Regenerative Pharmacology: Mechanisms of Action for Curative Therapeutics

This article explores the emerging paradigm of regenerative pharmacology, a field dedicated to developing curative therapies that restore the structure and function of damaged tissues and organs, moving beyond symptomatic...

Regenerative Pharmacology: Mechanisms of Action for Curative Therapeutics

Abstract

This article explores the emerging paradigm of regenerative pharmacology, a field dedicated to developing curative therapies that restore the structure and function of damaged tissues and organs, moving beyond symptomatic management. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it provides a comprehensive analysis of the foundational principles, key mechanisms of action, and advanced methodologies driving this discipline. The content delves into the integration of pharmacology with systems biology and regenerative medicine, examines the pharmacological toolkit for directing tissue regeneration, addresses critical translational and manufacturing challenges for Advanced Therapy Medicinal Products (ATMPs), and outlines the rigorous validation and comparative frameworks necessary for clinical success. By synthesizing current research and future directions, this article serves as a strategic guide for navigating the complexities of creating transformative regenerative pharmacotherapies.

The New Paradigm: From Symptom Management to Curative Restoration

Regenerative pharmacology represents a transformative paradigm in biomedical science, emerging from the convergence of pharmacological principles with regenerative medicine and tissue engineering. Defined operationally as "the application of pharmacological sciences to accelerate, optimize, and characterize (either in vitro or in vivo) the development, maturation, and function of bioengineered and regenerating tissues," this discipline aims to cure disease through restoration of tissue and organ function, rather than merely ameliorating symptoms [1] [2]. This strategic focus distinguishes it fundamentally from standard pharmacotherapy, which predominantly addresses symptom management rather than underlying functional restoration [1].

The field was formally coined in 2007 to describe the enormous possibilities at the interface between pharmacology, regenerative medicine, and tissue engineering [1] [2]. As a rapidly evolving multidisciplinary enterprise, regenerative pharmacology seeks to advance technologies for the repair and replacement of damaged cells, tissues, and organs, with the pharmacological sciences playing a critical role in accelerating translational progress and clinical utility [1].

Core Principles and Conceptual Framework

Foundational Principles

Regenerative pharmacology is built upon several interconnected principles that guide its research and application:

Curative Focus: Unlike conventional pharmacology that manages symptoms, regenerative pharmacology seeks to restore normal tissue and organ function through targeted interventions that promote healing and regeneration [1] [3]. This approach leverages the body's innate healing mechanisms, enhancing what the body naturally attempts to accomplish [4] [5].

Structural and Functional Restoration: The field emphasizes both the improvement of functional outcomes and the restoration of structural integrity at the tissue and organ levels [3]. This involves understanding and recapitulating the complex internal milieu that permits new functional tissue formation [1].

Multidisciplinary Integration: Success in regenerative pharmacology demands global multidisciplinary collaboration at the intersections of pharmacology, biomaterials, biomedical engineering, nanotechnology, stem cell biology, and developmental biology [1]. This integration enables a systems-level approach to therapeutic development.

Spatiotemporal Control: Effective regenerative strategies must replicate the exquisite spatiotemporal regulation characteristic of morphogen gradients in normal development, requiring sophisticated control over the delivery and presentation of bioactive compounds [1].

The Integrative and Regenerative Pharmacology (IRP) Framework

A contemporary extension of this field, termed Integrative and Regenerative Pharmacology (IRP), merges pharmacology with systems biology and regenerative medicine [3]. IRP represents a paradigm shift from traditional drug discovery models toward systems-based, healing-oriented therapeutic approaches. Its conceptual foundations include:

- Systematic investigation of drug-human interactions at molecular, cellular, organ, and system levels [3]

- Application of pharmacological rigor to regenerative medicine processes [3]

- Development of transformative curative therapeutics that improve symptomatic relief while modulating tissue formation and function [3]

Table 1: Comparison of Conventional Pharmacology and Regenerative Pharmacology

| Aspect | Conventional Pharmacology | Regenerative Pharmacology |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Goal | Symptom management, disease progression alteration | Tissue/function restoration, curative intervention |

| Therapeutic Approach | Single target, selective mechanisms | Complex mixtures, multiple pathways |

| Molecular Weight | Small molecules (<500-800 MW) | Large molecules (growth factors, 10,000->100,000 MW) |

| Temporal Focus | Chronic management | Curative outcome |

| Development Approach | Standard drug discovery pipeline | Integrated, multidisciplinary strategies |

Operational Roles in Tissue Engineering and Regenerative Medicine

Regenerative pharmacology plays both passive (characterizing) and active (directing) roles throughout the tissue engineering and regenerative medicine (TERM) process [1]. These roles can be categorized as follows:

Passive/Characterizing Roles

Functional evaluation of engineered and regenerating tissues through preclinical assessment and pharmacological characterization of tissue/organ phenotype in vitro and in vivo [1]

Mechanistic investigation of regeneration processes, including defining the mechanisms of action for stem cell-derived therapies and understanding the "basic pharmacology" controlling regenerative pathways [6]

Active/Directing Roles

Modulation of stem/progenitor cell expansion and differentiation through screening of growth factor and small molecule libraries and development of improved culture systems [1]

Development of novel drug delivery systems including biomaterials, nanomaterials, and bifunctional compounds that target active agents to specific tissue locations [1] [3]

Creation of functionalized "smart" biomaterials that serve as reservoirs for bioactive agents and cell delivery vehicles for accelerated tissue formation [1]

Pharmacological modulation of the entire regenerative process to replicate the spatiotemporal regulation characteristic of normal development [1]

Key Research Methodologies and Experimental Approaches

In Vitro Tissue Characterization Platforms

Regenerative pharmacology employs advanced in vitro systems to study and direct tissue development:

Bioreactor Technologies: Laboratory devices that recapitulate relevant aspects of the in vivo physiologic environment (stretch, flow, compression) to create advanced three-dimensional tissue constructs in vitro prior to implantation [1]. These systems allow for preclinical assessment and pharmacological characterization of tissue/organ phenotype under controlled conditions.

Bioprinting Approaches: Technologies that simultaneously deposit cells and materials in complex geometries reminiscent of native tissue architectures, providing feasible methods for the creation and assembly of 3D tissues and organs [1]. These systems enable precise spatial control over the distribution of bioactive compounds.

Organ-on-a-Chip Platforms: Microfluidic devices that emulate human organ functionality, providing sophisticated systems for drug screening and mechanistic studies in a human-relevant context [3].

Investigating the Paracrine Hypothesis

A central methodology in regenerative pharmacology involves elucidating the paracrine effect observed in cell-based therapies [6]. This hypothesis proposes that cells delivered to sites of organ injury secrete factors that have beneficial effects on tissue function through:

- Enhancement of surviving cell function

- Prevention of cell loss through activation of survival pathways

- Stimulation of resident stem cell niches

The experimental approach to investigating this hypothesis includes:

- Conditioned media analysis from therapeutic cell cultures

- Factor identification through proteomic and transcriptomic profiling

- Ligand-receptor interaction studies to identify new pharmacological targets

- Functional validation in relevant disease models

Pharmacological Modulation of Stem Cell Biology

Understanding and controlling stem cell behavior through pharmacological intervention is a critical methodology:

Directed Differentiation: Using small molecules and growth factors to steer stem cell differentiation toward specific lineages [6]. This includes modulation of complex transcription pathways involved in differentiation.

Cell Migration Control: Investigating how pharmacological agents affect stem cell homing and engraftment, such as the demonstrated inhibition of progenitor cell migration by heparin through interference with SDF-1/chemokine receptor type 4 signaling [6].

Drug-Cell Interactions: Studying how conventional medications (e.g., aspirin, COX-2 inhibitors) interact with stem cell biology, as these interactions can significantly impact the efficacy of regenerative therapies [6].

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents in Regenerative Pharmacology

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| Growth Factors | FGF, EGF, VEGF, IGF, BMPs, NGF | Modulation of cell proliferation, differentiation, and tissue formation [1] |

| Stem Cell Markers | CD34+, CD105+, Muse cells | Identification, isolation, and characterization of stem cell populations [5] |

| Biomaterial Scaffolds | Gelatin sponges, atelocollagen, amnion membrane | Providing three-dimensional frameworks for tissue development [5] |

| Small Molecule Modulators | COX-2 inhibitors, Wnt/β-catenin pathway modulators | Investigation of signaling pathways controlling regeneration [6] |

| Analytical Tools | Omics technologies, biosensors, real-time monitoring systems | Characterization of tissue development and function [3] |

Signaling Pathways and Mechanistic Foundations

Understanding the signaling networks that control regeneration is fundamental to regenerative pharmacology. Several key pathways have emerged as critical regulators:

Key Regenerative Signaling Pathways

Wnt/β-catenin Signaling: This pathway plays crucial roles in stem cell proliferation and differentiation. Research has shown that aspirin inhibits mesenchymal stem cell proliferation through mechanisms involving inhibition of PGE2 formation and subsequent down-regulation of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway [6]. Treatment with PGE2 increases cell proliferation and enhances activation of this pathway.

