Optimizing Reprogramming: A Comprehensive Comparison of Yamanaka Factor Combinations for iPSC Generation

This article provides a systematic analysis of the efficiency, safety, and application-specific suitability of various Yamanaka factor combinations for induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) reprogramming.

Optimizing Reprogramming: A Comprehensive Comparison of Yamanaka Factor Combinations for iPSC Generation

Abstract

This article provides a systematic analysis of the efficiency, safety, and application-specific suitability of various Yamanaka factor combinations for induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) reprogramming. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it covers foundational mechanisms, methodological delivery systems, strategies for troubleshooting and optimizing reprogramming protocols, and comparative validation of established and emerging factor cocktails. The review synthesizes current evidence to guide the selection of optimal reprogramming strategies for disease modeling, drug screening, and clinical applications, addressing key challenges such as tumorigenicity and low efficiency.

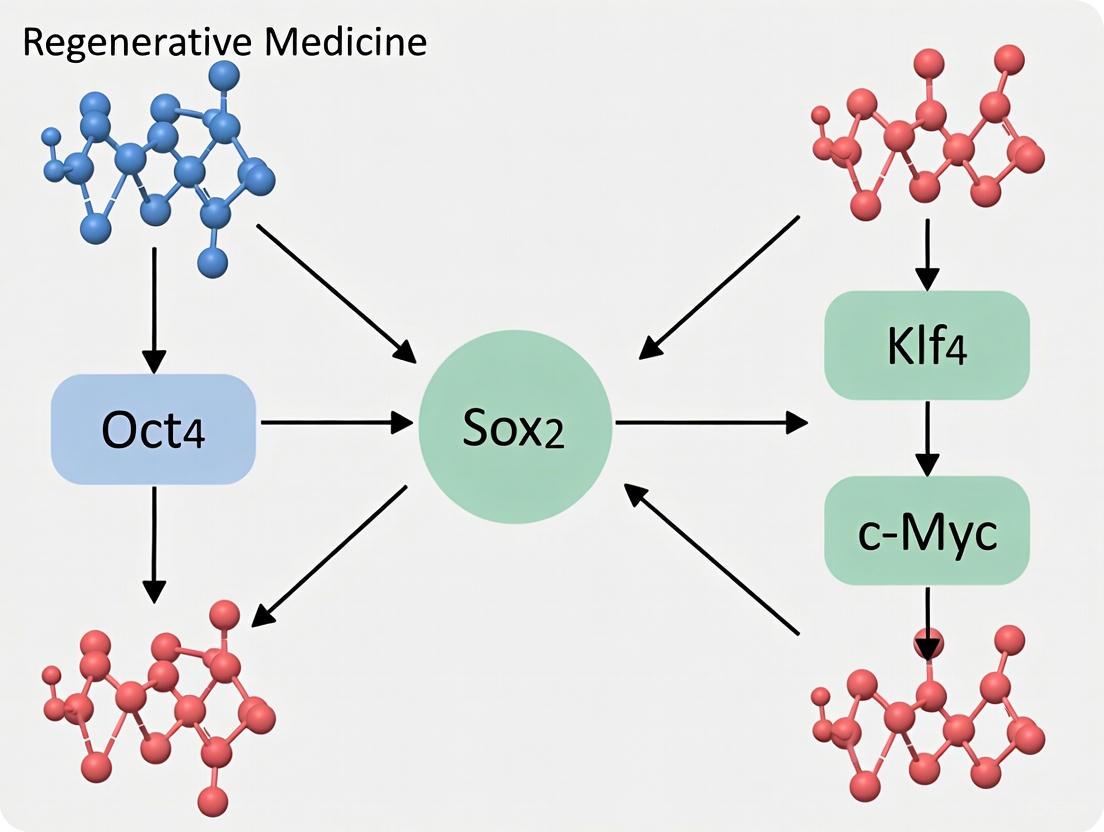

The OSKM Blueprint and Beyond: Core Principles of Reprogramming Factor Combinations

Since their groundbreaking discovery in 2006, the OSKM transcription factors—OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, and c-MYC—have represented the gold standard for reprogramming somatic cells into induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) [1] [2]. This revolutionary combination demonstrated that mature, differentiated cells could be returned to an embryonic-like state through the forced expression of just four defined factors, fundamentally changing the landscape of developmental biology and regenerative medicine [2] [3]. While numerous alternative reprogramming approaches have emerged over the past two decades, the original Yamanaka factors continue to serve as the essential benchmark against which all new methodologies are measured. This review examines the enduring role of OSKM as the reference standard in reprogramming research, comparing its performance metrics against subsequently developed factor combinations and delivery systems, with particular focus on efficiency, safety, and practical application in research and therapeutic development.

Core Mechanisms and Molecular Pathways

The reprogramming process initiated by OSKM factors involves profound remodeling of the chromatin structure and epigenome, transitioning through distinct phases [2]. During the early phase, somatic genes are silenced while early pluripotency-associated genes are activated—a process characterized by stochastic binding events, particularly to closed chromatin sites [4] [2]. The late phase involves more deterministic activation of late pluripotency-associated genes, establishing a self-reinforcing pluripotency network [1].

OSKM Reprogramming Pathway

c-MYC initiates reprogramming by associating with histone acetyltransferase complexes to induce global histone acetylation, enabling exogenous OCT4 and SOX2 to access their target loci [1]. OCT4 and SOX2 then cooperate as key transcription factors that inhibit differentiation-associated genes while activating the pluripotency network [1]. KLF4 plays a dual role, simultaneously suppressing somatic gene expression and activating pluripotency-associated genes [1]. This coordinated action ultimately leads to the establishment of a self-sustaining pluripotent state maintained by endogenous factor expression.

Comparative Performance Analysis of Reprogramming Factor Combinations

Efficiency Metrics Across Factor Combinations

Table 1: Comparative Efficiency of Reprogramming Factor Combinations

| Factor Combination | Reprogramming Efficiency | Time to iPSC Formation | Key Advantages | Notable Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OSKM (Original) | <0.1%-1% [5] | 3-4 weeks [5] | Gold standard, reliable, extensively validated | Low efficiency, tumorigenic risk with c-MYC |

| OSK (c-MYC omitted) | Significantly lower than OSKM [6] | Similar to OSKM | Reduced tumorigenic risk | Greatly reduced efficiency |

| OSNL (OCT4, SOX2, NANOG, LIN28) | Comparable to OSKM [1] | Similar to OSKM | Avoids c-MYC oncogene | LIN28 may affect proliferation similarly to c-MYC |

| OSKMNL (Six factors) | ~10x higher than OSNL [1] | Potentially reduced | Enables reprogramming of cells from aged donors | Increased genetic manipulation burden |

| OKS (OCT4, KLF4, SOX2) | Lower than OSKM but functional [7] | Not specified | Reduced oncogenic load, effective for partial reprogramming | Not sufficient for full reprogramming in all contexts |

| AI-Enhanced Variants | >50x higher than wild-type OSKM [5] | Markers appear days sooner [5] | Dramatically improved efficiency, enhanced DNA damage repair | Novel technology requiring further validation |

The original OSKM combination establishes the fundamental benchmark for reprogramming efficiency, typically achieving successful conversion in fewer than 1% of treated cells over approximately three weeks [5]. As illustrated in Table 1, efforts to improve upon this baseline have followed several strategic approaches: reducing oncogenic risk through factor omission (OSK), substituting alternative factors (OSNL), expanding the factor repertoire (OSKMNL), or recently, using artificial intelligence to engineer enhanced variants [6] [1] [5].

The critical role of c-MYC is evidenced by the significant efficiency reduction observed with its omission, though it is not strictly essential for reprogramming [6]. Similarly, the OSNL combination developed by Thomson's group demonstrates that completely different factor combinations can achieve similar outcomes, with LIN28 potentially functioning as a functional analog to c-MYC by accelerating cell proliferation [1]. The most dramatic efficiency improvements have recently emerged through AI-guided protein engineering, with OpenAI and Retro Biosciences reporting redesigned SOX2 and KLF4 variants that achieve over 50-fold higher expression of pluripotency markers compared to wild-type OSKM [5].

