Preventing Exosome Aggregation: A Comprehensive Guide to Stable Storage and Freeze-Thaw Protocols for Translational Research

This article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a systematic framework for preserving exosome integrity during storage and processing.

Preventing Exosome Aggregation: A Comprehensive Guide to Stable Storage and Freeze-Thaw Protocols for Translational Research

Abstract

This article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a systematic framework for preserving exosome integrity during storage and processing. It synthesizes the latest evidence on the fundamental causes of exosome aggregation and instability, presents optimized methodological protocols for both short- and long-term preservation, offers troubleshooting strategies for common challenges, and establishes validation criteria for assessing exosome quality post-storage. The guidance is designed to enhance reproducibility and accelerate the clinical translation of exosome-based diagnostics and therapeutics.

Understanding Exosome Aggregation: The Science of Instability During Storage

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What are the primary causes of exosome aggregation during storage? Exosome aggregation occurs primarily due to insufficient electrostatic repulsion between particles and physical stresses induced by freezing. When the absolute value of the surface charge (zeta potential) approaches zero, electrostatic repulsion fails to counteract natural attractive forces, leading to clumping [1]. Furthermore, during freezing, the formation of ice crystals can disrupt vesicle membranes and force particles into close proximity, promoting fusion and aggregation [2] [3] [4].

How does aggregation affect the biological function of my exosome samples? Aggregation directly compromises exosome function by reducing their bioavailability and altering their interaction with recipient cells. Studies show that aggregated exosomes exhibit inconsistent biological activity. For instance, one study demonstrated that aggregated beta-cell extracellular vesicles showed lower TNF-alpha cytokine secretion stimulation indexes in macrophage immune assays compared to well-dispersed samples, indicating impaired bioactivity [1]. Furthermore, aggregation can change cellular uptake patterns and biodistribution, fundamentally altering experimental outcomes [5].

Can I simply vortex or pipette my exosome samples to reverse aggregation? Forceful mechanical disruption like vortexing is not recommended as it can damage exosome integrity through shear forces, potentially causing membrane rupture and cargo leakage. While gentle pipetting might disperse loose aggregates, it is ineffective for fusion-induced aggregates. The preferred approach is preventive—using appropriate buffers and storage conditions to avoid aggregation from the outset [1] [2].

How do freeze-thaw cycles contribute to exosome aggregation? Each freeze-thaw cycle subjects exosomes to substantial physical stress. Research demonstrates that multiple freeze-thaw cycles lead to a significant decrease in particle concentration, an increase in average particle size, and a wider size distribution—all indicative of aggregation and fusion events [5] [4]. One study employing fluorescently tagged exosomes provided direct evidence of fusion phenomena after freeze-thaw cycles, observing a new population of double-positive particles that did not exist in fresh samples [4].

Is storing exosomes in pure PBS sufficient to prevent aggregation? No, storage in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) alone is suboptimal for preventing aggregation. PBS lacks protective agents to shield exosomes from freezing-induced damage and aggregation. Multiple studies have shown that exosomes stored in PBS exhibit increased particle size and aggregation after freezing compared to those stored in specialized buffers containing cryoprotectants like trehalose [1] [4].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Increased Particle Size After Storage

Symptoms:

- Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis (NTA) shows an increase in mean and mode particle size.

- Broader size distribution (increased polydispersity index).

- Visible clumping or precipitation in the sample vial.

Solutions:

- Revise Storage Buffer: Add 25 mM trehalose to your PBS storage buffer. Research shows this natural disaccharide narrows particle size distribution and maintains individual particle integrity by preventing fusion and aggregation [1].

- Optimize Freezing Protocol: Implement rapid freezing rates (snap-freezing in liquid nitrogen or dry ice-ethanol baths) to minimize ice crystal formation that promotes aggregation [2] [3].

- Avoid Freeze-Thaw Cycles: Aliquot exosomes into single-use volumes to avoid repeated freezing and thawing, which significantly increases aggregation [5] [4].

Problem: Loss of Biological Activity After Freezing

Symptoms:

- Reduced efficacy in functional assays (e.g., cell uptake, immune response activation).

- Inconsistent results between freshly isolated and frozen batches.

- Decreased therapeutic potency in in vivo models.

Solutions:

- Use Cryoprotectants: Incorporate 25-50 mM trehalose into isolation and storage buffers. Studies confirm that trehalose preserves exosome functionality, as evidenced by consistently higher TNF-alpha stimulation indexes in immune assays [1].

- Control Storage Temperature: For long-term preservation, store exosomes at -80°C. Evidence indicates that -80°C storage better preserves biological functionality compared to -20°C [5] [3].

- Consider Lyophilization: For certain applications, lyophilization (freeze-drying) in the presence of trehalose can provide excellent stability while maintaining function, though this requires optimization for different exosome sources [2].

Problem: Low Particle Recovery After Thawing

Symptoms:

- Significant decrease in particle concentration measured by NTA after thawing.

- High loss of sample during post-thaw handling.

- Increased protein-to-particle ratio, indicating preferential particle loss.

Solutions:

- Minimize Freeze-Thaw Cycles: Subjecting exosomes to multiple freeze-thaw cycles dramatically reduces particle concentration. One study showed significant losses after just the first cycle [4].

- Use Appropriate Containers: Store exosomes in siliconized low-protein-binding vials to minimize adhesion to container walls [4].

- Add Stabilizing Agents: Beyond trehalose, consider other stabilizers like human serum albumin (HSA) or polyethylene glycol (PEG) to protect against surface adsorption and aggregation [2].

Data Presentation Tables

Table 1: Impact of Storage Temperature on Exosome Integrity Over Time

Data compiled from multiple studies [5] [3]

| Storage Temperature | Storage Duration | Particle Concentration Recovery | Mean Size Change | RNA Content Preservation | Recommended Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4°C | 7 days | ~60-70% | +15-25% | ~50-60% | Short-term experiments (<1 week) |

| -20°C | 28 days | ~50-60% | +30-50% | ~40-50% | Temporary storage (2-4 weeks) |

| -80°C | 28 days | ~85-90% | +10-15% | ~80-85% | Long-term preservation (>1 month) |

| -80°C with Trehalose | 28 days | ~90-95% | +5-10% | ~85-90% | Critical long-term applications |

Table 2: Effects of Multiple Freeze-Thaw Cycles on Exosome Quality

Quantitative data showing degradation trends [5] [4]

| Number of Freeze-Thaw Cycles | Particle Recovery (%) | Mean Size Increase | RNA Integrity | Functional Activity Retention |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 (Fresh) | 100% | Baseline | 100% | 100% |

| 1 | 70-80% | 15-20% | 80-85% | 75-80% |

| 3 | 40-50% | 35-50% | 50-60% | 40-50% |

| 5 | 20-30% | 60-80% | 20-30% | 15-25% |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Evaluating Exosome Stability with Trehalose

Objective: To assess the protective effect of trehalose on exosome integrity during storage and freeze-thaw cycles.

Materials:

- Purified exosome sample

- Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)

- D-(+)-Trehalose dihydrate

- Ultracentrifuge and tubes

- Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis instrument

- Materials for functional assay (e.g., macrophage TNF-α secretion assay)

Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Isolate exosomes using your standard method (e.g., differential ultracentrifugation). Split the purified exosome sample into two equal aliquots.

- Buffer Exchange: Resuspend one aliquot in PBS (control) and the other in PBS containing 25 mM trehalose (experimental) [1].

- Baseline Characterization: Analyze both samples using NTA to determine initial particle concentration, size distribution, and zeta potential. Assess biological activity using your relevant functional assay.

- Storage Intervention: Divide each sample further into multiple aliquots. Subject aliquots to:

- Short-term storage: 4°C for 1 week

- Long-term storage: -80°C for 4 weeks

- Freeze-thaw stress: 1, 3, and 5 cycles between -80°C and room temperature

- Post-Storage Analysis: After each storage condition, repeat the characterization in step 3. Compare the results to baseline measurements and between PBS and trehalose groups.

Expected Outcomes: Exosomes stored in trehalose should demonstrate higher particle recovery, minimal size increase, narrower size distribution, and better preservation of biological function compared to PBS-stored controls, particularly after freeze-thaw cycles [1].

Protocol: Testing Exosome Fusion During Storage

Objective: To detect fusion events between distinct exosome populations during storage using fluorescent tagging.

Materials:

- Two cell lines expressing different fluorescent membrane proteins (e.g., GFP and mCherry)

- Standard exosome isolation equipment

- Flow cytometer equipped for vesicle analysis

- Cryogenic vials for storage

Methodology:

- Fluorescent Exosome Production: Culture two separate populations of donor cells—one expressing GFP-tagged membrane protein and another expressing mCherry-tagged membrane protein.

- Isolation and Mixing: Isolve exosomes from each cell line separately using standard methods. Mix the two exosome populations in equal particle concentrations to create a fresh control sample [4].

- Storage and Analysis: Split the mixed sample into aliquots and subject them to different storage conditions (e.g., -80°C in PBS, -80°C with cryoprotectant). Analyze by flow cytometry immediately after mixing (fresh control) and after each storage condition.

