Navigating the Double-Edged Sword: Strategies to Control Cellular Senescence in Reprogramming for Regenerative Medicine

Cellular reprogramming, while holding immense potential for rejuvenation and regenerative medicine, is intrinsically linked to cellular senescence—a process that acts both as a barrier and a paradoxical facilitator.

Navigating the Double-Edged Sword: Strategies to Control Cellular Senescence in Reprogramming for Regenerative Medicine

Abstract

Cellular reprogramming, while holding immense potential for rejuvenation and regenerative medicine, is intrinsically linked to cellular senescence—a process that acts both as a barrier and a paradoxical facilitator. This article synthesizes current research to provide a comprehensive guide for scientists and drug developers. We explore the foundational biology of the senescence-reprogramming axis, detail methodological advances from genetic to chemical reprogramming, and present optimization strategies for mitigating senescence-associated risks. Finally, we discuss rigorous validation frameworks and comparative analyses of emerging techniques, aiming to equip researchers with the knowledge to harness reprogramming's potential safely and effectively for combating age-related diseases and cancer.

The Senescence-Reprogramming Axis: Understanding a Complex Bidirectional Relationship

Cellular senescence and cellular reprogramming represent two fundamentally intertwined biological processes that profoundly influence aging, regeneration, and cancer. While cellular senescence is characterized by permanent cell-cycle arrest and represents a barrier to proliferation, cellular reprogramming demonstrates the remarkable plasticity of cell identity, offering potential for rejuvenation. Understanding the hallmarks of both processes is crucial for researchers aiming to mitigate senescence-associated pathologies and harness reprogramming for therapeutic applications.

This technical support guide provides troubleshooting resources for scientists navigating the complex interplay between these processes, with a specific focus on experimental challenges encountered when senescence arises in reprogramming experiments.

Core Hallmarks and Molecular Mechanisms

Hallmarks of Cellular Senescence

Cellular senescence is a complex, multi-factorial state of irreversible cell cycle arrest triggered by various stressors. Its defining hallmarks are summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Core Hallmarks and Biomarkers of Cellular Senescence

| Hallmark Feature | Key Biomarkers | Detection Methods | Experimental Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Irreversible Cell Cycle Arrest | p16INK4a, p21CIP1, p53, Phospho-Rb | WB, IHC, IF, RT-qPCR | Arrest is mediated by p53/p21 and p16INK4A/Rb pathways [1] [2]. |

| Senescence-Associated Secretory Phenotype (SASP) | IL-6, IL-8, IL-1, CCL5, MMPs, TGF-β | ELISA, Multiplex Assays, WB | A pro-inflammatory secretome; heterogeneous and context-dependent [3] [4]. |

| Morphological & Metabolic Changes | Enlarged, flat cell shape; Increased lysosomal mass | Phase-contrast microscopy, SA-β-Gal staining | Morphology is a primary but non-specific indicator [2] [5]. |

| DNA Damage Response (DDR) | γH2AX foci, 53BP1, ATM/ATR activation | IF (foci counting), WB | A common mediator from telomere attrition or external stress [3] [6]. |

| Altered Nuclear Architecture | Loss of Lamin B1, SAHF formation | IF (DAPI staining), WB for Lamin B1 | SAHFs are repressive chromatin domains [2] [5]. |

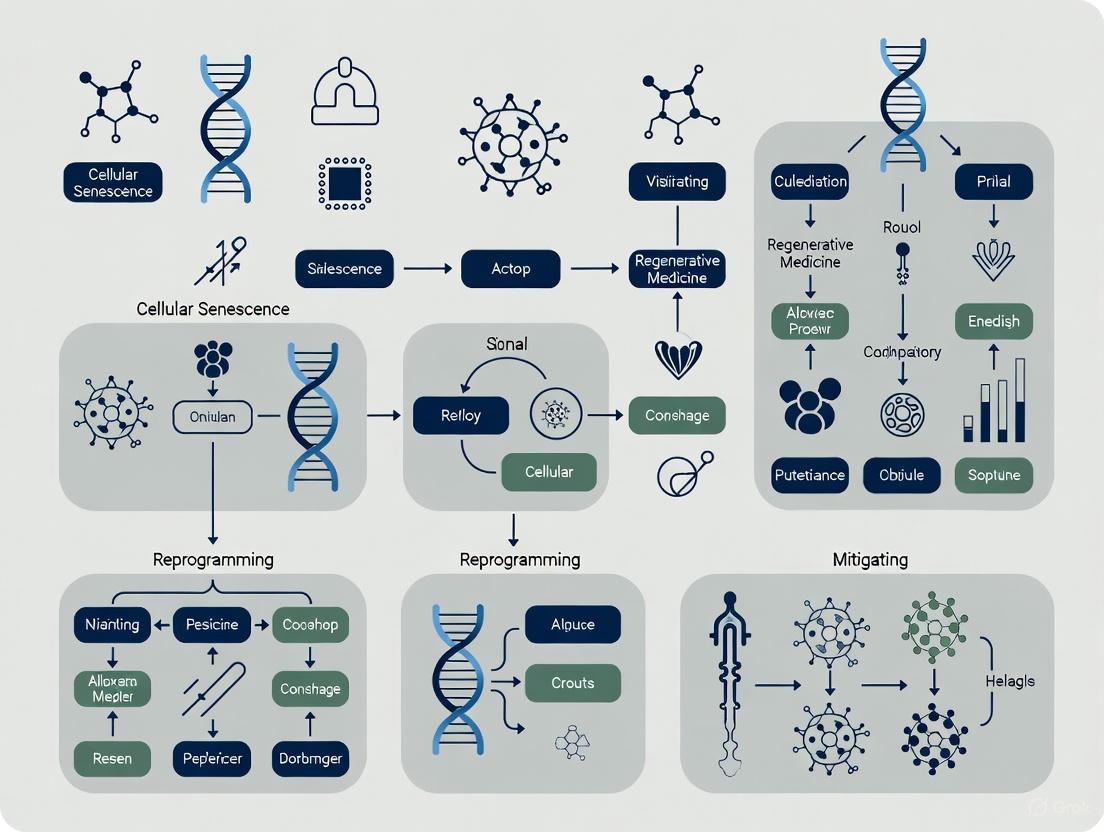

The following diagram illustrates the primary signaling pathways that initiate and maintain cellular senescence, integrating the key biomarkers from Table 1.

Hallmarks of Cellular Reprogramming

Cellular reprogramming, typically via the introduction of Yamanaka factors (OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, c-MYC, collectively OSKM), resets epigenetic marks and cellular age. Key hallmarks include:

- Epigenetic Remodeling: Resetting of DNA methylation and histone modification patterns to a pluripotent state.

- Telomere Elongation: Restoration of telomere length through reactivation of telomerase.

- Metabolic Reprogramming: A shift from oxidative phosphorylation to glycolysis.

- Loss of Somatic Identity: Downregulation of tissue-specific genes.

- Acquisition of Pluripotency: Activation of core pluripotency network genes.

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

FAQ 1: Why do my reprogramming experiments consistently induce cellular senescence in a subset of cells, and how can I mitigate this?

Answer: The induction of senescence during reprogramming is a common and biologically significant response. The OSKM factors themselves can trigger stress responses, including DNA damage and oncogenic stress (via c-MYC), which activate the p53/p21 senescence pathway as a barrier to complete reprogramming [7] [8].

Troubleshooting Steps:

- Modulate p53 Pathway: Transiently suppress p53 using RNAi or small molecules (e.g., Pifithrin-α) during the initial phase of reprogramming. Caution: Monitor for genomic instability or tumorigenic transformation.

- Utilize Partial Reprogramming: Implement transient, non-integrating reprogramming protocols (e.g., using mRNA or Sendai virus) to avoid permanent genetic modification and reduce the stress that leads to irreversible senescence.

- Supplement with Antioxidants: Since oxidative stress is a key inducer of senescence, supplementing culture media with antioxidants like N-Acetylcysteine (NAC) can reduce ROS levels and senescence incidence [6].

- Employ Senolytics Post-Reprogramming: After the reprogramming process, treat cultures with senolytic drugs (e.g., Navitoclax, Fisetin) to selectively eliminate senescent cells that may inhibit the function of the resulting induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) [4].

FAQ 2: My senescence detection assays are giving contradictory results. How can I reliably identify and quantify senescent cells in my cultures?

Answer: A major challenge in the field is the lack of a single, universal biomarker for senescence. Senescent cells are highly heterogeneous, and no single marker is sufficient for unequivocal identification. Contradictory results often arise from relying on a single method [2] [9].

Troubleshooting Steps:

- Use a Multi-Marker Panel: Always combine at least two or three distinct hallmark assays. A recommended combination is:

- SA-β-Gal Staining: A common initial screen, but can be positive in non-senescent cells like macrophages.

- Immunofluorescence for p21 and p16: Key cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors indicating cell cycle arrest.

- DDR Marker Detection (e.g., γH2AX foci): Confirms an underlying trigger for senescence.

- Employ a New Machine Learning Approach: Recent advances use nuclear morphology features (e.g., area, texture) analyzed by machine learning classifiers to accurately predict senescence state. This method can distinguish senescence from quiescence and DNA damage, and is applicable across cell types [5].

- Validate with Functional Assays: Correlate biomarker presence with functional readouts, such as a persistent lack of proliferation in long-term EdU/BrdU incorporation assays.

FAQ 3: The SASP from senescent cells in my culture is affecting the behavior of neighboring non-senescent cells. How can I isolate its effect?