Species-Specific and Cell-Type Specific Variations

Table 2: Mouse vs. Human Reprogramming Characteristics with OSKM

| Characteristic | Mouse System | Human System |

|---|---|---|

| Reprogramming Timeline | 1-2 weeks [4] | 3-4 weeks [4] |

| c-MYC Dependency | Less critical; OSK often sufficient [4] | More critical for efficient reprogramming [4] |

| OSKM Binding Distribution | c-MYC binds proximally to TSS [4] | c-MYC binds distally to TSS [4] |

| Conserved Binding Events | Limited conservation in syntenic regions [4] | Limited conservation in syntenic regions [4] |

| Endpoint Pluripotency | Naïve state [4] | Primed state [4] |

Comparative analyses reveal significant differences in OSKM-mediated reprogramming between mouse and human systems, as summarized in Table 2. Mouse cells reprogram approximately twice as fast as human cells, with different dependencies on individual factors—notably, c-MYC plays a more essential role in human reprogramming [4]. Chromatin interaction studies demonstrate that while the general features of OSKM binding are largely conserved between species, including target genes and binding motifs, the specific genomic binding locations show limited conservation in syntenic regions [4]. These differences highlight the importance of considering species-specific effects when evaluating reprogramming efficiency across experimental systems.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standard OSKM Reprogramming Workflow

Fibroblast Reprogramming Protocol (Based on Original Yamanaka Method [2]):

- Factor Delivery: Introduce OSKM factors via integrating retroviral or lentiviral vectors into mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) or human dermal fibroblasts

- Culture Conditions: Maintain cells in ESC culture conditions with serum-containing media or defined formulations

- Timeline: Continue culture for 2-3 weeks (mouse) or 3-4 weeks (human) with regular medium changes

- Colony Identification: Monitor for emergence of ESC-like morphology with tight, dome-shaped colonies

- Validation: Confirm pluripotency through marker expression (SSEA-4, TRA-1-60, NANOG), teratoma formation, or differentiation potential [5]

Experimental Workflow for Reprogramming Efficiency Comparison

Advanced Methodology: Sequential Factor Delivery for Enhanced Efficiency

Recent optimization efforts have identified sequential delivery of reprogramming factors as a key strategy for improving knock-in efficiency in iPSCs. The following protocol has demonstrated success in achieving knock-in efficiencies exceeding 30%:

- Day 0: Preparative Culture - Switch to enriched culture medium two days prior to nucleofection to enhance cell fitness [8]

- Day 1: Donor Plasmid Delivery - Perform first nucleofection with donor plasmid DNA only, using 3×10ⶠcells per cuvette in P4 Nucleofection Buffer (Lonza 4D Nucleofector, program CA-167) [8]

- Post-Nucleofection Recovery - Incubate cells in RPMI medium for 10 minutes immediately after nucleofection to significantly improve cell survival [8]

- Day 2: RNP Complex Delivery - Perform second nucleofection with ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes containing Cas9/Cas12a nucleases and guide RNA [8]

- Cold Shock Incubation - Maintain cells at 32°C for enhanced homology-directed repair [8]

- Screening and Validation - Employ limiting dilution cloning and flow cytometry-based screening for modified clones [8]

This sequential approach demonstrates the continued optimization potential of reprogramming methodologies while maintaining compatibility with Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) requirements for therapeutic applications [8].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for OSKM Reprogramming Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Delivery Systems | Retroviral/lentiviral vectors, Sendai virus, mRNA transfection, recombinant protein [6] | Factor delivery with varying integration risks and efficiency |

| Reprogramming Enhancers | Valproic acid, 8-Br-cAMP, Sodium butyrate, RepSox [6] | Small molecules that improve reprogramming efficiency |

| Pluripotency Markers | SSEA-4, TRA-1-60, NANOG, alkaline phosphatase [5] | Validation of successful reprogramming |

| Selection Systems | Antibiotic resistance, FACS sorting markers [8] | Enrichment for successfully reprogrammed cells |

| Culture Media | DMEM/F12, defined media formulations, serum-free conditions [6] | Maintenance of pluripotent state |

| 4-Chloro-2-pyridin-3-ylquinazoline | 4-Chloro-2-pyridin-3-ylquinazoline|CAS 98296-25-4 | 4-Chloro-2-pyridin-3-ylquinazoline (CAS 98296-25-4) is a quinazoline-based chemical building block for anticancer research. This product is for research use only and not for human use. |

| 4-Chloro-2,6-bis(hydroxymethyl)phenol | 4-Chloro-2,6-bis(hydroxymethyl)phenol|CAS 17026-49-2 |

Applications and Therapeutic Translation

The original OSKM factors continue to enable diverse applications across regenerative medicine, disease modeling, and drug discovery. In disease modeling, iPSCs generated with OSKM have been particularly valuable for investigating neurodegenerative diseases like amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), where patient-specific iPSCs can be differentiated into affected cell types like motor neurons to recapitulate disease pathology [6]. In the therapeutic realm, partial reprogramming approaches using reduced factor combinations (often OKS without c-MYC) have shown promise for restoring youthful epigenetic patterns in aged tissues without completely reversing cell identity [7]. This approach has demonstrated efficacy in mitigating intervertebral disc degeneration by reducing senescence markers and restoring extracellular matrix homeostasis [7].

The emergence of HLA-matched iPSC banks, such as the initiative at Kyoto University led by Yamanaka, aims to provide allogeneic iPSC lines that could cover most of the Japanese population, potentially overcoming the limitations of autologous iPSC generation [1]. These developments, built upon the foundational OSKM technology, highlight the continuing translational impact of the original Yamanaka factors.

Nearly two decades after their discovery, the original Yamanaka factors (OSKM) maintain their status as the gold standard in cellular reprogramming. While numerous alternative factor combinations and methodologies have emerged—from reduced cocktails like OKS to expanded sets like OSKMNL—all are evaluated against the benchmark established by OSKM [6] [1] [7]. The recent development of AI-enhanced factor variants achieving unprecedented efficiency gains represents the next evolutionary step in this field, yet still relies on the original OSKM factors as both a conceptual framework and experimental control [5]. As reprogramming research progresses toward increasingly refined therapeutic applications, the original Yamanaka factors continue to provide the fundamental reference point for evaluating efficiency, safety, and practical utility across diverse biological contexts and applications.

The seminal discovery of induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) using the OSKM (OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, c-MYC) transcription factors revolutionized regenerative medicine, offering a potential workaround to the ethical concerns of embryonic stem cell research [6] [9]. However, the clinical translation of this technology is significantly hampered by safety concerns, primarily the tumorigenic risk associated with the use of the oncogene c-MYC [6] [9]. This safety profile is a critical determinant for researchers and drug development professionals selecting a reprogramming system. Consequently, the quest for safer alternative factor combinations has become a central focus in the field. Among the most prominent alternatives is the OSNL combination, which replaces KLF4 and c-MYC with NANOG and LIN28 [6] [10]. This guide provides a objective comparison of these core combinations, detailing their performance, underlying mechanisms, and practical application in a research setting.

Core Combination Comparison

The choice of reprogramming factors profoundly impacts the efficiency, safety, and applicability of the resulting iPSCs. The table below provides a detailed comparison of the established OSKM and the alternative OSNL combination.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of OSKM and OSNL Reprogramming Factor Combinations

| Feature | OSKM (OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, c-MYC) | OSNL (OCT4, SOX2, NANOG, LIN28) |

|---|---|---|

| Core Components | OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, c-MYC [6] | OCT4, SOX2, NANOG, LIN28 [6] [10] |

| Key Replacement | N/A | Replaces KLF4 and c-MYC with NANOG and LIN28 [6] |

| Primary Rationale | Original reprogramming "gold standard" [6] | To address tumorigenic risks associated with c-MYC [6] |

| Reprogramming Efficiency | High [6] | Sufficient, but reported to have lower success rates than OSKM in some comparative studies [10] |

| Tumorigenic Risk Profile | High; c-MYC is a potent oncogene, and its overexpression contributes to tumorigenesis [6] | Lower; avoids the use of the c-MYC oncogene, thereby reducing inherent oncogenic risk [6] [9] |

| Noted Advantages | High efficiency, well-characterized [6] | Reduced risk of tumor formation, successful reprogramming of human somatic cells demonstrated [6] [6] |

| Reported Limitations | Use of oncogene c-MYC poses significant safety risks for clinical applications [6] | May exhibit lower reprogramming efficiency compared to the OSKM combination [6] [10] |

Experimental Insights and Performance Data

Empirical data is crucial for evaluating the practical performance of these factor combinations. A comparative study offers direct insight into how OSNL and OSKM (delivered via the STEMCCA system) stack up against each other.

Table 2: Experimental Data from a Comparative Study of hiPSC Derivation

| Experimental Parameter | OSNL System | STEMCCA (OSKM) System |

|---|---|---|

| Reprogramming Efficiency | Significantly lower [10] | Significantly higher [10] |

| Success Rate of Generation | Lower [10] | Higher [10] |

| Pluripotency of Generated hiPSCs | Confirmed; all analysed hiPSCs were pluripotent and showed characteristics similar to human embryonic stem cells [10] | Confirmed; all analysed hiPSCs were pluripotent and showed characteristics similar to human embryonic stem cells [10] |

| Somatic Cell Source Impact | Successfully generated hiPSCs from hair keratinocytes, bone marrow cells (MSCs), and skin fibroblasts, though with varying efficiencies [10] | Successfully generated hiPSCs from hair keratinocytes, bone marrow cells (MSCs), and skin fibroblasts, with higher overall efficiency [10] |

| Downstream Differentiation (Cardiomyocytes) | All hiPSC lines could differentiate into functional cardiomyocytes [10] | All hiPSC lines could differentiate into functional cardiomyocytes [10] |

The same study also highlighted that the source of somatic cells significantly influences reprogramming outcomes. For instance, bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) were more easily reprogrammed than keratinocytes and subsequently exhibited a significantly higher efficiency in spontaneously differentiating into beating cardiomyocytes, regardless of the reprogramming system used [10]. This underscores the importance of considering cell source in experimental design.

