Renal Cortex Injection of MSCs for AKI: Enhancing Paracrine Therapy and Overcoming Clinical Translation Barriers

Acute kidney injury (AKI) remains a significant clinical challenge with limited treatment options.

Renal Cortex Injection of MSCs for AKI: Enhancing Paracrine Therapy and Overcoming Clinical Translation Barriers

Abstract

Acute kidney injury (AKI) remains a significant clinical challenge with limited treatment options. Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) offer promising therapeutic potential primarily through their paracrine secretion of bioactive factors that promote tissue repair, modulate immune responses, and reduce inflammation. However, the clinical efficacy of MSC-based therapies is hampered by low cell retention and survival rates post-systemic delivery. This article explores renal cortex injection as a targeted local administration strategy to enhance MSC engraftment and paracrine activity in AKI settings. We examine the foundational mechanisms of MSC paracrine action, methodological considerations for renal cortex delivery, optimization strategies including preconditioning and 3D culture, and comparative efficacy against conventional administration routes. The synthesis of current evidence positions localized MSC delivery as a crucial advancement for realizing the full therapeutic potential of MSC-based AKI treatments.

Understanding AKI Pathophysiology and MSC Paracrine Mechanisms

Global Epidemiology of Acute Kidney Injury

Acute Kidney Injury represents a significant and growing clinical syndrome worldwide, characterized by a rapid decline in kidney function. Its epidemiology underscores a substantial public health burden.

Table 1: Global Epidemiology and Burden of Acute Kidney Injury

| Metric | Estimated Global Burden | Key Context |

|---|---|---|

| Annual Incidence | Approximately 13.3 million people per year [1] [2] | A leading cause of in-hospital mortality [3] |

| In-Hospital Mortality | As high as 62% [3] | |

| AKI in Critical Care | 5-6% of critical patients require renal replacement therapy [4] | Overall mortality in these critical patients is 58-62.6% [4] |

| Post-Transplant AKI | Incidence ranges from 17% to 95% (average ~40.7%) [5] | A common complication post-liver transplantation [5] |

| Progression to CKD | AKI is a major risk factor for new-onset CKD and accelerated progression [4] [6] |

The connection between AKI and Chronic Kidney Disease is particularly critical. AKI is now firmly established as a major risk factor for new-onset CKD and for accelerating the progression of pre-existing CKD [4] [6]. This progression is mediated through complex pathophysiological mechanisms, including maladaptive repair, persistent inflammation, and fibrotic pathways. The severity, duration, and frequency of AKI episodes are key determinants for the subsequent risk of CKD progression and mortality [4].

Experimental Protocols: Renal Cortex Injection of MSCs

The therapeutic potential of Mesenchymal Stem Cells for AKI is a cornerstone of regenerative nephrology. The following section provides a detailed protocol for the renal cortex injection of MSCs, a localized delivery method designed to maximize engraftment and paracrine effects at the injury site.

Protocol: Renal Subcapsular Injection of MSCs in a Rodent AKI Model

Objective: To administer MSCs directly into the renal cortex to enhance cell retention and survival in the injured kidney, thereby leveraging their paracrine therapeutic effects for AKI.

Materials and Reagents:

- MSCs: Human-derived MSCs (e.g., bone marrow, umbilical cord, or adipose tissue-derived), characterized by surface markers (CD73+, CD90+, CD105+, CD45-, CD34-, CD14-) [7] [4].

- Animal Model: Sprague-Dawley or Wistar rats (200-250 g), with AKI induced by ischemia-reperfusion, cisplatin, or gentamicin [3].

- Anesthesia: Isoflurane or ketamine/xylazine mixture.

- Surgical Tools: Sterile scalpel, forceps, retractors, and 6-0 silk suture.

- Injection Setup: Hamilton syringe (e.g., 50 µL) with a 30-gauge needle.

- Cell Preparation Solution: Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) or sterile saline.

- Fluorescent Tracer: PKH26 red fluorescent cell linker dye for cell tracking [3].

Methodology:

- Preoperative Preparation:

- Culture and expand MSCs in standard conditions. Ensure they meet the minimal criteria for MSCs (plastic-adherent, specific surface marker expression, trilineage differentiation) [4].

- Cell Labeling and Harvest: Prior to injection, label MSCs with a fluorescent dye like PKH26 according to the manufacturer's protocol to enable subsequent tracking [3]. Harvest MSCs using trypsin-EDTA, wash with PBS, and resuspend in sterile saline at a concentration of 1–5 x 10^7 cells/mL. Keep the cell suspension on ice until use.

- Anesthetize the rat and shave the fur from the dorsal lumbar region. Sterilize the surgical site with betadine and ethanol.

Surgical Procedure:

- Make a 1.5–2 cm dorsal lateral incision to expose the left kidney.

- Gently mobilize the kidney and place it on sterile gauze.

- Using the Hamilton syringe with a 30-gauge needle, slowly inject 10–50 µL of the cell suspension (containing approximately 1–2 x 10^6 cells) into the upper and lower poles of the renal cortex, just beneath the renal capsule. A successful injection is indicated by a visible bleb.

- Hold the needle in place for 30 seconds after injection to prevent backflow.

- Return the kidney to the retroperitoneal space.

- Suture the muscle layer and skin separately.

Postoperative Care:

- Monitor animals until they fully recover from anesthesia.

- Administer analgesics (e.g., buprenorphine) for post-surgical pain.

- House animals under standard conditions with free access to food and water.

Analysis and Validation:

- Functional Assessment: Monitor renal function by measuring serum creatinine (Cr) and blood urea nitrogen (BUN) levels at baseline and days 1, 3, and 7 post-injection [3] [8].

- Histological Analysis: At the experimental endpoint, harvest kidney tissues. Process for histology (e.g., PAS staining) to evaluate tubular injury score, necrosis, and cast formation [3] [8].

- Cell Tracking: Analyze frozen kidney sections by fluorescence microscopy to detect PKH26-labeled MSCs, confirming their localization within the renal cortex [3].

- Mechanistic Studies: Perform TUNEL staining for apoptosis, immunohistochemistry for oxidative stress markers (e.g., 8-OHdG), and Western blot for apoptosis-related proteins (Bax, Bcl-2) and ER stress markers [3].

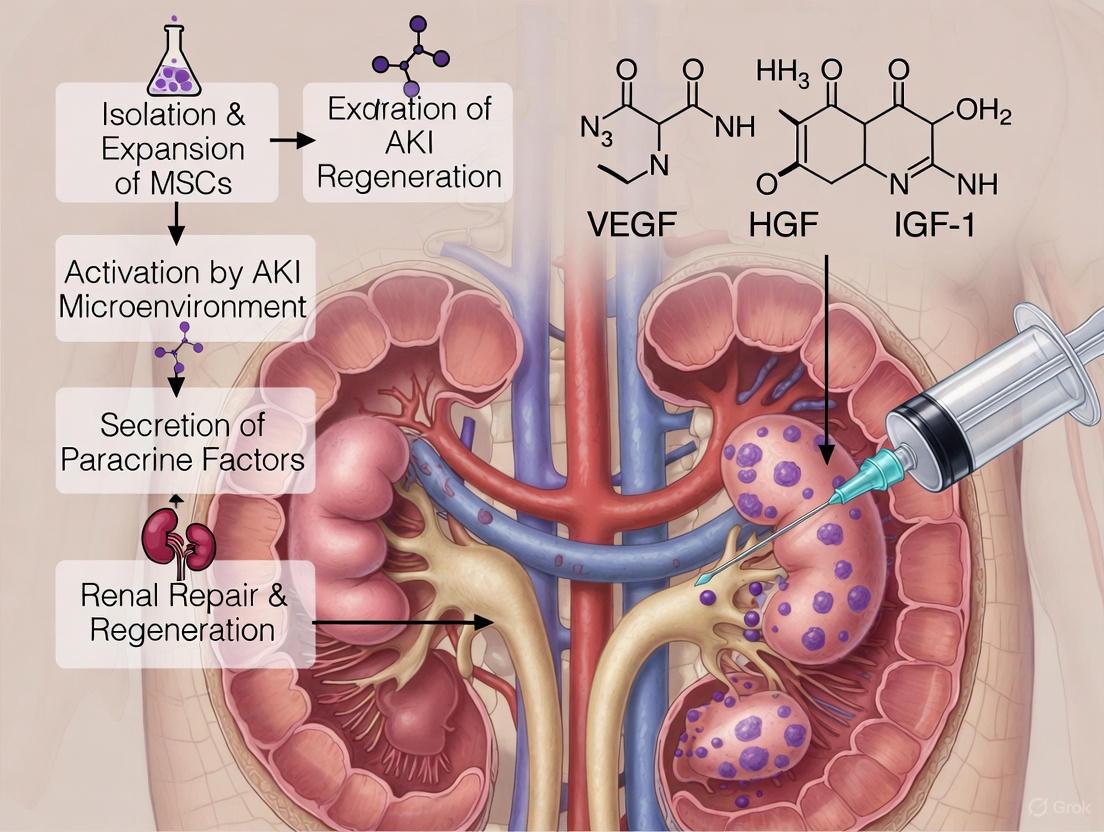

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for renal cortex injection of MSCs in an AKI model.

Key Mechanisms of MSC Paracrine Therapy in AKI

The therapeutic benefits of MSCs are primarily mediated through their paracrine activity rather than direct differentiation and engraftment [9] [4]. The secreted factors and extracellular vesicles (EVs) act on multiple injury pathways in the damaged kidney.

