Paracrine Signaling: The Primary Mechanism Driving Adult Stem Cell Therapy

This article comprehensively reviews the paradigm shift in understanding adult stem cell therapy, where paracrine signaling is now recognized as a primary mechanism of action, surpassing the initial focus on...

Paracrine Signaling: The Primary Mechanism Driving Adult Stem Cell Therapy

Abstract

This article comprehensively reviews the paradigm shift in understanding adult stem cell therapy, where paracrine signaling is now recognized as a primary mechanism of action, surpassing the initial focus on direct differentiation. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational biology of stem cell-secreted factors, methodologies for studying and harnessing these mechanisms, strategies to overcome therapeutic challenges, and the current clinical validation landscape. The synthesis of preclinical and clinical evidence underscores the potential of paracrine factor-based approaches, including cell-free therapies, to revolutionize regenerative medicine for conditions like heart failure, neurodegenerative disorders, and autoimmune diseases.

Deconstructing the Paracrine Secretome: Key Mediators and Mechanisms

The foundational paradigm of adult stem cell therapy has undergone a significant evolution over the past two decades. Initial research was predominantly anchored in the concept of direct differentiation, wherein transplanted stem cells were hypothesized to engraft and transdifferentiate into functional target cells, thereby directly regenerating damaged tissues. However, a confluence of animal studies and preliminary human trials has compellingly demonstrated that the functional benefits observed post-therapy are frequently disproportionate to the frequency of stem cell engraftment and direct differentiation. This discrepancy has catalyzed a paradigm shift towards the understanding that the secretion of bioactive molecules by stem cells—acting via paracrine mechanisms—plays a predominant role in mediating therapeutic effects. This whitepaper delineates the evidence driving this shift, details the core paracrine mechanisms involved, and outlines the advanced experimental and computational methodologies essential for profiling these complex signaling networks, thereby providing a strategic framework for researchers and drug development professionals in the field of regenerative medicine.

The initial premise of adult stem cell therapy was elegantly straightforward: the transplantation of stem cells would lead to their direct incorporation into damaged tissues, where they would differentiate into cardiomyocytes, vascular endothelial cells, or neurons to replace those that were lost or dysfunctional [1]. This direct differentiation hypothesis was supported by early, promising studies. For instance, research by Anversa's laboratory suggested that Lin− c-kit+ bone marrow-derived cells could regenerate a significant portion of infarcted mouse myocardium with newly formed cardiomyocytes [1]. Similarly, Tomita et al. showed that mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) pretreated with 5-azacytidine could differentiate into cardiac-like muscle cells in cryoinjured rat hearts [1].

However, the reproducibility of these findings became a subject of intense scientific debate. Subsequent investigations frequently failed to detect substantial long-term engraftment or robust transdifferentiation of transplanted cells [1]. The central challenge to the direct differentiation model was the repeated observation that significant improvements in organ function—such as enhanced cardiac output after myocardial infarction—occurred despite a notably low number of newly generated, donor-derived functional cells [1]. This critical inconsistency necessitated a re-evaluation of the fundamental mechanisms of action.

The alternative hypothesis, which has now gained substantial traction, posits that the transplanted stem cells function as bioactive "factories," secreting a plethora of soluble factors that act locally on resident cells in a paracrine fashion. These factors are now understood to orchestrate therapeutic outcomes through cytoprotection, stimulation of neovascularization, modulation of the immune response, and activation of endogenous resident stem cells, rather than through large-scale direct replacement of lost tissue [1]. This whitepaper will explore the evidence for this paradigm shift and its implications for the future of regenerative medicine.

Establishing the Paracrine Hypothesis: Key Evidence

The transition from the direct differentiation model to the paracrine signaling paradigm is supported by multiple lines of rigorous experimental evidence.

Functional Benefits Without Significant Engraftment

A cornerstone of the paracrine argument is the dissociation between cell engraftment and functional recovery. In many animal models of disease, the administration of adult stem cells results in measurable functional improvement, even though the transplanted cells are only present transiently. This suggests that the cells initiate a reparative process during their short-term residence, rather than by becoming a permanent part of the organ architecture.

Efficacy of Conditioned Medium

Perhaps the most compelling evidence for the paracrine hypothesis comes from experiments utilizing conditioned medium (CM) collected from stem cell cultures. If the therapeutic effect were solely due to direct differentiation, then the cell-free CM should be ineffective. Contrarily, multiple studies have demonstrated that CM alone can recapitulate the benefits of whole-cell therapy.

- Cardioprotection: Culture medium conditioned by MSCs, particularly those overexpressing Akt-1 (Akt-MSCs), was shown to reduce apoptosis and necrosis in isolated rat cardiomyocytes subjected to low oxygen tension. This cytoprotective effect was also confirmed in vivo in a rat model of myocardial infarction [1].

- Neovascularization and Repair: Injection of CM from bone marrow mononuclear cells (BM-MNCs) into acutely infarcted hearts resulted in increased capillary density, decreased infarct size, and improved cardiac function compared to controls [1].

- Osteogenesis: Studies on dental-derived stem cells, such as SHEDs (stem cells from human exfoliated deciduous teeth), have indicated that they can mediate osteogenesis through paracrine mechanisms rather than solely through direct differentiation [2].

These findings collectively indicate that the soluble factors secreted by stem cells are both necessary and sufficient to elicit significant therapeutic effects.

Complex Paracrine Signaling in Pathophysiology

The importance of paracrine signaling is not limited to regenerative therapy but is also a critical mechanism in disease processes such as cancer metastasis. A stark example is the EGF/CSF-1 paracrine loop between mammary tumor cells and macrophages. Tumor cells secrete CSF-1, which activates macrophages and stimulates their secretion of EGF. The EGF, in turn, promotes the motility and invasiveness of the tumor cells [3]. This sophisticated cell-cell communication system highlights the potency of paracrine signaling and provides a rationale for targeting such pathways therapeutically. Computational modeling of this loop has shown it to be essential for the co-migration of these cell types, and blocking either the EGF or CSF-1 receptor drastically reduces cell invasion and intravasation [3].

Table 1: Key Experimental Evidence Supporting the Paracrine Hypothesis

| Experimental Approach | Key Finding | Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Engraftment Tracking | Functional improvement occurs despite low long-term engraftment of transplanted cells [1]. | Therapeutic effects are not primarily due to direct tissue replacement by donor cells. |

| Conditioned Medium (CM) Studies | CM from MSCs and other stem cells reproduces therapeutic effects (e.g., cytoprotection, angiogenesis) in disease models [1] [2]. | Soluble factors secreted by cells are sufficient to mediate repair. |

| Genetic Manipulation | CM from Akt-overexpressing MSCs shows enhanced cytoprotective potency [1]. | The paracrine profile and efficacy of stem cells can be genetically modulated. |

| Receptor Blocking Studies | Blocking EGF or CSF-1 receptors disrupts tumor cell-macrophage co-migration and invasion [3]. | Validates specific ligand-receptor pairs as critical paracrine mediators and therapeutic targets. |

Core Mechanisms of Paracrine Action

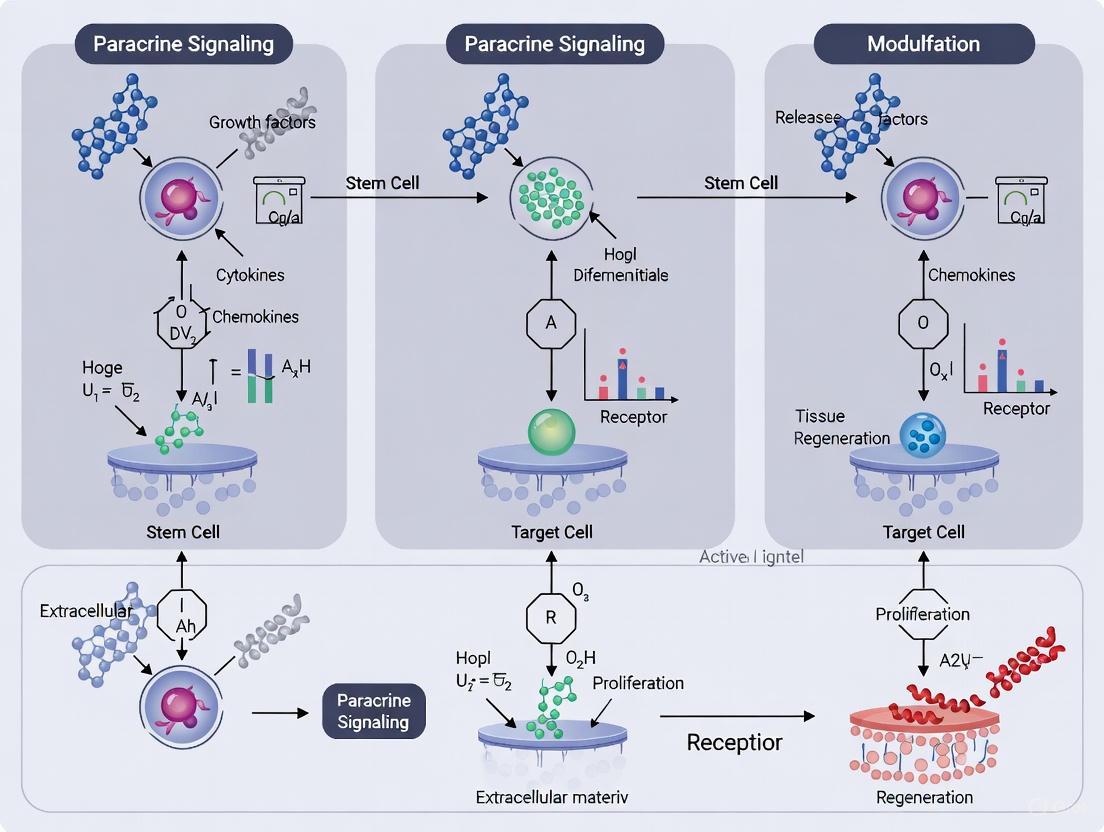

The paracrine factors released by adult stem cells orchestrate tissue repair through several coordinated mechanisms. The following diagram illustrates the key signaling pathways and their primary functions in cardiac repair, based on findings from adult stem cell therapy research.