- Fusion Detection: In fresh samples, expect two distinct populations: GFP-positive and mCherry-positive. The appearance of a double-positive (GFP+mCherry+) population after storage indicates fusion events between vesicles from the two different sources [4].

Interpretation: The percentage of double-positive events quantifies the extent of fusion occurring during storage. Effective cryoprotectants should minimize the emergence of this population.

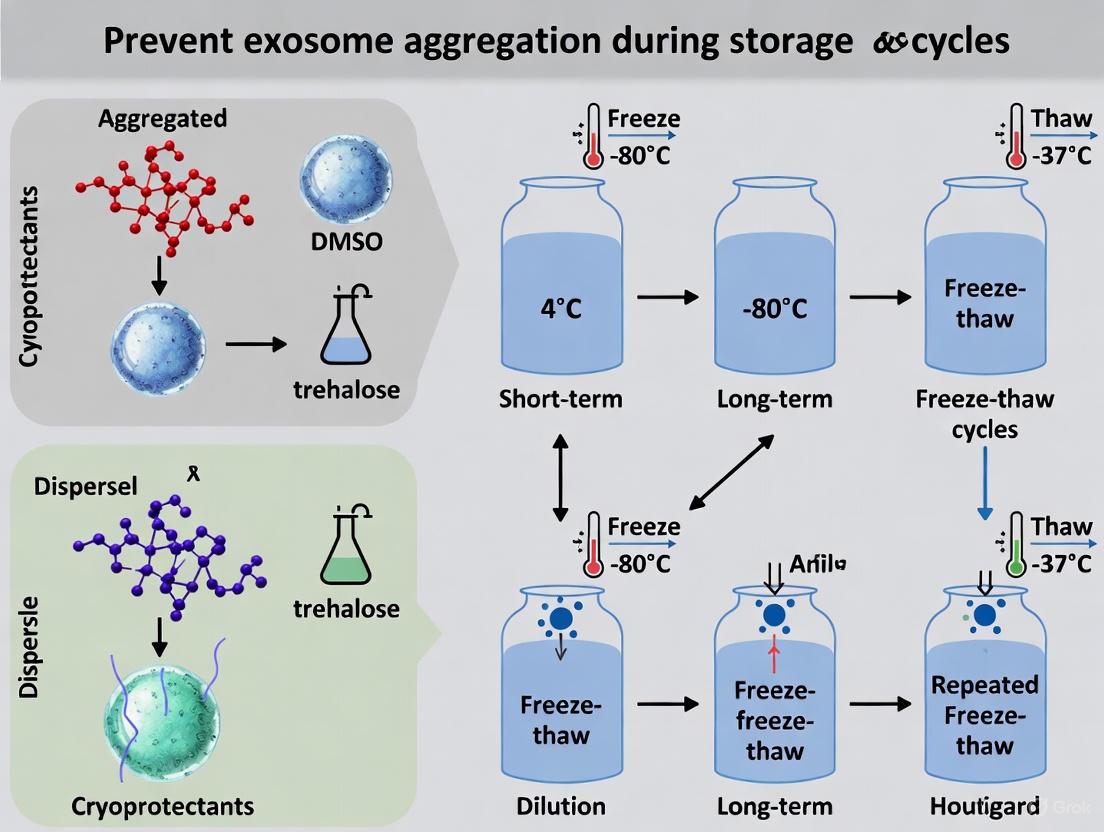

Signaling Pathways, Workflows, and Relationships

Diagram: Experimental Workflow for Testing Storage Conditions

Diagram: Mechanisms of Exosome Aggregation and Protection

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Reagents for Preventing Exosome Aggregation

| Reagent | Function/Mechanism | Application Protocol | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Trehalose | Natural cryoprotectant that stabilizes membranes through water replacement and vitrification mechanisms; prevents fusion and aggregation | Add to PBS at 25-50 mM final concentration for exosome resuspension and storage | [1] [2] |

| Dimethyl Sulfoxide (DMSO) | Penetrating cryoprotectant that reduces ice crystal formation; use at low concentrations to minimize toxicity | 6-10% in PBS; requires removal before functional assays | [4] |

| Protease Inhibitor Cocktails | Prevent protein degradation that can expose hydrophobic regions and promote aggregation | Add according to manufacturer instructions during isolation and storage | [4] |

| Siliconized Low-Binding Tubes | Minimize surface adhesion and particle loss during storage and handling | Use for all exosome storage and processing steps | [4] |

| Glycerol | Non-penetrating cryoprotectant that provides extracellular protection; less effective than trehalose for exosomes | 30% in PBS; may interfere with some downstream applications | [4] |

Frequently Asked Questions: Managing Exosome Aggregation

What are the primary triggers for exosome aggregation during storage? The main triggers are multiple freeze-thaw cycles and storage in simple buffers like PBS without protective additives. Freeze-thaw cycles cause ice crystal formation, which can mechanically damage exosome membranes and promote fusion. Storage at standard freezer temperatures (e.g., -20°C or -80°C) can still lead to slow aggregation and a reduction in sample purity over time [4].

How do freeze-thaw cycles damage my exosome samples? Each freeze-thaw cycle inflicts cumulative damage. The freezing process leads to ice crystal formation, which can pierce and disrupt the exosome lipid bilayer. Upon thawing, this damage manifests as vesicle fusion, increased particle size, and a loss of individual particles. Multiple cycles significantly decrease particle concentration and increase sample heterogeneity [6] [4].

What is the best temperature for short-term storage of exosomes? For short-term storage (e.g., 24 hours), 4°C has been shown to maintain exosome concentration and marker proteins better than -80°C, -20°C, or higher temperatures [6]. For any storage beyond a few days, freezing at -80°C with a cryoprotectant is recommended [2].

Can I simply avoid aggregation by storing my samples at -80°C? While -80°C is better than -20°C, it is not a perfect solution. Storage at -80°C still leads to a time-dependent reduction in particle concentration and sample purity, and can still increase particle size and variability [4]. The use of a cryoprotectant like trehalose is critical to mitigate these effects.

Are there any additives that can prevent aggregation? Yes, the non-reducing disaccharide trehalose has been extensively documented as an effective stabilizer. When added to storage buffers at concentrations such as 25 mM, it narrows the exosome size distribution, increases particle yield, and helps maintain biological activity by preventing aggregation and fusion during freeze-thaw cycles [1] [2] [4].

Table 1: Impact of Freeze-Thaw Cycles on Exosome Integrity

| Freeze-Thaw Cycles | Particle Concentration | Mean Particle Size | Exosomal Markers (ALIX, TSG101, HSP70) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Cycle | Decrease [4] | Increase [4] | Decrease [6] |

| Multiple Cycles (1-5) | Cycle-dependent decrease [6] [4] | Cycle-dependent increase [6] [4] | Cycle-dependent decrease [6] |

Table 2: Effect of Short-Term (24-hour) Storage Temperature

| Storage Temperature | Particle Concentration | Cellular Uptake | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 4°C | Highest concentration maintained [6] | Lower compared to frozen samples [6] | Best for very short-term preservation of concentration [6] |

| -80°C | Decrease [6] | Increase [6] | |

| -20°C | Decrease [6] | Increase [6] | |

| 37°C | Decrease [6] | Increase [6] | Significant degradation [6] |

Table 3: Effect of Cryoprotectants on Exosome Stability

| Storage Condition | Particle Aggregation | Particle Count per μg Protein | Preservation of Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| PBS (control) | High [1] | Low [1] | Reduced biological activity [1] |

| Trehalose 25 mM | Reduced [1] | 3x higher than PBS control [1] | Improved preservation of TNF-α stimulation [1] |

Experimental Protocol: Evaluating Aggregation Using Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis (NTA)

This protocol allows you to quantitatively assess the impact of different storage conditions on your exosome preparations.

- Exosome Isolation: Isolate exosomes from your cell culture medium or biofluid using your standard method (e.g., differential ultracentrifugation, size-exclusion chromatography, or precipitation). Note the isolation method, as it can affect initial exosome stability [1] [6] [4].

- Sample Aliquot and Treatment:

- Divide the freshly isolated exosome sample into multiple aliquots.

- Control: Resuspend one aliquot in PBS.

- Stabilized: Resuspend another aliquot in PBS containing 25 mM Trehalose [1].

- Subject aliquots to your chosen stress conditions (e.g., 1-5 freeze-thaw cycles, storage at different temperatures for set durations).

- NTA Measurement:

- Dilute each exosome sample in sterile, particle-free PBS or water to achieve a concentration within the ideal detection range of your NTA instrument (typically 10^8-10^9 particles/mL).

- Load the sample into the instrument chamber using a sterile syringe.

- Perform measurements with consistent settings (camera level, detection threshold) across all samples. Capture three 60-second videos for each sample.

- Ensure the environment is vibration-free and at a stable temperature.

- Data Analysis:

- Use the built-in NTA software to analyze the videos and generate data for particle concentration (particles/mL) and mode/mean particle size (nm).

- Compare the particle size distribution and concentration between the fresh sample and treated aliquots. An increase in mean/mode size and a widening of the size distribution (increased standard deviation) indicates aggregation and fusion [1] [4].