Detailed Experimental Workflow

To ensure reproducibility, this section outlines a generalized protocol for deriving and characterizing iPSCs using these factor combinations, based on methodologies cited in the literature [10] [11].

Somatic Cell Preparation and Reprogramming

- Cell Source Isolation and Culture: Obtain and expand the chosen somatic cell population (e.g., dermal fibroblasts, bone marrow MSCs, or hair keratinocytes) in their respective standard culture media [10].

- Factor Delivery: Introduce the transcription factors (OSKM or OSNL) into the somatic cells. This is typically achieved using viral delivery systems.

- Lentiviral Vectors: The STEMCCA system, a lentiviral vector expressing OSKM in a single polycistronic cassette, is noted for its high reprogramming efficiency [10].

- Retroviral Vectors: Traditional for expressing the original Yamanaka factors [6].

- Non-Integrating Methods: For higher clinical safety, consider Sendai virus (an RNA virus that does not integrate into the genome) or episomal plasmids [6] [11].

- iPSC Colony Formation: After transduction, culture the cells on a feeder layer or in feeder-free conditions using media that support pluripotent stem cells (e.g., mTeSR1). Monitor for the emergence of compact, ESC-like colonies over 3-4 weeks.

iPSC Characterization and Validation

- Molecular Analysis of Pluripotency:

- In Vitro Differentiation: Subject iPSCs to spontaneous differentiation via embryoid body (EB) formation. Assess the resulting cells for markers of all three germ layers (e.g., α-fetoprotein for endoderm, α-actinin for mesoderm, βIII-tubulin for ectoderm) [10] [9].

- Karyotype Analysis: Perform G-banding karyotyping to ensure genomic integrity and the absence of major chromosomal abnormalities.

- Teratoma Assay: For a gold-standard test of pluripotency, inject iPSCs into immunodeficient mice. After 8-12 weeks, a teratoma should form containing differentiated tissues from all three germ layers [9].

Molecular Mechanisms and Signaling Pathways

The OSNL and OSKM combinations work by reactivating the core pluripotency network, but they engage this network through partially distinct mechanisms. The following diagram illustrates the key pathways and logical relationships involved in OSNL-mediated reprogramming.

The OSNL combination operates by directly activating the core pluripotency circuitry while leveraging alternative pathways to enhance reprogramming. OCT4 and SOX2 form a heterodimer that binds to and activates the expression of genes essential for pluripotency, including itself and NANOG [6]. NANOG acts as a key reinforcing factor, stabilizing the pluripotent state by suppressing alternative differentiation pathways [6]. A distinctive mechanism of the OSNL combination is the action of LIN28. LIN28 promotes reprogramming primarily by inhibiting the let-7 family of microRNAs [6]. Since let-7 miRNAs repress several pro-reprogramming factors, including c-MYC, LIN28 inhibition effectively derepresses the c-MYC pathway without the need for the potentially dangerous c-MYC oncogene itself [6]. This results in a safer profile while still leveraging a critical proliferative and metabolic network.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The following table catalogs key reagents and their functions essential for conducting reprogramming experiments with the OSNL and OSKM factor combinations.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for iPSC Reprogramming Experiments

| Reagent / Solution | Function in Reprogramming | Specific Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Reprogramming Factor Vectors | Deliver genes encoding transcription factors into somatic cells. | Lentiviral (e.g., STEMCCA for OSKM [10]), Retroviral, or non-integrating Sendai virus systems. |

| Pluripotency Support Media | Culture medium providing essential nutrients and signaling molecules to maintain pluripotency. | TeSR-E8, mTeSR1; used after transduction to support emerging iPSC colonies. |

| Feeder Cells / Substrate | Provides a physical and biochemical support layer for iPSC growth. | Mitotically-inactivated mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) or defined, feeder-free substrates like Matrigel. |

| Pluripotency Marker Antibodies | Detect expression of key proteins to validate pluripotent state via immunocytochemistry. | Antibodies against OCT4, SOX2, NANOG, SSEA-4, TRA-1-60, TRA-1-81 [10] [9]. |

| Differentiation Induction Media | Directs iPSC differentiation into specific lineages to confirm functional pluripotency. | Media formulations for generating cardiomyocytes, neurons, hepatocytes, etc. [10] |

| Small Molecule Enhancers | Chemicals that improve reprogramming efficiency or replace transcription factors. | Valproic acid (VPA), RepSox, Tranylcypromine; can be used to enhance efficiency or in novel chemical cocktails [6] [12] [13]. |

| 3-Amino-4-(phenylamino)benzonitrile | 3-Amino-4-(phenylamino)benzonitrile, CAS:68765-52-6, MF:C13H11N3, MW:209.25 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 5'-Phosphopyridoxyl-7-azatryptophan | 5'-Phosphopyridoxyl-7-azatryptophan, CAS:157117-38-9, MF:C18H21N4O7P, MW:436.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The comparative data clearly illustrates the fundamental trade-off between the high efficiency of the OSKM system and the superior safety profile of the OSNL combination. For therapeutic applications where minimizing oncogenic risk is paramount, OSNL presents a compelling alternative, despite its potential efficiency drawbacks [6] [10] [9]. The field continues to evolve beyond these initial combinations, exploring factors like GLIS1 and ESRRB as substitutes, and moving towards non-genetic methods such as chemically-induced reprogramming to further enhance safety [6] [12] [14]. Innovations like the 2c small molecule cocktail (RepSox and Tranylcypromine) and the discovery of novel single-gene targets like SB000 promise a new generation of rejuvenation therapies that avoid the risks of pluripotency induction entirely [15] [13]. For researchers, the choice between OSKM, OSNL, or newer approaches must be strategically aligned with the specific goals of their work, whether for high-throughput basic research or the development of clinically translatable therapies.

The discovery that somatic cells can be reprogrammed into induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) through the ectopic expression of specific transcription factors revolutionized regenerative medicine and developmental biology [3]. The classic "Yamanaka factors" — OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, and c-MYC (OSKM) — provide a powerful combination for resetting cellular identity [16]. However, each factor contributes distinct mechanistic functions to the reprogramming process, with specific structural features, molecular interactions, and epigenetic activities that collectively orchestrate the transition from somatic to pluripotent state. This review systematically compares the functional mechanisms of these four core factors, examining how their individual properties influence reprogramming efficiency, trajectory, and the quality of resulting iPSCs.

Factor-by-Factor Functional Analysis

OCT4: The Master Pluripotency Regulator

Structural and Functional Domains: OCT4 (POU5F1) contains a bipartite POU DNA-binding domain composed of POU-specific (POUS) and POU-homeodomain (POUHD) regions connected by a linker, flanked by N-terminal (NTD) and C-terminal (CTD) effector domains [17]. While the DNA-binding domain is essential for both reprogramming and pluripotency maintenance, recent research has identified Short Linear Peptides Essential for Reprogramming (SLiPERs) within the intrinsically disordered regions (IDRs) of OCT4 that are critical for reprogramming but dispensable for embryonic stem cell self-renewal [17].

Key Functional Mechanisms:

- DNA Binding and Nucleosome Engagement: The structured POU domain enables OCT4 to bind specific DNA sequences and interact with nucleosomes, which is essential for accessing chromatin during reprogramming [17].

- Context-Specific Functionality: SLiPER domains within IDRs adopt quasi-ordered states and recruit unique protein complexes to closed chromatin specifically during reprogramming, but not during pluripotency maintenance [17].

- Developmental Essentiality: Removing SLiPERs prevents embryos from developing beyond late gastrulation and derails the transition of ESCs out of pluripotency [17].

- Dosage Sensitivity: OCT4 expression levels are critical for successful reprogramming, with both insufficient and excessive expression impairing the process [1].

Table 1: Functional Domains of OCT4 and Their Roles in Reprogramming

| Domain | Location | Key Functions | Essential for Reprogramming | Essential for ESC Self-Renewal |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| POU-Specific Domain (POUS) | a.a. 47-70 | DNA binding, nucleosome interaction | Yes | Yes |

| Linker Region | a.a. 71-78 | Connects POUS and POUHD domains | Partially (unstructured portions) | Yes (structured portions) |

| POU-Homeodomain (POUHD) | a.a. 79-95 | DNA binding, nucleosome interaction | Yes | Yes |

| N-Terminal Domain (NTD) | a.a. 1-47 | Contains SLiPER sequences | Yes (specific peptides) | No |

| C-Terminal Domain (CTD) | a.a. 271-352 | Contains SLiPER sequences | Yes (specific peptides) | No |

SOX2: The Chromatin Accessibility Factor

Structural and Functional Domains: SOX2 contains a high-mobility group (HMG) DNA-binding domain that enables sequence-specific DNA recognition and bending, facilitating chromatin remodeling [16].

Key Functional Mechanisms:

- Cooperative DNA Binding: SOX2 frequently binds DNA in partnership with OCT4, with the two factors recognizing adjacent binding sites to form enhanceosome complexes that activate pluripotency genes [16].

- Chromatin Architecture Remodeling: The HMG domain of SOX2 bends DNA, which helps remodel chromatin structure and make regulatory regions accessible during reprogramming [16].