The therapeutic impact of stem cell paracrine signaling is a summation of multiple distinct but interconnected biological processes.

Myocardial Protection (Cytoprotection)

An immediate effect of stem cell paracrine signaling in an ischemic environment is the protection of imperiled host cells from apoptosis and necrosis. Soluble factors such as Insulin-like Growth Factor-1 (IGF-1), Adrenomedullin (ADM), and Thymosin-β4 (TMSB4) have been identified as key mediators of this cytoprotection [1]. They act by activating pro-survival signaling cascades, such as the PI3K/Akt pathway, within endangered cardiomyocytes, thereby increasing their resistance to ischemic stress. This cytoprotective effect preserves viable tissue in the peri-infarct zone, which is critical for maintaining overall cardiac function and limiting adverse remodeling.

Stimulation of Neovascularization

A well-documented and reproducible effect of stem cell therapy is the enhancement of blood vessel formation in ischemic tissues, which restores oxygen and nutrient supply. This is largely driven by the secretion of potent angiogenic factors, including:

- Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF)

- Basic Fibroblast Growth Factor (b-FGF or FGF2)

- Hepatocyte Growth Factor (HGF)

- Angiopoietin-1 (AGPT1) [1]

These factors promote the proliferation, migration, and tube formation of existing endothelial cells, leading to the formation of new capillaries (angiogenesis) and contributing to the stabilization of the newly formed vascular networks.

Activation of Endogenous Regeneration

Rather than solely acting as direct building blocks, transplanted stem cells can stimulate the body's own regenerative capacity. The release of factors like Stem Cell-Derived Factor-1 (SDF-1), Kit Ligand (Stem Cell Factor), HGF, and IGF-1 can activate resident tissue-specific stem and progenitor cells, such as resident cardiac stem cells (CSCs) [1]. This activation promotes the proliferation and differentiation of these endogenous pools, which then contribute to the regeneration of functional tissue in a more physiologically integrated manner.

Immunomodulation and Anti-Fibrotic Effects

The secretome of stem cells, particularly MSCs, has powerful effects on the immune system. Factors such as Transforming Growth Factor-β (TGF-β), prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), and interleukins can modulate the activity of T-cells, B-cells, and macrophages, polarizing them towards a more anti-inflammatory and pro-regenerative phenotype [2]. This suppression of detrimental inflammation creates a more favorable microenvironment for repair. Furthermore, by modulating the activity of fibroblasts and the deposition of extracellular matrix, paracrine signaling can also attenuate pathological fibrotic scarring, which impairs tissue compliance and function.

Table 2: Key Paracrine Factors and Their Functions in Tissue Repair

| Secreted Factor | Abbreviation | Primary Proposed Functions in Repair |

|---|---|---|

| Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor | VEGF | Angiogenesis, Cytoprotection, Cell proliferation & migration [1] |

| Insulin-like Growth Factor-1 | IGF-1 | Cytoprotection, Cell migration, Improved contractility [1] [4] |

| Hepatocyte Growth Factor | HGF | Cytoprotection, Angiogenesis, Cell migration [1] |

| Fibroblast Growth Factor-2 | FGF2 | Angiogenesis, Cell proliferation & migration [1] [4] |

| Stem Cell-Derived Factor-1 | SDF-1 | Progenitor cell homing [1] |

| Transforming Growth Factor-β | TGF-β | Immunomodulation, Vessel maturation, Cell proliferation [1] [5] [4] |

| Thymosin-β4 | TMSB4 | Cell migration, Cytoprotection [1] |

Advanced Methodologies for Profiling Paracrine Signaling

The investigation of paracrine mechanisms requires a sophisticated toolkit that moves beyond traditional cell culture and histology. The following workflow outlines a multi-faceted approach to experimentally validate paracrine effects, from in vitro conditioning to in vivo functional assessment.

Experimental Protocols for Paracrine Analysis

A. Generation of Conditioned Medium (CM)

Principle: To collect the soluble factors secreted by stem cells for use in downstream functional and analytical assays.

Detailed Protocol:

- Cell Culture: Culture the stem cells of interest (e.g., MSCs, DPSCs) to 70-80% confluence in standard growth medium.

- Wash: Thoroughly wash the cells with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) to remove serum-derived proteins.

- Serum-Free Incubation: Incubate the cells with serum-free medium for 24-48 hours. To mimic the ischemic stress encountered after transplantation, hypoxia (e.g., 1% O₂) can be applied during this period, as it is known to increase the production of many therapeutic factors [1].

- Collection: Collect the medium and centrifuge (e.g., 2000 × g for 10 minutes) to remove any cellular debris.

- Concentration (Optional): Concentrate the CM using centrifugal filter units (e.g., 3-5 kDa molecular weight cutoff) to augment the concentration of secreted factors.

- Storage: Aliquot and store the CM at -80°C until use. A control medium (serum-free medium incubated without cells) must be prepared and processed identically.

B. In Vitro Functional Assays with CM

1. Cytoprotection Assay (e.g., Cardiomyocyte Apoptosis)

- Objective: To quantify the ability of CM to protect cells from induced apoptosis.

- Method:

- Isolate primary cardiomyocytes from neonatal rats or use a relevant cardiomyocyte cell line.

- Pre-treat cells with either CM or control medium for 1-2 hours.

- Expose the cells to a lethal insult, such as low oxygen tension (hypoxia) or hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂) to simulate ischemia/reperfusion injury.

- After 12-24 hours, quantify apoptosis using TUNEL staining or by measuring the activity of executioner caspases (e.g., Caspase-3/7) with a luminescent assay [1].

2. Angiogenesis Assay (e.g., Endothelial Tube Formation)

- Objective: To assess the pro-angiogenic potential of CM.

- Method:

- Pre-chill µ-Slide Angiogenesis plates and pipette tips.

- Thaw Growth Factor Reduced Matrigel on ice and carefully pipette it into each well. Incubate the plate at 37°C for 30 minutes to allow polymerization.

- Seed Human Umbilical Vein Endothelial Cells (HUVECs) onto the surface of the Matrigel in either CM or control medium.

- Incubate for 4-16 hours and then image the formed capillary-like structures using a phase-contrast microscope.

- Quantify the total tube length, number of master junctions, and number of meshes per field using image analysis software (e.g., ImageJ with the Angiogenesis Analyzer plugin).

Computational Inference of Cell-Cell Communication

The advent of single-cell RNA-sequencing (scRNA-seq) has enabled the systematic inference of paracrine signaling networks within complex tissues. Tools like CellChat have been developed specifically for this purpose [6].

Principle: CellChat quantitatively infers intercellular communication probabilities by integrating scRNA-seq data with a manually curated database of ligand-receptor interactions (CellChatDB). This database includes heteromeric complexes and key co-factors, providing a more biologically accurate representation than simple ligand-receptor pairs [6].

Workflow:

- Input: A scRNA-seq dataset with cell group labels (either user-defined or identified computationally).

- Database Matching: CellChat overlays the gene expression data onto its knowledgebase of validated molecular interactions.

- Probability Calculation: The communication probability for each ligand-receptor pair between two cell groups is computed based on the average expression of the ligand in the "sender" population and the receptor (and its cofactors) in the "receiver" population, employing a mass action-based model.

- Statistical Validation: The significance of the inferred interactions is assessed by comparing them to a null distribution generated through random permutation of cell labels.

- Systems-Level Analysis: The resulting network is analyzed using methods from graph theory (e.g., centrality measures to identify key senders/receivers) and pattern recognition (to identify coordinated signaling modules) [6].

