Optimizing MSC Exosome Therapy for Wound Healing: A Comprehensive Guide to Dosing and Administration Routes

This article provides a critical analysis of current strategies for dosing and administering mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes (MSC-Exos) in wound therapy.

Optimizing MSC Exosome Therapy for Wound Healing: A Comprehensive Guide to Dosing and Administration Routes

Abstract

This article provides a critical analysis of current strategies for dosing and administering mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes (MSC-Exos) in wound therapy. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it synthesizes findings from recent clinical trials and preclinical studies to establish foundational principles of MSC-Exo biology and therapeutic mechanisms. The content explores methodological considerations for production and characterization, identifies key challenges in standardization and optimization, and offers comparative validation of different approaches. By integrating the latest evidence, this review aims to support the development of safe, effective, and standardized MSC-Exo therapies to advance regenerative medicine for wound healing.

The Science Behind MSC Exosomes: Mechanisms and Sources for Wound Repair

The therapeutic benefits of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) were initially attributed to their direct differentiation and replacement of damaged cells. However, emerging evidence demonstrates that these effects are primarily mediated through robust paracrine activity, with extracellular vesicles—particularly exosomes (Exos)—serving as crucial delivery vehicles for bioactive molecules [1] [2]. MSC-derived exosomes (MSC-Exos) are nanoscale (30-150 nm), lipid bilayer-enclosed vesicles that facilitate intercellular communication by transferring functional proteins, nucleic acids, and lipids to recipient cells [1] [3]. In the context of wound healing, MSC-Exos have demonstrated remarkable abilities to modulate immune responses, promote angiogenesis, stimulate cellular proliferation and migration, and regulate extracellular matrix (ECM) remodeling [1] [4]. Their composition reflects their parent cells, carrying specific therapeutic cargos that collectively address the multifaceted challenges of impaired wound healing, offering a promising cell-free therapeutic alternative with advantages including low immunogenicity, absence of tumorigenic risk, and enhanced stability [5] [2].

Key Therapeutic Cargos of MSC-Exos

The therapeutic efficacy of MSC-Exos is mediated by their diverse cargo, which includes proteins, miRNAs, lipids, and other nucleic acids. These components work in concert to regulate multiple signaling pathways in recipient cells within the wound microenvironment.

Table 1: Key Protein Cargos in MSC-Exos and Their Functions in Wound Healing

| Protein Cargo | Function in Wound Healing | Mechanism of Action |

|---|---|---|

| Cytokines (IL-10, TGF-β1) [4] | Immunomodulation | Polarization of macrophages toward anti-inflammatory M2 phenotype; reduction of pro-inflammatory cytokines |

| Growth Factors (VEGF, HGF) [4] | Angiogenesis | Stimulation of endothelial cell proliferation and migration; formation of new blood vessels |

| Heat Shock Proteins (HSP70, HSP90) [3] | Cytoprotection | Protection of cells against stress and apoptosis; promotion of cell survival |

| ECM Proteins [3] | Tissue Remodeling | Structural support for cell migration and tissue regeneration |

| Transcription Factors [3] | Epigenetic Regulation | Modulation of gene expression in recipient cells to promote repair processes |

Table 2: Key miRNA Cargos in MSC-Exos and Their Therapeutic Roles

| miRNA Cargo | Therapeutic Role | Target Pathways/Genes |

|---|---|---|

| miR-21 [6] | Anti-apoptosis, Neuroprotection | PTEN/PDCD4 signaling pathway |

| miR-133b [6] | Axon Regeneration, Neural Recovery | Not specified; promotes expression of neurofilament, GAP-43 |

| miR-200c-3p [4] | ECM Remodeling, Anti-fibrotic | Regulates glutaminase; targeted by lncRNA-ASLNCS5088 |

| Anti-ferroptotic miRNAs [3] | Antioxidant, Cell Protection | Regulation of GPX4, SLC7A11; inhibition of lipid peroxidation |

Beyond proteins and miRNAs, MSC-Exos contain long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) that play pivotal regulatory roles. For instance, the lncRNA KLF3-AS1 from bone marrow MSC-Exos promotes angiogenesis by increasing VEGFA expression [4], while lncRNA MEG3 helps prevent keloid formation by reducing fibrosis-related protein and collagen expression [4]. The lipid components of the exosomal membrane itself are functional, contributing to membrane stability, cellular uptake, and signaling processes such as the resolution of inflammation [3].

Experimental Protocols for MSC-Exos Research

Protocol 1: Production and Isolation of MSC-Exos Using an Upscaling Approach

Principle: Efficient production of high-quality MSC-Exos is a prerequisite for therapeutic and research applications. This protocol describes a 3D culture-based upscaling method, which significantly enhances exosome yield compared to conventional 2D cultures [7].

Materials:

- Source Cells: Canine Adipose-Derived MSCs (cAD-MSCs) or human MSCs from bone marrow, adipose tissue, or umbilical cord [2] [7]

- Exosome-Collecting Medium: In-house serum-free medium (e.g., VSCBIC-3) or commercial serum-free alternatives [7]

- Culture System: Microcarrier-based 3D bioreactor system or conventional 2D flasks for comparison

- Isolation Equipment: Tangential Flow Filtration (TFF) system with appropriate molecular weight cut-off filters [2] [7]

- Characterization Instruments: Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis (NTA) system, Transmission Electron Microscope (TEM), Western blot apparatus [2]

Procedure:

- Cell Culture and Expansion: Culture MSCs in growth medium (e.g., DMEM with 10% FBS) until ~80% confluence. Use early passages (P3-P5) to avoid senescence [2].

- Conditioning with Exosome-Collecting Medium: Replace growth medium with serum-free exosome-collecting medium (e.g., VSCBIC-3). Maintain cells for 48-72 hours.

- Conditioned Medium (CM) Harvesting: Collect the CM and centrifuge at 2,000 × g for 30 minutes to remove cells and debris. Follow with a 10,000 × g centrifugation for 45 minutes to eliminate larger vesicles and apoptotic bodies [2] [7].

- Exosome Concentration and Purification (TFF): Concentrate and purify the clarified CM using a TFF system. This method is scalable and maintains exosome integrity better than ultracentrifugation [2].

- Post-Isolation Processing: Concentrate the purified exosome suspension. Aliquot and store at -80°C. Avoid repeated freeze-thaw cycles.

Validation and Quality Control:

- Yield Quantification: Use NTA to determine particle concentration and size distribution (expected peak: 30-150 nm) [8] [2].

- Purity Assessment: Confirm the presence of exosomal markers (CD63, CD81, CD9, TSG101, Alix) and the absence of negative markers (e.g., calnexin) via Western blot [2].

- Morphology: Verify spherical, cup-shaped morphology using TEM [2].

Diagram 1: MSC-Exos isolation and characterization workflow.

Protocol 2: In Vitro Bioactivity Assessment for Wound Healing

Principle: This protocol assesses the functional effects of isolated MSC-Exos on key cellular processes in wound healing, including fibroblast migration and proliferation.

Materials:

- Test Cells: Primary dermal fibroblasts

- MSC-Exos Preparations: Isolated MSC-Exos and a negative control (e.g., PBS)

- Equipment: Cell culture incubator, microscope, materials for scratch assay (e.g., pipette tip), cell proliferation assay kit (e.g., resazurin-based) [7]

- Analysis Tools: RT-qPCR system, primers for wound healing-related genes (e.g., collagen types I and III, fibronectin, α-SMA) [7]

Procedure:

- Fibroblast Culture: Seed fibroblasts in appropriate growth medium in multi-well plates. Allow to adhere and reach ~90% confluence.

- Scratch Assay / Migration Test: Create a uniform scratch in the cell monolayer using a sterile pipette tip. Wash to remove dislodged cells.

- Exosome Treatment: Add MSC-Exos (e.g., 10-100 μg/mL based on protein content) to the treatment wells. Use serum-free medium with PBS as a negative control.

- Incubation and Monitoring: Incubate cells and capture images of the scratch at regular intervals (0, 12, 24 hours) under a microscope.

- Proliferation Assay: In a separate plate, seed fibroblasts at a lower density. Treat with MSC-Exos or control. After 24-72 hours, measure cell proliferation using a resazurin assay [7].

- Gene Expression Analysis: Post-treatment (e.g., 24 hours), lyse fibroblasts and extract RNA. Perform RT-qPCR to analyze the expression of genes related to wound healing [7].

Data Analysis:

- Migration: Calculate the percentage of wound closure at each time point compared to the initial scratch area.

- Proliferation: Compare fluorescence/absorbance values between treated and control groups.

- Gene Expression: Analyze fold-changes in gene expression using the 2^(-ΔΔCt) method.