Answer: The paracrine signaling of the SASP is a major confounding factor in mixed cultures. Senescent cells secrete IL-6, IL-8, and other cytokines that can promote stemness, reprogramming, or inflammation in nearby cells [7] [3].

Troubleshooting Steps:

- Physical Separation: Use transwell co-culture systems to expose target cells to soluble SASP factors without direct cell-cell contact.

- SASP Neutralization: Treat cultures with senomorphic agents (e.g., JAK Inhibitors (Ruxolitinib), NF-κB inhibitors) to suppress SASP secretion without killing the senescent cell. Alternatively, use neutralizing antibodies against specific SASP factors like IL-6.

- Conditioned Media Experiments: Collect conditioned media from pure populations of senescent cells and apply it to target cells. This allows for controlled investigation of SASP effects. Ensure you include proper controls with conditioned media from non-senescent cells.

Key Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Multi-Parameter Assessment of Senescence

Objective: To reliably identify senescent cells using a combination of established biomarkers.

Workflow:

Materials:

- Senescence Inducer: Etoposide (10-50 µM for 3-10 days) or Hydrogen Peroxide (H₂O₂, 100-400 µM for 2 hours).

- SA-β-Gal Staining Kit: Commercial kit available (e.g., from Cell Signaling Technology #9860).

- Primary Antibodies: Anti-p21 (Abcam ab109199), Anti-γH2AX (Ser139, Millipore Sigma 05-636), Anti-Lamin B1 (Abcam ab16048).

- EdU/BrdU Proliferation Kit: (e.g., Click-iT Plus EdU Alexa Fluor 488 Imaging Kit, C10637).

Protocol: Mitigating Senescence During Fibroblast Reprogramming

Objective: To generate iPSCs with reduced senescent cell burden.

Workflow:

Materials:

- Reprogramming Vector: CytoTune-iPS Sendai Reprogramming Kit (Invitrogen) featuring non-integrating Sendai virus vectors for OSKM.

- p53 Suppressor: Validated p53 shRNA lentiviral particles or Pifithrin-α (10 µM).

- Antioxidant: N-Acetylcysteine (NAC, 1 mM).

- Senolytic: Fisetin (10-20 µM).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Senescence and Reprogramming Research

| Reagent Category | Specific Example | Function & Application |

|---|---|---|

| Senescence Inducers | Etoposide, Doxorubicin, H₂O₂ | Induce DNA damage and trigger premature senescence for experimental models [2] [6]. |

| Senescence Detectors | SA-β-Gal Staining Kit, Anti-p16 antibody, Anti-γH2AX antibody | Key tools for detecting hallmark features of senescent cells (Table 1) [3] [2]. |

| Reprogramming Factors | CytoTune-iPS Sendai Reprogramming Kit (OSKM) | Gold-standard, non-integrating method for safe and efficient cellular reprogramming. |

| Senolytics | Navitoclax (ABT-263), Fisetin, Venetoclax | Selectively eliminate senescent cells by inhibiting SCAPs (e.g., BCL-2 family) [1] [4]. |

| Senomorphics | Ruxolitinib (JAK Inhibitor), SP600125 (JNK Inhibitor) | Suppress the deleterious SASP without killing senescent cells, allowing study of its effects [3]. |

| Machine Learning Tools | CellProfiler (open-source), IN Carta | Image analysis software for extracting nuclear features to train senescence classifiers [5]. |

FAQs: Understanding the SASP Paradox

FAQ 1: What is the fundamental paradox of SASP in cellular reprogramming?

The paradox lies in the dual, opposing roles of the Senescence-Associated Secretory Phenotype (SASP). SASP can create a physical barrier that inhibits reprogramming by reinforcing stable cell cycle arrest and promoting a pro-inflammatory environment. Conversely, certain SASP factors can enhance cellular plasticity in neighboring cells, paradoxically facilitating their reprogramming into induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) [7] [8]. The outcome—inhibition or facilitation—depends critically on context, including the duration of SASP exposure (acute vs. chronic) and the specific composition of the SASP secretome [10] [11].

FAQ 2: Which specific SASP factors are known to facilitate reprogramming?

Interleukin-6 (IL-6) is a key SASP factor identified in facilitating reprogramming. In landmark mouse models, senescent cells releasing IL-6 (and other cytokines) acted in a paracrine fashion to enhance the efficiency of OSKM (Oct4, Sox2, Klf4, c-Myc) factor-mediated conversion of surrounding somatic cells into iPSCs [7] [8]. The table below summarizes the roles of key SASP factors.

Table 1: Key SASP Factors and Their Roles in the Reprogramming Paradox

| SASP Factor | Primary Role in Paradox | Mechanism of Action |

|---|---|---|

| IL-6 | Facilitates Reprogramming | Enhances neighboring cell plasticity via paracrine signaling [7] [8]. |

| IL-8 | Context-Dependent | Recruits immune cells; can promote a pro-tumorigenic niche. |

| CCL5 | Context-Dependent | Enhances immune cell trafficking; can recruit regulatory T cells. |

| TGF-β | Inhibits Reprogramming | Reinforces growth arrest and stabilizes the senescent state. |

FAQ 3: How does the senescence-associated epigenetic landscape influence SASP and reprogramming?

Senescent cells undergo extensive epigenetic reprogramming, which directly regulates SASP expression. Key changes include:

- Formation of Senescence-Associated Heterochromatin Foci (SAHF): These repressive chromatin structures help silence proliferation-promoting genes but can also influence SASP gene accessibility [12].

- Cytoplasmic Chromatin Fragments (CCF): Cytoplasmic DNA from CCFs is detected by the cGAS-STING pathway, leading to NF-κB activation and robust SASP expression [12].

- Histone Modifications: Depletion of proteins like HMGB2 can trigger a shift in heterochromatin, coinciding with increased SASP gene expression [12].

This remodeled epigenetic environment not only maintains senescence but also dictates the secretome that can impact the reprogramming efficiency of nearby cells.

FAQ 4: What are the primary experimental strategies to mitigate the negative effects of SASP during reprogramming?

Two main therapeutic strategies are employed:

- Senolytics: Drugs that selectively induce apoptosis in senescent cells. Examples include Dasatinib + Quercetin (D+Q) and Navitoclax (ABT-263), which target pro-survival pathways (e.g., BCL-2 family) in senescent cells [13].

- Senomorphics: Compounds that modulate the SASP without killing the senescent cell. These include inhibitors of key SASP regulatory pathways like NF-κB, p38 MAPK, or JAK-STAT [11] [12]. The goal is to suppress the pro-inflammatory, tissue-destructive aspects of SASP while potentially preserving its beneficial functions.

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Low Reprogramming Efficiency in an Aged Cell Culture System

Potential Cause: Accumulation of senescent cells with a chronic, pro-inflammatory SASP that inhibits cellular plasticity.

Solution:

- Pre-treatment Assessment: Quantify senescence burden before reprogramming. Assay for SA-β-gal activity and markers like p16INK4a and p21.

- Intervention: Pre-treat culture with senolytic cocktails (e.g., 100 nM Dasatinib + 10 µM Quercetin for 24-48 hours) to clear senescent cells [13].

- Alternative Strategy: Use low-dose senomorphic compounds (e.g., an NF-κB inhibitor) during the early phase of reprogramming to suppress the inhibitory SASP signals.

- Validation: Post-intervention, re-measure senescence markers and key SASP factors (e.g., IL-6, IL-1α) via ELISA to confirm reduction.

Problem: Inconsistent Reprogramming Outcomes Potentially Driven by Paracrine SASP

Potential Cause: The heterogeneous secretome of senescent cells creates a variable microenvironment, leading to unpredictable outcomes where reprogramming is facilitated in some contexts and inhibited in others.

Solution:

- Characterize the SASP Profile: Use cytokine array or proteomic analysis to define the specific SASP composition in your experimental system. Note the factors present (e.g., high IL-6 vs. high TGF-β).

- Conditioned Media Experiments: Apply conditioned media from your senescent cell culture to naive reprogramming experiments. This will directly test the net effect of your specific SASP secretome.

- Targeted Neutralization: If reprogramming is inhibited by conditioned media, use neutralizing antibodies against specific inhibitory SASP factors (e.g., anti-TGF-β) to block their function.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Assessing the Senescence Burden in a Cell Population Pre- and Post-Reprogramming

Objective: To quantitatively evaluate the presence of senescent cells, a key variable influencing reprogramming efficiency.

Materials:

- Senescence-associated β-galactosidase (SA-β-gal) Staining Kit

- Lysis Buffer and Western Blotting Equipment

- Antibodies: anti-p16INK4a, anti-p21, anti-Lamin B1

- qPCR reagents and primers for CDKN2A (p16), CDKN1A (p21)

- ELISA kits for IL-6 and IL-8

Method:

- SA-β-gal Staining: Follow manufacturer's protocol. Fix cells and incubate with X-Gal solution at pH 6.0. Senescent cells will stain blue. Quantify by counting positive cells in multiple fields of view.

- Protein Analysis: Lyse cells. Perform Western blot for p16, p21, and Lamin B1 (loss of Lamin B1 is a senescence marker).

- Gene Expression: Extract RNA, synthesize cDNA, and perform qPCR for CDKN2A and CDKN1A.

