Predicting Patient Response to Therapy: A Comprehensive Guide to Outcome Prediction Models in Clinical Research

This article provides a comprehensive overview of outcome prediction modeling for therapeutic response, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals.

Predicting Patient Response to Therapy: A Comprehensive Guide to Outcome Prediction Models in Clinical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of outcome prediction modeling for therapeutic response, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational principles of using clinical and genomic data to forecast treatment outcomes, details advanced methodological approaches including deep learning and ensemble models, and addresses critical challenges such as model instability and bias. Furthermore, it offers a comparative analysis of algorithm performance and validation strategies to ensure model reliability and clinical utility, synthesizing insights from the latest research to guide the development of robust, clinically applicable prediction tools.

Core Principles and Data Foundations for Therapy Response Prediction

In the evolving field of precision medicine, defining the prediction goal is a critical first step in developing models that can forecast patient response to therapy. This foundational process requires precise specification of three core components: the target population, the outcome measures, and the clinical setting. These elements collectively determine the model's validity, generalizability, and ultimate clinical utility [1] [2]. Research demonstrates that machine learning (ML) approaches now achieve an average accuracy of 0.76 and area under the curve (AUC) of 0.80 in predicting treatment response for emotional disorders, highlighting the significant potential of well-defined prediction models [3].

The careful definition of these components directly addresses a key challenge in medical ML research: the demonstration of generalizability and regulatory compliance required for clinical implementation [1]. This guide systematically compares how contemporary research protocols define these core elements across different therapeutic domains, providing a framework for researchers developing prediction models for therapeutic response.

Comparative Analysis of Prediction Goal Definitions Across Studies

Table 1: Comparison of Target Population Definitions in Therapeutic Prediction Research

| Study/Model | Medical Domain | Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria | Sample Size | Data Sources |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AID-ME Model [2] | Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) | Adults (≥18) with moderate-severe MDD; acute depressive episode | Bipolar depression, MDE from medical conditions, mild depression | 9,042 participants | 22 clinical trials from NIMH, academic partners, pharmaceutical companies |

| EoBC Prediction Study [4] | Early-Onset Breast Cancer | Women ≥18 to <40 years with non-metastatic invasive breast cancer | Metastatic cancer, malignancy 5 years prior to diagnosis | 1,827 patients | Alberta Cancer Registry, hospitalization databases, vital statistics |

| Stress-Related Disorders Protocol [5] | Stress-Related Disorders (Adjustment Disorder, Exhaustion Disorder) | Primary diagnosis of AD or ED; participants in RCT | N/A (protocol paper) | 300 participants | Randomized controlled trial data |

| Emotional Disorders Meta-Analysis [3] | Emotional Disorders (Depression, Anxiety) | Patients with emotional disorders receiving evidence-based treatments | Studies without ML for treatment response prediction | 155 studies (meta-analysis) | PubMed, PsycINFO (2010-2025) |

Table 2: Outcome Measures and Clinical Settings in Prediction Research

| Study/Model | Primary Outcome | Outcome Measurement Tool | Outcome Timing | Clinical Setting | Intervention Types |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AID-ME Model [2] | Remission | Standardized depression rating scales | 6-14 weeks | Clinical trials (primary/psychiatric care) | 10 pharmacological treatments (8 antidepressants, 2 combinations) |

| EoBC Prediction Study [4] | All-cause mortality | Survival status | 5 and 10 years | Hospital-based cancer care | Surgical interventions, chemotherapy, radiation, hormone therapy |

| Stress-Related Disorders Protocol [5] | Responder status | Perceived Stress Scale-10 (PSS-10) with Reliable Change Index | Post-treatment | Internet-delivered interventions | Internet-based CBT vs. active control |

| Emotional Disorders Meta-Analysis [3] | Treatment response (responder vs. non-responder) | Various standardized clinical scales | Variable across studies | Multiple clinical settings | Psychotherapies, pharmacotherapies, other evidence-based treatments |

Experimental Protocols for Predictive Model Development

Data Sourcing and Participant Selection

The AID-ME study exemplifies a rigorous approach to data sourcing, utilizing clinical trial data from multiple sources including the NIMH Data Archive, academic researchers, and pharmaceutical companies through the Clinical Study Data Request platform [2]. Their protocol implemented strict inclusion/exclusion criteria: studies were required to focus on acute major depressive episodes in adults, with trial lengths between 6-14 weeks to align with clinical guidelines for remission assessment. Participants receiving medication doses below the minimum effective levels defined by CANMAT guidelines were excluded, as were those remaining in studies for less than two weeks, ensuring adequate outcome assessment [2].

The early-onset breast cancer study demonstrates a comprehensive registry-based approach, linking data from the Alberta Cancer Registry with hospitalization records, ambulatory care data, and vital statistics [4]. This population-based method captures complete clinical trajectories, though it presents challenges in data harmonization across sources. The protocol emphasized transparent reporting following TRIPOD guidelines for multivariable prediction models [4].

Machine Learning Methodologies and Validation

Recent systematic reviews of ML applications in major depressive disorder identify Random Forest (RF) and Support Vector Machine (SVM) as the most frequently used methods [1]. Models integrating multiple categories of patient data (clinical, demographic, molecular biomarkers) consistently demonstrate higher predictive accuracy than single-category models [1].

The stress-related disorders protocol employs a comparative methodology, testing four classifiers: logistic regression with elastic net, random forest, support vector machine, and AdaBoost [5]. This approach includes hyperparameter tuning using 5-fold cross-validation with randomized search, with dataset splitting (70% training, 30% testing) to evaluate model performance using balanced accuracy, precision, recall, and AUC [5].

For the emotional disorders meta-analysis, moderator analyses revealed that studies using robust cross-validation procedures exhibited higher prediction accuracy, and those incorporating neuroimaging data achieved superior performance compared to models using only clinical and demographic data [3].

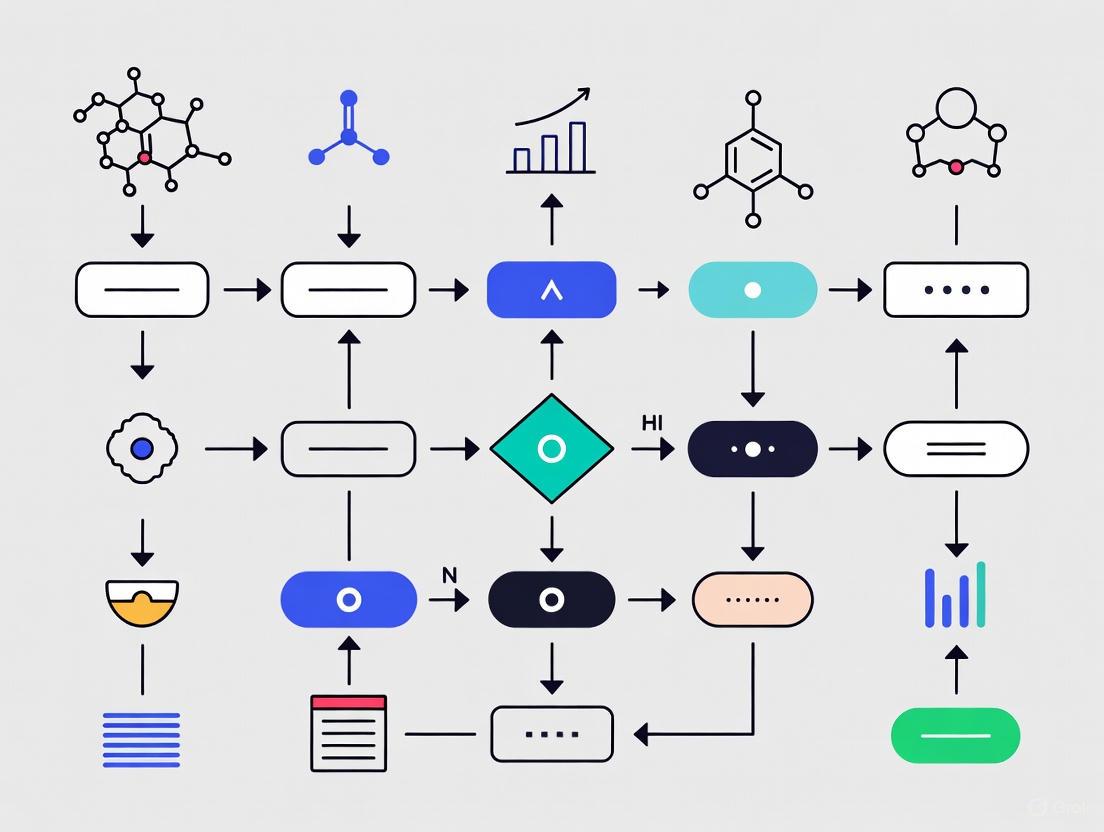

Diagram 1: Workflow for Defining Prediction Goals in Therapeutic Research

Performance Assessment and Validation Frameworks

The emotional disorders meta-analysis established comprehensive performance benchmarks, reporting mean sensitivity of 0.73 and specificity of 0.75 across 155 studies [3]. The stress-related disorders protocol proposes a balanced accuracy threshold of ≥67% as indicative of clinical utility [5].

