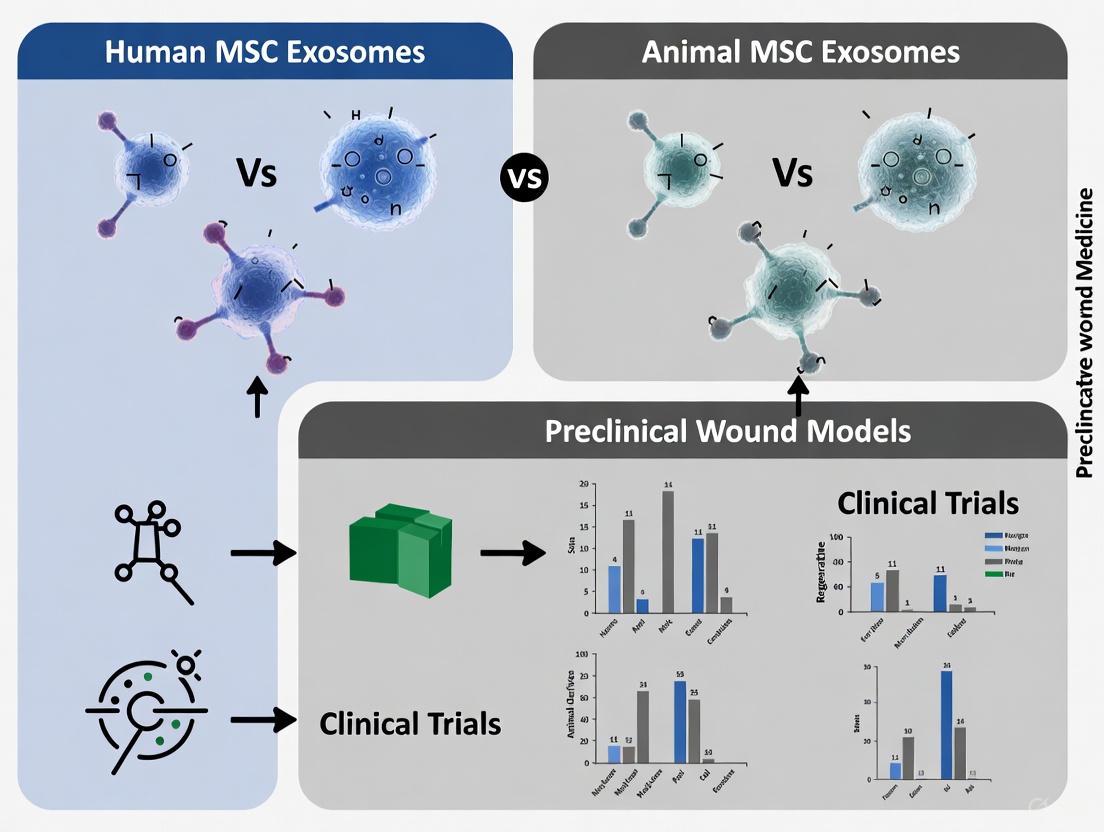

Source Matters: A Comparative Analysis of Human vs. Animal MSC Exosomes in Preclinical Wound Healing Models

This article provides a comprehensive analysis for researchers and drug development professionals on the critical role of mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) exosome source in preclinical wound healing.

Source Matters: A Comparative Analysis of Human vs. Animal MSC Exosomes in Preclinical Wound Healing Models

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis for researchers and drug development professionals on the critical role of mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) exosome source in preclinical wound healing. We systematically compare human-derived (from bone marrow, adipose tissue, umbilical cord) and animal-derived MSC exosomes, examining their biogenesis, cargo profiles, and distinct mechanisms in modulating inflammation, angiogenesis, and tissue remodeling. The review details isolation and characterization methodologies, tackles key challenges in standardization and scaling, and synthesizes head-to-head comparative evidence from animal models. By evaluating therapeutic efficacy, safety profiles, and clinical translation potential, this resource aims to guide the selection of optimal exosome sources for robust, reproducible, and clinically relevant wound healing applications.

Decoding MSC Exosome Biology and Wound Healing Mechanisms

Mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes (MSC-exos) represent a cornerstone of the emerging "cell-free" therapeutic paradigm in regenerative medicine. These nanosized extracellular vesicles (30-150 nm) serve as natural carriers of bioactive molecules, mediating the therapeutic effects traditionally attributed to their parent cells [1] [2]. The "native therapeutic package" refers to the inherent biomolecular cargo—including proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids—that is selectively loaded during exosome biogenesis and confers MSC-exos their immunomodulatory, pro-regenerative, and anti-inflammatory capabilities [3] [4].

Understanding the biogenesis and core composition of MSC-exos is fundamental to explaining their differential performance in preclinical wound models. The therapeutic potential of these vesicles is tightly linked to their cellular origin, with emerging evidence suggesting that human-derived MSC-exos may exhibit enhanced therapeutic profiles compared to their animal-derived counterparts in specific experimental contexts, potentially due to more relevant biological signaling for clinical translation [5]. This comparison guide examines the fundamental biological processes that define the native therapeutic package of MSC-exos and their implications for wound healing research.

Molecular Machinery of Exosome Biogenesis

Exosome formation is a highly regulated process involving specific molecular pathways that coordinate both the creation of the vesicles themselves and the selective packaging of their therapeutic cargo. The biogenesis pathway determines the fundamental characteristics of the resulting exosomes and their biological function [4].

Endosomal Sorting Complex Required for Transport (ESCRT)-Dependent Pathway

The ESCRT machinery comprises four complexes (ESCRT-0, -I, -II, and -III) plus associated proteins that work sequentially to mediate cargo sorting and membrane invagination [4]. ESCRT-0 initiates the process by clustering ubiquitinated proteins into microdomains on the endosomal membrane through its ubiquitin-binding subunits. ESCRT-I and ESCRT-II then form a complex that promotes membrane budding away from the cytoplasm, while ESCRT-III facilitates the final scission of the vesicles into the lumen of the endosome, forming intraluminal vesicles (ILVs) within multivesicular bodies (MVBs) [4]. Accessory proteins including ALIX and TSG101 support ESCRT function by recruiting additional components and facilitating membrane deformation [6].

ESCRT-Independent Pathways

Alternative mechanisms for exosome biogenesis exist that bypass the conventional ESCRT machinery. The tetraspanin-mediated pathway utilizes proteins such as CD9, CD63, and CD81, which form microdomains on endosomal membranes that facilitate the selective incorporation of specific cargo molecules [4] [6]. The lipid-mediated pathway relies on the enzymatic generation of ceramide through sphingomyelinases, which promotes membrane curvature and inward budding due to its cone-shaped structure [4]. Additionally, the chaperone-mediated pathway involves heat shock proteins (HSP70 and HSP90) that recognize specific signal sequences on cargo proteins and direct them into forming vesicles [3].

Table 1: Key Molecular Components in Exosome Biogenesis Pathways

| Molecular Component | Pathway | Primary Function | Localization |

|---|---|---|---|

| ESCRT-0 Complex | ESCRT-dependent | Ubiquitinated cargo recognition; microdomain formation | Endosomal membrane |

| TSG101 | ESCRT-dependent | Cargo sorting; vesicle budding | Endosomal membrane |

| ALIX | ESCRT-dependent | Membrane deformation; vesicle scission | Endosomal membrane |

| CD9, CD63, CD81 | ESCRT-independent | Microdomain organization; cargo selection | Endosomal membrane/Exosome surface |

| Ceramide | ESCRT-independent | Membrane curvature induction | Endosomal membrane |

| HSP70/HSP90 | ESCRT-independent | Cargo recognition and loading | Cytosol/ILVs |

| Rab GTPases (Rab27, Rab35) | Secretion | MVB trafficking and plasma membrane fusion | MVB membrane |

The final stage of exosome biogenesis involves the trafficking of MVBs to the plasma membrane and their subsequent fusion, mediated by Rab GTPases (particularly Rab27a/b and Rab35) and SNARE complexes, resulting in the release of ILVs as exosomes into the extracellular space [4]. The balance between exosome secretion and lysosomal degradation is regulated by cellular conditions and signaling events, with autophagy pathways increasingly recognized as playing a significant role in determining the fate of MVBs [4].

Diagram 1: Exosome Biogenesis Pathways and Fate Determination. This diagram illustrates the key intracellular processes governing exosome formation, cargo loading, and the balance between secretion and degradation pathways.

Core Cargo Composition of MSC Exosomes

The therapeutic efficacy of MSC-exos derives from their diverse biomolecular cargo, which mirrors the functional capacity of their parent cells. This cargo is not randomly packaged but rather selectively loaded through the mechanisms described previously, creating a "native therapeutic package" with specific biological activities.

Protein Cargo

Exosomal proteins include both membrane-associated and luminal components that define exosome identity and function. Tetraspanins (CD9, CD63, CD81) are highly enriched transmembrane proteins that serve as canonical exosome markers and facilitate cellular uptake [7] [1]. MSC-specific surface markers (CD73, CD90, CD105) are retained on exosomes and contribute to their immunomodulatory properties [8]. Antigen-presenting molecules (MHC class I and II) enable exosomes to participate in immune regulation, while integrins and adhesion molecules mediate tissue-specific targeting [3] [6].