- Statistical analysis (e.g., student's t-test) should be performed to confirm the significance of observed differences.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Reagents for Exosome Storage and Stability Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Key Details |

|---|---|---|

| Trehalose | Cryoprotectant & Aggregation Inhibitor | Stabilizes lipid membranes and proteins via water replacement and vitrification mechanisms; use at 25 mM in PBS [1]. |

| Phosphate-Buffered Saline (PBS) | Standard Storage Buffer | Serves as a control and base buffer; alone, it offers poor protection against aggregation and freeze-thaw damage [1] [4]. |

| Dimethyl Sulfoxide (DMSO) | Cryoprotectant | Can be used at 6-10% concentration; however, potential cytotoxicity and interference with downstream applications should be considered [2] [4]. |

| Protease Inhibitor Cocktail | Prevent Protein Degradation | Added to storage buffers to prevent proteolytic degradation of exosomal surface and cargo proteins during storage [4]. |

| Size-Exclusion Chromatography (SEC) Columns | Exosome Isolation | Provides a gentle method for isolating exosomes with high purity, minimizing co-isolation of contaminants that could affect stability [4]. |

Diagram: Mechanisms of Exosome Aggregation and Stabilization

Troubleshooting Guide: Freeze-Thaw Damage in EV Experiments

FAQ: What are the specific detrimental effects of freeze-thaw cycles on my EV samples?

Repeated freeze-thaw cycles cause measurable damage to extracellular vesicles across multiple parameters. The primary mechanisms include particle aggregation, membrane deformation, cargo loss, and reduced bioactivity [3] [2].

Aggregation and Size Changes: Multiple freeze-thaw cycles significantly decrease particle concentrations while increasing average EV size due to aggregation. Studies consistently show the proportion of particles larger than 400 nm (indicative of aggregates) increases substantially after freezing at -70°C [7] [2].

Membrane Integrity Compromise: Electron microscopy reveals vesicle enlargement, fusion, and membrane deformation following suboptimal freezing protocols. Membrane disruption is particularly evident in EVs frozen in liquid nitrogen followed by storage at -80°C [3].

Cargo and Functional Loss: Freeze-thaw cycles decrease RNA content and impair biological functionality. The structural damage directly correlates with reduced cellular uptake and therapeutic efficacy [3] [7] [2].

Table 1: Quantitative Impacts of Freeze-Thaw Cycles on EV Parameters

| Parameter Measured | Impact of Freeze-Thaw Cycles | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| Particle Concentration | Significant decrease | NTA shows lower total particle counts after freezing [7] |

| Size Distribution | Increase in particles >400 nm | Aggregation measured by NTA and FE-SEM [7] |

| RNA Content | Decreased content | Reduced RNA yield and integrity after multiple cycles [3] [2] |

| Membrane Morphology | Deformation, enlargement, fusion | Electron microscopy observations [3] [2] |

| Biological Function | Impaired bioactivity | Reduced cellular uptake and functional efficacy [3] [7] |

FAQ: What methods can effectively reverse EV aggregation after freeze-thaw cycles?

Water-Bath Sonication effectively disperses aggregated EVs. Experimental data demonstrates that sonication at power level 3 (40 kHz, 100 W) for 15 minutes significantly increases detectable EV concentration and reduces aggregation [7]. This treatment restores cellular uptake efficiency comparable to fresh EVs in vivo.

Critical Note on Pipetting: Regular tip-based pipetting does not effectively disperse aggregated EVs and may promote re-aggregation in previously sonicated samples [7].

Molecular Dynamics Evidence: Simulations confirm that sonication provides sufficient energy to overcome adhesion forces between EV membranes, quantified at approximately 0.167 J/m² for phospholipid bilayers [7].

FAQ: What are the optimal storage conditions to prevent freeze-thaw damage?

Temperature Optimization: Constant storage at -80°C provides the best preservation of EV quantity, cargo integrity, and bioactivity across most EV types and sources [3]. Storage at -20°C shows significant particle aggregation and size increase compared to -80°C [3] [2].

Stabilization Strategies:

- Cryoprotectants: Addition of stabilizers like trehalose helps maintain EV integrity during freezing [3] [2].

- Native Environment: EVs stored in native biofluids show improved stability over purified EVs in buffers [3] [2].

- Formulation Advances: Encapsulation in hyaluronic acid-based microneedles or supplementation with trehalose and cellulose enables EV preservation for up to 12 months at room temperature [2].

Table 2: EV Preservation Under Different Storage Conditions

| Storage Condition | Preservation Performance | Recommended Application |

|---|---|---|

| -80°C (long-term) | Optimal for particle concentration, RNA content, morphology, and bioactivity | Standard storage for most EV types; suitable for >1 week to long-term [3] |

| -20°C | Significant particle aggregation and size increase; suboptimal | Not recommended for critical applications [3] [2] |

| Liquid Nitrogen (-196°C) | Less commonly used; may cause membrane disruption | Not generally recommended; limited comparative data [3] |

| 4°C (short-term) | Moderate stability for limited durations | Suitable for very short-term storage only [7] |

| With Stabilizers (trehalose) | Improved integrity maintenance | Recommended for sensitive applications [3] [2] |

Experimental Protocols for Freeze-Thaw Studies

Protocol: Evaluating Freeze-Thaw Impact on EV Integrity

Sample Preparation:

- Isolate EVs using preferred method (ultracentrifugation, SEC, or other)

- Divide into equal aliquots for experimental groups

- Use fresh EVs as control group (no freezing)

Freeze-Thaw Cycling:

- Freezing condition: -80°C for minimum 3 hours

- Thawing: Room temperature water bath (5-10 minutes)

- Repeat cycles as needed (1, 3, 5, 10 cycles)

- Include stabilizer-treated groups (e.g., 5-10% trehalose)

Assessment Methods:

- Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis (NTA): Measure concentration and size distribution pre- and post-freezing [7]

- Electron Microscopy: Evaluate morphology and aggregation state via FE-SEM [7]

- RNA/Protein Analysis: Quantify cargo preservation

- Functional Assays: Test cellular uptake and bioactivity [7]

Protocol: Sonication-Mediated Dispersion of Aggregated EVs

Equipment Setup:

- Water-bath sonicator (40 kHz frequency, 100 W power)

- Temperature control maintained at 20-25°C

- Timer

Procedure:

- Thaw frozen EV samples completely at room temperature

- Mix gently by hand swirling (avoid pipetting)

- Place sample tube in sonication water bath

- Sonicate at power level 3 for 15 minutes

- Remove sample and proceed immediately to experiments

Validation Steps:

- Confirm dispersion efficiency by NTA (reduction in >400nm particles)

- Test cellular uptake in relevant models

- Compare to fresh EV controls for functionality [7]

Research Reagent Solutions for EV Freeze-Thaw Studies

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for EV Freeze-Thaw Research

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Usage Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Trehalose | Cryoprotectant that stabilizes EV membranes during freezing | Use at 5-10% concentration; improves integrity preservation [3] [2] |

| Dimethyl Sulfoxide (DMSO) | Traditional cryoprotectant | Use with caution due to potential cytotoxicity [3] |

| Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) | Common EV suspension buffer | Suboptimal for freezing; native biofluids provide better stability [3] [2] |

| Hyaluronic Acid (HA) | Matrix for EV encapsulation in stabilization systems | Enables room temperature storage in microneedle formats [2] |

| Cellulose-based Stabilizers | Structural support for EV preservation | Used in combination with trehalose for long-term stability [2] |

| Water-bath Sonicator | Dispersion of aggregated EVs post-thaw | Optimal at 40 kHz, 100 W power for 15 minutes [7] |

| POPC Lipids | Model membranes for molecular dynamics studies | Representative phospholipid for adhesion energy calculations [7] |

Key Technical Considerations for EV Storage

Critical Parameter: Freezing Rate and Temperature Consistency

Rapid freezing procedures and maintaining constant subzero temperatures are critical for optimal EV preservation. Temperature fluctuations during storage or processing can accelerate degradation processes [3] [2].

Solution: Minimize Freeze-Thaw Cycles Through Aliquot Strategy

The most effective approach is to avoid repeated freezing and thawing through proper experimental planning:

- Divide EV samples into small single-use aliquots

- Use cryoprotectants in storage buffers

- Characterize fresh samples whenever possible

- Implement proper inventory tracking systems

The evidence consistently demonstrates that careful attention to freezing protocols, stabilization strategies, and post-thaw processing methods can significantly mitigate the damaging effects of freeze-thaw cycles on EV samples, enabling more reproducible research outcomes and maintaining therapeutic efficacy [3] [7] [2].

How do different storage temperatures affect the stability and functionality of extracellular vesicles (EVs)?