Critical to performance assessment is the distinction between internal and external validation. The MDD systematic review found limited external validation of applied ML approaches, noting this as a significant barrier to clinical implementation [1]. Well-calibrated models are essential, as evidenced by the breast cancer study which evaluated both discrimination (AUC) and calibration, finding that PREDICT v2.1 overestimated 5-year mortality in high-risk groups despite good discrimination [4].

Research Reagent Solutions for Predictive Modeling

Table 3: Essential Research Materials and Computational Tools for Predictive Modeling

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function in Research | Implementation Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data Sources | Clinical trial data repositories (NIMH, CSDR), Cancer registries, Electronic Health Records | Provides structured, curated patient data with outcome measures | Data harmonization across sources; privacy-preserving access methods [2] [6] |

| Machine Learning Algorithms | Random Forest, Support Vector Machines, Deep Learning, LASSO Cox regression, Random Survival Forests | Pattern detection; handling complex nonlinear relationships in patient data | Algorithm selection based on data type and sample size; computational resources [1] [4] [3] |

| Validation Frameworks | k-fold cross-validation, bootstrapping, hold-out testing, time-dependent ROC analysis | Assess model performance and generalizability | Nested cross-validation preferred; external validation essential for clinical utility [4] [3] |

| Performance Metrics | AUC-ROC, Balanced Accuracy, Sensitivity, Specificity, Calibration plots (Emax, ICI) | Quantify predictive performance and clinical utility | Balance between discrimination and calibration; domain-specific thresholds [4] [3] [5] |

| Privacy/Compliance Tools | Tokenization, Clean Room technology, Expert Determination method, De-identification algorithms | Enable privacy-preserving analysis of sensitive health data | Compliance with GDPR, HIPAA; balance between data utility and privacy [6] |

Critical Considerations in Prediction Goal Definition

Methodological and Ethical Challenges

A significant finding across studies is that prediction models may yield "harmful self-fulfilling prophecies" when used for clinical decision-making [7]. These models can harm patient groups while maintaining good discrimination metrics post-deployment, creating an ethical challenge for implementation. This underscores the limitation of relying solely on discrimination metrics for model evaluation [7].

The systematic review of MDD prediction models identified ongoing challenges with regulatory compliance regarding social, ethical, and legal standards in the EU [1]. Key issues include algorithmic bias mitigation, model transparency, and adherence to Medical Device Regulation (MDR) and EU AI Act requirements [1] [6].

Domain-Specific Adaptations

The comparison reveals important domain-specific considerations in defining prediction goals. In oncology, prediction models must account for extended timeframes (5-10 year survival) and competing risks [4]. In mental health, standardized outcome measures with appropriate timing (6-14 weeks for depression remission) are critical, while also considering functional outcomes and quality of life measures [2] [5].

Diagram 2: Data Integration and Modeling Approaches in Therapeutic Prediction

Emerging Trends and Future Directions

Research indicates a shift toward multimodal data integration, combining clinical, demographic, molecular, and neuroimaging data to enhance predictive accuracy [1] [3]. There is also growing emphasis on privacy-preserving AI techniques that enable analysis without compromising patient confidentiality [6].

The field is moving beyond traditional clinical trial endpoints to incorporate real-world evidence and patient-reported outcomes, facilitated by technologies like wearable devices and digital biomarkers [8] [6]. This expansion of data sources enables more comprehensive prediction goals but introduces additional complexity in data standardization and harmonization.

Future research should focus on developing standardized frameworks for defining prediction goals across domains, addressing ethical implementation challenges, and demonstrating real-world clinical utility through impact studies rather than just performance metrics [1] [7].

In the pursuit of accurate outcome prediction modeling for patient response to therapy, researchers face a fundamental choice in data sourcing: highly controlled clinical trials or observational real-world data (RWD). This decision significantly influences the predictive models' development, validation, and ultimate clinical utility. Clinical trials, long considered the gold standard for establishing causal inference, generate data under standardized conditions that minimize variability and bias [9]. In contrast, real-world data, collected from routine clinical practice, offers insights into therapeutic performance across diverse patient populations and heterogeneous care settings, better reflecting clinical reality [10] [9].

The integration of both data types is increasingly crucial for comprehensive evidence generation throughout the medical product lifecycle. As regulatory agencies like the FDA recognize the value of RWD and its derived real-world evidence (RWE), understanding the complementary strengths and limitations of each source becomes essential for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals aiming to build robust prediction models for therapeutic response [9].

Clinical Trial Data: The Controlled Environment

Clinical trials are prospective studies conducted according to strict protocols to evaluate the safety and efficacy of interventions under controlled conditions [11]. The data generated follows standardized collection procedures with prespecified endpoints and rigorous monitoring to ensure data integrity through principles like ALCOA (Attributable, Legible, Contemporaneous, Original, Accurate) [12].

Phase I trials focus primarily on safety and tolerability in small populations, often healthy volunteers, establishing preliminary pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic profiles [11]. Subsequent phases (II-IV) expand to larger patient populations to confirm efficacy and monitor adverse events. The controlled nature of these trials enables high internal validity through randomization, blinding, and protocol-specified comparator groups.

Real-World Data: The Clinical Practice Environment

Real-world data encompasses information collected from routine healthcare delivery outside the constraints of traditional clinical trials [10] [9]. According to regulatory definitions, RWD sources include electronic health records (EHRs), medical claims data, product and disease registries, patient-generated data from digital health technologies, and data from wearable devices [9].

Unlike clinical trial data, RWD is characterized by its heterogeneity in data collection methods, formats, and quality across different healthcare systems [13]. This diversity presents both opportunities and challenges for outcome prediction modeling, as it captures broader patient experiences but requires sophisticated methodologies to address inconsistencies and potential biases [10].

Comparative Analysis: Key Distinctions

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of Clinical Trial Data vs. Real-World Data

| Characteristic | Clinical Trial Data | Real-World Data |

|---|---|---|

| Data Collection Environment | Controlled, protocol-driven | Routine clinical practice |

| Patient Population | Strict inclusion/exclusion criteria; homogeneous | Broad, diverse; represents actual patients |

| Data Quality & Consistency | High consistency; standardized procedures | Variable quality; requires extensive curation |

| Sample Size | Limited by design and resources | Potentially very large |

| Follow-up Duration | Fixed by protocol | Potentially longitudinal over long term |

| Primary Strength | High internal validity; establishes efficacy | High external validity; establishes effectiveness |

| Primary Limitation | Limited generalizability; high cost | Potential biases; data heterogeneity |

Methodological Rigor and Data Integrity

Clinical trials employ systematic quality control measures throughout the data lifecycle. These include source data verification (SDV), rigorous training of all personnel, and independent monitoring committees (DMCs) that maintain confidentiality of interim results to prevent bias [12]. The implementation of risk-based monitoring approaches, as emphasized in ICH GCP E6(R2), further enhances data integrity while optimizing resource allocation [12].

Real-world data integrity faces different challenges, including variable documentation practices across healthcare settings and potential data missingness [13]. Ensuring RWD quality requires specialized methodologies such as validation studies to assess data accuracy, sophisticated statistical adjustments for confounding factors, and advanced data curation techniques to handle heterogeneous data structures [13] [10].