- Retroviral Silencing Trigger: When co-expressed with c-MYC, SOX2 can trigger immediate retroviral silencing, which explains why previous attempts to generate iPSCs without OCT4 using retroviral vectors failed [18].

- Lineage Specifier Counterbalance: In the "seesaw model" of pluripotency, SOX2 counteracts OCT4's effects by promoting neuroectoderm specification while OCT4 promotes meso-endoderm specification [18].

KLF4: The Dual-Function Regulator

Structural and Functional Domains: KLF4 contains three carboxyl-terminal zinc fingers that mediate binding to GC-rich sequences (CACCC) in gene regulatory regions, plus distinct domains for gene activation and repression [19].

Key Functional Mechanisms:

- Chromatin Organization: KLF4 can form liquid-like biomolecular condensates with DNA that recruit OCT4 and SOX2, facilitating the assembly of pluripotency transcription complexes [19].

- Dual Regulatory Capacity: KLF4 can function as both an activator and repressor, suppressing somatic cell identity genes while simultaneously activating pluripotency genes [1].

- Epigenetic Flexibility: KLF4 uniquely binds both unmethylated and CpG-methylated DNA, allowing it to initiate stem-cell gene expression profiles during reprogramming despite repressive epigenetic marks [19].

- Self-Renewal Promotion: In embryonic stem cells, KLF4 works in synchrony with KLF2 and KLF5 to regulate self-renewal and expression of pluripotency genes like Nanog [19].

c-MYC: The Chromatin Priming Factor

Structural and Functional Domains: c-MYC belongs to the basic helix-loop-helix leucine zipper (bHLHLZ) family and requires heterodimerization with MAX for transcriptional activity [20].

Key Functional Mechanisms:

- Chromatin Opening: c-MYC associates with histone acetyltransferase complexes to induce global histone acetylation, creating a more open chromatin environment that allows other factors access to their targets [1].

- Metabolic Reprogramming: c-MYC promotes a transition to energy metabolism typical of cancer cells, enhancing cell proliferation during the early stages of reprogramming [1].

- Transcriptional Amplification: With binding sites far exceeding those of OCT4 and SOX2, c-MYC acts as a broad amplifier of transcriptional changes during reprogramming [1].

- Dispensability with Trade-offs: While c-MYC significantly enhances reprogramming efficiency, it is dispensable for iPSC generation, and its exclusion reduces transformation risk but slows the process [16].

Table 2: Comparative Functions of Yamanaka Factors in Reprogramming

| Factor | Main Function | Essentiality | Binding Specificity | Key Partners |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OCT4 | Master pluripotency regulator | Conditionally essential | DNA sequence-specific | SOX2, KLF4, nucleosome remodeling complexes |

| SOX2 | Chromatin accessibility factor | Conditionally essential | DNA sequence-specific with OCT4 | OCT4, c-MYC |

| KLF4 | Dual activator/repressor | Replaceable | GC-rich sequences | OCT4, SOX2, KLF2/5 |

| c-MYC | Chromatin priming factor | Dispensable | E-box sequences | MAX, histone acetyltransferases |

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies

Reprogramming Efficiency Assays

Colony Formation Assays: The gold standard for quantifying reprogramming efficiency involves counting alkaline phosphatase-positive or pluripotency marker-positive (e.g., Nanog-GFP) colonies following factor expression [17] [18]. Typical protocols involve:

- Transducing somatic cells (usually mouse embryonic fibroblasts) with reprogramming factors

- Inducing factor expression for defined periods (typically 5-21 days)

- Fixing and staining for alkaline phosphatase or quantifying GFP-positive colonies

- Normalizing colony counts to initial cell numbers

Tetraploid Complementation Assays: This stringent test for developmental potential involves injecting iPSCs into tetraploid blastocysts and assessing their ability to generate entire mice [18]. iPSCs generated without OCT4 overexpression show significantly improved developmental potential in this assay compared to traditional OSKM-iPSCs [18].

Molecular Mechanism Studies

Domain Mapping Approaches: Systematic deletion mapping studies using overlapping 5-amino-acid deletions across OCT4 have identified functionally distinct regions [17]. This approach revealed SLiPER domains specifically required for reprogramming but not pluripotency maintenance.

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP): Genome-wide binding analyses show that the core pluripotency factors (OCT4, SOX2, NANOG) co-occupy target genes at levels well beyond chance expectation, suggesting cooperative binding and function [16].

Biomolecular Condensate Imaging: Advanced microscopy techniques have demonstrated that KLF4 can form liquid-like biomolecular condensates with DNA that recruit OCT4 and SOX2, providing a mechanism for transcription hub formation [19].

Figure 1: Temporal Phases of Cellular Reprogramming Showing Distinct Factor Activities

Alternative Factor Combinations and Replacements

Research has identified several alternative factor combinations that can generate iPSCs, providing insights into the core requirements for reprogramming:

OCT4-Independent Reprogramming: The combination of SOX2, KLF4, and c-MYC (SKM) can reprogram mouse somatic cells to pluripotency, though with delayed kinetics and reduced efficiency compared to OSKM [18]. This process requires high cell proliferation rates and is facilitated by the observation that SOX2 and c-MYC co-expression triggers retroviral silencing [18].

Alternative Pluripotency Factors: The combination of OCT4, SOX2, NANOG, and LIN28 (OSNL) can also reprogram human somatic cells, with NANOG functioning as an essential pluripotency maintainer and LIN28 accelerating cell proliferation similarly to c-MYC [1].

GATA Factor Substitution: Endoderm lineage specifiers GATA3, GATA4, and GATA6 can replace OCT4 in reprogramming cocktails, supporting the "seesaw model" where pluripotency represents a balance between opposing developmental lineages [18].

Table 3: Experimentally Validated Alternative Reprogramming Factor Combinations

| Factor Combination | Efficiency vs. OSKM | Key Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| SKM (SOX2, KLF4, c-MYC) | ~30% efficiency, 2-day delay | Improved developmental potential, fewer epigenetic aberrations | Requires high proliferation, cell type dependent |

| OSKM + Enhancers (e.g., Glis1) | Enhanced efficiency | Reduces partially reprogrammed colonies | Additional factors required |

| OSNL (OCT4, SOX2, NANOG, LIN28) | Comparable efficiency | Avoids oncogenic KLF4 and c-MYC | LIN28 has oncogenic potential |

| GATA + SKM (GATA3/4/6, SOX2, KLF4, c-MYC) | Higher than OSKM in some contexts | Provides alternative lineage balancing | May bias differentiation potential |

Research Reagents and Experimental Tools

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Reprogramming Studies

| Reagent/Tool | Function | Example Applications | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| dox-Inducible Lentiviral Vectors | Controlled factor expression | Sequential reprogramming studies, kinetics analysis | Integration risks, potential silencing |

| Oct4-GFP Reporter MEFs | Visualization of reprogramming | Efficiency quantification, colony isolation | GFP activation indicates endogenous OCT4 expression |

| Episomal Vectors | Non-integrating factor delivery | Clinical-grade iPSC generation, safety studies | Lower efficiency, transient expression |

| TetO-Polycistronic Cassettes | Coordinated factor expression | OSKM, SKM, OSN combinations | Fixed factor ratios, compact design |

| Small Molecule Enhancers | Replace specific factors | Chemical reprogramming, efficiency boosting | Defined mechanisms, concentration critical |

The functional comparison of OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, and c-MYC reveals a sophisticated division of labor in cellular reprogramming. OCT4 serves as the master regulator with context-specific functionalities embedded in its disordered regions, while SOX2 provides chromatin accessibility and partnership. KLF4 offers dual regulatory capacity and biomolecular condensate formation, and c-MYC primes chromatin for broad transcriptional changes. The discovery that OCT4 can be omitted under specific conditions challenges long-standing dogmas and highlights the plasticity of reprogramming pathways.

These findings have substantial implications for regenerative medicine applications, particularly in optimizing factor combinations for specific cell types and clinical applications. The improved developmental potential of SKM-reprogrammed iPSCs suggests that factor selection significantly impacts the epigenetic fidelity and functionality of resulting stem cells. Future research directions should focus on further elucidating the mechanistic basis of SLiPER domain functions, biomolecular condensate dynamics, and developing small molecule approaches to mimic or enhance the specific functional contributions of each factor while minimizing oncogenic risk.

The discovery that somatic cells could be reprogrammed into induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) using the transcription factors OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, and c-MYC (OSKM) revolutionized regenerative medicine and disease modeling [6] [21]. Subsequent research has focused on optimizing this reprogramming cocktail to enhance efficiency and safety, particularly by addressing the oncogenic potential of factors like c-MYC [6] [22]. A critical advancement in this optimization has been the identification of substitute factors capable of replacing their original counterparts in the reprogramming process while modulating functional outcomes.

Factor substitutability refers to the capability of certain transcription factors from the same family or with similar functional domains to replace the core Yamanaka factors in somatic cell reprogramming [6] [23]. Research has demonstrated that KLF2 and KLF5 can substitute for KLF4; SOX1 and SOX3 can replace SOX2; and L-MYC and N-MYC can stand in for c-MYC [6] [23]. Understanding the relative performance, efficiency, and safety profiles of these alternative factors is essential for designing optimized reprogramming protocols for specific research and therapeutic applications. This guide provides a systematic comparison of these substitute factors, presenting experimental data and methodologies to inform their use in scientific investigations.

