge. While various strategies exist, including incubation, electroporation, sonication, extrusion, freeze-thaw cycling, and transfection, inadequate loading efficiency is a common problem [30]. Each method has potential drawbacks, such as causing exosome aggregation, damaging the exosome membrane, or being inefficient for certain types of cargo (e.g., small molecules, nucleic acids, or proteins) [30]. The field is actively developing more efficient and gentle loading techniques to enable reliable exosome-based drug delivery.

Q5: How should exosomes be stored to maintain stability?

Exosomes can be stored in PBS with 0.1% BSA [28]. Isolation efficiency is not changed after freezing at -80°C compared to freshly made exosomes. For direct isolation from cell culture media or urine, freezing without cryo-protectants like glycerol is possible [28]. However, standardized protocols for long-term storage are still an area of investigation to ensure functional consistency.

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Issue 1: Inconsistent Functional Effects in Recipient Cells

Potential Cause: The problem may stem from the unrecognized heterogeneity of your exosome preparation. Your isolated "exosome" sample is likely a mixture of subpopulations, and variations in the relative abundance of these subpopulations between preparations can lead to inconsistent biological outcomes [25] [26].

Solution:

- Characterize Subpopulations: Move beyond basic characterization. Use techniques like density gradient centrifugation to separate and identify distinct subpopulations within your exosome samples [26]. Research shows that low-density exosomes (LD-Exo) and high-density exosomes (HD-Exo) have different protein and RNA contents and elicit differential effects on recipient cells [26].

- Standardize Production: Control upstream process parameters that influence heterogeneity. This includes using a consistent MSC source, culture conditions (2D vs. 3D, bioreactors), and medium composition [1] [31]. One study demonstrated that using a defined system (Hollow Fiber 3D bioreactor with RoosterBio exosome-harvesting system) allowed for stable production of exosome subpopulations over a 28-day culture period, ensuring more consistent bioactive components [31].

Issue 2: Low Yield or Purity of Isolated Exosomes

Potential Cause: The isolation method may be inefficient, may not be suited to your starting material, or may be co-isolating contaminants.

Solution:

- Optimize Isolation Protocol: The choice of isolation method depends on the downstream application and starting material. Ultracentrifugation is common but can lead to vesicle loss and aggregation. Consider alternatives like size-exclusion chromatography (SEC), which preserves exosome integrity and improves purity [26].

- Combine Methods: For complex samples like plasma, a combination of methods is often necessary. A recommended approach is to perform a pre-clearing step using SEC prior to isolation with immunocapture beads (e.g., targeting CD9) [28].

- Validate Purity: Always confirm the purity of your isolates by checking for the absence of organelle-specific markers (e.g., calnexin for ER) [28].

Issue 3: Difficulty in Tracking Exosome Uptake by Recipient Cells

Potential Cause: The mechanisms of exosome uptake and delivery are not fully understood and can be cell-type specific, involving endocytosis, direct fusion, or receptor-ligand interactions [32].

Solution:

- Use Multiple Tracking Methods: Employ a combination of fluorescent lipid dyes to label membranes and fluorescently tagged exosomal cargo (e.g., miRNAs or proteins) to track both the vesicle and its contents [32].

- Investigate Biodistribution: For in vivo studies, use advanced tracking methods. One study successfully used isotopic labeling with Zirconium-89 (89Zr) to trace the biodistribution of intravenously injected MSC exosomes in rats, finding predominant accumulation in the liver [31]. This highlights the importance of administration route selection.

Quantitative Data on Exosome Subpopulations

Table 1: Characteristics of Distinct Exosome Subpopulations Isolated from B16F10 Melanoma Cells [26]

| Subpopulation | Density (g/ml) | Peak Size (nm) | Key Proteomic Features | Functional Impact on Recipient Cells |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low-Density Exosomes (LD-Exo) | 1.12 - 1.19 | 117 nm | Enriched in proteins involved in endocytosis, membrane trafficking, and signal transduction. | Mediated distinct alterations in the gene expression programs of recipient cells. |

| High-Density Exosomes (HD-Exo) | 1.26 - 1.29 | 66 nm | Enriched in ribosomal proteins, translation initiation factors, and mitochondrial proteins. | Mediated distinct alterations in the gene expression programs of recipient cells. |