Applications in Outcome Prediction Modeling

Clinical Trial Data for Prediction Modeling

Clinical trials provide high-quality, structured data ideally suited for developing initial predictive models of treatment response. The detailed phenotyping of patients and standardized outcome assessments enable researchers to identify potential biomarkers and build multivariate prediction models with reduced noise.

The Nemati sepsis prediction model, developed using clinical trial data, demonstrates this application effectively. This early-warning system for sepsis development in ICU patients was built using carefully curated clinical trial data and subsequently validated in real-world settings, where it demonstrated improved patient outcomes [14].

Real-World Data for Prediction Modeling

RWD offers distinct advantages for model refinement and validation across broader populations. In oncology, for example, RWD from diverse sources enables researchers to develop more robust prediction models for rare cancer subtypes or special populations typically excluded from clinical trials [13] [15].

The FDA has acknowledged RWD's growing role in regulatory decision-making, including supporting hypotheses for clinical studies, constructing performance goals in Bayesian analyses, and generating evidence for marketing applications [9]. This regulatory recognition further validates RWD's utility in developing clinically relevant prediction models.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Clinical Trial Data Collection Protocol

A standardized protocol for collecting clinical trial data for outcome prediction modeling includes these critical components:

- Protocol Development: Comprehensive study protocol specifying objectives, endpoints, sample size justification, randomization procedures, and statistical analysis plan [11].

- Site Selection and Training: Choosing qualified investigative sites with appropriate expertise and ensuring all personnel receive standardized training on the protocol and data collection procedures [12] [11].

- Data Collection Procedures: Implementing uniform data collection methods across all sites, including electronic data capture systems with built-in edit checks [12].

- Quality Control Measures: Establishing ongoing monitoring procedures, including source data verification, query resolution processes, and regular quality control audits [12].

- Endpoint Adjudication: Implementing blinded independent committee review for subjective endpoints to minimize assessment bias.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions for Clinical Data Research

| Research Tool | Function in Data Research |

|---|---|

| Electronic Data Capture (EDC) Systems | Standardized data collection across sites with audit trails |

| Clinical Trial Management Systems (CTMS) | Centralized management of trial operations and documentation |

| ALCOA+ Principles Framework | Ensures data integrity throughout collection process |

| Statistical Analysis Plans (SAP) | Pre-specified analytical approaches to minimize bias |

| Sample Size Calculation Tools | Determines adequate power for detecting predicted effects |

| Randomization Systems | Unbiased treatment allocation sequences |

Real-World Data Curation Protocol

Transforming raw real-world data into analyzable evidence requires a rigorous curation process:

- Data Source Evaluation: Assessing the suitability of RWD sources for the research question based on completeness, accuracy, and representativeness [9].

- Data Extraction and Harmonization: Extracting relevant variables from source systems and mapping to common data models to enable pooling and analysis [10].

- Quality Assessment and Validation: Implementing quality checks for data plausibility, completeness, and consistency across sources [13].

- Bias Assessment and Mitigation: Identifying potential selection, measurement, and confounding biases, then applying appropriate statistical adjustments [13].

- Privacy Protection: Implementing data anonymization or de-identification techniques while preserving data utility for analysis [13].

Figure 1: RWD Curation to Evidence Pipeline

Integrated Approaches and Future Directions

Hybrid Designs: Leveraging Both Worlds

Innovative trial designs that integrate clinical trial and RWD methodologies are emerging as powerful approaches for therapeutic response prediction. These include:

- Pragmatic Clinical Trials: Maintain randomization while implementing more inclusive eligibility criteria and flexible interventions to better reflect real-world practice [16].

- External Control Arms: Use carefully curated RWD to create historical controls when randomization to standard-of-care is impractical or unethical [9].

- Registry-Based Randomized Trials: Embed randomization within clinical registries to combine trial rigor with efficient long-term follow-up through RWD [9].

Artificial Intelligence and Advanced Analytics

AI and machine learning techniques are increasingly bridging the gap between clinical trial and real-world data by:

- Enhancing RWD Quality: Using natural language processing to extract structured information from unstructured clinical notes [13].

- Identifying Digital Phenotypes: Discovering novel patient subgroups and their differential treatment responses using unsupervised learning on multimodal RWD [15].

- Improving Generalizability: Testing prediction models developed in clinical trials against RWD to assess real-world performance and identify potential drift [14].

Figure 2: Data Integration for Prediction Modeling

The critical role of data sourcing in outcome prediction modeling for therapeutic response necessitates a purpose-driven approach rather than a universal preference for either clinical trials or real-world data. Clinical trial data provides the methodological foundation for establishing causal relationships and initial predictive signatures under controlled conditions. Meanwhile, real-world data offers the contextual validation needed to ensure these models perform effectively across diverse clinical settings and patient populations.

For researchers and drug development professionals, the most robust approach involves strategic integration of both data types throughout the therapeutic development lifecycle. This includes using clinical trial data for initial model development, followed by validation and refinement using carefully curated real-world data. As regulatory frameworks continue to evolve, with agencies like the FDA providing clearer pathways for RWD/RWE incorporation, this integrated approach will become increasingly essential for developing prediction models that are both scientifically valid and clinically actionable [9].

The future of outcome prediction modeling lies not in choosing between these data sources, but in developing sophisticated methodologies that leverage their complementary strengths while acknowledging and mitigating their respective limitations. This balanced approach will ultimately accelerate the development of more personalized and effective therapeutic interventions.

Predicting a patient's response to therapy remains a central challenge in modern precision medicine. While traditional models have relied on clinical variables alone, a growing consensus indicates that a holistic approach, integrating molecular-level omics data with clinical and demographic information, is needed to unveil the mechanisms underlying disease etiology and improve prognostic accuracy [17] [18]. This integrated approach leverages the fact that biological information flows through multiple regulatory layers—from genetic predisposition (genomics) to gene expression (transcriptomics), protein expression (proteomics), and metabolic function (metabolomics). Each layer provides a unique and complementary perspective on the patient's health status and disease pathophysiology [19] [20]. The integration of these diverse data types creates a more comprehensive model of the individual, which can lead to refined prognostic assessment, better patient stratification, and more informed treatment selection [17] [18]. This guide provides an objective comparison of the data types, computational methods, and their performance in therapy response prediction.

Data Landscape: Variables and Their Predictive Value

The predictive models discussed in this guide are built upon three primary categories of data, each contributing unique information.

Clinical and Demographic Variables

Clinical and demographic information often serves as the foundational layer for prognostic models. These variables typically include:

- Patient Phenotype: Age, sex, and body mass index.

- Disease Characteristics: Tumor stage, grade, and histology in oncology; symptom severity and functioning in mental health care.

- Treatment History: Prior therapies and treatment sequences. Clinical variables alone have demonstrated varying prognostic power across cancer types, with concordance indices (C-index) ranging from 0.572 to 0.819 in a pan-cancer analysis [18].

Omics Data Types and Repositories

Omics data provides a deep molecular characterization of the patient's disease state. Key data types and their sources include:

Table 1: Multi-Omics Data Types and Repositories

| Omics Data Type | Biological Information | Key Repositories |

|---|---|---|

| Genomics | DNA sequence and variation (germline and somatic) | TCGA, ICGC, CCLE [19] |

| Transcriptomics | RNA expression levels (coding and non-coding) | TCGA, TARGET, METABRIC [19] |

| Proteomics | Protein abundance and post-translational modifications | CPTAC [19] |

| Metabolomics | Small-molecule metabolite concentrations | Metabolomics workbench, OmicsDI [19] |

| Epigenomics | DNA methylation and chromatin modifications | TCGA [19] |

Among these, mRNA and miRNA expression profiles frequently demonstrate the strongest prognostic performance, followed by DNA methylation. Germline susceptibility variants (polygenic risk scores) consistently show lower prognostic power across cancer types [18].

Integrated Data Workflow

The process of integrating these disparate data types requires a structured framework to ensure interoperability and reproducibility. The following diagram illustrates a generalized workflow for multi-modal data integration.