PI3K/Akt Pathway: This survival pathway has been engineered into cells to enhance their therapeutic potential through paracrine mechanisms [6]. Activation of this pathway promotes cell survival and tissue protection in injury models.

SDF-1/CXCR4 Signaling: Critical for stem cell homing and migration, this pathway can be inhibited by heparin, demonstrating how commonly used clinical agents can interfere with regenerative processes [6]. This has important implications for the choice of anticoagulants in cell therapy protocols.

Regulatory Considerations and Clinical Translation

Expedited Development Pathways

The regulatory landscape for regenerative pharmacology therapies includes special expedited programs:

RMAT Designation: The Regenerative Medicine Advanced Therapy designation was created under the 21st Century Cures Act to support development and approval of regenerative medicine products that target unmet medical needs in patients with serious conditions [7] [8]. As of September 2025, the FDA has received almost 370 RMAT designation requests and approved 184, with 13 designated products ultimately approved for marketing [8].

Accelerated Approval Pathways: The FDA encourages innovative trial designs for regenerative medicine therapies, including use of natural history data as historical controls when populations are adequately matched, and clinical trials where multiple sites participate with the intent of sharing combined data to support licensing applications [8].

Manufacturing and Quality Control Considerations

The development of regenerative pharmacology therapies faces unique manufacturing challenges:

Chemistry, Manufacturing, and Controls: Expedited clinical development timelines create challenges in aligning product development activities, potentially requiring more rapid CMC development programs [8].

Manufacturing Changes: Post-change products may no longer qualify for RMAT designation if comparability cannot be established with the pre-change product, necessitating careful risk assessment when planning manufacturing changes [8].

Long-term Safety Monitoring: Regenerative therapies likely raise unique safety considerations that benefit from long-term monitoring, including both short-term and long-term safety assessments in clinical trials [8].

Future Perspectives and Challenges

Emerging Innovations

The future of regenerative pharmacology will be shaped by several technological advances:

Advanced Biomaterials: Development of 'smart' biomaterials that can deliver bioactive compounds in a temporally controlled manner represents a key frontier [3]. Stimuli-responsive biomaterials that alter their characteristics in response to external or internal triggers represent particularly promising approaches.

Artificial Intelligence Integration: AI holds promise for transforming regenerative pharmacology by enabling more efficient targeted therapeutic development, predicting drug delivery system effectiveness, and anticipating cellular responses [3].

Personalized Approaches: Utilizing patient-specific cellular or genetic information, advanced therapies can be tailored to maximize effectiveness and minimize side effects, moving toward truly personalized regenerative treatments [3].

Implementation Challenges

Despite its promise, regenerative pharmacology faces significant translational barriers:

Investigational Obstacles: Unrepresentative preclinical animal models impact the definition of therapeutic mechanisms of action and raise questions about long-term safety and efficacy [3].

Manufacturing Issues: Scalability, automated production methods, and the need for Good Manufacturing Practice present significant hurdles [3].

Economic Factors: High manufacturing costs and reimbursement uncertainties limit accessibility, particularly in low- and middle-income countries [3].

Regulatory Complexity: Diverse regional requirements and lack of unified guidelines create challenges for global development [3].

Overcoming these challenges will require interdisciplinary collaboration between academia, industry, clinics, and regulatory authorities to establish standardized procedures and ensure consistency in therapeutic outcomes [3]. As the field continues to evolve, regenerative pharmacology holds the potential to fundamentally transform therapeutic approaches from symptomatic treatment to curative intervention, ultimately redefining how we treat degenerative diseases, injuries, and age-related tissue dysfunction.

The convergence of pharmacology, systems biology, and regenerative medicine represents a paradigm shift in biomedical science, moving beyond symptomatic treatment toward the restoration of biological structure and function. This integrated framework, termed Integrative and Regenerative Pharmacology (IRP), applies the principles of regenerative medicine and the toolkit of systems biology to drug discovery and therapeutic development [3]. IRP aims to develop transformative curative therapeutics that not only improve symptomatic relief of target organ disease but also modulate tissue formation and function, marking a fundamental departure from traditional pharmacology's focus on symptom reduction and disease course alteration [3].

The conceptual foundation of IRP rests on the systematic investigation of drug interactions with biological systems across multiple levels—from molecular and cellular to organ and system levels—while incorporating signaling pathways, bioinformatic tools, and multi-omics technologies (transcriptomics, genomics, proteomics, epigenomics, metabolomics, and microbiomics) [3]. This approach facilitates the prediction of potential targets and pathways that could inform the development of more effective therapeutics designed to repair, renew, and regenerate rather than merely block or inhibit pathological processes [3].

Core Principles and Conceptual Framework

The Triad of Integration

The integrative approach rests on three foundational pillars that create a synergistic relationship between previously distinct disciplines:

Pharmacology in Regenerative Context: Regenerative pharmacology has been defined as "the application of pharmacological sciences to accelerate, optimize, and characterize the development, maturation, and function of bioengineered and regenerating tissues" [3]. This represents the application of established pharmacological principles to cutting-edge regenerative medicine, fusing pharmacological techniques with regenerative medicine principles to develop therapies that promote the body's innate healing capacity [3].

Systems Biology as the Connective Tissue: Systems biology provides the holistic analytical framework necessary for understanding complex biological systems. It constructs comprehensive models of biological processes by incorporating data from multiple levels (molecular, cellular, organ, and organism) [9]. This multi-scale perspective enables researchers to gain deeper insights into disease mechanisms and predict how therapeutic interventions will interact with the human body [9].

Reciprocal Enhancement: The relationship between these fields is mutually reinforcing. Pharmaceutical innovations can improve the safety and efficacy of regenerative therapies, while regenerative medicine approaches offer new platforms (e.g., 3D models, organ-on-a-chip) for both drug development and testing [3]. This complementary relationship accelerates progress in both domains.

Quantitative Systems Pharmacology as a Bridge

A critical manifestation of this integration is the emergence of Quantitative Systems Pharmacology (QSP), which leverages systems biology models to simulate drug behaviors, predict patient responses, and optimize drug development strategies [9] [10]. By incorporating QSP into the drug discovery process, pharmaceutical companies can make more informed decisions, reduce development costs, and ultimately bring safer, more effective therapies to patients [9] [10]. The growing importance of QSP has stimulated collaborative industry-academia partnerships to develop educational programs that equip the next generation of scientists with the necessary multidisciplinary expertise [9] [10].

Key Methodologies and Experimental Approaches

Network Pharmacology and Multi-Omic Integration

Network pharmacology has emerged as a powerful methodological framework for implementing the integrative approach. This interdisciplinary strategy integrates systems biology, omics technologies, and computational methods to identify and analyze multi-target drug interactions, validate therapeutic mechanisms, and advance integrative drug discovery [11]. A representative workflow applied to studying traditional medicines illustrates this approach:

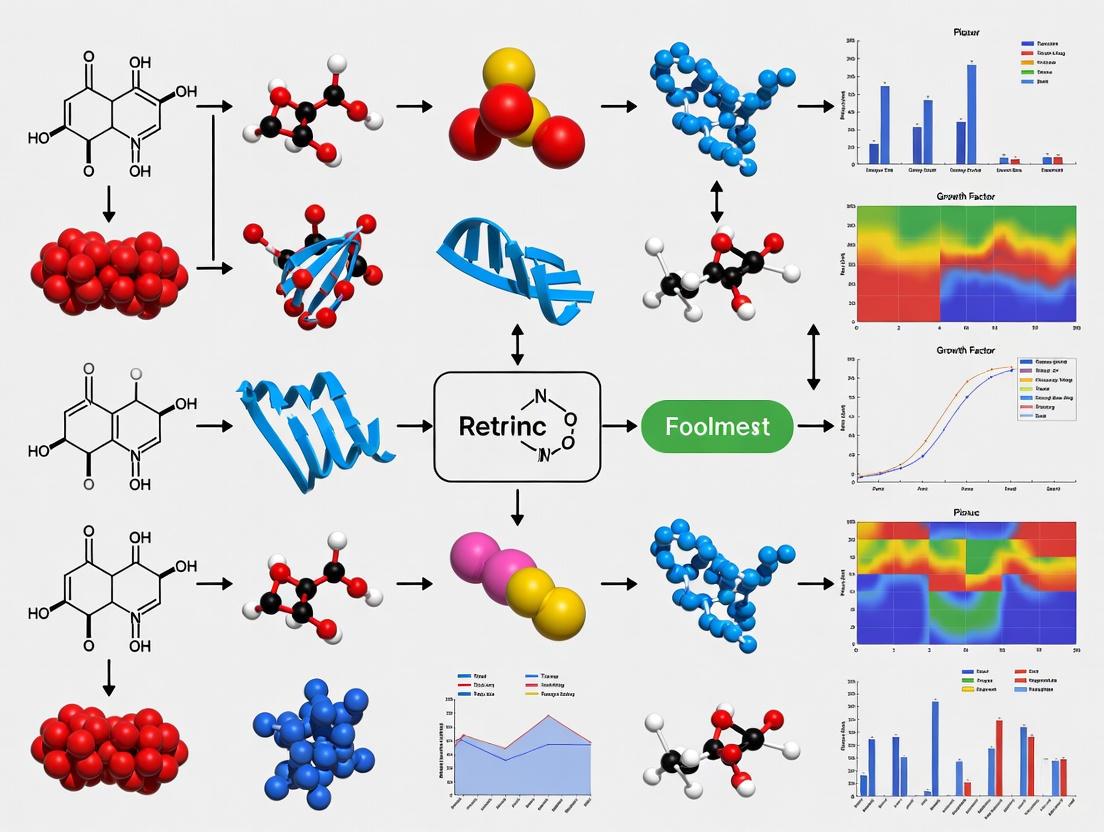

Diagram 1: Network pharmacology workflow for therapeutic mechanism elucidation.

