Overcoming the Vascularization Bottleneck: Advanced Strategies for Engineering Thick, Clinically Relevant Tissues

The inability to create functional, perfusable vascular networks remains a primary obstacle in tissue engineering, preventing the clinical translation of thick, metabolically active tissues and organs.

Overcoming the Vascularization Bottleneck: Advanced Strategies for Engineering Thick, Clinically Relevant Tissues

Abstract

The inability to create functional, perfusable vascular networks remains a primary obstacle in tissue engineering, preventing the clinical translation of thick, metabolically active tissues and organs. This article provides a comprehensive analysis for researchers and drug development professionals, covering the foundational biology of vascularization, cutting-edge engineering methodologies from 3D bioprinting to self-assembly, and critical troubleshooting of persistent bottlenecks like cell source limitations and immune integration. It further explores advanced validation techniques using in vitro microphysiological systems for disease modeling and drug screening. By synthesizing insights across these four core intents, this review aims to equip the field with an interdisciplinary roadmap to overcome diffusion limits and achieve the grand challenge of engineering scalable, vascularized human tissues.

The Biological Imperative: Why Vascularization is the Gatekeeper to Thick Tissue Engineering

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the 100-200 µm diffusion limit and why is it a critical bottleneck in tissue engineering? The 100-200 µm diffusion limit refers to the maximum distance oxygen and nutrients can effectively travel through biological materials to reach cells before being consumed. This creates a critical barrier because in tissue-engineered constructs thicker than this, cells located in the core region face oxygen deprivation and nutrient shortage, leading to hypoxia (oxygen levels <5%) and ultimately cell death via apoptosis or necrosis. This phenomenon severely restricts the size and clinical applicability of engineered tissues [1] [2] [3].

Q2: How does the initial inflammatory response after implantation further exacerbate hypoxia? Following implantation, the host's inflammatory response increases the local metabolic demand for oxygen, creating a paradoxical situation where oxygen demand rises precisely when its supply is most limited. Furthermore, before the implanted tissue achieves functional connection to the host's blood vessels (anastomosis), the tissue is depleted of oxygen, resulting in hypoxic (<5% dissolved oxygen) followed by anoxic (<0.5% dissolved oxygen) microenvironments in the scaffold's core [1].

Q3: What are the primary differences between hypoxia and hyperoxia, and why is the balance crucial? Hypoxia is a condition of insufficient oxygen supply, which forces cells to rely on inefficient anaerobic respiration, leading to acidification from lactic acid build-up and the initiation of apoptosis. Hyperoxia is an excess of oxygen, which can lead to overproduction of reactive oxygen species (ROS), causing significant oxidative damage to cells. A precise balance is crucial because both extremes are detrimental to cell survival, function, and integration of tissue constructs [2] [3].

Q4: Beyond oxygen, what other transport limitations exist in large tissue constructs? The diffusion challenge extends beyond oxygen. Cells in the core of large constructs also suffer from:

- Nutrient Deprivation: Essential nutrients like glucose are consumed by cells on the construct's periphery, failing to reach the center.

- Waste Accumulation: Metabolic waste products (e.g., lactic acid) build up in the core, leading to toxic microenvironments and low pH.

- Impaired Signaling: Diffusion limitations can disrupt vital paracrine signaling between cells, affecting tissue development and repair [2].

Q5: What key signaling pathway is activated by hypoxic conditions, and what is its dual role? The primary pathway activated by hypoxia is mediated by Hypoxia-Inducible Factors (HIFs). Under normal oxygen levels, HIF subunits are constantly degraded. In hypoxia, HIFs stabilize, move to the nucleus, and bind to Hypoxia Response Elements (HREs), activating genes involved in angiogenesis (like VEGF), cell survival, and metabolism. While this is a protective cellular response, its chronic activation in tissue constructs can indicate unresolved diffusion limitations and may promote unfavorable outcomes like inflammation [4] [3].

Diagram Title: HIF Signaling Pathway in Hypoxia

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Diagnosing and Mitigating Hypoxia in 3D Constructs

Problem: Cell death and necrotic core formation in thick (>200 µm) tissue constructs.

Symptoms:

- Significant increase in apoptotic markers (e.g., activated caspase-3) in the construct's core after 48-72 hours in culture [2].

- Low pH and buildup of lactic acid in the culture medium, indicating a shift to anaerobic metabolism [2].

- Upregulation of hypoxia markers (e.g., HIF-1α stabilization) and downstream genes like VEGF in the core region [3].

- Poor cell viability specifically in the central regions of the scaffold, while periphery cells remain healthy.

Solutions and Methodologies:

Table 1: Strategies to Overcome the Oxygen Diffusion Limit

| Strategy | Mechanism of Action | Key Experimental Protocols | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oxygen-Generating Biomaterials (OGBs) [1] | Solid peroxides (e.g., CaO₂, MgO₂) react with water to release oxygen over time. | 1. Incorporate CaO₂ particles (5-50 µm) into polymers like PLGA or PCL.2. Fabricate scaffolds via solvent casting/particulate leaching or electrospinning.3. Validate oxygen release using a dissolved oxygen meter over 10-14 days in PBS at 37°C.4. Assess cell viability under hypoxic conditions (1-5% O₂) vs. control scaffolds. | Provides sustained, localized oxygen supply for up to 10 days. Can be tailored for controlled release kinetics. | Risk of burst release and toxic ROS generation. pH shifts may occur. Release kinetics depend on scaffold porosity and hydration. |

| Perfluorocarbons (PFCs) [1] [3] | Chemically inert compounds with high oxygen solubility act as synthetic oxygen carriers. | 1. Emulsify PFCs or incorporate PFC-nanoparticles into hydrogels or scaffolds.2. Pre-saturate scaffolds with oxygen before cell seeding or during culture.3. Measure oxygen tension within the construct using microsensors or fluorescent probes. | High oxygen-dissolving capacity (e.g., 20x greater than water). Biocompatible and inert. Linear oxygen release relative to partial pressure. | May require pre-saturation. Can be expensive. Long-term biocompatibility of some formulations requires further study. |

| Prevascularization Strategies [4] [2] | Creating a primitive vascular network within the construct in vitro before implantation. | 1. Co-culture endothelial cells (ECs) with supportive cells (e.g., fibroblasts, MSCs) in a 3D scaffold (e.g., fibrin, collagen).2. Use patterned scaffolds or bioprinting to create channeled architectures.3. Supplement with pro-angiogenic factors (VEGF, bFGF) to promote vessel maturation.4. Apply shear stress in a bioreactor to enhance endothelial network formation. | Creates a native-like transport system. Promotes rapid anastomosis with host vasculature upon implantation. | Technically complex and time-consuming. Ensuring functionality and stability of the engineered network is challenging. |

| Bioreactor-Enhanced Culturing [2] | Uses convective flow to perfuse media through the construct, overcoming diffusion limits. | 1. Place the construct in a perfusion bioreactor system.2. Optimize flow rates to ensure sufficient nutrient delivery and waste removal without causing shear stress damage.3. Monitor metabolic parameters (glucose, lactate, O₂) in the inlet and outlet media in real-time. | Ensures uniform cell distribution and viability throughout large constructs. Mimics physiological shear forces. | Requires specialized, often costly equipment. Optimization of flow dynamics is necessary for each construct type. |

Diagram Title: Troubleshooting Workflow for Hypoxic Constructs

Guide 2: Designing Experiments to Quantify Diffusion and Cell Viability

Objective: Accurately measure oxygen gradients and their correlation with cell survival in a 3D scaffold.

Experimental Workflow:

Scaffold Fabrication & Instrumentation:

- Fabricate scaffolds with a known, reproducible geometry (e.g., 5mm diameter x 2mm thick discs).

- If possible, embed optical fluorescent oxygen sensors (e.g., based on ruthenium complexes) at different depths within the scaffold during fabrication [5].

Cell Seeding and Culture:

- Seed scaffolds at a clinically relevant cell density (e.g., 10-50 million cells/mL). Ensure uniform seeding using dynamic methods (e.g., orbital shaking or perfusion) [6].

- Culture under standard (normoxic) and controlled hypoxic (e.g., 1-2% O₂) conditions in an incubator to simulate pre-vascularization conditions.

Real-Time Oxygen Mapping:

- Use a fiber-optic oxygen microsensor to manually profile the oxygen tension from the surface to the core of the scaffold at predetermined time points (e.g., days 1, 3, 7) [5].

- Alternatively, use a fluorescence lifetime imaging microscope (FLIM) to read the embedded oxygen sensors non-invasively and create a 2D oxygen map.

Endpoint Viability and Hypoxia Analysis:

- Viability Staining: Perform a live/dead assay (e.g., Calcein-AM/Propidium Iodide) on cross-sectioned scaffold slices. Quantify the ratio of live to dead cells as a function of distance from the surface.

- Hypoxia Staining: Immunofluorescence staining for HIF-1α or use pimonidazole hydrochloride, a hypoxic marker that forms protein adducts in cells with oxygen tension <1.3%. Co-stain with DAPI for nuclei [5].

- Histological Analysis: Process scaffolds for histology (H&E staining) to identify pyknotic nuclei and necrotic regions.