Performance Comparison: Integrated Models vs. Single Data Type Models

Numerous studies have benchmarked the performance of integrative models against those using single data types. The following table summarizes key findings from comparative analyses.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Integrative vs. Non-Integrative Models

| Study / Context | Integration Method | Comparison Baseline | Performance Metric | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pan-Cancer Analysis [18] | Multi-omic kernel machine | Clinical variables alone | Concordance Index (C-index) | Integration improved prognosis over clinical-only in 50% of cancers (e.g., C-index for clinical: 0.572-0.819 vs. mRNA: 0.555-0.847) |

| Supervised Classification Benchmark [17] | DIABLO, SIDA, PIMKL, netDx, Stacking, Block Forest | Random Forest on single or concatenated data | Classification Accuracy | Integrative approaches performed better or equally well than non-integrative counterparts |

| Mental Health Care Prediction [21] | LASSO regression on routine care data | - | Area Under Curve (AUC) | AUC ranged from 0.77 to 0.80 in internal and external validation across 3 sites |

| Emotional Disorders Meta-Analysis [3] | Various Machine Learning models | - | Average Accuracy / AUC | ML models showed mean accuracy of 0.76 and mean AUC of 0.80 for predicting therapy response |

| Radiotherapy Response Prediction [22] | Multi-scale Dilated Ensemble Network (MDEN) | RNN, LSTM, 1D-CNN | Prediction Accuracy | Proposed MDEN framework outperformed individual deep learning models |

A critical finding from these comparisons is that the integration of multi-omics data with clinical variables can lead to substantially improved prognostic performance over the use of clinical variables alone in half of the cancer types examined [18]. Furthermore, integrative supervised methods consistently perform better or at least equally well as their non-integrative counterparts [17].

Experimental Protocols for Data Integration

To ensure reproducibility, this section outlines detailed methodologies for key integration experiments cited in this guide.

Protocol 1: Kernel Machine Learning for Pan-Cancer Prognosis

This protocol is derived from a study that integrated clinical and multi-omics data for prognostic assessment across 14 cancer types [18].

1. Data Acquisition and Preprocessing:

- Data Source: Download multi-omics data (somatic mutations, copy number, DNA methylation, mRNA/miRNA expression, RPPA) and clinical data from TCGA portal.

- Quality Control: Remove features with excessive missing values. Impute remaining missing values using appropriate methods (e.g., k-nearest neighbors).

- Data Normalization: Normalize each omics dataset to make features comparable (e.g., convert read counts to counts per million for RNA-Seq, use beta values for methylation).

2. Similarity Matrix Construction:

- For each omics data type and each patient pair, compute a linear kernel (similarity score).

- For a given omics profile

X(withpbiomarkers), the similarity between patientsiandjis calculated asK(i,j) = Σ (x_ik * x_jk) / pfork=1 to p. - This results in an

N x Nomic similarity matrix for each data type, whereNis the sample size.

3. Model Training and Validation:

- Outcome: Overall survival (time-to-event data).

- Integration: Use a kernel-based Cox proportional hazards model. The hazard for a patient is modeled based on the similarity of their omics profiles to all other patients.

- Clinical Variable Adjustment: Include clinical variables (e.g., age, sex, stage) as traditional covariates in the model.

- Validation: Perform cross-validation (e.g., 5-fold) and evaluate prognostic performance using the concordance index (C-index).

Protocol 2: Supervised Integrative Analysis with DIABLO

This protocol details the use of DIABLO (Data Integration Analysis for Biomarker discovery using Latent cOmponents) for classification problems, as featured in a benchmark study [17].

1. Experimental Setup:

- Input Data: Collect multiple matched omics datasets (

X1, X2, ..., Xm) from the sameNsamples and a categorical outcome vectorY(e.g., treatment responder vs. non-responder). - Design Matrix: Define a

m x mdesign matrix specifying whether omics views are connected (usually 1 for connected, 0 for not).

2. Model Training:

- Objective: DIABLO seeks

Hlinear combinations (components) of variables per view that are highly correlated across connected views and discriminatory for the outcome. - Optimization: It solves a sparse generalized canonical correlation analysis (sGCCA) problem for each component

h:maximize { Σ a_{ij} cov(X_i w_i^{(h)}, X_j w_j^{(h)}) }subject to penalties onw_i^{(h)}for variable selection. - Parameter Tuning: Use cross-validation to determine the number of components and the number of variables to select per view and per component to minimize prediction error.

3. Prediction and Evaluation:

- Classification: Project new samples into the latent space and classify them based on a weighted majority vote across views.

- Evaluation Metrics: Calculate classification accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, and area under the ROC curve (AUC) on a held-out test set.

Protocol 3: Cross-Site Validation in Mental Health Care

This protocol is based on a multisite study predicting undesired treatment outcomes in mental health care using routine outcome monitoring (ROM) data [21].

1. Data Standardization:

- Predictors: Extract a common set of variables from routine care data across all sites, including demographics (age, sex), diagnosis, baseline symptom severity (OQ-45.2 score), and early treatment response patterns.

- Outcome Definition: Define the undesired outcome (e.g., non-improvement) as improving less than a medium effect size on the Symptom Distress subscale between start and end of treatment.

2. Model Development:

- Algorithm: Apply Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator (LASSO) regression for model fitting and variable selection.

- Internal Validation: For each site, perform internal validation using cross-validation (e.g., 10-fold) within the site's own data.

3. External Validation:

- Process: Train a model on the complete dataset from one site (Site A) and then evaluate its performance on the untouched datasets from the other sites (Site B and C).

- Performance Reporting: Report the performance metrics (AUC, accuracy) for both internal and external validations to assess model robustness and generalizability.

Methodological Landscape: Choosing an Integration Strategy

The choice of integration methodology is critical and depends on the biological question, data structure, and desired outcome. The approaches can be broadly categorized as shown below.

Successfully implementing a multi-omics integration project requires a suite of computational tools, data resources, and analytical packages.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Multi-Omics Integration

| Tool / Resource | Type | Primary Function | Key Features / Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| TCGA / ICGC Portals [19] | Data Repository | Provides comprehensive, curated multi-omics and clinical data for various cancers. | Foundational data source for training and validating predictive models in oncology. |

| mixOmics (DIABLO) [17] | R Package | Performs supervised integrative analysis for classification and biomarker selection. | Uses sparse generalized CCA to identify correlated components across omics views that discriminate sample groups. |

| xMWAS [20] | R-based Tool | Performs association analysis and creates integrative networks across multiple omics datasets. | Uses PLS-based correlation to identify relationships between features from different omics types and visualizes them as networks. |

| WGCNA [20] | R Package | Identifies clusters (modules) of highly correlated genes/features from omics data. | Used to find co-expression networks; modules can be linked to clinical traits or used for integration with other omics. |

| LORIS & CBRAIN [23] | Data Management & HPC Platform | Manages, processes, and analyzes multi-modal data (imaging, omics, clinical) within a unified framework. | Automates workflows, ensures provenance tracking, and facilitates reproducible analysis across HPC environments. |

| SuperLearner / Stacking [17] | R Package | Implements ensemble learning (late integration) by combining predictions from multiple base learners. | Flexible framework for integrating predictions from omics-specific models into a final, robust prediction. |

| netDx [17] | R Package | Builds patient similarity networks using different omics data types for classification. | Uses prior biological knowledge (e.g., pathways) to define features and integrates them via patient similarity networks. |

Ethical Considerations and Bias Assessment in Model Foundations

The integration of advanced AI and foundational models into patient response to therapy research represents a paradigm shift in predictive healthcare. These large-scale artificial intelligence systems, trained on extensive multimodal and multi-center datasets, demonstrate remarkable versatility in predicting disease progression, treatment efficacy, and adverse events [24]. However, their clinical integration presents complex ethical challenges that extend far beyond technical performance metrics, particularly concerning patient data privacy, algorithmic bias, and model transparency [24]. The stakes are exceptionally high in medical applications, where model failures can directly impact patient outcomes and perpetuate healthcare disparities.

