Small Extracellular Vesicles vs. Apoptotic Vesicles: A Comparative Analysis for Advanced Skin Regeneration

This article provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of two prominent classes of extracellular vesicles—small extracellular vesicles (sEVs) and apoptotic vesicles (ApoEVs)—for therapeutic skin regeneration.

Small Extracellular Vesicles vs. Apoptotic Vesicles: A Comparative Analysis for Advanced Skin Regeneration

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of two prominent classes of extracellular vesicles—small extracellular vesicles (sEVs) and apoptotic vesicles (ApoEVs)—for therapeutic skin regeneration. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it synthesizes foundational biology, biogenesis, and cargo. The content delves into methodological considerations for isolation and characterization, explores preclinical efficacy in diabetic and non-diabetic wound models, and directly compares therapeutic outcomes, including wound closure rates, collagen deposition, and revascularization capacity. Furthermore, it addresses critical challenges in production scalability, standardization, and clinical translation, offering a validated, evidence-based perspective to guide future research and therapeutic development in regenerative dermatology.

Decoding the Biology: Origins, Biogenesis, and Cargo of sEVs and ApoEVs

In the field of skin regeneration, extracellular vesicles (EVs) have emerged as pivotal mediators of intercellular communication, offering promising therapeutic potential. Among these, two major classes have gained significant research attention: small extracellular vesicles (sEVs) and apoptotic extracellular vesicles (ApoEVs). sEVs, which include exosomes and ectosomes, are secreted by living cells and play crucial roles in maintaining tissue homeostasis. In contrast, ApoEVs are generated during programmed cell death and participate in clearance mechanisms and immune regulation. Understanding the fundamental distinctions between these vesicle types is essential for researchers and drug development professionals seeking to harness their regenerative capabilities for wound healing and skin repair. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of their biological characteristics, functional efficacy, and experimental methodologies based on current scientific evidence.

Definitions and Key Characteristics

Classification and Biogenesis

EVs are classified based on their biogenesis pathways, size ranges, and compositional characteristics. The table below summarizes the key distinguishing features of sEVs and ApoEVs:

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of sEVs and ApoEVs

| Characteristic | sEVs (Small Extracellular Vesicles) | ApoEVs (Apoptotic Extracellular Vesicles) |

|---|---|---|

| Biogenesis | Secreted by living cells via endosomal pathway (exosomes) or plasma membrane budding (ectosomes) [1] [2] | Generated during apoptotic cell disassembly [2] [3] |

| Size Range | 30-200 nm (sEVs); exosomes: 30-150 nm; ectosomes: 100-1000 nm [4] | Highly heterogeneous: ApoSEVs (<1 μm), ApoBDs (1-5 μm) [5] [2] |

| Key Markers | Tetraspanins (CD9, CD63, CD81), TSG101, ALIX [4] | Phosphatidylserine exposure, histones (in ApoBDs) [2] [3] |

| Morphology | Cup-shaped (exosomes), spherical [4] | Heterogeneous; often contain organelles [2] |

| Primary Functions | Intercellular communication, signal transduction, homeostasis maintenance [6] [4] | Efferocytosis mediation, immunomodulation, "find me" and "eat me" signaling [7] [3] |

Subtype Classification

Both sEVs and ApoEVs encompass distinct subtypes that vary in their biogenesis and physical properties:

sEV Subtypes: The sEV category primarily includes exosomes (originating from multivesicular bodies) and ectosomes/microvesicles (budding directly from the plasma membrane) [1]. The International Society for Extracellular Vesicles recommends using "sEV" as an operational term for vesicles under 200nm that may include both biogenesis pathways [5] [8].

ApoEV Subtypes: ApoEVs include apoptotic small EVs (ApoSEVs, <1μm), apoptotic microvesicles (ApoMVs, 100-1000nm), and apoptotic bodies (ApoBDs, 1-5μm) [5] [3]. These subtypes differ in content and function; for instance, ApoBDs often contain intact organelles and nuclear fragments, while ApoSEVs are richer in specific signaling molecules [3].

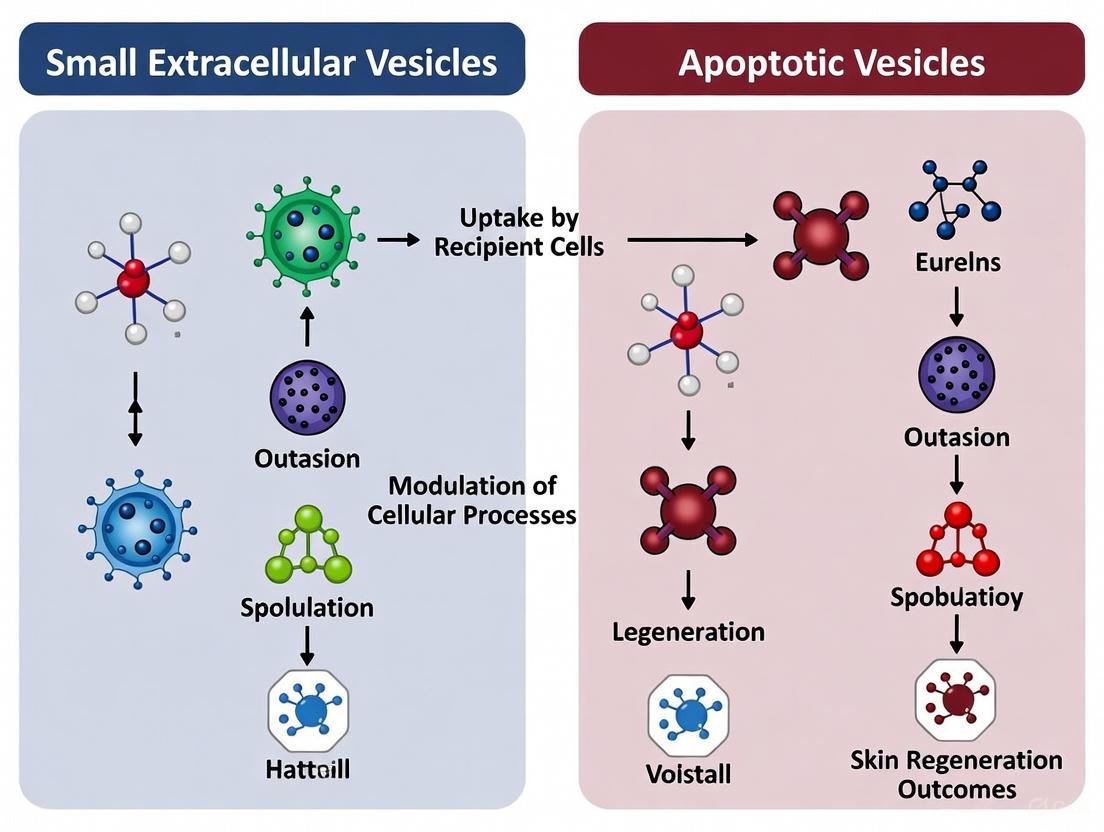

Figure 1: Biogenesis Pathways of sEVs and ApoEVs. sEVs originate from living cells via endosomal (exosomes) or plasma membrane budding (ectosomes) pathways. ApoEVs are generated during apoptotic cell disassembly through membrane blebbing and fragmentation processes.

Quantitative Therapeutic Efficacy in Skin Regeneration

Comparative Performance in Preclinical Models

Recent meta-analyses of preclinical studies provide quantitative evidence for the therapeutic potential of both sEVs and ApoEVs in wound healing and skin regeneration. The following table summarizes key efficacy metrics from animal studies:

Table 2: Therapeutic Efficacy of sEVs vs. ApoEVs in Skin Regeneration Models

| Efficacy Parameter | sEVs Performance | ApoEVs Performance | Comparative Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wound Closure Rate | Significant improvement in both diabetic and non-diabetic models [8] | ApoSEVs showed better efficacy than ApoBDs and sEVs in wound closure outcome [5] | ApoSEVs > sEVs > ApoBDs |

| Collagen Deposition | Enhanced collagen fiber organization and density [8] | ApoSEVs superior to ApoBDs and sEVs in collagen deposition [5] | ApoSEVs > sEVs > ApoBDs |

| Revascularization | Promoted angiogenesis and increased blood vessel density [5] [8] | sEVs displayed better revascularization than ApoEVs [5] | sEVs > ApoEVs |

| Scar Width | Reduced scar formation in full-thickness wounds [5] | Limited comparative data available | Similar beneficial effects |

| Anti-inflammatory Effects | Modulated macrophage polarization toward M2 phenotype [8] [6] | Significant anti-inflammatory properties via immune cell regulation [7] [3] | ApoEVs may have superior immunomodulatory capacity |

Optimal Administration and Source Selection

Beyond vesicle type, administration parameters and cellular sources significantly influence therapeutic outcomes:

Administration Route: Subcutaneous injection demonstrated superior wound closure, collagen deposition, and revascularization compared to topical dressing/covering approaches [5].