Table 2: Key Paracrine Mechanisms of MSCs in AKI

| Mechanism of Action | Functional Impact | Key Mediators |

|---|---|---|

| Anti-Apoptosis | Reduces programmed cell death in tubular epithelial cells [3] [4]. | Growth factors, EVs carrying anti-apoptotic miRNAs; Upregulation of Bcl-2, downregulation of Bax and cleaved caspase [3]. |

| Anti-Inflammation & Immunomodulation | Modulates the immune response, reduces inflammatory cell infiltration [10] [7]. | Cytokines and EVs that increase regulatory T cells (Tregs); decrease pro-inflammatory cytokines [7]. |

| Anti-Oxidative Stress | Mitigates oxidative damage to renal cells [3]. | Enhancement of antioxidant defenses (e.g., GPx, catalase); reduction of oxidative markers (e.g., urinary 8-OHdG) [3]. |

| Pro-Angiogenic Effects | Promotes vascular regeneration and protects peritubular capillary density [10]. | Release of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and other angiogenic factors [10]. |

| Anti-Fibrotic | Inhibits progression to chronic kidney disease and fibrosis [8]. | Suppression of pro-fibrotic factors like TGF-β; reduction in extracellular matrix deposition [8]. |

Diagram 2: MSC paracrine mechanisms and therapeutic effects in AKI.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This table outlines essential materials and reagents for investigating MSC-based paracrine therapy for AKI, with a focus on renal cortex injection protocols.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for MSC-based AKI Therapy

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Examples / Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs) | Core therapeutic agent; source of paracrine factors and EVs. | Bone marrow (BM-MSCs), umbilical cord (UC-MSCs), adipose (AD-MSCs). Must be CD105+, CD73+, CD90+, CD45-, CD34-, CD14- [7] [4]. |

| Cell Tracking Dyes | Labeling and visualization of administered MSCs to monitor homing and engraftment. | PKH26 (red fluorescent dye) [3]. |

| AKI Model Inducers | To establish experimental kidney injury models in rodents. | Gentamicin (70 mg/kg/day IP) [3], Cisplatin, Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury (IRI) models. |

| Renal Function Assay Kits | Quantitative assessment of kidney function impairment and recovery. | Commercial kits for Serum Creatinine (Cr) and Blood Urea Nitrogen (BUN) [3] [8]. |

| Antibodies for Mechanism | Detection of key proteins involved in AKI pathogenesis and repair. | Anti-Bax, Anti-Bcl-2 (apoptosis) [3]; Anti-Kim-1, Anti-NGAL (tubular injury) [8]; Anti-CD31, Anti-α-SMA (vascular and fibrosis). |

| ELISA Kits | Measurement of specific biomarkers in serum, urine, or tissue homogenates. | Urinary 8-OHdG for oxidative stress [3]; Cytokine kits for TNF-α, IL-6. |

| Extracellular Vesicle Isolation Kits | Isolation of EVs from MSC-conditioned media for mechanistic studies. | Based on differential ultracentrifugation, size-exclusion chromatography, or precipitation [4] [8]. |

| Hydrogel Polymers (for 3D Culture/Delivery) | Enhance MSC survival, retention, and paracrine function post-transplantation. | Natural polymers: Alginate, Chitosan, Agarose [2]. |

Risk Factors for AKI to CKD Progression

Understanding the factors that predispose patients to progression from AKI to CKD is critical for identifying at-risk populations for targeted therapies.

Table 4: Identified Risk Factors for Progression from AKI to CKD

| Risk Factor Category | Specific Factor | Impact (Odds Ratio or Risk Association) |

|---|---|---|

| Preoperative Comorbidities | Diabetes Mellitus [5] | OR 2.62 (95% CI 1.32–5.21) [5] |

| Hepatic Malignancy [5] | OR 1.95 (95% CI 1.06–3.57) [5] | |

| Elevated Preoperative Serum Creatinine [5] | OR 1.02 (per unit increase) (95% CI 1.01–1.03) [5] | |

| Postoperative Kidney Course | Transition from AKI to Acute Kidney Disease (AKD) [5] | OR 3.99 (95% CI 1.94–8.23) [5] |

| AKD Stages 2 and 3 [5] | OR 2.48 (95% CI 1.33–4.61) [5] | |

| eGFR < 60 mL/min/1.73 m² within 30 days post-op [5] | OR 3.03 (95% CI 1.70–5.40) [5] | |

| Protective Factors | Higher Preoperative Hematocrit [5] | Associated with reduced risk (OR 0.00; 95% CI 0.00–0.26) [5] |

| Recovery from AKD [5] | Associated with reduced risk (OR 0.49; 95% CI 0.27–0.86) [5] |

The Global AKI Burden and Limitations of Current Care

Acute Kidney Injury (AKI) represents a significant global health challenge, affecting approximately 13.3 million individuals annually and contributing to high rates of morbidity and mortality [1] [11]. Current management strategies primarily consist of supportive and preventive measures, with a notable absence of targeted pharmacological treatments that directly halt disease progression or promote tissue repair [11]. This therapeutic gap is particularly concerning given AKI's potential to advance to chronic kidney disease (CKD) and end-stage kidney disease, conditions that substantially diminish patients' quality of life and impose considerable financial strain on healthcare systems [11].

Mesenchymal Stem Cell Therapy: Mechanisms and Promise

Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) have emerged as a promising therapeutic intervention for AKI due to their multifaceted mechanisms of action, which extend beyond differentiation to include potent paracrine effects [11]. The therapeutic potential of MSCs is mediated through several key mechanisms:

- Paracrine Signaling: Secretion of bioactive molecules including cytokines, chemokines, growth factors, and extracellular vesicles that promote cell proliferation, inhibit apoptosis, enhance angiogenesis, and facilitate tissue repair [11].

- Immunomodulation: Modification of immune responses through anti-inflammatory capabilities and interaction with immune cells [11].

- Mitochondrial Transfer: Direct transfer of healthy mitochondria to injured renal cells via tunneling nanotubes, boosting cellular energy metabolism and contributing to tissue repair [11].

- Extracellular Vesicle-Mediated Effects: MSC-derived vesicles carrying therapeutic cargo that can modulate inflammatory pathways and promote recovery [12].

Table 1: Key Therapeutic Mechanisms of MSCs in AKI

| Mechanism | Biological Components | Functional Outcomes |

|---|---|---|

| Paracrine Signaling | Cytokines, chemokines, growth factors | Enhanced cell proliferation, reduced apoptosis, improved angiogenesis |

| Immunomodulation | Anti-inflammatory factors, regulatory enzymes | Reduced inflammation, altered immune cell polarization |

| Mitochondrial Transfer | Healthy mitochondria | Improved cellular energy metabolism, tissue repair |

| Vesicle-Mediated Effects | Extracellular vesicles (EVs), exosomes | Modulation of macrophage polarization, anti-inflammatory effects |

Critical Limitations in MSC-Based Therapies

Despite promising preclinical results, the clinical translation of MSC therapies faces significant challenges that limit their efficacy:

- Low Cell Retention and Survival: Transplanted MSCs exhibit poor retention and limited survival in the injured renal microenvironment, drastically reducing their therapeutic impact [11].

- Suboptimal Secretion of Therapeutic Factors: The hostile environment of injured renal tissues often leads to suboptimal production and secretion of the paracrine factors essential for renal repair [11].

- Homing Inefficiency: Systemically administered MSCs may fail to adequately migrate to and engraft within target tissues, with many cells becoming trapped in filtering organs like the lungs [11].

- Variable Patient Responses: Individual differences in disease etiology, severity, and patient physiology contribute to inconsistent therapeutic outcomes [13].

Strategic Approaches to Enhance MSC Efficacy

Preconditioning Strategies

Hypoxic Preconditioning Culturing MSCs under low oxygen conditions (1-5% O₂) prior to transplantation enhances their proliferation, survival, homing, differentiation, and paracrine activities [11]. This approach mimics the hypoxic microenvironment MSCs encounter post-transplantation and upregulates critical protective pathways:

- 1% O₂ preconditioning of human adipose-derived MSCs (hADMSCs) in rat IRI models demonstrated improvements in apoptosis reduction, enhanced anti-oxidative capacity, and increased vascularization [11].

- 5% O₂ preconditioning of human umbilical cord MSCs (hUCMSCs) increased expression of hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), integrins, and stromal-derived factor-1, ameliorating renal function in gentamicin-induced AKI models [11].

Chemical and Drug Preconditioning

- Chlorzoxazone (CZ): FDA-approved muscle relaxant that enhances MSC anti-inflammatory cytokine expression and strengthens immunosuppressive capacity without increasing immunogenicity [11].

- Atorvastatin (Ator): Statin medication with anti-apoptotic, antioxidant, and anti-inflammatory properties that synergistically enhances BMSC therapeutic effects [11].

Table 2: Preconditioning Strategies to Enhance MSC Efficacy

| Strategy Type | Specific Approach | Mechanistic Basis | Documented Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physical Preconditioning | Hypoxic culture (1-5% O₂) | Upregulation of HIF-1α, CXCR4, enhanced paracrine function | Improved survival, angiogenesis, antioxidant capacity |

| Chemical Preconditioning | Chlorzoxazone | FOXO3 phosphorylation, anti-inflammatory phenotype | Reduced T-cell activation, decreased glomerular necrosis |

| Drug Preconditioning | Atorvastatin | Synergistic enhancement of inherent BMSC effects | Anti-apoptotic, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory benefits |

Advanced Delivery and Formulation Strategies

Three-Dimensional Culture Systems Advanced 3D culture methods, including hydrogels and spheroid formation, help recreate a more physiologically relevant microenvironment that enhances MSC functionality prior to transplantation [11].