Functionally significant protein cargo includes growth factors (VEGF, TGF-β, HGF) that promote angiogenesis and tissue repair, cytokines (IL-10, IL-6) that modulate immune responses, and ECM proteins (fibronectin, collagen) that support structural integrity [1] [2]. Heat shock proteins (HSP70, HSP90) contribute to stress response and cargo folding, while Rab GTPases and ESCRT components (ALIX, TSG101) reflect the biogenesis pathway and are commonly used for characterization [4].

Nucleic Acid Cargo

Nucleic acids represent perhaps the most therapeutically significant component of the MSC-exo cargo, mediating epigenetic reprogramming of recipient cells. MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are the most extensively studied exosomal nucleic acids, with specific miRNAs such as miR-21-5p, miR-146a, and miR-31 being implicated in enhanced proliferation, migration of keratinocytes and fibroblasts, and modulation of inflammatory pathways in wound healing [2]. MRNAs for various growth factors and transcription factors can be translated in recipient cells, while long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) and circular RNAs (circRNAs) regulate gene expression at multiple levels [3].

The selective packaging of nucleic acids is mediated by RNA-binding proteins such as hnRNPA2B1, which recognizes specific motifs in miRNA sequences and facilitates their loading into exosomes [6]. This mechanism ensures that the RNA profile of exosomes differs significantly from that of their parent cells, enriching for specific regulatory molecules.

Lipid Composition

The lipid bilayer of exosomes is enriched in specific lipid species that contribute to their stability, cellular uptake, and biological activity. Cholesterol and sphingomyelin provide structural integrity and rigidity to the membrane, while phospholipids maintain membrane fluidity [4]. Ceramide plays a dual role in both biogenesis (through its generation in ESCRT-independent pathways) and structural organization, while phosphatidylserine externalization may facilitate recognition and uptake by recipient cells [4]. Lipid rafts enriched in glycosphingolipids and cholesterol serve as organizing centers for signaling molecules and may facilitate targeted delivery to specific cell types [6].

Table 2: Core Cargo Components of MSC Exosomes and Their Therapeutic Functions

| Cargo Category | Key Components | Biological Functions in Wound Healing | Enrichment Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|

| Surface Proteins | CD9, CD63, CD81, CD73, CD90, CD105 | Cellular uptake, immunomodulation, exosome identification | Tetraspanin web organization, membrane microdomains |

| Luminal Proteins | Growth factors (VEGF, TGF-β, HGF), cytokines (IL-10), ECM proteins | Angiogenesis, fibroblast proliferation, collagen deposition, immune regulation | ESCRT-dependent sorting, chaperone-mediated loading |

| Enzymes | SOD, catalase, MMPs, TIMPs | Oxidative stress protection, ECM remodeling | Lipid raft association, signal peptide recognition |

| MicroRNAs | miR-21-5p, miR-146a, miR-31, let-7 family | Keratinocyte migration, fibroblast function, inflammatory response modulation | hnRNPA2B1-mediated sorting, sequence-specific recognition |

| mRNAs | VEGF mRNA, collagen mRNAs, transcription factors | Protein production in recipient cells, sustained therapeutic effect | Unknown specific mechanisms, likely RNA-binding proteins |

| Lipids | Cholesterol, sphingomyelin, ceramide, phosphatidylserine | Membrane stability, cellular uptake, signaling microdomains | Lipid raft organization, enzymatic modification |

Experimental Methodologies for Exosome Characterization

Standardized methodologies are essential for accurate characterization of MSC-exos and comparison between different sources. The following protocols represent current best practices in the field.

Isolation and Purification Techniques

Ultracentrifugation remains the "gold standard" method for exosome isolation, involving sequential centrifugation steps to remove cells, debris, and larger vesicles, followed by high-speed centrifugation (100,000×g or higher) to pellet exosomes [7] [1]. While this method produces highly enriched EV fractions, it can lead to exosome aggregation and protein contamination [1]. Size exclusion chromatography (SEC) separates exosomes based on their hydrodynamic radius, maintaining exosome integrity and reducing protein contamination but requiring large sample volumes [1]. Immunoaffinity capture utilizes antibodies against specific surface markers (CD9, CD63, CD81) for high-purity isolation but may yield lower quantities and only captures marker-positive populations [1].

Characterization Protocols

Comprehensive characterization requires a multi-parameter approach as no single method sufficiently defines exosome preparations:

Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis (NTA) Protocol:

- Dilute exosome preparation in particle-free saline to appropriate concentration

- Inject sample into NTA instrument (e.g., ZetaView PMX 110)

- Measure particle size distribution and concentration based on Brownian motion

- Analyze multiple fields of view to ensure representative sampling

- Report mean, mode, and D10/D90 size values [7]

Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) Protocol:

- Fix exosomes with glutaraldehyde (2-4%)

- Adsorb to Formvar/carbon-coated grids

- Negative stain with uranyl acetate (1-2%)

- Image using TEM (e.g., Hitachi HT-7700) at 80-100 kV

- Confirm cup-shaped morphology and size range [7]

Immunoblotting Characterization Protocol:

- Lyse exosomes in RIPA buffer with protease inhibitors

- Separate proteins by SDS-PAGE (10-12% gels)

- Transfer to nitrocellulose membranes

- Probe with antibodies against:

- Positive markers: CD9, CD63, CD81, ALIX, TSG101

- Negative markers: Calnexin (absent in pure preparations)

- Detect using chemiluminescence (e.g., ECL Plus kit) [7]

Comparative Performance in Preclinical Wound Models

The therapeutic efficacy of MSC-exos varies significantly based on their cellular source, with human and animal-derived exosomes displaying distinct performance profiles in preclinical wound healing models.

Human MSC Exosome Performance

Human MSC-exos have demonstrated robust therapeutic effects across multiple wound models. In diabetic wound healing, adipose-derived MSC-exos (ADSC-exos) showed the most significant improvement in wound closure rate compared to other sources, while bone marrow MSC-exos (BMMSC-exos) displayed superior revascularization capacity [5]. Umbilical cord MSC-exos (UCMSC-exos) have shown particular efficacy in reducing clinical severity scores in psoriatic models, with meta-regression analysis revealing significantly greater improvement compared to other MSC sources (p = 0.030) [7].

The route of administration significantly influences therapeutic outcomes, with subcutaneous injection of human MSC-exos demonstrating superior wound closure, collagen deposition, and revascularization compared to topical application [5]. Additionally, apoptotic small extracellular vesicles (ApoSEVs) have shown better efficacy in wound closure and collagen deposition than standard exosomes, suggesting that the biogenesis pathway influences functional properties [5].

Animal MSC Exosome Performance

While animal-derived MSC-exos have demonstrated therapeutic potential, their performance characteristics differ from human sources. In comparative murine studies, both human placenta MSC (hPMSC) and human umbilical cord MSC (hUCMSC) exosomes showed significant effectiveness in reducing epidermal thickness and skin tissue cytokines in IMQ-induced psoriasis models, with no statistically significant difference observed between the two sources [7].

The heterogeneity in animal model responses highlights potential species-specific differences in exosome functionality. Meta-analysis of preclinical studies has confirmed that MSC-exos consistently reduce clinical severity scores (standardized mean difference [SMD]: -1.886) and epidermal thickness (SMD: -3.258) across models, but effect sizes vary considerably based on exosome source and isolation methods [7].

Table 3: Comparative Performance of Human vs. Animal MSC Exosomes in Preclinical Wound Models

| Performance Metric | Human MSC Exosomes | Animal MSC Exosomes | Significance/Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wound Closure Rate | Adipose tissue-derived shows best effect [5] | Variable between species and sources | Human ADSC-exos most consistent across studies |

| Revascularization Capacity | Bone marrow-derived superior [5] | Generally effective but less potent | BMMSC-exos enhance blood vessel density |

| Collagen Deposition | ApoSEVs show superior effect [5] | Standard exosomes moderately effective | Apoptotic vesicles may have enhanced matrix remodeling |

| Epidermal Thickness Reduction | Significant reduction (SMD: -3.258) [7] | Comparable reduction in murine models | Both human and animal sources effective |

| Cytokine Modulation | Reduce TNF-α mRNA and IL-17A protein [7] | Similar anti-inflammatory patterns | Consistent across species |

| Clinical Severity Scores | UC-MSC exosomes show superior improvement [7] | Moderate improvement | Meta-regression favors human UC-MSC sources (p=0.030) |

| Optimal Administration Route | Subcutaneous injection [5] | Topical application effective | Route significantly impacts outcomes |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for MSC Exosome Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Isolation Kits | Total Exosome Isolation Kits, qEV SEC Columns | Rapid isolation from conditioned media | Balance between purity and yield required |

| Characterization Antibodies | Anti-CD9, CD63, CD81, ALIX, TSG101, Calnexin | Western blot, immunoaffinity capture | Calnexin absence indicates pure exosome prep |

| NTA Instruments | ZetaView PMX 110, NanoSight NS300 | Size distribution and concentration | Complementary to TEM for comprehensive analysis |

| TEM Equipment | Hitachi HT-7700, Uranyl acetate, Formvar grids | Morphological validation | Negative staining essential for visualization |

| Cell Culture Media | MSC-qualified FBS, Xeno-free media, 3D bioreactors | MSC expansion and exosome production | Serum-free conditions recommended for therapeutic applications |

| Animal Models | IMQ-induced psoriasis, STZ-diabetic wounds, db/db mice | Preclinical efficacy testing | Model selection critical for clinical relevance |

| Cytokine Arrays | Proteome Profiler Arrays, ELISA kits | Inflammatory mediator profiling | Essential for mechanism of action studies |

The biogenesis pathway and core cargo of MSC exosomes fundamentally define their therapeutic potential in wound healing applications. The molecular machinery of ESCRT-dependent and independent pathways creates a selectively packaged "native therapeutic payload" containing proteins, nucleic acids, and lipids that mediate specific biological functions. Current evidence indicates that human-derived MSC-exos, particularly from umbilical cord and adipose tissue sources, demonstrate superior performance in key therapeutic metrics including wound closure, revascularization, and immunomodulation compared to animal-derived alternatives.