Table 2: Impact of MSC Source on Exosome Function [1]

| MSC Tissue Source | Documented Therapeutic Effects / Specialties |

|---|---|

| Bone Marrow | Inhibition of inflammatory/apoptotic cells; impact on B-cell maturation; most prevalent source in research. |

| Umbilical Cord | Suppression of oxidative stress in kidney injury; promotion of angiogenesis for wound healing. |

| Adipose Tissue | Used for skin, inflammation, and transplantation diseases; less used in cancer or pancreatic diseases. |

| Placenta | Used for a diversity of diseases, except for autoimmune conditions. |

| Pluripotent Stem Cell-Derived | Low immunogenicity; used for liver, inflammation, transplantation, and musculoskeletal diseases. |

Key Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Isolation of Exosome Subpopulations via Density Gradient Centrifugation

This protocol is adapted from a key study that demonstrated the existence of functionally distinct exosome subpopulations [26].

Workflow Diagram: Isolation of Exosome Subpopulations

Materials:

- Ultracentrifuge and fixed-angle or swinging-bucket rotors

- Sucrose solutions in deuterium oxide (D2O) or heavy water (e.g., 2.5 M, 2.0 M, 1.3 M, 1.16 M, 0.8 M, 0.5 M, 0.25 M)

- Phosphate-Buffered Saline (PBS)

- Opti-MEM or exosome-depleted FBS medium

Procedure:

- Collect conditioned medium from cells grown in Opti-MEM or medium with exosome-depleted FBS.

- Pre-clear the medium of cells and debris by centrifugation at 2,000 × g for 20 minutes, followed by 10,000 × g for 30 minutes.

- Pellet total exosomes by ultracentrifugation of the supernatant at 110,000 × g for 70 minutes.

- Resuspend the exosome pellet (P110) in a small volume of PBS or gradient base solution.

- Load the resuspended exosomes at the bottom of a discontinuous sucrose density gradient.

- Perform ultracentrifugation in a swinging-bucket rotor at 210,000 × g for 16 hours to allow exosomes to float to their equilibrium density.

- Collect fractions from the top of the gradient. Typically, low-density exosomes (LD-Exo) will be found in fractions with a density of 1.12-1.19 g/ml, and high-density exosomes (HD-Exo) will be found in denser fractions (1.26-1.29 g/ml) [26].

- Analyze fractions for particle concentration (NTA), marker expression (Western Blot), and density.

Protocol 2: Evaluating the Functional Consistency of MSC-Derived Exosomes

This protocol is based on a recent study that established a long-term biomanufacturing workflow for MSC-exosomes [31].

Workflow Diagram: Evaluating Functional Consistency of MSC-Exosomes

Materials:

- Hollow Fiber 3D Bioreactor system

- RoosterBio exosome-harvesting system (or similar defined medium)

- hUC-MSCs (or other MSC sources)

- Characterized exosome purification kit (e.g., based on SEC or precipitation)

- Disease model (e.g., silica-induced mouse silicosis model)

Procedure:

- Expand MSCs in a Hollow Fiber 3D bioreactor integrated with an exosome-promoting system to ensure scalable production.

- Harvest exosomes repeatedly over an extended period (e.g., over 28 days) from the same culture to assess production stability.

- Purify and rigorously characterize the exosomes at each harvest point. Key characterization includes:

- Particle concentration and size (via NTA)

- Marker expression (CD9, CD63, CD81 via Western Blot or flow cytometry)

- Subpopulation profile analysis (e.g., via density gradient) to check for consistency over time.

- Evaluate therapeutic efficacy in a relevant disease model. The cited study used a silica-induced mouse silicosis model.

- Compare administration routes. Importantly, the study found that respiratory delivery significantly improved disease progression, whereas intravenous infusion did not yield notable therapeutic effects in this pulmonary model [31]. This underscores the critical importance of route selection.