Current research reveals significant gaps in existing predictive frameworks. A recent systematic review of predictive models for metastatic prostate cancer found that most identified models require additional evaluation and validation in properly designed studies before implementation in clinical practice, with only one study among 15 having a low risk of bias and low concern regarding applicability [25]. This underscores the urgent need for rigorous ethical frameworks and bias assessment methodologies in medical AI systems. As foundational models become more prevalent in healthcare, establishing comprehensive guidelines for their ethical development and deployment is paramount to ensuring they enhance clinical decision-making without compromising ethical integrity or patient safety [24].

Comparative Analysis of Model Performance in Therapeutic Prediction

Quantitative Performance Metrics

The evaluation of predictive models for therapeutic response requires a multi-dimensional assessment approach. The table below summarizes key performance indicators across different model architectures as reported in recent literature:

Table 1: Performance comparison of AI models in medical prediction tasks

| Model Architecture | Clinical Application | Key Performance Metrics | Reported Performance | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Multi-scale Dilated Ensemble Network (MDEN) [22] | Patient response prediction during radiotherapy | Accuracy, Error Rate | 0.79-2.98% improvement over RNN, LSTM, 1DCNN | Requires extensive computational resources |

| Traditional Prognostic Models [25] | Metastatic prostate cancer treatment response | Risk of Bias, Applicability | Only 1 of 15 studies had low risk of bias | High risk of bias in many studies |

| Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN) [22] | Forecasting patient response to chemotherapy | Predictive Capacity | Widely used but limited by data scarcity | Requires large annotated datasets |

| Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) [22] | Radiation-induced fibrosis prediction | Model Generalizability | Effective for learning complex relationships | Demands exceptionally large data volumes |

| Neural Network Ensemble [22] | Radiation-induced lung damage prediction | ROC curves, Bootstrap Validation | Superior to Random Forests and Logistic Regression | Limited multi-institutional validation |

Bias Assessment Across Model Types

The evaluation of bias in predictive healthcare models requires careful consideration of multiple dimensions. The following table synthesizes bias assessment findings from recent research:

Table 2: Bias assessment in therapeutic prediction models

| Bias Category | Impact on Model Performance | Assessment Methodology | Mitigation Strategies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data Collection Bias [24] | Perpetuates healthcare disparities across demographic groups | Historical data disparity analysis | Systematic bias detection and mitigation strategies |

| Annotation Bias [22] | Limits predictive accuracy and generalizability | Inter-annotator disagreement measurement | Multi-center, diverse annotator pools |

| Representation Bias [24] | Compromises diagnostic accuracy for underrepresented populations | Demographic parity metrics | Federated learning across diverse populations |

| Measurement Bias [25] | Impacts clinical applicability and real-world performance | PROBAST criteria for risk of bias | Robust validation in clinical settings |

| Algorithmic Bias [24] | Leads to discriminatory outcomes in treatment recommendations | Fairness-aware training procedures | Bias auditing and regulatory compliance strategies |

Experimental Protocols for Ethical Model Assessment

Comprehensive Bias Detection Framework

The systematic assessment of bias in foundational models for therapeutic prediction requires rigorous experimental protocols. A robust methodology should incorporate multiple complementary approaches:

Data Provenance and Characterization: The initial phase involves comprehensive audit trails for training data sources, with detailed documentation of demographic distributions, clinical settings, and data collection methodologies. This includes analyzing patient intrinsic factors such as lifestyle, sex, age, and genetics that significantly influence therapeutic outcomes [22]. Studies must explicitly report inclusion and exclusion criteria, with particular attention to underrepresented populations in medical datasets.

Multi-dimensional Bias Metrics: Implementation of quantitative bias metrics should span group fairness, individual fairness, and counterfactual fairness measures. Techniques include disparate impact analysis across racial, ethnic, gender, and socioeconomic groups, with statistical tests for significant performance variations across patient subgroups [24]. For metastatic prostate cancer models, this involves assessing whether prediction accuracy remains consistent across different disease stages, treatment histories, and comorbidity profiles [25].

Cross-institutional Validation: Given the sensitivity of medical models to data heterogeneity, rigorous external validation is essential. This involves testing model performance across multiple healthcare facilities with varying imaging devices, treatment protocols, and patient populations [24]. The PROBAST tool provides a structured approach for assessing risk of bias and applicability concerns in predictive model studies [25].

Performance Benchmarking Methodology

Standardized evaluation protocols are critical for meaningful comparison across therapeutic prediction models:

Stratified Performance Assessment: Models should be evaluated using stratified k-fold cross-validation with stratification across key demographic and clinical variables. This ensures representative sampling of patient subgroups and reliable performance estimation [22]. For radiotherapy response prediction, this includes stratification by cancer stage, treatment regimen, and prior therapy exposure.

Composite Metric Reporting: Beyond traditional accuracy metrics, comprehensive evaluation should include clinical utility measures such as calibration metrics, decision curve analysis, and clinical impact plots [25]. These assess how model predictions influence therapeutic decision-making and patient outcomes, providing a more complete picture of real-world applicability.

Robustness Testing: Models must undergo rigorous robustness evaluation against distribution shifts, adversarial examples, and data quality variations [24]. This is particularly crucial in medical contexts where model failures can have severe consequences. Techniques include stress testing with corrupted inputs, evaluating performance degradation with missing data, and assessing resilience to domain shifts between institutions.

Visualization of Ethical Assessment Workflows

Comprehensive Bias Assessment Framework

Model Performance and Ethics Evaluation Workflow

Patient Response Prediction Pipeline

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key research reagents and computational tools for ethical model development

| Research Reagent/Tool | Primary Function | Application in Therapeutic Prediction |

|---|---|---|

| PROBAST Tool [25] | Risk of bias assessment | Systematic evaluation of prediction model study quality |

| REE-COA Algorithm [22] | Feature selection and optimization | Enhances prediction performance by optimizing feature weights |

| Multi-scale Dilated Ensemble Network [22] | Patient response prediction | Integrates LSTM, RNN, and 1DCNN for improved accuracy |

| Federated Learning Framework [24] | Privacy-preserving model training | Enables multi-institutional collaboration without data sharing |

| Homomorphic Encryption [24] | Data privacy protection | Secures patient confidentiality during model training |

| Explainable AI Modules [24] | Model interpretability | Provides insights into model decisions for clinical trust |

| Bias Detection Toolkit [24] | Algorithmic fairness assessment | Identifies discriminatory patterns across patient demographics |

| CHARMS Checklist [25] | Data extraction standardization | Ensures consistent methodology in systematic reviews |

Discussion and Future Directions

The integration of comprehensive ethical frameworks into foundational models for therapeutic prediction represents both a moral imperative and a technical challenge. Current evidence suggests that without systematic bias assessment and mitigation strategies, AI models risk perpetuating and amplifying existing healthcare disparities [24]. The recent finding that only one of 15 predictive models for metastatic prostate cancer had a low risk of bias underscores the pervasive nature of this problem [25]. Furthermore, the heterogeneous nature of medical imaging data, with variations across imaging devices and institutional protocols, creates substantial challenges for developing unified models that can process and interpret diverse inputs effectively [24].

Future research must prioritize the development of standardized evaluation frameworks that simultaneously assess predictive performance and ethical implications. This includes advancing privacy-preserving technologies such as federated learning and homomorphic encryption to enable collaborative model development without compromising patient confidentiality [24]. Additionally, the implementation of explainable AI mechanisms is crucial for fostering clinician trust and facilitating regulatory compliance. As foundational models continue to evolve in medical imaging, maintaining alignment with core ethical principles while harnessing their transformative potential will require ongoing collaboration between AI researchers, clinical specialists, ethicists, and patients [24]. The establishment of clear guidelines for development and deployment, coupled with robust validation protocols, will be essential for realizing the promise of AI in personalized therapy while preserving the fundamental principles of medical ethics and patient-centered care.

Advanced Algorithms and Implementation in Clinical Workflows

The accurate prediction of patient response to therapy is a cornerstone of modern precision medicine, enabling more effective treatment personalization and resource allocation. The selection of an appropriate modeling approach is a critical step that researchers and drug development professionals must undertake, balancing model complexity, interpretability, and predictive performance. The modeling landscape spans traditional regression techniques, various machine learning algorithms, and advanced deep learning architectures, each with distinct strengths, limitations, and optimal application domains.