Data Correlation:

- Correlate the measured oxygen gradients with the spatial distribution of cell death and hypoxia markers. This data can be used to validate mathematical models of oxygen diffusion and consumption in your specific scaffold [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Investigating and Overcoming Diffusion Limits

| Item / Reagent | Function / Application | Key Considerations & Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Calcium Peroxide (CaO₂) | Oxygen-generating material. Releases O₂ upon hydrolysis. | Considerations: Purity affects O₂ release kinetics. Can increase pH and generate H₂O₂. Use in composite polymers (PLGA, PCL) to control release [1]. |

| Perfluorocarbons (PFCs) | Synthetic oxygen carriers with high O₂ solubility. | Examples: Perfluorodecalin, Perfluoro-15-crown-5-ether. Can be used as emulsions or encapsulated in nanoparticles for integration into hydrogels [1] [3]. |

| Pimonidazole HCl | A chemical probe that forms irreversible adducts in hypoxic cells (<1.3% O₂). | Application: Detected via specific antibodies; allows for immunohistochemical identification and quantification of hypoxic regions in fixed tissue constructs [5]. |

| Hydrogel ECM Models (e.g., MaxGel) | A model extracellular matrix hydrogel for studying diffusion. | Application: Used in Multiple Particle Tracking (MPT) analysis to study how nanoparticle shape and size affect diffusion through biological gels, informing drug delivery system design [7]. |

| Recombinant VEGF / bFGF | Pro-angiogenic growth factors. | Application: Added to culture media to induce and stabilize the formation of endothelial tubules in prevascularization strategies [4] [2]. |

| HIF-1α Antibody | For immunofluorescence detection of stabilized HIF-1α protein. | Application: A key marker for confirming cellular hypoxic response. Nuclear localization indicates pathway activation [3]. |

| Dissolved Oxygen Probe | For measuring oxygen concentration in solution or culture media. | Considerations: Essential for validating the oxygen release profile from OGBs or O₂-saturated PFCs in real-time [1]. |

| Matrigel | Basement membrane extract for tubule formation assays. | Application: Used in standard in vitro angiogenesis assays where endothelial cells form capillary-like tubule networks [4]. |

Diagnostic Techniques & Quantitative Biomarkers

How can I non-invasively monitor vascularization and predict implant failure in real-time?

Ultrasound-guided photoacoustic (US/PA) imaging is an emerging, non-invasive technology that allows for longitudinal monitoring of vascular changes around subcutaneous implants. It can detect signs of vascular compromise approximately 2–4 weeks before visible skin necrosis occurs [8].

The table below summarizes key quantitative biomarkers measurable with this technique.

Table 1: Key Biomarkers for Photoacoustic Imaging Monitoring

| Biomarker | Wavelength (nm) | Measured Parameter | Significance in Predicting Failure |

|---|---|---|---|

| PA Vasculature | 532 nm | Vascular density and structure | Most sensitive biomarker; reduction of up to 48% correlates strongly with skin health (R >0.85) [8] |

| Total Hemoglobin | 700-950 nm | Hemoglobin concentration | Indicates local blood volume and oxygen-carrying capacity [8] |

| Spatial Hemoglobin Maps | 700-950 nm | Local distribution of vasculature | Local reductions precede specific sites of skin breakdown (dehiscence) [8] |

Experimental Protocol: Longitudinal US/PA Imaging

- Animal Model: Subcutaneous implantation in SKH1-Elite hairless mice (or similar).

- Implant Types: 3D-printed porous poly-ɛ-caprolactone implants (e.g., unimodal cube, bimodal cube, unimodal dome) [8].

- Imaging Schedule: Perform US/PA imaging bi-weekly over a 12-week period [8].

- Data Correlation: Correlate PA biomarkers (vasculature at 532 nm, total hemoglobin) with a clinical skin health score (e.g., a modified National Pressure Injury Advisory Panel system) [8].

Figure 1: Experimental workflow for longitudinal photoacoustic monitoring of implant integration, showing key biomarkers and their prognostic outcomes.

Evidence-Based Graft Selection

What does the evidence say about vascularized vs. non-vascularized bone grafts for repairing non-union fractures?

In the context of scaphoid nonunion fractures, a meta-analysis of 62 studies demonstrates superior outcomes for vascularized bone grafts (VBGs) compared to non-vascularized bone grafts (NVBGs). VBGs directly address the core problem of poor blood supply, leading to faster and more reliable healing [9].

Table 2: Comparative Efficacy of Bone Graft Types for Scaphoid Nonunion

| Graft Type | Union Rate | Time to Healing | Key Functional Outcomes | Considerations & Drawbacks |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vascularized Bone Graft (VBG) | Significantly Higher | Shorter | Better grip strength and functional wrist scores (MMWS) [9] | Higher technical complexity, longer surgery, risk of donor-site morbidity [9] |

| Non-Vascularized Bone Graft (NVBG) | Lower | Longer | Improved but generally inferior to VBG outcomes [9] | Donor-site morbidity (5-10%), higher risk of graft failure in avascular environments [9] |

| Bone Biomaterial Graft | Promising, comparable to NVBG | Data Limited | Potential for good functional recovery [9] | Emerging technology; limited clinical data; requires more validation [9] |

Conclusion for Clinical Practice: VBGs are strongly indicated for complex cases with compromised blood supply (e.g., proximal pole fractures). NVBGs may suffice for simpler, well-vascularized non-unions. Bone biomaterials represent a promising less-invasive alternative but are not yet a gold standard [9].

Therapeutic Strategies & Molecular Pathways

What signaling pathways can be targeted to enhance osteogenesis and vascularization in smart implants?

"Smart" bone implants are engineered to actively promote healing by releasing bioactive ions or molecules that influence key cellular signaling pathways. These pathways regulate bone-forming cells (osteoblasts), blood vessel-forming cells (endothelial cells), and immune cells [10].

Table 3: Key Signaling Pathways and Smart Implant Strategies for Bone Repair

| Signaling Pathway | Implant Material / Strategy | Molecular/Cellular Mechanism | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| BMP/Smad | Silica-coated GO/GelMA scaffold [10] | Adsorbs and releases endogenous BMPs; released Si⁺ ions upregulate BMP2 [10] | Enhanced osteogenic differentiation of BMSCs [10] |

| Wnt/β-catenin | Mg-1Ca/PCL scaffolds [10] | Release of Mg²⁺ ions activates the canonical Wnt pathway [10] | Promotes proliferation and osteogenesis of human BMSCs [10] |

| TGF-β | Nano-Mg(OH)₂ films on Ti [10] | Release of Mg²⁺ and creation of a weakly alkaline microenvironment [10] | Promotes osteogenesis in murine mesenchymal cells [10] |

| MAPK | Hydrogel delivery of Mg²⁺ and Zn²⁺ [10] | Synergistic release of ions upregulates the MAPK pathway [10] | Enhanced osteogenesis of human BMSCs [10] |

| Angiogenesis | Biomaterials incorporating VEGF [9] | Delivery of Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF) [9] | Stimulates new blood vessel formation at the implant site [9] |

Figure 2: Signaling pathways activated by smart implant materials, leading to enhanced bone and blood vessel formation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Materials and Reagents for Vascularized Implant Research

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Specific Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 3D-Printed Porous Polymers | Fabrication of subcutaneous implants for studying tissue integration and vascularization. | Poly-ɛ-caprolactone (PCL) implants (unimodal/bimodal cubes, domes) [8]. |

| Bioactive Ions & Delivery Systems | To create "smart" implants that release osteogenic and angiogenic factors. | Mg²⁺, Zn²⁺, Si⁺ ions; delivery via hydrogels, nano-films, or composite scaffolds (e.g., Mg-1Ca/PCL) [10]. |

| Growth Factors | Directly stimulate bone and blood vessel growth. | Bone Morphogenetic Protein-2 (BMP-2) for osteogenesis; Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF) for angiogenesis [9]. |

| Extracellular Matrix (ECM) Gels | Provide a 3D, biologically active scaffold for in vitro and in vivo cell growth and vessel formation. | Matrigel; brain-derived ECM for stroke models; bladder-derived ECM [11] [12]. |

| Mesenchymal Stromal Cells (MSCs) | Cell-based therapy to promote vascular regeneration via paracrine signaling. | Adipose-derived or bone marrow-derived MSCs; can be delivered peri-adventitially with a collagen scaffold [11]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What are the primary bottlenecks in achieving vascular regeneration for clinical applications?

The major bottlenecks include:

- Elastin Regeneration: In conditions like aortic aneurysms, protecting existing elastin and stimulating new elastin production remains a significant challenge. Current research explores stabilizers like PGG (penta galloyl glucose) and cell-based therapies [11].

- Integration with Host Vasculature: Ensuring that pre-formed vascular networks in implants rapidly connect with the host's blood circulation upon implantation is critical for the survival of thick tissue constructs [12].

- Biomaterial Limitations: The foreign body response, suboptimal biocompatibility, and variable resorption rates of biomaterials can hinder vascular integration [9].

- Spatial Complexity: Recapitulating the organ-specific density and architecture of vasculature (e.g., over 2000 capillaries/mm³ in organs like the heart and liver) is technically demanding [12].