Application: This approach can delineate conserved and context-specific signaling pathways, predict key incoming/outgoing signals for specific cell types, and systematically compare communication networks across different biological conditions (e.g., healthy vs. diseased, pre- vs. post-treatment) [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Tools for Paracrine Signaling Research

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Specific Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Serum-Free Media | Base for generating conditioned medium; eliminates confounding factors from serum. | DMEM, RPMI-1640. Must be optimized for cell type to maintain viability during conditioning. |

| Cytokine/Growth Factor Arrays | Multiplexed profiling of secreted proteins in conditioned medium. | Proteome Profiler Arrays; allow simultaneous detection of dozens of factors [1]. |

| ELISA Kits | Quantitative, specific measurement of individual secreted factors. | Commercial kits for VEGF, IGF-1, HGF, etc.; used for validating array results. |

| Extracellular Matrix (ECM) | Substrate for 3D functional assays like angiogenesis and cell migration. | Growth Factor Reduced Matrigel is standard for endothelial tube formation assays. |

| Primary Cells / Cell Lines | Targets for assessing CM bioactivity. | HUVECs (angiogenesis), primary cardiomyocytes (cytoprotection), fibroblast lines (fibrosis) [1] [5]. |

| scRNA-seq Platform | Generation of input data for computational inference of cell-cell communication. | 10x Genomics; required for tools like CellChat to map ligand-receptor expression to cell types [6]. |

| CellChat R Package | Computational inference and systems-level analysis of intercellular communication networks from scRNA-seq data. | Uses a curated database (CellChatDB) that includes heteromeric complexes [6]. |

| Neutralizing Antibodies / Small Molecule Inhibitors | Functional validation of specific ligand-receptor pairs. | e.g., anti-VEGF antibody, EGF/CSF-1 receptor inhibitors (e.g., Erlotinib, BLZ945) [3]. |

The paradigm shift from direct differentiation to paracrine signaling represents a fundamental maturation in our understanding of how adult stem cell therapies mediate their benefits. This refined model posits that stem cells are sophisticated signaling entities that orchestrate tissue repair by modulating the local microenvironment. This new understanding has profound implications for the future of regenerative medicine:

- Next-Generation Therapeutics: The focus is shifting from the cells themselves to their secreted products. This includes the development of "cell-free" therapies using engineered exosomes or purified combinations of key paracrine factors, which could offer improved safety, scalability, and storage profiles over live cell transplants.

- Potency Optimization: Strategies are being developed to enhance the therapeutic potency of stem cells through "priming" or genetic modification (e.g., Akt-overexpression) to boost the secretion of beneficial factors [1].

- Precision Targeting: As computational tools like CellChat [6] continue to map the complex signaling networks in health and disease, we can identify critical, context-specific nodal points for intervention. This will enable the development of highly targeted drugs, such as monoclonal antibodies or small molecules, to modulate these key paracrine pathways.

In conclusion, embracing the paracrine paradigm does not diminish the value of stem cell therapy but rather refines it. It provides a more robust and nuanced framework for explaining experimental observations and directs the field toward more controlled, predictable, and effective regenerative strategies. The future lies in harnessing and optimizing this sophisticated cellular communication system to develop a new generation of therapeutics for a wide range of degenerative diseases and injuries.

The therapeutic potential of adult stem cells, particularly Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs), was initially attributed to their ability to differentiate and replace damaged cells. However, a paradigm shift has occurred in regenerative medicine, with growing evidence demonstrating that their benefits are predominantly mediated through paracrine signaling [7]. Rather than integrating into tissues, transplanted stem cells release a complex mixture of bioactive molecules that orchestrate repair processes. This mixture, collectively known as the secretome, has emerged as a critical mediator of tissue regeneration, immunomodulation, and cellular homeostasis [8] [7].

The secretome encompasses a diverse array of components, including soluble proteins, cytokines, growth factors, and Extracellular Vesicles (EVs) such as exosomes and microvesicles [7]. These elements act as a coordinated communication network, allowing stem cells to influence their local microenvironment. Upon release, these factors can modulate immune responses, enhance angiogenesis, protect surviving cells from apoptosis, and activate resident progenitor cells [1] [9]. This cell-free approach presents significant advantages over whole-cell therapies, including reduced risks of immune rejection, tumorigenicity, and simplified manufacturing and storage logistics [10] [7]. Cataloging these components and understanding their functions is essential for harnessing the full potential of secretome-based therapeutics in adult stem cell research and drug development.

Composition of the Stem Cell Secretome

The stem cell secretome is a highly complex biological entity. Its composition is dynamic and can be influenced by the source of the MSCs (e.g., bone marrow, umbilical cord, adipose tissue), the donor's health status, and the culture conditions used during production [11] [7]. The secretome can be broadly categorized into two functional delivery systems: soluble factors and encapsulated factors within extracellular vesicles.

Table 1: Major Soluble Factors in the MSC Secretome and Their Functions

| Factor Category | Key Examples | Primary Documented Functions | Therapeutic Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pro-angiogenic Factors | VEGF, HGF, IGF-1, FGF2 [1] [7] | Stimulate blood vessel formation, promote endothelial cell survival and migration. | Cardiac repair, wound healing, limb ischemia [1] |

| Immunomodulatory Factors | IL-10, TSG-6, PGE2, TGF-β [10] [7] | Suppress pro-inflammatory cytokine release, polarize macrophages to an M2 phenotype, inhibit T-cell proliferation. | Multiple sclerosis, Crohn's disease, GvHD, organ injury [11] [10] |

| Anti-apoptotic & Pro-survival Factors | IGF-1, HGF, bFGF, STC-1 [1] [7] | Activate pro-survival pathways (e.g., PI3K/Akt), reduce programmed cell death in stressed tissues. | Myocardial infarction, acute kidney injury, stroke [1] |

| Anti-fibrotic Factors | HGF, MMPs, decorin [11] [1] | Degrade excess extracellular matrix, inhibit TGF-β1 mediated pro-fibrotic signaling. | Liver fibrosis, pulmonary fibrosis, chronic kidney disease [11] |

Table 2: Key Components of Extracellular Vesicles (EVs) in the Secretome

| EV Component Type | Key Examples | Function & Mechanism | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Proteins | Tetraspanins (CD9, CD63, CD81), Annexins, Flotillins [12] | Define EV subtypes, facilitate membrane fusion and recipient cell uptake. | Single-particle imaging confirms distinct sEV subtypes based on tetraspanin composition [12] |

| Lipids | Cholesterol, Sphingomyelin, Phosphatidylserine [12] | Determine membrane fluidity/packing, influence stability and cellular uptake. | CD63+ sEVs exhibit greater membrane packing than CD81+ sEVs [12] |

| Nucleic Acids (RNAs) | mRNA, miRNA (e.g., miR-21, miR-146a), tRNA [7] | Modify gene expression in recipient cells; miR-21 modulates inflammatory pathways. | Engineered MSCs produce EVs with enriched miRNAs for targeted therapy [7] |

Extracellular Vesicles: Specialized Paracrine Carriers

Extracellular Vesicles (EVs), particularly small EVs (sEVs), are now recognized as primary effectors of the secretome's therapeutic function. These lipid-bilayer nanoparticles facilitate intercellular communication by transferring proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids to recipient cells [12] [7]. The internalization of sEVs by recipient cells is a regulated process. Recent research using single-particle tracking and super-resolution microscopy has shown that paracrine adhesion signaling facilitates sEV uptake. Binding of sEVs to the recipient cell plasma membrane triggers Ca2+ mobilization via Src family kinases and phospholipase Cγ, leading to the activation of calcineurin and dynamin, which promotes sEV internalization primarily via clathrin-independent endocytosis [12].

Methodologies for Secretome Analysis and Functional Characterization

Rigorous and standardized methodologies are required to isolate, characterize, and validate the secretome's composition and function. The following workflow outlines the key experimental stages, from cell culture to functional analysis.

Experimental Protocol: Secretome Collection and Analysis

1. Cell Culture and Pre-conditioning:

- Source and Culture: Isolate and culture MSCs from a chosen source (e.g., human gingiva, bone marrow, umbilical cord). Use defined, xeno-free culture medium to avoid contamination with animal serum-derived factors [10]. Cells are typically cultured to 70-80% confluence.

- Pre-conditioning: To enhance the therapeutic potency of the secretome, MSCs can be subjected to pre-conditioning stimuli. Common methods include exposure to hypoxic conditions (e.g., 1-3% O2) or priming with inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IFN-γ, TNF-α) [1] [8]. This mimics the inflammatory or ischemic microenvironment of damaged tissue and can significantly alter the secretome's composition, enriching it with beneficial factors [9].

2. Secretome Collection:

- Once MSCs reach the desired confluence, wash the cells thoroughly with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) to remove residual serum.

- Incubate the cells with a serum-free basal medium for 24-48 hours.

- Collect the Conditioned Medium (CM), which contains the soluble secretome and EVs released by the cells [10].

3. Fractionation and Isolation:

- Concentration: The CM is concentrated using ultrafiltration devices (e.g., centrifugal filters with a 3-5 kDa molecular weight cut-off) [10].

- EV Isolation: Several techniques can be employed to isolate EVs from the soluble fraction:

- Ultracentrifugation: The gold standard, involving sequential centrifugation steps at high speeds (e.g., 100,000× g) to pellet EVs [12].

- Size-Exclusion Chromatography (SEC): Uses columns with porous beads to separate EVs from soluble proteins based on size. This method, using tools like qEVoriginal columns, is effective for obtaining high-purity EV preparations [10].

- Tangential Flow Filtration (TFF): A scalable method suitable for industrial-grade biomanufacturing of EVs for clinical applications [7].