Comparative Performance Data of Substitute Factors

Table 1: Functional Classification and Key Characteristics of Substitute Factors

| Original Factor | Substitute Factor | Family/Type | Key Reported Functions in Reprogramming | Oncogenic Risk Profile |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| KLF4 | KLF2 | Krüppel-like factor (KLF) | Activates pluripotency genes, suppresses somatic gene expression [6] | Lower than c-MYC [6] |

| KLF4 | KLF5 | Krüppel-like factor (KLF) | Similar transcriptional activation profile to KLF4 [6] | Lower than c-MYC [6] |

| SOX2 | SOX1 | SRY-related HMG-box (SOX) | Maintains pluripotency network, can bind similar targets [6] [23] | Not typically associated with high oncogenic risk |

| SOX2 | SOX3 | SRY-related HMG-box (SOX) | Functional redundancy with SOX2 in establishing pluripotency [6] [23] | Not typically associated with high oncogenic risk |

| c-MYC | L-MYC | MYC proto-oncogene family | Enhances proliferation with reduced tumorigenic potential compared to c-MYC [6] | Lower than c-MYC [6] |

| c-MYC | N-MYC | MYC proto-oncogene family | Promotes cell cycle progression and metabolic changes [23] | Lower than c-MYC, but caution is still advised [23] |

Table 2: Reported Reprogramming Efficiency and Key Experimental Findings

| Substitute Factor | Reprogramming Efficiency Relative to Original Factor | Key Experimental Observations and Context |

|---|---|---|

| KLF2 | Significantly lower efficiency than KLF4 [6] | Can establish pluripotency but with slower kinetics [6] |

| KLF5 | Significantly lower efficiency than KLF4 [6] | Shows overlapping target gene activation with KLF4 [6] |

| SOX1 | Significantly lower efficiency than SOX2 [6] | Effective in neural differentiation contexts [23] |

| SOX3 | Significantly lower efficiency than SOX2 [6] | Demonstrated functional redundancy in reprogramming circuitry [6] [23] |

| L-MYC | Comparable efficiency to c-MYC, with improved safety profile [6] | Associated with reduced teratoma formation in derived iPSCs [6] |

| N-MYC | Lower efficiency than c-MYC, but safer profile [23] | Used in alternative factor combinations (e.g., with Oct4, Sox2, Klf4) [23] |

Experimental Protocols for Evaluating Substitute Factors

Protocol for Fibroblast Reprogramming with Substitute Factors

This standard protocol is used to assess the efficacy of substitute factors in generating iPSCs from mouse or human fibroblasts [6] [21].

Cell Culture Preparation:

- Isolate and culture mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) or human dermal fibroblasts in standard fibroblast medium (e.g., DMEM with 10% FBS).

- Ensure cells are actively dividing and are at a low passage number for optimal reprogramming.

Factor Delivery:

- Vector Preparation: Clone the cDNA of the substitute factors (e.g., KLF2, SOX1, L-MYC) into appropriate delivery vectors. For comparative studies, use the same vector system (e.g., lentivirus, Sendai virus, or episomal plasmids) for all factors to ensure consistency [6] [21].

- Transduction/Transfection: Infect or transfect fibroblasts with viruses or plasmids carrying the reprogramming cassette. A common experimental setup includes:

- Use a defined multiplicity of infection (MOI) for viral delivery or optimized concentrations for non-viral methods to ensure consistent expression levels across groups.

Pluripotency Induction and Colony Culture:

- 24-48 hours post-transduction, replace the medium with specialized iPSC/ESC culture medium (e.g., containing KnockOut Serum Replacement, bFGF) [23].

- Culture cells on a feeder layer of mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) or on defined substrates like Matrigel in feeder-free conditions [23].

- Change the medium daily. Colonies with embryonic stem cell-like morphology will typically appear in 2-3 weeks.

Colony Picking and Expansion:

- Manually pick individual iPSC colonies based on morphology and transfer them to new culture plates for expansion.

- Expand clonal lines and characterize them for pluripotency markers.

Protocol for Pluripotency Validation

Rigorous validation is required to confirm the successful reprogramming of colonies generated with substitute factors [23] [21].

Immunofluorescence Staining:

- Fix iPSC colonies using 4% paraformaldehyde.

- Permeabilize cells with Triton X-100 and block with serum.

- Incubate with primary antibodies against core pluripotency transcription factors (e.g., Anti-Oct4, Anti-Nanog) and surface markers (e.g., Anti-SSEA-4, Anti-TRA-1-60).

- Incubate with fluorophore-conjugated secondary antibodies and visualize using a fluorescence microscope.

In Vitro Differentiation (Embryoid Body Formation):

- Harvest iPSCs and culture them in low-attachment plates in medium without bFGF to promote the formation of embryoid bodies (EBs).

- After 7-10 days, plate EBs on gelatin-coated dishes and allow for spontaneous differentiation for another 7-14 days.

- Analyze the resulting cells for markers of the three germ layers (ectoderm, mesoderm, endoderm) via immunofluorescence or RT-qPCR.

In Vivo Teratoma Formation Assay:

- Inject a suspension of iPSCs subcutaneously into immunodeficient mice (e.g., NSG mice).

- After 6-12 weeks, dissect the resulting tumors and fix them for histological analysis.

- Section and stain tumors with H&E. The presence of tissues derived from all three germ layers (e.g., neural rosettes for ectoderm, cartilage for mesoderm, gut-like epithelium for endoderm) confirms pluripotency [23]. This assay also provides critical safety data on the tumorigenic potential of the iPSCs.

Signaling Pathways and Molecular Mechanisms

The reprogramming process involves a complex network of interactions where the Yamanaka factors and their substitutes collaboratively suppress the somatic cell program and activate the pluripotency network. The diagram below illustrates the core functional relationships and the position of substitute factors in this process.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents for Reprogramming and Characterization Experiments

| Reagent / Material | Function in Experiment | Specific Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Delivery Vectors | Introducing reprogramming genes into somatic cells [6] | Retrovirus, Lentivirus (integrating); Sendai virus, Episomal plasmids (non-integrating) [6] [21]. Choice affects biosafety and efficiency. |

| Culture Matrix | Provides a scaffold for cell attachment and growth, supporting self-renewal [23] | Matrigel, recombinant Laminin, Vitronectin, or defined synthetic hydrogels [23]. |

| Defined Culture Medium | Maintains iPSCs in a pluripotent state; supports reprogramming [23] | TeSR1, mTeSR1, or similar formulations containing essential nutrients and growth factors like bFGF [23]. |

| Small Molecule Enhancers | Improve reprogramming efficiency by modulating epigenetic or signaling pathways [6] [23] | Valproic acid (VPA, HDAC inhibitor), 5-Azacytidine (DNA methyltransferase inhibitor), SB431542 (TGF-β inhibitor), PD0325901 (MEK inhibitor) [6] [23]. |

| Pluripotency Antibodies | Validation of successful reprogramming via immunostaining or flow cytometry [23] | Primary antibodies against Oct4, Nanog, Sox2, SSEA-4, TRA-1-60. |

| In Vivo Model | Testing pluripotency through teratoma formation [23] | Immunodeficient mice (e.g., NOD-scid gamma (NSG) mice). |

| 3,5-Dibromo-4-pyridinol | 3,5-Dibromo-4-pyridinol, CAS:141375-47-5, MF:C5H3Br2NO, MW:252.89 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 3,4-Dimethyl-5-propyl-2-furannonanoic Acid | 3,4-Dimethyl-5-propyl-2-furannonanoic Acid|CAS 57818-38-9 | 3,4-Dimethyl-5-propyl-2-furannonanoic acid is a high-purity furan fatty acid (9D3) for lipid oxidation research. This product is For Research Use Only and not for human or veterinary diagnostics or therapeutic applications. |

The systematic comparison of KLF2, KLF5, SOX1, SOX3, L-MYC, and N-MYC reveals a critical trade-off in factor substitutability: while these alternatives generally offer improved safety profiles by reducing oncogenic risk, they often do so at the cost of significantly lower reprogramming efficiency compared to the original Yamanaka factors [6] [23]. This efficiency-safety balance is a central consideration for research applications.

Future work must focus on optimizing culture conditions and leveraging small molecule enhancers to close the efficiency gap [6] [21]. Furthermore, the choice between autologous iPSCs derived from a patient's own cells and the use of HLA-matched allogeneic iPSCs from biobanks will significantly influence which factor combinations are most appropriate for therapeutic development, with safety being paramount for clinical translation [21] [1]. Continued research into the mechanisms of these substitutes will further refine their application, pushing the field toward more efficient and safer reprogramming protocols.

In the field of regenerative medicine, induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) technology has revolutionized biological research and therapeutic development since its discovery by Shinya Yamanaka. The original Yamanaka factors—OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, and c-MYC (OSKM)—enable reprogramming of somatic cells into pluripotent stem cells, but with notoriously low efficiency, typically converting less than 0.1% of treated cells [5]. Defining and quantifying reprogramming efficiency is therefore critical for comparing different reprogramming factor combinations and advancing both basic research and clinical applications. This guide examines the key metrics, benchmarks, and experimental frameworks that researchers employ to objectively measure reprogramming efficiency, with particular emphasis on emerging technologies that are reshaping the landscape of iPSC generation.