This guide provides an objective comparison of these approaches within the specific context of outcome prediction modeling for patient response to therapy research. We synthesize performance metrics across multiple therapeutic domains and present detailed experimental methodologies to inform model selection decisions. The comparative analysis focuses on practical implementation considerations, data requirements, and validation frameworks relevant to researchers working across the drug development pipeline—from early discovery to clinical application.

Comparative Performance of Modeling Approaches

Quantitative Performance Metrics Across Domains

Extensive research has evaluated the performance of different modeling approaches across various therapeutic domains. The table below synthesizes key performance indicators from multiple studies to enable direct comparison.

Table 1: Performance comparison of modeling approaches for therapeutic outcome prediction

| Modeling Approach | Application Domain | Accuracy (%) | AUC | Sensitivity | Specificity | Key Advantages | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cox Regression | SARS-CoV-2 mortality | 83.8 | 0.869 | - | - | Interpretable, established statistical properties | [26] |

| Artificial Neural Network (ANN) | SARS-CoV-2 mortality | 90.0 | 0.926 | - | - | Handles complex nonlinear relationships | [26] |

| Machine Learning (Multiple Algorithms) | Emotional disorders treatment response | 76.0 | 0.80 | 0.73 | 0.75 | Good balance of performance and interpretability | [3] [27] |

| Deep Learning (Sequential Models) | Heart failure preventable utilization | - | 0.727-0.778 | - | - | Superior for temporal pattern recognition | [28] |

| Logistic Regression | Heart failure preventable utilization | - | 0.681 | - | - | Computational efficiency, interpretability | [28] |

| Neural Networks (TensorFlow, nnet, monmlp) | Depression treatment remission | - | 0.64-0.65 | - | - | Moderate accuracy for psychological outcomes | [29] |

| Generalized Linear Regression | Depression treatment remission | - | 0.63 | - | - | Similar performance to complex models for this application | [29] |

| Multi-scale Dilated Ensemble Network | Radiotherapy patient response | - | - | - | - | Error minimization through ensemble approach | [22] |

Performance Analysis and Interpretation

The comparative data reveals several important patterns. First, deep learning approaches generally achieve superior performance for complex prediction tasks with large datasets and nonlinear relationships. The significant advantage of ANN over Cox regression for SARS-CoV-2 mortality prediction (90.0% vs. 83.8% accuracy, p=0.0136) demonstrates this capacity in clinical outcome prediction [26]. Similarly, for heart failure outcomes, deep learning models achieved precision rates of 43% at the 1% threshold for preventable hospitalizations compared to 30% for enhanced logistic regression [28].

However, this performance advantage is not universal. For depression treatment outcomes, neural networks provided only marginal improvement over generalized linear regression (AUC 0.64-0.65 vs. 0.63) [29], suggesting that simpler approaches may be adequate for certain psychological outcome predictions. The machine learning approaches for emotional disorders treatment response prediction show consistently good performance (76% accuracy, 0.80 AUC) [3] [27], positioning them as a balanced option between traditional regression and deep learning.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Model Development Workflows

The predictive performance of different modeling approaches is heavily influenced by methodological choices during development. The following diagram illustrates a generalized experimental workflow for developing and comparing predictive models of treatment response.

Diagram 1: Model development workflow for 76px

Detailed Methodological Protocols

Traditional Regression Approaches

Cox regression and logistic regression models typically follow a structured development process. In the SARS-CoV-2 mortality prediction study, researchers used a parsimonious model-building approach with clinically relevant demographic, comorbidity, and symptomatology features [26]. The protocol included:

- Feature Selection: Predictors were chosen based on previously published literature and included age, sex, comorbidities, symptoms, and days of symptoms prior to admission.

- Data Splitting: The dataset was randomly split into training (80%) and test (20%) sets.

- Model Building: All predictors were initially included irrespective of univariable significance, with subsequent backward elimination of non-significant predictors.

- Validation: k-fold cross-validation was used on the training set with model selection based on the lowest Akaike information criterion (AIC) score and highest concordance index (c-index).

- Performance Assessment: Models were evaluated using accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, negative predictive value, and calibration metrics (Brier score) [26].

Deep Learning Approaches

Deep learning implementations require more specialized preprocessing and training protocols. In the SARS-CoV-2 study comparing ANN to Cox regression, the methodology included:

- Data Preprocessing: Feature-wise normalization was implemented, with each feature centered around zero by subtracting the mean and dividing by its standard deviation [26].

- Architecture Optimization: Hyperparameters (number and size of layers, batch size, dropout, regularization) were adjusted using k-fold cross-validation on the training set.

- Implementation: The TensorFlow machine learning library was used to construct the ANN [26].

- Validation Framework: The dataset was randomly split into training (80%) and test (20%) sets, with performance metrics calculated similarly to the Cox model for direct comparison.

For more complex deep learning applications such as predicting preventable utilization in heart failure patients, sequential models (LSTM, CNN with attention mechanisms) utilized temporal patient-level vectors containing 36 consecutive monthly vectors summing medical codes for each month [28]. This approach captured dynamic changes in patient status over time, which traditional models typically cannot leverage effectively.

Machine Learning Protocols for Emotional Disorders

The meta-analysis of machine learning for emotional disorder treatment response prediction revealed important methodological considerations [3] [27]:

- Data Requirements: Studies using more robust cross-validation procedures exhibited higher prediction accuracy.

- Predictor Selection: Neuroimaging data as predictors were associated with higher accuracy compared to clinical and demographic data alone.

- Outcome Balancing: Studies with larger responder rates and those that did not correct for imbalances in outcome rates were associated with higher prediction accuracy, though this may reflect methodological artifacts rather than true performance advantages.

Technical Implementation and Architecture

Deep Learning Architectures for Therapeutic Response Prediction

Advanced deep learning approaches employ sophisticated architectures tailored to specific data structures and prediction tasks. The following diagram illustrates architectural components of deep learning models used in therapeutic response prediction.

Diagram 2: Deep learning model architectures for 76px

Implementation Considerations

Data Requirements and Feature Engineering

The performance of different modeling approaches is heavily dependent on data quality and feature engineering:

- Traditional Models: Work effectively with structured clinical data (demographics, comorbidities, lab values) and require careful handling of confounding variables. Feature selection is often knowledge-driven based on clinical expertise [26] [28].

- Machine Learning: Can incorporate both knowledge-driven features and data-driven representations. Random forest models have demonstrated effectiveness with molecular fingerprints for drug response prediction [30].

- Deep Learning: Most effective with large sample sizes and can utilize raw data representations with minimal preprocessing. Sequential deep learning models excel with temporal data representations [28]. For drug permeation prediction, ANN models have shown RMSE values of 14.0, outperforming some traditional approaches [31].

Computational Requirements

Computational demands vary significantly across approaches:

- Traditional Regression: Can be implemented on standard computing resources with statistical software packages.

- Machine Learning: Requires moderate computational resources, with tree-based methods (random forests, gradient boosting) being more computationally intensive than linear models.

- Deep Learning: Often requires specialized hardware (GPUs) for efficient training, particularly for complex architectures like LSTM networks and ensemble approaches [22]. Training deep learning models for pharmaceutical applications has been successfully implemented using Tesla K20c GPU accelerators [32].

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Successful implementation of predictive models requires appropriate computational tools and data resources. The table below details key solutions used across the cited studies.

Table 2: Essential research reagents and computational tools for predictive modeling

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Example Applications | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TensorFlow | Deep Learning Library | Neural network development and training | ANN for SARS-CoV-2 mortality prediction | [26] |

| Scikit-learn | Machine Learning Library | Traditional ML algorithms implementation | Drug permeation prediction | [31] |

| Python | Programming Language | Data preprocessing, model development, analysis | Heart failure utilization prediction | [28] |

| RDKit | Cheminformatics Library | Molecular fingerprint calculation | Drug discovery and ADME/Tox prediction | [32] |

| Electronic Health Records | Data Source | Clinical features and outcome labels | SARS-CoV-2 mortality, heart failure outcomes | [26] [28] |

| Patient-Derived Cell Cultures | Experimental System | Functional drug response profiling | Drug response prediction in precision oncology | [30] |

| FCFP6 Fingerprints | Molecular Descriptors | Compound structure representation | Drug discovery datasets, ADME/Tox properties | [32] |

The selection of modeling approaches for predicting patient response to therapy requires careful consideration of multiple factors, including dataset characteristics, performance requirements, and interpretability needs.