4. Characterization and Analysis:

- Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis (NTA): Determines the particle size distribution and concentration of EVs in suspension [10].

- Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM): Provides visual confirmation of EV morphology and size via negative staining [10] [12].

- Western Blot: Confirms the presence of classic EV marker proteins (e.g., CD9, CD63, CD81, TSG101) and the absence of negative markers (e.g., calnexin) [10] [12].

- Proteomic and Transcriptomic Analysis: Liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) and next-generation RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq) are used to comprehensively profile the protein, miRNA, and mRNA content of the secretome and its subsets [10] [7].

5. Functional Validation (In Vitro and In Vivo):

- In Vitro Assays:

- Immunomodulation: Co-culture secretome-treated macrophages with inflammatory stimuli (e.g., LPS) and measure cytokine secretion (e.g., TNF-α, IL-10) via ELISA. Assess macrophage polarization flow cytometry [10].

- Myogenic/Cardiac Repair: Treat relevant progenitor cells (e.g., skeletal muscle progenitors, cardiomyocytes) with the secretome and quantify the expression of myogenic transcription factors (e.g., MyoD, Myogenin) via qPCR or immunofluorescence [10] [1].

- In Vivo Models:

- Administer the secretome/EVs into animal models of disease (e.g., rat tongue defect model for muscle regeneration [10], rodent myocardial infarction model for cardiac repair [1], or mouse models of BPD/NEC for neonatal disorders [7]).

- Evaluate outcomes through histological analysis, functional measurements (e.g., echocardiography), and assessment of scar size, inflammation, and angiogenesis.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents for Secretome Research

| Reagent / Tool | Specific Example | Function in Secretome Research |

|---|---|---|

| Xeno-Free Cell Culture Medium | STEMCELL Technologies' StemiMacs MSC XF Medium | Provides a defined, animal-serum-free environment for MSC expansion to prevent contaminating bovine EVs in the secretome [10]. |

| Size-Exclusion Chromatography Columns | IZON Science's qEVoriginal columns (35 nm) | Isolates high-purity small Extracellular Vesicles (sEVs) from soluble proteins and other contaminants in conditioned medium [10]. |

| Ultrafiltration Devices | Amicon Ultra Centrifugal Filters (e.g., 10 kDa MWCO) | Concentrates the dilute conditioned medium collected from MSC cultures prior to further fractionation or analysis [10]. |

| Nanoparticle Tracking Analyzer | Malvern Panalytical's NanoSight NS300 | Characterizes the concentration and size distribution of EV preparations [10]. |

| Membrane Packing/Defect Probe | ApoC-TAMRA (Apolipoprotein C-I derived peptide) | Quantifies the membrane packing density and fluidity of different sEV subtypes, a key physical property [12]. |

| Tetraspanin Reporter Cell Lines | MSCs stably expressing CD63-mGFP and CD9-Halo7-TMR | Enables single-particle imaging and tracking of distinct sEV subpopulations released by donor cells [12]. |

Signaling Pathways Activated by the Secretome

The therapeutic effects of the secretome are mediated through the activation of multiple, interconnected signaling pathways in recipient cells. The following diagram summarizes the key signaling cascades triggered by secretome components leading to core therapeutic outcomes.

The activation of these pathways is initiated when ligands within the secretome, such as IGF-1, VEGF, and HGF, bind to their respective receptors on recipient cells. For instance, IGF-1 binding to the IGF-1 receptor triggers the PI3K/Akt pathway, a critical pro-survival signal that inhibits apoptosis in cardiomyocytes and neurons after injury [1]. Similarly, FGF2 activates the ERK1/2 pathway, promoting cell proliferation and tissue repair [1]. Furthermore, modulation of the Wnt/β-catenin and Notch signaling pathways by secretome components can influence the fate of resident stem cells, promoting endogenous regeneration [10]. A key anti-inflammatory mechanism involves the suppression of the NF-κB pathway by factors like TSG-6 and IL-10, leading to reduced production of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α [7]. The transfer of regulatory miRNAs via EVs can also post-transcriptionally repress genes involved in cell death and inflammation, providing another layer of control [7].

The systematic cataloging of the stem cell secretome—encompassing its diverse cytokines, growth factors, and extracellular vesicles—has fundamentally advanced our understanding of paracrine mechanisms in adult stem cell therapy. Moving beyond the initial cell-replacement paradigm, the field now recognizes the secretome as a powerful, cell-free therapeutic agent capable of modulating inflammation, protecting at-risk tissue, and activating endogenous repair programs. The continued refinement of isolation protocols, analytical techniques, and functional assays, as outlined in this guide, is crucial for standardizing secretome-based products. As research progresses, the strategic engineering of MSCs to produce enriched or targeted secretomes holds the promise of a new class of highly effective, off-the-shelf regenerative medicines for a wide spectrum of diseases.

The therapeutic potential of adult stem cells, particularly Mesenchymal Stem/Stromal Cells (MSCs), extends far beyond their capacity for direct differentiation and tissue repopulation. A paradigm shift has occurred in the field, with research increasingly demonstrating that the primary mechanism through which MSCs exert their beneficial effects is paracrine signaling—the secretion of bioactive molecules that modulate the host environment [13]. These secreted factors, collectively known as the secretome, facilitate tissue repair and regeneration by orchestrating three core protective mechanisms: cytoprotection (enhancing cell survival), angiogenesis (promoting new blood vessel formation), and immunomodulation (regulating immune responses) [14] [15]. This in-depth technical guide synthesizes current research to elucidate these mechanisms, providing researchers and drug development professionals with a detailed framework of the molecular pathways, experimental methodologies, and reagent tools driving innovation in stem cell-based therapeutics.

The MSC secretome is a composite of soluble proteins (growth factors, cytokines, chemokines) and extracellular vesicles (EVs) such as exosomes and microvesicles, which carry proteins, lipids, and genetic material [14]. Its composition is not static; it varies significantly based on the tissue source of the MSCs (e.g., bone marrow, adipose tissue, umbilical cord) and is dynamically shaped by the local microenvironment [14] [16]. Preconditioning or "priming" of MSCs—through hypoxia, inflammatory cytokine exposure, or pharmacological agents—further alters the secretome's profile, enabling its optimization for specific clinical applications [14] [15] [17]. This cell-free, paracrine-based approach offers considerable advantages, including a reduced risk of immune rejection, elimination of concerns related to cell engraftment and persistence, and simpler regulatory and manufacturing pathways [14].

Molecular Mechanisms of Paracrine-Mediated Protection

Cytoprotection: Enhancing Cellular Survival and Homeostasis

Cytoprotection refers to the mechanisms that enhance the survival and function of endogenous cells in damaged or stressed tissues. The MSC secretome mitigates apoptosis and maintains cellular homeostasis through several coordinated strategies.

Anti-apoptotic Signaling: Secreted factors directly inhibit programmed cell death pathways. Molecules like VEGF, HGF, and IGF-1 activate intracellular pro-survival pathways such as PI3K/Akt in target cells, leading to the inactivation of pro-apoptotic proteins like Bad and caspase-9 [14] [13]. The transfer of specific microRNAs (e.g., miR-21) via EVs can also downregulate key apoptotic genes in recipient cells [14].

Oxidative Stress Reduction: MSCs secrete antioxidants and enzymes that scavenge reactive oxygen species (ROS), thereby reducing oxidative damage. For instance, extracellular vesicles carry superoxide dismutase and glutathione peroxidase, which directly neutralize free radicals [13]. Furthermore, the secretome can upregulate endogenous antioxidant defense systems in host cells.

Metabolic Support: In ischemic or nutrient-deprived environments, MSCs provide metabolic support by secreting metabolites, lipids, and enzymes that help sustain the energy production of stressed cells, preventing bioenergetic failure [13].

The following diagram illustrates the key cytoprotective pathways activated by the MSC secretome.

Angiogenesis: Orchestrating Vasculogenesis and Vascular Remodeling

Adequate blood supply is fundamental to tissue repair. The MSC secretome potently induces angiogenesis through a complex interplay of growth factors, cytokines, and EVs. Bone marrow-derived MSC (BM-MSC) and adipose tissue-derived MSC (AT-MSC) secretomes are particularly rich in pro-angiogenic factors [14].

Growth Factor-Driven Angiogenesis: Key secreted growth factors include Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF), Basic Fibroblast Growth Factor (bFGF), Platelet-Derived Growth Factor (PDGF), and Transforming Growth Factor-β (TGF-β) [14]. These ligands bind to their respective receptors on endothelial cells (e.g., VEGFR, FGFR), activating the ERK/Akt signaling pathway and promoting endothelial cell proliferation, migration, and tube formation [14].

Extracellular Vesicle-Mediated Angiogenesis: EVs are now recognized as primary mediators. They are taken up by endothelial cells, transferring an active cargo that includes pro-angiogenic proteins (e.g., VEGF, FGF) and regulatory RNAs [14]. For example, EVs from hypoxia-preconditioned BM-MSCs are enriched with miR-125a, which suppresses the anti-angiogenic factor DLL4, thereby enhancing vessel sprouting [14]. Similarly, miR-30b promotes tube formation by targeting PDGFA [14].