Extracellular Vesicle-Based Approaches MSC-derived extracellular vesicles (MSC-EVs) offer numerous advantages over whole-cell therapies, including lower immunogenicity, reduced risk of tumor formation, and enhanced targetability [1] [12]. Specific findings include:

- Adipose-derived MSC-EVs (AMSC-EVs) attenuate AKI through modulation of the TXNIP-IKKα/NFκB signaling pathway in renal CX3CR1⁺ macrophages [12].

- EVs from induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSC-EVs) demonstrate superior efficacy compared to adipose-derived MSC-EVs in preserving mitochondrial integrity and regulating oxidative stress defense genes [1].

Genetic Modification Techniques Genetic engineering of MSCs to overexpress therapeutic factors can optimize their functionality and enhance secretory profiles, though this approach requires careful safety evaluation [11].

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Renal Cortex Injection of Preconditioned MSCs

MSC Preparation and Preconditioning

Materials Required:

- Primary human MSCs (bone marrow, adipose, or umbilical cord derived)

- Standard culture medium: DMEM/F12 supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin

- Hypoxia chamber or workstation

- Preconditioning agents: Chlorzoxazone (CZ) or Atorvastatin (Ator)

Procedure:

- Culture MSCs in standard conditions (37°C, 5% CO₂, 21% O₂) until 70-80% confluency.

- For hypoxic preconditioning: Transfer cells to hypoxia chamber (1-5% O₂, 5% CO₂, balanced N₂) for 24-48 hours prior to harvest.

- For chemical preconditioning: Treat MSCs with CZ (optimal concentration to be determined by dose-response studies) or Atorvastatin (5 μM) for 24 hours.

- Harvest cells using 0.25% trypsin-EDTA and resuspend in sterile PBS at concentration of 10,000-50,000 cells/μL for injection.

Surgical Procedure: Renal Cortex Injection in Rodent AKI Model

Animal Model: Male C57BL/6 mice (8-10 weeks old, 20-25g) AKI Induction: Cisplatin-induced model (single intraperitoneal injection, 20 mg/kg) or ischemia-reperfusion injury model (renal pedicle clamping, 30 minutes)

Injection Protocol:

- Anesthetize animal using isoflurane (3% induction, 1.5% maintenance) and place in right lateral decubitus position.

- Make a left flank incision and exteriorize the kidney using blunt dissection.

- Using a 30-gauge needle connected to a Hamilton syringe, slowly inject 10-20 μL of cell suspension (approximately 100,000-500,000 cells) at 2-3 sites within the renal cortex.

- Apply gentle pressure with sterile cotton tip for 30 seconds to prevent backflow.

- Return kidney to abdominal cavity and close incision in layers.

- Administer postoperative analgesia (buprenorphine, 0.1 mg/kg) and monitor until recovery.

Assessment and Analysis

Functional Assessment:

- Serum creatinine measurements at 24, 48, 72, and 96 hours post-AKI induction

- Blood urea nitrogen (BUN) levels

- Urine output measurement

Histological Analysis:

- Kidney tissue collection at 96 hours post-injury

- Paraffin embedding, sectioning (4μm), H&E staining

- Tubular injury scoring based on percentage of tubules showing epithelial necrosis, cast formation, or dilation

Molecular Analysis:

- Immunoblotting for TXNIP, IKKα, NFκB pathway components [12]

- Immunofluorescence for macrophage polarization markers (CD86 for M1, CD206 for M2)

- Cytokine profiling of renal tissue homogenates

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflow

MSC Therapeutic Mechanisms and Signaling Pathways

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for MSC-based AKI Research

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| MSC Sources | Bone marrow-derived MSCs, Adipose-derived MSCs, Umbilical cord MSCs | Primary therapeutic agents with multilineage differentiation potential |

| Preconditioning Agents | Chlorzoxazone (CZ), Atorvastatin, Hypoxic chambers | Enhance MSC survival, paracrine function, and therapeutic efficacy |

| Extracellular Vesicle Isolation | Differential centrifugation kits, Ultracentrifugation equipment, Size exclusion chromatography | Isolation and purification of MSC-derived vesicles for cell-free therapy |

| AKI Modeling Compounds | Cisplatin, Gentamicin, Ischemia-reperfusion surgical equipment | Induction of controlled kidney injury for experimental therapeutic testing |

| Molecular Analysis Tools | TXNIP antibodies, NFκB pathway inhibitors, CX3CR1 detection assays | Mechanism investigation and pathway modulation studies |

| Cell Tracking Methods | Fluorescent dyes (DiI, DiD), Lentiviral GFP labeling, Magnetic nanoparticles | Monitoring MSC migration, retention, and distribution post-delivery |

The development of targeted AKI interventions represents a critical unmet need in nephrology. While MSC-based therapies offer considerable promise through multiple mechanistic pathways, current limitations in cell retention, survival, and paracrine functionality must be addressed through strategic preconditioning, optimized delivery methods, and potentially cell-free alternatives such as extracellular vesicles. The renal cortex injection approach detailed in this protocol provides a targeted method for delivering enhanced MSCs directly to the site of injury, maximizing therapeutic potential while minimizing systemic losses. Future research directions should focus on optimizing preconditioning protocols, developing more efficient delivery systems, and conducting rigorous safety and efficacy studies to translate these promising approaches into clinical practice.

Acute Kidney Injury (AKI) represents a significant global health burden, with an estimated 13.3 million cases annually and strong associations with chronic kidney disease (CKD), end-stage renal disease (ESRD), and mortality [11] [14]. Current management remains predominantly supportive, creating an urgent need for targeted therapeutic interventions [11] [2]. Mesenchymal Stem/Stromal Cell (MSC)-based therapy has emerged as a promising regenerative strategy. Initially, the therapeutic potential of MSCs was attributed to their ability to differentiate and replace damaged renal cells [15]. However, accumulating preclinical and clinical evidence now indicates that the primary regenerative mechanism is paracrine action, mediated through the secretion of bioactive factors rather than direct cell replacement [16] [15] [17].

The MSC "secretome" comprises a complex mixture of soluble proteins (cytokines, chemokines, growth factors) and Extracellular Vesicles (EVs)—including exosomes and microvesicles—which deliver proteins, mRNAs, microRNAs, and lipids to recipient cells [16] [15] [17]. These factors collectively mitigate renal injury by inhibiting apoptosis, modulating immune responses, reducing oxidative stress, and promoting angiogenesis and tubular cell proliferation [16] [14] [18]. This application note details the composition of the MSC secretome, provides protocols for its study and application, and frames this within the context of direct renal cortex injection, a delivery method that enhances target engagement for AKI paracrine therapy research.

Composition of the MSC Secretome

The therapeutic efficacy of the MSC secretome is derived from its diverse cargo, which can be categorized into soluble factors and vesicular components.

Soluble Factors: Cytokines and Growth Factors

Proteomic analyses of MSC-conditioned media have identified a wide array of soluble factors central to renal repair. The table below summarizes the key functional categories and their principal constituents.

Table 1: Key Soluble Factors in the MSC Secretome and Their Roles in Renal Repair

| Factor Category | Key Constituents | Primary Functions in Renal Repair |

|---|---|---|

| Cytokines | IL-6, IL-10, IL-1RN (IL-1 receptor antagonist), LIF, TGF-β [15] [18] | Immunomodulation; shifting macrophages from pro-inflammatory M1 to anti-inflammatory M2 phenotype; suppressing T-cell activation [18]. |

| Growth Factors | HGF (Hepatocyte Growth Factor), VEGF (Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor), IGF-1 (Insulin-like Growth Factor 1), FGF-2 (Fibroblast Growth Factor 2), BMP-7 (Bone Morphogenetic Protein 7) [15] [14] [19] | Promoting tubular cell proliferation; inhibiting apoptosis; enhancing angiogenesis; attenuating fibrosis [15] [14]. |

| Chemokines | CCL2, CCL5, CXCL1, CXCL12 (SDF-1) [15] | Orchestrating cell migration and homing of progenitor cells to sites of injury. |

Extracellular Vesicles: Exosomes and Microvesicles

MSC-derived EVs are membrane-enclosed particles that act as primary mediators of intercellular communication by transferring bioactive molecules. Their cargo is selectively packaged and reflects the functional state of the parent MSCs [16] [17].

Table 2: Cargo and Function of MSC-Derived Extracellular Vesicles

| Cargo Type | Key Components | Documented Functions in AKI Models |

|---|---|---|

| mRNAs | mRNAs for transcription factors (e.g., POU3F1), angiogenesis (e.g., HGF, HES1), TGF-β signaling (e.g., TGFB1, TGFB3), and extracellular matrix remodeling (e.g., COL4A2) [16] [15]. | Transferred mRNAs can be translated in recipient cells, altering their phenotype and promoting repair processes. RNase treatment of EVs abolishes their therapeutic effects, underscoring the critical role of RNA cargo [15]. |

| MicroRNAs (miRNAs) | Various miRNAs (e.g., those targeting apoptotic and inflammatory pathways) [14]. | miRNAs inhibit the expression of target genes in recipient cells, leading to anti-apoptotic and anti-inflammatory effects. For instance, MSC-EVs upregulate anti-apoptotic genes (Bcl2, Bcl-xL) and downregulate caspases [14]. |

| Proteins | EV biogenesis markers (CD9, CD63, CD81), cytoskeletal proteins, and immunomodulatory factors [16] [15] [17]. | Proteins can directly activate signaling pathways in recipient cells. EVs from different MSC sources (adipose, bone marrow, umbilical cord) show heterogeneous protein content, influencing their restorative capacity [19]. |

The following diagram illustrates the biogenesis of these key secretome components and their subsequent actions on recipient renal cells.

Experimental Protocols for Secretome Analysis and Application

This section provides detailed methodologies for isolating the MSC secretome, establishing an in vitro AKI model, and evaluating therapeutic outcomes.