MSC Source Efficacy: In sEV therapies, adipose-derived stem cells (ADSCs) showed the best effect on wound closure rate and collagen deposition, while bone marrow MSCs (BMMSCs) displayed superior revascularization potential [5].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Isolation and Characterization Standards

Robust experimental protocols are essential for reliable vesicle research. The following methodologies represent current best practices:

Table 3: Standardized Methodologies for EV Research

| Experimental Step | Standard Protocol | Key Quality Controls |

|---|---|---|

| Vesicle Isolation | Differential ultracentrifugation (current gold standard) [4]; Alternative methods: ultrafiltration, size-exclusion chromatography, polymer precipitation [9] | Assessment of yield and purity; combination of methods often required for high purity [4] |

| MSC Characterization | International Society for Cell & Gene Therapy (ISCT) criteria: plastic adherence, multilineage differentiation, surface marker expression (CD73+, CD90+, CD105+, CD34-, CD45-) [5] [8] | 79.5% of studies in recent meta-analysis met all three ISCT criteria [5] |

| EV Characterization | MISEV2018/2023 guidelines: size distribution (NTA, TRPS), morphology (EM), marker detection (tetraspanins, TSG101 for sEVs; phosphatidylserine for ApoEVs) [5] [8] [9] | Protein quantification, particle concentration, assessment of contaminating proteins |

| Functional Assays | In vitro: migration, proliferation, tube formation assays; In vivo: full-thickness excisional wounds in murine models (most common) [5] [8] | Inclusion of appropriate controls; standardization of dosing (particles/wound area) |

Experimental Workflow Visualization

Figure 2: Standard Experimental Workflow for EV Skin Regeneration Studies. This diagram outlines the key steps from vesicle isolation through functional validation, highlighting critical quality control checkpoints.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful investigation of EVs for skin regeneration requires specific reagents and methodologies. The following table catalogs essential research tools and their applications:

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for EV Studies in Skin Regeneration

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| MSC Culture Media | MesenCult, StemMACS, DMEM/F12 with FBS/exosome-free FBS | Maintenance of MSC sources prior to EV collection [5] [10] |

| EV Isolation Kits | Total Exosome Isolation Kit, exoEasy Kit, PEG-based precipitation reagents | Alternative to ultracentrifugation for small-scale studies [4] [9] |

| Characterization Antibodies | Anti-CD63, CD81, CD9, TSG101, ALIX (sEVs); Annexin V, Phosphatidylserine (ApoEVs) | Western blot, flow cytometry, and immuno-EM validation of EV identity [5] [3] [9] |

| Characterization Instruments | Nanoparticle Tracking Analyzer (NTA), Tunable Resistive Pulse Sensing (TRPS), Electron Microscope | Size distribution and concentration analysis [9] |

| Animal Models | C57BL/6 mice, SD rats; diabetic models (STZ-induced, db/db) | In vivo efficacy testing in physiologically relevant systems [5] [8] |

| Histological Stains | H&E, Masson's Trichrome, Picrosirius Red, CD31 immunohistochemistry | Assessment of tissue architecture, collagen deposition, and angiogenesis [5] |

sEVs and ApoEVs represent distinct classes of extracellular vesicles with unique biogenesis pathways, structural characteristics, and functional properties in skin regeneration. While both demonstrate significant therapeutic potential, current evidence suggests they may excel in different aspects of wound healing: ApoSEVs appear superior for wound closure and collagen deposition, while sEVs show enhanced revascularization capacity. These differential efficacy profiles highlight the importance of vesicle selection based on specific therapeutic objectives. For researchers pursuing EV-based skin regeneration therapies, adherence to standardized characterization protocols (MISEV guidelines), careful consideration of administration routes, and selection of appropriate cellular sources are critical factors influencing experimental outcomes and translational potential. The growing body of comparative evidence provides a foundation for rational design of EV-based therapeutics tailored to specific clinical needs in dermatology and regenerative medicine.

In the rapidly advancing field of regenerative medicine, particularly for skin regeneration, extracellular vesicles (EVs) have emerged as potent therapeutic agents. These nano-sized lipid bilayer vesicles facilitate intercellular communication by transferring functional proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids to recipient cells, thereby modulating physiological responses and promoting tissue repair [11] [12]. However, all EVs are not created equal. Their biological functions and therapeutic potential are fundamentally dictated by their distinct biogenesis pathways. This guide provides a comprehensive objective comparison between two primary EV classes: small extracellular vesicles (sEVs), which originate from the endosomal system, and apoptotic vesicles (ApoEVs), which are generated through apoptotic cell dismantling. Understanding these differences is crucial for researchers and drug development professionals selecting the optimal EV type for specific skin regeneration applications.

Defining the Vesicles: Origins and Key Identifiers

Small Extracellular Vesicles (sEVs/Exosomes)

Small Extracellular Vesicles, commonly known as exosomes, are defined by their endosomal origin. Their biogenesis begins with the inward budding of the endosomal membrane, leading to the formation of multivesicular bodies (MVBs) filled with intraluminal vesicles (ILVs) [13] [12]. These MVBs subsequently fuse with the plasma membrane, releasing the ILVs into the extracellular space as exosomes or sEVs [12]. They are typically 30-200 nm in diameter and are characterized by a specific set of protein markers reflective of their biogenesis pathway, including tetraspanins (CD63, CD81, CD9), ESCRT-related proteins (TSG101, Alix), and heat shock proteins (Hsp70, Hsp90) [13] [11] [12].

Apoptotic Vesicles (ApoEVs)

Apoptotic Vesicles are a broad category of EVs produced during the programmed cell death process of apoptosis. This process involves cytoplasmic and nuclear condensation, followed by the cell membrane contracting and splitting to enclose cellular components within membrane-bound vesicles [7]. ApoEVs can be further sub-classified based on their size and formation stage, including microvesicles (MVs, 100 nm-1 μm) and apoptotic bodies (ApoBDs, 100 nm-5 μm) [14] [7]. They display "find-me" and "eat-me" signals, such as phosphatidylserine exposure, which promote their recognition and clearance by phagocytes, a process critical for tissue homeostasis known as efferocytosis [7].

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of sEVs and ApoEVs

| Characteristic | Small Extracellular Vesicles (sEVs/Exosomes) | Apoptotic Vesicles (ApoEVs) |

|---|---|---|

| Biogenesis Origin | Endosomal system; released upon MVB fusion with plasma membrane [13] [12] | Apoptotic cell dismantling; formed through membrane blebbing and fission [7] |

| Size Range | 30-200 nm [12] | 100 nm - 5 μm [14] [7] |

| Key Morphology | Spheroid or cup-shaped [12] | Heterogeneous in size and content [7] |

| Common Markers | Tetraspanins (CD63, CD81, CD9), TSG101, Alix [13] [12] | Phosphatidylserine exposure, Caspase-cleaved products [7] |

Comparative Analysis of Biogenesis Mechanisms

The journey of a vesicle from its cellular origin to its release is a complex process governed by distinct molecular machinery. The diagrams below delineate these pathways for sEVs and ApoEVs.

sEV Biogenesis via the Endosomal System

sEV formation is a multi-step process occurring within the endosomal network. It involves the coordinated effort of various molecular complexes to create, sort, and eventually release the vesicles.

The sEV biogenesis pathway involves:

- Initiation and Cargo Sorting: Early endosomes mature into late endosomes or MVBs. The formation of ILVs within MVBs is driven primarily by the Endosomal Sorting Complex Required for Transport (ESCRT) machinery, which includes proteins like TSG101 and Alix that sort ubiquitinated cargoes [13] [12]. ESCRT-independent mechanisms also exist, often involving tetraspanin-enriched microdomains (CD9, CD63) and lipids like ceramide [13].

- MVB Fate and Vesicle Release: MVBs face one of two fates: degradation via fusion with lysosomes or secretion. For sEV release, MVBs are transported along the cytoskeleton to the plasma membrane, where they dock and fuse, a process mediated by SNARE proteins and RAB GTPases [12]. This fusion releases the ILVs into the extracellular space as sEVs [13].

ApoEV Biogenesis via Apoptotic Dismantling

The formation of ApoEVs is a hallmark of apoptosis, designed to package the dying cell's contents for efficient disposal and signaling.

The ApoEV biogenesis pathway involves:

- Apoptotic Trigger and Caspase Activation: Both intrinsic (cellular stress) and extrinsic (death ligands) pathways converge on the activation of caspases, a family of proteases that are the executioners of apoptosis [7].

- Membrane Blebbing and Vesicle Formation: Caspase activity leads to the disassembly of the cytoskeleton and activation of enzymes like ROCK I. This causes the cell membrane to bleb and fragment, pinching off into ApoEVs of various sizes [7].

- "Find-Me" and "Eat-Me" Signals: A critical step is the exposure of phosphatidylserine (PS) on the outer leaflet of the ApoEV membrane. This serves as a key "eat-me" signal for phagocytic cells like macrophages, initiating efferocytosis—the clearance of apoptotic debris [7].

Functional Outcomes in Skin Regeneration

The distinct origins of sEVs and ApoEVs endow them with different biological functions, which directly influences their therapeutic potential in skin regeneration, a process involving inflammation control, matrix remodeling, and tissue growth.

Mechanisms of sEVs in Skin Rejuvenation

sEVs, particularly those derived from mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), have shown remarkable promise in combating skin aging and promoting repair. Their mechanisms are largely mediated by their cargo of proteins and miRNAs [11].

- Anti-Oxidative Stress: HucMSC-derived sEVs have been shown to reduce reactive oxygen species (ROS) production in skin cells exposed to UVB radiation or H₂O₂. They can activate the SIRT1-dependent antioxidant pathway and inhibit the MAPK/AP-1 pathway, thereby reducing oxidative damage and cell senescence [11].