- SASP Secretion: Collect cell culture supernatant. Use ELISA to quantify levels of secreted IL-6 and IL-8.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Senescence and Reprogramming Studies

| Reagent / Tool | Function | Application in Paradox Research |

|---|---|---|

| OSKM Factors | Core reprogramming transcription factors | To induce pluripotency in somatic cells; studying how SASP modulates their efficiency. |

| Dasatinib + Quercetin | Senolytic combination | To selectively eliminate senescent cells and test their required role in facilitating reprogramming. |

| NF-κB Pathway Inhibitor | Senomorphic compound | To suppress SASP production without killing senescent cells, allowing dissection of SASP's role. |

| Recombinant IL-6 | Pro-inflammatory cytokine | To directly test the effect of a specific SASP factor on reprogramming efficiency in naive cultures. |

| Anti-TGF-β Antibody | Neutralizing antibody | To block the function of an inhibitory SASP factor and assess its contribution to the paradox. |

Protocol 2: Modulating SASP to Test its Role in Reprogramming

Objective: To experimentally determine whether SASP from your system facilitates or inhibits reprogramming.

Materials:

- OSKM induction system (e.g., Doxycycline-inducible lentivirus)

- Senomorphic compound (e.g., NF-κB inhibitor)

- Neutralizing antibodies against specific SASP factors

- Reprogramming efficiency readout (e.g., Nanog-GFP reporter, immunostaining for pluripotency markers)

Method:

- Establish Co-culture or Conditioned Media System: Generate a population of senescent cells (e.g., via irradiation or oncogene activation). Use conditioned media from these cells or establish a direct co-culture with target somatic cells.

- Initiate Reprogramming: Introduce OSKM factors to the target somatic cells.

- Experimental Modulation:

- Group 1: Control (reprogramming + senescent conditioned media/co-culture).

- Group 2: Add senomorphic compound to Group 1.

- Group 3: Add neutralizing antibody to a specific SASP factor (e.g., IL-6) to Group 1.

- Quantify Reprogramming Efficiency: After 7-14 days, quantify the number of emerging iPSC colonies (e.g., by counting Nanog-GFP positive colonies). Compare efficiency between groups to determine the net effect of the SASP and the contribution of specific factors.

Signaling Pathways and Workflows

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Challenges

FAQ: My reprogramming efficiency is low. Could cellular senescence be a factor?

Yes, cellular senescence is a major barrier to reprogramming. The process of inducing pluripotency can itself trigger senescence checkpoints, halting cell cycle progression.

- Root Cause: The activation of the p53-p21 and/or p16INK4a-Rb pathways is a primary defense mechanism against dedifferentiation. When you introduce reprogramming factors like OSKM (Oct4, Sox2, Klf4, c-Myc), cells perceive this as an oncogenic or stressful insult, activating these tumor suppressor pathways and inducing a stable cell cycle arrest [8].

- Solution: Consider transiently inhibiting the p53-p21 pathway. Studies have shown that pharmacological inhibition of p53 (e.g., using PFT-α) can enhance proliferation and improve reprogramming efficiency without inducing genomic instability [14].

- Preventive Measure: Utilize early-passage primary cells, as replicative senescence driven by telomere shortening and the p16INK4a-Rb pathway increases with serial passaging [15] [16].

FAQ: Why do my senescent cell cultures show such heterogeneous secretome profiles?

The Senescence-Associated Secretory Phenotype (SASP) is highly dynamic and context-dependent, varying by cell type, inducer, and time post-induction.

- Root Cause: The SASP is not a single, uniform set of factors but a complex mixture of cytokines, chemokines, growth factors, and proteases. Its composition is regulated by multiple signaling hubs, including the NF-κB and p38 MAPK pathways [17] [18]. The specific stressor (e.g., DNA damage vs. oncogenic stress) can activate different upstream signals, leading to a unique SASP "fingerprint."

- Solution: Table 1 provides a quantitative overview of core SASP factors. Always characterize the SASP in your specific experimental model using multiplex ELISAs or antibody arrays rather than relying on a single marker.

- Investigation Protocol:

- Induce Senescence: Treat cells with a precise dose of a stressor (e.g., 100-200 µM H₂O₂ for oxidative stress, 10 Gy irradiation for DNA damage).

- Confirm Senescence: Verify establishment of senescence 3-7 days post-induction using SA-β-Gal staining and p16/p21 western blotting.

- Collect Conditioned Media: Replace growth media with serum-free media 48 hours before collection to avoid serum protein interference.

- Analyze Secretome: Use a validated proteomic platform to quantify SASP factors in the conditioned media.

FAQ: I inactivated pRb in my human senescent cells, but they still won't proliferate. Why?

In human cells, sustained p16INK4a expression can establish a fail-safe, irreversible arrest that is independent of pRb and p53.

- Root Cause: When p16INK4a is highly expressed and has fully activated pRb, it can initiate a second barrier involving reactive oxygen species (ROS) and protein kinase C delta (PKCδ). This pathway irreversibly blocks cytokinesis, preventing cell division even if pRb is subsequently inactivated [19].

- Solution: This phenomenon underscores the need to target the upstream driver, p16INK4a, or its downstream effectors like ROS. Using antioxidants (e.g., N-acetylcysteine) may help mitigate this secondary block [19].

- Key Difference: Note that this irreversible arrest is more characteristic of human cells; senescence is often more readily reversible in murine cells [19].

Table 1: Core Senescence-Associated Secretory Phenotype (SASP) Factors

| SASP Category | Key Factors | Primary Function/Effect | Common Detection Methods |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inflammatory Cytokines | IL-6, IL-1β, IL-8 | Autocrine reinforcement of senescence; Paracrine immune cell recruitment & chronic inflammation [20] [17] | ELISA, Multiplex Immunoassay |

| Chemokines | CCL2, CCL5 | Recruitment of monocytes and T-cells [17] | ELISA, Multiplex Immunoassay |

| Growth Factors | VEGF, TGF-β | Angiogenesis, tissue fibrosis [17] | ELISA, Multiplex Immunoassay |

| Proteases | MMP-3, MMP-13 | Extracellular matrix (ECM) remodeling [17] [21] | Zymography, Western Blot |

| Other Regulators | cGAS-STING | Intracellular DNA sensing pathway that drives NF-κB activation and SASP, including IL-6 production [20] | Western Blot, Immunofluorescence |

Table 2: Key Senescence Marker Expression in Different Contexts

| Senescence Marker | Replicative Senescence | Oncogene-Induced Senescence (OIS) | Therapy-Induced Senescence (TIS) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| p16INK4a | High [16] | High [17] | Variable [22] | More stable marker, crucial for long-term arrest. |

| p21CIP1 | Transiently High [15] | High [15] | High [22] | Often an early, p53-driven response; can be transient. |

| SA-β-Gal Activity | Positive [21] | Positive [18] | Positive [18] | A hallmark of increased lysosomal mass, not senescence-specific. |

| DNA-SCARS (γ-H2AX) | Present [15] | Present [15] | Strongly Present [17] | Foci of persistent DNA damage response. |

| Lamin B1 | Loss [21] | Loss [18] | Loss [18] | Nuclear envelope breakdown, a common feature. |

Pathway Diagrams and Experimental Workflows

Core Senescence Signaling Pathways

Diagram Title: Core Senescence Signaling Pathways

Senescence and Reprogramming Workflow

Diagram Title: Cell Fates in Reprogramming

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Senescence and Reprogramming Research

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Example & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| p53 Inhibitor (PFT-α) | Transiently inhibits p53 transcriptional activity to test its necessity in senescence arrest and improve reprogramming efficiency [14]. | Pifithrin-α (PFT-α). Use at low micromolar ranges (e.g., 10-30 µM) for transient treatment. |

| Antioxidants (NAC) | Reduces reactive oxygen species (ROS) to investigate the role of oxidative stress in senescence and to bypass the p16-mediated cytokinetic block [19]. | N-acetylcysteine (NAC). A general antioxidant; effective at 1-5 mM. |

| Recombinant IL-6 | Used to treat cells exogenously to study the paracrine effects of SASP. Also used to validate IL-6 function in autocrine senescence loops [20]. | Confirm activity on your cell type. Often used at 10-50 ng/mL. |

| IL-6 Neutralizing Antibody | Blocks extracellular IL-6 to determine its specific contribution to autocrine/paracrine signaling in senescence maintenance [20]. | Critical for distinguishing intracrine vs. paracrine IL-6 functions. |

| SA-β-Gal Staining Kit | Histochemical detection of senescence-associated β-galactosidase activity at pH 6.0, a common senescence biomarker [21]. | Available from various suppliers (e.g., Cell Signaling Technology). |

| OSKM/OKS Plasmids | Delivery of reprogramming factors (Oct4, Sox2, Klf4, c-Myc or OKS variant) to induce pluripotency and study senescence as a barrier [21] [8]. | Can be delivered via plasmids, viruses, or modified exosomes (e.g., OKS@M-Exo) [21]. |

| CRISPR-Cas9 System | For precise genetic knockout of TP53 (p53) or CDKN1A (p21) to dissect their roles in senescence pathways [14]. | Enables creation of stable knockout cell lines to study long-term effects. |

| Phospho-Histone γ-H2AX Antibody | Immunofluorescence detection of DNA double-strand breaks, a marker of persistent DNA damage in senescent cells (DNA-SCARS) [15] [21]. | Quantify foci per nucleus; increased numbers indicate DNA damage response. |

Cellular senescence and cellular reprogramming represent two fundamentally intertwined processes that profoundly influence aging and cancer [8] [7]. While reprogramming somatic cells to induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) using Yamanaka factors (OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, MYC - collectively OSKM) resets cellular aging markers and rejuvenates aged cells, the process itself often triggers senescence as an intrinsic barrier [8] [7]. This technical guide explores the molecular mechanisms through which senescence creates roadblocks to efficient reprogramming and provides researchers with practical strategies to overcome these challenges.