This methodology was successfully applied to elucidate the anti-inflammatory mechanisms of Xianlinggubao (XLGB), an approved Chinese herbal remedy for osteoarthritis [12]. The study integrated bioactive compound identification from TCMSP, ETCM, and SymMap databases with target prediction through STITCH and SEA approaches, then connected these with osteoarthritis-related inflammatory targets identified through differential expression analysis of GEO datasets (GSE1919) and database mining of OMIM and GeneCards [12]. Protein-protein interaction network analysis revealed that XLGB alleviates osteoarthritis inflammation by modulating key genes including COX-2, IL-1β, TNF, IL-6, and MMP-9, with functional enrichment analysis suggesting involvement of IL-17, TNF, and NF-κB pathways [12]. These computational predictions were subsequently validated through molecular docking, dynamics simulations, RT-PCR, and immunofluorescence assays [12].

Multi-Scale Systems Biology Approaches

Advanced systems biology applications in neurodegeneration research demonstrate the power of integrative methodologies. A recent study combined an unbiased, genome-scale forward genetic screen for age-associated neurodegeneration in Drosophila with multi-omic profiling (proteomics, phosphoproteomics, and metabolomics) in Drosophila models of Alzheimer's disease [13]. This was further integrated with human Alzheimer's genetic variants that modify gene expression in disease-vulnerable neurons, using network modeling to connect these diverse data types with previously published Alzheimer's disease proteomics, lipidomics, and genomics [13].

The experimental workflow for this multi-scale integration is visually summarized below:

Diagram 2: Multi-scale systems biology approach for neurodegeneration mechanism identification.

This comprehensive approach led to the computational prediction and experimental confirmation of how HNRNPA2B1 and MEPCE enhance toxicity of the tau protein, a key pathological feature of Alzheimer's disease, and demonstrated that screen hits CSNK2A1 and NOTCH1 regulate DNA damage in both Drosophila and human stem cell-derived neural progenitor cells [13]. The study identified 198 genes that promoted age-associated neurodegeneration in Drosophila after knockdown, including orthologs of APP and presenilins (genes mutated in familial Alzheimer's disease), establishing a direct connection between the model organism screen and human disease mechanisms [13].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms

Table 1: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Integrative Pharmacology Research

| Category | Specific Reagents/Platforms | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Models | RAW264.7 cells [12], induced Pluripotent Stem Cells (iPSCs) [13] [14], neural progenitor cells [13] | In vitro screening, toxicity assessment, disease modeling |

| Bioactive Compounds | Xianlinggubao prescription [12], small molecule reprogramming cocktails [14] | Mechanism of action studies, cellular reprogramming, therapeutic screening |

| Omics Technologies | Proteomics, phosphoproteomics, metabolomics platforms [13], RNA-sequencing [13] | Multi-omic profiling, pathway analysis, biomarker identification |

| Computational Tools | Cytoscape [12] [11], STRING [12] [11], Molecular docking (AutoDock) [12] [11], GROMACS [12] | Network construction, target identification, binding affinity assessment |

| Database Resources | TCMSP [12] [11], ETCM [12], DrugBank [11], GEO [12], OMIM [12], GeneCards [12] | Compound-target data, disease gene information, expression datasets |

| In Vivo Models | Drosophila neurodegeneration models [13], chemically-induced pluripotent stem cells (CiPSCs) [14] | Genetic screening, disease modeling, transplantation studies |

Applications and Case Studies

Neurodegenerative Disease Mechanisms

The integrative approach has generated significant insights into neurodegenerative disease mechanisms, particularly Alzheimer's disease. The genome-scale Drosophila screen followed by multi-omic integration revealed candidate pathways that could be targeted to ameliorate neurodegeneration [13]. Analysis of human orthologs of the neurodegeneration screen hits demonstrated that their expression declines with age and Alzheimer's disease in the human brain, with particularly strong associations in vulnerable regions like the hippocampus and frontal cortex [13]. This cross-species validation exemplifies how integrative approaches can bridge model organism and human studies to identify clinically relevant therapeutic targets.

Cardiovascular Drug Development

In cardiovascular medicine, integrative approaches combining AI, omics, and systems biology are helping scientists design targeted drugs for disease pathways once considered "untreatable" [15]. This innovation paradigm leverages omics approaches that provide detailed information about cellular molecules, systems biology that examines how networks of genes and proteins interact to shape disease, and AI that analyzes disease pathways to identify new drug targets and design therapeutics for specific proteins and genes [15]. The approach is particularly promising for RNA-based therapeutics, which can be designed to influence almost any gene and may be quicker to develop than conventional drugs, with early trials already demonstrating potential for cholesterol management superior to standard treatments [15].

Stem Cell-Based Regenerative Therapies

The integrative framework has accelerated the development of stem cell-based regenerative therapies. Recent advances include the generation of chemically-induced pluripotent stem cells (CiPSCs) using only small molecules, providing a new platform for cellular reprogramming [14]. Most notably, chemically-induced stem cell-derived islets (CiPSC-islets) have been transplanted into human patients, resulting in rapid reversal of diabetes [14]. This breakthrough demonstrates the clinical potential of integrating pharmacological approaches (small molecule reprogramming) with regenerative medicine (cell transplantation) for treating degenerative diseases.

Technical Protocols for Core Methodologies

Protocol 1: Network Pharmacology Analysis for Multi-Target Therapeutic Characterization

Purpose: To systematically identify the multi-target mechanisms of complex therapeutic formulations using network pharmacology.

Materials:

- Compound databases: TCMSP, ETCM, SymMap, ChEMBL

- Target prediction tools: STITCH, Similarity Ensemble Approach (SEA)

- Disease databases: OMIM, GeneCards, PubMed Gene

- Network analysis software: Cytoscape 3.7.2 with CytoHubba plugin

- Functional enrichment: ClusterProfiler package in R

- Molecular docking: AutoDock, GROMACS for dynamics simulations

Procedure:

- Bioactive Compound Screening: Retrieve all chemical components from relevant databases. Apply screening criteria (oral bioavailability ≥30%, drug-likeness ≥0.18) to identify bioactive ingredients [12].

- Target Prediction: Identify targets associated with candidate bioactive compounds using STITCH, SEA, SymMap, and ChEMBL databases with "Homo sapiens" setting. Standardize genetic data through UniProt [12].

- Disease Target Identification: Obtain disease-related targets through differential expression analysis of relevant datasets (e.g., GEO GSE1919 for osteoarthritis) using "limma" package in R (p<0.05, |log2FC|≥2). Cross-reference with inflammation-related genes from OMIM, GeneCards, and PubMed Gene [12].

- Network Construction:

- Build compound-target network linking TCM compounds to their respective targets

- Construct protein-protein interaction (PPI) network using STRING database

- Visualize interconnected network using Cytoscape 3.7.2

- Analyze topological properties through "Network Analysis" plugin [12]

- Hub Gene Identification: Use "CytoHubba" plugin to assess topological characteristics of network nodes and identify hub genes most critical to the therapeutic effect [12].

- Functional Enrichment Analysis: Perform Gene Ontology and KEGG pathway analysis of gene clusters using ClusterProfiler package in R [12].

- Experimental Validation:

- Conduct molecular docking with protein structures from PDB (e.g., PTGS2: 5F19, IL-1β: 6Y8M)

- Perform molecular dynamics simulations for 100 ns per protein-drug complex in GROMACS

- Validate key targets experimentally through RT-PCR and immunofluorescence assays [12]

Protocol 2: Multi-Omic Integration for Disease Mechanism Elucidation

Purpose: To integrate multiple omics datasets with genetic screening data for identifying novel disease mechanisms.