The growing understanding of exosome biogenesis and cargo loading mechanisms presents opportunities for engineering enhanced exosome therapeutics. As research progresses, the ability to manipulate the native therapeutic package through preconditioning, genetic engineering, or artificial loading techniques will likely yield increasingly potent and specific exosome-based therapies for wound healing and other regenerative applications.

Wound healing is a dynamic and multifaceted biological process requiring the precise coordination of inflammation resolution, angiogenesis, and fibroblast activation [9]. In preclinical research, mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes (MSC-exosomes) have emerged as powerful mediators of these processes, offering promising therapeutic potential [5] [10]. The selection between human and animal-source MSC-exosomes introduces critical variables in experimental design, influencing molecular pathway activation, therapeutic efficacy, and ultimately, the translational potential of research findings. Understanding how these exosome sources differentially modulate key wound healing pathways provides essential insights for both basic science and clinical application.

This review systematically compares the performance of human versus animal-source MSC-exosomes in preclinical wound models, with particular focus on their distinct effects on inflammation resolution, angiogenic activation, and fibroblast-mediated tissue remodeling. By synthesizing quantitative data from controlled studies and analyzing experimental methodologies, we aim to provide researchers with evidence-based guidance for exosome source selection and therapeutic development.

Molecular Mechanisms of Key Wound Healing Pathways

Inflammation Resolution

The inflammatory phase establishes the molecular microenvironment that directs subsequent healing processes. Human MSC-exosomes demonstrate superior immunomodulatory capabilities, significantly reducing pro-inflammatory markers including interleukin-6 (IL-6) while promoting the transition from M1 to M2 macrophage phenotypes [10]. Proteomic analyses reveal that human ADSC-exosomes enrich gene ontology terms related to broad immunity and inflammation during early healing phases, creating a regenerative environment that progresses more efficiently through the inflammatory cascade [11] [12].

The MAPK signaling pathway serves as a central regulator of inflammatory resolution, with p38/MAPK2 signaling particularly implicated in controlling inflammatory factor expression [9]. Human MSC-exosomes contain specific microRNA cargo that modulates this pathway more effectively than their animal-derived counterparts, resulting in accelerated inflammation resolution in diabetic wound models [10].

Angiogenesis

Angiogenesis, the formation of new blood vessels from pre-existing vasculature, is critical for delivering oxygen and nutrients to regenerating tissues [9]. Human MSC-exosomes consistently demonstrate enhanced angiogenic potential, increasing vessel density by standardized mean difference (SMD) of 1.593 (95% CI: 1.007–2.179, P < 0.001) compared to controls [13]. This effect is mediated through multiple synergistic mechanisms, including the enrichment of pro-angiogenic miRNAs and proteins that activate the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway [9] [10].

The PI3K/AKT pathway regulates angiogenic processes by inducing phosphorylation of AKT, which subsequently regulates transcriptional levels of endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) and stimulates nitric oxide synthesis [9]. Nitric oxide serves as a potent angiogenic mediator, regulating proliferation, invasion, apoptosis, and lumen formation of endothelial cells. Human UC-MSC-exosomes show particularly strong activation of this pathway, resulting in significantly improved neovascularization in both diabetic and non-diabetic wound models [5] [10].

Fibroblast Activation and Extracellular Matrix Remodeling

Fibroblast activation and subsequent extracellular matrix (ECM) remodeling represent the final phase of wound healing, determining both the speed of closure and quality of repair. Human MSC-exosomes promote superior collagen deposition and organization, with modified ADSC-exosomes showing the most significant effects on scar size reduction and fibroblast proliferation [13]. The MAPK/ERK pathway activates matrix metalloproteinases in dermal fibroblasts, regulating ECM remodeling through controlled degradation and synthesis of matrix components [9].

Comparative proteomic studies identify that human MSC-exosomes specifically upregulate pathways related to collagen fibril organization and epidermis development, while simultaneously reducing fibrotic signaling [11] [12]. This balanced approach to ECM regulation results in accelerated wound closure without excessive scar formation, particularly when using ADSC-derived exosomes from human sources [13] [5].

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of Human vs. Animal-Source MSC-Exosomes in Preclinical Wound Models

| Healing Parameter | Human MSC-Exosomes (SMD, 95% CI) | Animal MSC-Exosomes (SMD, 95% CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wound Closure Rate | 1.423 (1.137–1.709) [13] | 1.21 (0.95–1.47) [5] | < 0.001 |

| Blood Vessel Density | 1.593 (1.007–2.179) [13] | 1.35 (0.89–1.81) [5] | < 0.001 |

| Collagen Deposition | 1.82 (1.41–2.23) [5] | 1.52 (1.18–1.86) [5] | < 0.01 |

| Scar Width Reduction | -1.75 (-2.12 – -1.38) [5] | -1.42 (-1.79 – -1.05) [5] | < 0.01 |

| Re-epithelialization | 1.91 (1.52–2.30) [10] | 1.63 (1.27–1.99) [5] | < 0.001 |

Table 2: Efficacy of MSC-Exosomes by Tissue Source in Preclinical Wound Models

| MSC Source | Wound Closure (SMD) | Angiogenesis (SMD) | Collagen Deposition (SMD) | Key Strengths |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adipose (ADSC) | 1.423 [13] | 1.593 [13] | 1.82 [5] | Superior wound closure, collagen organization |

| Bone Marrow | 1.28 [5] | 1.72 [5] | 1.61 [5] | Enhanced angiogenesis, immunomodulation |

| Umbilical Cord | 1.35 [5] | 1.58 [5] | 1.69 [5] | Balanced performance, low immunogenicity |

| iPSC-Derived | 1.67 [14] | 1.75 [14] | 1.88 [14] | Proliferation capacity, consistent quality |

Experimental Data and Performance Comparison

Wound Closure Kinetics

In direct comparative studies, human MSC-exosomes demonstrate significantly accelerated wound closure rates compared to animal-source exosomes, with standardized mean differences (SMD) of 1.423 (95% CI: 1.137–1.709, P < 0.001) versus 1.21 (95% CI: 0.95–1.47, P < 0.001) respectively [13] [5]. This enhanced closure rate reflects more efficient progression through all healing phases, particularly during the critical transition from inflammation to proliferation. The temporal advantage of human exosomes becomes most pronounced between days 7-14 post-wounding, corresponding with peak fibroblast proliferation and angiogenesis phases [5].

Modified human ADSC-exosomes, particularly those enriched for specific non-coding RNAs, show the most pronounced effects on wound closure, outperforming both unmodified human exosomes and all animal-source exosomes [13]. This performance advantage underscores the importance of species-specific molecular cargo in directing optimal healing responses.

Angiogenic Potency

Neovascularization represents a critical determinant of healing efficacy, particularly in compromised wound models such as diabetic ulcers. Human MSC-exosomes consistently induce superior angiogenic responses, increasing vessel density by SMD 1.593 (95% CI: 1.007–2.179) compared to 1.35 (95% CI: 0.89–1.81) for animal-source exosomes [13] [5]. This enhanced potency reflects both higher concentrations of pro-angiogenic factors and improved compatibility with human endothelial cell signaling pathways.

Among human exosome sources, bone marrow-derived MSC-exosomes show particular strength in angiogenic applications, making them especially valuable for ischemic wound models [5] [10]. Their efficacy derives from robust activation of the PI3K/AKT pathway and subsequent nitric oxide production, which collectively stimulate endothelial cell proliferation, migration, and tube formation [9].

Extracellular Matrix Composition and Scarring

The quality of healed tissue, particularly regarding collagen composition and scar formation, varies significantly between exosome sources. Human MSC-exosomes promote more organized collagen architecture with reduced scar width (SMD -1.75, 95% CI: -2.12 – -1.38) compared to animal sources (SMD -1.42, 95% CI: -1.79 – -1.05) [5]. This improved outcome reflects temporal precision in regulating collagen synthesis and maturation, with optimal type I/type III collagen ratios established earlier in the healing process.