The interplay between senescence and reprogramming reveals a complex relationship: while senescence acts as a barrier to reprogramming, senescent cells and their associated secretory phenotype (SASP) can paradoxically enhance cellular plasticity and facilitate the reprogramming of nearby cells in certain contexts [8] [7]. Understanding this duality is crucial for developing effective strategies to mitigate senescence during reprogramming experiments.

Quantitative Data: Senescence Markers in Reprogramming

Table 1: Key Senescence Markers to Monitor During Reprogramming Experiments

| Marker Category | Specific Marker | Detection Method | Change in Senescence | Impact on Reprogramming |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Cycle Regulators | p16INK4a (p16) | Western Blot, Immunofluorescence | Increased [21] | Creates irreversible cell cycle arrest [17] |

| p21CIP1 (p21) | Western Blot, qPCR | Increased [21] | Mediates p53-dependent arrest [17] | |

| p53 | Western Blot, qPCR | Increased [21] | Activates DNA damage response [17] | |

| DNA Damage Response | γ-H2A.X | Immunofluorescence (foci counting) | Increased foci [21] | Indicates nuclear DNA double-strand breaks [21] |

| Epigenetic Marks | H4K20me3 | Western Blot, Immunofluorescence | Increased [21] | Associated with heterochromatin formation [21] |

| H3K9me3 | Western Blot, Immunofluorescence | Decreased [21] | Loss of transcriptional regulation [21] | |

| Senescence-Associated Secretory Phenotype | IL-6 | ELISA, qPCR | Increased [8] | Can paradoxically enhance reprogramming in nearby cells [8] |

| Functional Assays | SA-β-Gal Activity | Histochemical staining | Increased [21] | Visual confirmation of senescent state [21] |

Table 2: Efficacy of Senescence-Mitigating Strategies in Reprogramming

| Intervention Strategy | Experimental Model | Key Senescence Markers Reduced | Impact on Reprogramming Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|

| OKS (Oct4, Klf4, Sox2) Partial Reprogramming | Senescent human NPCs [21] | p16, p21, p53, γ-H2A.X foci, H4K20me3 [21] | Restored proliferation capacity, reduced SA-β-Gal activity [21] |

| OSKM Cyclical Induction (2-day pulse, 5-day chase) | LAKI progeric mice [23] | Mitochondrial ROS, H3K9me levels [23] | Extended lifespan 33%, no teratoma formation [23] |

| OSK (without c-Myc) AAV9 Delivery | 124-week-old wild-type mice [23] | Frailty index score [23] | Extended remaining lifespan by 109% [23] |

| Chemical Reprogramming (7c cocktail) | Mouse fibroblasts [23] | Epigenetic clocks, mitochondrial OXPHOS [23] | Multi-omics scale rejuvenation, reduced aging metabolites [23] |

Experimental Protocols for Mitigating Senescence in Reprogramming

Protocol 1: Partial Reprogramming with OKS Factors to Ameliorate Senescence

Background: Complete reprogramming to pluripotency often triggers senescence in a subset of cells, while partial reprogramming approaches have demonstrated efficacy in reducing senescence markers without complete dedifferentiation [21] [23].

Materials:

- Plasmid vectors expressing OKS (Oct4, Klf4, Sox2) genes

- Senescent cell model (e.g., replicative senescent NPCs at passage 6)

- Transfection reagent or exosome-based delivery system (e.g., Cavin2-modified exosomes)

- Senescence detection reagents: SA-β-Gal staining kit, antibodies for p16, p21, p53, γ-H2A.X

Procedure:

- Culture senescent NPCs (P6) in appropriate growth medium until 70-80% confluent [21].

- Transfert cells with OKS plasmid using your preferred method. For enhanced efficiency, utilize exosome-based delivery (OKS@M-Exo) [21].

- Incubate for 48-72 hours to allow gene expression.

- Assess transfection efficiency by analyzing OKS expression levels via qRT-PCR or Western blot [21].

- Evaluate senescence markers:

- Assess functional outcomes:

Troubleshooting:

- If transfection efficiency is low, optimize vector:transfection reagent ratio or switch to exosome-based delivery [21].

- If senescence markers remain high, extend treatment duration or consider cyclical induction protocol [23].

Protocol 2: Cyclical Induction of Reprogramming Factors for In Vivo Applications

Background: Continuous expression of Yamanaka factors promotes teratoma formation, while cyclical induction enables rejuvenation without complete dedifferentiation, effectively reducing senescence burden [23].

Materials:

- Doxycycline-inducible OSKM or OSK polycistronic cassette

- AAV9 delivery system for in vivo applications

- Doxycycline for induction control

- Wild-type or progeric mouse model

Procedure:

- For transgenic models: Utilize mice carrying Tet-inducible OSKM cassette [23]. For non-transgenic models: Deliver OSK (without c-Myc) vectors via AAV9 capsid for broad tissue distribution [23].

- Administer doxycycline cyclically:

- Continue cycles for desired duration (study-dependent, ranging from 1 month to 10 months) [23].

- Monitor outcomes:

- Assess teratoma formation histologically [23].

- Evaluate transcriptome, lipidome, and metabolome rejuvenation through multi-omics analyses [23].

- Measure functional improvements: skin regeneration capacity, frailty index, lifespan extension [23].

- Analyze tissue-specific senescence markers: mitochondrial ROS, H3K9me levels [23].

Troubleshooting:

- If teratoma formation occurs, exclude c-Myc from factor combination or shorten induction periods [23].

- If rejuvenation effects are suboptimal, adjust cycle frequency or extend treatment duration [23].

Signaling Pathways and Molecular Mechanisms

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Senescence and Reprogramming Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Reagent | Function/Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reprogramming Factors | OSKM (Oct4, Sox2, Klf4, c-Myc) | Complete reprogramming to pluripotency | High teratoma risk; use cyclical induction [23] |

| OKS (Oct4, Klf4, Sox2) | Partial reprogramming with reduced senescence | Lower tumorigenic potential than OSKM [21] | |

| Delivery Systems | Plasmid Vectors | Gene delivery for reprogramming factors | Moderate efficiency; optimize transfection protocol [21] |

| Exosome-based Delivery (e.g., Cavin2-modified) | Enhanced cellular uptake of genetic material | Improved transfection efficiency for senescent cells [21] | |

| AAV9 Capsid | In vivo delivery with broad tissue distribution | Suitable for whole-organism approaches [23] | |

| Senescence Detection | SA-β-Gal Staining Kit | Histochemical detection of senescent cells | Standard marker but can have specificity issues [21] |

| Antibodies: p16, p21, p53 | Protein-level detection of key senescence regulators | Quantify by Western blot or immunofluorescence [21] | |

| γ-H2A.X Antibody | Detection of DNA double-strand breaks | Count foci per nucleus for quantitative assessment [21] | |

| H4K20me3/H3K9me3 Antibodies | Epigenetic senescence markers | Altered patterns indicate epigenetic aging [21] | |

| Chemical Interventions | 7c Chemical Cocktail | Non-genetic partial reprogramming | Small molecule approach; different pathway from OSKM [23] |

| ABT263 (Navitoclax) | Senolytic agent to eliminate senescent cells | Can reverse immunosuppression in TME [17] | |

| Venetoclax | BCL-2 inhibitor with senolytic potential | Used in combination therapies [17] | |

| Induction Control | Doxycycline-Inducible Systems | Temporal control of reprogramming factor expression | Enables cyclical induction protocols [23] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why does reprogramming trigger senescence in some cells? Reprogramming imposes significant stress on cells, including replication stress, DNA damage, and metabolic alterations. These stressors activate the DNA damage response (DDR) pathway, which upregulates tumor suppressor genes including TP53 and CDKN2A (p16), leading to irreversible cell cycle arrest and senescence as a protective mechanism against potential malignant transformation [17]. Essentially, senescence acts as a fail-safe mechanism to prevent damaged cells from acquiring pluripotency.

Q2: How can SASP both inhibit and enhance reprogramming? The SASP creates a complex microenvironment with dual effects. In cells undergoing reprogramming, autocrine SASP signaling can reinforce senescence and inhibit reprogramming. However, paracrine SASP signaling to neighboring cells can promote cellular plasticity and enhance reprogramming efficiency through factors like IL-6 [8] [7]. The net effect depends on context, including concentration, timing, and cell type.

Q3: What are the advantages of partial versus complete reprogramming for mitigating senescence? Partial reprogramming using shorter exposure to reprogramming factors or modified factor combinations (e.g., OKS without c-Myc) can rejuvenate cells by resetting epigenetic aging markers without pushing cells through complete dedifferentiation. This approach reduces the risk of teratoma formation and more effectively targets senescence reversal while maintaining cellular identity [21] [23]. Complete reprogramming often triggers senescence in a subset of cells and carries higher tumorigenic risks.

Q4: How can I optimize delivery methods to minimize senescence induction? Exosome-based delivery systems (e.g., Cavin2-modified exosomes) show enhanced transfection efficiency in senescent cells compared to traditional methods [21]. For in vivo applications, AAV9 vectors provide broad tissue distribution with minimal immune activation [23]. The key is balancing delivery efficiency with minimal cellular stress, which often requires empirical optimization for specific cell types.