- Promoting Matrix Synthesis: sEVs can enhance collagen production and suppress its degradation. For instance, they increase the expression of type I collagen in fibroblasts while decreasing the expression of matrix metalloproteinase-1 (MMP-1), a key enzyme that breaks down collagen. This helps restore the skin's extracellular matrix, reducing wrinkles and improving elasticity [11].

- Modulating Inflammation: sEVs from MSCs can downregulate pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6, and inhibit the NF-κB signaling pathway, creating an anti-inflammatory environment conducive to healing [11].

Mechanisms of ApoEVs in Skin Repair

ApoEVs, once considered mere waste bags, are now recognized as active regulators of tissue regeneration, primarily through their role in efferocytosis and immune modulation.

- Efferocytosis and Inflammation Resolution: The clearance of ApoEVs by macrophages via efferocytosis is not a passive process. It actively promotes the release of regenerative cytokines and drives macrophages toward an anti-inflammatory (M2) phenotype, which is crucial for resolving inflammation and initiating tissue repair [7].

- Activation of Regenerative Pathways: Studies indicate that MSC-derived ApoEVs can promote wound healing and hair growth by activating the Wnt/β-catenin pathway in skin and hair follicle stem cells [15]. This pathway is fundamental for cell proliferation and tissue regeneration.

- Direct Anti-inflammatory Action: ApoEVs possess intrinsic anti-inflammatory properties. They can polarize anti-inflammatory macrophages and suppress the activity of pro-inflammatory T helper cells (Th1, Th17), while activating regulatory T cells. This makes them a promising therapeutic tool for various inflammatory disorders [7].

Table 2: Functional Comparison in Skin Regeneration Context

| Functional Aspect | Small Extracellular Vesicles (sEVs) | Apoptotic Vesicles (ApoEVs) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Role in Skin | Delivery of bioactive cargo (miRNA, proteins) to modulate cell activity [11] | Orchestrating immune-mediated clearance and resolution of inflammation [7] |

| Key Signaling Pathways Modulated | MAPK/AP-1, NF-κB, PI3K/Akt, SIRT1 [11] | Wnt/β-catenin, S1P/S1PR [7] [15] |

| Effect on Extracellular Matrix | ↑ Collagen I synthesis, ↓ MMP-1 expression [11] | Emerging role in tissue remodeling via efferocytosis [7] |

| Immune/Inflammatory Response | Downregulation of pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-6) [11] | Induction of anti-inflammatory macrophage polarization; suppression of Th1/Th17 cells [7] |

| Therapeutic Evidence in Skin | Protection against UV-induced photoaging; enhanced fibroblast proliferation & migration [11] | Promotion of wound healing and hair growth in models [15] |

Experimental Protocols for Isolation and Characterization

Accurate isolation and characterization are paramount for conducting valid research. The following protocols are standard in the field.

Standard Isolation Workflow

The journey from biofluid or cell culture medium to purified vesicles requires careful technique to minimize cross-contamination.

Key Isolation Methods:

- Differential Ultracentrifugation: The most common method. It involves a series of increasing centrifugal forces to pellet different vesicle types sequentially. sEVs are typically pelleted at high speeds of 100,000-120,000g [13] [14].

- Density Gradient Centrifugation: Used following ultracentrifugation for further purification, separating vesicles based on their buoyant density in a sucrose or iodixanol gradient [13].

- Size-Based Filtration: Using filters with specific pore sizes to isolate vesicles within a certain diameter range [13].

- Immunoaffinity Capture: Using magnetic beads conjugated with antibodies against specific surface markers (e.g., anti-CD63 for sEVs) for highly specific isolation [13].

Essential Characterization Techniques

- Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis (NTA): Measures the size distribution and concentration of particles in a solution by tracking their Brownian motion [13].

- Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM): Provides high-resolution images to confirm the morphology (e.g., cup-shaped for sEVs) and approximate size of the vesicles [13].

- Western Blotting: Used to detect the presence of specific protein markers associated with the vesicle type (e.g., CD63, TSG101 for sEVs) and the absence of contaminants from cellular organelles [13].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

A selection of critical reagents for studying EV biogenesis and function is listed below.

Table 3: Essential Reagents for EV Research

| Reagent / Solution | Primary Function in Research | Specific Example Targets |

|---|---|---|

| Anti-Tetraspanin Antibodies | Immunoaffinity capture and characterization of sEVs [13] | CD63, CD81, CD9 [13] [12] |

| Anti-ESCRT Protein Antibodies | Validation of sEV identity and study of biogenesis mechanism [13] [12] | TSG101, Alix [13] [12] |

| Annexin V | Detection of phosphatidylserine exposure on ApoEVs for identification and functional studies [7] | Phosphatidylserine [7] |

| Protease Inhibitors | Preservation of protein cargo integrity during vesicle isolation and processing. | Caspase inhibitors (for ApoEV studies) [7] |

| Sucrose/Iodixanol Solutions | Formation of density gradients for high-purity isolation of vesicles away from protein aggregates and other contaminants [13] | N/A |

| RAB GTPase Modulators | Investigating the molecular regulation of MVB trafficking and sEV secretion [12] | Various RAB proteins (e.g., RAB27) [12] |

| Caspase Inhibitors/Activators | To modulate or inhibit the apoptotic process, thereby controlling ApoEV production for functional studies [7] | Caspase-3, Caspase-8 [7] |

The choice between sEVs and ApoEVs for skin regeneration research is not a matter of superiority, but of strategic application. sEVs, born from the endosomal system, function as precision delivery vehicles, directly transferring miRNAs and proteins to recipient skin cells to combat oxidative stress, enhance collagen production, and modulate inflammation. In contrast, ApoEVs, products of apoptotic dismantling, serve as potent orchestrators of the immune landscape, promoting tissue repair by resolving inflammation through efferocytosis and activating regenerative pathways like Wnt/β-catenin. The decision for researchers should be guided by the specific pathological context of the target skin condition—whether the primary need is for direct cytoprotective and matrix-stimulating signals (favoring sEVs) or for immune modulation and clearance of damage to initiate healing (favoring ApoEVs). A deep understanding of these biogenesis pathways and their functional consequences is therefore the foundation for harnessing the full therapeutic potential of extracellular vesicles in regenerative dermatology.

The field of regenerative medicine is increasingly exploring cell-free therapies, with extracellular vesicles (EVs) emerging as promising candidates for skin regeneration. Among these, small extracellular vesicles (sEVs), including exosomes (30-150 nm in diameter), and apoptotic extracellular vesicles (ApoEVs), which include apoptotic small EVs (ApoSEVs, <1 μm) and apoptotic bodies (ApoBDs, 1-5 μm), are of significant interest [5] [8]. These vesicles are natural carriers of diverse biological cargo—including proteins, lipids, and microRNAs (miRNAs)—which they horizontally transfer between cells to modulate recipient cell behavior [8]. Understanding the distinct cargo profiles of sEVs and ApoEVs is crucial for evaluating their therapeutic potential, mechanisms of action, and eventual clinical application for skin repair and regeneration. This guide provides a comparative analysis of their characteristic miRNA, protein, and lipid signatures, underpinned by experimental data and methodologies relevant to skin regeneration research.

Comparative Cargo Profiles of sEVs and ApoEVs

The therapeutic efficacy of vesicles is largely dictated by their molecular cargo, which varies significantly based on the vesicle's cellular origin and biogenesis pathway.

MicroRNA (miRNA) Signatures

MiRNAs are powerful regulators of gene expression and play a central role in the therapeutic effects of EVs. Comparative analysis reveals distinct miRNA profiles between vesicles from different cellular sources.

Table 1: Characteristic miRNA Profiles of sEVs from Different Cell Sources

| Cell Source | Highly Expressed miRNAs | Putative Target Genes / Affected Pathways | Experimental Model / Functional Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells (iPSCs) | hsa-miR-16-5p, hsa-miR-25-3p, hsa-miR-93-5p (3 overlapping miRNAs) [16] | MAN2A1, ZNFX1, PHF19, GPR137C, ENPP5, B3GALT2, FNIP1, PKD2, FBXW7 [16] | Model: Human articular chondrocytes (hACs) [16]. Outcome: Promoted cartilage matrix formation (GAG, Col2), downregulated fibrocartilage matrix (Col1), suppressed senescence [16]. |

| Bone Marrow-MSCs (BM-MSCs) | hsa-miR-16-5p, hsa-miR-25-3p, hsa-miR-93-5p (3 overlapping miRNAs); 11 highly expressed miRNAs total [16] | Genes involved in cell growth, bone ossification, cartilage development via MAPK signalling pathway [16]. | Model: Human articular chondrocytes (hACs) [16]. Outcome: Greatest effect on maintaining hAC viability and function compared to iPSC-Exos and ADSC-Exos [16]. |

| Adipose-Derived Stem Cells (ADSCs) | hsa-miR-16-5p, hsa-miR-25-3p, hsa-miR-93-5p (3 overlapping miRNAs); 13 highly expressed miRNAs total [16] | Similar target genes as BM-MSCs, with 7 miRNAs overlapping between ADSC- and BMSC-Exos [16]. | Model: Human articular chondrocytes (hACs) [16]. Outcome: Promoted normal cartilage matrix formation and prevented senescence [16]. |

| ADSCs (in other contexts) | miR-126, miR-21, miR-146a, miR-16-5p [17] | miR-126: Activates PI3K/Akt in endothelium; miR-146a/miR-16-5p: Target TLR4/IRAK1/TRAF6 to inhibit NF-κB [17]. | Model: Lung injury, ARDS [17]. Outcome: Reduced inflammation, decreased vascular permeability, enhanced tissue regeneration [17]. |

A systematic review and meta-analysis directly compared the therapeutic efficacy of MSC-derived sEVs and ApoEVs in wound healing, indicating that ApoSEVs showed better efficacy than sEVs in wound closure outcome and collagen deposition, while sEVs displayed better performance in revascularization [5]. Furthermore, among easily accessible MSC sources, ADSCs demonstrated the best effect on wound closure rate, whereas BM-MSCs were more effective in revascularization [5].