Protocol 1: Isolation and Characterization of MSC-Derived Extracellular Vesicles

Principle: EVs are isolated from MSC-conditioned medium via sequential ultracentrifugation to separate them from soluble factors and cellular debris, followed by characterization of their identity and concentration [12] [19].

Materials:

- Source: Human adipose-derived MSCs (AMSCs), bone marrow MSCs (BM-MSCs), or umbilical cord MSCs (UC-MSCs) [19].

- Culture Medium: DMEM/F12 or MEM-α supplemented with 10% EVs-depleted Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS) [12] [19].

- Reagents: Phosphate-Buffered Saline (PBS), Trypsin-EDTA.

- Equipment: Ultracentrifuge, fixed-angle rotor, Nanoparticle Tracking Analyzer, Transmission Electron Microscope, Western blot apparatus.

Procedure:

- Cell Culture and Supernatant Collection: Culture MSCs until 80% confluency. Replace medium with serum-free medium or medium containing EVs-depleted FBS. Collect conditioned medium after 24-48 hours.

- Differential Centrifugation:

- Centrifuge at 400 × g for 5-10 minutes to remove floating cells.

- Transfer supernatant and centrifuge at 10,000-20,000 × g for 20-30 minutes to remove apoptotic bodies and large debris.

- Filter the supernatant through a 0.22 µm filter.

- Ultracentrifugation: Transfer the filtered supernatant to ultracentrifuge tubes. Pellet EVs at 110,000 × g for 70-90 minutes at 4°C. Carefully discard the supernatant.

- Washing: Resuspend the EV pellet in a large volume of PBS. Perform a second ultracentrifugation under the same conditions to remove contaminating soluble proteins.

- Final Resuspension: Resuspend the final, clean EV pellet in a small volume of PBS and store at -80°C.

- Characterization:

- Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis (NTA): Dilute EVs in PBS and inject into the NTA to determine particle size distribution and concentration [12].

- Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM): Apply EVs to a formvar-carbon coated grid, negative stain with uranyl acetate, and image to confirm classic "cup-shaped" morphology [16] [12].

- Immunoblotting: Confirm the presence of EV-positive markers (CD9, CD63, CD81) and the absence of negative markers (e.g., Calnexin) [12].

Protocol 2: In Vitro Modeling of AKI and Secretome Treatment

Principle: Chemically induce ischemic injury in human proximal tubule epithelial cells to model AKI and assess the restorative effects of the MSC secretome [19].

Materials:

- Cell Line: Human proximal tubule epithelial cells.

- Chemicals: Antimycin A (complex III inhibitor), 2-deoxy-D-glucose (glycolysis inhibitor) [19].

- Treatment: MSC-conditioned medium or characterized EVs.

Procedure:

- Induction of Ischemic Injury: Culture proximal tubule cells until 70-80% confluency. Induce injury by treating cells with 10 nM Antimycin A and 20 mM 2-deoxy-D-glucose in serum-free medium for 24 hours. Maintain under normoxic (21% O₂) or hypoxic (1% O₂) conditions to better mimic ischemia [19].

- Treatment Application: After 24 hours, wash cells with HBSS to remove chemical inhibitors. Treat injured cells with:

- MSC-conditioned medium, or

- Isolated EVs (dose: bioproduct equivalent from 2 MSCs per tubule cell) [19].

- Include controls: sham (healthy), vehicle (serum-free medium), and reperfusion (serum-containing medium).

- Incubation: Incubate cells with the secretome treatment for 24 hours.

Protocol 3: Assessing Therapeutic Efficacy

Principle: Quantify the restoration of cellular health and function post-treatment using a suite of biochemical and metabolic assays.

Key Assays:

- Cell Metabolic Activity: Measure using PrestoBlue or MTT assay. Expect a significant increase in metabolic activity in treated groups versus injured controls [19].

- ATP Production: Quantify using a luciferase-based assay. Successful treatment should restore ATP levels, a key indicator of bioenergetic recovery [19].

- Apoptosis Assay: Perform TUNEL staining or caspase-3/7 activity assay. MSC secretome treatment should significantly reduce apoptotic activity [14].

- Metabolomic Analysis: Utilize LC-MS or GC-MS to profile cellular metabolites. Look for increased levels of glycolysis intermediates and antioxidant metabolites (e.g., glutathione) post-treatment, indicating metabolic restoration and reduced oxidative stress [19].

- Macrophage Polarization Assay: Co-culture treated injured cells with monocytes or use in vivo models. Flow cytometry for M2 markers (CD206) vs. M1 markers (CD86) can demonstrate the immunomodulatory effect of the secretome, a key mechanism in vivo [12].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The table below lists critical reagents and their applications for researching the MSC secretome in renal repair.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for MSC Secretome Studies

| Research Reagent / Tool | Function and Application | Example Usage in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| EVs-depleted FBS | Essential for cell culture during EV production. Standard FBS contains bovine EVs that contaminate preparations. EVs are removed via ultracentrifugation. | Used in Protocol 1 for conditioning media to ensure isolation of pure, human MSC-derived EVs [12] [19]. |

| CD9, CD63, CD81 Antibodies | Surface markers characteristic of exosomes and other EVs. Used for immunoblotting or flow cytometry to confirm EV identity and purity. | Used in Protocol 1, Step 6 (Immunoblotting) for the characterization of isolated EVs [12] [17]. |

| Antimycin A & 2-deoxy-D-glucose | Chemical inducers of in vitro ischemia. They inhibit mitochondrial respiration and glycolysis, respectively, mimicking the bioenergetic collapse in AKI. | Used in Protocol 2, Step 1 to induce a reproducible and controlled ischemic injury in proximal tubule cells [19]. |

| PrestoBlue / MTT Reagent | Cell-permeable dyes used as indicators of cell viability and metabolic activity. The conversion rate correlates with the number of viable cells. | Used in Protocol 3 to quantitatively assess the recovery of cellular health following secretome treatment [19]. |

| TXNIP Antibodies / siRNA | Tools to investigate a key molecular mechanism. TXNIP is a protein that regulates the NF-κB signaling cascade and macrophage polarization. | Used in mechanistic studies to validate the TXNIP-IKKα/NF-κB pathway, through which AMSC-EVs promote M2 macrophage polarization [12]. |

Research Context: Renal Cortex Injection for AKI Therapy

The route of administration is a critical factor for the success of MSC secretome-based therapies. While intravenous (IV) infusion is common, it results in significant entrapment of cells or EVs in the lungs and liver, reducing the fraction that reaches the kidneys [2]. Direct renal cortex injection is an advanced delivery method that offers distinct advantages for preclinical research and potential clinical translation.

This targeted approach involves the precise inoculation of MSCs or their secretome (e.g., concentrated EVs) directly into the renal parenchyma. It is typically performed under ultrasound or surgical guidance to ensure accuracy [2]. The primary advantage is the bypass of systemic filtration, enabling a high local concentration of therapeutic agents to be delivered directly to the site of injury. This maximizes paracrine signaling and minimizes off-target distribution [2]. Studies have shown that local injection increases cell engraftment and enhances functional recovery in animal models of AKI, without reported significant safety concerns like renal embolism when performed appropriately [2].

For researchers, this model is highly relevant for investigating the localized paracrine effects of MSCs. It allows for the precise tracking of EV uptake, the analysis of local immune modulation (e.g., CX3CR1+ macrophage polarization within the kidney), and the assessment of direct tubular repair mechanisms [12]. The workflow below outlines the key stages of a research project utilizing renal cortex injection.

The MSC secretome, through its rich composition of cytokines, growth factors, and EVs, represents a powerful, cell-free therapeutic tool for renal repair, effectively attenuating apoptosis, inflammation, and bioenergetic failure in AKI. The efficacy of this paracrine action can be significantly amplified by employing direct renal cortex injection, which ensures optimal delivery to the target tissue. The protocols and tools detailed in this application note provide a foundational framework for researchers to rigorously isolate, characterize, and test the MSC secretome, advancing the translational path towards a novel and effective therapy for Acute Kidney Injury.

Macrophage Polarization: Mechanisms and Experimental Evidence

Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs) promote the polarization of pro-inflammatory M1 macrophages towards the anti-inflammatory, reparative M2 phenotype through multiple paracrine signaling pathways. This immunomodulatory action is a cornerstone of their therapeutic effect in Acute Kidney Injury (AKI).

Key Signaling Pathways in Macrophage Polarization

The table below summarizes the primary mechanisms by which MSCs and their derivatives modulate macrophage polarization, as evidenced in preclinical AKI models.

Table 1: Mechanisms of MSC-Mediated Macrophage Polarization in AKI

| Mechanism / Signal | MSC Source | Experimental Model | Key Finding | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| miR-146a-5p inhibits TRAF6/STAT1 | Umbilical Cord (hUMSCs-Exo) | Diabetic Kidney Disease (DKD) Model | Facilitated M1-to-M2 transition, reducing inflammation and improving renal function. | [20] |

| miR-486-5p activates PI3K/Akt pathway | Umbilical Cord (hUMSCs-Exo) | DKD Model | Promoted M2 polarization, alleviating tubular injury and glomerulosclerosis. | [20] |

| TFEB-mediated autophagy | Bone Marrow (BMSCs) | Diabetic Nephropathy Model | Promoted M2 polarization, inhibiting inflammation and mesangial matrix expansion. | [20] |

| TXNIP-IKKα/NF-κB suppression | Adipose Tissue (AMSC-EVs) | Cisplatin-induced AKI Mouse Model | Promoted polarization of renal CX3CR1+ macrophages to reparative M2 type. | [12] |

| Inflammatory Priming (IL-1β, TNF-α, IL-17) | Wharton's Jelly (WJ-MSCs) | In vitro macrophage co-culture | Primed MSC secretome significantly enhanced ability to polarize macrophages to M2 phenotype. | [21] |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Evaluating Macrophage PolarizationIn Vivo

The following protocol is adapted from studies investigating MSC therapy in murine AKI models [12] [20].