The stability of extracellular vesicles (EVs) is highly dependent on storage temperature. Based on a systematic review of current evidence, the following table summarizes the effects of different storage conditions on EV integrity:

| Storage Condition | Impact on EV Concentration | Impact on EV Size & Morphology | Impact on Molecular Cargo & Bioactivity |

|---|---|---|---|

| -80 °C (Constant) | Appropriate preservation of particle quantity [2]. | Maintains size distribution; appropriate preservation of morphology [2]. | Appropriate preservation of RNA and protein content [2]. |

| Repeated Freeze-Thaw Cycles | Decreased particle concentration [2] [1]. | Increased particle size and aggregation; vesicle enlargement, fusion, and membrane deformation observed [2] [1]. | Decreased RNA content; impaired bioactivity [2]. |

| Room Temperature (with lyophilization & trehalose) | Maintained count for up to 12 months in microneedles [2]. Lyophilization with trehalose preserves particle concentration [8]. | Maintained size for up to 12 months in microneedles; prevents aggregation during lyophilization [2] [8]. | Protein and RNA content, as well as cargo function, preserved after lyophilization with trehalose [8]. |

| 4 °C (with stabilizers) | Significant decrease in EVs stored in PBS over time; negligible decrease when encapsulated in hyaluronic acid microneedles for up to 6 months [2]. | Not specified in results. | Protein activity lost in PBS within 2 weeks; preserved over 99% in hyaluronic acid microneedles at 4°C for 6 months [2]. |

Key Experimental Protocol: To assess stability, researchers often isolate EVs via methods like size exclusion chromatography or tangential flow filtration. The EVs are then aliquoted and stored under different conditions (e.g., -80°C, with/without multiple freeze-thaw cycles, or lyophilized). Key parameters measured post-storage include:

- Concentration & Size: Using Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis (NTA) or Tunable Resistive Pulse Sensing [2] [1].

- Morphology: Using transmission electron microscopy (TEM) or cryo-electron tomography to visualize membrane integrity and aggregation [2] [1] [8].

- Cargo Integrity: Using techniques like qRT-PCR for RNA content, Western blot for protein markers, and functional immune assays (e.g., TNF-α secretion) for bioactivity [2] [1] [8].

What is the role of trehalose in preventing exosome aggregation during freeze-thaw cycles?

Trehalose is a natural, non-toxic disaccharide that acts as a highly effective cryoprotectant and stabilizer for exosomes. Its role is crucial in mitigating the damage caused by freezing and thawing.

Mechanism of Action: Trehalose protects exosomes through multiple proposed mechanisms. It can physically shield fragile vesicle membranes by replacing water molecules around the lipid bilayer, a process known as the "water replacement" theory. It can also form a stable, glassy matrix (vitrification) that immobilizes the exosomes and prevents ice crystal formation that could pierce and fuse vesicles [1] [8].

Experimental Evidence: A key study demonstrated that adding 25 mM trehalose to phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) used for exosome isolation and storage had several positive effects compared to PBS alone [1]:

- Reduced Aggregation: Trehalose narrowed the particle size distribution and reduced the mean particle size, indicating less aggregation.

- Increased Yield: A three-fold increase in the number of individual particles per microgram of protein was observed.

- Preserved Integrity: During repeated freeze-thaw cycles, exosomes in PBS showed an increase in particle concentration and wider size distribution (indicating aggregation and fragmentation), while exosomes in trehalose showed no significant changes.

- Maintained Bioactivity: Macrophage immune assays showed that exosomes stored in trehalose consistently stimulated higher TNF-α secretion, indicating better preservation of biological activity.

Detailed Protocol for Using Trehalose:

- Solution Preparation: Prepare your storage buffer, such as PBS, and supplement it with 25 mM trehalose [1].

- Isolation/Resuspension: Isolate exosomes via your standard method (e.g., differential centrifugation) and resuspend the final pellet in the trehalose-supplemented buffer [1].

- Freezing: Aliquot the exosome suspension to avoid repeated freeze-thaw cycles and freeze at -80°C [2].

- Thawing: When needed, thaw aliquots rapidly in a 37°C water bath and mix gently by pipetting before use.

My exosome samples are aggregating after lyophilization. How can I prevent this?

Aggregation after lyophilization is a common issue caused by stresses during the freezing and drying process. The most effective preventive strategy is the use of cryoprotectants.

Primary Solution: Use of Trehalose in Lyophilization Research has shown that lyophilizing exosomes in the presence of trehalose successfully prevents aggregation. One study found that while exosomes lyophilized without a cryoprotectant formed large aggregates, those lyophilized with trehalose maintained a dispersed state and showed no signs of aggregation under transmission electron microscopy [8].

Lyophilization Workflow with Trehalose:

Detailed Lyophilization Protocol:

- Prepare Exosome Sample: Isolate exosomes using your preferred method (e.g., ultracentrifugation, size-exclusion chromatography).

- Add Cryoprotectant: Mix the exosome suspension with a solution of trehalose. The specific concentration can be optimized, but studies have used it successfully as a cryoprotectant [8].

- Freeze: Place the mixture in a freezer (-80°C) or on a shelf of a freeze-dryer for freezing.

- Lyophilize: Transfer the frozen sample to a lyophilizer. The process involves a primary drying phase to sublimate ice under vacuum, followed by a secondary drying phase to remove residual water.

- Store: The resulting lyophilized powder can be stored sealed at room temperature or 4°C. When needed, rehydrate with sterile water or an appropriate buffer by gentle pipetting or vortexing.

How does the composition of a buffer solution impact cellular and molecular outcomes in experiments like dielectrophoresis (DEP)?

Buffer composition is a critical, yet often overlooked, factor that can significantly influence cell viability, morphology, and gene expression, thereby affecting the outcome and interpretation of sensitive experiments.

Key Findings from DEP Buffer Studies: A study investigating the impact of four different buffers on two cancer cell lines (Caco-2 and K562) revealed that even buffers that support good cell viability can induce significant molecular changes [9].

Summary of Buffer Composition Impact:

| Parameter Assessed | Influence of Buffer Composition |

|---|---|

| Cell Viability & Growth Recovery | Buffer composition differently influenced the viability of Caco-2 and K562 cells. Some buffers maintained viability and allowed growth recovery after 24 hours, while others were cytotoxic [9]. |

| Cell Morphology & Size | NaCl concentration in the buffer was found to influence both flow cytometry outcomes and cell size. Morphology was stable for up to 1 hour in certain buffers but not others [9]. |

| Gene Expression | Buffer composition significantly modulated the expression of inflammation (IL-6), oxidative stress (iNOS), and metabolism (GAPDH) markers in both cell lines, even under apparently non-cytotoxic conditions [9]. |

Experimental Protocol for Buffer Evaluation: To assess the impact of a buffer for your application, the following methodology can be employed:

- Buffer Preparation: Prepare the buffers of interest, measuring and adjusting their conductivity to the required level (e.g., 33 mS/m for DEP) using solutions like KCl [9].

- Cell Treatment: Incubate the target cells in the different buffers for a set duration (e.g., 1 hour).

- Viability & Morphology Assay: Use the MTT assay to evaluate cell viability and flow cytometry to analyze cell size and granulocyte stress formation [9].

- Molecular Analysis: Perform quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) to evaluate the gene expression levels of key markers relevant to your study, such as IL-6, iNOS, and GAPDH [9].

Interpretation: The key takeaway is that a buffer should be selected not only based on its electrokinetic performance but also on its ability to preserve the native biochemical and molecular state of the cells. A buffer that induces stress responses can confound experimental results.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function in Experimentation |

|---|---|

| Trehalose | A non-reducing disaccharide used as a cryoprotectant and stabilizer to prevent exosome/EV aggregation during freezing, thawing, and lyophilization [1] [8]. |

| Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) | A common isotonic buffer for washing cells and diluting biological samples. It often serves as a base solution, but may require additives like trehalose for sensitive applications [1]. |

| Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS) | Provides a rich mixture of growth factors, hormones, and lipids to support the growth of cells in culture. It is often used as a supplement in cell culture media [9]. |

| Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) | Used as a protein stabilizer and to block non-specific binding in assays like Western blotting and immunoassays. It is also added to buffer solutions to reduce surface adhesion [9]. |

| Sucrose | Used to create isotonic or hypertonic conditions in buffers, helping to maintain osmotic balance and protect cells and vesicles from osmotic shock [9]. |

| Radioimmunoprecipitation Assay (RIPA) Buffer | A harsh lysis buffer containing detergents and salts, used to lyse cells and vesicles for protein extraction, particularly for Western blotting [10]. |

| β-mercaptoethanol | A reducing agent that breaks disulfide bonds between cysteine residues in proteins, aiding in protein denaturation for Western blot analysis [10]. |

What are the best practices for preparing biofluid samples to ensure analytical reproducibility?

Proper sample preparation is fundamental for obtaining accurate and reproducible data, especially when working with complex matrices like biofluids.

Core Principles of Biofluid Sample Prep: The goal is to extract and concentrate the analyte while removing sample constituents that might interfere with the analysis. Key considerations are outlined in the following workflow:

Detailed Methodologies:

- General Handling for Serum/Plasma:

- Thawing: Thaw frozen samples completely, then vortex mix thoroughly.

- Clarification: Centrifuge samples at a minimum of 10,000 x g for 5-10 minutes to remove particulates, lipids, and cells. For viscous samples, centrifugation may need to be repeated [11].

- Protein Precipitation (PPT): Primarily used for blood-based samples. Adding excess organic solvent (e.g., acetonitrile) precipitates proteins, which are then removed by centrifugation or filtration. This is quick and simple but only removes proteins, not other interferents like phospholipids [12].