Beyond bone, what is the significance of a necrotic core in other tissues like tumors?

A necrotic core is not merely a passive zone of cell death. In tumors, it actively promotes metastasis. Research has shown that the necrotic microenvironment is rich in factors like angiopoietin-like 7 (A-7), which remodels the tumor surroundings, induces the formation of dilated, leaky blood vessels, and facilitates the escape of circulating tumor cells (CTCs) to other parts of the body [13]. Suppressing A-7 in models dramatically reduced necrosis, CTC count, and metastasis, highlighting it as a potential therapeutic target [13].

What advanced in vitro models are available to study vascularization before animal testing?

Several 3D models provide more physiologically relevant platforms:

- Organs-on-a-Chip (OOaC): Microfluidic devices that can mimic blood flow, shear stress, and oxygen gradients, allowing for the formation of perfusable vascular networks [12].

- 3D Bioprinting: Enables the precise deposition of cells (e.g., endothelial cells, pericytes) and biomaterials ("bioinks") to create complex, predefined vascular-like structures [12].

- Spheroids and Organoids: 3D cell cultures that can self-assemble and be coaxed to develop internal endothelial networks. These can also be integrated into larger bioreactors for perfusion [12].

FAQs: Core Concepts and Definitions

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between vasculogenesis and angiogenesis?

A1: Vasculogenesis is the de novo formation of a primitive vascular network from progenitor cells called angioblasts, which differentiate into endothelial cells [14] [15]. In contrast, angiogenesis is the growth of new capillaries from pre-existing blood vessels [14] [15]. In the embryo, both processes occur, while in adults, new vessel formation primarily happens through angiogenesis, except in certain pathological conditions where vasculogenesis can re-occur [15].

Q2: What are the key growth factors and their primary roles in these processes?

A2: The key growth factors are members of the Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF) and Fibroblast Growth Factor (FGF) families [14] [15]. Their roles are outlined below:

- Table: Key Growth Factors in Vascular Development

| Growth Factor/Receptor | Primary Role | Key Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| VEGF-A | Crucial for vasculogenesis and the growth phase of angiogenesis; promotes endothelial cell proliferation, migration, and permeability [14]. | Heterozygous knockout mice die in utero with aberrant blood vessel formation [15]. |

| VEGF-R2 (flk-1/KDR) | Essential for the differentiation of angioblasts; a very early marker of endothelial commitment [14] [15]. | Knockout mice show early defects in angioblastic lineages and die by E8.5 [15]. |

| VEGF-R1 (flt-1) | Appears to play a role after VEGF-R2, involved in the correct assembly of endothelial cells into functional vessels [14] [15]. | Knockout mice produce angioblasts but fail to form proper vessels and die at E8.5 [15]. |

| FGF2 (bFGF) | Implicated in vasculogenesis and is a potent angiogenic factor [14] [15]. | Strictly required for the formation of vascular structures in quail blastodisc cultures [15]. |

| TGF-β, PDGF-BB, Angiopoietin-1 | Critical for the stabilization phase of angiogenesis; inhibit proliferation, recruit pericytes/SMCs, and promote vessel maturation [14] [15]. | Gene inactivation leads to lethality due to edemas and hemorrhages from defective vascular maturation [15]. |

Q3: What are the main in vitro models used to study vasculogenesis?

A3: The primary models are:

- Embryonic Stem (ES) Cell-Derived Embryoid Body (EB) Assay: When murine ES cells are cultured without leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF), they form three-dimensional embryoid bodies. Within these EBs, a primitive vascular plexus forms, recapitulating the differentiation of angioblasts, endothelial cell assembly, and vascular morphogenesis [15].

- Blastodisc Cultures: Adherent or suspension cultures of dissociated cells from quail blastodiscs can generate both hematopoietic and endothelial cells that aggregate into blood islands and vascular structures, dependent on FGF2 [15].

Troubleshooting Guides for Common Experimental Challenges

Q1: My endothelial cells in 3D culture are failing to form stable, mature vessels. The structures regress or undergo apoptosis. What could be wrong?

A1: Vessel regression often indicates a failure in the transition from the growth phase to the stabilization phase [15].

- Problem: Lack of vessel stabilization.

- Possible Causes and Solutions:

- Cause 1: Deficiency in stabilization factors. The culture environment may be rich in pro-growth factors like VEGF but lacking factors that promote maturation.

- Solution: Add critical stabilization factors to your medium, such as TGF-β, PDGF-BB (for pericyte recruitment), and Angiopoietin-1 [15].

- Cause 2: Incorrect timing of factor presentation. Presenting growth and stabilization factors simultaneously can be counterproductive.

- Solution: Develop a timed protocol. First, provide pro-angiogenic factors (VEGF, FGF) to promote sprouting. Then, switch to or add stabilization factors (TGF-β, PDGF-BB) to halt proliferation and promote mural cell coverage and basement membrane reconstruction [14] [15].

- Cause 3: Lack of proper co-culture. Vessels require pericytes or smooth muscle cells for stability.

- Solution: Establish a co-culture system with pericytes or smooth muscle cells to invest the endothelial tubes [14].

Q2: I am not observing any vascular sprouting (angiogenesis) in my assay. What are the potential issues?

A2: A lack of sprouting suggests a failure in the initial activation phase.

- Problem: Absence of angiogenic sprouting.

- Possible Causes and Solutions:

- Cause 1: Insufficient pro-angiogenic stimulus.

- Solution: Ensure your growth factors (e.g., VEGF-A or FGF2) are present at an effective concentration and are bioavailable [14] [15].

- Cause 2: Over-stabilized initial endothelium. The pre-existing vessel monolayer might be too quiescent.

- Solution: Use a pro-angiogenic matrix (like Matrigel or fibrin) that supports migration and invasion. You can also gently wound the monolayer to initiate the process [15].

- Cause 3: Inadequate matrix degradation. Sprouting requires local degradation of the extracellular matrix (ECM).

- Solution: Verify that the protease systems (e.g., matrix metalloproteinases) are active. The basal lamina of the "mother" vessel must be dissolved for migration to occur [14].

Q3: My 3D bioprinted cardiac construct lacks sufficient integration with the host vasculature after implantation. How can I improve this?

A3: This is a key challenge in tissue engineering of thick tissues [16].

- Problem: Poor host-graft vascular integration.

- Possible Causes and Solutions:

- Cause 1: The implanted construct lacks a pre-formed microvascular network. Relying solely on host vessel ingrowth is too slow for thick tissues.

- Solution: Pre-vascularize the construct by 3D bioprinting with bioinks containing endothelial cells (e.g., using a layer-by-layer grid method) to create an internal microvascular network. This network can then anastomose (connect) with the host's invading vessels, as demonstrated in recent studies [16].

- Cause 2: The bioink or construct environment is not conducive to vascular survival and remodeling.

- Solution: Optimize bioink composition to ensure long-term stability and functionality. It must support both cardiomyocyte and endothelial cell viability and allow for the release of angiogenic factors to attract host vessels [16].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists key reagents and their functions for setting up experiments in vascular development and engineering.

- Table: Essential Research Reagents for Vascular Engineering

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| VEGF-A | The primary pro-angiogenic factor; induces endothelial cell proliferation, permeability, and migration. Essential for initiating vasculogenesis and angiogenesis [14] [15]. |

| FGF2 (bFGF) | A potent angiogenic factor; crucial for in vitro vasculogenesis models and endothelial cell proliferation [15]. |

| TGF-β & PDGF-BB | Vessel stabilization factors; TGF-β inhibits endothelial proliferation and PDGF-BB recruits pericytes/smooth muscle cells to stabilize nascent vessels [15]. |

| Embryonic Stem (ES) Cells | Used in the Embryoid Body (EB) assay to model embryonic vasculogenesis and study endothelial differentiation de novo [15]. |

| Specialized Bioinks | Hydrogels for 3D bioprinting that support the encapsulation and survival of endothelial and parenchymal cells (e.g., cardiomyocytes) and enable the fabrication of microvascular networks [16]. |

| Integrin αvβ3 Inhibitors | Used to study the role of adhesion molecules in tumor angiogenesis; however, its role is less crucial in developmental angiogenesis [15]. |

| VE-Cadherin Antibodies | For studying and blocking endothelial cell-cell adhesion, which is essential for vessel integrity and tube formation [15]. |

Key Experimental Protocols & Workflows

A. Protocol: Murine ES Cell Embryoid Body (EB) Assay for Vasculogenesis

This protocol allows for the in vitro study of the entire vasculogenesis process [15].

- Maintenance of Undifferentiated ES Cells: Culture mouse ES cells on a feeder layer or in gelatinized flasks with media supplemented with Leukemia Inhibitory Factor (LIF).

- EB Formation (Differentiation Initiation): Harvest ES cells and transfer them to non-adherent bacterial-grade Petri dishes. Culture in media without LIF. Cells will aggregate to form simple embryoid bodies.

- Maturation and Vasculogenesis: Continue culturing EBs for up to 10-15 days. During this period, they may develop into cystic EBs. Spontaneous differentiation will occur, leading to the formation of blood islands and vascular channels within the EB walls.