Q5: What are the most reliable markers to confirm senescence reduction? A multi-parameter approach is essential. Key markers include:

- Reduced expression of cell cycle inhibitors p16, p21, and p53 [21]

- Decreased γ-H2A.X foci indicating reduced DNA damage [21]

- Normalization of epigenetic marks (decreased H4K20me3, increased H3K9me3) [21]

- Reduced SA-β-Gal activity [21]

- Restoration of proliferative capacity (EdU incorporation) [21] No single marker is sufficient; multiple confirmatory assays are recommended.

Q6: How does chemical reprogramming compare to factor-based approaches for overcoming senescence? Chemical reprogramming using small molecule cocktails (e.g., 7c) offers a non-genetic alternative that may bypass some senescence checkpoints. Interestingly, chemical reprogramming upregulates the p53 pathway (unlike OSKM-mediated approaches), potentially offering a safer profile with reduced cancer risk [23]. However, efficiency and protocol standardization remain challenges compared to established factor-based methods.

Core Mechanisms at a Glance

The table below summarizes the fundamental ways in which DNA Damage Response (DDR) and epigenetic remodeling influence each other, creating a bidirectional relationship crucial for genomic integrity and cell fate.

| Mechanism | Impact on DDR/Epigenetics | Experimental Readout |

|---|---|---|

| Chromatin State Dictates Repair Pathway [24] [25] [26] | Open chromatin (H3K27ac, H3K4me3) favors HR; Closed chromatin (H3K9me3, H3K27me3) favors NHEJ. | ChIP-qPCR for histone marks at damage sites; Reporter assays for repair pathway usage. |

| Histone Modifications as DDR Hubs [26] [27] | γH2AX formation is an early DDR signal; H2AK119ub by PRC1/BMI1 promotes end resection for HR. | Immunofluorescence for γH2AX foci; Proximity Ligation Assay (PLA) for repair factor recruitment. |

| Epigenetic Alterations from DDR Signaling [24] [25] | DNA repair machinery can deposit/remove histone marks during repair, altering the local epigenetic state. | ChIP-seq on cells recovered from DNA damage; Tracking histone mark dynamics post-irradiation. |

| DNA Methylation Influences Damage Susceptibility [25] [27] | Hypermethylation of gene promoters can silence DNA repair genes (e.g., MLH1, MGMT), increasing mutation risk. | Whole-Genome Bisulfite Sequencing (WGBS); qRT-PCR of repair gene expression after DNMT inhibitor treatment. |

Frequently Asked Questions & Troubleshooting

FAQ 1: Why is my DNA damage persisting longer than expected after irradiation, and how can I investigate the epigenetic context?

- Potential Cause: The persistent damage may be located in a transcriptionally silent, compact chromatin region (heterochromatin), which is less accessible to the repair machinery.

- Solution:

- Correlate damage sites with chromatin marks: Perform immunofluorescence for γH2AX (damage marker) co-stained with antibodies for heterochromatin marks like H3K9me3 or HP1α. Co-localization suggests damage in repressed regions.

- Increase chromatin accessibility: Treat cells with a low dose of a Histone Deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitor (e.g., Trichostatin A) prior to damage induction. This loosens chromatin, potentially accelerating repair in these zones. Re-measure γH2AX foci decay.

- Validate mechanistically: Use CRISPR/dCas9 to tether a transcriptional activator to the specific genomic locus where damage is persistent to force an open chromatin state and re-test repair efficiency [24] [25] [27].

FAQ 2: My cellular reprogramming efficiency is low, with high rates of senescence. Could DDR and epigenetics be linked to this?

- Potential Cause: Yes, this is a classic barrier. The reprogramming process induces significant replication stress and DNA damage, which can trigger senescence. The epigenetic landscape of the starting somatic cell can impede efficient DDR and successful reprogramming.

- Solution:

- Monitor DDR activation: Check for markers of a sustained DDR (e.g., phospho-ATM, p53-Ser15, p21) early in your reprogramming timeline. High levels indicate stress-induced senescence.

- Target the epigenome: Incorporate small-molecule inhibitors to modulate the epigenetic state.

- Use a DNMT inhibitor (e.g., 5-Azacytidine) to promote a more open chromatin landscape, facilitating access for reprogramming factors [27].

- Use an HDAC inhibitor (e.g., Valproic Acid) to enhance histone acetylation, which has been shown to improve reprogramming efficiency and mitigate some senescence pathways [27].

- Employ senolytics: Add a senolytic cocktail (e.g., Dasatinib + Quercetin) to your protocol to selectively eliminate senescent cells that have arrested due to DNA damage, thereby enriching the population for successfully reprogrammed cells [1] [28] [29].

FAQ 3: How does the cell choose between NHEJ and HR for DSB repair, and what epigenetic factors are involved?

- Answer: The choice is highly influenced by cell cycle phase (HR is active in S/G2) and the local chromatin environment. Key epigenetic players include:

- 53BP1: Promotes NHEJ by protecting DNA ends from resection, often enriched in heterochromatic regions [26].

- BRCA1: Promotes HR by antagonizing 53BP1 and facilitating end resection, often associated with active chromatin marks [26].

- Histone Modifications: H4K20me2 is a binding site for 53BP1, favoring NHEJ. Acetylation of H3K56 or H4K16 promotes an open chromatin state that facilitates resection and HR [24] [26].

- Experimental Tip: To manipulate pathway choice, you can deplete 53BP1 to shift the balance towards HR, or inhibit BRCA1 to favor NHEJ. Monitor pathway usage with specialized reporter constructs (e.g., DR-GFP for HR, EJ5-GFP for NHEJ).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

This table lists essential reagents for investigating the DDR-Epigenetics interplay, with a focus on mitigating senescence.

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Mechanism | Example Application in Senescence Mitigation |

|---|---|---|

| HDAC Inhibitors (e.g., Trichostatin A) [27] | Blocks histone deacetylation, leading to a more open chromatin state. | Increases accessibility for DNA repair machinery, potentially reducing damage-induced senescence during reprogramming [24] [27]. |

| DNMT Inhibitors (e.g., 5-Azacytidine) [27] | Inhibits DNA methylation, reactivating silenced genes. | Prevents hypermethylation and silencing of tumor suppressor and pro-repair genes, maintaining genomic health [25] [27]. |

| Senolytics (e.g., Dasatinib + Quercetin) [1] [28] [29] | Selectively induces apoptosis in senescent cells by targeting pro-survival pathways (SCAPs). | Clears senescent cells that accumulate during prolonged cell culture or after genotoxic stress, enriching for healthy proliferating cells [1] [28]. |

| ATM/ATR Inhibitors (e.g., KU-55933) [30] [31] | Pharmacologically inhibits the key kinases that initiate the DDR signaling cascade. | Used to experimentally dissect the role of DDR in triggering senescence. Caution: Can be genotoxic if used improperly. |

| p53 Inhibitor (e.g., Pifithrin-α) | Temporarily inhibits p53 transcriptional activity, a central mediator of damage-induced senescence. | Can be used transiently to bypass stress-induced senescence arrest during challenging manipulations like reprogramming [1]. |

| NAD+ Precursors (e.g., Nicotinamide Riboside) | Boosts cellular NAD+ levels, activating sirtuins (e.g., SIRT1, SIRT6) which are deacetylases linked to genomic stability and aging. | Enhances DNA repair capacity and has been shown to reduce markers of cellular senescence in aging models [28]. |

Key Signaling Pathways Visualized

The following diagrams illustrate the core signaling pathways that integrate DNA damage response with epigenetic remodeling, providing a visual guide for experimental design and troubleshooting.

DDR - Epigenetic Feedback Loop

Senescence Activation & Clearance

From Theory to Practice: Methodologies to Induce Reprogramming While Controlling Senescence

This technical support guide provides troubleshooting and methodological support for researchers aiming to leverage cellular reprogramming to mitigate cellular senescence. A primary challenge in this field is balancing the profound rejuvenating potential of reprogramming factors with the critical need to maintain cellular identity and avoid tumorigenesis. This resource distills the latest research on using OSKM (OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, c-MYC) and OKS (OCT4, SOX2, KLF4) factors to achieve safer epigenetic rejuvenation, offering practical guidance for your experiments.

★ Key Concepts FAQ

What is the core difference between full and partial reprogramming in the context of rejuvenation?

Full reprogramming involves the continuous expression of reprogramming factors (typically OSKM) until a somatic cell is completely converted into an induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC). This process resets epigenetic aging markers but entirely erases cellular identity, posing a high risk of teratoma formation in vivo [32]. Partial reprogramming, in contrast, applies the factors transiently or cyclically. This exposure is sufficient to restore a more youthful epigenetic state and reverse age-related phenotypes—such as reducing senescence markers and restoring gene expression profiles—without pushing the cell into pluripotency, thereby preserving its original identity and avoiding tumorigenic risks [32] [33] [23].

Why is the "c-MYC" factor often omitted (OKS vs. OSKM) in rejuvenation strategies?

c-MYC is a potent proto-oncogene. Its inclusion in the OSKM cocktail significantly increases the efficiency of full reprogramming but also dramatically elevates the risk of cancer in vivo [23]. For therapeutic rejuvenation, where the goal is not pluripotency but age reversal, omitting c-MYC (resulting in the OKS combination) has been shown to be a safer strategy. Studies have demonstrated that OKS delivery can effectively reverse epigenetic age, improve tissue function (e.g., in the optic nerve and intervertebral disc), and extend lifespan in mouse models without reported tumor formation [23] [21].

How does cellular senescence directly interact with the reprogramming process?