Key Metrics for Assessing Reprogramming Efficiency

To systematically compare the performance of different Yamanaka factor combinations, researchers track multiple quantitative metrics throughout the reprogramming process. These parameters collectively provide a comprehensive picture of how effectively somatic cells are being converted to a pluripotent state.

Table 1: Core Metrics for Evaluating Reprogramming Efficiency

| Metric Category | Specific Metrics | Measurement Technique | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Early Pluripotency Markers | SSEA-4 expression [5] | Flow cytometry, immunostaining | Indicates initiation of reprogramming |

| Late Pluripotency Markers | TRA-1-60, NANOG expression [5] | Immunostaining, RNA analysis | Confirms establishment of pluripotency |

| Functional Pluripotency | Alkaline phosphatase (AP) activity [5] | AP staining | Demonstrates functional pluripotency |

| Temporal Efficiency | Time to colony appearance [5] | Microscopy observation | Measures acceleration of process |

| Throughput Efficiency | Percentage of cells converting [5] | Colony counting, flow cytometry | Quantifies overall success rate |

| Characterization | Germ layer differentiation [5] | In vitro differentiation assays | Validates trilineage potential |

| Safety | Genomic stability [5] | Karyotyping, DNA sequencing | Ensures clinical suitability |

Benchmarking Yamanaka Factor Combinations

The original OSKM factors remain the benchmark against which novel reprogramming combinations are evaluated. However, recent advances have identified more efficient alternatives, including both modified versions of the original factors and completely new factor combinations.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Reprogramming Factor Combinations

| Factor Combination | Reprogramming Efficiency | Key Advantages | Limitations | Experimental Validation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional OSKM | <0.1% cell conversion [5] | Established benchmark, widely validated | Low efficiency, tumorigenic risk (c-MYC) [6] | Fibroblast reprogramming in 3+ weeks [5] |

| OSK (without c-MYC) | Lower than OSKM [6] | Reduced tumorigenic risk [6] | Significantly decreased efficiency [6] | Demonstrated in mouse and human fibroblasts [6] |

| OSNL (OCT4, SOX2, NANOG, LIN28) | Comparable to OSKM [6] | Avoids c-MYC oncogene [6] | May require additional enhancers | Human somatic cell reprogramming [6] |

| L-Myc substitution | Similar to c-MYC [6] | Reduced tumorigenic potential [6] | Potentially tissue-dependent effects | Mouse and human cell studies [6] |

| RetroSOX/RetroKLF + OK | >30% cell conversion (SSEA-4, TRA-1-60) [5] | 50x higher marker expression, faster onset [5] | AI-engineered, requires further validation | Multiple donors, cell types, and delivery methods [5] |

| Chemical Reprogramming | Varies with cocktail composition [6] | Non-integrating, enhanced safety profile [6] | Often lower than genetic methods | Human fibroblast reprogramming [6] |

Experimental Protocols for Efficiency Assessment

Standardized experimental approaches are essential for generating comparable data across different studies of reprogramming factors. The following protocols represent current best practices in the field.

Protocol 1: Quantitative Assessment of Reprogramming Efficiency

Cell Culture and Transduction

- Isolate human fibroblasts from tissue samples or use established lines (e.g., HDF, BJ fibroblasts)

- Culture in standard fibroblast medium (DMEM + 10% FBS)

- Transduce with lentiviral or sendai viral vectors encoding reprogramming factors at MOI 5-10

- Include control groups: wild-type OSKM, experimental factors, and empty vector

- For non-integrating methods, use mRNA transfection or episomal vectors

Pluripotency Marker Analysis

- At days 7, 14, and 21 post-transduction, dissociate cells for analysis

- For flow cytometry: stain with anti-SSEA-4 and anti-TRA-1-60 antibodies

- Fix parallel samples for immunocytochemistry (NANOG, SOX2, OCT4)

- Perform alkaline phosphatase staining using commercial kits according to manufacturer protocols

- Quantify positive cells across multiple fields (minimum n=5) and normalize to total cell count

Molecular Validation

- Extract RNA from emerging iPSC colonies for qRT-PCR analysis of endogenous pluripotency genes (OCT4, SOX2, NANOG)

- Perform bisulfite sequencing of OCT4 and NANOG promoters to assess epigenetic reprogramming

- Verify trilineage differentiation potential through embryoid body formation and specific staining for ectoderm (βIII-tubulin), mesoderm (α-smooth muscle actin), and endoderm (SOX17)

Protocol 2: Functional Characterization of Reprogrammed Cells

Long-Term Culture and Stability Assessment

- Passage emerging iPSC colonies onto feeder layers or defined matrices

- Monitor morphological stability over 10+ passages

- Perform G-banding karyotype analysis at passages 5, 10, and 15

- Use whole-genome sequencing to identify potential genetic abnormalities

Advanced Pluripotency Validation

- Perform in vitro differentiation toward specific lineages (neuronal, cardiac, hepatic)

- Conduct teratoma formation assays in immunodeficient mice (for research purposes)

- Validate global gene expression profiles by RNA sequencing compared to reference hESC lines

Visualization of Reprogramming Pathways and Workflows

Reprogramming Pathway Progression

Reprogramming Efficiency Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful reprogramming experiments require carefully selected reagents and systems. The following table outlines critical components for iPSC generation studies.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Reprogramming Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reprogramming Factors | Wild-type OSKM, OSNL, RetroSOX/RetroKLF [5] | Induce pluripotency | Delivery method affects efficiency and safety |

| Delivery Systems | Lentivirus, Sendai virus, mRNA, episomal plasmids [6] | Introduce factors into cells | Integrating vs. non-integrating approaches |

| Cell Culture Media | Fibroblast medium, iPSC maintenance medium | Support cell growth and reprogramming | Defined media improve reproducibility |

| Characterization Antibodies | Anti-SSEA-4, Anti-TRA-1-60, Anti-NANOG [5] | Detect pluripotency markers | Validate species cross-reactivity |

| Detection Kits | Alkaline phosphatase staining kits [5] | Identify pluripotent colonies | Some kits work on live cells for sorting |

| Culture Surfaces | Matrigel, laminin-521, feeder cells | Provide adhesion and signaling | Defined matrices reduce variability |

| Enhancer Molecules | Valproic acid, sodium butyrate, 8-Br-cAMP [6] | Improve reprogramming efficiency | Concentration optimization required |

| Demethylamino Ranitidine Acetamide Sodium | Demethylamino Ranitidine Acetamide Sodium|CAS 112251-56-6 | Demethylamino Ranitidine Acetamide Sodium is a Ranitidine impurity for research. This product is For Research Use Only and is not intended for diagnostic or personal use. | Bench Chemicals |

| GLYCOLURIL, 3a,6a-DIPHENYL- | GLYCOLURIL, 3a,6a-DIPHENYL-, CAS:5157-15-3, MF:C16H14N4O2, MW:294.31 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Emerging Technologies and Future Directions

The field of cellular reprogramming is rapidly evolving with several emerging technologies poised to transform efficiency benchmarking.

AI-Guided Protein Engineering

Recent breakthroughs in artificial intelligence are enabling the design of novel reprogramming factors with significantly enhanced performance. The collaboration between OpenAI and Retro Biosciences has demonstrated that AI-generated variants of SOX2 and KLF4 (RetroSOX and RetroKLF) can achieve remarkable improvements in reprogramming efficiency—up to 50-fold higher expression of pluripotency markers compared to wild-type factors [5]. These AI-engineered factors also demonstrate enhanced DNA damage repair capabilities, suggesting improved rejuvenation potential alongside more efficient reprogramming [5].

Chemical Reprogramming

Small molecule approaches represent a promising alternative to genetic reprogramming methods. Chemical cocktails can replace some or all reprogramming factors, potentially offering enhanced safety profiles by avoiding genomic integration [6]. These approaches activate distinct molecular pathways compared to traditional OSKM-based reprogramming and may access different intermediate cell states [6].

Partial Reprogramming

For therapeutic applications targeting aging and cellular rejuvenation, partial reprogramming approaches are gaining traction. These methods involve transient expression of Yamanaka factors sufficient to restore youthful epigenetic patterns and cellular functions without completely reversing cell identity [24]. While promising, this approach requires precise control to avoid teratoma formation or loss of cellular identity [24].

The systematic assessment of reprogramming efficiency through standardized metrics and benchmarks is fundamental to advancing iPSC technology. As the field progresses beyond the original Yamanaka factors, rigorous comparison of novel factor combinations—including AI-engineered variants and chemical approaches—will be essential for identifying optimal strategies for both research and clinical applications. The experimental frameworks and benchmarks outlined in this guide provide a foundation for objective evaluation of reprogramming efficiency across different platforms and conditions. Future advances will likely focus not only on increasing efficiency but also on enhancing safety, reproducibility, and accessibility of iPSC generation across diverse cell types and donor backgrounds.