Based on the comparative evidence:

- Traditional regression models remain valuable for smaller datasets, when model interpretability is paramount, or when established clinical relationships exist. They provide a strong baseline against which to compare more complex approaches.

- Machine learning algorithms offer a balanced approach for medium-complexity problems, providing improved performance over traditional models while maintaining some interpretability. They are particularly effective when combining clinical and molecular data.

- Deep learning architectures deliver superior performance for complex problems with large datasets, particularly when dealing with temporal patterns, image data, or highly nonlinear relationships. However, they require substantial data and computational resources, and model interpretability remains challenging.

The optimal approach varies by application domain, with deep learning showing particular promise for mortality prediction and healthcare utilization forecasting, while traditional methods remain competitive for certain psychological treatment outcomes. Researchers should implement rigorous validation frameworks, including appropriate data partitioning and performance metrics relevant to the specific clinical context, when comparing modeling approaches for therapeutic response prediction.

Leveraging Ensemble and Multi-Scale Network Architectures for Enhanced Accuracy

In the pursuit of precision medicine, accurately predicting a patient's response to therapy is paramount for optimizing treatment outcomes and minimizing adverse effects. Traditional single-model approaches in machine learning often fall short in capturing the complex, multi-factorial nature of disease progression and therapeutic efficacy. Ensemble and multi-scale network architectures have emerged as powerful computational frameworks that address these limitations by integrating diverse data perspectives and model outputs. This guide provides a comparative analysis of these advanced architectures, detailing their methodologies, performance, and practical implementation for researchers and drug development professionals focused on outcome prediction modeling.

Comparative Performance Analysis of Ensemble and Multi-Scale Architectures

The table below summarizes the performance of various ensemble and multi-scale architectures as reported in recent scientific studies, providing a clear comparison of their capabilities in different therapeutic prediction contexts.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Ensemble and Multi-Scale Architectures in Therapeutic Response Prediction

| Architecture Name | Application Context | Key Components | Reported Performance | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Uncertainty-Driven Multi-Scale Ensemble | Pulmonary Pathology & Parkinson's Diagnosis | Bayesian Deep Learning, Multi-scale architectures, Two-level decision tree | Accuracy: 98.19% (pathology), 95.31% (Parkinson's) | [33] |

| Multi-scale Dilated Ensemble Network (MDEN) | Patient Response to Radiotherapy/Chemotherapy | LSTM, RNN, 1D-CNN, REE-COA optimization | Superior accuracy vs. RNN, LSTM, 1D-CNN | [22] |

| Multi-Model CNN Ensemble | COVID-19 Detection from Chest X-rays | Ensemble of VGGNet, GoogleNet, DenseNet, NASNet | Accuracy: 88.98% (3-class), 98.58% (binary) | [34] |

| Multi-Modal CNN for DDI (MCNN-DDI) | Drug-Drug Interaction Event Prediction | 1D CNN sub-models for drug features (target, enzyme, pathway, substructure) | Accuracy: 90.00%, AUPR: 94.78% | [35] |

| Multi-Scale Deep Learning Ensemble | Endometriotic Lesion Segmentation in Ultrasound | U-Net variants trained on multiple image resolutions | Dice Coefficient: 82% | [36] |

| Patient Knowledge Graph Framework (PKGNN) | Mortality & Hospital Readmission Prediction | GCN, Clinical BERT, BioBERT, BlueBERT on EHR data | Outperformed state-of-the-art baselines | [37] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Uncertainty-Driven Ensembles for Medical Image Classification

This approach employs a Bayesian Deep Learning framework to quantify uncertainty in classification decisions, using this metric to weight the contributions of different models within an ensemble.

- Architecture: The system integrates multiple deep learning architectures processing image data at various scales. The Bayesian nature of each classifier provides a principled measure of predictive uncertainty [33].

- Training: Individual networks are trained on medical image data (e.g., chest X-rays for pneumonia, neuroimages for Parkinson's). A two-level decision tree strategy is used for multi-class problems, such as dividing a 3-class classification (control vs. bacterial pneumonia vs. viral pneumonia) into two binary classifications [33].

- Inference & Fusion: During prediction, the uncertainty estimate of each classifier's decision is calculated. The final ensemble output is a weighted combination of all members' predictions, where the contribution of each model is inversely proportional to its uncertainty [33].

Multi-scale Dilated Ensemble Network for Radiotherapy Response

This framework predicts the likelihood of patients experiencing adverse long-term effects from radiotherapy and chemotherapy.

- Feature Selection: The Repeated Exploration and Exploitation-based Coati Optimization Algorithm (REE-COA) is employed to select the most predictive features from the collected patient data. This optimization aims to increase the correlation coefficient and minimize variance within the same classes [22].

- Ensemble Prediction: The selected weighted features are fed into the Multi-scale Dilated Ensemble Network (MDEN). This network integrates Long-Short Term Memory (LSTM), Recurrent Neural Network (RNN), and One-dimensional Convolutional Neural Networks (1D-CNN) to capture temporal and feature-level patterns [22].

- Output: The final prediction scores from LSTM, RNN, and 1D-CNN are averaged to produce a robust prediction of patient response, minimizing error rates and enhancing accuracy [22].

Multi-Modal CNN for Drug-Drug Interaction Prediction

The MCNN-DDI model predicts multiple types of interactions between drug pairs by integrating different data modalities.

- Input Representation: Four key drug features are used: chemical structure (SMILES), target proteins, involved enzymes, and biological pathways. Similarity matrices (e.g., Jaccard similarity) are computed for each feature type to represent drug pairs [35].

- Model Structure: Four separate 1D CNN sub-models are constructed, each dedicated to processing one type of similarity matrix. Each sub-model typically consists of an input layer with 5 kernels of filter size 1, followed by three dense layers with 1024, 512, and 256 neurons respectively [35].

- Fusion and Output: The representations learned by the four sub-models are concatenated. This fused representation is then used for the final prediction over 65 different DDI-associated events via an output layer of 65 neurons [35].

Conceptual Framework and Signaling Pathways

The following diagram illustrates the core logical workflow of an uncertainty-driven ensemble system, a representative architecture in this field.

Uncertainty-Driven Ensemble Workflow

The diagram below outlines the multi-modal data integration process for predicting complex biological outcomes like Drug-Drug Interactions.

Multi-Modal Data Integration for DDI Prediction

For researchers aiming to implement ensemble and multi-scale networks for therapeutic outcome prediction, the following computational tools and data resources are essential.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Ensemble Model Development

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function | Relevance to Ensemble Models |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-trained CNN Models (VGGNet, GoogleNet, DenseNet, ResNet50, NASNet) | Software Model | Feature extraction and base classifier | Building blocks for creating robust model ensembles [34] [38] |

| BioBERT / Clinical BERT | NLP Model | Processing clinical text from EHRs and medical notes | Extracting semantic representations from unstructured data for patient graphs [37] |

| DrugBank / ChEMBL / BindingDB | Chemical & Bioactivity Database | Source of drug features (target, pathway, enzyme, structure) | Constructing multi-modal input features for DDI and drug response prediction [39] [35] |

| Graph Convolutional Network (GCN) | Software Library | Learning from graph-structured data (e.g., patient knowledge graphs) | Modeling complex relationships between patients, diagnoses, and treatments [37] |

| MIMIC-IV Dataset | Clinical Dataset | Large-scale EHR data from ICU patients | Benchmarking mortality and readmission prediction models [37] |

Feature Selection and Optimization Strategies for High-Dimensional Data

In the field of patient response to therapy research, high-dimensional data has become increasingly prevalent, particularly with the rise of genomic data, medical imaging, and electronic health records (EHRs). These datasets often contain thousands to tens of thousands of features, while sample sizes remain relatively small, creating significant analytical challenges. High-dimensional data typically exhibits characteristics such as high dimensionality, significant redundancy, and considerable noise, which traditional computational intelligence methods struggle to process effectively [40]. Feature selection (FS) has thus emerged as a critical step in predictive model development, aiming to identify the most relevant and useful features from original data to enhance model performance, reduce overfitting risk, and improve computational efficiency [40] [41].