The interaction is bidirectional and paradoxical. On one hand, the process of inducing reprogramming can itself trigger senescence as an innate barrier, halting a subset of cells from undergoing identity change [7]. On the other hand, senescent cells, through their Senescence-Associated Secretory Phenotype (SASP), can create a pro-inflammatory microenvironment that paradoxically enhances the reprogramming efficiency and plasticity of neighboring cells [7]. Furthermore, a key goal of reprogramming for rejuvenation is to directly target and reverse the senescent state, reducing markers like p16INK4a and SA-β-Gal activity in aged tissues [21].

〠 Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Challenges

| Challenge & Phenomenon | Root Cause | Verified Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low Reprogramming EfficiencyPoor yield of rejuvenated cells. | Low transfection efficiency, particularly in senescent cells; suboptimal factor expression levels [21]. | Use advanced delivery vectors like Cavin2-modified exosomes (OKS@M-Exo), which show enhanced uptake by senescent nucleus pulposus cells [21]. |

| Induction of SenescenceUnexpected cell cycle arrest during reprogramming. | Activation of innate anti-cancer barriers like the p53 pathway in response to reprogramming stress [7] [23]. | Utilize partial (cyclic) reprogramming protocols. For chemical reprogramming with the "7c" cocktail, note that it upregulates p53, suggesting a different pathway than OSKM [23]. |

| Loss of Cellular IdentityDedifferentiation or teratoma formation. | Over-reprogramming due to prolonged or potent factor expression [32] [23]. | Implement short-term, cyclic induction protocols (e.g., 2-day ON, 5-day OFF for Dox-inducible systems) [32] [23]. Excluding c-MYC (using OKS) also mitigates this risk [21]. |

| Poor In Vivo DeliveryInefficient factor delivery to target tissues. | Limitations of viral (AAV) vectors, including immune responses and tissue tropism [33] [23]. | Explore chemical reprogramming cocktails as a non-genetic alternative [33] [23]. For genetic delivery, AAV9 has been used for systemic OSK delivery in mice [23]. |

★ Experimental Protocol: In Vivo Partial Reprogramming in Mouse Models

This protocol is adapted from studies that successfully reversed age-related phenotypes without tumor formation [32] [23].

1. Genetic Model Setup

- Use transgenic mice carrying a doxycycline (Dox)-inducible polycistronic cassette for OSKM or OKS (e.g., "LAKI" mice).

- Alternatively, for a more translational approach, use gene therapy. Administer AAV9 vectors carrying the OKS and rtTA genes systemically to wild-type mice [23].

2. Partial Reprogramming Induction Cycle

- Initiate the cycle when mice show signs of aging or in progeria models.

- Administer Dox in the diet or drinking water to induce transgene expression.

- Apply a cyclic protocol: A common and effective regimen is a 2-day pulse of Dox followed by a 5-day chase without Dox [32] [23].

- Repeat this cycle for multiple weeks (e.g., 35 cycles has been shown to be safe and effective) [23].

3. Monitoring and Validation

- Safety: Regularly monitor for teratoma formation via histology. The cyclic protocol should prevent this [23].

- Efficacy: Assess rejuvenation using:

- Epigenetic Clocks: Analyze DNA methylation patterns from blood or tissue samples [33] [23].

- Transcriptomic Analysis: RNA sequencing to show a shift to a younger gene expression profile [23].

- Functional Assays: Tissue-specific tests (e.g., visual acuity in eye models, grip strength, frailty index) [23] [21].

- Senescence Biomarkers: Measure p16INK4a, p21CIP1, and SA-β-Gal activity in target tissues [21].

◈ Visualizing the Senescence-Reprogramming Interplay

The following diagram illustrates the critical molecular and cellular interactions between senescence and reprogramming, which is central to troubleshooting experiments in this field [7].

The tables below synthesize key quantitative findings from recent studies on reprogramming-induced rejuvenation.

Table 1: In Vivo Outcomes of Partial Reprogramming in Mouse Models

| Reprogramming Factor(s) | Delivery Method | Key Result (Lifespan) | Key Result (Healthspan) | Safety Observation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OSKM (Cyclic) | Dox-inducible Transgene | Median lifespan increased by 33% in progeria mice [23] | Ameliorated cellular hallmarks; improved skin regeneration [23] | No teratomas after 35 cycles [23] |

| OSK (Cyclic) | AAV9 Gene Therapy | Remaining lifespan extended by 109% in old (124-week) wild-type mice [23] | Frailty index score improved from 7.5 to 6.0 [23] | No teratoma formation reported [23] |

| Chemical Cocktails | Small Molecules | N/A (In vitro human cell focus) | Restored youthful transcript profile in < 1 week [33] | Did not compromise cellular identity [33] |

Table 2: Cellular & Molecular Rejuvenation Markers Following OKS/S Treatment

| Rejuvenation Marker | Observation After OKS/S Treatment | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|

| Senescence Markers (p16, p21) | Significant downregulation [21] | Senescent human nucleus pulposus cells [21] |

| DNA Damage (γ-H2A.X foci) | Significant reduction [21] | Senescent human nucleus pulposus cells [21] |

| Epigenetic Age | Reversion of transcriptomic age [33] | Human fibroblasts in vitro [33] |

| Cell Proliferation | Significant increase (EdU+ cells) [21] | Senescent human nucleus pulposus cells [21] |

◈ The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

| Reagent / Material | Function in Reprogramming & Rejuvenation Research |

|---|---|

| Doxycycline (Dox)-Inducible System | Allows precise, temporal control over the expression of OSKM/OKS factors in transgenic animal models or cells, which is crucial for achieving partial rather than full reprogramming [32] [23]. |

| AAV9 Vectors | A gene therapy delivery tool capable of systemic administration to distribute OKS factors broadly across tissues in adult animals, providing a translational alternative to transgenic models [23]. |

| Cavin2-modified Exosomes | Engineered exosomes that serve as highly efficient, non-immunogenic delivery vehicles for plasmid DNA (e.g., OKS plasmid), enhancing transfection of hard-to-transfect senescent cells [21]. |

| Chemical Cocktails (e.g., 7c) | Defined mixtures of small molecules that can induce epigenetic reprogramming and rejuvenation without genetic integration, offering a potentially safer and more controllable therapeutic path [33] [23]. |

| NCC Reporter System | A fluorescence-based biosensor (Nucleocytoplasmic Compartmentalization) used to distinguish young, old, and senescent cells in high-throughput screens for rejuvenating compounds [33]. |

This technical support center provides specialized guidance for researchers aiming to mitigate cellular senescence during cellular reprogramming experiments. Cellular senescence, a state of irreversible cell cycle arrest, is a significant barrier in regenerative medicine. While it acts as a tumor-suppressive mechanism, its chronic presence contributes to aging and age-related pathologies and can impede efforts to reverse cellular aging [13] [34]. Chemical reprogramming using non-genetic cocktails offers a promising avenue to reverse aging and bypass senescence, but the process is fraught with technical challenges. This resource, framed within the broader thesis of mitigating senescence in reprogramming research, offers detailed troubleshooting guides, FAQs, and methodological support to help you navigate these complexities.

Core Concepts: Senescence and Reprogramming

Cellular Senescence is a complex physiological process characterized by irreversible cell cycle arrest, activation of tumor suppressor pathways (p53/p21 and p16INK4A/Rb), and a pronounced secretory phenotype known as the Senescence-Associated Secretory Phenotype (SASP) [17] [34]. The SASP comprises proinflammatory cytokines, chemokines, and proteases that can remodel the tissue microenvironment [8].

Chemical Reprogramming involves using defined cocktails of small molecules to revert differentiated cells to a pluripotent state or to reverse age-associated markers without using genetic factors like OSKM (OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, MYC) [8]. A key challenge is that the induction of reprogramming itself can trigger senescence as a stress response, creating a barrier to successful age reversal [8].

The interplay between these processes is critical. Emerging research shows that senescent cells, through their SASP, can paradoxically enhance the reprogramming efficiency of nearby cells by secreting factors like IL-6 [8]. However, for the goal of producing healthy, rejuvenated cells, the persistent presence of senescent cells is detrimental and must be managed.

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: High Senescence Rates in Starting Cell Population

Issue or Problem Statement: The primary cells (e.g., fibroblasts) used for reprogramming experiments exhibit high levels of senescence before the protocol begins, leading to low reprogramming efficiency.

Symptoms or Error Indicators:

- High percentage of cells positive for Senescence-Associated Beta-Galactosidase (SA-β-Gal) staining before reprogramming.

- Poor cell proliferation and enlarged, flattened cell morphology at baseline.

- Elevated expression of senescence markers (p16, p21, p53) in pre-reprogramming RNA/protein analysis.

Possible Causes:

- Donor Age: Cells isolated from aged donors have a higher intrinsic senescent burden due to factors like telomere attrition and accumulated DNA damage [35].

- Suboptimal Cell Culture: Replicative exhaustion from excessive passaging or oxidative stress from subculture conditions.

- Cell Isolation Stress: Enzymatic and mechanical stress during cell isolation from tissue can induce damage and senescence.

Step-by-Step Resolution Process:

- Characterize Senescent Burden: Before initiating reprogramming, quantify the baseline senescent population using SA-β-Gal staining and analysis of p16 and p21 expression [34].

- Pre-treatment with Senolytics: Treat the starting cell population with a senolytic cocktail (e.g., 100 nM Dasatinib + 10 µM Quercetin) for 48 hours to selectively eliminate senescent cells [13]. Remove the senolytics and allow the culture to recover for 24 hours before starting reprogramming.