Materials:

- Drosophila RNAi screening: UAS-GAL4 system with elav-GAL4 driver

- Omics platforms: Proteomics, phosphoproteomics, metabolomics capabilities

- Human tissue analysis: Laser-capture microdissection system for neuron isolation

- RNA-sequencing: Bulk or single-cell RNA-seq capabilities

- Computational resources: Network modeling infrastructure, statistical analysis tools

Procedure:

- Genetic Screening:

- Perform genome-scale transgenic RNAi knockdown of target genes (e.g., 5,261 fly genes) using UAS-GAL4 system with pan-neuronal elav-GAL4 driver [13]

- Age adult flies for 30 days and assess brain integrity on tissue sections representing entire brain

- Score neuronal loss and vacuolation in blinded fashion

- Identify hits as genes causing neuronal loss or vacuolation in properly developed brains [13]

- Multi-Omic Profiling:

- Conduct proteomic, phosphoproteomic, and metabolomic analyses in disease model systems (e.g., Drosophila Alzheimer's models) [13]

- Process samples using standardized extraction protocols appropriate for each omics platform

- Human Tissue Analysis:

- Data Integration:

- Cross-Species Validation:

- Test predicted functional effects of candidate targets in original model system (e.g., Drosophila)

- Validate mechanisms in human cellular systems (e.g., iPSC-derived neural progenitor cells) [13]

- Assess conservation of pathways and mechanisms across species

Quantitative Data Synthesis

Multi-Omic Data Types in Integrative Studies

Table 2: Multi-Omic Data Types and Applications in Integrative Pharmacology

| Data Type | Key Measurements | Applications in IRP | Example Insights |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genomics | Genetic variants, mutations, polymorphisms | Identification of disease-risk genes, personalized therapy | Drosophila screen identified 198 neurodegeneration-associated genes [13] |

| Transcriptomics | Gene expression levels, RNA sequences | Pathway activity assessment, biomarker discovery | eQTL analysis in human neurons linked genetic risk to expression changes [13] |

| Proteomics | Protein expression, post-translational modifications | Target engagement assessment, mechanism elucidation | Phosphoproteomics revealed signaling alterations in disease models [13] |

| Metabolomics | Metabolite profiles, metabolic pathway fluxes | Metabolic dysfunction identification, therapeutic monitoring | Metabolic rewiring identified in neurodegenerative models [13] |

| Lipidomics | Lipid species composition and abundance | Membrane biology assessment, inflammatory mediator profiling | Integrated with genomics in Alzheimer's network models [13] |

The integrative approach merging pharmacology, systems biology, and regenerative medicine represents a fundamental transformation in therapeutic development. By combining the mechanistic rigor of pharmacology with the holistic perspective of systems biology and the regenerative capacity of regenerative medicine, this framework enables the development of transformative curative therapies that address the root causes of disease rather than merely managing symptoms. The methodologies, protocols, and applications outlined in this whitepaper provide researchers with the tools to implement this approach in their own work, accelerating progress toward truly regenerative therapeutics.

As the field advances, key areas for continued development include standardized manufacturing processes for regenerative products, improved computational models that better predict human therapeutic responses, and expanded clinical validation through rigorously designed trials. With these advances, the integrative approach promises to redefine therapeutic landscapes across neurodegenerative diseases, cardiovascular disorders, and numerous other conditions characterized by tissue degeneration and dysfunction.

Regenerative pharmacology represents a paradigm shift from conventional disease management, aiming to restore tissue structure and function by directly modulating the body's innate repair mechanisms. This in-depth technical guide focuses on the core cellular targets—stem cells, progenitor cells, and the regenerative niche—which are central to this therapeutic strategy. Stem cells are defined by their capacity for self-renewal and differentiation, while progenitor cells are more lineage-committed but retain significant regenerative potential [16]. The concept of the "niche" is critical; it is the dynamic microenvironment that houses these cells and regulates their fate through a complex interplay of cellular interactions, signaling molecules, and physical cues [17]. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding and pharmacologically targeting these components is key to developing novel treatments for a range of intractable diseases, from degenerative disorders to impaired wound healing. This guide synthesizes current mechanistic understanding, quantitative data, and experimental approaches to illuminate the path for future therapeutic discovery.

Core Concepts and Definitions

- Stem Cells: Cells with extensive self-renewal capacity and the potential to differentiate into multiple cell types. They are categorized as:

- Embryonic Stem Cells (ESCs): Pluripotent cells derived from early-stage embryos.

- Adult Stem Cells (Somatic Stem Cells): Multipotent cells resident in specific tissues (e.g., bone marrow, skin, intestine) responsible for maintenance and repair.

- Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells (iPSCs): Adult cells that have been genetically reprogrammed to a pluripotent state, offering a patient-specific cell source without the ethical concerns of ESCs [18] [17].

- Progenitor Cells: Cells that are more lineage-committed than stem cells and have limited self-renewal capacity. They serve as an intermediate population, proliferating and differentiating to produce mature, functional cells [16].

- The Regenerative Niche: The specialized, dynamic microenvironment that hosts stem and progenitor cells. It is composed of heterologous cell types, the extracellular matrix (ECM), secreted factors, and physical parameters (e.g., oxygen tension, stiffness). The niche maintains stem cell quiescence, directs self-renewal and differentiation, and responds to injury [17]. The interaction between stem cells and their niche is reciprocal, creating a feedback loop that is essential for tissue homeostasis and regeneration [17].

Quantitative Profiling of Stem and Progenitor Cell Dynamics

Understanding the quantitative behavior of hematopoietic and other stem cell systems is fundamental for predictive toxicology and therapeutic development. The following table summarizes key quantitative parameters from recent research, including a Quantitative Systems Pharmacology (QSP) model of in vitro hematopoiesis and clinical cell therapy dosing data.

Table 1: Quantitative Parameters in Hematopoiesis and Cell Therapy

| Parameter | Value / Range | Context / System | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| HSC In Vitro Proliferation (Model Output) | Matches day 2-6 kinetic data [19] | Human CD34+ stem cell culture (MLTA) [19] | Validated system parameters for control (untreated) cell growth, serving as a baseline for drug perturbation studies. |

| Effective MSC:Immune Cell Ratio | 1:10 or greater [20] | In vitro immunomodulation co-culture (MSCs:PBMCs) [20] | Defines the stoichiometry required for a measurable T-cell suppressive response, a key pharmacodynamic relationship. |

| Effective Co-culture Duration | ~3 days [20] | In vitro immunomodulation co-culture (MSCs:PBMCs) [20] | The time variable required for the immunomodulation reaction, informing pharmacokinetic goals for in vivo persistence. |

| Clinical MSC Dose (Systemic) | 100–200 million cells [20] | IV infusion in a 70 kg patient (clinical trials) [20] | A typical human dose for systemic immunomodulation, highlighting the challenge of scaling from in vitro effective ratios. |

| IV-MSC Half-Life | ~24 hours [20] | Biodistribution studies in animal models [20] | Explains transient therapeutic effects; most IV-infused MSCs are rapidly cleared, primarily via lung entrapment. |

| IC90 of Granulocyte-Macrophages | Compound-specific [19] | Pre-clinical in vitro toxicity assay [19] | A historical predictor of a drug's maximum tolerated dose (MTD) in animals and humans for myelosuppressive agents. |

Experimental Protocols for Niche and Cell Analysis

Multi-Lineage Toxicity Assay (MLTA) for Myelosuppression

Purpose: To quantify the concentration-response effects of anti-cancer agents on multiple hematopoietic cell lineages simultaneously and infer mechanisms of action (anti-proliferation vs. cell-killing) [19].

Methodology:

- Cell Source: Isolate human CD34+ hematopoietic stem cells from donor tissue.

- Culture and Differentiation: Seed cells in a 96-well format and culture under conditions that support simultaneous differentiation into multiple lineages (erythroid, megakaryocyte, granulocyte, monocyte, lymphocyte).

- Drug Treatment: Expose the differentiating cultures to a range of concentrations of the drug candidate.

- Measurement: At assay endpoint, use flow cytometry with lineage-specific cell surface markers to quantify the number of viable cells in each lineage.

- Data Analysis:

- Generate dose-response curves for each cell lineage.

- Use a calibrated QSP model of in vitro hematopoiesis to deconvolute the observed net cell count decreases. The model is fit to the data to infer the magnitude and dose-dependence of drug effects (either anti-proliferation or cell-killing) on individual progenitor and mature cell populations [19].

Quantitative Systems Pharmacology (QSP) Model Calibration for Trispecific T-Cell Engagers

Purpose: To gain mechanistic insight into the dose-response of a novel trispecific antibody (targeting CD3, CD28, and CD38) for multiple myeloma treatment [21].