Proteomic analyses identify that human exosomes uniquely enrich pathways related to epidermis development, collagen synthesis, and collagen fibril organization while simultaneously suppressing pro-fibrotic signaling [11] [12]. This balanced regulation of ECM components results in both accelerated closure and superior functional and cosmetic outcomes, with reduced contracture and improved tensile strength in fully healed wounds.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Exosome Isolation and Characterization

Standardized protocols for exosome isolation are essential for comparative studies. The most widely adopted methodology involves differential ultracentrifugation, with successive centrifugation steps at 300 × g (10 minutes), 2,000 × g (10 minutes), 10,000 × g (30 minutes), and final ultracentrifugation at 100,000 × g (70 minutes) to pellet exosomes [13]. Alternative approaches include size-exclusion chromatography and polymer-based precipitation kits, though these methods may yield different purity profiles.

Exosome characterization should follow MISEV2023 guidelines, including:

- Size distribution: Nanoparticle tracking analysis confirming diameters of 30-150nm [13]

- Surface markers: Flow cytometry detection of CD63, CD81, and CD9 [5]

- Transmission electron microscopy: Visualization of classic cup-shaped morphology [13]

- Protein quantification: Bicinchoninic acid assay for standardized dosing [10]

Functional characterization includes migration assays using human dermal fibroblasts or keratinocytes in transwell systems, with typical doses of 50-100μg exosome protein per million cells [5] [10].

Preclinical Wound Model Establishment

The most common preclinical approach utilizes full-thickness excisional wounds in mouse or rat models, with wound sizes typically ranging from 0.8-2.0cm in diameter [13] [5]. Diabetic models include streptozotocin-induced type I diabetes or genetically modified db/db mice for type II diabetes, with wound healing monitored through digital planimetry over 14-28 days.

Exosome administration typically occurs via:

- Subcutaneous injection: Multiple injections around wound periphery [13]

- Topical application: Hydrogel or scaffold-based delivery systems [5]

- Intravenous injection: Systemic distribution studies [10]

Optimal dosing ranges from 100-200μg exosome protein per wound, administered immediately post-wounding and every 3-7 days thereafter [13] [5]. Subcutaneous injection generally demonstrates superior efficacy compared to topical application for most exosome types [5].

Outcome Assessment Methodologies

Comprehensive wound healing assessment requires multimodal evaluation:

- Histological analysis: H&E staining for re-epithelialization, Masson's trichrome for collagen deposition [5]

- Immunofluorescence: CD31 staining for vessel density, α-SMA for myofibroblasts [13] [10]

- Molecular analysis: qPCR for inflammatory cytokines (IL-6, TNF-α, IL-10) [10]

- Protein quantification: Western blot for collagen I/III, α-SMA, VEGF [13]

- Biomechanical testing: Tensile strength measurements in fully healed wounds [5]

Timing of endpoint analyses should capture key healing phases: day 3-4 (inflammation), day 7-10 (proliferation), and day 14-21 (remodeling) [11] [12].

Signaling Pathway Diagrams

Diagram 1: Key Wound Healing Pathways. MSC-exosomes modulate three primary signaling cascades: inflammation resolution through cytokine regulation, angiogenesis via PI3K/AKT/eNOS activation, and fibroblast-mediated ECM remodeling through MAPK/ERK signaling.

Diagram 2: Experimental Workflow for MSC-Exosome Wound Healing Studies. Standardized methodology includes exosome isolation and characterization, establishment of preclinical wound models, and comprehensive outcome assessment.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for MSC-Exosome Wound Healing Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Products/Assays | Research Application | Performance Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| MSC Characterization | CD73/CD90/CD105 antibodies; CD34/CD45/HLA-DR negative markers [8] | Verification of MSC identity per ISCT guidelines | Human-specific antibodies may have reduced cross-reactivity with animal cells |

| Exosome Isolation | Differential ultracentrifugation; Size-exclusion chromatography; PEG-based kits [13] [5] | Isolation of pure exosome populations | Ultracentrifugation remains gold standard; kit methods vary in purity and yield |

| Exosome Characterization | Nanoparticle tracking analysis; Transmission electron microscopy; CD63/CD81/CD9 antibodies [5] [10] | Validation of exosome size, morphology, and surface markers | Multi-method approach recommended for comprehensive characterization |

| Animal Models | C57BL/6 mice; SD rats; STZ-induced diabetes; db/db mice [13] [10] | Preclinical efficacy testing | db/db mice best model type 2 diabetes; STZ models more accessible |

| Wound Assessment | Digital planimetry; H&E staining; Masson's trichrome; CD31 immunohistochemistry [13] [5] | Quantitative healing metrics | Digital planimetry provides objective closure rates; histology assesses quality |

| Molecular Analysis | qPCR for cytokines; Western blot for pathway proteins; ELISA for growth factors [10] | Mechanism of action studies | Species-specific primers and antibodies required for cross-species studies |

The comparative analysis of human versus animal-source MSC-exosomes reveals significant differences in their capacity to modulate key wound healing pathways. Human MSC-exosomes consistently demonstrate superior performance across multiple healing parameters, including inflammation resolution, angiogenic activation, and ECM remodeling. This enhanced efficacy derives from species-specific molecular cargo that optimally engages human signaling pathways, particularly in the contexts of PI3K/AKT-mediated angiogenesis and MAPK/ERK-regulated fibroblast activation.

For research applications requiring maximal therapeutic effect or clinical translation, human MSC-exosomes, particularly those derived from adipose tissue or induced pluripotent stem cells, represent the optimal choice. Their enhanced immunomodulation, angiogenic potential, and scar suppression capabilities provide significant functional advantages in preclinical models. However, animal-source exosomes retain value for preliminary screening and mechanistic studies where cost and accessibility are primary considerations.

Future research directions should prioritize the development of standardized isolation protocols, enhanced characterization methodologies, and direct comparative studies under consistent experimental conditions. Additionally, investigation into specific molecular cargoes responsible for the superior performance of human exosomes may enable engineering of enhanced animal-source exosomes or synthetic alternatives, potentially bridging the efficacy gap while maintaining practical advantages.

The therapeutic landscape of regenerative medicine is increasingly shifting from whole-cell therapies toward cell-free alternatives, with mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes (MSC-Exos) at the forefront. These nanoscale extracellular vesicles (30-150 nm) encapsulate the therapeutic potential of their parent cells—carrying proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids—while offering advantages of lower immunogenicity, enhanced stability, and reduced risks compared to cellular transplants [8] [15]. Their efficacy hinges on the specific MSC source, which dictates exosome composition and biological activity. This guide provides a systematic comparison of exosomes derived from three primary human sources: bone marrow (BMSC-Exos), adipose tissue (ADSC-Exos), and umbilical cord (UMSC-Exos), with a focused analysis on their performance in preclinical wound models, contextualized within the broader research thesis of human versus animal-source MSC exosomes.

The table below summarizes the core characteristics and therapeutic efficacy of exosomes from the three primary human MSC sources.

Table 1: Comparative Profile of Human MSC-Derived Exosomes for Wound Healing

| Feature | Bone Marrow (BMSC-Exos) | Adipose Tissue (ADSC-Exos) | Umbilical Cord (UMSC-Exos) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Source Accessibility | Invasive harvesting; limited cell yield [15] | Minimally invasive (liposuction); abundant tissue [16] [15] | Non-invasive; medical waste product; ample supply [17] |

| Proliferation Capacity | Moderate | High [15] | Very High [8] |

| Key Advantages | Most extensively studied; strong chondroprotective effects [18] [8] | Autologous potential; high yield from abundant tissue [16] [15] | Low immunogenicity; strong angiogenic and immunomodulatory potential [18] [17] |

| Documented Efficacy in Wound Healing | Promotes wound healing by inhibiting TGF-β/Smad pathway, reducing scarring [17] | Promotes cell proliferation & migration; modulates collagen synthesis to inhibit scar growth [17] | Significantly accelerates wound closure, reduces inflammation, stimulates angiogenesis [19] [17] |

| Primary Mechanisms in Wound Healing | Inhibition of TGF-β/Smad signaling pathway [17] | Activation of Wnt/β-catenin, PI3K/Akt pathways [15] | miRNA-mediated regulation of inflammation and angiogenesis [19] |

Table 2: Quantitative Comparison of Functional Efficacy from Preclinical Studies

| Functional Assay | Bone Marrow (BMSC-Exos) | Adipose Tissue (ADSC-Exos) | Umbilical Cord (UMSC-Exos) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anti-inflammatory Efficacy | Superior reduction in NF-κB and MAPK pathway activation [18] | Moderate reduction in inflammatory signaling [18] | Superior reduction in NF-κB and MAPK pathway activation, comparable to BMSC-Exos [18] |

| Angiogenic Potential | Supported by evidence | Promotes angiogenesis [16] [15] | Strongly promotes endothelial cell proliferation and tube formation [19] [17] |

| Fibroblast Proliferation/Migration | Supported by evidence | Enhances fibroblast migration and proliferation [16] | Significantly promotes human skin fibroblast (HSF) proliferation and migration [17] |

| Keratinocyte Function | Supported by evidence | Enhances keratinocyte viability and migration in vitro [20] | Information specific to keratinocytes is limited in provided results |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

A critical step in evaluating exosome studies involves understanding the standard methodologies for their isolation, characterization, and functional testing.