- Validate Clearance: Re-assess senescence markers post-treatment to confirm reduction of the senescent pool.

- Proceed with Reprogramming: Initiate the chemical reprogramming protocol on the pre-cleared cell population.

Validation or Confirmation Step: Compare the efficiency of induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) colony formation between pre-cleared and untreated control cultures. A significant increase in colony number and a reduction in differentiation-resistant flat cells indicate successful troubleshooting.

Additional Notes or References: Using low-passage cells and optimizing isolation protocols can minimize pre-existing senescence. The dasatinib and quercetin combination is a well-validated senolytic approach, but other specific BCL-2 family inhibitors like ABT-263 (Navitoclax) can also be explored, bearing in mind potential cell-type-specific toxicities [13].

Guide 2: Senescence Induction During Reprogramming

Issue or Problem Statement: Reprogramming factors or the stress of the process itself triggers a senescence response in a subset of cells, halting their progression to pluripotency.

Symptoms or Error Indicators:

- Emergence of SA-β-Gal-positive cells with large, flat morphology during the reprogramming process.

- Persistent expression of senescence markers in cells that fail to activate pluripotency genes (e.g., NANOG, SOX2).

- Culture stagnation, with a mix of small, reprogramming-competent cells and large, senescent cells.

Possible Causes:

- Stress-Induced Senescence: The metabolic and epigenetic stress of reprogramming activates the p53/p21 DNA damage response pathway [35].

- Oncogene-Induced Senescence: Ectopic expression or activation of certain reprogramming factors (e.g., c-MYC) can be perceived as an oncogenic signal, triggering OIS [17].

- SASP-Mediated Paracrine Senescence: Early senescent cells secrete SASP factors that can reinforce the senescent state in neighboring cells [17] [8].

Step-by-Step Resolution Process:

- Co-treatment with Senomorphics: Supplement the reprogramming cocktail with a senomorphic agent to suppress the SASP without killing cells. For example, add 5 µM of the p38 MAPK inhibitor SB203580 to the medium to inhibit a key SASP regulatory pathway.

- Transient p53 Inhibition: Include a small molecule p53 inhibitor (e.g., 1 µM Pifithrin-α) during the initial 5-7 days of reprogramming to temporarily bypass the stress-induced senescence checkpoint. Use with caution due to potential cancer risks.

- Mid-Process Senolytic Washout: At a defined midpoint (e.g., day 8-10), administer a pulse of senolytic drugs (e.g., Dasatinib/Quercetin for 24 hours) to eliminate cells that have entered senescence during the early phase, then resume the standard reprogramming protocol.

Validation or Confirmation Step: Monitor the dynamics of senescence markers weekly. Successful resolution should show a peak of senescence markers early in the protocol, followed by a decline after intervention, concomitant with a rise in pluripotency marker expression.

Additional Notes or References: The timing and concentration of interventions are critical. Pilot dose-response experiments are essential. Research indicates that transient reprogramming protocols may naturally avoid the full senescence response, making them a valuable alternative strategy [8].

Guide 3: Residual Senescence in Final Cell Population

Issue or Problem Statement: After the completion of the reprogramming protocol, the resulting cell population (e.g., iPSCs or rejuvenated somatic cells) contains a subpopulation of senescent cells.

Symptoms or Error Indicators:

- Heterogeneous cell population with sporadic SA-β-Gal-positive cells interspersed among pluripotent colonies.

- Impaired differentiation capacity of the iPSC line, potentially due to pro-inflammatory SASP signals.

- Genomic or proteomic analysis confirms the presence of senescent cells alongside fully reprogrammed cells.

Possible Causes:

- Incomplete Reprogramming: Some cells may have escaped the senescence checkpoint but failed to fully erase the epigenetic and metabolic marks of aging.

- Insufficient Senescent Cell Clearance: The protocols used did not fully eliminate all senescent cells.

- Spontaneous Senescence: Genomic instability in the newly reprogrammed cells can lead to spontaneous senescence.

Step-by-Step Resolution Process:

- Post-Reprogramming Senolytic Selection: Treat the final cell population with a senolytic cocktail. For iPSCs, which often rely on high BCL-2 family protein expression for survival, a specific BCL-XL inhibitor (e.g., A1331852 at 0.5 µM) may be more appropriate and less toxic than a pan-inhibitor like ABT-263 [13].

- Cell Sorting: Use fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) to isolate a pure population based on a specific surface marker of pluripotency (e.g., SSEA-4) and the absence of a senescence-associated marker (e.g., a specific epitope recognized by an antibody).

- Clonal Expansion: Isolate single-cell clones and expand them. Screen each clone for the absence of senescence markers and for robust pluripotency.

Validation or Confirmation Step: The resulting cell population should be 100% negative for SA-β-Gal staining and show homogeneous expression of pluripotency markers. In vitro differentiation into all three germ layers should be efficient and uniform.

Additional Notes or References: Regularly screening master cell banks for senescent contaminants is a critical quality control measure. Using "Aging Clocks" — multivariate models trained on omics data — can provide a quantitative measure of biological age and the success of senescence clearance in the final population [17].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the key markers I should use to reliably identify senescent cells in my reprogramming experiments? A1: There is no single universal marker. A combination is required for reliable identification:

- SA-β-Gal Activity: A common histochemical marker detectable at pH 6.0 [34].

- Protein Markers: Increased levels of tumor suppressors p16INK4a, p21WAF1/Cip1, and p53 [17] [34].

- SASP Factors: Detection of secreted proteins like IL-6, IL-8, and MMPs via ELISA or transcript analysis [8] [34].

- DNA Damage Foci: Immunofluorescence staining for γ-H2AX, a marker of DNA double-strand breaks often present in senescent cells [35].

Q2: How can I distinguish between oncogene-induced senescence (OIS) and stress-induced senescence during reprogramming? A2: Distinguishing them can be challenging as they share common pathways. However, you can infer the cause:

- Context: OIS is typically triggered by the specific action of a single factor known to be oncogenic, such as high c-MYC activity in your cocktail. Stress-induced senescence is a more general response to the culture conditions and metabolic stress of reprogramming [17].

- Marker Emphasis: OIS is often highly dependent on the p16INK4a/Rb pathway. Stressing these markers in your analysis can point towards OIS [17]. Stress-induced senescence often strongly activates the p53/p21 pathway in response to DNA damage [35].

Q3: Are there any pro-senescence factors I should deliberately AVOID in my chemical cocktails? A3: The field is still exploring this. Currently, the focus is less on specific "pro-senescence" chemicals to avoid and more on understanding that the reprogramming process itself is a potent senescence trigger. The key is to proactively include senolytic or senomorphic agents as countermeasures, as outlined in the troubleshooting guides. Some protocols using genetic factors suggest that high levels of c-MYC can potentiate OIS [8].

Q4: My reprogramming efficiency is low, but I don't see classic senescence markers. Could senescence still be the issue? A4: Yes. Cells can enter a state of "dormancy" or other non-proliferative states that are not captured by classic markers like SA-β-Gal. It is advisable to use a broader panel of markers, including analysis of cell cycle arrest genes (p21, p16) and a more comprehensive SASP analysis. Single-cell RNA sequencing can reveal heterogeneous subpopulations, including those in a pre-senescent or alternative arrest state.

Q5: What is the difference between a senolytic and a senomorphic agent, and when should I use each? A5:

- Senolytics: These are drugs that selectively induce apoptosis in senescent cells by targeting their pro-survival pathways (e.g., BCL-2/BCL-XL inhibitors like ABT-263, dasatinib/quercetin). Use them when your goal is to eliminate existing senescent cells from your culture [13] [34].

- Senomorphics: These agents suppress the SASP and other damaging phenotypes of senescent cells without killing them (e.g., NF-κB or p38 MAPK inhibitors). Use them when you need to mitigate the paracrine damaging effects of SASP on neighboring cells during the reprogramming process [34].

The following tables summarize key quantitative data on senolytic agents and senescence inducers relevant to chemical reprogramming research.

Table 1: Selected Senolytic Agents for Experimental Use

| Senolytic Agent | Primary Target(s) | Example Concentration (In Vitro) | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dasatinib + Quercetin [13] | Multiple tyrosine kinases (D); PI3K, BCL-2 family (Q) | 100 nM D + 10 µM Q | Broad-spectrum senolytic; well-studied combination. |

| ABT-263 (Navitoclax) [13] | BCL-2, BCL-W, BCL-XL | 1 µM | Potent but can cause thrombocytopenia due to BCL-XL inhibition in platelets. |

| A1331852 [13] | BCL-XL (specific) | 0.5 - 1 µM | More specific than ABT-263; potentially fewer off-target effects. |

| Fisetin [13] | Multiple pathways | 10 - 20 µM | Natural flavonoid; senolytic activity observed in multiple cell types. |

Table 2: Common Senescence Inducers and Markers

| Senescence Inducer / Type | Key Hallmarks / Markers | Associated Pathways |

|---|---|---|

| Replicative Senescence [17] [35] | Telomere shortening, DNA damage foci (γ-H2AX) | p53/p21 |

| Oncogene-Induced Senescence (OIS) [17] | Hyperproliferation stress, p16INK4a upregulation | p16INK4a/Rb |

| Therapy-Induced Senescence [34] | Persistent DNA damage response (DDR) | p53/p21, p16/Rb |

| Oxidative Stress Senescence [17] | High ROS, mitochondrial dysfunction | p53/p21 |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Pre-Clearance of Senescent Cells from Primary Fibroblasts

Objective: To reduce the baseline senescent cell burden in a primary fibroblast culture before initiating chemical reprogramming.