Methodology:

- Model Generation: Develop a rule-based QSP model using a model generation code. The code automatically creates ordinary differential equations (ODEs) based on predefined rules for:

- Cell types (e.g., T-cell subsets, tumor cells, PBMCs).

- Receptors (CD3, CD28, CD38).

- Synapse formation between cells based on receptor binding and collision rates.

- Intracellular processes (T-cell activation, tumor cell killing) [21].

- Staged Calibration: Optimize model parameters in stages against distinct in vitro datasets to minimize uncertainty:

- Step 1 - T-cell Activation: Optimize parameters for T-cell activation and synapse formation using data on the percentage of activated T-cells in PBMC incubations (lacking tumor cells).

- Step 2 - Tumor Killing: Optimize tumor cell killing rates and resistance parameters using data from co-cultures of pre-activated CD8+ T-cells with multiple myeloma cell lines (RPMI8226 and KMS-11).

- Step 3 - Cytokine Response: Calibrate cytokine emission parameters to data from the MIMIC assay, capturing the range of possible immune responses [21].

- Model Application: Use the qualified model to simulate complex dose-response relationships, predict "effective" receptor occupancy, and explain the superior efficacy of the trispecific format compared to bispecific engagers [21].

Diagram 1: Staged QSP model calibration workflow.

Signaling Pathways and Metabolic Regulation in the Niche

The behavior of stem and progenitor cells is intricately controlled by metabolic and redox signaling pathways that are highly sensitive to the niche. A key regulatory network involves the transcription factors HIF1α and HIF2α, which are stabilized under hypoxic conditions common in stem cell niches.

- Metabolic Programming: Pluripotent and quiescent stem cells preferentially utilize glycolysis rather than mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation for energy production. This metabolic state minimizes the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), preserving stemness [16].

- Redox Regulation: ROS levels act as a critical signaling mechanism within the niche. Low ROS levels help maintain HSC quiescence, while higher, non-toxic physiological levels promote proliferation, differentiation, and mobilization [16]. Pathological ROS levels, as seen in diabetes, induce oxidative stress, leading to niche dysfunction and reduced regenerative capacity of stem/progenitor cells [16].

- Key Molecular Players: The homeodomain transcription factor Meis1 is essential for activating HIF1α and HIF2α. HIF1α upregulates glycolytic enzymes, reinforcing the glycolytic metabolic state. HIF2α upregulates antioxidant enzymes to reduce cellular ROS levels. This Meis1-HIFs axis is therefore critical for maintaining the low-ROS, glycolytic state that characterizes quiescent stem cells [16].

Diagram 2: Meis1-HIFs axis in stem cell regulation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Tools for Stem Cell and Niche Research

| Research Tool / Reagent | Function / Application | Technical Context |

|---|---|---|

| CD34+ Stem Cells | Starting population for in vitro hematopoiesis and differentiation studies. | Sourced from human donors; used in the Multi-Lineage Toxicity Assay (MLTA) to generate multiple blood cell lineages [19]. |

| Rhosin (RhoA inhibitor) | Small molecule tool compound to investigate rejuvenation of aged hematopoietic stem cells. | Inhibits the protein RhoA, a mechanosensor that becomes highly activated with age. Treatment has been shown to reverse age-associated changes in HSCs in models [22]. |

| StemRNA Clinical iPSC Seed Clones | GMP-compliant, clinically relevant starting material for deriving consistent cell therapy products. | A master iPSC cell line; a Drug Master File (DMF) has been submitted to the FDA to streamline regulatory submissions for therapies using this platform [23]. |

| Trispecific T-Cell Engager | Research tool and therapeutic candidate for engaging T cells against tumor cells via multiple receptors. | A molecule binding CD3 (on T-cells), CD38 (on myeloma cells), and CD28 (co-stimulation on T-cells and additional tumor target). Used for QSP model development [21]. |

| Flow Cytometry with Lineage-Specific Markers | Quantification of specific cell populations in a heterogeneous mixture. | Essential for endpoint analysis in the MLTA to count cells in erythroid, megakaryocyte, granulocyte, monocyte, and lymphocyte lineages [19]. |

| 'Omics Tools (Genomics, Proteomics) | Comprehensive characterization of stem cell critical quality attributes (CQA), including identity and potency. | Used to understand stem cell biology, define mechanisms of action, and develop robust potency assays for regulatory compliance [24]. |

Clinical Translation and Regulatory Landscape

The transition from basic research to approved therapies is accelerating, with several landmark approvals and an expanding clinical trial pipeline.

- Recent FDA-Approved Stem Cell Products:

- Ryoncil (remestemcel-L): Approved in December 2024, it is the first MSC therapy for pediatric steroid-refractory acute graft-versus-host disease (SR-aGVHD). It utilizes allogeneic bone marrow-derived MSCs to modulate the immune response [23].

- Omisirge (omidubicel-onlv): Approved in April 2023, it is a nicotinamide-modified umbilical cord blood-derived hematopoietic progenitor cell product. It accelerates neutrophil recovery in patients with hematologic malignancies after transplantation [23].

- Lyfgenia (lovotibeglogene autotemcel): An autologous cell-based gene therapy approved in December 2023 for sickle cell disease. It involves genetically modifying the patient's own hematopoietic stem cells to produce anti-sickling hemoglobin [23].

- Advances in Pluripotent Stem Cell (PSC) Trials: As of late 2024, the global clinical trial landscape includes 115 trials involving 83 distinct PSC-derived products. Over 1,200 patients have been dosed, with no class-wide safety concerns emerging. Key therapeutic areas include ophthalmology, neurology, and oncology [23].

- Notable FDA-Authorized Clinical Trials:

- Fertilo: The first iPSC-based therapy to receive FDA IND clearance for a U.S. Phase III trial (Feb 2025). It uses iPSC-derived ovarian support cells to assist in oocyte maturation [23].

- OpCT-001: An iPSC-derived therapy for retinal degeneration, which received IND clearance for a Phase I/IIa trial in September 2024 [23].

- iPSC-Derived Neural Progenitors: Multiple therapies for Parkinson’s disease, spinal cord injury, and ALS received FDA IND clearance in 2025 [23].

Targeting stem cells, progenitor cells, and the regenerative niche represents a powerful mechanism of action for regenerative pharmacology. The field is moving beyond simple cell transplantation towards sophisticated pharmacological manipulation of endogenous repair systems. Key future directions include the development of more precise small molecules and biologics to target niche components [17], the application of QSP modeling to deconvolute complex mechanisms and optimize dosing [19] [21], and the rigorous clinical development of iPSC-derived therapies [23]. The successful translation of these strategies requires a deep, quantitative understanding of the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of cellular interventions [20]. As our knowledge of niche biology, redox regulation [16], and cell metabolism deepens, the potential to design therapies that can rejuvenate aged tissues, overcome disease-related niche dysfunction, and precisely control regenerative outcomes will fundamentally transform the treatment of degenerative diseases and tissue injury.

The paradigm of regenerative pharmacology has shifted from a focus on stem cell differentiation to understanding their paracrine activity. Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) exert therapeutic effects primarily through secreted bioactive molecules—the secretome—which includes extracellular vesicles (exosomes) and growth factors. This in-depth technical guide details the mechanisms by which these paracrine effectors mediate cardiac repair following myocardial infarction (MI), highlighting their roles in cytoprotection, angiogenesis, immunomodulation, and fibrosis inhibition. We provide structured quantitative data, experimental protocols for key methodologies, standardized signaling pathway visualizations, and essential research reagent solutions to support mechanistic research and therapeutic development in regenerative pharmacology.

The therapeutic use of stem cells, particularly Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs), has shown promise across diverse disease models, including myocardial infarction, Parkinson's disease, and Crohn's disease [25]. Initially, the regenerative potential was attributed to the direct differentiation of transplanted cells into target tissue phenotypes [25]. However, transient engraftment and poor cellular survival post-transplantation, coupled with observations that functional benefits often exceeded the differentiation capacity of the cells, challenged this mechanism [26] [25].

This led to the formulation of the paracrine hypothesis, which posits that stem cells facilitate repair and regeneration chiefly through the secretion of biologically active factors that modulate resident cells [25]. The MSC secretome comprises both soluble factors (growth factors, cytokines) and membrane-bound vesicles, notably exosomes, which collectively create a reparative tissue microenvironment [27]. These factors are pleiotropic, influencing multiple cell types and mechanisms in a spatiotemporal manner following injury [25]. This guide details the components, functions, and research methodologies for investigating these primary effectors.

Core Components of the Paracrine Apparatus

The MSC Secretome

The secretome is the complete set of molecules secreted by a cell, including soluble proteins and extracellular vesicles (EVs). In the context of MSCs, the secretome is "personalized" according to the local microenvironmental cues, and its therapeutic potential can be optimized through various preconditioning strategies [27]. Its composition determines its regenerative capacity, influencing processes in respiratory, hepatic, and neurological diseases [27].