- Analysis: Fix EBs and analyze vascular structure formation via immunohistochemistry for endothelial markers (e.g., PECAM-1, VE-cadherin, Flk-1) [15].

B. Protocol: General Workflow for a Sprouting Angiogenesis Assay

This workflow outlines the steps for assessing pro- or anti-angiogenic compound effects.

- Endothelial Cell Plating: Plate human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) or a similar cell type onto a layer of gelled extracellular matrix (e.g., Matrigel, Collagen) in a multi-well plate.

- Tube Formation (Initial Morphogenesis): Allow cells to form capillary-like tube networks over 4-18 hours.

- Compound Treatment: Add the test compound (angiogenic factor, inhibitor, etc.) to the medium.

- Incubation and Sprouting Assessment: Incubate for a further 6-48 hours. Quantify changes in the network by measuring parameters like total tube length, number of branch points, or number of sprouts using microscopy and image analysis software.

- Validation with Specific Assays: Follow up with targeted assays to understand the mechanism:

- Proliferation: Quantitate tritiated thymidine incorporation or perform cell counting [15].

- Migration: Use a Boyden chamber or a linear "wound healing" assay across a monolayer [15].

- Proteolysis: Test using zymographic assays for matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) [15].

- Apoptosis: Measure by the TUNEL method or quantitation of caspases [15].

Signaling Pathways in Vascular Development

The following diagram summarizes the core signaling pathways involved in the sequential processes of vasculogenesis and angiogenesis, highlighting the key factors and their primary functions.

A fundamental roadblock in tissue engineering is the inability to rapidly form functional vascular networks within thick, engineered tissues (>1 cm³). Without these networks, cells in the core of the construct perish due to hypoxia and insufficient nutrient supply, as the diffusion limit of oxygen is only 100–200 μm [4] [17]. This diffusion limit leads to necrosis and ultimate implant failure [4]. Overcoming this requires a deep understanding of the key cellular players responsible for building stable, functional blood vessels: Endothelial Cells (ECs), which form the vessel lining, and Mural Cells (Pericytes and Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells (vSMCs)), which provide structural support and stability [18] [19]. This technical support center provides targeted guidance for researchers aiming to harness these interactions to overcome vascularization limitations.

Core Concepts: Cellular Functions and Signaling Pathways

What are the distinct roles of endothelial cells, pericytes, and vascular smooth muscle cells?

The stability and function of blood vessels rely on the coordinated interactions between endothelial and mural cells. The table below summarizes their distinct roles and characteristics.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Vascular Cells.

| Cell Type | Location | Primary Functions | Key Identification Markers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Endothelial Cells (ECs) | Inner lining of all vessels (Tunica Intima) | Form a non-thrombogenic barrier; regulate vascular tone and permeability; initiate angiogenesis [6]. | VE-cadherin [19], CD31 [17] |

| Pericytes | Microvasculature (capillaries, post-capillary venules) embedded within the basement membrane [18] | Stabilize capillaries; regulate blood flow; induce blood-brain barrier properties [18] [19]. | PDGFR-β, NG2, CD13, α-SMA, Desmin [18] |

| Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells (vSMCs) | Larger vessels (arteries, veins) in the Tunica Media [18] | Provide structural strength and contractility; regulate vessel diameter and blood pressure [20] [6]. | α-SMA, SMMHC, SM22, Calponin, Desmin [21] |

How do these cells communicate to stabilize vessels?

Stable vascular maturation depends on precise bidirectional signaling between ECs and mural cells. The following diagram illustrates the key signaling pathways involved.

Diagram 1: Key EC-Pericyte Signaling Pathways for Vessel Stabilization.

The PDGF-BB/PDGFR-β axis is a primary recruitment signal where ECs secrete PDGF-BB, attracting PDGFR-β-positive pericytes [18] [19]. Subsequently, pericytes secrete Angiopoietin-1 (Ang-1), which binds to Tie2 receptors on ECs, promoting vessel quiescence and stability [18]. Additional factors like Endothelin-1 and PDGF-DD from ECs further support pericyte recruitment and proliferation [18]. Direct physical contact through adherens junctions (e.g., N-cadherin) and gap junctions (e.g., Connexin 43) is equally critical for communication and stabilization [18] [19]. A major function of this cross-talk is the coordinated production and maintenance of the vascular basement membrane, which is essential for preventing abnormal vessel expansion and elasticity [19].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful experimentation requires high-quality, well-characterized reagents. The following table lists essential tools for studying vascular cells.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Vascular Cell Biology.

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Key Considerations & Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Hydrogels | Provide a 3D extracellular matrix (ECM)-mimetic environment for cell culture and vessel formation [18]. | Collagen-I: Natural, fibrous, tunable stiffness [18]. Matrigel: Basement membrane extract; contains laminin and collagen IV [18]. GelMA (Gelatin Methacryloyl): Tunable, photopolymerizable [22]. |

| Growth Factors & Cytokines | Direct cell differentiation, proliferation, migration, and network formation. | PDGF-BB: Critical for pericyte/vSMC recruitment and proliferation [18] [21]. VEGF: Key driver of endothelial cell angiogenesis [18] [4]. TGF-β: Involved in mural cell differentiation and stabilization [19]. |

| Cell Isolation Reagents | Enzymatic digestion of tissues to isolate primary cells. | Collagenase: Digests collagen in connective tissue. Elastase: Breaks down elastic fibers in vessels [20]. Trypsin/TrypLE: Used for passaging adherent cells [21] [20]. |

| Cell Culture Media | Supports the growth and maintenance of specific cell types. | SmBm BulletKit: Commercial medium optimized for smooth muscle cells [20]. Endothelial Cell Growth Medium: Typically supplemented with VEGF, FGF, and EGF. |

| Antibodies for Characterization | Identify and confirm cell identity via immunofluorescence, flow cytometry. | α-SMA (Alpha-Smooth Muscle Actin): Marks contractile mural cells [21] [17]. NG2 (CSPG4): A common pericyte marker [18]. HuCD31/CD31 (PECAM-1): Specific for endothelial cells [17]. |

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Common Co-Culture Challenges

Q: In my 3D hydrogel co-culture, pericytes are not associating with the endothelial tubes. What could be wrong?

- A: This is typically a signaling or timing issue. Consider the following:

- Confirm Growth Factor Activity: Ensure your culture medium contains adequate PDGF-BB, the primary EC-derived chemoattractant for pericytes. Check the concentration and bioactivity of your stock [18].

- Optimize Seeding Timing: In some protocols, adding pericytes after ECs have begun to form tubules (e.g., 24-48 hours later) is more effective than co-seeding simultaneously, as it mimics the physiological sequence of events.

- Check Matrix Stiffness: The biomechanical properties of your hydrogel (e.g., Collagen-I, Fibrin) profoundly affect cell behavior. An inappropriate stiffness can inhibit both EC network formation and pericyte migration. Stiffness should mimic that of native soft tissues [18] [22].

Q: My engineered microvessels are unstable and regress after a few days in culture. How can I improve longevity?

- A: Vessel regression indicates a lack of maturation signals.

- Enhance Mural Cell Coverage: Ensure you have a sufficient ratio and viable population of pericytes or vSMCs. These cells provide essential survival signals like Angiopoietin-1 [18] [19].

- Promote Basement Membrane Formation: The cross-talk between ECs and pericytes is crucial for depositing a robust basement membrane (containing collagen IV, laminin). Allow sufficient culture time (7-14 days) for this matrix to assemble, as it is critical for mechanical stability [19].

- Introduce Physiological Cues: Use advanced platforms like microfluidic chips that provide interstitial flow, which has been shown to enhance vessel maturation and stability [18].

Cell Sourcing and Characterization Issues

Q: What are the best sources for obtaining pericytes and how can I confirm their identity?

- A: Pericytes can be sourced from multiple places, but they require validation with a panel of markers due to the lack of a single unique identifier.

- Primary Isolation: Can be isolated from microvessel-rich tissues like brain, retina, or adipose tissue [18]. This can yield tissue-specific pericytes but may involve complex isolation procedures.

- Stem Cell Differentiation: Human-induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) can be differentiated into pericytes, offering a scalable and patient-specific source [18].

- Validation: Use a combination of positive and negative markers. Positive markers include PDGFR-β, NG2, and CD13. Assess the expression of cytoskeletal proteins like α-SMA and Desmin. Confirm the absence of endothelial (e.g., VE-cadherin) and fibroblast markers [18] [21].

Q: My isolated vascular smooth muscle cells (vSMCs) are not expressing contractile markers. What is happening?

- A: VSMCs can undergo phenotypic modulation from a contractile to a synthetic/proliferative state in culture.

- Culture Conditions: Standard culture conditions on plastic with high serum promote the synthetic phenotype. To induce the contractile phenotype, reduce serum concentration and use specialized media (e.g., SmBm) [20].

- Use of TGF-β1: Treating cells with recombinant TGF-β1 is a well-established method to upregulate the expression of contractile genes like α-SMA, calponin, and SM22 [20].

- Passage Number: The contractile phenotype is often lost at higher passages. Use low-passage cells for experiments requiring a contractile phenotype.

In Vivo Integration Challenges

Q: After implantation, my prevascularized construct fails to anastomose with the host circulation. What host factors should I consider?