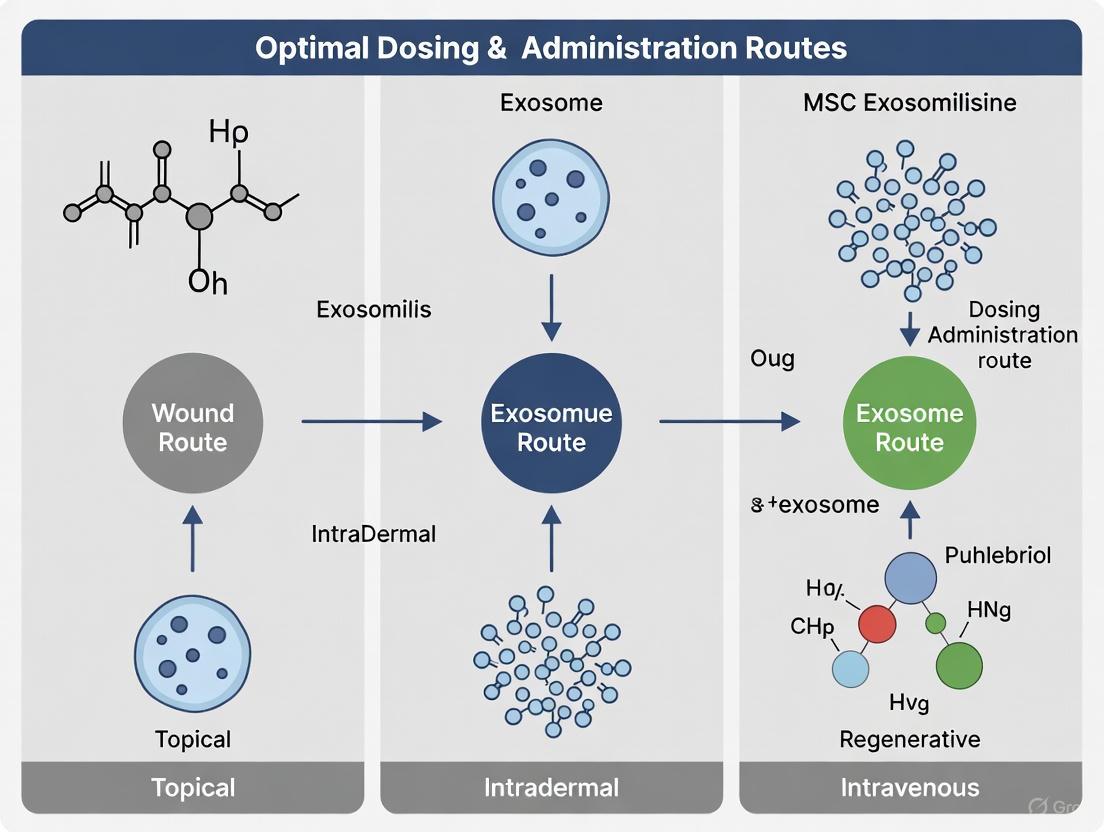

Dosing and Administration Considerations for Wound Therapy

Translating MSC-Exos bioactivity into clinical efficacy requires careful consideration of dosing and administration routes, which are critical elements of the user's thesis context.

Table 3: MSC-Exos Dosing in Preclinical and Clinical Studies

| Context | Reported Dose Range | Quantification Method | Administration Route |

|---|---|---|---|

| Preclinical (Rodent Models) [8] | 10 - 100 μg protein (approx. 2.0 x 10^10 - 2.0 x 10^11 particles) | Protein content (Bradford assay), Particle count (NTA) | Intravenous, Local injection |

| Clinical (Human Trials) [8] | Broad range: ~10^8 - 10^13 particles total dose | Particle count (NTA), Protein content, Cell-equivalent | Intravenous, Inhalation, Local/topical |

| Proposed "Working Range" (Human) [8] | 1 x 10^10 - 6 x 10^12 particles total dose | Particle count (NTA) | Route-dependent |

The administration route profoundly influences the required effective dose due to differences in bioavailability, distribution, and retention at the target site [8]. For cutaneous wound healing, local administration (e.g., topical application via hydrogels, direct injection) is often favored as it maximizes delivery to the wound site while minimizing systemic exposure and potential off-target effects [9] [2]. Evidence suggests that local application can achieve therapeutic effects at significantly lower doses compared to systemic routes like intravenous infusion [9]. The optimal dosing regimen (single vs. multiple doses) must be determined empirically for each specific wound type and exosome preparation.

Diagram 2: Key factors influencing MSC-Exos therapeutic efficacy.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for MSC-Exos Wound Healing Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Serum-Free Exosome Production Media | Provides nutrients for MSCs during exosome production without contaminating bovine exosomes. | Commercial serum-free media; In-house formulations (e.g., VSCBIC-3) [7]. |

| Tangential Flow Filtration (TFF) System | Scalable isolation and concentration of exosomes from large volumes of conditioned medium. | Preferable to ultracentrifugation for large-scale, GMP-compliant production [2] [7]. |

| Nanoparticle Tracking Analyzer (NTA) | Measures the size distribution and concentration of exosomes in a solution. | Essential for dose quantification and characterization (e.g., ZetaView, NanoSight) [8] [2]. |

| Exosomal Surface Marker Antibodies | Characterizing exosomes and confirming identity via specific surface proteins. | Antibodies against CD63, CD81, CD9, TSG101, Alix. Negative marker: Calnexin [6] [2]. |

| In Vitro Wound Healing Assay Kits | Functional validation of exosome bioactivity on target cells. | Scratch assay kits; Cell migration and proliferation assay kits (e.g., resazurin) [7]. |

| Biomaterial Scaffolds / Hydrogels | Serve as delivery vehicles for sustained release and localization of exosomes at the wound site. | Chitosan, collagen, hyaluronic acid-based hydrogels. Protect exosomes and enhance retention [5]. |

The field of regenerative medicine is undergoing a significant transformation, moving from whole cell-based therapies toward cell-free approaches utilizing exosomes and extracellular vesicles (EVs). Mesenchymal stem cell (MSC)-derived exosomes have emerged as promising therapeutic agents that retain many of the beneficial properties of their parent cells while exhibiting superior safety profiles. These nanoscale vesicles (30-150 nm) mediate intercellular communication by transferring bioactive molecules—including proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids—to recipient cells, thereby modulating immune responses and promoting tissue repair [10] [11]. This application note details the comparative advantages of MSC-derived exosomes, with a specific focus on their low immunogenicity and tumorigenicity relative to cell-based therapies, providing essential guidance for researchers developing exosome-based wound therapeutics.

The therapeutic benefits of MSCs were originally attributed to their differentiation potential and engraftment capabilities. However, accumulating evidence indicates that most administered MSCs exhibit limited long-term survival in host tissues, suggesting their effects are predominantly mediated through paracrine signaling [12]. MSC-derived exosomes contain a complex cargo of growth factors, cytokines, and regulatory RNAs that can modulate inflammation, promote angiogenesis, and stimulate regeneration—key processes in wound healing—without the risks associated with whole-cell transplantation [13] [12]. This paradigm shift toward acellular therapies addresses critical safety concerns while maintaining therapeutic efficacy.

Comparative Safety Profiles: Exosomes Versus Cell-Based Therapies

Immunogenicity

A primary advantage of MSC-derived exosomes is their low immunogenicity, which enables allogeneic administration without provoking significant immune responses. Unlike whole MSCs, which express Major Histocompatibility Complex (MHC) molecules that can trigger immune recognition and rejection, exosomes have reduced immunostimulatory properties [14] [15]. This characteristic makes them suitable for off-the-shelf therapeutics that don't require patient matching.

- Immune Cell Modulation: MSC-derived exosomes modulate immune responses through multiple mechanisms, including promoting macrophage polarization toward anti-inflammatory M2 phenotypes, suppressing T-cell proliferation, and regulating dendritic cell maturation [10] [16]. These immunomodulatory effects are particularly beneficial in wound healing, where controlling excessive inflammation is crucial for optimal tissue repair.

- Composition Advantages: The lipid bilayer membrane of exosomes protects their cargo from degradation while minimizing immune activation. Their small size and lack of complete cellular machinery contribute to their stealth properties, allowing wider biodistribution and longer circulation times compared to cellular therapies [17] [11].

Tumorigenicity

The risk of tumor formation represents a significant concern with stem cell-based therapies, particularly those utilizing cells with high proliferative potential. MSC-derived exosomes address this concern through several inherent characteristics:

- Non-Replicative Nature: As acellular vesicles, exosomes cannot self-replicate or form teratomas, effectively eliminating the risk of uncontrolled growth associated with undifferentiated stem cells [14] [15]. This fundamental difference in biology provides a critical safety advantage for clinical applications.

- Regulatory Cargo: Exosomes derived from MSCs typically lack oncogenic factors and may even deliver tumor-suppressive molecules. Multiple studies have demonstrated that MSC-derived exosomes do not induce tumor formation in appropriate experimental models [11] [15]. However, researchers should note that exosome cargo can vary based on cell source and culture conditions, emphasizing the need for thorough characterization.