Exosomes and Extracellular Vesicles

Exosomes are a specific subtype of extracellular vesicle, defined as naturally occurring nanovesicles with sizes ranging from 30 to 150 nm [26]. They are formed by the inward germination of the multivesicular body membrane and subsequent fusion with the plasma membrane [26].

Key Biometric Properties:

- Biomarkers: Tetraspanins (CD63, CD81, CD9), Alix, and heat shock proteins are widespread biomarkers [26].

- Cargo: Exosomes transport biologically active substances, including proteins, lipids, mRNAs, miRNAs, and long noncoding RNAs [26]. The Exo-Carta database has cataloged thousands of these molecules.

- Functional Advantages: Compared to their parental cells, MSC-derived exosomes (MSC-Exos) offer benefits such as long-term stability, more accessible storage, lower immunogenicity, less risk of tumorigenicity, and lower production costs. Their small size prevents capillary blockage [26].

Growth Factors and Soluble Factors

MSCs secrete a range of critical growth factors and cytokines that drive paracrine effects. Key factors include:

- Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF)

- Basic Fibroblast Growth Factor (bFGF)

- Hepatocyte Growth Factor (HGF)

- Insulin-like Growth Factor 1 (IGF-1)

- Transforming Growth Factor-beta (TGF-β)

- Prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) [25]

Elevated levels of these proteins are found in the heart following the injection of adult stem cells and are instrumental in promoting cardiac repair [25].

Quantitative Data on Paracrine Effectors in Myocardial Repair

The following tables summarize key quantitative data on the functions of specific paracrine molecules and exosomal microRNAs in myocardial infarction models.

Table 1: Key Paracrine Factors and Their Documented Effects in Myocardial Repair

| Paracrine Factor | Source | Primary Documented Functions | Experimental Model |

|---|---|---|---|

| Secreted Frizzled Related Protein 2 (Sfrp2) | Akt1-MSCs [25] | Binds Wnt3a; inhibits caspase activity and cardiomyocyte apoptosis [25] | Rat model of MI [25] |

| Hypoxic induced Akt regulated Stem cell Factor (HASF) | MSCs [25] | Activates PKCε; reduces TUNEL+ nuclei, inhibits caspase activation and mitochondrial pore opening [25] | Mouse model of MI [25] |

| Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF) | MSCs, BMMNCs [25] | Promotes angiogenesis; critical for neovascularization [25] | Porcine MI model [26] |

| miR-19a | hUCMSC-Exos [26] | Targets SOX6; activates AKT and inhibits JNK3/caspase-3 to reduce apoptosis [26] | In vitro model of acute MI damage [26] |

| miR-25-3p | BMMSC-Exos [26] | Downregulates pro-apoptotic genes (FasL, PTEN) to reduce apoptosis in hypoxic cardiomyocytes [26] | In vitro hypoxia model [26] |

Table 2: Exosomal MicroRNAs (miRNAs) and Their Mechanisms of Action

| Exosomal miRNA | Source | Target Pathway/Gene | Functional Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| miR-144 [26] | BMMSC-Exos | PTEN/PI3K/AKT pathway [26] | Inhibits apoptosis in hypoxic cardiomyocytes [26] |

| miR-486-5p [26] | BMMSC-Exos | PTEN/PI3K/AKT pathway [26] | Inhibits apoptosis in hypoxic cardiomyocytes [26] |

| miR-21 [26] | Endometrial MSC-Exos | PTEN/PI3K/AKT pathway [26] | Exerts significant antiapoptotic effects [26] |

| miR-129-5p [26] | BMMSC-Exos | TRAF3/NF-κB pathway [26] | Inhibits myocardial apoptosis and improves cardiac function in MI rats [26] |

| miR-338 [26] | BMMSC-Exos | MAP3K2/JNK signaling pathway [26] | Inhibits myocardial apoptosis and improves cardiac function [26] |

Experimental Protocols for Key Paracrine Studies

Protocol: Multicellular Calcium Imaging for Paracrine Signaling

This protocol assesses paracrine ATP signaling via mechanically induced calcium waves, adapted from studies on human lens epithelium [28].

1. Sample Preparation:

- Obtain human anterior lens capsules (LCs) during cataract surgery via continuous curvilinear capsulorhexis (5-5.5 mm circles) [28].

- Store LCs in physiological solution (in mM: NaCl 131.8, KCl 5, MgCl2 2, NaH2PO4 0.5, NaHCO3 2, CaCl2 1.8, HEPES 10, glucose 10; pH 7.24) at 37°C and 5% CO2 [28].

- Immobilize LCs in plastic glass-bottom Petri dishes, gently stretching and securing them with a harp-like grid [28].

2. Cell Loading and Dye Incubation:

- Load LCs with 2 µM Fura-2 AM (acetoxymethyl ester) dissolved in DMSO and suspended in 3 mL of physiological solution [28].

- Incubate for 30 minutes at 37°C and 5% CO2 [28].

- Wash twice for 10 minutes with fresh physiological solution [28].

3. Pharmacological Perturbation:

- Apply inhibitors to specific pathways:

- Apyrase (an ATP-hydrolyzing enzyme) to degrade extracellular ATP.

- Carbenoxolone (CBX) (a gap-junctional blocker) to inhibit direct intercellular communication [28].

4. Mechanical Stimulation and Data Acquisition:

- Induce Ca²⁺ waves via mechanical stimulation.

- Record Ca²⁺ waves using a multicellular Ca²⁺ imaging setup. Quantify the spatial extent, amplitude, duration, and propagation speed of the waves under control and treatment conditions [28].

5. Data Interpretation:

- A significant suppression of wave transmission by CBX indicates strong gap-junctional coupling.

- A reduction in wave extent or duration by apyrase indicates a role for ATP-mediated paracrine signaling [28].

- A hybrid mechanism is implicated if neither blocker alone fully abolishes propagation [28].

Protocol: Evaluating MSC-Exo Function in Vitro

1. Exosome Isolation and Characterization:

- Isolate exosomes from MSC conditioned media via ultracentrifugation, precipitation, size-exclusion chromatography, or immunoaffinity capture [26].

- Characterize isolates by nanoparticle tracking analysis for size distribution (30-150 nm) and Western blot for biomarkers (CD63, CD81, CD9, Alix) [26].

2. In Vitro Modeling of Ischemic Injury:

- Culture target cells (e.g., primary cardiomyocytes, cardiomyocyte cell lines).

- Induce injury by exposing cultures to hypoxia (e.g., 1% O₂) and/or serum starvation [26] [25].

3. Functional Assays:

- Apoptosis Assay: Treat injured cells with MSC-Exos or purified paracrine factors. Measure apoptosis via TUNEL staining or caspase-3/7 activity assays [26] [25].

- Gene Expression Analysis: Use qPCR or Western blot to assess the expression of pro-apoptotic (e.g., FasL, PTEN) and anti-apoptotic genes in treated vs. untreated cells [26].

- Pathway Analysis: Utilize specific pathway inhibitors (e.g., PI3K/AKT inhibitors) to confirm the involvement of suspected signaling pathways in the observed cytoprotection [26].

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

The following diagrams, generated using Graphviz, illustrate core paracrine signaling concepts and experimental workflows.

Paracrine Signaling in Cardiomyocyte Survival

Diagram Title: MSC-Exosome miRNA Inhibits Apoptosis

Experimental Workflow for Paracrine Mechanism Analysis

Diagram Title: Calcium Wave Assay Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Paracrine Signaling Studies

| Research Reagent | Function/Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Fura-2 AM [28] | Ratiometric fluorescent calcium indicator for live-cell imaging. | Loading into human lens epithelium to visualize mechanically induced Ca²⁺ waves and paracrine signaling [28]. |

| Apyrase [28] | ATP-hydrolyzing enzyme; degrades extracellular ATP. | Pharmacological perturbation to assess the contribution of purinergic (ATP-mediated) paracrine signaling to intercellular communication [28]. |

| Carbenoxolone (CBX) [28] | Gap-junctional blocker; inhibits connexin channels. | Pharmacological perturbation to assess the contribution of direct gap-junctional communication (e.g., of IP₃) to intercellular signaling [28]. |

| CD63 / CD81 / CD9 Antibodies [26] | Tetraspanin markers for exosome characterization via Western blot, immunoaffinity capture. | Isolating and confirming the identity of exosomes isolated from MSC conditioned media [26]. |

| TUNEL Assay Kit [25] | Detects DNA fragmentation characteristic of apoptosis in cells or tissue sections. | Evaluating the cytoprotective effect of MSC secretome or specific factors (e.g., HASF) on cardiomyocytes after ischemic injury in vitro or in vivo [25]. |

| Akt1 Overexpression Construct [25] | Genetic modification to enhance the pro-survival and cytoprotective potential of MSCs. | Engineering MSCs to produce a more potent, cytoprotective secretome for therapeutic testing [25]. |

The field of regenerative medicine is undergoing a fundamental transformation, moving beyond merely managing symptoms toward achieving true tissue restoration. Central to this shift is the emerging discipline of Integrative and Regenerative Pharmacology (IRP), which unites pharmacology, systems biology, and regenerative medicine to develop transformative curative therapeutics [3]. This approach represents a significant departure from traditional pharmacology, which primarily focuses on symptom reduction and disease course alteration [3].