- A: The host environment is critical for successful integration, and the choice of animal model can drastically alter outcomes.

- Animal Model Discrepancies: Studies show identical engineered tissues can have divergent vascularization and engraftment in athymic nude mice versus athymic rats. Mice may support better guided vascularization, while rats might support better survival of certain cell types like cardiomyocytes [17].

- Implantation Site: The anatomic location (e.g., subcutaneous space, intraperitoneal fat pad, epicardial surface of the heart) influences vascular ingrowth, inflammatory response, and the stability of the implanted construct [17].

- Host Inflammation: A strong inflammatory response can degrade the graft and disrupt patterned vessels. Strategies to modulate the host immune response may be necessary for successful anastomosis [17].

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Establishing a 3D EC-Pericyte Co-Culture in Collagen-I Hydrogel

This protocol is adapted from methods used to investigate EC-pericyte interactions and capillary network co-assembly [18].

Diagram 2: Workflow for 3D EC-Pericyte Co-Culture.

Materials

- High-concentration Rat Tail Collagen-I (e.g., ~8-10 mg/mL)

- Endothelial Cells (e.g., HUVECs, human retinal ECs)

- Pericytes (e.g., primary human brain or iPSC-derived)

- Cell culture medium (e.g., EGM-2 for ECs, pericyte growth medium, or a shared co-culture medium)

- Neutralization Solution (e.g., 0.1-1M NaOH, 10x PBS)

- Sterile tissue culture plates (e.g., 24-well plate)

Step-by-Step Procedure

- Prepare Collagen-I Working Solution: On ice, mix the high-concentration Collagen-I with neutralization solution and 10x PBS according to the manufacturer's instructions to achieve a final working concentration of 2.5 - 3.0 mg/mL at a physiological pH (pink color). Keep on ice to prevent premature polymerization [18].

- Seed Cells and Polymerize Hydrogel: Quickly mix the cell suspensions (e.g., a 3:1 or 5:1 ratio of ECs to Pericytes) with the neutralized collagen solution. Gently pipette the cell-collagen mixture into the wells of a culture plate. Incubate the plate at 37°C for 30-45 minutes to allow for complete gel polymerization.

- Add Culture Medium: After polymerization, carefully add pre-warmed culture medium on top of the hydrogel without disturbing it. The medium can be supplemented with pro-angiogenic factors like VEGF (50 ng/mL) and other relevant factors identified in studies, such as SCF, IL-3, and SDF-1α [18].

- Maintain and Monitor Culture: Change the culture medium every 48 hours. Observe the development of endothelial tubular networks and pericyte association daily using an inverted light microscope.

- Analyze Networks: After 7-14 days in culture, fix the constructs and perform immunostaining for markers like CD31 (ECs) and NG2 or α-SMA (Pericytes) to visualize network morphology and pericyte coverage. Quantify parameters such as branch length, junction numbers, and pericyte association index.

Expected Outcomes

Within 3-7 days, you should observe extensive EC tubular networks. Pericytes should migrate along and wrap around these tubes, leading to more mature and stable structures compared to EC-only cultures.

Advanced Models: From Microfluidics to Application

To truly overcome the limitation of vascularizing thick tissues, moving beyond simple hydrogels to more sophisticated models is essential.

- Microfluidic Vasculature-on-a-Chip: These platforms allow for the precise control of physiochemical cues, such as interstitial flow and shear stress, which are critical for guiding angiogenesis and enhancing barrier function [18]. They enable high-resolution, real-time imaging of the dynamic interactions between ECs and pericytes during vascular morphogenesis.

- Guided Vascularization In Vivo: For implantation, research shows that pre-patterning endothelial cells into specific geometries (e.g., parallel "cords") within engineered tissues can act as "railroad tracks," guiding the formation of chimeric host-graft vessels that efficiently anastomose with the host circulation [17]. This approach has been shown to improve the survival of embedded functional cells, such as hepatocytes and cardiomyocytes [17].

- Bioreactors for Maturation: The use of dynamic bioreactor systems that provide pulsatile flow and mechanical conditioning is a final, critical step for developing implantable large-scale blood vessels with sufficient mechanical strength to withstand physiological blood pressures [6].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the primary cellular mechanism by which engineered vascular networks connect to the host circulation? Engineered vascular networks connect to the host vasculature through a previously unidentified process called "wrapping-and-tapping" anastomosis [23] [24]. This process does not rely on tip cell connections or vacuole fusion. Instead, at the host-implant interface, implanted endothelial cells (ECs) first wrap around nearby host vessels [23]. These wrapping ECs then express high levels of matrix metalloproteinase-14 (MMP-14) and matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9), which facilitate the reorganization of the host vessel's basement membrane and pericytes, and the localized displacement of the underlying host endothelium [23]. In this way, the implanted ECs effectively replace segments of the host vessel wall to directly tap into the host blood supply and divert flow into the implanted network [23] [24].

Q2: My implanted tissues vascularize poorly in my current animal model. Could the host species or anatomic location be the cause? Yes, the host model and anatomic implant location are critical factors that can lead to divergent outcomes, even when using identical engineered tissues [17]. For instance, guided vascular networks formed and anastomosed robustly in both the intraperitoneal space and on the heart of athymic nude mice [17]. However, the same tissues elicited substantive inflammatory changes when implanted onto the hearts of athymic rats, which disrupted vascular patterning and led to graft degradation [17]. This underscores that the host environment can override the intrinsic vascularization capacity of an engineered tissue.

Q3: Besides endothelial cells, what other cell types are crucial for building stable, implantable vascular networks? Creating stable, implantable vasculature requires a multi-lineage approach that recapitulates the structure of native blood vessels.

- Smooth Muscle Cells (SMCs) and Pericytes: These cells provide structural support and are effectors of vascular tone. They form the tunica media around larger vessels, while pericytes abut the endothelium in capillaries [25] [6]. The presence of α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA)+ cells partially or fully encircling engineered endothelial lumens is a marker of mature, stabilized microvessels [17].

- Stromal Cells/Fibroblasts: These cells are a key component of the tunica adventitia, providing connective tissue and ECM to maintain the overall vessel structure [6]. The inclusion of mesenchymal precursor cells or fibroblasts with endothelial cells significantly enhances the formation of perfused, vascular networks in vivo [23] [25].

Q4: How quickly can I expect blood perfusion to be established in a prevascularized implant? In optimized models, anastomosis between host vessels and implanted EC networks can occur as early as two weeks after implantation [23]. The "wrapping-and-tapping" mechanism facilitates this rapid connection. Furthermore, studies have shown that by 7 days post-implantation, a high percentage of pre-patterned endothelial cords can become associated with lumens containing host red blood cells, indicating successful anastomosis and perfusion [17].

Q5: What are the major structural requirements for an engineered tissue to integrate successfully with the host vasculature? Successful integration depends on recapitulating key structural and biological features:

- Trilaminate Structure: Ideal engineered vessels mimic native anatomy with a tunica intima (endothelial cell layer for anti-thrombogenicity), a tunica media (smooth muscle cells for mechanical strength), and a tunica adventitia (fibroblasts in connective tissue for structural integrity) [25] [6].

- Mechanical Properties: The construct must have sufficient mechanical strength to withstand physiologic blood pressures (approximately 2000–3000 mmHg burst strength for arteries) and surgical handling, such as stitching during implantation [6].

- Non-thrombogenic Surface: The luminal surface must be lined with a confluent layer of endothelial cells to prevent clot formation and ensure patency [25] [6].

Troubleshooting Guide

Problem 1: Lack of Perfusion in Engineered Grafts

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| No blood flow in implanted networks 2+ weeks post-implantation. | Insufficient or unstable anastomosis with host vasculature. | Co-implant stromal cells (e.g., 10T1/2, MSCs) with ECs at a ratio of 1:4 (stromal:EC) to enhance network stability and anastomosis [23]. |

| Graft necrosis or central cell death. | Delayed perfusion; diffusion limit of oxygen (100-200 μm) exceeded [17]. | Pre-form patterned endothelial networks (e.g., "cords") within the graft to act as "railroad tracks" for guided host-graft vessel formation and faster perfusion [17]. |

| Inflammatory degradation of the graft. | Host-dependent foreign body response or inflammation [17]. | Consider switching host animal models (e.g., from rat to mouse) or anatomic location based on pilot studies [17]. Use immunodeficient models to minimize rejection. |

Problem 2: Host-Dependent Variability in Vascularization & Engraftment

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Robust vascularization but sparse survival of co-implanted functional cells (e.g., cardiomyocytes). | Host factors that differentially support vascularization vs. parenchymal cell engraftment [17]. | Athymic mice supported robust guided vascularization but relatively sparse cardiac grafts, while athymic rats supported >3-fold larger cardiomyocyte grafts despite disrupted vessels [17]. Test multiple host models for your specific cell type. |

| Patterned vascular networks fail to form; severe inflammation at implant site. | Aggressive host inflammatory response degrading the graft or disrupting patterning [17]. | This was observed in athymic rats [17]. Pre-assess the host inflammatory response to your biomaterial in the target anatomic location before large-scale studies. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Investigating Anastomosis via the Cranial Window Model

This protocol is adapted from methods used to discover the "wrapping-and-tapping" mechanism [23].