The importance of feature selection in therapy response prediction extends beyond mere model improvement. In clinical and pharmaceutical research, identifying the most biologically significant features can provide valuable insights into disease mechanisms and treatment efficacy. For instance, in genomic studies, feature selection helps pinpoint genetic markers directly associated with treatment response, enabling more personalized therapeutic approaches [42]. Furthermore, by reducing dataset dimensionality, feature selection facilitates model interpretability—a crucial factor in clinical decision-making where understanding why a model makes certain predictions is as important as the predictions themselves [43].

Taxonomy of Feature Selection Methodologies

Filter Methods

Filter methods represent the most straightforward approach to feature selection, ranking features based on statistical measures without incorporating any learning algorithm. These methods evaluate features solely on their intrinsic characteristics and their relationship to the target variable. Common statistical measures used in filter methods include Pearson correlation coefficient, chi-squared test, information gain, and Fisher score [44] [45]. The recently proposed weighted Fisher score (WFISH) method enhances traditional Fisher scoring by assigning weights based on gene expression differences between classes, prioritizing informative features while reducing the impact of less useful ones [42].

Filter methods offer several advantages, including computational efficiency, scalability to very high-dimensional datasets, and independence from specific learning algorithms [46]. However, their primary limitation lies in the inability to capture feature dependencies and interactions with learning algorithms, potentially leading to suboptimal model performance [46]. They also tend to select large numbers of features, which may include redundant variables [44].

Wrapper Methods

Wrapper methods employ a specific learning algorithm to evaluate feature subsets, using the model's performance as the objective function for subset selection. This approach typically yields feature subsets that perform well with the chosen classifier. Common wrapper techniques include sequential feature selection, genetic algorithms (GA), and other metaheuristic algorithms such as Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) and Differential Evolution (DE) [47] [45].

While wrapper methods generally achieve higher accuracy in feature selection and better capture feature interactions compared to filter methods, they come with significant computational demands, particularly for high-dimensional datasets [47]. They are also more prone to overfitting, especially with limited samples, and the selected feature subsets may not generalize well to other classifiers [45]. Recent innovations in wrapper methods include the development of enhanced algorithms such as the Q-learning enhanced differential evolution (QDEHHO), which dynamically balances exploration and exploitation during the search process [47].

Embedded Methods

Embedded methods integrate the feature selection process directly into model training, combining advantages of both filter and wrapper approaches. These methods perform feature selection as part of the model construction process, often through regularization techniques that penalize model complexity. Examples include LASSO regression, which uses L1 regularization to drive less important feature coefficients to zero, and tree-based methods like Random Forests that provide inherent feature importance measures [44] [45].

Embedded methods strike a balance between computational efficiency and selection performance, automatically selecting features while optimizing the model [46]. However, they are model-specific, meaning the feature selection is tied to a particular algorithm and may not transfer well to other modeling approaches [47]. Additionally, they may struggle with high-dimensional datasets containing substantial noise [47].

Hybrid Methods

Hybrid methods attempt to leverage the strengths of multiple approaches, typically combining the computational efficiency of filter methods with the performance accuracy of wrapper methods. These approaches often begin with a filter method to reduce the feature space, then apply a wrapper method to the pre-selected subset [46]. The recently developed FeatureCuts algorithm exemplifies this approach by first ranking features using a filter method (ANOVA F-value), then applying an adaptive filtering method to find the optimal cutoff point before final selection with PSO [46].

While hybrid methods can achieve superior performance with reduced computation time, they face challenges in determining the optimal transition point between methods [46]. The effectiveness of these methods depends heavily on properly balancing the components and avoiding the pitfalls of either approach when combined.

Table 1: Comparison of Feature Selection Methodologies

| Method Type | Key Characteristics | Advantages | Disadvantages | Representative Algorithms |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Filter Methods | Uses statistical measures independent of learning algorithm | Fast computation; Scalable; Model-agnostic | Ignores feature interactions; May select redundant features | WFISH [42], Pearson Correlation [47], Fisher Score [47] |

| Wrapper Methods | Evaluates subsets using specific learning algorithm | High accuracy; Captures feature interactions | Computationally expensive; Risk of overfitting | QDEHHO [47], TMGWO [41], BBPSO [41] |

| Embedded Methods | Integrates selection with model training | Balanced performance; Model-specific optimization | Algorithm-dependent; Limited generalizability | LASSO [44], Random Forest [44], SCAD [44] |

| Hybrid Methods | Combines multiple approaches | Superior performance; Reduced computation | Complex implementation; Parameter tuning challenges | FeatureCuts [46], Fisher+PSO [45] |

Comparative Performance Analysis of Feature Selection Algorithms

Experimental Framework and Evaluation Metrics

To objectively compare feature selection strategies, we established a standardized evaluation framework using multiple benchmark datasets relevant to therapy response prediction. The experimental design incorporated three well-known medical datasets: the Wisconsin Breast Cancer Diagnostic dataset, the Sonar dataset, and the Differentiated Thyroid Cancer recurrence dataset [41]. These datasets represent diverse medical scenarios with varying dimensionalities and sample sizes, providing a comprehensive testbed for algorithm performance.

Performance evaluation employed multiple metrics to assess different aspects of feature selection effectiveness. Classification accuracy measured the predictive performance of models built on selected features, while precision and recall provided additional insights into model behavior [41]. The feature selection score (FS-score) was used in some studies as a composite metric balancing both model performance and feature reduction percentage, calculated as the weighted harmonic mean of these two factors [46]. Computational efficiency was assessed through training time and resource requirements, particularly important for high-dimensional biomedical data [46].

Performance Comparison Across Methodologies

Recent comparative studies have yielded insightful results regarding the performance of various feature selection approaches. Hybrid methods have demonstrated particularly strong performance, with the FeatureCuts algorithm achieving approximately 15 percentage points more feature reduction with up to 99.6% less computation time while maintaining model performance compared to state-of-the-art methods [46]. When integrated with wrapper methods like PSO, FeatureCuts enabled 25 percentage points more feature reduction with 66% less computation time compared to PSO alone [46].

Among wrapper methods, the Two-phase Mutation Grey Wolf Optimization (TMGWO) hybrid approach achieved superior results, outperforming other experimental methods in both feature selection and classification accuracy [41]. Similarly, the weighted Fisher score (WFISH) method demonstrated consistently lower classification errors compared to existing techniques when applied to gene expression data with random forest and kNN classifiers [42].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Feature Selection Algorithms on Medical Datasets

| Algorithm | Type | Average Accuracy | Feature Reduction | Computational Efficiency | Best Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TMGWO | Wrapper | 98.85% [41] | High | Moderate | High-dimensional classification with balanced data |

| WFISH | Filter | Lower classification errors vs benchmarks [42] | Moderate | High | Gene expression data with RF/kNN classifiers |

| FeatureCuts | Hybrid | Maintains model performance [46] | 15-25% higher reduction [46] | 66-99.6% faster [46] | Large-scale enterprise datasets |

| QDEHHO | Wrapper | High accuracy [47] | High | Low | Complex medical data with nonlinear relationships |

| LASSO | Embedded | Varies by dataset [44] | High | High | Linear models with implicit feature selection |

| Random Forest | Embedded | High with important features [44] | Moderate | Moderate | Nonlinear data with interaction effects |

Domain-Specific Performance in Therapy Response Prediction

In the specific context of outcome prediction modeling for patient response to therapy, feature selection performance varies based on data characteristics and clinical objectives. For genomic data with extremely high dimensionality (where features far exceed samples), filter methods like WFISH and SIS (Sure Independence Screening) have shown particular utility [42] [44]. The WFISH approach specifically leverages differential gene expression between patient response categories to assign feature weights, enhancing identification of biologically significant genes [42].