Objective: To assess the effect of renal cortex-injected MSCs on macrophage polarization in kidney tissue of mice with cisplatin-induced AKI.

Materials:

- Animal Model: C57BL/6 mice (8-10 weeks old)

- AKI Induction Agent: Cisplatin (e.g., from MedChemExpress, HY-17394)

- MSCs: Human adipose-derived MSCs (AMSCs) or bone marrow-derived MSCs (BMSCs), passages 3-8.

- Key Reagents:

- Flow Cytometry Antibodies: Anti-mouse F4/80 (APC), CD86 (FITC) for M1 markers, CD206 (PE) for M2 markers.

- ELISA Kits: Mouse IL-1β, TNF-α, IL-10, TGF-β.

- RNA Isolation Kit and qPCR reagents.

- Primary Antibodies for IHC: iNOS (M1), Arginae-1 (M2).

Procedure:

- AKI Induction and MSC Administration:

- Induce AKI in mice via a single intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection of cisplatin (10-12 mg/kg).

- At 24 hours post-cisplatin injection, randomly assign mice to treatment groups.

- Under anesthesia, administer MSCs (e.g., 1-2x10^5 cells in 50µL PBS) via renal cortex injection into both kidneys using a 30-gauge insulin syringe. Control groups receive an equivalent volume of PBS.

- Tissue Collection:

- At 96 hours post-injury, euthanize mice and perfuse kidneys with cold PBS.

- Collect kidney tissues for:

- Flow Cytometry: Dispase/collagenase-digested single-cell suspension.

- RNA/Protein Analysis: Snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen.

- Histology: Fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and embedded in paraffin.

- Flow Cytometric Analysis:

- Prepare a single-cell suspension from kidney tissue.

- Stain cells with surface marker antibodies: F4/80 (macrophages), CD86 (M1), and CD206 (M2).

- Analyze using flow cytometry. Calculate the ratio of F4/80+CD206+ (M2) to F4/80+CD86+ (M1) cells.

- Cytokine Profiling:

- Homogenize kidney tissue and quantify supernatant levels of pro-inflammatory (IL-1β, TNF-α) and anti-inflammatory (IL-10, TGF-β) cytokines by ELISA.

- Gene Expression Analysis (qPCR):

- Extract total RNA from kidney tissue and synthesize cDNA.

- Perform qPCR to analyze expression of M1 markers (iNOS, CD86) and M2 markers (Arg-1, CD206, Ym-1). Normalize to GAPDH.

- Immunohistochemistry (IHC):

- Perform IHC on kidney sections using antibodies against iNOS and Arginae-1.

- Quantify positive cell infiltration in the renal tubulointerstitial area.

Diagram 1: MSC-Mediated Macrophage Polarization Signaling Pathways. MSCs and their extracellular vesicles (EVs) promote M2 macrophage polarization via multiple microRNA and protein-level pathways, suppressing key pro-inflammatory signaling cascades.

T-cell Suppression: Mechanisms and Experimental Protocols

MSCs suppress the activation and proliferation of T-cells, a major driver of inflammation in AKI, through both cell-to-cell contact and the release of soluble factors.

Key Mechanisms of T-cell Suppression

The primary mechanisms of T-cell suppression by MSCs include:

- Soluble Factor Secretion: MSCs secrete immunomodulatory factors such as Prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO), Transforming Growth Factor-β (TGF-β), and Human Leukocyte Antigen-G5 (HLA-G5) [22]. These molecules directly inhibit T-cell proliferation and effector functions.

- Metabolic Disruption: The enzyme IDO catalyzes the conversion of tryptophan into kynurenines. Depleting local tryptophan and accumulating kynurenines induces cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in activated T-cells [22].

- Chemical Preconditioning: Preconditioning MSCs with drugs like Chlorzoxazone (CZ), an FDA-approved muscle relaxant, enhances their immunosuppressive capacity. CZ promotes FOXO3 phosphorylation, boosting the expression of IDO and other anti-inflammatory cytokines, which more effectively attenuates renal inflammation in AKI models [11].

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Assessing T-cell Proliferation and ActivationIn Vitro

This protocol is used to evaluate the immunomodulatory potency of MSCs, particularly after preconditioning strategies [11] [22].

Objective: To measure the suppression of T-cell proliferation and activation by MSC-conditioned medium (MSC-CM) or via direct co-culture.

Materials:

- MSCs: Bone marrow or umbilical cord-derived MSCs.

- Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells (PBMCs): Isolated from human blood.

- T-cell Mitogen: Phytohemagglutinin (PHA) or Anti-CD3/CD28 antibodies.

- Cell Tracking Dye: CFSE (Carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester).

- Key Reagents:

- Cell Culture Media: RPMI-1640 for PBMCs, DMEM/F12 for MSCs.

- Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS), Penicillin/Streptomycin.

- Preconditioning Agent: Chlorzoxazone (CZ, e.g., from Sigma-Aldrich).

- Flow Cytometry Antibodies: Anti-human CD3 (APC), CD4 (FITC), CD8 (PerCP), CD25 (PE), CD69 (PE).

- ELISA Kits: Human IFN-γ, IL-2.

Procedure:

- Generation of MSC-Conditioned Medium (MSC-CM):

- Culture MSCs until 70-80% confluency.

- For preconditioning, treat MSCs with a non-cytotoxic dose of CZ (e.g., 50 µM) for 24-48 hours [11].

- Replace medium with fresh, serum-free medium for another 24-48 hours.

- Collect the supernatant, centrifuge to remove cell debris, and use as MSC-CM. Store at -80°C.

- T-cell Proliferation Assay (CFSE Dilution):

- Isolate PBMCs and label with CFSE according to manufacturer's instructions.

- Activate CFSE-labeled PBMCs (1-2x10^5 cells/well) with PHA (5 µg/mL) in a 96-well plate.

- Co-culture activated PBMCs with:

- Direct Co-culture: Various ratios of MSCs (e.g., 1:10, MSC:PBMC).

- Indirect Culture: Using MSC-CM (e.g., 50% v/v in PBMC media).

- Include controls: Non-activated PBMCs and PHA-activated PBMCs alone.

- After 3-5 days, harvest cells and stain with anti-CD3 antibody.

- Analyze CFSE fluorescence intensity in CD3+ T-cells by flow cytometry. Reduced CFSE fluorescence indicates cell division.

- T-cell Activation Marker Analysis:

- Co-culture PBMCs with MSCs or MSC-CM as described above.

- After 24-48 hours, harvest cells and stain with anti-CD3, anti-CD25 (IL-2 receptor α-chain), and anti-CD69 (early activation marker) antibodies.

- Analyze by flow cytometry. The percentage of CD3+ T-cells expressing CD25 and CD69 reflects the level of T-cell activation.

- Cytokine Analysis:

- Collect supernatant from the co-cultures after 48-72 hours.

- Measure levels of T-cell-derived pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IFN-γ, IL-2) using ELISA.

Table 2: The Scientist's Toolkit - Key Research Reagents for MSC Immunomodulation Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Chlorzoxazone (CZ) | Chemical preconditioning of MSCs to enhance anti-inflammatory phenotype and IDO expression. | Boosting MSC efficacy in suppressing T-cell proliferation in vitro and in AKI models. [11] |

| CFSE (Cell Tracking Dye) | Fluorescent dye that dilutes with each cell division, allowing quantification of T-cell proliferation by flow cytometry. | Tracking the suppressive effect of MSC-CM on mitogen-activated T-cell divisions. |

| Recombinant Human Cytokines (IL-1β, TNF-α) | Inflammatory priming of MSCs to enhance their immunomodulatory secretome. | Priming MSCs to increase secretion of TSG-6 and IL-6, enhancing macrophage polarization capacity. [21] |

| Flow Cytometry Antibodies (F4/80, CD86, CD206, CD3, CD25) | Cell surface marker identification for phenotyping macrophages (M1/M2) and activated T-cells. | Quantifying shifts in macrophage populations and T-cell activation status in co-cultures or kidney tissue. [12] [20] |

| ELISA Kits (IFN-γ, IL-2, IL-1β, IL-10) | Quantification of soluble inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines in culture supernatant or tissue homogenates. | Profiling the inflammatory microenvironment to confirm immunomodulatory action of MSCs. |

Diagram 2: Experimental Workflow for Analyzing MSC-Mediated T-cell Suppression. The process involves preconditioning MSCs to enhance their potency, followed by co-culture with activated T-cells and measurement of suppression outcomes through various assays.

The immunomodulatory actions of MSCs, particularly their capacity to polarize macrophages towards an M2 phenotype and suppress T-cell activation, form a robust mechanistic basis for their therapeutic application in AKI. Optimizing these effects through strategies like inflammatory priming, genetic modification, and precise delivery methods such as renal cortex injection is a critical focus of current research, holding significant promise for the development of effective cell-based therapies for inflammatory kidney diseases.

Acute kidney injury (AKI) is a prevalent clinical syndrome characterized by a rapid decline in renal function, associated with high morbidity and mortality, and currently lacks highly effective targeted therapies [23]. The kidney, particularly its proximal tubules, is an organ with high energy demands, consuming approximately 7% of the body's daily ATP expenditure to perform its filtration and reabsorption functions [23]. This high metabolic requirement makes it exceptionally susceptible to mitochondrial dysfunction, which is now recognized as a central pathophysiological event in AKI triggered by various insults, including ischemia-reperfusion (I/R) injury, sepsis, and nephrotoxic agents like cisplatin [23] [24].