- Phospholipid Depletion (PLD): A crucial step for LC-MS/MS analysis of blood samples. Phospholipids can cause significant ion suppression. They are removed using a specialized scavenging adsorbent, often following PPT [12].

- Supported Liquid Extraction (SLE): A targeted extraction technique based on the same principle as liquid-liquid extraction (LLE) but is easier to automate and avoids emulsion formation. An aqueous sample is loaded onto an inert solid support, and an immiscible organic solvent is passed through to elute the analytes [12].

FAQs on Sample Preparation:

- Q: Can I use a "dilute and shoot" approach for urine samples?

- A: Yes, for urine, a simple 1:10 dilution with water or buffer can sometimes be sufficient. However, this approach negatively impacts the limit of detection and does not remove matrix components that can foul instrumentation or suppress ionization [12].

- Q: Why is it important to remove phospholipids specifically?

- A: Phospholipids elute at various points in a chromatographic run and cause significant ion suppression in the mass spectrometer, leading to inaccurate quantification and loss of sensitivity [12].

Optimized Storage Protocols: Practical Strategies for Preserving Exosome Integrity

Technical Support Center: Preventing Exosome Aggregation

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: High Particle Count and Polydispersity Post-Thaw

- Question: My exosome samples show a significant increase in particle size and polydispersity index (PDI) after a single freeze-thaw cycle from -80°C. What is the cause and how can I prevent it?

- Answer: This is a classic sign of freeze-thaw-induced aggregation. The formation of ice crystals during freezing can disrupt exosome membranes, leading to fusion and aggregation upon thawing.

- Solution 1: Implement a Controlled, Slow Freezing Rate. Use an isopropanol-filled "Mr. Frosty" or a programmable freezer to cool samples at approximately -1°C per minute before transferring to -80°C. This reduces ice crystal formation.

- Solution 2: Introduce a Cryoprotectant. Add a non-penetrating cryoprotectant like 5-10% (w/v) trehalose to your exosome suspension. It forms a stable glassy matrix that separates exosomes and protects membranes.

- Solution 3: Aliquot Samples. Avoid repeated freeze-thaw cycles by aliquoting exosomes into single-use volumes.

Problem: Poor Recovery After Lyophilization

- Question: I am experiencing low particle recovery and loss of functional biomarkers after lyophilizing my exosome sample. What steps am I likely missing?

- Answer: Lyophilization without a proper lyoprotectant causes massive aggregation and membrane damage due to mechanical and osmotic stress.

- Solution 1: Optimize the Lyoprotectant Formulation. Use a combination of cryo- and lyo-protectants. A standard formulation is 5% trehalose + 1% sucrose in your resuspension buffer prior to freezing and lyophilization.

- Solution 2: Control the Lyophilization Cycle. Ensure a primary drying phase that is long enough to remove all ice without collapsing the cake structure. Use a pilot study to optimize time and temperature.

- Solution 3: Validate Reconstitution. Rehydrate the lyophilized cake gently with the original volume of a compatible buffer (e.g., PBS or 0.9% saline). Avoid vortexing; use gentle pipetting or slow rotation.

Problem: Rapid Degradation at 4°C

- Question: My exosomes are stable for less than a week at 4°C, showing a drop in CD63 expression. Is this expected?

- Answer: Yes, this is expected. 4°C is not suitable for long-term storage. Hydrolytic and enzymatic degradation processes remain active, and exosomes can sink and aggregate in the tube over time.

- Solution: For any storage beyond 48-72 hours, move to -80°C or lyophilization. If you must use 4°C for short-term experiments, ensure your buffer contains protease inhibitors and use low-protein-binding tubes to minimize surface adsorption.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: What is the single most important factor for preserving exosome function during freeze-thaw?

- A: The use of a cryoprotectant, specifically trehalose, is the most critical factor. It stabilizes the lipid bilayer without being internalized, significantly reducing aggregation and preserving surface protein integrity.

Q: Can I store my exosomes at -20°C for a few months?

- A: It is not recommended. The -20°C environment is within the eutectic point range where recrystallization can occur, causing more damage than -80°C storage. For any storage beyond a few weeks, -80°C is the minimum standard.

Q: How does lyophilization prevent aggregation when it removes water?

- A: Lyophilization prevents aggregation by immobilizing the exosomes in a rigid, amorphous glassy matrix formed by the lyoprotectants (e.g., sugars). This matrix physically separates the exosomes, preventing their membranes from contacting and fusing, both during the dried state and upon rehydration.

Q: My downstream application is RNA sequencing. Which storage method is best?

- A: For RNA integrity, rapid freezing and storage at -80°C with a cryoprotectant like trehalose is superior. Lyophilization can also be effective but requires rigorous validation, as the process can sometimes induce minor RNA degradation if not perfectly optimized.

Table 1: Impact of Storage Conditions on Exosome Integrity

| Parameter | 4°C (7 days) | -20°C (30 days) | -80°C (6 months) | Lyophilization (12 months) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Particle Concentration Recovery | 60-75% | 50-70% | 80-95%* | 70-90% |

| Mean Particle Size Increase | 15-30% | 20-50% | 5-15%* | 10-20% |

| Polydispersity Index (PDI) Change | +0.08 to +0.15 | +0.10 to +0.25 | +0.02 to +0.08* | +0.05 to +0.12 |

| Surface Marker Preservation (e.g., CD81) | Low | Moderate | High* | High |

| Functional Cargo Retention (e.g., miRNA) | Low | Moderate | High* | Moderate-High |

*With use of 5-10% trehalose as a cryoprotectant.

Table 2: Recommended Applications and Limitations

| Storage Method | Recommended Storage Duration | Best For | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| 4°C | < 72 hours | Immediate use, in-process handling | Rapid degradation, aggregation, bacterial growth. |

| -20°C | < 2 weeks | Temporary holding | High risk of ice crystal damage; not for long-term. |

| -80°C with Cryoprotectant | 6 months - 2 years | Long-term biobanking, functional assays | Requires reliable freezer; dependent on freeze-thaw protocol. |

| Lyophilization | > 2 years | Shipping, room-temperature storage | Complex process; potential for oxidative damage; requires reconstitution. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Assessing Cryoprotectant Efficacy for -80°C Storage

- Isolate Exosomes via ultracentrifugation or SEC and resuspend in PBS.

- Aliquot into 100 µL portions.

- Add Cryoprotectants: To separate aliquots, add trehalose (5%, 10%), sucrose (5%), or DMSO (5%).

- Control: Leave one aliquot in PBS only.

- Freeze: Place all aliquots in a Mr. Frosty freezing container at -80°C for 24 hours.

- Thaw: Rapidly thaw in a 37°C water bath with gentle agitation.

- Analyze: Use Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis (NTA) to measure particle concentration, size, and PDI. Validate with Western Blot for marker proteins (CD9, CD63, CD81).

Protocol 2: Lyophilization of Exosomes for Long-Term Stability

- Prepare Exosome Formulation: Dialyze the exosome pellet against a solution of 5% trehalose and 1% sucrose in ultrapure water to remove salts.

- Aliquot: Dispense 200 µL volumes into sterile lyophilization vials.

- Snap Freeze: Place vials in a bath of liquid nitrogen or a -80°C freezer for 2 hours.

- Lyophilize: Transfer vials to a pre-cooled (-40°C) lyophilizer. Run a primary drying cycle at -40°C for 24 hours under vacuum (< 100 mTorr). Follow with a secondary drying cycle, ramping to 25°C over 8 hours.

- Store: Seal vials under inert gas (e.g., Argon) if possible and store at 4°C or room temperature, protected from light.

- Reconstitute: Add 200 µL of nuclease-free water or PBS and allow to rehydrate for 30 minutes with gentle inversion.

Visualizations

Title: Exosome Storage Decision Guide

Title: Freeze-Thaw Aggregation Pathway

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Exosome Storage

| Reagent/Material | Function | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Trehalose | Non-penetrating cryo-/lyo-protectant. Forms a glassy state to separate and stabilize exosomes. | Preferred over sucrose due to higher glass transition temperature (Tg) and stability. |

| Sucrose | Lyoprotectant used in combination with trehalose to enhance matrix formation during lyophilization. | Can be more susceptible to hydrolysis than trehalose. |

| Mr. Frosty / Nalgene Freezing Container | Provides a consistent -1°C/minute cooling rate for controlled freezing to -80°C. | Essential for standardizing the freezing process across samples. |

| Low-Protein-Bind Microtubes | Minimizes exosome adhesion to tube walls, maximizing recovery. | Critical for all steps, especially with low-concentration samples. |

| Protease Inhibitor Cocktails | Prevents proteolytic degradation of exosome surface markers during short-term storage at 4°C. | Must be added fresh to buffers. |

Extracellular vesicles (EVs), including exosomes, are promising tools in regenerative medicine and drug delivery. However, their clinical translation faces significant challenges, particularly in maintaining stability during storage. The nanoscale properties of EVs make them sensitive to environmental conditions, leading to aggregation, cargo loss, and functional impairment during freeze-thaw cycles. Optimal cryoprotectants are therefore crucial for preserving EV structural, molecular, and functional integrity. This guide evaluates the efficacy of trehalose, sucrose, Human Serum Albumin (HSA), and Dimethyl Sulfoxide (DMSO) to help you select the right protocol for your research.