At the core of successful tissue regeneration lies the concept of immunomodulation – the active control of the immune response to create a microenvironment conducive to repair. The immune system is no longer seen merely as a defense mechanism but as a central director of healing processes. The therapeutic goal has evolved from simple immunosuppression to precise immune tuning, where the dynamic interactions between immune cells, signaling molecules, and tissue-specific factors are carefully balanced to support regeneration while controlling inflammation [29]. This paradigm recognizes that the inflammatory microenvironment can be either a barrier to or an essential component of successful tissue repair, depending on how effectively it is modulated.

Fundamental Mechanisms of Immune-Mediated Repair

Cellular Effectors in the Inflammatory Microenvironment

The repair microenvironment is orchestrated by a complex interplay of immune and stromal cells. Macrophages are particularly crucial, demonstrating remarkable plasticity between different functional states [30]. Inflammatory (M1) macrophages typically dominate early phases, clearing pathogens and debris, while reparative (M2) macrophages emerge later to promote tissue remodeling and angiogenesis. Successful regeneration often depends on the timely transition from pro-inflammatory to pro-resolving phenotypes, a process known as macrophage repolarization [30].

Mesenchymal Stromal Cells (MSCs) have emerged as master regulators of the repair microenvironment. Rather than functioning primarily through direct differentiation, MSCs exert their therapeutic effects largely through paracrine signaling and immunomodulation [31] [32]. They release a diverse array of bioactive molecules – including growth factors, cytokines, and extracellular vesicles – that modulate the local cellular environment [32]. MSCs interact with various immune cells, including T lymphocytes, B lymphocytes, natural killer cells, and dendritic cells, shaping the immune response toward a pro-regenerative state [33].

Molecular Pathways and Signaling Networks

Several key molecular pathways serve as critical regulators of the immune response in tissue repair:

TLR/NF-κB Signaling Pathway: This pathway functions as a core mediator of inflammation, integrating signals from various pathogen-associated and damage-associated molecular patterns. The GBOD-PF hydrogel demonstrates the therapeutic potential of targeting this pathway, effectively dampening the inflammatory cascade in chronic wound healing [30]. TLR4 activation particularly drives pro-inflammatory cytokine production, contributing to tissue degradation in conditions like osteoarthritis [31].

TLR3 Signaling: This pathway is activated by double-stranded RNA and initiates signaling cascades involving transcription factors NF-κB and IRF3, leading to production of pro-inflammatory cytokines and type I interferons [31]. In orthopedic diseases, TLR3 plays a dual role by modulating immune responses and influencing tissue repair processes, with recent studies suggesting involvement in cartilage degeneration and bone remodeling regulation [31].

Other crucial pathways include JAK/STAT signaling, inflammasome activation, and resolution-phase mediators such as specialized pro-resolving lipid mediators. The convergence of these pathways determines whether inflammation resolves appropriately or becomes chronic and tissue-destructive.

Therapeutic Strategies and Applications

Advanced Biomaterial Systems

Smart biomaterial platforms represent a frontier in immunomodulatory strategies. The GBOD-PF hydrogel is a prime example of a microenvironment self-adaptive multifunctional hydrogel dressing with intrinsic hemostasis, antimicrobial, and anti-inflammatory properties [30]. Composed of aldehyde-functionalized dextran (ODT) and gelatin (Gel) cross-linked through dynamic Schiff base bonds in the presence of borax and paeoniflorin (PF), this system exhibits remodeling and self-healing properties, enhanced adhesion strength, and biocompatibility [30].

This advanced biomaterial demonstrates broad-spectrum antibacterial activity and superior hemostasis while targeting the TLR4/NF-κB signaling pathway to dampen the inflammatory cascade [30]. In diabetic chronic wound models, it enhanced immune response, induced M1-to-M2 macrophage repolarization to establish an anti-inflammatory microenvironment, regulated MMP-9, and promoted angiogenesis, thereby inducing a pro-regenerative response [30].

Cellular Therapeutics and Their Mechanisms

Cell-based therapies harness the body's innate regenerative potential, with MSCs serving as a cornerstone approach. The therapeutic profile of MSCs is characterized by several key attributes:

- Multipotent Differentiation Capacity: MSCs can differentiate into various mesodermal lineages including osteoblasts, chondrocytes, and adipocytes [32].

- Paracrine Signaling: MSCs secrete a wide range of bioactive molecules that modulate inflammation, stimulate tissue repair, and promote regeneration [31].

- Immunomodulation: MSCs interact with various immune cells, modulating the immune response through both direct cell-cell interactions and release of immunosuppressive molecules [32].

- Trophic Support: MSCs provide growth factors and other molecules that support survival and function of resident tissue cells.

The International Society for Cell and Gene Therapy (ISCT) has established standard criteria for defining MSCs, including plastic adherence, specific surface marker expression (CD73, CD90, CD105 ≥95%; hematopoietic markers ≤2%), and tri-lineage differentiation potential [32]. These standards ensure consistent characterization across research and clinical applications.

Table 1: MSC Sources and Their Therapeutic Properties

| Source Tissue | Therapeutic Properties | Clinical Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Bone Marrow | High differentiation potential, strong immunomodulatory effects | Orthopedic injuries, graft-versus-host disease [32] |

| Adipose Tissue | Easier harvesting, higher yields, comparable therapeutic properties | Regenerative procedures, inflammatory conditions [32] |

| Umbilical Cord | Enhanced proliferation, lower immunogenicity, suitable for allogeneic transplantation | Various regenerative applications, immune disorders [32] |

| Dental Pulp | Unique regenerative properties | Dental and maxillofacial applications [32] |

Clinical Translation and Outcomes

Regenerative immunomodulation strategies have demonstrated promising results across various clinical applications:

Orthopedic Diseases: MSC-based therapies have shown safety and feasibility for conditions like osteoarthritis, with improvements in pain reduction and function observed in many cases [31]. For cartilage repair, the Matrix-induced Autologous Chondrocyte Implantation (MACI) technique has demonstrated 80-90% success rates over time [34].

Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD): MSCs have gained interest in IBD treatment due to their unique ability to differentiate and secrete regulatory factors, including extracellular vesicles that play crucial roles in abnormal tissue organization [35]. Various administration routes – including intraperitoneal, intravenous, and local delivery – have been explored in preclinical and clinical studies [35].

Chronic Wound Healing: Multifunctional hydrogels like GBOD-PF have demonstrated accelerated large-scale chronic wound healing in infection and diabetic models by enhancing immune response, promoting angiogenesis, and regulating the inflammatory microenvironment [30].

Table 2: Clinical Success Rates of Select Regenerative Therapies

| Therapy | Condition | Success Rate / Outcome | Key Mechanisms |

|---|---|---|---|

| MACI | Cartilage defects | 80-90% success over time [34] | Chondrocyte implantation, cartilage regeneration |

| BMAC (Stem Cells) | Osteonecrosis of hip | >90% avoided collapse after 2 years [34] | Delivery of reparative cells, growth factors, tissue modulation |

| MSC Therapy | Autoimmune conditions | ~80% success for immune modulation [34] | Anti-inflammatory cytokine secretion, immune system modulation |

| Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplant | Blood cancers | 60-70% success for certain types [34] | Immune system reconstitution, cancer cell targeting |

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies

In Vitro Immunomodulation Assessment

Standardized in vitro approaches provide essential platforms for screening immunomodulatory therapeutics before advancing to complex in vivo models. The RAW264.7, J774A.1, THP-1, and U937 cell lines serve as ideal model systems for preliminary investigation and dose selection for in vivo studies [36]. More than 40 different assays have been standardized to investigate the immune modulatory effects of therapeutic candidates.

Key methodologies include:

- Cell Viability and Proliferation: MTT assay for metabolic activity assessment

- Phagocytic Activity: Neutral red uptake assay for macrophage function

- Inflammatory Mediator Production: Griess reaction for nitric oxide detection

- Gene Expression Analysis: PCR for evaluating expression of TLRs, COX-2, iNOS, TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β [36]

These in vitro systems enable researchers to dissect specific mechanisms of immunomodulation in controlled environments, providing crucial data for rational therapeutic development.

Macrophage Repolarization Assay Protocol

Objective: To evaluate compound-induced macrophage polarization from M1 to M2 phenotype.