Proteomic and Functional Heterogeneity: The angiogenic potential of the secretome is source-dependent. A comparative proteomic analysis revealed that AT-MSC-derived EVs contain higher levels of VEGF, von Willebrand factor (vWF), and TGF-β1, correlating with greater tubulogenic efficiency in vitro compared to BM-MSC EVs [14]. Furthermore, stimulation of MSCs with PDGF enhances EV release and upregulates angiogenic cargo such as c-kit and stem cell factor (SCF) [14].

Table 1: Key Pro-Angiogenic Factors in the MSC Secretome

| Molecule | Type | Primary Function in Angiogenesis | Key Signaling Pathway |

|---|---|---|---|

| VEGF | Growth Factor | Endothelial cell proliferation, migration, and permeability | VEGFR2 / PI3K-Akt |

| bFGF (FGF-2) | Growth Factor | Endothelial cell proliferation & tube formation | FGFR / ERK |

| Angiopoietin-1 | Growth Factor | Vessel maturation and stabilization | Tie2 / PI3K-Akt |

| PDGF | Growth Factor | Pericyte recruitment & vessel stabilization | PDGFR / ERK |

| IL-8 | Chemokine | Endothelial cell chemotaxis | CXCR1/2 |

| miR-125a | microRNA (in EVs) | Suppresses anti-angiogenic DLL4 | Notch Pathway |

| EMMPRIN | Protein (in EVs) | Induces matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) | ERK/Akt |

Immunomodulation: Balancing the Immune Response

MSCs are potent regulators of the immune system, modulating both innate and adaptive immunity to resolve inflammation and create a pro-regenerative environment. This occurs via direct cell-cell contact and, more significantly, through paracrine signaling [13] [15].

Soluble Factor-Mediated Suppression: MSCs secrete a plethora of immunoregulatory molecules in response to inflammatory cues. Key among these are Prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO), TGF-β, HGF, and IL-10 [13] [15]. These factors collectively suppress the proliferation and effector functions of pro-inflammatory T cells (Th1, Th17) and natural killer (NK) cells, while promoting the expansion and activity of regulatory T cells (Tregs) [13].

Extracellular Vesicle-Driven Modulation: MSC-derived EVs carry immunomodulatory cargo that mirrors their parental cells. They can induce a shift in macrophages from a pro-inflammatory M1 phenotype to an anti-inflammatory, pro-healing M2 phenotype [14] [13]. This is partly mediated by the transfer of CD73 to recipient immune cells, which catalyzes the production of anti-inflammatory adenosine from extracellular ATP [15]. EVs also modulate dendritic cell maturation and B cell antibody production [15].

Dynamic and Context-Dependent Action: The immunomodulatory function of MSCs is not universally suppressive but is highly adaptable to the host's inflammatory state. In a low-inflammatory context, MSCs may have a neutral or mildly stimulatory effect. However, in a high-inflammatory milieu (e.g., high levels of IFN-γ and TNF-α), they become powerfully immunosuppressive, a phenomenon known as "licensing" [15]. This dynamic regulation makes them attractive for treating autoimmune diseases and mitigating graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) [13].

The diagram below summarizes the complex immunomodulatory network orchestrated by the MSC secretome.

Experimental Protocols for Investigating Paracrine Mechanisms

Isolation and Characterization of the MSC Secretome

Objective: To collect, concentrate, and characterize the protein and extracellular vesicle components of the MSC-conditioned medium (CM).

Detailed Methodology:

MSC Culture and Conditioning:

- Culture MSCs from a chosen source (e.g., bone marrow, adipose tissue) in standard media until 70-80% confluent.

- Wash cells thoroughly with PBS to remove serum contaminants.

- Incubate with a serum-free, defined basal medium (e.g., DMEM/F-12) for 24-48 hours. Preconditioning with hypoxia (1-3% O₂) or inflammatory cytokines (e.g., 10-50 ng/mL IFN-γ or TNF-α) can be applied during this period to modulate secretome composition [14] [15].

- Collect the conditioned medium (CM).

Processing of Conditioned Medium:

- Centrifuge CM at 2,000 × g for 20 minutes to remove dead cells and debris.

- Concentrate the supernatant using ultrafiltration centrifugal devices (e.g., 3 kDa molecular weight cut-off) or tangential flow filtration.

- For EV isolation, subject the concentrated CM to differential ultracentrifugation:

- Centrifuge at 10,000 × g for 30 minutes to remove apoptotic bodies and large vesicles.

- Centrifuge the resulting supernatant at 100,000 × g for 70-120 minutes to pellet EVs.

- Resuspend the EV pellet (containing exosomes and microvesicles) in PBS or a suitable buffer [14]. Alternative purification methods include size-exclusion chromatography or density gradient ultracentrifugation.

Secretome Characterization:

- Protein Quantification: Use colorimetric assays like BCA or Bradford to determine total protein concentration.

- EV Characterization: Perform Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis (NTA) to determine particle size and concentration. Confirm the presence of EV markers (e.g., CD63, CD81, TSG101) and the absence of negative markers (e.g., Calnexin) via western blot, in accordance with MISEV (Minimal Information for Studies of Extracellular Vesicles) guidelines [14].

- Proteomic Analysis: Utilize liquid chromatography with tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) to identify and quantify the protein components of the secretome and EV cargo [14].

In Vitro Functional Assays for Core Protective Mechanisms

Objective: To quantitatively evaluate the cytoprotective, angiogenic, and immunomodulatory potential of the isolated secretome/EVs.

Detailed Methodology:

Table 2: Key In Vitro Functional Assays for Paracrine Activity

| Mechanism | Assay | Protocol Outline | Key Readouts |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cytoprotection | Hydrogen Peroxide (H₂O₂) Challenge | 1. Seed target cells (e.g., cardiomyocytes, neurons) in a plate.2. Pre-treat with MSC secretome/EVs for 4-24h.3. Induce oxidative stress with H₂O₂ (e.g., 100-500 µM) for several hours.4. Assess cell viability. | - Cell Viability: MTT, MTS, or Calcein-AM assay.- Apoptosis: Caspase-3/7 activity assay or Annexin V/PI staining by flow cytometry. |

| Angiogenesis | Tube Formation Assay | 1. Coat a plate with a basement membrane matrix (e.g., Matrigel or Geltrex).2. Seed human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) or human microvascular endothelial cells (HMEC-1) on the matrix.3. Treat with MSC secretome/EVs.4. Incubate for 4-16 hours and image. | - Total Tube Length: Quantified using image analysis software (e.g., ImageJ Angiogenesis Analyzer).- Number of Nodes & Junctions. |

| Immunomodulation | T Cell Proliferation Assay | 1. Isolate peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from human blood.2. Label T cells with a cell division tracker (e.g., CFSE).3. Activate T cells with anti-CD3/CD28 beads or mitogens (e.g., PHA).4. Coculture with MSC secretome/EVs or MSCs in a transwell system for 3-5 days.5. Analyze by flow cytometry. | - % of Divided T Cells: CFSE dilution.- Cytokine Profiling: ELISA for IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-10 in supernatant. |

The following diagram maps the workflow for a comprehensive in vitro and in vivo validation of paracrine functions.

Advanced Spatial Analysis of the Stem Cell Niche

Objective: To identify and characterize in vivo stem cell niches and their paracrine signaling activities using spatially resolved omics technologies.

Detailed Methodology:

Advanced computational tools like NicheCompass are designed to model cellular communication and identify functional niches from spatial omics data [18]. The protocol involves:

Data Acquisition and Preprocessing: Generate high-resolution spatial transcriptomic or multi-omic data (e.g., using 10x Visium, MERFISH, or seqFISH). Construct a spatial neighborhood graph where nodes represent cells/spots and edges represent spatial proximity [18].

Model Application and Niche Identification: Input the data into NicheCompass, which uses a graph neural network to learn cell embeddings that encode signaling events based on prior knowledge (e.g., ligand-receptor pairs) and de novo spatial gene programs. Cluster these embeddings to identify spatially contiguous cell communities (niches) with coordinated functions [18].