Mitochondrial dysfunction in AKI manifests through multiple interconnected processes: impaired mitochondrial biogenesis (the generation of new mitochondria), disrupted mitochondrial dynamics (the balance between fission and fusion), and defective mitophagy (the selective removal of damaged mitochondria) [23]. These alterations lead to ultrastructural changes such as mitochondrial swelling and fragmentation, decreased ATP production, elevated oxidative stress due to reactive oxygen species (ROS) overproduction, and initiation of apoptotic pathways—collectively culminating in renal tubular epithelial cell death and loss of renal function [23] [24].

Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) have emerged as promising therapeutic candidates for AKI, not only through their paracrine activities but also via a more novel mechanism: intercellular mitochondrial transfer [25]. This process involves the delivery of functional mitochondria from MSCs to injured renal cells, thereby restoring cellular bioenergetics and promoting survival. This Application Note details the protocols and mechanistic insights for harnessing mitochondrial transfer as a therapeutic strategy within the broader context of renal cortex-directed MSC therapy for AKI.

Mechanisms of Mitochondrial Transfer from MSCs to Injured Renal Cells

MSCs utilize several distinct yet potentially overlapping mechanisms to transfer mitochondria to recipient cells, each with unique structural and functional characteristics.

Table 1: Mechanisms of Mitochondrial Transfer in AKI

| Transfer Mechanism | Key Mediating Structures/Components | Process Description | Functional Significance in AKI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tunneling Nanotubes (TNTs) | Actin-based cytoplasmic bridges [25] [26] | Formation of thin, open-ended channels enabling direct transfer of organelles, including intact mitochondria, between cells. | Direct, targeted delivery of healthy mitochondria to stressed tubular cells, restoring ATP production [25]. |

| Extracellular Vesicles (EVs) | Exosomes, microvesicles [25] | Packaging of mitochondria or mitochondrial components into membrane-bound vesicles released into extracellular space for uptake by recipient cells. | Paracrine delivery of mitochondrial material; can be engineered for enhanced therapeutic delivery [12] [27]. |

| Direct Cell-Cell Contact | Gap junctions, adhesion molecules [26] | Close membrane apposition facilitating transfer of cellular contents, potentially including small mitochondrial fragments or components. | Coordination of metabolic responses in adjacent cells within the tubular epithelium [25]. |

The transfer process is typically initiated by distress signals from injured renal tubular cells, such as elevated reactive oxygen species (ROS) or the release of ADP [25] [28]. MSCs sense these signals and respond by initiating the formation of TNTs or packaging mitochondria into EVs. The efficiency of this process can be enhanced by engineering MSCs to overexpress Miro1, a protein critical for mitochondrial trafficking along the cytoskeleton [25].

Diagram 1: Mitochondrial Transfer Pathway in AKI. This diagram illustrates the sequence from initial kidney injury to cellular recovery via different mitochondrial transfer mechanisms.

Quantitative Data on Mitochondrial Transfer Efficacy in Preclinical AKI Models

Evidence from preclinical studies robustly supports the therapeutic potential of MSC-mediated mitochondrial transfer in AKI. The following table summarizes key quantitative findings from recent research.

Table 2: Efficacy of MSC-Mediated Mitochondrial Transfer in Preclinical AKI Models

| AKI Model / Intervention | Key Measured Outcomes | Reported Results | Proposed Primary Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cisplatin-induced AKIMSC co-culture with damaged renal cells | Mitochondrial function restorationReduction in tubular cell apoptosis | Recovery of aerobic respirationSignificant decrease in cell death markers | Mitochondrial donation via TNTs [25] |

| Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury (IRI)Miro1-overexpressing MSCs | Mitochondrial retention in renal tissueFunctional recovery | Enhanced functional kidney recoveryImproved survival of tubular cells | Enhanced TNT-mediated transfer [25] |

| Cisplatin-induced AKIBMSC-derived Exosomes (BMSCs-exo) | Serum creatinine & urea nitrogenTubular injury markers (NGAL, KIM1) | Significant reduction in creatinine/ureaDownregulation of NGAL and KIM1 | EV-mediated paracrine signaling & component transfer [27] |

| General AKI ModelsAdipose-derived MSC-EVs (AMSC-EVs) | Macrophage polarizationInflammatory cytokine levels | Promotion of anti-inflammatory M2 phenotypeAlteration of inflammatory microenvironment | EV-mediated modulation of TXNIP-IKKα/NFκB signaling [12] |

Experimental Protocols for Evaluating Mitochondrial Transfer

Protocol: In Vitro Co-culture System for Visualizing Mitochondrial Transfer

Objective: To directly observe and quantify the transfer of mitochondria from MSCs to cisplatin-injured renal tubular epithelial cells (TECs) in a controlled environment.

Materials:

- Primary Human Renal Proximal Tubular Epithelial Cells (RPTECs): Target recipient cells.

- Human MSCs: Isolated from bone marrow (BMSCs) or adipose tissue (AMSCs). Use passages 3-8.

- Cell Culture Trackers: MitoTracker Deep Red (for MSC mitochondria, red fluorescence) and MitoTracker Green (for total mitochondria, green fluorescence).

- Cisplatin: Nephrotoxic agent to induce injury in TECs.

- Confocal Live-Cell Imaging System: For real-time visualization.

Procedure:

- Cell Preparation and Labeling:

- Culture RPTECs in a 2-chamber co-culture system until 70% confluency.

- Induce injury by adding cisplatin (1-5 µg/mL) for 24 hours.

- Simultaneously, label MSCs with MitoTracker Deep Red (100 nM) for 30 minutes to stain their mitochondria.

- Wash MSCs thoroughly to remove excess dye.

- Co-culture and Imaging:

- Add labeled MSCs to the injured RPTECs in a ratio of 1:10 (MSC:RPTEC).

- After 6-24 hours of co-culture, counterstain all cells with MitoTracker Green (200 nM) for 30 minutes to identify total mitochondrial network.

- Fix cells and image using a confocal microscope with appropriate laser lines.

- Quantification: Mitochondrial transfer is confirmed by the presence of double-positive puncta (red from MSCs within green TECs) and quantified as the percentage of TECs containing MSC-derived mitochondria.

Protocol: In Vivo Evaluation of Mitochondrial Transfer Following Renal Cortex Injection

Objective: To assess the therapeutic efficacy and mitochondrial transfer of MSCs delivered via renal cortex injection in a murine model of cisplatin-induced AKI.

Materials:

- Animals: C57BL/6 mice (8-10 weeks old).

- MSCs: Expressing a fluorescent mitochondrial reporter (e.g., Mito-DsRed).

- Cisplatin: Single intraperitoneal injection (10-15 mg/kg).

- In Vivo Imaging System (IVIS): For tracking cell localization.

- Reagents for Renal Function: Kits for serum creatinine and blood urea nitrogen (BUN).

Procedure:

- AKI Induction and MSC Administration:

- Induce AKI in mice via a single intraperitoneal injection of cisplatin.

- 24 hours post-injury, anesthetize mice and perform a flank incision to expose the kidney.

- Using a Hamilton syringe with a 30-gauge needle, slowly inject 1-2 x 10^5 MSCs suspended in 50 µL of PBS directly into the renal cortex at multiple sites to minimize backflow.

- Include control groups: sham-operated and cisplatin-injected mice receiving PBS only.

- Tissue Collection and Analysis:

- 72-96 hours post-MSC injection, collect blood for creatinine/BUN analysis.

- Perfuse mice with cold PBS, then harvest kidneys.

- Process kidney tissue for:

- Histology (PAS staining): Assess tubular injury score.

- Immunofluorescence: Stain for TEC markers (e.g., Aquaporin-1) and analyze co-localization with the Mito-DsRed signal to confirm mitochondrial transfer in vivo.

- Biochemical Assays: Homogenize cortical tissue to measure ATP levels (using a luciferase-based assay) and ROS (using DCFDA fluorescence).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents for Investigating Mitochondrial Transfer in AKI

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| MitoTracker Probes | Fluorescent dyes that label live-cell mitochondria. | Distinguishing donor vs. recipient mitochondria in co-culture experiments [25]. |

| MSCs with Fluorescent Mitochondrial Reporters | Genetically encoded tags (e.g., Mito-DsRed, Mito-GFP) for stable mitochondrial labeling. | Long-term tracking of transferred mitochondria in vitro and in vivo. |

| Cisplatin | Chemotherapeutic agent used to establish nephrotoxic AKI models. | Inducing mitochondrial damage and dysfunction in renal tubular cells [27]. |

| Miro1-Overexpressing MSCs | Genetically modified MSCs with enhanced mitochondrial motility. | Boosting the efficiency of TNT-mediated mitochondrial transfer in therapeutic applications [25]. |

| Extracellular Vesicle Isolation Kits | Ultracentrifugation or polymer-based kits for purifying MSC-EVs. | Investigating the EV-mediated mitochondrial transfer pathway [12] [27]. |

| Antibodies for CD9, CD63, CD81 | Surface markers for characterizing and validating isolated extracellular vesicles. | Confirming the successful isolation of EVs from MSC conditioned media [12]. |

Mitochondrial transfer represents a paradigm shift in understanding how MSCs facilitate tissue repair in AKI, moving beyond traditional paracrine mechanisms to direct organelle-based bioenergetic rescue. The protocols outlined herein for visualizing and quantifying this process—from in vitro co-cultures to renal cortex injection models—provide a robust framework for researchers to explore and enhance this novel therapeutic avenue. As the field advances, strategies to improve the efficiency of mitochondrial transfer, such as MSC preconditioning or genetic engineering, hold significant promise for developing next-generation regenerative therapies for acute kidney injury.