Table 1: Comparative Safety Profiles of MSC-Based Therapies

| Safety Parameter | Whole MSC Therapy | MSC-Derived Exosomes |

|---|---|---|

| Immunogenicity | Moderate to high; risk of immune rejection | Low; suitable for allogeneic use |

| Tumorigenic Potential | Low but documented risk of differentiation complications | Minimal; non-replicative vesicles |

| Infusion Toxicity | Risk of cell clumping and embolization | Reduced risk due to nanoscale size |

| Long-term Engraftment | Potential for unwanted differentiation | No engraftment risk |

| Storage Stability | Limited; requires cryopreservation | High stability; lyophilization possible |

Quantitative Assessment of Safety Parameters

Immunogenicity Metrics

Recent meta-analyses of preclinical studies provide compelling quantitative evidence supporting the low immunogenicity of MSC-derived exosomes. Systematic evaluation of multiple murine models reveals consistent patterns of immune tolerance:

- Cytokine Profile Modulation: Treatment with MSC-exosomes significantly reduces pro-inflammatory cytokines including TNF-α (SMD: -0.880; 95% CI: -1.623 to -0.136) and IL-17A (SMD: -2.390; 95% CI: -4.522 to -0.258) while elevating anti-inflammatory mediators such as IL-10 and TGF-β [14]. This immunomodulatory activity is particularly relevant for chronic wounds characterized by persistent inflammation.

- Dose-Response Relationship: Studies examining different administration routes have identified that nebulization therapy achieved therapeutic effects at approximately 10^8 particles, significantly lower than intravenous routes, demonstrating high bioavailability with minimal immune activation [9].

Tumorigenicity Assessment

Comprehensive analysis of tumor formation across animal studies and early-phase clinical trials confirms the favorable safety profile of MSC-derived exosomes:

- Zero Tumor Incidence: A review of 66 registered clinical trials involving MSC-EVs and Exos reported no cases of tumor formation directly attributable to exosome administration [9]. This finding is particularly significant given that many of these trials utilized allogeneic exosome sources without HLA matching.

- Long-term Safety: Follow-up studies in murine models extending to 6 months post-treatment have documented absent tumorigenicity even with repeated administrations of MSC-derived exosomes [14]. The non-replicative nature of exosomes provides a fundamental safety advantage over living cell therapies.

Table 2: Efficacy and Safety Outcomes of MSC-Exosomes in Preclinical Models

| Disease Model | Exosome Source | Dose Range | Immunogenicity Markers | Tumor Incidence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Psoriasis (IMQ-induced) | Human UCMSC | 1×10^8 particles | ↓ Epidermal thickness, ↓ TNF-α, ↓ IL-17A | 0/6 animals |

| Osteoarthritis | BMSC, ADSC, UCMSC | 50-1000 μg/mL | ↓ NF-κB, ↓ MAPK signaling | Not detected |

| Retinal Injury | BMSC | 50 μg/mL | ↓ Apoptotic cells, ↑ Cell viability | 0/5 donors |

| Myocardial Injury | iPSC | 10^10 particles | Improved function, ↓ Inflammation | Not reported |

Experimental Protocols for Safety Assessment

Protocol: Immunogenicity Assessment

Objective: To evaluate the immune response following administration of MSC-derived exosomes in a wound healing model.

Materials:

- MSC-derived exosomes (characterized per MISEV guidelines)

- Control articles (vehicle buffer, whole MSCs)

- Animal wound model (e.g., diabetic mouse excisional wound)

- Multiplex cytokine assay platform

- Flow cytometry equipment with immune cell markers

Procedure:

- Administration: Apply exosomes (10^8-10^10 particles/wound) topically to full-thickness wounds every 48 hours until closure.

- Sample Collection: At days 3, 7, and 14 post-wounding, collect:

- Wound tissue homogenates for cytokine analysis

- Peripheral blood for immune cell profiling

- Draining lymph nodes for lymphocyte activation assessment

- Cytokine Profiling: Quantify pro-inflammatory (TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-17) and anti-inflammatory (IL-10, TGF-β) cytokines using multiplex immunoassay.

- Immune Cell Phenotyping: Analyze T-cell populations (CD4+, CD8+, Tregs), macrophage polarization (M1/M2 ratio), and dendritic cell activation markers by flow cytometry.

- Histological Assessment: Evaluate immune cell infiltration in wound sections using H&E staining and immunohistochemistry for CD45+ cells.

Acceptance Criteria: Exosome-treated groups should show significantly reduced pro-inflammatory cytokines and increased regulatory T-cell populations compared to MSC-treated groups while maintaining comparable wound closure rates.

Protocol: Tumorigenicity Assessment

Objective: To assess the potential for tumor formation following repeated administration of MSC-derived exosomes.

Materials:

- Test articles: MSC-derived exosomes from multiple donors

- Control articles: Vehicle buffer, pluripotent stem cell-derived exosomes

- Immunodeficient mouse model (e.g., NOD/SCID)

- In vivo imaging system (IVIS)

- Histopathology equipment

Procedure:

- Study Design: Randomize immunodeficient mice (n=10/group) to receive:

- Test article: MSC-derived exosomes (10^10 particles/dose)

- Negative control: Vehicle buffer

- Positive control: Pluripotent stem cell-derived exosomes

- Dosing Regimen: Administer test articles via subcutaneous injection adjacent to wound sites twice weekly for 8 weeks.

- In Vivo Monitoring:

- Weekly palpation for mass formation

- Biweekly IVIS imaging (if exosomes are labeled)

- Monthly body weight and clinical observations

- Terminal Assessment:

- Necropsy with gross examination of organs and injection sites

- Histopathological evaluation of all major organs and any suspicious masses

- Assessment of metastatic potential through lung and liver sections

- Cell Transformation Assay: Evaluate potential procarcinogenic effects using in vitro soft agar colony formation assays with recipient cells exposed to exosomes.

Acceptance Criteria: No gross or histological evidence of tumor formation at injection sites or distant organs in exosome-treated groups beyond background levels observed in negative controls.

Signaling Pathways in Exosome-Mediated Safety and Efficacy

The therapeutic effects and safety profile of MSC-derived exosomes are mediated through specific signaling pathways that modulate cellular responses without inducing excessive immune activation or proliferation.

Pathway Analysis:

- NF-κB and MAPK Suppression: MSC-derived exosomes significantly reduce phosphorylation of p65 (pp65) and MAPK pathway components (p38, JNK, ERK) compared to IL-1β-stimulated controls, attenuating inflammatory signaling without complete pathway inhibition [10]. This balanced modulation is critical for controlling excessive inflammation in chronic wounds while maintaining essential immune functions.

- Immunomodulatory Cargo: Exosomes from umbilical cord and bone marrow MSCs demonstrate superior efficacy in delivering anti-inflammatory miRNAs (e.g., miR-146a-5p, miR-150-5p) that target key pro-inflammatory mediators while avoiding complete immune suppression [10] [11]. This targeted approach reduces immunogenicity while preserving host defense mechanisms.

- Proliferation Regulation: Unlike whole MSCs that retain proliferative capacity, exosomes transfer regulatory RNAs that modulate cell cycle progression without driving uncontrolled division. Studies confirm that exosome-treated cells maintain normal contact inhibition and do not form colonies in soft agar assays [14] [15].

Research Reagent Solutions for Exosome Studies

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for MSC-Exosome Wound Therapy Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Safety Assessment Utility |

|---|---|---|---|

| Isolation Kits | Total Exosome Isolation Kit, miRCURY Exosome Kit | Rapid exosome purification | Standardized yield for dosing |

| Characterization Antibodies | Anti-CD63, Anti-CD81, Anti-CD9, Anti-Alix, Anti-Calnexin | Exosome identification and purity assessment | Confirmation of minimal cellular contaminants |

| Nanoparticle Tracking | ZetaView PMX 110, NanoSight NS300 | Size distribution and concentration analysis | Batch-to-batch consistency |

| Cytokine Arrays | Proteome Profiler Array, Luminex Assays | Inflammatory mediator profiling | Immunogenicity potential |

| Cell Fate Assays | Annexin V Apoptosis Kit, CellTiter-Glo Viability | Functional response assessment | Tumorigenicity screening |

MSC-derived exosomes represent a transformative approach in regenerative medicine, offering significant advantages in safety profiles and manufacturing control compared to traditional cell-based therapies. Their inherently low immunogenicity and tumorigenicity, combined with demonstrated efficacy in modulating key wound healing processes, position them as ideal candidates for next-generation wound therapeutics. The experimental frameworks and safety assessment protocols outlined in this document provide researchers with standardized methodologies for advancing exosome-based wound therapy development.

As the field progresses toward clinical translation, attention to standardized characterization, potency assays, and scalable manufacturing will be essential for realizing the full potential of these promising acellular therapeutics. Future research directions should focus on engineering approaches to enhance target specificity and therapeutic payload, further improving the already favorable benefit-risk profile of MSC-derived exosomes in wound healing applications.

Application Notes: Comparative Therapeutic Profiles

The therapeutic efficacy of mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes (MSC-Exos) in wound healing exhibits significant source-dependent variability, influencing their mechanistic actions and clinical applicability. The table below summarizes the comparative therapeutic profiles of exosomes derived from adipose tissue (ADSC-Exos), bone marrow (BMSC-Exos), and umbilical cord (UCMSC-Exos).