From Theory to Practice: Delivery Systems and Application-Specific Cocktails

The discovery that somatic cells can be reprogrammed into induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) using the Yamanaka factors (OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, and c-MYC) has revolutionized regenerative medicine and disease modeling [25] [21]. A critical determinant of reprogramming success is the method used to deliver these factors into target cells. The choice between viral and non-viral delivery systems involves significant trade-offs between efficiency, safety, and clinical applicability. This guide provides a objective comparison of the most commonly used delivery methods—retrovirus, lentivirus, Sendai virus, and episomal vectors—focusing on their performance in reprogramming experiments, to inform researchers and drug development professionals.

Vector Comparison Tables

The following tables summarize the core characteristics and performance metrics of the four primary delivery vectors used for iPSC generation.

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of Delivery Vectors

| Feature | Retrovirus | Lentivirus | Sendai Virus (SeV) | Episomal Vectors |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vector Type | Viral, Integrating | Viral, Integrating | Viral, Non-integrating | Non-viral, Non-integrating |

| Genetic Material | RNA | RNA | RNA | DNA |

| Genomic Integration | Yes | Yes | No | No (Episomal) |

| Target Cell Requirement | Dividing cells only | Dividing & non-dividing cells | Dividing & non-dividing cells | Dividing & non-dividing cells |

| Primary Safety Concern | Insertional mutagenesis | Insertional mutagenesis | Cytopla smic persistence | Low transgene expression |

| Residual Transgene Expression | Yes, unless silenced | Yes, unless silenced | Diluted upon cell division | Diluted upon cell division |

Table 2: Experimental Performance Metrics in iPSC Generation

| Performance Metric | Retrovirus | Lentivirus | Sendai Virus (SeV) | Episomal Vectors |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reprogramming Efficiency | High [21] | High [26] | Highest among non-integrating methods [27] | Lower than SeV [27] |

| Typical Time to iPSC Colony | ~2-3 weeks | ~2-3 weeks | ~3-4 weeks | ~3-4 weeks |

| Aberrant Methylation Sites | Higher [28] | Not specified in results | Lowest number [28] | Intermediate [28] |

| Stability of Reprogramming | Stable | Stable | Stable, but virus must be lost | Can be unstable |

| Key Advantage | Robust, stable integration | Broad tropism, integrates non-dividing cells | High efficiency, non-integrating | Non-integrating, non-viral |

| Key Disadvantage | Silencing in pluripotent cells; safety risk | Safety risk of insertional mutagenesis | Requires protocol to clear virus | Low efficiency; requires optimization |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To ensure reproducibility, this section outlines standardized protocols for implementing the two most prevalent non-integrating reprogramming methods, as derived from biobanking practices [27].

Sendai Virus (SeV) Reprogramming Protocol

- Source Cells: Fibroblasts or Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells (PBMCs).

- Transduction: Cells are transduced using a CytoTune Sendai Reprogramming Kit, which typically includes four separate SeV vectors, each expressing one of the factors hOCT4, hSOX2, hKLF4, and hC-MYC, alongside a reporter gene like EmGFP [27].

- Post-Transduction Culture: Twenty-four hours after transduction, the medium is refreshed. Cells are cultured for approximately 6 additional days, with medium exchanged every other day.

- Assessment: Transduction efficiency is estimated by examining GFP-positive cells using fluorescence microscopy.

- Rep plating: Approximately 7 days post-transduction for fibroblasts (or 3 days for PBMCs), the cells are harvested and replated onto feeder cells or a suitable substrate like Matrigel.

- Colony Picking: After an additional 2–3 weeks, emergent iPSC colonies reach the appropriate size for transfer. At this stage, at least 24 colonies are manually picked for further expansion and characterization [27].

Episomal Vector Reprogramming Protocol

- Source Cells: Lymphoblastoid Cell Lines (LCLs) or fibroblasts.

- Nucleofection: Cells are nucleofected (electroporation) using an Amaxa Nucleofector II device with specific programs (e.g., U-015 for LCLs, U-023 for fibroblasts). The vectors used are OriP/EBNA1 episomal plasmids expressing hOCT3/4, hSOX2, hKLF4, hL-MYC, LIN28, and a marker like EGFP [27].

- Post-Nucleofection Culture: Post-nucleofection, cells are maintained in a 5% O2 incubator and fed every other day.

- Assessment: Nucleofection efficiency is monitored by tracking GFP-positive cells.

- Rep plating: On days 6–7 after nucleofection, the transfected cells are replated.

- Colony Picking: After 1–2 additional weeks, at least 24 clones are manually selected for expansion, leading to master and distribution bank freezes [27].

Research Reagent Solutions

Critical quality control (QC) measures are paramount for ensuring the reliability and reproducibility of generated iPSC lines. The following table details key reagents and tests used in this process [27].

Table 3: Essential Reagents for iPSC Generation and Quality Control

| Reagent / Test | Function / Purpose | Example Details |

|---|---|---|

| CytoTune Sendai Kit | Delivers OSKM factors via non-integrating SeV | Contains separate viruses for hOCT4, hSOX2, hKLF4, hC-MYC [27] |

| Episomal Plasmids | Delivers reprogramming factors without viral components | OriP/EBNA1 vectors with hOCT3/4, hSOX2, hKLF4, hL-MYC, LIN28 [27] |

| mTeSR1 Medium | Defined, feeder-free culture medium for pluripotent stem cells | Used for maintaining established iPSCs; sometimes with "double feeding" protocol [27] |

| Y-27632 (ROCK inhibitor) | Improves survival of single pluripotent stem cells | Added to medium for 20-24 hours after thawing or passaging cells [27] |

| Alkaline Phosphatase (AP) Staining | Marker of pluripotency; undifferentiated cells stain positively | Standard QC test performed on iPSC colonies [27] |

| Karyotyping | Detects gross chromosomal abnormalities | Standard QC test (e.g., G-banding) to ensure genomic integrity [27] |

| Short Tandem Repeat (STR) Analysis | Confirms cell line identity and rules for cross-contamination | Standard QC test comparing the iPSC line to the source material [27] |

| Mycoplasma Testing | Ensures cell cultures are free from mycoplasma contamination | Essential routine test using dedicated kits on spent medium/cell suspension [27] |

Visualizing Reprogramming Workflows

The diagrams below illustrate the logical workflow for the two primary non-integrating reprogramming methods and the subsequent quality control pipeline.

Sendai Virus vs. Episomal Reprogramming Workflow

iPSC Line Quality Control Pipeline

The choice of delivery vector for iPSC generation is a critical decision that balances efficiency against safety. Retroviruses and lentiviruses offer high reprogramming efficiency and stable integration but carry the inherent risk of insertional mutagenesis, making them less suitable for clinical applications [26] [21]. Among non-integrating methods, the Sendai virus consistently demonstrates superior reprogramming efficiency and a lower number of aberrant methylation sites compared to episomal vectors [28] [27]. However, episomal vectors, while less efficient, provide a completely non-viral alternative, eliminating concerns related to viral components entirely [27]. The optimal vector is thus highly dependent on the research or therapeutic objective: SeV is ideal for robust iPSC generation where transient viral presence is acceptable, episomal vectors are preferable for applications demanding the highest safety profile, and lentiviral vectors remain powerful tools for research requiring stable genetic modification.

The generation of human induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPSCs) has revolutionized biomedical research, offering unprecedented opportunities in disease modeling, drug screening, and regenerative therapies [27]. Since the groundbreaking discovery of cellular reprogramming, the field has progressively shifted from integrating viral vectors to non-integrating reprogramming methodologies to minimize the risk of genomic alterations and enhance the clinical safety profile of resulting hiPSCs [27] [29]. Among the various non-integrating methods available, Sendai virus (SeV) and episomal (Epi) reprogramming have emerged as two of the most prevalent approaches due to their relative ease of manipulation and efficiency [27] [29].

Despite their widespread use, a clear consensus regarding their comparative success rates has been lacking, with different studies reporting apparently conflicting findings. This analysis directly addresses this uncertainty by synthesizing current scientific evidence to provide a definitive comparison of reprogramming success rates between Sendai viral and episomal methods. Framed within a broader investigation into the efficiency of different Yamanaka factor delivery strategies, this guide provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with the experimental data and methodological details necessary to inform their reprogramming platform selection.

Defining and Quantifying Reprogramming Success

In hiPSC generation, "success" is typically evaluated through two primary metrics: reprogramming efficiency and reprogramming success rate.

- Reprogramming Efficiency refers to the percentage of starting somatic cells that give rise to iPSC colonies [29]. This metric provides a precise measure of how productive a specific reprogramming method is with a particular cell sample.

- Reprogramming Success Rate describes the percentage of independent somatic cell samples for which a method can generate at least three bona fide iPSC colonies [29]. This metric is particularly relevant for biobanking and clinical applications where generating lines from diverse donor samples is essential.

The following sections present a direct, data-driven comparison of these metrics for Sendai virus and episomal reprogramming methods.

Direct Comparative Analysis of Success Rates

Comprehensive Success Rate and Efficiency Data

A systematic comparison of non-integrating reprogramming methods provides the most direct evidence for their relative performance. Key findings from a landmark study are summarized in Table 1 [29].