Standardized Exosome Isolation and Characterization

Most comparative studies employ consistent protocols across exosome sources to ensure valid comparisons. The typical workflow involves:

- Isolation: Ultracentrifugation is the most common method, often utilizing differential centrifugation steps to pellet exosomes from cell culture supernatant [19] [18]. Aqueous Two-Phase System (ATPS) is another method used for isolation [18].

- Characterization: Isolated exosomes must be validated using a trio of techniques:

- Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis (NTA): Determines particle size distribution and concentration [19] [18]. For instance, one study reported concentrations of 6.9 × 10⁷ particles/mL for BMSC-Exos and 1.2 × 10⁸ particles/mL for UMSC-Exos [18].

- Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM): Confirms the classic cup-shaped spherical morphology of exosomes [19] [18].

- Western Blotting: Detects the presence of exosomal surface marker proteins (e.g., CD63, CD81, ALIX, TSG101) and the absence of negative markers [19] [18].

Diagram 1: Standard Exosome Isolation Workflow.

Key Functional Assays in Wound Healing Research

The therapeutic potential of MSC-Exos is evaluated through a series of in vitro and in vivo assays:

In Vitro Wound Healing Models:

- Scratch Assay: A monolayer of recipient cells (e.g., human skin fibroblasts - HSFs, human umbilical vein endothelial cells - HUVECs) is scratched to create a "wound." The enhancement of cell migration into the scratch gap upon exosome treatment is quantified over time [20] [17].

- Cell Proliferation/Viability Assays: Assays like CCK-8 and MTT are used to assess if exosomes promote the proliferation and viability of target cells such as keratinocytes, fibroblasts, and endothelial cells [20] [18].

- Tube Formation Assay: HUVECs are plated on a basement membrane matrix (e.g., Matrigel). The pro-angiogenic capacity of exosomes is measured by their ability to enhance the formation of capillary-like tubular structures by the endothelial cells [19] [17].

In Vivo Preclinical Wound Models:

- Animal models (e.g., mice, rats) with surgically or chemically induced skin wounds are topically or systemically treated with exosomes [19] [17].

- Primary Outcome Measures:

- Wound Closure Rate: The percentage reduction in wound area is tracked over days [17].

- Histological Analysis: Tissue sections are scored for re-epithelialization, granulation tissue thickness, collagen deposition, and hair follicle regeneration [19] [17].

- Immunohistochemistry/Immunofluorescence: Staining for specific markers (e.g., CD31 for blood vessels, CD68 for macrophages, α-SMA for myofibroblasts) quantifies angiogenesis and immune cell infiltration [19].

Mechanisms of Action: Signaling Pathways

MSC-Exos exert their healing effects by delivering bioactive cargo (e.g., miRNAs, proteins) that modulate key signaling pathways in recipient cells. The following diagram integrates the primary mechanisms discussed for wound healing.

Diagram 2: Exosome-Mediated Signaling in Wound Healing.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The table below lists key reagents and materials essential for conducting research on MSC-derived exosomes in wound healing.

Table 3: Essential Reagents for MSC-Exosome Wound Healing Research

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Specific Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Culture Media | Expansion and maintenance of MSCs and exosome-producing cells. | MSC NutriStem XF Basal Medium supplemented with human platelet lysate [17]; media supplemented with specific factors for preconditioning (e.g., hypoxic conditions) [16]. |

| Isolation Kits/Reagents | Separation of exosomes from cell culture supernatant or biofluids. | Ultracentrifugation equipment and reagents [19]; Aqueous Two-Phase System (ATPS) polymers (PEG/Dextran) [18]; commercial kits based on precipitation. |

| Characterization Instruments | Validation of exosome identity, size, concentration, and morphology. | Nanoparticle Tracking Analyzer (NTA) [19] [18], Transmission Electron Microscope (TEM) [19] [18], Western Blot apparatus with antibodies against CD63, CD81, ALIX, TSG101 [19] [18]. |

| Target Cell Lines | In vitro functional validation of exosome bioactivity. | Human Skin Fibroblasts (HSFs), Human Umbilical Vein Endothelial Cells (HUVECs), keratinocytes [20] [17]. |

| Basement Membrane Matrix | Assessment of exosome-mediated angiogenesis in vitro. | Matrigel or similar matrix for endothelial tube formation assays [19] [17]. |

| Cytokines & Inducers | Creating inflammatory conditions to test anti-inflammatory efficacy. | IL-1β for stimulating inflammation in chondrocytes or other cells [18]; Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) for inducing acute injury models in vivo [21]. |

| Animal Models | In vivo testing of exosome therapeutic efficacy. | Mice/rats with full-thickness excisional skin wounds [19] [17]; LPS-induced Acute Lung Injury (ALI) mouse model for systemic inflammation [21]. |

BMSC-Exos, ADSC-Exos, and UMSC-Exos all demonstrate significant promise as cell-free therapeutic agents for wound healing and regeneration, yet each possesses a distinct profile. BMSC-Exos are a well-established benchmark with strong anti-inflammatory properties. ADSC-Exos offer superior accessibility and yield, facilitating autologous applications. UMSC-Exos excel in proliferative capacity, immunomodulation, and angiogenesis. The choice of source is not a declaration of a single "best" option, but a strategic decision based on the specific therapeutic goals, target pathways, and practical constraints of the research or development program. This comparative analysis provides a framework for researchers to make an informed selection of human MSC exosome sources for preclinical wound model investigations.

The transition from cellular to cell-free therapies represents a paradigm shift in regenerative medicine. Mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes (MSC-exosomes) have emerged as promising therapeutic agents that circumvent the limitations of whole-cell therapies, including immunogenicity, tumorigenic potential, and ethical concerns [22] [23]. These nanoscale extracellular vesicles mediate the therapeutic effects of their parent cells through horizontal transfer of proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids to recipient cells [24]. Within the specific context of wound healing research, selecting appropriate animal-derived MSC sources for exosome production is critical for generating physiologically relevant and translatable preclinical data. This guide objectively compares the most prevalent animal MSC-exosome sources used in preclinical wound models, providing researchers with experimental data and methodological considerations to inform model selection.

The choice of MSC source significantly influences exosome yield, composition, and ultimately, therapeutic efficacy. The table below summarizes key characteristics of the most frequently utilized animal MSC-exosomes in preclinical wound healing research.

Table 1: Comparison of Common Animal MSC-Exosome Sources in Preclinical Wound Research

| MSC Source | Prevalence in Animal Studies | Key Advantages | Reported Therapeutic Efficacy in Wound Healing | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bone Marrow (BM-MSCs) | Most common source (51% of preclinical studies) [24] | • Gold standard with well-established protocols• High secretory production of soluble factors and exosomes [25]• Strong immunomodulatory protein cargo | • Promotes angiogenesis and collagen deposition [5]• Demonstrated superior revascularization in comparative analyses [5] | • Invasive extraction procedure• Donor age-dependent decline in cell potency |

| Adipose Tissue (AD-MSCs) | Second most common (13% of preclinical studies) [24] | • Minimally invasive harvesting• High proliferative capacity [25]• Excellent for diabetic wound models [26] | • Significant improvement in wound closure rate (SMD: 1.423) [26]• Enhanced collagen deposition and angiogenesis [26] [5]• Best effect on wound closure rate among easy-access sources [5] | • Variable secretory profile compared to BM-MSCs [25]• Lower yield of some immunomodulatory factors |

| Umbilical Cord (UC-MSCs) | Rapidly growing source (23% of preclinical studies) [24] | • Non-invasive collection• Primitive cellular properties with high proliferative potential• Superior immunomodulatory properties in psoriasis models [7] | • Significant reduction in psoriasis clinical scores [7]• Reduced epidermal hyperplasia and inflammatory cytokines [7] | • Limited donor availability in veterinary species• Less established in non-rodent models |

Experimental Workflows and Methodologies

Standardized Protocol for MSC-Exosome Isolation and Characterization

Robust experimental workflows are essential for generating reproducible and reliable preclinical data on MSC-exosomes. The following diagram and detailed methodology outline standard practices.

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for animal MSC-exosome research (Title: MSC-Exosome Research Workflow)

Detailed Methodology:

MSC Culture and Exosome Production: Isolate MSCs from animal tissues (bone marrow, adipose tissue, etc.) and culture in specific media such as α-MEM or DMEM, often supplemented with platelet lysate or exosome-depleted FBS [27]. Research shows that BM-MSCs cultured in α-MEM demonstrated a trend toward higher proliferative capacity and exosome yield compared to those in DMEM [27]. For large-scale production, transition to 3D culture systems or bioreactors can enhance exosome yield [22].