- Correlate the consistent subpopulation profile with the stable therapeutic outcome to define an optimal collection window for production.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Kits for Exosome Heterogeneity Research

| Reagent / Kit | Function / Application | Example & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Tetraspanin Antibodies | Detection and validation of exosome markers via Western Blot, Flow Cytometry. | Anti-CD9, CD63, CD81. Note: Not all exosomes express all tetraspanins (e.g., Jurkat exosomes are CD9-). Validate for your system [28]. |

| ESCRT Protein Antibodies | Detection of exosome biogenesis markers. | Anti-ALIX, Anti-TSG101. Commonly used as positive markers for exosomes [26]. |

| Contaminant Antibodies | Assessing purity of exosome isolates by detecting non-exosomal proteins. | Anti-Calnexin (ER), Anti-GM130 (Golgi), Anti-Cytochrome C (Mitochondria), Anti-Histones (Nucleus) [28]. |

| Dynabeads (Immuno-capture) | Isolation of specific exosome subpopulations based on surface markers. | Exosome Human CD9/CD63/CD81 Isolation Reagents. Useful for enriching subpopulations from complex samples like plasma [28]. |

| RoosterBio Exosome System | Scalable production of MSC-exosomes in 3D bioreactors. | Includes culture media and harvesting system. Enables long-term, stable production of exosomes with consistent subpopulations [31]. |

| Sucrose/Density Gradient Media | Separation of exosome subpopulations based on buoyant density. | Sucrose or Nycodenz solutions. Critical for resolving low-density and high-density exosome subpopulations [26]. |

Strategies and Engineering Solutions to Control and Harness Exosome Heterogeneity

The production of mesenchymal stem cell (MSC)-derived exosomes begins with upstream bioprocessing, which encompasses all initial steps from cell culture to the point of harvest. This phase is critical in biopharmaceutical production as it establishes the foundation for the yield, quality, and heterogeneity of the final exosome product [33] [34]. Upstream process optimization focuses on cultivating cells to produce therapeutic extracellular vesicles (EVs), including exosomes, by providing a meticulously controlled environment for cell growth [33].

For MSC-derived exosomes, upstream processing presents a unique challenge: the heterogeneity of the final product is intrinsically linked to the conditions in which the parent cells are cultivated [1]. The composition of exosomes—their cargo of proteins, RNA, and lipids—is largely determined by the cell source and its physiological state [1]. Furthermore, process parameters such as the culture system (2D vs. 3D), medium composition, the use of bioreactors, and exposure to hypoxia can crucially affect the resulting therapeutic properties and biological functions of the exosomes [1]. Therefore, optimizing upstream processes is not merely about increasing yield; it is about controlling and directing the inherent variability of MSC-derived exosomes for specific therapeutic applications, such as heart repair, immunomodulation, and drug delivery [1] [35].

Key Challenges in Upstream Optimization

Researchers face several interconnected challenges when optimizing upstream processes for MSC exosome production. The table below summarizes the primary hurdles and their direct impacts on exosome yield and quality.

Table 1: Key Challenges in Upstream Process Optimization for MSC Exosomes

| Challenge Category | Specific Challenge | Impact on MSC Exosomes |

|---|---|---|

| Culture System | Transitioning from 2D to 3D culture systems [36] | Alters exosomal RNA content, secretion efficiency, and therapeutic efficacy [37] [35]. |

| Process Control | Maintaining precise environmental control (pH, O₂, temperature) [33] | Deviations decrease cell growth and product yield, affecting exosome cargo [33]. |

| Cell Source & Health | Managing MSC source (bone marrow, umbilical cord, adipose) and health [1] | Different sources produce exosomes with varying molecular composition and functional specificity [1]. |

| Scalability | Scaling up from laboratory to industrial production [33] | Fluid dynamics and mass transfer changes can alter exosome characteristics and yield [33]. |

| Heterogeneity | Controlling exosome population and cargo diversity [1] [11] | Influences batch-to-batch consistency, therapeutic reproducibility, and functional reliability [1]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Successful upstream optimization relies on a foundation of high-quality materials and reagents. The following table details essential components for experiments aimed at controlling MSC exosome heterogeneity.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Upstream Process Optimization