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of MSC-Exos from Different Sources

| Parameter | Adipose (ADSC-Exos) | Bone Marrow (BMSC-Exos) | Umbilical Cord (UCMSC-Exos) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Key Therapeutic Strengths | Potent immunomodulation; Enhanced angiogenesis; Superior collagen deposition [18] [19] [20]. | Effective neuroprotection; Cartilage/bone repair; Established research history [16]. | Superior proliferation & migration; High angiogenic capacity; Low immunogenicity [21] [14]. |

| Proposed Primary Mechanisms in Wound Healing | Deliver anti-inflammatory miRNAs (e.g., miR-126); Promote M2 macrophage polarization; Activate PI3K/Akt pathway [18] [19]. | Inhibit TGF-β/Smad pathway to reduce scarring; Modulate inflammatory response [21]. | Enrich specific miRNAs to inhibit TGF-β/Smad; Promote fibroblast functions & tube formation [21]. |

| Evidence Level (Wound Healing) | Extensive preclinical data; Prominent in meta-analyses [20]. | Strong preclinical evidence [20]. | Strong preclinical evidence; Promising clinical data [21]. |

| Considerations for Dosing & Administration | High yield facilitates frequent/repeated dosing [19]. | Well-established isolation protocols [16]. | High proliferative capacity ensures exosome supply; Often used allogeneically [21] [16]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Isolation and Characterization of MSC-Exos

This standard protocol for isolating exosomes from MSC culture supernatant via ultracentrifugation is adapted from multiple methodologies detailed in the search results [21] [14] [22].

Key Research Reagent Solutions:

- Mesenchymal Stem Cells: Source from adipose tissue, bone marrow, or umbilical cord, characterized per ISCT guidelines (plastic adherence, trilineage differentiation, surface marker expression) [16] [20].

- Culture Medium: Use MSC NutriStem XF Basal Medium supplemented with human platelet lysate or other serum-free, exosome-depleted media to avoid contaminating vesicles [21].

- Isolation Reagents: Phosphate-Buffered Saline (PBS), sterile and pre-cooled for dilution and resuspension steps.

- Characterization Reagents:

Procedure:

- Cell Culture and Supernatant Collection: Culture MSCs until 80% confluency. Replace with fresh culture medium. After 48-72 hours, collect the conditioned medium.

- Pre-Clearing Centrifugation:

- Centrifuge the medium at 2,000 × g for 30 minutes at 4°C to remove cells and large debris.

- Transfer the supernatant to a new tube and centrifuge at 10,000 × g for 45 minutes at 4°C to remove apoptotic bodies and larger vesicles.

- Carefully filter the supernatant through a 0.22 µm pore filter to sterilize and remove remaining particulates.

- Ultracentrifugation:

- Transfer the filtered supernatant to ultracentrifuge tubes. Balance tubes precisely.

- Perform ultracentrifugation at 110,000 × g to 120,000 × g for 70-90 minutes at 4°C.

- Discard the supernatant carefully. The exosome pellet may not always be visible.

- Resuspend the pellet in a large volume of PBS (e.g., 30-35 mL) and perform a second ultracentrifugation under the same conditions to wash the exosomes.

- Discard the supernatant and resuspend the final, purified exosome pellet in 100-500 µL of PBS.

- Characterization:

- Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis (NTA): Dilute the exosome suspension and inject it into the NTA system to determine particle size distribution (expected peak ~30-150 nm) and concentration [21] [14].

- Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM): Fix a small volume of exosomes on a grid, negative stain with uranyl acetate, and image to confirm a cup-shaped spherical morphology with a size of approximately 30-150 nm [21] [14].

- Western Blotting: Lyse exosomes and analyze proteins for the presence of positive markers (e.g., CD9, CD63, TSG101, Alix) and the absence of the negative endoplasmic reticulum marker Calnexin [14].

Protocol: In Vivo Assessment of MSC-Exos in a Murine Wound Healing Model

This protocol outlines the methodology for evaluating the efficacy of MSC-Exos using a full-thickness excisional wound model in mice, as commonly employed in the cited studies [14] [20] [22].

Procedure:

- Animal Model Preparation:

- Use 6-8 week-old male BALB/c mice. Anesthetize the animals according to approved institutional protocols.

- Create one or more full-thickness excisional wounds on the dorsum using a sterile biopsy punch. The wound area should be recorded (e.g., by photography) immediately post-creation (Day 0).

- Treatment Administration:

- Randomly assign mice to experimental groups: Vehicle Control (e.g., PBS), and treatment groups (e.g., ADSC-Exos, UCMSC-Exos).

- The primary and most effective route for wound healing is local subcutaneous injection around the wound periphery [20].

- A common effective dose, based on particle count, is 1 × 10^8 particles in a volume of 25-50 µL PBS per wound, administered daily or every other day [14] [22]. Dosing frequency and total number of administrations should be optimized based on the study design.

- Efficacy Monitoring:

- Wound Closure Rate: Monitor and photograph wounds daily. Use image analysis software (e.g., ImageJ) to calculate the percentage reduction in wound area over time.

- Histological Analysis: After euthanasia at a predetermined endpoint (e.g., Day 7-14), harvest wound tissue.

- Fix samples in formalin, embed in paraffin, and section.

- Perform Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) staining to evaluate tissue architecture, epidermal thickness, and re-epithelialization.

- Perform Masson's Trichrome staining to assess collagen deposition, organization, and scar width.

- Immunohistochemistry/Immunofluorescence: Stain tissue sections with antibodies against specific markers to evaluate key processes.

- CD31: To quantify blood vessel density and angiogenesis.

- α-Smooth Muscle Actin (α-SMA): To identify myofibroblasts and assess scar formation.

Signaling Pathways in MSC-Exos Mediated Wound Healing

MSC-Exos from different sources promote wound healing through complex, interconnected signaling pathways, primarily driven by their cargo of miRNAs, proteins, and cytokines.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Materials for MSC-Exos Wound Healing Research

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Equipment

| Item | Function/Application | Examples/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Ultracentrifuge | Isolation of exosomes from conditioned media or biofluids via high-speed centrifugation. | Beckman Coulter Optima series with fixed-angle rotors (e.g., Type 50.2 Ti) [14]. |

| Nanoparticle Tracking Analyzer (NTA) | Measures the size distribution and concentration of exosomes in suspension. | ZetaView PMX 110 system (Particle Metrix); Malvern Panalytical NanoSight [21] [14]. |

| Transmission Electron Microscope (TEM) | Visualizes the morphology and ultrastructure of isolated exosomes. | Hitachi HT-7700; samples are negative-stained with uranyl acetate [21] [14]. |

| Specific Antibodies | Characterizes exosomes and analyzes tissue response via Western Blot (WB) and Immunohistochemistry (IHC). | WB: Anti-CD9, CD63, TSG101, Alix, Calnexin (negative control) [14]. IHC/IF: Anti-CD31 (vessels), α-SMA (myofibroblasts) [22]. |

| PKH67 / PKH26 Fluorescent Dyes | Labels the lipid membrane of exosomes for in vitro and in vivo tracking and uptake studies. | Labeled exosomes can be visualized after co-culture with cells (e.g., fibroblasts) to confirm internalization [22]. |

| Animal Model | In vivo testing of exosome therapeutic efficacy. | BALB/c or C57BL/6 mice; full-thickness excisional wound model is standard [20] [22]. |

Application Notes: Core Biological Functions and Therapeutic Mechanisms

Mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes (MSC-Exos) are nanoscale extracellular vesicles (30-150 nm in diameter) that serve as primary mediators of the therapeutic effects of their parent cells [23]. They function as sophisticated natural delivery systems, transferring bioactive cargo—including proteins, lipids, mRNAs, and microRNAs (miRNAs)—to recipient cells, thereby orchestrating key processes in tissue repair [23] [24]. Their cell-free nature confers significant advantages, including lower immunogenicity, a high safety profile, and the ability to avoid entrapment in lung microvasculature, which poses a risk when administering whole cells [23] [25]. The following sections detail the mechanistic basis of their three core inherent biological functions.

Immunomodulation

MSC-Exos exert profound immunomodulatory effects by interacting with a wide array of immune cells, facilitating a shift from a pro-inflammatory to an anti-inflammatory and pro-healing state [24]. This immunomodulation is a cornerstone of their effectiveness in treating inflammatory conditions and creating a conducive environment for tissue regeneration.

Key Mechanisms:

- Macrophage Polarization: MSC-Exos promote the polarization of macrophages from the pro-inflammatory M1 phenotype to the anti-inflammatory M2 phenotype [24]. This shift is mediated through the delivery of specific miRNAs (e.g., let-7b, miR-146a, miR-181c) and bioactive proteins like Prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) and TNF-stimulated gene 6 (TSG-6) [24]. M2 macrophages subsequently secrete immunosuppressive factors such as IL-10 while reducing levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines like TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-12, IL-6, and IFN-γ [24].

- Lymphocyte Regulation: MSC-Exos modulate adaptive immune responses by suppressing the proliferation and activation of pro-inflammatory T cells (e.g., Th1 and Th17) and promoting the expansion and function of regulatory T cells (Tregs) [24]. This regulation helps restore immune homeostasis and dampens excessive immune reactions that can impede healing [26].

- Anti-inflammatory Signaling: The cargo within MSC-Exos, including miR-21, miR-146a, and miR-182, can inhibit key pro-inflammatory signaling pathways, such as the Toll-like Receptor (TLR) and NF-κB pathways, further contributing to inflammation resolution [24].

Angiogenesis

The promotion of new blood vessel formation is critical for supplying oxygen and nutrients to regenerating tissue. MSC-Exos robustly stimulate angiogenesis through the delivery of pro-angiogenic factors and genetic materials [27] [26].