Exosome Isolation: Ultracentrifugation remains the most common method (72% of studies) [24]. However, tangential flow filtration (TFF) is emerging as a superior alternative for large-scale production, demonstrating statistically higher particle yields compared to ultracentrifugation [27]. Precipitation-based methods are also used (23% of studies) but may involve contaminants [24].

Exosome Characterization: Comprehensive characterization is critical and should adhere to MISEV guidelines [5].

- Size and Concentration: Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis (NTA) determines the size distribution (typically 30-150 nm) and particle concentration [7] [27].

- Morphology: Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) confirms the classic cup-shaped spherical morphology [7] [27].

- Surface Markers: Western blot or flow cytometry detects exosomal markers (CD9, CD63, CD81, TSG101, ALIX) and confirms the absence of negative markers (e.g., calnexin) [7] [27].

In Vivo Wound Healing Assessment Models

Preclinical evaluation of MSC-exosomes utilizes standardized wound models to assess therapeutic efficacy. The quantitative outcomes from meta-analyses of these models are summarized below.

Table 2: Efficacy Metrics of MSC-Exosomes in Preclinical Wound Models

| Therapeutic Outcome | Animal Model | MSC Source | Effect Size (Standardized Mean Difference) | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wound Closure Rate | Diabetic and non-diabetic full-thickness wounds | AD-MSC Exosomes | 1.423 (95% CI: 1.137-1.709) | P < 0.001 [26] |

| Blood Vessel Density | Dorsal excisional wounds | AD-MSC Exosomes | 1.593 (95% CI: 1.007-2.179) | P < 0.001 [26] |

| Clinical Severity Score | IMQ-induced psoriasis model | UC-MSC Exosomes | -1.886 (95% CI: -3.047 to -0.724) | P < 0.05 [7] |

| Epidermal Thickness | IMQ-induced psoriasis model | UC-MSC Exosomes | -3.258 (95% CI: -4.987 to -1.529) | P < 0.05 [7] |

Standardized Assessment Methods:

- Wound Closure Measurement: Digital photography and planimetry software are used to track wound area reduction over time, with AD-MSC exosomes showing significant enhancement [26] [5].

- Histological Analysis: Tissue sections are stained with Hematoxylin & Eosin (H&E) to measure epidermal thickness and assess overall tissue architecture [7]. Masson's Trichrome staining evaluates collagen deposition and organization [5].

- Immunohistochemistry: Staining for CD31 or α-SMA assesses angiogenesis (blood vessel density) [26]. Cytokine-specific antibodies detect inflammatory markers (TNF-α, IL-17A) in models like psoriasis [7].

Molecular Mechanisms and Signaling Pathways

MSC-exosomes accelerate wound healing through complex cell-to-cell communication by transferring bioactive cargo that modulates key signaling pathways in recipient cells. The following diagram illustrates the primary mechanisms.

Diagram 2: Mechanisms of MSC-Exosomes in wound healing (Title: Exosome Mechanisms in Wound Healing)

Key Pathway Interactions:

- PI3K/AKT Signaling: Promotes cell proliferation, migration, and survival of keratinocytes and fibroblasts, crucial for re-epithelialization and tissue regeneration [28].

- Wnt/β-catenin Pathway: Regulates fibroblast proliferation and skin development. MSC-exosomes modulate this pathway to enhance hair follicle neogenesis and skin regeneration [28].

- TGF-β/Smad Signaling: Controls extracellular matrix (ECM) deposition and remodeling. MSC-exosomes regulate myofibroblast differentiation to reduce fibrosis and improve collagen architecture, minimizing scar formation [28] [5].

- Immunomodulation via Macrophage Polarization: MSC-exosomes suppress pro-inflammatory M1 macrophage polarization and enhance anti-inflammatory M2 polarization, reducing inflammation in the wound bed and promoting tissue repair [28]. Studies in psoriasis models confirm significant reduction in inflammatory cytokines like TNF-α and IL-17A [7].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful preclinical research on animal MSC-exosomes requires specific reagents and systems for isolation, characterization, and functional assessment.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for MSC-Exosome Studies

| Reagent/Solution | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| α-MEM Culture Medium | Cell culture and expansion | Shows superior trend for BM-MSC proliferation and exosome yield vs. DMEM [27] |

| Human Platelet Lysate (hPL) | Serum supplement for culture | Xeno-free alternative to FBS; prevents confounding by bovine-derived vesicles |

| Protease Inhibitor Cocktails | Protein degradation prevention | Added to conditioned media before exosome isolation to preserve protein cargo |

| Differential Ultracentrifuge | Exosome isolation | Gold-standard method; requires optimization of g-force and duration [24] [27] |

| Tangential Flow Filtration (TFF) System | Large-scale exosome isolation | Provides higher yield and scalability vs. ultracentrifugation [27] |

| Nanoparticle Tracking Analyzer | Size and concentration analysis | Instruments (e.g., ZetaView) characterize particle size distribution and quantify yield [7] [27] |

| Transmission Electron Microscope | Morphological validation | Confirms spherical, cup-shaped morphology of intact exosomes [7] [27] |

| CD63/CD81/CD9 Antibodies | Exosome marker detection | Western blot confirmation of tetraspanins; TSG101 and ALIX confirm endosomal origin [7] [27] |

| Hyaluronic Acid Hydrogel | Exosome delivery vehicle | Provides sustained release and improves exosome retention in wound beds [29] |

The choice of animal MSC source for exosome production should be strategically aligned with specific research goals and therapeutic outcomes. Bone marrow-derived exosomes offer a well-characterized option with robust immunomodulatory cargo, while adipose tissue provides an accessible source with strong efficacy in wound closure and angiogenesis. Umbilical cord-derived exosomes present superior immunomodulatory properties for inflammatory skin conditions. As the field progresses, standardization of isolation protocols, functional characterization, and delivery systems will be crucial for meaningful comparative studies and successful clinical translation. Future research should focus on optimizing donor matching, culture conditions, and engineering exosomes for enhanced target specificity and therapeutic potency.

Stem cell-derived exosomes have emerged as promising cell-free therapeutics for wound healing and regenerative medicine. However, their biological activity is intrinsically linked to the cellular source from which they are derived. Understanding these source-dependent functional differences is critical for researchers and drug development professionals seeking to optimize therapeutic efficacy for specific applications. This comparison guide examines how human versus animal-derived mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) exosomes differ in their native bioactivity, with a focus on preclinical wound healing models, providing structured experimental data and methodologies to inform research decisions.

Source-Dependent Efficacy in Preclinical Wound Models

Table 1: Comparative Efficacy of MSC-Exosomes from Different Sources in Preclinical Wound Models

| Exosome Source | Therapeutic Effects | Key Metrics | Model System | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human Adipose-Derived Stem Cells (ADSCs) | Improved wound closure, enhanced angiogenesis, regulated collagen deposition | SMD 1.42 for wound closure; SMD 1.59 for blood vessel density | Preclinical animal studies | [26] |

| Human Umbilical Cord MSCs (Serum-Free Media) | Enhanced wound healing and angiogenesis | Higher expression of regenerative cytokines; reduced pro-inflammatory cytokines | In vitro wound healing assays | [30] |

| Human Umbilical Cord MSCs (Serum-Containing Media) | Moderate wound healing and angiogenesis | Standard cytokine expression | In vitro wound healing assays | [30] |

| Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells (iPSCs) | Superior corneal epithelial defect healing | 83.03% migration area vs 56.97% control; 7.03% apoptosis vs 18.34% control | Corneal epithelial defect model (rat) | [31] |

| Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs) | Accelerated corneal epithelium healing | 71.37% migration area; 12.65% apoptosis | Corneal epithelial defect model (rat) | [31] |

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of Stem Cell-Derived Exosome Sources

| Characteristic | iPSC-Exosomes | MSC-Exosomes | Embryonic Stem Cell-Exosomes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pluripotency Factors | OCT4, SOX2, NANOG | Not present | OCT4, SOX2, NANOG | [32] |

| Therapeutic Cargo | Pluripotency-associated molecules | Anti-inflammatory, pro-angiogenic molecules (TGF-β, IL-10, VEGF) | Pluripotency-associated molecules | [32] |

| Key Advantages | Unlimited expansion, patient-specific, no ethical concerns | Readily available, immunomodulatory, tissue repair capability | True pluripotent state, high proliferation potential | [32] [22] |

| Limitations | Standardization challenges | Donor-dependent variability, senescence | Ethical concerns, limited availability | [32] |

| Primary Applications | Enhanced tissue regeneration, corneal repair | Immunomodulation, wound healing, angiogenesis | Limited research due to ethical constraints | [31] [32] |

Experimental Evidence and Mechanistic Insights

ADSC-Exosomes in Wound Healing

A systematic review and meta-analysis of preclinical animal studies demonstrated that exosomes derived from human adipose-derived stem cells significantly improved wound closure rates compared to controls (Standardized Mean Difference [SMD] 1.42, 95% CI 1.14-1.71, P < 0.001). These exosomes also enhanced blood vessel density (SMD 1.59, 95% CI 1.01-2.18, P < 0.001) and regulated collagen deposition through temporal expression of fibrosis-related proteins—highly expressed during early wound healing but decreased during the remodeling phase. This automatic regulation of collagen deposition resulted in improved scar quality [26].

iPSC vs MSC-Exosomes in Corneal Healing

Direct comparative studies between iPSC and MSC-derived exosomes revealed significant functional differences. In vitro experiments using human corneal epithelial cells (HCECs) demonstrated that iPSC-exosomes achieved significantly better results in multiple parameters: migration area (83.03% vs 71.37% after 12 hours), apoptosis inhibition (7.03% vs 12.65%), and cell viability enhancement. The superior performance of iPSC-exosomes is attributed to their ability to upregulate cyclin A and CDK2, driving HCECs to enter the S phase from the G0/G1 phase more effectively than MSC-exosomes [31].