Protein and Lipid Cargo

Proteins and lipids are integral functional components of EVs, contributing to their structure, targeting, and bioactivity.

Table 2: Characteristic Protein and Lipid Profiles of EVs

| Cargo Type | Vesicle Type | Key Components | Functional Role / Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Proteins | sEVs / Exosomes | CD9, CD63, CD81, Alix, TSG101 (characteristic markers); growth factors, cytokines, extracellular matrix components [17]. | Role: Vesicle identification, cell targeting, immunomodulation, tissue remodeling [17]. Context: Universal sEV markers used for characterization across studies [18]. |

| ApoEVs | Specific protein profiles are less defined but differ from sEVs; enriched in endoplasmic reticulum, proteasome, and mitochondrial proteins [17]. | Role: May reflect the apoptotic state of the parent cell and influence immunomodulation [17]. | |

| Lipids | sEVs / Exosomes | Higher concentration of glycolipids and free fatty acids [17]. | Role: Membrane stability, formation of lipid rafts, cellular signaling [17]. |

| ApoEVs | Enriched with ceramides and sphingomyelins [17]. | Role: Involvement in apoptotic signaling pathways [17]. | |

| Hypoxia-induced Exosomes | Increased unsaturated fatty acid-containing Lysophosphatidylcholine (LPC) [19]. | Context: Intestinal epithelial cell-derived exosomes after ischemia-reperfusion injury [19]. Outcome: Activated NF-κB pathway and inflammation in monocytes [19]. |

Experimental Protocols for Vesicle Analysis

To ensure the reliability and reproducibility of research findings, adherence to standardized experimental protocols and reporting guidelines is paramount.

Vesicle Isolation and Characterization

A. Isolation Methods:

- Ultracentrifugation (UC): The classical "gold standard" method for pelleting vesicles based on size and density. However, it can be time-consuming and may yield impure preparations [18].

- Tangential Flow Filtration (TFF): A scalable method that uses tangential flow across filters to separate vesicles based on size. Studies show TFF provides a statistically higher particle yield than UC, making it more suitable for large-scale production required for clinical translation [18].

- Polymer-Based Precipitation: Methods using solutions like ExoQuick-TC to precipitate vesicles out of solution. Useful for processing large volumes of conditioned medium [19].

B. Characterization (Adhering to MISEV Guidelines): Researchers must characterize vesicles based on size, concentration, and specific markers [5] [8].

- Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis (NTA): Determines the size distribution and concentration of particles in a solution [18].

- Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM): Visualizes the cup-shaped morphology of sEVs/exosomes, confirming their structure [18].

- Immunoblotting: Confirms the presence of positive protein markers (e.g., CD9, CD63, CD81, TSG101 for sEVs) and the absence of negative markers (e.g., calnexin, an endoplasmic reticulum protein) [18].

Cargo Profiling and Functional Assays

A. miRNA Profiling:

- Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS): A high-throughput method used to identify and comprehensively profile the full spectrum of miRNAs in vesicle samples [16].

- Bioinformatics Analysis: Used post-sequencing to predict putative target genes of identified miRNAs and to perform enrichment analyses (e.g., Gene Ontology - GO, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes - KEGG) to elucidate involved biological pathways [16].

B. Functional In Vitro Assays:

- Cell Viability and Proliferation Assays: (e.g., CCK-8, MTT). Used to assess the protective or proliferative effects of vesicles on recipient cells. Example: H₂O₂-damaged ARPE-19 cells treated with BM-MSC-sEVs showed increased viability from 37.86% to over 52% [18].

- Apoptosis Assays: (e.g., flow cytometry with Annexin V/PI staining). Used to quantify the anti-apoptotic effect of vesicles. Example: BM-MSC-sEVs significantly reduced the total percentage of apoptotic ARPE-19 cells [18].

- Reporter Assays: Used to study specific signaling pathway activation. Example: THP-1 Blue NF-κB reporter monocytes were used to demonstrate that exosomes from hypoxic IECs activate the NF-κB inflammatory pathway [19].

Signaling Pathways in Skin Regeneration Modulated by Vesicular Cargo

The therapeutic effects of sEVs and ApoEVs in skin regeneration are mediated through the regulation of key signaling pathways by their cargo, particularly miRNAs.

The diagram above summarizes the complex interplay between vesicular cargo and cellular pathways. For instance:

- miR-146a and miR-16-5p from ADSC-Exos target the TLR4/IRAK1/TRAF6 complex, leading to inhibition of NF-κB signaling, a master regulator of inflammation. This results in reduced levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., TNF-α, IL-6), which is crucial for mitigating chronic inflammation in non-healing wounds [17].

- miR-126, also found in ADSC-Exos, activates the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway in endothelial cells. This promotes angiogenesis (revascularization), a critical process for supplying nutrients and oxygen to the regenerating tissue [17].

- Bioinformatics predictions from miRNA profiles of stem cell exosomes suggest involvement in the MAPK signaling pathway, which regulates cell growth, differentiation, and matrix formation—all vital for skin structure and function [16].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for EV Research in Skin Regeneration

| Item | Function / Application | Example from Search Results |

|---|---|---|

| Bovine Exosome-Depleted FBS | Used in cell culture to supplement media while preventing contamination by bovine-derived vesicles, ensuring that isolated EVs are of cellular origin. | Used in culture of hiPSCs, hBMSCs, and hADSCs for exosome collection [16]. |

| Human Platelet Lysate (hPL) | A xeno-free supplement for MSC culture, supporting cell proliferation and expansion under GMP-compliant conditions. | Used as a serum supplement in DMEM and α-MEM for BM-MSC culture [18]. |

| ExoQuick-TC | A polymer-based solution used for precipitating exosomes/EVs from conditioned cell culture medium. | Used for isolating exosomes from intestinal epithelial cell conditioned medium [19]. |

| CD9, CD63, CD81 Antibodies | Positive marker antibodies used in immunoblotting (Western Blot) or Exo-Check arrays to confirm the presence of sEVs/exosomes. | Confirmed via Western Blot as markers for BM-MSC-sEVs [18]. |

| Annexin V / Propidium Iodide (PI) | Reagents used in flow cytometry to detect and quantify apoptotic cells, used to validate anti-apoptotic effects of EVs. | Used to show BM-MSC-sEVs reduce apoptosis in ARPE-19 cells [18]. |

| THP-1 Blue NF-κB Reporter Cells | A monocytic cell line engineered to secrete alkaline phosphatase upon NF-κB activation, used to screen for pro- or anti-inflammatory effects of EV cargo. | Used to demonstrate pro-inflammatory effects of exosomes from hypoxic IECs [19]. |

| Streptozotocin (STZ) | A chemical used to induce Type 1 diabetes in animal models (e.g., rats, mice), creating a diabetic wound model for testing EV therapeutics. | Used in STZ-induced diabetic rodent wound models [5] [8]. |

sEVs and ApoEVs present distinct biological tools for skin regeneration, each with unique cargo profiles and functional strengths. The current body of evidence, including a recent meta-analysis, suggests that ApoSEVs may be superior in promoting wound closure and collagen deposition, while sEVs excel in enhancing revascularization [5]. The choice of producer cell (e.g., ADSCs for wound closure, BM-MSCs for revascularization) further fine-tunes the therapeutic outcome [5]. The characteristic cargo of miRNAs, proteins, and lipids underlies these differences by modulating key inflammatory, proliferative, and matrix-forming pathways in the skin. Future work must focus on standardizing isolation and characterization protocols, deepening our understanding of ApoEV biology, and engineering vesicles to maximize their regenerative potential for clinical translation.

The therapeutic potential of Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs) in skin regeneration and wound healing represents a paradigm shift in regenerative medicine. These multipotent adult stem cells, first identified in bone marrow, possess the capacity to differentiate into multiple cell lineages, modulate immune responses, and enhance tissue repair [20]. The International Society for Cellular Therapy (ISCT) establishes three defining criteria for MSCs: adherence to plastic; specific surface antigen expression (CD73, CD90, CD105 positive; CD11b, CD14, CD19, CD34, CD45, CD79α, HLA-DR negative); and tri-lineage differentiation potential into osteoblasts, adipocytes, and chondrocytes in vitro [20]. What makes MSCs particularly valuable for therapeutic applications includes their relative ease of isolation from multiple tissue sources, reduced ethical concerns compared to embryonic stem cells, lower risk of teratoma formation than induced pluripotent stem cells, and innate ability to migrate to sites of tissue damage via chemoattraction [20].