Key Mechanisms:

- Growth Factor and miRNA Delivery: MSC-Exos are enriched with pro-angiogenic factors such as Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF), Hepatocyte Growth Factor (HGF), and Insulin-like Growth Factor-1 (IGF-1) [26]. They also carry specific miRNAs (e.g., miR-126, miR-130a, miR-132) that are known to enhance angiogenic signaling [26].

- Activation of Signaling Pathways: A principal mechanism involves the transfer of Wnt4 to endothelial cells, which stimulates the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway [26]. This, in turn, activates the AKT pathway, promoting endothelial cell proliferation, migration, and survival, and ultimately leading to the formation of new vascular structures [26].

- Direct Pro-angiogenic Effect: The exosomal cargo directly targets endothelial cells, encouraging tube formation and enhancing cell-to-cell communication, which is vital for establishing a functional vascular network in the wound bed [27].

Fibroblast Activation

Fibroblasts are the primary cells responsible for depositing the extracellular matrix (ECM) that forms the structural basis of new tissue. MSC-Exos directly activate fibroblasts, driving the proliferative phase of wound healing [26].

Key Mechanisms:

- Proliferation and Migration Stimulation: MSC-Exos enhance fibroblast proliferation and migration by upregulating the expression of genes and proteins critical for cell division and motility, including N-cadherin, cyclin-1, and Proliferating Cell Nuclear Antigen (PCNA) [26].

- Collagen Synthesis: Treatment with MSC-Exos leads to a significant increase in the production of Collagen I and Collagen III, the main structural components of the ECM, thereby improving the tensile strength of the healing wound [26].

- Pathway Activation: The therapeutic effects on fibroblasts are mediated through the activation of key signaling pathways, including ERK and AKT, which are stimulated by exosomal components [26].

Table 1: Summary of Key Molecular Mediators in MSC-Exos Functions

| Biological Function | Key Molecular Mediators | Primary Effects |

|---|---|---|

| Immunomodulation | let-7b, miR-146a, PGE2, TSG-6, IL-10 | Macrophage polarization to M2; Treg induction; Suppression of TNF-α & IL-1β [24] |

| Angiogenesis | Wnt4, miR-126, miR-130a, VEGF, HGF | Activation of Wnt/β-catenin & AKT pathways; Endothelial cell proliferation [27] [26] |

| Fibroblast Activation | PCNA, N-cadherin, Collagen I, Collagen III | Enhanced fibroblast proliferation, migration, and ECM synthesis [26] |

Experimental Protocols for Validating Biological Functions

To empirically validate the inherent functions of MSC-Exos, standardized in vitro and in vivo protocols are essential. The following sections provide detailed methodologies for assessing immunomodulation, angiogenesis, and fibroblast activation.

Protocol: In Vitro Assessment of Macrophage Polarization

This protocol evaluates the immunomodulatory capacity of MSC-Exos by measuring their ability to induce a shift from M1 to M2 macrophages [24].

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Primary Human Monocytes: Source cells for deriving macrophages.

- MSC-Exos Preparation: Isolated from human bone marrow or adipose tissue-derived MSCs (100 µg/mL stock concentration).

- LPS & IFN-γ: For M1 macrophage polarization (e.g., 100 ng/mL LPS + 20 ng/mL IFN-γ).

- IL-4 & IL-13: For classical M2 macrophage polarization (positive control).

- Flow Cytometry Antibodies: Anti-CD86 (M1 marker) and Anti-CD206 (M2 marker).

- ELISA Kits: For quantifying TNF-α (pro-inflammatory) and IL-10 (anti-inflammatory) cytokines.

Procedure:

- Macrophage Differentiation: Isolate peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from human blood. Differentiate monocytes into naïve macrophages (M0) by culturing in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 50 ng/mL Macrophage Colony-Stimulating Factor (M-CSF) for 6 days.

- M1 Polarization: Polarize the M0 macrophages towards an M1 phenotype by treating with 100 ng/mL LPS and 20 ng/mL IFN-γ for 48 hours.

- Exosome Treatment: Divide the M1-polarized macrophages into three groups:

- Test Group: Treat with MSC-Exos (50 µg/mL).

- Positive Control: Treat with 20 ng/mL IL-4 and IL-13.

- Negative Control: Treat with PBS. Incubate for 48 hours.

- Flow Cytometry Analysis: Harvest the macrophages. Stain cells with fluorescently labeled anti-CD86 and anti-CD206 antibodies. Analyze using flow cytometry to determine the percentage of CD86+ (M1) and CD206+ (M2) populations.

- Cytokine Secretion Profiling: Collect cell culture supernatants. Use ELISA kits to quantify the secretion levels of TNF-α and IL-10, following the manufacturer's instructions.

- Data Interpretation: Successful immunomodulation is indicated by a statistically significant decrease in CD86+ cells and TNF-α secretion, coupled with an increase in CD206+ cells and IL-10 secretion in the test group compared to the negative control.

Protocol: In Vitro Tubule Formation Assay (Angiogenesis)

This protocol assesses the pro-angiogenic potential of MSC-Exos by measuring their ability to stimulate human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) to form capillary-like tubule structures in vitro [27].

Research Reagent Solutions:

- HUVECs: Primary human umbilical vein endothelial cells (passage 3-5).

- Growth Factor-Reduced Matrigel: Extracellular matrix substitute for tubule formation.

- MSC-Exos Preparation: As per Protocol 2.1.

- VEGF: Positive control (e.g., 50 ng/mL).

- Microscope with Image Analysis Software: For quantifying tubule formation.

Procedure:

- Matrigel Coating: Thaw Growth Factor-Reduced Matrigel on ice. Coat each well of a pre-chilled 96-well plate with 50 µL of Matrigel. Incubate the plate at 37°C for 30-60 minutes to allow polymerization.

- Cell Seeding and Treatment: Trypsinize and harvest HUVECs. Resuspend cells in serum-free medium and seed onto the polymerized Matrigel at a density of 1.5 x 10^4 cells per well.

Immediately add treatments to the wells:

- Test Group: Serum-free medium containing MSC-Exos (50 µg/mL).

- Positive Control: Serum-free medium containing 50 ng/mL VEGF.

- Negative Control: Serum-free medium only.

- Incubation: Incubate the plate at 37°C with 5% CO2 for 6-8 hours to allow tubule networks to form.

- Image Acquisition and Analysis: After incubation, capture images of the tubule networks using an inverted microscope (4x or 10x objective) in at least three random fields per well.

Use image analysis software (e.g., ImageJ with the Angiogenesis Analyzer plugin) to quantify the following parameters:

- Total Tubule Length: The combined length of all formed tubules.

- Number of Junctions: The number of branch points in the network.

- Number of Meshes: The number of enclosed areas within the network.

- Data Interpretation: A significant increase in total tubule length, number of junctions, and number of meshes in the MSC-Exos-treated group compared to the negative control indicates potent pro-angiogenic activity.

Protocol: In Vitro Fibroblast Proliferation and Migration (Scratch Assay)

This protocol evaluates the effect of MSC-Exos on the proliferative and migratory capacity of human dermal fibroblasts, which are critical for wound closure and ECM deposition [26].

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Human Dermal Fibroblasts (HDFs): Primary cells (passage 3-7).

- MSC-Exos Preparation: As per Protocol 2.1.

- Mitomycin C: (e.g., 10 µg/mL) to inhibit cell proliferation for migration-specific assays (optional).

- Cell Culture Inserts: For a standardized scratch (optional).

- Image Analysis Software.

Procedure:

- Cell Seeding: Seed HDFs in a 12-well plate at a high density (e.g., 2.5 x 10^5 cells/well) and culture until they form a 100% confluent monolayer.

- Creating a "Scratch": Use a sterile 200 µL pipette tip to create a straight, vertical scratch ("wound") through the cell monolayer. Gently wash the wells with PBS to remove detached cells. Alternatively, use a culture-insert to create a uniform gap.

- Exosome Treatment: Add serum-free medium containing MSC-Exos (50 µg/mL) to the test group. The control group receives serum-free medium only. To isolate the effect on migration from proliferation, pre-treat cells with 10 µg/mL Mitomycin C for 2 hours before creating the scratch.

- Image Acquisition: Immediately after creating the scratch (T=0h), capture images of the wound area using an inverted microscope (4x objective). Mark the plate to ensure imaging of the same locations at later time points.

- Incubation and Final Imaging: Incubate the plate for 24-48 hours. Capture images of the same locations at the end of the incubation period (T=24h or 48h).

- Wound Closure Analysis: Measure the width of the scratch at T=0h and T=24/48h using image analysis software. Calculate the percentage of wound closure using the formula:

% Wound Closure = [(Area T=0 - Area T=24) / Area T=0] x 100 - Data Interpretation: A significantly higher percentage of wound closure in the MSC-Exos-treated group compared to the control group indicates enhanced fibroblast migration and/or proliferation.