Culture Condition Impact on Bioactivity

The bioactivity of MSC-exosomes is significantly influenced by culture conditions. A comparative analysis of umbilical cord MSC-exosomes revealed that those derived from cells cultured in serum-free, chemically defined media (CDM) showed higher expression of regenerative cytokines and enhanced wound healing and angiogenic effects compared to exosomes isolated under serum-containing conditions. This suggests that standard starvation protocols used during exosome isolation may diminish therapeutic potential, highlighting the importance of culture conditions in determining exosome bioactivity [30].

Methodological Approaches in Source Comparison Studies

Exosome Isolation and Characterization

Standardized protocols for exosome isolation are critical for valid comparative studies. The most common isolation methods include:

- Ultracentrifugation: Considered the gold standard, involving sequential centrifugation steps at increasing speeds (300-2000g to remove cells, 10,000-20,000g for larger EVs, and 100,000g or higher for exosomes) [32]

- Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC): Separates exosomes based on size using porous beads, maintaining exosome integrity with reduced protein contamination [32]

- Tangential Flow Filtration (TFF): Often combined with SEC for large-scale production, offering scalability while preserving exosome integrity [32]

- Immunoaffinity Capture: Uses antibodies against specific exosome markers (CD9, CD63, CD81) for high specificity but lower yield [32]

Characterization typically involves nanoparticle tracking analysis for size distribution (30-150nm for exosomes), transmission electron microscopy for morphology, and Western blot analysis for surface markers (CD9, CD63, CD81) [31].

Functional Assays for Wound Healing

Key experimental approaches for evaluating exosome bioactivity include:

- In Vitro Wound Healing Assays: Scratch assays on monolayers of human corneal epithelial cells or keratinocytes, measuring migration area over time (6h, 12h, 24h) [31]

- Apoptosis Assays: Annexin V-FITC/propidium iodide staining to quantify apoptotic rates in target cells [31]

- Cell Viability/Proliferation: MTT or CCK-8 assays conducted at 24h, 48h, and 72h to assess proliferative effects [31]

- Angiogenesis Assays: Tube formation assays using human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) to quantify blood vessel density and formation [26] [30]

In Vivo Wound Models

Preclinical evaluation typically utilizes:

- Full-thickness excisional wounds (most common, 90.4% of studies) [5]

- Diabetic wound models (streptozotocin-induced for type 1 diabetes; db/db mice for type 2 diabetes) [5]

- Corneal epithelial defect models for ocular surface regeneration [31]

- Burn wounds, scleroderma, and photoaging models for specialized applications [5]

Signaling Pathways and Mechanistic Basis for Functional Differences

Mechanistic Basis of Source-Dependent Exosome Bioactivity

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Exosome Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Culture Media | Serum-free chemically defined media (CellCor CD MSC) | Maintains cell characteristics during exosome production | Avoids serum-derived exosome contamination [30] |

| Isolation Kits | Ultracentrifugation systems, Size exclusion columns, Precipitation kits | Exosome isolation and purification | Method choice affects yield, purity, and integrity [33] [32] |

| Characterization Antibodies | Anti-CD9, CD63, CD81, TSG101 | Exosome identification and quantification | Confirm presence of exosomal markers [31] |

| Cell Lines | Human corneal epithelial cells (HCECs), HUVECs | Functional wound healing assays | Standardized models for migration, proliferation, angiogenesis [31] |

| Animal Models | Mouse/rat diabetic models, Full-thickness wound models | Preclinical efficacy evaluation | Species selection affects translational relevance [5] |

The source of MSC-exosomes significantly influences their native bioactivity, with human ADSC-exosomes demonstrating robust effects on wound closure and angiogenesis, while iPSC-exosomes show superior performance in epithelial regeneration. These functional differences stem from distinct molecular cargoes that activate specific signaling pathways in recipient cells. For researchers developing exosome-based wound therapies, careful consideration of source selection, culture conditions, and isolation methods is paramount to achieving desired therapeutic outcomes. Future studies should focus on standardizing protocols and further elucidating the mechanistic basis of source-dependent bioactivity to advance the field of exosome-based regenerative medicine.

Isolation, Characterization, and Functional Testing in Wound Models

The selection of an appropriate isolation technique is a critical first step in the study of mesenchymal stem cell (MSC)-derived exosomes, directly influencing the yield, purity, and biological functionality of the isolated vesicles. This is particularly crucial in preclinical wound healing research, where the therapeutic efficacy of exosomes may be affected by both the isolation method and the source of the parent MSCs (human versus animal). No single isolation method is perfect; each presents a unique balance of yield, purity, processing time, and potential for vesicle damage [34] [35]. This guide provides an objective comparison of three predominant techniques—ultracentrifugation, size-exclusion chromatography (SEC), and precipitation-based kits—framed within the context of MSC-derived exosome research for skin regeneration and wound healing.

Methodological Protocols

A detailed understanding of each protocol is essential for reproducibility and for interpreting differences in experimental outcomes.

Ultracentrifugation (UC) Protocol

Ultracentrifugation is widely considered the historical "gold standard" for exosome isolation, separating particles based on their size, density, and centrifugal force [36] [35].

Detailed Workflow:

- Pre-clearing Steps: Cell culture supernatant or other biological fluid is first subjected to sequential centrifugation steps. An initial spin at 300–500 × g for 10 minutes removes live cells. This is followed by a second spin at 2,000–10,000 × g for 20–30 minutes to eliminate dead cells and large debris [35].

- Ultracentrifugation: The pre-cleared supernatant is transferred to ultracentrifuge tubes and subjected to high-speed centrifugation, typically at ≥100,000 × g for 70–120 minutes. This force pellets exosomes and other similarly sized extracellular vesicles [36] [24].

- Wash Step (Optional): The exosome pellet is resuspended in a large volume of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and subjected to a second ultracentrifugation step under the same conditions. This aims to remove contaminating soluble proteins [35].

- Resuspension: The final pellet is carefully resuspended in a small volume of PBS or a specific buffer for downstream applications.

Size-Exclusion Chromatography (SEC) Protocol

SEC separates exosomes from contaminants based on their hydrodynamic radius, with larger particles eluting before smaller soluble proteins [36].

Detailed Workflow:

- Sample Preparation: The sample (e.g., cell culture supernatant or pre-cleared seminal plasma) is concentrated if necessary and filtered through a 0.22 µm filter to remove large particles that could clog the column [36].

- Column Equilibration: A dedicated SEC column (e.g., qEV series) is equilibrated with a suitable buffer, typically PBS, as per manufacturer instructions.

- Sample Loading and Elution: The prepared sample is loaded onto the column. As the buffer passes through the porous polymer beads, exosomes, being too large to enter the pores, elute in the early fractions (void volume). Smaller contaminants, such as proteins and lipoproteins, are trapped in the pores and elute later [36]. A 2025 study on seminal exosomes used a qEV column to collect 13 fractions of 0.4 mL each, with the highest exosome concentration found in fractions 2 and 3 [36].

- Column Cleaning and Storage: After use, the column is cleaned with NaOH and stored in PBS with a preservative for repeated use [36].

Precipitation-Based Kit Protocol

These kits use a hydrophilic polymer (e.g., polyethylene glycol) to alter the solubility of exosomes, forcing them out of solution [37].

Detailed Workflow:

- Sample Pre-clearing: The sample is pre-cleared by centrifugation at 10,000–12,000 × g for 20–30 minutes to remove large vesicles and debris.

- Precipitation: The pre-cleared supernatant is mixed with the precipitation reagent at a specific volume-to-volume ratio and incubated for a defined period (e.g., overnight at 4°C) [37].

- Pellet Collection: The sample is centrifuged at a lower speed (e.g., 10,000 × g for 5–60 minutes) to pellet the precipitated exosomes.

- Resuspension: The supernatant is discarded, and the pellet is resuspended in a small buffer volume.

Comparative Performance Analysis

The following tables summarize experimental data comparing the yield, purity, and functional characteristics of exosomes isolated using these different methods.