Cell Preparation:

- Culture Human Umbilical Vein Endothelial Cells (HUVECs) in endothelial growth medium.

- Culture mouse mesenchymal precursor cells (e.g., 10T1/2) in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) with 10% FBS.

- Optionally, transduce HUVECs with a fluorescent protein (e.g., GFP) using retrovirus for in vivo tracking.

Construct Fabrication:

- Suspend 8x10⁵ HUVECs and 2x10⁵ 10T1/2 cells in 1 mL of ice-cold rat-tail type I collagen (1.5 mg/mL) solution mixed with human plasma fibronectin (90 μg/mL).

- Adjust pH to 7.6 using 1N NaOH.

- Pipette the cell suspension into a multi-well plate and incubate at 37°C for 30 minutes to allow collagen polymerization.

- Cover the solidified gel with culture medium and culture for 18-24 hours.

Implantation:

- Use a 4-mm biopsy punch to create disk-shaped gels for implantation.

- Implant the gel into a cranial window preparation in a severe combined immunodeficient (SCID) mouse [23].

Intravital Imaging & Analysis:

- Visualize host vasculature by intravenous injection of a fluorescently labeled mouse-specific CD31 antibody.

- Track blood flow by injecting mouse red blood cells labeled with lipophilic carbocyanine dyes (DiI or DiD).

- Use confocal laser-scanning microscopy for intravital imaging at various time points (e.g., from day 3 to 7 and beyond) to observe the wrapping and tapping process.

Protocol 2: Assessing Guided Vascularization with Endothelial Cords

This protocol details the creation of tissues with patterned endothelial cords for improved perfusion [17].

Cord Patterning:

- Suspend HUVECs and stromal cells in a collagen solution.

- Pipette the cell-collagen suspension into a polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) mold containing an array of parallel microchannels.

- Allow the collagen to polymerize, forming solid "endothelial cords" within the channels.

Tissue Encapsulation:

- Carefully encapsulate the patterned cord structure within a fibrin hydrogel to create the final 3D engineered tissue.

Implantation and Analysis:

- Implant the engineered tissue into the desired animal model (e.g., sutured to the intraperitoneal gonadal fat pad or the epicardial surface of the heart in athymic nude mice).

- For analysis, perfuse the animal with a biotinylated lectin intravenously prior to harvest to label perfused vessels.

- Harvest tissues at set time points (e.g., 3 and 7 days).

- Fix, section, and perform immunohistochemistry for human CD31 (to identify graft-derived endothelium) and mouse-specific markers (e.g., TER-119 for red blood cells) to confirm perfusion and pattern retention.

Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| HUVECs & Stromal Cells (10T1/2) | Foundation for self-assembling vascular networks; stromal cells enhance stability and anastomosis [23]. |

| Collagen-Fibronectin Matrix | A natural hydrogel that supports 3D cell organization, lumenogenesis, and matrix remodeling crucial for anastomosis [23]. |

| Patterned PDMS Molds | Used to create "endothelial cords," which guide the formation of structured, parallel vascular networks in vivo [17]. |

| Fluorescently Labeled Antibodies (e.g., α-mCD31) | Allows for clear visualization and distinction of the host vasculature during live imaging [23]. |

| Labeled Red Blood Cells (DiI/DiD) | Enable direct tracking and confirmation of blood flow and perfusion within the engineered networks [23]. |

| Matrix Metalloproteinase (MMP) Inhibitors | Tool to investigate the mechanistic role of MMP-14 and MMP-9 in the "wrapping-and-tapping" anastomosis process [23]. |

Process Diagrams

Building the Vascular Blueprint: From Prevascularization to 3D Bioprinting Strategies

A major obstacle in engineering thick, clinically relevant tissues is the diffusion limit of oxygen and nutrients, which is approximately 100–200 μm [4]. Without a functional vascular network, cells in the core of these constructs suffer from hypoxia and insufficient nutrient supply, leading to necrosis and ultimate graft failure [4]. Cell-based prevascularization is a promising strategy to overcome this limitation. This approach involves the co-culturing of endothelial cells (ECs) and supportive stromal cells within three-dimensional (3D) scaffolds before implantation, aiming to pre-form organized vascular networks that can rapidly anastomose with the host circulation upon grafting [4] [26] [25]. This technical support center provides targeted troubleshooting and foundational protocols to help researchers navigate the challenges of creating robust, pre-vascularized tissues.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is the primary goal of prevascularizing a tissue-engineered construct? The primary goal is to create an integrated, self-assembled network of vessel-like structures within the tissue construct in vitro that, after implantation, can quickly connect to the host's blood circulation. This anastomosis provides immediate perfusion, overcoming the diffusion limit and ensuring the survival and function of cells throughout a thick tissue graft [4] [17].

2. Why is it necessary to co-culture endothelial cells with support cells? Endothelial cells alone often form unstable and transient tubular structures. Co-culturing them with support cells—such as mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), fibroblasts, or pericytes—is crucial because these cells provide vital paracrine signals and physical support that stabilize the newly formed vascular networks, promote lumen formation, and enhance maturation by recruiting perivascular cells [4] [25].

3. What are the critical host-related factors affecting implant success? The host animal model and anatomic implantation site critically influence vascularization and engraftment. Studies show significant differences in outcomes between immunodeficient athymic nude mice and rats. Mice may support better guided vascularization of human microvessels, while rats might support better cardiomyocyte survival but exhibit more disruptive inflammation or degraded vascular patterning depending on the implant site [17].

4. How can I assess the functionality of the pre-formed networks in vitro? While full functionality (blood perfusion) can only be confirmed in vivo, several in vitro assays can indicate potential functionality. These include immunostaining for endothelial markers (e.g., CD31) to visualize network morphology, and measuring the expression of key angiogenic growth factors like VEGF, bFGF, and angiopoietins [4].

Troubleshooting Guides

Common Experimental Issues and Solutions

| Problem | Possible Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Poor Network Formation | Incorrect EC-to-support cell ratio; Suboptimal scaffold stiffness; Lack of pro-angiogenic factors. | Systemically test cell ratios (e.g., 1:1 to 1:5 ECs/Support); Tune scaffold mechanical properties to mimic native ECM; Incorporate angiogenic factors (VEGF, bFGF). |

| Networks Are Unstable/Regress | Lack of continuous biochemical cues; Insufficient ECM remodeling; Absence of mechanical stabilization. | Use a sustained-release hydrogel for growth factors; Incorporate enzymes for ECM degradation (e.g., MMP-sensitive peptides); Apply cyclic mechanical strain during culture. |

| Low Cell Viability in Construct Core | Scaffold thickness exceeds oxygen diffusion limit; High cell seeding density; Pre-formed networks are not perfusable. | Use a bioreactor for enhanced medium perfusion during culture; Pattern internal channels to mimic a rudimentary flow circuit; Optimize cell seeding density. |

| Lack of Host Anastomosis In Vivo | Host inflammatory response; Mismatch in vessel maturity; Surgical model or site is not optimal. | Use immunodeficient host models; Assess pericyte coverage (α-SMA) pre-implantation; Test different anatomic implant sites (e.g., intraperitoneal vs. epicardial). |

Quantitative Data for Experimental Planning

Table: Key Growth Factors in Prevascularization [4]

| Growth Factor | Primary Role in Angiogenesis |

|---|---|

| VEGF (Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor) | Promotes EC proliferation, migration, and survival; increases vascular permeability. |

| bFGF (Basic Fibroblast Growth Factor) | Stimulates proliferation of ECs and support cells; promotes ECM degradation. |

| PDGF (Platelet-Derived Growth Factor) | Recruits and stabilizes support cells (pericytes, SMCs) around nascent vessels. |

| TGF-β1 (Transforming Growth Factor Beta-1) | Modulates EC proliferation and stimulates ECM production by support cells. |

Table: Host Model Comparison for In Vivo Implantation [17]

| Host Model / Implant Site | Observed Vascular Outcomes | Cell Engraftment Survival |

|---|---|---|

| Athymic Nude Mouse (IP) | Robust, guided vascularization; patterned vessels anastomose with host. | Sparse cellular grafts. |

| Athymic Nude Mouse (Epicardial) | Robust, guided vascularization; patterned vessels anastomose with host. | Sparse cellular grafts. |

| Athymic Rat (Abdomen) | Substantial inflammation; graft degradation. | Not specified. |

| Athymic Rat (Epicardial) | Disrupted vascular patterning. | >3-fold larger cardiomyocyte grafts vs. mice. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Materials for Prevascularization Experiments

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Endothelial Cells (ECs) | Form the inner lining of the vascular tubes. | HUVECs, induced pluripotent stem cell-derived ECs. |

| Support / Stromal Cells | Stabilize EC networks and promote maturation. | Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs), fibroblasts, pericytes. |

| 3D Scaffold / Hydrogel | Provides a 3D environment for cell growth and network formation. | Fibrin, collagen gels, synthetic PEG-based hydrogels. |

| Angiogenic Growth Factors | Stimulate EC sprouting, tube formation, and network stability. | VEGF, bFGF (FGF-2), PDGF-BB. |

| Temperature-Responsive Dishes | Enable harvest of intact, contiguous cell sheets for layering. | Poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) grafted dishes. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Methodology: This protocol uses temperature-responsive culture dishes to create and stack 2D co-culture sheets into a 3D tissue.