Table 2: Summary of Key Experimental Parameters for Functional Assays

| Assay | Cell Type | MSC-Exos Dose | Key Readouts | Critical Reagents |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Macrophage Polarization | Human monocyte-derived macrophages | 50 µg/mL | CD86+/CD206+ ratio; TNF-α/IL-10 secretion [24] | M-CSF, LPS, IFN-γ, IL-4/IL-13 |

| Tubule Formation | HUVECs (Passage 3-5) | 50 µg/mL | Total tubule length; Number of junctions [27] | Growth Factor-Reduced Matrigel, VEGF |

| Scratch Assay | Human Dermal Fibroblasts | 50 µg/mL | Percentage of wound closure at 24h [26] | Mitomycin C (optional) |

Visualization of Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

MSC Exosome Mediated Immunomodulation Pathway

MSC Exosome Mediated Angiogenesis Pathway

Experimental Workflow for Functional Validation

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for MSC-Exos Functional Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example Usage in Protocols |

|---|---|---|

| Bone Marrow or Adipose-derived MSCs | Cellular source for exosome production and isolation [16] [20]. | Culture and expand MSCs to ~80% confluency for exosome collection. |

| Ultracentrifugation System | Gold-standard method for isolating and purifying exosomes from conditioned medium [23]. | Pellet exosomes at 100,000-120,000 x g for 70-120 minutes. |

| Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis (NTA) | Characterizes exosome size distribution and concentration [23] [24]. | Dilute exosome sample in PBS and analyze to confirm a size peak of 30-150 nm. |

| CD63, CD81, TSG101 Antibodies | Western Blot detection of positive exosomal protein markers for validation [25] [24]. | Confirm exosome identity post-isolation via immunoblotting. |

| Human Umbilical Vein Endothelial Cells (HUVECs) | In vitro model for studying exosome-induced angiogenesis [27]. | Seed on Matrigel for tubule formation assay (Protocol 2.2). |

| Growth Factor-Reduced Matrigel | Synthetic basement membrane matrix for 3D tubule formation assays [27]. | Coat wells and allow to polymerize for HUVEC seeding. |

| Human Dermal Fibroblasts (HDFs) | In vitro model for studying exosome effects on proliferation, migration, and ECM production [26]. | Create a confluent monolayer for the scratch/wound healing assay. |

| Flow Cytometry Antibodies (CD86, CD206) | Quantification of macrophage surface markers to determine M1/M2 polarization status [24]. | Stain and analyze macrophages after exosome treatment (Protocol 2.1). |

| ELISA Kits (TNF-α, IL-10, etc.) | Quantification of secreted pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines in cell culture supernatants [25] [24]. | Measure cytokine levels from macrophage culture media. |

From Production to Patient: MSC Exosome Isolation, Characterization, and Delivery Methods

Within advanced therapeutic medicinal products, mesenchymal stem cell (MSC)-derived exosomes represent a promising cell-free therapeutic paradigm, particularly for wound therapy. A pivotal challenge in translating this promise into clinical reality is the establishment of robust, reproducible, and scalable Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP)-grade production processes. The quality, safety, and efficacy of the final exosome product are profoundly influenced by the upstream isolation and downstream purification strategies employed. This application note details standardized protocols for three cornerstone technologies—Ultracentrifugation, Tangential Flow Filtration (TFF), and Chromatography—framed within the specific context of producing MSC exosomes for wound healing research and development. Adherence to these GMP-compliant methodologies ensures the consistent production of exosomes with defined characteristics, which is a critical prerequisite for meaningful investigation into optimal dosing and administration routes.

Ultracentrifugation for Exosome Isolation

Ultracentrifugation remains a widely used benchmark technique for the isolation of exosomes from conditioned cell culture media. Its principle relies on the sequential application of centrifugal forces to separate particles based on their size, density, and shape.

Application Notes and Protocol

Differential ultracentrifugation is the most common approach, though it requires specialized equipment and can subject exosomes to high shear forces [28]. The following protocol is adapted for GMP-compliant production of MSC exosomes.

Detailed Experimental Protocol:

- Conditioned Media Harvesting: Collect conditioned media from serum-free cultures of MSCs (e.g., bone marrow, adipose, or umbilical cord-derived). Centrifuge at 300 × g for 10 minutes to remove live cells.

- Cellular Debris Removal: Transfer the supernatant to new tubes and centrifuge at 2,000 × g for 20 minutes to eliminate dead cells.

- Large Particle Clearance: Further clarify the supernatant by centrifugation at 10,000 × * g for 30 minutes to remove large vesicles and apoptotic bodies.

- Exosome Pelletion: Transfer the resulting supernatant to ultracentrifuge tubes. Pellet the exosomes via ultracentrifugation at ≥100,000 × g for 70 minutes at 4°C.

- Washing (Optional): Resuspend the pellet in a large volume of sterile, cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and repeat the ultracentrifugation step (100,000 × g, 70 minutes) to enhance purity.

- Final Resuspension: Gently resuspend the final exosome pellet in a small volume of PBS or a formulation buffer suitable for wound therapy applications (e.g., containing cryoprotectants). Aliquot and store at –65°C to –85°C [29].

Table 1: Quantitative Parameters for Ultracentrifugation-Based Exosome Isolation

| Parameter | Typical Value/Description | GMP Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Starting Material | Serum-free MSC conditioned media | Use of GMP-grade cell lines and media components is mandatory [29]. |

| G-Force for Exosome Pellet | ≥100,000 × g | Equipment must be validated and undergo regular calibration [30]. |

| Duration | 70-120 minutes | Process parameters must be fixed and documented in batch records. |

| Yield | Variable; highly dependent on MSC source and culture | In-process controls to monitor consistency between batches. |

| Purity | Moderate to high; potential for co-precipitation of proteins | Orthogonal characterization (e.g., NTA, CD63/81 detection) required for release [29]. |

GMP Data Integrity and Software

For AUC, which is used for the biophysical characterization of isolated exosomes, GMP compliance requires specialized software to address data integrity. Modern solutions like UltraScan GMP software provide automated workflows, role-based user management, electronic signatures, and comprehensive audit trails, which are essential for regulatory compliance and moving AUC towards full GMP validation [31] [32].

Tangential Flow Filtration for Scalable Purification

Tangential Flow Filtration (TFF) is a scalable and gentle separation technique ideal for processing large volumes of conditioned media. In TFF, the feed flow moves parallel to the filter membrane, continuously sweeping away retained particles and minimizing membrane fouling, making it suitable for concentrating and purifying exosomes.

Application Notes and Protocol

TFF is highly advantageous for GMP manufacturing as it can be integrated into a fully closed system, reducing contamination risk and facilitating scale-up for clinical trial material production [29]. Its market growth, with a projected CAGR of 12.13%-12.44%, underscores its adoption in bioprocessing [33] [34].

Detailed Experimental Protocol:

- System Setup and Equilibration: Assemble a single-use TFF system with a membrane pore size of 300-500 kDa or 0.1 µm. Flush and equilibrate the system with PBS or a suitable buffer.

- Clarified Media Processing: Pump the clarified conditioned media (pre-cleared by steps 1-3 in 1.1) through the TFF system. The exosomes are retained (retentate) while small molecules and contaminants pass through the membrane (permeate).

- Diafiltration: Continuously add diafiltration buffer (e.g., PBS) to the retentate at the same rate as the permeate flow. This step exchanges the solution and removes soluble impurities. Typically, 5-10 volume exchanges are performed.

- Concentration: Once diafiltration is complete, stop the buffer input and continue circulating the retentate until the desired exosome concentration is achieved.

- Product Recovery: Recirculate the retentate briefly in the reverse direction or use a flush to recover the concentrated exosome product from the system.

- Sterile Filtration: The final concentrate is passed through a 0.22 µm sterile filter into a sterile bag. The product is aliquoted and stored at –65°C to –85°C [29].

Table 2: Quantitative Parameters for TFF-Based Exosome Purification

| Parameter | Typical Value/Description | GMP Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Membrane Material | Polyethersulfone (PES), Regenerated Cellulose | Use of GMP-grade, single-use membranes to prevent cross-contamination [33] [29]. |

| Pore Size / MWCO | 300-500 kDa or 0.1 µm | Membrane selection validation is critical for yield and purity. |

| Volume Reduction | 10- to 50-fold concentration | Process consistency must be demonstrated across batches. |

| Diafiltration Volumes | 5-10 volumes | Ensures effective removal of process-related impurities. |

| Scale | From 100 mL to >100 L | A closed-system design supports scalable, aseptic processing [29]. |

Chromatography for High-Purity Exosome Preparation

Chromatography offers high-resolution purification of exosomes based on intrinsic properties such as size, charge, or affinity, and is invaluable for obtaining a highly pure product for therapeutic use.

Application Notes and Protocol

Among various modes, Anion Exchange Chromatography (AEC) is particularly effective, exploiting the inherent negative surface charge of exosomes. This method can be combined with TFF or ultrafiltration to create a powerful two-dimensional purification strategy [28].

Detailed Experimental Protocol:

- Sample Preparation: The exosome sample, preferably pre-concentrated using TFF or ultrafiltration, is diluted with a binding buffer (e.g., 20-50 mM Tris-HCl, pH ~8.0) to ensure a low ionic strength.

- Column Equilibration: Equilibrate an AEC column (e.g., quaternary amine resin) with 5-10 column volumes (CV) of binding buffer.