Cell replenishment is critical for adult tissue repair after damage. Unlike the liver, the kidney has a limited inherent regeneration capacity. For years, it was even considered unable to regenerate itself [29] [30]. However, recent research has demonstrated that mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) contribute significantly to renal repair primarily through paracrine mechanisms rather than direct differentiation [29] [30] [31]. When MSCs are administered, they secrete a diverse array of bioactive molecules that collectively create a regenerative milieu capable of constraining renal damage and amplifying endogenous repair processes [29] [30].

Among the numerous factors secreted by MSCs, Hepatocyte Growth Factor (HGF), Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF), and Insulin-like Growth Factor-1 (IGF-1) have emerged as crucial mediators of tubular regeneration [29] [30] [31]. These factors work in concert to modulate inflammation, inhibit apoptosis, counteract oxidative stress, and stimulate the proliferation of surviving tubular epithelial cells [31] [20]. This Application Note delineates the specific roles, mechanisms, and experimental assessment methodologies for these key paracrine factors within the context of MSC-based therapy for Acute Kidney Injury (AKI), providing researchers with essential protocols for investigating tubular regeneration.

Factor-specific Mechanisms and Assessment

Hepatocyte Growth Factor (HGF)

Mechanisms in Tubular Regeneration: HGF demonstrates potent anti-apoptotic, anti-inflammatory, and mitogenic properties specifically targeted to renal tubules. It inhibits TLR2 and TLR4 signaling pathways, thereby alleviating high glucose-induced inflammatory responses in podocytes and tubular cells [20]. Furthermore, HGF plays a role in reversing epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT), a key process in fibrosis development, thereby preserving the epithelial phenotype of tubular structures and preventing pathological transition to a profibrotic state [32].

Quantitative Assessment of HGF Efficacy: Table: Experimental Outcomes of HGF-Associated Interventions in Preclinical AKI Models

| Intervention Type | AKI Model | Key Efficacy Parameters | Outcome Measures | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| hUMSCs secreting HGF | Diabetic Nephropathy Mice | Glomerulosclerosis, Renal Fibrosis, TLR2/4 Pathway | Significant reduction in fibrosis markers and inflammatory pathway activation | [20] |

| MSC-Conditioned Medium (HGF-rich) | Albumin-Induced Tubulinjury | Tubular Inflammation, Fibrosis | Amelioration of tubular injury via HGF and TSG-6 | [31] |

| Low Serum Cultured Adipose Stromal Cells | Acute Kidney Injury | Tubular Repair, Functional Recovery | Primary mediator of renoprotective effect identified as HGF | [31] |

Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF)

Mechanisms in Tubular Regeneration: VEGF is a master regulator of angiogenesis, the process of forming new blood vessels. It is critically important for restoring the peritubular capillary network that is often compromised during ischemic AKI [29] [33]. By promoting endothelial cell survival, proliferation, and migration, VEGF ensures adequate oxygen and nutrient delivery to the regenerating tubules, facilitating their repair [11]. Its expression is upregulated in early stages of chronic allograft nephropathy, highlighting its role in the initial tissue response to injury [34].

Quantitative Assessment of VEGF Efficacy: Table: Experimental Outcomes of VEGF-Associated Interventions in Preclinical AKI Models

| Intervention Type | AKI Model | Key Efficacy Parameters | Outcome Measures | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hypoxic Preconditioned MSCs (↑VEGF) | Gentamicin-Induced Renal Failure | Renal Function, HGF/VEGF/Integrin Expression | Ameliorated renal function, increased VEGF expression | [11] |

| 5% O₂ Preconditioned AD-MSCs | Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury | EVs Number, Protein Concentration, Oxidative Reactions | Reduced oxidative stress, protected kidney function | [11] |

| Growth Factor-Modified MSCs | Acute Kidney Injury | Renal Repair, Capillary Density | Superior therapeutic potential via paracrine signaling | [33] |

Insulin-like Growth Factor-1 (IGF-1)

Mechanisms in Tubular Regeneration: IGF-1 is a powerful stimulator of cellular proliferation and differentiation. In the context of tubular repair, it enhances the proliferation and dedifferentiation of surviving tubular epithelial cells, enabling them to repopulate damaged segments of the nephron [29] [33]. IGF-1 signaling activates downstream pathways such as PI3K/Akt and MAPK, which promote cell cycle progression and inhibit pro-apoptotic signals, thus creating a favorable environment for tubular regeneration [31]. Its signaling pathway is significantly upregulated in moderate to severe chronic kidney injury, indicating a sustained role in the repair process [34].

Quantitative Assessment of IGF-1 Efficacy: Table: Experimental Outcomes of IGF-1-Associated Interventions in Preclinical AKI Models

| Intervention Type | AKI Model | Key Efficacy Parameters | Outcome Measures | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human Amniotic Fluid Stem Cells | Cisplatin-Induced Kidney Injury | Paracrine Mediators (IGF-1, IL-6, VEGF) | Renoprotective effect mediated by IGF-1 and other factors | [31] |

| Bone Marrow-Derived MSCs | Ischemic Acute Kidney Injury | Apoptosis Inhibition, Endogenous Cell Proliferation | Protected kidney via trophic factors including IGF-1 | [31] |

| Meta-analysis of CAN/IFTA | Transplant Nephropathy | IGF-1 Signaling Pathway | Significant upregulation in moderate/severe chronic injury | [34] |

Integrated Signaling Pathways in Tubular Regeneration

The factors HGF, VEGF, and IGF-1 mediate their regenerative effects through interconnected signaling networks that coordinate the repair of damaged renal tubules. The following diagram illustrates the key pathways and their cellular outcomes:

Experimental Protocols for Factor Analysis

Protocol: In Vivo Assessment of Paracrine Factors in MSC-Treated AKI

Objective: To evaluate the therapeutic efficacy and mechanism of action of MSC-derived paracrine factors (HGF, VEGF, IGF-1) in a rodent model of gentamicin-induced AKI [3].

Materials:

- Sprague-Dawley rats (200-250g)

- Gentamicin sulfate

- MSC population (e.g., Bone Marrow-MSCs, Tonsil-MSCs, or Adipose Tissue-MSCs)

- PKH26 fluorescent cell linker dye

- ELISA kits for HGF, VEGF, IGF-1, BUN, Creatinine

- Antibodies for TUNEL staining, Bax, Bcl-2, KIM-1, NGAL

Procedure:

- AKI Induction: Administer gentamicin (70 mg/kg/day, i.p.) for 10 consecutive days.

- MSC Preparation and Labeling:

- Culture MSCs to 80% confluence in standard conditions.

- Label 1×10^7 cells with PKH26 dye according to manufacturer's protocol for in vivo tracking.

- Cell Administration: On day 11, inject labeled MSCs via tail vein in 500μL saline solution.

- Tissue and Fluid Collection: On day 16, sacrifice animals and collect:

- Blood for BUN and creatinine measurement

- Urine for biomarker analysis (KIM-1, NGAL, 8-OHdG)

- Kidney tissue for histology and protein analysis

- Tract MSCs: Localize PKH26-labeled MSCs in renal cortex using fluorescence microscopy.

- Assess Renal Function: Quantify BUN and creatinine levels using commercial assay kits.

- Evaluate Apoptosis: Perform TUNEL staining on kidney sections; analyze apoptotic ratio (TUNEL-positive cells/total cells).

- Measure Oxidative Stress: Quantify urinary 8-OHdG using oxidative DNA damage ELISA kit.

- Analyze Factor Expression: Determine HGF, VEGF, and IGF-1 levels in serum and renal tissue lysates via ELISA.

Expected Outcomes: The GM+MSC group should show significantly lower BUN, creatinine, tubular damage scores, apoptosis, and oxidative stress markers compared to the GM-only group. PKH26 staining should demonstrate MSC localization in renal tubules, confirming engraftment.

Protocol: In Vitro Coculture System for Paracrine Factor Analysis

Objective: To investigate the direct paracrine effects of MSCs on injured renal tubular epithelial cells (NRK cells) in a controlled microenvironment [3].

Materials:

- NRK-52E rat renal tubular epithelial cell line

- MSC population (any source)

- Transwell coculture system (0.4μm pore size)

- Gentamicin for injury induction

- Conditioned media collection facilities

- HGF, VEGF, IGF-1 neutralizing antibodies

- Apoptosis detection kit (Annexin V/PI)

- DCFDA assay for ROS detection

Procedure:

- Cell Culture Setup:

- Plate NRK-52E cells in the lower chamber of transwell system.

- Plate MSCs in the upper chamber insert.

- Tubular Cell Injury: Add gentamicin (2-5mM) to both chambers for 24-48 hours.

- Conditioned Media Collection: Harvest media from coculture system after 48 hours for subsequent factor analysis.

- Viability and Apoptosis Assessment:

- Detect apoptosis in NRK cells using Annexin V/PI flow cytometry.

- Measure cell viability via MTT assay.

- Oxidative Stress Measurement: Quantify intracellular ROS in NRK cells using DCFDA fluorescent dye.

- Factor Neutralization Studies:

- Add neutralizing antibodies against HGF, VEGF, or IGF-1 individually or in combination to the coculture system.

- Assess which antibody treatment most significantly abrogates the protective effects of MSCs.

- Pathway Analysis: Perform Western blotting on NRK cell lysates to analyze activation of PI3K/Akt, MAPK, and other downstream pathways.