- Surface Preparation: Use temperature-responsive culture dishes (e.g., grafted with poly(N-isopropylacrylamide)).

- Cell Seeding and Co-culture: Seed and culture a mixture of endothelial cells (e.g., HUVECs) and the target parenchymal cell (e.g., cardiomyocytes, fibroblasts). Culture until a confluent, contiguous cell sheet is formed.

- Cell Sheet Harvest: Reduce the culture temperature (e.g., to below 32°C). The surface becomes hydrophilic, allowing the intact cell sheet to detach spontaneously without enzyme treatment. The sheet preserves its deposited extracellular matrix and cell-cell junctions.

- 3D Stratification: Using a manipulator, gently transfer the harvested cell sheet onto a previously deposited sheet. A plunger coated with a fibrin gel can be used to handle and stack the delicate sheets. Repeat this process to create multi-layered, 3D tissues.

- Maturation and Analysis: Culture the layered construct to allow for the self-organization and formation of endothelial network structures throughout the 3D tissue.

Methodology: This protocol pre-patterns endothelial cells into defined geometries to guide vascular network formation.

- Cord Fabrication: Suspend human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) and stromal cells (e.g., MSCs) in a collagen solution.

- Molding: Pipette the cell-collagen suspension into a polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) mold featuring an array of parallel micro-channels (e.g., 50-100 µm apart). Allow the collagen to gel, forming solid "endothelial cords" within the channels.

- Tissue Encapsulation: Carefully encapsulate the entire patterned cord structure within a fibrin-based hydrogel. This bulk hydrogel can also be seeded with other cell types, such as cardiomyocytes.

- In Vitro Culture: Maintain the construct in culture to allow for preliminary network maturation.

- Implantation and Analysis: Implant the engineered tissue in vivo (e.g., suture to the epicardial surface of the heart or intraperitoneal site). Upon explantation, the guided formation of patterned, chimeric host-graft vessels can be analyzed.

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is scaffold-based vascularization critical for engineering thick tissues? Without a built-in vascular network, thick tissue constructs (>1-2 mm) face central necrosis because oxygen and nutrients cannot diffuse more than 100–200 μm from the nearest blood vessel [27] [4]. Scaffolds provide the initial 3D template to guide the formation of this essential, life-sustaining vascular network, thereby overcoming this diffusion limit and ensuring cell viability throughout the construct post-implantation [4].

Q2: What are the primary scaffold properties that influence angiogenesis? The key properties can be categorized as follows:

- Architectural: High porosity and pore interconnectivity are vital for cell migration, tissue infiltration, and formation of interconnected vascular networks. Recommended pore sizes often range from 150 to 500 μm for optimal vascularization [28] [29].

- Mechanical: Stiffness and elasticity must be appropriate for the target tissue, as these properties directly influence cell behavior, including endothelial cell sprouting and differentiation [27] [28].

- Biological: Biocompatibility ensures cell adhesion and survival without a severe immune response. Biodegradability at a rate matching new tissue formation is crucial to prevent the scaffold from obstructing growth [30] [28].

Q3: Which cell sources are most promising for building vascular networks within scaffolds? Common cell sources include:

- Mature Vascular Cells: Autologous Endothelial Cells (ECs) and Smooth Muscle Cells (SMCs), which are directly functional but have limited expansion capability [31] [32].

- Progenitor/Stem Cells: Endothelial Progenitor Cells (EPCs) and Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs) offer greater proliferative potential and can differentiate into vascular lineages [32].

- Pluripotent Stem Cells (PSCs): Both embryonic stem cells (ESCs) and induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) provide an unlimited, self-renewing source for generating ECs and SMCs, though oncogenic risk must be managed [32].

Q4: What key biochemical signals should be incorporated into scaffolds to promote angiogenesis?

- Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF) is a primary stimulator for EC migration and proliferation [32] [4].

- Basic Fibroblast Growth Factor (FGF-2) promotes vessel sprouting and mural cell recruitment [32].

- Platelet-Derived Growth Factor (PDGF) helps stabilize new vessels by recruiting supporting pericytes or smooth muscle cells [32] [4].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Poor Cell Seeding and Inhomogeneous Distribution

| Potential Cause | Solution | Underlying Principle |

|---|---|---|

| Low Scaffold Porosity/Interconnectivity | Optimize fabrication parameters to increase pore size and interconnection. Use techniques like porogen leaching or 3D-bioprinting for precise control [28] [29]. | Enhances cell penetration and uniform distribution. Interconnected pores allow for nutrient/waste exchange in deep regions [30]. |

| Hydrophobic Scaffold Surface | Functionalize material with cell-adhesive peptides (e.g., RGD sequence) or natural polymers like collagen or fibronectin [31] [28]. | Increases initial cell attachment by mimicking the natural extracellular matrix (ECM), improving seeding efficiency [28]. |

| Static Seeding Methods | Utilize dynamic seeding in a bioreactor, where the cell suspension is perfused or agitated [31]. | Promotes higher and more uniform cell distribution by actively driving cells into the scaffold's pores [31]. |

Problem: Inadequate or Immature Vascular Network Formation

| Potential Cause | Solution | Underlying Principle |

|---|---|---|

| Lack of Pro-Angiogenic Signals | Incorporate sustained-release systems for growth factors (e.g., VEGF, FGF) within the scaffold material [32] [4]. | Provides a continuous, localized signal to guide and stimulate the multi-stage process of angiogenesis [32]. |

| Absence of Supporting Cells | Co-culture ECs with pericytes or MSCs within the scaffold [32] [33]. | Recapitulates the natural cellular environment; supporting cells stabilize nascent vessels and prevent regression [32]. |

| Suboptimal Scaffold Stiffness | Tune the mechanical properties of the scaffold to match the compliance of the native target tissue [27] [28]. | Cells sense and respond to substrate stiffness (mechanotransduction). An appropriate mechanical environment is crucial for proper EC and SMC function [28]. |

Problem: Scaffold Degradation Outpaces Tissue Formation

| Potential Cause | Solution | Underlying Principle |

|---|---|---|

| Overly Fast Degradation Rate | Select a biomaterial with a slower degradation profile or increase crosslinking density [30] [28]. | The scaffold must provide mechanical support long enough for the new tissue and vascular network to become self-supporting [30]. |

| High Inflammatory Response | Use more biocompatible or purer materials. Consider decellularized ECM scaffolds to minimize immune rejection [27] [30]. | A severe inflammatory response can accelerate scaffold degradation through the release of enzymes and reactive oxygen species [30]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Fabrication of a Porous Angiogenic Scaffold via Porogen Leaching

This is a widely used method to create scaffolds with high, interconnected porosity [28].

Workflow Diagram: Porogen Leaching Scaffold Fabrication

Materials:

- Biomaterial: e.g., PLGA, PCL, or Chitosan.

- Solvent: e.g., Chloroform (for synthetic polymers) or Aqueous Acetic Acid (for Chitosan).

- Porogen: Sodium Chloride (NaCl) or Sucrose crystals, sieved to a specific size range (e.g., 150-250 μm).

- Equipment: Glass vial, magnetic stirrer, Teflon mold, lyophilizer, UV lamp.

Step-by-Step Method:

- Prepare Polymer Solution: Dissolve your chosen polymer in a suitable solvent at a concentration of 5-10% w/v under constant stirring until a clear solution is obtained.

- Incorporate Porogen: Add the sieved porogen particles to the polymer solution at a high weight ratio (e.g., 70-90% porogen to polymer). Mix thoroughly to ensure a homogeneous suspension.

- Cast the Mixture: Pour the polymer-porogen mixture into a pre-defined mold (e.g., Teflon dish). Spread evenly.

- Evaporate Solvent: Place the mold in a fume hood for 24-48 hours to allow the solvent to evaporate completely, forming a solid composite.

- Leach Out Porogen: Immerse the solid composite in deionized water for 48 hours, changing the water every 6-8 hours to fully dissolve and leach out the porogen particles.

- Dry and Sterilize: Remove the now-porous scaffold from the water and freeze-dry it. Sterilize under UV light for 1 hour per side or using ethanol immersion before cell culture.

Protocol: Assessing Angiogenesis in a 3D Scaffold

Workflow Diagram: Angiogenesis Assessment Pipeline

Materials:

- Cells: Human Umbilical Vein Endothelial Cells (HUVECs), optionally with Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs) or fibroblasts in co-culture.

- Scaffold: Your fabricated 3D scaffold.

- Culture Media: Endothelial Cell Growth Medium.

- Fixative: 4% Paraformaldehyde (PFA).

- Staining Antibodies: Primary antibody against CD31/PECAM-1 (endothelial cell marker) and a fluorescently-labelled secondary antibody.

- Equipment: Confocal microscope, cell culture incubator, qPCR machine.

Step-by-Step Method:

- Cell Seeding: Seed HUVECs (with or without supporting cells) onto the sterile scaffold using a high-density suspension. Allow 2-4 hours for cell attachment before adding culture media.