Troubleshooting Guide: Cryoprotectant Performance and Common Issues

Problem 1: EV Aggregation After Thawing

- Potential Cause: Inadequate cryoprotection leading to ice crystal formation and membrane fusion.

- Solution: Incorporate non-reducing disaccharides like trehalose or sucrose at 25-50 mM into your storage buffer. These sugars act as water substitutes and form stable glassy matrices that prevent vesicle-vesicle contact [1] [13].

Problem 2: Loss of Biological Activity in Functional Assays

- Potential Cause: Cryodamage to membrane proteins or leakage of bioactive cargo.

- Solution: Use trehalose (25 mM) as a cryoprotectant. Studies demonstrate that EVs cryopreserved with trehalose maintain their ability to stimulate immune responses and support the expansion of hematopoietic stem cells, outperforming PBS-only controls [1] [14].

Problem 3: Decreased Particle Concentration and Increased Size After Freeze-Thaw Cycles

- Potential Cause: Vesicle rupture and the formation of aggregates from multiple fusion events.

- Solution: Avoid multiple freeze-thaw cycles. Aliquot EVs in a 5% sucrose solution. Research shows sucrose provides superior preservation of EV size distribution and concentration compared to PBS after storage at -80°C [15] [13].

Problem 4: Concerns About Cytotoxicity or Introduction of Exogenous Contaminants

- Potential Cause: Use of cryoprotectants like DMSO, which can inhibit specific downstream processes, or HSA, which may introduce unknown variables.

- Solution: Opt for trehalose or sucrose. These are natural, non-toxic sugars widely used in food and drug industries. They do not require a washing step post-thaw and avoid potential cytotoxicity associated with DMSO [1] [14].

Quantitative Comparison of Cryoprotectants

The following table summarizes key experimental data on the performance of different cryoprotectants for EV storage.

Table 1: Efficacy of Cryoprotectants in EV Preservation

| Cryoprotectant | Typical Concentration | Key Findings on EV Integrity | Impact on Biological Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Trehalose | 25 mM | • Narrowed particle size distribution & reduced aggregation [1]• Higher particle concentration per μg of protein [1]• Maintained integrity over 12 freeze-thaw cycles in microneedles [2] | • Consistently higher TNF-α stimulation in macrophages [1]• Maintained HSC-supportive potential [14] |

| Sucrose | 5% (w/v) | • Better preservation of size/concentration vs. PBS at -80°C [15] [13]• More prevalent molecular surface protrusions & transmembrane proteins [13] | Data specific to functional assays not provided in available sources. |

| HSA (Human Serum Albumin) | Not Specified | • Improved EV quality after short & long-term storage vs. PBS alone [16] | Data specific to functional assays not provided in available sources. |

| DMSO | 6% (v/v) | • Increased EV yield & procoagulant activity from platelets [17] | • Potential cytotoxicity & inhibition of downstream processes [2] |

| Control (PBS) | N/A | • Particle aggregation & increased size after freeze-thaw [2] [1]• Decreased particle concentration & RNA content [2] | • Rapid loss of protein activity & impaired bioactivity [2] |

Experimental Protocols for Cryoprotectant Evaluation

Protocol 1: Assessing the Anti-Aggregation Efficacy of Trehalose

This protocol is adapted from a study demonstrating that trehalose prevents the aggregation of pancreatic beta-cell exosome-like vesicles (beta-ELVs) [1].

- EV Isolation and Preparation: Isolate EVs from your cell culture supernatant (e.g., MIN6 beta-cells) using differential centrifugation and ultrafiltration.

- Buffer Exchange: Resuspend the final EV pellet in two different buffers:

- Experimental Buffer: Phosphate-Buffered Saline (PBS) supplemented with 25 mM Trehalose (TRE).

- Control Buffer: PBS alone.

- Freeze-Thaw Cycling: Subject the EV suspensions to repeated freeze-thaw cycles (e.g., 3-5 cycles). Freeze at -80°C and thaw rapidly at 37°C.

- Characterization and Analysis:

- Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis (NTA): Measure the particle concentration and size distribution (mode, mean, and standard deviation) after freeze-thaw cycles. A lower standard deviation and span in the TRE group indicates a narrower size distribution and less aggregation [1].

- Cryo-Electron Tomography: Confirm the presence of individual, circular nanovesicles and the absence of large aggregates in the TRE group.

Protocol 2: Testing Functional Preservation in Hematopoietic Stem Cell (HSC) Expansion

This protocol is based on research showing that MSC-derived EVs cryopreserved with trehalose retain their ability to expand HSCs in vitro [14].

- EV Cryopreservation: Isolate Microvesicles (MVs) and exosomes from Mesenchymal Stromal Cell (MSC) conditioned medium. Aliquot the EVs and cryopreserve them at -80°C in:

- Experimental Buffer: PBS supplemented with 25 mM Trehalose.

- Control Buffer: PBS alone.

- HSC Co-culture: After thawing, co-culture freshly isolated mouse bone marrow HSCs with the cryopreserved EVs (MVs or exosomes) in a suitable expansion medium for 5-7 days.

- Functional Assessment:

- Stemness Maintenance: Analyze the co-cultured cells for the preservation of stem cell markers (e.g., Sca-1, c-Kit) using flow cytometry. EVs stored with trehalose should better maintain the stem cell population [14].

- Clonogenic Assay: Plate the cells in methylcellulose-based media to assess colony-forming unit (CFU) potential. A higher number of colonies indicates retained EV functionality [14].

- Migration Assay: Perform a transwell migration assay towards a SDF-1α gradient to evaluate the homing capacity of the expanded HSCs, a key functional outcome [14].

Experimental Workflow for EV Cryoprotectant Testing

Cryoprotectant Mechanism of Action

Cryoprotectant Mechanisms and Outcomes

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Reagents for EV Cryopreservation Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function in Protocol | Example Usage & Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Trehalose | Non-reducing disaccharide cryoprotectant | Used at 25 mM in PBS to prevent aggregation and preserve biological activity during freeze-thaw cycles and long-term storage [1] [14]. |

| Sucrose | Cryoprotectant and buffer component | Used as a 5% (w/v) solution for -80°C storage to better maintain EV size distribution, concentration, and membrane integrity compared to PBS [15] [13]. |

| Human Serum Albumin (HSA) | Protein-based stabilizer | Added to storage buffers to improve EV quality and stability over time by reducing vesicle adhesion and surface-induced stress [16]. |

| Dimethyl Sulfoxide (DMSO) | Penetrating cryoprotectant | Used at ~6% for freezing platelet-derived EVs to increase yield and procoagulant activity, but carries risk of cytotoxicity for sensitive applications [17]. |

| Phosphate-Buffered Saline (PBS) | Standard ionic storage buffer | Serves as a common control and base buffer for cryoprotectant studies, though alone it often leads to aggregation and damage [2] [1]. |

| Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis (NTA) | Instrument for particle characterization | Measures hydrodynamic diameter and concentration of EVs to quantify aggregation (increased size) and particle loss after thawing [1]. |

| Cryo-Electron Microscope | High-resolution imaging instrument | Visualizes EV morphology and membrane integrity directly, confirming the presence of intact, non-aggregated vesicles post-thaw [1] [13]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Can I use sucrose instead of trehalose for lyophilizing exosomes? Yes, both sucrose and trehalose are effective lyoprotectants. They work by forming a stable, amorphous glassy matrix that immobilizes the EVs and protects their membrane during the freeze-drying process and subsequent storage at room temperature. The choice may depend on optimization for your specific EV type, but both have been shown to outperform buffers like PBS [16] [18].

Q2: How many freeze-thaw cycles can exosomes tolerate when stored with trehalose? The number of safe freeze-thaw cycles is limited even with cryoprotectants. One study incorporating EVs into a hyaluronic acid-based microneedle formulation with trehalose showed negligible degradation after 10 freeze-thaw cycles [2]. However, for EVs in liquid suspension, it is strongly recommended to avoid multiple freeze-thaw cycles. Best practice is to aliquot your EV samples into single-use volumes to minimize repetitive freezing and thawing.

Q3: Why is DMSO less preferred than trehalose for EV cryopreservation? While DMSO is a highly effective cryoprotectant for whole cells, its use for EVs is limited due to potential cytotoxicity and its tendency to inhibit specific downstream biological processes or assays [2]. In contrast, trehalose is a natural, non-toxic sugar that does not require a washing step after thawing and does not interfere with cellular functions, making it a safer and more practical choice for most EV-based applications [1] [14].

Q4: Does storing exosomes in their native biofluid offer any advantage? Yes. Evidence suggests that storing EVs in their native biofluid (e.g., plasma, serum) offers improved stability compared to storing purified EVs in buffers like PBS. The native environment likely contains natural stabilizing factors that help protect the vesicles from degradation and aggregation [2].

Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ 1: How can I prevent exosome aggregation and function loss during long-term storage?