Materials:

- Primary human dermal fibroblasts (low passage, if possible)

- Senolytic cocktail: Dasatinib (100 nM stock) and Quercetin (10 mM stock)

- Fibroblast growth medium

- Phosphate-Buffered Saline (PBS)

- Trypsin-EDTA

- SA-β-Gal Staining Kit

Methodology:

- Cell Seeding: Seed fibroblasts at a density of 10,000 cells/cm² and allow them to adhere overnight in standard growth medium.

- Senolytic Treatment: Replace the medium with fresh growth medium containing 100 nM Dasatinib and 10 µM Quercetin.

- Incubation: Incubate the cells for 48 hours under normal culture conditions (37°C, 5% CO₂).

- Recovery: Aspirate the senolytic-containing medium, wash the cells gently with PBS, and add fresh growth medium without senolytics. Incubate for a further 24 hours.

- Validation (Optional but Recommended): Harvest a subset of cells and perform SA-β-Gal staining according to the manufacturer's protocol. Compare the percentage of SA-β-Gal-positive cells to an untreated control culture. A >50% reduction is typically observed [13].

- Proceed: The pre-cleared fibroblast population is now ready for use in chemical reprogramming experiments.

Protocol 2: Monitoring Senescence Dynamics During Reprogramming

Objective: To track the emergence and resolution of senescent cells throughout a chemical reprogramming timeline.

Materials:

- Cells undergoing chemical reprogramming

- SA-β-Gal Staining Kit

- RNA extraction kit

- cDNA synthesis kit

- qPCR reagents

- Antibodies for p16, p21, and a pluripotency marker (e.g., NANOG)

Methodology:

- Sample Planning: Designate time points for analysis (e.g., Day 0, 3, 7, 10, 14, and endpoint).

- Morphological Analysis: At each time point, capture bright-field images to document changes in cell morphology. Senescent cells appear large, flat, and granular.

- SA-β-Gal Staining: At each time point, fix and stain a culture well for SA-β-Gal. Quantify the percentage of positive cells.

- Molecular Analysis: Harvest cells for RNA and protein at each time point.

- Perform qPCR for senescence genes (CDKN2A/p16, CDKN1A/p21) and pluripotency genes (NANOG, SOX2).

- Perform Western blotting for p16, p21, and NANOG protein levels.

- Data Integration: Plot the dynamics of senescence markers against the emergence of pluripotency markers. This will identify the critical window where senescence peaks and informs the optimal timing for interventional strategies.

Signaling Pathways and Workflows

Senescence and Reprogramming Crosstalk

Experimental Workflow for Senescence Mitigation

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Senescence Mitigation in Reprogramming

| Item Name | Function / Purpose | Example / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Dasatinib & Quercetin [13] | Broad-spectrum senolytic cocktail. Selectively eliminates senescent cells by targeting pro-survival pathways. | Used for pre-clearance and mid-process pulses. Commercially available from major chemical suppliers. |

| ABT-263 (Navitoclax) [13] | Potent BCL-2/BCL-XL inhibitor senolytic. Effective for senescent cell types reliant on these specific anti-apoptotic proteins. | Can cause platelet toxicity; use specific concentrations and durations. |

| p38 MAPK Inhibitor (e.g., SB203580) | Senomorphic agent. Suppresses the SASP by inhibiting the p38 MAPK signaling pathway, a key regulator of inflammatory cytokine production. | Used during reprogramming to mitigate paracrine effects of SASP without killing cells. |

| SA-β-Gal Staining Kit [34] | Histochemical detection of lysosomal β-galactosidase activity at pH 6.0, a common biomarker for identifying senescent cells in culture. | Essential for quantifying senescent burden before, during, and after experiments. |

| Antibodies for p16 & p21 [17] [34] | Protein-level detection of key cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors that enforce senescence-associated cell cycle arrest. | Used in Western Blot or Immunofluorescence for confirmatory analysis alongside SA-β-Gal. |

| Cellular Aging Clocks [17] | Multivariate models (e.g., based on DNA methylation) that predict biological age. Provides a quantitative measure of rejuvenation success. | Used to validate the final output of reprogramming experiments, confirming reversal of aging signatures. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between a senolytic and a senomorphic strategy?

A1: Senolytics are compounds that selectively induce apoptosis (cell death) in senescent cells, thereby reducing their overall burden in tissues [28] [36]. In contrast, senomorphics are compounds that suppress the Senescence-Associated Secretory Phenotype (SASP) without killing the senescent cell [28]. They modulate the harmful, pro-inflammatory secretome that drives tissue dysfunction and chronic inflammation.

Q2: Why would a researcher choose a co-treatment strategy over a single-agent approach?

A2: A co-treatment strategy can target multiple pathways simultaneously, potentially leading to enhanced efficacy. For instance, a senolytic can clear senescent cells, while a co-administered senomorphic can immediately suppress the inflammatory SASP from any remaining cells and may also inhibit pro-survival signals, making the environment less favorable for senescent cell persistence [28]. This approach can be more effective than either strategy alone in mitigating the negative impacts of cellular senescence.

Q3: A common problem is the low specificity of first-generation senolytics. What new strategies are being developed to improve cell-type specificity?

A3: Researchers are developing more targeted delivery systems. One promising strategy involves exploiting the high senescence-associated β-galactosidase (SA-β-gal) activity as a trigger. This includes designing prodrugs like SSK1 (galactose-modified gemcitabine) and GMD (galactose-modified duocarmycin), which are activated specifically in senescent cells, minimizing off-target effects [36]. Additionally, immunological approaches such as antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs) and CAR-T cells are being explored to target specific surface markers on senescent cells [36].

Q4: In the context of cellular reprogramming, how can senescent cells interfere with the process, and how can senotherapeutics help?

A4: Cellular reprogramming, using factors like OSKM (OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, MYC), can itself induce senescence as a barrier to full reprogramming [8]. Furthermore, the SASP from senescent cells can create a pro-inflammatory environment that compromises the efficiency and fidelity of reprogramming neighboring cells. Using senolytics to clear these cells or senomorphics to quell the SASP can create a more permissive microenvironment, improving reprogramming efficiency and reducing the risk of aberrant outcomes [8].

Q5: What are the key biomarkers I should use to confirm senescence in my in vitro models before and after senolytic/senomorphic treatment?

A5: A combination of biomarkers is recommended, as no single marker is entirely specific. Key markers include:

- SA-β-galactosidase activity: A widely used histochemical marker [28] [37].

- Protein levels of p16INK4a and p21CIP1: Core regulators of the senescence growth arrest [28] [17].

- SASP components: Measure the secretion of factors like IL-6, IL-8, or other model-specific cytokines via ELISA or multiplex assays [28] [12].

- Persistent DNA Damage Foci (e.g., γH2AX): Indicates activation of the DNA damage response [17].

The following table summarizes the mechanisms and limitations of common senotherapeutics.

Table 1: Overview of Senolytic and Senomorphic Agents

| Agent Name | Class | Primary Mechanism of Action | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dasatinib + Quercetin (D+Q) [28] [36] | Senolytic | Inhibits tyrosine kinase receptors (Dasatinib) and BCL-2 family proteins (Quercetin) to target SCAPs. | Limited specificity; can affect non-senescent cells. |

| Fisetin [28] [36] | Senolytic | Flavonoid that targets senescent cell anti-apoptotic pathways (SCAPs). | Bioavailability and pharmacokinetics can be variable. |

| Navitoclax (ABT-263) [17] [36] | Senolytic | Inhibits BCL-2, BCL-xL, and BCL-w to induce apoptosis. | Can cause thrombocytopenia as a side effect [28]. |

| SSK1 [36] | Senolytic (Prodrug) | SA-β-galactosidase-activated prodrug of gemcitabine; selectively toxic to senescent cells. | Requires high SA-β-gal activity for specificity. |

| Rapamycin [28] | Senomorphic | Inhibits mTOR pathway, a key regulator of SASP expression. | Can cause immunosuppression with chronic use. |

| Metformin [28] | Senomorphic | AMPK activator; can reduce SASP and inflammation. | Effects are pleiotropic and not exclusively senomorphic. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol for In Vitro Senescence Induction and Senotherapeutic Validation

This protocol outlines a standard workflow for inducing senescence in a cell culture model and testing the efficacy of senolytic/senomorphic compounds.

Workflow Diagram:

Materials:

- Cell Line: (e.g., Human diploid fibroblasts like IMR-90, WI-38)

- Senescence Inducer: (e.g., 10 Gy X-ray irradiation, 200 µM H₂O₂ for 2 hours, 1 µM Etoposide for 48 hours)

- Senotherapeutic Agents: (e.g., 100 nM Dasatinib + 10 µM Quercetin, 5 µM Fisetin)

- Staining Reagents: SA-β-gal Staining Kit, antibodies for p16/p21 immunofluorescence.

- Assay Kits: Cell viability assay (e.g., MTT, CellTiter-Glo), ELISA kits for SASP factors (e.g., IL-6).

Step-by-Step Methodology:

- Cell Seeding: Seed cells at an appropriate density (e.g., 10,000 cells/cm²) in culture plates.

- Senescence Induction: Once cells are ~70% confluent, expose them to the chosen stressor.

- For Irradiation: Use an X-ray irradiator to deliver a 10 Gy dose.