- Culture: Maintain the cell-scaffold constructs in culture for 7-14 days, changing the media every 2-3 days.

- Fixation: At the desired time point, carefully wash the constructs with PBS and fix with 4% PFA for 30-60 minutes.

- Immunostaining:

- Permeabilize and block the fixed constructs.

- Incubate with primary anti-CD31 antibody overnight at 4°C.

- Wash and incubate with a fluorescent secondary antibody.

- Counterstain nuclei with DAPI and the actin cytoskeleton with Phalloidin.

- Imaging and Analysis: Image the entire scaffold using a confocal microscope with Z-stacking capability. Use image analysis software (e.g., ImageJ with Angiogenesis Analyzer plugin) to quantify key parameters from the 3D reconstructions.

Key Quantitative Measures for Analysis:

- Total Tube Length: The combined length of all CD31-positive structures.

- Number of Branch Points: Points where three or more tubules intersect.

- Number of Meshes: Closed loops formed by the tubular network.

Research Reagent Solutions

A table of essential materials for scaffold-based angiogenesis studies.

| Category | Item / Reagent | Primary Function in Angiogenesis Research |

|---|---|---|

| Biomaterials (Natural) | Collagen [30] [29] | Highly biocompatible; mimics native ECM; promotes cell adhesion and tubulogenesis. |

| Chitosan [30] [29] | Biodegradable polysaccharide; can be modified to enhance bioactivity and control degradation. | |

| Fibrin [27] | Natural hydrogel derived from blood clot; inherently pro-angiogenic; used as a matrix for EC network formation. | |

| Biomaterials (Synthetic) | PLGA [27] [30] | Tunable degradation and mechanical properties; excellent for controlled release of growth factors. |

| PEG [27] [33] | "Blank slate" hydrogel; highly modifiable with bioactive peptides (e.g., RGD, VEGF-mimetic). | |

| Cells | HUVECs [32] [4] | Standard primary EC model; robustly forms tubular structures in 3D cultures. |

| Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs) [32] | Pericyte-like function; stabilizes new vessels; secretes pro-angiogenic paracrine factors. | |

| Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells (iPSCs) [32] [33] | Source for generating autologous ECs and SMCs; unlimited expansion potential. | |

| Bioactive Factors | Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF) [32] [4] | Key mitogen and chemoattractant for ECs; essential for initiation of angiogenesis. |

| Basic Fibroblast Growth Factor (FGF-2) [32] | Promotes EC proliferation and protease production; works synergistically with VEGF. | |

| RGD Peptide [28] | Cell-adhesive ligand; grafted onto materials to enhance integrin-mediated cell attachment. |

A critical obstacle in tissue engineering is the inability to develop large-scale, functional tissues that fully mimic native organs. A primary reason for this limitation is the lack of integrated, perfusable vascular networks, which are essential for delivering oxygen and nutrients to cells and removing waste products. The diffusion limit of oxygen and nutrients is approximately 100–200 µm from a blood vessel, meaning that cells located beyond this distance in a thick tissue construct will face hypoxia, nutrient deficiency, and eventual necrosis [4] [34]. Consequently, engineered tissues exceeding a few hundred micrometers in thickness require an internal vascular system to remain viable [35].

Advanced biofabrication, particularly 3D bioprinting, has emerged as a promising strategy to overcome this bottleneck. This technical support document provides a foundational guide and troubleshooting resource for researchers aiming to implement these sophisticated biofabrication strategies in their work on thick tissue constructs.

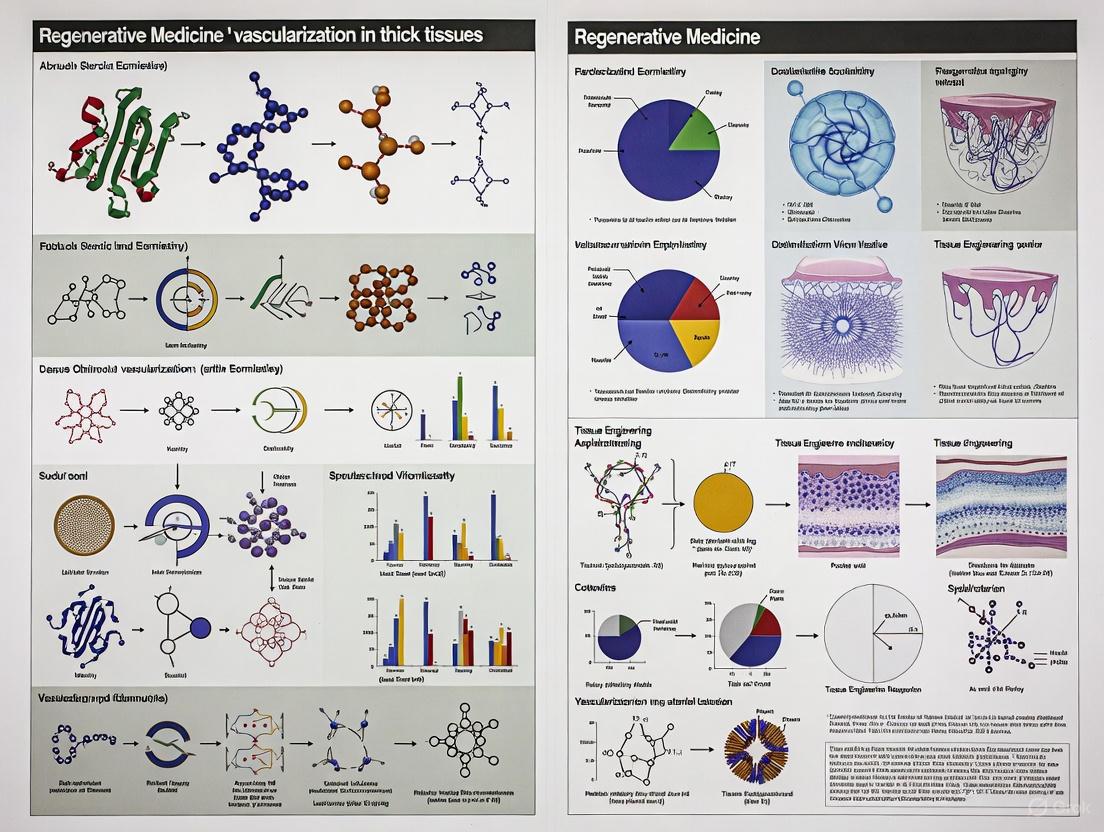

Core Bioprinting Strategies for Vascular Networks

Several 3D bioprinting strategies have been developed to create the hierarchical, branched structures characteristic of native vasculature. The table below summarizes the key approaches, their core principles, and associated technical considerations.

Table 1: Core 3D Bioprinting Strategies for Fabricating Vascular Networks

| Strategy | Fundamental Principle | Key Advantages | Inherent Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sacrificial Bioprinting | A fugitive bioink (e.g., Pluronic F-127, carbohydrate glass) is printed into a network, embedded in a cell-laden hydrogel, and then liquefied and removed to create hollow channels [35] [34]. | Creates complex, free-form channel geometries; allows for subsequent endothelialization. | Requires a multi-step process; removal of sacrificial material can be incomplete in large constructs. |

| Direct Coaxial Extrusion | Uses a concentric multilayered nozzle to directly deposit a hollow, tubular filament in a single step. An inner core solution (e.g., CaCl₂) can crosslink a shell bioink (e.g., alginate-GelMA blend) [36]. | One-step fabrication of perfusable tubes; enables continuous fabrication. | Limited to simpler, often straight or gently curving geometries; requires specialized nozzle systems. |

| Embedded Bioprinting (e.g., FRESH) | Bioinks are printed within a temporary support bath (e.g., a yield-stress gelatin slurry), which holds the soft ink in place until crosslinking is complete [34]. | Enables printing of complex, overhanging structures with high fidelity using low-viscosity bioinks. | Support bath removal required; potential for contamination; process can be slow. |

The following workflow diagram illustrates a generalized experimental process for creating vascularized tissues, integrating elements from sacrificial and direct bioprinting approaches.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful bioprinting of vascular networks relies on a carefully selected suite of materials. The following table catalogs key reagents and their specific functions in the biofabrication process.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Vascular Bioprinting

| Reagent/Material | Core Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Gelatin Methacryloyl (GelMA) | A photopolymerizable hydrogel providing natural cell-adhesive motifs (e.g., RGD sequences) to support cell spreading and proliferation [36] [35]. | Degree of functionalization and concentration tune mechanical properties. A common concentration is 8-10% (w/v) [35]. |

| Sodium Alginate | A natural polysaccharide used to provide immediate structural integrity via rapid ionic crosslinking with calcium ions (Ca²⁺) [36] [37]. | Blended with other hydrogels (e.g., GelMA) to improve bioink shear-thinning and shape fidelity during printing [36]. |

| 4-arm Poly(Ethylene Glycol)-Tetra-Acrylate (PEGTA) | A synthetic polymer used to enhance the mechanical strength and crosslinking density of bioinks due to its branched, tetravalent structure [36]. | Increases mechanical robustness without significantly compromising the porous structure needed for cell growth [36]. |