The emergence of cell-free therapies utilizing extracellular vesicles (EVs) derived from MSCs has further accelerated research in dermatological applications. These vesicles, particularly small extracellular vesicles (sEVs) and apoptotic vesicles (ApoEVs), have demonstrated remarkable efficacy in promoting skin regeneration while potentially mitigating risks associated with whole-cell transplantation [5] [8]. This review systematically compares the impact of primary MSC tissue sources on their therapeutic potential, with a specific focus on their secreted vesicles for skin regeneration outcomes, providing evidence-based guidance for researchers and therapeutic developers.

MSCs can be isolated from multiple tissue sources, each with distinct advantages and limitations for clinical translation. The table below summarizes key characteristics of major MSC sources investigated for skin regeneration applications.

Table 1: Comparison of Primary Mesenchymal Stem Cell Sources for Skin Regeneration

| Source | Relative Abundance | Isolation Complexity | Key Advantages | Documented Efficacy in Skin Regeneration |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adipose Tissue (AD-MSCs) | High | Moderate | Minimal morbidity; high yield; strong paracrine signaling | Superior wound closure rate and collagen deposition [5] |

| Bone Marrow (BM-MSCs) | Low | High (invasive) | Gold standard; extensive characterization | Enhanced revascularization capacity [5] |

| Umbilical Cord (UC-MSCs) | Moderate | Low (non-invasive) | Immunologically naive; high proliferation rate | Improved healing rates; reduced scarring [20] [5] |

| Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells (iMSCs) | Unlimited in vitro | High (reprogramming) | Unlimited scalability; consistent batches | Accelerated wound closure in porcine burn models [21] |

Adipose-Derived MSCs (AD-MSCs)

Adipose tissue represents a particularly abundant and accessible source of MSCs for regenerative applications. AD-MSCs demonstrate superior wound closure rates and enhanced collagen deposition compared to other sources in preclinical models, making them exceptionally promising for dermatological applications [5]. The minimally invasive harvesting procedure (via liposuction) combined with high cell yield positions AD-MSCs as a frontrunner for clinical translation in skin regeneration therapies.

Bone Marrow-Derived MSCs (BM-MSCs)

As the originally discovered MSC source, bone marrow-derived MSCs represent the most extensively characterized population. While their harvesting is more invasive and yields are lower compared to adipose tissue, BM-MSCs exhibit exceptional revascularization capacity, a critical factor in wound healing and skin regeneration [5]. This robust angiogenic potential makes BM-MSCs particularly valuable for treating chronic wounds with compromised vascularization.

Umbilical Cord-Derived MSCs (UC-MSCs)

Umbilical cord tissue, including Wharton's jelly and cord blood, provides MSCs with notable immunomodulatory properties and high proliferative capacity [20]. These cells are considered immunologically naive, making them promising candidates for allogeneic therapies. Studies indicate UC-MSCs contribute to improved healing rates with reduced scarring, potentially through modulation of inflammatory responses during wound healing [20] [5].

iPSC-Derived MSCs (iMSCs)

The differentiation of induced pluripotent stem cells into MSCs represents a innovative approach to overcome limitations of primary tissue sources. iMSCs offer theoretically unlimited scalability and batch-to-batch consistency, addressing critical manufacturing challenges for standardized therapies [21]. Recent research demonstrates that iMSCs seeded onto dermal regeneration templates significantly accelerate wound closure in porcine burn models, supporting their potential as an ideal cell source for skin regeneration [21].

MSC-Derived Vesicles: Mechanisms and Therapeutic Applications

The therapeutic effects of MSCs are increasingly attributed to their paracrine signaling via secreted extracellular vesicles rather than direct cellular engraftment. These vesicles are broadly categorized based on their biogenesis, size, and cargo.

Table 2: Characteristics of MSC-Derived Therapeutic Vesicles for Skin Regeneration

| Vesicle Type | Size Range | Biogenesis | Key Cargo | Primary Mechanisms in Skin Repair |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Small EVs (sEVs/exosomes) | 30-200 nm | Endosomal origin; exocytosis | miRNAs, proteins, lipids | Anti-inflammatory, pro-angiogenic, fibroblast proliferation [8] |

| Apoptotic EVs (ApoEVs) | 50-5000 nm | Apoptotic cell blebbing | Nuclear fragments, organelles, miRNAs | Macrophage polarization to M2 phenotype, efferocytosis, tissue remodeling [22] [7] |

| ApoSEVs (Apoptotic Small EVs) | <1 μm | Apoptotic cell fragmentation | Specific mRNAs, phosphatidylserine | Enhanced collagen deposition, Wnt/β-catenin pathway activation [5] [15] |

Small Extracellular Vesicles (sEVs)

sEVs, including exosomes, are nano-sized vesicles (30-200 nm) formed through the endosomal pathway and released upon fusion of multivesicular bodies with the plasma membrane [8]. They carry diverse cargo including miRNAs, proteins, and lipids that mediate intercellular communication. In skin regeneration, sEVs demonstrate potent immunomodulatory effects by polarizing macrophages toward the anti-inflammatory M2 phenotype and enhancing angiogenesis through transfer of pro-angiogenic factors [20] [8]. Their small size potentially enables better tissue penetration compared to larger vesicles, though their circulation time may be limited by rapid clearance.

Apoptotic Vesicles (ApoEVs)

ApoEVs are membrane-bound vesicles released during programmed cell death, encompassing a broader size range (50-5000 nm) that includes apoptotic bodies (ApoBDs, 1-5 μm) and apoptotic small EVs (ApoSEVs, <1 μm) [22] [5]. These vesicles contain nuclear fragments, organelles, and specific genetic material from their parent cells. ApoEVs exhibit unique immunosuppressive properties and promote tissue repair primarily through efferocytosis - the process by which phagocytic cells clear apoptotic debris, leading to production of regenerative cytokines and polarization of anti-inflammatory macrophages [22] [7]. Recent evidence suggests ApoSEVs demonstrate superior collagen deposition compared to sEVs in wound healing models [5].

Comparative Efficacy in Skin Regeneration

A comprehensive meta-analysis of preclinical studies directly comparing MSC-derived vesicle types revealed distinct therapeutic advantages:

- ApoSEVs demonstrated superior efficacy in wound closure rates and collagen deposition compared to both sEVs and larger apoptotic bodies [5]

- sEVs exhibited enhanced revascularization capacity compared to ApoEVs, promoting greater blood vessel density in regenerating tissue [5]

- Administration route significantly influenced outcomes, with subcutaneous injection proving more effective than topical application for both vesicle types across multiple healing parameters [5]

These findings suggest that the optimal vesicle type may depend on the specific healing priorities - ApoSEVs for structural restoration and sEVs for vascularization - potentially enabling combination approaches targeting multiple aspects of the healing process.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

MSC Characterization and Vesicle Isolation

Standardized protocols for MSC characterization and vesicle isolation are critical for reproducible research and therapeutic development. The following workflow outlines key methodological steps:

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for MSC characterization and vesicle isolation

MSC Characterization Protocol

According to ISCT guidelines, comprehensive MSC characterization must include three key assessments:

- Plastic Adherence: Confirm adherence to tissue culture plastic under standard culture conditions [5]

- Surface Marker Expression: Flow cytometric analysis demonstrating ≥95% expression of CD73, CD90, and CD105, and ≤2% expression of CD34, CD45, CD11b, CD19, and HLA-DR [20] [18]

- Tri-lineage Differentiation: Functional differentiation into osteocytes, adipocytes, and chondrocytes under appropriate induction conditions, confirmed by specific staining (Alizarin Red, Oil Red O, and Alcian Blue, respectively) [21] [18]

A recent systematic review noted that 79.5% of published studies on MSC-EVs for skin regeneration met all three ISCT characterization criteria, while 20.5% met two of the three criteria [5].

Vesicle Isolation Methods

The methodology for vesicle isolation significantly impacts yield, purity, and potentially therapeutic efficacy:

- Ultracentrifugation (UC): Traditional gold standard involving sequential centrifugation steps to separate vesicles based on size and density [18]

- Tangential Flow Filtration (TFF): Scalable method using cross-flow filtration, demonstrating significantly higher particle yields compared to UC while maintaining vesicle integrity [18]

Comparative studies indicate TFF provides statistically higher particle yields than ultracentrifugation, making it particularly suitable for large-scale therapeutic production [18].

In Vivo Assessment of Therapeutic Efficacy

Preclinical evaluation of MSC-derived vesicles for skin regeneration typically utilizes well-established animal models:

- Animal Models: Mouse (73.5%) and rat (26.5%) models predominately used; porcine models more closely mimic human skin physiology but are less common due to cost and handling complexity [5] [20]

- Wound Types: Full-thickness excisional wounds (90.4% of studies), diabetic wounds (47.0%), burn models, and photoaging models [5]

- Key Outcome Measures: Wound closure rate, scar width, blood vessel density, collagen deposition, and histopathological analysis [5]

Notably, a comprehensive meta-analysis of 83 preclinical studies demonstrated that MSC-EVs significantly promoted skin regeneration in both diabetic and non-diabetic animal models, influencing multiple facets of the healing process regardless of cell source, production protocol, or disease model [5].