Quantitative Niche Characterization: Characterize the identified niches by analyzing the activity of specific signaling pathways (e.g., Fgf17, Calca, Cthrc1) that define their identity and functional state. This allows for the quantitative dissection of how stem cells and their neighbors communicate via paracrine signals within the tissue architecture [18].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents for Studying MSC Paracrine Mechanisms

| Reagent / Tool | Category | Specific Example(s) | Research Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fura-2 AM | Calcium Indicator | Invitrogen Fura-2 AM [19] | Multicellular Ca²⁺ imaging to study intercellular communication, such as gap-junctional vs. paracrine wave propagation. |

| Carbenoxolone (CBX) | Gap Junction Blocker | Sigma-Aldrich C4790 [19] | Pharmacologically disrupts direct cell-cell communication via connexin channels, allowing isolation of paracrine effects. |

| Apyrase | ATP-hydrolyzing Enzyme | Sigma-Aldrich A6237 [19] | Degrades extracellular ATP, a key purinergic signaling molecule, to investigate ATP-mediated paracrine pathways. |

| Matrigel / Geltrex | Basement Membrane Matrix | Corning Matrigel [14] | Provides a physiological substrate for in vitro endothelial tube formation assays to assess angiogenic potential. |

| CD63 / CD81 / TSG101 Antibodies | EV Markers | Abcam, System Biosciences [14] | Western blot validation of extracellular vesicle isolates to confirm successful purification and characterization. |

| Recombinant Cytokines (IFN-γ, TNF-α) | Preconditioning Agents | PeproTech [15] | "Prime" or "license" MSCs to enhance the immunomodulatory potency of their secretome prior to collection. |

| Cell Tracker Dyes (CFSE, PKH67) | Cell Labeling | Thermo Fisher Scientific [15] | Track cell proliferation (CFSE) or the uptake and trafficking of secreted EVs (PKH67) in co-culture systems. |

| NicheCompass | Computational Tool | Python Package [18] | Identify and quantitatively characterize stem cell niches and their paracrine signaling from spatial omics data. |

The profound therapeutic impact of adult stem cells is largely mediated by their paracrine activity, which coordinately regulates cytoprotection, angiogenesis, and immunomodulation. The move towards using the defined secretome and its components, particularly extracellular vesicles, represents a pivotal shift from cell-based to cell-free therapeutics, mitigating key clinical risks while retaining efficacy. As the field progresses, the challenge lies in standardizing the production and characterization of these complex biological products, understanding their context-dependent actions, and translating robust preclinical findings into effective clinical therapies. By leveraging the advanced experimental and computational tools detailed in this guide, researchers are poised to unlock the full potential of paracrine signaling, heralding a new era of precision regenerative medicine.

The therapeutic application of adult stem cells has undergone a significant paradigm shift, moving from a focus on direct cell differentiation and replacement toward understanding their potent secretome-mediated effects. Paracrine signaling—the process by which cells release biologically active factors that influence neighboring and distant cells—is now recognized as a primary mechanism through which transplanted stem cells exert their reparative and regenerative effects [20]. These secreted factors create a dynamic tissue microenvironment that coordinately regulates processes including cell survival, angiogenesis, immunomodulation, and endogenous regeneration in a temporal and spatial manner [20]. This in-depth technical guide examines the unique paracrine fingerprints of three clinically significant adult stem cell types: Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs), Cardiac Stem Cells (CSCs), and Endothelial Progenitor Cells (EPCs), providing researchers with a comparative analysis of their secretory profiles, signaling pathways, and methodological considerations for experimental investigation.

Molecular Composition of Stem Cell Secretomes

Defining the Paracrine Fingerprint

The "paracrine fingerprint" of a stem cell type encompasses the complete repertoire of molecules it secretes, including growth factors, cytokines, chemokines, and extracellular vesicles (EVs) containing proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids. These fingerprints are highly cell-type-specific and are influenced by both the tissue of origin and the surrounding microenvironmental conditions [20] [13] [21]. The therapeutic potential of these secretomes is largely mediated through their modulation of key biological processes in recipient tissues.

Comparative Secretome Profiles

Table 1: Key Paracrine Factors Secreted by Different Stem Cell Types and Their Primary Functions

| Stem Cell Type | Key Secreted Factors | Primary Biological Functions |

|---|---|---|

| MSCs | VEGF, HGF, FGF, IGF-1, Sfrp2, HASF, PGE2, IL-6, IDO, TGF-β [20] [13] | Cytoprotection, immunomodulation, angiogenesis, anti-fibrosis, stimulation of endogenous stem cells [20] [13] [22] |

| CSCs | Not fully characterized in search results; likely cardiac-specific regenerative factors [23] | Cardiomyocyte proliferation, protection, and survival; cardiac repair [23] [24] |

| EPCs | Angiogenic cytokines; pro-inflammatory factors (MCP-1); tissue factor (under LPS stimulation) [20] [25] | Neovascularization, vascular repair, endothelial regeneration [20] [25] |

Table 2: Extracellular Vesicle Characteristics and Cargo

| Stem Cell Type | EV Cargo Components | Documented Effects |

|---|---|---|

| MSCs | miRNAs, growth factors, cytokines [22] | Anti-apoptotic, anti-inflammatory, angiogenic; improved cardiac function in MI models [22] |

| EPCs | Pro-angiogenic miRNAs and proteins [25] | Enhanced endothelial cell migration and tubule formation [25] |

| CSCs | Information limited in search results | Information limited in search results |

Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs): Versatile Paracrine Communicators

Secretome Profile and Mechanisms of Action

MSCs release a diverse array of bioactive molecules that mediate their extensive therapeutic effects. Key identified factors include secreted frizzled related protein 2 (Sfrp2) and hypoxic induced Akt regulated stem cell factor (HASF), both of which demonstrate significant cytoprotective effects by inhibiting caspase activity and preventing apoptosis in cardiomyocytes [20]. The immunomodulatory strength of MSCs is mediated through factors like prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO), and transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β), which collectively inhibit T-cell proliferation, prevent dendritic cell maturation, and modulate macrophage polarization toward a regenerative M2 phenotype [20] [13].

Regulatory Signaling Pathways

The paracrine activity of MSCs is finely regulated by several intrinsic signaling pathways. The Akt signaling pathway is particularly crucial, as its activation significantly enhances the cytoprotective capabilities of MSC-conditioned media [20]. Additionally, the Wnt/β-catenin pathway interacts with MSC-derived Sfrp2 to modulate apoptotic signaling in target cells [20]. Research indicates that transcriptional regulators including Twist1/2, OCT4, and SOX2 play important roles in maintaining MSC stemness and secretory capacity, with their expression influencing the therapeutic potential of MSCs during ex vivo expansion [26].

Figure 1: Key regulatory pathways and mechanisms governing the paracrine functions of MSCs. Transcription factors Twist and OCT4 enhance secretome production. The Akt pathway, activated by hypoxic conditions, upregulates key factors Sfrp2 and HASF which inhibit apoptosis via Wnt inhibition and PKCε activation, respectively. The resulting secretome drives core therapeutic effects.

Endothelial Progenitor Cells (EPCs): Vascular Regeneration Specialists

Defining EPC Populations

EPCs are bone marrow-derived cells that circulate in the bloodstream and contribute to adult vasculogenesis and endothelial repair [25]. There is ongoing debate regarding their precise definition, but researchers commonly identify EPCs by their surface marker expression, particularly CD34+CD133+KDR+ triple-positive cells [25]. These cells exhibit high clonogenic potential, which serves as a predictor of their angiogenic capability [25]. Subpopulations with lineage-negative markers (e.g., CD14−/CD45−) have also been identified and may possess enhanced angiogenic capacity [25].

Paracrine Mechanisms in Vascular Repair

While EPCs can directly incorporate into nascent vessels, their paracrine activity significantly contributes to vascular regeneration. EPCs secrete a cocktail of pro-angiogenic cytokines that promote the migration, proliferation, and tubulogenesis of mature endothelial cells [25]. Interestingly, in contrast to MSCs, EPCs can secrete pro-inflammatory cytokines like MCP-1 and, under specific conditions such as lipopolysaccharide (LPS) stimulation, the procoagulant protein tissue factor [20]. This highlights the context-dependent nature of EPC paracrine activity and underscores the importance of understanding their functional state before therapeutic application.

Cardiac Stem Cells (CSCs): Cardiac-Specific Regenerative Signaling

Paracrine Role in Heart Repair

CSCs reside within the heart and possess the ability to differentiate into major cardiac lineages, including cardiomyocytes, endothelial cells, and smooth muscle cells [23] [24]. While the specific factors comprising the CSC secretome are not fully detailed in the provided search results, their therapeutic benefits in advanced heart failure are increasingly attributed to paracrine mechanisms [23]. Clinical trials using cardiosphere-derived cells (CDCs), a CSC-containing population, have demonstrated safety and signals of efficacy, with recent attention shifting toward their paracrine signaling effects [23].

Mechanisms of Cardiac Repair

The CSC paracrine factors are believed to promote cardiomyocyte proliferation and survival, stimulate angiogenesis, and activate endogenous repair mechanisms [23] [24]. These combined actions can potentially reduce infarct size, improve ventricular remodeling, and enhance cardiac function after injury. The direct comparison of CSC secretomes with those of MSCs and EPCs remains an important area of ongoing research, as understanding these differences is crucial for selecting the optimal cell type for specific cardiac pathologies.

Experimental Approaches for Paracrine Analysis

Standardized Methodologies for Secretome Characterization

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Methodologies for Paracrine Factor Analysis

| Research Tool | Specific Application | Technical Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Conditioned Media Collection | Culture in serum-free/XF media for 24-48h; concentration via ultrafiltration [20] [21] | Source of soluble paracrine factors for functional assays |

| High-Throughput ELISA/Multiplex Assays | Quantification of VEGF, HGF, IGF-1, FGF, cytokines (PGE2, IL-6) [20] [21] | Comprehensive protein-level secretome profiling |

| EV Isolation (Ultracentrifugation/SEC) | Separation of sEVs (50-150 nm) from conditioned media [22] | Isolation of vesicular fraction of secretome |

| Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis | Characterization of EV size distribution and concentration (e.g., ZetaView, NanoSight) [21] | Quantitative and qualitative EV analysis |

| miRNA qRT-PCR Arrays | Profiling of EV-embedded miRNAs (e.g., miR-21, miR-146a) [21] [22] | Functional RNA cargo characterization |

| Flow Cytometry | Immunophenotyping of surface markers (CD73, CD90, CD105 for MSCs; CD34, CD133, KDR for EPCs) [25] [13] [21] | Cell population identification and purity assessment |

Functional Assays for Paracrine Activity Validation

- In Vitro Cytoprotection Assay: Subject cardiomyocytes or other target cells to hypoxia/reoxygenation injury. Treat with conditioned media (CM) from stem cells. Quantify apoptosis rates using TUNEL staining or caspase-3/7 activity assays [20].