- Sample Loading: Load the prepared exosome sample onto the column at a controlled flow rate. Exosomes bind to the positively charged resin.

- Washing: Wash the column with 5-10 CV of binding buffer to remove unbound or weakly bound contaminants.

- Elution: Elute the purified exosomes using a linear or step-wise gradient of elution buffer (binding buffer with increasing NaCl concentration, typically up to 1-2 M). Exosomes typically elute at specific salt concentrations.

- Fraction Collection & Buffer Exchange: Collect the eluate in fractions. Pool the fractions containing exosomes and perform a buffer exchange into a storage buffer like PBS using TFF or size-exclusion chromatography.

Table 3: Quantitative Parameters for AEC-Based Exosome Purification

| Parameter | Typical Value/Description | GMP Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Chromatography Type | Anion Exchange (AEC) | Columns and resins must be GMP-grade. Lifecycle and cleaning validation are required [30]. |

| Binding Buffer | Low salt buffer (e.g., 20 mM Tris, pH 8.0) | All reagents require certificates of analysis (CoA) [29]. |

| Elution Method | Linear NaCl gradient (e.g., 0 to 2 M) | Method robustness and reproducibility must be established. |

| Yield | Can be lower than TFF but offers higher purity | Balance between yield and purity is a key process decision. |

| Purity | Very high, separation from protein aggregates | Excellent for removing co-isolated impurities from other methods. |

Integrated Workflow and Dosing Considerations for Wound Therapy

For clinical translation, these techniques are often combined into an integrated, closed-system workflow to maximize product yield, purity, and safety.

Workflow Diagram

This integrated process ensures a consistent and well-characterized exosome product, which is the foundation for reliable dosing studies.

Dosing and Administration in Wound Therapy

The production process directly influences the critical quality attributes (CQAs) of the exosome product, which in turn impacts therapeutic dosing. Research indicates that administration route is a key determinant of the effective dose. For instance, topical application for wound healing may require different dosing compared to intravenous routes. Clinical trials for MSC-EVs have shown that aerosolized inhalation can achieve therapeutic effects at doses around 10⁸ particles, which is significantly lower than doses required for intravenous infusion [9]. This highlights the importance of standardizing dose units (e.g., particle number, protein content) and developing potency assays linked to the wound healing mechanism (e.g., angiogenesis, fibroblast proliferation) [9] [29].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key materials and reagents essential for implementing the GMP-grade protocols described above.

Table 4: Essential Materials for GMP-Grade MSC Exosome Production

| Item | Function / Role | GMP-Grade Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| GMP-Grade MSC Cell Bank | Source and starting material for exosome production. | Well-defined, characterized, and tested for adventitious agents to ensure batch-to-b consistency [29]. |

| Chemically Defined, Serum-Free Media | Supports MSC expansion and vesiculation without introducing foreign contaminants. | Eliminates variability and safety risks associated with animal sera; requires CoA [29]. |

| Single-Use TFF Cassettes | For concentration and purification of exosomes from large volumes of media. | Prevents cross-contamination, reduces cleaning validation, and supports a closed system [33] [29]. |

| Chromatography Resins & Columns | High-resolution purification based on charge (AEC) or other properties. | Must be qualified for intended use. Documentation for traceability and leachables testing is critical [30]. |

| Reference Standards & Buffers | Used in system suitability testing, calibration, and as process buffers. | All reagents must have Certificates of Analysis (CoA) confirming identity, purity, and strength [29] [30]. |

| Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis (NTA) | Instrument for characterizing particle size and concentration. | Part of quality control for identity and quantity; requires regular calibration and method validation [9] [29]. |

| ELISA/Ligand Blinding Assays | Detection of specific surface markers (e.g., CD9, CD63, CD81). | Used as a purity and identity test; assays must be validated for accuracy, precision, and specificity [29]. |

For researchers and drug development professionals advancing mesenchymal stem cell exosome (MSC-exosome) wound therapies, standardized characterization is not merely a preliminary step but the fundamental basis for generating reproducible, reliable, and clinically translatable data. The inherent heterogeneity of extracellular vesicle (EV) preparations, including exosomes, presents a significant challenge in correlating therapeutic efficacy with specific biological entities [9] [28]. The Minimal Information for Studies of Extracellular Vesicles (MISEV) guidelines, established by the International Society for Extracellular Vesicles (ISEV), provide a critical framework to overcome this challenge by defining the minimal biochemical, biophysical, and functional criteria required to robustly claim the presence of EVs in isolates [35] [36]. Adherence to these guidelines is particularly crucial in the context of wound therapy research, where understanding the relationship between exosome characteristics, dosing parameters, and mechanisms of action—such as promoting angiogenesis, modulating inflammation, and enhancing fibroblast proliferation—is essential for developing effective treatments [37] [13].

This application note details practical protocols for characterizing MSC-exosomes according to MISEV principles, with a specific focus on nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA) and surface marker characterization—two core techniques mandated for establishing vesicle identity, quantity, and purity. Furthermore, it contextualizes these characterization data within the broader scope of optimizing dosing and administration routes for cutaneous wound healing applications.

Core Principles of the MISEV Guidelines

The MISEV guidelines have evolved through several iterations (MISEV2014, MISEV2018, and the latest MISEV2023) to address the growing complexity and methodological diversity in EV research [36]. The fundamental principle underpinning these guidelines is the need for comprehensive reporting of experimental conditions, from sample collection and pre-processing through to separation, concentration, and characterization [36]. For MSC-exosomes intended for wound healing, this begins with detailed documentation of the parental cell source (e.g., bone marrow, adipose tissue, umbilical cord), culture conditions, and the methods used to harvest the cell culture medium [9] [16].

MISEV2023 recommends a multifaceted approach to characterization, requiring researchers to:

- Define the presence of EVs by quantifying transmembrane or GPI-anchored proteins (Category 1, e.g., tetraspanins CD63, CD81, CD9) and cytosolic proteins (Category 2, e.g., TSG101, flotillins) [35] [36].

- Assess sample purity by testing for common co-isolated contaminants (Category 3), such as apolipoproteins in blood-derived EVs or albumin from culture medium supplements [35].

- Report quantitative metrics using at least two different, complementary techniques, such as NTA for particle concentration and size, and a protein assay for total mass [8].

The MISEV guidelines emphasize that no single isolation method is perfect, and the choice of technique—whether differential ultracentrifugation, size-exclusion chromatography (SEC), or others—must be reported along with its specific performance metrics for the given sample type [28] [36]. This rigorous reporting, potentially facilitated by the EV-TRACK knowledgebase, ensures that experimental outcomes in wound healing models can be properly interpreted and reproduced across different laboratories [36].

Experimental Protocols for MISEV-Compliant Characterization

Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis (NTA) for Concentration and Size

Principle: NTA utilizes light scattering and Brownian motion to determine the hydrodynamic diameter and particle concentration of a vesicle preparation in liquid suspension [8]. This provides a critical quantitative parameter for dosing in therapeutic applications.

Sample Preparation:

- Isolate MSC-exosomes from conditioned culture medium using a standardized method (e.g., SEC or ultracentrifugation). The culture medium should be devoid of serum-derived EVs or supplemented with EV-depleted serum [28].

- Resuspend the final exosome pellet in a filtered (0.1 µm), particle-free phosphate-buffered saline (PBS).

- For wound healing studies, note that the biological source of MSCs (e.g., adipose tissue vs. bone marrow) can influence the resulting exosome size distribution [9].

Instrument Calibration and Measurement:

- Calibrate the NTA instrument (e.g., Malvern Nanosight NS300) using latex beads of a known size (e.g., 100 nm) according to the manufacturer's protocol.

- Dilute the exosome sample to achieve an optimal concentration of 20-100 particles per frame, ensuring accurate tracking while minimizing coincidence errors. The required dilution factor (often between 1:100 and 1:10,000) must be empirically determined and recorded.

- Perform five recordings of 60 seconds each per sample, ensuring the camera level and detection threshold are kept consistent across all samples within an experiment.

Data Analysis and Reporting (MISEV Compliance):

- Report the mode, mean, and D10/D90 diameters to describe the particle size distribution.

- Report the final particle concentration in particles per milliliter (particles/mL), applying the appropriate dilution factor.

- A representative screenshot of the particle movement video and the size distribution graph should be retained for publication.

- MISEV requires reporting the yield of particles (e.g., particles per cell, or per mL of culture medium) [8] [36].

Surface Marker Analysis by Liquid Chromatography Tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS)

Principle: While Western blotting is conventionally used, targeted LC-MS/MS offers a high-throughput, multiplexed, and quantitative approach to confirm the presence of EV-associated proteins and absence of contaminants, as recommended by MISEV to enhance rigor [35]. This is especially valuable for characterizing clinical-grade MSC-exosome batches for wound therapy.

Sample Preparation:

- Lyse a volume of MSC-exosome preparation containing 5-20 µg of total protein (quantified by a compatible assay like BCA).

- Reduce, alkylate, and digest the proteins into peptides using a protease (typically trypsin).

- Desalt the resulting peptides using C18 solid-phase extraction tips.

Targeted LC-MS/MS Analysis (Multiple Reaction Monitoring - MRM):

- Separate the peptides using reverse-phase liquid chromatography.