Materials:

- RAW264.7 or primary bone marrow-derived macrophages

- Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (100 ng/mL) and IFN-γ (20 ng/mL) for M1 polarization

- IL-4 (20 ng/mL) and IL-13 (20 ng/mL) for M2 polarization

- Test compounds (e.g., MSC-conditioned medium, immunoceuticals)

- RNA extraction kit and qPCR reagents

- ELISA kits for TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-10, TGF-β

- Flow cytometry antibodies for CD86 (M1) and CD206 (M2)

Procedure:

- Seed macrophages in appropriate culture plates and allow to adhere overnight.

- Polarize macrophages to M1 phenotype using LPS + IFN-γ for 24 hours.

- Treat M1-polarized macrophages with test compounds for 48 hours.

- Collect supernatant for cytokine analysis by ELISA.

- Harvest cells for RNA extraction and gene expression analysis of M1 markers (iNOS, TNF-α, IL-12) and M2 markers (Arg1, Ym1, Fizz1).

- Analyze surface markers by flow cytometry for CD86 and CD206.

- Calculate repolarization efficiency based on marker expression ratios.

This protocol enables quantitative assessment of a compound's ability to shift macrophage phenotype, a crucial mechanism in resolving inflammation and promoting regeneration.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Immunomodulation Studies

| Reagent/Cell Line | Function/Application | Specific Examples |

|---|---|---|

| RAW264.7, J774A.1 | Macrophage model systems for in vitro screening | Phagocytosis, cytokine production, polarization studies [36] |

| THP-1, U937 | Monocyte/macrophage cell lines for differentiation studies | PMA-induced differentiation, inflammation models [36] |

| LPS (Lipopolysaccharide) | TLR4 agonist for M1 macrophage polarization | Inflammatory activation at 100 ng/mL [36] |

| - Flow Cytometry Antibodies | Immune cell phenotyping and polarization assessment | CD86 (M1), CD206 (M2), CD73, CD90, CD105 (MSCs) [32] |

| ELISA Kits | Cytokine and inflammatory mediator quantification | TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-10, TGF-β measurement [36] |

| PCR Primers | Gene expression analysis of immune targets | TLRs, COX-2, iNOS, TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β [36] |

Signaling Pathways in Immunomodulation

The following diagrams visualize key signaling pathways involved in immunomodulation for tissue repair, created using Graphviz DOT language with high color contrast for clarity.

Diagram 1: Macrophage polarization pathways and MSC-mediated immunomodulation. The diagram illustrates signaling pathways driving M1 (pro-inflammatory) and M2 (pro-reparative) macrophage polarization, along with key molecular mediators through which mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs) influence immune cell function.

Future Perspectives and Challenges

The field of immunomodulation for regenerative pharmacology continues to evolve rapidly, with several emerging trends and persistent challenges shaping its trajectory. Artificial intelligence (AI) holds significant promise for transforming regenerative pharmacology by enabling more efficient therapeutic development, predicting drug delivery system effectiveness, and anticipating cellular responses [3]. The integration of multi-omics approaches (transcriptomics, genomics, proteomics, epigenomics, metabolomics, and microbiomics) with advanced computational methods will provide unprecedented insights into the complex networks governing immune responses in tissue repair [3].

Despite substantial progress, significant translational barriers remain. These include investigational obstacles such as unrepresentative preclinical animal models, manufacturing issues related to scalability and automated production, complex regulatory pathways with varying regional requirements, ethical considerations, and economic factors such as high manufacturing costs [3]. Additionally, the high cost of advanced therapy medicinal products (ATMPs) limits accessibility, particularly in low- and middle-income countries [3].

Future advancements will likely focus on developing increasingly sophisticated 'smart' biomaterials that can deliver bioactive compounds in a temporally and spatially controlled manner in response to specific microenvironmental cues [3]. The convergence of targeted drug delivery systems, precision immunomodulation, and patient-specific cellular and genetic information will enable truly personalized regenerative therapies that maximize effectiveness while minimizing off-target effects [3] [34]. As the field matures, long-term follow-up clinical investigations and standardized, scalable bioprocesses will be essential for widespread clinical adoption and global accessibility of these transformative therapies.

The Pharmacological Toolkit for Directing Regeneration

Smart Biomaterials and Controlled Drug Delivery Systems (DDSs) for Spatiotemporal Control

Regenerative pharmacology represents a paradigm shift in therapeutic strategy, aiming not merely to manage symptoms but to restore the physiological structure and function of damaged tissues and organs. [3] Within this innovative framework, smart biomaterials for controlled Drug Delivery Systems (DDSs) are foundational. These materials are engineered to interact dynamically with biological systems, providing precise spatiotemporal control over the release of therapeutic agents—a critical capability for orchestrating complex biological processes like tissue regeneration and immune modulation. [3] [37] By applying pharmacological rigor to regenerative medicine, these systems enable transformative curative therapeutics that move beyond palliative care. [3]

The convergence of biomaterials science with regenerative pharmacology addresses a core challenge: the need for localized, sustained, and stimulus-responsive therapeutic action. This integration is essential for developing next-generation Advanced Therapy Medicinal Products (ATMPs), including cell and gene therapies, which require precise microenvironments to function effectively. [38] Smart biomaterials act as the central platform for achieving this precise control, thereby enhancing therapeutic efficacy while minimizing systemic side effects.

Fundamental Mechanisms: Stimulus-Responsive Biomaterials

Smart biomaterials achieve spatiotemporal precision through engineered responses to specific biological or external triggers. These "stimulus switches" allow for drug release that is contingent upon the presence of a specific signal at a specific time and location. [39] The mechanisms can be broadly categorized based on the source of the stimulus.

Endogenous Stimuli

Endogenous stimuli are intrinsic to the disease microenvironment or specific physiological processes. Key triggers include:

- pH: The slightly acidic microenvironment of pathological sites like tumors or inflamed tissues can trigger the degradation of acid-labile bonds (e.g., hydrazone, acetal) in a polymer, leading to drug release. [39]

- Enzymes: Overexpressed enzymes (e.g., matrix metalloproteinases, MMPs; phosphatases) at the target site can cleave specific peptide or chemical sequences incorporated into the biomaterial, resulting in a highly specific release profile. [39]

- Redox Potential: The significant difference in redox potential between the intracellular (high glutathione, GSH) and extracellular compartments can be exploited. Biomaterials with disulfide linkages remain stable in circulation but rapidly degrade and release cargo upon cell internalization. [39]

Exogenous Stimuli

Exogenous stimuli are applied externally, offering remote control over drug release. Common modalities include:

- Light: Near-infrared (NIR) light, which has superior tissue penetration, can be used to trigger drug release. For instance, gold nanorods or other photothermal agents absorb NIR light, generating heat that melts a surrounding thermal-sensitive polymer matrix (e.g., pluronic) to release the drug. [40]

- Temperature: Mild hyperthermia induced by external sources can activate thermal-sensitive biomaterials like poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) (pNIPAM). [40]

- Magnetic Fields: Magnetic nanoparticles can be guided to a specific site using an external magnet and then activated to release drugs via heat generation (magneto-thermal effect) or mechanical force. [37]

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow of how these stimuli trigger drug release from smart biomaterials.

Stimulus-Response Logic for Smart DDSs

Advanced Platforms for Spatiotemporal Control

Recent research has yielded sophisticated biomaterial platforms that exemplify these mechanisms:

- NIR-Triggered Supramolecular Hydrogels: Yang et al. developed hydrogels incorporating MXene (a photothermal nanomaterial) complexed with doxorubicin. Upon NIR irradiation, the photothermal effect disrupts the hydrogel supramolecular network, providing excellent tumor localization and spatiotemporal control over chemotherapeutic release. [40]

- Enzyme-Responsive Bioinks: Han et al. created a cerebrovascular-specific extracellular matrix bioink for 3D bioprinting of blood-brain barrier models. The microenvironment provided by this bioink supports the self-assembly of endothelial cells and pericytes, responding to physiological and pathological enzymatic cues. [40]

- Polymer-based mRNA Delivery: Lee et al. systematically investigated how the structure and ratio of poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG)-lipids in lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) influence the efficacy and immunogenicity of repeated mRNA administrations. This work highlights the critical role of biomaterial chemistry in avoiding accelerated blood clearance, a key challenge for chronic dosing. [40]

Table 1: Summary of Key Stimulus-Responsive Mechanisms in Smart Biomaterials

| Stimulus Type | Example Trigger | Material/Biomaterial Response | Therapeutic Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Endogenous / Biochemical | Low pH (e.g., tumor microenvironment) | Degradation of acid-labile bonds in polymer backbone or side chains [39] | Targeted drug release in pathological tissues |

| Overexpressed Enzymes (e.g., MMPs) | Cleavage of specific peptide sequences crosslinking the material [39] | Site-specific release and enhanced tissue penetration | |

| High Redox Potential (High GSH) | Reduction and cleavage of disulfide bonds within the material [39] | Intracellular drug delivery following endocytosis | |