| Item | Function/Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Chemically Defined Media | Provides essential nutrients, vitamins, and growth factors without introducing unknown variables from serum [34]. | Enables process consistency; critical for optimizing nutrients like amino acids and trace elements for specific exosome cargo [1] [34]. |

| 3D Scaffolds & Matrices | Provides an ECM-mimicking 3D environment for cell growth (e.g., HYDROX, hydrogels) [36]. | Influences cell morphology, differentiation, and the yield and molecular content of secreted exosomes [1] [36]. |

| Microcarriers | Beads that provide a high surface-to-volume ratio for 3D cell culture in stirred-tank bioreactors [36]. | Facilitates the scale-up of MSC cultures for large-volume exosome production [36]. |

| Bioreactor Systems | Provides a controlled environment (temperature, pH, O₂, agitation) for cell cultivation at various scales [33] [36]. | Perfusion bioreactors enable high cell densities and improved productivity; dynamic mechanical stimulation affects cell behavior and exosome output [33] [36]. |

| Cell Lines | Source of exosomes (e.g., Bone Marrow MSCs, Umbilical Cord MSCs, Adipose-derived MSCs) [1]. | The choice of MSC source dictates the baseline protein and RNA footprint of the derived exosomes, affecting their therapeutic function [1]. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Upstream Processes

Protocol: Establishing a 3D Spheroid Culture for Enhanced Exosome Yield

Objective: To create a 3D culture environment that increases the yield and modifies the cargo of MSC-derived exosomes compared to traditional 2D monolayer culture [37] [35].

Materials:

- Mesenchymal Stem Cells (e.g., from bone marrow or umbilical cord)

- Low-attachment U-bottom 96-well plates or hanging drop plates

- Complete cell culture medium (e.g., DMEM/F12 supplemented with specific growth factors)

- Centrifuge

- Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS)

Methodology:

- Cell Preparation: Harvest and count MSCs from a 2D culture. Create a single-cell suspension with a viability of >95%.

- Seeding for Spheroid Formation:

- For U-bottom plates: Prepare a cell suspension at a concentration of 1x10⁵ cells/mL. Aliquot 100 µL per well (10,000 cells/well) into the low-attachment plate.

- For Hanging drop plates: Place a 20 µL drop of cell suspension (at a higher density, e.g., 2.5x10⁴ cells/drop) onto the lid of a culture dish, which is then inverted.

- Incubation: Culture the plates at 37°C with 5% CO₂ for 72-96 hours. Monitor daily for spheroid formation. Compact, spherical structures should form within this period.

- Harvesting Spheroids and Conditioned Media: After spheroid formation, carefully collect the culture medium (conditioned media) containing the secreted exosomes by centrifugation at 300 x g for 5 minutes to remove any loose cells or debris.

- Exosome Isolation: Proceed with standard exosome isolation techniques (e.g., ultracentrifugation, size-exclusion chromatography) from the collected conditioned media.

Data Interpretation: The success of spheroid formation is confirmed by visual inspection under a microscope. A successful protocol will demonstrate a higher yield of exosomes and potentially different miRNA or protein profiles compared to 2D culture-derived exosomes, which can be verified by nanoparticle tracking analysis and western blotting, respectively [37] [35].

Protocol: Optimizing a Perfusion Bioreactor for Continuous Production

Objective: To utilize a perfusion bioreactor system to maintain high cell densities over an extended period for continuous harvest of MSC-derived exosomes [33] [34].

Materials:

- Stirred-tank bioreactor system with perfusion capabilities (including cell retention device)

- MSC seed train culture

- Bioreactor-specific culture medium

- Peristaltic pumps for media addition and harvest

- pH, dissolved oxygen (DO), and temperature probes and controllers

Methodology:

- Bioreactor Setup and Sterilization: Assemble the bioreactor vessel and all fluid paths. Sterilize in-place (SIP) or autoclave components as per manufacturer's instructions.

- Inoculation: Transfer the expanded MSC culture from the seed train into the bioreactor vessel to achieve a target initial cell density (e.g., 2.0x10⁵ cells/mL).