- Tube Formation Assay: Plate endothelial cells (e.g., HUVECs) on Matrigel and treat with stem cell CM or EVs. Measure tubule length, number of nodes, and closed structures after 4-18 hours to assess angiogenic potential [25].

- Immune Cell Modulation Assay: Co-culture stem cell CM with activated T-cells (e.g., using anti-CD3/CD28 antibodies). Measure T-cell proliferation via CFSE dilution or 3H-thymidine incorporation to quantify immunomodulatory capacity [20] [13].

- In Vivo Efficacy Testing: Utilize rodent myocardial infarction models (e.g., permanent LAD ligation). Administer stem cell CM, EVs, or cells via intramyocardial or intravenous injection. Assess functional outcomes by echocardiography (ejection fraction, fractional shortening) and histological analysis (infarct size, capillary density) [20] [22].

Figure 2: Comprehensive experimental workflow for the isolation, characterization, and functional validation of stem cell paracrine factors. The process begins with conditioned media collection, followed by parallel analysis of soluble proteins and extracellular vesicles, culminating in functional assays that inform an integrated paracrine fingerprint.

Technical Considerations and Challenges

Critical Variables Affecting Secretome Composition

The paracrine fingerprint of any stem cell population is not static but is significantly influenced by multiple technical and biological variables that researchers must carefully control and document:

- Culture Conditions: The choice of expansion media (e.g., FBS, human platelet lysate, or serum/xeno-free formulations) creates divergent secretome signatures, with demonstrated functional consequences on immune cells and chondrocytes [21].

- Oxygen Tension: Physiological hypoxia (e.g., 1-5% O2) often enhances the secretion of cytoprotective factors like HASF and influences the expression of transcriptional regulators such as OCT4 [20] [26].

- Passage Number and Donor Variability: Increasing passage number leads to replicative senescence and reduced secretory function, while donor-specific characteristics introduce inherent variability in secretome potency [26].

- Cell Source and Purity: The tissue origin of MSCs (e.g., bone marrow, adipose, umbilical cord) affects their secretory profile, and the definition and purification of EPC subpopulations (e.g., early vs. late EPCs) remain challenging [26] [25] [13].

Translation to Clinical Applications

The progression of stem cell paracrine biology toward clinical therapy requires addressing several key challenges. Standardization of manufacturing protocols according to Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) guidelines is essential for consistent secretome production [21] [27]. Additionally, developing robust potency assays that reliably predict the therapeutic efficacy of a given secretome remains a significant hurdle in the field [27]. Finally, the shift toward using the acellular secretome or isolated EVs as biologicals—which offers advantages in safety, storage, and dosing—requires the development of appropriate regulatory frameworks [22] [27].

The distinct paracrine fingerprints of MSCs, EPCs, and CSCs represent a sophisticated biological communication system that can be harnessed for therapeutic purposes. MSCs demonstrate remarkable versatility through their immunomodulatory and cytoprotective secretome, EPCs specialize in orchestrating vascular repair, and CSCs likely secrete factors tailored to the cardiac regenerative niche. For researchers advancing this field, meticulous attention to cell source, culture conditions, and characterization methodologies is paramount. Future directions will focus on engineering these native secretomes for enhanced potency and specificity, potentially through genetic modification or preconditioning strategies, and standardizing EV-based products as next-generation acellular therapeutics for regenerative medicine.

From Bench to Bedside: Methodologies and Therapeutic Applications

The therapeutic potential of adult stem cells, particularly mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs), is now largely attributed to their paracrine activity rather than direct differentiation and engraftment. These cells release a complex mixture of bioactive molecules, collectively known as the secretome, which includes proteins, growth factors, cytokines, chemokines, and extracellular vesicles (EVs) containing proteins, RNA, and lipids [28] [13] [29]. This secretome mediates intercellular communication, modulating immune responses, promoting tissue repair, and enhancing angiogenesis [30] [13]. Consequently, precise characterization of the secretome is fundamental to understanding the mechanisms of action in stem cell therapies. This technical guide details the core analytical techniques—proteomics and RNA sequencing—used to profile the secretome, providing a framework for researchers and drug development professionals to decipher this critical cellular "sign language" [31].

Core Analytical Techniques for Secretome Profiling

Proteomic Analysis of the Secretome

Proteomic technologies enable the comprehensive identification and quantification of proteins within a secretome. The typical workflow involves separating complex protein mixtures followed by mass spectrometry (MS) analysis.

Methodology and Workflow:

- Sample Preparation: Secretomes are collected from serum-free cell culture conditioned media to avoid contamination from serum proteins, particularly those from fetal bovine serum (FBS) [29]. Proteins are then concentrated and digested into peptides.

- Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS): This is the cornerstone of modern secretome proteomics. As utilized in key studies, high-resolution two-dimensional LC-MS/MS allows for the separation of thousands of peptides and their subsequent identification by mass analysis [32].

- Data Analysis: Computational pipelines are used to match acquired mass spectra to protein sequence databases, enabling identification and label-free or label-based quantification. This reveals proteins that are differentially secreted under various conditions (e.g., resting vs. inflamed) [32] [31].

Key Applications:

- Defining Phenotypic Signatures: Proteomics can distinguish between different MSC activation states. For instance, resting MSC secretomes are rich in extracellular matrix (ECM) and pro-regenerative proteins, whereas secretomes from MSCs licensed with IFN-γ and TNF-α are enriched for immunomodulatory and chemotactic factors like IDO [32].

- Comparing Cellular Sources: Proteomic profiling reveals that secretome composition varies significantly with the MSC source. Induced pluripotent stem cell-derived MSCs (iMSCs) and umbilical cord-derived MSCs (UC-MSCs) show signatures related to proliferative potential, while adult tissue-derived MSCs (from bone marrow or adipose tissue) express higher levels of fibrotic and ECM-related proteins [32].

RNA Sequencing of Extracellular Vesicles

While the cellular secretome includes soluble factors, a significant portion of its regulatory capacity is housed within extracellular vesicles (EVs), such as exosomes and microvesicles. These vesicles carry nucleic acids, including RNA, which can be delivered to recipient cells to alter their function.

Methodology and Workflow:

- EV Isolation: EVs are purified from conditioned media using techniques like ultracentrifugation, density gradient separation, or size-exclusion chromatography [28].

- RNA Extraction and Library Preparation: RNA is isolated from the EV pellet. For single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-Seq), systems like the 10x Genomics Chromium Controller or Parse Biosciences' Evercode kit are used to barcode RNA from thousands of individual cells or vesicles, preserving the resolution of cellular heterogeneity [33].

- Sequencing and Bioinformatic Analysis: Next-generation sequencing is performed, followed by alignment and quantification of transcripts. This can identify the repertoire of mRNAs, microRNAs (miRNAs), and other non-coding RNAs contained within EVs [28] [33].

Key Applications:

- Mechanistic Insight: Sequencing of EV-derived RNA can reveal how MSCs influence recipient cells. For example, MSC-EVs contain miRNAs and mRNAs that regulate processes such as angiogenesis, immune modulation, and oxidative stress response in injured tissues [28].

- Functional Phenotyping: Technologies like the Bruker IsoSpark system integrate secretome analysis with single-cell resolution, allowing researchers to link the secretion of specific cytokines (a functional output) to individual cells within a heterogeneous population [33] [34].

Table 1: Comparison of Core Secretome Profiling Techniques

| Feature | Proteomics (LC-MS/MS) | RNA Sequencing (of EVs) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Focus | Identifies and quantifies proteins, cytokines, and growth factors. | Identifies and quantifies RNA species (mRNA, miRNA, etc.). |

| Key Technology | Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS). | Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS), e.g., 10x Genomics, Parse Biosciences. |

| Sample Type | Cell-conditioned media (serum-free). | Isolated Extracellular Vesicles (EVs). |

| Reveals | Direct effector molecules and post-translational modifications. | Regulatory codes and potential for altering recipient cell gene expression. |

| Information Gained | Functional protein composition and signaling pathways (e.g., VEGF, IL-6). | Cargo that can modulate protein synthesis in target cells. |

Integrated Experimental Workflows

Modern secretome analysis often integrates multiple omics technologies to build a comprehensive picture of paracrine signaling. The following diagram illustrates a generalized workflow for a multi-omics secretome study.