Problem: Exosomes rapidly lose structural integrity and biological function when stored in standard buffers like PBS, even at recommended freezing temperatures [2] [19].

Solutions:

- Incorporate trehalose: Add 25 mM trehalose to your storage buffer. This natural disaccharide acts as a cryoprotectant by stabilizing lipid bilayers and preventing fusion [1] [8].

- Utilize hyaluronic acid microneedles (EV@MN): Encapsulate exosomes within dissolvable hyaluronic acid-based microneedles. This matrix maintains exosome bioactivity for over six months at 4°C [19].

- Avoid repeated freeze-thaw cycles: Aliquot exosomes to minimize freeze-thaw cycles, which cause irreversible damage including particle aggregation, cargo loss, and membrane deformation [2] [4].

Table 1: Comparison of Exosome Storage Strategies

| Storage Method | Storage Duration | Key Findings | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| PBS at -80°C | 6 months | Significant decrease in EVs, protein activity lost within 2 weeks | [2] [19] |

| PBS with 25 mM Trehalose at -80°C | - | Prevents aggregation, maintains particle concentration and biological activity | [1] [8] |

| Hyaluronic Acid Microneedles (EV@MN) at 4°C | 6 months | >85% particles remained, >99% protein activity preserved | [19] |

| Lyophilization with Trehalose at RT | 1 week | Preserved physical properties, protein/RNA content, and functionality | [8] |

FAQ 2: What is the optimal strategy for transdermal delivery of exosomes while maintaining stability?

Problem: The skin's stratum corneum barrier limits exosome penetration for topical applications, and conventional storage methods degrade exosome functionality before application [19] [20].

Solutions:

- Fabricate hyaluronic acid dissolving microneedles: Use low molecular weight HA (30-50 kDa) to form dissolvable microneedle tips that encapsulate exosomes [19] [20].

- Utilize micromolding technique: Centrifuge HA-exosome mixture into PDMS molds to form needle structures, then air-dry at 25°C with desiccant [19].

- Characterize microneedle performance: Verify skin penetration capability, exosome release profile, and biological activity post-fabrication [19].

Experimental Protocol: Fabrication of HA Microneedles Loaded with Exosomes

- Isolate exosomes from your cell source of interest using standard methods (ultracentrifugation, size exclusion chromatography)

- Prepare 30% (w/v) hyaluronic acid (MW 30-50 kDa) aqueous solution

- Mix exosomes with HA solution at appropriate ratio for your application

- Cast mixture onto polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) micromolds

- Centrifuge at 2380× g for 15 minutes to remove air bubbles and fill mold cavities

- Dry in oven at 25°C with dry silica gel for complete solidification

- Demold carefully and store in sealed container with desiccant [19]

FAQ 3: How does trehalose prevent exosome damage during freezing and lyophilization?

Problem: Conventional freezing without cryoprotectants causes exosome damage through ice crystal formation, osmotic stress, and membrane phase transitions [2] [1].

Solutions:

- Leverage multiple protective mechanisms: Trehalose protects through water replacement, vitrification, and preferential exclusion [1] [21].

- Optimize concentration: Use 25 mM trehalose for liquid storage or 100-250 mM for lyophilization protocols [1] [8] [22].

- Control freezing rate: Implement rapid freezing for trehalose-containing formulations to enhance glass formation [2].

Experimental Protocol: Lyophilization of Exosomes with Trehalose

- Isolate and concentrate exosomes using standard methods

- Add trehalose to exosome suspension to achieve final concentration of 100-250 mM

- Aliquot into lyophilization vials and freeze at -80°C for 12 hours

- Transfer to freeze-dryer with condenser temperature maintained at -54°C

- Perform primary drying at 54×10⁻³ bar for 36 hours without heating

- Complete secondary drying to reduce residual moisture

- Store lyophilized exosomes at room temperature with desiccant [8] [22]

Table 2: Troubleshooting Common Exosome Stabilization Issues

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution | Preventive Measures |

|---|---|---|---|

| Exosome aggregation in storage | Insufficient electrostatic repulsion, buffer incompatibility | Add 25 mM trehalose to storage buffer | Avoid phosphate buffers; use HEPES or trehalose solutions |

| Loss of biological activity after freezing | Ice crystal damage, membrane phase separation | Use rapid freezing rates, incorporate cryoprotectants | Aliquot to avoid repeated freeze-thaw cycles |

| Poor skin penetration | Stratum corneum barrier function | Incorporate into dissolving microneedles | Optimize microneedle length (600μm) and shape |

| Low microneedle mechanical strength | Suboptimal polymer concentration or molecular weight | Increase HA concentration to 30%, use appropriate MW HA | Ensure complete drying with desiccant |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Exosome Stabilization Research

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Hyaluronic Acid (30-50 kDa) | Base polymer for dissolving microneedles | Provides mechanical strength while maintaining biocompatibility and dissolution rate |

| Trehalose | Cryoprotectant and lyoprotectant | 25 mM for liquid storage, 100-250 mM for lyophilization; non-reducing properties prevent browning reactions |

| Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) Molds | Microneedle fabrication | Reusable molds with specific needle dimensions (e.g., 600μm height, 300μm base diameter) |

| Size Exclusion Chromatography Columns | Exosome isolation | Maintains exosome integrity compared to precipitation methods; reduces contaminant proteins |

| Protease Inhibitor Cocktails | Prevention of proteolytic degradation | Particularly important for long-term storage of complex biofluids |

| Dimethyl Sulfoxide (DMSO) | Alternative cryoprotectant | Use at 6-10% concentrations; may interfere with downstream biological assays |

| Hydroxyethyl Starch | Macromolecular cryoprotectant | Increases glass transition temperature when combined with trehalose |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is buffer selection critical for exosome storage? The buffer composition is a primary factor in maintaining exosome integrity. Suboptimal buffers can lead to particle aggregation, a drastic loss in concentration, and damage to the lipid bilayer, ultimately compromising the exosomes' biological activity and function [16] [23]. The ionic strength, pH, and presence of cryoprotectants in the buffer directly influence exosome stability during both freezing and refrigeration.

Q2: Is PBS always the best choice for storing exosomes? While Phosphate-Buffered Saline (PBS) is the most commonly used buffer, research shows its performance is highly variable and often suboptimal. Studies indicate that PBS can cause significant damage to EVs during storage, leading to a drastic loss in particle recovery [16] [23]. Its suitability depends on the storage duration and method. One study found PBS superior for maintaining exosome concentration in short-term storage (≤2 weeks), but it is often outperformed by specialized buffers for long-term preservation [16] [24].

Q3: What are the observed drawbacks of using Normal Saline (NS) or 5% Glucose Solution (5%GS)? Comparative studies have shown that exosomes stored in Normal Saline (NS) and 5% Glucose Solution (5%GS) can exhibit specific physical drawbacks:

- Normal Saline (NS): Exosomes in NS can display shriveled morphology and are prone to progressive aggregation, especially under lyophilization [24].

- 5% Glucose Solution (5%GS): Similar to NS, exosomes in 5%GS show aggregation and less of the characteristic biconcave shape compared to those in PBS [24]. These observations suggest that while isotonic, these solutions may lack components that prevent membrane stress and particle-particle interactions.

Q4: How do freeze-thaw cycles affect exosomes, and how can this be mitigated? Multiple freeze-thaw cycles are particularly detrimental to exosomes. They can lead to decreased particle concentrations, loss of RNA content, impaired bioactivity, and an increase in vesicle size due to aggregation and fusion [2] [3]. To mitigate this damage, you should:

- Aliquot exosome samples into single-use volumes to avoid repeated freezing and thawing.

- Use cryoprotectants like trehalose, which has been shown to prevent aggregation and preserve biological activity across freeze-thaw cycles [1].

- Employ rapid freezing procedures to minimize the formation of damaging ice crystals.

Q5: What are the advantages of lyophilization (freeze-drying) for long-term exosome storage? Lyophilization offers significant logistical advantages by enabling the direct preservation of exosomes at room temperature, thereby reducing costs associated with ultra-low temperature freezers and simplifying transportation [16]. However, the process itself poses risks, including ice crystal formation and osmotic stress, which can compromise exosomal structure. The success of lyophilization is highly dependent on using appropriate lyoprotectants (e.g., trehalose, sucrose) in the buffer to maintain size distribution, morphological integrity, and cargo content [16].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Low Exosome Recovery After Thawing

Possible Causes and Solutions:

- Cause 1: Storage in plain PBS. PBS alone is known to cause a significant drop in particle recovery after freezing.

- Cause 2: Multiple freeze-thaw cycles.

- Cause 3: Slow or inconsistent freezing.

- Solution: Use a controlled-rate freezer or snap-freeze aliquots in a slurry of dry ice and ethanol before transferring to -80°C for consistent and rapid freezing [3].

Problem: Exosome Aggregation and Size Increase

Possible Causes and Solutions:

- Cause 1: Unsuitable buffer ionic strength or composition.

- Solution: If aggregation is observed in PBS, consider testing buffers with additives. Trehalose has been demonstrated to narrow exosome size distribution and prevent aggregation by providing a physical shield to the vesicle membrane [1].