- Parameter Control: Set and maintain critical process parameters (CPPs):

- Temperature: 37°C

- pH: 7.2 (controlled through CO₂ sparging and base addition)

- Dissolved Oxygen (DO): 40% air saturation (controlled by adjusting air/O₂ sparging and agitation speed)

- Agitation: Use a low-shear impeller to prevent cell damage while ensuring homogeneity.

- Initiating Perfusion: Once the cell density reaches a pre-defined threshold (e.g., 2.0x10⁶ cells/mL), initiate the perfusion process.

- Start adding fresh medium at a defined perfusion rate (e.g., 1 vessel volume per day).

- Simultaneously, harvest spent medium through the cell retention device (e.g., acoustic settler, tangential flow filtration) to keep the working volume constant.

- Continuous Monitoring and Harvest: Monitor cell density, viability, and nutrient/metabolite levels (e.g., glucose, lactate) daily. The harvested spent medium from the perfusion process is the source for continuous exosome isolation.

Data Interpretation: A stable perfusion process will maintain high cell viability (>90%) and a steady-state cell density for several weeks. The exosome yield per day from the harvest stream will be significantly higher and more consistent than from a batch or fed-batch process [33].

Diagram 1: Upstream process parameter influence on exosome output.

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: Why is my 3D MSC spheroid culture producing exosomes with different cargo profiles than my 2D culture? The 3D culture environment more accurately mimics the in vivo physiological conditions, altering cell-to-cell and cell-to-matrix interactions. This change in the cellular microenvironment directly influences the molecular sorting mechanisms that load cargo into exosomes. Consequently, exosomes from 3D cultures often have RNA and protein profiles that are more representative of in vivo conditions and can exhibit enhanced therapeutic efficacy [37] [36].

Q2: How can I increase the yield of exosomes from my MSC cultures without scaling up vessel size? Transitioning to a 3D culture system, such as using microcarriers in a bioreactor or forming spheroids, can significantly increase cell density and thus exosome yield per unit volume compared to 2D monolayers [36] [35]. Furthermore, implementing a perfusion bioreactor system allows for continuous nutrient supply and waste removal, supporting very high cell densities over prolonged periods and enabling the continuous harvest of exosomes from the spent media [33] [34].

Q3: My bioreactor parameters (pH, DO) are deviating from setpoints. What is the immediate impact on my exosome product? Deviations in critical process parameters like pH and dissolved oxygen (DO) can cause immediate cellular stress. This stress alters the metabolic state of the MSCs, which in turn can change the cargo (e.g., stress-related miRNAs, proteins) packaged into exosomes and potentially affect their yield. Consistent deviation can lead to increased batch-to-batch heterogeneity, compromising product consistency and therapeutic reproducibility [33] [1].

Q4: Does the source of my MSCs (e.g., bone marrow vs. umbilical cord) matter for the resulting exosomes? Yes, the source is a primary determinant of exosome heterogeneity. MSCs from different tissues (bone marrow, umbilical cord, adipose) have distinct molecular and functional identities. These differences are reflected in their exosomes, which will have varying protein, lipid, and RNA compositions. This means exosomes from different sources may have preferential efficacy for specific therapeutic applications (e.g., bone marrow for immunomodulation, umbilical cord for angiogenesis) [1].

Troubleshooting Common Problems

Table 3: Troubleshooting Common Upstream Process Issues

| Problem | Potential Causes | Solutions & Recommendations |

|---|---|---|

| Low Exosome Yield | 1. Suboptimal cell viability/density.2. Nutrient depletion in media.3. Using 2D instead of 3D culture. | 1. Monitor cell health and optimize medium formulation [33].2. Switch to fed-batch or perfusion modes [34].3. Transition to a 3D culture system (spheroids, bioreactors) [35]. |

| High Heterogeneity Between Batches | 1. Inconsistent culture conditions.2. Uncontrolled MSC differentiation.3. Variations in serum lots (if used). | 1. Strictly control CPPs (pH, DO, temp) using bioreactors [33].2. Monitor MSC surface markers and limit passages.3. Use chemically defined, serum-free media [1] [34]. |

| Contamination in Bioreactor | 1. Failure in sterilization procedures.2. Leak in seals or tubing. | 1. Validate sterilization protocols (e.g., SIP).2. Perform pre-culture leak tests and integrity checks. |

| Poor Cell Growth in 3D System | 1. Excessive shear stress in bioreactor.2. Inadequate nutrient diffusion in spheroids.3. Incorrect matrix/scaffold choice. | 1. Optimize agitation speed; use low-shear impellers [36].2. Control spheroid size to prevent necrotic cores.3. Screen different 3D matrices for your MSC type [1]. |