Diagram Title: Integrated Multi-Omics Secretome Analysis Workflow

Critical Research Reagents and Solutions

The following table details key reagents and tools essential for conducting secretome profiling experiments, as derived from the cited methodologies.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Secretome Profiling

| Item | Function / Application | Examples / Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| MSC Culture Media | Expansion and maintenance of mesenchymal stromal cells. | DMEM/RPMI-1640, supplemented with MSC-qualified FBS [32] [30]. For secretome collection, serum-free media is critical [29]. |

| Inflammatory Cytokines | For licensing MSCs to an immunomodulatory (MSC2) phenotype. | Recombinant human IFN-γ and TNF-α (e.g., 15 ng/mL each for 48h) [32]. |

| Proteomic Kits | Sample preparation for LC-MS/MS. | Trypsin/Lys-C for protein digestion, TMT/Isobaric tags for multiplexed quantification. |

| EV Isolation Kits | Purification of extracellular vesicles from conditioned media. | Ultracentrifugation protocols; commercial kits based on precipitation or size-exclusion [28]. |

| Single-Cell Barcoding | Partitioning cells/vesicles for RNA-Seq. | 10x Genomics Chromium (GemCode tech); Parse Biosciences Evercode (split-pool combinatorial barcoding) [33]. |

| Cytokine Panels | Multiplexed protein detection at single-cell resolution. | Bruker IsoCode Chips (32-plex panels for Human/Mouse Adaptive/Innate immunity) [34]. |

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Findings

Secretome profiling has been instrumental in mapping the molecular pathways activated by paracrine signaling. A prime example is the inflammatory licensing of MSCs, a key process that enhances their immunomodulatory function.

Diagram Title: MSC Inflammatory Licensing and Secretome Shift

This pathway, validated by proteomic studies [32], shows how environmental cues reshape the MSC secretome. The licensed MSC2 phenotype is defined by a marked upregulation of IDO secretion and surface HLA expression, alongside a broader shift toward an anti-inflammatory and pro-regenerative protein profile [32]. This demonstrates how secretome analysis directly illuminates the mechanisms behind observed therapeutic effects, such as the suppression of T-cell proliferation and polarization of macrophages toward an M2 reparative state [30] [13].

The synergistic application of proteomics and RNA sequencing provides an unparalleled, multi-dimensional view of the stem cell secretome. These techniques move beyond cataloging secreted factors to revealing the dynamic and regulated nature of paracrine communication. As standardization in secretome production and analysis improves [29], these profiling technologies will be crucial for qualifying potency, ensuring batch-to-batch consistency, and rationally designing the next generation of cell-free regenerative therapeutics. For drug development professionals, mastering these analytical techniques is no longer optional but essential for leveraging the full potential of paracrine signaling in adult stem cell research.

The paradigm of adult stem cell therapy has undergone a significant shift over the past decade. Initially, the therapeutic potential of stem cells was attributed primarily to their ability to engraft and differentiate into tissue-specific cells to replace damaged areas [20]. However, substantial evidence now supports that stem cells exert their reparative and regenerative effects largely through the release of biologically active molecules that act in a paracrine fashion on resident cells [20]. This paracrine hypothesis posits that transplanted stem cells create a tissue microenvironment where secreted factors influence cell survival, inflammation, angiogenesis, repair, and regeneration in a temporal and spatial manner [20]. The validation of this mechanism relies on robust functional assays that can demonstrate these effects both in controlled laboratory settings (in vitro) and in living organisms (in vivo).

The development of the paracrine hypothesis emerged from observations that functional improvement occurred despite poor cellular survivability and minimal engraftment of transplanted cells [20] [1]. Critical evidence came from studies showing that administration of conditioned medium (CM) from cultured stem cells could recapitulate the therapeutic benefits of the cells themselves [20] [1]. This discovery redirected research focus toward identifying the specific factors responsible for these effects and developing assays to quantify their biological activities. This guide provides a comprehensive technical framework for validating these paracrine effects through established functional assays.

Key Paracrine Mechanisms and Their Assay Targets

Stem cell paracrine signaling mediates therapeutic effects through multiple interconnected mechanisms. The table below summarizes the primary mechanisms, their functional outcomes, and key factors involved, providing critical targets for assay development.

Table 1: Key Paracrine Mechanisms and Assay Targets

| Mechanism | Functional Outcome | Key Soluble Factors | Affected Cell Types |

|---|---|---|---|

| Survival/Cytoprotection | Reduced apoptosis and necrosis in injured tissue [20] [1] | Sfrp2, HASF, VEGF, HGF, IGF-1, Akt1 [20] [1] | Cardiomyocytes, Neurons |

| Immunomodulation/Inflammation | Damped inflammatory response; macrophage polarization [20] | PGE2, IL-6, TGF-β, IL-1ra, TSG-6 [20] | T-cells, B-cells, Macrophages, Dendritic cells |

| Neovascularization | Increased capillary density; improved blood flow [1] | VEGF, FGF2, HGF, Angiopoietin-1 [20] [1] | Endothelial cells, Pericytes |

| Tissue Regeneration | Activation and differentiation of resident stem cells [1] | IGFBP5, CTGF, SDF-1 [1] [35] | Resident tissue-specific stem and progenitor cells |

These mechanisms are not isolated; paracrine factors are often pleiotropic, acting on multiple cell types and processes simultaneously [20]. Furthermore, the composition of the secretome can be dynamically influenced by the local microenvironment, such as hypoxia, which can upregulate the production of beneficial factors [20] [36]. The following sections detail the assays used to quantify these functional outcomes.

In Vitro Validation Assays

In vitro assays provide a controlled system for deconstructing complex paracrine interactions and establishing direct causal relationships between secreted factors and cellular responses.

Conditioned Medium (CM) Preparation

The foundation of in vitro paracrine studies is the production of high-quality conditioned medium.

Detailed Protocol: CM from Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs)

- Cell Culture: Expand human Adipose-derived MSCs (Ad-MSCs) in standard culture medium (e.g., DMEM with 10% FBS) until 70-80% confluency [36].

- Serum Deprivation: Wash the cell monolayer twice with 1X Phosphate-Buffered Saline (PBS) to remove residual serum. Incubate the cells in a serum-free medium (e.g., OPTIMEM) under defined conditions (e.g., normoxia or hypoxia at 2% O2) for 24 hours [36].

- Collection and Clarification: Collect the medium and centrifuge at 1200 × g for 10 minutes to remove cellular debris [36].

- Concentration and Standardization: Adjust the protein concentration of the clarified supernatant (e.g., to 100-200 µg/mL) using serum-free medium. Sterilize by filtration through a 0.22 µm filter and store at -20°C until use [36].

Functional Cellular Assays

Survival/Cytoprotection Assay

This assay tests the ability of CM to protect cells from injury-induced death.

Protocol:

- Induce Injury: Subject recipient cells (e.g., cardiomyocytes or photoreceptors) to a lethal insult, such as oxygen-glucose deprivation, hydrogen peroxide, or exposure to cytotoxic drugs [20] [35].

- Apply CM: Treat the injured cells with the test CM, control medium (unconditioned), or purified candidate factors.

- Quantify Viability:

- Apoptosis Assay: Measure caspase-3/7 activity using luminescent or fluorescent substrates [20].

- Necrosis Assay: Use membrane integrity dyes like propidium iodide.

- Metabolic Activity: Employ MTT or WST-1 assays as a proxy for cell health.

Table 2: Key Outcomes from Cytoprotection Assays

| CM Source | Injury Model | Target Cell | Key Identified Factor(s) | Effect on Viability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Akt1-overexpressing MSCs [20] | Hypoxia/Reoxygenation | Rat cardiomyocytes | Sfrp2, HASF [20] | Significant reduction in caspase-3 activity and apoptosis [20] |

| Retinal Mueller Glial Cells [35] | Serum starvation | Primary photoreceptors | IGFBP5, CTGF [35] | Significant increase in photoreceptor survival [35] |

| Bone Marrow Mononuclear Cells [20] | Ischemia | Cardiomyocytes | VEGF, PDGF, IGF-1 [20] | Inhibition of apoptosis; preserved contractility [20] |

Migration and Wound Healing Assay

This assesses the chemoattractant or pro-migratory capacity of paracrine factors, crucial for recruitment of progenitor cells and vascular healing.

Protocol (Wound Healing/Scratch Assay):

- Create a "Wound": Culture recipient cells (e.g., endothelial cells or myoblasts) to full confluency in a multi-well plate. Create a scratch in the monolayer using a sterile pipette tip.

- Apply CM: Wash away dislodged cells and add test CM or controls.

- Image and Quantify: Capture images of the scratch at 0, 12, 24, and 48 hours. Use image analysis software (e.g., Fiji/ImageJ) to measure the change in wound area over time, calculating the rate of migration [37].

Non-Contact Co-Culture System

This system models paracrine interactions between two distinct cell types without direct physical contact.

Protocol (for Neural Crest Cell - Myoblast signaling) [37]:

- Cell Preparation: Culture signal-sending cells (e.g., Neural Crest Cells, NCCs) and signal-receiving cells (e.g., C2C12 myoblasts) separately.

- Co-Culture Setup: Seed the signal-receiving cells in the bottom of a multi-well plate. Place a cell culture insert with a porous membrane (permeable to proteins but not cells) into the well. Seed the signal-sending cells onto this insert.