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Non-Integrating Reprogramming Methods

| Reprogramming Method | Reprogramming Efficiency (Mean %) | Overall Success Rate (% of Samples) | Time Until Colony Picking (Days) | Relative Hands-on Time (Hours) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sendai Virus (SeV) | 0.077% | 94% | ~26 | 3.5 |

| Episomal (Epi) | 0.013% | 93% | ~20 | 4.0 |

| mRNA | 2.1% | 27% (improves to 73% with miRNA) | ~14 | 8.0 |

| Lentiviral (Lenti) | 0.27% | 100% | Not Specified | Not Specified |

The data reveals a critical distinction: while the Sendai virus method offers a significantly higher reprogramming efficiency (approximately 6-fold higher) than the episomal method, both techniques demonstrate an equally high and reliable success rate exceeding 90% [29]. This means that for the vast majority of somatic cell samples, both methods are very likely to yield iPSC colonies, but the Sendai virus protocol typically generates a greater number of colonies from the same number of starting cells.

A more recent 2025 study corroborates the superior efficiency of the Sendai virus system, confirming that it "yields significantly higher success rates relative to the episomal reprogramming method" [27] [30]. However, an earlier study reported a contrasting finding, observing a higher colony count with episomal transfection [31]. This discrepancy highlights that success can be influenced by specific experimental protocols, vector designs, and source cell types.

Methodological Impact on Success

The experimental workflow for reprogramming involves several key stages where methodological choices can influence the final outcome. The diagram below illustrates the general workflow and critical decision points for Sendai virus and episomal methods.

Figure 1: A generalized workflow for hiPSC generation comparing the initial steps of the Sendai virus and episomal reprogramming paths. Key methodological differences in the delivery and expression of reprogramming factors significantly influence outcomes.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Sendai Virus Reprogramming Protocol

The Sendai virus protocol utilizes a non-integrating, cytoplasmic RNA virus to deliver and express reprogramming factors.

Key Reagents:

- CytoTune-iPS Sendai Reprogramming Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific): Contains four SeV-based vectors, each encoding one of the Yamanaka factors (Oct4, Sox2, Klf4, c-Myc) [32].

- Somatic Cells: Fibroblasts, Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells (PBMCs), or Lymphoblastoid Cell Lines (LCLs) [27].

- Culture Medium: Appropriate medium for the somatic cell type, followed by transition to human iPSC medium post-transduction.

Detailed Workflow:

- Day 0: Plate somatic cells at an optimal density (e.g., 5 x 10^5 cells per well of a 6-well plate) and culture overnight [32].

- Day 1: Transduce cells with a combination of the four CytoTune Sendai virus vectors. The Multiplicity of Infection (MOI) should be optimized; a total MOI of 3-5 is often used [27] [32].

- Day 2: Refresh the culture medium 24 hours after transduction to remove viral particles.

- Days 3-7: Continue culturing, exchanging the medium every other day. Transduction efficiency can be estimated if using a vector expressing a fluorescent reporter like EmGFP [27].

- Approximately Day 7: Harvest and re-plate the transduced cells onto feeder layers or Matrigel-coated plates.

- Days 10-28: Continue daily feeding with hiPSC medium. Colonies typically become large enough for manual picking around day 26 post-transduction [27] [29].

- Colony Expansion: Pick at least 24 individual colonies for expansion and screening. The SeV genome is gradually diluted out over 10-15 passages [29] [33].

Episomal Reprogramming Protocol

The episomal method uses OriP/EBNA1-based plasmids that replicate extra-chromosomally in dividing cells but are gradually lost in the absence of selection.

Key Reagents:

- Episomal Plasmids: Typically a combination of plasmids expressing OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, L-MYC, LIN28, and an shRNA against p53 [27] [34].

- Somatic Cells: Fibroblasts or LCLs.

- Nucleofection Device: Such as the Amaxa Nucleofector II (Lonza) [27].

Detailed Workflow:

- Day 0: Prepare somatic cells for nucleofection.

- Day 1: Co-nucleofect cells with the episomal plasmid combination using a cell-type-specific nucleofection program (e.g., U-023 for fibroblasts) [27]. Culture transfected cells in a low-oxygen (5% O2) incubator to enhance efficiency [27].

- Days 2-6: Feed cells every other day. Transfection efficiency can be monitored if plasmids contain a reporter like EGFP [27].

- Days 6-7: Re-plate the transfected cells onto feeder layers or Matrigel.

- Days 14-21: Feed daily. Colonies are often ready for picking around day 20, slightly earlier than with SeV [29].

- Colony Expansion: Manually pick and expand at least 24 clones. Passaging cells continuously is required to dilute out the episomal plasmids. A significant fraction of lines (over 30%) may retain plasmids even at passage 10-11, necessitating PCR validation [29].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Successful reprogramming relies on a suite of specialized reagents and tools. Table 2 lists the core components of a reprogramming toolkit for the methods discussed.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for hiPSC Reprogramming

| Reagent/Material | Function/Purpose | Example Product/Catalog Number |

|---|---|---|

| Sendai Virus Vectors | Delivery of OSKM factors; non-integrating | CytoTune-iPS Sendai Reprogramming Kit (Thermo Fisher, A1378001) [32] |

| Episomal Vectors | Delivery of OSKM, L-MYC, LIN28, sh-p53; non-integrating | OriP/EBNA1-based plasmids (e.g., Addgene #41855-41858) [27] |

| Nucleofector Device | High-efficiency plasmid delivery for episomal method | Amaxa Nucleofector II Device (Lonza) [27] |

| Y-27632 (ROCK inhibitor) | Improves survival of single pluripotent cells; used during passaging and thawing | Y-27632 (e.g., Thermo Fisher, PHZ1234) [27] |

| mTeSR1 Medium | Defined, feeder-free culture medium for hiPSCs | mTeSR1 (StemCell Technologies, 85850) [27] |

| Matrigel | Extracellular matrix for feeder-free culture of hiPSCs | Matrigel (Corning, 354230) [27] |

| Alkaline Phosphatase Staining Kit | Identification of pluripotent colonies | e.g., Millipore Sigma, SCR004 |

| Pluripotency Antibodies | Immunostaining for markers (TRA-1-60, SSEA4, NANOG) | Anti-Tra-1-60 (Thermo Fisher, 41-1000), Anti-SSEA4 (Thermo Fisher, 41-4000) [29] [32] |

| Tetrabutylammonium bibenzoate | Tetrabutylammonium bibenzoate, CAS:116263-39-9, MF:C30H47NO4, MW:485.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Decapreno-|A-carotene | Decapreno-|A-carotene, CAS:5940-03-4, MF:C50H68, MW:669.1 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Critical Considerations Beyond Success Rate

While success rate is a primary concern, other factors are crucial for method selection, particularly for clinical applications. The diagram below illustrates the multi-faceted decision-making process.

Figure 2: Key decision factors beyond initial success rate for selecting a reprogramming method. Colors indicate relative advantage (green), caution (red), or neutral (yellow).

Summary of Critical Factors:

Genomic Safety and Transgene Clearance: Both methods are "footprint-free" in principle. However, the Sendai virus is an RNA virus that remains in the cytoplasm and is reliably diluted out over passages [32]. In contrast, episomal plasmids can be retained in a significant subset of hiPSC lines (over 30% at passage 10), requiring rigorous quality control to confirm loss [29]. A noted concern with Sendai virus is the potential for persistence, particularly when hiPSCs are cultured in naive media conditions, which may select for cells retaining the virus and its exogenous factors [35].

Genetic Stability: Karyotypic analyses reveal that Sendai virus-derived hiPSCs have a lower rate of aneuploidy (4.6%) compared to episomal-derived lines (11.5%) [29]. This makes SeV a potentially safer choice from a genetic integrity standpoint.

Workload and Practicality: The Sendai virus method demands the least hands-on time (approximately 3.5 hours until colony picking) and is relatively straightforward, involving a single transduction step [29]. The episomal method requires nucleofection expertise and slightly more hands-on time (4 hours). However, the need to screen a larger number of SeV-derived clones for viral clearance and Epi-derived clones for plasmid retention adds to the downstream workload for both [29].

The direct comparative analysis of Sendai virus and episomal reprogramming methods reveals a nuanced picture. The Sendai virus method demonstrates a statistically significant advantage in reprogramming efficiency, generating more iPSC colonies per input cell, while both methods show equally high success rates in terms of being able to reprogram most somatic cell samples [27] [29].

For research applications where the highest efficiency and lowest aneuploidy rate are prioritized, and where rigorous screening for viral clearance is feasible, the Sendai virus method is often the superior choice. Conversely, for projects or facilities where viral vectors are prohibited or heavily restricted, the episomal method provides a robust, non-viral alternative, albeit with a requirement for careful monitoring of plasmid retention.

Future advancements in reprogramming will likely focus on refining these protocols further, perhaps through the use of optimized small-molecule cocktails that can modulate signaling pathways like TGF-β to enhance efficiency, particularly for challenging senescent or pathologic somatic cells [34] [14]. The ultimate goal remains the consistent generation of clinically safe, high-quality hiPSCs, a pursuit for which this direct comparison provides essential guidance.