Diagram 2: Troubleshooting high exosome heterogeneity.

Mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes (MSC-exosomes) have emerged as a promising cell-free therapeutic platform, offering the regenerative and immunomodulatory benefits of their parent cells without the risks associated with live cell transplantation [16] [38]. However, a significant challenge hindering their clinical translation is heterogeneity—variations in exosome yield, molecular cargo, and subsequent biological activity [1]. This heterogeneity stems from differences in MSC sources, culture conditions, and the physiological state of the cells [1].

Preconditioning strategies involve exposing MSCs to specific environmental cues before collecting their exosomes. This process is not merely a stress response; it is a method to deliberately steer the MSC phenotype, thereby tailoring the content and enhancing the functional consistency and efficacy of the resulting exosomes [16] [39] [40]. By controlling these variables, researchers can actively combat heterogeneity and produce exosome populations with more predictable and potent therapeutic profiles for applications in regenerative medicine, immunomodulation, and drug delivery [16] [41].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) on Preconditioning

Q1: How does preconditioning specifically address the problem of heterogeneity in MSC-exosome research? Preconditioning addresses heterogeneity by providing a defined and controlled stimulus to the parent MSCs. This stimulus creates a more uniform cell population that, in turn, secretes exosomes with a more consistent and enriched cargo profile. For instance, hypoxia preconditioning consistently upregulates pro-angiogenic miRNAs like miR-126 and miR-210-3p across different MSC sources [42] [39] [43]. This standardization reduces batch-to-batch variability and enhances the reliability of experimental and therapeutic outcomes.

Q2: What are the key signaling pathways activated by hypoxia preconditioning, and how do they alter exosome cargo? Hypoxia preconditioning primarily activates the HIF-1α (Hypoxia-Inducible Factor 1-alpha) signaling pathway [42]. HIF-1α acts as a master regulator, leading to specific changes in the exosomal cargo:

- miRNA Enrichment: Upregulates miRNAs such as miR-125a-5p (targeting RTEF-1 to protect endothelial cells [43]), miR-210-3p (promoting angiogenesis [42]), and miR-486-5p (inhibiting MMP19 to enhance angiogenesis [41]).

- Protein Enrichment: Increases the load of pro-angiogenic factors like VEGF (Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor) and angiopoietin-1 [42]. The mechanism also involves upstream regulators like HMGB1, which activates the JNK pathway to induce HIF-1α/VEGF expression [42].

Q3: Can inflammatory preconditioning make exosomes too immunosuppressive, potentially promoting cancer growth? The dual role of MSC-exosomes in cancer is a critical consideration. While preconditioning with factors like TNF-α or IFN-γ enhances immunomodulatory miRNAs (e.g., miR-146a and miR-21-5p) for anti-inflammatory therapy [39], there is a theoretical risk that this could suppress immune surveillance in an oncological context. The effect is highly dependent on the specific cytokine, dose, MSC source, and tumor microenvironment [44]. Therefore, thorough safety and efficacy testing in relevant disease models is mandatory before clinical application.

Q4: How do I choose between different preconditioning strategies for my specific research application? The choice of preconditioning strategy should be directly aligned with your desired therapeutic outcome. The following table provides a guideline:

| Desired Therapeutic Outcome | Recommended Preconditioning Strategy | Key Mediators in Exosomes |

|---|---|---|

| Angiogenesis & Vascular Repair | Hypoxia (1-5% O₂) [42] [41] | miR-125a-5p, miR-210-3p, miR-486-5p, VEGF [42] [43] [41] |