Signaling Pathways in Vesicle-Mediated Skin Repair

MSC-derived vesicles exert their therapeutic effects through activation of specific signaling pathways in recipient cells. The following diagram illustrates key mechanistic pathways:

Diagram 2: Signaling pathways in vesicle-mediated skin repair

Key Mechanistic Insights

- ApoEV Internalization: Apoptotic vesicles are internalized via phosphatidylserine-dependent macropinocytosis, a mechanism distinct from classical endocytosis pathways used by sEVs [23]

- Wnt/β-catenin Activation: MSC-derived ApoEVs activate the Wnt/β-catenin pathway in skin and hair follicle stem cells, promoting wound healing and hair growth [15]

- Metabolic Regulation: Exogenous ApoEVs are partially metabolized in integumentary skin and hair follicles, with their migration enhanced by mechanical forces such as exercise [15]

- mRNA Transfer: ApoEVs carry specific functional mRNAs that are transferred to recipient cells and translated into functional proteins, enabling direct phenotypic modification [23]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for MSC and Vesicle Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Culture Media | α-MEM, DMEM, Xeno-free media | MSC expansion | Optimal growth environments; α-MEM shows superior proliferation rates for BM-MSCs [18] |

| Characterization Antibodies | CD73, CD90, CD105, CD34, CD45, HLA-DR | MSC phenotyping | Flow cytometric verification of ISCT criteria [20] [18] |

| Differentiation Kits | Osteo-, Adipo-, Chondrogenic kits | Tri-lineage differentiation | Functional validation of MSC multipotency [21] [18] |

| Vesicle Isolation Kits | TFF systems, Ultracentrifugation | EV purification | Isolation of sEVs and ApoEVs from conditioned media [18] |

| Characterization Tools | NTA, TEM, Western Blot | EV validation | Size distribution, morphological analysis, marker confirmation (CD9, CD63, TSG101) [18] |

| Animal Models | C57BL/6 mice, SD rats, db/db mice | In vivo testing | Diabetic and non-diabetic wound healing assessment [5] |

The cellular origin of mesenchymal stem cells significantly influences their therapeutic profile for skin regeneration applications. Adipose-derived MSCs demonstrate superior wound closure and collagen deposition, bone marrow MSCs excel in revascularization, umbilical cord MSCs offer immunological advantages, and iPSC-derived MSCs provide unprecedented scalability. The emergence of vesicle-based therapeutics further refines this landscape, with apoptotic small vesicles (particularly ApoSEVs) showing enhanced efficacy in wound closure and collagen deposition, while sEVs demonstrate superior revascularization potential.

Future research directions should prioritize standardization of vesicle isolation and characterization protocols, direct comparative studies of MSC sources under consistent conditions, investigation of combination approaches leveraging complementary vesicle types, and rigorous safety profiling to facilitate clinical translation. The ongoing refinement of MSC-derived vesicle therapies holds significant promise for addressing the substantial clinical need for effective skin regeneration strategies across diverse wound etiologies.

The transition from cellular to acellular therapies in regenerative medicine has brought small extracellular vesicles (sEVs) and apoptotic vesicles (ApoEVs) to the forefront of dermatological research. These nanoscale, lipid bilayer-enclosed particles, secreted by virtually all cell types including mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), function as natural biocommunication systems that transfer functional proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids to recipient cells [24] [14]. Their inherent biocompatibility stems from their endogenous origin and natural lipid bilayer structure, while their low immunogenicity arises from evolutionary conservation and surface molecule profiles that minimize immune activation [25] [14]. This biological foundation positions both sEVs and ApoEVs as promising therapeutic agents, particularly for complex processes like skin regeneration where controlled immune activation and tissue remodeling are critical.

Comparative Analysis of sEVs and ApoEVs for Skin Regeneration

Biophysical Properties and Cargo Composition

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of sEVs and ApoEVs

| Parameter | Small Extracellular Vesicles (sEVs) | Apoptotic Vesicles (ApoEVs) |

|---|---|---|

| Size Range | < 200 nm [26]; typically 30-150 nm [24] | Highly heterogeneous: 0.1-5 μm [27] [7] |

| Biogenesis Origin | Endosomal pathway (exosomes) or plasma membrane (ectosomes) [24] [26] | Apoptotic cell membrane blebbing and fragmentation [7] |

| Key Markers | Tetraspanins (CD9, CD63, CD81), TSG101, ALIX [24] [26] | Phosphatidylserine exposure, DNA fragments [7] |

| Lipid Composition | Enriched in cholesterol, sphingomyelin, ceramide [24] | Similar to parent cell membrane with increased phosphatidylserine [7] |

| Nucleic Acid Cargo | miRNAs, mRNAs, circRNAs promoting proliferation and angiogenesis [24] | Genomic DNA fragments, distinct miRNA profiles [7] |

| Protein Profile | Growth factors (VEGF, TGF-β, EGF), tetraspanins [24] | Caspase-cleaved proteins, organellar components [7] |

Functional Efficacy in Skin Regeneration Models

Table 2: Therapeutic Efficacy in Preclinical Skin Regeneration Models

| Therapeutic Outcome | sEVs Performance | ApoEVs Performance | Comparative Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wound Closure Rate | Significantly enhance wound closure in diabetic and non-diabetic models [27] | Apoptotic small EVs (ApoSEVs) show superior efficacy to sEVs [27] | ApoSEVs demonstrate better wound closure outcomes [27] |

| Collagen Deposition | Promote organized collagen deposition [27] | ApoSEVs induce more effective collagen deposition [27] | ApoSEVs show superior collagen remodeling capacity [27] |

| Revascularization | Strong pro-angiogenic effects, increase blood vessel density [27] | Moderate angiogenic potential [27] | sEVs demonstrate better revascularization outcomes [27] |

| Anti-inflammatory Effects | Modulate macrophages toward anti-inflammatory phenotype [14] | Polarize anti-inflammatory macrophages, suppress inflammatory immune cells [7] | Both show significant immunomodulation via different mechanisms |

| Cellular Proliferation | Promote keratinocyte and fibroblast proliferation [24] | Stimulate proliferation through efferocytosis-linked pathways [7] | Both enhance proliferation through distinct signaling mechanisms |

Experimental Protocols for Functional Assessment

Standardized Isolation and Characterization Workflow

In Vivo Wound Healing Assessment Protocol

Animal Models:

- Diabetic Wounds: Streptozotocin (STZ)-induced diabetic mice or genetically modified db/db mice (Type 2 diabetes) [27]

- Non-Diabetic Wounds: Full-thickness excisional dorsal wounds in wild-type mice or rats [27]

- Wound Creation: 6-8mm diameter full-thickness excisional wounds [27]

Treatment Administration:

- Route: Subcutaneous injection around wound periphery vs. topical dressing/covering [27]

- Dosing: Typically 100-500 μg EV protein per application [27]

- Frequency: Multiple administrations (e.g., days 0, 2, 4, 6 post-wounding) [27]

Outcome Measures:

- Primary Endpoint: Wound closure rate measured by planimetry daily [27]

- Histological Analysis: H&E staining for re-epithelialization, Masson's trichrome for collagen deposition [27]

- Immunohistochemistry: CD31 staining for blood vessel density, α-SMA for myofibroblasts [27]

- Scar Assessment: Scar width measurement at endpoint [27]

Mechanism of Action: Signaling Pathways in Skin Regeneration

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Critical Reagents for EV Research in Skin Regeneration

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Isolation Kits | Total Exosome Isolation Kits, qEV Size Exclusion Columns | Rapid isolation from cell culture media or biofluids | Enable reproducible yields with minimal equipment [26] |

| Characterization Antibodies | Anti-CD9, CD63, CD81, TSG101, ALIX, Annexin V | EV identification, quantification, and subtyping by flow cytometry, WB | MISEV guidelines recommend multiple markers [27] |

| Extracellular Matrix Proteins | Collagen I, Fibronectin, Laminin | Assessment of EV effects on fibroblast function and ECM remodeling | Critical for 3D skin equivalent models [27] |

| Cell Culture Models | Human dermal fibroblasts, HaCaT keratinocytes, HUVECs | In vitro assessment of EV bioactivity | Primary cells preferred over immortalized lines [27] |

| In Vivo Tracking Agents | DIR, DiD lipophilic dyes, GFP/RFP reporters | Biodistribution and pharmacokinetic studies | Confirm EV integrity post-labeling [25] |

| Analytical Instruments | Nanoparticle Tracking Analyzer, TEM, Western Blot | EV quantification, sizing, and characterization | Multi-method approach essential for validation [27] [26] |

Discussion: Clinical Translation Considerations

The therapeutic advantages of biocompatibility and low immunogenicity position both sEVs and ApoEVs as promising clinical candidates, yet they present distinct translational profiles. sEVs benefit from extended research history and established isolation protocols, with 64 registered clinical trials already demonstrating safety and applicability across various diseases, including complex wound healing [14]. Their nanoscale dimensions facilitate enhanced tissue penetration and biological barrier crossing, while their well-characterized pro-angiogenic properties make them particularly suitable for ischemic wound environments [27] [14].

Conversely, ApoEVs present a more complex clinical profile. Their heterogeneous size distribution may create manufacturing challenges for standardized therapeutic applications [7]. However, their superior performance in specific wound healing parameters, particularly wound closure and collagen deposition, indicates unique therapeutic value [27]. The efferocytosis-mediated mechanism of ApoEVs creates a more nuanced immunomodulatory response, potentially offering advantages in chronic inflammatory wound environments [7].