- On a triple quadrupole mass spectrometer, program MRM transitions to detect and quantify specific peptides representing:

- Category 1 (Transmembrane) Proteins: CD9, CD63, CD81.

- Category 2 (Cytosolic) Proteins: TSG101, Flotillin-1, Flotillin-2.

- Category 3 (Contaminants): Apolipoproteins (APOA1, APOB), Albumin (ALB).

- Use stable isotope-labeled (SIL) versions of the target peptides as internal standards for precise quantification [35].

Data Analysis and Reporting (MISEV Compliance):

- Quantify the abundance of each target protein in the sample.

- Calculate the ratio of EV-positive markers (e.g., CD81) to contaminant proteins (e.g., APOA1) to establish a purity index for the preparation.

- Report the presence of at least three EV-positive protein markers (preferably two transmembrane and one cytosolic) and the absence or low abundance of contaminants relevant to the sample source (e.g., culture medium supplements) [35] [36].

The workflow below illustrates the integrated process of sample preparation, characterization, and data analysis for MSC-exosomes, culminating in the critical link to functional wound healing studies.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table details key reagents and instruments required for the standardized characterization of MSC-exosomes for wound therapy research.

Table 1: Key Research Reagents and Solutions for MSC-Exosome Characterization

| Item | Function/Application | Specific Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Particle-Free PBS | Diluent and suspension buffer for exosomes prior to NTA. | Must be filtered through a 0.1 µm filter to eliminate background particulate interference. |

| Size Standard Beads | Calibration of NTA instrument for accurate size measurement. | 100 nm polystyrene latex beads; essential for protocol standardization. |

| Trypsin, Sequencing Grade | Proteolytic enzyme for digesting exosome proteins into peptides for LC-MS/MS. | High-purity grade ensures reproducible and efficient digestion. |

| Stable Isotope-Labeled (SIL) Peptides | Internal standards for absolute quantification of proteins in targeted LC-MS/MS. | Allows precise measurement of EV markers (e.g., CD9, CD81) and contaminants [35]. |

| C18 Desalting Tips | Desalting and cleaning of peptide mixtures prior to LC-MS/MS analysis. | Improves sample quality and instrument performance. |

| NTA Instrument | Measurement of particle size distribution and concentration. | Instruments such as the Malvern Panalytical Nanosight NS300. |

| Triple Quadrupole Mass Spectrometer | Targeted, quantitative analysis of specific protein markers via MRM. | Enables multiplexed, high-sensitivity quantification of the EV proteome [35]. |

Integrating Characterization Data with Dosing and Administration in Wound Healing

Robust characterization directly informs the optimization of dosing and administration routes for MSC-exosome therapies. Clinical data reveal that the effective dose is highly dependent on the administration route. For instance, aerosolized inhalation for respiratory diseases can achieve therapeutic effects at doses around 10^8 particles, which is significantly lower than the doses typically required for intravenous routes [9]. This underscores the existence of a narrow, route-dependent effective dose window.

For topical application to wounds, characterizing the particle number and protein content becomes paramount for establishing a dose-response relationship. A working range for total MSC-EV dose in humans has been proposed, spanning from ~1 × 10^10 particles (an absolute minimum based on rodent studies) to an upper limit of ~6 × 10^12 particles (based on endogenous EV levels in human blood) [8]. The table below summarizes how characterization parameters feed into dosing considerations for wound therapy.

Table 2: Linking Characterization Data to Dosing Parameters in Wound Therapy

| Characterization Parameter | Influence on Dosing Strategy | Considerations for Wound Therapy |

|---|---|---|

| Particle Concentration (NTA) | Enables dosing based on absolute particle number. | Facilitates precise and reproducible dosing in animal models and clinical trials (e.g., particles/cm² of wound area) [8]. |

| Protein Content (e.g., BCA Assay) | Allows alternative dosing based on total protein mass. | Common but can be confounded by co-isolated protein contaminants; must be interpreted alongside purity metrics [8]. |

| Size Distribution (NTA) | May influence tissue penetration and retention within the wound bed. | Smaller vesicles (30-150 nm) may diffuse more readily through the wound extracellular matrix [28]. |

| Purity Ratio (e.g., CD81/APOA1 from LC-MS/MS) | Ensures that the therapeutic effect is attributed to exosomes and not contaminants. | High-purity preparations reduce the risk of unintended side effects and improve batch-to-batch consistency [35] [13]. |

| Surface Marker Profile | Correlates specific molecular signatures with therapeutic potency. | Certain marker combinations may be linked to enhanced pro-angiogenic or anti-inflammatory activity, guiding potency assay development [37] [13]. |

Adherence to MISEV guidelines through standardized application of NTA and surface marker analysis is not an end in itself, but a prerequisite for generating meaningful data that can accelerate the clinical translation of MSC-exosome wound therapies. By providing a robust and reproducible framework for defining the identity, quantity, and purity of exosome preparations, researchers can confidently correlate these critical quality attributes (CQAs) with biological activity in wound healing models. This disciplined approach is the cornerstone for establishing reliable potency assays, optimizing dosing regimens based on particle number and route of administration, and ultimately developing effective, off-the-shelf regenerative therapies for patients suffering from chronic wounds [9] [13].

The therapeutic application of mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes (MSC-Exos) represents a paradigm shift in regenerative medicine, particularly for challenging wound healing scenarios such as diabetic foot ulcers and other chronic wounds [38] [39]. While the therapeutic potential of these nanovesicles is well-established, the optimal delivery strategy remains a critical translational challenge. The selection between subcutaneous injection and topical dressing/covering transcends mere application methodology; it directly influences the bioavailability, biodistribution, and ultimate therapeutic efficacy of MSC-Exos at the wound site [20]. Route selection impacts key pharmacokinetic parameters, including retention time, penetration depth into wound tissue, and the ability to sustain a therapeutic microenvironment conducive to the complex processes of regeneration [40]. This document provides a structured comparison of these two primary administration routes, synthesizing current preclinical and clinical evidence to guide researchers in aligning delivery strategies with specific wound healing objectives and experimental models.

Quantitative Efficacy Comparison of Administration Routes

A comprehensive meta-analysis of preclinical studies provides direct comparative data on the efficacy of subcutaneous injection versus topical dressing/covering for MSC-EVs in wound healing. The table below summarizes the key outcome measures, demonstrating route-dependent therapeutic profiles [20].

Table 1: Efficacy Comparison of Subcutaneous Injection vs. Topical Dressing/Covering from Preclinical Meta-Analysis

| Administration Route | Wound Closure Rate | Revascularization (Blood Vessel Density) | Collagen Deposition | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subcutaneous Injection | Superior Improvement | Greater Improvement | Greater Improvement | Enhanced deep tissue delivery; superior stromal remodeling. |

| Topical Dressing/Covering | Effective | Effective | Effective | Simpler application; less invasive; suitable for large surface areas. |

The underlying mechanism for the enhanced performance of subcutaneous injection appears to be its ability to deliver exosomes deeper into the wound bed, facilitating more robust interactions with dermal and stromal components critical for regeneration [20]. Topical application, while effective, may be more susceptible to clearance and may not achieve the same penetration depth, potentially limiting its access to key cellular targets in the deeper dermal layers.

Experimental Protocols for Route-Specific Administration

Protocol for Subcutaneous Injection

The subcutaneous route delivers exosomes directly into the tissue surrounding the wound, promoting diffusion throughout the wound bed from the inside out [20].

Materials:

- Purified MSC-Exos suspension in PBS

- Insulin syringe (e.g., 0.3-0.5 mL, 29-31 gauge)

- Animal restraint device (if applicable)

- Sterile swabs and disinfectant

Procedure:

- Exosome Preparation: Thaw the purified MSC-Exos suspension on ice and dilute to the desired working concentration in sterile, endotoxin-free PBS. Gently mix by pipetting; avoid vortexing to preserve vesicle integrity [39].

- Site Preparation: Identify multiple injection sites around the perimeter of the wound, approximately 3-5 mm from the wound edge. Cleanse the area with a disinfectant according to standard aseptic techniques.

- Administration: Using an insulin syringe, slowly administer a volume of 20-50 µL per injection site. The number of sites should be adjusted based on wound size to ensure even distribution (e.g., 4-8 sites for a standard murine dorsal wound) [20].

- Post-Procedure: Apply gentle pressure if needed. The treatment frequency can vary from a single injection to multiple injections spaced days apart, depending on the experimental design.

Protocol for Topical Application with Hydrogel

Topical application often utilizes a hydrogel vehicle to retain exosomes at the wound site, protect them from the environment, and provide a moist healing environment [40] [39].

Materials:

- Purified MSC-Exos

- Biocompatible hydrogel (e.g., Hyaluronic Acid-based, Carboxymethyl Cellulose (CMC) gel)

- Sterile PBS

- Wound dressing (e.g., Tegaderm, non-adhesive gauze)

Procedure:

- Exosome-Hydrogel Formulation: Mix the purified MSC-Exos pellet thoroughly with the hydrogel matrix. A typical ratio for a hyaluronic acid hydrogel is 100-500 µg of exosome protein per mL of hydrogel precursor solution [40]. Ensure homogenous distribution by gentle stirring.