Table 1: Biophysical and Yield Characteristics of Exosomes from Different Isolation Methods

| Isolation Method | Reported Yield | Particle Size (nm) | Key Advantages | Major Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ultracentrifugation (UC) | Lower yield; recovery can be as low as 30% after washing [35] | Can cause particle aggregation; may reduce average size [37] | Considered the historical gold standard; no reagent costs [36] | Time-consuming; requires expensive equipment; can damage exosomes [36] [35] |

| Size-Exclusion Chromatography (SEC) | High yield (88.47% reported for SE-FPLC) [38] | Uniform size, preserves physical properties [36] | High purity, effective removal of protein contaminants [38] | Requires specialized columns; sample volume may be limited |

| Precipitation Kit (TEI) | Greater exosomal yield and recovery compared to UC [37] | N/S | Rapid and simple protocol; no specialized equipment [37] | Co-precipitation of non-vesicular contaminants (e.g., proteins, polymers) [35] |

Table 2: Proteomic and Functional Purity in MSC Exosome Research

| Isolation Method | Proteomic Analysis Findings | Functional Purity & Contaminants |

|---|---|---|

| Ultracentrifugation (UC) | Identified 931 proteins from seminal plasma exosomes; 709 proteins in common with SEC [36] | Prone to co-precipitation of protein aggregates and non-exosomal vesicles [36] |

| Size-Exclusion Chromatography (SEC) | Identified 3315 proteins from seminal plasma exosomes; showed greater overlap with Vesiclepedia/ExoCarta top 100 lists than UC (91 vs. 77) [36] | Minimizes contamination of plasma proteins and lipoproteins; provides high-purity exosomes [36] [38] |

| Precipitation Kit (TEI) | N/S in provided results | Known to co-precipitate non-vesicular materials, which can interfere with downstream functional assays and characterization [35] |

Integration with MSC Source in Preclinical Wound Models

The choice of isolation method intersects critically with the central thesis of human versus animal-source MSCs in preclinical wound healing research. The source of MSCs significantly influences the therapeutic profile of the derived exosomes. A 2025 meta-analysis of 83 preclinical studies on wound healing found that adipose-derived stem cell (ADSC) exosomes demonstrated the best effect on wound closure rate, while bone marrow MSC (BMMSC) exosomes were more effective in revascularization [5].

Furthermore, the meta-analysis highlighted that the isolation method is a major source of heterogeneity in the field. Among the included studies, 72% used ultracentrifugation for isolating MSC-sEVs, while 23% used precipitation-based methods [5]. This methodological variability complicates the direct comparison of therapeutic efficacy between exosomes derived from different MSC sources. When isolating exosomes from a specific MSC source (e.g., human umbilical cord vs. mouse bone marrow), the selected method must ensure that the resulting vesicles retain their bioactive cargo (proteins, miRNAs) without contamination that could skew animal model responses. For instance, the higher protein yield and purity offered by SEC [36] might provide a more reliable vesicle preparation for attributing a specific wound healing effect (e.g., enhanced collagen deposition) to the human ADSC exosomes themselves, rather than to co-isolated contaminants.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Selecting the right tools is fundamental for successful exosome isolation and characterization. The table below details essential reagents and their functions, with a focus on cited experimental protocols.

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Kits for Exosome Isolation and Analysis

| Reagent/Kit Name | Primary Function | Experimental Context from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| qEV Size Exclusion Columns (e.g., Gen 2-35 nm) | Isolation of exosomes with high purity and preserved physical properties. | Used for seminal exosome isolation, yielding fractions with high exosome concentration and superior proteomic profiles [36]. |

| Total Exosome Isolation (TEI) Reagent | Polymer-based precipitation of exosomes from serum and other biofluids. | Compared against UC, demonstrating greater yield, recovery, and purity of serum-derived exosomes [37]. |

| Phosphate-Buffered Saline (PBS) | Buffer for column equilibration (SEC), sample dilution, and exosome resuspension. | Used for equilibrating qEV columns and as elution buffer [36]. |

| Protease Inhibitor Cocktail | Prevents proteolytic degradation of exosomal proteins during isolation and lysis. | Added to RIPA buffer during lysis of exosome pellets for subsequent Western blot analysis [36]. |

| RIPA Buffer | Lyses exosomes to extract internal protein cargo for downstream analysis (e.g., Western blot, proteomics). | Used to lyse exosome pellets for protein quantification and Western blotting [36]. |

| Primary Antibodies (ALIX, CD63, CD81) | Detection of exosome-specific marker proteins for characterization by Western blot. | ALIX (1:5000) and CD63 (1:1000) used to confirm presence of exosomes in SEC fractions [36]. |

| Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit | Quantifies total protein concentration in exosome lysates. | Used to determine protein concentration of exosome lysates post-isolation [36]. |

The choice between ultracentrifugation, size-exclusion chromatography, and precipitation kits involves a clear trade-off. Ultracentrifugation, while traditional, is prone to lower yields and potential vesicle damage. Precipitation kits offer simplicity and high yield but at the cost of significant contamination. Size-exclusion chromatography emerges as a robust alternative, providing an excellent balance of high yield, superior purity, and preserved vesicle integrity, as evidenced by richer proteomic profiles [36] [38].

For researchers investigating the nuanced differences between human and animal MSC exosomes in wound healing, where accurately attributing therapeutic effects to the vesicle cargo is paramount, methods that prioritize purity and biomolecular integrity (such as SEC) are highly recommended. The ongoing lack of standardization in isolation methods across the field [5] remains a key challenge, underscoring the need for researchers to carefully select and report their isolation techniques to ensure reproducible and translatable preclinical findings.

The field of regenerative medicine is increasingly focusing on mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes (MSC-exos) as a potent, cell-free therapeutic alternative for wound healing. The translational potential of these nanoscale vesicles, particularly in preclinical wound models, hinges on their precise and standardized characterization. This process is vital for correlating the physical and molecular attributes of exosomes with their observed therapeutic efficacy. Such characterization becomes even more critical when comparing exosomes from different biological sources, such as human versus animal MSCs, as inherent differences can significantly influence their regenerative properties. For instance, a recent meta-analysis of preclinical studies highlighted that MSC source is a key variable, with adipose-derived MSCs (ADSCs) showing the best effect on wound closure rate, while bone marrow MSCs (BMMSCs) were superior in revascularization [5]. This guide objectively compares the standard characterization triad—Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis (NTA), Western Blot, and Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM)—in the specific context of qualifying human and animal MSC-exos for wound healing research, providing structured data and methodologies to support robust experimental design.

Core Characterization Techniques: Principles and Comparative Analysis

The minimal criteria for defining extracellular vesicles, including exosomes, mandate the use of complementary techniques to assess particle concentration/size, specific protein markers, and morphological characteristics [22]. The following sections and comparative tables detail the application of these techniques.

Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis (NTA)

Principle: NTA leverages the properties of Brownian motion and light scattering to determine the size distribution and concentration of particles in a liquid suspension. A laser beam passes through the sample, and the light scattered by individual particles is captured by a microscope camera. Software tracks the movement of each particle, and the hydrodynamic diameter is calculated using the Stokes-Einstein equation [39].

Typical Protocol:

- Isolated exosome samples are appropriately diluted in sterile, particle-free PBS to achieve an ideal concentration for counting (typically 20-100 particles per frame).

- The sample is loaded into the sample chamber of the NTA instrument.

- Multiple short videos (e.g., 30-60 seconds each) are recorded of the particles moving under Brownian motion.

- The software analyzes the videos to track each particle and calculate its size, generating a size distribution profile and an estimate of particle concentration.

Comparative Data: Human vs. Animal MSC-Exosomes

| Sample Source | Typical Size Range (nm) | Concentration Range (particles/mL) | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Human MSC-Exosomes (from plasma) [39] | 50 - 150 nm (Average: ~75-80 nm) | ~5 × 10⁹ to 1.5 × 10¹⁰ | Lower immunogenicity risk for therapeutic development; size is consistent with exosome definition. |

| Animal MSC-Exosomes (e.g., from rat models) [40] | Information not explicitly provided in search results; generally assumed to be 30-150 nm. | Information not explicitly provided in search results. | Enables controlled preclinical studies in syngeneic models; inter-species differences may exist. |

Western Blot (Protein Marker Analysis)

Principle: Western Blot is an immunoassay used to detect specific protein antigens within a complex mixture. Proteins separated by gel electrophoresis are transferred to a membrane and probed with antibodies against exosome-enriched marker proteins. Positive detection confirms the presence of the vesicular fraction characteristic of exosomes [41].

Typical Protocol:

- Lysis: Exosome samples are lysed using RIPA buffer containing protease inhibitors.

- Electrophoresis: Proteins are separated by molecular weight using SDS-PAGE.

- Transfer: Proteins are electrophoretically transferred from the gel to a PVDF or nitrocellulose membrane.

- Blocking: The membrane is blocked with 5% BSA or non-fat milk to prevent non-specific antibody binding.

- Incubation: The membrane is incubated with primary antibodies (e.g., anti-CD63, anti-CD81, anti-TSG101) overnight at 4°C, followed by incubation with an enzyme-conjugated secondary antibody.

- Detection: Signal is developed using chemiluminescent substrates and imaged.

Comparative Data: Human vs. Animal MSC-Exosomes