- Cause 2: Storage temperature is too high.

- Solution: For long-term storage, ensure a constant temperature of -80°C. Storage at -20°C has been shown to induce significant aggregation and size increase compared to -80°C [3].

- Cause 3: Lyophilization without protectants.

- Solution: When using lyophilization, incorporate lyoprotectants like trehalose or sucrose into the buffer formulation to protect against dehydration and membrane damage that leads to aggregation [16].

The following table summarizes key quantitative findings from a comparative study on the stability of MSCs-derived exosomes in different buffers under cryopreservation and lyophilization [16] [24].

Table 1: Comparative Stability of Exosomes in Different Buffers Over a 4-Week Period

| Storage Buffer | Storage Method | Short-Term Concentration (≤2 wk) | Long-Term Concentration (4 wk) | Size Homogeneity | Key Morphological Observations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PBS | Cryopreservation (-80°C) | Superior maintenance | Progressive loss | Moderate | More uniform distribution, biconcave-disk shape |

| Normal Saline (NS) | Cryopreservation (-80°C) | Significant loss | Significant loss | Low | Shriveled and aggregated vesicles |

| 5% Glucose (5%GS) | Cryopreservation (-80°C) | Significant loss | Significant loss | Low | Shriveled and aggregated vesicles |

| PBS | Lyophilization | Induced concentration loss | Induced concentration loss | High | Maintained size integrity despite concentration loss |

| Normal Saline (NS) | Lyophilization | N/A | N/A | Low | Progressive aggregation |

| 5% Glucose (5%GS) | Lyophilization | N/A | N/A | Low | Progressive aggregation |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Assessing Exosome Stability in Different Buffers

This protocol is adapted from studies comparing PBS, NS, and 5% GS for exosome storage [16] [24].

Key Research Reagent Solutions:

- Purified Exosomes: Isolated from cell culture media (e.g., MSCs) via ultracentrifugation or tangential flow filtration.

- Storage Buffers: Sterile PBS (pH 7.4), 0.9% Normal Saline, 5% Glucose Solution.

- Cryoprotectant Solution: 25mM - 100mM Trehalose in PBS.

- Characterization Instruments: Nanoparticle Tracking Analyzer (NTA), Transmission Electron Microscope (TEM), Western Blot apparatus.

Methodology:

- Isolate and Purify Exosomes from your chosen cell source using your standard method (e.g., differential ultracentrifugation).

- Resuspend and Divide the final exosome pellet equally into three aliquots.

- Centrifuge again if needed to replace the original medium with the test buffers.

- Resuspend one aliquot in PBS, one in Normal Saline, and one in 5% Glucose Solution.

- Optional: Add a cryoprotectant like trehalose to a subset of each buffer to test its effect.

- Store Aliquots at your desired temperatures (e.g., -80°C, 4°C) and timepoints (e.g., Fresh, 1-week, 2-week, 4-week).

- Characterize the exosomes at each timepoint.

- Concentration & Size: Use NTA to measure particle concentration and size distribution.

- Morphology: Use TEM to visually assess structural integrity and aggregation.

- Marker Integrity: Use Western Blot to confirm the presence of exosomal markers (e.g., CD63, TSG101).

Protocol 2: Testing the Efficacy of Cryoprotectants

This protocol is based on research demonstrating the protective effect of trehalose [1] [23].

Methodology:

- Prepare your purified exosome sample as in Protocol 1.

- Divide the sample into two equal aliquots.

- Resuspend one aliquot in standard PBS. Resuspend the other aliquot in PBS supplemented with 25mM trehalose.

- Subject both samples to multiple (e.g., 3-5) freeze-thaw cycles. For each cycle, freeze at -80°C for at least 1 hour and thaw at room temperature.

- Analyze the samples after the final thaw.

- Use NTA to compare particle concentration and size distribution between the PBS and PBS-Trehalose groups.

- For functional assessment, treat recipient cells with the exosomes and measure a relevant bioactivity (e.g., macrophage immune response, cytokine secretion).

Visualization of Workflows and Relationships

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Reagents for Exosome Storage Buffer Optimization

| Reagent / Solution | Function / Rationale | Key Findings / Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Phosphate-Buffered Saline (PBS) | Isotonic, pH-stabilizing buffer; the current most common choice. | Superior for short-term (≤2 wk) concentration stability, but can lead to major particle loss and function impairment over time [16] [23]. |

| Normal Saline (0.9% NaCl) | Isotonic solution providing basic osmotic balance. | Observed to cause exosome shrinkage and aggregation; not recommended for purified exosomes [24]. |

| 5% Glucose Solution (5%GS) | Isotonic sugar solution providing osmotic balance. | Similar to NS, leads to aggregation and is less effective than PBS for maintaining stability [24]. |

| Trehalose | Non-reducing disaccharide cryo- & lyo-protectant. | Prevents aggregation, narrows size distribution, preserves biological activity across freeze-thaw cycles, and serves as a lyoprotectant [1] [23]. |

| Human Serum Albumin (HSA) / Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) | Protein additive that stabilizes vesicles. | Prevents adsorption to tube walls and improves recovery. PBS-HAT buffer (with HSA & Trehalose) shows drastically improved preservation [23] [25]. |

| Specialized EV Storage Buffer | Optimized, pre-formulated buffer (e.g., with Trehalose & BSA). | Shown to better protect EV cargo (e.g., DNA), maintain particle numbers, and preserve targeting functionality compared to PBS [25]. |

Technical Support Center

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is it critical to minimize freeze-thaw cycles for exosome samples? A: Each freeze-thaw cycle induces mechanical and osmotic stress, leading to exosome membrane rupture, loss of cargo (e.g., RNA, proteins), and increased aggregation. This compromises downstream experimental results, including functional assays and biomarker profiling.

Q2: What is the optimal aliquot volume to prepare? A: The optimal volume is the exact amount required for a single experiment. Common practice is 10-100 µL, depending on the assay. This minimizes the volume of sample subjected to repeated thawing and avoids the need for re-freezing any leftover material.

Q3: What is the recommended cooling rate for "rapid" freezing? A: A cooling rate of -1°C to -3°C per minute is often recommended until the sample passes the freezing point, after which it can be transferred to long-term storage. This controlled rate minimizes ice crystal formation that can damage exosomes.

Q4: Can I use liquid nitrogen for flash-freezing my exosome aliquots? A: Direct immersion in liquid nitrogen is not recommended for small aqueous volumes in standard tubes due to the risk of tube rupture and potential sample contamination. Using a pre-cooled rack in a -80°C freezer or a specialized controlled-rate freezer is safer and more effective.

Troubleshooting Guide

Problem: Low exosome recovery post-thaw.

- Potential Cause: Exosomes are adhering to the tube walls.

- Solution: Use low protein-binding tubes (e.g., siliconized tubes). Briefly centrifuge the tube before opening to collect the entire sample.

Problem: Increased particle size and polydispersity after thawing.

- Potential Cause: Exosome aggregation due to slow freezing or the absence of a cryoprotectant.

- Solution: Ensure rapid freezing protocols are followed. Incorporate a cryoprotectant like trehalose (e.g., 5-10% w/v) or HSA (0.5-1%) into the resuspension buffer.

Problem: Loss of biological activity in functional assays.

- Potential Cause: Damage to surface proteins from ice crystal formation during freezing.

- Solution: Implement single-use aliquoting strictly. Verify the use of a cryoprotectant and avoid any refreezing of thawed samples.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Single-Use Aliquoting and Rapid Freezing

- Preparation: Pre-chill a box of 1.5 mL or 2.0 mL low-protein-binding microcentrifuge tubes on ice.

- Mixing: Gently vortex the purified exosome suspension to ensure a homogeneous solution. Avoid foaming.

- Aliquoting: Using a calibrated pipette, dispense the desired single-experiment volume into each pre-chilled tube. Work quickly to minimize time at room temperature.

- Cryoprotection (Optional but Recommended): If using, add trehalose from a sterile stock solution to a final concentration of 5-10% and mix gently by pipetting.

- Freezing:

- Place the aliquots in a pre-chilled (4°C) isopropanol freezing jar or a passive cooling device.

- Immediately transfer the jar to a -80°C freezer for a minimum of 2 hours. This ensures a controlled cooling rate of approximately -1°C/min.

- Long-Term Storage: After rapid freezing, transfer the aliquots to a designated rack in the -80°C freezer for long-term storage. Maintain a detailed inventory to track aliquot usage.

Protocol 2: Assessing Exosome Integrity Post-Thaw (NTA and Protein Assay)

- Thawing: Remove one single-use aliquot from -80°C and thaw it rapidly in a 37°C water bath for 60-90 seconds. Gently mix the tube by inversion.

- Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis (NTA):

- Dilute the thawed aliquot in sterile, particle-free PBS to a concentration within the ideal detection range of the NTA instrument (e.g., 10^8-10^9 particles/mL).

- Load the sample and perform particle sizing and concentration analysis according to the manufacturer's instructions. Compare the mean/median particle size and mode size to a freshly prepared sample.

- Protein Assay (e.g., BCA):

- Lyse a separate portion of the thawed aliquot with RIPA buffer.