For clinical translation, administration route optimization is critical. Subcutaneous injection has demonstrated superior outcomes compared to topical application for multiple regenerative parameters, including wound closure, collagen deposition, and revascularization [27]. Additionally, source selection impacts therapeutic efficacy, with adipose-derived stem cells (ADSCs) showing particular promise for wound closure, while bone marrow MSCs excel in revascularization potential [27]. The ongoing challenge of standardization in collection conditions, separation methods, storage protocols, and dosing regimens must be addressed before widespread clinical adoption [27] [14].

From Bench to Bedside: Production, Characterization, and Preclinical Application

Standardized Isolation and Purification Techniques

The field of regenerative medicine is increasingly focused on harnessing the therapeutic potential of extracellular vesicles (EVs), particularly for complex applications such as skin regeneration. EVs are broadly categorized based on their biogenesis, size, and content. Small extracellular vesicles (sEVs or exosomes), ranging from 30-150 nm, are of endocytic origin and formed within multivesicular bodies (MVBs) [28] [29]. In contrast, apoptotic vesicles (50-5000 nm) are generated during programmed cell death through membrane blebbing [29] [18]. The distinct biological messages carried by these vesicles—sEVs often mediate intercellular communication, while apoptotic vesicles are primarily involved in clearance of apoptotic cells—lead to dramatically different functional outcomes in skin regeneration, influencing processes like inflammation, collagen synthesis, and tissue remodeling [28] [29] [30]. However, a significant challenge complicates this promising field: the inability of standard isolation methods to perfectly separate these vesicle subtypes from complex biological fluids, leading to heterogeneous preparations and confounding research outcomes [31] [32]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of current isolation and purification techniques, presenting experimental data to help researchers select the optimal method for their specific research on skin regeneration.

Comparative Analysis of Key Isolation Method Performance

The ideal isolation method would be simple, fast, high-throughput, and yield a pure, functional vesicle population. In reality, all methods involve trade-offs between yield, purity, and practicality. The table below summarizes the quantitative performance of common methods based on recent comparative studies.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of sEV Isolation Methods from Plasma/Serum

| Isolation Method | Reported Particle Yield (Particles/mL) | Reported Size Distribution (nm) | Purity (Particle-to-Protein Ratio) | Key Advantages | Major Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ultracentrifugation (UC) [32] [33] | ~1.02E+10 (Plasma) [33] | 45-335 nm [32] | High [31] [33] | Considered the "gold standard"; cost-effective consumables [29] | Time-consuming; low throughput; potential for vesicle damage/aggregation [31] [29] |

| Density Gradient UC (DGUC) [31] | Lower than UC [31] | N/A | Very High [31] | Superior purity by separating particles by density; minimal co-enrichment [31] | Cumbersome preparation; very long duration; low yield [31] [29] |

| Polymer Precipitation (e.g., TEI Kit) [32] [33] | ~1.76E+11 (Plasma) [33] | 45-535 nm (broad distribution) [32] | Low [31] [32] | Simple, fast protocol; high particle yield [32] | High co-precipitation of contaminants (e.g., lipoproteins) [31] [32] |

| Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC) [31] [33] | Lower than precipitation [33] | Wide variation (heterogeneous) [33] | High [31] [33] | Good purity; maintains vesicle integrity and function [31] | May require sample pre-concentration; can be less effective with complex fluids [31] [33] |

| Tangential Flow Filtration (TFF) [18] | Higher than UC [18] | N/A | Moderate to High [18] | Scalable for manufacturing; gentle on vesicles [18] | Requires specialized equipment [18] |

| Affinity Capture (e.g., MagNet) [31] | Modest yield [31] | Narrowest size distribution [31] | Very High [31] | Exceptional purity and specificity (e.g., PS+ EVs) [31] | High cost; may select for subpopulations [31] |

| Combined Methods (e.g., UCT/CPF) [32] [33] | Intermediate between component methods [32] | 55-385 nm [32] | Moderate to High [32] [33] | Balances yield and purity better than single methods [32] [33] | More complex protocol [32] |

The choice of method profoundly impacts downstream proteomic analysis. A 2025 study found that despite modest yield, affinity-based methods like MagNet and MagCap provided the highest proteome coverage for plasma sEVs, while polymer-based precipitation kits, despite high particle yield, resulted in significant contamination with lipoproteins and other non-EV proteins [31]. Another study comparing UC, a precipitation kit (TEI), and a combined method (UCT) found that UC and UCT isolates from breast cancer cell lines showed higher expression of canonical sEV markers (CD9, CD63, CD81) and higher purity than TEI isolates [32].

Detailed Experimental Protocols for Key Methods

To ensure reproducibility, detailed protocols for three commonly used and contrasted methods are outlined below.

This protocol is considered the traditional benchmark for sEV isolation.

- Sample Preparation: Centrifuge thawed plasma at 3000g for 10 minutes at 4°C to remove cells and debris.

- Dilution and Initial Run: Dilute 100 µL of pre-cleared plasma with 11.9 mL of cold PBS. Transfer to an ultracentrifuge tube. Centrifuge at 150,000g for 3 hours at 4°C using a swinging-bucket rotor.

- Wash Step: Carefully aspirate the supernatant. Resuspend the pellet in 12 mL of PBS.

- Second Run: Centrifuge the resuspended solution again at 120,000g for 3 hours at 4°C.

- Resuspension: Aspirate the supernatant and resuspend the final EV pellet in 100 µL of PBS for downstream analysis.

This method enhances purity by separating particles based on density.

- Gradient Preparation: Layer solutions of iodixanol (OptiPrep) at 5%, 10%, 20%, and 40% (w/v) in PBS sequentially in a 13.2 mL ultracentrifuge tube to form a discontinuous density gradient.

- Sample Loading: Resuspend the crude EV pellet (obtained from an initial UC step) in PBS and carefully overlay it onto the top of the prepared gradient.

- Centrifugation: Centrifuge the gradient at 120,000g for 18 hours at 4°C.

- Fraction Collection: After centrifugation, collect the fraction containing the EVs (typically found within the 6 mL upper fraction).

- Washing and Concentration: Dilute the collected fraction with an equal volume of ice-cold PBS and centrifuge at 120,000g for 4 hours at 4°C to pellet the purified EVs. Resuspend the final pellet in a suitable buffer.

This hybrid method aims to balance the high yield of precipitation with the purity of other methods.

- Precipitation: Mix the biofluid (e.g., plasma, cell culture media) with a polyethylene glycol (PEG)-based precipitation solution. Incubate the mixture overnight at 4°C.

- Low-Speed Centrifugation: Centrifuge the sample at low speed (e.g., 1,500g) for 30 minutes to pellet the precipitated vesicles and contaminants.

- Resuspension: Resuspend the pellet in PBS.

- Two-Step Filtration: Pass the resuspended solution through a 0.22 µm syringe filter to remove larger particles and aggregates.

- Ultrafiltration: Use an ultrafiltration device (e.g., 10-100 kDa molecular weight cutoff) to concentrate the sEVs and remove residual soluble proteins and polymer, exchanging the buffer to PBS.

Functional Pathways in Skin Regeneration

The cargo of sEVs and apoptotic vesicles differentially regulates key signaling pathways in skin cells, leading to distinct regenerative outcomes. sEVs, particularly from mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), promote a regenerative environment, while apoptotic vesicles can have dual roles, often resolving inflammation but potentially contributing to tissue degradation if not properly cleared.

sEVs promote skin regeneration through several key mechanisms [28] [30]:

- Activation of Regenerative Pathways: sEV cargo, including miRNAs like miR-1246 and growth factors, activates signaling pathways such as TGF-β/Smad and Wnt/β-catenin, which are crucial for tissue repair [28].

- Stimulation of Matrix Synthesis: These activated pathways lead to fibroblast proliferation and increased synthesis of essential extracellular matrix (ECM) components like Type I and III collagen and elastin, improving skin elasticity and thickness [28] [30].

- Inhibition of Matrix Degradation: sEVs can downregulate the expression of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) like MMP-1 and MMP-3, thereby protecting the existing collagen structure from degradation [28].

Apoptotic vesicles play a more complex role [29] [30]:

- Proper Clearance and Resolution: The efficient phagocytosis of apoptotic vesicles is critical for resolving inflammation and initiating tissue repair. This process typically promotes an anti-inflammatory environment.

- Contribution to Pathology: However, if not properly cleared, or if derived from stressed cells, their cargo can perpetuate a state of chronic inflammation (inflammaging), which is a known driver of tissue degradation and impaired regeneration, ultimately leading to collagen breakdown [28] [30].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful isolation and characterization require a suite of specific reagents and instruments. The following table details key solutions used in the experiments cited in this guide.