Expected Outcomes: MSC coculture should significantly reduce gentamicin-induced apoptosis and ROS generation in NRK cells. Neutralization of HGF, VEGF, and IGF-1 should partially reverse these protective effects, confirming their role in the paracrine mechanism.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table: Key Reagents for Investigating Paracrine Factors in Renal Regeneration

| Reagent / Assay | Specific Example | Research Application | Experimental Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| ELISA Kits | HGF, VEGF, IGF-1 ELISA | Quantification in serum, urine, tissue lysates | Measures concentration of target growth factors |

| Neutralizing Antibodies | Anti-HGF, Anti-VEGF, Anti-IGF-1 | In vitro coculture neutralization studies | Blocks specific factor activity to confirm mechanistic role |

| Cell Tracking Dyes | PKH26, PKH67 | In vivo cell fate studies | Fluorescently labels MSCs for localization post-transplantation |

| Renal Injury Markers | KIM-1, NGAL ELISA | Assessment of tubular damage | Quantifies severity of kidney injury and recovery |

| Apoptosis Assays | TUNEL Staining, Annexin V/PI | Detection of programmed cell death | Evaluates anti-apoptotic effects of paracrine factors |

| Oxidative Stress Kits | 8-OHdG ELISA, DCFDA Assay | Measurement of ROS and DNA damage | Assesses oxidative stress levels in renal tissue and cells |

| Pathway Inhibitors | PI3K/Akt inhibitors, MAPK inhibitors | Mechanistic signaling studies | Blocks specific downstream pathways to elucidate mechanisms |

Strategic Enhancement of MSC Paracrine Activity

Research indicates that the native paracrine activity of MSCs can be substantially enhanced through various preconditioning strategies to improve therapeutic outcomes for AKI [11]:

Hypoxic Preconditioning: Culturing MSCs under low oxygen conditions (1-5% O₂) significantly enhances their secretion of HGF, VEGF, and other regenerative factors, improving their survival, migration, and therapeutic potential after transplantation into the ischemic kidney microenvironment [11].

Pharmacological Preconditioning: Treatment with FDA-approved drugs like Chlorzoxazone can induce MSCs to adopt an anti-inflammatory phenotype, strengthening their immunosuppressive capacity without increasing immunogenicity. Similarly, Atorvastatin pretreatment synergistically enhances the inherent therapeutic effects of BMSCs [11].

Genetic Modification: Engineering MSCs to overexpress specific growth factors (HGF, VEGF) or pro-survival genes further amplifies their paracrine activity and renal protective effects, offering a promising strategy to maximize therapeutic efficacy [11] [33].

The paracrine factors HGF, VEGF, and IGF-1 serve as critical mediators of tubular regeneration in MSC-based therapies for AKI. Through their coordinated actions on multiple cellular processes—including apoptosis inhibition, proliferation stimulation, angiogenesis, and inflammation modulation—these factors create a regenerative microenvironment conducive to renal repair. The protocols and methodologies outlined in this Application Note provide researchers with robust tools for investigating these mechanisms and developing enhanced therapeutic strategies for acute kidney injury.

Technical Implementation of Renal Cortex Injection for MSC Delivery

A critical challenge in mesenchymal stem cell (MSC)-based therapy for acute kidney injury (AKI) is the efficient delivery of cells to the target site. The administration route directly determines the initial biodistribution of MSCs, influencing engraftment, retention, and ultimate therapeutic efficacy [35] [36]. This application note examines the fundamental advantage of local administration strategies, particularly renal cortex injection, over systemic delivery, with a focus on the critical mechanism of bypassing pulmonary trapping to enhance renal-specific homing. This is framed within the broader research context of optimizing MSC paracrine therapy for AKI, where delivering a sufficient concentration of cells to the injured renal tissue is paramount for harnessing their reparative effects.

Comparative Analysis: Local vs. Systemic Administration

The Pulmonary First-Pass Effect in Systemic Administration

Intravenous (IV) infusion, the most common systemic route, is hindered by the pulmonary first-pass effect. Upon injection, a significant proportion of MSCs are physically trapped in the capillary networks of the lungs [35] [36]. This occurs because MSCs are larger than most capillaries and exhibit adhesive interactions with the pulmonary endothelium [36]. The liver also sequesters a considerable number of cells [35]. This nonspecific distribution results in an inadequate therapeutic concentration of MSCs reaching the kidneys and necessitates higher, potentially risky, cell doses to achieve a therapeutic effect in the target organ [35] [36].

Local Administration for Targeted Delivery

In contrast, local administration methods, such as direct renal injection, inoculate MSCs precisely into the kidney, circumventing the systemic circulation and the pulmonary filter [35] [2]. This approach significantly increases the number of cells initially present at the site of injury, enhancing the potential for local engraftment and paracrine activity [35].

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of Administration Routes for MSC Delivery to Kidney

| Administration Route | Key Advantage | Primary Limitation | Reported Renal Retention/Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intravenous (IV) | Minimally invasive, simple [35] | High pulmonary/liver sequestration; low renal delivery [35] [36] | Low engraftment; inadequate therapeutic concentration [35] |

| Intra-arterial (IA) | Bypasses pulmonary filter [35] | Risk of cell embolism; more traumatic [35] | More efficacious than IV, but safety concerns [35] |

| Local (e.g., Renal Cortex/Parenchymal Injection) | Direct delivery to site of injury; avoids pulmonary trap [35] [2] | More invasive; potential for injection-site injury [35] | High initial retention; superior functional and histological improvement in preclinical AKI models [35] [37] |

Table 2: Preclinical Evidence Supporting Local Administration for AKI

| Reference | Year | Animal Model | MSC Source | Local Injection Method | Key Renal Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Huang et al. [35] | 2022 | Mice (I/R) | Umbilical Cord | Subcapsular / Parenchymal | Improved renal function and tubular repair; Reduced injury and fibrosis |

| Wang et al. [35] | 2020 | Mice (I/R) | Human Placenta | Subcortical | Recovery of function; Facilitated angiogenesis; Decreased fibrosis |

| Paglione et al. [35] | 2020 | Rats (I/R) | Human Omental | Parenchymal | Accelerated functional recovery; Ameliorated tubular injury |

| Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology [37] | 2024 | Mice (UUO) | Human Adipose | Local vs. Systemic | Local delivery reduced collagen deposition and increased IL-10; Systemic administration showed no significant effect. |

Experimental Protocols for Local Renal Administration

Protocol 1: Ultrasound-Guided Renal Artery Injection in Mice

This protocol describes a minimally invasive method for local delivery of MSCs to the kidney via the renal artery, adapted from a study that achieved high initial renal cell retention [38].

Key Materials:

- Luciferase/GFP-expressing human Adipose-Derived Stem Cells (ADSCs)

- Silica-coated Gold Nanorods (GNRs) for photoacoustic imaging

- 0.6% (w/v) Alginate solution in saline

- Small animal ultrasound system with high-frequency transducer (e.g., 40 MHz)

- Isoflurane anesthesia system

Methodology:

- Cell Preparation: Label ADSCs with silica-coated GNRs (incubate for 24 hours). Post-incubation, wash and resuspend 2x10^5 cells in 100 µL of 0.6% alginate solution [38].

- Animal Preparation: Anesthetize a 6-8 week old female nude mouse and position it in the left lateral decubitus position. Maintain body temperature at 37°C [38].

- Ultrasound Guidance: Using the ultrasound platform, acquire a colour Doppler image of the right kidney to visualize the renal artery and vein. Use pulsed-wave Doppler to confirm vessel identity based on flow waveforms [38].

- Injection Procedure: Under real-time ultrasound guidance, advance a needle through the paravertebral muscle and into the renal artery. Slowly inject the 100 µL cell-alginate suspension over approximately 15 seconds. Hyperechogenicity from the alginate will be visible around the renal cortex upon successful injection [38].

- Post-injection: Hold the needle in place for 15 seconds after injection before slow withdrawal to prevent backflow. Confirm return of renal artery flow via colour Doppler within 20 seconds post-injection [38].

- Cell Tracking: Serially track cell viability and localization using bioluminescence imaging (BLI) and photoacoustic (PA) imaging over 7 days. This study reported approximately 29% of the total BLI signal in the target kidney at 1 hour post-injection, with signals persisting for 3 days [38].

Protocol 2: Direct Renal Parenchymal/Cortex Injection

This method involves the direct injection of MSCs into the renal tissue, a common approach in preclinical AKI studies [35].

Key Materials:

- Bone Marrow or Adipose-derived MSCs

- Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) or Hydrogel carrier (e.g., Alginate, Collagen)

- Sterile surgical instruments for laparotomy

- Hamilton syringe with a 30-gauge needle

Methodology:

- Cell Preparation: Harvest and resuspend MSCs (e.g., 1x10^6 cells) in an appropriate carrier, such as 50 µL of PBS or a biocompatible hydrogel, to enhance retention [35] [2].

- Surgical Exposure: Perform a minimally invasive laparotomy on an anesthetized rodent (e.g., rat or mouse) to expose the kidney.

- Injection Procedure: Using a Hamilton syringe, carefully inject the cell suspension at multiple sites (e.g., 2-3 sites) into the renal cortex or subcapsular space to distribute the cells. Control injection speed to minimize tissue damage and backflow.

- Post-injection Monitoring: After injection, return the kidney to the abdominal cavity and close the surgical site. Monitor animals for recovery and signs of distress. Assess renal function (serum creatinine, BUN) and histology (H&E, Masson's Trichrome) at predetermined endpoints to evaluate efficacy [35].

Visualization of Administration Routes and Cell Fate

MSC Administration Routes and Biodistribution

Experimental Workflow for Local MSC Delivery

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Local MSC Delivery Experiments

| Research Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Gold Nanorods (GNRs), silica-coated | High-contrast agent for photoacoustic cell tracking; allows non-invasive visualization of MSC localization post-delivery [38]. | Tracking ADSCs in mouse kidney for 7 days post ultrasound-guided renal artery injection [38]. |