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Kits for EV Isolation and Characterization

| Reagent / Kit Name | Provider Examples | Primary Function in Research | Key Application in EV Studies |

|---|---|---|---|

| MagCapture Exosome Isolation Kit | Fujifilm/Wako [31] | Affinity Enrichment | Isolates phosphatidylserine-positive (PS+) EVs via Tim4 protein binding for high-purity populations. |

| Total Exosome Isolation (TEI) Kit | Invitrogen [32] | Polymer Precipitation | Rapid isolation of high-yield EVs from various biofluids by reducing solubility. |

| qEVsingle / Size Exclusion Columns | Izon Science [31] | Size Exclusion Chromatography | Separates EVs from smaller soluble proteins based on hydrodynamic radius. |

| MagResyn SAX | ReSyn Biosciences [31] | Electrostatic Interaction | Isolates negatively charged EVs using strong anion exchange magnetic resin. |

| OptiPrep Density Gradient Medium | Sigma-Aldrich [31] | Density Gradient Centrifugation | Forms iodixanol-based density gradients for high-purity EV separation in DGUC. |

| Antibodies: CD9, CD63, CD81 | Multiple (e.g., Cell Signaling, R&D Systems) [31] [32] | EV Characterization | Western Blot, Flow Cytometry: Detection of canonical EV surface markers for validation. |

| Antibodies: Apolipoprotein A1/B | R&D Systems [31] | Purity Assessment | Western Blot: Detection of common lipoprotein contaminants in plasma EV preparations. |

The selection of an isolation technique is a foundational decision that directly influences the validity and interpretation of research on vesicles in skin regeneration. No single method is superior in all aspects; the choice must be aligned with the specific research question. For discovery-phase proteomics where purity is paramount, affinity-based methods or DGUC are recommended despite their lower yield [31]. For functional cell-based assays where yield and vesicle integrity are critical, SEC or TFF may be ideal [18]. For high-throughput screening where speed and simplicity are priorities, polymer precipitation remains a popular, if less pure, option [32]. As the field advances, hybrid methods like UCT and CPF that balance multiple performance metrics are showing great promise for comprehensive translational research [32] [33]. Ultimately, rigorous characterization of the isolated vesicle population—using NTA, Western blot, and EM—is non-negotiable, and reporting the isolation methodology in detail is essential for reproducibility and scientific progress in the quest to harness vesicles for regenerative medicine.

In the rapidly advancing field of vesicle-based therapies for skin regeneration, the critical characterization of small extracellular vesicles (sEVs) and apoptotic extracellular vesicles (ApoEVs) forms the foundation of rigorous research and reliable therapeutic application. Accurate differentiation between these vesicle types is paramount, as their distinct biological origins and compositions directly influence their mechanistic roles and functional outcomes in wound healing, skin repair, and regeneration. This guide provides a systematic comparison of the essential characterization metrics—size, morphology, and surface markers—enabling researchers to make informed decisions when selecting vesicle types for specific dermatological applications and ensuring reproducibility across experimental studies.

Comparative Analysis of Fundamental Physical Properties

The physical properties of sEVs and ApoEVs directly reflect their different biogenesis pathways and influence their biological functions and therapeutic potential. The table below summarizes their key distinguishing characteristics.

Table 1: Comparative Physical Properties of sEVs and ApoEVs

| Characteristic | Small Extracellular Vesicles (sEVs) | Apoptotic Extracellular Vesicles (ApoEVs) |

|---|---|---|

| Size Range | 30-200 nm [26] [14] | 50-5000 nm, with subpopulations of ApoSEVs (<1 μm) and ApoBDs (1-5 μm) [5] [34] |

| Morphology | Cup-shaped, spherical; observed via Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) [18] [26] | Highly heterogeneous; includes spherical, irregular shapes, and complex structures [34] |

| Biogenesis Origin | Endosomal system; released upon MVB fusion with plasma membrane [6] [14] | Plasma membrane blebbing and cell fragmentation during apoptosis [35] [34] |

| Key Biogenesis Regulators | ESCRT complexes, Rab GTPases, tetraspanins (CD9, CD63, CD81) [26] | ROCK1, MLCK, caspase-mediated cleavage of structural proteins [34] |

Surface Marker Profiles and Functional Implications

Surface markers serve as essential fingerprints for vesicle identification, quality control, and functional prediction. The proteomic and lipidic landscape of sEVs and ApoEVs reveals their origins and suggests their mechanistic roles.

Table 2: Surface Marker and Cargo Profiles of sEVs and ApoEVs

| Component | Small Extracellular Vesicles (sEVs) | Apoptotic Extracellular Vesicles (ApoEVs) |

|---|---|---|

| Universal EV Markers | Tetraspanins (CD9, CD63, CD81), TSG101, Alix [18] [26] | Tetraspanins (CD9, CD63, CD81), TSG101, Alix [34] |

| Distinctive Markers | Flotillin-1, MHC classes [6] | Phosphatidylserine (PS) externalization, Caspase-3 [35] [34] |

| Lipid Composition | Enriched in cholesterol, sphingomyelin, ceramide [6] | High in phosphatidylserine; substrates for enzymes like sPLA2-X [35] |

| Characteristic Cargo | Growth factors (VEGF, TGF-β, EGF), miRNAs (e.g., miR-21-3p, miR-27b) [6] | Nuclear fragments, mitochondrial components, amplified parent cell cargo [34] |

The externalized phosphatidylserine (PS) on ApoEVs is not merely a marker but a critical functional component. It acts as an "eat-me" signal for phagocytic cells like macrophages, promoting clearance of apoptotic debris and actively modulating the immune response. This lipid also serves as a substrate for enzymes like group X secretory phospholipase A2 (sPLA2-X), generating anti-inflammatory lipid mediators such as resolvin D5 (RvD5) that accelerate cutaneous wound healing [35].

Experimental Characterization Workflows

A robust characterization pipeline is non-negotiable for definitive vesicle identification. The following workflow integrates multiple complementary techniques to confirm vesicle identity and purity.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

1. Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis (NTA)

- Principle: Tracks Brownian motion of individual particles in suspension to calculate hydrodynamic diameter and concentration.

- Protocol: Dilute purified vesicle samples in sterile, particle-free PBS to achieve an ideal concentration of 10^8-10^9 particles/mL. Load into the sample chamber of an NTA instrument (e.g., Malvern NanoSight). Capture multiple 60-second videos, ensuring particle count per frame is within the manufacturer's recommended range (20-100 particles/frame). Analyze data with built-in software to determine mean, mode, and distribution of vesicle size and concentration.

2. Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM)

- Principle: Provides high-resolution images to assess vesicle morphology and ultrastructure.

- Protocol: Adsorb vesicles onto a Formvar/carbon-coated EM grid by floating the grid on a 10 μL drop of sample for 10-20 minutes. Fix with 2.5% glutaraldehyde, then contrast with 1-2% uranyl acetate. Alternatively, use phosphotungstic acid for negative staining. Wash gently with distilled water and air-dry thoroughly. Image using a TEM operated at 80-100 kV. The classic "cup-shape" of sEVs is a common artifact of chemical fixation and dehydration [18].

3. Western Blot Analysis

- Principle: Detects presence or absence of specific protein markers to confirm vesicle type and purity.

- Protocol: Lyse vesicles in RIPA buffer with protease inhibitors. Determine protein concentration via BCA assay. Separate 10-30 μg of protein by SDS-PAGE and transfer to a PVDF membrane. Block with 5% non-fat milk or BSA. Probe overnight at 4°C with primary antibodies against:

- Positive Markers: CD9, CD63, CD81 (tetraspanins), TSG101, Alix (ESCRT-associated) [18].

- Negative Markers: Calnexin (endoplasmic reticulum marker, indicates cellular contamination) [18].

- Apoptosis Marker: Cleaved Caspase-3 (for ApoEVs) [35]. Incubate with appropriate HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies and develop using enhanced chemiluminescence.

4. Flow Cytometry for Surface Markers

- Principle: Identifies and quantifies surface antigens on vesicles.

- Protocol: Vesicles must be captured or enlarged for detection on standard flow cytometers. Bind vesicles to aldehyde/sulfate latex beads via incubation and gentle rotation. Block unoccupied sites with BSA or glycine. Incubate bead-bound vesicles with fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies against surface markers (e.g., CD9, CD63, CD81) or Annexin V (to detect PS exposure). Include isotype controls. Analyze on a flow cytometer; high-throughput advanced flow cytometers are now capable of analyzing individual nanosized vesicles without beads.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful characterization requires a suite of reliable reagents and instruments. The table below details key solutions for comprehensive vesicle analysis.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Vesicle Characterization

| Reagent/Kit | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Anti-tetraspanin Antibodies (CD9, CD63, CD81) | Immunodetection of conserved EV surface proteins | Western Blot, Flow Cytometry, Immuno-EM for general EV identification [18] [26] |

| Annexin V (FITC/APC conjugated) | Detection of phosphatidylserine (PS) exposure | Flow Cytometry to distinguish ApoEVs via PS externalization [35] [34] |

| Anti-Caspase-3 (Cleaved) Antibody | Detection of activated caspase-3, an apoptosis executor | Western Blot to confirm apoptotic origin of ApoEVs [35] |

| Particle-Free PBS/BSA | Diluent and blocking agent | Sample preparation for NTA and blocking in immunoassays to prevent non-specific binding [18] |

| Uranyl Acetate / Phosphotungstic Acid | Negative stain for electron microscopy | Enhances contrast for TEM morphological analysis [18] |

| Exosome Isolation Kits (e.g., polymer-based) | Rapid isolation of EVs from biofluids/cell media | Alternative to ultracentrifugation for fast preparation [26] |

| NTA Instrumentation (e.g., NanoSight) | High-resolution size and concentration analysis | Critical quality control for all EV preparations [18] |

Functional Correlation and Therapeutic Selection